|

|

Alan Allbon’s Early FRV Models

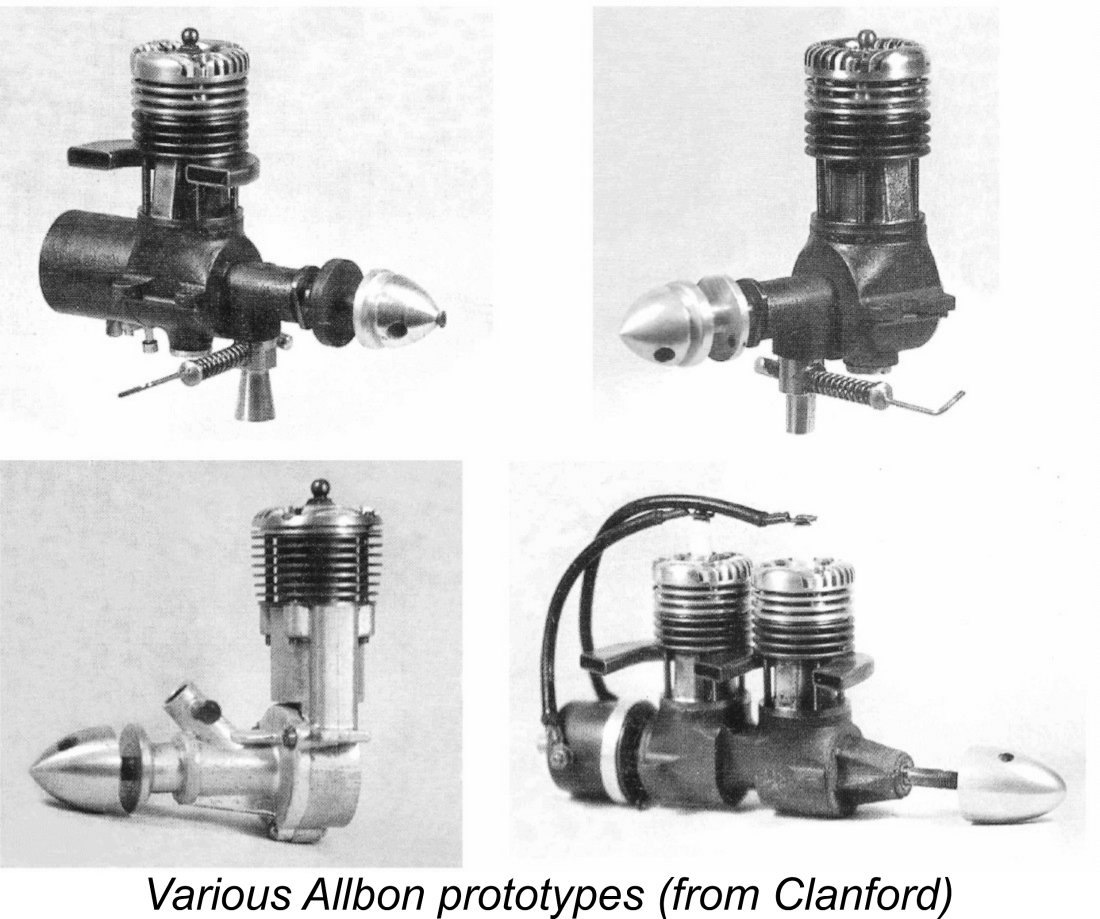

Included in that story was the 1949 arrival of Dennis Allen at Allbon Engineering to assist Alan Allbon in the production and further development of his range. Allen's arrival appears to have coincided with (or perhaps triggered) a period of intensive development at Allbon Engineering. Apart from the ongoing development of the 2.8, a number of other projects were being pursued in addition. For example, the Allbon 2.8 was included in the table of British diesels which formed an appendix to Ron Warring's early 1949 book "Miniature Aero Motors". Most interestingly, there was also an entry for a diesel called the Allbon 3.5! Bore and stroke of this engine were given as 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) and 0.7375 in. (18.73 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.226 cuin. (3.70 cc). The bore and stroke figures prove that this was not simply a bored-out 2.8, since both There's no doubt that prototypes of other potential new models were completed during Allbon's independent period prior to his joining Davies-Charlton in 1952 (see below). Examples exist of such rarities as a 10 cc spark ignition twin, several progressively more refined variants of a 5 cc glow-plug model and a 2.5 cc diesel. None of these ever saw production either - Allbon and Allen were evidently merely exploring the possibilities. Some of these prototypes might have entered production if other factors had not intervened - see below. However, several designs which had their genesis during this period undoubtedly did make a considerable impact upon the market. The limited production capacity of Allbon’s modest premises at Sunbury-on-Thames forced him to make some hard choices, evidently causing him to decide at some point in mid 1949 that the old 2.8 had no future. That design looked very much to the past, while Allbon now had his eyes very much focused on the road ahead, no doubt encouraged in this by Dennis Allen. The consequence was Allbon's decision to give up on the 2.8. Let’s commence our look at where he went from there………… Alan Allbon Looks to the Future By August 1949 the old 2.8 diesel had disappeared from Allbon's advertising, being supplanted by the then-new Allbon Arrow 1.5 cc glow-plug model, of which much more below. The final listing of the 2.8 by its distributor Henry J. Nicholls appeared in Nicholl's advertising placement in the December 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The clear implication is that production of that model had ceased prior to that time, leaving Nicholls with no further stock to supply to his customers as 1950 approached. However, it seems that he had previously distributed a number of examples to other retailers, since (presumably) New Old Stock examples of the Allbon 2.8 continued to be offered by Ripmax as late as November 1951.

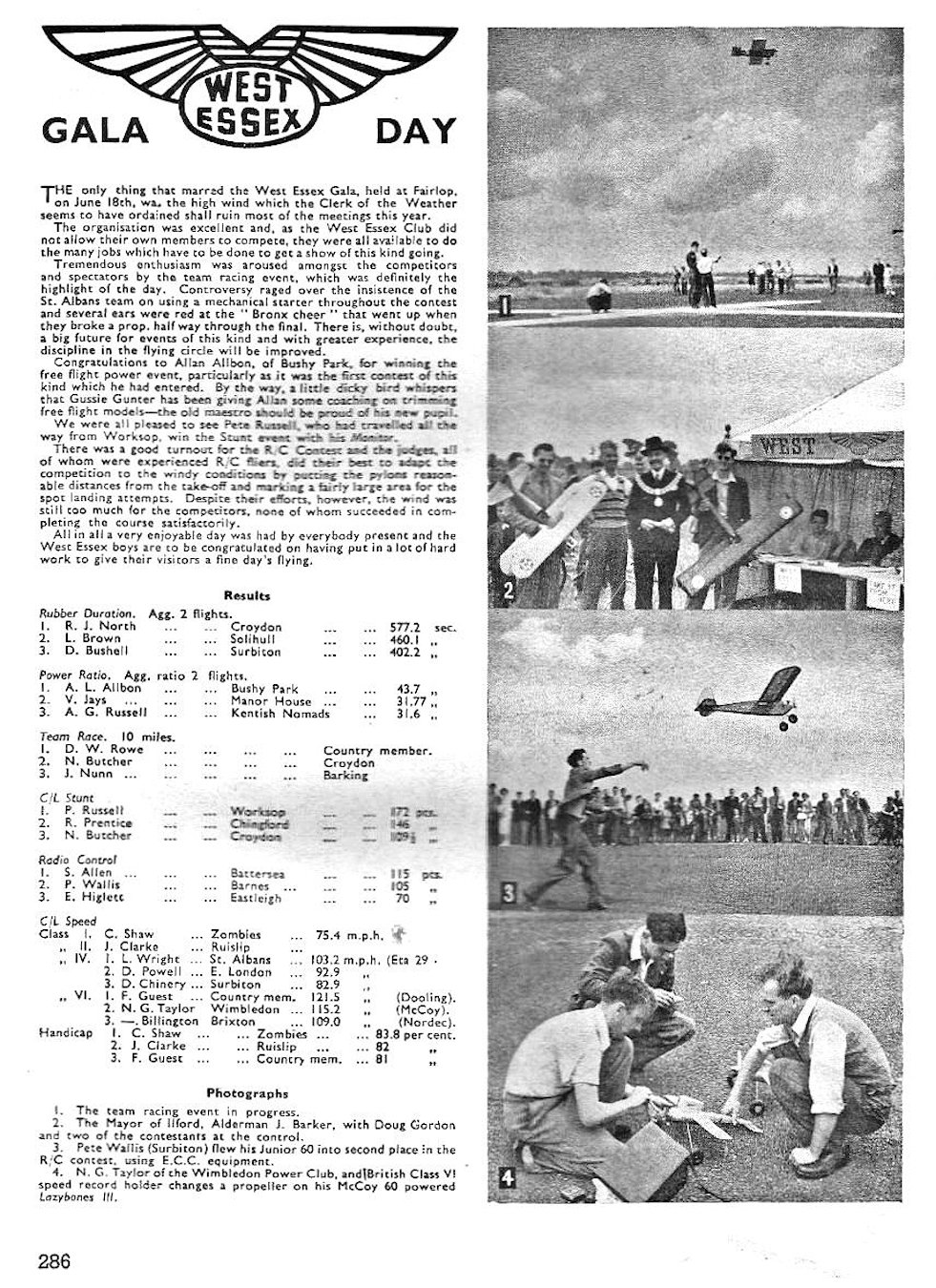

As an aside, it should be mentioned that Allbon evidently maintained an active involvement with aeromodelling throughout the period just described. Some evidence of this is to be found in the attached results of the 1950 West Essex Gala, held at Fairlop Aerodrome on June 18th, 1950. At that contest, one Alan L. Allbon is listed as having won the free flight power event. Greatly to his credit, this was apparently the first major free flight power event which he had entered, following some coaching on trimming by the well-known veteran competitor “Gussie” Gunter. This does not appear to have been a one-off, since Allbon was identified as a member of the Bushy Park club, which flew regularly at the Royal Park of that name adjacent to Hampton Court, a little to the east of Sunbury-on-Thames. Try that today.............!! Regardless, Allbon’s active membership in his local club certainly implies an ongoing hands-on involvement with aeromodelling. Now let’s look at the next chapter of the Allbon model engine saga. This took the form of a bold move into a new form of ignition. A False Start - the Allbon Arrow

By mid 1948, increasing attention was being paid to the potential of the glow-plug motor both by modellers and manufacturers in Britain. The manufacture of miniature glow-plugs in Britain began quite early on - KeilKraft glow-plugs were being advertised by February 1948. The long-established firm of Smith's Motor Accessories Ltd. soon joined the fun by having their subsidiary K.L.G. Sparking Plugs Ltd. commence production of the famous "Miniglow" plugs in various sizes. Nordec created quite a stir in August 1948 with the RG10 glow-plug version of their McCoy-influenced 10 cc racing engine, with Rowell quickly following suit. But perhaps the greatest early boost to the glow-plug cause in Britain came with the mid 1948 release of the FROG 160 glow-plug version of International Model Aircraft's (IMA's) well-established FROG 175 sparker. This neat little unit proved extremely popular right out of the starting gate. Not to be left out, Davies-Charlton offered a glow-plug conversion kit for their 5 cc Wildcat diesel, while Edward Reeves followed suit by supplying a glow-plug conversion kit with his 3.4 cc diesel model.

The result was the August 1949 appearance of Allbon's second design to see commercial production, the 1.49 cc Arrow glow-plug motor. The first advertisement for this engine that I can find appeared in the October 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller” (which actually hit the news-stands in mid September), implying that the first examples must have been in existence by August of that year.

It's also interesting to note in passing that while earlier Allbon advertisements relating to the 2.8 had been placed directly by Allbon Engineering, mentioning Mercury as the "sole distributor", the Arrow was first announced by Mercury Models, as were a number of subsequent Allbon models. The close relationship between Alan Allbon and Henry J. Nicholls was evidently continuing, no doubt reinforced by the involvement of Dennis Allen. Although the design of the Arrow must be credited to Alan Allbon given the fact that he owned the company and thus had the final say on design matters, there can be no doubt that Dennis Allen had a lot to do with the development of this and subsequent early Allbon models. The Arrow was apparently intended primarily for control-line speed This marked the beginning of a trend towards more tightly-regulated competition engine displacement limits which spelled the end of the various "odd-ball" displacements like that of the Allbon 2.8 which had previously been very common. The S.M.A.E.’s later adoption of the 1.5 cc displacement limit for the British ½A competition category consolidated this change, making the 1.5 cc displacement category a very important one in the context of the British model engine market.

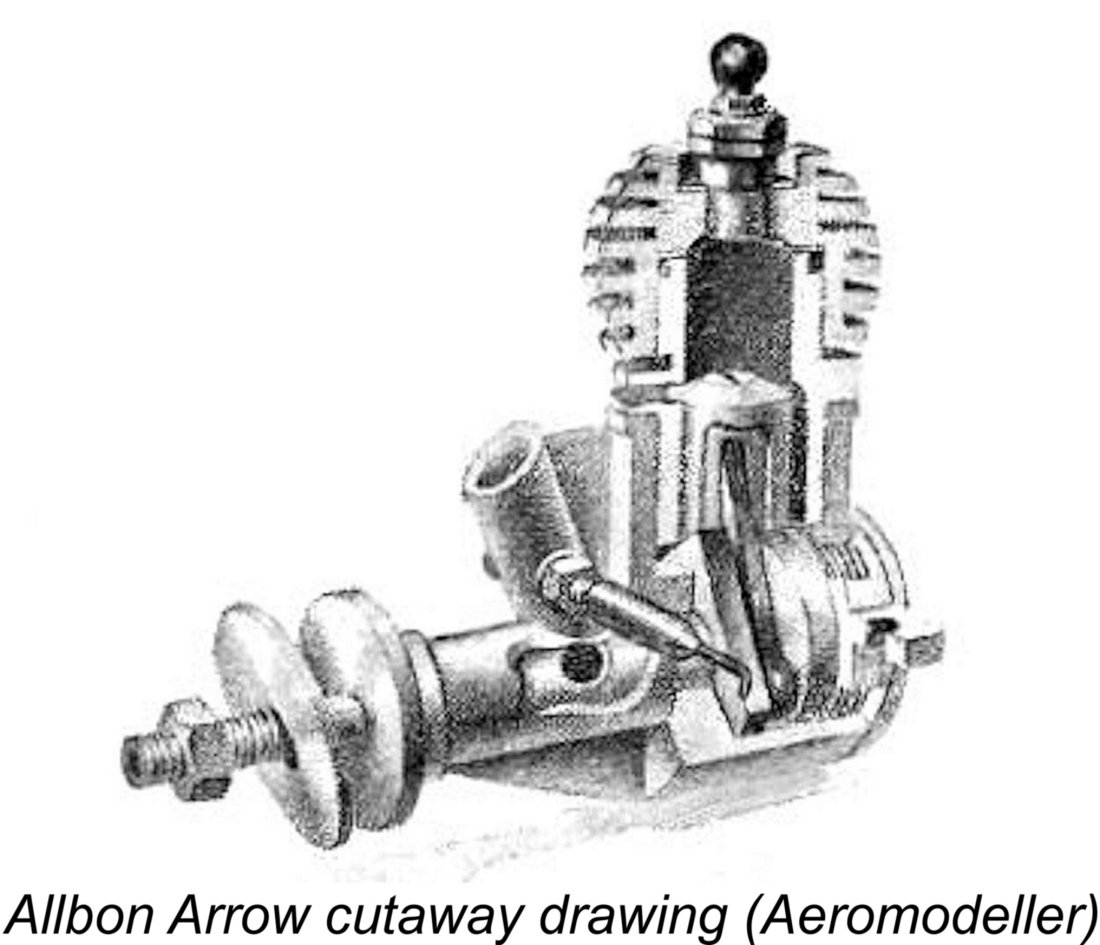

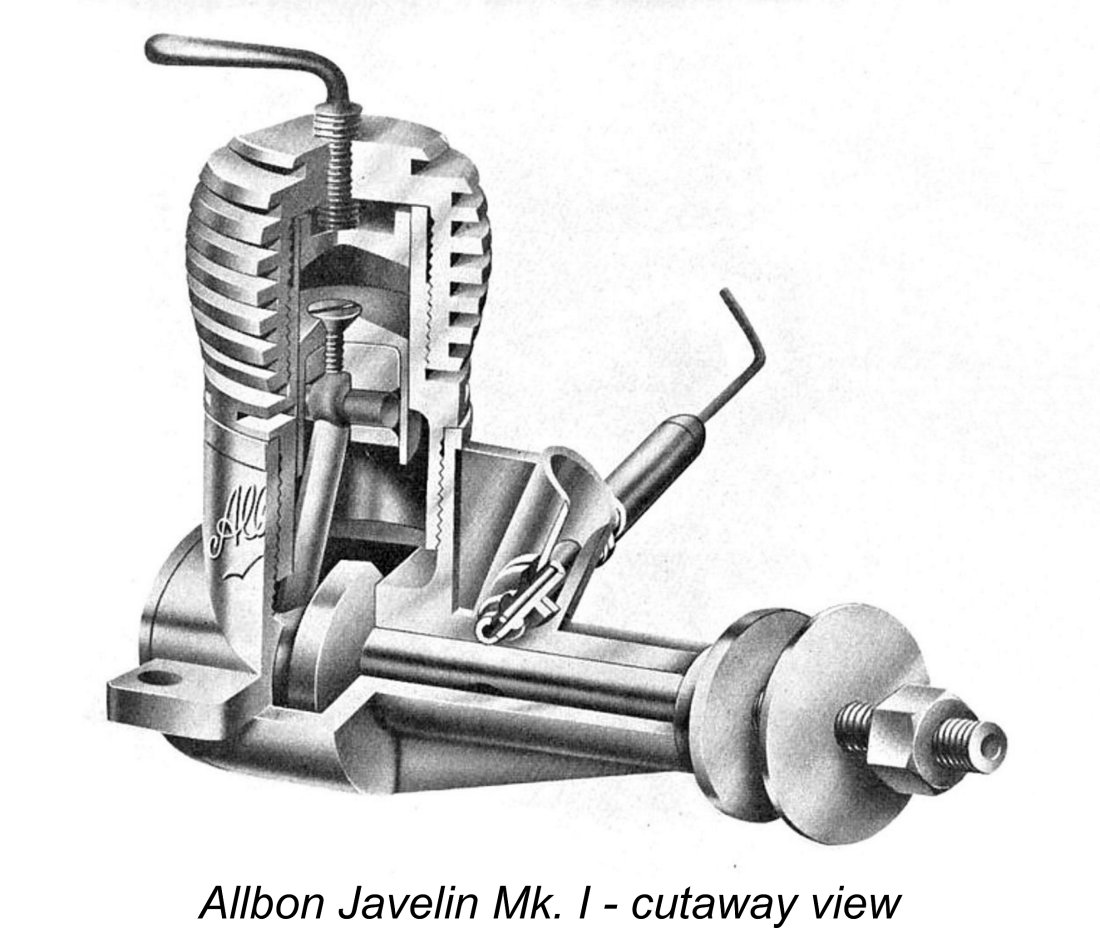

The construction of the Arrow was about as simple as one could get and still end up with an operable engine. The construction was based entirely upon screw-in assembly, no fasteners being used at any point other than to secure the spraybar, mount the prop and fasten the piston/rod assembly. As a result, the Arrow used only 18 separate components, including the glow-plug and all prop and needle valve fasteners as well as the head gasket. Of these, only 12 items had The Arrow was basically a completely conventional plain bearing radial-ported FRV motor built very much in accordance with the emerging "British style" which had been pioneered in the USA by Arden and first adopted in Britain by Aerol Engineering with their very successful Aerol and Elfin designs. The only major departure from established British practise was the use of glow-plug ignition in place of the more usual compression ignition. As such, there seems to be little need to enter into a detailed description here - the images tell the story. That having been said, a few points are worth noting. One design feature of the old 2.8 that was carried over to the Arrow was the use of an aluminium alloy yoke for the steel gudgeon pin and forged alloy conrod which was secured inside the piston with a countersunk screw through the piston crown. As I noted in connection with the 2.8, the potential for problems with this screw becoming loose during operation was obvious.

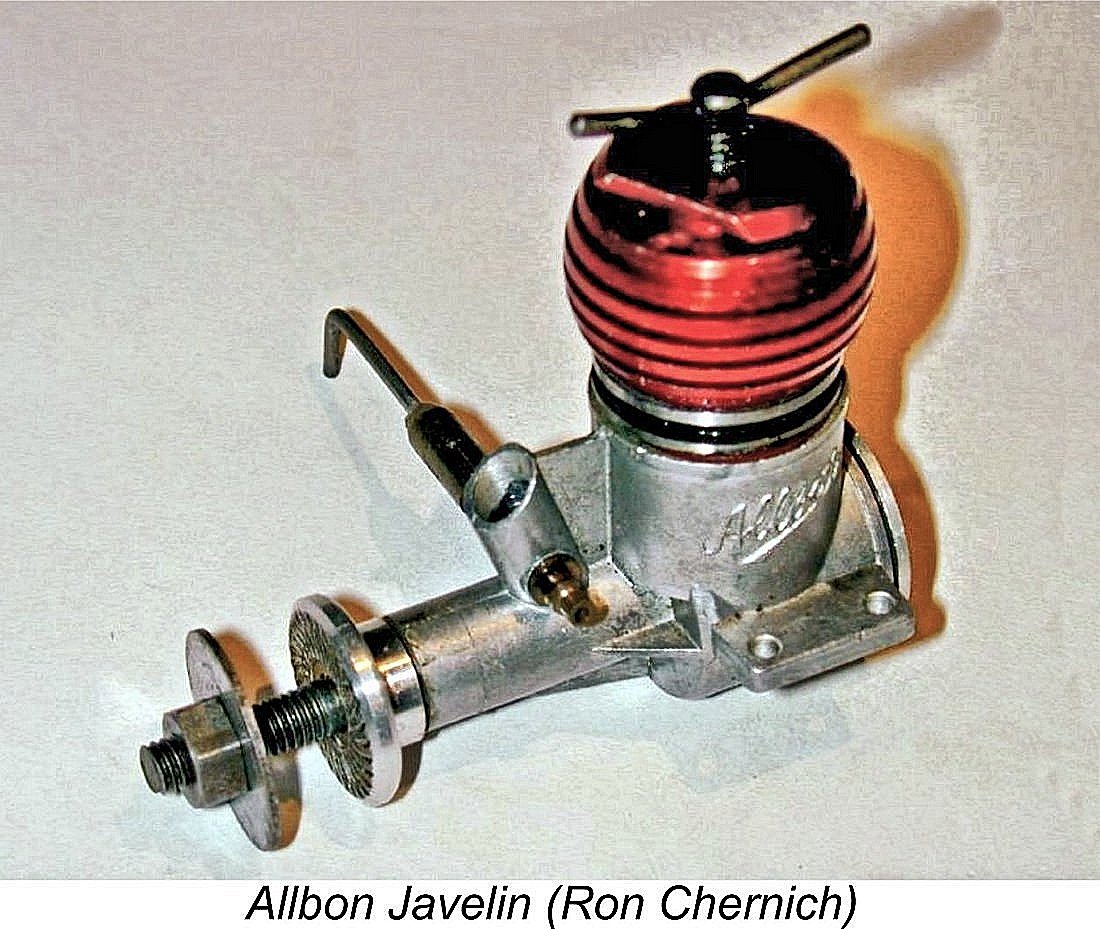

The head seal was provided by a soft copper washer which served as a gasket. Herein lay another of the engine's Achilles heels - it was necessary to tighten the jacket quite forcefully to maintain a seal and prevent the jacket from unscrewing during running. When this was done, the wedging effect of the screw threads acting directly upon the cylinder liner tended to pinch the bore near the top of the stroke, resulting in an excessively tight spot at that point. Otherwise, the engine's construction was completely conventional, right down to the forged alloy conrod, screw-in backplate and one-piece steel shaft running directly in the material of the crankcase casting. The early crankcase castings featured only a single stiffening web on the bottom of the main bearing housing, but later variants sported two additional webs, one on each side. This change was probably introduced to improve the strength of the casting following experience with the Arrow-based diesel Javelin Mk. I (see below), the early examples of which also had only the single web.

The main problem with the Arrow was pretty fundamental, namely a marked lack of performance, at least on the straight fuel then in general use in Britain. It must be recalled that even in mid 1949 the use of glow-plug ignition was still relatively new both to British modellers and manufacturers, the result being that most British manufacturers fell into the trap of creating their glow-plug models by simply converting their existing diesel models to glow-plug operation or by applying standard diesel design practises to glow-plug ignition. The Arrow is a classic example of the latter approach.

Nevertheless, the Arrow was undoubtedly different! Its very light weight, compact dimensions and handsome appearance coupled with the solid reputation which Allbon had established with the 2.8 led a good few modellers to give it a try, at least initially. Moreover, our old mate Lawrence Sparey was sufficiently intrigued to put it through a test. The resulting report appeared in the January 1950 issue of “Aeromodeller”, only five months or so after the engine's initial marketplace entry. Unfortunately, Sparey's test report probably did as much as anything else to doom the poor old Arrow. For one thing, he encountered both of the issues noted during our earlier description of the engine. The screw which retained the gudgeon pin carrier inside the piston came loose, fortunately without doing any lasting damage. In addition, it was found impossible to keep the head sufficiently tight to maintain a seal without excessive tightening, as a result of which the bore was badly pinched at the top of the stroke during the test. As if this wasn’t enough bad news, the blue anodizing on the cooling jacket was found to resist the passage of electrical current, creating difficulties in getting the plug to light up for starting. The obvious cure was to scrape the anodizing off the plug seating area.

There's little doubt that Sparey was quite right about the negative effect of the tight pinch at the top of the stroke. Had this tight spot not been present, there seems to be no question that he would have been able to report a somewhat more encouraging set of figures than the very lacklustre 0.051 BHP @ 11,500 rpm that was actually recorded. A healthy dose of nitromethane would doubtless have helped too, but that additive was almost unobtainable in Britain at the time as well as being prohibitively expensive even if a source could be found. On the bright side, and doubtless wishing to find something positive to say, Sparey reported that the Arrow was "the most easy starting engine I have ever handled". Needle response was characterized as "exceptional". While these are doubtless valid points, they do appear to represent a case of Sparey trying to repair the damage by praising the engine with faint damns ................ No doubt in large part due to this doubtless fair but inescapably negative report, the Arrow failed to make much of a long-term impression upon the market. It continued to be listed in Allbon advertisements into 1951 at the same price of £2 15s 0d (£2.75) but faded away very quietly during that year, after which no more was heard of it. Clean original examples are relatively uncommon today. The Allbon Arrow Re-Evaluated Don't ever let anyone tell you that lightning never strikes twice! At around the same time as the original publication of this article on MEN in 2012, not only did the example of the Allbon 2.8 “Mk. 1.5” reviewed in the companion article drop into my lap, but I also acquired the previously-illustrated example of the Allbon Arrow - my first ever! This engine was in far from pristine condition, having clearly seen a lot of hard service, during the course of which it had suffered from some owner abuse. However, it remained in excellent mechanical condition. It was also completely original, even including a K.L.G. Miniglow plug in working order! It is one of the later examples with the two extra stiffening webs at the sides of the main bearing housing.

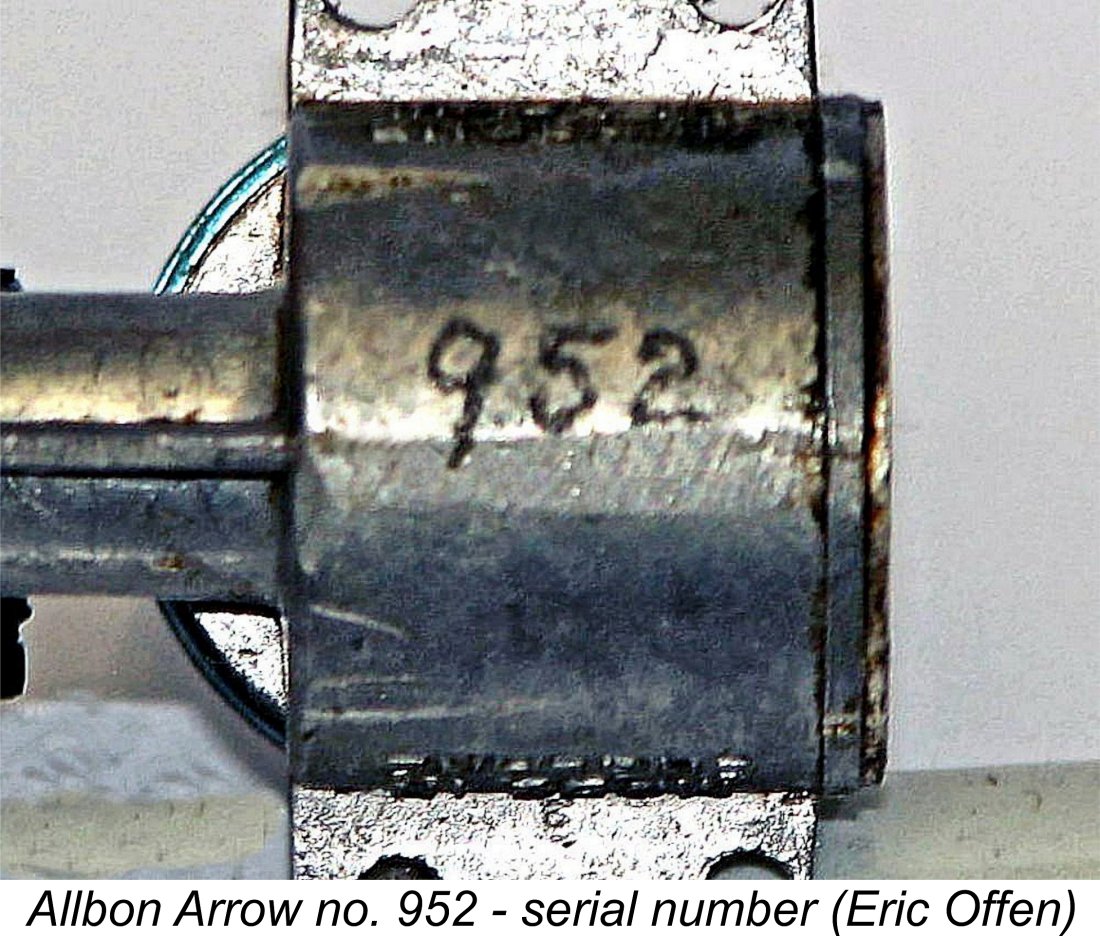

A problem arising from this finding is that we can no longer rely upon serial numbers for an accurate estimate of production figures for the Arrow. Serial number evidence attests to the production of at least 2130 numbered examples of the engine, to which we now have to add an unknown number of engines which were not engraved. All indications continue to be that the number of Arrows produced in total was not large by industry standards, but we’d need a far larger sample to establish a persuasive figure. This includes reports of non-engraved examples so that we can form an estimate of the relative occurrence of numbered and un-numbered engines. So far, it’s running 3 to 1 for the numbered examples. All additional contributions welcome .........

All of this naturally opened the door to a present day test of an example of the Arrow which is free from the issues which evidently held Sparey's example in check. No sooner envisioned than done! My new acquisition went into the test stand for a few runs on some appropriate airscrews. I used an oily castor-based fuel containing 10% nitromethane - probably a fairly typical "hot" brew in 1950 Britain where nitro was both hard to get and prohibitively expensive when you could find it. I also used a different plug, wishing to preserve the engine's original K.L.G. Miniglow plug in good working order. As noted by Sparey, the Arrow was a doddle to handle. It needed a fairly hefty prime, but once that was given it gave no trouble at all - a few lazy flicks and it was away, every time. Needle settings were easily found, and the engine ran very smoothly, particularly at the higher speeds. The dreaded unscrewing problem with the piston assembly didn’t rear its ugly head at any time. The results achieved were as follows:

Frankly, although it does represent a modest improvement over the figures obtained by Sparey, this is still a pretty dismal performance for a 1.5 cc engine, even by 1949 standards. The engine clearly develops little in the way of torque, requiring a very small prop to deliver its best output. In fact, running qualities improve noticeably as speed goes up. The implied output of around 0.061 BHP in the general vicinity of 11,400 rpm is little more than what one would expect from a sports engine of around half the displacement, even in 1949. That said, the output is actually not too bad for a 1949 engine weighing only 63 gm. Just for fun, I tried the effect of running the Arrow on the same suite of test props using a fuel containing 30% nitro. Quite a difference, as the following figures demonstrate:

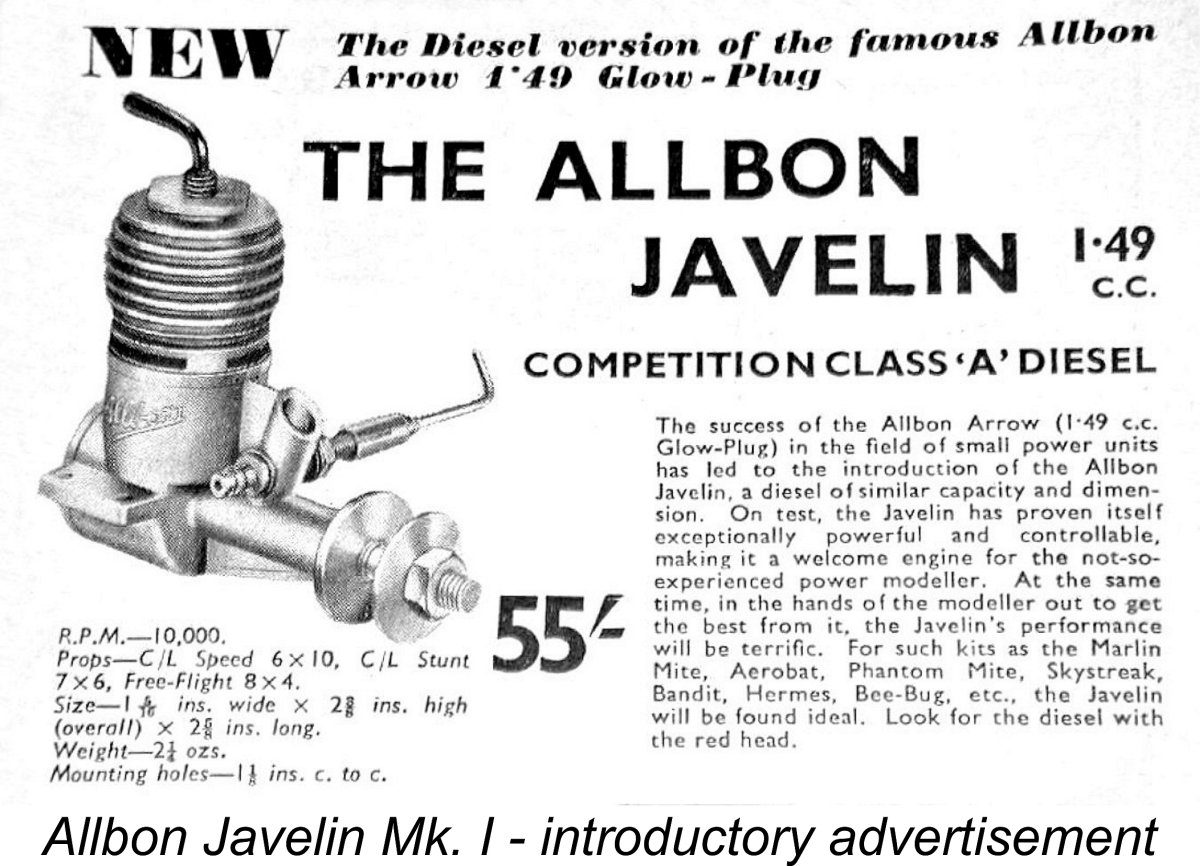

This is certainly more promising, since it implies a peak output of somewhere near 0.082 BHP at around 12,100 rpm. However, these figures still fall considerably short of those which were later to be reported for the soon-to-appear diesel version of the Arrow - the famous Javelin Mk. I to be discussed in the following section. Moreover, there could have been few modellers in Britain at this time who could even contemplate running this amount of nitro. The stuff was near impossible to get and prohibitively expensive when it could be found. All in all, while the Arrow wasn't quite as bad as Sparey's test suggested, it remains hard to see the engine as anything other than a failure in performance terms. A 2013 communication with the late Gordon Cornell of E.D. and Dynamic fame reinforced this impression. Gordon recalled that he and a few of his fellow Croydon Model Aero Club members tried the Arrow but quickly gave up on it after they discovered that as far as they were concerned, it didn't deliver enough power to fly a control-line model satisfactorily! Reputations like that travelled fast, even in the days before email and the Internet ……... All of this having been said, the old speed tuner that still lurks within me can see a number of easily-applied modifications which would undoubtedy improve performance very substantially. I have little doubt that a skilfully-tuned example would pull a "Midge" around at a fair turn of speed by 1950 standards. Perhaps there were a few capable tuners back then .......... Comeback: The Allbon Javelin Mk I The Allbon story up to this point in time had been one of qualified success with the Allbon 2.8 followed by what can really only be regarded as a failure with the Arrow. Even before Sparey's unflattering report appeared, the word regarding the Arrow's performance shortcomings was already going the rounds. Unless something was done very quickly, the Arrow setback could have had very negative consequences in terms of the ongoing position of the Allbon range in the marketplace. Fortunately, Alan Allbon was not the man to waste time worrying about setbacks which lay in the past and hence could not be undone - rather, his approach was to take immediate action to move things forward and get the Allbon marque back on track. Even before Sparey's not unjustified criticisms of the Arrow were published in January 1950, he had clearly recognised the engine’s deficiencies. What to do? The obvious answer was - come up immediately with a new product that would perform at a level which would cause the modelling public to forget about the shortcomings of the Arrow very quickly! The main challenge inherent in the above concept was the word "immediately" - only fast and effective action would re-establish Allbon's tarnished credentials. The quickest way to develop a new model and get it into production was undoubtedly to take an existing model for which tooling was already in place and rework it into the product that was required. Fortuitously enough, a potentially-suitable existing model was ready to hand - the Arrow! It hadn't worked out as well as expected in glow-plug form - how would it perform if converted to compression ignition? The conversion would be very simple indeed - just make the cylinder a little taller to accommodate a contra-piston, add a new cooling jacket with a comp screw, and there you are! All of the other components were already in the Arrow production program, thus requiring no additional tooling. A side benefit arising from this conversion would be that the head-sealing and cylinder distortion issues with the Arrow would be completely eliminated.

The Javelin seems to have entered production in December 1949, only some 4 months after the Arrow, since the first advertisement for the new model took the form of an insert in the full-page Mercury Models placement in the February 1950 issue of “Aeromodeller” which hit the stands in mid-January. Mercury Models' action in stepping in to advertise the new Allbon model directly may perhaps represent an effort to shore up the new product given the negative aura then surrounding the Arrow and its manufacturer. If so, the The Javelin has been covered in an earlier article on the “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. However, a few descriptive points are included here for convenience. Apart from the necessary revisions to the upper cylinder and cooling jacket (which was anodized red), the Javelin was identical to the Arrow. Continued use was made of an aluminium alloy yoke for the conrod small end which was secured inside the piston with a countersunk screw. The Javelin also retained the same bore and stroke measurements. The only measurable change was a slight increase in weight from 2.2 ounces (63 gm) to 2.4 ounces (68 gm), due no doubt to the taller cylinder with its contra-piston. Accordingly, the introduction of the Javelin required only very minor amendments to the established production schedule. The two models shared everything but the cylinders and cooling jackets (with contra piston and comp screw), meaning that very few additional components had to be added to the production program. Even the cylinders differed only in the length of their upper portions - the same tooling could be used to form the porting and cut the threads. This allowed Allbon to get the Javelin onto the market very quickly indeed, more or less coincidentally with the public appearance of Lawrence Sparey's less-than-stellar report on the Arrow.

Sparey was careful not to mention the Arrow in his report on the Javelin! The tone of the new test was as different as it could have been from the earlier effort - the engine received the very highest marks in all respects. After commenting at some length upon the ever-improving power-to-weight ratio being achieved by the latest smaller-displacement model engine designs, Sparey went on to praise the way in which the Javelin withstood the fairly arduous conditions to which it was subjected during the test, clearly implying that its structural design was well up to the task. He characterized the engine as "exceptionally flexible for one of this type" and stated that starting was "excellent under all conditions". The engine was reported as running "well and evenly at all speeds from 5,000 to 14,000 rpm" and was said to have "performed well throughout (the) tests", with particularly steady running at the higher end of the speed range. A peak output of 0.99 BHP was found at 12,000 rpm, which Sparey clearly considered to be exceptional for an engine of this displacement. Perhaps it was by 1950 standards ………….overall, this test represented a complete vindication of Allbon's design approach following the set-back with the Arrow.

Despite this issue, Chinn actually recorded a slightly higher peak output than Sparey, albeit at significantly lower revs, measuring a peak of 0.105 BHP @ 10,000 rpm. It appears that Chinn's example out-torqued that tested by Sparey by a considerable margin. Chinn summarized his findings by stating that the Javelin was "one of the most powerful of 1.5 cc class engines currently available", commenting also upon its exceptional power-to-weight ratio. He felt that the engine should be "a popular choice for all types of small high-performance power models".

The restoration of the Allbon reputation seems to have encouraged Alan Allbon and Dennis Allen to begin looking ahead once more to the further expansion of the range. Gordon Cornell recalled that George Fletcher, future International Model Aircraft (IMA) designer of the FROG range, joined the venture at around this point to assist in the achievement of the increased production requirements which were triggered by the success of the Javelin and its Dart successor. Quite an array of talent under one roof! Turning Point: The Allbon Dart Up to the point which we have now reached, Allbon Engineering had remained a small company, still operating from rather confined premises at 51a Thames Street in Sunbury-on-Thames. It appears that the scale of their manufacturing facilities limited the company's ability to meet the growing demand for their products. This situation was about to be further exacerbated by the introduction of their next new design .............. As of mid 1950, the smallest displacement category which was generally viewed by British manufacturers as being worth pursuing commercially was 1 cc or a little less. The Mills .75 was selling like hot cakes, but it was the smallest-displacement model engine that remained widely available in Britain at the time. It was also a rather "old-fashioned" sideport design, which limited its ultimate performance.

A major reason for the failure of the early sub-miniatures to maintain a foothold in the marketplace was the fact that their relatively modest power outputs limited their applicability to small sport free-flight models. For the most part they seem to have been viewed quite legitimately as substitutes for rubber power in small free flight models. Control-line was all the rage as Britain entered the 1950's, and none of the earlier sub-miniatures were really suitable for that application. It appears to have occurred to Alan Allbon in early to mid-1950 that this opened up a potential market niche which remained untapped. If a miniature engine having sufficient power to fly a small control-line model could be developed, the market prospects would almost certainly be very bright indeed!

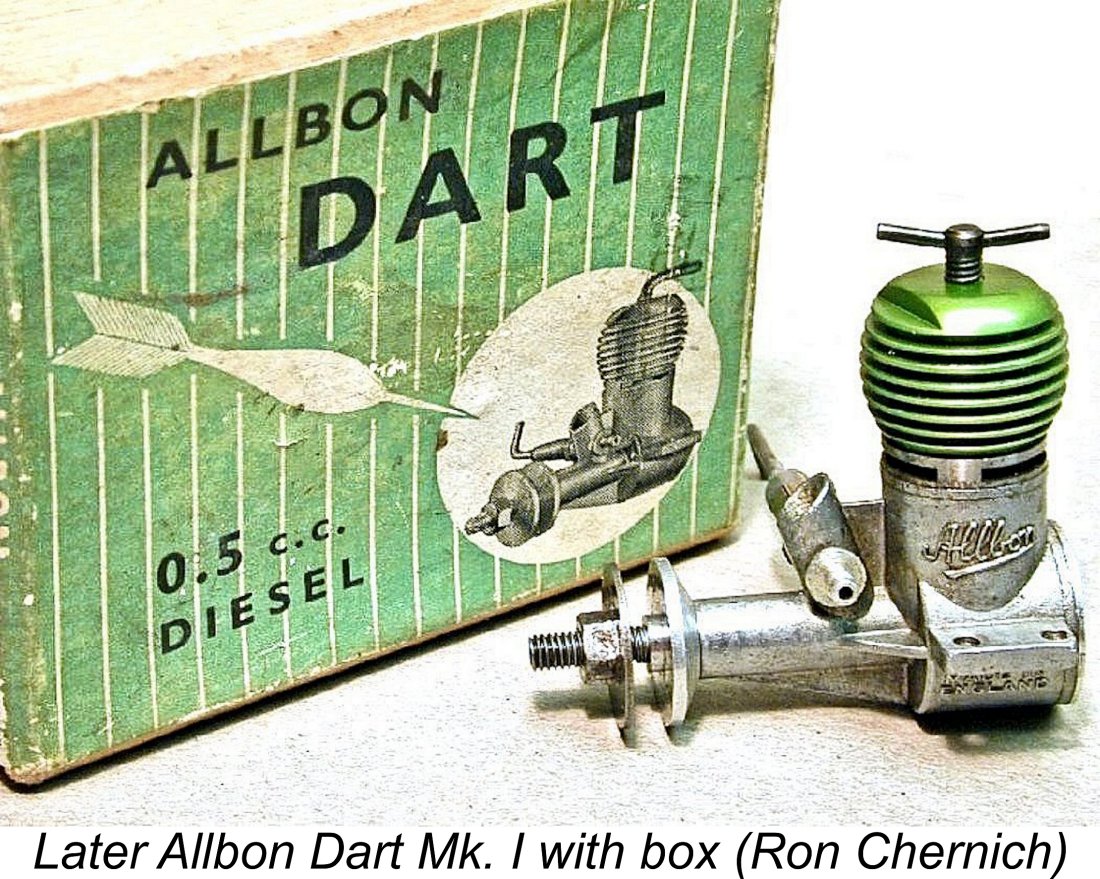

With the assistance of Dennis Allen and George Fletcher, such a model was soon developed. In-house tests showed that it did indeed deliver a level of performance that vastly exceeded that of any previous miniature diesel. Accordingly, the decision was quickly made to proceed to the production stage, the result being that the iconic Allbon Dart was born. The missile-based nomenclature was continuing! The Dart was introduced in August 1950. As far as I can determine, the first advertisement for this engine appeared in the October 1950 issue of “Aeromodeller”, again To all intents and purposes, the Dart was simply a reduced-scale version of the highly successful Javelin. The engine followed the general layout of the Javelin in almost all respects. It featured square bore and stroke measurements of 0.350 in. (8.89 mm) apiece for an actual displacement of 0.55 cc (0.034 cuin.). There have been reports that the early Darts had a displacement of only 0.50 cc, but this is incorrect - direct present-day measurements from multiple early examples confirm the above figures. Weight was a remarkably low 1.2 ounces (34 gm) without tank, since none was fitted as supplied, nor was any provision made for the fitting of a tank. Induction and cylinder porting were effectively identical to those of the Javelin. The earliest examples of the Dart retained the internal yoke system for con-rod installation in the piston, although they were the last Allbon products to do so. These earlier examples also received serial numbers which were hand-engraved on the underside of the crankcase, just as in the case of the Arrow. However, this practise was soon stopped, doubtless due to the production The cooling jackets on the original Darts were mostly anodized dark green. These early examples also featured L-shaped single-arm compression screws. At some point, a small batch of heads was anodized blue, doubtless as a result of having been included in an anodizing batch for some Arrow jackets. Later still, the anodizing was changed to a paler shade of green. Concurrently with this latter change, the piston design was amended to eliminate the alloy yoke in favour of a conventional fully-floating gudgeon pin. In addition, a change was made to a shallow Y-shaped two-armed compression screw.

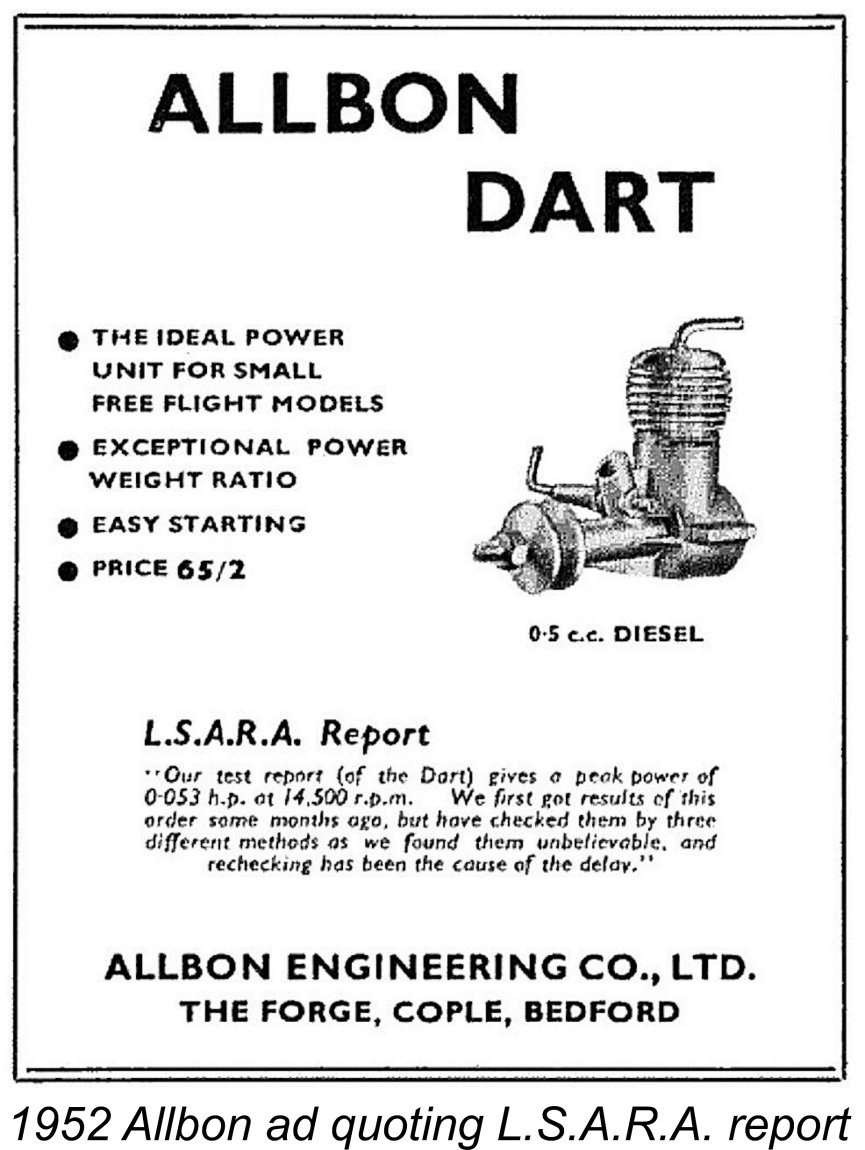

To say that Sparey was impressed with the Dart would be if anything an understatement. He started right out by noting that the engine's power-to-weight ratio of 0.575 BHP per pound represented "a big advance on anything previously found for engines of under 1 cc capacity", going on to note that this figure compared favourably with that of many far larger engines. Equally impressively, the actual measured peak power output of 0.0445 BHP @ 13,300 rpm Sparey characterized starting as "extremely good", although he did comment quite rightly that such small engines required a little more care in use than their larger brothers if handling damage was to be avoided. Running was described as "very steady over a wide range of speeds". Interestingly enough, the Low Speed Aerodynamics Research Association (L.S.A.R.A.) later reported even higher performance figures of 0.053 BHP @ 14,500 rpm. In his 1952 advertising for the Dart, Allbon quoted a statement from the Association to the effect that they had delayed publishing their figures pending a series of re-checks since they found this level of performance from such a small engine difficult to accept! Clearly Sparey's results were by no means unrepresentative. The publication of a further positive test by Peter Chinn in the April 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft” reinforced Sparey's findings in every respect. Chinn came even closer to the figures reported by the L.S.A.R.A., citing an output of 0.049 BHP @ 13,000 rpm. A recent test of my own example of the original Dart, engine number 295, confirmed Chinn's findings almost exactly. The engine started easily and ran flawlessly, generating the following data.

As can be seen, my test unit developed a peak output of around 0.049 BHP @ 12,800 rpm, thus duplicating Chinn's findings almost exactly. Overall, these test reports were about as positive as Alan Allbon could have wished for. Small wonder that modellers immediately started rushing out in droves to buy their own examples! Somewhat paradoxically, this was to force Allbon into a very difficult position, as we shall see in a later section of this article. However, before moving on to that part of our tale, we need to spend a little time briefly reviewing the influence which the success of the Dart had upon the activities of other British manufacturers. The Dart's Influence on Other Manufacturers Allbon's immediate and overwhelming success with the Dart in late 1950 was by no means lost upon other British firms. Indeed, it appears that a form of "gold-rush" mentality quickly took over, with other manufacturers falling over themselves to get in on what they evidently saw as an insatiable market for miniature diesels. No-one seems to have stopped to think that the sudden saturation of what had yet to be shown to be anything more than a "surge" or "fad" market could have negative consequences upon the potential long-term return on investment. Regardless, no fewer than three other competing manufacturers (Aerol Engineering (Elfin), International Model Aircraft (FROG) and E.D.) quickly followed Allbon's lead by developing ½ cc diesels of their own. This gave rise to the British ½ cc diesel "revolution" of 1951/52, which foreshadowed the similar contest of 1959-60 featuring British-made 0.81 cc (.049 cuin.) glow-plug motors. It also resulted in the rapid saturation of the market for miniature diesels in Britain.

The new breed of ½ cc diesels handily outperformed their sub-miniature 1940's predecessors, to the point where the best of them could actually give a few of the contemporary American .049 glow-plug models a run for their money. Despite this, they undeniably had their limitations. For one thing, they extended no appeal whatsoever to those modellers who were primarily interested in the competitive side of the hobby where large engines prevailed. Paradoxically, their appeal to beginners was constrained by the fact that they were both trickier to manage and more susceptible to handling damage than their larger counterparts. For another thing, the power output of these small units was still on the marginal side, especially when it came to the control-line field which was then so popular in Britain. Finally, they tended to wear out more rapidly than their larger contemporaries due to the greater sensitivity of smaller diesels to piston/cylinder wear in particular - the same amount of wear has a far greater negative effect on compression leak-down with small bores and displacements. For the above reasons, the immediate surge in demand for miniature diesels in Britain was soon satisfied. Consequently, the British ½ cc fad didn't last all that long, even though several of the protagonists remained in production for quite a few years. The Dart proved to be the only long-term survivor, outliving all of its rivals by several decades in its later versions as manufactured by Davies-Charlton Ltd. How that situation came about will be summarized in the following section. Major Problems for Allbon As 1950 drew towards its close, Alan Allbon found himself with a serious problem - he had several best-selling model engines which he was quite unable to produce at a rate which matched demand. It must have been abundantly clear that effective steps would have to be taken in very short order to increase Allbon’s production capacity very significantly. Unfortunately, we’ll never know how Allbon might have responded to this challenge, because a far more serious factor outside of his control was about to cast a very long shadow over his ongoing activities. This was the outcome of the infamous purchase tax case, of which much more elsewhere.

Sadly, Alan Allbon had evidently made no provision for such an outcome, hence being forced to sell up both his Sunbury workshop and his nearby residence to meet his back tax obligations. He moved his family back to his wife’s parents’ home in Bedford, subsequently resuming model engine production on a greatly reduced scale at a rather bucolic location in an old forge at the small village of Cople, a little to the east of Bedford. Naturally, this situation simply made a bad production shortfall even worse. The fallout from this unhappy affair was not borne by Alan Allbon alone - it also left both Dennis Allen and George Fletcher out of jobs as of early 1951. In the case of George Fletcher, his exile from the model engine field was quite brief. In early 1952, after completing the design of the FROG 50 Mk. I, IMA designer Bert Judge moved over to Wilmot, Mansour & Co. to assist in the development of their Jetex range. This left a vacancy at IMA which George Fletcher was immediately available to fill. No doubt the experience gained during his association with Alan Allbon stood him in very good stead in his new position. Dennis Allen also landed firmly on his feet, although it took a little longer. After spending some time working in general precision engineering, he returned to the model engine field by accepting a late 1952 invitation to assist the newly-established Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. in resuming production of the AMCO 3.5 cc models to which they had acquired the rights from the original manufacturers, the Anchor Motors Co. of Chester. In this venture he was joined by his long-time friend, club-mate and co-worker Len “Stoo” Steward, former owner of the "K” Model Engineering Co.

Returning now to early 1951, we left Alan Allbon working at Cople to produce the Dart as fast as he could with his greatly reduced resources. Demand for the Dart was continuing at a high level during this period, completely overwhelming Allbon’s ability to produce it at his much-reduced facility. His evident inability to meet demand for the Dart left the small-engine market wide open for other manufacturers, three of whom - E.D., Elfin and International Model Aircraft (FROG) - were quick to commence the development of competing ½ cc diesel models. However, the development of new designs from scratch takes time. In the interim, the ½ cc field remained the exclusive preserve of the Allbon Dart throughout 1951. It wasn’t until January 1952 that the first of the competing models, the Elfin 50, was announced. The Elfin was quickly followed by the FROG 50 (February 1952) and the E.D. Baby (March 1952). Alan Allbon was doubtless aware of the development of all three of these competing models well prior to their actual release. It must have been obvious to Allbon that his inability to match the production of the Dart to demand meant that these new competing models would represent major threats to his marketing position. The same was true of the still-popular Javelin, which now faced stiff 1.5 cc competition from Elfin and FROG. Something had to be done! The only solution was to increase production of the Dart (and the Javelin) to levels which matched demand. Since this was impossible at Allbon’s rather makeshift and understaffed facilities in Cople, he was forced to look elsewhere for help.

The end result was that manufacture of the Allbon engines by that name was now openly consolidated at Davies-Charlton's Barnoldswick plant in Lancashire along with that of the continuing Davies-Charlton 350 model which had been designed independently by Hefin Davies. This marked the beginning of a seven-year hiatus in Alan Allbon's career as an independent model engine manufacturer. An interesting sidebar matter is the fact that Allbon appears never to have got around to formally dissolving his old company! A notice published in the London Gazette for November 22nd, 1974 served three month's official notice that Allbon Engineering Co. (Sunbury) Ltd. was about to be struck off the British Company Register unless reasonable cause was shown why this step should not be taken. This notice was published pursuant to Section 353 of the Companies Act (1948) which permitted removal if the Registrar of Companies had unchallenged reason to believe that the company in question was no longer in business. Clearly, Allbon did not bother to present any arguments to counter this decision, which accordingly took effect on March 14th, 1975 through the publication of a further notice in the London Gazette of that date. I’ve now completed my review of Alan Allbon’s involvement with the model engine manufacturing business up to the point at which he was forced by circumstances to surrender some of his independence by joining forces with others. Allbon’s later career has been fully recounted in my companion biographical article covering his life and work. Those interested in the full details are referred to that article. For the convenience of readers who are not familiar with the full story, I’ll briefly summarize the rest of Allbon’s career below. The Later Years - a Summary

The introduction of domestic competition had done little to moderate consumer acceptance of the Dart, which continued to outsell its ½ cc competitors. The Elfin 50 and FROG 50 models both fell by the wayside fairly early on for one reason or another, but both the Dart and the 0.46 cc E.D. By all reports, Hefin Davies possessed a somewhat incendiary personality which made him a challenging individual to work with over the long term. A gulf progressively developed between the irascible Davies and the easy-going Alan Allbon which eventually resulted in Allbon severing his connection with Davies-Charlton in mid 1955 following the company's move to the IOM. He was replaced as D-C’s Works Manager by a chap named Ted Saunders. Following his severing of ties with D-C Ltd., Allbon established himself in business on his own account in premises located on the IOM in Douglas. These premises were made available to him by the Manx government on condition that he provide employment for a number of Manx residents. His new venture had nothing to do with model engines - instead, he acted as a sub-contractor on a variety of government precision engineering projects. By early 1959, Alan Allbon had been operating successfully from his Douglas premises for well over three years. However, it was at this time that the winds of change began to blow once more …………Allbon’s next career move was prompted not by any initiative on his part but rather as the result of a lengthy unsolicited visit to Allbon’s Laxey home from the aforementioned Ted Saunders in early 1959. An agreement was eventually reached to the effect that the two would establish a new precision engineering business named Allbon-Saunders on the English mainland. The new venture was established at Milton in Berkshire. The Allbon-Saunders operation was based in an old mill on Pembroke Lane on the outskirts of the village. At the time in question, Milton was a small rural community lying some 3 miles to the south of Abingdon. As of 1959 it seemed an unlikely location for a precision engineering company, but then so was Allbon’s earlier location at the old forge in Cople, Bedfordshire!

Saunders apparently did not share Alan’s enthusiasm, but the partners agreed that Allbon could pursue this line of business as a sideline provided that it did not interfere with the company’s main business focus. Having obtained the green light from his partner, Allbon went to work on the design of the first of what he intended to be a range of model engines to be marketed under the Allbon-Saunders name. This was the A-S 55, a superb little 0.55 cc diesel engine which became very highly regarded by its users.

This ended Alan Allbon's involvement with model engines once and for all. It would be difficult to overstate the loss to the modelling world which his departure represented. Allbon eventually retired from business, passing away rather unexpectedly from a heart attack in late 1978 at the age of only 72 years. Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed this retrospective look back at the early accomplishments of an individual who richly deserves to be remembered as one of Britain's most successful and influential model engine designers of the mid 20th century. It's been both a pleasure and a privilege to record this tribute to Alan Allbon's immense contribution to our favourite hobby during the pioneering era! As always, I don't claim to know it all, nor can I guarantee that I've got it all right. Accordingly, if anyone out there is able to correct me at any point or add to our shared knowledge as presented here, please get in touch! Any published contributions will be gratefully and openly acknowledged! _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN December 2012 This revised edition published here June 2023 |

||

| |

In a

In a  dimensions were increased. However, the fact that no selling price was included in the table implies that this was a prototype model which never saw actual production. Certainly, no more was ever heard of the 3.5 unit to my knowledge. I am not aware of the existence of any examples.

dimensions were increased. However, the fact that no selling price was included in the table implies that this was a prototype model which never saw actual production. Certainly, no more was ever heard of the 3.5 unit to my knowledge. I am not aware of the existence of any examples. From this point onwards, Allbon focused his full attention upon the development and manufacture of the engine style for which he is best remembered - the radial-ported reverse-flow scavenged crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) layout which was to dominate British model diesel design for the next two decades.

From this point onwards, Allbon focused his full attention upon the development and manufacture of the engine style for which he is best remembered - the radial-ported reverse-flow scavenged crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) layout which was to dominate British model diesel design for the next two decades. Although the concept of glow-plug ignition had originated during the early years of full-sized internal combustion engine development, the commercial miniature glow-plug was a late 1947 American innovation which was largely the creation of

Although the concept of glow-plug ignition had originated during the early years of full-sized internal combustion engine development, the commercial miniature glow-plug was a late 1947 American innovation which was largely the creation of  The British glow-plug movement continued to gain momentum in 1949. The

The British glow-plug movement continued to gain momentum in 1949. The  Somewhat inexplicably, the engine was claimed to be "Britain's first entry into the small glow-plug engine field". Given the fact that their 1.66 cc FROG 160 glow-plug model had been on the market and selling well for a full year at the time, one wonders what IMA made of this statement ...............

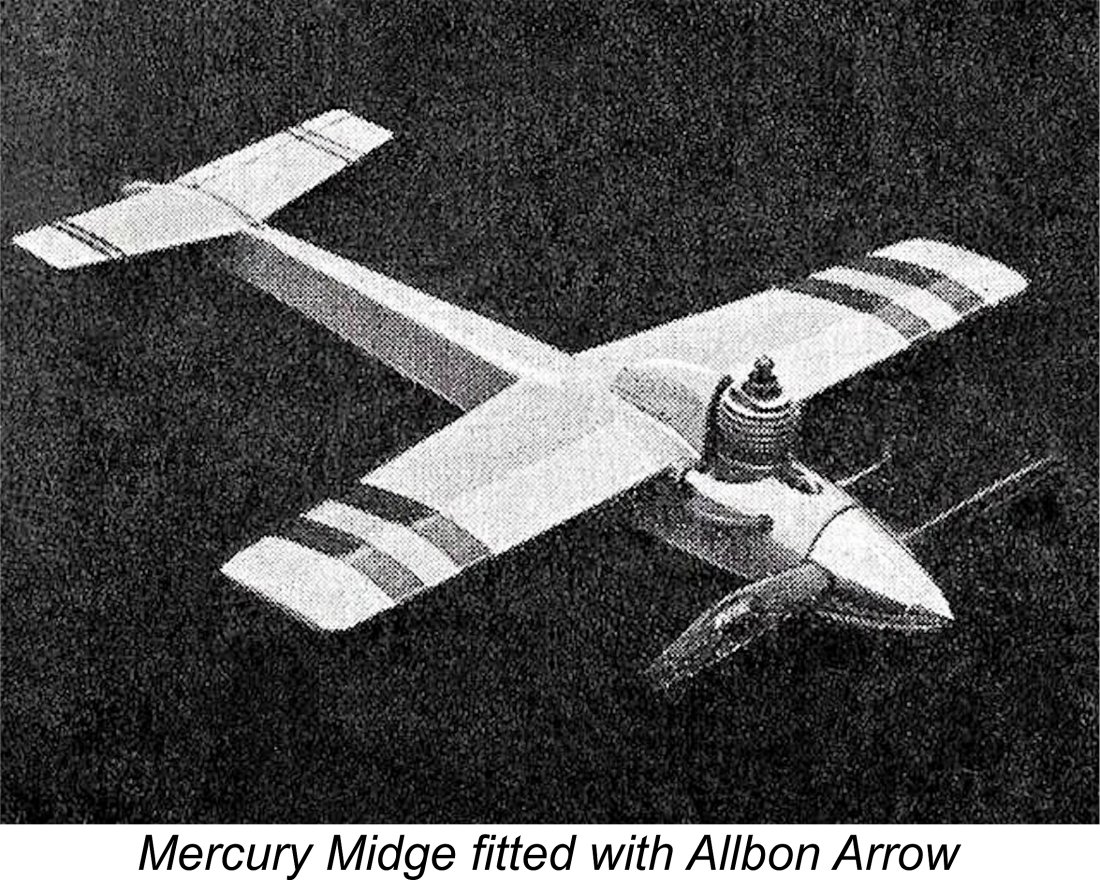

Somewhat inexplicably, the engine was claimed to be "Britain's first entry into the small glow-plug engine field". Given the fact that their 1.66 cc FROG 160 glow-plug model had been on the market and selling well for a full year at the time, one wonders what IMA made of this statement ...............  model work. Hoping to encourage wider participation in this branch of the hobby, the Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.) which governed competition aeromodelling in Britain had then recently introduced the new "low budget" Class I speed model category for engines of up to 1.5 cc displacement. The Arrow could legitimately lay claim to being the first British glow-plug engine specifically produced to meet that displacement limit - the FROG 160 was a little over that limit at 1.66 cc. Mercury Models quickly produced a kit version of Cyril Shaw’s matching “Midge” Class I control line speed model to encourage this class.

model work. Hoping to encourage wider participation in this branch of the hobby, the Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.) which governed competition aeromodelling in Britain had then recently introduced the new "low budget" Class I speed model category for engines of up to 1.5 cc displacement. The Arrow could legitimately lay claim to being the first British glow-plug engine specifically produced to meet that displacement limit - the FROG 160 was a little over that limit at 1.66 cc. Mercury Models quickly produced a kit version of Cyril Shaw’s matching “Midge” Class I control line speed model to encourage this class. The Arrow was about as different from the old 2.8 diesel as it was possible to get! For starters, it utilized glow-plug ignition. In addition, it dispensed with side-port induction by embracing the emerging design trend towards crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction allied to reverse flow scavenging by means of radial cylinder porting. It was very much a short stroke design, having bore and stroke measurements of 0.526 in. (13.36 mm) and 0.420 in. (10.67 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.49 cc (0.091 cuin.). It was extremely light for its displacement, having an all-up weight (with plug) of only 2.2 ounces even (63 gm). Finally, it was substantially cheaper than the 2.8 at only £2 15s 0d (£2.75).

The Arrow was about as different from the old 2.8 diesel as it was possible to get! For starters, it utilized glow-plug ignition. In addition, it dispensed with side-port induction by embracing the emerging design trend towards crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction allied to reverse flow scavenging by means of radial cylinder porting. It was very much a short stroke design, having bore and stroke measurements of 0.526 in. (13.36 mm) and 0.420 in. (10.67 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.49 cc (0.091 cuin.). It was extremely light for its displacement, having an all-up weight (with plug) of only 2.2 ounces even (63 gm). Finally, it was substantially cheaper than the 2.8 at only £2 15s 0d (£2.75). to be manufactured - the rest were off-the-shelf items obtainable in bulk from outside suppliers. Clearly, control of production costs was foremost in the minds of the design team.

to be manufactured - the rest were off-the-shelf items obtainable in bulk from outside suppliers. Clearly, control of production costs was foremost in the minds of the design team.

Like the 2.8, the Arrows were given serial numbers, although in the case of the Arrow these were hand-engraved into the underside of the crankcase. Allbon’s usual practise was to start his serial number sequences at 1, and there seems to be no reason to believe that he departed from this practise in the case of the Arrow. The highest number of which I am presently aware is 2130 reported by my good mate Allan Brown. This seemingly confirms that at least that many were made. At some later date, the practise of numbering the Arrow cases was discontinued, as we shall see in a following section of this article.

Like the 2.8, the Arrows were given serial numbers, although in the case of the Arrow these were hand-engraved into the underside of the crankcase. Allbon’s usual practise was to start his serial number sequences at 1, and there seems to be no reason to believe that he departed from this practise in the case of the Arrow. The highest number of which I am presently aware is 2130 reported by my good mate Allan Brown. This seemingly confirms that at least that many were made. At some later date, the practise of numbering the Arrow cases was discontinued, as we shall see in a following section of this article. Yulon

Yulon As a result of these factors, Sparey stated that he was conscious of the fact that the engine "was not giving of its best" during the test. For this reason, he actually made the somewhat unfortunately-worded statement that this test had been "one of the most unsatisfying - from my point of view - of any yet undertaken". In making the latter statement, he was actually trying to be kind to the manufacturers by implying that the engine could doubtless do better, but many readers probably took this statement at face value.

As a result of these factors, Sparey stated that he was conscious of the fact that the engine "was not giving of its best" during the test. For this reason, he actually made the somewhat unfortunately-worded statement that this test had been "one of the most unsatisfying - from my point of view - of any yet undertaken". In making the latter statement, he was actually trying to be kind to the manufacturers by implying that the engine could doubtless do better, but many readers probably took this statement at face value.

A further highly significant indication derived from this engine is the fact that by no means all of them suffered from the issues encountered by Sparey in his test. The cylinder head on this example is well screwed down to create a very good seal, but the engine exhibits no sign whatsoever of any excessive pinching at top dead centre or indeed at any other point of the stroke. The engine turns over freely, with very good compression and relatively little bearing wear despite the extensive use which it has clearly received. I was able to confirm by direct volumetric measurement that the geometric compression ratio of this example is 8.5:1 - a quite reasonable figure, albeit a little less than the 10:1 figure reported by Sparey.

A further highly significant indication derived from this engine is the fact that by no means all of them suffered from the issues encountered by Sparey in his test. The cylinder head on this example is well screwed down to create a very good seal, but the engine exhibits no sign whatsoever of any excessive pinching at top dead centre or indeed at any other point of the stroke. The engine turns over freely, with very good compression and relatively little bearing wear despite the extensive use which it has clearly received. I was able to confirm by direct volumetric measurement that the geometric compression ratio of this example is 8.5:1 - a quite reasonable figure, albeit a little less than the 10:1 figure reported by Sparey.

So this is what Allbon did, no doubt ably assisted by Dennis Allen. A new diesel model to be known as the Javelin (sticking with the missile motif!) was quickly brought into production. This was an interesting case of a reversal of the usual sequence - while most British glow-plug engines of the era were conversions of existing diesel models, the Javelin was a diesel conversion of an existing glow-plug model. Indeed, the introductory advertisements said as much, proclaiming the Javelin to be "the Diesel version of the famous Allbon Arrow 1.49 Glow-Plug" rather than the other way round.

So this is what Allbon did, no doubt ably assisted by Dennis Allen. A new diesel model to be known as the Javelin (sticking with the missile motif!) was quickly brought into production. This was an interesting case of a reversal of the usual sequence - while most British glow-plug engines of the era were conversions of existing diesel models, the Javelin was a diesel conversion of an existing glow-plug model. Indeed, the introductory advertisements said as much, proclaiming the Javelin to be "the Diesel version of the famous Allbon Arrow 1.49 Glow-Plug" rather than the other way round. need for this didn't last long - within a very short time Mercury was back to focusing very much upon their expanding kit range, while the ongoing advertisements for the Allbon engines reverted to being placed directly by Allbon Engineering, with Mercury Models remaining the sole distributors.

need for this didn't last long - within a very short time Mercury was back to focusing very much upon their expanding kit range, while the ongoing advertisements for the Allbon engines reverted to being placed directly by Allbon Engineering, with Mercury Models remaining the sole distributors. It didn't take Sparey long to get around to testing the Javelin. Presumably he welcomed the opportunity to make amends for his rather negative test (albeit fairly so) of the ill-fated Arrow! Be that as it may,

It didn't take Sparey long to get around to testing the Javelin. Presumably he welcomed the opportunity to make amends for his rather negative test (albeit fairly so) of the ill-fated Arrow! Be that as it may,  A further

A further  The modelling public certainly agreed with this assessment, consequently lining up to buy the engine in substantial numbers. The name Allbon was definitely restored to its former high status in the eyes of the modelling public as a result of the Javelin's appearance. Despite its less-than-stellar reputation, the Arrow continued to be listed alongside its new sibling for a considerable time, although it's unclear whether or not this represented ongoing manufacture or merely the selling-off of existing unsold stock.

The modelling public certainly agreed with this assessment, consequently lining up to buy the engine in substantial numbers. The name Allbon was definitely restored to its former high status in the eyes of the modelling public as a result of the Javelin's appearance. Despite its less-than-stellar reputation, the Arrow continued to be listed alongside its new sibling for a considerable time, although it's unclear whether or not this represented ongoing manufacture or merely the selling-off of existing unsold stock. Of course, there had been previous British attempts to tap into the market for sub-miniature diesels. As the first British ½ cc diesel, the

Of course, there had been previous British attempts to tap into the market for sub-miniature diesels. As the first British ½ cc diesel, the  The Javelin diesel had proved itself to be an exceptional performer by the standards of its day. Allbon evidently reasoned that a scaled-down version of the Javelin might well deliver a level of performance which would overcome the prevailing prejudice against really small engines, thus in effect opening up a whole new market area.

The Javelin diesel had proved itself to be an exceptional performer by the standards of its day. Allbon evidently reasoned that a scaled-down version of the Javelin might well deliver a level of performance which would overcome the prevailing prejudice against really small engines, thus in effect opening up a whole new market area. referring to Mercury Models as the distributors rather than Allbon Engineering as the manufacturers. This advertisement is reproduced here at the left. The engine was an immediate and overwhelming success, fully vindicating Allbon's foresight in making the commitment to its development and manufacture.

referring to Mercury Models as the distributors rather than Allbon Engineering as the manufacturers. This advertisement is reproduced here at the left. The engine was an immediate and overwhelming success, fully vindicating Allbon's foresight in making the commitment to its development and manufacture. pressures which demand for the engine imposed upon the company. Eric Offen had engine number 144, while my own numbered example bears the serial number 295. Reader Terry Chapman has reported owning Dart no. 506, which is the highest number reported to date. I have no idea how much further the numbering sequence went. All I know is that numbered examples of the Dart are relatively rare today, implying that the quantity to which serial numbers were assigned was not large.

pressures which demand for the engine imposed upon the company. Eric Offen had engine number 144, while my own numbered example bears the serial number 295. Reader Terry Chapman has reported owning Dart no. 506, which is the highest number reported to date. I have no idea how much further the numbering sequence went. All I know is that numbered examples of the Dart are relatively rare today, implying that the quantity to which serial numbers were assigned was not large. On this occasion, Lawrence Sparey was clearly itching to get his hands on an example of this latest British attempt to create a successful miniature diesel. His

On this occasion, Lawrence Sparey was clearly itching to get his hands on an example of this latest British attempt to create a successful miniature diesel. His

The attractiveness of these small engines to mainstream British modellers arose from a number of factors. They weren't significantly cheaper than many of their larger brethren since they required if anything even more care and precision in their manufacture. However, models for these little units were both easy and inexpensive to build (this was in the far-off days when most aeromodellers lived up to their hobby's name by actually building their own models, often of their own design!). They were also far easier to transport, an important consideration at a time when many younger modellers (such as myself) used public transport to get to and from flying sites. Moreover, such models (particularly those of the control-line variety) could be flown on smaller fields. And finally, the noise levels and fuel costs associated with running these little powerplants were far lower than those of the larger engines generally used by competition fliers.

The attractiveness of these small engines to mainstream British modellers arose from a number of factors. They weren't significantly cheaper than many of their larger brethren since they required if anything even more care and precision in their manufacture. However, models for these little units were both easy and inexpensive to build (this was in the far-off days when most aeromodellers lived up to their hobby's name by actually building their own models, often of their own design!). They were also far easier to transport, an important consideration at a time when many younger modellers (such as myself) used public transport to get to and from flying sites. Moreover, such models (particularly those of the control-line variety) could be flown on smaller fields. And finally, the noise levels and fuel costs associated with running these little powerplants were far lower than those of the larger engines generally used by competition fliers. In a nutshell, this case centred upon the 1948 Government decision to apply Purchase Tax to model engines (among many other model-related products which had previously been exempt as having educational value). A test case had been initiated by the model trade in mid 1948 through the organized non-payment of tax, with Eddie Keil volunteering his KeilKraft company as the defendant of record. After over two years of legal argument, a final judicial ruling was handed down in late 1950. Somewhat unexpectedly, this ruling upheld the government’s decision regarding the applicability of Purchase Tax to such products, hence imposing a significant bill for well over two years’ back taxes, which the parties to the case had not been paying since mid 1948.

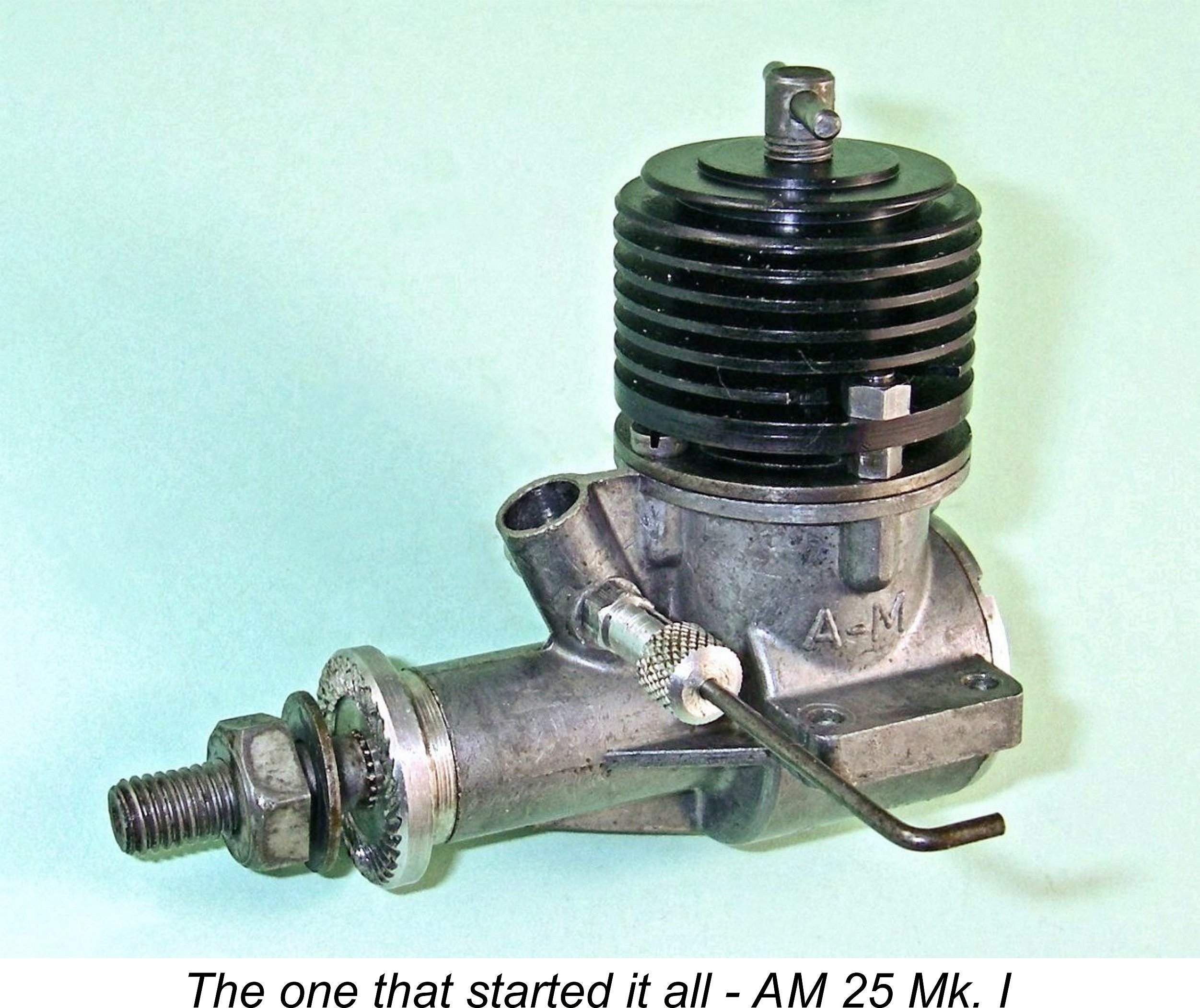

In a nutshell, this case centred upon the 1948 Government decision to apply Purchase Tax to model engines (among many other model-related products which had previously been exempt as having educational value). A test case had been initiated by the model trade in mid 1948 through the organized non-payment of tax, with Eddie Keil volunteering his KeilKraft company as the defendant of record. After over two years of legal argument, a final judicial ruling was handed down in late 1950. Somewhat unexpectedly, this ruling upheld the government’s decision regarding the applicability of Purchase Tax to such products, hence imposing a significant bill for well over two years’ back taxes, which the parties to the case had not been paying since mid 1948. Allen and Steward spent over a year working on the revived AMCO range, which benefited considerably from their involvement, as I‘ve shown elsewhere. On the side, they worked together on the design of a new 2.5 cc model, which Allen offered to his new employers. They were not interested, but this did nothing to shake Allen's unswerving belief in the commercial potential of the new design. His faith led him to seek other avenues for getting it into production. In mid 1954 both Allen and Steward left Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. to commence the independent manufacture of the first diesel to be marketed under Allen’s own name, the Mk. I

Allen and Steward spent over a year working on the revived AMCO range, which benefited considerably from their involvement, as I‘ve shown elsewhere. On the side, they worked together on the design of a new 2.5 cc model, which Allen offered to his new employers. They were not interested, but this did nothing to shake Allen's unswerving belief in the commercial potential of the new design. His faith led him to seek other avenues for getting it into production. In mid 1954 both Allen and Steward left Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. to commence the independent manufacture of the first diesel to be marketed under Allen’s own name, the Mk. I  In late 1951, Allbon’s urgent need to increase production of his designs to meet the forthcoming competition led him to enter into a production agreement with Hefin Davies of

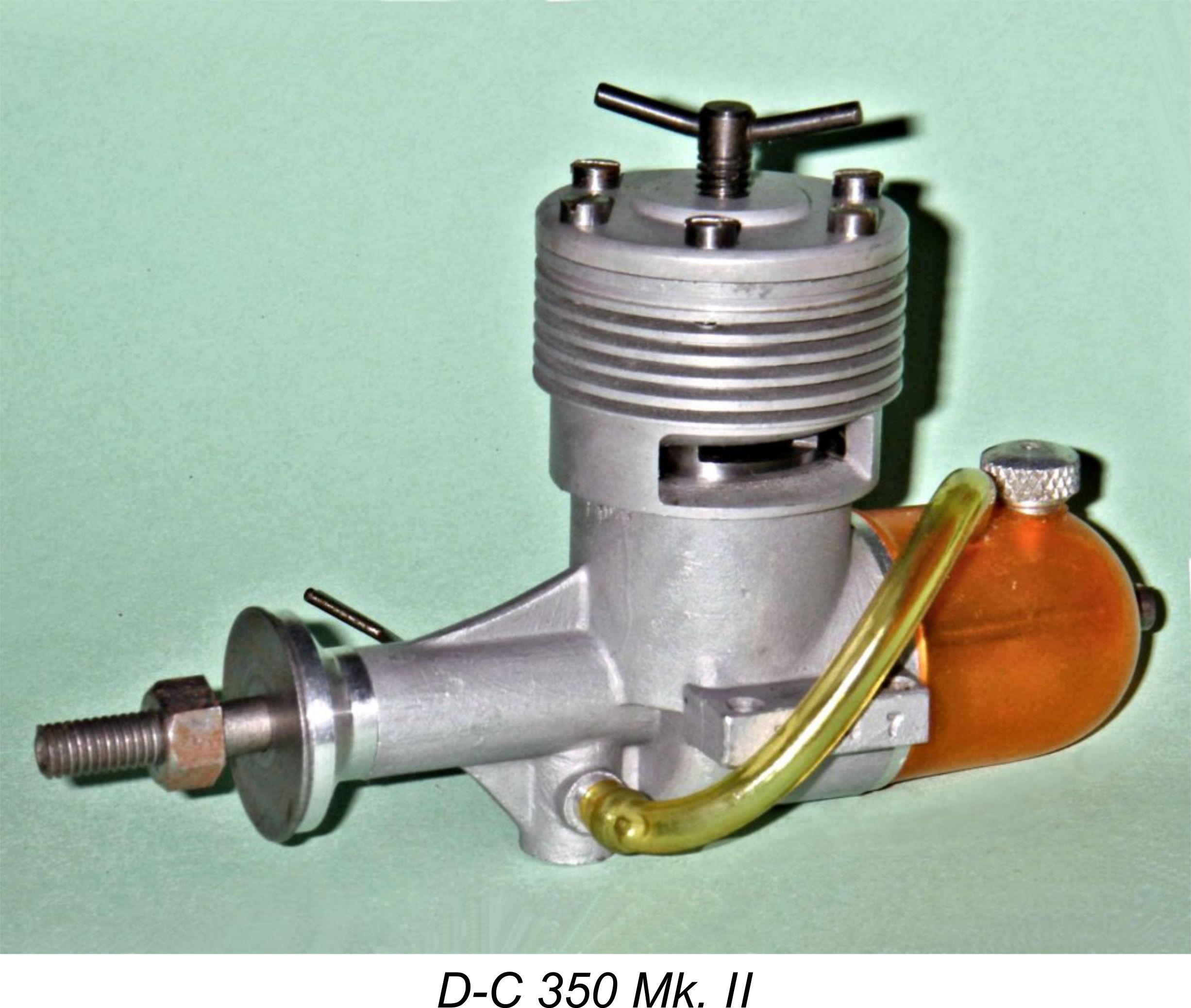

In late 1951, Allbon’s urgent need to increase production of his designs to meet the forthcoming competition led him to enter into a production agreement with Hefin Davies of  Following the merger, the distinct identity of the D-C and Allbon ranges was maintained for some years, with Mk. II versions of both the Allbon Dart (now with a red head in place of the original green) and the Allbon Javelin appearing more or less concurrently with the co-location of all production at Barnoldswick, along with the newly-introduced 1 cc Allbon Spitfire Mk. I. Moreover, the Allbon name continued to be applied to other new designs as time went by, including the 0.154 cc

Following the merger, the distinct identity of the D-C and Allbon ranges was maintained for some years, with Mk. II versions of both the Allbon Dart (now with a red head in place of the original green) and the Allbon Javelin appearing more or less concurrently with the co-location of all production at Barnoldswick, along with the newly-introduced 1 cc Allbon Spitfire Mk. I. Moreover, the Allbon name continued to be applied to other new designs as time went by, including the 0.154 cc  Baby

Baby

This fine little unit made its initial appearance in November 1959 to widespread critical acclaim. As detailed elsewhere, the A-S 55 was an outstanding product which did great credit to Allbon's reputation as a designer but which failed to make much of an impression in the marketplace. This was due not to any shortcomings in the engine itself but rather to Allbon's characteristic insistence upon the maintenance of construction standards which precluded its being priced competitively. Rather than continuing to compete in a marketplace which had become dominated by low prices rather than high quality and performance standards, Allbon joined with Saunders in focusing his efforts upon other more remunerative business lines. In this, the company was to prove eminently successful. A successor company still operates today from the same premises.

This fine little unit made its initial appearance in November 1959 to widespread critical acclaim. As detailed elsewhere, the A-S 55 was an outstanding product which did great credit to Allbon's reputation as a designer but which failed to make much of an impression in the marketplace. This was due not to any shortcomings in the engine itself but rather to Allbon's characteristic insistence upon the maintenance of construction standards which precluded its being priced competitively. Rather than continuing to compete in a marketplace which had become dominated by low prices rather than high quality and performance standards, Allbon joined with Saunders in focusing his efforts upon other more remunerative business lines. In this, the company was to prove eminently successful. A successor company still operates today from the same premises.