|

|

The Life and Work of Alan Allbon

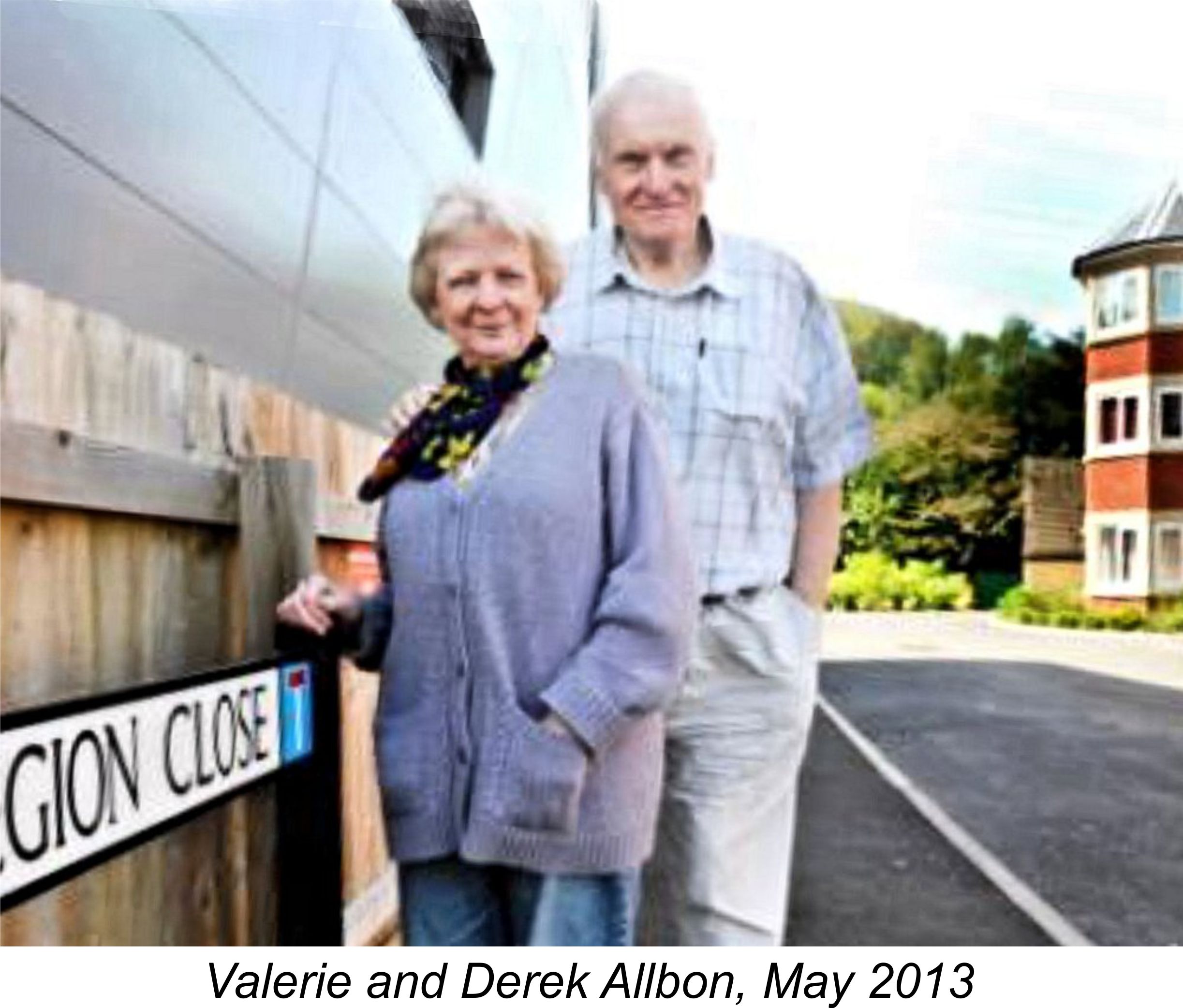

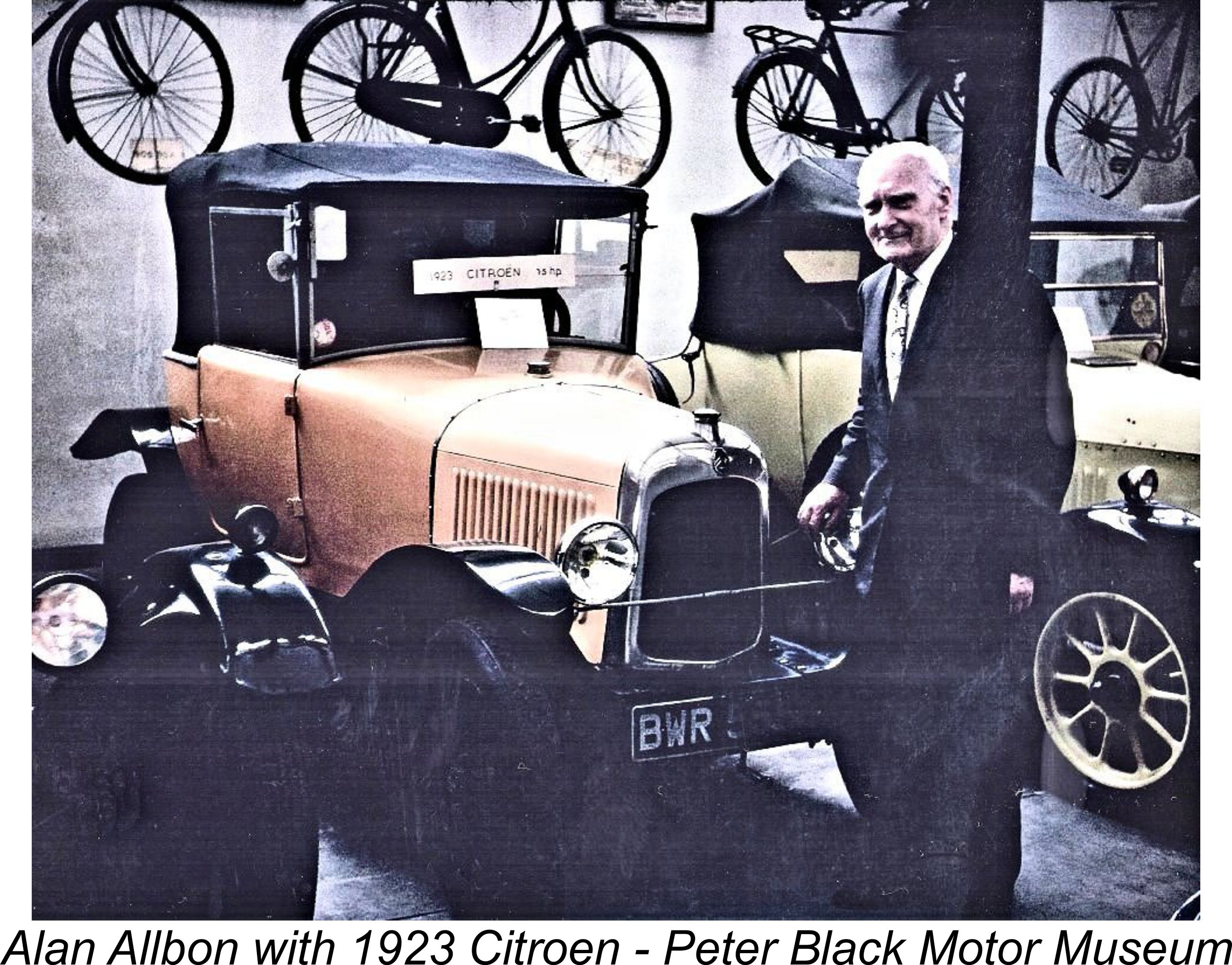

Those interested in the technical aspects of the Allbon engines are advised to consult my focused articles on the Allbon 2.8 model and the FRV Allbon designs, since the present piece will be more biographical in nature - no sense re-inventing the wheel! I will include appropriately-placed links to other articles in what follows. At the time when my original articles were published on MEN, absolutely nothing of substance had been learned about Alan Allbon himself. His engines were quite well documented, but the man himself remained a complete enigma. A search of British genealogical records did turn up some very basic information on a certain Alan L. Allbon who seemed to fit the broad profile of the model Thankfully, that situation no longer applies! Solely due to the kind assistance of MEN reader Geoff Peacock, a former resident of Barnoldswick in Lancashire, I was granted access to a wealth of authoritative first-hand personal information on Alan Allbon. This came about because Geoff Peacock was a school-friend of one of Alan Allbon’s sons, Derek Allbon, during the period in which Allbon lived and worked in Barnoldswick in partnership with Hefin Davies of Davies-Charlton Ltd. Although he had lost touch over the years, Geoff spent some time tracking down his old school chum Derek, finally locating him still living at Dursley in Gloucestershire, England.

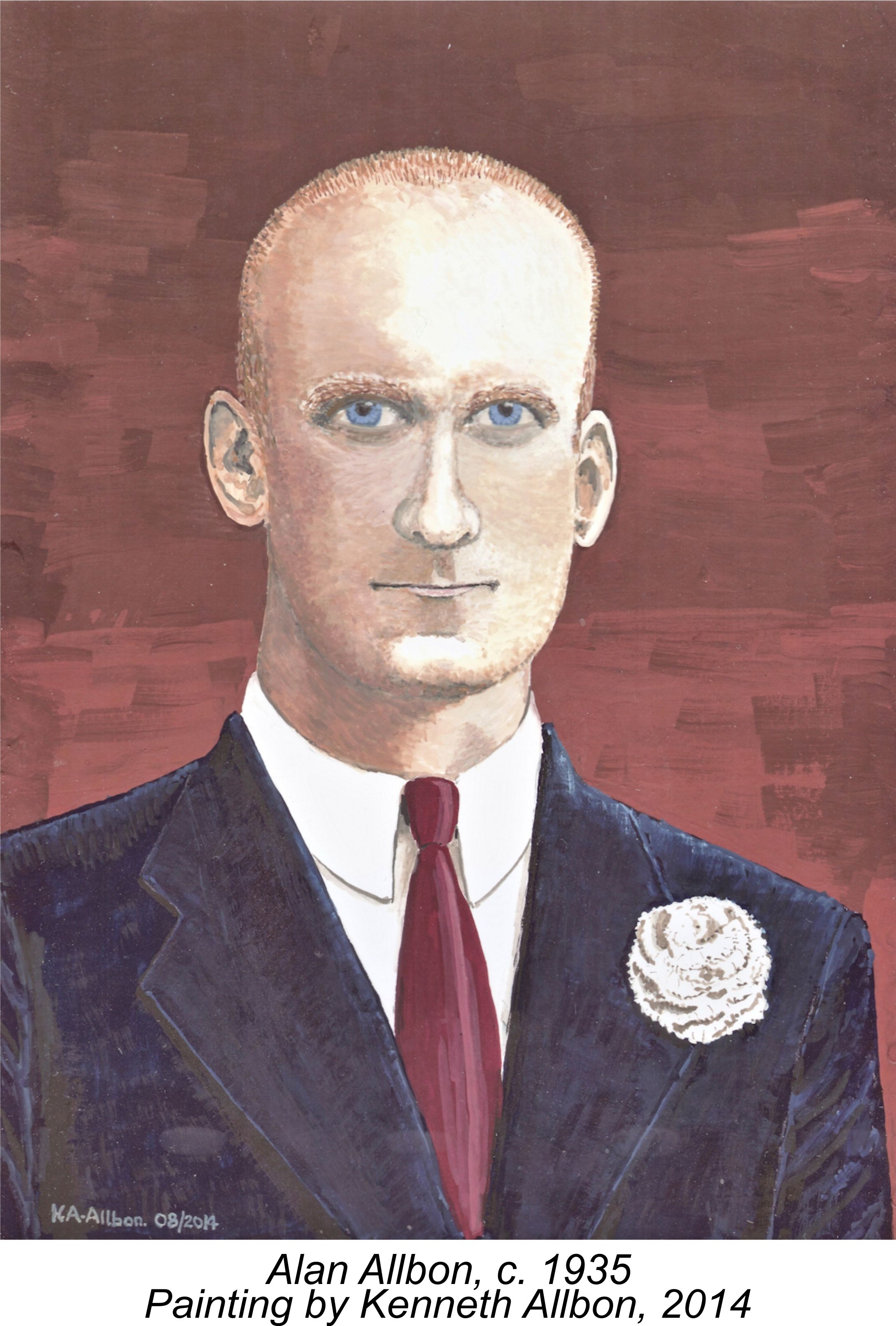

Derek remembered Geoff very well, accordingly being very happy that contact had been re-established. He was glad to help fill in some of the details about his father’s life and work, although he recommended that contact be made with his older brother Kenneth Allbon, who was also still alive and well and living at Seaford in Sussex, England. Derek felt that Kenneth would know far more than he did. Regardless, Derek has our very sincere thanks for his contribution to this article. Thanks entirely to Geoff’s efforts in establishing direct contact with the Allbon family, I was privileged to speak at great length with Kenneth Allbon, who did indeed retain a great deal of knowledge about his father’s life and work which he was happy to share. I'd also like to add a word of appreciation to Bernie Bowler, who was Alan Allbon's employee and later partner during his final working years. Bernie came across this article in April 2016, over a year after it was first published on MEN. He immediately contacted me not only to express his appreciation for the article about his old "gentleman partner" but also to bring to my attention a considerable amount of additional information regarding those later years at Allbon-Saunders, when Bernie was personally involved. There can be no finer reward for the effort involved in putting a story like this together than to hear from one who was "there". My very sincere thanks to Bernie! Although the article which follows is a synthesis of information obtained from many sources in addition to the hands-on experience gained through a modelling lifetime spent using engines designed by Alan Allbon, I must stress that the responsibility for any errors or omissions in what follows rests solely with myself. Now, on with our story ...... The Early Years It's always very satisfying to receive confirmation that one’s earlier deductions based on rather marginal evidence were actually correct! In this case, I now have unimpeachable corroboration of the fact that the individual with whom we are concerned here was indeed the same Alan L. Allbon who was cited in my earlier articles as the most likely candidate to be our subject individual. Alan Leslie Allbon was born on July 4th, 1906 at Hitchin, a small market town in northern Hertfordshire. He had two brothers named Norman and John (the latter always known as Jack). Kenneth Allbon has told us that as youths both his father and Uncle Jack were mad about all things mechanical, notably motorcycles and cars. Kenneth characterized them both as “incorrigible petrol-heads”! As might be expected from a chap having an interest in technical matters, young Alan also built models of various kinds.

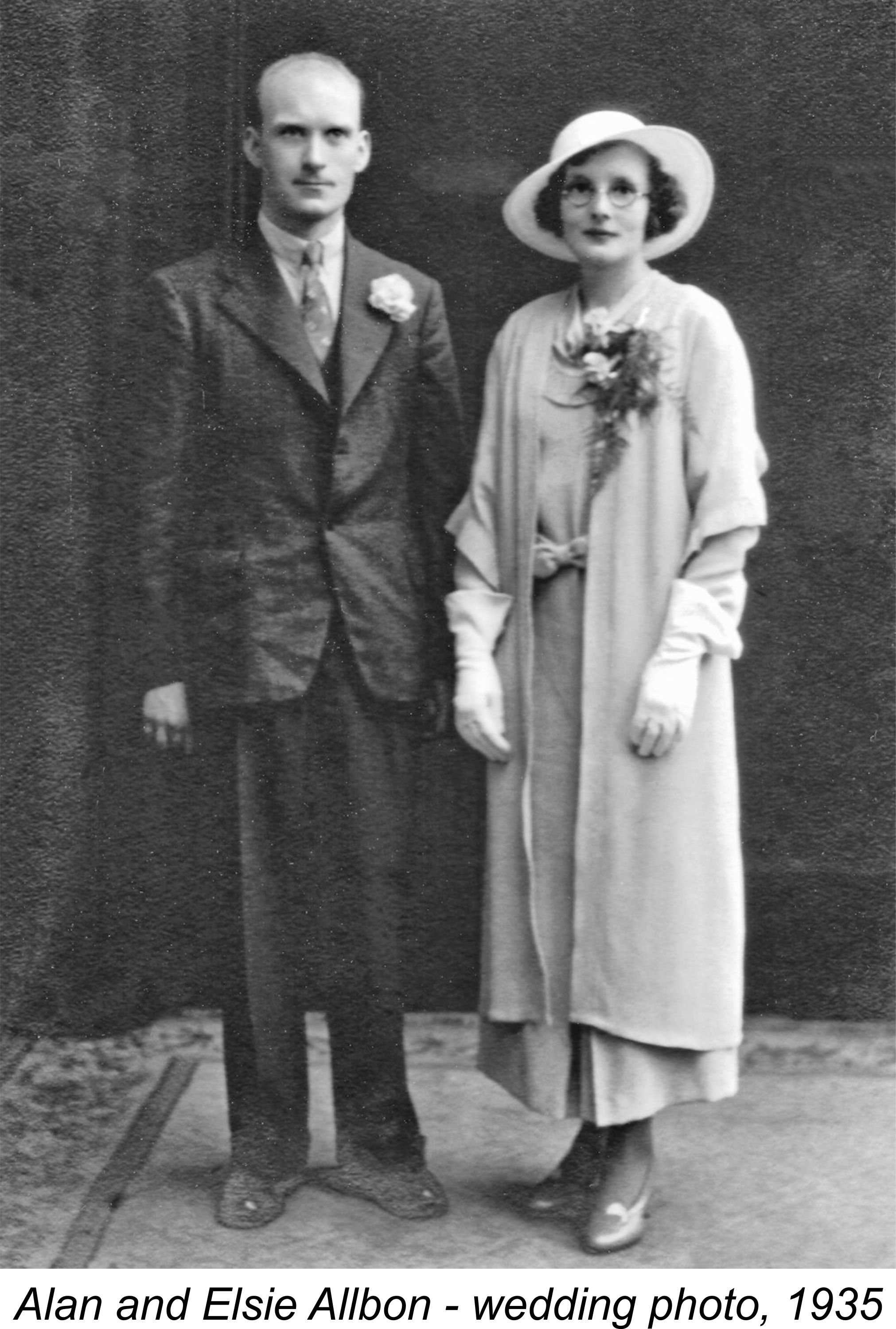

Allbon's time at the Polytechnic constituted the primary element of his formal technical training, a matter on which I had no previous information. Although his studies at the Polytechnic did not make him a formally-trained mechanical engineer, Allbon became a fully-qualified and highly skilled engineering design draftsman, subsequently working in that capacity. As any engineer (like myself) with roots in the pre-CAD era will know, the skilled engineering draftsman was the backbone of the engineering profession at the time. By the early nineteen-thirties, Allbon was to be found working in Bedford for an old-established company named Cryselco, which manufactured a range of electrical lighting products. One of the secretaries at this firm was a certain Miss Elsie Milnes, to whom Allbon was very much attracted. In 1935 at the age of 29, Alan Two sons (Kenneth b. December 1939 and Derek b. July 1943) resulted from this union. Interestingly enough, the Cryselco company remained very much in business right up to May 6th, 2018, when it was dissolved over 120 years after its establishment in 1895. Alan and Elsie both left Cryselco soon after their marriage, moving south to Sunbury-on-Thames where Allbon established himself independently in premises at 51a Thames Street. Their new hometown was then located in the county of Middlesex, although it was later incorporated into the county of Surrey as part of the 1965 county boundary reorganization resulting from the work of the Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London. Kenneth Allbon recalled that the Thames Street premises were actually a former retail shop located on what was then the main street of the community. Allbon ran a precision engineering business at this location, being joined for at least some of his time there by his equally mechanically-minded brother John. Kenneth Allbon recalls that his “Uncle Jack” was an engaging personality who was a bit of a “ladies’ man”, an aspect of his character of which Kenneth’s rather straight-laced mother Elsie did not approve!

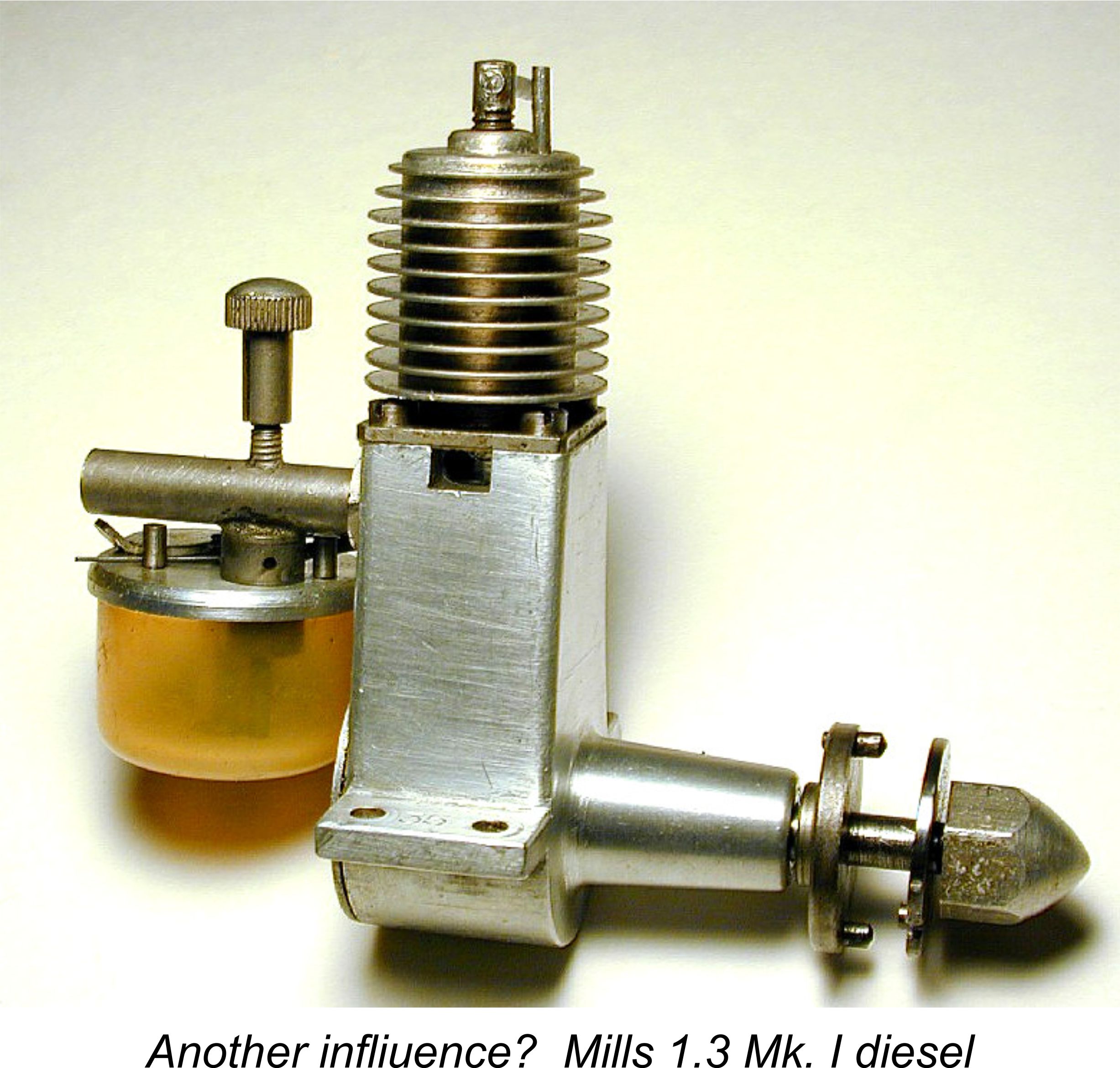

In September 1939, WW2 broke out. 33 year old Alan Allbon was exempted from military service due to his being in what was considered a reserved occupation. Individuals in this category were officially considered to contribute more to the war effort by remaining at their posts than by joining the ranks of the military. Accordingly, Allbon worked in his Sunbury premises throughout the war on government-initiated technical projects in support of the war effort. After the war, the forty year-old Allbon continued working at Sunbury in the general precision engineering field, presumably for the most part under contract to others. However, it’s clear that by 1947 he was ready for a change in focus. His long-standing mechanical interests had combined with his parallel interest in Allbon’s active involvement in aeromodelling doubtless gave him ample opportunity to examine the products of some of the manufacturers with whom he would be competing. He must surely have been familiar with such pioneering model diesels as the Majesco engines from Parkstone in Dorset, the E.D. 2 cc sideport models from Kingston-on-Thames, the Mills 1.3 from Woking, the FROG range manufactured by International Model Aircraft (IMA) at Morden and the Kemp range from Gravesend in Kent. These models must have given him much to think about when considering his own designs. Another factor that doubtless stood Allbon in good stead was his ability to get along with other people. Kenneth objectively characterized his father as a “very nice chap” having an unusually even temperament and From the beginning of his model engine manufacturing career, Allbon traded under the company name of Allbon Engineering Co. (Sunbury) Ltd., working from the Thames Street address in Sunbury-on-Thames. It’s possible and perhaps even likely that he had been operating under this company name all along, but we don’t know this for sure. Interestingly enough, Sunbury-on-Thames is located in an area of south-west London in which a number of competing model engine manufacturers conducted their business. Sunbury lies just across the River Thames from the successive haunts of the E.D. company at Kingston-on-Thames, West Molesey and Surbiton, and not all that far from the IMA plant just to the south-east at Merton, where the FROG range was manufactured. The Mills Bros. workshops at Woking were also relatively nearby. The model engine industry was a significant employer in South-West London in 1948! Think of the craic in all those engine-maker’s pubs …………. Independence - the Sunbury Era The Allbon workshops at the Thames Street premises in Sunbury were very small by comparison with those of their major rivals from across the river. Kenneth Allbon recalled that to maximize the efficient use of floor space, the entire second floor of the former shop premises had been removed, creating a ground floor of twice the original height. This was very convenient for the accommodation of the machinery used by the company. A flight of wooden stairs led up to a small elevated cubicle-style office which was located at the former second floor level in one corner of the building. This was Alan Allbon’s design and business office. This “suspended office” arrangement saved some space on the main floor, which could thus be used in its entirety for manufacturing purposes. Thames Street has moved well up-market since Allbon's time there. Many of the buildings on the street have since been converted into riverside flats, restaurants or office space. The modest red brick building at 51 Thames Street, which may well be the one formerly occupied by Allbon, was occupied at my original time of writing (2015) by a branch office of A. A. Telecom Ltd.

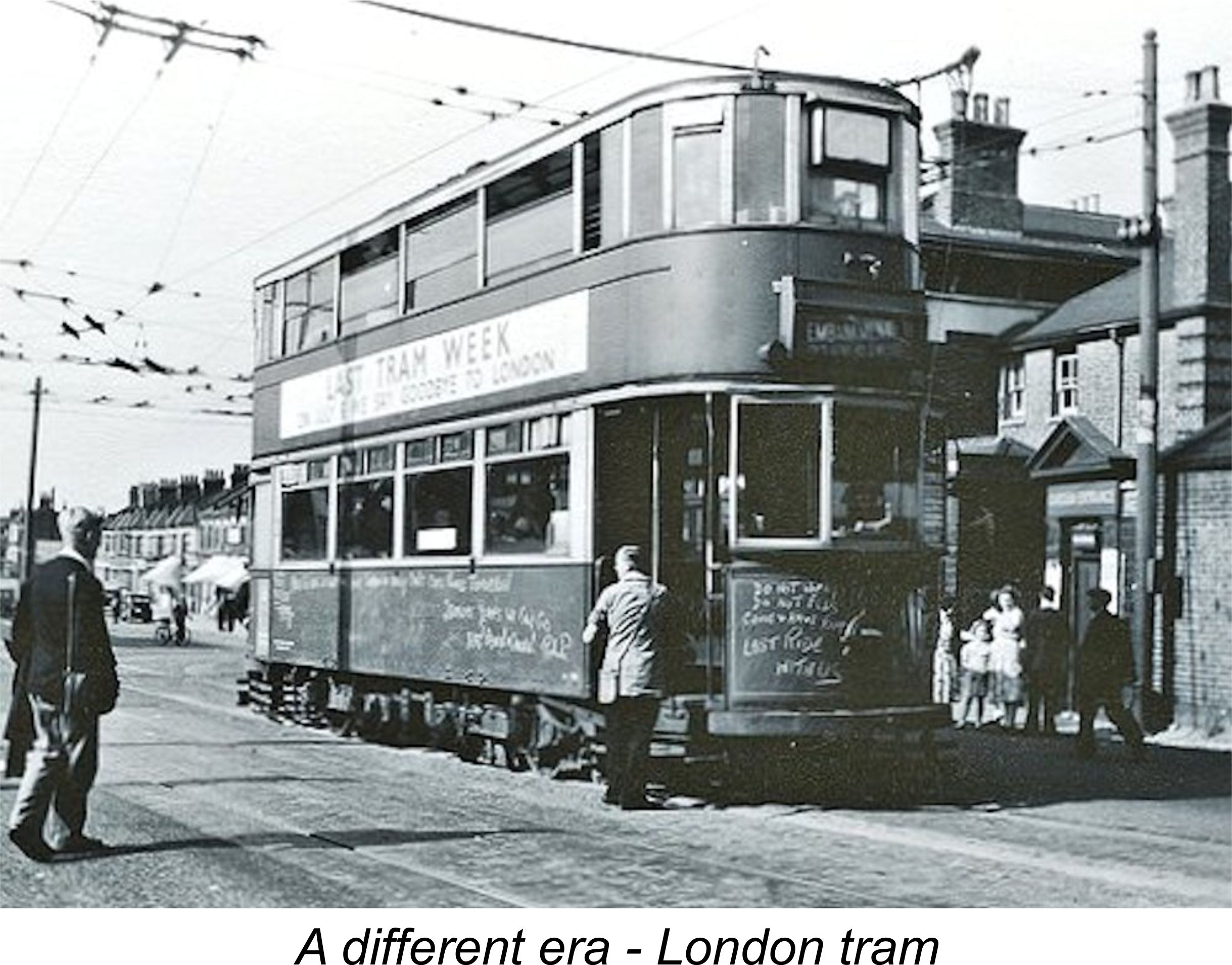

As a young boy, Kenneth Allbon used to spend time hanging about the workshop during this period. He particularly recalled two of his father’s employees who were both named Mickey. One was always quite cleanly turned out, while the other invariably presented a grimy face and a grubby appearance to the world. Young Kenneth cheekily called them “Clean Mickey” and “Dirty Mickey” respectively! Apparently “Clean Mickey” promised to make young Kenneth a model tram but never delivered, a slight which Kenneth still recalled when interviewed almost 70 years later in 2015!

At some point during this period, Allbon was joined at Thames Street by future Allen-Mercury manufacturer Dennis J. Allen. There can be no doubt that Allen was a valuable asset since he knew model engines very well indeed, both as a practical user and on account of his previous employment with the engine repair service operated by Henry J. Nicholls as an adjunct to his famous shop at 308 Holloway Road in London. Since Nicholls’ Mercury Model Aircraft Supplies division had been the distributor and servicing agent for the Allbon 2.8 since its introduction at the beginning of 1948, Allen already had a close working familiarity with that engine. Initially, Allen remained an employee of Henry J. Nicholls Ltd., being in effect "loaned" to Alan Allbon to assist him in the ongoing production of the 2.8 and the development of potential new models. However, it turned out that the proportion of Allen's time required to meet Allbon's need for assistance soon made this arrangement impracticable. The result was that Allen became a full-time employee of Allbon Engineering during the latter part of 1949, joining the others already working there. In this capacity, Allen was closely involved in the ongoing development and manufacture of the company's various products which appeared over the course of the following year. There is always a synergistic effect when two talented individuals join forces to work towards common goals, and there can be little doubt that both Allen and Allbon gained immensely from their collaboration in terms of their grasp of the challenges inherent in model engine design and manufacture. Kenneth Allbon recalled that after Dennis Allen joined his father at Thames Street, the two of them used to travel up to London fairly regularly to meet with Henry J. Nicholls at “308”. Presumably these trips were undertaken at least in part to deliver batches of engines and spare parts, since Nicholls continued to be the Allbon distributor and servicing agent at this time. Kenneth actually recalled accompanying his father on a number of these trips.

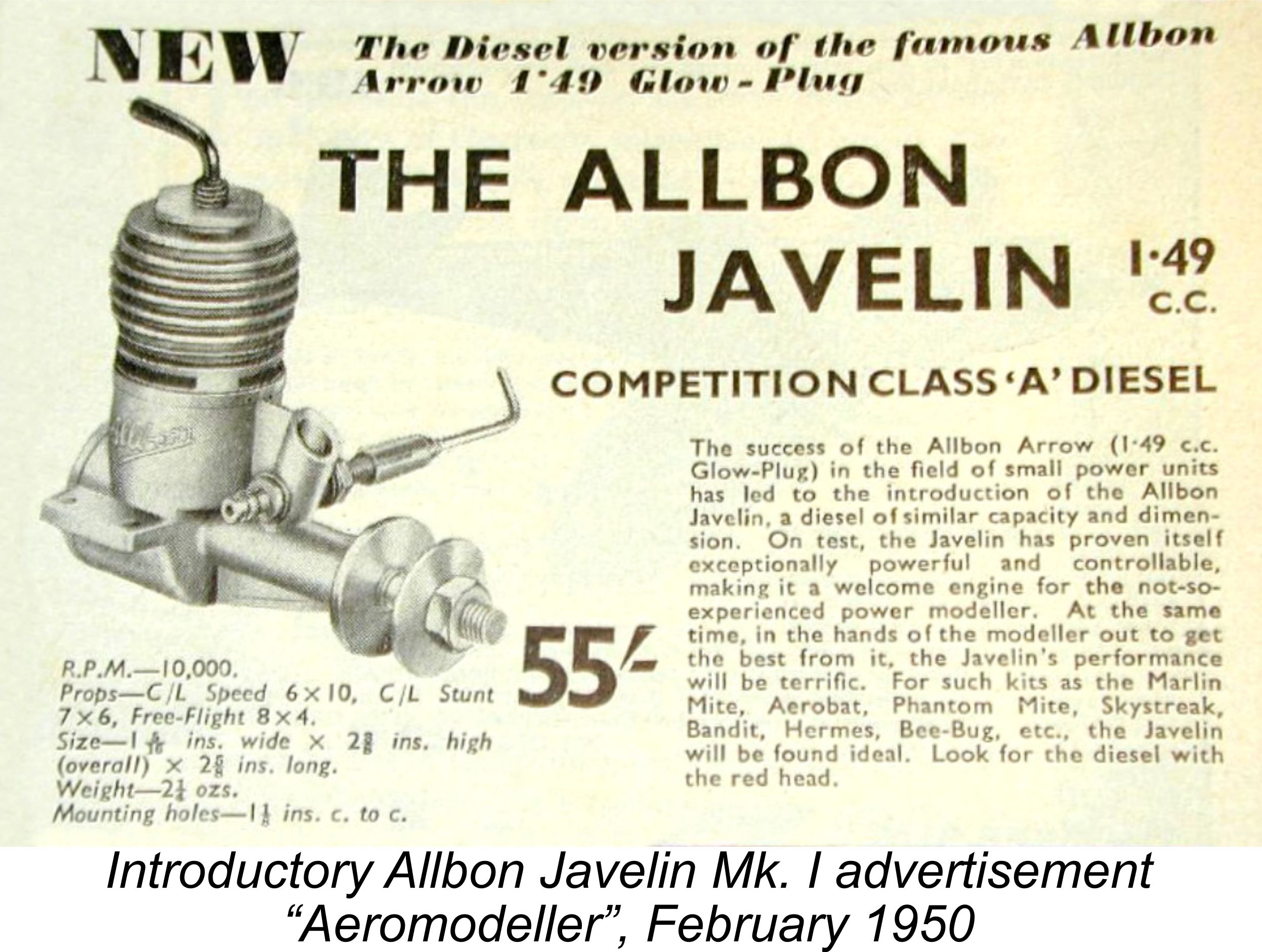

The first advertisement for this engine that I could find appeared in the October 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Interestingly enough, the Arrow was claimed to be "Britain's first entry into the small glow-plug engine field". Given the fact that their 1.66 cc FROG 160 glow-plug model had been on the market and selling well for over a year at the time, one wonders what IMA made of this statement! Unfortunately, the Arrow proved to be perhaps Alan Allbon’s sole error of judgment during his distinguished model engine design career. Although it was a well-made, very light and good-looking motor having excellent handling qualities, its performance fell well short of meeting expectations for an engine of its displacement, particularly in light of the fanfare with which it was introduced. As a replacement flagship product for the highly regarded but admittedly outdated 2.8, it was never in the running. Sales were not totally dismal - serial number evidence suggests that a total of some 2,200 examples were made over the following 16 months or so. However, the engine never overcame its reputation as a chronic under-performer. Alan Allbon clearly recognized this immediately. Unless something was done very quickly, the Arrow’s performance shortcomings could have had very negative consequences in terms of the ongoing perception of the Allbon range in the marketplace. To his credit, Allbon didn’t waste any time wringing his hands over what can really only be regarded as a set-back. He needed to act quickly to restore his reputation as a designer and manufacturer!

Several published tests of the Javelin quickly confirmed that it was one of the best-performing engines in its displacement category then available to the British modelling public, outperforming the Arrow by a substantial margin. It was also very well made, like all Allbon products. British power modellers agreed completely with this assessment, consequently lining up to buy the engine in substantial numbers. At one fell swoop, the Javelin had restored the Allbon name to its former high status in the eyes of the British modelling community. The Arrow continued in production, but the flagship role had been decisively assumed by the Javelin.

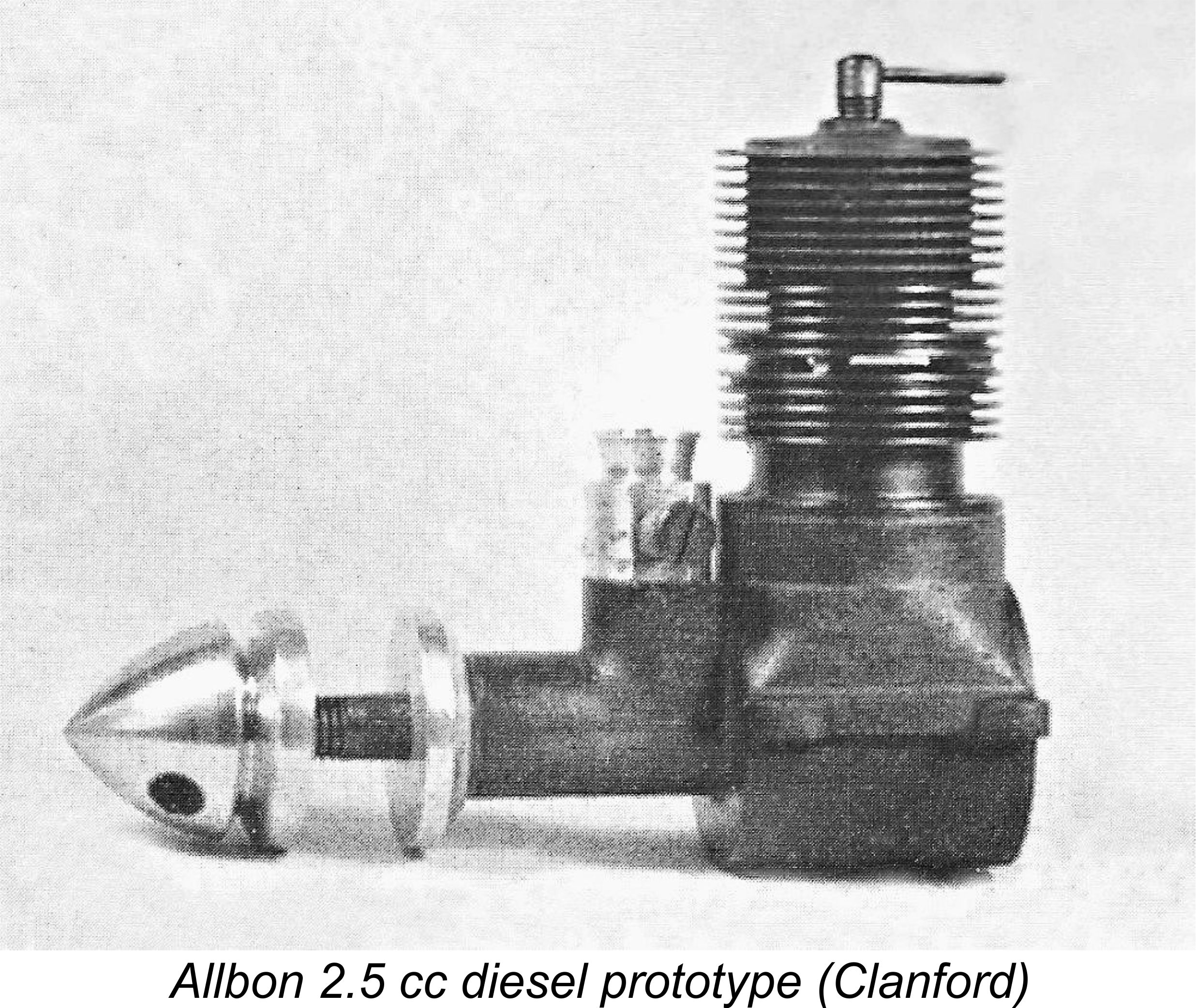

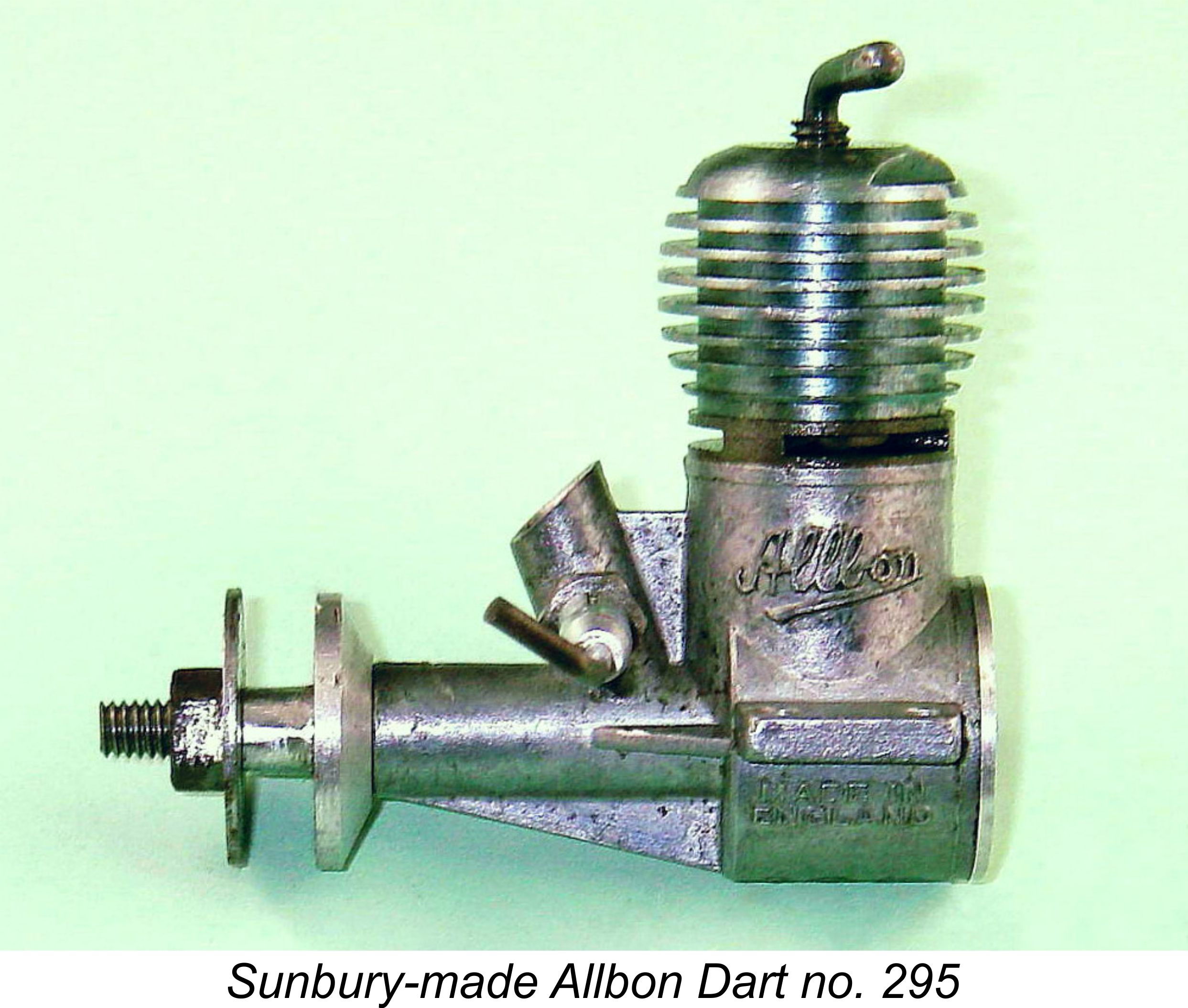

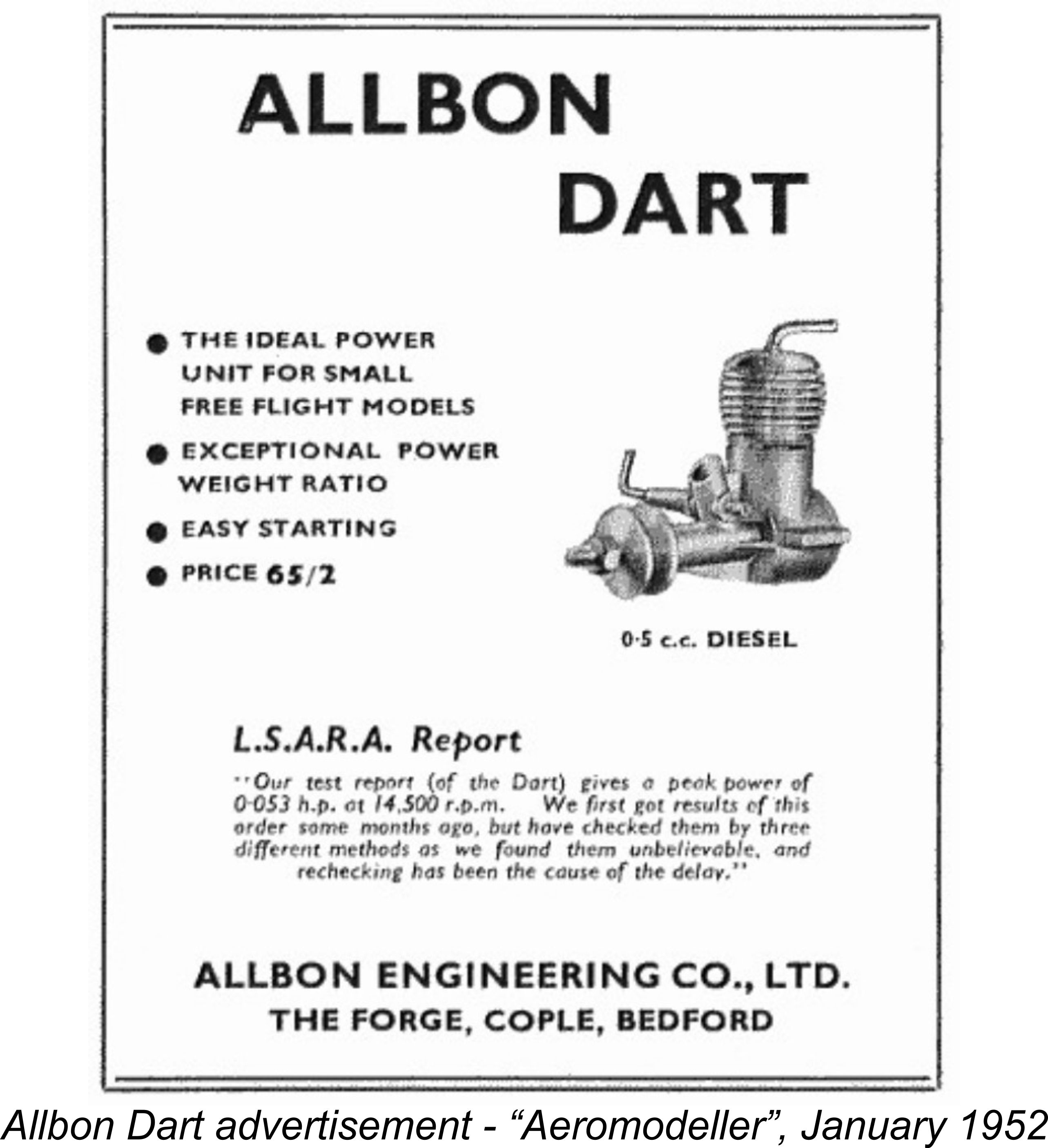

As if this wasn't enough, Alan Allbon also somehow managed to find time to continue his modelling activities as a member of the Bushy Park club which flew at the nearby Royal Park of that name. Try flying a power model at Bushy Park today ......... regardless, Allbon achieved some contest success, actually winning the free flight power competition at the 1950 West Essex Gala held at Fairlop Aerodrome near Ilford The development of the prototypes mentioned above appears to confirm that the overwhelming success of the Javelin had provided strong encouragement for Alan Allbon and Dennis Allen to begin looking ahead once more to the further expansion of the range. They were joined by future IMA chief engine designer George Fletcher at around this time - quite an array of talent under one roof! Fletcher had previously been working for D-C Ltd. at Barnoldswick in Lancashire. One gets the impression that Alan Allbon was staffing up to facilitate a considerable expansion of his company's activities, almost certainly involving a move to more spacious premises ............. The initial result of their joint deliberations was the October 1950 introduction of an all-time classic - the 0.55 cc Allbon Dart. The name of the new model preserved the Allbon tradition of naming their FRV models after various types of missile! Once again, the model engine testers of the day fell over themselves to praise the new product, the result being that Allbon Engineering suddenly found themselves with a far greater level of demand for their products than The examples of the Dart and other models that were manufactured at Sunbury may be distinguished today by the fact that they bore serial numbers. These numbers were hand-engraved on the underside of the crankcase. My own illustrated example bears the number 295. The highest such number reported to date for the Dart is reader Terry Chapman's engine number 506, and there may well have been even more than this. However, events were unfolding which would terminate production at Sunbury before the Dart had time to really get into its stride in sales terms. We’ll never know how the firm might have responded to the sudden massive overall increase in the demand for their engines created by the immediate success of the Dart combined with the ongoing demand for the Javelin, because another far more serious factor was about to cast a very long shadow over Allbon’s activities. This was the infamous purchase tax case, of which much more in the following section. The Purchase Tax Case and its Impact At the time when I wrote my original (and now frozen) article on the early years at Allbon, I had yet to make contact with the surviving members of the Allbon family. I was therefore unaware of the full circumstances surrounding Allbon's abandonment of his Sunbury-on-Thames workshop. Based on the information provided by Kenneth Allbon, we now know that this was far more complex than I had believed. The underlying factor was the infamous purchase tax case. To understand the issue of the purchase tax case and its impact upon Allbon’s fortunes, we have to go back to April 1948, at which time Allbon was just getting started as a model engine manufacturer. Prior to that date, the Government of the day had been undertaking a review of the application of purchase tax to various classes of goods manufactured in Britain. In April 1948 the Commissioners of Customs & Excise announced their decision with respect to modelling goods. Up to that point in time, kits and accessories of a constructional nature had been classified under "Toys and Games", a category of products considered to have some educational value and hence being exempt from purchase tax. The Government announcement in April 1948 stated that thenceforth model aircraft parts and accessories, including "power units of all kinds" would be classified as "Amusements" under the Purchase Tax Schedules, thereby discounting any educational value and making them subject to taxation. This change in policy had the immediate effect of imposing a whopping 331/3% purchase tax upon modelling goods of all kinds. The tax was calculated not on the retail price but on the manufacturer's wholesale price, presumably making them primarily responsible for collection, reporting and payment. Generously, nuts and bolts were exempt! Manufacturers now had only two choices, neither of them palatable - they could absorb the tax themselves, thus further eroding an already marginal profit picture, or they could pass the tax on to their customers in the form of dramatically increased over-the-counter prices. The first course would significantly reduce any financial incentive to continue in the model manufacturing business. As for the second course, such a drastic increase in retail prices would be bad news indeed in the context of the cash-starved post-war British economy given the inescapable fact that the model trade relied totally upon the discretionary spending capacity of its customers.

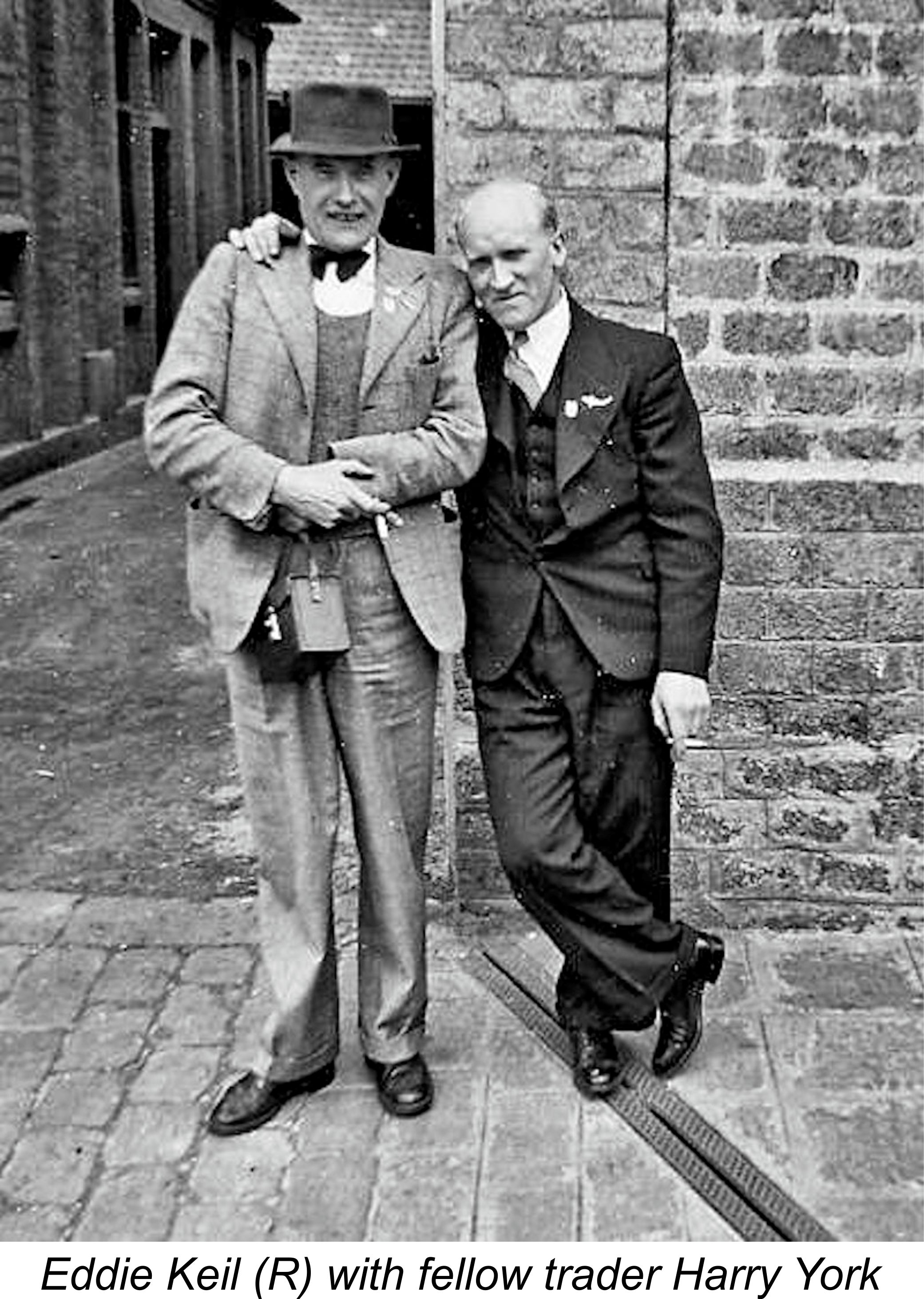

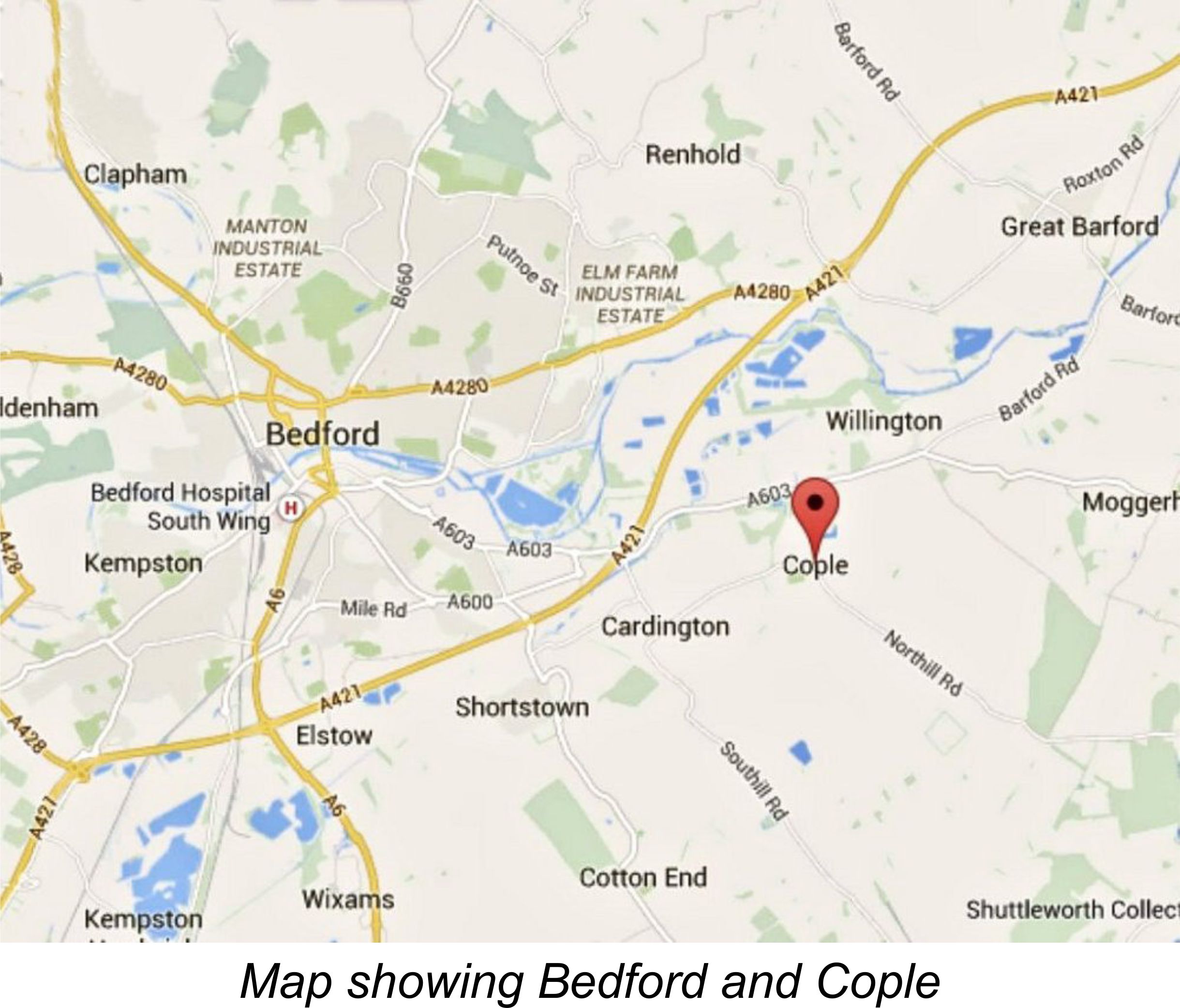

To fight this Government decision, the model trade leadership banded together to form a sub-committee comprising Eddie Keil (KeilKraft), Jack Ballard (E.D.), Arnold L. Hardinge (Mills Bros.) and Alan Allbon’s associate Henry J. Nicholls (Mercury Model Supplies Ltd.). The sub-committee received legal advice to the effect that a challenge stood a good chance of success and that the best strategy would accordingly be for at least one of their members to withhold the payment of purchase tax, thus forcing the raising of a test case by the Government. Eddie Keil volunteered his company, E. Keil & Co. Ltd., to act in the recommended manner. In the event, it appears that a number of other model trade participants rolled the dice by adopting this course also, one of them being Allbon Engineering. Primarily at the instigation of Eddie Keil, trade participation in the effort to reverse the tax decision was coordinated through the formation of a new organization called It’s not known whether or not Allbon Engineering joined this group. Certainly, they never displayed the Federation's logo on their advettisements, unlike both E.D. and Yulon. However, it's likely that they were in fact members, since their distributor Henry J. Nicholls was centrally involved in the Federation's efforts. It's difficult to see how Alan Allbon could have stood aside from the issue, particularly given his financial stake in the outcome of the test case. Be that as it may, the FMAMW took up the test case on behalf of its members and the model trade in general. As agreed by the sub-committee, E. Keil & Co. Ltd. were named as the defendants of record, with the Commissioners of Customs & Excise as plaintiffs. Based upon legal advice received, it was widely anticipated that the test case would result in the handing down of a favorable decision on the tax issue by the Court. Such a decision was expected to be backdated to January 1, 1949. Nevertheless, prudence would appear to have dictated that adequate provision be made by potentially affected parties to address the financial consequences of an adverse decision. Unfortunately as things turned out, many did not. One such firm was Allbon Engineering. The test case dragged on for the better part of two years, finally ending on October 23rd, 1950 with the court quite unexpectedly upholding the Government position. To add insult to injury, the court re-instated the tax on kits along with the rest of the taxable modelling goods. As a result, British model engine and kit manufacturers approached 1951 facing either a whopping bite out of future profits, which were already very much on the marginal side by normal precision engineering standards, or the imposition of a massive price increase which would doubtless drive many customers away. They also faced a major book-keeping headache. Worse yet, those firms which had joined E. Keil & Co. in not paying taxes while the test case was before the courts now faced a very substantial government bill for two years' worth of unpaid back taxes. Ouch .....!! Sadly, Alan Allbon was one of those who had not made adequate provision for the payment of back taxes in the event of this outcome. The consequent impact upon his financial situation was both disastrous and immediate. The tax bill that was presented to Allbon Engineering by the Government immediately following the failure of the test case was of such magnitude that in late 1950 Allbon was forced to sell his house in Sunbury to cover the bill. This of course was a disaster for the family. Kenneth Allbon has told us that in the short term the family moved into rented accommodation on Nursery Road in Sunbury, some distance to the north-west of the Thames Street workshop. In Kenneth’s recollection, this situation quite understandably created considerable tension between Alan Allbon and his wife Elsie, to the extent that Allbon apparently lived separately for a time at the Thames Street workshop while trying to maintain some level of production and hence income. It’s pleasant to be able to record that he and Elsie did eventually reconcile and move on from this episode. As far as Kenneth could recall in 2014, his father continued to work at Thames Street for a time while living there, but was soon forced to surrender that property as well along with some of his machine tooling in order to get clear of his tax bill. This effectively ended the production of the serial-numbered versions of the Dart just as the engine was getting into its stride in sales terms. It was probably in production at Sunbury for only two or three months at most. The Javelin and Arrow were of course similarly affected. Crucially, Allbon seems to have retained ownership of some of his key machinery and tooling despite this setback. Once production at Thames Street ended, Allbon was left without an income, hence lacking the financial means to purchase or even continue to rent a replacement home for his family. Moreover, he no longer had any business premises which tied him to remaining in Sunbury. These circumstances forced him to return with his family to Bedford in early 1951 to live with his wife’s parents. Although imposed upon the family by circumstances, this cannot have been a comfortable situation for anyone involved. However, Alan Allbon appears to have been nothing if not resilient. We saw in the case of the Allbon Arrow that he was not a man to allow a set-back to get the better of him! He immediately began to explore options for re-establishing his business in the Bedford area. After all, he had a very successful product line in the form of the Allbon Dart and Javelin. He also had the assets of the machinery, dies and tooling that he had been able to salvage from the tax disaster. There was far too much commercial potential in these assets to simply walk away from the opportunity that they represented. It’s interesting to note that Allbon understandably went to some lengths to keep the details of his predicament out of the modelling media. It can’t be doubted that the enforced termination of production at Sunbury must have created an immediate backlog of orders for the very popular Dart and Javelin models. This situation could not have escaped the notice of either the model trade or the aeromodelling community at large, hence obviously requiring some kind of explanation for public consumption. An announcement in the “Over the Counter” feature of the April 1951 issue of “Model Aircraft” (clearly written some time previously to met Editorial deadlines) confirmed that Allbon Engineering had been compelled to temporarily suspend production. However, the reason for this was given as a need to move to “larger premises”, thus putting a positive public relations spin on the situation. The announcement went on to state that “with improved facilities they will be producing more motors as from March and should soon catch up with any backlog of orders”. This of course confirmed that such a backlog had quickly developed as a result of the enforced closure of the Sunbury workshop. There can be little doubt that the sharp increase in production pressure resulting from the immediate success of the Dart would have required Allbon to make other production arrangements in any case. However, the insertion of the purchase tax issue into the broader picture undoubtedly constrained his options very severely. Indeed, it’s likely that this situation had a dramatic effect upon the course of Allbon’s entire subsequent career, as we shall see in the following sections of this article. The Cople Interlude

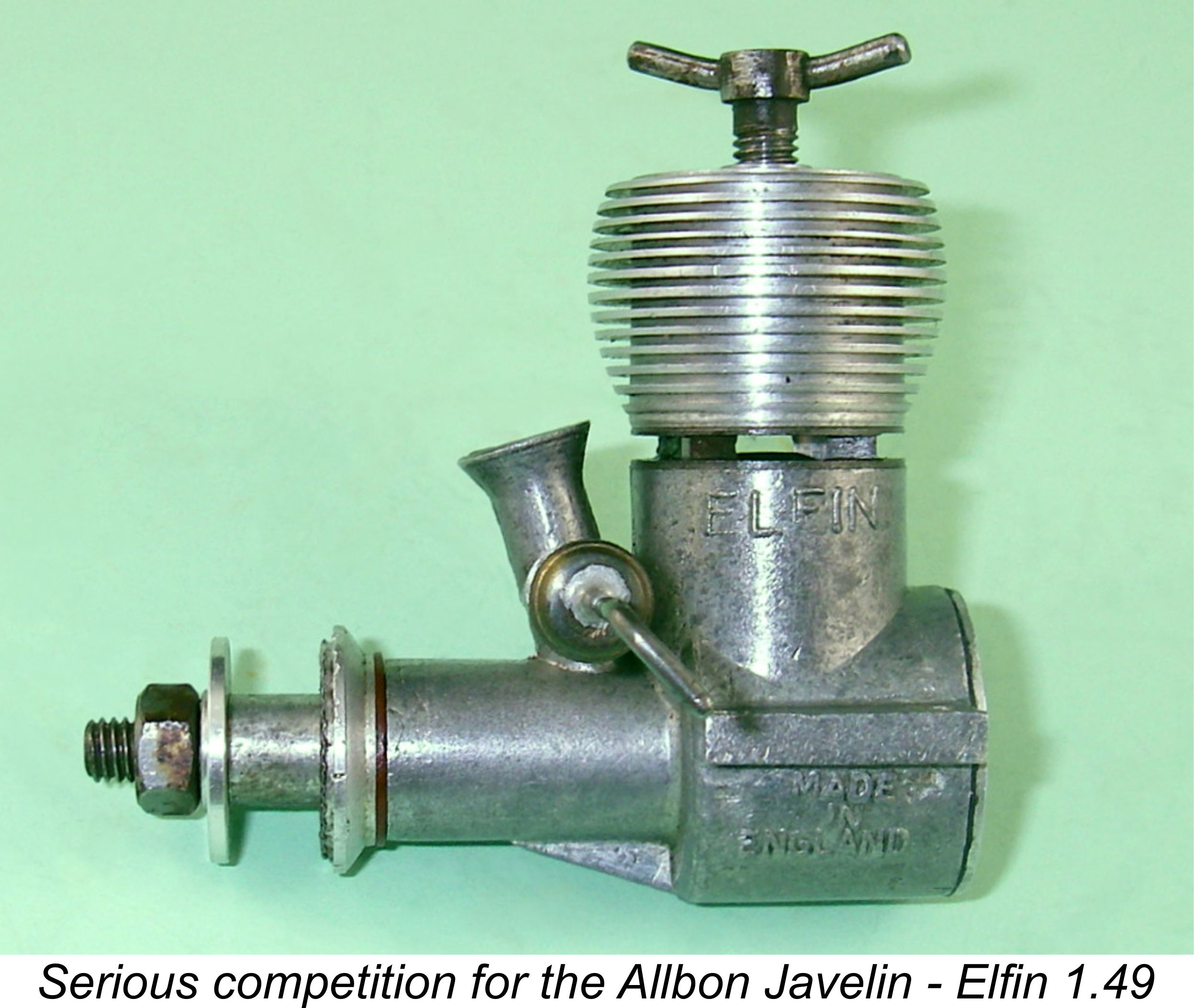

Although somewhat rudimentary, the old forge structure provided sufficient space to set up the limited machine tooling which Allbon had been able to salvage from the tax disaster. After a transition period of a few months during which no production took place, Allbon resumed work at the Cople location, albeit with a much reduced machine tool inventory and a far smaller staff. As far as Kenneth Allbon could recall, his father did much of the work himself, never having more than one or two assistants at the Cople location. So much for the “larger premises” and “improved facilities” to which the “Model Aircraft” article had referred! Still, Allbon was back in business remarkably quickly despite the purchase tax set-back. During this period, financial circumstances forced him to continue to live with his family at his in-laws’ residence in Bedford. Kenneth Allbon recalled that he commuted to Cople each day from Bedford by car. However, Allbon had simply exchanged one problem for another. He had a couple of model engine designs which were in great demand - in fact, the market could absorb many more than he could make. The trouble was that using the diminished resources at the Cople location, he simply couldn’t make that many! It’s an interesting indication of the production pressures under which Allbon was working at this time that the practise of applying serial numbers to his engines appears to have ended with the relocation to Cople. This almost certainly reflected a need to cut manufacturing time and effort to the bone. The examples of the Dart produced at Cople were essentially identical to those manufactured at Sunbury apart from the omission of serial numbers, which eliminated one manufacturing step. The unnumbered Even with the elimination of the Arrow from the ongoing production program, deliveries of the Dart and Javelin still fell well short of meeting demand, forcing many prospective buyers to go looking for alternatives. For a manufacturer wishing to retain a leading position in the model engine field, Allbon’s inability to meet demand was not a good situation - nothing that forces potential buyers to look elsewhere can be viewed positively. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that viable alternatives were now readily available to those who found themselves unable to acquire an Allbon product. In the 1.5 cc category, the Javelin already faced stiff competition from the very successful 1950 Elfin 1.49 PB model from Liverpool. Although Things were even worse in the ½ cc displacement category. Noting the success of the Dart, and perhaps sensing that Allbon was not then in a position to meet demand, no fewer than three other competing manufacturers (Aerol Engineering (Elfin), IMA (FROG) and E.D.) quickly followed Allbon's lead by developing ½ cc Given his highly compromised financial capacity at this time, Allbon’s options in the face of this unsatisfactory situation were very limited. The chief constraint was his lack of the necessary capital to make a further personal investment in expanded production facilities, which would have allowed him to meet demand while retaining full ownership and control of the business. It’s likely that he would have pursued this course either at Sunbury or elsewhere if the purchase tax crisis had not intervened. As matters stood, Allbon was left with only two remaining alternatives. On the one hand, he could seek an outside investor who would put up the required additional funding at the cost of the surrender of Allbon's autonomy in terms of controlling the future of the business. On the other hand, he could enter into some form of working arrangement with an established precision engineering firm which might be willing to take on the task of producing his engines at levels which would match demand. The latter approach would at least allow Allbon to retain control over the evolution of the Allbon range.

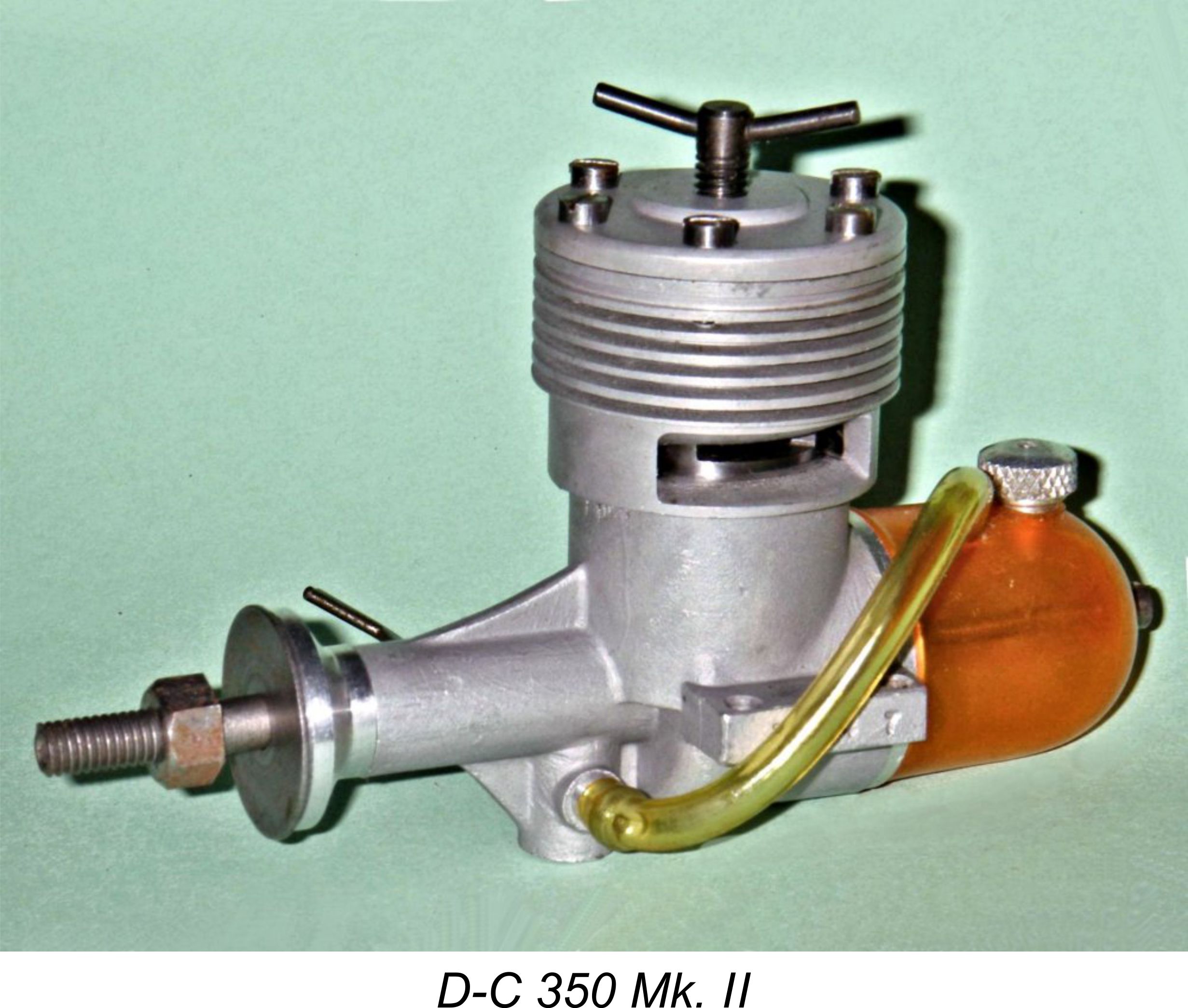

Davies-Charlton were very experienced and capable model engine manufacturers, having been in the business themselves since 1947. Moreover, at the time in question they were not in direct competition with Allbon since their very limited model engine range was confined to a pair of 3.5 cc models which did not correspond to the displacement of any Allbon products. One of the main reasons for the very limited scope of the D-C range during this period was the fact that Hefin Davies’ time was increasingly being diverted away from the model engines which were always his first love towards the very lucrative high-tech sub-contract work for Rolls-Royce and others which formed the mainstay of Davies-Charlton's growing business at the time. The fact that D-C Ltd. appears to have been largely unaffected by the outcome of the purchase tax test case in late 1950 may well have been due to the model engine side representing more of a minor sideline than anything else at this time. It’s also likely that the company’s growing income from sources other than model engine manufacture had placed Davies in a position to make financial provision for an unfavorable outcome of the test case. Whatever the reason, D-C Ltd. remained very much in the model engine business as of 1951, albeit with a far smaller range than Davies would have liked. Whatever his apparent personality flaws (of which more below), Davies was unquestionably a genuine model engine enthusiast at heart. If a way could be found to allow the expansion of D-C Ltd.’s model engine manufacturing activities without deflecting Davies away from his lucrative sub-contract work, no-one would be better pleased than he! Accordingly, Davies was doubtless very much open to the concept of what would amount to a merger with Allbon on the model engine side. The ability to tap into the expertise of an experienced model engine designer and manufacturer like Allbon would allow the development of the new model engine designs which Davies wished to market but lacked the time to develop himself. The ensuing discussions between Allbon and Davies clearly proceeded well enough that some kind of agreement was eventually reached. At this stage, the agreement seems to have been purely contractual. Although the specific terms are not known, it appears from what followed that the original agreement covered only the manufacture of the Dart by Davies-Charlton. Like the true reason for Allbon’s abandonment of his Sunbury facilities, this agreement was kept very much under wraps at this stage, at least as far as the modelling public was concerned. The sole indication of a major change in the wind was a further temporary period of non-availability of the Allbon range in the latter part of 1951 - the second such occurrence in less than a year. This was mentioned in several contemporary model trade listings in the modelling media, more or less in passing. It seems certain that this represented a late 1951 hiatus in production separating Allbon’s abandonment of Dart production at Cople from Davies-Charlton’s commencement of Dart manufacture at Barnoldswick.

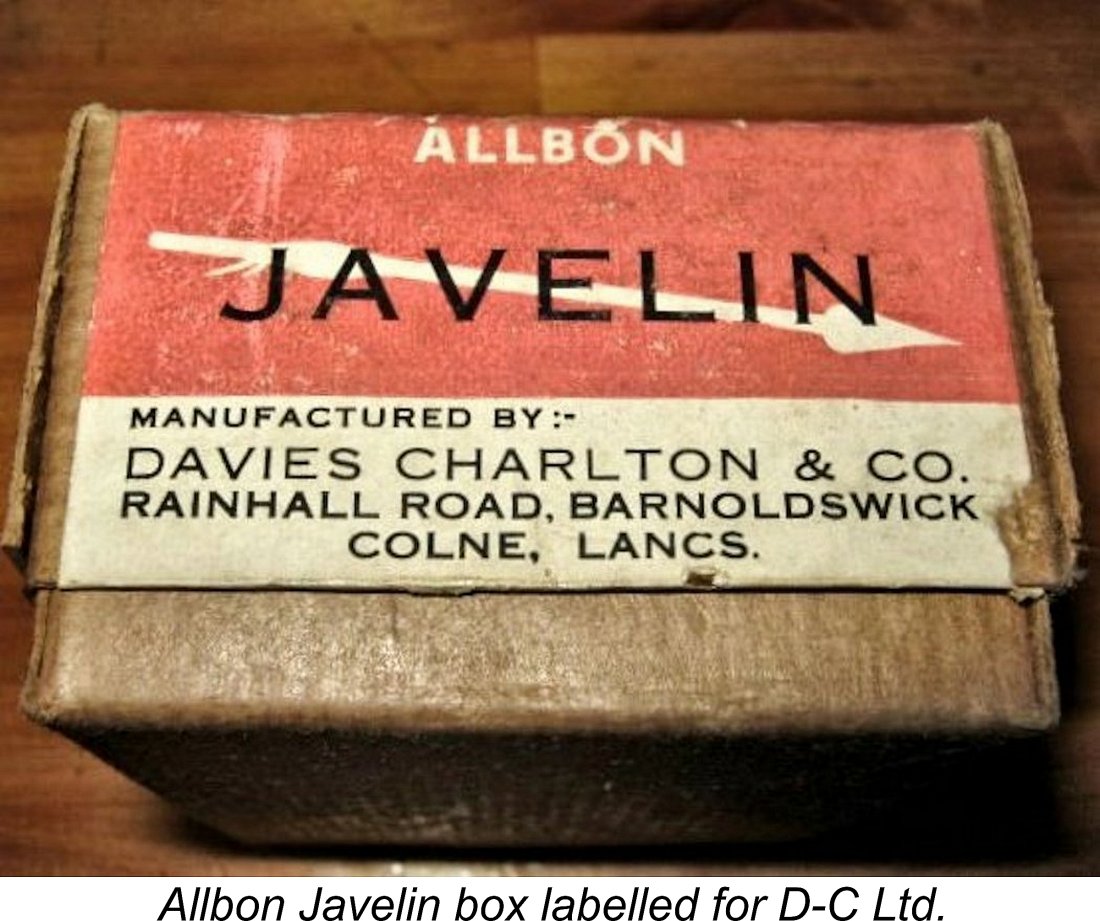

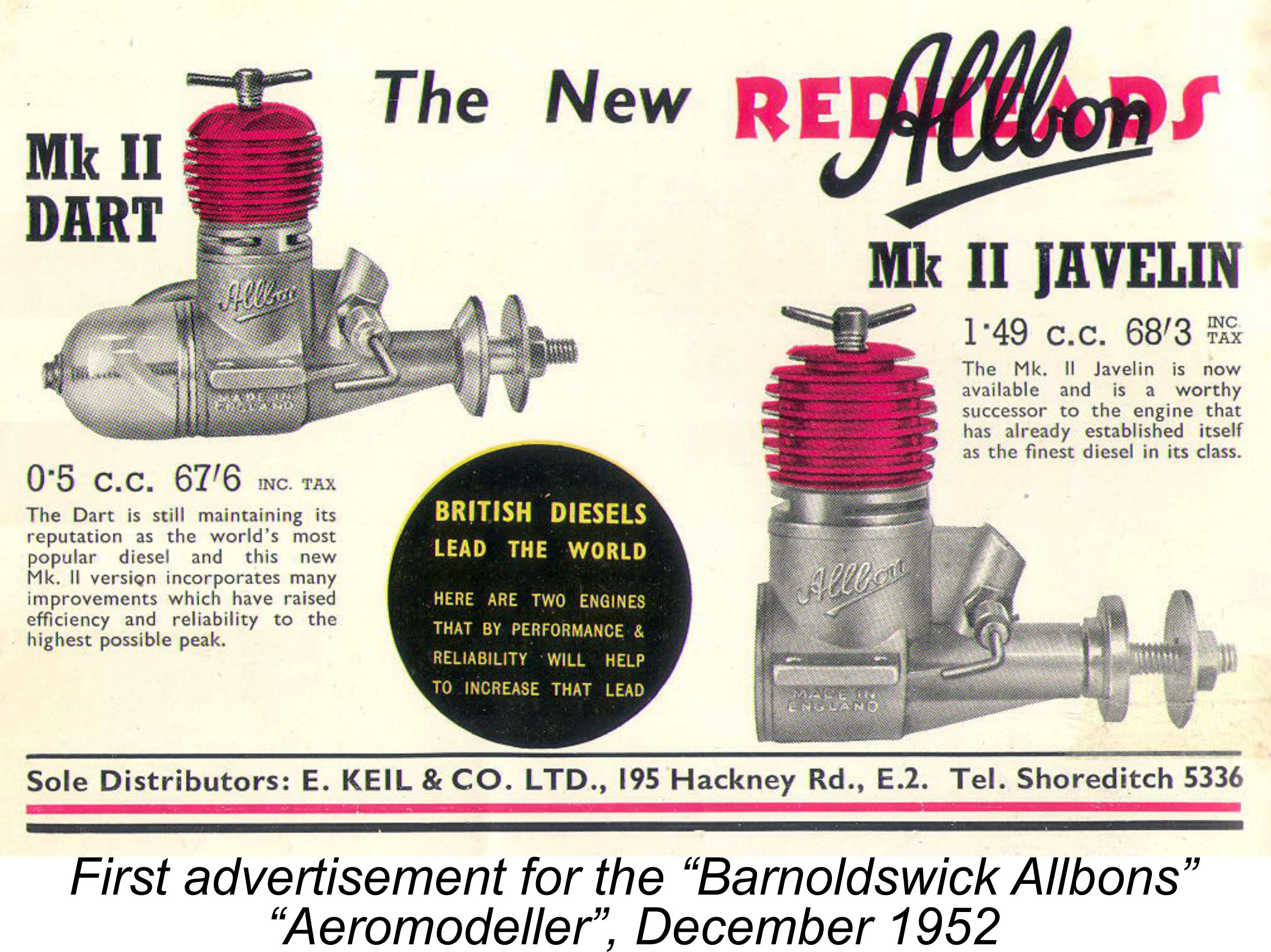

The fact that the Dart was the only advertised Allbon model during most of 1952 would seem at first sight to imply that the manufacture of both the Mk. I Javelin and the Arrow had been suspended. New Old Stock examples of both the Javelin Mk. I and the Arrow which had been manufactured by Allbon Engineering remained available from specific retailers during this period, but there's little or no doubt that the production of the somewhat lacklustre Arrow was never resumed following the wind-up of Allbon's Cople operation. However, the same does not seem to be true of the Javelin Mk. I. Australian reader Bob Allan has kindly provided irrefutable evidence for the fact that at least some examples of the Javelin Mk. I were manufactured by D-C Ltd. at Barnoldswick. This evidence takes the form of a Mk. I Javelin box which expressly states that the manufacturer was D-C Ltd. It would appear that as the stock of Mk. I Javelins which had been manufactured at Cople ran out, Allbon understandably wished to maintain some level of supply for that very popular model, hence contracting with D-C Ltd. for the manufacture of an unknown number of examples of the Javelin at Barnoldswick.

The fact that the two companies continued to advertise independently clearly implies that at this stage no actual merger had taken place. In all probability, Allbon had taken advantage of Davies-Charlton's well-known willingness to undertake contract work for others by simply contracting out the manufacture of the Dart to Davies-Charlton on a trial basis. Hence the relationship at this stage was probably purely contractual. This arrangement must have worked out well for both parties, since the next step towards a full merger was the combination of the distribution arrangements for the Allbon and Davies-Charlton ranges. This was a logical move given the fact that the Dart was in reality being manufactured by Davies-Charlton despite Allbon's ongoing reluctance to openly admit this fact. By mid 1952, Allbon's advertisements were confirming that the distribution (as opposed to the manufacturing) of the Dart had been taken over by Davies-Charlton, although Allbon still continued to advertise separately from his Cople location and still stopped short of crediting Davies-Charlton with the manufacture of the Dart. Allbon was still advertising the Dart independently from his business address at Cople in October of 1952, but the distribution of both the Allbon and Davies-Charlton ranges had by then been taken over by E. Keil & Co. This arrangement was to continue for some time following the completion of the merger.

The end result of all this was that manufacture of the Allbon engines by that name was now openly consolidated at Davies-Charlton's Barnoldswick plant in Lancashire along with that of the continuing Davies-Charlton models. This marked the beginning of a seven-year hiatus in Alan Allbon's career as an independent model engine manufacturer.

Returning now to late 1952, it’s readily apparent that on the surface this merger conferred clear benefits upon both parties. Hefin Davies was now free to put most of his energies into leading the doubtless-lucrative contract work for Rolls Royce and others which was a mainstay of Davies-Charlton's then-current business plan. For his part, Allbon assumed primary responsibility for the subsidiary model engine development and manufacturing programs. The arrangement neatly solved both Allbon's production and financial problems, allowing the development and expansion of the Allbon range at production levels which could be tailored to meet demand. However, the question of Allbon's remuneration remains on the table - he had to pay the family bills! Neither Kenneth nor Derek Allbon (who were still at school during this period) retained any knowledge regarding the terms of the agreement between their father and Hefin Davies. What is known for certain from other sources is that Allbon’s name was never added to the registered company title, implying that the arrangement had some basis other than joint ownership. After the initial appearance of this article on MEN, Mrs. Christina ("Chris") Crosby was kind enough to contact us to share some memories. Chris was employed at Davies-Charlton as a clerk/typist and general factotum to Hefin Davies from early 1953 until his departure for the Isle of Man (IOM) in 1955, thus working in the office during the entire period of Alan Allbon's presence in Barnoldswick. Among other things, Chris was responsible for maintaining the company's wage records. It’s undoubtedly significant that she did not recall ever preparing or even seeing any wage/salary statements for Alan Allbon while she was employed at Davies-Charlton, although she was very familiar with his name thanks to its appearance on the engines. This implies that his remuneration must have taken the form of some kind of periodic dividend or royalty payment. Reader Marcus Tidmarsh considered these circumstances and applied his own considerable business experience to the development of what I find to be a highly convincing interpretation of the circumstances. The key clue to what may have transpired is the recorded fact that in early 1953 the name of the company was changed from Davies-Charlton & Co. to Davies-Charlton Ltd. Marcus pointed out that the legal effect of this would have been to transfer ownership of the company from a single named individual (presumably Davies) to a group of shareholders having limited liability. It seems highly likely (albeit not conclusively proven) that this was how Alan Allbon was brought on board without becoming an employee or drawing a salary - he would have been made a shareholder and would be paid for any work that he did both through dividends based on his share holdings and through any increases in the value of his shares. If the company did well, so did Alan, in theory at least. It's entirely possible that future M.E. manufacturer Walter Kendall was similarly favored in recognition of his work for the company beginning in 1947. Unfortunately for Alan, it's abundantly clear that Davies fit the image of the ruthless hard-nosed businessman far better than his new associate did! Marcus suggested that matters probably went somewhat along the lines of Davies agreeing to convert D-C into a limited company and to assign an agreed value of shares to Allbon, telling him that he would thus receive a share of D-C Ltd.'s profits without having to pay national insurance, etc., since he wouldn't be a salaried employee. This may well have been the carrot dangled in front of Allbon - in addition to solving both his production problems and financial difficulties, he became a shareholder in the very successful company in whose interest he would thenceforth be working. Doubtless an attractive proposition! For his part, Allbon agreed to continue to design engines for D-C Ltd. and also to act as works manager on the shop floor, with the expected dividends being his source of income. What may have caught Allbon out was the fact that Davies undoubtedly retained control of the company, hence being in a position to regulate the scale of share dividends regardless of the profits being made. However, he may have omitted to mention this fact to Allbon during their negotiations! It may well have been his putting a financial squeeze on Allbon (and perhaps on Kendall) by exercising tight control over his dividend income that was a major cause of the progressive breakdown of the relationship between the individuals concerned. Quite apart from the above possibility, it's readily apparent that Allbon and Davies had very different personalities which were bound to come into conflict sooner or later. Allbon may have realized fairly early on that he had merely exchanged one set of problems for another. But before we look into the way in which these problems played out, it’s necessary to finally clear up a mystery which has been the subject of a good deal of speculation over the years – the involvement or otherwise of an individual named Charlton. Allbon or Charlton? We are very fortunate indeed that Mrs. Christina “Chris” Crosby, Hefin Davies’ former secretary, was good enough to share her reminiscences of her time at Davies-Charlton, which more or less exactly coincided with the period from late 1952 through mid 1955 during which Alan Allbon also worked at Barnoldswick. One matter regarding which Chris shared her personal recollections was the much-debated issue of the existence or otherwise of a Mr. Charlton as a partner in the Davies-Charlton enterprise. Chris iadvised that in her recollection there was indeed a Mr. Charlton (first name not recalled), a fact which had never been previously asserted from a position of first-hand knowledge. Chris’s stated understanding was that like Hefin Davies, Charlton was a former Rolls-Royce employee who left that company in 1947 to join Davies in starting the Davies-Charlton enterprise which was to make their fortunes. I may as well say right up front that she may well have been confusing "Charlton" with Davies' former Rolls-Royce colleague Walter Kendall, who undoutedly did leave Rolls-Royce in 1947 to work with Davies. Now it gets a bit weird!! Chris claimed to have no recollection of ever meeting Alan Allbon despite the fact that he was undoubtedly working at Davies-Charlton during almost her entire time there. She was of course familiar with Allbon’s name from its appearance on the engines which they were then manufacturing, but could not recall ever seeing him at the company offices where she worked. However, she did recall seeing Charlton on a number of occasions, characterizing him as a "quiet, studious and gentle man", in direct contrast to the somewhat volatile Hefin Davies. In her recollection, Charlton kept a very low profile while collaborating with Davies on the design side and acting as works superintendent. He reportedly spent much of his time working in the design office, which Chris recalled as being located separately from the company's main Rainhall Road location in Barnoldswick. The amazingly low profile which Charlton (assuming he existed) somehow managed to maintain over an extended period of time has long been one of the enduring mysteries surrounding the history of the Davies-Charlton enterprise. I was expecting that Kenneth or Derek Allbon might be able to shed some light upon this elusive character, since if he was still an active participant in the company when their father worked there, as suggested by Chris Crosby, they must surely have encountered him. They certainly recalled encountering Hefin Davies in his capacity as their father’s business associate, so why not Charlton? However, neither Kenneth nor Derek could recall ever meeting anyone by the name of Charlton! Still hoping to settle this vexing matter once and for all, Geoff Peacock went so far as to return to Barnoldswick to speak with a number of older long-time residents, all of whom claimed to have heard of Charlton but never actually met him! In fact, the only person who has ever claimed to have actually met Charlton was Chris Crosby. In a relatively small and somewhat isolated community like Barnoldswick, it's really hard to imagine how Charlton could have remained so invisible to so many people for so long. At this point, it’s necessary to pause for a moment to review the implications of this odd situation. The fact that no-one apart from Chris Crosby seems to have had any direct contact with Charlton at any time has always been very difficult to accept. If he was an active participant in the Davies-Charlton enterprise during the mid ‘50’s, surely others would have met him? In particular, surely Alan Allbon would have had sufficient contact that his family would remember Charlton as well as they do Hefin Davies? After all, Allbon’s association with Davies-Charlton would have made Charlton his partner just as much as Davies. In fact, Chris’s story would make far more sense if the individual to whom she referred as Charlton was in fact Alan Allbon!! It seems quite possible that the passage of some 55 years might have been sufficient to re-arrange some of Chris’s memories. This is a hypothesis that warrants testing ………….. And indeed, as soon as we substitute Alan Allbon for Chris Crosby’s “Charlton”, the whole thing falls neatly into place! We know from Alan Allbon's two sons that Allbon was living and working in Barnoldswick more or less throughout the period of Chris’s employment there. In addition, we know that he was placed in charge of the model engine design program, also taking responsibility for overseeing the ongoing production of the engines. These are precisely the duties which Chris assigned to the mysterious “Charlton”! Allbon surely couldn’t have carried out these duties without spending at least some time at the office discussing design and production issues with Hefin Davies. This after all was what had motivated Davies to bring him on board in the first place. This being the case, surely Chris Crosby must have seen him in the office at some point, and more than once at that?!? It appears that in fact she did so, but somehow gained the impression that he was Charlton rather than Allbon! Chris’s description of “Charlton” as a “quiet, studious and gentle man” is completely consistent with what we now know of Alan Allbon’s character, as recorded earlier. "Charlton's" reported activities as Davies’ design collaborator and works superintendent are equally consistent with the roles that Allbon was undoubtedly brought on board to fulfill. This view also makes perfect sense of Chris’s additional comment to the effect that the company’s design/drawing office was maintained in separate premises on the outskirts of Barnoldswick, some distance from the main workshops and business offices which were located near the centre of town on Rainhall Road. This is surely a rather odd arrangement if the design office was in fact an element of the company's premises. Be that as it may, the design/drawing office is precisely where we would expect Alan Allbon to have spent much of his time. Chris recalled that “Charlton” spent most of his time at this location, away from the centre of the company’s activities (and perhaps away from the vagaries of Hefin Davies’ temperament!). Once again, if we substitute Alan Allbon for “Charlton”, this makes complete sense. Although Kenneth Allbon was certain that his father did not do his design work at home in Salterforth, Allbon may very well have done most of that work at a separate office near his home, away from the distractions of the main factory. This would place the design office on the outskirts of Barnoldswick, just as Chris Crosby recalled. If Allbon's relationship with D-C Ltd. was strictly that of a shareholder, as suggested earlier, then Allbon naturally remained free to set up his own design office at any location of his choosing. Taking all of these comments into account, the conclusion becomes almost inescapable that the “quiet, studious and gentle man” recalled by Chris Crosby as having a key role in the design program as well as the supervision of the manufacturing operations was none other than Alan Allbon! Any other view would imply that there were two individuals (Allbon and Charlton) having exactly the same responsibilities and personal characteristics! Moreover, one of them appeared periodically at the company offices, while the other was never seen there at any time. It’s really difficult to imagine such a situation being sustained over a period of years. Now that we know for sure that Allbon both lived and worked in Barnoldswick during the period of his association with Davies-Charlton, a fact which was not firmly established prior to my contacts with Geoff Peacock and Kenneth Allbon, I for one find this argument compelling. It’s no discredit to the 82 year old Chris Crosby that her recollections might have become a little blurred over half a century on - I have the same problem with memories which are far less old than that!! However, it seems to be the case that there has been some transference of identities in this instance. Which unfortunately brings us right back to the original questions which for a time I had believed to have been answered - was there a Charlton; what was his role; and (assuming that he really existed) why did no-one other than Chris Crosby ever actually see him? My new insights set out above force me to go back and review some of the previously-identified possibilities in light of the new information now available. One such possibility is that a person named Charlton really did exist and that Chris’s previously-stated understanding of Charlton’s role in helping to found the company in 1947 was substantially correct. However, he must have disappeared from the scene by 1952, since his name does not appear as an owner of Davies-Charlton & Co. If this is how it went, there’s a ready explanation for the seeming disappearance of Charlton from the scene at an early stage. Given Hefin Davies’ unquestionably difficult character as a colleague, it would be quite understandable if Charlton (assuming that he existed) quickly found himself unable to work with Davies and either got out or was bought out. No-one else seems to have managed to work collegially with Davies for more than a few years at a stretch - why should Charlton have been any different? It’s also possible that he remained involved but stepped aside and slipped into the role of a sleeping partner, as suggested by Derek Allbon. However, Kenneth Allbon came down firmly in support of the alternative possibility that Hefin Davies simply added the Charlton name to his own to impart a more “up-market” aura to the company name. Double-barreled names were a strong indication of elevated social stature in Britain during this era. There were a number of documented precedents for the creation of such company names out of thin air. In support of his views on this matter, Kenneth actually retained a very clear recollection of his mother commenting that the name “Davies-Charlton” was that of Hefin Davies’ own solely-owned company and that the additional name had been chosen by Davies, possibly from among those of his former associates at Rolls Royce, simply to move the company’s profile up-market. This hypothesis has always seemed eminently credible to me, to the extent that Chris Crosby’s affirmation of Charlton’s reality as a partner in the business actually took me very much by surprise. I suppose it’s also possible that someone named Charlton may have provided some financial assistance to Davies during the start-up phase in the form of a loan which Davies repaid early on without ever making Charlton a partner. In such a case, the use of the name would simply be a way of recognizing Charlton’s assistance, while also moving the company name up-market as a bonus. At this distance in time, we’re highly unlikely to uncover any evidence of such a transaction if it took place. As matters now stand in the light of Kenneth’s evidence, and unless someone comes forward with compelling evidence to the contrary, I personally believe that the mystery of “Mr. Charlton’s” reality or otherwise is solved - he was an “invention” on the part of Hefin Davies as opposed to being a partner in the business. Geoff Peacock need look no further!! Unhappy Times at Davies-Charlton As of late 1952 when Allbon moved to Barnoldswick and presumably became a shareholder, the Davies-Charlton enterprise was enjoying a boom. One of Hefin Davies’ primary ambitions upon leaving his former employment as a skilled toolmaker at Rolls-Royce’s Barnoldswick plant in 1946 to establish his own business had been to undertake sub-contract work for Rolls Royce on his own account rather than as an employee. In this he had been very successful, perhaps even exceeding his own expectations.

We have already seen that the result of this situation was that by 1952 the company’s ongoing involvement with sub-contract work for Rolls Royce and others had grown to the point at which it was taking up an increasingly disproportionate amount of Hefin Davies’ time. The fact that this was deflecting him away from the development of further new model aero engine designs was clearly not a situation which he relished – whatever else he may have been, Davies was unquestionably a genuine model engine enthusiast. He had managed to find time to maintain his own very limited model engine range, but that aspect of Davies-Charlton’s work had become very much a sideline by the time in question. It was doubtless his desire to increase the company’s involvement with model engines that had made Davies very receptive to the notion of joining forces with Alan Allbon. Over the years, there have been consistent reports from a number of independent sources to the effect that Hefin Davies was a very difficult man with whom (and for whom) to work, also having a notably parsimonious side to his nature. Generally speaking, the majority of former employees of the company who have shared their recollections with various researchers over the years have tended to remember Davies-Charlton as a somewhat unhappy work-place. The name of Hefin Davies invariably comes up in the context of such recollections.

Kenneth Allbon recalled that the relationship between Davies and his father began cordially enough. Had this not been the case, it’s most unlikely that Allbon would have consummated the merger in the first place. However, Davies was undoubtedly a very pushy individual with a short fuse who liked to be on top of everyone and everything at all times - all sources agree As time went on, Davies apparently displayed these aspects of his character to an ever-increasing extent in his dealings with Alan Allbon, quite possibly extending to his squeezing Alan financially through authorizing dividend payments which were less than expected. Kenneth recalled meeting him on several occasions during this period and taking an instant dislike to him due to his brash “in yer face” personality! A very direct contrast to the reported character of Alan Allbon, in fact. It's scarcely to be expected that two such divergent personalities would get along well. Over time, Davies’ bulldozer style and fiscal parsinomy began increasingly to grate upon the quiet and even-tempered Allbon. This did not prevent Allbon from fulfilling his side of whatever bargain had been struck by producing a number of very successful new designs for production by Davies-Charlton under the Allbon name. There were the previously-mentioned Mk. II versions of the Dart and Javelin which were announced in December 1952 as well as the Mk. I version of the 1 cc Spitfire, which appeared in June 1953 and became one of the all-time classic beginner’s engines.

Chris Crosby recalled that the management and staff at Davies-Charlton were very proud of this groundbreaking little model. Our previous article on the story of the Bambi may still be found on MEN. Also in 1954, Allbon began work on a design which was quite distinct from that of his previous models, with minimal production cost seemingly being the primary design objective. The defining characteristics of what was to become the “classic” Davies-Charlton small-engine design were sturdy and ultra-simple The first manifestation of this new design approach appeared in October 1954 in the shape of the instantly popular Allbon Merlin of 0.76 cc displacement. This was a very good engine to use - I certainly had a lot of fun with mine - but in many ways it represented a retrograde step from Allbon's earlier models in design terms. The very loose fit of the cylinder in the cooling jacket which compromised cylinder cooling was doubtless a consequence of the push for lower manufacturing cost, as was the design of the needle valve assembly. The push for lower costs almost certainly came from Hefin Davies, who was embarking on a price war with competing manufacturers at this time. British modellers were to pay dearly for this in later years. The Merlin was an immediate sales success, but behind the scenes all was far from well. Kenneth Allbon stated that Hefin Davies’ grating personality and ruthlessly opportunistic business attitude had led to an increasing degree of friction between him and Alan Allbon, with the result that by early 1955 the relationship between the two men had broken down completely. Given Allbon’s well-attested ability to get along with almost anyone, responsibility for this unhappy outcome must surely be laid firmly at Davies’ door. It only took just over two years .......... A recollection from this period which Alan Allbon shared years later with his then-colleague Bernie Bowler during the Allbon-Saunders era (see below) perhaps best typifies the yawning gulf between the respective approaches of the two men to their business. Alan recalled an occasion on which Davies became impatient with him as he was slowly working through an inspection of a batch of engines and was spending a lot of time on one in particular. "What's the problem, Alan?" asked Davies. "Well, this one is a bit low on compression, and I'm wondering why" replied Alan. Davies' retort?!? "We're selling engines, not f.....g compression - put it in the box!!" Thus it may well be imagined that as 1955 came around, Allbon found himself in an increasingly untenable situation. Fortuitously, the opportunity to escape from this predicament lay only just around the corner. Relocation to the Isle of Man The introduction of the very popular Allbon Merlin in October 1954 apparently created something of a crisis at Davies-Charlton Ltd. It would appear that the model engine production capacity of the company had been approaching its limit even prior to this event, and the immediate demand which developed for the Merlin was apparently the final straw. The development of new production facilities had now become an urgent necessity. Fortuitously enough, this requirement coincided with a series of initiatives on the part of the government of the Isle of Man (IOM) to attract industry to the Island. Politically speaking, the IOM is something of an anomaly - it is part of the British Isles but is not part of the United Kingdom, having its own laws and government under the ultimate authority of the British Crown. It is in fact legally defined as a self-governing British Crown Dependency.

This was one of the instances in which Davies displayed what former long-time D-C employee Arthur Firth characterized as his “utter ruthlessness”. He had built up a valuable company as a result of the dedicated work and skill of his employees in Barnoldswick, who might have expected him to show some loyalty towards them in return. However, the deal with the IOM government expressly stipulated that their support for the venture was conditional upon Davies providing work for existing IOM residents rather than bringing his own experienced workforce to the Island. The fact that he would have to cast adrift many of the very workers who had loyally contributed to his success presented no dilemma for Davies – he jumped at the opportunity without a backward glance. Under the terms of the agreement with the IOM government, Davies was allowed to bring only three of his experienced shop floor workers with him. One of these was Arthur Firth, who was seen as an indispensable member of the D-C workforce on account of his expertise at cylinder honing. Three IOM residents were sent over to Barnoldswick in advance of the move to receive training from the very workers whom they were going to displace. It may well be imagined that D-C Ltd. was a rather unhappy workplace during this period. Despite such shenanigans, the move was duly completed by June 1955. All subsequent Davies-Charlton model engines, including the Allbon designs, were manufactured at the new location. It might appear at first sight that this move would have rendered Davies-Charlton’s ongoing contract work for Rolls Royce somewhat problematic from a logistical standpoint given the fact that the two companies were no longer co-located. However, it turns out that the Barnoldswick plant remained in operation with a reduced workforce for some years after the move, presumably to facilitate the ongoing sub-contract work for Rolls Royce. It was also later used for a time as a centre for the production of the model engine fuels marketed by Davies-Charlton.

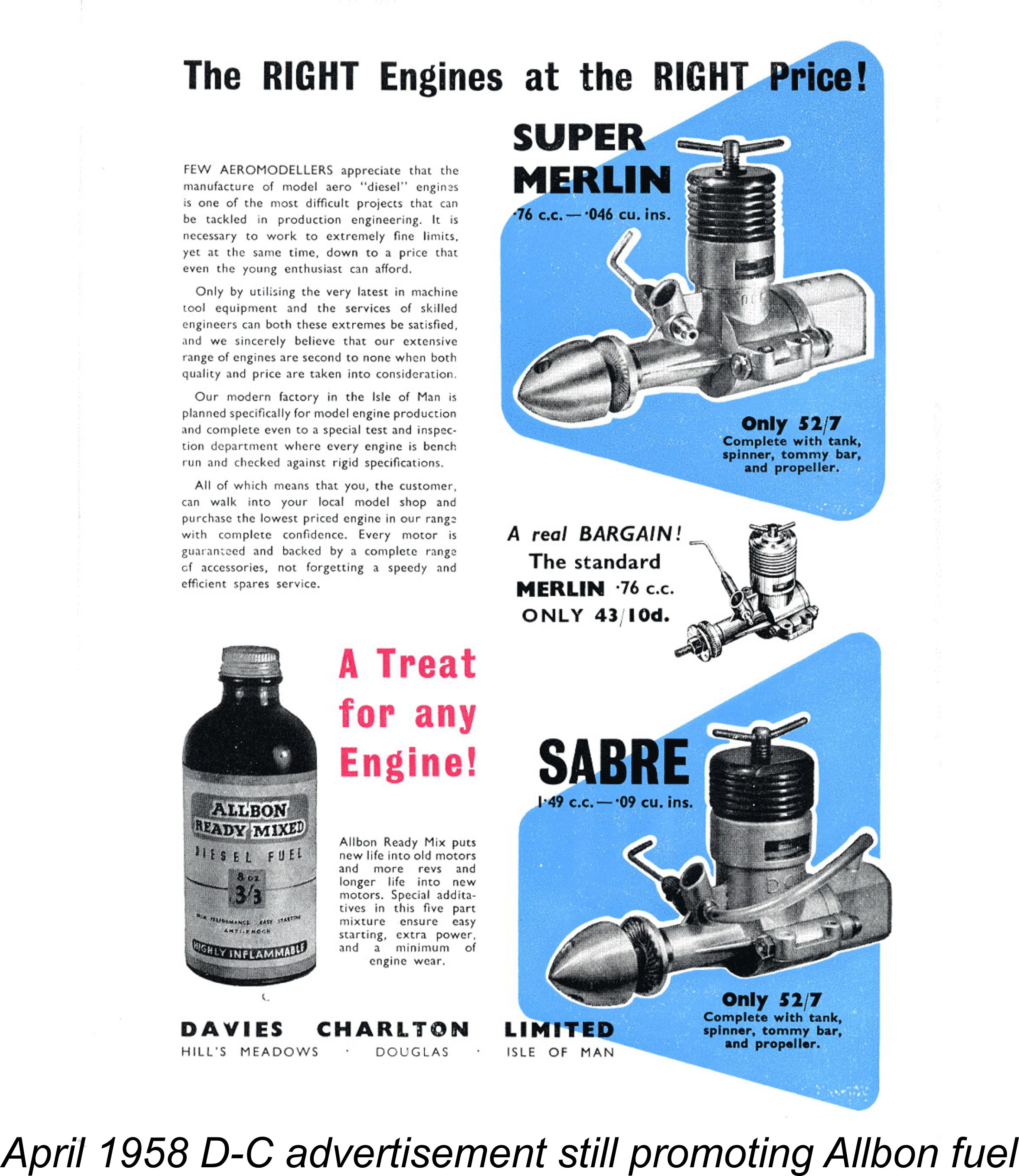

One such company was Marown Engineering, which was founded in the late 1950's by none other than Hefin Davies' former associate Walter Kendall. This firm and its successor Moore Enginering were to provide serious competition to D-C Ltd. in the form of their M.E. diesel range. Reading between the lines, it's hard to avoid recognizing the possibility that some degree of friction may have developed between Davies and Kendall and that the 1960 introduction of the M.E. range was a way of "getting back" at Davies ........... however, there's no hard evidence one way or the other. Returning to 1955, Alan Allbon had made the move to the IOM along with Davies and the three transferred workers from Barnoldswick. However, there's no question at all that by this time he definitely wanted out - both his personality rift with Davies and the latter's probable squeezing of Allbon financially made this inevitable. Allbon was doubtless keenly aware of the desire of the Manx government to encourage the development of high-tech industry on the Island. Kenneth Allbon did not know at whose instigation this came about, but confirmed that immediately following the move to the IOM, the Manx government offered Alan Allbon the independent use of a vacant factory located in Douglas on the condition that he provide employment for a certain number of Manx residents. Given the irreparable breakdown of his relationship with Davies, Allbon was more than happy to accept this offer. It's actually not unlikely that Allbon commenced the negotiations leading to this offer even before the move to the IOM was accomplished, otherwise it's hard to see why he would have gone along with the move at all as matters stood. It was accordingly at this point in mid 1955, far earlier than had previously been believed, that Allbon formally ended his direct working association with Davies-Charlton Ltd., setting up his own independent operation at the Douglas facility. During the following four-year period, Allbon and his family lived in Laxey, some eight miles to the north of Douglas. Score up yet another family move ………the fourth in five years. According to Bernie Bowler, Alan Allbon's later business partner and ultimately successor, Alan was replaced as works manager at D-C Ltd. by a certain Ted Saunders, of whom we shall hear much more later on. Although he lacked Alan Allbon's engineering expertise, Saunders had apparently managed a team of unskilled munitions assembly workers during WW2, hence having some relevant management experience to bring to this position. The precise point in time at which Saunders joined D-C Ltd. is now unknown. Alan Allbon’s new venture had nothing to do with model engines - instead, he took on a variety of government sub-contract work, in common with many of the other small-scale industries which had been attracted to the IOM by this time. Kenneth Allbon recalled that his father employed some four or five men during this period, thus fulfilling his commitmnt to the IOM government. Following Allbon's departure, Hefin Davies continued to develop and market additional expressions of the basic Allbon design which had been introduced in 1954 with the Merlin. These took the form of the 0.76 cc Allbon Super Merlin (July 1955), the 1.5 cc Allbon Sabre (November 1955) and the 1 cc Allbon Spitfire Mk. II (February 1957). It's important to note that Alan Allbon had left the company prior to the release of these models. It's highly unclear whether or not Allbon's engineering sensibilities would have allowed him to approve the upsizing of the basic Merlin design without significant design improvements, particularly in the 1.5 cc Sabre with its ridiculously heavy piston and undernourished crankshaft and conrod. It's hard to envision Alan Allbon coming up with that design!

Surviving members of the Allbon family contend that Davies had no legal right to continue to do this without Alan Allbon’s agreement and without compensation given the fact that the association of the two men had effectively ended. However, as far as Kenneth and Derek are aware based on discussions with their father, Allbon was never compensated in any way either for Davies’ continued marketing of his engine designs (which continued past Davies’ death in 1980) nor the ongoing use of the Allbon name for promotional purposes, which the record proves to have continued well into 1958, some three years after the end of their association. No doubt surviving members of the Davies family would tell a different version of this story. If any of them read this article, they are hereby cordially invited to do so for the record - I am reporting these assertions entirely without prejudice and will gladly publish any further insights received from that side of the issue! In fairness to Davies, I must record my own view that D-C Ltd.'s right to the use of the Allbon name may well have formed part of the now-lost agreement by which Allbon became a shareholder in early 1953. If that was the case, Alan's departure in 1955 to run his own show would not have upset any such agreement - he would still be a D-C shareholder. I think it to be far more likely that the Allbon family's very negative recollections have more to do with Davies characteristically putting the financial squeeze on Alan through less-than-anticipated divident payments despite D-C Ltd.'s ongoing success, much of which was due to Alan's efforts. Whatever the truth, it's clear from my personal interactions with them that this behaviour left some lasting scars among members of the Allbon family – I can confirm from my personal interactions with them that Kenneth and Derek Allbon both still bore those scars decades after the event. Derek went so far as to characterize Davies as “a bit of a shyster who ripped my father off mercilessly through their “partnership”! Ouch………Derek’s feelings were clearly based upon long-ago discussions with his father. There is some documentary evidence to suggest that Allbon may in fact have attempted to recover what he saw as money owed to him by Davies. This takes the form of an otherwise very puzzling series of actions by Davies beginning in early 1958. In a nutshell, he initiated a series of company dissolutions and re-registrations which were not publicised and which are rather difficult to explain. A search of IOM corporate records by Marcus Tidmarsh showed that until January 1958 D-C Ltd. retained its British company registration by that name, hence being listed in IOM records as a “foreign company” operating in the IOM. We would not expect otherwise in normal circumstances – there would be no reason to change. However, on January 25th, 1958, Davies actually dissolved the foreign-registered D-C Ltd. company, transferring its assets to a completely new and distinct IOM registered company called Davies Engineering Ltd. Despite this, the advertising continued to bear the Davies-Charlton name throughout. This is interesting insofar as that company had ceased to exist in a legal sense! Perhaps even more strangely, this re-named company only lasted until November 8th, 1958, when it too was dissolved and replaced with yet another IOM-registered company which reverted to the original Davies Charlton Ltd. name! It’s important to note that this was not a revival of the “old” Davies-Charlton Ltd. company in which Alan Allbon was a shareholder - it was another completely new company bearing the same name. However, it did bring the company's name back into alignment with its advertising identification. A straw in the wind in relation to the initial January 1958 dissolution of the "original" Davies-Charlton Ltd. company is the fact that it coincides more or less exactly with the company's discontinuation of the use of the Allbon name. It's hard to avoid the suspicion that since this dissolution would clearly extinguish Alan Allbon's position as a shareholder (the company in which he held shares no longer existed), it also extinguished any rights to Davies' continued use of the Allbon name, assuming that this was a feature of the original shareholder agreement. However, Davies continued to produce Allbon's model engine designs, albeit no longer by that name. The reconstituted Davies-Charlton company carried on by that name until October 1st, 1963, when it too was dissolved and replaced by yet another new company which was registered in the IOM under the Davies Engineering Ltd. name! Once again, this change was not reflected in the company's advertising. This company too didn’t last long – on March 31st, 1964 the second Davies Engineering Ltd. company was dissolved in turn, being replaced as before by yet another new company bearing the original name of Davies-Charlton Ltd.! This last company was destined to survive on paper at least until April 20th, 1994, when it was dissolved for the last time, long after it had ceased to trade. It must surely be obvious that there had to be a compelling motive behind these frequent dissolutions and re-registrations. One plausible possibility (and it’s no more than a possibility as opposed to an established fact) is that these moves represented a strategy to circumvent the serving of legal documents relating to an attempt by some party or parties to collect money owed to them by Davies-Charlton. However, there may be other explanations - I’d welcome any plausible alternative suggestions. There’s a good chance that surviving members of the Davies family could clear up any uncertainties regarding the reasons for this rather extraordinary chain of events. A few years ago I actually established contact with Hefin Davies’ nephew Rhodri Dafis, who initially agreed quite readily to help. The family was thus made aware of this article and my interest in hearing their side of the story. However, Rhodri then went silent on me, for reasons of which I naturally remain unaware. As previously stated, I would welcome further contact from the Davies family - there’s much that they could probably clear up for us. Readers who require further detail on the history of Davies-Charlton both before and after the interlude with Alan Allbon are referred to my companion article on that subject which appears elsewhere on this web-site. Enter Allbon-Saunders By the middle of 1958, Alan Allbon had been operating successfully from his Douglas premises for some three years. However, it was at this time that the winds of change began to blow once more ………… Here we become very much indebted to Allbon's later employee, partner and eventual successor Bernie Bowler for a great deal of clarification. Bernie was naturally far more directly involved with Alan Allbon's business affairs than Kenneth Allbon, hence being able to supply a lot of details that were understandably unknown to Kenneth and his brother Derek. Allbon’s next career move was prompted not by any specific initiative on his part but rather as the end result of a series of meetings at Allbon’s Laxey home with a former colleague, the previously-mentioned D-C works manager Ted Saunders. Kenneth Allbon clearly recalled these meetings, which evidently centred upon the possibility of the two men going into the light engineering business on their own account, initially at least with a focus on model engine manufacturing. These meetings must have taken place in 1956 or 1957, because Saunders (who was a few years younger than Allbon) subsequently left D-C Ltd. and "retired" to (of all places!) Gibraltar in company with a woman whom he had met on the Isle of Man while working for D-C Ltd. However, Bernie tells us that Ted quickly became "fed up" with retirement (translation - soon began to run low on funds!). This led him to renew contact with his former colleague Alan Allbon to reiterate his proposal that the two of them should go into business together. Ted evidently saw himself as the promoter and business manager of the prospective partnership, with Alan providing the technical expertise.

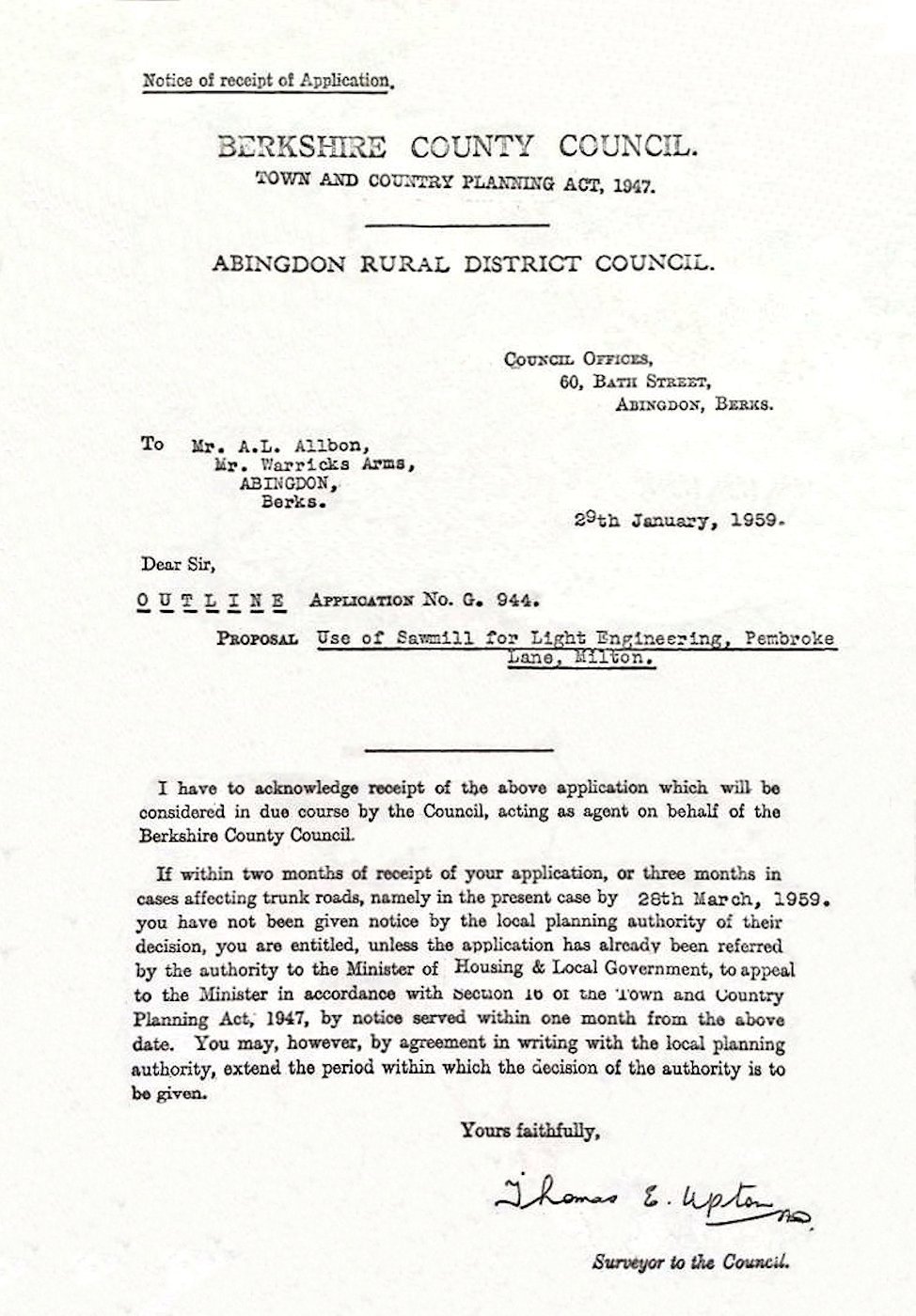

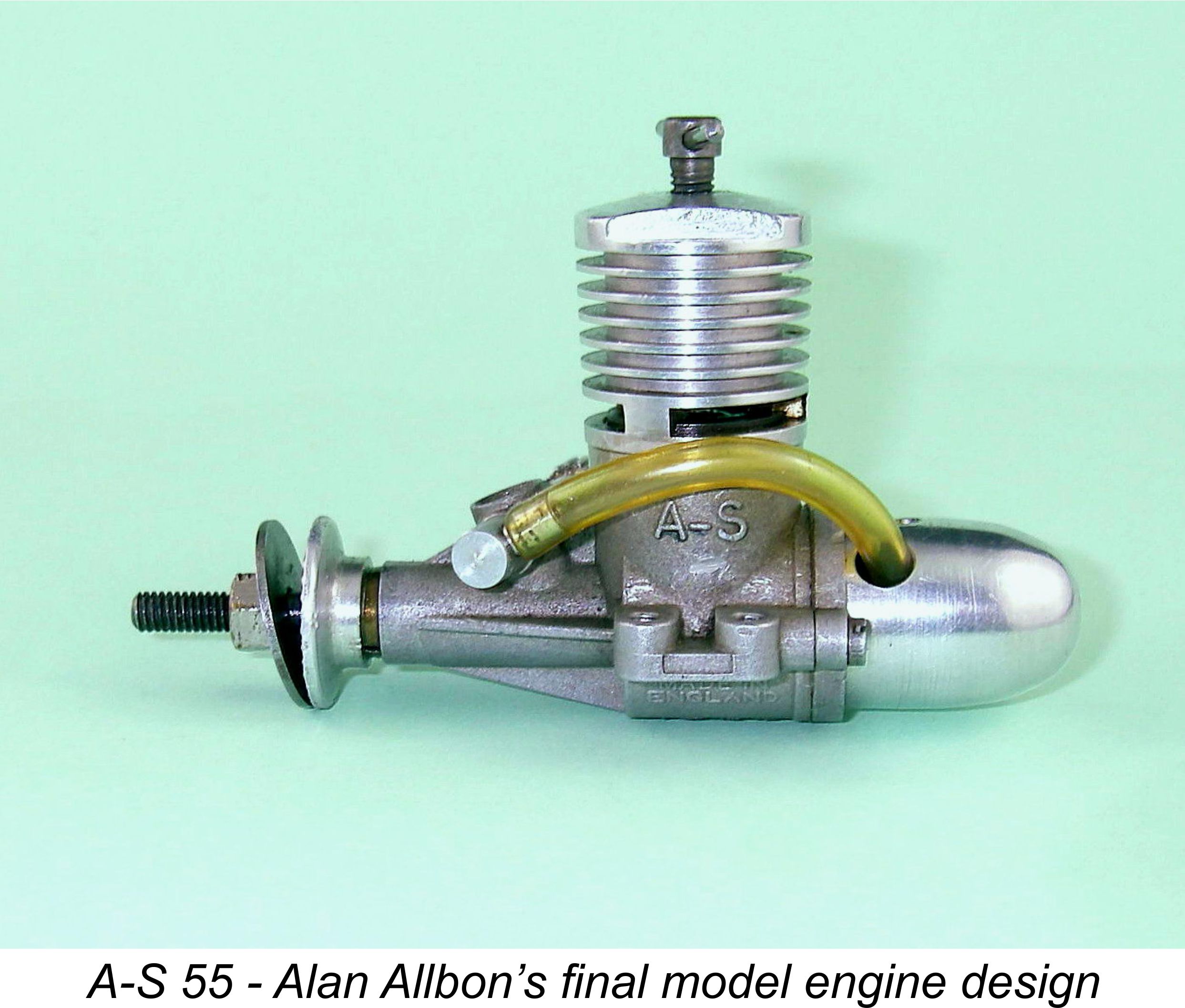

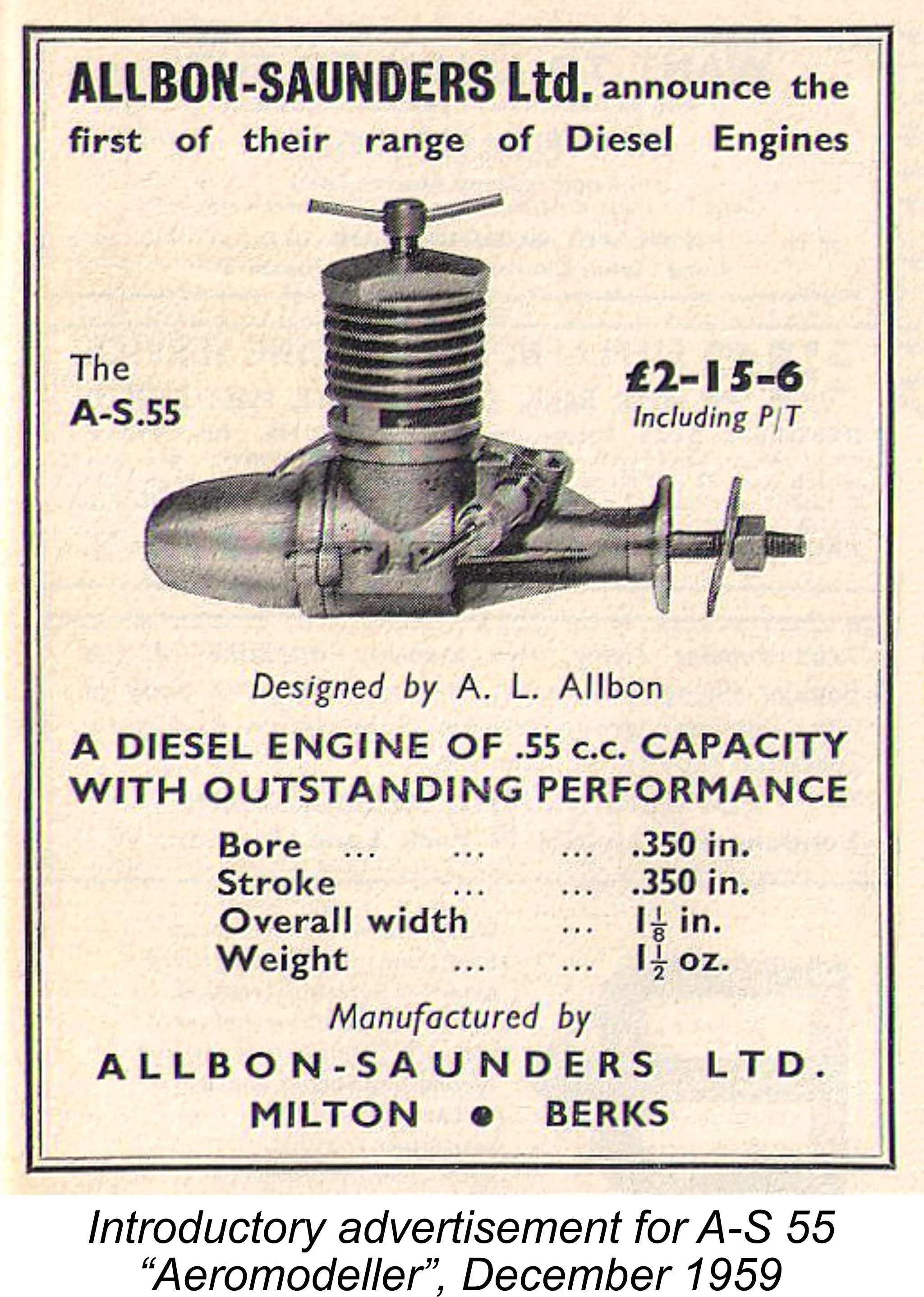

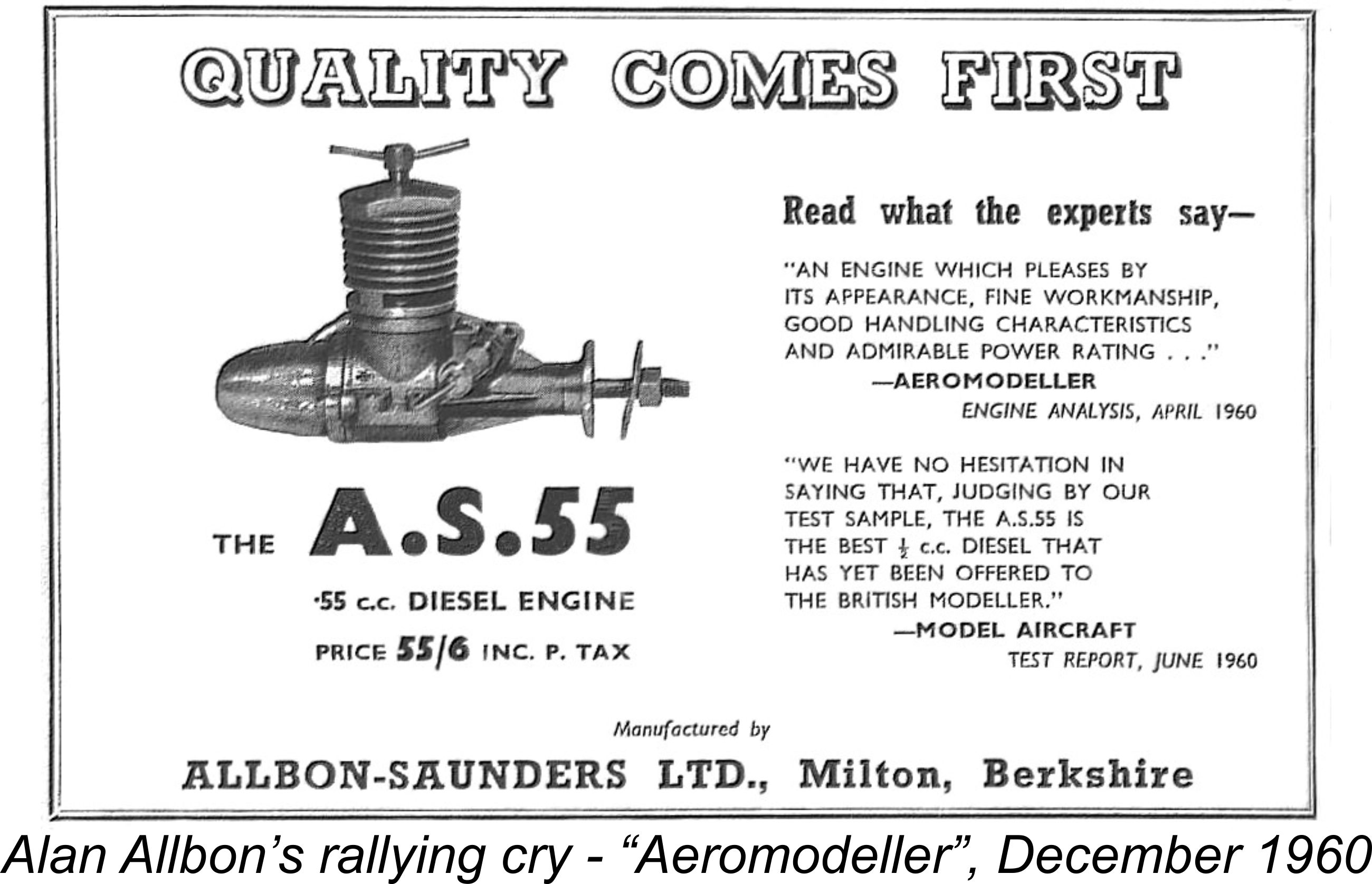

Accordingly, it was agreed that the two prospective partners would meet to look around together for suitable premises in the English Midlands, preferably (according to Kenneth Allbon) somewhere near Harwell. Bernie Bowler understood from later conversations with the two individuals that Alan Allbon met Ted Saunders at Heathrow Airport in the latter part of 1958, after which the two of them drove to the area in which they wished to locate. After driving around in circles for a while, they came upon a derelict Having agreed on this location, the two partners secured temporary lodgings in the area. Alan Allbon stayed at a local pub in Abingdon called the Warwick Arms (which remains in business today). It was from this address that he applied in January 1959 to the Abingdon Rural District Council for a permit to use the Pembroke Lane premises for light engineering purposes. A copy of the Council's acknowledgement dated January 29th, 1959 survives in Bernie Bowler's records and is reproduced here. Once the required permit had been secured, the partners in what was thenceforth to be known as Allbon-Saunders Ltd. took the necessary steps to become established on Pembroke Lane. It seems that Allbon and Saunders had reached an agreement whereby Allbon would secure the premises, which Saunders would then equip. In strict accordance with this agreement, Alan Allbon secured these premises and their associated freehold, but did so under his own name rather than that of the company. As a result, the property never at any time became an asset of the Allbon-Saunders company. This was to have ramifications down the road. During this period, Alan Allbon's family had continued to live in the Isle of Man. However, this was soon to change. Kenneth Allbon recalled traveling to Milton with his father in early 1959 to inspect the new premises and also look for a place to live. Yet another family move in the offing …….. Allbon found suitable accommodation for his family in the small village of Upton, some three miles south of nearby Didcot and quite close to Harwell.

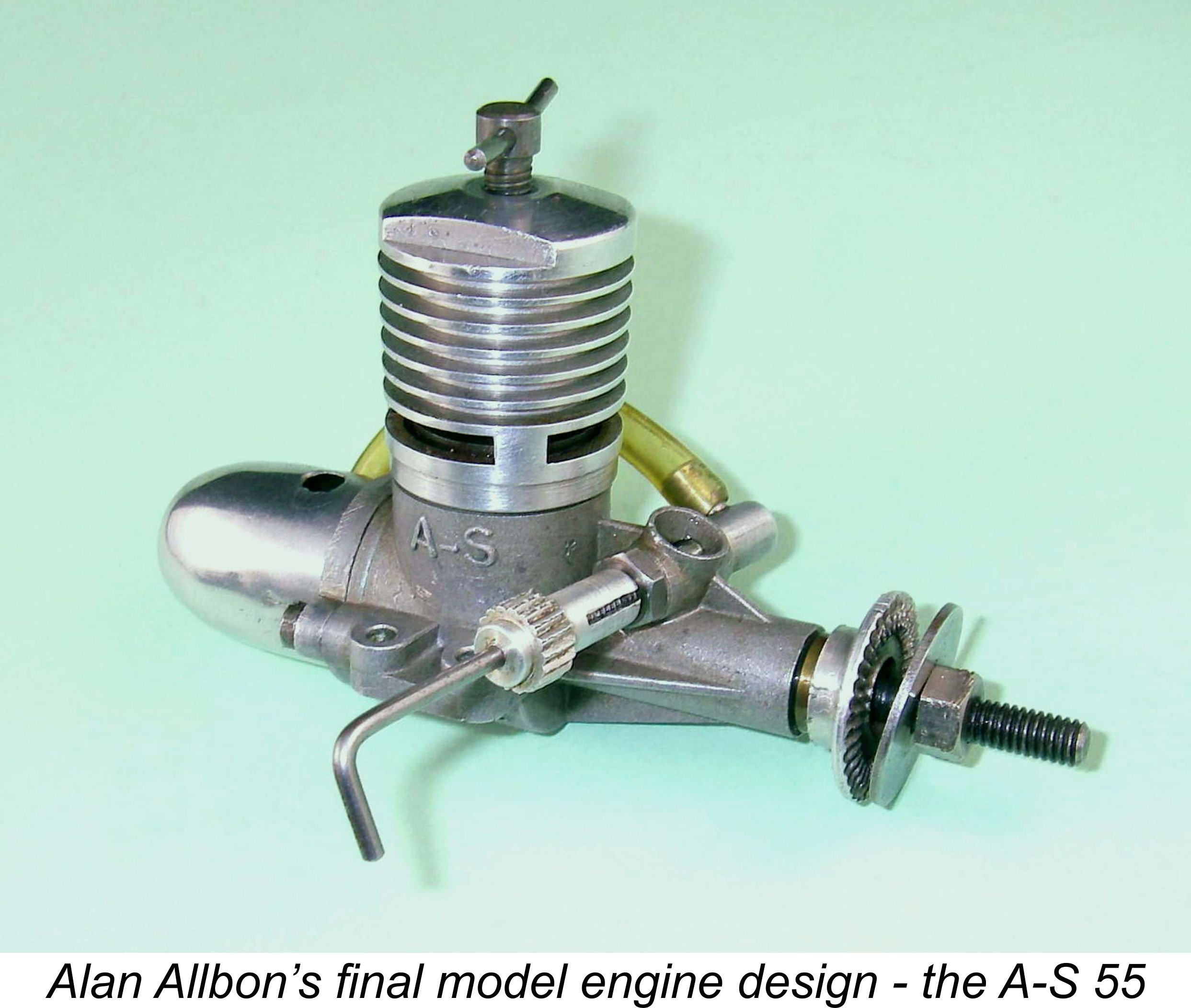

Whatever ambitions Ted Saunders may have harboured, the fact seems to be that at this stage he had no contacts within the Harwell nuclear research establishment, or anywhere else for that matter. Accordingly, Alan Allbon was given the green light to proceed with development of the first of what was intended to be a range of A-S model engines. However, this took time. Ted Saunders apparently became impatient and began pressing Allbon for his ideas on alternative forms of production which could be implemented in the shorter term. It was at this stage that Alan apparently recalled a former employee of his who had shown himself to be an exceptional craftsman while working for Alan in his pre-Isle of Man days (whether at Allbon Engineering or at D-C Ltd. is not now clear). This was none other than Mike Hewland, who had established his own small gear-cutting business at Maidenhead in 1957 and by 1959 had entered the competition gearbox field for which the Hewland company remains famous today. Contact was evidently made, as a result of which Allbon-Saunders negotiated a contract under which they would produce gear blanks for Mike Hewland. Since this was a production issue rather than an engineering challenge, Ted Saunders apparently siezed it with both hands, considering it as "his" area from that point onwards.