|

|

The FROG 1.5 cc Models

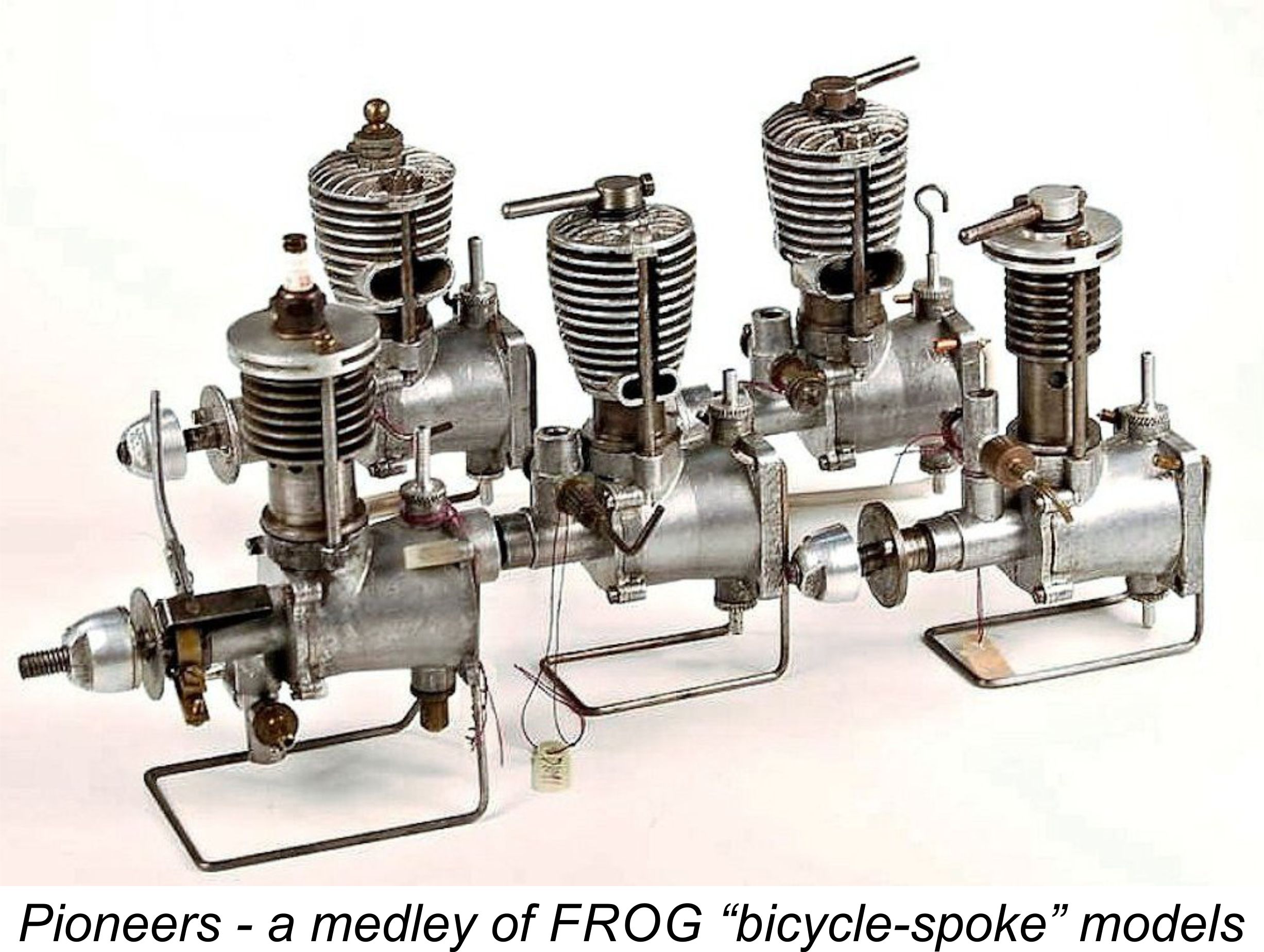

In other articles to be found elsewhere on this website, I've covered both the FROG 2.5 cc models and one of my personal favourites, the FROG 349 diesel which was the largest diesel ever manufactured by International Model Aircraft (IMA). Finally, by way of a complete contrast, I've also examined the history of the FROG models of less than 1 cc displacement. All of the above engines are very familiar to collectors and I/C vintage model fliers alike. However, there's yet another well-populated category that has hitherto remained unaddressed. Time to rectify that omission and further expand the in-depth coverage of the FROG model engine range! It’s an often-overlooked fact that the real mainstays of the FROG range throughout the 1950’s were the FROG models in the 1.5 cc displacement category which successively replaced the old “bicycle spoke” designs beginning in 1951. With a couple of notable exceptions, the engines in this series were not in the These somewhat unexciting attributes have led to these engines being rather under-appreciated by today’s collectors and vintage fliers. This despite the fact that they did a splendid job of serving as the “first diesels” for a significant number of modellers during their era. Moreover, the later designs achieved levels of performance which were very much in line with the highest then-current standards for mass-produced model engines of their displacement. However, these facts don’t seem to have done as much to raise the profile of these motors as we might expect. In this article, I’ll do what I can to characterize these engines in the context of their time and place, leaving it up to readers to form their own judgements regarding the relative merits of these models. In my personal view, they’re well worthy of consideration. Let’s see if I can convince you! Background

The “FROG” trade name was used from the outset by IMA, even before their tie-in with Lines Brothers. Their original focus was on the manufacture of ready-to-fly model aircraft and model kits - FROG model engine production was strictly a post-WW2 development. IMA are notable for having been the first company in the world to introduce non-flying molded plastic model aircraft kits, which they did in 1936 with their “Penguin” range. The name arises from the fact that a penguin is a bird that doesn’t fly……………..

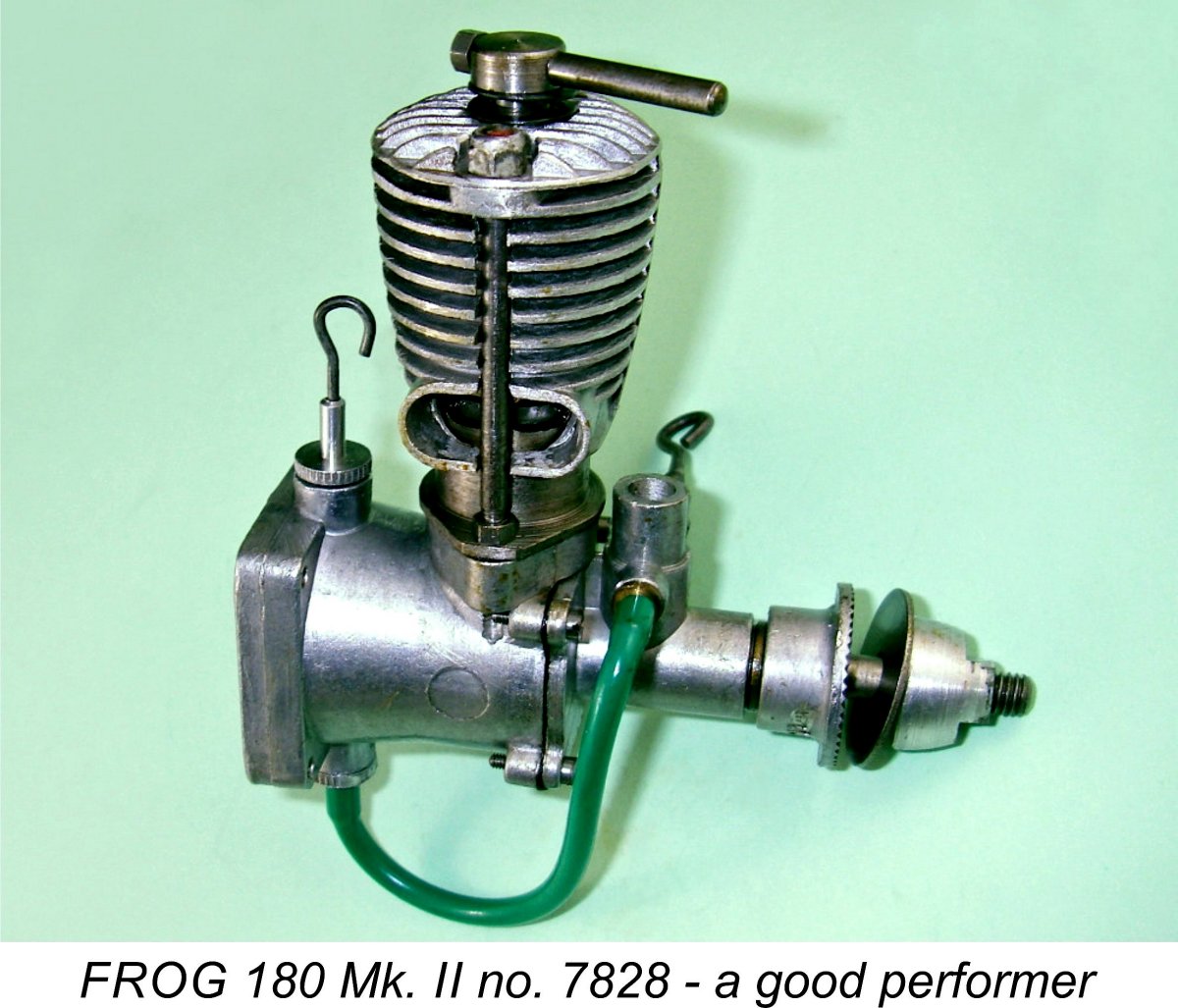

Their first model engine, the FROG 175 spark ignition motor, appeared in early 1946. It was based upon a prototype which had been developed by George Court. For more informtion on George Court, please refer to my separate article on the early FROG models. The manufacture of model engines was an activity which was highly distinct from IMA’s previous production programs. It is therefore greatly to the credit of 1936 Wakefield Trophy winner A. A. “Bert” Judge, who had been with the company since 1936 and was put in charge of the post-war engine manufacturing program, that the company’s entry into this new market area was such an immediate success. Under Judge’s direction, the company produced a very successful series of their original “bicycle spoke” engines, For the record and for later comparison, the FROG 160 glow-plug model of 1.66 cc displacement developed some 0.083 BHP @ 10,850 RPM (“Aeromodeller” test, August 1949) using a low-nitro fuel. My own test of an example of the FROG 160 measured a somewhat higher peak output of 0.102 BHP @ 10,500 RPM, admittedly using a fuel containing 15% nitromethane. The 1.77 cc FROG 180 Mk. II diesel managed a quite respectable 0.108 BHP @ 10,500 RPM based on latter day tests conducted independently by my mate Maris Dislers and myself. All of these early FROG models passed through a succession of variants, the full story of which has been set out in a separate article on this site. In late 1949 IMA released the FROG 500 glow-plug model, which also passed through several variants, including a retrospective spark ignition version. That story too has been told elsewhere. However, time marches on …………….as IMA looked ahead into the 1950’s, it was clear that their venerable and increasingly outdated early models in the 1 cc to 1.77 cc displacement range urgently required replacement. The 175 sparker had already been dropped, and now it was obvious that the 100, 160 and 180 models would have to follow.

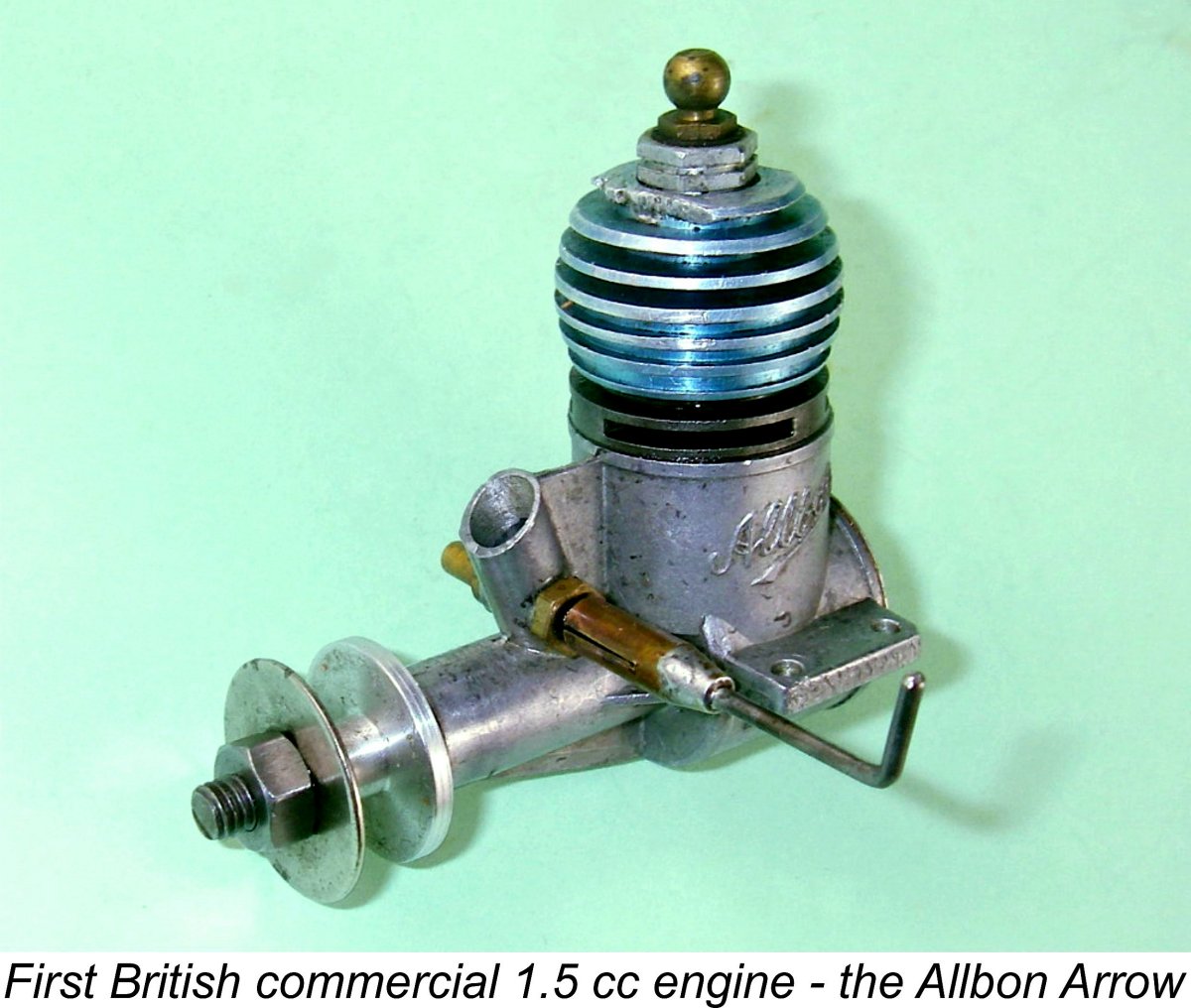

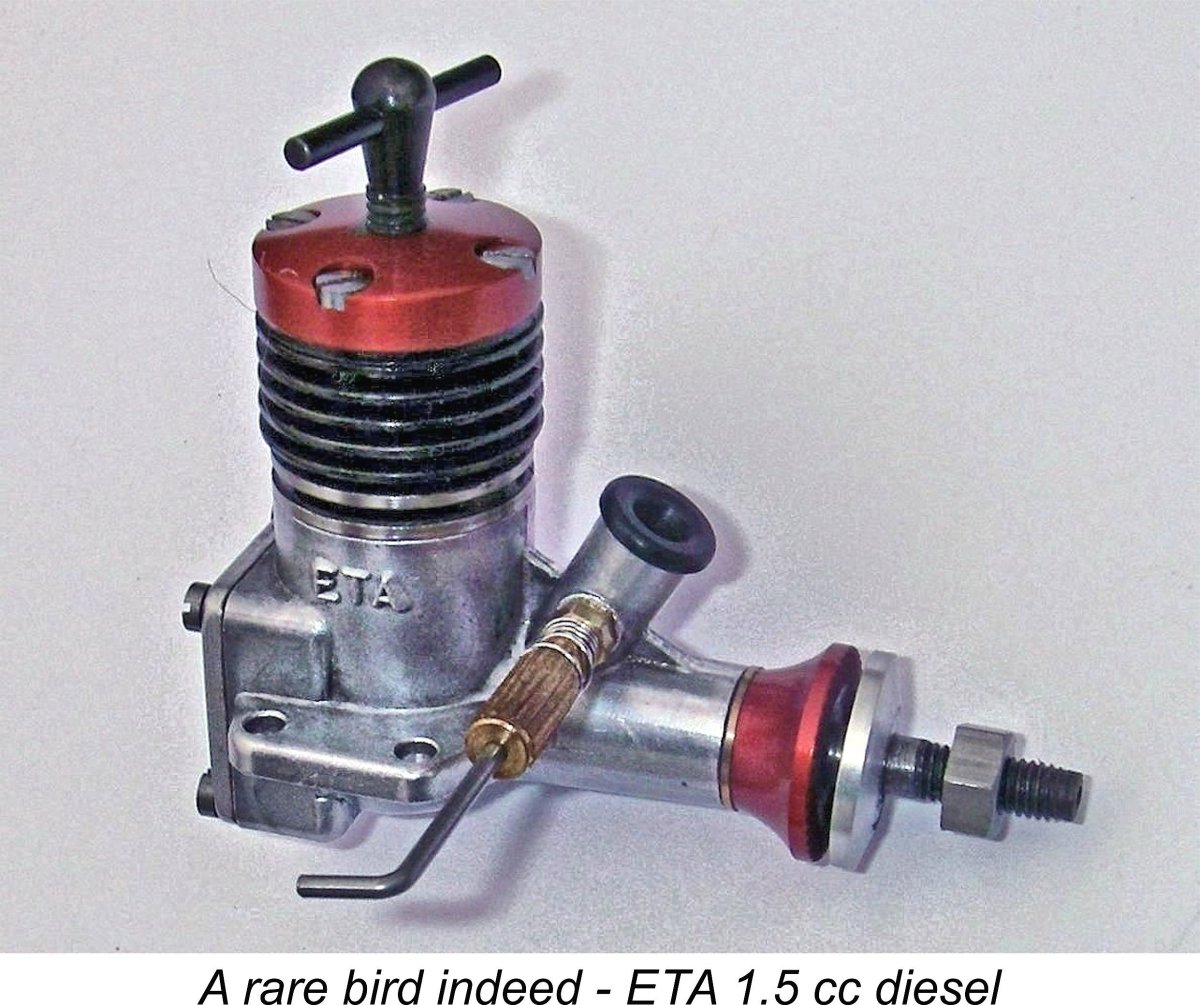

The well-known designer and manufacturer Alan Allbon had been the first to seriously tackle the 1.5 cc field, which he did with his Arrow glow-plug model of October 1949. Although a compact, well-made and ultra-lightweight design, the Arrow fell somewhat short of meeting performance expectations, resulting in the speedy development of a diesel version, the famous Allbon Javelin. This fine engine made its debut in February 1950. I’ve recounted the Allbon story in a separate article on this website. Aerol Engineering of Liverpool, makers of the Aerol and (later) Elfin engines, were not slow to pick up on the An indication of the attraction which the 1.5 cc class was then exerting upon manufacturers is the seemingly little-known fact that ETA Instruments also contemplated entering the 1.5 cc class at around this time with a design of their own. A 1.5 cc ETA diesel prototype was designed in late 1950 by Ken Bedford’s older brother Eric, who played a larger role behind the scenes at ETA than most people realize. A few prototypes were completed, one of which was later submitted to Dennis Allen to assess as a possible subject for licensed larger-scale mass production than ETA were then able to contemplate. However, for reasons which remain unclear the design was not pursued, although Peter Chinn somehow obtained an example much later, publishing a thumbnail retrospective review in the May 1968 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine.

Miles and I had the opportunity to test one of these examples together in early 2017, measuring a peak output of around 0.170 BHP @ 13,200 RPM. This implied significantly better-than-average torque development for an early 1950's engine of this displacement – no other 1.5 cc diesel of the period came close. However, we also found the engine to be somewhat temperamental to start. Perhaps this was why it never achieved production status – there was certainly nothing wrong with its power output by the standards of its day. Another manufacturer who considered entering the 1.5 cc sweepstakes was Gordon Burford of Australia. In 1951 he produced a short series of prototype examples of the Sabre 150 diesel. However, he was unable to offer this engine at a price which would make it competitive with the other 1.5 cc models then available from British manufacturers. Accordingly, it was never put into full-scale series production. Those that did appear did well in competition, while Peter Chinn somehow obtained an example which he tested for the July 1953 issue of "Model Aircraft", finding it to have a very competitive level of performance. Too bad - Gordon clearly had a good 'un there! Looking at the competing products which had made it into production, IMA clearly felt that they too needed an entry into the 1.5 cc field. It was readily apparent that the rather antiquated design of their earlier models would not form a suitable basis for the creation of an engine that could compete successfully with Allbon and Elfin – a more up-to-date design was called for. Radial 360 degree porting was then all the rage, as was crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction. Bert Judge was tasked with the job of coming up with a design for just such an engine. Thus the FROG 150 was born. The FROG 150

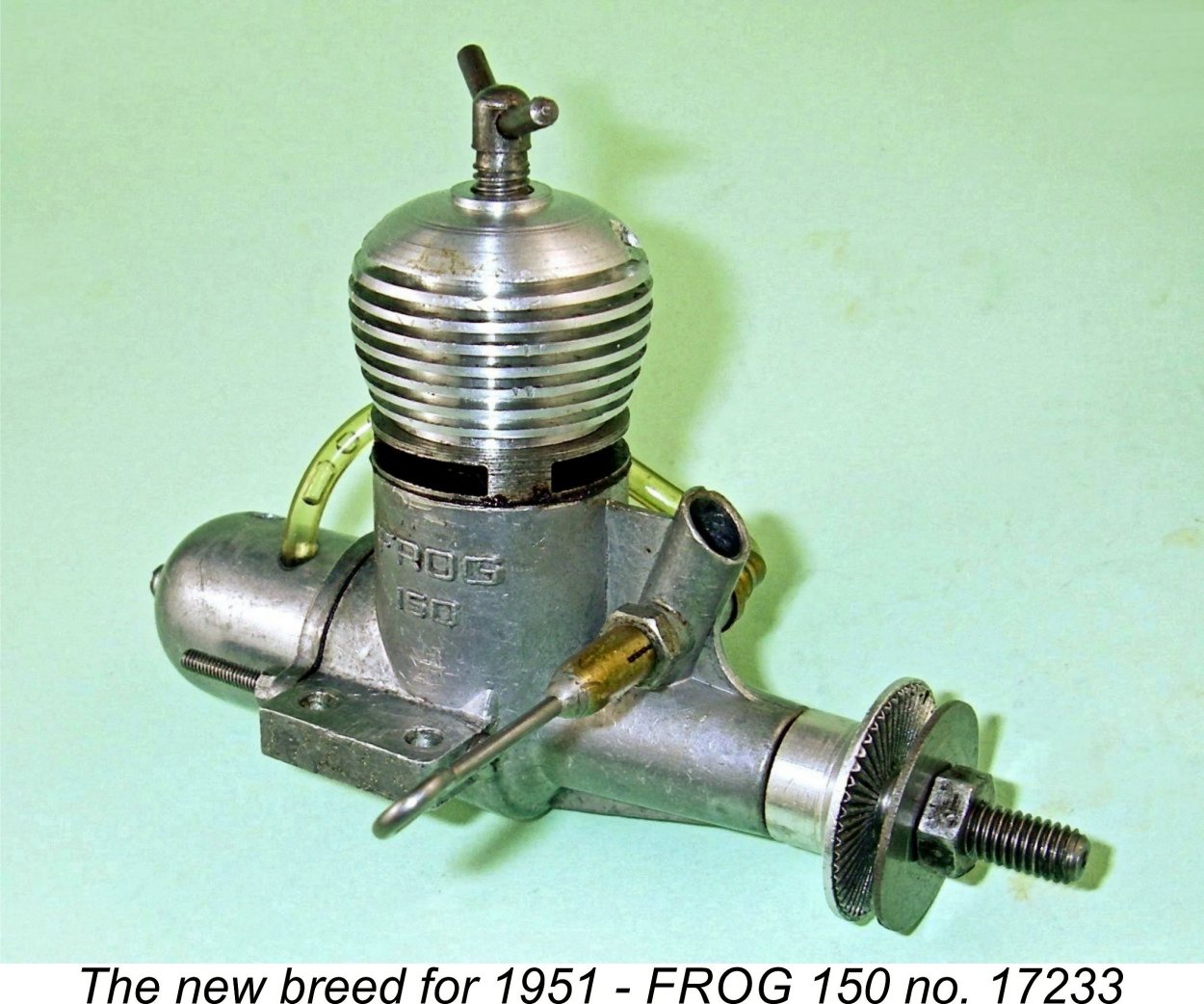

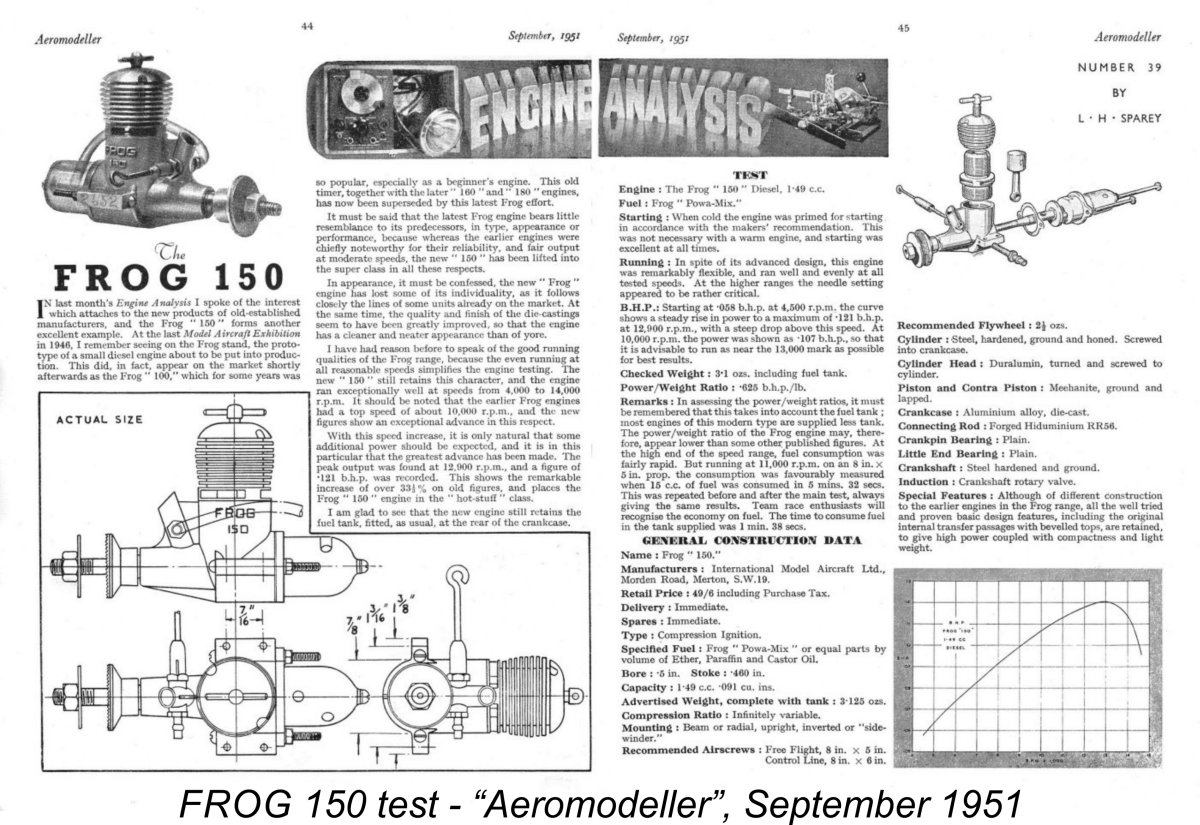

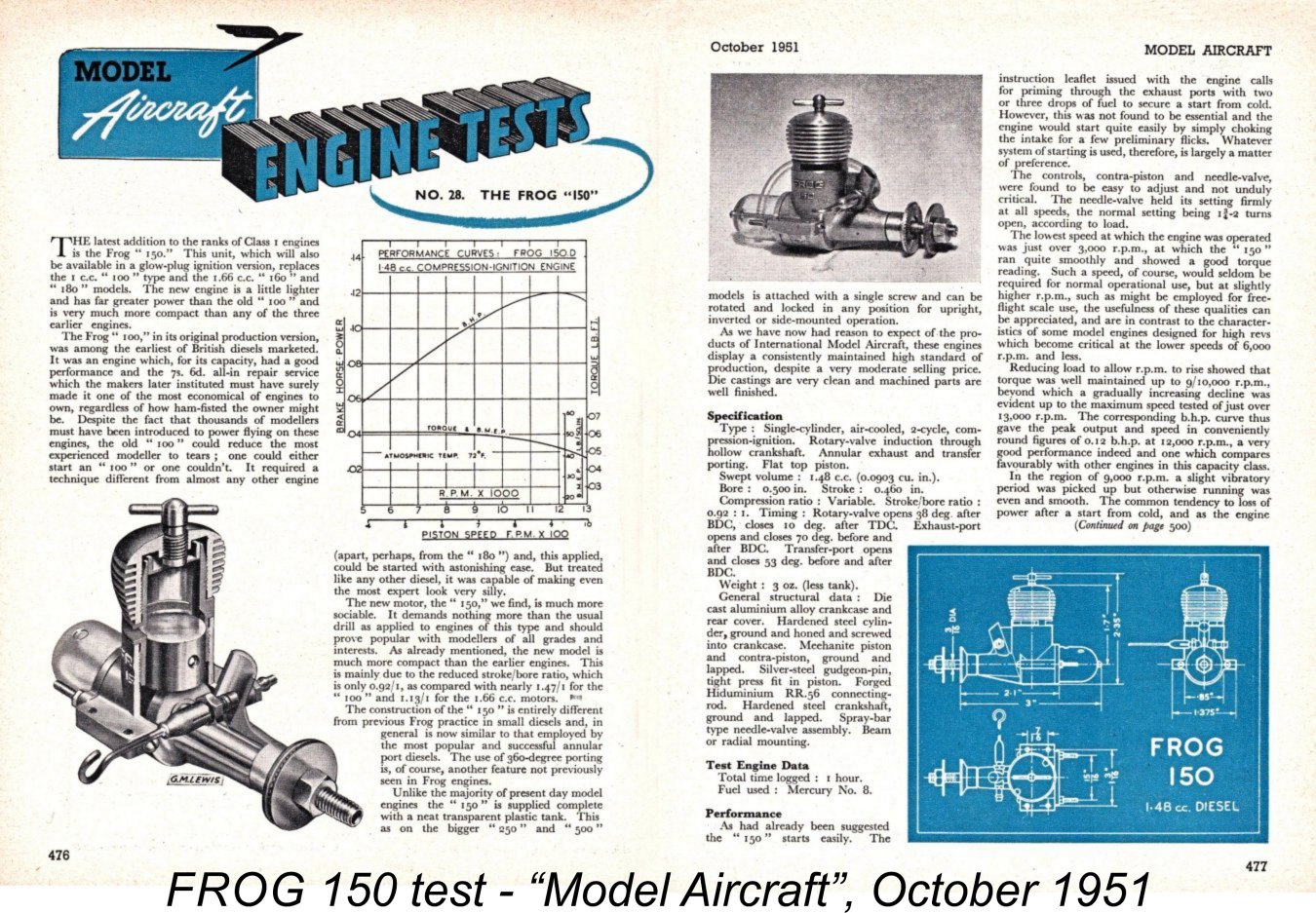

It’s a largely forgotten fact that at the time of its introduction the FROG 150 was offered in both diesel and “Red Glow” glow-plug versions at the same price of £2 9s 6d (£2.48). However, the glow-plug variant doesn’t seem to have lasted long on the market – by December of 1951 it had already disappeared from IMA’s advertising. Examples are akin to hen’s teeth today. Presumably, like the ill-fated Allbon Arrow, it under-performed by comparison with its diesel counterpart. Bore and stroke of the FROG 150 were nominally 0.500 in. (12.70 mm) and 0.460 in. (11.68 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.48 cc (0.090 cuin.). The engine weighed a checked 3.31 ounces (94 gm) complete with tank and fuel tubing. Bypass and transfer functions were accomplished through the use of three internally-formed flutes in the lower cylinder wall. These were located between three milled exhaust apertures of generous proportions. The transfer ports overlapped the exhaust ports to a significant extent. A conical-topped piston was employed.

Sparey was clearly very impressed with the 150. He noted that it ran “exceptionally well at speeds from 4,000 to 14,000 RPM”. Starting was found to be “excellent at all times”. A prime was required for cold starting, but this was found to be unnecessary when the engine was hot. A peak output of 0.128 BHP @ 12,900 RPM was recorded – a significant improvement over the measured output of the old FROG 180. Sparey commented that this performance placed the 150 in what he termed the “hot stuff” class. He was also quite impressed with the engine’s flexibility, noting that it ran “well and evenly” at all speeds tested. His one slightly adverse comment was that the needle setting became “rather critical” at the higher speeds. Overall, Sparey’s published test represented a strong endorsement of the FROG 150. Considering that he had previously measured peak outputs of 0.099 BHP @ 12,000 RPM for the Allbon Javelin (“Aeromodeller”, July 1950) and 0.100 BHP @ 13,700 RPM for the Elfin 149 (“Aeromodeller”, June 1950), the FROG actually A test of the FROG 150 also appeared in the rival “Model Aircraft” magazine in October 1951. Although unattributed (as were all “Model Aircraft” tests at that time), the author was undoubtedly Peter Chinn. Like Sparey, Chinn found the engine to be a very responsive starter, with easily-adjusted controls which were not unduly critical. The quality of the engine’s construction also came in for commendation. Chinn reported an output of some 0.120 BHP @ 12,000 RPM, thus more or less confirming Sparey’s findings. He took note of the glow-plug version, but did not undertake any testing of that ephemeral variant.

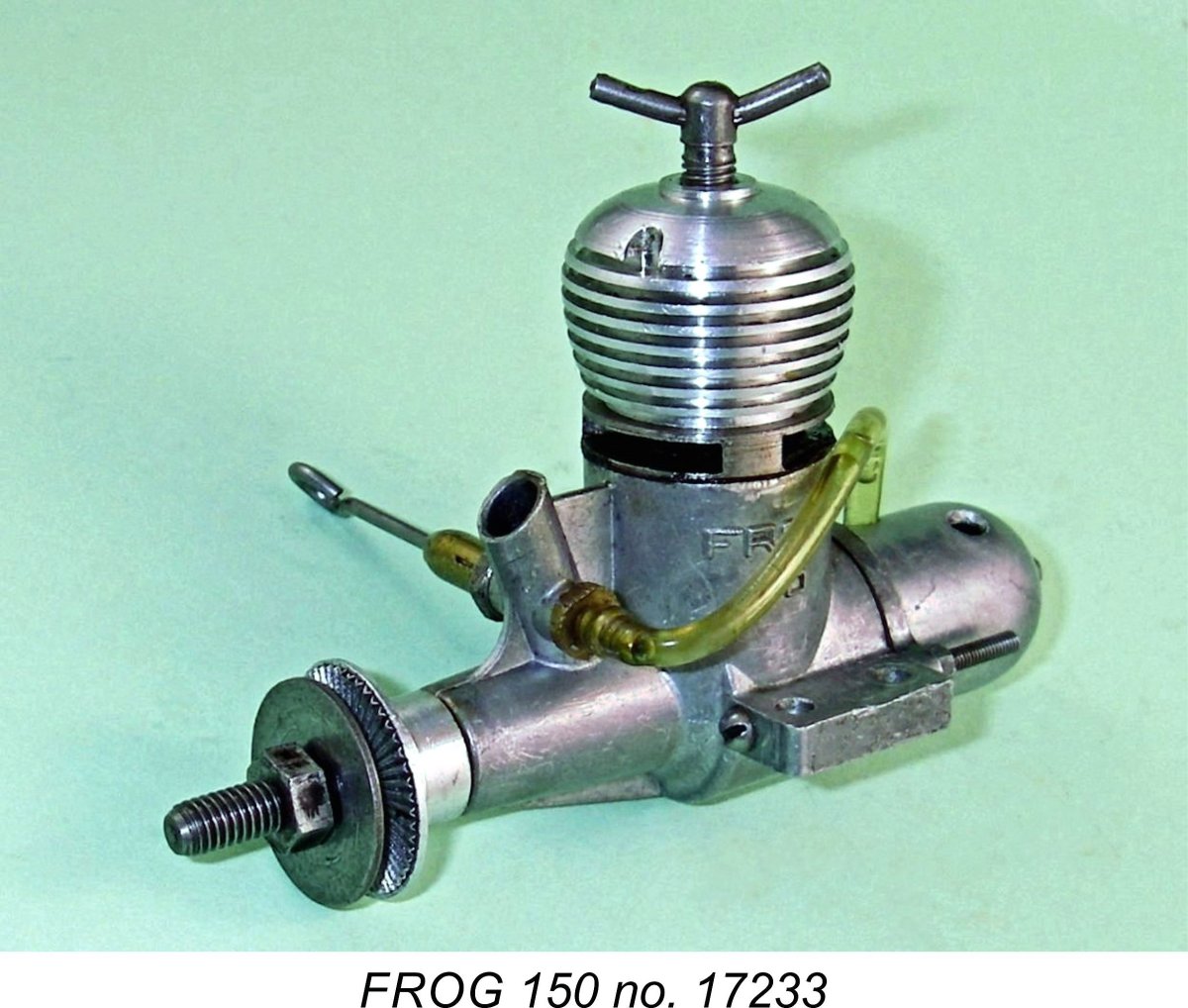

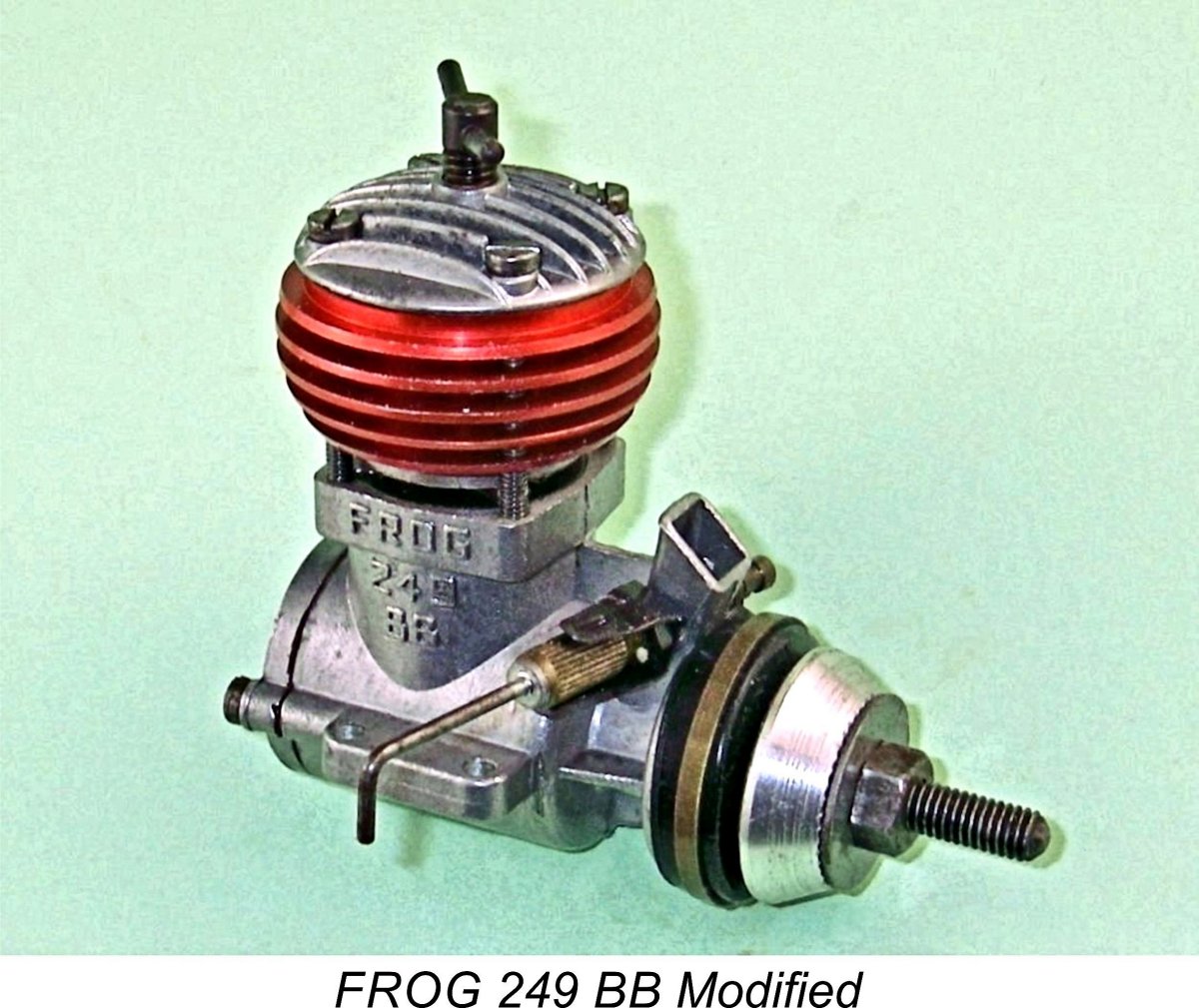

Allbon's revised model was a significantly better performer than the original Javelin, developing around 0.135 BHP @ 11,000 RPM based on Ron Warring’s test (“Aeromodeller”, January 1953). However, the published performance of the FROG 150 was still sufficiently close to that of the revised Javelin that IMA evidently felt no need to pursue any further development at this time. They were still at or near the top of the commercial heap in that displacement category. After designing the FROG 50, which was basically a scaled-down FROG 150, Bert Judge had left IMA in early In mid 1954, Aerol Engineering set the British model engine market on its ear by introducing their highly original Elfin 149 BB unit featuring reed valve induction. This engine established a new British performance standard for the commercial 1.5 cc class by developing 0.158 BHP @ 13,600 RPM during Ron Warring’s test (“Aeromodeller”, January 1955). Peter Chinn’s test in the February 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” more or less duplicated Warring’s figures. The fly in the ointment was the fact that by now the variability in quality of the Elfin engines due to aging and worn-out equipment had become highly problematic - not all examples performed up to that standard. At around the same time, both the FROG 150 and the Allbon Javelin Mk. II were re-tested by Ron Warring using the Eddy Current Dynamometer which had been in use since June 1954, generally giving somewhat lower results than the torque reaction equipment used previously. Using the new equipment, the Mk. II Javelin could only manage 0.121 BHP @ 11,000 RPM, while the FROG 150 was found to develop 0.111 BHP @ 10,800 RPM. The tested example of the 150 (which was evidently not the one tested over three years earlier by Sparey) was reportedly still quite tight, leading Warring to suggest that a fully freed-up example should develop around 0.120 BHP at somewhat higher RPM. The poor old 1.46 cc E.D. Hornet was Tail End Charlie in this re-testing exercise with a measured output of only 0.092 BHP @ 11,200 RPM. Setting aside the performance of the Elfin 149 BB, which was not competing for sales in the sports market in any case, it’s clear from this that the FROG 150 was continuing to hold its own in the sport 1.5 cc diesel sweepstakes. Neither the arrival of the J.B. Atom in October 1955 nor that of the Allbon Sabre (manufactured by D-C Ltd.) in November 1955 did Even so, it must have been evident to IMA management that by late 1955 the British 1.5 cc category was becoming increasingly crowded and hence competitive. IMA finally decided that they could no longer afford to stand still in the face of this ever-evolving competition - they needed to go in search of a performance edge. Accordingly, once George Fletcher had completed the design of the FROG 249 BB (which was launched in December 1955 as the updated replacement for Bert Judge’s old FROG 250), he was immediately tasked with upgrading IMA’s 4 year old 1.5 cc model. This project was initiated in the latter part of 1955. It's worth noting in passing that the initial version of the FROG 150 seems to have sold quite well. I own engine number 17233, confirming that at least that many were made during the 4 years or so that the engine was in production. Naturally, the number may have been considerably higher, but even so 18,000 or more examples over a four year production period was pretty good going by British standards. The FROG 150 Mk. II

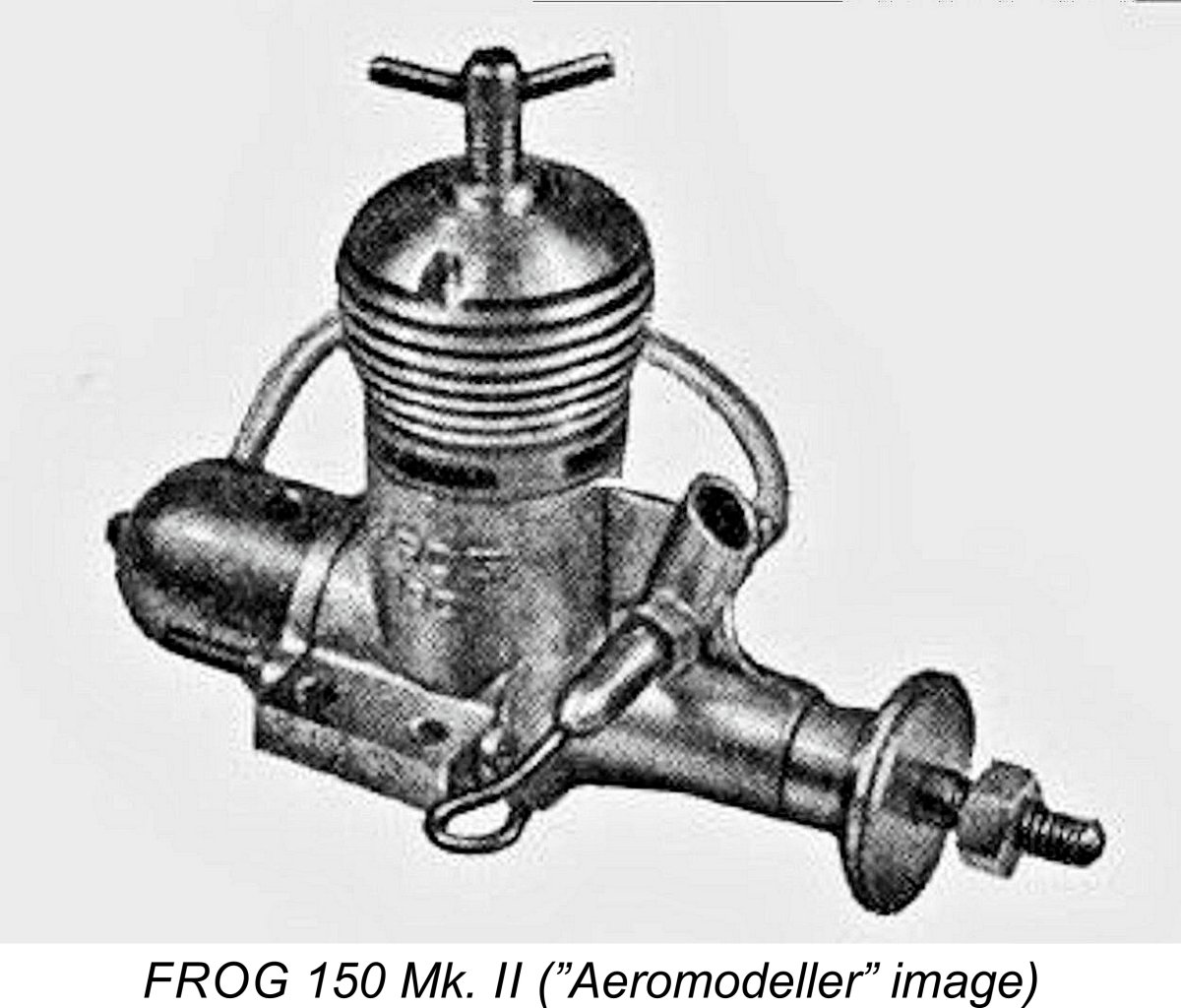

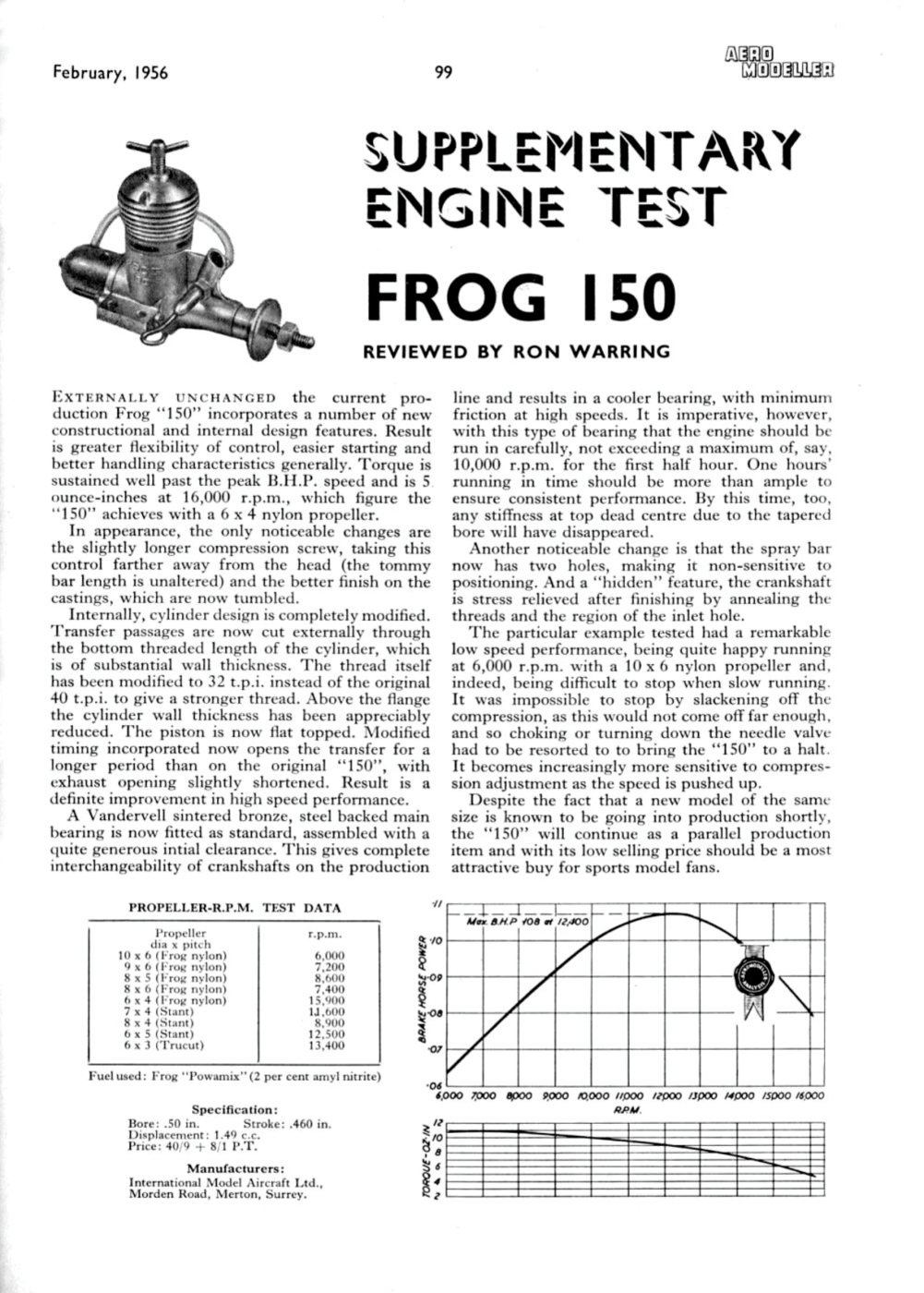

Internally however, it was a very different story. The cylinder porting was completely revised, with the bypass passages now being formed externally on the outer lower cylinder wall, hence interrupting the male installation thread The transfer period was slightly increased, while the exhaust period was a little reduced so as to shorten the blow-down period and lengthen the power stroke. A flat-topped piston replaced the former conical-topped component. The final significant change was the introduction of a Vandervell sintered bronze bushing for the main bearing. The resulting variant first appeared in January 1956, being advertised by IMA as the FROG 150 Mk. II. A marine version of the engine was announced at the same time. Unfortunately, it appears that these revisions had little or no effect upon the engine’s performance. A summary re-test of the modified engine appeared in the February 1956 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Tester Ron Warring measured a peak output of only 0.108 BHP @ 12,400 RPM. Odd – slightly less power but at a considerably higher speed! Warring did comment that the engine’s handling and flexibility seemed to have been improved by these modifications, but that was about all. Evidently both IMA and George Fletcher were looking for a little more than this! Accordingly, Fletcher’s next move was to re-consider the induction system of the 150. The result was the April 1956 appearance of the next engines in our survey – the two FROG 149 “Vibramatic” models. The FROG 149 “Vibramatic” Diesel and Glow-plug Models

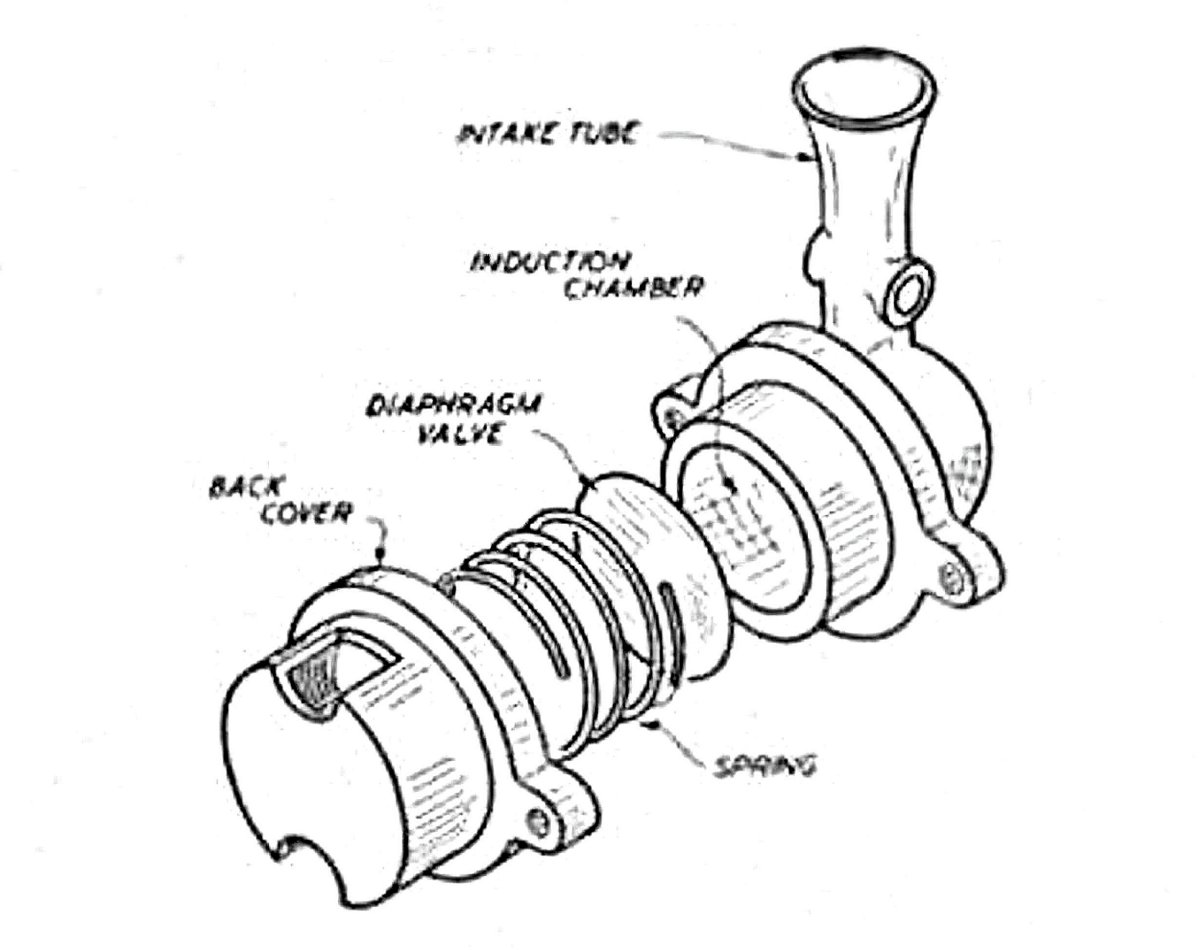

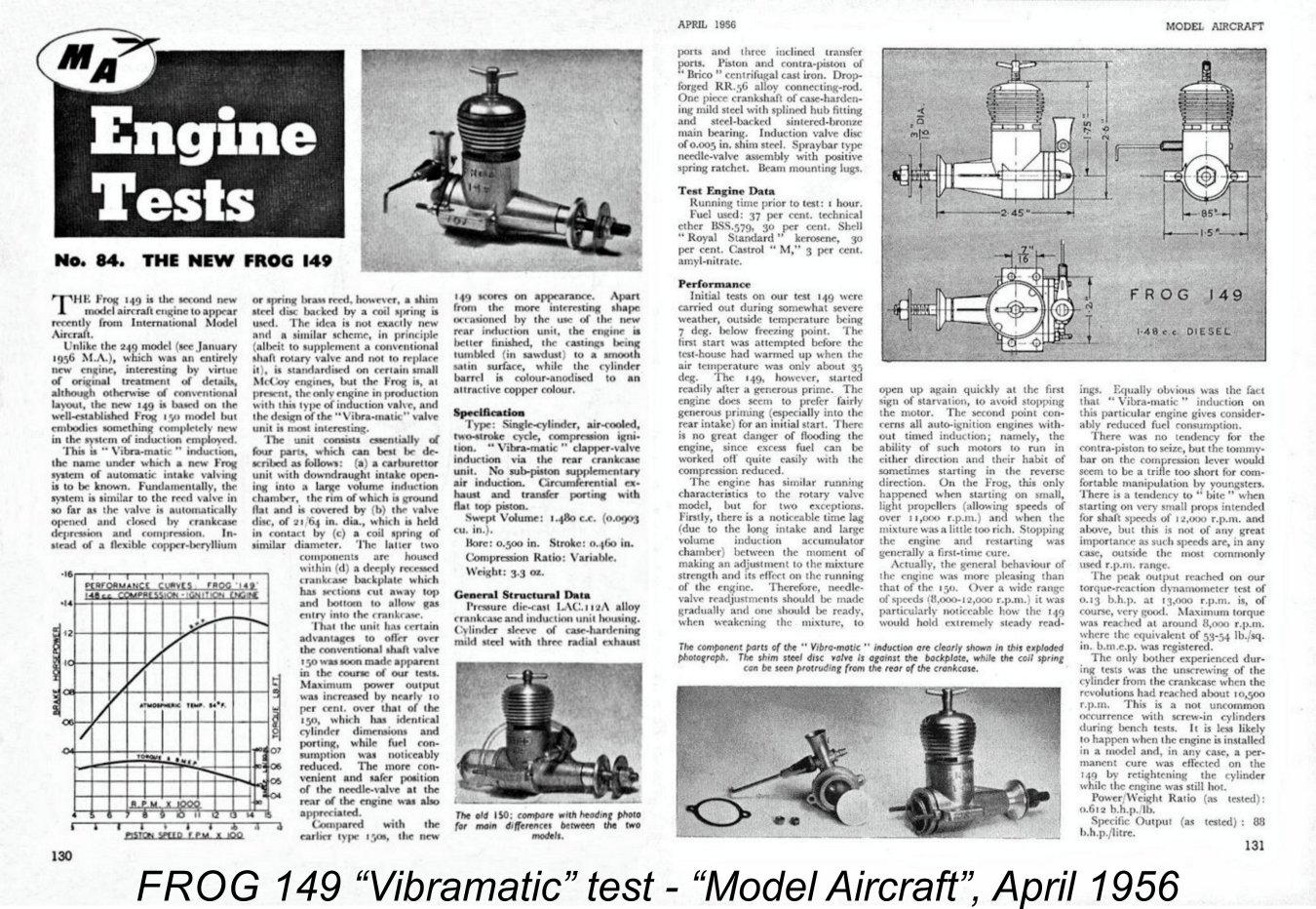

Reed valve induction was of course by no means new – it was widely used in America, while even in Britain it had appeared earlier in the Elfin twin ball-race models. However, George Fletcher elected to use a spring-loaded shim steel disc instead of a reed. In effect, this was a form of diaphragm induction. The advantages of Fletcher’s system were a significant increase in the area of the reed upon which the pressure variations which drove the system could act, together with a significantly longer reed-seat interface through which induced gas could pass. The tension of the light coil spring which controlled the diaphragm (as I will henceforth call it) was clearly a critical design factor which must have been the subject of considerable experimentation, since it would significantly affect the system's response characteristics.

Naturally, the use of the same piston/cylinder combination meant that the bore and stroke of the FROG 149 were unchanged at 0.500 in (12.70 mm) and 0.460 in. (11.68 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.48 cc (0.090 cuin.). The engine weighed a checked 3.39 ounces (96 gm), almost unchanged from the 150 Mk. II, although the 149 was not fitted with a tank. The engine’s introductory selling price was £2 14s 9d (£2.74), a little more than the asking price of £2 7s 6d (£2.38) for the FROG 150 Mk. II. The main features of the “Vibramatic” induction system are clearly shown in the attached exploded diagram When the engine was at rest, the coil spring kept the diaphragm pressed lightly against the circular seat formed in the main backplate, thus sealing the crankcase. The rising piston after bottom dead centre created a vacuum within the crankcase which allowed the external atmospheric pressure to push the diaphragm off its seat against the spring pressure, thus allowing the ingress of fuel mixture around the perimeter of the diaphragm. As soon as the piston stopped ascending and began its descent on the power stroke, the spring closed the diaphragm and allowed the build-up of crankcase pressure. This continued until the transfer ports opened, at which point the scavenging process continued in normal two-stroke mode.

On the negative side of the ledger, the system resulted in a somewhat larger than normal crankcase volume. This might be expected to adversely impact the engine’s base pumping efficiency and hence its ultimate power potential. The fact that the volume of the crankshaft induction porting was eliminated in the revised design did something to alleviate this issue, but it was still a factor. The presence of the "induction chamber" on the atmospheric (intake venturi) side of the diaphragm resulted in the volume of the induction tract also being considerably greater than normal. This might be expected to allow a significant volume of mixture to accumulate between induction cycles as well as potentially "damping" the response of the venturi section to changes in mixture demand originating in the crankcase. This in turn might be expected to influence needle response to some extent. Even so, one simply has to give George Fletcher points for originality with this arrangement. OK, so how well did it work? To find out, the resident engine testers for both “Model Aircraft” and “Aeromodeller” magazines were not slow to put the engine through its paces on the test bench.

After describing the innovative and hence unfamiliar “Vibramatic” induction system in some detail, Chinn proceeded to comment upon the engine’s performance. He found that the 149 started readily enough, but seemed to like a generous prime. Running characteristics were similar to those of the 150 model. We would expect this given the underlying similarities of the two models apart from the induction system. However, Chinn commented upon an anomaly with respect to the engine’s response to the needle. He found that there was an appreciable time-lag between the making of a mixture adjustment and the manifestation of its effect on running. This was doubtless due in part to the unusually large volume of the inlet tract, upon which comment was made earlier in this article. However, other reed valve engines have shown similar tendencies, so this characteristic almost certainly has something to do with the change in induction timing which will inevitably result from any change in engine speed - lacking any form of direct mechanical synchronization, the system will require some time to re-stabilize. Regardless of the cause, Chinn found it necessary to make adjustments in small increments and then to wait a few second to observe the effects. Two other handling attributes came in for comment as well. Firstly, the atmospherically-activated induction system meant that the engine could run equally well in either direction. Like all engines having this capability, it started backwards at times. However, this only happened on the smaller propellers and if the engine was a bit on the rich side. The other attribute was a slight tendency towards viciousness on smaller props, but Chinn commented that the prop sizes with which a “bite” was experienced were generally smaller than would normally be used with the engine.

Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” seemingly had to secure his own example of the engine, since his report did not materialize until the July 1956 issue of the magazine. Like Chinn, he spent a fair bit of time describing the unusual induction system before turning to the engine’s handling and performance. Warring noted the same time-lag in terms of needle response that had been a finding of Chinn’s report. Particular care was evidently needed as one approached the optimum lean setting – a little too lean, and by the time the operator realised that the engine was starving at that setting, it had stopped!! Latter-day experience shows that one has to make needle adjustments in small discrete increments, pausing for a few seconds between adjustments to judge the effect of each change. In terms of the engine’s performance, Warring too found that the FROG 149 developed somewhat more power than its FROG 150 Mk. II companion. Since the two engines were essentially identical in other functional respects, Warring quite logically reasoned that this must be down to the induction system, which clearly worked well. He measured a peak output of 0.122 BHP @ 12,750 RPM – not too far out of line with Chinn’s earlier findings and some 11% higher than his own earlier figure for the 150 Mk. II. His overall comment was that the FROG 149 was “easy to handle, flexible in the extreme and with an extremely good power output”. Warring also made reference to some extended testing which had been undertaken at the IMA factory. Two examples of the 149 diesel were reportedly run for a total of 21 hours before being torn down for inspection. They were found to exhibit minimal wear. One of them was sent to Warring for his inspection and confirmation of these findings, while the other was put into service as one of IMA’s factory test powerplants for their new model kit designs.

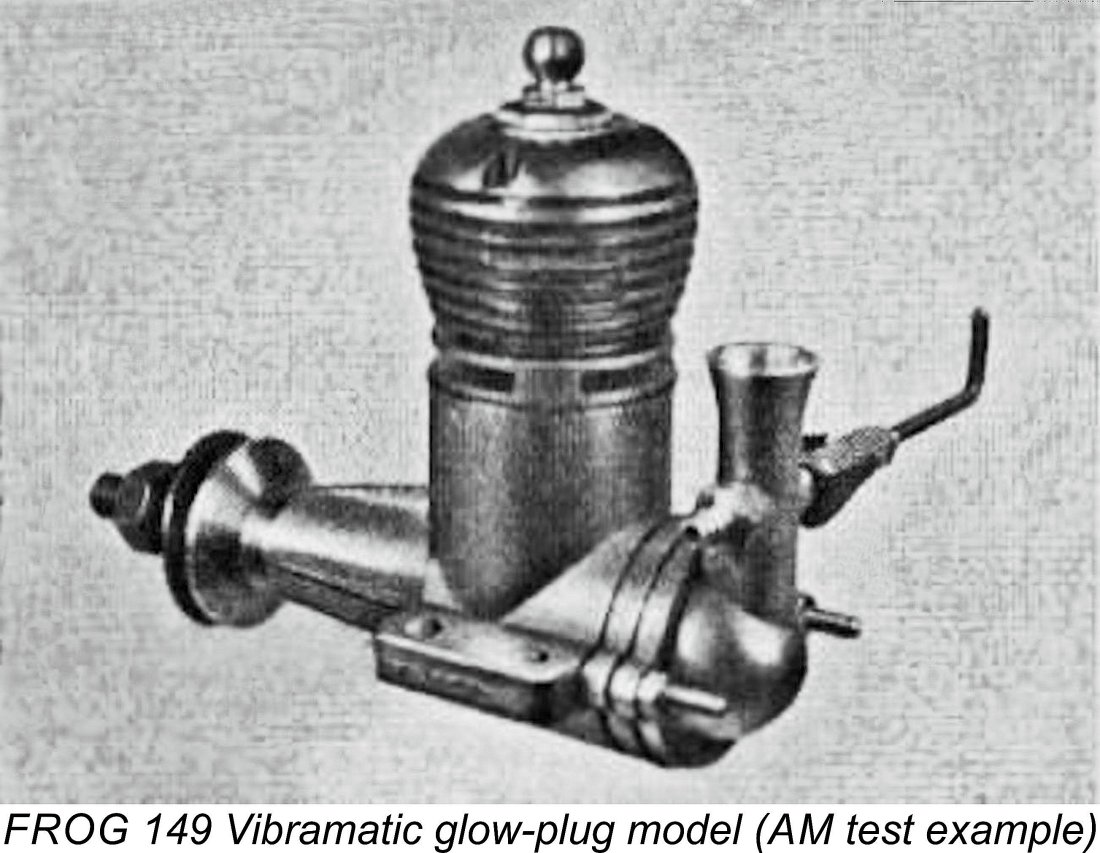

The conversion was accomplished using a flanged aluminium alloy head insert in place of the diesel contra-piston. This was centrally tapped to accommodate the plug and was retained by the screw-on cooling jacket. The insert was sealed to the cylinder with a gasket beneath the locating flange. Warring stressed that this assembly needed to be screwed on really tightly to ensure a seal and prevent unscrewing during operation. Warring found that the 149 glow-plug model’s main recommendation was its incredibly easy starting. Unless it was completely flooded, it started first flick almost every time. As might be expected, it did however display a tendency to start backwards, particularly on small propellers. As far as performance went, the 149 glow-plug model wasn’t even in the hunt! Its basic problem was an inability to come close to matching the torque development of its diesel counterpart. Using standard low-nitro FROG “Red Glow” fuel with 10% extra nitromethane, Warring could only extract some 0.078 BHP @ 14,000 RPM from his example. This translated into a shortfall of around 1,200 RPM on any given airscrew compared with the diesel version.

In contrast to its short-lived glow-plug companion, the 149 “Vibramatic” diesel model did attract some sales attention, remaining in production for well over two years. Based upon serial number evidence to date, at least 8,000 examples seem to have been produced, and the total may well have been higher. The FROG 150 Mk. II also continued in production as a lower-cost entry-level alternative. Between them, these two models maintained IMA’s very strong position in the British 1.5 cc sports diesel market as of mid 1956. However, changes to that market were in the offing which would soon force IMA to take further action in terms of upgrading their 1.5 cc models. Busy Times at IMA

Meanwhile, IMA’s position in the British 1.5 cc market was considerably strengthened by the departure of two of its domestic competitors in that displacement category. The manufacturers of both the Elfin and J.B. ranges placed their final advertisements in January 1957 before disappearing forever from the market, taking their respective 1.5 cc models with them. This left IMA competing for 1.5 cc sales only with D-C Ltd. and E.D. with their Allbon Sabre and E.D. Hornet offerings respectively. Neither of these engines was a match for the FROG 149 and 150 Mk. II models. Once again, IMA ruled the commercial 1.5 cc roost! This highlights a point that I made right at the outset. The FROG 1.5 cc models up to 1958 seem to be generally remembered as rather unexciting performers. I hope that this account up to this point has demonstrated the reality that throughout the period from mid 1951 to mid 1958 they were actually at or near the top of the British sports engine heap in this displacement category. Context is everything ...........

At this point in time George was coming under increasing pressure from IMA management. We’ve seen that the FROG engines up to early 1957 had all been budget-priced sports types having relatively modest levels of performance by all-out competition standards (for which they were not primarily designed). However, the request from World Engines had alerted the management of IMA’s Lines Brothers parent company to the fact that the FROG model engine range in general was in danger of falling behind its competitors unless wholesale upgrades were undertaken. It was recognized that performance was becoming an increasingly important factor affecting sales, even in the sports categories. This situation prompted a request from the top (in the person of Graham Lines himself) that George set about upgrading the entire FROG model engine range to keep the IMA engines fully competitive with those of other competing UK manufacturers. We already noted George's immediate response with respect to their 249 BB model. However, this directive undoubtedly extended to the 1.5 cc FROG models as well. As if this wasn’t enough, management had also noticed that the FROG range lacked a 1 cc model, which was not a situation to be ignored in view of the growing importance of the 1 cc class as the “standard” beginners’ displacement category. Finally, the Directors had noted the rising profile of the R/C market, hence being keen for George to develop a larger model suitable both for R/C service and the control line stunt and combat applications which still remained very popular. Things were rapidly reaching the point at which George urgently needed help! Fortunately, George Fletcher was an open-minded individual who was able to recognize a potential source of well-qualified assistance whenever and wherever he saw it. His opportunity came in mid 1957 when he attended a major model flying meeting at Woburn Abbey near Milton Keynes in Bedfordshire, the home of the Duke of Bedford. This was the event at which the American aces Howard Bonner and Bob Palmer gave demonstrations in R/C and control-line stunt flying respectively as part of an international tour. The event was reported in the July 1957 issues of both “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft”. At that meeting, several members of the Croydon club, namely Gordon Cornell and Norman Butcher, distinguished themselves by winning their respective events. George Fletcher took note of these performances and introduced himself to Gordon and Norman. Gordon later told me that this was the first-ever meeting between himself and George Fletcher. He could not recall if George introduced himself at the event or at the subsequent club meeting/celebration.

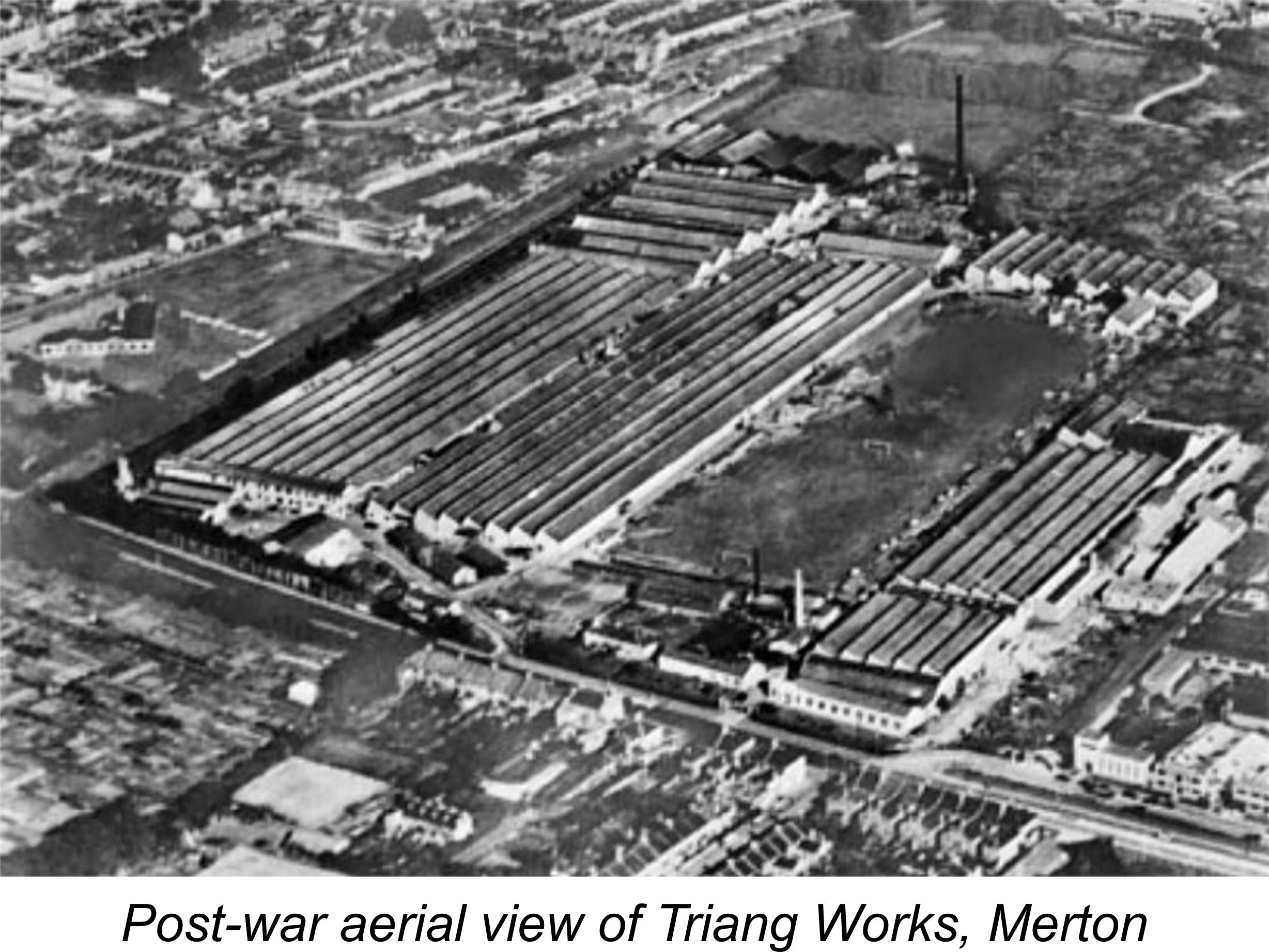

Once the new development team was established, the evolving engines and models were flight-tested on the Lines Bros. sport field which was part of the factory complex. This field may be clearly seen to the right of the main factory complex in the accompanying air photograph. Gordon recalled that factory visits occurred on most Saturdays. Additional flight testing took place in Beddington Park and on Wimbledon Common close to the Windmill Pub (an inducement, perhaps?!?).

A prototype of the new design was soon in existence. The prototype FROG 349, as it was to become known, looked generally similar to the later production version, although it utilized a head and cooling jacket seemingly borrowed from the contemporary FROG 249 BB. Overall, the prototype undeniably needed a little "cleaning-up". This prototype was sent to Peter Chinn, who was recognized at the time as Britain's leading tester of model engines as well as being an objective and knowledgeable critic whose assessments of prototype models were greatly valued by manufacturers. After testing the 349 prototype and reporting back to IMA, Chinn published a photograph of the tested engine in the February 1958 issue of "Model Aircraft", noting the fact that it had been just "one of the manufacturers'experimental models tested during the (previous) year". At the time of publication of this photograph, the decision to put the new However, towards the end of 1958 the IMA Directors finally took the plunge by deciding to proceed with production of the new model. The engine eventually saw the light of day in production form in early 1959, well over a year after its initial inception. I’ve set out the FROG 349 story in a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website. Suffice it to say here that while it was a bit on the heavy and bulky side for the power that it developed, the 349 was a well-made engine which upheld IMA's reputation for design originality with its cross-flow loop scavenging, sidestack exhaust and "centrifugal" drum valve induction. While all of this was going on in late 1957 and early 1958, Gordon Cornell had been testing the now 2-year old FROG 150 Mk. II. His findings demonstrated that, despite the previously-described modifications implemented by George Fletcher in late 1955, that model All such comments notwithstanding, it was clear that IMA needed a new flagship product in the 1.5 cc category. This category was very much in an expansionist stage in Britain at the time. In addition to the emergence of ½A combat, the ½A team race category was in its early stages of development as a competitive class. American readers should take note that the British ½A class was for 1.5 cc (0.091 cuin.) powerplants. It’s important to avoid confusion with the American ½A class for .049 cuin. motors. This prompted an expansion of Gordon Cornell’s involvement with IMA’s development programs from flight testing into the engine design field. While George Fletcher worked on the designs of the late-blooming FROG 349 and a proposed new FROG 1 cc model (see below), Gordon undertook a review of the FROG 150 and came up with a new flagship 1.5 cc design to be marketed as the FROG 150R. We’ll look at that model next. The FROG 150R

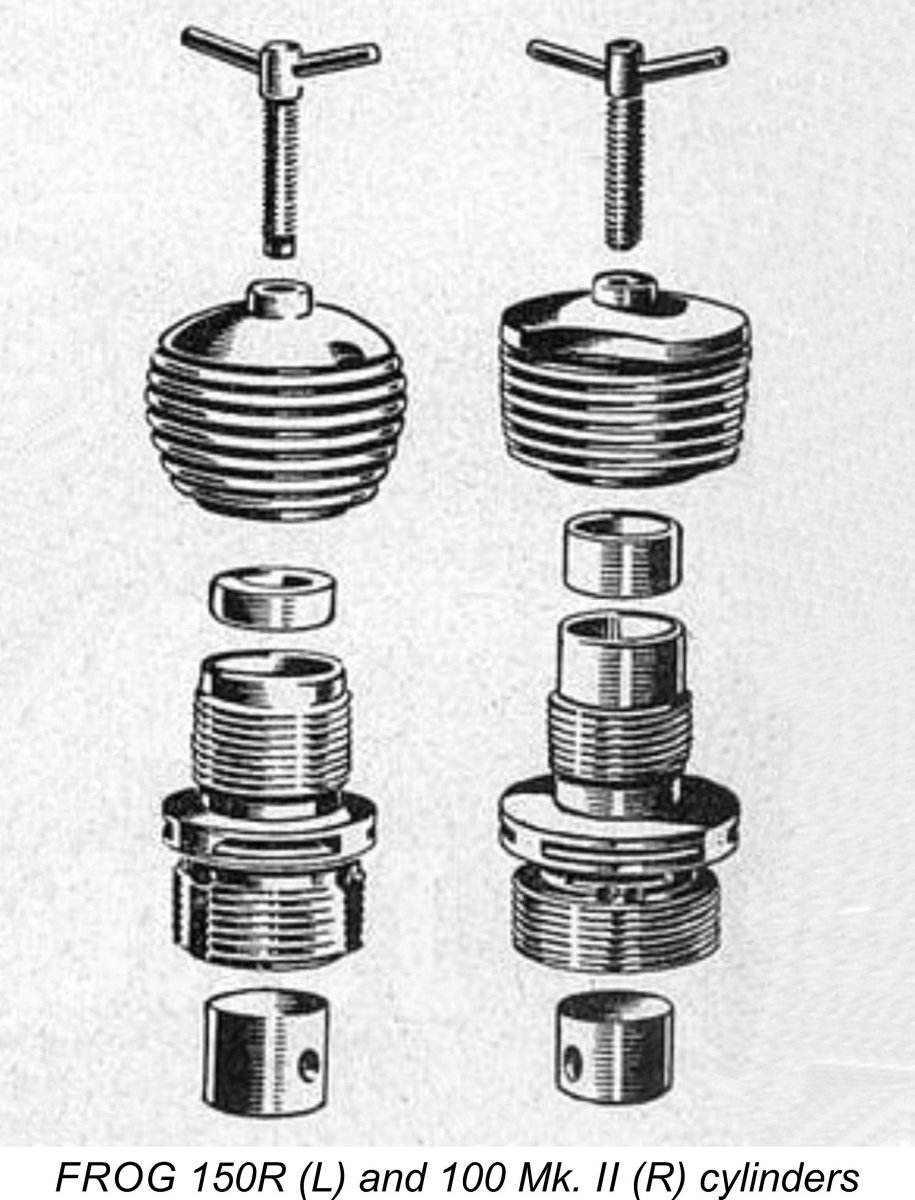

The FROG 150R eventually made its IMA advertising debut in the June 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. It was just in time to meet the very serious competition presented by the release of the long-anticipated 1.5 cc Allen-Mercury (A-M) 15 in the same month as well as that of the reed valve E.D. Fury 1.5 cc model which had appeared a month or so earlier. The 150R was basically very similar to its 150 predecessor. It retained the 150’s bore and stroke measurements of 0.500 in (12.70 mm) and 0.460 in. (11.68 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.48 cc (0.090 cuin.). The new model weighed 3.4 ounces (96 gm) with tank, although most users discarded the tank immediately since it was of no practical use for the control line applications in which the engine was most frequently employed. Few examples encountered today retain their tanks. Apart from the 150R’s blue-anodized cooling jacket, the only design feature which set the two engines apart was a considerable shortening of the piston skirt in the 150R. This had the dual effect of lightening the piston and introducing a considerable period of sub-piston induction extending for some 40 degrees either side of top dead centre. The result was a very significant increase in power output as well as improved high speed running characteristics due to the reduced reciprocating mass.

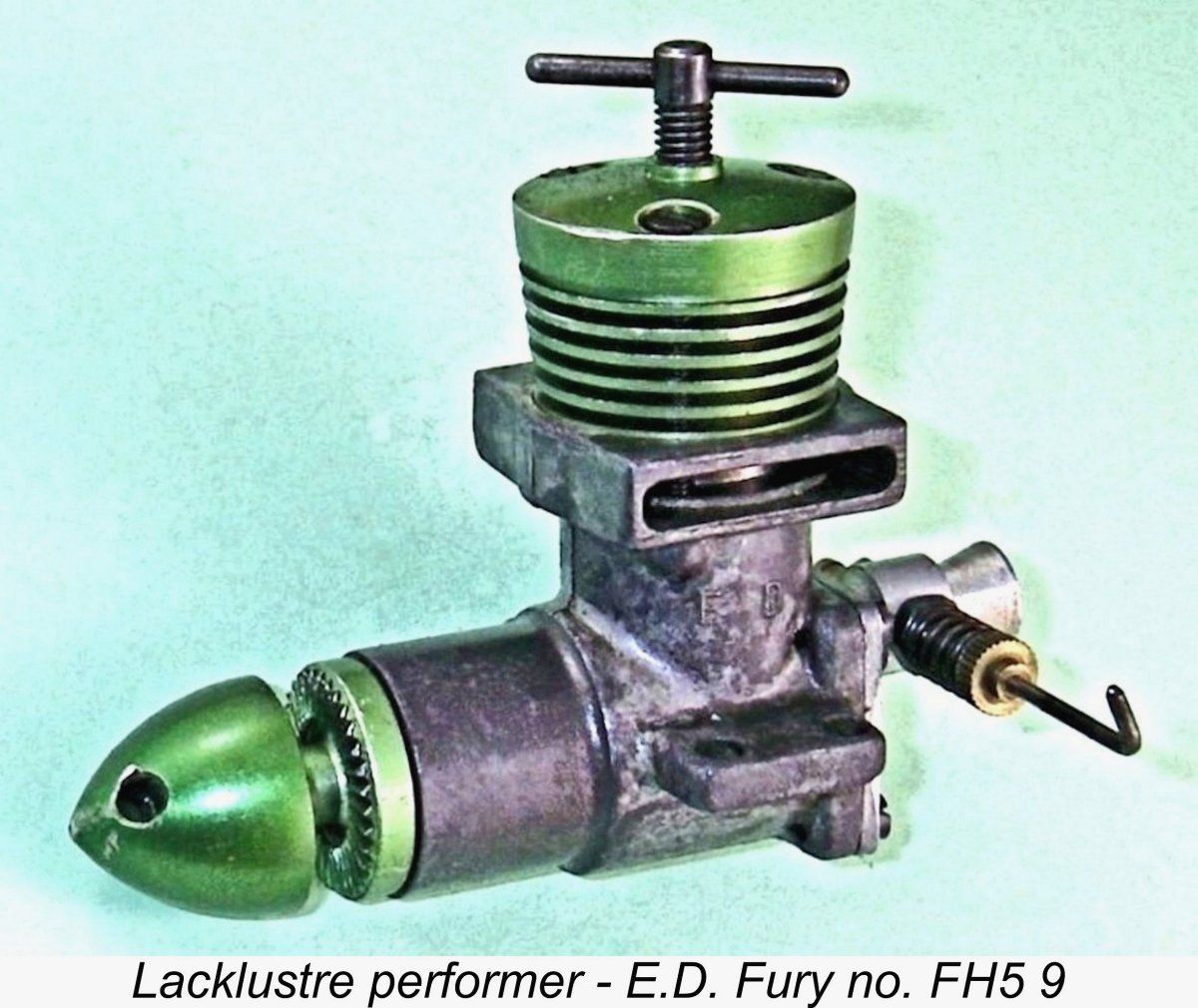

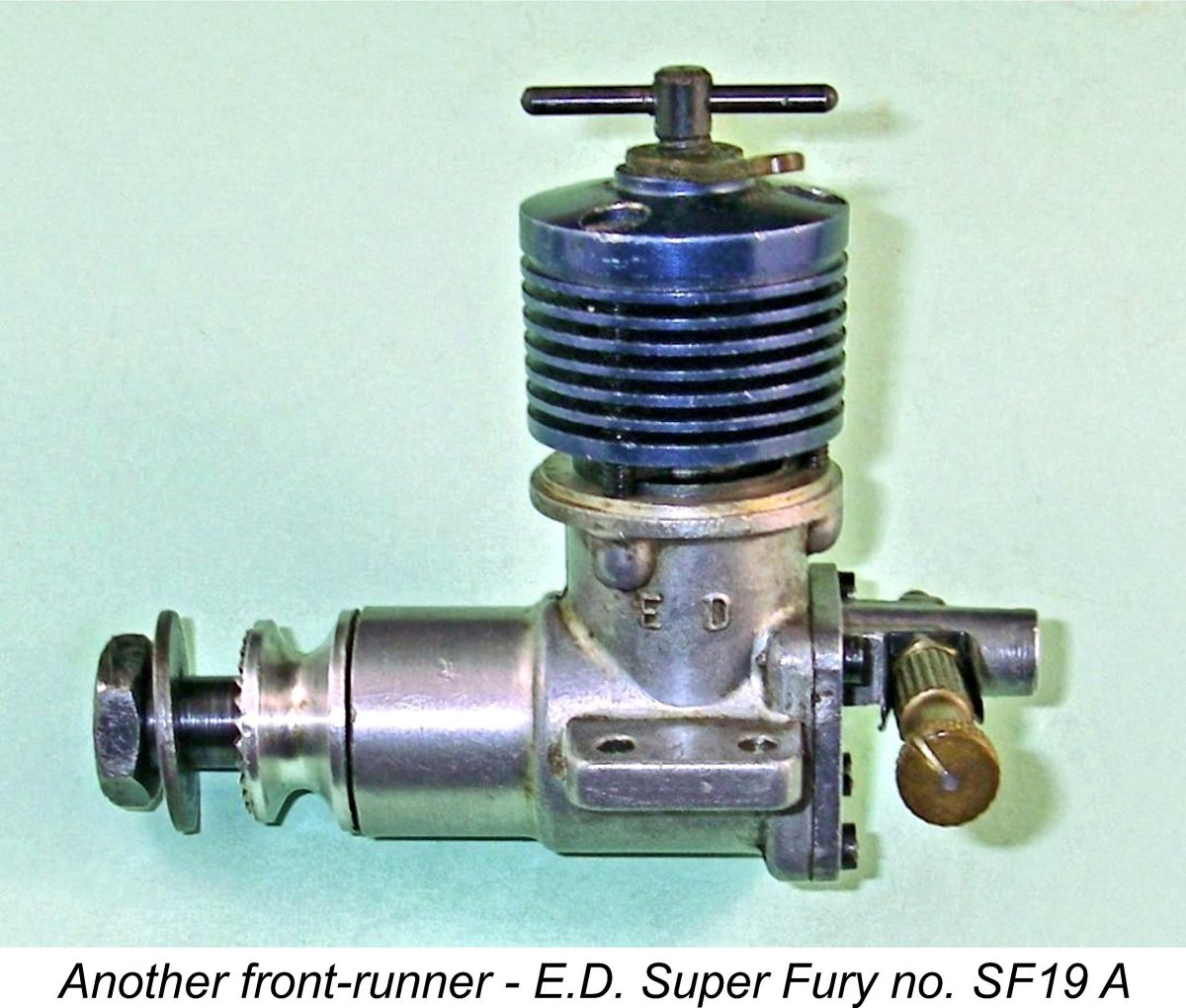

In terms of their performances in the field, there was little to choose between the two units, although the FROG 150R developed slightly more torque than the A-M 15, which accounted for its lower peaking speed. Even the prices were similar, although the FROG had a slight edge with a price of £2 15s 0d (£2.75) against the A-M’s figure of £2 19s 8d (£2.97). Although it was a well-made and durable engine which started very easily and ran well enough, the poor old E.D. Fury was The combination of high price and reported performance shortfall was enough to consign the Fury to the sidelines, where it languished until early 1960 before making a triumphant return to prominence in the shape of Gordon Cornell’s outstanding disc valve E.D. Super Fury model. The advent of the FROG 150R spelled the end of the road for the FROG 150 Mk. II. That engine’s final appearance in an IMA advertisement came in May 1958, after which no more was heard of it. The 149 “Vibramatic” remained on offer for some time thereafter, making its final IMA advertising appearance in October 1958. It is of course possible that this delayed withdrawal was due to a desire to sell off existing stocks of the engine. The FROG 150R remained on offer until March 1961, at which time it was replaced in the range with the vastly updated FROG Viper diesel and its companion glow-plug model, the FROG Venom. More of those models in their place below.

Gordon Cornell’s work on the FROG 150R during late 1957 and early 1958 had stimulated his interest in the ½A team race class which was then gaining popularity, to the point that it was finally added to the British National Championship schedule in 1960. Gordon’s interest was further stimulated when his fellow Croydon clubmate Peter Frazer expressed an interest in teaming up with Gordon to become actively involved in ½A team racing. At the time, the ½A team race class was of course ruled by the Oliver Tiger Cub 1.5 cc Mk. I model. Some readers may already have been wondering why this engine has not been previously mentioned in this article. The reason is that the Oliver cannot be seen as a commercial production aimed at the British modelling market in general – rather, it was a custom-made individually-built competition special for which one had to pay handsomely and languish on the order book for quite some time. None of the commercial British manufacturers whose products have been mentioned here were competing with the Oliver for sales – they were going after the mass market. Hence the Oliver cannot be seen as a legitimate basis for comparison.

My own tests have shown that this one-off engine (which I currently own) was a truly outstanding performer which started easily and simply buried the rest of the contemporary 1.5 cc opposition (including the Oliver) in performance terms. It's actually possible that its performance was its undoing - to make power you have to burn fuel, and the TR 1.48's main problem in a team racing context was excessive fuel consumption by comparison with the Oliver. This generally required it to make an extra pit stop, which negated its speed advantage. Of course, further development might well have led to a resolution of this issue. Gordon did make IMA aware of this design, but it would have been quite expensive to develop and produce in series as well as having a somewhat more limited appeal, hence not fitting in with IMA’s marketing strategies. I’ve recorded the fascinating story of the TR 148 in a separate article which appears elsewhere on this website. At the same time as Gordon’s work on the FROG 150R and the TR 148 was proceeding, George Fletcher was pursuing the design of a new FROG 1 cc model. We’ll take a side trip at this point to look at that design even though it doesn’t fit into our displacement category. This is justified by the fact that the FROG 100 Mk. II, as it was designated, was such a close relative of the FROG 150R that it makes no sense to treat the two models separately. The FROG 100 Mk. II

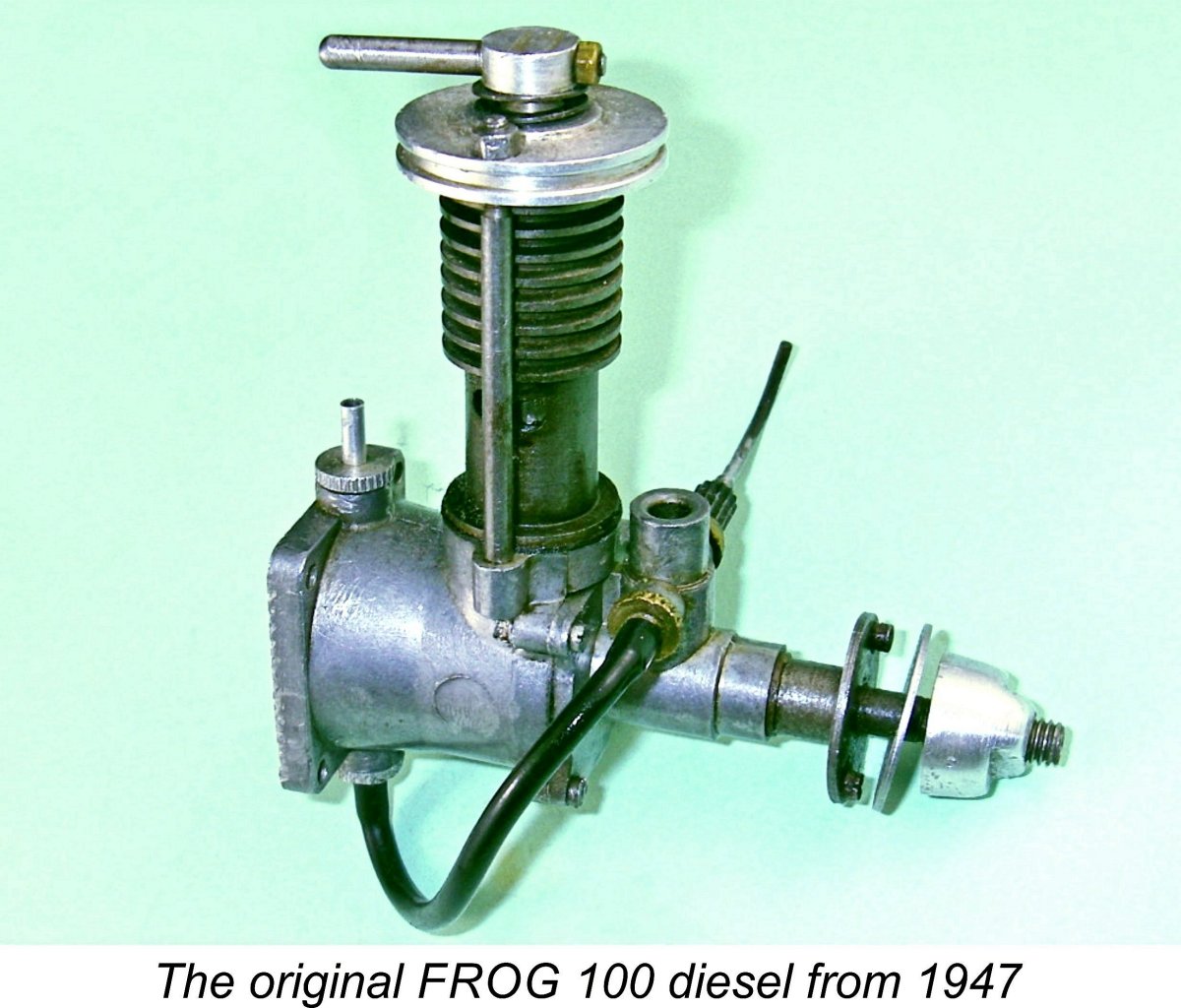

Accordingly, from late 1950 through to mid 1958 the FROG model engine range did not include a 1 cc model of any kind. During that same period, E.D. had enjoyed substantial sales of their famous 1 cc Mk. I “Bee”, which passed through a number of design variants along the way. The 1 cc Allbon Spitfire Mk. I had appeared in December 1952, becoming a great sales success in its own right and morphing into its Sabre-based D.C. Spitfire Mk. II version in February 1957. The J.B. Bomb 1 cc diesel had appeared in early 1956, although material selection shortcomings led to its having a very short production life. Finally, the May 1956 appearance of the 1 cc A-M 10 had really shaken the British modelling world since the engine was found to perform at a level which almost matched that of established 1.5 cc sport models such as the Allbon Sabre and FROG 150 Mk. II. By the second half of 1957 IMA management had decided that they too needed an entry into the 1 cc field, which was increasingly seen as the ideal diesel engine size for beginners as well as sport fliers in general. George Fletcher had completed his work on the FROG 249 BB Modified and was now preparing to tackle the 1.5 cc upgrade challenge discussed earlier along with the initial development of the larger 349 model which management had also requested. The development of a 1 cc model was now added to his already-full design brief. It will be recalled that George had just formed an association with Gordon Cornell at this time. Given the multiple design brief now set out before him, George handed the 1.5 cc upgrade program over to Gordon, while George himself tackled the 1 cc and 349 design projects.

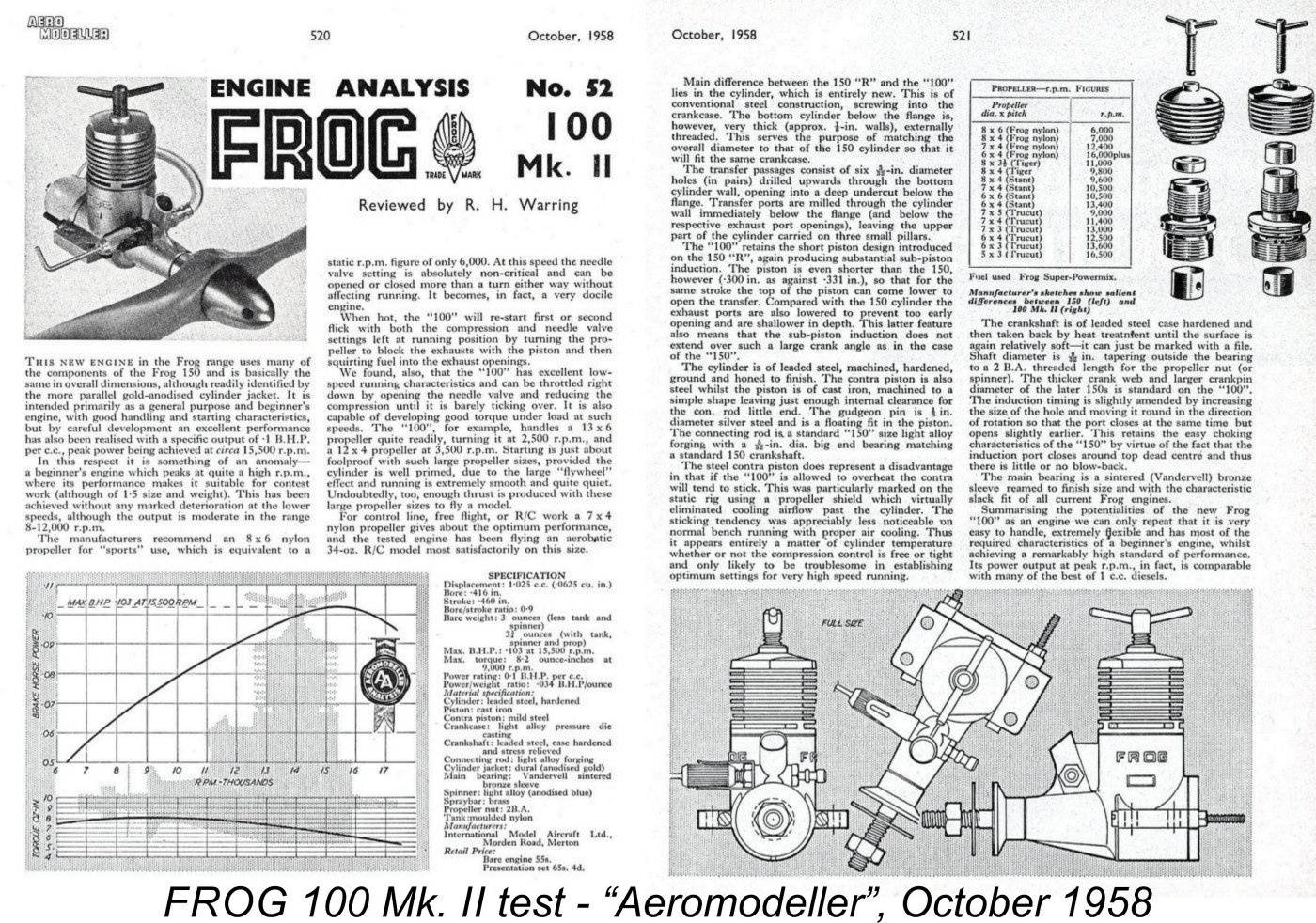

Cost considerations dictated the use of as many of the 150’s components as possible in order to take full advantage of existing tooling and fixtures. The same crankcase, backplate, needle valve, comp screw, prop driver and crankshaft were retained unchanged, the reduced displacement being achieved entirely through a reduction in the bore from 0.500 in. (12.70 mm) to 0.416 in. (10.57 mm), making the new model a long-stroke unit. With an unchanged stroke of 0.460 in (11.68 mm), the engine had a calculated displacement of 1.025 cc (0.062 cuin.). It weighed a checked 3.1 ounces (88 gm) including tank, spinner nut and fuel tubing, more or less the same as its 1.5 cc companion in the range.

The advantages of this system included the fact that the male cylinder installation thread was no longer interrupted by the bypass grooves used in the 150. The six bypass holes were free from any friction losses which might be induced by the female installation threads protruding into them. In addition, transfer port area was considerably greater. On the downside, this style of porting eliminated any possibility of providing any overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports, thus limiting transfer duration. Of course, the larger transfer port area and smoother bypass passages made this less of a concern than it might otherwise have been.

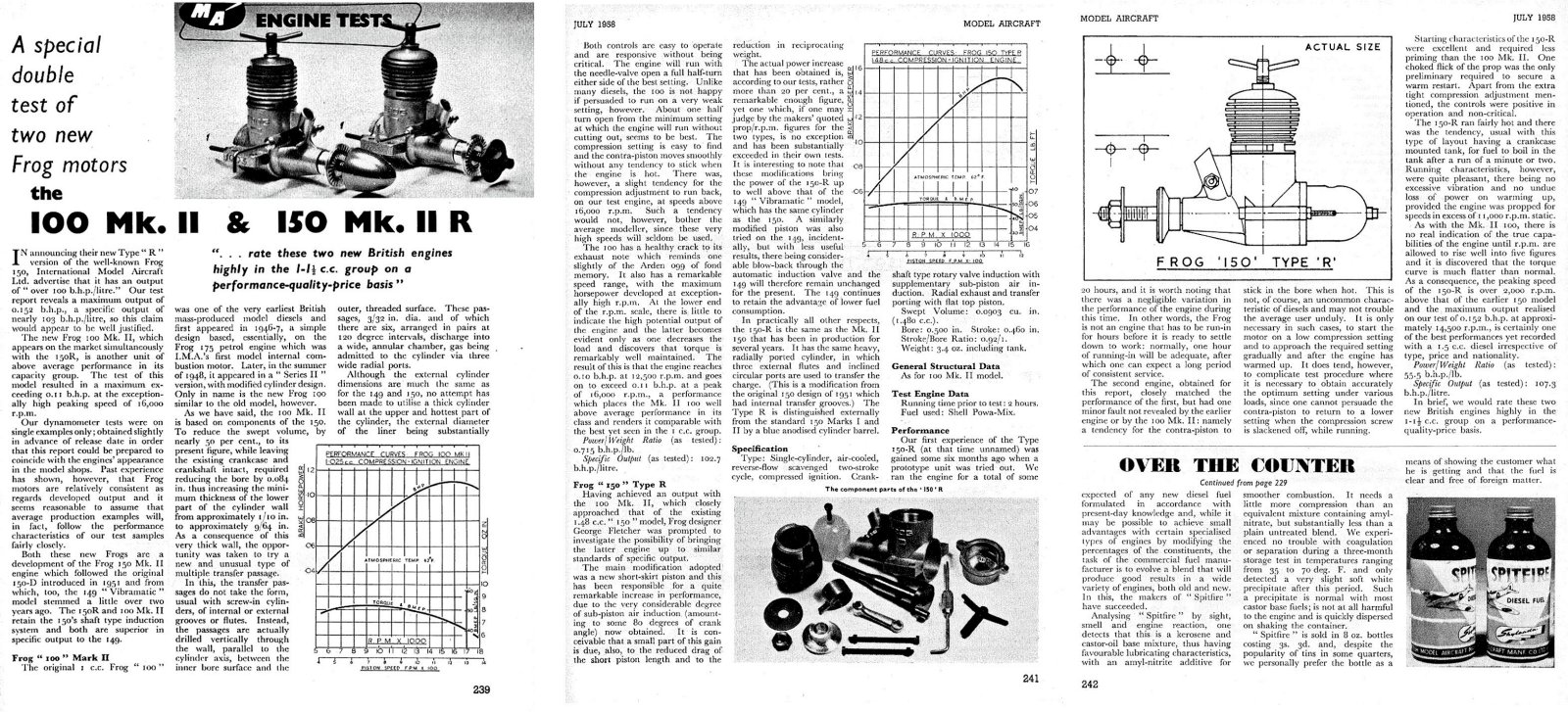

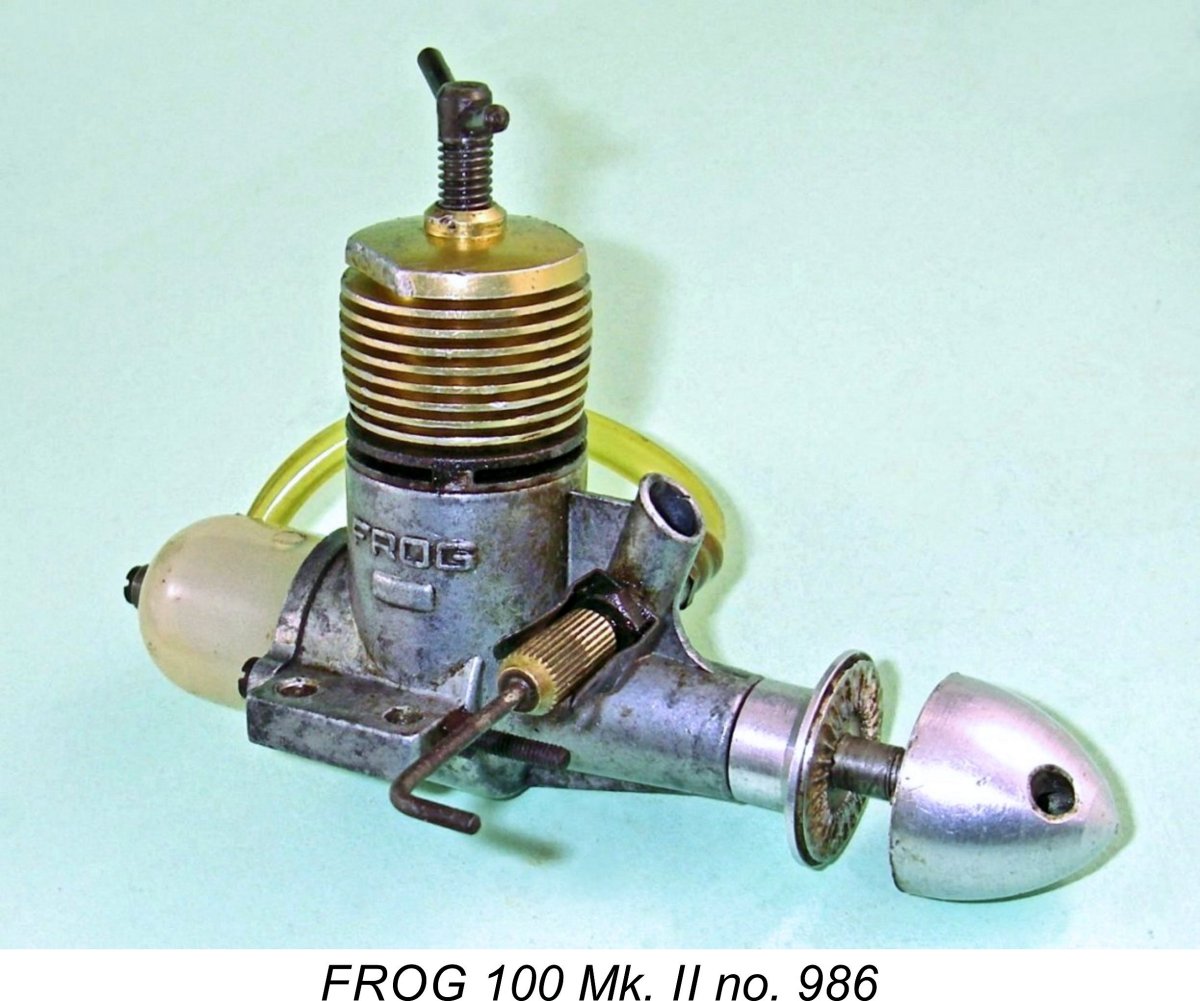

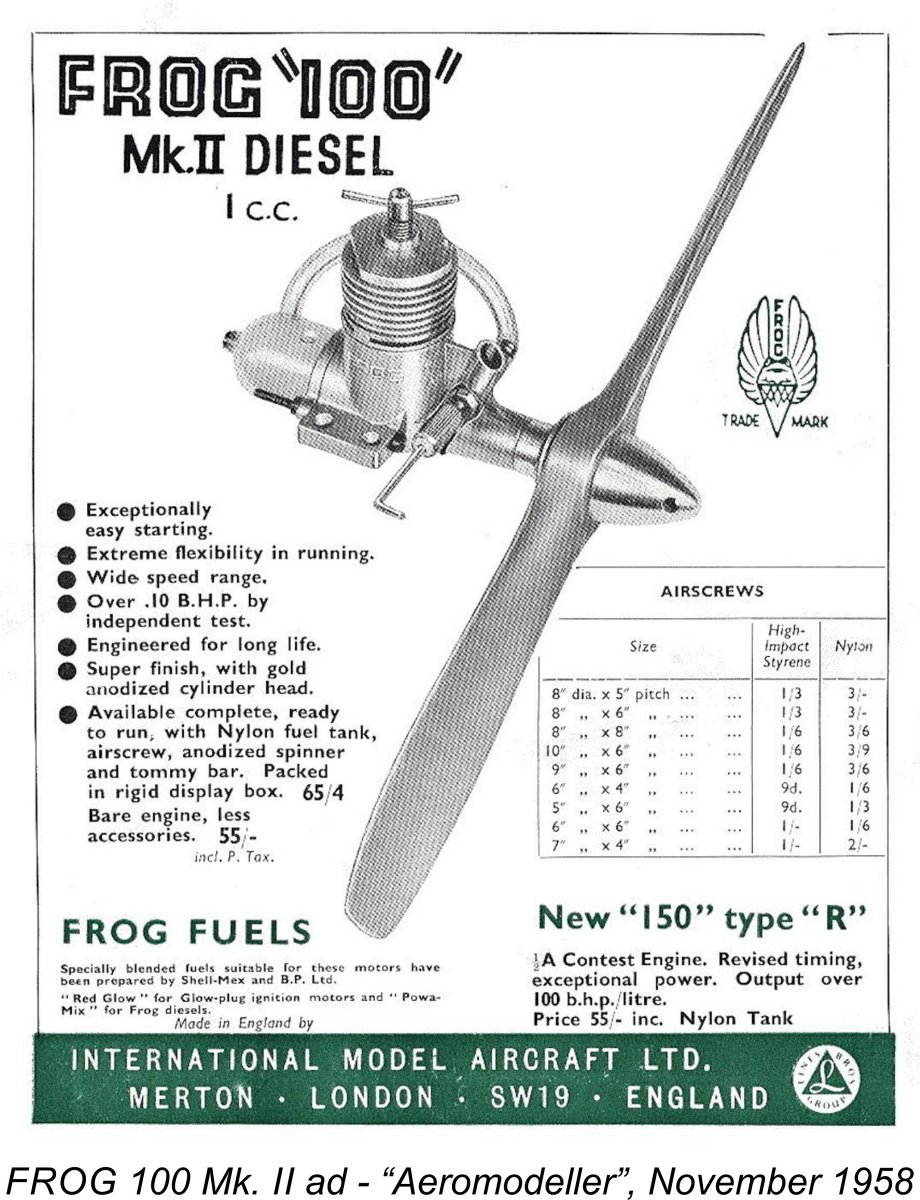

Peter Chinn included a test of the FROG 100 Mk. II in his July 1958 “Model Aircraft” report on the FROG 150R which was reproduced earlier with the discussion of the latter model. After describing the design changes which had combined to create the smaller model, Chinn proceeded to evaluate its performance. He found the FROG 100 Mk. II quite easy to start, but commented that it liked to be fairly wet for starting. Both controls were reportedly easy to operate without being overly critical. The only issue encountered was a slight tendency for the compression to run back at speeds over 16,000 RPM, but this was not seen as a problem given the fact that most users would not be operating the engine that fast. I Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” also tested the FROG 100 Mk. II, with his report appearing in the October 1958 issue of the magazine. He was just as impressed with the engine as Chinn had been, citing its excellent low-speed running characteristics as well as its unusually high peaking speed. He found the engine very easy to handle, although the steel contra piston of his example did have a tendency to stick in the bore when hot. This is in fact a characteristic of engines having steel contra pistons operating in steel bores. In terms of the engine’s performance, Warring reported apeak output of 0.103 BHP @ 15,500 RPM, thus more orless confirming Chinn’s findings. He summarized the engine as “very easy to handle, extremely flexible and(having) most of the required characteristics of I recently had the chance to renew old acquaintance with this model thanks to a decision to use it as a test engine for some possibly suspect fuel that I had on hand. My trusty well-used FROG 100 Mk. II no. 986 started up right away on this fuel, turning an APC 7x5 airscrew at 11,000 RPM (around 0.105 BHP – a very good performance indeed). Clearly, the fuel was A-OK, while the FROG had lost none of its willingness to perform very well over the years! A few subsequent re-starts just for fun amply confirmed the engine's excellent handling qualities as well as its ability to run the tank out cleanly.

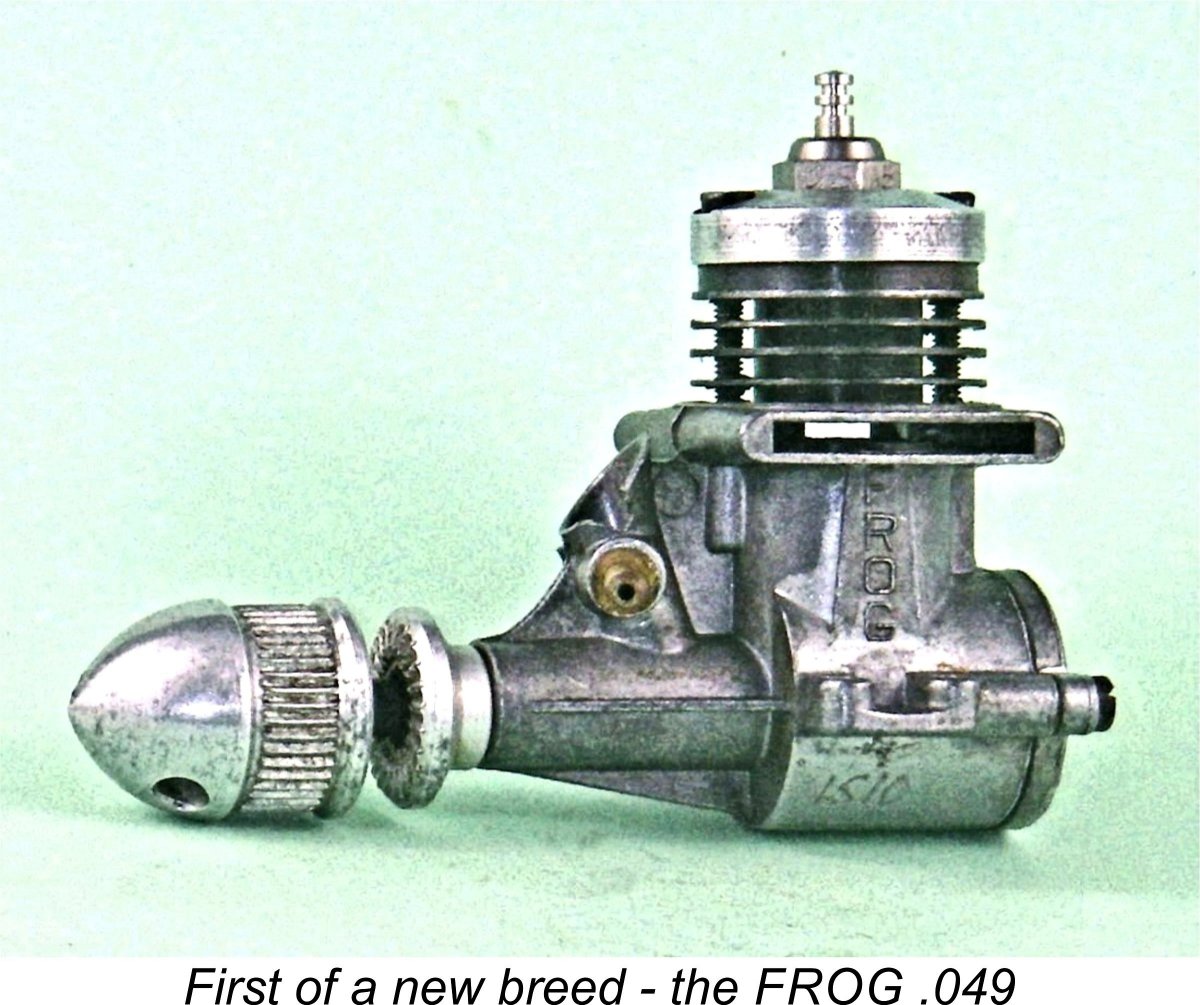

The price of the basic FROG 100 Mk. II as of late 1958 was £2 15s 0d (£2.75), exactly the same as the 150R. The engine was also available in a rigid display box with full accessories (tank, spinner, fuel tubing, airscrew and tommy bar) for £3 5s 4d (£3.27). Clearly anyone buying a 100 Mk. II was not motivated by price – they definitely wanted a 1 cc engine! The competing A-M 10 sold for a slightly higher price of £2 18s 6d (£2.93) at the same time, giving the FROG 100 Mk. II a minimal price edge. It's actually notable that throughout its market tenure the FROG range generally enjoyed a slight price advantage over its most direct competitors. This was doubtless a benefit arising from the fact that IMA was just a small part of a far larger organization. The FROG 100 Mk. II actually outlasted its 150R companion in the range, continuing to appear in IMA’s advertising after the April 1961 appearance of the Viper and Venom 1.5 cc models which displaced the 150R. The FROG 100 Mk. II maintained its position in the range right up to the cessation of IMA’s manufacturing of the FROG engines in early 1962. More Busy Times at IMA During late 1958 George Fletcher received a letter from Jim Donald, then Managing Director of E.D., suggesting that Fletcher join them to fill the gap left by the final severing of ties with their long-time design consultant Basil Miles. George did not wish to leave IMA at that time, suggesting instead that Gordon Cornell contact Jim Donald regarding this opportunity. Gordon was quite happy to do so, resulting in an offer from E.D. which Gordon accepted. Accordingly, in late 1958 Gordon moved over from IMA to become the chief engineer for E.D. His services were thus lost to IMA. Fortuitously, Gordon’s departure coincided with a bit of a hiatus in what had been a frenzied pace of new model development at IMA from 1956 through 1958. After the market entry of the FROG 100 Mk. II and FROG 150R in mid 1958, no new models materialized until the early 1959 appearance of the long-delayed Once the FROG 349 was launched, George Fletcher was next asked to embark upon the creation of a glow-plug version of the FROG 80 diesel, now in its third year in production. Designated the FROG .049, this engine made its appearance on the market in July 1959, thus becoming the first of a series of British-made .049 glow-plug engines from various manufacturers. The story of the FROG under-1 cc models has been recounted in detail elsewhere. Meanwhile, things stood relatively still on the 1.5 cc front. The FROG 150R and the A-M 15 continued to vie for market attention, neither of them having a particular edge. The E.D. Hornet and Fury remained on offer, as did the Allbon (now D-C) Sabre, but none of these models offered any performance competition for the two front-runners. However, all of this began to change with a vengeance as 1959 drew on. The growing popularity of the British ½ A class for control-line team racing and combat had raised the performance stakes in this category to the point at which manufacturers wishing to remain in the 1.5 cc game had to take a hard look at their products.

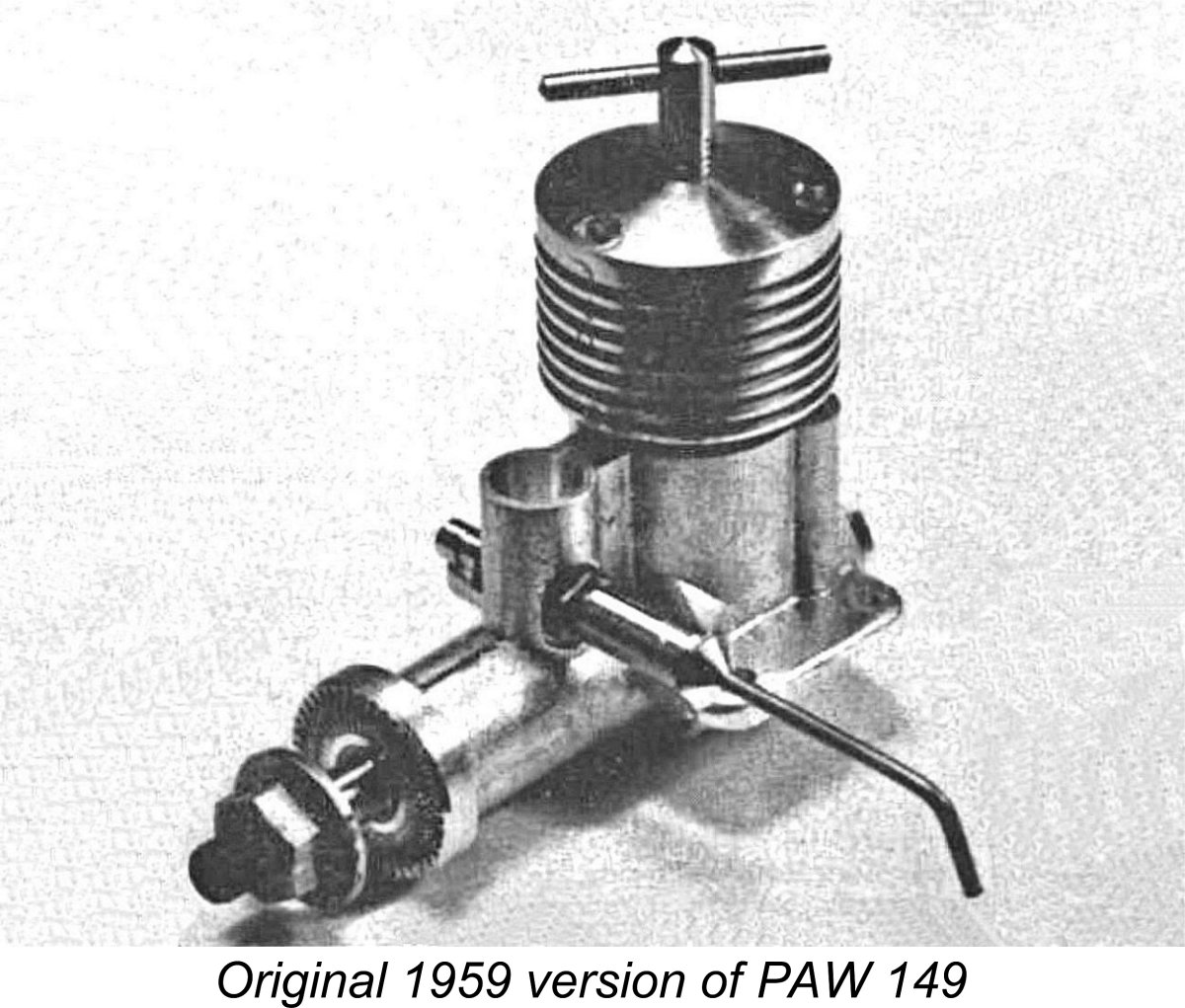

Ron Warring did even better in his subsequent test of the engine – he reported a peak output of 0.176 BHP @ 17,000 RPM for his test example (“Aeromodeller”, March 1960). Although comparable outputs could be extracted from the FROG 150R by knowledgeable tuners, this performance very definitely placed the new PAW at the head of the over-the-counter commercial 1.5 cc pack. At a price of £4 6s 0d (£4.30), it was quite a bit more expensive than the FROG and A-M opposition, but its quality and performance edge attracted many customers. And there was more competition in the offing – things were developing over at E.D. It will be recalled that Gordon Cornell had moved to E.D. in late 1958 to become their chief engine designer. He had of course shown his TR 1.48 prototype to E.D. management, who were duly impressed with the engine. However, E.D.’s financial position was then becoming increasingly tenuous, as recounted elsewhere. Accordingly, Gordon was directed to pursue cost-effective upgrades to E.D.’s existing models rather than embark upon the development of any all-new designs.

At a price of £3 15s 3d (£3.76), the new E.D. model was more expensive than the FROG and A-M alternatives, but did undercut the PAW 149 somewhat. It attracted many buyers who might otherwise have chosen one or the other of the alternatives. In the face of this standard of competition, IMA’s options were somewhat limited. Firstly, they could simply stand pat with their existing 150R model, continuing to service the popular sports engine "consumer" market and relying upon their substantial price edge (£2 13s 4d or £2.66) to maintain their sales base. This was the course adopted by both A-M and D-C Ltd. The FROG 150R was still highly competitive in that market. Secondly, they could abandon the 1.5 cc field altogether rather than continue with what might be seen by some as a “second-tier” product. However, neither of these options evidently appealed to IMA management. Instead, they gave George Fletcher a free hand (finally!) to develop an all-new design intended to bring the FROG 1.5 cc series back up to the top level for commercially-produced engines. The direction to commence work on this project evidently came in late 1959 after the FROG .049 had been launched. Presumably it was IMA's response to the appearance of the PAW 149. George Fletcher rose splendidly to this challenge, developing perhaps the finest model engine every to carry the FROG logo – the 1.48 cc FROG Viper. We’ll look at that model next. The FROG Viper

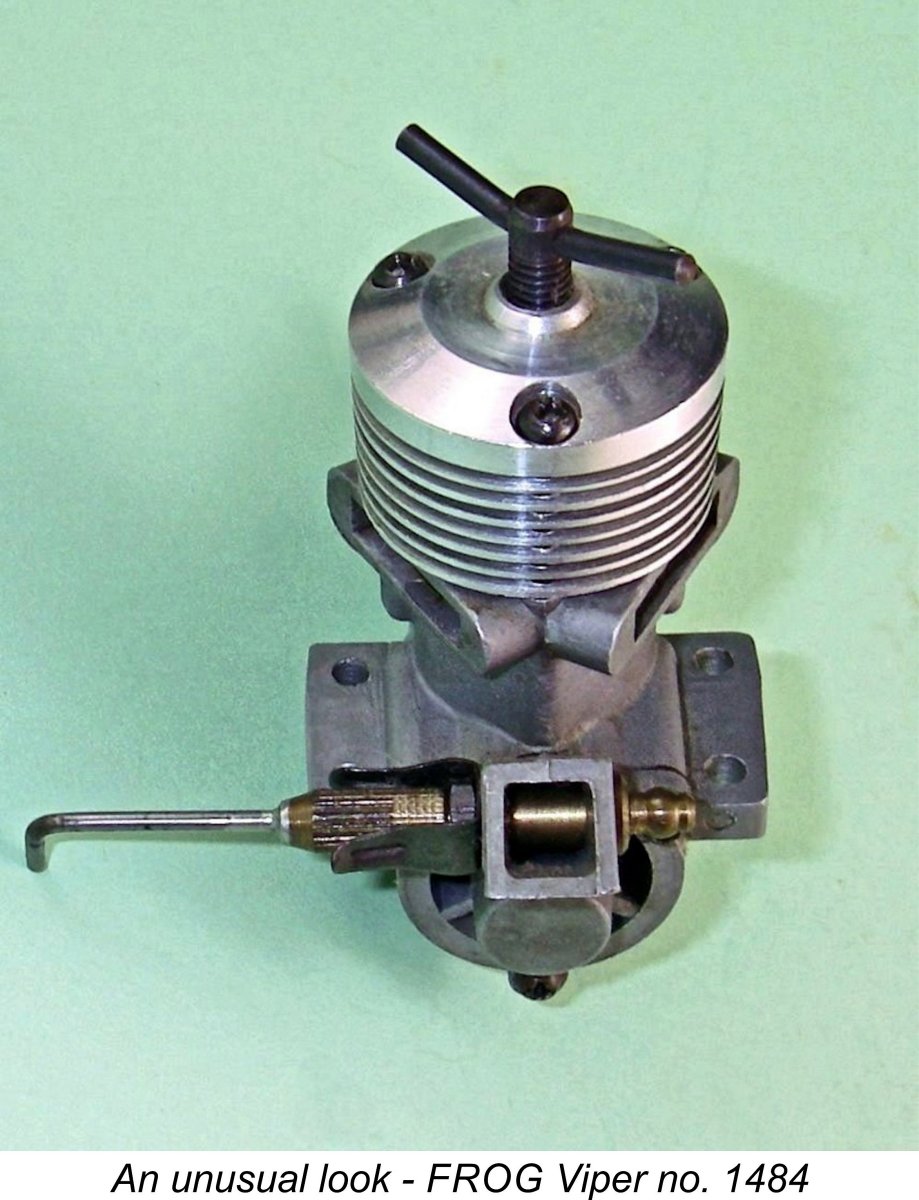

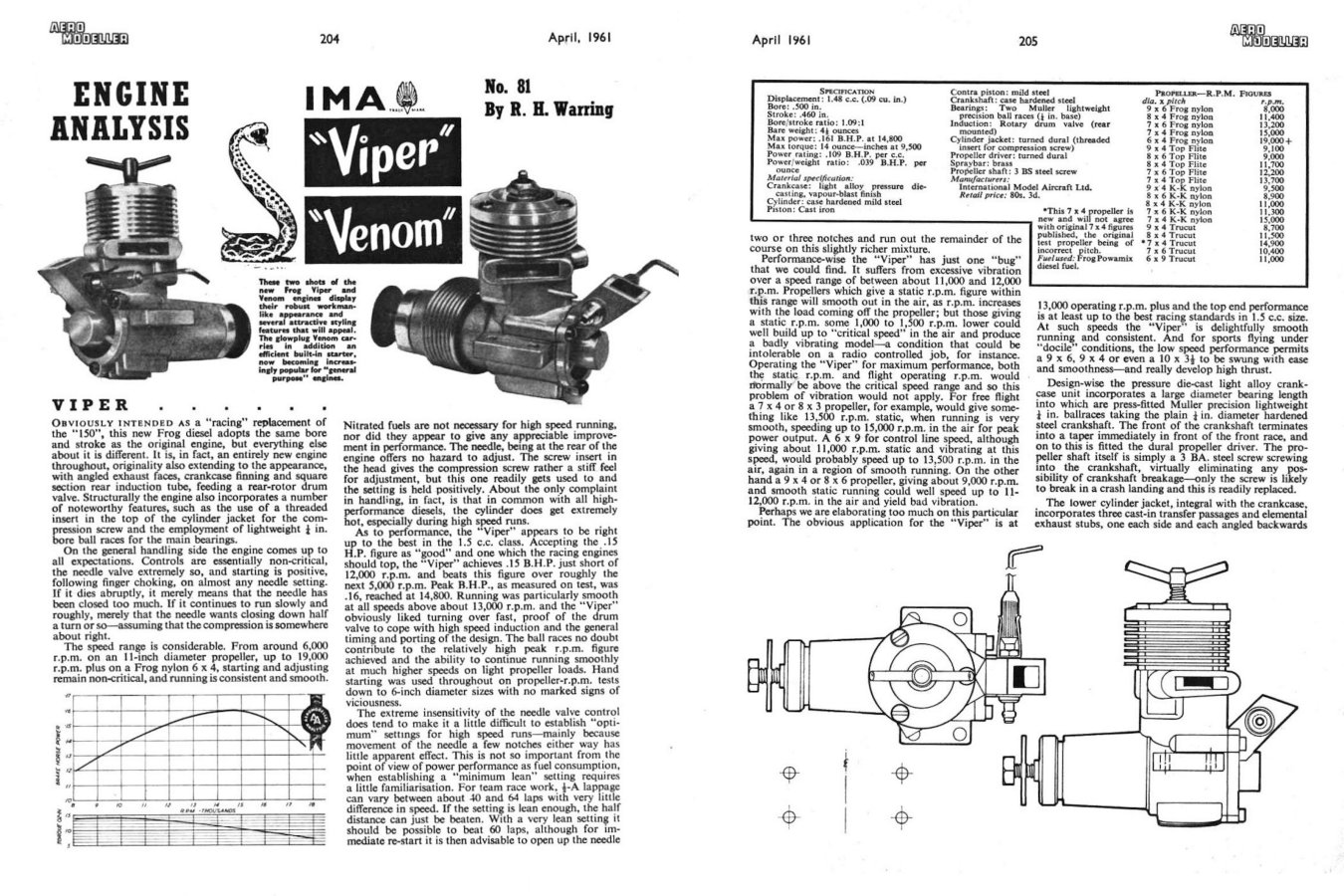

Unlike all of its 1.5 cc predecessors in the FROG line-up, the Viper was in no sense a derivative of the original FROG 150 of 1951 – rather, it was an all-new design from the ground up. The only feature that it carried over from the earlier models was their internal geometry – bore and stroke were unchanged at 0.500 in (12.70 mm) and 0.460 in. (11.68 mm) respectively for a displacement of 1.48 cc (0.090 cuin.). The Viper was clearly designed from the outset with all-out performance rather than economy of construction in mind. The exhaust ports opened into an annular exhaust collector ring cast into the upper crankcase which in turn discharged through a pair of rearward-angled exhaust stacks also cast in unit with the main crankcase. Combined with the rectangular intake venturi, these stacks gave the engine a highly individualistic appearance. Naturally the need to align the transfer ports with their respective bypass passages meant that the former screw-in cylinder design could no longer be used. Instead, the cylinder was secured using a turned alloy slip-on cooling jacket which was retained by three Phillips-head screws. Cylinder port timing was quite aggressive. The exhausts opened at only 95 degrees after top dead centre for an unusually long total exhaust period of 170 degrees. The transfer ports opened only 10 degrees later for a total transfer period of 150 degrees. I personally believe that the engine's overall performance might well have been somewhat improved by the use of rather less aggressive figures. Induction timing was also quite long – the induction port opened at 40 degrees after bottom dead centre and closed at 30 degrees after top dead centre for a total induction period of a respectable 170 degrees. The efficiency of this system was enhanced by the use of a rectangular-section induction port of considerable size which registered with the matching rectangular base of the intake venturi. This gave very rapid opening and closing of the system. Given this arrangement’s effectiveness, George Fletcher did not feel the need to include any sub-piston induction in this model. The quality of the engine was beyond reproach. A nice touch was the use of high-precision German-made Muller high-speed ball bearings, which gave the engine a remarkably “free” feel when turned over. Another quality feature was the use of a steel Armstrong Helicoil thread insert to accommodate the compression screw.

The sole criticism which Warring noted was a certain tendency towards “excessive” vibration in a speed range from 11,000 to 12,000 RPM. However, he also pointed out that to take best advantage of the engine’s power characteristics it would normally be operated at speeds well in excess of this range. At such speeds, the Viper was reportedly “delightfully smooth-running and consistent”. As far as performance went, Warring reported a peak output of 0.161 BHP @ 14,800 RPM. This was rightly characterised as “right up to the best in the 1.5 cc class”. The quality of the engine’s construction also came in for commendation.

Chinn measured a peak output of 0.162 BHP @ 15,800 RPM, thus more or less duplicating Warring’s findings, albeit at somewhat higher speed. This was undoubtedly a fine performance, but euphoria is somewhat tempered by the recollection that Chinn had previously measured an output of 0.152 BHP @ 14,500 RPM for the significantly less expensive, far simpler and considerably lighter FROG 150R. The plain fact is that all that expense and complexity had not translated into anything like as much of a performance increase as one might have hoped for. Chinn's overall characterisation was that the engine was “a refreshing departure from usual practise, and its design is matched by good workmanship and an attractive appearance”. Reading between the lines, the absemce of any reference to the engine's performance in this summation suggests that Chinn was a little disappointed by the engine's measured output. Nonetheless, the Viper was unquestionably a very fine engine by any objective measure. It remains one of my personal favourites. The FROG Venom Glow-Plug Model

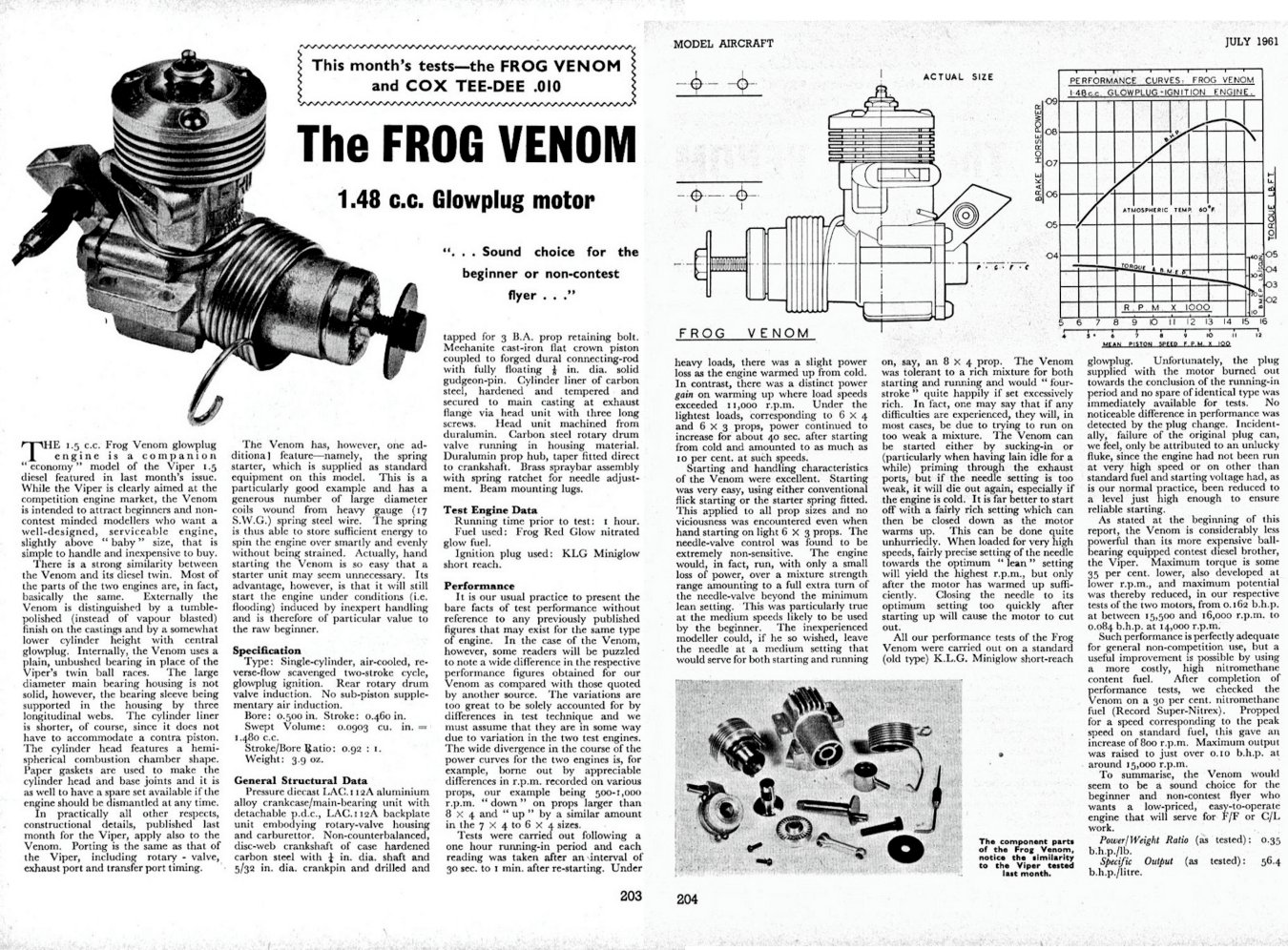

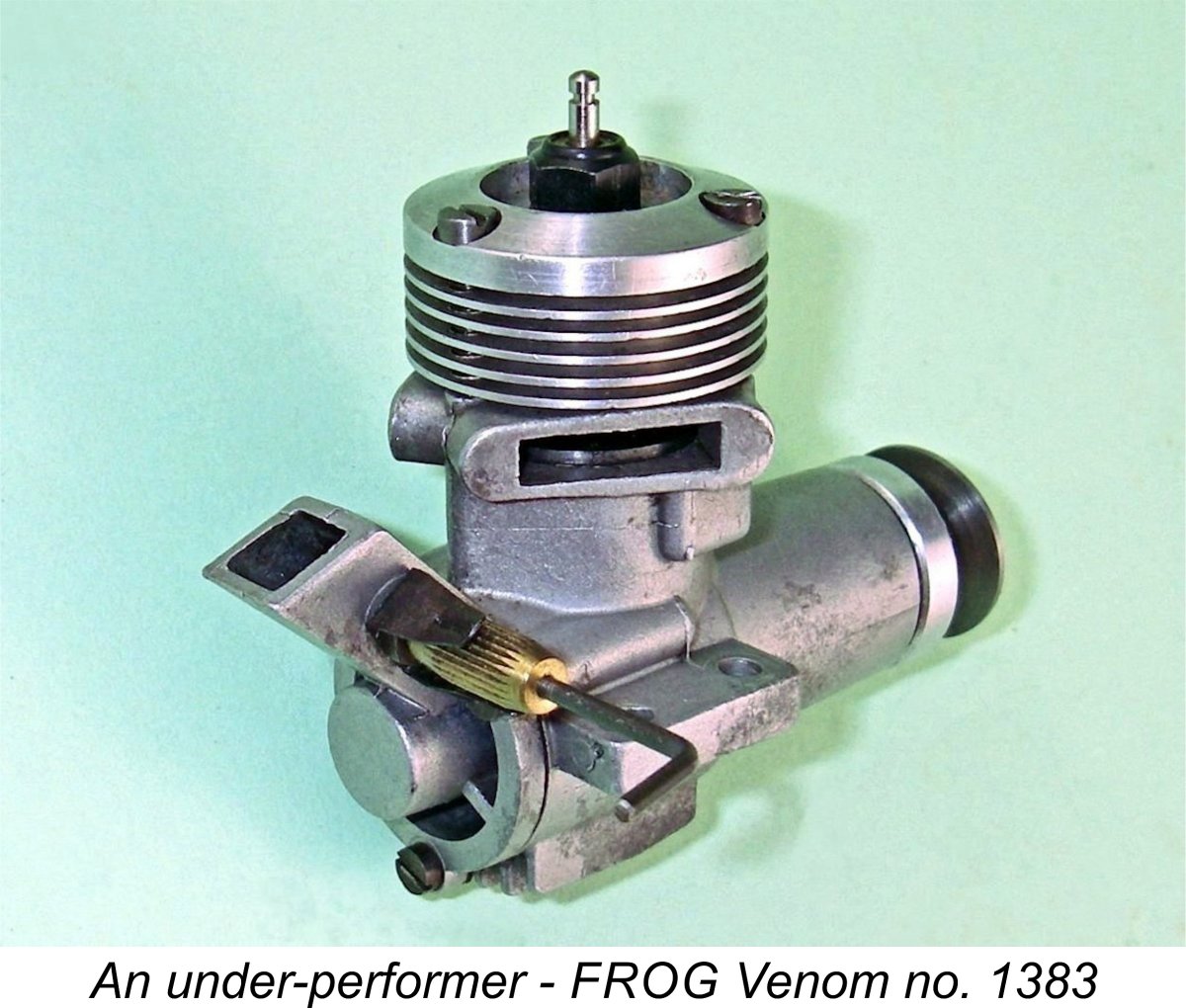

The conversion to glow-plug ignition was accomplished by shortening the upper cylinder somewhat and creating a different cooling jacket which doubled as the cylinder head and accommodated the glow-plug. Somewhat surprisingly, the Venom’s compression ratio was set at a rather high 11:1. Presumably this was to accommodate the use of the low nitro fuels which cost considerations might dictate for many beginners and sport fliers. The engine’s intended purpose as a beginner’s engine was underscored by the inclusion of a coil spring starter of the type (unfortunately) introduced by D-C Ltd. in 1959 as their “Quickstart” unit. I say “unfortunately” because the use of such a device relieved a new owner of the need to master the art of starting a model engine by hand, leaving that skill to be acquired later (as it inevitably had to be) with other engines. The reality was that, like most other designs fitted with such devices, the Venom’s starting qualities were actually so good that this spring was completely unnecessary, hence being dispensed with by most owners. Good riddance .......... Ron Warring included a test of the Venom with his previously-mentioned report on the Viper which appeared in the April 1961 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. He found that hand-starting the Venom was “perfectly straightforward”, with the needle setting and response being essentially non-critical. Running qualities were characterised as “smooth and consistent at all load speeds up to about 10,000 RPM” although for reasons which Warring could not explain his example seemed reluctant to run at speeds which greatly exceeded this figure. Looking at the engine's design features, I too am rather puzzled by this finding..........it should have been good for more. As one might expect from an engine which drew comments of this nature, the measured performance was very far from spectacular. Using standard FROG "Red Glow" fuel, which at the time was a rather odd mixture containing 70% methanol, 25% castor oil and 5% amyl nitrate, Warring reported a peak output of only 0.075 BHP @ 10,000 RPM, a figure which almost any contemporary 1 cc diesel would handily exceed. In fact, it fell short of the performance of the 1948 FROG 160 "bicycle spoke" glow-plug model, which had managed a reported 0.083 BHP @ 10,850 RPM ("Aeromodeller", August 1949). Warring also tried a fuel containing 15% nitromethane, but inexplicably found no significant improvement. He concluded that the Venom was “a docile engine, best left as it is and run on straightforward standard fuel to realise fully the advantages of its easy handling qualities”.

The differences were of such magnitude that Chinn openly expressed doubts that they could have arisen from different testing methods. He was convinced that there must have been significant differences between the two tested examples of the engine. The suggestion appeared to be that there was something fundamentally wrong with Warring's test example. Chinn's engine was quite happy to run at higher speeds, although it didn't develop much torque to go with those speeds. As a result, Chinn was only able to report a peak output of 0.084 BHP @ 14,000 RPM - only a little more power than Warring's example, but at much higher speed. Chinn found that his example was some 500-1,000 RPM down on Warring's example on props larger than 8x4 and up by a similar amount on props in the 7x4 to 6x4 range. Clearly Warring's example developed a lot more torque up to 10,000 RPM or so. The result was that Chinn's power curve was basically similar but skewed 4,000 rpm to the right!

Clearly looking for positive things to say, Chinn praised the engine's handling just as Warring had done. With respect to the spring starter, he characterised it as being "a particularly good example" of this type of starting aid, but then added what I consider to be the completely valid comment that "hand starting the Venom is so easy that a starter may seem unnecessary". He did his best for the manufacturer by characterising the Venom as "a sound choice for the beginner and non-contest flyer who wants a low-priced, easy-to-operate engine that will serve for F/F or C/L work". With such lukewarm reviews against its published record, the Venom stood no chance in the British modelling marketplace of 1961. Even with a bargain price tag of £2 18s 0d (£2.90) it failed to attract much sales interest. Although it continued to be featured in IMA’s advertising throughout 1961, it’s clear that it made very little impression upon the market. Examples in good condition are relatively rare today. In any case, major changes were in the offing which would spell a premature end to both the Venom and its outstanding Viper diesel companion. A Change of Ownership and Manufacturer Even while the FROG Viper and Venom were making their March 1961 debuts, the management of IMA’s parent company, the Lines Brothers organization, was already re-evaluating the ongoing involvement of their IMA subsidiary in the flying model aircraft industry. In early 1962 a decision was finally taken by Lines Brothers that IMA would end their involvement with this industry. Accordingly, IMA ceased all model engine and flying model kit production in the early part of that year. Naturally, this included the FROG Viper and Venom 1.49 cc models, both of which were thus terminated after less than a year on the market. No-one missed the Venom, but the premature loss of the Viper was a blow to all knowledgeable British power modellers. I myself was beginning to save up for one when it vanished from the market with little warning.

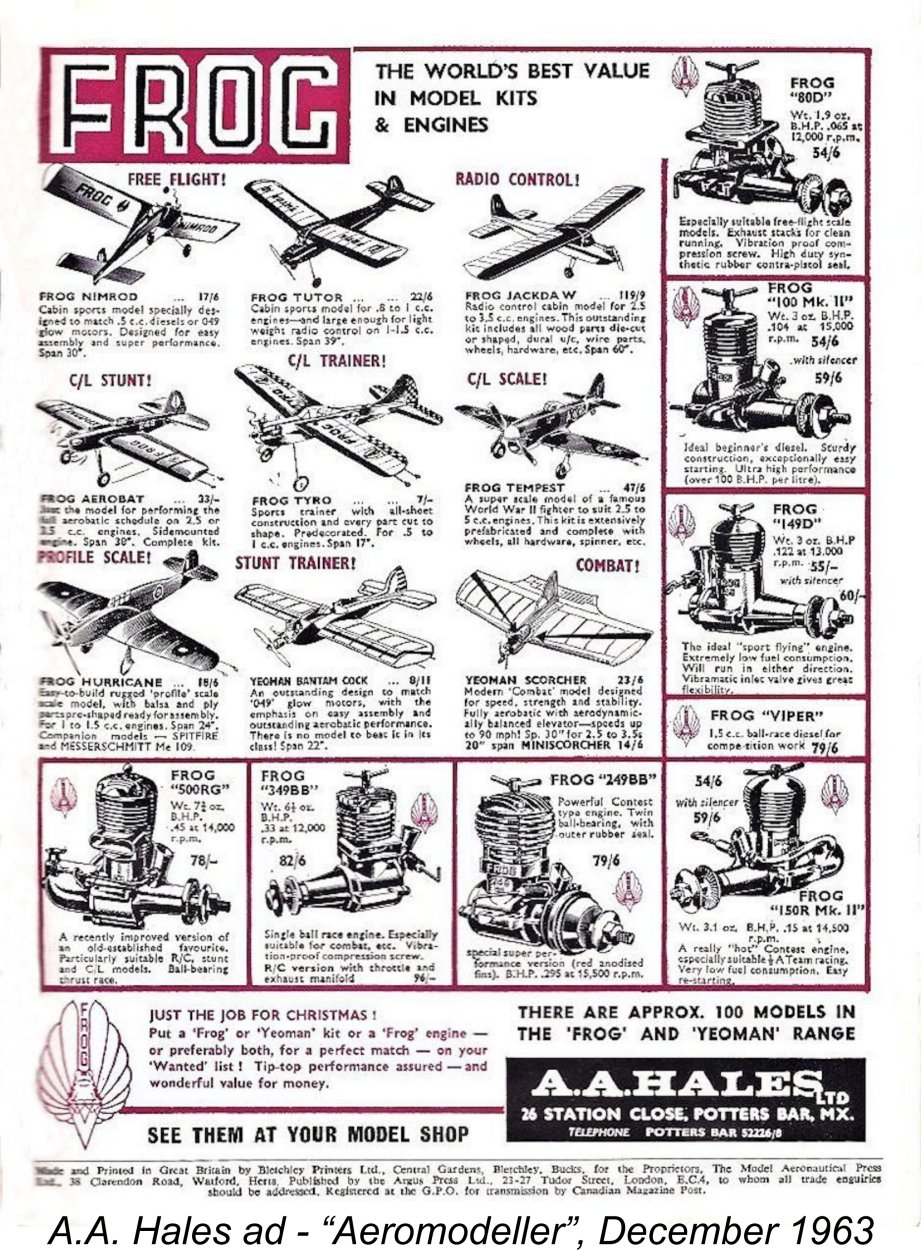

A major distibutor of the FROG model engines had been the A. A. Hales organization of Potters Bar in Hertfordshire, just north of London. In the latter part of 1962, Lines Brothers purchased a majority shareholding in the A. A. Hales company, a move which was announced in the "Trade Notes" feature in the February 1963 issue of "Aeromodeller". This made A. A. Hales a Lines Brothers subsidiary as opposed to an independent company. At the time of this transaction, there were significant numbers of completed engines and model kits already in existence. A. A. Hales was charged with the responsibility for the future marketing of the various FROG products. After 1962, no more was to be heard of IMA in connection with the FROG marque. Hales produced their own range of model kits under the "Yeoman" label (who remembers the "Dixielander", the "Bantam Cock" and the "Scorcher"?). Despite apparently being in competition with themselves, they continued to market many of the established FROG model kits, although these were almost certainly existing stock acquired at the time of the transfer of responsibility for the FROG marque to Hales from Lines Brothers. It’s interesting to note that the unsold stocks of previously-manufactured FROG engines evidently included a sizeable number of examples of the old 149 “Vibramatic” and 150R models as well as the FROG 100 Mk. II. All of these models were included in A. A. Hales’ advertising up to March 1965. It's apparent that there were minimal residual unsold stocks of the Venom, because that model ceased to appear in Hales' advertising after December 1962. The Viper lingered on as an un-illustrated mail order item until November 1964, when stocks of that model too appear to have dried up. The Vibramatic followed suit after March 1965. One suspects that production of those units may already have been terminated in late 1961 as a preliminary to Lines Brothers’ decision to end all IMA model engine manufacture in early 1962. In April 1962, shortly prior to the transfer of responsibility for the FROG model engine range to A. A. Hales, the challenge of selling off the residual stocks of the IMA 1.5 cc FROG engines had been made a little more difficult by the introduction of the M.E. Snipe 1.5 cc diesel from Glen Vine on the Isle of Man. This excellent model had been preceded onto the market by the 1 cc M.E. Heron which had appeared in mid 1960 to offer competition to the FROG 100 Mk. II along with the D-C Spitfire Mk. II and the vastly improved 1960 E.D. Bee which had been another of Gordon Cornell's accomplishments while at E.D..

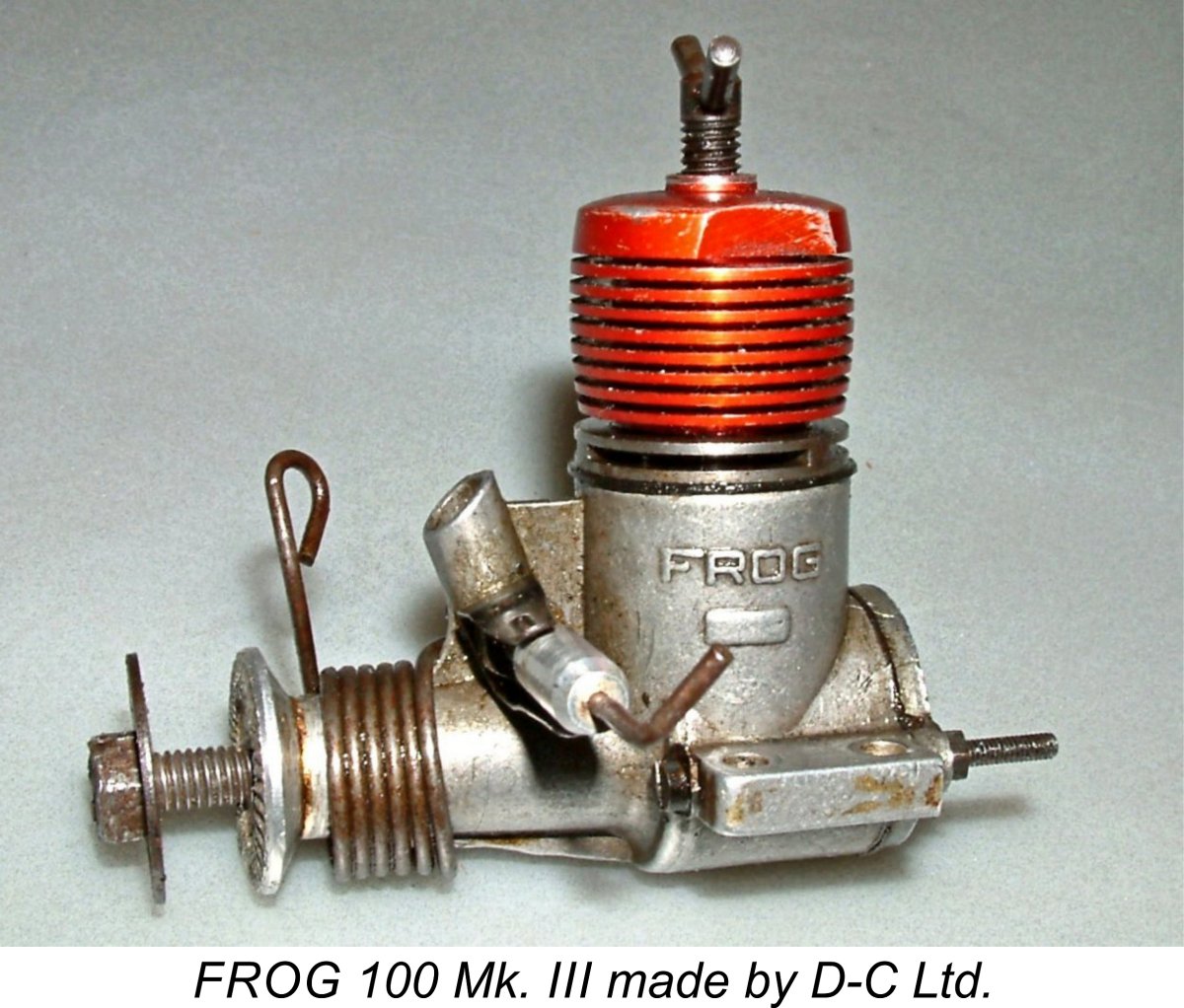

Accordingly, in early 1964 after the majority of existing IMA stocks had been sold off, Hales made arrangements with Lines Brothers to take over outright ownership of the range. A provision of this deal was the transfer of all of the FROG engine tooling and residual parts inventory to Davies-Charlton (D-C) Ltd. on the Isle of Man. Thenceforth the FROG engines were manufactured by D-C Ltd. under contract to A. A. Hales. Not all of the FROG engine range went into reproduction by D-C Ltd. Sadly, the casualties included the Viper diesel as well as the 149 "Vibramatic" model, the venerable FROG 500 and the rather unsuccessful FROG .049 glow model (although a very few unadvertised examples of the latter two models were apparently assembled by D-C Ltd. from existing IMA parts). The sole representative of the FROG 1.5 cc series which made it onto D-C’s production schedule was the 150R. This continued to be available in its D-C version as the FROG 150 Mk. III, although in reality it was just a re-styled and repackaged 150R. The FROG 100 Mk. II was also continued more or less unchanged as the FROG 100 Mk. III. The 150 Mk. III featured a restyled blue-anodized cooling jacket suggestive of the original 150R, while the 100 Mk. III sported a red-anodized head.

This being the case, it’s always relevant to establish the manufacturing source of any FROG engine which you may be considering as a possible acquisition. Fortunately, this is a very straightforward matter. Apart from the different cooling jacket styles, the FROG engines manufactured by D-C Ltd. all used standard D-C needle valve assemblies of the type fitted to the mainstream D-C models. These had plain un-knurled aluminium alloy thimbles instead of the serrated brass thimbles used on the IMA FROG engines. They also used a far stiffer and less effective leaf spring tensioning system. Personally, I’ve always preferred the original IMA needle valve assembly. Reader Bob Beaumont wrote in to tell me that he had a late New-in-Box example of the FROG 100 Mk. III bearing the serial number H10389. The guarantee certificate for this unit is dealer date-stamped February 1973, making it one of the very last FROG engines to be sold. Interestingly, this engine features the early IMA needle valve assembly, making it appear that towards the end D-C Ltd. were using up residual components obtained in the original 1964 deal with A. A. Hales. Quite apart from any other differences, the serial numbering system puts manufacturer identification issues beyond doubt. In early 1964 when A. A. Hales arranged for D-C Ltd. to resume manufacture of certain models in the FROG range, they introduced the use of a letter prefix to identify the model in question. This was a very sensible idea, as IMA had simply numbered the engines of each displacement sequentially starting from 1, consequently generating complete sets of duplicate serial numbers. The approach taken by A. A. Hales eliminated the duplicates by making each number unique. The following table shows the system used:

† Probably assembled from IMA parts by D-C, not manufactured by them. Very few examples. This of course raises the question of whether A. A. Hales continued the numerical sequence started by IMA or whether they restarted the sequence at 1 using the letter prefix to differentiate between the older and new models. There is strong evidence to suggest that they restarted the sequence. My good mate Kevin Richards is aware of an IMA FROG 150R bearing the number 28031 and a later D-C-made FROG 150 Mk III with the lower number of F19920. This implies that D-C Ltd. may have produced as many as 20,000 examples of the FROG 150 Mk. III.

This manufacturing arrangement between Hales and D-C Ltd. appears to have lasted for some time. New examples of FROG engines from this source continued to be available from dealers up into the early 1970's. Kevin Richards confirmed that he bought new D-C manufactured examples of both the FROG 349 BB and the FROG 249 BB from his local hobby shop in 1970, both accompanied by their 1970 dealer date-stamped guarantee certificates. And then there's Bob Beaumont's FROG 100 Mk. III with it's dealer date-stamped February 1973 guarantee certificate. Of course, these dealer date-stamps provide no evidence of continued manufacture at those dates - the engines in question were almost certainly New Old Stock which were date-stamped at the time of eventual sale. In January 1972 Alan Hales bought back the A. A. Hales brand from the Lines Brothers liquidators. He continued to advertise the FROG engines periodically through to September 1972. This cannot of course be taken as hard evidence of continuing manufacture as of that date - it’s far more likely that the company was simply selling off new old stock by that time. However, it does confirm that at least some new FROG models remained available from dealers for a considerably longer period than might otherwise be supposed. Whatever the truth of that matter, stocks of the FROG 150 Mk. III appear to have been exhausted by mid to late 1972, since that models was among those not featured in the Hales advertisement of September 1972 which appears to have been that company's very last advertisement for the FROG engines. Hales continued to advertise in "Aeromodeller" until June 1980, but there was no further mention of the FROG engines after September 1972. Conclusion I hope that you’ve enjoyed this in-depth look at a series of 1.5 cc engines that survived in the British marketplace for at least 20 years and served many modellers very well indeed, as some of them still do today (2024). During that period, the manufacturers of the FROG model engines (both IMA and D-C Ltd.) between them produced no fewer than nine distinct variants of their 1.5 cc offerings (count ‘em!), a number which was well over 60% of the total number of distinct 1.5 cc models produced during the same period by all other British manufacturers combined (Allbon, P.A.W., E.D., Elfin, J.B., A-M, D-C, M.E., Oliver). Quite a record! I’ve personally always had a bit of a soft spot for this series, having experienced many hours of enjoyable model flying with them. Anyone acquiring an example of any of these engines will find them to be excellent examples of British commercial model engine manufacture. Thanks, IMA!! ______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published July 2017 Updated July 2021 |

|

| |

In a separate article on this site, I’ve covered the story of the

In a separate article on this site, I’ve covered the story of the

The FROG model engines were produced by International Model Aircraft (IMA) Ltd., whose slogan “Flies Right Off Ground” gave rise to the company’s FROG trade-mark. The name FROG should always be rendered all in capitals as written because it was actually an acronym for IMA’s original 1930's motto. IMA themselves always rendered it as such.

The FROG model engines were produced by International Model Aircraft (IMA) Ltd., whose slogan “Flies Right Off Ground” gave rise to the company’s FROG trade-mark. The name FROG should always be rendered all in capitals as written because it was actually an acronym for IMA’s original 1930's motto. IMA themselves always rendered it as such. IMA was founded in 1931 as a partnership between Joseph Mansour and the Wilmot brothers Charles and John. In 1932, in order to enhance their production and marketing capabilities, the trio entered into partnership with the prominent Lines Brothers organization, whose marketing reach extended not only throughout Britain but also to many other parts of the world. Their Triang toy brand was a household word in many market areas worldwide.

IMA was founded in 1931 as a partnership between Joseph Mansour and the Wilmot brothers Charles and John. In 1932, in order to enhance their production and marketing capabilities, the trio entered into partnership with the prominent Lines Brothers organization, whose marketing reach extended not only throughout Britain but also to many other parts of the world. Their Triang toy brand was a household word in many market areas worldwide. During WW2, IMA’s production facilities at the massive Triang Works on Morden Road in Merton, Surrey were naturally turned over to defence production. However, following the conclusion of hostilities in mid 1945, the company quickly resumed its former model aircraft manufacturing activities. The refurbished Triang factory at Morden Road was then one of the largest toy and model production facilities in the world, and it wasn’t long before the manufacture of model engines was added to the other product lines marketed under the IMA banner.

During WW2, IMA’s production facilities at the massive Triang Works on Morden Road in Merton, Surrey were naturally turned over to defence production. However, following the conclusion of hostilities in mid 1945, the company quickly resumed its former model aircraft manufacturing activities. The refurbished Triang factory at Morden Road was then one of the largest toy and model production facilities in the world, and it wasn’t long before the manufacture of model engines was added to the other product lines marketed under the IMA banner.

Having far more recently acquired the residue of the ETA 1.5 cc diesel project from Eric Bedford’s estate, my friend and colleague Miles Patience was able to arrange for the completion of a further nine engines by others using a mixture of original and replica parts. It's interesting to note that the engine seems to display a certain degree of stylistic influence from the OK Cub engines from America.

Having far more recently acquired the residue of the ETA 1.5 cc diesel project from Eric Bedford’s estate, my friend and colleague Miles Patience was able to arrange for the completion of a further nine engines by others using a mixture of original and replica parts. It's interesting to note that the engine seems to display a certain degree of stylistic influence from the OK Cub engines from America. The FROG 150 made its market debut in June 1951, over a year after the appearances of the Allbon Javelin and the Elfin 149. In many ways it was quite similar to its two leading competitors, featuring radial porting allied to FRV induction and a plain bearing crankshaft.

The FROG 150 made its market debut in June 1951, over a year after the appearances of the Allbon Javelin and the Elfin 149. In many ways it was quite similar to its two leading competitors, featuring radial porting allied to FRV induction and a plain bearing crankshaft.

The above published test results placed the FROG 150 among the leading performers in the British 1.5 cc diesel ranks as of late 1951. Those ranks were swelled at the end of 1951 by the introduction of the

The above published test results placed the FROG 150 among the leading performers in the British 1.5 cc diesel ranks as of late 1951. Those ranks were swelled at the end of 1951 by the introduction of the

Warring’s summary report appeared in the January 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine.

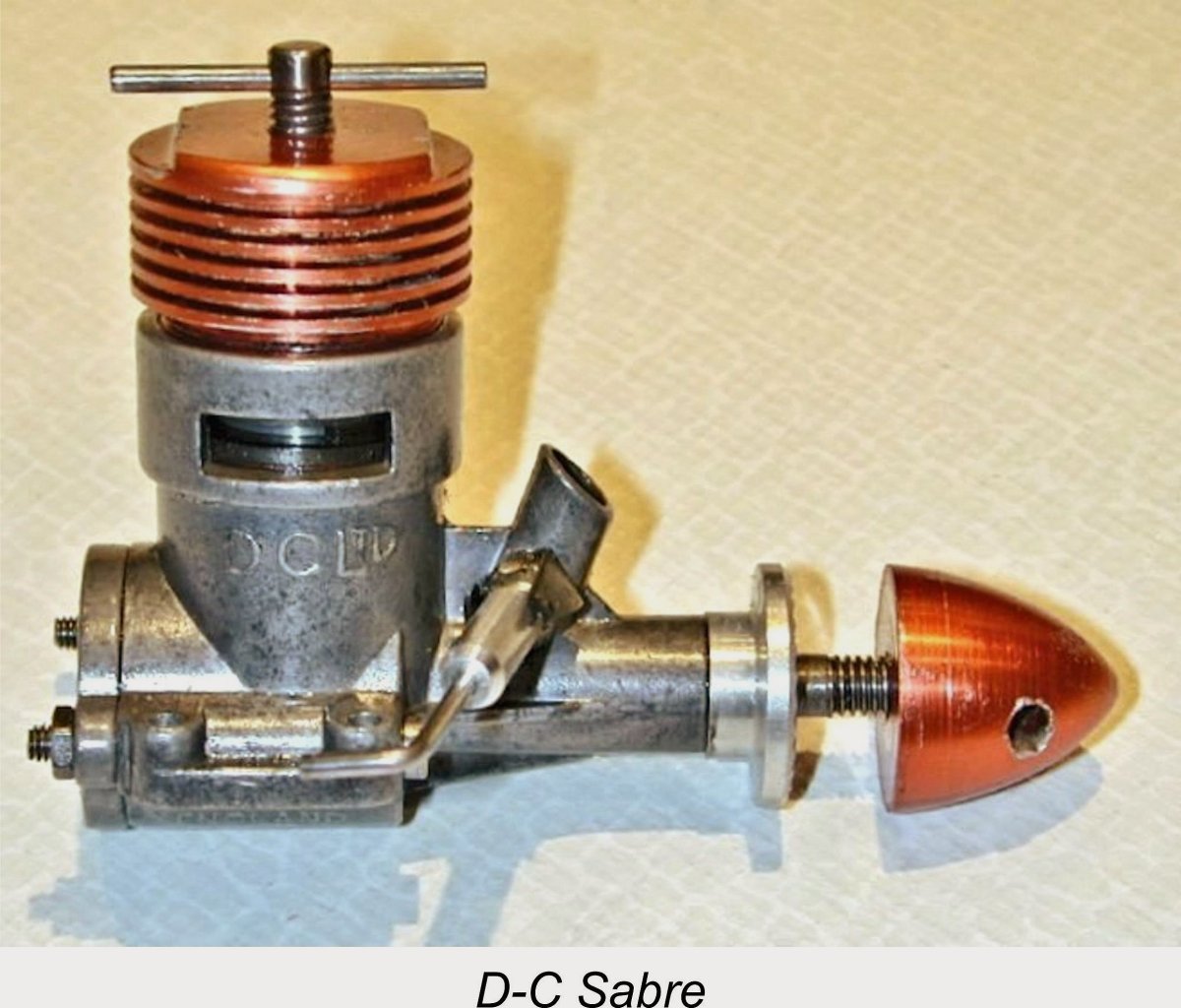

Warring’s summary report appeared in the January 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. anything to upset the balance of power, since Ron Warring’s tests found outputs of only 0.090 BHP @ 10,700 RPM and 0.104 BHP @ 13,300 RPM for the Atom and Sabre respectively (“Aeromodeller”, February and April 1956 issues). No alarm bells going off at IMA based on those results!

anything to upset the balance of power, since Ron Warring’s tests found outputs of only 0.090 BHP @ 10,700 RPM and 0.104 BHP @ 13,300 RPM for the Atom and Sabre respectively (“Aeromodeller”, February and April 1956 issues). No alarm bells going off at IMA based on those results! Fletcher adopted a two-stage approach to his new task. To achieve quick results, he initially pursued the path of least resistance by quickly redesigning certain aspects of the old 150. Externally, the revised version of the engine looked essentially identical to its predecessor, the only visible change being a slightly longer comp screw.

Fletcher adopted a two-stage approach to his new task. To achieve quick results, he initially pursued the path of least resistance by quickly redesigning certain aspects of the old 150. Externally, the revised version of the engine looked essentially identical to its predecessor, the only visible change being a slightly longer comp screw.

Over the years, IMA acquired quite a reputation for their often innovative and unusual model engine designs. Their original “bicycle spoke” engines had been well out of the rut, and now they broke new ground once again by playing a new tune upon an old fiddle. The new 1.5 cc models which appeared in March 1956 utilised a significantly re-thought variant of the old reed valve induction principle, which was associated with the engines under the name “Vibramatic”.

Over the years, IMA acquired quite a reputation for their often innovative and unusual model engine designs. Their original “bicycle spoke” engines had been well out of the rut, and now they broke new ground once again by playing a new tune upon an old fiddle. The new 1.5 cc models which appeared in March 1956 utilised a significantly re-thought variant of the old reed valve induction principle, which was associated with the engines under the name “Vibramatic”. The FROG 149, as it was designated, was in effect a diaphragm-induction version of the revised FROG 150 Mk. II described earlier. The piston, cylinder, cooling jacket and con-rod were identical apart from the red anodizing on the cooling jacket. The crankshaft too was identical apart from the omission of the induction passages of the FRV 150 Mk. II model as well as a slight lengthening of the crankpin. The Vandervell main bearing bushing was also carried over. A new crankcase die was produced both to eliminate the redundant front intake and to display the revised 149 identification. Otherwise, from the backplate forward the two models were more or less identical.

The FROG 149, as it was designated, was in effect a diaphragm-induction version of the revised FROG 150 Mk. II described earlier. The piston, cylinder, cooling jacket and con-rod were identical apart from the red anodizing on the cooling jacket. The crankshaft too was identical apart from the omission of the induction passages of the FRV 150 Mk. II model as well as a slight lengthening of the crankpin. The Vandervell main bearing bushing was also carried over. A new crankcase die was produced both to eliminate the redundant front intake and to display the revised 149 identification. Otherwise, from the backplate forward the two models were more or less identical.

There were of course both pros and cons to this system. On the plus side, the induction was self-timing to a significant extent, being theoretically able to accommodate a wide range of speed-related pressure fluctuation regimes within the crankcase. Naturally the system’s mechanical inertia would affect this somewhat, but overall the engine might be expected to show an enhanced degree of operational flexibility. Moreover, the diaphragm itself was not subject to bending cycles, unlike a conventional reed valve. Hence it might be expected to prove very durable in service.

There were of course both pros and cons to this system. On the plus side, the induction was self-timing to a significant extent, being theoretically able to accommodate a wide range of speed-related pressure fluctuation regimes within the crankcase. Naturally the system’s mechanical inertia would affect this somewhat, but overall the engine might be expected to show an enhanced degree of operational flexibility. Moreover, the diaphragm itself was not subject to bending cycles, unlike a conventional reed valve. Hence it might be expected to prove very durable in service. Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” was unusually quick off the starting blocks. His

Peter Chinn of “Model Aircraft” was unusually quick off the starting blocks. His  In terms of performance, Chinn measured an output of 0.130 BHP @ 13,000 RPM. This was over 8% greater than the output which Chinn had measured for the

In terms of performance, Chinn measured an output of 0.130 BHP @ 13,000 RPM. This was over 8% greater than the output which Chinn had measured for the

As we might expect with such a lacklustre published test performance, the FROG 149 glow-plug model followed the example set by the 1951 glow-plug version of the FROG 150 by sliding rapidly into oblivion. It was never featured in IMA’s advertising and apparently remained on offer for only a very short time, with few takers. It is a very rare engine indeed today – I have personally only encountered one example in years of looking. As of 2017 when this article first appeared, the only photo that I could find was the one from the “Aeromodeller” test report which is reproduced above. I was able to acquire the example that I fortuitously encountered in 2022, finding it to be a great starter and a good runner, albeit not especially powerful.

As we might expect with such a lacklustre published test performance, the FROG 149 glow-plug model followed the example set by the 1951 glow-plug version of the FROG 150 by sliding rapidly into oblivion. It was never featured in IMA’s advertising and apparently remained on offer for only a very short time, with few takers. It is a very rare engine indeed today – I have personally only encountered one example in years of looking. As of 2017 when this article first appeared, the only photo that I could find was the one from the “Aeromodeller” test report which is reproduced above. I was able to acquire the example that I fortuitously encountered in 2022, finding it to be a great starter and a good runner, albeit not especially powerful.  After completing the design of the FROG 149 and seeing it safely into production alongside its 150 Mk. II companion, George Fletcher was immediately tasked by his employers with the job of designing a 0.8 cc model with which IMA could challenge the extremely popular 0.76 cc Allbon Merlin which had been introduced in October 1954 and had since ruled the British under-1 cc category along with the perennial Mills .75 sideport model. The result of George’s deliberations was the appearance of the initial version of the

After completing the design of the FROG 149 and seeing it safely into production alongside its 150 Mk. II companion, George Fletcher was immediately tasked by his employers with the job of designing a 0.8 cc model with which IMA could challenge the extremely popular 0.76 cc Allbon Merlin which had been introduced in October 1954 and had since ruled the British under-1 cc category along with the perennial Mills .75 sideport model. The result of George’s deliberations was the appearance of the initial version of the  The continued pre-eminence of the FROG 1.5 cc models as of early 1957 was a fortuitous state of affairs because it left George Fletcher free (for the moment at least) to focus upon his next priority, which was the development of performance improvements to the

The continued pre-eminence of the FROG 1.5 cc models as of early 1957 was a fortuitous state of affairs because it left George Fletcher free (for the moment at least) to focus upon his next priority, which was the development of performance improvements to the

Prototypes of the new 1.5 cc model were apparently in existence as of early 1958, since Peter Chinn later made reference to having received an example (then un-named) for test at that time. He reported having run the engine for a total of 20 hours with no variation in performance over that period.