|

|

The Rise and Fall of Davies-Charlton

As far as I'm aware, the full start-to-finish story of the Davies-Charlton enterprise had never been summarized in a single published article prior to the mid 2010 appearance of my earlier article on the subject on the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful but now frozen “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. Although now somewhat out of date and in error in certain aspects, that original article may still be accessed through the above link. Portions of the story had certainly been told, and in fact the outlines of the company’s golden years were reasonably well documented due to the regular ongoing coverage of the range in the British modelling media during its hey-day. However, the early and later periods had been relatively veiled by comparison prior to the appearance of our earlier article. There was also a considerable amount of unreported behind-the-scenes activity which did much to add human interest to the story.

Secondly, I’d like to express my gratitude to Jim Woodside for making me aware of a number of facets of this saga from his own personal knowledge. It’s this kind of background detail that really breathes life into these studies of early model engine history! The late and much-missed Ron Moulton was good enough to add a few details from his extensive store of first-hand knowledge about English modelling matters during the period in question. In addition, former D-C Managing Director Bill Callow was kind enough to correct a number of errors in my original text relating to the later years of the company. Bill was also able to fill in a number of other fascinating details which had escaped my notice. It’s a great pleasure to acknowledge the very generous contribution of Mrs. Christina “Chris” Crosby, who worked in the Davies-Charlton office for several years during the mid 1950’s. After reading this article in its original form, Chris was kind enough to provide me with a number of first-hand recollections which did much to add interest and authority to this essay. In the five years since the initial publication of this article on MEN, a great deal of additional information has come to light, due in large part to the kindness of various readers in pointing me towards potentially First and foremost, I owe a great deal to the kindness of Alan Allbon’s sons Kenneth and Derek for generously sharing their inside knowledge of the interactions between Alan Allbon and Hefin Davies of Davies-Charlton during the period 1952-55. The inclusion of this information was made possible solely through the efforts of reader Geoff Peacock, whose kind assistance in this regard is gratefully acknowledged. It was largely the considerable body of new information resulting from this contact that created the need to publish this updated article on this site. I'd like to acknowledge a particular debt of gratitude to Kenneth Allbon for kindly painting a portrait of his Another latter-day source of first-hand information materialized in 2014 through the publication in SAM35 Speaks of an article by Brian Waterland on the subject of Davies-Charlton. The catalyst for the preparation of Brian’s article was the suggestion by John Moore, one-time D-C employee and eventual owner of the ME model engine range, that Brian would do well to seek an interview with Arthur Firth, who worked for D-C Ltd. from 1948 through to 1970 with a short break during which he found alternative employment. A fit and active 91 year old when Brian interviewed him in December 2013, Arthur retained many very clear memories of his time with D-C Ltd. which he was happy to share. I’m immensely grateful to both Arthur and Brian for sharing this information with us.

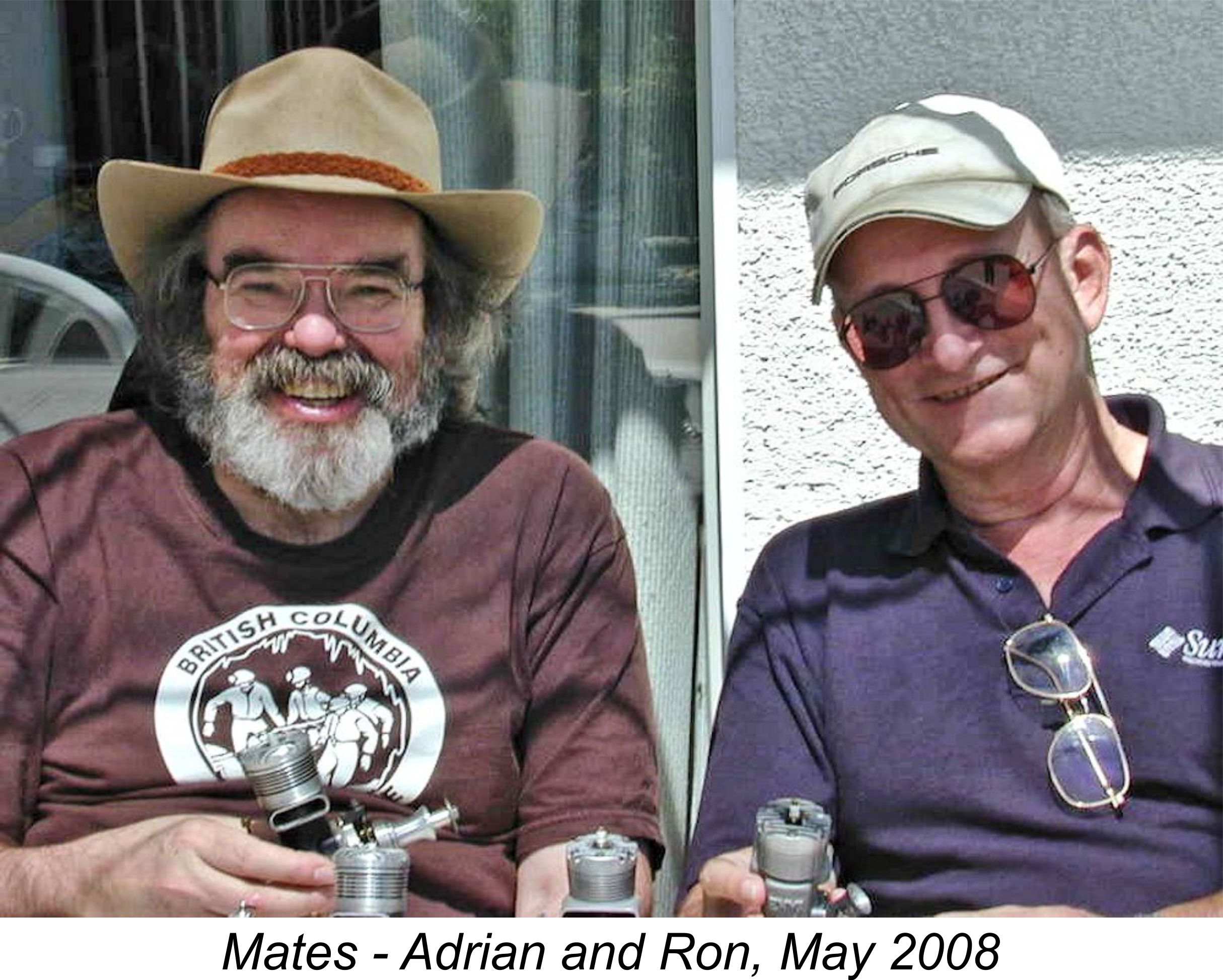

Lastly, I cannot proceed with this updated article without as ever acknowledging the immeasurable assistance and encouragement provided to me by my late and much-missed mate Ron Chernich during the preparation of the original article in 2010. Without Ron’s wholehearted support and enthusiastic participation, the project would never have gone anywhere. Indeed, it’s Ron’s example that continues to encourage me in my ongoing search for a greater understanding of the model engine industry as it existed in its golden era. Thanks, mate! OK, onwards into our story …………….. Origins Nothing definite was known of Hefin Davies’ origins until Ron and I heard from Mrs. Christina Crosby following the initial publication of this article on MEN in mid 2010. Although then 82 years old, Chris retained some very clear recollections of her time with Davies-Charlton which she was kind enough to share with us. As far as Chris could recall from her conversations with him, Hefin Nathaniel Davies came from a small community in the vicinity of St. David’s in South Wales. He remained very proud of his Welsh heritage throughout his life. He was also a dedicated Freemason. One interesting recollection of Chris’s which adds human interest to our story is the fact that Hefin Davies was always known as "Efyn" (pronounced Evan) to his colleagues and employees. Presumably this was simply an Anglicized corruption of Hefin, which is pronounced as Hevin in the Welsh language. Chris’s comment is somewhat at variance with the stated recollections of Arthur Firth, who recalled that the D-C workforce on the shop floor referred to Davies behind his back perhaps somewhat irreverently as "Taffy"!!

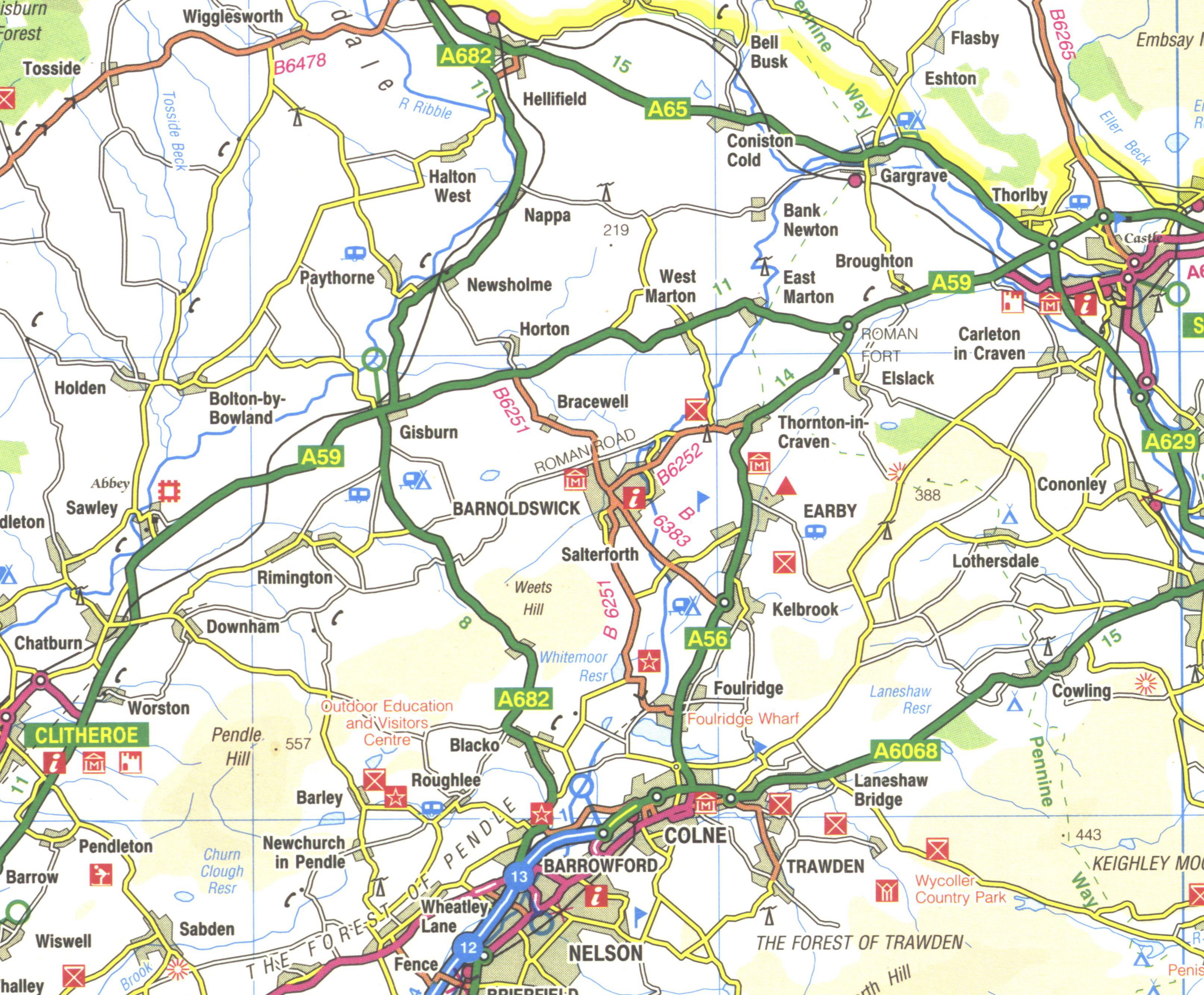

It comes as something of a surprise to learn that despite the town’s relatively small size, cotton mill background and seeming isolation, Davies-Charlton were by no means the first precision engineering firm to be located in the community. Beginning in June 1941, the Rover automobile company had taken over a disused cotton mill in Barnoldswick and converted it into a hush-hush aero engine development facility. This move was prompted by the fact that Rover had become involved in the initial development of the turbojet engine in association with Frank (later Sir Frank) Whittle. The first test engines built at Barnoldswick by Rover to Whittle’s design were completed and subjected to initial testing in October 1941 - very quick work! Increasingly strained relations between Rover and Whittle led to an agreement being reached in January 1943 whereby no less a company than Rolls-Royce would take over the jet engine program from Rover, who would in turn assume responsibility for the production and further development of the Rolls-Royce Meteor tank engine, a derivative of the famous Merlin aero engine. Under the terms of the deal, Rover took over the Rolls-Royce tank engine factory in Nottingham, surrendering their Barnoldswick jet engine plant to Rolls-Royce in exchange. The official hand-over date was April 1st, 1943. Rolls-Royce immediately established their own jet engine design center at the site. Rolls-Royce have remained a major employer in the town ever since, having relatively recently (2010) completed a new plant there to manufacture a range of specialized jet engine components.

Ron Moulton characterized Davies as being a somewhat “fiery” individual, which fits with the bulk of our later knowledge of his interactions with others. By all accounts, he had a rather volatile temperament which could make him a difficult individual to work with. This may have an influence on the fact that, whether by choice or due to a falling-out with his Rolls-Royce colleagues, Davies parted company with Rolls-Royce in 1946 to branch out on his own, thus becoming his own boss. Chris Crosby confirmed that Davies did indeed have a somewhat incendiary personality. However, in her recollection his energy and enthusiasm were contagious. Although she was by no means immune from being yelled at by Davies in one of his more “excitable” states, these moods apparently did not last and left no scars, at least as far as Chris was concerned. Chris always liked him very much despite this tendency. However it came about, the year 1946 found Davies working on his own account from retail premises on Rainhall Road in the town, at the back of which he soon set up a very basic workshop and design office. Arthur Firth had first-hand knowledge of this because it was at this very time, at the age of 24 years, that he began working in Barnoldswick as the foreman of a bakery after serving in the Royal Navy during the war years as a cook on minesweepers. Arthur recalled that at this time Davies appeared to be living very much on a shoestring – he evidently used to take meals at a café run by Arthur’s sister, who commented sympathetically that Davies must be rather hard up because he wore shoes which were patched with pieces of cardboard!

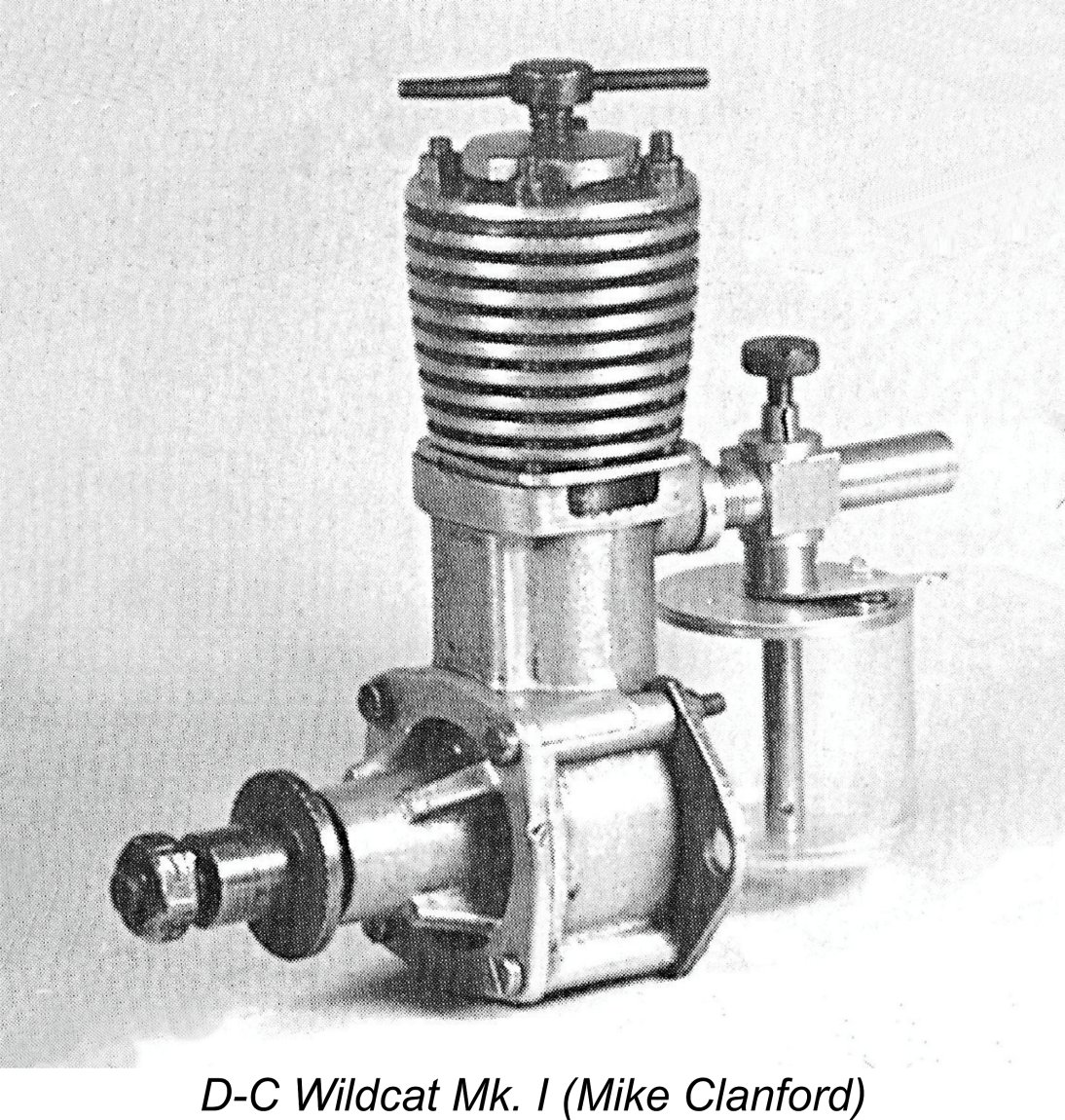

Apart from his retail activities, the details of which were not recalled by Arthur Firth, Davies ran a small design office from his premises in Barnoldswick. Whatever his character flaws, he appears to have been a genuine model engine enthusiast all along, and his initial focus was on providing support services to the model engineering community. At the outset, he produced drawings for the use of home constructors, but soon expanded his range of services to include sets of castings and machined components for the featured designs. These materials were produced by others at this stage. A forerunner of the 5 cc Wildcat diesel was one of the designs offered for sale in this form, along with a similarly-designed 2 cc model. There was also a hot air (Stirling cycle) engine which was the ancestor of the later tabletop unit marketed by the company (see below).

At the same time, Davies adopted the company name of Davies-Charlton & Co. usually abbreviated to its initials D-C. This name would appear to imply the involvement of an individual named Charlton. However, with a single exception to be discussed below, years of intensive research and close inquiry have failed to turn up any evidence whatsoever of the actual existence of a partner by that name. As we shall see in a later section of this article, it now appears most probable that Davies simply attached the name Charlton to his own to move the perception of his company up-market given the enhanced social status implied by the use of double-barreled names in early post-WW2 England. In enhancing the status of his company name in this manner, Davies may have simply selected the name of one of his former associates at Rolls-Royce. It’s also possible that someone by the name of Charlton provided short-term financial assistance to enable Davies to acquire the equipment necessary to commence in-house production in 1947. If the latter was the case, Davies presumably paid back the loan early on without Charlton ever becoming a partner - there's no record of his ever having done so. In this case, the application of the name would simply be a way of recognizing the timely assistance provided at a key moment in Davies’ career. Hefin Davies’ former secretary Christina "Chris" Crosby remains the sole individual who has ever claimed to have first-hand knowledge that there was indeed a Mr. Charlton. As far as I'm aware, the reality of Charlton’s existence has never been asserted by any other individual on the basis of authoritative first-hand knowledge. Chris stated her sincerely-held belief that Charlton was a former associate of Hefin Davies at Rolls-Royce who left that company in 1947 to join Davies in starting the Davies-Charlton enterprise. She recalled meeting Charlton at the company offices on a number of occasions. As we shall see later, a considerable body of persuasive evidence gathered since 2010 is entirely consistent with the notion that the individual recalled by Chris Crosby as Charlton was in fact none other than Alan Allbon and that the former Rolls Royce colleague in question was Walter Kendall! We shall examine these probabilities in detail below in their place.

The Wildcat Mk. II proved to be a very successful design which was destined to remain in production for some 18 months. It was offered in both ready-to-run and kit forms. A glow-plug conversion kit was also developed for the engine. The company recommended that the use of this kit be restricted to engines which had been well used previously in diesel configuration. Arthur Firth recalled that the big break for Hefin Davies came in 1948 when he was actively pursuing the expansion of his manufacturing activities, which naturally required him to take on additional staff. He was successful in persuading the talented production engineer Walter Kendall, the future founder of Marown Engineering and the M.E. model engine marque, to leave Rolls-Royce for the purpose of joining him at Davies-Charlton & Co. It seems more than likely that Chris Crosby was confusing the mysterious "Charlton" with Walter Kendall when recalling that Davies had a colleague who left Rolls-Royce in 1947 to join him at Davies-Charlton. Quite apart from bringing his engineering talents to the venture, Kendall also just happened to be engaged to (and subsequently married) the daughter of the sub-contract manager for Rolls-Royce! From that point onwards, Kendall’s father-in-law routinely passed the pick of the sub-contract work to Davies-Charlton & Co., thus laying a firm foundation for the company’s later success. It appears that Hefin Davies had always seen the undertaking of custom precision engineering work for Rolls-Royce and others under contract as a cornerstone of his company’s broader long-term portfolio. He became increasingly successful in this area of endeavor once he commenced the development of his own in-house manufacturing capabilities in 1947, subsequently benefiting from the influence of Walter Kendall’s family connection. Indeed, this type of activity was destined to occupy a substantial proportion of the company’s technical resources over much of its active lifetime. Bill Callow later recalled that during its heyday Davies-Charlton was one of the most successful aerospace sub-contracting companies in the whole of the UK. The model engine manufacturing which was carried on from the outset soon became a secondary albeit important source of revenue for the company during this period. The fact that this subsidiary activity was maintained throughout despite the ever-growing pressures of other work undoubtedly reflects Hefin Davies’ personal passion for model engines which lasted throughout his lifetime, as clearly recalled by Bill Callow. We might expect that Barnoldswick would have provided Davies with a sizeable pool of skilled workers from which to staff his company as the scope of its activities expanded over time. The successive presence of Rover and Rolls-Royce would have ensured that as of 1947 the town was home to a significant pool of highly skilled precision engineering personnel, a few of whom might have been surplus to Rolls-Royce’s immediate requirements or might have been persuaded to make a change. Alternatively, skilled workers might have been enticed there by the prospect of subsequently being taken on by the prestigious Rolls-Royce company on the basis of their experience with Davies-Charlton. However, it appears from Arthur Firth’s recalled experiences that Davies did not always follow established practises when hiring workers. One talented individual who was living in Barnoldswick at the time and working for Davies-Charlton & Co. was none other than George Fletcher, later to become chief engine designer for both International Model Aircraft (IMA – FROG) and (briefly) Electronic Developments (E.D.). Fletcher was a personal friend of Arthur Firth’s and suggested to him that he could do worse than ask for a try-out at Davies-Charlton as a cylinder honer. Arthur did so and quickly found that he had a real knack for this simple and repetitive but exacting process. Having demonstrated his ability to Davies’ satisfaction, he was quickly offered a job at a princely £12 per week – an above-average pay packet in Britain at the time and a significant increase over Arthur’s former £7 per week income as a bakery foreman! Arthur recalled that he was able to hone some 120 piston/cylinder sets per working day. Arthur’s recollection provides very interesting and rather unexpected evidence of Davies’ willingness to look outside the engineering field for talented workers to fill specialized positions, at least during the start-up years. Arthur Firth had been a baker, while fellow early D-C employee John Moore (later to found Moore Engineering and take over the M.E. range from Walter Kendall) had been a carpenter and builder, although he had spent some At this early stage, Davies appears to have been quite happy to employ anyone from any background as long as he could capably perform whatever specialized task he was assigned to. Moreover, he paid such people fair wages, not downgrading their pay scales on the basis of their lack of previous direct experience. As long as they could do the job well, Davies seems to have been happy to pay them accordingly. In this somewhat unusual fashion, Davies progressively built up his workforce to meet the increasing volume of business now being generated. Now that he was set to become financially secure, Davies clearly felt himself to be in a position to start a family. It must have been at around this time that he married his wife Anne, also a former Rolls-Royce employee. The marriage was apparently very successful, surviving until Davies’ death in 1980. The Mk. II Wildcat remained in production until September 1949, when it was replaced by a further updated Mk. III model. This revised version of the Wildcat featured such refinements as a lighter piston and a stronger crankshaft along with revisions to the cylinder porting.

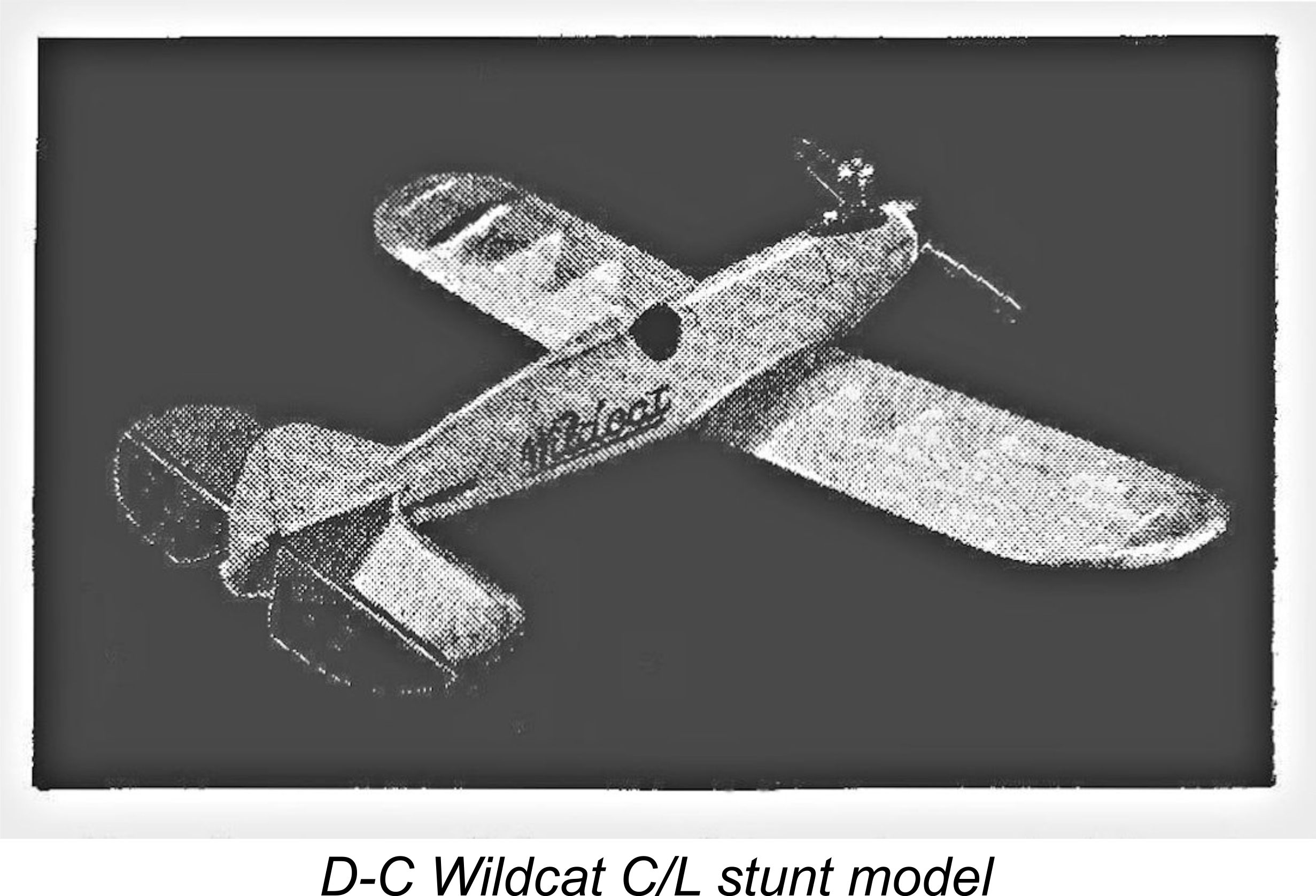

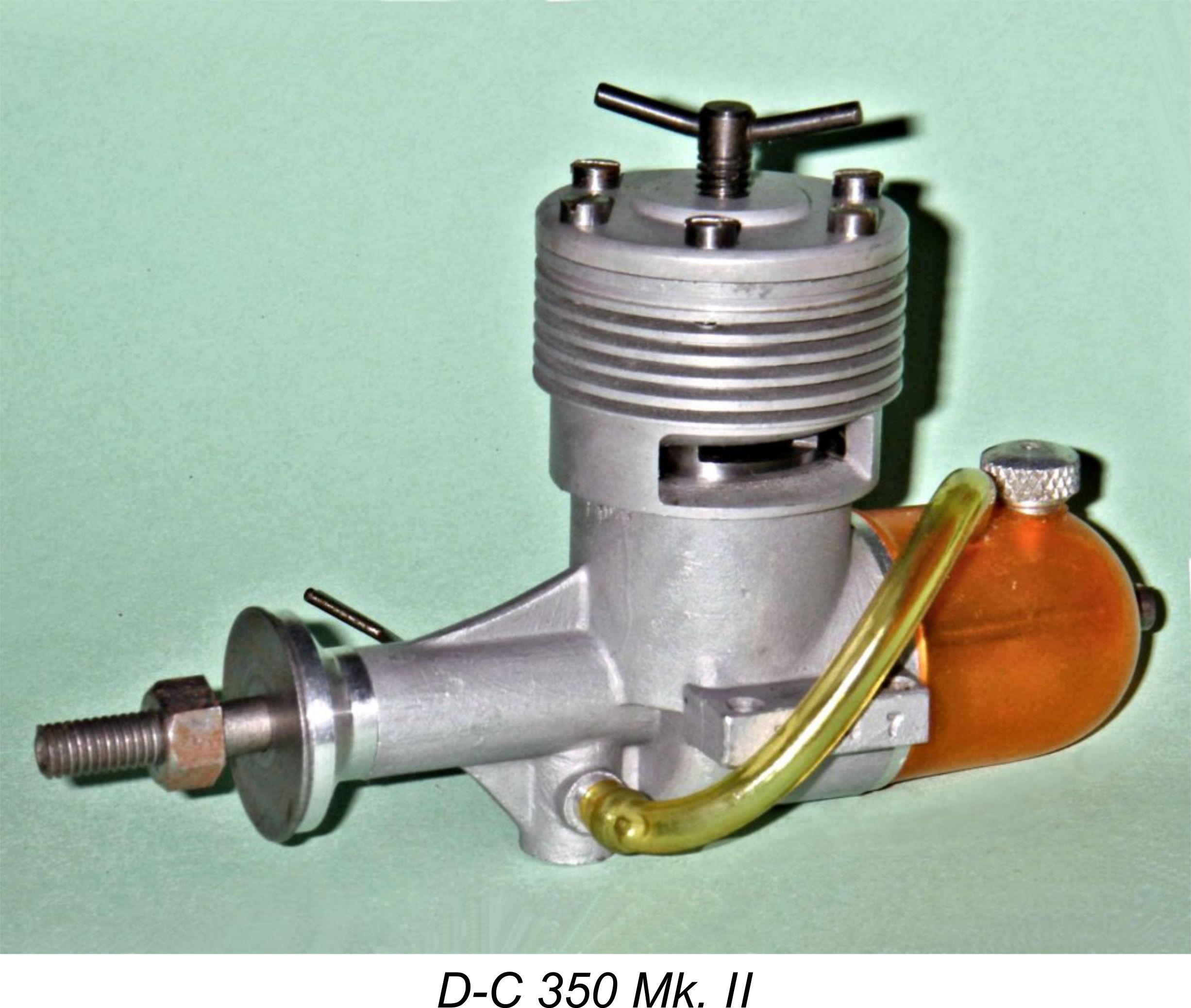

Returning to 1949, it was during this period that Davies-Charlton first entered the balsa-wood flying model kit market. They did so with a 36 in. span control-line stunt model designed expressly for the Wildcat diesel and sharing the “Wildcat” name. The kit was being advertised along with the Wildcat Mk. II as of April 1949, also sharing the billing with the Wildcat Mk. III in that engine's introductory advertisement of September 1949. As far as the record shows, this was the only kit produced by the company during the early years. It’s After a production run of the better part of three years which earned the company a good reputation among modellers, the trusty Wildcat was replaced in September 1950 by the far more up-to-date and equally well-made 3.44 cc D-C 350. This model again appeared in several variants and was offered in both diesel and glow-plug versions. It attracted very favourable media reviews, resulting in its being well received by the modelling public. Consequently, it was destined to enjoy a comparatively long production run. As far as we know, these early products were designed primarily by company founder Hefin Davies. Meanwhile, the scope of the company’s sub-contract work for Rolls-Royce and others was still growing rapidly. This soon began to create difficulties for Davies, forcing him to look around for creative solutions. Amalgamation During the early 1950’s the company’s expanding and very lucrative involvement with contract work through Rolls-Royce and others began to take up an increasingly disproportionate amount of Hefin Davies’ time, deflecting him away from the design of further new model aero engines. This situation prompted a significant change in 1952 when Davies-Charlton progressively joined forces with Alan Allbon, who had been marketing his own rather more diverse engine line since early 1948.

The Allbon engines were initially manufactured at a plant located at 51a Thames Street, Sunbury-on-Thames, Middlesex (later transferred to Surrey), just to the west of London. This was nowhere near Barnoldswick but was very close to the successive haunts of the E.D. company at Kingston-on-Thames, West Molesey and Surbiton, and not all that far from the International Model Aircraft (IMA) plant just to the east at Merton, where the FROG range was manufactured and where early D-C employee George Fletcher was later to become chief model engine designer after a brief period working with Alan Allbon at Sunbury. The Mills Bros. workshops at Woking were also comparatively nearby. The model engine manufacturing industry was a significant employer in south-west London in 1948! Think of the craic in all those engine-maker’s pubs ………….

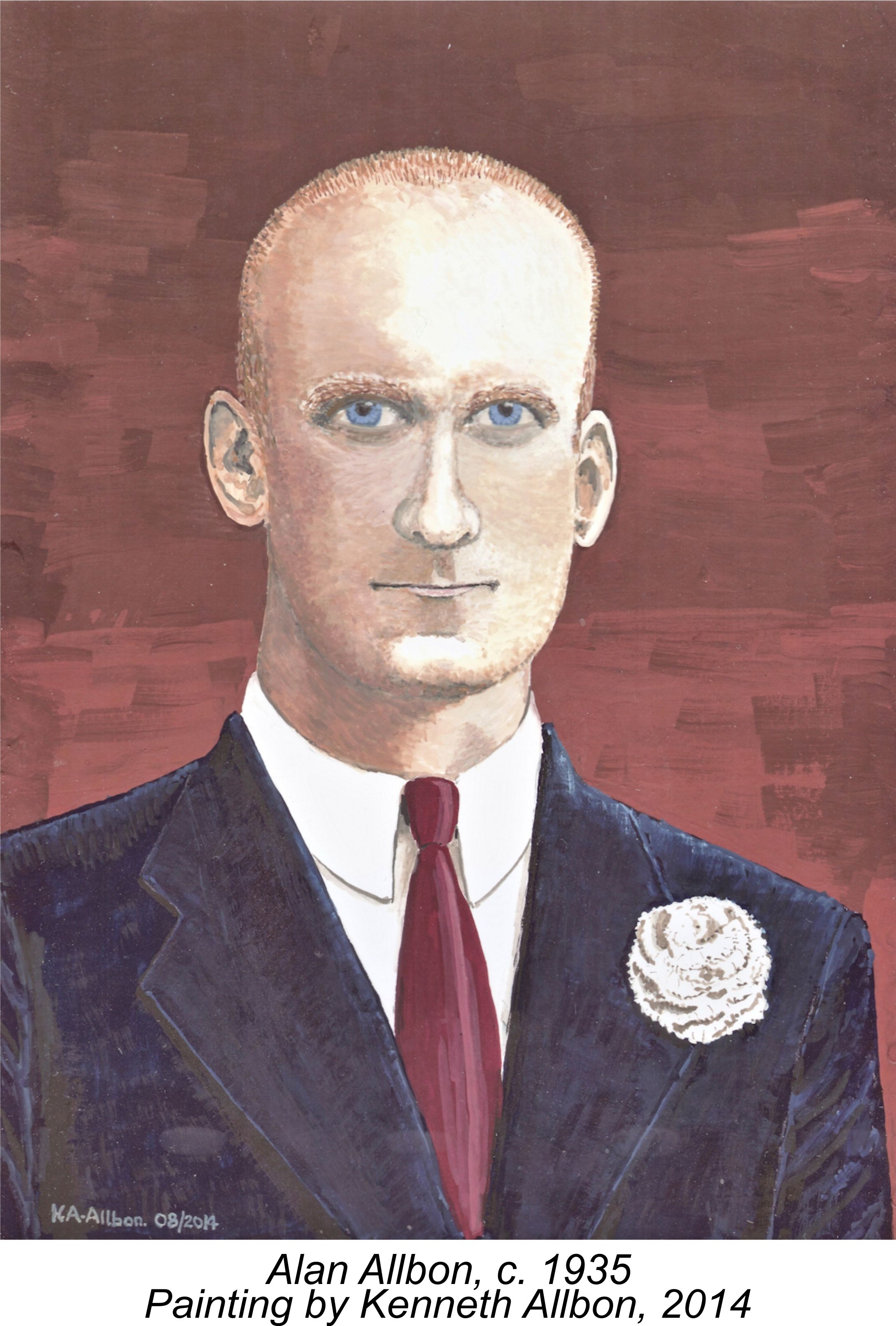

This October 1950 decision by the Court left British model engine manufacturers facing either a massive bite out of future profits, which were already very much on the marginal side by normal precision engineering standards, or the imposition of a significant price increase upon a relatively cash-starved market. They also faced a major book-keeping headache. Worse yet, those firms which had not paid taxes while the test case was before the courts now faced a very substantial government bill for two years' worth of unpaid back taxes. Ouch .....!! Sadly, Alan Allbon had been among those who had not paid tax while the case was before the Court. Worse, he had failed to make adequate financial provision for the possibility of an unfavorable outcome of the test case, a result which came as a major surprise to everyone involved in the model trade. The fall-out from this came close to driving Allbon out of business at the very time when his product line was reaching its peak of its popularity. In order to meet his tax obligations, he was forced not only to sell his house in Sunbury but also to relinquish his Sunbury workshop along with much of his machine tooling. This ended model engine manufacture at Sunbury.

As a result, by mid 1951 Allbon found himself faced with a significant challenge - he had an extremely successful product line but was unable to produce the engines at a rate which matched the demand. This situation appears to have been the primary catalyst in prompting Allbon to enter into discussions with Hefin Davies regarding the possible mutual benefits of some level of cooperation. It appears that D-C Ltd. had weathered the tax crisis more or less unscathed. Certainly, their production of model engines was unaffected. Either they had prudently made provision against the possibility of a negative outcome to the case, or the fact that their primary source of income was by now the high-tech subcontracting work for Rolls-Royce and others cushioned the blow. Either way, their sub-contract business was still growing, leaving Hefin Davies in urgent need of well-qualified assistance on the model engine design and manufacturing fronts. He must have been anything but reluctant to enter into discussions which could bring a designer of the calibre of Alan Allbon into the D-C model engine venture. These discussions proved sufficiently fruitful that a move towards eventual amalgamation was soon initiated.

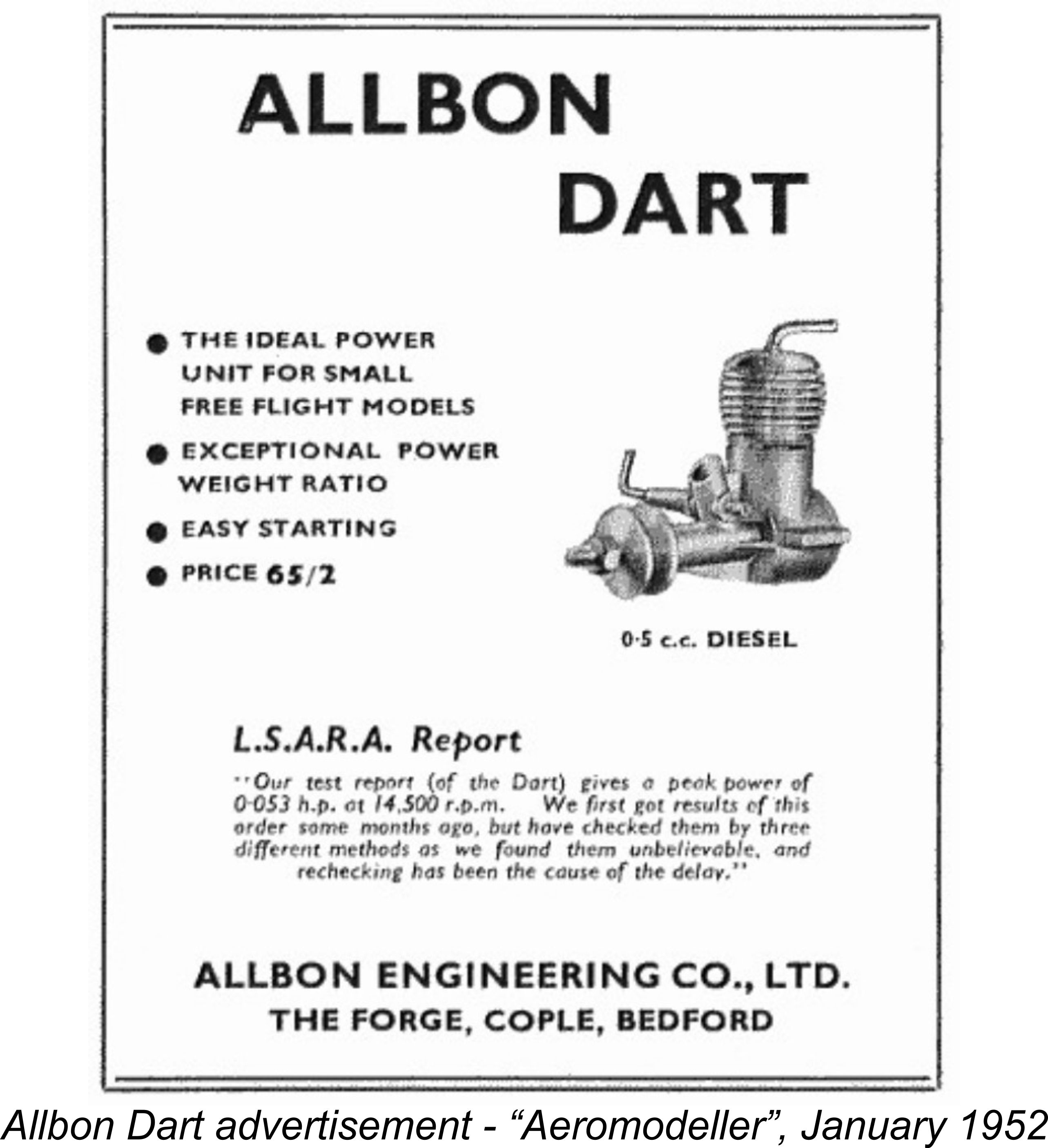

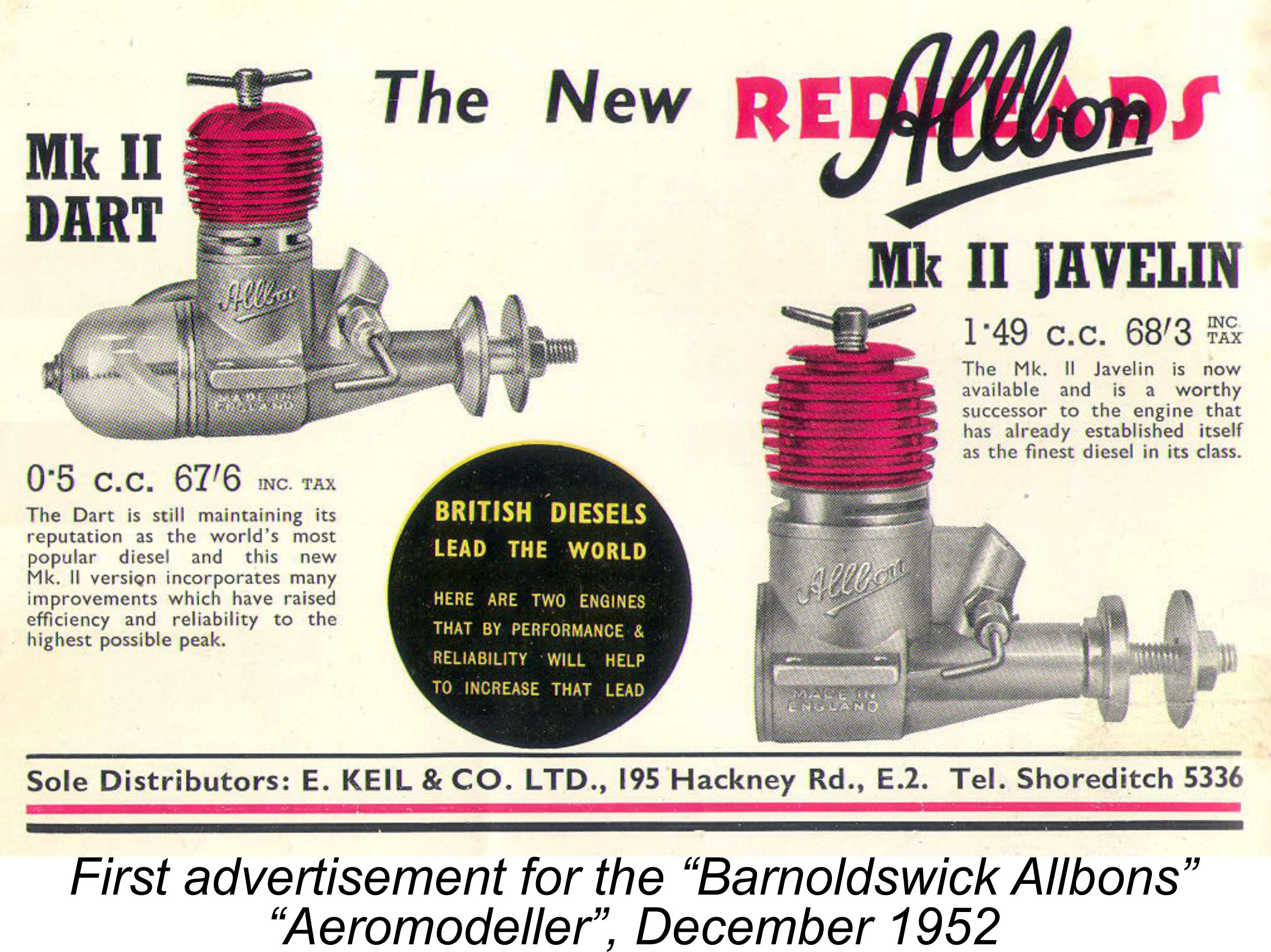

However, in his “Accent on Power” column in the April 1952 issue of “Model Aircraft” (probably written in late February 1952 given the editorial deadlines involved), the always well-informed Peter Chinn gave the game away by letting slip the fact that the manufacture of the Dart had actually been taken over by Davies-Charlton. The fact that Allbon continued to advertise independently from his Cople location under the Allbon Engineering banner while Davies-Charlton in turn continued to advertise their own distinct range from the Barnoldswick address clearly implies that at this stage no actual merger of the two companies had taken place. In all probability, Allbon had simply taken advantage of Davies-Charlton’s previously-mentioned willingness to undertake contract work for others by contracting out the manufacture of the Dart to Davies-Charlton. Hence the relationship at this stage was almost certainly purely contractual. It’s also significant to note that the only Allbon model advertised during most of 1952 was the Dart. This implies that Allbon had ceased to manufacture the Javelin at Cople, evidently preferring to recoup his heavily depleted fortunes by simply collecting his agreed share of the proceeds from sales of the very popular Dart. He may have manufactured a few examples of the Javelin at Cople just to keep it before the modelling public on retail shelves, but we have no firm evidence for this apart from the fact that the Javelin did appear in the advertised lists of a few major national retailers during 1952. This arrangement must have worked out well for both parties, since the next step towards a full merger was the combination of the distribution arrangements for the Allbon and D-C ranges. This was a logical move given the reality that the Dart was actually being manufactured by Davies-Charlton despite Allbon’s ongoing reluctance to openly admit this fact. By mid 1952, Allbon’s advertisements were confirming that the distribution (as opposed to the manufacturing) of the Dart had been taken over by Davies-Charlton, although Allbon still continued to advertise separately from his Cople location and still stopped short of crediting Davies-Charlton with the manufacture of the Dart. Allbon was still advertising the Dart independently from his address at Cople in October of 1952, but the distribution of both the Allbon and D-C ranges had then been taken over by E. Keil & Co. This arrangement was to continue for some time following the completion of the merger.

Of course, Allbon had to pay his family's bills, hence requiring an income from some source. Unfortunately but quite understandably given the fact that they were still at school during this period, neither Kenneth nor Derek Allbon retained any knowledge regarding the terms of the agreement between their father and Davies-Charlton. What is known for certain from other sources is that Allbon’s name was never added to the registered company title, implying that the arrangement had some other basis. It was during this period that Christina “Chris” Crosby was employed at Davies-Charlton. Chris's presence in Barnoldswick resulted from her engineer husband being recruited to assist Rolls-Royce in their ongoing experimental jet aero engine program. While her husband worked for Rolls-Royce, 25 year old Chris found employment with Davies-Charlton as a clerk/typist and general factotum to Hefin Davies from early 1953 until his departure for the Isle of Man (IOM) in 1955. Among other things, Chris was responsible for maintaining the company's wage records. It’s undoubtedly significant that she did not recall ever preparing or even seeing any wage/salary statements for Alan Allbon while she was the clerk/typist at Davies-Charlton, although she knew his name very well thanks to its appearance on the engines. This implies that his remuneration must have taken the form of some kind of periodic dividend or royalty payment. Reader Marcus Tidmarsh has considered these circumstances and has applied his own considerable business experience to developing what I find to be a convincing interpretation of the facts. The key clue to what may have transpired is the fact that in early 1953 the registered name of the company was changed from Davies-Charlton & Co. to Davies-Charlton Ltd. Marcus points out that the legal effect of this would have been to transfer ownership of the company from a single named individual to a group of shareholders having limited liability. It seems highly likely that this was how Alan Allbon was brought on board without becoming an employee or drawing a salary - he would have been made a shareholder and would be paid for any work that he did both through dividends based on his share holdings and through increases in the value of his shares. If the company did well, so did Alan! Unfortunately for Alan, it's abundantly clear that Davies fit the image of the ruthless hard-nosed businessman far better than his new associate did! Marcus suggests that matters probably went somewhat along the lines of Davies agreeing to convert D-C into a limited company and to assign an agreed value of shares to Allbon, telling him that he would thus receive a share of D-C Ltd.'s profits without having to pay national insurance, etc., since he wouldn't be a salaried employee. This may well have been the carrot dangled in front of Allbon - in addition to solving both his production problems and financial difficulties, he became a shareholder in the very successful company in whose interest he would thenceforth be working. Doubtless an attractive proposition! For his part, Allbon agreed to continue to design engines for D-C Ltd. and also to act as works manager on the shop floor, with the expected dividends being his source of income. What may have caught Allbon out was the fact that Davies undoubtedly retained control of the company, Regardless of the actual form which it took, the merger allowed Davies to continue to lead the increasingly lucrative sub-contract work while Allbon assumed primary responsibility for the subsidiary model engine development and production programs. It also allowed the expansion of the Allbon range at production levels which could be tailored to meet demand. Hence there were clear immediate benefits for both parties. Chris Crosby recalled preparing wage statements for at least 20 people, thus providing us with a good estimate of the workforce at this time (Arthur Firth thought that the number of employees at Barnoldswick might have reached a peak of 30 or more individuals). However, as stated earlier Chris could not recall Alan Allbon’s name ever appearing among those for whom such statements were prepared. Chris recalled that the office staff during this period consisted only of herself, a book-keeper and a semi-retired man who packed and posted shipments of the company’s products. All of the other employees worked in the various technical fields with which the company was involved. The Charlton Mystery We mentioned earlier that Chris Crosby was alone in expressing a very definite view regarding the much-debated issue of the existence or otherwise of a Mr. Charlton as a partner in the Davies-Charlton enterprise. Arthur Firth had no recollection of any actual individual by that name. By contrast, Chris Crosby informed us that there was indeed a Mr. Charlton, although his first name was not recalled. Her stated understanding was that like Hefin Davies, Charlton was a former Rolls-Royce employee who left that company in 1947 to join Davies in establishing the Davies-Charlton enterprise. Ron Chernich and I included this information in the revised text of our original MEN article on the history of Davies-Charlton, citing it as an established fact. However, that was before I gained access to the first-hand evidence of Arthur Firth, who had absolutely no recollection of any actual person by the name of Charlton. Perhaps even more importantly, at that time I had not yet been put in touch with Kenneth and Derek Allbon, from whom I received confirmation that Alan Allbon actually relocated to Barnoldswick following the commencement of his association with Davies-Charlton in late 1952. This now-confirmed fact throws a real spanner into the works as far as the existence or otherwise of an individual called Charlton is concerned! The key point to note in this context is that Chris Crosby specifically claimed to have no recollection of ever meeting Alan Allbon despite the fact that he was undoubtedly living in Barnoldswick and working at Davies-Charlton during the whole of her time there. She confirmed that she was of course familiar with Allbon’s name from its appearance in connection with many of the engines which they were then manufacturing, but could not recall ever seeing him at the company offices where she worked. However, she did recall seeing "Charlton" on a number of occasions, characterizing him as a "quiet, studious and gentle man", in direct contrast to the “fiery” Hefin Davies. In her recollection, Charlton kept a very low profile while collaborating with Davies on the design side and acting as works superintendent. She recalled in particular that when he was not on the shop floor in his supervisory role he spent most of his time working in a design office located on the outskirts of town quite separate from the main D-C factory. The amazingly low profile which Charlton somehow managed to maintain over an extended period of time has long been one of the enduring mysteries surrounding the history of the Davies-Charlton enterprise. I was expecting that Kenneth or Derek Allbon would be able to shed some light upon this elusive character, since if he was still an active participant in the company when their father worked there, as suggested by Chris Crosby, they must surely have encountered him. They certainly recalled meeting Hefin Davies on a number of occasions in his capacity as their father’s business associate, so why not Charlton? However, neither Kenneth nor Derek could recall ever meeting anyone by the name of Charlton! Nor did Arthur Firth recall having met anyone of that name. This is really odd, because if Charlton was in fact the works superintendent, he would have had daily supervisory contact with Arthur. Still hoping to settle this vexing matter once and for all, Geoff Peacock went so far as to return to Barnoldswick in 2013 and again in 2015 to speak with a number of older long-time residents, many of whom claimed to have heard of Charlton but none of whom ever actually met him! Perhaps the most persuasive evidence collected by Geoff in this regard was his conversation with a former Rolls-Royce department manager from the 1950's and 1960's who had never met or even heard of any actual person named Charlton despite his firmly expressed certainty that he would have done so if such a person had actually existed. In fact, the only person who has ever claimed to have actually encountered Charlton was Chris Crosby. At this point, it’s necessary to pause for a moment to review the implications of this odd situation. The fact that no-one apart from Chris Crosby seems to have had any direct contact with Charlton at any time has always appeared very difficult to accept. If he was an active participant in the Davies-Charlton enterprise during the mid 1950’s, surely others (including Arthur Firth, who would have worked under his direction) would have met him and someone would remember him? In particular, surely Alan Allbon would have had sufficient contact that his family would remember Charlton as well as they do Hefin Davies? After all, Allbon’s association with Davies-Charlton would have made Charlton just as much his partner as Davies. In fact, Chris’s story would make far more sense if the individual to whom she referred as Charlton was in fact Alan Allbon!! It seems quite possible that the passage of some 55 years might have been sufficient to confuse some of Chris’s memories. This is a hypothesis that warrants testing …………..

Allbon surely couldn’t have carried out these duties without spending at least some time at the office discussing design and production issues with Hefin Davies. This after all was what had motivated Davies to bring him on board in the first place. This being the case, surely Chris Crosby must have seen him in the office at some point, and more than once at that? It now appears that in fact she did so, but somehow gained the impression that he was Charlton rather than Allbon! Chris’s description of “Charlton” as a “quiet, studious and gentle man” is completely consistent with what we now know of Alan Allbon’s character from his immediate family – that is exactly how Kenneth and Derek objectively characterize their father. His reported activities as Davies’ design collaborator and works superintendent are equally consistent with the roles that Allbon was undoubtedly brought on board to fulfill. This view also makes perfect sense of Chris’s additional comment to the effect that the company’s design/drawing office was maintained in separate premises on the outskirts of Barnoldswick, some distance from the main workshops and business offices which were located near the centre of town on Rainhall Road. The design/drawing office is precisely where we would expect Alan Allbon to have spent much of his time. And indeed, Chris recalled that “Charlton” spent much of his time at this location, away from the centre of the company’s activities (and perhaps away from the vagaries of Hefin Davies’ temperament!). Once again, if we substitute Alan Allbon for “Charlton”, this makes complete sense. Although Kenneth Allbon was certain that his father did not do his design work at the family residence in Salterforth, Allbon may very well have done most of that work at a separate office near his home away from the distractions of the main factory and the head office. This would place the design office on the outskirts of Barnoldswick, just as Chris recalled. It’s actually quite likely that Allbon took such premises on his own initiative to provide himself with a working environment free from outside distraction. If his formal relationship with Davies-Charlton was based purely upon his status as a shareholder, as seems likely, he would have been completely free to do so. Taking all of these comments into account, the conclusion becomes almost inescapable that the “quiet, studious and gentle man” recalled by Chris Crosby as having a key role in the design program as well as the supervision of the manufacturing operations was none other than Alan Allbon! Any other view would imply that there were two individuals (Allbon and Charlton) concurrently sharing exactly the same responsibilities and personal characteristics! Moreover, one of them appeared periodically at the company offices, while the other was never seen there at any time. It’s really difficult to see how such a situation could have arisen or been sustained. Now that we know for sure that Allbon both lived and worked in Barnoldswick during the period of his association with Davies-Charlton, I for one find this argument compelling. It’s no discredit to the 82 year old Chris Crosby that her recollections might have become a little blurred well over half a century on - I have the same problem with memories which are far less old than that!! However, it does seem to be the case that there has been some transference of identities in this instance. Another such example would appear to be Chris's recollection of the identity of Davies' fellow Rolls-Royce employee who laft Rolls-Royce in 1947 to join him. It seems almost certain that this was Walter Kendall rather than "Charlton" as recalled by Chris. Which unfortunately brings us right back to the original questions which we had for a time believed to have been answered - was there a Charlton; what was his role; and (assuming that he really existed) why did no-one other than Chris Crosby ever actually see him? Our new insights set out above force us to go back and review some of the previously-identified possibilities in light of the new information now available. One such possibility is that Charlton did exist and that Chris’s previously-stated understanding of his role in helping to found the company in 1947 was substantially correct. If this was so, there’s a ready explanation for the seeming disappearance of Charlton from the scene at an early stage. Given Hefin Davies’ unquestionably difficult character as a colleague, it would be quite understandable if Charlton (assuming that he existed) quickly found himself unable to work with Davies and either got out or was bought out. No-one else seems to have managed to work collegially with Davies for more than a few years at a stretch - why should Charlton have been any different? It’s entirely possible that he simply stepped aside and slipped into the role of a sleeping partner, as suggested by Derek Allbon. It’s also possible that someone named Charlton may have provided some financial assistance to Davies during the start-up phase in the form of a loan which Davies repaid early on without ever making Charlton a partner. In such a case, the use of the name would simply be a way of recognizing Charlton’s assistance, while also moving the company name up-market as a bonus. At this distance in time, we’re highly unlikely to uncover any evidence of such a transaction if it took place. However, Kenneth Allbon came down firmly in support of the third alternative possibility that Hefin Davies simply added the Charlton name to his own to impart a more “up-market” aura to his company's name. Double-barreled names were a strong indication of elevated social stature in Britain during this era. There were a number of documented precedents for the creation of such company names. In support of his belief, Kenneth shared a clear recollection of quizzing his mother on this very point and being told that the name “Davies-Charlton” had been assigned to Hefin Davies’ own solely-owned company. She conveyed her very clear understanding that the additional name had been chosen by Davies, possibly from among those of his former associates at Rolls-Royce, simply to move the company’s profile up-market. This hypothesis has always seemed eminently credible to me, to the extent that Chris Crosby’s affirmation of Charlton’s reality as a partner in the business actually took me very much by surprise. As matters now stand in the light of Kenneth’s evidence, and unless someone comes forward with compelling evidence to the contrary, I personally believe that the mystery of “Mr. Charlton’s” reality or otherwise is solved - he was an “invention” on the part of Hefin Davies as opposed to being a partner in the business. Geoff Peacock need look no further!! Unhappy Interlude at Barnoldswick Kenneth Allbon recalled that the relationship between Davies and his father began quite cordially. Had this not been the case, it’s unlikely that Allbon would have consummated the merger in the first place. However, all sources who knew him personally agree that Davies was a very pushy individual with a short fuse who liked to be on top of everyone and everything at all times. He also acquired a legend for being very “careful” with money! As time went on, he apparently displayed these aspects of his character to an ever-increasing extent in his dealings with Alan Allbon, quite possibly extending to his squeezing Alan financially through authorizing dividend payments which were less than expected. Kenneth recalled meeting Davies on several occasions during this period and taking an instant dislike to him due to his brash “in yer face” personality! A very direct contrast to the reported character of Alan Allbon, in fact.

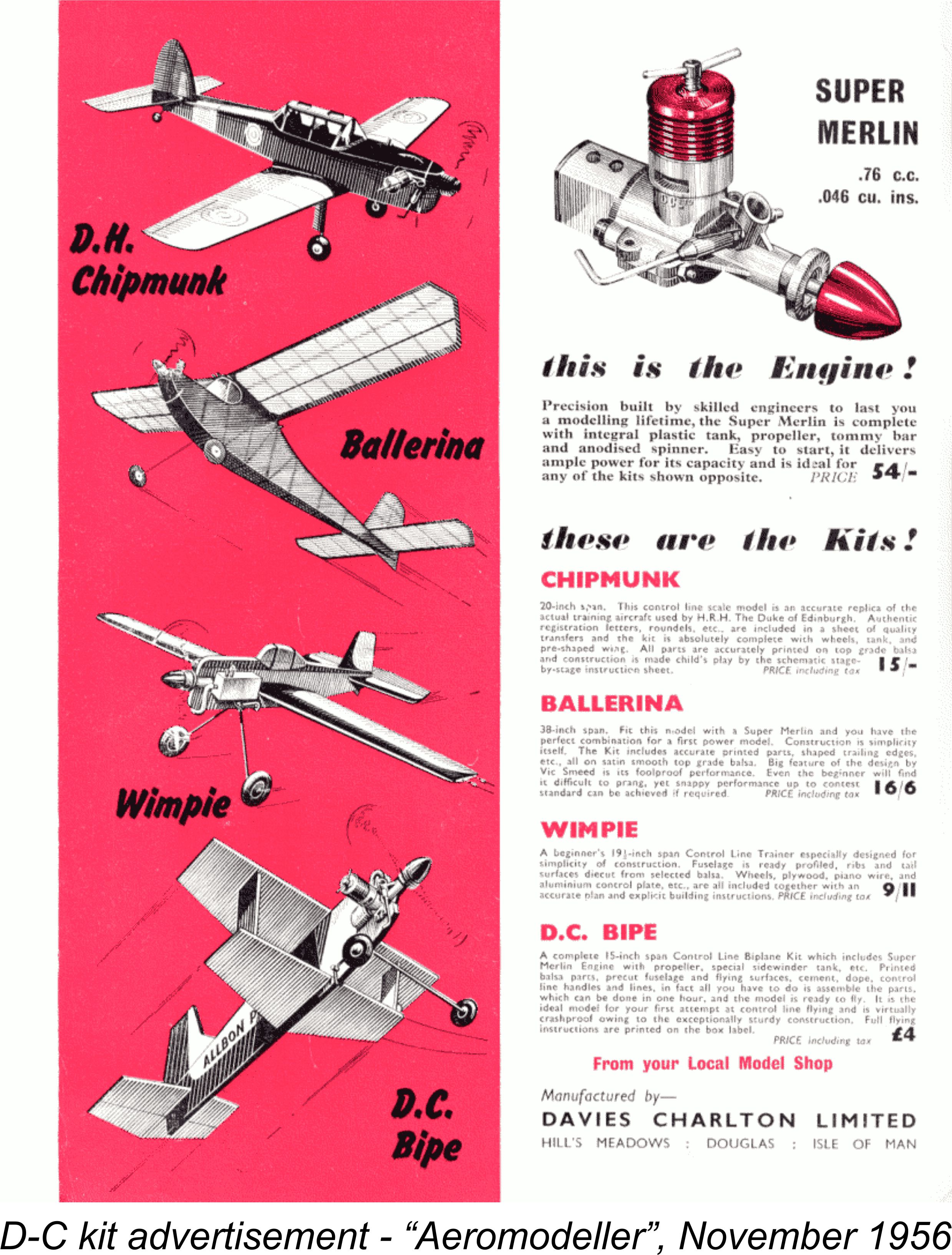

There were the previously-mentioned Mk. II versions of the Dart and Javelin which were announced in December 1952 as well as the Mk. I version of the 1 cc Spitfire, which appeared in June 1953 and became one of the all-time classic beginner’s engines. The well-established 350 models (diesel and glow) remained in production under the D-C banner throughout this period, as they were to do for some time to come. Allbon of course had had nothing to do with their inception and design since they pre-dated his involvement. In June 1954 Allbon’s famous Bambi 0.15 cc diesel appeared. This was the smallest-displacement model engine ever to enter series production up to that time, a record which it probably still holds today. Arthur Chris Crosby recalled that the management and staff at Davies-Charlton were very proud of this groundbreaking little model. Our previous article on the story of the Bambi may still be found on MEN. Also in 1954, Allbon began work on a design which was quite distinct from that of his previous models, being intended from the outset to be constructed at minimal cost. The defining characteristics of what was to become the “classic” Davies-Charlton small-engine design were sturdy and ultra-simple construction allied to low production costs. The first manifestation of this new However, behind the scenes all was far from well. Kenneth Allbon told me that Hefin Davies’ grating personality had led to an increasing degree of friction between him and Alan Allbon. We have also seen that Davies may have exercised control over shareholder dividends which resulted in the arrangement falling well short of meeting Allbon's financial expectations. Whatever the reasons, the result was that by early 1955 the relationship between the two men had broken down completely. Given Allbon’s well-attested ability to get along with almost anyone, responsibility for this unhappy outcome must surely be laid firmly at Davies’ door. It only took just over two years.......... As 1955 came around, Allbon thus found himself in an increasingly untenable situation. Indeed, he may well have been in urgent need of a boost to his financial situation if Davies was indeed putting the squeeze on dividends. Fortuitously, the opportunity to end this predicament lay only just around the corner. Relocation and the Glory Years The amalgamation of the D-C and Allbon ranges must have severely taxed the existing model engine production facilities at Barnoldswick. Moreover as mentioned earlier, by mid 1954 plans were well advanced for the introduction of several new models to augment the existing ranges. All of this must have underscored the need for expanded production capacity. The introduction of the instantly popular Allbon Merlin in October 1954 was apparently the final straw. It just so happened that the resulting production crisis coincided with a number of initiatives on the part of the government of the Isle of Man (IOM) to attract industry to the island in order to alleviate a chronic unemployment problem there. Hefin Davies was quick to sense his opportunity.

Upon the successful conclusion of negotiations with the Manx government, a move to the Isle of Man was quickly put in hand. The company continued to advertise from their Barnoldswick location through the early part of 1955, but by June of 1955 the move to the company’s modernised factory at Hills Meadow, Douglas, Isle of Man was evidently complete. All subsequent Davies-Charlton model engines were manufactured at the new location, including their Allbon designs. This was one of the instances in which Hefin Davies displayed what Arthur Firth characterized as his “utter ruthlessness”. He had built up a valuable company as a result of the dedicated work and skill of his employees in Barnoldswick, who might have expected him to show some loyalty towards them in return. However, the deal with the IOM government stipulated that their support for the venture was conditional upon Davies providing work for existing IOM residents rather than bringing his own experienced workforce to the Island. The fact that he would have to cast adrift many of the very workers who had loyally contributed to his success presented no dilemma for Davies – he jumped at the opportunity without a backward glance. Under the terms of the agreement with the IOM government, Davies was allowed to bring only three of his experienced shop floor workers with him. One of these was Arthur Firth, by now seen as an indispensable member of the D-C workforce. Three IOM residents were sent over to Barnoldswick in advance of the move to receive training from the very workers whom they were going to displace. It may well be imagined that D-C Ltd. was a rather unhappy workplace during this period............ Chris Crosby was another employee who was offered the opportunity to relocate to the IOM with Davies. However, she and her husband declined this opportunity, remaining in Barnoldswick and starting their family there. This ended her direct involvement with Davies-Charlton. Once again, our sincere thanks to Chris for so generously sharing her most interesting recollections. The few employees and associates who made the move with Davies were allocated housing near the location of the new Hills Meadow factory, which was still under construction at the time of the move. One of these was Alan Allbon, who still retained some connection with D-C Ltd. at this stage – he was assigned a house in Laxey. Arthur Firth recalled that while construction of the Hills Meadow factory was being completed, the first engines manufactured (or at least assembled) on the IOM were completed in a temporary facility which took the form of a shed in a corner of a property occupied by a company called Vulfix which made (and still makes!) high-end shaving brushes! Back to the basics, at least temporarily! The housing situation provided another example of Davies' ruthless opportunism which was recalled by Arthur Firth. Apparently upon Davies’ arrival on the Island, most of the factory employees were immediately put to work carrying out renovations and re-decorating work on both Davies’ house and that assigned to Alan Allbon! As noted earlier, Davies was reportedly a bit “careful” about money, going so far as to install a punch-card machine in his own house to confirm that the employees were putting in the required hours while giving his home a make-over! This frugality probably stemmed from his experiences during the early sixpence-saving days. Another example of Davies’ “frugality” came a few years later when, after starting to feel frustrated and undervalued, Arthur Firth told Davies that he was leaving D-C Ltd., with a request that he be paid off for work already done. Davies did not react well to this news – he responded by immediately locking Arthur’s severance pay-packet in his safe! Arthur actually had to retain the services of a solicitor to finally get his hands on the money that he was owed. After relating this sorry incident, it’s rather astonishing to record the fact that after Arthur had been working for his new employer, the Dowty undercarriage manufacturing firm, for only some three months, Davies evidently recognized the vacuum in D-C Ltd.’s production capabilities which Arthur’s departure had created. This led to Davies approaching Arthur, all sins forgiven, with an offer of a substantial pay raise and a job as milling superintendent for Arthur’s son Kevin if he would return!

Returning now to 1955, one individual who did not remain long with the company following the move to the IOM was Alan Allbon. He was no doubt keenly aware of the desire of the Manx government to encourage the further development of high-tech industry on the Island. Kenneth Allbon did not know how this came about, but there’s no doubt that the Manx government quickly offered Allbon the independent use of a vacant factory located in Douglas on the condition that he provide employment for a certain number of Manx residents. Given the irreparable breakdown of his relationship with Davies, Allbon was more than happy to accept this offer. Indeed, it's likely that he actively sought such a means of escape if our suspicion that Davies was putting the fiscal squeeze on him has any basis - his financial situation may well have mandated a change. Of course, as a shareholder in D-C Ltd. rather than a partner, Allbon was completely free to undertake such an action - he would have remained a shareholder unless someone bought up his shares. He would also have remained entitled to any shareholder dividends that were going. It was accordingly at this point in mid 1955, far earlier than had previously been widely believed, that Allbon terminated his direct working association with Davies-Charlton, setting up his own independent precision engineering operation at the Douglas facility. During the following four-year period, Allbon and his family continued to live in Laxey, some eight miles to the north of Douglas. Allbon's place as works manager for D-C Ltd. was taken by the far less experienced Ted Saunders, with whom Allbon was to become closely associated down the road when he and Saunders formed the Allbon-Saunders company in 1959. It might appear at first sight that the move from Rolls-Royce’s back yard in Barnoldswick to the somewhat remote environs of the Isle of Man must have rendered Davies-Charlton’s ongoing contract work for Rolls-Royce somewhat more problematic from a logistical standpoint given the fact that the two companies were no longer co-located. However, it turns out that the Barnoldswick factory remained in operation at a somewhat reduced scale for some years after the move, presumably to facilitate the ongoing sub-contract work for Rolls-Royce. It was of course no longer involved with model engine production, but it was used for a time as a centre for the production of the model engine fuels marketed by Davies-Charlton. Moreover, there were other high-tech aviation-related industries located on the Isle of Man at this time, including Ronaldsway Aircraft, Manx Engineers, the Dowty undercarriage-making firm and the Martin-Baker company which made ejection seats for the RAF and others. There have been credible suggestions that Davies-Charlton (and probably Alan Allbon) undertook contract work for local firms such as these, which may have taken up some of the slack for a time at least. Regardless, there are clear indications that it was from this time onwards that model engine manufacturing began to assume a greater relative importance in the affairs of Davies-Charlton. This may well have resulted from the increased competition represented by other IOM companies such as Alan Allbon's Douglas operation. Another factor that could potentially have had an impact would be a cooling-off of the relationship between Davies and his long-time associated Walter Kendall. It may be recalled that Kendall had been highly instrumental in influencing Rolls-Royce's assignment of sub-contract work to Davies Charlton, since he was married to the daughter of their sub-contract manager. Clearly, this influence could have worked both ways - Kendall retained his influence with Rolls-Royce and could easily have induced them to reduce the amount of contract work sent D-C Ltd.'s way. We have no hard evidence to support the notion of a cooling-off in the relationship beyond the undoubted fact that Kendall left D-C Ltd. in the late 1950's, subsequently setting up his own M.E. operation in direct competition with D-C Ltd. However it came about, the company's increased dependence upon participation in the model trade is undoubtedly consistent with the obvious fact that model engines remained Hefin Davies' first love throughout. Whatever the reasons for this change in company focus, it is certainly true that following the completion of the move to the Isle of Man the company acted quickly to expand both its model engine range and its line of associated products.

The appearance of the Sabre actually marks something of an often-overlooked turning point in the history of the D-C range and indeed of the British model engine manufacturing industry as a whole. In the opinion of many (including myself) the 1.49 cc Javelin Mk. II had been a significantly better engine, and one which had considerable development potential waiting to be exploited. Thanks in large part to its being built down to a price, the Sabre displayed a number of rather negative characteristics, most notably the ridiculously heavy piston which played havoc with vibration and conrod life; the simplified cylinder porting which forced quite inappropriate port timings on the design (exhaust period 170 degrees, transfer period 90 degrees); a totally inadequate conrod; and the excessive clearance between the cooling jacket and cylinder which pretty much guaranteed overheating of the cylinder liner. All of these factors were directly related to the obvious goal of minimizing production costs, regardless of the impact upon performance and longevity.

It's important to note that none of this was down to Alan Allbon, who had ended his own direct involvement with D-C Ltd. well before either the Sabre or the Spitfire Mk. II made their appearances. He would undoubtedly have seen at once that the scaling up his excellent 0.76 cc design would necessarily have to be accompanied by some design changes. For example, it's highly unlikely that he would have gone along with the absurdly heavy pistons used in these two engines. Moreover, he would probably have developed a far more sturdy conrod and (in the case of the Sabre) a beefed-up crankshaft. The slavish scaling-up of Allbon's smaller design was unquestionably down to Hefin Davies.

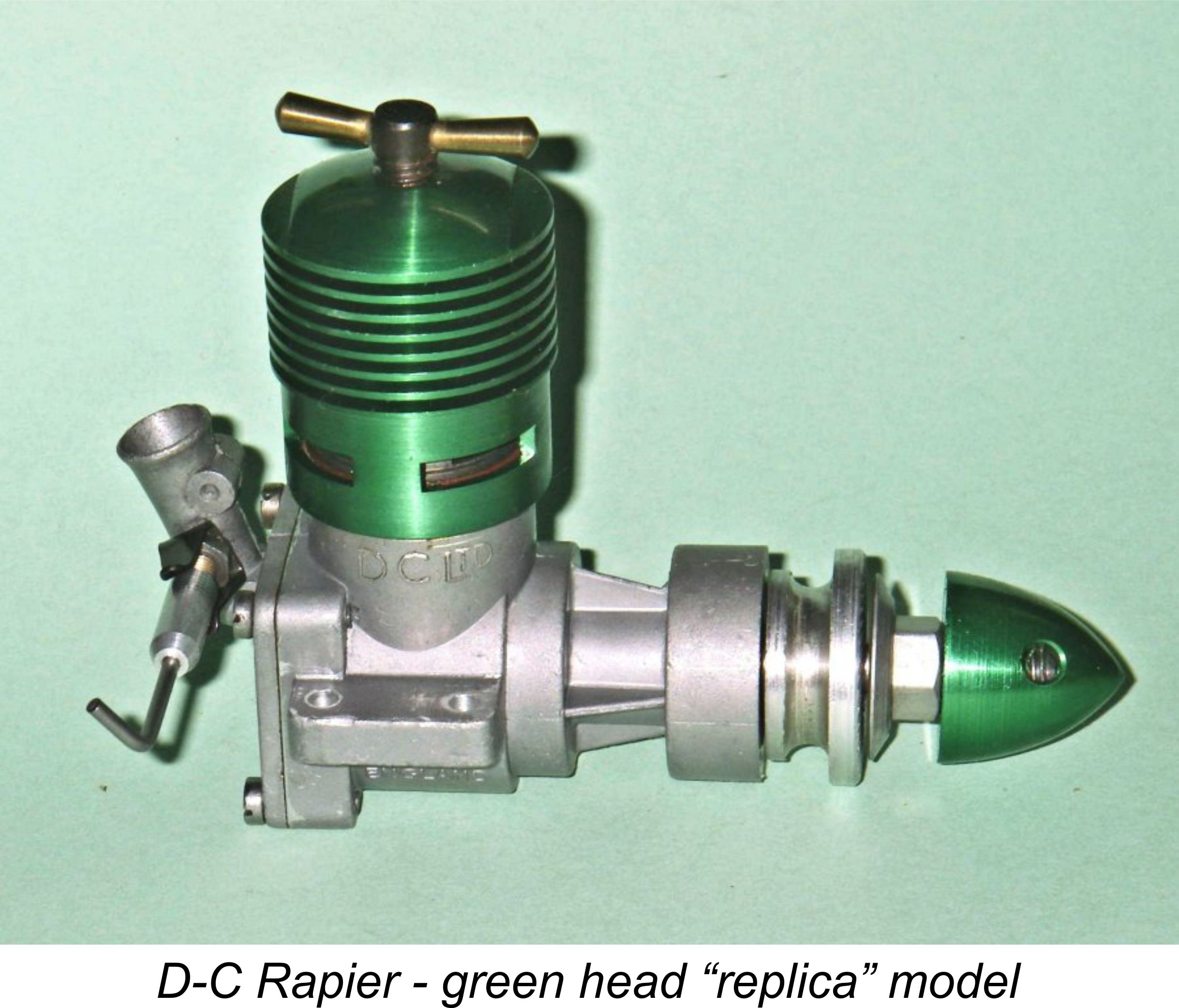

It’s presently unclear whether or not the kits were actually manufactured by Davies-Charlton at their IOM facility. They were after all set up as a speciality precision metalworking concern, and the manufacture of wooden kits was a highly distinct business line requiring quite different tooling. Moreover, woodworking and precision metalworking don’t mix well in the same premises due to the oil ‘n sawdust factor…………It seems entirely possible that the kits were manufactured by others under contract, perhaps by KeilKraft, with whom Davies-Charlton had been closely associated only a few years previously. If anyone knows more about this, please speak up!! The company also produced a neat and very practical engine test stand as well as fuel tanks, radial mounts, fuel cut-outs, airscrews and an adjustable control-line handle. There was also the Allbon diesel fuel, which was tailored to the company’s engine range. Another interesting product of the company during these years was their hot air (Stirling Cycle) stationary engine, which sold for 30 shillings and was advertised as the “Hot Air Engine for boys of all ages”! These intriguing Having recounted the history of the company’s early years in the IOM, it’s necessary now to highlight a less happy issue which reportedly arose during this period. We’ve seen in the above account that despite the effective parting of the ways with Alan Allbon, Davies continued to sell Allbon’s engine designs (some of them by that name), also freely applying the highly respected Allbon name to his line of accessories and diesel fuels. Even engine designs which were released after the split, such as the 3.5 cc Manxman (March 1956), were initially sold under the Allbon banner - reader Bill Wells advises that he has a boxed example of the Manxman, the box for which is clearly labelled as containing an "Allbon Manxman", also recommending the use of Allbon diesel fuel. I have heard presently-unsubstantiated reports that the 2.5 cc Rapier of February 1957 was also initially marketed under the Allbon name.

No doubt surviving members of the Davies family would tell a different version of this story. If any of them read this article, they are hereby cordially invited to do so for the record - I have no axe to grind and will gladly present their side of the issue. However, as matters stand, I am only able to comment on this matter on the basis of the Allbon family's view of the affair. In fairness to Davies, I must record my own view that D-C Ltd.'s right to the use of the Allbon name may well have formed part of the now-lost agreement by which Allbon became a shareholder in early 1953. If that was the case, Alan's departure in 1955 to run his own show would not have upset any such agreement - he would still be a D-C shareholder. I think it to be far more likely that the Allbon family's very negative recollections have more to do with Davies characteristically putting the financial squeeze on Alan through less-than-anticipated divident payments despite D-C Ltd.'s ongoing success, much of which was due to Alan's efforts. Whatever the truth, it's clear from my personal interactions with them that this behaviour left some lasting scars among members of the Allbon family – I can confirm from my personal interactions with them that Kenneth and Derek Allbon both still bore those scars decades after the event. Derek went so far as to characterize Davies as “a bit of a shyster who ripped my father off mercilessly through their “partnership”! Ouch………Derek’s feelings were clearly based upon long-ago discussions with his father. Most intriguingly, there is some documentary evidence to suggest that Allbon may in fact have attempted to recover what he saw as money owed to him by Davies. This takes the form of an otherwise very puzzling series of actions by Davies beginning in early 1958. In a nutshell, he initiated a series of company dissolutions and re-registrations which were not publicised and which are otherwise rather difficult to explain. A search of IOM corporate records by Marcus Tidmarsh showed that until January 1958 D-C Ltd. retained its British company registration by that name, hence being listed in IOM records as a “foreign company” operating in the IOM. We would not expect otherwise in normal circumstances – there would be no reason to change. However, on January 25th, 1958, Davies actually dissolved the British-registered D-C Ltd. company, transferring its assets to a completely new and distinct IOM registered company called Davies Engineering Ltd. Despite this, the advertising continued to bear the Davies-Charlton name throughout. This is interesting insofar as that company had ceased to exist in a legal sense! Perhaps even more strangely, this re-named company only lasted until November 8th, 1958, when it too was dissolved and replaced with yet another IOM-registered company which reverted to the original Davies Charlton Ltd. name! It’s important to note that this was not a revival of the “old” Davies-Charlton Ltd. company in which Alan Allbon was a shareholder - it was another completely new company bearing the same name. However, it did bring the company's name back into alignment with its advertising identification. A straw in the wind in relation to the initial January 1958 dissolution of the "original" Davies-Charlton Ltd. company is the fact that it coincides almost exactly with the company's final discontinuation of the use of the Allbon name. It's hard to avoid the suspicion that since this dissolution would clearly extinguish Alan Allbon's position as a shareholder (the company in which he held shares no longer existed), it also extinguished any rights to Davies' continued use of the Allbon name, assuming that this was a feature of the original shareholder agreement. However, Davies continued to produce Allbon's model engine designs, albeit no longer by that name. The rights and wrongs of this are beyond my qualifications to determine. This company carried on by that name until October 1st, 1963, when it too was dissolved and replaced by yet another new company which was registered in the IOM under the Davies Engineering Ltd. name! Once again, this change was not reflected in the company's advertising. This company too didn’t last long – on March 31st, 1964 the second Davies Engineering Ltd. company was dissolved in turn, being replaced as before by yet another new and distinct company bearing the original name of Davies-Charlton Ltd.! This last company was destined to survive on paper at least until April 20th, 1994, when it was dissolved for the last time, long after it had ceased to trade. It must surely be obvious that there had to be a compelling motive behind these frequent dissolutions and re-registrations. One plausible possibility (and it’s no more than a possibility as opposed to an established fact) is that these moves represented a strategy to circumvent the serving of legal documents relating to an attempt by some party or parties to collect money owed to them by Davies-Charlton. However, there may be other explanations - I’d welcome any other plausible suggestions. There’s a good chance that surviving members of the Davies family could clear up any uncertainties regarding the reasons for this rather extraordinary chain of events. A few years ago I actually established contact with Hefin Davies’ nephew Rhodri Dafis, who initially agreed quite readily to help. The family was thus made aware of this article and my interest in hearing their side of the story. However, Rhodri then went silent on me, for reasons of which I naturally remain unaware. As previously stated, I would welcome further contact from the Davies family - there’s much that they could probably clear up for us. I have no axe to grind - I'm simply interested in establishing the facts!

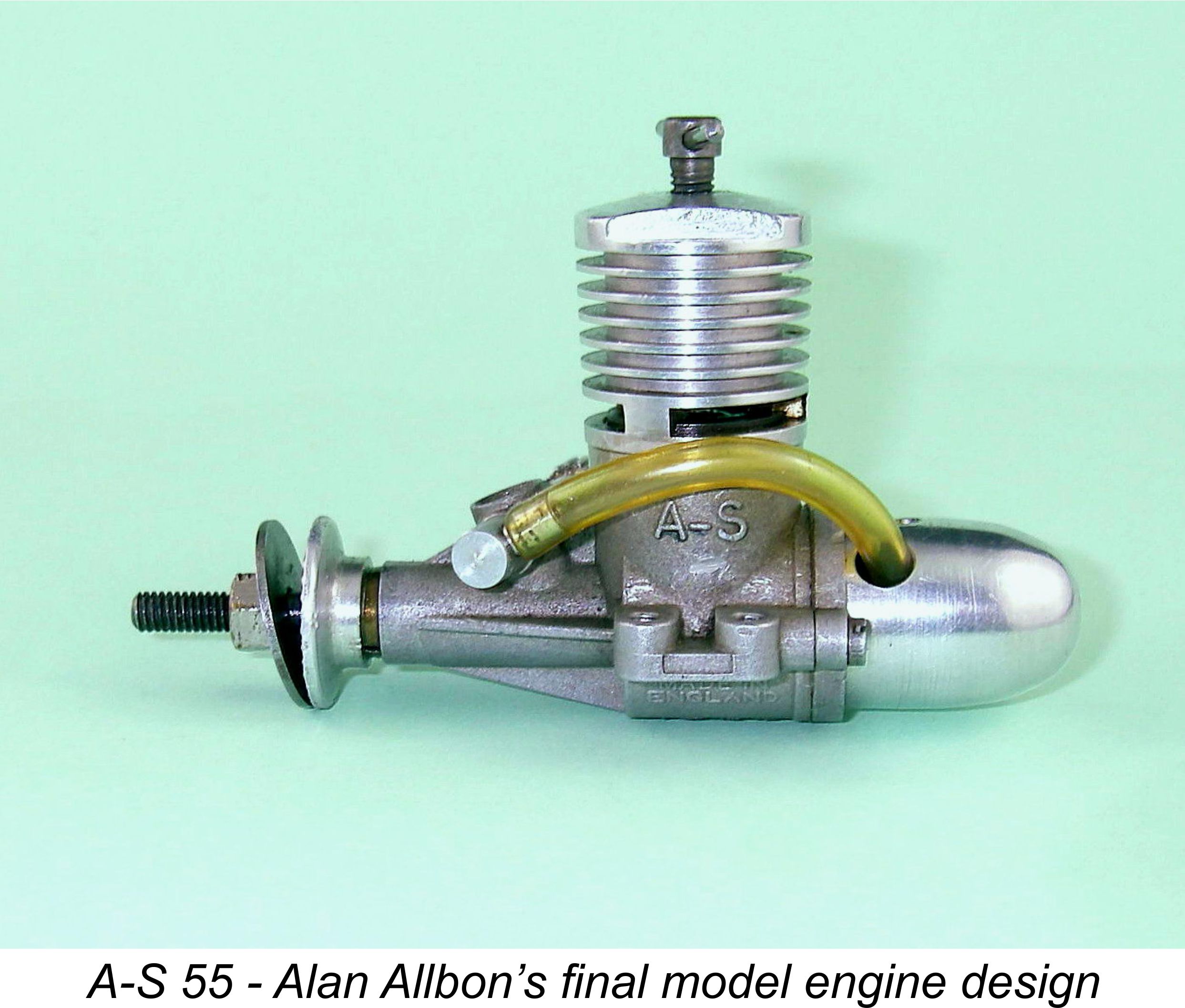

Mainly as a result of the increasing preoccupation of the British model engine marketplace with cost as opposed to quality and performance, (for which British modellers were to pay dearly), this fine little unit was at best a rather modest seller. Not being prepared to join the race to the bottom which had developed in the British model engine manufacturing sector, the company became increasingly preoccupied with the provision of precision engineering services to such clients as Mike Hewland of Hewland gearbox fame and the nearby National Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell, near Didcot in Berkshire. Only some 2200 examples of the A-S 55 were manufactured before Alan Allbon abandoned the model engine field entirely. Readers interested in learning more about this excellent little motor are referred to my focused article on the engine. After retiring from Allbon-Saunders in 1970 at age 64, Alan Allbon died prematurely and most unexpectedly of a heart attack at Ilkley in Yorkshire in 1978 at the age of 72 years. The full story of the life and work of Alan Allbon may be found in a separate article on this website.

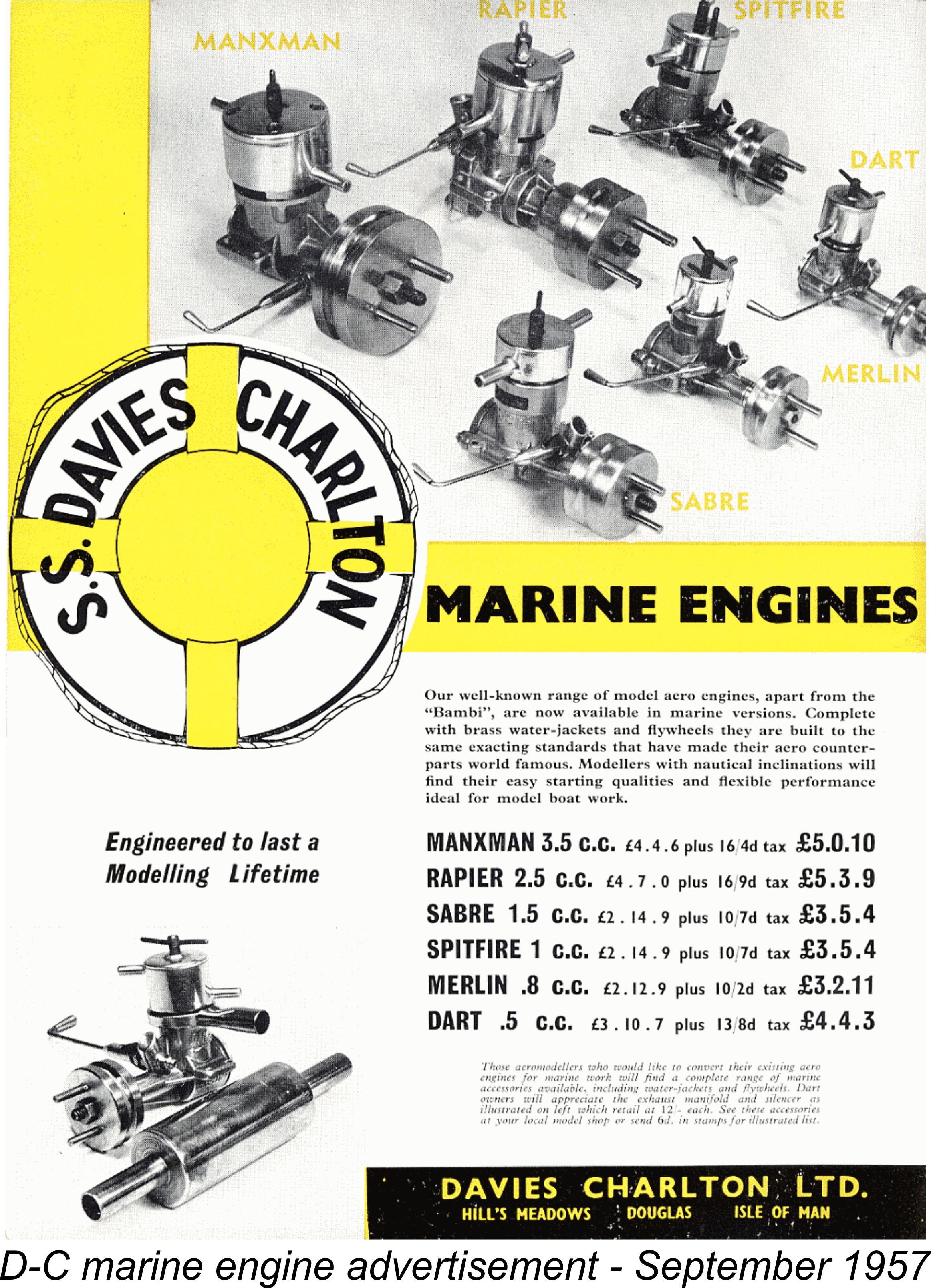

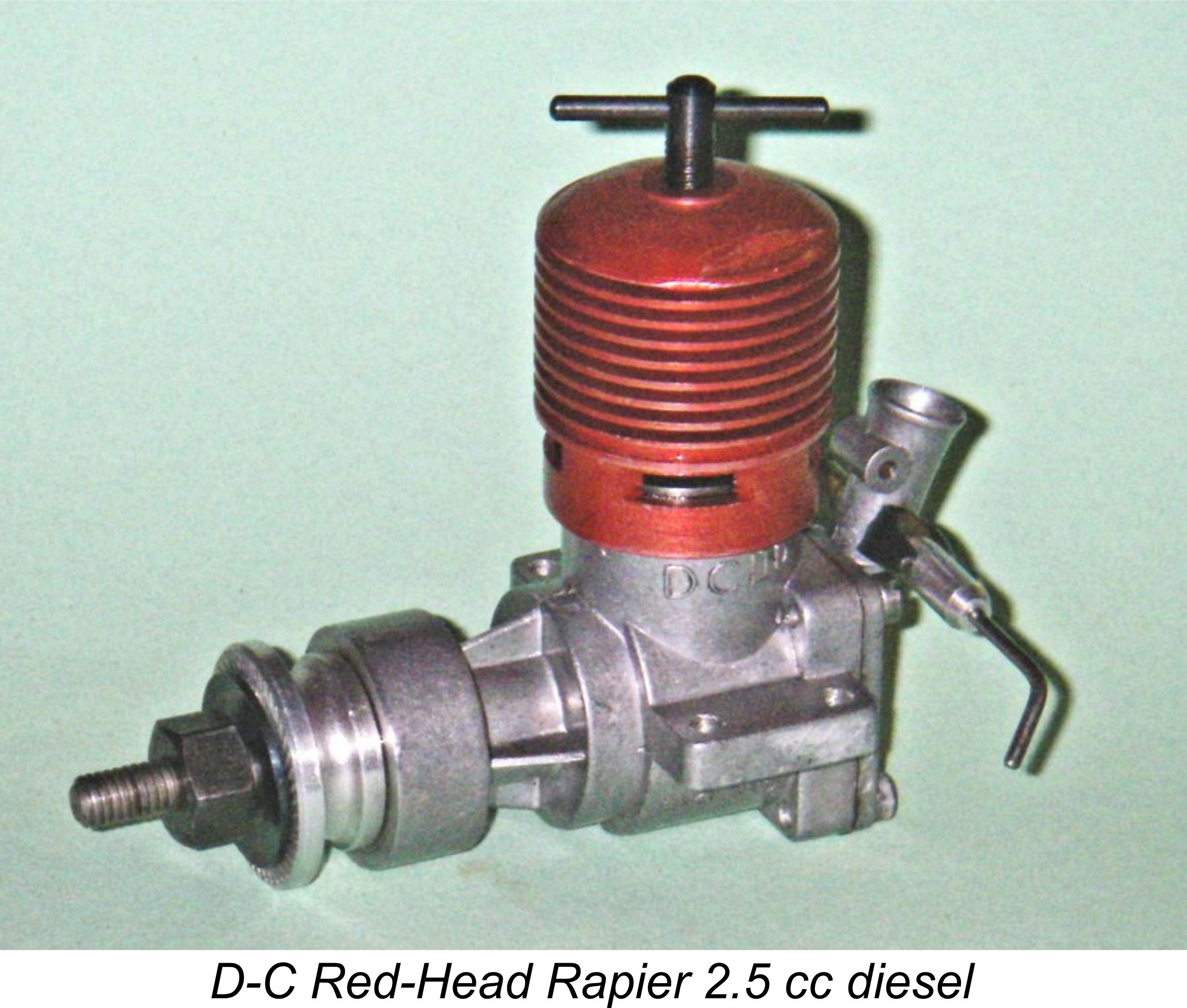

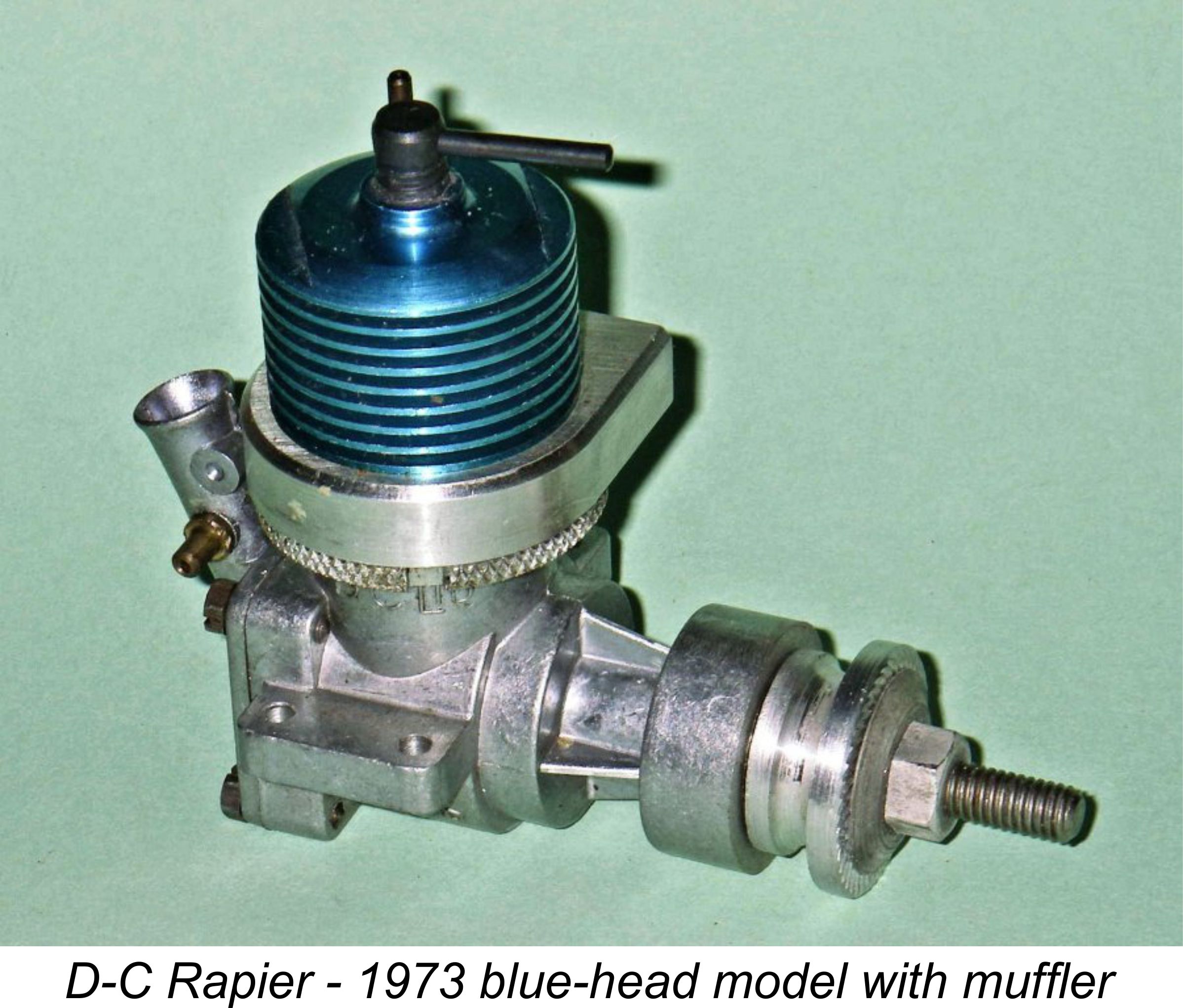

There were of course disappointments along the way. The 3.5 cc Manxman diesel which replaced the trusty old D-C 350 in March 1956 was an extremely well-made and attractive engine, but it seems to have enjoyed rather limited sales success, being phased out relatively quickly as a result. To make up for In 1958 a small batch of Rapiers was produced with red-anodized heads, but otherwise identical to the original green-head model. Very few of these were produced - a former employee of the company suggested around 200 in total. Most likely this was more a case of saving a few bob by adding some Rapier heads to a red-anodizing batch of components for other models than a conscious effort to produce a Although the Dart, the Merlin and the Spitfire and Sabre ”twins” were all initially marketed under the Allbon name, that name was progressively dropped from 1956 onwards, seemingly disappearing entirely in 1958 after lingering for a while on the company’s diesel fuel labels. Soon thereafter, the staff of Davies-Charlton was strengthened by the addition of Harry Hundleby, a former editor of “Aeromodeller” magazine who was then resident in the IOM. Meanwhile, Davies-Charlton maintained their prominent position in the British model engine industry in addition to continuing their contract precision engineering work for Rolls-Royce, among others. In mid 1958 Hefin Davies decided that Davies-Charlton would re-enter the glow-plug field. With this in mind he The immediate result of this initiative was the December 1958 introduction of the innovative and technically very successful Tornado Twin 5 cc glow-plug motor. This simultaneous-firing opposed twin used a pair of rotary valves which were fed by a single carburettor. The use of a one-piece crankshaft required the conrod big-end bearings to be split, very much along "full sized" lines. The design also placed a premium on the accurate fitting and alignment of the crankshaft bearings at front and rear. D-C Ltd. made a fine job of overcoming these manufacturing challenges. In my personal view, and speaking as a former user of this outstanding engine, this was Davies-Charlton’s finest achievement in the model engine field. It was quickly followed in late 1959 by the far more mundane but commercially successful Bantam 0.76 cc glow-plug motor, which was a derivative of the Dart diesel model.

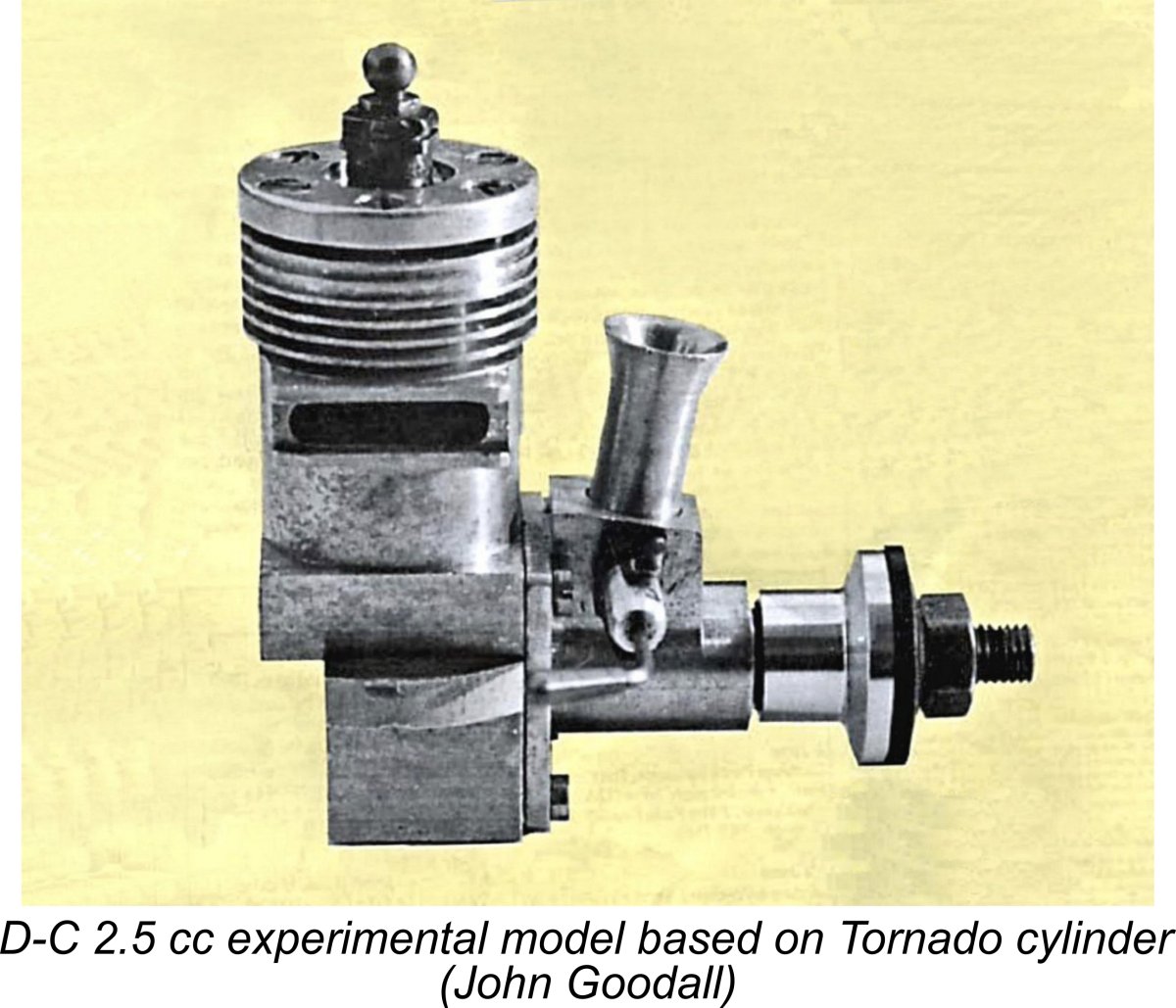

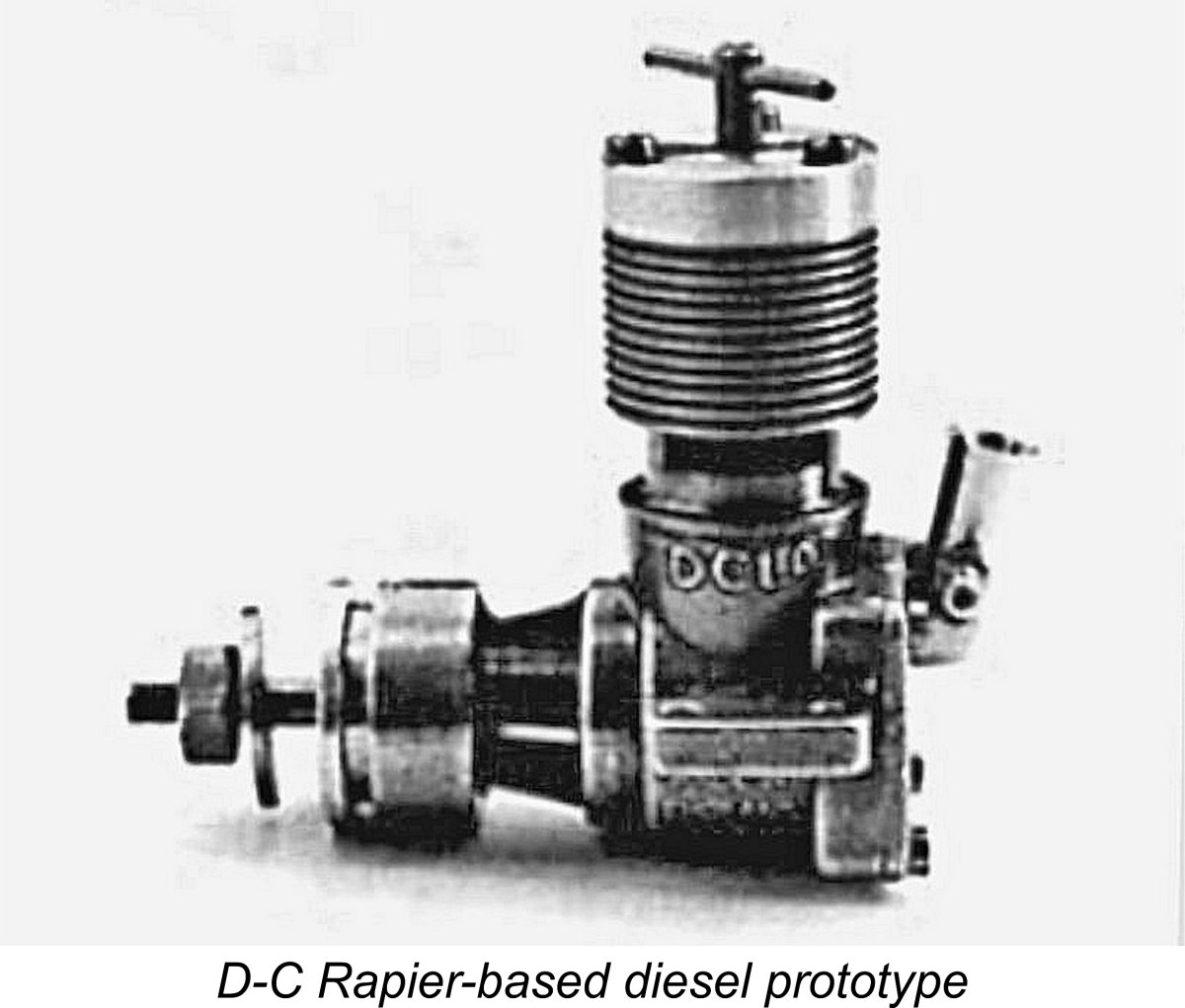

No single-cylinder D-C glow-plug unit based on this prototype ever materialized in production form. However, the recent eBay appearance of an original D-C triangular box labelled for a 2.5 cc engine named the Comet sheds some light on this project The indisputable existence of this box clearly implies that some form of 2.5 cc glow-plug project did progress at least to The Tornado Twin was an outstanding technical achievement which richly deserved to succeed, but it must have cost a great deal to develop and in all likelihood never repaid its development costs. It didn’t find that many buyers and only lasted a few years in rather limited production. It seems likely that this experience had its effect upon Davies-Charlton’s appetite for the development of new models, since such development appears to have stalled for quite a few years following the demise of the Tornado. In fact, One experiment which did reach the prototype stage at around this time was an upgraded version of the Rapier. This was constructed around the Rapier crankcase and backplate, but featured a screw-in cylinder having comprehensively revised cylinder porting arrangements. The engine employed twin opposed exhaust ports at the sides and twin opposed transfer flutes fore and aft. It was built in both diesel and glow-plug configurations. According to the owner of the surviving example of this prototype, the diesel version had a performance which approached that of the contemporary Oliver Tiger model. However, nothing ever came of this seemingly promising development project.

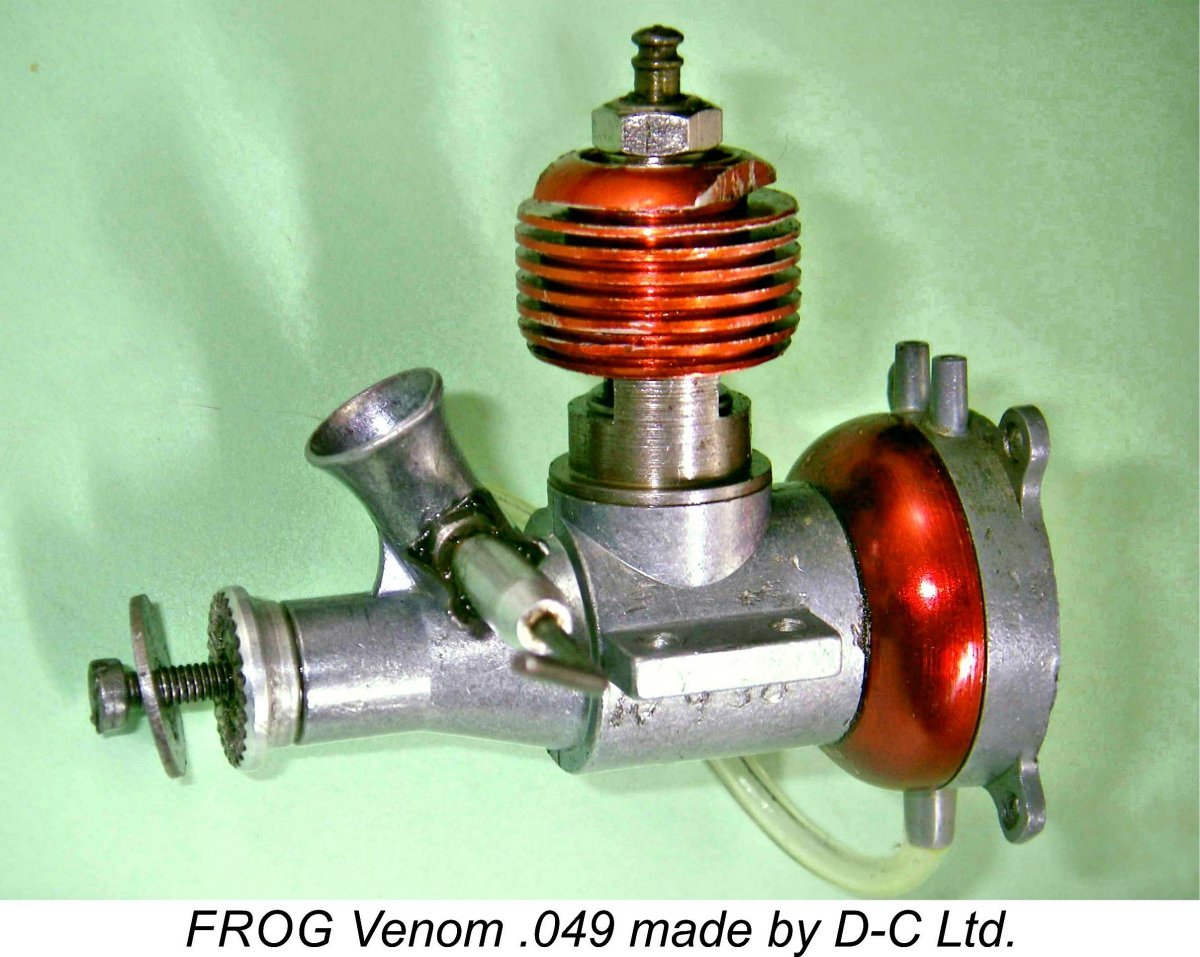

But the really aggravating thing about the Quickstart device was the fact that it was quite unnecessary - provided there were no base compression leaks, the D-C engines were actually very easy starters using Finally, the latter part of 1959 saw the introduction of Davies-Charlton’s unique triangular box, along with the adoption of the “Quickstart” label for their engines and fuel. The box was inspired by the three-legged emblem of the Isle of Man with its associated motto “Whichever way you throw me, I stand”. It was doubtless relatively costly to produce and was only used for a few years before the company reverted to the use of more conventional cubical boxes. Thanks mainly to its extremely low price, the Bantam achieved great popularity despite being a less-than-stellar performer, ushering Davies-Charlton into the 1960’s Along with the Bantam, Davies-Charlton maintained production of the sports diesels for which the firm had become well-known during the 1950’s, and these continued to sell well also. In 1964 they also took over the manufacture of the FROG range of engines on behalf of the A. A. Hales organization, which had become a subsidiary of Lines Brothers in 1962 and had been assigned responsibility for the future marketing of the FROG range. This is perhaps another indication that Davies-Charlton’s involvement with outside contract work had entered a decline, leaving them with more resources to devote to model engine manufacture.

In June 1960, some very serious local competition for Davies-Charlton had appeared in the form of the M.E. engines. These were manufactured by a new company known as Marown Engineering located in Glen Vine on the Isle of Man. This venture had been established in late 1959 by Walter Kendall, who had previously been a long-time associate of Hefin Davies in the Davies-Charlton business.

To add insult to injury, in early 1963 the Marown Engineering company relocated to expanded premises in nearby Union Mill, thereafter becoming Davies-Charlton’s direct competitor in vying for a share of the lucrative aerospace subcontracting work from Rolls-Royce and others! As stated earlier, Walter Kendall may have enjoyed a significant advantage in attracting business from Rolls-Royce stemming from his marriage "into the family"! His 1959 departure may have played a significant role in reducing D-C Ltd.'s share of the Rolls-Royce contract work, contributing to their increasing reliance on model engine production. Stagnation Throughout the 1960’s Davies-Charlton continued to maintain a strong position in the model engine marketplace with their established D-C and FROG line-ups. My informant Bill Callow began his career with D-C Ltd. during this period, starting as an engineering apprentice in 1968 and advancing to the position of charge-hand on the grinding section before leaving for a period of 5 years to work for others as a Rolls-Royce approved inspector. Bill estimated that the company’s workforce at its peak may have totalled as many as 120 individuals. During this busy period, the company had no fewer than three distinct facilities in operation. Firstly, there was the main Hills Meadow factory near Douglas, which was fully occupied with the aerospace sub-contracting work as well as the production of the FROG and D-C engine components. There was also a second IOM facility housed in an ex-WW2 Nissen hut a few hundred yards away from the main factory on the Hills Meadow estate. This included the company’s model engine assembly, testing, packaging and warehousing operations as well as the gravity die-casting and painting operations involved in the production of D-C’s well-known and very popular adjustable control line handles and test stand. The Barnoldswick plant also remained in operation at some level well into the 1960’s, although it was eventually closed down later in the decade and sold for other uses. From that point onwards, all of D-C Ltd.’s activities were concentrated in the IOM. It should be clear from the above account that the company had entered the 1960’s as a major player in the British model engine industry. However, new models signally failed to appear as the decade of the swinging ‘60’s wore on, with the result that as the 1970’s began both the D-C and FROG ranges (the latter still owned by A. A. Hales) were effectively "frozen" in design terms, hence falling increasingly behind the times. Advertising of the FROG range by A. A. Hales ceased altogether as of September 1972, after which no more was heard of that once-famous marque, although examples continued to be available through certain retail outlets. Quite apart from the frozen design status of the range, people were beginning to notice that quality control was undeniably suffering………….. The slow but steady decline in manufacturing standards at Davies-Charlton probably commenced relatively soon after Alan Allbon’s departure in mid 1955. Allbon was reportedly a very even-tempered individual who got along well with everyone except Davies, making him the ideal kind of person to be in charge of the production program. He had of course fulfilled this role for the final few years at Barnoldswick, thus serving as a buffer between Davies and his employees. He seems to have been the type of character who would naturally command loyalty among the workforce under his direct control, thus inspiring them to make their best efforts. Furthermore, he was far better qualified technically than his replacement Ted Saunders. A story which Allbon related to his later Allbon-Saunders colleague Bernie Bowler is perhaps indicative of the relative importance attached by Davies to cost as opposed to quality. At some point during the period in which Alan Allbon was still involved with the company, Davies apparently noticed Alan examining a batch of engines prior to boxing and spending a considerable time checking one of them very closely. When Davies asked what Allbon was doing, he replied that this particular engine seemed to be low on compression. Davies' retort as recalled by Alan?!? "We're not selling f*****g compression, we're selling engines! Put it in the box!!" This incident further underscores the widespread recollection that Hefin Davies was not at all an easy man to work for. It might be thought that anyone finding it difficult to work for Davies would have an option - go to work for someone else. However, it wasn't as simple as that. The number of high-tech industries on the IOM was relatively small and although there were undoubtedly opportunities for employee mobility between these firms, few individuals would have been willing to risk being in effect “black-listed” by the doubtless close-knit group of engineering firms on the Island. This gave such employers a considerable amount of collective “leverage” over their employees. Once freed from any moderating influence which the presence of Alan Allbon might have represented, all accounts from ex-employees agree that Hefin Davies exercised the resulting domination over his own “captive” work force to the full. In consequence, former employees have generally characterized Davies-Charlton as a somewhat unhappy workplace. Under such circumstances, a diminished level of attention to the quality issue might be expected - an unhappy workforce never delivers its best work. In fact, it may well have gone even further than that! In later discussions with David Owen, IOM resident O. F. W. “Peter” Fisher of Performance Kits fame intimated that employee sabotage of engines was not unknown. Fisher went so far as to express his personal conviction that this took place with the full collaboration of the engine testing and quality control staff, the result being that some faulty D-C products were quite deliberately sent out to unsuspecting buyers, to the detriment of Davies-Charlton's reputation. Looking back on this period, I may have been a victim myself! I actually recall buying a new Super Merlin in the mid 1960’s that wouldn’t start for love nor money. When I checked, I found that the spraybar had not been cross-drilled for the jet holes! At the time, I assumed that this was merely an incidental error, and one which I was easily able to fix myself. However, I’m not so sure now ……… David Owen had parallel recollections from his time as a D-C distributor in Australia. Overall, the impression was that the quality of the D-C engines marketed during the 1960’s was noticeably inferior to that of the company’s 1950’s offerings. This is of particular interest given Arthur Firth’s clearly-stated recollection that during his time at D-C Ltd. (up to 1970 with a three-month hiatus in the late 1950’s) all engines were tested prior to despatch to his certain knowledge. There’s no way that my Super Merlin could have passed a test run, implying that it could only have been sent out to the hobby shop from which I bought it with the active connivance of the engine testing staff, as implied by Fisher. Either that, or it was nobbled following its test………….. Marcus Tidmarsh has pointed out that the introduction of such errors into the production line would have been very difficult for an individual machinist to accomplish due to random checking of their ongoing work following completion. However, at a time when there was no video surveillance of the shop floor, it would have been easy for somebody in a higher position to arrange for a compete process to be left out. Inspectors check work which has just been done, but not a process believed to have taken place earlier and hence checked previously. Even a single disgruntled employee in a position where they were able to bypass a carefully chosen operation would be a plausible culprit. The person in the best position to achieve this would have been the works manager, but there might well have been several others in a position to act to similar effect without raising questions from their workshop colleagues.