|

|

Original Mills 1.3 Comparison

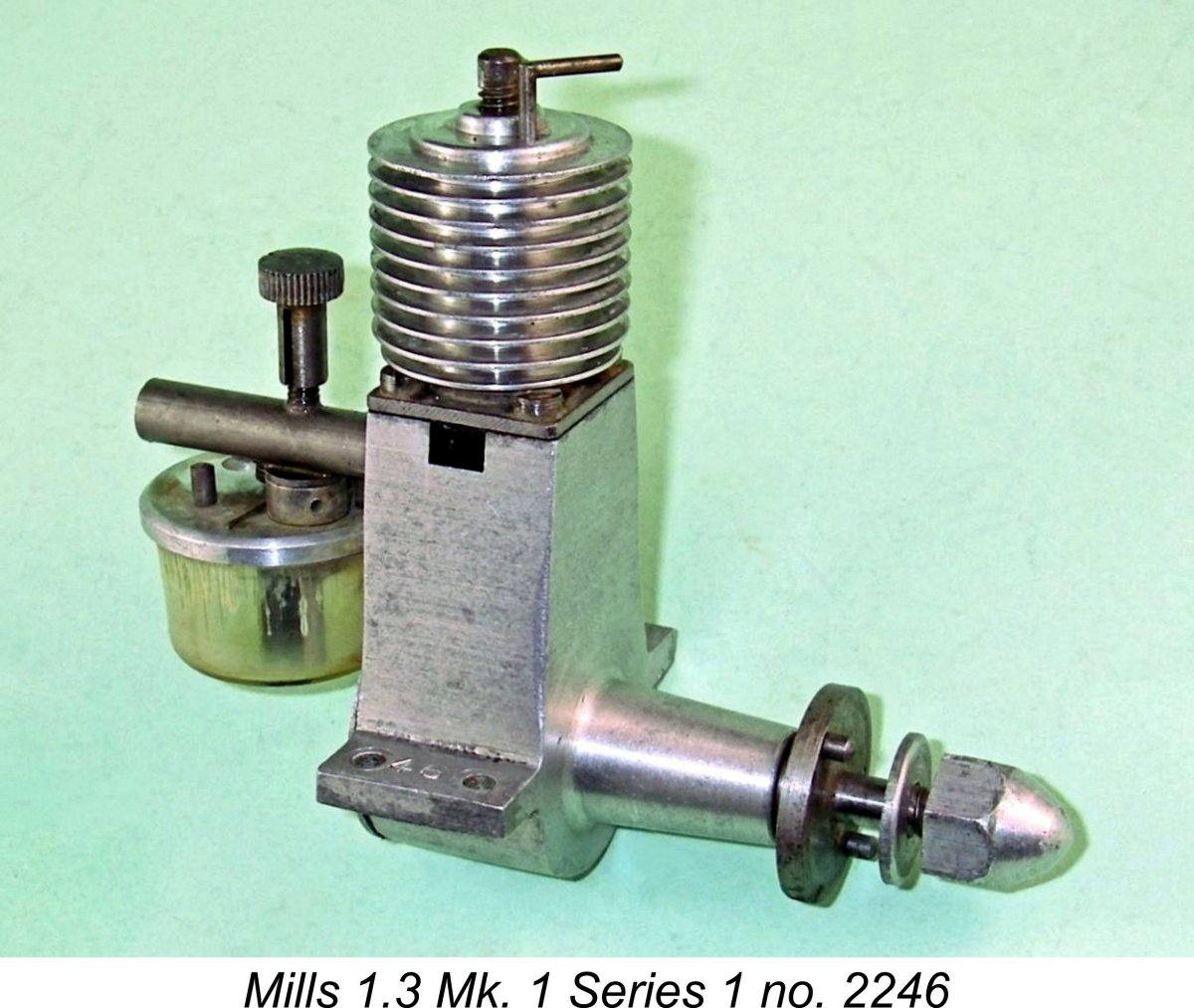

For a brief period of time I found myself with simultaneous access to nice examples of all four models, thanks entirely to the kindness of reader Derek Butler of Queensland, Australia, who generously made a loan of his pristine Mk. 1 Series 1 model. Being placed in this happy situation, I thought that it might be interesting to run a side-by-side comparative test of all four to see how they compared in performance terms. No sooner thought of than done! I never pass up an excuse to run one (or more!) of these finely-built and user-friendly engines which have given so much pleasure to so many modellers (including myself) over the past seventy years. I think that the best way to present the results of this multiple test is to report on each model individually and then to discuss the results in comparative terms in a subsequent section of the article. That decision having been made, here goes……………. Mills Mk. 1 Series 1 no. 2246

Before getting started on this portion of the test, I think that it's appropriate to interject a hitherto largely ignored and perhaps controversial matter in relation to the design origins of the Mills 1.3 Mk. I. This is the very strong probability that Arnold Hardinge's design was based to a certain extent upon that of the earlier Allouchéry 1.25 cc sideport diesel from France. The Allouchéry 1.25 cc sideport diesel appeared in late 1943 or early 1944. It was a fine little engine which quickly acquired a very high reputation. There's no doubt at all that the original Mills 1.3 bore what appears to be a far more than coincidental resemblance to the earlier Allouchéry model, even down to the displacement. The latter point appears not to have escaped Prosper Allouchéry's notice! In a late 1946 article by one "R.F." which appeared in the French modelling media, Allouchéry was directly quoted as follows:

The late 1946 timing of Allouchéry's statement makes it appear almost certain that he was referring to the July 1946 appearance of the Mills 1.3 diesel in England. There's no doubt at all that the Mills conveys a distinct impression of having been influenced to some extent by the design of the Allouchéry 1.25 cc model. It's also an indisputable fact that the Allouchéry 1.25 cc model had been seen in England, since it won a major contest at Eaton Bray in the same year of 1946. The range also received quite comprehensive coverage in D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson's late 1946 book "Model Diesels". The design was thus available in England to serve as a source of design inspiration, and perhaps it did exert some influence.........but really, so what?!? All model engines reflect the designs of their predecessors to some degree - look at all the Dyno clones from a number of countries. The Allouchéry's design owed as much to that of the Dyno as the Mills did to the Allouchéry. In my personal view, a far more appropriate reaction on Allouchéry's part would have been to take any perception of imitation as a compliment - imitation is surely the most sincere form of flattery! Stepping back now from this controversy, let's get down to the testing! The Mills 1.3 Mk. I was never the subject of a published test in the contemporary modelling media. This is not due by any means to neglect but rather to the fact that the production of this model had ceased some eighteen months prior to the May 1948 commencement of the long-running series of model engine tests which appeared over the years in “Aeromodeller” magazine. The parallel series of tests which graced the pages of the rival magazine “Model Aircraft” did not make its debut until June 1949. This being the case, I was starting from scratch as far as performance expectations were concerned. Throughout the series of tests reported here, I used a fuel containing 30% castor oil (to protect the engines) plus a small proportion (c. 1%) of ignition improver. I have found that the later Mills engines do perform better with a little improver, particularly as speeds climb past the 9,000 rpm mark. At lower speeds, the improver makes little appreciable difference. The engine had not been run for some time, and a small prime was necessary to achieve an initial start. Thereafter, in common with all other Mills diesels of my acquaintance, a prime was never necessary at any time. A couple of choked flicks followed by a few starting flicks invariably did the trick. These excellent starting qualities undoubtedly played a major role in securing the early widespread acceptance of the model diesel in Britain and elsewhere given the fact that the Mills 1.3 was the most widely-available model during the early diesel pioneering period beginning in Britain in mid 1946. The engine thus served in effect as an By contrast, British and Commonwealth modellers were indeed fortunate that the Mills led the way and created such a positive first impression of diesels in general. In a very real sense, the Mills set the stage for the later success of other British diesel manufacturers. Once running, the engine proved very easy to set. The contra-piston was perfectly fitted and control response was extremely positive without being excessively critical. That said, I found that the needle setting for the absolute maximum speed on any given prop was fairly critical. The absolute maximum speed was found just at the point at which a very slight “crackle” first intruded into the exhaust note. However, the engine would run consistently within a hundred RPM of the maximum over a fairly wide range of slightly richer settings. The needle is only critical when it comes to extracting the absolute maximum – for practical purposes, this is not an issue at all. For the sake of consistency, I would happily run very slightly on the rich side of the optimum setting and accept the loss of 100 or so RPM! A characteristic which I did not expect was the engine’s tendency to run a little “dirty”. When leaned out to the max, the oil residue took on a somewhat dark colour, implying less-than-optimal combustion. This may clearly be seen in the accompanying photograph. There was no hint of any polychromatic appearance which might indicate rapid bearing wear, nor did any such wear manifest itself in a physical sense – it was simply a characteristic of the engine’s combustion residues when fully leaned out. I ran an extensive suite of airscrews for which power absorption coefficients were reliably known. The results were as follows, along with the derived power curve.

The APC 8x4 WB (wide blade) is an APC 9x4 which has been cut down and calibrated to fill an otherwise glaring gap in my calibrated test airscrew set. As can be seen, the engine peaked at around 6,400 RPM, at which speed it was developing some 0.048 BHP. Not all that impressive for a 1.3 cc engine, you might say. Well, it must be recalled that the Mills was the first widely-available small-bore diesel to appear on the British market, hence having no direct competition at the time of its introduction. Viewed in isolation from a mid 1946 standpoint, this is a more than acceptable performance for a small sports diesel of the day, especially given the fact that it enabled its owners to dispense with the heavy, complex and potentially unreliable spark ignition support system of its predecessors. Plenty of power there to fly the small sport free-flight models in which the engine was doubtless most commonly employed. Taken together with its excellent handling and high-quality construction, there’s no wonder that the engine took the British market by storm! Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 2 no. 9757

The test of this variant was more or less a carbon copy of that undertaken for the Mk. 1 Series 1 model. Starting and handling qualities were identical in all respects. The one difference that became apparent was the fact that this example ran very cleanly indeed, displaying none of the dark colouration of the exhaust residues that was a characteristic of the model tested previously. I have no explanation for this. It must be pointed out in fairness that engine number 9757 had received a fair amount of use in the past. Apart from having clearly spent a fair bit of time in the air, it had been bench-tested previously by myself, proving itself to be a very good runner on that occasion. By contrast, engine number 2246 appears to have seen very little use at any time. The main interest in conducting a test of this particular engine stemmed from a desire to see if there was any evidence to suggest that Mills Bros. had incorporated any performance-enhancing changes into the Mk. 1 Series 2 variant. The speeds obtained using the same fuel and props as for the earlier model tell the story:

As can be seen, the performance of this engine was almost exactly the same as that extracted from Mk. 1 Series 1 engine number 2246. The observed peak output was once again 0.048 BHP @ 6,400 RPM. The only observable difference was that the power dropped off somewhat less sharply beyond the peak. This could well be due to nothing more than the significant difference in running time between the two examples. The main point is that there was no indication whatever of any performance-enhancing changes having been made between the two variants. It’s also worth recording the fact that despite the passage of some years as well as the use of a completely different set of calibrated test props, the performance measured for engine number 9757 on this occasion was identical to that determined during my earlier test of the same engine. On that earlier occasion, I recorded an identical output of 0.048 BHP @ 6,400 RPM, exactly as in the present test. Clearly my calibration coefficients for the two prop sets were mutually consistent, despite the fact that they were independently derived. Mills 1.3 Marine Model no. 30282

In his very useful but often misleading “Pictorial A-Z” book of 1987, Mike Clanford included an image of a Mills 1.3 having a similar appearance to the forthcoming Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 model (see below) but featuring an aluminium case as opposed to the chromate-blackened magnesium cases of the Mk. 2 models. This aluminium case also featured tapped holes below the exhaust apertures. Clanford claimed that this was one of a “few” such examples made in June 1948 and that the holes were created to facilitate the mounting of a pair of exhaust stubs (missing in Clanford’s photo). In his 1991 survey of the Mills engines undertaken for the late Tim Dannels’ “Engine Collector’s Journal” (ECJ), the late Roger Schroeder characterised this aluminium-case variant as the “Mills 1.3 Anniversary Model”, apparently solely on the basis of anecdotal information from contacts in England. This was the first appearance of that identification, which seems to have stuck ever since. Elsewhere on this website, Maris Dislers and I have presented what we believe to be a compelling case for this very rare model being correctly identified as the Mills 1.3 Marine model which is definitely known to have been introduced in June 1948. Mills Brothers themselves never referred to any “Anniversary Model”, nor did any references to such a model ever appear either in the contemporary modelling media or in the advertising record. Maris and I will be happy to be proved wrong if any reader can produce compelling evidence to support the legitimacy of the “Anniversary Model” designation.

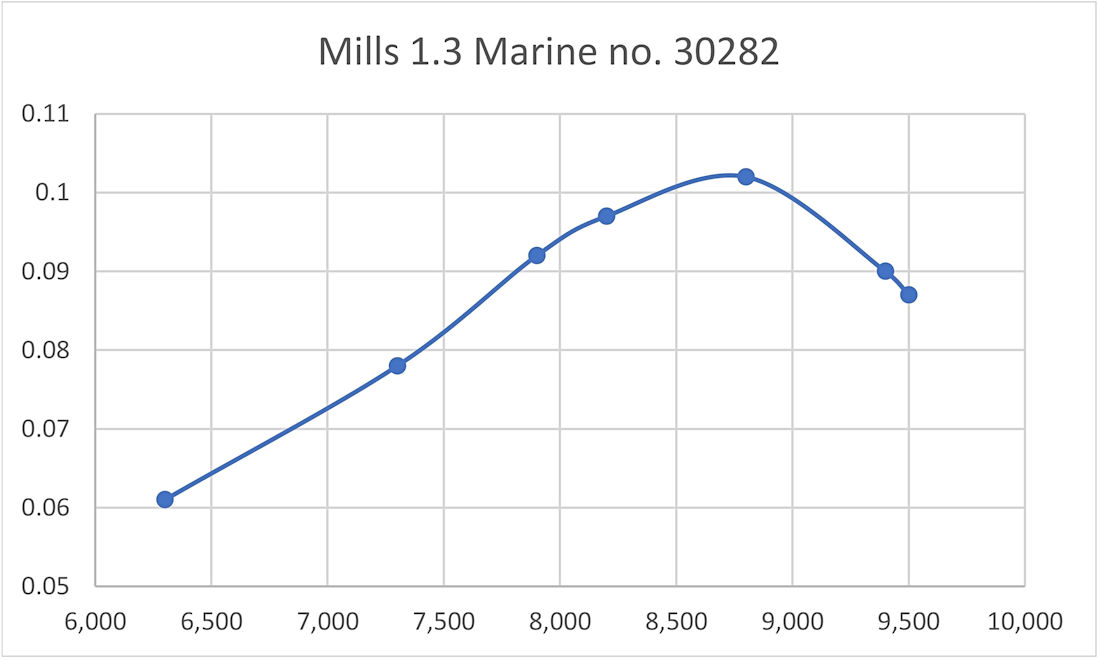

Serial number evidence suggests that no more than 300 examples were produced in total, making this the rarest Mills production model of them all. Understandably in view of its relative obscurity, this variant of the Mills 1.3 was never the subject of a published test. I ran a series of tests on engine number 30282 of this rare series – a very late example which appears to have the short-skirt piston fitted. The props were chosen from those used in my earlier tests of the other Mills 1.3 models. The engine was every bit as user-friendly as all of the other models tested earlier. It started very promptly, with only a couple of finger-chokes being required as a preliminary. Running qualities were outstanding, as we have come to expect from Mills engines. The following data were recorded.

As can be seen, the later rendition of the Mills Marine model performed at a significantly higher level than the Mills 1.3 Mk. I Series 2 model upon which it was loosely based. It developed around 0.102 BHP @ 8,800 RPM. The superior performance is evidently a consequence of the fitting of the short-skirt piston which gave a significantly longer induction period. It would be most interesting to learn at what point in the Marine model production sequence the use of the short-skirt piston was adopted Mills Mk. 2 Series 1 no. 19106

The timing of both of these reports is of some interest for almost diametrically opposite reasons! Given the fact that the Mk. 2 Series 1 variant of the Mills 1.3 only reached the market in June 1948, it’s clear that Lawrence Sparey must have been provided with one of the very first examples off the production line, possibly even during the pre-release inventory build-up stage. At the time in question, the “Aeromodeller” test series was the only game in town (the initial appearance of the “Model Aircraft” series was then still a year in the future) and was thus seen by manufacturers as a highly desirable vehicle for the promotion of new designs. There seems to be little doubt that promotional considerations led to Mills Bros. facilitating Sparey’s early acquisition of his test example. By contrast, Peter Chinn’s published test of the same model appeared some eight months after the Mk. 2 Series 1 variant had been replaced by the Mk. 2 Series 2 version of the engine (see below). Chinn stated that his test example had been in use in his hands for some 15 months prior to the test being undertaken. He was well aware that the design had been revised – indeed, he included a summary test report on the revised model in his article. However, his major findings applied to the earlier version of the Mk. 2 engine. For the purposes of the present report, it will suffice to say that Sparey reported an output for his presumably new example of 0.078 BHP @ 7,250 RPM, with a relatively flat peak. Chinn found a maximum output for his well-used example of 0.079 BHP at a slightly higher peaking speed of 7,900 RPM. Relatively speaking, these are remarkably consistent findings, especially given the widely differing previous running times for the two examples. I tested my well-used example of the Mk. 2 Series 2 engine (no. 19106) using the same props and fuel as applied to the two Mk. 1 engines. Starting and handling characteristics were once again exactly as those experienced with the other two models. However, the same can’t be said of the results obtained, which were way above expectations! My engine is admittedly a highly “experienced” example, clearly having done a lot of running in the past, but even so I was not prepared for the results obtained. Check out the following figures:

A quick inspection soon supplied the answer. Removal of the intake quickly revealed that some previous owner had very neatly filed a step in the rear of the lower piston skirt to increase the induction period to more or less the same as that of the later version. It’s entirely possible that the transfer port had also been re-worked, although I didn’t disturb the well-sealed and firmly “glued” cylinder base joint to check this. Regardless, this engine had clearly been reworked very competently and successfully to enable it to perform on par with the later Mk. 2 Series 2 variant. As such, this can’t be viewed as a representative test of the Mk. 2 Series 2 model. Even so, a comparison of my results for the two Mk. 1 engines with the very consistent published figures from both Sparey and Chinn clearly demonstrate that the Mk. 2 Series 1 variant of the Mills 1.3 was a significant step forward from the Mk. 1 version in performance terms. The main puzzle is why it took Mills Bros. some 18 months to realize the full potential of the engine! The unknown owner of engine number 19106 clearly did so........................ Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 2 no. 36627

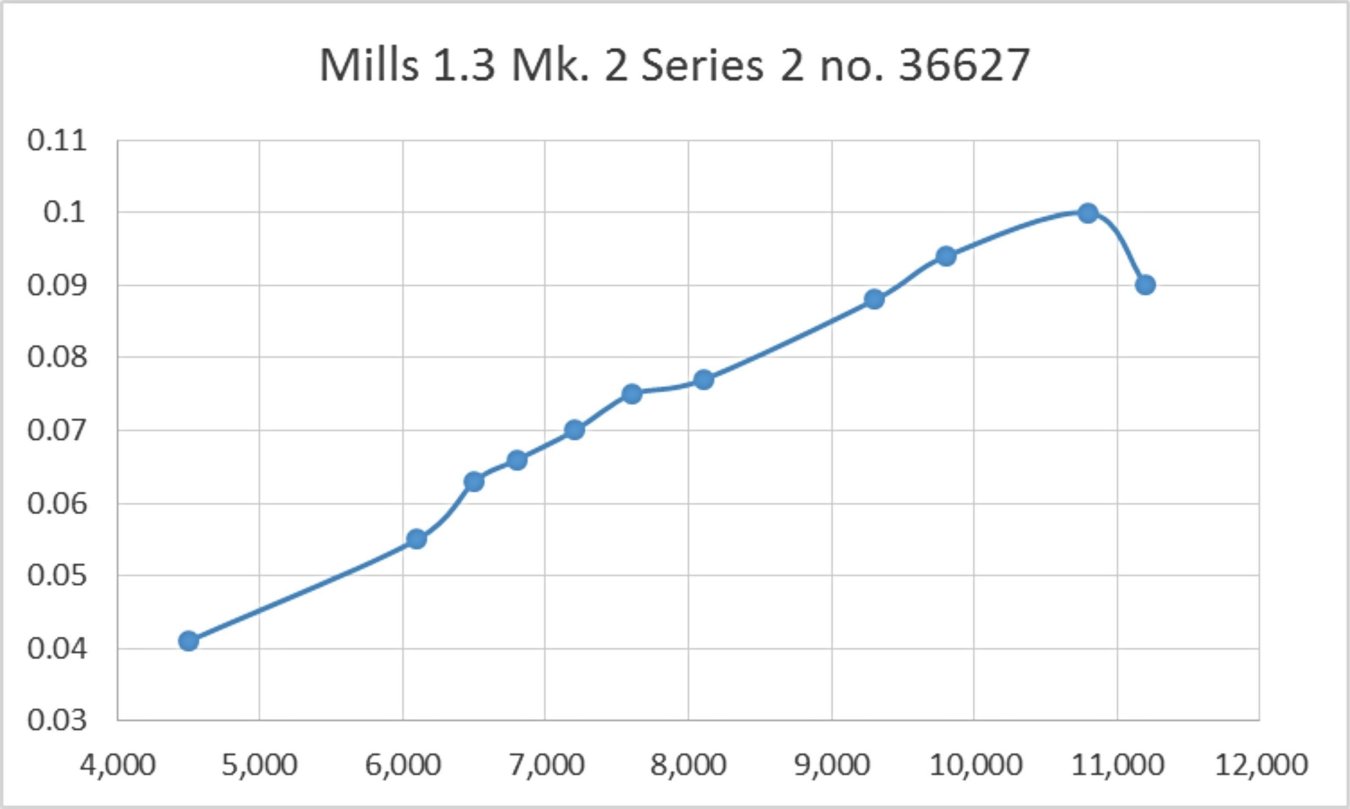

It’s worth noting that Chinn’s December 1960 horsepower figure almost exactly matched that which I obtained for my reworked example of the earlier Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 apart from the fact that my engine peaked at a significantly lower speed. A ringing endorsement of the effectiveness of the modifications applied by the unknown previous owner of my engine! His efforts clearly demonstrate the ease with which the earlier variant could be brought up to parity with its successor in performance terms – anyone who truly understood what he was doing and could used a Swiss file could have done the same. Why Mills Bros. took so long to do so is one of those insoluble mysteries …………… The published figures also highlight another well-recognized trait of the Mills engines, namely a certain “variability” in performance levels between different examples of the same model. This is an issue upon which comment has frequently been made in the past - owners of different examples of ostensibly the same model have often reported widely differing performance figures. The reasons for this are unclear, After my experiences with engine number 19106, I began my evaluation of engine number 36627 by inspecting its induction port! All appeared to be well – there was no step in the piston skirt. Indeed, this particular example of the Mills 1.3 seems to have seen very little use in the past. I had tested it myself some years ago but had never flown it. Once again, this engine exhibited all of the very positive starting and handling characteristics of the other examples tested. The excellent control response made these tests a genuine pleasure, while the very effective cut-out greatly facilitated testing by keeping the required running time on each prop down to a minimum while retaining the running needle setting. I could easily test two props on one tank of fuel. The results obtained on this occasion once again closely matched my earlier figures obtained using a different set of calibrated test props. The actual numbers obtained this time are shown below:

The above figures imply an output of around 0.102 BHP @ 10,600 RPM – more or less right in the middle of the range reported in the contemporary modelling media. As can be seen, there’s a sizeable gap in my figures between 9,800 and 10,800 RPM, in which range the peak evidently lies. The actual peak output figure is thus somewhat imprecise. However, for all practical purposes this test confirmed the validity of previously-published figures. Conclusion I undertook these tests primarily for three main reasons:

Taking the first objective first, these tests showed that the Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 1 model which appeared in July 1946 developed around 0.048 BHP @ 6,400 RPM. Unimpressive as these figures may appear, they actually represent a more than acceptable performance in a mid-1946 context, especially for a model diesel of this displacement. Moreover, the engine’s excellent starting, handling and running characteristics made it a perfect ambassador for the model diesel concept. In this respect, the Mills probably did much to bring about the immediate and widespread acceptance of the model diesel among British modellers. With respect to the second objective, these tests produced no evidence whatsoever to suggest that any performance-enhancing modifications were applied at any time to the Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 model. The measured Finally, the fact that the tested example of the Mills 1.3 Mk. 2 Series 1 turned out to have been modified by a previous owner into more or less Series 2 configuration prevented me from confirming published performance figures for the Series 1 variant of that model. However, the figures that were obtained both from the modified engine and from unmodified Mk. 2 Series 2 engine number 36627 pretty much confirmed the range of published figures for the Mk. 2 Series 2. It’s abundantly clear that the Mk. 2 variants of the Mills 1.3 both represented a significant step forward in performance terms from the Mk. 1 models. Perhaps it’s fitting that I acknowledge the outstanding co-operation extended to me by Derek Butler by allowing him to have the last word. Derek stated his opinion that “….all mythology and hoop-la aside, the Mills 1.3 Mk.1 Series 1 succeeded because it was a good, honest engine. It started easily, ran smoothly and was well made of good materials. The engine is one of my favourites, though not for any aesthetic reason. It is just a good honest product”. A very fair assessment which applies to all of the engines produced by Mills Brothers! ______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2016 |

||

| |

As readers of this website's

As readers of this website's  This is the engine which was so kindly lent to me by Derek Butler. It is unquestionably an all-original example of the type – Derek is only its second owner. It appears to have had very little use.

This is the engine which was so kindly lent to me by Derek Butler. It is unquestionably an all-original example of the type – Derek is only its second owner. It appears to have had very little use.

ambassador for the new type of engine. A less user-friendly pioneering model from another maker might have greatly retarded the progress of the diesel - look at the influence of the infamous

ambassador for the new type of engine. A less user-friendly pioneering model from another maker might have greatly retarded the progress of the diesel - look at the influence of the infamous

Once again, we are dealing here with a model which was never the subject of a published test in the British modelling media. Production ended in May 1948, just as the “Aeromodeller” series of model engine tests conducted by Lawrence H. Sparey was getting underway with a review of the

Once again, we are dealing here with a model which was never the subject of a published test in the British modelling media. Production ended in May 1948, just as the “Aeromodeller” series of model engine tests conducted by Lawrence H. Sparey was getting underway with a review of the

This model is an anomaly in the context of the Mills 1.3 series, because it stands apart from the main sequence. Since it appears to be a derivative of the Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 2 model just described, this seems to be an appropriate point at which to discuss it.

This model is an anomaly in the context of the Mills 1.3 series, because it stands apart from the main sequence. Since it appears to be a derivative of the Mills 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 2 model just described, this seems to be an appropriate point at which to discuss it.  In terms of its construction, the Marine model was built up around a re-machined Mk. 1 crankcase, hence having a case made from aluminium alloy. It retained the Mk. 1 piston/cylinder/conrod assembly but featured the stronger Mk. 2 crankshaft and the Mk. 2 carburettor. It was in effect a beefed-up and slightly re-styled version of the 1.3 Mk. 1 variant. It seems highly likely that it performed little if any better than the Mk. 1 Series 2 model given the fact that it used the same crankcase, cylinder, piston and rod. It was presumably for this reason that the later examples evidently switched to the Mk. 2 piston with its shorter skirt, creating a significantly longer induction period which would be expected to enhance performance significantly.

In terms of its construction, the Marine model was built up around a re-machined Mk. 1 crankcase, hence having a case made from aluminium alloy. It retained the Mk. 1 piston/cylinder/conrod assembly but featured the stronger Mk. 2 crankshaft and the Mk. 2 carburettor. It was in effect a beefed-up and slightly re-styled version of the 1.3 Mk. 1 variant. It seems highly likely that it performed little if any better than the Mk. 1 Series 2 model given the fact that it used the same crankcase, cylinder, piston and rod. It was presumably for this reason that the later examples evidently switched to the Mk. 2 piston with its shorter skirt, creating a significantly longer induction period which would be expected to enhance performance significantly.

We now come to the first Mills 1.3 model for which contemporary published performance figures are available. This variant was tested twice back in the day – once by

We now come to the first Mills 1.3 model for which contemporary published performance figures are available. This variant was tested twice back in the day – once by

Despite the fact that I clearly missed the setting on the APC 9x6, these figures (a number of which I re-checked to confirm that I hadn’t mis-read the tach!) imply an output of some 0.115 BHP @ 9,100 RPM. This is way up in the reported range for the later Mk. 2 Series 2 model! In fact, it suggests a greater level of torque development than the later variant given the lower peaking speed. How could this be?!?

Despite the fact that I clearly missed the setting on the APC 9x6, these figures (a number of which I re-checked to confirm that I hadn’t mis-read the tach!) imply an output of some 0.115 BHP @ 9,100 RPM. This is way up in the reported range for the later Mk. 2 Series 2 model! In fact, it suggests a greater level of torque development than the later variant given the lower peaking speed. How could this be?!? This final variant of the Mills 1.3 was also the subject of a number of contemporary published test reports. As previously mentioned, Peter Chinn included a summary report on this model as an addendum to his July 1950 “Model Aircraft” test of its predecessor, reporting an output of 0.108 BHP @ 10,600 RPM. A further supplementary test of this model appeared in the May 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller”, where a somewhat lower output of 0.093 BHP @ 10,000 RPM was recorded. Finally, Peter Chinn published a retrospective re-test of both the Mills .75 and 1.3 models in the

This final variant of the Mills 1.3 was also the subject of a number of contemporary published test reports. As previously mentioned, Peter Chinn included a summary report on this model as an addendum to his July 1950 “Model Aircraft” test of its predecessor, reporting an output of 0.108 BHP @ 10,600 RPM. A further supplementary test of this model appeared in the May 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller”, where a somewhat lower output of 0.093 BHP @ 10,000 RPM was recorded. Finally, Peter Chinn published a retrospective re-test of both the Mills .75 and 1.3 models in the  but there can be no doubt that this is a Mills characteristic. They all start and run very nicely, but the real trick is to pick a good ‘un!!

but there can be no doubt that this is a Mills characteristic. They all start and run very nicely, but the real trick is to pick a good ‘un!!

performance of the tested example of the 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 2 was essentially identical to that for the Series 1 variant. The slightly less abrupt fall-off beyond the peak was most likely down to the fact that the Series 2 example had a good deal more running time in advance of the tests.

performance of the tested example of the 1.3 Mk. 1 Series 2 was essentially identical to that for the Series 1 variant. The slightly less abrupt fall-off beyond the peak was most likely down to the fact that the Series 2 example had a good deal more running time in advance of the tests.