|

The Genesis of Allen-Mercury and MERCO

Although today’s enthusiasts often appear to think of them as synonymous, A-M and MERCO actually originated as two completely separate companies with entirely different owners, goals and timeframes. One of my main purposes in writing this article is to clarify the manner in which the two companies had their completely separate origins but eventually came together. The one common link throughout was the fact that all of the key individuals involved were members of the West Essex club, that hot-bed of aeromodelling activity during the first few decades of the post WW2 period in Britain. An earlier article on the A-M engines may still be found on Ron Chernich's outstanding (although now frozen) "Model Engine News" (MEN) website. However, a great deal more information is now available, hence the need for the following greatly expanded text covering that range. My friend and colleague Ian Russell made a very worthy attempt to record the Merco side of this story in an article which appeared in the May 2002 issue of the now-defunct “Model Engine World” (MEW) magazine. I freely acknowledge having drawn extensively upon Ian’s work during the preparation of that section of the present article. Now on with our tale ……………. The Genesis of Allen-Mercury

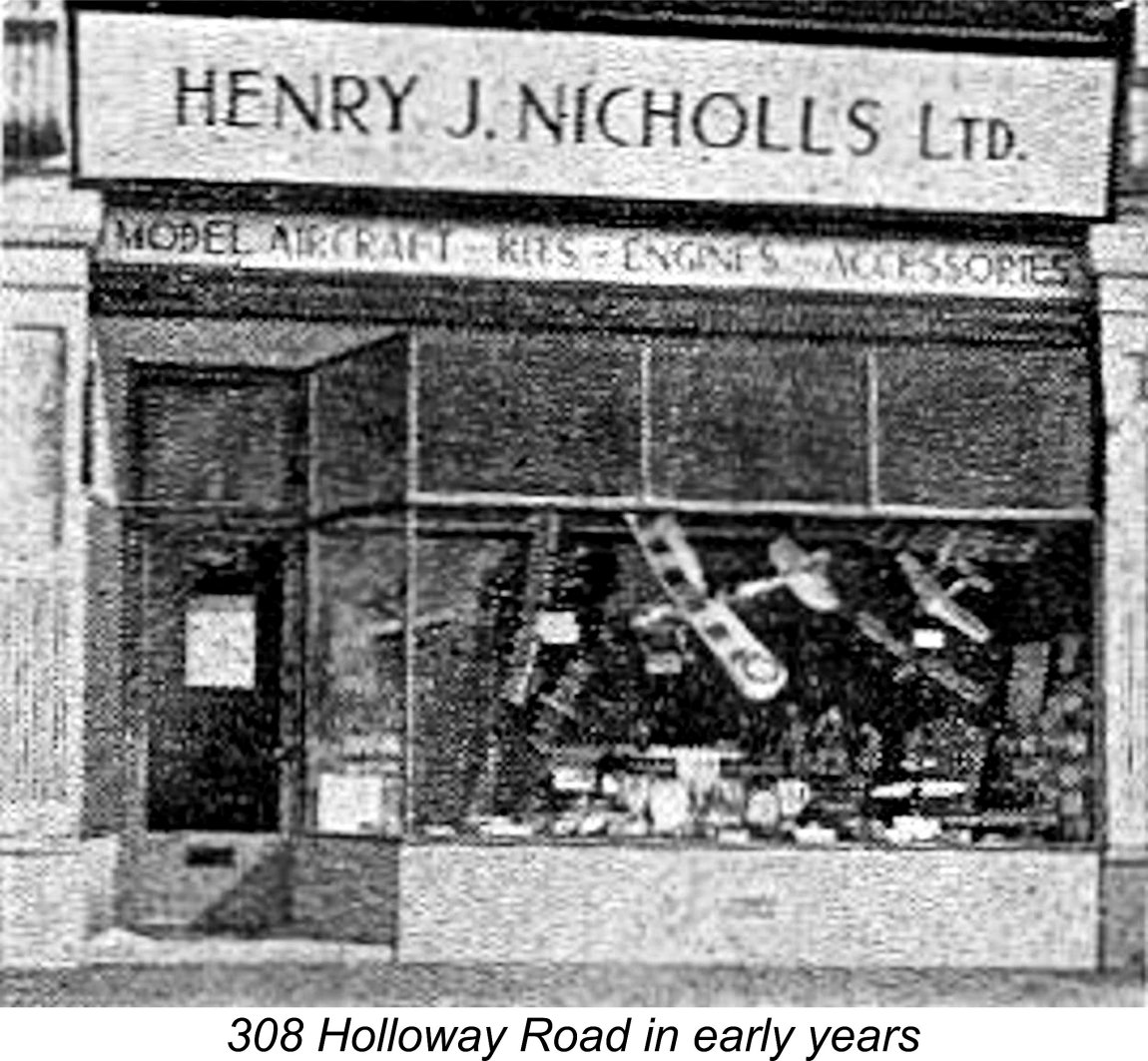

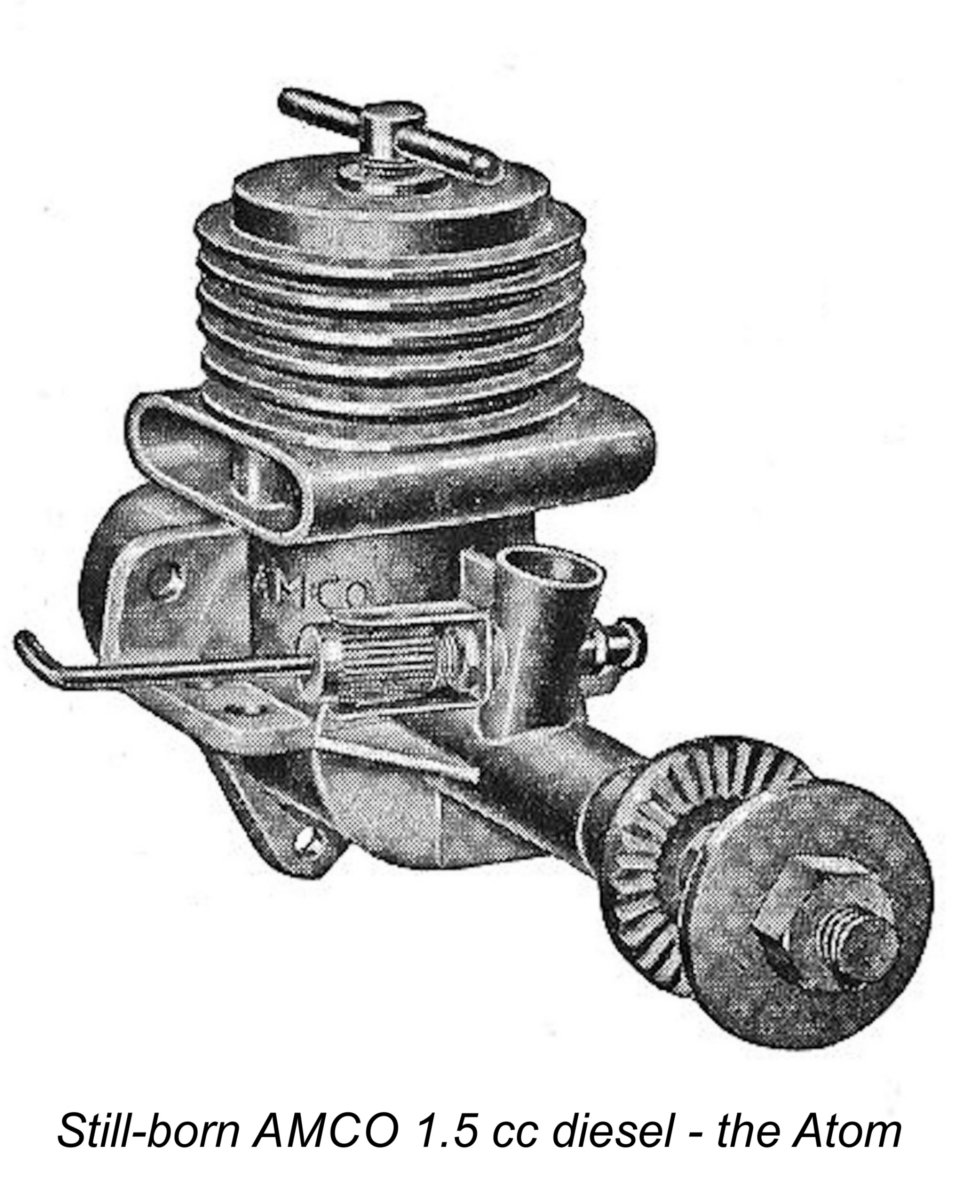

Allen, Nicholls and Steward possessed a very compatible mix of talents which would unquestionably stand any model engine manufacturing venture with which they became involved in very good stead. Both Allen and Steward had considerable engineering/production know-how, while Nicholls possessed both the required marketing capability and the necessary contacts to secure adequate start-up financing. Nicholls and Allen had a long association both as fellow modellers and as business associates. In 1946 Nicholls At some point in 1949, economic considerations forced Nicholls to suspend his engine repair service. At that point, Allen was “loaned” by Nicholls to Allbon Engineering of Sunbury-on-Thames (then in Middlesex) to assist Allan Allbon in the production of the Allbon 2.8 and the development of the Arrow and Javelin 1.5 cc models. As matters turned out, the time pressures arising from the work with Allbon eventually led to Allen becoming a full-time Allbon employee. He was closely involved with the development of the famous Allbon Dart .55 cc diesel which appeared in late 1950. Future FROG engine designer George Fletcher was also working for Allbon at this time. However, when tax problems forced Allbon to downsize and relocate his operation, as related elsewhere, Allen was out of a job. He spent some time working in the Among other things, Allen appears to have been primarily responsible for a number of very worthwhile improvements which appeared on the ultimate green-head version of the AMCO 3.5 PB. This was certainly the best-ever version of that model. The Alperton operation was well staffed with experienced model engine designers and constructors. Apart from Allen himself, the prominent model engineer Arthur Weaver also worked there. Weaver was the designer and original builder of the well-known Weaver 1 cc home-built engine which is fully documented elsewhere on this website. In addition, Allen’s old friend Len Steward also found a job with the new company. An experienced and successful control-line competitor, Steward was a very competent machinist who had cut his Thereafter, Steward produced a series of crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) engines which included the 0.2 cc Hawk Mk. II, the 1 cc Eagle Mk. II, the 2 cc Kestrel and Falcon diesels, the 2 cc Tornado glow-plug model and the 5 cc Vulture in both glow-plug and diesel configuration. While these were very competently designed and well constructed for the most part as well as being quite keenly priced, some widely-publicised early teething troubles with the Vulture more or less destroyed the company’s reputation, ultimately forcing a final cessation of production in 1950. Steward was thus available to help his friend Dennis Allen at the Alperton factory. He was particularly noted for his skill in honing model engine cylinders. At this time, the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. was effectively controlled by Jack E. Ballard, former Managing Director of the E.D. company. Ballard seems to One golden opportunity that Ballard chose to ignore was a new design which Dennis Allen concocted in his spare time with help from Len Steward. This was a lightweight radially-ported FRV plain bearing diesel having a nominal displacement of 2.5 cc which Allen firmly believed to have considerable commercial potential. According to an article which appeared in the June 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Allen offered this design to his new employers, but Jack Ballard was evidently not interested. There have been unsubstantiated reports that he also sounded out E.D., with the same result. These rejections had far-reaching consequences for all concerned, since Allen’s unswerving belief in the new design led him to seek other avenues for getting it into production. He had maintained his close As it was, the new model was manufactured by Allen’s own newly-established company, D. J. Allen Engineering of Edmonton, North London. It was marketed by Mercury Models, hence the name. After leaving Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co., Allen initially worked on his own in a relatively small workshop, producing the engines at a rate of around 12 per week. However, demand soon picked up to the point at which he had to take on two assistants to help. This raised production to around 50 units weekly, all of which found ready buyers. The potential for significantly expanded sales was obvious. It was at this point that Allen invited his old friend Len Steward to leave Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. to come on board. Steward brought his own wealth of skill and experience over to the new venture, soon raising production figures to over 100 units per week. In one exceptional week the team managed to The successive departures of Allen and Steward deprived Jack Ballard of his two most experienced engine designers/constructors, a blow from which Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. was unable to recover. AMCO production was terminated in March 1955, after which Ballard went on to promote the attractive but unsuccessful J.B. range. That rather sad story has been recounted in detail elsewhere. Others who became involved with Allen’s new company as time went by included Les Parker, who was cited as a “partner proprietor” in a September 1960 “Aeromodeller” article about a move into larger premises which took place at around that time. A certain Ron Ward, known as the designer of the PAA-load model “Ward’s Wagon”, was also employed by the company, as was a reader of this website, Michael “Mick” Clarke. Other employees included Brian Howard and George Thomas. The A-M Diesel Models The classic Allen-Mercury (A-M) diesels are far too well known to require a particularly detailed description here. They were all very simple lightweight radially-ported plain bearing FRV units of entirely conventional design. All of them were the subject of published tests in the British modelling media as well as frequent mentions in trade-related articles, making them among the best-documented British model engines of them all. Those published tests may all be accessed on line on the extremely useful Sceptre Flight model engine test pages established and maintained by Brian Hampton of Adelaide, Australia - I will not reproduce them here. Full details of all models may be found in those test reports, to which active links are provided throughout the following text. All that is really necessary for present purposes is to record the chronology as well as report on any unusual design features and significant design changes, of which there were a few along the way. One matter which needs to be dealt with right away is the issue of the engines’ model designations. Readers from the USA and certain other countries in which cubic inches, as opposed to cubic centimetres, are routinely used to delineate engine displacements need to adjust to the fact that the Allen-Mercury engines were designated by their nominal displacements in cubic centimetres (cc) rather than cubic inches (cuin.). Thus the A-M 25 is nominally a 2.5 cc unit, the A-M 35 is nominally a 3.5 cc engine, and so forth.

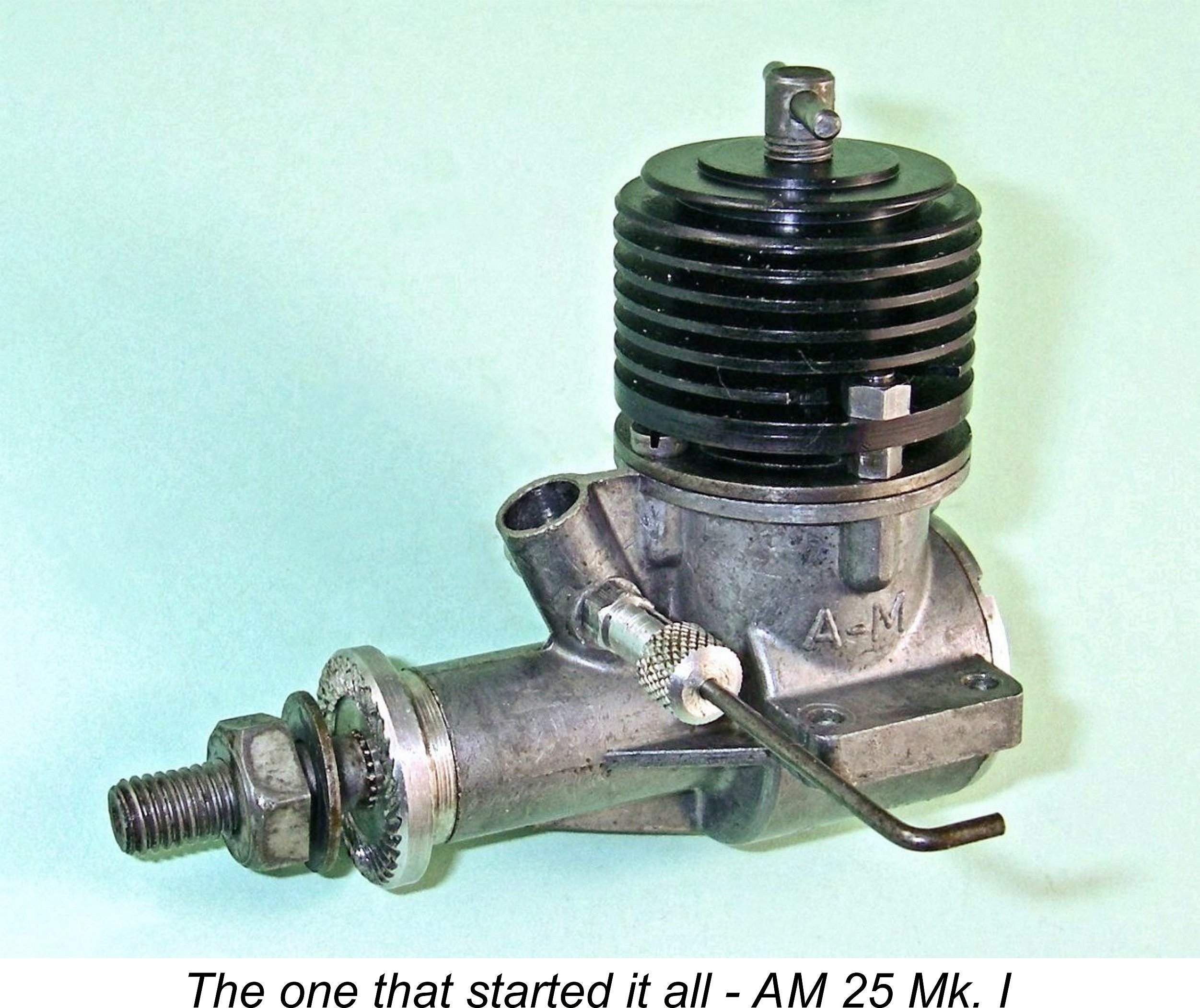

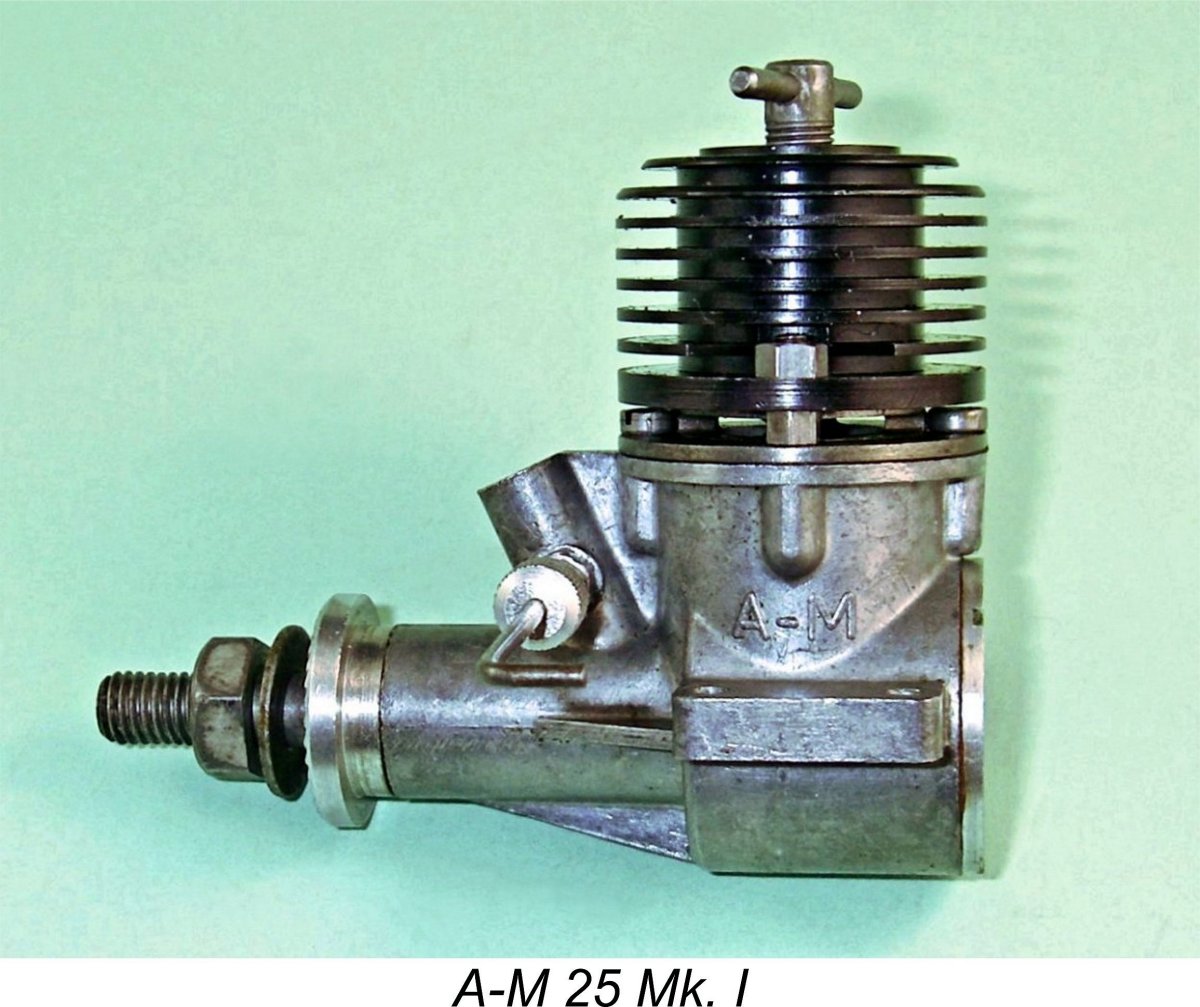

Bore and stroke of this unit were 0.570 in. (14.48 mm) and 0.562 in. (14.27 mm) respectively for an actual displacement of 2.35 cc (0.143 cuin.), somewhat below the nominal 2.5 cc figure suggested by the engine’s name. The motor weighed a creditably light 4 ounces (114 gm). Porting was completely conventional, with sawn slots being formed in the cylinder walls to serve as transfer and exhaust ports respectively. The original A-M 25 differed from subsequent models primarily in the means of cylinder attachment. The Meehanite cast iron cylinder was provided with a large-diameter location flange immediately below the sawn exhaust ports. The upper crankcase deck was provided with four 6 BA tapped holes, with four corresponding holes being drilled in the cylinder location flange. The two fasteners at the sides were actually studs having hexagonal nut sections in the middle which bore against the cylinder flange. They served as bolts to secure the cylinder, leaving a protruding threaded section above the hexagonal portion. The other two fore and aft locations utilized conventional slot-head machine screws. The attached images should make this clear. Once the cylinder itself was firmly tightened down using these four fasteners, the black-anodized slip-on cooling jacket was installed onto the cylinder. The two protruding studs at the sides aligned with two holes drilled through the jacket’s lowest cooling fin. A pair of nuts was installed above that fin to allow for tightening down of the cooling jacket. This was basically identical to the system used on the well-known home-built Sugden Special design. Hopefully the accompanying illustration below will make this arrangement clear.

The other noteworthy design feature was the fact that both the cylinders and pistons of these early models were machined from Meehanite cast iron. While at first glance this is a reasonable choice of materials, experience has shown that a cast iron on cast iron system tends to exhibit excessive wear rates. This led to some unkind jokes to the effect that the A-M name signified that the engines would run in the morning (am) but would be worn out by the afternoon (pm)! My own experience shows that things are not quite that bad if the engines are properly run in, allowing sufficient time to subject the components to the required series of full-range heat cycles while also allowing the cast iron surfaces to work-harden. Sadly, all too few owners seem to have paid sufficient attention to this crucial requirement. The engines also have to be kept scrupulously clean and supplied with enough oil. Even so, there’s little doubt that the earlier A-M engines with their Meehanite piston/cylinder combinations don’t wear as well as many other contemporary models. In other respects, the design of the A-M 25 was quite unremarkable - what you saw was what you got, with no surprises. Despite its relatively low weight for its displacement, the engine’s construction was quite sturdy, with a generous crankshaft main journal diameter of 0.375 in. (9.52 mm). Naturally enough, the introduction of this new model prompted the appearance of test reports in the major British modelling magazines. The “Aeromodeller” test by Ron Warring was published in that magazine’s October 1954 issue, quite soon after the engine’s release. Warring was very complimentary about the A-M 25, citing it as an extremely good lightweight general-purpose unit which was “very definitely a modeller’s engine - produced by a modeller”. He reported a peak output of 0.181 BHP @ 12,200 rpm - somewhat short of the manufacturer’s claim but still a quite acceptable performance by mid 1954 standards for a lightweight plain bearing 2.5 cc diesel. One point of criticism was a seemingly contradictory tendency for the contra piston to either seize or run back during operation. Warring put this down to a combination of an excessively tight contra piston and a less than optimal fit of the compression screw in its thread. The manufacturers clearly took this criticism to heart, because a revised compression screw having a very fine closely fitted Model Engineer thread was soon adopted in place of the earlier coarser thread. The contra piston length was also increased to allow it to be somewhat more loosely fitted. The rival “Model Aircraft” magazine was unaccountably slow in publishing a test of the A-M 25. Their unattributed report (which was almost certainly authored by Peter Chinn) appeared rather belatedly in their June 1955 issue. This report was equally complimentary - in fact, the tester reported a significantly higher peak output of 0.220 BHP @ 12,750 rpm, thereby almost matching the manufacturer’s claim.

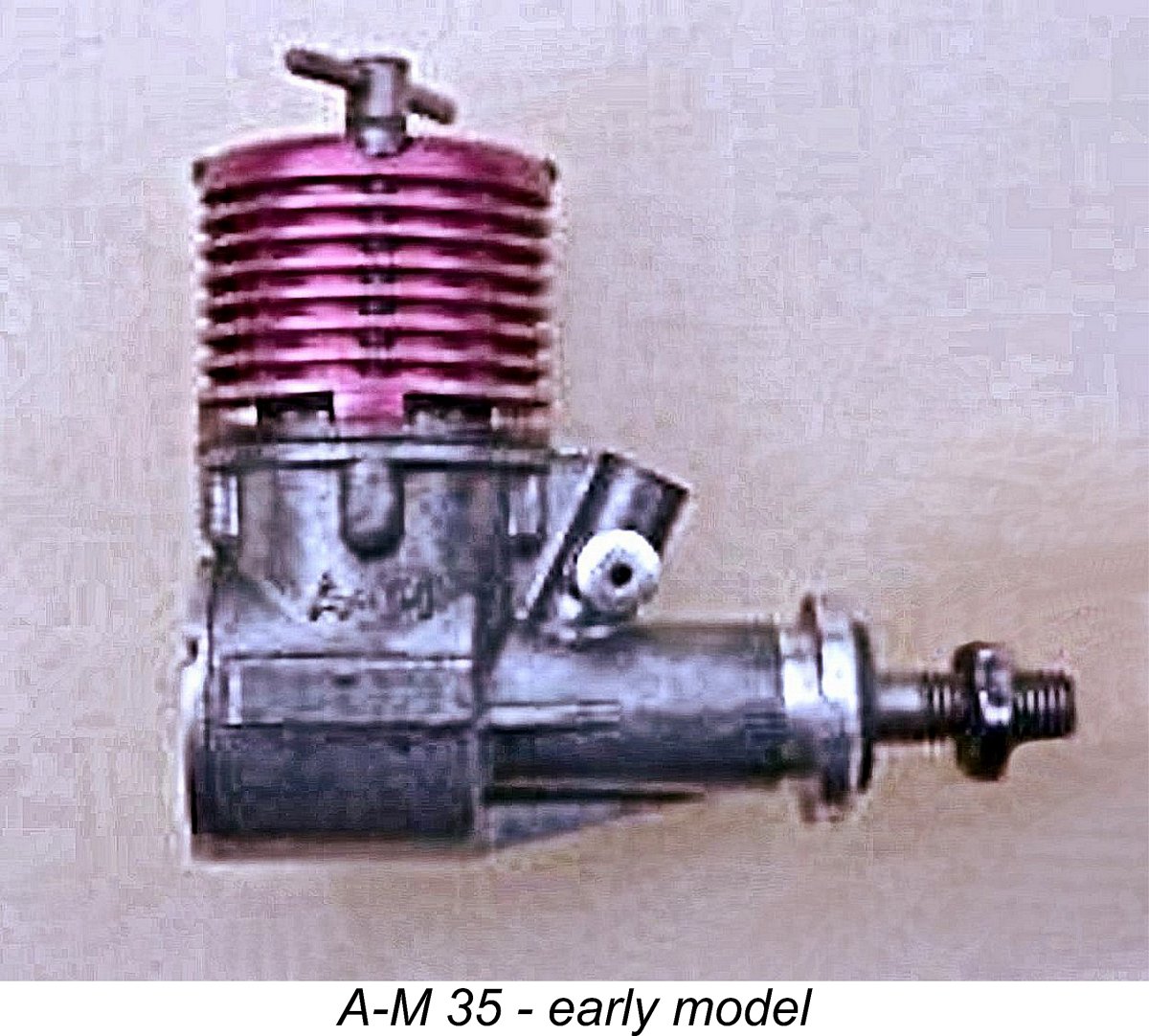

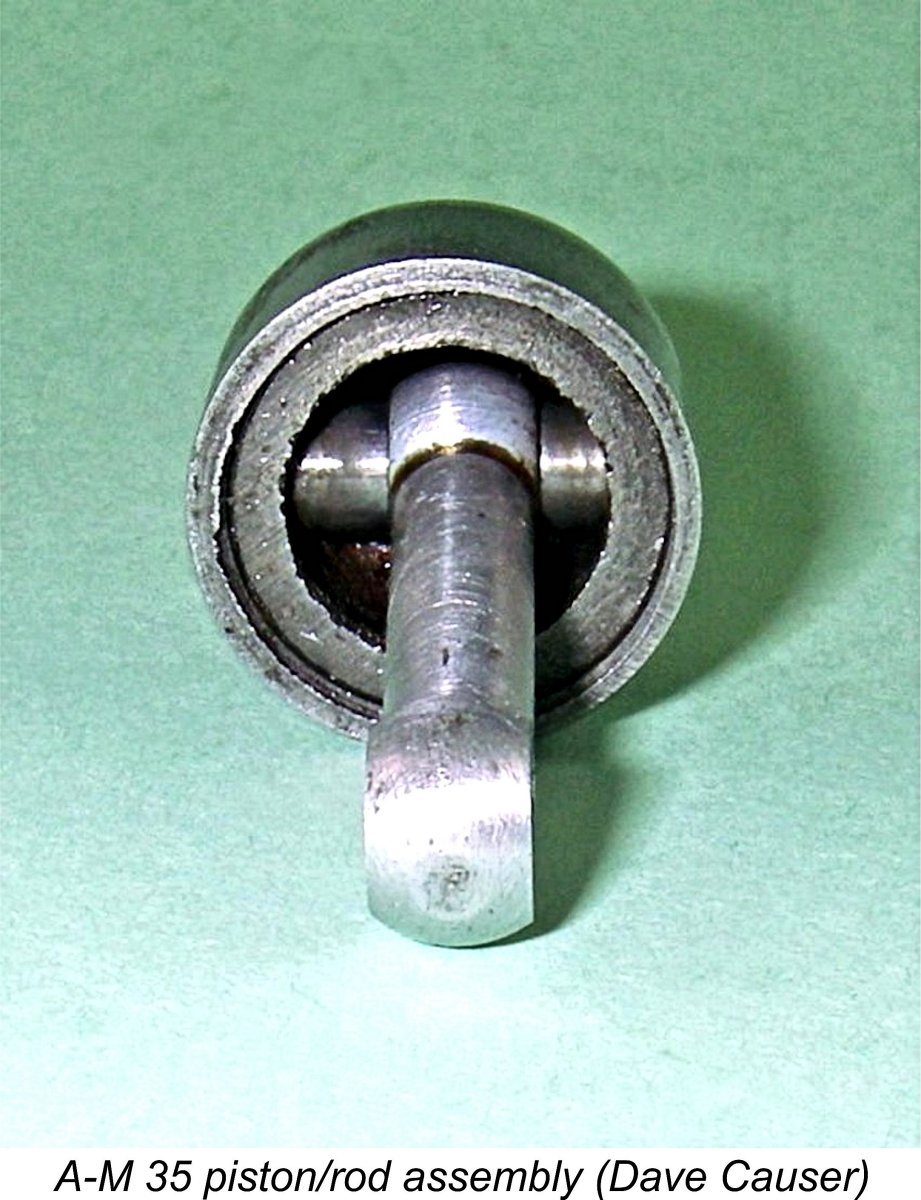

The additional displacement was achieved entirely through an increase in the bore from 0.570 in. (14.48 mm) to 0.6875 in. (17.46 mm), with the 0.562 in. (14.27 mm) stroke remaining unchanged - indeed, the same very sturdy crankshaft was used. The bore increase yielded an actual displacement of 3.42 cc (0.209 cuin.), once again a little below the nominal 3.5 cc figure. A test of the A-M 35 by Ron Warring appeared in the November 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Although he found his test example to have been assembled excessively tightly, he still rated the engine quite highly. He reported a peak output of 0.260 BHP @ 11,400 rpm - a very acceptable figure for an engine weighing only 4.44 ounces (126 gm), reflecting good torque development. Experience shows that a well freed-up example can easily improve upon these figures. Indeed, the application of some well thought-out tuning measures can turn the A-M 35 into a really strong performer, especially considering its low weight for its displacement. One-time FROG, E.D. and Dynamic designer Gordon Cornell recalled using one of these engines to very good effect in his combat models during the 1950's, when engines of up to 3.5 cc were permitted in S.M.A.E. combat as then flown in Britain. I still fly It’s worth noting in passing that Warring cited the engine’s bore incorrectly, giving it as no less than 0.890 in. (22.61 mm) while correctly recording the stroke as 0.562 in. (14.27 mm). Warring’s figures yield a calculated displacement of a monumental 5.73 cc (0.350 cuin.)! However, he quoted the true displacement more or less accurately as 3.44 cc (0.210 cuin.). It’s very difficult to find a rational explanation for this lapse - clearly, the figures were not checked. I suspect that this was simply an un-caught typsetting error. Apart from the increased bore and the larger-bored cooling jacket which this required, the new model was essentially identical to the 25, even using the same crankshaft. It also retained the Meehanite piston/cylinder combination with its potential for wear issues. The mounting hole pattern was also identical, making the A-M 35 a bolt-in replacement for the A-M 25 in the same model. Another carry-over was the wide cylinder installation flange below the exhaust ports. However, the former studs were now gone - This was a far more convenient arrangement for dismantling and reassembling the engine for servicing purposes. Moreover, it retained the former system’s advantage of eliminating any assembly stresses from the upper cylinder walls. The same bolt pattern soon appeared on the companion A-M 25. Another unusual feature of the A-M 35 was the method of installing the gudgeon pin. The pin was installed in what appears to be a standard A-M 25 piston which has been externally threaded. The actual working piston is a relatively thin Meehanite shell with unbroken walls, trapping the gudgeon pin inside. This shell is internally threaded to accommodate the externally threaded A-M 25 piston which now serves as a gudgeon pin carrier. This assembly results in an extremely heavy piston, which is not good either for power development or vibration levels. It also poses a challenge when it comes to servicing issues such as conrod or gudgeon pin replacement. An article by reader Dave Causer detailing the required approach to the disassembly of this set-up may be found elsewhere on this website.

Initially the companion A-M 25 continued unchanged. However, the merits of the A-M 35 cylinder assembly were clearly apparent, leading to the November 1955 adoption of a revised A-M 25 cooling jacket featuring the 35’s four pillars. This change was presumably delayed until existing stocks of the earlier components were used up. At the same time, the wide cylinder installation flange was eliminated on both models in favour of the lower edge of a slightly expanded port belt being used to support the cylinder. The revised jacket bore against the stepped upper edge of the port belt, making the four pillars in effect dummies which served no practical function. The anodizing on the revised jacket of the 25 continued to be black, while the updated 35 model generally featured a maroon jacket, although a few early examples like that illustrated here continued to sport a purple/pink jacket. Interestingly enough, the early examples of the revised A-M 25 bore serial numbers - the only A-M engines to do so. The highest such number of my present acquaintance is my own engine no. 2802, but I know of several other numbered examples. Clearly the practise was dropped fairly quickly. The original wide-flange version of the A-M 35 was thus only in production for some 7 months at most. It is one of the rarer Allen-Mercury engines today - I don't have one myself. The original stud-equipped A-M 25 runs it a close second in that department. Although its production life was considerably longer, it was never produced at a rate which approached that achieved in later years.

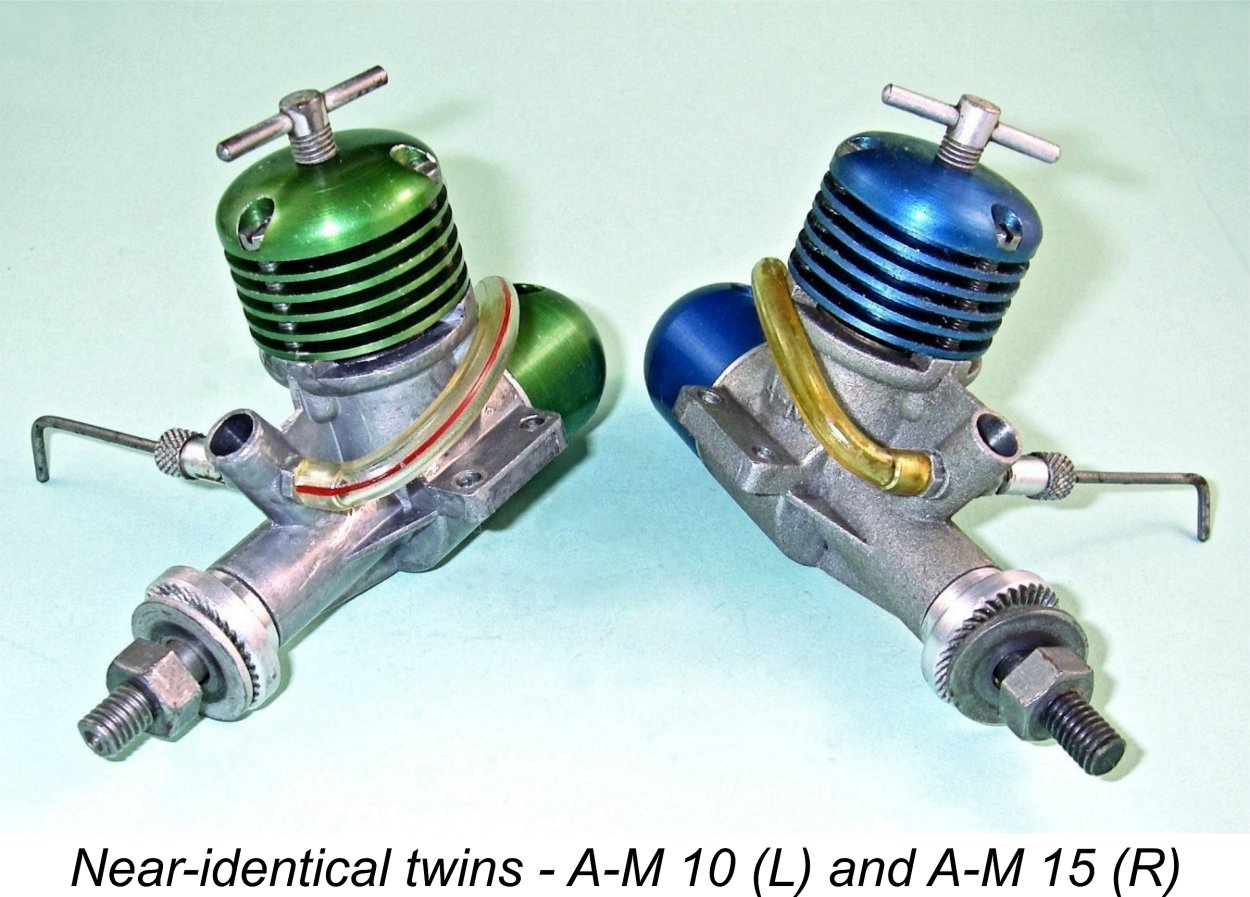

Bore and stroke of the new model were 0.426 in. (10.82 mm) and 0.430 in. (10.92 mm) respectively for a displacement of exactly 1.00 cc (0.061 cuin.). Both the cooling jacket and the back tank were anodized green. The engine weighed in at a fairly healthy 3.0 ounces (85 gm) with tank. Rumours of the engine’s exceptional performance for a 1 cc diesel quickly began circulating, prompting both “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft” to publish detailed tests in short order. On this occasion, “Model Aircraft” got in ahead of the rival magazine, publishing its unattributed test of the A-M 10 (almost certainly by Peter Chinn) in its July 1956 issue. This test represented a sweeping endorsement of the new design. The tester reported a peak output of 0.118 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, which was stated quite truthfully to be substantially in excess of any figures measured previously for a 1 cc diesel. The quality of the engine’s construction also came in for commendation. This was closely followed by Ron Warring’s test of the A-M 10 which appeared in the August 1956 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Warring was equally impressed with the engine, recording a peak output of 0.113 BHP @ 14,200 rpm, thereby more or less matching Chinn’s previously-reported figure. At a listed price of £2 18s 6d (£2.92), the engine clearly represented outstanding value for money.

Cutting through all of the euphoria, it fell to Ron Warring to make one of the more pertinent comments. Warring stated that while he would endorse the claim that the A-M 10 was a match for many then-current 1.5 cc engines in terms of output, it was also well up to typical 1.5 cc bulk and weight. Put like that, one has to wonder if it represented any real gain in practical terms. I must confess to having held a very similar view of the A-M 10 during my own early years of power modelling - might as well go for the extra power of a 1.5 cc model of comparable size and weight! This issue of the A-M 10's weight and bulk for its displacement might have become a moot point if the FAI had followed up on the then-current suggestion made from several quarters that a new International competition class for 1 cc engines be established. The A-M 10 would have fared very well in such a class if it had ever been adopted. Super Tigre, Barbini and MVVS all produced high-performance 1 cc diesels in anticipation of such a move, but in the end it never came to anything. Of course, many people apart from Warring noticed the engine's unusual size and bulk for its displacement. There was widespread speculation that the physical size of the A-M 10 might indicate an intention on the part of the manufacturer to produce an over-bored 1.5 cc model, thus following the pattern established previously with the A-M 25 and 35 models.

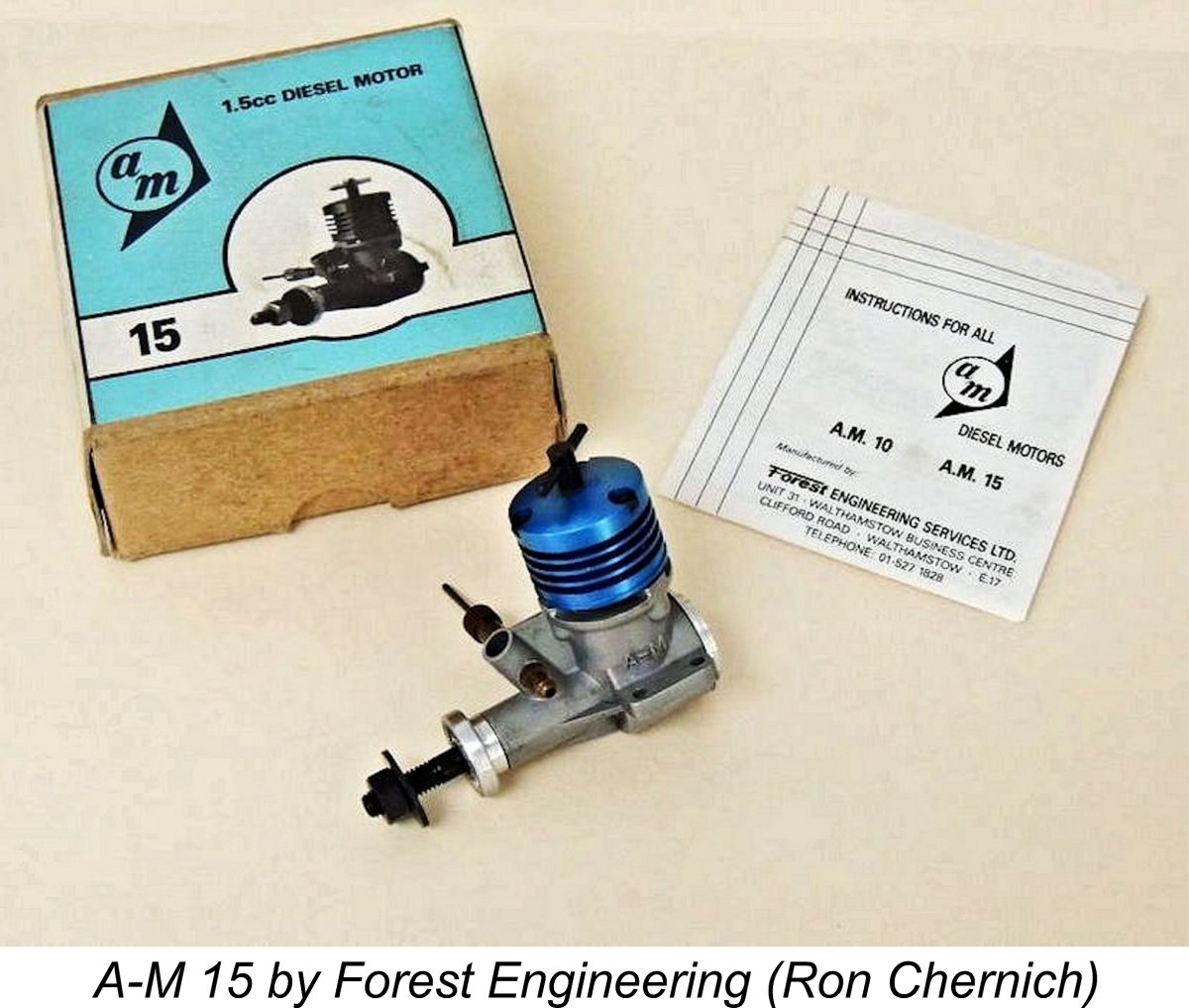

During the first half of 1958, the staff of “Model Aircraft” paid a visit to the expanded Allen-Mercury workshops at the new Angel Factory Colony location. A report on this visit appeared in the June 1958 issue of the magazine. The article included a number of photographs of manufacturing processes being carried out. It also confirmed that the main protagonists in the venture were very much hands-on participants - Dennis Allen, Les Parker and Len Steward were all shown hard at work, as were Brian Howard, Mick Clarke and George Thomas. At more or less exactly the same time, the speculation regarding the possibility of a 1.5 cc version of the A-M 10 was finally proved to have been well founded. It turned out that such a duality of displacements had been envisioned from the outset - the earlier appearance of the A-M 10 had simply been a marketing decision. The next model to appear in the ever-expanding Allen-Mercury range was an over-bored A-M 10 having a nominal displacement of 1.5 cc. This model appeared in June 1958 as the A-M 15 at an advertised price of £2 19s 6d (£2.97), only a shilling more than the companion A-M 10.

Not surprisingly, the established reputation of the A-M 10 gave rise to some rather elevated expectations regarding the performance potential of the new A-M 15. The manufacturers claimed an peak output of 0.170 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, which was right up there with the best of them at the time. The resident engine testers for the two British magazines “Aeromodeller” and “Model Aircraft” were quick to put this claim to the test. Ron Warring’s test of the A-M 15 appeared very promptly in the July 1958 issue of the magazine. Once again, Warring found very little to criticize and much to commend in this design. He reported a peak output of 0.152 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. While not quite matching the factory claim, this was still an excellent performance for a simple lightweight 1.5 cc plain bearing diesel.

There seems to be little doubt that the advent of the A-M 15 must have had a markedly adverse effect upon sales of the A-M 10. After all, the new model offered a 50% increase in power output for an unchanged weight of 3 ounces and only a shilling extra cost. Moreover, the mounting hole pattern was identical, making the A-M 15 a bolt-in replacement for the A-M 10 in the same model. It’s always rather puzzled me why anyone would have bought an A-M 10 once the 15 appeared. As matters were to transpire, the A-M 15 proved to be the last diesel model offered commercially by D. J. Allen Engineering during the classic era. In 1960 there was a brief flicker of hope that a new high performance 2.5 cc diesel might emerge from the company's workshops. This was the prototype "Steward Special" with which Gordon Yeldham and Chas Taylor contested the 1960 World Team Race Championship, ending up in a very creditable third place. This engine was touted at the time as the prototype of a forthcoming new A-M model, but in the event it never materialized in commercial form. Wonder where that prototype is now?!? All four A-M production models remained available for many years, undergoing a few more design changes along the way. At some point in time, the material of the cylinders was changed from Meehanite to hardened steel, a far superior material from the standpoint of wear. The four pillars at the base of the 25 and 35 cooling jackets were eventually also omitted, since they actually served no function once the wide cylinder base flange had been eliminated. The later versions of the A-M 10 and 15 both featured cooling jackets which were squared off at the top rather than being rounded. This brings us up to the point in 1959 at which Allen-Mercury took a real flier by entering the .049 cuin. glow-plug field which was then something of a craze in Britain. Let’s have a look at that model next. Side-Stepping Out of Character - the A-M .049

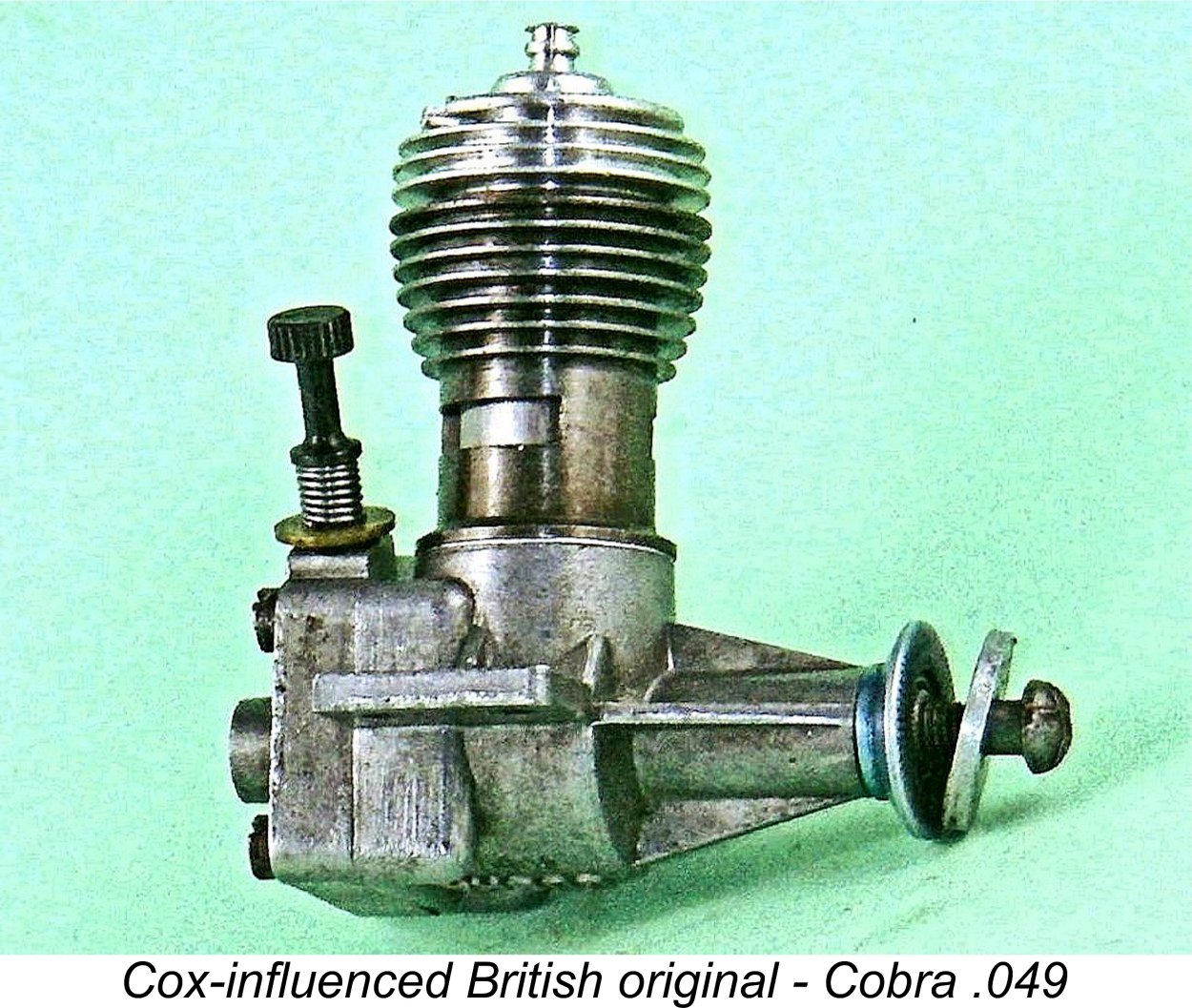

The rising interest prompted a number of British manufacturers to enter the ½A glow-plug market themselves beginning in mid 1959. There were three potential pathways to entry into this market - innovate, convert or copy. The first option involved the development of an all-new design from scratch - an expensive proposition, albeit the one with perhaps the greatest potential. The makers of the Cobra .049 were the only British company to follow this route. Although they drew quite heavily upon the design of the Cox reed valve models, their engine was undoubtedly as original a design as any other. The second option was to take the very simple route of producing a glow-plug conversion of an established diesel Allen-Mercury did not have an established diesel design in the appropriate displacement category, so the conversion option was not open to them. However they clearly wanted to participate in this new market sector while at the same time minimizing both the time and the costs associated with the development of their own .049 glow-plug model. They therefore elected to take the third option, which was to side-step the entire development process at one fell swoop by simply purchasing the rights to an established design which had already been fully developed by others.

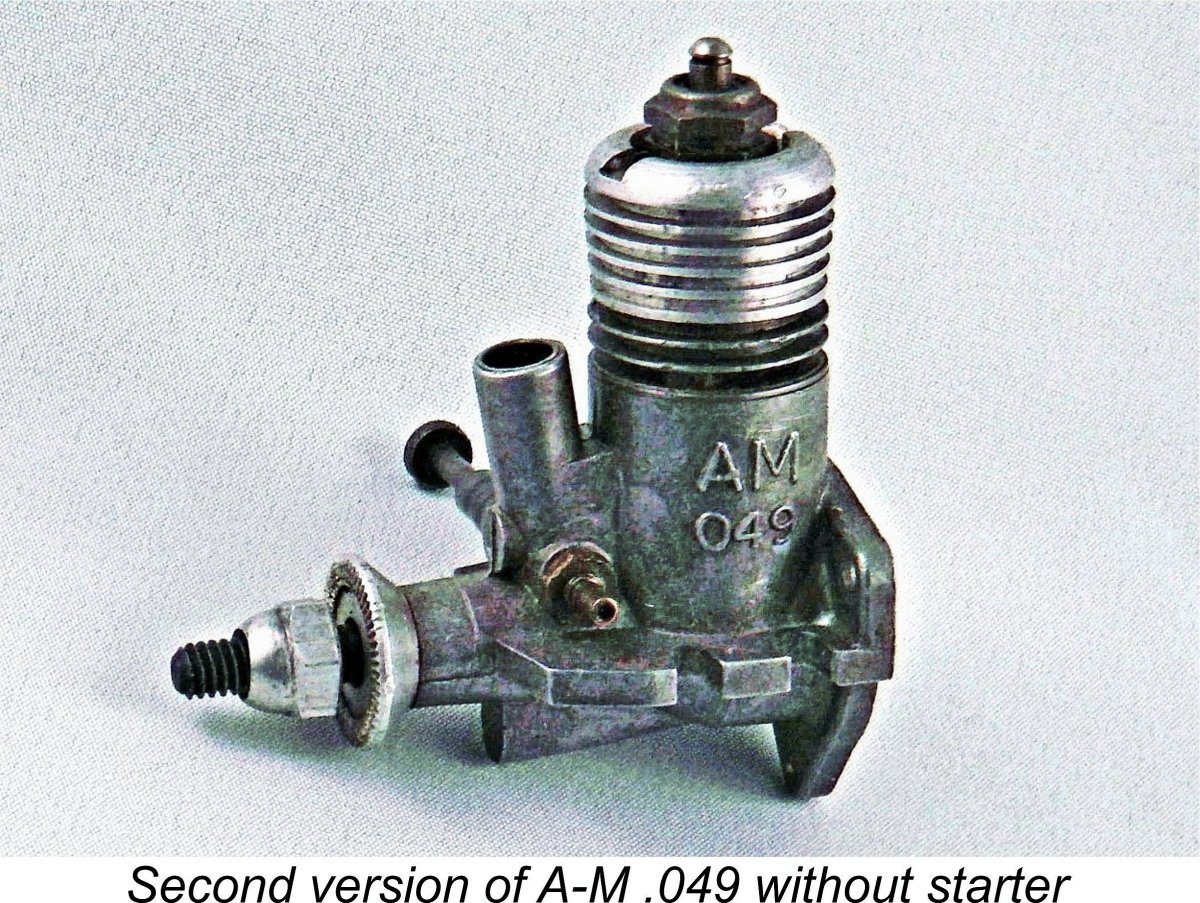

A detailed article on the A-M .049 appears elsewhere on this website. In that article, I've presented compelling evidence to suggest that the A-M .049 was not simply a Wen-Mac clone made by Allen Engineering - it was actually a Wen-Mac product made in American using a special batch of re-lettered cases. Former A-M employee Mick Clarke, who was working at the Edmonton factory throughout this period, did not recall any manufacturing of the A-M .049 ever taking place there, although he did recall components coming in from elsewhere to be assembled by A-M employees. The likely instigator of this arrangement was Henry J. Nicholls - as a staunch diesel man, Dennis Allen may actually have been a somewhat reluctant participant! The AM .049 was one of the subjects of an unusual triple engine test by Ron Warring which appeared in the January 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller”. This test featured three of the four contenders in the British ½A glow-plug sweepstakes going head to head. The only one missing was the Cobra .049, the appearance of which was delayed until later in 1960. Warring’s test report on the Cobra was finally published in the October 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller”. In his report on the A-M .049, Warring stated that the new engine was “basically the American “Wenmac” motor, with certain material modifications consistent with British practise”. Direct examination of actual examples yields little support for the latter half of this statement - the engine comes across as Wen-Mac all the way apart from the British-threaded spraybar. The report also identified D. J. Allen Engineering as the “manufacturers” of the A-M .049 - another point which appears to be wide open to question, as discussed in detail elsewhere. Warring was very complimentary about the engine’s handling and performance, finding a peak power output figure of 0.052 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, a very good figure for a sports glow-plug .049 and one which matched or exceeded the performance of several contemporary small diesels of similar displacement and weight. When one considers that the engine weighed only 1.16 ounces (33 gm) without the starter, the reported power-to-weight ratio was actually pretty impressive by then-current standards. Warring commented in particular upon the engine’s better-than-average torque development and its consequent ability to turn larger-than-normal props for a glow-plug motor of its displacement. “Model Aircraft” tester Peter Chinn delayed the appearance of his test of the A-M .049 until April 1960. His report was generally very positive, characterizing the engine as a likeable little motor which was particularly suitable for young beginners (largely a lost breed today!). He found a peak output of 0.052 BHP @ 14,300 rpm, thereby more or less exactly matching the figures obtained by Warring.

Not only that, but the Rotomatic starter quickly proved itself to be the engine’s Achilles’ Heel. Former A-M employee Mick Clarke actually recalled that the entire first batch of 50 engines sent out from the factory following assembly were promptly returned under guarantee with broken starter springs! A return rate of 100% must surely have few if any precedents within the model engine manufacturing industry! Moreover, the replacement springs doubtless broke as quickly as their predecessors. In Mick’s recollection, shipments of the engine in Rotomatic form ground to a halt fairly quickly thereafter, and he didn’t think that very many more such models were released. To their credit, Allen-Mercury doubtless heard the criticisms and tried to deal with the starter issue at least. They quickly came up with a batch of engines that were not fitted with the Rotomatic starter. In America, the Wen-Mac versions of the starter-less engines were sold as Wen-Mac Hustlers, but the more or less identical A-M versions were simply offered as an alternative to the Rotomatic version under the same A-M .049 name. These models were being offered for sale by Henry J. Nicholls as early as April 1960, selling for a mere £1 14s 3d (£1.71) and thus undercutting the competing D-C Bantam by a princely 3 pence!! This actually makes this version of the A-M .049 the cheapest model engine ever offered to the British public by a British manufacturer. They were far more useable engines than the Rotomatic models, being both lighter at only 1.16 ounces (33 gm) and more amenable to beam mounting due to the absence of the starter.

This lack of sales success goes far towards explaining the engine’s relative present-day rarity. Good examples are very infrequently encountered today, and when the Rotomatic versions do show up they almost invariably prove to have broken starter springs! Along with the early A-M 25 and 35 diesels, these are undoubtedly among the rarest Allen-Mercury models today. We’ve now seen the Allen-Mercury range entering the 1960’s with continuing strong sales figures for all models apart from the .049. In fact, overall production had increased to the point where a further expansion into larger premises was required. This led to a move into nearby premises at 30 Lea Valley Trading Estate on Angel Road, still in Edmonton. This relocation seems to have taken place in around July 1960. The move was timely, since we’re now approaching the point in time at which the MERCO engines were added to the production portfolio of D. J. Allen Engineering. This being the case, it’s time to re-direct our attention towards the Merco range. Genesis of the MERCO Range In writing about the MERCO range, my main claim to any expertise is the fact that I’m a former very satisfied user of the engines as well as being a current owner of several examples. I wish to freely acknowledge the fact that in writing up this part of the story I have drawn heavily upon the recollections of my late friend and colleague Ian Russell, who was a former co-owner and manufacturer of the MERCO range during the later years.

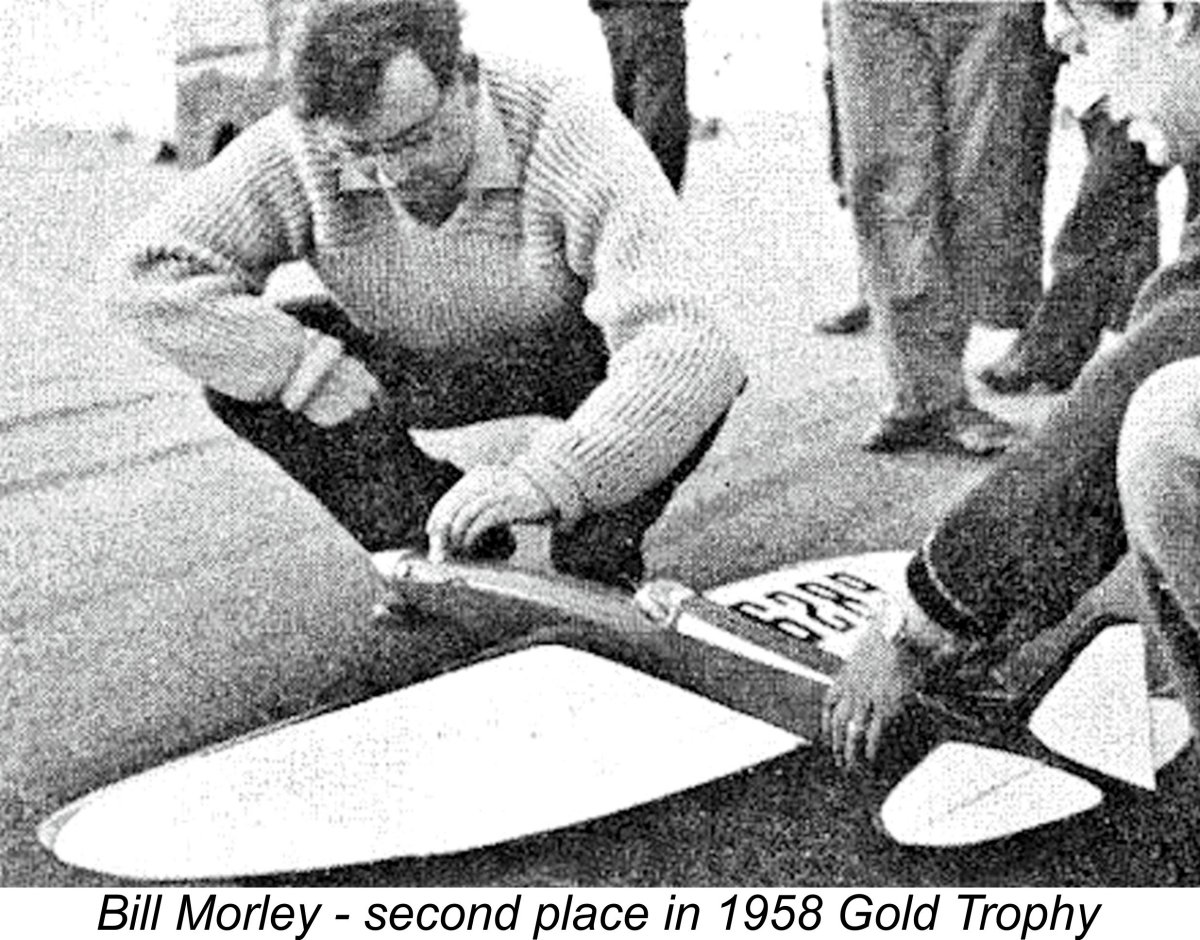

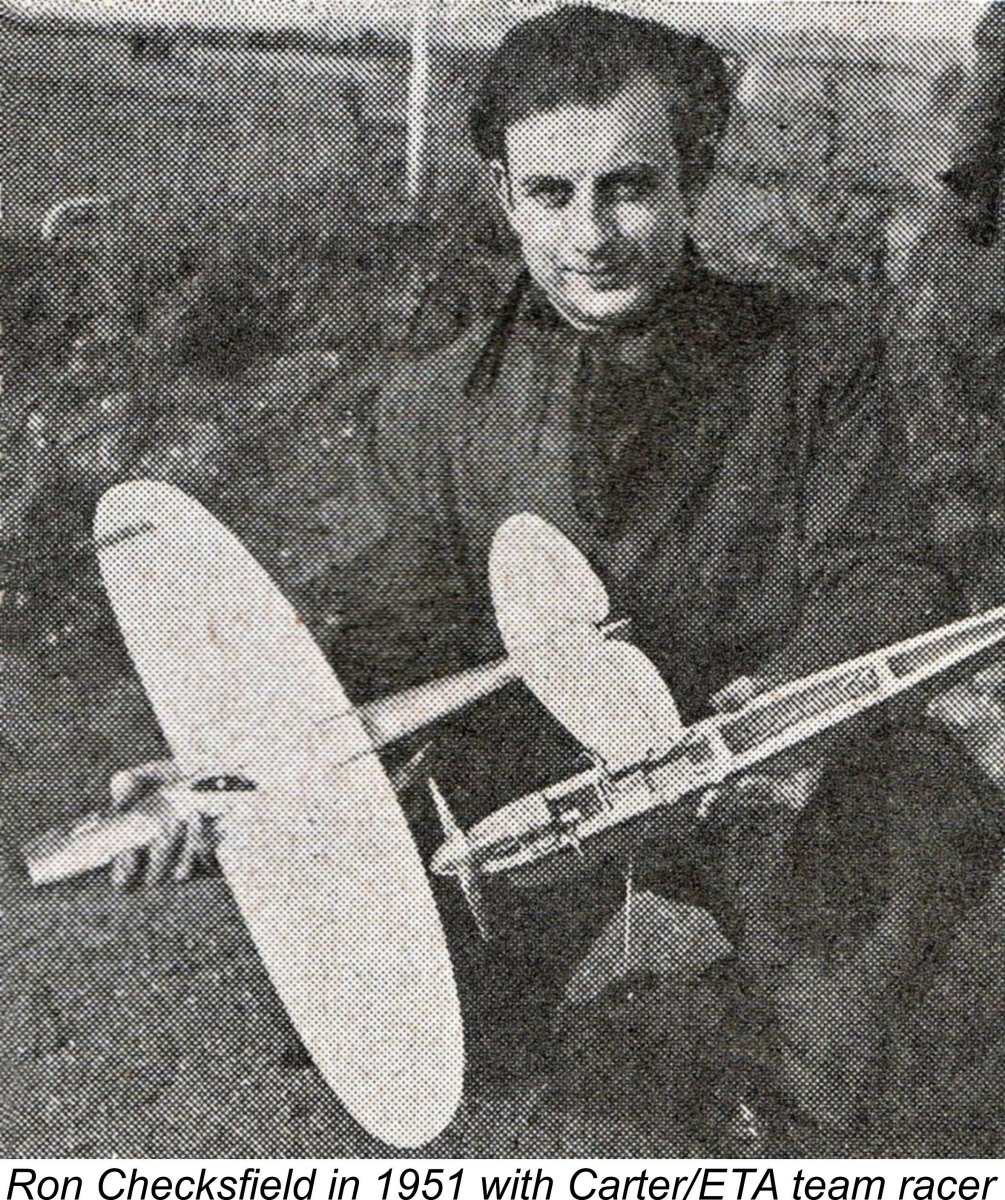

Morley was one of the top British C/L stunt competitors of the ‘50’s and ‘60’s, regularly placing high in the annual Gold Trophy contest and gaining places on a number of British international teams of the time. His designs included the Thunderbolt, which was published by the Aeromodeller Plans Service (APS), and the Scimitar, which became the basis for the KeilKraft Spectre kit. The Thunderbolt was one of the most aesthetically pleasing models of all time, being quite widely imitated as a result. With a wingspan of 48 in., the Thunderbolt was just that little bit smaller than most contemporary designs such as Bob Palmer’s Thunderbird, falling into a niche one size down from the largest 35 size models of the day. A good 29 suited it perfectly. Ron Checksfield was a somewhat retiring character with a highly unusual personal history. He apparently grew up with his family, went to school, reached leaving age and ended his education at that point with no formal qualifications. It seems that he never obtained any regular employment, continuing to live at home supported by his seemingly very tolerant parents. In due course he reached National Service age, duly fulfilled his patriotic duty and then returned home to resume living with his family, still without a paying job.

One technical area in which Ron developed a strong interest was aeromodelling in general and model engine design in particular. As of the early 1950’s he was competing in Class B team racing using a Fred Carter reworked ETA 29. However, he soon developed his own ideas regarding model racing engine development. Initially he collaborated with Fred Carter in the construction of several high performance engines, but eventually struck out on his own to produce the famous Checksfield Specials. By the late 1950’s Ron had become world famous for his high-performance rebuilds of various engines, particularly the Checksfield Special speed and T/R engines based on the McCoy and Dooling motors. He also did some Oliver Tiger Mk. III reworks which are not quite so well known. As stated earlier, Ron was a relatively retiring person who preferred to keep out of the limelight. That said, when Ian Russell was privileged to meet him on several occasions in later years, he proved to be a pleasant, sociable individual who was quite happy to talk at length about a common interest - model engines.

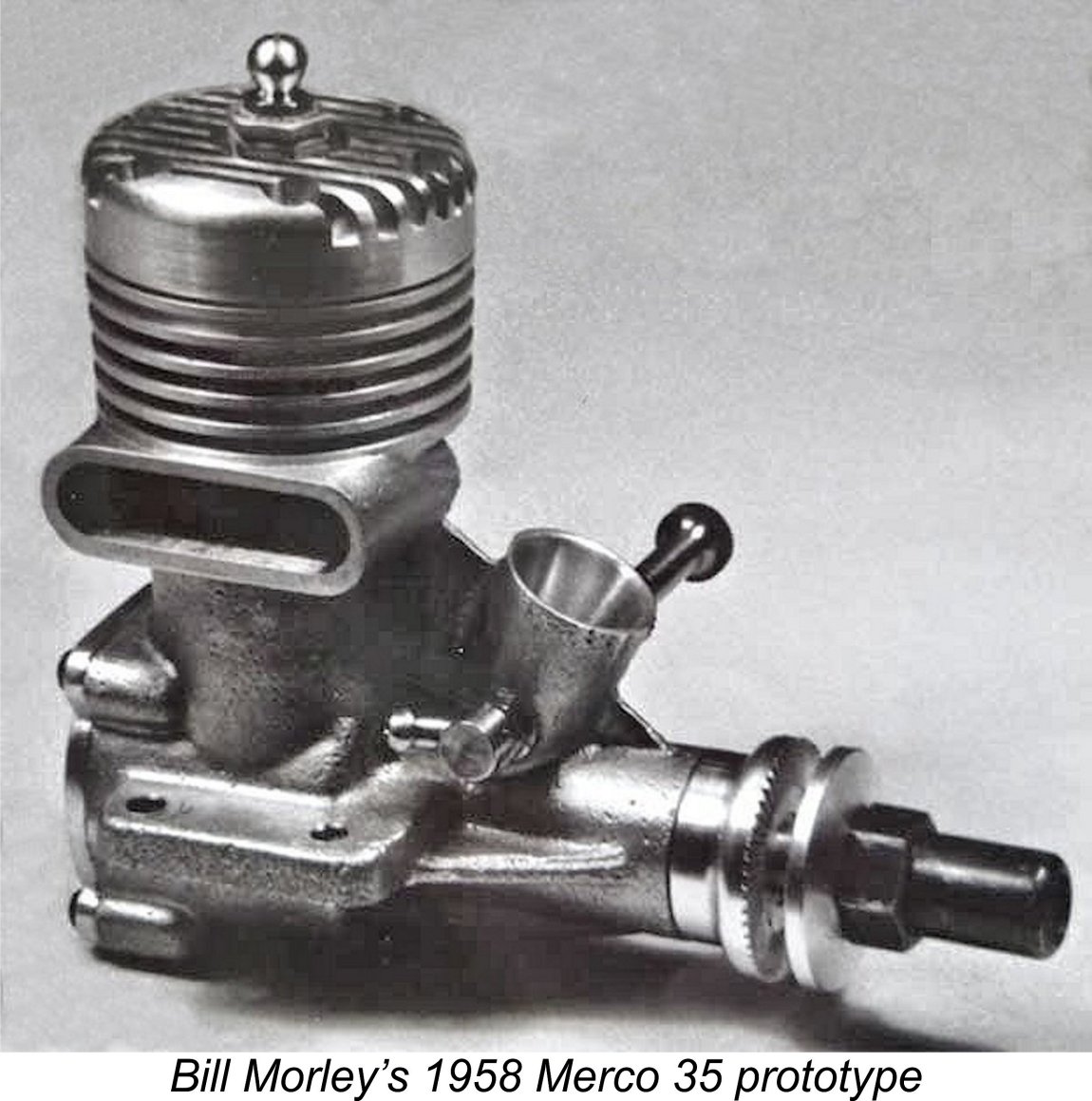

The primary intention was to make such an engine more readily available to enthusiasts in this country, (at a profit of course, otherwise it would be a pointless exercise). The definitive stunt engine of the time, the American Fox 35, was difficult and expensive to obtain in Britain during the late 1950’s. If the new motor could be equal to or better than a Fox 35 while selling for a competitive price, the two men would have a winner. When Bill put this suggestion to him, Ron was over 30 years of age and had still never held a regular job. Liking the sound of what Bill was saying, Ron did all the design work and made all the drawings, dies, jigs and tooling necessary to produce what was to become the original MERCO glow-plug engine in both .29 cuin. and .35 cuin. displacements. The fact that Ron had no “day job” to distract him gave him all the time that he needed to complete these tasks.

The results must have provided strong encouragement to the two MERCO protagonists. Despite his use of a completely untested model/motor combination, Morley finished a strong second just behind winner Pete Ridgeway (flying a much smaller P.A.W. 2.49 diesel-powered model). The prototype MERCO 35 was fully described in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” column in the August 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”, with further commentary being provided in the following month’s column. Additional improvements to the design were made following Morley’s further contest experience with the prototype. Some form of production agreement was reached with a company named Bi-Metals, who had established production facilities at 1A Balfour Mews, Bridge Street in Edmonton, North London. Perhaps not coincidentally, this location was not far from the Allen-Mercury workshops at Angel Factory Colony. It would appear that Morley and Checksfield somehow made arrangements to have the MERCO engines manufactured on the Bi-Metals premises, presumably using their surplus production capacity. Despite this, Morley and Checksfield traded under their own distinct company name of the Model Engine Research Co. Ltd., from which the MERCO name was of course derived, giving their address as that of Bi-Metals at 1A Balfour Mews. My valued English friend and colleague Marcus Tidmarsh undertook some valuable research into the history of the Bi-Metals company. The firm's full name was BI-METALS (BRITINOL) Ltd. Established in 1949, the company was a family-run business operated by the Heyer family, being located in premises called St. Mary’s Works at 1A Balfour Mews, Bridge Road, Edmonton, London. The building was a new build in about 1949, possibly a re-development following bomb damage to the original Mews buildings during WW2.

This arrangement continued through to mid-1961, when the MERCO business and its assets were sold to Dennis Allen’s D. J. Allen Engineering company which was located nearby at 28 Angel Factory Colony. It appears that the manufacture of the MERCO engines by Bi-Metals may well have continued despite this sale, because they continued to be cited as the spares and service providers for the MERCO engines. Indeed, they may have taken a hand in the ongoing production of the Allen-Mercury range.

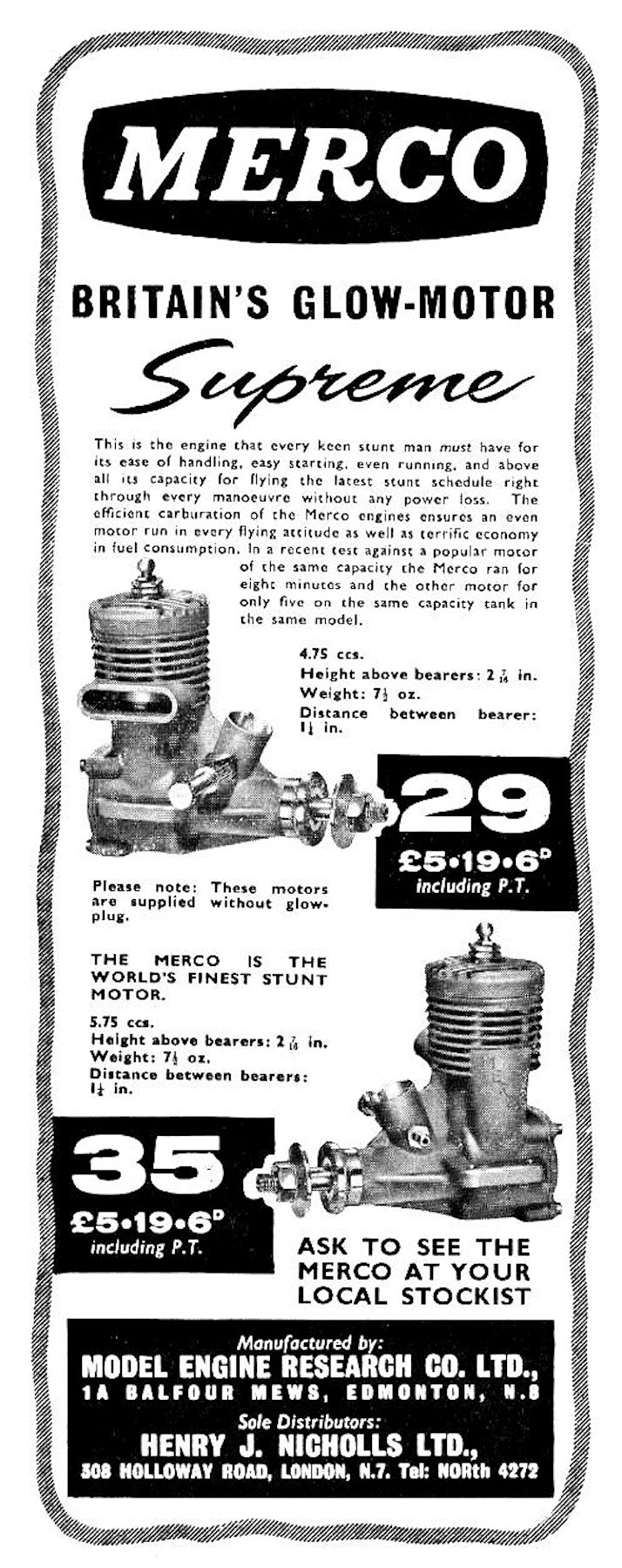

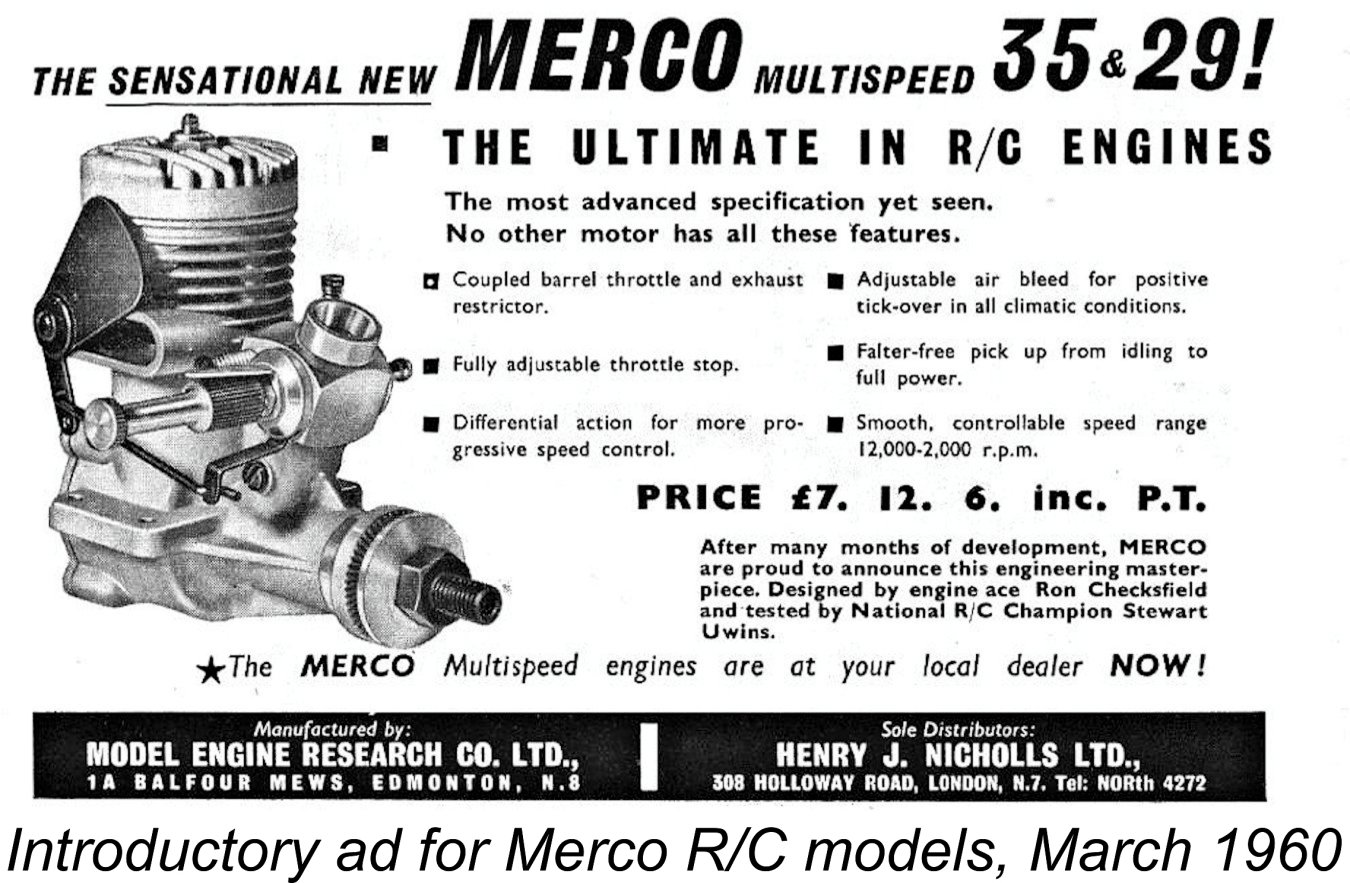

The Bi-Metals company continued in business until 1992, when it was dissolved. Their building at 1A Balfour still existed in 2023, having functioned latterly as a carpet warehouse. Returning now to late 1958, when the MERCO engines first appeared, Henry J. Nicholls was appointed as sole trade distributor for the fledgling MERCO range. This established a direct business link with the nearby Allen-Mercury It was apparently hoped that the production versions of the MERCO 29 and 35 might be ready for Christmas 1958. However, it took a little longer than anticipated to get production underway. In his April 1959 “Latest Engine News” column in that month’s edition of “Model Aircraft”, Peter Chinn reported that the delays arose chiefly from difficulties with the creation of the required dies for the pressure die-cast crankcases. He expected that production units would still reach the market in time for the 1959 contest season. As predicted, the first production units began to appear in the shops in May 1959 at a price of £5 19s 6d (£5.97) for both 29 and 35 models. With their matte-finished pressure die-cast crankcases and bright red-painted cylinder heads, the engines p Considerable success was achieved on the contest field during 1959. The advertisement from the October 1959 issue of "Model Aircraft" which is reproduced at the left typifies the very serious promotional effort made during that introductory year. Somewhat strangely in view of this, the model engine testers of the two leading British modelling magazines ignored the two Mercos completely during 1959. It was not until January 1960 that Peter Chinn finally got around to publishing a test of the Merco 35 in the pages of “Model Aircraft”. The delay possibly resulted from Chinn’s awareness that a number of changes were being made to the original design on the basis of field experience during 1959. He evidently preferred to wait until all of these improvements had been implemented. The model tested by Chinn was the revised 1960 version of the engine. While retaining the same matte-finished pressure die-cast crankcase and red-painted head of the original production version, it now featured a leaded steel cylinder liner in place of the Meehanite cast iron component used formerly. It also incorporated a lighter piston along with a little extra counterbalancing on the crankweb. The latter changes were evidently a response to criticisms regarding the engine’s vibration levels. Bore and stroke were unchanged at 0.800 in. (20.32 mm) and 0.703 in. (17.86 mm) respectively for a displacement of 5.79 cc (0.353 cuin.). Weight was 7.6 ounces (215 gm). The companion 29 model was identical apart from a reduced bore of 0.734 in. (18.64 mm) for a displacement of 4.87 cc (0.297 cuin.). It also weighed fractionally less at 7.5 ounces (212 gm). Chinn was highly impressed with the MERCO 35 as tested, characterizing it as “one of the best engines of its type yet offered to the British modeller”. He reported an output of 0.57 BHP @ 14,000 rpm, which was a very competitive performance for a .35 cuin. stunt engine of the period. Ron Warring of the rival “Aeromodeller” magazine was not far behind Chinn in getting to grips with the MERCO 35. His test report on the engine appeared in the February 1960 issue of the magazine. He was just as impressed with the MERCO as Chinn had been, citing its easy starting and consistent running. He found a peak output of 0.55 BHP @ 13,400 rpm, thus offering solid support for Chinn’s earlier findings.

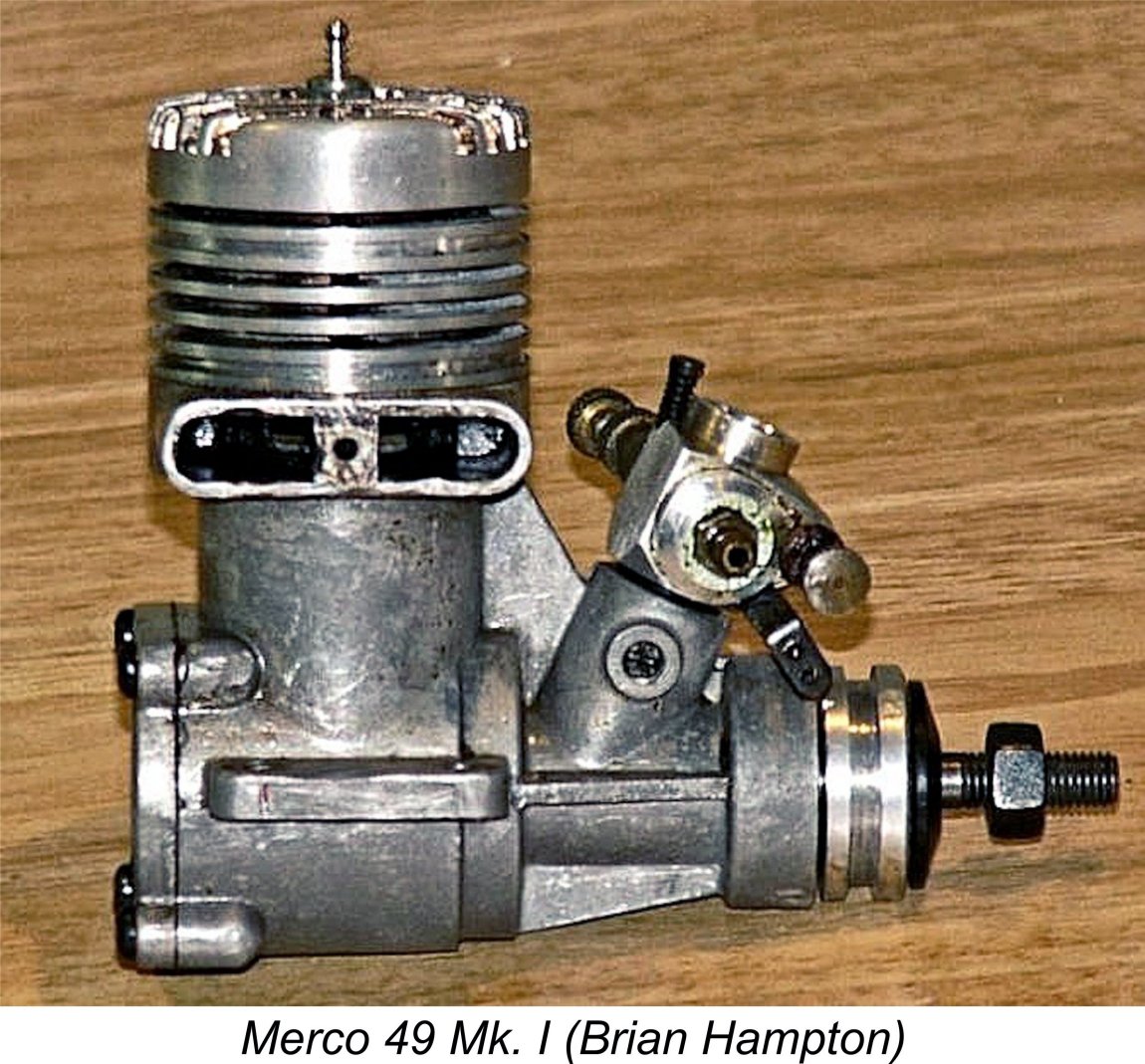

Having got the two original MERCO models off to an excellent start, Ron Checksfield soon started work on a larger .49 cuin. model intended primarily for R/C applications. Like Dennis Allen with his A-M diesel models, Ron envisioned this engine being made available in a larger .61 cuin. version down the road, tailoring his design to accommodate this possibility. As design and development work progressed, both Dennis Allen and Bill Morley provided valuable assistance. Allen produced the crankshafts, cylinder liners and cooling jackets for the prototypes, while Morley carried out the grinding operations on the crankshafts and cylinders. The first three prototypes of the new design were completed in June 1961. All three were started for the first time on June 29th 1961, after which air-testing was undertaken by the well-known British R/C expert Frank Van den Bergh. An example was also sent to Peter Chinn, who presented his report on the new design in his “Latest Engine News” column in the September 1961 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The results of the prototype evaluation and testing were sufficiently encouraging to make it obvious that the MERCO 49 would be an immediate sales success, building upon the very positive reputations of the earlier MERCO 29 and 35. It was readily apparent that the small MERCO manufacturing operation would be quite unable to keep up with demand. For this reason, discussions were initiated with D. J. Allen Engineering during the development of the Merco 49 prototype, leading to the sale of the MERCO business and all its assets to Dennis Allen’s company in mid 1961. The successful development of the three MERCO 49 prototypes was the final accomplishment of the Model Engine Research Co. before handing the project off to Allen Engineering. Happily for all concerned, Ron Checksfield went along with the changed manufacturing arrangements, thus becoming an ongoing employee of the company. He finally had a regular job!!

Production of the MERCO 49 was finally initiated under the new arrangements in March 1962, with the new engine being launched at that year’s Brighton Trade Fair. The illustrated example from the collection of Sceptre Flight's Brian Hampton is reportedly the first example to be sold commercially, having been made available to Brian by its original owner. It wasn't long before tests of the R/C version appeared in both of the major British modelling publications. Peter Chinn was first off the line with his test report on the engine which appeared in the July 1962 issue of “Model Aircraft”. He lavished praise upon the new model, characterizing it as “a new engine that is truly among the world’s best”. He reported a peak output of 0.71 BHP @ 11,250 rpm - a very good figure for an R/C engine of this displacement by the standards of the day. Ron Warring’s test of the same model appeared in the October 1962 issue of “Aeromodeller”. He was equally unsparing of praise for the engine, citing it as “probably the finest British production engine which has appeared to date”. He duplicated Chinn’s earlier results almost exactly, finding a peak output of 0.72 BHP @ 12,000 rpm. With these extremely positive endorsements from two of the most respected engine testers of their day, the success of the MERCO 49 was assured. It did not disappoint its numerous owners, achieving outstanding results on the contest field. Having described the separate origins and eventual coming together of the Allen-Mercury and MERCO ventures, I have now brought the story up to the point at which the primary intent of this article has been fulfilled. However, for convenience I will now summarize the later history of the combined venture. The Later Years The wisdom of the MERCO takeover by D. J. Allen Engineering was amply demonstrated by ongoing sales trends. By 1962 the larger R/C glow-plug motor was well and truly in the ascendant, with the market for smaller diesels and control line engines in general now beginning to shrink. As time went on, the Merco R/C engines increasingly came to dominate the sales picture for the company.

With the MERCO engines selling as fast as they could be manufactured and the A-M diesel range still in production, the company was working at full stretch. It has been reported that at its peak, D. J. Allen Engineering employed as many as 30 people in making the two ranges. At some point during 1963, Dennis Allen sold his interest in the company to others, quite possibly to Les Parker. Allen’s departure may have been prompted by the firm’s increasing focus on glow-plug engines - he remained a staunch diesel man, as his later activities were to demonstrate quite convincingly. However, Allen was by no means a diesel bigot - in fact, his primary activity for some years following the sale was the manufacture of glow-plugs!

The later owners focused upon the MERCO trade-name rather than that of A-M, although the A-M range still soldiered on. By the 1980’s, MERCO was owned by an engineering company called Ferraris, whose chief business was making medical instruments such as respiration gauges. Ron Checksfield was still associated with the business at this time, and he dragged Ferraris into the electronic age, characteristically teaching himself electronics and then redesigning all the medical instruments to feature electronic/digital sensing and readout capabilities. Ian Russell gained the impression that this exercise actually ensured the company’s survival. Round about 1983, Ferraris decided to sell the MERCO/A-M model engine side of the business. One of their employees at the time was a man named Reg Hills, who had been with the company since the Dennis Allen days. He became the buyer, setting up production facilities at Walthamstow in East London under the name Forest Engineering, derived from his residential location at nearby Waltham Forest. This was a landmark event, because for the first time since the venture’s inception the MERCO range no longer enjoyed a direct association with Ron Checksfield. He remained with Ferraris, who continued their other product lines with his participation. However, he remained on very good terms with Reg Hills, being consulted for his advice on various matters from time to time. At this time, Ian Russell was working as a civil engineer on the British railway system but was a keen model enthusiast in his spare time. He became friendly with Reg Hills and started working on a voluntary basis at Forest Engineering on weekends. This work was unpaid of course, but Ian was in heaven learning how to operate the machines and assemble the engines. He recalled his sense of incredulity along with the associated thrill when the first batch of engines went out of the door with cylinders which he had personally honed! In due course it became apparent that the company was not progressing as one might have wished. In hindsight, it’s possible to see that this was largely the result of the steady erosion of the overall model engine market which had begun almost unnoticed in the mid to late 1960’s. This was largely due to the increasing prominence of the far more expensive R/C field which progressively excluded the numerous entry level modellers (like myself in the late ‘50’s and early ‘60’s) who had hitherto supported the engine manufacturers through participation in the lower-cost disciplines of free flight and control line. With a staff of only two full time employees, things had come a long way from the halcyon years at Allen Engineering when there were 30 or so workers.

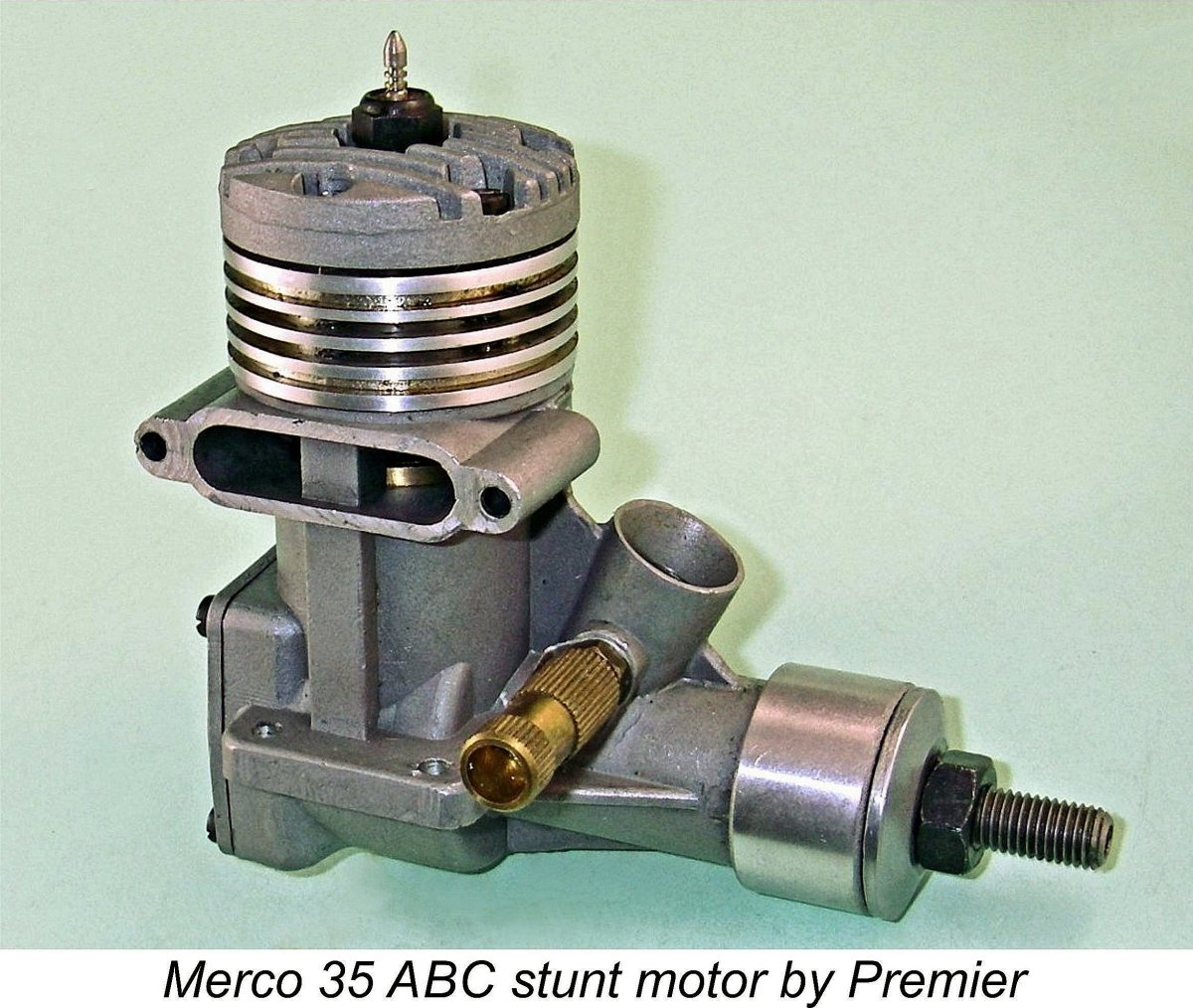

In a move designed to inject some extra capital into the business, an agreement was eventually reached whereby Ian would acquire a half share in the company by matching Reg’s investment. Ian’s hope was that his cash injection would be used to buy some more up-to-date machinery - perhaps some second-hand CNC equipment. Such an investment might enable the company to increase production to the extent that when Ian eventually left the railway, there would be a nice little business to which he could “retire” and live happily ever after. Ah, the best laid plans of mice and men!! In Ian’s time with Forest Engineering, he felt that MERCO were swimming against the current in trying to compete in the modern R/C market. After all, their flagship designs were now quite dated in design terms, while production methods had not progressed in the previous 25 years. The cheap ultra-modern units coming in from Taiwan and mainland Asia offered formidable competition, as did the updated models from countries like Japan. That said, the one area in which Ian felt that the company still had a solid edge was the C/L stunt market. There was still a widespread perception that the traditional loop scavenged engine remained the best format for C/L stunt, while the 60 displacement was now the size for the serious stunt flier to have. The MERCO 61 was the last such engine still in production in the world! Ian did persuade his partner Reg that the company should produce the MERCO 61 SS (Super Stunt), using data derived from an excellent research project undertaken by an American stunt enthusiast/engineer/academic named Scott Bair. This engine might have improved MERCO’s fortunes substantially. With only a venturi to produce instead of a throttle, it was significantly quicker and cheaper to produce than the R/C version. Since throttles are relatively complex components, it may come as a surprise to learn that making a throttle took about 20% of the manufacturing time needed to produce a complete R/C engine. Consequently, there was an immediate 25% increase in production/revenue at no cost, since the stunt model sold at the same price as the R/C motor, (and was still excellent value). However, production of the 61 SS was held back by a desire to cater to the home-market R/C fliers, which Reg continued to see as the main priority. The A-M 10 and 15 diesels were still in limited production at this time. The dies for the A-M 25/35 diesels had disappeared into the mists of antiquity, and it’s not known what became of them. A small run of A-M 25’s was produced by Forest Engineering using the remaining stocks of original crankcases. These are among the best A-M 25’s ever made, having excellent piston/cylinder assemblies, a testament to Reg Hills’ skill with the hone. Subsequently, Merco Engines (see below) produced a very few 25’s based on some sandcast cases made using one of the die-cast cases as a pattern. Unfortunately, no updated machinery was ever bought with Ian’s money. As the first experiments with ABC piston/cylinder technology commenced, Ian became aware of two things. Firstly, the business seemed to be in a state of suspended animation, neither going forward nor backward. Secondly, a company called Premier Plastics had begun to show an interest in the MERCO range. Premier already had a flourishing kit/accessories business, and now wanted to add engines to their portfolio.

Thus Premier Engines & Plastics was born. They arranged for the use of premises at Southminster in Essex. During their reign, various modifications to the engines were introduced. The ABC experiments initiated at Forest Engineering were brought to fruition, albeit ultimately in ABN form. The dies were modified to facilitate an increase in size of the 29/35 range to include a 40, while the 49 became a 50. The transfer passages on the 29/35/40 and 50/61 series were also significantly enlarged. The word MERCO was modified, incorporated in much larger letters on a diagonal raised plinth on the transfer passage. The cases of the larger engines were anodized black and the large MERCO lettering polished to make it stand out. All this was chiefly an exercise in marketing, but it also resulted in a further slight increase in weight, of which the engines already had plenty. Throughout it all, the now rather antiquated cross-flow loop scavenging system was retained.

However, the world had changed. The shops were not ordering in any significant numbers, saying “It’s a new world. Everything is R/C now”. So the thought was put to the retailers: “What would you think if the 10 and 15 were updated to feature Schnuerle porting, R/C throttles and silencers? And a glow version made available?” “Brilliant!” said all the shops. “We’ll sell thousands!”. So the deed was done, the model shops were informed, and Premier sat back waiting for the orders to flood in. Back came the responses, “Oh, all right, send us one, and if we sell it we’ll order another one”. Or even worse, “We’ll mention it, and if anyone wants one we’ll bring it in for them”. And of course, the vintage/classic market was lost completely - what enthusiast of that genre wants a “modern” Schnuerle-ported silenced R/C motor? There’s a seeming parallel here with the PAW company, who also introduced glow-plug versions of their engines which didn't remain in the range for very long. The one source of solace for collectors is the fact that these latter-day A-M and PAW engines are now quite rare and hence very collectable!

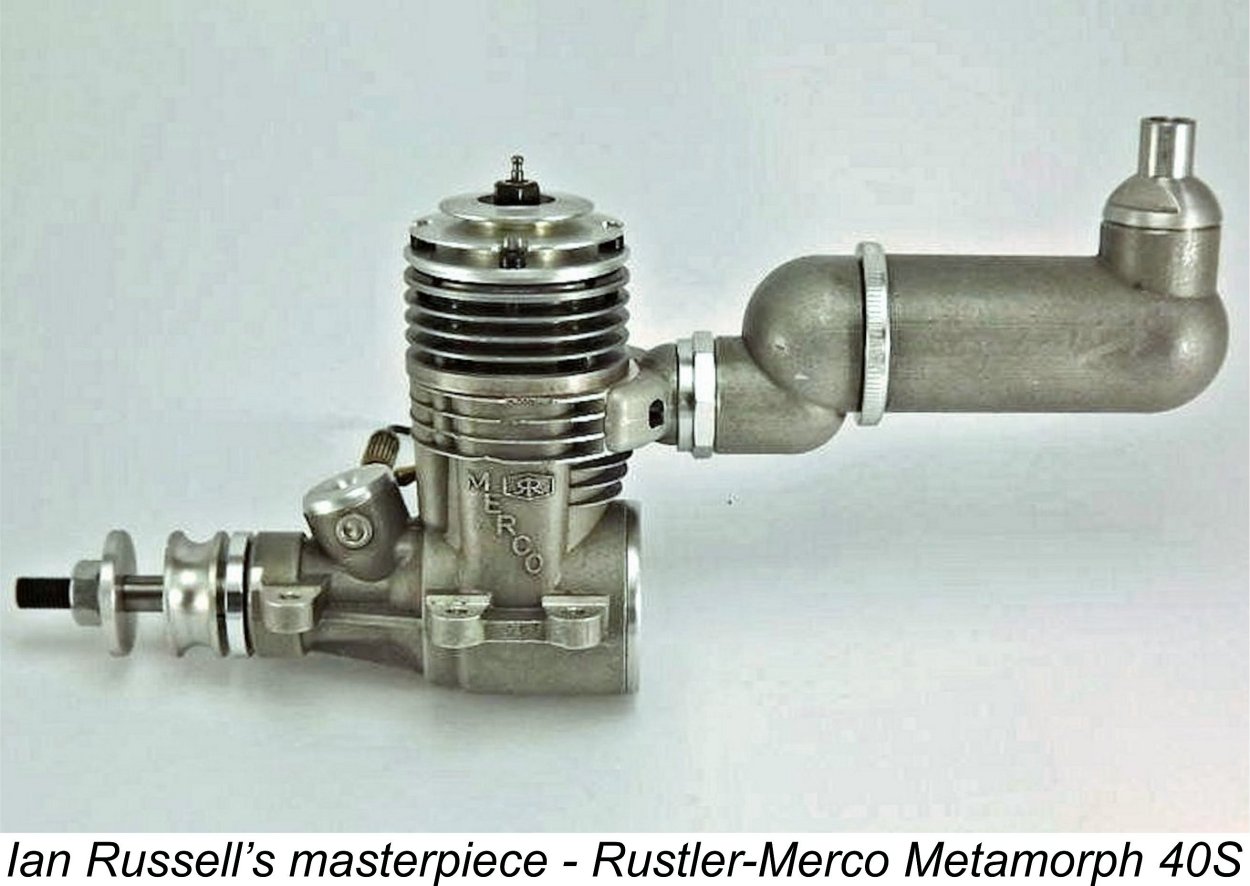

Since Reg and Ian were still waiting to be paid, they still owned A-M/MERCO. Reg moved the business to new premises and soldiered on doing sterling work with development and production, now trading under the name Merco Engines. During this time, preliminary sketches and drawings were prepared for a 10 cc side valve four stroke unit, a layout which resulted in an exceptionally small engine for the displacement. Diesel versions of the Merco’s were produced, and there was also a spark ignition version of the 61. Finally Reg designed and produced the awesome MERCO 120 Flat Twin. This necessitated the addition of yet more metal to the “front face” of the crankcase. Since this change was carried over to the single cylinder 61, even more weight was gained! Less than a hundred examples of the Twin were built, so if you own one you have a rare piece of model engine history. For his part, Ian had not lost his interest in model engines. He started trading on his own account under the name Rustler, sub-contracting the manufacturing work where the value was best and producing engines for niche markets which were too small to be exploited by the remaining major manufacturers. This entailed farming out components and doing final inspection, fitting, and assembly himself.

Ian’s first batch of Rustler-MERCO units was his Rustler-MERCO 61S, a true ABC C/L Stunt motor. He also came up with an all-new C/L stunt unit called the Rustler-MERCO Metamorph 40S. This was the first all-new design bearing the MERCO name for 40 years, and was so called because it boasted Ian’s unique silencer system which could be assembled in either side exhaust or rear exhaust configuration. One of these Metamorph 40’s placed second in the Classic Stunt event at the 2002 US National Championships.

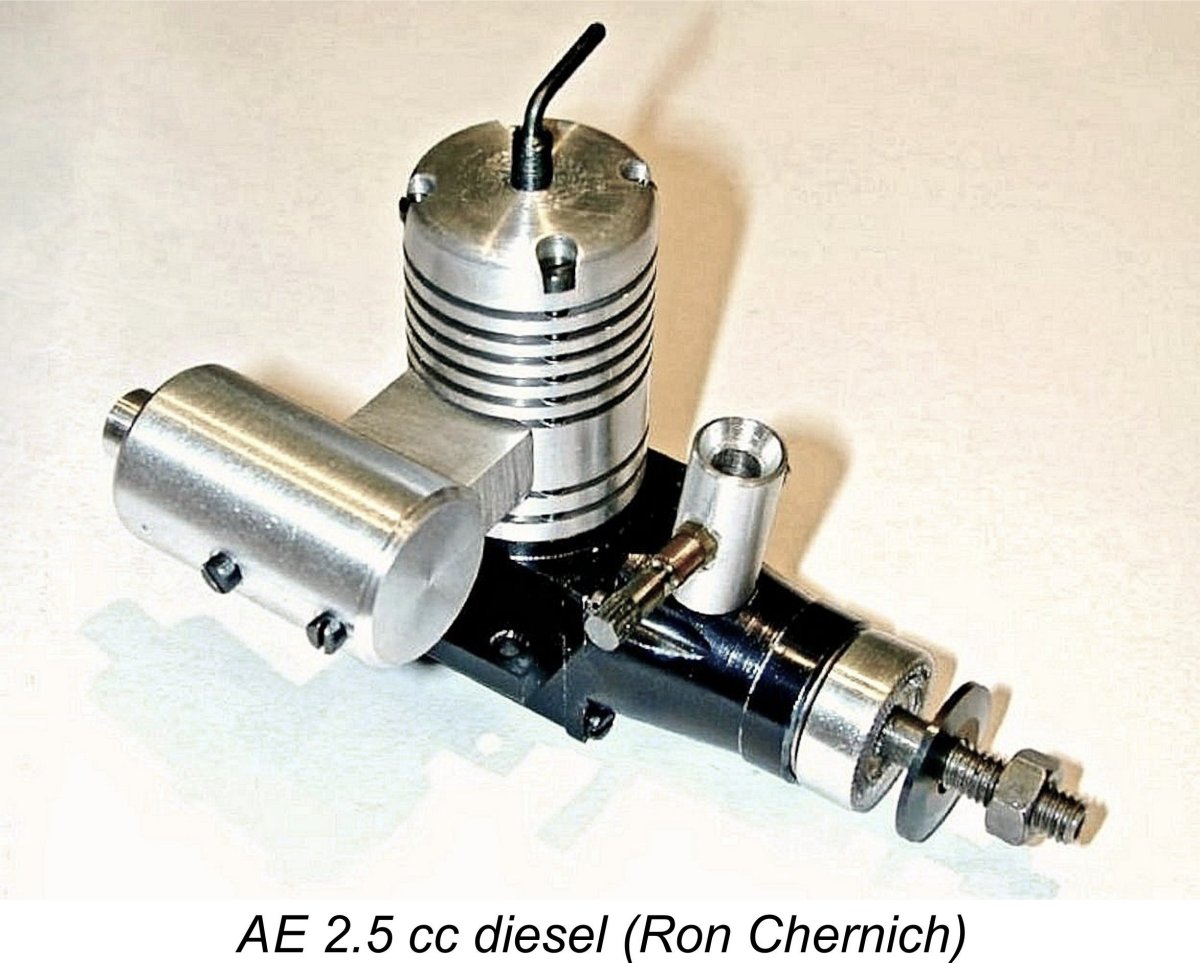

Dennis’s next venture was his Allen Engineering (AE) range of diesels which were manufactured during the early to mid 1990’s. These unusual engines were designed to be constructed without castings, all components being machined from bar stock. They appeared in a wide range of displacements from 0.1 cc through 0.2 cc, 0.5 cc, 1.0 cc, 1.5 cc up to 2.5 cc. They were very well made and ran nicely, although the tiny 0.1 cc model was a bit on the “finicky” side. As far as I’m aware, this was Dennis Allen’s final fling as a model engine manufacturer. A highly informative article on the AE series by the late Ron Chernich may be found on Ron’s fascinating “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. Conclusion Reviewing the broad history of the model engine manufacturing industry, one comes to realize that while there were many and varied engine-producing companies during the classic era, the number of individuals involved in engine design and production was surprisingly small. In America the classic example must be Bill Atwood - just one person who became involved with a truly amazing number of engines of different makes over a period of many decades. In Britain, model engine development really took off immediately after WW2, and we find many cases of a given individual moved from one company to another, or perhaps starting up their own business after initially working for another company. The A-M and MERCO stories and their antecedents provide notable examples of this tendency - the same names keep on cropping up. Sometimes there has been excellent cooperation between various companies which one would assume would be rivals. For example, it’s a little-known fact that a large number of the components of the early Dunham replica engines were made for them by MERCO, who also advised Dunham on suitable production methods and machinery as they moved towards 100% in house production. However you slice it, the combined A-M/MERCO story represents an extremely significant chapter in the history of model engine manufacturing in Britain. The engines remain a lasting testament to the combined abilities of Dennis Allen, Len Steward, Bill Morley, Ron Checksfield, Les Parker, Reg Hills, Ian Russell and their colleagues. Long may their fine engines continue to be seen and heard in action! _________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published March 2020 |

| |

In this article we’ll be taking a detailed look at the first decade or so of the Allen-Mercury (A-M) model engine manufacturing venture which supplied a series of excellent engines to the British and overseas modelling public during the classic era. Apart from manufacturing a succession of very useful and highly regarded diesel models, the company also marketed an intriguing but unsuccessful .049 cuin.

In this article we’ll be taking a detailed look at the first decade or so of the Allen-Mercury (A-M) model engine manufacturing venture which supplied a series of excellent engines to the British and overseas modelling public during the classic era. Apart from manufacturing a succession of very useful and highly regarded diesel models, the company also marketed an intriguing but unsuccessful .049 cuin.  The Allen-Mercury (A-M) model engine manufacturing venture was established in 1954 as a collaboration between three people - Dennis Allen, Henry J. Nicholls, and Len Steward. All three individuals were experienced hands-on power modellers who knew each other very well as a result of their shared membership in the very active West Essex club. That club could boast a number of very prominent members of the British modelling community among its membership. Apart from the above-named individuals, both Eddie Keil and Ron Moulton were also members.

The Allen-Mercury (A-M) model engine manufacturing venture was established in 1954 as a collaboration between three people - Dennis Allen, Henry J. Nicholls, and Len Steward. All three individuals were experienced hands-on power modellers who knew each other very well as a result of their shared membership in the very active West Essex club. That club could boast a number of very prominent members of the British modelling community among its membership. Apart from the above-named individuals, both Eddie Keil and Ron Moulton were also members.

personal ties with Henry J. Nicholls and Mercury Models, and in July 1954 this association resulted in the introduction of Allen’s first diesel under his own name, the Mk. I Allen-Mercury (A-M) 25. This was of course the very design which had been rejected by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. It’s interesting to contemplate how differently matters might have unfolded for all concerned if it had been released in early 1954 as the AMCO 2.5!

personal ties with Henry J. Nicholls and Mercury Models, and in July 1954 this association resulted in the introduction of Allen’s first diesel under his own name, the Mk. I Allen-Mercury (A-M) 25. This was of course the very design which had been rejected by Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. It’s interesting to contemplate how differently matters might have unfolded for all concerned if it had been released in early 1954 as the AMCO 2.5!

This was undeniably a rather complicated and somewhat “fiddly” means of achieving a very simple end. Its chief merit was the fact that it eliminated the development of any installation stresses within the upper cylinder walls - always a potential cause of bore distortion, especially with a cast iron liner. It also discouraged unnecessary tampering with the engine by curious owners!

This was undeniably a rather complicated and somewhat “fiddly” means of achieving a very simple end. Its chief merit was the fact that it eliminated the development of any installation stresses within the upper cylinder walls - always a potential cause of bore distortion, especially with a cast iron liner. It also discouraged unnecessary tampering with the engine by curious owners!

A final comment on the A-M 35 is the fact that while most examples feature maroon or (later) red-anodized cooling jackets, a few of the earlier examples (like that illustrated at the right) sport bright pink components. The late Ron Chernich voiced the quite rational suspicion that this was not the intended colour and that one sizeable batch of jackets went through an anodizing bath that was less acidic than optimal for color take-up. For whatever reason, the relatively uncommon pink 'uns do certainly stand out from the crowd!

A final comment on the A-M 35 is the fact that while most examples feature maroon or (later) red-anodized cooling jackets, a few of the earlier examples (like that illustrated at the right) sport bright pink components. The late Ron Chernich voiced the quite rational suspicion that this was not the intended colour and that one sizeable batch of jackets went through an anodizing bath that was less acidic than optimal for color take-up. For whatever reason, the relatively uncommon pink 'uns do certainly stand out from the crowd!  The next model to appear in the A-M range was the one that really put Allen-Mercury on the map - the A-M 10. This iconic unit made its appearance in May 1956 and promptly set the British modelling world on its ear! To all appearances, it was nothing special - just a simple radially-ported plain bearing 1 cc FRV diesel of completely conventional design. However, by the standards of its day there was nothing at all conventional about its performance! Even designer Dennis Allen confessed to having been surprised!

The next model to appear in the A-M range was the one that really put Allen-Mercury on the map - the A-M 10. This iconic unit made its appearance in May 1956 and promptly set the British modelling world on its ear! To all appearances, it was nothing special - just a simple radially-ported plain bearing 1 cc FRV diesel of completely conventional design. However, by the standards of its day there was nothing at all conventional about its performance! Even designer Dennis Allen confessed to having been surprised!  There was much speculation regarding the basis for the engine’s unexpectedly superior performance. To all appearances, it was a completely conventional sports design similar to many others, with no particularly noteworthy features which would suggest such an output. Most observers put its performance down to the unusually thick Meehanite cylinder which was well able to resist both assembly and thermal distortion. The excellent piston/cylinder fit (well done, Len Steward!) also drew its share of positive commentary.

There was much speculation regarding the basis for the engine’s unexpectedly superior performance. To all appearances, it was a completely conventional sports design similar to many others, with no particularly noteworthy features which would suggest such an output. Most observers put its performance down to the unusually thick Meehanite cylinder which was well able to resist both assembly and thermal distortion. The excellent piston/cylinder fit (well done, Len Steward!) also drew its share of positive commentary.  Understandably, the very positive reception accorded to all three A-M models to reach the market by this time placed the company’s production capabilities under considerable pressure. In May 1957 this led to a move into new expanded premises at 28 Angel Factory Colony, still in Edmonton. The financing of this move was arranged in part by bringing in Les Parker, who had been involved in light engineering for many years, latterly specializing in the production of such items as needle valve assemblies for a number of model engine manufacturers. The company was to remain at this location for some years thereafter.

Understandably, the very positive reception accorded to all three A-M models to reach the market by this time placed the company’s production capabilities under considerable pressure. In May 1957 this led to a move into new expanded premises at 28 Angel Factory Colony, still in Edmonton. The financing of this move was arranged in part by bringing in Les Parker, who had been involved in light engineering for many years, latterly specializing in the production of such items as needle valve assemblies for a number of model engine manufacturers. The company was to remain at this location for some years thereafter.  The A-M 15 was essentially identical to the A-M 10 apart from having a larger bore of 0.518 in. (13.16 mm) to go along with an unchanged stroke of 0.430 in. (10.92 mm). This yielded a displacement of 1.49 cc (0.0906 cuin.). The new model sported a blue-anodized head and back tank to distinguish it from the green-headed A-M 10 - the two engines were otherwise difficult to distinguish from each other. The only other change was a small increase in the gudgeon pin diameter, with a revised conrod to match.

The A-M 15 was essentially identical to the A-M 10 apart from having a larger bore of 0.518 in. (13.16 mm) to go along with an unchanged stroke of 0.430 in. (10.92 mm). This yielded a displacement of 1.49 cc (0.0906 cuin.). The new model sported a blue-anodized head and back tank to distinguish it from the green-headed A-M 10 - the two engines were otherwise difficult to distinguish from each other. The only other change was a small increase in the gudgeon pin diameter, with a revised conrod to match.  The tester for “Model Aircraft” (almost certainly Peter Chinn) didn’t get his

The tester for “Model Aircraft” (almost certainly Peter Chinn) didn’t get his

The design with which they became associated was that of the American Wen-Mac .049, then in its seventh year of production. Their A-M .049 offering proved to be a virtual clone of the contemporary Series 8 Wen-Mac Mk. II unit, even down to the Rotomatic spring starter. It differed only in the cast-on model identification on the crankcase and the British thread used on the spraybar assembly. The engine was first announced in July 1959, finally appearing in the hobby shops in September 1959 at a list price of £1 19s 6d (£1.97).

The design with which they became associated was that of the American Wen-Mac .049, then in its seventh year of production. Their A-M .049 offering proved to be a virtual clone of the contemporary Series 8 Wen-Mac Mk. II unit, even down to the Rotomatic spring starter. It differed only in the cast-on model identification on the crankcase and the British thread used on the spraybar assembly. The engine was first announced in July 1959, finally appearing in the hobby shops in September 1959 at a list price of £1 19s 6d (£1.97).

Despite Warring’s and Chinn’s positive comments, the engine failed to achieve any real commercial success. Too many British modellers noted that awkwardly-placed and very vulnerable needle valve, the inconvenient arrangements for beam mounting and above all, the very bulky, heavy and completely unnecessary starter. I was one of them, and I recall my own reaction in exactly those terms. I wasn’t interested, and neither was anyone else………..

Despite Warring’s and Chinn’s positive comments, the engine failed to achieve any real commercial success. Too many British modellers noted that awkwardly-placed and very vulnerable needle valve, the inconvenient arrangements for beam mounting and above all, the very bulky, heavy and completely unnecessary starter. I was one of them, and I recall my own reaction in exactly those terms. I wasn’t interested, and neither was anyone else………..  Despite this effort, the damage was done. The A-M .049 found little success in the British market, being completely overwhelmed by the totally gutless but nonetheless very successful

Despite this effort, the damage was done. The A-M .049 found little success in the British market, being completely overwhelmed by the totally gutless but nonetheless very successful

Ron evidently did have one abiding interest……….the quest for technical knowledge. He seems to have spent most of his time in his local public library, reading anything and everything of a technical nature that he could lay hands on. He also possessed the most amazingly retentive mind. It appears that once a set of facts were absorbed into his brain, they were there permanently and could be recalled as needed. To complement this facility, he also possessed the intelligence and natural ability required to apply his knowledge to the resolution of technical problems and design issues far better than most professionals, despite having no formal training.

Ron evidently did have one abiding interest……….the quest for technical knowledge. He seems to have spent most of his time in his local public library, reading anything and everything of a technical nature that he could lay hands on. He also possessed the most amazingly retentive mind. It appears that once a set of facts were absorbed into his brain, they were there permanently and could be recalled as needed. To complement this facility, he also possessed the intelligence and natural ability required to apply his knowledge to the resolution of technical problems and design issues far better than most professionals, despite having no formal training. The MERCO venture was apparently born from a suggestion made by Bill Morley to Ron Checksfield in early 1958 that they should design and produce a British .35 cuin. glow-plug C/L stunt engine. Bill had previously attempted to interest a number of established British manufacturers in pursuing such a venture, but without success. It had become apparent to Bill that he was on his own. However, he recognized the fact that he needed expert help, hence his approach to Ron Checksfield.

The MERCO venture was apparently born from a suggestion made by Bill Morley to Ron Checksfield in early 1958 that they should design and produce a British .35 cuin. glow-plug C/L stunt engine. Bill had previously attempted to interest a number of established British manufacturers in pursuing such a venture, but without success. It had become apparent to Bill that he was on his own. However, he recognized the fact that he needed expert help, hence his approach to Ron Checksfield. The first .35 cuin. prototype of the new engine was completed only 10 days prior to the 1958 British National Championship meeting at RAF Waterbeach. Bill Morley was working at the same time on the construction of a new Bob Palmer Thunderbird model to accommodate the engine. The just-completed model was united with the prototype engine only 24 hours before the Gold Trophy was set to commence! When they arrived at Waterbeach, the model/motor combination had never flown.

The first .35 cuin. prototype of the new engine was completed only 10 days prior to the 1958 British National Championship meeting at RAF Waterbeach. Bill Morley was working at the same time on the construction of a new Bob Palmer Thunderbird model to accommodate the engine. The just-completed model was united with the prototype engine only 24 hours before the Gold Trophy was set to commence! When they arrived at Waterbeach, the model/motor combination had never flown. The company’s original activity was the production of spirit blowlamps and other soldering equipment. The accompanying 1955 advertisement typifies their offerings in this line of business. In 1955 they expanded their activities to include the manufacture of a range of petrol-driven heavy-duty power tools. They first became involved with model engines in late 1958, when Bill Morley and Ron Checksfield arranged for production of the then-new MERCO 29 and 35 stunt glow-plug engines to take place at 1A Balfour Mews as noted previously.

The company’s original activity was the production of spirit blowlamps and other soldering equipment. The accompanying 1955 advertisement typifies their offerings in this line of business. In 1955 they expanded their activities to include the manufacture of a range of petrol-driven heavy-duty power tools. They first became involved with model engines in late 1958, when Bill Morley and Ron Checksfield arranged for production of the then-new MERCO 29 and 35 stunt glow-plug engines to take place at 1A Balfour Mews as noted previously.  Bi-Metals continued to occupy the premises at 1A Balfour Mews throughout the entire period under discussion here. They were still very much a going concern when they began to be cited as the spares and service agents for the

Bi-Metals continued to occupy the premises at 1A Balfour Mews throughout the entire period under discussion here. They were still very much a going concern when they began to be cited as the spares and service agents for the

It was only at this point that the manufacture of the A-M and MERCO ranges was finally consolidated under one management. It seems likely that manufacture of the MERCO engines continued to take place at the established Bi-Metals facility at 1A Balfour Mews on Bridge Street, while the production of the Allen-Mercury range presumably carried on at the expanded Allen-Mercury factory at 30 Lea Valley Trading Estate on Angel Road in Edmonton. Certainly, the separate identity of the two ranges was maintained. The company Directors at this time were given as D. Jackson-Fielding (Managing Director); T. A. Munn, (Secretary), D. J. Allen; L.C. Parker and E. B. Payne.

It was only at this point that the manufacture of the A-M and MERCO ranges was finally consolidated under one management. It seems likely that manufacture of the MERCO engines continued to take place at the established Bi-Metals facility at 1A Balfour Mews on Bridge Street, while the production of the Allen-Mercury range presumably carried on at the expanded Allen-Mercury factory at 30 Lea Valley Trading Estate on Angel Road in Edmonton. Certainly, the separate identity of the two ranges was maintained. The company Directors at this time were given as D. Jackson-Fielding (Managing Director); T. A. Munn, (Secretary), D. J. Allen; L.C. Parker and E. B. Payne. It didn’t take Ron Checksfield long to commence the development of the larger model that he had envisioned all along - the MERCO 61. Prototypes of this model were completed and ready for testing by June 1963, with test examples appearing at both the 1963 British Team Trials and the British National Championship meeting for that year. After further field testing, the engine finally reached production status in the first part of 1964. It proved to be another outstanding success for the manufacturers.

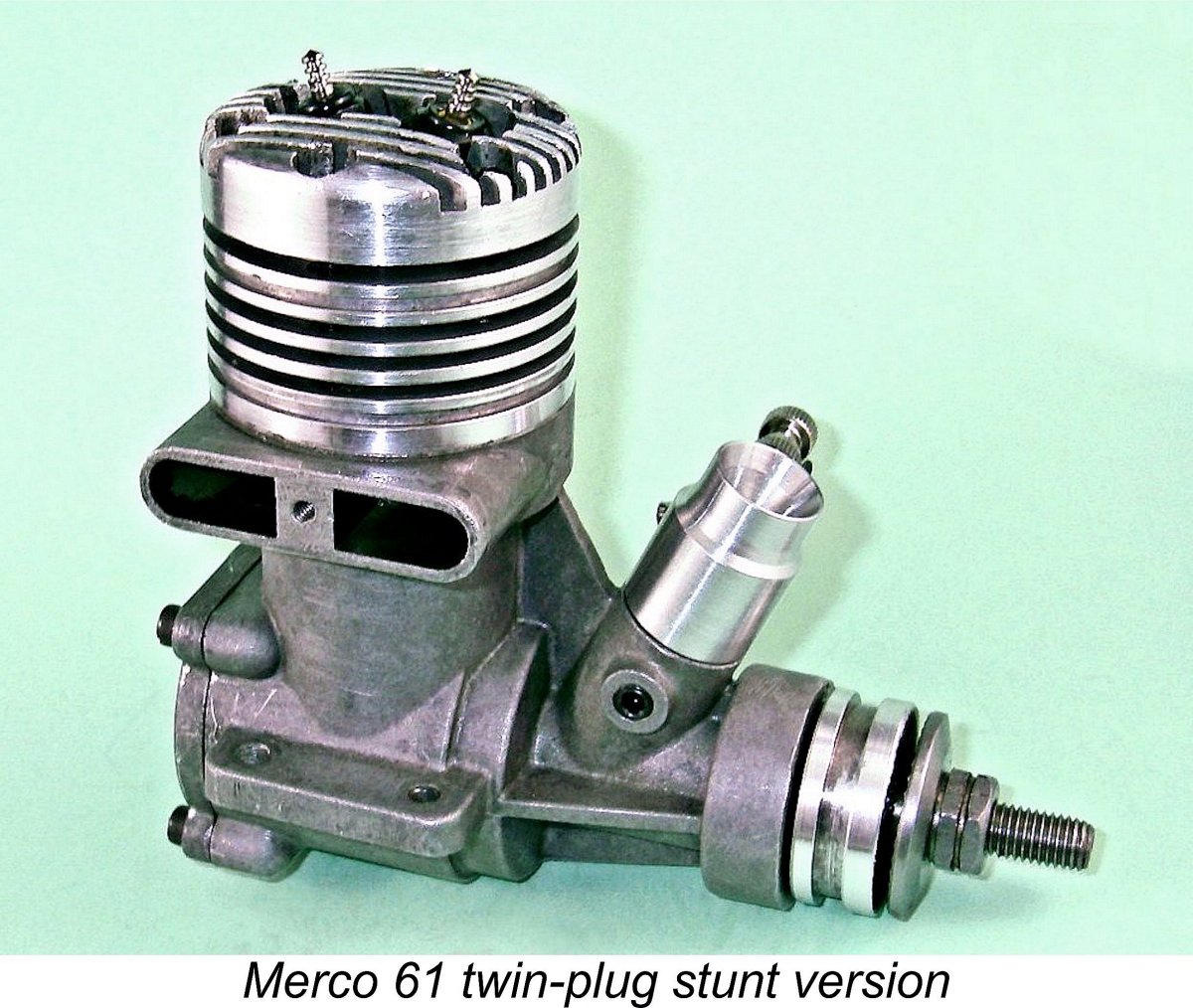

It didn’t take Ron Checksfield long to commence the development of the larger model that he had envisioned all along - the MERCO 61. Prototypes of this model were completed and ready for testing by June 1963, with test examples appearing at both the 1963 British Team Trials and the British National Championship meeting for that year. After further field testing, the engine finally reached production status in the first part of 1964. It proved to be another outstanding success for the manufacturers. Thereafter, the company passed through a series of ownership changes, with modifications being made along the way to the various engines in the range. A notable design change was the 1965 introduction of a twin-plug head for the MERCO 49 and 61 models. These required a somewhat different operational approach, as detailed in my separate article on

Thereafter, the company passed through a series of ownership changes, with modifications being made along the way to the various engines in the range. A notable design change was the 1965 introduction of a twin-plug head for the MERCO 49 and 61 models. These required a somewhat different operational approach, as detailed in my separate article on

Premier made an offer to acquire the range which Ian considered to be acceptable. He therefore agreed to sell his half of the business. The deal specified that Ian was to bow out altogether, while after receiving his payment for his share of the company, Reg was to remain as a Director and General Manager. During the Premier years Ian had absolutely no input to or connection with the company, except that until he finally received his money he still legally owned half of it!

Premier made an offer to acquire the range which Ian considered to be acceptable. He therefore agreed to sell his half of the business. The deal specified that Ian was to bow out altogether, while after receiving his payment for his share of the company, Reg was to remain as a Director and General Manager. During the Premier years Ian had absolutely no input to or connection with the company, except that until he finally received his money he still legally owned half of it! The now-venerable A-M 10 and 15 diesels were also brought into the modern world by modifying the dies to accommodate a silencer, a “built-in” throttle, and ultimately Schnuerle porting. This exercise represents a classic example of the dilemmas facing an engine manufacturer in a changing market. There was a steady if relatively modest ongoing demand for the 10 and 15 (the 25 and 35 had been dropped apart from the few A-M 25 "specials" mentioned earlier). The engines appealed to purchasers primarily because they were in effect classic vintage diesels with a pedigree which remained in current production and hence readily available. They thus appealed to “Classic” and “Nostalgia” enthusiasts.