|

|

Strong-Man's Special - the "K" Vulture

This design has carried a somewhat chequered reputation down through the years, being noted for its handling challenges as well as a few structural issues which have reared their ugly heads periodically. This has not prevented it from becoming quite a sought-after collector's item. In fact, it is one of my own personal favourites, not least because of the immense satisfaction to be derived from getting on top of the operation of one of these units! Before going any further, it’s necessary to eliminate one potential source of confusion. This is the fact that the far later Aurora model engines from Calcutta, India were also marketed under the K designation, being identified by the letter K followed by their displacements. The use of the letter K in that case stood for the Kumar family which was responsible for the development of that range. The important point to make here is that the early post-WW2 "K" range from Gravesend now under discussion and the later K series engines manufactured in India have absolutely nothing in common beyond the use of the letter K. I’ve covered the Aurora/Kumar story in detail in a separate article to be found on this website. Returning now to my main subject here, I'll be looking into the basis for the "K" Vulture's chequered reputation through first-hand evaluations of a number of examples to which I have access as well as my own fairly extensive past experience in actually using these engines. I'll also try to sort out the production history of the Vulture in terms of the various forms in which it appeared. Finally I'll offer such advice as I can to present-day owners who may wish to give one of these cantankerous beasts a run. It can be done, trust me!

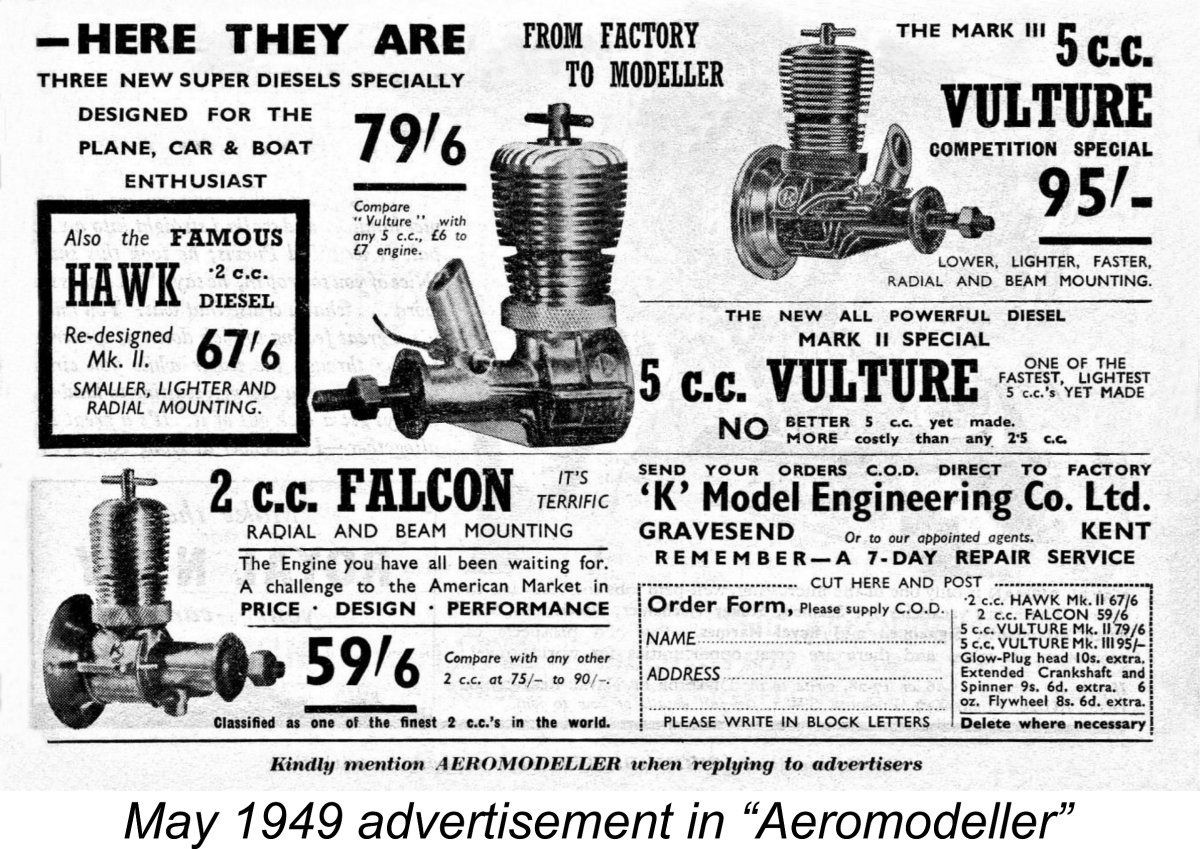

I'd also like to pay tribute to my other much-missed Aussie friend and mentor, the late MEN Editor Ron Chernich, for his enthusiastic assistance in seeking out those elusive advertisements of over 70 years ago. As will become apparent, those advertisements constitute perhaps the most important body of evidence informing the telling of this story. Much appreciated, mate!

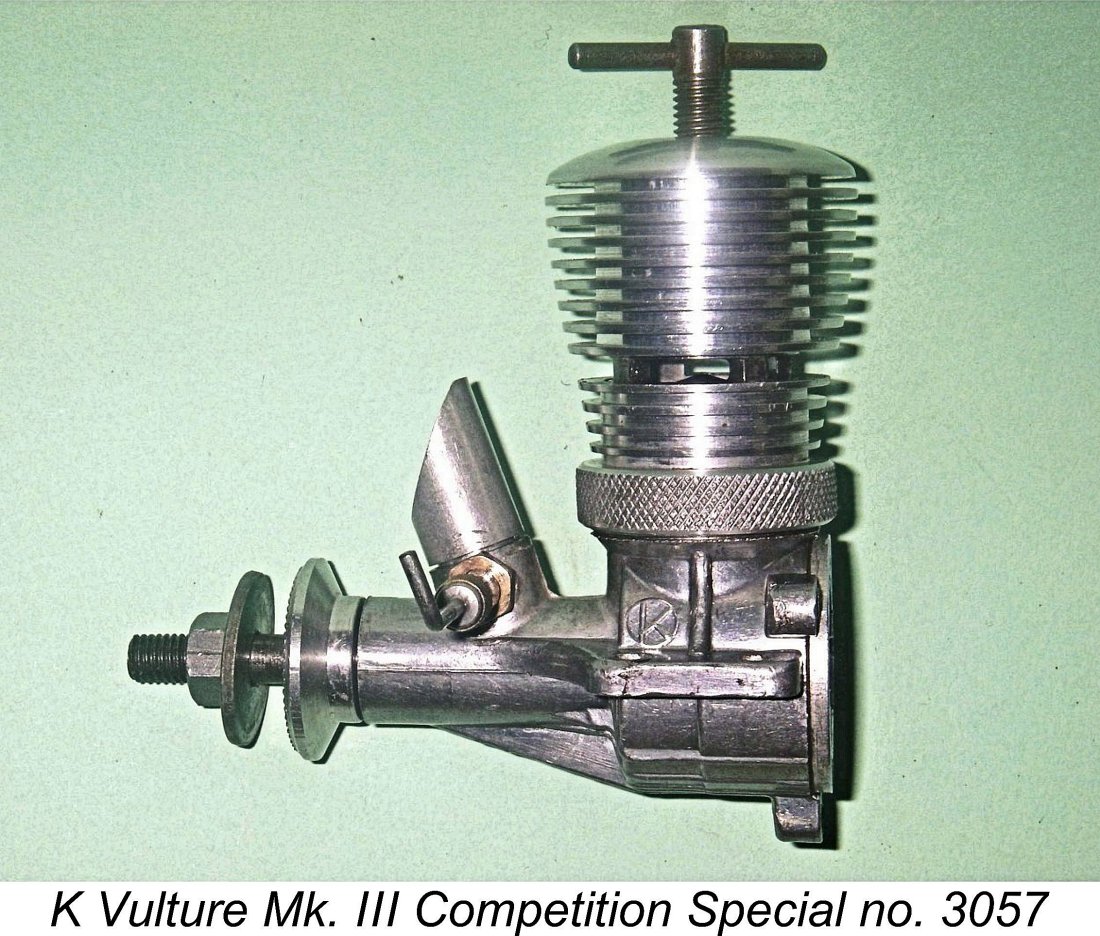

Brian Cox was able to supply some additional serial numbers which extended the known production figures for the Mk. I Vulture. Perhaps even more significantly, my late friend Paul Rossiter supplied an actual example of the Mk. III "Competition Special" version of the Vulture which added greatly to my understanding of the changes embodied in that model. Finally, Alan Strutt kindly supplied an interesting variant of the Mk. I Vulture which contributed greatly to my understanding of the issues of production figures, factory upgrades and serial numbering. The additional information is incorporated in the text below. My very sincere thanks to Brian, Alan, and Paul! So why this updated edition of the article, years after its initial publication? For two reasons - first, a number of new facts together with some fresh insights have surfaced during the intervening years. These deserve to be recorded. Since Ron didn’t leave us with the encryption codes for MEN, it’s no longer possible to update articles on that site, forcing me to do it here. And second, there are disquieting signs that the material on MEN is beginning to degrade to a small but noticeable degree. A few of the functions there no longer work properly, while access to a few of the articles is becoming impaired. Since administrative access to the site is no longer possible, neither is any maintenance activity. Consequently, more glitches will doubtless surface as time goes by. For this reason, I have begun the process of transferring some of my material from MEN to my own site. The present article is an example of this process in action and there have been others, with more certain to follow. Now, on with the story! First, a little background is in order. Background

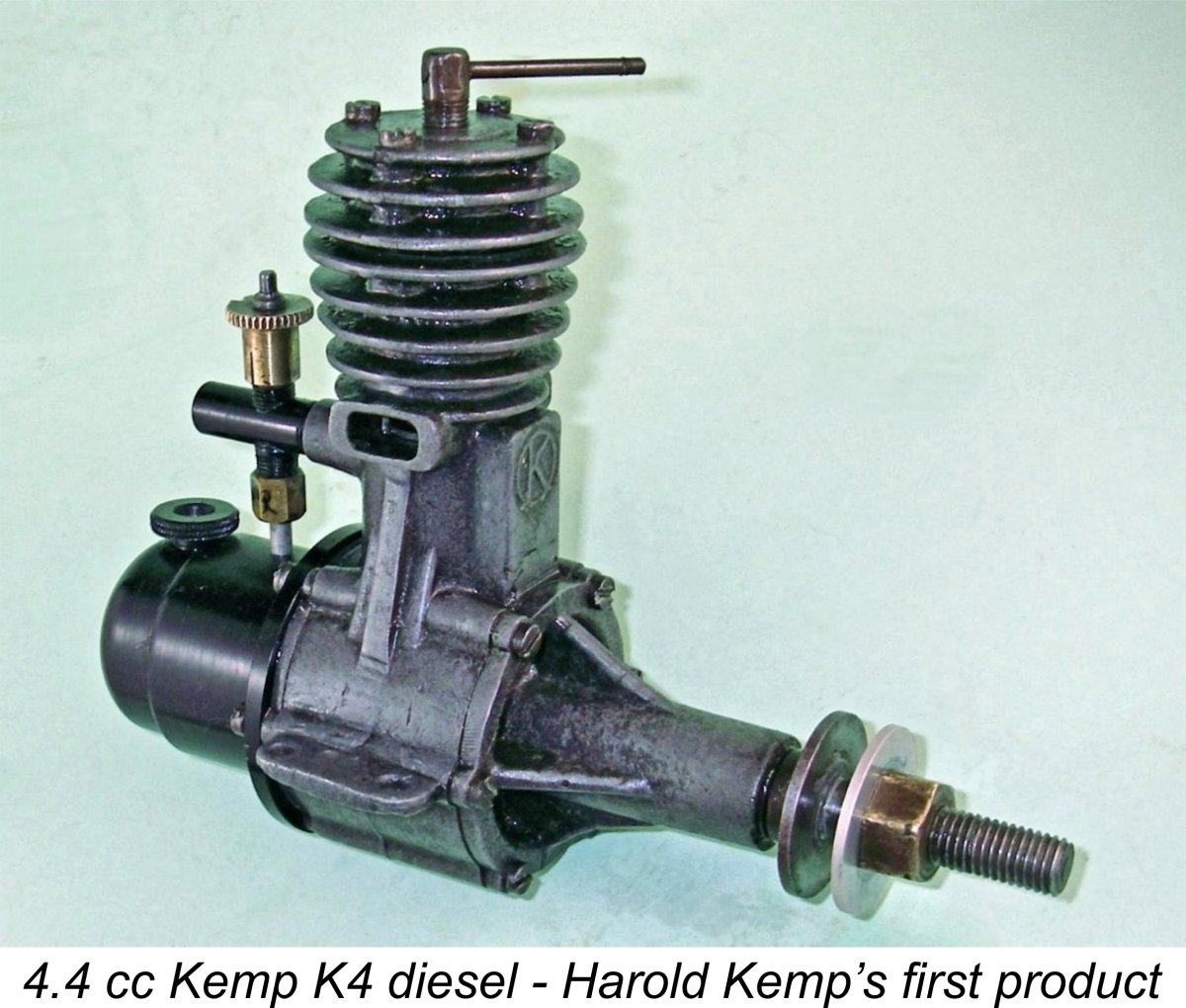

As one might expect from an individual with such a background, Steward's influence over the affairs of the re-named company was very much directed towards the development and manufacture of engines suitable for use in control-line stunt flying. This made complete business sense given the fact that control-line stunt was probably the fastest-growing branch of aeromodelling in Britain during the late 1940's. How times change ............the sideport engines which had been the primary focus of the former Kemp Engines company in no way met the requirements of this burgeoning field of activity, and their production was soon terminated once Steward took over.

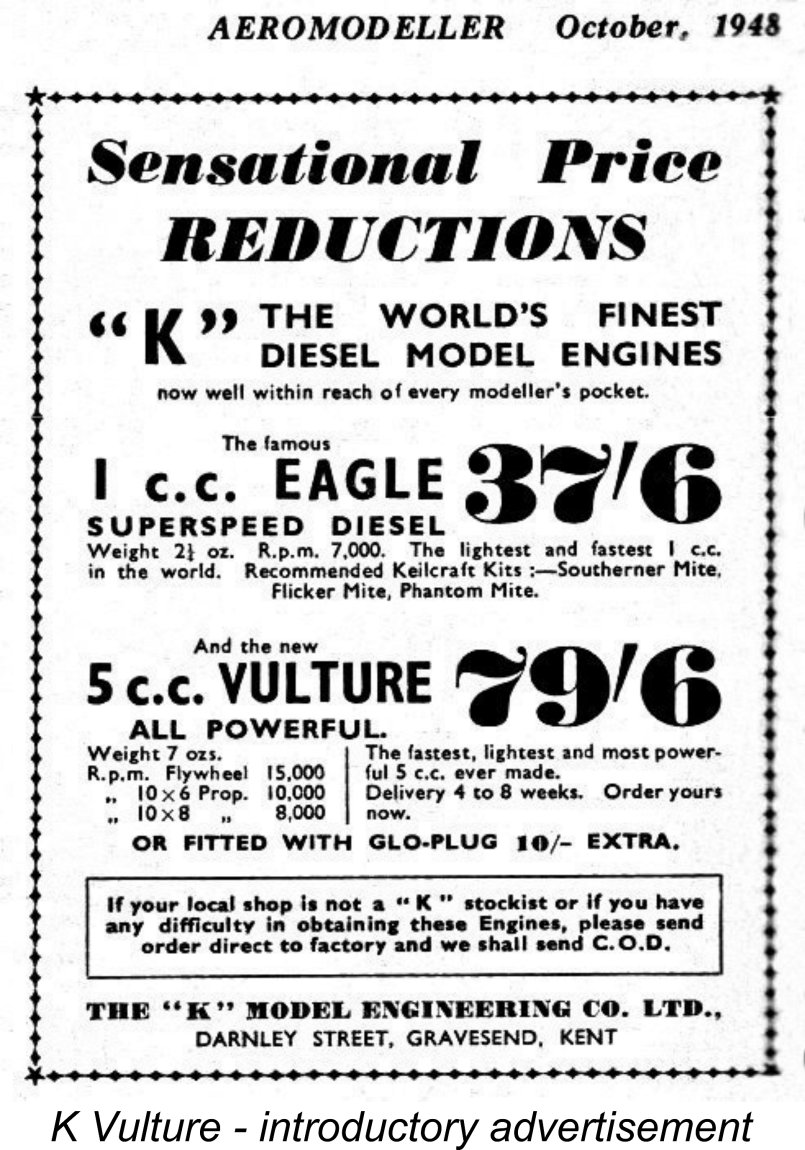

Accordingly, Steward immediately set about the development of an updated range of engines featuring this form of induction. These were to be sold under the “K” trade-name. Kemp’s sideport 4.4 cc K4 model had already been dropped well prior to Steward taking over, and plans now went ahead at full speed for the replacement of both that design and the sideport 1 cc Eagle model which had appeared in March 1948 and continued in production for a time following the take-over pending its December 1948 replacement by the FRV Eagle Mk. II. The little sideport 0.25 cc Kemp Hawk Mk. I, which was always aimed at the free-flight market, was still selling well at the time and its production too was continued The first hint of what was to come was dropped in an initial advertisement by the new company which appeared in the 1948 issue of the annual compendium “Model Aviation”. This advertisement focused upon the little sideport "K" (formerly Kemp) Hawk which remained in production, presumably to maintain a cash flow while new models were developed. However, there was also a rather cloak-and-dagger reference to a pair of new models which would shortly be appearing - the 1 cc Eagle in its Mk. II FRV form and the 5 cc Vulture which forms my present subject. No details were provided, but the advertisement claimed that these two forthcoming designs would be "the talk of the model world!" Quite an advance billing to live up to! This announcement seems to date that advertisement to September 1948 - there had been no mention of these new models in the company’s August advertisement in “Aeromodeller”, which focused on the Eagle Mk. I and the sideport Hawk. Unlike some other announcements of a similar nature for models which never materialized, this one proved to be well founded. Both the Vulture and the FRV Eagle Mk. II duly made their market appearances prior to the end of 1948. The Eagle Mk. II was a replacement for the discontinued sideport 1 cc diesel of the same name, while the Vulture was clearly intended as a updated replacement for the old sideport K4 diesel of 4.4 cc displacement. From this point onwards, I’ll focus entirely upon the Vulture. The Mk. I Vulture - Description

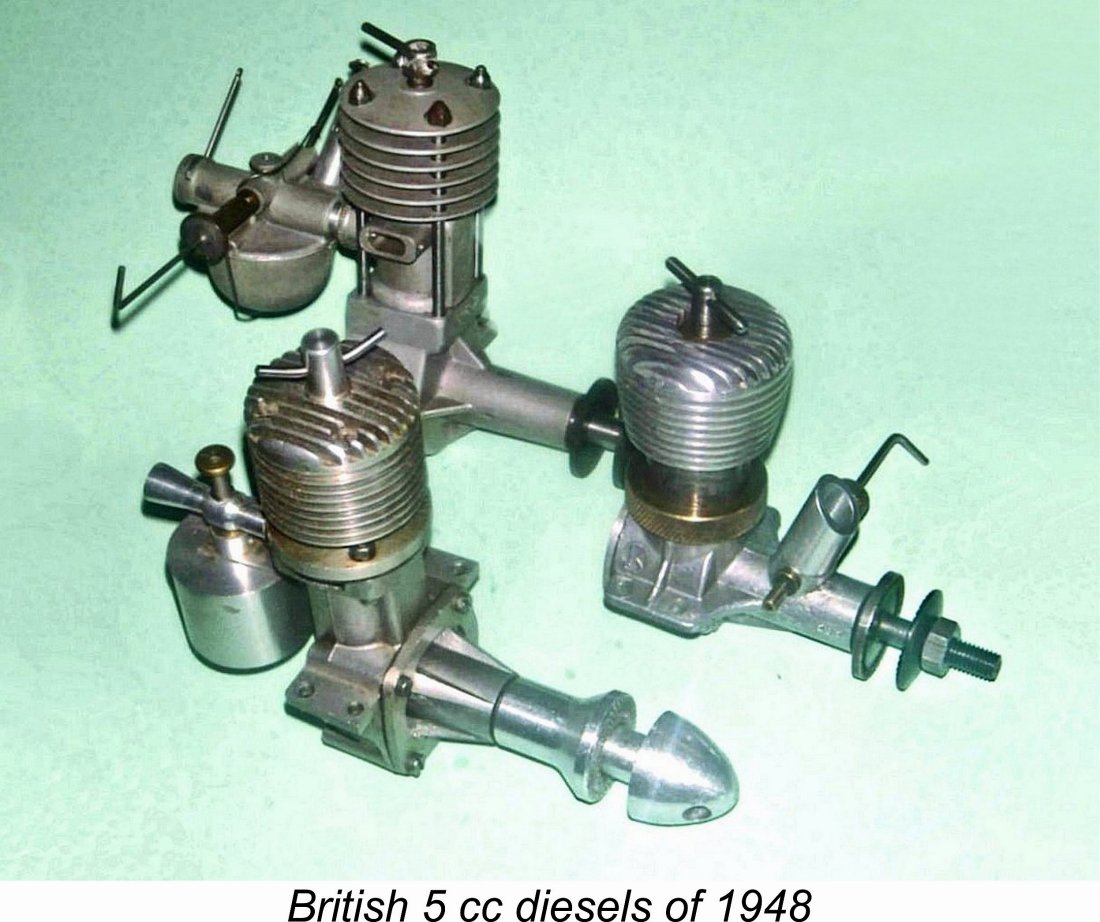

During the period of which we are speaking, British precision engineers persisted in working to nominal dimensions expressed in fractions of an inch despite their invariable designation of the engines’ displacements in cc. Go figure ……….nominal bore and stroke of the Vulture were 0.750 in. (3/4 in. - 19.05 mm) and 0.6875 in. (11/16 in. - 17.46 mm) respectively for a displacement of 4.98 cc (0.304 cu. in.). These figures put the Vulture just over the 0.299 cu. in. limit for US Class B competition, but the engine complied with the British Class B rules (5 cc displacement limit) and there's no evidence that the "K" Model Engineering Co. ever seriously contemplated exports to the USA, although they did export to British Commonwealth markets such as Australia. These figures also put the Vulture well and truly into the "short-stroke" category at a time when the British market was still dominated by long-stroke designs.

This simplicity of construction allowed the makers to offer the engine for sale at a very competitive price of £3 19s 6d (£3.98), which presented a notable contrast to the whopping £7 19s 6d ((£7.98) price tag of the ETA 5 diesel and even the £4 19s 6d (£4.98) cost of the D-C Wildcat Mk. II, to take just two contemporary examples. Both of those units appear in the accompanying illustration.

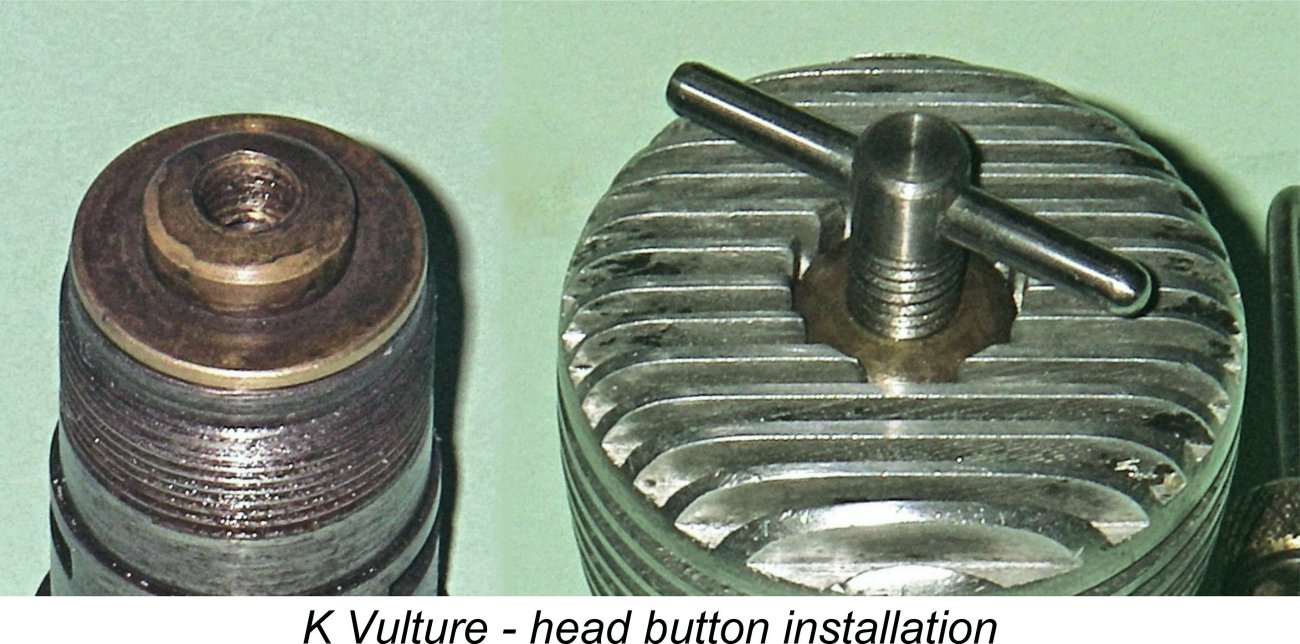

Unusually, there was no "spigot" length below this flange to locate the cylinder laterally on the crankcase. Instead, the cylinder was both secured and laterally located by an internally-threaded ring having a shoulder which bore on the top of the cylinder flange. This ring screwed onto an externally threaded portion of the upper crankcase. The ring quickly became known colloquially as the "dog collar", a highly descriptive term which has stuck to this day! The dog collar on the Mk. I Vulture was made of brass and took the form of a simple knurled ring with an internal shoulder above the threaded portion. A gasket between the cylinder base flange and the upper crankcase deck ensured a good seal. The upper cylinder was equipped with a conventional contra-piston made of hardened steel. This gives rise to one of the Vulture's more annoying handling characteristics - the steel contra-piston tends to stick in the bore when the engine warms up. This is not good, because with this design it's generally necessary to reduce compression considerably as the engine warms up. It appears that some owners have taken steps to relieve the fit by lapping or honing, and examples with very loose contra pistons are not infrequently encountered as a result, even in engines which have clearly done relatively The fully machined cylinder jacket featured both barrel fins and head fins combined in a single light alloy component. Unusually, the thread for the compression screw was not formed in the centre of the head - instead, the cylinder was topped by a hard brass disc with a central spigot which protruded through an oversized hole in the centre of the head. This brass disc was sandwiched between the head and the top of the cylinder when the jacket was screwed down. The 1/4-26 BSF thread for the comp screw was formed in the protruding spigot rather than in the head itself - a good feature, since a worn thread could be rectified simply by replacing the brass insert rather than the entire cylinder jacket.

The arrangements described above had the advantage of allowing the cylinder to be tightened in a radial configuration which ensured that the head fins were in their correct fore-and-aft alignment when the cooling jacket was tightened down. The cylinder alignment was easily re-adjusted using the dog collar if the relationship between the jacket and the cylinder changed over time due to repeated tightening. Do not decide against buying a Vulture simply because the head fins are misaligned - it's easily sorted!

This arrangement was perhaps less than ideal in that it provided minimal directional control of the incoming charge and must have resulted in significant losses of unburned mixture out of the exhaust ports. You can actually both see and smell this when the engine is running. The design must also have resulted in reduced transfer gas velocities due to the extreme circumferential length of the transfer port. In addition, it militated against the retention of a prime in the cylinder since there was no opportunity for a prime to "pool" even partially on the piston crown - the fuel either went straight down into the crankcase or was shot out of the exhaust. Lawrence Sparey actually commented upon this characteristic in his published test of the Vulture, of which more below. These issues undoubtedly played a part in creating the Vulture’s reputation for being a somewhat difficult starter.

However, the used of a hardened steel piston was pretty much forced on the Vulture designer by the fact that the engine also used a hardened steel connecting rod which was joined to the piston by a ball-and-socket bearing rather than the more usual gudgeon pin arrangement. This system had in fact been introduced to British model diesel manufacture in the former Kemp Eagle 1 cc sideport diesel and was thus something of a Kemp/K trade-mark. It was to be featured in all of the models released by the “K” Model Engineering Co. apart from the short-lived little K Hawk Mk. II. In one respect, the use of a ball-and-socket small end was a good move in view of the bypass arrangements used - unless it was well secured, a conventional fully floating gudgeon pin might have tended to foul the bore at the top of the bypass flutes. The downside was that since both components were hardened after installation, replacement of the rod was impossible - if that requirement arose, one had to replace both piston and rod, and that would mean a rebore or a new cylinder into the bargain. The system also prevented the re-swaging of the ball-and-socket joint if it became loose - any attempt to do so would likely result in a fracture of the hardened socket. Be warned!

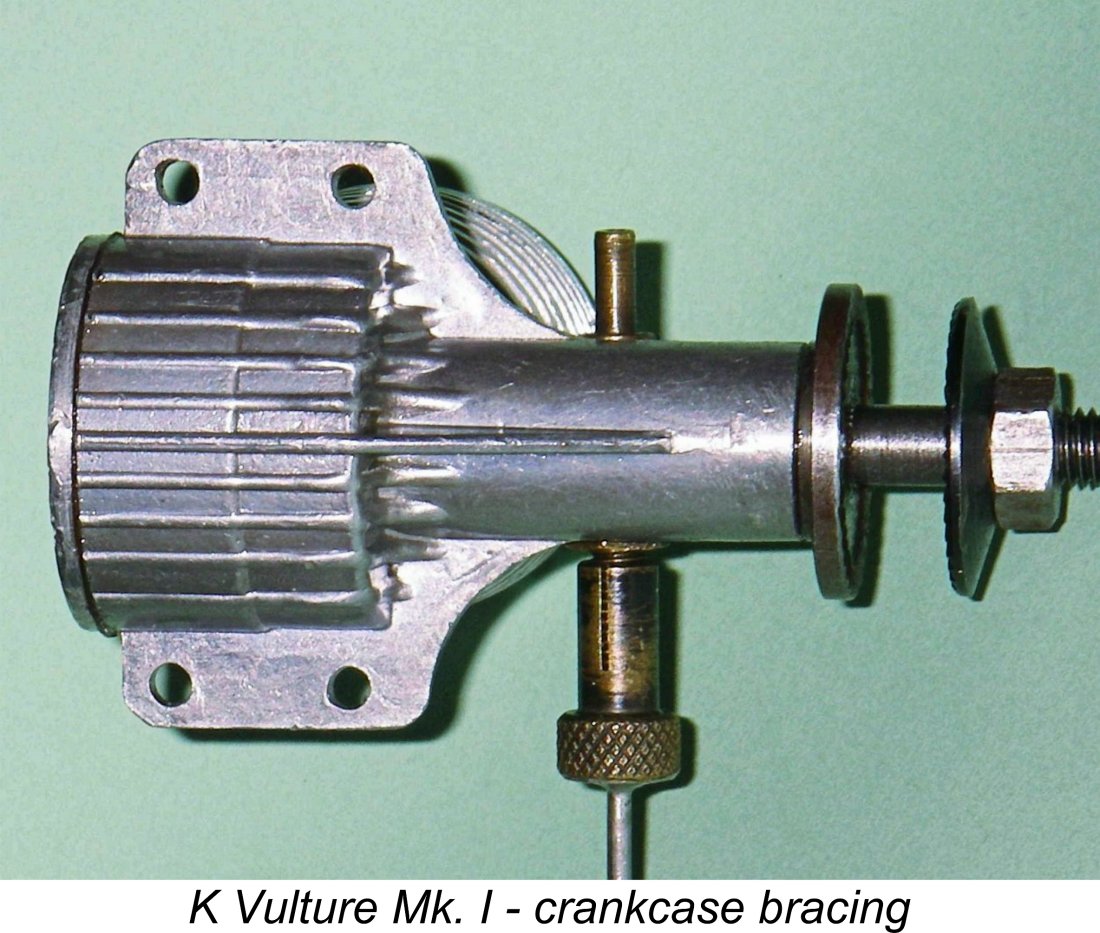

The hardened steel crankshaft was of conventional form but was considerably more lightly constructed than would have seemed ideal for a big-bore diesel of this displacement. The crankweb was relatively skimpy and featured only a small counterbalance. The shaft ran in a well-fitted steel bushing which was pressed into an alloy housing cast integrally with the main crankcase. A round induction port was used in conjunction with a venturi base of similar shape formed in the bushing.

The steel prop driver was secured to the shaft by being pressed onto a short splined section of shaft forward of the locating shoulder. The splines used were somewhat more skimpy than would appear desirable with a diesel engine of this displacement. A standard prop nut and prop washer were used to secure the prop against the driver, although a spinner nut could be purchased as an optional extra.

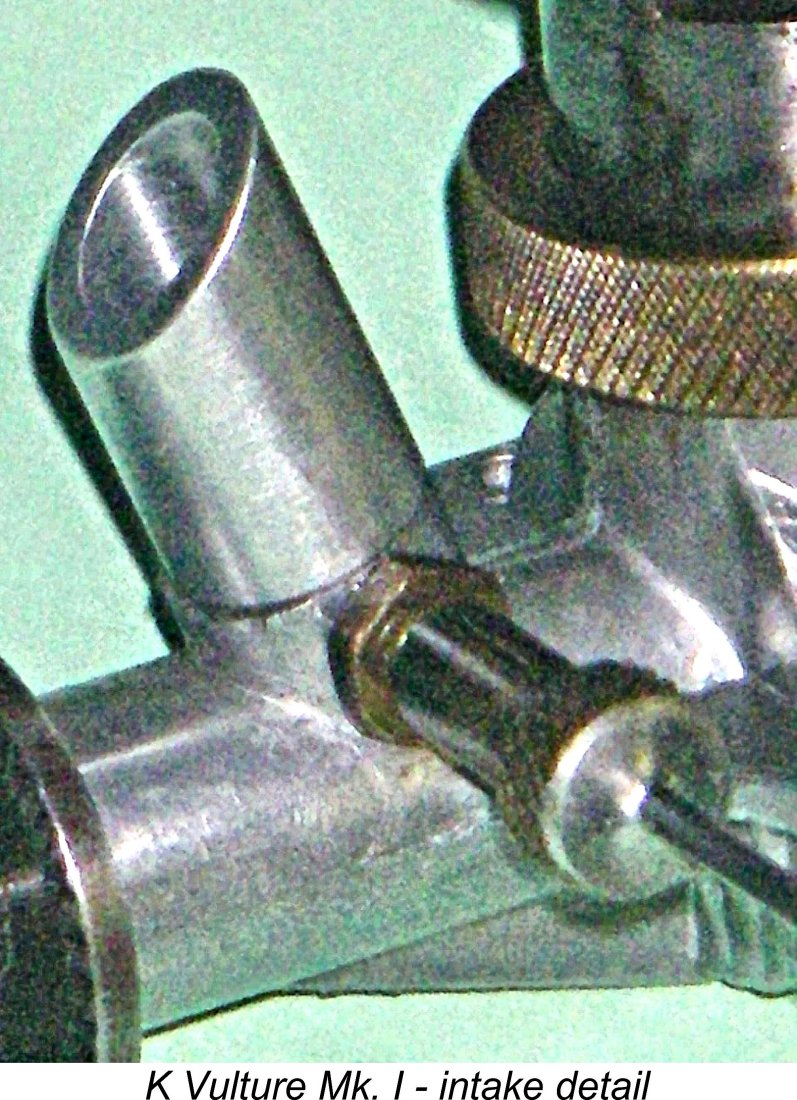

The spraybar was a very solid piece of work indeed, having an outside diameter of no less than 0.186 inch (nominally 3/16 inch or 4.76 mm) with unusually large jet holes. The thread used was 2BA, with the needle being tensioned using a split thimble. In conjunction with a venturi throat diameter of 0.325 inch (8.25 mm), this spraybar size resulted in quite adequate suction. Reference to Maris Dislers’ invaluable Intake Choke Area Calculator confirms that this combination yields a choke area of 16.5 mm2, with a minimum consistent operating speed of 6,800 rpm for a 5 cc engine running on suction. Given the engine’s established performance characteristics (see below), this is a completely appropriate arrangement. However, a lot of owners seem to have fallen headlong into the yawning trap of misguidedly trying to extract more power by "waisting" the spraybar and/or boring out the venturi. It doesn’t take very much of this to move the minimum operating speed for adequate suction up to a point above the engine’s peaking speed of around 8,500 rpm. Consequently, such a modification is counter-productive in the extreme in that it makes the engine almost impossible to start! More of this below in its place……. my advice is to leave well alone. This is not a high-performance engine - take what it offers and be happy!

A fillet between the rear of the stub and the front of the case would have greatly increased the strength of this arrangement and in addition would have stiffened the main bearing quite appreciably. It's a complete mystery why such a fillet wasn't provided. Having said this, it's only fair to point out that examples with the boss broken in the anticipated manner are very rarely encountered. There may have been underlying reasons for this, of which more later. The main bearing was braced at the sides by forward extensions of the mounting lugs and was also provided with a long bracing web on its underside. In addition, the front face of the crankcase below the centre line was plentifully equipped with cast-on bracing/cooling fillets. It's odd that a similar level of concern for strength wasn't displayed above the centre-line.

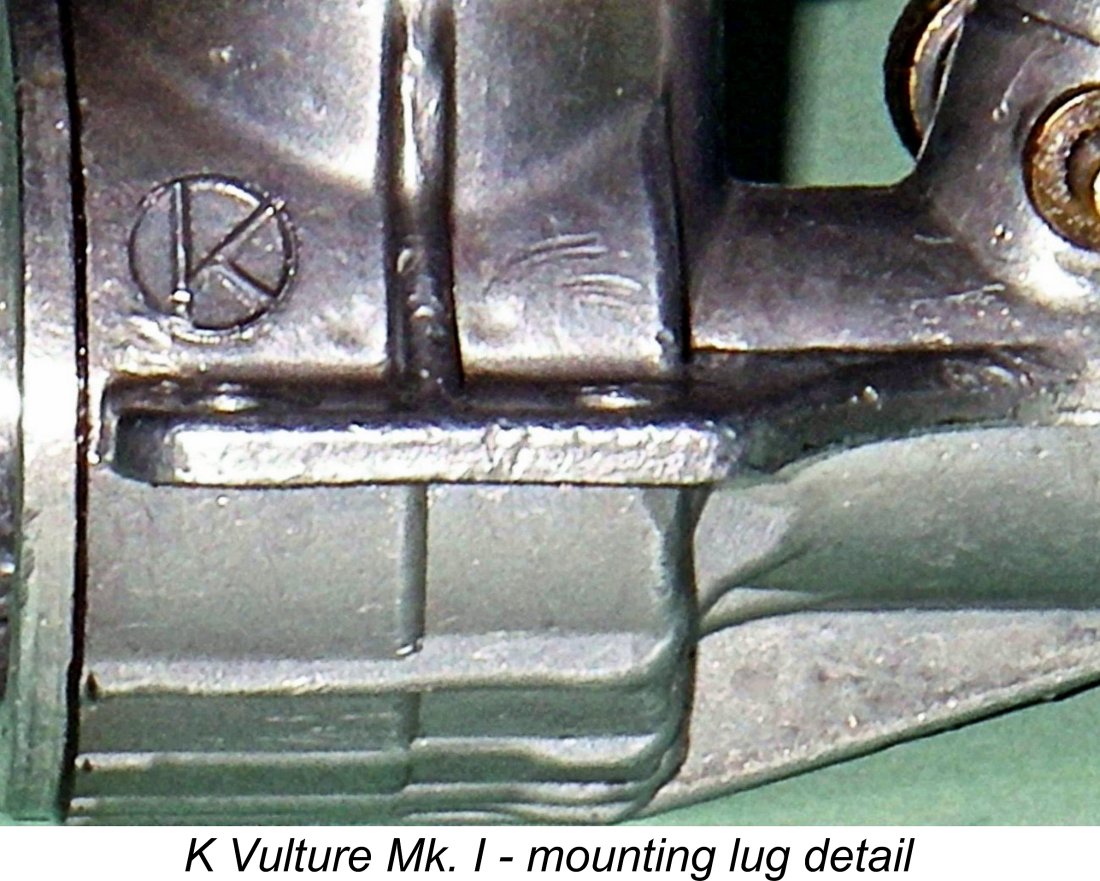

The same weakness was in fact carried over to the company's 2 cc FRV models (of which more elsewhere), and those models didn't even have the stiffening webs and forward extensions. As an experienced control-line flier himself, it's really strange that Len Steward was so slow to reach an understanding of this issue. Finally, the backplate was a simple screw-in item turned from solid aluminium alloy bar stock. It sealed to the rear of the case with a gasket.Two indentations were machined into the interior perimeter of the backplate recess to facilitate tightening and removal. If you really must remove the backplate of one of these engines, please use a suitable tool to avoid marring the component! The engines all carried serial numbers which were stamped upon the right front surface of the main bearing housing just behind the prop driver. The numbering appears to have followed the usual procedure for the Kemp and "K" companies by starting at engine number 1. The lowest presently-confirmed serial number for an authenticated Mk. I Vulture is 114, while the highest reported number is 959. Since no four-digit serial numbers are known for this model, it appears that no more than 1000 examples of the Mk. I Vulture were produced. The serial number of the all-original example featured in the majority of the accompanying component illustrations is 282. It’s not uncommon to encounter Mk. I Vulture cases which have been fitted with the stronger Mk. II working components (of which more below) - engine numbers 631 and 867 are examples of this. The key to recognizing an original Mk. I case is the magnitude and location of the number. If it's a three-digit number and appears at the right front of the main bearing, the case was originally fitted to a Mk. I, whatever the working components which it contains.

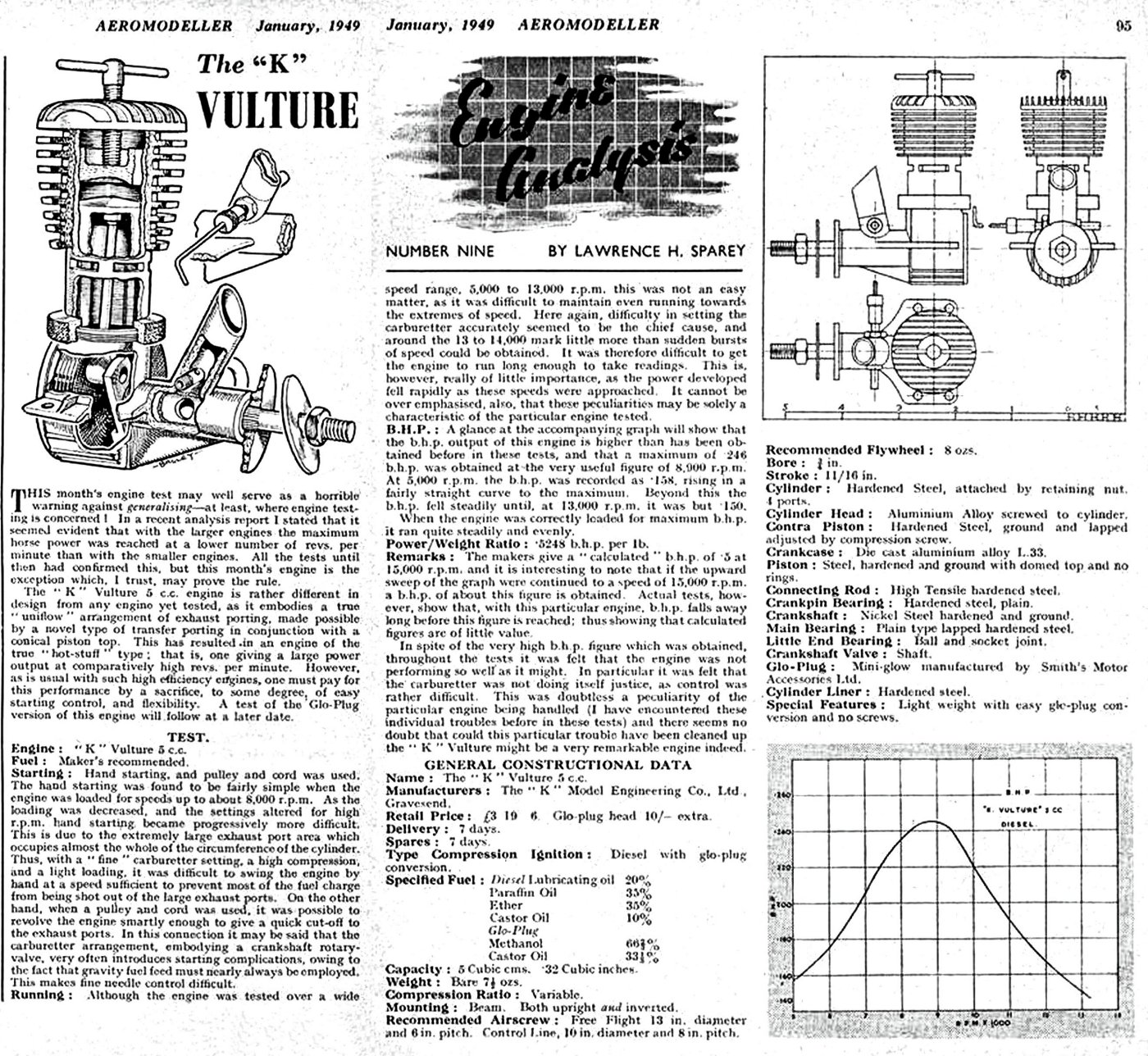

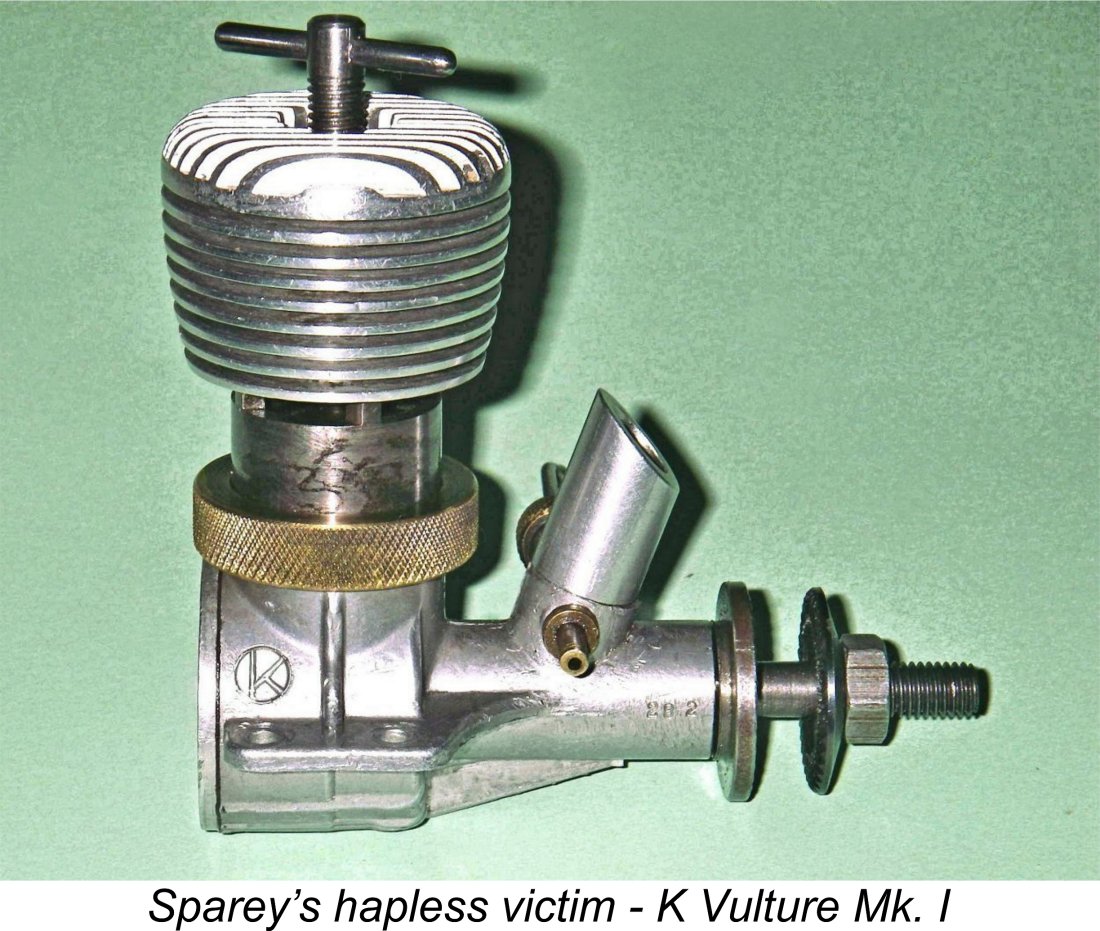

Once the far stronger working components which were later used in the Mk. II "Special" version of the Vulture were put into production, probably in around February 1949, it immediately appears to have become normal practice for the company to fit Mk. II internal components as replacements for any failed Mk. I items. Hence examples of the Mk. I Vulture with Mk. II internal components are quite frequently encountered. Such engines are dependable runners. Considerable additional confusion has arisen from the fact that it is also not uncommon to encounter correctly-numbered examples of the Mk. I Vulture which have been retro-fitted with the far stronger Mk. III crankcase, of which more below. Illustrated engine number 311 which was kindly made available to me by Alan Strutt is an example of this. Alan obtained this low-numbered example from the original owner, who confirmed that he had returned it to the factory for a case replacement following a lug breakage of the kind mentioned above. The factory fitted the stronger Mk. II internal components as well as a new Mk. III case which was however stamped with the original three-digit serial number in the correct Mk. I location. Company practice Apart from the serial number, the only other identification to appear on the engine was the company's well-known "K in a circle" trade mark. On the Mk. I models, this appeared on both sides of the crankcase above the mounting lugs at the rear. The result was a handsome-looking unit which was both compact and relatively light for a diesel engine of its displacement. It was well out of the contemporary British design rut for such engines, also selling for a most attractive price as noted previously. Not only that, but Len Steward got it off to an excellent start from a publicity standpoint by personally using it to win the first major contest in which it was entered. This was the stunt category of the London Area Control-Line Championship competition held at Fairlop Aerodrome on October 10th, 1948. Small wonder that the Vulture quickly attracted the attention of the resident engine tester for “Aeromodeller” magazine - the redoubtable Lawrence H. Sparey. Let's see what he had to say about the new model. The Mk. I Vulture On Test Lawrence Sparey's test of the Mk. I Vulture appeared in the January 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine as number 9 of the series of 47 tests that Sparey was destined to carry out for the magazine over a four-year period beginning in May of 1948. Allowing for editorial lead time, the publication date of this test reflects unusually quick work by Sparey, since the Vulture had only been on the market for a few months at the time of publication of this test. Sparey must have been remarkably quick off the mark in obtaining his test example, or perhaps the publicity-minded Len Steward ensured that he got one of the first engines off the line. If so, Steward would have made sure that it was a good ‘un!

Sparey comforted himself by noting that there was a price to be paid for this level of performance in terms of the engine's handling qualities and its flexibility. He made several references to difficulties in establishing an optimum needle setting. However, he stated that when loaded for its optimum speed range, the Vulture ran "quite steadily and evenly". He also reported that with such a load hand starting was "fairly simple", although he stopped short of detailing any starting procedures which he had found helpful.

Engines peak at a given speed because that's where their various operating processes combine most efficiently, and designers have a right to expect that users will operate their engines at or near that speed. It's completely unreasonable to expect anything other than reduced efficiency beyond that point and totally unfair (and irrelevant) to criticise an engine on this basis. Sparey appeared to be unable to grasp this fact. Actual torque readings were taken over a speed range extending from 5,000 to over 13,000 rpm. Again, one wonders why the latter figure given the fact that the engine peaked at a little under 9,000 rpm. All that operation at speeds significantly beyond the peak would accomplish would be to impose unnecessary stresses upon the engine! Despite what would appear to have been an unwarrantably severe test in Sparey's hands, the test Vulture evidently survived unscathed - at least, Sparey did not report any failures, and other tests show that he generally did so when they occurred. The final power figure arrived at was 0.246 BHP at 8,900 rpm - not very impressive by later standards, but considerably better than the contemporary sideport opposition as of late 1948. As an example, the far heavier and more costly ETA 5 tested by Sparey only a few months previously (presumably using the same methods) had developed only 0.1805 BHP at 6,250 rpm. So the Vulture came out of this test looking pretty good by comparison with the domestic opposition. Sparely promised a future test of the glow-plug version of the Vulture, but this never materialized. Interestingly enough, the rival magazine “Model Aircraft” never ran a test on the Vulture at any time. The Mk. II Vulture "Special"

The company's very prompt response to these issues was to develop a stronger shaft and con-rod for the engine. The first imperative was to minimize the occurrence of additional failures. To that end, it seems that by February 1949 at the latest they had begun to fit these stronger components into new Mk. I engines (such as engine no. 867 mentioned earlier), also using them as replacements for units which had been returned for service following a failure (like engine no. 311). However, this did nothing to openly promote the fact that the company had moved energetically to address the original shaft and con-rod design issues, regarding which the word was now definitely "out" in aeromodelling circles. It was obviously desirable to put some clearly-delineated distance between the company's ongoing products and the now-notorious Vulture Mk. I offering. In an attempt to accomplish this, in March of 1949 the company introduced what they characterised as a revised version of the "K" Vulture which was advertised from April 1949 onwards as the "Vulture Mk. II Special". However, the reality was that this model was actually nothing more than a cosmetically-modified Mk. I Vulture which had been fitted with the stronger shaft and con-rod. The company had seemingly been marketing such units as Mk. I examples for some time prior to their coming up with the Mk. II "Special" marketing strategy. Naturally, the company was anxious to establish a very clear distinction between this nominally "new" offering and the original Mk. I Vulture which had acquired such an unsavory reputation by this time. To that end, they initiated a new serial number sequence beginning at engine no. 2001. To underscore the change, the number was relocated to the left side of the main crankcase. This makes it a trivial exercise to distinguish between cases used originally in Mk. I and Mk. II examples. The crankcase itself was unchanged - only the serial number and its location were different, together with the stronger internal components.

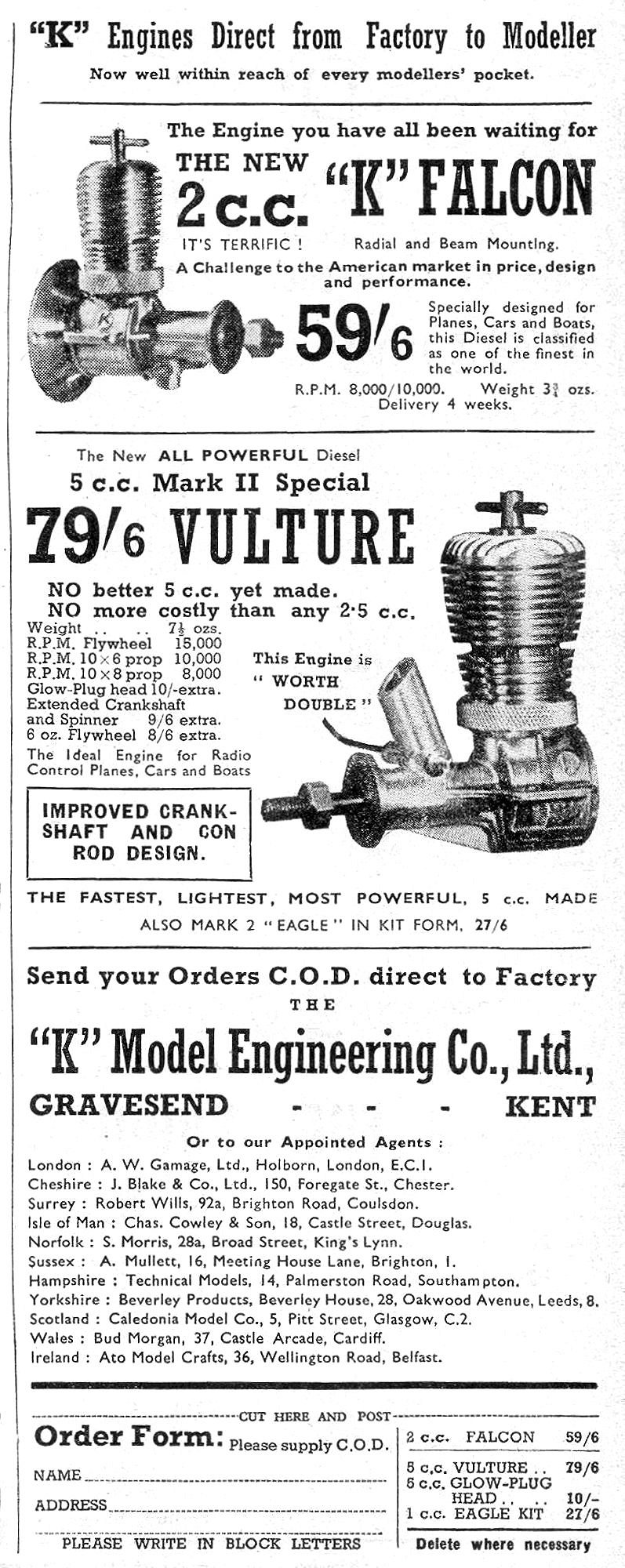

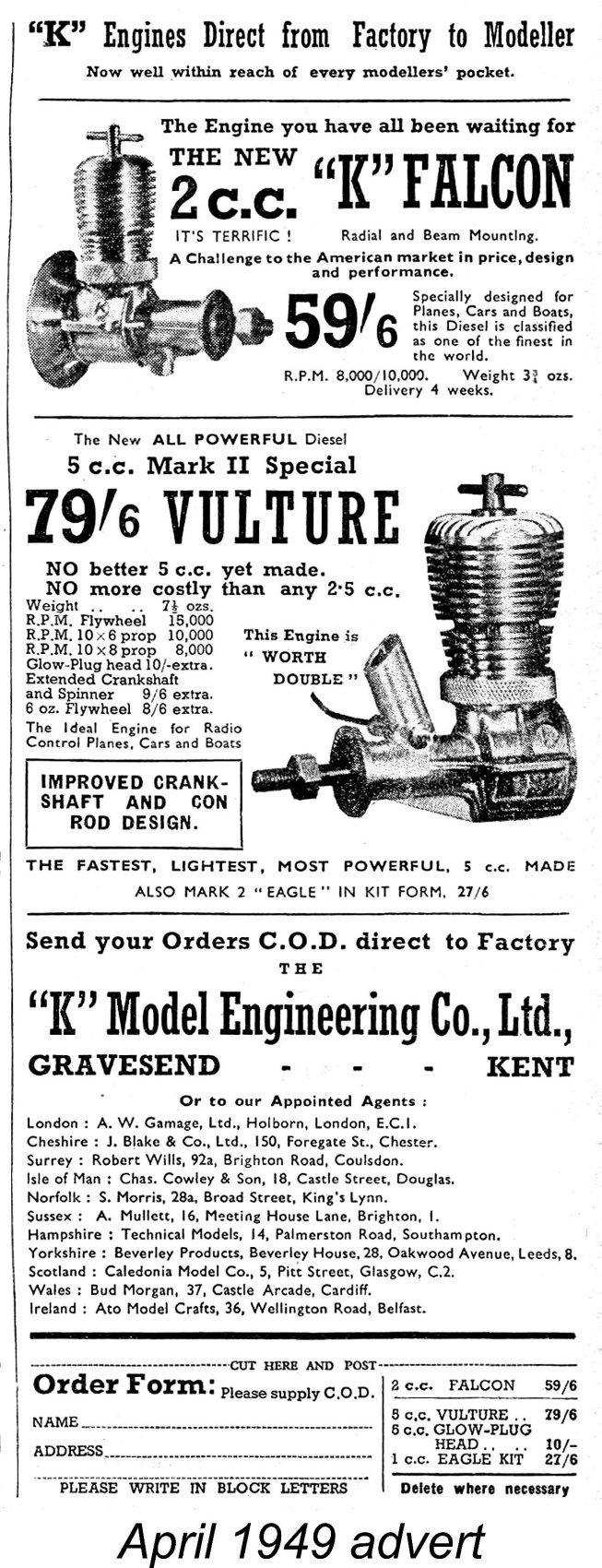

This cosmetically revised and internally strengthened model was first advertised in "Aeromodeller" magazine in April 1949, although its production very likely commenced a little earlier than that. The relevant advertisement is reproduced at the left. To anyone who was paying attention, the fact that this was only five months or so after the engine's initial appearance was a pretty clear indication that the Mk. II "Special" represented a quick reaction to significant problems which had become apparent with the Mk. I version. It's also illuminating to note that once the Mk. II "Special" appeared, no more was heard of the Vulture Mk. I. Doubtless Len Steward was hoping that people would forget about that model very quickly! Every confirmed Mk. II serial number reported to date is within the 2xxx range. Based on this fact, there appears to be no doubt whatsoever that the serial numbering sequence was restarted at 2001 for the new model. Presumably the 2 was inspired by the Mk. II designation of the engine. The crankcase used in the Mk. II model was unchanged apart from the previously-noted relocation of the serial number from the right front of the main bearing to the left side of the case beneath the mounting lug on that side. One interesting exception to this is previously-mentioned engine number 867, which has excellent provenance since it was owned until quite recently by its original purchaser. He confirmed that the engine remains in the same configuration in which it was sold. This unit is clearly based on a correctly-numbered Mk. I case but has the Mk. II dog collar fitted. The internal components are unknown, but it would appear that once the revised stronger components were developed the company adopted the practise of fitting them into all Mk. I Vultures coming off the line, in effect turning them into Mk. II models in advance of the official launch of that variant. It's quite possible that when the Mk. II "Special" was officially introduced the company had a number of unsold Mk. I's still on hand, which they ended up converting into Mk. II "Specials" and selling them under that designation - few buyers would be paying attention to the serial numbers! Only a detailed internal examination of the engine in question would further clarify this point, but at present I'd guess that it would be found to incorporate the stronger working components. Thanks to Kevin Richards for making me aware of this possibility!

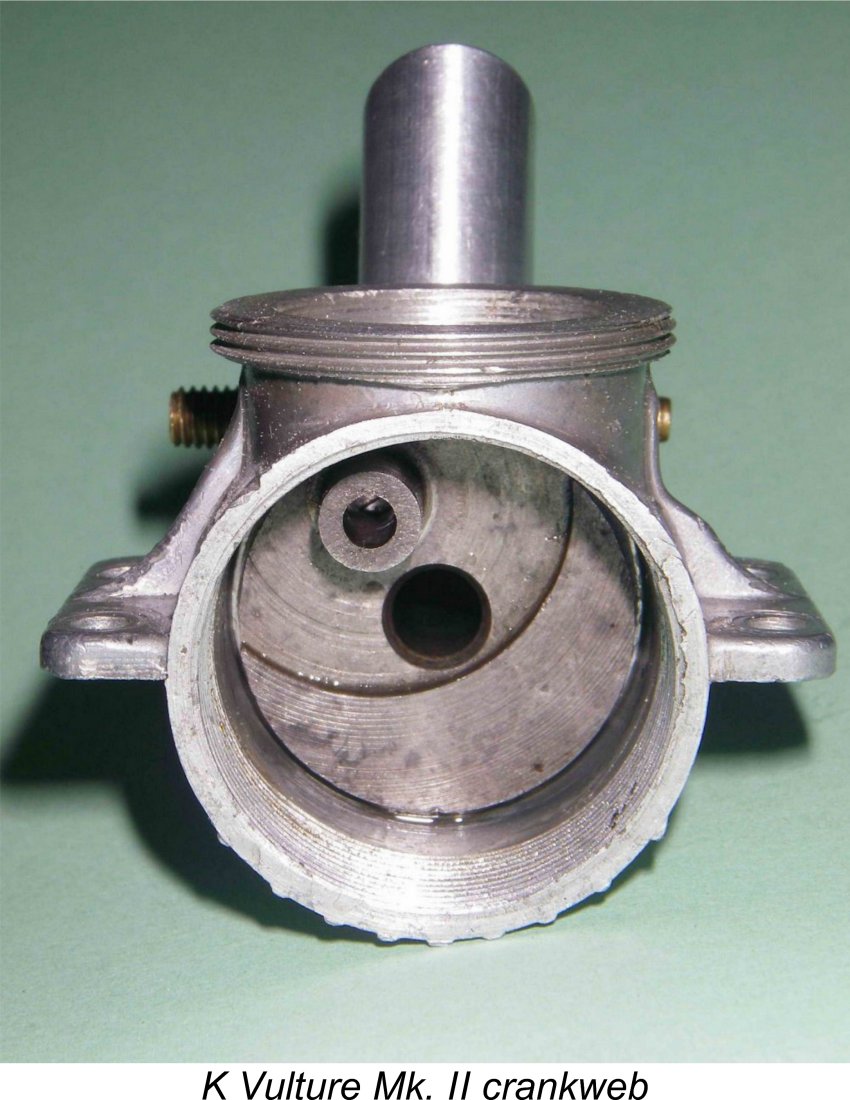

Bore and stroke of the new Mk. II variant were unchanged, as indeed they were throughout the production life of the Vulture. The only external change was the replacement of the former brass dog collar with the previously-described light alloy component with its finned upward tubular extension. On a more functional note, the Mk. II "Special" naturally featured the strengthened lower end working components which had been developed in response to the failures experienced with the Mk. I Vulture. We saw previously that the shaft and rod in the Mk. I Vulture appear rather skimpy for their allotted tasks, and it's clear that experience in the field had reinforced this i The revised crankshaft featured a full-disc crankweb which incorporated a substantial crescent-shaped counterbalance. This was used in conjunction with a far stronger rod having a considerably greater column diameter as well as a longer big end bearing. The same relatively skinny crankshaft journal diameter of 0.375 inch was retained, but the diameter of the internal gas passage was reduced from 0.250 inch to 0.228 inch, creating a modest increase in the shaft wall thickness of some 0.011 inch (from 0.0625 inch to 0.0735 inch). This represented an approximately 15% increase in the cross-sectional area of the crankshaft wall which had to resist the cyclic shear, bending and torsional stresses imposed by the operating loads transmitted through the con-rod to the crankweb. Still a bit marginal, but an improvement nonetheless. Indeed, these shafts have proved themselves to be quite dependable in service. The extra metal represented by the full-disc crankweb, the thicker crankshaft walls and the more substantial rod caused the weight to rise a little to around 7.8 ounces (221 gm). However, the additional space occupied by the more massive components also resulted in a reduction in the already-small crankcase volume. The increased base compression ratio resulting from this may well have contributed to a useful increase in transfer gas In all other respects, the engine was more or less unchanged from the Mk. I. The "Special" hyping of what was in reality the same engine with stronger working components was almost certainly motivated by a desire to obscure the fact that the most significant changes had been forced on the makers by design flaws in the original model! The engine was promoted as a "Special" rather than as a response to original design shortcomings - an understandable marketing ploy, albeit one which probably didn’t fool many people. Despite putting a bold face on it, the company seems to have accepted the fact that the word was "out" in informed modelling circles regarding the strength issues associated with the Mk. I Vulture's shaft and rod. It would clearly take some effort to restore customer confidence. The advertising of the engine initiated in April 1949 (see above) expressly stated that the Mk. II "Special" version of the Vulture featured "improved crankshaft and con rod design". This was as close as Len Steward evidently felt he could come to admitting that the original design had been seriously flawed in those areas. Presently-known serial numbers for this variant start at 2076 and go up to a high figure of 2863. It thus appears that around 900 Vultures were produced in total in this numerical series. Based on the number of reported examples, this appears to be the most common surviving variant of the Vulture. As with the Mk. I Vulture, examples are encountered which have been retro-fitted with the far stronger Mk. III crankcase (see below), presumably following a mounting lug breakage. As noted earlier, the company appears to have maintained the unique practice of transferring the original serial number to replacement or substitute cases. It also appears that the company took to fitting the stronger cases to the later examples at the manufacturing stage - the regular occurrence of examples numbered in the higher 2xxx range certainly suggests this. In effect, the company seems to have created what amounted to a Mk. III version of the Vulture, although it was never advertised as such. My own engine number 2863 is an example of this, as is engine number 2804. I'll discuss the implications in a subsequent section of this article. The Mk. II Vulture on Test

This example has had its radial mounting lugs neatly removed by a previous owner, giving it the appearance of a standard Mk. II Vulture apart from the thicker beam mounting lugs. Those of course are a definite functional improvement. In all other respects, this engine is a standard Mk. II model, hence being my “flyer” example since it is by no means in pristine original condition. It has actually seen some service in the air in my hands, although not for quite a few years now. During the course of that activity, I field-tested the mounting lugs on several occasions! They survived all attempts to break them!

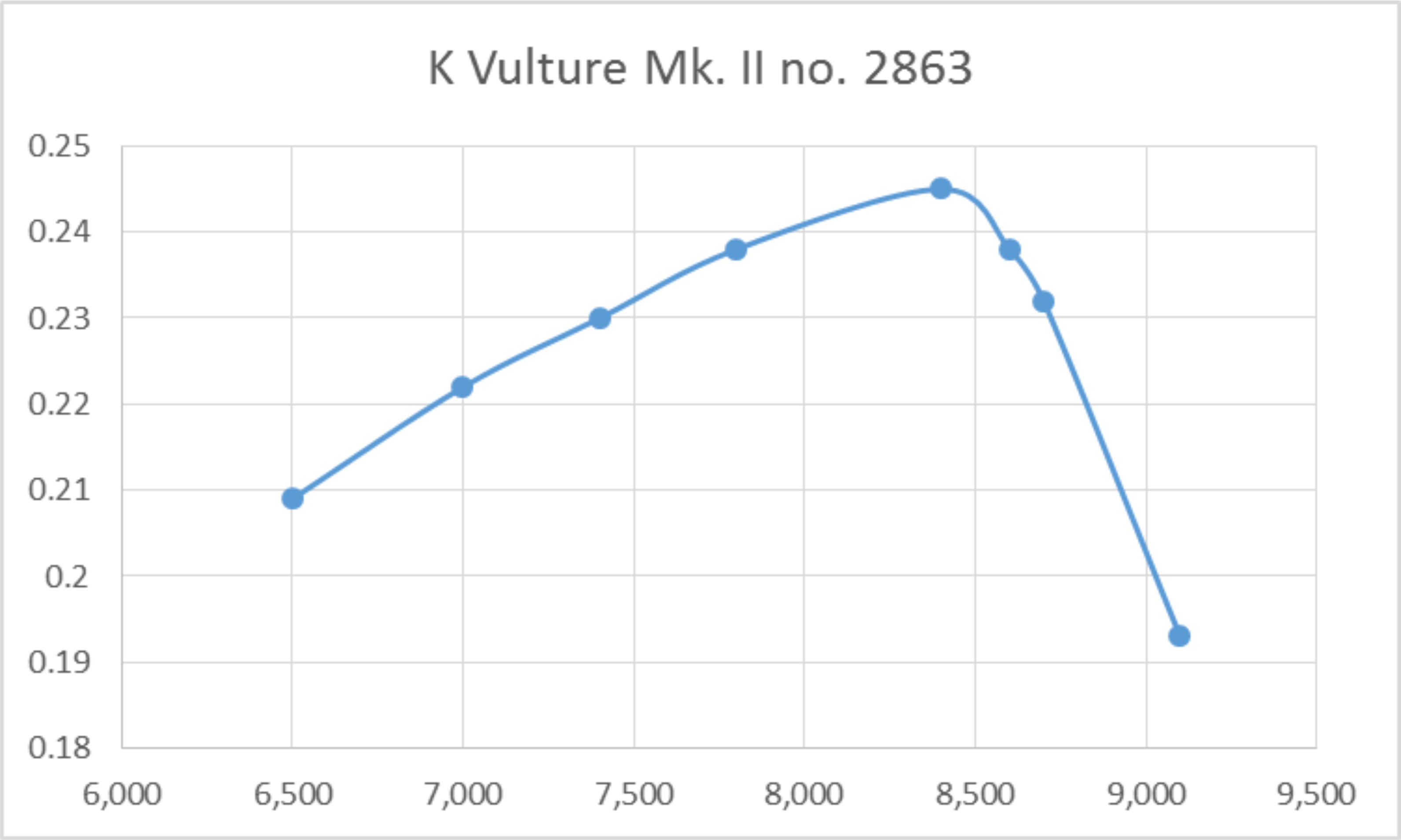

I won’t go into great detail regarding the engine’s handling characteristics, since that issue will be fully covered in a later section of this article. I will confine myself here to saying that the engine is one of my easiest-starting Vultures, never giving me any trouble at all provided the correct procedure is followed (see below). It also runs perfectly at all times, preferring the mixture to be set very slightly on the rich side for smoothest performance. Response to both controls is well marked, making the establishment of optimum settings on a given prop a very straightforward matter. Contrary to Lawrence Sparey’s reported experience with his Mk. I test engine, this unit needles very well. I recorded the following data for this engine.

As can be seen, the peak output measured on this test matched the figure obtained by Sparey for the Mk. I Vulture almost exactly. My engine appeared to develop around 0.245 BHP @ 8,400 rpm. Sparey’s example developed almost exactly the same peak output but did so at slightly higher rpm. The difference may well be down to the fact that my tested Mk. II model has the stronger shaft with the 16% smaller gas passage to go along with a slightly reduced crankcase volume. These differences could account both for the lower peaking speed and the slightly higher torque developed by my engine. That said, the two sets of figures are well within the range of variation to be expected from two different examples of basically the same engine. Overall, I found this example of the Mk. II Vulture to be a pleasant enough engine to handle, with a very solid performance on tap by the standards of its day. Experience shows that it does well in a vintage control line model using a 10x8 prop, exactly as recommended by the manufacturer. An 11x6 or 12x5 would work very well for free flight. An Unadvertised Variant - the Mk. III Vulture It will be appreciated that the design revisions noted above with respect to the Mk. II "Special" Vulture did nothing to address the evident weaknesses in the main crankcase casting. Chief among these were the very thin mounting lugs, which even a cursory examination suggests to be quite inadequate for an engine of this weight, displacement and torque.

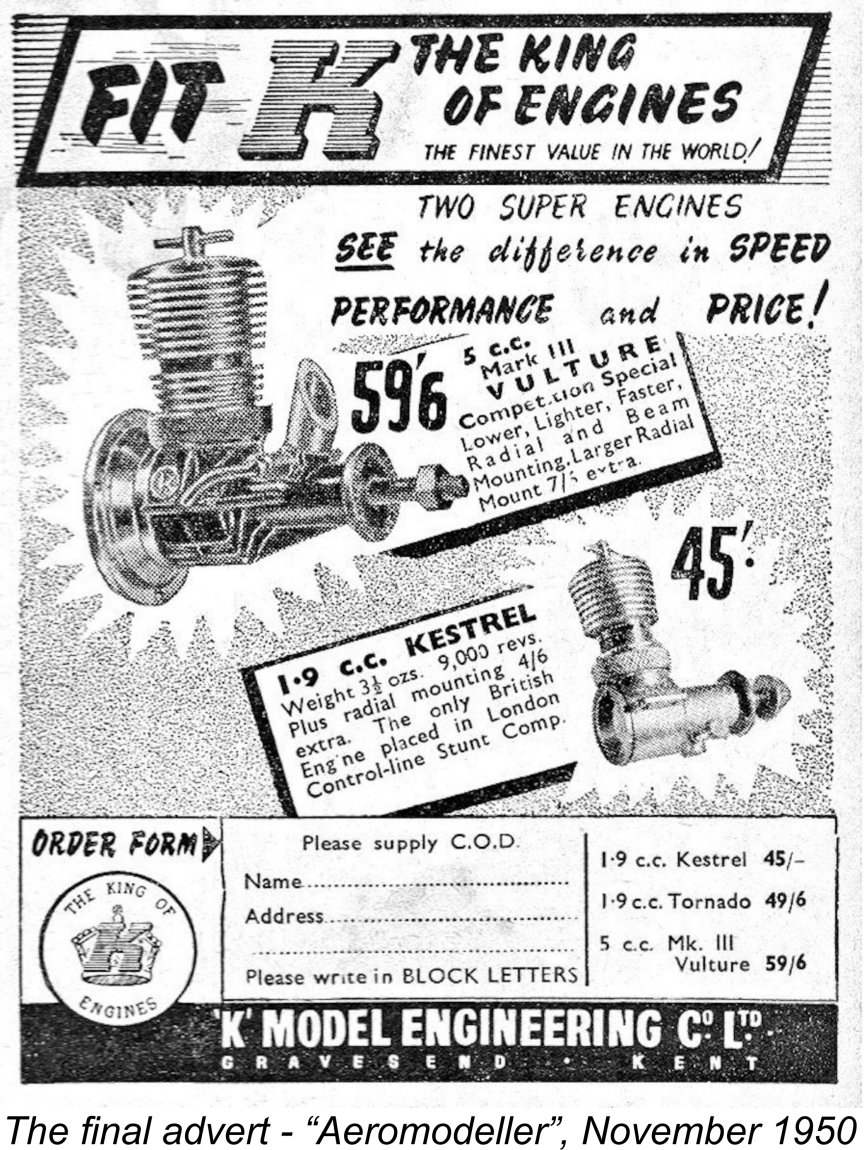

This was the third advertised variant in a space of only 8 months - clear evidence of the company chasing a series of design issues. Note that once again the company dressed up a response to a design shortcoming in the guise of a "special" product! The idea was clearly to create a distinction between this model and its predecessors. Having taken note of the above advertising effort, it must be said that there's a considerable body of evidence to the effect that many of the changes which resulted in the appearance of the Mk. III "Competition Special" were actually introduced somewhat earlier in the units which bore the higher serial numbers in the Mk. II 2xxx sequence. De facto, this amounted to the appearance of a Mk. III variant of the Vulture. although it was never advertised as such.

Apart from the elimination of a manufacturing step, another advantage of the revised finless head was the avoidance of the need to align the top fins by adjusting the cylinder orientation using the dog collar - both cylinder and cooling jacket could be tightened independently. This represented a significant simplification of the assembly process. Another visual effect of the use of the revised head was to reduce the height of the engine a little, since the smooth head was machined off level with the top of the brass head button which continued to be used. The resulting finless look gave rise to the name by which this engine is often informally identified today - the "Bald Headed Vulture"! Another externally-visible change on the Vulture Mk. III was a slight reduction in the length of the venturi insert together with a significant steepening of the rake angle at the intake. This may possibly have been intended to reduce the stress imposed on the venturi mounting boss during a crash impact, as discussed earlier. It had little functional effect apart from representing a very minimal weight reduction.

A further change was the provision of three "mouse-ear" lugs at the rear of the crankcase for the purpose of allowing for radial mounting of the engine. At the time in question (mid 1949), radial mounting was enjoying something of a vogue among British modellers, with several British manufacturers producing engines featuring this type of mounting. In addition, the "K in a circle" trade mark which had appeared on each side of the case at the rear above the mounting lugs was relocated to the front, still on the sides above the mounting lugs. The frequency with which higher-numbered examples of the Vulture in the Mk. II sequence have shown up with the strengthened case, the finless head and the shortened venturi while retaining the original cylinder, head button and prop driver is sufficiently high to cast serious doubt on the idea of all such combinations having been assembled by owners. All examples of which I am aware having serial numbers above 2600 are of this type. This simply cannot be a coincidence. It appears that the revised components were developed by the factory and fitted by them to many of the higher-numbered "Mk. II" units as they came off the line, thus creating the unadvertised "Mk. III" variants. I share the view of my friend Brian Cox that this combination must be seen as amounting to the creation of a hitherto-unacknowledged Mk. III variant of the Vulture, although it was never advertised as such. The notion that the manufacturers saw this as a distinct variant is supported by the fact that the serial numbers on these examples invariably appeared on the right-hand side of the case beneath the right-hand beam mounting lug, although the numbers continued the established Mk. II sequence in the 2xxx range which had previously appeared on the left-hand side.

The rod is also made from hardened steel - in fact, it looks like the standard rod with the ball at the small end drilled and reamed for the gudgeon pin prior to hardening. An owner would almost certainly follow Dave’s approach in using a high-strength alloy rod along with a cast iron piston. To me, this looks like a factory experiment. I wonder if there are any more out there?!? The engine certainly runs very well indeed, with nice tight rod bearings.

This assembly was unaccompanied by its cylinder and crankcase, so I have no idea which variant of the engine it came from. All that is certain is that it had suffered the all-too common fate of having a bent rod. The bending had imposed sufficient stress on the big end bearing to cause it to split.

This was an ingenious approach to the replacement of the standard ball-and-socket joint with a conventional gudgeon pin assembly. However, it had the disadvantage that, like the original ball-and-socket arrangement, it precliuded the replacement of the rod if that requirement arose (as it clearly did in the present instance!). The conventional gudgeon pin assembly featured in the previously-discussed experimental unit was far more practical in that regard. The final model of the Vulture to be advertised by the "K" Model Engineering Co. was the afore-mentioned Mk. III "Competition Special" variant. We'll look at that design next. A Final Fling - the Mk. III "Competition Special" Vulture

This changed with the advent of the Mk. III "Competition Special", which incorporated a number of modifications aimed both at reducing weight and improving performance. Thanks to the kindness of the late Paul Rossiter in supplying a somewhat ratty but eminently restorable example of this latter model for direct examination, I'm in a position to document the changes. One externally-visible change was the elimination of the steel prop driver in favour of an item machined from aluminium alloy. A few early examples retained the steel prop driver, but this was almost certainly a simple case of using up components already on hand. Most (but not all) examples also featured head buttons machined from light alloy instead of brass. In all probabilty the use of light alloy components was simply a weight-saving measure. The same material changes were also applied to the companion 2 cc Kestrel diesel, presumably for the same reason. The illustrated restored Mk. III "Competition Special" Vulture with the alloy driver bears the serial number 3057. I'm also aware of engine number 3047 showing the same head button modification. The latter example is the highest-numbered unit to retain the steel prop driver as far as I'm presently aware.

In addition to my own engine no. 3057, reader David Farmer reports owning engine no. 3002 which has a cylinder of this type. Both of these examples retain the standard ball-and-socket conrod connection. Apart from any improvement in performance, the change in the bypass configuration would have had two positive side-effects. One would have been a further modest reduction in weight, while piston cooling would undoubtedly have been considerably enhanced. To allow for the greater depth of the revised bypass flutes, the top flange of the Mk. III "Competition Special’s" crankcase casting was given an internal chamfer to eliminate the abrupt "step" in the bypass pathway which would otherwise have resulted. This chamfer may be seen very clearly in the image below.

The serial number on the Mk. III "Competition Special" appeared on the right side of the case beneath the mounting lug on that side, thus continuing the placement established with the Mk. III variant. Logically enough, the serial numbering for the Mk. III Vulture "Competition Special" evidently started at 3001, the 3 presumably denoting the Mk. III designation just as the 2 had done with the Mk. II version. We saw earlier that engines with Mk. III cases are encountered with lower serial numbers (in some instances far lower), but those numbered below 2600 or thereabouts appear to have been factory retro-fittings following the failure of the weaker Mk. I and Mk. II cases. The examples numbered above 2600 are evidently original factory fittings which created the earlier unadvertised Mk. III examples, of which perhaps 300 units ended up being made. The company's evident practise of transferring original serial numbers to replacement cases in the correct locations has done much to confuse the issue here. As stated earlier, known serial numbers for this variant start at 3009, with the highest Mk. III "Competition Special" serial number of which I’m presently aware being 3383. It appears from this that perhaps 400 or so examples of the Mk. III Vulture "Competition Special" may have been produced at most before the Vulture series was finally abandoned. This made the Mk. III "Competition Special" the least prolific "official" variant of the Vulture in production terms. A great pity, because it was also the best. If it had been released as the Mk. I Vulture, as it certainly could have been, both the engine and the marque would doubtless be far better remembered today.

It seems likely that the illustration was based upon a prototype unit made up from a Mk. II case which was fitted with a Mk. III cooling jacket and venturi as well as a screw-in radial mount back plate. This was most likely assembled purely to serve as a model for the illustration, or perhaps this was the intended configuration at the outset. If so, it clearly didn't last! This being the case, it's a little odd that they didn't change the illustration at any time - presumably this decision was based upon advertising budget constraints. The hybrid Mk. III "Competition Special" was still featured in the final "K" advertisement of them all in November 1950, as seen at the right. I must concede the very slight possibility that a few Mk. III engines were in fact sold in the illustrated configuration, but if so the number must have been very small indeed. I’ve certainly never encountered one. Even if a few examples had been produced, it's likely that the screw-in radial mount would have unscrewed under the considerable rotational stresses imposed by flicking the engine over to start! Serial Numbers and Production History

The best information at our present disposal indicates that the Mk. I Vulture first appeared in late September or early October of 1948, since it was in the latter month that the engine first appeared in one of the company’s advertisements as seen at the left. The engine also made its successful major contest debut on the 10th of that month, as noted earlier. An interesting side observation is the evidence provided by this advertisement to the effect that the company had now ended production of the 1 cc Eagle Mk. I, since that model was now being offered at an obvious stock-clearance price of only £1 17s 6d (£1.88). The company was clearly paving the way for the introduction of the FRV Eagle Mk. II which appeared in December 1948, just in time for Christmas. We’ve seen that authentic surviving serial numbers for the Mk. I Vulture point to around 1000 examples being produced before the Mk. II "Special" version took over in March 1949. Examples of Vultures in Mk. I configuration with serial numbers in the 2xxx range are not uncommon, but these are collector-assembled hybrids using Mk. II cases - the one illustrated in Clanford's "A-Z Pictorial" bearing the serial number 2330 in the wrong location for a Mk. I is an example. The serial number gives it away. Not really a big deal, but it has contributed to some confusion of the serial numbering picture. Present evidence (to be summarized below) suggests that the Vulture was produced at a relatively high rate when it was first introduced, doubtless in anticipation of a strong demand. As we shall see, it appears that production rates may have been as high as 300 units per month at the outset. However, once the company became painfully aware of the durability issues with the Mk. I Vulture’s working components (which wouldn't have taken long), it’s logical to assume that they would have terminated production of those components immediately pending the development of more durable replacements - why add to your company's image problems by continung to send out components which you know to be faulty?!?

It thus seems certain that a fair number of Mk. I Vultures received those stronger components either as after-sales replacements or as original factory installations in the later examples. In effect, some of the later Mk. I Vultures seem to have been converted into what was to become the Mk. II "Special" model prior to their initial sale. Other examples were brought to the same configuration through the replacement of components following in-service failures. This left the company facing the problem of distancing themselves from the Mk. I Vulture with its doubtless widely-discussed problems. They quickly came up with the idea of dressing the engine up a little and re-naming it the Mk. II "Special", probably in March 1949. This was clearly done in order to create the impression that it was a new model, which it wasn't in reality. The re-named model was first advertised in April 1949, as seen at the right. We saw earlier that the Mk. III Vulture "Competition Special" made its initial advertising appearance in May of 1949, only one month after the advertising debut of the Mk. II "Special" offering. It might appear from this that it took a little longer for the company to realize that the mounting lugs on the Mk. I and Mk. II "Special" models were also seriously deficient. For this weakness to become apparent, a considerable number of the engines had to get into the air so that they had an opportunity to crash hard and shear off their lugs - bench running wouldn’t uncover this weakness. I suppose that getting them into the air did represent some progress with the the upgraded Mk. I units and the Mk. II "Special" ....…… but it was not enough. So the failures continued to pile up ........... the company seemingly realized pretty quickly that something would have to be done to address this issue as well. It's apparent that they soon came up with the revised and far stronger crankcase which was to be featured in both the Mk. III and Mk. III "Competition Special" models.

We saw earlier that perhaps as many as 300 examples of the Mk. II "Special" were fitted with the strengthened crankcases which had been developed in response to the mounting lug weakness of the original offerings. This step seems to have been initiated prior to the announcement of the Mk. III "Competition Special", creating what I believe to be an unadvertised Mk. III model. Those Mk. III units also featured the revised finless cylinder head and the shortened intake venturi which were to be carried over to the Mk. III "Competition Special" variant. Indeed, the Mk. III and Mk. III "Competition Special" were in most respects the same engine, the main practical differences being the increased use of light alloy in the "Competition Special" as well as its revised bypass passages. However, the implied notion that the two concurrently-advertised models were produced simultaneously makes no sense whatsoever. Why would the company even contemplate producing two basically identical models at the same time, particularly two variants of a model that wasn't selling in any case? Among other things, they would have to produce two distinct cylinder components simultaneously. The fact that the serial numbering of the two models is consecutive strongly supports the notion that the two productions were consecutive as well. This bears closer examination. Here I have to emphasize that what follows is in many ways conjectural and cannot be read as authoritatively established fact. I very much doubt that we'll ever know the truth for certain after the passage of 75 or more years. I merely claim that the following scenario explains all of the observed facts, and I have been unable to think of another scenario that does so as well. It's surely better to lay out one possible chain of events that explains the available facts than to do nothing at all?!? At least it opens the door for further discussion. With this caveat in mind, let's proceed............ The first point of interest arising from this situation relates to production rates. We've seen that the confirmed serial numbers for the original Mk. I variant imply a total production figure of around 1000 units from September 1948 to, say, February 1949. Thereafter, the reported numbers for the Mk. II "Special" and its unadvertised Mk. III variant suggest that some 900 units of those models were manufactured up to the point at which the Mk. III "Competition Special" entered production. Since that model appeared in May of 1949, and since the different variants appear to have been produced consecutively, it follows inescapably that a combined total of 1900 examples of the Mk. I, Mk. II and Mk. III Vultures must have been produced over the 7 month period prior to May of 1949 as a minimum. Since the engine was apparently introduced in late September or early October 1948, this works out to the quite impressive average monthly production rate of some 270 engines, and it was almost certainly higher at the outset. This was in addition to the production of the Mk. II Eagle 1 cc model which was being manufactured concurrently from November 1948 onwards. The April 1949 release of the 2 cc Falcon would have imposed additional production pressures. No wonder that they felt the need for those expanded production facilities at Darnley Street! This data unquestionably implies that the company must have foreseen a strong immediate demand for an up-to-date FRV 5 cc diesel among contemporary modellers. We may safely assume that "Stoo" Steward had taken the pulse of his fellow flyers regarding this point, and as an active and very prominent competition modeller himself he was in the best possible position to do so. He must surely have demonstrated prototypes to his immediate colleagues at West Essex and elsewhere, who may well have been quite impressed. It seems clear that the initial production rate of the Vulture would have been tailored to meet an anticipated sales boom for the design immediately following its release. However, it appears that this boom, if it occurred, didn't last long. Most likely the early buyers soon found that the engine was somewhat less than user-friendly to operate, while the built-in engineering design weaknesses of the Mk. I Vulture would surely have manifested themselves quite rapidly as well. Word of this would have spread very quickly within the tight-knit aeromodelling community, with an immediate negative effect on the marketplace view of the engine (and perhaps of the manufacturer). Such impressions are hard to overcome, and the task of doing so becomes more difficult with the passage of time.

The most probable answer is that they already had a stockpile of cases for the Mk. I and wanted to realize on the investment that these represented. The numbers suggest that they may have contracted for the initial production of 2000 cases, with a few hundred either flawed in some way or designated as un-numbered replacement parts. Engines with un-numbered cases are encountered from time to time, showing that some Mk. I cases were indeed used up as spare part replacements without the serial number being transferred as they were later with the Mk. III cases. The first 900 cases had gone into Mk. I Vultures, but that still left them in March 1949 with 800 or 900 paid-for cases waiting to be turned into complete engines. So they dressed the engine up a little with its revised dog collar, installed the stronger working parts, promoted it as a "Special" and hoped for the best. But the weak mounting lugs remained and likely began to break with increasing frequency as the more internally-durable Mk. II and refurbished Mk. I engines took to the air in greater numbers. The switch to the unadvertised Mk. III version with its stronger lugs was a logical response to this issue. Presumably the lower end components of the surviving early Mk. I Vultures which remained in circulation also continued to fail. This would undoubtedly have contributed to ongoing sales resistance, and all the available evidence suggests that the rate at which the Mk. II and Mk. III were manufactured far exceeded the demand from the marketplace. Consequently, the company soon found themselves with a significant inventory of unsold Mk. II Vultures, some of which had been upgraded to Mk. III configuration. This of course represented precious capital which was tied up in an over-large inventory of unsold engines, hence being unavailable to the company for other purposes. This problem was further compounded by the fact that the companion 2 cc Falcon model (an excellent engine, of which much more in a separate article) also apparently failed to meet sales expectations, probably due to an increasingly negative customer perception of the "K" range in general because of the problems with the Vulture. Whatever the reason, this created an additional tie-up of capital in the form of unsold Falcons. It must have become glaringly apparent from this that further steps would have to be taken to remedy an increasingly unfavourable market position. The company had already responded very effectively to the structural deficiencies of the original Mk. I Vulture by developing a stronger case for use with their already beefed-up working components. By demonstrating their speedy responsiveness to design issues identified in the field, they must have hoped to re-build consumer confidence. It's clear that they planned all along to use the stronger cases as replacement parts for broken Mk. I and Mk. II engines, as documented earlier. They also appear to have installed Mk. III cases at the outset on some of the later examples of the Mk. II Vulture, creating the unofficial "Mk. III" version which was never advertised as such and continued to be numbered in the Mk. II sequence. Presumably they arranged for the production of additional Mk. III cases to allow for this.

It’s worth noting in passing that a similar pattern was to be followed with the "K" 2 cc models. From August 1949 onwards for many months, the Falcon and the succeeding lower-priced Kestrel were offered concurrently despite the fact that Falcon production had almost certainly ceased by August of 1949. As with the Vulture, this dual marketing strategy undoubtedy represented an attempt to liquidate an inventory overstock of Falcons and thus free up capital which was urgently needed for production improvements.

To manage this situation, the company continued to offer the Mk. II Vulture at its original price of £3 19s 6d, but increased the price of the Mk. III "Competition Special" to £4 15s 0d at the same time, thus giving the Mk. II a consumer price edge over the Mk. III. Presumably their hope was that word of the improved durability of the Mk. III might get around, possibly persuading some more customers to get in on the act and at the same time save a few bob by purchasing one of the left-over Mk. II's. The latter model did after all have the same strengthened lower end components as the Mk. III variants and should have been just as reliable as long as it didn't hit the ground too hard. The examples which had been retro-fitted with Mk. III cases were perfectly durable engines which would give excellent service, as my own example certainly did. If this is the way that things went, the plan does not appear to have succeeded. We've seen that although a combined total of around 900 examples of the Mk. II and Mk. III seem to have been made during the "gold rush" production period prior to May 1949, we presently have evidence for only around 400 examples of the doubtless superior Mk. III "Competition Special" having been manufactured before production of the Vulture was finally suspended. This was less than two month's production at the former rates. The implication is that all Vulture production had almost certainly ceased as of August 1949. It appears that the company had finally recognized that the reputation of the Vulture was beyond saving and that the best that they could hope for was to sell off the completed engines already in existence. In that regard, even at the point where Vulture production had ended it's clear that the company had substantial stocks of unsold engines on hand. Advertisements for both the Mk. II and Mk. III "Competition Special" Vultures continued into early 1950, indicating that they still had unsold Mk. II's on hand at least 10 months after production of that model had evidently been suspended in favour of the improved Mk. III. This is about as clear an indication of ongoing sales resistance as one could find - it took them over a year to sell 900 engines! Overall, the structural shortcomings of the Mk. I and Mk. II Vultures may have done as much as any other single factor to undermine the company's market position and financial viability through an erosion of consumer confidence in their products and a consequent tie-up of their capital. By May of 1950 it appears that all of the 900 examples of the Mk. II Vulture (including the "Mk. III" renditions) had finally been sold, since the Mk. II's final advertising appearance came in April 1950. From that point onwards the company's regular advertisement in “Aeromodeller” offered only the Mk. III "Competition Special" variant. It's actually almost certain that production of that model too had ended in August 1949 and that they were simply selling off unsold examples at this stage. The far more user-friendly 2 cc Kestrel diesel and Tornado glow models were the only other "K" models offered at this point - the FRV Hawk Mk. II models had been dropped in mid 1949 and the Falcon made its final appearance in a February 1950 advertisement, ironically just after the appearance of its only published test (and a positive one at that) in the January 1950 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The farewell appearance of the Vulture came in the previously-reproduced advertisement placed by the "K" Model Engineering Co. in the November 1950 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Indeed, this was the very last advertisement placed by the company as far as I'm presently aware, giving the Vulture the dubious honor of being the “last man standing”! But the truly astonishing thing is that this was some 18 months after the advertising introduction of the Mk. III "Competition Special", and they still had not sold off all of the 400 or so examples that they had manufactured during all of that time! The fact that production had long ceased and the company was simply liquidating its assets is pretty clearly demonstrated by the fact that the price of the Mk. III "Competition Special" Vulture had dropped from its former £4 15s 0d (£4.75) to a mere £2 19s 6d (£2.98). See my companion article on the K Hawk for a detailed analysis of the reasons for the company having been wound up. Based on the known serial numbers, some 2300 or so examples of the Vulture had been manufactured, probably in a period of less than a year. The fact that quite a few of these appear to be still in existence and in relatively unscathed condition may well reflect the possibility that most of them received very little use once their handling difficulties became appreciated and word got around regarding some of their structural issues. Certainly, it's almost unheard-of to encounter a Vulture that is anywhere near worn out through use! It's interesting to note that the value of the Vulture as a second-hand engine plummeted rather quickly following the cessation of production. As of November 1951, Roland Scott's advertisement in “Aeromodeller” was offering good second-hand Vultures in both diesel and glow configurations for only 35 shillings (£1.75)! Dream on……………… The untimely end of the "K" Model Engineering Co. was very far from the end of Len Steward's involvement with model engines. He went on to work with his close friend and fellow West Essex club member Dennis Allen, first with the Aeronautical Electronic & Engineering Co. of Alperton, Middlesex during the period of their manufacture of the AMCO 3.5 engines and then with the development and manufacture of Allen's own Allen-Mercury (A-M) range at Edmonton in North London. Perhaps Len Steward's finest achievement as a model engine designer was his 1960 one-off “Steward Special” 2.5 cc diesel, using which the British team of Taylor/Yeldham managed a very competitive 4:45 time in finishing 3rd at the 1960 World Team Race Championship meeting. He was still active in the late 1960's, offering a highly-regarded reboring service on his own account. At this point, we’ve completed our in-depth look at the design and production history of the "K" Vulture. If that’s as far as your interest goes, you’ve come to the end of the relevant portion of this article. However, if your interests extend to the possibility of actually running one of these beasts, read on …………. So You Want To Run a Vulture? Well, fair enough - a worthy and entirely achievable ambition for any diesel aficionado, albeit not one for the faint of heart! Roll up your sleeves, fellow ether-heads, and let’s get stuck in!

As usual, how much you'll pay will be extremely dependent upon condition. In that regard, it's important to be clear from the outset regarding what you want to do with the engine once acquired. If you simply want a Vulture for display purposes, there's little problem - if it's complete and looks good, buy it! As noted earlier, it's almost unheard-of to find a Vulture with poor compression, so that's generally not an issue. However, if you want to actually run the thing, that's another matter! The Mk. I is undeniably a bit fragile as far as its internals go, and I personally wouldn't recommend doing too much running with an unmodified example unless you have a really good feel for diesel management, have access to good fuel, are able to keep the stress levels down through appropriate handling of the old comp screw and (above all) are not umbilically attached to an electric starter. The Mk. II and Mk. III with their beefed-up internals seem to be far less fragile. You may also encounter a Mk. I Vulture that has been internally upgraded to Mk. II specification, either through the replacement of the original working components following a failure or as originally fitted by the factory prior to sale. I have such an engine myself, and it's a dependable runner. Apart from the basic design, there are a number of issues that can affect the ability of a given example to serve in an operational capacity either on the bench or in the air. Here's a summary of the most commonly-encountered problems:

None of the above points are necessarily reasons not to buy a Vulture - it all depends on what you expect of the engine. Just be aware that any of these problems can occur - they've all been encountered on more than one occasion! If you want a Vulture to run, the safest thing to do is to buy an engine that has been test-run by the seller. A Vulture that has been successfully run and the settings established will generally keep running as long as it's handled properly. The other operational point that may affect your decision to buy is whether you want to merely bench-run the engine or actually (gulp!) try flying it! If your ambitions extend to in-flight use, I'd strongly recommend that you stick to the Mk. III Vulture or an earlier unit fitted with a Mk. III case and internals, preferably an example that already shows some signs of previous use. The other two variants retain those rather skimpy mounting lugs, so unless you're pretty confident of your ability to keep it out of the ground, the Mk. III case is the safest option - it seems to take a "rough landing" pretty well (I've tested it!). OK, let's assume that you have a Vulture which is mechanically sound and has carburettor components of the correct dimensions. Let me assure you that you do have a working engine in such a case! It may just take a little time and effort to prove it! Before attempting to run the engine, make sure that the dog collar is tight, using a tool that won't mar the component. It's never happened to me, but two of my friends have had this component come loose while running. The results can be unfortunate. Also, check that there are no crankcase leaks past either the cylinder base or the backplate rim. Replace the gaskets if necessary and make sure that the backplate is tightly screwed down. Good crankcase compression is a must for successful operation of a Vulture!

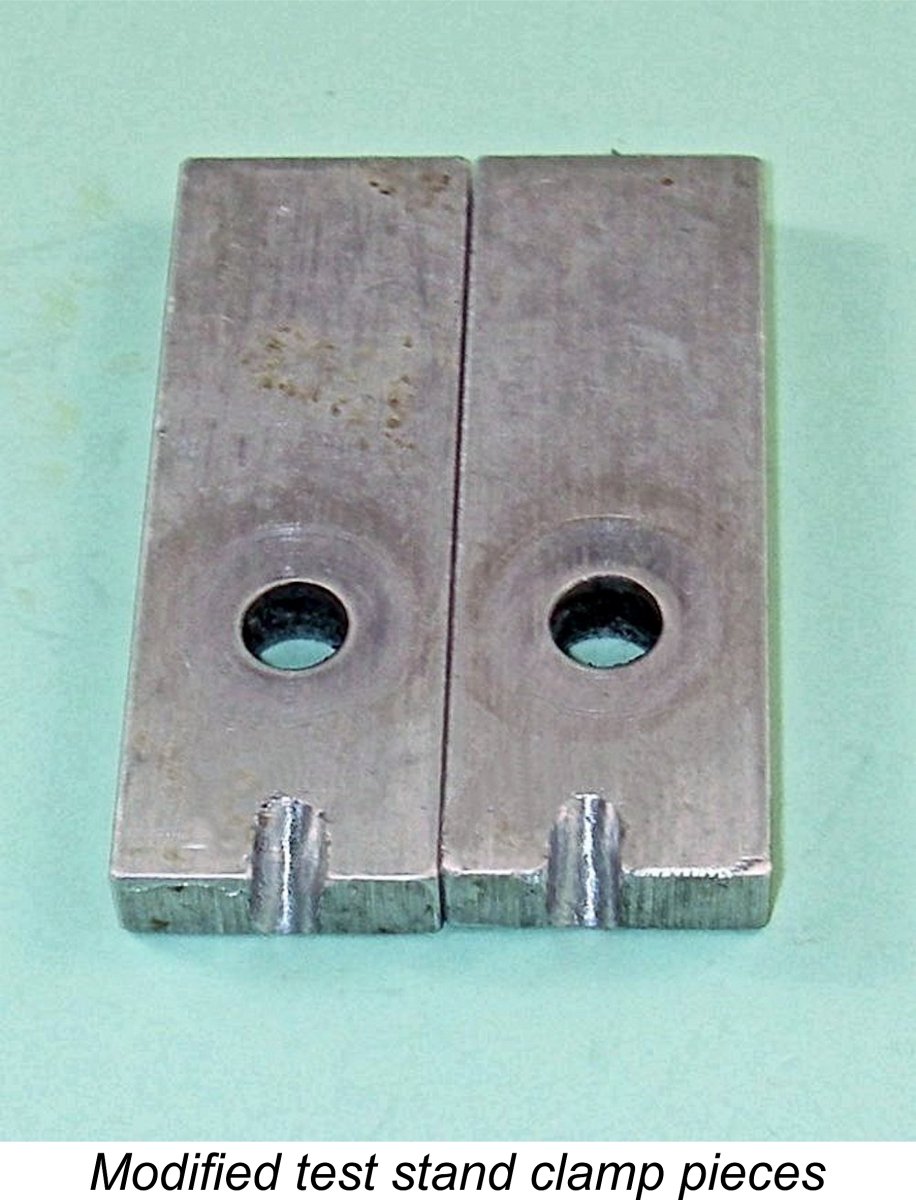

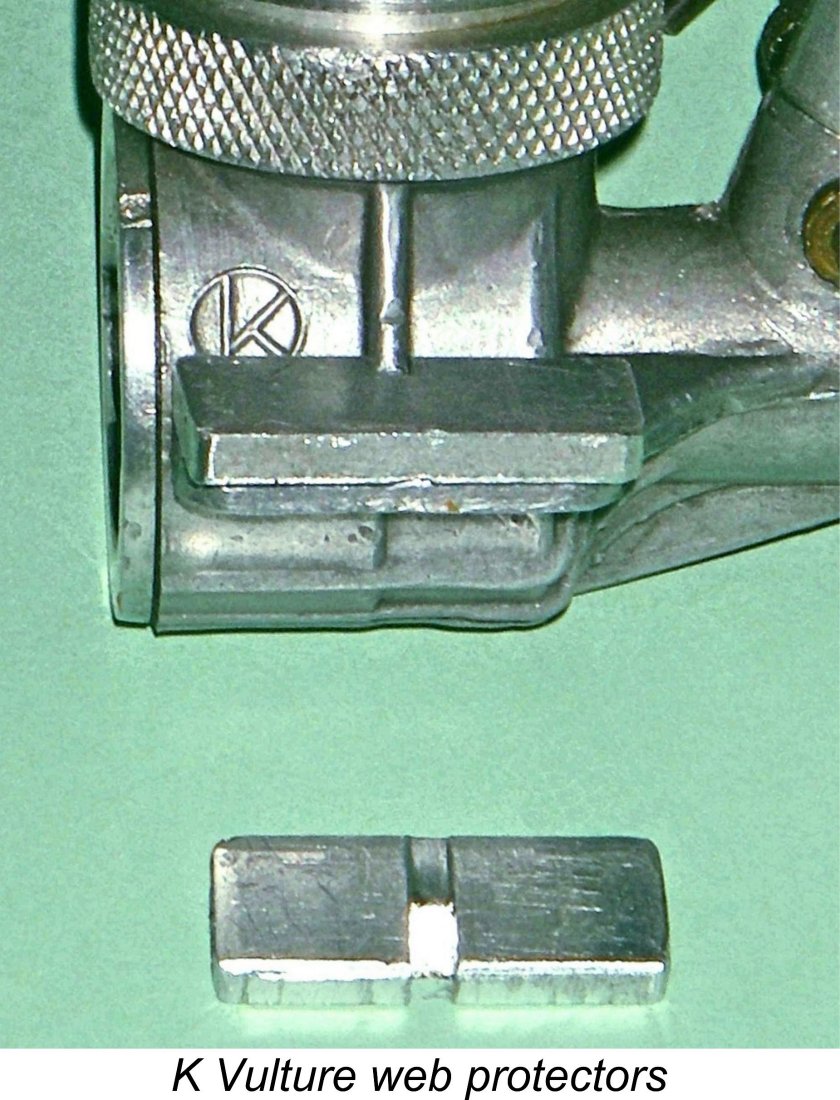

There are two approaches to the protection of the webs. First, you can cut grooves in the bearing surfaces of your test stand jaws, as shown in the accompanying image. These grooves must be sized to accommodate the webs. This modification doesn’t affect the utility of the stand for engines having un-encumbered lugs - it simply allows the stand to clamp the engine on both sides of the webs without actually touching the webs themselves. It’s useful for a number of other engines having similar webs.

Either way, mount the engine very securely in the stand with the top of the fuel tank as close to level with the spraybar as possible without setting up a gravity feed situation (which will flood the engine). This will ensure that fuel supply during starting is not an issue and will make it far easier to find the correct needle setting. The Vulture has pretty good suction once running, but first we have to get it running! A fuel line that stays full is a great help here. Next we get to the first Big Secret when it comes to starting a Vulture for the first time! Ron Warring actually commented on this point in retrospect in his March 1955 “Aeromodeller” test of the 5 cc Miles Special diesel. He noted correctly that the larger diesels of the pioneer era had a tendency to "brake" themselves when flicked over due to the high compression loads and bearing friction involved, to the point where it was often difficult to get such an engine to carry over from the first firing stroke to the next. This is certainly true of the Vulture. Warring commented that this as much as anything else was the reason why few of the early 5 cc diesels survived long in production. Warring also noted (again correctly) that one aid to improved starting was to reduce bearing friction through the use of ball-race shaft support, as seen in the Miles Special and Mk. II Drone 5 cc diesels, for example. However, the Vulture was not so equipped. Therefore, the cure in this case is to use a big prop with plenty of flywheel to help the engine carry over from one firing stroke to the next. I've had good results with an 11x7 wood prop, and I don't recommend anything smaller for the initial starts. A 12x5 is also very good. Next important point - use decent fuel! The Vulture likes a fair bit of ether in the fuel, and also responds very well to a modest dose of ignition improver (amyl nitrate or equivalent). It's also wise to use plenty of castor oil - that ball-and-socket joint is pretty heavily loaded! I find that a fuel blend of 35-35-28-2% ether-kerosene-castor-ignition improver works very well in these engines. If you don't know the settings, you're undeniably in for a bit of a struggle! The Vulture needs quite a bit of compression for cold starting - this is a typical characteristic of higher-displacement diesels due to the large surface areas of their combustion chambers, which extract significant amounts of heat from the compressed mixture. At the correct cold-starting compression setting, the resistance around top dead centre is considerable. However, it's always best to start low and move high - set the compression by "feel" so that the engine fights back a bit when flicked, but not unduly so. You should be able to snap it over quite vigorously without dislocating your starting finger! The needle setting is more problematic - with the stock system in place, somewhere between 2 and 3 turns usually seems to work, but that's assuming it hasn't been tampered with, as many of them have. The mixture needs to be slightly on the rich side for cold starting, and you'll just have to find out where that is by trial and error. When choked, the fuel should jump along the fuel line pretty smartly when the engine is turned over slowly. Now it's time to go for a start! Get yourself a good finger protector - you'll need it! Not because the engine is vicious - it isn't in the least. Merely because it takes some effort to flick it over, and you may do that for a while before you achieve that first start. A piece of rubber hose or a bicycle handlebar grip both work great. Chicken sticks are both useless and unnecessary. As a preliminary, choke to fill the fuel line - no more. This brings up another of the Big Secrets relating to starting a Vulture - do not get the crankcase flooded! I suspect that the bypass and transfer arrangements have something to do with the fact that clearing a flooded crankcase is very challenging with these engines. The Vulture doesn't need a lot of fuel in the case for starting - it needs it up in the working portion of the cylinder. Too much fuel in the case, and you've set yourself a problem! What makes this really problematic is the fact that the Vulture needs a port prime for starting. The difficuly here arises from the fact that with that 360 degree transfer port at the bottom of the bore along with those long radial exhaust ports, there's nowhere for the prime to pool in the cylinder - it all either goes down the transfers to flood the crankcase or gets shot out of the exhaust! Sparey actually noted this latter tendency in his test report. So one way or another, a prime doesn't stay in the cylinder for very long. If too much of it gets down into the case, you've started down the road towards flooding! To get around this, set the piston so that the transfer port is closed on the upstroke (piston crown just below the bottom of the exhaust ports), inject a modest prime, give one slow turn over top dead centre to ensure that you're not in a hydraulic lock and then immediately start flicking hard and don't stop! Don't give the cylinder any time to drain! If the compression is anywhere near right, a quick series of hard flicks should produce some reaction in the form of a few pops and bangs. If not, we have to try again.