|

|

Beating the Drum - the FROG 349

This is yet another article which first appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. That original article was published way back in December 2008 and may still be accessed through this link. However, upon re-reading that article I found it to be rather poorly organised by my own present standards. In addition, it was sparsely illustrated, while many of the associated images were of indifferent quality - I can do better now! Finally, I’ve also developed a few enhanced insights relating to the engine which deserved inclusion, including some updated test figures and corrected dates. The problem is that since Ron left us in early 2014 without passing on the access codes to his heavily encrypted site, it’s no longer possible to edit articles there or even carry out necessary site maintenance. As a result, MEN is slowly My reasons for liking the FROG 349 so much are threefold. Firstly, it displays a great deal of technical interest in its design, being well out of the rut in terms of "classic" British diesel design. Secondly, it's very well made indeed, appearing to run forever if properly used and maintained. And finally, it handles extremely well for a relatively large diesel, while producing a good helping of very useable power at moderate rpm - notably user-friendly and pulls a pretty substantial model. Before diving in, it’s probably worth mentioning at this point that the name of this range is correctly rendered as “FROG”, not “Frog” as often used. This is because it’s an acronym for the company’s motto “Flies Right Off Ground”. The manufacturer’s advertising always used the upper case rendition, which also appeared on the engines themselves as well as on the company's trade-mark. A small point, but we may as well get it right! Remember .......a FROG is a model aero engine - a Frog is an amphibian! OK, let's go back to the beginning........... always a good place to start! Genesis Of A New Design

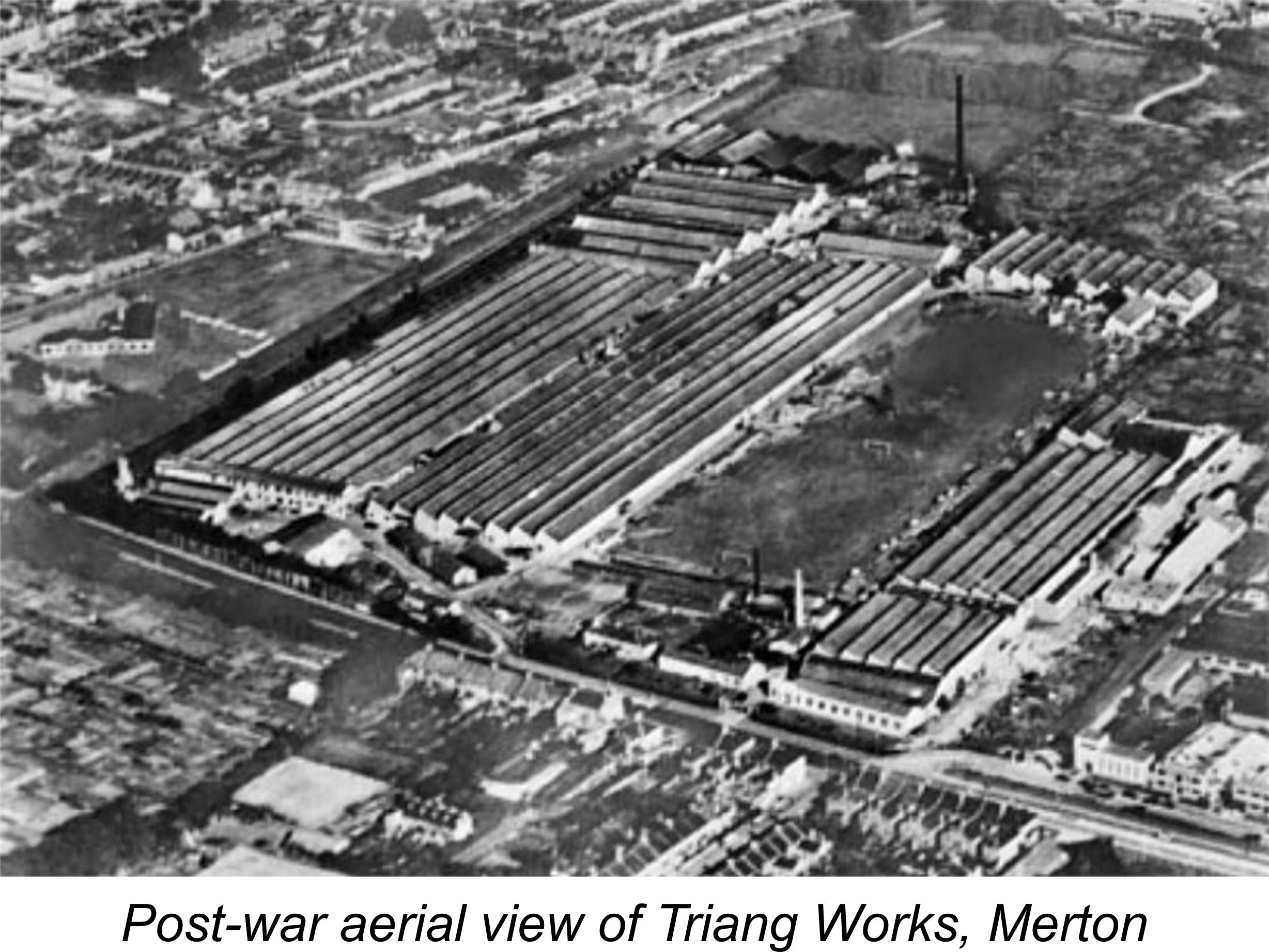

Lines Brothers had been major players in the toy industry since 1919 following a family involvement in that industry which had begun in around 1850. The trade-name "FROG" ("Flies Right Off Ground") was used by IMA from the outset for their kits and was carried over to their later engines. Lines Brothers owned the famous Triang toy brand, the triangle emblem of which represented the three Lines brothers who owned the company - after all, three Lines make a triangle! The production facilities of IMA were quickly co-located with those of the company’s other product lines at their huge Morden Road factory known as Triang Works.

Following the cessation of hostilities, Lines Brothers resumed their former activities, including the manufacture of model products by their IMA subsidiary. Their refurbished factory at Morden Road was then one of the largest toy and model manufacturing facilities in the world. Production of model engines soon commenced at the factory, the first such product being the 1.75 cc spark ignition motor which appeared in early 1946. A detailed article about the early FROG model engines may be found elsewhere on this website. Incidentally, the Morden Road factory was quite close to that of IMA's rival engine producers E.D., who were located in nearby Kingston-on-Thames and also began producing model engines later in 1946. The presence nearby of several scrap metal yards from which raw materials could readily be procured was doubtless of benefit to both firms.

The release of the FROG 349 thus represented the continuation of a FROG tradition which by then had become well-established, namely the introduction of model engine designs exhibiting a significant degree of outside-the-box thinking. Much of the credit for this must go to George Fletcher, who was IMA's chief engine designer throughout the main period under discussion. However, it’s important to recognize the In mid 1957 George Fletcher was tasked by management with the job of developing a 3.5 cc model. The obvious question to ask at this point is why? Well, as of that time IMA had models in the popular 0.8 cc, 1 cc, 1.5 cc. 2.5 cc and 5 cc displacement categories. This left a gap in their coverage of the British marketplace - the 3.5 cc category. It appears that management finally noticed this gap in early 1957. It may be asked why this displacement category was important. There were probably two reasons - firstly, a 3.5 cc engine that did not weigh substantially more than the 2.5 cc opposition could be used in a sport-flying context to give more zip to models designed originally for 2.5 cc engines, particularly in control line aerobatic applications. Since control line was then the Secondly, the prevailing rules for the very popular S.M.A.E. combat class permitted engines of up to 3.5 cc displacement. Finally, the growing popularity of R/C flying made engines of larger displacements increasingly attractive. Hence there was a definite niche for a powerful new 3.5 cc diesel. A few designs of this displacement were already on the market, including the E.D. 3.46 Mk. IV Hunter, the D-C Manxman and the A-M 35, but none of these exhibited anything special by way of performance - any of the then-current crop of 2.5 cc contest diesels could out-power them handsomely. If IMA could come up with a new 3.5 cc design which significantly out-performed these others, its sales prospects might be quite promising. It's worth noting that at .209 cuin., the FROG 349 was just over the US displacement limit of .200 cuin. for Class A. So although FROG engines were marketed in the USA (by World Engines of Cincinnati, Ohio), the American market evidently had minimal influence on the decision to develop the new 349 model. It was clearly the home and British Commonwealth markets that were the greater concern.

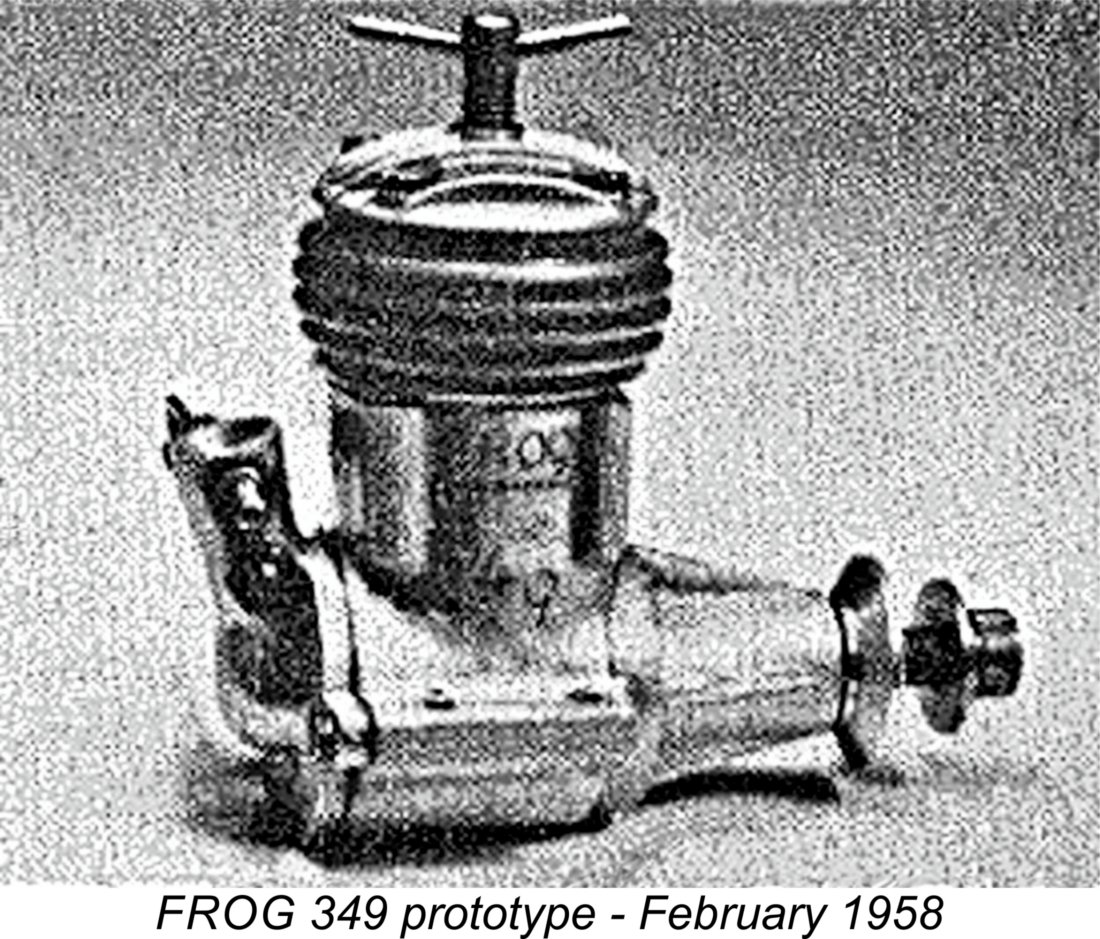

Fletcher must have relished this challenge, setting to work immediately. A prototype of the new design was soon in existence. It looked generally similar to the later production version, although it utilized a head and cooling jacket seemingly borrowed from the contemporary FROG 249 BB, hence undeniably needing a little "cleaning-up". As previously noted, Gordon Cornell was assisting George Fletcher during this period, hence having opportunities to put forward suggestions for improvements to the new design. Many years later he told me that Fletcher agreed that many of his suggestions had merit but could not be taken up due to the overriding management demand that production costs be kept to a minimum. Gordon’s overall comment to me was that the FROG 349 could have been a far better engine than it turned out to be. I’ll be exploring this statement in a later section of this article.

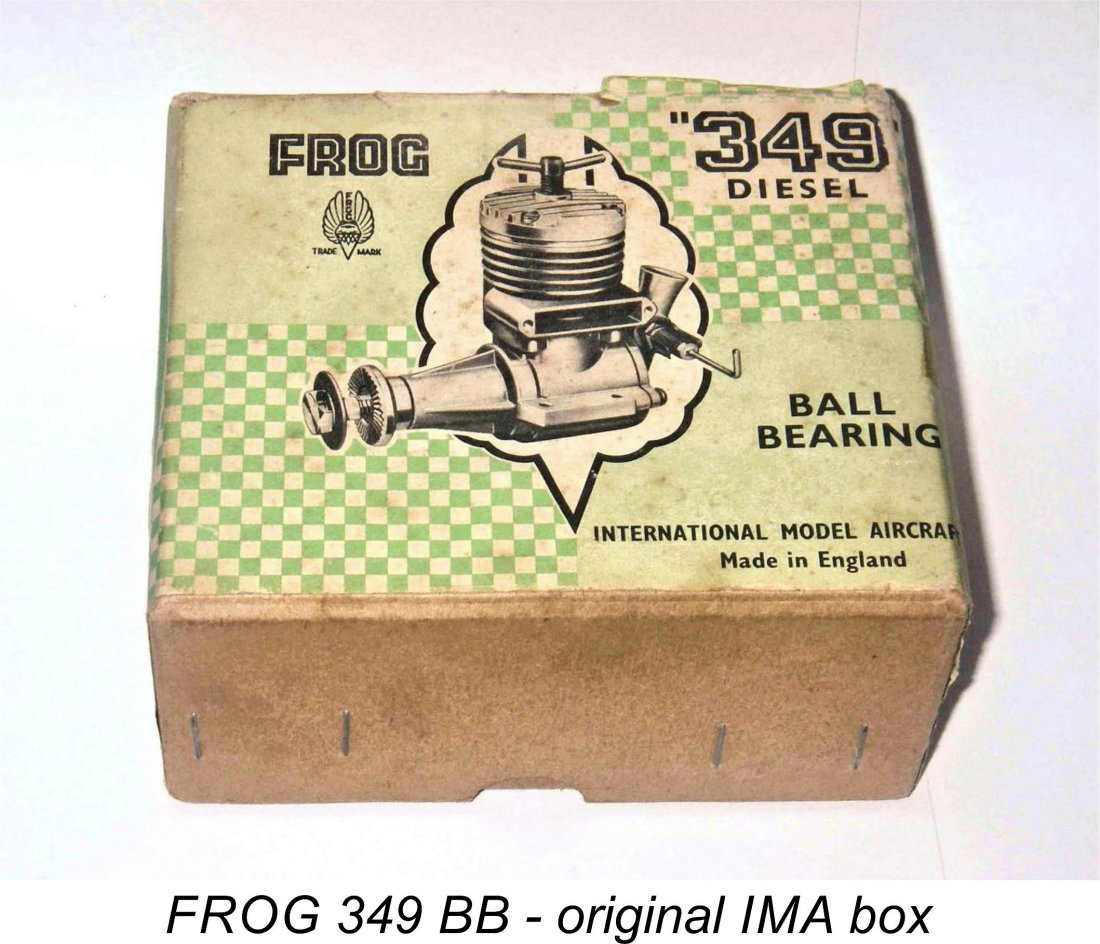

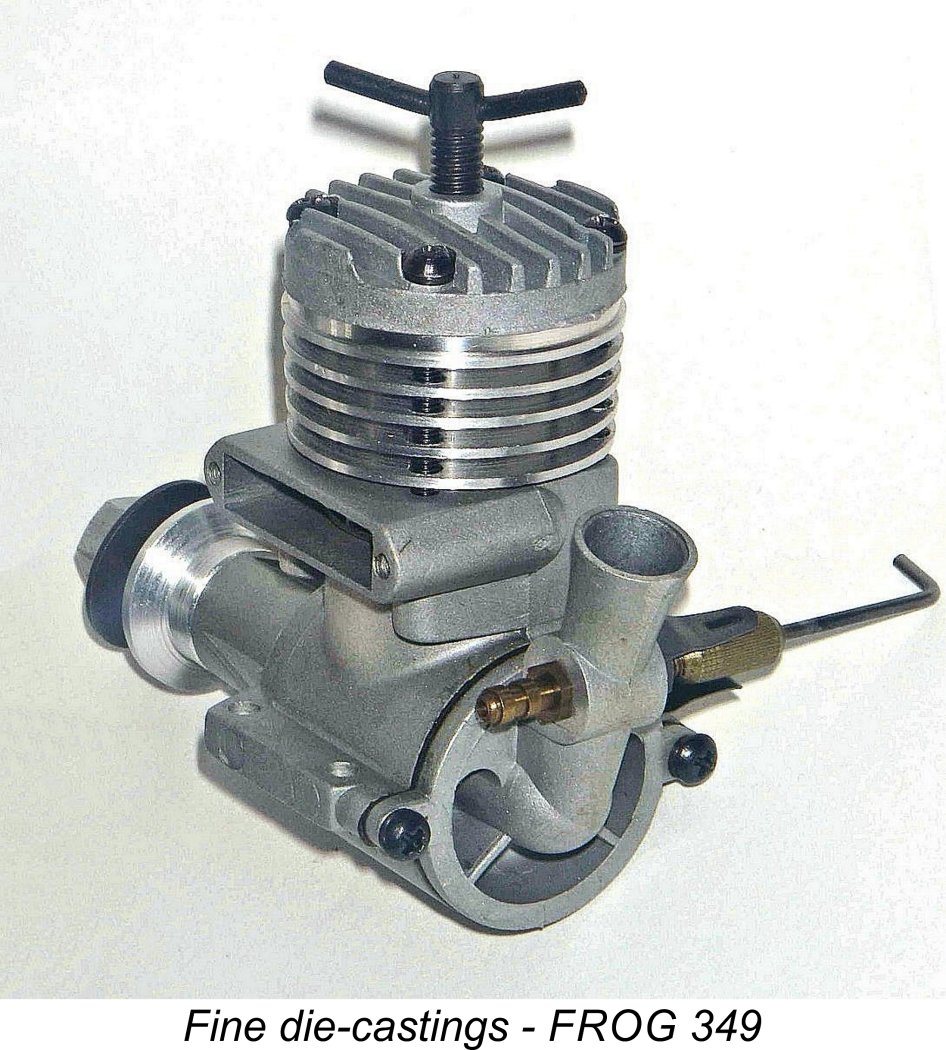

Following the completion of his test of the FROG 349 prototype, the results of which were not made public but were presumably communicated to Fletcher and IMA, Chinn published a photograph of the tested engine in the February 1958 issue of "Model Aircraft", noting the fact that it had been just "one of the manufacturer's experimental models tested during the (previous) year". The prototype appears to have made use of the rounded cooling muff of FROG's front induction 249 BB "Modified". At the time of publication of this photograph, which is However, towards the end of 1958 management had a change of heart, deciding to proceed with the production of the new model. After being informed of this decision and taking it as a “green light”, Chinn published further details of the prototype engine in his regular “Latest Engine News” column in the November 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”. That November 1958 column was unusually interesting in that it contained so many gems, including the Basil Miles glow-plug engine with the unusual transfer ports and John Oliver's MG TD hood ornament seen at the right. How many seconds do you think that would last in the street today? The eventual entry of the new model into the marketplace was first reported in the March 1959 issue of "Aeromodeller" in their regular "Motor Mart" feature. This was some 18 months after the initial inception of the FROG 349. It was By May of 1959 examples of the engine were appearing regularly on British flying fields, and "Aeromodeller" reportedly had their own example running-in on their test bench. Statements were made in that month’s "Motor Mart" feature that the engine was proving itself to be most impressive and had "already ...raised a few eyebrows in combat circles". The quality of the main casting was highly praised, being described as "the best crankcase casting yet seen on a British engine". This being the case, it's a little odd that the "Aeromodeller" test of the engine (see below) was not published until December 1959! For reasons which must forever remain unclear, the FROG 349’s appearance in IMA advertisements was delayed for some months following its actual market entry. At the time in question, IMA and KeilKraft advertisements alternated on the back cover of “Model Aircraft”. June 1959 was Keil Kraft's turn, so although the June 1959 Both plain bearing and ball race versions of the FROG 349 were offered at the outset. There was also a watercooled marine variant which became very popular, due in large part to the convenient location of the carburettor relative to the flywheel. The engines were supplied in sturdy cardboard boxes with the graphics presented against a green checkerboard background. So what made this seemingly-impressive engine tick? Let's find out................... Description

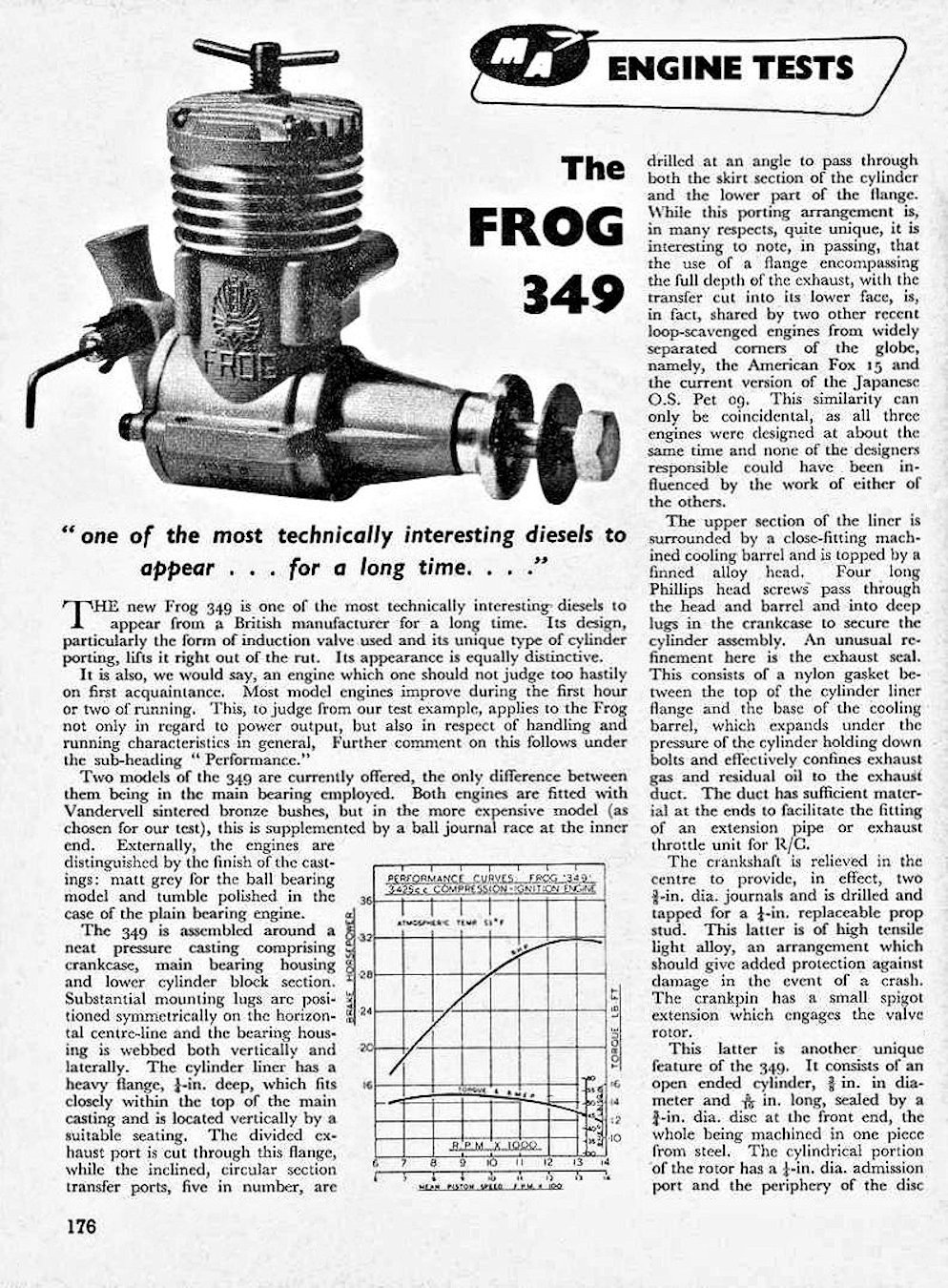

When Peter Chinn described the FROG 349 as "one of the most technically interesting diesels to appear from a British manufacturer for a long time", he was certainly by no means overstating the case. The new design fairly bristled with features which were new to the British model diesel design scene. For a start, the cylinder design was refreshingly different. Cross-flow loop scavenging was employed along with a side exhaust stack, giving the engine a rather "glow motor" appearance. The only previous British diesels to adopt this style of scavenging were the E.D. 346 Mk. IV Hunter (which dispensed with a stack), the 1 cc Series 2 E.D. Bee, the Dyne 3 cc model and the far earlier Comet 0.4 cc diesel.

Transfer was accomplished through five substantial holes drilled upwards through this flange at an angle. These overlapped the exhaust ports to a modest extent and provided good upward direction to the incoming mixture despite the enforced absence of an upstanding baffle. The drilled transfer holes were fed through an external bypass passage cast into the main crankcase in the conventional "glow motor" manner, albeit on the right hand side in K&B style. Although this bypass passage was of relatively modest dimensions, the result was a very free-breathing transfer system with a relatively long transfer period. Somewhat unusually for an engine using this style of porting, the FROG was provided with a significant amount of sub-piston induction. One might expect that much of what might be drawn in from the confines of the stack would be spent exhaust gases! However, other notable engines such as the ETA 29 Mk. VIc used the same approach successfully.

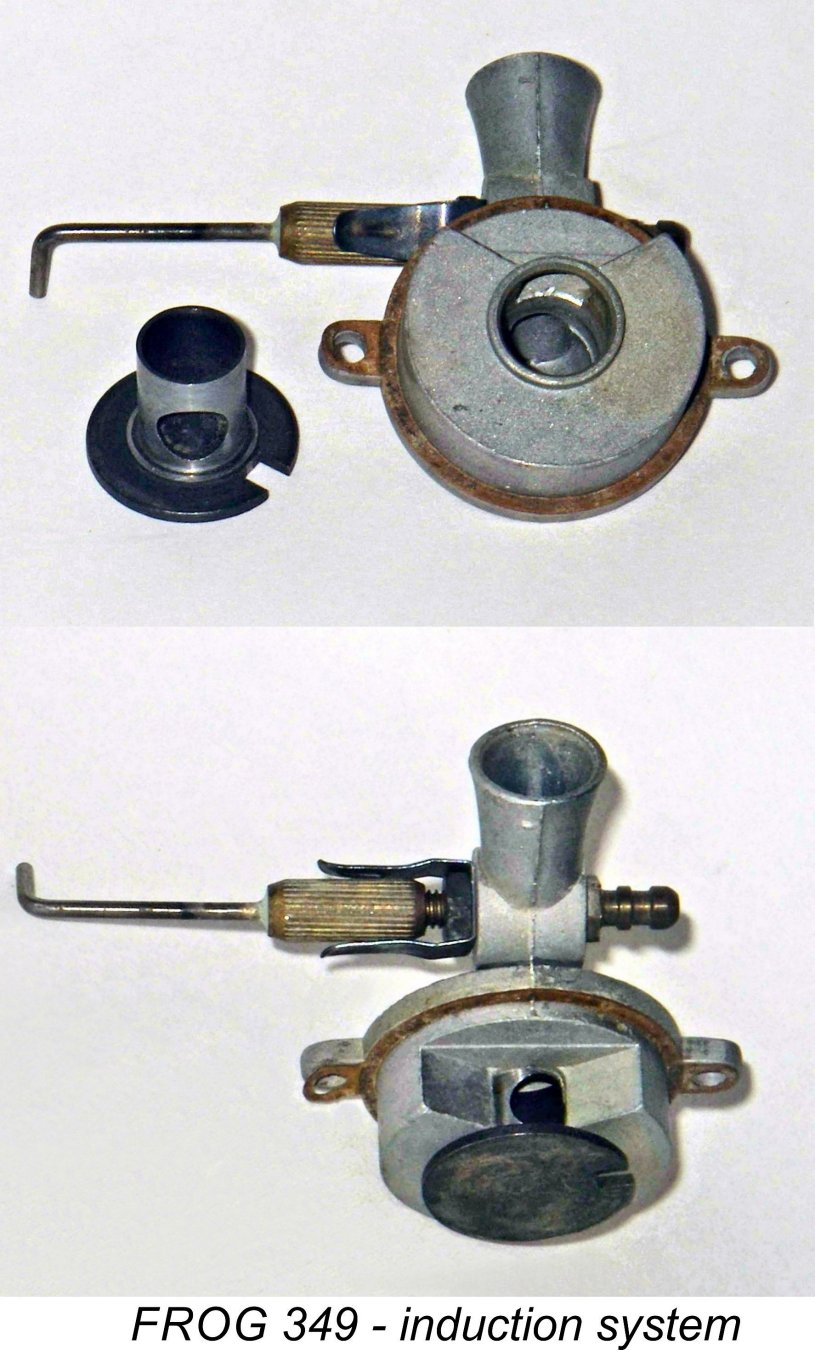

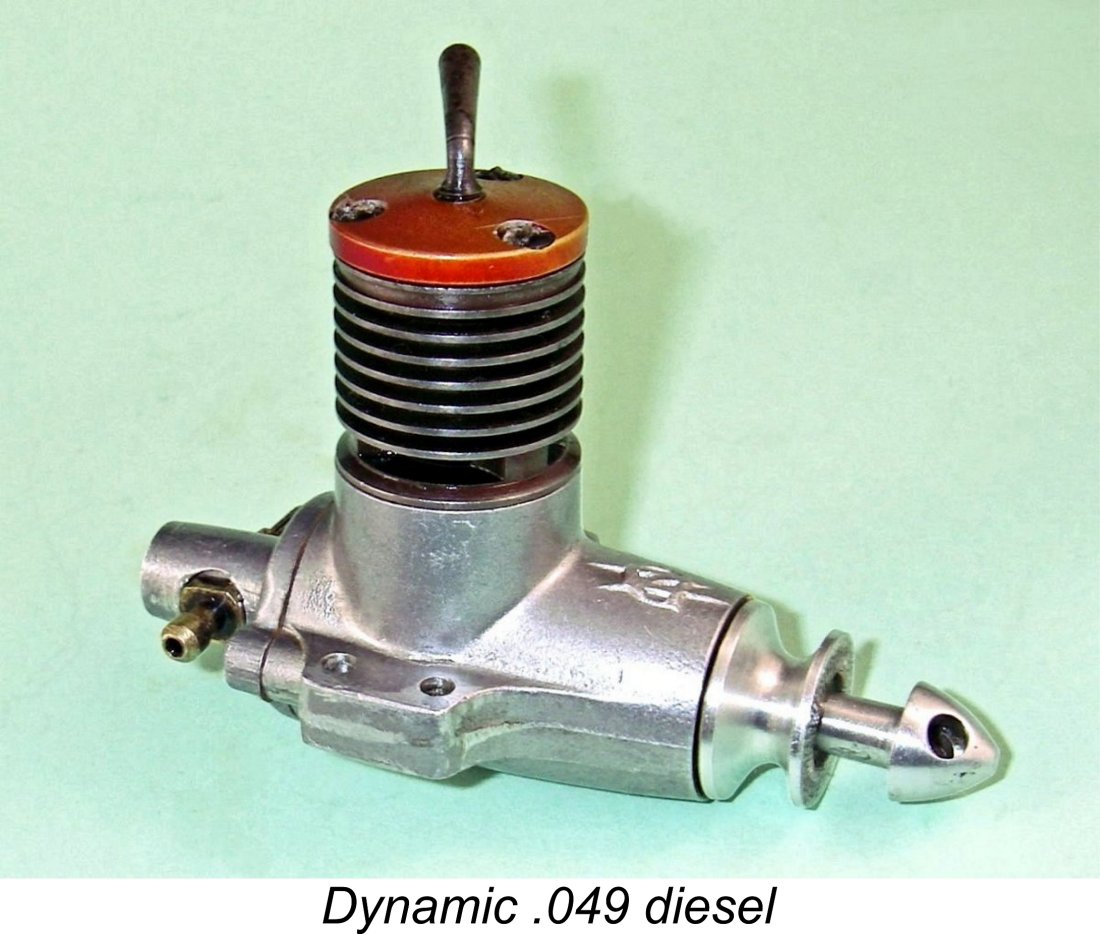

An innovation here was the use of a thick nylon ring between the cooling jacket and the upper surface of the port belt against which it bore. The reason for the use of this nylon ring has always been given as the provision of a good oil seal between the jacket and the crankcase in order to confine oil residues within the exhaust stack, but this has always seemed more than a little thin to me. For one thing, it's somewhat less than effective in practise! For another, why is an oil seal at this point important?!? I've always suspected (but cannot prove) that the real reason for the inclusion of this component may have been rather more subtle and was possibly related to internal stress management. Internal stresses in large diesels are considerable, and Fletcher may have chosen this approach to help deal with this issue in the new 349. The nylon ring created some built-in resilience to the system and gave the cylinder the freedom Nylon was also to be found in the cylinder head, which featured an internally-fitted threaded nylon insert which formed part of the compression screw thread and served as a friction lock to discourage movement of the compression screw during airborne operation. This was very effective in practise. The entire cylinder assembly was held down by four long screws which engaged with tapped holes in the main casting. A nice touch was the use of locking washers in conjunction with the assembly screws to encourage them to remain snugly tightened. Another really innovative feature of the FROG 349 was the form of rear drum valve used. This was of the "inside out" variety in that the internal gas passage in the steel drum was open to the atmosphere via the downdraft venturi rather than to the crankcase as with In effect, this was a crankshaft rotary valve in reverse! The arrangement was not a George Fletcher original - a somewhat similar design had been used some fifteen years previously in the May Rocket 45 sparker from America. However, the FROG 349 was apparently the first of many diesels to feature this configuration. This arrangement provides both a very direct induction passage and a smaller-than-usual crankcase volume since the interior of the drum valve does not form part of the crankcase volume during the engine's base compression cycle. This should theoretically improve the engine’s base pumping efficiency. In addition, the fact that the drum valve is un-stressed by the con-rod and does not have to transmit the engine's torque to the propeller allows the designer to take as large a "bite" as necessary for the internal gas passage and associated induction port to maximize efficiency without worrying about mechanical strength. Clearly having taken favourable note of this arrangement, Gordon Cornell was later to use the concept in both his wonderful TR 247 team race “special” of 1960 and his fabulous and extremely rare little Dynamic .049 ball race diesel of 1961, calling it the “centrifugal” drum valve. The system was quite widely taken up by makers of leading-edge team race diesels in the 1960’s and 1970’s A slightly odd feature of the 349’s drum valve was the fact that while the port in the bearing itself was square, the corresponding port in the drum was round. This resulted in opening and closing being considerably less rapid and complete than it might have been. Presumably this was related to the need to keep costs down. Another somewhat questionable feature was the use of only two screws to secure the backplate unit. It's true that this unit was unstressed, but the maintenance of a good seal could be problematic even with the use of a gasket. Like the cylinder screws, these two screws were equipped with locking washers. The cast iron piston in the FROG had a very steeply conical crown, with the mild steel contra-piston being shaped to match. The piston was relatively heavy and the crankshaft was unbalanced. As a result, vibration levels were perhaps a little higher than they could have been, although the nylon ring mentioned earlier may have helped a bit in this respect. Regardless, the engine was not a major offender in this respect. Presumably the fact that the piston was not lightened by internal milling and the crankweb was left in its plain disc configuration were cost-related design decisions.

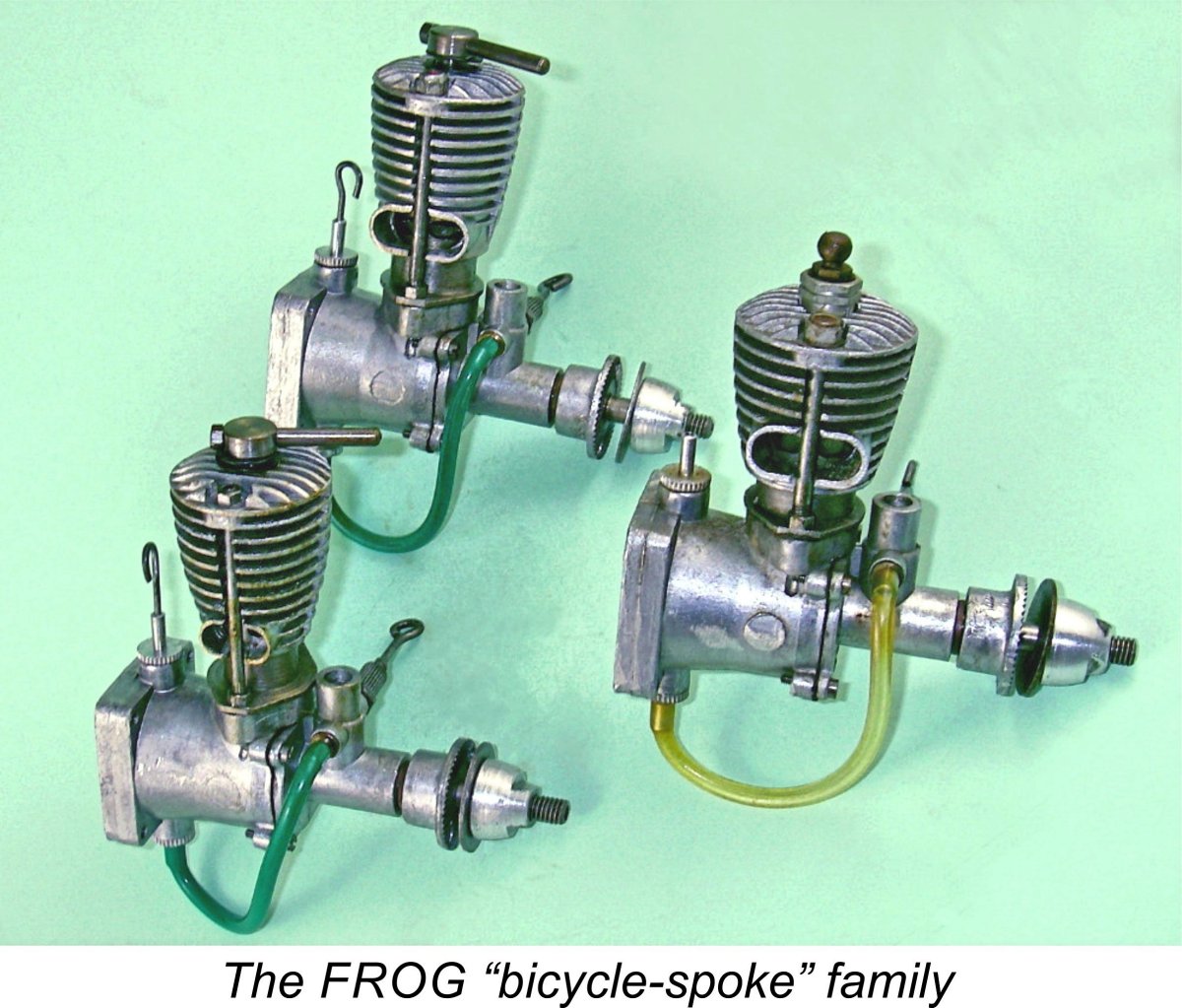

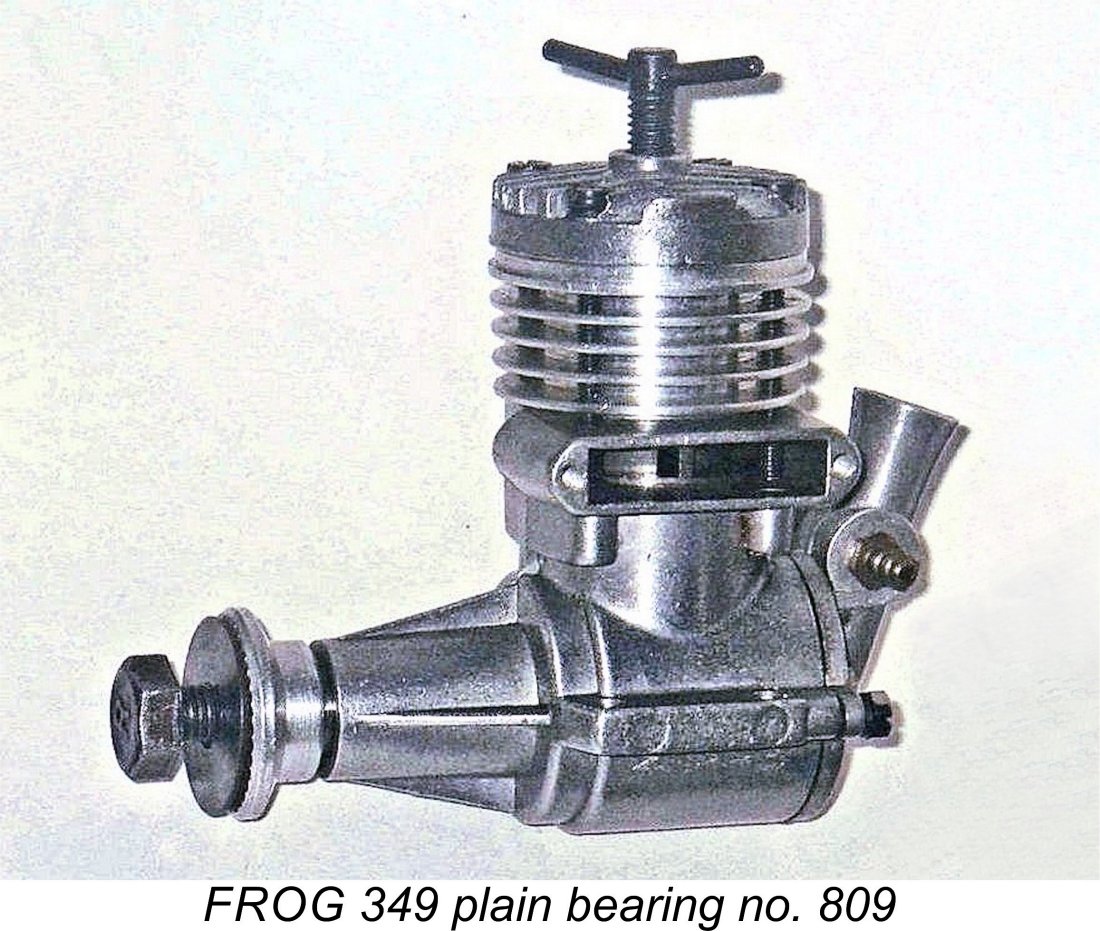

It was likely for this reason that the plain bearing model of the FROG 349 apparently found few takers, being phased out fairly early on. That model appears to be very rare today - my illustrated low-numbered example no. 809 is the sole example that I've ever encountered in the metal. I actually doubt that the numbers for that variant went much higher, but am very much open to being proved wrong! The two variants of the FROG 349 were visually distinguished by the fact that the ball bearing version displayed a very attractive matte grey finish applied to its castings by vapor blasting, while the plain bearing version had a shiny tumbled finish. This difference is readily apparent in the above illustration. After the phasing-out of the plain bearing model, the tumbled finish was applied to the ball bearing version as well and the matte finish cases were no longer produced.

The use of a downdraft intake kept the length of the engine quite reasonable and also placed the needle in a very convenient and safe location from the operator's standpoint. Another good feature was the use of a light alloy bolt to mount the propeller, in place of the more usual threaded extension of the shaft. In a hard crash, the prop bolt would bend or break rather than the shaft - a far less daunting replacement! Advantage was taken of this fitting to carry the necessary tapped central hole in the shaft back to a point just short of the plain crankweb, thus minimizing the weight of the crankshaft while maintaining the smallest possible crankcase volume. The cost-cutting measures noted above were clearly effective, since the price of the engines was by no means unreasonable considering the value for money that they represented. Price of the ball bearing model in 1959 was £3 19s 2d (£3.97) including purchase tax, while the plain bearing model sold for £3 13s 3d (£3.66) including tax. Overall, the new FROG presented the market with a relatively large-displacement diesel displaying a wide range of unusual features along with excellent handling qualities and a good performance. It was also very well made indeed in addition to being competitively priced. Small wonder then that it quickly became a familiar sight on flying fields in Britain and elsewhere! The FROG 349 On Test

In the test report, Chinn commented upon the design originality of the engine, also praising its compact and robust construction. He was quite complimentary regarding its handling qualities, particularly with respect to its control response. He stated that there had been "more poor large diesels than good ones" but unhesitatingly placed the new FROG in the latter class. In fact, he noted that it was the most powerful British 3.5 cc diesel then available. One point upon which Chinn dwelled at some length was the fact that the FROG 349 needed a lot of running-in time to reach its optimum performance levels. He found it necessary to give his own example some four hours of running-in prior to taking his test readings, and noted that it was only after the third hour that the engine really began to show its true potential. On test, Chinn was able to measure an output of 0.318 BHP @ 13,000 rpm. It may be true that this figure was matched or even exceeded by several contemporary 2.5 cc competition diesels, but those engines produced their peak power at significantly higher revs and were relatively costly in addition. The higher torque of the FROG 349 allowed it not only to produce a power output which matched the contemporary 2.5 cc competition diesels (and beat some), but to do so at significantly lower rpm. Hence it produced a lot of very useable power and could swing a large and hence efficient prop very comfortably. It was also priced very competitively by comparison. Overall, Chinn's test was a highly positive endorsement of the new model. Given the very high level of respect in which Chinn was held by most power modellers, It must have done much to encourage more modellers to give the engine a try.

Once again, this test was very favourable. Warring described the engine much as Chinn had done, noting that the 349 appeared to be built to rather closer tolerances than previous FROG engines. He cited this as the reason for the engine requiring an extended running-in period, again just as Chinn had done. He described the handling characteristics as "very good" and repeated Chinn's comment regarding the non-critical control response. One issue on which Warring focused in particular was the potential of the 349 for radio control use. He conducted a number of experiments with speed control, finding that the sub-piston induction represented a considerable impediment to effective throttling, as one would expect. He decided that the best results could be achieved with a combination of an exhaust restrictor fitting and an intake throttle. He drew attention to the fact that the intake of the engine was equipped with an oversized boss at the needle valve location to allow for drilling-out and installation of a throttle, while the exhaust stack was dimpled to make provision for a bolt-on exhaust fitting. It seems possible that Warring did not run-in his examples for as long as Chinn had done, because he was unable to match Chinn's performance figures. He found a power output of 0.3025 BHP @ 12,200 rpm for the ball bearing model, with the plain bearing version achieving 0.28 BHP @ 12,000 rpm. Later History

It's not hard to understand why this was so. The plain bearing model was only some 6 shillings (£0.30) cheaper than the ball bearing version. It was also a little less powerful while being only fractionally lighter in weight. Finally, it would never have stood up to long hard use as well as the ball bearing version. The outlay of an extra six shillings must have appeared more than worthwhile to most purchasers. At some point after the plain bearing model was discontinued, the matte finish formerly used on the castings of the ball bearing version ceased to be applied. Instead, the same kind of shiny tumbled finish which had previously been reserved for the plain bearing model was now applied to the ball bearing version. This change has led quite a few people to believe that they have a rare plain bearing model, when in fact they have a later ball bearing example. Check those serial numbers ..............

In 1960 an R/C version of the 349 was introduced. This had a neat bolt-on exhaust collector which rendered the sub-piston induction more or less ineffective, thus improving the throttle response. It also allowed for easy connection to an exhaust pipe for getting exhaust residues away from the model. A simple barrel throttle was installed in the oversized boss which had been present all along on the intake venturi. Weight crept up to 7.1 ounces as a result of these additions. As usual with IMA, a suitable kit was soon provided to complement this engine as well. This took the form of the 60 in. wingspan “Jackdaw” high-wing cabin model. Despite IMA’s best efforts, the R/C glow-plug engine had reached a relatively high level of effectiveness and user acceptance by this time, generally being considered superior to the diesel for applications requiring speed control. Consequently, the diesel FROG R/C model appears to have had trouble drawing much sales attention - examples are relatively uncommon today. A test by Peter Chinn was published in the March 1962 issue of "Model Aircraft", but the cited performance figures were rather unspectacular. It actually seems a little odd that IMA never tried a glow-plug version of this engine for R/C - with some adjustment to the timing, it might have worked out quite well.

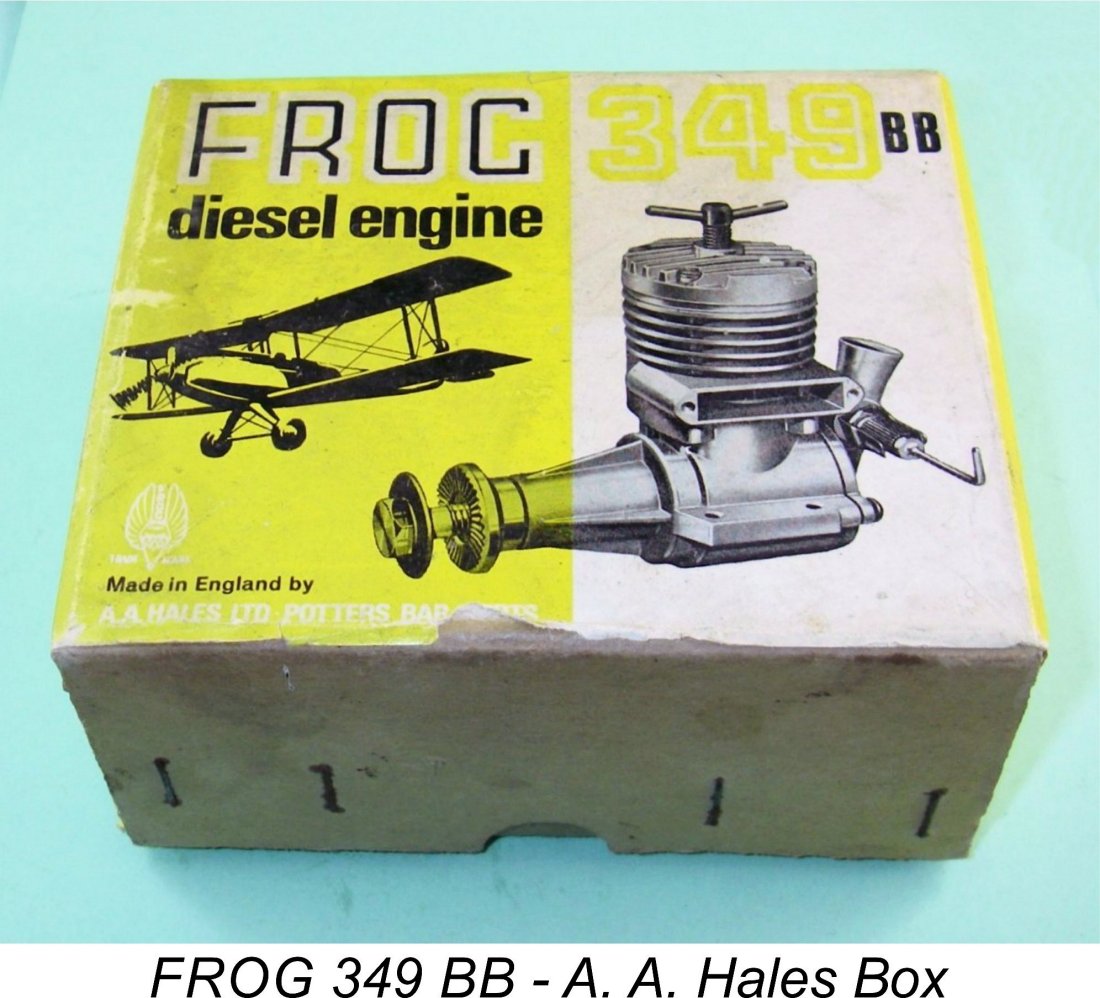

However, none of this effort was evidently sufficient to induce Lines Brothers to remain in the flying model business. In 1962, IMA ceased all model engine and wood kit production. Naturally, this included the FROG 349 BB and also (sadly) the outstanding Viper 149 diesel which had been introduced only a year previously and was one of the best FROG engines ever made. At this time IMA were still producing their plastic kit range in great volume, but they ceased all advertising in "Aeromodeller" after June 1966, doubtless because that publication catered primarily to model flying enthusiasts. A major distibutor of the FROG model engines had been the A. A. Hales organization of Potters Bar in Hertfordshire, just north of London. In the latter part of 1962, Lines Brothers purchased a majority shareholding in the A. A. Hales company, a move which was announced in the "Trade Notes" feature in the February 1963 issue of "Aeromodeller". At the time of this transaction, there were significant numbers of completed engines already in existence. A. A. Hales was charged with the responsibility for the future marketing of the various FROG products. After 1962, no more was to be heard of IMA in connection with the FROG model engine range. Hales already produced their own range of model kits under the "Yeoman" label (who remembers the "Dixielander", the "Bantam Cock" and the "Scorcher"?). Despite apparently being in competition with themselves, they continued to market many of the established FROG model kits, although these were almost certainly existing stock acquired at the time of the transfer of responsibility for the FROG marque to Hales from Lines Brothers.

The cessation of engine production by IMA left George Fletcher looking for fresh employment, which he soon found with the nearby E.D. company. Interestingly enough, he replaced his former colleague Gordon Cornell as chief designer for E.D., the latter having left E.D. following some philosophical differences of opinion with E.D. management at the time. Returning to the FROG 349 story, the Hales organization must have detected some level of continuing demand for the FROG model engine range as remaining stocks of IMA-produced units ran low, because in 1964 they made arrangements with Lines Brothers to acquire outright ownership of the FROG model engine range. This transaction involved the transfer of all of the FROG engine dies and tooling to Davies-Charlton Ltd. (D-C Ltd.) on the Isle of Man. Thenceforth manufacture of the FROG engines was resumed by D-C Ltd. under contract to A. A. Hales. The serial number sequences were evidently restarted with a code letter preceding the digits, thus making it easy to distinguish between IMA and D-C-made engines. More discussion of this point in due course below………

Not all of the FROG engine range went into reproduction by D-C Ltd. The abandoned designs included the outstanding drum-valve 1.5 cc Viper diesel and its less noteworthy Venom glow-plug relative, the venerable FROG 500, the Vibramatic 149 diesel and the rather unsuccessful FROG .049 glow model. A very few examples of the latter two models appear to have been assembled by D-C Ltd. from residual IMA components, but there does not appear to have been any resumption of actual manufacture of these models. It must be said that the quality of the FROG engines appeared to suffer somewhat by the change of manufacturer. It's my personal impression that the 349's (and other FROG’s) made by D-C Ltd. never quite matched the IMA originals for consistency in terms of quality. However, they generally ran OK, and at least spare parts continued to be available for a few more years.

In August 1971, Hales announced the incipient arrival of a new .049 FROG glow-plug model which revived the old Venom name. The FROG Venom glow-plug model duly appeared in September 1971, but turned out to be just a red-head radial mount version of the glow-plug D-C Wasp, thus being a text-book case of badge engineering - a D-C Wasp with the FROG name substituted. It is not to be confused with the earlier 1.5 cc FROG Venom glow-plug unit. The .049 Venom continued to be advertised by Hales along with some other FROG models until September 1972. The FROG 349 was one of the models which was featured in that very last Hales ad for the range. That advertisement is reproduced below at the left. It confirms that the FROG 349 BB was among the "last men standing" in the FROG range, having enjoyed a market presence of over 13 years. Certain models continued to appear in retailer listings right up to mid 1974. although these were obviously New Old Stock. My very sincere thanks to Gordon Beeby for his invaluable assistance in clarifying these details.

For a while I was confused by the fact that I own another example bearing what I took to be the number 27230, suggesting that about 30,000 engines had been made. However, it turns out that the leading "2" is actually the letter Z! The fact that these numbers were engraved by hand makes it easy to mistake one for the other, but this is highly significant as the leading letter indicates that it was manufactured by Davies Charlton Ltd, not IMA! Let me digress to explain this matter........ One of the most rewarding outcomes arising from the publication of articles like this is the receipt of further information from interested and knowledgeable readers. In the case of this article, after the first version appeared on MEN in December 2008, I was contacted by Kevin Richards of England, who is best known as an expert on the E.D. range but also knows his FROG’s pretty well. Kevin set me straight on the serial numbering and production period, requiring some serious editing of the original page. The first issue that required attention was a startling correction to my imperfect understanding of the serial numbering system. It appears that at the beginning of 1964 when A. A. Hales arranged for D-C Ltd. to resume manufacture of certain models in the FROG range, they introduced the use of a letter prefix to identify the model in question. This was a very sensible idea, as IMA had simply numbered the engines in each displacement category sequentially from 1, consequently generating as many complete sets of duplicate serial numbers as there were engine series! The approach taken by A. A. Hales eliminated the duplicates and made each number unique. The following table shows the system used:

† Probably assembled by D-C Ltd. from residual IMA parts, not manufactured by them. One of the remaining questions is whether Hales/D-C Ltd. continued the sequences started by IMA, or whether they restarted the sequences using the letter prefix to differentiate between the older and new examples. There is overwhelming evidence to suggest that they restarted the sequences. For one thing, Kevin Richards is aware of an IMA FROG 150R bearing the number 28031 and a later D-C-made FROG 150 Mk III with the lower number of F19920. Of course, it's possible that the 150 Mk III was seen as a different engine, justifying a sequence restart, but the FROG 349 numbers also support the global restart hypothesis. As previously stated, the highest serial number known to me without the Z prefix is 13225. The lowest numbered Z-prefix example of the engine presently known to me is Z83, owned by Chris Ottewell. I see this as representing conclusive evidence confirming that the count was restarted when D-C Ltd. took over the manufacturing. The highest Z-prefix serial number of my present acquaintance is Z8189 reported by Kevin Richards. My own engine number Z6015 is highly significant in that it is New In Box, still retaining its dealer date-stamped guarantee certificate. The box used for this engine was one of the previously-described yellow-labelled A. A. Hales examples. The guarantee certificate bears both the matching number of the engine in the box (Z6015) and the date of original sale by The Experimental & Model Co. of 62 Lower Ford Street in Coventry - September 4th, 1967. This does not necessarily date the actual manufacture of the engine - merely the date on which it was sold, which triggered the guarantee period. Significantly enough, this number confirms that D-C Ltd. had manufactured at least 6015 examples of the FROG 349 BB by mid 1967, only three years after they took up the manufacturing.

So how many examples of the FROG 349 were made? Assuming that IMA followed their usual practise of starting at 1, it appears that at least 13,225 examples of the 349 were manufactured by IMA between January 1959 and some time in 1962 when they ceased engine manufacture. Less than 4,500 examples a year - not all that great a production record, but remember that the engine was in a displacement category that was a bit off the mainstream. Since we have persuasive evidence to confirm that D-C Ltd. restarted the count at Z1 in 1964 when they commenced manufacture, we appear to have evidence that they produced at least another 8,189 examples of the engine, over 6,000 of which were produced during their first three years of manufacture. So the total produced by both manufacturers combined would seem to be around the 22,000 mark. Kevin Richards provided three other valuable points which are well worth recording. Firstly, previously-mentioned engine number Z8189 had a red-anodized cooling jacket. Kevin reported having seen at least one other example of the engine that was similarly equipped. It appears that this represented a last-ditch attempt by A. A. Hales to tart the engines up a little, thus hoping to promote more sales. Secondly, Kevin confirmed from personal experience that some of the last Hales/D-C examples of the 349 came in boxes which bore orange labels rather than green or yellow. It appears that as the end of production drew near, the manufacturers must have run out of green or yellow box labels, hence being forced to create a small number of additional boxes having orange labels. Finally, Kevin was able to confirm that new examples undoubtedly remained available through dealers as of 1970. Kevin bought new unrun boxed examples of both the 349 BB and the 249 BB from his local hobby shop in that year. He still has that 249 BB new in the box complete with 1970 dealer-stamped factory guarantee! Naturally, this cannot be taken as evidence of continuing manufacture as of 1970 - it’s far more likely that they were simply selling off New Old Stock by that time. But it does confirm that new examples of the engines remained available from dealers for a considerably longer period than might be supposed. My sincere thanks to Kevin Richards for his generous help in setting the record straight! The final chapter in the FROG saga came in 1972, when Alan Hales bought back the A. A. Hales brand from the Lines Brothers liqidators, presumably at a fire-sale price. A few advertisements for the FROG engines were placed thereafter (February and September 1972), but these almost certainly represented nothing more than an attempt to sell off some remaining New Old Stock. User Impressions Here I can speak with some authority because I've been using the FROG 349 BB continuously for over 50 years now! I have two examples which receive semi-regular use, and I wouldn't like to guess how many running hours they now have on them. I've had to rebore one of them, but the other one (a tuned example - see below) is still going strong on the original bore. These engines really last if you fuel them and use them correctly! The FROG likes a fuel with around 2% amyl nitrate or equivalent, but seems relatively unresponsive to greater percentages of nitrate. I suppose this is because it is a moderate speed engine. On un-doped fuel it runs rather harshly - the nitrate really smooths it out. The engine also likes at least 25% oil and has a marked preference for the oil being of the castor variety, probably because it tends to run very hot by diesel standards - another reason not to overdo the nitrate! The previously-noted fact that the type of drum valve used tends to starve the big end bearing of oil while allowing it to run hot also suggests the use of a high oil content in the fuel. The plain bearing at the front of the shaft reportedly wears relatively quickly unless you apply ample lubrication. It's also very important to balance the prop very carefully if you want that bearing to last.

Once running, the engine delivers on its reputation. Controls are very responsive without being overly sensitive, and there's ample feedback to help you to get the setting right. Once set correctly, I find that a well run-in example like both of my "flyers" will start and run at the same settings - very user-friendly! Vibration is present, but is less than one would expect - perhaps the nylon cylinder hold-down ring noted earlier helps here? Suction is very good, and the engine runs very consistently in the air. However, it does tend to get very hot, seeming to do best on a slightly rich mixture. Prop choice is a bit of a puzzle. An 8x6 prop under-props the engine, while a full 9x6 seems to be just a little too much prop for optimum results. For control line, I use a "fat" 9x6 nylon cut down to 8½x6, which gives a nice wide-bladed prop which really moves some air and will survive a crash with no problems. The engine turns this at a little over 11,000 rpm on the ground, which should allow it to reach its peak in the air. Prop it for higher speeds on the ground and you'll go past the peak in the air for sure. Remember that this is not a high-speed engine! But it can be! Let’s now explore the potential of this engine to which Gordon Cornell referred! The FROG 349 - Performance Potential

Most people at the time were using Oliver, Rivers and P.A.W. powerplants. Liking the engine very much, I really wanted to try a FROG 349 BB. However, I recognised the fact that it was no better than a typical 2.5 cc unit in terms of power output. It was clear to me that steps would have to be taken to make it competitive, especially given its modest weight handicap. I therefore took one of several examples that I then owned and stripped it down to take a long hard look at what might be done to raise its performance to competitive levels. A number of possibilities immediately presented themselves. After planning the work carefully, I began by milling and turning out the piston interior to lighten it to the extent possible while retaining piston bosses of adequate length. I also added some counterbalance to the crankdisc by grinding wedge-shaped segments off the disc perimeter on the crankpin side. Both of these measures were calculated to reduce vibration - any energy that is used to shake the engine and airframe is not available to turn the prop. Hence vibration reduction is in itself a very effective performance-enhancing step. Next came the issue of maximizing the engine’s ability to pack fuel mixture into the combustion chamber. Beginning with the induction arrangements by which mixture is drawn into the crankcase, I squared off the drum valve induction port to match the square shape of the crankcase register in the backplate. This would enhance the engine’s induction capacity by increasing its rate of opening and closure, also increasing its “fully open” area considerably. I left the induction timing alone, since this seemed OK to me. Turning next to the bypass/transfer arrangements, I decided that the transfer timing was unwarrantably conservative - the blow-down period was far longer than desirable for the operating speeds at which I was aiming. However, I was familiar with the progressive transfer timing concept pioneered by Enya and MVVS, which made sense to me. Accordingly, I raised the tops of the two outer transfer ports to create a blow-down period of only 7 degrees of crank angle. The next two transfers were also raised, but by lesser amounts. Finally, the central port was raised very little. I also carefully streamlined the entries from the bypass into each of the transfer ports. The result was that the outer two transfer ports opened first, followed progressively by their immediate neighbours and finally by the central opening. Those two outer ports should produce high-velocity jets which are directed across the exhausts rather than primarily in their general direction. Those jets should form a high-velocity “curtain” which will encourage the flows from the later-opening ports to move upwards rather than across to the exhausts. Having got as much fuel mixture as possible into the combustion chamber, I wanted it to burn as efficiently as possible. To that end, I made a new cast iron contra piston incorporating a squish band cut at an angle which matched that of the piston crown. I calculated the volume of the combustion chamber itself so that when set for a 20:1 compression ratio the squish band clearance would only be in the order of 10 thou. This seemed to work out pretty well. I couldn’t see anything else that could be done to the standard engine to improve its functional efficiency. However, there was also the issue of weight. My modifications to the piston, crankweb and drum valve had already reduced weight a little. All that seemed to be left to do in that regard was to drill out both the comp screw and prop bolt to the extent possible. The result was a far more free-breathing engine which ran considerably better than stock, developed very manageable levels of vibration and weighed only 183 gm (6.45 ounces) as opposed to the 188 gm (6.62 ounces) of the unmodified unit. Not much of a reduction, but every little bit counts! In the air it had the legs on all of the classic 2.5 cc opposition, only being topped very slightly by the somewhat heavier 202 gm (7.12 ounce) Rivers Silver Arrow.

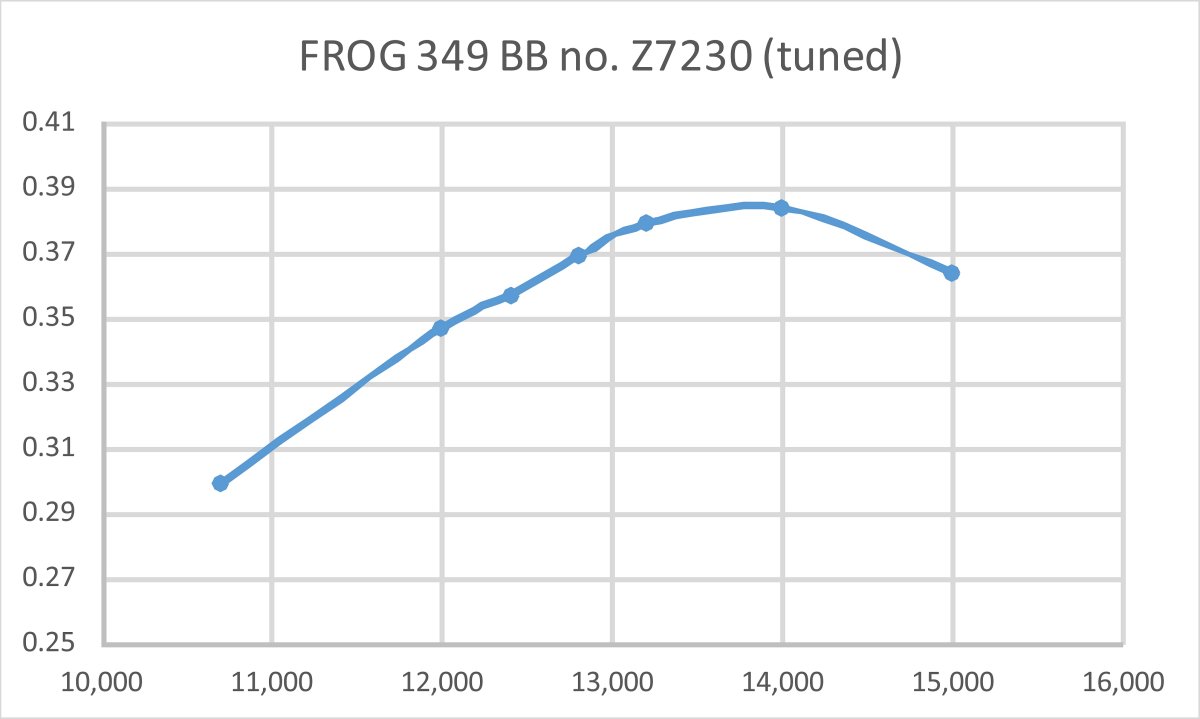

I ended up tuning a few of these engines, both for myself and a few friends. Finding that it held more stable settings in service, I invariably used a P.A.W. needle valve in conjunction with my own custom-fitted spraybar. The illustrated example is so equipped. For the purposes of this updated article, I re-tested the sole modified FROG 349 that remains in my possession today. Since it bears the serial number Z7230, it’s one of the later examples manufactured by D-C Ltd. It did me proud, starting very easily and running superbly with relatively little vibration. It thus confirmed my long-established user impressions completely. The following data were obtained on test.

As can be seen, the modified FROG 349 BB was found to develop around 0.385 BHP @ 13,900 rpm, with a relatively flat peak to the power curve. It was developing at least 0.370 BHP at all speeds between 12,800 and 14,800 rpm, offering a wide choice of practical airscrews. Both peak output and the speed at which that output was realised are considerably higher than the figures reported earlier by Peter Chinn and Ron Warring. However, the increase in the peaking speed was probably far less significant than the actual power developed, since the relatively modest peaking speed increase coupled with a large output increase implies that torque development and hence Brake Mean Effective Pressure (BMEP) had been increased across the range, reaching a peak of around 55 psi at some 12,000 rpm. In terms of usability, this is a far more meaningful improvement than peaking speed. All of my modifications (or close approximations thereof) could easily have been applied by IMA to the production version, albeit at a modest increase in manufacturing cost. So Gordon Cornell was quite right - the FROG 349 could easily have been further developed into a front-runner in the 3.5 cc diesel category. If its development had been carried to a conclusion, it would be remembered today as one of the most powerful and best-handling of the British 3.5 cc diesels. Conclusion The FROG 349 was a very popular engine, and deservedly so. It remains one of my own favourite engines for flying purposes, and I expect to keep using mine until I can no longer fly! I also consider it to be among the most interesting and innovative British diesel designs of the 1950's. Because of the engine's popularity over a considerable period of time, examples in fine condition remain both relatively obtainable and affordable today. Anyone who wants to try one should be able to find a reasonable example without too much trouble. And I recommend that you do so! This one is a bona fide British classic which is sure to be appreciated by anyone who likes model diesel engines. _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN December 2008 This revised edition first published August 2021 |

||

| |

This time we take a look at a true British classic - the 3.43 cc (0.209 cuin.) FROG 349 diesel. I have to confess that this engine has always been a great favourite with me - I've been a continuous FROG 349 BB user since the mid 1960's and still fly them regularly when chance offers. So if any of what follows reads like a bit of a plug, I'm OK with that!

This time we take a look at a true British classic - the 3.43 cc (0.209 cuin.) FROG 349 diesel. I have to confess that this engine has always been a great favourite with me - I've been a continuous FROG 349 BB user since the mid 1960's and still fly them regularly when chance offers. So if any of what follows reads like a bit of a plug, I'm OK with that!

The original manufacturers of the FROG 349 were International Model Aircraft (IMA) Ltd. of Morden Road in the London suburb of Merton in Surrey. IMA was one of the oldest-established model aircraft manufacturers in the world, having been founded in 1931, thereafter quickly becoming a subsidiary of the very prolific Lines Brothers organization.

The original manufacturers of the FROG 349 were International Model Aircraft (IMA) Ltd. of Morden Road in the London suburb of Merton in Surrey. IMA was one of the oldest-established model aircraft manufacturers in the world, having been founded in 1931, thereafter quickly becoming a subsidiary of the very prolific Lines Brothers organization.  During the Second World War Lines Brothers not surprisingly stopped making toys and model products altogether, turning all their efforts to war production. 7,000 people were employed at the Merton factory, eventually making over 1,000,000 machine guns and 14,000,000 magazines for Hurricane and Spitfire aircraft, as well as shell cases, land mine cases and special optical apparatus to help troops see in the dark. Their IMA subsidiary at the same location produced scale model aircraft for target identification training. In 1940 the Merton factory was partially destroyed by enemy bombing, but repairs were soon effected and production was maintained.

During the Second World War Lines Brothers not surprisingly stopped making toys and model products altogether, turning all their efforts to war production. 7,000 people were employed at the Merton factory, eventually making over 1,000,000 machine guns and 14,000,000 magazines for Hurricane and Spitfire aircraft, as well as shell cases, land mine cases and special optical apparatus to help troops see in the dark. Their IMA subsidiary at the same location produced scale model aircraft for target identification training. In 1940 the Merton factory was partially destroyed by enemy bombing, but repairs were soon effected and production was maintained. IMA were notable for their interesting and often innovative engine designs. Their early FROG

IMA were notable for their interesting and often innovative engine designs. Their early FROG  contribution of the late Gordon Cornell, who worked with Fletcher at IMA during the latter part of the 1950's. After being primarily responsible for the changes to the FROG 150 Mk. II which resulted in the excellent

contribution of the late Gordon Cornell, who worked with Fletcher at IMA during the latter part of the 1950's. After being primarily responsible for the changes to the FROG 150 Mk. II which resulted in the excellent

However they came to their decision, it must have been in mid 1957 that IMA management asked George Fletcher to design a new model that would give the FROG marque a presence in the 3.5 cc category, and to do so with a product that was clearly a FROG original in design terms. Since radio control (R/C) was just beginning to find its feet in the British modelling spectrum, it seems clear that the new engine was to be designed to cater to both control line/free flight and R/C applications.

However they came to their decision, it must have been in mid 1957 that IMA management asked George Fletcher to design a new model that would give the FROG marque a presence in the 3.5 cc category, and to do so with a product that was clearly a FROG original in design terms. Since radio control (R/C) was just beginning to find its feet in the British modelling spectrum, it seems clear that the new engine was to be designed to cater to both control line/free flight and R/C applications.

reproduced above at the left, the decision to put the new design into production had not yet been taken - indeed, Chinn specifically commented that the engine was "not likely to go into production". Evidently IMA management were struck with a case of cold feet, at least temporarily.

reproduced above at the left, the decision to put the new design into production had not yet been taken - indeed, Chinn specifically commented that the engine was "not likely to go into production". Evidently IMA management were struck with a case of cold feet, at least temporarily.

Looking first as usual at the tale of the tape, bore and stroke of the FROG 349 were a slightly over-square 16.93 mm (0.666 in.) and 15.24 mm (0.600 in.) respectively for an actual displacement of 3.43 cc (.209 cuin). Weight of the ball bearing model was 6

Looking first as usual at the tale of the tape, bore and stroke of the FROG 349 were a slightly over-square 16.93 mm (0.666 in.) and 15.24 mm (0.600 in.) respectively for an actual displacement of 3.43 cc (.209 cuin). Weight of the ball bearing model was 6

The cylinder was conventionally located on an internal shelf formed in the crankcase below exhaust port level, with a gasket to ensure a good seal. The cooling jacket was a separate turning in light alloy which fitted over the plain cylinder liner and bore against the top surface of the port belt. The working cylinder liner was thus kept free from any installation stresses which might have caused distortion.

The cylinder was conventionally located on an internal shelf formed in the crankcase below exhaust port level, with a gasket to ensure a good seal. The cooling jacket was a separate turning in light alloy which fitted over the plain cylinder liner and bore against the top surface of the port belt. The working cylinder liner was thus kept free from any installation stresses which might have caused distortion.

the more usual crankshaft rotary valve or rear drum valve set-up. The inner end of the gas passage in the drum was sealed by an integrally-turned disc which was slotted at the perimeter to engage with a small spigot on the end of the crankpin which thus drove the drum. The induction port fed directly from the interior of the drum upwards into the crankcase through a wedge-shaped aperture formed in the backplate installation spigot.

the more usual crankshaft rotary valve or rear drum valve set-up. The inner end of the gas passage in the drum was sealed by an integrally-turned disc which was slotted at the perimeter to engage with a small spigot on the end of the crankpin which thus drove the drum. The induction port fed directly from the interior of the drum upwards into the crankcase through a wedge-shaped aperture formed in the backplate installation spigot. under the designation “pipe valve”. However, it was eventually found to have a significant Achilles’ Heel for that application. It tended to starve the conrod big end of oil, also being less effective in cooling that heavily-stressed bearing. As oil contents in team race fuels steadily decreased in the quest for range, this type of valve fell increasingly out of favour. However, it worked well enough in the FROG 349 running at lesser speeds on fuels having more “normal” oil contents.

under the designation “pipe valve”. However, it was eventually found to have a significant Achilles’ Heel for that application. It tended to starve the conrod big end of oil, also being less effective in cooling that heavily-stressed bearing. As oil contents in team race fuels steadily decreased in the quest for range, this type of valve fell increasingly out of favour. However, it worked well enough in the FROG 349 running at lesser speeds on fuels having more “normal” oil contents.  At the outset, the FROG 349 was made available in two distinct versions. One used a conventional plain bearing of the

At the outset, the FROG 349 was made available in two distinct versions. One used a conventional plain bearing of the  All of the castings used in the FROG 349 were of the highest quality, representing a striking demonstration of IMA's (or perhaps their contractor's) expertise in producing high-quality pressure die-castings of quite complex components. The crankcase and backplate in particular were very impressive examples of the precision die-casting process applied to quite complex components.

All of the castings used in the FROG 349 were of the highest quality, representing a striking demonstration of IMA's (or perhaps their contractor's) expertise in producing high-quality pressure die-castings of quite complex components. The crankcase and backplate in particular were very impressive examples of the precision die-casting process applied to quite complex components. The first published

The first published  Although the rival "Aeromodeller" magazine had reportedly had their own example of the FROG 349 running-in as of May 1959 (as noted earlier), it was not until December 1959 that

Although the rival "Aeromodeller" magazine had reportedly had their own example of the FROG 349 running-in as of May 1959 (as noted earlier), it was not until December 1959 that  It appears that the plain bearing version of the FROG 349 did not attract much sales attention, hence being dropped relatively quickly. As a result, this version of the 349 is quite rare today - in all my years of flying and collecting, I have personally only encountered one example in the metal. That example is illustrated here.

It appears that the plain bearing version of the FROG 349 did not attract much sales attention, hence being dropped relatively quickly. As a result, this version of the 349 is quite rare today - in all my years of flying and collecting, I have personally only encountered one example in the metal. That example is illustrated here. The company made a serious effort to supply kit models which complemented their new 349 diesel. Prominent among these was the “Gladiator” combat model which appeared in June 1959 soon after the engine itself. With its 36 in. wingspan it had the wing area to deal with the slightly greater weight of the 349. In later years curiosity led me to build several examples of this model, finding that it was a very capable performer with the FROG 349 powerplant fitted. There was also the 38 in. wingspan “Aerobat” control line stunter which again appeared to have been designed with the 349 in mind.

The company made a serious effort to supply kit models which complemented their new 349 diesel. Prominent among these was the “Gladiator” combat model which appeared in June 1959 soon after the engine itself. With its 36 in. wingspan it had the wing area to deal with the slightly greater weight of the 349. In later years curiosity led me to build several examples of this model, finding that it was a very capable performer with the FROG 349 powerplant fitted. There was also the 38 in. wingspan “Aerobat” control line stunter which again appeared to have been designed with the 349 in mind.

Initially these engines were sold in the same yellow-labelled boxes which had come into use following the A. A. Hales take-over of the FROG range. Interestingly enough, the label identified A. A. Hales as the “manufacturers” of the engine, even though they were in fact produced by D-C Ltd. in the Isle of Man.

Initially these engines were sold in the same yellow-labelled boxes which had come into use following the A. A. Hales take-over of the FROG range. Interestingly enough, the label identified A. A. Hales as the “manufacturers” of the engine, even though they were in fact produced by D-C Ltd. in the Isle of Man. Gordon Beeby of Melbourne, Australia was kind enough to undertake a thorough search of A. A. Hales advertisements in "Aeromodeller" for the period during which Hales was responsible for marketing the range. A typical Hales advertisement for the FROG engines manufactured by D-C Ltd. is the April 1966 placement in "Aeromodeller" magzine which is reproduced at the right. Similar advertisements featuring the same models continued to appear right up to July 1971.

Gordon Beeby of Melbourne, Australia was kind enough to undertake a thorough search of A. A. Hales advertisements in "Aeromodeller" for the period during which Hales was responsible for marketing the range. A typical Hales advertisement for the FROG engines manufactured by D-C Ltd. is the April 1966 placement in "Aeromodeller" magzine which is reproduced at the right. Similar advertisements featuring the same models continued to appear right up to July 1971.  How many examples of the 349 were made? Like all FROG engines, the 349 was numbered sequentially starting from 1, the serial number being hand-engraved onto the lower crankcase rather than being stamped. The lowest FROG 349 serial number so far reported is 283, owned by Chris Ottewell. I own engine number 471, while my highest-numbered example carries the number 2305. The very highest such number of which I’m aware is 13225, which is owned by an Australian collector friend of mine.

How many examples of the 349 were made? Like all FROG engines, the 349 was numbered sequentially starting from 1, the serial number being hand-engraved onto the lower crankcase rather than being stamped. The lowest FROG 349 serial number so far reported is 283, owned by Chris Ottewell. I own engine number 471, while my highest-numbered example carries the number 2305. The very highest such number of which I’m aware is 13225, which is owned by an Australian collector friend of mine. By the time we get to NIB engine number Z7223, we find that the box has been changed to a somewhat less sturdy and very slightly larger container bearing a revised green label. A distinct label was printed for use on boxes containing the popular marine version of the 349 which continued in production at this time. A number of air-cooled examples (including this one) appear to have been sold in this marine model box, with the “marine” designation concealed with tape and the word “Aero” hand-written on the box.

By the time we get to NIB engine number Z7223, we find that the box has been changed to a somewhat less sturdy and very slightly larger container bearing a revised green label. A distinct label was printed for use on boxes containing the popular marine version of the 349 which continued in production at this time. A number of air-cooled examples (including this one) appear to have been sold in this marine model box, with the “marine” designation concealed with tape and the word “Aero” hand-written on the box. I find the FROG very easy to start as long as you don't flood the crankcase. If you do that, the thing tends to become quite vicious and can go into hydraulic lock mode very easily. And being a largish diesel, it can clobber your flicking finger hard! I usually just choke to fill the fuel line, give it one choked flick (and no more) and then go at it with a good hard flick to start (wearing a rubber hose finger shield!). A light prime helps sometimes, but keep it light - the 349 starts on just a smell of fuel. This is especially true of hot re-starts - just a whiff of fuel is enough.

I find the FROG very easy to start as long as you don't flood the crankcase. If you do that, the thing tends to become quite vicious and can go into hydraulic lock mode very easily. And being a largish diesel, it can clobber your flicking finger hard! I usually just choke to fill the fuel line, give it one choked flick (and no more) and then go at it with a good hard flick to start (wearing a rubber hose finger shield!). A light prime helps sometimes, but keep it light - the 349 starts on just a smell of fuel. This is especially true of hot re-starts - just a whiff of fuel is enough.

The modified 349 was actually a good motor for combat because it had plenty of useable power at moderate revs, while its stack and rear intake meant that it didn't fill up with dirt every time it hit the ground. Moreover, its rear-mounted needle valve tended to survive most crashes. Its excellent hot restarting qualities were another great asset in this event. The main trick was to mount it in a model having the wing area to deal with its extra weight over the predominantly Oliver and P.A.W. opposition - its extra grunt allowed it to haul such models very well. I had good luck with a series of thick-wing “Chaos” models having leading edge recesses built in to accommodate the FROG’s intake.

The modified 349 was actually a good motor for combat because it had plenty of useable power at moderate revs, while its stack and rear intake meant that it didn't fill up with dirt every time it hit the ground. Moreover, its rear-mounted needle valve tended to survive most crashes. Its excellent hot restarting qualities were another great asset in this event. The main trick was to mount it in a model having the wing area to deal with its extra weight over the predominantly Oliver and P.A.W. opposition - its extra grunt allowed it to haul such models very well. I had good luck with a series of thick-wing “Chaos” models having leading edge recesses built in to accommodate the FROG’s intake.