|

|

Berkshire’s Best - the A-S 55

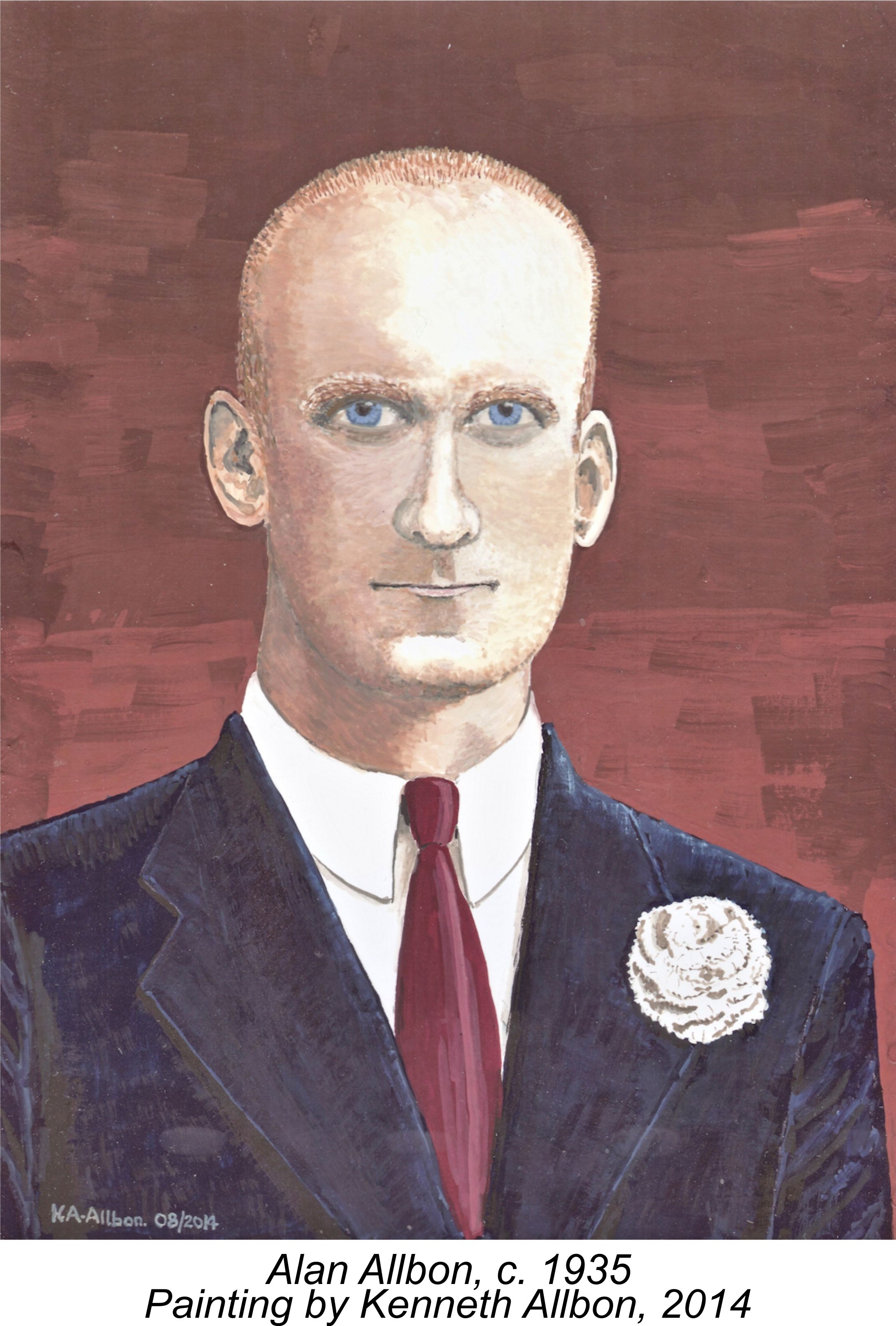

I’ve written previously about the A-S 55 in an article which is still to be found on the late Ron Chernich’s long-frozen but enduringly fascinating “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. However, since the appearance of that article in April 2012, I’ve received a very significant amount of new and corrected information about the engine and the circumstances surrounding its production. I’ve also learned a great deal more about the engine’s designer Alan Allbon, largely thanks to my having been put in touch with Alan Allbon’s eldest son Kenneth, to whom my very sincere thanks are due. Kenneth was also good enough to paint the fine portrait of his dad which appears below. The preservation of an accurate and comprehensive record absolutely necessitated a major updating of the MEN article, which could no longer be undertaken on that site due to its frozen state. Accordingly, I've had no choice other than to present the revised article here. As a preliminary to taking a close look at this engine, it’s appropriate to examine the chain of circumstances leading up to its introduction. Here goes …………. Background

Alan Allbon was a lifelong model aircraft enthusiast who began marketing his own model engine line under the Allbon Engineering banner in early 1948, at which time he was 41 years old. The Allbon engines were initially manufactured at Allbon’s own small machine shop located at 51A Thames Street, Sunbury-on-Thames, a little to the west of London on the north bank of the River Thames. Sunbury-on-Thames lies in the county of Surrey today, although prior to the 1965 county boundary reorganization resulting from the Royal Commission on Local Government in Greater London it was located in Middlesex. Regardless, the community lies just across the River Thames from the successive haunts of the E.D. company at Kingston-on-Thames, West Molesey and Surbiton, and not all that far from the International Model Aircraft (IMA) plant just to the east at Merton, where the FROG range was manufactured. The Mills Brothers factory at Woking was also only a short distance to the south-west. The model engine industry was a significant employer in South-West London in 1948! Think of the craic in all those engine-maker’s pubs ………….

The Allbon model engine range got its start in early 1948 with two successive variants of a very workmanlike 2.8 cc sideport diesel. The range was soon augmented by the successive appearances of the somewhat lacklustre 1.5 cc Arrow glow-plug motor, the far more successful Mk. I version of the famous 1.5 cc Javelin (a highly-regarded diesel version of the Arrow) and the iconic green-headed 0.55 cc Dart Mk. I diesel. Dennis Allen of subsequent Allen-Mercury fame was associated with the Allbon venture during this early period, as was future FROG designer George Fletcher.

In a nutshell, this case centred upon the 1948 Government decision to apply Purchase Tax to model engines (among many other model-related products which had previously been exempt as having educational value). A test case had been initiated by the model trade in mid 1948 through the non-payment of taxes, with a final judicial ruling being handed down in late 1950. Rather unexpectedly, this ruling upheld the government’s decision regarding the applicability of Purchase Tax to such products, hence imposing a significant bill for well over two years’ back taxes, which the parties to the case had not been paying since mid 1948. Sadly, Alan Allbon had evidently made no provision for such an outcome, hence being forced to sell up both his Sunbury workshop and his residence to meet his back tax obligations. He moved his family back to his wife’s parents’ home in Bedford, subsequently resuming model engine production on a greatly reduced scale at a rather bucolic location in an old forge building at the small village of Cople, a little to the east of Bedford.

Recognizing the growing threat to his marketing position, Allbon entered into a production agreement with Hefin Davies of Davies-Charlton (D-C) Ltd., then located at Barnoldswick in Lancashire. Under the terms of this agreement, D-C Ltd. took over the manufacture of the Dart, albeit still under the Allbon banner. This arrangement had been fully implemented by late 1952, after which Allbon abandoned his Cople location and moved his family to Barnoldswick to be near the facilities at which his engines were now produced. At this point in time he took up the position of D-C's Works Manager.

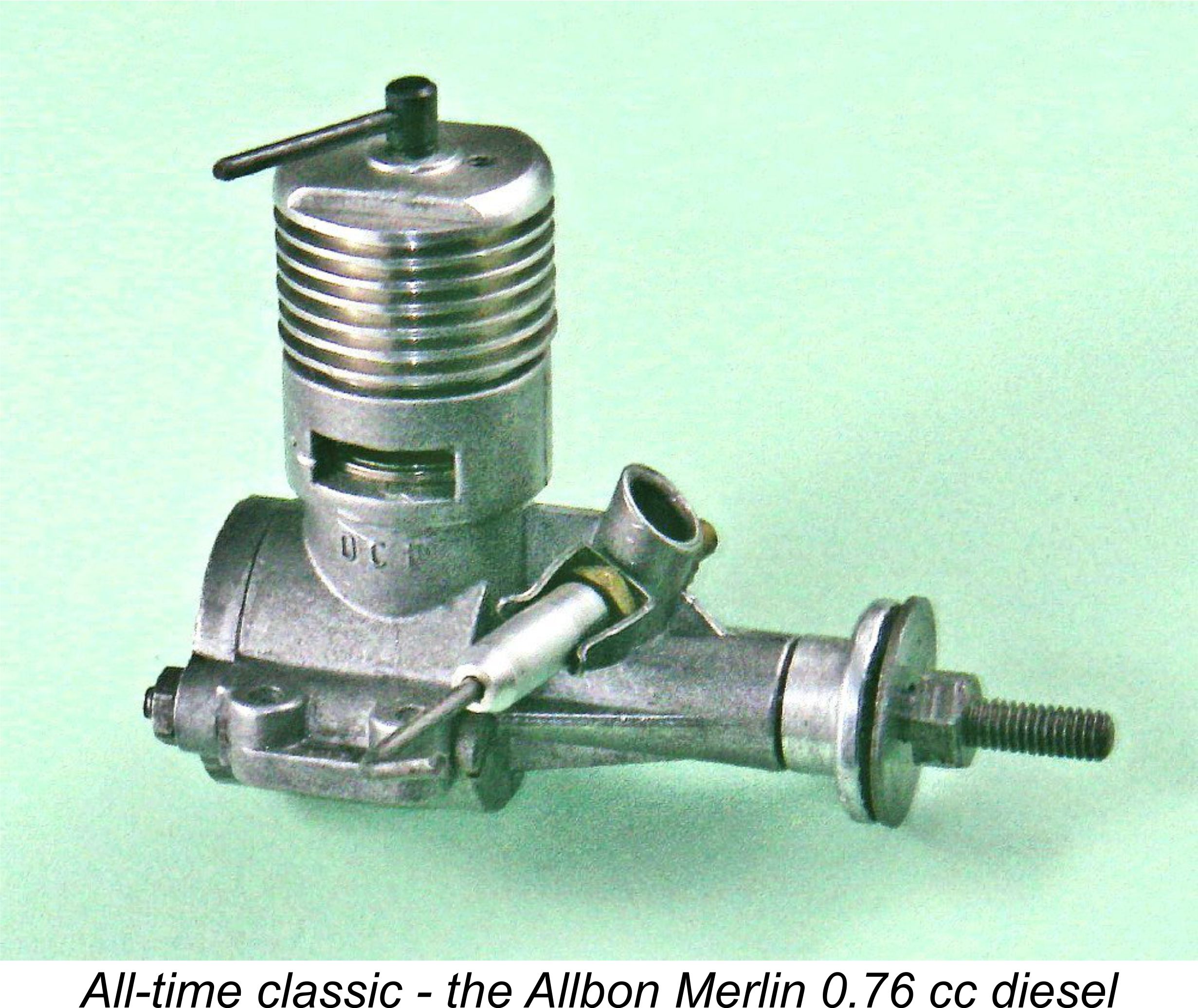

The introduction of domestic competition had done little to moderate consumer acceptance of the Dart, which continued to outsell its ½ cc competitors. The Elfin 50 and FROG 50 models fell by the wayside fairly early on for one reason or another, but both the Dart and the 0.46 cc E.D. Baby went on to enjoy extended production lives. The Baby lingered on into 1960, while the Dart actually survived in its later Davies-Charlton form until 1984, when a 34-year production run finally ended. This made it one of the longest-running continuous productions in British model engine history - only the PAW range can show anything approaching a matching record. It must however be mentioned in passing that the later Davies-Charlton versions were pale reflections of the Allbon originals. If you have one of the original green-head models, treasure it!

Allbon’s departure was very much Davies-Charlton’s loss, since although Ted Saunders was a capable enough manager, he lacked the technical expertise which Allbon had contributed to the company. It is from this time onwards that we can begin to trace the steady erosion in quality as well as the design stagnation which were to bedevil the D-C range in later years. Although the Dart, the Merlin and the Spitfire Following his severing of ties with D-C Ltd., Allbon established himself in business on his own account in premises located in Douglas on the IOM. These premises were made available to him by the Manx government on condition that he provide employment for a number of Manx residents. His new venture had nothing to do with model engines - instead, he acted as a sub-contractor on a variety of government precision engineering projects, in common with many of the other small-scale high-tech industries which had been attracted to the IOM at this time by government grants and tax incentives. His son Kenneth Allbon, then in his late ‘teens, recalled that his father employed some four or five men during this period, thus fulfilling his obligation to the Manx government. By early 1959, the 53 year old Alan Allbon had been operating successfully from his Douglas premises for well over three years. However, it was at this time that the winds of change began to blow once more …………Allbon’s next career move was prompted not by any initiative on his part but rather as the result of a lengthy unsolicited early 1958 visit to Allbon’s Laxey home by the aforementioned Ted Saunders, who was still acting as D-C Ltd.’s Works Manager at this time. It’s clear that Saunders was now ready to follow Allbon’s lead in moving on from D-C Ltd. to pursue his own business interests. It’s noteworthy that few people managed to maintain a collegial working relationship with Hefin Davies for any length of time…………future M.E. manufacturer Walter Kendall was another notable departee during this period. Ted Saunders was apparently some fifteen or so years younger than Alan Allbon, but he was a young man with a vision. He came with a very definite proposal for the consideration of the older man. Kenneth Allbon recalled his father having extended discussions with Saunders at Allbon’s home, eventually leading to an agreement that the two would establish a new precision engineering business named Allbon-Saunders back on the English mainland.

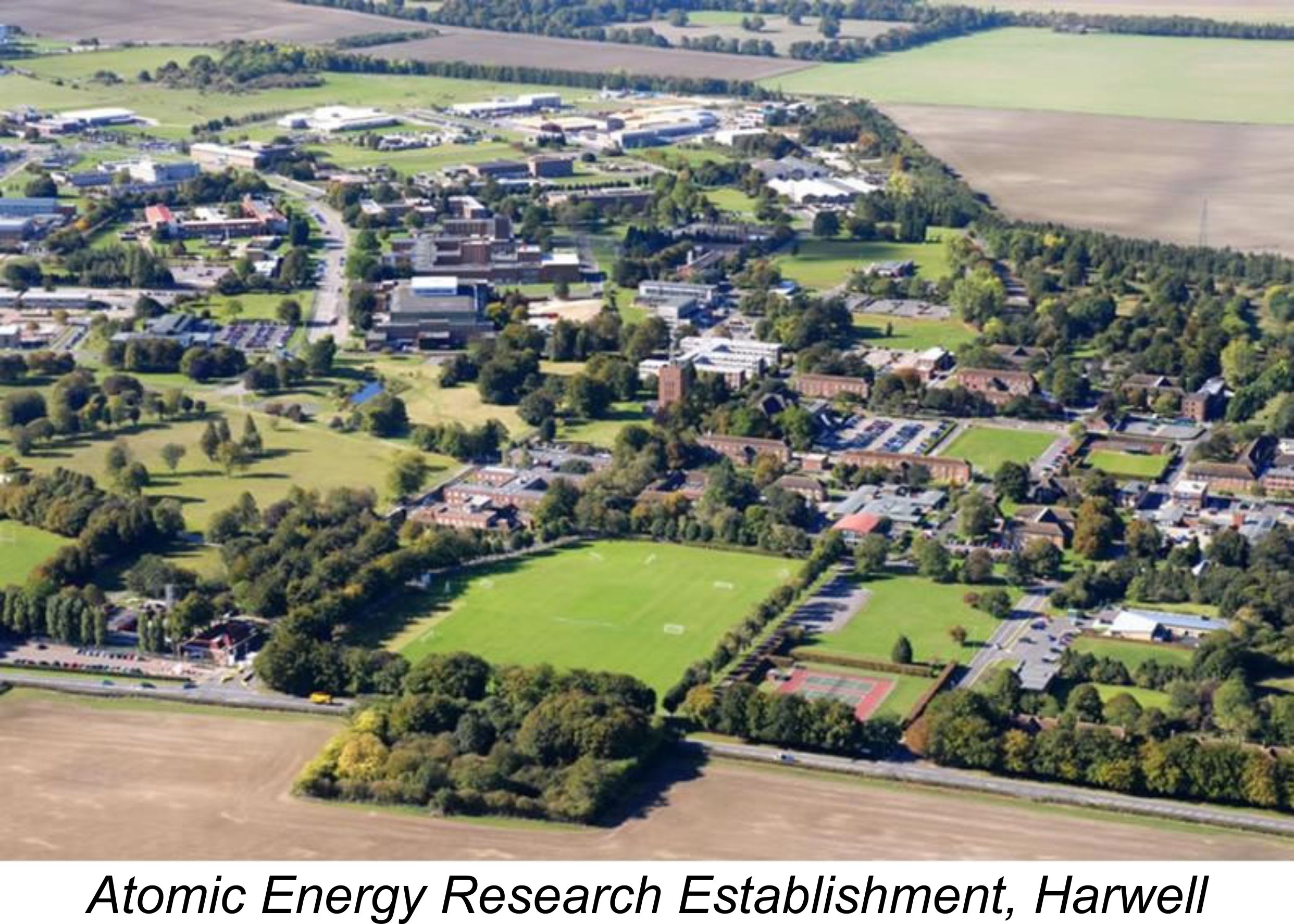

Kenneth Allbon recalled traveling to Milton with his father to inspect the proposed new premises and also to look for a place to live. Yet another family move in the offing - the fourth in six years! Allbon found suitable accommodation for his family in the small village of Upton, some three miles south of nearby Didcot and quite close to Harwell. The actual premises in Milton in which the Allbon-Saunders operation was to be based were an old sawmill on Pembroke Lane on the outskirts of the village. At the time in question, Milton was a small rural community lying some 3 miles to the south of Abingdon. As of 1959 it seemed an unlikely location for a precision engineering company, but then so was Allbon’s earlier location in the old forge at Cople in Bedfordshire!

Kenneth remembered Saunders as being a somewhat controversial character from a social standpoint! He was unmarried but “lived in sin” with a female partner in nearby Blewbury, immediately adjacent to Upton. Kenneth recalled that his rather straight-laced mother Elsie did not approve of the somewhat risqué Mr. Saunders! However, Alan Allbon evidently got along fine with his new partner, at least initially. By mid 1959 the move was complete and the venture was well underway. Saunders’ business plan was evidently followed from the outset. The mainstay of the company was the high-tech and rather secretive precision engineering work that they carried out as sub-contractors to the National Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell. In most cases they had no idea of the function of the components that they were making - frequently, they were not even informed of the name or mechanical properties of the supplied material! They simply had to evaluate its machining characteristics for themselves and then make the components according to the very exacting specifications provided. Kenneth Allbon recalled that his father relished the technical challenges which this work presented. Throughout the entire four-year period from the termination of his direct association with D-C Ltd. up to the commencement of the Allbon-Saunders operation, Alan Allbon had never lost his love of the model engines which had played such a major role in his professional career over the previous decade and more. This led him to propose that Allbon-Saunders enter the model engine field in their own right. Saunders apparently did not share Alan’s enthusiasm, but the partners agreed that Allbon could pursue this line of business as a sideline provided that it did not interfere with the company’s main business focus. Having obtained the green light from his partner, Allbon went to work on the design of the first of what he intended to be a range of model engines to be marketed under the Allbon-Saunders name. This was our main subject, the A-S 55. It was a superb little 0.55 cc diesel engine which became very highly regarded by its users. Let’s have a close look at this excellent little motor. The A-S 55 - description

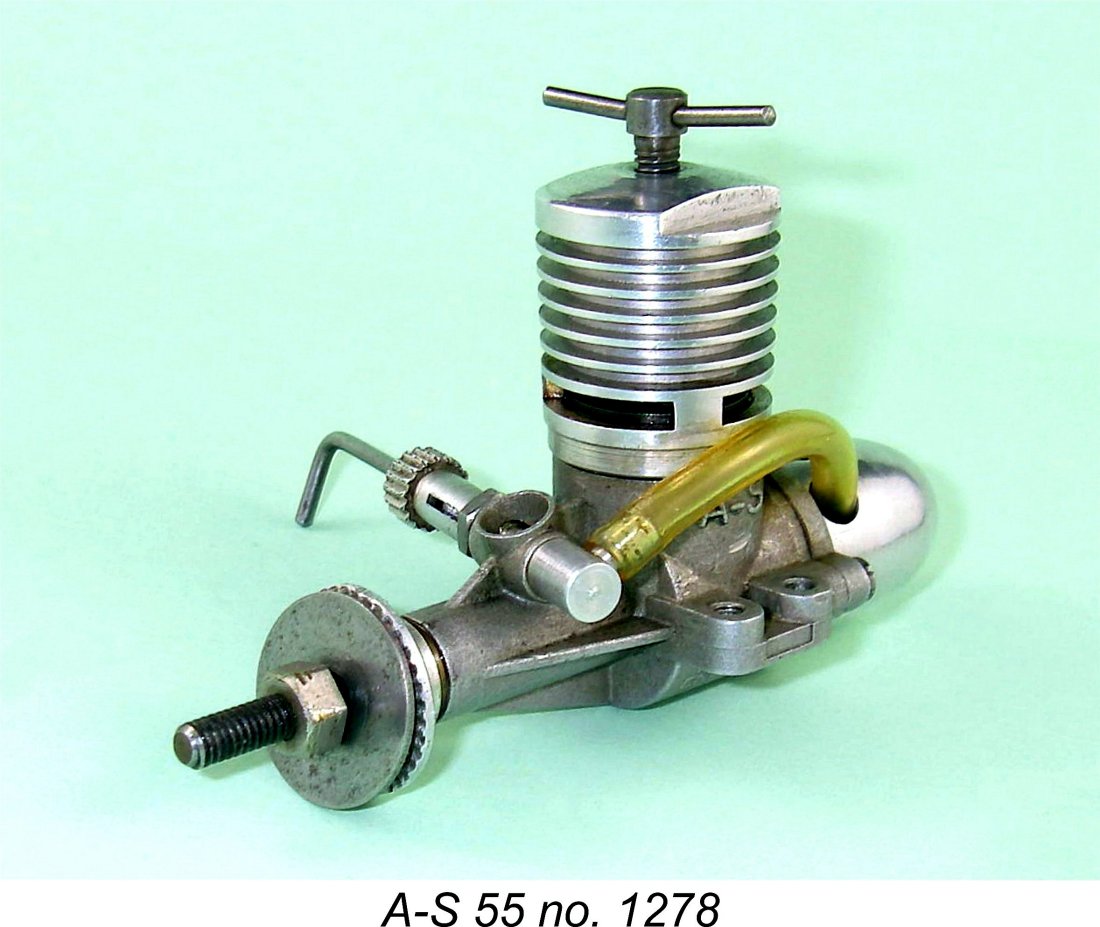

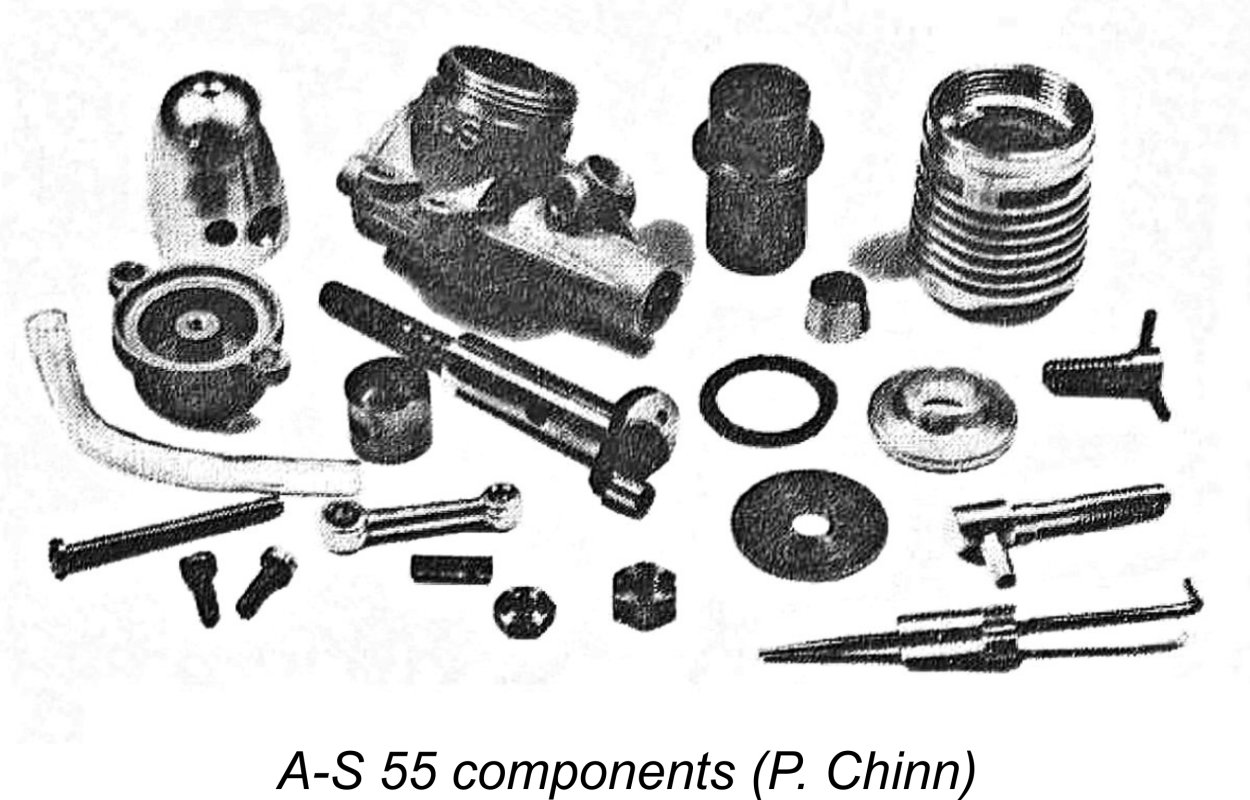

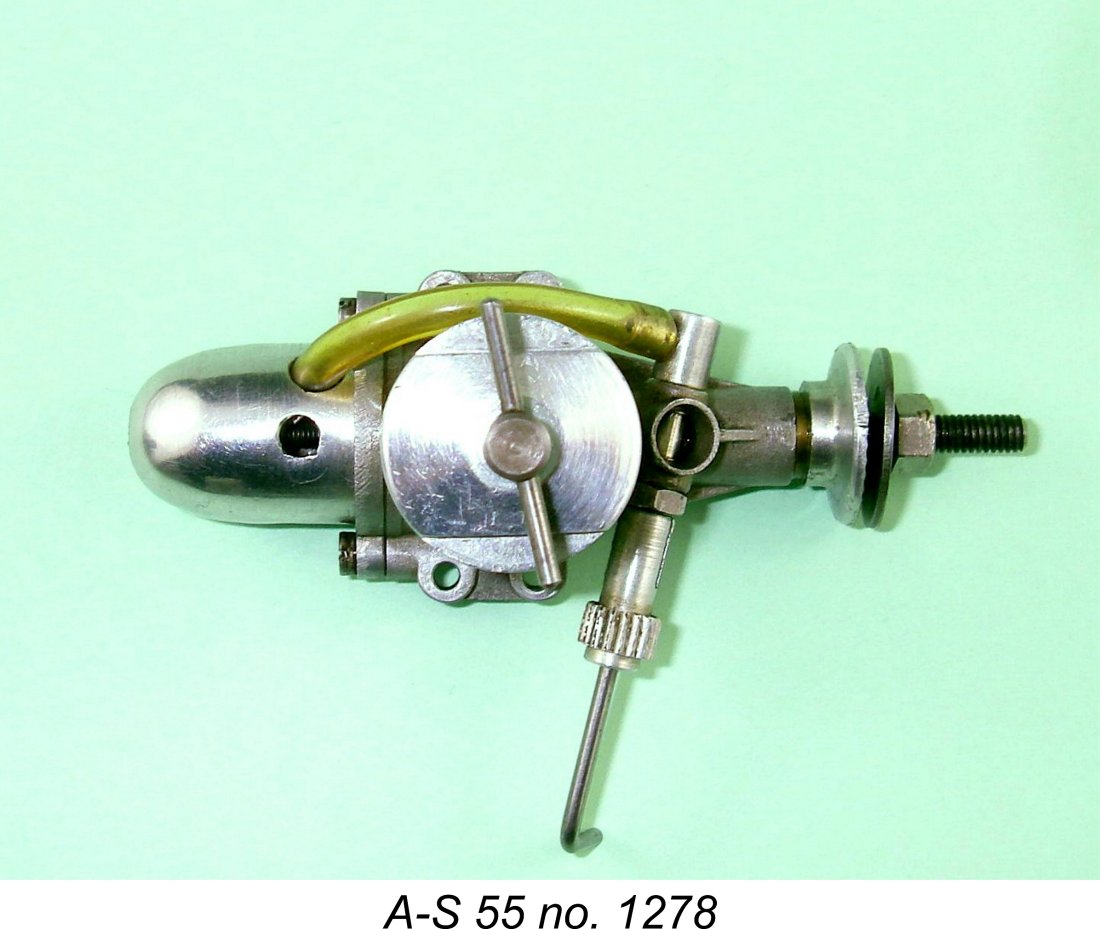

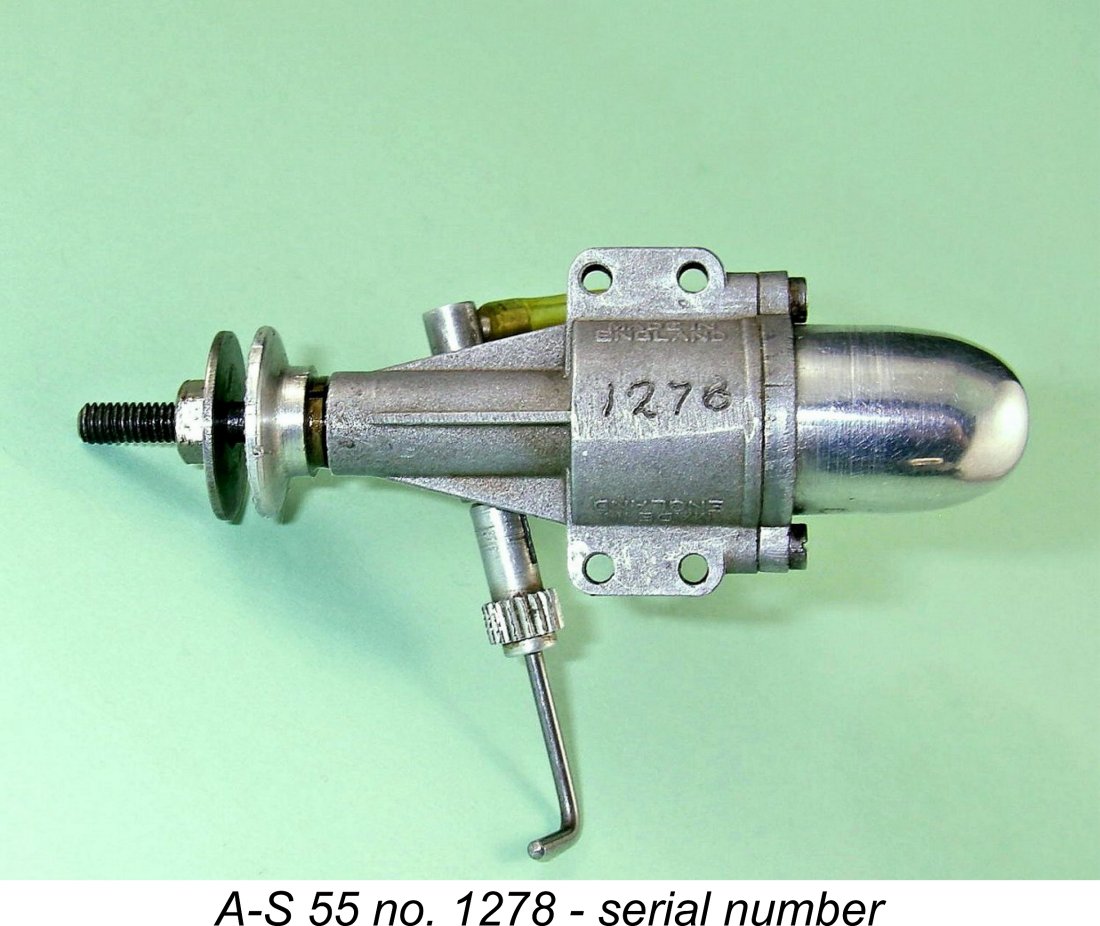

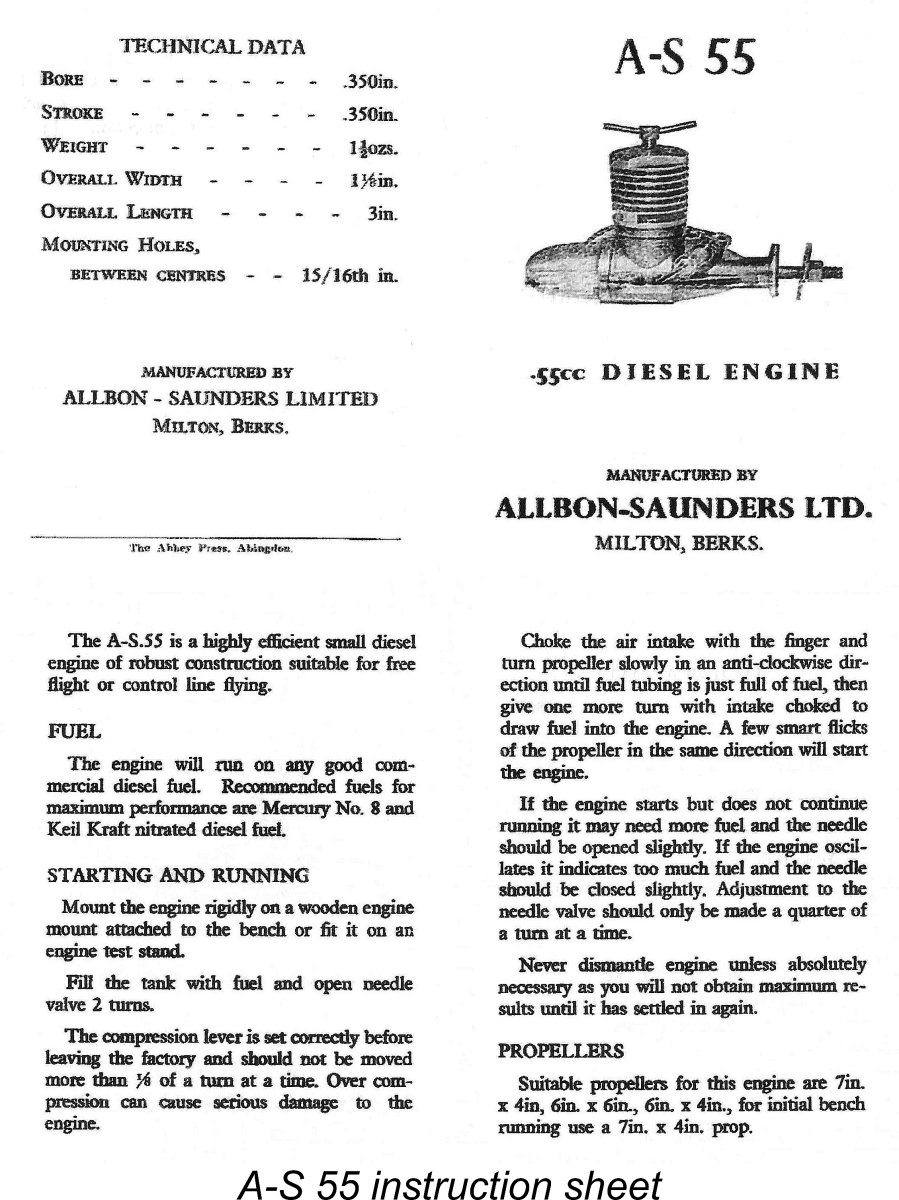

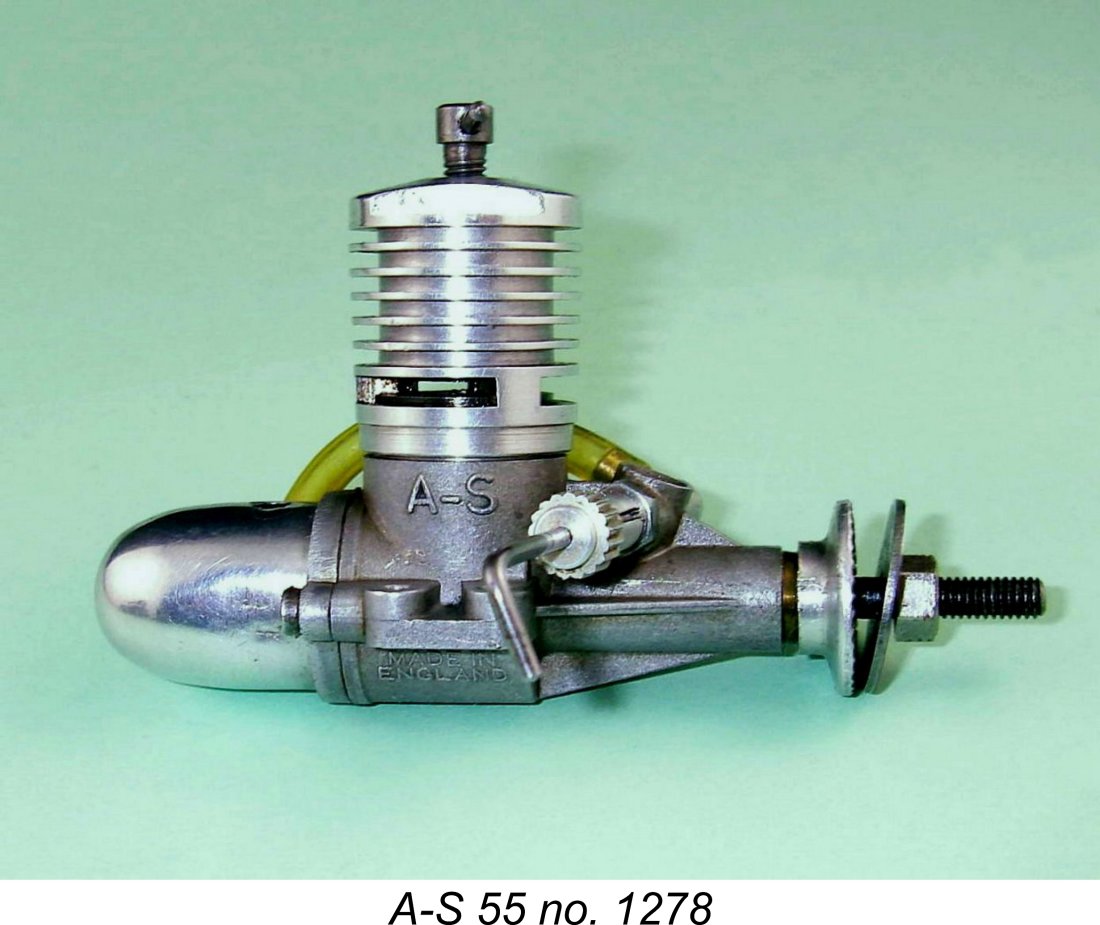

Like its D-C and Allbon forebears, the A-S 55 was a completely conventional small sports diesel having the then-standard British combination of a pressure die-cast crankcase, radial porting, crankshaft front rotary valve induction and a plain un-bushed main bearing. Bore and stroke were equal at 0.350 in. each (8.89 mm) for a displacement of exactly 0.55 cc (0.033 cuin.). These dimensions were carried over directly from those of the Allbon-designed Dart. Weight of the illustrated example complete with tank and fuel tubing is 1.5 ounces (44 gm), exactly as claimed by the manufacturers. Hopefully the accompanying component view extracted from the “Model Aircraft” test will help to clarify the following description.

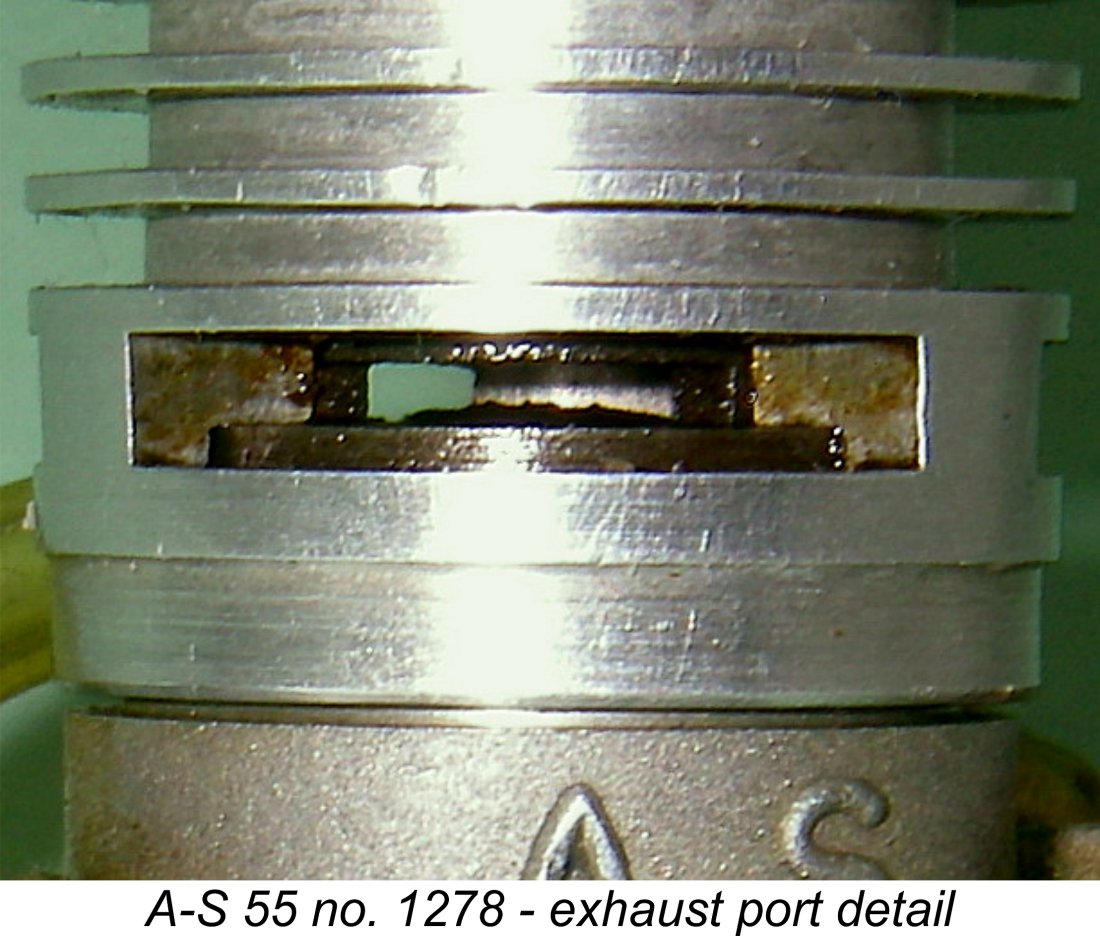

By contrast, the transfer porting adheres to the design of the Dart, bringing with it the advantage of allowing a degree of overlap between the transfer and exhaust ports. The three transfer ports are drilled from below the cylinder location flange to enter the bore at an upward angle between the exhaust ports, slightly overlapping those ports in doing so. The most noteworthy feature of the transfer ports is their very small size - only 1/16 in. diameter. This may be expected to result in relatively high transfer gas velocities, which are generally beneficial in terms of starting characteristics. The cylinder liner is secured in a manner analogous to the Merlin using a separate screw-on alloy cooling jacket which is a close plug fit over the un-threaded upper cylinder. The inner diameter of the jacket is increased near the bottom to accommodate the cylinder location flange, with the resulting shoulder bearing directly upon the upper surface of the flange immediately below the exhaust ports. This results in the cylinder liner above the flange being unaffected by installation stresses and potential distortion. A gasket is used below the flange to ensure a seal. Hopefully the attached close-up view of an exhaust port will clarify this description.

A noteworthy point is the care which was taken during assembly to match the exhaust ports in the liner with those in the cooling jacket. Three milled slots are provided in the lower jacket to allow for the passage of exhaust gasses. In all examples that I have seen, these slots have been carefully matched to the locations of the cylinder ports when the jacket is fully tightened, thus ensuring unrestricted gas passage. This would have required a degree of trial and error during assembly, and it’s a convincing argument against dismantling a correctly-assembled engine unless there is a pressing need to do so. I have elected not to disturb my own near-pristine boxed example. As in the Merlin, the diameter of the lower cylinder below the location flange is turned substantially smaller than that of the interior of the upper crankcase casting, the cylinder being axially located solely by the locating flange and cooling jacket. The bypass passage is formed by the resulting 360 degree annular gap between the inner crankcase wall and the outer wall of the lower cylinder. The piston and contra-piston are both of cast iron and are extremely well fitted to the bore. Somewhat unusually, the top of the piston is domed rather than being conical in form, the contra piston being dished to match. A forged alloy con-rod with un-bushed bearings is used in conjunction with a 3/32 in. diameter fully floating gudgeon pin. There is no sub-piston induction.

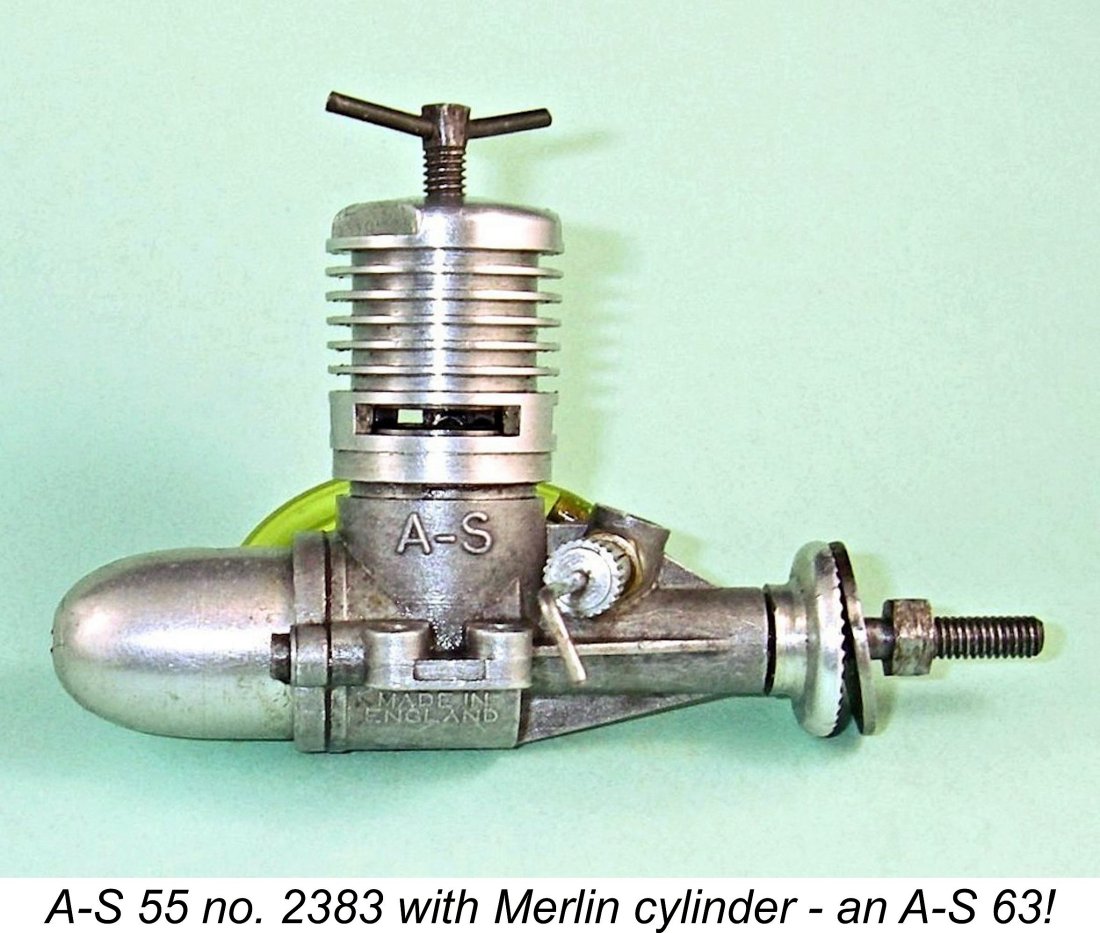

That having been said, my friend Gordon Beeby drew my attention to a note by Peter Chinn in his "Latest Engine News" column in the January 1961 issue of "Model Aircraft" to the effect that a number of examples of the A-S 55 had broken their crankshafts across the web rather than in the main journal. Chinn stated that steps had been taken to address this issue. This may well explain the fact that a later example of the engine, number 2383, was found upon subsequent examination to have a plain disc crankweb, although the shaft was otherwise unchanged. It appears likely that the elmimination of the counterbalance was the step taken to strengthen the crankweb. The manufacturers may also have come to doubt the value of incorporating the counterbalance Engine no. 2383 was found upon close inspection to be highly unusual in another respect - it has a modified Allbon Merlin cylinder fitted! It uses a Merlin piston with an Allbon Dart rod. These components fit right in when appropriately shimmed. The cylinder has to be raised to establish proper timing, while upwardly-angled scallops have been very neatly added to the upper internal edge of the transfer ports to reduce the blow-down period and simulate the tops of the standard drilled transfers. This was a challenging modification, requiring a high level of skill on the part of its perpetrator. It has been flawlessly executed. The result is an increase in the engine's bore from 8.89 mm to 9.52 mm, giving an increased It's unclear whether this is a modification undertaken by a highly skilled former owner or a factory experiment carried out by Alan Allbon himself. Subsequent testing revealed that although the engine started and ran very well, its performance was very little improved over that of the standard version. See below for full test details. Returning to the description of the standard engine, the backplate is very reminiscent of that used in the Merlin, being a pressure die-casting which is a plug fit in the rear of the crankcase and is secured by two screws, one at each side. Unlike the Merlin, these fastenings do not extend through the mounting lugs but are threaded into tapped holes at the rear of the engine mounting lugs. The latter are of the “twin expansion” form seen on the Merlin and its various Allbon-designed relatives. The engine features a highly polished stamped metal tank which is secured by a central screw as on the Dart rather than being retained by the backplate retaining screws as in the case of the Merlin. This has ample capacity for free flight applications. The tank retaining screw is neatly countersunk - very elegant! The backplate is provided with a tapped central spigot to accept the screw, but is otherwise very similar to its Merlin counterpart. At the front end, the shaft is an extremely accurate fit in the un-bushed plain bearing which is reamed into the main casting. The prop driver is very well secured using a brass split collar in the conventional manner. The 4 BA prop nut thread is of ample length for the full range of airscrews which might be used.

The one criticism of this assembly is the fact that it is angled back to the right of the engine (looking forward in the direction of flight). While the angling makes the control very accessible to the fingers, it has the limitation that it cannot be reassembled on the left for sidewinder control-line use. This is an issue that All of the A-S 55 engines bore serial numbers. These were hand-engraved on the underside of the crankcase. My own illustrated example bears the serial number 1278. The boxes in which the engines were supplied had a panel on their end-face labels in which the serial number of the enclosed engine was hand-written, thus matching box to engine. In summary, the A-S 55 may best be described as an amalgam of Dart and Merlin features which embodies the best elements of both designs in a very attractive package while adding a few improvements over both previous designs. Moreover, the engine is extremely well made, all fits being of the highest order throughout. Clearly this was a sincere and successful attempt by Alan Allbon to produced a real quality piece of modelling merchandise despite his partner’s indifference to the project. The A-S 55 on test It didn’t take resident “Aeromodeller” tester Ron Warring long to get his hands on an example of the A-S 55 for testing. Warring’s report appeared in the April 1960 issue of the magazine. Then-current “AeroModeller” Editor Andrew Boddington confirmed that at this point in time “Aeromodeller” appeared on the 15th or third Thursday of the month prior to the cover date and that the content had to be compiled by the end of the month before that. This means that Warring’s report had to be publication-ready by the end of February 1960, only some four months after the engine’s introduction. Allowing for the time required for testing, and writing, this represents very quick work. Overall, Warring’s report was extremely complimentary. He began by drawing his readers’ attention to Alan Allbon’s long experience with model engine design and manufacture, going on to praise the latest Allbon design very highly. Starting was characterized as “easy” following a prime, and the engine was reported to run “strongly and smoothly” up to speeds well in excess of that at which peak power was developed. Response to both compression screw and needle valve was described as “not at all critical”. Finally, the standard of workmanship was commended.

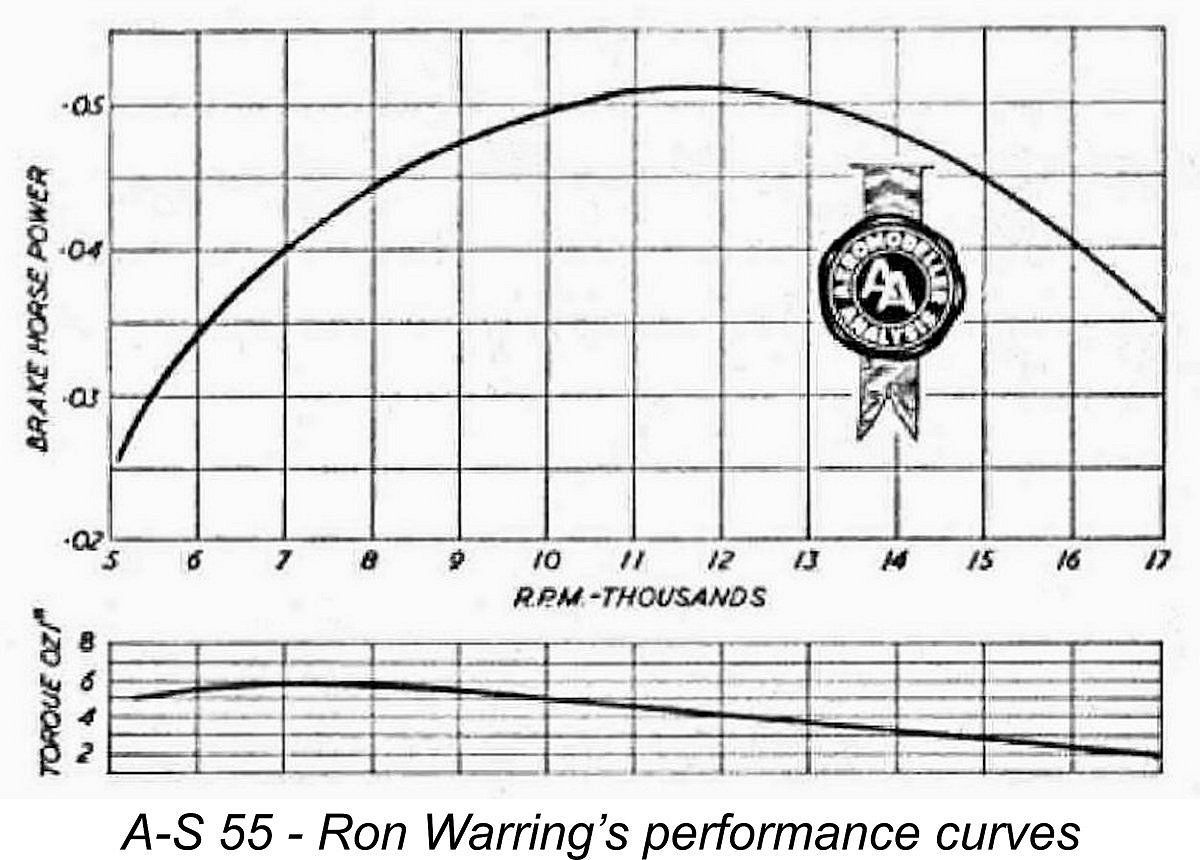

The specific output represented by this figure was very impressive indeed for such a small engine. At the time in question, specific outputs tended to fall with reduced displacements, making the 0.095 BHP/cc figure achieved by the A-S 55 quite impressive. This was at a time when makers of plain bearing sports diesels of any size struggled to beat the 0.100 BHP/cc figure. Many substantially larger contemporary diesels could not match the A-S 55 in this respect. It’s also interesting to compare this performance with that obtained by Warring in his April 1953 test of the D-C-built Allbon Dart Mk. II which was still in production in 1960 as the D-C Dart and had generally been considered to be the ½ cc standard for performance. Warring reported a peak output of only 0.042 BHP @ 11,000 rpm for that model, somewhat down from the figure of 0.045 BHP @ 13,300 rpm measured by Lawrence Sparey in his January 1951 test of the original Allbon-built Mk. I Dart. It was also below the figures of 0.049 BHP @ 12,800 rpm reported by Peter Chinn for the original model in his “Model Aircraft” test of April 1951. Interestingly enough, actual present-day experience with the Dart confirms that the original green-head Allbon-built Mk. I engines did indeed have a higher performance than the later D-C-built Mk. II red-head models, as mentioned earlier. Regardless, the A-S 55’s larger crankshaft induction port was clearly effective in releasing more power. Even the 0.76 cc Allbon Merlin could only manage an output of 0.058 BHP @ 13,000 rpm based on Warring’s December 1954 test, yielding a substantially lower specific output figure of only 0.076 BHP/cc. The smaller A-S 55 came remarkably close to matching the output of the Merlin and was in fact more or The fact that the engine developed unusually high torque for its size meant that the recommended airscrews were larger than one might expect. The manufacturers recommended 7x4, 6x6 and 6x4 airscrews for the A-S 55, sizes which appear well in line with the reported performance figures but are more typical of those generally applied to diesels in the 0.8 cc category. Warring found that the engine turned a 7x4 FROG nylon prop at a very respectable 9,000 rpm and a 6x4 FROG nylon at 12,500 rpm. The latter figure was past the measured peak, indicating that the test engine would have been under-propped on the 6x4. The much faster D-C nylon 6x4 prop was even worse in this respect, since the engine got this up to 14,500 rpm. A cut-down 7x4 or an untrimmed 7x3 would likely have worked well for free flight applications. For control line, a 6x5 or the FROG nylon 5x6 would likely have been happy choices, since the engine turned the latter prop at 11,000 rpm on the bench. Warring’s overall summation was extremely complimentary. He characterized the A-S 55 as “an engine which pleases by its appearance, fine workmanship, good handling characteristics and admirable power rating for its capacity”. Such a positive finding must have harmonized well with Allbon-Saunders’ efforts to popularize the engine.

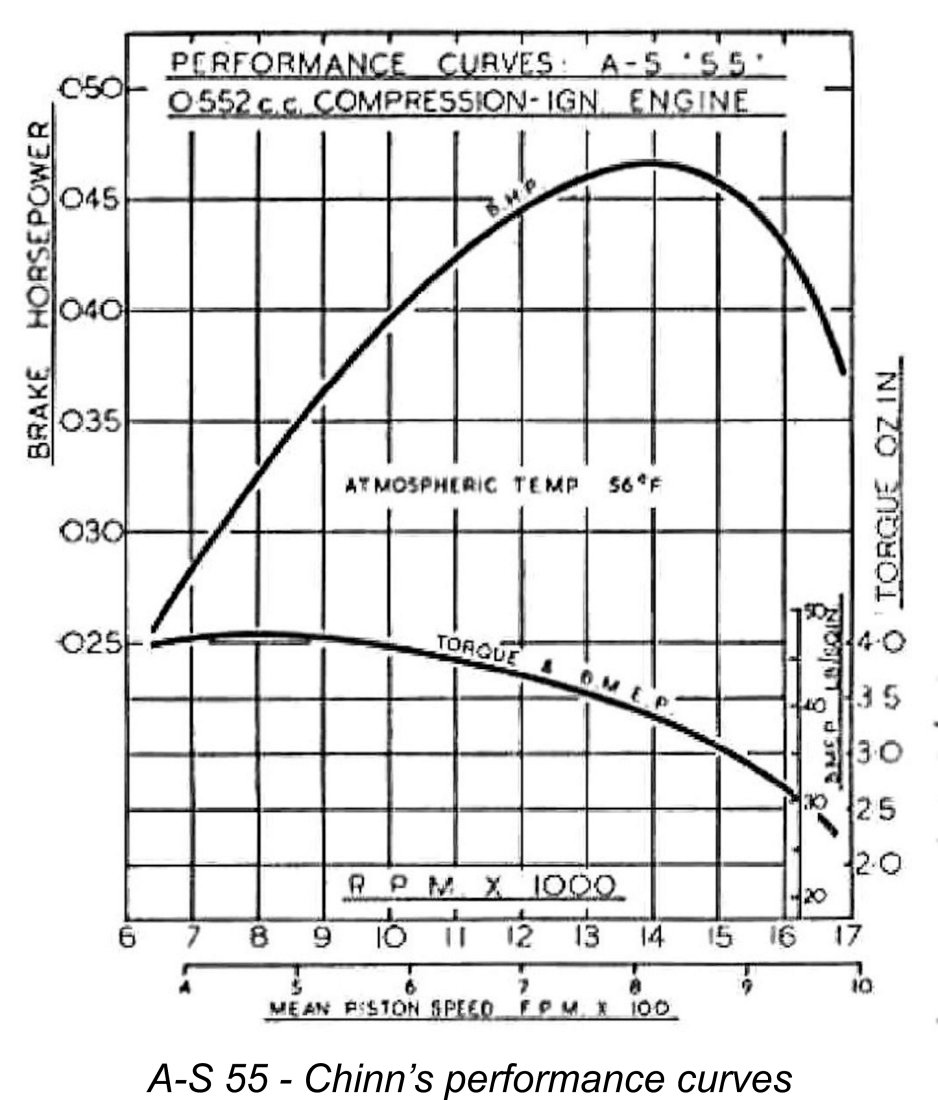

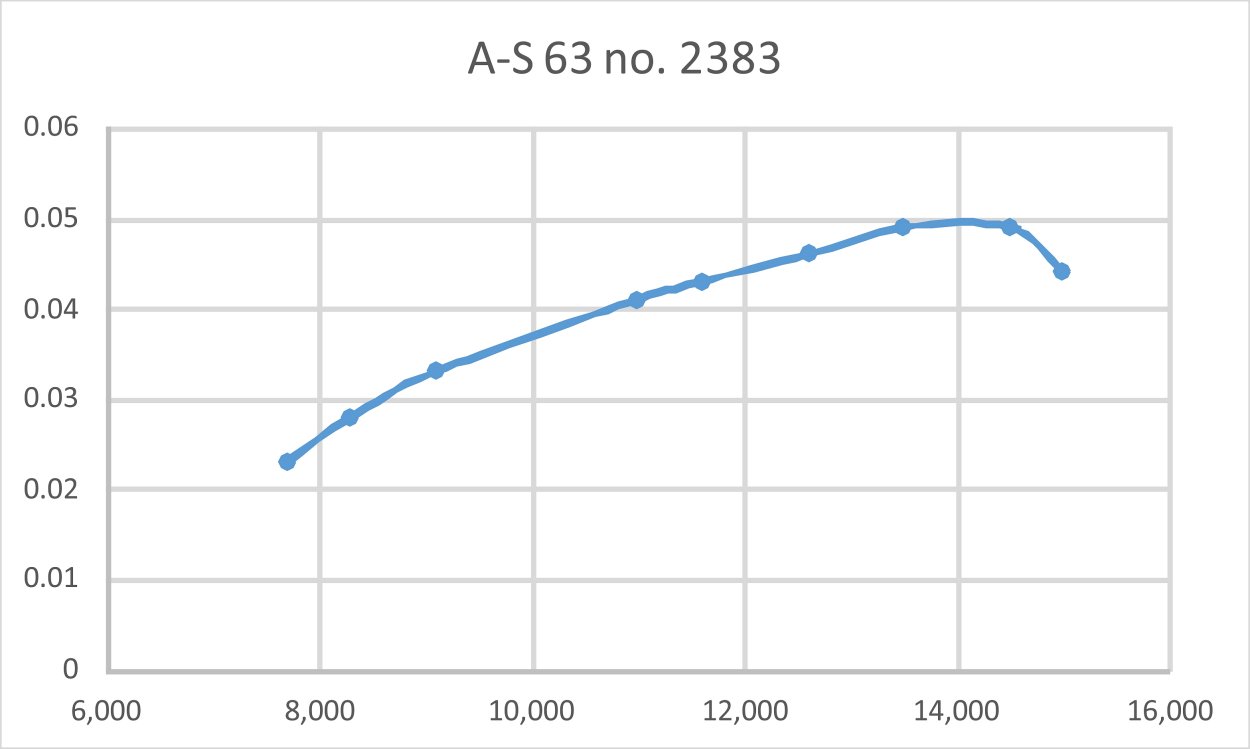

The output recorded by Chinn was slightly less than that found by Warring - an unusual circumstance since Chinn generally tended to find more power than Warring in tests on the same engine. Moreover, Chinn found peak power to occur at substantially higher rpm than Warring, reporting a figure of 0.047 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. Clearly he extracted less torque from the engine than Warring. This may simply be a reflection of the undoubted fact that the effects on performance of incidental manufacturing differences between different examples of the same engine tend to be magnified with decreasing My own tests on the illustrated example of the engine have done nothing to contradict either Warring’s or Chinn’s findings. The engine is undoubtedly very well made indeed. It is also a notably easy starter and a fine runner with excellent control response and a very sprightly performance for its displacement. The controls themselves are conveniently sized and positioned. Tests on examples of the contemporary props used by Warring which remain in my possession yielded figures which were invariably within 100 rpm or so of Warring’s data. Basically, I confirmed Warring’s findings in every respect. What a fine little engine! As mentioned earlier, I also conducted a test of modified engine no. 2353 which had been very competently retro-fitted with a modified D-C Merlin piston/cylinder set, making it an A-S 63! The modified engine had clearly seen a fair bit of previous use, hence having a somewhat "softer" compression seal than ideal. Even so, it started very easily and ran very well indeed. Probably in part due to the soft compression seal, it was noticeably happier at the higher speeds, at which there's less real time during each cycle for cylinder leak-down to affect performance. The following data were recorded.

As can be seen, the modified engine seems to develop very slightly more peak power than the standard model, delivering around 0.051 BHP @ 14,100 RPM. However, the difference appears to me to be scarcely worth the bother! The engine would doubtless do a little better if it were rebored, but I have no plans to use it, making such a step seem unwarranted. Still, an interesting exercise in shoe-horning components of one engine into another! The A-S 55 - Production and Marketing History

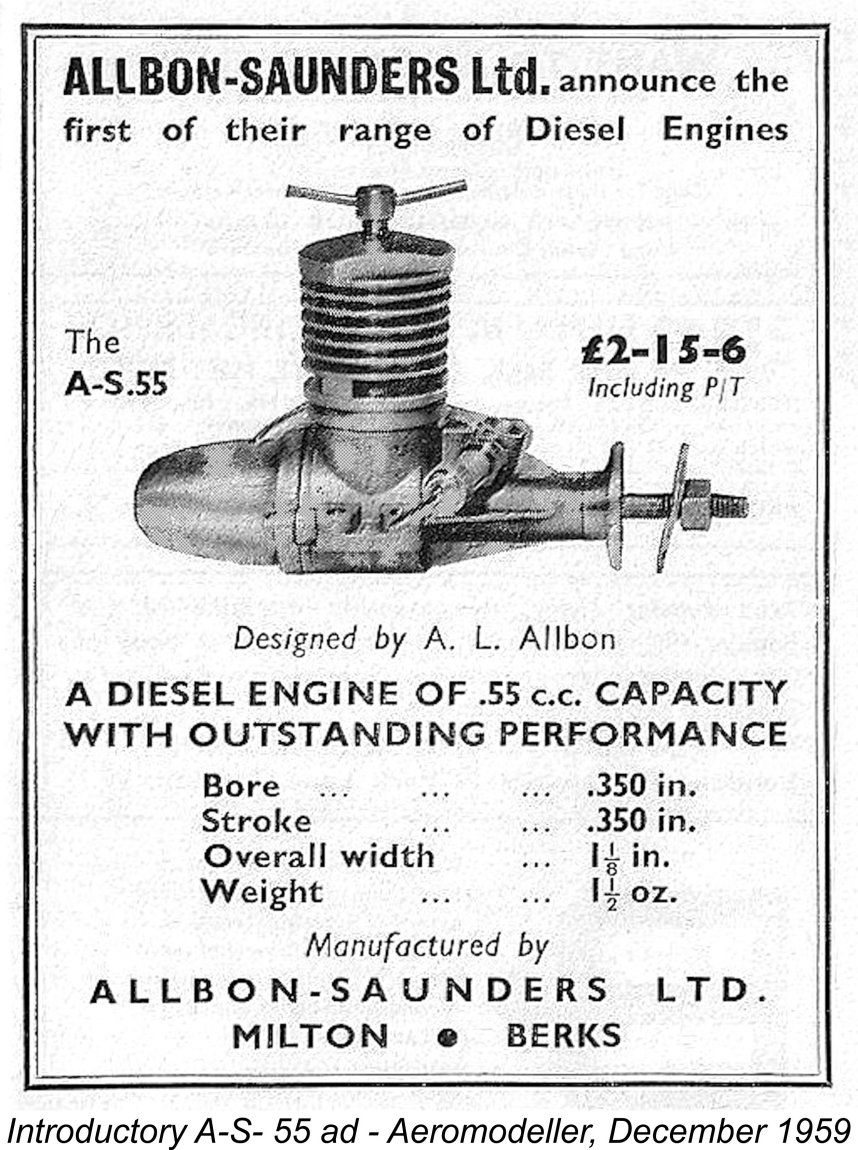

The selling price of the engine was £2 15s 6d (£2.77 in modern money) inclusive of all taxes. This was quite a bit more than the cost of a number of contemporary competing models, particularly the new breed of British-made ½A glow-plug motors which were appearing more or less concurrently. Presumably Alan Allbon was hoping that the engine would recommend itself on merit regardless and/or would dissuade many diesel fanciers from switching their allegiance to glow. As events were to prove, Allbon’s confidence was justified to a certain degree. The A-S 55 was viewed very favourably by the discriminating modelling public, being widely considered to However, there was a downside to all of this. The basic problem was that Allbon had chosen the wrong displacement category in which to launch his new model engine range. Thanks to the influx of a number of British-made ½A glow-plug models as well as the 0.81 cc E.D. Pep diesel at around the same time as the arrival of the A-S 55, the British marketplace was suddenly flooded with low-priced small engines. Moreover, this situation coincided with what may be seen in hindsight as the commencement of a steady decline in the demand for I/C engines in general and small engines in particular among British modellers. The accelerating expansion of the far more financially-demanding R/C market had much to do with this. As a result, the A-S 55 was launched into a shrinking market for small engines at the very time when that market was becoming saturated with low-cost domestic offerings. As events were to prove, the only long-term survivors of this period were the Dart-based Davies-Charlton Bantam glow-plug model, the long-established Davies-Charlton Dart Mk. II diesel successor to the original Allbon Dart model of 1950 and the Allbon-designed Merlin 0.76 cc diesel. All the others fell by the wayside, sadly including the A-S 55.

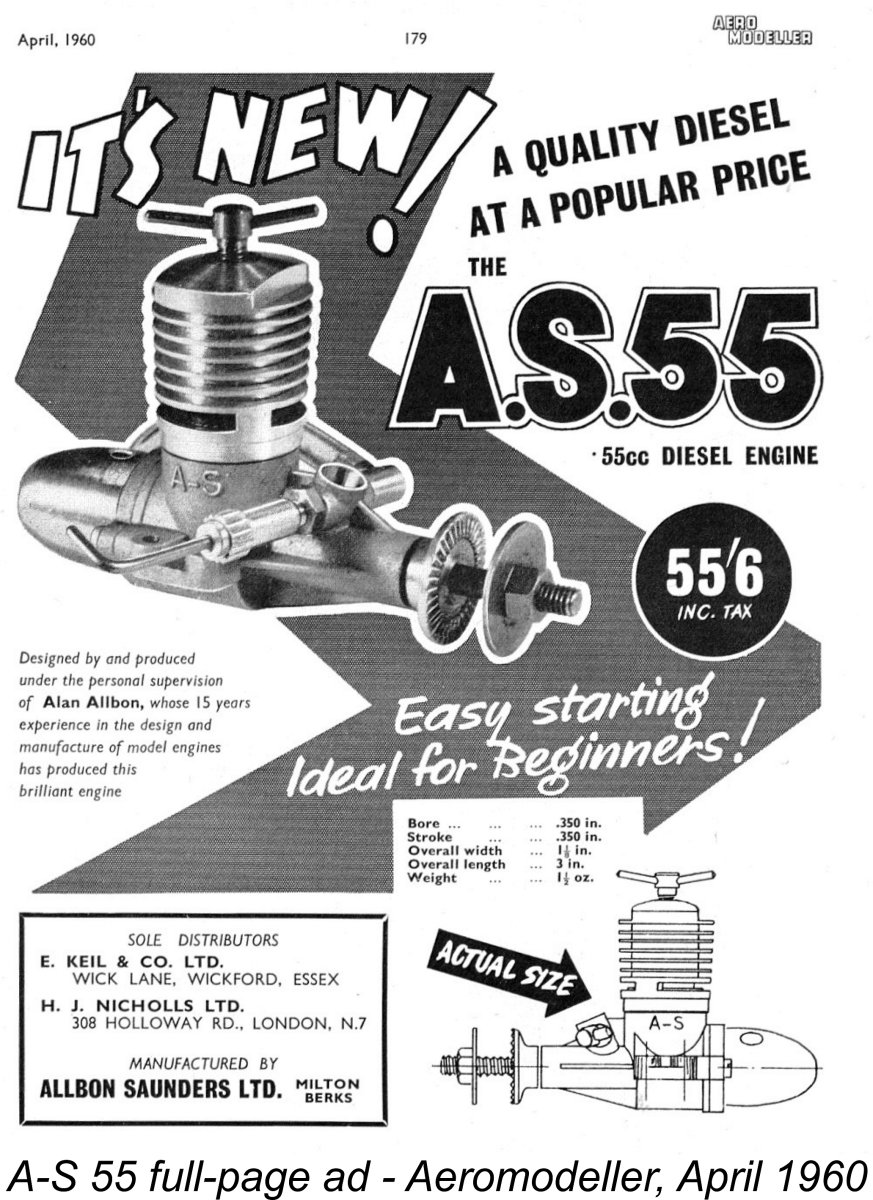

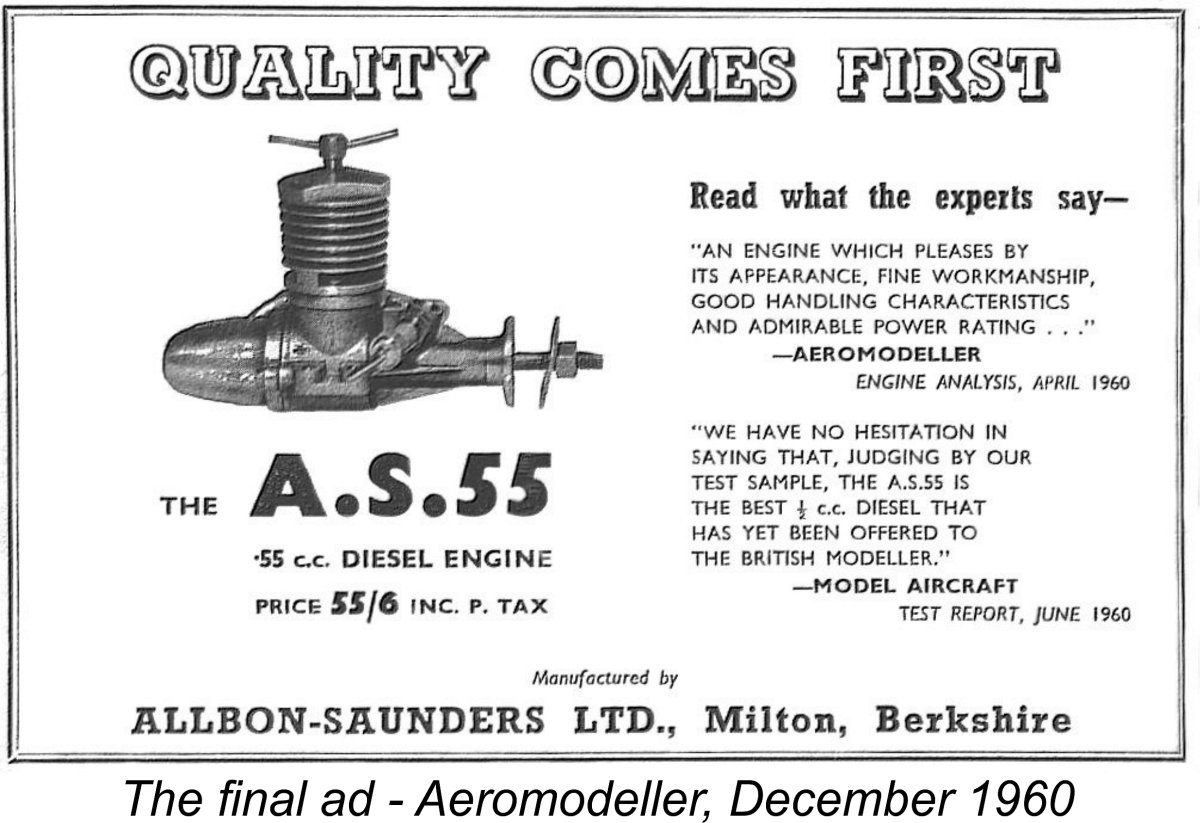

Even in “Aeromodeller”, advertisements appeared on a highly irregular basis. There were only three in the first half of 1960, the most serious promotional effort being a full-page advertisement in the April 1960 issue, clearly coordinated with the appearance of Ron Warring’s test report. That advertisement was significant in that it confirmed that Allbon-Saunders had succeeded in bringing both E. Keil & Co. and Henry J. Nicholls Ltd. on board as distributors. Both of these companies had distributed Allbon’s engines in the past. A further advertisement placed in the May 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller” made reference to Warring’s very positive summation in his April test report. It appears that Allbon-Saunders may understandably have seen the appearance of Peter Chinn’s equally laudatory report in the June 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft” as constituting the best possible form of advertising (and free at that!), making a separate advertisement by the company redundant in that month.

It’s even stranger to have to report that the December 1960 “Aeromodeller” advertisement was the final advertising placement of them all! The engine continued to appear in dealer listings for some years thereafter, but that was it as far as the company’s promotion was concerned. The implication is that the company had become increasingly preoccupied with their main line of business, hence no longer greatly caring about their involvement with model engines. This explains both the early loss of advertising momentum and the relatively low production figures for their fine little diesel. Indeed, Kenneth Allbon was able to confirm that this was the case. As time went on, Allbon-Saunders’ business volume and workforce both grew substantially. It seems to have been a combination of low financial returns from the model engine venture coupled with the increasing workload from other sources that eventually forced Allbon to abandon his model engine interests once and for all. Basically, he no longer had the necessary spare time to devote to the further development and promotion of the A-S range. The A-S 55 seemingly continued to be manufactured in small batches on and off as the overall workload permitted, but all thoughts of expanding the range had evaporated.

It’s clear in retrospect that the advent of the Bantam was in many ways a disaster for the British model engine industry, since it firmly established price rather than value as the foremost yardstick by which the average modeller judged an engine. The two terms are by no means synonymous - the value of an item is a reflection of its quality and performance, while price is merely what the manufacture charges for it. Prior to the appearance of the Bantam, most British modellers accepted the concept that one got what one paid for and that quality and performance came at a price. Sadly, the inflated view of the Bantam largely created by Ron Warring’s highly unrepresentative and unwarrantably positive test report of January 1960 created an impression that quality and performance could and therefore should be obtainable at a bargain price. I’ve discussed this issue in depth in my companion article on the D-C Bantam.

It’s greatly to Alan Allbon’s credit that he clearly decided very early on that he was unwilling to join the race to the bottom which the Bantam had inaugurated. The quality of the A-S 55 was maintained, as was its price. The advertisements in May and December 1960 were both headed by the slogan “Quality Comes First”, which was Allbon’s unmistakable rallying cry against the Bantam and its ilk. Allbon clearly intended to find out whether British modellers were prepared to pay for quality and performance or whether price was all that mattered. Sadly, it appears that Allbon got the answer to this question very quickly, soon recognizing that his fine little creation stood a very poor chance of long-term survival in the price-driven marketplace which had developed largely as a result of Davies-Charlton’s aggressive cost-cutting at the expense of quality and performance. Allbon and his colleagues were clearly not prepared to continue to engage in a marketplace in which value was subordinate to price. One can only admire Allbon’s integrity in this regard. Time soon proved Allbon’s views to be correct - in retrospect, the British modelling community ended up paying heavily for its preoccupation with low price as opposed to value, both in terms of the non-appearance of superior models from established manufacturers and the loss of a number of fine producers, Allbon-Saunders among them. With a few notable exceptions, low-priced mediocrity became the prevailing principle - the development and production of quality products costs money, which the modelling public were no longer willing to subsidize through their purchases. Even so, despite its price disadvantage as well as the seeming lack of attention to its promotion, the A-S 55 maintained a presence in the marketplace for some years, still selling in 1964 at a slightly reduced price of £2 11s 0d (£2.55 in today’s money). This was still substantially more than the asking price of competing models such as the Bantam, but the A-S more than matched the Bantam for performance and was both sturdier and far better-made to boot. In addition, it was a diesel, a form of ignition to which large numbers of British modellers retained a strong allegiance at the time. However, this was not enough to save it in the long term, and the engine had disappeared from the market by the end of 1964. As matters stand, I can’t present a credible estimate of overall production figures. The actual number could only be estimated by the assembly of a statistically-reliable sample of serial numbers, which I don’t have. The highest confirmed serial number currently reported is 2401, the lowest being 175. This makes it fairly certain that the sequence started at engine number 1 and that probably some 2500 examples were manufactured in total. I’d be most grateful to any reader(s) out there who are able to supply confirmed serial numbers which extend the presently-known range. The Later Years

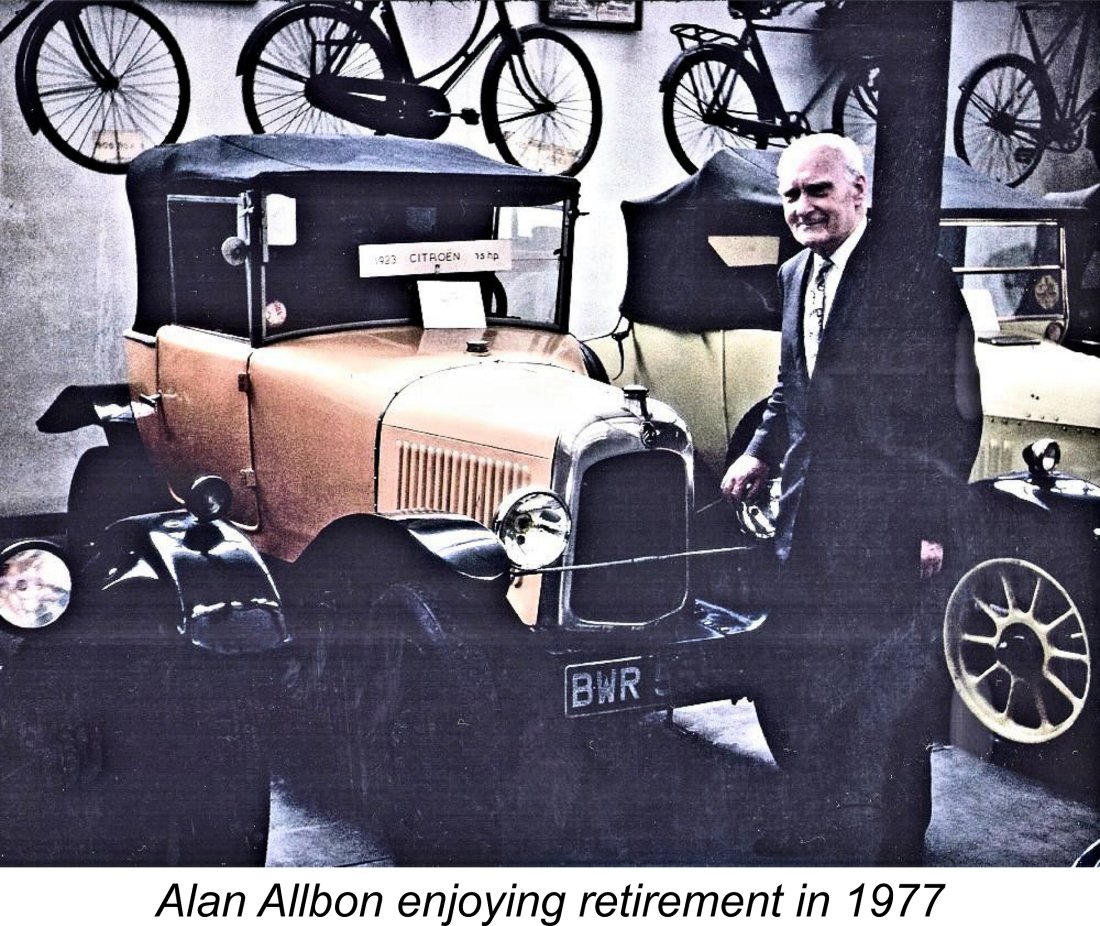

Alan Allbon eventually retired from business, passing away rather unexpectedly from a heart attack in late 1978 at the age of only 72 years. It’s nice to be able to record the fact that several of Allbon’s designs outlasted the man himself as well as his former sparring partner Hefin Davies, who died in late 1980. The Allbon-designed Merlin and Dart were among the final Davies-Charlton products of them all, remaining available right up to the Dav-Cal era which began in late 1982. The Dart was the ultimate survivor, remaining in production at some level until 1984, when it finally ended a 34 year production run - almost certainly a record for a British model engine. However, the reader is reminded once again that the Darts produced by Davies-Charlton and Dav-Cal never equaled the performance or quality of the Allbon originals. See my detailed article about Davies-Charlton for the full story. There's an interesting postcript to the A-S 55 story. It appears that Alan Allbon's former colleague Walter Kendall, instigator of the M.E. model diesel range, may have acquired the residue of the A-S 55 project after its abandonment by Allbon-Saunders in 1965. There's evidence to suggest that the intention was to re-release it as the M.E. Wren. However, as the 1960's drew on Kendall increasingly lost interest in the M.E. range, eventually transferring its manufacture in 1972 from his own Marown Engineering company to Moore Engineering of Peel, IOM. The Wren was never released by either Marown or Moore. The only two mentions of the Wren in print came in the 1980's, beginning with a January 1981 advertisement by the London dealer Michael's Models (with whom I had many pleasant interactions) which announced the forthcoming availability of the "New for 1981" 0.55 cc M.E. Wren diesel. There seem to have been thoughts of releasing this unit at the time, but these never came to anything - there were no further advertising references.

The Allbon-Saunders company continued to be very successful long after Alan Allbon’s departure, remaining in operation using that name but under different ownership until December 12th, 1996. On that date the company name was changed in conjunction with a further change of ownership. The successor company was named The Machining Centre Ltd., its stated business continuing to be precision engineering. This company remained in business as of 2021, still at the same location on Pembroke Lane in Milton, with 25 employees as of that date. Interestingly, it claimed to have been established in 1959 - a clear reference to the original Allbon-Saunders operation at the same location as well as a sign that it saw itself as a direct successor. One of the great pleasures of undertaking research of this nature is the fact that it stimulates ongoing contact with valued friends and colleagues from around the world. Following the initial publication of this article on MEN in 2012, my good mate Jim Woodside was kind enough to contact me to confirm that his positive recollections of the two A-S 55 engines that he once owned were very much in step with my own assessment. Jim also recalled that some years previously a collection of tooling and “bits” from the old A-S model engine enterprise had been put up for auction on eBay UK by none other than our friend Ted Saunders, who stated at the time that he was retiring and wished to pass this material along to someone having an interest. Jim had no knowledge of who may have acquired this collection, but it would be of the greatest interest to learn what was included and where it ended up. Conclusion

In view of the general excellence of the A-S 55, it’s a matter for great regret that this proved to be the sole model that was ever manufactured by Allbon-Saunders. Their initial advertisement of December 1959 had touted the A-S 55 as being the first of a “range of Diesel engines”, a promise which was never fulfilled. We’ve noted the likelihood that sales of the A-S 55 suffered as a result of a combination of lower-priced competition from the likes of Davies-Charlton, E.D. and FROG coupled with what may be seen in hindsight as an already-shrinking market for model I/C engines in general and smaller engines in particular. The consequent dampening effect on sales trends coupled with the increasing influence of price over value seemingly led Allbon to join with Saunders in looking elsewhere for his economic future quite soon after the introduction It’s also a little surprising to find that although a reasonable number of these engines appear to have been sold, surviving examples in good original condition seem to be relatively thin on the ground today. Consequently, such examples as are offered for sale tend to be snapped up by collectors at surprisingly high prices, reflecting the influence of supply and demand. Presumably in their day these little engines were seen as very useable powerplants which were run into the ground and then discarded as low-cost “throw-away” units either when they were worn out or when their owners had moved on to other things. It’s the marginally useable and/or larger and more expensive engines that tend to survive unscathed ………….. Having said all of this, good examples of the A-S 55 do appear on eBay and elsewhere on a fairly regular basis. Anyone acquiring an example in good condition will be very well satisfied - these are really nice little engines which are sure to please any model diesel enthusiast! _____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN April 2012 This comprehensively revised edition published here February 2022 |

||

| |

The designer of the A-S 55 was

The designer of the A-S 55 was  Thames Street has moved well upmarket since Allbon’s time there. Many of the buildings on the street have been converted into flats, restaurants or office space. The red brick building at 51 Thames Street, which may well be the one formerly occupied by Allbon, was latterly occupied by a branch office of A. A. Telecom Ltd., although that office appears to have since been relocated further down Thames Street to number 38. Allbon’s residence was at a separate location nearby.

Thames Street has moved well upmarket since Allbon’s time there. Many of the buildings on the street have been converted into flats, restaurants or office space. The red brick building at 51 Thames Street, which may well be the one formerly occupied by Allbon, was latterly occupied by a branch office of A. A. Telecom Ltd., although that office appears to have since been relocated further down Thames Street to number 38. Allbon’s residence was at a separate location nearby.  The immediate and overwhelming popularity of the Dart following its late 1950 introduction forced Allbon to limit production of other models, the Arrow in fact soon joining the original 2.8 cc model in being dropped altogether. Presumably Allbon would soon have taken effective steps to relieve his production problems. However, we’ll never know how he might have addressed this challenge, because a far more serious factor outside of his control was about to cast a very long shadow over his ongoing activities. This was the infamous purchase tax case, of which much more

The immediate and overwhelming popularity of the Dart following its late 1950 introduction forced Allbon to limit production of other models, the Arrow in fact soon joining the original 2.8 cc model in being dropped altogether. Presumably Allbon would soon have taken effective steps to relieve his production problems. However, we’ll never know how he might have addressed this challenge, because a far more serious factor outside of his control was about to cast a very long shadow over his ongoing activities. This was the infamous purchase tax case, of which much more  Demand for the Dart continued at a high level during this period, completely overwhelming Allbon’s ability to produce it at his much-reduced facility and putting a temporary halt to the production of the equally popular Javelin. His inability to meet demand for the Dart left the small-engine market wide open for other manufacturers, three of whom -

Demand for the Dart continued at a high level during this period, completely overwhelming Allbon’s ability to produce it at his much-reduced facility and putting a temporary halt to the production of the equally popular Javelin. His inability to meet demand for the Dart left the small-engine market wide open for other manufacturers, three of whom -  The distinct identities of the D-C and Allbon ranges were maintained initially, with Mk. II versions of both the Allbon Dart (now with a red head in place of the original green) and the Allbon Javelin appearing more or less concurrently with the co-location of all production, along with the newly-introduced 1 cc Allbon Spitfire Mk. I. Moreover, the Allbon name continued to be applied to other new designs as time went by, including the 0.154 cc

The distinct identities of the D-C and Allbon ranges were maintained initially, with Mk. II versions of both the Allbon Dart (now with a red head in place of the original green) and the Allbon Javelin appearing more or less concurrently with the co-location of all production, along with the newly-introduced 1 cc Allbon Spitfire Mk. I. Moreover, the Allbon name continued to be applied to other new designs as time went by, including the 0.154 cc  By all reports, Hefin Davies possessed a somewhat grating personality which made him a challenging individual to work with. The ever-diplomatic Ron Moulton characterized him as a rather “fiery” individual! A gulf progressively developed between the seemingly irascible Davies and the easy-going Alan Allbon which eventually resulted in Allbon severing his connection with Davies-Charlton in mid 1955 following the move to the IOM. He was replaced as D-C’s Works Manager by a chap named Ted Saunders, of whom we shall be hearing much more later.

By all reports, Hefin Davies possessed a somewhat grating personality which made him a challenging individual to work with. The ever-diplomatic Ron Moulton characterized him as a rather “fiery” individual! A gulf progressively developed between the seemingly irascible Davies and the easy-going Alan Allbon which eventually resulted in Allbon severing his connection with Davies-Charlton in mid 1955 following the move to the IOM. He was replaced as D-C’s Works Manager by a chap named Ted Saunders, of whom we shall be hearing much more later.

Indeed, Kenneth Allbon recalled that these “adapted” premises were in many ways quite reminiscent of Allbon’s earlier Sunbury and Cople workshops. The site has been comprehensively re-developed today as part of the Milton Industrial Estate, although a successor precision engineering company still occupies the same location in a replacement building.

Indeed, Kenneth Allbon recalled that these “adapted” premises were in many ways quite reminiscent of Allbon’s earlier Sunbury and Cople workshops. The site has been comprehensively re-developed today as part of the Milton Industrial Estate, although a successor precision engineering company still occupies the same location in a replacement building.  To anyone familiar with the Davies-Charlton range as it evolved during Alan Allbon’s tenure there, the A-S 55 has an immediately familiar look about it. The engine displays relatively little in the way of original design thinking, embodying in effect a combination of the designs of the D-C Dart and the D-C Merlin (as they were known by this time following D-C’s dropping of the Allbon name). Both of these models had originally been developed by Alan Allbon, so it comes as no surprise to find him borrowing from himself by combining what he evidently believed to be the best features of both models into his new offering. However, the A-S 55 did embody a number of features which set it well apart from its D-C rivals.

To anyone familiar with the Davies-Charlton range as it evolved during Alan Allbon’s tenure there, the A-S 55 has an immediately familiar look about it. The engine displays relatively little in the way of original design thinking, embodying in effect a combination of the designs of the D-C Dart and the D-C Merlin (as they were known by this time following D-C’s dropping of the Allbon name). Both of these models had originally been developed by Alan Allbon, so it comes as no surprise to find him borrowing from himself by combining what he evidently believed to be the best features of both models into his new offering. However, the A-S 55 did embody a number of features which set it well apart from its D-C rivals.  The cast iron cylinder exhibits a combination of features carried over from the Dart and Merlin designs. Like that of the Merlin, it is not threaded at any point. It features a thin flange immediately below exhaust port level which seats on a shelf machined into the top of the main crankcase casting. The three sawn exhaust ports are cut immediately above this flange. Thus the main form of the cylinder generally follows the Merlin pattern, the exception being that the exhaust ports are cut above the locating flange rather than through it. The resulting thinner flange represents a saving in weight of the cylinder.

The cast iron cylinder exhibits a combination of features carried over from the Dart and Merlin designs. Like that of the Merlin, it is not threaded at any point. It features a thin flange immediately below exhaust port level which seats on a shelf machined into the top of the main crankcase casting. The three sawn exhaust ports are cut immediately above this flange. Thus the main form of the cylinder generally follows the Merlin pattern, the exception being that the exhaust ports are cut above the locating flange rather than through it. The resulting thinner flange represents a saving in weight of the cylinder.  The lower portion of the jacket is internally threaded to match a set of male threads machined onto the upper crankcase casting. The assembly is thus identical to that used in the Merlin with the exception that the jacket threads externally over the upper main casting instead of internally as on the Merlin. In characteristic Allbon fashion, a pair of flats is machined into the upper part of the cooling jacket to facilitate tightening.

The lower portion of the jacket is internally threaded to match a set of male threads machined onto the upper crankcase casting. The assembly is thus identical to that used in the Merlin with the exception that the jacket threads externally over the upper main casting instead of internally as on the Merlin. In characteristic Allbon fashion, a pair of flats is machined into the upper part of the cooling jacket to facilitate tightening.

in the crankweb in any case. It’s perfectly true that the beneficial effects of a counterbalanced crankweb decrease with decreasing displacement. The elimination of this feature would also have simplified the machining of the crankshaft a little.

in the crankweb in any case. It’s perfectly true that the beneficial effects of a counterbalanced crankweb decrease with decreasing displacement. The elimination of this feature would also have simplified the machining of the crankshaft a little.

The needle valve assembly is well worthy of comment. Unusually for such a small engine, the spraybar features a right-angled spigot at the fuel pick-up end. This keeps the fuel tubing very close to the main body of the engine without the risk of kinking, thus being a very welcome feature matched among contemporary small British engines only by the 0.46 cc

The needle valve assembly is well worthy of comment. Unusually for such a small engine, the spraybar features a right-angled spigot at the fuel pick-up end. This keeps the fuel tubing very close to the main body of the engine without the risk of kinking, thus being a very welcome feature matched among contemporary small British engines only by the 0.46 cc  seems to have escaped the attention of many British engine designers during the period in question. Odd, because many Continental makers did in fact angle their needle valves to the left……………

seems to have escaped the attention of many British engine designers during the period in question. Odd, because many Continental makers did in fact angle their needle valves to the left……………  Peak power output was reached at a relatively moderate speed by small engine standards. However, the torque developed by the engine was clearly well above average for a design of this specification and displacement, since the actual peak recorded was unusually high for such a small plain bearing sports diesel. Warring recorded an output of 0.052 BHP @ 12,000 rpm. The peak power figure was well in line with outputs recorded by Warring for the three competing British .049 glow-plug models on which he had reported in January 1960, making the A-S 55 a direct competitor with those models for customers who preferred diesel operation. Moreover, this power was developed at significantly lower revs, allowing the use of larger and hence more efficient airscrews.

Peak power output was reached at a relatively moderate speed by small engine standards. However, the torque developed by the engine was clearly well above average for a design of this specification and displacement, since the actual peak recorded was unusually high for such a small plain bearing sports diesel. Warring recorded an output of 0.052 BHP @ 12,000 rpm. The peak power figure was well in line with outputs recorded by Warring for the three competing British .049 glow-plug models on which he had reported in January 1960, making the A-S 55 a direct competitor with those models for customers who preferred diesel operation. Moreover, this power was developed at significantly lower revs, allowing the use of larger and hence more efficient airscrews.

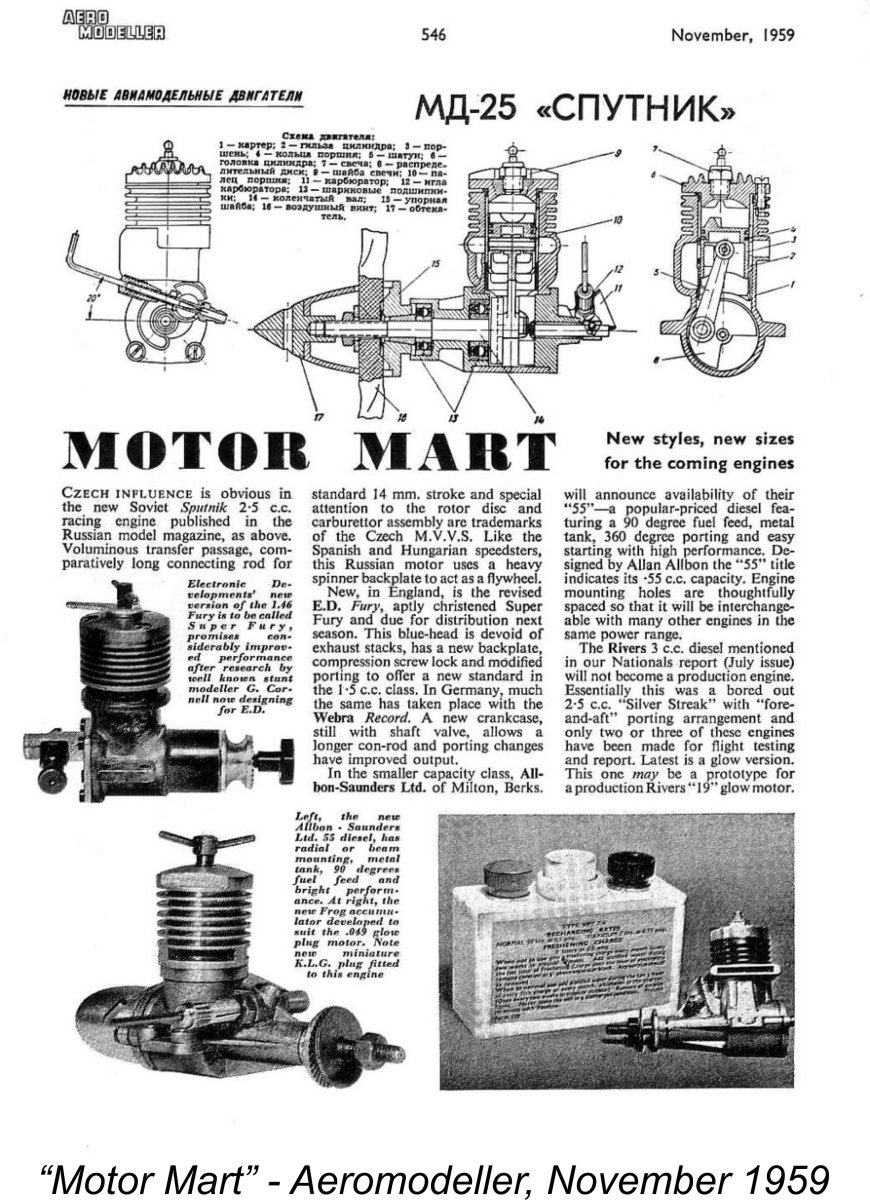

The design and tooling for the A-S 55 were developed in 1959 with the obvious goal of getting it onto the market in time for Christmas of that year. Allbon-Saunders were clearly successful in meeting this goal by some margin. The initial announcement of the A-S 55 appeared in the “Motor Mart” feature of the November 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, together with a photo of the engine, proving beyond question that completed examples must already have been in existence as of early September 1959. The introductory advertisement appeared in the December 1959 issue of the magazine, just in time for the Christmas rush. A follow-up ad appeared in the January 1960 issue, which would have appeared on December 15

The design and tooling for the A-S 55 were developed in 1959 with the obvious goal of getting it onto the market in time for Christmas of that year. Allbon-Saunders were clearly successful in meeting this goal by some margin. The initial announcement of the A-S 55 appeared in the “Motor Mart” feature of the November 1959 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, together with a photo of the engine, proving beyond question that completed examples must already have been in existence as of early September 1959. The introductory advertisement appeared in the December 1959 issue of the magazine, just in time for the Christmas rush. A follow-up ad appeared in the January 1960 issue, which would have appeared on December 15

Although the A-S 55 remained on sale well into 1964, it’s always appeared puzzling that Allbon-Saunders appear to have made only desultory efforts to promote it. As far as I can ascertain, the company never placed a single advertisement in “Model Aircraft”. Presumably the fact that “Aeromodeller” enjoyed a wider circulation at the time made that magazine the best value for the advertising pound.

Although the A-S 55 remained on sale well into 1964, it’s always appeared puzzling that Allbon-Saunders appear to have made only desultory efforts to promote it. As far as I can ascertain, the company never placed a single advertisement in “Model Aircraft”. Presumably the fact that “Aeromodeller” enjoyed a wider circulation at the time made that magazine the best value for the advertising pound.  However, it’s a rather odd fact that following the appearance of the “Model Aircraft” test of the engine, no further adverts were placed in “Aeromodeller” until December 1960. That placement was clearly aimed at the Christmas 1960 rush. It included quotes from both Warring’s and Chinn’s test reports.

However, it’s a rather odd fact that following the appearance of the “Model Aircraft” test of the engine, no further adverts were placed in “Aeromodeller” until December 1960. That placement was clearly aimed at the Christmas 1960 rush. It included quotes from both Warring’s and Chinn’s test reports.  Another factor which appears to have had a considerable influence was the increasing tendency of the British model engine marketplace to be driven by price at the expense of quality. The fact that the A-S 55 was most definitely built up to a standard had placed it at a great disadvantage price-wise from the outset compared with such competing offerings as the

Another factor which appears to have had a considerable influence was the increasing tendency of the British model engine marketplace to be driven by price at the expense of quality. The fact that the A-S 55 was most definitely built up to a standard had placed it at a great disadvantage price-wise from the outset compared with such competing offerings as the  Unfortunately, enough British modellers embraced this short-sighted philosophy to cause a serious erosion of the potential profitability of ongoing participation in the British model engine industry. The result was the loss of a number of very capable manufacturers and the stagnation of others, a situation which was hardly to the benefit of the modelling public in the longer term. Sadly, Allbon-Saunders was among the casualties, as were the manufacturers of the excellent

Unfortunately, enough British modellers embraced this short-sighted philosophy to cause a serious erosion of the potential profitability of ongoing participation in the British model engine industry. The result was the loss of a number of very capable manufacturers and the stagnation of others, a situation which was hardly to the benefit of the modelling public in the longer term. Sadly, Allbon-Saunders was among the casualties, as were the manufacturers of the excellent  The abandonment of the A-S model engine venture ended Alan Allbon's 15 year involvement with model engines once and for all. It would be difficult to overstate the loss to the British modelling community which his departure represented. His final design, the A-S 55, stands as a testimonial to his abilities. The engine is a highly prized collectible today, and justifiably so.

The abandonment of the A-S model engine venture ended Alan Allbon's 15 year involvement with model engines once and for all. It would be difficult to overstate the loss to the British modelling community which his departure represented. His final design, the A-S 55, stands as a testimonial to his abilities. The engine is a highly prized collectible today, and justifiably so.

We’ve seen that the A-S 55 was manufactured in modest numbers and was marketed over a 4½ year period. Its actual production life may have been considerably less than this, since it’s quite likely that production had been undertaken in batches and that the final batch had been produced well prior to 1964 as Allbon-Saunders expanded its involvement with other business lines. The engines sold during the final couple of years at slightly reduced prices may very well have been New Old Stock being liquidated to recover tied-up capital.

We’ve seen that the A-S 55 was manufactured in modest numbers and was marketed over a 4½ year period. Its actual production life may have been considerably less than this, since it’s quite likely that production had been undertaken in batches and that the final batch had been produced well prior to 1964 as Allbon-Saunders expanded its involvement with other business lines. The engines sold during the final couple of years at slightly reduced prices may very well have been New Old Stock being liquidated to recover tied-up capital.