|

|

The One that Got Away - the Cobra .049

Although the Cobra .049 was evidently made in reasonable numbers, it is one of the less commonly-encountered ½A motors today, being viewed by serious ½A collectors as one of the more challenging such units to track down in good original condition. The fact that there turn out to be two quite distinct variants of the engine adds significantly to the challenge. As a result, many people to whom one speaks about the Cobra have never actually handled or even seen one. Moreover, many of those having some familiarity with the engine appear to believe that it was an amalgam of Cox components grafted onto a set of British-made castings. While this may be a forgivable error in view of the engine's general appearance, it is very far from being the case in reality! Time to set the record straight once and for all. My intent here is to do my best to set out the facts regarding this engine on the basis of a detailed examination of a number of surviving examples as well as reference to its relatively few appearances in the contemporary modelling media. I’ll also attempt to place the engine in context and in doing so gain a few insights into the British ½A glow-plug revolution of which it was a largely unappreciated part. Finally, I’ll include some present-day test results which do much to clarify our view of the Cobra. The initial version of this article appeared in April 2008 on the late Ron Chernich’s ever-informative but now long-frozen “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. Since then, I’ve gained a considerably enhanced understanding both of the engine itself and the context in which it appeared. Since MEN is now frozen, I have no alternative other than to present the comprehensively updated article here. Before proceeding any further, I’d like to express my appreciation for the invaluable contribution made by my good mate Maris Dislers of Glandore, Australia to the preparation of this expanded article. Maris contributed both advertising information and several invaluable suggestions to the project. Thanks, mate! I’ll start as usual by presenting some background to the story of the Cobra .049. Background Prior to 1948, the compression ignition or (incorrectly) "diesel" engine enjoyed a distinct early advantage in the early post-WW2 race to produce ever-smaller and lighter model engines. This was due to the fact that it didn't require the heavy and bulky ignition support system required by its spark-ignition rivals. As the displacement and hence the power potential of a spark ignition engine went down, the proportion of the overall powerplant weight accounted for by the ignition system went up, with dire impacts upon the effective power-to-weight ratio of the power unit as a whole. At some point, a limit was reached below By contrast, several European commercial manufacturers soon showed what was possible in terms of making useable sub-miniature model diesels down to displacements which were completely impracticable using spark ignition. Prosper Allouchéry of Paris established an early mark with his jewel-like 0.16 cc Eclair diesel of 1946. British makers were not long in following with such designs as the AMCO .87, the Mills 0.75 cc, the Ace 0.5 cc, the Comet 0.4 cc, the Kalper 0.32 cc and the Kemp Hawk 0.20 cc. I've covered the full story of the early micro-diesels in a separate article to be found on this website. However, the commercial introduction of the miniature glow-plug by Ray Arden in late 1947 eliminated the aforesaid ignition system, thus paving the way towards far smaller and lighter assisted-ignition model engines than had previously been dreamed of. By 1949, only some eighteen months after the development of the commercial model glow-plug, engines of .049 cuin. (0.81 cc) displacement or even less were appearing on the American market in ever-increasing numbers. These quickly assumed a position of considerable market importance in the USA. They were the first engines for tens of thousands of young modellers, greatly encouraging widespread involvement with the hobby.

As a result of the ensuing competition for sales, a price war quickly developed in America, forcing manufacturers to minimize their production costs. This had the effect of reducing the selling prices of such engines to the point where they were readily affordable by almost anyone who wanted to become involved with powered model flying. A new class known as ½A (not to be confused with the British S.M.A.E. ½A class for 1.5 cc engines) was soon established in the USA to accommodate these then-revolutionary little powerplants in a competition context.

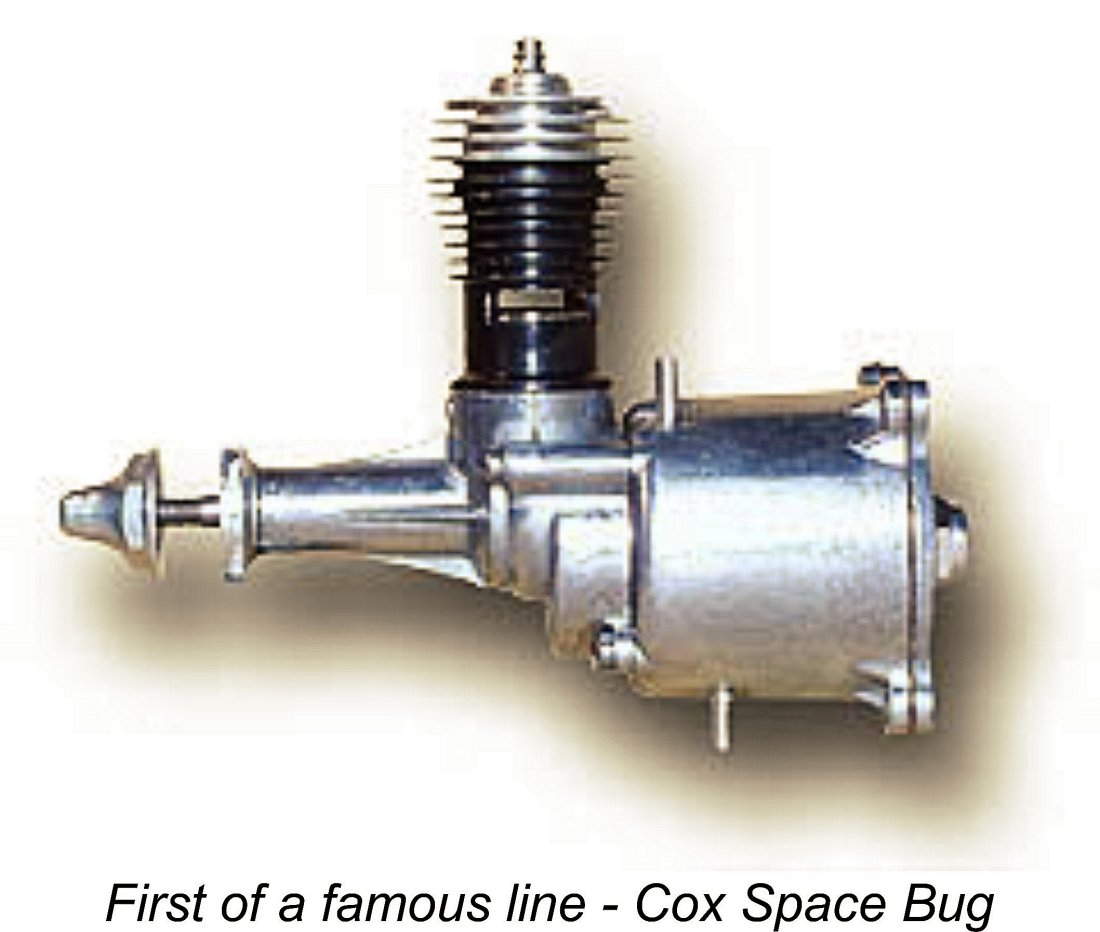

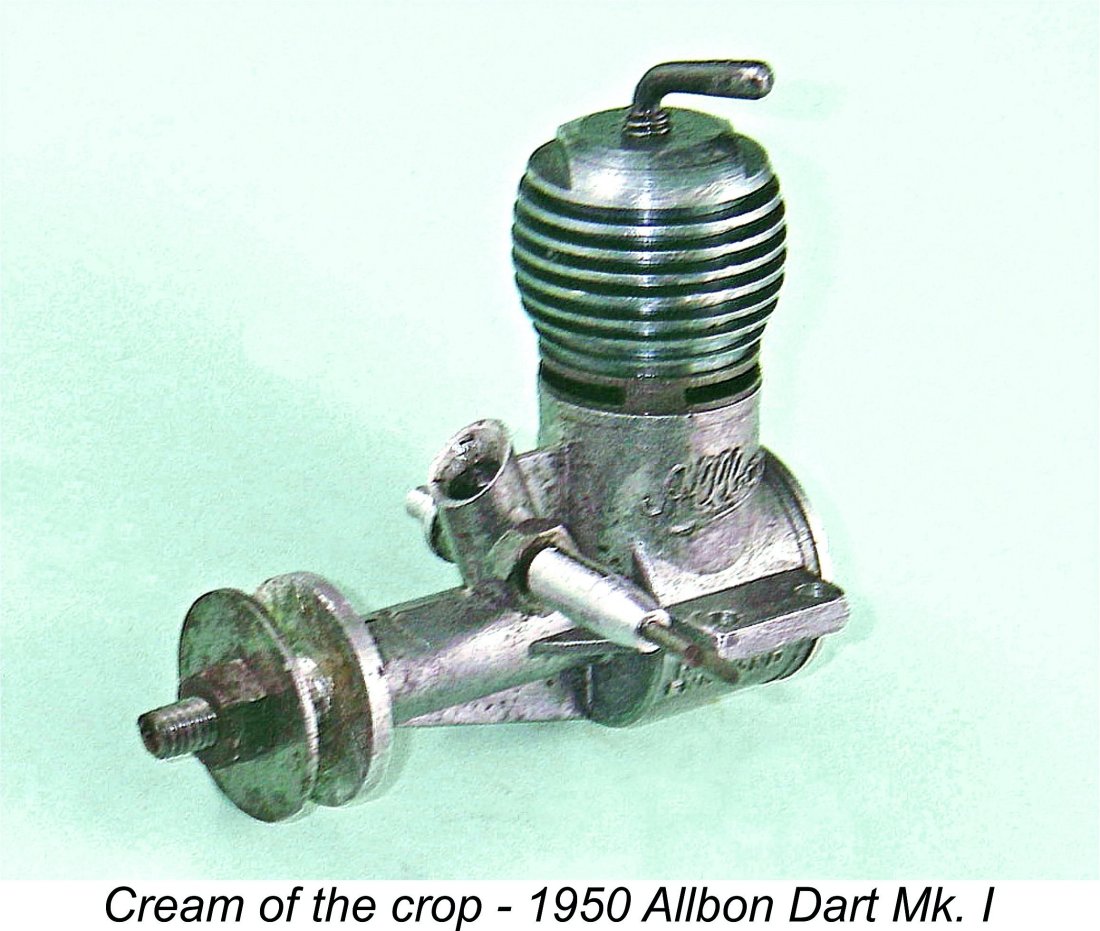

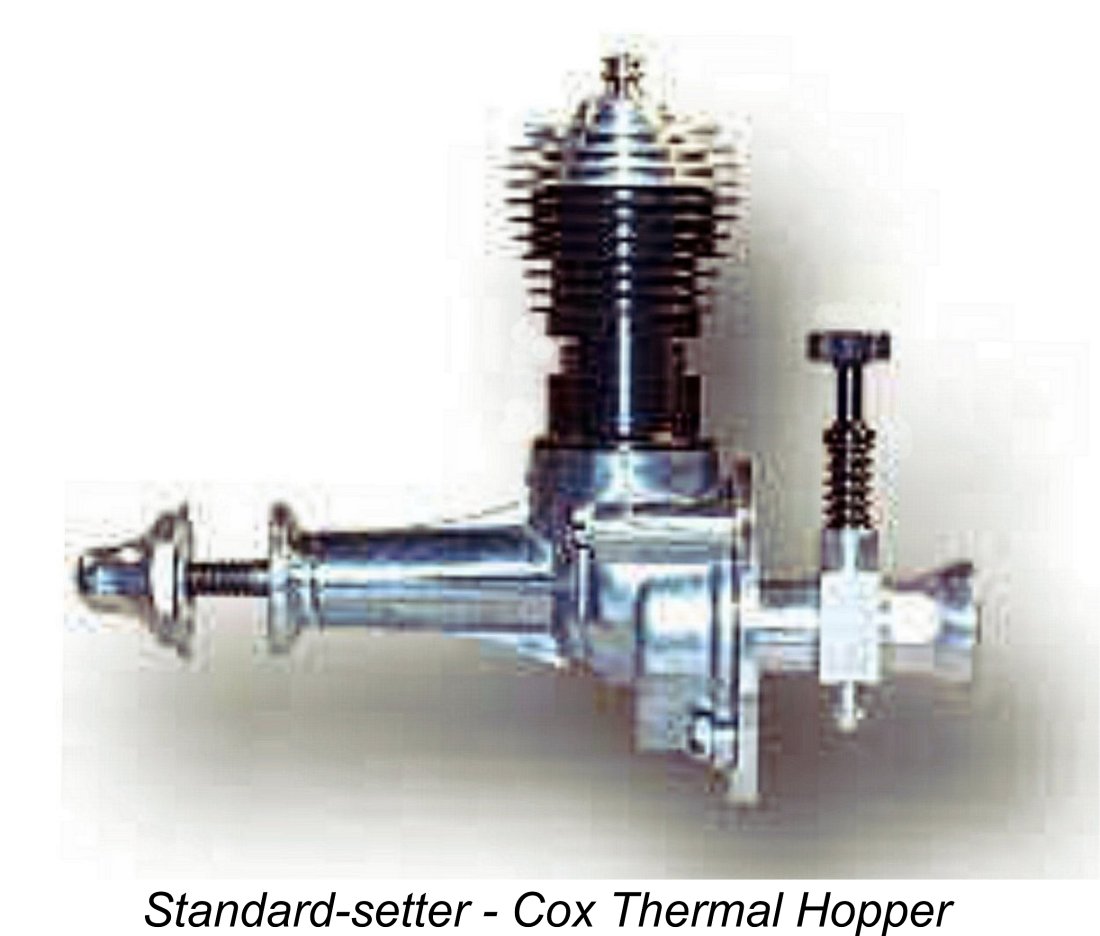

Meanwhile, the majority of modellers over in Europe remained true to the compression-ignition ("diesel") engines with which they had become far more comfortable than had their American colleagues, at least in the smaller and mid-displacement categories. It was generally recognized that the glow-plug motor enjoyed certain advantages in the larger displacements (over 3.5 cc) as well as in a pure speed context, but for the lesser displacements and for more general uses the diesel was widely considered superior by European enthusiasts. The attractions of small models were just as evident to the Europeans as they were to the Americans. In 1950-52 there was a minor revolution within the British marketplace, with no less than four established British engine ranges (Allbon, FROG, E.D. and Elfin) being expanded to include new second-generation radially ported rotary valve 0.5 cc (.030 cuin.) diesel models. Despite their small displacement and light weight, these performed very respectably, generally being considered by their British owners to perform in a sport-flying context at least on a par with the American .049 glows which were appearing on British flying fields in small but ever-increasing numbers by that time. The best of the half-cc diesel offerings was the first to appear - the late 1950 Allbon Dart. However, all of this was blown right out of the water in 1953 with the introduction by Cox of the famous .049 Thermal Hopper. The performance of this fabulous little reed-valve glow-plug engine leapfrogged that of the Davies-Charlton fought back vigorously with their excellent little Allbon-designed 0.76 cc Merlin diesel of 1954, which was in fact a superior engine to the Cox for sport-flying use, while International Model Aircraft (IMA) also joined in the fun in 1956 with their equally good Frog 80 Mk. I diesel. However, the ultimate performance of these fine little diesel powerplants still fell well short of that of the Cox model. The 1957 introduction of the Holland Hornet further underlined the fact that when it came down to all-out performance, the glow-plug motor no longer needed to take a back seat to the diesel in any displacement category. Since its inception, the glow-plug motor had maintained a place in British modelling in the larger sizes, where its general superiority to the diesel had long been recognized, particularly for control-line speed and Class B team racing. However, the advent of engines like the Cox and Holland .049 contest models as well as the championship-winning Japanese O.S. Max 15 of the mid-1950's contributed to the commencement of a period of re-appraisal of the glow-plug motor on the part of British and Continental modellers in terms of its broader applicability to the smaller displacement categories which they had hitherto seen as being largely the preserve of the diesel. This movement began to take shape in around 1958 and had gained considerable momentum by 1959, to the point that the editors of the 1959 "Aeromodeller Annual" specifically commented upon the fact that the "attempted comeback of the glowplug engine" had been a noteworthy point of interest during the 1959 season! The 1959-1960 British ½A “Glow-Plug Revolution”

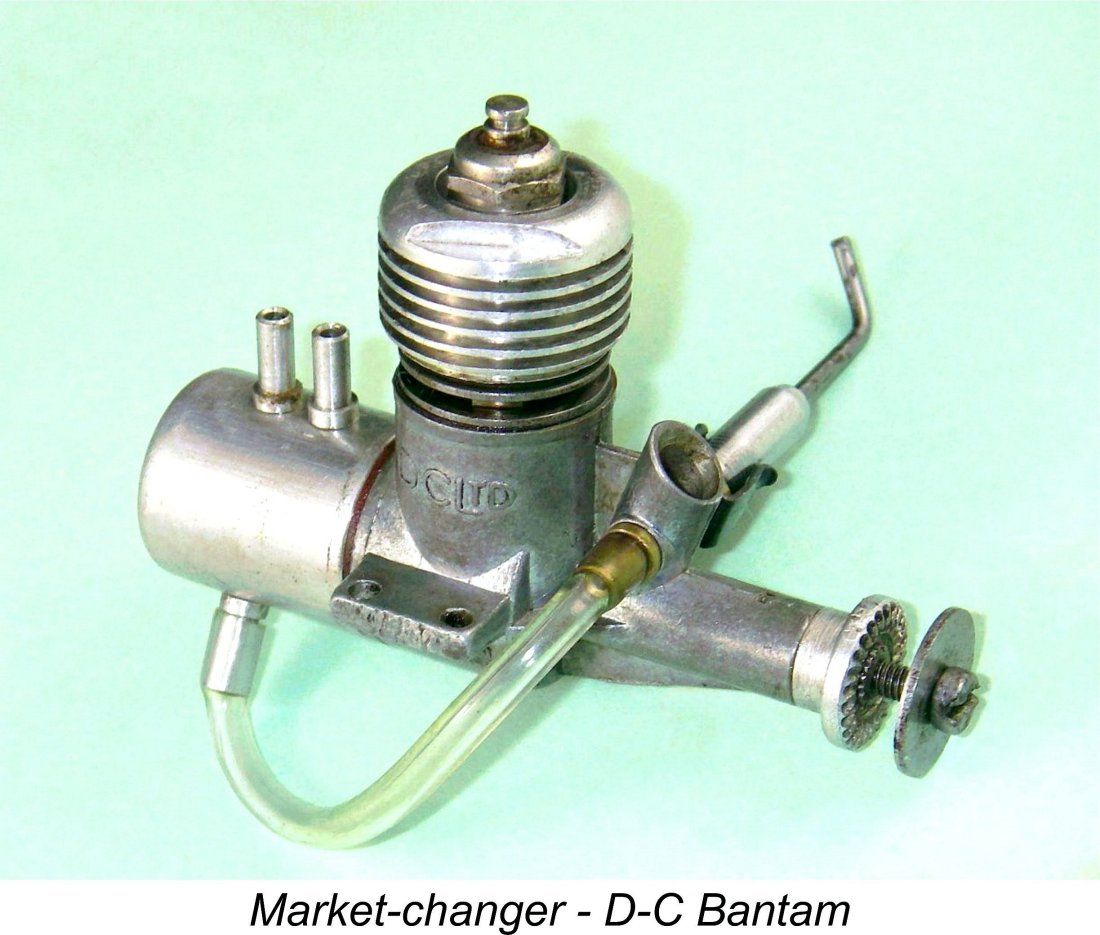

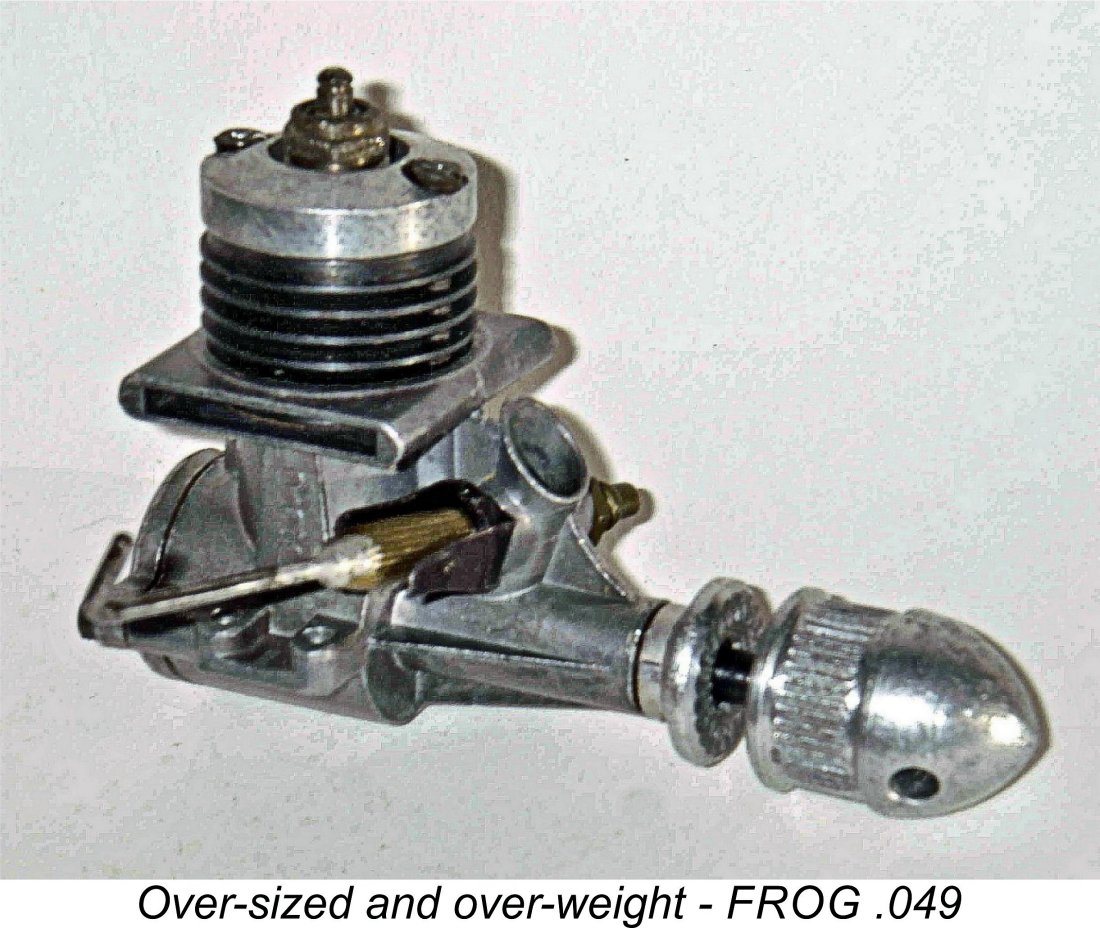

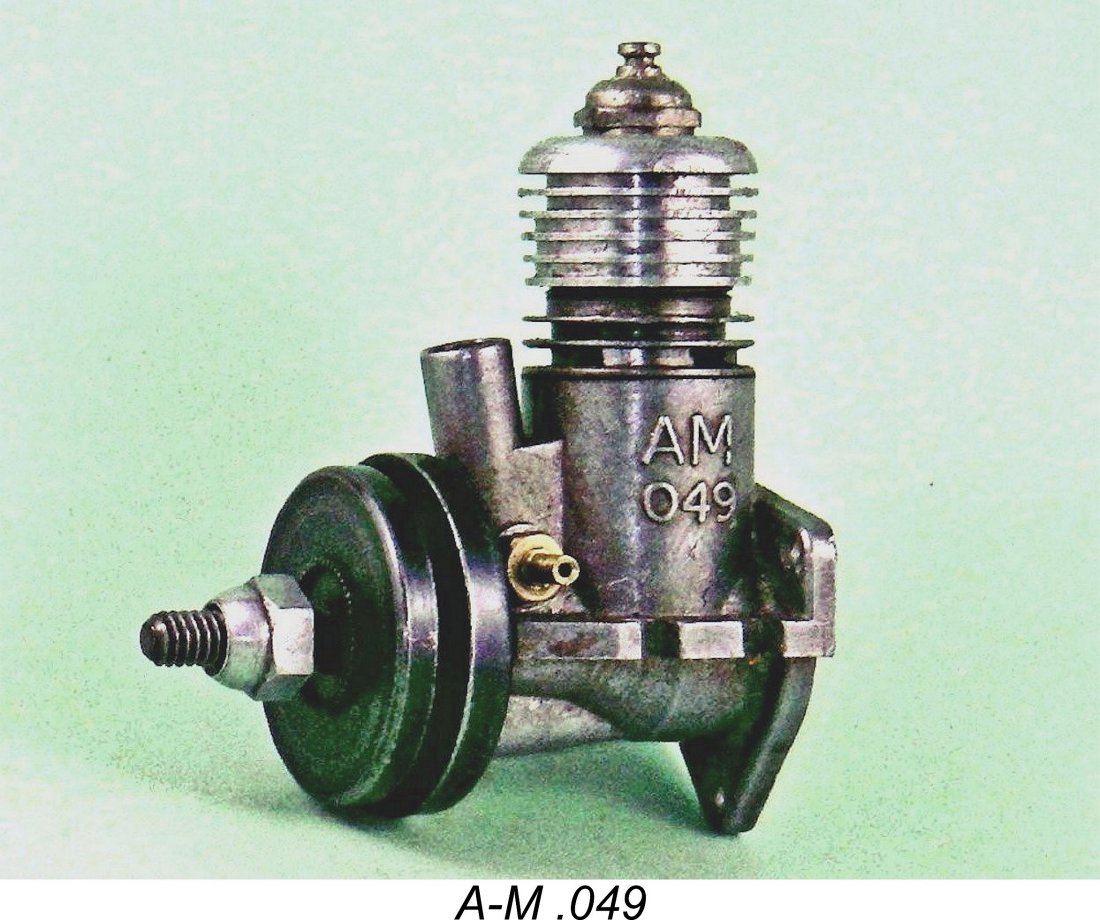

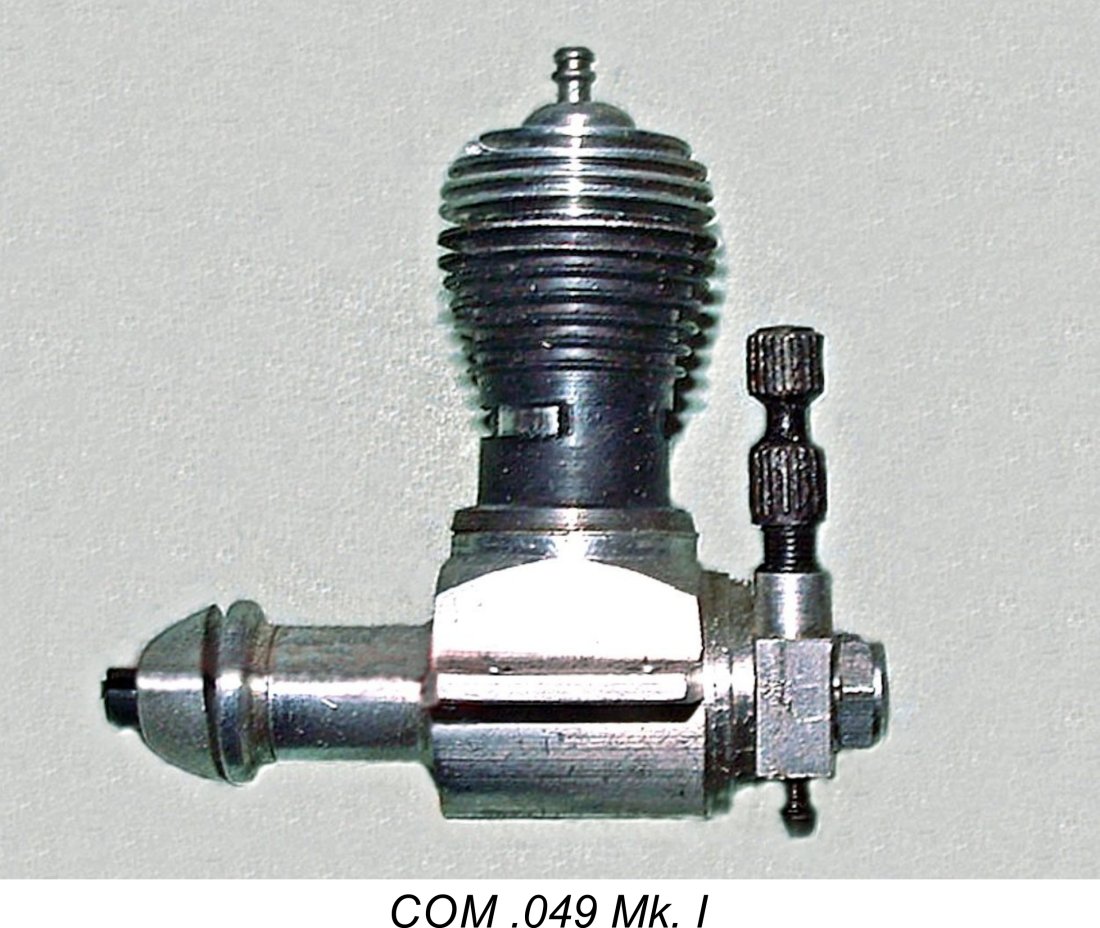

IMA got the ball rolling in July 1959 by introducing the FROG .049 glow-plug version of their established FROG 80 diesel. In September 1959 Allen-Mercury released the A-M .049, which was simply a badge-engineered copy of the well-established American Wen-Mac .049 glow motor. These latter engines were assembled in Britain under license from Wen-Mac, evidently using a number of components actually manufactured in America by Wen-Mac. Finally Davies-Charlton's response came in late October 1959 with the release of the D-C Bantam, which was to all intents and purposes a bored-out glow-plug version of their well-established 0.55 cc Allbon-designed Dart diesel. All three of these new British ½A motors were tested together as a group by Ron Warring, the results being published in an unusual head-to-head triple test which appeared in the January 1960 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, then edited by Ron Moulton. Now it's noteworthy that none of the above three designs embodied any original thinking whatsoever in their conception. All three of them either borrowed heavily from existing diesel models already in production by their respective manufacturers or (in the case of the A-M) were nothing short of a licensed badge-engineered rendition of an established American design. This probably reflects the undeniable fact that when it came to manufacturing engines at the kind of low unit production costs that could be achieved by American volume producers such as Cox and Wen-Mac, the British makers with their far smaller market couldn’t hope to compete, hence looking for savings elsewhere, such as sidestepping development costs and minimizing investments in new dies and tooling. In hindsight, this was probably a mistake, of which much more in its place below. Such thinking was by no means confined to the above three British engine manufacturers at this time. During 1959 the major British firm of E. Keil & Co., producers of the very popular KeilKraft line of model kits, was quietly finalizing arrangements with a hitherto unknown model engine manufacturer to market an .049 glow-plug unit which followed Allen-Mercury’s lead in drawing its inspiration from an American design. The difference was that far from being a straight copy like the A-M, the proposed engine incorporated a significant number of original design features intended to tailor it to the British market. It was also very logically based upon a successful glow-plug model as opposed to being a converted diesel like its D-C and FROG rivals.

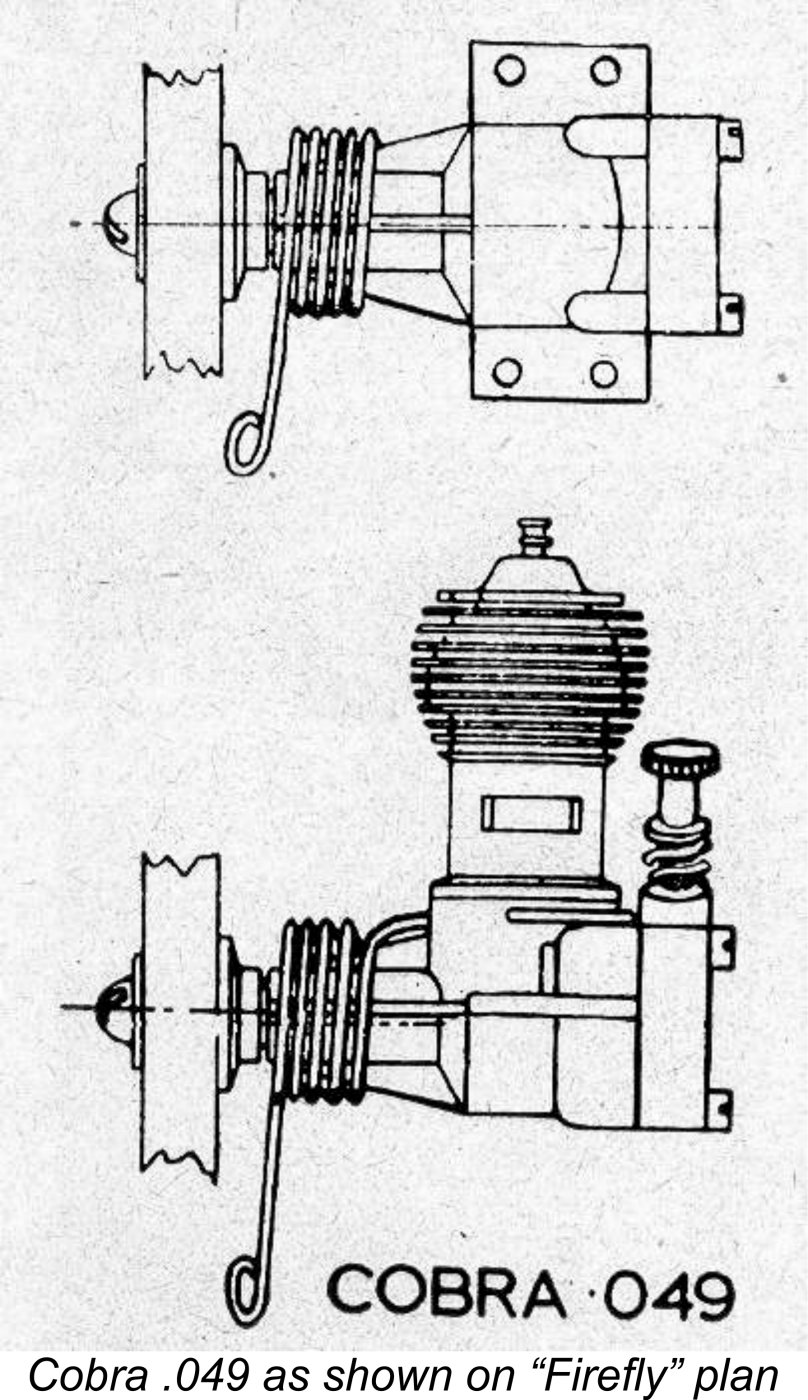

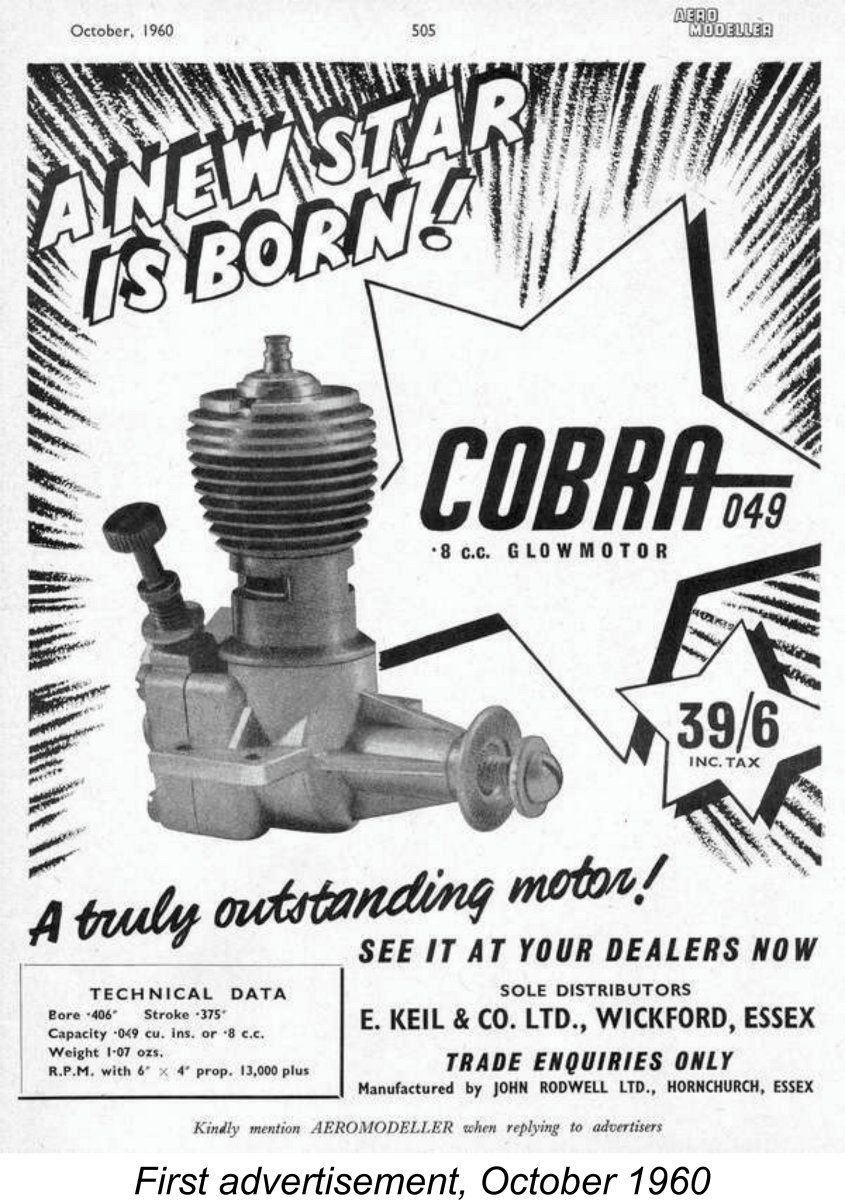

The "Motor Mart" article was clearly written in October or November 1959 to meet the late November editorial deadline for the January 1960 issue. It stated that inquiries regarding the manufacturer of this engine (presumably directed to Eddie Keil and/or Eddie Cosh, General Manager at KeilKraft and past editor of the rival magazine “Model Aircraft”) had drawn a blank beyond eliciting the information that they were "…....London-based and not without modelling experience". All that was said at the time regarding the release of the engine was that it was "not yet ready for distribution" but that it "should be in the shops in the new year “(i.e., 1960). Clearly, the two Eddies were playing their cards very close to the chest when it came to discussing this engine - rather odd given the fact that KeilKraft themselves had already well and truly blown the whistle with their "Firefly" plan depiction! It’s hard to see why they failed to take full advantage of this golden opportunity to promote the engine in advance of its release. The "Aeromodeller" article was necessarily illustrated with reproductions of the "Firefly" plan images, since no photograph was apparently made available by KeilKraft. As a relatively impecunious 12-year old schoolboy at the time in question, I was a regular flier of ½A models, a major attraction being that one could obtain used ½A engines very cheaply at the time. There So when a wealthier club-mate bought a "Firefly" kit I shamelessly borrowed the plan (sorry, Eddie!) and constructed my own example for my battle-scarred but still highly serviceable old fifth-hand Allbon Merlin diesel. Lots of fun! However, I noted the Cobra .049 shown on the plan with great interest, eagerly awaiting its further appearances in the media and on the market. “Aeromodeller” subsequently reported that the Cobra was displayed in its final packaging at the KeilKraft Trade Show held in Manchester on June 27-30th, 1960. It’s clear that the pre-release stock build-up was underway at this time, since engines were being packaged for sale. There is persuasive evidence to suggest that the first production examples reached the market by late July or early August at the latest, although the first national advertisement for the Cobra didn’t appear until October 1960, a full year after the appearance of its three British-made rivals. The manufacturers and promoters had evidently missed the bus!

A little surprisingly, Warring also stated that the engine had been under development for "three or four years". It had evidently taken Rodwell some time to get things right! Since the development of a highly derivative design like that of the Cobra doesn’t take three or four years if pursued vigorously, the clear implication is that model engine development and manufacture were sidelines for Rodwell, who evidently pursued these activities at his own pace as and when time permitted. It’s entirely possible that Rodwell was an active modeller who pursued model engine development as a “labour of love” in his spare time. One wonders if he was a member of the very active West Essex club along with his marketing ally Eddie Keil ………. he was certainly in the right location! This might well have been the “modelling experience” cited in the “Motor Mart” article. I’ve been unable to determine what Rodwell’s main business line(s) may have been during this period. I found a record which stated that his full name was John Andrew Commercial listings give the 1960 address of John Rodwell Ltd. as 199-209 Hornchurch Road in Hornchurch. Most interestingly, the building at this site today (2021) is still called Rodwell House! It is evidently still owned by Rodwell's successors, now being occupied by several property development businesses bearing the Rodwell name as well as being host to a personal fitness training company called RAW Inc. and a toddler nursery called Harmony House. This may well be the building in which the Cobra engines were manufactured. John Rodwell Ltd. subsequently relocated to an address in Basildon, still in Essex and even closer to Wickford. At some point after 1982 it became listed as a “dormant company”. Later company registrations confirm that Rodwell (or his successors) went into the property development and construction business, still using the Rodwell name. Several of those Rodwell companies remained active in 2021, a few of them having offices in Rodwell House as mentioned earlier.

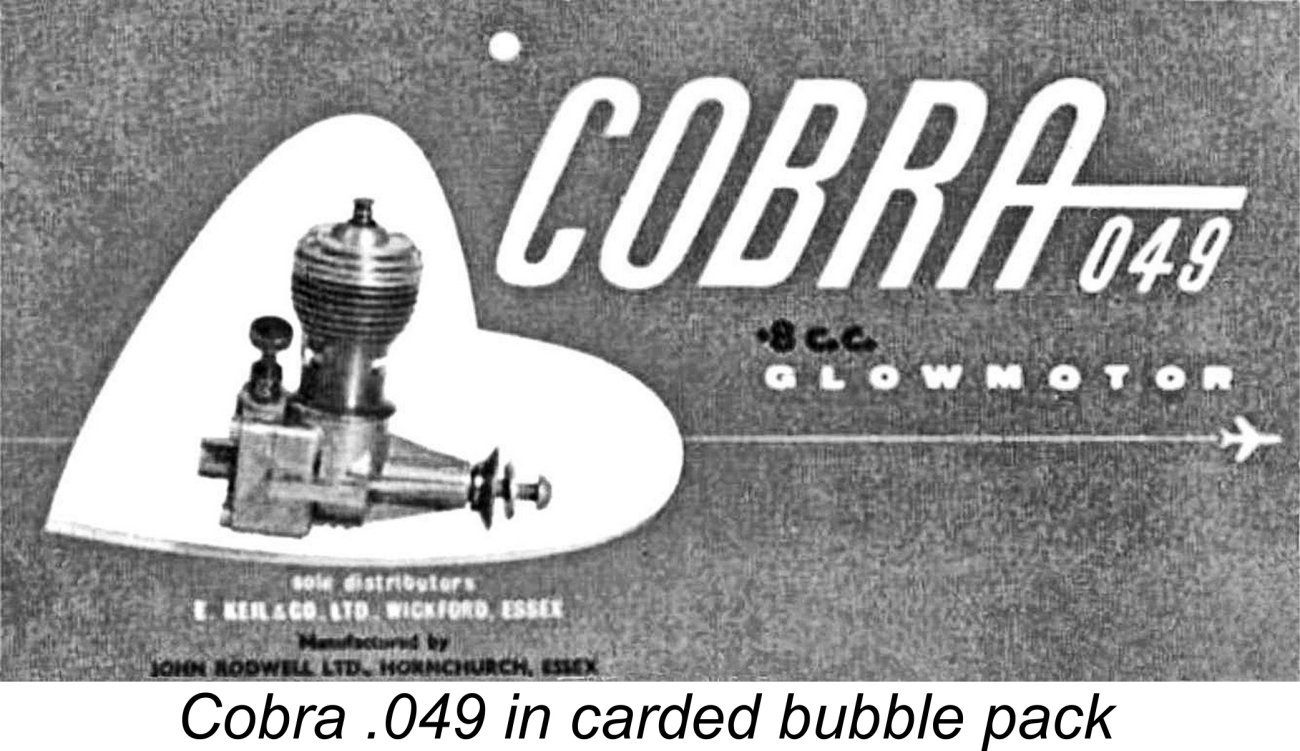

The Cobra .049 was marketed exclusively by E. Keil & Co. Ltd., selling for the very competitive price of £1 19s 6d (£1.97). The central role of E. Keil & Co. Ltd. in the marketing of this engine has all too often led to it being referred to as the "KeilKraft Cobra". Remarkably, the usually precise Peter Chinn was among the offenders! This identification is undoubtedly incorrect - KeilKraft had absolutely nothing to do with the Cobra's manufacture. Their role was confined to the promotion and distribution of the engine. Neither KeilKraft nor John Rodwell ever referred to the engine as the "KeilKraft Cobra" at any time. The packaging was outstanding by British standards - a carded American-style bubble pack which presented the engine very attractively. The previously-reproduced initial advertisement placed in "Aeromodeller" in October 1960 was also very eye-catching. My informant Alan Strutt advised that the cards on which the engines were packaged were distinguished by an eye-catching blue background colour. This doesn't show in the black-and-white rendition below which is all that I've been able to come up with. Can anyone provide a colour photo of this packaging?!? However, the engine does not In fact, as far as I was concerned the initial public appearance of the Cobra took the form of a test by Ron Warring which appeared in the October 1960 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine. The previously-mentioned introductory advertisement also appeared in that same October 1960 issue. However, allowance of time for the test to be carried out and Warring’s report to be finalized to meet the late August editorial deadline for the October issue (which actually appeared in mid-September) clearly implies that the engine must have been in existence and available for testing no later than early August 1960, as noted earlier.

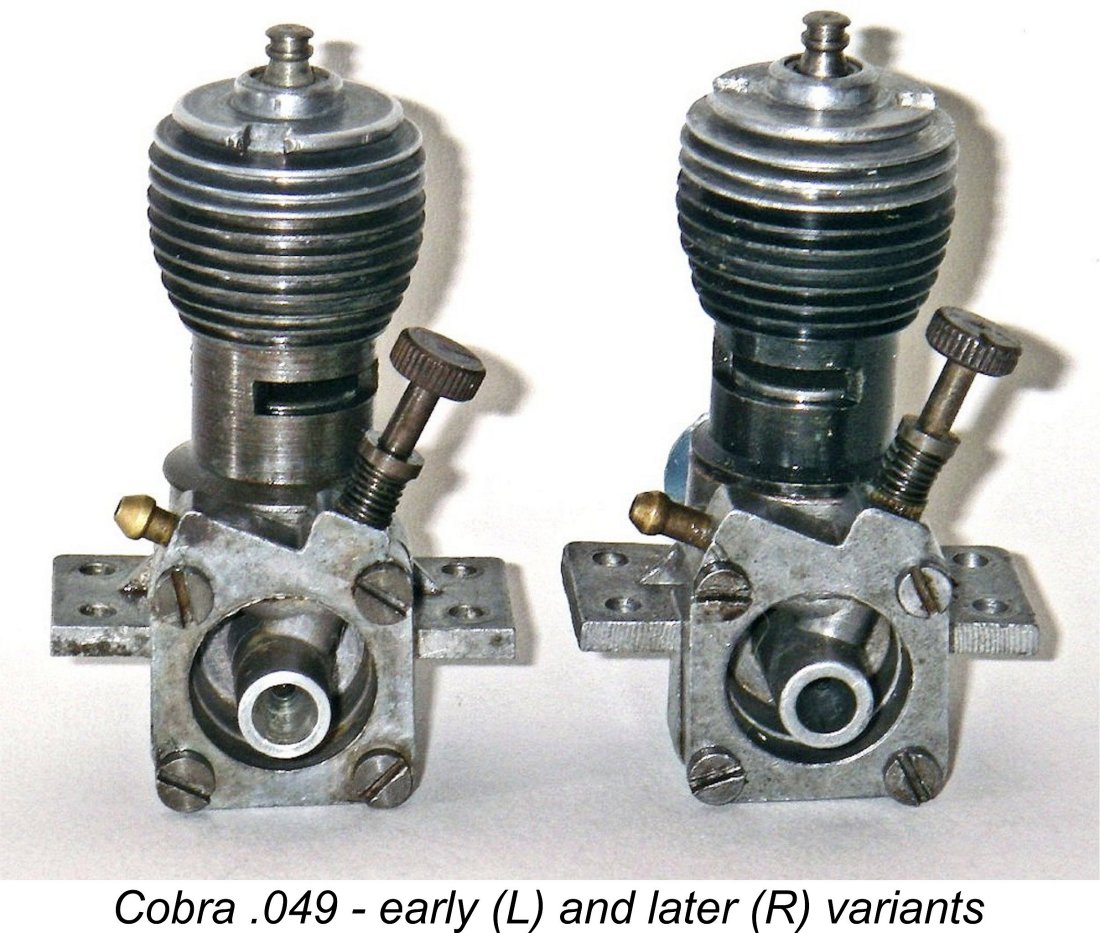

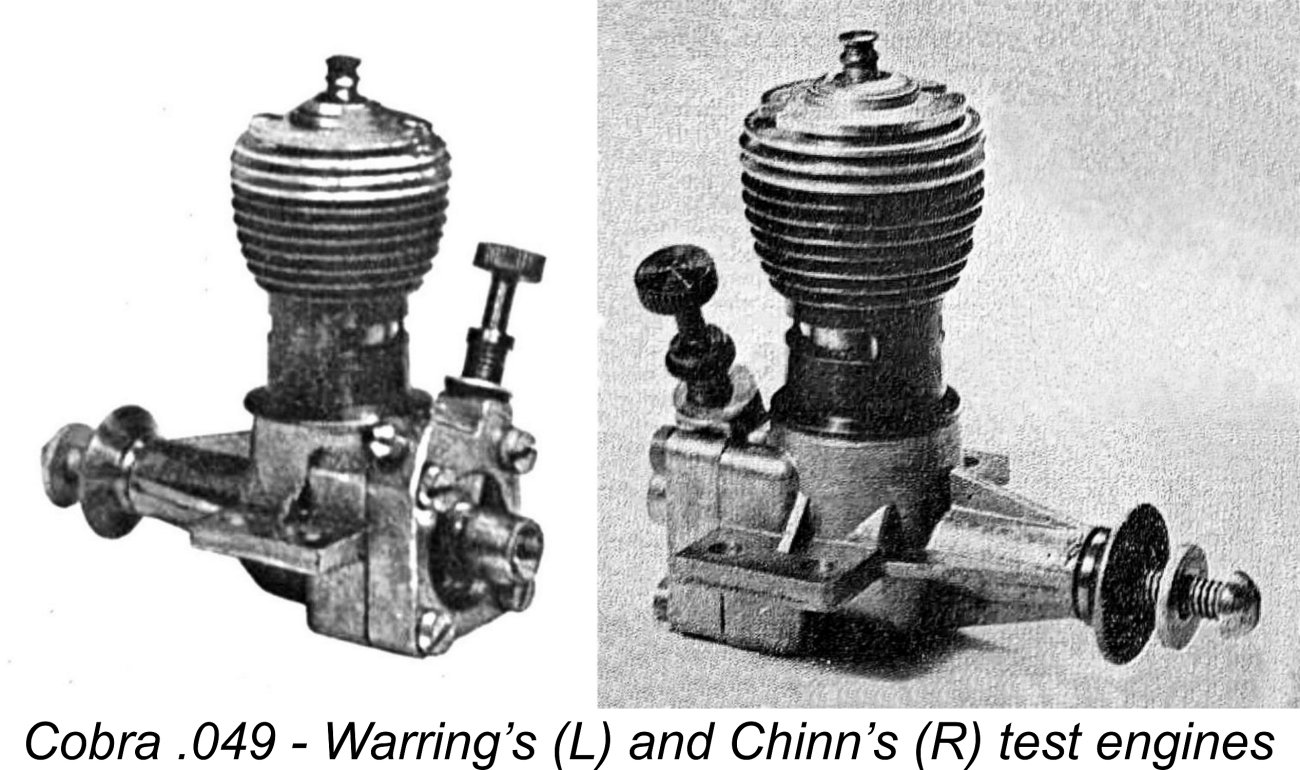

An interesting point arising from a very close examination of the images included with Waring’s test report shows without a doubt that the example of the engine which he tested was a distinct early variant which differed in several key respects from the later and more common version of the Cobra. I’ll be reviewing the differences between the two variants in a subsequent section of this article. Suffice it to say for now that all things being equal, I would expect the later version of the engine to out-perform the example tested by Warring to a modest degree. A second test of the Cobra appeared in the January 1961 issue of the rival publication “Model Aircraft”. Although unattributed, This test report was guardedly positive rather than being universally complimentary. Chinn had two examples for test, the first of which proved to be hard to start due to an excessively loosely-fitted main bearing assembly. The second example was far better, hence being used for the test. Chinn made the entirely appropriate comment that none of the then-current crop of British .049 glow-plug engines were as good as they might be, the Cobra being no exception. Nonetheless, handling and high-speed running qualities of Chinn’s better example were stated to be very good, although needle settings reportedly became rather critical at higher speeds. Using a fuel containing 15% nitro, Chinn found a very slightly lower output than Warring, a peak of 0.049 BHP being recorded at 14,600 rpm. Nonetheless, this represented the highest power-to-weight ratio of any of the four British .049 glow-plug engines which had then been tested by Chinn. As seen at the left, a synopsis of the Cobra test from “Aeromodeller” appeared in the 1961-62 "Aeromodeller Annual", directly above similar entries for the Cox Babe Bee and Golden Bee .049 models. But despite what appeared to be quite a promising send-off, actual examples of the Cobra still failed to put in an appearance, in my area at least. That said, Maris Dislers has kindly trolled his magazine collection, confirming that the engine did in fact receive fairly widespread geographic distribution, albeit for a relatively brief period of time. Between November 1960 and November 1961 the Cobra was included in nationally advertised lists from a number of retailers, including:

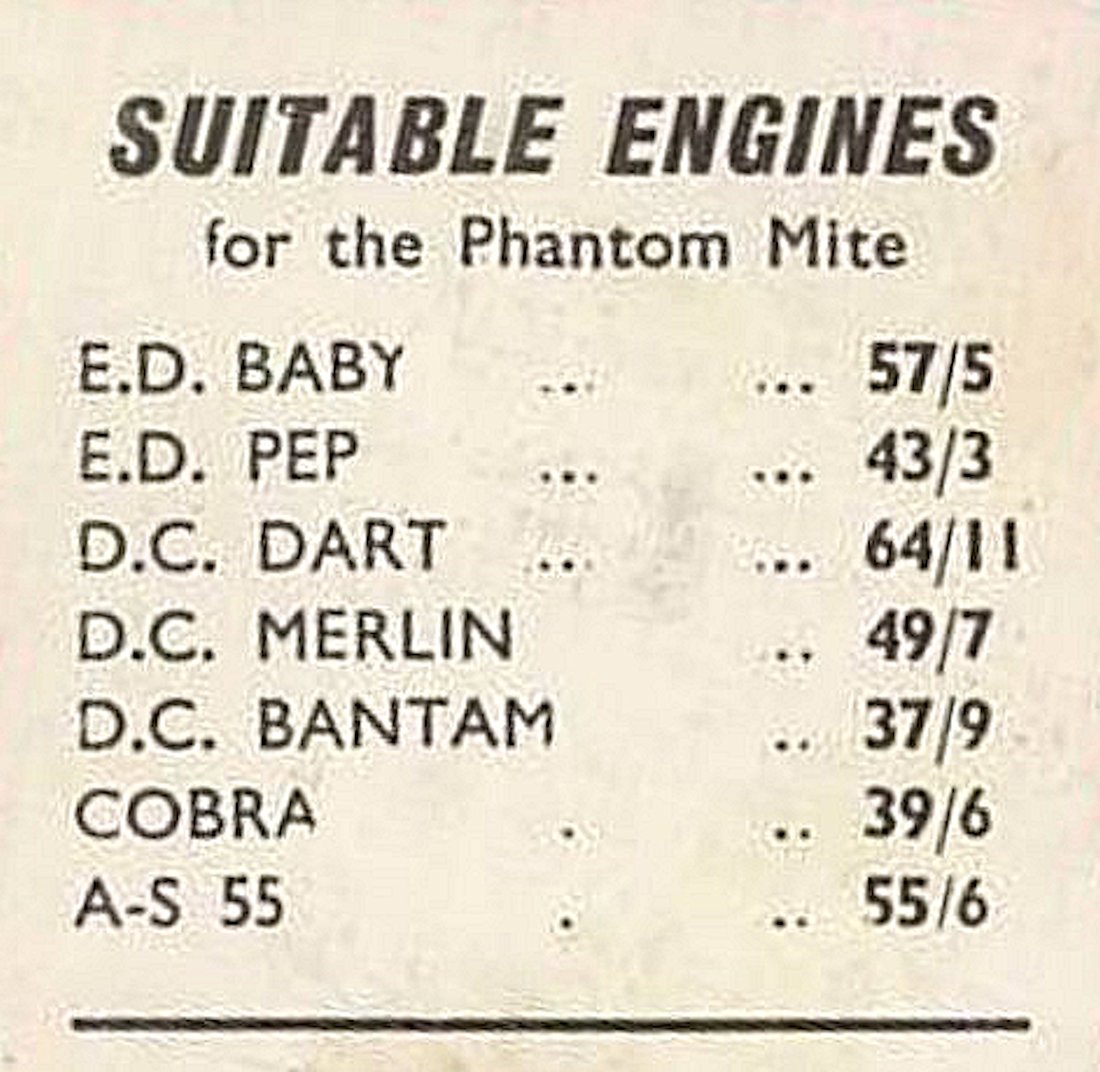

After that initial advertisement of October 1960, Rodwell appears to have completely lost interest in promoting the engine. Distribution to regional hobby outlets seems to have peaked in early 1961 - no fewer than four nationally-advertising firms were featuring the engine as of February 1961. However, My informant Alan Strutt recalled buying a Cobra .049 in 1960 just after its appearance on the market, obtaining his example from a small model shop called Don's Models on Atlantic Road in Brixton, South London. It would thus appears that the engines were sold by some of the smaller retail outlets - just none in my area. Alan confessed to having sold the engine to a school-mate of his after becoming bored with it thanks to its excessively easy starting and operation - he preferred the "cantankerous fun" offered by a typical diesel! After Rodwell bowed out of the fray, KeilKraft’s own promotional efforts soon lost momentum. As far as Maris and I can determine, the final KeilKraft advertising picture of the Cobra itself appeared on the back cover of the June 1961 issue of “Aeromodeller”, where it was featured in company with several matching KeilKraft kits - not hard to figure out where the profit came from! The engine was subsequently featured as the powerplant of the illustrated Phantom Mite when that very popular kit was first advertised in August 1961. That illustration remained in use for some time thereafter.

As can be seen, that list highlighted the basis for the very negative effects which the price war engendered by the woefully under-performing but very cheap D-C Bantam had initiated in the British marketplace. That price war was certainly the reason why the vastly superior A-S 55 diesel failed to survive in the marketplace, much to the hobby’s loss. The Cobra may well have been another casualty. If the Cobra had been forced to compete only with the other listed diesel models, it could have been sold at a price which might have greatly enhanced its commercial viability from the manufacturer’s point of view. By 1963 the Cobra wasn’t even a memory - certainly it failed to appear in the "World's Model Engines" feature of the 1963 "Aeromodeller Plans Handbook" published during the latter part of that year. For the I was therefore pleasantly surprised to finally encounter not one but two real live examples being offered for sale simultaneously by the same individual! These had been bought new in 1961 as a pair by the seller, who had intended to build a twin-engine model for them but never got around to doing so, although he did use them both individually for a while. Since they were both complete and in quite nice original condition, I quickly snapped them up, thus becoming only their second owner. I found them to be very useful little motors which performed well by comparison with contemporary rivals such as the Cox Babe Bee. I am thus in a position to describe this neat little unit in detail for the record, a task which is long overdue in my book. But first we need to understand the market forces which may have prompted the development of this engine. Why the New Model? Even the limited amount of information apparent from the two views of the engine presented in late 1959 on the "Firefly" plan made it abundantly clear at the outset that the design of the Cobra .049 owed much to that of the Cox ½A series of engines. Although the "Motor Mart" article refrained from saying so, the similarities were so obvious that at the time I and many others felt it to be likely that the engine must have been planned in cooperation with, or at least with the blessing of, the L. M. Cox company of California, USA. But then, why would Cox go along with this? By 1959 their own engines were being imported into Britain in ever-increasing numbers by the A. A. Hales organization and were beginning to sell quite well - why participate in an exercise which could only increase the competition for their own products by lending their support to a rival domestic production which on the face of it was to all practical purposes one of their own designs?

Maris Dislers has suggested quite plausibly that Rodwell’s development of the Cobra may well have been instigated by KeilKraft rather than being undertaken on Rodwell’s own initiative. The suggestion is that KeilKraft may already have entertained ambitions of entering the Ready-to-Fly (RTF) market but wished to do so with their own British-made powerplant. It’s undoubtedly true to say that the very unusual orientation of the Cobra’s needle valve and fuel nipple seem to be far more appropriate for an RTF installation than a hobby engine - the attached images from the Cox Model Engine Forum showing the Cobra’s inverted installation in the KeilKraft Hurricane RTF model of early 1961 certainly support such a notion. However, we’ll never be able to verify this supposition……………… In any event, most examples of the Cobra were clearly packaged and sold as hobby engines - their application to RTF models was very brief, as we shall see in a later section of this article. So what factors might have been expected to make the engine seem attractive to British modellers?

The accommodation of a radially-mounted engine like the Cox ½A range up to 1959 generally required considerable modification to the front end of the fuselage of the average British design. Many people resisted the need to do this, and I actually recall this being a frequently-stated criticism of the Cox engines in Britain at the time, whether valid or otherwise. At the time, control-line was all the rage in Britain, with free flight still attracting a strong following as well. R/C was growing in popularity but was restricted to those who had This led to another frequently-voiced criticism of the Cox engines in my personal recollection - the fact that one was more or less compelled to use the integral tank supplied with these engines give the fact that it formed an integral part of the radial mounting and carburetion arrangements. These tanks took up quite a bit of space directly behind the engine, and some of them were less than completely suitable for control-line flying - the illustrated Cox Golden Bee was an exception. In addition, the fuel load was well forward of the model's centre of gravity, which thus changed during flight as the tank ran out. In a free flight context, the Cox metal tanks were obviously unsuitable for timing free flight runs by observing the residual fuel level in the tank. Their fuel capacities were also quite excessive for this application. British modellers tended to favour the flexibility of being able to use a tank of their own choosing that was tailored to the application in question and could be located more flexibly. A non-technical factor that may also have come into play was the fact that the slogan "Buy British!" still meant something in those far-off days of over sixty years ago. For better or worse, people in Britain were still positively influenced by the term "Made in England" applied to most forms of goods. Accordingly, if a British product of comparable quality and performance to its overseas counterpart could be obtained for anything like a comparable price, it was inherently likely to be preferentially received in the British marketplace.

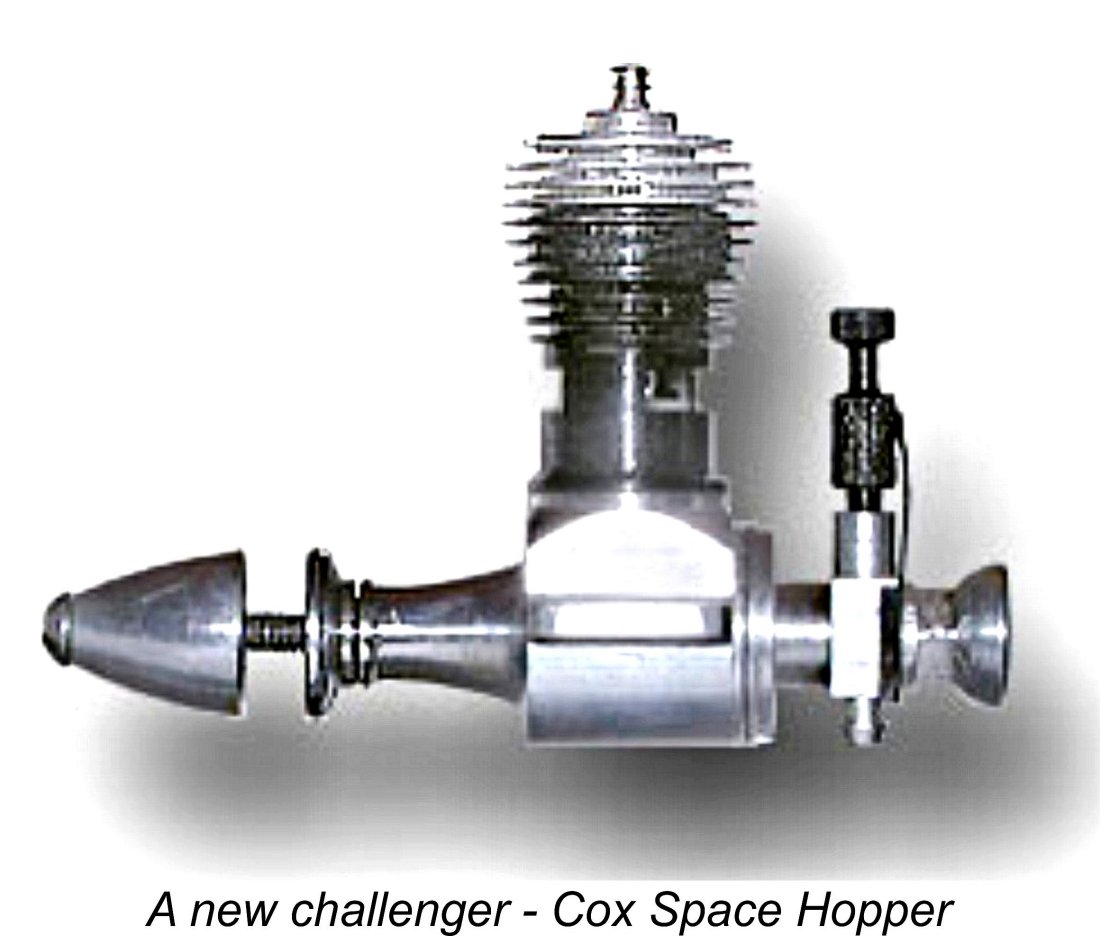

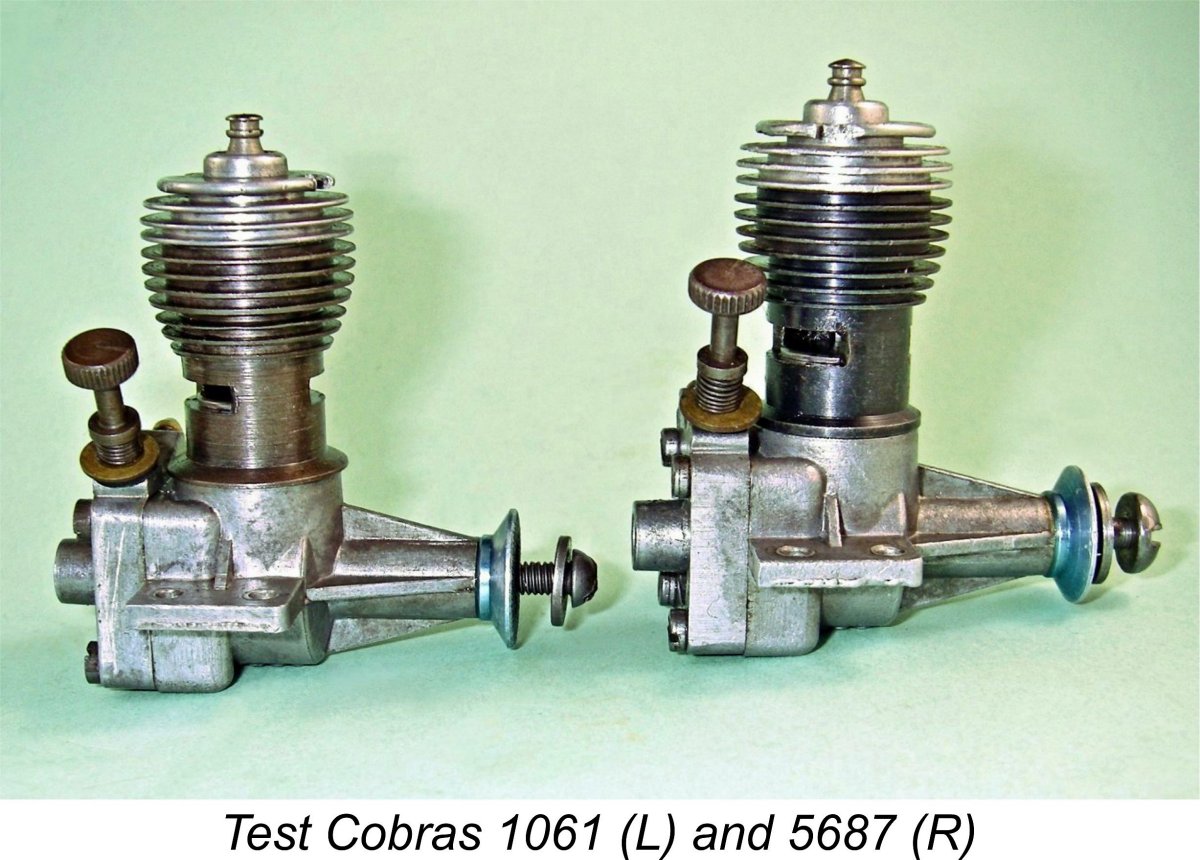

The clincher was the belief, mistaken or otherwise, that such an engine could be produced in Britain at an economically-viable price which would be competitive with that of both the domestic diesel competition and the Cox glow-plug imports after payment of import duty. That theory was comprehensively scuppered in October 1959 by the appearance of the D-C Bantam at a price which undercut the imports by what must surely have been an unforeseen amount. Sadly, the Bantam's dismal failure to match either the domestic or imported competition in terms of performance had no effect upon its attraction for British modellers - all that they saw was its low price. Any new .049 model would be competing with the Bantam in a price-driven domestic marketplace rather than taking on the imports on a level playing field based upon value as opposed to price (two very different criteria). The And it only got worse .......unfortunately for the promoters of the Cobra, another factor had now intruded. Cox themselves were in the process of addressing some of the very issues discussed above! Their wonderful little .049 cuin. Space Hopper of 1959 not only employed beam mounting but also did away with the built-in tank, leaving the choice of tank up to the user in accordance with the intended application. It also used a twin-transfer cylinder which allowed it to reach levels of performance which put all of its British .049 rivals to shame - Peter Chinn measured a peak output of 0.097 BHP @ 17,500 rpm. This cannot have helped the cause of the British .049 glow-plug offerings, now caught between a domestic price war and a superior product from overseas. At this point in our story, as a preamble to a detailed description of the Cobra .049, it’s necessary to deal with a somewhat unexpected issue which arose from my research. This is the previously-unacknowledged existence of multiple variants of the engine. The Two Variants of the Cobra .049 Prior to undertaking this in-depth research, I had always assumed that the form in which the Cobra was released remained unchanged throughout its production life. In other words, like everyone else I believed that there was only one variant of the engine. Following the initial publication of this article, I continued to hold a watching brief for the appearance of further examples of the Cobra on the collector market. Eventually I was fortunate enough to locate a low serial number example in fine condition, which I acquired for further study. This unit bore the serial number 1061. There are indications (see below) that the serial numbering sequence may have started at engine no. 1001, a common strategy intended to inflate perceived production numbers. If this is the case here, this would actually be engine no. 61 - a very early example.

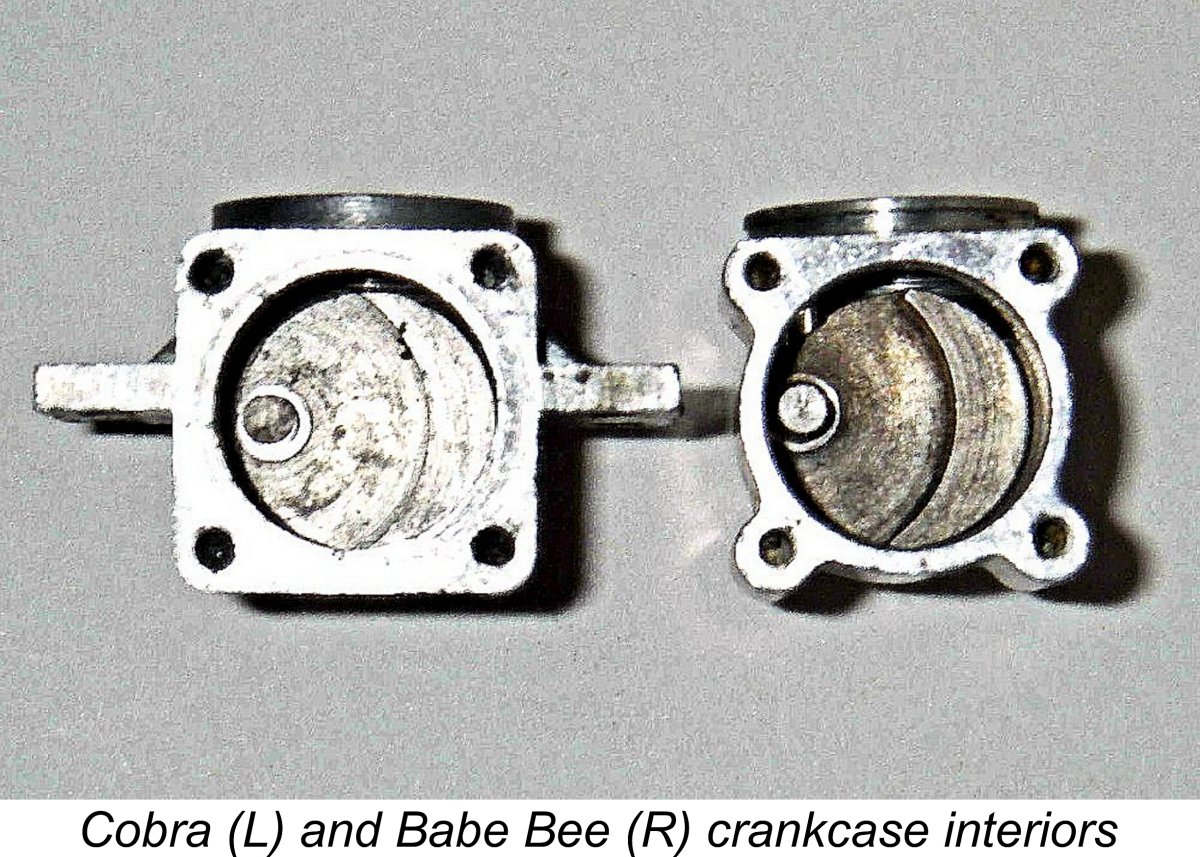

Closer inspection quickly revealed further subtle differences. This led to my disassembling and measuring the engine, with very interesting results. I ended up undertaking a direct side-by-side comparison with the components of one of my later examples. This proved to be unexpectedly revealing! First, the cylinder installation flange of engine no. 1061 turned out to be significantly larger in diameter than those of the higher-numbered units, actually overhanging the crankcase seat. Moreover, the exhaust ports were smaller in vertical height and located lower down the cylinder, being 0.018 in. narrower, with the top of the port 0.012 in. lower than the ports of the later models. Internally, it appeared that the blow-down period (the lag between the respective openings of exhaust and transfer) was of about the same relatively short duration on the early model, but the resulting lower top edge of the transfer port inevitably resulted in a reduced transfer period. Taken all together, the changes displayed in the later examples would be expected to increase top end output, probably at some expense in terms of fuel economy.

The rest of the engine’s components were unchanged. I subsequently acquired a fourth example, engine no 4061, which matched the other two higher-numbered units originally acquired. It’s quite clear from these observations that there was more than one variant of the Cobra .049. The question becomes one of interpretation of this evidence. It seems that at some point, evidently quite early on in the production sequence, Rodwell decided (or was told by KeilKraft) that he needed to beef up the engine’s top end performance a little. It may be that if there's any truth to the previously-stated possibility that the Cobra was seen by KeilKraft primarily as a potential RTF engine, they may have found through flight testing that a little more power was required for that application. Rodwell’s response was to make the exhaust ports vertically wider, adding most of the extra width on the top edge to give earlier opening. He shifted the transfer port up by the same amount to have it open earlier as well, maintaining roughly the same relatively short blow-down period. In this way, both exhaust and transfer periods were increased. Finally, he added 16% more throat area to the intake venturi, also slightly reducing the length of the induction tract. This is all completely consistent with an objective of improving the engine’s top-end performance a little. All of this seems to say that the engine was effectively still under development when it was released. These findings also show the value of examining as many examples as possible from all stages of an engine’s production life. So far, it seems to be a pretty straightforward tale of two variants, doesn't it? Well, just to really complicate matters, reader Bob Parry contacted me to report that neither of his two examples of the Cobra fits neatly into the above classification! Bob's lower-numbered example, no. 4294, has an early-style small-port overhanging cylinder as described above which is nonetheless chemically blackened. It also features what appears to be a Type 2 backplate with a short intake and long fuel nipple, but just to really mess me up, that backplate also features the small venturi bore from the Type 1 variant! What this engine is doing in the higher serial numbering sequence is anyone's guess! Just to really confuse the issue, Bob's other engine, no. 5942, has an un-blackened cylinder with small exhaust ports - seemingly an early Type 1 cylinder except for the fact that its installation flange does not overhang the crankcase! To add to the confusion (as if we needed that!), this engine's backplate has a longer intake like that of the earier variants but also incorporates the larger bore and longer fuel nipple which are features of the second variant! AAAAARRRRGGGGHHHH!@?! What to make of all of this? Well, engine no. 4294 could well be an example of the manufacturer using up parts already on hand from the earlier variant during the transition period - it seems to date from quite early on in the transitional sequence. By contrast, engine no. 5942 is the highest-numbered unit yet reported, hence almost certainly being a very late example. It too could be a case of simply using up remaining stocks of whatever components were still on hand as operations were winding down. The other examples which have been reported to me all fit nicely into the Type 1/Type 2 sequence described above - Bob's engines appear to be anomalies.

This being the case, the question arises why Chinn actually found slightly less power than Warring had done. In my opinion, the reason almost certainly relates to the cylinder design. The use of a single bypass/transfer flute has an enhanced potential to create substantial differences in performance between individual examples depending on where the single bypass flute ends up when the screw-in cylinder is fully tightened. Detailed internal examination of an actual example shows that if the bypass ends up at either the front or rear of the crankcase, gas access to the lower bypass will be severely restricted by the piston skirt at and around bottom dead centre. The ideal transfer location for unrestricted gas access would be to the side of the crankcase, with the exhaust ports accordingly oriented more or less fore and aft. Examination of the previously-reproduced photographs included with the two published tests shows that Chinn’s test example was indeed arranged in the least favourable orientation, with the single transfer flute at either the front or the rear of the crankcase and the exhaust ports at the sides. By contrast, Warring’s engine had its cylinder oriented in the ideal position with the exhausts facing pretty much fore and aft. I think that this completely explains the difference between the results reported by the two testers. For best results, it would be necessary to use thin metal shims or fibre gskets to set the cylinder with the exhausts fore and aft. This was a standard modification with the Cox single-bypass engines - I used to assemble them in this way myself, with very positive results. Having settled the matter of the two variants in which the Cobra .049 may be encountered, it’s now time to find out just how closely the designer of the Cobra actually followed the Cox pattern. Description

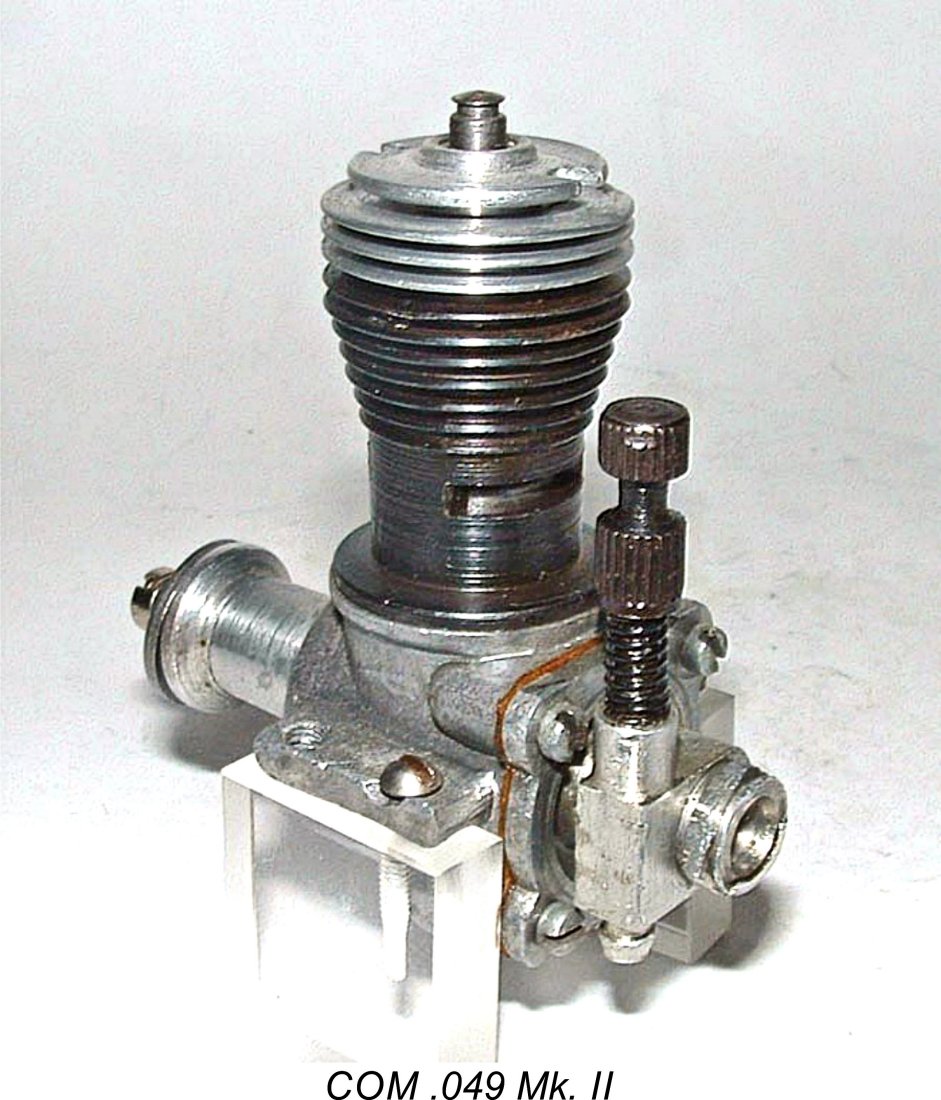

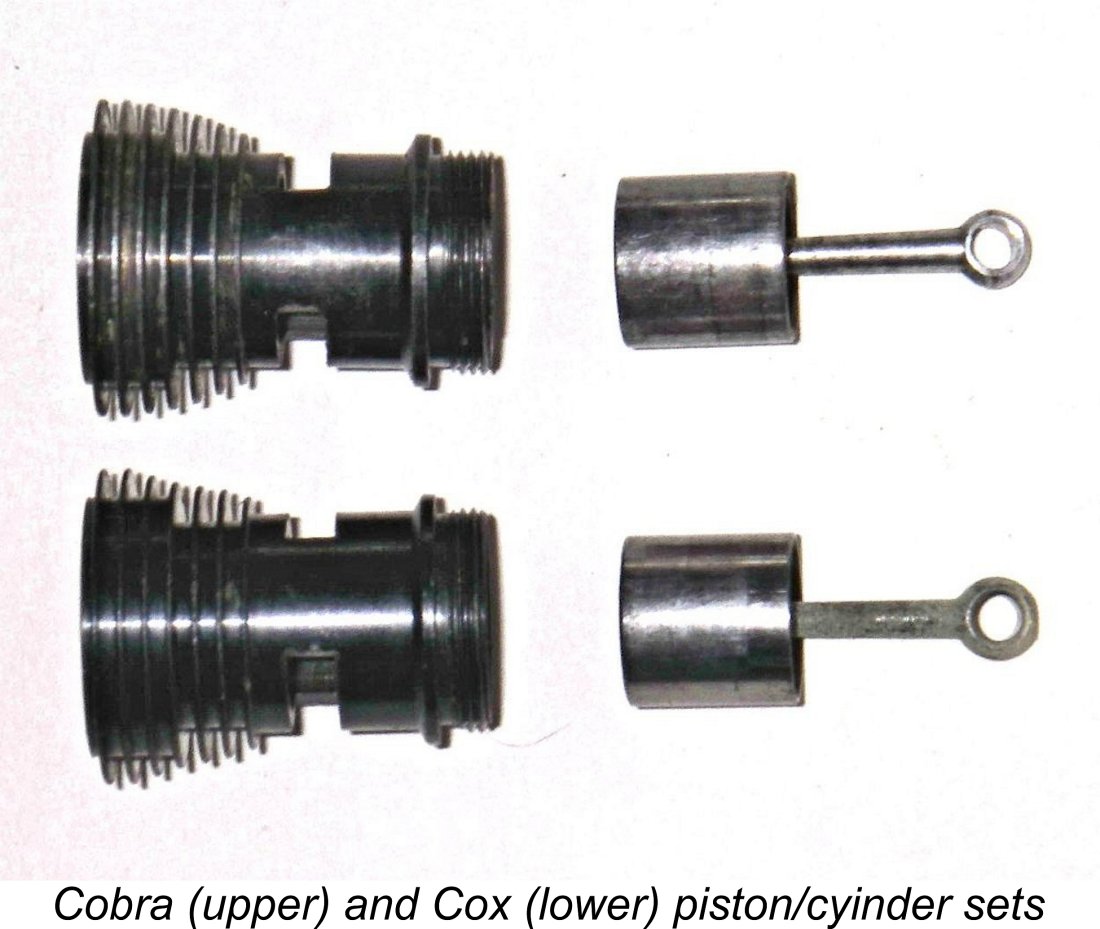

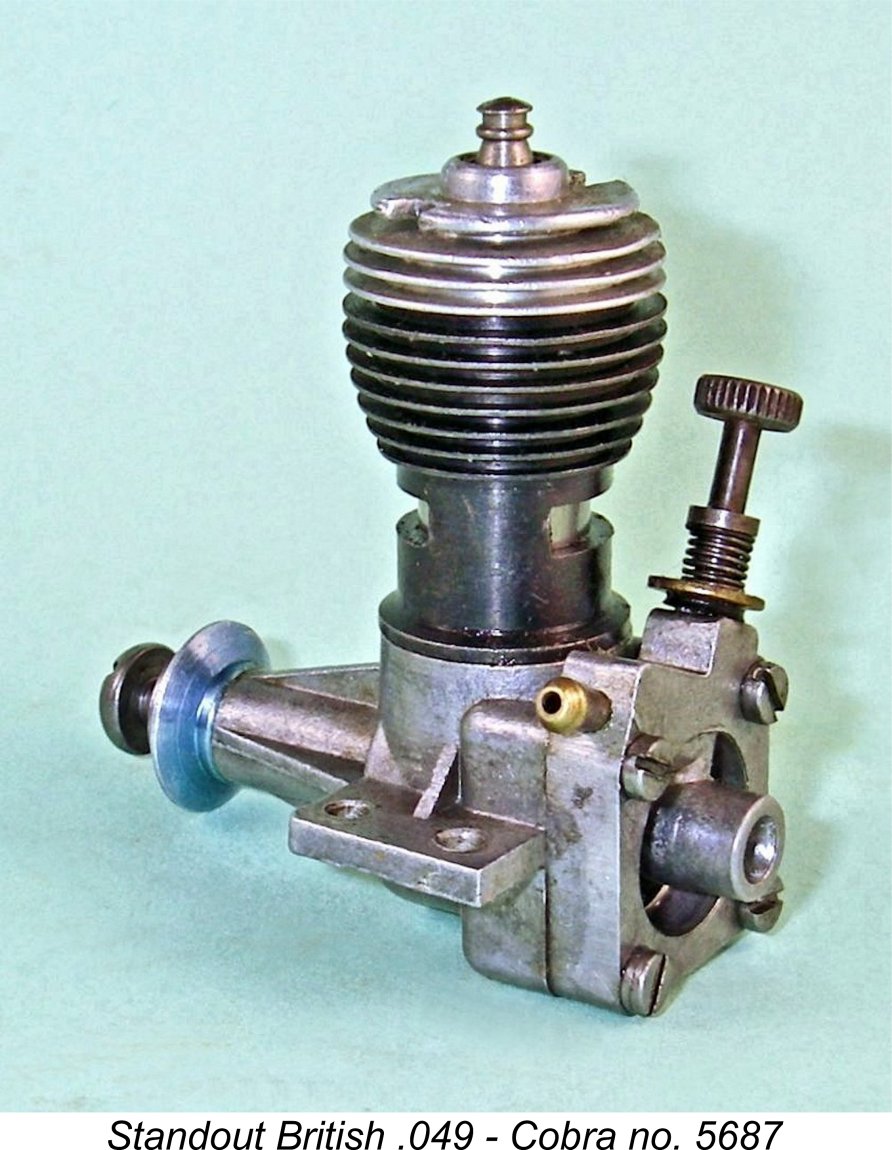

There's no doubt at all that at first glance the Cobra conveys a strong impression of being a Cox product - previous assumptions regarding some level of Cox involvement are completely understandable. It's also an indisputable fact that the engine was produced to a close approximation of Cox standards of quality. Despite the previous use which they have clearly received, all fits and finishes in my four examples are beyond reproach. Prior to becoming a Cobra owner myself, the few people that I ever talked to who claimed to know anything at all about this engine invariably told me that it was an amalgamation of some bought-in Cox components grafted onto a set of British-made castings. Seemed reasonable to me at the time - KeilKraft were big enough to have brokered a deal of that kind with Cox. Accordingly I'd never questioned this assumption in the past. But now that we have a few actual examples to dissect, let's check this out at first hand with a view towards replacing legend with fact! And where better to start than at the heart of the motor and the most obviously "Cox" component - the cylinder? I may as well come right out and say that, appearances to the contrary, the Cobra cylinder is not a standard Cox item. It certainly shares enough common features to eliminate any doubt that it was directly inspired by the Cox design. But it is most definitely not a bought-in Cox cylinder of the type fitted to their .049 engines.

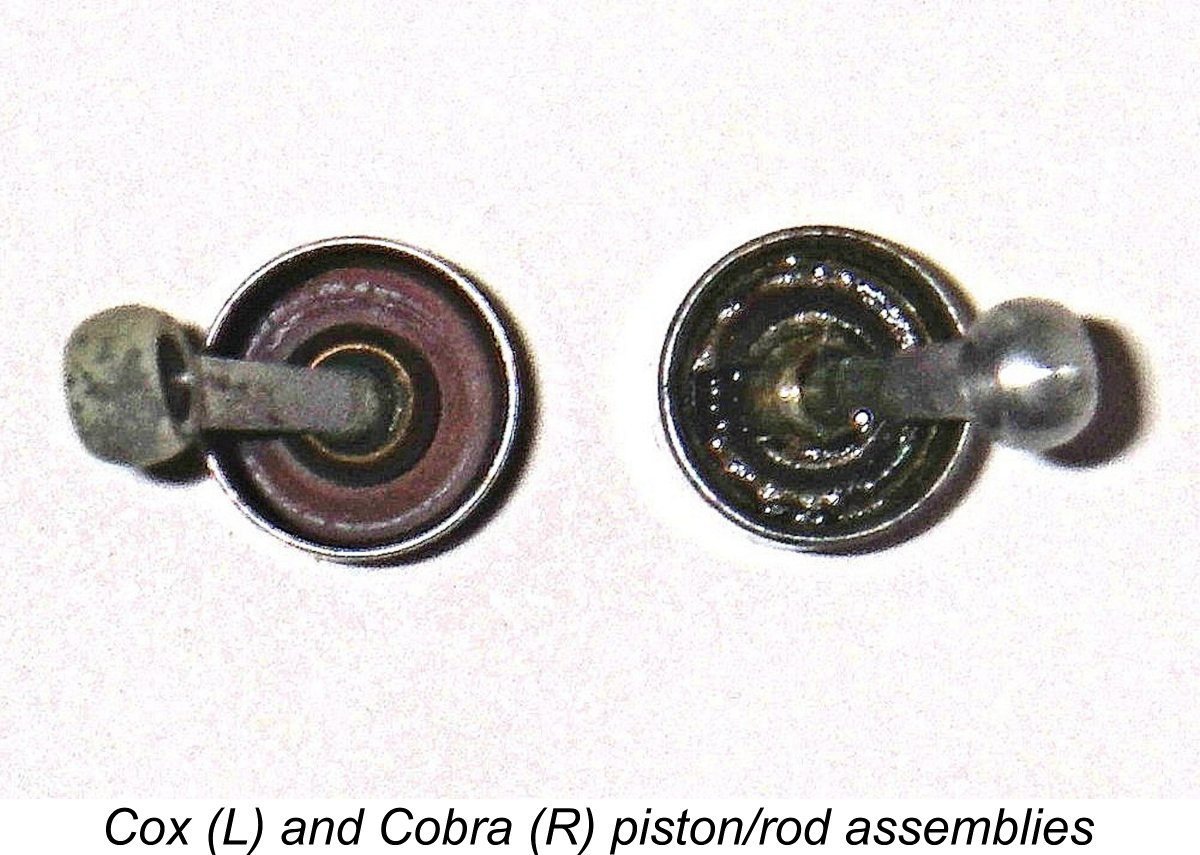

The differences are less obvious, but they're there regardless! First off, it's easy to spot the more "rounded" side profile of the cylinder fins on the Cobra cylinder. The more observant scrutinizers will also note that the threaded spigot which screws into the top of the crankcase is longer on the Cobra than it is on the Cox - the Cobra spigot extends for 0.140 in. below the seating flange, while that on the Cox only extends down by 0.114 in. The thread pitches on the sockets are identical, however, and the Cobra cylinder will screw right into a Cox case, and vice versa. The fact that the conrod lengths and crankpins are also identical actually means that the piston/cylinder sets can be interchanged and used with either motor. Another difference which may be spotted is the fact that the Cobra cylinder wall is far thicker above the exhaust level than its Cox counterpart. This is consistent with then-established British practise of generally using thicker cylinders than American manufacturers. The external diameter of the Cobra cylinder at exhaust port level (0.506 in.) is slightly less than that of the Cox (0.515 in.), but this diameter continues unchanged above the exhaust ports at the base of the cooling grooves, whereas the Cox cylinder wall is substantially thinner above the lowest cooling fin. The rounding of the cooling fin contour on the Cobra may well be intended to restore lost cooling fin depth due to the thicker cylinder walls at the base of the fins. A more subtle difference which was reported by Warring in his published test was the fact that the Cobra cylinder again reflected standard British practise by being made of hardened steel, in contrast to the unhardened mild steel used in the Cox cylinders. Since the piston of the Cobra was also of hardened steel, this placed a premium upon the initial fit of the two components since running-in wear would be negligible. All of my examples leave absolutely nothing to be desired in this respect. My engines all arrived with what I took at first sight to be standard off-the-shelf Cox glow heads of the period which sealed to the cylinder using thin copper gaskets. These appeared either to be Cox items or exact copies thereof. As noted earlier, the depths of the glow-head sockets on both the Cox and the Cobra cylinders are identical, as is the thread pitch used. I can't see this being merely coincidental. These observations led me to the initial conclusion that the Cobra used Cox glow heads which were obtained in bulk at wholesale prices through A. A. Hales. However, closer observation has seriously challenged this supposition. Firstly, the threads on the Cobra appear to be cut to the British Whitworth standard of some 55° included angle, while the threads on the Cox glow-heads were cut to the American standard of 60°. Now 60 into 55 will go, but can make for a slightly tight fit.

Maris went further into this question, supplying the attached very informative images of his original Cobra head alongside its Cox equivalent. The Cox head is a late 1950's Bee component, which the Cobra most closely mimics. The slight difference in the side profile of the fins is very evident in the upper view - the Cobra head profile is clearly more rounded, in keeping with the more rounded profile of the cylinder fins. It also turns out that the Cobra's thick top fin with the wrench engagement slots is very slightly larger in diameter than the Cox item, to the point that a "full circle" Cox glow-head wrench will not quite fit (although an open-ended Cox wrench fits well enough for the task). A further external difference is to be seen in the form of the protruding central contact post. The Cobra's post is very slightly taller and has a flat top surface, while the shorter Cox post is slightly rounded on top. Looking internally, there are further differences. The Cobra head has a wider sealing surface which actually extends into the bore diameter to give a very slight and probably ineffectual squish configuration. The combustion chamber itself is less generously cut to match, creating a smaller combustion chamber volume in the Cobra head. Maris did some measurements and calculations which indicated that the geometric compression ratio of the Cobra with its original head is around 5.6 to 1, while the Cox head yields a geometric compression ratio of only 4.7 to 1. The increase was most likely in deference to the fact that the average British owner would probably use less nitro in these engines. Reader Bob Parry provided very strong support for Maris's comments by reporting that his example no. 4294 is fitted with what appears to be an original Cobra glow-head, since it differs slightly in profile from a standard Cox item. He also notes that the wrench engagement slots have rounded ends rather than being square. In support of his observation, he has a spare New Old Stock (NOS) glow-head which is clearly labelled as a Cobra replacement. This NOS Cobra head is identical to that fitted to his engine. Reader Chris Murphy of New Zealand reports having an engine with a similar head, so it was evidently a standard production. The manufacture of glow heads is a highly specialized process which has little in common with engine manufacture as such. Until Maris and Bob shared these invaluable observations with me, I had assumed that Rodwell most likely side-stepped the need to develop the very specialized manufacturing capability required to make near-exact replicas of Cox glow-heads. He could certainly have used KeilKraft's influence to obtain Cox glow-heads in bulk at wholesale prices through A. A. Hales. It now appears that Rodwell did nothing of the sort, instead somehow arranging for Cox-influenced Cobra glow heads to be manufactured in Britain using an installation thread cut to a British standard. The slightly different dimensions as well as the different combustion chamber volume all speak to this notion. This in turn speaks to an amazingly high level of determination to keep the Cobra an all-British production.

The replacement of a Cobra head with a Cox component works most convincingly when using one of the earlier Cox heads from the original Bee models - there still seem to be plenty of them around. With those heads, it's actually possible to duplicate the Cobra head's side profile if you have access to a lathe. The use of a later Cox head is quite practicable in functional terms, but this combination results in an engine with a rather non-standard appearance, as seen in the attached image supplied by Maris Dislers. My sincere thanks to Maris and Bob for their sterling efforts in clearing up this particular issue! You can also drill out a burned-out Cobra head and tap it 1/4-32 to accept a standard glow-plug, although this alters the engine's appearance quite significantly and will likely under-perform by comparison with the original. If you go this route, I'd strongly recommend that you machine the head to accept a Turbo glow-plug as opposed to a conventional component - this should bring the performance of the conversion more or less up to that of the original head. Turning now to the piston/rod set-up, it’s once again clear that we're looking at direct Cox influence - the same basic ball-and-socket small-end design is employed and conrod working lengths are identical. However, there are some interesting departures. The main one is the fact that the Cobra uses a light alloy rod which is retained in its socket by a slotted steel retaining cup which in turn is held in place by a steel circlip This represents another almost irrefutable argument in favour of the Cobra's all-British manufacture. If Cox piston/rod assemblies had been used, they would undoubtedly have been of the 1959 pattern with the steel rod and swaged-in-place ball and socket small end. At first sight it seems a little odd that the makers of the Cobra would elect to go back to the earlier and in some ways less satisfactory system in which rod wear could not be taken up. But if we believe Warring's previously-noted assertion that the Cobra had been under development for "three or four years", it is possible to make sense out of it. Cox appear to have made the switch from the system used in the Cobra to their later all-steel set up at some point during 1957. If Warring is to be believed, the Cobra was already well into the development stage by that time. It's quite likely that the early prototypes actually used Cox piston/cylinder assemblies, probably of the alloy rod type. Hence the design of (and tooling for) the rod and piston may well have been already finalized as of 1957 using the then still-current Cox arrangement as a guide. The decision to stick with this arrangement despite Cox's abandonment of it was presumably production-based. One visible consequence of this difference in approach is the fact that the Cobra’s hardened steel piston is not copper-plated either internally or on the crown. This was done in the revised Cox engines to prevent the hardening process applied to the piston wearing surfaces from affecting the area of the con-rod bearing cup so that it remained malleable enough to be swaged over after the rod was installed. With the type of small-end retention system used on the Cobra, this is not necessary, allowing the entire piston to be hardened.

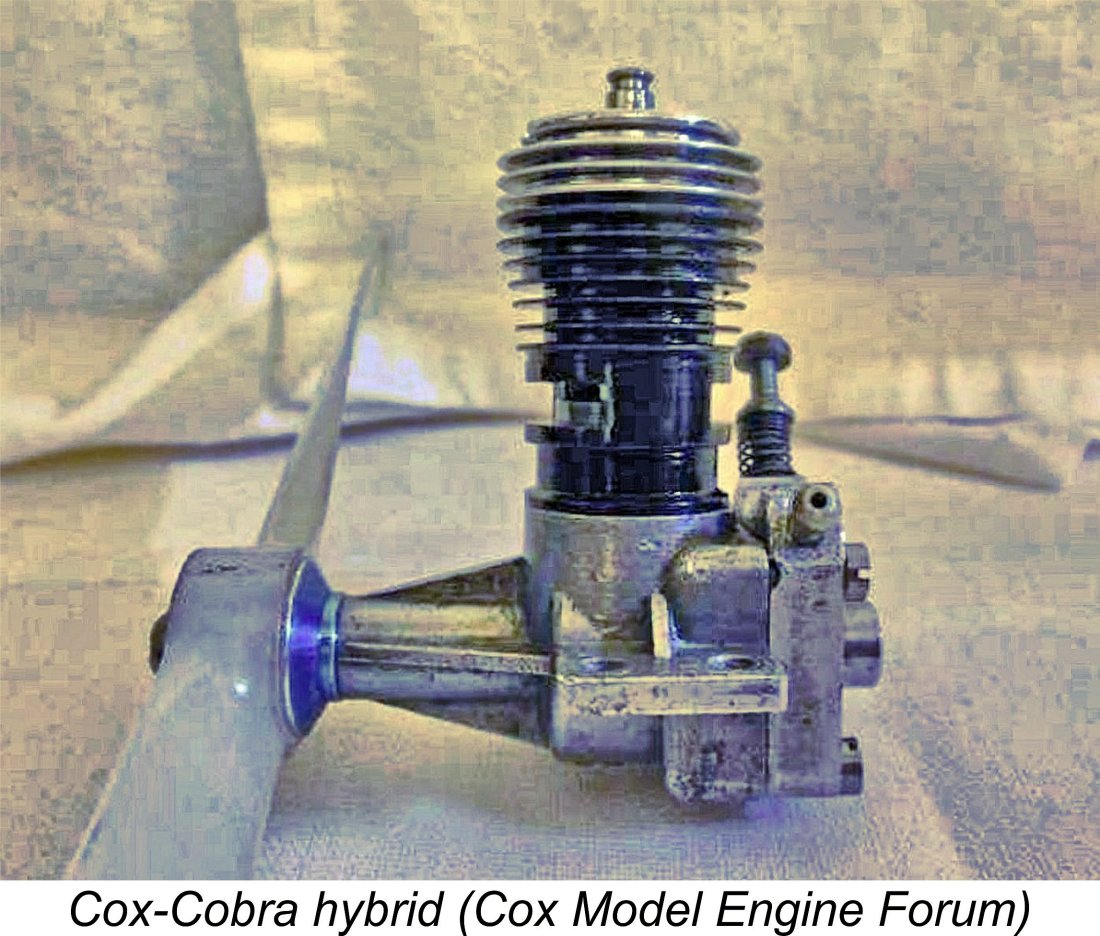

As mentioned earlier, the bores of the Cobra and Cox engines are identical, to the point that direct experimentation has shown that a Cox piston/rod unit fits the Cobra cylinder/shaft combination perfectly. It seems more than likely that Jon had a unit that was retrofitted in this manner. There's no doubt that the later Cox system is far more durable as well as being adjustable, making it a very rational replacement for a worn or broken original Cobra assembly. Indeed, since a Cox cylinder fits perfectly into a Cobra crankcase, the option exists of using a complete Cox piston/cylinder combination as a replacement for the Rodwell originals. The example illustrated above at the right which appeared on the Cox Model Engine Forum was equipped with such a combination, having both a Cox cylinder and piston/rod assembly. It’s extremely likely that there are other similar examples out there. Of course, they’re not true Cobras!

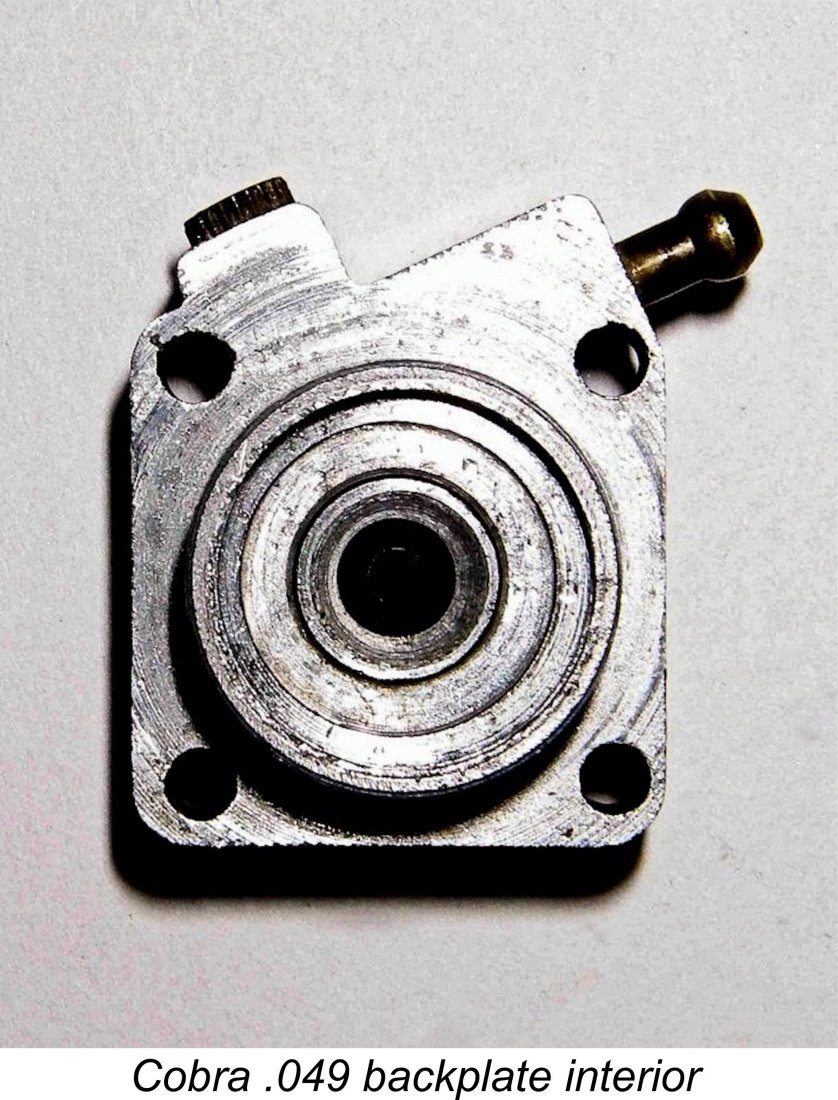

In fact, the only difference here is that the Cobra backplate fixing screws are 8 BA items rather than the 2-56 items used by Cox. Hence a Cox Babe Bee backplate can be used with the Cobra case and working components if one uses 8 BA screws of sufficient length, and likewise the Cobra backplate can be fitted to a Cox reed-valve front end using 2-56 screws. Of course, the latter approach leaves the engine without a means of mounting! Turning now to the crankshaft, this appears at first sight to be dimensionally identical to that used in the Cox series. Certainly the nominal journal diameter of 0.216 in. is identical, as are the overall length, the counter-balanced crank-disc and the crankpin diameter. However, the stroke of the Cobra is fractionally shorter at 0.376 in. as opposed to 0.382 in. for the Cox. Combined with the shared bore of 0.406 in., this gives the Cobra an actual displacement of 0.798 cc as opposed to the 0.810 cc of the Cox. Presumably the manufacturers of the Cobra saw the 0.8 cc cut-off as being potentially significant in the context of the British market given the possibility that any new European contest class for these small motors might well be based on the metric displacement limit of 0.8 cc rather than the 0.05 cubic inch limit used by the Americans. One feature noted by both Warring and Chinn in their respective tests is the fact that the fit of the shaft in its plain bearing was a little on the loose side. This was almost certainly a design decision - the Cox reed valve engines also featured relatively loose shaft fits. However, it seems that this feature was carried a little too far in the case of one of Chinn’s test examples! My own units all display some evidence of this, although not to a problematic extent. The only other observable difference in the shaft is that the Cobra prop screw is threaded 5 BA instead of the 5-40 thread used by Cox. All of this confirms that the shaft is not a bought-in standard Cox component. The prop driver looks exactly like its Cox counterpart, but is anodized blue.

The form of the induction tract on the reed side of the fuel orifice is also quite different. The Babe Bee’s induction tract expands uniformly from just past the 0.058 in. dia. throat to the back of the reed, the diameter at that point being 0.141 in. The Cobra induction tract expands more gradually as it progresses from the 0.0625 in. dia. throat towards the reed, reaching an internal diameter of 0.125 in. some distance behind the reed but then expanding sharply at about a 60 degree angle to yield a diameter at the back of the reed of 0.200 in. This significantly increases the area of the reed which is affected by the differential pressures inside and outside the crankcase, also increasing the circumference of the reed seat across which gas has to flow when the reed lifts off. This should in theory result in a more responsive reed set-up and one which can pass more gas for a given reed opening.

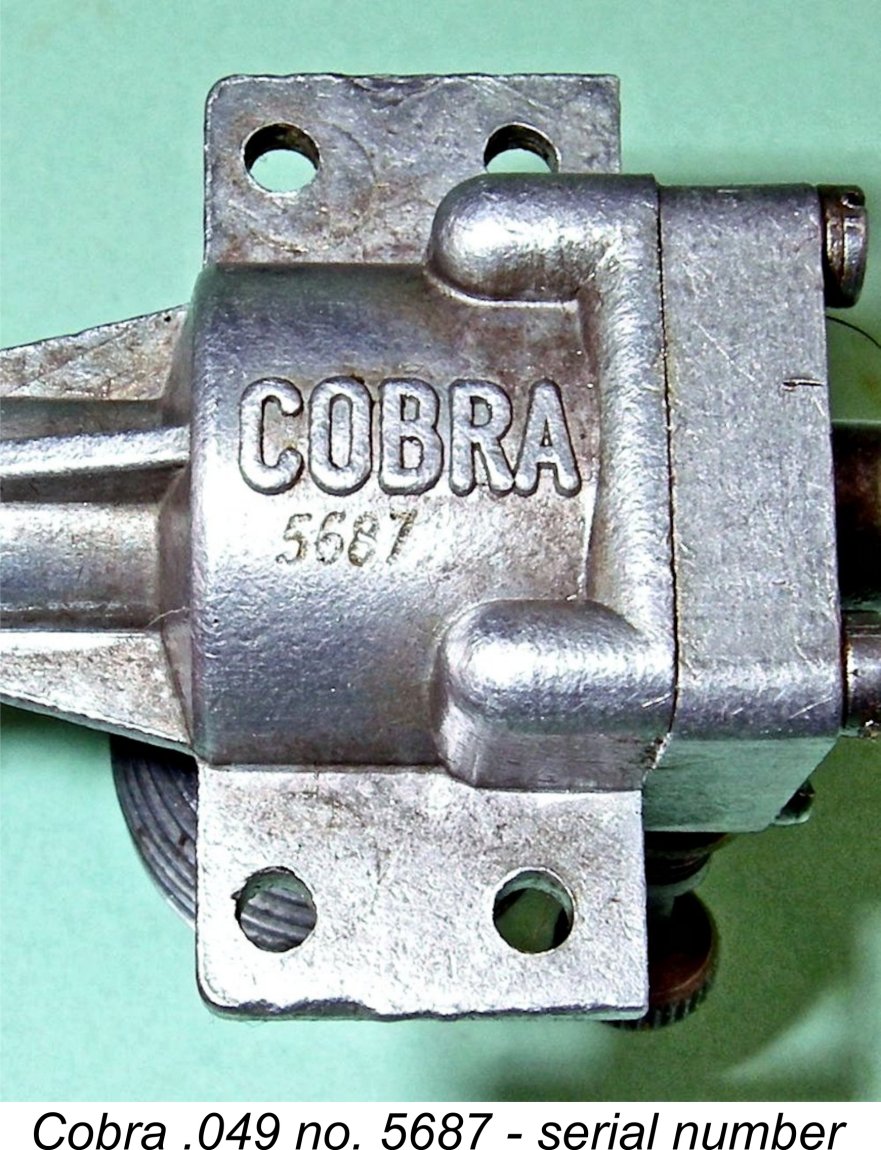

The one point worth noting is the presence on the Cobra of a small brass washer under the backplate end of the coil spring used to tension the needle. This component is clearly visible in many of the attached images. Its presence greatly improves the smoothness of the needle's operation. A small rubber ring was located under the washer to promote a good seal around the needle where it entered the backplate. The form of the backplate on the Cobra is highly unusual - like the Cox, it can be located in any one of four positions to accommodate differing mounting configurations, but it's a fact that all of these positions place the needle and fuel pickup in a rather odd and sometimes awkward orientation. Cox were later to use a rather similar backplate unit on their RTF "Spook" model, but that unit featured a more conventional needle orientation. The rather odd orientation of the Cobra needle valve appears to have been forced upon the designer by considerations of clearance between the needle and the cylinder. So what does all of the above tell us? In summary, that the only components which could conceivably be bought-in standard Cox components are the reed and the reed’s retaining circlip! Everything else differs in some key respects from the components used on the then-contemporary Babe Bee model which the Cobra most closely mimics in functional terms. A formal connection with Cox could scarcely be justified by the need to obtain reeds or circlips, leaving us with the inescapable conclusion that, legends and rumours to the contrary, the Cobra was indeed an all-British production and a highly commendable one at that. Serial Numbers All authentic examples of the Cobra that have come to my personal attention have borne a four-digit serial number stamped very neatly into the underside of the crankcase below the "Cobra" name. There are no letters or symbols involved, suggesting that the engines were simply numbered sequentially as they came off the line. My own examples are numbered 1061, 4060, 5687 and 5892 respectively (the latter two originally bought new as a pair, remember), while Tim Dannels had Type 1 engine number 1679. Another Type 1 engine bearing the number 1516 is owned by Chris Murphy of New Zealand. Engine numbers 5531 and 5591 are confirmed by photos on the Internet, while engine number 5111 has been reported from Australia by Brian Hampton of “Sceptre Flight” fame. Engine numbers 4350 and 4994 appear in the Cox Model Engine Forum. Reader Bob Beaumont reports owning Type 2 engine number 4142, which his father bought new in 1963. Finally, Bob Parry reports owning engine nos. 4294 and 5942, the latter being the highest number yet reported.

When I first wrote this article way back in 2008, I was struck by the fact that at that time there were no reported numbers in the 2000 - 3999 range. This seemed rather odd given the size of the previously-reported serial number database. It opened up the possibility that the numbering for the earlier variant started at engine no. 1001 as suggested above, but that the sequence was re-started at 4001 when the previously-described design revisions were introduced. Again, a desire to inflate the implied sales figures might well explain such a move. However, my good mate Maris Dislers upset this particular apple cart quite comprehensively by providing photographic evidence of the fact that his example of the Cobra displays the serial number 3834! It remains a bit of a puzzle why there's such a large gap in the presently-reported sequence, currently extending from 1679 up to 3834. The possibility remains open that my original interpretation was correct - I may simply have got the starting number for the later series wrong. It's clear that we really need more serial numbers to nail this point down. Maris's engine number 3834 is one of the later Type 2 variants. Consequently, we seem to have serial number evidence for the production of at least 2108 examples of the second variant (5942 minus 3834) and 679 examples of the first variant, assuming that the sequence started at engine no. 1001. Naturally, the true figures could be significantly larger than this if the sequence was continuous and we're simply missing a lot of numbers in between. If the numbering was in fact continuous throughout, the implication would be that at least 5000 and possibly more examples must have been made and presumably sold - a puny total by comparison with Cox, but a worthy figure nonetheless for a British production by a new manufacturer engaging in a highly competitive marketplace. But then one would have to wonder where they all are now - indeed, where were they all then? With such production numbers, they really should have appeared more often back in the day and should be far more common today than they appear to be! If we accept the alternative suggestion that the engines were produced in two distinct series each having its own serial number sequence, then we would be looking at an implied production figure of no more than, say, 3,000 examples in total for both variants combined - perhaps less. I have to say that the frequency with which these engines turn up today is far more in keeping with this possibility than the alternative scenario. The one thing that would help to clarify this issue would be the confirmed existence of examples of the Cobra .049 bearing original serial numbers in the present "vacant" range from 1680 - 3833. If you have such an engine, please send photographic evidence! This section of the article is easily amended if necessary- it's very much a work in progress. A Present-Day Comparative Test A major omission from my original article which appeared on MEN in April 2008 was the presentation of any latter-day test results for the Cobra .049. The development of this updated article provided a perfect opportunity to rectify this omission.

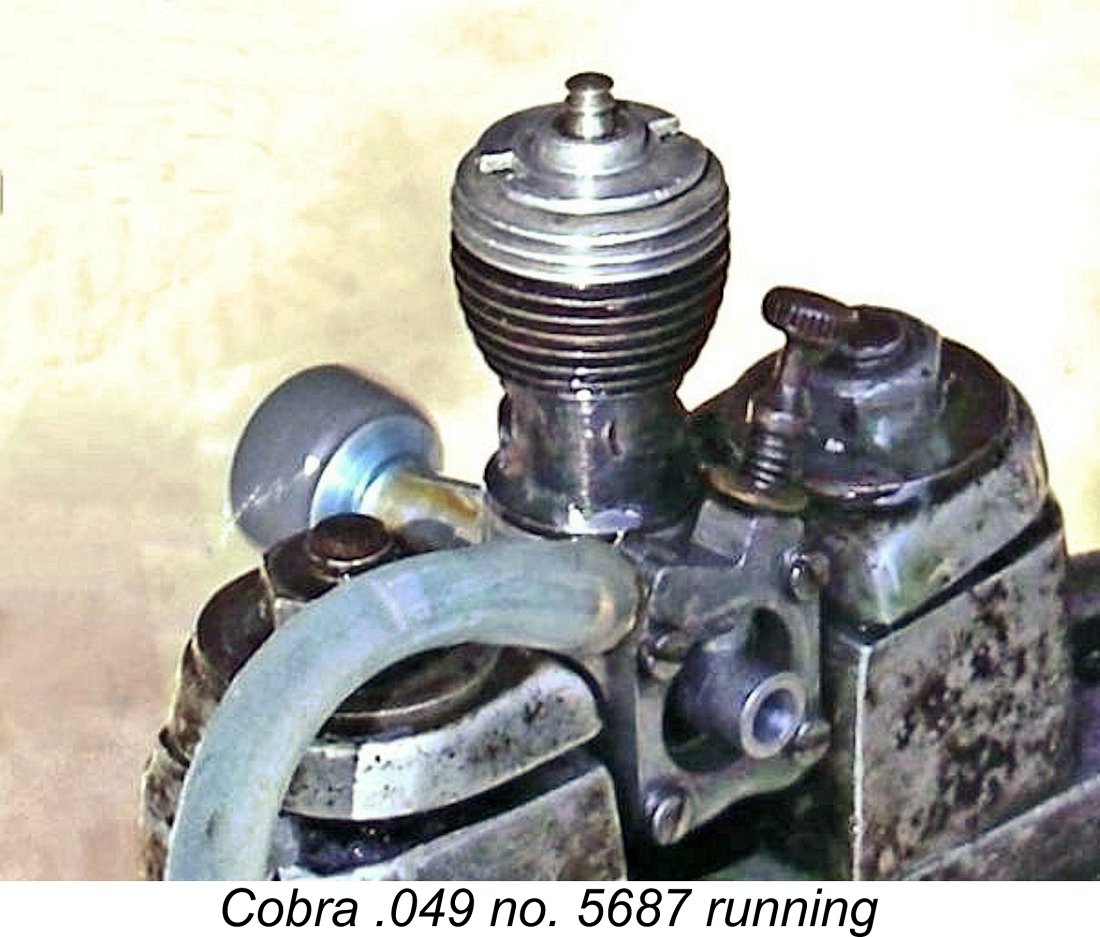

Looking back in the log book which I’ve kept up for many decades now, I found that I had last run engine number 5687 in March 2008 prior to finalizing the original version of this article. My notes confirmed that it started very easily and ran flawlessly on that occasion. Unfortunately, the only performance data which I recorded at that time was a speed of 14,300 rpm on a Top Flite 5¼ x4 nylon prop using 15% nitro fuel - a quite respectable performance by the standards of the engine's day. A present-day re-test with dependably calibrated test props would clearly prove interesting! I chose these two examples because an examination of both engines confirmed that their cylinders were both oriented to bring the single transfer flute to within 30 degrees of the ideal location on the left side of the crankcase (looking forward in the direction of flight). In fact, the cylinder orientation of both engines was almost identical, thus eliminating cylinder orientation as a potential basis for any performance differential. I decided to use a fuel containing 15% nitro and 25% castor oil to allow a fair comparison of my results with those reported by Warring and Chinn. My use of a castor-based fuel with plenty of oil was inspired by my awareness of the fact that motors like these having ball-and-socket conrod connections require at least 20% castor oil in the fuel. Joints of this type give rise to extremely elevated unit working pressures between the ball and socket along with relatively high temperatures given the socket's direct connection with the piston crown. Synthetic oils are far less effective than castor oil in resisting this combination. Indeed, back in the ball-and-socket days the warranties on Cox engines were specifically invalidated if the fuel used was not primarily castor-based. I elected to begin with a 6x3 Cox airscrew, which I didn’t think would bog the engine down too much. Given the limited range of ignition timing with glow-plug motors, it’s always wise to avoid overloading them, especially when dealing with a unit like this one which is expected to peak at relatively high speeds by the standards of its day. Based on the data generated by Warring and Chinn, I was expecting the Cobra to peak in the 14,000 - 15,000 rpm range. Once I had learned how fast the 6x3 prop turned, it would just be a matter of going down the load range to find the peak itself.

I'd never run this example before, but it offered no real surprises, performing very much along the lines reported by Warring and Chinn. It started readily enough on a modest port prime, its only vice in that respect being a rather chronic tendency to start backwards. This is a common reed valve issue which Peter Chinn reported experiencing with his test example of the Cobra. Flicking in reverse was quite effective in dealing with this difficulty - if you can't beat 'em, fool 'em!! The engine's other somewhat problematic characteristic was a far greater than usual sensitivity to the needle setting. The amount of needle adjustment necessary to go from fast four-stroking on the break through two-stroking to cutting out completely was very small. This made it quite challenging to find the precise sweet spot - go just a little either way and the engine either went back to four-stroking or cut dead! Setting the engine for a flight situation would have been quite problematic. A finer needle thread like that used by Cox would have really helped here. The only other operational issue was a slight delay in responding to changes in the needle setting. This is a normal reed valve characteristic which is caused by the fact that the induction timing in such engines varies with speed. When the speed changes as a result of a needle adjustment, the engine requires a few seconds to stabilize at the new timing. Still, all of these issues were perfectly manageable with care. Once set, the engine ran very nicely. The power output proved to be more or less what I had been expecting, as reflected in the following data.

As can be seen, this example of the Cobra .049 managed a peak output of around 0.052 BHP @ 13,500 rpm - pretty much the same output as measured by Warring but at a somewhat lower peaking speed. This level of performance was well up on that achieved by the FROG .049 and the D-C Bantam as tested by Peter Chinn. It was more or less on par with the A-M .049, putting it at the top of the British .049 glow motor heap as of 1960. Having taken engine number 1061 through its paces, I then put engine number 5687 into the stand. It handled pretty much exactly like its predecessor in all respects, including the tendency to start in reverse and the sensitivity to the needle setting. It also like a modest prime to start. However, once running it performed flawlessly, running extremely smoothly up to the highest speeds. It quickly became apparent that this example was going to out-perform its predecessor by some margin. It proved to be quite a bit faster on all props tested. The following data tell the story.

Now that's more like it! As can be seen, the later variant of the Cobra was up on its predecessor by some 400 - 600 rpm across the board. It appeared to develop around 0.060 BHP @ 14,200 rpm - a very respectable figure These results certainly bear out my previous speculation that the design amendments introduced soon after the engine's introduction were aimed at enhancing its top end performance somewhat. The various changes described earlier were clearly very effective in unlocking something closer to the engine's true potential. One is forced to wonder how the Cobra might have performed with a twin bypass cylinder ...... Both engines came through their tests with absolutely no signs of distress of any kind. Overall, I'd give the Cobra very high marks for quality, handling and performance. I would certainly not have been disappointed if I had managed to get one back in the day! The only design change that I would have favoured would have been the use of a finer thread on the needle valve. The End of the Line

During this same period, the competing D-C Bantam glow-plug model was still soldiering merrily on, selling in tens of thousands despite its well-established and fully justified reputation for total gutlessness. The second variant of the Cobra was unquestionably a far better performer than the Bantam, also being only a few shillings more expensive. So why would a quality product like the Cobra which was competitively priced, attractively presented and ahead of the competition in performance terms vanish so relatively swiftly from the market, leaving so few survivors in a relative sense? There appear to be three possibilities:

If this latter scenario is correct, the spotty distribution, the half-hearted advertising effort, the early departure from the marketplace and the relative scarcity of surviving examples would all be explained. Rodwell would have become painfully aware of the unsustainable profit situation quite early on in the game, consequently terminating production immediately after fulfilling the minimum production requirement under the terms of his agreement with KeilKraft. Having done so, why would he continue to advertise the engine on his own account? Such a step would have left KeilKraft with the challenge of selling off those engines that had been produced, which they did over the next few years. The previously-noted lack of the required fervor by KeilKraft in promoting and distributing the engines would also be explained under this scenario - why push a product that you already knew to have no future? Furthermore, the fact that spare parts would no longer have been available would lead to any worn or broken engines simply being discarded, hence being lost to posterity. This would have a very negative effect upon survival rates. Personally, I think that the last of the above three scenarios is by far the most likely - it completely explains all of the surrounding circumstances. I believe that what probably killed the Cobra in the end was the painful fact that it was simply impossible for a small British manufacturer to make economic sense out of producing an engine to Cox standards while being forced to compete with the low unit cost figures with which Cox was able to work with their multiple rows of automated machines. In an interview with Leroy Cox which was published years later in the “Engine Collector's Journal” (ECJ), Cox noted that he costed the engines simply on the number of manufacturing operations required to produce them, using a figure of I cent per operation!! Based on that standard, the Babe Bee was being produced at a manufacturer's cost of about thirty cents each (approximately 2s 6d or £0.13 at the time)! How could any small British engineering firm compete with that and make any money? And then there was the Bantam .............. Whichever way it went, the Cobra was undeniably a brave and at least technically successful attempt to meet the American manufacturers head-on and compete with them on the basis of their own standards. There seems to be equally little doubt that on merit alone the disappearance of the Cobra from the scene was both undeserved and premature. The Cobra Seen in Context

In retrospect, it appears to me that three of the four British ½A glow-plug motor manufacturers made a fundamental error in 1959 when they decided to jump on the .049 glow bandwagon after sales of such engines began to take off in Britain. Instead of developing their own designs, they went the cheap 'n easy route of either taking an existing diesel design of their own and modifying it for glow operation or (in the case of Allen-Mercury) simply buying the right to market a straight copy of an existing American design. None of these firms put any real effort into developing their own purpose-built glow-plug model. In his published test of the Cobra, Peter Chinn commented insightfully upon this very point. After expressing his view that none of the British ½A glow-plug units were as good as they could have been, he made the following statement: “It is probably true to say that our (British) manufacturers embarked on the production of glow Half-A’s with no great confidence in the glow .049’s ability to wrest the lead from the well-established small diesels as the favoured type of power-plant for beginners and small non-contest type models and, in consequence, one suspects there was a reluctance to invest too much time and money in their development and tooling. This attitude is understandable and appears to be confirmed by the fact that two manufacturers (FROG and D-C Ltd.) actually used parts of their existing diesel designs as a basis for their .049 glowpluggers”. In other words, the British ½A glow motor manufacturers other than Rodwell believed themselves to be taking a bit of a flier in entering that market, hence being keen to hedge their bets by minimizing their financial exposure in case things didn’t work out. The least confident British manufacturers were undoubtedly E.D., who appear to have bet that the ½A glow-plug motor would not catch on, showing their opinion by staying with the diesel principle in developing their OK Cub-influenced 0.81 cc E.D. Pep with which to challenge the competition. Sadly, the Pep suffered greatly from a mismanaged development program, never making much of a mark. I’ve recounted the rather sad story of the Pep in detail elsewhere. While embracing the glow-plug principle wholeheartedly, the manufacturers of the Cobra were alone in accepting the desirability of designing their all-new offering from the ground up as a glow-plug model and the consequent need to create the required dies and tooling from scratch. That's why the Cobra stands out for me from among the 1959-60 British .049 glow-plug crop. In my opinion, Rodwell took a very commendable and logical approach towards the development of that engine - he resisted the temptation to re-invent the wheel, instead taking the most demonstrably successful American .049 glow-plug motor of the day as his starting point (no diesel heritage to overcome) but reconfiguring his design to appeal to the British market (beam mounting, no integral fuel tank, etc.) while introducing a few functional design changes of his own (improved induction system, etc.). This was a very well-focused approach which contrasts sharply with that taken by Allen-Mercury, who simply copied. And it's also far more rational than the approach taken by both D-C and FROG, who produced simple glow-plug conversions of existing diesels. Experience had already shown that the successful conversion from diesel to glow was seldom that straightforward or effective. Not only that, but Rodwell appears to have adopted American production techniques as well, thereby achieving a highly comparable level of overall quality. He really deserved better success than he seems to have achieved.

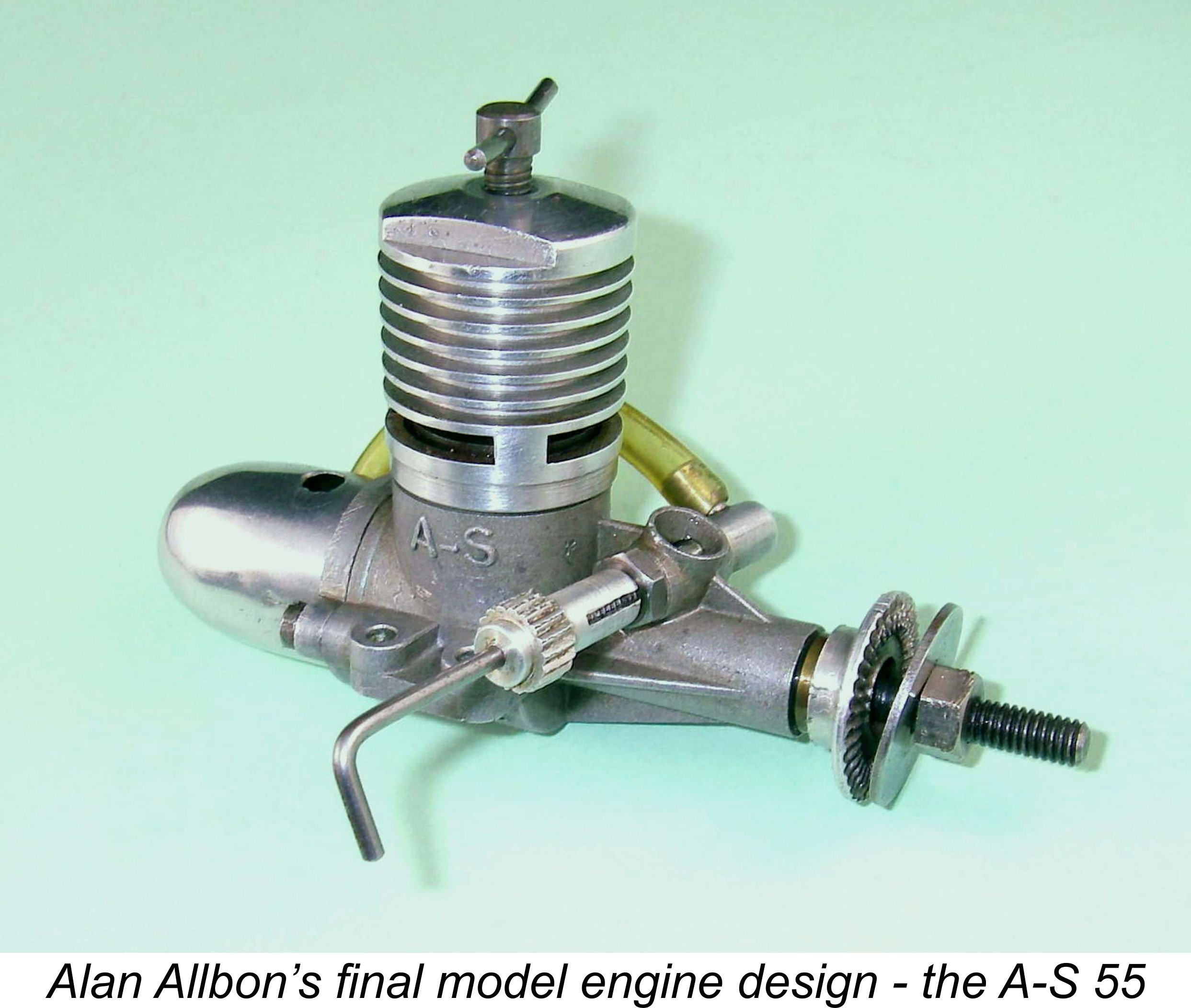

The Bantam was released with great fanfare in late October 1959, receiving a glowing accolade from Ron Warring in his January 1960 test. The performance figures that he reported compared very favourably with those of competing domestic and imported ½A designs apart from the all-out competition models from the likes of Cox and Holland. Unfortunately, examples as good as the one that Warring tested turned out to be scarcer than antelopes in Antarctica! As I’ve shown elsewhere, Warring’s test example of the Bantam was almost certainly a prototype model having a significantly higher performance than the production version. Peter Chinn’s March 1960 test of the Bantam was undoubtedly far more representative of the production model’s true potential, showing greatly reduced levels of performance compared to Warring's figures. My own tests reported elsewhere have confirmed Chinn's findings completely. Unfortunately, Warring’s very positive January 1960 test report was never openly challenged or corrected in the modelling media of the day, hence triggering a form of gold-rush mentality and luring many people into rushing out to buy a Bantam, undoubtedly to the detriment of sales of the superior but more expensive competing models. Most of those Bantams that found their way into the field quickly proved themselves to be gutless wonders, albeit very light, compact and quite well made. The sense of let-down was widespread at the time, causing the Bantam to become looked upon by the cognescenti as a bit of a scam in which both D-C Ltd. and (sad to say) Ron Warring were complicit. The engine probably did more to turn the tide of prejudice against the British .049 glows among serious modellers than any other product. The release of a radial mount “Deluxe” version of the Bantam in 1962 did little to change this perception since its performance was essentially identical, as Chinn’s April 1963 test of that model confirmed. As a very active 12 year old modeller living in Britain at the time, I actually recall most of the keener fliers giving up on their Bantams in disgust when they found out how gutless they really were. I always suspected that Warring must have got a non-standard example of the engine from the factory - certainly, my faithful old Allbon Merlin diesel would bury an over-the-counter Bantam any day! I did pick up a slightly used Bantam myself for a few bob from a disgruntled owner, and it was (and still is!) just as gutless as its reputation suggested - my present-day Cobras certainly out-perform it by a very wide margin. The only way to get a Bantam to go is to pour in the nitro and hope for the best! Either that, or modify it extensively (but only if you really know what you’re doing) - performance can be substantially improved by going that route, as I’ve shown elsewhere. As Peter Chinn said, the Bantam could have been a lot better than it was. The real lasting harm inflicted upon the British engine manufacturing industry by the Bantam debacle was the massive change in the marketplace perception of the criteria governing a decision whether or not to purchase a given engine. Prior to the appearance of the Bantam, most modellers had accepted the principle that you got what you paid for and that performance and quality played a major role in determining an engine's value (a very different criterion from price). After the Bantam appeared This created a marketplace for model engines that was driven by price as opposed to value - the two things are very different. To take one very sad example, the superb little A-S 55 diesel was worth way more than the Bantam, being priced accordingly. However, far too few potential buyers so much as gave it a look - all they saw was the price tag. The A-S 55 quickly succumbed, much to the loss of the British modelling scene since it took the very talented model engine designer Alan Allbon with it. The Cobra .049 appears to have been another regrettable casualty. After the Bantam debacle, most of the more serious ½A modellers either went back to the Cox's that they knew performed dependably and well or re-activated their trusty diesels. However, for all its dismal lack of performance the Bantam was undeniably an inexpensive, well-made, light, easy-handling and very docile engine well suited to low-key sport flying and beginner familiarization. These qualities helped it to continue to sell well as a sport/beginner engine. It survived in production until 1971, when it was replaced by the far superior D-C Wasp and its radial mount companion which was marketed for a few years as the FROG .049 Venom.

In hindsight, if they had done so instead of adapting a smaller diesel to .049 glow operation, there's little doubt that D-C Ltd. would have had a far more positive impact on the domestic market, doing much to overcome the prejudice against British .049's that the Bantam helped to engender. In short, the Wasp was the D-C .049 model that could and therefore should have been released in 1959 instead of the Bantam. I’ve recounted the Bantam story in greater detail elsewhere. Although it did outperform the Bantam (what didn't?), the 1959 FROG .049 was an almost equally under- This further underscores my earlier point - why develop a glow-plug model of an existing diesel which clearly failed to perform up to the same standard as its diesel counterpart? Surely it would have been far better to develop an all-new purpose-built glow model, or use a successful glow-plug prototype rather than a diesel? The A-M .049 was head and shoulders above both the Bantam and the FROG in performance terms, but was so obviously a straight copy of the Wen-Mac .049 from America that any Reviewing the above litany, it becomes clear in hindsight that, far from being merely the "Cox clone" of its rather dismissive legend, the Cobra was in fact the most progressive and original production of the four British .049 glows which appeared in 1959-60. If the D-C Wasp had been released in 1959 as it certainly could have been, it would have been an equally worthy contender and the ultimate fate of the British .049 glows in general and the Cobra in particular might have been very different. The RTF Dalliance

However, as of February 1962 KeilKraft were back to advertising their balsa model kits. RTFs received no further mention for a full year until the regular Keilkraft back page of the January 1963 issue of Aeromodeller was devoted to the imported Wen-Mac RTF range. No mention of the Cobra powered Hurricane ever appeared again.

However, the dies for a plastic RTF model represented a major investment which KeilKraft were quite understandably reluctant to simply discard. Consequently, the Hurricane resurfaced almost two years later in a corner of KeilKraft’s “Aeromodeller” back page advertisement for December 1964, where it was surrounded by Wen-Mac RTF imports. The model now sported an upright mounted Wen-Mac .049 with its patented (and problematic) Rotomatic starter. In this form, the Hurricane carried on for over ten years. The page shown here at the right is taken from the Keilkraft Handbook of 1969. These Handbooks appeared more or less annually between 1946 and 1980. Not surprisingly, they are viewed as highly collectable references today. To close the book on the Hurricane, those hard-working dies soldiered on well into the 1970's, with one more "engine change", this time to a McCoy .049. Truth be told, the only real difference between this powerplant and its Wen-Mac predecessor was the manufacturer’s name and the engraving in the crankcase die, but that's another story. For the record, the McCoy-powered version first appeared on the February 1971 back cover, while the chrome plated "Silver Hurricane" (which added a few pence short of £2 to the price) made its debut on the December 1974 back cover. Ron Chernich’s Black Mamba

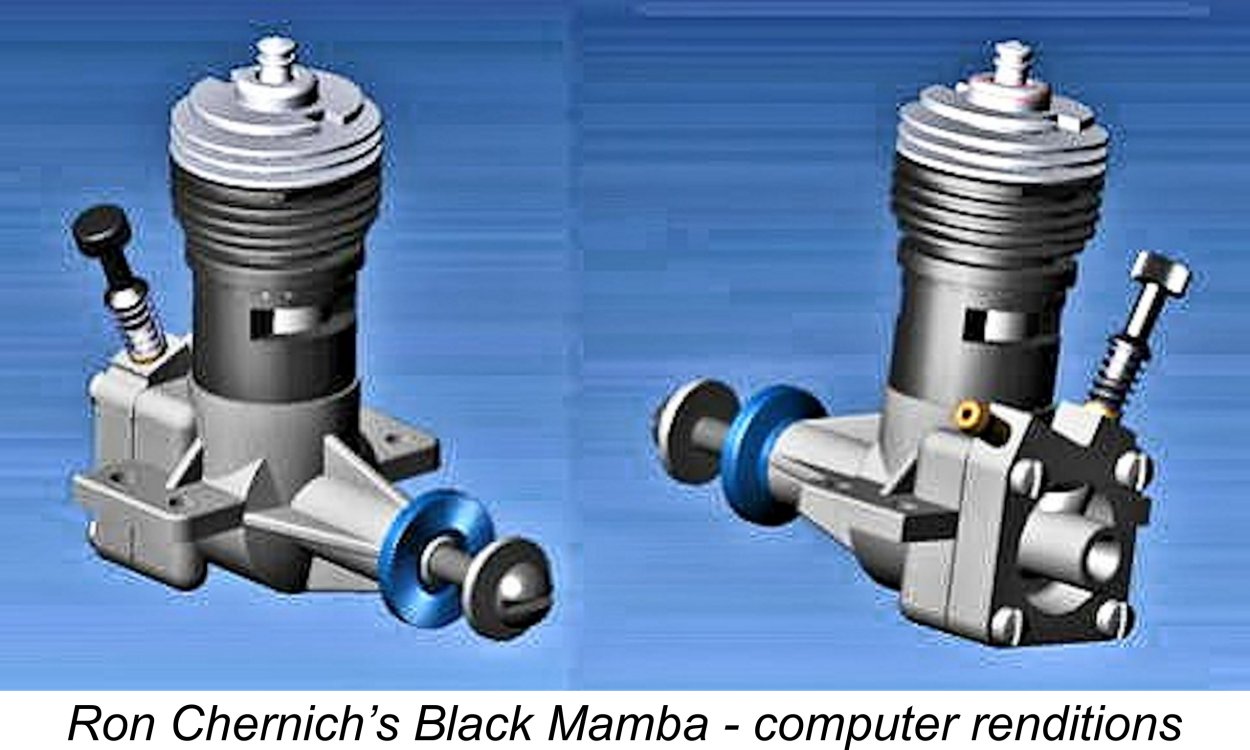

Ron was a great one for turning thought into reality, leading him to develop a design which would use a set of sand-castings in combination with some original Cox components to produce a Cobra look-alike. He called this rendition of the engine the Black Mamba. Ron took the time and trouble to produce a fine set of detailed CAD plans for this engine, together with several 3D graphic representations as reproduced here. These plans found their way into the Motor Boys International Members Only Plan Book. That publication complete with the Black Mamba plans is available elsewhere on this website. I have since heard several rumours to the effect that someone produced a few castings based upon Ron’s design. However, I’ve been unable to confirm this one way or the other. I am also presently unaware of any examples of the Black Mamba which may have been produced on the basis of Ron’s plans. If any reader can set me straight on this matter, I’d be extremely grateful. Regardless, Ron’s effort is without doubt part of the Cobra’s legacy! A Cobra Look-Alike