|

|

The Atwood Crown Champion Series

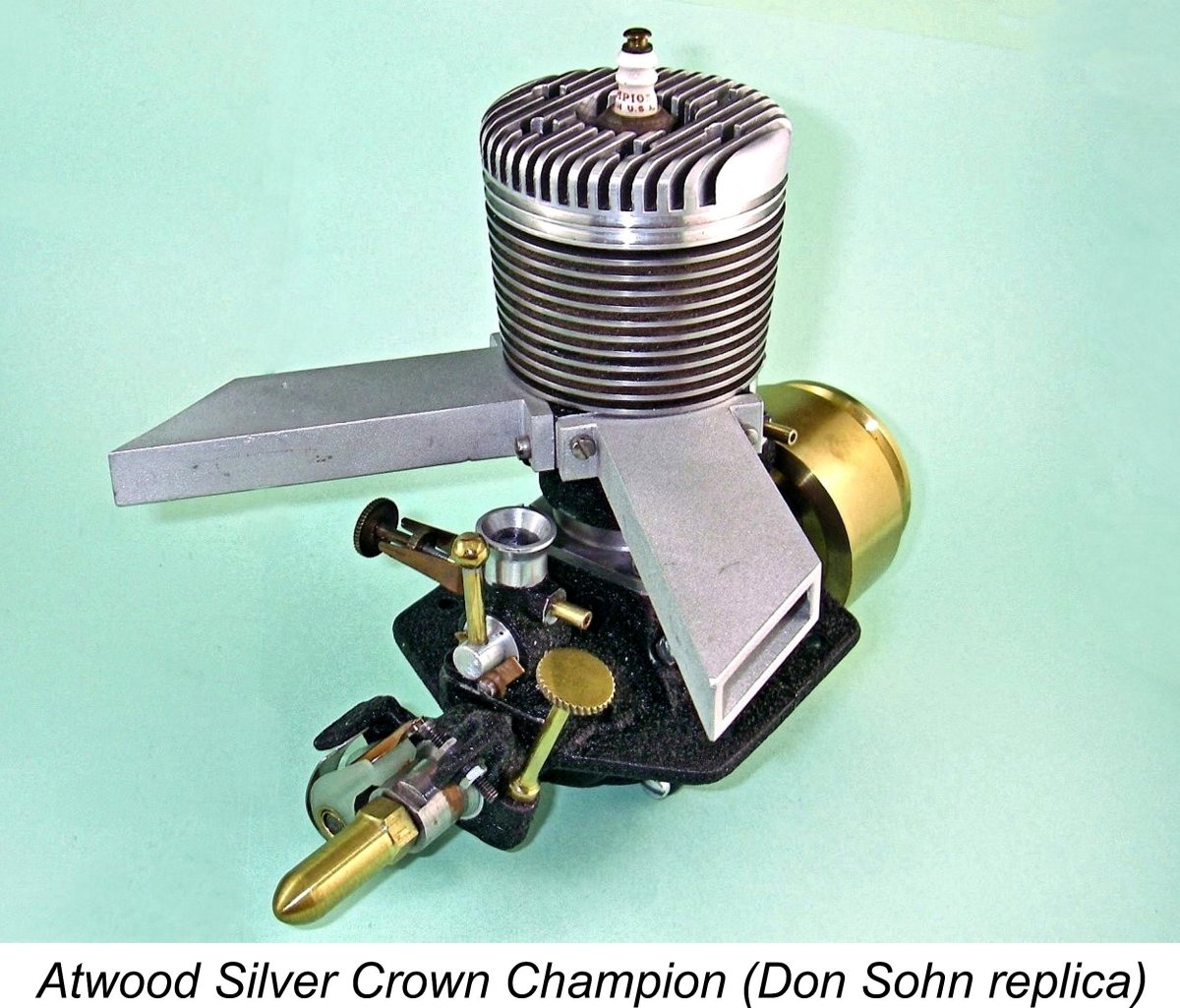

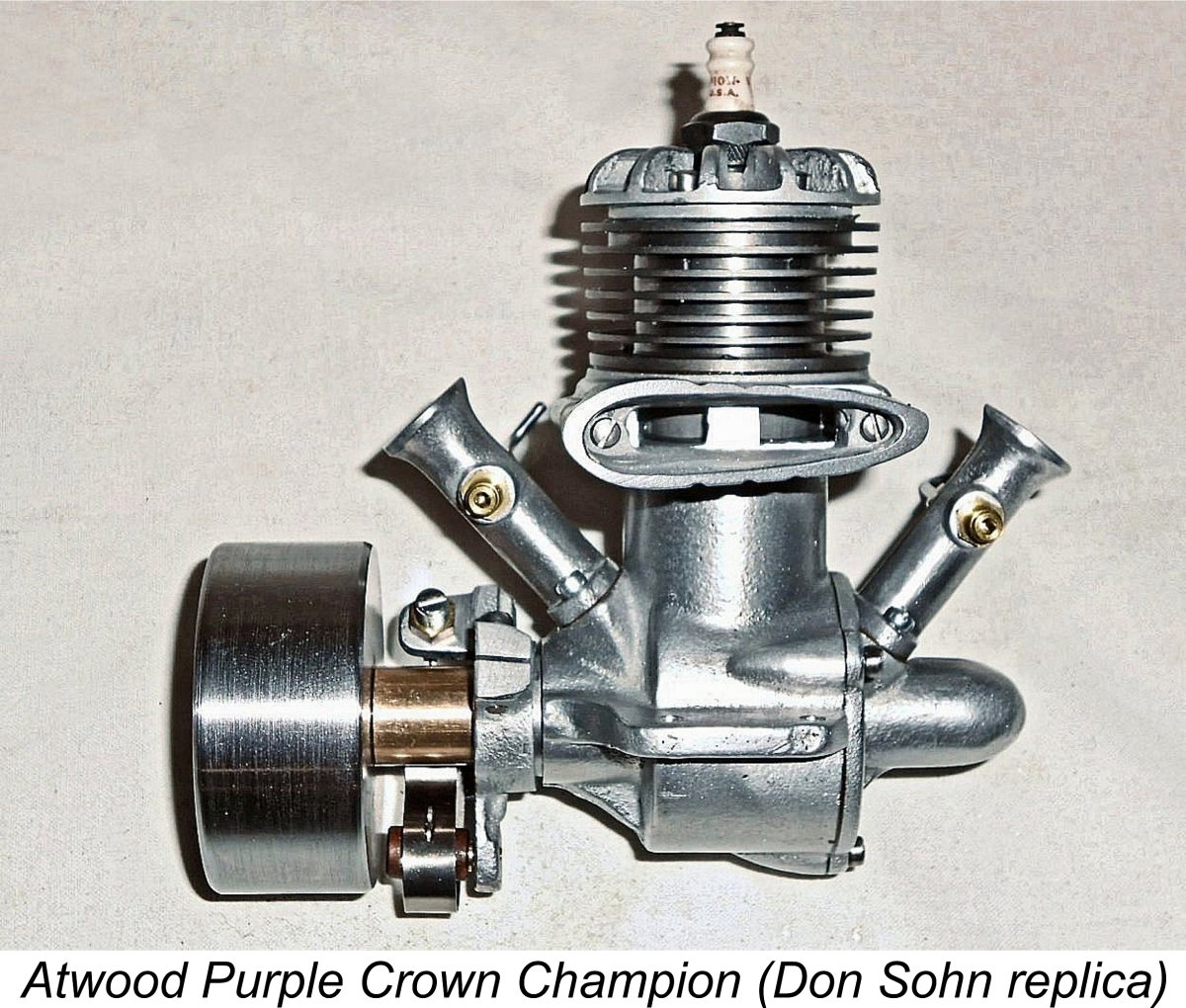

In this article I’ll focus upon the first dozen years of Bill’s remarkable career by examining the circumstances which led up to the creation of one of his more ephemeral and hence legendary design achievements – the Crown Champion series. I'll also take advantage of the opportunity to record something of the career of this towering figure among pioneering model engine designers. The Crown Champion series appeared (or were at least advertised) in five highly distinct variants - the Silver Crown, Blue Crown, Red Crown, Green Crown and Purple Crown Champion models. First appearing by those names in March 1940, these technically-innovative engines enjoyed only a very short manufacturing life of well under a year before Bill’s ever-active mind developed new designs which replaced them. Shortly thereafter, America’s entry into World War 2 in December 1941 put a temporary stop to all model engine production in the USA. As a result, the Crown Champions were made in unusually small numbers – indeed, there are no known surviving original examples of one member of the series, as we shall see. Despite their color-coded names, none of these models actually had colored cylinder heads – they all sported heads having natural finishes with no coloration. The cited colors were simply convenient “labels” to distinguish one variant from another for promotional purposes. The odd example shows up today with a head which has been painted in the appropriate colour – this is not original, having been applied for presumably cosmetic reasons by an over-enthusiastic owner.

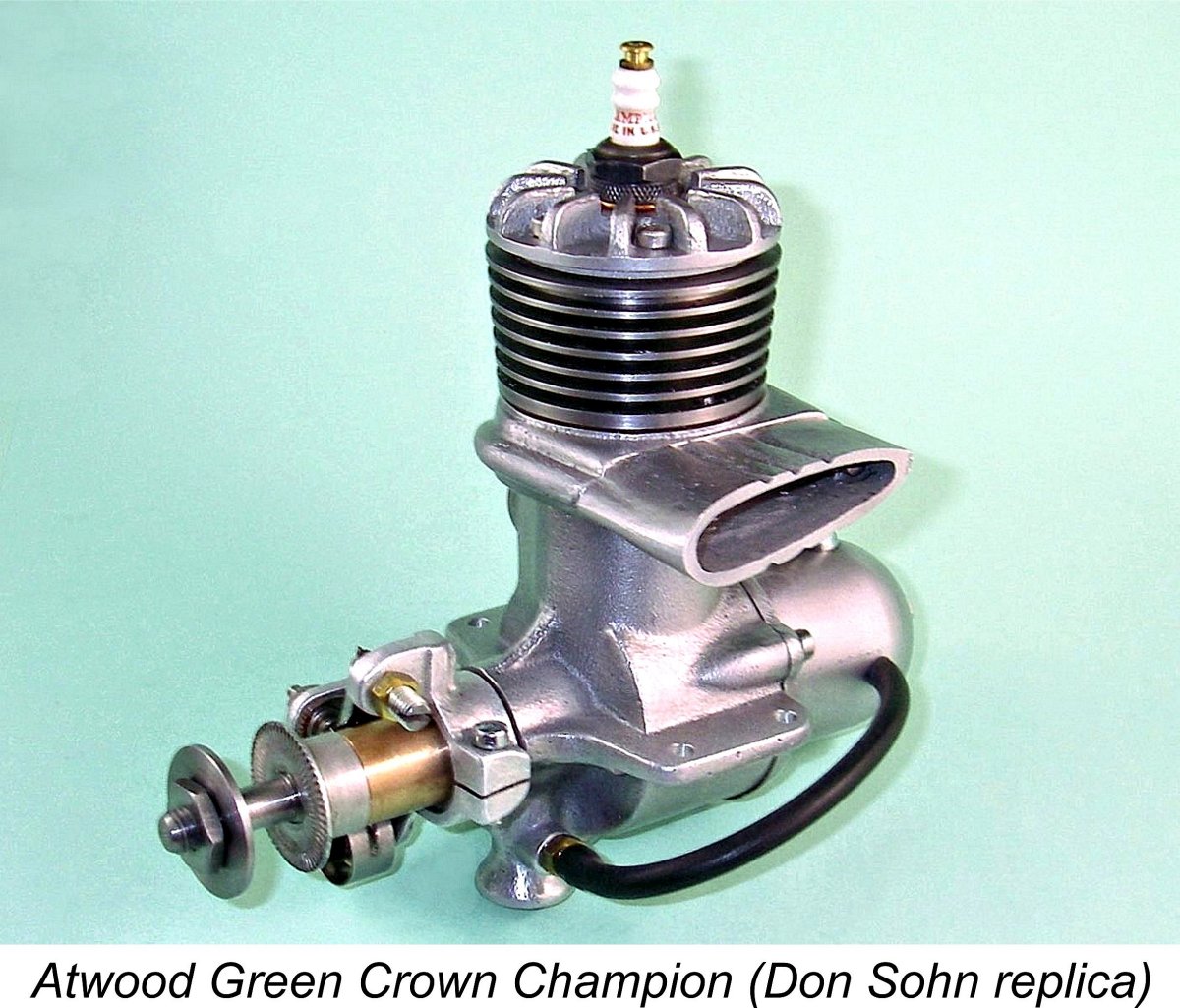

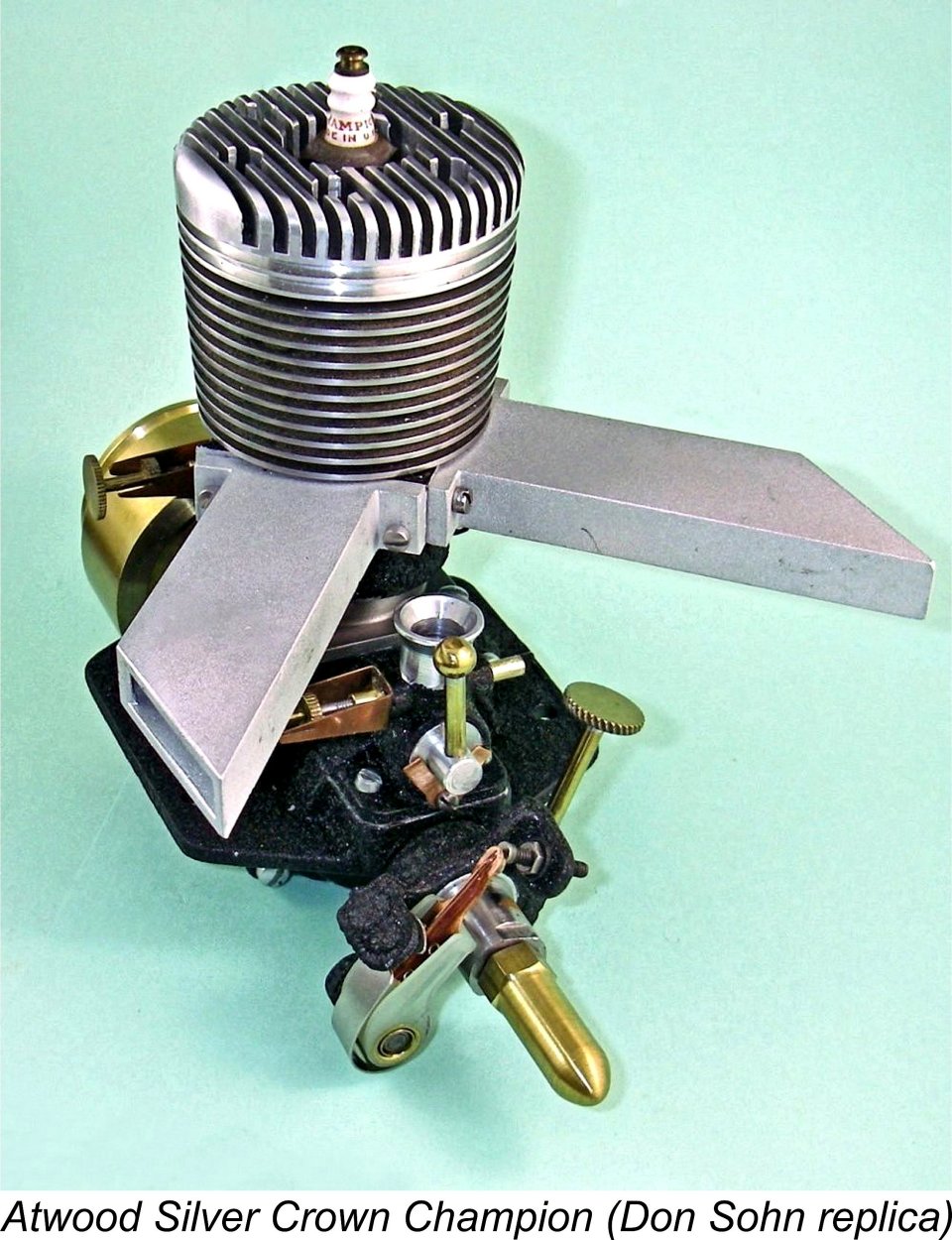

Don is a highly skilled model engineer who is one of America’s most respected constructors of classic model engine and tether car reproductions. His outstanding creations have appeared in a number of my earlier articles on this website, including my history of the life and work of Ira Hassad (which includes a brief biography of Don himself) as well as my focused article covering Hassad’s legendary barstock special. Don is also a very sincere Atwood enthusiast who has taken immense pains to produce extremely faithful replicas of all five Crown Champion variants. With his cooperation, I was able to obtain my own accurate replicas of the Green Crown and Silver Crown models. In addition, I was provided with photographs of Don’s fine replicas of other members of the series, along with literature in Don's possession relating to these very rare model powerplants. A number of illustrations of Don’s outstanding work grace the following account. Without Don's help, this article could not have been written. I also wish to acknowledge the invaluable information extracted from the relevant issues of Tim Dannel's indespensable "Engine Collector's Journal" (ECJ). Issue no. 143 of that fine publication carried an article by Charlie Bruce regarding the Champion engines, while issue no. 144 included some further commentary by Tim himself on the Silver Crown model. I freely acknowledge having drawn upon those sources during the preparation of this article, with my sincere thanks to the authors. Now, before embarking upon a description of the various Atwood Crown Champion models, I think that it’s well worthwhile setting the scene by going back to the beginning to trace Bill Atwood’s career up to the point in March 1940 at which the Crown Champion series began to appear under that name. In doing so, I’ll draw heavily upon the published biographies of Bill Atwood by Charles A. Mackey and Dr. T.C. O’Meara as well as the very informative Atwood timeline table prepared by Art Swift. All three of these documents may be found on the AMA History Project website through this link. Bill Atwood – Early Career William E. Atwood was born on July 22, 1910, in Riverside, California, some 60 miles east of Los Angeles, where he grew up. From his early years, he presented a somewhat mild-mannered and seemingly shy exterior to the world. However, hidden beneath that façade was an intensely focused drive to succeed at everything to which he turned his hand. Fellow competitors would remember that at competitions Bill spent little time in casual conversation - he wasn't unfriendly, but victory was his goal and careful attention to model performance was therefore his first priority. People would overhear him mutter what for him was an eternal question, “Now, why did it do that?”. This insatiable desire to understand how and why things worked (or didn’t work!) as they did was a major factor in Bill’s long-term success in so many fields.

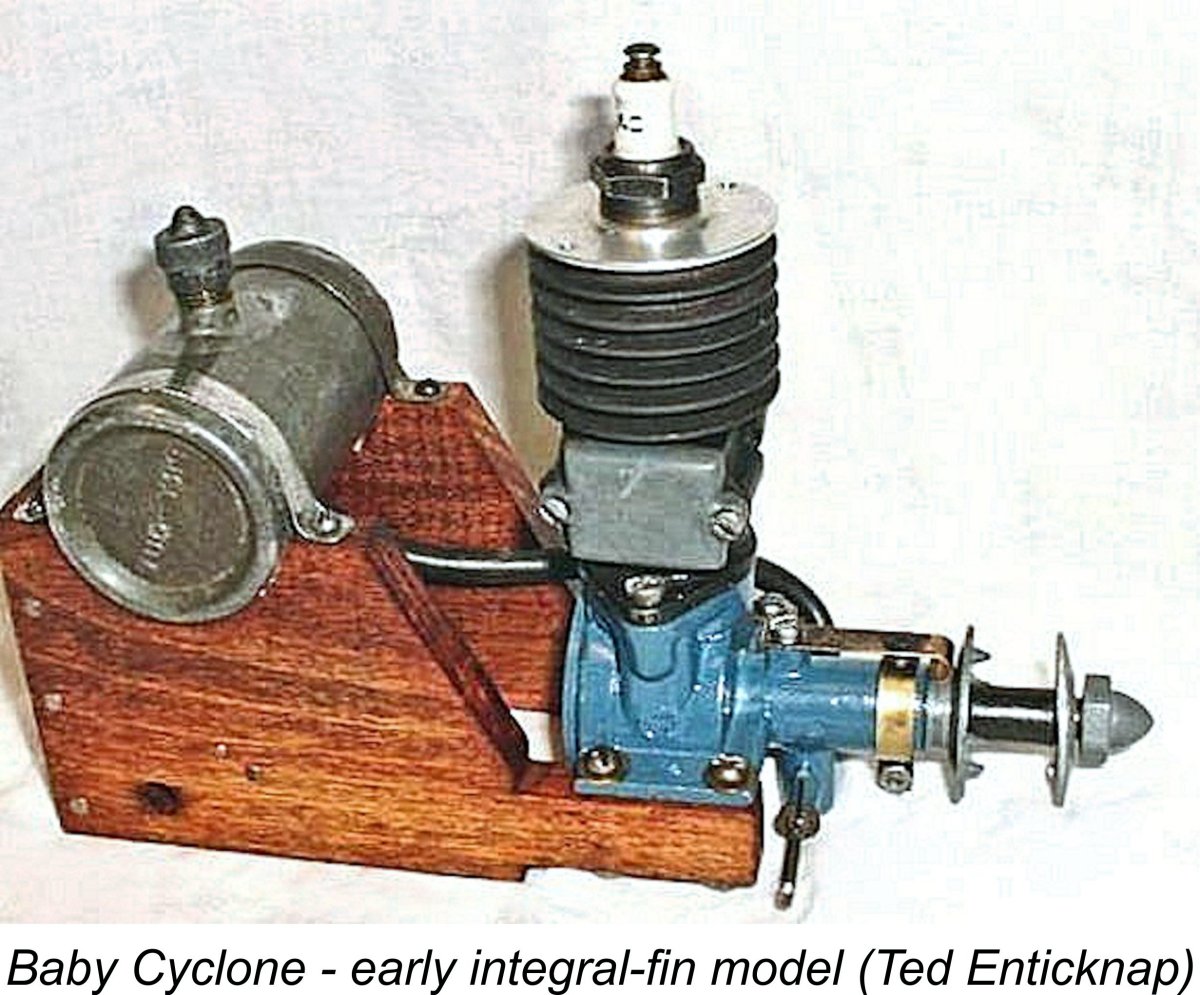

From this starting point Bill further developed his flying skills, to the point that by 1930 he had qualified for some powered flight instruction in Curtiss Jennies. He also maintained his interest in gliding, taking only 16 months to design and construct his own full-sized contest-winning sailplane having a wingspan of 60 feet. While resident in Santa Monica in the early 1930's (see below), he flew this aircraft successfully in sailplane competitions at nearby Pacific Palisades, which remains a noted hang gliding site to this day. During the same period, Bill also became very interested in model aircraft, competing in his first US National Championship event in 1927 at Memphis, Tennessee at the age of 17. His aeromodelling activities soon extended to indoor flying as well, an interest which he was to maintain for many years. He also became attracted to the sport of I/C powered tethered model hydroplane racing, which was gaining ground in the Riverside area at the time. This branch of the power modelling hobby had originated in England in 1908, as recounted in a very interesting article to be found on the highly informative “On The Wire” (OTW) website which is devoted to tethered car and hydroplane racing. A machinist friend of Bill’s named Bert Cundiff was buying castings from England and using them to construct examples of the model boat engines designed by Edgar T. Westbury. In 1928, after studying Westbury's articles and Bert's engines, Bill characteristically decided that he could do better, forthwith designing his own first engine, which he built in 1928 while still enrolled in high school. One wonders how many of today's 17-year olds could match this accomplishment ........... The castings for this 30 cc two-stroke water-cooled boat engine were produced by Bill Atwood in his own backyard. Bill machined the components in his friend Bert’s machine shop. The two-piece crankcase contained a crankshaft-driven rotary intake valve and supported a cast-iron cylinder with a screwed-on bypass passage. The aluminum piston had a single ring and the combustion chamber in the head was contoured for improved gas flow. For the next four years, Bill used this and other engines that he subsequently made to compete with other local boat modellers, including Maynard Clark and Mel Anderson. One of Bill's large boat engines was acquired by none other than his friend Irwin Ohlsson, who converted it for aero use and installed it in an eight-foot wingspan cabin model. They built 'em big way back then! Upon leaving school in 1928, Bill went to work as a junior aeronautical engineer for the Douglas Aircraft Company at Santa Monica, California. However, his involvement with full-sized aircraft by no means diminished his interest in models. In 1932 he built a nine-foot span (!!) model of spruce covered with butcher paper. To power this behemoth, Bill designed and built a 30 cc aluminum-case two-stroke engine with cooling fins cast onto the iron cylinder. Using this combination, and consuming a quart of fuel in the process, he managed a 26-minute timed flight, thus actually anticipating Maxwell Basset’s much-publicized “first official flight” with a gasoline-powered model aircraft on September 10th, 1932 at the U.S. National Championship meeting held at Atlantic City, New Jersey. An unpublicized feature of Bill’s flight (especially back home in Riverside) which has passed into legend was the fact that It was obvious that models of this massive size were impracticable for the majority of would-be fliers. Clearly, smaller models and smaller engines to power them were both needed. Accordingly, in 1933 Atwood designed a new and far more compact model airplane engine of .364 cuin. (5.96 cc) displacement. This was destined to develop into the famous Baby Cyclone. It featured an iron cylinder, initially using integral fins as illustrated at the right, but later employing a shrunk-on finned aluminum sleeve for cooling, as illustrated below. Induction was through a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV), a feature for which the fair-minded Bill Atwood openly gave his friend and soon-to-be colleague Mel Anderson a full half share of the credit. This engine proved to be quite successful, leading Bill and his other noted engine-building buddy Irwin Ohlsson to show up at the 1934 US Nationals at Akron, Ohio with models powered by further-developed examples of this engine. Unfortunately, the weather at this meeting was extremely hot, and the two mixed their fuel using oil of too light a grade. As a result, the engines failed to perform well at this meeting.

In addition to his managerial duties for Curtiss-Wright, Moseley ran a sideline business of his own called Aircraft Industries Corporation which was located at Grand Central Terminal. The main business of Mosely’s company was the provision of full-scale aircraft maintenance and repair services. However, Moseley was interested in model aviation and saw the potential of Bill Atwood’s very successful model engine. Accordingly, in 1934 he entered into negotiations with Atwood to purchase the design. As part of the deal, Atwood left his job at the Douglas Aircraft Company to go to work for Moseley at Glendale. Among his colleagues at his new company were Ira Hassad and Mel Anderson, both to become noted model engine designers in their own right. Mel Anderson was actually brought into Moseley’s operation on Atwood’s advice. Quite an assembly of engine design talent under one roof!

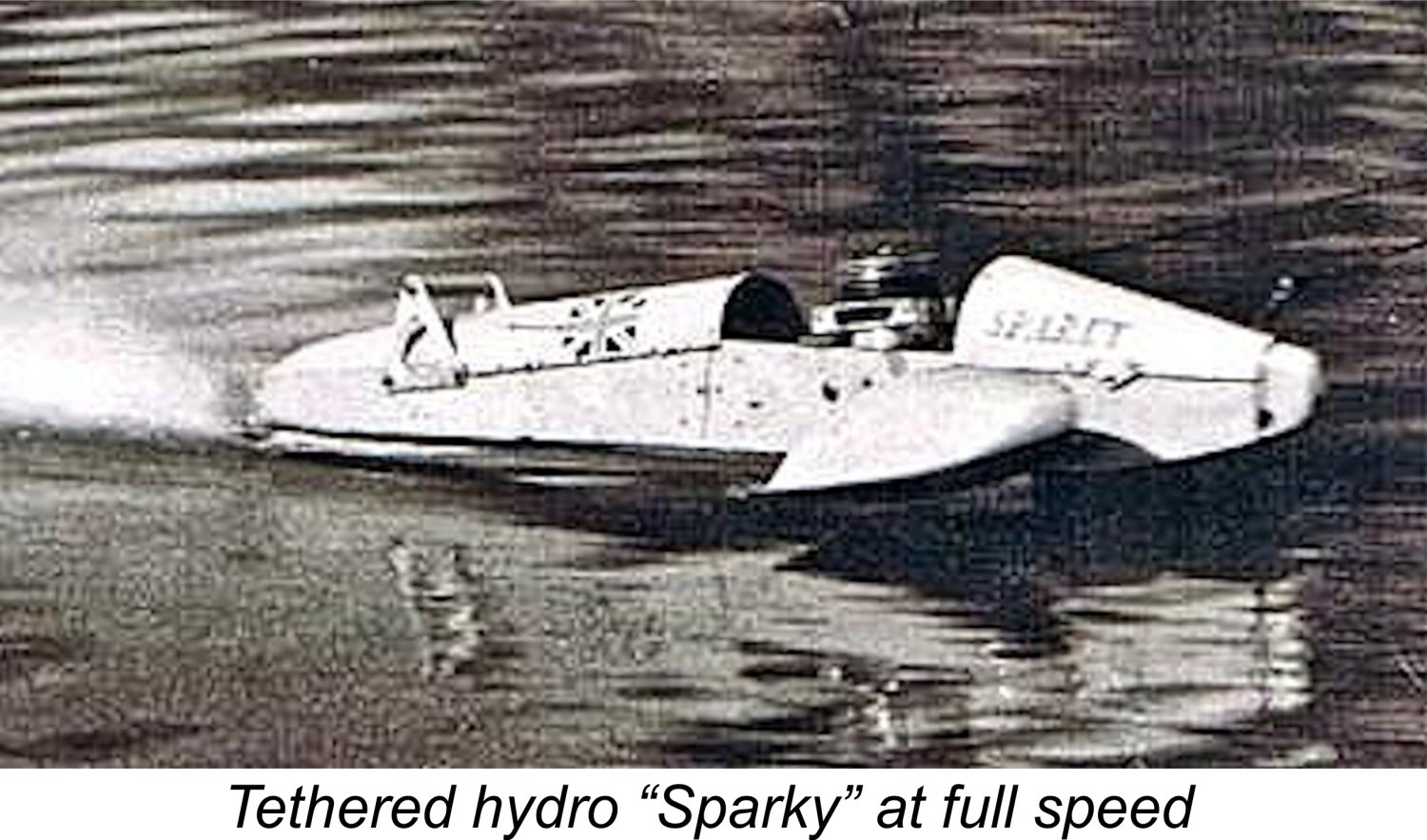

The engine was an immediate success in commercial terms, with almost 20,000 examples being produced during the next four years. Bill Atwood's winning gas models, the California Chief and California Champ, were also kitted by Aircraft Industries. The final and most prolific version of the Baby Cyclone, the Model F, was tested by Model Airplane News in 1938, with the results appearing in the July 1938 issue of the magazine. An output of some 0.22 BHP @ 6,800 RPM was reported - both quite acceptable figures by the standards of 1938. During the period in which he was involved with the production of the Baby Cyclone, Bill rekindled his interest in tethered hydroplane racing. It is at this point that the story of the Atwood Crown Champion series really begins. Seeking a worthwhile goal, Bill developed an ambition to establish a 15 cc World Speed Record for model boats. He planned to attack both one mile and ¼ mile records. This ambition gets us into an extremely clouded area which has been poorly researched by previous biographers of Bill Atwood. In reality, there was no such thing as a universally-recognized “world record” for model boats at the time. There was only an absolute record regardless of class along with a set of Class records for a given jurisdiction. Since each country had its own classes and operating rules along with its own system of record-keeping, only the absolute record really had any international significance, and even that was of highly questionable validity given the lack of standardization of classes and operating criteria as well as the low level of international communication between jurisdictions. No attempt was made at this time to standardize those criteria between jurisdictions or confirm the world record status of any particular measured performance by comparison with marks established under the same criteria in other countries - indeed, no such direct comparison was legitimately possible. Accordingly, although "World Records" were undeniably claimed in many jurisdictions throughout the world, the reality was that such claims were actually National or Regional records set under the criteria in place in the particular jurisdiction within which the speed was established - there were no universally-recognized World Records as such. Indeed, at the time there was no international authority to which application could be made for recognition of a given measured performance as a World Record, a function fulfilled today by NAVIGA.

However, as of 1938 Suzor did not hold any 31 mph "world record" that we can find which matched the criteria set by Bill for his attempt. Indeed, Suzor undoubtedly had hydros which would comfortably beat 31 mph by that date. The lack of a recognizable match is hardly surprising given the previously-noted fact that events in France (and Britain) were run to very different criteria from those in America. The French timed their runs over metric distances of well under a mile, while many American speed claims were based on the best time for a single lap rather than the average over a distance. The distances over which Bill challenged himself were somewhat unusual even in an American context. In addition, Hugh advised that the European and British hydroplane classes were delineated at the time in part by boat weight rather than by engine displacement alone. Even assuming that it really existed, the criteria applicable to the “31 mph” record performance at which Bill was aiming thus cannot be clarified on the basis of present information. All we can say is that the absolute 1938 "world record" (which didn't really exist, all claims to the contrary) was certainly higher than 31 mph! As of 1939, British competitor Ken Williams held what was recognised in Britain at least as the outright World Record at 47.5 mph, using his Class A (30 cc four-stroke) hydro "Faro". The recognized Class B record (15 cc) was held by J. P. Orme's "Skua" at 40.78 mph. This information was extracted from an excellent historical summary of the development of tethered hydroplane racing to be found at OTW. Well worth a read! That said, what is apparent is that Bill’s actual performance claims (which I for one do not doubt given the extent to which they were publicized in America without challenge) were achieved for distances over which no-one else was establishing timed speeds. In effect, any performance which Bill put up would constitute a new “world record” because Bill was setting his own criteria which no-one else was applying at the time. In particular, no-one outside America was running tethered hydros over a one-mile course. Setting all of this aside, Bill proceeded to use the facilities of his own home workshop to develop and construct a completely new model engine design on his own time. At the time in question, four-stroke engines generally ruled the tethered hydroplane racing roost along with their flash steam competition (which had held all the records until 1936). However, Bill elected to follow the lead of the aforementioned Gems Suzor by continuing to pursue the two-stroke approach, just as he had been doing since 1928 as mentioned earlier. The result was a very advanced air-cooled single cylinder twin-carburettor two-stroke unit having a nominal displacement of 15 cc. It incorporated fore-and-aft power take-off shafts, each of which had its own shaft valve induction system. This was the engine which was later to become known to the American model boat racing world as the Atwood Silver Crown Champion. Much more detail to follow below .........

While the claimed “world record” status of these performances is certainly open to question for the reasons discussed earlier, there’s no doubt at all that they represented very impressive accomplishments. Indeed, since no-one else that we can find had put up a 15 cc record claim for the mile distance, there's little doubt that that speed at least was a world record of sorts. A factor which enhances the impressiveness of that particular claim is the fact that the hydro would have to average the timed speed for over 90 seconds of continuous running. Looking at the difference between the ¼ mile and mile speeds, it’s apparent that the combination of boat and motor may well have been pushing 50 mph at the outset. For a 15 cc boat in 1938, this was some going! The closest comparable British category that Hugh Blowers could think of is the “Miniature Hydroplane” class (Class B) which was established in Britain during the 1930’s. The Model Power Boat Association (MPBA) rules applicable to this class restricted I/C engine displacement to 15 cc, so Bill's hydro would have been in full compliance. The British record for that class stood at 34 mph in 1936, but was pushed up to over 40 mph just prior to the September 1939 outbreak of WW2, albeit over a distance of well under a mile. Note that this speed fell well short of matching Bill Atwood's ¼ mile speed, which certainly adds credibility to his World Record claim for that distance too, with or without international sanction. It's thus clear that whether or not his performances should be viewed as genuine World Records, Bill had a very fast 15 cc boat! It was certainly faster than any comparable American combination at the time. Moreover, his ¼ mile speed comfortably exceeded the pre-WW2 British Class B records. World Records or not, these impressive achievements naturally created a demand for Bill’s engine from other US boat modellers. To meet this demand while still working for others, Bill established his own sideline business called Aero-Marine Model Lab which was based upon his home workshop. Under this company name, Bill somehow managed to find the time to produce casting kits and boat plans for his record holding combination.

It will be recalled that this company had actually done much of the machining for the Baby Cyclone engines, so they were no strangers either to model engine manufacture or to Bill’s design work. A new entity called Phantom Motors, Hi–Speed Division was established by the company, whereupon Bill proceeded to design and develop the very successful Phantom line of Bullet, Hi-Speed and Torpedo engines for his new employers. In designing the Phantom series of engines, Bill introduced one of his most significant design innovations. Up to that time, induction bypass passages had typically been fastened to the outsides of cylinders by welds, clamps or screws. Bill now devised the “drop-in” cylinder, which utilized an expanded crankcase casting to provide a passage for bypass gas flow between crankcase and cylinder. This method reduced weight and potentially distorting stresses upon the cylinder walls. It continued to be used on most latter-day model engines, as well as on some industrial two-cycle engines. Unfortunately, production of the Phantom, Bullet, and Hi Speed engines was pushed so rapidly at the outset that design flaws which would have been sorted out through a more protracted development program found their way into the earlier examples. Notable among these were too-thin heads, which frequently warped and caused compression leaks. To reduce the propensity for corrosion of the magnesium castings, some models were given a crackle-finish paint coating.

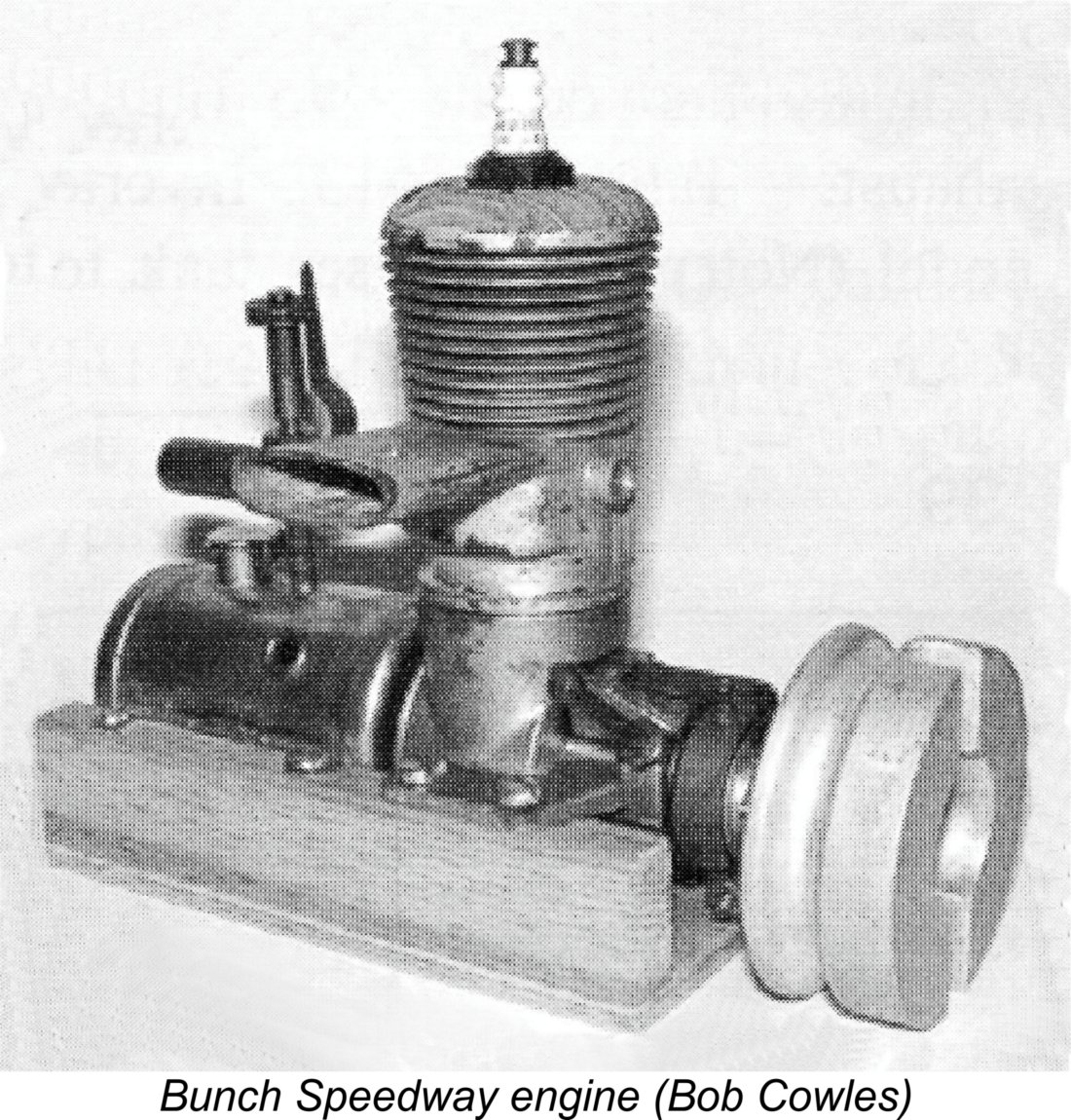

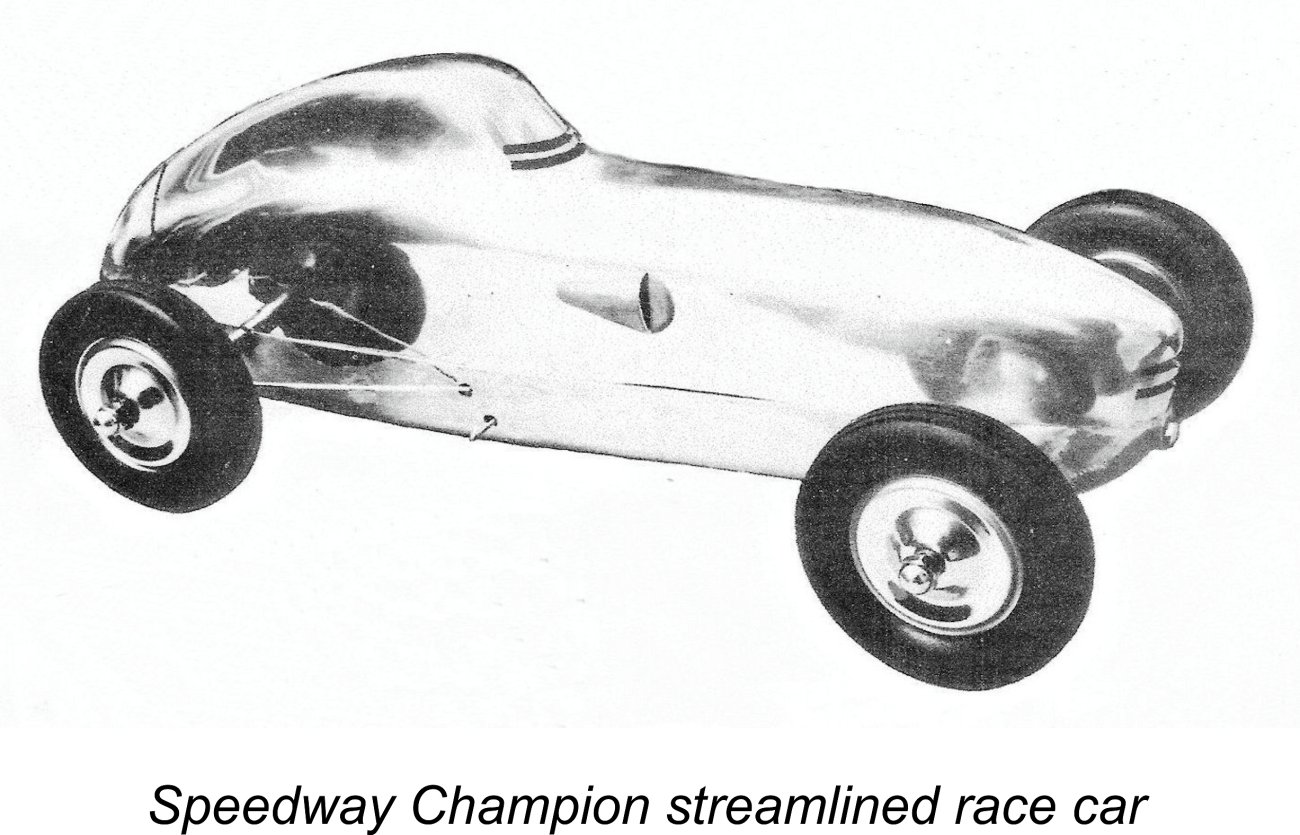

Bill Atwood looked over the cars and engines being used by the growing number of competitors in this field as of early 1939. The powerplants were mostly Dennymites (designed by Walter Righter), Bunch Speedways and the odd Brown Junior at this early stage – the Super Cyclone and Hornet models had yet to appear. Characteristically, Bill immediately decided that he could do better! While still with Phantom Motors, Bill designed and constructed his own 10 cc engine in his home shop. After installing this in a Bunch car, Bill proceeded to amaze the other car buffs with its performance, eventually setting a new American Miniature Car Racing Association (AMCRA) record for the one mile distance at Culver City, California on Labor Day 1939. He was soon selling casting kits for this model too, as well as a few completed engines. The design in question was subsequently to become known as the Atwood Blue Crown Champion model – the second in the series which forms our main focus here. This 10 cc powerplant followed the lead of the earlier 15 cc boat engine by featuring a combination of rear drum valve (RDV) and crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction. Each of these induction systems had its own independent fuel supply and needle valve. More details to follow.............

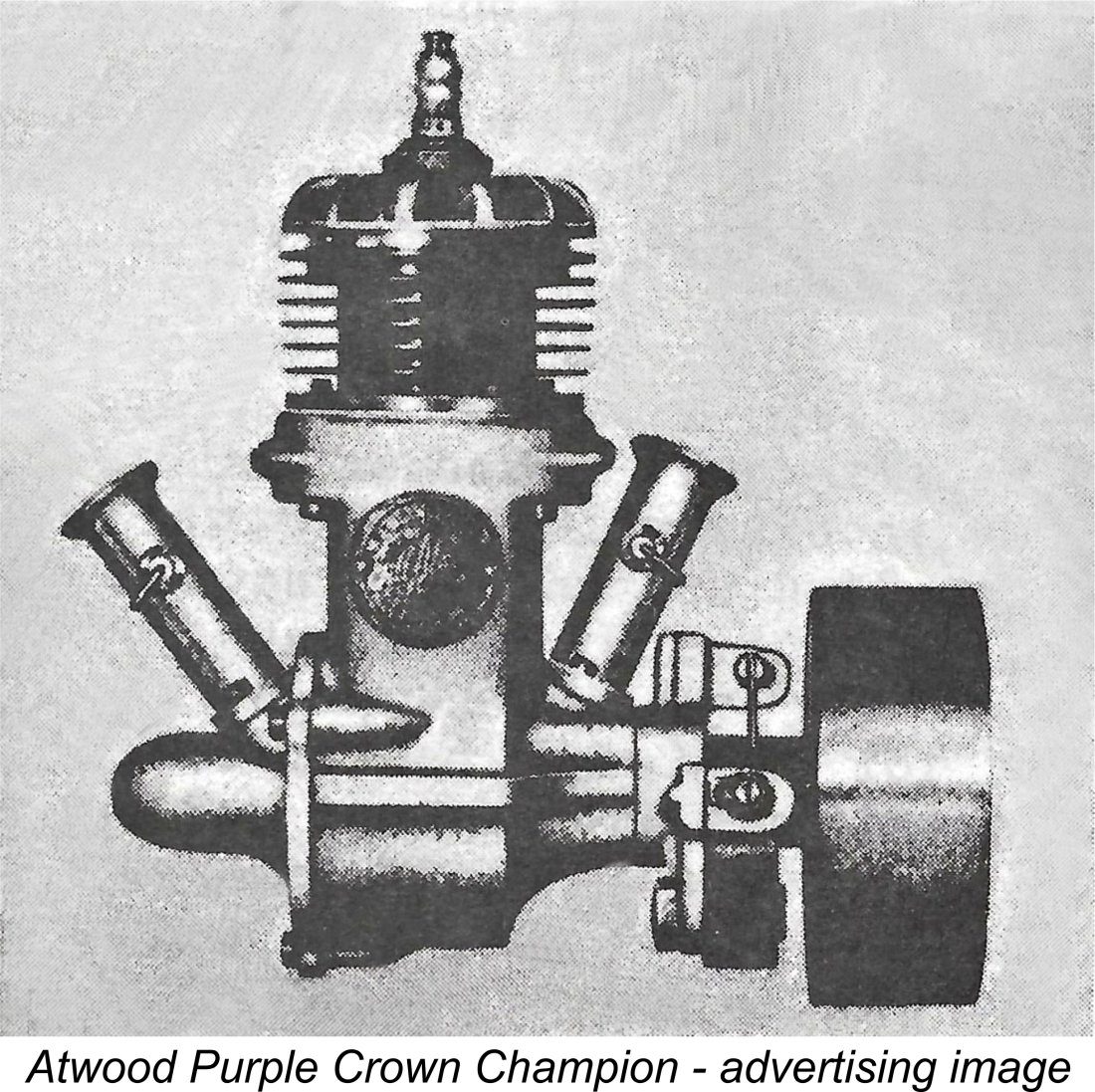

Recognizing that the 10 cc engine could also serve quite effectively as a model aircraft powerplant, a third variant was also developed for this purpose. It was known as the Green Crown Champion. There was also a fourth variant of the same basic design which was in effect a somewhat simplified 10 cc version of the 15 cc Silver Crown Champion, being also intended for boat use. It featured the unique twin downdraft carburettor layout pioneered in the larger boat engine. This model was designated the Purple Crown Champion. However, it seems to have been manufactured in extremely small numbers, if at all – no surviving examples are known today. Now, having set out the chain of events leading up to the introduction of the Atwood Crown Champion engines, let’s have a closer look at the various models in this series. The Silver Crown Champion

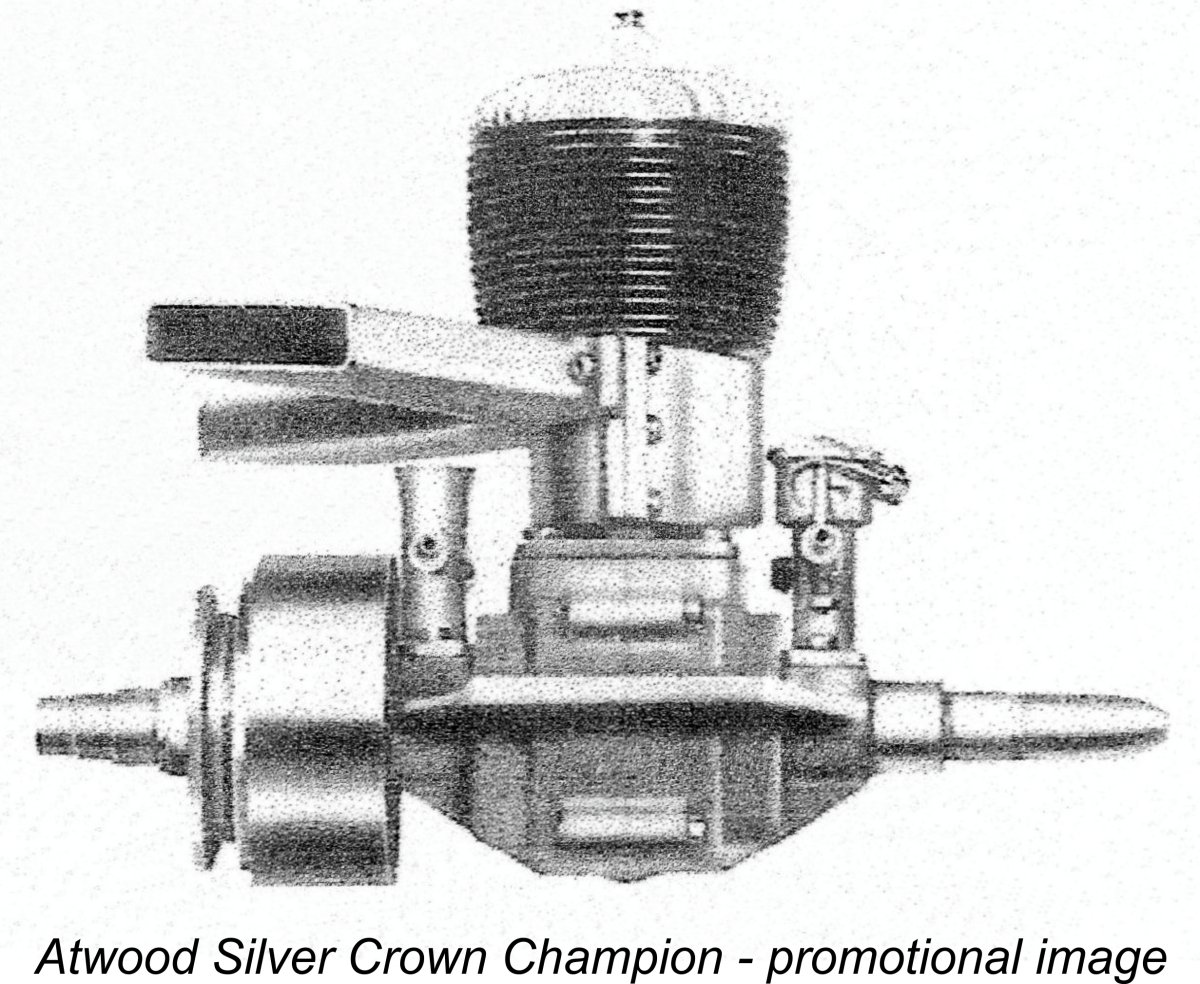

As noted earlier, the Silver Crown Champion made its public debut in 1938, when Bill Atwood unleashed it upon the model boat racing world by establishing his previously-cited new "World Records" with it. Thereafter the engine was offered in casting kit form for home construction, although Bill did reportedly make a few complete engines himself to special order. Beginning in early 1940, the kits for this engine were manufactured, or at least marketed, by the Champion Products Co. with which Bill was by then associated. This very innovative model was an air-cooled dual intake two-stroke spark ignition unit which was expressly designed for model hydroplane service. Indeed, its weight and bulk were such that it would have been quite unsuitable for any other application. The engine weighed in at a megalithic 1166 gm (41.13 ounces) with stacks, plug and flywheel but minus its ignition support system. The massive brass flywheel accounted for a significant proportion of this weight. The main externally-visible features of the Silver Crown are readily apparent from an examination of the attached images of Don Sohn’s superb replica. Like all of the Crown Champion series, the cast components were all sand castings. The crankcase is vertically split up its centre line, the two more or less identical halves each having its own inner ball race housing and outer plain bearing for the twin crankshafts. The bolt-on cylinder can be mounted in either fore or aft orientation to allow the timer assembly to be located on the engine either between the stacks or at the front in an unencumbered position.

The engine’s cylinder porting was somewhat unusual for its era. It featured a single bolt-on bypass passage at the front of the crankcase, with a transverse piston baffle to direct incoming mixture from the single transfer port upwards into the combustion chamber. Two exhaust apertures were provided, discharging rearward on both sides at a 45 degree angle. A basically similar arrangement was subsequently to be used by Bill's old friend Ira Hassad in a number of Ira's designs. The exhaust apertures were fitted with spectacular bolt-on exhaust stacks which were clearly intended to direct the exhaust outward and to the rear in the opposite direction to the boat’s movement. All ports were of course bridged to prevent fouling of the piston rings. The fact that twin shafts were used, one at each end, allowed the drive to the propeller shaft to be taken off either end of the engine. As noted earlier, the bolt-on cylinder could be rotated through 180 degrees to orient the exhaust either towards or away from the flywheel, with the engine naturally being mounted in the model to keep the exhausts pointing towards the stern of the boat. That orientation would of course determine the power take-off point - flywheel end or timer end. Space considerations dictated that the timer be at the opposite end from the flywheel, but either end could serve as the power take-off point with the exhaust oriented accordingly. As a result, different examples may have the flywheel either at the front (opposite the stacks and the timer) or the rear of the engine (between the stacks).

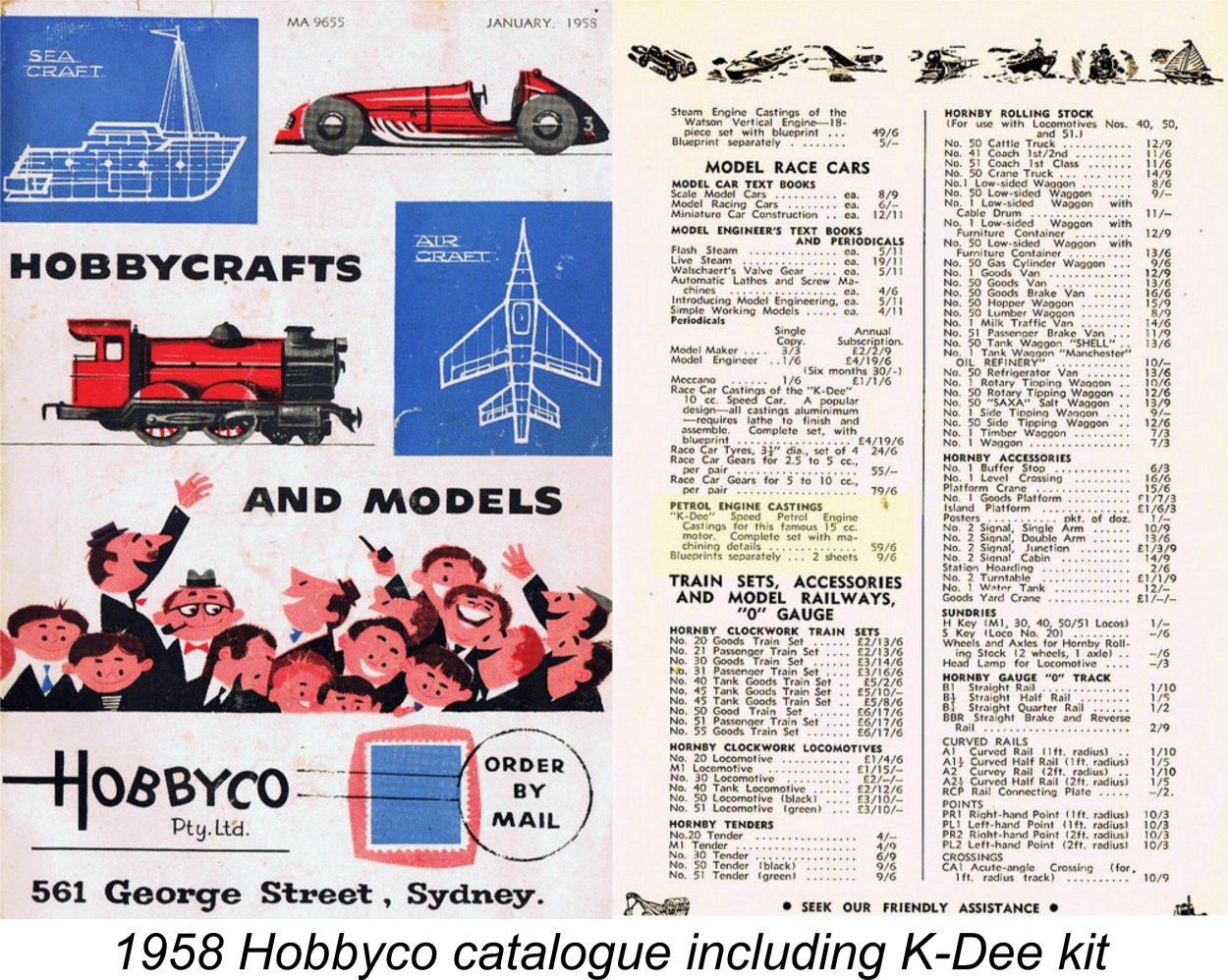

As previously noted, the Silver Crown was offered to the public primarily in kit form, although a few examples were apparently completed by Bill Atwood himself to special order. One inevitable consequence of this is the fact that many builders applied various modifications of their own to the engines that they constructed from the kits. Moreover, a number of producers other than Bill Atwood have offered casting kits for this engine. We know of an American kit produced by Denny Hitson, and there was also an Australian kit made by "K-Dee" and There’s some confusion with respect to the origin and dating of the Australian K-Dee kits. The K-Dee Pty. Ltd. company was started way back in 1935 by Robert Lowe, being named after his wife's initials. In 1947, Lowe changed the name of the company to Hobbyco Pty. Ltd. This implies that the castings were actually made sometime before 1947, hence being identified with the K-Dee name. This led to them continuing to appear in later Hobbyco catalogs under the original name while stocks lasted. The identity of the actual producer(s) of the K-Dee/Hobbyco castings is now lost forever in the mists of time. What all of this means is that by no means all examples of this engine which may be encountered today are directly associated with Bill Atwood personally, nor do they necessarily follow his original design in all respects. In fact, it’s effectively impossible to nail down the provenance or originality of any such examples. One simply has to trust one’s instincts or deal with a knowledgeable and honest source. In my own case, my illustrated example of the engine was constructed by Don Sohn using original plans along with his own replica castings. It is as true to the originals as Don’s research was able to make it – one can’t legitimately claim more. The most technically intriguing feature of the engine is undoubtedly its use of dual rotary valves and intakes. These intakes are completely independent of one another since there is no intervening plenum to connect them. They each have their own fuel supply and needle valve. Adjusting those twin needles might be a chore – indeed, at first sight the idea itself seems somewhat open to question.

I would guess that the most practical approach to the management of this system would be to begin by starting the engine with the restrictor at the timer end fully closed, taking that intake completely out of the operational picture and making the engine handle exactly like a conventional single intake model using the needle valve at the flywheel end alone. Once having set that intake to run a bit rich on its own, one could then try the effect of progressively opening the other intake and its needle valve to gauge the effect. This action would reduce suction at the front intake, hence the need for an initial rich setting. My valued mate Maris Dislers did some hard thinking about this feature and came up with an approach to its operation in a hydroplane which makes a lot of sense. Two issues had to be overcome. First, upon starting with the hydro out of the water, the unloaded engine could rev up pretty high, possibly to the point where structural failure became a possibility. The use of the front intake alone at a rich setting would greatly alleviate this tendency. Moreover, if the boat was placed in the water with the engine running fast in a leaned-out condition, the large high-pitch prop typically used with hydroplanes of the era would almost certainly kill the engine by slowing it to the point where fuel suction failed. It would be far better to start at a lower speed on a rich mixture and allow the boat to accelerate smoothly and progressively, with the mixture coming to its optimal setting as this occurred. To achieve this with the Silver Crown, the engine could be started with the timer-end intake fully closed, setting the other intake to run rich so that the engine ran at reduced speed. In this mode, the motor would keep running when the boat was placed in the water, albeit relatively slowly. Upon release, the boat would accelerate relatively slowly and smoothly. As the speed increased, so would the centripetal force acting upon the engine and its components. This would tend to pull the top of the intake control lever from the closed "vertical" position to the horizontal (open) position, bringing the second intake into play. Additional weights could be deployed in various ways to facilitate this action, which would both lean out the mixture and enhance the engine's induction capacity. All that would be necessary would be to establish a needle setting for the second intake which would yield maximum performance with everything wide open and the boat running at full speed. Trial and error would soon establish such a setting. Maris's analysis has been endorsed by no less an authority than Hugh Blowers, manager of the previously-cited OTW website. Hugh pointed out that many approaches have been taken to achieving the mode of operation described above. Hugh also pointed out that there have been many experiments with multiple intakes, perhaps must notably by the renowned French expert Gems Suzor. A fascinating account of Gems Suzor's life and work may be found at OTW - well worth reading! This still leaves us with the question of why Atwood chose to use dual intakes in the first place. Couldn't a single higher-capacity inlet equipped with a centrifugally-activated throttle have had the same effect? One might perhaps argue that having two opposed sources of fuel/air entering the crankcase may somehow provide better atomization and mixing. However, given the transfer arrangements on the Silver Crown, this seems a bit optimistic. OK, so perhaps the idea was to increase the engine’s induction capacity?!? The problem here is that there is a practical limit on total venturi throat area for a given crankcase volume and pumping efficiency. As total throat area increases, a point is reached where the engine is no longer able to draw and atomize fuel without pressure feed assistance. Doubling the number of inlets will do nothing to change this situation, as an engine’s ability to induct fuel mixture is limited by a combination of its displacement, primary compression and crankcase volume, regardless of the number and combined area of intakes.

Now a single bore of this diameter would undeniably be a bit marginal to feed a 15 cc gasoline (petrol) engine. Recalling that the ideal stoichiometric ratio (air to fuel) for gasoline is between 12.4:1 and 14.7:1, it’s clear that the air requirement is far higher than that for methanol-based fuels, where the air/fuel ratio falls to between 4.0:1 and 6.45:1 (with no nitromethane content). This engine would clearly need to draw in a lot of air! Assuming that the crankcase geometry provides adequate pumping capacity, by using two inlet valves Atwood doubled the gas passage area without the need to compromise crankshaft strength, hence increasing the engine's ability to draw in air and thus providing a heavier optimized fuel/air mix to feed the large 15 cc displacement cylinder.

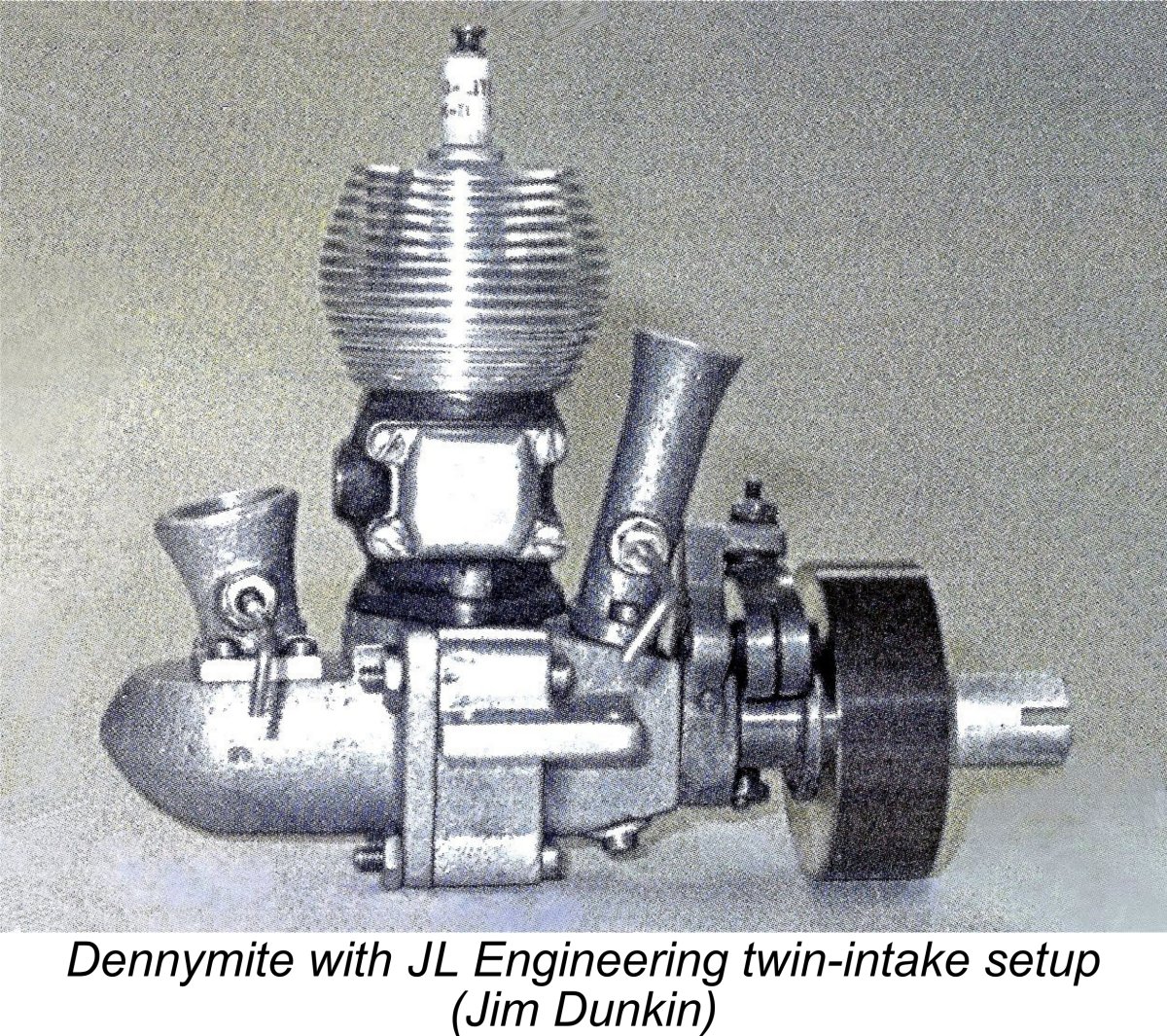

That's rather enormous, but still might have been a better choice because - all things being equal - friction in a plain bearing is more or less proportional to half the journal diameter (remember, only one ball race is used at the inner ends of each shaft). Hence, the bearing friction of the large shaft would be less than that for two smaller ones. Fair enough, but Ron saw several downsides to the “big single shaft” approach. For one thing, the crankcase would have to be reconfigured to accommodate a significantly larger ball-race. More weight and bulk ....... In addition, it's obvious that the diameter of the (now) single intake venturi and its register would also have to be increased to provide an area equal to that of the two intakes actually employed. Ron calculated that the achievement of the same inlet duration in the large diameter shaft with the larger venturi opening would require that the induction port opening in the journal occupy 91° of the shaft, as compared to 75° for the smaller shafts. This would weaken the shaft, meaning thicker walls might be needed, meaning increased diameter, requiring an even larger ball race, meaning an even greater port width and an even bulkier crankcase...... you get the idea! It’s noteworthy that apart from Bill Atwood with his Champion series, few other engine designers have pursued the twin rotary valve concept. That having been said, a designer of Bill Atwood’s calibre would never have pursued the concept if he had not seen some value in it. Bill not only pursued it – he stuck with Interestingly, all of these later designs had a single needle valve and "smoke-stack" venturi at the rear with a plenum chamber under the engine feeding fuel/air mix from the single intake to both inlet valves. This of course greatly eased the operation of these engines – only one fuel adjustment to make, and no need for the adjustable restrictor on one intake. These later Champion models are the subject of a separate article set to appear on this website in due course. Research indicates that only one other company tried this combination, that being JL Engineering who attempted to keep the 1940 Dennymite sideport engine competitive in car racing against the emerging powerhouses from the likes of Hassad and Hornet by offering replacement front and rear assemblies for the Dennymites. The owner plugged the sideport inlet, then fitted either the accessory front rotary valve crankcase/crankshaft unit or the rear drum valve component - or both! Strangely, the idea did not seem to catch on – perhaps these accessories still fell short of matching the ever-improving opposition from other makers. The Blue Crown Champion We saw earlier that the 15 cc Silver Crown Champion boat engine preceded the other 10 cc Crown Champion models by at least a year, albeit not initially by that name. In 1939 Bill Atwood became interested in the emerging field of model car racing, as mentioned earlier. Deciding as usual that he could improve upon the designs then in use, Bill decided to design a car engine of his own.

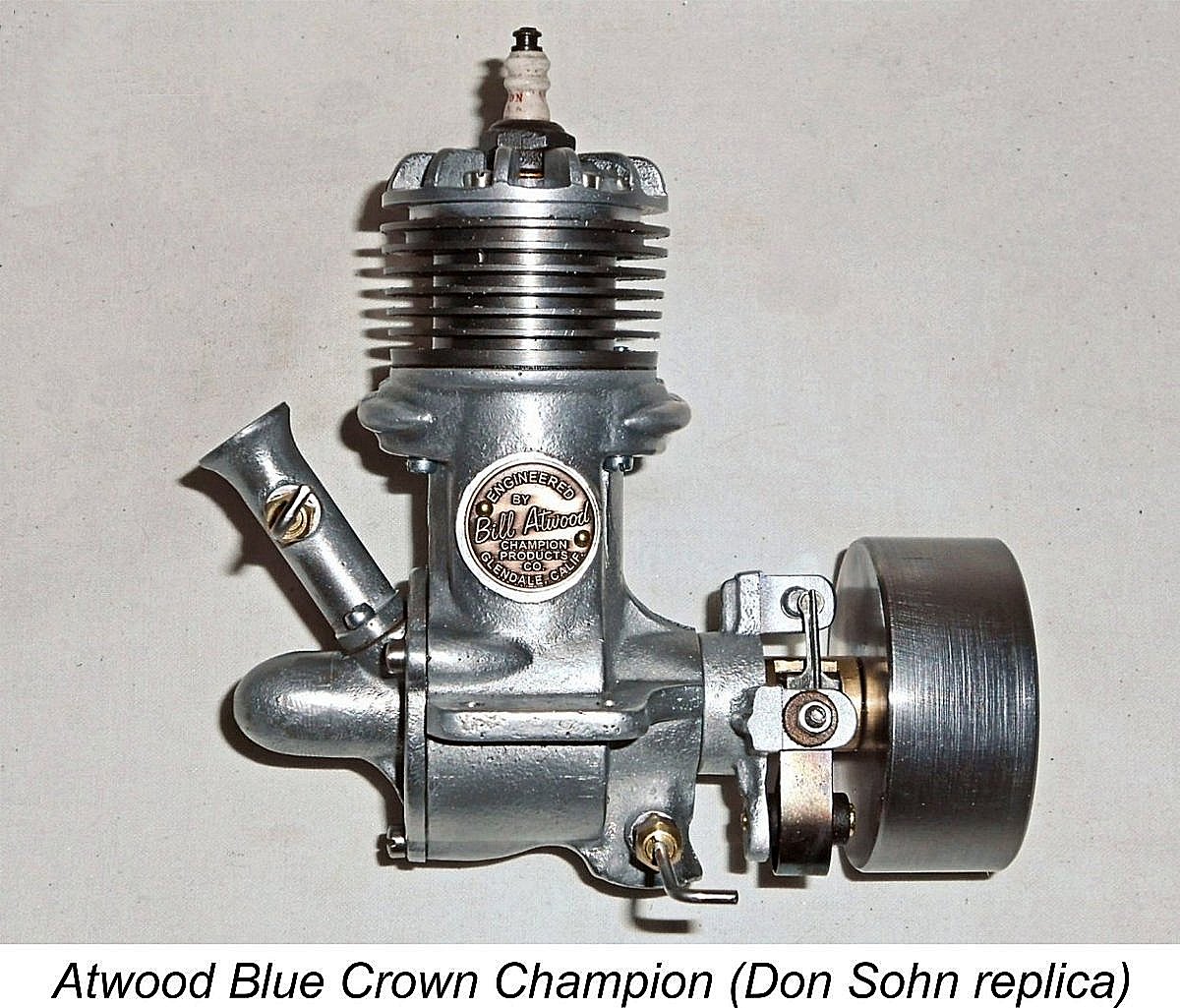

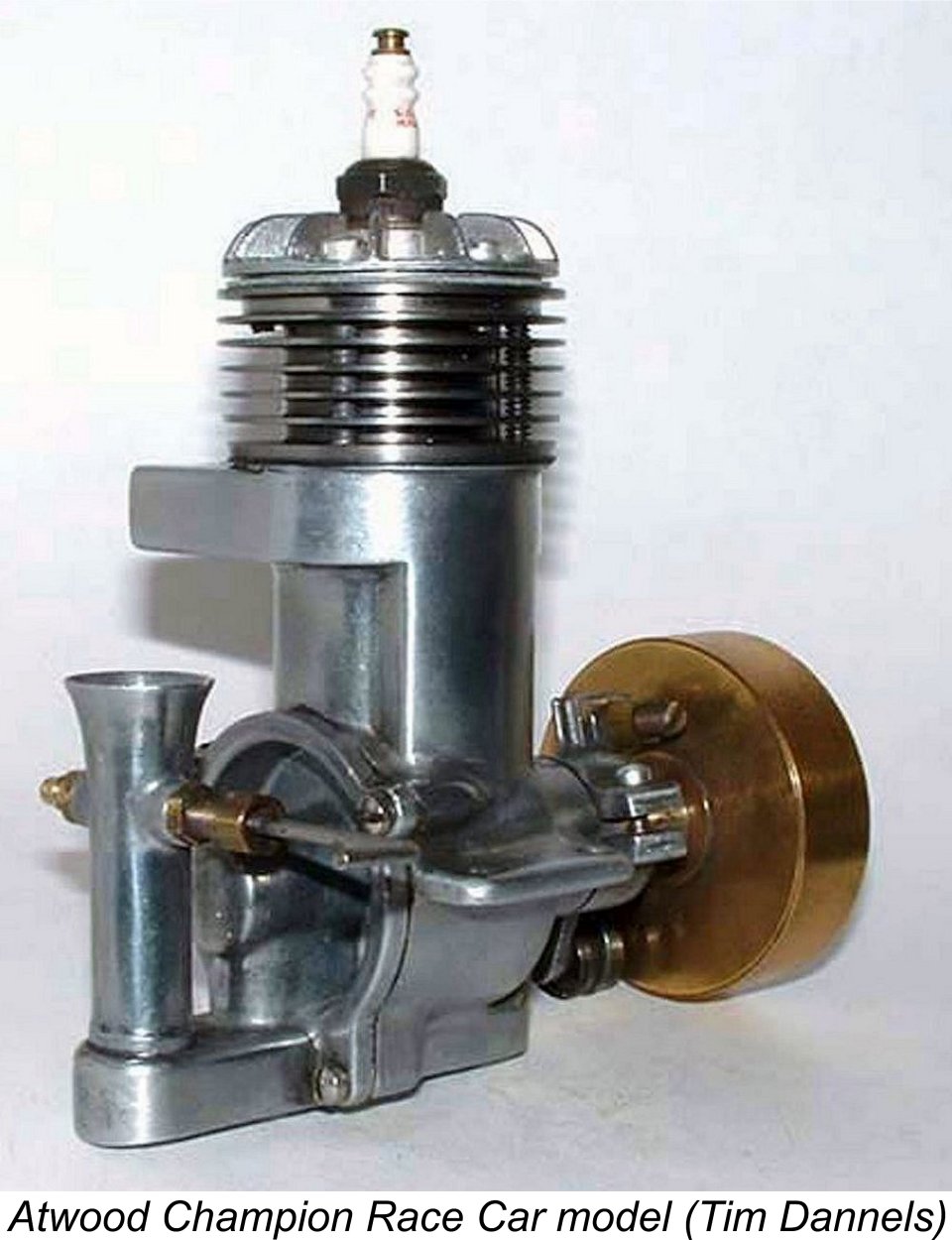

To meet these challenges, Bill designed an all-new 10 cc unit, which was destined to become the Blue Crown Champion as of March 1940. The 1939 prototypes of this engine had impressed everyone with their performance, which had allowed Bill to establish a new AMCRA speed record at the 1939 Labor Day meeting at Culver City, California, as mentioned earlier. The Blue Crown’s reduced displacement was achieved through a reduction in both bore and stroke from the earlier model – the Blue Crown measured up at 0.925 in. (23.49 mm) bore and 0.900 in. (22.86 mm) stroke, giving an actual displacement of 0.605 cuin. (9.91 cc). Claimed output was 0.250 BHP plus at speeds between 10,000 and 15,000 rpm. Compression ratio was cited as 6:1.

In addition to these changes, the Blue Crown crankcase was no longer vertically split. Rather, the main bearing and updraft intake were cast integrally with the main case, while the rear intake now took the form of a bolt-on downdraft drum valve unit which served as the backplate for the crankcase. The new model also featured a single bolt-on sidestack exhaust instead of the two swept-back stacks of the Silver Crown. Finally, the ball races used in the Silver Crown were omitted from the new model, presumably in the interests of economy.

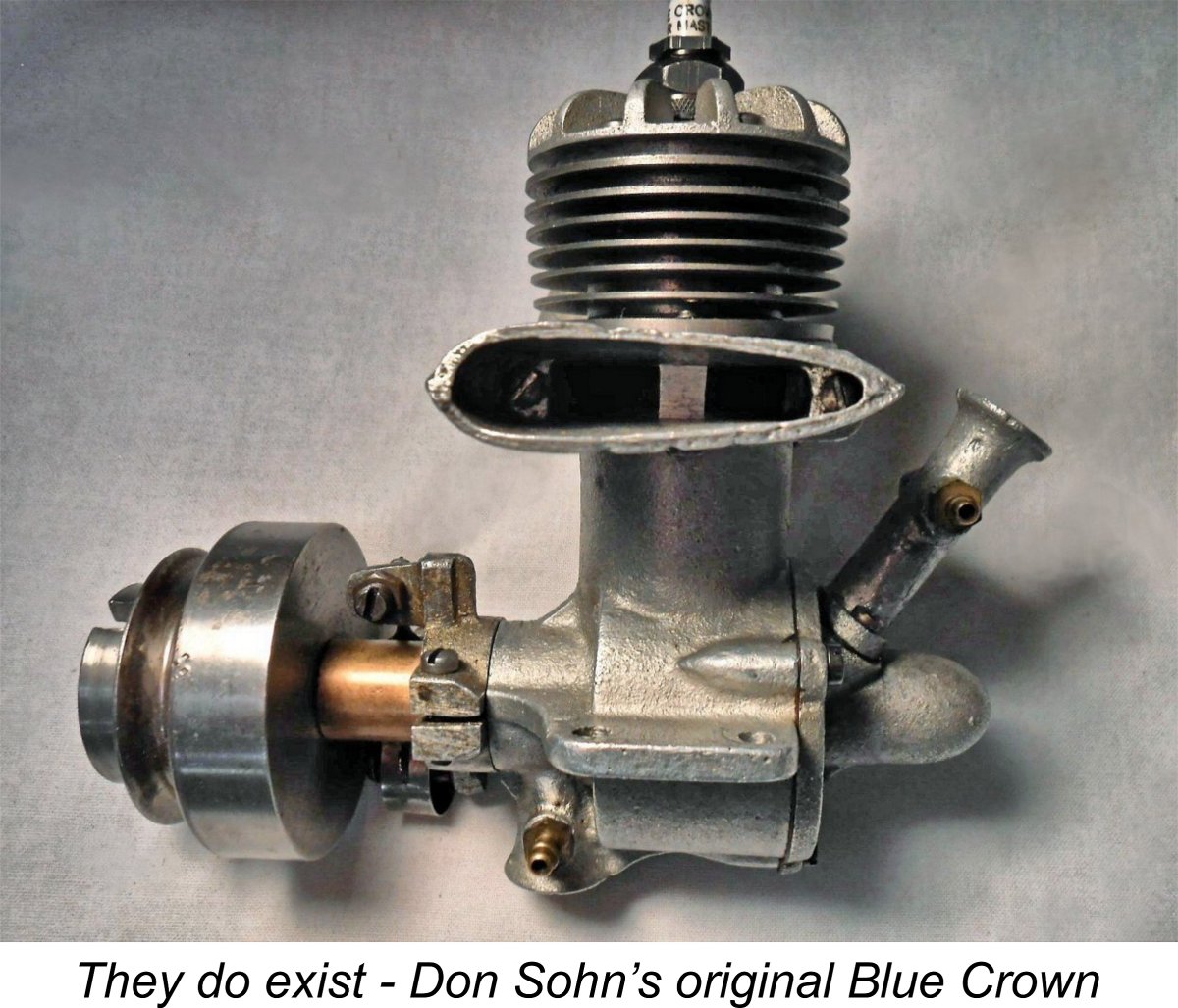

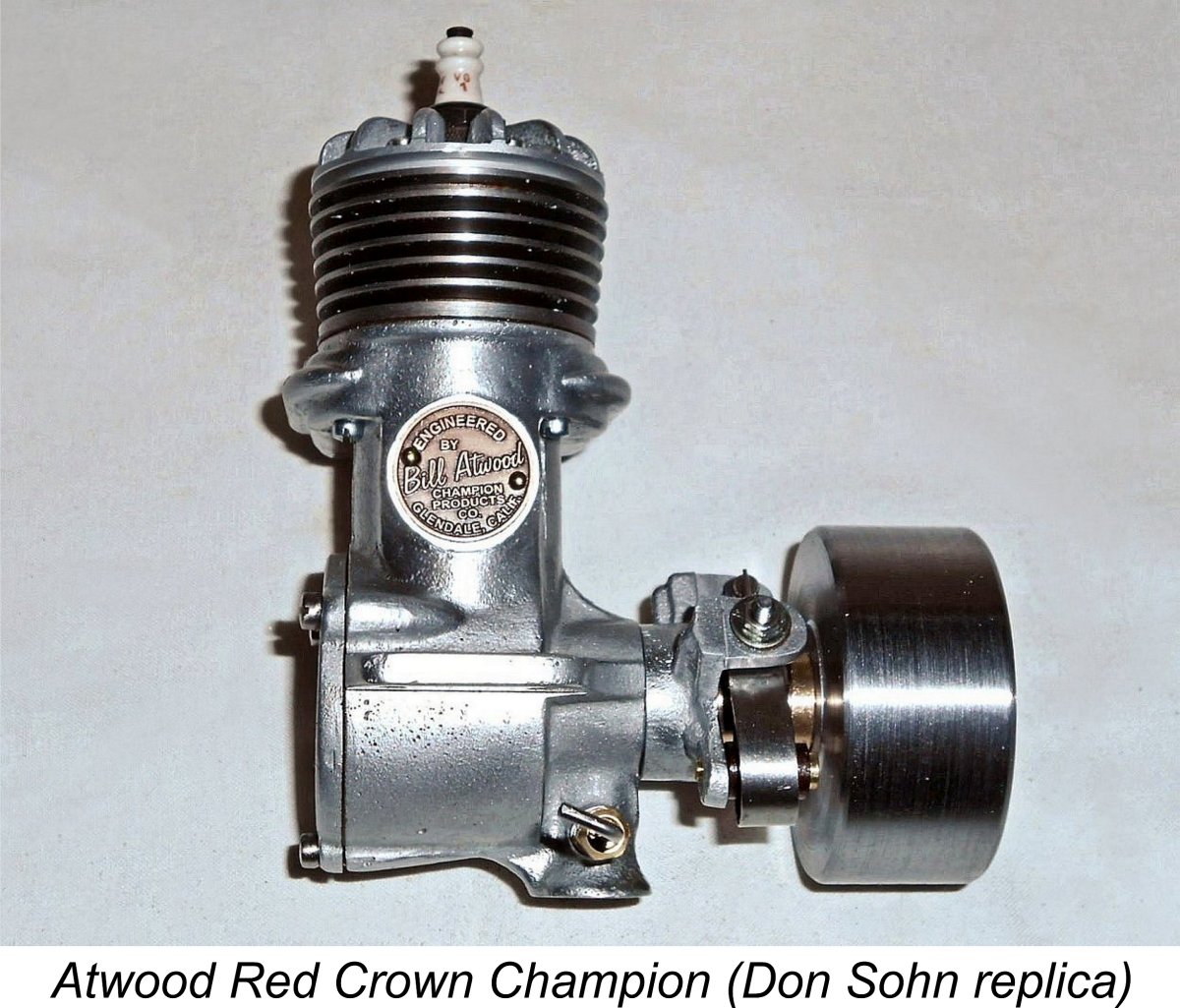

Although a few examples may have been previously made by Bill Atwood Based on the number of surviving original examples (one of which is owned by Don Sohn and was used as a major reference for his replicas), this model was produced in the largest numbers of any of the Crown Champion designs. Even so, it is very far from common today, implying that production was relatively small. In large part, this may be due to the evident fact that the production life of the Crown Champion series was very brief – see below. The Blue Crown Champion was immediately joined in the Champion Products Co. range by the previously-mentioned Silver Crown kits which Bill had been producing for some time previously. But things didn’t stand still – Atwood evidently recognized the fact that an “economy” version of the Blue Crown might attract buyers. This led to the April 1940 introduction of the next model in our survey – the Red Crown Champion. The Red Crown Champion

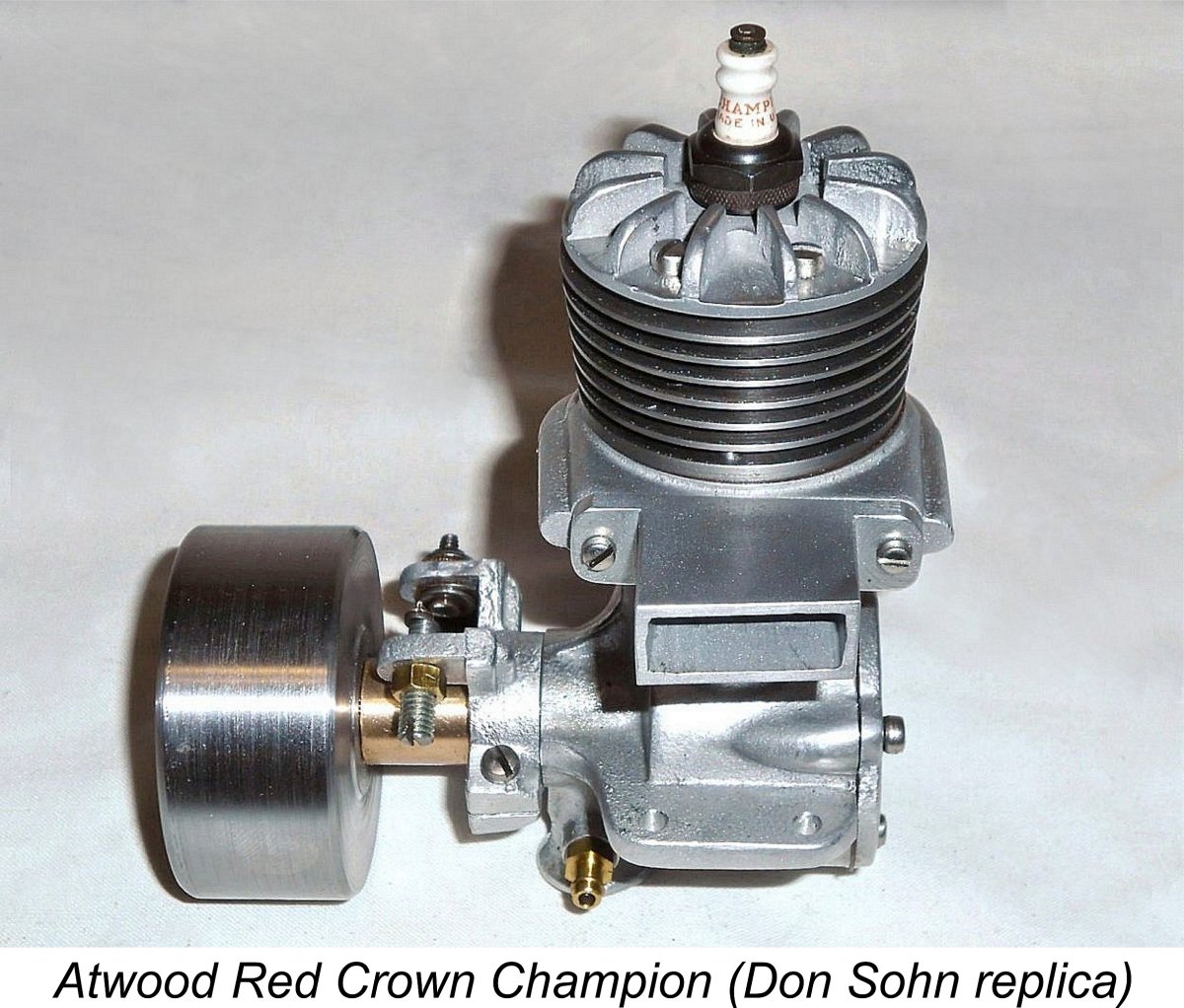

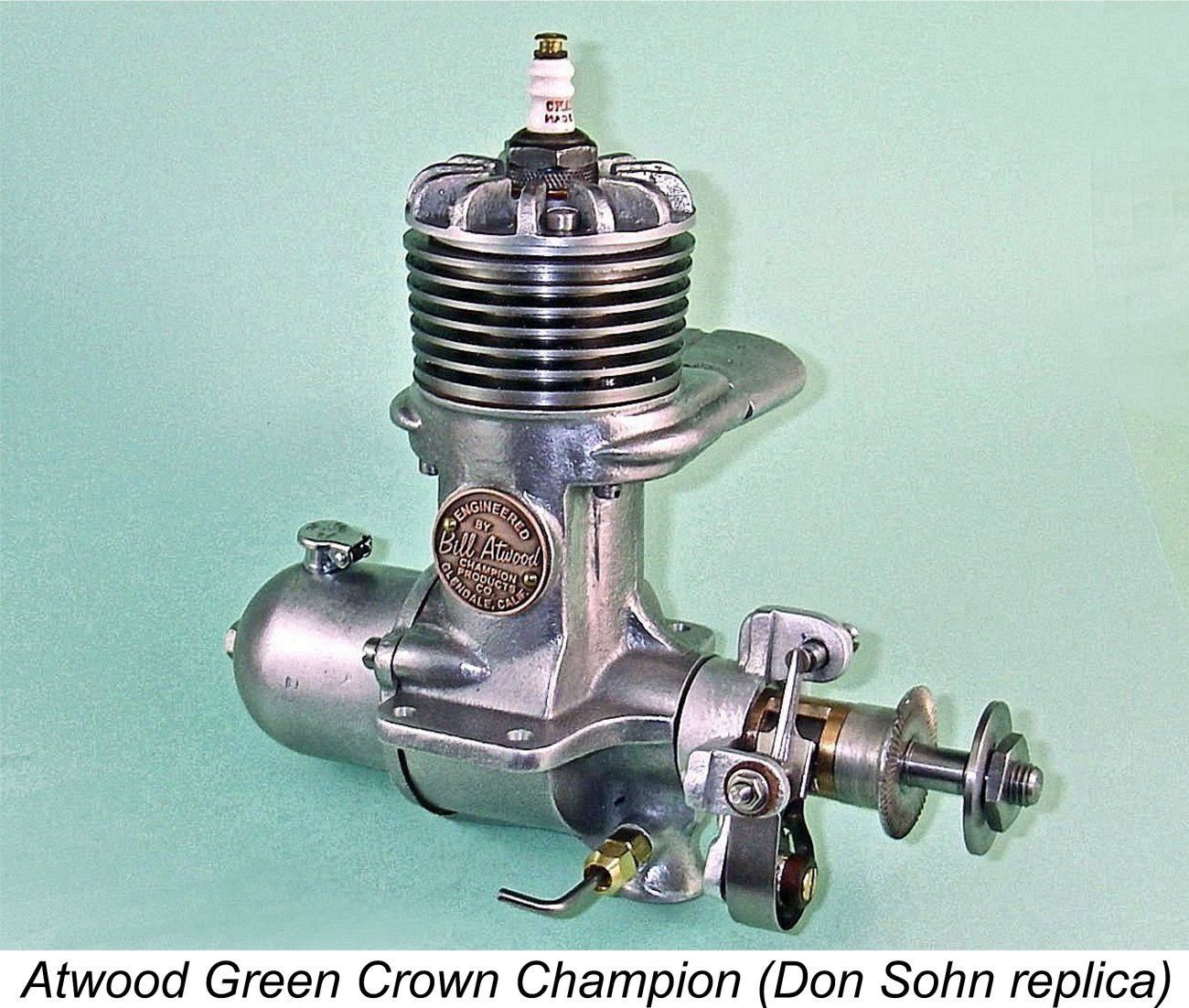

Apart from its lower price, a feature which may have attracted customer attention to the Red Crown was its use of only a single intake. We’ve seen that the updraft intake at the flywheel/timer end of the engine was retained, but the rear drum valve was eliminated. Although this would have reduced the overall intake area of the engine, it In the absence of any opportunity to conduct a comparative test, it’s impossible to authoritatively gauge the effect on performance of the omission of the rear intake. We would expect a potential loss of high-speed output due to the more restrictive intake arrangements (assuming that the intake geometry remained unchanged), but this would have been offset to a significant degree by the more precise mixture setting which the use of a single carburettor would doubtless facilitate. Even so, the Red Crown Champion does not appear to have matched the Blue Crown in terms of sales figures. The number of surviving examples is extremely small – even lower than that of the Blue Crown. Having jumped into the model car market with his two car engine offerings, Bill Atwood went further by offering three alternative chassis/body combinations to suit these and other engines. The third car offering, the Wasp Champion, was a smaller model intended for engines in the 1/7 HP range. It seemingly originated in what appears to have been a short-lived prior association with Wasp Model Supply of 4128 Wade Ave., Venice, California. That company offered an engine called the Atwood Special (which may well have been an earlier rendition of the Blue or Red Crown) along with a car called the Wasp Special. The Wasp Champion car was likely a smaller version of that model under the Champion name. It was advertised as being suitable for a wide range of smaller engines, including the Hi-Speed, Ohlsson, Phantom and Trojan models. The Green Crown Champion Although Bill Atwood had been very closely involved with both hydroplane and car racing during the late 1930's, he had not by any means abandoned his involvement with model aircraft. Recognizing that his basic Crown Champion design would doubtless make a very acceptable aero engine, he offered an aero version designated the Green Crown Champion. This model was first offered by Champion Products Co. in April 1940. It was cited as a “super” performer with 13 in. or 14 in. dia. props. The claim was made that the engine could be used to fly models having wing spans as large as 15 feet! Wouldn’t fit in my car ……..!!

The attached images of the superb replica made by Don Sohn show the engine’s arrangement clearly. This replica weighs in at a not unreasonable 381 gm (13.44 ounces) with plug and tank but minus its ignition support system. The original engine sold for $18.50 complete with coil and condenser. Like the Red Crown, the extreme scarcity of surviving original examples of this engine make it apparent that production figures were very small indeed. This is a pity, because the engine is actually a very sturdy and well thought-out design which would have given its owners very good service. Once I’ve assembled a suitable spark ignition test stand, I hope to conduct a test of my replica engine when time and opportunity combine. When and if that happens, I’ll add the results to this article. The Purple Crown Champion

There is actually some question as to whether or not this model was ever actually put into production. The promotional photograph proves that at least one prototype was constructed, and the engine was certainly advertised at a basic price of $22.50. However, no surviving examples are known today. Such replicas as do exist, including the illustrated example made by Don Sohn, are based upon dimensions taken from other members of the Crown Champion series as well as an examination of the advertising images of the engine.

In making his superb replica, Don Sohn was guided by the surviving advertising image as well as measurements taken fom his original Blue Crown Champion. While his rendition may not be precisely accurate in all respects, it certainly reflects the general arrangement of the original very well indeed! Further Champion Developments To judge by the number of surviving examples, the manufacture of the Crown Champion engines does not appear to have been pursued with any great vigor. This lends support to the previously-noted possibility that Champion Products Co. was simply Bill Atwood working on his own in his “spare” time (what spare time?!?) producing the engines in very limited numbers using the facilities of his home workshop. The model that seems to have been manufactured in the largest numbers was the Blue Crown Champion car engine. Very few original examples of the Red and Green Crown engines survive, and there are no reported original survivals of the Purple Crown model. While all of the development work on the Crown Champion series had been going on, Bill Atwood had retained his connection with the Phantom Motors company, designing the Hi-Speed Bullet, Phantom Bullet and Phantom Torpedo models for them. This had not prevented his ever-fertile mind from identifying potential improvements to his Crown Champion series. Before the end of 1940 he had designed and put into production a revised car engine called the Champion Race Car model – no mention of any Crown coloration! It One of Bill Atwood’s goals in developing this revised model was clearly to facilitate production. To this end, the formerly sand-cast components were now produced by die-casting using permanent molds. In terms of its functional design, the new model also addressed one of the obvious shortcomings of the earlier Blue Crown model, namely the difficulty of establishing a good mixture setting using the dual needle valves of that model. The Champion Race Car unit retained the dual rotary valves of its predecessor, but there was only a single downdraft intake and needle valve at the rear. This supplied mixture to both a rear drum valve and a front crankshaft rotary valve through a plenum which ran fore and aft beneath the main crankcase. Naturally enough, Bill recognized the potential of this revised design for aircraft use. Accordingly, before the end of 1940 an aero version of the new unit was also on offer under the designation of the Champion Aircraft model. It was basically the same engine with the flywheel replaced by a prop driver. Those members of the Champion series that did find buyers, particularly the car models, seem to have impressed those who saw them perform. As a result of their evident success, a couple of individuals named Shaw and Kaw persuaded Bill to finally leave Phantom (and Champion Products) in early 1941 to join them in manufacturing and further promoting the latest Champion engines. Bill did so, at the same time retaining all rights to the Torpedo, Bullet and Champion designs. The later Phantom P-30, postwar Bullet 100 and Torpedo Special were not Atwood designs. The association with Shaw and Kaw proved to be a very brief one, for reasons which are now lost. Thereafter, Bill joined forces with Wetzel Motors of 420 S. Manhattan Place, Los Angeles, California, with whom he continued to manufacture his revised Champion designs. The entry of America into WW2 signalled a major change for Bill, since his talents were now needed for the war effort. After working for a time as a toolmaker and maintaining a “hobby” connection with the Champion engines, he became a full-time glider pilot instructor for the US Army Air Corps. Wetzel kept the dies and parts inventory, assembling a few engines during the war years from pre-war parts stock. Having now completed our survey of the Crown Champion series, it remains for context to summarize the later career of Bill Atwood. Bill Atwood – the Later Years In early 1945, as war production was slowing down, metals were once more available in limited quantities for non-military purposes. Atwood resumed his association with Wetzel under the name Wetzel & Atwood, once more producing Champion engines. These engines were popularized in the control line stunt field by Davis Slagle, who used a Champion to win everything in sight during 1946. He later switched to Super Cyclone power, continuing his run of success with that unit. The Wetzel and Atwood partnership did not long survive the end of WW2. There appears to have been a difference of opinion over who owned what. When the partnership split, each partner evidently thought that he had rights to earlier Atwood designs. During the war, the dies for the Torpedo had been lost. Nonetheless, Wetzel transferred the rights to the Torpedo to Miniature Motors, while Bill sold the Torpedo name and goodwill to John Brodbeck (the B of K&B), along with a promise never to compete with John in the .29 class. As history records, Brodbeck came out on top in that particular ownership split!

Even with these alterations, Atwood’s production capacity was insufficient to keep pace with demand. Ken Adams had greater production facilities, so Atwood joined him at 732 North Lake Street in Burbank. A subsequent redesign resulted in the model JH Super-Champion with aluminum castings, higher compression, an enlarged bypass, squared ports and a more compact timer assembly. A straight-in carburetor as opposed to the standard downdraft “smokestack” was available, chiefly for inverted operation. The exhaust stack orientation had now switched to the right (seen from the rear). At some point in 1945, Bill decided that he would no longer compete in power competitions with his own engine customers, accordingly turning his attention back to indoor flying, in which he had first competed way back in the 1920’s. He was just as successful in this field as he had been in others, winning four consecutive indoor titles at the US National Championship meetings from 1945 through 1948 inclusive. He was to win again at the 1952 US Nationals at Los Alamitos, California.

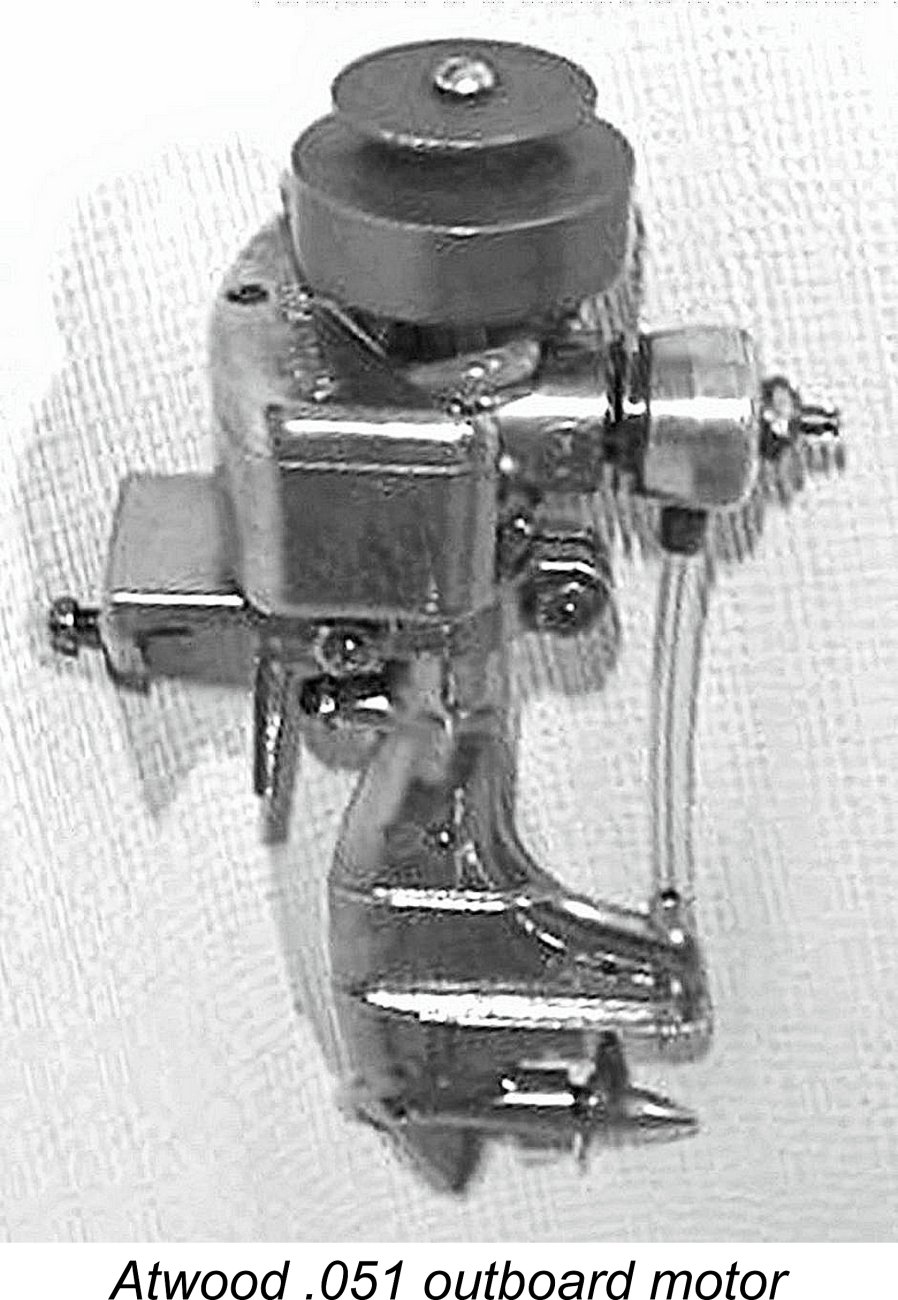

It was in 1948 that Bill finally abandoned the twin rotary valve arrangement after having used it for 10 years. He did so by bringing out the Triumph line of high performance engines in .49 and .51 cuin. displacements. Both spark and glow-plug ignition versions were offered. This design was used by Gene Stiles to bring to the USA the first Free Flight speed record (81.587 mph) with his June 1949 flights. His plane was subsequently placed in the Smithsonian Institute. It was during this period that Atwood established a close working relationship with Shigeo Ogawa, founder of the well-known Japanese O.S. company. It appears that in 1947 Atwood and Ogawa began discussing the possibility of Atwood assisting in the marketing of a suitable introductory O.S. product in the USA.

That model and its .29 cuin. and .099 cuin. twin-stack companions in the O.S. range were preceded in 1948 by a sandcast .29 cuin. twin-stack spark ignition model which appears to have been the direct ancestor of all the subsequent O.S twin-stack models It seems certain that Atwood had a hand in influencing the design of this limited production unit, even to the extent of supplying surplus Phantom 29 timers which were adapted to the new O.S. product. A full analysis of this very rare engine may be found elsewhere on this website. Meanwhile back in the USA, the December 1948 appearance of the K&B Infant Torpedo opened up a new era in power modelling, made possible by Ray Arden's late 1947 introduction of glow-plug ignition. Engine designers My good mate Maris Dislers has written a very informative summary of the development of ½A engines in the USA. Maris's article may be found elsewhere on this website. When Wen-Mac and Jim Walker needed engines for their RTF airplanes, Atwood and Holland became the suppliers. They also produced B and B Timertanks (possibly inspired by the pre-war Korda timer tank).

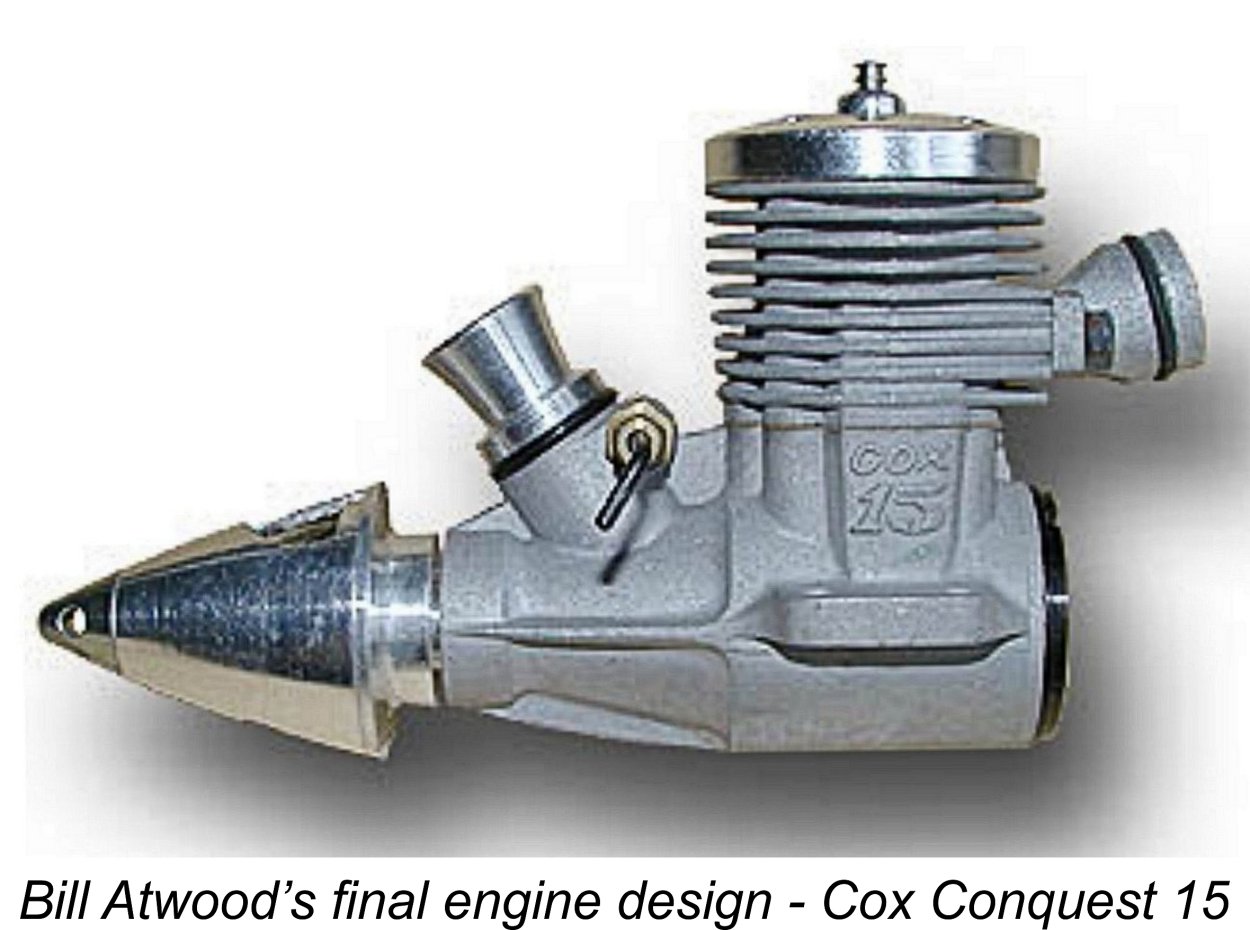

Meanwhile, Bill’s interest in steamboats had been stimulated by his seeing the movie “The African Queen”. In 1956 a model steam-powered launch called the “Jungle Boat“ was designed and manufactured by Atwood. This project turned into a financial disaster, forcing Bill to withdraw from the industry as a manufacturer in his own right, selling out in 1959. Bill’s ingenuity was thus available in 1960 when Roy Cox needed help with the design of a tiny .010 cuin. (0.166 cc) engine that he hoped to produce. Roy wanted to continue using reed-valve induction in all his engines, but the tiny one simply refused to work in this format. Roy thereupon employed Atwood to find a solution.

Because of the significant increase in power which resulted, Cox was persuaded to produce a few of these drum valve Olympics for use in FAI competition. Meanwhile, Bill was now experimenting with a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) version of the engine. The FRV experiment was almost abandoned during testing because Bill initially used a stock head instead of a “hot” one, hence failing to get as much out of the engine as it actually had to give. However, he persevered, eventually selling Roy Cox on the idea of applying the front rotary valve to a new line of competition engines which were designated the Cox Tee Dee (TD) line. This famous series appeared in 1961. Of course, i Also in 1961, Bill got back into indoor competition with a vengeance. In 1963, after a tremendous round of eliminations in Santa Anna, he managed to secure a place on the American FAI indoor team for that year’s World Championship meeting. Unfortunately, the 1963 event was subsequently canceled and Bill failed to make the team in 1964. Thereafter, he turned his attention to R/C sailplanes. In an effort to keep the Cox range competitive, Bill developed prototype .35 and .40 cuin. engines, of which a few were given to prominent modellers for field testing in 1967 and 1968. Unfortunately, projections of sales volume versus production cost were unfavorable, leading to a decision not to produce From 1970 on, Bill Atwood was employed as a project engineer for Cox. During those years, he designed a pull starter for cars, helped develop bicycle and industrial engines and directed upgrading of the model engine lines. The Cox Conquest .15 was the last all-new Atwood design to go into production. Bill retired in 1975, but retained a consultancy relationship with Cox as Conquest production progressed. The Cox Conquest thus became Bill’s final design before he retired. Bill devoted his few remaining years to R/C glider design and flying. He was thus active as a competition pacesetter until his rather untimely death at age 67 on April 28, 1978, 50 years after he built his first engine. His genius, influence and contributions had been felt by three generations of modellers. He richly deserved his induction into the AMA Hall of Fame in 1982. ____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published March 2018

|

| |

Few individuals who take a serious interest in classic model engines will not have some degree of familiarity with the name of Bill Atwood. For a full half-century Bill was one of the most prolific and inventive figures in the field of model engine design and manufacture. The listing of the engines with which he was involved in his own right occupies over 8 pages in Tim Dannel’s indispensable “

Few individuals who take a serious interest in classic model engines will not have some degree of familiarity with the name of Bill Atwood. For a full half-century Bill was one of the most prolific and inventive figures in the field of model engine design and manufacture. The listing of the engines with which he was involved in his own right occupies over 8 pages in Tim Dannel’s indispensable “ Before getting started on this article, it's both my duty and my very sincere pleasure to make one very important acknowledgement. Original examples of the Crown Champion models are very rare indeed today, to the point that my chances of obtaining access to such examples for photographic and/or testing purposes were somewhere between slim and nil. This is where my valued friend and colleague Don Sohn of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, USA stepped into the information vacuum.

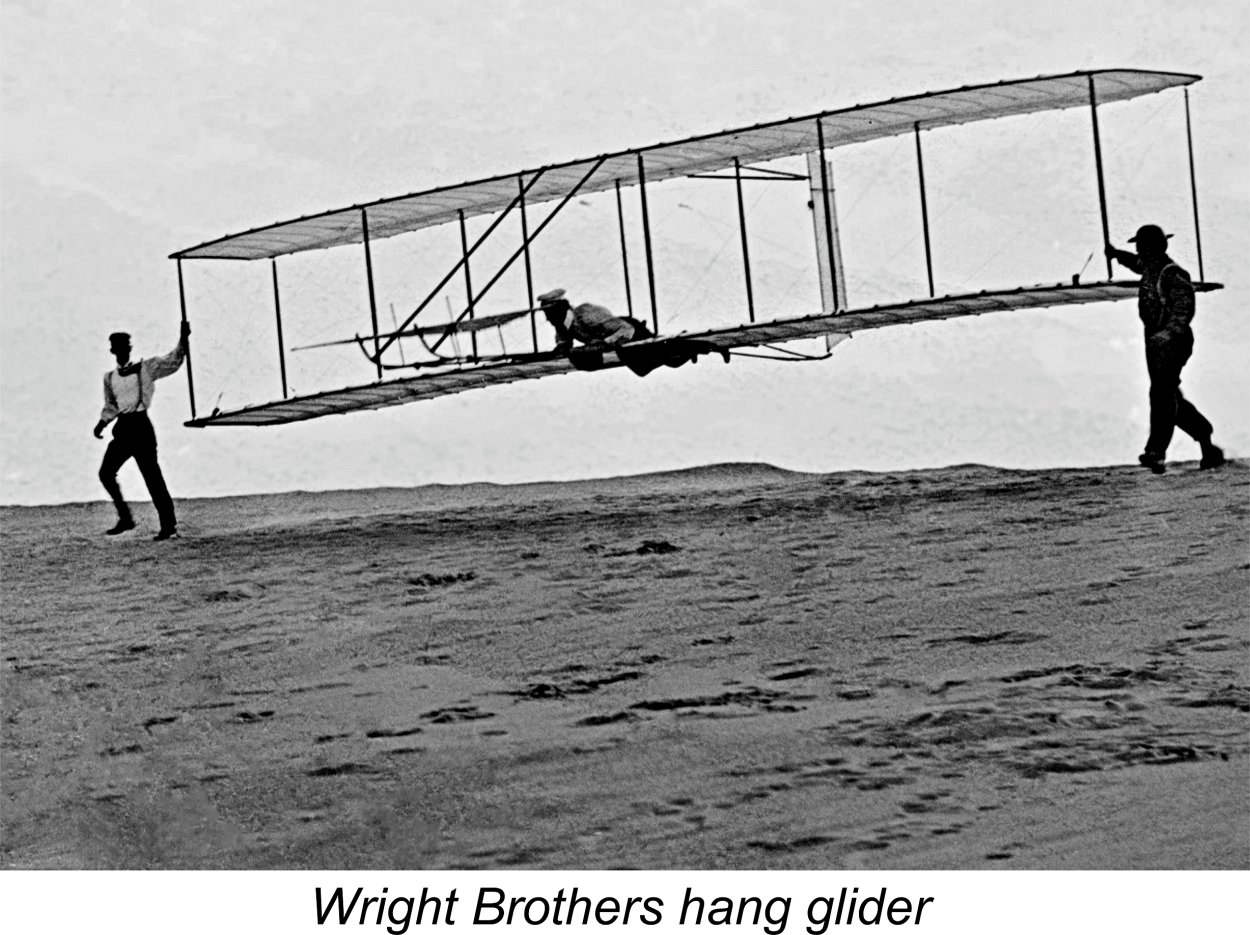

Before getting started on this article, it's both my duty and my very sincere pleasure to make one very important acknowledgement. Original examples of the Crown Champion models are very rare indeed today, to the point that my chances of obtaining access to such examples for photographic and/or testing purposes were somewhere between slim and nil. This is where my valued friend and colleague Don Sohn of Oshkosh, Wisconsin, USA stepped into the information vacuum.  Although Bill had other interests, flight soon became the chief one. His early interest in aviation was first manifested when in 1925 at the age of 15 he constructed a 20 foot wingspan Wright Brothers hang-glider, which he flew with the Riverside Glider Club (and you thought that hang-gliding was a relatively recent sport!).

Although Bill had other interests, flight soon became the chief one. His early interest in aviation was first manifested when in 1925 at the age of 15 he constructed a 20 foot wingspan Wright Brothers hang-glider, which he flew with the Riverside Glider Club (and you thought that hang-gliding was a relatively recent sport!).

However, that was just one event. At other contests, Bill’s little engine performed very well indeed, enabling him to win the California State Free Flight Power Championship in both 1934 and 1935. These successes did not go un-noticed. Among those who took a close interest was a certain

However, that was just one event. At other contests, Bill’s little engine performed very well indeed, enabling him to win the California State Free Flight Power Championship in both 1934 and 1935. These successes did not go un-noticed. Among those who took a close interest was a certain  The commercial rendition of Bill’s engine was christened the Baby Cyclone, a name very familiar to connoisseurs of classic spark ignition powerplants. Although ostensibly manufactured at Moseley’s Glendale plant, in reality much of the machining work was actually carried out under contract by the Automatic Screw Machine Company on Gage Avenue in Los Angeles. However, the fitting, assembly, testing and packaging were carried out at Moseley’s facility along with some machining.

The commercial rendition of Bill’s engine was christened the Baby Cyclone, a name very familiar to connoisseurs of classic spark ignition powerplants. Although ostensibly manufactured at Moseley’s Glendale plant, in reality much of the machining work was actually carried out under contract by the Automatic Screw Machine Company on Gage Avenue in Los Angeles. However, the fitting, assembly, testing and packaging were carried out at Moseley’s facility along with some machining.  Previous Atwood biographers have cited Bill’s target as the beating of a “world record” supposedly held as of 1938 by one “Zukor” of France at 31 mph. First off, I can find no record of any leading French contender of that name in France at the time. I consulted on this matter with my very knowledgeable friend and colleague Hugh Blowers, who along with his wife Lynn maintains the previously-cited “

Previous Atwood biographers have cited Bill’s target as the beating of a “world record” supposedly held as of 1938 by one “Zukor” of France at 31 mph. First off, I can find no record of any leading French contender of that name in France at the time. I consulted on this matter with my very knowledgeable friend and colleague Hugh Blowers, who along with his wife Lynn maintains the previously-cited “ Bill’s new design was a stunning success. In 1938, after fully sorting it out and designing a suitable lightweight balsa and plywood hull for it (he was an aeromodeller who built light, remember!), Bill achieved officially-timed runs at 44 mph for the ¼ mile distance and 38 mph for the full mile, claiming both marks as new 15 cc World Records (which under his criteria they probably were!). Bill actually raised his own mile record to 39.24 mph at a later date.

Bill’s new design was a stunning success. In 1938, after fully sorting it out and designing a suitable lightweight balsa and plywood hull for it (he was an aeromodeller who built light, remember!), Bill achieved officially-timed runs at 44 mph for the ¼ mile distance and 38 mph for the full mile, claiming both marks as new 15 cc World Records (which under his criteria they probably were!). Bill actually raised his own mile record to 39.24 mph at a later date.  1938 was a pivotal year for Bill Atwood in more ways than one, because it was also in that year that he left Moseley and Aircraft Industries Corporation to go to work for the Automatic Screw Machine Company in Los Angeles. He was soon joined there by another of his former colleagues at Moseley’s operation, namely Ira Hassad.

1938 was a pivotal year for Bill Atwood in more ways than one, because it was also in that year that he left Moseley and Aircraft Industries Corporation to go to work for the Automatic Screw Machine Company in Los Angeles. He was soon joined there by another of his former colleagues at Moseley’s operation, namely Ira Hassad.  While working for his new employers, Bill continued on the side to offer casting kits for his record-breaking 15 cc boat motor along with plans for the matching record-breaking hydroplane which he had also designed. However, a new market area was now just beginning to loom larger on the horizon. Primarily thanks to the efforts of a pioneering group of Los Angeles area enthusiasts which included the

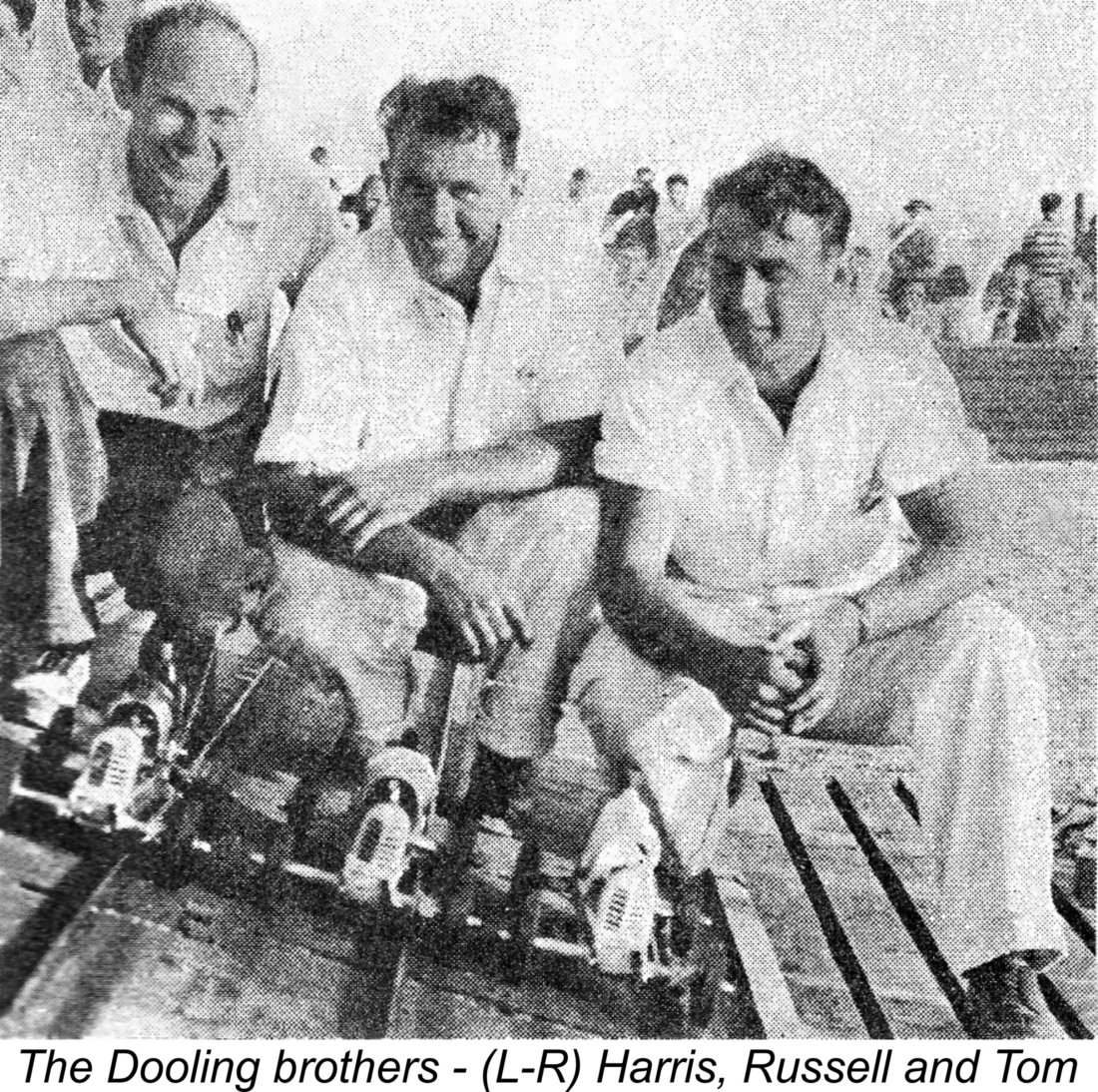

While working for his new employers, Bill continued on the side to offer casting kits for his record-breaking 15 cc boat motor along with plans for the matching record-breaking hydroplane which he had also designed. However, a new market area was now just beginning to loom larger on the horizon. Primarily thanks to the efforts of a pioneering group of Los Angeles area enthusiasts which included the  The success achieved by these engines naturally created a demand which Bill was anxious to fill. It appears that Phantom Motors wasn’t interested in producing these units, because Bill undertook the manufacture of this series independently, beginning in early 1940 to market the engines under the trade name of the Champion Products Co. of Glendale, California. Bill’s exact role with respect to this company’s manufacturing activities is now unclear – it may well have simply represented a new name for the products of his own workshop, a notion supported by the fact that Bill clearly owned the Champion name, continuing to use it right up to 1948. That said, the possibility undeniably exists that it may represent a completely different manufacturer working in association with Bill. Regardless, it was only at this point that Bill began to apply the Crown Champion name to the engines.

The success achieved by these engines naturally created a demand which Bill was anxious to fill. It appears that Phantom Motors wasn’t interested in producing these units, because Bill undertook the manufacture of this series independently, beginning in early 1940 to market the engines under the trade name of the Champion Products Co. of Glendale, California. Bill’s exact role with respect to this company’s manufacturing activities is now unclear – it may well have simply represented a new name for the products of his own workshop, a notion supported by the fact that Bill clearly owned the Champion name, continuing to use it right up to 1948. That said, the possibility undeniably exists that it may represent a completely different manufacturer working in association with Bill. Regardless, it was only at this point that Bill began to apply the Crown Champion name to the engines.  The 10 cc Blue Crown Champion was the first model to be released by Champion Products, along with the 15 cc Silver Crown Champion in casting kit form. This took place in March 1940. The Blue Crown Champion was soon joined by a simplified version of the same engine called the Red Crown Champion. This dispensed with the RDV induction system, retaining only the FRV induction. It was an "economy" model which was also intended for model car applications. Atwood designed a series of three different model cars to utilize these powerplants, which were also advertised by Champion Products.

The 10 cc Blue Crown Champion was the first model to be released by Champion Products, along with the 15 cc Silver Crown Champion in casting kit form. This took place in March 1940. The Blue Crown Champion was soon joined by a simplified version of the same engine called the Red Crown Champion. This dispensed with the RDV induction system, retaining only the FRV induction. It was an "economy" model which was also intended for model car applications. Atwood designed a series of three different model cars to utilize these powerplants, which were also advertised by Champion Products.  This is the model which laid the foundation of the Crown Champion series with which we are primarily concerned here. An

This is the model which laid the foundation of the Crown Champion series with which we are primarily concerned here. An  Internally, the engine’s nominal bore and stroke were 1.000 in. (25.4 mm) and 1.125 in. (28.58 mm) respectively for an actual displacement of 0.884 cuin. (14.48 cc), although the displacement was always cited as 15 cc. A cast alloy piston having two rings was used. The twin shafts were each supported by single ball races at their inner ends, the outer ends running in plain bearings.

Internally, the engine’s nominal bore and stroke were 1.000 in. (25.4 mm) and 1.125 in. (28.58 mm) respectively for an actual displacement of 0.884 cuin. (14.48 cc), although the displacement was always cited as 15 cc. A cast alloy piston having two rings was used. The twin shafts were each supported by single ball races at their inner ends, the outer ends running in plain bearings.  Don’s replica has the flywheel mounted at the front, which keeps it clear of the exhaust stacks. This orientation unquestionably makes the use of a starting cord far more convenient, at the expense of somewhat encumbering access to the timer. Nonetheless, if I were planning to actually use the engine, this would certainly be my personal choice. The example illustrated in the previously-reproduced Atwood Champion promotional sheet has its flywheel mounted at the rear between the stacks, as seen at the left. It's interesting to note that this example is missing its timer, the vacant boss for which can be seen to the right in the image!

Don’s replica has the flywheel mounted at the front, which keeps it clear of the exhaust stacks. This orientation unquestionably makes the use of a starting cord far more convenient, at the expense of somewhat encumbering access to the timer. Nonetheless, if I were planning to actually use the engine, this would certainly be my personal choice. The example illustrated in the previously-reproduced Atwood Champion promotional sheet has its flywheel mounted at the rear between the stacks, as seen at the left. It's interesting to note that this example is missing its timer, the vacant boss for which can be seen to the right in the image!

The main operational challenge which the dual intake system poses is one of balancing them. Bill Atwood very thoughtfully made provision for a progressive approach to this issue. The intake at the timer end of the engine (opposite the flywheel) is provided with a leaf spring-tensioned rotary barrel restrictor which can be adjusted to restrict the intake area at that end to any desired degree, from fully open (horizontal) to fully closed (vertical). In effect, this is a form of barrel throttle without the fuel mixture adjustment – all it does is restrict the inflow of air to any desired extent.

The main operational challenge which the dual intake system poses is one of balancing them. Bill Atwood very thoughtfully made provision for a progressive approach to this issue. The intake at the timer end of the engine (opposite the flywheel) is provided with a leaf spring-tensioned rotary barrel restrictor which can be adjusted to restrict the intake area at that end to any desired degree, from fully open (horizontal) to fully closed (vertical). In effect, this is a form of barrel throttle without the fuel mixture adjustment – all it does is restrict the inflow of air to any desired extent.  The late Ron Chernich considered this question carefully and came up with one possible reason for Atwood’s design choice. The crankshaft diameter shown on the plan is 0.436 in. with an internal gas passage diameter of 0.282 in. (9/32 in. assumed - the plan is unclear on this). That means that the crankshaft walls are only 0.077 in. thick at the highly stressed end near the crankweb – a bit marginal for an engine of this size, certainly offering no scope for enlargement of the gas passage.

The late Ron Chernich considered this question carefully and came up with one possible reason for Atwood’s design choice. The crankshaft diameter shown on the plan is 0.436 in. with an internal gas passage diameter of 0.282 in. (9/32 in. assumed - the plan is unclear on this). That means that the crankshaft walls are only 0.077 in. thick at the highly stressed end near the crankweb – a bit marginal for an engine of this size, certainly offering no scope for enlargement of the gas passage.  Ron then asked himself whether the same effect could have been achieved more simply by using a larger diameter crankshaft, allowing the use of a larger gas passage and a single intake? Well, of course! The total gas passage area provided by the two shafts combined is 0.124 square inches. If we maintain the same 0.077 inch wall thickness, the larger shaft would need to be 0.553 inches in diameter to provide an internal gas passage diameter of 0.399 inch, which has the same area as that of the two shafts actually used.

Ron then asked himself whether the same effect could have been achieved more simply by using a larger diameter crankshaft, allowing the use of a larger gas passage and a single intake? Well, of course! The total gas passage area provided by the two shafts combined is 0.124 square inches. If we maintain the same 0.077 inch wall thickness, the larger shaft would need to be 0.553 inches in diameter to provide an internal gas passage diameter of 0.399 inch, which has the same area as that of the two shafts actually used.

The Blue Riband category in car racing at the time was the 10 cc class. As of 1939 the

The Blue Riband category in car racing at the time was the 10 cc class. As of 1939 the  It’s clear that Bill continued to see merit in the dual intake system pioneered in the Silver Crown, because the Blue Crown Champion was basically a somewhat simplified and scaled-down version of the earlier model. It retained the Silver Crown’s dual intake valves, although the arrangement of these two valves differed somewhat and the barrel restrictor on one intake which had been a feature of the Silver Crown was omitted. The “front” intake on the main crankshaft at the flywheel/timer end was of updraft pattern, while the “rear” drum valve was of downdraft configuration. Each of these intakes had its own independent needle valve and fuel supply with no supplementary restrictor.

It’s clear that Bill continued to see merit in the dual intake system pioneered in the Silver Crown, because the Blue Crown Champion was basically a somewhat simplified and scaled-down version of the earlier model. It retained the Silver Crown’s dual intake valves, although the arrangement of these two valves differed somewhat and the barrel restrictor on one intake which had been a feature of the Silver Crown was omitted. The “front” intake on the main crankshaft at the flywheel/timer end was of updraft pattern, while the “rear” drum valve was of downdraft configuration. Each of these intakes had its own independent needle valve and fuel supply with no supplementary restrictor.  All of the original Crown Champion engines except for the Silver Crown were identified by a very classy little bronze emblem which was riveted to the crankcase on the bypass side. This emblem stated that the engines were “Engineered by Bill Atwood”, also bearing the name of the Champion Products Co. along with their Glendale, California location. This is perhaps the most challenging component of them all to replicate. Don Sohn has done a superb job with his fine replica engines. The illustrated example at the left is original, being photographed on Don Sohn’s previously-illustrated original Atwood Blue Crown Champion.

All of the original Crown Champion engines except for the Silver Crown were identified by a very classy little bronze emblem which was riveted to the crankcase on the bypass side. This emblem stated that the engines were “Engineered by Bill Atwood”, also bearing the name of the Champion Products Co. along with their Glendale, California location. This is perhaps the most challenging component of them all to replicate. Don Sohn has done a superb job with his fine replica engines. The illustrated example at the left is original, being photographed on Don Sohn’s previously-illustrated original Atwood Blue Crown Champion.

The Blue Crown Champion sold for a price of $22.50 in basic ready-to-run form, or $23.95 as a complete package with coil and condenser. By 1940 standards these were quite high prices. Seeing a market for a lower-priced alternative, Bill quickly developed a simplified version of the engine which dispensed with the rear drum valve of the Blue Crown in favor of a conventional bolt-on backplate. This was the Red Crown Champion, which was also intended from the outset to serve as a car powerplant. It was offered at a basic price of $16.75, with the complete package including coil and condenser being advertised at $18.20.

The Blue Crown Champion sold for a price of $22.50 in basic ready-to-run form, or $23.95 as a complete package with coil and condenser. By 1940 standards these were quite high prices. Seeing a market for a lower-priced alternative, Bill quickly developed a simplified version of the engine which dispensed with the rear drum valve of the Blue Crown in favor of a conventional bolt-on backplate. This was the Red Crown Champion, which was also intended from the outset to serve as a car powerplant. It was offered at a basic price of $16.75, with the complete package including coil and condenser being advertised at $18.20.  would certainly simplify operation to a significant degree. The only other visible change was the use of a different exhaust stack having a rectangular section instead of the aerofoil shape used on the Blue Crown. In all other respects, the Red Crown Champion was identical to the Blue Crown.

would certainly simplify operation to a significant degree. The only other visible change was the use of a different exhaust stack having a rectangular section instead of the aerofoil shape used on the Blue Crown. In all other respects, the Red Crown Champion was identical to the Blue Crown.

The Green Crown Champion was in effect nothing more than a Red Crown Champion with the flywheel replaced by a prop driver and a fuel tank added to the backplate. It retained the single updraft intake of its car-racing companion, also sharing the same bore and stroke dimensions. It also reverted to the aerofoil exhaust stack of the Blue Crown as opposed to the Red Crown’s rectangular-section stack.

The Green Crown Champion was in effect nothing more than a Red Crown Champion with the flywheel replaced by a prop driver and a fuel tank added to the backplate. It retained the single updraft intake of its car-racing companion, also sharing the same bore and stroke dimensions. It also reverted to the aerofoil exhaust stack of the Blue Crown as opposed to the Red Crown’s rectangular-section stack.  The fifth and final member of the Crown Champion series was the .604 cuin. (10 cc) Purple Crown hydroplane engine which was announced in April 1940 along with its Red Crown and Green Crown companions. It was basically a downsized and somewhat simplified version of the 15 cc Silver Crown. Bore and stroke matched those of the other .604 cuin. Crown models.

The fifth and final member of the Crown Champion series was the .604 cuin. (10 cc) Purple Crown hydroplane engine which was announced in April 1940 along with its Red Crown and Green Crown companions. It was basically a downsized and somewhat simplified version of the 15 cc Silver Crown. Bore and stroke matched those of the other .604 cuin. Crown models.

In mid-1945, having split with Wetzel, Bill set up shop in the Ace Model Shop in Pasadena, where he produced magnesium-casting Champions under the trade name of Atwood Motors. The Model H had a lapped Meehanite piston and radial fins on the head. The change to Model J entailed streamlined fins on the head, a ringed aluminum piston, and drilled cylinder ports.

In mid-1945, having split with Wetzel, Bill set up shop in the Ace Model Shop in Pasadena, where he produced magnesium-casting Champions under the trade name of Atwood Motors. The Model H had a lapped Meehanite piston and radial fins on the head. The change to Model J entailed streamlined fins on the head, a ringed aluminum piston, and drilled cylinder ports.  The Adams-Atwood partnership did not last long either. Its dissolution resulted in the re-establishment of Atwood Motors at 734 North Lake Avenue in Burbank, at first selling Super Champions and then their Glo-Devil successors. A detailed article covering the later Atwood Champions will be found elsewhere on this website in due course.

The Adams-Atwood partnership did not last long either. Its dissolution resulted in the re-establishment of Atwood Motors at 734 North Lake Avenue in Burbank, at first selling Super Champions and then their Glo-Devil successors. A detailed article covering the later Atwood Champions will be found elsewhere on this website in due course.  It's worth recalling at this point that O.S. had in fact succeeded in selling a few engines in the USA prior to WW2 getting in the way. So this scenario would have made perfect sense in the context of an attempt by Ogawa to resume a commercial activity that had been rudely interrupted by the war. And it's an established fact that Atwood did assist Ogawa on the post-war marketing side in the USA, to the extent that Atwood's name appeared cast in relief onto the cases of the of the 1953 O.S. "New 36" twin-stack model, which was specifically aimed at the US market.

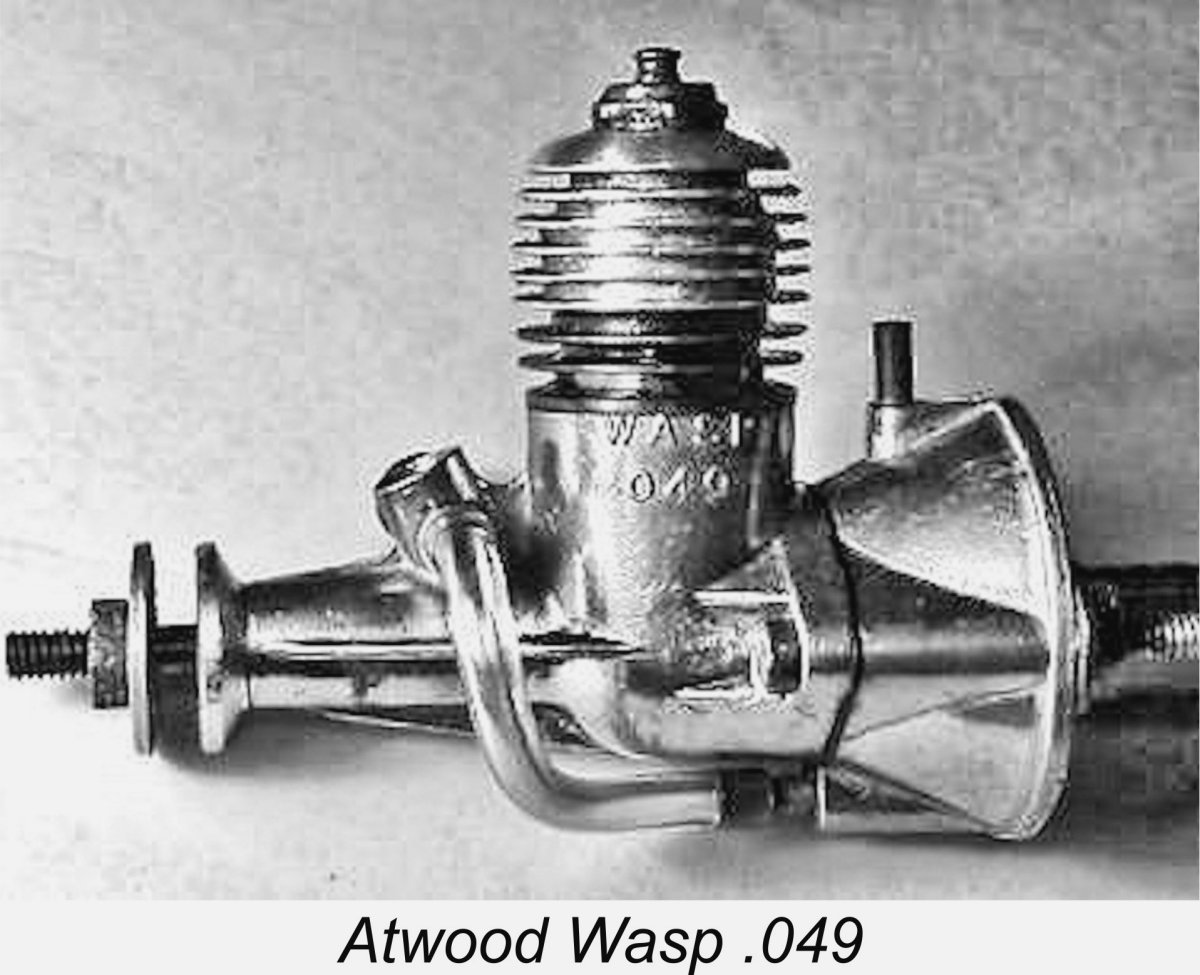

It's worth recalling at this point that O.S. had in fact succeeded in selling a few engines in the USA prior to WW2 getting in the way. So this scenario would have made perfect sense in the context of an attempt by Ogawa to resume a commercial activity that had been rudely interrupted by the war. And it's an established fact that Atwood did assist Ogawa on the post-war marketing side in the USA, to the extent that Atwood's name appeared cast in relief onto the cases of the of the 1953 O.S. "New 36" twin-stack model, which was specifically aimed at the US market. began thinking “small” in order to appeal to the mass market, Atwood included. Bill joined forces with Bob Holland to design and produce the first Wasp .049’s, which were outstanding performers among the 1949 crop of small glow-plug units which quickly appeared to join the K&B offerings. Those engines were later marketed as the Atwood .049.

began thinking “small” in order to appeal to the mass market, Atwood included. Bill joined forces with Bob Holland to design and produce the first Wasp .049’s, which were outstanding performers among the 1949 crop of small glow-plug units which quickly appeared to join the K&B offerings. Those engines were later marketed as the Atwood .049.  In 1953, Bill Atwood and Bob Holland split over divergent production philosophies, with Holland taking the rights to the Wasp. Atwood continued to improve the basic design with improved versions named Atwood, Cadet, and Signature – all in .049 and .051 sizes. He made a .15 prototype, but its power was not competitive and none were produced for sale. During 1953 Bill also introduced the O.S. line of Japanese glow engines to the USA.

In 1953, Bill Atwood and Bob Holland split over divergent production philosophies, with Holland taking the rights to the Wasp. Atwood continued to improve the basic design with improved versions named Atwood, Cadet, and Signature – all in .049 and .051 sizes. He made a .15 prototype, but its power was not competitive and none were produced for sale. During 1953 Bill also introduced the O.S. line of Japanese glow engines to the USA.