|

|

Tokyo Trendsetters - the Classic 2.5 cc Enya 15D Diesels

I’ve covered the history of the early years of the Enya model engine manufacturing enterprise in a separate article to be found on this website. I do not intend to repeat any of that material here - my focus will be directed towards the diesel models manufactured by Enya during the classic era. Before getting started on my task, I wish to pay tribute to Bob Allan of Australia and Pat King of the USA, both of whom are dyed-in-the-wool Enya enthusiasts (aka Enya-philes!) with a vast store of knowledge and experience in connection with this famous range. They were both extremely generous in providing a great deal of the background material upon which this and other Enya articles are based, also reviewing and commenting upon the draft texts of my various Enya summaries. With that pleasant duty fulfilled, let's get down to it ................!! Development of the Concept

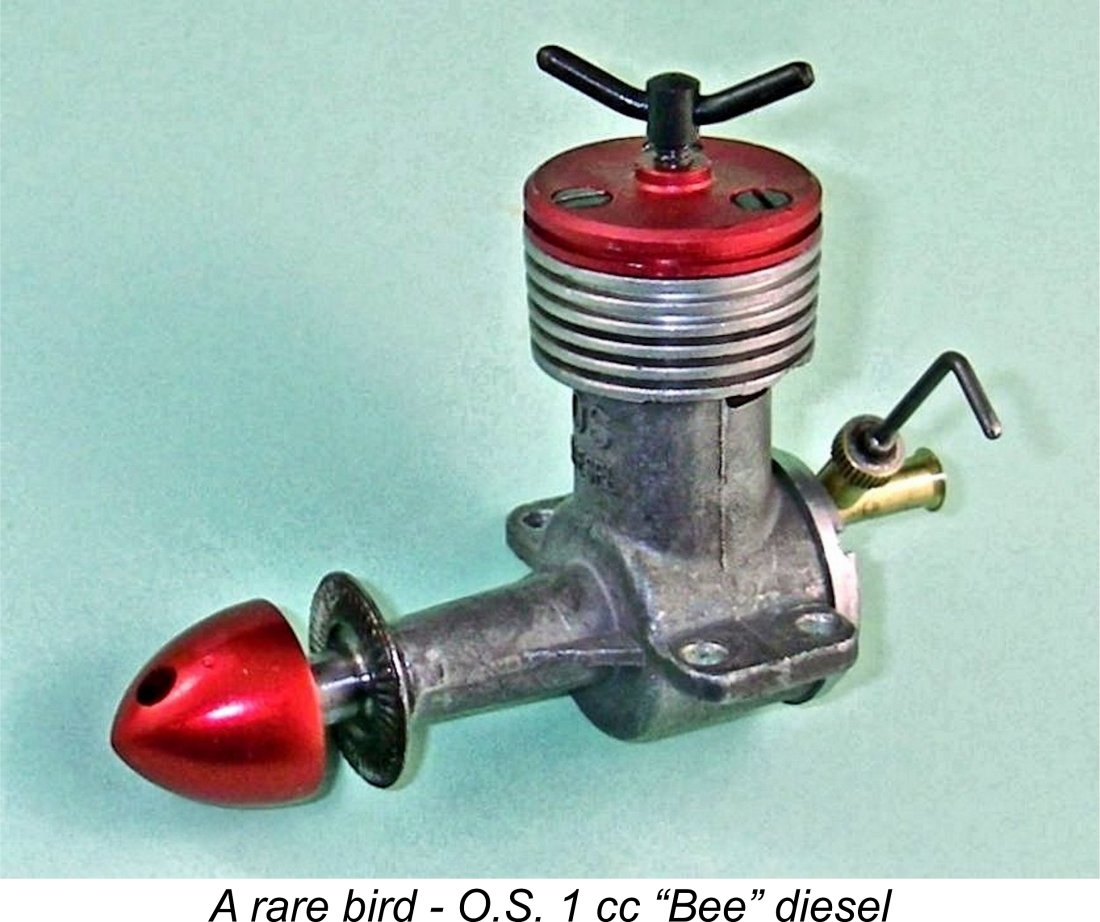

An underlying factor which very likely contributed was the doubtless mutually respectful but nonetheless intense technological and commercial rivalry which had developed over the years between Enya and their Osaka-based competitors over at O.S. During the early 1950’s, Shigeo Ogawa of O.S. had already tried his hand at producing a diesel model, the 1 cc O.S. “Bee”. This was a close copy of the Series 1 E.D. Mk. I Bee which had appeared in England in mid 1948. Although very well executed, the O.S. rendition of the early ‘50’s had attracted very little sales attention, hence being withdrawn after only some 500 examples had been made. A full review and test of this very rare model may be found elsewhere on this website.

The FAI’s 1955 adoption of the 2.5 cc displacement limit for all International power competitions (excluding control line stunt and R/C) had placed that displacement category at the centre of the design thinking of model engine manufacturers worldwide. Enya’s chief designer Saburo Enya was by no means immune from the attraction of this category. A 2.5 cc diesel of reasonable weight and adequate performance would be competitive in both the FAI free flight power and control-line team race classes. Enya set out to develop just such a model, with the clear intention of beating their O.S. rivals to the punch!

When considering the creation of a diesel to supplement an existing glow-plug model in a given range (or vice versa) any manufacturer could be forgiven for looking first at the possibility of simply grafting a different ignition system onto basically the existing model, thus avoiding a great deal of development and re-tooling work. A number of British manufacturers followed this route, notably AMCO, K, D-C, E.D., J.B. and IMA (FROG), as did Webra in Germany. The Japanese Mamiya company also adopted this approach in creating .09 and .15 cuin. diesels from their existing glow-plug models. The trouble is that such a conversion really isn’t that straightforward! Apart from the need for structural changes suggested by the far higher stresses generated during diesel operation, the plain fact is that the very different functional characteristics of the two ignition types really require an individual approach to such matters as scavenging and combustion if the best results are to be obtained. Accordingly, during the “classic” era straight conversions between the two ignition types using the same basic design as a basis were seldom completely successful, as a number of British manufacturers and their customers were to learn the hard way. It is thus enormously to Saburo Enya’s credit that when he set out to develop the initial rendition of Enya’s soon-to-be renowned .15 cuin. diesel, he clearly recognized the above impediments to success. He had a very successful .15 cuin. glow-plug model already on the market, and the fact that he decided to start afresh with a clean sheet of paper when designing the companion diesel model is a very real reflection of his maturity as an engine designer. The resulting 2.5 cc diesel engine was completely distinct from the company’s contemporary glow-plug model, featuring an entirely different design layout. In fact, the only common component between the .15 glow and diesel models turned out to be the needle valve assembly!

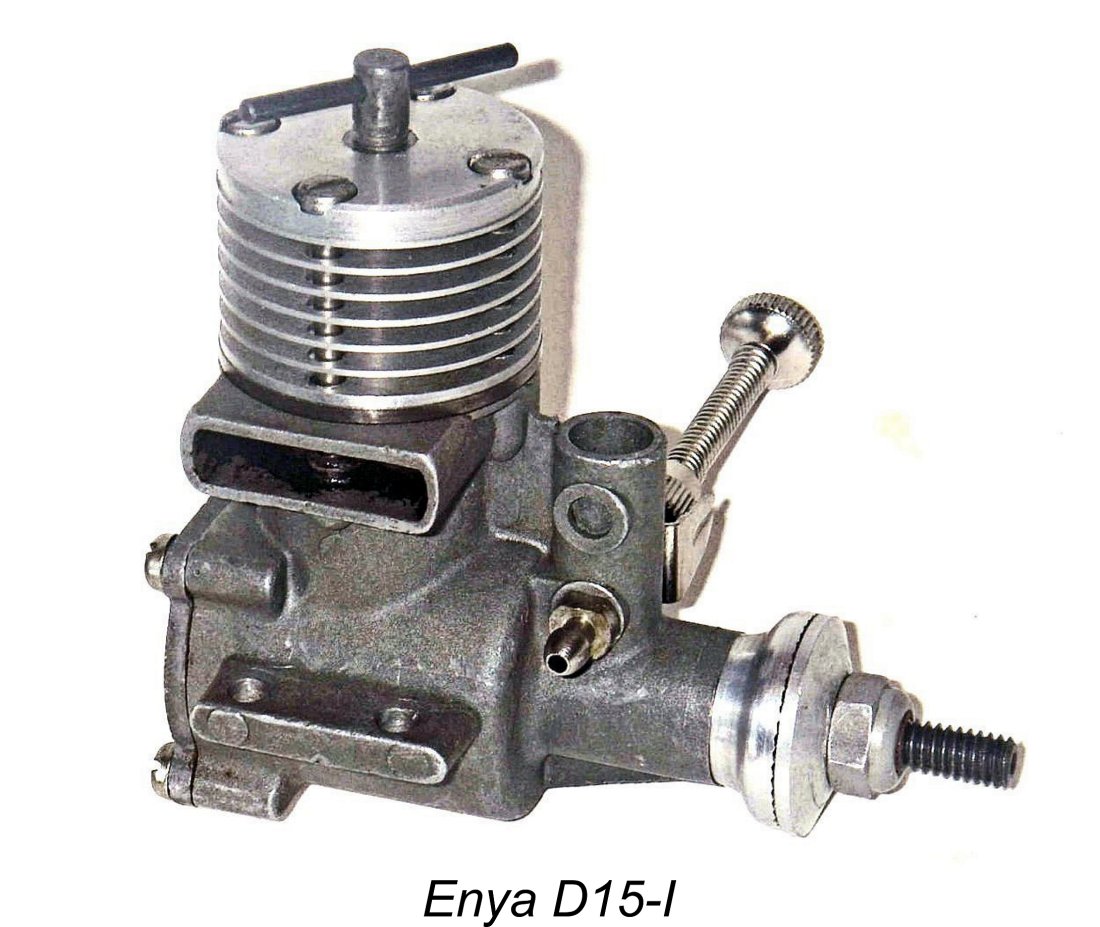

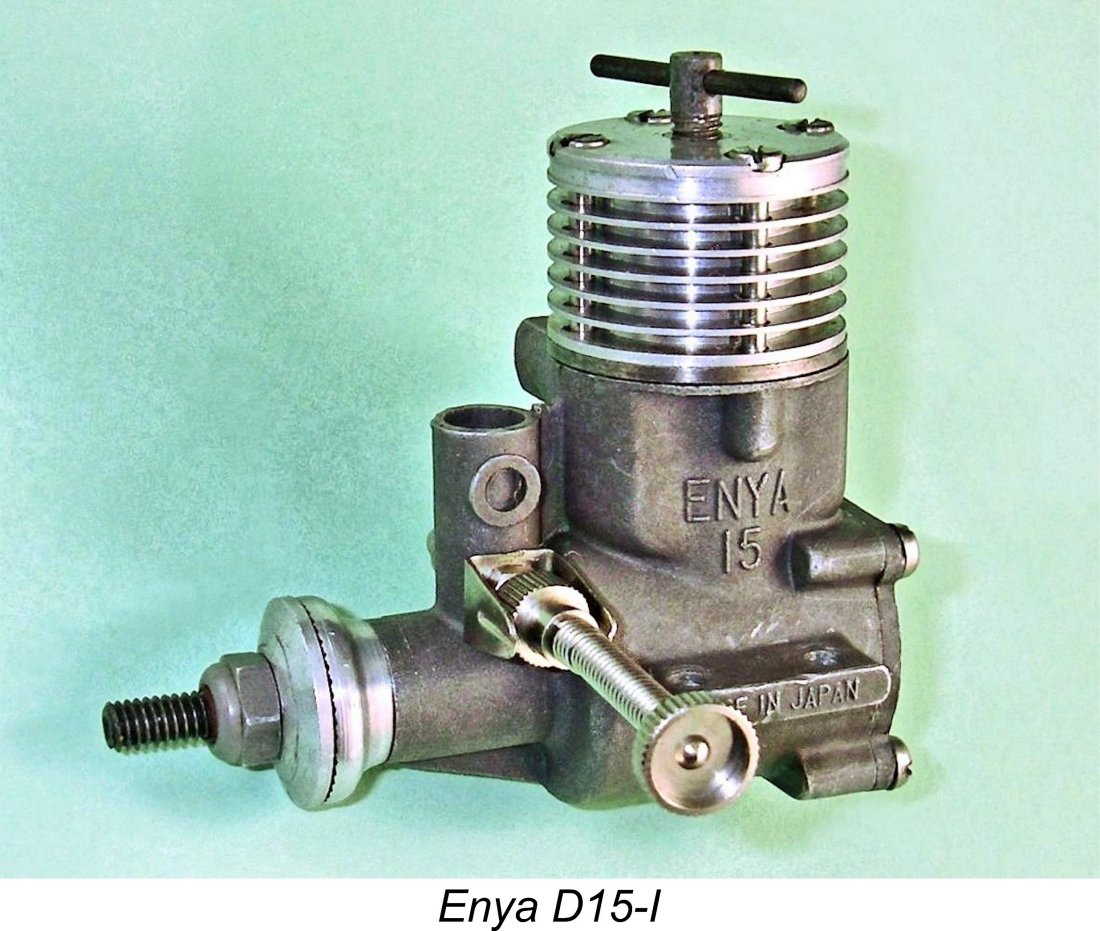

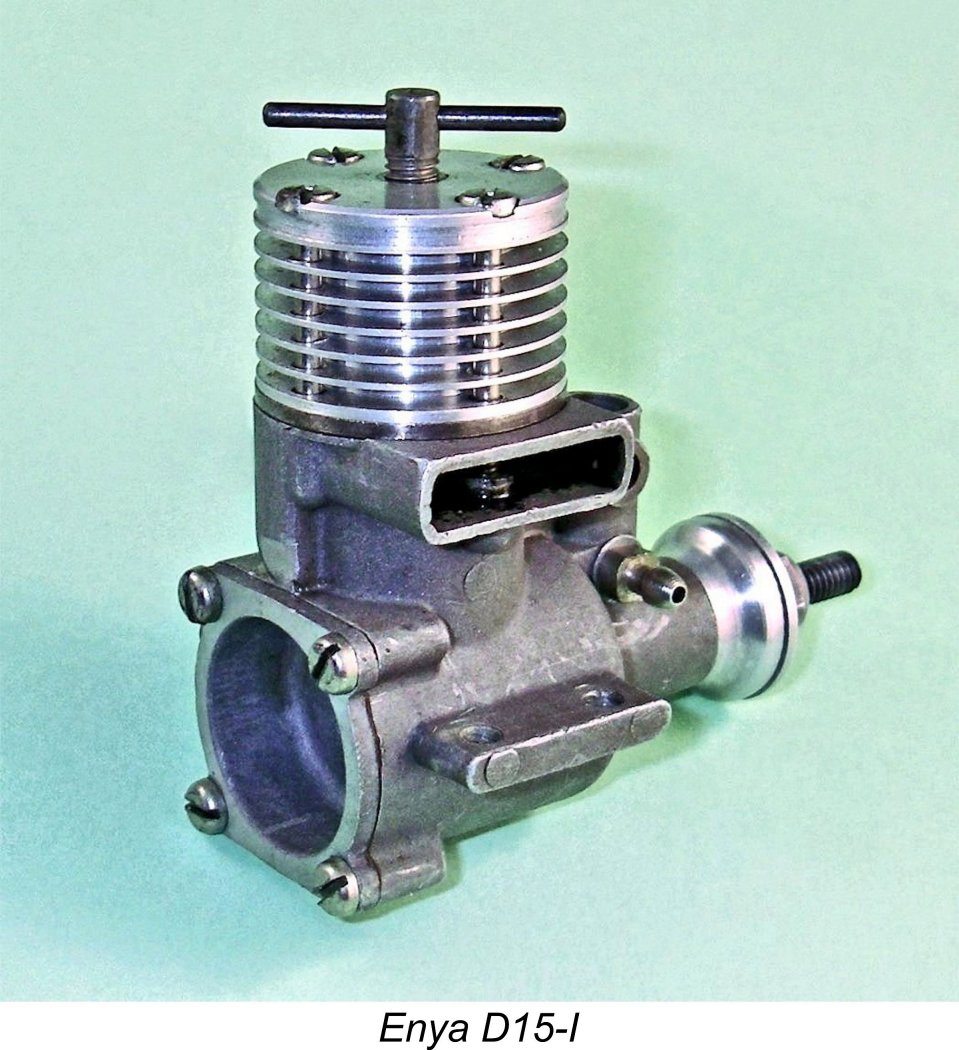

The Enya D15-I Appears The modelling community in the English-speaking world first became aware that Enya were looking at joining the world’s manufacturers of 2.5 cc diesels as a result of Peter Chinn’s mention of such an engine in his “Power Topics” article in the September 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft” magazine. Although it seems likely that Chinn was quite well-informed on the matter, he confined himself in this article (probably written in July 1956) to a statement that “Enya is working on a 2.5 cc diesel of promising design”.

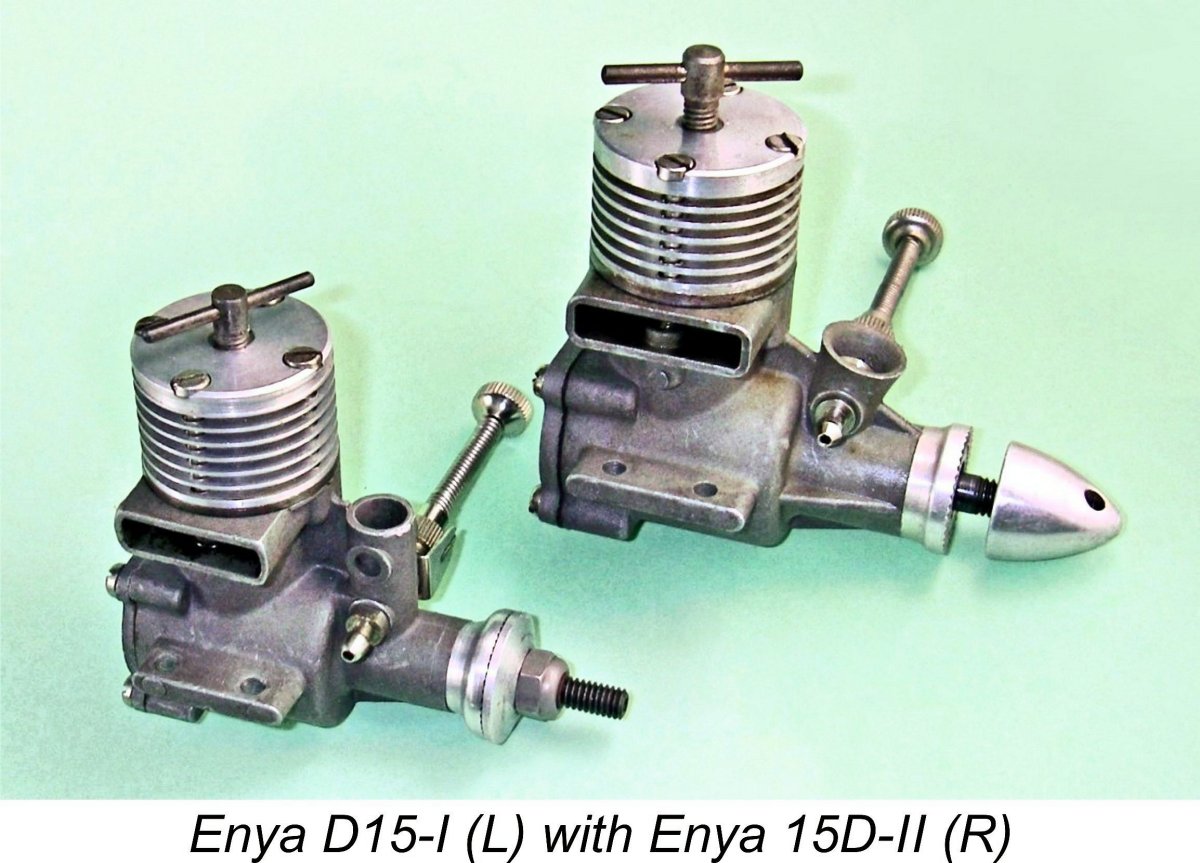

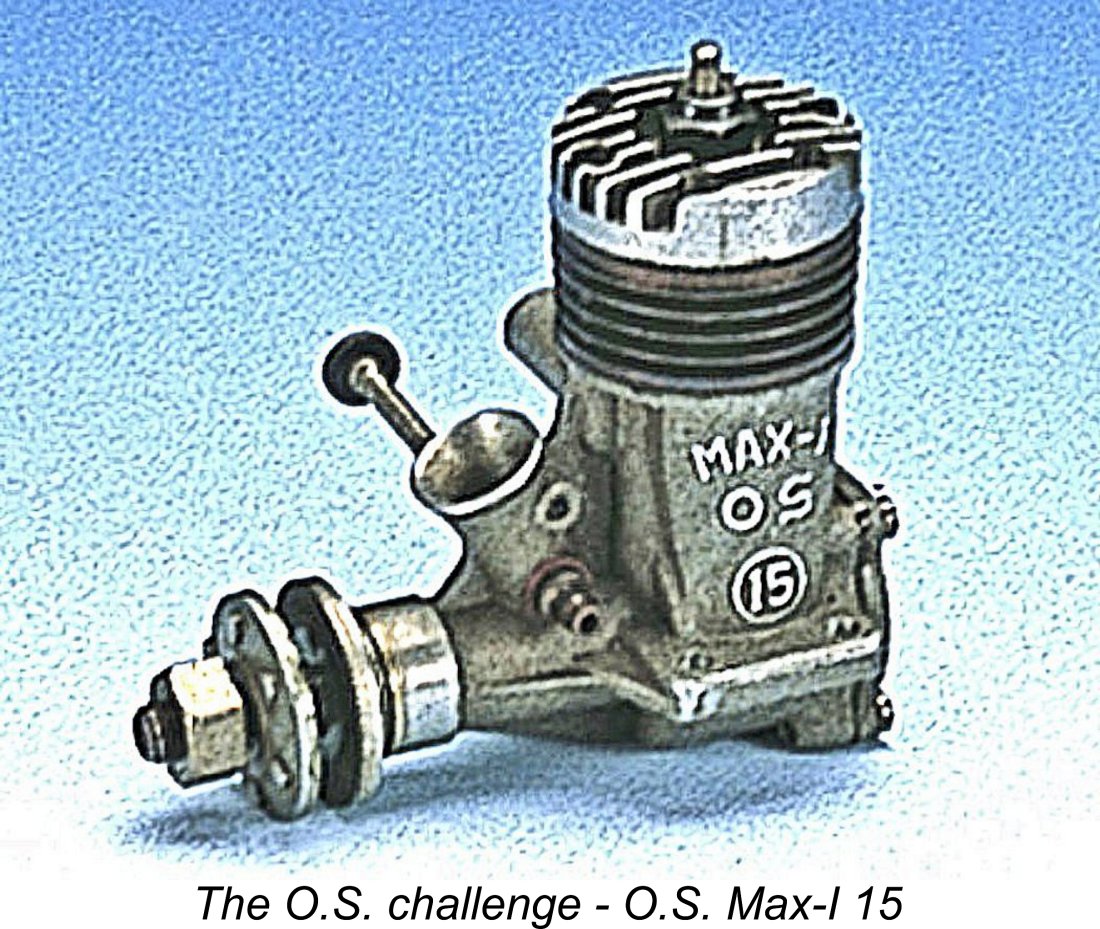

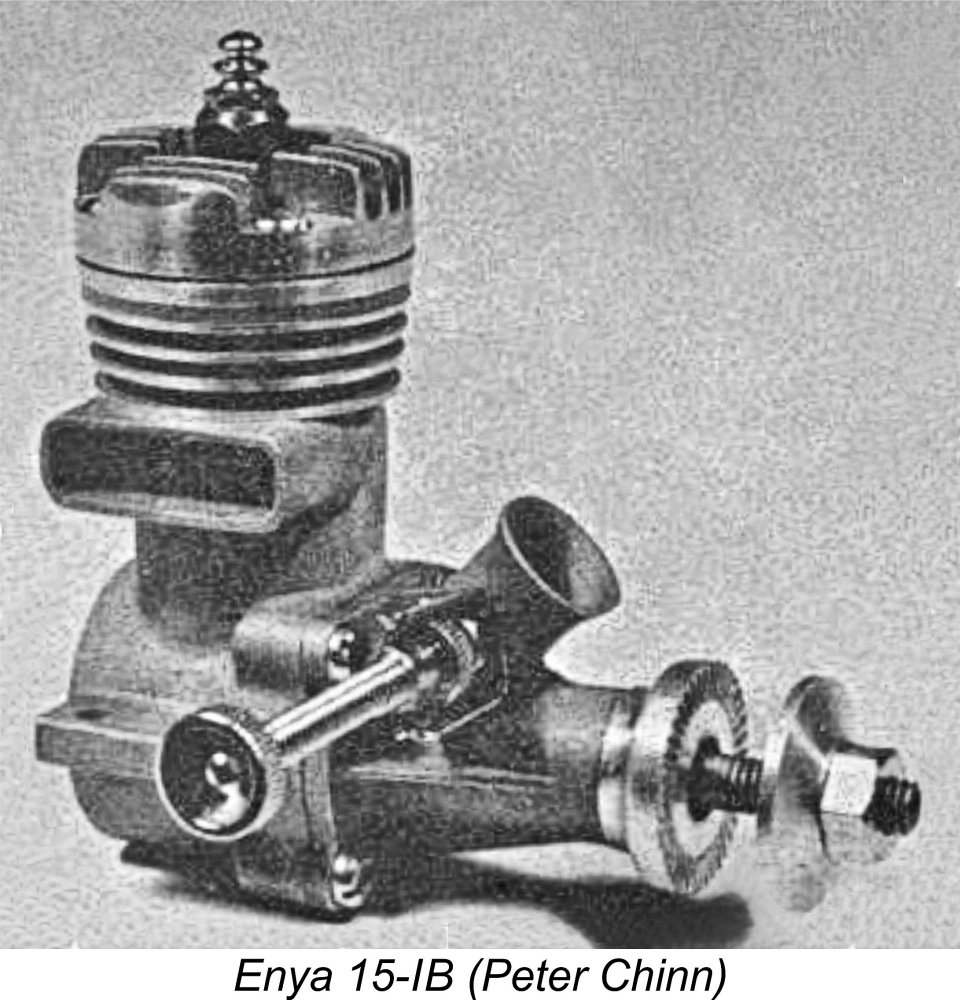

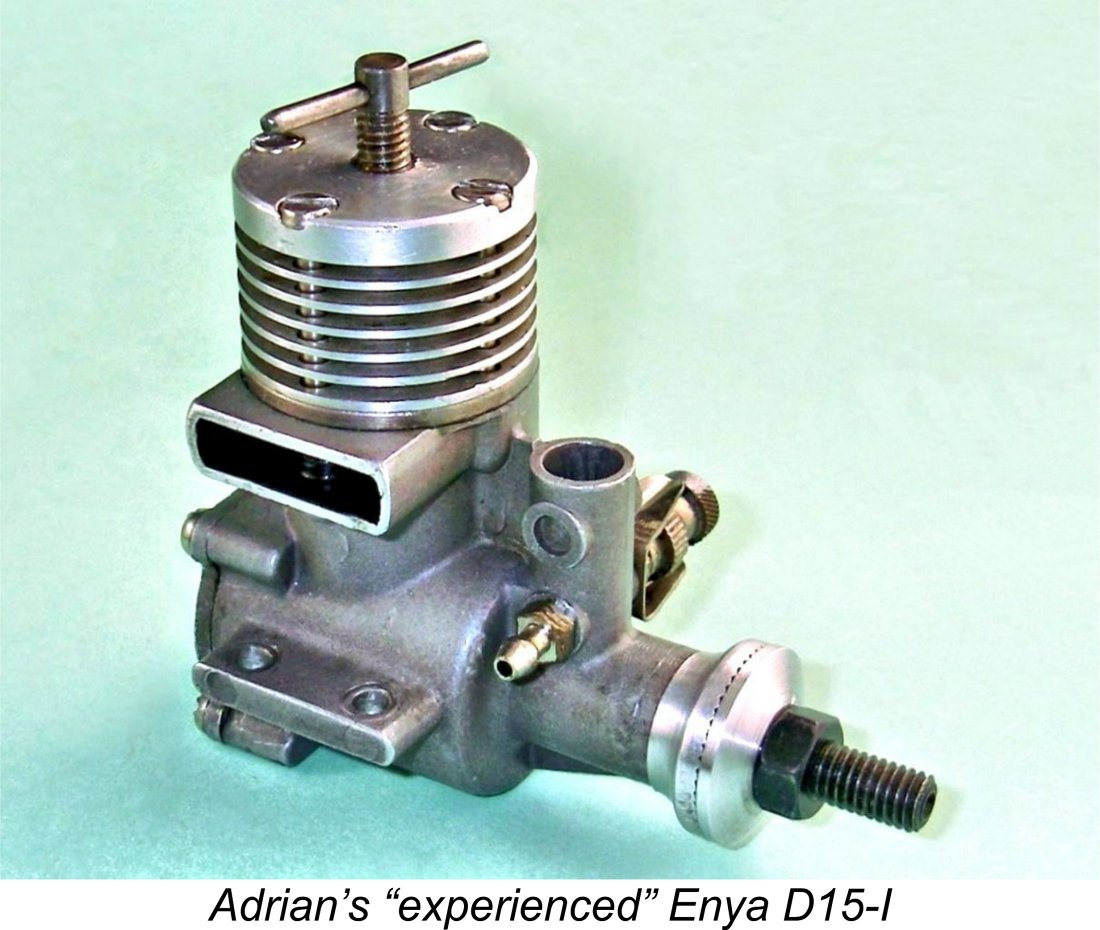

Nominal bore and stroke of the new Enya were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a design displacement of 2.47 cc. The engine weighed 148 gm (5.2 ounces), a very reasonable figure for a high-performance 2.5 cc competition diesel featuring a ball-race crankshaft. The development of this model was a very ambitious and in many ways ground-breaking project. It was the first Enya design to employ a ball race crankshaft (a single ball race at the rear), also breaking tradition among diesel designs of the day with its then-unique scavenging set-up. This involved the use of a single rectangular transfer port located opposite the single exhaust port in typical loop-scavenged glow-motor fashion. So far, so good, but the fact that this was a diesel created obstacles to the provision of an upstanding baffle to prevent short-circuiting of incoming mixture straight out the exhaust. The best that could be done was to apply a conical profile to the piston crown. Clearly this wouldn’t be enough to prevent short-circuiting of incoming mixture if conventional cross-flow loop scavenging was employed. The really ingenious feature of the porting arrangements was the fact that Another innovation with this motor was the provision made on the vertical intake for the fitting of 2 needle valve assemblies, one above the other. By setting one for optimum performance and the other to run rich, a crude form of 2-speed control could be obtained for those enthusiasts who were attracted by the early “steam powered” radio control (R/C) systems of the day. The rest of the engine was more or less conventional. The counterbalanced crankshaft was supported in a single ball-race at the rear and a bronze bushing at the front. The crankshaft’s main journal diameter was a The decision to use a single ball-race at the rear of the main crankshaft journal provided further evidence of Saburo Enya’s comprehensive grasp of his business. He had clearly recognized the fact that a front ball-race would contribute relatively little to performance, mainly adding weight, bulk, complexity and cost to an engine intended for series production at a competitive price. A quality ball-race at the heavily-loaded rear combined with a well-fitted bronze bushing at the more lightly-loaded front would perform at a whisker-close level compared with a twin ball-race setup for the same engine. P.A.W. were quick to follow the Enya lead when designing their own 2.5 cc “Special” model of 1957, as Naturally enough given their well-established rivalry, the O.S. company of Osaka immediately took note of the Enya diesel initiative. They were always quick to cover the moves of their Tokyo rivals (and vice versa!), promptly commencing the development of their own 2.5 cc contest diesel. However, for a variety of reasons the appearance of the resulting O.S. Max-D 15 was delayed until the latter part of 1959, by which time it had really missed the boat, never posing a real challenge to the Enya product and being withdrawn from production relatively quickly. I’ve covered the somewhat unhappy story of the O.S. Max-D 15 in a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website. Returning to the Enya D15-I, the unique features of that design made modellers all over the world very keen to learn how it performed. They didn’t have long to wait ………… The Enya D15-1 on Test It’s quite clear that Peter Chinn had been keeping a close watching brief on the development of this new design. This naturally gave him an edge when it came to being first in print with a review of the engine. His test of the Enya D15-1 appeared in the April 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

Turning to the engine’s performance on the test bench, Chinn found that an exhaust prime was helpful for cold starting. However, a single choked flick was the only required prerequisite for hot or warm re-starts. Overall, he reported that “the engine started easily under all loads”, even with small props. Running qualities were said to be excellent. In terms of outright performance, Chinn measured a peak output of 0.298 BHP @ 14,700 rpm, an outstanding figure for a series-production 2.5 cc diesel in early 1957. Maximum Brake Mean Effective Pressure (BMEP) was found to be 62 lb/in2 @ 10,800 rpm, an exceptionally high figure which underscored an enhanced ability to swing larger props at useful speeds. Overall, Chinn was clearly extremely impressed with the Enya D15-1 in terms of its design, construction and performance. His very positive review can’t have harmed the engine’s sales prospects one bit!

Even so, Warring summed up the Enya D15-I as “a truly excellent 2.5 cc diesel in all respects”, also commenting on the fact that such results had been achieved at little or no weight penalty or sacrifice of ruggedness.

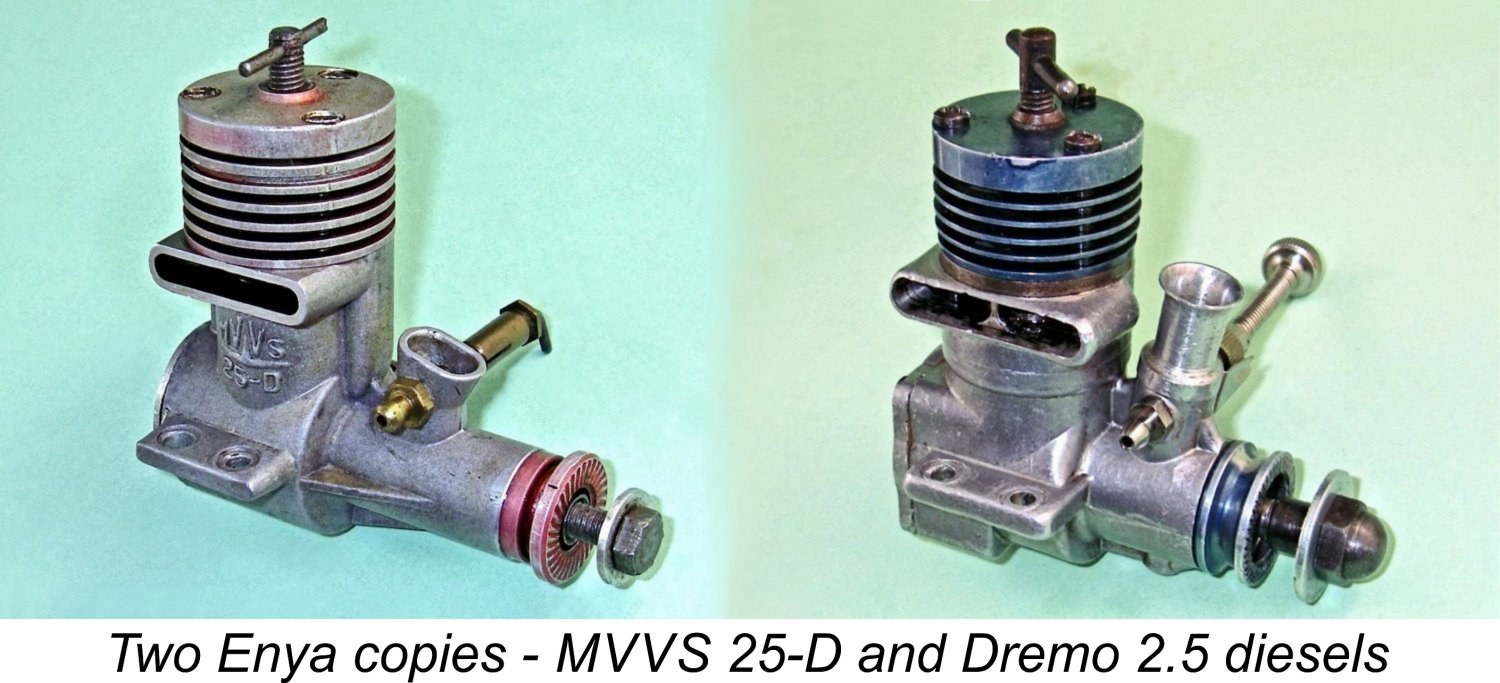

The levels of performance achieved by Saburo Enya with his radically new cylinder porting system were by no means lost on others. The MVVS institute in Czechoslovakia (as the Czech Republic was then) immediately set to work to develop their own model using this porting arrangement, resulting in the appearance of the MVVS 25-D/1958 twin ball race diesel in time for the 1958 World Free Flight Championships. They followed this up with the excellent plain-bearing MVVS 25-D model which received fairly wide circulation. The Enya's influence actually extended through the Iron Curtain which was then very much in place. The East German designer Hans Drenkhahn got in on the act with a similarly-ported 2.5 cc diesel of his own. That unit has been reviewed and tested for this website. The Russians too succumbed to Enya influence, producing what amounted to a clone of the MVVS 25-D in the shape of the Kharkov MK-25 of 1960. The Enya Crankshaft Controversy The timing of the Enya D15-I’s introduction more or less coincided with that of a major rule change introduced by the FAI for their International free flight power category. This change was to be implemented for the 1958 World Championships, although the FAI’s intentions were officially announced in advance in 1957, shortly after the appearance of the new Enya diesel. When the O.S. Max-I 15 glow-plug model won the 1956 Free Flight Power World Championship for Britain’s Ron Draper, the use of a powerful ultra-lightweight powerplant such as the 100 gm (3.5 ounce) Max-I 15 had conferred a significant flight performance advantage in terms of reduced wing loading. However, for the If so, the rule change worked! The majority of the competitors at the 1958 Free Flight World Championship meeting at Cranfield in England were back to using diesel engines. To give some idea of the breakdown, no fewer than 25 entrants (over a third of the entry) were using Oliver Tigers, followed by 15 Webra Mach I’s and 6 Enya D15-I’s along with a handful of the new Czech MVVS 25-D/1958 diesels featuring their Enya-based transfer porting.

In the May 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Chinn announced the appearance of a slightly revised version of the Enya D15-I having a stronger shaft made from chrome-moly steel, a 6 mm prop installation thread, a ball bearing of superior quality, bronze bushings at both ends of the conrod instead of only the big end and slightly more sturdy gudgeon pin bosses. He also shared an interesting account of the manner in which the changes to the shaft specification evidently came about. He stated that when he was testing the D15-I in 1957 for an American modelling publication, he found himself struggling to find something to complain about, on the theory that no engine is so good that it is beyond criticism and that any test which gave a totally clean bill of health would be immediately suspect in terms of its integrity. In Chinn’s own words: “Eventually, but without much conviction, we decided that the 5 mm threaded shaft end was a possible weak point on an otherwise robust engine! When the Enya company heard about this, they took it seriously. Within a few weeks a new type of shaft, in 85 ton chromium molybdenum steel and with a 6 mm end, had been put into production. This shaft has been fitted to all production models since the end of last year (1957) and the current model now incorporates one or two other minor changes. These include a superior type of ball bearing, a con-rod bronze bushed at both ends (instead of the big-end only) and slightly enlarged gudgeon-pin bosses in the piston”. This tale is mainly significant in that it demonstrates how sensitive Saburo Enya was to constructive criticism of his designs from reputable sources like Chinn and how rapidly the company was able to respond to such criticisms. Small wonder that their products tended to improve over time .................. Efforts by individual users to improve the engine’s performance continued in the run-up to the 1958 World Free Flight Championship. However, such efforts appear to have come at a price. Reports soon began to circulate suggesting that when pushed to its limits the new Enya had a bit of a tendency to break crankshafts despite the improved material then in use. Indeed, this model is somewhat unfortunately remembered today as much for breaking crankshafts as anything else! Given the care which Enya characteristically exercised in testing their products prior to release, it’s difficult to avoid reaching the conclusion that these shaft failures were the result of competition modellers simply trying to extract more extra power than the engine’s structure was able to absorb, especially if modified. Nonetheless, the engine’s reputation as a shaft-breaker seems to have stuck. The company made one more effort to address the problem - in the January 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Chinn noted that the latest models featured an even stronger crankshaft made from nickel-chrome steel. As a consequence of the above sequence of events, there were actually 3 variants of the D15-I using different crankshaft materials, oddly enough initiated by a “contrived” criticism of the original crankshaft! Peter Chinn later stated quite frankly that despite these successive crankshaft material changes, the D15-I never entirely shook a tendency to experience shaft fractures through the main journal. He proffered the opinion that, conversely to what one might think, the fault may have been due to the unusual rigidity of the piston and rod assembly, which transmitted too much ignition-related shock loading to the journal.

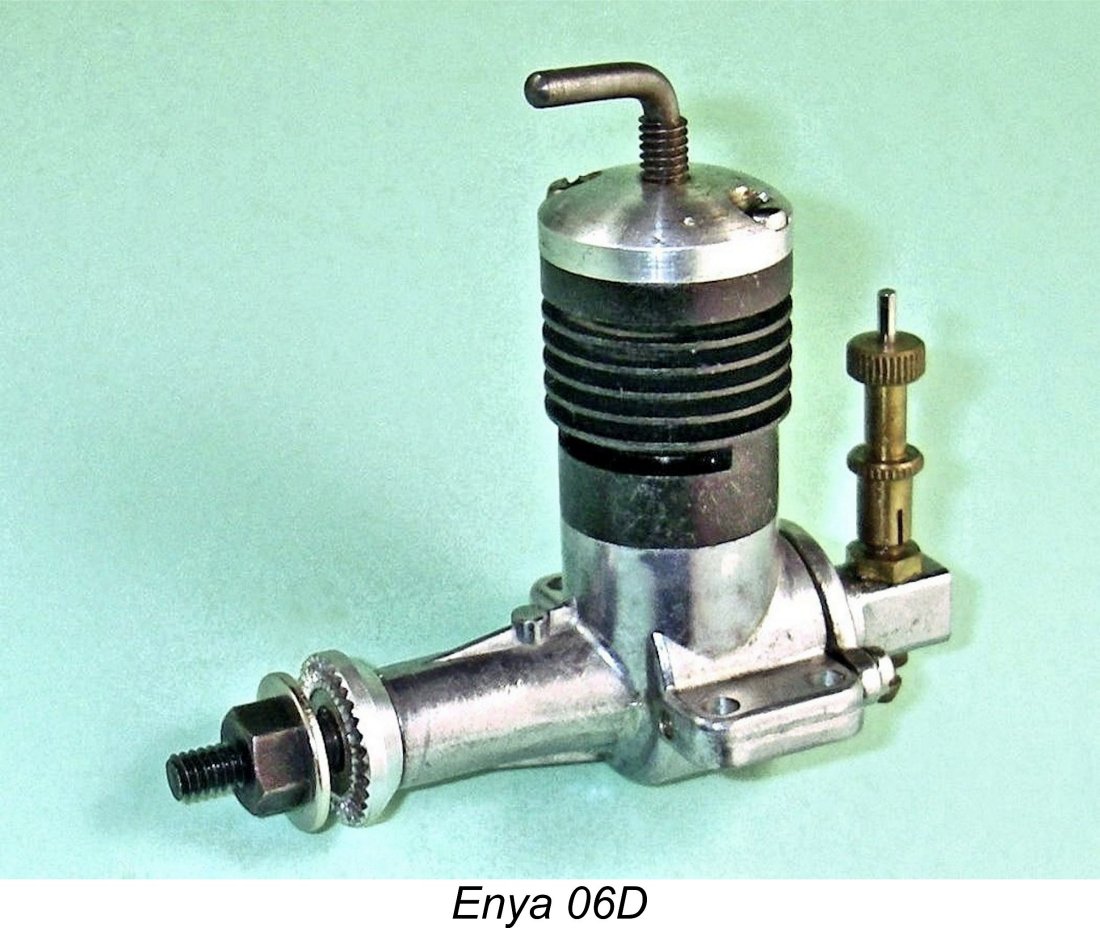

To underscore this point, I have an example of the D15-1 which I’ve owned and periodically used over a period of some 30 years now, much of it in vintage combat and stunt models and running at or near the peak in the air. The engine has accumulated an untold number of running hours, also spearheading a good few spirited attacks upon the Big Green Thing along the way! Indeed, its piston/cylinder fit has worn to the point where it must be nearing the end of its useful life on the original bore, although it still starts easily and runs very well indeed. Despite all of the hard use which it has received, this engine is still going strong on its original crankshaft! Even now it runs at a level which strongly suggests that it must be matching or even exceeding the performance figures measured by Peter Chinn. It would seem that the crankshaft breakage issue was by no means universal. My engine’s crankshaft has a 6 mm prop installation stud, confirming that it is either the second or third variant, but I have no way of knowing which of the two possible crankshafts is installed. Be that as it may, Saburo Enya had become highly sensitized to this issue, eventually leading him to make an all-out effort to eliminate it once and for all by revising the design quite comprehensively. The results of his deliberations were to appear in late 1960 in the shape of the significantly updated Enya 15D-II diesel. We’ll take a close look at that model in a subsequent section of this article. But before doing that, it seems worthwhile spending a little time examining Enya’s second foray into the field of model diesel design. Interlude - the Enya 06D Diesel Although Saburo Enya had been the chief designer of all of the classic Enya models during the 1950’s, his younger brother Yoshiro was also keen to have a go at developing a design of his own. In 1958 he was given the green light to work on the design of an .06 cuin. (1 cc) glow-plug model. Peter Chinn announced the late 1958 appearance of this design in his column which was published in the February 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

The little Enya 06 glow-plug motor appears to have been quite successful on the home market. Its positive reception encouraged the Enya brothers to turn their attention towards the development of a diesel version of the same model. Peter Chinn announced the September 1959 appearance of just such a variant in his December 1959 column in “Model Aircraft”. This was another instance in which the conversion of a glow-plug model to compression ignition worked out very well. Alan Allbon had achieved similarly positive The Enya 06D diesel was essentially the same engine as its 06 glow-plug predecessor, albeit with a little beefing-up of its structure. In order to deal with the higher levels of operating stress arising from diesel operation, the diesel version featured a stronger crankshaft, a thicker cylinder wall and a steel conrod. Otherwise, it was little changed from its glow-plug companion in the range apart from the incorporation of a contra-piston and comp screw. My own experience with both diesel and glow-plug versions of this engine suggests that the diesel model develops significantly more torque than its glow companion. This impression is reinforced by the manufacturer’s claims of 0.10 BHP for the glow with an operating speed range of 10,000 to 17,000 rpm and 0.12 BHP for the diesel with an operating speed range of 8,000 to 15,000 rpm. Personal impressions are that these claims are not greatly exaggerated, although those impressions remain to be tested. The two Enya 06 models appear to have enjoyed considerable market success, continuing in production for a further 5 years. Indeed, they were successful to the point that in late 1964 both the diesel and its glow-plug companion were drastically revised to feature crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction in place of the reed valve induction used previously. The primary reason for this change was evidently a desire to render the engine more suitable for use with an R/C throttle - the R/C field was well advanced upon its take-over of the model engine market by this time. The FRV diesel model was designated the Enya 06D-II.

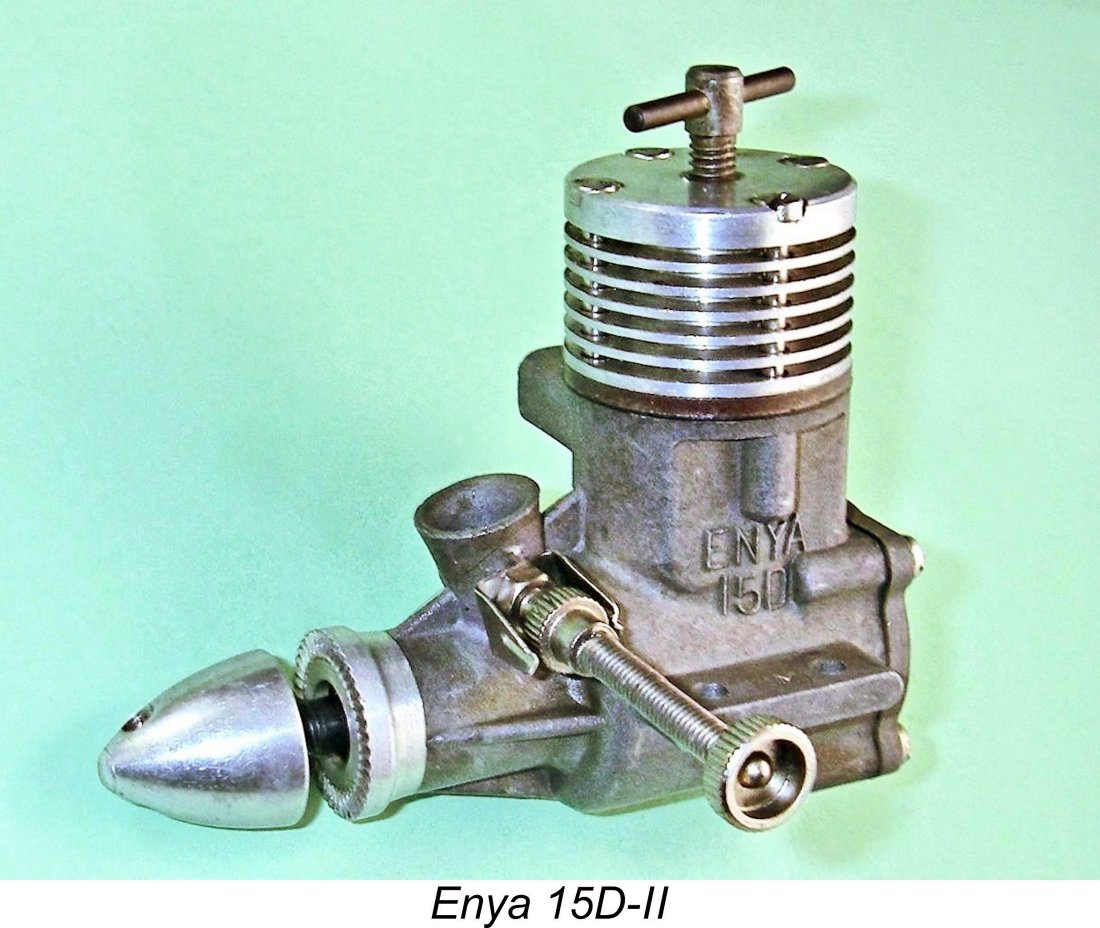

Despite its seemingly excessive bulk, weight and complexity, both the Enya 06D-II and its glow-plug companion appear to have been well received, hence remaining on offer for many years thereafter. They were probably made in batches as demand dictated. The glow-plug version seems to have outlasted the diesel model, eventually being exported in limited quantities to other countries. However, the diesel variant never appears to have been exported, hence being a very rare engine outside of Japan today. These interesting little engines richly deserve a full article of their own, including bench tests. Such a project will have to await an appropriate conjunction of time and opportunity. In the meantime, let’s get back to our main subject - the 2.5 cc Enya diesel models! The Enya 15D-II As stated earlier, a significantly updated version of the 2.5 cc Enya diesel appeared in late 1960, being first announced by Peter Chinn in his column in the December 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. It was designated by the factory as their Model 15D-II. It should be noted at this point that Enya were less than consistent in The 15D-II clearly demonstrated the lengths to which Saburo Enya was prepared to go in order to erase the stigma of the earlier model’s reported tendency to break shafts. It featured a main journal diameter of a truly monumental 11.5 mm allied to a modestly increased central gas passage diameter of 6.35 mm. The crankshaft induction port continued to be a perfectly round hole, minimizing the potential creation of stress concentrations at this always-vulnerable point. On top of this, the revised design also featured a hard-chromed mild steel cylinder liner. It was one of the first two Enya engines to feature the latter then-new technology, the other being the contemporary and rather unsuccessful .29 “Special” glow-plug model known as the "Speedy". The combination worked very well in the 2.5 cc diesel but caused problems for the 5 cc glow-plug unit due to thermal expansion issues with the piston at the elevated temperatures reached during high-speed glow-plug operation. More of those problems in a separate article to be published in due course.

An unfortunate side-effect of the “overkill” solution to the shaft breakage issue was a substantial increase in weight relative to the earlier version. The new model weighed all of 178 gm (6.25 ounces), which was over a full ounce more than the original model and was only some half an ounce less than the contemporary and far more powerful Enya 29-IIIB glow-plug engine! However, the performance had also increased substantially, as presumably had the engine’s durability. As with the original model, the engine testers of the day were very keen to get to grips with the revised model. Let’s see how the engine fared in their hands. The Enya 15D-II on Test

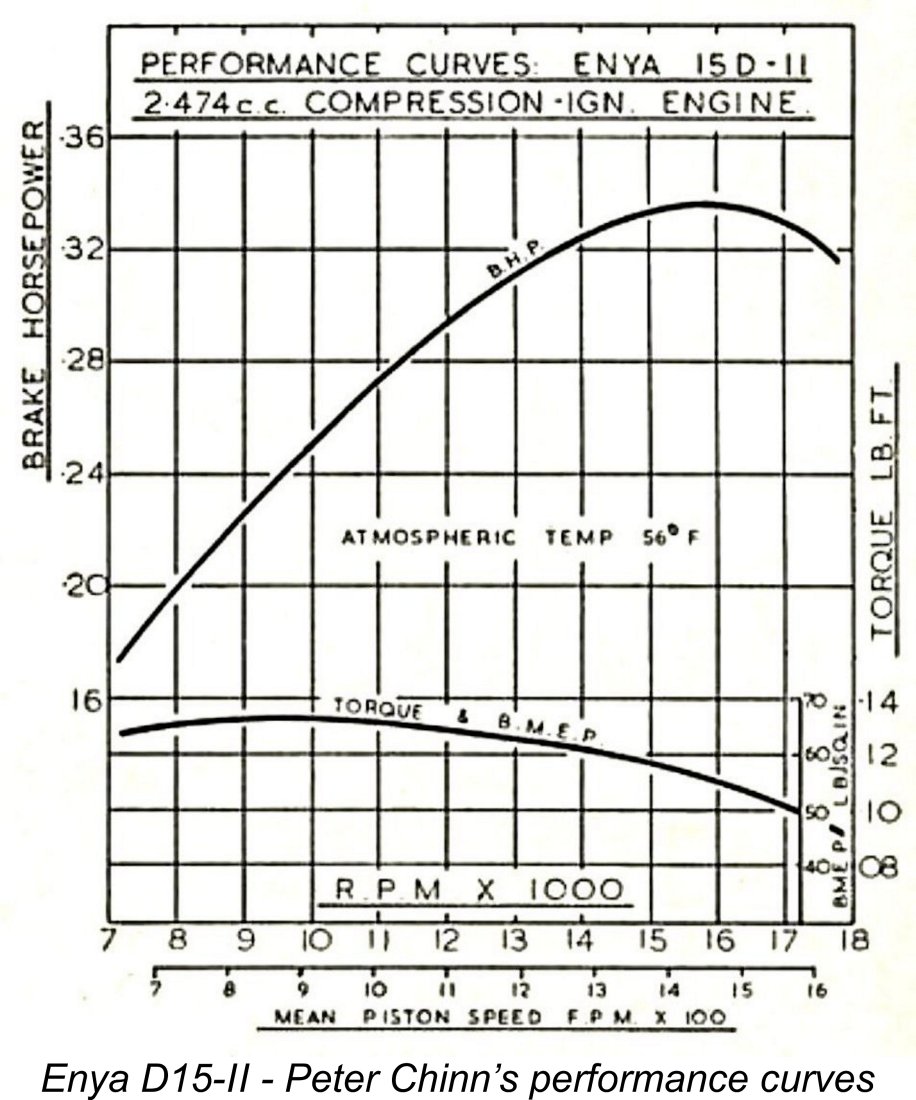

Warring’s test report was another ringing endorsement of Saburo Enya’s efforts. He characterized the revised model as “an exceptionally well-made high-performance engine” having “generally excellent” handling characteristics. His one comment which might have affected the engine’s perceived usefulness was the fact that he found an exhaust prime to be ”virtually essential” for starting - hardly a positive characteristic when considering team race applications, although matters might have been improved with the engine inverted, as it generally would be in a team racer. Warring reported a peak output of no less than 0.332 BHP @ 15,000 rpm, putting the new Enya diesel way up in the Oliver class as far as performance went. It seems clear that this engine represented a very sincere attempt by Saburo Enya to beat the Olivers at their own game with a standard mass-produced engine. In pure performance terms, he was undoubtedly successful in challenging the Oliver.

Unlike Warring, Chinn found that exhaust port priming was not necessary for starting. He reported that starting was easy, although the engine apparently became a little vicious on smaller props. Once running, the Enya apparently performed very steadily at all times. Chinn reported a peak output of 0.337 BHP @ 15,700 rpm, figures which for once agreed very well with those reported by Warring. Overall, he was clearly every bit as impressed with the engine as Warring had been. Speaking personally once more, I have to confess that I’ve never had an Enya 15D-II in a model and in the air - my experience has been confined to some bench running of several examples. I can confirm that it is indeed a top-class performer by comparison with other 2.5 cc diesels of the early 1960’s. However, I must side with Warring on the starting issue - I have always found a port prime to be an essential preliminary to a quick cold start, at least with the engine mounted upright on the test bench. Moreover, experience in the field reportedly suggested that contrary to Chinn’s opinion, the Enya was somewhat more thirsty than its Oliver competitor - another major disadvantage for team racing. Consequently, although the Enya was very easy to handle for a world class racing diesel, the Tiger III continued to reign supreme for a few more years. Despite this, it’s important to remember that the Enya was very much a mass produced engine which made a surprisingly good showing against the meticulously hand made (and individually tuned) model of unsurpassed quality which the Oliver embodied. My Scottish friend Don Imrie has shared his own experiences, which are quite revealing. Don recalled the days back in 1959/60 when he was a typical teenager learning the aeromodelling trade the hard way. Being fairly naïve typical teenagers, Don and his friends naturally thought that they could conquer the world at whatever they turned their hands to! So when local dealer Bill McWilliams informed them that he had ordered a few Enya D15-I diesels, they reckoned that they might be in a position to conquer the world of C/L team racing. Unlike the all-conquering Oliver, the Enya was both available and affordable. Don and his mates ran in two of their new Enya diesels very carefully, finding them to be pretty good performers. Accordingly, two team race models were duly built and lots of practice was indulged in, with disastrous effect on their pocket money, most of which went on fuel! Come the 1960 Scottish Nationals at Beveridge Park, Kirkcaldy, he and his team-mate got through the heats and made the final! Hey, they were on their way - it was all working out as planned! However, one of their clubmates had a couple of Olivers and squeezed enough out of one of them to ensure that the all-conquering Tiger thwarted their best Enya-powered efforts! Despite this setback, the team stuck with Enya power, but for 1961 they had switched to a 15D-II. However, their participation in the 1961 Scottish Nationals was pretty much a repeat of the previous year - once again they made the final but were bested by the Oliver opposition. Their conclusion was that while the Enya was a very good engine which was readily available at a competitive price, it just wasn't quite good enough to beat the Ollie. Still, Don agrees that it was a remarkably good effort by Saburo Enya to create a mass-produced engine that could make the individually hand-made Oliver work quite hard! Of course, at around this time Ken Bedford was just releasing the ETA 15D which put paid to both the Olly and the Enya............... None of this detracted from the fact that the Enya 15D-II was a great engine for general purpose use, serving many owners very well indeed in such applications. It survived in production until 1965 or thereabouts, adding its own share of lustre to the name of its talented designer Saburo Enya. Summary and Conclusion

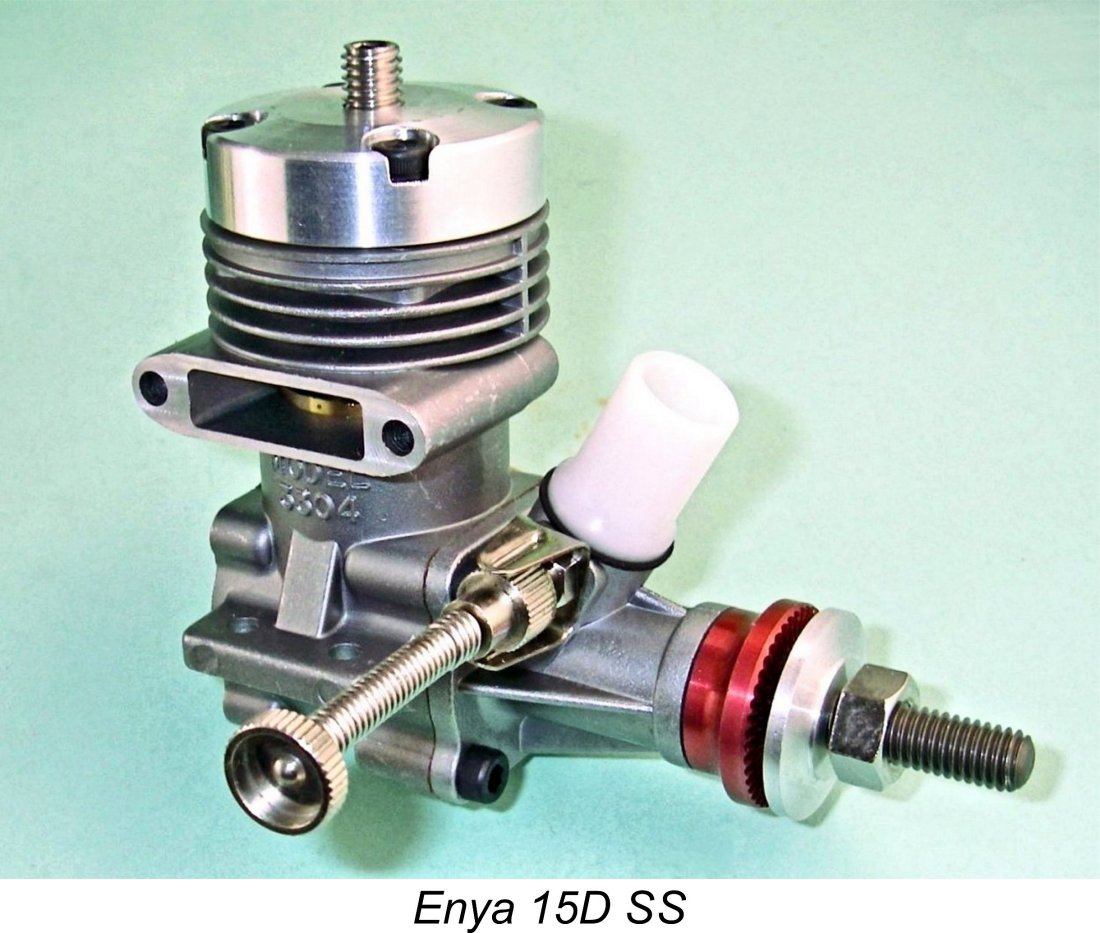

At some point during this period, probably in the early 1980’s, the little 06D-II diesel also disappeared after a long production run. Enya only returned to the diesel fold in 2004, when they released a new .15 cuin. diesel based on their Schnuerle ported 15 SS glow-plug model. This all-new diesel was a fine performer, featuring modern ABC technology with an alloy piston. A .28 cuin. diesel followed in 2008, again based upon the glow-plug SS model. Other diesel models in .11 and .25 cuin. displacements appeared in their turn. To crown their involvement with diesels, in 2006 the company achieved a world “first” by releasing the initial Incidentally, it's probably worth avoiding confusion by mentioning here in passing that what appears to be a glow-plug fitted to the illustrated 36-4CD is actually a solid metal plug which is used to fine-tune the engine's fixed compression ratio to suit different loads, fuels and atmospheric conditions. By varying the number and thickness of the washers used with this plug, the compression ratio can be varied quite considerably.

The two “classic” versions of the Enya 2.5 cc diesel were made in quite large numbers and were highly valued by their owners. Consequently, a fair number of them survive today for us to enjoy. If you get the chance to acquire one or even just to experience it in operation, don’t hesitate - no die-hard diesel enthusiast can fail to enjoy the experience! __________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published January 2022 |

| |

In this article I’ll take a look at a truly ground-breaking model diesel from Tokyo, Japan - the iconic Enya 15D diesel of 2.5 cc displacement. This engine is highly significant for several reasons. It was the first model diesel to be manufactured by Enya, also featuring a highly innovative cylinder porting system which was first emulated and then improved upon by a number of other manufacturers. Moreover, its outstanding quality and head-turning performance did much to accelerate the growing worldwide recognition of Japan as a nation to be reckoned with when it came to designing and producing high quality model engines.

In this article I’ll take a look at a truly ground-breaking model diesel from Tokyo, Japan - the iconic Enya 15D diesel of 2.5 cc displacement. This engine is highly significant for several reasons. It was the first model diesel to be manufactured by Enya, also featuring a highly innovative cylinder porting system which was first emulated and then improved upon by a number of other manufacturers. Moreover, its outstanding quality and head-turning performance did much to accelerate the growing worldwide recognition of Japan as a nation to be reckoned with when it came to designing and producing high quality model engines.

Consequently, as of early 1956 O.S. didn’t have a diesel model on the market. Here was an opportunity for Enya to steal a march on their Osaka competition by coming up with a high-performance International-class diesel model of their own! Their desire to put one over on O.S. was doubtless inflamed by the fact that an O.S. Max-I 15 glow-plug model powered Britain’s Ron Draper to the 1956 World Free Flight Championship. It was definitely pay-back time!

Consequently, as of early 1956 O.S. didn’t have a diesel model on the market. Here was an opportunity for Enya to steal a march on their Osaka competition by coming up with a high-performance International-class diesel model of their own! Their desire to put one over on O.S. was doubtless inflamed by the fact that an O.S. Max-I 15 glow-plug model powered Britain’s Ron Draper to the 1956 World Free Flight Championship. It was definitely pay-back time! Of course, Enya already had a very capable 2.5 cc performer on offer in the shape of their excellent

Of course, Enya already had a very capable 2.5 cc performer on offer in the shape of their excellent

The original version of the Enya 15 diesel first appeared in late 1956 as the Enya Model D15-1, although it is often referred to simply as the Enya 15D Mk. I. Once again, Chinn showed himself to be very well informed, since he was able to provide a general description of the new model in his column in the February 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”, adding a few further details in the March issue.

The original version of the Enya 15 diesel first appeared in late 1956 as the Enya Model D15-1, although it is often referred to simply as the Enya 15D Mk. I. Once again, Chinn showed himself to be very well informed, since he was able to provide a general description of the new model in his column in the February 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”, adding a few further details in the March issue.

Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” magazine was a fair way behind Chinn in getting to grips with the Enya - his

Ron Warring of “Aeromodeller” magazine was a fair way behind Chinn in getting to grips with the Enya - his  The overall effect of these two published tests was to confirm that Saburo Enya had come up with a 2.5 cc diesel having a performance which challenged that of the then all-conquering Oliver Tiger Mk. III while matching the Ollie for weight and undercutting it substantially on price. Not bad for a first attempt! Not surprisingly, the engine was very well received by the modelling public, becoming a very steady seller worldwide.

The overall effect of these two published tests was to confirm that Saburo Enya had come up with a 2.5 cc diesel having a performance which challenged that of the then all-conquering Oliver Tiger Mk. III while matching the Ollie for weight and undercutting it substantially on price. Not bad for a first attempt! Not surprisingly, the engine was very well received by the modelling public, becoming a very steady seller worldwide.

One individual who tried his hand at tuning an example of the Enya D15-I for this contest was none other than Britain’s Ron Draper, who had won the 1956 event using an O.S. Max-I 15. In his column in the October 1957 issue of ”Model Aircraft”, Peter Chinn illustrated some modifications which were then being tried by Draper. These included the careful reconfiguration and polishing of the transfer ports as well as some substantial modifications to the crankshaft. Chinn reported that although it was then not fully run in, Draper’s modified Enya was already developing over 0.30 BHP.

One individual who tried his hand at tuning an example of the Enya D15-I for this contest was none other than Britain’s Ron Draper, who had won the 1956 event using an O.S. Max-I 15. In his column in the October 1957 issue of ”Model Aircraft”, Peter Chinn illustrated some modifications which were then being tried by Draper. These included the careful reconfiguration and polishing of the transfer ports as well as some substantial modifications to the crankshaft. Chinn reported that although it was then not fully run in, Draper’s modified Enya was already developing over 0.30 BHP. Speaking from a personal point of view, I find this explanation of the issue to be somewhat less than compelling. I would have said that the D15-I crankshaft was particularly stress-resistant, having what appeared to be adequate wall thickness and featuring a perfectly circular crankshaft induction port with no sharp corners to give rise to stress concentrations. In fact, I would have thought that the shaft was particularly well-designed from the standpoint of stress-resistance. This being the case, I'm at a bit of a loss to understand how the engine came by its "shaft-breaker" reputation.

Speaking from a personal point of view, I find this explanation of the issue to be somewhat less than compelling. I would have said that the D15-I crankshaft was particularly stress-resistant, having what appeared to be adequate wall thickness and featuring a perfectly circular crankshaft induction port with no sharp corners to give rise to stress concentrations. In fact, I would have thought that the shaft was particularly well-designed from the standpoint of stress-resistance. This being the case, I'm at a bit of a loss to understand how the engine came by its "shaft-breaker" reputation.  The new Enya model was a compact plain bearing reed valve unit which owed much to the design of the contemporary Cox models from America. Bore and stroke were 11.1 mm and 10.3 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.99 cc. The cylinder porting followed the established Cox pattern, with twin opposing exhaust ports having twin internally-formed bypass flutes located between them. The conrod was a somewhat chintzy-looking bronze stamping. The engine was arranged for beam mounting, but a radial mount was supplied with each unit, as was a simple spring starter. At the outset, the engine was only made available to the Japanese home market, being targeted primarily at beginners in that country.

The new Enya model was a compact plain bearing reed valve unit which owed much to the design of the contemporary Cox models from America. Bore and stroke were 11.1 mm and 10.3 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.99 cc. The cylinder porting followed the established Cox pattern, with twin opposing exhaust ports having twin internally-formed bypass flutes located between them. The conrod was a somewhat chintzy-looking bronze stamping. The engine was arranged for beam mounting, but a radial mount was supplied with each unit, as was a simple spring starter. At the outset, the engine was only made available to the Japanese home market, being targeted primarily at beginners in that country.

As might be expected, the switch to FRV induction seems to have released more power from the basic design. The manufacturers published a claim of 0.16 BHP for the 06D-II with an operating speed range of 9,000 - 15,000 rpm Pretty impressive if true - a test would be most interesting! Oddly enough, the throttle-equipped glow-plug 06-II model was claimed to develop exactly the same output as its un-throttled reed-valve predecessor at 0.10 BHP. Of course, it’s by no means unusual for a throttle-equipped engine to under-perform by comparison with its open-venturi equivalent.

As might be expected, the switch to FRV induction seems to have released more power from the basic design. The manufacturers published a claim of 0.16 BHP for the 06D-II with an operating speed range of 9,000 - 15,000 rpm Pretty impressive if true - a test would be most interesting! Oddly enough, the throttle-equipped glow-plug 06-II model was claimed to develop exactly the same output as its un-throttled reed-valve predecessor at 0.10 BHP. Of course, it’s by no means unusual for a throttle-equipped engine to under-perform by comparison with its open-venturi equivalent. assigning model identification figures to these engines. Somewhat unusually, both models were identified in ciphers which were clearly cast in bold relief onto their respective backplates rather than on the cases in the more common fashion. The original model was clearly identified as the D15-I, while the revised variant bore the cast-on identification 15D-II - the letter D was re-positioned.

assigning model identification figures to these engines. Somewhat unusually, both models were identified in ciphers which were clearly cast in bold relief onto their respective backplates rather than on the cases in the more common fashion. The original model was clearly identified as the D15-I, while the revised variant bore the cast-on identification 15D-II - the letter D was re-positioned.  The design of the intake was also revised. The original model had featured a vertical intake having provision for a twin needle valve arrangement whereby a measure of speed control could be achieved by setting one needle lean and the other rich, switching between the two as required. Peter Chinn had tried this arrangement in his test of the original model, finding that it worked reasonably well. However, this would no longer satisfy the growing number of R/C modellers as of the early 1960’s - they demanded greater precision of control. The revised model featured a forward-angled intake in place of the earlier vertical structure, with the throat enlarged sufficiently to accommodate the well-designed RC throttle which was made available to suit a number of Enya models, including the 15D-II. A steel venturi insert was fitted for use in free flight or control line service.

The design of the intake was also revised. The original model had featured a vertical intake having provision for a twin needle valve arrangement whereby a measure of speed control could be achieved by setting one needle lean and the other rich, switching between the two as required. Peter Chinn had tried this arrangement in his test of the original model, finding that it worked reasonably well. However, this would no longer satisfy the growing number of R/C modellers as of the early 1960’s - they demanded greater precision of control. The revised model featured a forward-angled intake in place of the earlier vertical structure, with the throat enlarged sufficiently to accommodate the well-designed RC throttle which was made available to suit a number of Enya models, including the 15D-II. A steel venturi insert was fitted for use in free flight or control line service. On this occasion, Ron Warring won the race to be first into print with a test of the revised Enya diesel design. His

On this occasion, Ron Warring won the race to be first into print with a test of the revised Enya diesel design. His  Peter Chinn’s test of the Enya 15D-II

Peter Chinn’s test of the Enya 15D-II

Even after all this innovation, the old D15-II wasn’t quite done! In 2014 Enya produced a limited edition commemorative run of 60 examples of this engine, for which they retained the dies and tooling. Each engine was supplied in a classic 1960’s red-and-yellow Enya box complete with both an R/C throttle and a set of control line venturi inserts. Unlike the original models, these units were all individually numbered. They were built to the same very high standards as their 1960’s fore-runners. I was fortunate enough to acquire illustrated engine no. 55 of this very exclusive series. It’s one of my more prized possessions!

Even after all this innovation, the old D15-II wasn’t quite done! In 2014 Enya produced a limited edition commemorative run of 60 examples of this engine, for which they retained the dies and tooling. Each engine was supplied in a classic 1960’s red-and-yellow Enya box complete with both an R/C throttle and a set of control line venturi inserts. Unlike the original models, these units were all individually numbered. They were built to the same very high standards as their 1960’s fore-runners. I was fortunate enough to acquire illustrated engine no. 55 of this very exclusive series. It’s one of my more prized possessions!