|

|

The O.S. Max-D 15 Diesel Reappraised

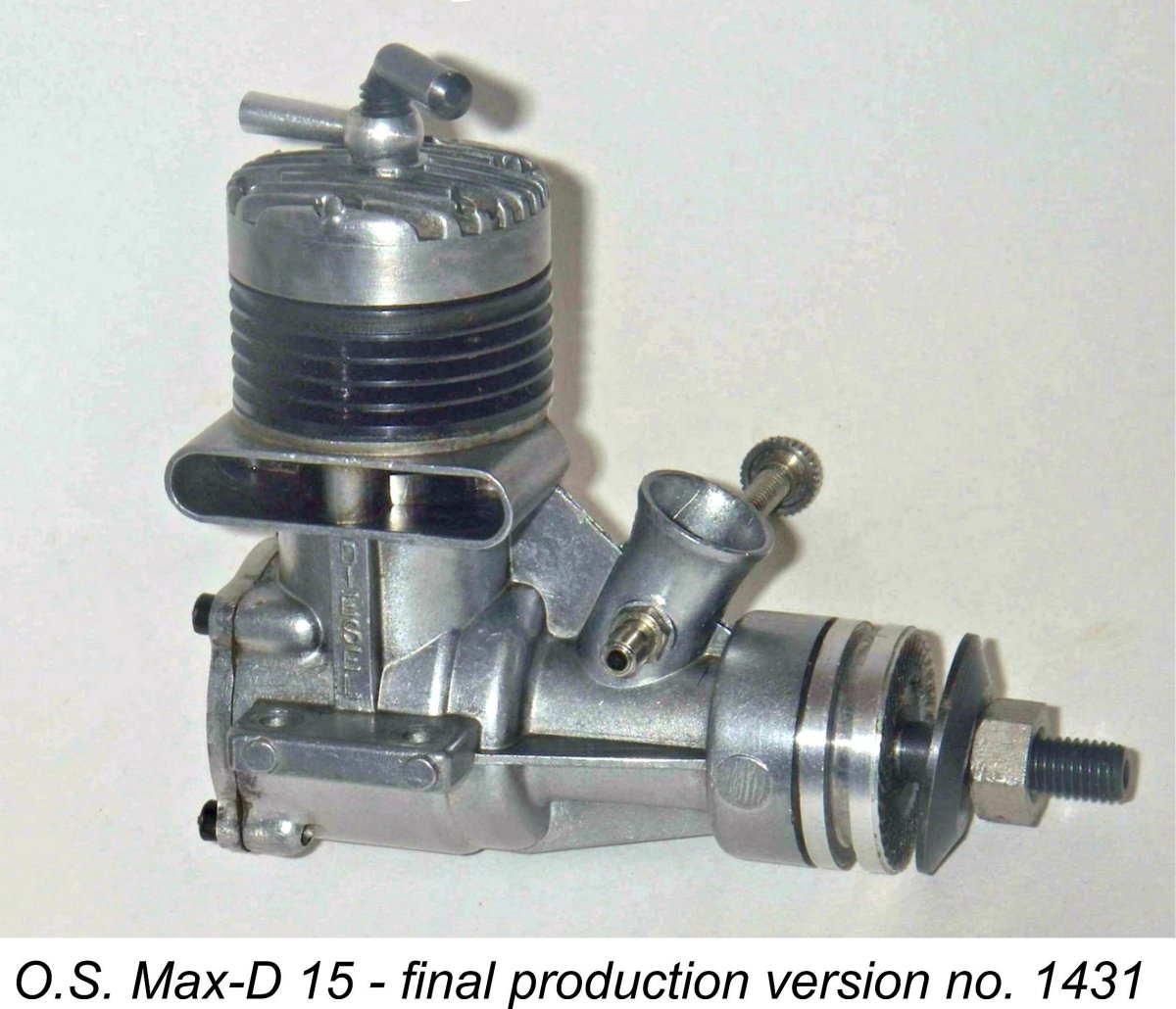

Consequently, the engine did not remain long in production, resulting in relatively few being made, especially by O.S. standards. In all honesty, it must be viewed as one of the O.S. company's very few marketing failures. The development history of this engine was previously covered in detail in my September 2008 article which may still be found on the late Ron Chernich’s frozen but still wonderful “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. In the interests of convenience I will summarize the key points here, also including some additional comments as well as a few images which were omitted from my earlier article. I'm also able to add some bench test results to this updated version of the article. Even among those who are aware of this engine, its characteristics are frequently misunderstood. It has commonly been thought of as simply a twin ball-race diesel conversion of the then-current O.S. Max-II 15 glow-plug model. As we shall see, this is very far from being the case – the O.S. Max-D 15 was in fact an all-original design from the ground up. In order to understand how this engine’s brief existence came about at all, it’s worth summarizing the history of the O.S. enterprise and its relationship with its commercial rivals, particularly Enya. So here goes........... Background

An excellent source of information on the O.S. marque is to be found in the Shigeo Ogawa entry at the ever-informative Internet Craftsmanship Museum. Another very useful reference is the late Peter Chinn's article on the history of O.S. to be found in the February 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft” magazine. Finally, O.S. themselves created and for many years maintained a most informative on-line pictorial history of their entire model engine range which could be freely accessed online, although this was taken off line for some unaccountable reason some years ago. It has now thankfully been updated to 2020 and re-instated. The updated version may be viewed here. During the period when the feature was not available from O.S., I added the printed version of that listing to this website in order to maintain the accessibility of at least a partial record going up to 1976. However, I subsequently learned that thanks to the foresight of others, the main O.S. pictorial history pages remained available at the invaluable Web Archive site. The blue-background images below were extracted from that site with my grateful appreciation.

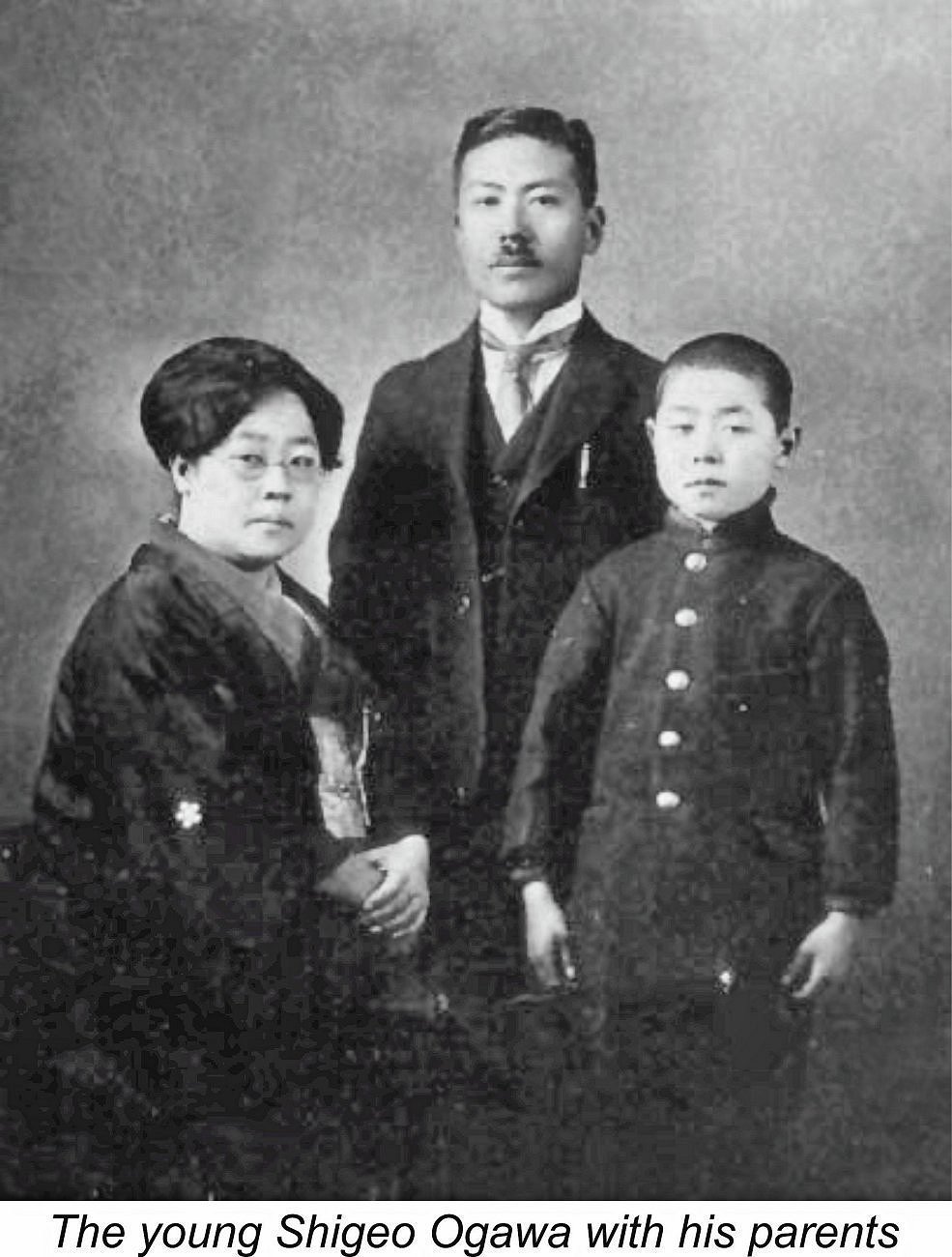

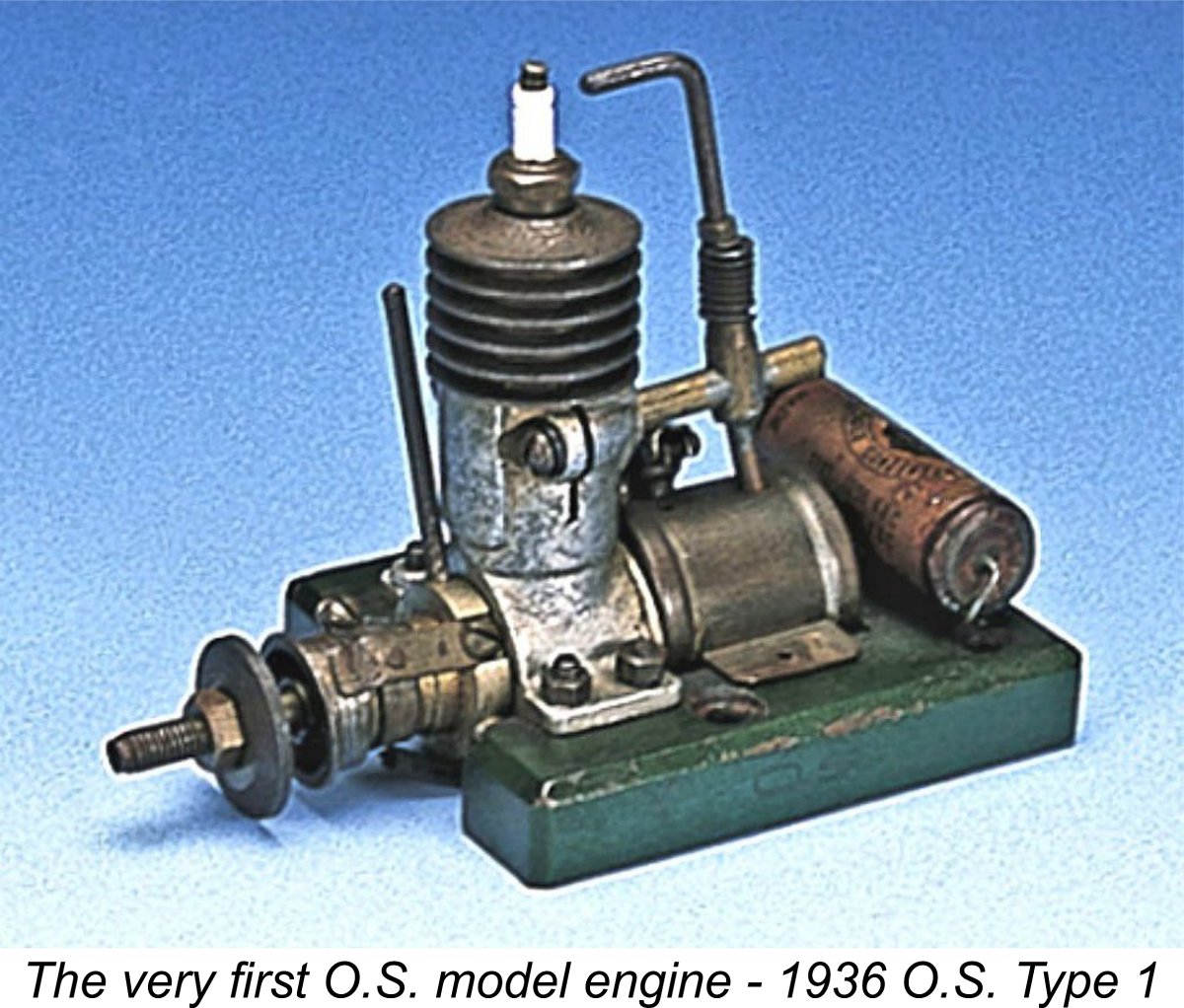

In 1936, while still in his teens, young Ogawa somehow scraped together enough money to buy a lathe and drill press. The lathe was reportedly purchased for 100 yen (around US$29.00 at the then-prevailing exchange rate)! Using this very basic equipment, Ogawa began making model steam engines and live steam locomotives, an interest which he was to maintain throughout his working life. Even at this young age he had already become a skilled machinist. In that same year of 1936, the 19-year old Ogawa made his first model internal combustion engine, a 1.6 cc (0.10 cuin.) side-port spark ignition job which he initially installed in a model boat. The little engine performed so well that other Japanese modellers who saw it in use were sufficiently impressed to ask Ogawa to make copies for their use also. He was also encouraged by an American buyer then resident in Japan, one Paul Houghton. Accordingly, a few more examples of this engine were made and distributed to a small circle of Japanese and American modellers during 1936. The majority of these were put to model aircraft use. Ogawa-san’s initial efforts drew sufficient attention from his fellow Japanese modellers that in 1937 at the age of 20 he was encouraged to commence small-scale commercial production of the first of what was The first O.S. design to be put into commercial series production was the neat little .10 cuin. displacement sideport unit which had been Ogawa’s initial design effort in 1936. It was released as the O.S. Type 1 model. Production of this engine was initially restricted to around 20 units per month - a very far cry from the scale of things to come! However, the continuing positive reception of this engine soon encouraged Ogawa to expand his fledgling range beginning later in 1937, and by 1941 he had designed and put into limited production a series of spark-ignition engines covering no less than six additional displacement categories from 4.4 cc (.27 cuin.) up to 9.5 cc (.58 cuin.). These included an impressive three-cylinder unit intended for marine use. With the ongoing encouragement of Paul Houghton, Ogawa even succeeded in getting a few of his engines sold in the USA, no small feat for a fledgling Japanese manufacturer at that time. The Ogawa enterprise was well on its way!! However, at this point WW2 intervened, and that unhappy event naturally put the brakes on Ogawa’s model engine development activities - international trade opportunities ceased immediately; the sale of engines to the Japanese public was stopped; and in any case his production capabilities were needed for other purposes. Even so, he did manage to produce a few examples of several 9.43 cc models during the wartime period. The explanation for this doubtless lies in the fact that the Japanese military authorities encouraged (or perhaps required) trainee pilots to construct and fly powered model aircraft as part of their training. The required engines had to come from somewhere.

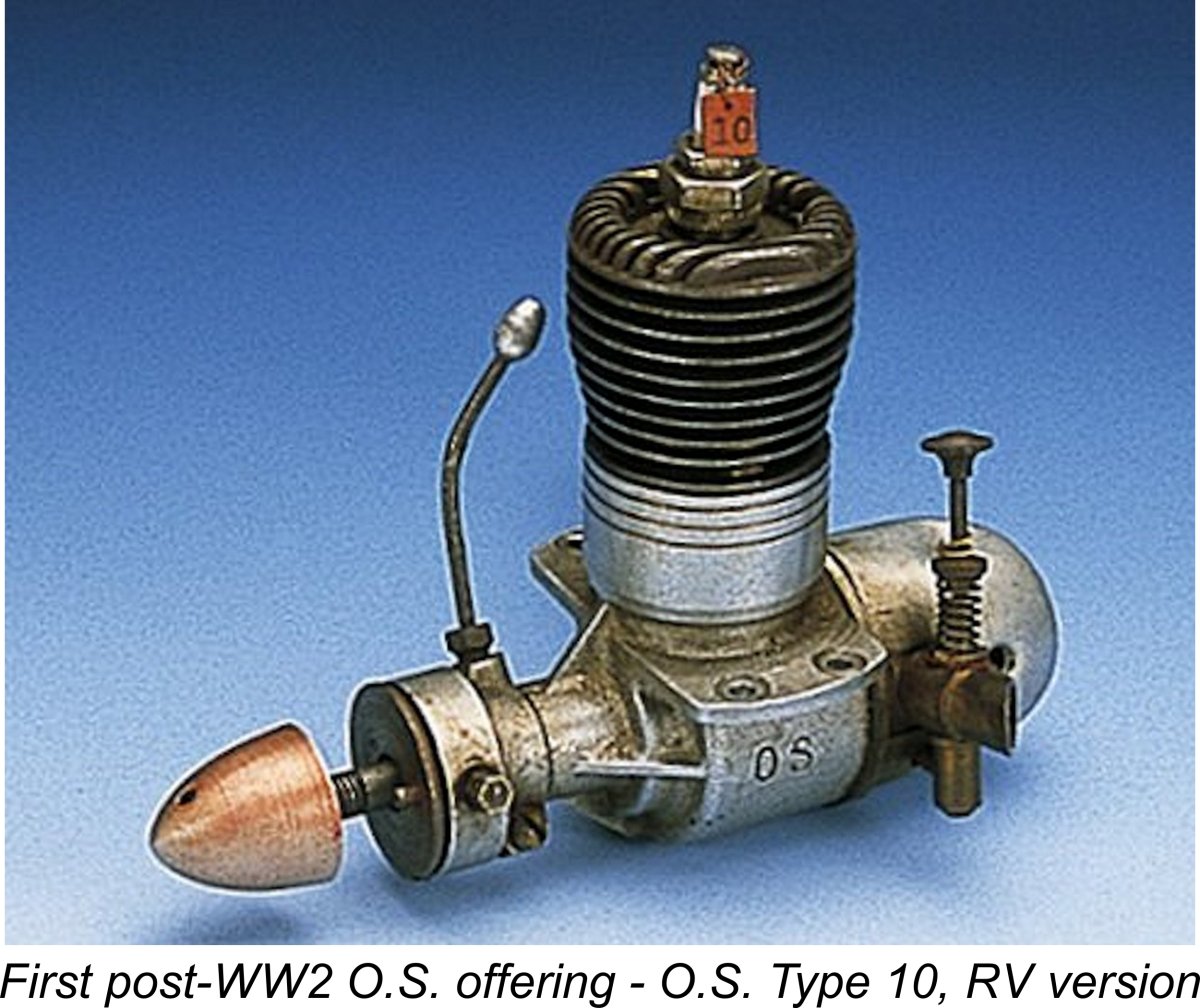

Taking full advantage of this opportunity, Shigeo Ogawa lost no time in re-establishing his factory in Osaka on a larger scale. Still only 29 years old, he was back in full production by 1946 with a 9.7 cc model which was offered in both crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) and rear induction (RV) forms - the O.S. Type 10. The illustrated example is one of the RV models. I have a nice example of the FRV version which has been very capably converted to glow-plug operation. The Type 10 was further refined with an updated 9.3 cc model later in the same year, followed by a revised 9.85 cc design in 1947. Spark ignition was naturally retained in all of these models It was also in 1947 that the first of several O.S. model pulse jet engines appeared in commercial form.

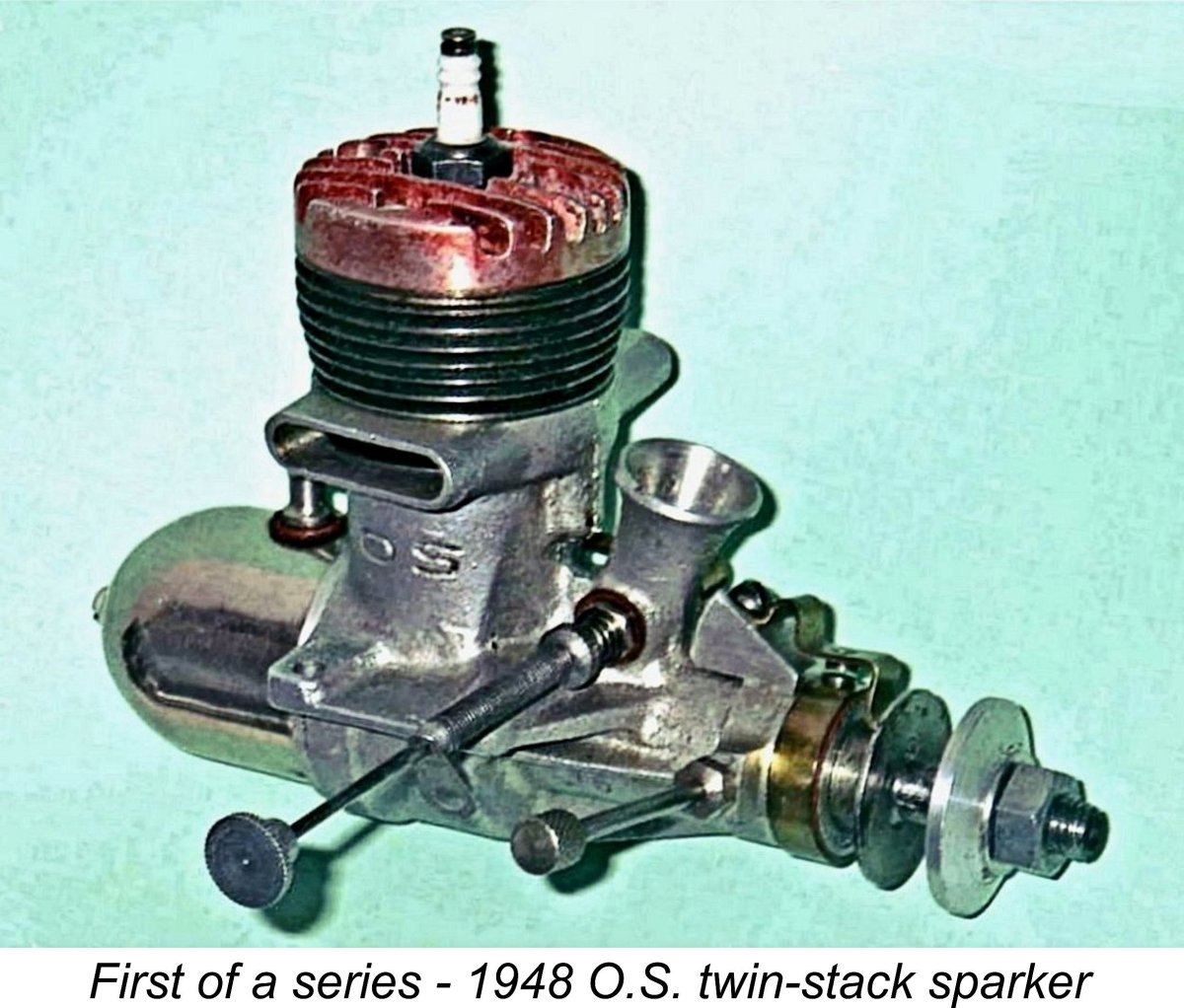

By then, Shigeo Ogawa had developed his iconic 1949 twin-stack .29 cu. in. glow-plug model from the 1948 spark ignition version, and it was the 1950 “New 29” version of this engine which finally put O.S. on the international modelling map. On the strength of that model's success, Ogawa was ultimately successful in reaching an agreement with Bill Atwood to distribute this model within the United States, resulting in production soon reaching 1000 units per month.

The result was the early 1950's appearance of a fairly close copy of the Series 1 E.D. Bee with a few detail modifications (including the omission of a tank) and some metrication of the dimensions. It was a handsome unit of extremely high quality which ran very well. The fact that it was identified on the front of the case in bold relief as an "OS DIESEL" implies that Ogawa had thoughts of eventually introducing this model to English-speaking markets. However, it doesn't appear to have been a great sales success, apparently never being marketed outside Japan. It appears that only some 500 or so examples ended up being made. The engine is very rare today, even in its native Japan. A full review and test of this reclusive model appears elsewhere on this website.

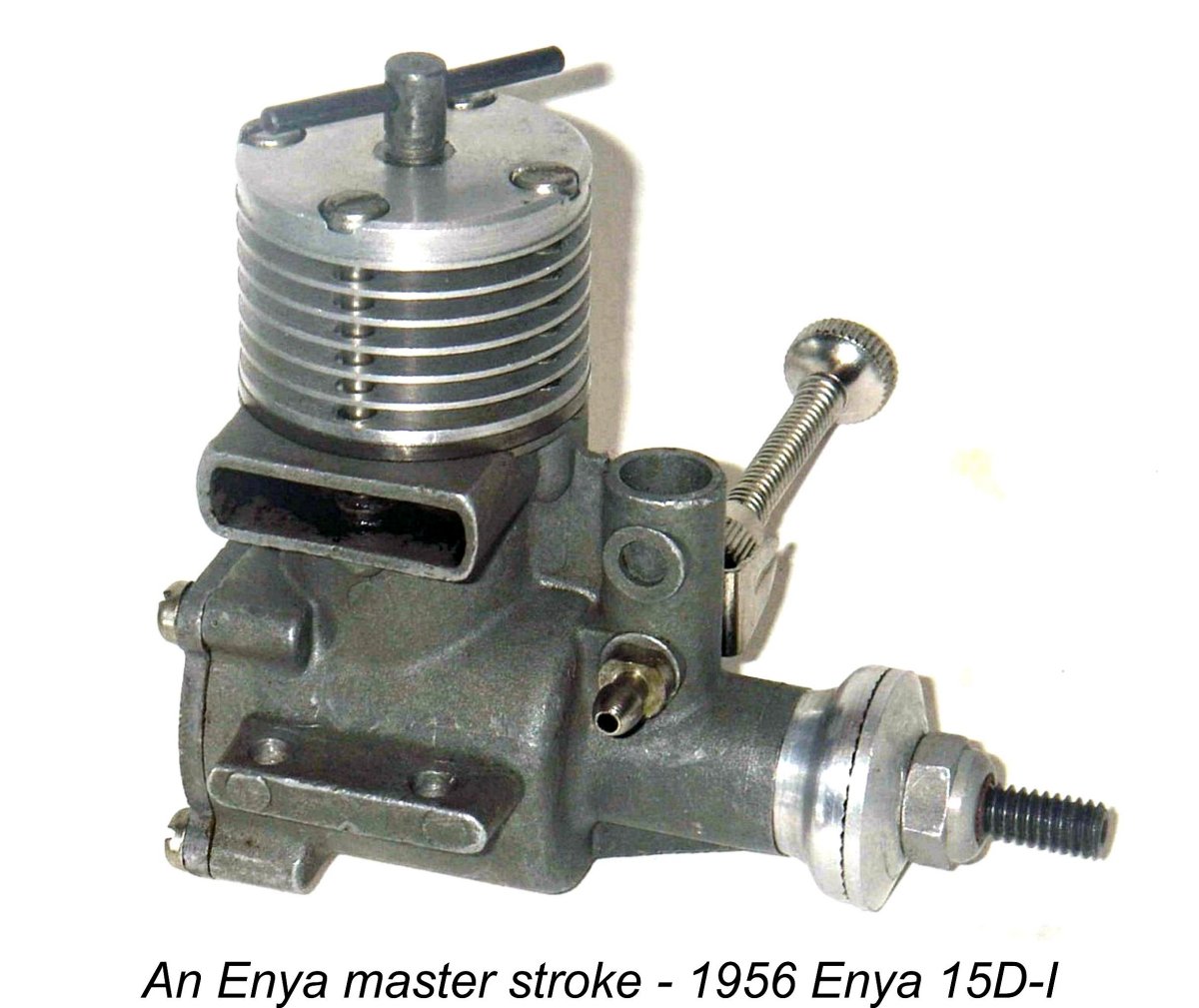

Enya fought back in late 1956 with an improved version of their own 1955 15-I glow model, the excellent Enya 15-IB (originally designated the 15-IS). They also produced a limited number of high-performance “factory specials” based on the 15-IS and 15-IB. This evened the performance score for a time, but O.S. were always quick to respond to any challenge from Enya, soon countering vigorously with an updated version of their established 15 model, the even more powerful and still ultra-lightweight 1958 O.S. Max-II 15.

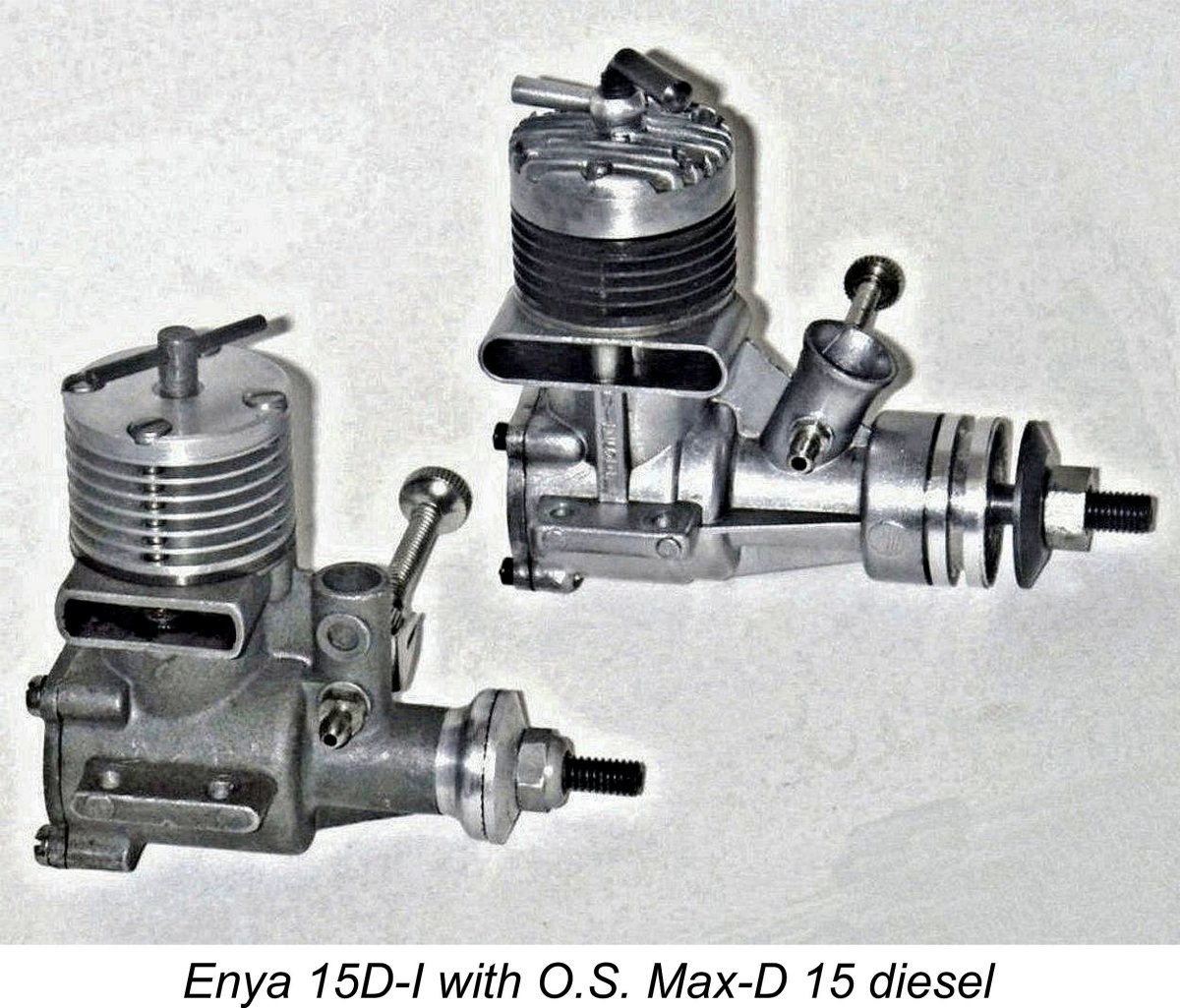

The quality, design and performance of the Enya D15-I turned a lot of heads, particularly in Europe where diesels were still the dominant type of model engine, at least in the displacement categories up to 3.5 cc (.21 cuin.). At least two European manufacturers (MVVS and Dremo) paid Enya the compliment of adapting the 15D's transfer porting arrangement to diesel designs of their own. The Russians paid Enya the compliment of producing their own close copy of the MVVS derivative in the shape of the Kharkov MK-25 diesel from Ukraine. Back in Japan, O.S. naturally felt that they couldn’t take this lying down! Beginning in early 1957 they embarked upon a development program of their own with the intention of producing a .15 cuin. diesel that would beat anything that their Enya rivals could produce. The eventual result was the main subject of this essay – an almost-forgotten classic, the O.S. Max-D 15. The O.S. Max-D 15 in the Modelling Media

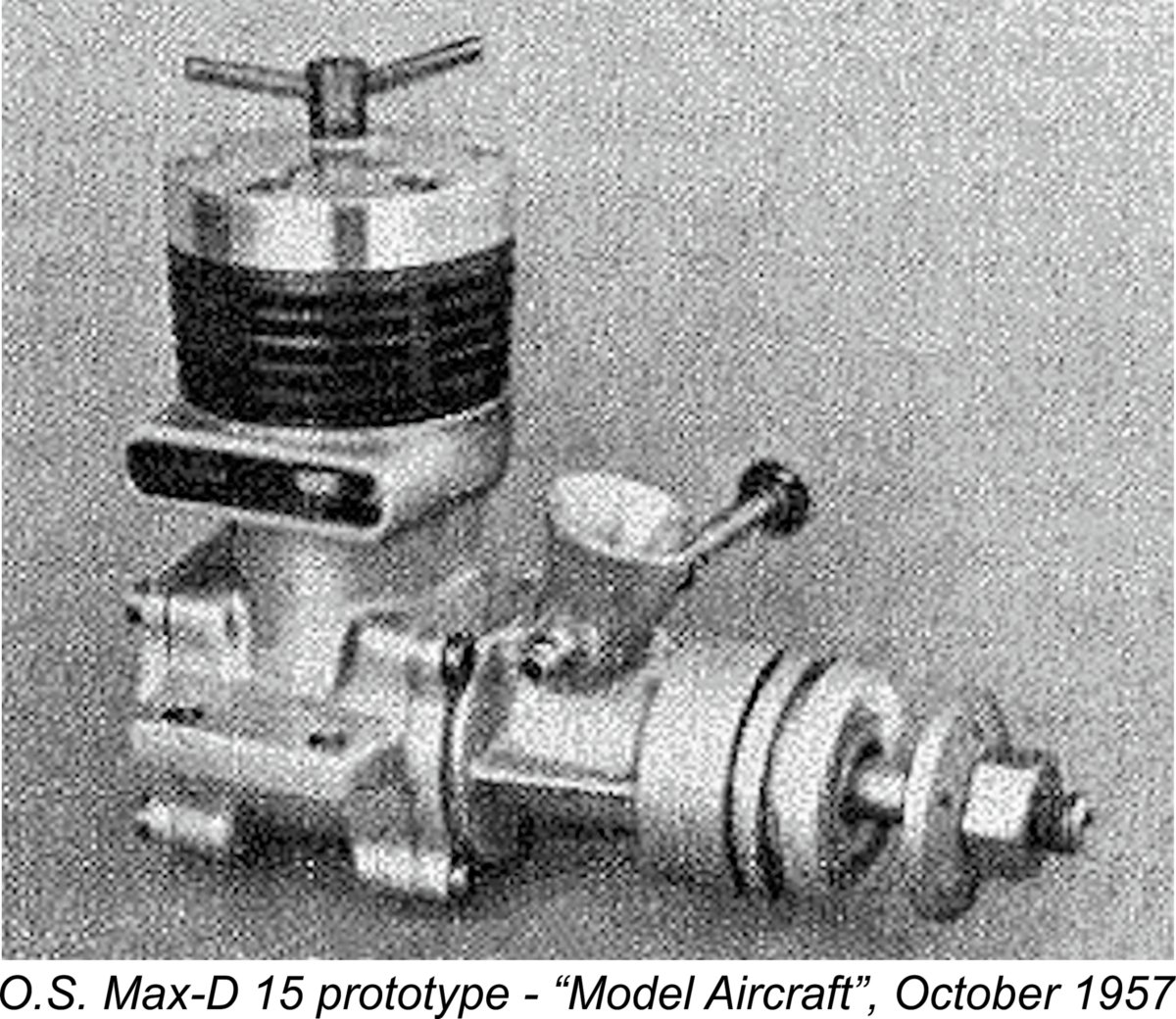

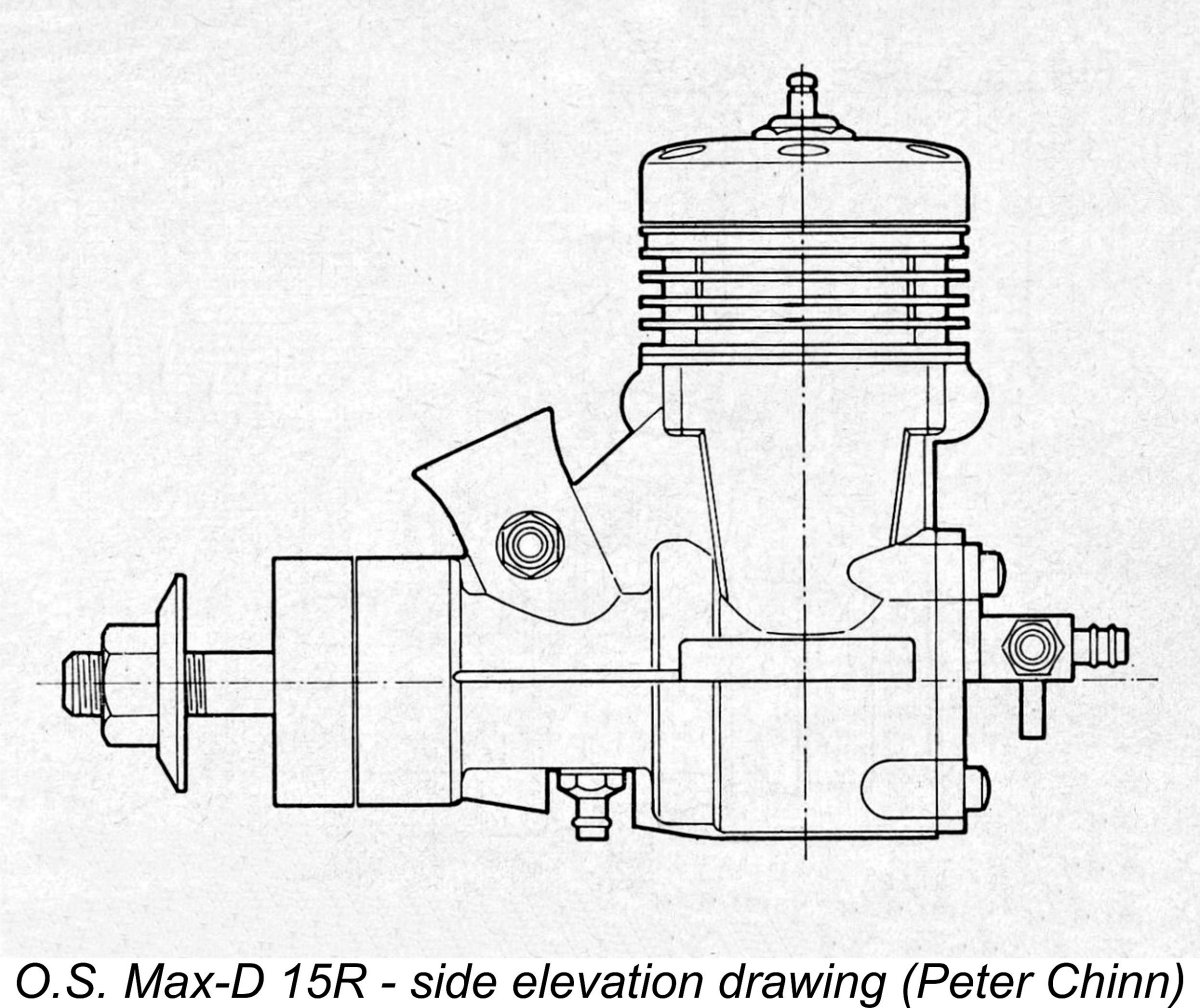

The attention of readers in the English-speaking countries was first drawn to the fact that O.S. were in the process of developing a 2.5 cc diesel by Peter Chinn’s “Accent on Power” article which appeared in the October 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Chinn included a capsule description as well as several photographs of one of a number of prototypes which had apparently been in the development stage for much of 1957. It's clear that he was in close and constant communication with O.S. during this period. The illustrated unit seen at the right looked not unlike the final production version apart from the use of a detachable front housing as opposed to the integrally-cast housing used later. Chinn reported that its main journal diameter was 9.5 mm, a dimension which was later increased to a whopping 10.5 mm in the production model. The unique baffle piston and matching contra-piston design which were later to be featured in the production model had already been developed at this time.

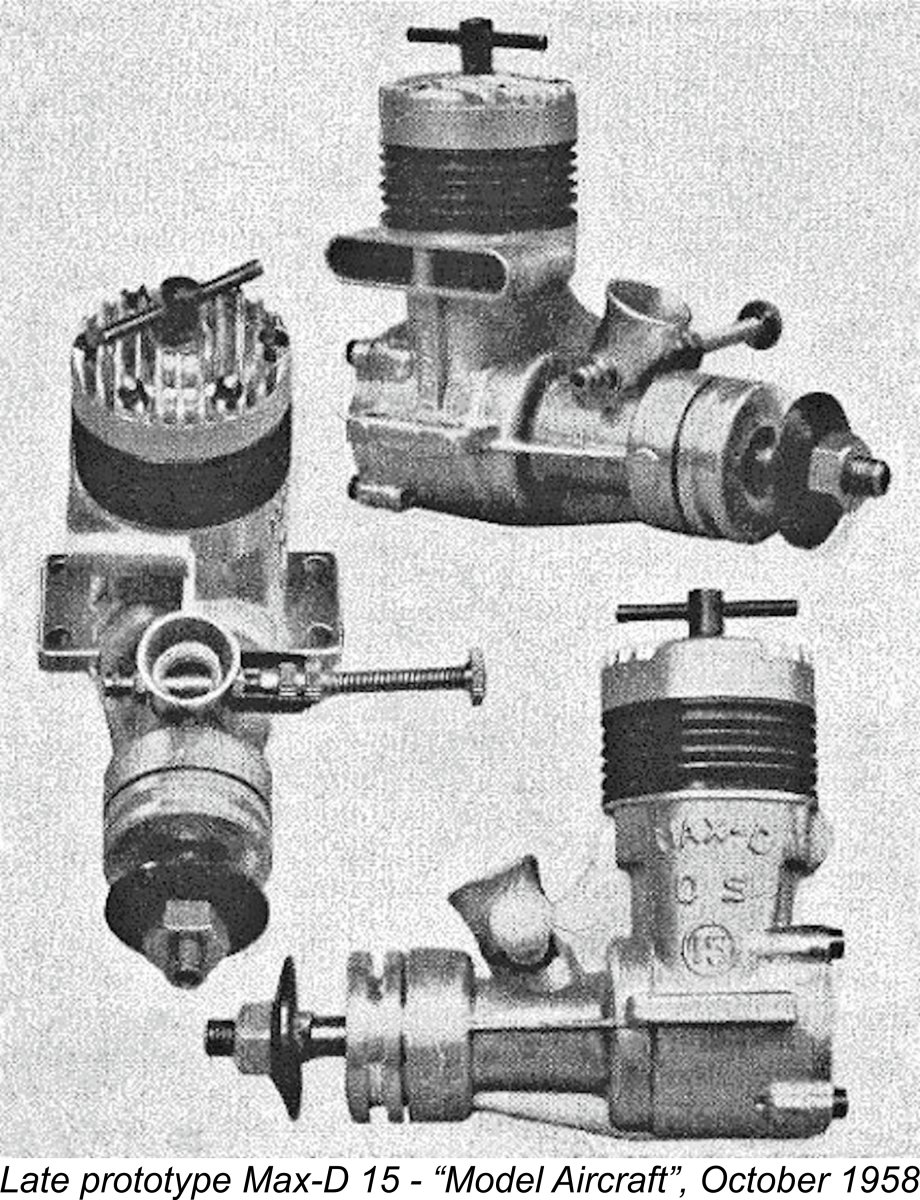

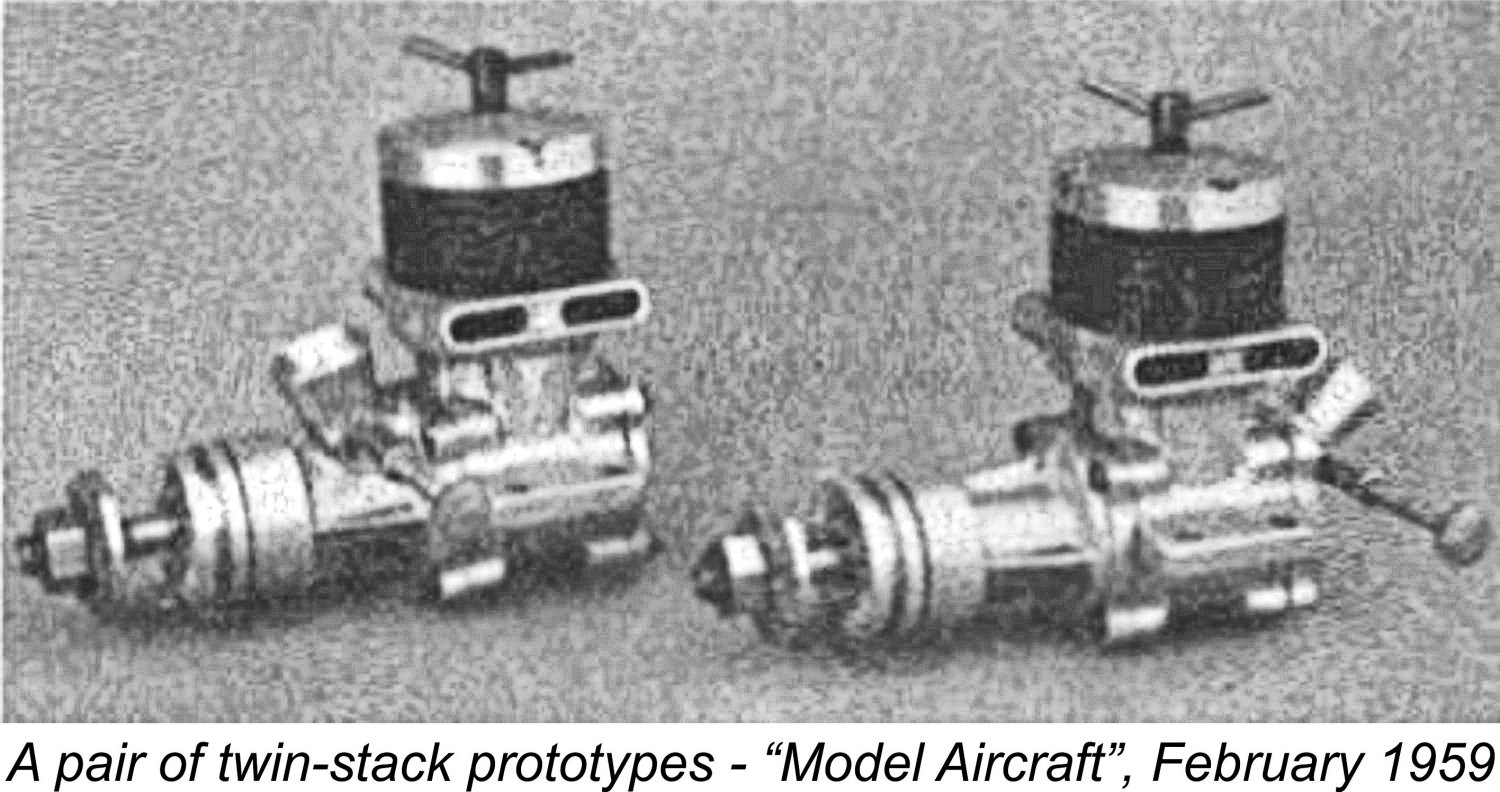

Nothing more was heard of the O.S. diesel project for some time thereafter. The next mention of the engine appeared in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” feature in the October 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Several illustrations of the then-current prototype were included, confirming that the design of the engine had now been more or less finalized. In particular, the crankcase appeared to be the same pressure-diecast component which was to be used for the production models. The detachable front end had been replaced by a main bearing housing which was cast in unit with the main crankcase. Chinn’s comments regarding the motivation for the development of this engine are quite enlightening. When However, following the 1957 event the rules were changed to require a 50% greater minimum combined weight of model and motor. This negated the weight advantage of lightweight glow-plug engines, instead favouring the greater torque development potential of the diesel and its consequent ability to turn a larger and more efficient prop. Indeed, it would appear that the return of the diesel to competition prominence was the rule-makers' primary goal. If so, the rule change worked! The vast majority of the competitors at the 1958 Free Flight World Championship meeting at Cranfield in England were back to using diesel engines. To give some idea of the breakdown, no fewer than 25 entrants were using Oliver Tigers, followed by 15 Webra Mach I’s and 6 Enya 15D’s along with a handful of the new Czech MVVS 25-D/1958 diesels featuring their Enya-based transfer porting. It had evidently been the goal of O.S. to have their new 2.5 cc diesel model ready to compete in that 1958 contest. However, Chinn stated that “the heavy demand for Max glow engines and the need for further development work on the diesel” had combined to delay the release of the latter model. Chinn stated his understanding that “the design has been finalized and the production engine will closely resemble this model”. This latter assumption ultimately proved to be well founded. Somewhat strangely, the engine continued to remain absent from the marketplace throughout In his previously-noted history of the O.S. marque which appeared in the February 1959 issue of “Model Aircraft”, Chinn included an image of two of the early twin-stack prototypes (one FRV model and one having rear induction) without commenting further on the engine’s availability. His possession of all these prototype images shows that he had clearly remained privy to the development of the engine from the outset. It was not until his September 1959 “Latest Engine News” column in “Model Aircraft” (undoubtedly written in July 1959 to account for Editorial lead time) that Chinn was finally able to announce that the O.S. Max-D 15 was “at last in production” following a drawn-out gestation period of over two years. This appears to date the market appearance of the engine to around June 1959.

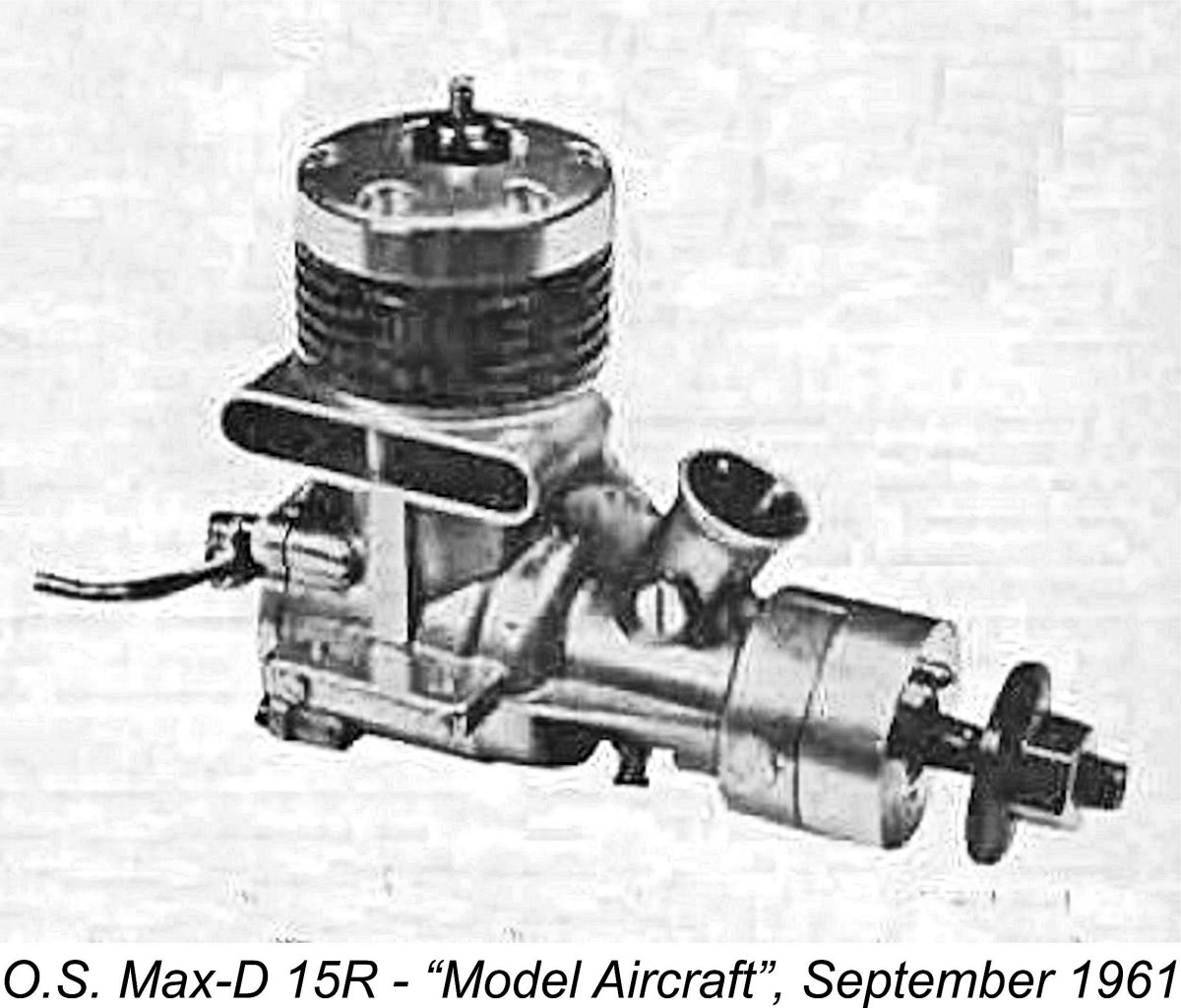

These units evidently materialized as anticipated, since Chinn subsequently provided a full illustrated description of the engine in his "Latest Engine News" column in the November 1959 issue of "Model Aircraft". His comments on the engine at that time were universally positive. In view of this, it's rather strange to have to record the fact that Chinn’s anticipated test of the Max-D 15 never materialized despite his indisputable possession of two examples as well as his clearly-stated intention to test them. The engine was next mentioned in the "Motor Mart" feature in the July 1960 issue of "Aeromodeller", the comment being made that the first examples were "now entering the country" (Britain). The example illustrated in the article was said to have been borrowed from Henry J. Nicholls. Despite the magazine's indisputable access to an example, the engine was never the subject of a published test in "Aeromodeller" - the writer of the article confined himself to stating that "it remains to be seen whether the Japanese company's efforts to perfect a motor in (sic) this type have been worthwhile". This implies that initial tests either by Nicholls or "Aeromodeller" staff may have been somewhat less than encouraging, or that some structural failure had prevented the completion of a full test. See below ........ At this point, the engine fell off the radar completely. The sole further mention of the O.S. Max-D 15 that I can find came in Peter Chinn’s test of the derivative O.S. Max-D 15R racing glow-plug model (“Model Aircraft”, September 1961 – see below), in which it was briefly recalled. Chinn was unstinting in his praise of the glow-plug unit, commenting that it used the crankcase casting from the earlier and “somewhat less successful” diesel model but was “totally unrelated as regards performance and handling qualities, the glow engine being vastly superior in every respect”. These comments make it appear probable that Chinn did indeed test the Max-D 15 diesel just as he said he would, since he was able to draw comparisons between it and its glow-plug derivative. Evidently he found it wanting in a number of respects. Shortcomings in both performance and handling are very clearly implied by his comments. To really allow the mind to wander over to the dark side, it is also not impossible that the built-in crankshaft weakness for which there is considerable evidence (see below) had reared its ugly head, resulting in the test engine breaking its shaft. Whatever the reason, it seems to be beyond question that Chinn must have tested the Max-D 15, finding little to enthuse about. Not wishing to embarrass a respected manufacturer with whom he clearly enjoyed an excellent working relationship, Chinn evidently followed his usual practise in such cases of saying nothing. His silence is eloquent ..............

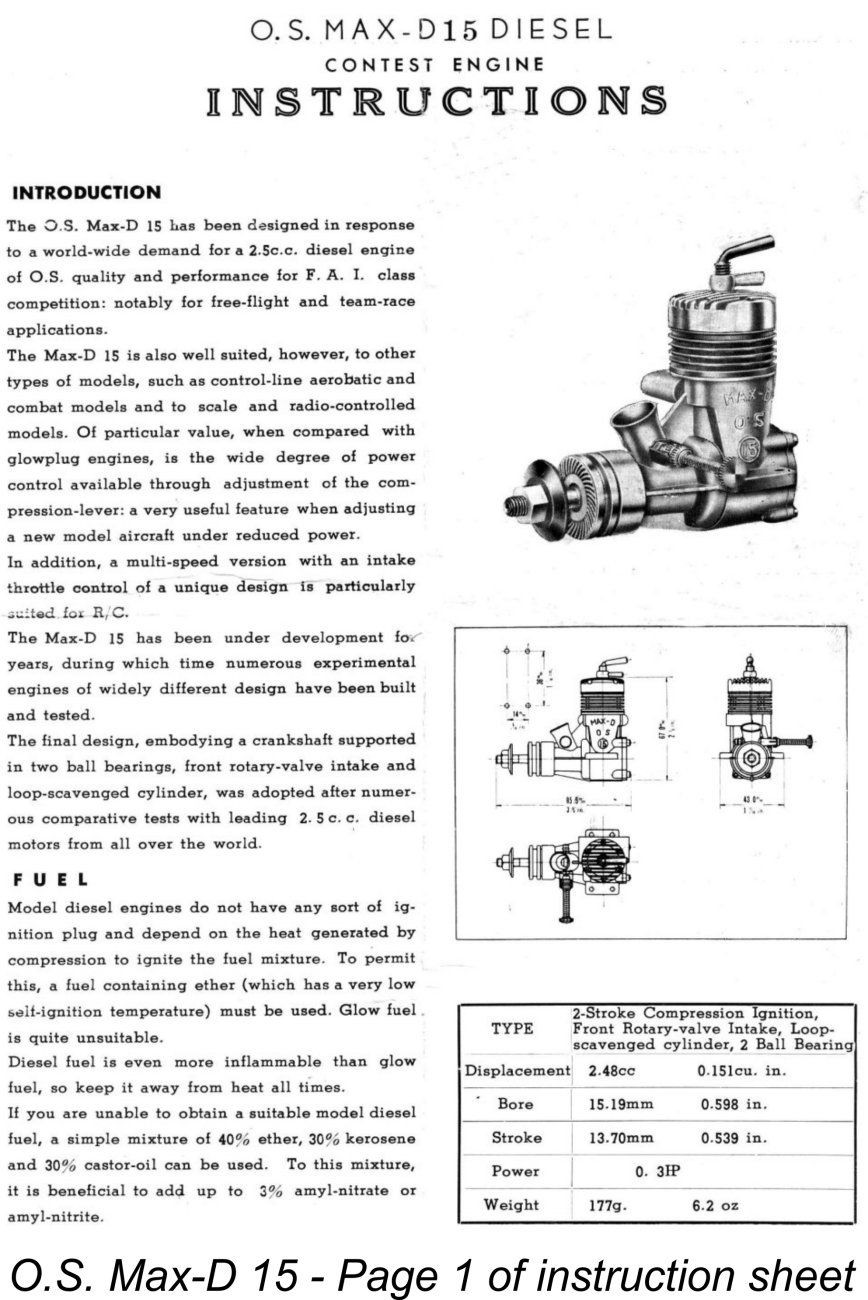

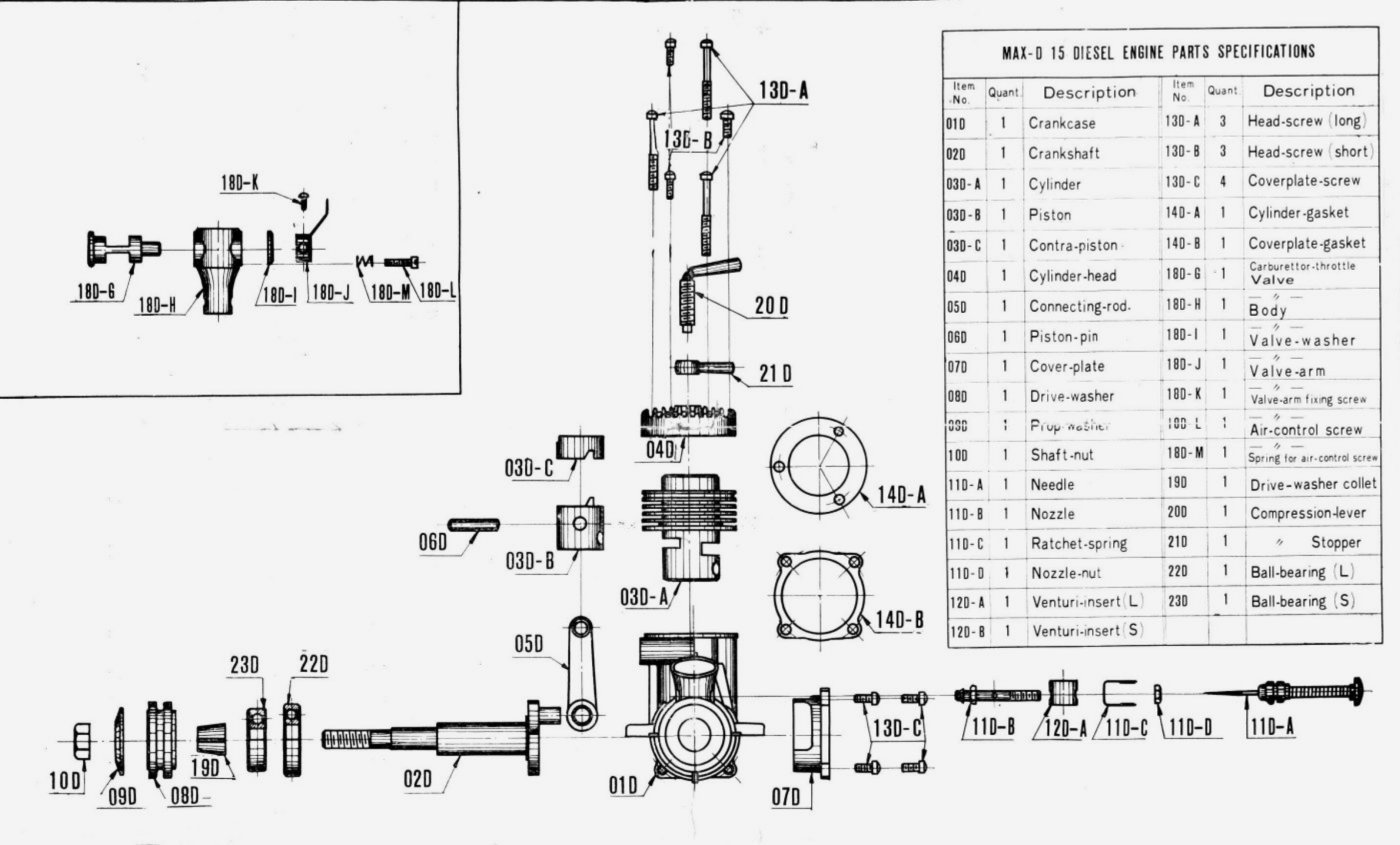

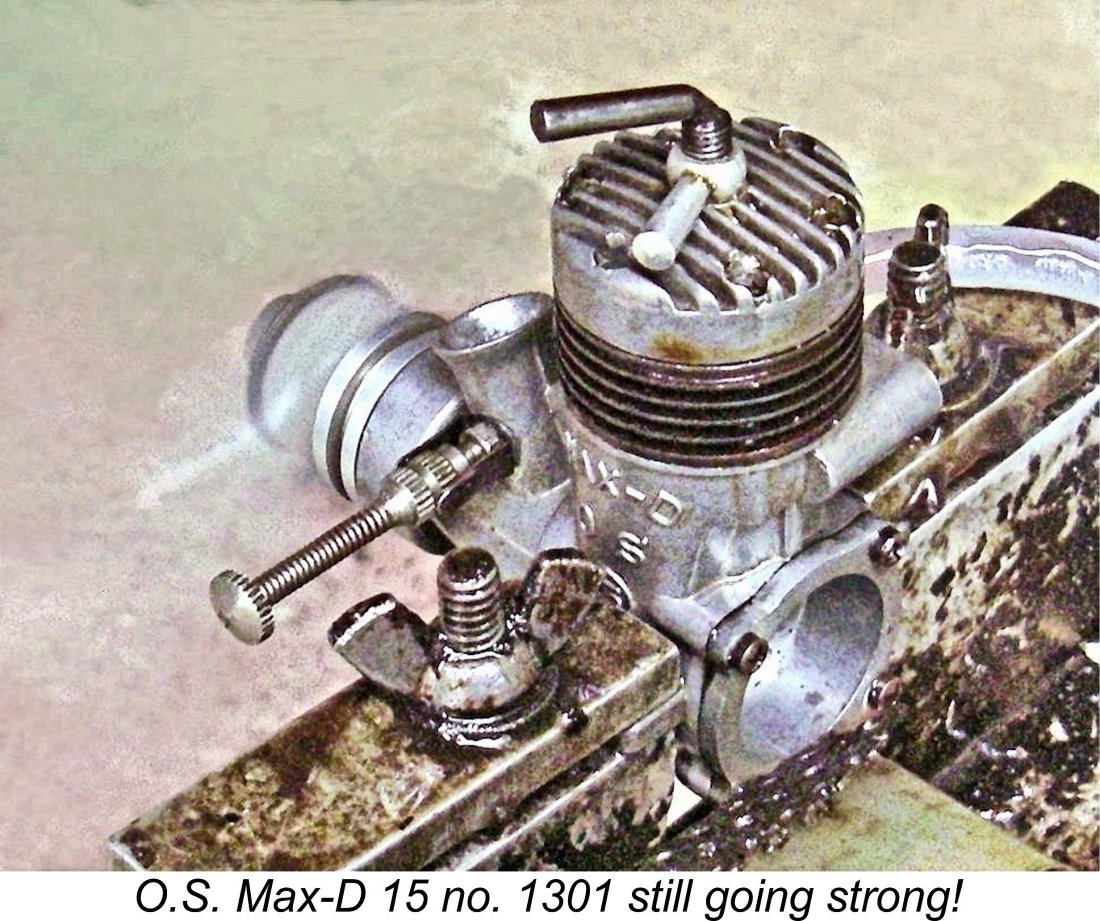

In terms of its free flight potential, it’s hard to see the engine offering any power advantage over a good contemporary competition glow-plug motor (many fine examples of which were on the market by the time that the Max-D 15 appeared in mid 1959) or even a tuned competition diesel such as an Oliver. Furthermore, it weighed substantially more than the glow (and even some of the diesel) competition. These factors would appear to argue against any likelihood of its greatly distinguishing itself in free flight competition. If it had been released as originally intended in early to mid 1958, it might have stood a chance. As things were, by mid 1959 it had missed the boat. Perhaps these factors explain why the Max-D 15 appears to have remained in production for a relatively short time. In a sense, it made its much-delayed appearance as an engine without a clear purpose. It’s impossible to be certain, but all indications are that production had ceased well before the end of 1960. An R/C version appeared on eBay in 2008 bearing the serial number 2274 and having a guarantee card dated 1960, confirming that the engine was still in production during that year. That is the highest serial number that has yet come to my attention. The engine appears to have disappeared from the market later in the same year. It’s presently unclear how many examples of the O.S. Max-D 15 were produced - all that can be said with some confidence is that by O.S. standards the figure was not large. The serial numbers of my present examples are 1301 and 1431, while the other example that I owned years ago was numbered 1651. My good mate Peter Valicek owns engine number 1527. The late Jim Dunkin included a photograph of engine number 1794 in his indispensable book on the world’s 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin.) engines, while the R/C model noted above was numbered 2274. Reader Ian Howlett reports owning engine number 1790. while my valued mate Alistair Bostrom of Hawaii owned engine number 1847. Tracking the infrequent offerings of other examples on eBay over the years has thrown up the additional numbers 1129, 1256, 1455 and 1853. Those are the only confirmed serial numbers that I'm currently able to report for this engine. I find it extremely interesting to note that these numbers all fall within a sequence extending from 1000 up to 2300. Twelve engines is not a large sample, but you'd expect to find at least one example within the 0-999 range in a sample of that size if such engines existed. This suggests very strongly (to me at least) that The rival Enya 15D fared a great deal better in the international marketplace - this particular round undoubtedly went to Enya! During its four-year production life, the original D15-I variant acquired a certain reputation for breaking crankshafts when pushed to its limits, but that didn't prevent it from becoming a very popular engine for general purpose use - I've used one myself for decades with no problems. The far more sturdy 15D-II variant of late 1960 became even more highly regarded, surviving in production well into 1965 and re-appearing in 2014 in a limited edition factory reproduction. A full review of the Enya 2.5 cc diesels appears elsewhere on this website. Now, having traced the development and production history of the O.S. Max-D 15 diesel, let’s have a look at the engine which finally began to come off the production line in mid 1959. The O.S. Max-D 15 - Description In describing the Max-D 15 for the original version of this article, I was only prepared to go so far in terms of dismantling my own examples - among other things, I didn’t want to damage the original gaskets. This was no issue as far as the cylinder heads went, because the fact that this is a diesel meant that there is no gasket up there! The backplates came away easily too - the gaskets were not bonded either to the cases or the backplate flanges. But the cylinder in all examples was well and truly bonded to its base gasket, and I was not prepared to disturb it and risk damaging the seal. This being the case, the details of the cylinder and the crankshaft assembly will best be appreciated by examining the exploded drawing supplied with the parts list for the engine which is reproduced below. It shows all the major details quite clearly.

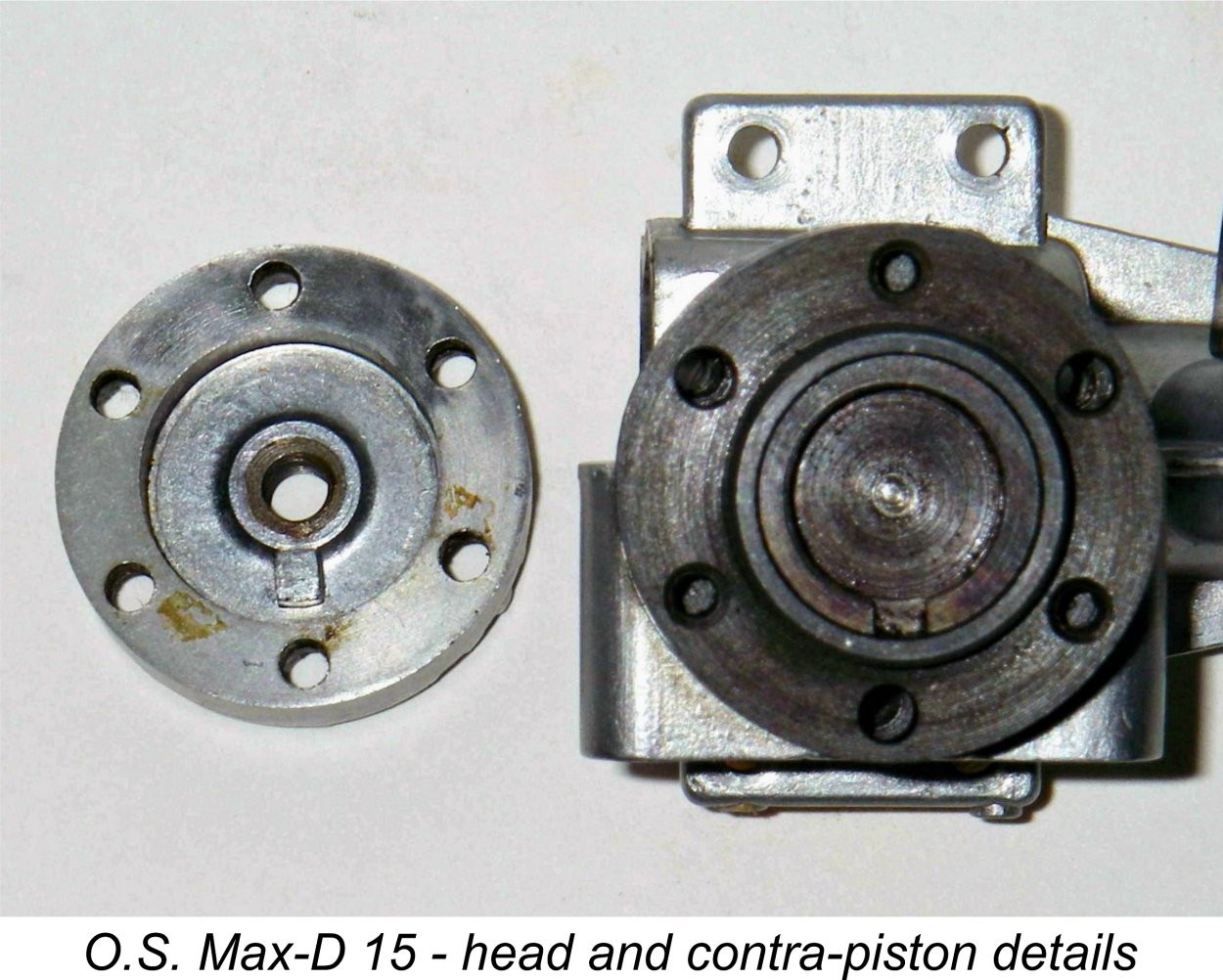

The cylinder porting too is essentially identical to that of the glow-plug model, displaying the well-established cross-flow loop scavenging arrangement. The real trickery is to be found up at the top of the cylinder. Three requirements had to be met here. First, enough room had to be created for the contra-piston and its operating mechanism, preferably without making the engine too tall in the process. Secondly, the presence of the baffle on the piston crown had to be accommodated in a manner which did not result in an overly inefficient combustion chamber configuration. And thirdly, the accommodation of the baffle in the contra-piston had to be maintained at all times regardless of the compression setting and of any tendency for the contra-piston to creep out of its required radial alignment in the bore.

In this way, the additional extra overall height of the unit is minimized. Despite this, the engine is considerably taller than its glow-plug counterpart as well as being quite a bit longer. The second of the above requirements - the need to accommodate the piston baffle - was met quite simply by milling a slot into the underside of the contra-piston which accommodated the baffle at top dead centre. But the designer did not stop there with merely achieving the required clearance. Apart from being made oversize to allow adequate clearance, this slot is actually somewhat bevelled towards the exhaust side so that the baffle does not by any means fill it at top dead centre. As the piston nears top dead centre, an ever-greater proportion of the remaining space above the piston is represented by the slot around the baffle and the gas above the piston will increasingly be forced by displacement to concentrate in that area. This will have the effect of causing mixture to move rapidly in from the cylinder side walls towards the area around the baffle as the piston nears top dead centre. The baffle slot thus performs much the same function as the squish bowl in a model glow motor cylinder head by concentrating the charge and promoting swirl within the combustion chamber. This should result in higher combustion efficiency once ignition has been initiated. The principle had of course long been applied to glow-plug engines, but this was among the first examples of its use in a commercial model diesel.

The top of the engine is completed by a perfectly conventional single-arm compression screw. This is fitted with an extremely neat and effective compression locking lever. The contra-piston in the example that I'd run previously proved to be a relatively slack fit in the bore by normal diesel standards, making this locking lever appear to be a necessary feature. The example owned by my good friend Peter Valicek was also rather loose, to the point that Peter chose to make a new contra piston for his engine. OK, so there we are with a very practical top end setup for our new world-beating diesel! Now, how about the matter of dealing with the additional stresses imposed upon the working parts by diesel operation? The mechanical loadings encountered in a diesel are inevitably considerably greater than those generated in a glow-plug model of similar displacement and design. To deal with this factor, a number of steps were taken. Firstly, in order to accommodate the radial stresses imposed by the lapped contra-piston, the cylinder walls were very sensibly made significantly thicker than those on the companion glow-plug model. This extra thickness was carried the full way down to the locating spigot at the base, resulting in a very sturdy and dimensionally-stable cylinder overall. To maintain cooling fin depth, the outside diameter of the cylinder fins was made larger as well, resulting in the hardened steel cylinder of the diesel model being substantially bulkier and heavier than that of its glow-plug relative.

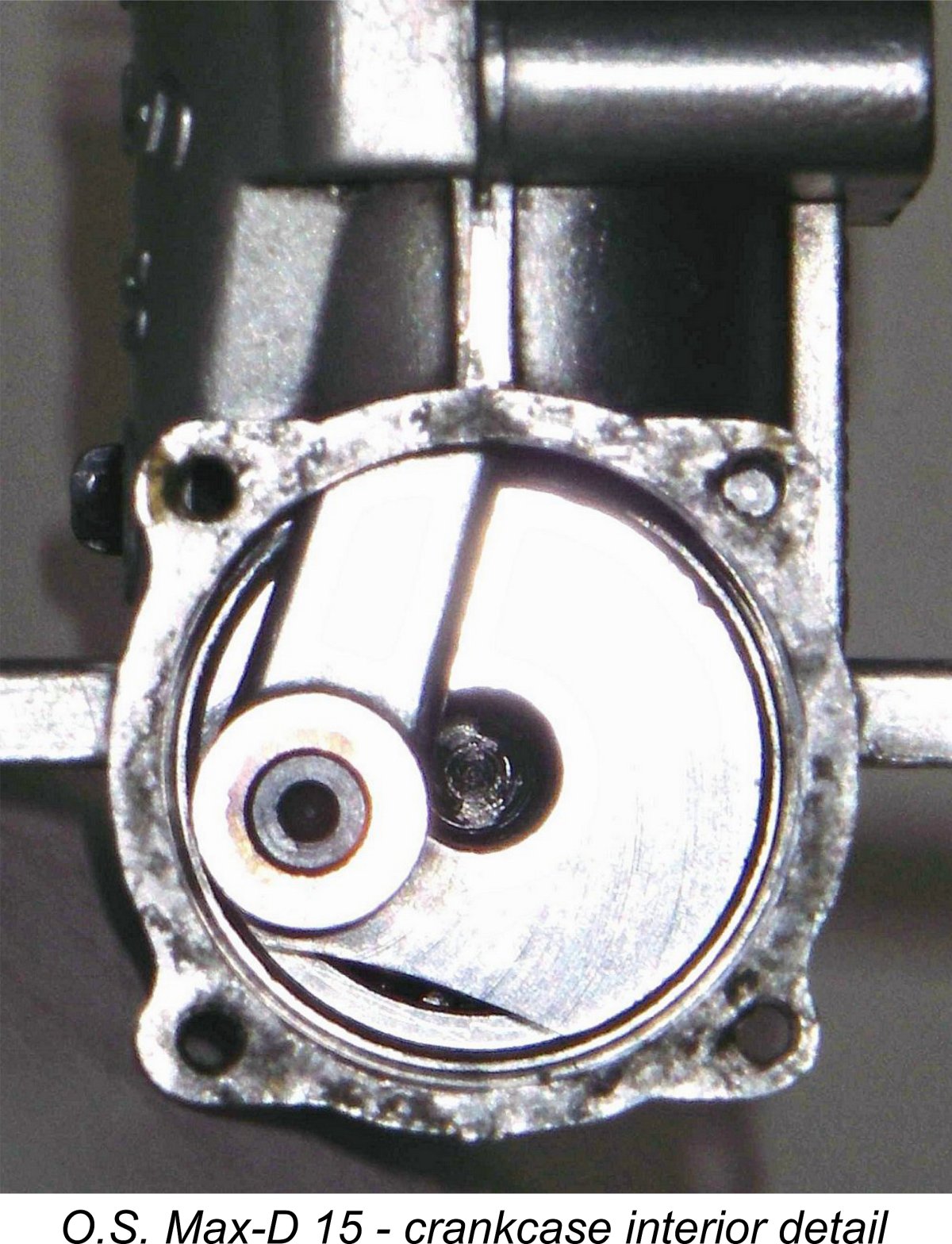

A possibly negative but inevitable consequence of the modified crankcase was the fact that the mounting between the diesel and glow models was not interchangeable. The lateral spacing of the diesel mount holes is considerably greater than that of the glow-plug model, as is the required bearer spacing. The O.S. Max-D 15 used a revised conrod which was substantially more sturdy than that of its glow-plug counterpart. The big The rest was perfectly conventional model engineering design. The re-configured crankcase accommodated the twin ball bearings, with a revised crankshaft being developed to fit those bearings and provide adequate strength. The revised crankcase die naturally incorporated the Max-D 15 designation, also confirming the seemingly obvious fact that this was a DIESEL! The latter information appeared on a vertical rib cast into the right side of the new crankcase below the exhaust stack, presumably for added strength below the location of one of the three main cylinder hold-down bolts. The glow-plug model only used two such bolts, but the designer clearly felt that the diesel required the extra bolt. The very sturdy-looking one-piece hardened steel crankshaft was perfectly conventional apart from its main journal diameter. The main journal had an impressively heroic diameter of 10.5 mm, stepping down to 6.0 mm at the rear of the front ball race in the usual manner. These are very generous dimensions for a 2.5 cc diesel. A healthy degree of counterbalance was built into the crankweb, as seen in the above image. The internal gas passage was drilled to a generous 0.250 in. (6.35 mm), still seemingly leaving ample wall thickness for strength. The shaft featured the usual perfectly rectangular O.S. induction port which gives very rapid opening and closing. Fair enough, but this appears to me to be the only weakness in the design – a port formed in this way will inevitably have sharp corners which will act as localized stress-raisers, quite possibly initiating a fatigue failure down the road. The fact that O.S. failed to appreciate this point and construct the crankshaft accordingly can only be put down to inexperience with this type of engine - the Max-D 15 was their first-ever FRV diesel. An opening of round-ended “race track” form would have been far better.

The fix requires one to dismantle the engine to remove the shaft. It should first be checked very carefully for existing cracks - if they are present, the shaft is useless. If all is well, it's quite straightforward to carefully round off the sharp corners with a small Dremel diamond-coated bit. This greatly reduces the potential for stress concentrations to develop. I tore down my intended test engine engine no. 1301, finding that this engine's previous owner, my late and much-missed mate David Owen, was well on top of this issue and had already modified the shaft for me. Thanks, mate!! The modified shaft in this engine is shown in the accompanying image. My advice would be not to run one of these units at all unless the shaft was modified in this way - why take chances with an engine of this rarity? However, once the shaft is modified as described, I suspect that the engine can be used with complete confidence - the shaft appears to be very sturdy otherwise.

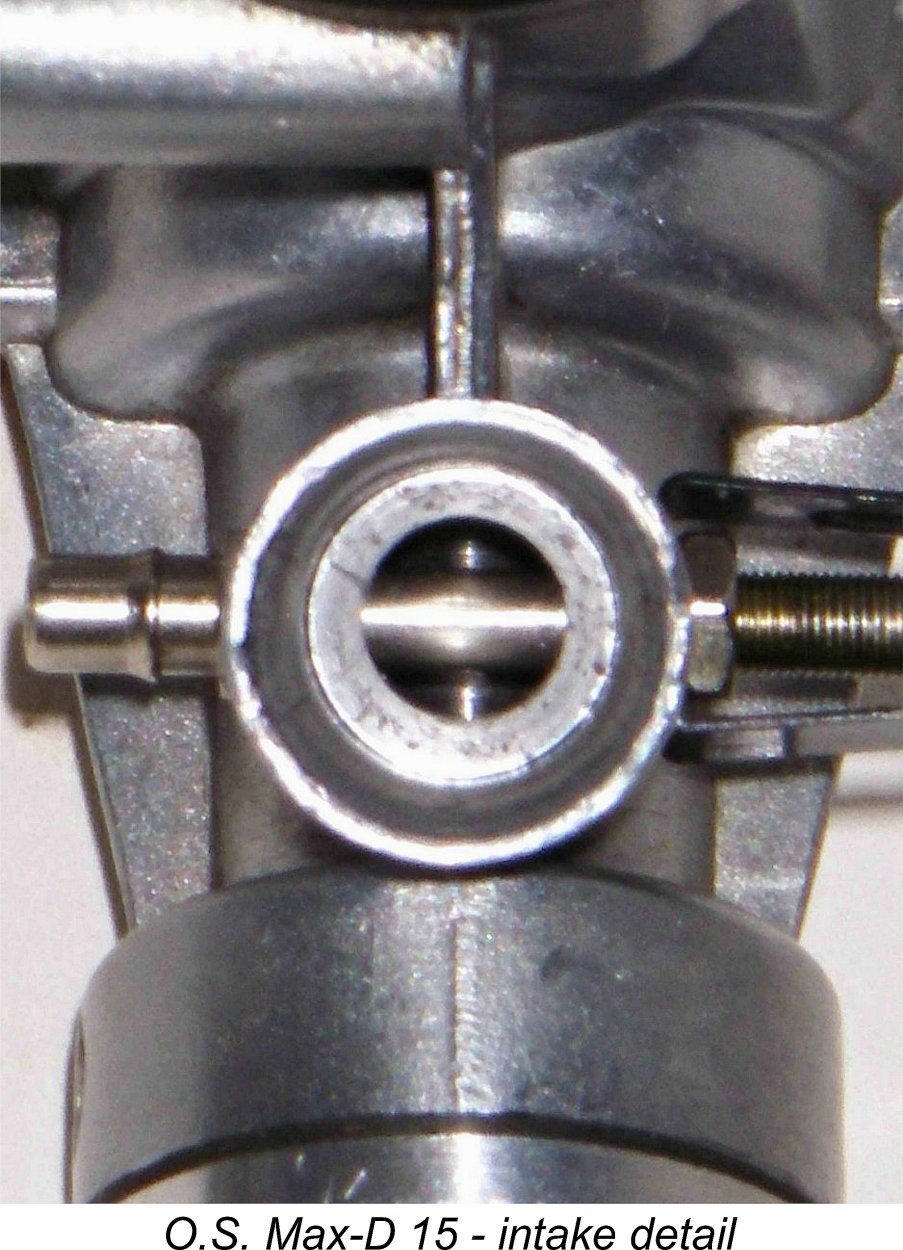

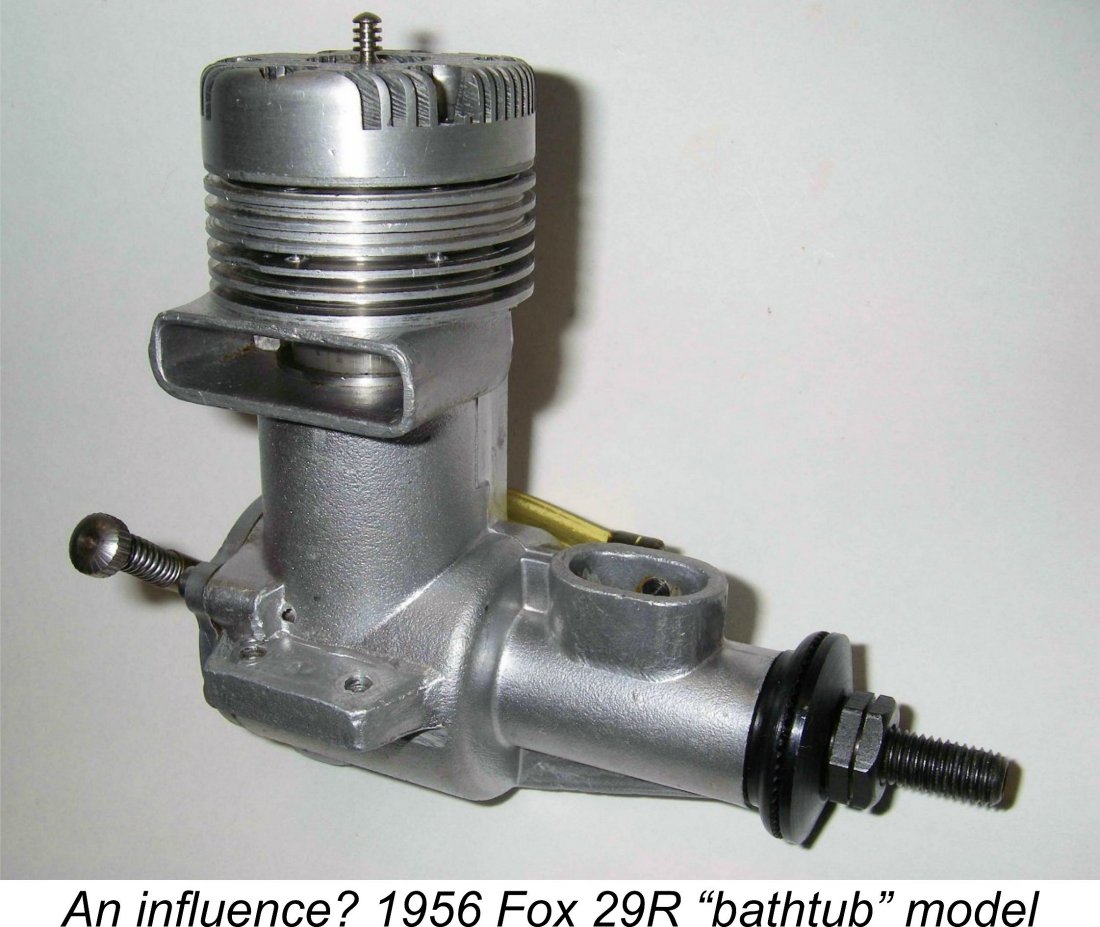

If necessary for all-out competition work, the venturi insert could of course be drilled out, although a larger sized insert was available as an optional extra, allowing some fine-tuning of the induction system. As noted earlier, an R/C throttle was also available for this engine - a clear precursor of the emerging dominance of R/C engines in the model engine marketplace. The prop driver was locked to the shaft by means of a tapered split collar in the usual manner. Oddly enough considering the engine’s Japanese origin, the thread used for the prop-nut was a very non-metric 12-36 UNS! The needle valve assembly was the same as that used on the contemporary O.S. Max 15-II glow-plug model. Another of the engine's interesting features was its adoption of a Desaxe crankshaft alignment - i.e., offset slightly to the transfer side of the cylinder. This arrangement has the advantage of decreasing the rod swing angle on the power stroke. The result is an increase in the leverage applied by the piston to the crankpin on the power stroke, together with concurrently reduced piston side-thrust and associated friction losses. The arrangement also promotes a measure of additional piston “dwell” at the top of the stroke, which can offer combustion benefits in addition to lengthening the angular duration of the power stroke by comparison with the compression stroke. The system was routinely employed in the Fox engines, among others.

That said, the extra weight and mass have been put to good use - the engine seems very sturdy with the possible exception of that rectangular induction port. Even that potential problem is easily rectified, as described earlier. The standard of manufacture is up to the best that O.S. could produce, which is to say as good as that of any commercial manufacturer anywhere in the world. The engines were supplied with a neat rubber exhaust plug to assist the owner in keeping dust and dirt out of the engine when not in use. A nice touch ……….. all in all, a class package. The modifications that O.S. were forced to make to their basic glow-plug model to produce the Max-D 15 were sufficient in number that, like its Enya counterpart, the Max-D 15 ended up sharing very few components with its glow-plug stablemate. Indeed, as the above comparative image clearly shows, it was a completely different engine throughout. The two models used the same needle valve assembly and prop-nut, but that was it - everything else was different!! So although they didn’t throw away the standard design blueprint, O.S. ended up being forced to follow Enya’s lead by making an entirely new engine as opposed to a modified version of their existing glow-plug model. Performance

As previously stated, the O.S. Max-D 15 was never the subject of a published test in the English-language modelling media. Consequently, all I had to guide me going into my own test were a few pages of my notes made many years ago during some test running of a less pristine example (no. 1651) which I once owned and tried on the bench. Unfortunately, I failed to take note of any prop-rpm figures - at the time, I didn't own a rev-counter of any kind. I was also blissfully unaware of the potential shaft failure issue. Thankfully, the shaft survived my test running with no problems. My notes from those long-ago test runs are fairly detailed. They record one characteristic that the Max-D 15 shares with its Enya counterpart, namely the need for a slightly unusual approach to starting by diesel standards. Like its Enya D15-I counterpart, I found it extremely reluctant to start or even fire unless quite heavily primed. This would be a considerable disadvantage for team racing, which was one of the uses to which reference was specifically made in the instruction manual. Perhaps things would be better with the engine inverted, as it usually would have been in a team racer ……………. However, I noted that a shot of fuel through the exhaust soon livened things up, with a start being achieved reasonably easily thereafter. I included the comment that once running, the exhaust note was rather “odd” when the engine was running rich - it evidently didn’t sound at all like a diesel! I characterized the sound as quite “throaty” - more like a rich-running glow-plug unit than a diesel. This is probably a reflection of the porting used. But as I leaned it out, things apparently returned to normal and it began to make a more familiar and very powerful noise! I reported finding the engine to be perfectly straightforward to adjust, with extremely smooth running once properly set. The contra-piston proved to be quite loosely fitted, but the comp screw locking lever took care of that. As mentioned earlier, I never took any prop/rpm readings off the engine, but I did note for the record that it appeared to be in the upper echelon of 2.5 cc diesels of its late 1950's period as far as performance went. That of course was a purely subjective evaluation with no data to back it up. The O.S. factory claimed an output of 0.30 BHP at unspecified rpm for the Max-D 15, which exceeds the measured figure of 0.252 BHP at 14,200 rpm obtained by Ron Warring for the Enya 15D-I and matches the value of 0.298 BHP at 14,700 rpm reported by Peter Chinn for the Enya offering. Based on my memory plus the fairly detailed comments recorded in my notes, I have never seen any reason whatsoever to doubt the O.S. claim. A video of one of these engines running may be viewed here. The implied performance was nothing to shout about - only 11,600 rpm on an 8x4 Master airscrew. I would have expected more .............The tester had a lot of trouble starting the engine - the needle was obviously set too lean, but it took him forever to figure this out! So not very representative of the engine's starting qualities! I get the impression that the tester was somewhat less than fully conversant with the black art of getting the best from a model diesel............. OK, so much for past experience and manufacturer’s claims! Time to run a latter-day reality check – let’s head for the test stand! The O.S. Max-D 15 Diesel on Test My original “runner” example of the O.S. Max-D 15 (engine no. 1651) has long ago passed into other hands. Of my two present examples of this engine, one (no. 1431) is New in Box, and I have elected not to run it. However, my other example, engine no. 1301 from the collection of my late and much-missed mate David Owen, has clearly done a fair bit of running in the past, even showing distinct signs of having been mounted in a model. It was this unit which was used for the following test. With its modified shaft port, I wasn't too worried about any potential crankshaft failures - the shaft had clearly stood up to a considerable amount of previous running. It was clear that no break-in was required - I could get straight down to the testing.

The engine certainly lived up to its advance billing! Finger-choking alone produced no result whatsoever - the thing just sat there between flicks, doing a convicing impression of a useless lump of inanimate metal! The one thing that became immediately obvious was how free-running the shaft was in its bearings - the engine oscillated forever between flicks. The ball races used are clearly perfectly aligned as well as being of absolutely top quality. Even when I switched to priming the cylinder, it took a while to elicit any response. It appeared that the amount of fuel in the cylinder had to be "just right" for starting. Following a prime, one flicked away for a while with no response - then suddenly the mixture in the cylinder would hit the sweet spot and the engine would burst into life. Although this generally didn't take long, I can't honestly rate this as an easy engine to start - it requires a certain amount of patience and a lot of knowing. Throughout the test, it continued to behave in the same way, whether hot or cold. Once running, things improved a lot. Response to both controls was excellent, making the establishment of peak settings a very straightforward matter. Once set, running was completely smooth, with no tendency to sag and no misfiring. Both controls held their settings dependably - the contra piston in this example proved to be perfectly fitted, making the compression screw locking lever redundant. However, I understand that other examples do require this accessory, making it a worthwhile inclusion. My long-ago test example no. 1651 certainly needed it. The engine turned the 8x6 APC prop with which I started at a steady 11,200 rpm, which was a little disappointing - I had been expecting more. Still, it was what it was! I proceeded to make a series of test runs on a range of different calibrated airscrews which I judged would allow me to bracket the peak. The following data were obtained.

The implied peak output falls somewhat short of the factory claim - my engine only appears to have managed around 0.280 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. Not exactly a bad performance by late 1950's standards, but nothing to brag about either considering the figures reported for other 2.5 cc competition diesels of the period. In particular, it falls a little short of Peter Chinn's reported figures for the Enya D15-I with which it was expressly designed to compete.

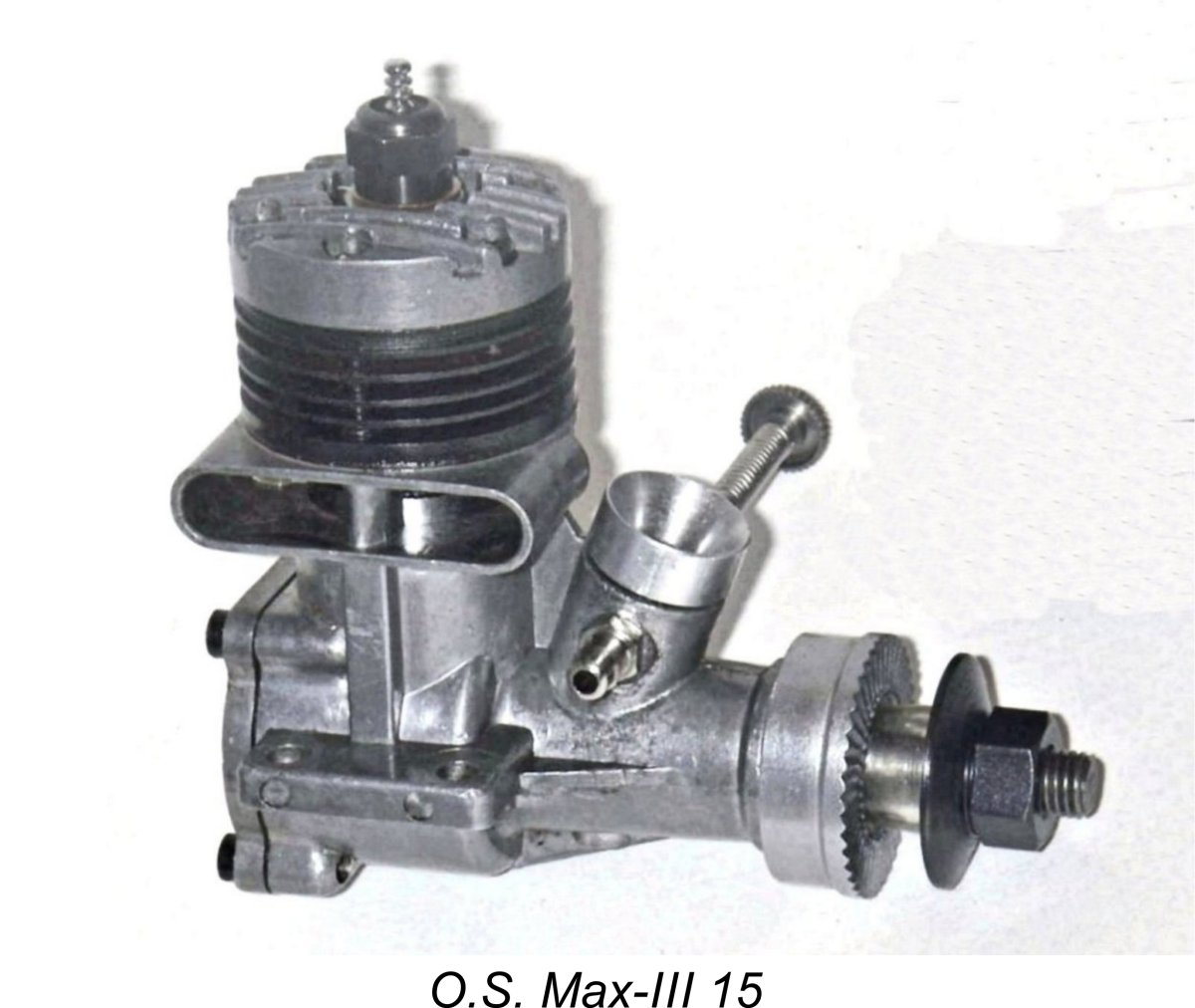

That said, by mid-1959 standards even an output of 0.30 BHP at, say, 14,500 rpm consigned the Max-D 15 to the status of an also-ran. Coupled with its problematic starting, it's not hard to see how it might quickly have become seen as a somewhat unsuccessful attempt to break into the 2.5 cc diesel market, as implied by Peter Chinn. Its handling characteristics certainly disqualify it from any consideration as a team-race diesel. On the positive side, my engine came through its test running completely unscathed, showing no signs of mechanical distress at any time. I suspect that with its modified shaft port it is probably a completely dependable runner. This particular unit has clearly seen service in a model, and I would be quite prepared to put it to such use again. It's an extremely well-made diesel which runs very smoothly and generates plenty of power to fly a model. The main strike against it is its somewhat problematic starting, but familiarity would doubtless do much to overcome that issue. A Successor - the O.S. Max-D 15R As noted above, the Max-D 15 appears to have ended its brief production life by the latter part of 1960. This was doubtless due primarily to the engine's failure to match the performance levels then being achieved by competing 2.5 cc diesels. However, knowing what I know about the unmodified engine's inherent potential for breaking crankshafts, I can't help wondering if a rash of such failures contributed to its speedy withdrawal. The fact that Peter Chinn never published a test despite undoubtedly having two examples at his disposal may be due to his test engine having failed in this way, although it's just as likely that it was the engine's handling and performance that let it down in his eyes. When pushed to say anything uncomplimentary about a new product from a respected manufacturer with whom he enjoyed a good working relationship, Chinn's usual practise was to say nothing ............ his silence in this case following his very positive initial coverage speaks rather loudly! However, that was not quite the end of the story. In fact, what occurred in 1960 was in effect a reversal of the process through which the Max-D 15 diesel had come into being in the first place! As of early 1960, O.S. had a twin ball-race diesel which had been in many ways a technological success but was evidently proving to be a sales and performance failure. It actually appears that the decision was probably taken in mid 1960 to suspend production of the Max-D 15 diesel. This left O.S with a number of components which were presumably considered surplus to anticipated spare parts requirements. What to do with them?!? A little thought brought about the realization that there was no reason why the same basic twin ball-race lower end could not be successfully applied to a competition glow-plug model! After all, the glow-plug motor was now very much in the ascendant in competition circles other than team racing. The O.S. 15 diesel had failed, but there was no reason why a glow-plug model based upon the remaining diesel components would not prove successful.

At the time when Chinn was writing his article, the engine had not entered regular production. Indeed, it was not clear that regular production was even contemplated - instead, Chinn stated that the engine would be "available to special order". The new model was designated the O.S. Max-D 15R. Below the exhaust stack it was essentially identical to the diesel model, even using the same presumably surplus crankcases which were still marked Max-D 15, also still claiming to be a DIESEL! The main changes here were the milling away of part of the lower bracing gusset on the main bearing beneath the intake to accomodate a tapped hole drilled through into the journal for a crankshaft-timed pressure fitting; and an increase in the internal gas passage diameter in the shaft from 6.35 mm to 7.5 mm.

One very interesting feature of this model was the fact that it had a remote needle valve mounted at the rear of the backplate. This fed a simple fixed jet in the intake, mirroring the set-up used on the legendary Fox 29R “bathtub” model of 1956. Of course, a conventional spraybar and venturi insert could also be fitted if desired. As supplied, the venturi insert which was provided with the diesel model was omitted, requiring the engine to draw through the full 9 mm diameter of the completely unobstructed venturi. This obviously required that the engine be operated on pressure fuel feed. Another intriguing refinement was the use of a prop driver which was counterbalanced using small lead inserts. This was apparently intended to reduce vibration at high speeds, although Peter Chinn reported one user as having found by experience that this feature actually increased vibration when the engine was mounted in a model. In view of the considerable longitudinal distance between the prop driver and the engine's major reciprocating components, I would actually have expected this.

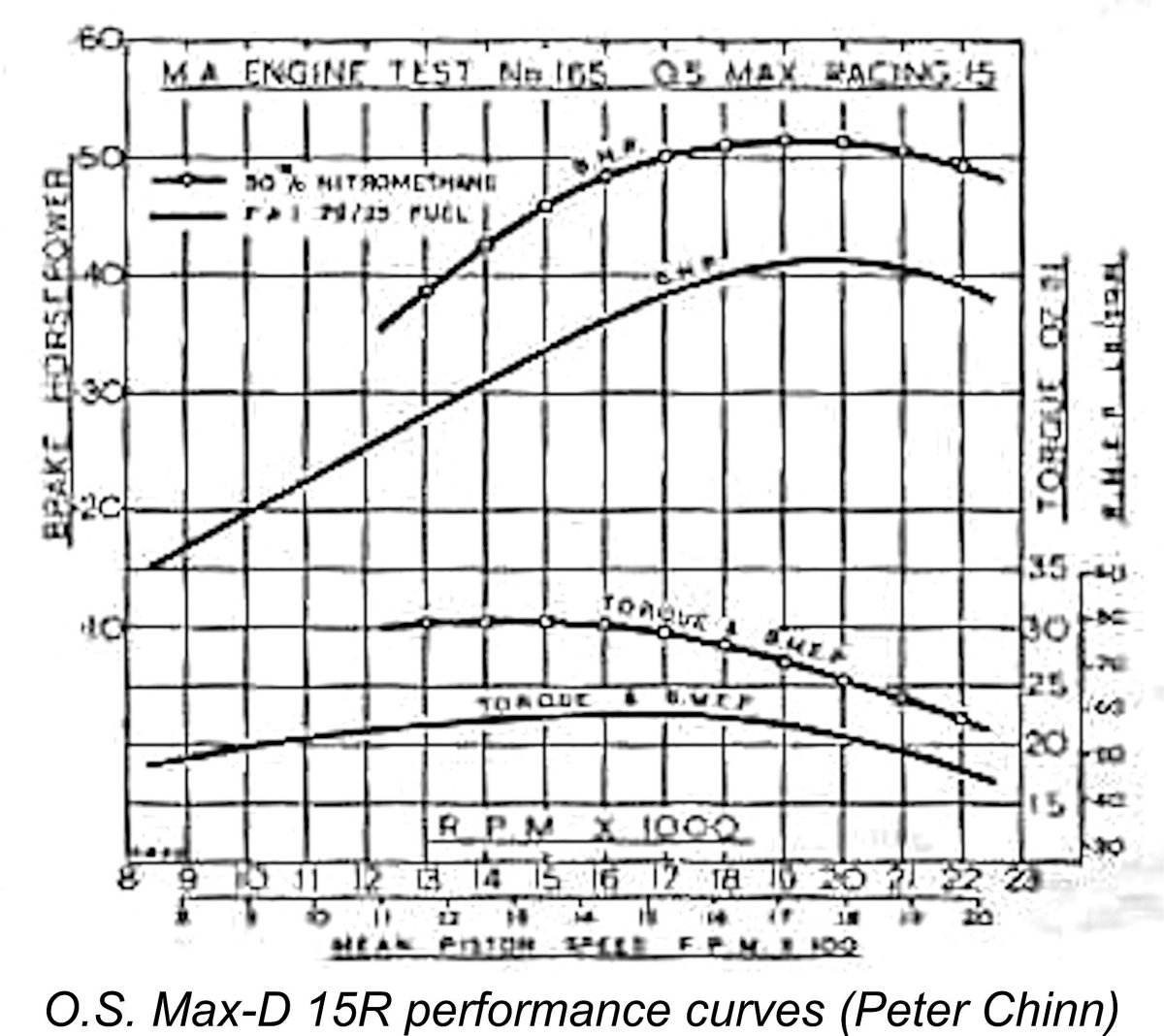

Even after it was finally released, the new model was produced in very small numbers by O.S. standards. It actually seems to have remained more or less a special order item. Chinn's test example was one of only six examples which had reached Britain by his time of writing in mid 1961. One of these had been used by George French to take first place in the British team trials for the 1961 World Free Flight Power Championships. Using the straight methanol/castor fuel by then required in FAI competition, Chinn reported a peak output of 0.41 BHP @ 20,000 rpm, a highly competitive figure at the time. Switching to an all-out racing fuel containing 50% nitromethane yielded an amazing output of no less than 0.515 BHP @ 19,500 A rather odd point upon which Chinn unaccountably failed to comment was the fact that the peaking speed on 50% nitro was lower than the peaking speed on straight fuel. This strongly suggests that the hotter fuel had induced a pre-ignition condition during leaned-out operation. The implication is that the engine required a colder plug on the hotter fuel - a not unusual requirement. Switching to a colder plug might well have released even more power. Even so, this performance highlights the fact that the basic functional design of the Max-D 15 diesel was extremely sound – after all, it was essentially identical to its glow-plug successor from the cylinder porting down. The only real differences were the area of the intake venturi, which greatly favored the glow-plug model, the glow's somewhat larger internal crankshaft induction passage and the type of ignition. Despite its outstanding performance, the Max-D 15R was too specialized to survive for long in the marketplace - like their rivals over at Enya, O.S. were becoming increasingly interested in sticking to bread-and-butter designs which could be produced and sold in significant numbers worldwide. In keeping with this focus, far greater emphasis was now being placed upon the development of R/C models as the relative popularity of control line and free flight entered their steady decline. There was no place for the Max-D 15R in such a business plan. It seems possible that O.S. only continued sporadically producing the engine to When the Max-III 15 glow-plug model emerged in 1961, traces of its Max-D 15R heritage were still obvious. Although it reverted to a plain bearing, it used a modified version of the Max-D 15R cylinder along with a revised (albeit far less bulky) crankcase which retained the strengthening rib beneath the exhaust stack as well as an undrilled tapping point beneath the intake for pressure operation if desired. It also featured the same tumbled finish on the castings. The weight had crept up to 3.9 oz., but it remained a far more compact engine than either the Max-D 15 diesel or its Max-D 15R glow-plug descendant. I must confess here (not for the first time!) to being a complete idiot - I actually had a used but still pretty nice example of the Max-D 15R many years ago, but traded it on to a friend who simply “had to have it” for his collection!! He naturally sold it almost immediately at a handy profit, and I never saw it or any other example again (nor did I ever deal with my “friend” again either – with me, you get to try that once!!)! Should have had more sense ……. I do recall that it was a real screamer on the test bench, though!! Conclusion Well, there it is - as much as I can tell you about one of the forgotten classics of the model engine industry. It’s a great pity that this design didn’t achieve greater sales success - if it had, there’d be more of them around today! And it really is a lovely engine which would be a real treat to fly once one got on top of the starting issue. But with these engines being as rare as they seem to be, I doubt that we’ll see many of them in the air in the future. Still, an engine to remember and to really enjoy if you’re ever lucky enough to acquire one! Just look after that shaft .............. ______________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN September 2008 This revised edition published October 2021 |

||

| |

The primary purpose of this article will be to record a series of tests which I conducted in 2021 on an engine that is seldom encountered today, hence having been more or less consigned to the status of legend when it is remembered at all. I’ll be evaluating the 1959 O.S. Max-D 15 diesel, a fine design in its own right but one which seemingly missed the boat, appearing some two years too late at a time when its chances of success were severely limited by the surrounding circumstances.

The primary purpose of this article will be to record a series of tests which I conducted in 2021 on an engine that is seldom encountered today, hence having been more or less consigned to the status of legend when it is remembered at all. I’ll be evaluating the 1959 O.S. Max-D 15 diesel, a fine design in its own right but one which seemingly missed the boat, appearing some two years too late at a time when its chances of success were severely limited by the surrounding circumstances.  It’s astonishing how few of today’s modellers seem to be aware of the fact that the familiar O.S. trade-name enjoys a unique distinction which is highly unlikely ever to be superseded by any other - it has been continuously associated with the model engine market for the longest period of time of any trade-name in modelling history. With each passing year, this respected Japanese company’s record of continuous involvement in model engine production grows another year longer, and it seems extremely doubtful that any other maker will ever surpass the production record of O.S., now deep into its second half-century and still going strong in today’s vastly changed marketplace. You have to be at least 85 years old as of the present time of writing (2021) to have lived at a time when O.S. model engines were not being manufactured!

It’s astonishing how few of today’s modellers seem to be aware of the fact that the familiar O.S. trade-name enjoys a unique distinction which is highly unlikely ever to be superseded by any other - it has been continuously associated with the model engine market for the longest period of time of any trade-name in modelling history. With each passing year, this respected Japanese company’s record of continuous involvement in model engine production grows another year longer, and it seems extremely doubtful that any other maker will ever surpass the production record of O.S., now deep into its second half-century and still going strong in today’s vastly changed marketplace. You have to be at least 85 years old as of the present time of writing (2021) to have lived at a time when O.S. model engines were not being manufactured!  The O.S. company was formally named the Ogawa Model Manufacturing Co. Ltd. - O.S. is merely a trade-name consisting of the company founder's initials in their Japanese order. The company was established between the two World Wars by Shigeo Ogawa (1917 – 1992). Born in 1917 in the Gifu Prefecture of Tajimi City, Japan, the young Ogawa became addicted to tinkering with machinery from early childhood. When he became old enough, he attended an industrial school where he learned the fundamentals of precision engineering. As a student project he built a model engine that won a special award at a student science fair. This pointed him towards his very successful career as a commercial manufacturer of model engines.

The O.S. company was formally named the Ogawa Model Manufacturing Co. Ltd. - O.S. is merely a trade-name consisting of the company founder's initials in their Japanese order. The company was established between the two World Wars by Shigeo Ogawa (1917 – 1992). Born in 1917 in the Gifu Prefecture of Tajimi City, Japan, the young Ogawa became addicted to tinkering with machinery from early childhood. When he became old enough, he attended an industrial school where he learned the fundamentals of precision engineering. As a student project he built a model engine that won a special award at a student science fair. This pointed him towards his very successful career as a commercial manufacturer of model engines.

It was not until after the end of WW2 that Ogawa was able to return his undivided focus to commercial model engine manufacture. The conclusion of the war found large numbers of American servicemen stationed in Japan with the occupation forces. This created a sizeable market constituency with discretionary spending power far in excess of that of the average Japanese citizen in the immediate post-WW2 Japanese economy. A proportion of these service personnel were of course modellers in their spare time, creating an obvious market niche to be filled in supplying their need for model engines and related products. Every American base had its own hobby shop, offering an open marketing opportunity for Japanese manufacturers to attempt to exploit.

It was not until after the end of WW2 that Ogawa was able to return his undivided focus to commercial model engine manufacture. The conclusion of the war found large numbers of American servicemen stationed in Japan with the occupation forces. This created a sizeable market constituency with discretionary spending power far in excess of that of the average Japanese citizen in the immediate post-WW2 Japanese economy. A proportion of these service personnel were of course modellers in their spare time, creating an obvious market niche to be filled in supplying their need for model engines and related products. Every American base had its own hobby shop, offering an open marketing opportunity for Japanese manufacturers to attempt to exploit.  1948 saw the appearance of a low-production sand-cast

1948 saw the appearance of a low-production sand-cast  A seldom-recalled but highly relevant fact dating to this period was Ogawa's initial venture into the field of model diesel manufacture. It appears that he somehow got his hands on an example of the 1 cc

A seldom-recalled but highly relevant fact dating to this period was Ogawa's initial venture into the field of model diesel manufacture. It appears that he somehow got his hands on an example of the 1 cc  The range continued to expand as the 1950’s went on, with a healthy commercial and technological rivalry developing between the Osaka-based O.S. company and the Enya Metal Products Co. of Tokyo as both companies expanded their marketing efforts world-wide. O.S. achieved a major publicity coup in 1956 when their powerful and ultra-lightweight 1955

The range continued to expand as the 1950’s went on, with a healthy commercial and technological rivalry developing between the Osaka-based O.S. company and the Enya Metal Products Co. of Tokyo as both companies expanded their marketing efforts world-wide. O.S. achieved a major publicity coup in 1956 when their powerful and ultra-lightweight 1955  However, in the meantime Enya had achieved a master stroke of their own, to which O.S. had no immediate reply - in late 1956 Enya had introduced the first model of their deservedly famous 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) diesel, the D15-I (often referred to simply as the

However, in the meantime Enya had achieved a master stroke of their own, to which O.S. had no immediate reply - in late 1956 Enya had introduced the first model of their deservedly famous 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) diesel, the D15-I (often referred to simply as the

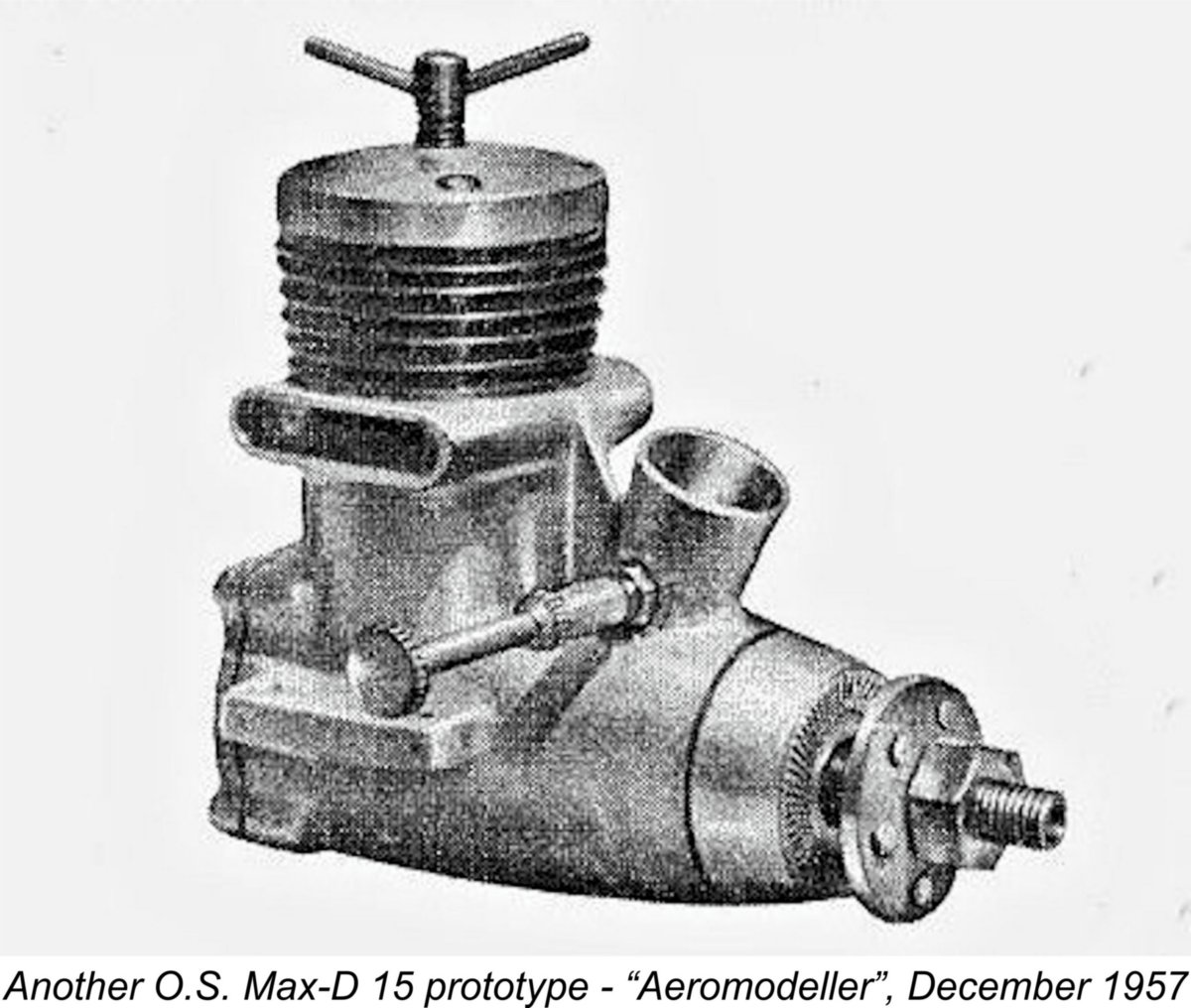

The “Motor Mart” feature in the December 1957 issue of the rival “Aeromodeller” magazine included an illustration of a completely different prototype. This one retained the crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction of the unit illustrated by Chinn, but featured twin exhaust stacks along with a streamlined crankcase design not unlike that seen later in the

The “Motor Mart” feature in the December 1957 issue of the rival “Aeromodeller” magazine included an illustration of a completely different prototype. This one retained the crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction of the unit illustrated by Chinn, but featured twin exhaust stacks along with a streamlined crankcase design not unlike that seen later in the

Chinn noted that the production unit appeared to be essentially identical to that which had been illustrated in his October 1958 article mentioned earlier. It would appear that he had remained in direct contact with the manufacturers, since he included an official factory image of the production model. He stated that he expected to receive two examples for testing in the near future.

Chinn noted that the production unit appeared to be essentially identical to that which had been illustrated in his October 1958 article mentioned earlier. It would appear that he had remained in direct contact with the manufacturers, since he included an official factory image of the production model. He stated that he expected to receive two examples for testing in the near future.  A relevant hint may be derived from the wording of the well-written and quite comprehensive English-language instruction manual which accompanied the engine. The manual stated that the engine was intended specifically for FAI free flight and team race applications. If this is the case, we may be seeing a clue regarding the engine’s apparent failure to make much of an impression upon the market. As we shall soon see, the engine’s starting qualities are undeniably rather less than stellar, especially when considered in a team race context. This would have militated strongly against this unit finding much success as a team race motor.

A relevant hint may be derived from the wording of the well-written and quite comprehensive English-language instruction manual which accompanied the engine. The manual stated that the engine was intended specifically for FAI free flight and team race applications. If this is the case, we may be seeing a clue regarding the engine’s apparent failure to make much of an impression upon the market. As we shall soon see, the engine’s starting qualities are undeniably rather less than stellar, especially when considered in a team race context. This would have militated strongly against this unit finding much success as a team race motor.  the numbering sequence started at engine no. 1001 and that only perhaps some 1500 examples were manufactured in total. If any reader has examples which extend the present sequence in either direction, I'd be most grateful to receive the information along with photographic evidence! Whatever the true figures, the O.S. Max-D 15 is certainly a relatively rare and much sought-after engine today.

the numbering sequence started at engine no. 1001 and that only perhaps some 1500 examples were manufactured in total. If any reader has examples which extend the present sequence in either direction, I'd be most grateful to receive the information along with photographic evidence! Whatever the true figures, the O.S. Max-D 15 is certainly a relatively rare and much sought-after engine today.  The O.S. Max-D 15 retains the glow-plug O.S. Max-II 15's bore and stroke of 15.19 mm and 13.70 mm respectively for an identical displacement of 2.48 cc. In addition, at an early stage in the design process the decision was taken to stick with the same kind of baffle piston as that used on the companion glow-plug model. Consequently, the piston used in the Max-D 15 is essentially identical in overall form to that used in the Max-II 15 - it is a completely conventional but very light cast iron baffle-topped unit which is lapped to a truly superb fit in the hardened steel cylinder. It has two 4.5 mm dia. skirt ports below the crown on the transfer side which align at bottom dead centre with two corresponding ports drilled through the cylinder wall below the transfer port. This feature is clearly intended to facilitate the passage of gas through the bypass to the transfer port itself as well as to promote improved piston cooling by encouraging cool incoming mixture to pass through the piston interior.

The O.S. Max-D 15 retains the glow-plug O.S. Max-II 15's bore and stroke of 15.19 mm and 13.70 mm respectively for an identical displacement of 2.48 cc. In addition, at an early stage in the design process the decision was taken to stick with the same kind of baffle piston as that used on the companion glow-plug model. Consequently, the piston used in the Max-D 15 is essentially identical in overall form to that used in the Max-II 15 - it is a completely conventional but very light cast iron baffle-topped unit which is lapped to a truly superb fit in the hardened steel cylinder. It has two 4.5 mm dia. skirt ports below the crown on the transfer side which align at bottom dead centre with two corresponding ports drilled through the cylinder wall below the transfer port. This feature is clearly intended to facilitate the passage of gas through the bypass to the transfer port itself as well as to promote improved piston cooling by encouraging cool incoming mixture to pass through the piston interior.  The first issue, that of creating enough room for the compression adjustment system, was accomplished quite simply by making a revised cylinder which had a considerable length of additional bore added above the region of top dead centre. This cylinder has integrally-turned cooling fins. The diesel cylinder actually has an extra cooling fin above the exhaust level by comparison with its glow-plug companion in the range, and there is an unfinned additional length of bore which extends above the finned section like a spigot. This extension accommodates the contra piston. The cylinder head fits over this spigot - a clever arrangement because it means that the lapped contra-piston operates for the most part inside the head rather than below it.

The first issue, that of creating enough room for the compression adjustment system, was accomplished quite simply by making a revised cylinder which had a considerable length of additional bore added above the region of top dead centre. This cylinder has integrally-turned cooling fins. The diesel cylinder actually has an extra cooling fin above the exhaust level by comparison with its glow-plug companion in the range, and there is an unfinned additional length of bore which extends above the finned section like a spigot. This extension accommodates the contra piston. The cylinder head fits over this spigot - a clever arrangement because it means that the lapped contra-piston operates for the most part inside the head rather than below it.  OK, so much for accommodating the baffle ……… now, how to ensure that once the engine is assembled, things remain correctly aligned? Quite simple, really - the makers cut a notch into the upper wall of the contra piston on the exhaust side (opposite the cut-away for the baffle) and cast a corresponding key into the underside of the die-cast aluminium alloy cylinder head. Assembly is slightly complicated by the fact that the contra piston has to be installed in the precisely correct alignment to begin with, but an installation error (and potential damage to the engine when turned over) is precluded by the fact that if the contra piston is not installed in its correct alignment, the cylinder head simply will not fit! And once the head is installed with the notch correctly aligned with the key, there’s no way that the contra piston can get out of alignment by rotational creeping in the bore. Very simple, and very effective!

OK, so much for accommodating the baffle ……… now, how to ensure that once the engine is assembled, things remain correctly aligned? Quite simple, really - the makers cut a notch into the upper wall of the contra piston on the exhaust side (opposite the cut-away for the baffle) and cast a corresponding key into the underside of the die-cast aluminium alloy cylinder head. Assembly is slightly complicated by the fact that the contra piston has to be installed in the precisely correct alignment to begin with, but an installation error (and potential damage to the engine when turned over) is precluded by the fact that if the contra piston is not installed in its correct alignment, the cylinder head simply will not fit! And once the head is installed with the notch correctly aligned with the key, there’s no way that the contra piston can get out of alignment by rotational creeping in the bore. Very simple, and very effective!  This in turn led to a requirement to increase the size of the crankcase casting to accommodate the larger cylinder base. While they were about this, the designers also took the opportunity to increase the wall thickness of the crankcase. Hence, the revised crankcase was significantly bulkier and far sturdier than that of the glow-plug model, while the extra size was also useful in accommodating the ball-bearing shaft. The diesel case was tumbled to a fine satin finish, unlike that of the Max-II 15 which was sand-blasted to a matte finish.

This in turn led to a requirement to increase the size of the crankcase casting to accommodate the larger cylinder base. While they were about this, the designers also took the opportunity to increase the wall thickness of the crankcase. Hence, the revised crankcase was significantly bulkier and far sturdier than that of the glow-plug model, while the extra size was also useful in accommodating the ball-bearing shaft. The diesel case was tumbled to a fine satin finish, unlike that of the Max-II 15 which was sand-blasted to a matte finish.

Indeed, shaft failures appear to be by no means unheard-of with this engine. I have personally encountered one example and have been reliably informed at second hand of another, both of which had broken their shafts at the induction port after an indeterminate amount of running. Two such failures within my relatively small database do nothing to inspire confidence.

Indeed, shaft failures appear to be by no means unheard-of with this engine. I have personally encountered one example and have been reliably informed at second hand of another, both of which had broken their shafts at the induction port after an indeterminate amount of running. Two such failures within my relatively small database do nothing to inspire confidence.

The result was a very handsome engine of obvious O.S. heritage, looking exactly like what it was - a .15 cuin. diesel based very broadly upon the design of the Max-II 15 but with the addition of twin ball-races and compression ignition. However, the various design changes required to create the diesel model sent the weight up to a healthy albeit not completely unmanageable 6.2 ounces (177 gm) - a lot more than its 3.5 oz. (100 gm) glow-plug stablemate and also well in excess of its 5.2 oz. (145 gm) Enya D15-I 2.5 cc diesel rival! It’s also far more bulky overall.

The result was a very handsome engine of obvious O.S. heritage, looking exactly like what it was - a .15 cuin. diesel based very broadly upon the design of the Max-II 15 but with the addition of twin ball-races and compression ignition. However, the various design changes required to create the diesel model sent the weight up to a healthy albeit not completely unmanageable 6.2 ounces (177 gm) - a lot more than its 3.5 oz. (100 gm) glow-plug stablemate and also well in excess of its 5.2 oz. (145 gm) Enya D15-I 2.5 cc diesel rival! It’s also far more bulky overall.  OK, so now we know what it looks like and how it's configured internally. Next question - how does it run?? In particular, how does it compare with the engine with which it was specifically designed to compete - the Enya D15-I diesel?

OK, so now we know what it looks like and how it's configured internally. Next question - how does it run?? In particular, how does it compare with the engine with which it was specifically designed to compete - the Enya D15-I diesel?

So the ignition switch of 1957-1959 was reversed, and starting in early 1960 the development of a glow-plug version of the O.S. Max-D 15 diesel was pursued. By mid 1960 at least two examples of this model had been produced, as recorded by Peter Chinn in his September 1960 "Latest Engine News" column in "Model Aircraft". One of these had been acquired by Australia's Tony Farnan, while the other had been sent to Chinn for evaluation.

So the ignition switch of 1957-1959 was reversed, and starting in early 1960 the development of a glow-plug version of the O.S. Max-D 15 diesel was pursued. By mid 1960 at least two examples of this model had been produced, as recorded by Peter Chinn in his September 1960 "Latest Engine News" column in "Model Aircraft". One of these had been acquired by Australia's Tony Farnan, while the other had been sent to Chinn for evaluation. Naturally, the revised model featured a conventional glow-plug cylinder head in place of the contra-piston and associated arrangements. The upper spigot was of course omitted from the revised cylinder since the extra bore length was no longer needed. This reduced the height of the engine considerably.

Naturally, the revised model featured a conventional glow-plug cylinder head in place of the contra-piston and associated arrangements. The upper spigot was of course omitted from the revised cylinder since the extra bore length was no longer needed. This reduced the height of the engine considerably. The entry of this model into limited production was finally announced in the "Motor Mart" feature which appeared in the June 1961 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine. Peter Chinn eventually got around to publishing a

The entry of this model into limited production was finally announced in the "Motor Mart" feature which appeared in the June 1961 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine. Peter Chinn eventually got around to publishing a