|

|

From Cameras to Con-Rods -The Mamiya Range

I used the term "overview" in the previous paragraph because that's exactly what this article will be - an overview of the Mamiya range, and nothing more. The technical details of these engines are in many cases quite fascinating, as are the variants through which most of the models passed. I'm well aware that for serious collectors the devil's in the details, making the documentation of the distinctions between different variants quite important. However, a single article which included full technical details and test results for the entire range would be unmanageably long. As it is, this one will be quite long enough! Accordingly, it's my present intention to present a basic summary of the various Mamiya models, leaving the full details for inclusion in future articles which will cover the various displacement categories in full detail. I hope to include tests of actual examples in those future articles. For now, the overview which follows will have to suffice.

I also wish to express my indebtedness to my late mate Ron Chernich for his sterling co-operation despite the significant challenges which he was facing at the time when the development of this article commenced in 2013. Ron, your example of carrying on under very trying circumstances continues to serve as an inspiration to us all - thanks, mate!! We still miss you ............ The only accessible English-language article about the Mamiya engines that I've been able to uncover appeared as number 51 in a series of model engine designer and manufacturing profiles written by the late David R. Janson (1930-2011). This very interesting series of articles was published over a period of some years in the newsletter of the Denver chapter of the Society of Antique Modellers (SAM). A compilation of the entire series was released in small numbers as a private publication in 2006. David's relatively brief but nontheless informative article on the Mamiya engines was reproduced with permission on Ron Chernich's now-frozen "Model Engine News" (MEN) web-site. I freely acknowledge my debt to David for his kindness in making this information available to us. With those important words set down for the record, let’s proceed with some background. Background The pre-war and early post-WW2 history of the majority of Japanese model engine manufacturers is very poorly documented in the English language. This is especially true of the various “second-tier” ranges which did not survive past the 1950’s, hence being largely forgotten today after the lapse of over two-thirds of a century. Like a well-built model aircraft, time flies ............ For the most part (O.S. being a notable exception), the actual manufacturers contributed little to the preservation of their own history during the early post-war period. This is completely understandable when we recognize the fact that their primary concern at the time was economic survival in the midst of a shattered and re-building post-war economy. Under such conditions, the preservation of their early history for the benefit of future generations of modellers could hardly have been seen as a priority.

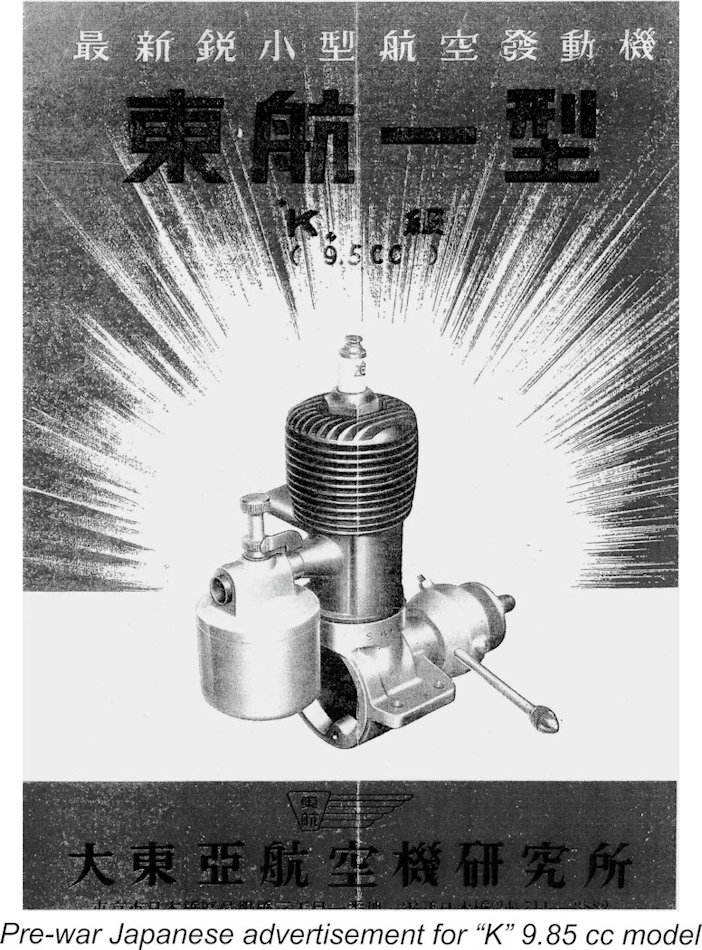

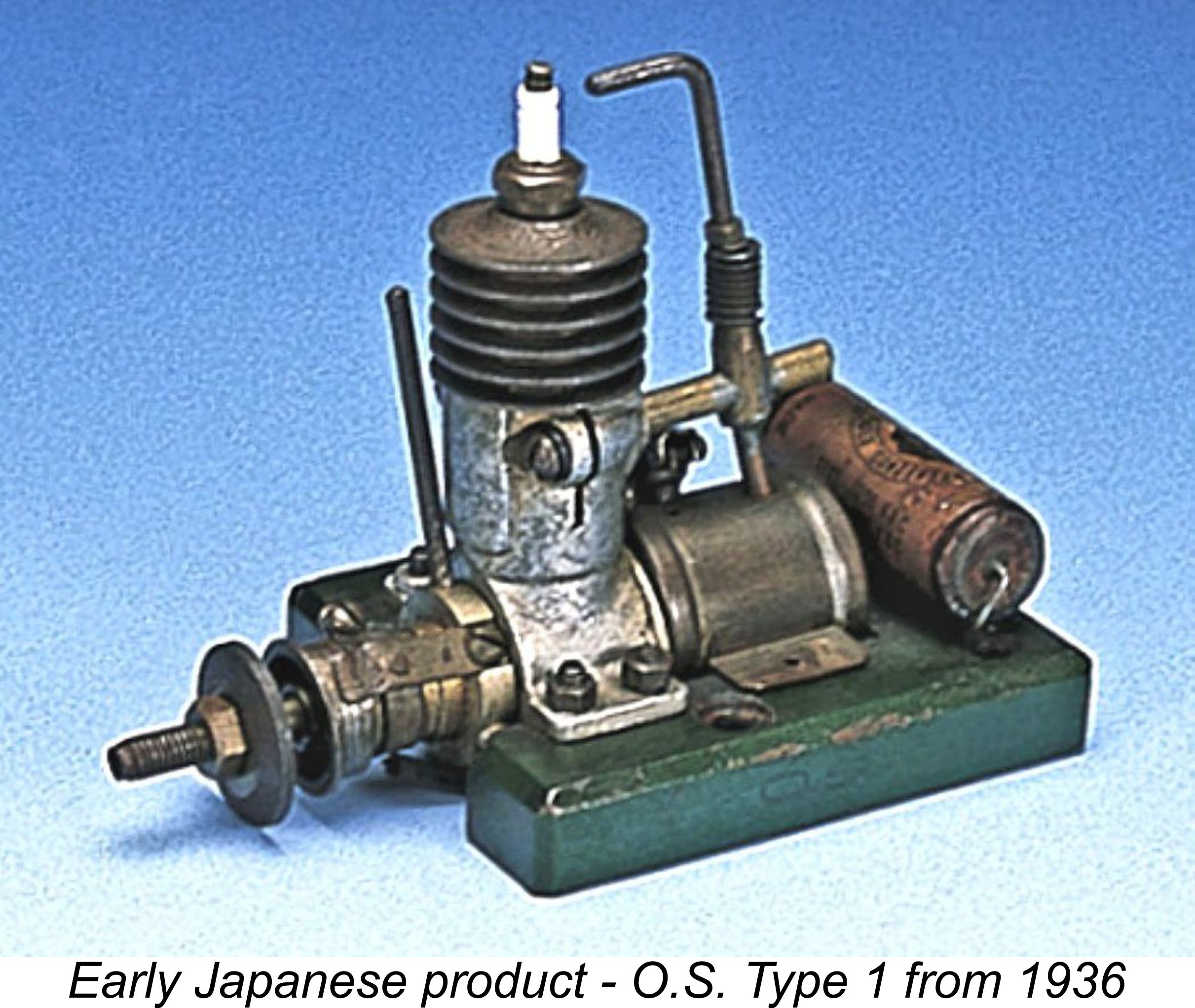

Contrary to a seemingly widely-held impression, a thriving power modelling scene had flourished in Japan during the pre-war years. To meet the consequent demand for model engines, the commercial manufacture of such units in Japan was well established by the late 1930's, hence paralleling similar developments in America. We may safely assume that the pre-war and early post-war history of the various Japanese engine manufacturers was documented in the pages of the Japanese-language modelling media in the form of articles and advertisements. However, that's of little help to the modern researcher who does not have access to the periodicals in question and in any case isn't fluent in reading and comprehending Japanese script. Even so, all would be well if the evolving story had been covered at least in outline in the English-language modelling media. Unfortunately, this was not the case. Consequently the pre-war Japanese power modelling scene remained effectively invisible to observers outside Japan. Even during the early post-war period, documentation in languages other than Japanese was virtually non-existent. The one exception to this general observation was an article which was published in the July 1946 issue of "Air Trails", shedding a great deal of light on this period. This article was written by Frank Nekimken, an American military troop carrier pilot who arrived in Japan with US forces a few days after VJ Day (September 2nd, 1945). The article included the substance of an interview with Mr. K. Shimozin, owner of Tokyo's largest model shop (which had somehow resumed business following the wartime bombing) and then-President of the Japanese Model Industry Association. Apart from his retail activities, Mr. Shimozin had been a major kit manufacturer for some thirty-four years at the time of the interview. Before the B-29's wiped out his factory, he had been Japan's largest kit producer, employing 12 men who produced approximately 12,000 kits per month. This included both flying and static models. Mr. Shimozin reported that there had been as many as three hundred kit manufacturers in Japan prior to the war. Their products were marketed through some seventy wholesale jobbers and 600 retail outlets nationwide. Clearly a thriving industry! The article pointed out that the building and flying of kites and model aircraft had been part of every child's education both before and during the war. Aircraft recognition had been an integral part of the wartime school curriculum. As a result, Nekimken went so far as to state his view that there were almost certainly more model airplane builders in Japan than there were in the USA despite the discrepancies in terms of population! Of particular relevance to the present discussion, Mr. Shimozin advised that some ten percent of Japanese aeromodellers were involved with power modelling. This level of interest supported the activities of some 10 model engine manufacturers, who produced around 500 engines monthly between them. Most notable among these was the O.S. marque which had become well established in Osaka following its initial market entry in 1936 and had even succeeded in penetrating the pre-war US market to a small extent. But O.S. was far from being alone - Mr. Shimozin confirmed that there were quite a few other pre-war Japanese makers.

The reality of course was that Japanese precision engineering capabilities were unquestionably well up to par with those of the countries which tended to look down their noses at their Japanese counterparts. Not only that, but the application of these skills to the manufacture of model engines was by no means a new activity in Japan during the early post-war period. We saw earlier that there had been a thriving power modelling scene in Japan before WW2, with a number of model engine manufacturers such as O.S. (among others) becoming well established in the 1930’s on the strength of it. However, all of this activity had been invisible to commentators outside Japan, largely due to a combination of langauge and polictical barriers. The inevitable result was that the capabilities of the Japanese in this field of endeavour had gone unreported in the pre-war international modelling media. As a result of this pre-war activity, the various individuals who entered the commercial model engine field after WW2 were for the most part experienced power modellers who had managed to survive the war years. However, these facts were universally unappreciated in the English-speaking world. Accordingly, it was not until the mid-1950’s that contributors to the English-language modelling media began to sit up and take any real notice of the Japanese model engine industry and its products. As a result, the first decade of the post-war Japanese model engine industry is barely covered at all in the contemporary English-language modelling media.

This is a task which brooks no further delay because the majority of those who were “there” during this period will soon leave us - indeed, many have already done so. It’s therefore high time to assemble such facts as can still be derived from the available evidence while the possibility still exists that there may still be some knowledgable individuals around who can potentially correct me when I go wrong (as I undoubtedly will!). This is my ongoing challenge to my valued readers - if you know something that I don’t, please share it with the rest of us!! In the present article, I intend to summarize another of the short-lived “forgotten” Japanese model engine marques from the early post-war era - the Mamiya range. This unusually interesting and diverse series of high-quality model engines was in production for only a decade or so beginning in the late 1940’s, consequently being remembered today only by the elder statesmen of the modelling world (like myself!) as well as by the growing number of present-day engine collectors who are attracted to the early post-war products of the Japanese model engine industry. This comparative neglect is undeserved, because the Mamiya range included a number of designs having considerable interest from a technical standpoint as well as possessing a number of highly individual visual characteristics which set them apart from their competitors. They were also manufactured to very high standards at a time when the ability of Japanese manufacturers to achieve such standards was widely under-appreciated. Interested?? OK then, let’s get right to it! Origins The origins of the Mamiya engines are somewhat shrouded in obscurity because the range was established only a few years after the conclusion of WW2 during the previously-noted period when the Japanese model engine industry was not under scrutiny by the Western modelling media. Furthermore, the Mamiya range did not survive past the first few years of the period from 1954 onwards when Japan finally came to be recognized as a major model engine-producing nation, and one to be reckoned with. Hence we're dealing here with one of the more poorly-documented Japanese model engine lines, in the English language at least. In attempting to correct this situation, I'll just have to do the best that I can using such information as can be gleaned from the few sources available to me. The engines themselves are our best witnesses, but some additional information can be picked up here and there if one digs deep enough. Contacts within Japan have done what they can to assist despite the limitations imposed by language difficulties on both sides. A question which comes up immediately whenever the Mamiya engines are mentioned today is the degree (if any) to which their manufacturers were connected to the far more famous Mamiya camera company, which still (in 2020) remains very much in business. It turns out that there was a connection, albeit rather less direct than might be supposed. Indeed, it remains something of an unresolved puzzle even today as far as the details go. Let’s look into this aspect of our subject to begin with ………..

For context, it’s vitally important to recall that as of May 1940 Japan had yet to enter WW2, although the country was heavily embroiled in the Second Sino-Japanese War which lasted from July 7, 1937 through to September 9, 1945. Consequently, the establishment of the Mamiya camera enterprise took place in the context of the pre-war peace-time Japanese economy as far as relations with the rest of the world other than China were concerned. Since the USA was also still at peace, the US market theoretically remained open to Japanese goods, although tensions were even then rising between the two nations. However, the widespread conflict of WW2 then engaging many of the world’s other major nations undoubtedly stifled Japanese access to European and British Commonwealth markets. It was undeniably a somewhat unstable period in which to be starting a new business manufacturing consumer products. Seichi Mamiya was one of three Mamiya brothers, all of whom were apparently keen model aircraft enthusiasts in their spare time. Herein lay the eventual connection with model engines. The youngest of the three brothers was still an active model flier in the 1980’s - one of my Japanese contacts used to fly R/C models with him during that period.

The Mamiya facilities in Tokyo were completely destroyed during WW2, making it necessary to rebuild the entire company from the ground up after the war. Mamiya was fortunate enough to receive large orders from the United States armed forces immediately following the commencement of the occupation of Japan, a windfall which generating the considerable revenue necessary for the rebuilding effort. The company’s entire initial postwar camera production was sold to Allied Forces personnel rather than to the Japanese public. A great many of the original Mamiya-6 folding cameras thus found their way to both the USA and the UK, along with the Mamiya name. This process paralleled that which jump-started the post-war resurgence of the Japanese model engine manufacturing industry, many early products of which were sold to members of the Allied occupation forces through the hobby shops which were established at the major military bases in the country.

In 1949 the Allied Forces of Occupation made a rather strange regulatory decision - they suspended all domestic sales of Japanese-made cameras! Under the new regulation, Japanese camera manufacturers could only resume sales to the Japanese public if their overseas sales volumes were large enough for them to be considered a “top camera exporter”, whatever that meant. In effect, they had to prove that their wares met with overseas approval before they could sell domestically! This of course created a pent-up demand in their front yard that Mamiya could not tap despite the excellence of their products. Odd ........ and one wonders why! One also wonders why the camera industry was singled out for this dubious distinction - others such as automobile and model engine manufacturers were apparently unaffected. Mamiya reacted vigorously by establishing branch offices in New York and London to accelerate international demand and thus achieve “top camera exporter” status as rapidly as possible. Their efforts quickly bore fruit - by 1950, the company was re-incorporated as the Mamiya Camera Company Ltd. By 1951, it was listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange and by May 1956 Mamiya was exhibiting cameras at the prestigious Photokina international trade show. So much for the early years of the Mamiya company’s involvement with the camera industry, an association which famously continues today (2020). Tsunejiro Sugawara died in April 1988, to be followed by Seichi Mamiya in January 1989, but the company which they founded together in 1940 has maintained its leading position in the world camera industry into the digital age, latterly under the name Mamiya Digital Imaging. The Mamiya model engine manufacturing enterprise appears to have had no direct operational connection with the Mamiya camera business. Rather, it was an offshoot of that business, being independently owned and operated throughout. It was based at an entirely separate manufacturing facility in Tokyo. My Japanese contacts have confirmed that the Mamiya model engines were manufactured by a company registered as “Tokyo Hobbycrafts” which was owned and operated by a certain Mr. Minoru Sato. This information is consistent with Peter Chinn’s 1955 article on the Japanese modelling scene which was published in the September 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”. That article also attributed the Mamiya engines to Minoru Sato. The connection arose from the fact that during the early to mid 1940’s, Sato-san was a close colleague of Seichi Mamiya, whose name was then fast becoming famous for his increasingly high-profile involvement in the camera business. Sato was actually a full-time employee of the Mamiya camera company during this period, working as Seichi Mamiya’s personal assistant in the camera design field. He thus enjoyed an unusually close relationship with Mamiya - the two men appear to have been friends and fellow modelling enthusiasts as well as professional colleagues. This relationship continued for some years after the war before Sato made the bold decision to branch out on his own into model engine production. The weight of evidence suggests that he most likely took this step in early 1948, some eight years after the founding of the already very successful Mamiya camera business with which he had been actively involved up to that point. This highly tentative dating does however require corroboration. If any reader can provide greater clarity on this point, please share what you know with the rest of us! Reports from Japan indicate that Seichi Mamiya shared Minoru Sato’s interest in modelling, hence encouraging him in his new venture. This is underscored by the fact that he allowed (or perhaps required) Sato to apply the Mamiya name to his new model engine line. It appears from this that Mamiya’s support may well have gone beyond mere encouragement to include the provision of financial and/or technical assistance to Sato in setting up his Tokyo production facilities. However, there is presently no direct evidence to support this scenario. Although the exact nature and extent of Mamiya’s support for the new model engine line remains unclear, all sources agree that Tokyo Hobbycrafts had no formal connection with the Mamiya camera company despite the use of the Mamiya name on its products. Still, however it came about, the authorized use of that name would have had considerable value to Minoru Sato’s new model engine venture since Mamiya was already becoming a well-known and highly respected name in the field of precision optical engineering, both at home and abroad. My friend and colleague Mel Reid has pointed out that this may actually have been a mutually-beneficial arrangement. The use of the Mamiya name on the engines may have had value to the Mamiya camera company. During the previously-mentioned period during which Mamiya cameras could not be sold in Japan, the presence on the market of a range of high-precision model aero engines bearing that name may have contributed to the clearly desirable goal of keeping the Mamiya name before the Japanese public pending a return of that name to the domestic camera market. Regardless of the basis for the association, the attachment to his products of a name like Mamiya required that Minoru Sato deliver the kind of quality with which Mamiya had already become associated through the camera business. Seichi Mamiya would certainly have expected no less of any product bearing his name. He need not have worried - the new company delivered handsomely on this imperative. The Mamiya engines easily met the highest quality standards then expected from commercial manufacturers of these high-precision little creations, regardless of their country of origin.

As events were to prove, it was in fact the launching of their .099 cu. in. series with the “Chochin” model that really set the Mamiya model engine manufacturing venture on the road to wider success, since it ensured them a share of the “popular” model engine market, in which there were always far more prospective customers than there were for the larger and more specialized models. The .099 series was to become by far Mamiya’s most popular product line. However, that success came later. Let’s start at the beginning …… Early 1948 - The Mamiya 60 FRV Appears

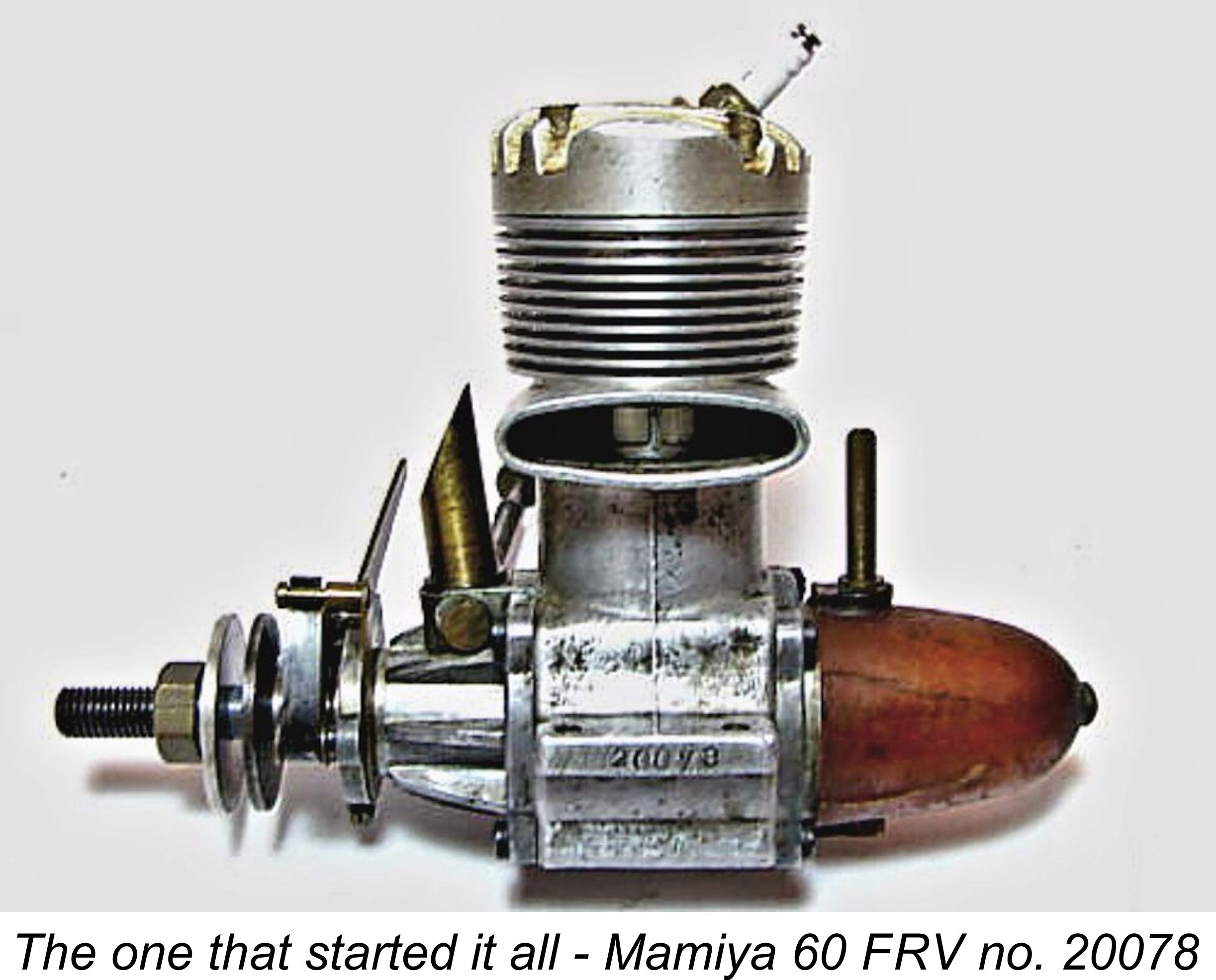

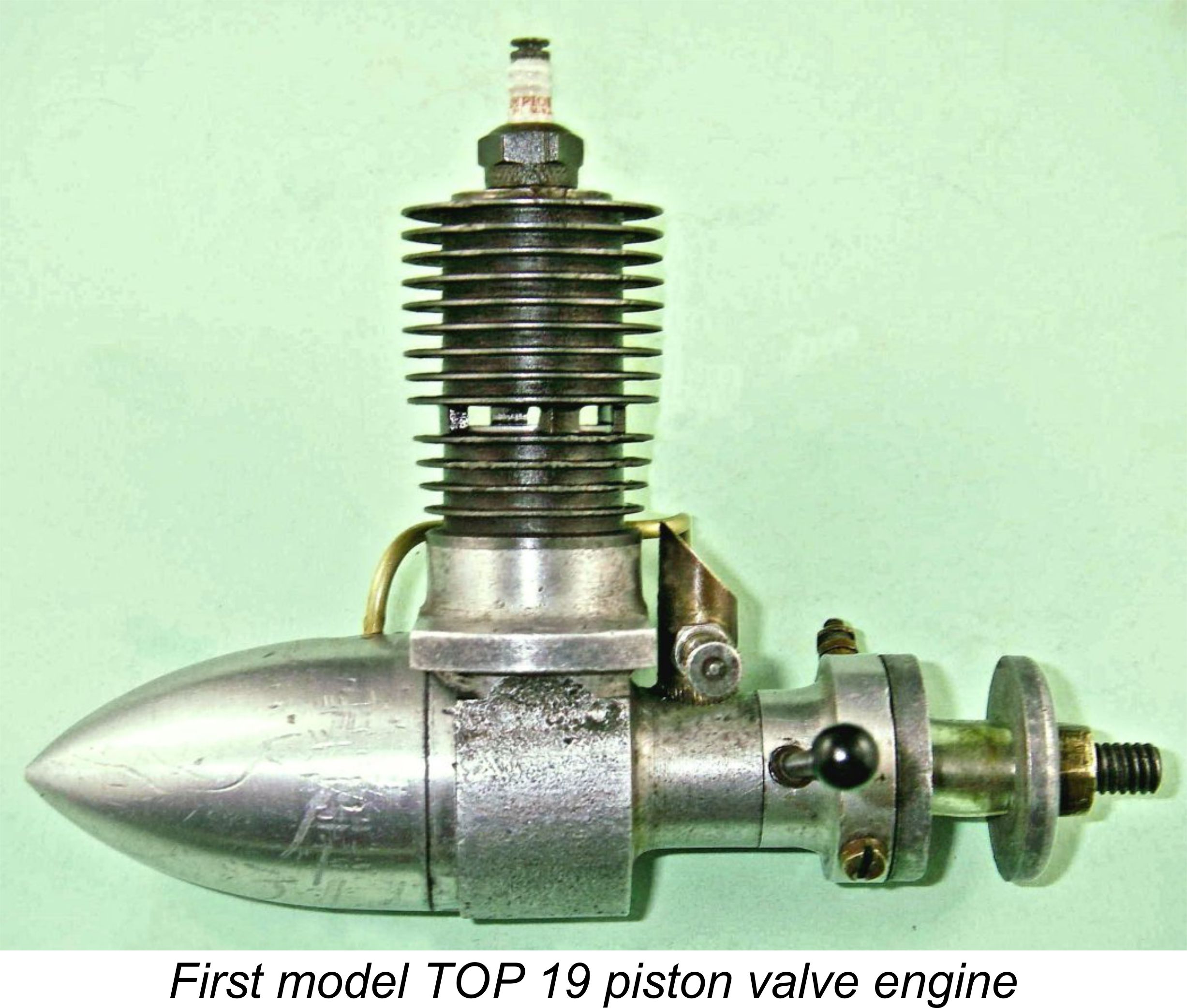

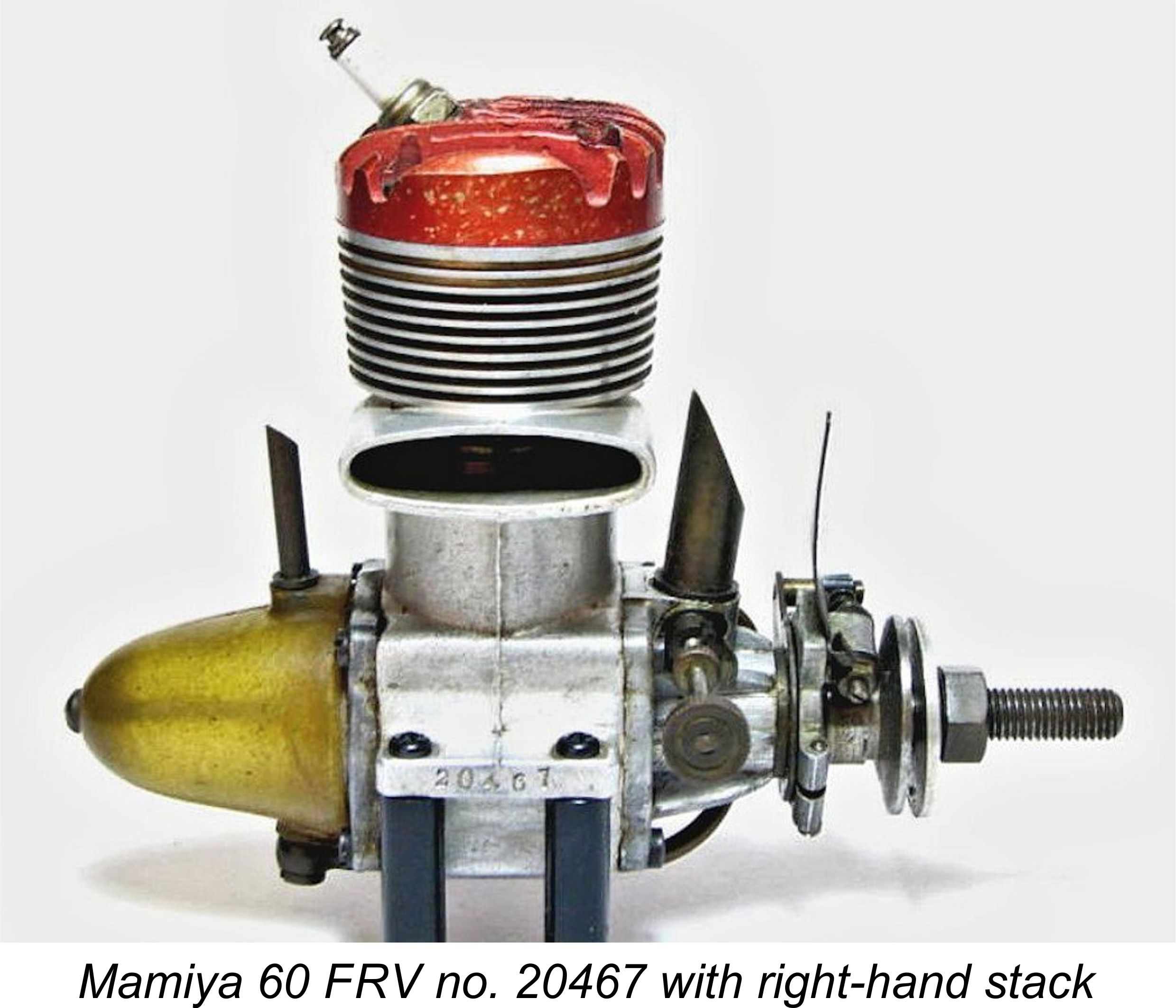

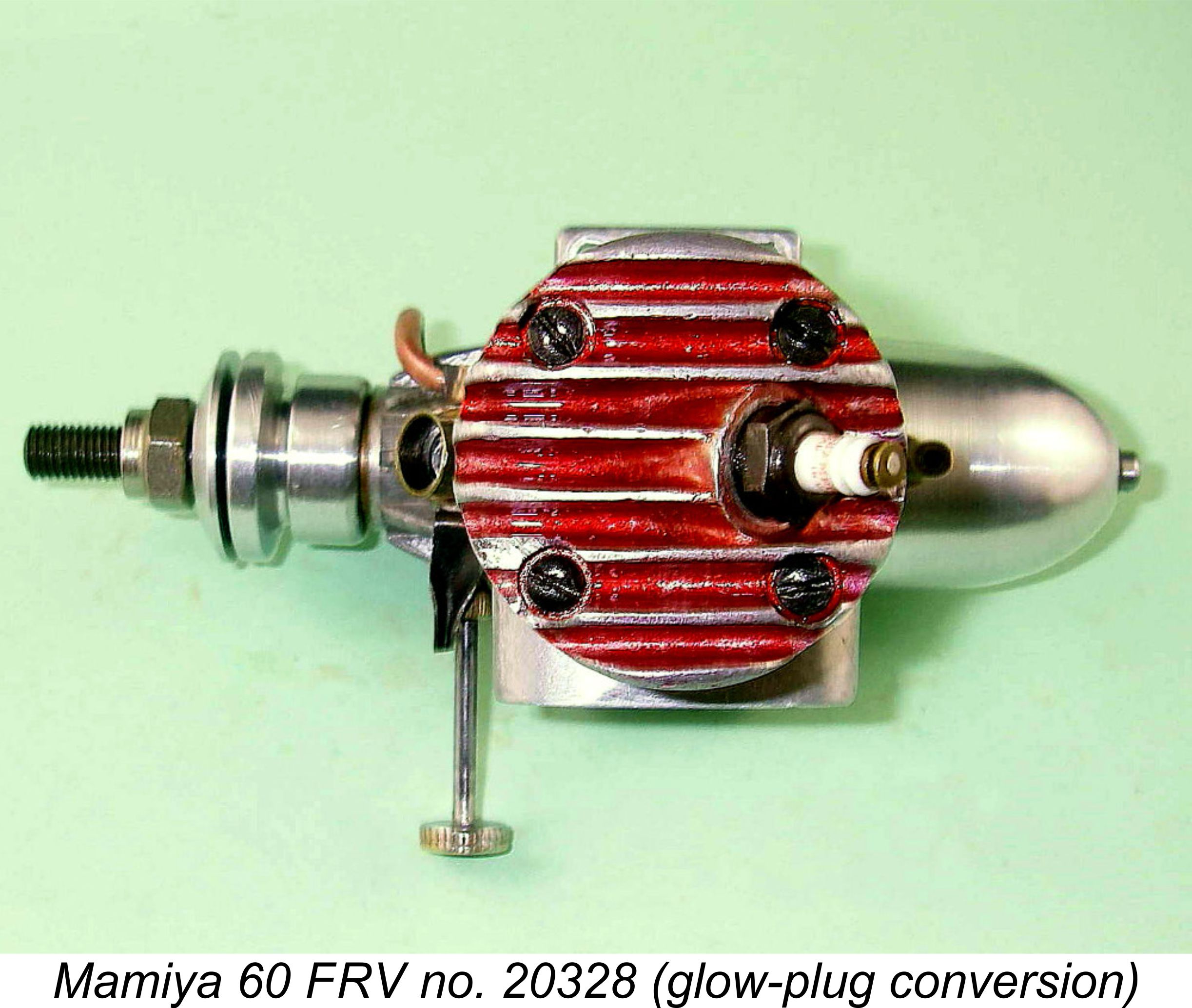

The archive page on the Model Engine Company of America (MECOA) web-site claims on the basis of unspecified evidence that the FRV Mamiya 60 originated in 1949. While this is undeniably possible, I’d have said that an introductory date of 1948 or perhaps even late 1947 makes far more sense given the fact that the FRV Mamiya 60 was unquestionably introduced in spark ignition form, apparently never being offered in a purpose-built factory glow-plug version. This seems to leave little room for doubt that these engines were first marketed at a time when spark ignition was still the favoured system in Japan, strongly suggesting that the earliest Mamiya engines appeared no later than early to mid 1948. By late 1948/early 1949 the glow-plug was very much in the Measured bore and stroke of the Mamiya 60 FRV were 23.90 mm and 22.20 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 9.96 cc (0.61 cuin). Notable features included an unusual rear-angled orientation of the ¼ inch spark plug along with the striking aerofoil exhaust stack. The fuel supply system too was of an unusual complexity. A final touch of originality was the use of a ringed aluminium alloy piston having a high baffled crown. As far as I’m presently aware, this was the first commercial Japanese engine to use this technology - previous Japanese models had invariably employed lapped pistons. The engine was offered in both left-hand and right-hand stack configurations. This required two distinctly different head castings given the plug orientation together with the need to provide clearance for the A highly unusual and somewhat questionable feature of these engines was their use of only four screws to secure the cylinder head. In an engine of this displacement, this might be expected to give rise to significant difficulties in maintaining a head seal. Indeed, such problems have been experienced by some users. The issue becomes most acute when the engines are operated in glow-plug mode, as many of them were. It may be that the four-screw system was adequate for spark-ignition operation but fell short in the context of glow-plug ignition - it’s hard to believe that Minoru Sato would have marketed an engine which had not amply demonstrated its ability to perform as designed. That said, my own illustrated example no. 20328 which has been very neatly converted to glow-plug operation by a previous owner starts and runs very well indeed. On this model, the Tokyo Hobbycrafts name appeared These engines and their later Mamiya 60 RV descendants (see below) were the only Mamiya models to carry serial numbers apart from the first few Mamiya 29 RV models, of which more below in their place. Without exception, all numbers reported to date for the 60 FRV model have the form 20xxx, making it appear almost certain that the initial "20" digits were a model identification element of the overall number. The presently-confirmed range extends from a low of 2003x (x undecipherable) up to a present high of 20730, implying that in all likelihood the sequence started at 20001 and went up from there. If this is the case, it would appear that as many as 750 examples may have been manufactured in total over an approximately 18 month period.

My own illustrated operating example no. 20328 had been used in glow-plug form, hence missing both its tank and timer as received. It has been fitted with a correctly-shaped metal tank of my own manufacture. I would strongly advise against running one of these engines using the original tank if you're lucky enough to have one. Fortunately for posterity, the Mamiya 60 engines are rather too large to be readily “lost” or simply discarded. They are also sufficiently well built that a good proportion of those which were produced are evidently still with us today. They appear from time to time on eBay, albeit selling in recent years for some pretty inflated prices ……………… Late 1948 - The Range Expands

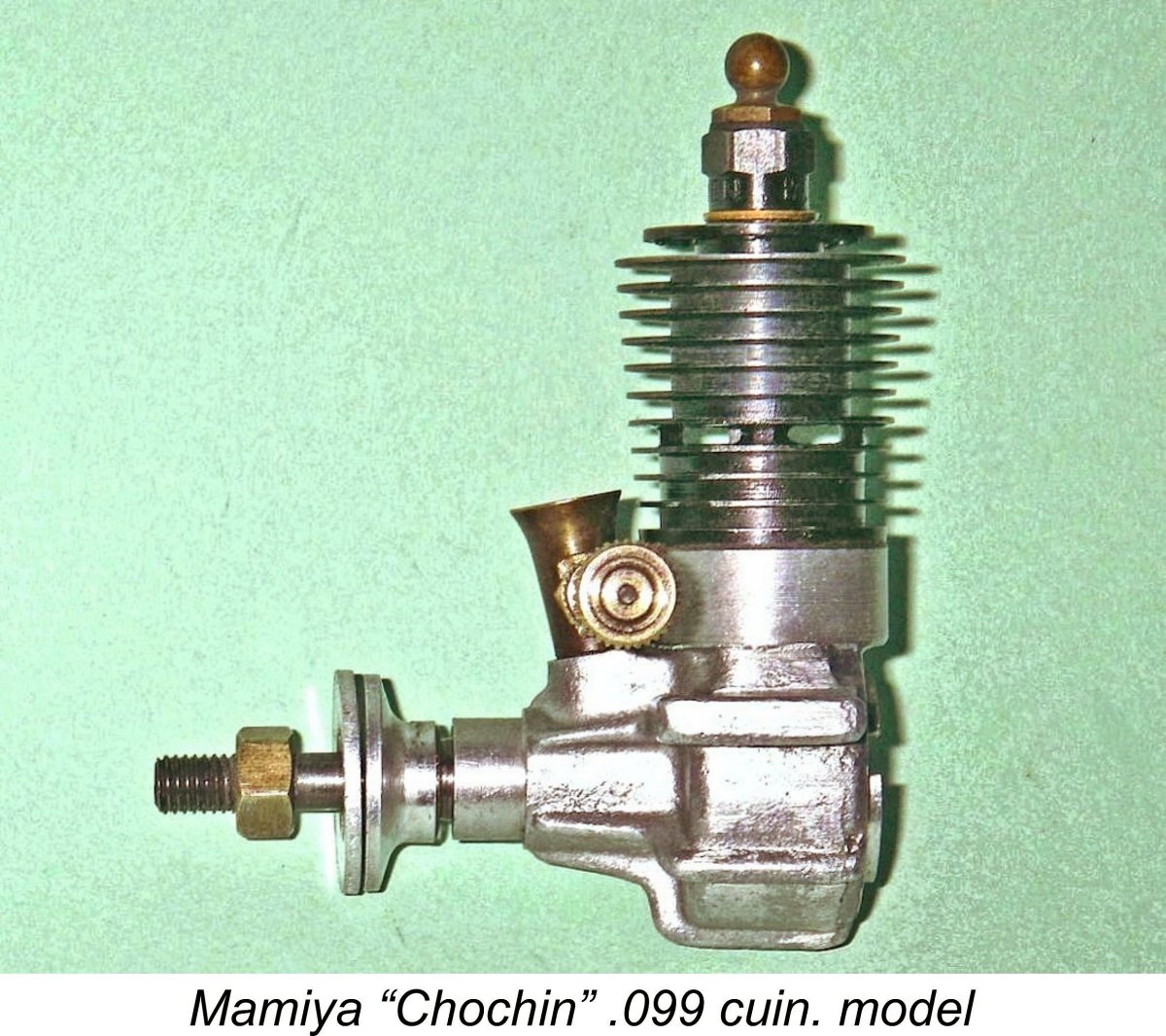

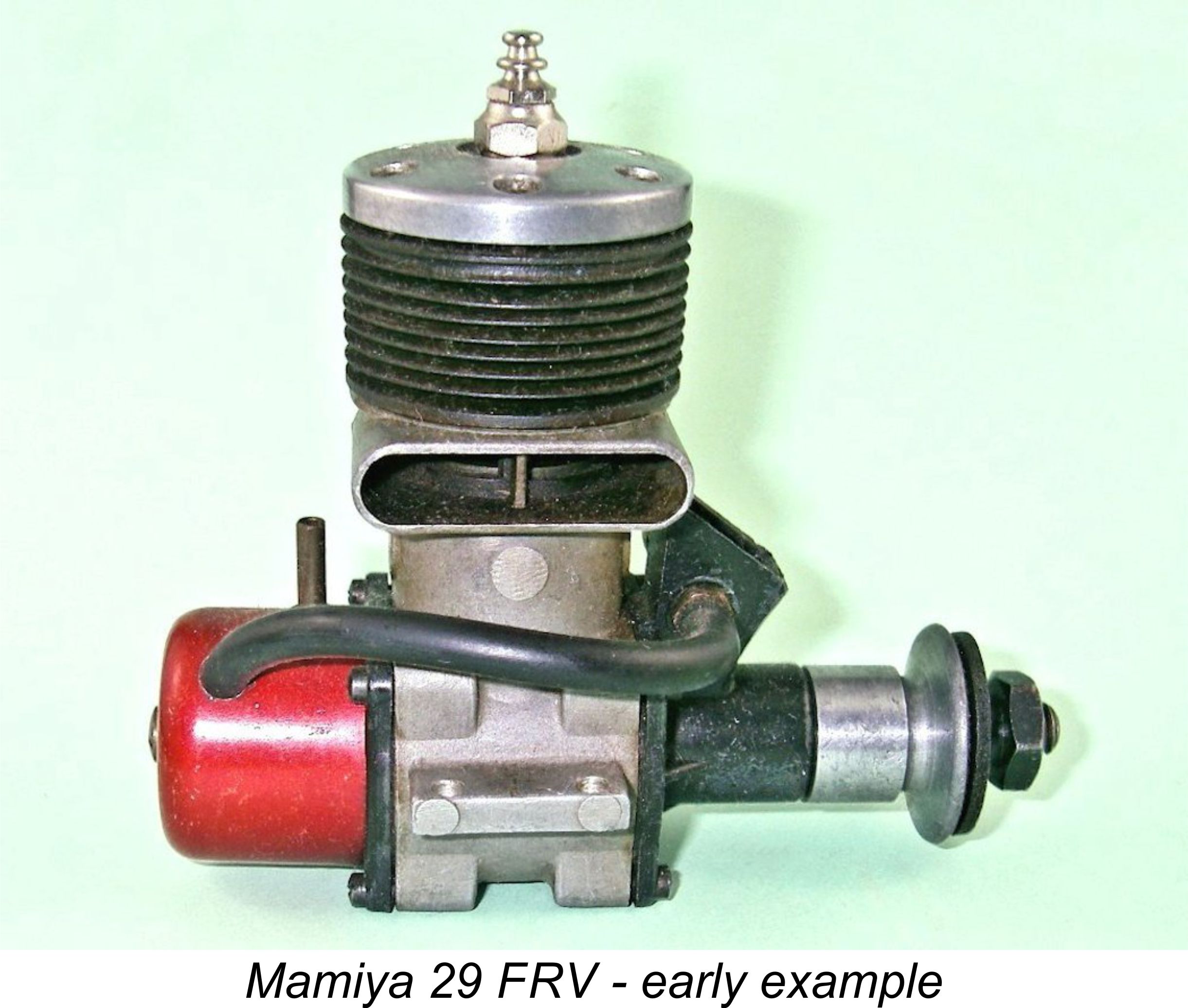

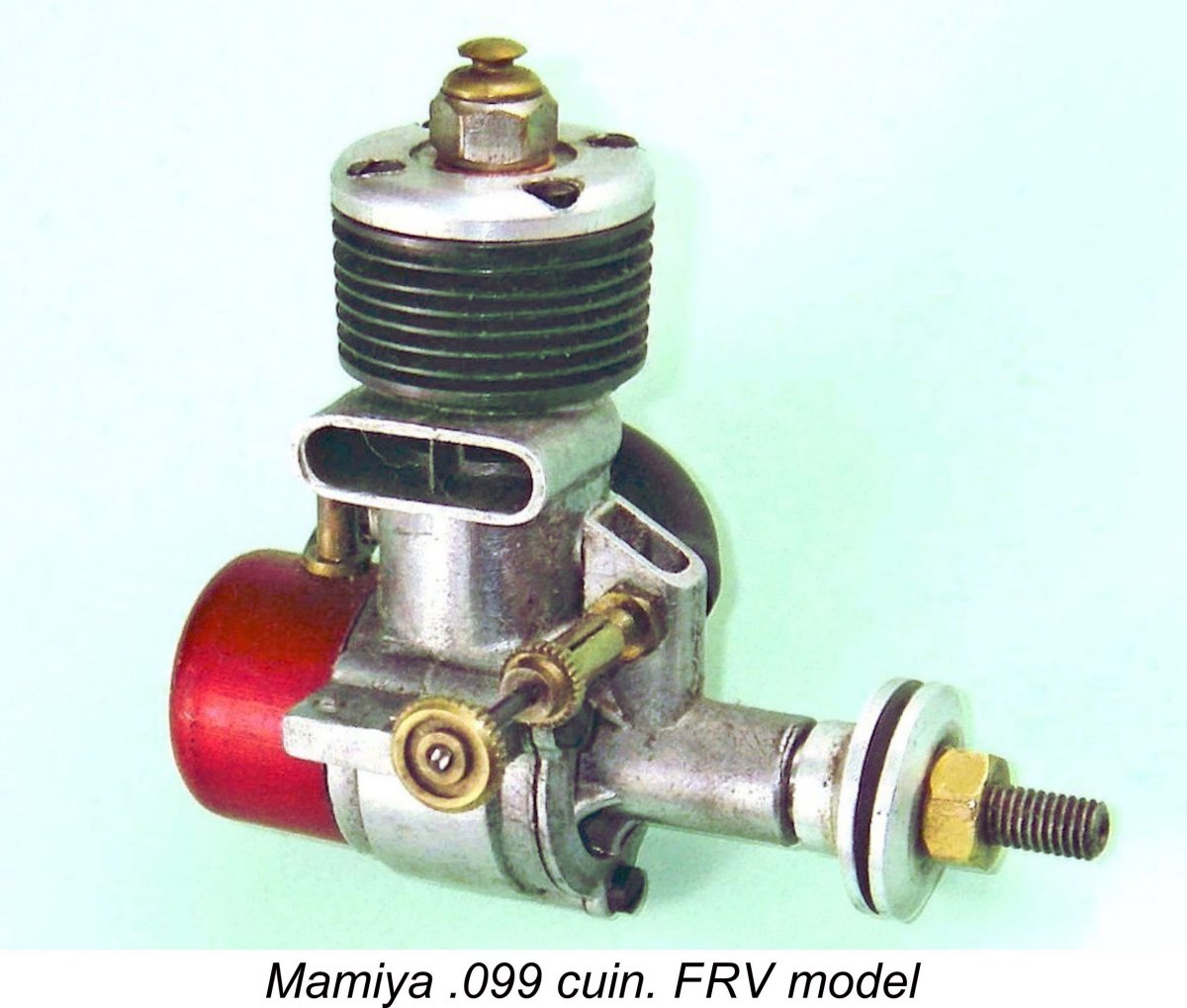

The “Chochin” models featured radial porting allied to tall cast iron cylinders with integral cooling fins and blind bores in combination with a lapped piston. It was this cylinder configuration which gave rise to the “Chochin” nickname due to its undeniable visual similarity to the shape of the traditional “chochin” lanterns which still appear outside many Japanese business establishments. In adopting the above piston/cylinder configuration, the design harked back to the early post-war products The relative present-day rarity of the “Chochin” models appears to be a direct result of the fact that they did not remain long on the market. By late 1949 the company had developed far more up-to-date models in the .099 and .29 cuin displacement categories. Both of these revised units shared a very similar design configuration - in fact, they were essentially the same engine constructed at two different scales. They were loop-scavenged engines using die-cast alloy components and featuring steel cylinders with integral cooling fins and separate bolt-on alloy cylinder heads. The cylinders of both models were permanently secured to their cases by a pair of welds fore and aft below exhaust port level, in a manner very reminiscent of the famous O&R engines from America. The early examples of the 29 also featured a pair of upwardly-inserted screws to provide added security, although these screws were later omitted.

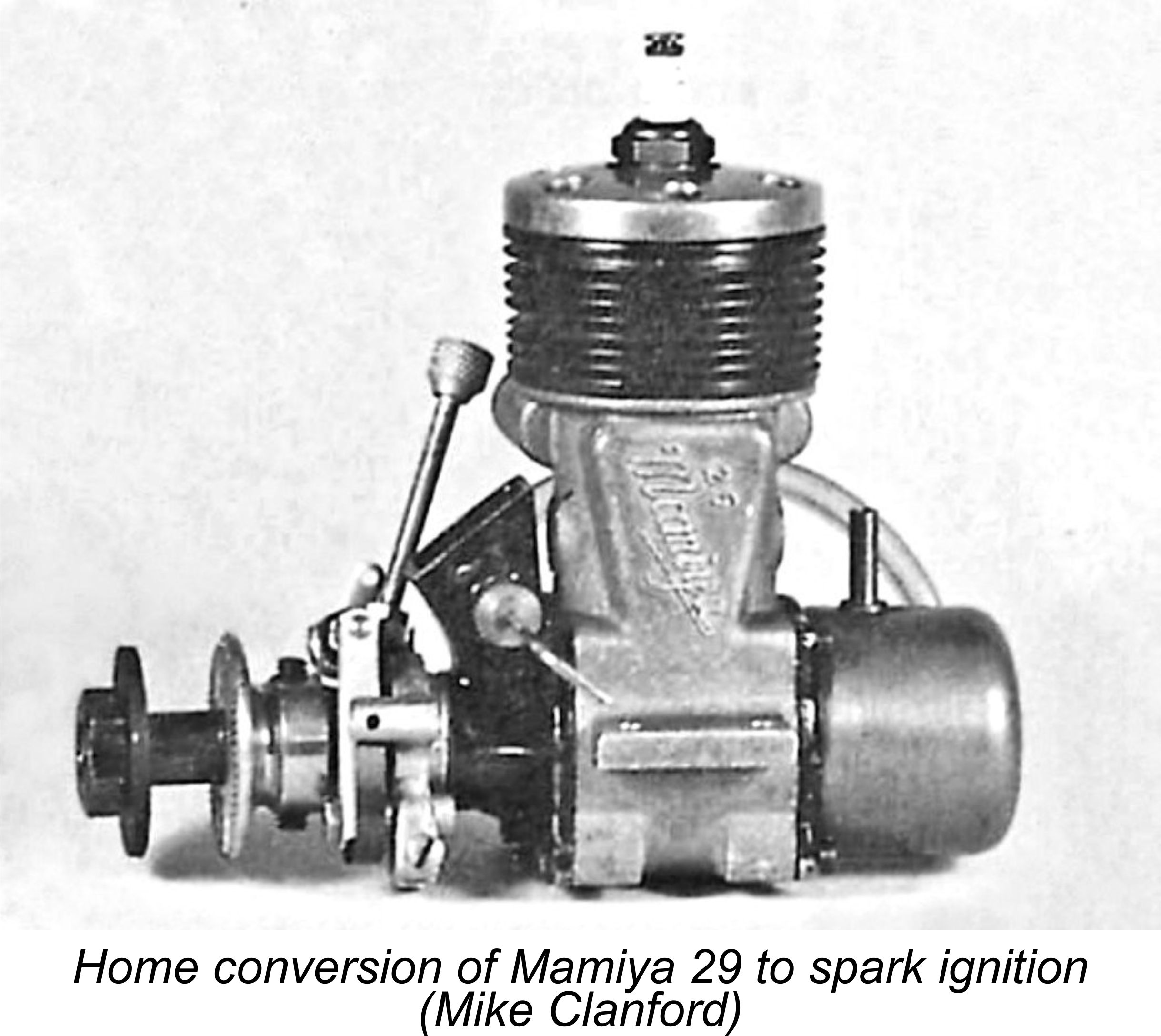

By this time, of course, the glow-plug had more or less completely supplanted spark ignition as the ignition system of choice, at least in the Asian and North American markets. In this context, I consider it necessary to dispel what I sincerely believe to be a significant piece of widely-disseminated misinformation regarding the loop-scavenged Mamiya 29 model. This is the issue of the existence of a factory-built spark-ignition version of this design. Mike Clanford’s well-known book "A-Z of Model Airplane Engines" includes the attached illustration of a spark-ignition version of the loop-scavenged Mamiya 29. Aha, you say - this proves that at least one example does exist!! Alas, herein lies the confusion! Alan Strutt has personally In Alan’s well-informed view, the engine shown in Clanford’s book has been fitted by a previous owner with what appears to be a standard Cyclone timer made in the USA. Furthermore, neither Alan nor I are aware of any other reported examples of an unquestionably original spark-ignition version of this model. Hence it is our considered opinion that no such model ever left the factory. In my own view, the clincher is the fact that the illustrated engine is clearly a later example, since it lacks the extra cylinder retention screws which were included for added security on the early examples. If a factory-built spark-ignition version of this engine existed, it would undoubtedly be of the earliest pattern and would hence feature those screws. It’s possible (and indeed likely) that other retrofit examples exist, but I would require some very persuasive evidence indeed before accepting any spark ignition example of this engine as a genuine Mamiya product.

Returning to our main thread, there is documentary evidence to the effect that a .19 cu. in. glow-plug model of generally similar design and appearance to the companion loop-scavenged .099 and .29 models was also produced, most probably at around the same time or soon thereafter. Published data on this model indicates that it was pretty much a scaled-down version of the 29 FRV model described earlier. Its production dates are presently obscure. This design appears to be one of the rarest Mamiya models - at present I do not have access to an example or even an image for illustrative purposes. If anyone out there can help us out, I’d be very grateful! 1950 - 1954 - The Range Evolves

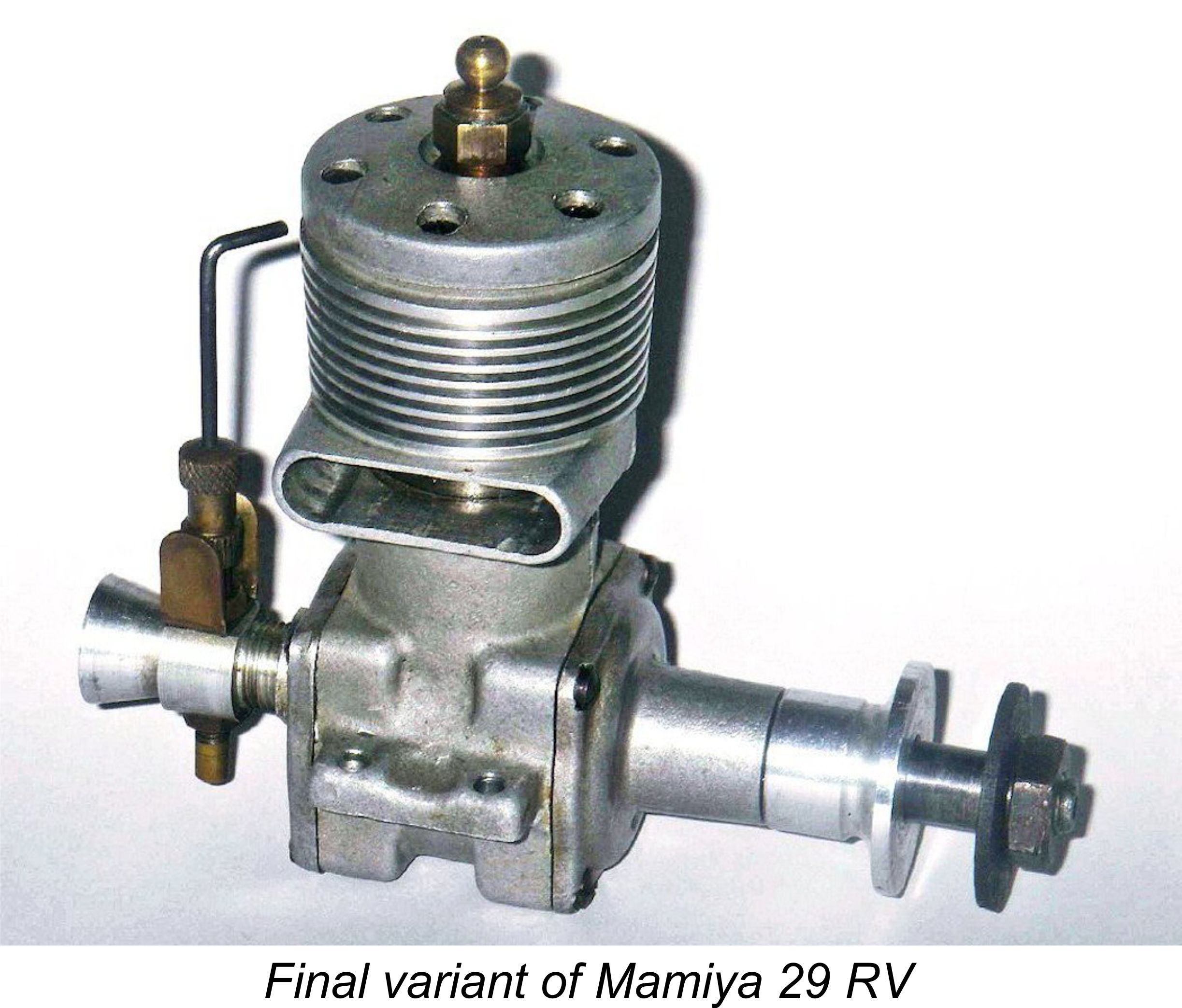

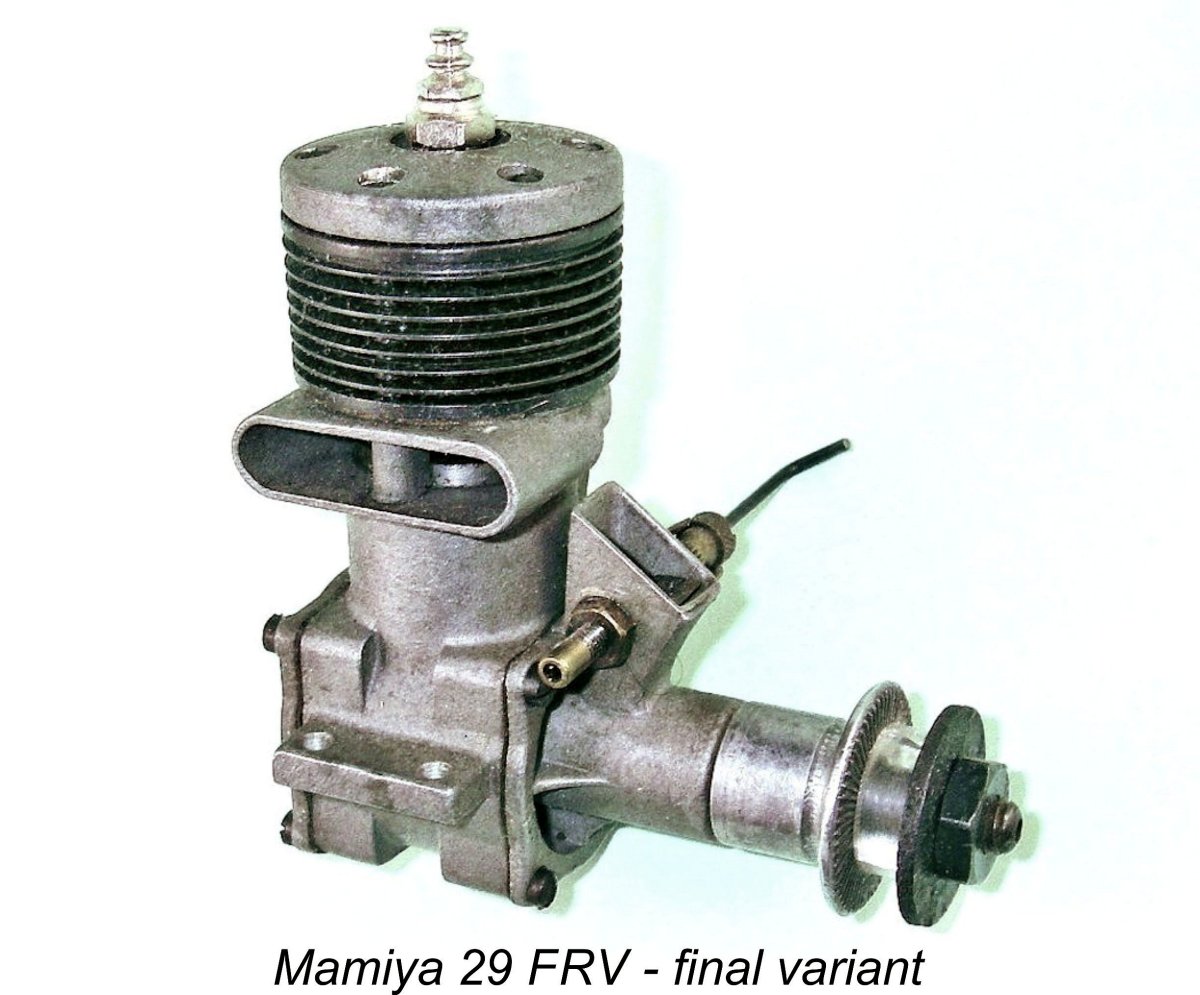

Both the Mamiya 29 and 60 racing models followed a generally similar design pattern, adhering more or less to the established design pattern for racing glow-plug motors at the time in question. They were based upon a central main casting which incorporated the bypass, exhaust stack and cooling fins, allied to bolt-on front and rear covers. They featured cross-flow loop scavenging along with ringed lightweight alloy pistons having high baffled crowns. Rear disc valve induction was used in both models. In both models, the main departure from the established racing engine formula was the use of a single inboard ball race for crankshaft support as opposed to the more usual twin ball-race set-up. At first sight this feature might appear a little odd for a racing engine, but in reality there was sound reasoning behind it. The fact had long been recognized that the contribution of front ball races to classic model engine performance is relatively small, since they are located at the most lightly-loaded end of the shaft (assuming that the prop is well balanced). The one exception to this principle would be in the case of engines intended for car or hydroplane service, where the weight of the flywheel and/or the reactive forces generated by gearing may impose a significant lateral loading on the front of the shaft. A ball race at the loaded (rear) end of the shaft does far more to absorb loads, offset friction losses and minimize wear than a front race. In addition, the need to accommodate a second ball race inevitably adds extra weight and bulk to the engine. In reality, this additional weight contributes relatively little to the engine’s effectiveness. Finally, the extra ball race represents an increase in cost for relatively little return. In fact, the contribution of the front race had the potential to be negative unless great care was taken during construction. The two bearings have to be in perfect alignment in order to work together efficiently. The noted English diesel engine designer "Gig" Eifflaender of P.A.W. fame used to quip that a single ball-race engine might be 10% faster than its plain bearing equivalent, but a twin ball-race version of the same engine could be up to 3% slower! For many years Eifflaender practised what he preached by sticking with single ball-race shafts in his P.A.W. diesels. It's very likely that the thinking behind this design decision followed the above lines. Attentive readers may recall my earlier comment to the effect that Japanese model engine design thinking at this time went very much along minimalist lines - a feature was only included if it contributed materially to the engine's performance or longevity. The omission of the front ball-race was entirely consistent with this design philosophy.

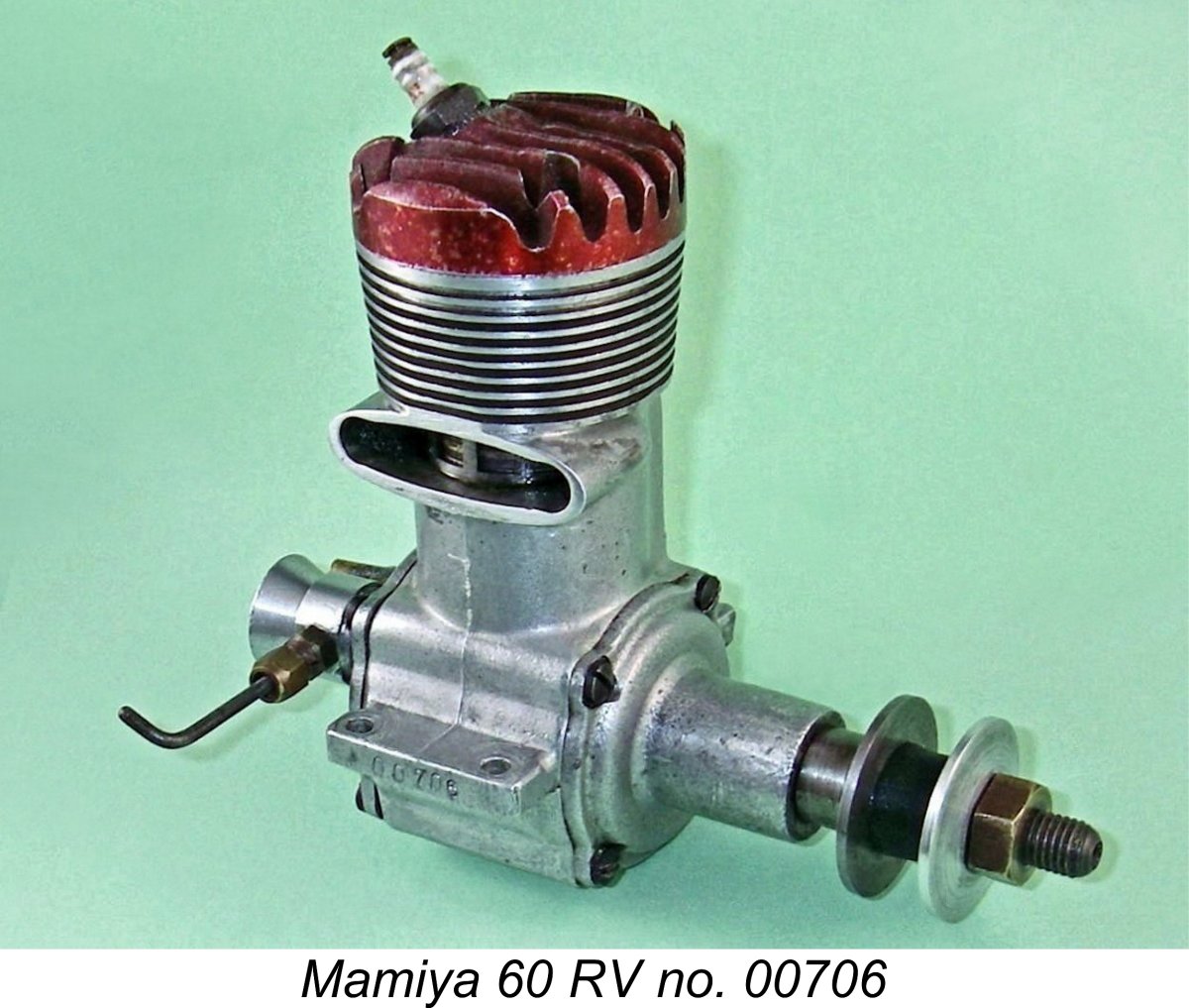

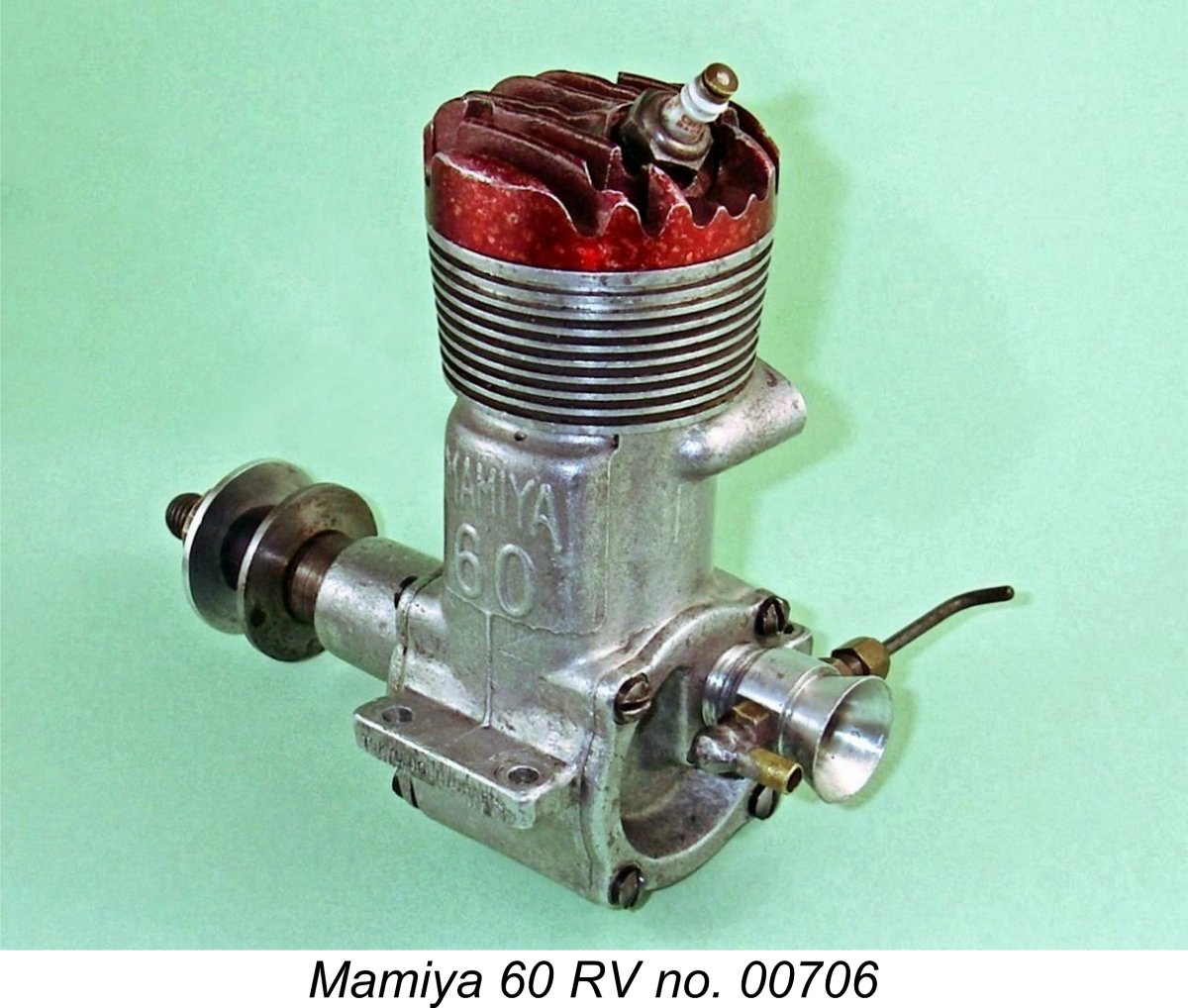

It seems likely that this initial variant was produced in extremely small numbers as a racing “special” for use in promoting the Mamiya name through competition success in the hands of selected Japanese modellers. It was probably never offered as an “over the counter” item. The engine starts and runs extremely well, although I've never pushed it all the way through a full-blown test. Subsequent to the early 2019 update of this article, I unexpectedly acquired another example of the Mamiya 29 RV. This one retained the 13.5 mm diameter front bearing housing but now featured the gravity die-cast crankcase which was to be used on all subsequent versions of the Mamiya 29 RV. More importantly, it also bore the serial number 2712. It had previously been thought that only the original sand-cast models were numbered. Evidently the first die-cast variants with the 13.5 mm diameter front bearing housing were also numbered. The external diameter of that housing was later increased to 14.0 mm, at which point the numbers were dropped. I own two examples of the Mamiya 60 RV. What appears to be the earlier of the two features a cylinder head which at first sight seems to be of the type used on the earlier sparkers, with rear-angled plug. However, a closer examination of the actual engine reveals that the combustion chamber is internally configured like that used in the later examples of the Mamiya 60 RV to accommodate a straight-across piston baffle instead of the shallow V-shaped baffle of the FRV sparker. It's actually a different casting featuring the same plug orientation.

The measured compression ratio with this head fitted is a very healthy 11:1, and it certainly feels like it when the engine is flipped over with a plug installed! This implies that the motor was configured to run on straight methanol/castor oil fuel. This is not really surprising given the fact that nitromethane was almost impossible to obtain in early post-WW2 Japan and was prohibitively expensive when it was available. The exhaust stack of this example has been quite cleanly removed, presumably to conform to a cowling, while the fuel jet has been equipped with a neatly-executed 90 degree fuel line attachment. The motor thus appears to have been intended for use in a control-line speed application. Although it has clearly been mounted and has obviously done some running, it remains in excellent mechanical condition. Despite the fact that its front housing has no provision for a timer, this example also has a steel prop driver of the earlier spark ignition pattern, complete with cam. Closer internal examination reveals that it is also fitted with a standard FRV crankshaft complete with induction port, which serves no function other than supplying lubricant to the middle of the main bearing.

All of these observations point towards the conclusion that this unit may have begun life as a standard Mamiya 60 FRV spark ignition model which was used as a test-piece for the development of the RV version. The conversion was effected (possibly in successive stages) by replacing the cylinder head and piston, replacing the front housing with a new casting which lacks provision either for a timer or for FRV induction, and also replacing the standard backplate with an RV disc valve assembly. All other components are of the standard FRV spark ignition pattern - further revisions to the cylinder head and prop driver came later. This implies that engine number 00706 is a transition model which is one of the very earliest examples of the RV variant produced, at a time when these engines were being created simply by installing a few replacement components on a standard spark ignition unit. Perhaps they were using up left-over and now redundant FRV components.

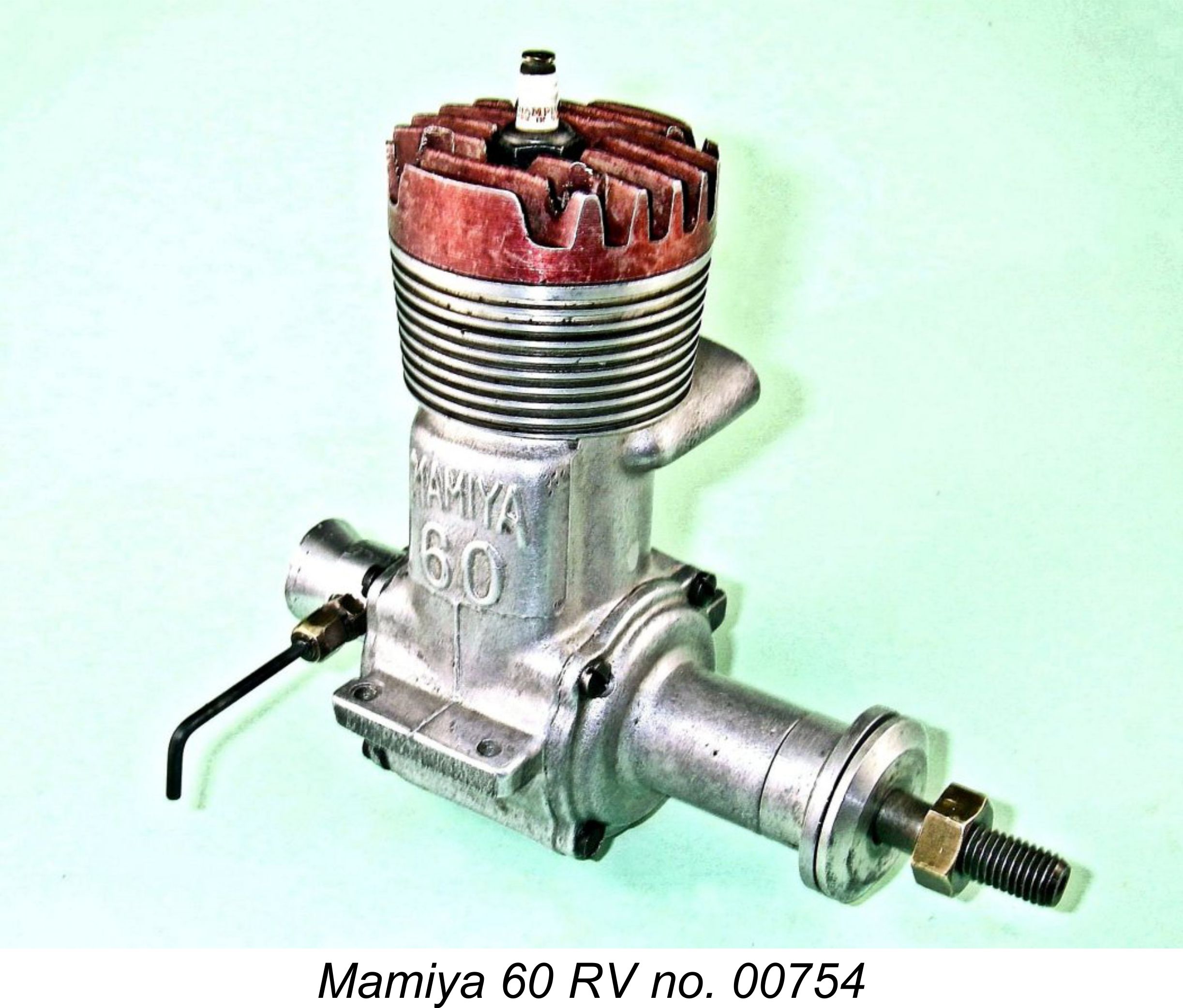

Using this technique, the Mamiya was a one or two-flick starter every time. Suction proved to be perfectly acceptable, while the needle response was perfect - not unduly sensitive, but a very well-marked sweet spot. Running qualities were beyond reproach, with no hint of misfiring or sagging. There was some seepage of oil through the head joint, presumably due to the previously-noted use of only four cylinder head attachment screws. However, the seal held up OK with no obvious adverse effects upon running. A few prop/rpm figures obtained during this test indicated that the engine developed a peak outut of My second example of the Mamiya 60 RV bears the serial number 00754 on the exhaust-side mounting lug, but does not display the Tokyo Hobbycrafts stamping on the bypass-side lug. It is unmodified and seemingly very little used. It features an updated head having a vertically-oriented glow-plug which is offset towards the transfer side. Rather surprisingly, the head continues to be retained by only four screws - a seemingly inadequate arrangement, particularly for a racing engine. The motor also has a nicely-executed aluminium alloy prop driver in place of the earlier steel item. Alan Strutt owns identical engine number 00763. The cited figures were the only three confirmed serial numbers for this model as of early 2019, when this article was last reviewed and updated. The Mamiya 60 RV appears to have been manufactured in very limited quantities - examples are extremely rare today. The engine starts and runs very well indeed, as my own bench tests have confirmed, although maintaining a good head seal is an ongoing challenge.

I suspect that the first two "00" digits are model identifiers for the disc valve glow-plug version of the Mamiya 60, just as the "20" digits appear to have been for the spark ignition FRV model. It also seems probable that the serial numbering sequence for the Mamiya 60 RV started at some intermediate figure - quite possibly 00701. Such a starting point would be completely consistent with the previously-expressed idea that my lower-numbered example is one of the first such engines produced. The fact that it features an earlier-style head along with a spark ignition prop driver and shaft certainly seems consistent with the idea that it was made at a time when the design was still evolving. However, only the provision of more serial numbers for this model would help to resolve this question. Contributions, please!! The Mamiya racing models passed through several evolutions as the 1950’s wore on. I have actual examples of four distinct variants of the 29 RV model showing progressive design improvements, among which was the previously-noted increase in the external diameter of the front bearing housing to 14.0 mm. The fact that development of this model seems to have continued through much of the 1950's implies both that it attracted some sales attention and that it must have achieved a measure of competition success. There is also documentary evidence for at least one more variant of the larger .61 cuin. design, although I had been unable to gain access to an example or even an image of the reported final variant up to early 2019. The existence of a later .61 cuin. variant The main clue is the fact that there is a substantial discrepancy in the weight figures. The table in the referenced publication gives the weight of the Mamiya 60 RV as a very hefty 16 ounces, a typical figure for a 10 cc racing engine but one which is very much at odds with the unusually light 9.80 ounce figure measured for the engines owned by Alan and myself. It is this weight discrepancy which suggests the existence of a distinct later variant of the engine. However, only the location of an actual example would confirm this supposition. The FRV version of the Mamiya 29 also evolved in minor detail during this period. Early versions used a pair of small asymmetrically-placed screws (the fasteners that are missing in the illustration of a Mamiya 29 FRV sparker in Mike Clanford's book) in addition to the two welds to hold the cylinder in place in the case. Presumably these screws were intended to secure the cylinder pending the completion of the welds as well as to provide backup in the event of weld failure. They were inserted from below.

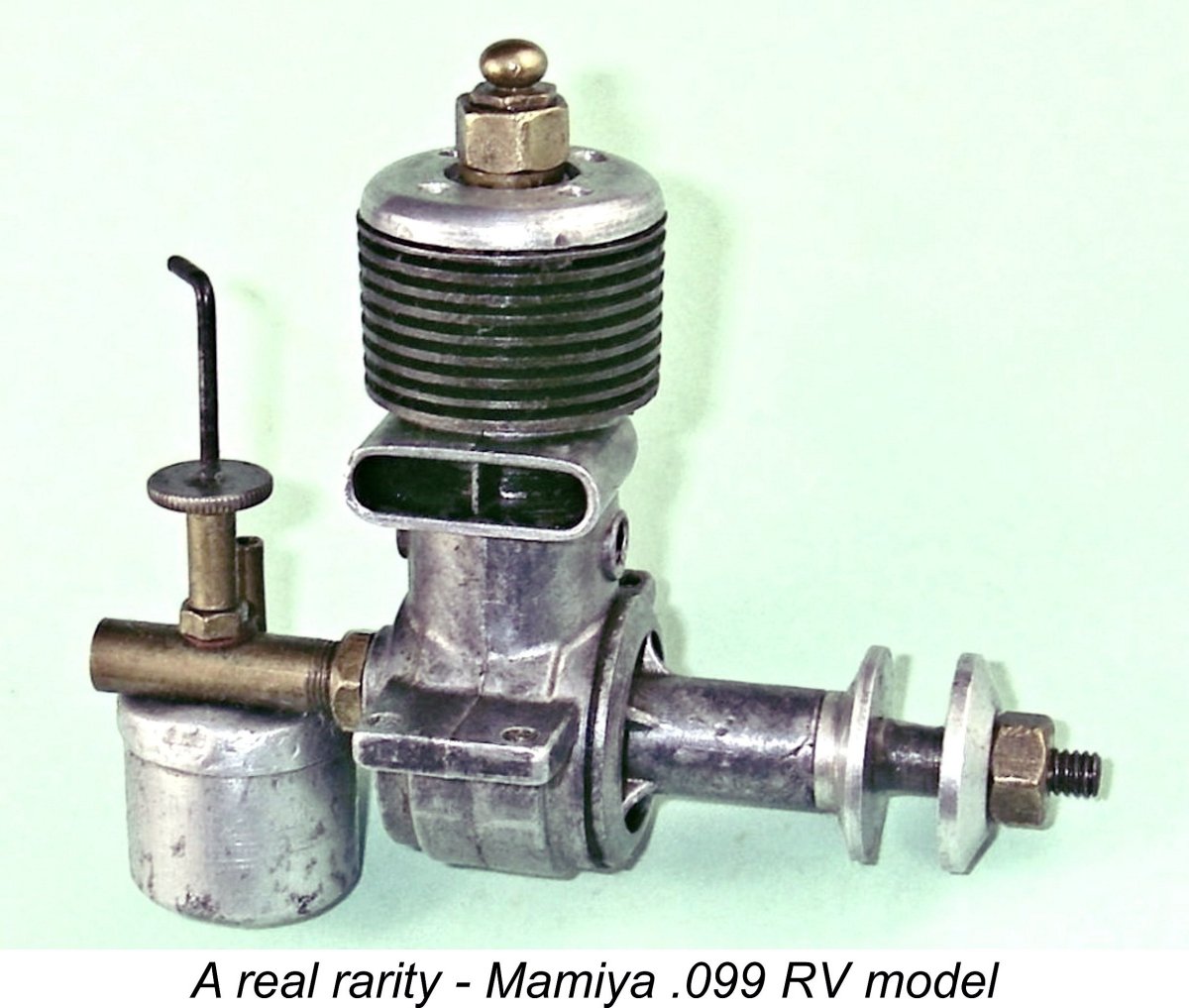

This final model also embodied a number of functional changes. The geometric compression ratio was reduced to only 7:1 from the earlier checked figure of 9:1. In addition, the cylinder port timing was amended, while the sub-piston induction featured in the earlier FRV models was eliminated. The resulting engine was clearly optimized for control-line stunt use - on the bench at least, it needles very well indeed, with a perfect two-stroke/four-stroke break. The omission of the tank made complete sense in the context of this application, since the back tank was completely unsuitable for stunt use and would accordingly have been discarded immediately by any stunt-minded owner. During this same period, the .099 model was by no means neglected. It seems likely that this excellent little engine was actually Mamiya’s “bread-and-butter” model, since there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the .099 displacement category occupied much the same “popular” market niche in Japan as the .049 The loop-scavenged .099 FRV design passed through at least four relatively minor design evolutions in the years 1950-1954, including one with a finned cylinder head. The frequency with which examples turn up on eBay and elsewhere suggests that the various renditions of this model were manufactured in quite large numbers. There was also a rear disc-valve version of the .099, although this model was never noted in the English-language literature. Indeed, it is so rarely encountered that it may well have been more of a short-run pilot-scale project than anything else. If I hadn't run across an actual example some years ago, I would have been unaware of this model's existence! When time permits, I hope to document the different variants through which the Mamiya .099 model passed over time. However, that will form the subject of a separate article. 1954 - Circling the Wagons By 1954 it must have become evident to Tokyo Hobbycrafts that the Mamiya range was failing to make much if any impression upon the international marketplace, possibly losing ground domestically as well. This being the case, the long-term future of the range must have appeared increasingly insecure. The engines were by then becoming somewhat old-fashioned in design terms. Consequently, changes were clearly needed if the range was to survive even in the domestic market.

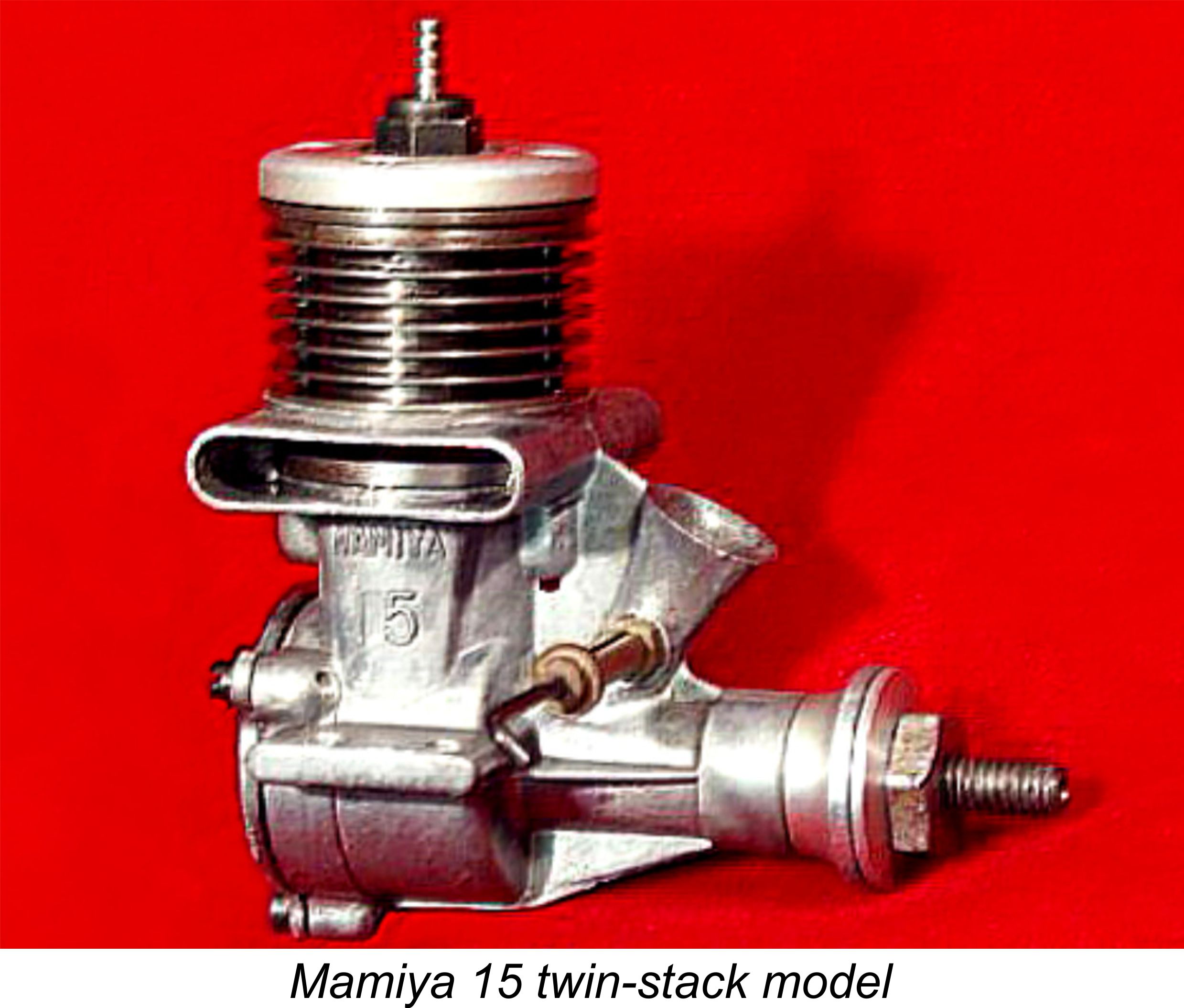

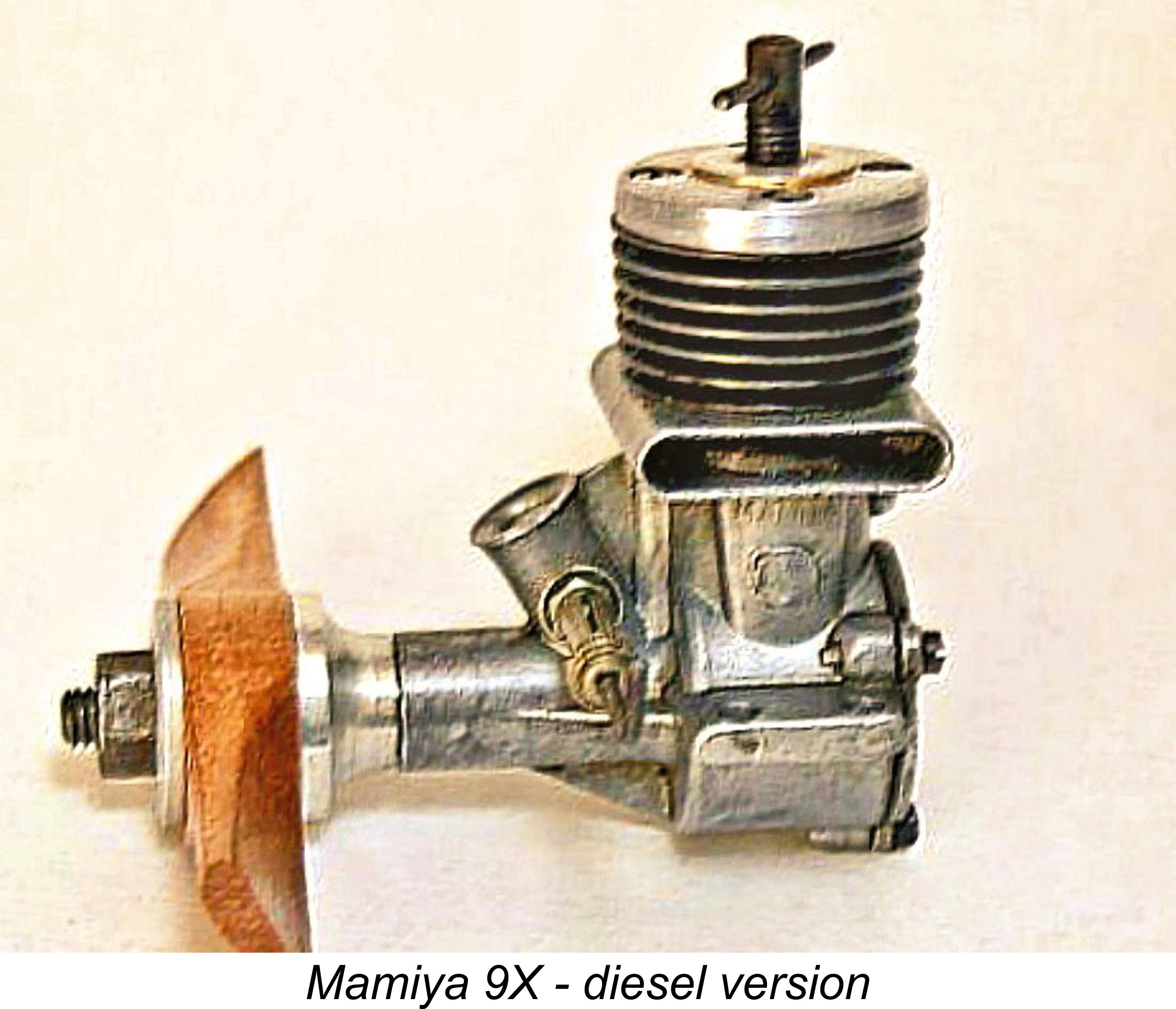

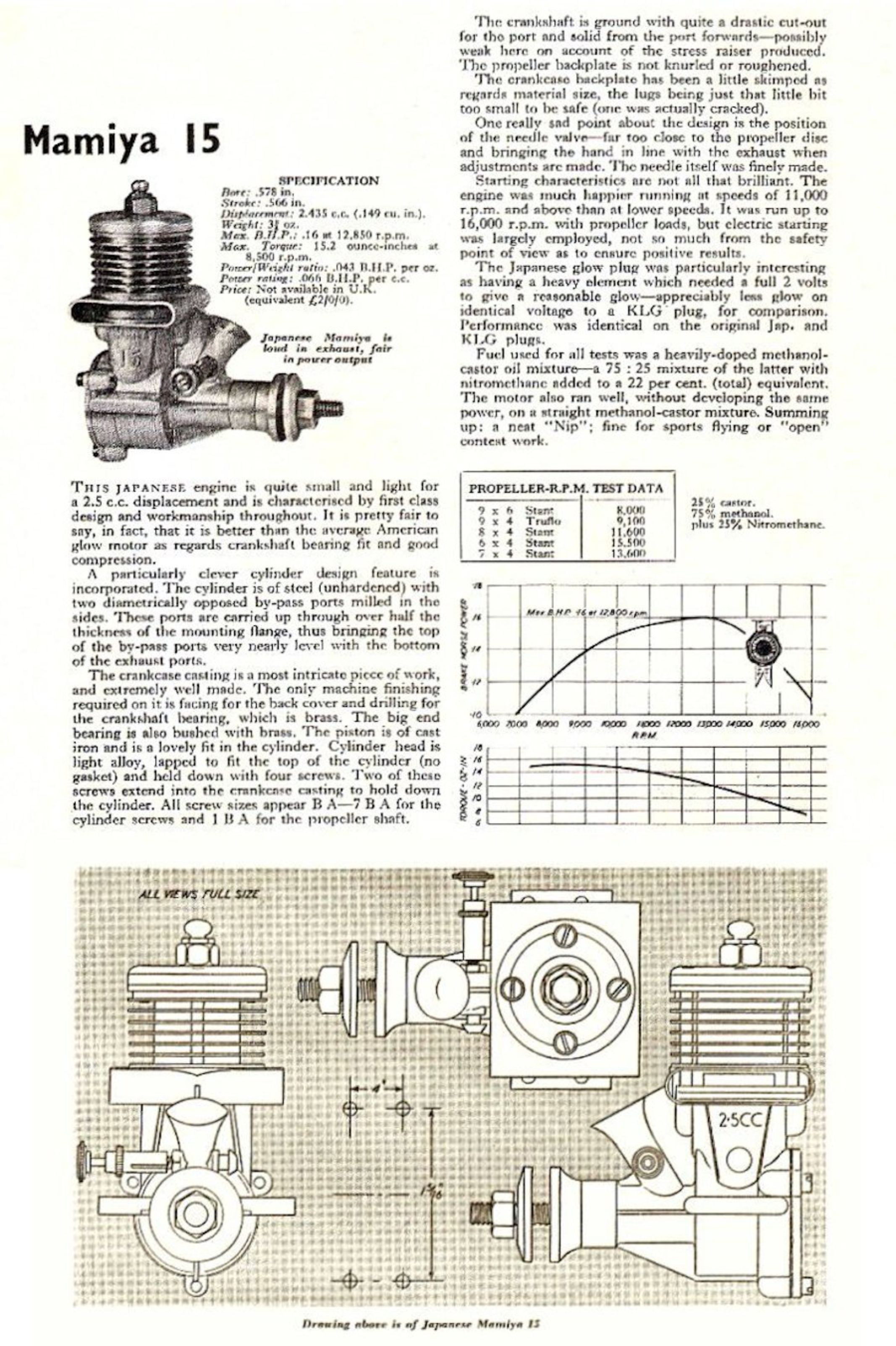

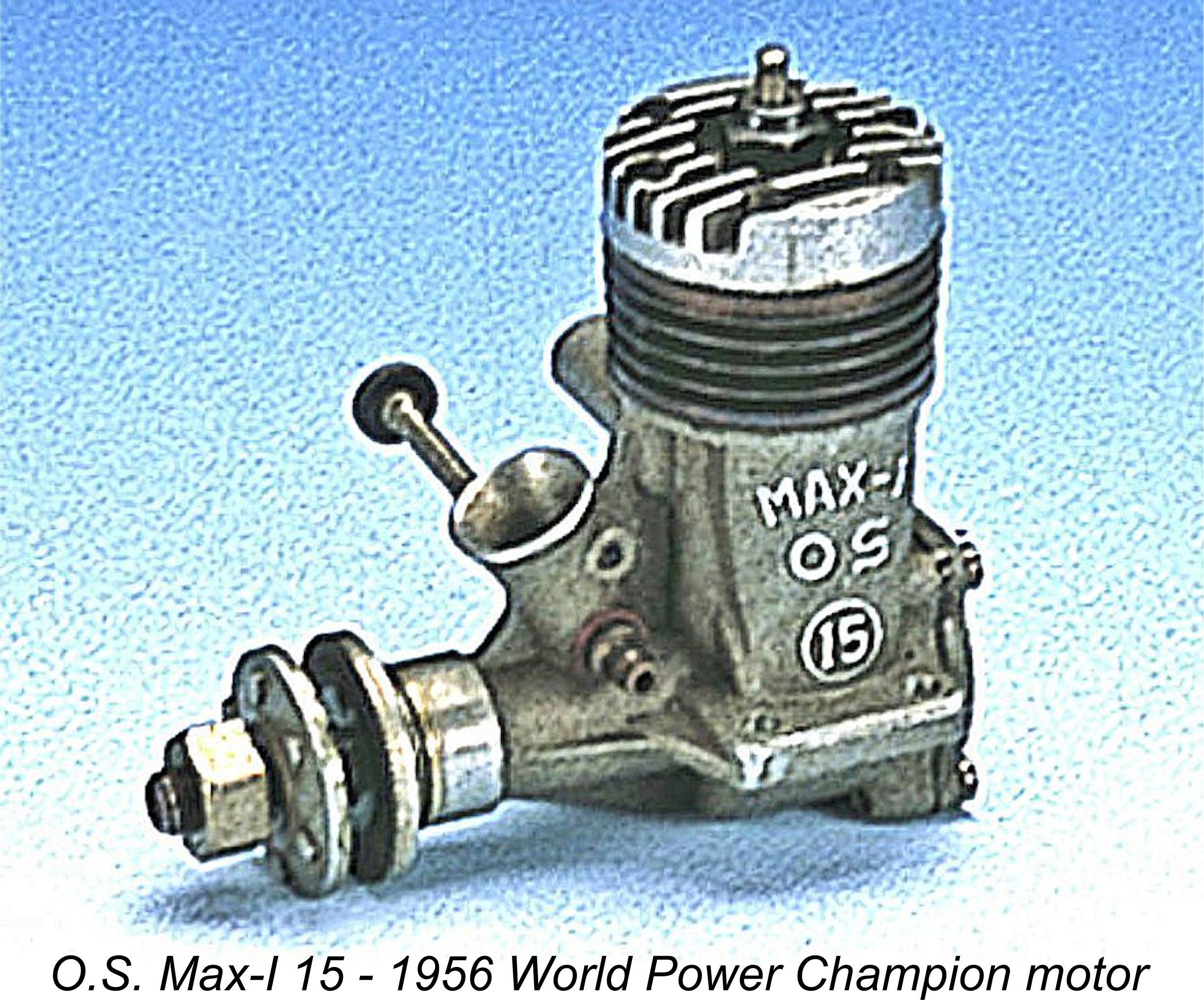

The rival Fuji company had led the Japanese charge in the latter regard in early 1954, when they launched Japan’s first-ever commercially-produced model engine built to meet the forthcoming International competition displacement limit of 2.5 cc (.152 cuin). They had done so with a twin-stack model which was still a radially-ported engine despite the twin stacks. The new Mamiya 15 model which appeared a little later in the same year also sported twin stacks, as did a number of other contemporary Japanese designs from makers such as O.S. and K.O. Clearly this was a fashionable design layout in Japan at this time! The new Mamiya .099 design which appeared at more or less the same time as the companion .15 model was more or less identical in design terms - indeed, one model was pretty much a re-scaled version of the other. In a number of ways, the two new models, designated the Mamiya 9X and the Mamiya 15 respectively, upheld Mamiya’s established tradition - both were refreshingly out-of-the-rut designs as well as being extremely well made. The Sadly, the design revisions did not translate into any spectacular levels of performance. Ron Warring’s March 1956 test of the Mamiya 15 (see below) revealed a relatively modest peak output of only 0.160 BHP @ 12,800 rpm using a fuel containing 25% nitromethane. It may be anticipated that the functionally identical Mamiya 9X would have performed at a similarly modest level in Warring's hands. Hopefully a future test will shed light upon this assumption. Consequently, competing products from rival Japanese manufacturers continued to outstrip the performance of their Mamiya counterparts for the most part. An attempt was made to upgrade the Mamiya 9X through the revision of the cylinder port timing, but to very little effect.

The racing versions of the 29 and 60 models seem to have continued in production at some level during this period. Indeed, there is some evidence to support the notion that the racing versions of both models outlasted their FRV counterparts. The previously-mentioned listing of the world’s model engines which appeared in the early 1958 British publication “Model Aero Engine Encyclopaedia” included only the disc-valve racing versions of both the Mamiya 29 and 60 models in addition to the .099, .15 and .19 designs. It’s perfectly possible and indeed likely that there may have been other models in the Mamiya range, but if there were I have yet to encounter either a reference to them or any surviving examples. If any reader has authoritative information regarding other Mamiya models not included in the above summary, please let me know! Late 1950’s - The End of The Line In the present absence of any hard data, I'm unable to provide any reliable information regarding the year in which production of the Mamiya engines finally ceased. I can however summarize such evidence as I have so far been able to uncover.

A valuable snapshot of the Japanese model engine industry as of 1956 is to be found in Peter Chinn’s article entitled “Made in Japan” which appeared in the November 1956 issue of “Model Airplane News”. The Mamiya engines were mentioned once again in this article, albeit in passing, implying that as far as Chinn knew they were still in production as of the second half of 1956 when the article was written. It’s worth dwelling on this article for a moment since it highlights a rather subtle and insidious factor relating to the indisputable cost advantages enjoyed by Japanese manufacturers at this time. Because of these advantages, the emerging Japanese manufacturers clearly had the potential to undercut the prices of their competitors in the world marketplace. This alone would not have caused much concern among manufacturers in other countries if the quality and performance of Japanese products had fallen short of the overseas competition, as many Westerners still assumed at that time. But in reality this was far from being the case - Japanese model engines were increasingly comparable with (or even superior to) their foreign competition, both in terms of quality and performance. Knowledgeable insiders like Chinn were rapidly becoming aware of this indisputable fact. The securing of the 1956 Free Flight World Championship by Britain’s Ron Draper using an O.S. Max-1 15 glow-plug powerplant represented an irrefutable statement in this regard. It was this event which finally forced people to sit up and start paying serious attention to the Japanese model engine manufacturing industry. “These articles definitely do not suggest that the reader buy a foreign engine in preference to one made in this country (the USA). American mass-produced engines are known the world over for quality and high performance. The purpose of these articles is to give the interested American modeller the picture of what other nations are doing in his chosen hobby”. Clearly Chinn was taking pains to avoid upsetting the US manufacturers who generated a good share of the advertising revenue for MAN! Chinn’s implied acquiescence in the prevailing “siege mentality” was not to be continued for long - within a year or two Chinn and his colleagues were openly praising Japanese engines to the skies, comparing them directly and very favorably with US and European products. Moreover, the ongoing lingering public resentment against the Japanese arising from WW2 had largely run its course by that time. As the poet put it, the times they were a-changin’ ................... Returning to the closing year or two of the Mamiya range, Peter Chinn's retrospective look at the Mamiya 60 which formed the subject of his “Foreign News” feature in the May 1979 issue of “Model Airplane News” included a statement to the effect that the only Mamiya models listed for 1957 were the Mamiya .09X and Mamiya 15. They may well have been the last models to remain on offer from Tokyo Hobbycrafts. Thereafter, nothing more was heard of the Mamiya range, implying that 1957 was the final year of production. We saw earlier that certain Mamiya models were included in the listing of the world’s model engines which appeared as an appendix to the March 1958 first edition of the book "Model Aero Engine Encyclopaedia" compiled by Ron Moulton. However, close examination of that listing confirms that it was already considerably out of date at the time of its initial publication - a number of well-documented engines which were included are definitely known to have been out of production for some time prior to 1958. Hence the inclusion of the Mamiya range can in no way be interpreted as definite evidence of ongoing production as of early 1958. Moreover, I can find no other contemporary references to the range after that date, or indeed for some time previously. What can be stated with certainty is that the Mamiya engines had undoubtedly disappeared from the scene long before 1962, since they were missing entirely from the Global Engine Review compiled in 1962 for “American Modeller” magazine (almost certainly by Peter Chinn). Indeed, the Mamiya range was not even mentioned in retrospect. It thus seems probable on balance that the Mamiya model engine range finally disappeared from the market at some point during 1957. I cannot be any more definite than that pending the receipt of further information. If anyone knows more, please speak up!! Conclusion

The answer seems to be that the manufacturers made the mistake of standing pat on their original designs, waiting too long to respond to marketplace evolution through the introduction of new products and updated designs. Even when they did so (as with the 15 and 9X models mentioned above) the revised designs still failed to remain in step with the kind of technological advances and performance levels being achieved by other more progressive manufacturers. When we couple this with what appears to have been an extremely half-hearted international marketing effort coinciding with the already-shrinking world market for model engines which is clearly evident in hindsight, it’s not difficult to discern the seeds of eventual failure. The fact that as far as I'm aware Mamiya never introduced R/C versions of any of their designs may also have played a Still, the manufacturers of the Mamiya range left us with a legacy of some very attractive, well made and interesting model engines bearing a famous name which we can still appreciate and enjoy today. Long may it remain that way!! In closing, I'd like to note for the record that the preceding article was originally written in 2013 with the intention that it would appear on MEN, with further articles to follow covering the various displacement categories in full detail. Ron Chernich and I had followed precisely the same pattern in our earlier MEN coverage of the Fuji and Hope ranges Sadly, the changed circumstances arising from Ron Chernich’s illness and subsequent demise precluded the implementation of this plan on MEN. I hope that the above summary will represent the first step towards the rectification of this unhappy situation, at least to the extent possible. As and when time permits in the future, I will undertake some testing of these engines for inclusion in future articles dealing with the complete technical and performance details of the different variants in each displacement category. Meanwhile, I hope that you enjoyed the above summary! _________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2015 Updated February 2019 Updated June 2019 |

| |

Here I've presented an overview of a range of quality model engines from Japan which continues to command the attention of present-day model engine aficionados but is very poorly documented in the English language. This is the Mamiya marque, which was the namesake of a far more famous and long-lasting range of cameras. As we shall see, there

Here I've presented an overview of a range of quality model engines from Japan which continues to command the attention of present-day model engine aficionados but is very poorly documented in the English language. This is the Mamiya marque, which was the namesake of a far more famous and long-lasting range of cameras. As we shall see, there

Present-day opportunities for gathering first-hand information from such sources are few and far between - the majority of the original post-war Japanese manufacturers are no longer in existence, hence being unavailable for consultation by present-day researchers. Even among those few companies which remain active, almost all of the individuals who were involved “back then” have now left us.

Present-day opportunities for gathering first-hand information from such sources are few and far between - the majority of the original post-war Japanese manufacturers are no longer in existence, hence being unavailable for consultation by present-day researchers. Even among those few companies which remain active, almost all of the individuals who were involved “back then” have now left us.

This is a great pity, because those early years of the industry in post-war Japan were every bit as interesting and dynamic as those of their American and European counterparts. The publication of my series of articles on early post-war Japanese engine ranges on the MEN web-site represented my own attempt to do what can be done at this late stage to draw aside the veil by shedding at least some light on those undocumented early years of what was to become a world-leading model engine manufacturing industry. I've already covered the

This is a great pity, because those early years of the industry in post-war Japan were every bit as interesting and dynamic as those of their American and European counterparts. The publication of my series of articles on early post-war Japanese engine ranges on the MEN web-site represented my own attempt to do what can be done at this late stage to draw aside the veil by shedding at least some light on those undocumented early years of what was to become a world-leading model engine manufacturing industry. I've already covered the  The Mamiya camera business was founded on May 10, 1940 as a partnership between businessman Tsunejiro Sugawara and engineer Seichi Mamiya, trading initially as Mamiya Koki Seisakusho. Mamiya was an up-and-coming young camera design engineer with a bagful of bright ideas, while Sugawara provided the bulk of the start-up funding. A classic melding of technical expertise and capital, to the benefit of both parties. The partnership was to prove to be an enduring one, lasting until the deaths of the two men in the late 1980’s.

The Mamiya camera business was founded on May 10, 1940 as a partnership between businessman Tsunejiro Sugawara and engineer Seichi Mamiya, trading initially as Mamiya Koki Seisakusho. Mamiya was an up-and-coming young camera design engineer with a bagful of bright ideas, while Sugawara provided the bulk of the start-up funding. A classic melding of technical expertise and capital, to the benefit of both parties. The partnership was to prove to be an enduring one, lasting until the deaths of the two men in the late 1980’s. However, at the outset there was no thought of entering the model engine field - the camera business commanded the full attention of the new company. Their first product was the medium-format (120 film) folding Mamiya-6 camera. A fascinating feature of this model, and an excellent indication of Seichi Mamiya’s ability to think "outside the box", was the way in which it focused. The lens and bellows did not move while focusing - the film plane moved instead! Well made and highly successful, it was the predecessor of Mamiya's first 35 mm camera, the Mamiya 35-I rangefinder model which debuted after the war in 1949.

However, at the outset there was no thought of entering the model engine field - the camera business commanded the full attention of the new company. Their first product was the medium-format (120 film) folding Mamiya-6 camera. A fascinating feature of this model, and an excellent indication of Seichi Mamiya’s ability to think "outside the box", was the way in which it focused. The lens and bellows did not move while focusing - the film plane moved instead! Well made and highly successful, it was the predecessor of Mamiya's first 35 mm camera, the Mamiya 35-I rangefinder model which debuted after the war in 1949. Despite the above windfall (or perhaps in part because of it!), Mamiya faced many production problems in the early post-war years. Shutters and lenses were in short supply, forcing Mamiya to join other manufacturers in beginning to make these precision components themselves to meet their growing needs. Unable to buy a sufficient supply of shutters and lenses from their former supplier Chiyoda, Mamiya purchased a factory in Setagaya (Tokyo) to manufacture shutters and lenses for themselves. It was this Mamiya Setagaya factory (later called Setagaya Koki) that originated the soon-to-be-famous Sekor lens name.

Despite the above windfall (or perhaps in part because of it!), Mamiya faced many production problems in the early post-war years. Shutters and lenses were in short supply, forcing Mamiya to join other manufacturers in beginning to make these precision components themselves to meet their growing needs. Unable to buy a sufficient supply of shutters and lenses from their former supplier Chiyoda, Mamiya purchased a factory in Setagaya (Tokyo) to manufacture shutters and lenses for themselves. It was this Mamiya Setagaya factory (later called Setagaya Koki) that originated the soon-to-be-famous Sekor lens name. Early products of the Mamiya model engine company included a fine .61 cuin. spark ignition model as well as a pair of rather individualistic glow-plug motors in .099 and .275 cuin. displacements. It’s possible that these latter two models were first produced in spark-ignition form, but we have no direct evidence for this at present. Due to the resemblance of their rather tall integrally-finned cylinders to the traditional paper-and-bamboo “chochin” lanterns seen in Japanese bars and at festivals, these smaller models became colloquially known to Japanese modellers as the Mamiya “Chochin” engines. It appears that this name was not an official factory designation but was more of a “modeller’s nickname”.

Early products of the Mamiya model engine company included a fine .61 cuin. spark ignition model as well as a pair of rather individualistic glow-plug motors in .099 and .275 cuin. displacements. It’s possible that these latter two models were first produced in spark-ignition form, but we have no direct evidence for this at present. Due to the resemblance of their rather tall integrally-finned cylinders to the traditional paper-and-bamboo “chochin” lanterns seen in Japanese bars and at festivals, these smaller models became colloquially known to Japanese modellers as the Mamiya “Chochin” engines. It appears that this name was not an official factory designation but was more of a “modeller’s nickname”. There seems to be little doubt that the first Mamiya model engine was Minoru Sato’s fine .61 cuin. plain bearing FRV spark ignition model. Despite its actual displacement, this engine was officially designated the Mamiya 60 by its manufacturer. This is the only Mamiya design which appears to have been offered throughout its production life as a spark ignition engine - at least, there is at present no persuasive evidence to the contrary.

There seems to be little doubt that the first Mamiya model engine was Minoru Sato’s fine .61 cuin. plain bearing FRV spark ignition model. Despite its actual displacement, this engine was officially designated the Mamiya 60 by its manufacturer. This is the only Mamiya design which appears to have been offered throughout its production life as a spark ignition engine - at least, there is at present no persuasive evidence to the contrary.  ascendant, making it highly improbable that Mamiya would have introduced an all-new spark ignition design in the latter year - no-one else was then doing so commercially, although spark-ignition versions of a few established models remained available at that time and for a few years afterwards.

ascendant, making it highly improbable that Mamiya would have introduced an all-new spark ignition design in the latter year - no-one else was then doing so commercially, although spark-ignition versions of a few established models remained available at that time and for a few years afterwards. piston baffle. There were also alternative heads having different compression ratios - the standard 8.5:1 head was anodized red, while the high-compression 10:1 head was pale gold. The figures given here are geometric ratios based upon direct volumetric measurements of actual examples.

piston baffle. There were also alternative heads having different compression ratios - the standard 8.5:1 head was anodized red, while the high-compression 10:1 head was pale gold. The figures given here are geometric ratios based upon direct volumetric measurements of actual examples. stamped into the transfer-side mounting lug. Later models in other displacement categories were to dispense with this additional identification, retaining only the Mamiya name cast in relief onto the cases. However, the Tokyo Hobbycrafts name continued to appear on the boxes in which the Mamiya engines were supplied right up to the mid 1950’s.

stamped into the transfer-side mounting lug. Later models in other displacement categories were to dispense with this additional identification, retaining only the Mamiya name cast in relief onto the cases. However, the Tokyo Hobbycrafts name continued to appear on the boxes in which the Mamiya engines were supplied right up to the mid 1950’s. The quality of construction of these engines was truly superb - well up to the best standards then prevailing anywhere in the world-wide model engine field. Apart from the head screw issue, the only other Achilles heel was the fuel tank, which was made of some kind of vegetable-based plastic, likely synthesized from a form of bean curd. This material was quite unstable in the presence of model engine fuels, the result being that examples retaining their original tanks are few and far between today.

The quality of construction of these engines was truly superb - well up to the best standards then prevailing anywhere in the world-wide model engine field. Apart from the head screw issue, the only other Achilles heel was the fuel tank, which was made of some kind of vegetable-based plastic, likely synthesized from a form of bean curd. This material was quite unstable in the presence of model engine fuels, the result being that examples retaining their original tanks are few and far between today.  Although we can’t be absolutely certain, present indications are that the Mamiya range entered its major expansion phase in late 1948 with the introduction of the previously-mentioned radially-ported “Chochin” models in .099 and .275 cuin. displacements. These may have appeared initially in spark ignition form - in the present absence of supporting evidence, we can’t be sure. All examples of these quite rare engines of which I'm currently aware are purpose-built glow-plug versions.

Although we can’t be absolutely certain, present indications are that the Mamiya range entered its major expansion phase in late 1948 with the introduction of the previously-mentioned radially-ported “Chochin” models in .099 and .275 cuin. displacements. These may have appeared initially in spark ignition form - in the present absence of supporting evidence, we can’t be sure. All examples of these quite rare engines of which I'm currently aware are purpose-built glow-plug versions. of the Japanese model engine industry, when makers such as

of the Japanese model engine industry, when makers such as  Both models utilized bolt-on front housings with plain bearings and a rectangular-section induction tube for the crankshaft front rotary valve. The main difference was the fact that the .29 model used a bolt-on backplate as well, while the .099 model had a backplate which was cast integrally with the main case. The earliest examples of the .099 model had no tank, but this feature was soon added. The 29 FRV model sported a tank from the outset.

Both models utilized bolt-on front housings with plain bearings and a rectangular-section induction tube for the crankshaft front rotary valve. The main difference was the fact that the .29 model used a bolt-on backplate as well, while the .099 model had a backplate which was cast integrally with the main case. The earliest examples of the .099 model had no tank, but this feature was soon added. The 29 FRV model sported a tank from the outset.

Clanford’s book also includes a photograph of a Mamiya 29 FRV glow-plug model, for which he cites an introductory date of 1949. As stated above, I consider this date to be entirely credible, the one proviso being that I believe that this model was introduced from the outset as a glow-plug engine, with no spark ignition version of this engine ever being produced by the Mamiya factory. I invite any reader having persuasive information to the contrary to share that information with the rest of us.

Clanford’s book also includes a photograph of a Mamiya 29 FRV glow-plug model, for which he cites an introductory date of 1949. As stated above, I consider this date to be entirely credible, the one proviso being that I believe that this model was introduced from the outset as a glow-plug engine, with no spark ignition version of this engine ever being produced by the Mamiya factory. I invite any reader having persuasive information to the contrary to share that information with the rest of us. Although the precise dating is presently uncertain, it’s clear that Minoru Sato soon began to entertain visions of entering the high-performance arena with products that might help to reinforce the credentials of the Mamiya model engines through competition success. The result was the appearance of “racing” versions of both the original Mamiya 60 and the Mamiya 29. As far as is presently known, neither of these models was ever offered in spark ignition configuration, suggesting that they both post-dated the end of the spark ignition era. It thus seems most probable that these racing models first appeared in late 1949 or perhaps early 1950.

Although the precise dating is presently uncertain, it’s clear that Minoru Sato soon began to entertain visions of entering the high-performance arena with products that might help to reinforce the credentials of the Mamiya model engines through competition success. The result was the appearance of “racing” versions of both the original Mamiya 60 and the Mamiya 29. As far as is presently known, neither of these models was ever offered in spark ignition configuration, suggesting that they both post-dated the end of the spark ignition era. It thus seems most probable that these racing models first appeared in late 1949 or perhaps early 1950. The balance of the main journal ran in a plain bronze bushing.

The balance of the main journal ran in a plain bronze bushing.  Both 29 and 60 models carried serial numbers. The illustrated example of the original Mamiya 29 RV bears the number 0001, indicating that it was the very first example off the line. It features a sand-cast crankcase and a front housing having an external diameter of 13.5 mm immediately aft of the prop driver. Engine number 0003 of this type appeared on eBay some time ago, these being the only two confirmed numbers for this first model as of early 2019, when this article was last reviewed and updated.

Both 29 and 60 models carried serial numbers. The illustrated example of the original Mamiya 29 RV bears the number 0001, indicating that it was the very first example off the line. It features a sand-cast crankcase and a front housing having an external diameter of 13.5 mm immediately aft of the prop driver. Engine number 0003 of this type appeared on eBay some time ago, these being the only two confirmed numbers for this first model as of early 2019, when this article was last reviewed and updated.

At first sight, the serial number on Alan's example of the engine might be taken to imply that at least 763 examples were made. However, that in turn would suggest that the Mamiya 60 RV was manufactured in comparable quantities to its earlier FRV sibling. The relative numbers of known survivors argue very strongly against this possibility - the 60 RV is far less frequently encountered than the companion FRV variant, which is itself far from common.

At first sight, the serial number on Alan's example of the engine might be taken to imply that at least 763 examples were made. However, that in turn would suggest that the Mamiya 60 RV was manufactured in comparable quantities to its earlier FRV sibling. The relative numbers of known survivors argue very strongly against this possibility - the 60 RV is far less frequently encountered than the companion FRV variant, which is itself far from common.  is inferred solely through its inclusion in the list of the world’s engines which formed an appendix to the early 1958 British publication

is inferred solely through its inclusion in the list of the world’s engines which formed an appendix to the early 1958 British publication  At some later point in time, these extra screws were found to be unnecessary and were dropped. The machining specifications for the cylinder cooling fins and the cylinder head were also slightly changed. The relatively rare final variant dispensed altogether with the welded cylinder attachment system in favour of conventional hold-down screws which passed through the cylinder fins to engage with tapped holes in the main casting. It also lacked the black paint formerly applied to the crankcase and main bearing housing - presumably a cost-cutting measure. Finally, the back tank which had been included with the earlier variants was omitted.

At some later point in time, these extra screws were found to be unnecessary and were dropped. The machining specifications for the cylinder cooling fins and the cylinder head were also slightly changed. The relatively rare final variant dispensed altogether with the welded cylinder attachment system in favour of conventional hold-down screws which passed through the cylinder fins to engage with tapped holes in the main casting. It also lacked the black paint formerly applied to the crankcase and main bearing housing - presumably a cost-cutting measure. Finally, the back tank which had been included with the earlier variants was omitted. models did in the 1950’s American marketplace. Most of the mainstream Japanese manufacturers paid close attention to the .099 category during this period. By contrast, it’s noteworthy that with

models did in the 1950’s American marketplace. Most of the mainstream Japanese manufacturers paid close attention to the .099 category during this period. By contrast, it’s noteworthy that with

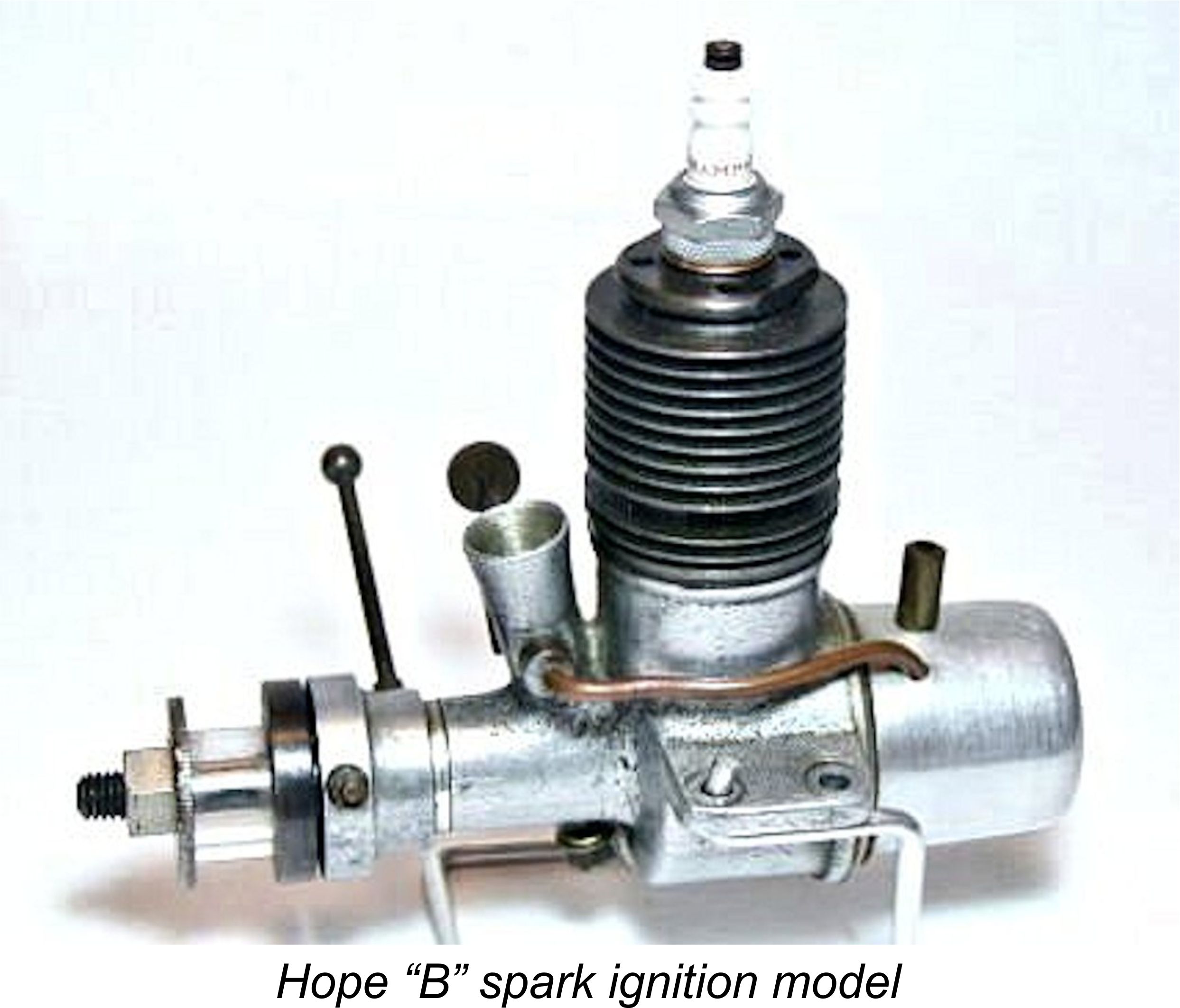

cylinder porting was of particular interest, being a highly unusual expression of the well-established reverse-flow scavenging principle.

cylinder porting was of particular interest, being a highly unusual expression of the well-established reverse-flow scavenging principle.

The Mamiya range was certainly still in production as of mid 1955 since the Mamiya 15 was discussed in the “Motor Mart” feature in the June 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. In addition, the range was mentioned as a going concern in an article by Peter Chinn on the Japanese modelling scene which was published in the September 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Furthermore, the Mamiya 15 was the subject of the previously-mentioned test by Ron Warring which appeared in the March 1956 issue of “Aeromodeller”. There was no indication in that test report that production had then ceased.

The Mamiya range was certainly still in production as of mid 1955 since the Mamiya 15 was discussed in the “Motor Mart” feature in the June 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. In addition, the range was mentioned as a going concern in an article by Peter Chinn on the Japanese modelling scene which was published in the September 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Furthermore, the Mamiya 15 was the subject of the previously-mentioned test by Ron Warring which appeared in the March 1956 issue of “Aeromodeller”. There was no indication in that test report that production had then ceased. The

The  The preceding summary of the Mamiya range leaves us asking the question - why did the Mamiya engines fail to “make the grade” in the world marketplace? They were well-made and quite distinctive engines which bore a famous name, were competitively priced, performed well for their intended purposes and were for the most part notably lightweight for their respective displacements.

The preceding summary of the Mamiya range leaves us asking the question - why did the Mamiya engines fail to “make the grade” in the world marketplace? They were well-made and quite distinctive engines which bore a famous name, were competitively priced, performed well for their intended purposes and were for the most part notably lightweight for their respective displacements.