|

|

Poole Pioneers - the Hallam Engines

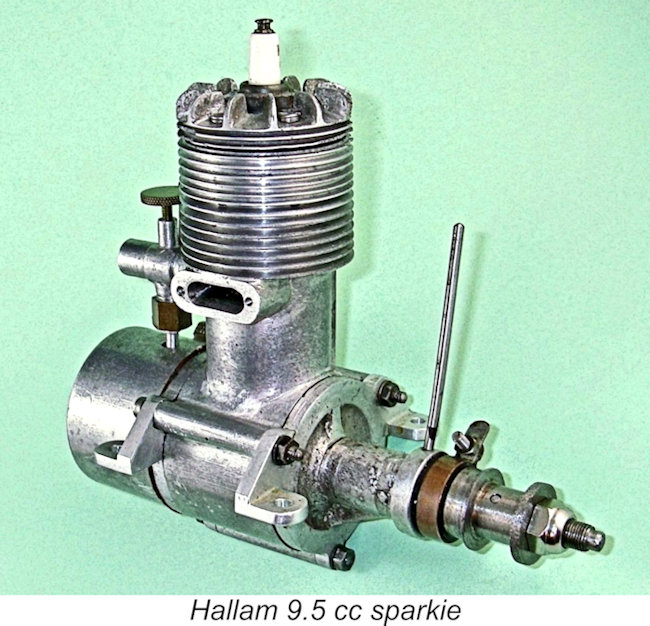

As far as I can tell, this is the first-ever attempt to bring together the entire chronological history of the Hallam range in a single article. A number of specific models have been the subjects of earlier focused articles, but no-one seems to have attempted to place all of the various designs in their historical context together with historical references. Here I’ll attempt to do just that! I may not succeed completely, but far better to have a go than to do nothing! I just hope that I haven’t left it too late! Having only a single imperfect example of a Hallam engine in my own possession (the illustrated 9.5 cc sparkie), I’m forced to rely upon a combination of images found in other sources along with a close scrutiny of the contemporary advertising and media records. Fortunately, the Hallam manufacturers promoted their engines quite energetically, creating a very clear advertising trail in doing so. Here I must acknowledge the outstanding assistance rendered to me by my good mate Gordon Beeby of Australia. Gordon spent hours tracking down pretty much all of the surviving literature relating to the Hallam engines, including a sizeable number of advertisements. Without such assistance, there’s no way that I could keep on cranking out these monthly stories, particularly those covering such obscure subjects. Thanks, mate!! Now let’s see what can be done to bring the saga of the Hallam engines back to life after so many years in the closet. Apologies for the quality of some of the accompanying images, but they’re all that I could find, and any image is surely better than none! Background

According to comments which appeared in their later advertising, the Hallam company was established in 1930. This date makes it important to appreciate the economic climate into which the new venture was launched. Firstly, there was essentially no national power aeromodelling movement in Britain at the time, since there were no Secondly, the collapse of the US New York Stock Exchange in October 1929 had triggered a This situation would obviously affect the sales prospects for high-priced luxury “toys” like model engines. It was certainly an un-propitious time for the establishment of a new company staking its economic future on participation in a field which depended upon the expenditure of scarce disposable income by its participants, particularly by those pursuing a hobby in which a market had yet to develop.

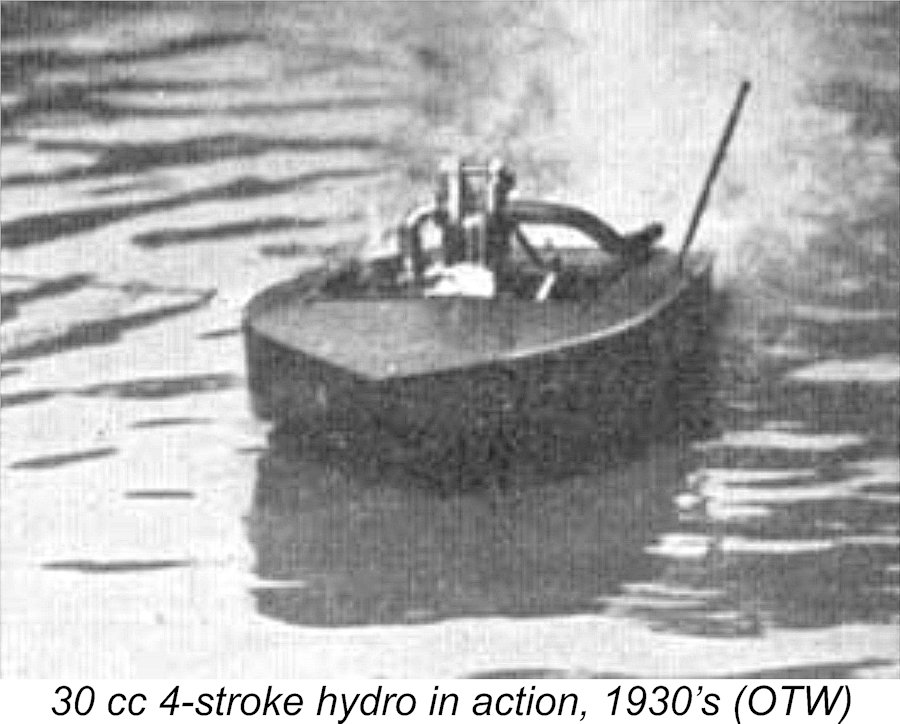

The “blue riband” model boating category was that of tethered hydroplanes, the racing of which had become an increasingly popular activity since the conclusion of WW1. The premier tethered hydroplane racing class was the 30 cc category, in which four-stroke I/C engines vied with their flash steam competitors for supremacy. By 1930 these models were achieving speeds well into the 30 mph range. These engines were of course far too heavy and bulky for practical use as model aircraft powerplants. For a great deal of information on the fascinating history of tethered hydroplane racing, visit the wonderful Onthewire website which is devoted to that topic along with the history of tethered car racing. I can't recommend that site highly enough! Naturally, the commercial supply of suitable engines for power boat modelling was almost as constrained as that for model aircraft. A few such engines were available from various sources, but were extremely expensive by the standards of the day - only the well-heeled need apply! This being the case, the majority of power model boat competitors either constructed their own engines or persuaded a talented friend to build one for them. This in turn raised the profile of an associated hobby – that of model engineering. A surprising number of model enthusiasts possessed some basic metalworking equipment such as a small lathe, or had access to such equipment through their places of work.

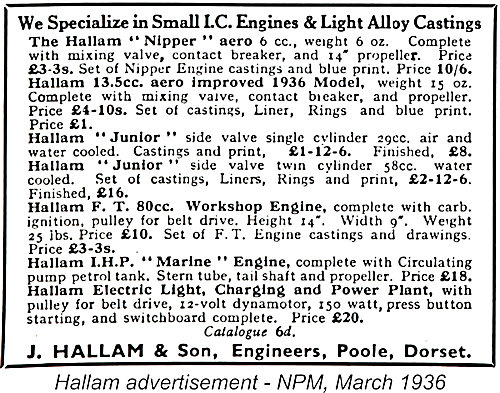

“Model Engineer & Practical Electrician” magazine was joined in October 1933 by a rival publication entitled “Newnes Practical Mechanics” (NPM) which was published by George Newnes Ltd. Fascinating reading!! Although this magazine dealt with a very wide range of do-it-yourself projects (fancy making your own car for £20?? How about your own full-sized airplane?), it did include quite extensive coverage of both model engineering and the development of the pioneering power aeromodelling movement in Britain. Indeed, prior to the appearance of "Aeromodeller" magazine in November 1935, it was the only regularly-published source of information on this topic. The Hallam company was a regular advertiser in this magazine, placing advertisements more or less continuously from December 1933 right up to the final placement in December 1949. It thus constitutes the most complete advertising record available for the Hallam engines. In view of the circumstances described above, the Hallam company did not confine itself to the production of finished model engines, for which a significant market had yet to develop. From the outset, it focused very strongly on meeting the needs of model engineers for plans, castings and materials upon which to base their creations. The majority of the company’s future designs were made available both as finished engines and as sets of plans, castings and materials. Having set the stage, let’s quickly survey the products of J. Hallam & Son over the active life of the company. The Hallam Engines – an Overview The secure identification of all of the model engines offered at various times by J. Hallam & Son represents a challenge, because a number of the designs appear to have been offered both by different names at various times and in different displacements! I can only do my best to present what I consider to be a reasonable interpretation of the available record, such as it is. I’m sure that I’ve made errors, and would be most happy to receive any authoritative corrections or additions! All contributions duly acknowledged! As nearly as I can determine, the advertised list of model engines offered by Hallam on a commercial basis runs something like this:

The above dates are best estimates based on the available evidence. I can't guarantee their absolute correctness, nor can I guarantee that the above list is complete. Apart from the last of these models, all of the company's offerings were spark ignition units. Almost all of them appeared in multiple variants, a few of which were even given different names and featured different displacements. In addition, many home constructors incorporated some of their own ideas into their creations based on the Hallam castings. Very few of these engines were exactly alike - very confusing! Understandably in view of the economic period during which the range got its start, the Hallam company did not confine

Here we are concerned with the company’s model engines. The focus of the balance of this article will be confined to those models, with which I will deal in what appears to be (but is not guaranteed to be) their chronological order of initial appearance. The Hallam Model Engine Series Before I get started on this more detailed section of the article, I feel that I must apologize once again for the very poor quality of some of the images which appear here. I can only plead that they are all that I’ve been able to find with respect to their subjects, and surely any image is better than none! I must also stress that considerable uncertainty remains with respect to the precise dating of some models as well as their nomenclature and displacements. Indeed, there may well have been other models of which I’m blissfully unaware! If any reader knows more or can set me straight on the basis of authoritative information, please get in touch – all contributions gratefully acknowledged! The Hallam Junior 29 cc Four-Stroke Model

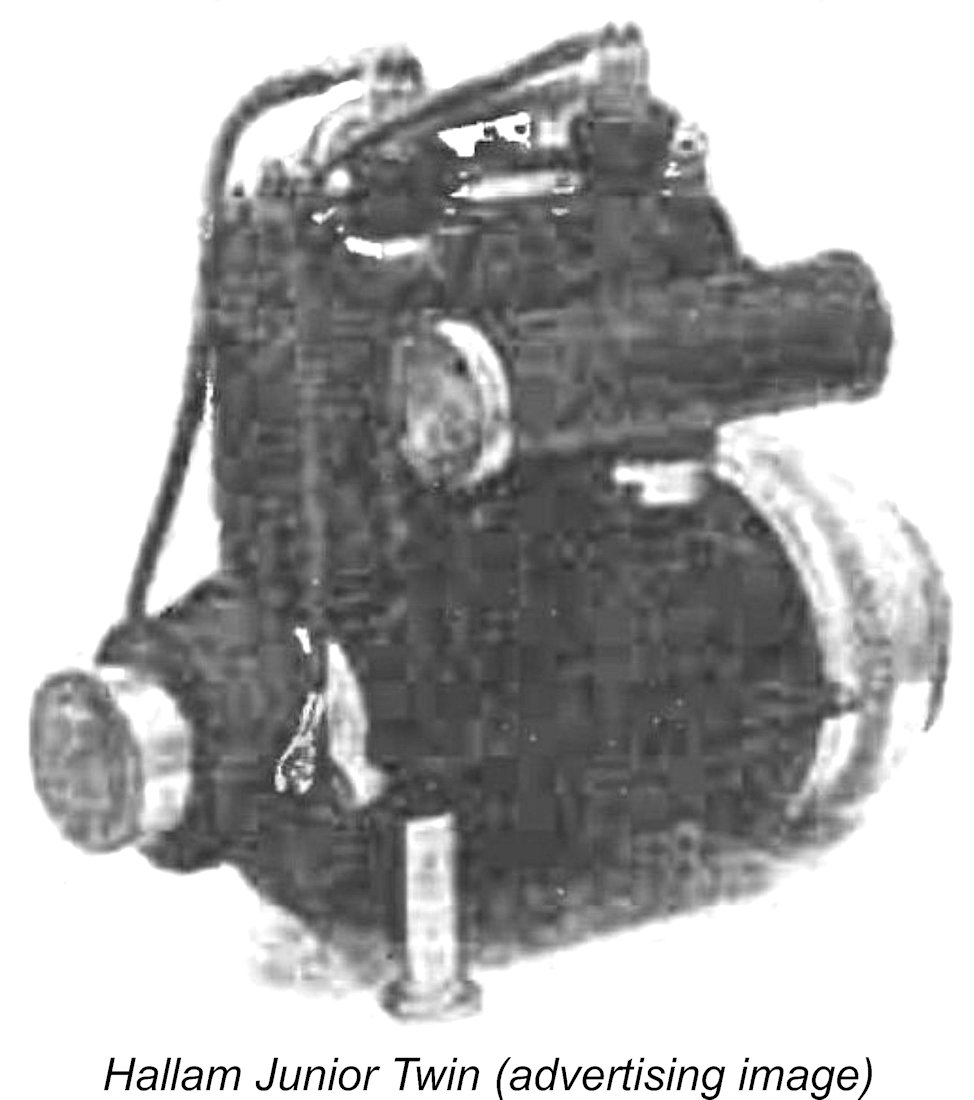

Unlike the majority of the four-stroke engines in the 30 cc bracket then in circulation in Britain, the Hallam Junior was clearly not aimed at the tethered hydroplane racing category. All of the competitive 30 cc I/C engines of the day were overhead valve four-stroke designs, with which speeds were then reaching well up into the 30 MPH range, whereas the Hallam Junior was a side-valve job. This feature made it a quite compact and “uncluttered” unit With a bore of 35 mm and a stroke of 30 mm, the Hallam Junior had a nominal displacement of 28.87 cc. The makers claimed that the lightness of its reciprocating components as well as what was termed “mechanical balance” (presumably a counterbalanced crankshaft) had reduced vibration to a minimum. In 1933 the Hallam company introduced what amounted to a twinning of the basic Junior design. This was the massive 58 cc Hallam Junior four-stroke twin-cylinder model, which was clearly intended purely for marine service. Although presumably intended to power large model boats, it could probably have propelled a small full sized dinghy at modest speeds! As of 1936, the Junior was priced at £1 12s 6d (£1.63) as a casting set and £8 complete ready to run. The Junior Twin was available at £2 12s 6d (£2.63) in casting form and £16 complete. I have no definitive information regarding how long these relatively complex and costly designs remained on offer. I can only report on my inability to find any advertisements for them after 1936. The Hallam 13.5 cc Aero Model

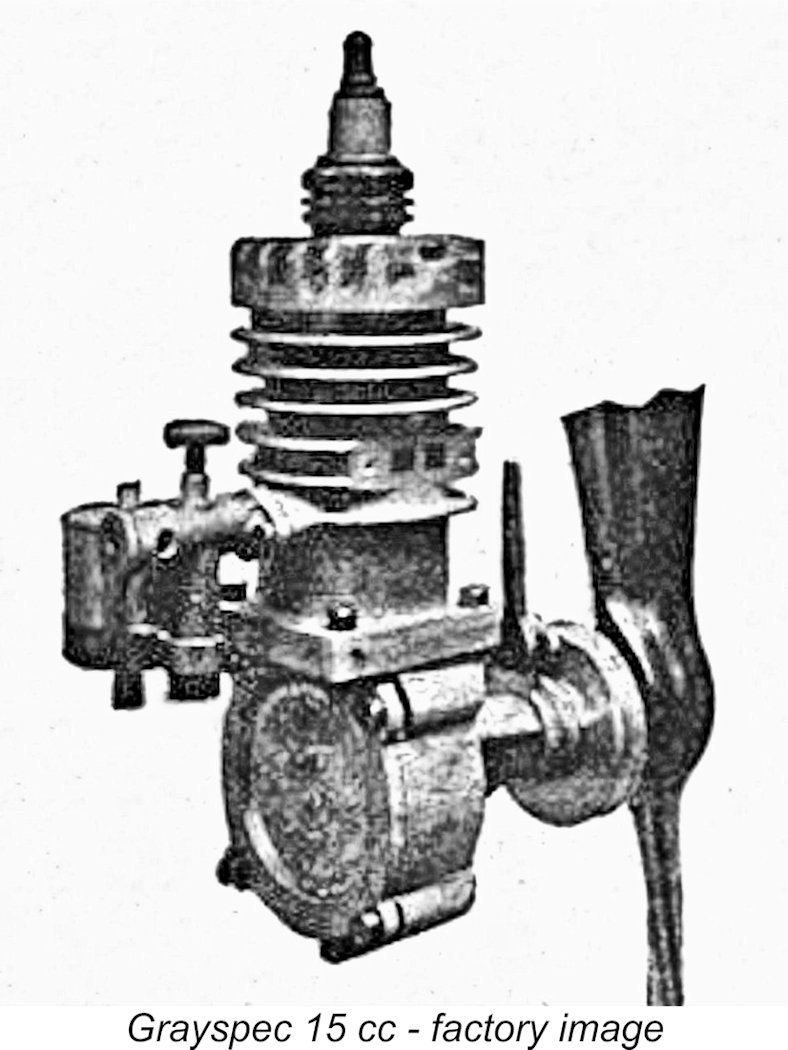

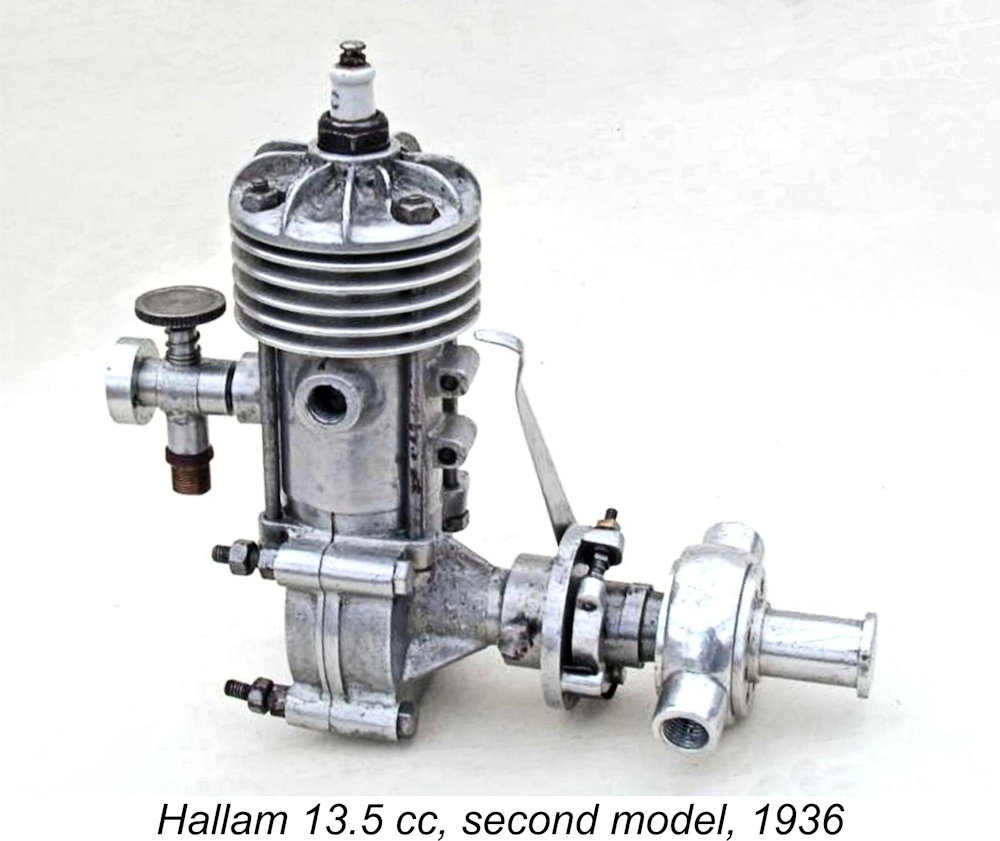

The Grayspec made its appearance in mid-1933, most likely serving as the catalyst for Hallam’s parallel moves in that direction. It was followed closely by the technically advanced but very expensive 14.5 cc Atom Minor two-stroke model from the London supply house of A. E. Jones, which appeared before the end of 1933. Hallam’s response to the appearance of the Grayspec and the Atom Minor was the development of their own lightweight aero model of similar displacement. This took the form of the Hallam 13.5 cc aero model which made its market debut in early 1934, being offered in both ready-to-run form and as a set of castings. The new model was mentioned in the “Model Aero Topics” feature in the June 1934 issue of NPM, but no really substantive information Based upon available photos (which are all that I have for reference), the Hallam 13.5 cc aero model was a more or less conventional side-port two-stroke spark ignition engine of its pioneering era. It featured a ringed aluminium alloy piston and an open-framed timer. Hallam’s own advertising cited a claimed weight of 15 ounces, also stating that the engine had successfully flown a model The engine’s construction was somewhat unusual. The main crankcase was vertically split along a transverse plane, being held together by four long bolts running fore and aft, with nuts being used to secure them. These bolts also served as radial mounting fasteners – the crankcase had no mounting lugs. The assembled crankcase only extended vertically to a point just above the upper diameter of the crankweb, where it terminated in a circular shelf. The cylinder liner had a sturdy flange at its base which was located on the shelf at the top of the crankcase. A cast alloy tubular section incorporating the intake and exhaust stubs surrounded the cylinder liner above this installation flange. This tubular section was vertically split at the front and secured in clamping fashion by a pair of machine screws engaging with integrally-cast lugs at the front. The slip-on cooling fins and cylinder As already stated, the Hallam 13.5 cc model first appeared in early 1934. It seems that some development work was undertaken on this model, because the Hallam advertising in early 1936 began to refer to an “improved 1936” version of this engine. In the absence of any specific data, I have no idea of the form which these “improvements” may have taken internally. The major external change was the substitution of the plain unfinned cylinder head with a radially-finned cast component similar to that used on the smaller Hallam Nipper (which appeared in early 1936) as well as the Junior four-stroke model. In addition, a re-designed timer assembly was now featured. Regardless, the improvements don’t seem to have enhanced the fortunes of the engine in the marketplace – by May 1937 it had disappeared from Hallam’s advertising, never to reappear. The smaller Nipper now took centre stage as Hallam’s flagship offering. The Hallam Nipper 6 cc Model

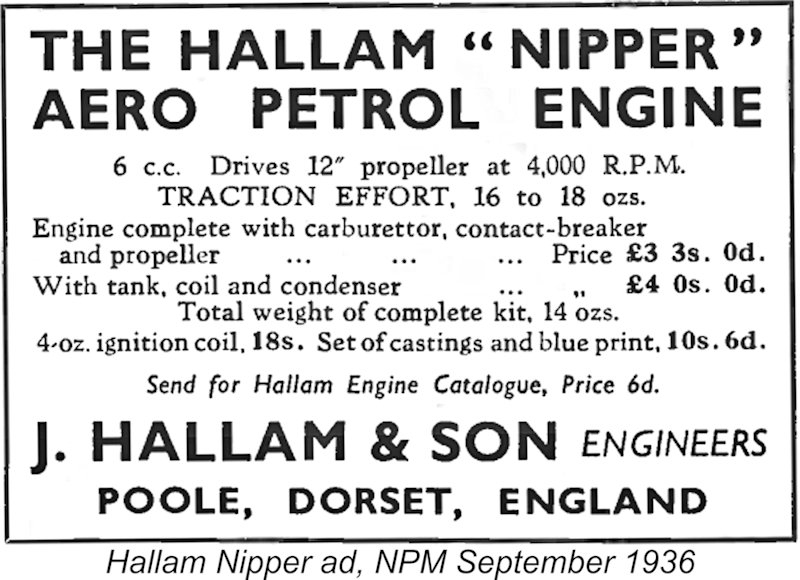

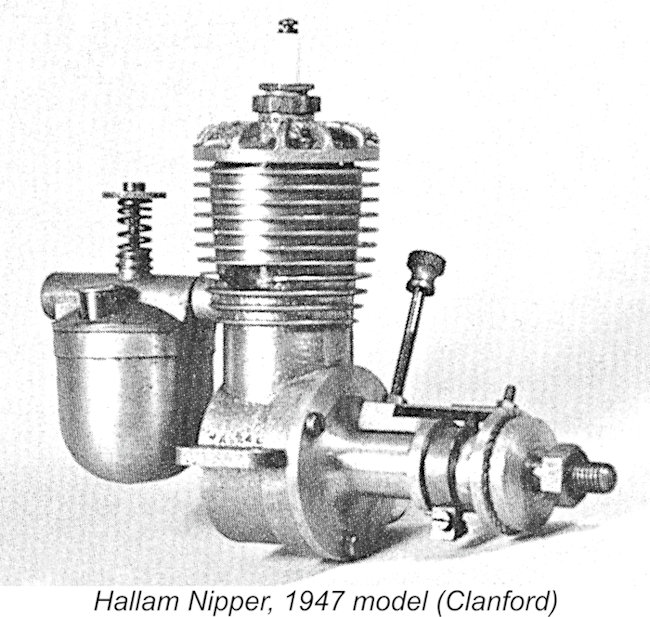

The Nipper made its first appearances in the Hallam company’s advertising in early 1936, being featured in the previously-reproduced advertisement of March 1936. It thus seems certain that the engine’s development took place in 1935, with the first examples appearing in early 1936. The engine was included in Hallam’s advertising from that point onwards, rapidly assuming a dominant position in those ads. An illustrated commentary on the Nipper appeared in the “Model Aero Topics” feature in the May 1936 issue of NPM.

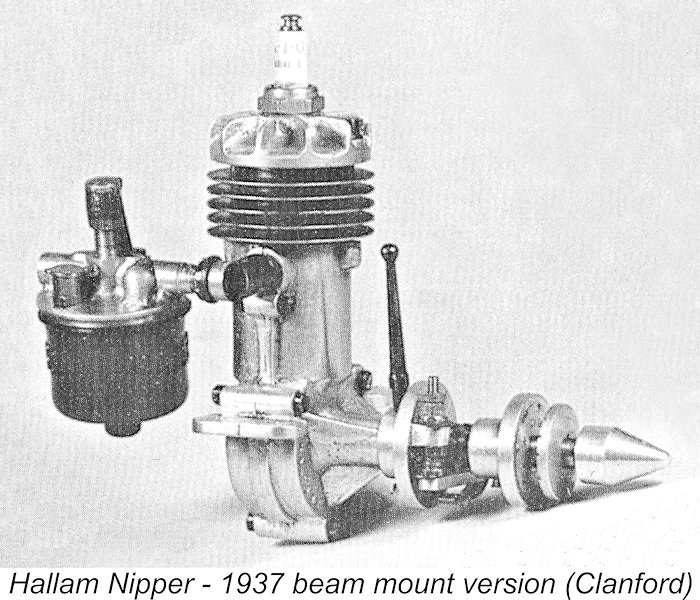

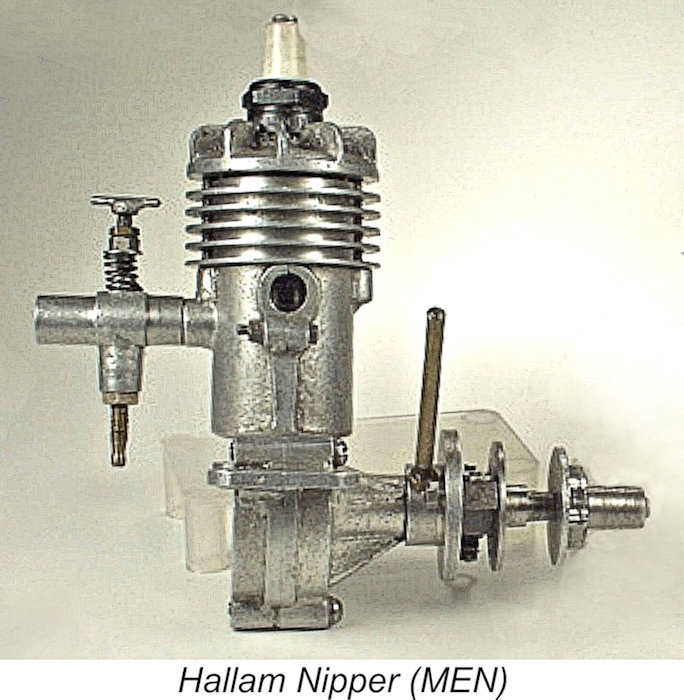

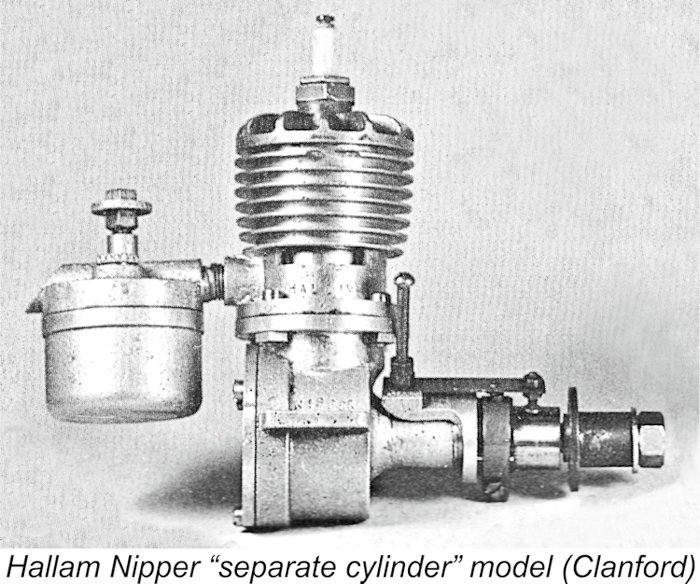

The example illustrated by Clanford in his well-known "A-Z" book (left) appears to have been fitted with a Majesco tank assembly. This type of modification is typical of surviving engines from this long-ago era. The example illustrated below at the right appears to have the original carburettor but is missing its tank. In many respects, the Nipper seems to have been a reduced-scale version of the contemporary 1936 variant of the 13.5 cc engine. The major externally-visible departure was that the vertically-split crankcase now extended to a The May 1936 review in NPM quoted a weight of 6 ounces and an awe-inspiring operating speed of 3,000 RPM using a 14 in. dia. airscrew. Presumably goaded by the somewhat mediocre performance implied by this review, by late 1936 the manufacturers had seemingly put some additional development effort into the Nipper design, because they were now claiming a speed of 4,000 RPM with a 12 in. dia. prop – a little more encouraging! There is much confusion over the various forms in which the Nipper appeared over the years. Although many minor sub-variants exist due to individual constructors incorporating their own ideas, four basic variants appear to be generally recognized, as follows:

Based upon a comment in the previously-cited May 1936 NPM article to the effect that the author was “glad to note that Messrs. Hallam have tackled the problem of producing even smaller petrol engines”, it would seem that the development of the next Hallam model to appear was already well underway at that time. Let’s look at that model next……….. The Hallam “Baby” 3 cc Model

Confusingly enough, the makers cited the Baby as being a 2 cc model initially. A later article which appeared in the May 1938 issue of “Aeromodeller” referred to the Baby’s displacement as being 3 cc, a figure which appears to be generally accepted today. This “Aeromodeller” reference took the form of a few short paragraphs which constituted part of the regular “At the Sign of the Windsock” feature, which was a predecessor of the later “Trade Notes” series. It included mentions of the 5.8 cc Nipper (stating the true displacement accurately) and 3 cc Baby as well as the recently-introduced “Little Briton” 1 cc model, of which more below in its place. Most intriguingly, the article also made specific reference to a 2.3 cc version of the Baby. It would seem from this that the Baby was offered in more than one displacement. The manufacturer’s own early reference to a 2 cc Baby, which was cited as Britain’s smallest-displacement model engine at that time, lends some credence to this possibility, although they later referred to it as a 3 cc engine. Moreover, in a few later advertisements the company cited The cited May 1938 “Aeromodeller” reference reported an operating speed of 4,000 RPM on a 10½ in. dia. prop for the 3 cc Baby. The 2.3 cc variant was said to manage 5,000 RPM on a 9 in. dia. airscrew. A typical rice pudding would have little to fear from either of these units! Regardless, this appears to confirm that the Baby was indeed offered in more than one displacement. The Baby seems to have remained on offer right up to the start of WW2 in September 1939. Indeed, castings for a 2.5 cc version were still on offer as of June 1940, although this was almost certainly a case of selling off existing old stock. The 3 cc Baby was offered briefly after the war, but this may simply reflect the existence of unsold castings even after the end of hostilities. Smaller Yet - the Little Briton

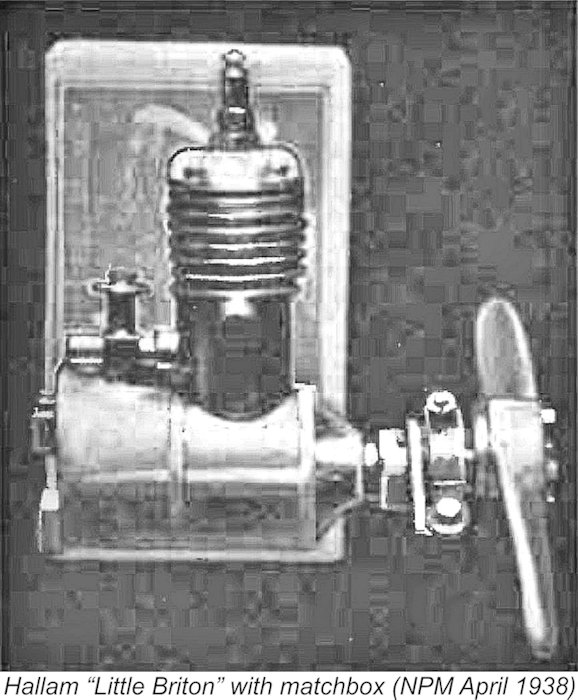

The engine was first described in the “Model Aero Topics” feature in the April 1938 issue of NPM. The engine’s tiny size by the standards of the day was emphasized by its appearance in the accompanying photograph showing it with a standard match-box! Reportedly, it started easily and turned an 8 in. dia. airscrew at a nerve-shattering 4,500 RPM. The introduction of this little sparkie at this time is actually quite remarkable. It will be appreciated that the total power-related payload in a model is represented by the sum of the respective weights of the engine, propeller, fuel and ignition support system. As the displacement decreases, the first three of these parameters decrease proportionally along with the power output. However, the contribution of the essential ignition support system (batteries, coil, condenser, wiring) remains unchanged. At the time of which we’re speaking, this system typically weighed around 3-4 ounces. The NPM review cited the Baby Briton’s bare weight as 3 ounces but acknowledged that this increased to 6 ounces when the airborne ignition support system was factored in. Hence the engine itself represented only around half of the total power-related payload which the model had to carry aloft. 6 ounces is a lot of weight for an engine of this displacement, especially one with a less-than-stellar performance!

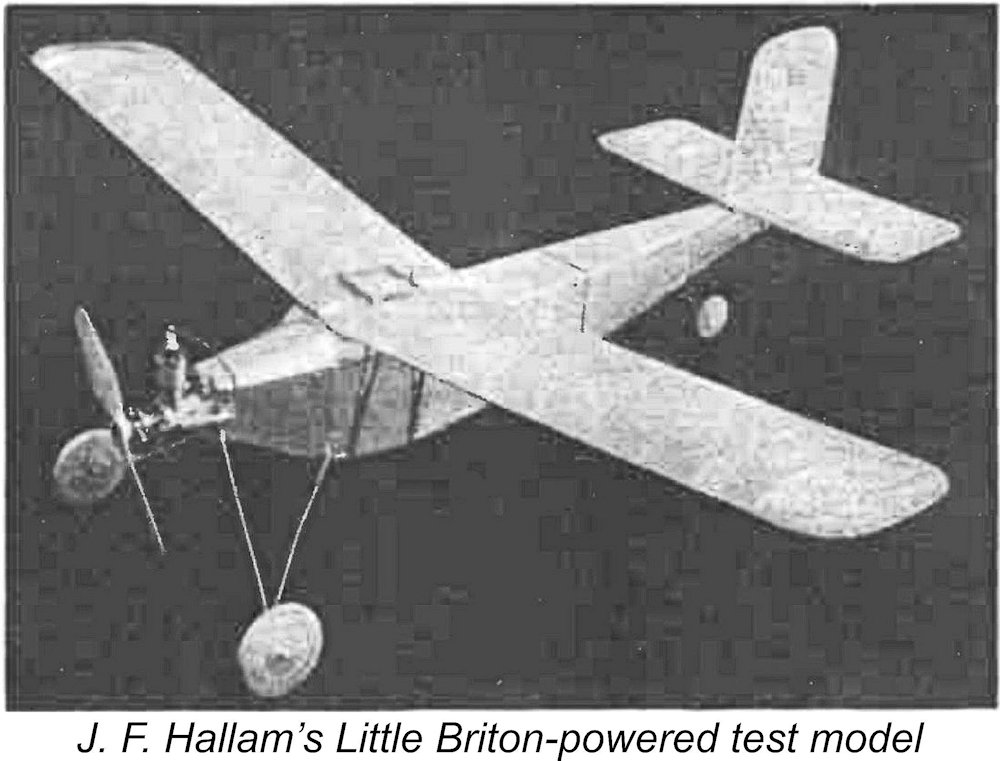

This being the case, as of 1938 many prospective puchasers must have had their doubts regarding the real-world utility of this little unit. Mr. J. F. Hallam was at pains to prove the practicality of his little design by subjecting it to extensive flight testing. He sent in a report on his activities in this regard, along with a number of photographs of his personally-constructed test model. This material appeared in the August 1938 issue of NPM. Hallam claimed that his testing had demonstrated the practicality of using his little 1 cc engine to fly a model provided that the overall weight could be held to less than 16 ounces. His model could apparently execute ROG take-offs on concrete or tarmac surfaces, but not on grass.

My late good friend Ken Croft made a lovely replica years later which had a displacement of 1.3 cc. Ken built this engine from his own replica castings. He commented that the finished engine ran well enough but developed insufficient power to pull the skin off even a lightly-cooked rice pudding! He never flew it. The Little Briton remained on offer in the Hallam company’s advertising more or less until the outbreak of WW2 but appears to have been dropped from the range at that point. It’s highly unlikely to have been a strong seller given the obvious limitations imposed by its unfavourable power-to-weight ratio. Ken Croft stated that he was aware of only two surviving original examples, to neither of which he had direct access. It seems that his experiences with the little 1 cc model may have convinced Hallam that it might be better to focus on aero engines having a somewhat greater displacement. Certainly, his next model was his second-largest yet. Time to look that one over! The Hallam 10 cc Model

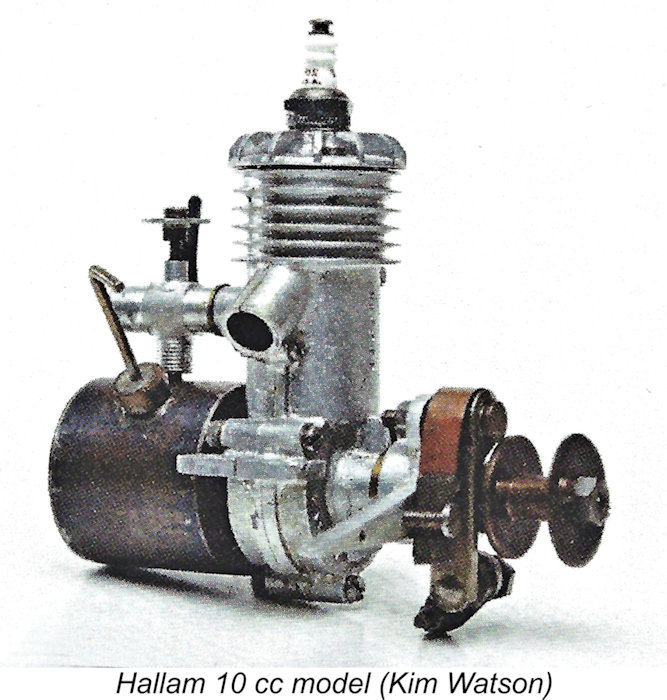

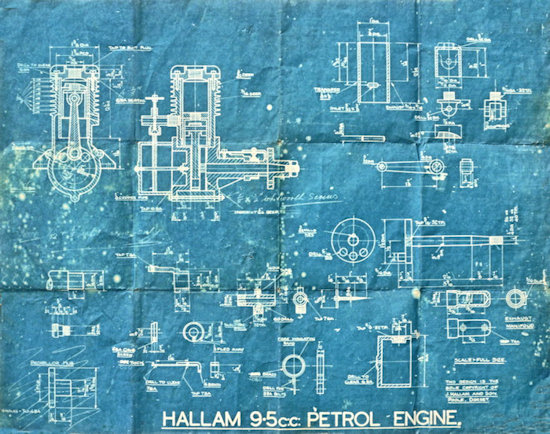

When looking at the Hallam 10 cc model, we are faced with the problem that the engine was referred to at different times by different names, while different models were sometimes referred to by the same name. In particular, the Hallam 9.5 cc model was generally referred to in the advertisements as the Hallam 10 cc model while being designated as the Hallam 9.5 cc model on the plans. To add the the confusion, neither designation was actually correct! The other problem facing the hapless Hallam researcher is the seeming absence of any descriptive material or even any contemporary images of the original Hallam 10 cc model. This being the case, we're forced to fall back on deducing what we can from the perusal of a few latter-day images as a well as some fuzzy advertising images from back in the day.

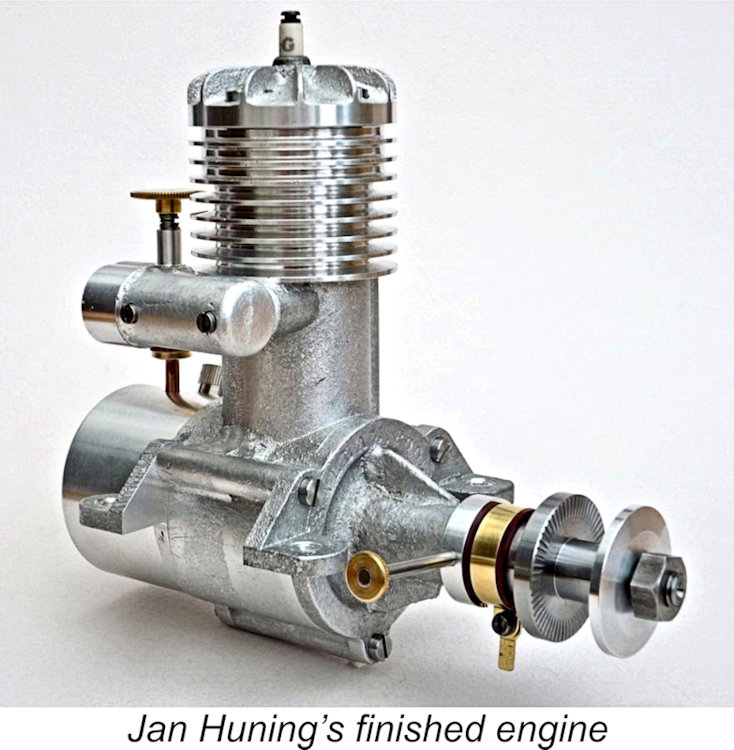

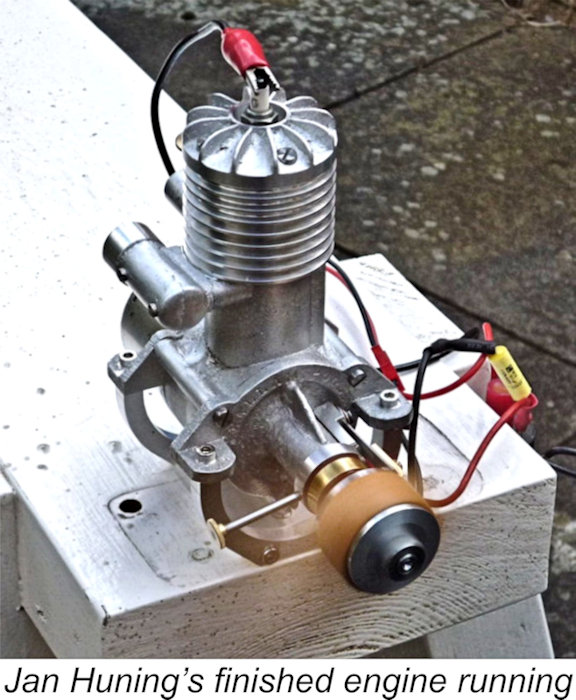

There is supporting evidence in the form of several fine images to be found on the previously-mentioned Miniature Engineering Museum website. These show what appears to be the same scaled-up 10 cc Nipper-based model in marine configuration. At some point along the way, the Hallam 10 cc model underwent a drastic re-design. In this instance, we’re fortunate enough to have an unimpeachable reference in the form of a set of original factory blueprints. The mega-talented English model engine constructor Jan Huning was fortunate enough to come into possession of an original Hallam c

In the attached view of the completed components provided by Jan Huning (right), the dark-hued bit with the hole in the top is the piston. It's basically a thin-wall cast-iron shell with a hole in the top, into which is inserted the light alloy gudgeon-pin carrier, seen just

Jan completed an all-original example of the engine from this kit to his usual very high standard. As might be expected from the simple, It appears from the promotional record that the Hallam 9.5 cc model just described was replaced after WW2 by a revised design designated as the “Little Nine”. The stroke remained unchanged at 0.875 in. but the bore was reduced from 1 in. to 0.875 in. to yield a displacement of 8.62 cc, hence presumably the "9" designation. I don't have a good image of this model, but the attached extremely fuzzy catalogue image shows that it was equipped with conventional beam mounting lugs. It seems to have remained on the books until around 1947, when it was evidently replaced by a new model designated as the “Super Nine”. We’ll have a look at that model next. The Hallam Super Nine

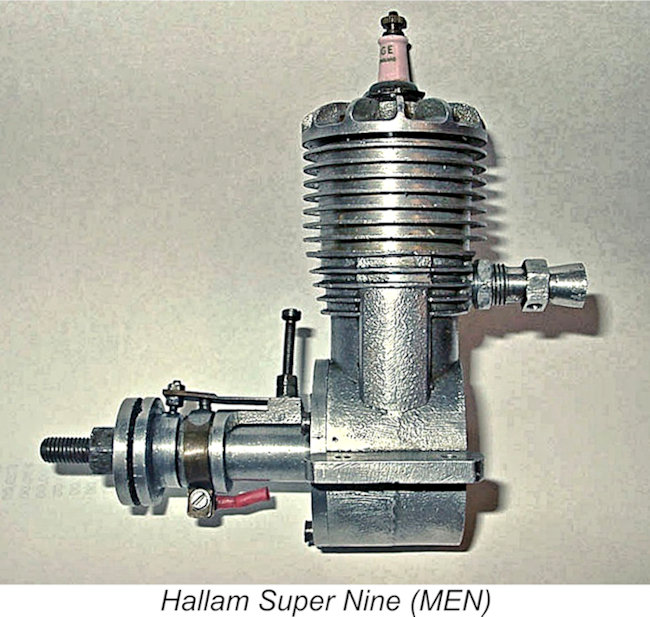

At the same time, a new larger model designated the “Super Nine” was introduced. This was basically an upsized rendition of the revised 1947 Hallam Nipper, replacing the earlier "Little Nine". It was a nice-looking engine constructed upon up-to-date but conventional lines for the time. Uncharacteristically, this model was only offered as a complete ready-to-run unit, never being made available in casting form for home construction.

This model was never described in any modelling media article, nor did the company ever publish any design details. As a result, I’m unable to provide any working dimensions or performance data relating to this engine. All that can be said is that the Super Nine enjoyed a production life of less than three years, consequently being an extremely rare engine today. Unfortunately, this was a case of “too little, too late”. As of early 1948 the spark ignition era was rapidly drawing to a close – Ray Arden’s late 1947 introduction of the commercial miniature glow-plug rendered spark ignition instantly obselete, while the new compression ignition (“diesel”) technology was rapidly establishing a stranglehold upon the British model engine market. The sun was unmistakably setting on the spark ignition model engine. Hallam had not failed to recognize this trend. In 1947 they responded by bringing out what turned out to be their only diesel design. We’ll look at that model next. The Hallam Baby 2.5 cc Diesel

Although there were one or two "false starts" like the Leesil from Bradford, the “diesel revolution” really got underway in Britain in mid-1946 with the release of the iconic Mills 1.3 Mk. I, initially from Sheffield and later from Woking. With its easy starting, excellent performance by then-current standards and outstanding durability, this fine engine served Spurred on by the very positive marketplace reponse to the Mills, other British diesels soon followed, including the Owat 5 cc, B.M.P. 3.5 cc, Majesco 2.2 cc, Aerol 2 cc and E.D. Mk. II 2 cc offerings. It was clear that in Britain at least, the diesel was very much in the ascendant. This must have been as obvious to Hallam as it was to everyone else. The result was the 1947 appearance of what was to prove to be the only Hallam diesel ever to appear – the Hallam Baby 2.5 cc diesel. The Hallam Baby Diesel was the actual name attached to the engine by the manufacturers, as seen at the left.

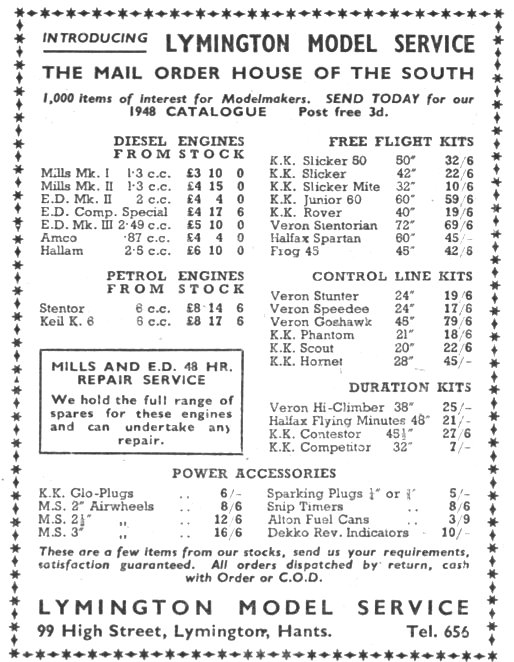

The attached August 1948 advertisement from Lymington Model Service, a dealer located in Lymington, Hampshire, tells the story. At a price of £6 10s (£6.50), the Hallam 2.5 cc diesel was a full pound more expensive than the rival 2.5 cc E.D. Mk. III. The Hallam’s price represented over a week’s wages for the average British working man at the time. Try that one on the wife!! The competing attraction of the Mills 1.3 at only £3 10s (£3.50) is surely obvious. As matters turned out, the Hallam company was pretty much at the end of the model engine manufacturing road at this point. Their diesel wasn’t selling and their spark ignition models were no longer attracting any interest as the diesel (plus a few glow-plug models) swept the old sparkies over the cliff into market oblivion. The company’s final advertisement in NPM appeared in the December 1949 issue. The Hallam 5 cc Spark-Ignition “BabyTwin”

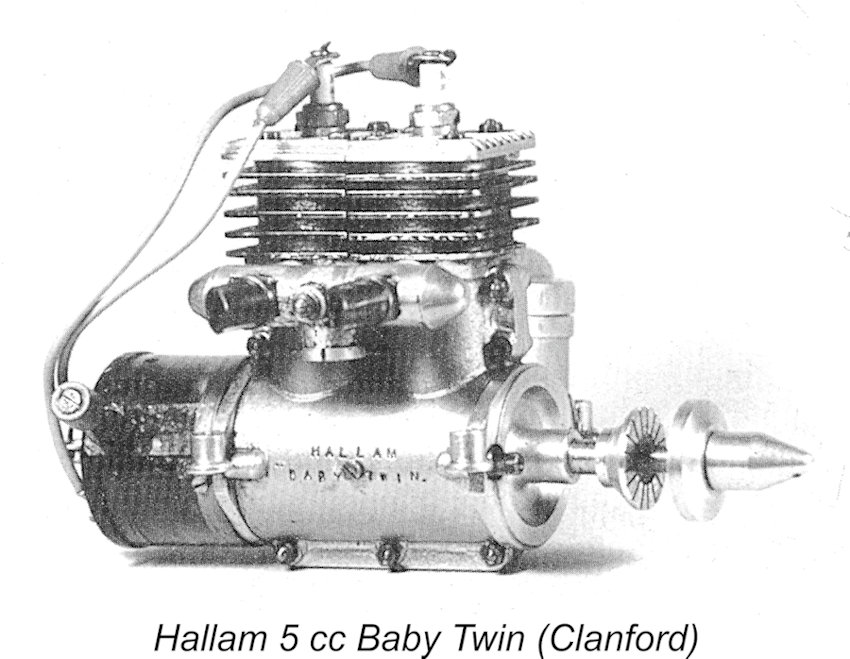

The 5 cc “Baby Twin”, a name recorded on the engine’s crankcase, appears to have been based upon the use of two of the cylinder units from the 2.5 cc diesel, sporting the same unusual square-sided cooling jackets. This implies that it appeared in 1947 concurrently with the diesel. Since it never featured in any Hallam advertisement of which I’m aware, the precise dating is obscure in the extreme. The absence of any advertising references or media descriptions implies very strongly that this model was either a one-off factory prototype built strictly for experimental purposes or was individually made to special order in extremely small numbers. In the absence of any published data on the model, I’m unable to say more about it here. The Hallam “Odd-Balls”

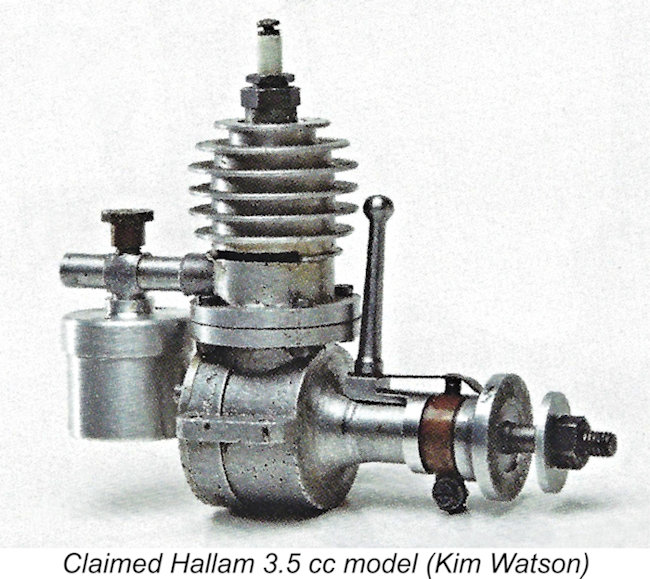

An example which may or may not be a genuine Hallam model appears in Ted Sladden’s excellent book “British Model Aero Engines 1946 – 2011”. Kim Watson’s fine image (left) shows what is claimed to be a Hallam 3.5 cc model. Although it’s clearly based upon a set of late-model Hallam Nipper ”separate cylinder” castings, there’s no advertising or media record of any such model ever being offered by Hallam. This raises the possibility (no more) that it’s actually some home constructor’s Hallam-based creation.

The point that I’m trying to make here is the fact that, as with any engine constructed from castings by numerous builders working independently, variants of the basic Hallam design are to be expected. Such variants should be recognized for what they are rather than being claimed as “official” Hallam factory designs. In the preceding article, I’ve tried to follow the contemporary published record of the Hallam models as closely as possible, but I have no doubt at all that there must be many examples which exhibit departures from the factory designs, some of them significant. The trick is to identify the Hallam model upon which they were based. Conclusion

This being the case, it’s important to see the role of this company in context. J. Hallam & Son appear to hold the honour of having been the first British manufacturer to offer model engines to the public on a commercial basis – indeed, they were among the first such firms anywhere in the world. Moreover, this was no fly-by-night operation – the Hallam company remained very active in the model engine business for 20 years, a period of continuous involvement which was matched by only a select few of the more prominent British firms – only E.D., ETA, Oliver, Davies-Charlton and P.A.W. come immediately to mind. A proud heritage indeed - even Mills Brothers only managed 18 years, while International Model Aircraft (FROG) only survived for 16 years in the model engine manufacturing business. The rest didn’t come close! The Hallam company appears to have had other irons in the fire all along – some measure of diversity was undoubtedly called for to ensure economic stability. The model engines may have been as much a labour of love as anything else – we know for certain that J. F. Hallam was an active hands-on aeromodeller. The company continued in business for some time following their withdrawal from the model engine field. It seems that their undoubted enthusiasm for aeromodelling may have led them periodically to entertain nostalgic thoughts of making a come-back, which their rational minds recognized as being economically unwise in the evolving marketplace of the 1950. Perhaps in the spirit of burning their bridges, they reportedly destroyed all of their patterns in around 1952-53. However, this decisive move didn’t save the company, which apparently ceased trading at some point in the mid-1950’s. Thus ended one of Britain’s most prolific and influential model engine manufacturers of the pioneering era, albeit one which seems to have been all but forgotten today. This neglect is undeserved - theirs is a story which richly merits our respectful remembrance! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published January 2026 |

| |

In this article, I’ll share a look at an almost-forgotten British model engine marque which was not only the first model engine range to be offered commercially in Britain but was among the first such ranges to be offered commercially anywhere in the world, including America. I’ll be reviewing the Hallam engines from Poole in Dorset, England which richly deserve recognition as one of the world’s more historically significant pioneering model engine ranges.

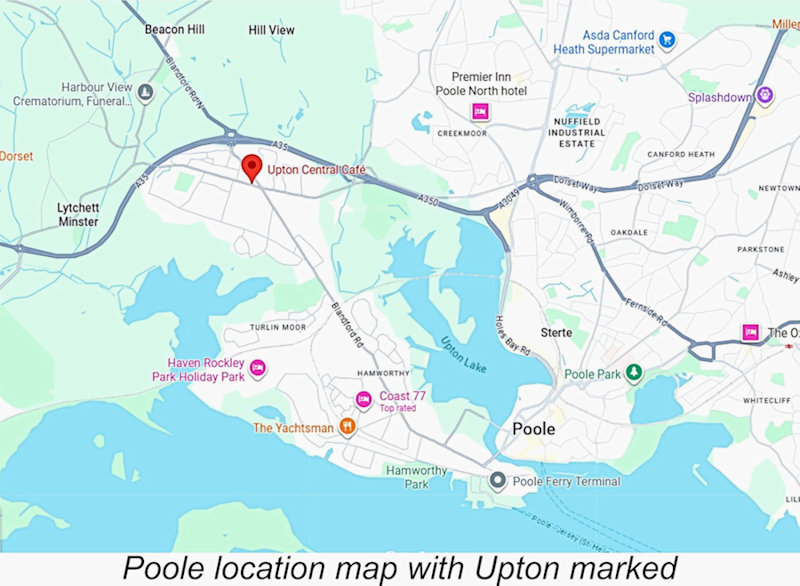

In this article, I’ll share a look at an almost-forgotten British model engine marque which was not only the first model engine range to be offered commercially in Britain but was among the first such ranges to be offered commercially anywhere in the world, including America. I’ll be reviewing the Hallam engines from Poole in Dorset, England which richly deserve recognition as one of the world’s more historically significant pioneering model engine ranges.  The Hallam engines were manufactured by a firm called J. Hallam & Son, who were located in Upton, a northern suburb of the seaport town of Poole in Dorset, England. The principal of this firm was an individual named J. F. Hallam, about whom I've been able to learn absolutely nothing beyond the fact that he was a practical hands-on aeromodeller among other things. The firm characterized themselves as engineers specializing in small I/C engines and light alloy castings.

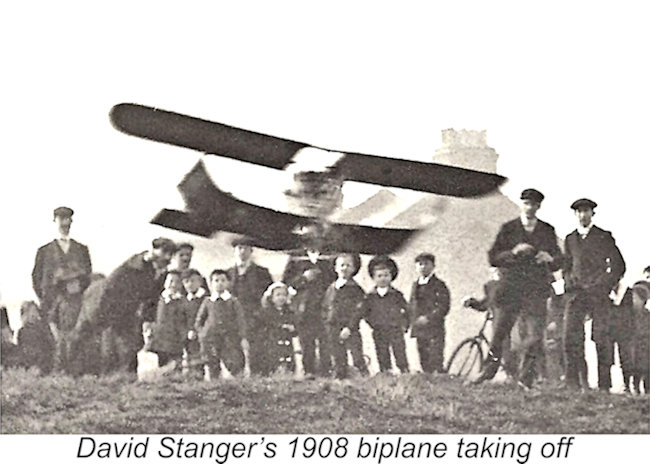

The Hallam engines were manufactured by a firm called J. Hallam & Son, who were located in Upton, a northern suburb of the seaport town of Poole in Dorset, England. The principal of this firm was an individual named J. F. Hallam, about whom I've been able to learn absolutely nothing beyond the fact that he was a practical hands-on aeromodeller among other things. The firm characterized themselves as engineers specializing in small I/C engines and light alloy castings. commercially-available I/C engines suitable for that service. A few pioneers such as David Stanger and

commercially-available I/C engines suitable for that service. A few pioneers such as David Stanger and

The one area of modelling in which small I/C engines were in fairly widespread use at this time was that of power model boating. It is thus completely understandable that the initial focus of the Hallam company was on designing and producing engines intended for that specific purpose.

The one area of modelling in which small I/C engines were in fairly widespread use at this time was that of power model boating. It is thus completely understandable that the initial focus of the Hallam company was on designing and producing engines intended for that specific purpose. The level of hands-on participation in this hobby in Britain was far higher than it is today, being sufficient to support the publication of a magazine devoted exclusively to the activities of its practitioners. At the time of which we are speaking, this magazine was entitled “Model Engineer & Practical Electrician”, later shortened to just “Model Engineer” (ME). Established in 1898, the magazine is still in publication today under the title “Model Engineer & Workshop”. The ready availability of low-cost machine tools from China and Taiwan has triggered something of a latter-day resurgence in this long-established hobby.

The level of hands-on participation in this hobby in Britain was far higher than it is today, being sufficient to support the publication of a magazine devoted exclusively to the activities of its practitioners. At the time of which we are speaking, this magazine was entitled “Model Engineer & Practical Electrician”, later shortened to just “Model Engineer” (ME). Established in 1898, the magazine is still in publication today under the title “Model Engineer & Workshop”. The ready availability of low-cost machine tools from China and Taiwan has triggered something of a latter-day resurgence in this long-established hobby.

The Hallam company’s first product relating to modelling seems to have been a 29 cc side-valve four-stroke unit called the Hallam Junior. This unit evidently appeared in 1930 or perhaps 1931, clearly being intended for model powerboat applications. It was advertised at the outset as being water-cooled, but was subsequently offered in air-cooled configuration as well, as illustrated here. It was available initially only in the form of a casting kit for home construction, but completed engines were later offered as well. The accompanying image originated on the outstanding

The Hallam company’s first product relating to modelling seems to have been a 29 cc side-valve four-stroke unit called the Hallam Junior. This unit evidently appeared in 1930 or perhaps 1931, clearly being intended for model powerboat applications. It was advertised at the outset as being water-cooled, but was subsequently offered in air-cooled configuration as well, as illustrated here. It was available initially only in the form of a casting kit for home construction, but completed engines were later offered as well. The accompanying image originated on the outstanding  by comparison with some of the others, a characteristic highlighted in the maker’s advertising, but its performance must have been somewhat below that of its competitors. It seems to have been aimed more at the scale model and run-for-fun categories than at competition use.

by comparison with some of the others, a characteristic highlighted in the maker’s advertising, but its performance must have been somewhat below that of its competitors. It seems to have been aimed more at the scale model and run-for-fun categories than at competition use.  By early 1934 the Hallam company had become aware of the emergence of a growing demand for lightweight engines from the small but increasing number of would-be participants in power aeromodelling. The competing manufacturers of the

By early 1934 the Hallam company had become aware of the emergence of a growing demand for lightweight engines from the small but increasing number of would-be participants in power aeromodelling. The competing manufacturers of the

At some indeterminate point during late 1935, the Hallam company decided to expand its model aero engine range by introducing what was to become perhaps its most famous and prolific model – the Hallam Nipper two-stroke sideport spark ignition unit. With bore and stroke measurements of 25/32 in. (0.78125 in. - 19.84 mm) and ¾ in (0.750 in. – 19.05 mm). the Nipper had a nominal displacement of 5.89 cc, although it was always advertised as a 6 cc model (Hallam frequently rounded-up the displacements of their engines). It was offered both as a casting set and in complete ready-to-run form.

At some indeterminate point during late 1935, the Hallam company decided to expand its model aero engine range by introducing what was to become perhaps its most famous and prolific model – the Hallam Nipper two-stroke sideport spark ignition unit. With bore and stroke measurements of 25/32 in. (0.78125 in. - 19.84 mm) and ¾ in (0.750 in. – 19.05 mm). the Nipper had a nominal displacement of 5.89 cc, although it was always advertised as a 6 cc model (Hallam frequently rounded-up the displacements of their engines). It was offered both as a casting set and in complete ready-to-run form. The Hallam Nipper was another basically conventional sideport unit of its day. It featured a lapped cast iron piston running in a steel cylinder and an open-frame timer similar to that used on the 1936 version of the 13.5 cc model. Bore and stroke were 25/32 in. (19.84 mm) and 3/4 in. (19.05 mm) respectively for a calculated nominal displacement of 5.89 cc.

The Hallam Nipper was another basically conventional sideport unit of its day. It featured a lapped cast iron piston running in a steel cylinder and an open-frame timer similar to that used on the 1936 version of the 13.5 cc model. Bore and stroke were 25/32 in. (19.84 mm) and 3/4 in. (19.05 mm) respectively for a calculated nominal displacement of 5.89 cc.

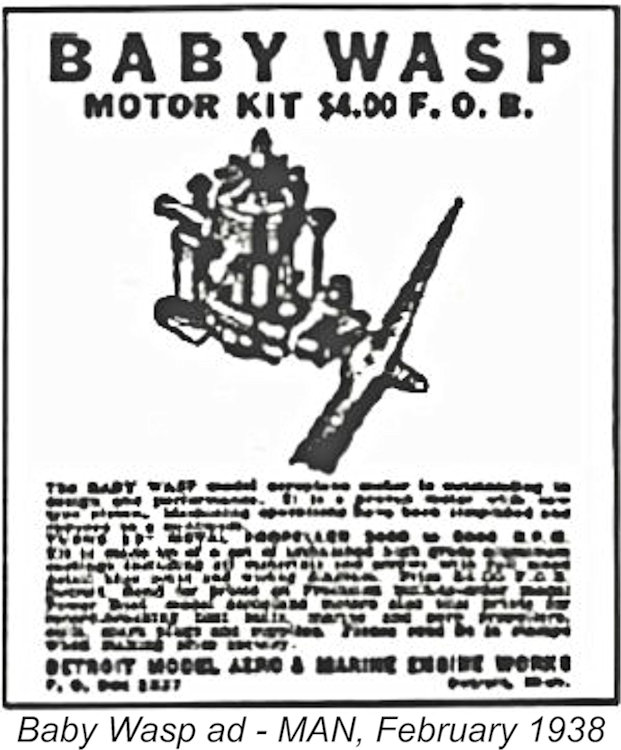

There’s an interesting side story to the production history of the Hallam Nipper! A company called the Detroit Model Aero & Marine Engine Works placed an advertisement in the February 1938 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN) for an engine called the Baby Wasp. This vanishingly rare unit has long been a near-legendary target for American collectors. However, in reality it was just a first-model radial-mounted Hallam Nipper with the name “Wasp” added to the front of the crankcase. It appears that this engine represented an attempt by Hallam to dispose of some of their earlier and now superseded stock on the US market. If so, it doesn’t seem to have been a success!

There’s an interesting side story to the production history of the Hallam Nipper! A company called the Detroit Model Aero & Marine Engine Works placed an advertisement in the February 1938 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN) for an engine called the Baby Wasp. This vanishingly rare unit has long been a near-legendary target for American collectors. However, in reality it was just a first-model radial-mounted Hallam Nipper with the name “Wasp” added to the front of the crankcase. It appears that this engine represented an attempt by Hallam to dispose of some of their earlier and now superseded stock on the US market. If so, it doesn’t seem to have been a success! The Hallam Baby first appears in the advertising record in May 1937. To all intents and purposes it was simply a reduced-scale version of the Nipper. Like the majority of Hallam engines, it was offered both in ready-to-run form and as a set of castings for home construction.

The Hallam Baby first appears in the advertising record in May 1937. To all intents and purposes it was simply a reduced-scale version of the Nipper. Like the majority of Hallam engines, it was offered both in ready-to-run form and as a set of castings for home construction. the Baby’s displacement as 2.5 cc, while a table of the better-known engines in Britain which appeared in the August 1942 issue of “Aeromodeller” (at a time when the manufacture of model engines in Britain had been suspended) cited the Baby’s displacement as 2.3 cc but gave its bore and stroke dimensions as 9/16 in. (14.29 mm) and 5/8 in. (15.875 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 2.54 cc. AAARRRGGHHH!! I guess that all you can do is measure your own example, assuming that you’re lucky enough to have one to measure!

the Baby’s displacement as 2.5 cc, while a table of the better-known engines in Britain which appeared in the August 1942 issue of “Aeromodeller” (at a time when the manufacture of model engines in Britain had been suspended) cited the Baby’s displacement as 2.3 cc but gave its bore and stroke dimensions as 9/16 in. (14.29 mm) and 5/8 in. (15.875 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 2.54 cc. AAARRRGGHHH!! I guess that all you can do is measure your own example, assuming that you’re lucky enough to have one to measure!  As of late 1937 the Hallam advertisements were confined to the promotion of their 3 cc and 6 cc models. However, by early 1938 a 1 cc model had been added to the roster. This was the “Little Briton”, which was the smallest engine yet to appear in Britain – indeed, one of the smallest to appear anywhere at this time. As usual, it was available both complete and in kit form.

As of late 1937 the Hallam advertisements were confined to the promotion of their 3 cc and 6 cc models. However, by early 1938 a 1 cc model had been added to the roster. This was the “Little Briton”, which was the smallest engine yet to appear in Britain – indeed, one of the smallest to appear anywhere at this time. As usual, it was available both complete and in kit form. It follows that considerations of power-to-weight ratio become increasingly unfavourable as the engine’s displacement, and hence its bare weight, decrease along with its power output. Right up until the early post-WW2 years it was generally held that .099 cuin. (1.6 cc) was more or less the lower practical limit for spark ignition engines intended for use on the flying field. The American Mighty Atom .099 piston valve sparkie was generally held up as the ultimate practical expression of the miniature spark ignition genre.

It follows that considerations of power-to-weight ratio become increasingly unfavourable as the engine’s displacement, and hence its bare weight, decrease along with its power output. Right up until the early post-WW2 years it was generally held that .099 cuin. (1.6 cc) was more or less the lower practical limit for spark ignition engines intended for use on the flying field. The American Mighty Atom .099 piston valve sparkie was generally held up as the ultimate practical expression of the miniature spark ignition genre. It appears that various constructors of this engine applied different displacements to it. John Goodall of “Model Engine World” (MEW) cited the bore and stroke of the Little Briton as ½ in. (12.7 mm) apiece, which gives a displacement of 1.61 cc. It's entirely possible that the marginal performance of the engine in 1 cc form led to an increase in its displacement without the name being changed.

It appears that various constructors of this engine applied different displacements to it. John Goodall of “Model Engine World” (MEW) cited the bore and stroke of the Little Briton as ½ in. (12.7 mm) apiece, which gives a displacement of 1.61 cc. It's entirely possible that the marginal performance of the engine in 1 cc form led to an increase in its displacement without the name being changed.  The first Hallam 10 cc design evidently appeared at some point during 1938. The writer of the brief report on Hallam’s flight-testing of the Little Briton (NPM August 1938) mentioned that Hallam had promised to send him “details of his 10 cc engine” very soon thereafter. This clearly implies that such an engine must have already been in existence as of that date, at least in prototype form.

The first Hallam 10 cc design evidently appeared at some point during 1938. The writer of the brief report on Hallam’s flight-testing of the Little Briton (NPM August 1938) mentioned that Hallam had promised to send him “details of his 10 cc engine” very soon thereafter. This clearly implies that such an engine must have already been in existence as of that date, at least in prototype form.

I mentioned earlier that the Hallam Nipper had long served as the flagship Hallam offering, remaining on offer almost to the end of the company’s 20-year involvement with model engines. I noted that in 1947 the Nipper underwent a fairly radical re-design which involved the elimination of the former separate upper cylinder casting in favour of a conventional one-piece casting incorporating the crankcase, backplate and upper cylinder barrel, with the separate front housing being attached using machine screws. The engine’s configuration was thus “modernized” to a significant extent. In its advertising, the company referred to this as the"1947 model" of the Nipper.

I mentioned earlier that the Hallam Nipper had long served as the flagship Hallam offering, remaining on offer almost to the end of the company’s 20-year involvement with model engines. I noted that in 1947 the Nipper underwent a fairly radical re-design which involved the elimination of the former separate upper cylinder casting in favour of a conventional one-piece casting incorporating the crankcase, backplate and upper cylinder barrel, with the separate front housing being attached using machine screws. The engine’s configuration was thus “modernized” to a significant extent. In its advertising, the company referred to this as the"1947 model" of the Nipper.  According to former owner Mike Beach, writing in MEW in February 1999, the Super Nine was a “strong running” engine. Mike used it to power his rendition of a 1936 Nash monoplane. In early 1948 the Super Nine replaced the Nipper as the flagship model depicted in the Hallam advertisements.

According to former owner Mike Beach, writing in MEW in February 1999, the Super Nine was a “strong running” engine. Mike used it to power his rendition of a 1936 Nash monoplane. In early 1948 the Super Nine replaced the Nipper as the flagship model depicted in the Hallam advertisements. To the surprise of many people, the model “diesel” engine (more accurately termed a “compression ignition” engine, since there’s no injector) is actually a very old concept, dating all the way back to 1928, when the first Patent covering a variable-compression injector-less two-stroke compression ignition engine was taken out by Ernst Thalheim of Switzerland. The concept was not widely pursued in the years prior to WW2, but both during that conflict and in the immediately-following years, successful engines utilizing this principle were developed by designers in a number of countries. Maris Dislers has done an admirable job of documenting this era in a

To the surprise of many people, the model “diesel” engine (more accurately termed a “compression ignition” engine, since there’s no injector) is actually a very old concept, dating all the way back to 1928, when the first Patent covering a variable-compression injector-less two-stroke compression ignition engine was taken out by Ernst Thalheim of Switzerland. The concept was not widely pursued in the years prior to WW2, but both during that conflict and in the immediately-following years, successful engines utilizing this principle were developed by designers in a number of countries. Maris Dislers has done an admirable job of documenting this era in a

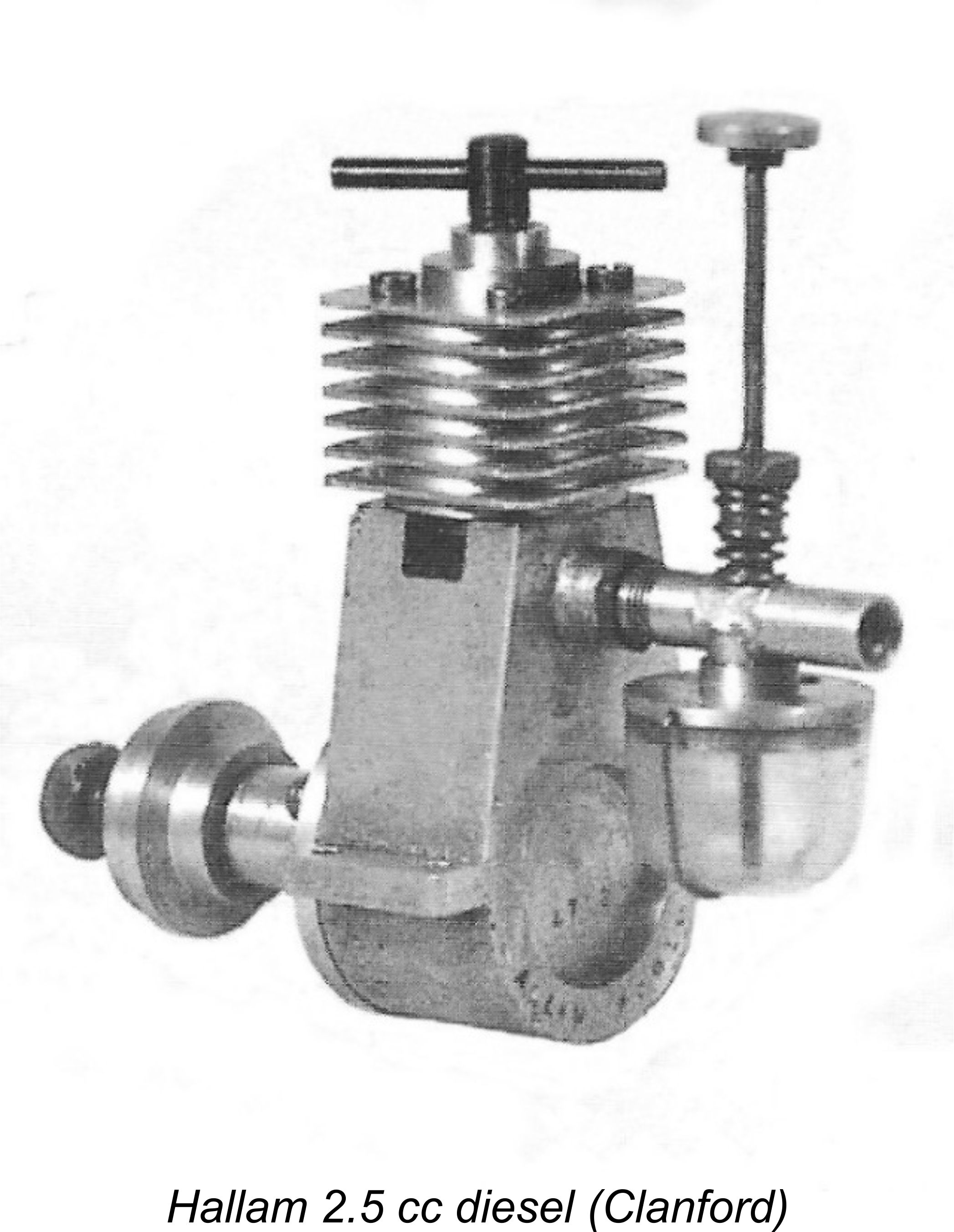

The Hallam Baby 2.5 cc diesel was a very neat and clean design bearing a more-than-passing resemblance to the Mills 1.3 Mk I apart from its greater displacement. Its most distinctive visual feature was its flat-sided cooling jacket. Like the majority of its competitors, it featured sideport induction. No information was ever published with respect to its working dimensions or its weight. However, it must have been a useful enough performer, since an example of this engine powered the winning model in the 1947 Bournemouth Model Aircraft Society Power Cup, an event sponsored by the well-known advocate of power modelling Col. C. E. Bowden.

The Hallam Baby 2.5 cc diesel was a very neat and clean design bearing a more-than-passing resemblance to the Mills 1.3 Mk I apart from its greater displacement. Its most distinctive visual feature was its flat-sided cooling jacket. Like the majority of its competitors, it featured sideport induction. No information was ever published with respect to its working dimensions or its weight. However, it must have been a useful enough performer, since an example of this engine powered the winning model in the 1947 Bournemouth Model Aircraft Society Power Cup, an event sponsored by the well-known advocate of power modelling Col. C. E. Bowden. Like the Super Nine, this model was only available in complete ready-to-run form. It was manufactured in very small numbers in 1947 and 1948, with two distinct crankcase castings being used along the way. However, it appears to have been withdrawn by early 1949. The engine’s relatively high price was doubtless a major contributing factor to this unhappy outcome.

Like the Super Nine, this model was only available in complete ready-to-run form. It was manufactured in very small numbers in 1947 and 1948, with two distinct crankcase castings being used along the way. However, it appears to have been withdrawn by early 1949. The engine’s relatively high price was doubtless a major contributing factor to this unhappy outcome. The existence of a 5 cc Hallam spark ignition twin is attested by the survival of at least one example, which was illustrated by Mike Clanford in his well-known

The existence of a 5 cc Hallam spark ignition twin is attested by the survival of at least one example, which was illustrated by Mike Clanford in his well-known  One of the problems faced by anyone trying to make some sense of the various Hallam products is the fact that since many of them were sold in the form of plans and casting sets, a surprising number of individual constructors applied their own design ideas to the units which they constructed from these castings. Unfortunately, the passage of time has resulted in many of these creations being identified as Hallam production designs, whereas in fact they’re actually home-constructed units which are based upon those designs and use the same castings.

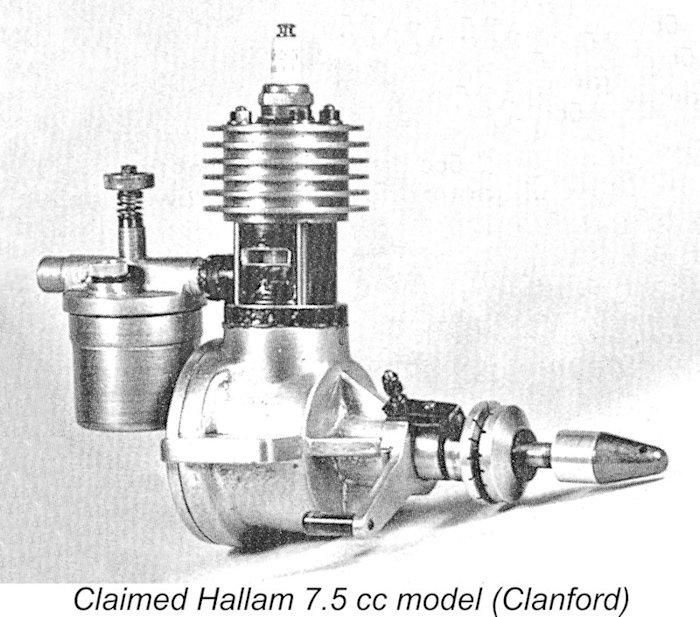

One of the problems faced by anyone trying to make some sense of the various Hallam products is the fact that since many of them were sold in the form of plans and casting sets, a surprising number of individual constructors applied their own design ideas to the units which they constructed from these castings. Unfortunately, the passage of time has resulted in many of these creations being identified as Hallam production designs, whereas in fact they’re actually home-constructed units which are based upon those designs and use the same castings. There’s also the unit which appears in Mike Clanford’s book under the designation “Hallam 7.5 cc”. The engine certainly seems to be based on a set of Hallam castings, but the cylinder design of this unit bears little resemblance to that of any attested Hallam model. Moreover, no Hallam model of this displacement appears anywhere in the media or advertising record. I'm not saying that it definitely isn't a Hallam model, but ............. It would be interesting indeed to see the provenance upon which this identification is based.

There’s also the unit which appears in Mike Clanford’s book under the designation “Hallam 7.5 cc”. The engine certainly seems to be based on a set of Hallam castings, but the cylinder design of this unit bears little resemblance to that of any attested Hallam model. Moreover, no Hallam model of this displacement appears anywhere in the media or advertising record. I'm not saying that it definitely isn't a Hallam model, but ............. It would be interesting indeed to see the provenance upon which this identification is based. As mentioned above, the Hallam company found the going increasingly difficult as their designs became more “dated” and new technologies assumed centre stage during the mid to late 1940’s. Rather than make the very considerable effort required to update their range, they decided to end their involvement in this line of work. Their final model engine advertisement was placed in NPM in December 1949. No doubt they continued to make castings and any remaining complete engines available to anyone who asked, but it's extremely doubtful that many people did so. The Hallam range was consigned to history ............

As mentioned above, the Hallam company found the going increasingly difficult as their designs became more “dated” and new technologies assumed centre stage during the mid to late 1940’s. Rather than make the very considerable effort required to update their range, they decided to end their involvement in this line of work. Their final model engine advertisement was placed in NPM in December 1949. No doubt they continued to make castings and any remaining complete engines available to anyone who asked, but it's extremely doubtful that many people did so. The Hallam range was consigned to history ............