|

|

The “British Micron” - the Owat 5 cc Diesel

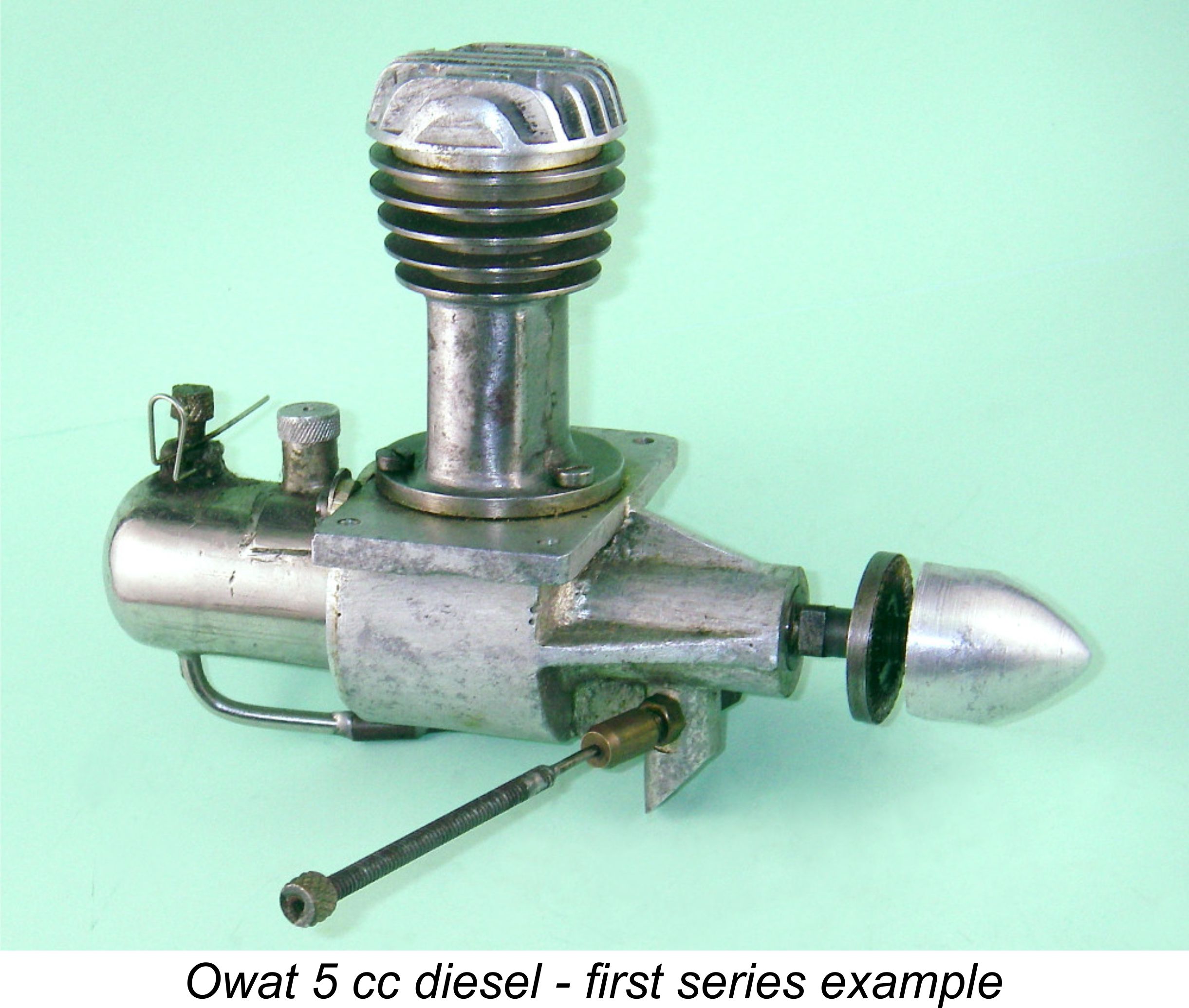

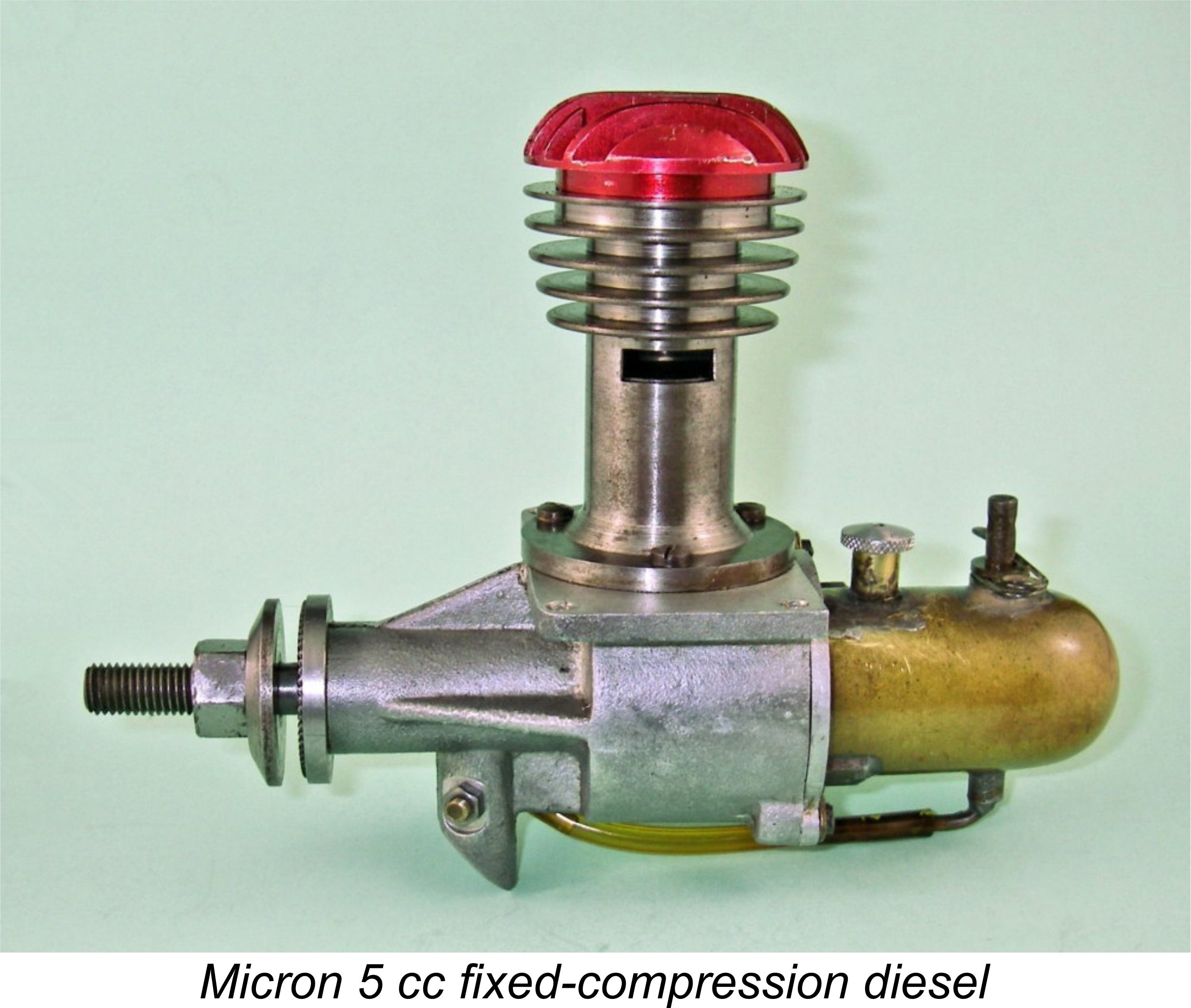

An earlier article about this engine appeared on Ron Chernich’s fascinating ”Model Engine News” (MEN) web-site in November 2008. However, since the publication of that article, a considerable amount of additional information has come to light, including the opportunity to conduct the first-ever published bench test of this unit. It is solely for this reason that the present updated and reorganized article has been written. The Owat has often been mistaken for the very similar French Micron 5 cc fixed-compression diesel (guilty as charged, yer honor!), of which it was undeniably a rather unashamed copy. In large part, this write-up is intended to set the differences in perspective in addition to pointing out the similarities. Vive la difference!! As usual in these articles, we’ll start off with some background ….. Background

Initial development took place in neutral Switzerland and Sweden, with further development occurring in occupied countries such as France, Holland, Norway and Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). Most other European countries formed part of the active battle zone, relegating model engine development very much to the lower end of the priority scale. However, a limited amount of activity did somehow take place in Germany and Italy. Although some relatively scanty information relating to the application of compression ignition to model engines had somehow filtered through to Britain during the war years, the development of model diesels in that country was naturally very much constrained by the pressures of the war effort. However, a certain amount of preliminary investigative work did take place in Britain during that period. Naturally, such investigations at the time in question were very much sideline initiatives, with contributions to the war effort taking center stage. Consequently, wartime progress in Britain was relatively minimal.

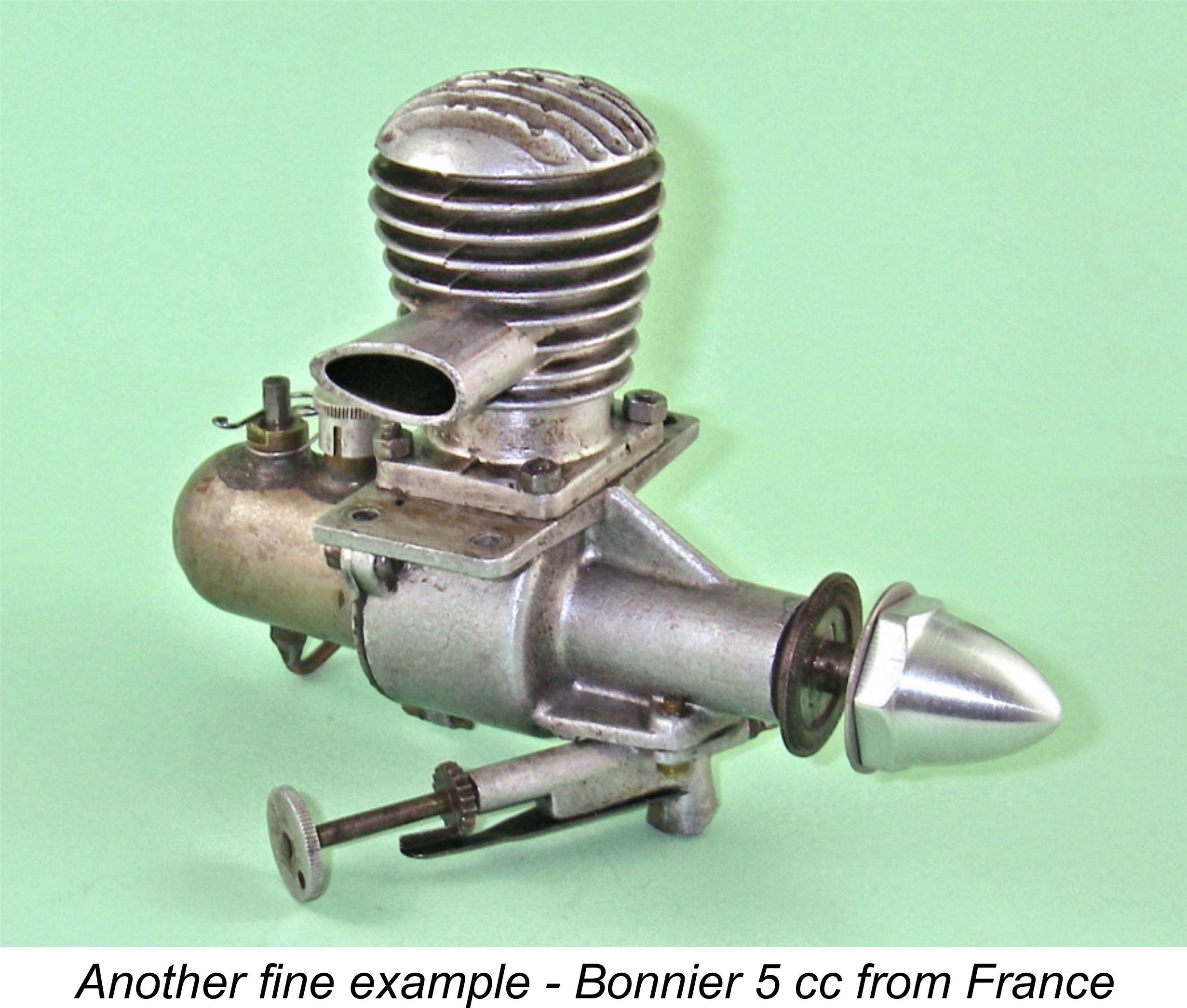

Because the Micron had been fully developed during the war years, its manufacturers were well positioned to introduce it to the open market very quickly following the conclusion of hostilities. By 1946 it had already become established as perhaps the most prominent European competition engine of its day, winning more or less everything in sight and holding an impressive number of records. Even in its own country, the Micron’s success sparked imitators, such as the 1946-47 Bonnier 5 cc model. Its influence also spread to America, where it directly inspired Leon Shulman to develop his deservedly famous Drone 5 cc fixed-compression diesels beginning in 1947. So enduringly popular did the Micron prove to be that it actually remained in production at some level right up to 1959, making it the last man standing among two-stroke fixed-compression diesels. Moreover, a limited Returning now to the conclusion of WW2, the long-suffering members of the British public who had survived the war years were understandably keen to put the hardships of war behind them by returning as quickly as possible to some semblance of their former peace-time lifestyle, very much including their hobbies. The fact that money was tight did nothing to dampen this desire. The key role of the RAF and allied air forces in bringing the war to a victorious conclusion had greatly enhanced the degree of air-mindedness among the British public at large. As a result, aeromodelling not only regained its pre-war prominence very rapidly but actually entered a period of rapidly-rising popularity during the immediate post-war period. This of course created a clear marketing opportunity for innovative products relating to the hobby. Such products naturally included model aero engines. Although these were very expensive by comparison with the average working man’s income, typically costing up to a week's before-tax wages, people were prepared to save up and pay for them regardless due to their novelty value. During the early post-war period, the development of British model compression ignition engines rapidly gained momentum, albeit with British designers naturally playing catch-up to their European colleagues. One factor driving this trend towards home-grown designs was the fact that imports of modelling goods such as engines into early post-war Britain were extremely restricted by law – the conflict had left Britain with an immense debt load, and the emphasis was all on exports to help to redress this situation. It was practically impossible to obtain a model engine from outside the country unless you had some well-disposed overseas relatives or knew one of the US servicemen who remained stationed in Britain for some years following the end of the war.

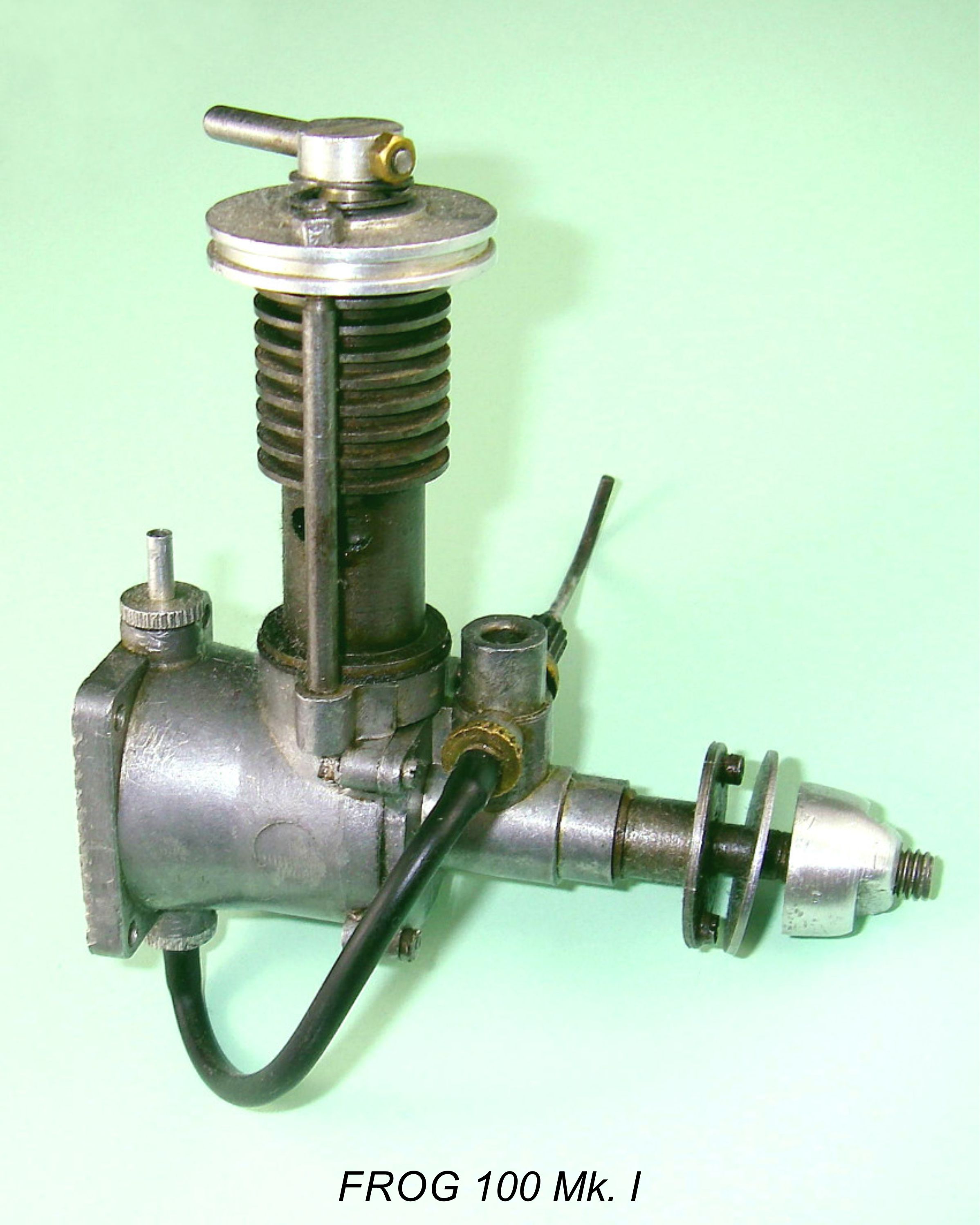

A typical example of the early post-war British development efforts which paralleled the publication of Sparey's article was the work of model engineer George Court (1899-1960) of North Kent, England. Court’s full-time employment was with the Vickers aircraft manufacturing company, perhaps most famous for their In late 1945, the 46 year old Court completed the development of a 1.75 cc spark ignition engine which was released commercially in early 1946 by International Model Aircraft (IMA) as the FROG 175. Immediately thereafter, Court commenced the development of a 1 cc diesel derivative of the FROG 175, which was destined to achieve great fame and popularity as the FROG 100 diesel. Prototypes of this design appeared at the 1946 Model Aircraft Exhibition in December of that year, although the production version did not appear in quantity until mid 1947. I've recounted the story of George Court's activities elsewhere on this website. Meanwhile, over at Mills Brothers, Arnold Hardinge was hard at work developing a model diesel design of his own. Hardinge’s first patent with respect to model diesels was taken out on May 20th, 1946, leading directly to the July 1946 market debut of the first Mills model diesel, the 1.3 Mk. I. This is generally credited with having been the first commercial British-made model diesel engine to reach the retail market. However, as we shall see, our subject model, the Owat 5 cc fixed-compression diesel, can lay a credible claim to a share of this accolade. Having said this, I freely admit that at this point in time it matters very little which model can claim priority. For all The diesel’s advantages over its spark ignition predecessors included the weight saving achieved through shedding of the ignition support system as well as the greatly enhanced dependability of compression ignition by comparison with spark. In particular, the rapid increase in the popularity of control-line flying during the early post-war years meant that engines were now routinely expected to perform dependably and consistently throughout runs of five minutes duration or more, as opposed to the 20-30 second runs expected in free flight service. The dependable achievement of consistent runs of these far greater durations was a constant challenge with spark ignition engines, whereas a diesel once running would continue to do so very consistently as long as its fuel supply was maintained, because there was basically nothing to go wrong! Naturally, these advantages were as obvious to British modellers as they were to their Continental colleagues. As soon as the word got out through such commentaries as Lawrence Sparey’s previously-noted December 1945 article, a considerable and ever-growing number of British modellers understandably became eager to get their hands on the new technology as quickly as possible. It must accordingly have been abundantly clear that the first comers in the British model diesel marketplace stood to do very well given the sizeable pent-up demand for such products which had quickly developed following the conclusion of the war and the publication of Sparey’s article. This being the case, there was an obvious incentive for British manufacturers to get their diesel designs out as rapidly as possible while competition was relatively thin on the ground.

From the nineteenth century onwards, Bradford’s prosperity had been largely based upon the textile industry. However, precision engineering was added to the town’s economic portfolio with the 1904 establishment of the automobile-making Jowett Motor Manufacturing Company. Precision engineering was thus a well-established activity in Bradford at the time of which we are speaking. Bradford’s industrial heritage is very effectively preserved today in the form of the fascinating Bradford Industrial Museum – well worth a visit! Clearly appreciating the potential benefits of an early entry into the marketplace, and seeing no reason to re-invent the wheel, Modella Engines decided to capitalize upon the French lead in model diesel development by basically copying the very successful Micron 5 cc model. Sound reasoning - borrowing from an established design would reduce development time to a minimum. Moreover, if you’re going to borrow, you might as well borrow from the best! The fact that Modella Engines chose the Micron as their basic prototype is surely completely understandable when we consider the Micron’s stellar contest record in a 1946 context. The resulting engine was of course our main subject, the Owat 5 cc fixed-compression diesel. The origin of the name “Owat” is undeniably rather obscure, bearing no evident relationship to the company name. No doubt there would be a story there if anyone were still around to tell it after the passage of 78 years (as of 2024)! The name is most likely that of the engine’s unknown designer – although uncommon, the surname Owat is by no means unknown in Northern Britain. It could also be based upon the amalgamation of several names – Owen and Atkins, as an entirely imaginary example?!? A more fanciful and entertaining possibility is the notion that someone associated with the engine was a devoted follower of Yorkshire’s sporting passion, cricket - “Owzzat?!?” All that is certain is that the engines were distributed by Richard Rogard Ltd. of 2 Carlisle Road, Bradford, making this an all-Bradford effort.

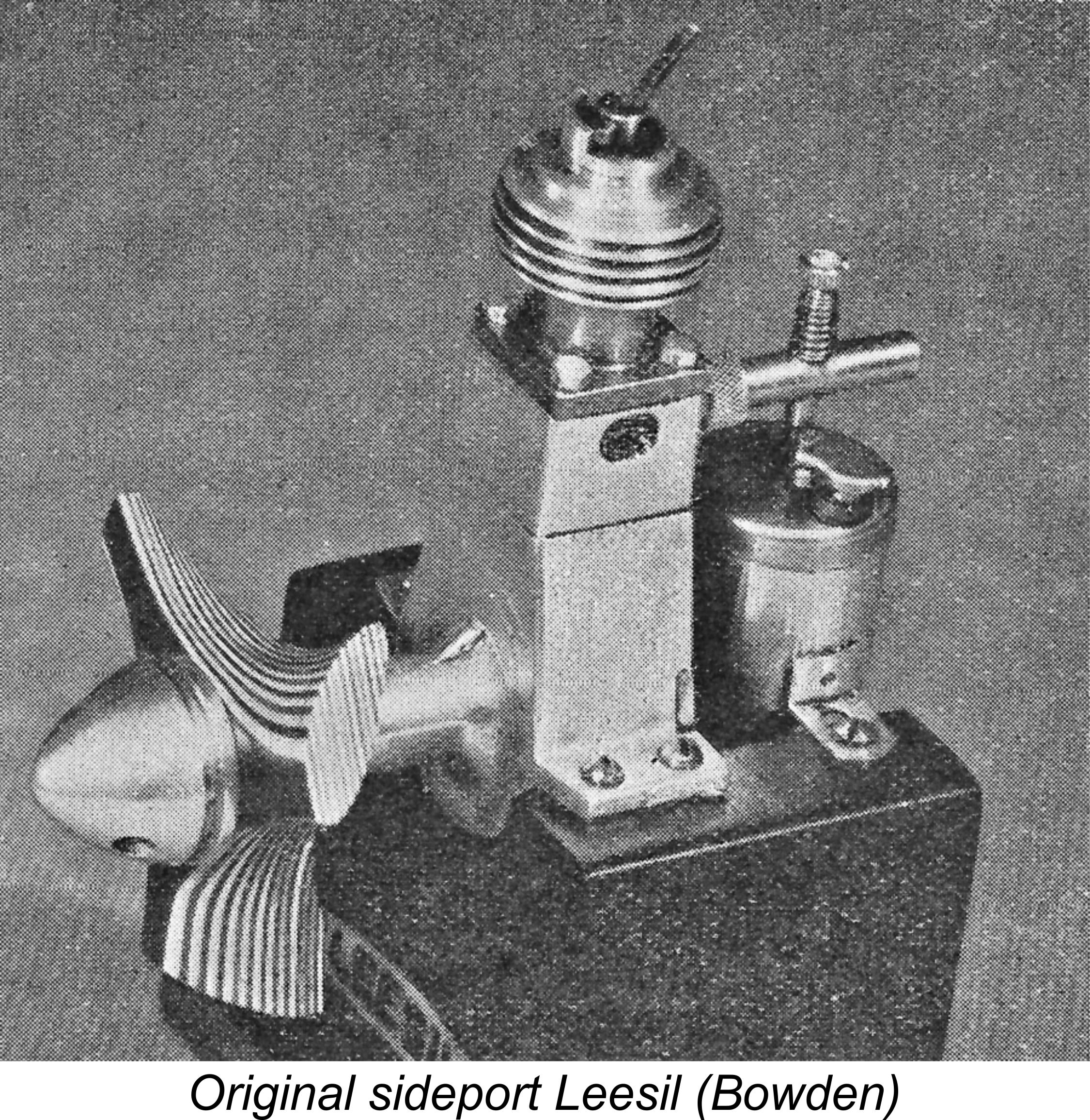

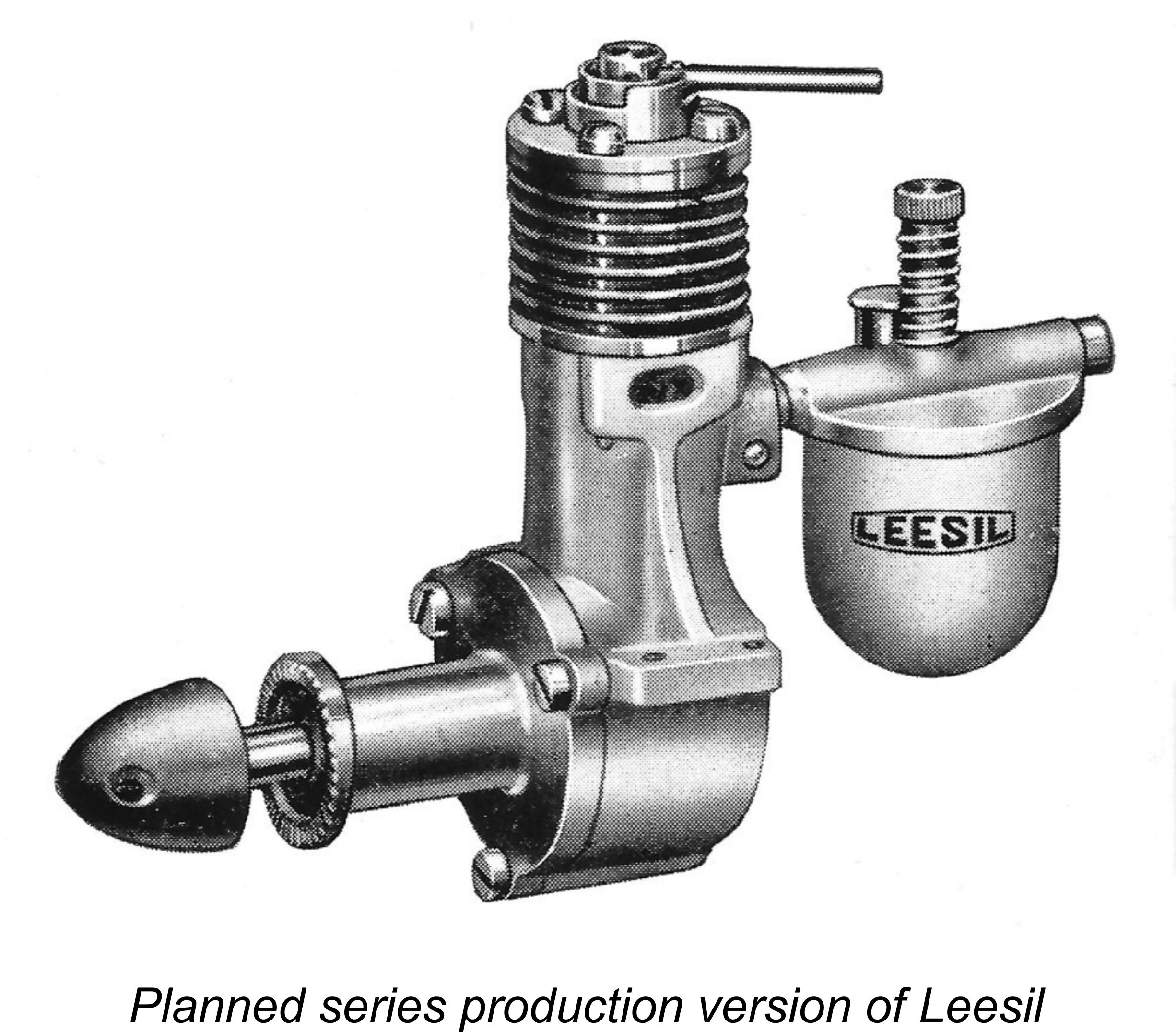

Model engine manufacture was added to the city’s list of industries in mid 1946 when two separate Bradford companies entered this field more or less simultaneously. Apart from our friends Modella Engines producing the Owat on Bridge Street, there was also Leesil Ltd. of 1 Arthington Street in Bradford. Two model engine manufacturers in one modest Yorkshire town at the same time during the early post-war development of the model diesel engine! One suspects a common connection, almost certainly through the The development of the Leesil 24, as it was known, was doubtless motivated by the same consideration which had prompted Modella Engines to develop the Owat, namely, get a model diesel onto the commercial market as quickly as possible in order to reap the potential windfall profits. Leesil designer Colin Wilkinson shared the view of Modella Engines that the quickest way to achieve this goal was to copy an established design. In the case of the Leesil, Wilkinson took as his model an example of the pioneering Swiss Dyno diesel which had been brought into England after the war by Bradford MAC member Silvio Lanfranchi. The Leesil was a long-stroke 2.4 cc sideport diesel engine bearing a close resemblance to its Dyno progenitor. It seems to have appeared at roughly the same time in mid 1946 as the Owat from just up the road. Bore and stroke were 12.7 mm x 19.05 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.41 cc. Being in a different displacement class, it was not of course in direct competition with the Owat. In some ways it was a more advanced design, featuring variable compression as opposed to the fixed compression of the Owat.

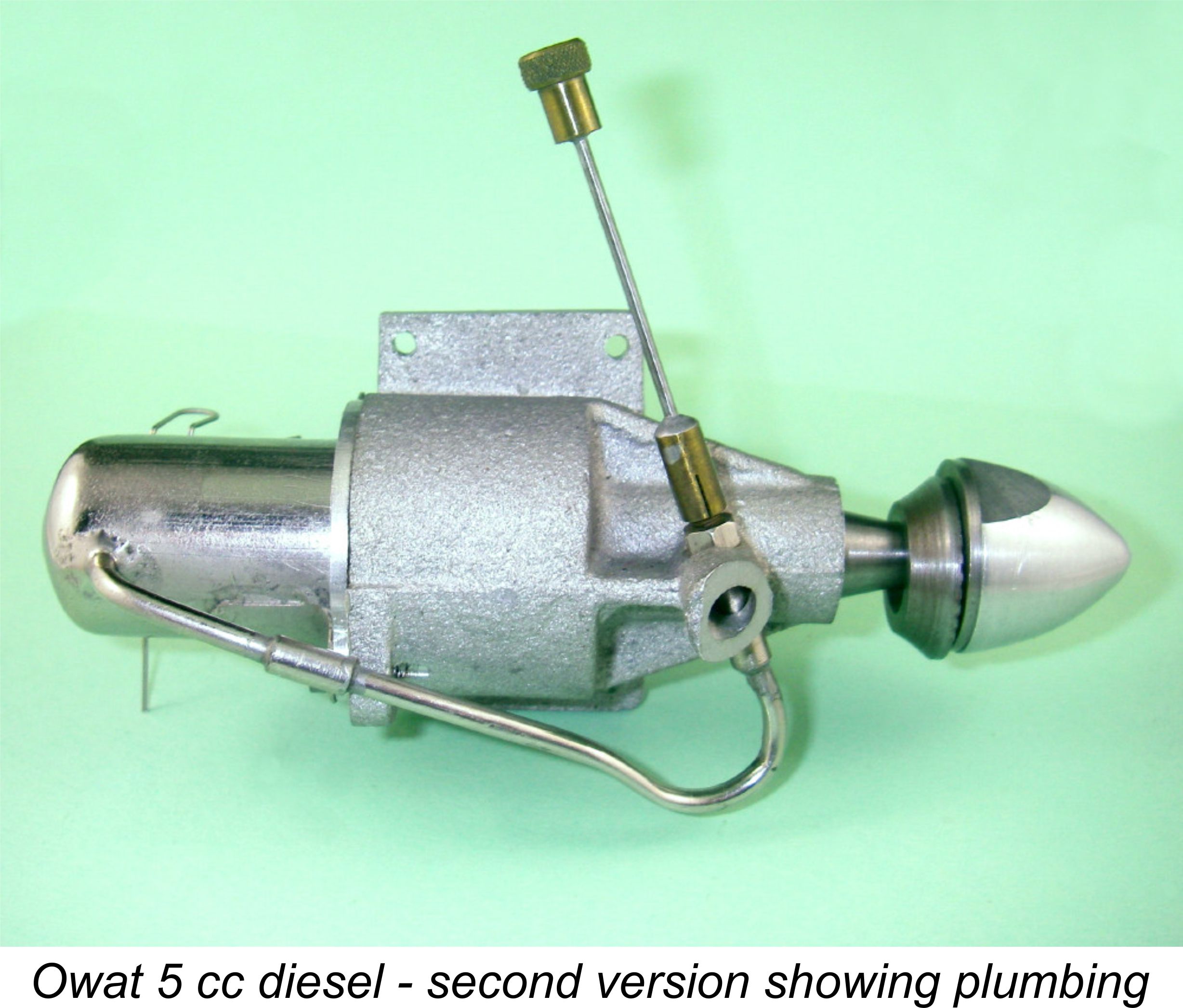

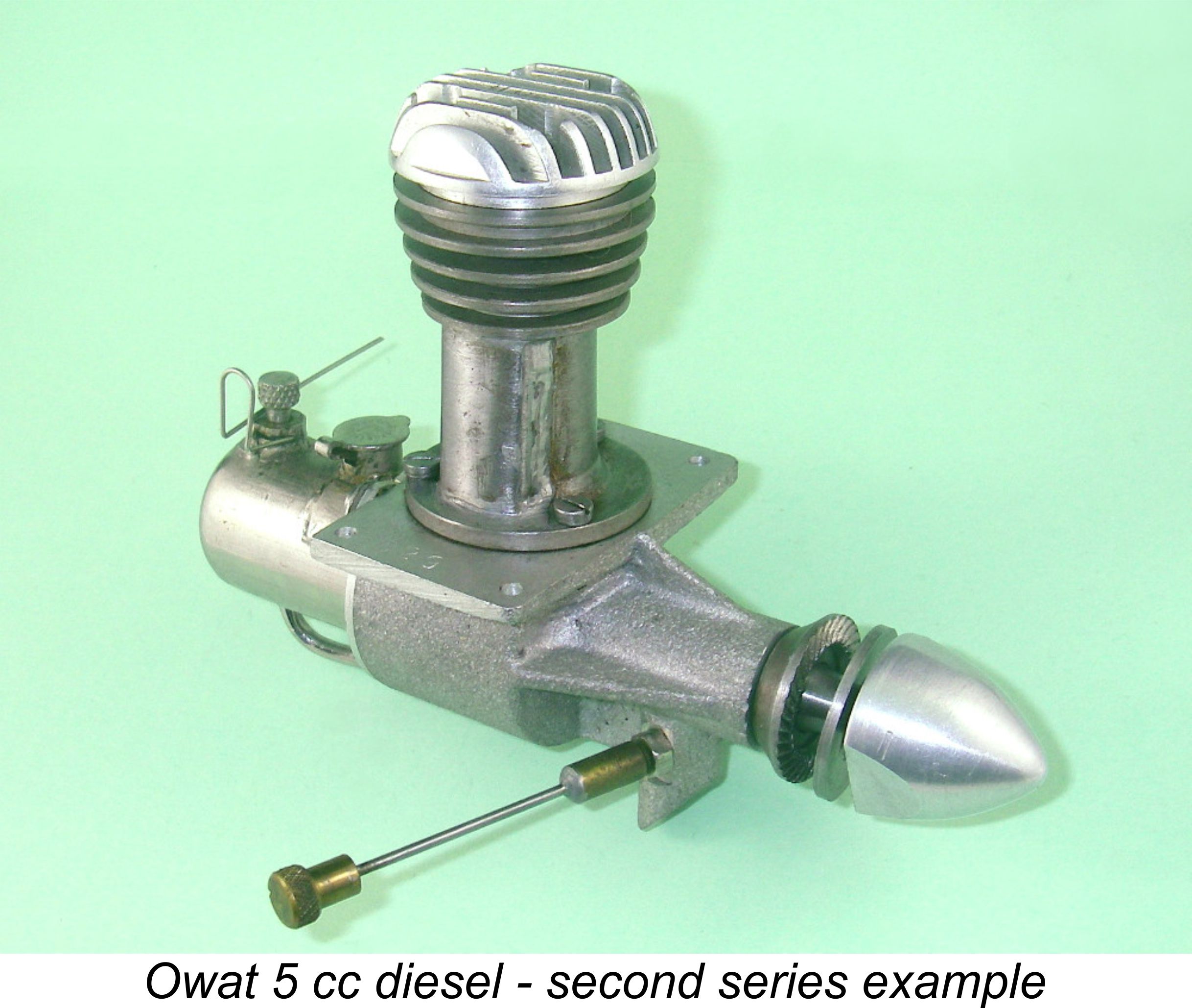

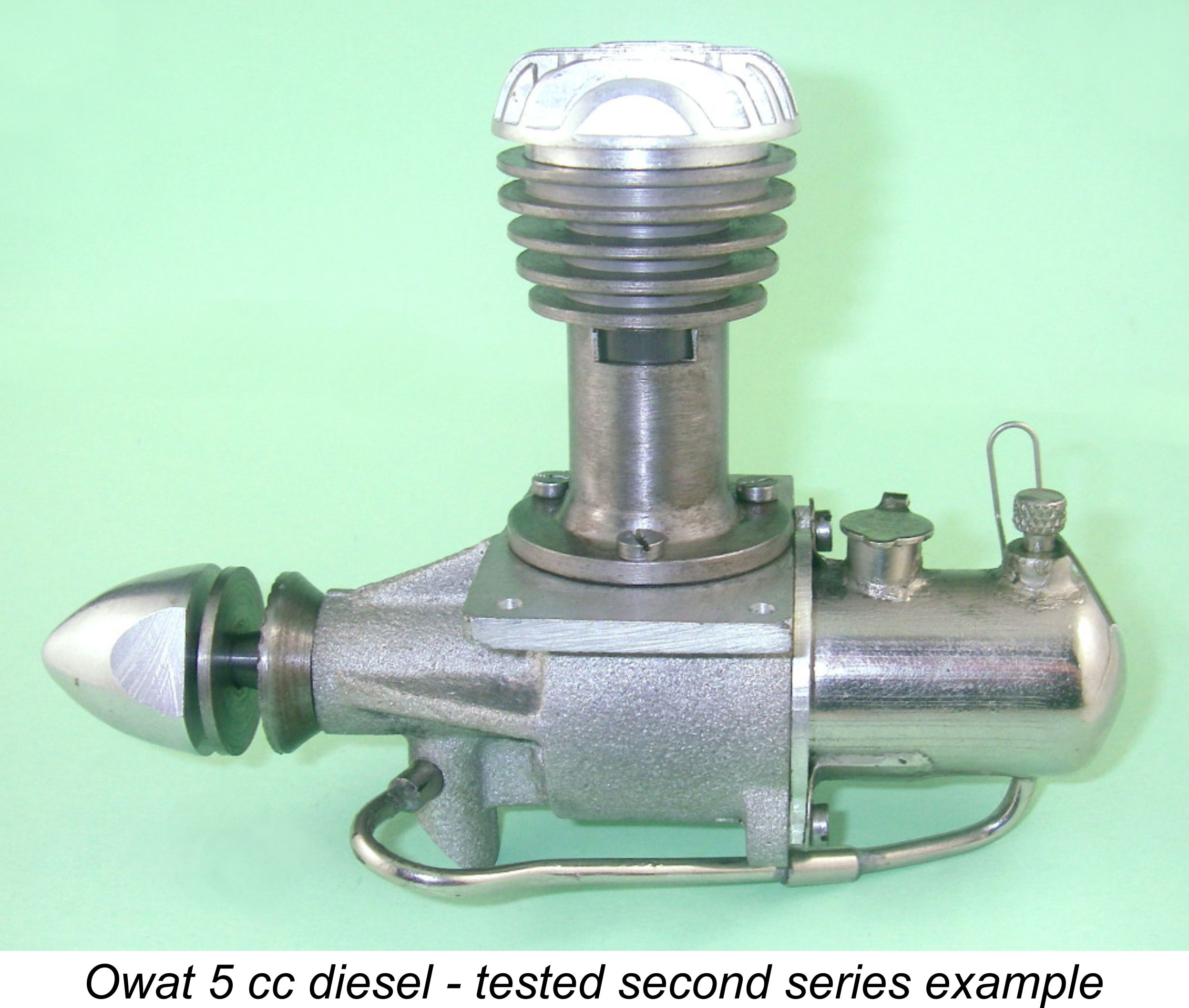

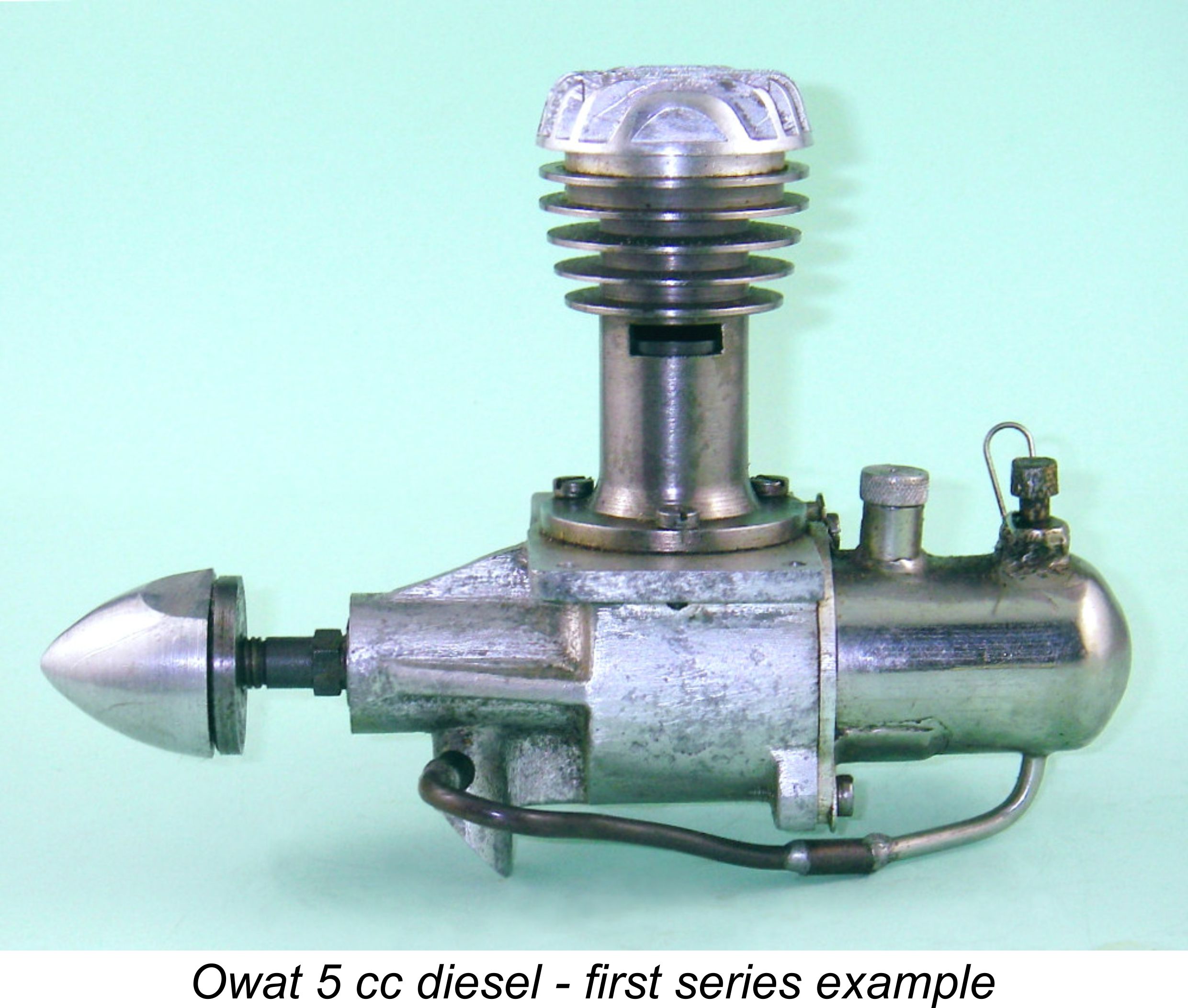

I've covered the full story of the Leesil in a separate article to be found here on this web-site. From this point onwards, we will focus exclusively upon the rival Owat. Let’s begin by looking at the engine’s construction. Description The Owat is basically a conventional long-stroke model diesel engine of its day, featuring FRV induction and cross-flow loop scavenging with a stepped piston crown. Its main departure from the diesel technology with which most of us are familiar is its use of fixed compression.

Although the manufacturers claimed a weight of 10.5 ounces for the Owat, the table included in Laidlaw-Dickson’s book gives a figure of 11 ounces. Both claims are a little on the low side by my own measurements, which yield a weight of 11.625 ounces with tank for engine number B29. Owat user Col. C. E. Bowden went even further – in the September 1947 first edition of his book “Diesel Model Engines” he reported a weight of no less than 12 ounces. The degree to which the design of the Micron was adopted in the Owat has understandably led to frequent confusion between the two models when it comes to identification. I actually obtained my first example (second series engine number B29) many years ago as a “Micron”, thinking that it was a different Micron variant from the one that I already had – it was only after examining it closely and comparing it with my existing Micron that I finally realized what it actually was!

By no means all Microns featured the red anodized head seen in the attached images of that engine, so that is not a definitive means of identification. The British threads used throughout in the Owat are a dead giveaway, but you have to have the engine actually in your hands to use that as a means of identification. Perhaps the most certain giveaway is the fact that the Owat has a stamped-on serial number, while the Micron does not display such a number. The Owat is very slightly bulkier overall than the Micron, also having a more roughly-cast crankcase – in fact, the external finish overall is a little rougher. The marginally bulkier construction of the Owat is reflected in its weight – as noted previously, the thing weighs 11.625 ounces complete with tank, which compares with 10.75 ounces for the Micron with tank. Removal of the Owat tank would doubtless get the weight down below 11 ounces, but the beast is undeniably heavy. Speaking of tanks, that used on the Micron is structurally identical to that of the Owat but is made of un-plated brass, while the Owat tank is plated. This is another dead giveaway in the case of engines which retain their tanks – no mistaking a Micron tank for that of an Owat! Material specification is pretty standard – hardened steel cylinder, cast iron piston, nickel-chrome steel shaft and alloy rod. In the latter regard, it’s my opinion that the Owat is superior to the original version of the Micron, which used a steel stamping for its rod. I’ve never really liked steel rods – they tend to chew up crankpins and gudgeon (wrist) pins, particularly when used in diesels. In my personal view, alloy is far superior, or steel with a bronze bushing. Indeed, a switch was eventually made to a bronze rod in the Micron, while the later examples featured alloy rods. A fully-floating steel gudgeon pin with brass end pads is employed in both designs. The pistons too are more or less identical – both models feature a cut-away on the transfer side of the piston crown, just like that used on the Mills and E.D. sideport engines to direct the incoming charge upwards into the combustion chamber. The bypass passage in both models is formed through the use of a soldered-on channel on the transfer side of the cylinder.

By contrast, the Micron very sensibly uses plastic fuel tubing between the tank and the spraybar, which means that the tank can be used in both upright and inverted positions. Alternatively, a completely different tank may readily be employed with the Micron. If you want to use an alternative tank with the Owat (which you pretty much have to do if you want to mount it in any orientation other than upright), then either a different needle valve assembly must be installed or the metal fuel line must be cut to allow the use of a different tank. Interestingly, the manufacturers clearly anticipated this problem – note the metal sleeve visible in the above underside view which appears part-way along the fuel line on the Series II version of the Owat. This is soft-soldered in place, a step which was presumably taken only after the tank and spraybar were both in place. Naturally, this connecting sleeve could just as easily be unsoldered! I’m sure that this was the maker’s intent – if the engine was to be used without the supplied back tank, then the line could be separated from the tank simply by unsoldering the sleeve. The connection could be re-established very easily at any time if desired. A thoughtful touch ……………

In the case of the Micron, the thimble is fixed to the needle, hence turning with it. This thimble is unthreaded and is split into four segments rather than the more usual two. It is a tight push fit over the unthreaded outer surface of the spraybar. The split thimble is tensioned against the spraybar by a strong wrap-around coil spring – neat, extremely effective and self-adjusting, albeit more complex than the Owat set-up. The fuel supply arrangements are also completely different. The Micron features a very handy 90 degree fuel line There are a few other visible differences between the Owat and the Micron. The tank of the Micron features a screw-in fuel filler cap, while the Owat sports either a made-in-England No. 3 Partridge Flip-Flap unit or a simple push-in split cap. Finally, the Owat features a neat streamlined alloy spinner nut for prop mounting, while the Micron contents itself with a plain nut and washer. The Owat was manufactured in two distinct series, although there was actually very little difference between the two. Although there’s no proof of this, it's actually possible that the Series II models were produced by a new manufacturer who had reportedly taken over the Owat project in mid 1947 if Col. Bowden is to be believed ("Diesel Model Engines", 1947 first edition, page 50). If this was the case, the evidence suggests that the new manufacturers (whose name is unknown) decided quite quickly that the economic return on the manufacture of the Owat was insufficient to justify its continuation. Both the Micron and the Series I Owat use an identical prop driver arrangement. In both cases, the prop driver is a simple relatively thin steel disc which keys onto a square-cut section of the shaft just in front of the main bearing. The accompanying images of Series I engine number ST45 show this clearly.

The different prop driver arrangements appear to be the only externally-visible differences between the Series I and Series II versions of the Owat. There may have been internal changes in addition, but I have never had both of my examples apart concurrently to compare them. No sense in disturbing good 75 year old seals without an extremely pressing reason to do so…………

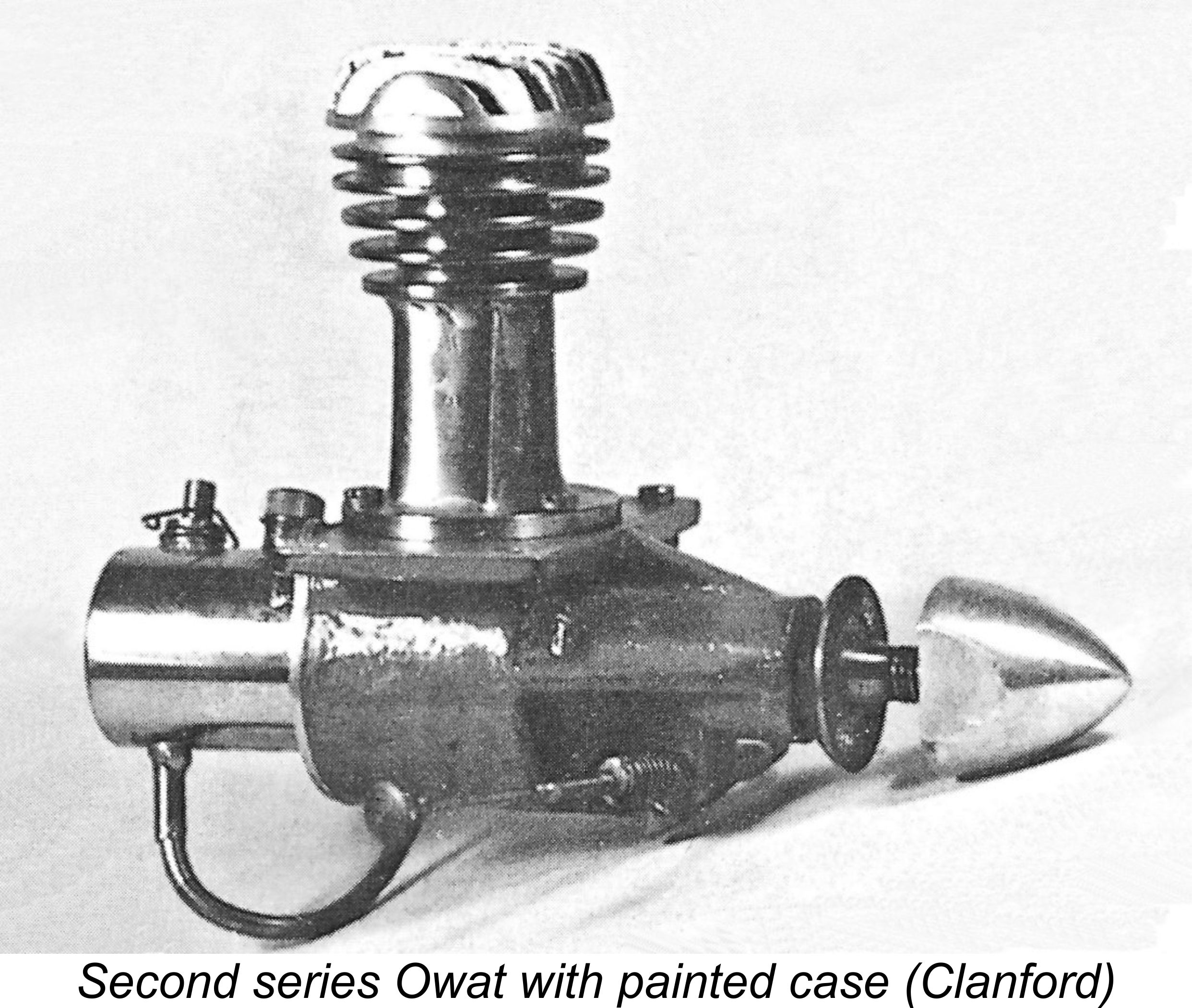

However, it must be said that the Series II example illustrated on page 47 of Col. Bowden’s previously-cited book appears to have a painted case, as did the ones illustrated by both Clanford and Fisher. Moreover, following the initial publication of this article, reader Dave Causer of Lincoln, England obtained an example of the Series I Owat which had an unquestionably original red-painted case and tank. Dave's excellent restoration of this engine included a re-painting job which matched the original color as closely as possible, giving us an excellent idea of what one of these engines looked like when new.

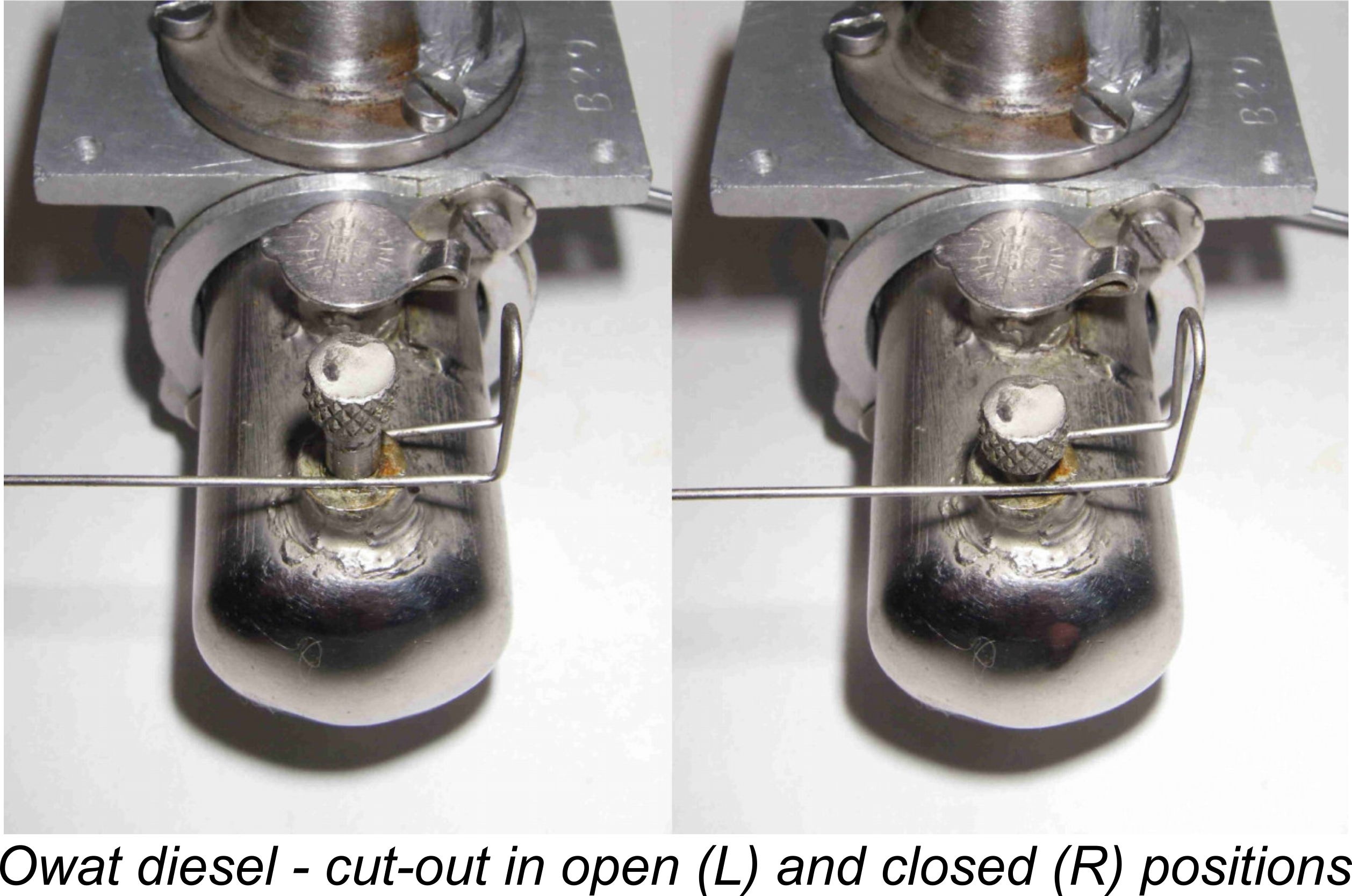

That aside, it should now be clear that there are plenty of clues through which the Micron and Owat engines may readily be distinguished from one another, with or without the red paint. Despite this, there’s no getting away from the fact that the Owat is basically a very close copy of the then highly regarded Micron, to the point of being a near replica. Despite its somewhat rougher external finish, the Owat is every bit the equal of the Micron where it counts – the mechanical workmanship and standard of fitting exhibited by both motors are up to the very highest model engineering standards throughout. One direct similarity is the fuel cut-off used on both engines. This is of the spring-loaded plunger type, with a wire arm that snaps into a circumferential groove formed around the plunger body to keep it open for running. The wire arm is differently formed on the Owat, but the principle remains exactly the same. When the arm is tugged backwards out of the restraining groove by whatever timer is used, the plunger snaps shut and cuts off the fuel supply at the tank.

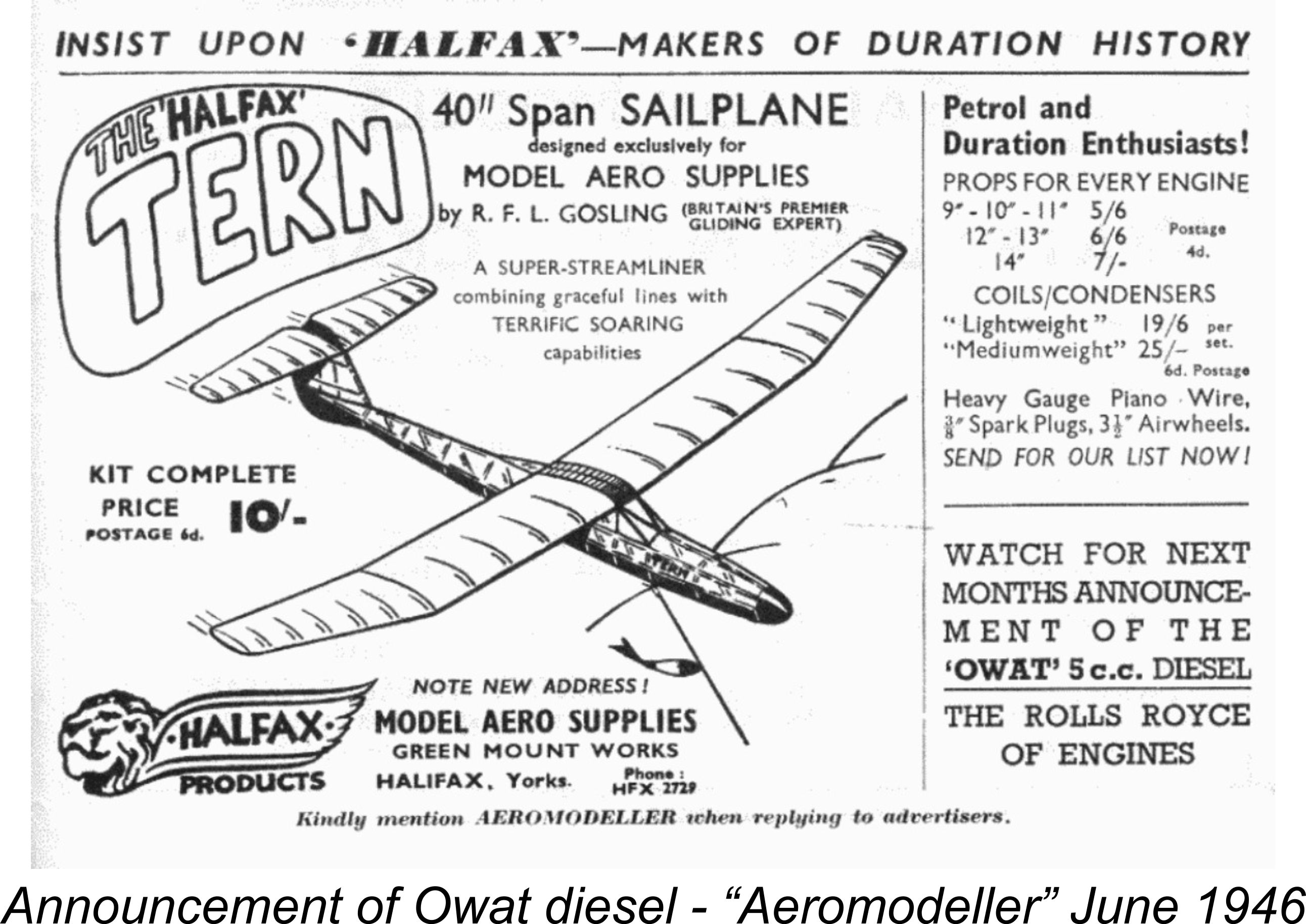

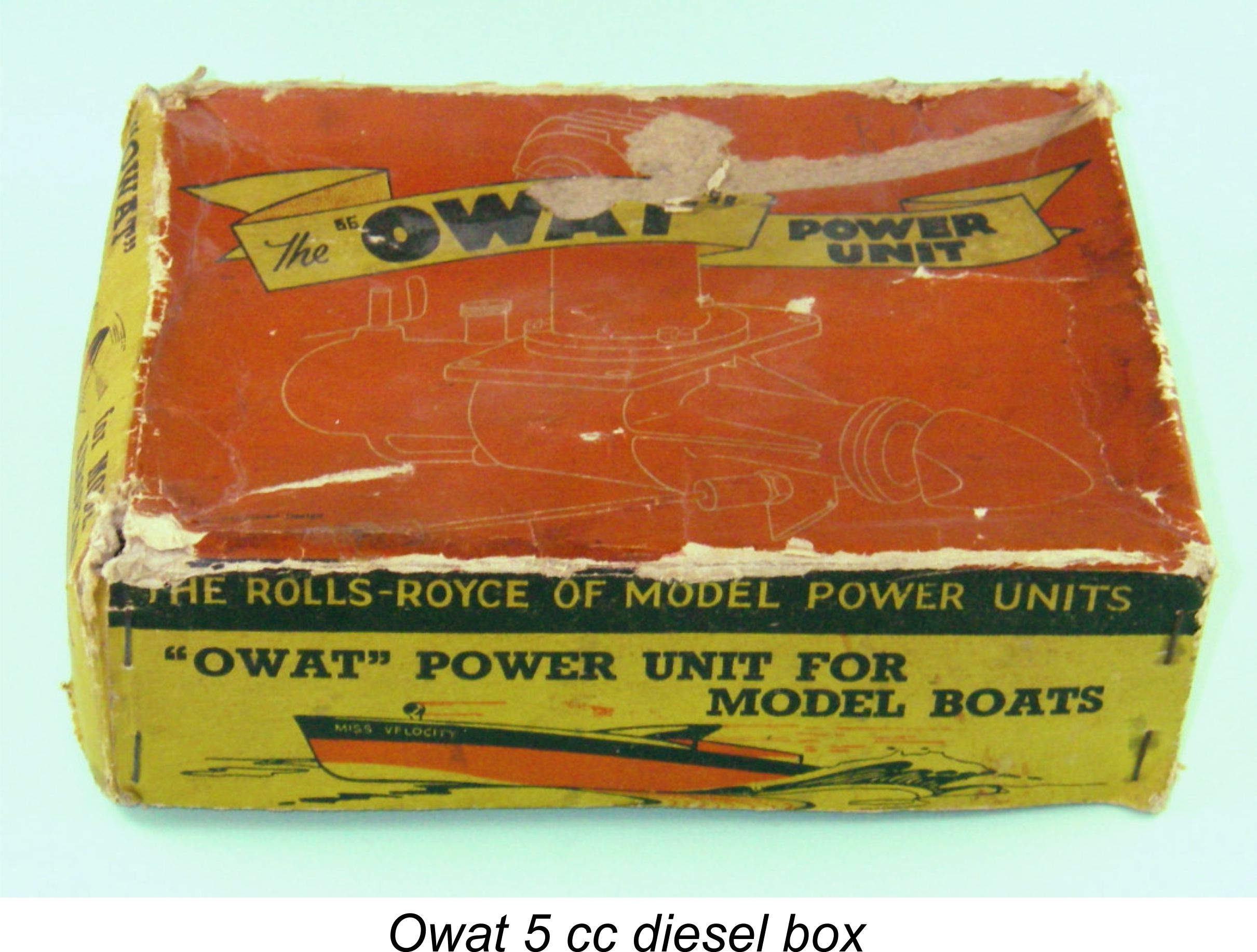

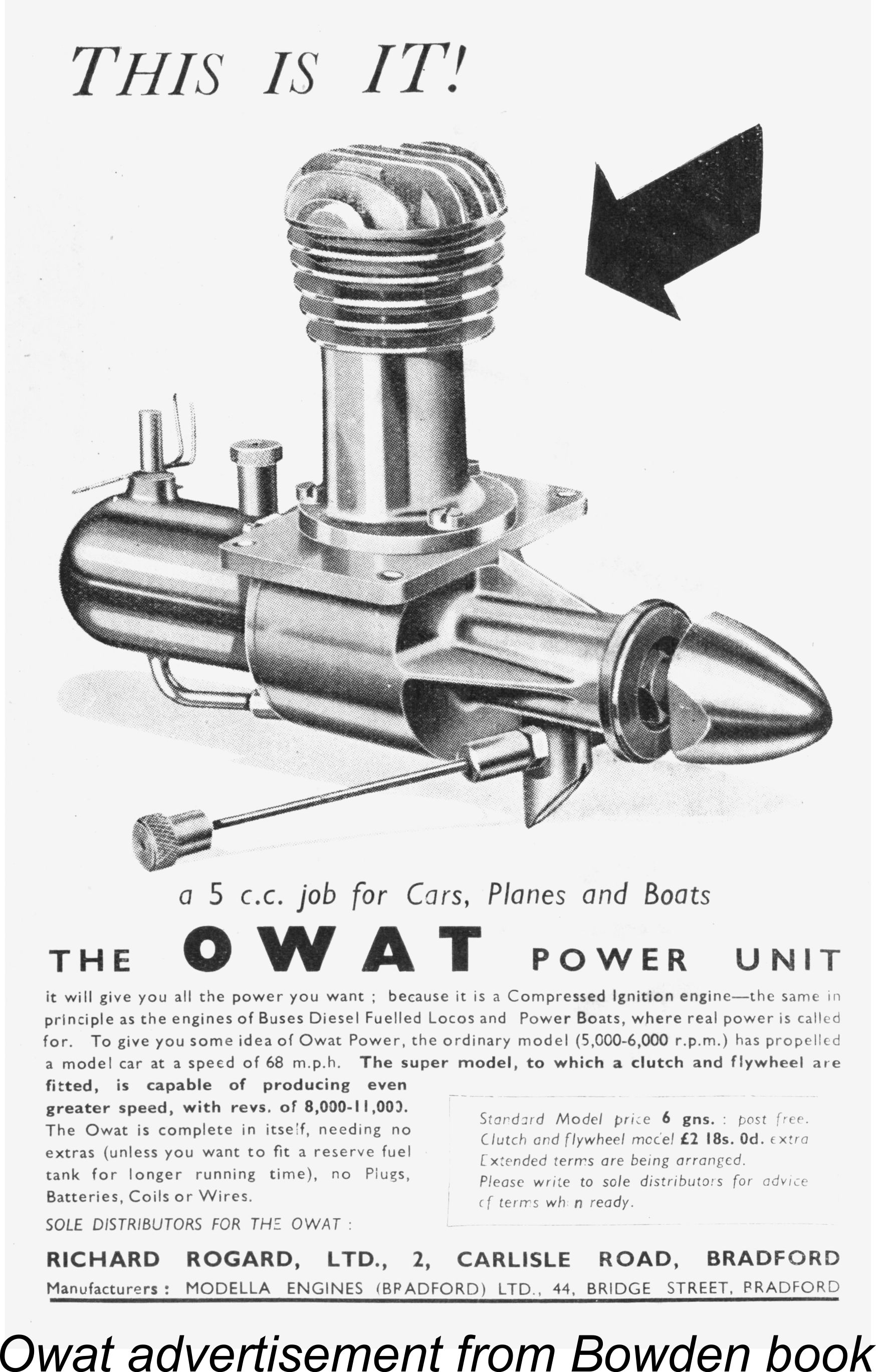

The upper surfaces of the mounting lugs on both the Owat and the Micron are machined flat, while the lower surfaces are left as cast, complete with draft angles which are not perfectly matched on both sides. So the bearers have to be located on top of the lugs (with an upright mount in the case of the Owat if the supplied tank is to be used). Moreover, the updraft location of the needle valve combined with its sharply rear-angled alignment causes it to pass directly beneath the mounting lugs in an upright mounting configuration. No problem in a model, but both of these issues prevent the use of a conventional test stand. For testing purposes, this necessitates the making of a custom-designed pair of metal mounting beams to allow the engine to be mounted in a test stand (see below). The Owat engines all appear to have carried serial numbers, although at the moment I don’t have sufficient data to allow for the identification of any kind of pattern. The only serial numbers in my present possession for the Series I Owat are my own engine number ST45, engine number D497 which appeared on eBay in 2024, engine number D573 restored to excellent running condition by Dave Causer and number D656 reported by Bob Parry. I'm aware of Series II Owats bearing the numbers B22 (Bob Parry's example, which is set up for car operation), my own B29, B102 which put in an appearance on eBay, and B193. It would appear that the numerical sequence was re-started for the Series II models after at least 656 Series I engines had been manufactured. Moreover, at least 200 examples of the Series II variant appear to have been produced. I have no suggestions regarding the possible significance of the ST prefix associated with my own Mk. I example. Regardless, that’s about all that I can say at the present time. I would need far more serial numbers to form any kind of reasonable estimate of production figures. If anyone out there has such numbers, please share them! As a final comment, it’s worth pointing out that the mounting geometry of the Owat and Micron is identical. The Owat’s lugs are very slightly wider and longer overall, but the hole spacing is perfectly matched. This cannot be coincidental - clearly Modella Engines were hoping to entice some Micron users into making the switch! Moreover, they seem to have succeeded - Col. Bowden actually mentions in his previously-cited 1947 book (pages 49-50) that he was accustomed to switching back and forth between his Owat and Micron 5 cc engines in the low-wing monoplane which he had built for these two units. The one potential problem in this regard is the fact that the mounting holes on the Micron are only drilled to clear 2.5 mm (0.098 in.) diameter bolts. This is insufficient to clear either the 0.110 in. dia. 6 BA screws which would doubtless be used in Britain or the 0.112 in. dia. 4-40 items which would likely be employed in the USA. The mounting holes of the Owat are drilled to clear both of the latter sizes as supplied. This means that any example of the Micron which has been used in either Britain or America will almost certainly be found to have had its mounting holes drilled out to clear the larger fasteners. A small point, but one of which serious collectors should be aware. My own late model example of the Micron has been drilled out in this manner, although my earlier one retains its 2.5 mm dia. holes. Marketing History of the Owat The manufacture of the Owat was confined to the period 1946 – 1947. At the time when D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson’s previously-cited book “Model Diesels” was being written in the latter half of 1946 it was just coming onto the market in quantity, hence being included in the table of British diesels scheduled for full-scale production in 1947. It was mentioned again in the September 1947 first edition of Col. Bowden’s previously-cited book “Diesel Model Engines”. On page 49 of that edition, Col. Bowden noted the Owat’s The advent of the Owat was first publicly announced in an advertisement placed by the Yorkshire model aircraft supply firm of Halifax Products of Leeds in the June 1946 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. This advertisement advised readers to “Watch for next month’s announcement of the “Owat” 5 c.c. diesel - the Rolls Royce of engines”. It’s clear from this that the engine was scheduled for release in July 1946, making it in fact a direct contemporary of the Mills 1.3 in terms of its release date and thus seemingly giving it a share of the honour of being one of the first two series-produced model diesels to appear on the British market. It would also seem that Halifax was intending to actively promote the local product. The term “The Rolls Royce of Model Power Units” was not an invention of Halifax Products, being applied to the Owat from The Owat was nationally advertised thereafter on a semi-regular basis in the modelling media of the day. It seems that the engine found customers in various parts of the country, not just in its native Yorkshire. It would also appear that the Owat performed quite well for its customers. As previously mentioned, the redoubtable Col. Bowden of Bournemouth in Dorset had one which he reported using with considerable success in his low-wing monoplane, while a report in the January 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller” referred to a 66 in. wingspan high-wing cabin model powered by an Owat making the first-ever diesel-powered flight by a member of the Darlington MAC, one A. Pearson, at Croft Aerodrome in November 1946.

A somewhat different advertisement appeared as a full-page placement on the inside front cover of the first edition of Col. Bowden’s 1947 first edition, along with similar ads for the ETA “5”, the Mills 1.3, the E.D. Mk. II and the AMCO .87 which appeared elsewhere in the same Oddly enough, the price of the standard model was given in this advertisement as 6 guineas (£6 6s 0d, or £6.30 in “modern” money), which was a lot less than the price quoted in the June 1947 placement mentioned earlier. Even so, this was still a pretty steep price in early post WW2 Britain. And that was just the basic model - one had to pay an extra £2 18s 0d for the “super” version with clutch and flywheel. It would appear from the content of this advertisement that the Owat was aimed as much at the then-thriving model car market as that for model aero engines. The precise date of the publication of Col. Bowden’s first edition in which the above-noted advertisement appeared is unclear at the present time. However, it must have been subsequent to August 1947, since the AMCO .87 diesel which formed the subject of one of the advertisements in the book was not formally released until that month. Taking the two Owat advertisements together, it seems that a significant price reduction was applied to the Owat at some point following May 1947 but prior to the appearance of Col. Bowden’s book, likely in September 1947 if the inclusion of the AMCO advertisement is any guide. It’s probable that this price reduction was a response to faltering sales coupled with increased competition as 1947 drew on. Whatever the truth of this matter, the production of the engine appears to have ended in the final few months of 1947. The Owat was not mentioned even retrospectively in the Colonel’s 1951 third edition (which is the version reproduced in the “modern” facsimile edition published by TEE Publishing - it differs quite substantially from the first edition). Moreover, production volumes appear to have been very much on the modest side. Consequently, the engine is relatively rare today, particularly in as pristine condition as my own two illustrated examples, one of which is New-in-Box. However, nice examples do still turn up from time to time. It appears from this that at least several hundred were probably made and sold. That said, it’s highly unlikely that production came anywhere near reaching four figures. Operational Considerations I've covered the subject of fixed-compression diesel operation in a separate in-depth article to be found on this web-site. However, for convenience I'll summarize some of the main points here. As anyone who has ever tried to run a fixed-compression diesel will know, the two major factors in achieving smooth and trouble-free operation are the use of the correct fuel together with a well-matched prop. Since you can’t change the compression ratio (and hence the ignition timing) of a fixed-compression diesel while it’s running, you have to prop it for a speed that is well harmonized with the warmed-up ignition timing which results from the combination of the built-in compression ratio and the particular fuel being used. You also have to use a fuel which is sufficiently cool-burning that excessive heating and a consequent need for compression reduction as the engine warms up are avoided.

As any user of conventional high-speed model diesels will know, the cold-starting compression for such an engine is generally somewhat less than the best running position. Compression is usually backed off a little for cold starting and then increased to smooth out the running once a start is achieved. Obviously, this is not possible with a fixed-compression engine – it has to run at its starting setting. The consequence is that the fixed compression model diesel is effectively restricted by its ignition timing to operation at relatively low speeds. This in turn means that such engines have to be propped for operation at such speeds – any attempt to prop them for higher speeds will simply guarantee that the engine will operate in an under-compressed mode, soon hitting a ceiling beyond which it won’t run significantly faster however much you unload it.

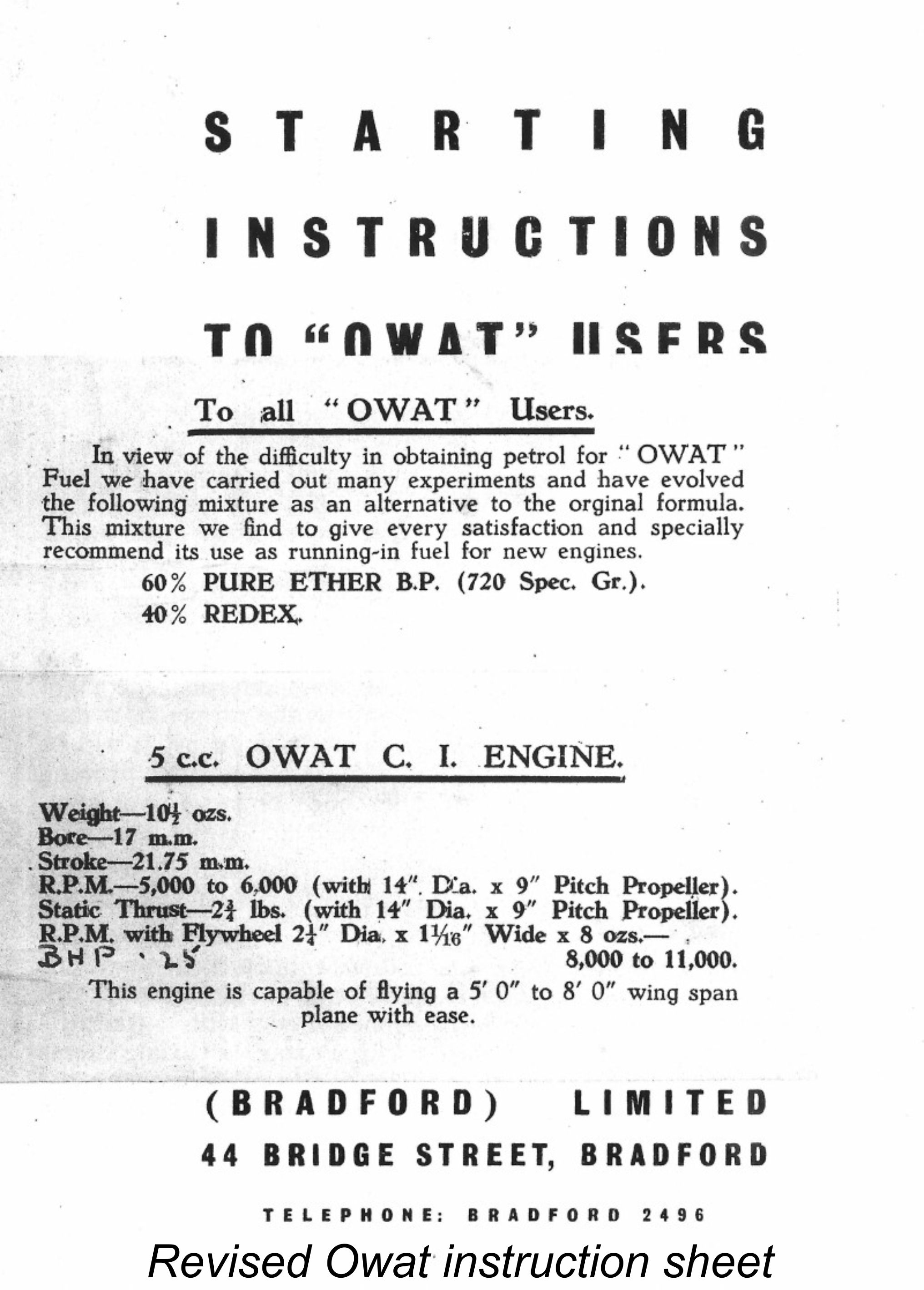

OK, so much for the prop – what about the fuel? Well, for reasons which are explained in detail in my separate article on fixed-compression diesel operation on this site, these engines run best on a fuel containing only straight ether and mineral-based lubricating oil. However, the Owat was manufactured at a time when the question of the best fuel for a given model diesel remained very much open, with different designers and users all having their own ideas on the subject. In the case of the Owat, this issue is further confused by conflicting recommendations from the same supposedly authoritative source, namely the manufacturers of the engine! Their originally-recommended fuel was 70% ether, 10% lubricating oil (Castrol XXL – a heavy mineral oil in widespread automotive use in Britain at the time) and 20% “pool” petrol (i.e., rot-gut grade gasoline!). EEEK!! Pretty thin on the oil content from a lubrication standpoint, while the very low oil content would have done little to "calm down" the ether and thus discourage detonation!

The “alternative” formula given in the revised instructions was 60% ether and 40% Redex. The latter was a well-known fuel additive in widespread automotive use in Britain at the time, hence being readily and cheaply available (a revised formulation remains available today in 2024). The Redex of the 1940’s contained both a solvent and a high-temperature upper cylinder lubricant. It was intended to work by first dissolving any deposits which might result in sticking valves or piston rings and then by lubricating the freed-up components. Speaking personally from my own dim ‘n distant recollections of the stuff (my Dad used it in the family car), I would have said that Redex was very much on the thin side for use as a model diesel lubricant, especially given the significant solvent content which would have diluted its lubricating qualities. However, the Owat manufacturers were clearly on top of this issue – they simply considered the solvent content in the Redex to be a combustible element of the fuel mixture, adjusting the amount added accordingly. This explains the relatively high proportion of Redex in the mix. In actual fact, the effective lubricant content of the recommended mix was probably at most around 15%, with the balance being a blend of combustible solvent and ether.

The theory behind this recommendation was doubtless the fact that a bit of excess liquid oil in the combustion chamber takes up space which is then unavailable to accommodate the gaseous fuel mixture. The result of this is a temporary increase in the engine’s effective compression ratio. This extra compression would have ensured that any ether in the combustion chamber would ignite, and might even have been sufficient to allow the naphtha (assuming that that’s what it was) to reach its auto-ignition temperature of 225 degrees Celcius (as opposed to the 160 degree Celcius figure for ether). I’ve tried this oil injection technique myself with other fixed-compression engines such as the Drone and Micron 5 cc models. The results have been quite impressive - on days when the ambient temperatures are low enough to inhibit starting or even firing, the use of this technique has proved to be extremely effective. Although the early post-war Redex formulation is no longer available, the present-day upper cylinder lubricant manufactured by Dura-Lube appears to be very similar in composition and certainly works well for the purpose. This lubricant is readily available in North America. Another effective Redex substitute is Marvel Mystery Oil if you can get it. You can also use straight lubricating oil for this purpose, although the absence of the solvent fraction means that it’s easier to overdo the priming. Still, it works well enough. An eye-dropper or industrial syringe serve very well for the administration of such a prime. If this oil priming is done correctly, you can easily feel the increase in the compression ratio when you turn the engine over slowly by hand following the injection. In fact, you should always do this before beginning to flick in order to ensure that you haven’t overdone it and approached or even achieved a hydraulic lock. In their instructions, Modella Engines very sensibly made a particular point of this, recommending that the engine be turned over slowly by hand prior to the commencement of flicking to ensure that no such condition existed. Wise advice, which should be followed .......... Although it is generally not necessary at “normal” temperatures, this technique is extremely effective in promoting more dependable starting during cold weather. This being the case, it’s actually a bit surprising that no other manufacturer of fixed-compression diesels appears to have picked up on the idea, nor did any of the model engine commentators in the contemporary media do so either. Full marks to Modella Engines for this very useful suggestion! Returning now to the subject of fuel, the issue of the “best” diesel fuel was still a subject upon which there was little agreement at this time - matters remained very much in the experimental stage. Col. Bowden had his own “recommended” mixture, which he claimed to be suitable for diesel engines of all types, fixed compression or otherwise. The gallant Colonel had the bottle to run his fixed-compression engines (and others) on a fuel consisting of 50% ether, 40% road diesel oil and a mere 10% Castrol XXL! In his book, he admits to having had to alter the compression ratios of his fixed-compers to accommodate this fuel - hardly surprising, since they would be bound to run pretty hot with that proportion of high-calorie diesel oil! He also recommended against the use of petrol as a constituent of model diesel fuels - wise man!! The Owat on Test

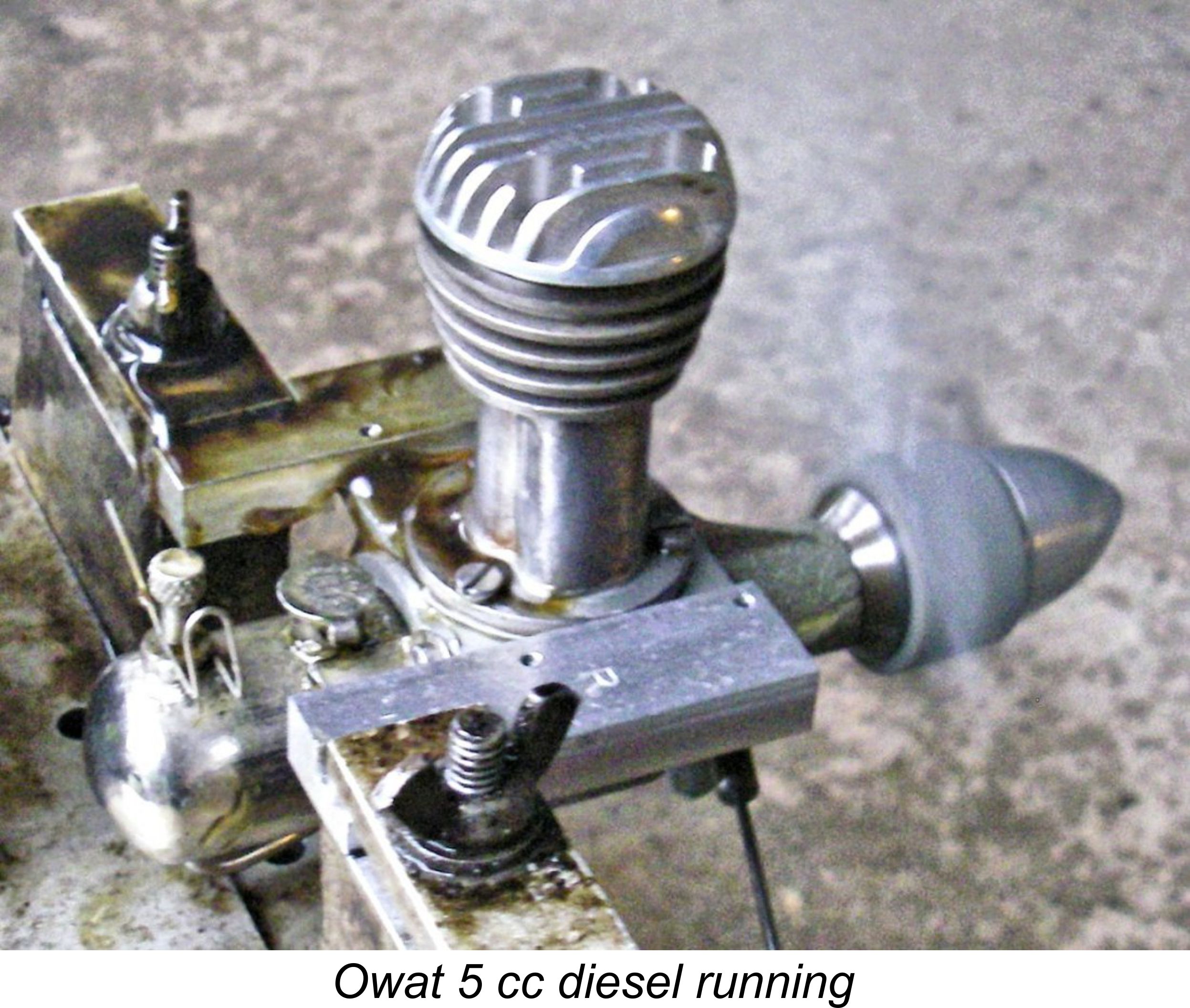

At the time in question, I had not made up the set of mounting beams which I now have on hand. Accordingly, for convenience of mounting and protection of the cases I ran both engines inverted in a conventional test stand of suitable height. This of course forced me to use a different needle valve and tank on the Owat. However, I was able to try the timer design by using the Micron with its tank as my test piece – the Owat tank would work in an identical manner. I couldn’t work up the bottle to try the Owat mix – I used my usual fixed-comp mix of 75% ether and 25% SAE 30 mineral oil, which worked perfectly. Both my notes and my recollections agree that both engines started quite readily. Once running, the smoothness of operation was very impressive indeed, with no trace of sagging. Although still quite stiff, the Owat seemed to have a performance that was quite comparable to that of the Micron, although I did not run any exhaustive comparative tests on that long-ago occasion. However, neither showed themselves to be as powerful as the American Drone which I tried at the same time.

However, all of this was in the dim and distant past! For the purposes of the present updated article, I decided that a re-test of the Owat would be well worthwhile. I had no intention of putting the old beastie through a protracted and arduous test – I just wanted to re-acquaint myself with its handling characteristics and relative performance levels. So perversely picking a day when it was both very cold and absolutely chucking with rain, I set up beneath the sundeck of my house in the ‘burbs. I figured that on such a day no-one would be outside anyway, and these things actually aren’t all that loud for their displacement. I elected to use previously-run Series II Owat no B29 once again for this test, keeping my NIB Series I example in what appears to be an unrun state. To provide a bench-mark as well as ensure that my batch of fuel was up to scratch, I also ran my faithful old Drone Mk. II no. 11899, which is always a dependable performer if the fuel is up to specification. If the Drone would run on this fuel, then any problems with the Owat would not be down to the fuel – one variable eliminated! I had actually run the Drone successfully on the same 75/25 ether/oil fuel batch only a month or two prior to the Owat test. I invariably weigh my cans of diesel fuel prior to storage, and a re-check of the weight of my residual fixed-compression brew prior to the present test confirmed that there had been essentially no loss of ether since the last time that fuel was drawn upon - my careful storage had paid off. Accordingly, I had no reason to expect any difficulties. As stated earlier, the manufacturers of the Owat recommended a 14x9 airscrew, which they claimed that the engine would turn at between 5,000 and 6,000 rpm. Not having such a prop on hand, I elected to begin with my usual 12x7 APC, which I have always found to be an excellent prop for bench-testing fixed compression diesels of this displacement. A 13x6 APC also works well. The very cold conditions were less than ideal for fixed compression operation, but even so the Drone started and ran as well as ever – in fact, it beat its previous best performance on the 12x7 APC prop, managing a smooth and effortless 6,400 rpm (~ 0.229 BHP) on this prop – a very spirited performance indeed! Perhaps it actually liked the cold conditions?!? As always, it ran superbly without sagging or missing a beat, also needling very well indeed. It certainly demonstrated that there was nothing wrong with the batch of fuel being used.

Another operational issue which the Owat shares with the Micron is the fact that the updraft intake makes it pretty well impossible to get any fuel into the engine by choking alone – it just drips out of the intake. I found that a small cylinder prime was necessary, something which is never required with the Drone thanks to its upright intake. After trying for a while with some rather unenthusiastic firing but no actual start, I ended up fitting a 14x6 APC prop to get some extra flywheel which would carry the engine over several compression strokes on each flick. I also applied the oil injection technique recommended by the manufacturers, using Dura-Lube upper cylinder lubricant. This did the trick – the engine quickly fired up and kept going, running a touch lean as usual until I opened the needle a little.

This being the case, how did the cut-off work on this occasion? Well, my old notes did not lie! The cut-off was extremely effective – as soon as it was triggered, the engine stopped very cleanly almost immediately – no messing about whatsoever! I was actually very impressed with the efficiency of this device – one of the best that I’ve tried. Frankly, I would not have expected it to work as well as it did! After a few shake-down runs on the 14x6 to free things up a little more, I tried a few slightly faster props. Starting proved to be no problem now that the engine was clear of storage residues as well as being a little more freed-up, and the Owat fired up very readily on the two 12 inch diameter props that I tried. It ran extremely smoothly on both props, showing no signs of entering the under-compressed condition at any time. It managed 5,800 rpm on the 12x7 (~ 0.170 BHP) and 6,000 rpm on the 12x6 (~0.176 BHP). These figures suggest that it was approaching its peak at around 6,000 rpm – I would guess that it might manage 0.180 BHP @ 6,200 rpm if further running-in and testing were undertaken. However, at this point the dreadful weather drove me indoors!

To put these performances into their 1946 context, it’s worth noting that the 1947 British ETA 5 variable compression 5 cc diesel was found to develop 0.181 BHP at 6,250 rpm during its 1948 test by Lawrence Sparey. Clearly as of 1946/47 both the Owat and Micron were very much in the hunt ……… The above figures suggest that the Owat is all about torque at the lower speeds. A “fast” 14x9 prop would in all likelihood have been a very well-matched load in actual flying service. Using such a prop, the manufacturers claimed that the Owat was “capable of flying a 5’ 0” to 8’ 0” wing span plane with ease”. Based on the measured performance, I see no reason to doubt this claim - those big props move a lot of air! The model would not be fast, but it would get up there! Overall, I was very favorably impressed with the Owat. It came across as a well-made unit which started easily and performed flawlessly. In the context of the 1946 power modelling scene, there was nothing wrong with its performance either. For me, the fact that it seems to have served at least some of its purchasers very well now comes as no surprise at all. Conclusion The fact that the Owat was pretty much an unashamed copy of the Micron 5 cc fixed-compression diesel effectively places it in the “replica” category, notwithstanding the fact that it was never promoted as such. This must surely establish its claim to be one of the earliest commercial replicas of them all! Both its wholesale adoption of the Micron design and its production to such a high engineering standard represent a clear case of flattery of the Micron design - why change a good thing?!?

The tragedy of the Owat (if it deserves that rather Shakespearian term) is that the fixed-compression era into which it was launched was so short-lived that in order to survive Modella Engines would very soon have had to completely revise the engine’s design to incorporate variable compression, or alternatively to develop an entirely new model. The fact that they did not do so suggests that they found the profits available from small-scale model engine production to be insufficient to justify continuation. Whatever the reason for their decision to abandon the field, the ultimate fate of the company remains unknown at this time. Anyway, there it is - another British lump with an interesting story to tell. I only wish that I could tell more of it! If anyone out there has further information, please share it with us! All contributions gratefully and openly acknowledged..... ____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN November 2008 Revised edition published here January 2015 |

| |

In this article, we take a close look at the Owat 5 cc (0.302 cuin.) diesel, incorrectly spelled Owatt by the late O. F. W. Fisher in his well-known “

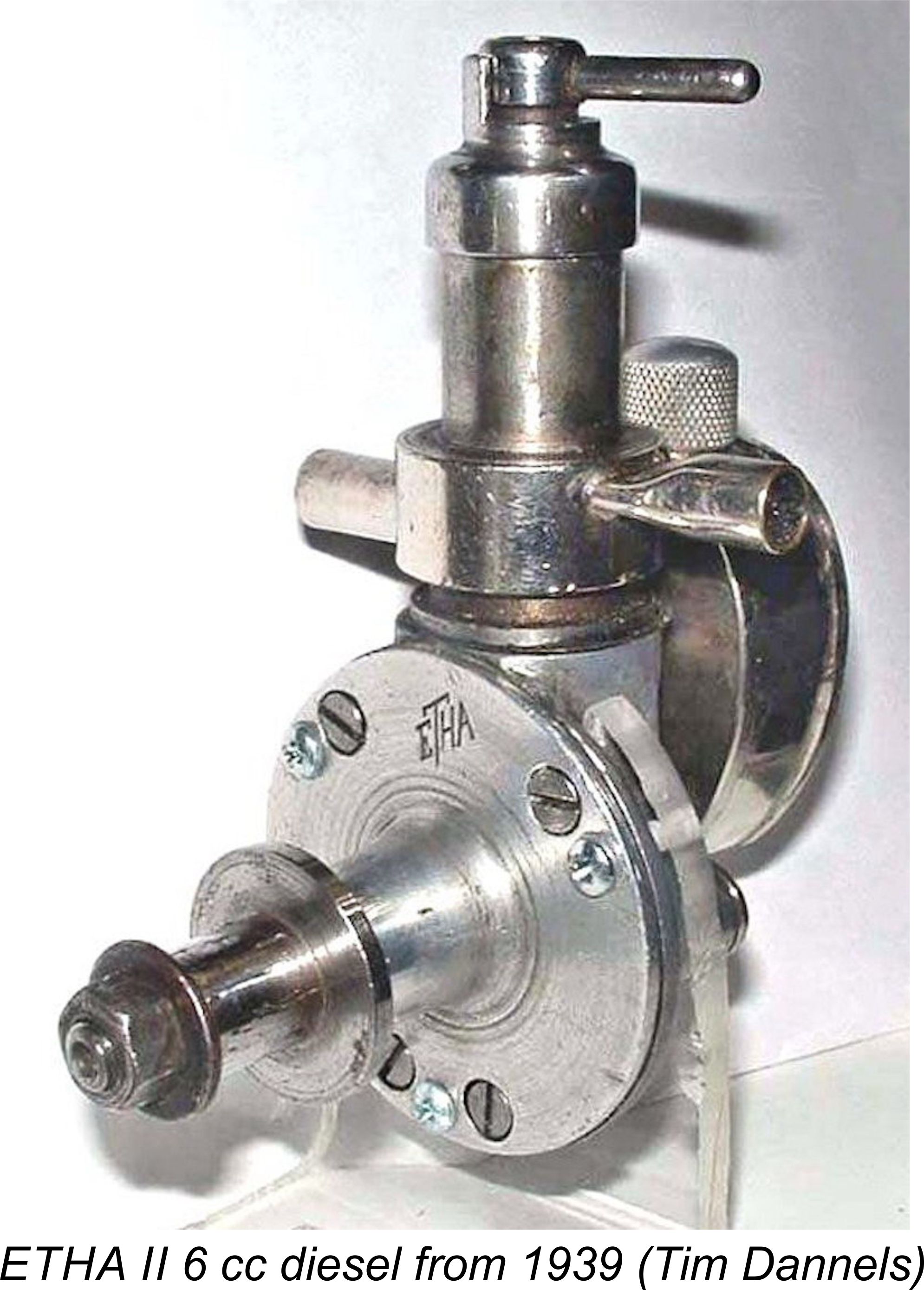

In this article, we take a close look at the Owat 5 cc (0.302 cuin.) diesel, incorrectly spelled Owatt by the late O. F. W. Fisher in his well-known “ Power modelling had become well established in pre-war Britain using the spark ignition engines which were all that were available at that time. Although the model diesel (or more properly, compression ignition) engine had its commercial origins in 1938 with the Swiss ETHA engines, the technology had not spread to Britain prior to the September 1939 onset of WW2. Consequently, the model diesel engine is properly seen as a pre-war European development which underwent further refinement during the war years, primarily in those countries which were uninvolved in the active hostilities either by virtue of neutrality or through forced occupation. Given the later stature of the United Kingdom as a nation of die-hard model diesel producers and users, it's a bit of a surprise to realize that Britain was very much a Johnny-come-lately in the model diesel design sweepstakes.

Power modelling had become well established in pre-war Britain using the spark ignition engines which were all that were available at that time. Although the model diesel (or more properly, compression ignition) engine had its commercial origins in 1938 with the Swiss ETHA engines, the technology had not spread to Britain prior to the September 1939 onset of WW2. Consequently, the model diesel engine is properly seen as a pre-war European development which underwent further refinement during the war years, primarily in those countries which were uninvolved in the active hostilities either by virtue of neutrality or through forced occupation. Given the later stature of the United Kingdom as a nation of die-hard model diesel producers and users, it's a bit of a surprise to realize that Britain was very much a Johnny-come-lately in the model diesel design sweepstakes. One of the most significant engines developed during the war years was the Micron 5 cc fixed compression diesel, which first appeared in occupied France during 1943. This model was of course developed during the Nazi occupation of that country when the French homeland had yet to resume the battleground role into which later events were to propel it once more.

One of the most significant engines developed during the war years was the Micron 5 cc fixed compression diesel, which first appeared in occupied France during 1943. This model was of course developed during the Nazi occupation of that country when the French homeland had yet to resume the battleground role into which later events were to propel it once more.

Consequently, the majority of British modellers wishing to acquire a model engine during this period were forced either to make their own or to seek a suitable model on the domestic market, such as it was at the time. There was a dawning awareness of the application of compression ignition to model engines, but what really set that particular ball rolling was the late 1945 appearance of an article by pioneer British diesel experimenter and later “Aeromodeller” magazine engine tester Lawrence H. Sparey. This article appeared in the December 1945 issue of “Aeromodeller” under the title “The Gen on Diesel Engines”. It proved to be highly influential in stimulating the development of model diesels in Britain.

Consequently, the majority of British modellers wishing to acquire a model engine during this period were forced either to make their own or to seek a suitable model on the domestic market, such as it was at the time. There was a dawning awareness of the application of compression ignition to model engines, but what really set that particular ball rolling was the late 1945 appearance of an article by pioneer British diesel experimenter and later “Aeromodeller” magazine engine tester Lawrence H. Sparey. This article appeared in the December 1945 issue of “Aeromodeller” under the title “The Gen on Diesel Engines”. It proved to be highly influential in stimulating the development of model diesels in Britain.

One approach to this challenge was of course to skip the developmental phase entirely by simply copying an established design rather than starting from scratch. Among the companies which elected to adopt this latter approach from the outset was Modella Engines (Bradford) Ltd. of 42-44 Bridge Street in Bradford, Yorkshire, just west of Leeds, makers of the Owat 5 cc diesel which forms our main subject.

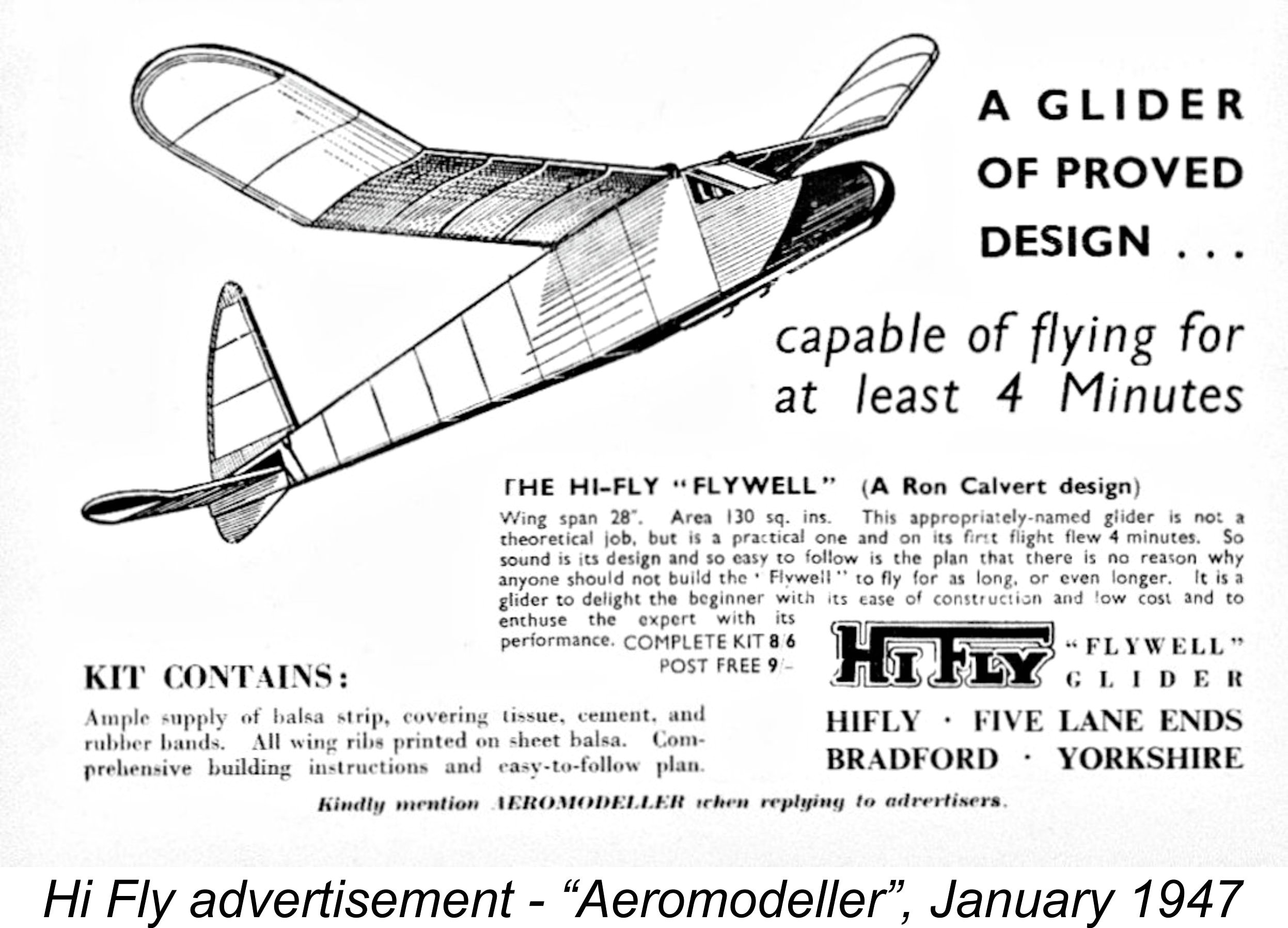

One approach to this challenge was of course to skip the developmental phase entirely by simply copying an established design rather than starting from scratch. Among the companies which elected to adopt this latter approach from the outset was Modella Engines (Bradford) Ltd. of 42-44 Bridge Street in Bradford, Yorkshire, just west of Leeds, makers of the Owat 5 cc diesel which forms our main subject.  As of the early post-war period, Bradford was one of Northern England’s most active aeromodelling centres. The thriving Bradford Model Aero Club (Bradford MAC) boasted such leading Northern Area competitors as Silvio Lanfranchi, Norman Lees and Ron Calvert among its members. The pioneering kit manufacturer Hi Fly was also based in Bradford at Five Lane Ends, producing several of Ron Calvert’s very successful designs in kit form. The town’s retail needs were served by Bradford Aero Model Co. Ltd. of 79 Godwin Street. Both of these latter two firms advertised nationally in “Aeromodeller”.

As of the early post-war period, Bradford was one of Northern England’s most active aeromodelling centres. The thriving Bradford Model Aero Club (Bradford MAC) boasted such leading Northern Area competitors as Silvio Lanfranchi, Norman Lees and Ron Calvert among its members. The pioneering kit manufacturer Hi Fly was also based in Bradford at Five Lane Ends, producing several of Ron Calvert’s very successful designs in kit form. The town’s retail needs were served by Bradford Aero Model Co. Ltd. of 79 Godwin Street. Both of these latter two firms advertised nationally in “Aeromodeller”.  Bradford MAC. However, there's no way of establishing this one way or another unless someone as knows summat steps oop ta t’ wicket................

Bradford MAC. However, there's no way of establishing this one way or another unless someone as knows summat steps oop ta t’ wicket................  The prototype version of the Leesil had a sand-cast case. The planned series production version featured a die-cast crankcase along with a number of other refinements which set it well apart from the Dyno–based version. Production of this variant was entrusted to a precision engineering firm in Baildon, Yorkshire, a little to the north of Bradford. However, this firm experienced difficulties in producing the engines to the required standard of precision, forcing the early abandonment of this version of the engine and leaving Wilkinson to make a very limited number of examples of the original Dyno-based model as well as an RRV variant before abandoning the project in the latter part of 1947, more or less at the same time as the termination of Owat production, as we shall see. Bradford’s reign as a Northern centre of model engine manufacture was thus very short!

The prototype version of the Leesil had a sand-cast case. The planned series production version featured a die-cast crankcase along with a number of other refinements which set it well apart from the Dyno–based version. Production of this variant was entrusted to a precision engineering firm in Baildon, Yorkshire, a little to the north of Bradford. However, this firm experienced difficulties in producing the engines to the required standard of precision, forcing the early abandonment of this version of the engine and leaving Wilkinson to make a very limited number of examples of the original Dyno-based model as well as an RRV variant before abandoning the project in the latter part of 1947, more or less at the same time as the termination of Owat production, as we shall see. Bradford’s reign as a Northern centre of model engine manufacture was thus very short!  In his ground-breaking book “

In his ground-breaking book “ The nominal bore and stroke measurements for the Micron are 17.00 mm x 22.00 mm for a displacement of 4.99 cc – near enough to the numbers for the Owat as makes no difference. The general design arrangement is also very similar indeed. However, there are many differences between the two models which make identification pretty straightforward if you know what to look for.

The nominal bore and stroke measurements for the Micron are 17.00 mm x 22.00 mm for a displacement of 4.99 cc – near enough to the numbers for the Owat as makes no difference. The general design arrangement is also very similar indeed. However, there are many differences between the two models which make identification pretty straightforward if you know what to look for.  On many examples of the Owat such as that illustrated here, the metal fuel line is plated in the same manner as the tank. Somewhat unusually, the fuel line is soldered at both ends to the tank and spraybar respectively. This means that as supplied, you have to use the tank provided with the Owat to run it. And that in turn dictates an upright mounting position since the tank only works in that position. Moreover, the fact that the tank is hard-wired to the spraybar means that, unlike that of the Micron, it cannot be remounted at 180 degrees for inverted running unless the fuel line is unsoldered and completely re-configured.

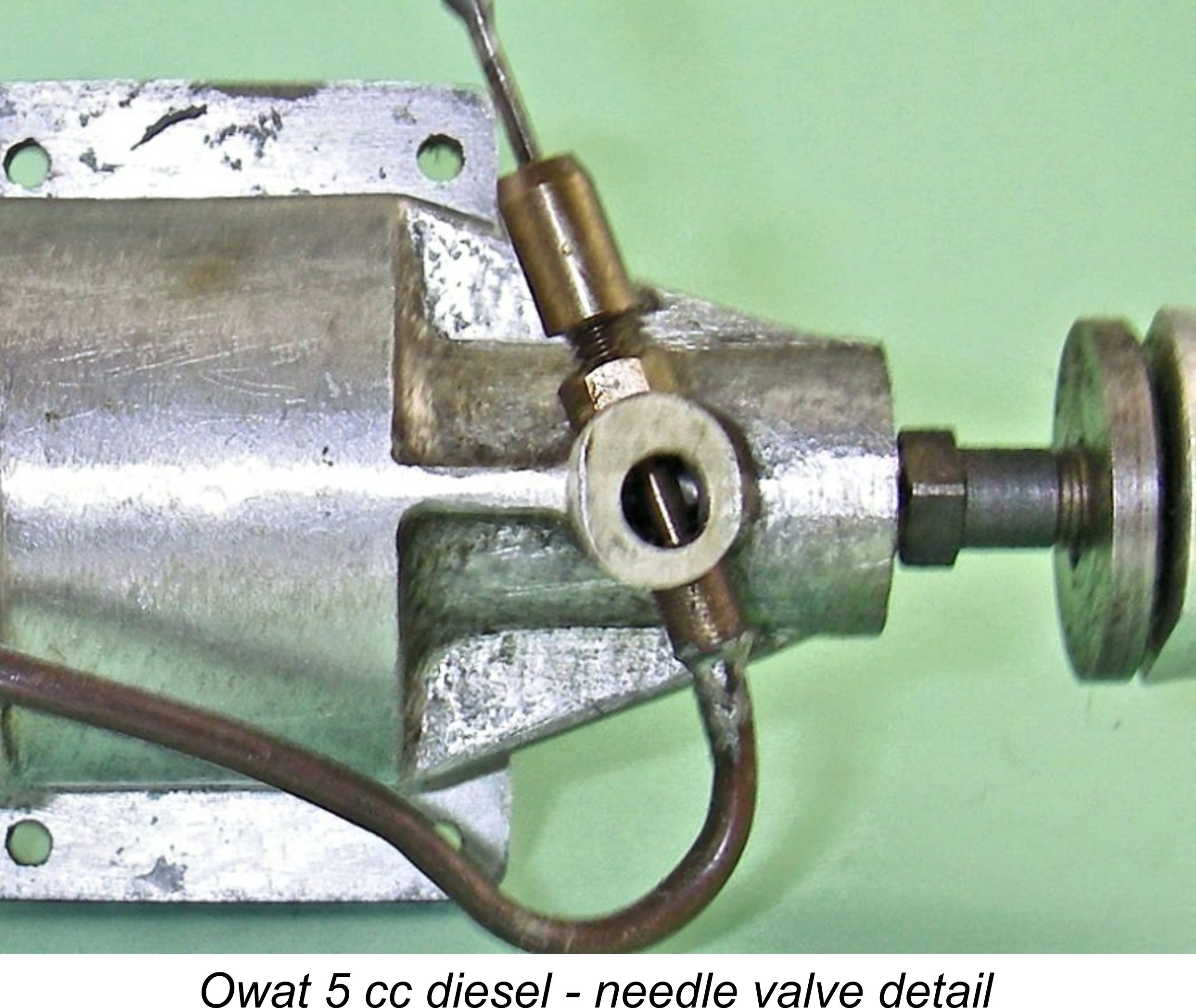

On many examples of the Owat such as that illustrated here, the metal fuel line is plated in the same manner as the tank. Somewhat unusually, the fuel line is soldered at both ends to the tank and spraybar respectively. This means that as supplied, you have to use the tank provided with the Owat to run it. And that in turn dictates an upright mounting position since the tank only works in that position. Moreover, the fact that the tank is hard-wired to the spraybar means that, unlike that of the Micron, it cannot be remounted at 180 degrees for inverted running unless the fuel line is unsoldered and completely re-configured.  Another obvious distinction between the two engines is the very different approach to the tensioning of the needle. Both models use an externally threaded steel needle in conjunction with an internally-threaded brass spraybar. However, the similarities end there. The Owat uses the same system found on many racing engines - the needle end of the spraybar is split, needle tension being provided by a stationary thimble which screws onto the external spraybar installation thread and pinches the split onto the needle thread in doing so. This thimble in effect acts as a gland nut, remaining stationary as the needle is turned. The needle has a spring extension with a small brass control knob at the outer end.

Another obvious distinction between the two engines is the very different approach to the tensioning of the needle. Both models use an externally threaded steel needle in conjunction with an internally-threaded brass spraybar. However, the similarities end there. The Owat uses the same system found on many racing engines - the needle end of the spraybar is split, needle tension being provided by a stationary thimble which screws onto the external spraybar installation thread and pinches the split onto the needle thread in doing so. This thimble in effect acts as a gland nut, remaining stationary as the needle is turned. The needle has a spring extension with a small brass control knob at the outer end.

However, the method of mounting the prop driver is different on the Series II Owat engines. These models, of which illustrated engine number B29 is an example, feature a thicker prop driver which is internally and externally tapered from the rear. This driver engages with a matching taper machined into the front of the shaft at the point where the diameter is reduced in front of the main bearing. The revised system appears to be the more dependable – no stress-raiser in the shaft and no interlocking to work loose by fretting. The knurling on the gripping face of the Owat driver is far coarser and probably more effective than that of the Micron.

However, the method of mounting the prop driver is different on the Series II Owat engines. These models, of which illustrated engine number B29 is an example, feature a thicker prop driver which is internally and externally tapered from the rear. This driver engages with a matching taper machined into the front of the shaft at the point where the diameter is reduced in front of the main bearing. The revised system appears to be the more dependable – no stress-raiser in the shaft and no interlocking to work loose by fretting. The knurling on the gripping face of the Owat driver is far coarser and probably more effective than that of the Micron.  The late O. F. W. Fisher stated on page 28 of his well-known “Collector’s Guide to Model Engines“ that most of the Owat engines had red-painted cases. In fact, this observation seems to have applied mainly to the Series II models, although I have to say that neither of my examples shows any evidence of ever having been painted at all. Neither engine appears ever to have been mounted in a model – in fact, I would judge them both to be almost unused. So I doubt that the paint has worn off or been removed.

The late O. F. W. Fisher stated on page 28 of his well-known “Collector’s Guide to Model Engines“ that most of the Owat engines had red-painted cases. In fact, this observation seems to have applied mainly to the Series II models, although I have to say that neither of my examples shows any evidence of ever having been painted at all. Neither engine appears ever to have been mounted in a model – in fact, I would judge them both to be almost unused. So I doubt that the paint has worn off or been removed. Accordingly, I’d say that Fisher may well have had some basis for making his statement - perhaps many or even most of these engines did indeed have red cases. Mike Clanford repeats this assertion for the Series II variant in his well-known and very useful but often unreliable “A-Z” book. Incidentally, my own illustrated unpainted NIB example of the Series I Owat (number ST45) is the actual example illustrated in Clanford’s book on page 158 - a number of clearly-visible incidental markings confirm this beyond any possible doubt. The impressive collection illustrated in Clanford’s book is now spread out all over the world - I have a number of other examples myself and am aware of the locations of quite a few more!

Accordingly, I’d say that Fisher may well have had some basis for making his statement - perhaps many or even most of these engines did indeed have red cases. Mike Clanford repeats this assertion for the Series II variant in his well-known and very useful but often unreliable “A-Z” book. Incidentally, my own illustrated unpainted NIB example of the Series I Owat (number ST45) is the actual example illustrated in Clanford’s book on page 158 - a number of clearly-visible incidental markings confirm this beyond any possible doubt. The impressive collection illustrated in Clanford’s book is now spread out all over the world - I have a number of other examples myself and am aware of the locations of quite a few more!  The attached comparison views show this cut-off in both running and stopped positions. Col. Bowden criticized this type of device on page 120 of his 1947 first edition on the grounds that there were few timing devices with the power to operate it! There’s no doubt that it takes a pretty good tug on the arm to activate the cut-off - the plunger spring is quite strong.

The attached comparison views show this cut-off in both running and stopped positions. Col. Bowden criticized this type of device on page 120 of his 1947 first edition on the grounds that there were few timing devices with the power to operate it! There’s no doubt that it takes a pretty good tug on the arm to activate the cut-off - the plunger spring is quite strong.  similarity to the Micron 5 cc model, also mentioning the fact that at his time of writing he had an Owat installed in the previously-mentioned large low-wing monoplane.

similarity to the Micron 5 cc model, also mentioning the fact that at his time of writing he had an Owat installed in the previously-mentioned large low-wing monoplane.

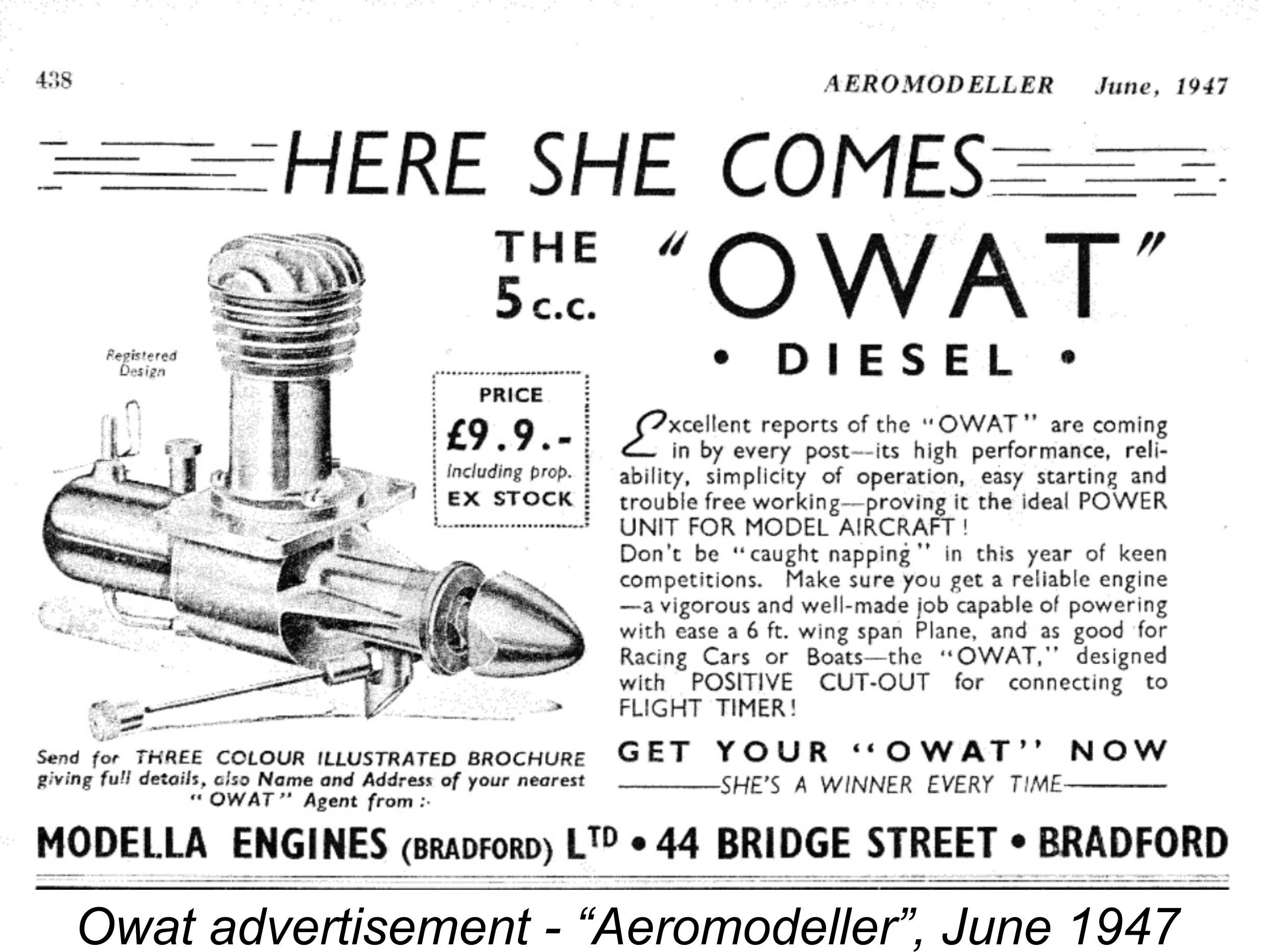

An Owat advertisement placed in the June 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller” quoted a selling price of 9 guineas (£9 9s 0d, or £9.45). This is presumably the figure at which the engine had been sold throughout its eleven month market tenure at that time - a very steep price indeed at a time when a man earning £8 per week before taxes would have been considered well off! It would be equivalent to at least $900 today……try that one on the wife!!

An Owat advertisement placed in the June 1947 issue of “Aeromodeller” quoted a selling price of 9 guineas (£9 9s 0d, or £9.45). This is presumably the figure at which the engine had been sold throughout its eleven month market tenure at that time - a very steep price indeed at a time when a man earning £8 per week before taxes would have been considered well off! It would be equivalent to at least $900 today……try that one on the wife!!  publication. This particular Owat ad included some rather impressive claims for the standard engine’s performance, a speed of 68 mph in a model car being quoted. By 1947 British standards, this was some going for a 5 cc model car! The ad also confirmed that there was a “super” version which was fitted with a clutch and flywheel and which was claimed to produce even higher performance. The presence of a clutch implies pretty clearly that this version was specifically intended for model car use.

publication. This particular Owat ad included some rather impressive claims for the standard engine’s performance, a speed of 68 mph in a model car being quoted. By 1947 British standards, this was some going for a 5 cc model car! The ad also confirmed that there was a “super” version which was fitted with a clutch and flywheel and which was claimed to produce even higher performance. The presence of a clutch implies pretty clearly that this version was specifically intended for model car use.  Designers of fixed-compression model diesels faced an inescapable dilemma which severely limited the potential performance of such engines. To begin with, it’s obvious that the fixed compression ratio had to be set at a level which would guarantee that the auto-ignition temperature of the fuel would be reached in the cylinder during cold hand-starting. However, the ratio had to be set at very little more than that in order to minimize difficulties with backfiring and flooding during starting.

Designers of fixed-compression model diesels faced an inescapable dilemma which severely limited the potential performance of such engines. To begin with, it’s obvious that the fixed compression ratio had to be set at a level which would guarantee that the auto-ignition temperature of the fuel would be reached in the cylinder during cold hand-starting. However, the ratio had to be set at very little more than that in order to minimize difficulties with backfiring and flooding during starting.  As far as the airscrew for the Owat goes, the manufacturers recommended a 14x9 prop. This seems to be a reasonable recommendation, although to be on the safe side it’s usually best to begin with a lighter-than-recommended load. You can’t harm such an engine by under-propping it – once the engine runs past the speed for which its ignition timing is optimized, it will simply become under-compressed and refuse to run much faster. Under-compression won't hurt anything! However, over-propping can lead to the engine running in a pre-ignition condition which will impose greatly amplified stresses upon the working components. I’ve found that a 12x7 APC prop is a safe starting point for testing the average 1940’s-vintage 5 cc fixed compression diesel.

As far as the airscrew for the Owat goes, the manufacturers recommended a 14x9 prop. This seems to be a reasonable recommendation, although to be on the safe side it’s usually best to begin with a lighter-than-recommended load. You can’t harm such an engine by under-propping it – once the engine runs past the speed for which its ignition timing is optimized, it will simply become under-compressed and refuse to run much faster. Under-compression won't hurt anything! However, over-propping can lead to the engine running in a pre-ignition condition which will impose greatly amplified stresses upon the working components. I’ve found that a 12x7 APC prop is a safe starting point for testing the average 1940’s-vintage 5 cc fixed compression diesel. By the time the instruction sheet for Series I engine number ST45 was printed, the manufacturers had revised their views on fuel somewhat. The original instruction sheet was amended through the use of a stick-on replacement panel which covered the former fuel recommendation. This stick-on panel included the interesting statement that “In view of the difficulty in obtaining petrol for “OWAT” fuel, we have carried out many experiments and have evolved the following mixture as an alternative to the original formula”. It’s clear from this that the manufacturers had been quite serious in their initial recommendation that the engine be operated on the previously-noted oil-starved gasoline-based fuel!! The mind boggles ………..

By the time the instruction sheet for Series I engine number ST45 was printed, the manufacturers had revised their views on fuel somewhat. The original instruction sheet was amended through the use of a stick-on replacement panel which covered the former fuel recommendation. This stick-on panel included the interesting statement that “In view of the difficulty in obtaining petrol for “OWAT” fuel, we have carried out many experiments and have evolved the following mixture as an alternative to the original formula”. It’s clear from this that the manufacturers had been quite serious in their initial recommendation that the engine be operated on the previously-noted oil-starved gasoline-based fuel!! The mind boggles ………..  The presence of a significant proportion of highly inflammable solvent in the Redex additive which was available at the time in question is underscored by the fact that the manufacturers recommended priming the engine with straight Redex rather than fuel mixture when attempting a cold start! Pretty inflammable stuff, it would seem…………it would be nice to know what that solvent actually was! In all likelihood it was naphtha, which was still used in later Redex formulations.

The presence of a significant proportion of highly inflammable solvent in the Redex additive which was available at the time in question is underscored by the fact that the manufacturers recommended priming the engine with straight Redex rather than fuel mixture when attempting a cold start! Pretty inflammable stuff, it would seem…………it would be nice to know what that solvent actually was! In all likelihood it was naphtha, which was still used in later Redex formulations.  Many years ago now at the very beginning of my fixed-compression operational career, I ran both my near-unused Series II Owat no. B29 and my well run-in example of the Micron, using suitable protection for the lugs to keep them from being marred. Although these comparative tests took place in the dim and distant past, the modelling log books which I have kept more or less since I started modelling preserve the detailed notes recording my findings.

Many years ago now at the very beginning of my fixed-compression operational career, I ran both my near-unused Series II Owat no. B29 and my well run-in example of the Micron, using suitable protection for the lugs to keep them from being marred. Although these comparative tests took place in the dim and distant past, the modelling log books which I have kept more or less since I started modelling preserve the detailed notes recording my findings.  Somewhat surprisingly, my notes state that the Micron’s fuel cut-off worked very well! I say surprisingly because the fact that fixed compression diesels will keep running on a very lean mixture, albeit with a lot of smoke and misfiring, would logically imply that it might take three or four seconds for the engine to drain the fuel line to the point where it stopped altogether. Despite this, the notes were clear – the timer was very effective in operation.

Somewhat surprisingly, my notes state that the Micron’s fuel cut-off worked very well! I say surprisingly because the fact that fixed compression diesels will keep running on a very lean mixture, albeit with a lot of smoke and misfiring, would logically imply that it might take three or four seconds for the engine to drain the fuel line to the point where it stopped altogether. Despite this, the notes were clear – the timer was very effective in operation.  Then it was the turn of the Owat. In order to mount it in the conventional test stand which I was using, I had to use the custom-fitted pair of mounting beams which I had made up for this engine and its Micron cousin. Unlike the Drone, this engine had not been run for many years, consequently being a bit encumbered with storage oil. In addition, it actually remains a bit on the tight side – it appears to have had little or no running in the past apart from my own rather limited testing of years ago. I cleared out the storage residues as best I could, but that first start of the rather stiff engine still proved a little elusive. No doubt the very cold weather didn’t help in this regard.

Then it was the turn of the Owat. In order to mount it in the conventional test stand which I was using, I had to use the custom-fitted pair of mounting beams which I had made up for this engine and its Micron cousin. Unlike the Drone, this engine had not been run for many years, consequently being a bit encumbered with storage oil. In addition, it actually remains a bit on the tight side – it appears to have had little or no running in the past apart from my own rather limited testing of years ago. I cleared out the storage residues as best I could, but that first start of the rather stiff engine still proved a little elusive. No doubt the very cold weather didn’t help in this regard.  Once running on the 14x6 at the optimum needle setting (1 turn even), the Owat performed flawlessly. Running was smooth and mis-free, with a very clean exhaust and no trace of sagging as things warmed up. The needle proved to be highly responsive without being overly sensitive, making the optimum setting very easy to establish. The engine turned the massive 14x6 prop at an effortless 5,100 rpm (~ 0.154 BHP) and seemed ready to do so all day if required. However, the tank only gave a run of around 3 minutes. Still, this is of course way more than required for free flight service, making the cut-off very necessary.

Once running on the 14x6 at the optimum needle setting (1 turn even), the Owat performed flawlessly. Running was smooth and mis-free, with a very clean exhaust and no trace of sagging as things warmed up. The needle proved to be highly responsive without being overly sensitive, making the optimum setting very easy to establish. The engine turned the massive 14x6 prop at an effortless 5,100 rpm (~ 0.154 BHP) and seemed ready to do so all day if required. However, the tank only gave a run of around 3 minutes. Still, this is of course way more than required for free flight service, making the cut-off very necessary. On the last occasion on which I ran my well freed-up Micron 5 cc model, it delivered 6,200 rpm on the same 12x6 APC prop (~ 0.196 BHP). While this is a little better than the figure achieved by the still-tight Owat, it’s clear that the performance of fully run-in examples of the two engines would be very similar indeed, just as we would expect. However, neither of them can match the Drone.

On the last occasion on which I ran my well freed-up Micron 5 cc model, it delivered 6,200 rpm on the same 12x6 APC prop (~ 0.196 BHP). While this is a little better than the figure achieved by the still-tight Owat, it’s clear that the performance of fully run-in examples of the two engines would be very similar indeed, just as we would expect. However, neither of them can match the Drone.  Modella Engines’ attempt to produce a worthy replica of the Micron succeeded completely, the result being a very well-made and highly serviceable British-made equivalent. The effort that clearly went into its manufacture certainly justified better commercial success than the engine seems to have achieved.

Modella Engines’ attempt to produce a worthy replica of the Micron succeeded completely, the result being a very well-made and highly serviceable British-made equivalent. The effort that clearly went into its manufacture certainly justified better commercial success than the engine seems to have achieved.