|

|

The Yin Yan/Silver Swallow Diesel Story "This is engine we have made for you and is the engine you will use." So say the quaintly translated instructions, and who are we to say no? Jokes about the Command Economy, Communism and aeromodelling by numbers aside, the classic Yin Yan/Silver Swallow models from Red China are nice little engines with an amazingly long and unexpectedly interesting history, complete with traps and pit-falls.

Even so, this is a sufficiently interesting tale that I continue to believe that it fully merits a more in-depth article. The other motivation is the fact that although out of production for a good few years now, these engines remain widely available at reasonable cost on eBay and elsewhere. This makes them a good choice for someone wanting a relatively inexpensive and (dare I say it) "expendable" classic model diesel to use in a particular application. That being the case, a source of comprehensive information about them should have value to prospective purchasers. The following text represents my attempt to fulfill that requirement. But before getting started, I’d like to express my very sincere thanks to my late and much-missed friend Ed Carlson of Carlson Engine Imports, former US Silver Swallow importer, for generously sharing his inside knowledge regarding the supply side of these engines from the mid 1980’s onwards. I'd also like to acknowledge the considerable assistance rendered by model marine engine collector Christian Farcy of France for providing invaluable information on the Silver Swallow marine offerings. Alan Strutt of England also provided some invaluable comments. Finally, I'd like to thank Steve Thomas of Australia for providing some additional dating information. With that pleasant obligation fulfilled, let’s begin at the beginning ........ Introduction The early history of aeromodelling and model engine manufacturing in China is perhaps more obscure than that of almost any other engine-producing nation. This is due both to the language barrier and the fact that at the time of which we will be speaking the nation remained under the tight control of the hard-line Communist regime, which kept all such activities completely invisible behind the Bamboo Curtain. Alan Strutt has done a fair bit of very useful research into the making of model aero engines in China during the classic era. This activity appears to have started in the 1950’s at the Shanghai Jiao Tong University and to have been further pursued at the Northwestern Polytechnical University at Xi'an from the late 1950’s onwards. Xi'an is the capital city of Shaanxi Province in Northwest China, very distant from Shanghai but not all that far from Chongqing where the T.Y.C. engines were manufactured in the late 1970's. There may be a connection ………….. My late friend and colleague Jim Dunkin also did some valuable research on this topic. As far as he was able to discover, it seems that in 1953 a facility called the Shang Jian factory was built in the town of Ju Cio in central China, with technical assistance from a number of Russian specialists. The primary purpose of this factory was to manufacture full-size piston engines for aircraft. A year or two after the establishment of this factory, it was assigned the additional task of producing limited numbers of model aero engines for the use of young Chinese individuals having a developing interest in aviation, an interest which the authorities wished to encourage. These engines were essentially copies of then-current Russian MK series diesels. They ranged in size from 1.5 cc up to 10 cc. Production at the Shang Jian factory was confined to the years 1954-58, after which the factory returned its full attention to full-sized aero engines, not to resume any involvement with model engines until 1978, when the Three Leaves range was launched. But that's another story ............ Following the withdrawal of the Shang Jian factory in 1958, the construction of model engines seems to have been continued by students at the Northwestern Polytechnical University, who were tasked with the design and construction of model engines for their own use and that of other Chinese modellers. The objective of these activities was apparently to maintain the availability of engines to Chinese competitors who would represent China’s interests at the various modelling meetings involving entrants from other communist countries. From the accounts that Alan Strutt has read, there doesn’t seem to have been any initial intention to sell the products on the open (Western) market.

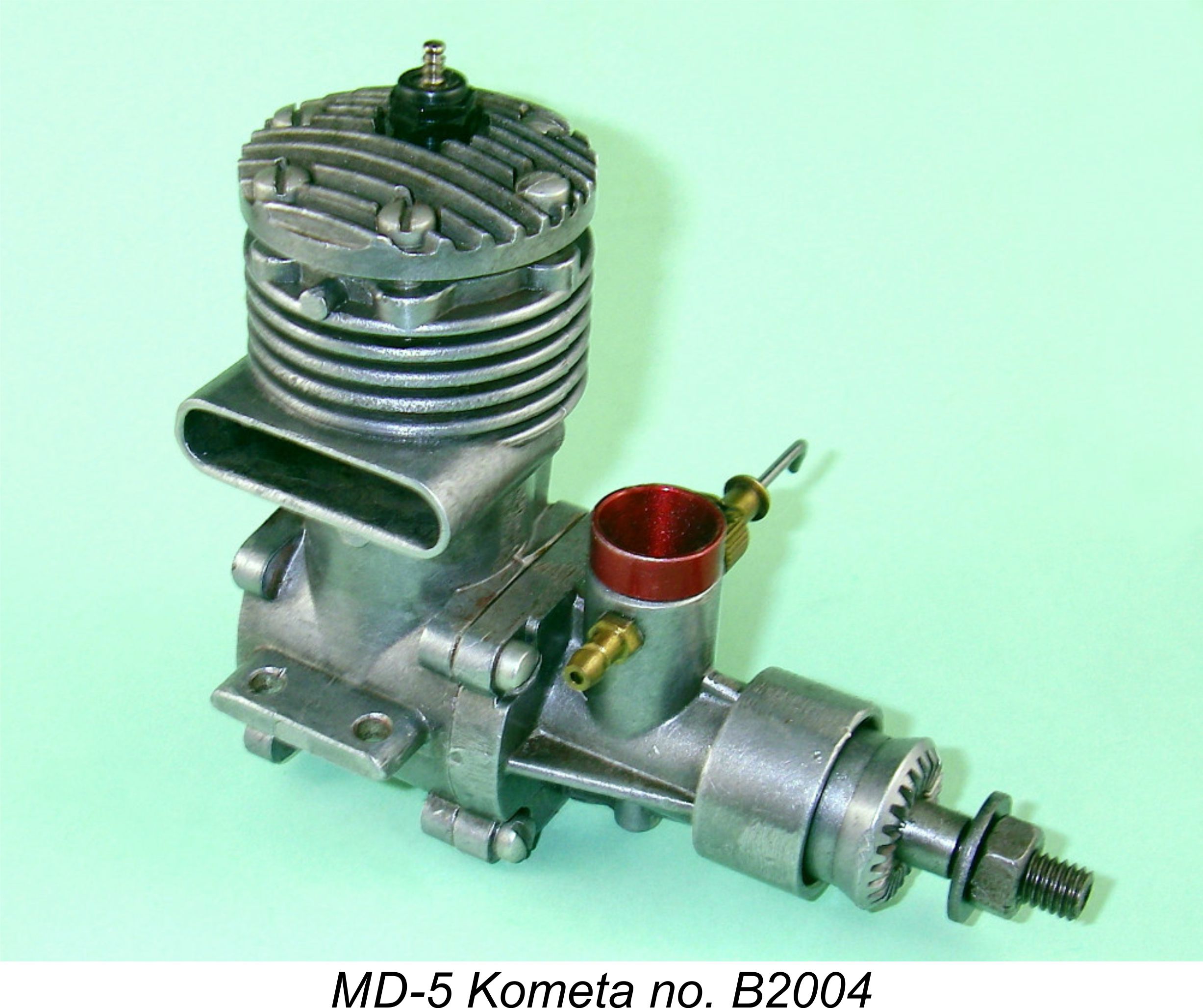

The products of this factory were initially sold at open international marketing venues such as Hong Kong, but export activity was subsequently expanded to other countries. The intention to market the engines in English-speaking countries is confirmed by the use of Latin-alphabet characters both on the boxes and on the engines themselves. Further confirmation comes from the inclusion of somewhat quaintly-worded English-language instructions. It was in 1963 that modellers in the world at large first became aware that commercial model engine manufacture was taking place in the People's Republic of China. In 1962, a number of good-quality Chinese-made model diesels had quietly made their appearance on the market in "open" ports like Hong Kong and Macau where they could readily be purchased by overseas visitors. These were the Yin Yan series of 2.47 cc model diesel engines, which were produced at the previously-mentioned factory in Shanghai. This was the first range of model diesels presently known to have been produced in the People's Republic of China on a commercial scale. It was certainly the first model engine marque to be exported from that country in commercial quantities. The target market for these engines at the time of their introduction may not have been confined to the export arena. The technological revolution was just beginning to be a factor in the planning of China’s long-term economic future, and the Chinese may have wanted a supply of home-grown model engines to be utilized in the encouragement of aeronautical and technical awareness among young Chinese at the school level. This approach had been successfully pursued by the Russians since 1957, possibly prompting the idealogically-aligned Chinese to follow suit. In terms of sheer numbers, the potential market arising from this concept alone was vast, even if they never sold a single engine outside of China. The Russian initiative had resulted in the appearance of mass-produced copies of noteworthy engines from beyond the Iron Curtain, including such offerings as the MD-5 Kometa, the MD-2.5 Meteor and the MK-12V, many of which ended up in the Soviet school system. The Chinese decision may possibly have been influenced by the earlier experience of their Russian ideological colleagues. Whether or not this is true, there can be no doubt that from the outset the Chinese envisioned these engines being distributed and used beyond the Bamboo Curtain! For one thing, the engines were clearly identified in Latin characters, complete with "Made in China" being proudly displayed along with the Yin Yan name. For another, an English (?!?) language translation of the instruction manual was quickly produced. This included such evocative gems as the starting direction to “Flip the propeller ....... and at the same time, turn the pressure adjusting rod with your left hand until you hear an explosive like sound “PA PA” bursting out from the engine”!! All such idiosyncacies aside, the intent of the instructions was clear enough, and they actually made a lot of sense. Their English was certainly far better than my Chinese!!

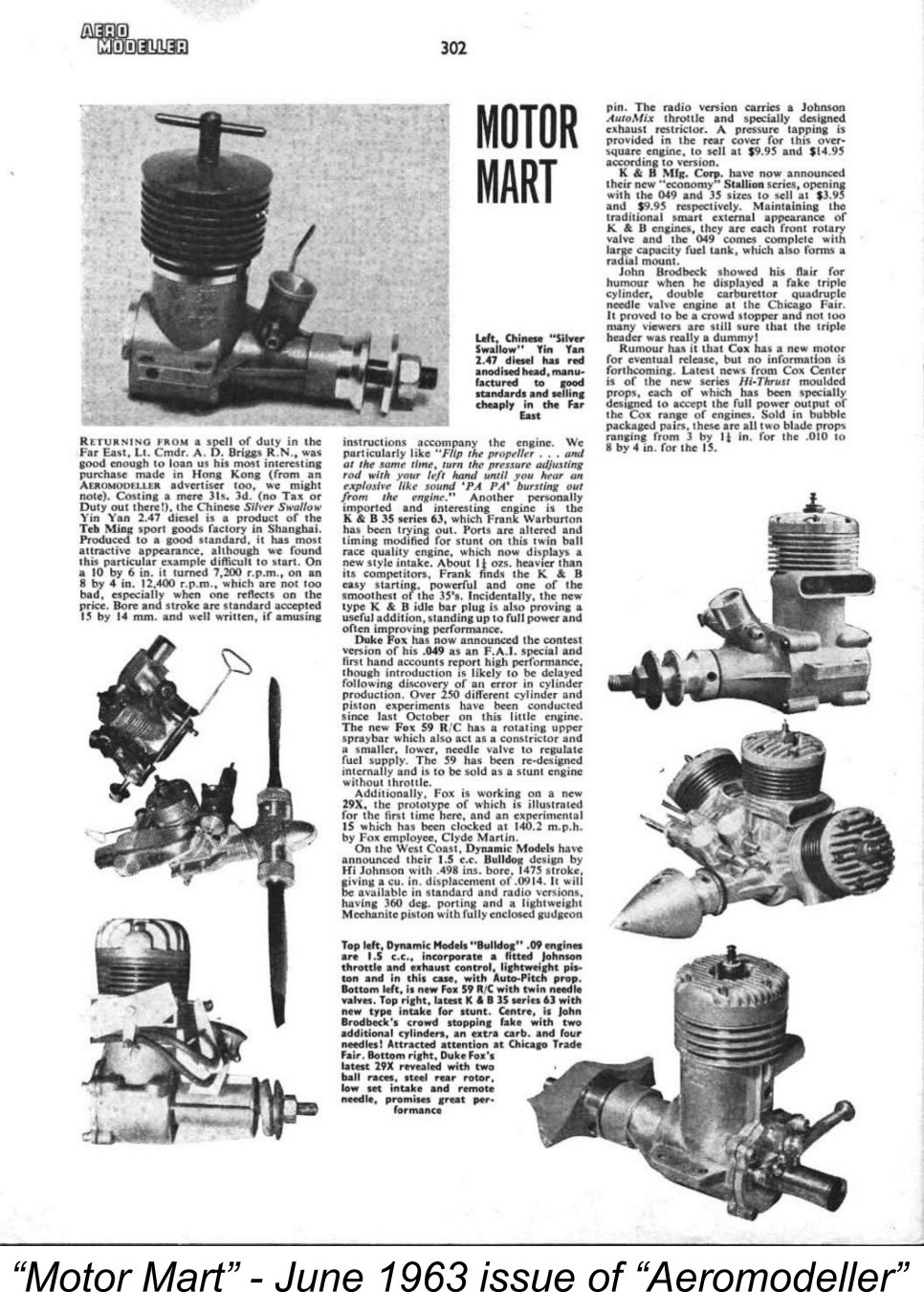

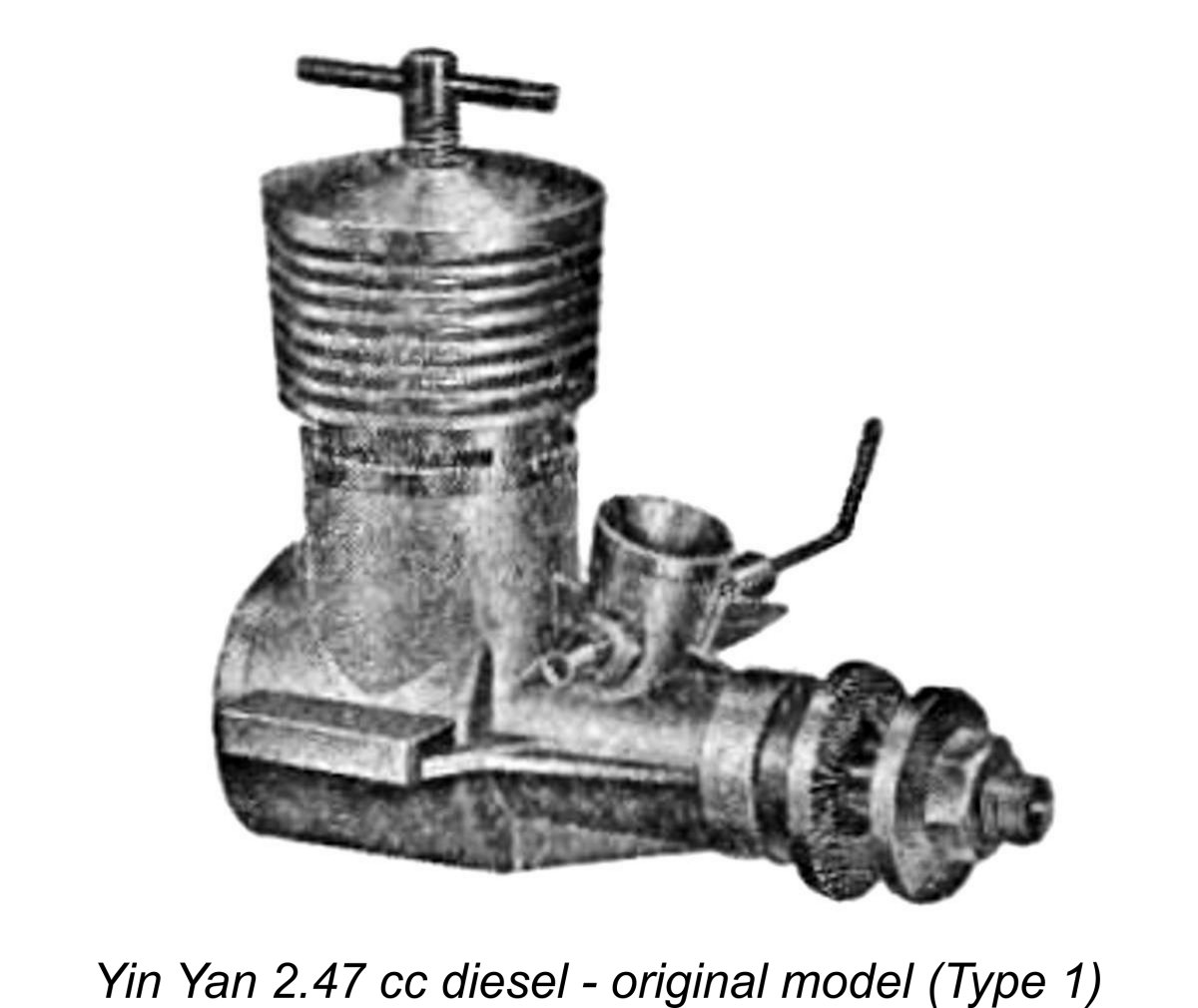

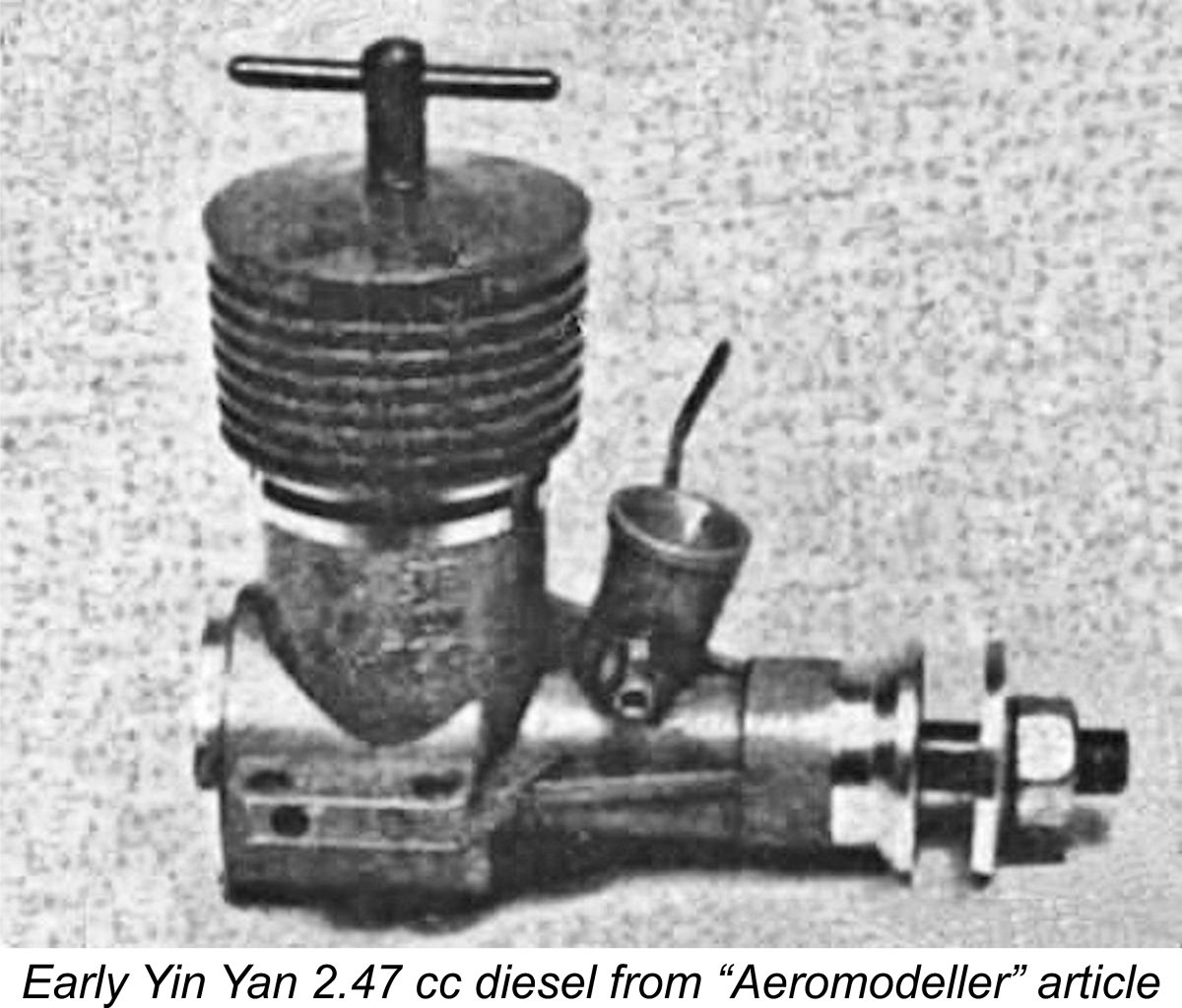

Inevitably, some of these units soon found their way back to Britain and elsewhere. One such purchaser was Lt. Cmdr. A. D. Briggs, R.N., who acquired his example of the Yin Yan 2.47 cc model in Hong Kong while on a tour of duty in the Far East. The price was a startlingly low 31s. 3d. (£1.56 in "modern" money), at least partially due to the absence of purchase tax and import duty in Hong Kong. Cmdr. Briggs was kind enough to send his purchase along to the offices of “Aeromodeller” magazine, resulting in the engine making an appearance in the regular “Motor Mart” feature in the June 1963 issue of that magazine. It was thus that the British modelling public first became aware of the then-startling fact that model diesel engines were being produced in Red China, and reportedly to a That article was almost certainly written by Peter Chinn, who went so far as to test the engine. He reported a peak output of 0.27 BHP @ 14,500 RPM, a very good figure for a lightweight plain-bearing sports diesel of its time. He characterized the quality of the Yin Yan's construction as being "as good as most and better than some diesels of quite similar design". It's really odd today to recall the fact that during the era in question, the term “Made in China” was almost universally seen in the developed nations as being synonymous with ultra-cheap crap quality mass merchandise. What a change today, when everything seems to be made there and people are very happy to buy Chinese-made high-tech goods! As a 15 year old “Aeromodeller” subscriber myself at the time, I clearly remember reading the article in question with a mixture of astonishment and skepticism. I recall my own feelings of extreme surprise upon learning that model diesel engines were being produced in "Red China", as well as my pre-conditioned and admittedly very elitist opinion that even if they were, there was no way that they could be made to anything like the required standards of precision!! I’m sure that many others must have experienced the same initial reactions……….. But the reality was that the engines were far better than our pre-conditioned “colonial” attitudes would allow us to conceive at the time. Objectively speaking, the early Yin Yan models were made to very acceptable standards by any measure, particularly with respect to their superb piston/cylinder fits. Admittedly, quality control did slide somewhat years later towards the end of the Silver Swallow era which began in 1966, but this takes nothing away from the standard to which those early examples were made. Now having set the stage, let’s begin our in-depth examination of these unexpectedly capable little engines! Influences and Origins It’s a noteworthy fact that the Yin Yan engines appeared more or less out of the blue in the fully developed form in which they and their descendants by other names were to continue essentially unchanged for the next four decades and more. This is a highly unusual scenario for a new design from a new manufacturer, especially in a country with no prior history of large-scale model engine manufacture – it's far more usual to find initial designs from new and presumably inexperienced makers undergoing a series of design changes as the various bugs are worked out. The fact that this did not occur with the Yin Yan and its descendants implies that the then-inexperienced Chinese got it more or less right at the outset. This in turn clearly suggests that they almost certainly began by examining a previously-developed design from elsewhere which they only had to copy, more or less.

A side-by-side comparison of the 2.5 cc Alag and Yin Yan models reveals that the two designs share a great deal in common, including main castings of very similar appearance, an identical bronze-bushed main bearing, identical cylinder porting, the same sub-piston induction, the same con-rod bearing spacing, nominally identical bore and stroke measurements, almost interchangeable pistons and conrods, etc., etc. Even more significantly, the mounting holes on the two models are identically spaced, making them intechangeable in the same model. I've taken advantage of this myself! As can be seen, the 2.47 cc Yin Yan cylinder is a little taller than its Alag counterpart due to the exhaust flange being thicker. In addition, the cooling jacket on the Yin Yan is bulkier and has a straight, as opposed to curved, side profile. The Chinese designers also dispensed with the use of thermo-plastic materials in making their intake venturis and backplates - a good move in my opinion. The prop driver design is also different. The Yin Yan 2.47 cc shaft is rather more massive than its Alag counterpart, having a 10 mm nominal diameter main journal instead of the 8.5 mm used in the Alag. It is otherwise identical in broad design terms. The designers took advantage of this change to use a larger 7.4 mm diameter gas passage inside the shaft as opposed to the 5 mm diameter passage used in the Alag. This latter change may or may not have been a good idea as events were to prove - more of that topic below in its place. Despite this difference, the fact remains that the two designs are sufficiently similar in terms of design fundamentals that it’s very difficult to believe that one did not at least influence the other. It's also possible that the Yin Yan design was influenced to some degree by that of the contemporary Hungarian VT engines and their BX and Engel Rebell cousins, although we have no real evidence to support this notion.

The Chinese undoubtedly had an opportunity to become familiar with the Alag design during the course of a demonstration tour of China by modellers from Hungary in 1958 or thereabouts - Peter Chinn mentioned this tour in his previously-cited "American Modeler" review of January/February 1964. Given the timing and the fact that both China and Hungary were within the Communist bloc during the period in question, it's not impossible that the Chinese makers of the Yin Yan subsequently acquired and modified the designs and patterns for the Alag engines from the Hungarian manufacturing operation which ceased production of the X-03 in 1959. However, it appears far more likely to me that they simply initiated a process that Chinese manufacturers (notably CS) were to repeat many times over the years by simply copying the Alag design using their own patterns, making a few modifications of their own in the process. General Description

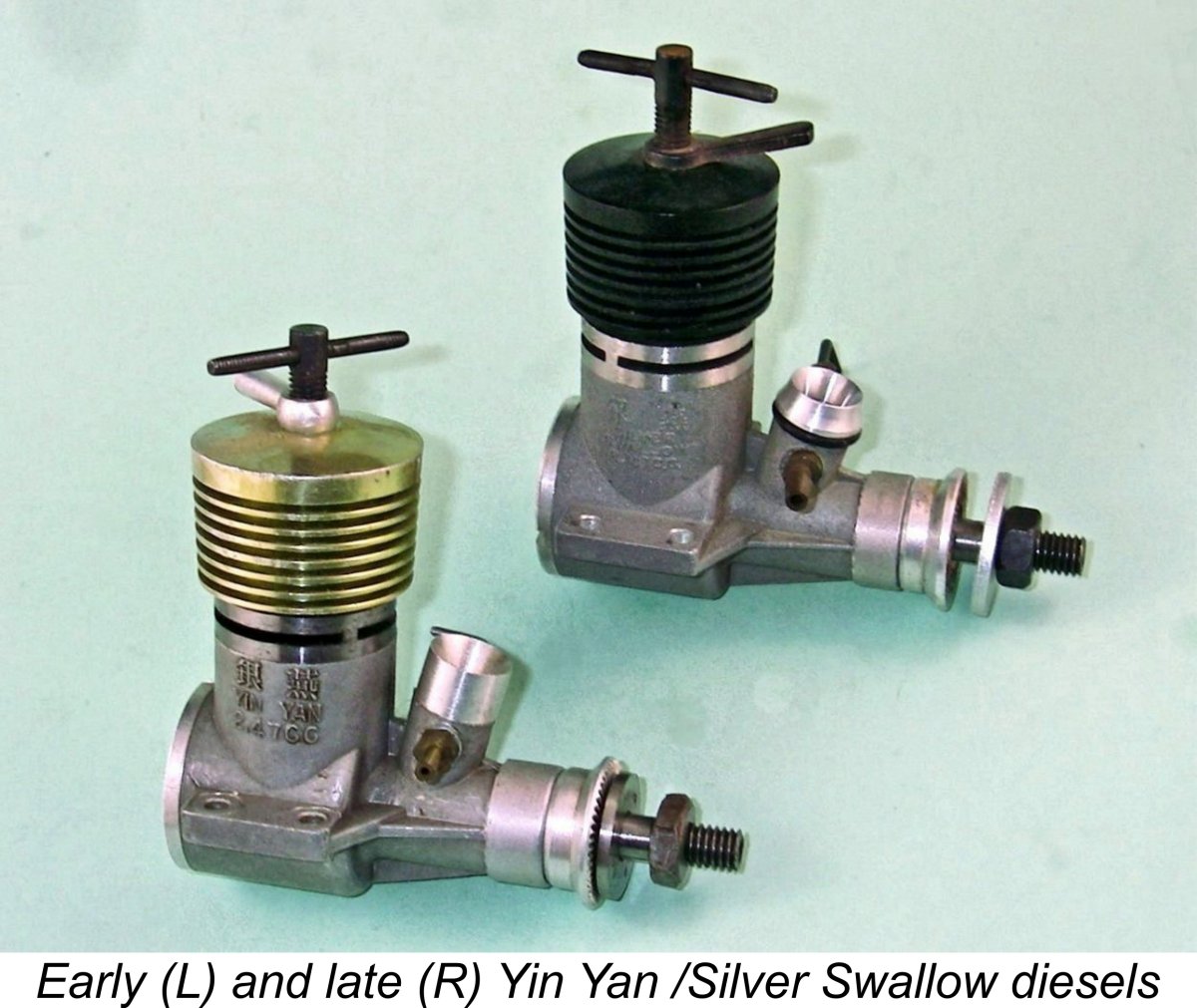

As can be seen from the comparative photograph included above, the crankcases of the Alag X-03 and the 2.47 cc Yin Yan differ in detail, although their common design heritage is obvious. The Yin Yan case is more sturdily braced at the front, but is otherwise very similar to that of the Alag – even the mount holes are identically spaced so that the Alag and the Yin Yan can be used interchangeably in the same model. Like the Alag models, the main bearing on the Yin Yan is bronze-bushed. Both cases also feature the characteristic cast-in expansion in the “front ball race” position on the main bearing, although that used on the early Yin Yan models is slightly longer than that featured on the Alag.

The Yin Yan cylinder once again mirrors the design of the Alag by screwing into a pressure die-cast crankcase, eliminating any need for assembly screws. The Yin Yan case displays very fine cast-on Chinese characters and English text. A screw-in backplate is also a common feature, although that of the Yin Yan is made from light alloy as opposed to the thermoset plastic used in the Alag. Like the backplate, the removable venturi insert used in the later 2.47 cc Yin Yan models is turned from light alloy rather than cast in thermo-set plastic like that of the Alag units. On the Yin Yan 2.47 cc models, the throat diameter of this venturi as supplied was 5.5 mm (0.216 in.), but the later Silver Swallow models were supplied with a very generous 7.1 mm (0.279 in.) diameter item. However, the accessory pack supplied with many of the later Silver Swallow engines included an alternative venturi of the smaller size as an optional extra. This was a The cast-iron piston on both 2.47 cc and 1.49 cc models has a conical crown, with the under-side of the contra-piston being contoured to match. The skirt length is such that a small period of sub-piston induction is provided around top dead centre. The "dog bone" conrod in both versions is machined from aluminium alloy and is quite a nice job on most examples. End bearing fits are typically very good as supplied. With the type of transfer porting employed, it is essential that the gudgeon (wrist) pin be restrained from lateral movement within the piston bosses, since it could otherwise foul the transfer ports and score the bore. To meet this requirement, the Yin Yan’s gudgeon pin was tightly swaged at both ends after installation to ensure that it could not float out of its bearings or rotate in them and thus cause premature wear in the piston bosses. This process was facilitated by the incorporation of deep conical recesses at each end of the gudgeon pin. After installation, the outer ends of the pin were spread through the application of force to a pair of opposing swaging tools having conical tips which matched the shape of the conical recesses in the pin.

Another noteworthy design deficiency, particularly with the 2.47 cc version, is the very minimal wall thickness of the piston at gudgeon pin level, resulting in equally minimal support for the ends of the gudgeon pin and a somewhat excessive unsupported gudgeon pin length, with consequently high repetitive bending stresses on that hard-worked component. The pins on these engines have been known (in my own experience) to work loose over time due to the cyclic strains thus imposed upon the ends of the pin. However, this takes quite a bit of running. The cooling jacket screws onto the externally-threaded cylinder liner. It is generally brightly anodized in a wide variety of colors ranging from yellow through gold, red, blue, purple and green all the way to black. That said, later examples of the 1.49 cc model are encountered with a plain aluminium cooling jacket finish, as are a few examples of the 2.47 cc model. More of those below in their place. The needle/spraybar assembly is quite conventional, with a single jet hole and a very effective phosphor-bronze double-leafed clicker spring for tension. The soldering The crankshaft features a rather steeply-tapered cone machined at its front end, onto which the prop driver seats by means of a matching taper. The matching of the two tapers is often a little imprecise, and the taper angle (approximately 35 degrees included) is too great to be self-locking. However, the arrangement is perfectly adequate for practical purposes once the prop is mounted. Until very recently, I would have said that the early engines (those from the 1960’s) all had serial numbers stamped under the left lug (viewed from the rear) along with a date stamp under the right lug. However, the recent discovery of a seemingly very early example of the Yin Yan 2.47 cc diesel has rather shaken this view, since it does not carry a serial number of any kind. Moreover, it does not even bear the Yin Yan name cast onto the crankcase. More of this seemingly rare variant below in its place. It appears that the numbering system that was used on the majority of the Yin Yan diesels had some commonality with the E.D. system described elsewhere in recording both the year and month of production and the position of the engine within that month’s batch. The right lug bears the last two digits of the year followed by the month. For example, 65-1 indicates that the engine was made in January 1965. The number under the left lug presumably indicates the number of the engine in that month’s production batch. The placement of these numbers is sometimed reversed between the two lugs. Unfortunately, later models dropped the serial numbering system and hence cannot be dated.

Bore and stroke too are slightly changed, the Silver Swallow featuring measurements of 12.8 mm and 11.6 mm respectively rather than the 13.0 mm and 11.2 mm measurements of the Alag. The longer stroke coupled with the use of a thicker exhaust flange results in the cylinder being somewhat taller and heavier than its Alag counterpart. In addition, the crankcase of the Silver Swallow is slightly larger in diameter to accommodate the larger crank throw. This in turn requires that the mounting holes be more widely spaced. Hence the 1.49 Alag and Silver Swallow models are not interchangeable in the same model as is the case with the larger engines. The overall result of the above changes is that the 1.49 cc Silver Swallow is noticeably bulkier and somewhat heavier than its remarkably compact Alag counterpart, although it retains a very similar overall appearance.

Certainly, the 1.49 cc models did not come to the attention of modellers outside of China until far later than the 2.47 cc versions – they were not mentioned in the “Global Engine Review” which appeared in the 1965 issue of “American Modeller Annual” (published in late 1964), although the 2.47 cc model was featured in that article. But it’s impossible to be certain at this point in time exactly when the smaller engine joined its big brother in the marketplace. All that can be stated for certain is that it was prior to April 1967 based upon serial number evidence. One point which is well worth noting here is the fact that on the early examples of both models, all key fits were superb, meeting the most exacting standards. Clearly the makers were going all out to try to overcome the negative impressions of Chinese manufacturing mentioned earlier! Later models displayed a less rigorous approach to the issue of quality control ...... but most of them at least ran!! 2.47 cc variants The 2.47 cc Yin Yan/Silver Swallow model is far more frequently encountered than its smaller 1.49 cc relative, which presumably reflects the relative popularity of the two models. In terms of its basic design, the engine remained essentially unchanged throughout its production life of some 30 years. But there were changes, and from a collector’s standpoint the devil’s in the details! So let’s look closely at the various forms in which this engine has appeared over the years. In doing so, I wish to emphasize that the type numbering system applied to the various models in what follows is entirely my own and is applied here strictly for convenience to indicate what I believe to be the correct chronology. As far as I can ascertain, the manufacturers never distinguished between the different variants through the use of different number designations. Yin Yan 2.47 cc – Type 1

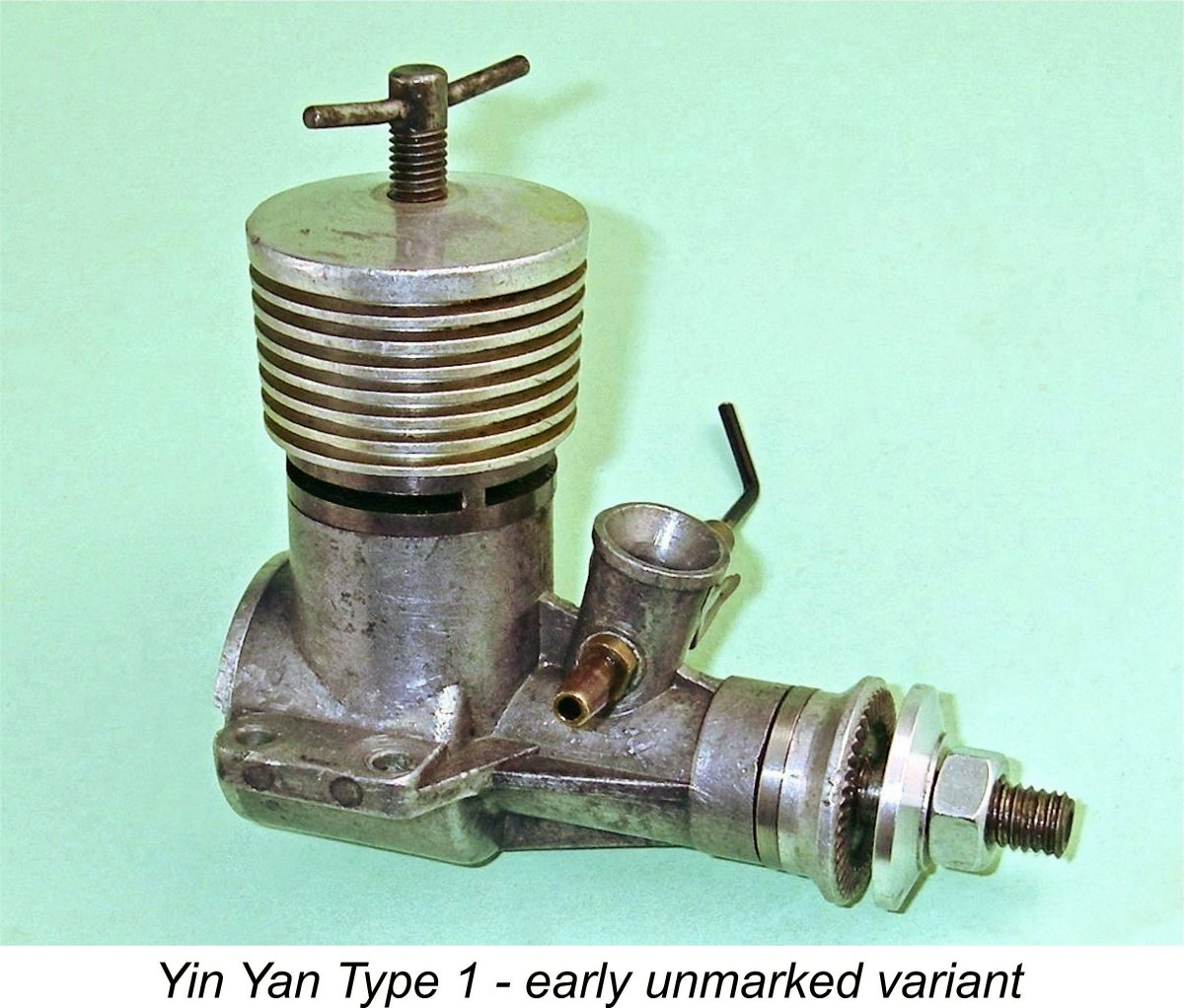

It turned out to be a very fortunate chance that I was able to acquire this extremely well-made engine, since its acquisition allowed me to document several previously-unrecognized features. The two main departures from earlier experience were the fact that this example bears neither a serial number nor the Yin Yan name and displacement cast onto the right-hand side of the crankcase. In fact, it bears no identification marks at all. This raised some initial doubts regarding the engine's identification, but a closer inspection of its structural features combined with the taking of key measurements for comparison purposes has confirmed beyond reasonable doubt that it is indeed an early Yin Yan. This identification forced me to re-evaluate the early history of this engine. It now appears that the serial numbering sequence was not started until a batch of engines had been produced without such numbers. Moreover, it seems that the cases for the very first examples were cast from a die which did not form the Yin Yan name on the right-hand side of the case. In keeping with other documented examples of the Type 1 Yin Yan, my newly-unearthed example lacks the compression screw locking lever which was later added to the engines. Moreover, it has a slightly shorter cooling jacket than those seen on my Type 2 examples of the Yin Yan (see below) - the relatively wider top fin has a somewhat reduced vertical height. The intake venturi is cast as a stand-alone feature lacking any kind of insert. Finally, the prop driver is a composite affair consisting of a fairly thick steel backing washer behind the alloy prop driver itself. This was definitely a designed part of the driver, since it is a very accurate fit onto the installation taper at the front of the shaft. Its function was to set the end float of the shaft at an appropriate dimension as well as eliminate any alloy-on-alloy rubbing contact between the prop driver and the main bearing housing during starting or in pusher mode. A quality feature, which was not carried over to the later examples. Indeed, the overall quality of this early example is beyond reproach.

Finally, to clinch the matter, the engine which is illustrated in the leaflet lacks any form of cast-on model identification on the visible right-hand side of the crankcase. I had wondered about that when I first encountered this image - could it have been an image reproduction error?!? Now I need wonder no more - such engines did indeed exist! The next question was whether or not this variant of the engine continued for long in production. Some evidence in this regard was provided by the image published in "Aeromodeller" magazine which accompanied the previously-cited "Motor Mart" article in the June 1963 issue of the magazine. It will be recalled that the illustrated engine had then recently been acquired in Hong Kong by a British naval officer, Lt. Cmdr. A. D. Briggs, during a tour of duty there. This being the case, it was unquestionably an early example.

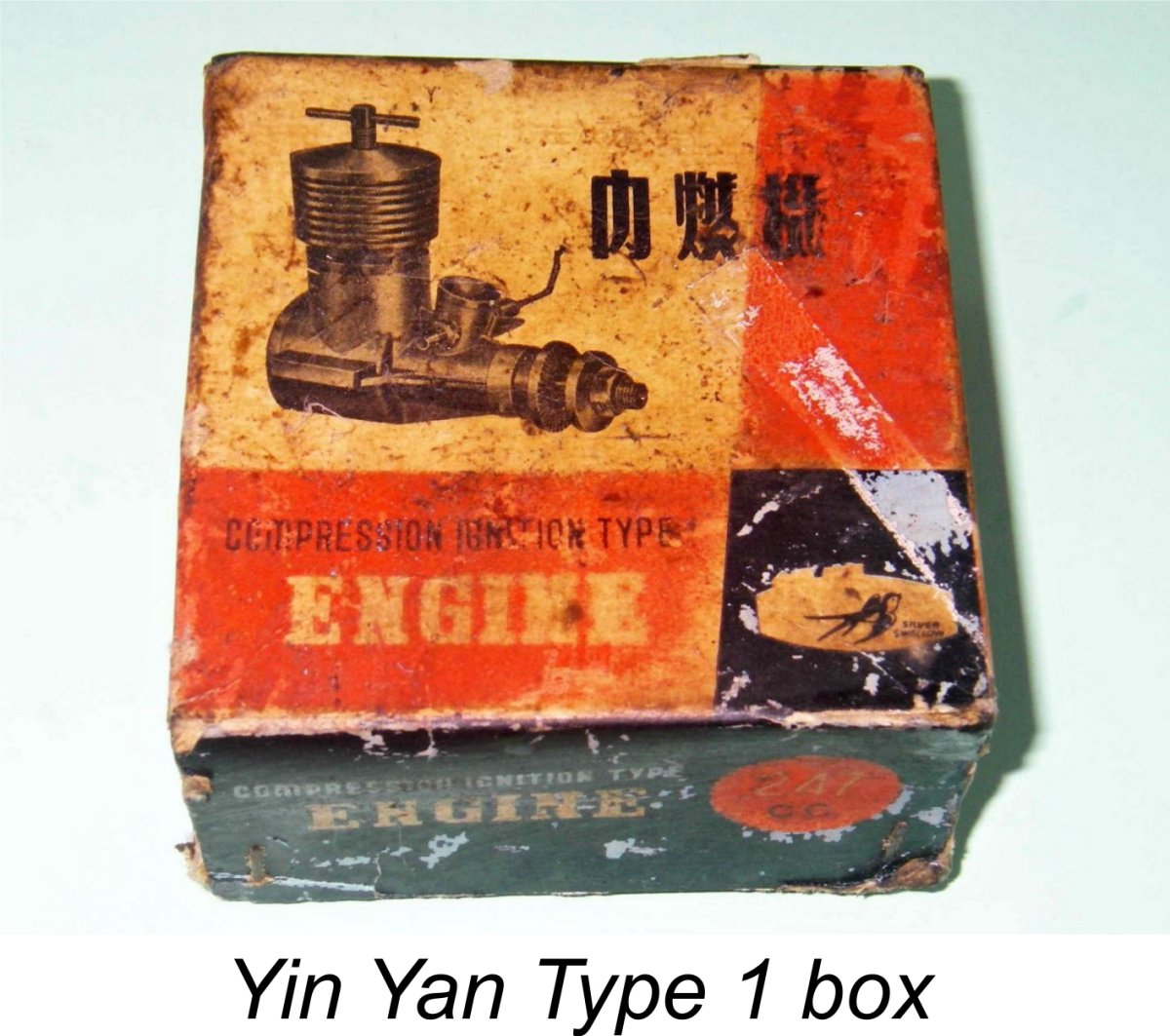

A close examination of a somewhat enhanced reproduction of the "Motor Mart" image reveals that the illustrated example unquestionably did display the usual Yin Yan model identification and displacement characters on the right-hand side of the crankcase, along with the thinner top fin and the absence of a venturi insert. It was not equipped with a compression screw locking lever, but also did not feature the composite prop driver. It thus appears that the composite prop drivers and plain unidentified cases were very short-lived features of a few of the earliest examples of the engine, all of which were seemingly manufactured in 1962. My good mate Maris Dislers has speculated that these early unidentified examples may in fact represent an initial run of "proof of tooling" examples made to check out the tooling, jigs and fixtures as well as identify any residual workforce training issues in advance of series production getting underway. Alternatively, they may simply represent the earliest production batch. It's possible that serial numbers and model identification were only added after the manufacturers commenced their international marketing efforts. It's unlikely that we'll ever know for sure. All such speculation aside, the most immediately obvious feature that distinguishes the Type 1 Yin Yan from its successors is its longer integrally-cast intake boss which does not employ a separate venturi insert. It also retains the thinner top fin on the cooling jacket in all documented examples, marked or otherwise. The vast majority of these engines (like the one illustrated in "Aeromodeller") were marked in Chinese characters on the right side of the case only (along with the name Yin Yan and the displacement of 2.47 cc) – the left side of the case remained blank. Head colors for these models reportedly varied, with red, yellow/gold and green examples evidently being encountered. No compression locking lever was fitted to any of these engines. It’s not clear how long this version of the Yin Yan remained in production, but it was certainly this model that was described and illustrated in the above-mentioned “American Modeller” article in January 1964 and subsequently featured in that magazine’s “Global Engine Review” which appeared in the 1965 issue of “American Modeller Annual” (compiled and published in late 1964). Yin Yan 2.47 cc - Type 2

Another visible change is the inclusion of a very neat compression locking lever made from turned aluminium alloy. It is unclear when these minor changes were introduced - the illustrated example bears the serial number 0216/65-1, hence having been made in January 1965, but I have an unsubstantiated report of another identical example made in late 1964. It thus appears that the change was made during late 1964 at the latest. It’s certainly beyond argument that the Yin Yan name was still in use as of mid 1965 - Yin Yan 2.47 cc engine number 627/65-6 in my possession proves as much, since it dates from June 1965. At this stage, the engines were supplied in a fairly sturdy 2-piece box which featured mainly Chinese characters. No insert was used in these boxes, which were actually a little undersized for the engine. This style of box remained in use for some time after the Type 3 variant (to be described next) was introduced. More of the various box styles below in a separate section of this article. An interesting observation regarding the undersized dimensions of this box was found in a note from the late Australian model engine icon Ivor F. This note arrived with a boxed example of the Type 3 Silver Swallow 2.47 cc model (see below) which had been owned by Ivor and was presented to me by Ivor's son Tahn Stowe. Ivor commented quite correctly that a fully assembled engine would not fit in the box without distorting it somewhat. The obvious fix was to remove the needle and comp screw. However, Ivor noted that the manufacturers had got around the latter problem by the simple expedient of screwing the comp screw down until the engine would fit! This of course pushed the contra piston down to the point where it contacted the working piston, preventing the engine from being turned over!! A somewhat drastic remedy .......... Silver Swallow 2.47 cc – Type 3 The next model to be discussed is unique in the Sliver Swallow series insofar as it is encountered in two quite distinct variants which originated from the same production run. For this reason, I have used the 3 and 3A (“alternate”) designations for these models.

The compression locking lever is retained, still in the form of the turned alloy component used on the Yin Yan Type 2. This version also continues to carry serial numbers. The illustrated engine number 1072/66-11 proves that the Type 3 models were unquestionably in production by November of 1966. It also proves that production rates remained in excess of 1000 units monthly at this stage. These engines were supplied with cooling jackets which were generally anodized in a variety of colours from gold through purple and blue to green. However, reader Steve Thomas reported the existence of an example from 1966 which features a plain unanodized cooling jacket. To prove that this was not a one-off, my good mate Tahn Stowe kindly presented me with Type 3 engine no. 024/67-8 (made in August 1967) which also features a plain unanodized cooling jacket.

By the late 1960's these engines were being packaged in small one-piece boxes of thin cardboard, with no insert. This packaging seems to have remained in use for a long time - former US distributor Ed Carlson of Carlson Engine Imports in Phoenix, Arizona recalled receiving a shipment in boxes of this type as late as July 1985, but did not retain a note of any serial numbers. Hence there is now no way of knowing whether or not those engines were of then-recent manufacture or if they still bore serial numbers at that time. It’s entirely possible that they were un-numbered examples of Type 4 (to be described later in its place).

This allowed the fitting of a plain-bored water-cooling jacket having an internal diameter identical to the external diameter of the plain cylindrical portion of the modified air-cooling jacket. The modified screw-on air-cooling jacket thus served the function of securing the water-cooling jacket in place. This arrangement had the great advantage of allowing the water cooling jacket to be set in any desired radial orientation to allow the convenient routing of the water supply and discharge tubes. Advantage was also taken of this arrangement to secure a neat exhaust manifold in any desired orientation. Our sincere thanks are due to French marine engine collector Christian Farcy for the provision of this information. Chris's illustrated example of the Type 3 Silver Swallow marine engine bears the serial number 0748/67-1, confirming that it was produced in January 1967 more or less concurrently with the early air-cooled versions of the same model. This fact will prove to be highly significant as we turn our attention to the "other" Type 3 Silver Swallow - the Type 3A variant. Silver Swallow 2.47 cc - Type 3A

I have designated this variant as Type 3A because in reality it appears to be nothing more than a modified version of the Type 3 model already described. It was certainly manufactured concurrently with that variant - the serial numbers prove as much. In terms of its fundamental design, this version of the engine is basically unchanged from the Type 3 version just described. The crankcase and all of the working components are identical. The major difference is to be found in the cooling jacket, which is radically different from that used on the Type 3 units. A minor departure is the omission of the compression locking lever on all examples which I have so far encountered.

The other component is a finned plain-finish aluminium sleeve which fits somewhat loosely around the turned-down sleeve beneath the cylinder head and is sandwiched between the cylinder head and the exhaust flange when the internal portion of the resulting composite jacket is screwed down onto the cylinder. The fins on this second component are fewer in number and the grooves are a lot shallower than those on the original cooling jacket. Taken together with the introduction of an air-gap which will act to some extent as a heat dam, this would appear to render cooling substantially less effective than with the standard one-piece component. Overall, a very odd proceeding – someone (likely the manufacturer in my opinion) took an engine having a perfectly good air cooling jacket which would have served the purpose extremely well, then removed its fins, presumably to allow the fitting of a water cooling jacket. At some later point in time a return to air cooling was desired, forcing the making of another less effective component to restore the air cooling! What prompted all this extra effort, and who went to this trouble?!? As far as I’m concerned, the explanation for this rather odd set-up almost certainly lies in the previously-noted fact that that when the decision was taken to make the switch to the Silver Swallow name with the Type 3 model (at some point in 1966), necessitating the changes to the crankcase die noted earlier, the manufacturers subsequently decided to release a water-cooled version of the engine. The designers could have elected to create a screw-on water cooling jacket to replace the air cooling jacket, but elected instead to go with an unthreaded water cooling jacket which was secured by the standard head after modification in the manner described above. The addition of a flywheel and exhaust collector completed the conversion. The fact that the air-cooling jackets to which this modification was applied were clearly finished components, including the colour anodizing, suggests that a number of already-completed air-cooled engines were simply pulled out of the line to be converted to water cooling in the manner described above. This in turn makes it appear likely that the decision to create a marine version was taken after production of the standard air-cooled Type 3 model had commenced. Rather than starting from scratch with the production of the marine variant, the manufacturers elected to save time and effort by simply modifying a batch of existing air-cooled engines, seemingly in late 1966 and early 1967.

One possible explanation for the appearance of the Type 3A variant is that the manufacturers found that they had over-produced the water-cooled engines, leaving them with a considerable unsold inventory. The approach described above would have enabled them to convert the unsaleable marine models back to air-cooling, thus presumably improving their marketing prospects. Of course, the above explanation assumes that this was a factory modification. However, another perfectly rational explanation that comes to mind is that some Asian wholesaler or North American importer ended up in the latter part of the 1960’s or the early 1970's with a crate full of water-cooled engines that he couldn’t sell, hence electing to take this approach to the conversion of these engines back to air-cooling to make them more saleable. In either case, there must be a large stash of discarded marine cooling jackets and flywheels lying about somewhere!

A further piece of evidence is provided by previously-illustrated Type 3 engine number 1072/66-11, which indisputably originates from the same November 1966 production batch as my two Type 3A examples. This one is still in the box and is identical to the Type 3A models described above except that it has a standard gold-anodized air-cooling jacket like the earlier examples. This proves beyond doubt that the purpose-built air-cooled models from that batch were completely standard, thus leaving us with little alternative to the water-cooled retro-conversion theory to explain the existence of the other style of jacket on air-cooled engines from the same batch. Evidently both air-cooled and water-cooled engines were assembled from the same batch, but some of the water-cooled examples were later converted back to aero models. The remaining question is - by whom?!? One thing that is certain is that this model is not a “one-off” home conversion – there must have been a few of them sold. I own two of them myself (both apparently new) and am acquainted with a third which is owned by a fellow collector of my acquaintance. I’ve seen a few others at swap meets as well, while further examples appeared in 2009 and 2011 on eBay. We’ll probably never know the full story of this model's creation or how many were produced ........ The serial number of the illustrated purple-headed example of this variant is 0684/66-11, confirming that it was made in November 1966. I also own the illustrated gold-topped engine number 0700/66-11 from the same November 1966 batch, which is identical apart from the head colour. The other example of this type with which I am directly acquainted comes from December 1966. Chris Farcy's unmodified marine engine number 0747/67-1 confirms that marine examples of the Type 3 Silver Swallow were still being produced in January 1967. One of my own examples came in what appeared to be a factory-sealed plastic bag complete with papers, which would appear at first glance to indicate that the engines were then still being produced by the Teh Ming Sport Goods Factory - at least, the same instruction leaflet was still being used. I don’t know if the bagged engine originally had a box, but I suspect that a box was never produced for the Type 3A model. Perhaps the explanation for the use of a sealed plastic bag is that the box in which the engine was originally supplied (either air-cooled or water-cooled) no longer accurately reflected the contents after the conversion was made. We'll probably never know ............... Whatever the truth, the source of the Type 3A engines remains a mystery. Can any kind reader help to clear it up…..?!? Silver Swallow 2.47 cc – Type 4

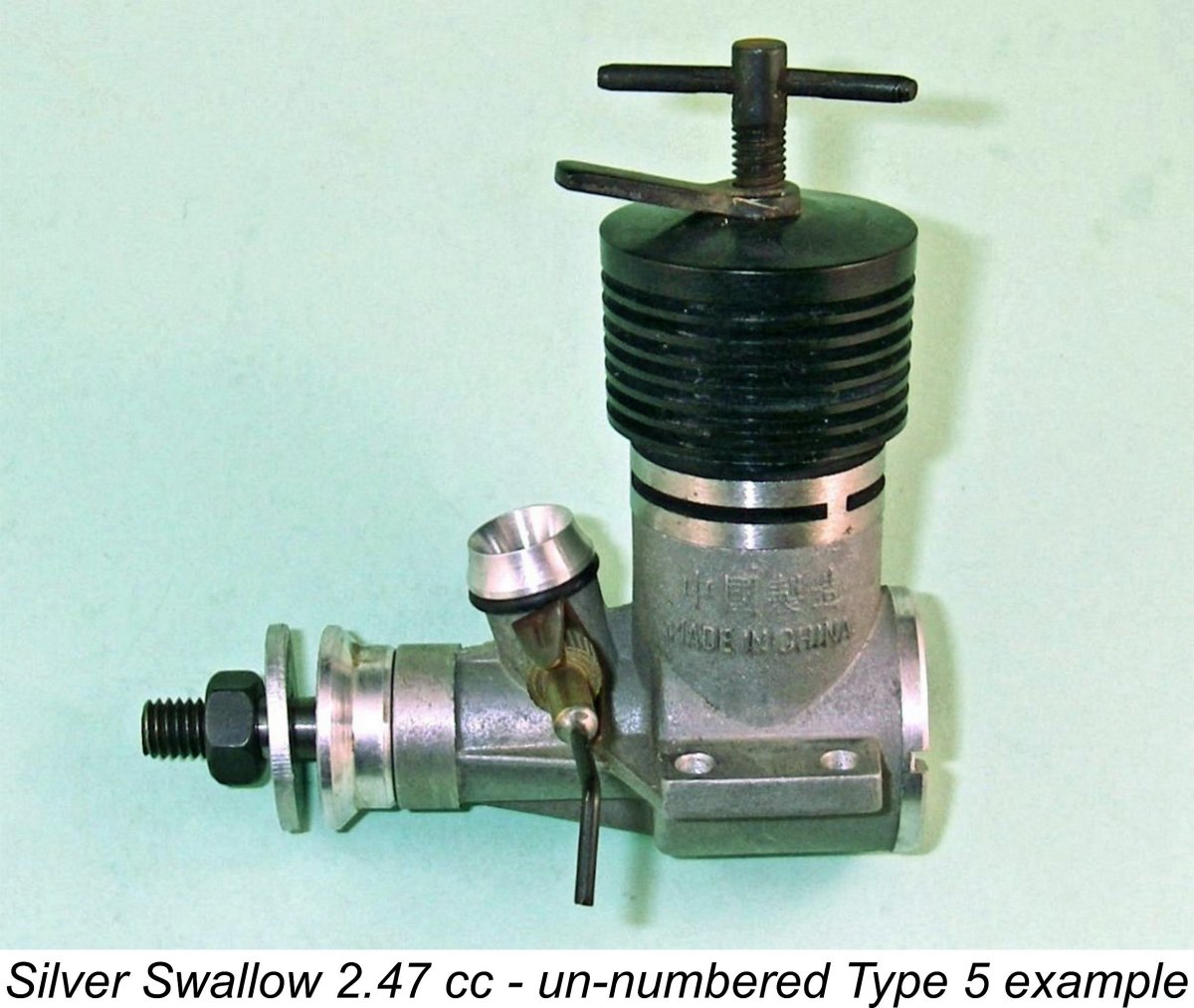

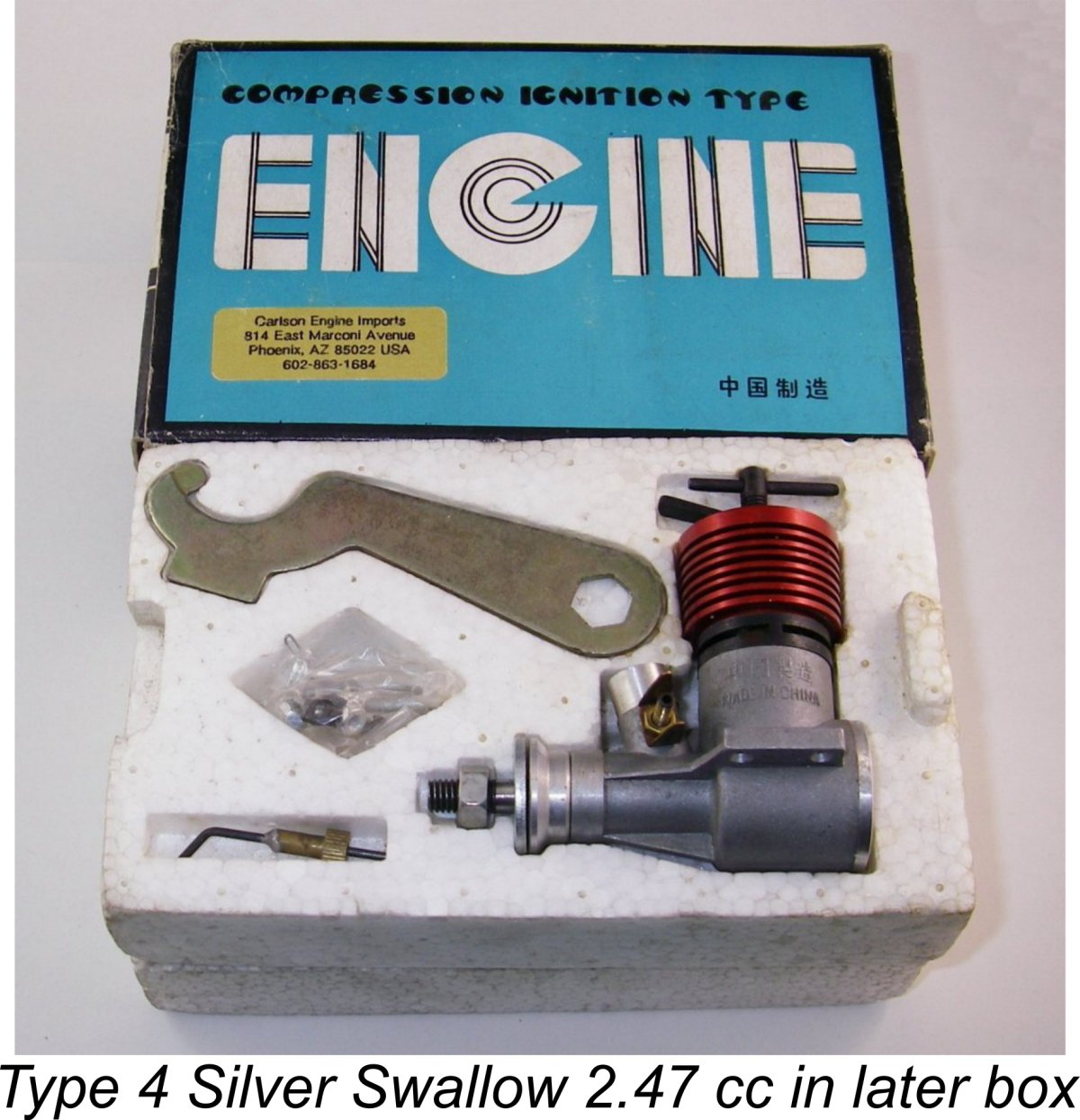

All that can be said for certain is that the engines were still being numbered in mid 1969, based upon the existence of Chris Farcy's 1.49 cc marine model no. 721/69-7 from July 1969 (see below). It seems highly unlikely that the manufacturers would have continued to number one series but not the other. Lacking any hard data, the best that can be done at present is to state that any un-numbered engines of this type date from 1970 or later. These engines were packaged in the more familiar large cardboard box with two-piece Styrofoam insert. As supplied, they were fitted with the larger 7.1 mm dia. venturi insert, but a smaller 5.5 mm dia. item was normally included as a standard accessory. Ed Carlson’s records showed that he received his first shipment of these models in October 1986, but this by no means precludes the possibility that their production commenced considerably earlier. A substantial number of these engines were sold over the years, many of which remain in circulation today. A significant proportion appear to be still barely if at all used. A change which was made at some indeterminate point in time prior to the appearance of this model (possibly during the Type 3 era) was the reduction of the internal gas passage diameter in the 10 mm O/D crankshaft from 7.4 mm down to 6.8 mm. This had the effect of significantly increasing the crankshaft's ability to resist torsional stresses. The change was almost certainly made in response to the engine's growing reputation as a crank-snapper. More of that problem below ............... One other point which is worth mentioning is the fact that the decline in quality control standards which bedevilled the later Silver Swallow engines seems to have developed at around the same time as this model was introduced. It's significant that the factory had clearly stopped testing their engines prior to shipment by this time - none of the New-in-Box examples which I now own or which have passed through my hands have ever been run at any time. In fact, they tended to be supplied in a completely "dry" un-oiled state. Silver Swallow 2.47 cc – Type 5

This appears to be the final version of the Silver Swallow to be produced by that name. It’s now unclear exactly when production actually ceased, but it seems most likely to have been in the early 1990’s. The decision to end production may well have been influenced by the increasing difficulty evidently being experienced by the makers in selling their now-venerable product, especially given the large number already in circulation by that time, many of them still unused or New-in-Box. It’s abundantly clear that large stocks of unsold engines must have remained in the warehouse at the time when production ceased. New-in-Box examples of the Type 4 and Type 5 engines continued to be available from Carlson Engine Imports for quite some time, although Ed informed me that the supply had finally dried up by around 2005, at least until someone unlocked another dusty warehouse somewhere! Evidently, that never happened ............... Packaging

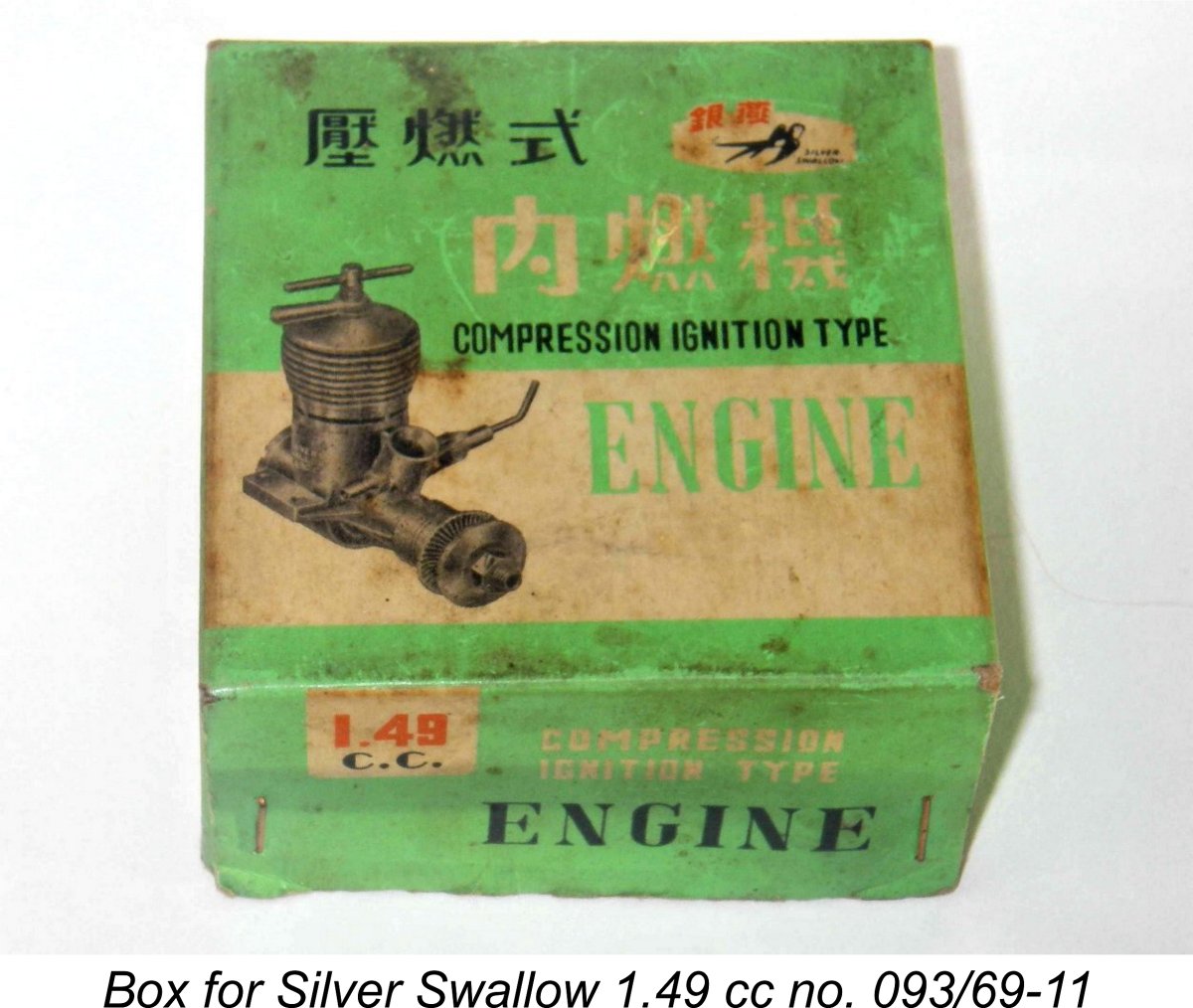

The third style is the one most commonly encountered today. It was used for the later examples of the Type 4 model as well as the Type 5 engines. It consists of a somewhat larger box of thin cardboard which fits tightly around a two-piece styrofoam insert hollowed out to accept the engine and accessories. Included are dual-language instructions (Chinese and Chinglish), a stamped steel "wrench", a spare venturi insert of smaller diameter and a set of mounting bolts. Ed Carlson recalled receiving his first shipment of engines packaged in this manner in October 1986. This style of box appears to have remained in use until the final transfer of manufacturing responsibility for the Silver Swallow design. This change seems to have taken place in the early 1990's, as we shall see in a later section of this article. The 1.49 cc Engines

Accordingly, unless or until contrary evidence comes to light we're forced to the conclusion that the 1.49 cc models first appeared after the name change from Yin Yan to Silver Swallow, seemingly in mid 1966 as noted earlier. How much later than this production of the 1.49 cc model began remains open to question. Serial number evidence provided by reader Steve Thomas in the form of engine number 1020/67-4 confirms that the smaller Silver Swallow model was undoubtedly in production by April of 1967. This implies that it was introduced relatively soon after the name change to Silver Swallow. This idea is consistent with the fact that Peter Chinn mentioned both the 2.47 cc and 1.49 cc Silver Swallow models in his "Latest Engine News" column which appeared in the May 1968 issue of "Aeromodeller". As of mid 1969, the compression locking lever continued to be of the turned alloy type first seen on the earlier Yin Yan 2.47 cc models. The 1969 1.49 cc models also featured a two-piece prop washer consisting of a machined alloy component at full prop driver diameter with a chamfer machined at the front, and a smaller stamped steel washer against which the prop-nut actually bears. This set-up uses up a great deal of the already-inadequate shaft length available for prop mounting.

Apart from these minor alterations, the design seems to have changed very little if at all over the years – certainly not sufficiently to warrant the assignation of differing Type numbers. The last shipment received by Ed Carlson included a number of engines which had plain un-anodized cooling jackets, but the engines were otherwise identical to their predecessors. One very annoying feature of the 1.49 cc Silver Swallows which unfortunately was never altered was the threaded prop mounting stud, which was machined integral with the crankshaft in the usual way. This was significantly too short – as supplied, the length of the threaded stud was only sufficient for the mounting of props having very thin hubs. This was particularly true of the early models with their two-piece prop washers. A 7x4 will just about mount, but most 7x6 or 8x4 props can’t be used – there simply isn’t enough thread. Even with the later models having plain prop washers, the length remains insufficient and the nut supplied is far too thin, having barely enough threaded length to do the job without risk of stripping the thread. The stud could have used an extra 4 mm or so of length, in which case a thicker nut could have been used with advantage. As it is, one has to set aside the standard prop nut and washers and instead make a McCoy-style prop “bolt” with an integral internally-threaded boss in order to mount props having thicker hubs. Oddly, the It's interesting to note that the manufacturers never adopted a generic box for use with both of their diesel models. Instead, they went to the trouble and expense of making up distinctly decorated boxes for each model. The box styles used for the 1.49 cc engines exactly paralleled those used for the 2.47 cc models, with the smaller 2-piece box preceding the larger box with two-piece styrofoam insert. Presumably the box styles were changed simultaneously for the two models, seemingly in the mid 1980's. Another oddity is the fact that while the earlier boxes correctly identified the displacement as 1.49 cc, the later box inexplicably disagreed with the instructions on the displacement of these engines, with the box claiming only 1.47 cc. This seemingly demonstrates that you can't always judge an engine by its box! Or perhaps the old abacus was a bit off song that day .......... If we give the tie-breaking vote to the engine itself, we find that the continuing 1.49 cc displacement is confirmed both by the crankcase inscription and by the bore and stroke dimensions. Production of these models apparently ceased at the same time as that of the Type 5 Silver Swallow 2.47 cc. The 1.49 cc models were never as popular as their larger relatives, and it took far longer for residual stocks to be sold off after production ceased. As of January 2008, new-in-box examples of this model remained available from Ed Carlson at a very reasonable price. However, Ed reported having At some indeterminate point in time in 1969 or possibly earlier, the manufacturers also released a marine version of the 1.49 cc Silver Swallow. This engine was supplied in a box which was identical to that used for the contemporary air-cooled version, as previously illustrated. Again our thanks are due to Christian Farcy for providing information on this model. Chris's illustrated example bears the serial number 721/69-7, indicating that it was manufactured in July 1969, a few months after the production of my own previously-illustrated air-cooled model number 093/69-3. I'm also aware of the existence of gold-anodized air-cooled engine number 053/69-3 from the same batch. Unlike the marine version of the 2.47 cc model, the 1.49 cc Silver Swallow used a conventional screw-on water jacket in place of the composite arrangement used on the marine version of the larger engine. There are thus no 1.49 cc equivalents of the previously-described Type 3A version of the 2.47 cc Silver Swallow. It is however possible that the later examples of the 1.49 cc Silver Swallow with plain unanodized cooling jackets are retro-converted marine models, with the colour-anodizing step omitted to minimize costs. Other versions of the Silver Swallow The later production history of the Silver Swallow engines is considerably complicated by the appearance during the 1990’s of several successive engines which went under different names but were to all intents and purposes identical to the old Silver Swallow. Let’s have a look ........ Jin Shi 2.47 cc

This transfer may in fact represent the continuation of production at the same plant under new management – it’s impossible to be certain. Certainly the engines were basically very similar to the Type 4 Silver Swallow units which had preceded them. In fact, the sole externally visible change was the replacement of the Silver Swallow name on the right side of the crankcase with the "J in a circle" Jin Shi logo, confirming the use of a revised die. Moreover, the instruction leaflet was identical to that which was formerly supplied with the Type 4 and Type 5 Silver Swallow engines, even down to the absence of any manufacturer information.

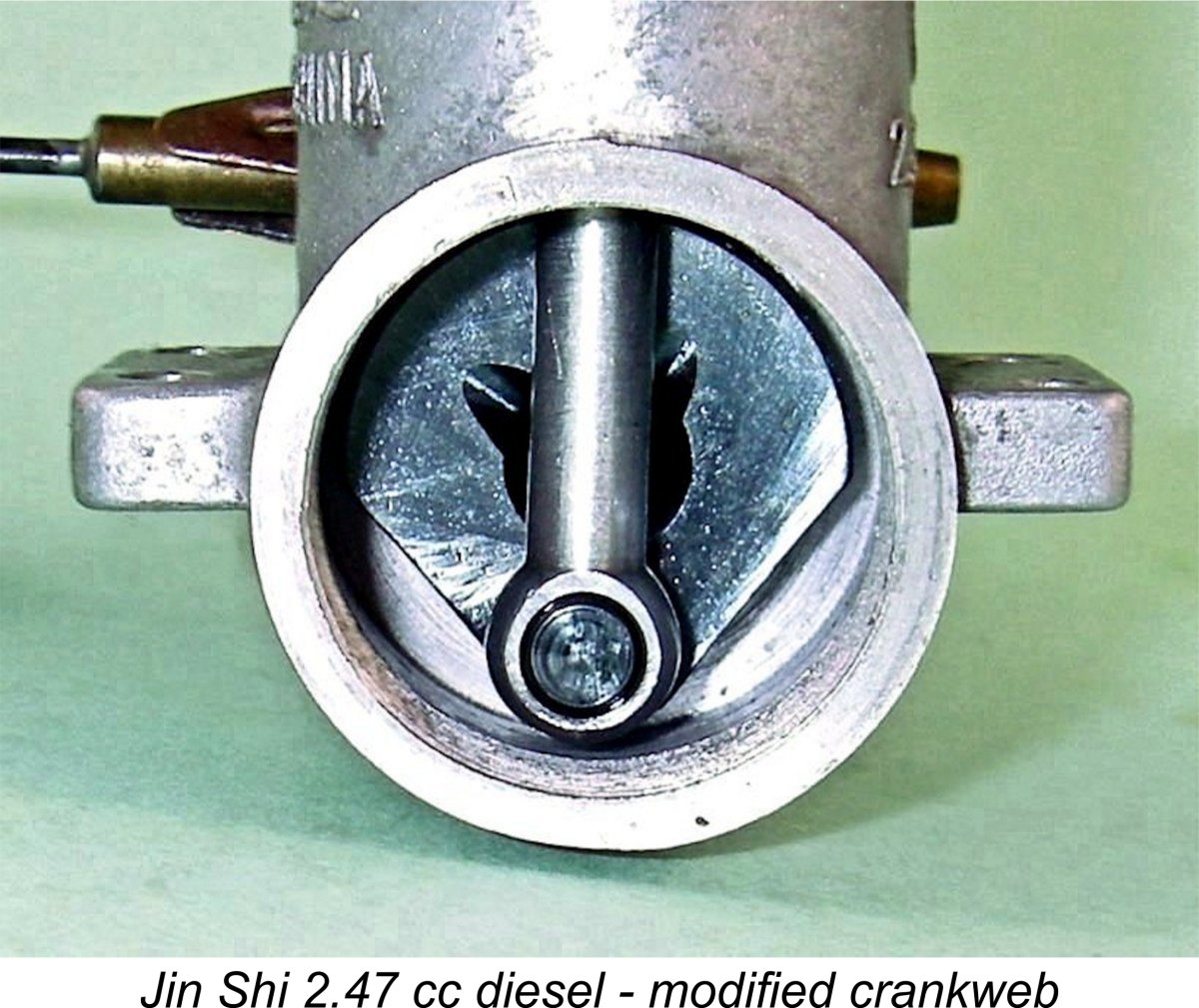

The Jin Shi 2.47 cc diesel incorporated the first performance-related changes in the design of the Silver Swallow since its introduction. To their credit, the new manufacturers were not content merely to continue production of the old Silver Swallow. They made a number of changes designed to improve both crash resistance and performance. Some of these changes had merit, while others did not! Naturally, the crankcase die had to be modified to reflect the Jin Shi name rather than the former Silver Swallow identification. Advantage was taken of this die change to introduce a structural improvement. The thickness of the mounting lugs was increased from 4 mm to 4.75 mm, presumably to increase crash resistance. Apart from the crankcase die change, the piston skirt was shortened slightly both to lighten the piston and to give a significantly longer period of sub-piston induction. Both of these measures might be expected to yield a performance improvement. Most significantly, the diameter of the central induction passage in the 10 mm diameter crankshaft was increased from 6.8 mm back to the 7.4 mm diameter of the original Yin Yan models. The idea was presumbly to help the breathing, but it came at the cost of returning the shaft to the weakened state which had been found wanting in the earlier examples of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow engines. The crankshaft induction port was also slightly enlarged, giving a modestly increased induction period but also further weakening the shaft. In other respects, the engines were essentially identical to the Type 4 Silver Swallow – the manufacturers reverted to the plain 7.1 mm dia. venturi without the O-ring seal. Unfortunately, these changes were not accompanied by any improvement in terms of quality control – in fact, the reverse was true. Consequently, the majority of the Jin Shi engines exhibited manufacturing faults of one sort or another, to the point that quite a few of them wouldn’t even run as supplied. The engines were clearly not tested at the factory prior to dispatch. In addition, it appears that new engines were not cleaned to the necessary standard either during or after assembly. Hence they all arrived plentifully impregnated with shop debris and with fits all over the place! As a result, this is undoubtedly the least satisfactory version of the Silver Swallow in terms of overall quality – US importer Ed Carlson was very open and honest about this all along, forewarning his customers and pricing the engines accordingly.

But you had to work to extract that performance ............ and you had to get a bit lucky in term of fits! The illustrated example of the Jin Shi has been subject to all of Ed's recommendations as well as having its crankshaft normalized (details below). So far, it has performed very well both on the bench and in the air. It appears that the Jin Shi company never got around to producing their own version of the 1.49 cc Silver Swallow design – at least, neither Ed Carlson nor I ever became aware of any such engines being offered at any time. None of the Jin Shi engines bore serial numbers. It’s unclear how long they remained in production, but it probably wasn’t long – the extremely poor quality control would have seen to that! They have not been offered on the wholesale market for many years now, and available retail stocks appear (perhaps thankfully!) to have been exhausted. Ed Carlson sold out his fairly large stock quite a few years ago.

I have an example of this model too, and it is certainly built up to the same standard as the better products from CS with which many “classic” modellers will be familiar. It stands head and shoulders above the original Jin Shi products in terms of quality, to the point where there could be no mistaking the one for the other even if it were not for the CS box in which the later productions were supplied. By 2008 Ed Carlson was advising that production of the revived Jin Shi was apparently once more at a standstill. It appears that demand never justified the production of further batches by CS, who subsequently abandoned the model engine business altogether in late 2015. The CSD PP series Returning now to the mid-1990’s, things took a distinct turn for the better when CS Model Equipment Ltd. of Shanghai, China, took over the Silver Swallow diesel designs, which they presumably did following the demise of the ill-fated and presumably short-lived Jin Shi effort in the mid-90’s. Ed Carlson received his first shipment of the revised CS models in January 1996.

The new CS diesels were to all intents and purposes exact copies of the old Silver Swallow models except that the crankcase die was once again modified to show the CS name along with the displacement of the engine on both sides of the case. Other changes to the case included the use of an integrally-cast intake venturi, thus eliminating the venturi insert formerly used, and a return to the thicker webs on each side of the main bearing as seen on the original Yin Yan models. These engines were noticeably better made and finished than the later examples of the Silver Swallow, and were infinitely better in those respects than the original Jin Shi line. However, they did not quite come up to the very high standard set by the original Yin Yan models of the early 1960’s. Interestingly enough, the text of the instruction leaflet supplied with these engines read almost word for word like that provided with the Silver Swallows of the mid 1960’s! Just like the Jin Shi, in fact ..............only the manufacturer’s information and the style of printing were changed. These engines did not carry any serial numbers. As of February 2008, new-in-box examples of the 2.47 cc version remained available from Ed Carlson, although production was apparently terminated soon thereafter and was never resumed at any time prior to CS's final departure from the scene in late 2015. Regardless, the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow design had lived on for a full 46 years following its introduction in 1962. Not a bad record of continuous production for any model engine design ....... The “Chalag” 2.47 We’ll finish up with a “mystery” engine which is nonetheless very clearly a Silver Swallow/Jin Shi derivative. Several examples of this odd-ball appeared on eBay and elsewhere in around 2010, being offered for sale by sellers in Eastern Europe as "Alag diesels". However, a close examination of my own example shows very clearly that it is in fact neither more nor less than a Silver Swallow/Jin Shi derivative! A clear case of coals to Newcastle, in fact..............

The crankshaft is identical to the large-hole version used on the Jin Shi models, and is actually interchangeable with an original Jin Shi crank in the same engine. So are the piston/rod assembly and the cylinder and backplate – in fact, the working components appear to be genuine Jin Shi items rather than copies. The engine has been given an “Eastern European” look by being fitted with red-anodized cylinder head and prop mounting components which are undeniably reminiscent of Alag and Jaskolka parts, but the fact remains that this is a Silver Swallow/Jin Shi at heart. It's definitely not an Alag!! At present, I have no information regarding the origin of this motor – can anyone out there help?? Regardless, it’s a very well-fitted and attractive engine – perhaps the best-looking member of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow clan - which must have an interesting tale behind it! Perhaps this is where the working components of some of the ill-fated Jin Shi engines finished up?!? The Silver Swallow Glow-Plug Engines

At some later point in time, the manufacture of these units appears to have been transferred to the makers of the Silver Swallow range (assuming that they had not been making these engines all along). Their variant of the R-2 was basically almost identical apart from having a plain unfinned cylinder head in place of the cast finned unit used originally. It was clearly identified as a Silver Swallow on the case. Silver Swallow versions of the R-4 and the larger R-5 were also produced. A series of 2.5 cc glow-plug models continued to appear under the Silver Swallow name until around the mid 1980's. The Silver Swallow rendition of the 1956 Super Tigre G.20 which had begun life as the R-4 seems to have remained in production right up to 1979. It was followed by several more up-to-date However, the Silver Swallow 2.5 cc competition glow-plug engines were not competitive, nor by all accounts were they all that well made. In around 1985 their further development and manufacture was taken up by CS, who tweaked them to good effect. In the early 1990’s, after transferring the manufacture of the venerable old Silver Swallow diesels to others, the makers returned their focus to the more contemporary glow-plug engine, marketing several versions of a basic ABC glow-plug model. As of 2009, Ed Carlson was still listing both aircraft and marine 6.5 cc R/C glows under the Silver Swallow designation, although they are now long gone. But that’s quite another story which has little to do with our main subject here ............ Operating Notes - Care and Feeding The above information is probably more than sufficient as far as the collector community is concerned. However, these engines are far more than mere collector’s items – they’re actually very attractive engines to use in practical aeromodelling applications where a compact and lightweight diesel of “classic” specification and relatively low replacement value is called for. There are enough of them about that they will likely remain readily available at reasonable cost for years to come. So I’ll spend a little time here passing on some tips for the successful operation of these engines for those who may be understandably tempted ……. the following comments apply to both sizes of engine unless otherwise noted. The Silver Swallow engines were quite widely used over the years in my part of the Pacific Northwest. Having used these motors extensively myself for over 25 years and having observed them in long-term use by a number of my flying mates, I am able to offer some practical observations which are solidly based upon many years of hands-on experience with a sizeable number of examples. I’ll begin with some possibly startling advice to would-be users - don’t even think about it unless you’re prepared to do some extensive preparatory work first! Having said so much, I clearly need to say more ..........as supplied, the Silver Swallow engines certainly do run for the most part, but their utility in practical terms is greatly compromised by the fact that quality control is all over the shop, especially in the later models. The earlier Yin Yan engines were extremely well made, and many of these comments do not apply to them. However, as a basic piece of sound advice, don’t even try to run or even turn over a new example of any of these engines unless you first remove at least the backplate (and preferably everything else!) and give the entire engine a really good clean-up, also checking for things like burrs at the cylinder and crankshaft port edges. Important note - as with all model engines having screw-in cylinders, make sure that the piston is at bottom dead centre and is well oiled and completely free to move before unscrewing the cylinder - scoring of the piston surface or twisting of the con-rod can easily result if you don’t do this. Also, do not unscrew the cylinder by putting anything in the exhaust ports, otherwise irreparable damage is inevitable. Better to use a strap wrench or some other non-marring means of gripping the cylinder. The combination wrench supplied with some examples is useless and should not be used. For cleaning, an ultrasonic cleaner with suitable solvent is recommended. You’ll be amazed at how much shop junk can be extracted from the average new example of one of these engines! Then use plenty of molybdenum disulphide when re-assembling to help deal with the initial hit upon the metal rubbing surfaces when the thing first starts up. Finally, run the engine in very carefully indeed, using the approach set out in my detailed article on breaking in a classic model diesel engine. You can stop there if you like, but you probably won’t be happy with the long-term results since a number of other issues are lurking in the background. One of these problematic issues is the shaft end-float. Many of the Silver Swallow models were supplied with excessive clearance between the front of the main bearing and the rear of the prop driver. This allows the shaft to float axially, often to the point where rod alignment is affected and the crankpin contacts the backplate both while starting and in a crash. Apart from the metal shavings which this can send through the engine, it’s not good for either the crankpin or the backplate! Moreover, it can place undue stresses upon the con-rod and cause it to be pushed off centre or even bent in a hard impact. I’ve seen this happen ........... The fix is either to insert a steel shim between the prop driver and the front of the main bearing to minimize the end-float, or to re-cut the 35 degree included angle self-releasing taper inside the driver to make it set further back on the shaft taper and give the same result. The first option is easily adopted by any potential user, since no machine tools are required. 5 to 10 thou end float is quite sufficient. Those with machine tools can now go a step further by re-machining the rear of the crankcase to allow the backplate to screw further into the case to the point where it almost (but not quite) contacts the crankpin when the shaft is set back with a prop fitted. This does two desirable things – it keeps the big end of the con rod completely on the crankpin (good for even bearing wear) and in correct alignment with the bore axis, and it reduces crankcase volume slightly (good for pumping efficiency). However, it’s not essential. Another issue with the 2.47 cc Silver Swallow as supplied is the venturi throat diameter. As supplied, most examples that you may encounter are fitted with the oversized 7.1 mm dia. venturi in combination with the standard 3 mm spraybar. Together with the sub-piston induction present on these motors, this results in a level of suction and hence airborne consistency which can only be fairly described as marginal. The engines display far greater flexibility in use when fitted with the smaller 5.5 mm diameter unit. Accordingly, if such a component is available it’s advisable to fit this for most practical purposes. If no such part is on hand, a short length of thin-walled aluminium tubing of suitable external and internal diameters can be transversely drilled through for the spraybar and then fitted inside the standard large-bore venturi to reduce the throat area. Or a replacement small-bore component can easily be made from scratch by anyone having a lathe handy. That's the approach that I've taken myself. I’ve actually found that a 6 mm throat diameter works very well indeed in control-line service. Thanks to the sub-piston induction, the loss of performance is surprisingly small and the improvement in suction, flexibility and consistency of operation is very significant. The throat diameter used on the 1.49 cc model appears to be well matched to the engine, and no modification to that feature appears necessary. If you take no more than the above basic steps, you should have little trouble in getting most examples of these engines to run OK. And the better-fitted ones run quite well – I’d say at the top of the scale for engines of their rather basic lightweight plain-bearing specification (just like the better examples of their distant Alag ancestors, in fact). The trouble is that even after the above preparation, they tend not to run for very long! The culprit here is the infamous Silver Swallow crankshaft. The precise cause of this behaviour is debatable, but the plain fact is that the average life of a 2.47 cc Silver Swallow crank is between 4 and 5 running hours – after that, it breaks in the vicinity of the induction port. They all do this – in all my years of experience with quite a few examples (mine and others), I have never seen a stock 2.47 cc Silver Swallow crank go much past 5 hours running time, and one of my mate’s cranks let go after only some 3 hours in the air. The Jin Shi shaft with its larger gas passage in the same diameter journal is even worse in this respect – a couple of hours usually sees them off. The 1.49 cc models appear less prone to shaft breakage, but I have heard second-hand reports of the occasional problem with them too, although I’ve never run one long enough myself to break a shaft. I noted earlier that the Yin Yan (and Silver Swallow) 2.47 cc models feature a crankshaft with a main journal diameter of 10 mm as opposed to the 8.5 mm used in the Alag X-03 upon which the Yin Yan appears to have been broadly based. I also noted that the Chinese designers took advantage of this to employ a 7.4 mm diameter internal gas passage as opposed to the 5.5 mm used in the Alag. Looks good at first glance, but my good mate Maris Dislers has done some calculations which indicate that despite the Yin Yan's greater main journal diameter, the larger gas passage meant that its shaft had only 75% of the torsional strength of the Alag, assuming the use of the same material. This alone would certainly increase the potential for crankshaft failure. This probably explains the previously-noted fact that later versions of the Silver Swallow featured a 6.8 mm internal gas passage. The other villain of this particular piece must surely be the material. The fractures that do occur with unmodified engines give the appearance of being brittle fatigue failures. There is clearly a problem either with the steel or the heat treatment of this item – this is true of a number of other Chinese engines of my acquaintance as well. The material tends to be brittle, hence being subject to brittle fatigue failure. Other than making a new shaft from proper material (which I’ve done with other engines), the only effective fix that I’ve found is to take the following steps in succession:

Although the above process does not guarantee that the shaft will stay in one piece, my own experience has been that Silver Swallow shafts treated in the above manner seem to hold out pretty well – in fact, I’ve yet to break one (touch wood!). The metal is softer, but work hardening creates rubbing surfaces which are sufficiently wear–resistant if adequately lubricated. Run them in respectfully, though – you have to allow the work-hardening to develop before really loading up the bearings! The Jin Shi shaft is inherently weaker than the Silver Swallow item, and I gather that they still tend to break even after being treated in this way, albeit only after some hours of useful service. Again, I have personally yet to break one.

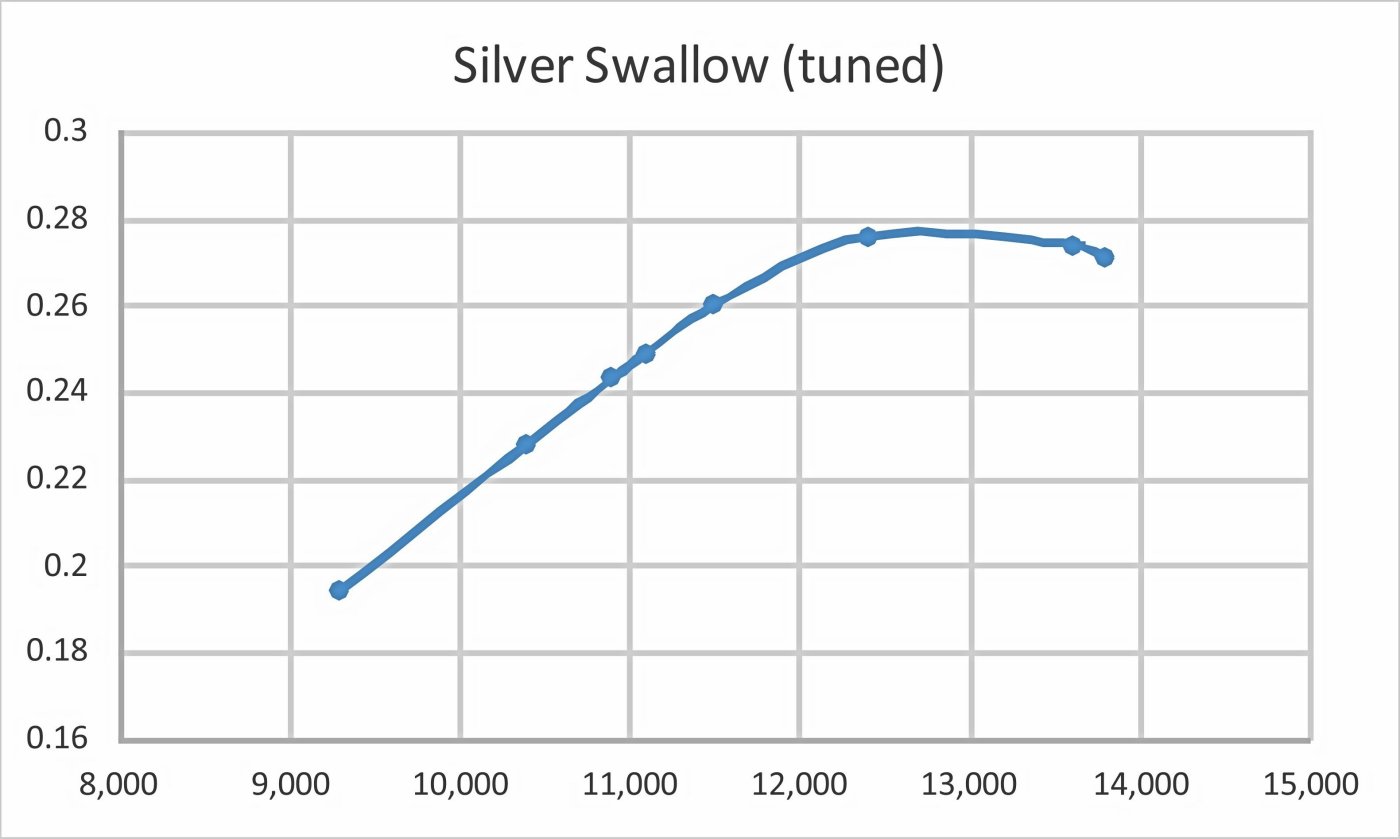

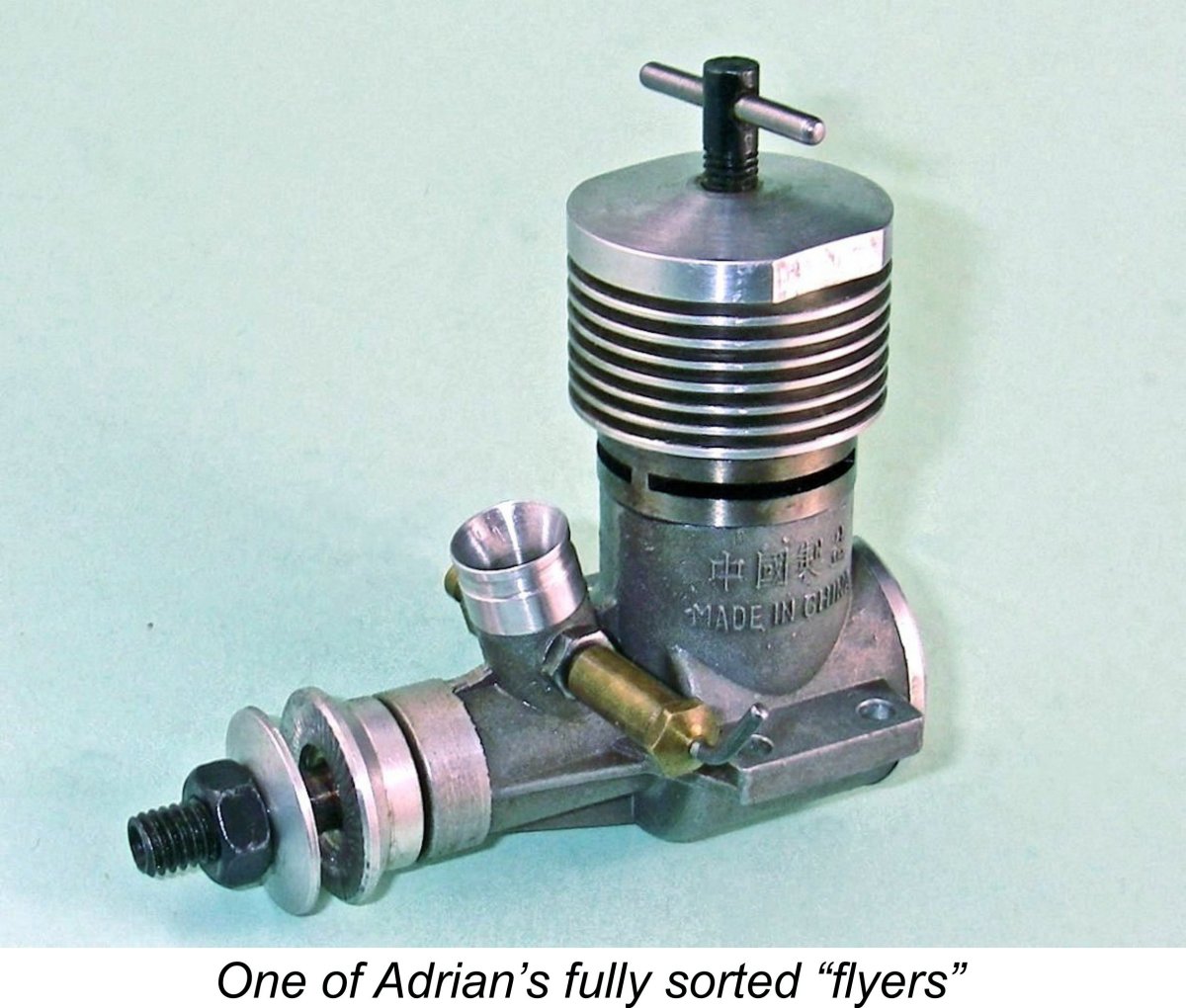

After the grinding is done, it’s a good idea to smooth the sharp edges of the ground-out areas. I recommend doing this and any other shaft modifications such as gas-flowing the exit of the central gas passage prior to the normalizing process described earlier. The bluish coloration of the illustrated Jin Shi shaft is the result of that process having been applied. The engine runs very well indeed and has so far stayed in one piece............... Now, none of the above improvements require the availability of machine tools or special mechanical skills. So by all means run that Silver Swallow after giving it a good clean, dealing with the end-float issue and balancing and normalizing the shaft. Run it in carefully, and you’ll have a nice little engine that will give you some very good service if you take care of it. When the rod wears out (which they do), you have a bit of a replacement problem, but it’s not by any means insurmountable. In any case, that’s no reason not to enjoy using these engines for their intended purpose! Use a little extra castor oil in the fuel – that will delay any rod wear issues. Many people run far too little oil in their diesel fuels, and there’s no substitute If you go to all this trouble, you’ll end up with a dependable and remarkably smooth-running motor having a very respectable performance, especially for a classic-era plain bearing engine, and weighing only about 4.6 ounces (130 gm) and 3.5 ounces (99 gm) respectively for the 2.47 and 1.49 cc models. I've used my own two “flyers” quite a bit, and have no complaints to make about the way they handle or perform. They can in fact be tuned up to give an even better performance, but that’s another story ................. My usual flying example of the engine seen in the accompanying illustration has been fully sorted in the manner described above. The cooling jacket seen in the image is of my own making, being used for flying purposes solely to preserve the coloration of the original jacket. It also features two opposing flats for convenient tightening. A recent test of the illustrated example fitted with my own 6 mm I/D venturi after some 4 hours of flying time following break-in yielded a very sprightly performance for a simple lightweight plain-bearing diesel of the classic era. The results obtained are shown below in tabular and graphical form.

The 8x4 APC WB is a cut-down APC 9x4 created and calibrated to fill an otherwise glaring gap in my test prop set. There's still a fairly wide gap in which the peak of this engine clearly lies. However, the data are very consistent, implying a peak output of around 0.280 BHP @ 13,000 rpm. This would have been considered a very acceptable performance for a lightweight plain-bearing sports diesel in 1962, when this engine first appeared. A published test by Dave Ridgway of the CS versions of the Silver Swallow .09 and .15 models appeared in the October 2000 issue of "Model Flyer" magazine. Athough no power curves were derived, Dave's propeller/RPM figures for the .15 model matched my results very closely for those props which featured in both tests. I've never tested my flying example of the 1.49 cc Silver Swallow. I will do this at some point when time permits and will add the results to this article. Dave Ridgway's previously-noted "Model Flyer" test reported that the CS .09 model turned an APC 8x6 prop at 8,800 RPM (c. 0.119 BHP), an APC 8x4 at 10,700 RPM (c. 0.133 BHP) and a Graupner 7x4 at 12,400 RPM. These are perfectly acceptable figures for a plain bearing sports diesel of "classic" configuration. One final comment – never having dismantled or attempted to run one, I have no way of knowing the extent to which the CS versions of these engines suffer from any of the problems exhibited by the Silver Swallow and Jin Shi originals. But as a precautionary measure, I would personally go through the above steps even with one of their products prior to use, just to be certain ................ it’s up to others to decide whether or not to follow suit. Conclusion Well, there it is – an in-depth look at one of the hardiest survivors of the “classic” era of model diesel engine manufacture! 46 years in production by various makers represents no small compliment to the design! These engines must have been over-produced by the warehouse-full to judge by the length of time that they remained on the market even after production ceased. Given the serial number evidence to the effect that production figures in the order of 1000 units monthly of each individual model were being achieved in the mid to late 1960's, it seems likely that the total number produced must have run well past the six figure mark for both 2.47 cc and 1.49 cc models combined. It would be very useful to have a larger tally of confirmed serial numbers, particularly those which extend the range reported in this article in either direction. If any reader has one or more of these engines whch display serial numbers, I'd be extremely grateful to hear from you! There's a Silver Swallow thread already set up on the blog site to which serial numbers and any other relevant information can be posted - please use it! With CS’s latter-day efforts, there’ll no doubt be plenty of these engines to go round for years to come. Moreover, as a relatively common and hence low-cost "replacable" engine, there’s no reason not to use them for the purpose for which they were intended either! I’ve been perfectly happy with my own flying examples, and I’m sure that others would be equally well satisfied if they were to take the trouble to prepare their engines properly and run them in carefully. Good luck!! __________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published November 2016

|

||

| |

The above paragraph is paraphrased from a brief article by the late Ron Chernich about the

The above paragraph is paraphrased from a brief article by the late Ron Chernich about the

In simplified colloquial Chinese, the name Yin Yan translates to Silver Swallow, and indeed the company's cute little "flying swallow" logo complete with the English rendition of the name appeared on the original boxes in which the early Yin Yan engines were supplied. The name of the range was officially anglicized in 1966 to the more familiar Silver Swallow, but that name had in fact been there all along. Presumably the change in linguistic emphasis was made to reflect the growing importance of English-speaking markets as time went by. The engines remained essentially unchanged despite the name switch, as we shall see.

In simplified colloquial Chinese, the name Yin Yan translates to Silver Swallow, and indeed the company's cute little "flying swallow" logo complete with the English rendition of the name appeared on the original boxes in which the early Yin Yan engines were supplied. The name of the range was officially anglicized in 1966 to the more familiar Silver Swallow, but that name had in fact been there all along. Presumably the change in linguistic emphasis was made to reflect the growing importance of English-speaking markets as time went by. The engines remained essentially unchanged despite the name switch, as we shall see.

Fair enough - is there any basis for identifying the design inspiration for the Yin Yan series? As it happens, there’s a very logical candidate ready to hand – the much (and in my view very unfairly) maligned

Fair enough - is there any basis for identifying the design inspiration for the Yin Yan series? As it happens, there’s a very logical candidate ready to hand – the much (and in my view very unfairly) maligned  The Alag has been much maligned over the years (rather unfairly in my personal view) for its supposedly very poor level of quality control. However, the basic design was perfectly sound and the better examples of the Alag (which did exist - I have several!) were really very good little engines. So if the Chinese could make an engine which was based on the Alag design but was perhaps improved in detail, they would completely side-step the usual development phase and would have a very viable product on their hands!

The Alag has been much maligned over the years (rather unfairly in my personal view) for its supposedly very poor level of quality control. However, the basic design was perfectly sound and the better examples of the Alag (which did exist - I have several!) were really very good little engines. So if the Chinese could make an engine which was based on the Alag design but was perhaps improved in detail, they would completely side-step the usual development phase and would have a very viable product on their hands!  The Yin Yan and later Silver Swallow diesels were marketed in both 2.47 cc and 1.49 cc displacements. Like their presumed Alag progenitors, both sizes of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow diesel engines are essentially identical in construction. They are both plain bearing, radially-ported reverse-flow scavenged crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) compression ignition engines which are very similar in all key functional design aspects to their presumed Alag ancestors.

The Yin Yan and later Silver Swallow diesels were marketed in both 2.47 cc and 1.49 cc displacements. Like their presumed Alag progenitors, both sizes of the Yin Yan/Silver Swallow diesel engines are essentially identical in construction. They are both plain bearing, radially-ported reverse-flow scavenged crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) compression ignition engines which are very similar in all key functional design aspects to their presumed Alag ancestors. Again like the Alags, the externally-threaded steel liner is hardened and ground. The 2.47 cc model features exactly the same porting arrangements as its Alag counterpart, with three wide but shallow sawn exhaust ports and six internal-flute transfer passages terminating just below the lower edge of the exhaust ports. This imposed a fairly lengthy blow-down period upon the designer, but this is compensated for by the fact that the total area of the bypass and transfer ports is also unusually large. Accordingly, this arrangement seems to be very forgiving of a short transfer period. It certainly worked well in the iconic