|

|

Alan McCulloch's Model Engines by David Owen and Maris Dislers

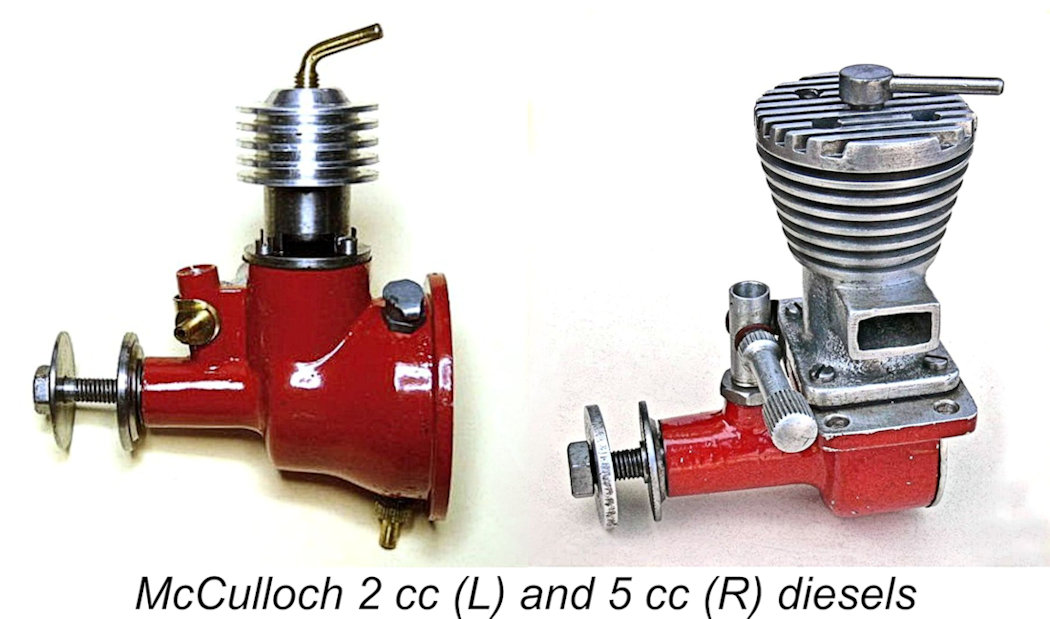

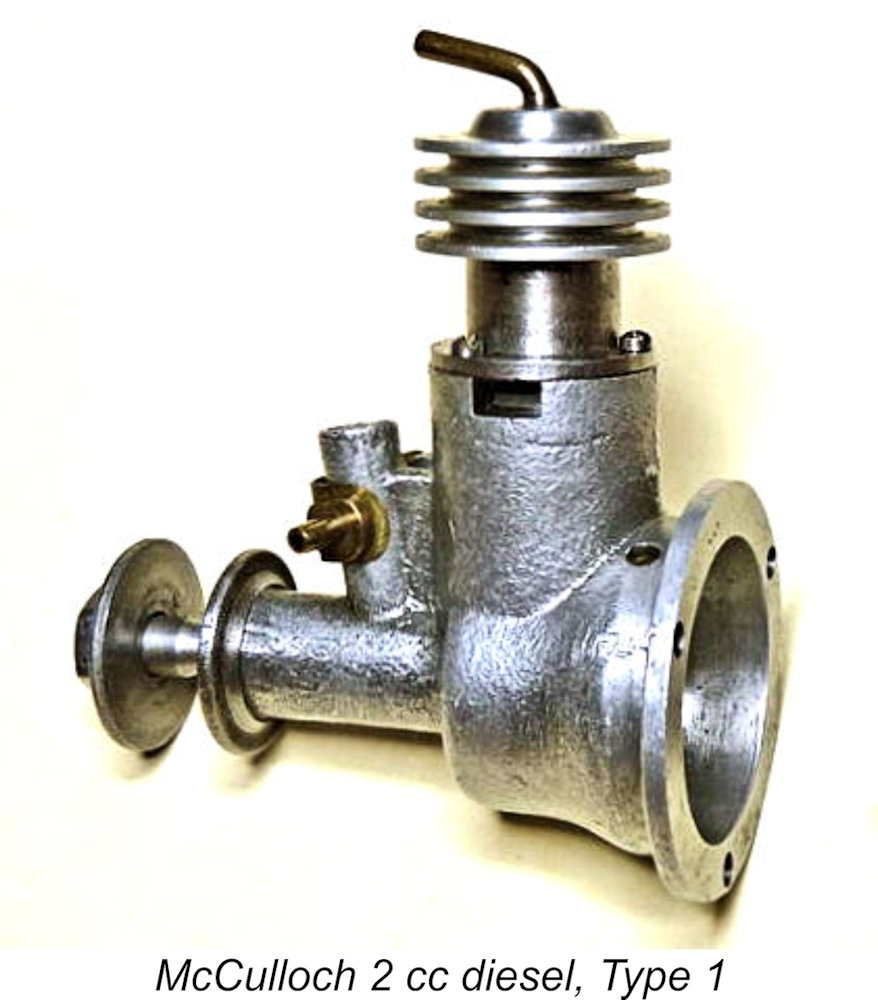

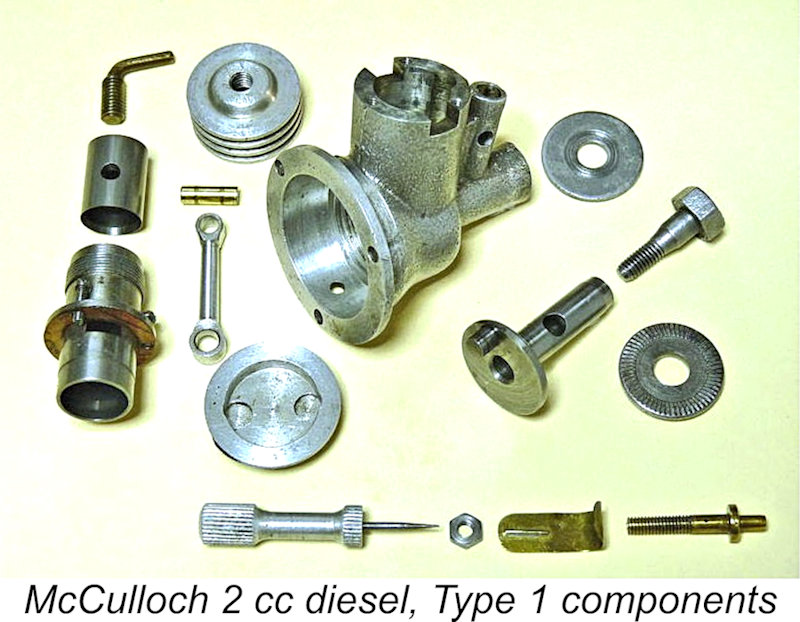

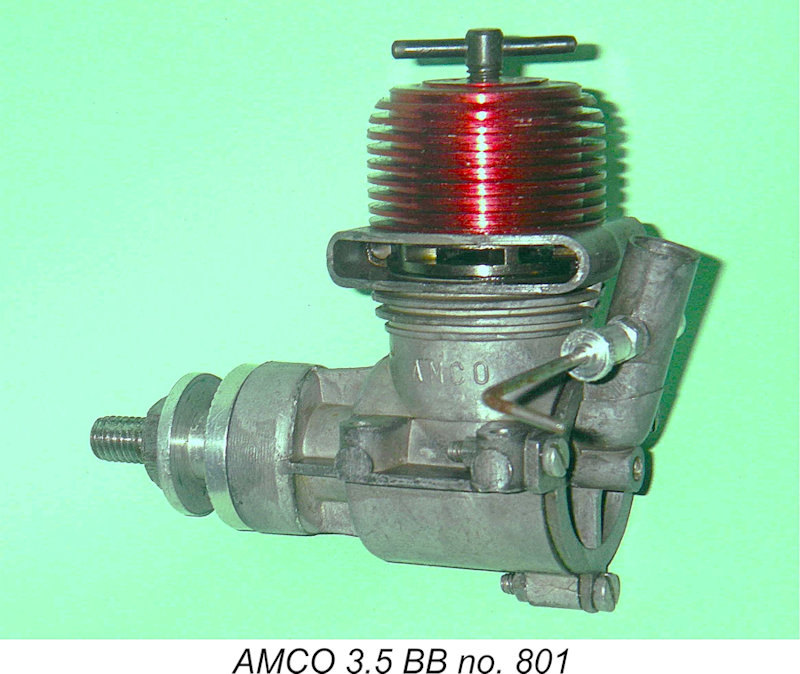

The original article on this subject appeared in December 2011 on MEN, where it may still be found. However, our greatly-missed mate Ron left us in early 2014 without passing on the access codes to his heavily encrypted site. Consequently, no maintenance of that site has since been possible, making it inevitable that a slow but inexorable deterioration is taking place over time. It’s this issue that has led Adrian to transfer a number of what he considers to be the more important or interesting articles over to his own site. This is viewed as being one of them. As in other parts of the world, the shortage in the supply of model engines in the years immediately after WW2 led a number of Australian enthusiasts to try their hand at making their own, with perhaps a few extras for their mates. Jack Black (Jay Bee 60), Harold Clisby (better known as the maker of Clisby air compressors), Bill Marden, Harold Stevenson and Gordon Burford (no introduction needed) all had a go. So did Adelaide resident Alan E. (“Billy”) McCulloch (b. 1927). Qualifying after the war as a fitter and turner, Alan purchased a new Qualos centre lathe in 1947. At the time, the 20-year-old Alan was working with his father William Wilson McCulloch, building and maintaining Ferris wheels and other carnival equipment. In his spare time, he built his first model aero engines. When visited in 1998 by David Owen, Alan was 71 years old and was quite surprised that anyone would be interested in his long-ago model engine endeavours. Unfortunately, his recollections were somewhat sketchy by that time. However, the impression is that he probably began with a 2 cc diesel of his own design. Let’s look at that model first. The McCulloch 2 cc diesel

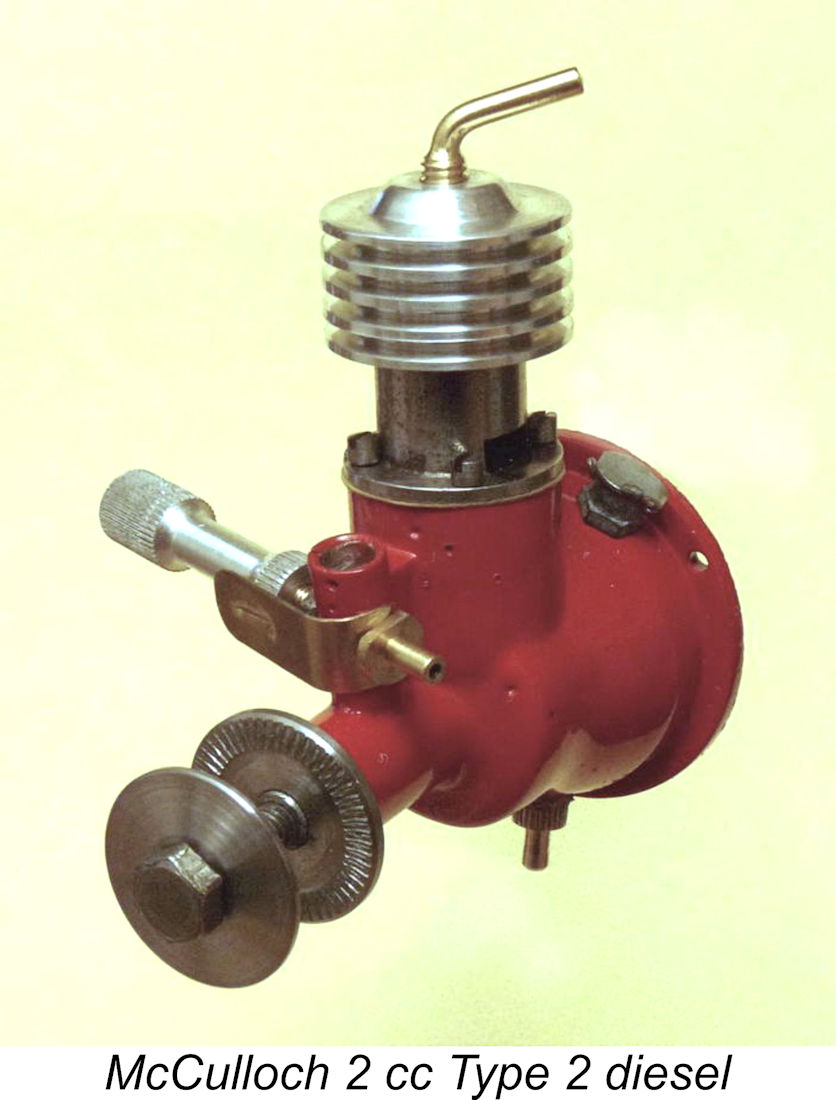

This engine is built to a relatively simple and compact design, achieved by utilizing front rotary valve (FRV) induction with the fuel carried in the rear crankcase cavity/radial mount. A commendably low weight of 113 gm (4 oz.) is a full one-third lighter than the contemporary and widely used E.D. Mk II. The McCulloch has a bore of 13.06 mm and stroke of 15.70 mm, giving it an actual displacement of 2.10 cc. The neat sand-cast aluminium crankcase incorporates a honed cast iron bush for the hardened steel crankshaft. This latter component has a hefty 8.5 mm journal and 3/16 in. dia. crankpin. The intake opens 50 degrees ABDC & closes around 25 degrees ATDC, giving an intake duration of 145 degrees. Design-wise, McCulloch clearly knew what he was doing!

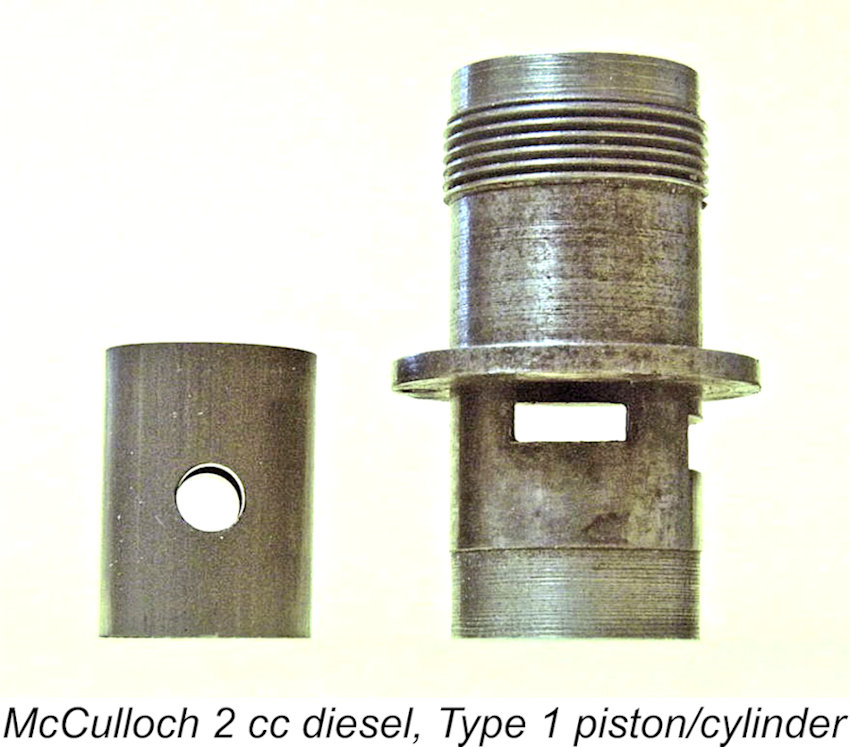

Three 3/32 in. BSW machine screws retain the hardened steel cylinder, which has two opposed exhausts Allan also used brass for the single-lever compression screw and red brass or bronze for the contra-piston. Like the later Red Special (see below), this engine shows the hallmark of a very competent model engineer, being very nicely finished and fitted.

Two channels milled into the crankcase allow unobstructed conrod travel. One also participated in the transfer function, as the other is closed at the top by the cylinder mounting flange located just below the exhaust port. Allan obviously took pains to get the port dimensions to his liking. Additional work with a fly cutter raised the top of the transfer and lowered the bottom of the exhaust port. Simply locating the transfer port below the cylinder flange and the exhaust above would not do.

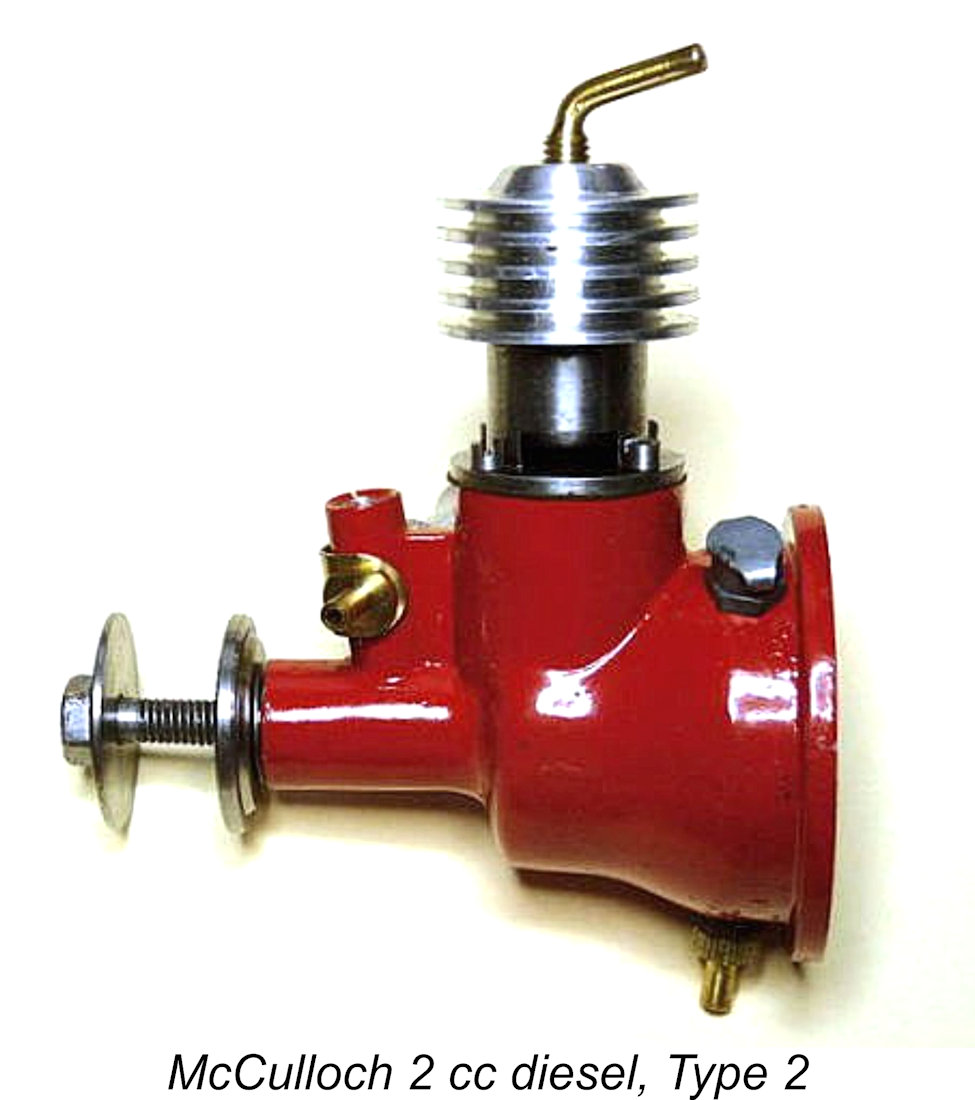

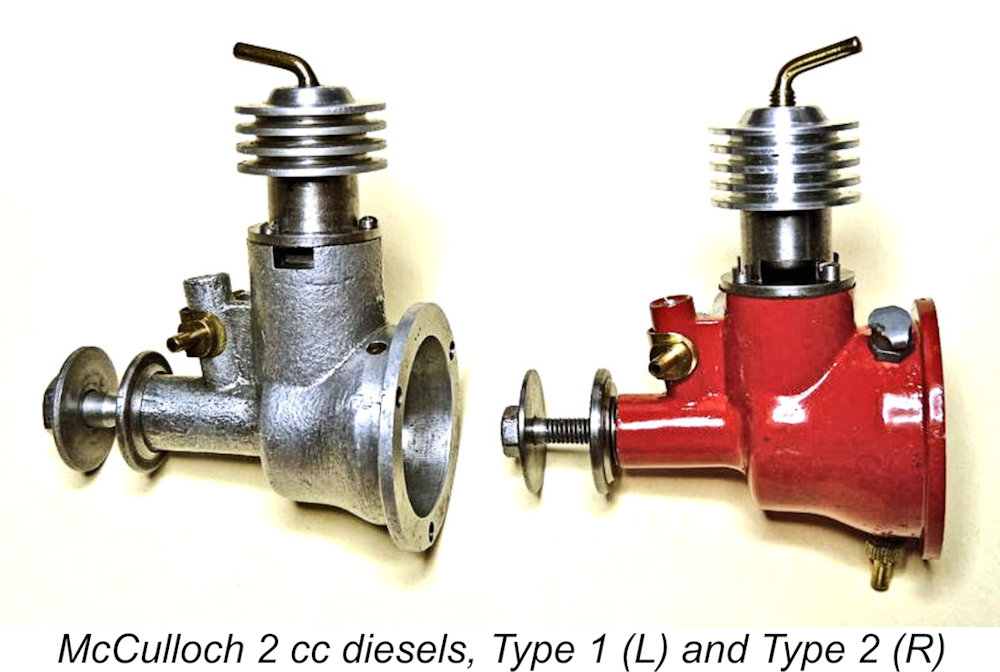

The Type 2 engine's crankcase extends further behind the cylinder, possibly to increase its on-board fuel capacity. Engine mounting is via three holes in the rear crankcase flange at 120 degree spacing. These holes were curiously small on Type 2. The final difference is crankcase finish. Type 1 was left as cast while Type 2's crankcase had been extensively fettled before receiving its coat of red Dulux. Running the McCulloch 2 cc diesels Type 1 was an easy starter and ran smoothly throughout its useable speed range. There was no need to adjust the compression setting for starting, which is just as well. The brass contra piston (a tight fit even when cold) soon jammed in the cylinder as the assembly reached running temperature. Frustrating when zeroing in on peak RPM readings, but generally the engine was quite accepting of compression settings "somewhere around the mark" - the setting was relatively non-critical. Response to mixture adjustment was predictable, and adjustments were comfortably made thanks to the swept-back spraybar location and large needle body. The engine's power output of 0.085 BHP between 6,100 and 7,700 RPM only just matches the Mk. 2 Mills 1.3 and was somewhat below expectations. Most probably, like so many of its contemporaries that have survived the years, this McCulloch has lost its optimum piston/cylinder fit after a long and useful life. On paper at least, it ought to match an E.D. Comp. Special for horsepower.

While it's likely that the Type 2 McCulloch cylinder porting and rotary valve induction had the potential to deliver even better performance, vibration levels at speeds over 9,000 RPM apply the brakes quite emphatically. That lovely needle reaches a harmonic vibration, winding out despite the best efforts of the strip brass ratchet. We did not explore whether it could leave the vibration zone behind and operate effectively at higher speeds - since the engine was past its peak anyway, there was no point in doing so. The McCulloch will run for two minutes on its on-board fuel supply, which is much longer than is prudent for free flight work. More likely, it was intended primarily to fly control line models using a separate tank. In that application, its power-to-weight performance would easily top the commercially-available alternatives of the day. So why did this promising design offering 30% more power than the E.D. Mk II at a lighter weight only lead to no more than a dozen examples being made in Alan's recollection? The answer may well lie in a "Flash News" announcement in the June 1949 "Australian Model Hobbies" magazine. Model Aircraft Industries (MAI) of Glenelg, South Australia were expecting delivery of the "up-to-the-minute" 2 cc Hawk/Falcon and 5 cc Vulture Mk. II and Mk. III diesels from the "K" Model Engineering Co. of Kent. Alan's engines, handmade as a side-line, were unlikely to compete successfully in the marketplace with these widely advertised, quantity-produced alternatives. The McCulloch 5 cc Red Special Diesel

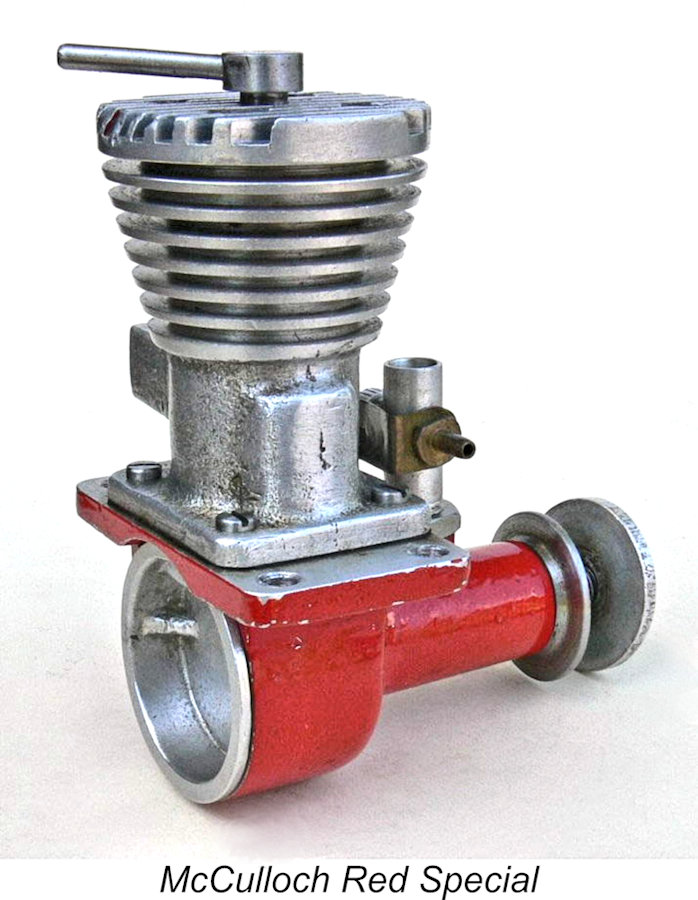

MAI added the red paint and marketed Alan's design initially as the .29 cuin. Red Sports model, although it was really just the McCulloch 5 cc diesel painted with red Dulux enamel. MAI's price list dated November 1948 was a small Roneo-printed affair boasting "the most comprehensive range of model materials available in Australia". Stock was available to the trade or to individual customers by direct mail order. Along with the E.D. Mk. II, FROG 100 and Milford Mite Mk. II diesels, MAI listed the ".325 GEE BEE" made by Gordon Already "superseded" by the Drone-influenced GEE BEE Stuntmota when the first issue of "Australian Model Hobbies" came out in June 1949, an advertisement in the subsequent September number by MAI stockist Curries Model Aerodrome in West Perth, Western Australia listed the McCulloch 5 cc model as the "G.B. Red Special 5 c.c." selling at a reduced £8/19/6 (£8.98). The implied connection with Gordon Burford is of course incorrect, but this advert in the mass media of the period gave Alan's engine its toe-hold in history, and the Red Special name has endured to this day. The Red Special's design was obviously heavily influenced by Leon Schulman's Drone Gold Crown engine introduced in 1947 in its original plain-bearing form. The Drone was effectively unobtainable but very desirable to the Australian enthusiast of the day, and Alan must surely have had access to an original example. Much of his engine is an outright copy, but Alan did not shy away from adding his own ideas to this American design.

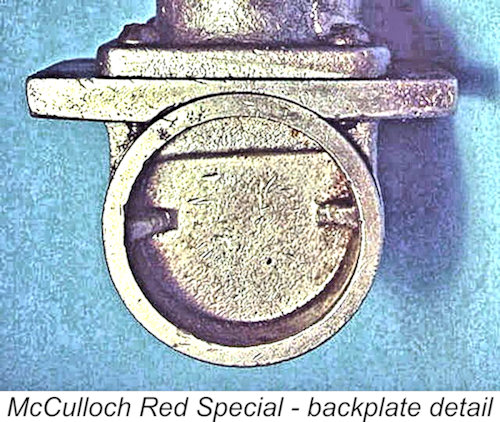

The Red Special varied in other details that necessitated a degree of individual attention not possible in a mass production scenario. For example, the backplate has an internal step to clear the piston at the bottom of its stroke. A corresponding bulge is cast into its outer profile. The backplate threads into the crankcase and must therefore align quite closely to a specific position when tightened. Presumably Alan made individual adjustments during the .machining of each engine to ensure that the parts aligned correctly.

Alan recalled a modest production run of approximately 60 engines. Anecdotally, painting them red was Bill Evans' idea for adding market appeal. Ferrari has done the same with their cars to this very day. However, not all of Alan's engines got that "treatment". The above photos show an engine with only the main crankcase painted, while others like that illustrated here are known to have the upper crankcase casting painted up to the lowest cylinder cooling fin. Heads and backplates are thought to have been left unpainted throughout. The Delta 490

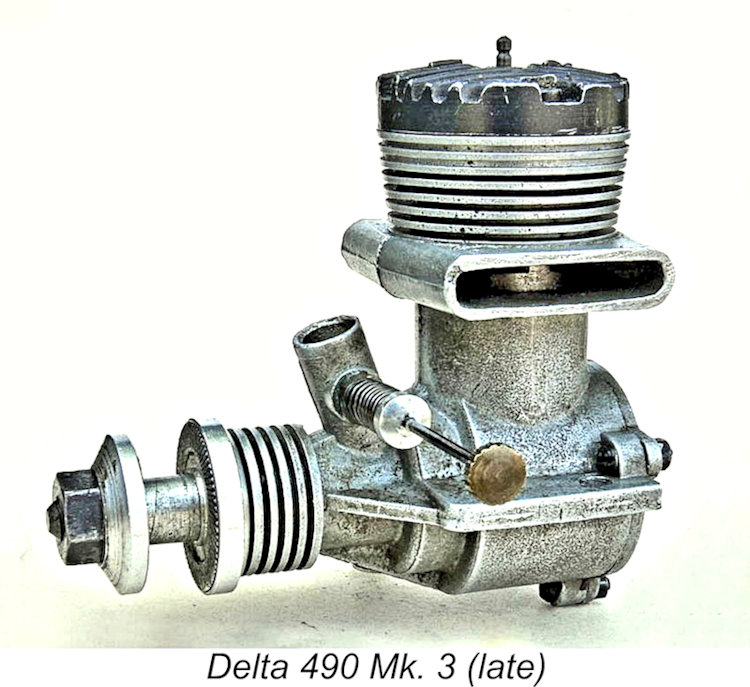

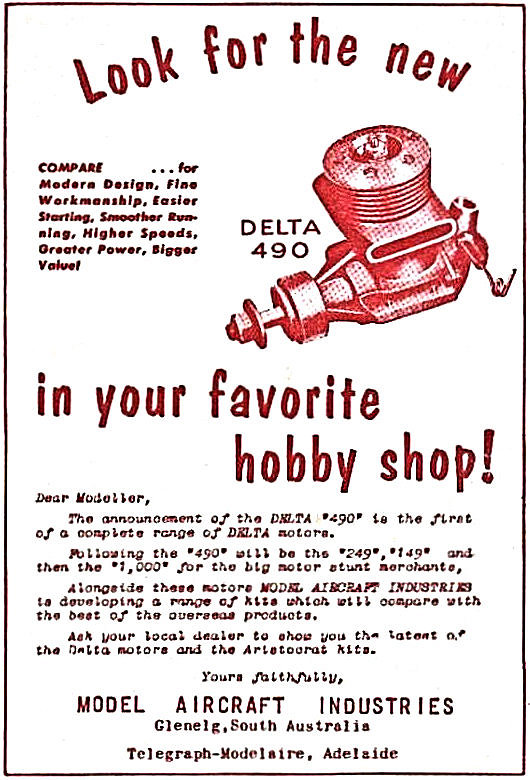

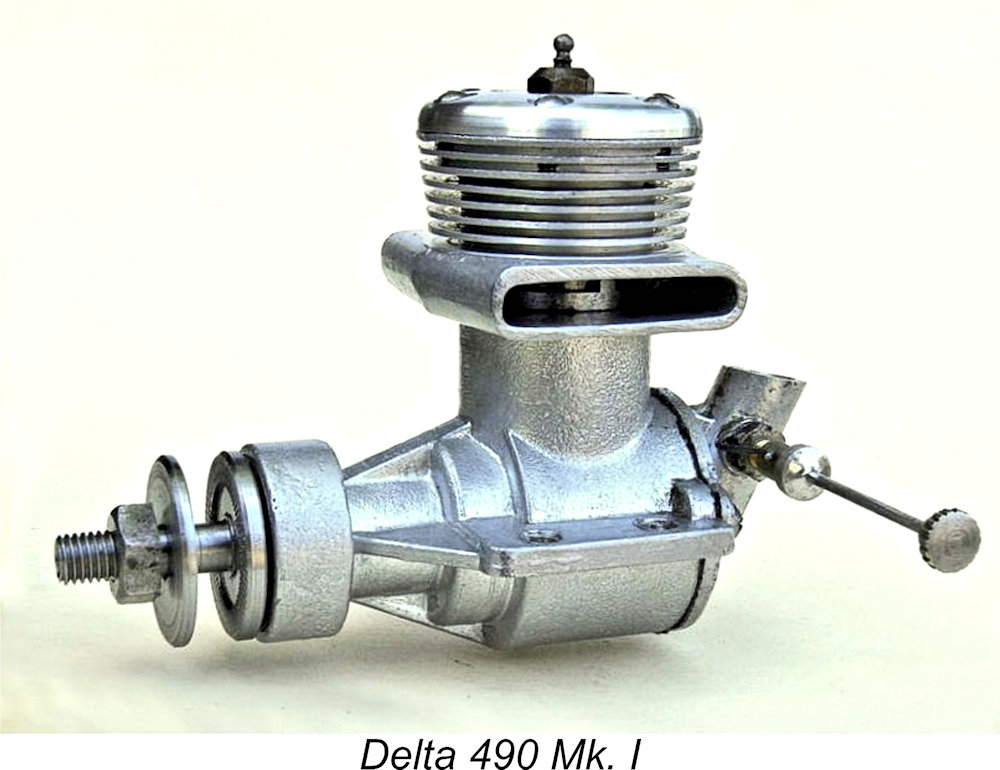

The "New Motor Preview" in the 1952 Spring issue of "Australian Model Hobbies" announced MAI's new 5 cc glow-plug engine thus: "The Delta 490, the latest motor to appear on the Australian market, was designed by Bill Evans - editor of Australian Model Hobbies - and developed in conjunction with Alan McCulloch, who has been responsible for several motors produced in Australia, such as the Gee Bee Red Special, and various parts of most Gee Bee motors. This has given him some considerable experience in model motor design and production, which coupled with his experience in the engineering field meant a lot of "know how" could be put into the "Delta" so as to produce a hot motor at a competitively low price". This announcement turned out to be somewhat pemature - the engines didn't reach the market until later in the year. The reference to the Gee Bee motors was incorrect – those engines were Gordon Burford’s efforts, and Alan McCulloch had nothing to do with them. Bill Evans’ design role may also be somewhat overstated. It’s more likely that Bill merely conceived and sketched out the general concept of a high-end engine which was clearly distinguished from the popular FROG 500 in the marketplace but more affordable than the imported ETA 29.

Coincidentally with the arrival of the Delta 490, Australia's balance of trade had plummeted to a massive 21% deficit in fiscal 1951-52, prompting the government to introduce immediate severe restrictions on imports. Quotas were introduced and modelling goods were suddenly in short supply, particularly imported items such as engines. It was very tough on the trade, but it did open up some opportunities for domestic producers like MAI. The situation led to Monty Tyrell leaving Hearns Hobbies in Melbourne and taking a position in Adelaide with MAI. This was later in 1952 when the Delta 490 had been announced but was not yet on the market. Here is Monty’s first-hand account: "When I hit the Model Aircraft Industries set up, my being there enabled Bill Evans to have more free time to get the engine manufacturing division started. He rented a factory in North Unley and along with George Nixon and Royce Ryan got the Delta 490 into production. In between running the shop in Franklin Street (Australian Hobby Centre) and packing kits in Model Aircraft Industries' factory, I used to spend the eighth day of the week hand-testing the Delta production run, as I felt a sport motor that couldn't be hand started was a useless object. The knock-back rate was high but I'll die happy knowing that most Deltas which got out into the market would actually run. The Delta was nothing but an import cuts special which enabled many to keep or start flying. It sold for eight quid ($16) which was about 60% of the weekly pay." The Delta 490's Design

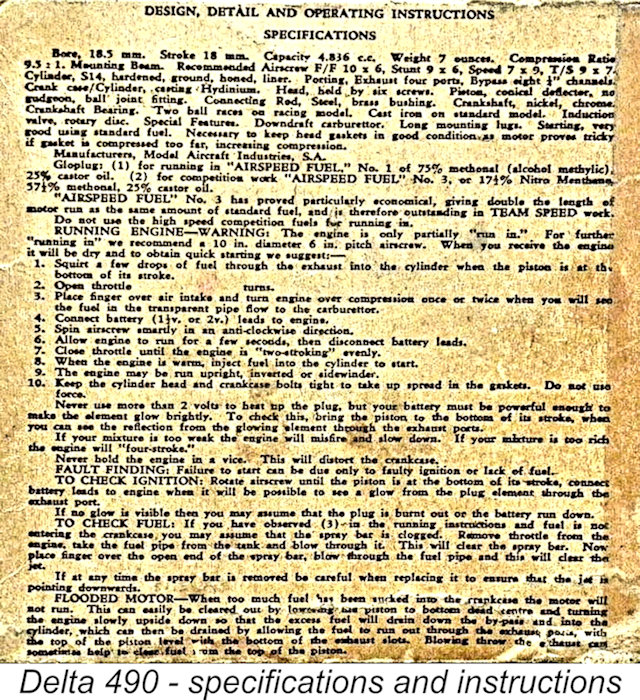

"Bore 18.5mm Stroke 18mm. Capacity 4.836cc. Weight 7 ounces. Compression ratio 9.5:1. Mounting beam. Recommended airscrew F/F 10x6, Stunt 9x6, Speed 7x9, T/S 9x7. Cylinder S14 hardened, ground, honed, liner. Porting Exhaust four ports, Bypass eight 14" channels. Crankcase/cylinder, casting hydinium. Head held by six screws. Piston conical deflector, no gudgeon, ball joint fitting. Connecting rod Steel, brass bushing. Crankshaft nickel chrome. Crankshaft bearing Two ball races on racing model, Cast iron on standard model. Induction valve rotary disc. Special features Downdraft carburettor. Long mounting lugs. Starting very good using standard fuel. Necessary to keep head gaskets in good condition as motor proves tricky if gasket is compressed too far, increasing compression."

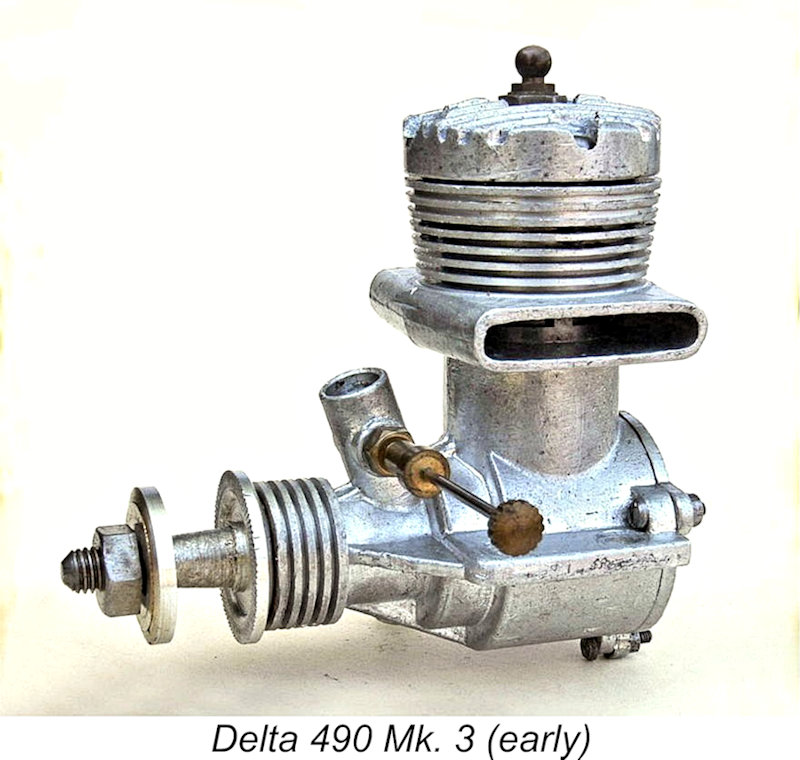

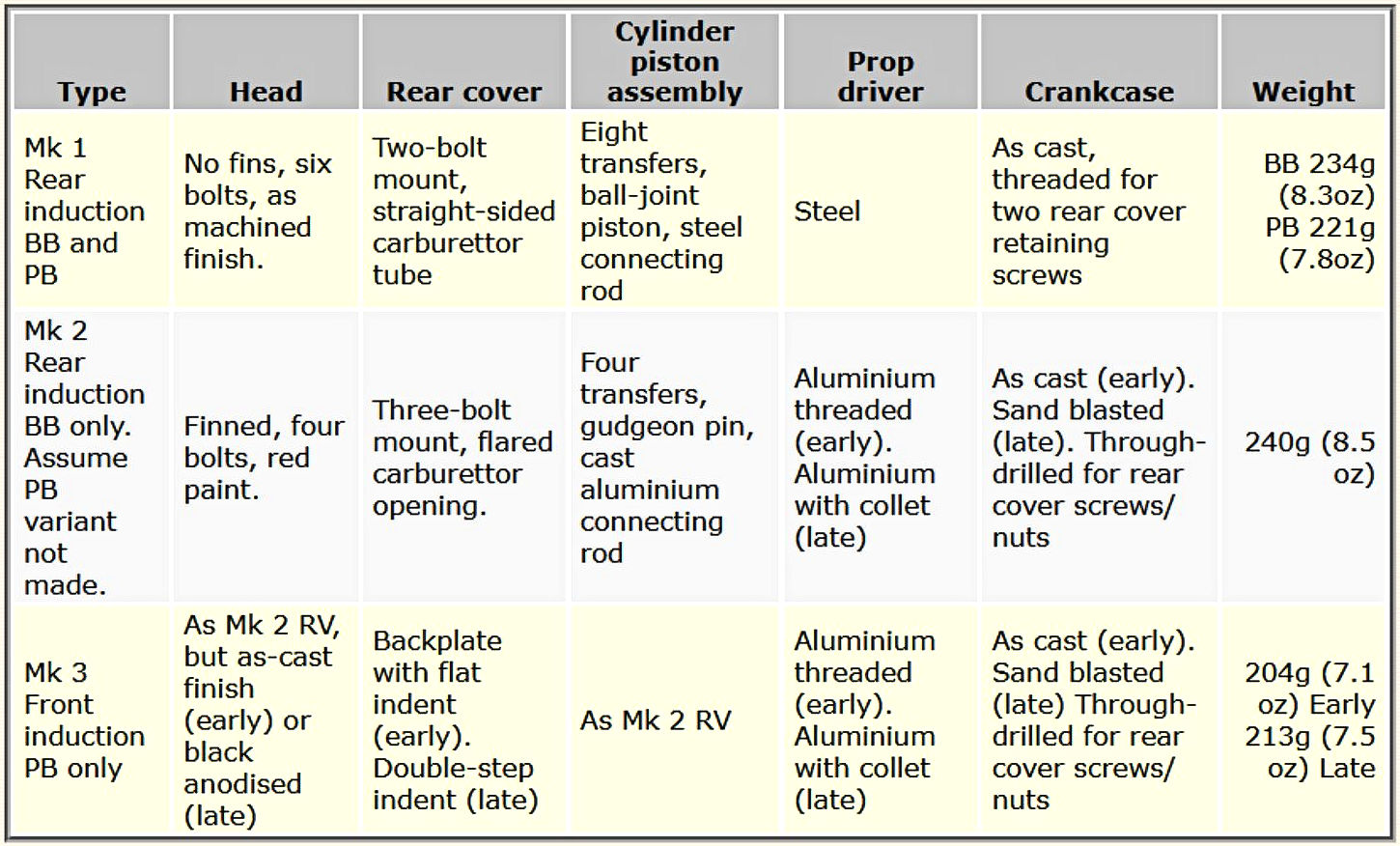

The original design was thoroughly revised inside and out to produce the Mk. 2 variant. The Mk. 2's new finned, cylinder head is held down by four (not six) screws and is typically painted a burgundy red colour. The crankcase has an additional lug giving three-point mounting for a new "back door" casting. This has a flared venturi profile and a gentler curved transition to the intake window. The backplate mounting lugs and backplate holes are through-drilled to permit the use of nuts and bolts for securing the backplate rather than relying on tapped holes in the aluminium alloy crankcase.

The Mk. 3's crankshaft jourmal diameter was upped to 7/16 in. (11.1 mm) versus the solid Mk. 1 and Mk. 2 crankshaft's 5/16 in. (7.95 mm) journal diameter. The Mk. 3's stroke was marginally increased from 18 to 18.5 mm, giving a nominal swept volume of 4.97 cc. Keen eyes will spot that the lower backplate mounting lug was made more substantial toward the very end of production. Minor changes in small component design (e.g. needle valves, prop drivers/washers) consistent with small batch production methods have been noted. This is summarised in the table below.

The rebored engine started easily, providing the exhaust was primed. It tended to run flat out. Richening the mixture from peak had little effect on engine speed. Even winding the thimble off the spraybar and drawing the needle out to give maximum flow failed to get the classic four-cycle run so generally favoured for stunt work these days. It appears that the effective choke area of over 15 mm2 is over-optimistic for this engine and a figure around 8-9 mm2 would make the engine far more tractable with little loss in useable performance.

When pondering these performance figures, it might be useful to keep the following data in mind. Checked exhaust duration is 140-146 degrees and around 90 degrees transfer duration for all Marks. The Mk. 1 & 2 intake opens very late at 80 degrees ABDC and closes 60 degrees ATDC. The Mk 3's intake is more conventional, opening at 60 degrees ABDC and closing at 55 degrees ATDC.

Clearly there are significant differences between individual engine outputs on the same propeller load. This is probably more influenced by piston/cylinder fit (which seems to be universally on the loose side) than anything else. Fit and finish of other components seems to be quite adequate, although the sharp-eyed reader will note that the big end of the Mk. 3's conrod was bored well off centre. The somewhat better result from the rebored Mk. 3 engine hints at what might have been if Alan McCulloch's high standards of internal fit and finish had been achieved by the manufacturer of the Delta 490. Furthermore, it seems that the added complexity and weight inherent in the designs of the Mk. 1 & 2 models did not pay off in terms of performance. Conclusions

Monty Tyrell observed that most of the 490's were of the ball bearing type. Going by the number of survivors, we'd say they were mainly Mk. 1's bought at the time when supply shortages encouraged modellers to simply buy what was available. The Australian balance of payments swung back to a healthy surplus of 26% in 1952-53, easing import restrictions considerably. Despite the doutless sincere efforts made to bring out the supposedly improved Mk. 2 and Mk. 3 models, the Delta's reputation as both noisy and gutless did not change. All hopes of producing a wider range of engines from 1.5 cc to 10 cc (foreshadowed in the attached 1952 advertisement in the unofficial Rules Book for Australia by Allan King and Monty Tyrell) went unfulfilled. The Delta engines dropped from the scene after a total production run of some two or three hundred examples of the 490 model. Those with a positive outlook might say that with a bit more time to optimize the design and get the quality problems sorted, the Delta could have been developed into a good engine. Perhaps it might have been if Alan McCulloch had remained involved. As it was, people who paid quite a hefty sum for one only to be underwhelmed by its performance would doubtless have been less conciliatory. It is believed that the backers who put up the capital for the engine manufacturing machinery lost heavily from the venture. Our thanks go to Mal Sharpe, Peter Lloyd, Don Howie and Anthony Williams for their assistance with this report. ____________________________ Article © David Owen & Maris Dislers, Australia First published on MEN December 2011 New edition published on this website November 2025

|

|||

| |

This article is a re-publication of an earlier piece on the same subject which appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s fabulous “

This article is a re-publication of an earlier piece on the same subject which appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s fabulous “ Thanks go to Mal Sharpe for drawing David Owen's attention to the almost forgotten McCulloch 2 cc diesel. The relatively simple design of this engine suggests that it was Alan's first go at making engines, possibly materializing (at least in its initial form) soon after the Qualos lathe was put to work in the McCulloch workshop in 1947.

Thanks go to Mal Sharpe for drawing David Owen's attention to the almost forgotten McCulloch 2 cc diesel. The relatively simple design of this engine suggests that it was Alan's first go at making engines, possibly materializing (at least in its initial form) soon after the Qualos lathe was put to work in the McCulloch workshop in 1947. The main casting features a radial mounting flange with a large internal cavity which is completely unsealed. The presence of a fuel outlet and fuel filler aperture makes it clear that this cavity was intended to serve as the fuel reservoir, although there is no indication of how Alan sealed it at the rear. The simplest set-up would be direct mounting onto the model's firewall, probably with a thick paper gasket to stop leaks. This tank could only be used with the engine mounted in an upright orientation.

The main casting features a radial mounting flange with a large internal cavity which is completely unsealed. The presence of a fuel outlet and fuel filler aperture makes it clear that this cavity was intended to serve as the fuel reservoir, although there is no indication of how Alan sealed it at the rear. The simplest set-up would be direct mounting onto the model's firewall, probably with a thick paper gasket to stop leaks. This tank could only be used with the engine mounted in an upright orientation.

Clearly a major redesign had occurred, perhaps quite some time after the earlier engine was made. Type 2's porting is of the cross-flow type, suggesting that this engine was not made until Alan had examined a

Clearly a major redesign had occurred, perhaps quite some time after the earlier engine was made. Type 2's porting is of the cross-flow type, suggesting that this engine was not made until Alan had examined a  Logic dictates that with more thread on the Type 2's upper cylinder, a longer cylinder jacket was intended and the extra thread length equates to one more cooling fin than the Type 1. Even so, the Type 2 engine is around 3 mm shorter than its partner owing to a shorter conrod and higher gudgeon pin hole in its piston, accentuated perhaps in the attached side-by-side photo by its lower cylinder flange location. Perhaps this engine was the guinea-pig for the same revision of the Drone design formula as it morphed into the subsequent Red Special (see below).

Logic dictates that with more thread on the Type 2's upper cylinder, a longer cylinder jacket was intended and the extra thread length equates to one more cooling fin than the Type 1. Even so, the Type 2 engine is around 3 mm shorter than its partner owing to a shorter conrod and higher gudgeon pin hole in its piston, accentuated perhaps in the attached side-by-side photo by its lower cylinder flange location. Perhaps this engine was the guinea-pig for the same revision of the Drone design formula as it morphed into the subsequent Red Special (see below). Type 2's piston and cylinder showed no such problems. Initial runs with classic un-nitrated equal-part fuel gave somewhat unsteady running and power output little better than the Type 1 engine. Switching to nitrated fuel did the trick, showing the superior cross-flow loop scavenging to maximum advantage. The resulting torque curve tops 18 ounce-inches at around 7,500 RPM and BHP touches its peak of 0.145 somewhere between 8,000 and 8,500 RPM.

Type 2's piston and cylinder showed no such problems. Initial runs with classic un-nitrated equal-part fuel gave somewhat unsteady running and power output little better than the Type 1 engine. Switching to nitrated fuel did the trick, showing the superior cross-flow loop scavenging to maximum advantage. The resulting torque curve tops 18 ounce-inches at around 7,500 RPM and BHP touches its peak of 0.145 somewhere between 8,000 and 8,500 RPM.  In 1948, presumably after developing his 2 cc Type 2 diesel, Alan produced a 5 cc diesel engine which was clearly based very closely upon the design of the previously-mentioned 1947

In 1948, presumably after developing his 2 cc Type 2 diesel, Alan produced a 5 cc diesel engine which was clearly based very closely upon the design of the previously-mentioned 1947  Burford and Alan McCulloch's ".29 cuin. "RED SPORTS MODEL", both priced at £9/9/-. The McCulloch engine was described as "same as the "Gee Bee" but Class "B", 5 cc and overall size has been reduced to facilitate close cowling etc. An ideal motor for Diesel speed models..." Depends how you define “speed”, one supposes…………….

Burford and Alan McCulloch's ".29 cuin. "RED SPORTS MODEL", both priced at £9/9/-. The McCulloch engine was described as "same as the "Gee Bee" but Class "B", 5 cc and overall size has been reduced to facilitate close cowling etc. An ideal motor for Diesel speed models..." Depends how you define “speed”, one supposes…………….

In terms of performance, reference should be made to Adrian Duncan’s test report on the original

In terms of performance, reference should be made to Adrian Duncan’s test report on the original  Always the energetic entrepreneur, by the early 1950's Bill Evans had expanded his MAI business to include a retail store on Franklin Street in Adelaide, a spot on local radio and a regular modelling publication (Australian Model Hobbies). Sales of his modelling magazine were booming. Next up was to increase model kit production under the Aristocrat brand and enter the field of model engine production using the Delta trade-name. The first (and as it turned out, only) model to appear by this name was the Delta 490 glow-plug model of 4.84 cc (0.295 cuin.) displacement.

Always the energetic entrepreneur, by the early 1950's Bill Evans had expanded his MAI business to include a retail store on Franklin Street in Adelaide, a spot on local radio and a regular modelling publication (Australian Model Hobbies). Sales of his modelling magazine were booming. Next up was to increase model kit production under the Aristocrat brand and enter the field of model engine production using the Delta trade-name. The first (and as it turned out, only) model to appear by this name was the Delta 490 glow-plug model of 4.84 cc (0.295 cuin.) displacement.  In all probability, it was Alan who finalized the engineering details as well as working on the prototype testing and tooling up for series production. However, his involvement with the actual quantity production is believed to have been minimal. Indeed, for whatever reason, Alan ended all involvement with model engines during the very early stages of the Delta program. This may have been among the causes of the delays in the engine's market debut.

In all probability, it was Alan who finalized the engineering details as well as working on the prototype testing and tooling up for series production. However, his involvement with the actual quantity production is believed to have been minimal. Indeed, for whatever reason, Alan ended all involvement with model engines during the very early stages of the Delta program. This may have been among the causes of the delays in the engine's market debut. When they finally appeared, the Delta 490 engines were sold in sturdy cardboard boxes which were extensively decorated. The box top bore an image of the engine, for which the claim was made that it was "the obvious choice for beginner or expert". Somewhat unusually, the specifications and operating instructions were printed on a label covering the outer suface of the bottom of the box.

When they finally appeared, the Delta 490 engines were sold in sturdy cardboard boxes which were extensively decorated. The box top bore an image of the engine, for which the claim was made that it was "the obvious choice for beginner or expert". Somewhat unusually, the specifications and operating instructions were printed on a label covering the outer suface of the bottom of the box.  Design inspiration for the Delta 490 probably came from the 1951

Design inspiration for the Delta 490 probably came from the 1951  The Delta appeared in a number of variants. No factory designations were applied to distinguish the different models, so we'll call the original model the Mk. 1 to clarify the distinctions. The engine’s design underwent two major revisions during its production run of around three years. The market may have seen these revised models concurrently; a revised rear induction model with lingering racing pretensions (we'll call it the Mk. 2) and a derivative front induction model (the Mk. 3) that was better suited to general purpose applications and stunt work.

The Delta appeared in a number of variants. No factory designations were applied to distinguish the different models, so we'll call the original model the Mk. 1 to clarify the distinctions. The engine’s design underwent two major revisions during its production run of around three years. The market may have seen these revised models concurrently; a revised rear induction model with lingering racing pretensions (we'll call it the Mk. 2) and a derivative front induction model (the Mk. 3) that was better suited to general purpose applications and stunt work. Internally, the revised model has a cast iron piston with a pressed-in gudgeon pin and cast aluminium connecting rod. Four of the original eight transfer flutes have been omitted from the cylinder. An aluminium prop driver screws onto the crankshaft threads, rather than the previous steel driver engaging a square shaft portion. The tendency of this set-up to come loose from a back-fire was eventually overcome by having a redesigned prop driver with a generous spigot locked against a tapered split collet that screwed onto the crankshaft threads.

Internally, the revised model has a cast iron piston with a pressed-in gudgeon pin and cast aluminium connecting rod. Four of the original eight transfer flutes have been omitted from the cylinder. An aluminium prop driver screws onto the crankshaft threads, rather than the previous steel driver engaging a square shaft portion. The tendency of this set-up to come loose from a back-fire was eventually overcome by having a redesigned prop driver with a generous spigot locked against a tapered split collet that screwed onto the crankshaft threads. We've yet to see a plain bearing Mk. 2 engine. More likely, that demand was better met by the Mk. 3 version. This shared the Mk. 2's piston/cylinder arrangement, but the crankcase die was again irrevocably modified for a front induction format. All Mk. 3's were of course of the plain bearing type, as there is inadequate space for a sufficiently large rear ball race to accommodate the necessarily larger-diameter front induction crankshaft.

We've yet to see a plain bearing Mk. 2 engine. More likely, that demand was better met by the Mk. 3 version. This shared the Mk. 2's piston/cylinder arrangement, but the crankcase die was again irrevocably modified for a front induction format. All Mk. 3's were of course of the plain bearing type, as there is inadequate space for a sufficiently large rear ball race to accommodate the necessarily larger-diameter front induction crankshaft.  Running the Delta 490

Running the Delta 490 We chose a late model Mk. 3 engine for testing. Initial runs were awful, owing to a poor piston/cylinder fit. In the course of the rebore, the cylinder bore was found to be significantly out of round and with a nasty bell-mouth at the top suggestive of poor honing practice. This was trued up reasonably well and a fresh piston was made and fitted.

We chose a late model Mk. 3 engine for testing. Initial runs were awful, owing to a poor piston/cylinder fit. In the course of the rebore, the cylinder bore was found to be significantly out of round and with a nasty bell-mouth at the top suggestive of poor honing practice. This was trued up reasonably well and a fresh piston was made and fitted.