|

|

The E.D. 346 Mk. IV “Hunter”

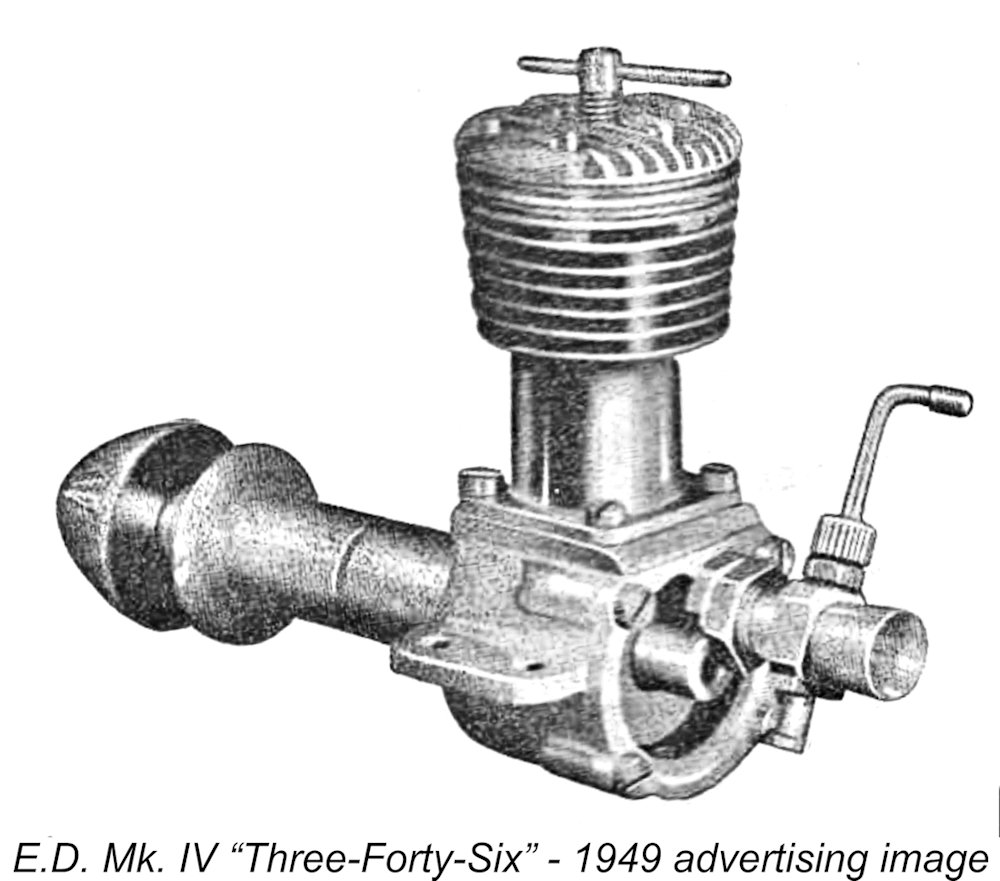

By comparison with some of the other E.D. models, the E.D. Mk. IV seems to have maintained a somewhat lower profile in the eyes of the latter-day aeromodelling and engine collector communities. That doesn’t alter the fact that it was a very capably-designed engine which handled and ran extremely well and which developed ample power for the purposes of most of its owners, also offering a long working life. These qualities plus a few well-publicized successes ensured its popularity among practical aeromodellers of its day.

In this article, I’ll focus on the E.D. Mk. IV as it was produced by its original manufacturers, Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd. (E.D.). Although engines bearing the E.D. Hunter name and sharing its displacement were produced by several successor companies, their designs bore little resemblance to that of the original. Accordingly, I’ll leave the discussion of those models for another time and/or place.

Before commencing the present review, it’s both a duty and a pleasure to acknowledge the invaluable assistance rendered to me by my friend and fellow ex-motorcycle racer Kevin Richards, who is undoubtedly the most knowledgeable individual around when it come to the E.D. marque. It’s impossible to write with authority about any E.D. model engine without consulting Kevin. I freely acknowledge that I couldn’t have undertaken this effort at all without Kevin’s unstinting assistance. Thanks, mate!! With that pleasant duty fulfilled, let’s have a look at the background to the introduction of this remarkably resilient design. In the Beginning

During the late 1940’s, the popularity of control-line stunt in Britain was growing by leaps and bounds. A number of British manufacturers introduced new models at this time which were more or less tailored to that application. These included the Elfin 1.8 (July 1948), the 5 cc "K" Vulture (October 1948), the Yulon 30 (January 1949), the Weston 3.5 cc Stunt Special (February 1949), the AMCO 3.5 As of 1949, the only E.D. model which might have appeared to represent competition for these designs in the control-line stunt field was the 2.49 cc Mk. III crankshaft front rotary valve model. However, by comparison with such contemporary designs as the AMCO 3.5 PB and the Elfin 249 PB, the Mk. III looked positively antiquated with its tall “stovepipe” cylinder, also failing to match its rivals in performance terms. It quickly became apparent to E.D. that they would have to counter the moves of their various competitors with a new model of their own. Accordingly, the company Directors tasked their engine design team with the creation of a new and up-to-date E.D. model which would represent a viable alternative to the excellent mid-sized engines now on offer from their competitors. The question which we must now consider is exactly who the E.D. design team actually were at this stage! Who Designed the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter?

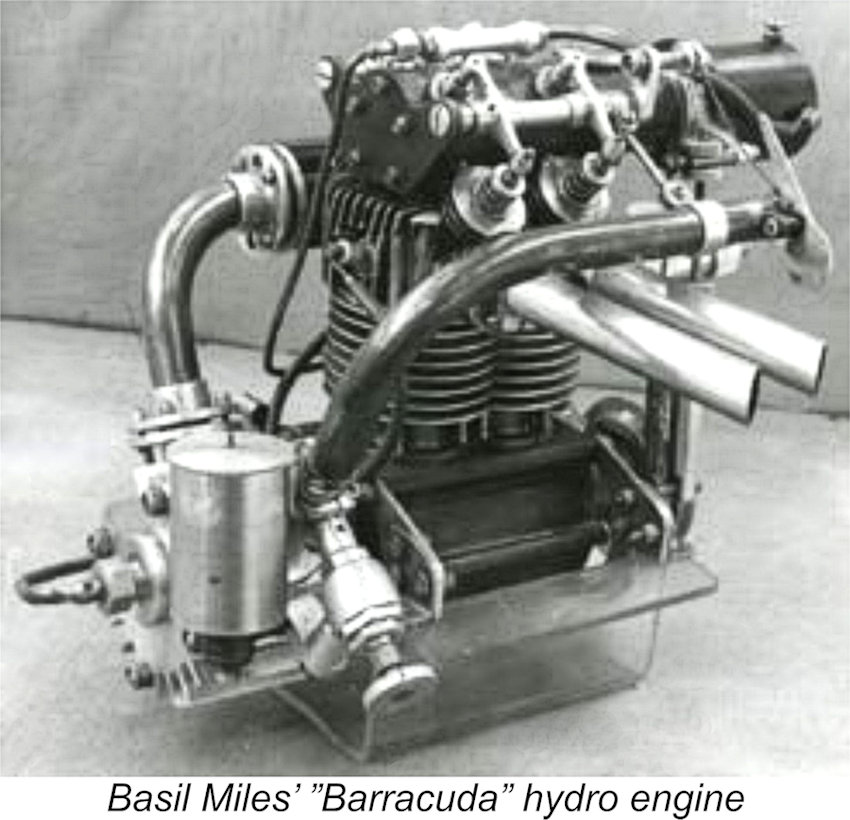

It's not clear exactly how Miles first established contact with the E.D. company following its early 1946 establishment. Whatever the facts of that matter, Alan Greenfield (latter-day owner of the E.D. marque) believed that Basil Miles was highly instrumental in persuading E.D. management that there was a bright future to By contrast, Miles’ friend and fellow club-member Charlie Cray was an E.D. employee, evidently being assigned to the model engine division upon its establishment in 1946. E.D.’s founding Managing Director Jack Ballard certainly credited Cray with such a role, although that role was somewhat over-stated in Ballard's account. There is evidence to confirm that Cray had at least some involvement in the design of the earliest E.D. “stovepipe” models, including the Mk. III – Alan Greenfield confirmed that his name appears on at least one of the design drawings. The relatively crude and “primitive” E.D. stovepipe models bear little design imprint of the far more sophisticated designs which Basil Miles had been producing since 1936, making it appear that his direct involvement at this stage, if any, was extremely limited.

My friend and fellow researcher Marcus Tidmarsh has pointed out that the engines produced by E.D. seem to have fallen into two categories – those in effect designed “in house” by E.D. staff and those designed primarily by an outside consultant. Charlie Cray seems to have been an E.D. employee, while Kevin Richards’ in-depth research has shown that Basil Miles was never an E.D. employee or official at any time. His design work for the company must therefore have been carried out on some kind of a contractual or royalty basis. Accordingly, it appears that the design rights to the early E.D. models designed at least in part by Charlie Cray remained with the company, since the engines were nominally designed by their employee(s). Miles may well have had input to the Mk. III with its rotary valve induction system, but any such work would have been undertaken in the capacity of an outside advisor – E.D. would have retained ownership of the designs. However, this changed as E.D. seemingly began to turn increasingly to Miles to guide the development of their later designs. At some stage, the relationship between Miles and E.D. appears to have developed to the point at which the ownership of the new designs remained with Miles rather than being transferred to E.D. It’s a little unclear exactly when this arrangement took effect. The design of the 1 cc E.D. Bee Mk. I Series 1 diesel of mid 1948 certainly bears a strong imprint of Miles’ design style, but his name was never cited as the designer of that model, nor as far as I’m aware did Miles ever lay claim to that design. However, the September 1949 appearance of my central subject, the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” is another matter entirely. Although Miles’ name was never mentioned by E.D. in connection with this engine, it seems all but certain that he was actually the primary designer of the Mk. IV. He is seen in the accompanying image testing one of these engines. If the “Three-Forty-Six” design did indeed originate with Basil, as seems very likely, then he would have retained ownership of Miles reportedly went so far as to remind Ken Day that the Hunter was his design, apparently producing documentary evidence to support this claim. Under the terms confirmed in these documents, any design changes had to be approved by Basil, and no such approval had been sought. At Basil’s insistence, Alan Greenfield became involved at this point to oversee the finalization of the two designs to Basil’s requirements. It appears to me at least that Ken Day's E.D. company effectively brought this criticism upon themselves. The design of the Super Hunter was so different from Basil Miles' original E.D. Hunter design that it was actually a completely original design as opposed to a derivative. If it had been released by some other name as an all-new model, it's difficult to see how Miles could have intervened to the extent that he did. Presumably Day & Co. wished to draw upon the nostalgic cachet attached to the Hunter name, but in doing so they opened the door to Miles' intervention.

The above account convinces me at least that the design of the E.D. “Three-Forty-Six” which appeared in August 1949 to expand the E.D. range should be credited to Basil Miles. I will continue to advance this view unless and until someone presents convincing evidence to prove me wrong! Go ahead ……..I dare you!! Having dealt with the issue of design accreditation, let’s have a look at the engine which resulted from Miles’ design deliberations. The E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” – General Description

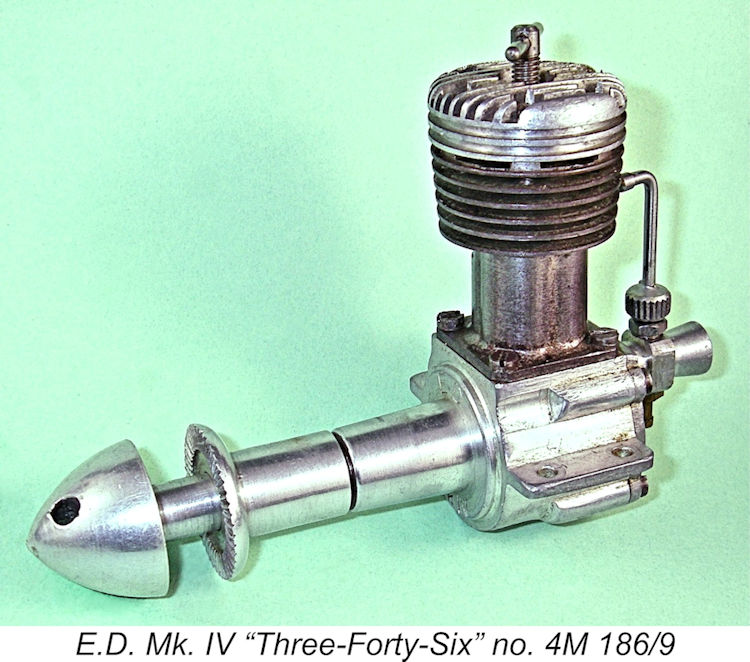

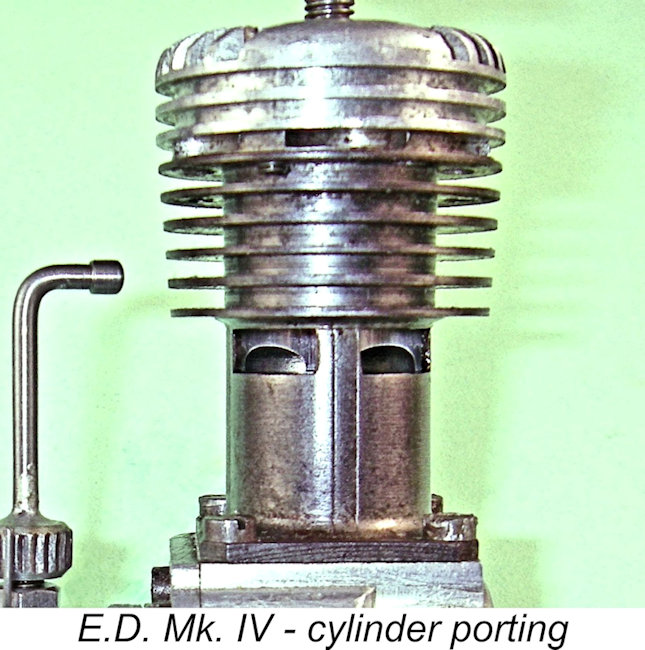

An important point which needs to be made at the outset is that despite the many visible architectural differences, in strictly functional terms the E.D. Mk. IV is in essence a re-dimensioned, re-styled and re-configured E.D. Mk. I Series 1 Bee! It shares the same basic cylinder porting arrangement, albeit turned through 90º to bring the exhaust ports to the right instead of the rear. It also shares the Bee’s rear disc valve induction, so characteristic of Basil Miles’ design style. In addition, it features over-square internal working geometry, again just like the Bee. The main differences are the Mk. IV’s use of an integrally-finned steel cylinder (later to be adopted for the Bee in its Series 2 form), the replacement of the Bee’s two drilled transfer ports with two internally machined bypass passages (a feature later applied to the Series 2 Bee for a time) and the inclusion of a single ball race at the rear of the crankshaft. These observations add considerable weight to the likelihood of Basil Miles having had considerable input into the design of the Mk. I Series 1 Bee. It appears that he took the basic functional design of the Bee as his starting point when designing the larger model, incorporating what he saw as a few design/architectural improvements in doing so. Kevin Richards reported owning an un-numbered prototype of the engine which featured both a machined and highly-polished bar-stock crankcase and a rear cover which was also fully machined from bar stock. A few early production engines were manufactured to this specification, but a change to a cast backplate was implemented quite early on.

The engine weighed in at a checked 185 gm (6.52 ounces), rather on the hefty side when compared with the competing 118 gm (4.16 ounce) AMCO 3.5 PB. However, experience in the field was to prove the E.D. to be significantly more sturdy and hence more durable than the AMCO, as well as being at least the AMCO’s equal in terms of performance. Although it was a short-stroke engine, the Mk. IV nonetheless had a somewhat “tall” appearance due to its use of an unusually long con-rod. This had the effect of reducing the rod's swing angle and hence the generated side-thrust, although it also increased the crankcase volume. At the top, the cylinder was surmounted by a finned cylinder head which was fully machined from light alloy bar stock. This head was secured to the cylinder using six short machine screws which engaged with tapped 6BA holes in the cylinder’s top flange. The head was centrally drilled and tapped 4BA to accommodate the T-shaped compression screw.

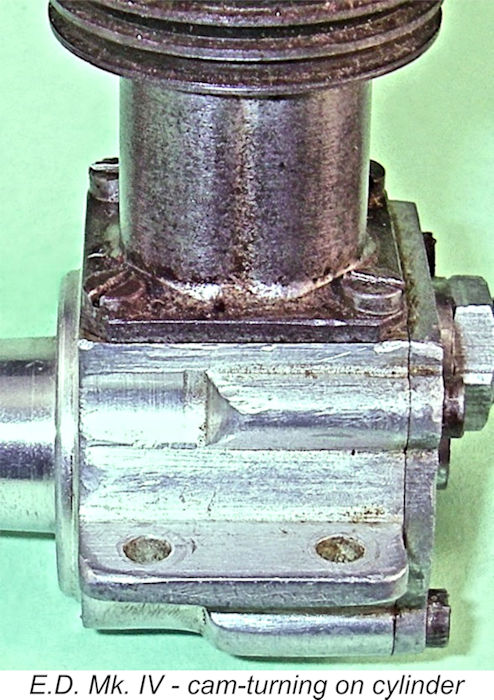

Cylinder porting consisted of twin internally-formed bypass channels of generous dimensions which also served as the transfer ports, with two rectangular exhaust ports of equally generous dimensions cut through the cylinder wall opposite the bypass/transfer channels. The transfer overlapped the exhaust to a considerable degree. Somewhat unusually, the external diameter of the lower cylinder below the cooling fins was cam-turned to accommodate the twin bypass channels without resorting to an excessively thick lower cylinder wall.

The engine used a lapped cast iron piston having a skirt length which provided a modest period of sub-piston induction around Top Dead Centre (TDC). The pistons used in the earlier examples were of composite construction, incorporating an internal yoke of aluminium alloy whose purpose appears to have been simply to reduce crankcase volume without adding excessive reciprocating weight. The yoke in the un-numbered prototype unit owned by Kevin Richards is retained by a circlip, as were the yokes in the earliest production models. However, at some point after September 1949 a change was made to a screw-in yoke. To ensure consistent alignment, the transverse hole for the gudgeon pin was evidently drilled after the yoke was screwed home. The pin was a moderate press fit in its location hole, performing the dual functions of providing the bearing for the conrod small end and preventing the yoke from unscrewing. The engine featured a hardened steel conrod – another carry-over from the design of the Bee. However, the big end of the Mk. IV’s rod was equipped with a floating bronze bushing, doubtless in recognition of the far heavier working loads to be expected. This bushing was easily replaced when worn – a very good servicing feature. Moreover, bronze-on-steel is a far better wearing combination than steel-on-steel.

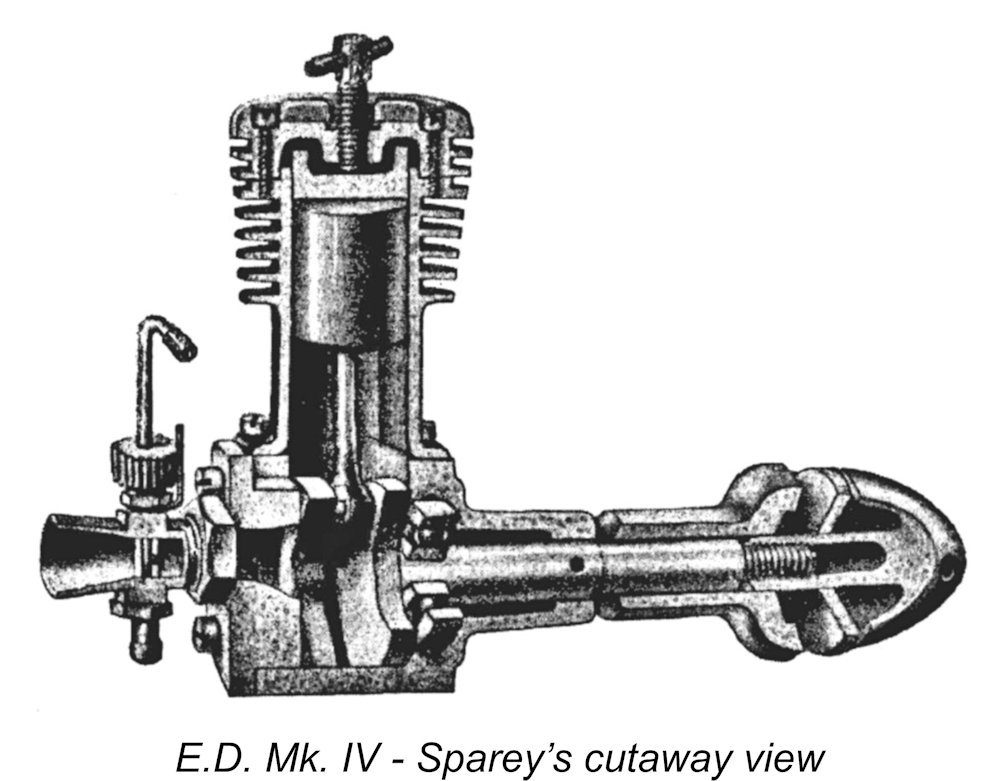

The shaft was carried in a ball bearing at the rear, with the front portion running in a plain bearing. Somewhat unusually, the front of the main journal ran in a comparatively short length of bearing material, with the balance of the front housing being bored to a larger diameter which eliminated any metal-to-metal contact. The cutaway view of the engine which accompanied Lawrence Sparey’s test report (see below) shows this very clearly. This design was presumably aimed at reducing friction and viscous drag on the shaft during operation. The prototype in Kevin Richards’ possession features a cast-iron sleeve to serve as the front portion of the crankshaft bearing, but no production example of the E.D. Mk. IV possessed this refinement.

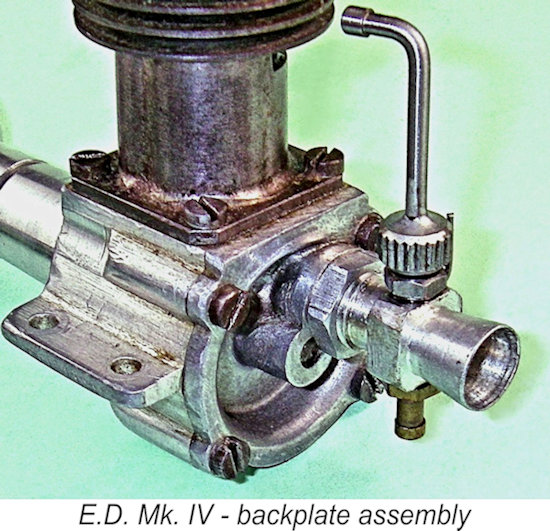

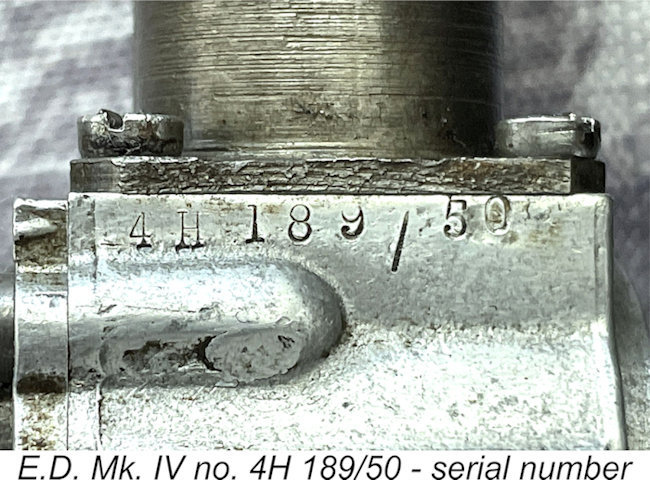

At the rear, the Mk. IV featured a cast light alloy backplate which was secured to the case with four 6BA machine screws. A rotary disc made from aluminium alloy was staked onto the front face of the backplate. This disc was driven in the usual way by engagement with the extended crankpin. The intake venturi was a separate component which threaded into its location boss in the backplate and was retained by a lock-nut. This arrangement allowed the needle valve to be oriented in any desired radial alignment. The needle valve assembly consisted of an internally-threaded spraybar which accommodated an externally-threaded needle. The security of the setting was ensured very effectively by a straight wire spring which engaged with a serrated disc mounted on the needle. The quality of the engine’s construction was well up to the best prevailing standards among British commercial model engine manufacturers of the day. The Mk. IV also turned out to be an excellent performer by then-current standards, as we shall see in due course. Small wonder that it rapidly gained considerable popularity among contemporary power modellers. All production variants of the E.D. Mk. IV bore serial numbers, which appeared in various locations depending on the model and variant involved. In general terms, the serial numbers applied to their engines by E.D. were more like a coding scheme than a sequence, hence appearing rather "opaque" to the uninitiated. The system used by E.D. is fully explained in my separate article covering the E.D. story. It is unusually informative, each sequence being unique to the type of engine, the year and month of production and the position of the engine within that month’s production sequence. Can't get any more informative than that!

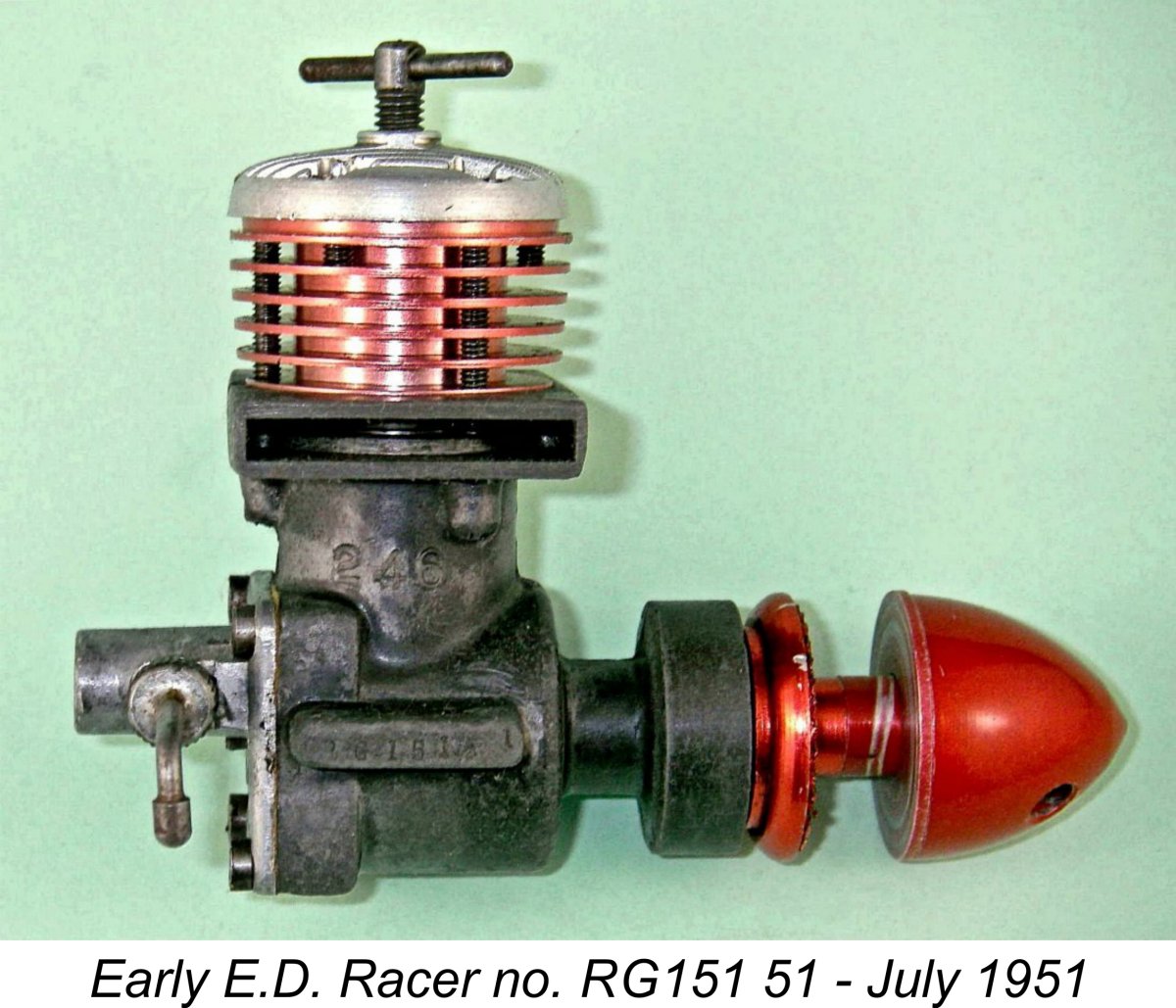

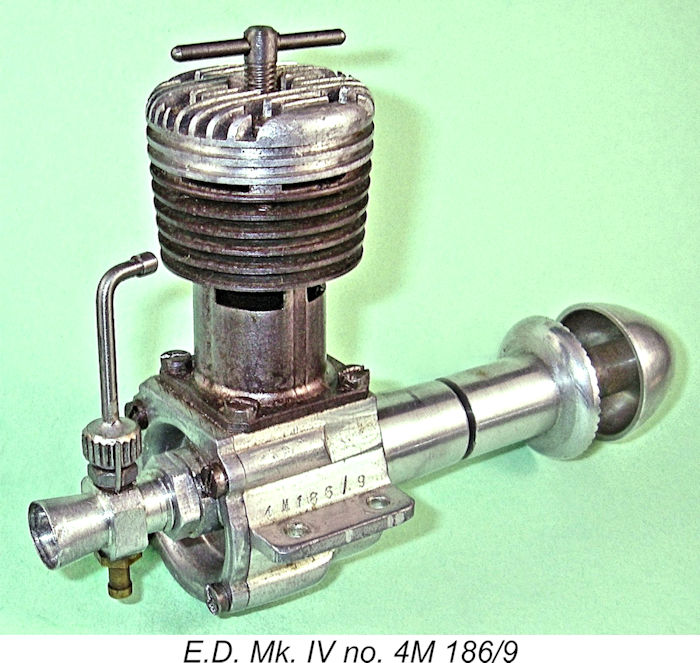

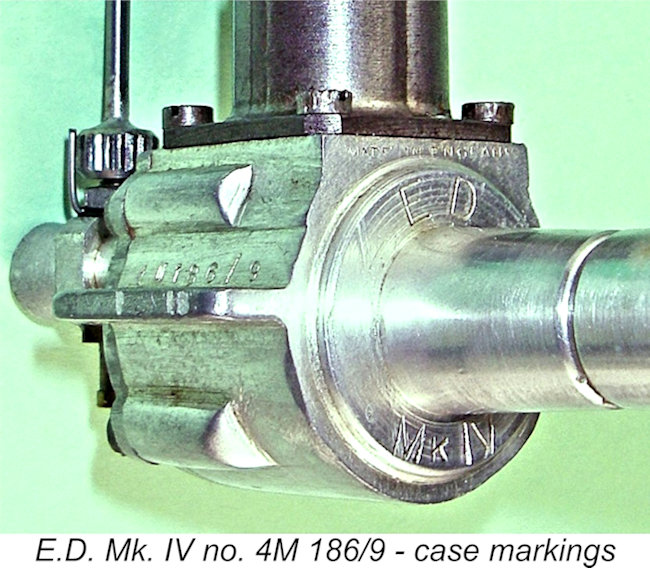

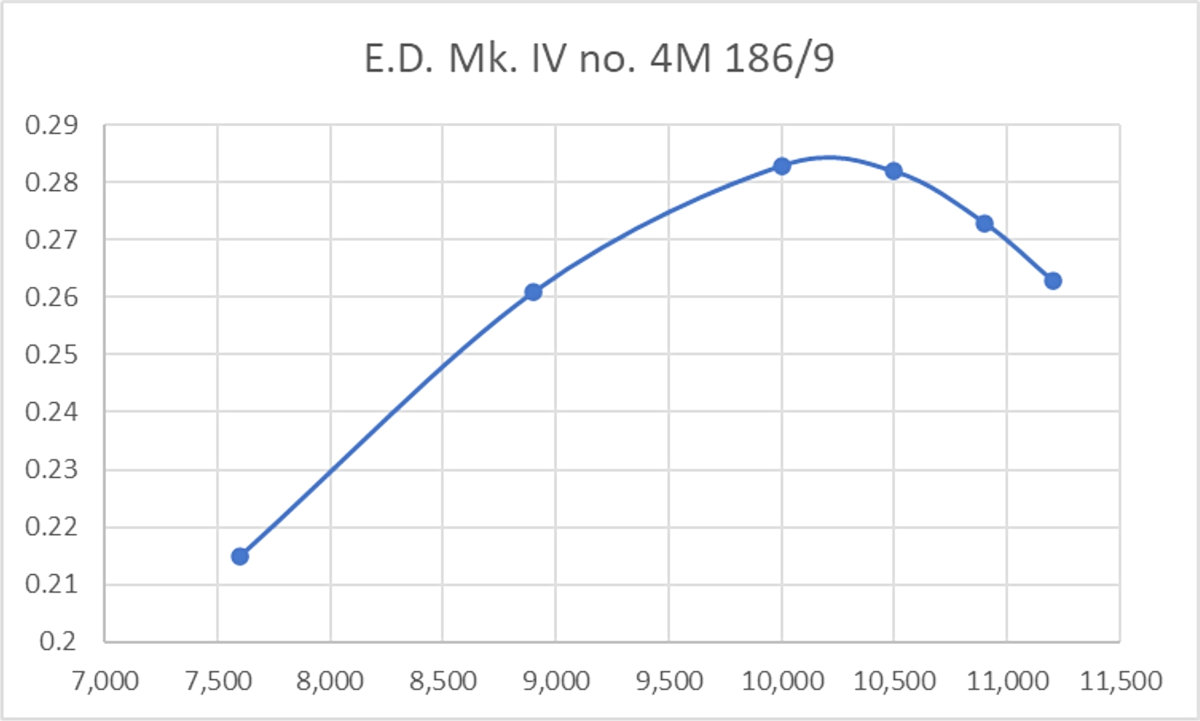

The E.D. Mk. IV was assigned the numeral “4” as its model designator, which it was to retain all along. So for example, E.D. Mk. IV no. 4M 186/9 was an E.D. Mk. IV which was the 186th example manufactured in November 1949, while engine no. 4B 520/52 was the 520th example of the E.D. Mk. IV manufactured in February 1952. The letter W before the 4 indicated a water-cooled marine example. So much for a general description of the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” as originally introduced. The merits of this engine’s design were such that it changed remarkably little over the 12 years or so during which it remained in production by its original manufacturers. However, there were a few changes along the way, resulting in the appearance of a number of distinct major variants of the engine. In point of fact, the E.D. Mk. IV was subject to frequent detail changes. This actually makes it difficult to identify specific “variants” with any precision. The best that I’ve been able to do is sort the engines into five major variants while recognizing that multiple sub-variants undoubtedly exist. With that caveat in mind, let’s now take a look at the major variants as I see them. The E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” – First Variant

The feature that distinguished this variant from those that were to follow was its use of a crankcase that was fully machined from bar-stock and then highly polished, rather than being cast. Although I'm not absolutely certain, I believe it to be likely that these cases were machined from a bar-stock extrusion - the techology certainly existed at the time. It’s possible that the original intention was to produce the engine in this form all along, although the production of cases created in this manner would have required a fair bit of skilled work along with some creative tooling and considerable wastage of material in the form of machining chips, thus adding significantly to manufacturing costs. However, it has also been suggested that the initial appearance of the engine in bar-stock form was due to some unforeseen difficulties arising in connection with the supply of the required crankcase castings. Rather than delay the engine’s introduction on these grounds once the design was completed, E.D. took steps to arrange for the cases of the early examples to be fully machined from bar stock. I freely admit that I’m unsure regarding which of these scenarios is correct.

In all other respects, the engine conformed to the general description given earlier. It’s a bit unclear how many such examples were produced – all I can say is that my two examples bear the serial numbers 4M 186/9 and 4M 660/9 respectively, indicating that they both date from November 1949. These numbers also confirm that at least 660 examples of the polished bar-stock Mk. IV were produced during that month alone – a surprisingly high figure. Regardless of the number produced, the use of the polished barstock case is the primary feature that defines what I’ve called the first variant of the E.D. “Three-Forty-Six”. The E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” – Second Variant

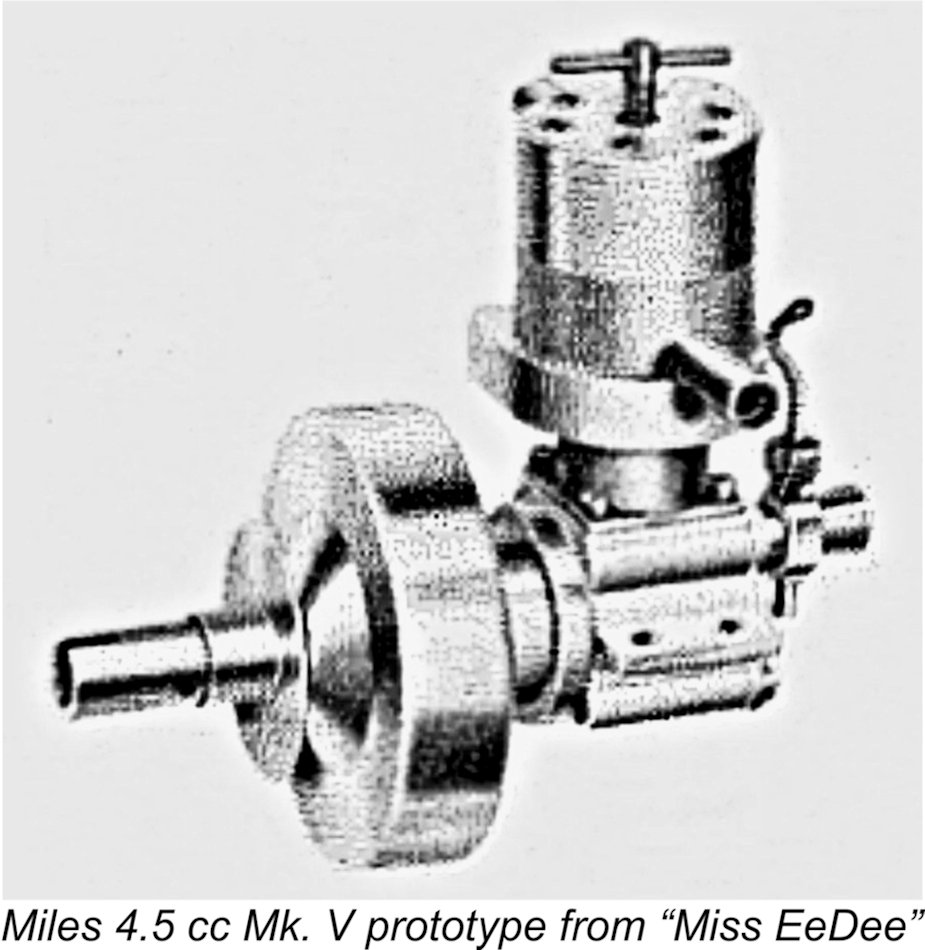

At my initial time of writing, the earliest confirmed serial number of one of these models was engine number 4H 189/50 dating from August 1950. However, the change likely predated this by some time. The use of a casting in place of the fully machined and polished bar-stock component must have saved the company a considerable amount of costly machining and hand-finishing. Even if the original intention had been to use a polished bar-stock case all along, considerations of production costs would surely have forced this change eventually. This is a point in favour of the unsubstantiated notion that the use of the bar-stock cases was actually a stop-gap measure forced upon the company by problems with the supply of cast cases. Further evidence of the impact of this change upon manufacturing costs comes from the Mk. IV’s early pricing history. The engine was first advertised in October 1949 at a price of £4 12s 6d (£4.63), a figure which was maintained through to May 1950 at least. However, in July 1950 we find the engine being advertised at a reduced price of only £3 12s 6d (£3.63). The £1 difference must surely be accounted for in This price was maintained until May 1951, when there was a marginal price increase to £3 15s 0d (£3.75). A further price increase to £4 2s 6d (£4.13) followed in early 1952. Further minor price fluctuations followed, but the selling price of the engine never again climbed back to its introductory figure. During this period, Basil Miles produced a prototype of a 4.5 cc marine diesel which was clearly based upon this variant of the E.D. Mk. IV. This prototype was used to power the the 5ft. 2 in. long “Miss EeDee” model motor launch to the first-ever crossing of the English Channel by a model boat, an accomplishment which took place on September 6th, 1951. This engine was apparently an over-bored marine E.D. Mk. IV which was envisioned by E.D. as potentially their Mk. V offering. In the event, nothing came of this plan, since Miles’s subsequent development of the 5 cc Miles Special superseded it. The E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” – Third Variant

At present I have no idea when or for how long the black finish was applied to the Mk. IV crankcases. All that I can report is that the three examples of my present acquaintance bear the serial numbers 4A 109/52 (January 1952), 4B 520/52 (February 1952), and 4D 58/52 (April 1952) respectively. As of early 1952, production numbers were clearly still holding up well.

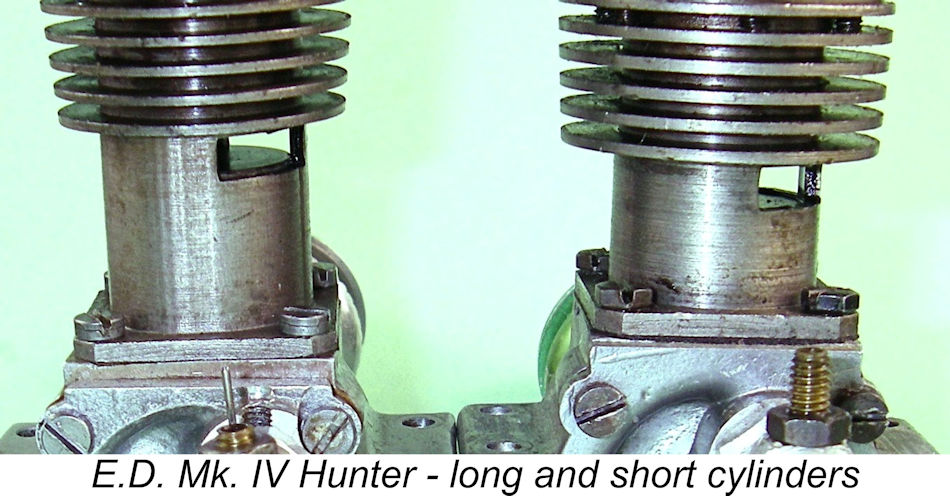

I noted at the outset of this article that the E.D. Mk. IV is perhaps better known to most model engine aficionados as the E.D. “Hunter”. In point of fact, it was not until February 1953 that the engine was first advertised by that name. This was over three years after the engine’s October 1949 introduction as the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six”! However, it is entirely appropriate to refer to the subsequent variants by the name “Hunter”. The E.D. Mk. IV “Hunter” – Fourth E.D. 3.46 cc Variant One commonly-levelled criticism of the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter (as we must now call it) was its height, which was due primarily to its use of an unusually long conrod. At some point in 1954, steps were taken to address this issue.

The cam-turning of the lower cylinder to accommodate the internal bypass flutes was omitted, presumably for cost reasons. This resulted in a substantial increase in the wall thickness of the lower cylinder. Both the crankcase and backplate casting were given a bead or vapour-blasted finish, although the front main bearing housing had a turned finish to match the prop-driver and spinner, which were unchanged at this stage. The finned cylinder head also continued in use at this time. The only other change was the use of a longer needle valve control arm. These changes must have been implemented at some point in 1954, since Kevin Richards reported owning engine number 4K 61 4 (October 1954) of this type. However, no evidence of the revised design appeared in any of E.D.’s advertising. The only reference to these revisions that I can find in the contemporary modelling media was Peter Chinn’s comment which appeared in the April 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” to the effect that the Hunter had then recently been “shortened” by the replacement of the unusually long conrod used prior to that point with the considerably shorter 2.46 cc E.D. Racer component. A few more changes were subsequently introduced along the way. Kevin Richards’ engine number 4M 64 4 (November 1954) displays a considerable reduction in the degree to which the crank-disc was counterbalanced. Kevin’s engine number 4C 160 5 (March 1955) features a revised needle valve assembly which was identical to that used in the contemporary E.D. Racer. As with the con-rod, commonalty of components was increasing – a logical cost control measure. A further change occurred at some later point in time when the finned cylinder head was replaced by a plain un-finned component. Kevin Richards believed that this change probably occurred in 1955 and survived for some years. Certainly, Kevin confirmed that engine number 4J 50 8 (September 1958) featured such a head, but exhibited no other changes. It’s my personal view that the successive changes described above were of themselves insufficient to constitute new variants of the engine. Rather, I’ve chosen to present them as sub-variants of the fourth major variant of the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter - the "short cylinder/long prop driver" version. The E.D. Mk. IV “Hunter” – Fifth E.D. 3.46 cc Variant

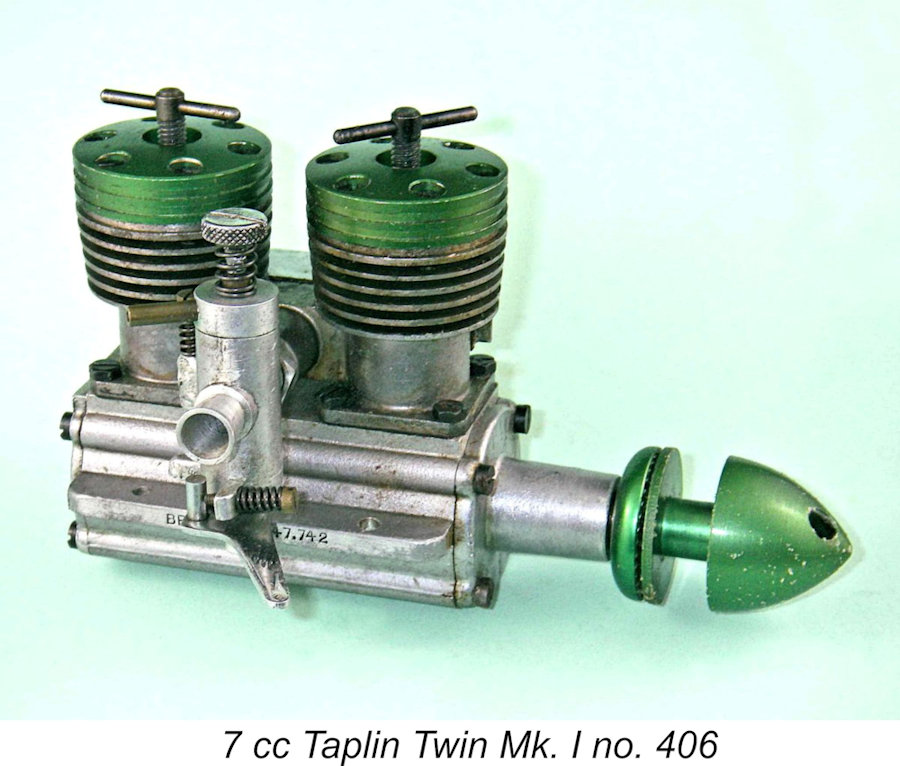

The key point of relevance to the present article is the fact that the cylinders for the Taplin Twin were modified E.D. Mk. IV Hunter short-cylinder components, as were the pistons, contra-pistons, comp screws, conrods and front crankshafts. This naturally got E.D. thinking about ways in which the commonality of components between the Taplin Twin and the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter could be increased, with resulting cost benefits.

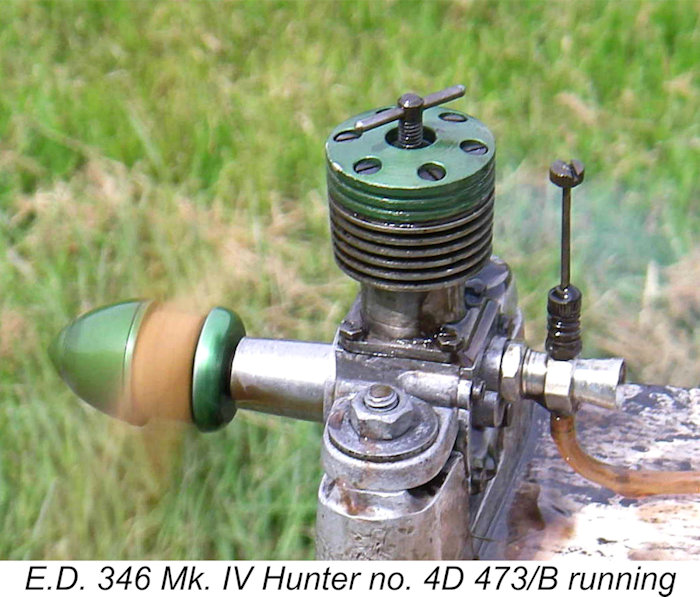

Initially the alloy components were un-anodized – Kevin’s engine number 4N 21/9 (December 1959) is of this type. However, engine number 4N 43/9 from the same December 1959 batch and only 22 units later in the production sequence features a green-anodized head, prop-driver, prop washer and spinner, matching the identical components used in the Mk. I Taplin Twin. The needle valve continued to be the same as that used in the contemporary E.D. Racer. My own two examples of this variant bear the serial numbers 4D 137 B and 4D 473 B, both dating from April 1961. The latter number shows that production of the Hunter was continuing at a quite respectable rate even at this relatively late date. This variant of the Hunter appears to have remained in production or at least on offer right up to April 1962, at which point the disastrous factory fire of April 29th, 1962 severely compromised E.D.’s production capacity, forcing the abandonment of a number of long-established models. Sadly, the Mk. IV Hunter was one of those abandoned designs. The Hunter name was to be resurrected in later years by the successor companies to the original manufacturers, but those offerings bore little resemblance to the classic E.D. Mk. IV of earlier years, merely “borrowing” the Hunter name. As such, I will leave them for separate discussion elsewhere. The E.D. Mk. IV – Promotion and Production History

The engine was introduced as the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six”. Thereafter, although the engine was referred to as a “three-forty-six” in the advertising copy, the engine’s designated identity was simply the E.D. Mk. IV, as displayed on the crankcases, first in Latin and then in Arabic numerals. It was not until February 1953 that the engine was first referred to in the advertising as the “E.D. 3.46 cc Hunter”. Somewhat unaccountably, the advertising designation of the engine then reverted to the “E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV” for a while! However, the “E.D. 3.46 cc Hunter” designation had returned to stay by October 1953. It continued to be featured in E.D.’s advertising right up to its final appearance in March 1962. From the outset, the Mk. IV was promoted as a control-line stunt engine. It was substantially heavier than the competing AMCO 3.5 PB while delivering roughly the same power, but the rash of crankshaft and con-rod failures which beset the AMCO during its introductory period led to the speedy and successful adoption of the Like the rest of the E.D. model engine range, the Mk. IV soon found its way to various Commonwealth countries around the world. In Australia, it proved that its potential functions were by no means limited to control-line stunt and scale applications by winning the over-2.5 cc free flight power event at the Queensland State Championships in 1951, 1952, 1954 and 1955. The Mk. IV also found success in New Zealand. An E.D. 346 Mk. IV powered the winner in the Hamilton, New Zealand “Champion of Champions” National contest in 1955. A similar engine also powered the C/L scale winner at the same meeting. Continued success followed in 1956 when the E.D. Mk. IV powered Laurie Ackroyd’s C/L scale-winning “Southern Cross” at the 1956 New Zealand Nationals held at New Plymouth. The engine used by Ackroyd had been won as a prize at the previous year’s New Zealand Nationals.

Further positive publicity came when a water-cooled E.D. Mk. IV powered the “Wavemaster” boat with which E.D.’s radio control guru George Honnest-Redlich won the 1955 International Model Boat Competition held on June 19th, 1955 in Paris, France. Fittingly enough, the winning boat used an E.D. Mk. IV radio control system! Naturally, this run of high-profile accomplishments couldn’t last. By the late 1950’s the E.D. 3.46 cc Hunter had settled into its place in the model engine marketplace as a sturdy, long-lasting, easy-handling and reasonably priced mid-sized sport-flying engine having ample performance to meet the requirements of most non-competition modellers. Its survival almost to the end of operations by the original E.D. company was clearly well deserved. The E.D. Mk. IV on Test

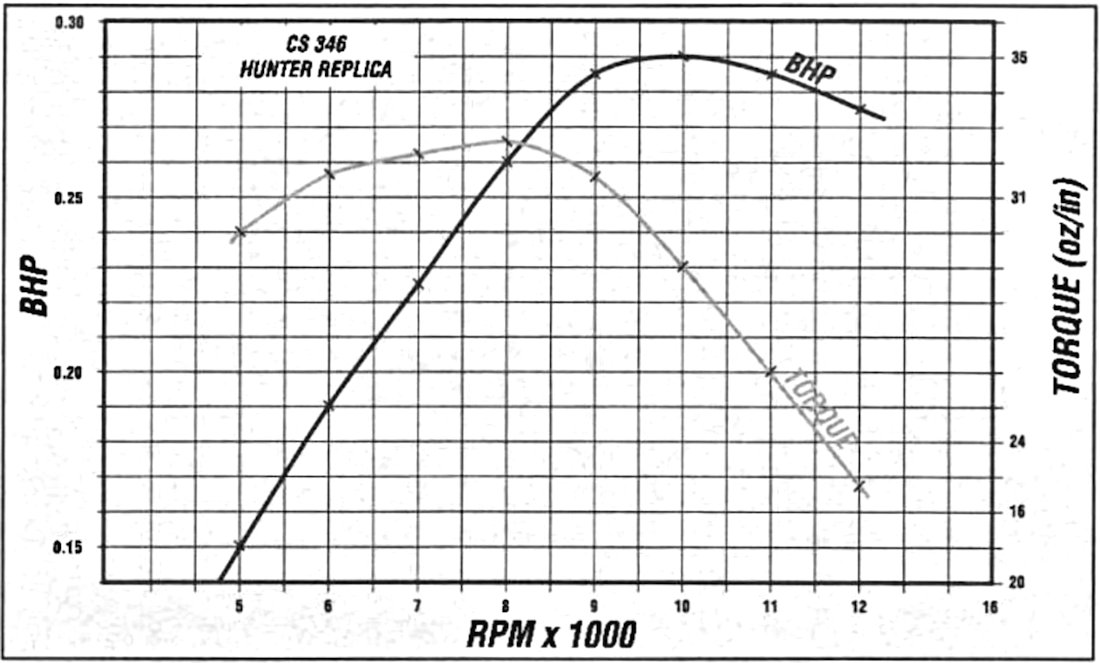

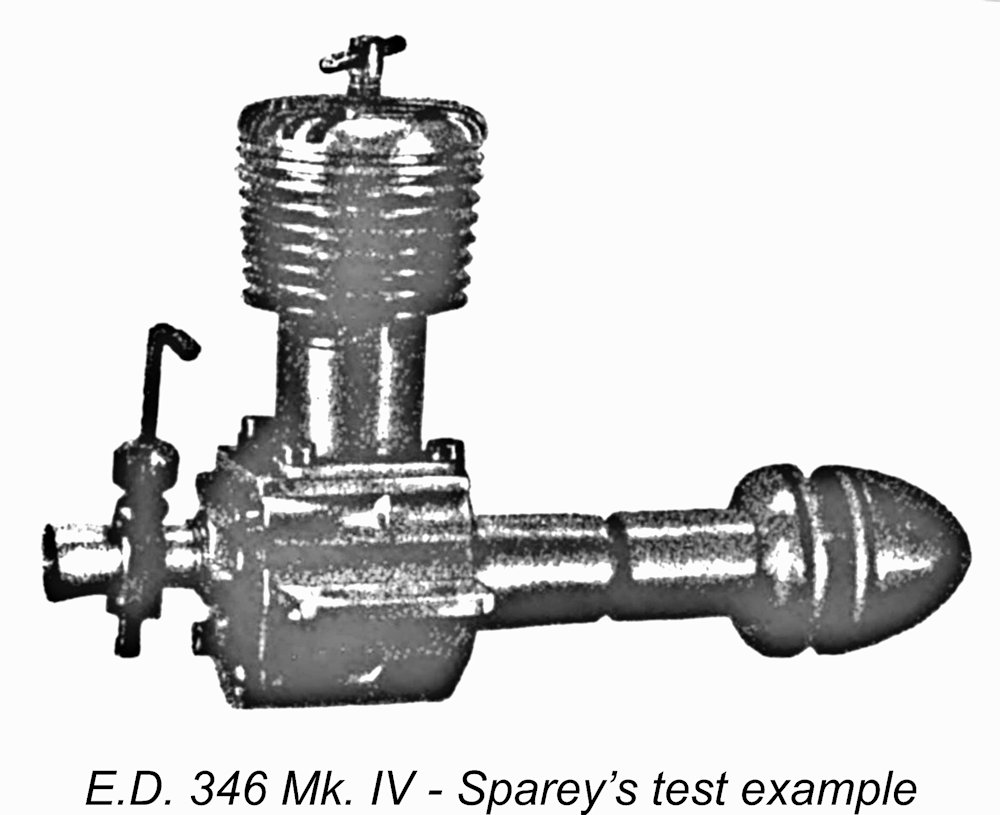

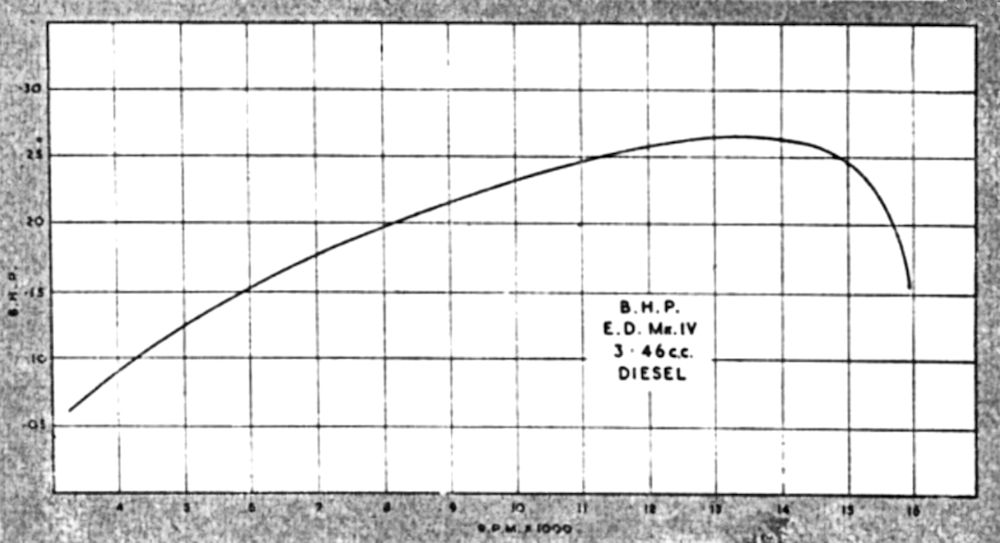

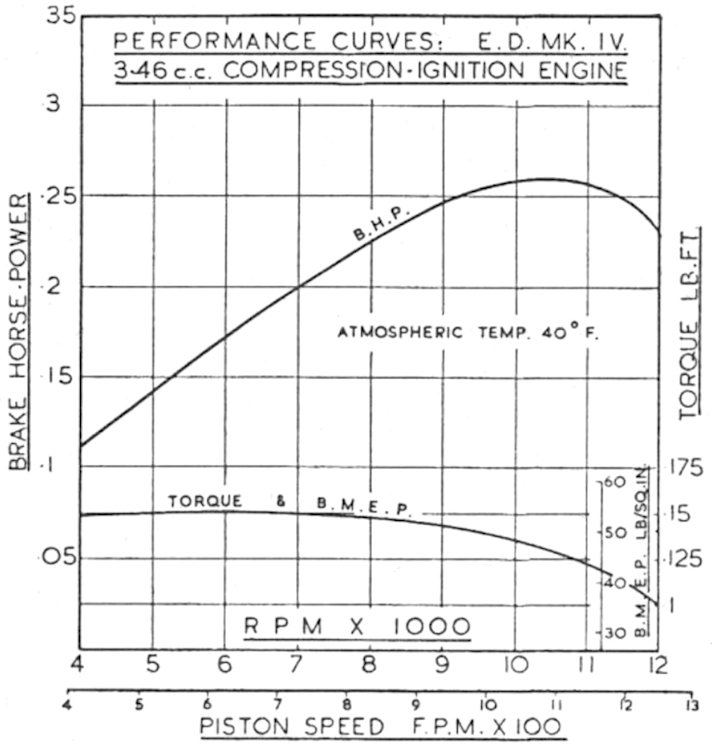

The first test of the engine to appear was Lawrence Sparey’s report which was featured in the March 1950 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. An amusing observation with respect to this test is the fact that the image of Sparey’s test engine was Sparey was very impressed with the engine, characterizing it as being “noteworthy for its high power output, easy handling and consistent running qualities”, with no mechanical issues arising during the test. He reported a peak output of 0.265 BHP @ 13,500 RPM, which he noted as being in excess of the manufacturer’s claimed output of 0.25 BHP.

Chinn was just as impressed with the Mk. IV as Sparely had been, stating that it “features a balance of those qualities most essential to both free flight and general C/L work”. Consequently, he considered that the design “possesses in adequate, if not large, measure many of the qualities most essential to entirely different types of model”. Chinn characterized the engine’s starting qualities as “easy”. The engine did not require a port prime – after the administration of two or three choked flicks, the engine would start from cold with only one or two starting flicks. He found the engine to be notably free from any tendency to sag when hot, putting this down to the used of integrally formed cooling fins. Chinn reported a peak power output of 0.26 BHP @ 10,500 RPM. The same peak output as that recorded by Sparey, but at significantly lower RPM. I have to say that my own experience with the E.D. Mk. IV supports Chinn’s findings very strongly – this is not a particularly high-speed engine. I can also fully support Chinn’s characterization of the engine as a very fine-handling unit. Well done, Basil Miles!! First and Last Variants – a Comparative Test

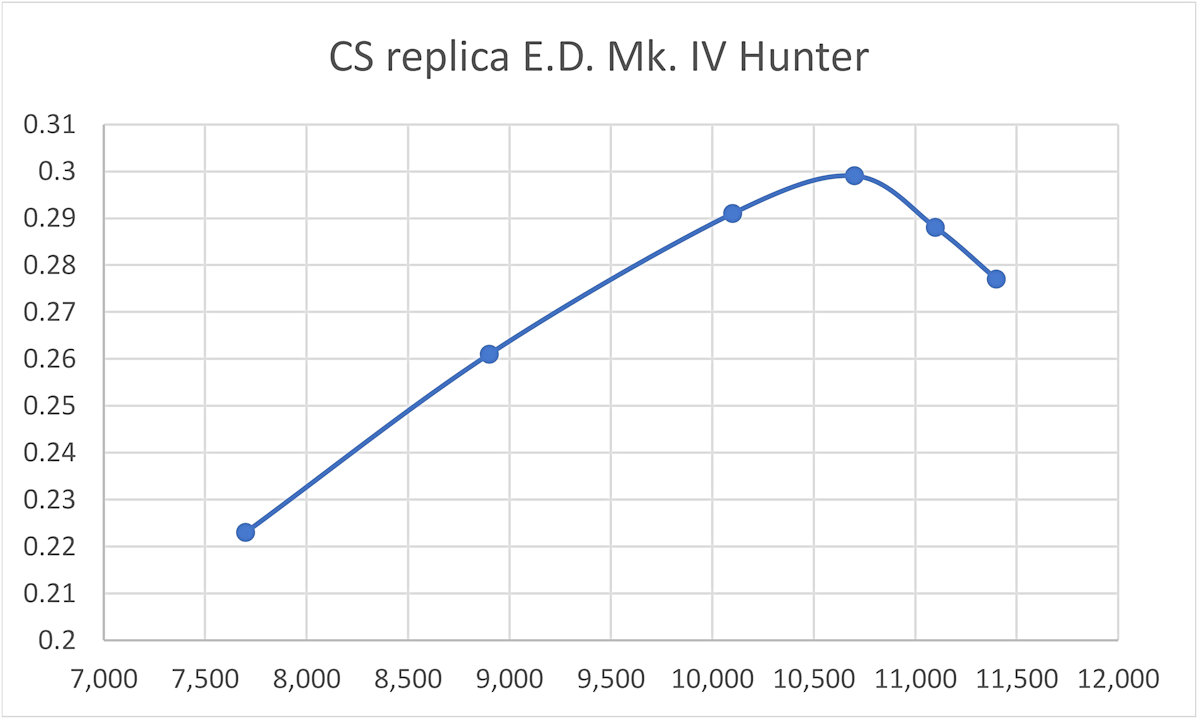

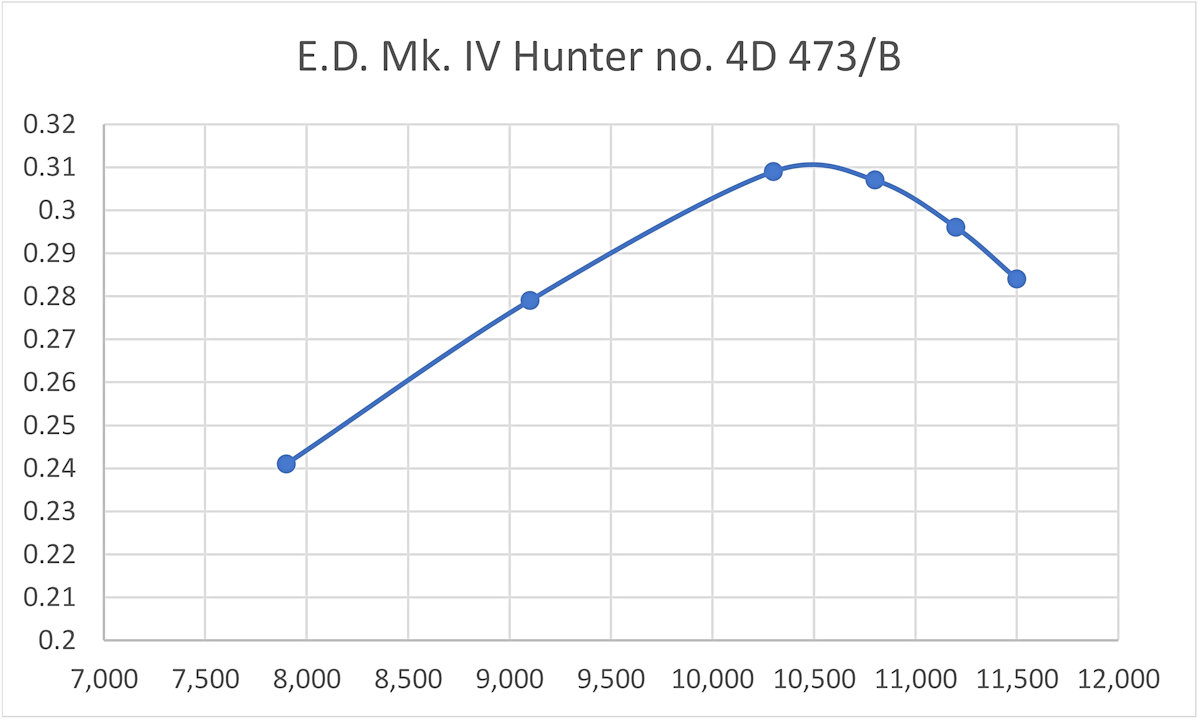

It seemed to me that the effect of these changes upon performance was well worth documenting. Since no test of the shortened-cylinder variants of the Hunter ever appeared in print, it was down to me to document this issue. Having fine complete and original examples of both the first and last variants of the E.D. 346 on hand, I was in a perfect position to undertake the required comparative testing.

First into the stand was first variant number 4M 186/9, a barstock-case example dating from November 1949. This engine has been used but remains in first-class mechanical and cosmetic condition. It started up right away and ran perfectly. I found that a small port prime was more or less essential for a fast cold start, while a hot re-start required only one or two choked flicks. Control response was excellent, allowing the easy establishment of optimal running settings. Some vibration was present, but it didn't appear to reach unmanageable levels at any tested speed. I had no difficulty testing the engine on any of the selected suite of test airscrews. As expected, these props covered the desired testing speed range very nicely.

Once running, the engine ran just as well as its predecessor. The only negative comment was its development of a detectably higher level of vibration than its companion - this was almost certainly down to the used of a un-counterbalanced full-disc crankweb as opposed to the heavily counterbalanced crankweb used originally. Despite this observation, the test proceeded very smoothly, with no difficuly in obtaining data for the full suite of test props. In order to compare the performances of the two engines (tested on the same fuel and the same day using the same props, remember), I've shown the results in a single table which facilitates a direct comparison. I've also attached the derived power curves.

As can be seen, the two engines produced power curves of more or less identical shape, but with a small but significant power edge for the later model right across the tested speed range. Given the close design similarity between the two models notwithstanding the 12 years between them, we shouldn't be too surprised that they peaked at near-identical speeds. The first variant from November 1949 topped out at around 0.284 BHP @ 10,200 RPM, while its April 1961 descendant managed 0.310 BHP @ 10,500 RPM. The later model's slight edge is doubtless due to its longer sub-piston induction period and its smaller crankcase volume. It can't be denied that these are very commendable figures for 3.5 cc sports diesels of their era. For comparison, it's worth noting that the figure for the 1961 version is well within sight of the 0.318 BHP @ 13,000 RPM reported by Peter Chinn for the early 1959 FROG 349 BB (also a single ball-race 3.5 cc diesel) in his published test of June 1959. Moreover, since the E.D.'s figure was established at only 10,500 RPM, it's clear that the Hunter out-torques the FROG by a substantial margin at low to moderate speeds. On larger props running at lower speeds, it's clearly the superior engine. Basil Miles designed a good 'un! A further observation which I find quite fascinating stems from my comment made at the outset that the E.D. Mk. IV is in essence an up-scaled and reconfigured E.D. Bee. It's interesting to note that my own tests have shown that the Mk. IV and the Bee both peak at more or less identical speeds while developing very similar specific outputs. There's a certain measure of design consistency here .............. The C.S. Replica Hunter

This interest was sufficient to encourage the CS company of Shanghai, China to introduce a near-replica of the engine, which they did in the early 1990’s. The CS rendition of the Mk. IV was a quite faithful replica of the second variant of the E.D. original, being sold as the CS “3.46 E.D. Mk. IV Hunter” replica. It was one of CS’s better efforts, following the original design very closely and sharing both its “tall” dimensions and its finned head. Moreover, most examples displayed a quite acceptable standard of workmanship, although some “fettling” was generally necessary to correct a few manufacturing errors, as usual with CS engines. Once this was done, the engines ran very well. Bore and stroke were "metricized" by being set at nominal dimensions of 16.5 mm and 16 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 3.42 cc - close enough! The major departure from the original E.D. “Three-Forty-Six” was the elimination of the cam-turning on the lower cylinder, although the cylinder was dimensioned to the original height rather than the lower height featured in the fourth and fifth variants of the original. This had the effect of making the lower cylinder considerably thicker in order to accommodate the twin internal bypass/transfer flutes, also adding a little extra weight. The CS replica actually weighed in at a checked 219 gm (7.72 ounces), significantly more than the original E.D. Mk. IV. The needle valve too was one of CS’s standard assemblies rather than a replica of the original. This had a rather skinny spraybar for the intake employed – I found that an original E.D. assembly having a greater spraybar diameter worked far better.

These CS replicas could be made to run at least as well as the originals, as I know from my own very successful experience with the illustrated example, which received a thorough “going-over” at my hands prior to its initial start - very advisable with all new CS engines. I would objectively rate this unit as a satisfyingly faithful replica with a potential performance at least equal to that of the original. My own example is a very strong runner which has seen good service in the air.

My own experience with this replica fully supports Richard Herbert’s findings. My example always gave the impression of performing at a somewhat higher level than any of my original examples of the second variant of the E.D. Mk. IV on which the CS replica was based. To test this impression, I put my CS replica into the test stand at the same session at which I tested the first and fifth variants, as reported earlier. It started and handled just as well as the two original E.D. units, also performing very strongly. Running the same suite of test props and using the same fuel, I recorded the following data:

These figures are generally quite consistent with those reported by Richard Herbert for the same engine. My example actually appeared to do a little better than Richard's unit, peaking at around 0.299 BHP @ 10,700 RPM. It also outperformed the original units tested years earlier by Sparey and Chinn as well as slightly exceeding the output found during my own previously-reported test of an original Version 1 example.

Unfortunately (in my personal opinion, which I know is not shared by others), the production of this replica inspired some unworthy thoughts among its potential users once its performance potential was fully appreciated. A number of US old time modellers saw the potential advantage of using the E.D. Hunter (or a replica thereof) in their Class A old-timer competitions. However, there was an impediment - the Hunter’s displacement of 3.46 cc (0.211 cuin.) precluded this given the American Class A displacement limit of 0.199 cuin. To get around this difficulty, the CS company made a run of “Hunters” which looked more or less exactly like the originals but were internally dimensioned to comply with the .199 cuin. displacement limit for Class A. The bore was reduced to 16.0 mm to yield a displacement of 0.196 cuin. (3.22 cc). The problem here, for me at least, is that no Hunter .19 ever left the E.D. factory!! It’s my personal view that this is carrying the replica engine thing (which I firmly support) one step too far. Nonetheless, the Society of Antique Modelers (SAM) homologated this “engine that never was” for use in US Class A competition. All such shenanigans aside, the CS replica Mk. IV was a very worthy effort by the Shanghai company, which unfortunately abandoned the model engine business in 2015. Although their products were by no means immune from legitimate criticism, most of them could be made to perform very creditably with a little knowledgeable “fettling” on the part of their owners. For me and for many others, that was half the fun! I’ve certainly derived a lot of satisfaction from sorting and using the various CS replicas which have come my way, very much including the illustrated E.D. Mk. IV Hunter replica. The company provided a valuable service to us fans of “classic” diesels – I for one really miss them! Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed making a closer acquaintance with one of the real classic model diesels of aeromodelling's Golden Years - I certainly did! The E.D. "Three-Forty-Six" and its direct descendants were a credit both to their designer and to the company which produced them. The engines were well-made, durable, fine-handling and strong-running powerplants which would have served their owners very well indeed. They represented excellent value for money. I doubt that any sport-flier who gave one a try was disappointed! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published October 2025 |

||||

| |

In other articles on this website I’ve covered the majority of the various model engines produced by the

In other articles on this website I’ve covered the majority of the various model engines produced by the  Introduced in the second half of 1949, the E.D. Mk. IV survived in production by the “original” E.D. company until early 1962, when the disastrous arson fire of April 29

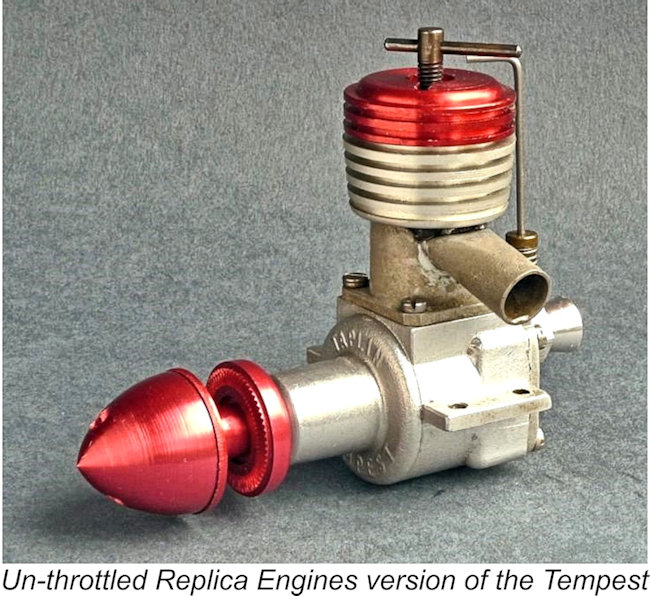

Introduced in the second half of 1949, the E.D. Mk. IV survived in production by the “original” E.D. company until early 1962, when the disastrous arson fire of April 29 The closest thing to a direct derivative of the Hunter design was actually produced under a completely different company name. This was the 1970 Taplin Tempest 3.46 cc diesel which was based in large part upon the E.D. 346 components which E.D. had produced for use in the construction of the Taplin Twin. I’ve described this engine in detail in a companion article on the

The closest thing to a direct derivative of the Hunter design was actually produced under a completely different company name. This was the 1970 Taplin Tempest 3.46 cc diesel which was based in large part upon the E.D. 346 components which E.D. had produced for use in the construction of the Taplin Twin. I’ve described this engine in detail in a companion article on the  In other articles, I’ve traced the early development of the E.D. model engine range. The company entered the model engine field with their

In other articles, I’ve traced the early development of the E.D. model engine range. The company entered the model engine field with their  PB

PB During the immediate post-WW2 period, one of the most respected members of the model engineering community in Southern England was Basil Miles (1906 – 1992), who had been a prominent constructor of model engines since 1936 and was a keen exponent of model hydroplane racing and other forms of power boat modelling. Miles was a member of the Malden hydroplane racing club along with his friend Charlie Cray. He had constructed such notable engines as his amazing four-stroke supercharged "Barracuda" twin seen below.

During the immediate post-WW2 period, one of the most respected members of the model engineering community in Southern England was Basil Miles (1906 – 1992), who had been a prominent constructor of model engines since 1936 and was a keen exponent of model hydroplane racing and other forms of power boat modelling. Miles was a member of the Malden hydroplane racing club along with his friend Charlie Cray. He had constructed such notable engines as his amazing four-stroke supercharged "Barracuda" twin seen below.

Despite this, it’s clear that Miles did exert a steadily increasing influence upon model engine design directions at E.D., at least in an advisory capacity. Initially, this influence was probably exerted through Miles' friendship with Cray. Although the E.D. Mk. II and Comp Special sideport “stovepipe” models displayed little if any imprint of Miles’ established design style, the use of crankshaft front rotary valve induction in the 2.49 cc

Despite this, it’s clear that Miles did exert a steadily increasing influence upon model engine design directions at E.D., at least in an advisory capacity. Initially, this influence was probably exerted through Miles' friendship with Cray. Although the E.D. Mk. II and Comp Special sideport “stovepipe” models displayed little if any imprint of Miles’ established design style, the use of crankshaft front rotary valve induction in the 2.49 cc  The engines appear to have been manufactured and marketed by E.D. under some sort of exclusive production license which transferred the manufacturing and marketing rights (but not the designs themselves) from Miles to E.D. on the basis of some kind of royalty payment to Miles for each engine sold. This would mean that any changes to the marketed designs would have to be developed or at least approved by Miles.

The engines appear to have been manufactured and marketed by E.D. under some sort of exclusive production license which transferred the manufacturing and marketing rights (but not the designs themselves) from Miles to E.D. on the basis of some kind of royalty payment to Miles for each engine sold. This would mean that any changes to the marketed designs would have to be developed or at least approved by Miles. the design. Basil certainly held this view himself – when reminiscing years later with his good friend Alan Greenfield, he recalled his anger at discovering what Ken Day (later owner of the E.D. marque) and Kevin Lindsey had done to the design of the E.D. Hunter (as the “Three-Forty-Six” was later called) to create the original exhaust-throttled versions of the E.D. “Super Hunter” and “Super Otter” designs of the mid-1960’s, neither of which bore much resemblance to the original design. As far as he was concerned, their modifications were a botch-up of his design.

the design. Basil certainly held this view himself – when reminiscing years later with his good friend Alan Greenfield, he recalled his anger at discovering what Ken Day (later owner of the E.D. marque) and Kevin Lindsey had done to the design of the E.D. Hunter (as the “Three-Forty-Six” was later called) to create the original exhaust-throttled versions of the E.D. “Super Hunter” and “Super Otter” designs of the mid-1960’s, neither of which bore much resemblance to the original design. As far as he was concerned, their modifications were a botch-up of his design. The fact that E.D. never credited Basil Miles openly with the design of the E.D. 346 Mk. IV seems to have rankled somewhat with Basil. Accordingly, it would appear that a stipulation of his agreement to design the next offering in the E.D. range, the iconic 2.46 cc

The fact that E.D. never credited Basil Miles openly with the design of the E.D. 346 Mk. IV seems to have rankled somewhat with Basil. Accordingly, it would appear that a stipulation of his agreement to design the next offering in the E.D. range, the iconic 2.46 cc  The 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV was first advertised in October 1949 at a price of £4 12s 6d (£4.63), being designated as the “Three-Forty-Six”. This advertisement (right) included a photograph of the engine, which must therefore have been in existence as of August 1949 in the illustrated form to allow for the inclusion of the image in that advertisement, for which the Editorial deadline was early September 1949.

The 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV was first advertised in October 1949 at a price of £4 12s 6d (£4.63), being designated as the “Three-Forty-Six”. This advertisement (right) included a photograph of the engine, which must therefore have been in existence as of August 1949 in the illustrated form to allow for the inclusion of the image in that advertisement, for which the Editorial deadline was early September 1949. Beginning with the tale of the tape, the E.D. Mk. IV featured nominal bore and stroke dimensions of 0.656 in. (16.66 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 3.46 cc (0.211 cuin.). For reasons which defy logical explanation, British model engine designers of the day generally worked in fractional inch dimensions, although they then quoted the resulting displacements in cc! Go figure .........anyway, the nominal bore and stroke of the Mk. IV were 21/32 in. and 5/8 in. respectively.

Beginning with the tale of the tape, the E.D. Mk. IV featured nominal bore and stroke dimensions of 0.656 in. (16.66 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 3.46 cc (0.211 cuin.). For reasons which defy logical explanation, British model engine designers of the day generally worked in fractional inch dimensions, although they then quoted the resulting displacements in cc! Go figure .........anyway, the nominal bore and stroke of the Mk. IV were 21/32 in. and 5/8 in. respectively. The hardened steel cylinder featured integrally-formed cooling fins – a very effective arrangement from a thermodynamic standpoint, since it eliminated any possibility of a heat dam being created at the interface between a steel liner and a separate light alloy jacket. Care needs to be exercised with those fins, since they’re quite brittle and easily fractured.

The hardened steel cylinder featured integrally-formed cooling fins – a very effective arrangement from a thermodynamic standpoint, since it eliminated any possibility of a heat dam being created at the interface between a steel liner and a separate light alloy jacket. Care needs to be exercised with those fins, since they’re quite brittle and easily fractured.

The one-piece steel crankshaft featured a heavily-counterbalanced crank-disc. It appeared to be a modified rendition of the same component that had been used in the earlier 2.49 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) E.D. Mk. III, albeit without the now-redundant crankshaft induction port. The central gas passage was however retained, both for lightness and to supply lubricant to the front of the main bearing. It did this through a pair of holes which were drilled transversely through the main journal near the front.

The one-piece steel crankshaft featured a heavily-counterbalanced crank-disc. It appeared to be a modified rendition of the same component that had been used in the earlier 2.49 cc crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) E.D. Mk. III, albeit without the now-redundant crankshaft induction port. The central gas passage was however retained, both for lightness and to supply lubricant to the front of the main bearing. It did this through a pair of holes which were drilled transversely through the main journal near the front. The prop driver and spinner nut were also identical to the equivalent components used in the Mk. III. The elongated prop driver engaged with a shallow-angled self-locking taper at the front of the shaft. This design resulted in the airscrew being located well forward of the actual powerplant – a useful feature for many streamlined scale model applications.

The prop driver and spinner nut were also identical to the equivalent components used in the Mk. III. The elongated prop driver engaged with a shallow-angled self-locking taper at the front of the shaft. This design resulted in the airscrew being located well forward of the actual powerplant – a useful feature for many streamlined scale model applications. Suffice it to say here that the E.D. numbering system began with either a letter or a single-digit number indicating the particular model of that engine. This was followed by a second letter indicating the month of production by alphabetical order from A to N representing January to December, with I and L being omitted to avoid confusion with other ciphers. This in turn was followed by the number of the engine in that month’s batch. The sequence was completed by an indication of the year of production. The relative order of the first two characters was occasionally reversed, but the system remained unchanged otherwise.

Suffice it to say here that the E.D. numbering system began with either a letter or a single-digit number indicating the particular model of that engine. This was followed by a second letter indicating the month of production by alphabetical order from A to N representing January to December, with I and L being omitted to avoid confusion with other ciphers. This in turn was followed by the number of the engine in that month’s batch. The sequence was completed by an indication of the year of production. The relative order of the first two characters was occasionally reversed, but the system remained unchanged otherwise. As stated earlier, the initial advertisement for the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” appeared in the October 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller”. In order to appear in that issue, the advertisement would have had to be submitted prior to the Editorial deadline of early September, 1949. This seems to confirm that the E.D. Mk. IV first materialized in August 1949. Kevin Richards’ engine number 4J 4/9 from September 1949 is the earliest numbered example of my acquaintance. It is generally similar to the prototype apart from the omission of the cast iron front bearing insert.

As stated earlier, the initial advertisement for the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” appeared in the October 1949 issue of “Aeromodeller”. In order to appear in that issue, the advertisement would have had to be submitted prior to the Editorial deadline of early September, 1949. This seems to confirm that the E.D. Mk. IV first materialized in August 1949. Kevin Richards’ engine number 4J 4/9 from September 1949 is the earliest numbered example of my acquaintance. It is generally similar to the prototype apart from the omission of the cast iron front bearing insert. The earliest examples of this variant displayed only the serial number just below the cylinder mounting flange. However, by November 1949 the engines bore the designation “Made in England” stamped horizontally in very small script on the crankcase’s front face along the top. The front face also displayed the model designation “ED Mk IV” stamped in larger characters above and below the main bearing housing. The serial number now appeared just above the right-hand mounting lug, while the word “Tested” was stamped in very small characters under the left-hand mounting lug. Illustrated engine number 4M 186/9 typifies this variant.

The earliest examples of this variant displayed only the serial number just below the cylinder mounting flange. However, by November 1949 the engines bore the designation “Made in England” stamped horizontally in very small script on the crankcase’s front face along the top. The front face also displayed the model designation “ED Mk IV” stamped in larger characters above and below the main bearing housing. The serial number now appeared just above the right-hand mounting lug, while the word “Tested” was stamped in very small characters under the left-hand mounting lug. Illustrated engine number 4M 186/9 typifies this variant.  At some point in the first half of 1950, the machined and polished bar-stock crankcase of the E.D. Mk. IV was replaced by a gravity die-cast component having substantially thicker mounting lugs. A few of these cases were polished, but most were left as cast. The designation “ED MK 4” was now cast as written in low relief onto the front face of the crankcase at the top. Note the change from Roman to Arabic numerals. In all other significant respects, the engine was unchanged.

At some point in the first half of 1950, the machined and polished bar-stock crankcase of the E.D. Mk. IV was replaced by a gravity die-cast component having substantially thicker mounting lugs. A few of these cases were polished, but most were left as cast. The designation “ED MK 4” was now cast as written in low relief onto the front face of the crankcase at the top. Note the change from Roman to Arabic numerals. In all other significant respects, the engine was unchanged.  part by the reduced production costs associated with the switch to cast crankcases. It was certainly not due to any lessening of the Mk. IV’s popularity – serial numbers show that production was to continue at an impressive level for over a decade yet to come.

part by the reduced production costs associated with the switch to cast crankcases. It was certainly not due to any lessening of the Mk. IV’s popularity – serial numbers show that production was to continue at an impressive level for over a decade yet to come. The next variant, the "black-case" model, is a bit of an anomaly! It only seems to have remained in production for a matter of a few months, after which the engine reverted to a plain as-cast crankcase finish. At the same time, the alloy insert in the piston was finally eliminated, with the cast iron piston now being machined in one piece. No other changes beyond the case finish were apparent.

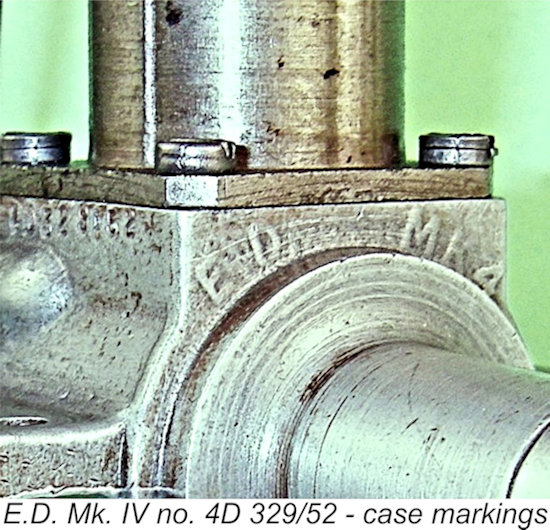

The next variant, the "black-case" model, is a bit of an anomaly! It only seems to have remained in production for a matter of a few months, after which the engine reverted to a plain as-cast crankcase finish. At the same time, the alloy insert in the piston was finally eliminated, with the cast iron piston now being machined in one piece. No other changes beyond the case finish were apparent. However, this experiment was not to last. By the time we get to engine number 4D 329/52 (later in April 1952), the engine has reverted to Variant 2 form, with a natural finish cast case but retaining the one-piece piston. It was to continue in this form for some time thereafter. Once again, no additional design changes accompanied this reversal. This being the case, I personally view the black-case model as a short-lived sub-variant of the third major variant of the E.D. Mk. IV.

However, this experiment was not to last. By the time we get to engine number 4D 329/52 (later in April 1952), the engine has reverted to Variant 2 form, with a natural finish cast case but retaining the one-piece piston. It was to continue in this form for some time thereafter. Once again, no additional design changes accompanied this reversal. This being the case, I personally view the black-case model as a short-lived sub-variant of the third major variant of the E.D. Mk. IV. The major change was the use of a cylinder which was considerably shortened below the cooling fins. This was made possible by the use of the shorter alloy conrod from the contemporary E.D. 2.46 cc Racer. The use of these components resulted in a significant increase in the engine’s sub-piston induction period, also slightly decreasing the crankcase volume.

The major change was the use of a cylinder which was considerably shortened below the cooling fins. This was made possible by the use of the shorter alloy conrod from the contemporary E.D. 2.46 cc Racer. The use of these components resulted in a significant increase in the engine’s sub-piston induction period, also slightly decreasing the crankcase volume. In the latter part of 1958, E.D. entered into an agreement with Col. H. J. Taplin’s Birchington Engineering Company to participate in the manufacture of the 7 cc

In the latter part of 1958, E.D. entered into an agreement with Col. H. J. Taplin’s Birchington Engineering Company to participate in the manufacture of the 7 cc  The result was the 1959 appearance of what I’ve called the fifth (and final) variant of the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter. The major visible change was the use of a much shorter prop driver and spinner nut which were identical to those used on the Taplin Twin. The same cylinder head was also used along with the shorter cylinder. The crankshaft also matched that used in the Taplin Twin at the front by featuring a full circle crank-disc having no counterbalance. The net result of the front-end changes was a considerable reduction in the engine’s axial length.

The result was the 1959 appearance of what I’ve called the fifth (and final) variant of the E.D. Mk. IV Hunter. The major visible change was the use of a much shorter prop driver and spinner nut which were identical to those used on the Taplin Twin. The same cylinder head was also used along with the shorter cylinder. The crankshaft also matched that used in the Taplin Twin at the front by featuring a full circle crank-disc having no counterbalance. The net result of the front-end changes was a considerable reduction in the engine’s axial length. Following its October 1949 advertising debut, the E.D. Mk. IV was promoted quite vigorously throughout the 1950’s and into the early 1960’s. Despite the largely cosmetic changes outlined above, the successive variants were never highlighted in E.D.’s advertising – the Mk. IV’s final illustrated advertising appearance in August 1961 featured the same depiction of the engine that had formed part of the introductory advertisement of October 1949!

Following its October 1949 advertising debut, the E.D. Mk. IV was promoted quite vigorously throughout the 1950’s and into the early 1960’s. Despite the largely cosmetic changes outlined above, the successive variants were never highlighted in E.D.’s advertising – the Mk. IV’s final illustrated advertising appearance in August 1961 featured the same depiction of the engine that had formed part of the introductory advertisement of October 1949!

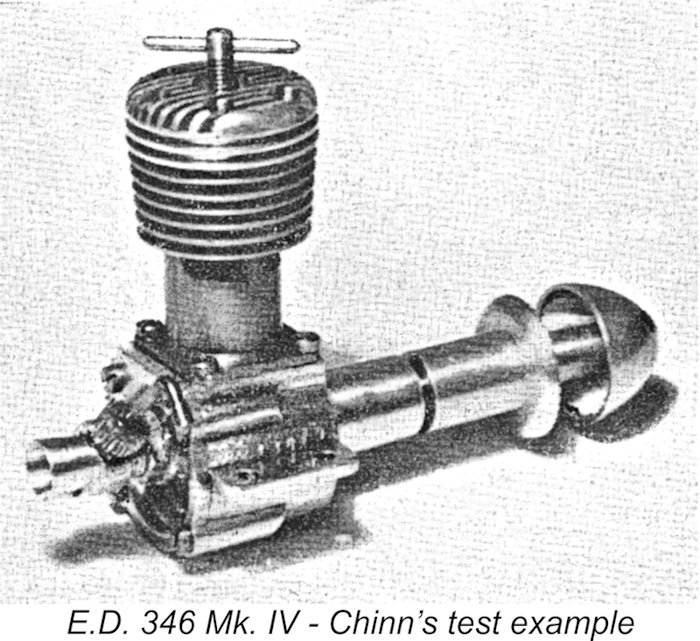

The E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV was the subject of two published tests, both of which appeared within the first year of the engine’s existence. Neither tester clarified whether the aluminium alloy crank-case was machined or cast, nor unfortunately did they record the serial numbers of their test engines. However, the images of their test engines plus the associated 3-view drawings make it clear that both test examples were first-variant units having polished bar-stock cases – the thin mounting lugs make this perfectly clear. Moreover, the serial number on Chinn’s illustrated test example appears to be 4N 114/9, which definitely makes it a first variant example.

The E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV was the subject of two published tests, both of which appeared within the first year of the engine’s existence. Neither tester clarified whether the aluminium alloy crank-case was machined or cast, nor unfortunately did they record the serial numbers of their test engines. However, the images of their test engines plus the associated 3-view drawings make it clear that both test examples were first-variant units having polished bar-stock cases – the thin mounting lugs make this perfectly clear. Moreover, the serial number on Chinn’s illustrated test example appears to be 4N 114/9, which definitely makes it a first variant example. printed as a mirror image, showing the exhaust ports on the left! Clearly an un-caught Editorial error, because the accompanying 3-view and sectional drawings showed the exhausts oriented correctly to the right. The rendition of Sparey’s image which appears here has been correctly re-oriented.

printed as a mirror image, showing the exhaust ports on the left! Clearly an un-caught Editorial error, because the accompanying 3-view and sectional drawings showed the exhausts oriented correctly to the right. The rendition of Sparey’s image which appears here has been correctly re-oriented. I must confess to being a little skeptical regarding Sparey’s performance figures, particularly his cited peaking speed. My experience with the E.D. Mk. IV suggests that it peaks at a significantly lower speed while delivering somewhat superior torque. This impression was supported by the findings of Peter Chinn, who published

I must confess to being a little skeptical regarding Sparey’s performance figures, particularly his cited peaking speed. My experience with the E.D. Mk. IV suggests that it peaks at a significantly lower speed while delivering somewhat superior torque. This impression was supported by the findings of Peter Chinn, who published  Put more plainly, he found the engine to be extremely versatile in terms of the range of its potential applications. He also characterized the engine’s performance as being “if anything, slightly above that anticipated”.

Put more plainly, he found the engine to be extremely versatile in terms of the range of its potential applications. He also characterized the engine’s performance as being “if anything, slightly above that anticipated”. The attentive reader will recall that perhaps the most significant change implemented during the production life of the E.D 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter was the shortening of the cylinder coupled with the use of a shortened conrod and front end. One of the results of these changes was to increase the engine’s sub-piston induction period quite appreciably. Along with the slightly reduced crankcase volume, this might well be expected to result in an improved performance, particularly at the top end.

The attentive reader will recall that perhaps the most significant change implemented during the production life of the E.D 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter was the shortening of the cylinder coupled with the use of a shortened conrod and front end. One of the results of these changes was to increase the engine’s sub-piston induction period quite appreciably. Along with the slightly reduced crankcase volume, this might well be expected to result in an improved performance, particularly at the top end.  Having both tested and used various examples of the engine in the past, I had a pretty good idea of the range of test props which would yield the required data. Armed with this information and having provided myself with some fresh nitrated castor-based fuel, I headed for the test stand.

Having both tested and used various examples of the engine in the past, I had a pretty good idea of the range of test props which would yield the required data. Armed with this information and having provided myself with some fresh nitrated castor-based fuel, I headed for the test stand. Then it was the turn of fifth-variant engine number 4D 473/B, a green-headed short-cylinder example dating from April 1961. This engine was also used, but remained in excellent working condition apart from a somewhat loose contra piston which nonetheless held its settings perfectly during operation. It proved to be an even easier starter than its 1949 forebear, since it started easily from cold with just a few preliminary choked flicks - no need for an exhaust prime. I suspect that this must be down to the smaller crankcase volume, which would promote enhanced base pumping efficiency.

Then it was the turn of fifth-variant engine number 4D 473/B, a green-headed short-cylinder example dating from April 1961. This engine was also used, but remained in excellent working condition apart from a somewhat loose contra piston which nonetheless held its settings perfectly during operation. It proved to be an even easier starter than its 1949 forebear, since it started easily from cold with just a few preliminary choked flicks - no need for an exhaust prime. I suspect that this must be down to the smaller crankcase volume, which would promote enhanced base pumping efficiency.

The original design of the E.D. Mk. IV may have been changed almost beyond recognition by later owners of the E.D. brand-name, but that design did not die. During the 1980’s and early 1990’s, a growing number of old-time fliers and collectors became interested in the "original" E.D. Mk. IV as a very useable engine for running and flying purposes. The resulting demand soon outstripped the supply of originals, driving their prices upwards.

The original design of the E.D. Mk. IV may have been changed almost beyond recognition by later owners of the E.D. brand-name, but that design did not die. During the 1980’s and early 1990’s, a growing number of old-time fliers and collectors became interested in the "original" E.D. Mk. IV as a very useable engine for running and flying purposes. The resulting demand soon outstripped the supply of originals, driving their prices upwards. The only other significant change was the elimination of the sub-piston induction which had been a feature of the E.D. original. This change was most likely made to allow the engine to function better in R/C mode with an intake throttle fitted. I’m aware of several examples that were in fact used successfully in this way.

The only other significant change was the elimination of the sub-piston induction which had been a feature of the E.D. original. This change was most likely made to allow the engine to function better in R/C mode with an intake throttle fitted. I’m aware of several examples that were in fact used successfully in this way.