|

|

A Basil Miles Masterpiece - the 5 cc Miles Special

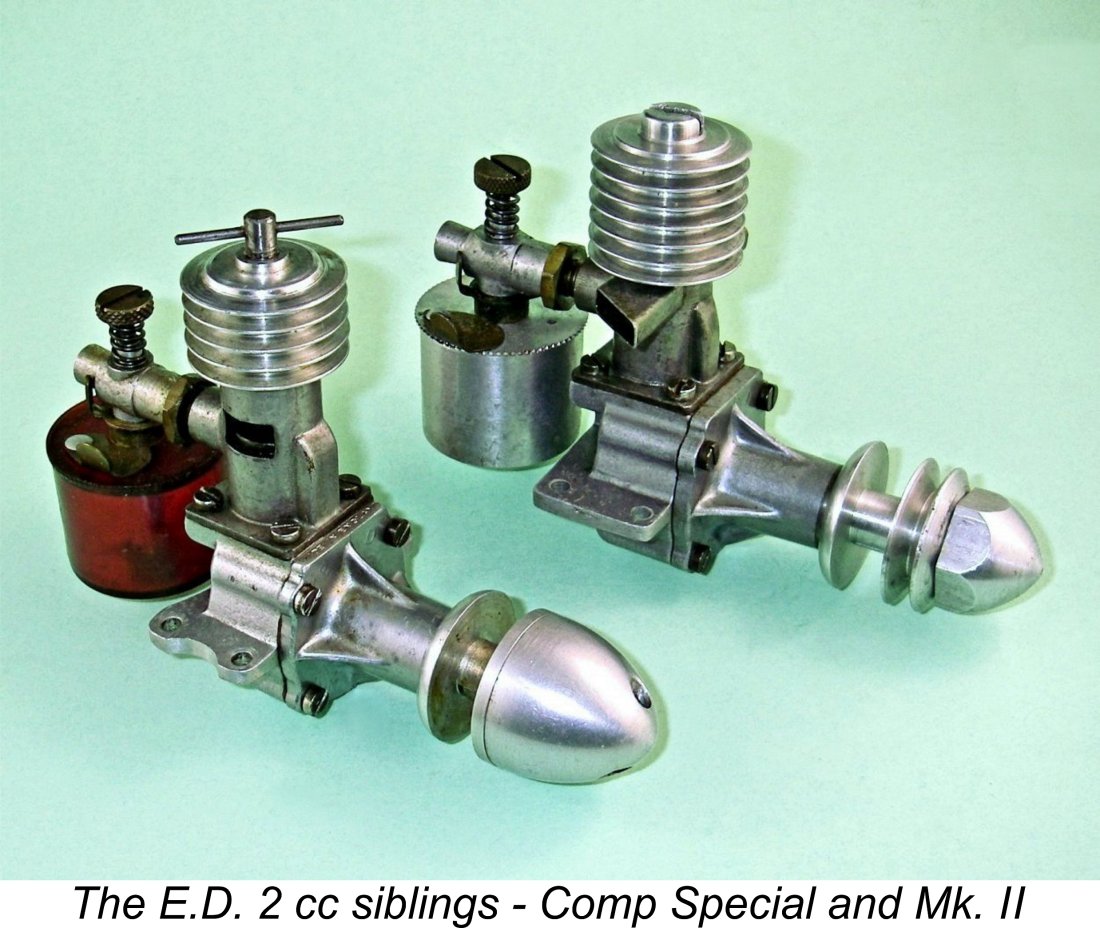

I use the term “marketed” rather than “manufactured” in the above paragraph because the Miles Special was actually manufactured in large part by Basil Miles himself in his own workshop. E.D. produced some of the simpler individual components, but all of the engines were finished and assembled by Basil Miles personally on his own premises, being delivered to E.D. for distribution upon completion. Before getting started on this article, I must acknowledge the assistance rendered to me by my valued mate Gordon Beeby of Australia. Gordon's assistance in chasing down references in support of this project was invaluable, as it has been so often in connection with previous articles. Thanks, mate!! The story of Basil Miles and his relationship with E.D. is a complex one. I’ll do my best to unravel it as I proceed. The Early Days at E.D. In other articles, I’ve traced the early development of the E.D. model engine range. The company entered the model engine field with their 2 cc Mk. II model of early 1947, following this up with the 2 cc Comp Special (December 1947), the 2.49 cc Mk. III (March 1948) and the 1 cc Mk. I Bee (August 1948). The introduction of the Bee signaled the end of the initial expansion phase of E.D.’s model engine range, which was now to remain unchanged for the following year or so.

As of 1949, the only E.D. model which might have appeared to represent competition for these designs was the 2.49 cc E.D. Mk. III crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model. However, by comparison with such contemporary designs as the AMCO 3.5 PB and the Elfin 249 PB, the Mk. III looked positively antiquated with its tall “stovepipe” cylinder, also failing to match its rivals in performance terms. It quickly became apparent to E.D. that they would have to counter the moves of their various competitors with a new model of their own. Accordingly, the company Directors tasked their engine design team with the creation of a new and up-to-date E.D. model which would represent a viable alternative to the excellent mid-sized engines now on offer from their competitors. The question which we must now consider is exactly who the E.D. design team actually were at this stage! Basil Miles’ Evolving Relationship with E.D.

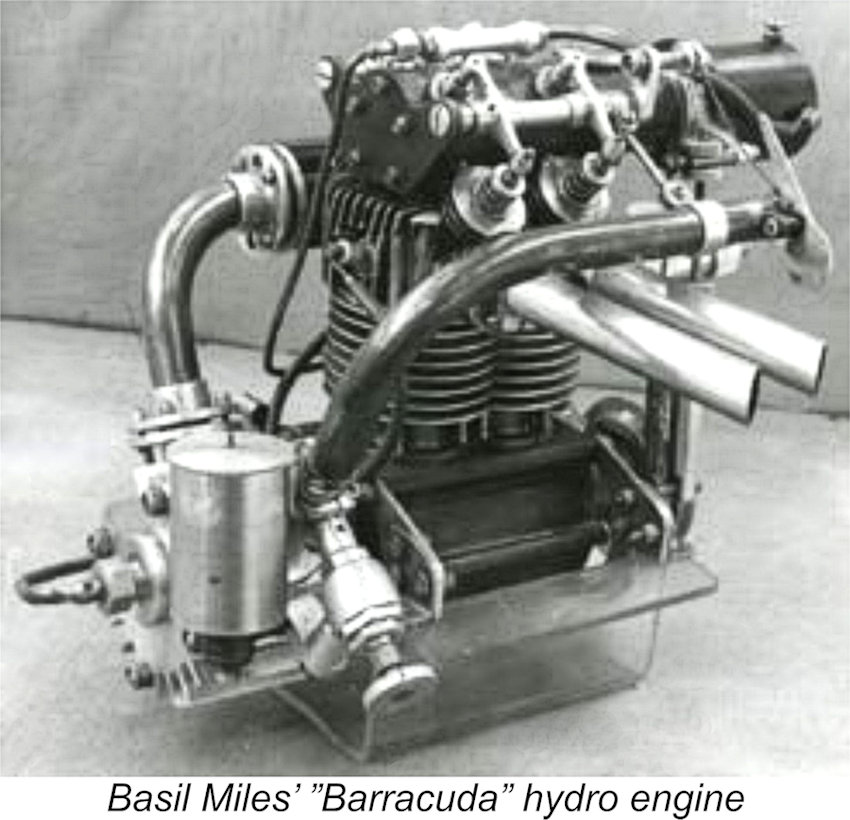

Miles had produced some truly remarkable model engine designs, including his amazing "Barracuda" Although it's not completely clear how Miles first became associated with the E.D. company following its establishment in early 1946, Alan Greenfield (who became the latter-day owner of the E.D. marque and remained so at the time of writing in 2025) believed that Basil Miles was highly instrumental in persuading E.D. management that there was a bright future to be pursued by entering the emerging model engine market, a step which they took in late 1946. However, Kevin Richards’ in-depth research has shown that Miles was never an E.D. employee at any time – he was not one of the original working shareholders in the company, nor did he ever hold an official position of any sort at E.D.

Despite this, it’s clear that Miles did exert a steadily increasing influence upon model engine design directions at E.D., at least in an advisory capacity. Although the E.D. Mk. II and Comp Special sideport “stovepipe” models display little if any imprint of Miles’ established design style, the use of crankshaft front rotary valve induction in the 2.49 cc E.D. Mk. III of March 1948 may indicate some level of involvement on Miles’ part. However, the next model to appear, the 1 cc E.D. Mk. I Series 1 Bee of August 1948, definitely did suggest a significant level of influence from Miles, embodying as it did Miles’ favourite rear disc valve induction system along with far more sophisticated bypass/transfer arrangements. My friend and fellow researcher Marcus Tidmarsh has pointed out that the engines produced by E.D. seem to have fallen into two categories – those in effect designed “in house” by E.D. staff and those designed by an outside consultant. Charlie Cray seems to have been an E.D. employee, while Kevin Richards’ in-depth research has shown that Basil Miles was never an E.D. employee or official at any time. His design work for the company must therefore have been carried out on some kind of a contractual or royalty basis. Accordingly, it appears that the design rights to the early E.D. models designed at least in part by Charlie Cray remained with the company, since the engines were nominally designed by their employee(s). Miles may well have had input to the Mk. III with its rotary valve induction system, but any such work would have been undertaken in the capacity of an outside consultant – E.D. would have retained ownership of the design.

It’s a little unclear exactly when some arrangement of this sort took effect. The design of the 1 cc E.D. Bee Mk. I Series 1 diesel of mid 1948 certainly bears a strong imprint of Miles’ design style, but his name was never cited as the designer of that model, nor as far as I’m aware did Miles ever lay claim to that design. However, the September 1949 appearance of the E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” is another matter entirely. Although Miles’ name was never mentioned by E.D. in connection with this engine, it seems all but certain that he was actually the primary designer of the Mk. IV. He is seen in the accompanying image testing one of these engines.

Miles reportedly went so far as to remind Ken Day that the Hunter was his design, apparently producing documentary evidence to support this claim. Under the terms confirmed in these documents, any design changes had to be approved by Basil, and no such approval had been sought. At Basil’s insistence, Alan Greenfield became involved at this point to oversee the finalization of the two designs to Basil’s requirements. It's my personal view that Day and his colleagues created this problem for themselves solely through their continued use of the E.D. Hunter name, presumably for promotional reasons. In point of fact, the Super Hunter bore almost no resemblance whatsoever to the original Basil Miles design. If Day & Co. had presented the Super Hunter as a completely new E.D. design under a different name, it's really hard to see how Miles could have intervened to the extent that he did. It was the continued use of the E.D. Hunter name that caused all the fuss.

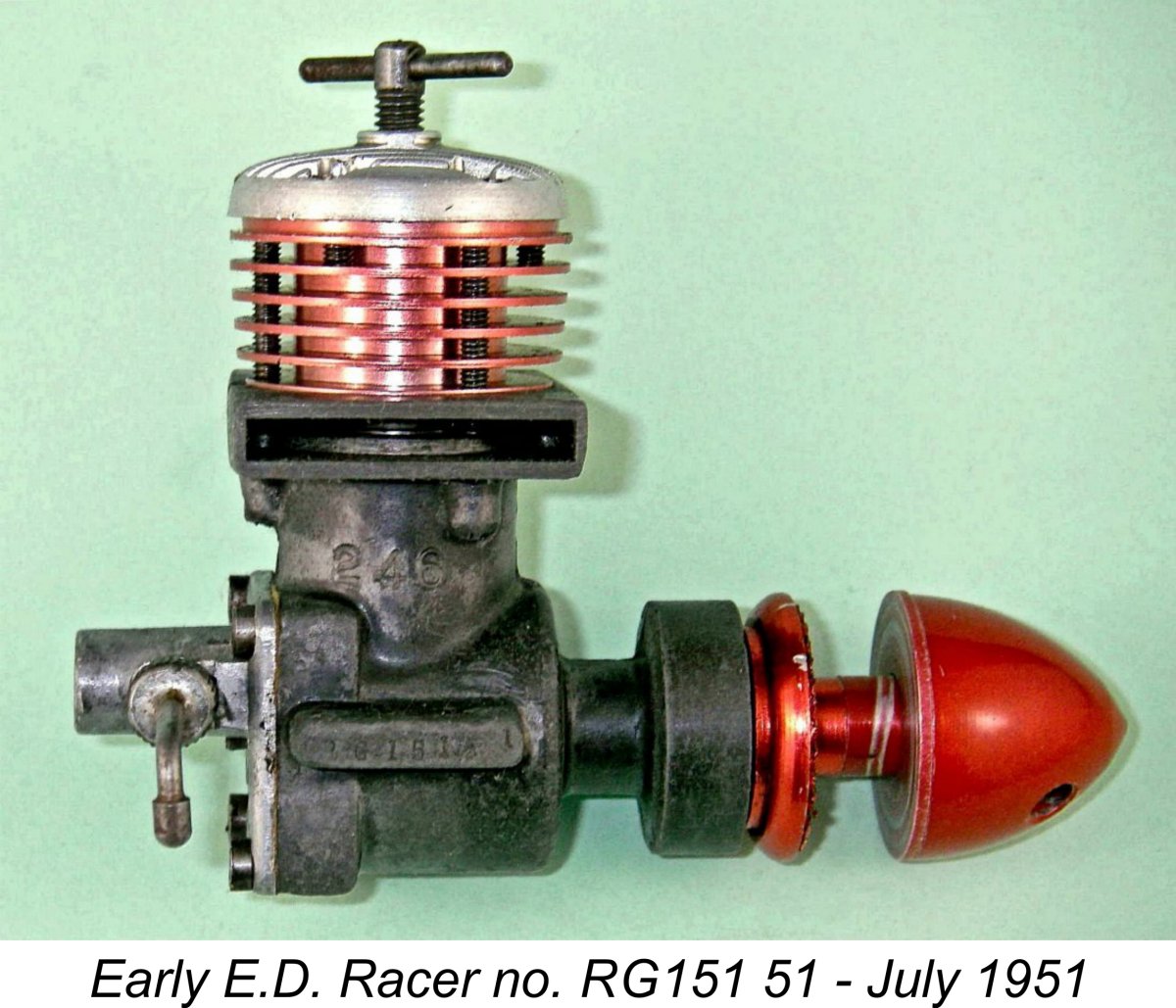

The Racer appeared on the market in March 1951, quickly assuming a dominant position in the British and Commonwealth 2.5 cc model engine markets. For much of the 1950’s it was one of Britain’s most successful 2.5 cc engines of them all, consequently achieving great popularity with both sport-fliers and contest participants. Its versatility allowed it to compete successfully in a wide variety of applications, both aero and marine. It was used in both disc valve and reed valve configurations. The success of the Racer soon got Basil Miles thinking about the possibility of the basic Racer design being applied to engines of differing displacements. This quickly led him to begin work on the engine which forms my central subject here – the 5 cc Miles Special. The Miles Special Appears

These figures yield a calculated displacement of 0.299 cuin. (4.91 cc). The stroke was actually the same as that of the 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” – the extra displacement was generated entirely by a bore increase of 1/8 in. (0.125 in.). The 5 cc engine weighed in at a very healthy 266 gm (9.38 ounces). The Miles Special, as the new design was known from the outset, shared the Racer’s features of a radially-ported cylinder, a light alloy cooling jacket, a twin ball-race crankshaft and disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction with a bolt-on backplate. The main visible design distinctions were; the use of four transfer and four exhaust ports instead of the Racer's three apiece; the provision of a circular exhaust collector ring having four radially-disposed outlets in place of the Racer’s twin stacks; the use of an extended bobbin-style prop driver along typical racing engine lines; and the use of a separate screw-in intake venturi. Despite these departures, the engine still looked like exactly what it was – an enlarged version of the Racer.

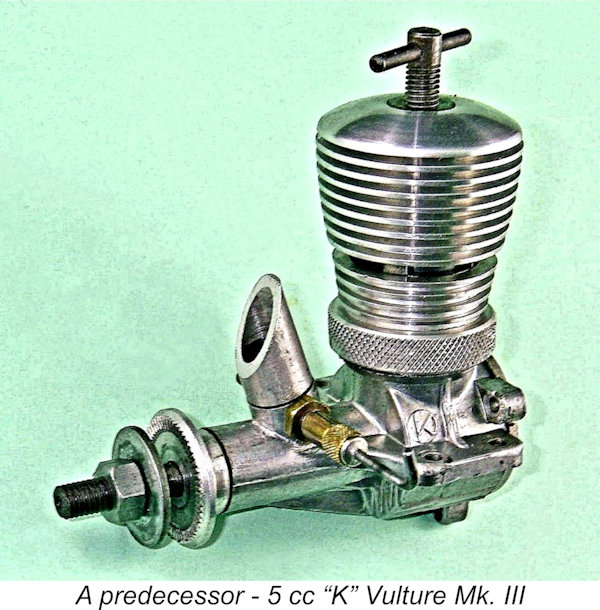

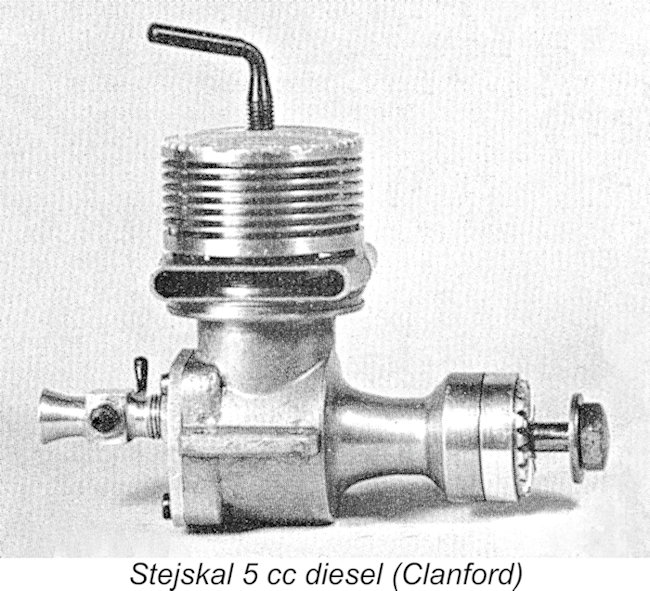

However, E.D. management balked. They had been promoting the very successful 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV “Three-Forty-Six” (later to be known as the “Hunter”) as being “the equal of any 5 cc diesel on the market”. This statement was undoubtedly true of all 5 cc diesels produced up to that point in time by various makers such as Owat, ETA Instruments, the Caledonia Model Co., the “K” Model Engineering Co., Drone Engineering and Davies-Charlton. Now here was Basil Miles offering a 5 cc diesel which would instantly render that Mk. IV claim invalid.

The perception among the E.D. Directors may have been that the above factors would generate sufficient sales resistance to a new 5 cc diesel to render its production uneconomic. They evidently shared a fairly widely-held contemporary view that 3.5 cc was effectively the upper displacement limit for a broadly useable model diesel. In their 3.46 cc E.D. Mk. IV, they already had a very effective and popular example of just such an engine. Whatever their reasons, the E.D. Directors rejected Basil’s design. However, if they thought that this rejection would kill the engine, they were dead wrong - their decision did nothing to diminish Miles’ belief in his brainchild. If E.D. wouldn’t produce it, he would do so himself in his own workshop, which was located in a small village called Ewell situated some 2 miles northeast of Epsom in Surrey and only 6 miles south of the E.D. factory at Kingston-upon-Thames. Accordingly, in 1952 Miles began producing the 5 cc Miles Special in small numbers in his own workshop. Not surprisingly in view of Miles’ standing among the model engineering and model building communities of the South London area, the engine was very well received, with Miles able to sell his entire limited output through word of mouth despite the lack of any serious advertising campaign. Somehow, the word just got around …………

E.D. took due note of what was to them an unexpected level of demand for the Miles Special. Despite their initial rejection of the Miles Special design, Basil’s relationship with E.D. had not changed – they still viewed him as “their” design consultant. They also considered that since he had first offered the engine to them, they remained free to reverse their earlier decision and accept the design, even if belatedly. According to Miles as related to David Owen during that 1989 interview, they told Basil in no uncertain terms that all further production of the Miles Special would have to be marketed through them.

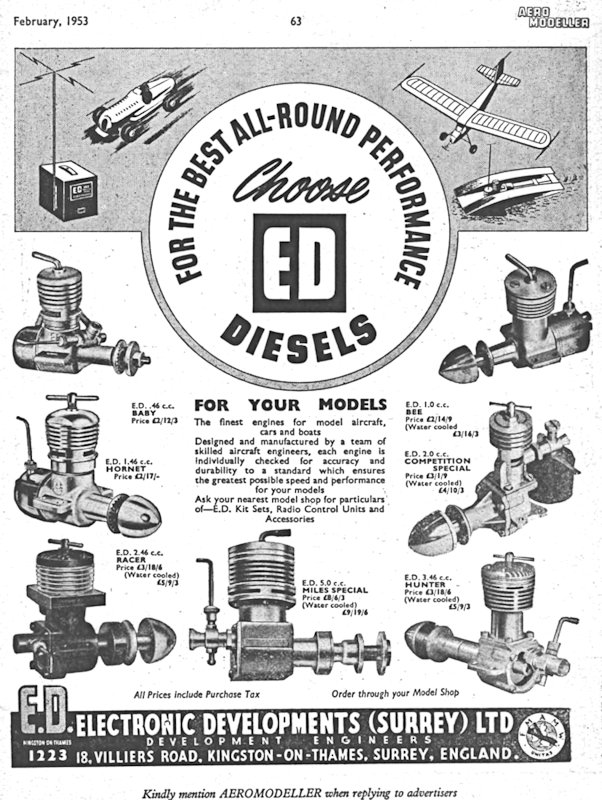

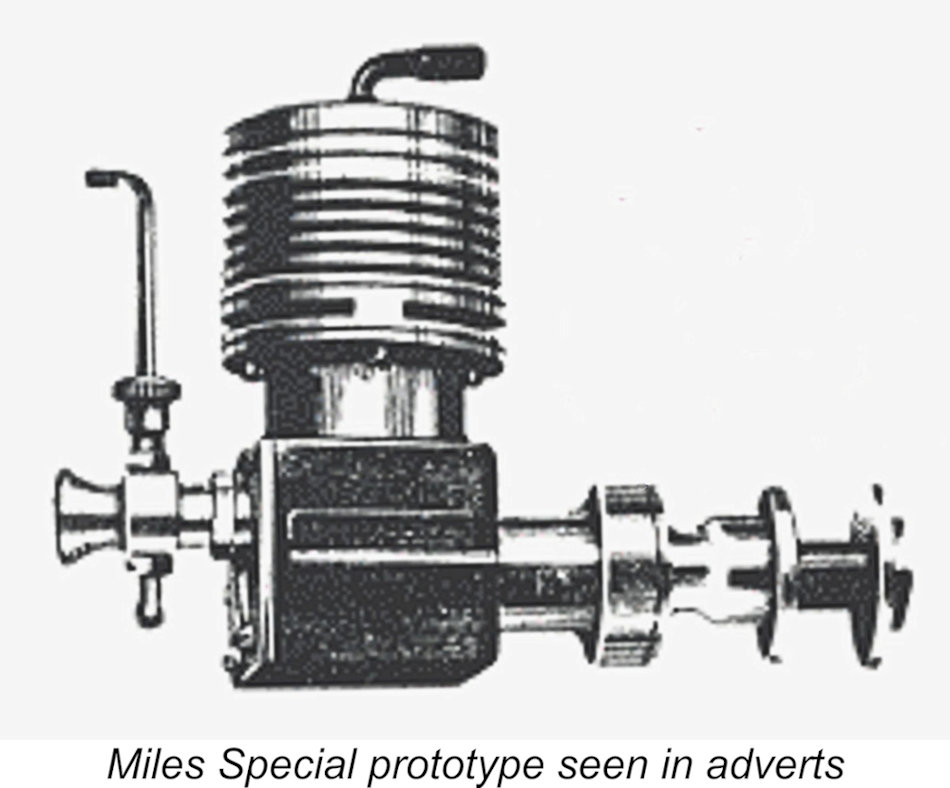

The terms of this agreement left Basil Miles free to sell all of his other models independently – the 5 cc Miles Special diesel was evidently the only model covered by the agreement. E.D. undertook to assist Basil by manufacturing certain components, but the majority of the components were manufactured by Basil in his Ewell workshop. The engines were also assembled and tested by Basil at Ewell, after which they were sent in batches to E.D. in Kingston-upon-Thames for distribution. For their part, E.D. undertook to promote the Miles Special diesel The E.D. Miles Special made its first national advertising appearance in February 1953, as reproduced at the right. Interestingly enough, the engine illustrated in this advertisement was one of the prototype examples, which had a “square” crankcase as opposed to the flanged cylindrical configuration of the production models marketed by E.D. It also featured a single-arm compression screw, which never appeared on the E.D. production variant. Even more remarkably, this illustration was to remain in use all the way up to mid-1958, when the image was finally replaced with one showing the Mk. II version of the Miles Special which had then been in production for over two years!

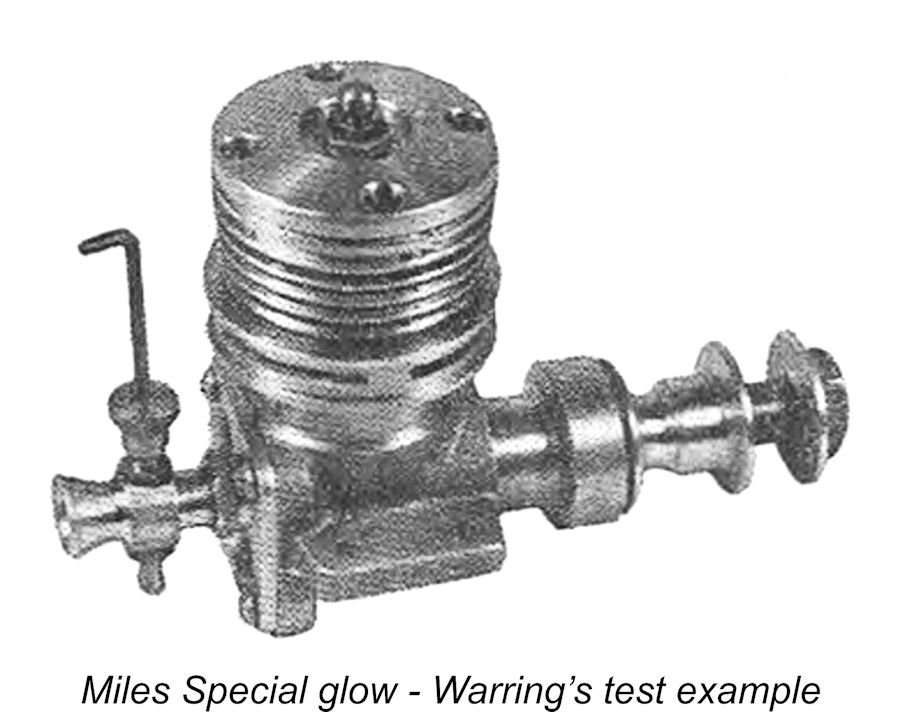

Due primarily to demand from the model hydroplane racing community, of which Basil was an active member, the 5 cc Miles Special was also offered in a glow-plug version. However, for reasons which are lost in the mists of time, this version was never advertised by E.D. at any time. Presumably the agreement whereby the Miles Special was marketed by E.D. as part of their range only covered the diesel version – the glow-plug variant seems to have been among Basil’s “other models” which he remained free to sell independently. Let’s have a look at the 5 cc Miles Special diesel which reached the broader market in early 1953 as part of the E.D. range. The Miles Special Diesel – Description

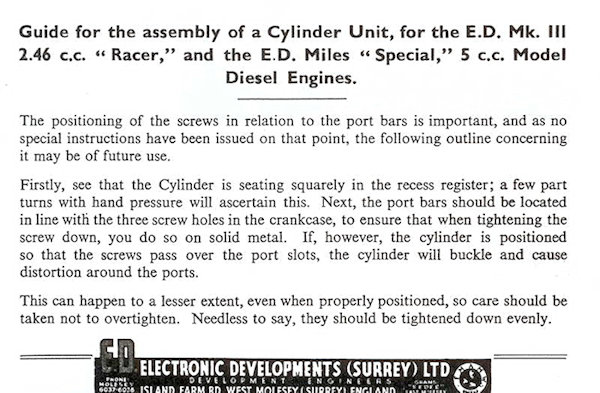

The Miles Special was built up around a massive sand-casting in DTD 424 alloy which was heavily machined to incorporate the front main bearing housing, the crankcase interior and the large-diameter exhaust collector ring which also located the cylinder. At the front, the main bearing housing An often-overlooked feature of the upper crankcase was the small semi-circular horizontal channel on its top surface at the rear, which was provided to allow clearance for the gudgeon (wrist) pin during assembly. This feature is most easily seen in the Mk. II version of the Miles Special, as shown in David Owen's image at the left, but it was common to all variants. The cylinder was more or less identical to that featured in the companion Miles- An important point relating to the engine’s assembly was the potential for distortion of the cylinder due to installation stresses. Miles had a keen appreciation

The one thing that I would have changed was the method of securing the racing engine-style bobbin prop driver to the shaft. The Miles Special used a Woodruff key for this purpose, in common with engines such as the McCoy 60 among others. In small-diameter shafts, a Woodruff key can generate considerable internal stress concentrations in the shaft unless it is extremely accurately fitted. These keys also have a tendency to wear loose and develop a “wobble” over time. In my own opinion, a split-taper collar is a far superior system at model sizes.

One of the most notable features of the Miles Special was the unique needle valve system developed by Basil and used on all of his engines. Like the previously-described front end, the fuel supply arrangements The visible “thimble” on the needle side did not turn with the needle as might be assumed. Rather, it threaded onto the outer end of the needle carrier, which was internally threaded to accommodate the externally-threaded needle. The interior of the “thimble” was packed with neoprene and could be tightened as required to grip the needle and maintain its setting. The gland formed in this way also precluded any possibility of air leakage past the needle. Very ingenious, and it worked extremely well. Writing in 1957, Peter Chinn characterized this needle valve arrangement as “the best of its kind ever devised for a model engine”. The intake assembly threaded into the backplate and was held securely by a lock-nut. This allowed the needle to be oriented in any desired direction as dictated by the As stated earlier, a glow-plug version of the 5 cc Miles Special was offered more or less from the outset, although this variant was never advertised by E.D., being sold by Basil Miles directly to his customers at the same prices as the diesel versions. This variant found considerable use in tethered hydroplane racing, also being tried in R/C boat and aero service in later years. In the aero application, however, its weight told against it. The illustrated variant of the Miles Special remained available until early 1956. Despite its production period of over three years, the number actually manufactured remained relatively small, reflecting the fact that this was essentially an individually-produced hand-made engine constructed for the most part by Basil Miles himself working in a small workshop. It appears that all of Basil’s limited output found ready buyers, but he simply couldn’t make them all that fast. He was also producing several other models in very small numbers at the same time, thus further limiting the rate at which he could manufacture the Miles Special.

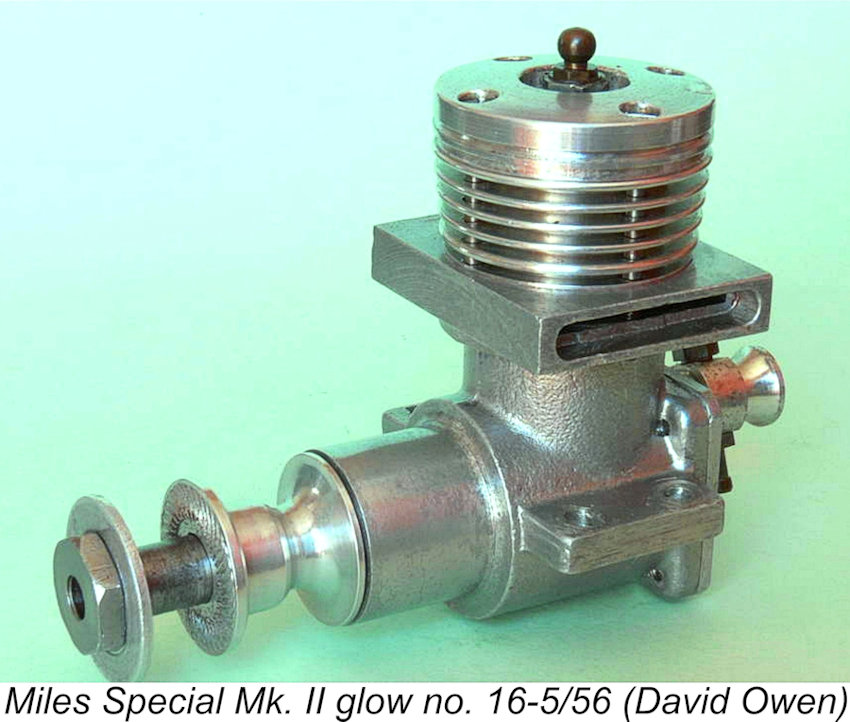

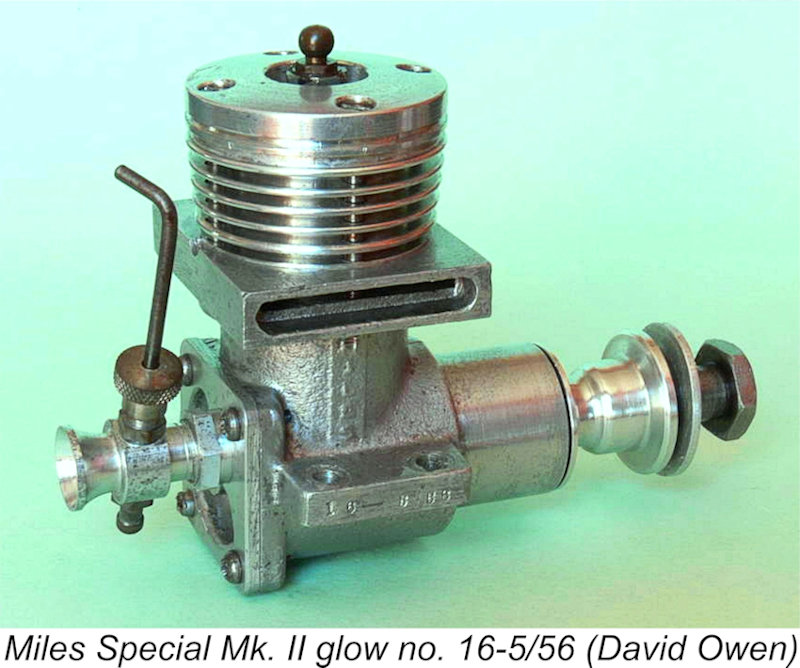

The major change which resulted in the creation of this model was a switch to a twin-stack case which looked even more like that of the E.D. Racer than the case of its predecessor had done. The internal design appears to have been unchanged, leading to an expectation that performance was unaffected by the design amendments. The revised cases now bore the name “MILES” cast in relief onto the right-hand side of the upper crankcase below the right-hand exhaust stack. In addition, the “waisting” of the main bearing between the front ball-race housing and the crankcase was omitted, presumably both as a cost-saving measure and to stiffen the main bearing somewhat. In other respects, the engine was essentially unchanged.

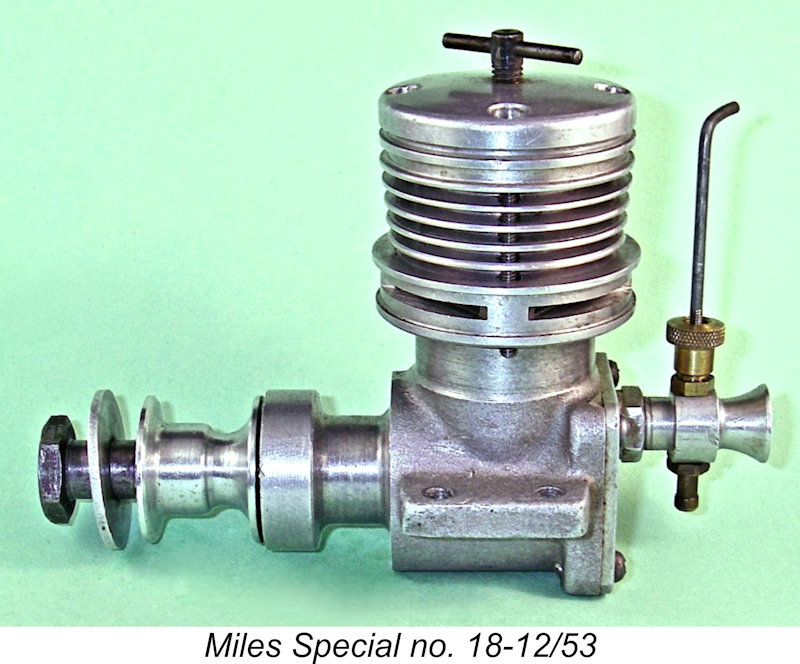

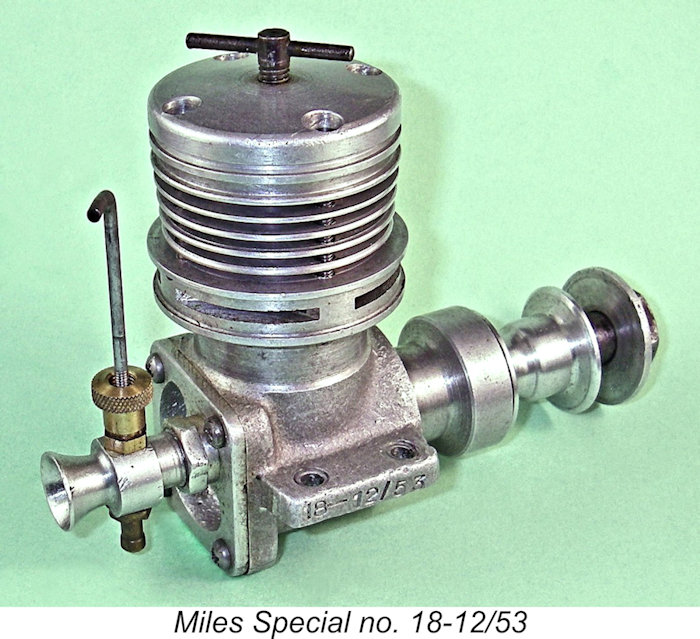

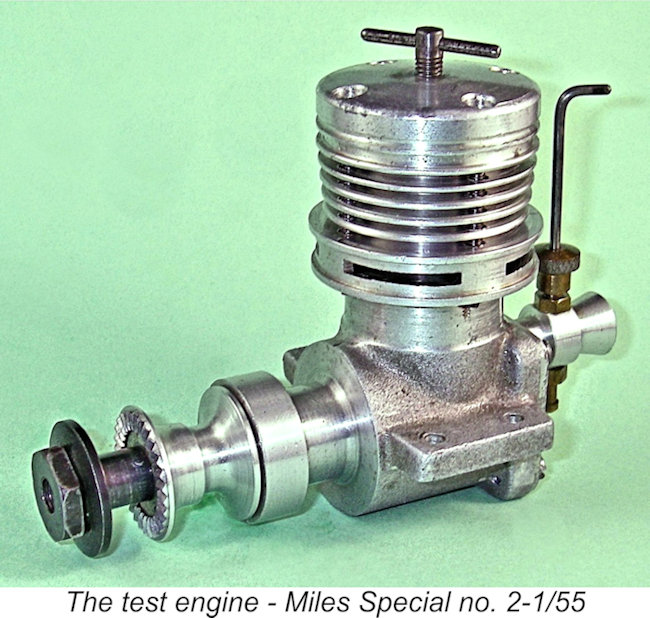

The introduction of this model was accompanied by the first price increase since the initial appearance of the Miles Special. The aero version was now offered at £8 10s 4d (£8.52), with the water-cooled marine variant selling for £10 4s 4d (£10.22). These prices were to hold until May 1957, when a final price increase to £10 4s 3d (£10.21) for the aero model and £11 16s 3d (£11.81) for the marine model came into effect. These prices were maintained right up to the final appearance of the Miles Special in E.D. advertising, a milestone which was reached in December 1958. The fact that Miles was able to continue to charge such prices for his engines is a glowing testament to the high regard in which they were held. The quality of their construction conformed to the highest model engineering standards from start to finish. That quality was emphasized by the fact that no gaskets were used in the assembly, metal-to-metal joints being relied upon throughout. All of the Miles Special engines produced by Basil bore serial numbers which were stamped onto the outer end of the right-hand mounting lug. The system used by Basil is very informative, with the displayed numbers representing the monthly batch number, the month of production and the year of production respectively. So for example, Miles Special no. 18-12/53 was the 18th example produced in December 1953: engine number 2-1/55 was the 2nd example completed in January 1955: and so it goes.

Following the split, Miles continued to make engines on his own account, also making several full-sized motorcycle engines along with the bikes to go with them. For their part, E.D. secured the services of Gordon Cornell to replace Miles as their chief designer, although a combination of shortfalls in available development funding together with some personality and philosophical clashes put an early end to that arrangement. Basil Miles lived on until early 1992, passing away at the age of 85 years. A very brief obituary appeared in the March 1992 issue of "Aeromodeller" magazine. It read simply: "Basil Miles, prodigious designer and maker of fast diesels for marine and aero use, the man behind the E.D. series, has also left us at 85 years, after a lifetime of creative invention. Peace be with him". A somewhat terse send-off for a man who cast such a long shadow over the modelling hobby's golden era. The Miles Special on Test

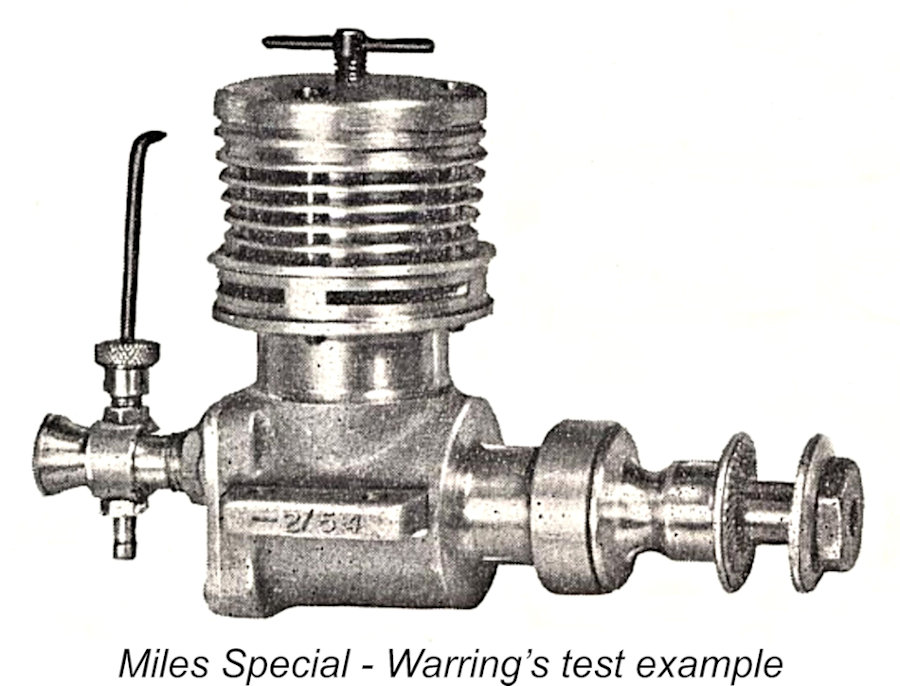

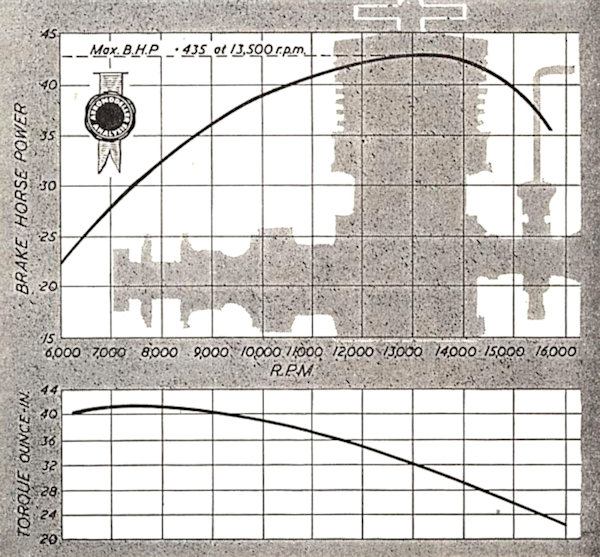

Warring very properly credited Basil Miles rather than E.D with the manufacture of this engine, although he did acknowledge that Miles did so "by arrangement with Electronic Developments (Surrey) Ltd." He spent a significant portion of his test report explaining why the design of the Miles Special did much to overcome the handling difficulties which had plagued the earlier 5 cc diesels following their respective market appearances. He viewed these design measures as being completely successful, stating that Warring found the engine’s response to the controls to be “quite flexible”. Using those controls, the engine could be controlled from slow, low-powered running up to leaned-out maximum speed operation regardless of propeller load. Warring reported a peak output of 0.435 BHP @ 13,500 RPM – a very good figure for a 5 cc diesel of 1953 vintage, and streets ahead of any previous 5 cc diesel. Warring had nothing but praise for the quality of the engine’s construction, stating that it exhibited an “extremely high standard of workmanship”. He summed up the Miles Special as “a really powerful, robust and well-made engine throughout, with a good output all through the operating speed range”. His only negative comment was that the engine’s weight of almost 10 ounces might count against its use in certain applications.

Warring was extremely complimentary with respect to the Miles Special’s starting qualities in glow-plug configuration. He stated that perhaps the engine’s most outstanding attributes were the “remarkably easy starting characteristics” that it displayed. He Warring reported that the Miles Special glow-plug model “gobbles up fuel at a tremendous rate”, hence saddling the owner with a significant fuel bill. He also found that a fairly healthy dose of nitromethane in the fuel was necessary for best performance. He used Mercury no. 7 (20% nitro) for his testing. Using this fuel, he found a peak output of 0.365 BHP @ 13,000 RPM, somewhat shy of the performance measured a few months earlier for the diesel version of the engine. He felt that the Miles Special glow-plug model would perhaps be best suited to flywheel operation such as in a boat, where its easy starting and broad power band might be best appreciated. The Miles Special Re-Visited

This being the case, I though that the least I could do was set one of them up in the test stand and renew auld acquaintance once again! For this purpose, I chose the more “experienced” of my two examples, engine number 2-1/55, which was the second example made by Basil Miles in January 1955, hence having just celebrating its 70th birthday at the time of the test. This one has been mounted and used quite extensively, but it has been well cared for, hence remaining in first-class complete and original condition despite showing a little evidence of wear.

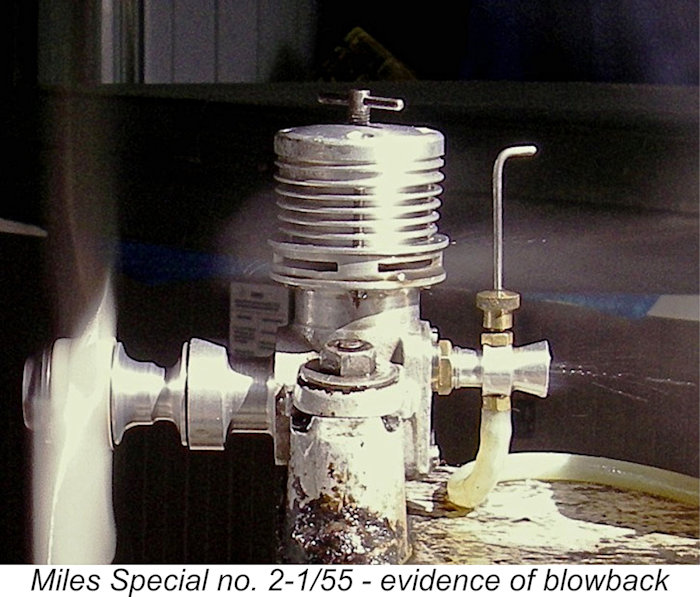

In keeping with Ron Warring’s comments, I found that the level of fuel in the tank relative to the engine’s fuel jet was fairly critical for starting. Too low, and the fuel line would drain back into the tank, leaving insufficient fuel in the line for immediate pick-up. Too high, and fuel would flow under gravity into the intake and flood the crankcase. The engine’s very late induction closure results in considerable blow-back at starting speeds, so the engine’s initial pick-up of fuel from the fuel line isn’t brilliant. That said, the engine’s suction once running appeared to be quite adequate, especially at the higher speeds.

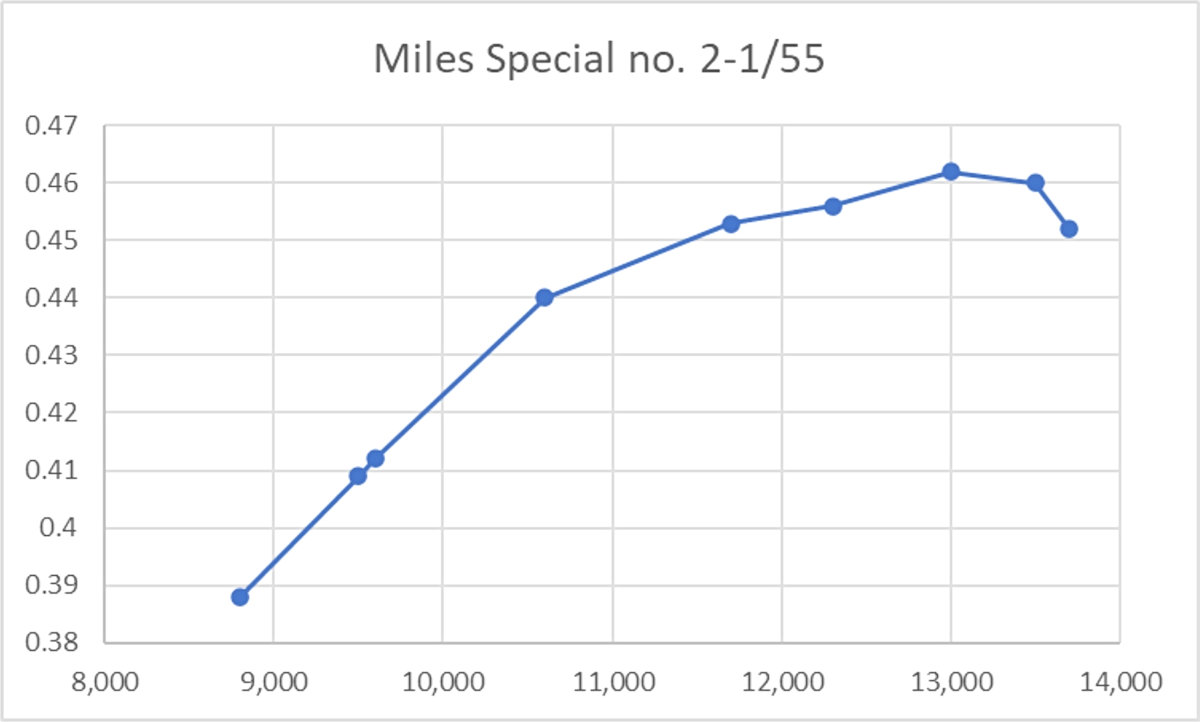

All of this having been said, if the fuel level is set at or minimally below the level of the engine’s fuel jet, the above procedure invariably produces a start within a few energetic flicks. I agree completely with Warring’s assessment that the Miles Special is indeed a perfectly straightforward starter provided the process is approached correctly. Once running, response to the controls was found to be both well-marked and progressive. The engine could be set to run slowly on an opened Thankfully, by the time speeds passed 12,000 RPM this behavior had largely disappeared. Thanks to the very progressive response to the controls, optimum settings were easily established for each prop tested. At full chat, the engine’s noise level was quite impressive – I was very glad of my industrial-grade earmuffs! Both controls held their settings perfectly while remaining fully adjustable at all times. Although some vibration was detectable, the levels appeared to be well within manageable limits. All in all, I found the Miles Special to be a very enjoyable engine to test - I had no difficulty in hand-starting it on an 8x6 airscrew, just as Warring had done before me! The following data were recorded:

As can be seen, Miles Special no. 2-1/55 fractionally out-torqued Warring's example, peaking with an output of around 0.462 BHP @ 13,000 RPM. This level of performance exceeded that of any previous 5 cc diesel by a very considerable margin. Indeed, it actually exceeded the performance of the far later 4.57 cc P.A.W. 29 diesel, for which the late Mike Billinton measured a peak output of 0.40 BHP @ 11,220 RPM in his published test which appeared in the July 1985 issue of "Aeromodeller". Quite an achievement by Basil Miles way back in 1953! So we're looking here at a sturdy, well-designed, fine-handling and powerful 5 cc diesel which was built to a superb standard of quality by a genuine craftsman. All very true, but in the end we do come up against the engine's potential Achilles' heel in the form of its weight. Ron Warring pointed out that this might be seen as an inhibiting factor when considering this engine's possible use in a model aircraft. I have to say that I agree with him - when compared with the 7 ounce weight (minus tank) of the competing FROG 500 glow-plug motor, which had a generally comparable level of performance given sufficient nitro, the Miles Special's 9.4 ounces is certainly a factor requiring consideration in an aeromodelling context. All that aside, this is unquestionably a quality product from the hands of one of the true masters of model engine design and construction. That alone would make it a desirable unit to use in my book! Basil Miles’ Other Engines

It will be recalled that the agreement whereby E.D. were able to market the Miles Special diesel as part of their range specifically left Basil free to market his other designs directly on his own account. The glow-plug version of the 5 cc Miles Special appears to have been one of the designs left in Basil’s own hands.

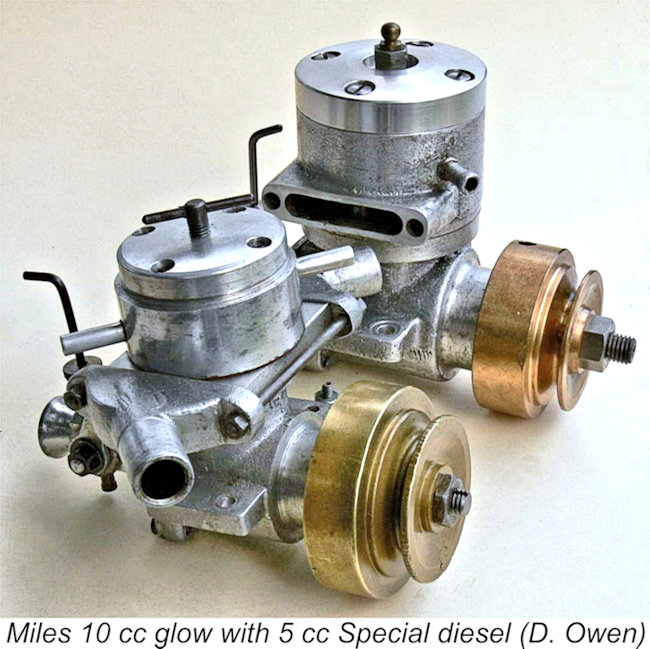

However, Miles didn’t stop there – he produced several larger water-cooled glow-plug models. Perhaps the most widely-used model of this type was his 10 cc marine unit. This was apparently manufactured in modest numbers over a period of several years, with detail changes being made periodically to produce a few minor variants. An example is seen here in company with a 5 cc Miles Special Mk. II marine diesel model complete with accessory exhaust collection manifolds. There was also a 15 cc marine design. The largest engine of this type made by Basil was a massive 30 cc glow-plug unit, of which only a few were made for hydroplane applications.

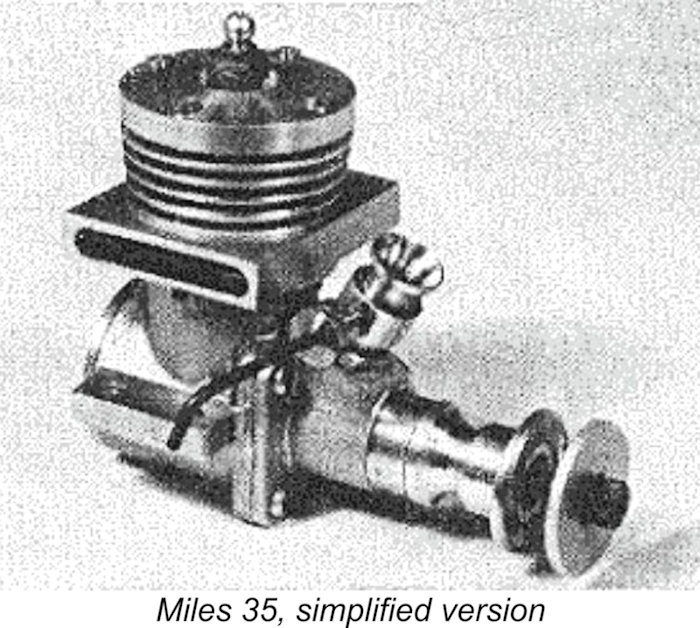

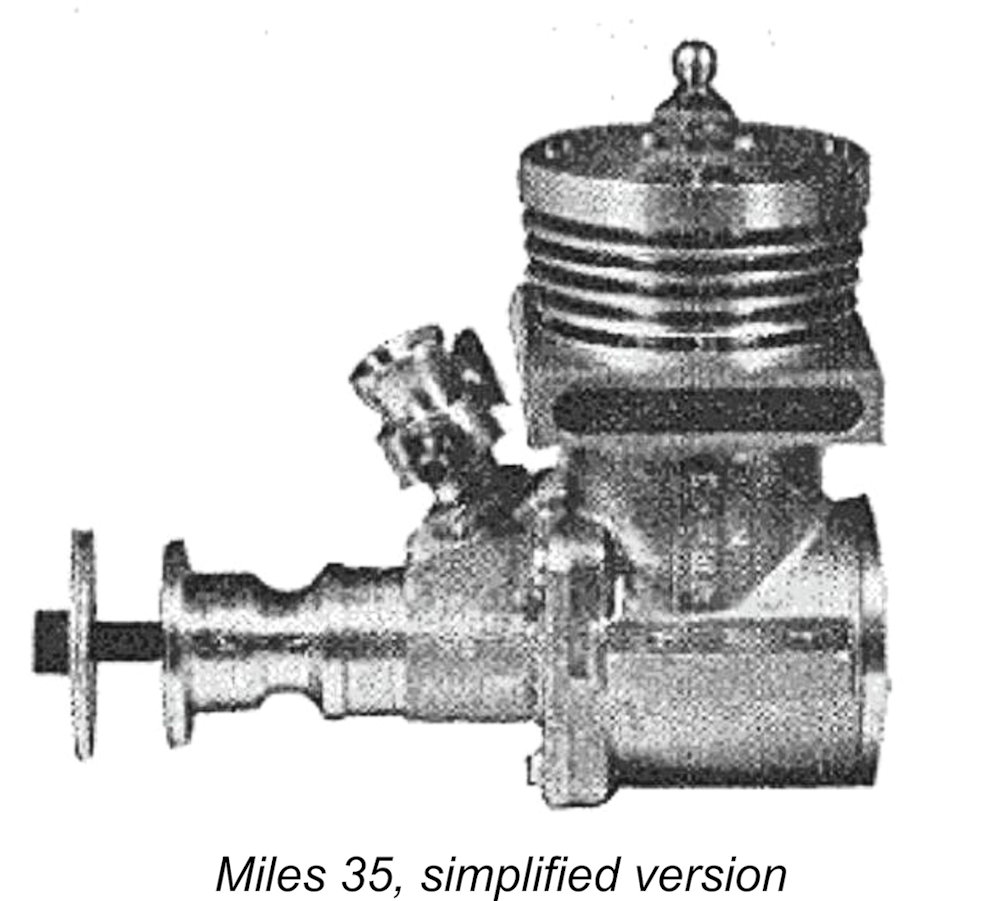

Chinn reported on Miles’ initial efforts in his article entitled “Mainly Motors” which appeared in the October 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Basil’s initial attempt to create the first British-made stunt 35 was more or less simply a bored-out Miles Special Mk. II glow-plug model, retaining the twin stacks and rear disc valve induction of that design as illustrated previously. The additional displacement was achieved through a bore increase to 0.844 in. (nominally 27/32 in.), with the same 0.625 in. stroke being retained. These dimensions yielded an actual displacement of 5.73 cc (0.350 cuin.) and an even more extreme bore/stroke ratio of 1.35 to 1. Basil claimed that this engine’s performance was “promising” and that it delivered “an output, over the whole RPM range, which is substantially in excess of that of the 5 cc diesel”. However, no actual figures were provided. Unfortunately, Chinn’s October 1956 article stirred up a storm of controversy which was reflected in the “Readers Letters” sections of the following issues of the magazine. As my late and greatly-missed mate Ron Chernich once said, the Brits seem to have a stranglehold on the noble art of writing vitriolic "Letters to the Editor"! A few of the letter-writers poured scorn on Miles’ efforts, claiming that his design was quite inappropriate, featuring radial porting, a twin ball-race crankshaft and rear disc valve induction, besides being excessively heavy. They stated bluntly that what was needed was a British-made glow-plug motor configured along American lines, with crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction, cross-flow loop scavenging and lightweight construction. Perhaps a fair comment given emerging trends, but rather than commending Miles for at least making an effort, they dismissed his design out of hand in sometimes derogatory and highly opinionated terms which were quite uncalled for. The diesel vs. glow brigade also traded barbs for a while. Entertaining stuff!!

Chinn’s basic point was that while enthusiasm for American design principles was understandable, a far more appropriate response to Basil Miles’ efforts would have been to simply wait to see what the Miles 35 could actually do. He drew attention to the fact that Miles had already responded to the initial criticism of his 35 disc-valve prototype by producing a simplified shaft-valve version of the engine, which he had sent to Chinn for evaluation. This unit was in effect an over-bored Miles Special Mk. II glow turned end for end, with a separate bolt-on FVR cover replacing the original model’s disc valve assembly and a single ball thrust race in lieu of the former twin ball races.

Although Miles had told Chinn that this engine would be put into production if sufficient interest was evident, it appears that relatively few examples ended up being made. What probably killed the Miles 35 project in the end was the early 1958 news that Bill Morley and Ron Checksfield were embarking upon the development of the US-influenced MERCO 35, a prototype of which finished second in the 1958 Gold Trophy. This was exactly what the previously-mentioned letter-writers had been pushing for. Seeing this performance, British stunt fliers were content to await the appearance of the MERCO 35 in production form, which took place in early 1959.

I’m sure that other models of which I’m presently unaware emerged from the Ewell workshop of Basil Miles. However, the above summary should suffice to show that Miles was a far more prolific producer of model engines than many enthusiasts recognize – his workshop must have been a busy place! He subsequently turned his attention to motorcycle engineering, making a few full-sized motorcycle engines and the complete cycles to go with them. A truly remarkable engineering talent! Other Twin Ball-Race 5 cc Diesels

In 1952, more or less concurrently with Miles' effort, the noted French model engine designer Jules Maraget produced a fine twin ball-race disc-valve 5 cc diesel independently under the Maraget-Météore trade-name. This was Maraget's last new design before his July 1952 merger with the Micron company. Initially the Micron and Maraget lines were kept separate despite the merger, with production of the 5 cc diesel continuing for a while under the designation of the Maraget-Météore 5 cc "Sport" diesel. In 1956 the two ranges were merged to form the Micron-Maraget line. The Maraget-Météore 5 cc "Sport" diesel duplicated the design of the Miles Special in featuring short-stroke bore and stroke dimensions of 19 mm and 17 mm respectively for a displacement of 4.82 cc. However, it differed in terms of its cylinder porting, featuring two large rectangular exhaust ports, one on each side, with two generously-dimensioned transfer ports located directly beneath the exhausts. These were fed by external bypass channels formed in the inner wall of the upper crankcase. In all other respects, the design of the engine generally reflected that of the Miles Special - both Maraget and Miles had independently recognized that a diesel of this displacement benefits more than most from having a ball-race crankshaft.

In 1957, Veenhoven introduced a 4.82 cc diesel unit based quite closely upon the earlier 5 cc racing glow-plug model. It shared the glow model’s bore and stroke, RRV induction and cross-flow loop scavenging, along with a twin ball-race crankshaft. It was a very well-made unit which started easily and ran very strongly. These qualities allowed it to remain in limited production almost right up to 1963, when Veenhoven abandoned the model engine business.

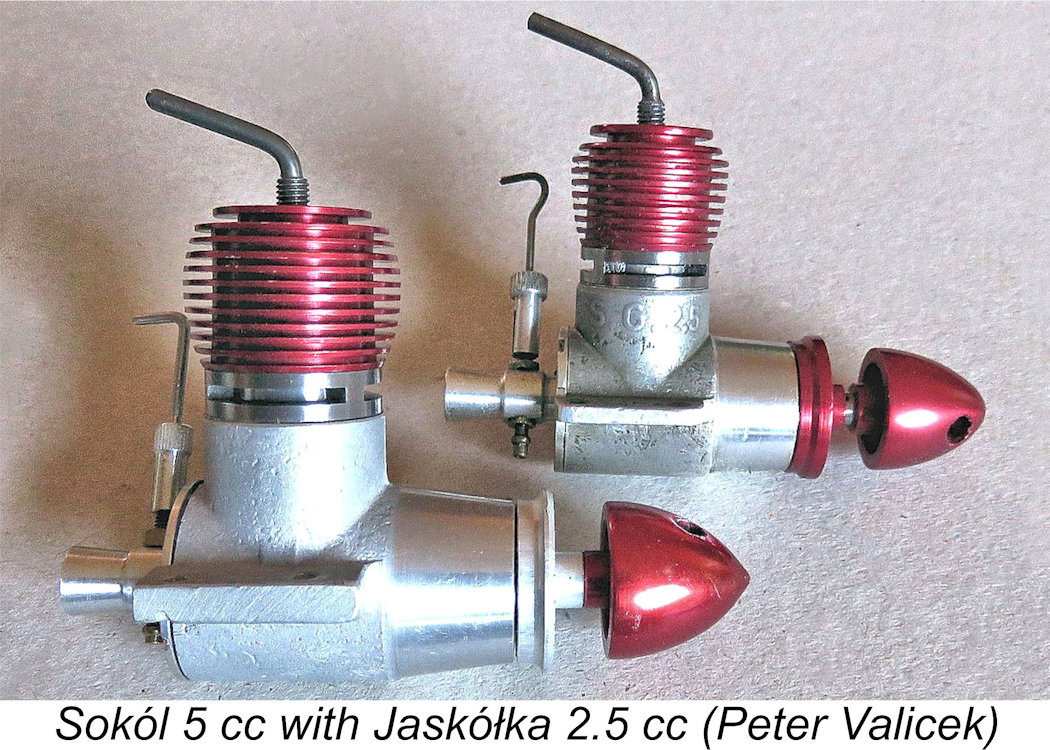

Poland’s best-known model engine designer was Stanislaw Górski (1923-1978). Górski is perhaps best remembered for his development of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka (Swallow) series of model As can be seen from the accompanying image, the original Sokól 5 cc model was pretty much an enlarged clone of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka model. It was made in the same three variants as the 2.5 cc units - plain bearing reed valve; twin ball bearing reed valve; and plain bearing FRV model. Bore and stroke dimensions were 19.0 mm and 16.40 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 4.65 cc. Weight averaged around 190 gm (6.7 ounces).

Unlike the earlier Sokóls, the Super version utilized cross-flow loop scavenging with a side-stack exhaust, being the first Polish engine of this type. It also featured a twin ball bearing shaft and disc RRV induction. A unique feature among diesels was its incorporation of a curved baffle on the piston, the contra piston being recessed to accommodate this feature and mechanically constrained to maintain the correct alignment at all times. The Japanese O.S. company had demonstrated the practicality of utilizing such a design in a diesel through the appearance of their O.S. Max-D 15 diesel of 1959.

More recently, in 1993 the Webra company, then of Enzesfeld in Austria, released their fine Webra Bluehead .28 cuin. diesel, which A slightly modified version of this engine (along with a few companion models of different displacements) remains available at the time of writing (2025) in the form of the "ED by West" diesels designed by Alan Greenfield of Weston UK. These too are outstandingly well-made engines which start and run extremely well.

All of these examples go to show that the early distrust of 5 cc diesels which caused E.D.'s initial cold feet had little basis in reality. Provided that their design is approached with a full understanding of the challenges involved, there's no reason at all why a 5 cc or even larger diesel should not be a perfectly useable model powerplant. Kudos to Basil Miles for leading the way towards the rehabilitation of large diesels through his development of the Miles Special! Conclusion I hope that you've enjoyed making the acquaintance of one of the most talented model engine makers of them all and a few of the engines that he produced. If you ever get the chance to acquire or even just handle one of Basil Miles' creations, grab the chance! You'll be handling a direct link with a true master of the model engineering craft! __________________________

Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2025 |

||

| |

In this article I’ll share what I know about one of the less frequently-encountered models to be marketed by the famous

In this article I’ll share what I know about one of the less frequently-encountered models to be marketed by the famous

During the immediate post-WW2 period, one of the most respected members of the model engineering community in Southern England was Basil Miles (1906 – 1992), who had been a prominent constructor of model engines since 1936 and was a keen exponent of model hydroplane racing and other forms of boat modelling. Miles was a member of the Malden hydroplane racing club along with his friend Charlie Cray.

During the immediate post-WW2 period, one of the most respected members of the model engineering community in Southern England was Basil Miles (1906 – 1992), who had been a prominent constructor of model engines since 1936 and was a keen exponent of model hydroplane racing and other forms of boat modelling. Miles was a member of the Malden hydroplane racing club along with his friend Charlie Cray.

By contrast, Miles’ friend and fellow club-member Charlie Cray was an E.D. employee, evidently being assigned to the model engine division upon its establishment in late 1946. Founding E.D. Managing Director

By contrast, Miles’ friend and fellow club-member Charlie Cray was an E.D. employee, evidently being assigned to the model engine division upon its establishment in late 1946. Founding E.D. Managing Director

If the “Three-Forty-Six” design did indeed originate with Basil, as seems very likely, then he would have retained ownership of the design. Basil certainly held this view himself – when reminiscing years later with his good friend Alan Greenfield, he recalled his anger at discovering what Ken Day (later owner of the E.D. marque) and Kevin Lindsey had done to the design of the E.D. Hunter (as the “Three-Forty-Six” was later called) to create the original exhaust-throttled versions of the E.D. “Super Hunter” and “Super Otter” designs of the mid-1960’s, neither of which bore much if any resemblance to the original design. As far as he was concerned, their modifications were a botch-up of his design.

If the “Three-Forty-Six” design did indeed originate with Basil, as seems very likely, then he would have retained ownership of the design. Basil certainly held this view himself – when reminiscing years later with his good friend Alan Greenfield, he recalled his anger at discovering what Ken Day (later owner of the E.D. marque) and Kevin Lindsey had done to the design of the E.D. Hunter (as the “Three-Forty-Six” was later called) to create the original exhaust-throttled versions of the E.D. “Super Hunter” and “Super Otter” designs of the mid-1960’s, neither of which bore much if any resemblance to the original design. As far as he was concerned, their modifications were a botch-up of his design.  The fact that E.D. never openly credited Basil Miles with the design of the E.D. Mk. IV seems to have rankled somewhat with Basil. Accordingly, it would appear that a stipulation of his agreement to design the next offering in the E.D. range, the iconic 2.46 cc

The fact that E.D. never openly credited Basil Miles with the design of the E.D. Mk. IV seems to have rankled somewhat with Basil. Accordingly, it would appear that a stipulation of his agreement to design the next offering in the E.D. range, the iconic 2.46 cc  The design which emerged from Basil Miles’ drawing board during 1952 was in essence neither more nor less than an oversized rendition of the E.D. Racer having a nominal displacement of 5 cc. This displacement was derived from bore and stroke figures of 0.781 in. (19.84 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively. For some unknown reason having no readily-discernable basis in logic, British designers at this time tended to work in fractions of an inch, although they always quoted their displacements in cubic centimetres (cc). Go figure ………..! The Miles Special’s nominal bore and stroke figures were 25/32 in. and 5/8 in. respectively.

The design which emerged from Basil Miles’ drawing board during 1952 was in essence neither more nor less than an oversized rendition of the E.D. Racer having a nominal displacement of 5 cc. This displacement was derived from bore and stroke figures of 0.781 in. (19.84 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively. For some unknown reason having no readily-discernable basis in logic, British designers at this time tended to work in fractions of an inch, although they always quoted their displacements in cubic centimetres (cc). Go figure ………..! The Miles Special’s nominal bore and stroke figures were 25/32 in. and 5/8 in. respectively.  The finished prototypes turned out to be quite useful performers by the standards of their day. In a 1989 conversation with my late and greatly-missed mate David Owen, Basil Miles recalled that on the strength of this positive performance, his next step was to offer the design to E.D. for their manufacture as a new 5 cc E.D. model, presumably under the same terms as those applied to the Racer.

The finished prototypes turned out to be quite useful performers by the standards of their day. In a 1989 conversation with my late and greatly-missed mate David Owen, Basil Miles recalled that on the strength of this positive performance, his next step was to offer the design to E.D. for their manufacture as a new 5 cc E.D. model, presumably under the same terms as those applied to the Racer.  A further sticking point was the fact that 5 cc diesels had acquired a not-undeserved reputation for being somewhat cantankerous and difficult to start. To a fairly large extent, this reputation had arisen from the fact that these large diesels had a tendency to “self-brake” when flicked over due to their very high compression resistance to rotation coupled with the friction developed by their shafts. As a result, they required a very healthy flick and a heavy prop with a pronounced flywheel effect to aid them in carrying over from the initial firing stroke to the next. They were also quite notorious for generating significant levels of vibration during operation.

A further sticking point was the fact that 5 cc diesels had acquired a not-undeserved reputation for being somewhat cantankerous and difficult to start. To a fairly large extent, this reputation had arisen from the fact that these large diesels had a tendency to “self-brake” when flicked over due to their very high compression resistance to rotation coupled with the friction developed by their shafts. As a result, they required a very healthy flick and a heavy prop with a pronounced flywheel effect to aid them in carrying over from the initial firing stroke to the next. They were also quite notorious for generating significant levels of vibration during operation.  The factor that E.D. had apparently overlooked was the extent to which the design of the Miles Special overcame the handling and vibrational difficulties associated not unreasonably with earlier 5 cc diesels. The use of a twin ball-race shaft was an innovation for such a large diesel which did much to overcome the tendency of such large units to “self-brake” during starting, as discussed earlier. In addition, the engine’s significantly over-square bore/stroke ratio of 1.25 to 1 reduced the amount of torque required to carry the engine over from one firing stroke to another during starting. Consequently, the Miles Special was really no more difficult to hand-start than any other diesel. Moreover, the engine’s short stroke coupled with its very light piston, counterbalanced crankweb and considerable overall weight did much to reduce the levels of operational vibration to very manageable levels.

The factor that E.D. had apparently overlooked was the extent to which the design of the Miles Special overcame the handling and vibrational difficulties associated not unreasonably with earlier 5 cc diesels. The use of a twin ball-race shaft was an innovation for such a large diesel which did much to overcome the tendency of such large units to “self-brake” during starting, as discussed earlier. In addition, the engine’s significantly over-square bore/stroke ratio of 1.25 to 1 reduced the amount of torque required to carry the engine over from one firing stroke to another during starting. Consequently, the Miles Special was really no more difficult to hand-start than any other diesel. Moreover, the engine’s short stroke coupled with its very light piston, counterbalanced crankweb and considerable overall weight did much to reduce the levels of operational vibration to very manageable levels.  Basil was probably not too upset by E.D.’s about-face. After all, their marketing outreach extended far beyond his own, tapping into both domestic and overseas markets. It appears that agreement was reached fairly amicably on the production and marketing of the Miles Special, since there were clear advantages for both parties.

Basil was probably not too upset by E.D.’s about-face. After all, their marketing outreach extended far beyond his own, tapping into both domestic and overseas markets. It appears that agreement was reached fairly amicably on the production and marketing of the Miles Special, since there were clear advantages for both parties.  through its inclusion in their advertising and to distribute it through their established national and international networks, although it was to be referred to as the E.D. Miles Special rather than being assigned any other name by the company after their usual practise – no E.D. Mk. V, thank you very much!! It’s clear that Basil Miles wished to ensure that his name remained firmly attached to this engine! Some form of financial arrangement must also have been included, but I have no details of any such arrangement.

through its inclusion in their advertising and to distribute it through their established national and international networks, although it was to be referred to as the E.D. Miles Special rather than being assigned any other name by the company after their usual practise – no E.D. Mk. V, thank you very much!! It’s clear that Basil Miles wished to ensure that his name remained firmly attached to this engine! Some form of financial arrangement must also have been included, but I have no details of any such arrangement.  From the outset, the engine was offered at a price of £8 6s 3d (£8.31) – a very high figure in 1953. A water-cooled marine version with flywheel was also offered at a price of £9 19s 6d (£9.98) – Basil was always first and foremost a boat modeller rather than an aeromodeller. E.D. were able to charge such elevated prices thanks to the very high reputation which Miles’ engines had established for themselves among knowledgeable enthusiasts, none of whom failed to understand that these engines were manufactured primarily by Basil Miles himself rather than E.D., consequently being more or less individually constructed to the very highest model engineering standards. Kevin Richards believed that E.D. became more directly involved with the manufacturing over time, but the Miles Special always remained very much a Basil Miles creation.

From the outset, the engine was offered at a price of £8 6s 3d (£8.31) – a very high figure in 1953. A water-cooled marine version with flywheel was also offered at a price of £9 19s 6d (£9.98) – Basil was always first and foremost a boat modeller rather than an aeromodeller. E.D. were able to charge such elevated prices thanks to the very high reputation which Miles’ engines had established for themselves among knowledgeable enthusiasts, none of whom failed to understand that these engines were manufactured primarily by Basil Miles himself rather than E.D., consequently being more or less individually constructed to the very highest model engineering standards. Kevin Richards believed that E.D. became more directly involved with the manufacturing over time, but the Miles Special always remained very much a Basil Miles creation.  As stated previously, the 5 cc Miles Special was in effect a re-dimensioned and slightly re-styled rendition of the E.D. Racer, with which most readers will be familiar. I already mentioned the engine’s bore and stroke dimensions of 0.781 in. (19.84 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.299 cuin. (4.91 cc) and a considerably over-square bore/stroke ratio of 1.25 to 1. I also drew attention to the engine’s very significant checked weight of no less than 266 gm (9.38 ounces) – a lot of weight for a 5 cc engine.

As stated previously, the 5 cc Miles Special was in effect a re-dimensioned and slightly re-styled rendition of the E.D. Racer, with which most readers will be familiar. I already mentioned the engine’s bore and stroke dimensions of 0.781 in. (19.84 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.299 cuin. (4.91 cc) and a considerably over-square bore/stroke ratio of 1.25 to 1. I also drew attention to the engine’s very significant checked weight of no less than 266 gm (9.38 ounces) – a lot of weight for a 5 cc engine.

The cast iron piston was extensively machined internally to reduce its weight to a minimum, also having its lower skirt radiused fore and aft to provide crank-web and disc valve clearance. It drove the massive one-piece steel crankshaft through a sturdy machined dural conrod. Wedges of material were cut away from the crankpin side of the circular crank-web to provide some counterbalance. The crankshaft’s main journal diameter was 3/8 in., stepping down to ¼ in. at the front. The two supporting ball-races were sized accordingly.

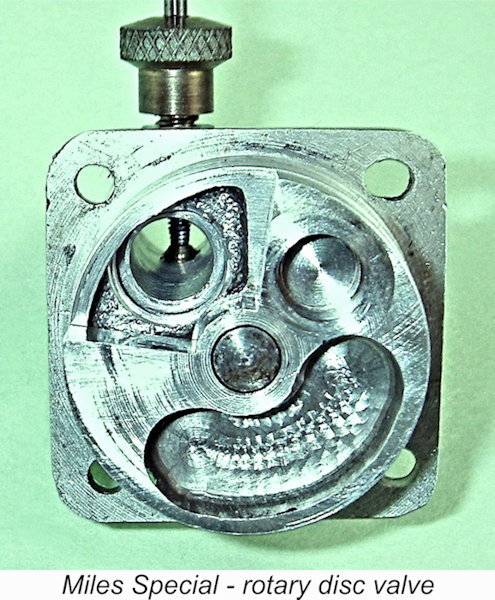

The cast iron piston was extensively machined internally to reduce its weight to a minimum, also having its lower skirt radiused fore and aft to provide crank-web and disc valve clearance. It drove the massive one-piece steel crankshaft through a sturdy machined dural conrod. Wedges of material were cut away from the crankpin side of the circular crank-web to provide some counterbalance. The crankshaft’s main journal diameter was 3/8 in., stepping down to ¼ in. at the front. The two supporting ball-races were sized accordingly.  At the rear, the Miles Special employed a cast and machined backplate, to which an alloy rotary disc was staked. This disc was heavily machined both to lighten and to achieve better balance. It provided a full 180º induction period which was unusually aggressively timed, opening and closing some 60º after Bottom Dead Centre and Top Dead Centre respectively. I would have thought that within the speed range in which this engine might be expected to operate, a somewhat earlier opening and closing would yield superior results………but Basil undoubtedly knew his business and must surely have considered such an option.

At the rear, the Miles Special employed a cast and machined backplate, to which an alloy rotary disc was staked. This disc was heavily machined both to lighten and to achieve better balance. It provided a full 180º induction period which was unusually aggressively timed, opening and closing some 60º after Bottom Dead Centre and Top Dead Centre respectively. I would have thought that within the speed range in which this engine might be expected to operate, a somewhat earlier opening and closing would yield superior results………but Basil undoubtedly knew his business and must surely have considered such an option.  followed typical racing engine practise, with separate fuel delivery and needle carrier components being screwed in from opposite sides of the intake.

followed typical racing engine practise, with separate fuel delivery and needle carrier components being screwed in from opposite sides of the intake.

Consequently, the original production version of the Miles Special, which might properly be called the Mk. I variant, is a relatively elusive engine today – one to grab if you get the chance. But its successor appears to be even more elusive. This is the Mk. II version of the Miles Special, which seems to have appeared in early 1956. Like its predecessor, it was offered in both aero and marine versions, also being available directly from Basil Miles in glow-plug configuration as illustrated here. A number of the latter units were sold in glow-plug form but accompanied by the components necessary to convert the engine to diesel configuration if desired. The late David Owen’s illustrated engine number 16–5/56 from May 1956 is such an example.

Consequently, the original production version of the Miles Special, which might properly be called the Mk. I variant, is a relatively elusive engine today – one to grab if you get the chance. But its successor appears to be even more elusive. This is the Mk. II version of the Miles Special, which seems to have appeared in early 1956. Like its predecessor, it was offered in both aero and marine versions, also being available directly from Basil Miles in glow-plug configuration as illustrated here. A number of the latter units were sold in glow-plug form but accompanied by the components necessary to convert the engine to diesel configuration if desired. The late David Owen’s illustrated engine number 16–5/56 from May 1956 is such an example.  Oddly enough, despite the replacement of the original Miles Special with this new variant, E.D.’s advertising continued to depict the 1952 prototype model which had been featured all along. It was not until mid-1958 that the advertising image was finally amended to reflect the new version of the engine.

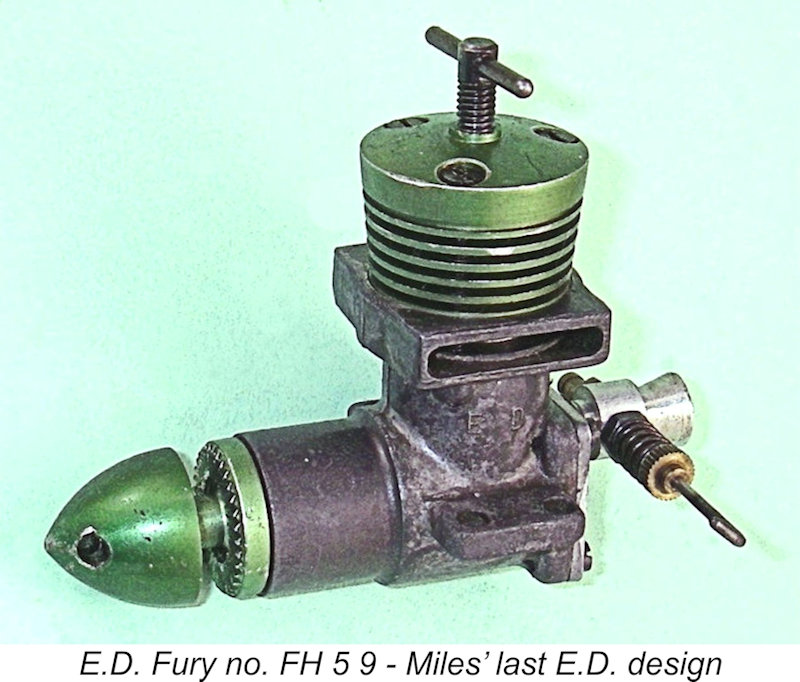

Oddly enough, despite the replacement of the original Miles Special with this new variant, E.D.’s advertising continued to depict the 1952 prototype model which had been featured all along. It was not until mid-1958 that the advertising image was finally amended to reflect the new version of the engine.  To summarize, the 5 cc Miles Special was conceived in 1952, joined the E.D. model engine range in early 1953, was replaced by a Mk. II twin-stack version in early 1956 and remained on E.D.’s books in that form until December 1958. However, for reasons which are now obscured by the mists of legend and are probably best forgotten if rumors be true, E.D.’s relationship with Miles came to an end during 1958 – his last design for E.D. was the reed-valve Fury of March 1958.

To summarize, the 5 cc Miles Special was conceived in 1952, joined the E.D. model engine range in early 1953, was replaced by a Mk. II twin-stack version in early 1956 and remained on E.D.’s books in that form until December 1958. However, for reasons which are now obscured by the mists of legend and are probably best forgotten if rumors be true, E.D.’s relationship with Miles came to an end during 1958 – his last design for E.D. was the reed-valve Fury of March 1958.  The 5 cc Miles Special was the subject of two published tests in the contemporary modelling media. The first of these was Ron Warring’s test of the

The 5 cc Miles Special was the subject of two published tests in the contemporary modelling media. The first of these was Ron Warring’s test of the

had been expecting the engine to reveal itself as a “dangerous brute” like some other large glow-plug motors, but was pleasantly surprised to find that the Miles Special in glow-plug form “quite failed to live up to any such notoriety”. He actually stated that the engine had proved to be “one of the easiest-starting of any size of engine we have encountered”. He was apparently able to hand-start the engine on a 7x4 propeller!

had been expecting the engine to reveal itself as a “dangerous brute” like some other large glow-plug motors, but was pleasantly surprised to find that the Miles Special in glow-plug form “quite failed to live up to any such notoriety”. He actually stated that the engine had proved to be “one of the easiest-starting of any size of engine we have encountered”. He was apparently able to hand-start the engine on a 7x4 propeller!  Neither version of the Miles Special is commonly encountered these days. The twin-stack Mk. II variant seems to be particularly elusive - I’ve never been lucky enough to encounter one in the metal myself. However, over the years I have somehow acquired the two very nice examples of the Mk. I version which have appeared in a number of the images which accompany this article.

Neither version of the Miles Special is commonly encountered these days. The twin-stack Mk. II variant seems to be particularly elusive - I’ve never been lucky enough to encounter one in the metal myself. However, over the years I have somehow acquired the two very nice examples of the Mk. I version which have appeared in a number of the images which accompany this article.

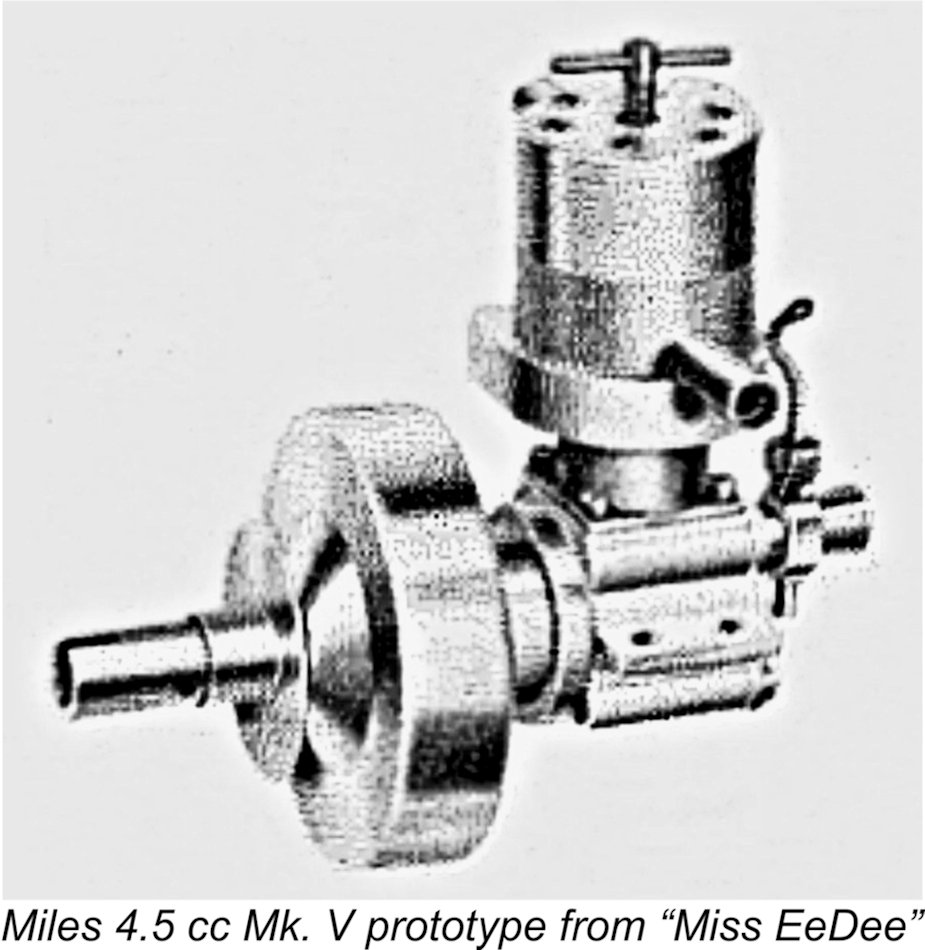

The Miles Special 5 cc diesel may have been Basil Miles’ best-known production thanks to its inclusion in E.D.’s marketing efforts, but it was very far from being the only model that he produced during the 1950’s. Among his notable yet less heralded achievements was the design and construction of the 4.5 cc marine diesel which powered the 5ft. 2 in. long “Miss EeDee” model motor launch to the first-ever crossing of the English Channel by a model boat, an accomplishment which took place on September 6

The Miles Special 5 cc diesel may have been Basil Miles’ best-known production thanks to its inclusion in E.D.’s marketing efforts, but it was very far from being the only model that he produced during the 1950’s. Among his notable yet less heralded achievements was the design and construction of the 4.5 cc marine diesel which powered the 5ft. 2 in. long “Miss EeDee” model motor launch to the first-ever crossing of the English Channel by a model boat, an accomplishment which took place on September 6 Miles was always far more of a model boat enthusiast than he was a participant in the aeromodelling field. I noted that the 5 cc Miles Special glow-plug model saw service in tethered hydroplane racing, while both diesel and glow-plug models were also offered in water-cooled marine versions which apparently drew their share of market attention.

Miles was always far more of a model boat enthusiast than he was a participant in the aeromodelling field. I noted that the 5 cc Miles Special glow-plug model saw service in tethered hydroplane racing, while both diesel and glow-plug models were also offered in water-cooled marine versions which apparently drew their share of market attention.

After putting up with this for a few months, the “Model Aircraft” Editor closed this correspondence, but not before asking the magazine’s resident model engine commentator Peter Chinn to summarize the controversy in a measured and rational way. Chinn responded to this request in an article entitled “Peter Chinn Sums Up the 35 Controversy” which appeared in the May 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

After putting up with this for a few months, the “Model Aircraft” Editor closed this correspondence, but not before asking the magazine’s resident model engine commentator Peter Chinn to summarize the controversy in a measured and rational way. Chinn responded to this request in an article entitled “Peter Chinn Sums Up the 35 Controversy” which appeared in the May 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”.  After indulging in a little speculation regarding design approaches which might bring Britain’s only then-current American-style glow-plug motor, the venerable

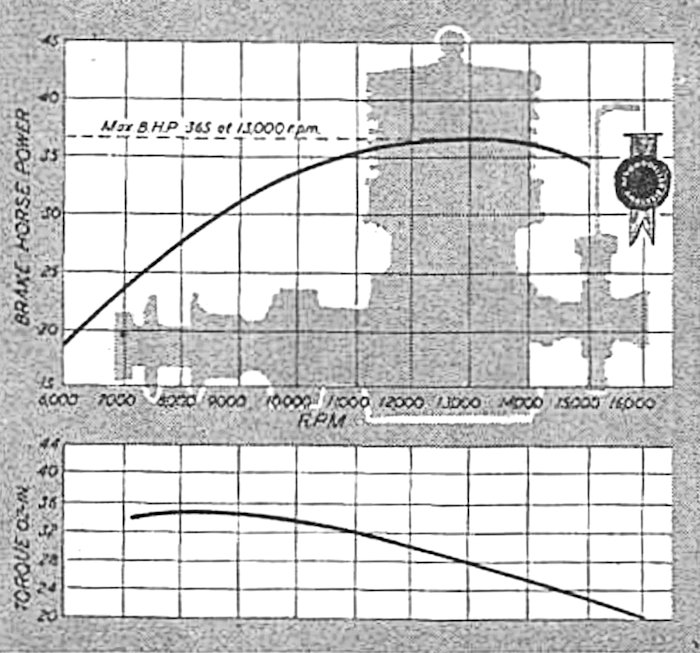

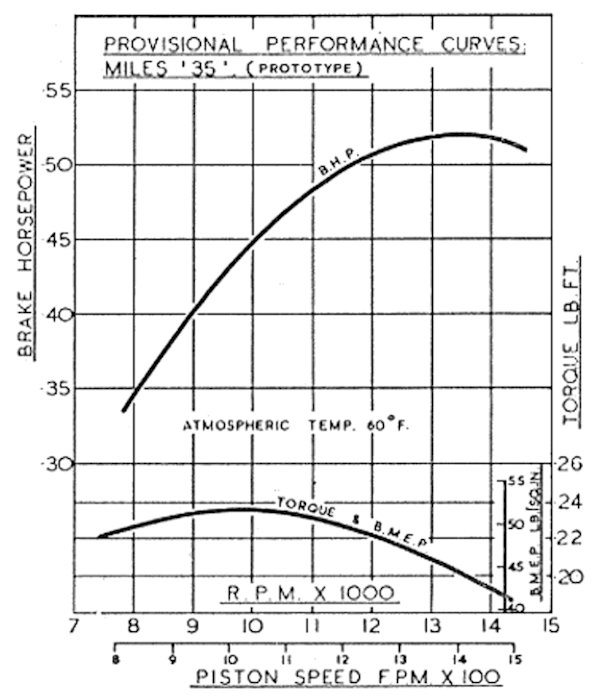

After indulging in a little speculation regarding design approaches which might bring Britain’s only then-current American-style glow-plug motor, the venerable  The rest of the article amounted to a detailed description and test of the simplified prototype Miles 35. Running on a fuel containing 25% nitromethane, Chinn reported a peak output of 0.52 BHP @ 13,500 RPM, as reflected in his power curves which are reproduced here. He found that “starting characteristics were good and running qualities were smooth and consistent”. The engine reportedly turned a 10x6 prop (a typical airscrew used with a 35 glow motor for stunt) at a steady 11,000 RPM. The reader may recall that my test example of the 5 cc Miles Special diesel only managed 10,600 RPM on a prop of that size.

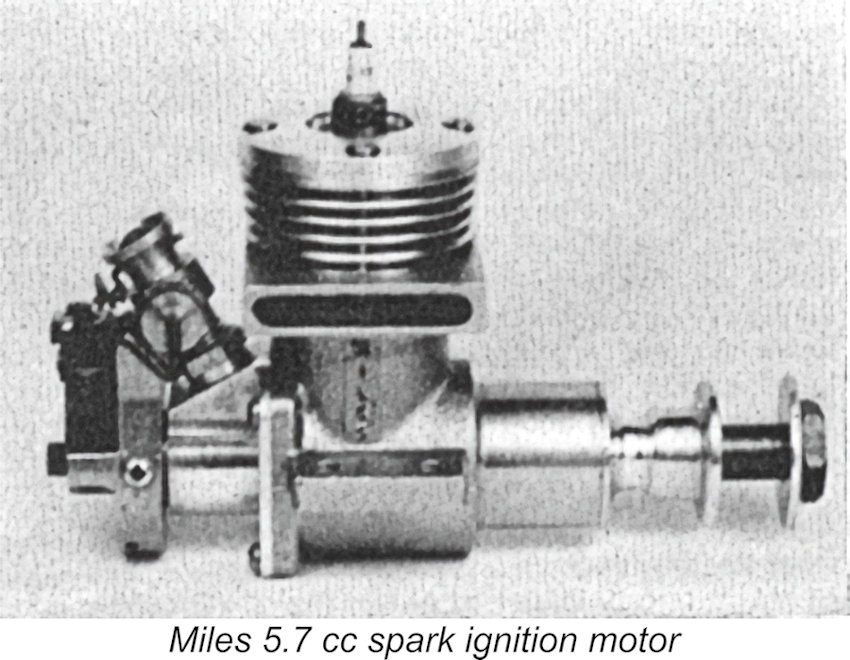

The rest of the article amounted to a detailed description and test of the simplified prototype Miles 35. Running on a fuel containing 25% nitromethane, Chinn reported a peak output of 0.52 BHP @ 13,500 RPM, as reflected in his power curves which are reproduced here. He found that “starting characteristics were good and running qualities were smooth and consistent”. The engine reportedly turned a 10x6 prop (a typical airscrew used with a 35 glow motor for stunt) at a steady 11,000 RPM. The reader may recall that my test example of the 5 cc Miles Special diesel only managed 10,600 RPM on a prop of that size.  Despite the lukewarm reception accorded to his simplified 35 glow-plug model, Miles did go so far as to produce a 5.7 cc R/C spark ignition motor based on his original twin ball-race 35 prototype but featuring rear drum valve induction using components from his simplified FRV model. The development of this unit had been mentioned in Chinn’s articles in the April and June 1957 issues of “Model Aircraft” and it had been put into limited production later that year. Chinn provided a description of this interesting design in his “Accent on British Motors” article which appeared in the magazine’s November 1957 issue. A fascinating feature of this model was the synchronization of the throttle with the timer to cause the timing to be retarded at lower throttle openings, providing an ultra-slow and dead reliable tick-over.

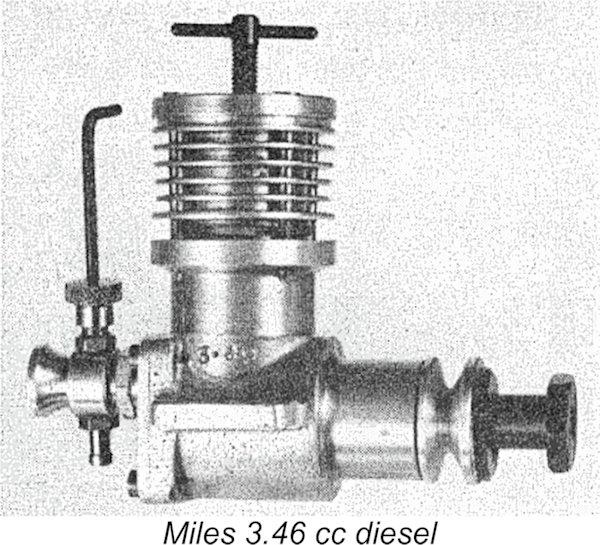

Despite the lukewarm reception accorded to his simplified 35 glow-plug model, Miles did go so far as to produce a 5.7 cc R/C spark ignition motor based on his original twin ball-race 35 prototype but featuring rear drum valve induction using components from his simplified FRV model. The development of this unit had been mentioned in Chinn’s articles in the April and June 1957 issues of “Model Aircraft” and it had been put into limited production later that year. Chinn provided a description of this interesting design in his “Accent on British Motors” article which appeared in the magazine’s November 1957 issue. A fascinating feature of this model was the synchronization of the throttle with the timer to cause the timing to be retarded at lower throttle openings, providing an ultra-slow and dead reliable tick-over.  Miles returned to diesel development in 1958, producing a short series of 3.46 cc diesels which were in effect up-sized versions of his iconic E.D. Racer design. According to the “Motor Mart” article in the August 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller”, most of these went into the hands of the contemporary control line combat crowd, since S.M.A.E. rules at the time permitted 3.5 cc engines in this category. The engine was claimed to be a very strong performer. Miles also produced a few glow-plug examples of the same 3.46 cc design. Peter Chinn described this latter model in some detail in his “Latest Engine News” feature which was published in the November 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”.

Miles returned to diesel development in 1958, producing a short series of 3.46 cc diesels which were in effect up-sized versions of his iconic E.D. Racer design. According to the “Motor Mart” article in the August 1958 issue of “Aeromodeller”, most of these went into the hands of the contemporary control line combat crowd, since S.M.A.E. rules at the time permitted 3.5 cc engines in this category. The engine was claimed to be a very strong performer. Miles also produced a few glow-plug examples of the same 3.46 cc design. Peter Chinn described this latter model in some detail in his “Latest Engine News” feature which was published in the November 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”.  While all this was going on, Miles also started work on a proposed 0.75 cc E.D. diesel, going so far as to produced at least one prototype. However, the 1958 termination of Miles' relationship with E.D. put an end to this initiative. E.D. eventually entered the under-1cc diesel arena with their

While all this was going on, Miles also started work on a proposed 0.75 cc E.D. diesel, going so far as to produced at least one prototype. However, the 1958 termination of Miles' relationship with E.D. put an end to this initiative. E.D. eventually entered the under-1cc diesel arena with their  Basil Miles may have been an early exponent of the use of twin ball-races and short strokes to overcome many of the handling difficulties associated with the operation of large diesels, but he certainly wasn't the only model engine designer to follow this path. He had actually been preceded by the American designer Leon Shulman, who added a single ball-race to the rear of the crankshaft in the famous 1948

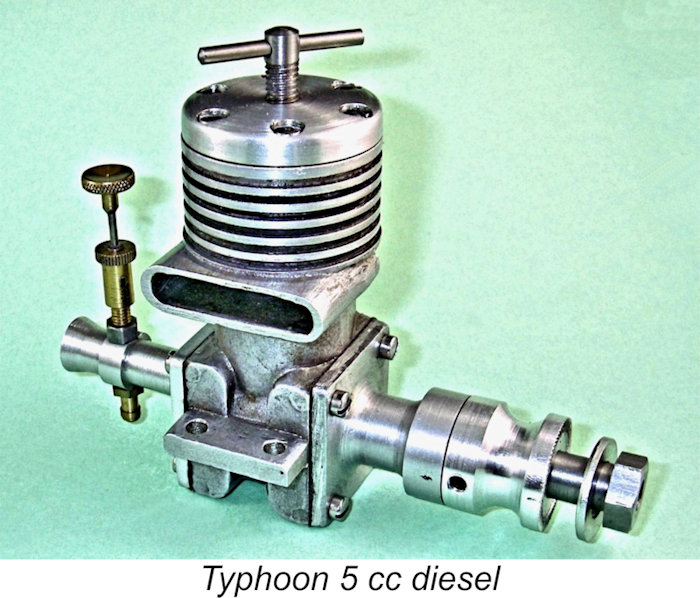

Basil Miles may have been an early exponent of the use of twin ball-races and short strokes to overcome many of the handling difficulties associated with the operation of large diesels, but he certainly wasn't the only model engine designer to follow this path. He had actually been preceded by the American designer Leon Shulman, who added a single ball-race to the rear of the crankshaft in the famous 1948  Jan G. Veenhoven of Amsterdam was the manufacturer of the Dutch Typhoon range, which first appeared in 1947. While Basil Miles was designing the Miles Special in 1952, Jan Veenhoven was in the process of designing a 5 cc twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) racing glow-plug engine called the Typhoon Mk. 4 “R” model. As in the Maraget-Météore, bore and stroke of this unit were 19 mm and 17 mm respectively for a displacement of 4.82 cc. The engine was a solid performer which was very well made, but it couldn't match the best 5 cc performers of its era such as the

Jan G. Veenhoven of Amsterdam was the manufacturer of the Dutch Typhoon range, which first appeared in 1947. While Basil Miles was designing the Miles Special in 1952, Jan Veenhoven was in the process of designing a 5 cc twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) racing glow-plug engine called the Typhoon Mk. 4 “R” model. As in the Maraget-Météore, bore and stroke of this unit were 19 mm and 17 mm respectively for a displacement of 4.82 cc. The engine was a solid performer which was very well made, but it couldn't match the best 5 cc performers of its era such as the

diesels, although he had other very considerable claims to fame in addition. In the late 1950's, Górski initiated production of a 5 cc diesel which was in effect a scaled-up version of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka engines which he had been producing for some time. The 5 cc units were given the series identification “Sokól” (Kestrel) to distinguish them from their smaller Jaskółka (Swallow) relatives.

diesels, although he had other very considerable claims to fame in addition. In the late 1950's, Górski initiated production of a 5 cc diesel which was in effect a scaled-up version of the 2.5 cc Jaskółka engines which he had been producing for some time. The 5 cc units were given the series identification “Sokól” (Kestrel) to distinguish them from their smaller Jaskółka (Swallow) relatives.

The above summary includes all of the 5 cc ball-race diesels of which I'm aware which had their origins in the "classic" era to which the Miles Special belongs. Other diesels of 5 cc or even greater displacements were to appear later from various manufacturers. In 1983 the renowned

The above summary includes all of the 5 cc ball-race diesels of which I'm aware which had their origins in the "classic" era to which the Miles Special belongs. Other diesels of 5 cc or even greater displacements were to appear later from various manufacturers. In 1983 the renowned  During the same period, the Russian makers of the

During the same period, the Russian makers of the