|

|

Czech Classics - the Atom Diesels

The Atom series became quite well-known in its day, even outside Czechoslovakia. Since the engines were made in considerable quantities, original examples still turn up on occasion, while the general excellence of the Atom design has led to its being replicated in substantial numbers as well. Consequently, there are a good few original and replica examples floating around whose owners would doubtless appreciate knowing more about them. This article represents my attempt to fill that need.

Chief among these are “Modelářské Motory” (Model Engines) by Jiří Kalina, published in 1980, and the more recent “Ĉeské Modelářské Motory” (Czech Model Engines) by Jiří Linka and Jan Kafka, published in 2004. The earlier book by Kalina covers engines of all types from many parts of the world, not only Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic (which did not exist when the book was published), while the work by Linka and Kafka focuses strictly upon Czech products, again of all types. Kalina’s book includes a considerable amount of descriptive text, while that of Linka and Kafka consists mainly of photographs and scans of advertisements. Taken together, these two publications constitute a fairly detailed record of my main subject. I freely acknowledge my immense debt to the authors, without whose efforts I would remain in near-total ignorance of the subject model engine range. This article is as much their work as mine - I’ve merely translated and re-organized their material a little to render it more accessible to English-speaking readers, also adding my own personal observations where appropriate. It’s a widely under-appreciated fact that Czech enthusiasts were very early in the field of model diesel development and manufacture. I’ll begin by setting the stage for the appearance of the Atom series. Background

One such individual was Antonín Půrok, who made very small numbers of individually-produced engines during this period. Půrok had been involved with aeromodelling during the mid-1930's, becoming well-known for making high-quality airscrews for rubber-powered models. As the decade drew on, he had increasingly gravitated to full-sized slope soaring (gliding). Being "grounded" following the German take-over, he reverted to aeromodelling as a compensatory activity. To support himself, Půrok worked in Prague at the automobile plant of a major Czech heavy engineering company called Praga, which operated multiple plants in the area. This company had been established in 1907 to manufacture automobiles, but expanded over time to include trucks, busses, trolley-busses, motorcycles, light tanks, artillery tractors and aircraft. The sprawling automobile plant at which Půrok worked was called Pragovka. It was located on the eastern outskirts of Prague.

The Praga company continued in operation following the German occupation and partitioning of Czechoslovakia which began on March 15th, 1939, some 6 months prior to the actual declared outbreak of WW2. At this point, Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. The area in which Prague was located became the German puppet state of Bohemia and Moravia. It quickly became a major producer of military materiel for the Nazi regime. The Praga company was a participant in this activity. The facilities at the Pragovka automobile factory were re-directed towards aircraft production at this time, while the company’s primary focus switched to the production of a light tank, the Panzerkampfwagen 38(t), which saw service in the Wehrmacht invasions of Poland, France and Russia. Over 1,400 examples were manufactured, along with numerous examples of the Praga T-9 artillery tractor. During this period, the manufacture of products such as model engines was illegal, since it was viewed as a waste of scarce materials, particularly light alloys, which were required for war-related production. Despite this ban, Půrok's pre-war associate Gustav Bušek remained engaged in making small numbers of spark ignition engines of his own design. Following his grounding from full-sized slope soaring, Půrok returned to aeromodelling as a substitute activity. Since rubber of suitable quality was no longer available, the only alternative to gliders was the use of I/C power.

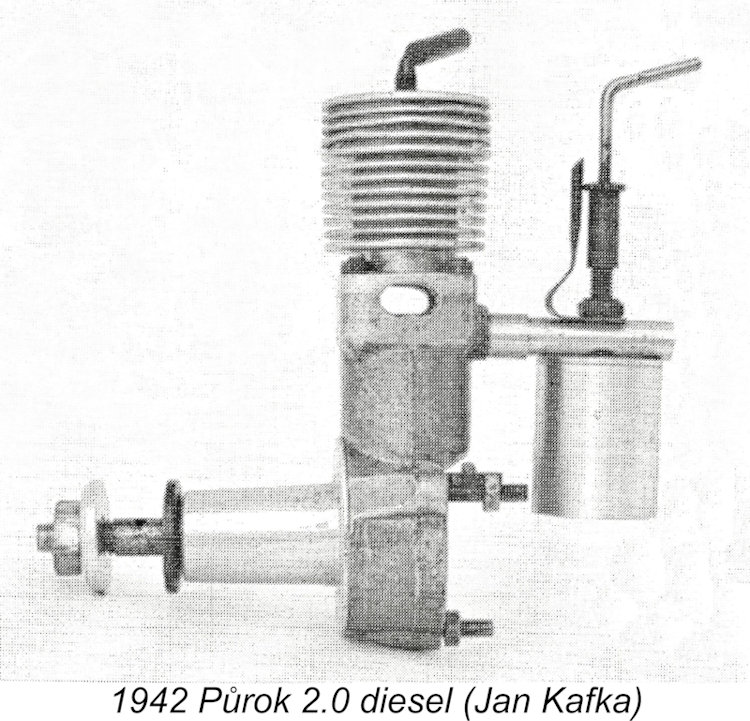

We’ll never know how it came about, but in late 1941 Antonín Půrok somehow acquired a copy of a promotional brochure describing the Swiss Dyno 1 diesel which had entered production in mid-1941. Using the descriptive material in this brochure as his sole guide, Půrok constructed a prototype of his own 2 cc diesel engine in late 1941. Půrok’s model engine construction activities were presumably conducted “on the side” using his employer's machine tooling along with materials "diverted" from their intended use. A measure of tolerance or "diplomatic blindness" on the part of management is implied here. It’s likely that much of the hand-filing, fitting and assembly of the engines was carried out after hours at home, but a certain amount of machining had to be carried out. According to Jiří Kalina, Půrok's initial effort was not a success. However, in the meantime Gustav Bušek had somehow gained access to a Dyno 1 diesel. After studying this engine in the metal, Půrok made some changes to his design, most notably by adding a second exhaust port and perhaps by re-fitting to closer tolerances. In this revised form, the engine apparently ran well. This seems to have been the first successful model diesel engine to appear in Czechoslovakia, and indeed one of the first such models anywhere. As far as I can tell, it was preceded only by the Swiss ETHA and Dyno models. It predated the earliest English commercial products by almost 5 years!

The illustrated engine is an example of this, being quite recognizably a variant of the original Půrok design. There has been some speculation that it may be an experimental variant constructed by Bušek - the placement of the split between the crankcase and upper cylinder is characteristic of his early work. A brief bench test of my own illustrated example showed that it was an easy starter and a smooth runner, albeit a little lacking in power by later standards. It's clear from all of this that there must have been an active aeromodelling community in Czechoslovakia at the time despite the German occupation. During this period, the Nazi authorities were still seemingly trying quite hard to engender a degree of acceptance of their dominating presence among the Czech people, apparently with some success. Tolerance of aeromodelling would have been a natural manifestation of such a policy.

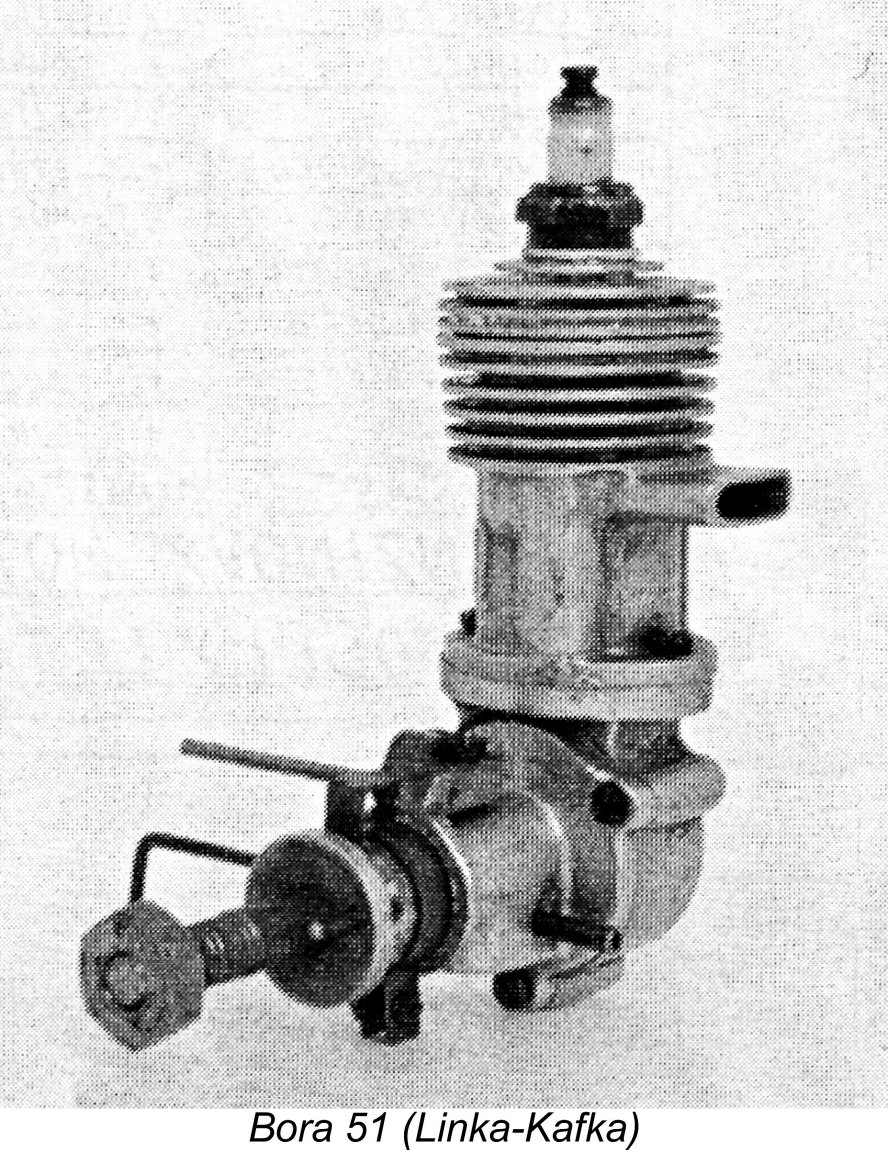

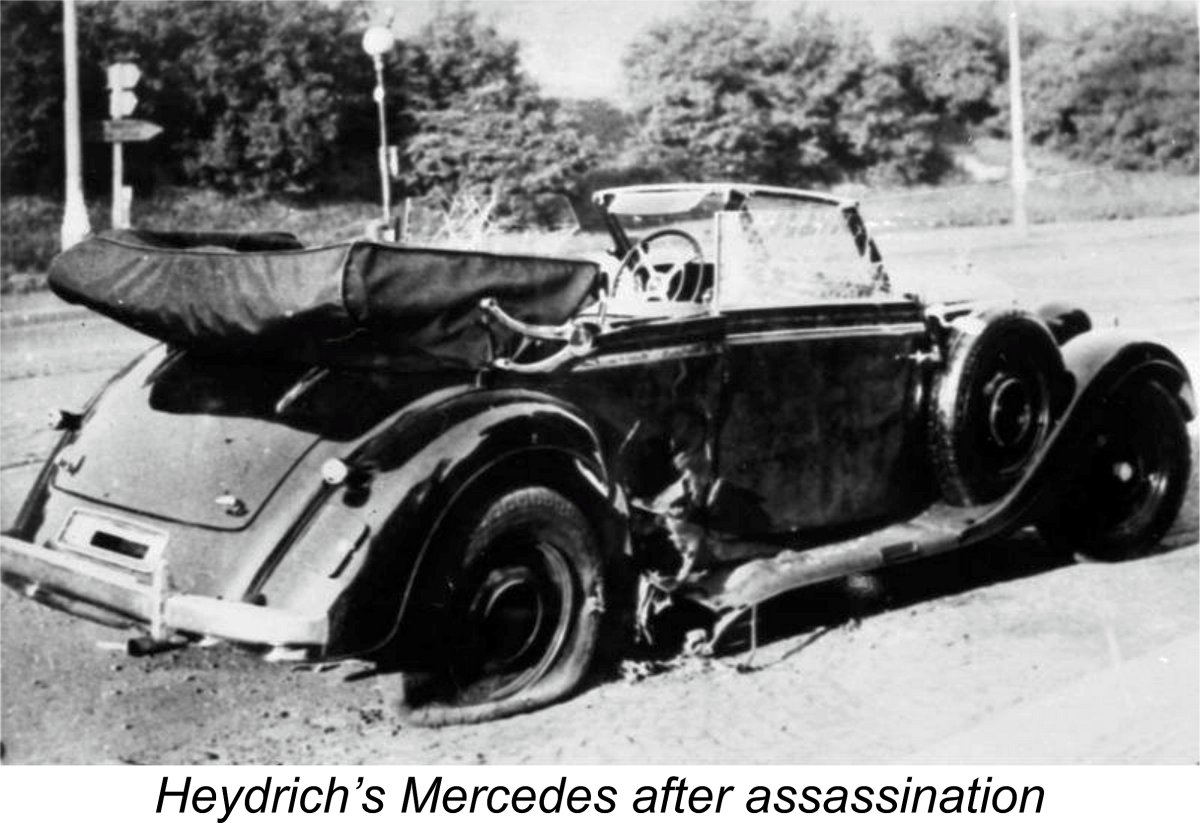

It was at around the same time that the man who was destined to develop the Atom series first appeared as a model engine designer and manufacturer. This was Vladislav Hruška, also of Prague. In the past, his first name has often been incorrectly rendered as Vladimir, but Kalina sets us straight on this matter. In 1942, in partnership with another individual named J. Choc, Hruška commenced production of a 5.1 cc spark ignition engine. This was known as the Bora 51. Unusually for the time, it was an over-square design featuring bore and stroke measurements of 19 mm and 18 mm respectively for an actual displacement of 5.1 cc (0.311 cuin.). It also looked ahead in design terms by incorporating crankshaft front rotary valve induction. Bare weight was 150 gm (5.29 ounces). Hruška and Choc must have somehow gained official sanction for this production, because it was apparently sold quite openly through the M. K. Moučka model shop in Prague both as a complete unit and as a set of plans and castings for home construction. However, this situation was not destined to last! In September 1941 the country had come under the sway of SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, aka the "Butcher of Prague", the "Blond Beast" and "Hangman Heydrich". By this time the Nazi hierarchy had decided that the soft-pedal approach to German domination of the Czech people was not working. After Heydrich had served as the primary architect of the infamous Nazi “Final Solution”, Adolf Hitler had appointed him to the post of Deputy Reich-Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, with a brief to apply a firmer hand. Despite the brutal methods used by Heydrich in fulfilling his mandate, the Allies had become concerned that the Germans were still having some success in bringing the Czech population at large to an acceptance of the Nazi regime, even including a certain level of support. It was to counter this trend that a group of nine Czech partisans trained in Scotland were parachuted into the country on December 28th, 1941 with the objective of mounting an assassination attempt. On May 27th, 1942, as Heydrich drove an established route in an open car to his Prague offices, he was attacked by members of the partisan group. The attack ultimately proved to be successful - Heydrich was wounded and died on June 4th from blood poisoning brought on by fragments of auto upholstery, steel shrapnel and his own uniform that had lodged in his spleen. Retaliation was predictably swift and characteristically extreme - among other things, the village of Lidice and its completely innocent residents alike ceased to exist. Tolerance of sidelines like Půrok’s and Bušek’s model engine production would seem to have been another casualty. Following his release from prison in November 1942, Půrok returned to work at the Pragovka factory but didn't resume model engine manufacture, instead wisely maintaining a very low profile for the rest of the war.

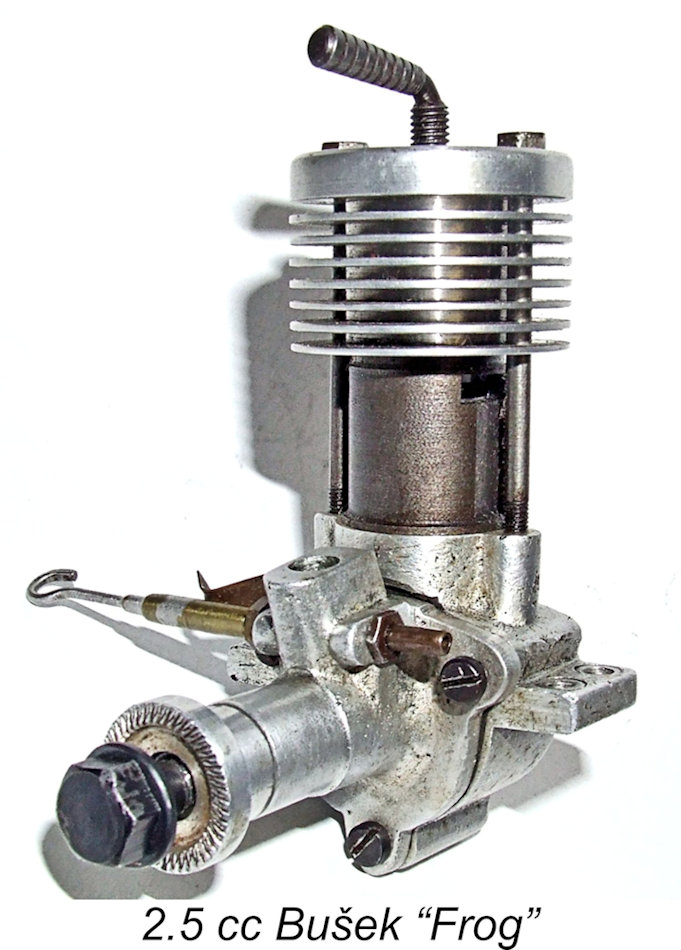

Gustav Bušek seems to have avoided any reprisals arising from his own model engine manufacturing activities. He evidently kept his head down during the fall-out from the Heydrich assassination, although he did satisfy himself regarding the efficacy of his original Dyno 1 engine, eventually making a close copy of his own. He demonstrated this engine in 1943, subsequently managing to produce a small series in time for the 1944 season, after which he developed a front rotary valve (FRV) design of his own. The latter design ended up being produced in quantity after the war in various displacements under the nickname "Frog". At the conclusion of WW2, Půrok made a small series of some 20 engines. Since he did not insist on having his name attached to these units, most of them were advertised and sold under the name "Uran" (in English, Uranium) by the well-known M. K. Moučka model shop of Vinohrady in Prague, as seen in the attached advertising After producing this short series of engines for Moučka, Půrok returned to full-size slope soaring, ending his involvement with model engines. By contrast, Bušek carried on to become one of the most prolific model engine manufacturers in post-war Czechoslovakia. As manufacturer of the Buš series of engines, Jiří Kalina rightly rated him as a "legendary" Czech engine designer. As stated earlier, Hruška and Choc never resumed production of their original Bora 51 spark ignition model after the war. The reason for this abandonment was that by 1945 their attention had been drawn away from spark ignition motors towards the emerging technology of compression ignition, the efficacy of which had been demonstrated very clearly by Půrok and Bušek. As soon as circumstances permitted, they set to work to create the first member of our main subject series - the original Atom 1.8 cc diesel of late 1945. From this point onwards, I’ll focus entirely upon that series. The Early Atoms

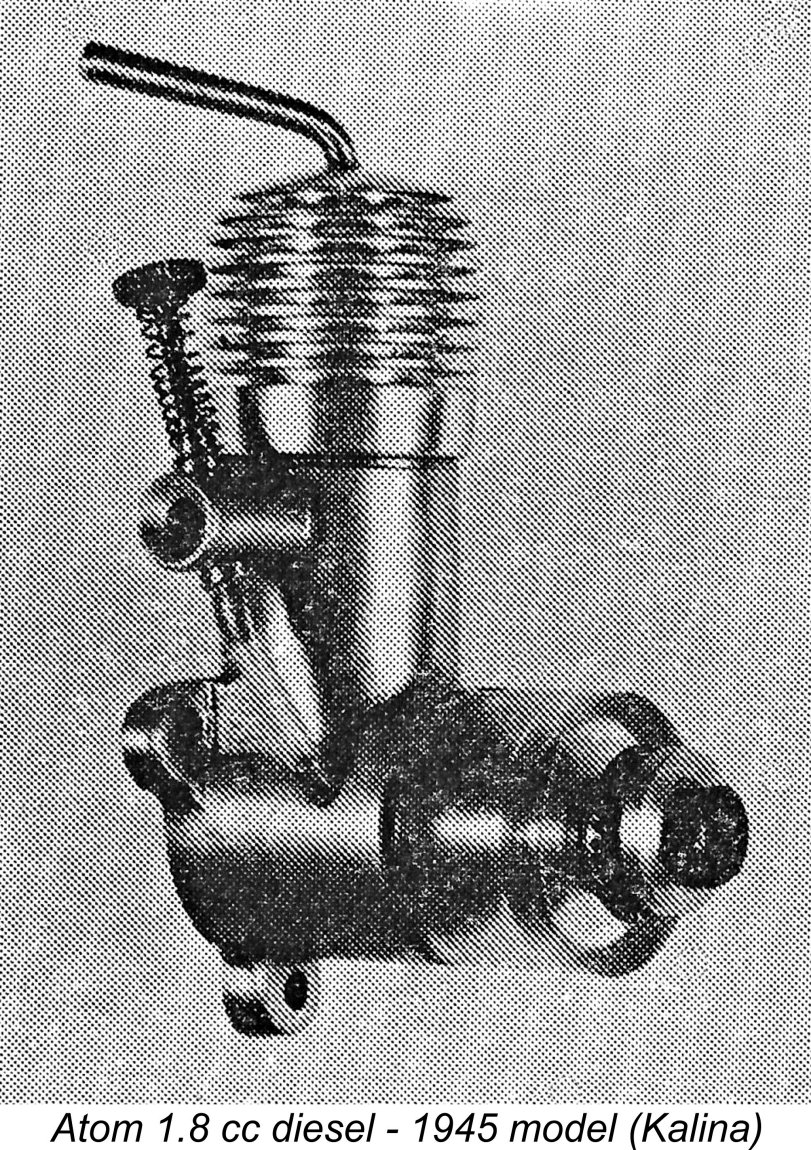

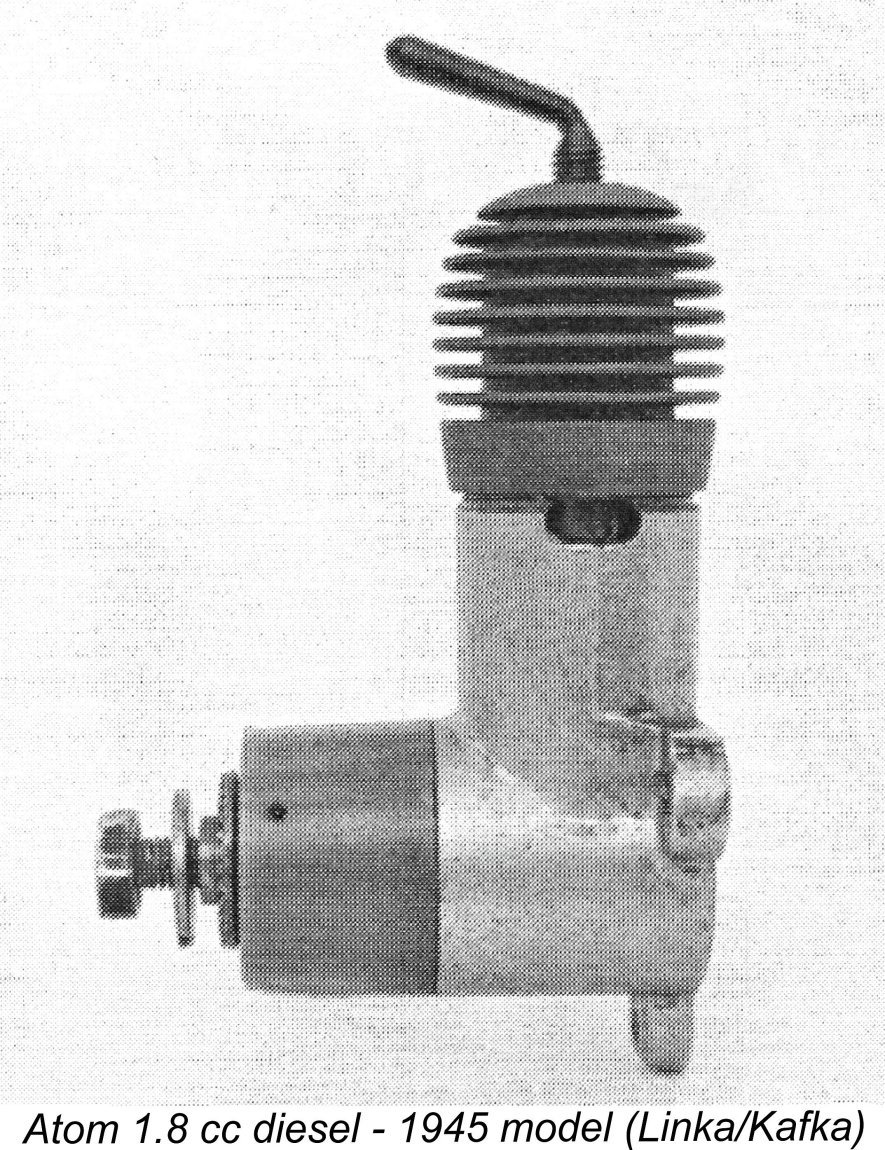

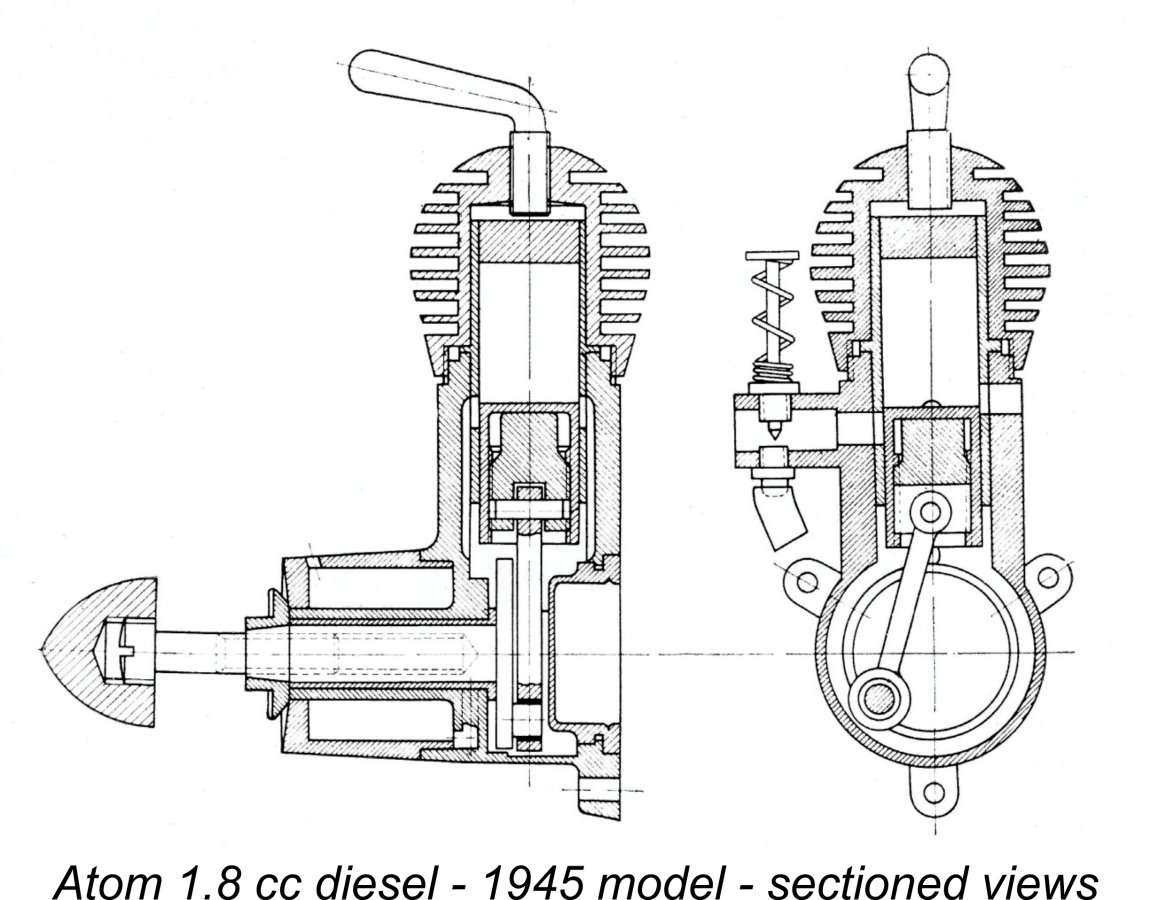

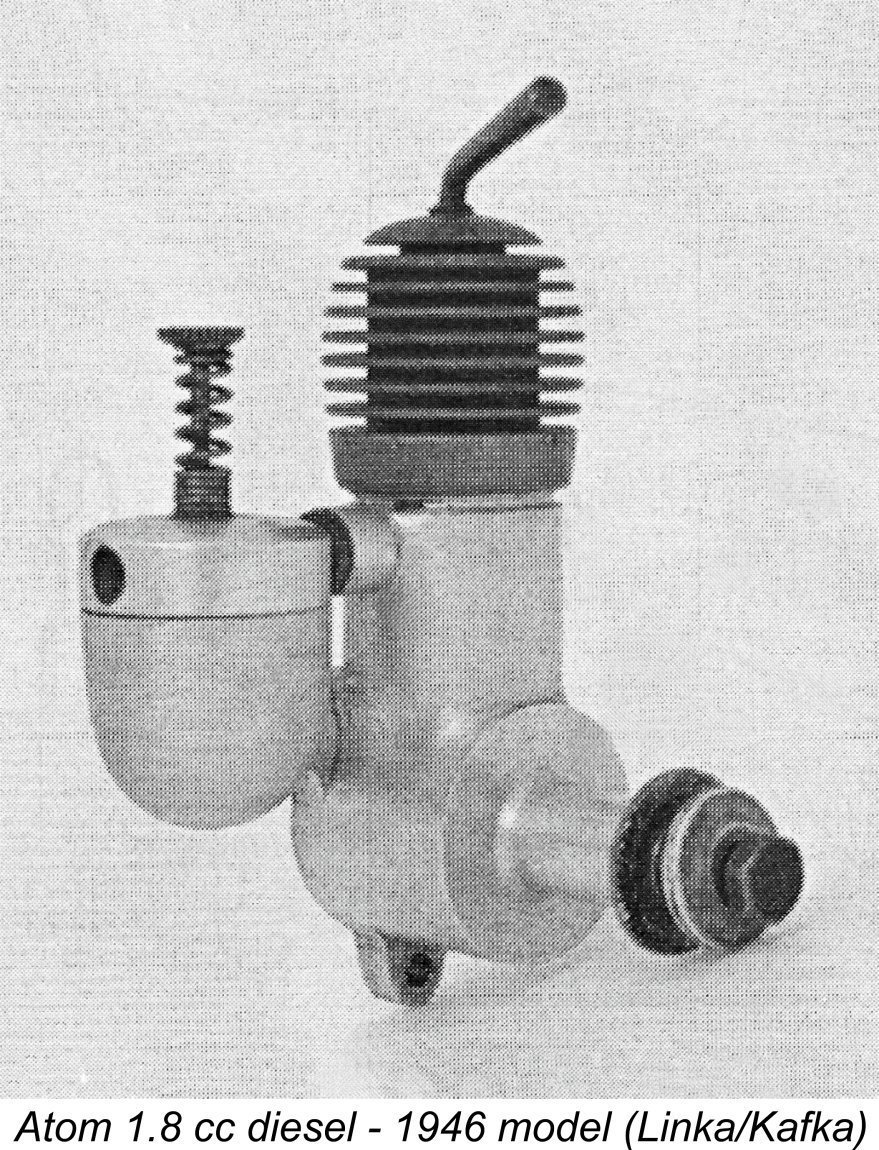

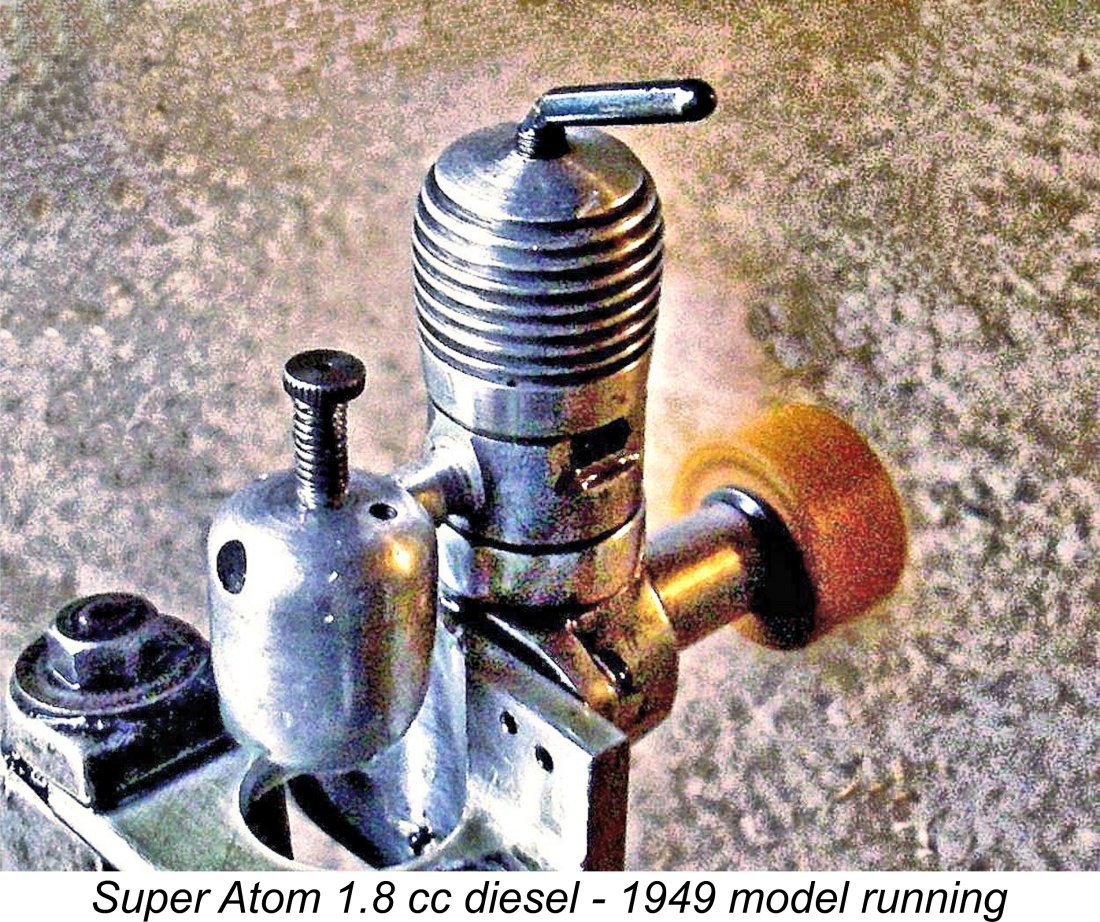

The speedy appearance of the Atom in production form so soon after the conclusion of the war implies that Hruška must have begun working on its design prior to the end of the conflict. The speed at which the two partners managed to establish production facilities and produce the required castings and tooling is a very impressive reflection of their enthusiasm and determination. Remember, this was still 6-8 months prior to the appearance of the first British production diesels! In basic design terms, the Atom was a fairly typical sideport model diesel engine of its day. It was a long-stroke design having bore and stroke dimensions of 12 mm and 16 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 1.81 cc (0.110 cuin.). It weighed 110 gm (3.88 ounces). It was arranged for three-point radial mounting through the provision of three sturdy protruding “mouse ear” lugs at the rear of the crankcase.

The engine used a cast iron cylinder liner. This was retained by a screw-on cooling jacket which engaged with threads cut around the top of the main casting above the exhaust ducts. On the original Atom models, this jacket was made from magnesium alloy. Unusually by British standards, the contra-piston was aluminium alloy, a material which was more or less guaranteed to freeze in the bore when the engine was hot thanks to its greater coefficient of thermal expansion. This tendency also gave rise to a considerable potential for splitting the cast iron liner, since cast iron is relatively weak in tension. Not the best choice of materials, but it did simplify construction while also reducing weight a little.

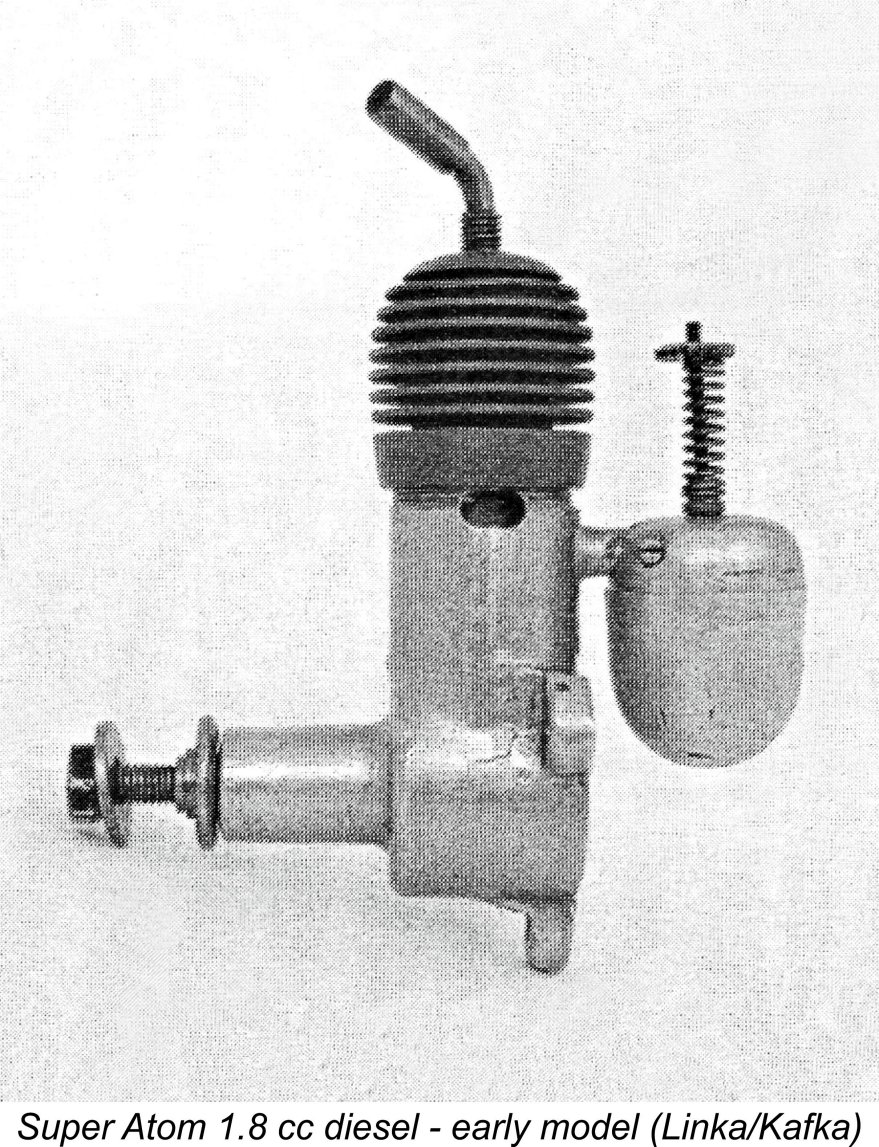

The piston was a composite affair having a hardened steel working shell and a separate alloy gudgeon (wrist) pin carrier which was secured on an internal thread cut into the The piston drove the unhardened silver steel crankshaft through a steel connecting rod having a bronze bushing at the big end. The shaft was also mounted in a bronze bushing. It appears that the front-mounted wrap-around fuel tank was not a great success. Reportedly it was prone to deterioration and eventual failure, requiring fairly regular replacement. Recognizing the undesirability of perpetuating such a situation, the manufacturers soon re-designed the fuel supply arrangements by replacing the former plastic front-mounted tank with the very elegant turned aluminium alloy “egg shaped” metal tank with which these engines became identified. This variant seems to have appeared in the first half of 1946. Initially the new tank was positioned at the side despite the fact that this was a rather awkward arrangement from a mounting point of view, also clearly exposing both tank and intake tube to damage in the event of a crash. However, it’s likely that the manufacturers had stocks of the original side-intake castings on hand and wished to use them up. Once the supply of the original castings was exhausted at some point during 1946, a further change was made to a conventional rear-mounted intake and tank. The resulting revised model was designated the Super Atom. The Super Atom

The neat egg-shaped tank incorporated the induction passage in its top section. This imparted a very elegant look to the whole assembly. The needle valve was a very intelligent design, utilizing a fuel jet which extended into the centre of the venturi throat where gas velocities and hence suction would be at their maximum while offering minimal resistance to airflow. The externally-threaded needle was tensioned by a coil spring. The material of the screw-on cooling jacket was also soon changed from magnesium alloy to aluminium alloy, although a few early examples of the Super Atom retained the magnesium alloy jackets, presumably once again to use up left-over components on hand. The conrod material was also changed from steel to aluminium alloy at some point. Kalina rightly observes that the Super Atom was arguably the most elegant-looking model diesel engine then being manufactured anywhere in the world. Contrast it with the E.D. Mk. II which appeared almost a year later……… In addition to being a good looker, the Super Atom was also a more than capable performer by 1946 standards. The manufacturers claimed that the engine would turn a The series production of the Super Atom and its consequent widespread availability had a profound influence upon the development of free-flight power modelling in Czechoslovakia. Up to the time of its appearance, the free flight power models of the day had typically been large-wingspan designs powered by relatively large spark ignition engines (such as the Bora 51). However, the use of the Super Atom permitted the reduction of a typical model wingspan to the range 1100 -1300 mm (43 - 51 in.) - cheaper to build and easier to transport.

The Super Atom continued in production for some years, almost certainly becoming the most widely-used engine in Czechoslovakia during this period. At some point along the way, J. Choc appears to have withdrawn from the project, leaving Hruška to continue on his own. The boxes for the later engines bore a V.H. cartouche representing Hruška‘s name, with no reference to Choc.

The most interesting aspect of this arrangement was its use of differential threads in the connecting collar. Both right-hand and left-hand fine-pitch metric threads were used. If the same right-hand thread had been used for both upper and lower crankcase components, it would have been a matter of trial and error using shims to assemble the components in their correct radial orientation. The use of opposite-hand threads allowed the collar to be set on the lower threads in whatever position resulted in all joints being tight when the components were firmly screwed together in the correct relative orientation. A very clever idea, but one is forced to wonder why such complexity was felt to be justified. I can only assume that the design permitted the incorporation of a more efficient bypass system. The Super Atom Replicas

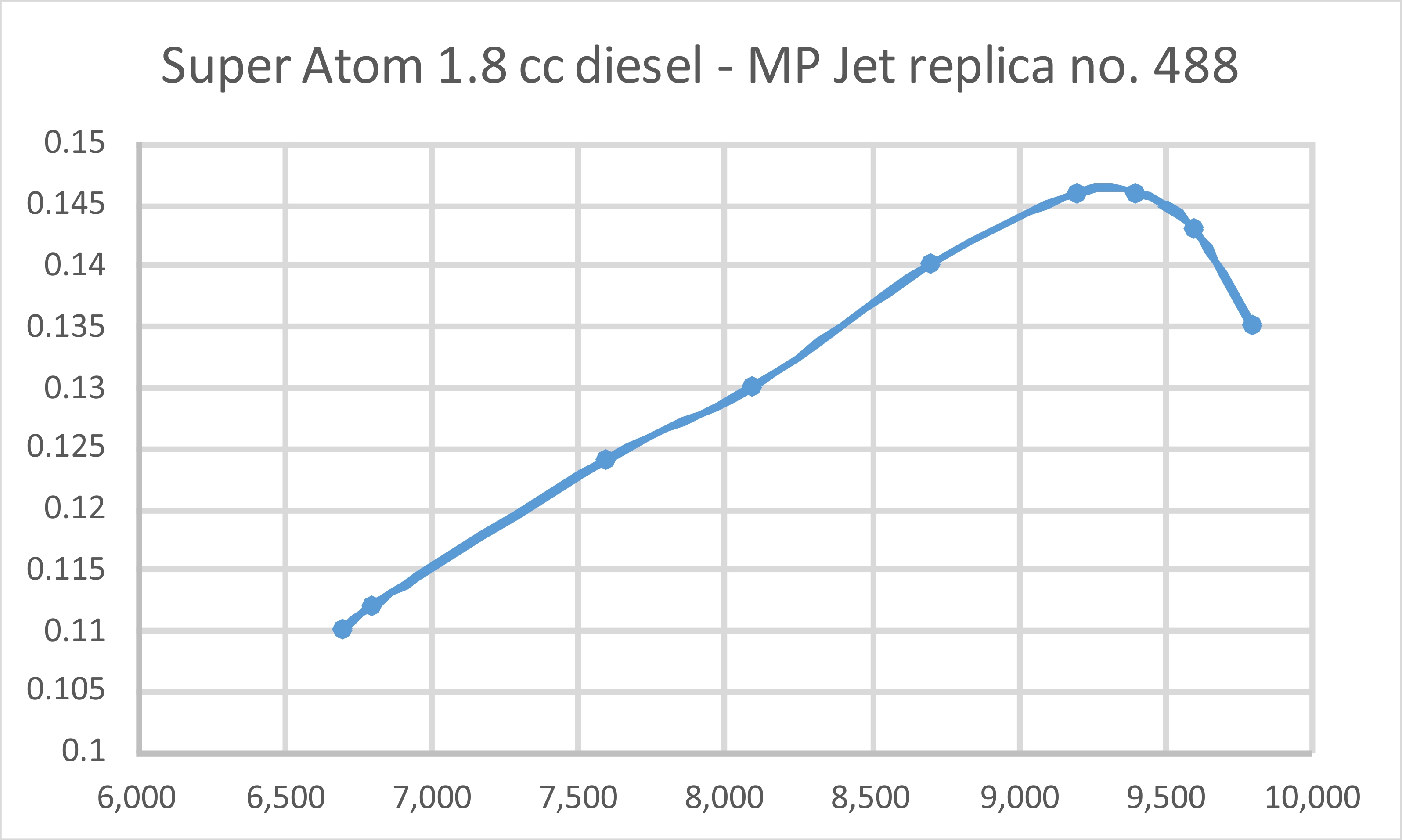

The best-known of these replicas is that produced in a limited series of 500 engines during the first decade of the present millemium by the MP Jet company of Ledenice in the Czech Republic. This is a latter-day rendition of the 1946-1948 model with the one-piece crankcase. Although extremely faithful to the original model in terms of its To begin with, the replica’s cylinder liner is made from nitrocarburized hardened steel, with a conventional one-piece Meehanite cast iron piston and contra-piston. This eliminates the problem of the contra-piston freezing in the bore when hot and potentially cracking the liner. The crankshaft is made from hardened heat-treated steel in place of the unhardened mild silver steel used in the originals - a far more durable material choice. The shape of the cylinder ports has also been slightly modified, resulting in claimed improvements to starting and power output. The revised material specification should undoubtedly contribute to an extended working life. A number of other replicas of the Super Atom were made by Jaroslav Rybák of Svitavy, also in the Czech Republic. Reports from users of these engines suggest that they were not quite as good as those made by MP Jet. However, they do appear to have run quite well enough to satisfy most enthusiasts. So how well do these engines run? Time to set about the enjoyable business of finding out! The Super Atom on Test

At the time when I embarked upon this project in late 2020, the MP Jet replica remained available from the Canadian company Icare RC of Montreal. The price was US$129.00. I was able to acquire one of these engines for examination and test. My example bears the serial number 488 - very near the end of the 500 engine series. One is forced to wonder if we're more or less looking at the end of the available supply ......... It should be readily apparent that one cannot mount these engines in a conventional test stand - it's necessary to make a radial mount to run them. I make such mounts out of extruded structural aluminium alloy T-section stock, adding a cutaway in the stem of the T to accommodate the back tank. The same mount can often be drilled to accommodate more than one radially-mounted engine, as in the present case. The stem of the T is readily clamped in a normal test stand intended for beam-mounted units. One feature of the MP Jet replica deserves particularly favorable comment. This is the fact that the three radial mounting holes are drilled at the same spacing as used on the original Super Atom engines. This makes the replica interchangable with an original in the same model or test mount. I have had occasion to comment in the past upon the desirability of replica manufacturers matching the original mounting holes, since it allows one to use an original example for occasional test or demonstration flying while permitting the use of a replica in regular service, thus conserving the original. In the case of a radially-mounted unit, it also relieves the owner of having to make multiple test mounts. MP Jet are to be commended for following the matching principle - if there's one thing that replica makers should get right, it's the mounting configuration. All too often, they don't ....................

For conservation reasons I also chose to use a conventional machine screw in place of the very neat composite bolt/spinner/washer assembly with which the engines are supplied. Finally, I chose a mineral oil-based fuel with a small proportion of ignition improver. It's not necessary to use castor oil in low-revving sideport diesels like this one, besides which the use of mineral oil side-steps the common problem of the engine suffering a static castor gum seizure during long-term storage. The replica was set up a little on the tight side as delivered, hence clearly requiring some break-in time. I chose to use a 10x6 APC prop for this purpose. I soon found that despite its tight set-up, the engine was an excellent starter with first-rate suction. It seemed to appreciate a small exhaust prime, after which it invariably started up within a few flicks. In keeping with my usual practise with a new iron-and-steel diesel, I kept the engine running slightly under-compressed and a little rich for around a 4½ minute stretch. At the end of this, I leaned the engine out and optimized the compression setting, allowing the engine to run in this mode for about 30 seconds before stopping it by pinching off the fuel line. This put the piston/cylinder assembly through the full-range heat cycles which are essential for a proper break-in, as detailed in my separate article on the subject.

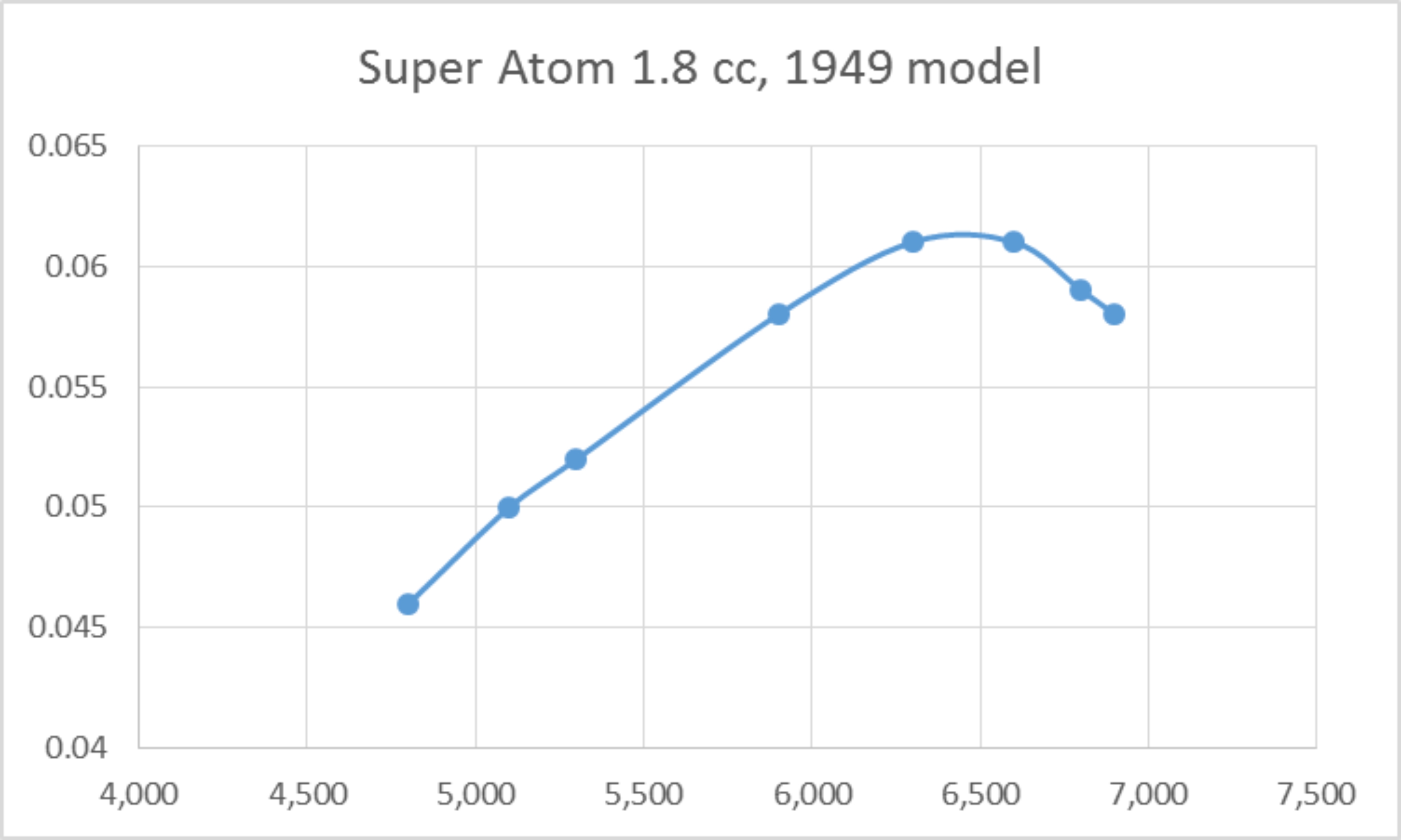

I proceeded to obtain leaned-out test figures for a wide range of loads. I continued to allow complete cooling between prop changes to subject the engine to additional full-range heat cycles, which are probably more important than running time for a proper break-in. The engine continued to start flawlessly throughout the test, although a small port prime seemed to be a necessity. Running was extremely smooth at all times, the one slightly negative point being a tendency to sag a little as the engine warmed up to full operating temperature on each prop. However, this was a very minor issue - the degree of sagging was only of the order of 100-200 rpm. The engine's output continued to increase well past the point that I had been expecting. The following data tell the story.

As can be seen, the MP Jet replica turned out to perform at a level which far exceeded my expectations. I actually went back and re-checked a few of the above readings just to make certain that I hadn't been mis-reading the tachometer! All was well - the engine evidently developed around 0.146 BHP @ 9,300 rpm. I realize that the measured figures apply strictly to this particular example of the replica, which has been tweaked by its manufacturer by his own open admission. Accordingly, one would expect the replica to perform at a higher level than the original, but not by that much! These are quite remarkable figures for a 1.8 cc sideport diesel having its design origins in the mid 1940's! At the end of the test, the engine felt absolutely superb. No trace of any detectable play developed in the bearings, while the piston fit seemed to have reached an optimal state based upon my extensive experience - extremely smooth with a very slight residual pinch at top dead centre. With its fine handling and smooth running to go along with its excellent fits and well-chosen material specification, this engine should deliver a very long and trouble-free working life. Well done, MP Jet!

To begin with, when the engine arrived in Peter’s workshop it turned out that the internal opposite-hand threads in the collar which secured the two crankcase halves to each other were too loose to hold the components securely. Peter had to make a new collar with left and right-hand threads cut to a tighter fit - a very challenging component in itself. He told me that getting the collar set correctly to ensure proper alignment of the cylinder was quite tricky! Again, one wonders why this arrangement was adopted …………. needless to say, I left Peter's fine work undisturbed! Another major problem turned out to be that the cast iron cylinder liner was cracked at the top around the contra-piston. As noted earlier, this problem is to be expected with a light alloy contra-piston operating in a thin cast iron liner. Peter made a new liner from steel, also fitting a new cast iron piston. While he was at it, he placed the transfer port at a lower elevation, with a bevelled upper edge to direct incoming gas upwards. The original un-chamfered port opened more or less concurrently with the exhaust, which is not an ideal arrangement with a low-revving sideport engine.

All in all, this example is now a “Peter Valicek 1.8 cc Special” based on the 1949 version of the Super Atom. However, it incorporates many original components and remains very close to the original in functional terms - the changes are mainly in the material selection. The sole change that might affect performance was the lowering of the transfer port and the bevelling of its upper edge. Naturally, I was unwilling to disturb Peter’s fine work, hence my decision not to take the engine apart for more detailed examination. It was clear that getting it set up correctly had been quite enough of a challenge!! That said, there was nothing preventing me from setting the engine up in the test stand to try it out - Peter had run it successfully folowing its rebuild. So without further ado it followed its MP Jet replica partner onto the test bench using the same test mounting thanks to MP Jet's duplication of the hole spacing. Given its minimal running time since its restoration, I decided that I would begin by giving it some slightly rich and under-compressed runs to break it in a little.

Accordingly, I made no attempt at first to take any speed readings. I contented myself with starting on a full tank and running the tank out slightly rich and under-compressed, leaning out and raising compression for a brief period near the end of the run. It turned out that the Super Atom barely sipped its fuel - although the metal tank isn’t all that large, it still gave a run of almost 4 minutes on a slightly rich needle. I suspect that this fuel economy is a result of Peter’s re-configuring of the transfer port - losses of incoming mixture out of the exhaust ports appear to be minimal. I would time the run for 3½ minutes and then lean out and raise compression slightly for the final twenty seconds or so to put the piston through the required sequence of full-range heat cycles necessary for a proper break-in. After a dozen runs in this manner, I decided that things had freed up enough that speed readings could now be taken. Although it had definitely improved, the engine still felt considerably tighter than ideal, but I didn’t want to subject it to the extended amount of running that seemed to be necessary to alleviate this condition - after all, I wasn't planning to fly it. So I went ahead with the test in the knowledge that the engine could doubtless do significantly better than this if fully freed up over a few hours’ running.

Running proved to be very smooth, although once again there was a tendency to sag a little as the cylinder warmed up. This was probably a reflection of the still-tight piston. I also found by experiment that, somewhat unusually for a sideport diesel, the Super Atom liked a little ignition improver in its fuel. Response to the controls was excellent - in particular the needle valve was far less sensitive than on some other sideport diesels of my acquaintance. I ended up taking my speed readings using a fuel consisting of 35% ether, 35% kerosene and 30% SAE 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120) with 1% improver added to the mix. While the engine seemed very happy running on this brew, the plain fact was that there simply wasn’t that much power being developed! The following figures tell the story.

The above figures imply a peak output of around 0.062 BHP @ 6,500 rpm, considerably less than the manufacturer’s previously-noted performance claim and the figures achieved with the MP Jet replica had led me to expect. As stated earlier, there’s little doubt that this example of the Super Atom would improve quite substantially on these figures if given some more running time, but I can’t see it becoming a world beater even then. It might get up to around 0.070 BHP @ 7,000 rpm, but almost certainly nothing more. Still, it proved itself to be a fine-handling smooth-running unit which would have given full satisfaction to any user who wasn’t expecting too much in the way of performance. I thoroughly enjoyed testing it! Other Versions of the Atom

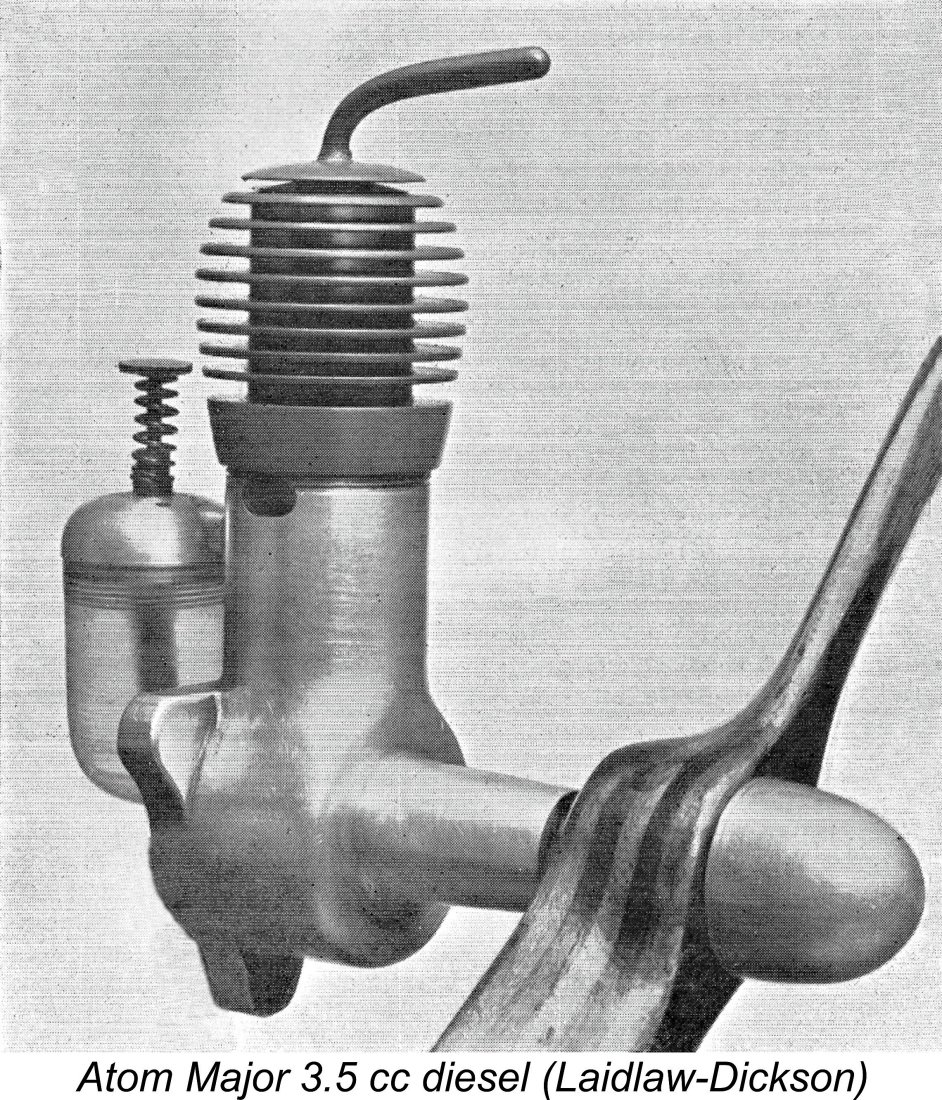

Somewhat paradoxically, the unit on which we have the closest dating information is also the most elusive. This is the greatly enlarged 3.5 cc variant known as the Atom Major. We only know about the undoubted existence of this model thanks to its inclusion complete with the accompanying very fine photograph in D. J. Laidlaw-Dickson’s late 1946 book entitled “Model Diesels” - I’m presently not aware of any surviving original examples. The engine must have been in existence by early to mid 1946 to permit its inclusion in the book. However, according to a number of individuals who are very knowledgeable about early Czech engines, this model was never put into series production, evidently being made only in a very limited prototype series for field test purposes. During that period, it did achieve enough notice to have its photograph taken, also somehow coming to the attention of Laidlaw-Dickson in far-off England on the other side of the Iron Curtain. It would be interesting to know how this came about - one would think that an Iron Curtain prototype of which only a few examples were made would be the last engine to come to his attention! This photograph confirms the prototype status of the illustrated example, since the mounting holes have not been drilled through the radial mounting lugs - as photographed, the engine could not be mounted and run. It may actually have been a mock-up............

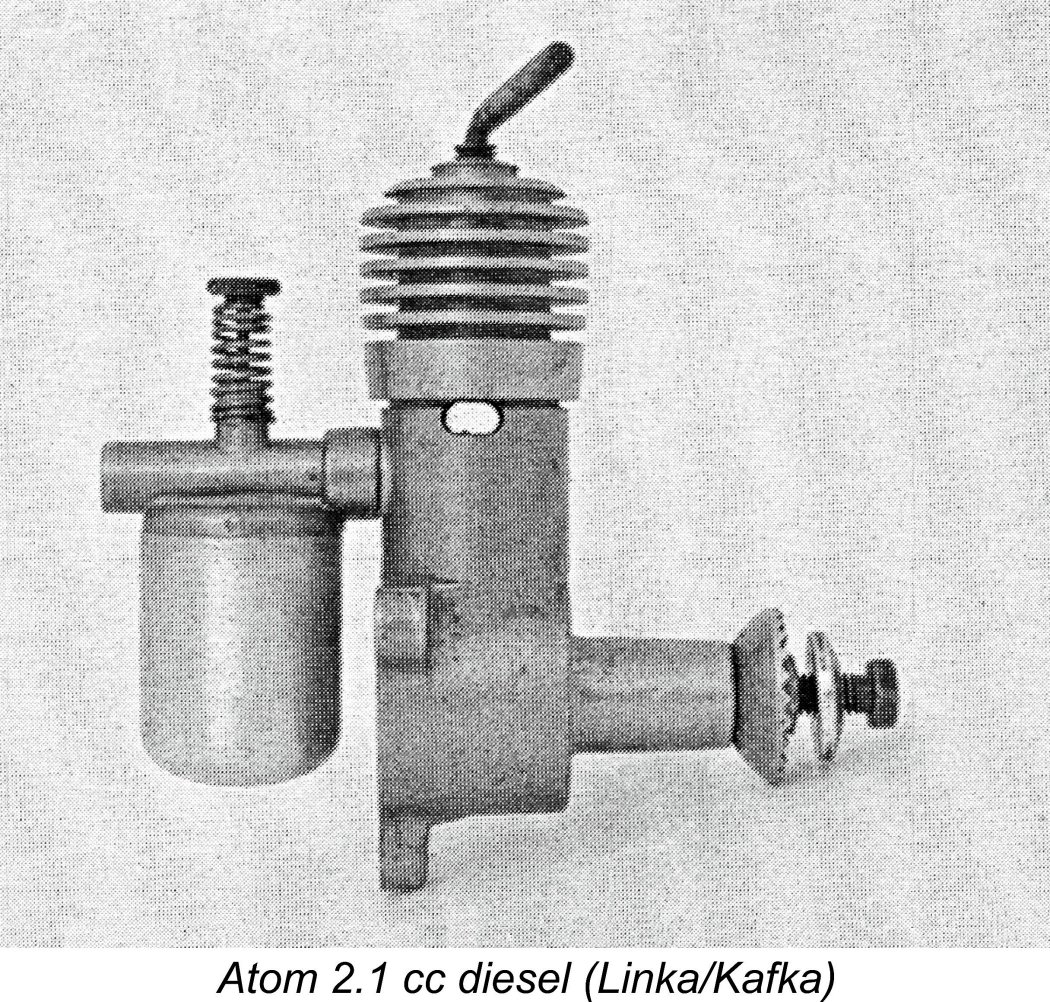

For reasons which remain unclear, the Atom Major apparently never saw series production. The next variant to appear seems to have been the Atom 2.0, which evidently fared a little better. This was basically the same engine as the 1.8 cc Super Atom with the aluminium alloy cooling jacket, but with the bore increased from 12 mm to 13 mm with the same 16 mm stroke. The resulting displacement was 2.12 cc (0.130 cuin.), slightly belying the engine’s designation. Weight crept up a little to 125 gm (4.41 ounces). This model was evidently produced in relatively small numbers. There was also a 2.5 cc variant of the Super Atom called the Atom 2.5, still using the same 16 mm stroke but with the bore further increased to 14 mm for a calculated displacement of 2.46 cc (0.150 cuin.). This variant weighed in at 140 gm (4.94 ounces). It too was marketed in a short series, also being made available in the early 1950’s as a casting set with drawings for home construction. The Atom Major Replica

However, some time previously Peter had made contact with a fellow model engine technician named Jindra Hala of the Czech Republic. Jindra had a small and relatively basic workshop in which he made very small batches of model engines as well as carrying out restoration projects for others. Peter had definitely found a kindred spirit!! Following discussions with Peter, Jindra agreed to make the Atom Major replicas himself.

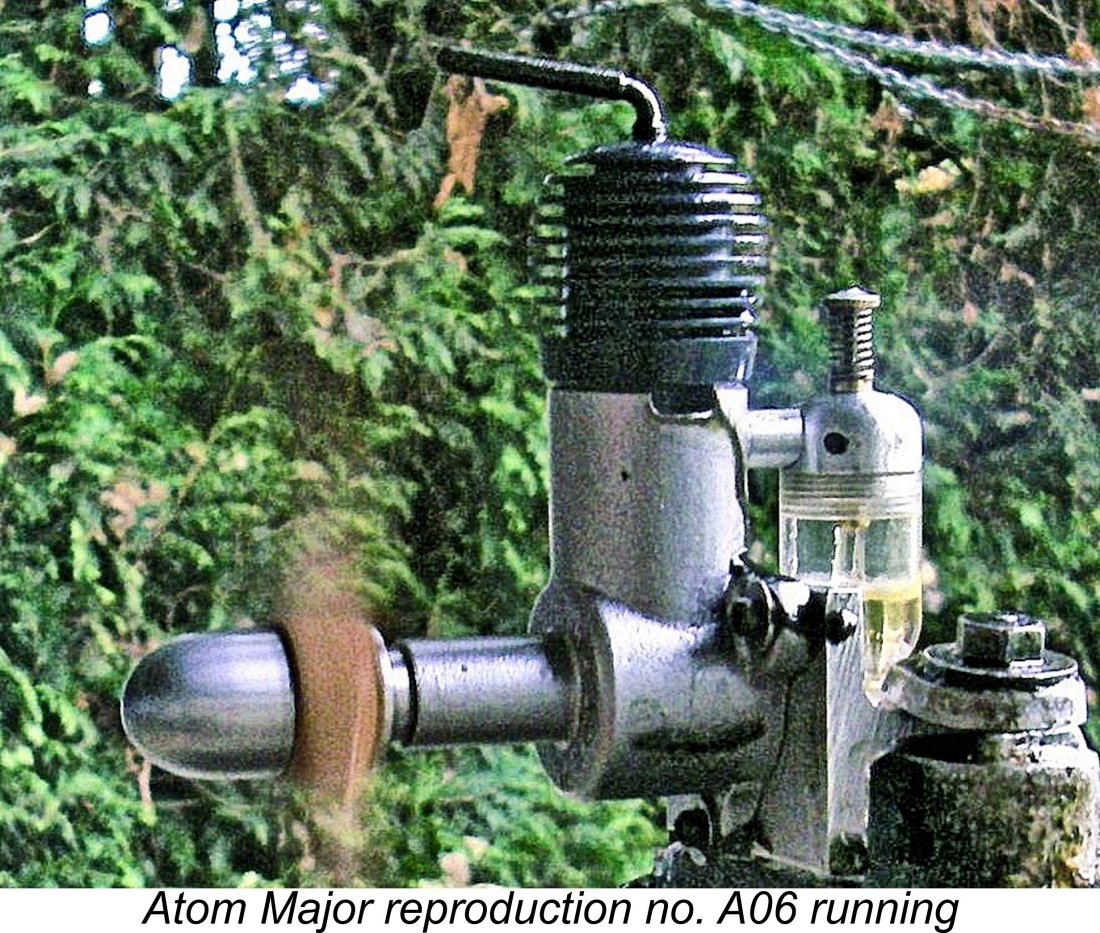

This makes it a “look-alike” rather than a true replica, but as can be seen from the accompanying images, it’s whisker-close! The reproduced engine features the previously-estimated bore and stroke dimensions of 15 mm and 20 mm respectively for a displacement of 3.53 cc. It weighs a fairly healthy 210 gm (7.41 ounces) complete with tank. The accompanying images show my example, engine no. A06, which I obtained through the great kindness of both Jindra and Peter. My sincere thanks to both! The I couldn’t resist setting up this outstanding creation on the test bench to see how it performed. Obviously I had to make a special mount to permit this, but that was a small price to pay for the pleasure of giving this rare beast a few runs! The Atom Major replica was one of those engines which was so well finished and fitted as supplied that it gave the impression of requiring little or no running in. Nevertheless, I decided that I would give it at least a short break-in prior to taking any speed readings. For this purpose, I fitted a Top Flite 12x8 wood prop as my initial test airscrew. I used the same modestly-nitrated mineral-based fuel that I had used earlier in the Super Atom. It turned out that this was a wise decision - subsequent experimentation showed that the engine definitely liked a little ignition improver in its diet. The Atom Major proved to be less easy to start than its smaller relatives. Like many larger sideport diesels, it needed the compression to be increased from the running setting to start from cold. It also appeared to need a small prime - finger choking tended to flood the case. The approach finally adopted was to increase the compression setting a little, administer a single choked flick and then inject a small exhaust prime. Even then, the engine seemed to be rather sensitive to the amount of fuel in the cylinder - it took a series of flicks with no respose to let the mixture stabilize at the required level. When that point was reached, the engine would suddenly begin firing, after which a start was achieved fairly quickly. Overall, I would not rate this engine as a particularly good starter - it's not that hard, but it does take some knowing. A rank beginner might have some trouble ........... This having been said, things improved a lot once the engine was running. Compression could be reduced considerably as it warmed up, while response to the needle was very well defined. Once properly adjusted, the Atom Major was a commendably smooth and steady runner. However, it did appear to be quite thirsty - the screw-on plastic tank with which it was supplied (as Since neither I nor anyone else is ever likely to actually fly one of these replicas, I saw no reason to subject it to a complete break-in and test. In all honesty its performance was of no more than academic interest. I therefore put around 20 minutes of running-in time on it and then leaned it out briefly on a few different props just to get an idea. The engine turned the Top Flite 12x8 wood at 5,100 rpm, a Zinger 12x5 wood at 6,400 rpm and a Top Flite 10x8 wood at 6,800 rpm. There's not enough data here to produce a meaningful power curve, but the engine is clearly past its peak on the 10x8. I'd guess around 0.206 BHP @ 6,500 rpm. Although this is no more than an educated guess based upon very limited data, I wouldn't expect it to be far out. The engine was still tighter than ideal at the end of this test, evidently still needing more running-in time. I would guess that performance would improve quite measurably with additional running time. It might be reasonable to anticipate an output of around 0.225 BHP @ 7,000 rpm under such conditions. Whatever the actual numbers, the Atom Major was clearly a very acceptable performer by the standards of its day - remember, the design dates back to early 1946! It was likely a combination of unfavorable market projections and handling challenges that caused its abandonment at the prototype stage. My congratulations to Jindra Hala for creating a really fine reproduction - I've certainly appreciated the opportunity to experience it at first hand! A Direct Descendant - the NV-21

The 1950 date of this design is confirmed by its appearance in an article published in the December 1950 issue of the Czech modelling magazine "Letecky Modelar" (Aero Modeller). My thanks to Maris Dislers for bringing this article to my attention! The article confirmed that the designer was Vladislav Hruška, but also designated the engine as having been produced by "Naše Vojsko", which translates into "Our (Czech) Army". This neatly resolves the mystery of what the engine's NV designation signifies! The engines were produced at the state-owned START Plant 06 in Prague, which was apparently under military control. It's clear from this that the development of this engine stemmed from an official military initiative to promote the wider use of aeromodelling as a training ground for future involvement with the Czech air force. In taking this approach, the Czechs were clearly following the Russian model. At the time when the article was written, availability of the engines was said to be restricted to members of established model clubs and experienced fliers - in other words, the more serious members of the Czech model flying establishment. The engines were reportedly available from regional Army stores and through recognized model aero clubs. If neither such outlet was available in one's area, prospective buyers could contact the Army Department of Aeronautical Services at an address in Prague. The cited price of the NV 21 was CZK 450, quite a sum for 1950 Czechoslovakia.

To this end, increased use was made of castings as opposed to machined components. The NV-21 retained the two-part crankcase of the 1949 Super Atom, but the two components were now fastened together using two machine screws, one on each side, rather than the far more “fiddly” multiple-thread collar connection used in the late-model Super Atom. The bypass passage was somewhat enlarged, with a ”bulge” being added to the castings at the front to accommodate this. The fuel supply arrangements were also simplified, sadly with the loss of the very elegant machined egg-shaped fuel tank with integral intake venturi in favor of a far more utilitarian cast U-shaped component with a cast intake structure which incorporated the tank top. The latter feature had actually been introduced earlier on the previously-mentioned Atom 2.0, of which the NV 21 is clearly a direct descendant. These changes resulted in a modest increase in weight from the Atom 2.0’s figure of 125 gm (4.41 ounces) to a still-reasonable 140 gm (4.94 ounces) with tank. The cited maximum operating speed of this revised design was raised to 7,800 rpm. The recommended airscrew was the metric equivalent of a 10½x6. The claim was made that the engine developed a peak output of no less than 0.30 BHP @ 7,000 rpm, but this was clearly an excursion into the realm of fantasy! See below for confirmation .............. The NV-21 was offered in two variants. The only externally visible difference was the cooling jacket - that used on the Type 1 version had thicker fins of a more or less constant diameter, while the Type 2 variant’s jacket featured thinner and more numerous fins having a rounded side profile. There may also have been internal differences, although these do not readily present themselves. It's presently unclear whether these two variants were successive or concurrent - the reported serial numbers are intermingled between the two. It's also unclear which came first - the illustrations which accompanied the December 1950 "Letecky Modelar" article seem to show show engines having the Type 2 jackets.

The NV-21 was produced by START in quite large numbers for distribution among Czech aeromodellers. It appears to have been responsible for a significant expansion in the use of power models among the various youth clubs sponsored by SVAZARM. It remained in production until 1955, when it was replaced in turn by the more powerful START 1.8 cc diesel, the initial Most of the NV engines seem to have borne serial numbers, although I have one Type 1 unit which does not bear a number. My other three examples display the numbers 2490, 2934 and 5354. In addition, I have photographic evidence of the existence of Type 2 engine no. 6171. If we assume that the numbering started at 0001, this seems to confirm the production of at least some 6,500 examples. Of course, the true number may have been far higher - I’d need more numbers to be any more definite. Any volunteers?!? I can say from personal experience that at one time these engines were very frequently encountered, even outside their country of origin. My present four examples all came to me from North American sources during the 1970's and 1980's, during which period they were viewed as rather commonplace. The implication is that they were indeed made in substantial numbers. I gather that they have become somewhat less common today. The NV-21 on Test

This particular engine arrived many years ago now as a basket case. Prior to my acquiring it in the late 1970's, the poor little beastie had shared the fate of my previously-tested 1949 Super Atom by suffering a broken conrod which had holed the crankcase and also damaged the backplate. I made a new high-strength alloy rod and had the case welded up very neatly - you wouldn’t detect the repair now unless I told you it was there! I also made a new backplate, restoring excellent crankcase compression. Finally, I replaced the aluminium alloy contra piston with a new component made of steel - far less chance of splitting the cast iron cylinder liner, plus it wouldn’t seize when hot. I then gave the engine a full break-in prior to use. After sorting out all these problems, I actually gave this unit a little air-time in a control line trainer which then served as one of my flying test beds for classic diesels. For that purpose, I had made a replacement tankless intake assembly using the original needle, retaining the original assembly for later re-installation to restore originality. The engine is pictured above in its tankless configuration. Since the bore configuration of this intake matched that of the original, its use would not affect performance in any way. However, it facilitated testing by allowing the use of a separate fuel tank, thus side-stepping the problem of filling the tank through the single absurdly small un-vented filler hole. Accordingly, I stayed with it for the test, although I did set up similar engine no. 2490 for the accompanying running photograph of a complete example.

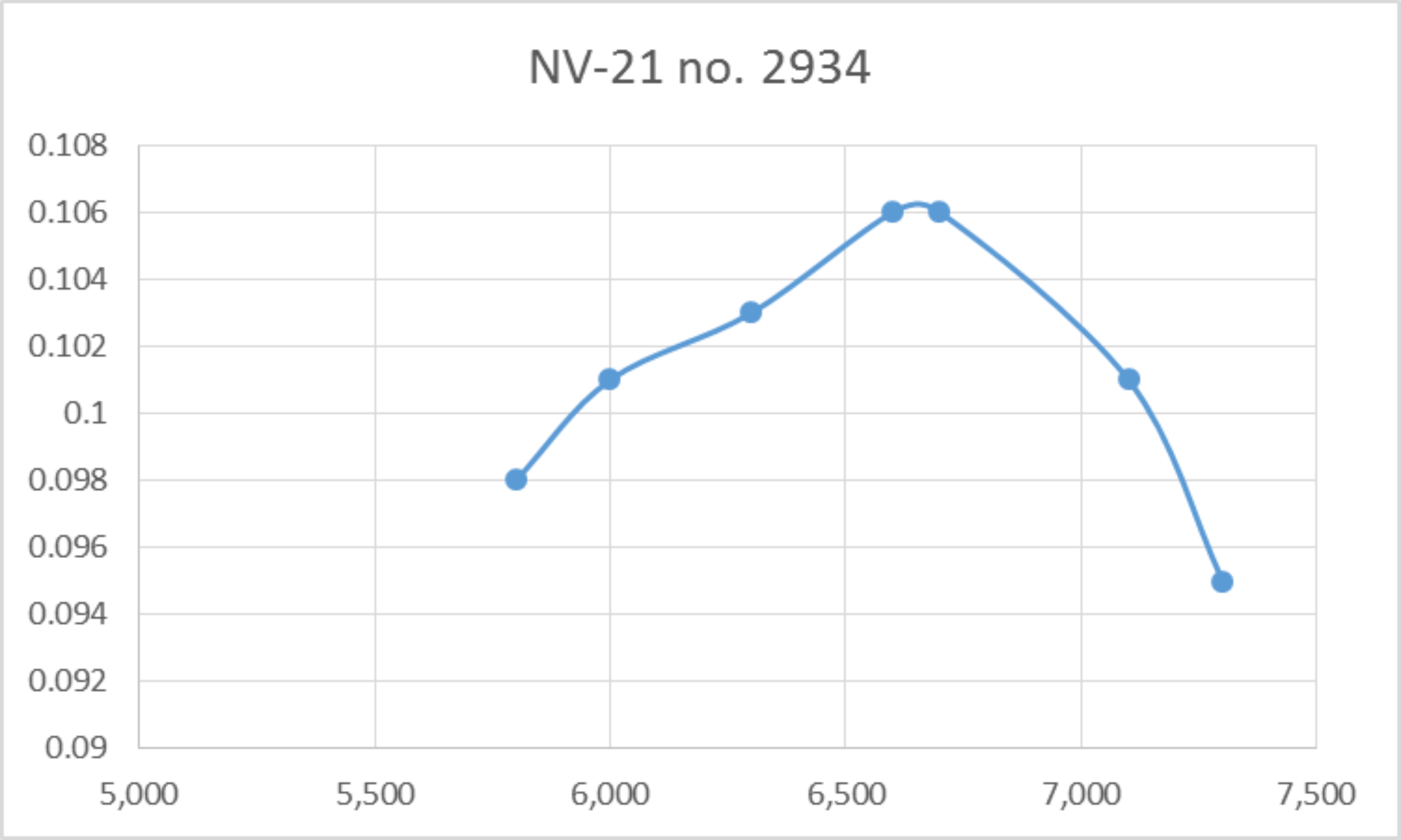

The test was made particularly enjoyable by the fact that the engine proved to be an outstanding starter! I’d noted as much in my log book entries for my long-ago initial test running and flying, and the present-day test amply confirmed my recorded impressions - quite a contrast from the previously-tested Atom Major! The engine never needed a prime at any time - two choked flicks were the only required preliminary, after which the engine started on the first or second un-choked flick every time. This made the testing a real pleasure! Since there’s no cutout fitted, I used the old fuel line pinch method to stop it between prop changes - another advantage of using a separate tank. Once running, the NV-21 was very easy to adjust for maximum speed on any given prop. It seemed to be quite happy running on the straight fuel mixture with which it was supplied. Both controls worked smoothly and held their settings firmly at all times. Running was very steady, the only issue being a tendency to sag just a little as the cylinder warmed up to maximum operating temperature. The following steady-state data were recorded.

I seem to have missed the setting on the APC 10x7! Regardless, the above figures imply a peak output of around 0.106 BHP @ 6,700 rpm, a little down from the 7,800 rpm claimed by the manufacturer and a long way shy of their 0.30 BHP claim! Even so, this isn’t too shabby a performance for a long-stroke sideport diesel of this displacement - the NV-21 was well up on the E.D. Mk. II and not all that far behind an unmodified E.D. Comp Special. The modest peaking speed reflects excellent torque development at the lower end. The manufacturer's recommendation of a 10½x6 prop appears to be quite appropriate based on these results. My notes show that I used a 9x7 quite successfully for control line flying purposes, choosing a slightly higer pitch to improve airspeed a little. The complete example no. 2490 which I ran for the photograph performed just as well. However, that tiny un-vented filler hole was a major pain in the neck to use, requiring the use of a fine-tipped syringe. I was glad of the ability to use a separate tank for the main test! If I was planning to actually fly a complete example, I would enlarge the filler hole and add a pin-hole air vent. However, since I don’t plan to fly engine no. 2490, I left well alone in the interests of conservation. Overall, I found the NV-21 to be an extremely user-friendly engine with a perfectly adequate performance for sport flying applications. In particular, it would have been a very suitable powerplant for the use of beginners to the hobby. Indeed, that may well have been its primary intended purpose. Summary and Conclusion

Indeed, the influence of the Atom went both ways. As I’ve noted in my separate article on Russian model engine development, the 1950 CAML-50 which was among the most widely-used diesels in early to mid 1950’s Russia was basically a Super Atom clone. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, the Russians paid Vladislav Hruška the highest-possible compliment! The various Atom engines in replica form remain quite readily available today. Even originals turn up now and then, as do examples of the successor NV-21. Anyone who enjoys flying or just running a well-made user-friendly model diesel can’t fail to be very satisfied with the experience of trying one of these powerplants! I've certainly enjoyed my own encounters! ______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published May 2021 Amended June 2021 - expanded section on NV-21

|

||

| |

In this article, I’ll present some information on a well-known series of early model diesel engines, albeit one on which detailed information seems to be in rather short supply in the English language. I’ll be looking at the series of such engines produced in Czechoslovakia (as the Czech Republic was then) between 1945 and 1952 under the Atom designation.

In this article, I’ll present some information on a well-known series of early model diesel engines, albeit one on which detailed information seems to be in rather short supply in the English language. I’ll be looking at the series of such engines produced in Czechoslovakia (as the Czech Republic was then) between 1945 and 1952 under the Atom designation.

During the 1930’s, aeromodelling was as popular a hobby in Czechoslovakia as it was elsewhere. However, most of the modelling activity centred upon gliders and rubber powered models. This was an inescapable consequence of the fact that model engines were very difficult to obtain in Czechoslovakia at this time. Generally speaking, if you wanted to engage in power modelling you either had to make your own engine or persuade some talented friend having both the required skills and access to the necessary equipment to make one for you.

During the 1930’s, aeromodelling was as popular a hobby in Czechoslovakia as it was elsewhere. However, most of the modelling activity centred upon gliders and rubber powered models. This was an inescapable consequence of the fact that model engines were very difficult to obtain in Czechoslovakia at this time. Generally speaking, if you wanted to engage in power modelling you either had to make your own engine or persuade some talented friend having both the required skills and access to the necessary equipment to make one for you.

A major challenge in responding to this need was the fact that the Germans maintained a security presence at all facilities involved in war-related production in order to discourage acts of industrial sabotage, including the "diversion" of strategically-important materials. This must have made the clandestine use of such facilities and materials problematic, to say the least.

A major challenge in responding to this need was the fact that the Germans maintained a security presence at all facilities involved in war-related production in order to discourage acts of industrial sabotage, including the "diversion" of strategically-important materials. This must have made the clandestine use of such facilities and materials problematic, to say the least. Půrok made a few more examples of this engine during the early months of 1942, possibly with help from Bušek. As is often the case with small-series artisan productions of this nature, the design appears to have been subjected to minor amendments from one example to the next - the very rare engine has shown up in a number of different but clearly-related variants.

Půrok made a few more examples of this engine during the early months of 1942, possibly with help from Bušek. As is often the case with small-series artisan productions of this nature, the design appears to have been subjected to minor amendments from one example to the next - the very rare engine has shown up in a number of different but clearly-related variants.

placement. A surprising feature of this advertisement is the image of the smiling youth sporting an unmistakable Hitler hairstyle - one would have thought that this would hardly have been viewed positively in post-WW2 Czechoslovakia, either by the Czechs themselves or by their new Russian overlords!

placement. A surprising feature of this advertisement is the image of the smiling youth sporting an unmistakable Hitler hairstyle - one would have thought that this would hardly have been viewed positively in post-WW2 Czechoslovakia, either by the Czechs themselves or by their new Russian overlords!  The original version of the Atom 1.8 cc diesel appeared in production form in the latter part of 1945. It was primarily designed by Vladislav Hruška and was manufactured in Prague by the re-established partnership of Hruška & Choc working from premises located at Vodickova 18, Prague II. Promotion and distribution of the engine was once again handled by M. K. Moučka of Vinohrady, Prague XII, whose business had somehow survived the war.

The original version of the Atom 1.8 cc diesel appeared in production form in the latter part of 1945. It was primarily designed by Vladislav Hruška and was manufactured in Prague by the re-established partnership of Hruška & Choc working from premises located at Vodickova 18, Prague II. Promotion and distribution of the engine was once again handled by M. K. Moučka of Vinohrady, Prague XII, whose business had somehow survived the war.

The changes which resulted in the Super Atom were by no means confined to the location of the tank. The revised location of the induction port at the rear necessitated a corresponding change in the cylinder porting arrangements. There were now two exhaust ports, one on each side. The layout dictated the use of a single transfer port at the front. This was supplied through a single greatly enlarged bypass passage formed in the main casting at the front.

The changes which resulted in the Super Atom were by no means confined to the location of the tank. The revised location of the induction port at the rear necessitated a corresponding change in the cylinder porting arrangements. There were now two exhaust ports, one on each side. The layout dictated the use of a single transfer port at the front. This was supplied through a single greatly enlarged bypass passage formed in the main casting at the front.

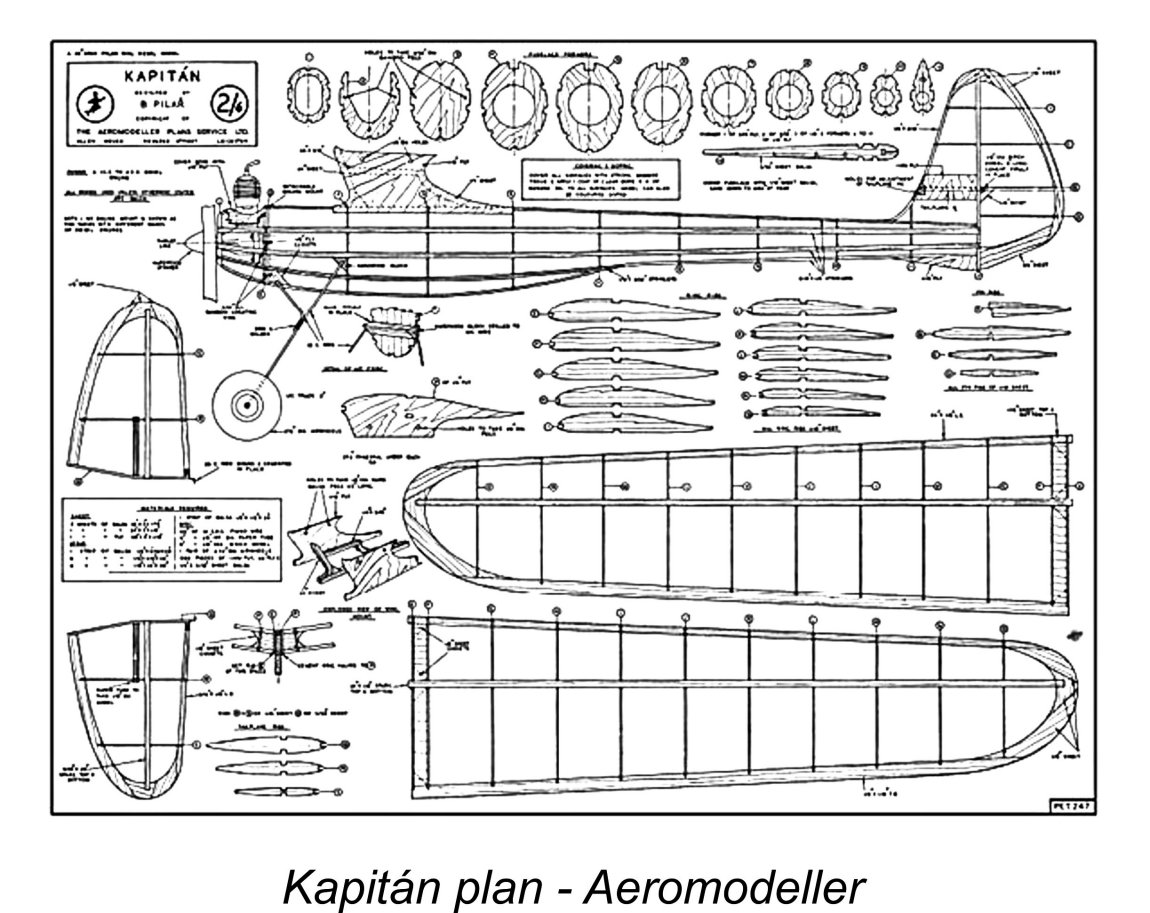

At the first post-war Czech National Championship meeting held in 1946 at Otrokovice, A. Jindra of Prague won with his small “Vega” model powered by a Super Atom engine. Another highly influential Super Atom-powered design was the “Kapitán” model designed by B. Pilar. Both the plan for this model and the Super Atom engine itself were offered by M. K. Moučka. The plan of the Kapitán model was also published in the English “Aeromodeller” magazine, with a very positive assessment of both engine and model. To add to the Super Atom’s laurels, the prominent Czech modeller Vladislav Procházka used his Super Atom-powered “Populár” model to establish the first post-WW2 Czech records for flight duration and distance - both highly-regarded categories in the Eastern Bloc countries.

At the first post-war Czech National Championship meeting held in 1946 at Otrokovice, A. Jindra of Prague won with his small “Vega” model powered by a Super Atom engine. Another highly influential Super Atom-powered design was the “Kapitán” model designed by B. Pilar. Both the plan for this model and the Super Atom engine itself were offered by M. K. Moučka. The plan of the Kapitán model was also published in the English “Aeromodeller” magazine, with a very positive assessment of both engine and model. To add to the Super Atom’s laurels, the prominent Czech modeller Vladislav Procházka used his Super Atom-powered “Populár” model to establish the first post-WW2 Czech records for flight duration and distance - both highly-regarded categories in the Eastern Bloc countries.  In 1949 the design was changed again for reasons which are somewhat unclear. The main functional design was unaltered, but the cylinder assembly was very different. The crankcase was now split below the exhaust ducts, which were now incorporated into a separate upper component along with the intake boss. The lower and upper halves of the resulting composite crankcase were externally threaded and connected by an internally threaded collar.

In 1949 the design was changed again for reasons which are somewhat unclear. The main functional design was unaltered, but the cylinder assembly was very different. The crankcase was now split below the exhaust ducts, which were now incorporated into a separate upper component along with the intake boss. The lower and upper halves of the resulting composite crankcase were externally threaded and connected by an internally threaded collar.  In later years, the general excellence of the Super Atom design and its homologation for use in SAM old-time contests combined to create a high level of interest in the engine. This interest was sufficient to encourage the production of several replicas of the unit.

In later years, the general excellence of the Super Atom design and its homologation for use in SAM old-time contests combined to create a high level of interest in the engine. This interest was sufficient to encourage the production of several replicas of the unit.

This portion of the article is greatly facilitated by the fact that I have two examples of the Super Atom on hand. One is an MP Jet replica of the 1946 - 1948 model as described above, while the other is a heavily restored original example of the 1949 version with the two-piece crankcase connected by a threaded collar.

This portion of the article is greatly facilitated by the fact that I have two examples of the Super Atom on hand. One is an MP Jet replica of the 1946 - 1948 model as described above, while the other is a heavily restored original example of the 1949 version with the two-piece crankcase connected by a threaded collar. For testing purposes, I elected to unscrew the standard tank and use a separate far larger tank. This relieved me of the need to constantly refuel the engine as well as allowing longer runs during the break-in process. It also permits the use of the fuel line pinch method to stop the engine - very handy given that there's no cut-out.

For testing purposes, I elected to unscrew the standard tank and use a separate far larger tank. This relieved me of the need to constantly refuel the engine as well as allowing longer runs during the break-in process. It also permits the use of the fuel line pinch method to stop the engine - very handy given that there's no cut-out.

Turning now to my example of the last model of the Super Atom with the split crankcase, this began its latter-day life as an all-original unit which was in far less than perfect condition. My acquisition of this relatively rare engine was brokered by my valued Netherlands friend Peter Valicek, who acquired it for me and then did an amazing amount of painstaking work in setting the engine up properly. I’m extremely grateful to Peter!

Turning now to my example of the last model of the Super Atom with the split crankcase, this began its latter-day life as an all-original unit which was in far less than perfect condition. My acquisition of this relatively rare engine was brokered by my valued Netherlands friend Peter Valicek, who acquired it for me and then did an amazing amount of painstaking work in setting the engine up properly. I’m extremely grateful to Peter! As if all of this wasn’t enough, the conrod had broken at some point in the engine’s past and had created a crack in the crankcase. This had been welded, but it was a rather untidy job which leaked a little and needed sealing and cleaning up. Obviously, a replacement conrod had necessarily been fitted, but Peter was not satisfied with the quality of this component, hence making a new one of far higher quality. To cap it all, Peter made a superb replica of an original box - you'd never know unless someone told you. What a craftsman!

As if all of this wasn’t enough, the conrod had broken at some point in the engine’s past and had created a crack in the crankcase. This had been welded, but it was a rather untidy job which leaked a little and needed sealing and cleaning up. Obviously, a replacement conrod had necessarily been fitted, but Peter was not satisfied with the quality of this component, hence making a new one of far higher quality. To cap it all, Peter made a superb replica of an original box - you'd never know unless someone told you. What a craftsman!  I decided to begin with an APC 10x7 prop, which I felt would suit the engine very well. I quickly discovered two things - one, the engine was an extremely good starter on a small cylinder prime; and two, it was set up very much on the tight side. Peter’s new piston was a very tight fit in the cylinder, hence needing some running in to achieve a reasonable fit for testing purposes.

I decided to begin with an APC 10x7 prop, which I felt would suit the engine very well. I quickly discovered two things - one, the engine was an extremely good starter on a small cylinder prime; and two, it was set up very much on the tight side. Peter’s new piston was a very tight fit in the cylinder, hence needing some running in to achieve a reasonable fit for testing purposes. Starting continued to be excellent throughout. Like the MP Jet replica tested earlier, the engine seemed to need a small exhaust prime - choking alone didn’t have much effect. It transpired that it also liked to have the needle opened about ½ a turn from the running setting for a cold start. However, it could be started on the running compression setting on any given prop. A few choked flicks, a small exhaust prime and it invariably started within a few additional un-choked flicks.

Starting continued to be excellent throughout. Like the MP Jet replica tested earlier, the engine seemed to need a small exhaust prime - choking alone didn’t have much effect. It transpired that it also liked to have the needle opened about ½ a turn from the running setting for a cold start. However, it could be started on the running compression setting on any given prop. A few choked flicks, a small exhaust prime and it invariably started within a few additional un-choked flicks.

I’m fortunate enough to have a fine reproduction of the mega-rare Atom Major made in the Czech Republic. The manner in which this unit came into existence is an interesting story in itself. My valued mate Peter Valicek saw the previously-reproduced photograph of the prototype engine in Laidlaw-Dickson’s book and liked the look of it so much that he toyed with the idea of producing his own castings and making a few examples himself.

I’m fortunate enough to have a fine reproduction of the mega-rare Atom Major made in the Czech Republic. The manner in which this unit came into existence is an interesting story in itself. My valued mate Peter Valicek saw the previously-reproduced photograph of the prototype engine in Laidlaw-Dickson’s book and liked the look of it so much that he toyed with the idea of producing his own castings and making a few examples himself.  The result was the production by Jindra of a batch of some eight fine re-creations of the Atom Major. Clearly, since no original examples are known to exist, this must be viewed as a reproduction rather than a replica. It had to be constructed using dimensions scaled to the extent possible from the Super Atom and the Atom Major photograph. In effect, it was simply a scaled-up Super Atom.

The result was the production by Jindra of a batch of some eight fine re-creations of the Atom Major. Clearly, since no original examples are known to exist, this must be viewed as a reproduction rather than a replica. It had to be constructed using dimensions scaled to the extent possible from the Super Atom and the Atom Major photograph. In effect, it was simply a scaled-up Super Atom.  engine is clearly identified as being Jindra’s work by having his stylized “H” logo cast in relief onto the crankcase. It also has the engine’s name “ATOM MAJOR” stamped onto the front of the crankcase as well as displaying the serial number A06. Like all of Jindra’s productions, it was supplied in a very classy wooden box having a transparent plastic slide-out lid.

engine is clearly identified as being Jindra’s work by having his stylized “H” logo cast in relief onto the crankcase. It also has the engine’s name “ATOM MAJOR” stamped onto the front of the crankcase as well as displaying the serial number A06. Like all of Jindra’s productions, it was supplied in a very classy wooden box having a transparent plastic slide-out lid.

In 1950, Vladislav Hruška designed a new model which was basically a revised version of the previously-mentioned Atom 2.0. This was the NV-21, which retained the Atom 2.0’s bore and stroke of 13 mm and 16 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.12 cc (0.130 cuin.). This time the engine’s name accurately reflected its true displacement!

In 1950, Vladislav Hruška designed a new model which was basically a revised version of the previously-mentioned Atom 2.0. This was the NV-21, which retained the Atom 2.0’s bore and stroke of 13 mm and 16 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.12 cc (0.130 cuin.). This time the engine’s name accurately reflected its true displacement!

We've seen that the development of the NV-21 in 1950 appears to have been driven by a military education initiative. In late 1951 a new organization named

We've seen that the development of the NV-21 in 1950 appears to have been driven by a military education initiative. In late 1951 a new organization named

It should be clear from an objective reading of the above account that the Atom series of model diesels occupies an honoured place in the history of model engine design and manufacture. The range did much to promote power modelling in its native Czechoslovakia by providing Czech modellers with dependable engines which allowed them to focus upon the attainment of higher-level model designing and flying skills. The merits of the Atom were such that it became one of the earliest Iron Curtain products to achieve quite widespread name recognition on the Western side of the Curtain.

It should be clear from an objective reading of the above account that the Atom series of model diesels occupies an honoured place in the history of model engine design and manufacture. The range did much to promote power modelling in its native Czechoslovakia by providing Czech modellers with dependable engines which allowed them to focus upon the attainment of higher-level model designing and flying skills. The merits of the Atom were such that it became one of the earliest Iron Curtain products to achieve quite widespread name recognition on the Western side of the Curtain.