|

|

One of Russia's Best - the 1.48 cc MK-16 Diesel

This will be a companion article to my review of Oleg Gajevski's contemporary 2.47 cc MK-12S diesel from the same dynamic period of Russian model engine development. Both of these engines were briefly mentioned in my earlier article on the overall history of model engine design and manufacture in the Soviet Union from its beginnings in the mid 1930’s up to the end of the ”classic” era in the late 1970’s However, I did not present any performance figures in that article. I'll cover that omission here. In order to appreciate the full significance of the MK-16, it’s necessary to review the background against which its design was developed. I’ll begin by doing just that. Background

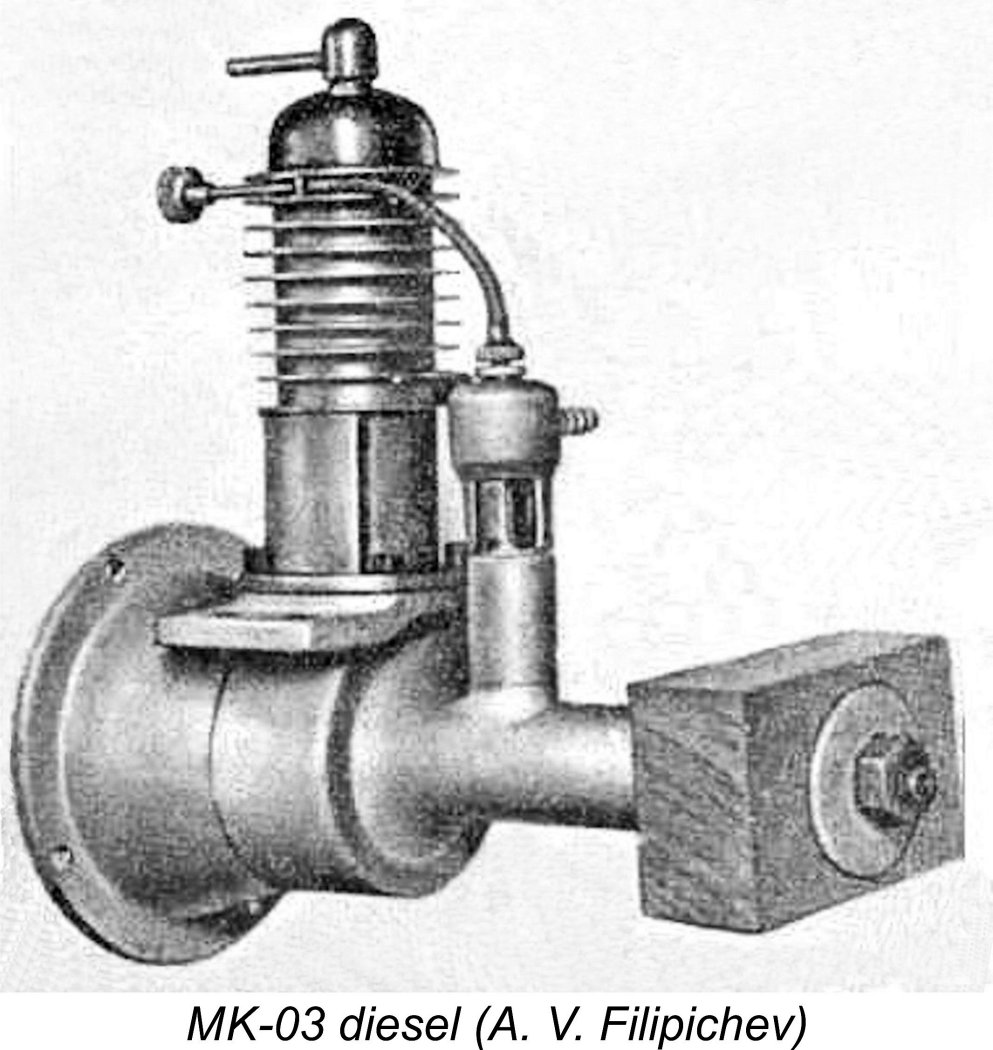

Up to that time, aeromodelling contests in the USSR had a very different character from those held elsewhere. Free flight and pioneering radio control models were the order of the day - control line only began to achieve any prominence in the late 1940's. Free flight power duration flying of the timed “climb ‘n glide” variety on a limited motor run was practised, but was seen as a bit of a sideshow to the main event, which was the establishment of records for free flight and R/C speed, distance, duration and altitude. The 7.5 cc MK-03 diesel illustrated here was designed by Vladimir Petukhov with such applications in mind. It was very succesful, setting several records during the late 1940's. Some of the Soviet records established in these categories are actually pretty impressive! In his 1954 book of which an English translation may be found elsewhere on this website, the prolific early post-WW2 model engine designer A. V. Filipichev tells us that by 1954 the main free flight (and R/C) records stood as follows: Duration - 6 hr 1 min Speed - 129 km/hr Distance - 378.756 km Altitude - 4,150 m The chase and spotting capabilities of the event officials must have been pretty impressive! I'd love to know how some of these records were measured! Given the focus upon the establishment of such records as opposed to the more familiar climb ‘n glide duration contests on a fixed motor run, it should come as no surprise to learn that Russian model engines up to 1950 were designed primarily with dependable operation at a steady power output over extended periods in mind. They also had to develop the grunt required to haul the necessary heavy fuel load aloft at the start of the flight.

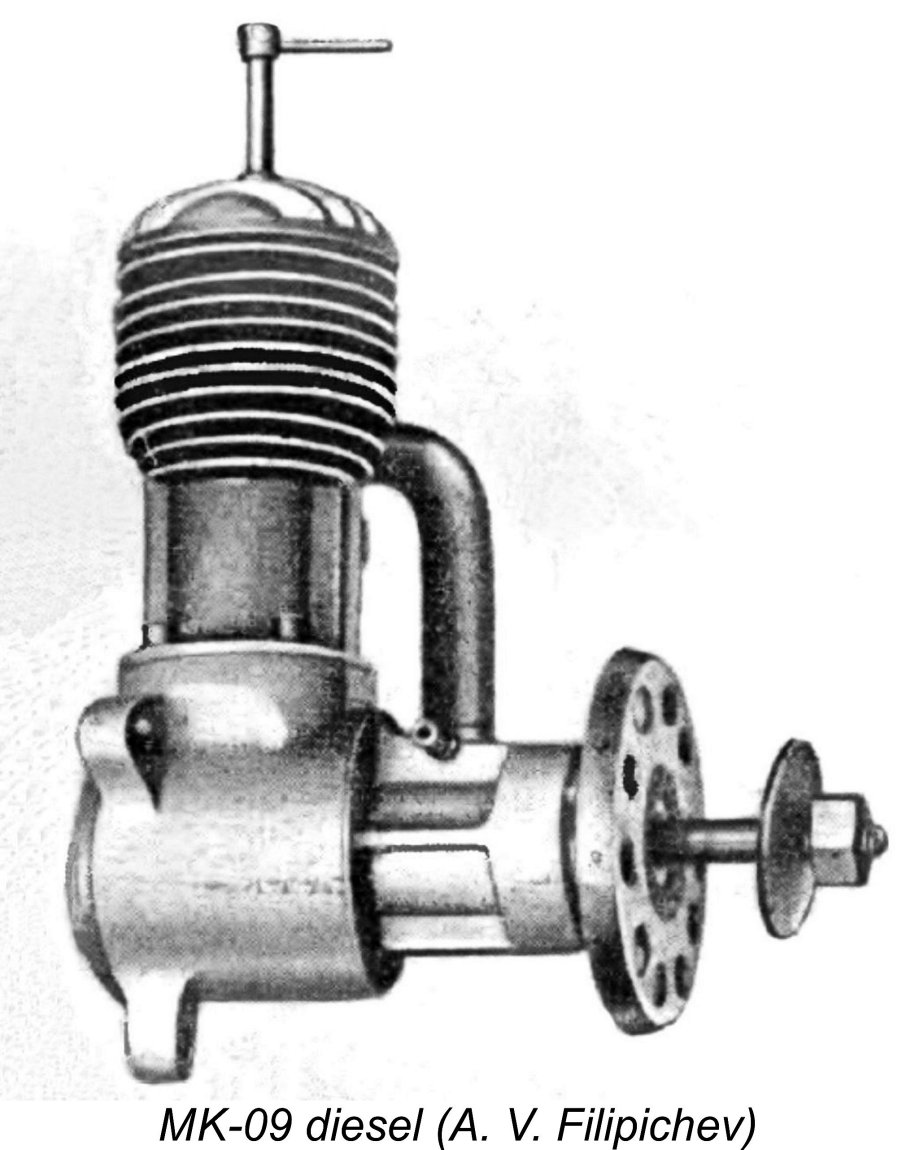

The 6.9 cc MK-09 diesel illustrated at the left is a case in point. It was another Petukhov design dating from 1949, notable as being the first Russian engine to feature a twin ball-race crankshaft. Petukhov himself used this engine in competition with great success, eventually extracting a claimed output of 0.62 BHP @ 10,500 rpm. The engine thus delivered the required mid-range grunt in buckets! Another widely under-appreciated factor is the extent to which participation in aeromodelling among young people was encouraged and supported by the Soviet State. Peter Chinn commented particularly on this factor in his previously-cited 1953 article. Until the early 1950’s, the State viewed the aeromodelling movement primarily as a vehicle for promoting air-mindedness and related skills and knowledge among young Russians who might develop into useful members or supporters of the Soviet Air Force. As such, the movement was seen as supportive of the military interests of the Soviet Union.

It's interesting to observe that all of the models in this image appear to be powered by 9.5 cc AMM spark ignition motors. The AMM 1 through 5 series engines were produced in large numbers, becoming the most widely-used powerplants in the USSR for at least a decade spanning the late 1930's to the late 1940's. They were slow-revving, torquey and very dependable units which were well suited to the Russian-style competitions of the day. Indeed, they were all that was available to many participants. During the early years of the 1950’s, the State's view of the role of aeromodelling began to expand. The authorities remained convinced of the value of aeromodelling in fostering air-mindedness and related skills among Russian youth, but now they also began to see success on the International aeromodelling contest field as a potentially important propaganda vehicle for promoting their claims to the superiority of their political system and technical capabilities.

For a variety of reasons, aeromodelling was a far more mainstream hobby at that time than it is today, with a very much higher proportion of younger and hence perhaps more impressionable participants worldwide (I was one of them from 1955 onwards!). The readership of the major Western modelling magazines therefore encompassed a very broad age group, with International contest results being reported, discussed and analysed in detail. Iron Curtain successes on the International aeromodelling stage thus reached the consciousness of a far wider audience than would be the case today, thereby furthering the political agendas of the countries involved. All well and good, but the achievement of success at the International level would require the Russians to engage in competition on International terms. Instead of their former record-breaking focus, they would now have to engage in climb-and-glide competitions on a limited motor run. Moreover, from 1949 onwards the International contest field began to expand to include various control-line categories. Both of these disciplines placed a far higher premium on power output, albeit over shorter periods during each flight. It was at this point that Russian model engine designers first began to direct their attention towards the development of higher-performance powerplants, at least a decade after designers in other countries had done so. This expanded State view of the role of aeromodelling brought another major hurdle into focus. The development of potentially contest-winning engines was not sufficient in itself - there was also a need to develop the skills of the model fliers who might use those engines successfully in competition. This required the development of a far larger pool of experienced competition fliers from among whom suitably skilled USSR representatives to International contests could be selected. In order to meet its objective of encouraging and supporting participation in aeromodelling, the State had already established clubs in numerous major communities as well as within the school system. These clubs represented a pool of fliers from among whom International representatives of the Soviet Union could be chosen. The problem was that the members of these clubs needed suitable engines to power their models and sharpen their skills, and these were in short supply. There were no private companies in the USSR to which the manufacture of model engines could be entrusted, leaving it to the State to fill this need.

Established in August 1951 through the merger of three earlier organizations, DOSAAF was in essence a para-military sport organisation concerned with the promotion of sporting activities which encouraged the development of skills which could be of service to the State in military capacities or which could enhance Soviet political prestige. Aeromodelling was one of those activities, as indeed was full-scale flying. DOSAAF was in the fortunate position of operating a number of full-sized aircraft maintenance facilities which could be tasked with model engine production as a sideline. They also had access to certain high-precision military workshops. During the Iron Curtain era, almost all series-production Russian model engines were manufactured at these State-owned facilities. It should be clear from the above discussion that the Soviet State’s motivation for becoming involved in commercial-scale model engine manufacture differed greatly from that in effect elsewhere. Engines in Western countries were developed primarily by private interests with the goal of making money through sales to the public in competition with one another. By contrast, those produced in the USSR during the hard-line Iron Curtain era were manufactured at the behest of the State with the short-term goal of using the engines as tools to develop a core population of experienced power modellers. The expanded long-term goal was now to have those modellers either go on to success on the International contest field, thus enhancing Russian prestige and political capital, or apply their developed technical skills to serving the State in military or technical capacities. Either way, the State came out ahead. Economic competition played little or no part in this until considerably later, when the Soviets began to open up their economy. In summary, the early 1950’s saw Russian model engine designers begin for the first time to direct their efforts towards the development of higher-performance engines which might serve the dual purposes of enabling a larger pool of young Russians to develop their aeromodelling skills while also enhancing the chances of selected participants achieving success at the International contest level. At the same time, the Soviet State (through DOSAAF) stepped up its efforts to make model engines more widely available in the USSR. Enter Vladimir I. Petukhov

From 1946 through to the early 1950’s, Petukhov developed an impressive series of diesel and spark ignition engines in a wide range of displacements. During this period, his designs generally addressed the previously-summarized requirements of model aircraft competitions as they then existed in the USSR. Many of Petukhov’s engines were very successful in these record-based competitions. His designs from this period are fully summarized in my separate article on the history of model engine development in the USSR. We’ve seen that as the 1950’s came around, the broadening State perception of the potential propaganda value of aeromodelling led to an increasing focus upon all-out short-term performance as opposed to dependable long-term operation. Petukhov was by no means immune to this - as a keen free flight competitor, he was doubtless mindful of the fact that the achievement of the hoped-for success on the International contest field under the limited motor run climb ‘n glide duration format which was applied to such contests placed a new emphasis on all-out engine performance.

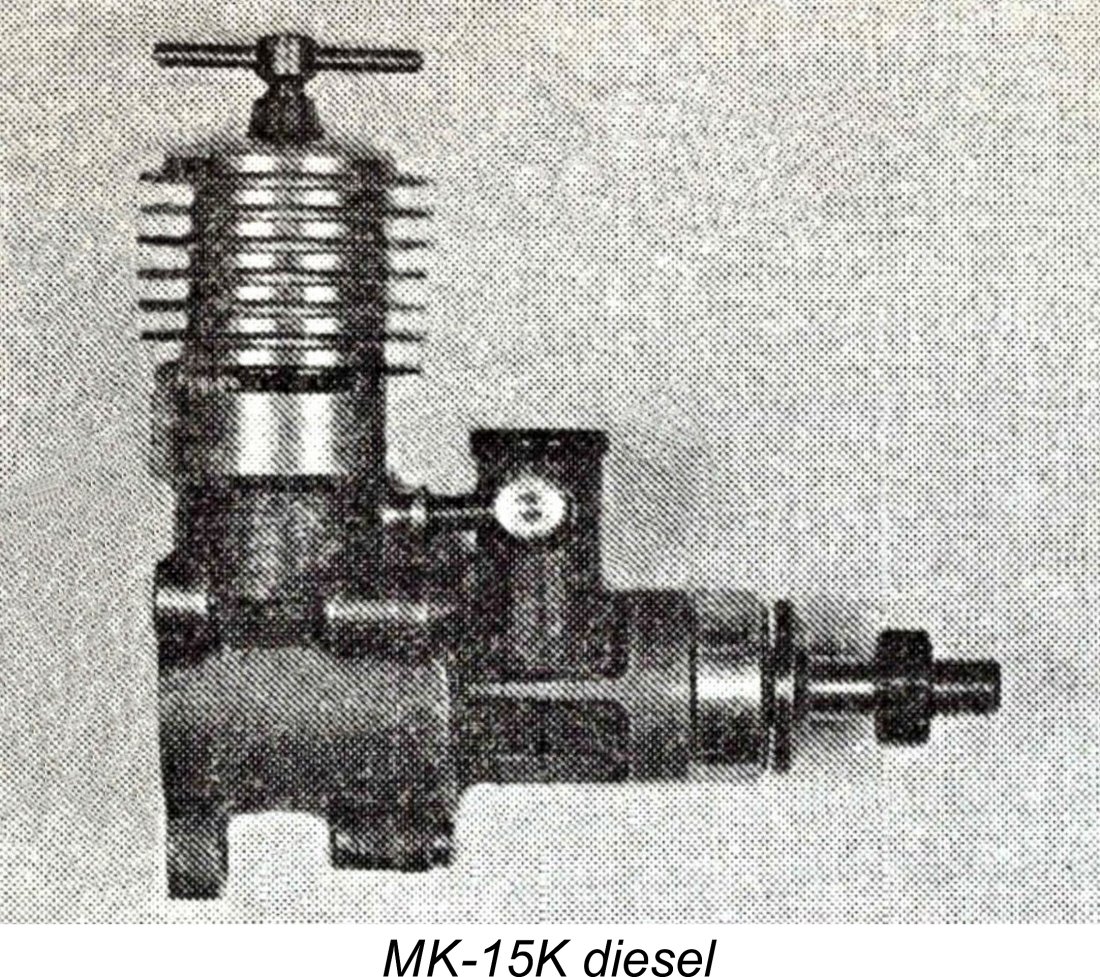

The engine’s initial output did not exceed 0.25 BHP, but over the following 4 years the design underwent steady development, its output eventually being brought up to 0.370 BHP at 18,500 rpm. Petukhov himself doubtless saw it all along as an FAI free flight powerplant, but his friend and fellow model engine designer Oleg K. Gajevski quickly recognized its potential as a control line speed motor. Using this engine, Gajevski Returning now to the early 1950’s, the MB-09KS undoubtedly represented a very impressive leap forward in the development of competitive model powerplants in Russia. Despite Gajevski’s very effective use of the engine in control line speed, Petukhov remained primarily interested in free flight competition, now in the context of the familiar FAI duration format based on a limited engine run as opposed to the former Soviet marathon record flights. Noting that 1.5 cc diesel engines with their matching smaller and lighter models were then showing very well in World Championship free flight competitions (1st place in 1952, Elfin 149 powered), he decided to develop his own 1.5 cc competition diesel specifically for free flight power models. A Predecessor - the MK-15K Diesel

The MK-15K was a twin ball-race FRV design featuring radial porting with a screw-on cooling jacket very like that used years later on the D-C Rapier. The front end looked a lot like a contemporary Super Tigre component. It was of the removable bolt-on variety, while the rear of the crankcase featured an integrally-cast backplate having three substantial lugs for radial mounting. I don't have bore and stroke figures for this engine, but I can report that the cited weight was a very light 72 gm (2.54 ounces). I have also been unable to locate any performance figures for the MK-15K, which never appears to have made it far if at all past prototype form. However, whatever those performance figures may have been, it's apparent that they did not satisfy Petukhov. He quickly went back to the drawing board and came up with a completely revised design based on RRV induction. The resulting prototypes of Petukhov's classic 1.48 cc MK-16 diesel appeared in 1954. At the time of this model's appearance in prototype form, it was still envisioned by its designer as a free flight contest engine. For this reason, the prototypes were once again assigned a K suffix standing for Конкуренция (Competition). It is this revised RRV model which forms our main subject here. From this point onwards, I'll focus strictly upon that model and its eventual successor, the MK-17. 1954 - the MK-16K Diesel Prototypes Appear

Bore and stroke were 12.85 mm and 11.40 mm respectively for a displacement of 1.48 cc (0.090 cuin.). The prototype unit weighed 102 gm (3.6 ounces). The cooling jacket was secured using three machine screws which bore against the lowest flange of the jacket, being accessed through long holes drilled through all of the cooling fins. The jacket's lowest The development of this engine was doubtless stimulated by DOSAAF’s announcement that in 1954 they would hold a competition for model engines as opposed to model aircraft. Their goal was to encourage Soviet model engine designers to come up with improved designs which might merit large-scale series production to meet the objectives discussed earlier. Their predecessor organization OSOAVIAHIM had held a similar competition in 1947, with very positive results. The prototype MK-16K diesel entered by Petukhov in the 1954 contest was an individually-constructed barstock model into which a great deal of care had been invested in fitting and tuning. There’s little doubt that corners had been cut in structural terms to minimize the engine’s reciprocating weight and maximize performance. This effort paid off - the MK-16K distinguished itself at the competition by demonstrating a peak power output of no less than 0.205 BHP @ 15,100 rpm. This was an outstanding performance for a 1.5 cc diesel at the time, although the engine was likely pushing the envelope in terms of structural integrity. It’s clear that the prototype MK-16K impressed the judges at the competition, because Petukhov was awarded first prize in the up to 1.5 cc category. Moreover, DOSAAF officials decided on the spot that this was one of a number of engines seen at the competition that merited series production. Oleg Gajevski’s 2.5 cc MK-12K was another, appearing in production form as the MK-12S in 1955. I’ve covered that model in a separate article. The MK-16 - Production History

The cast iron piston was provided with two shallow circumferential oil retention grooves above the gudgeon pin bosses. The cylinder porting used in the production version was of the familiar E.D. Racer reverse-flow pattern with three sawn exhaust ports in the port belt and three sawn transfer ports beneath them. The weakness of this design is the fact that it precludes any overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports. Consequently, the exhaust ports have to open somewhat earlier than ideal in order to secure an adequate transfer period. It's possible that the MK-16K prototypes used a more advance porting arrangement, but we have no evidence to this effect. Examination of my example shows that the exhaust ports of the MK-16 open at only 103 degrees after top dead centre for a rather lengthy exhaust period of 154 degrees. The transfers open very much later at 125 degrees after top dead centre for a relatively short transfer period of 110 degrees, with a lengthy 22 degree blow-down period. There is no sub-piston induction. The wide-open intake with a single nozzle for fuel delivery continued to be employed. The needle valve was of the externally threaded type, with a very neat split collet carrier for setting retention. The control arm was connected to the needle with a coil spring, allowing considerable latitude in the control's orientation during adjustments. A neat touch was the inclusion in the cylinder head of a steel insert having a similar split collet for the comp screw. This took care of any tendencies towards run-back of the compression setting. The balance of the design was seemingly little changed, although DOSAAF obviously recognized the fact that corners had been cut in terms of structural integrity to achieve the levels of performance demonstrated by the prototype at the competition. Accordingly, the engine was internally strengthened somewhat, resulting among other things in a rather higher reciprocating weight. Even so, the design was clearly still aimed at the extraction of maximum performance. The engine was equipped with an intake venturi having a very generous internal diameter of 5 mm. Allowing for the intrusion of the fuel nozzle which extended partway across this aperture, Maris Dislers' very helpful choke area calculator tells us that the effective area of this combination is of the order of 10 mm2. For a 1.48 cc engine, the minimum operating speed for good flexibility on suction is over 13,000 rpm! I'd say that this engine is definitely set up for maximum performance! I would anticipate suction and consistency issues with this unit unless operated at or near its peak.

Petukhov returned to the further development of his 2.5 cc MB-09KS glow-plug model, eventually coming up with an improved version of the engine which first appeared in prototype form in 1957 as the VIP-20. This model too was destined to enter series production in due course. It is included in my companion article on Soviet model engine development and manufacture. Petukhov also commenced his International free flight contest career at around this time, winning the 1956 Criterium of Europe meeting held that year at Subotica, Yugoslavia. Unfortunately, none of the Despite its demotion from full competition status, DOSAAF continued to see the MK-16 as a very useful engine to serve as a training powerplant for aspiring Russian aeromodellers at the club level. Consequently, the engine and its direct successors were destined to remain in production for many years, being manufactured in large numbers at various locations for distribution through model clubs and the school system to serve as a training powerplant. Interestingly enough, the various manufacturing facilities often appear to have adopted minor changes when setting up to produce the engines. Stan Pilgrim identified no fewer than 7 variants of the MK-16 in his collection. Generally speaking, the differences were very minor, not warranting the identification of the engines as separate series. However, it's worth noting that minor departures from the descriptions to be found here may be encountered. The quality of the various model engines produced as sidelines at DOSAAF’s aircraft The MK-16 and later MK-17 engines were favoured in this way, many of them being produced at the Moscow aircraft fuel systems plant (ZNAR). This explains their significantly higher-than-average quality by Russian standards. Writing years later in 1973, Peter Chinn recalled having been given an example of the original variant of the MK-16 with the detachable front bearing housing in the mid 1950’s. Chinn retrospectively characterized that variant as “quite the best Soviet-made model engine of its type that we had seen” (as of the mid 1950’s). High praise indeed from one of the world’s recognized model engine experts!

As recalled by Chinn, all three variants were constructed to very acceptable standards, also performing quite creditably. In fact, both the engine’s quality and performance were reportedly quite comparable with those of some highly-regarded contemporary British 1.5 cc models. Examination of present-day survivors bears out this assesment completely. The performance claim remained unchanged throughout at 0.14 BHP @ 14,000 rpm. The third and final version of the MK-16 was covered in Peter Chinn’s “Latest Engine News” column which appeared in the November 1973 issue of “Aeromodeller”. At that time, The Modeller’s Den had just begun to import the engine into England.

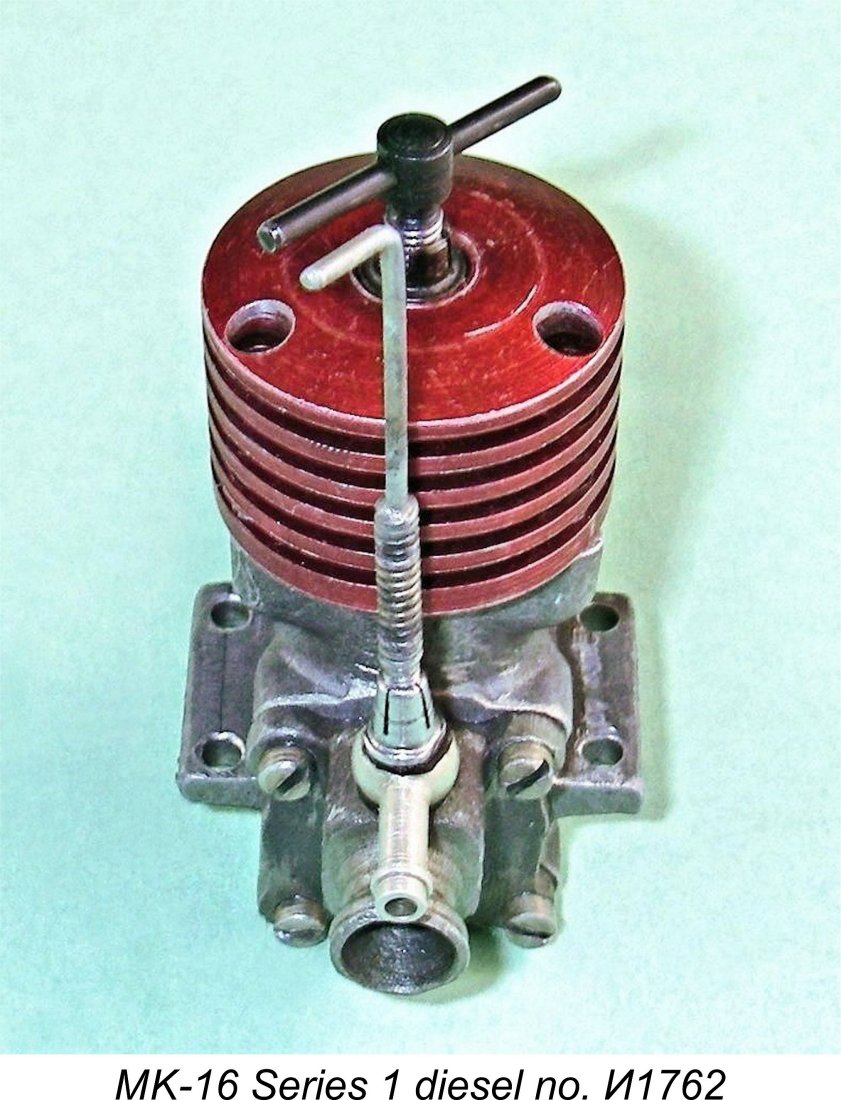

The MK-17 was envisioned from the start as a potential export model, being presented and packaged accordingly. Like its MK-16 predecessor, it was imported into England, first by The Modeller’s Den and later by Modusa. Through the ongoing efforts of the Production at some level appears to have continued into the early 1990's. New-in-Box examples were still widely available in the mid 1990’s following the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1989. The MK-17 was the subject of generally positive published test reports which appeared in 1987 and 1994 in the pages of “Model Builder” and “Aeromodeller” respectively. The engine was also covered in some detail in an article written by my late friend Ron Chernich, which may still be accessed on Ron’s now-frozen “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. Readers requiring more information on the MK-17 are referred to Ron's article. As an interesting post-script, I can report that a September 2021 phone call with my late friend Ed Carlson of Carlson Engine Imports in Phoenix, Arizona revealed that as of that time Ed still retained a fairly good stock of boxed MK-17 diesels which he was selling at quite reasonable prices. A 2024 check on the website, which is now maintained by Ed's son Randy, revealed that the MK-17 remained available along with a number of other engines from Ed's stock. If interested, give Randy a call at 602-863-1684. Having now traced the development and production history of the MK-16K and its successors, we can now get down to the main task confronting us - testing an example of the original 1955 production version of the MK-16 which Peter Chinn recalled so fondly. So let’s get down to it - break out the ether!! Mmmmm .........love that aroma!! The MK-16 on Test My test example of the MK-16 is one of the original production models, retaining the detachable front housing of the original MK-16K prototype. It bears the inscribed model identification MK-16 on the outer end of the left-hand mounting lug, while the serial number И1762 appears on the outer end of the opposite lug. The Cryllic character И is pronounced as E (as in teeth) in English. It is likely a batch indicator in this case. The engine also displays the previously-illustrated engraved star cartouche on the right hand side of the main bearing housing. All three MK-16 variants displayed this cartouche in one form or another.

I used a fuel consisting of 45% kerosene, 30% ether and 25% castor oil, to which I added 2% ignition improver. This should be a reasonably effective brew for a classic competition diesel. I got things started with an APC 9x4 airscrew fitted. The MK-16 proved to be a very easy starter, in large part thanks to its absolutely perfect piston/cylinder fit. John Oliver couldn't have done better! When cold, an exhaust prime was found to be helpful, but hot restarts required only one or two choked flicks. An immediate observation was the fact that with its very free-breathing induction system the MK-16 was a bit slow to pick up the fuel supply on a firing burst. It definitely liked to have the fuel in the tank set at around the same level as the centre of the intake venturi. However, once running, suction appeared to be quite acceptable.

I notice that in his 1993 test of the engine's MK-17 successor (published in "Aeromodeller" in March 1994), Richard Herbert reported exactly the same behaviour when running that engine on a 5 mm diameter venturi. It's pretty clear that on this venturi a wise user would employ a slightly rich mixture for flying. The engine continues to run very smoothly on a slightly rich mixture - it just slows down a little. Apart from this idiosyncracy, the engine ran flawlessly throughout the test, never missing a beat and with no tendency to sag. Starting remained excellent at all times. Both controls were extremely smooth in operation, also holding their settings perfectly at all speeds tested. The exhaust residue remained clear and free from any evidence of undue wear or poor combustion. At the end of the test, the MK-16 remained in perfect condition, seemingly all ready for more. I have to say that the engine exceeded my performance expectations by some margin. The following data were recorded on test.

The two WB props are wide-blade items created by cutting down standard APC props and then calibrating them to fill gaps in my stardard test set. As can be seen from the above data, the MK-16 developed some 0.168 BHP @ 13,800 rpm - about the claimed peaking speed, but significantly more power. As of 1955, very few British 1.5 cc diesels could match or even approach these figures. So much for any illusions about Russian modellers not having access to good model engines! With the engine's fine handling, excellent performance and seemingly more than acceptable quality, any British modeller would have been glad to have one of these units to use back in the Fifties!

This used un-boxed example is fitted with the 3.5 mm internal diameter venturi insert which seems to have been the "normal" fitting for this engine. However, the MK-17 was supplied with an optional 5 mm diameter insert for those who wanted a bit more urge. With the 3.5 mm insert in place, the MK-17 was a real sweetheart to handle, starting and running just as well as its MK-16 predecessor. Needle response was very smooth and predictable with none of the cutting-out tendency on a slightly lean mixture and far better fuel pickup on starting. However, it was inevitable that there would be a price to pay. Running on its 3.5 mm venturi, the MK-17 didn't come close to matching its MK-16 companion with its significantly larger 5 mm venturi. The data below speak for themselves.

As can be seen, the MK-17 delivered around 0.132 BHP @ 12,700 rpm - a little less than the claimed output, but at a slightly higher speed. This is still a very acceptable classic sports diesel performance, besides which the engine handles and runs extremely well at all times. A 7x6 prop would suit it very well for control line, while an 8x3 would doubtless work well for free flight. Just for fun (we all need more of that!), I made a venturi insert with a 5 mm internal diameter to test the effect. There was indeed a very marked improvement in performance, with prop speeds going up by 400-500 rpm. As we would expect, the improvement was most marked on the faster props, since the 3.5 mm venturi is evidently adequate to supply the engine's needs at the lower speeds. It only becomes really limiting as speeds go up. The following data were recorded using this venturi.

The change to the larger-bore venturi obviously released more power. The MK-17 now appeared to develop around 0.148 BHP @ 13,200 rpm. Interestingly enough, this is almost exactly the output cited by Peter Chinn, albeit at slightly higher rpm. It represents a very creditable performance for a classic 1.5 cc diesel whose design effectively dates back to the mid 1950's. However, it still falls some way short of matching the outstanding performance measured for my example of the original MK-16 of 1955. One point worth mentioning is the fact that the MK-17 now exhibited the same behaviour as observed with the MK-16 with its similar 5 mm venturi - fuel draw on starting was less secure, while the same tendency to cut dead on a lean mixture was also present. Richard Herbert's observations were completely validated. Conclusion

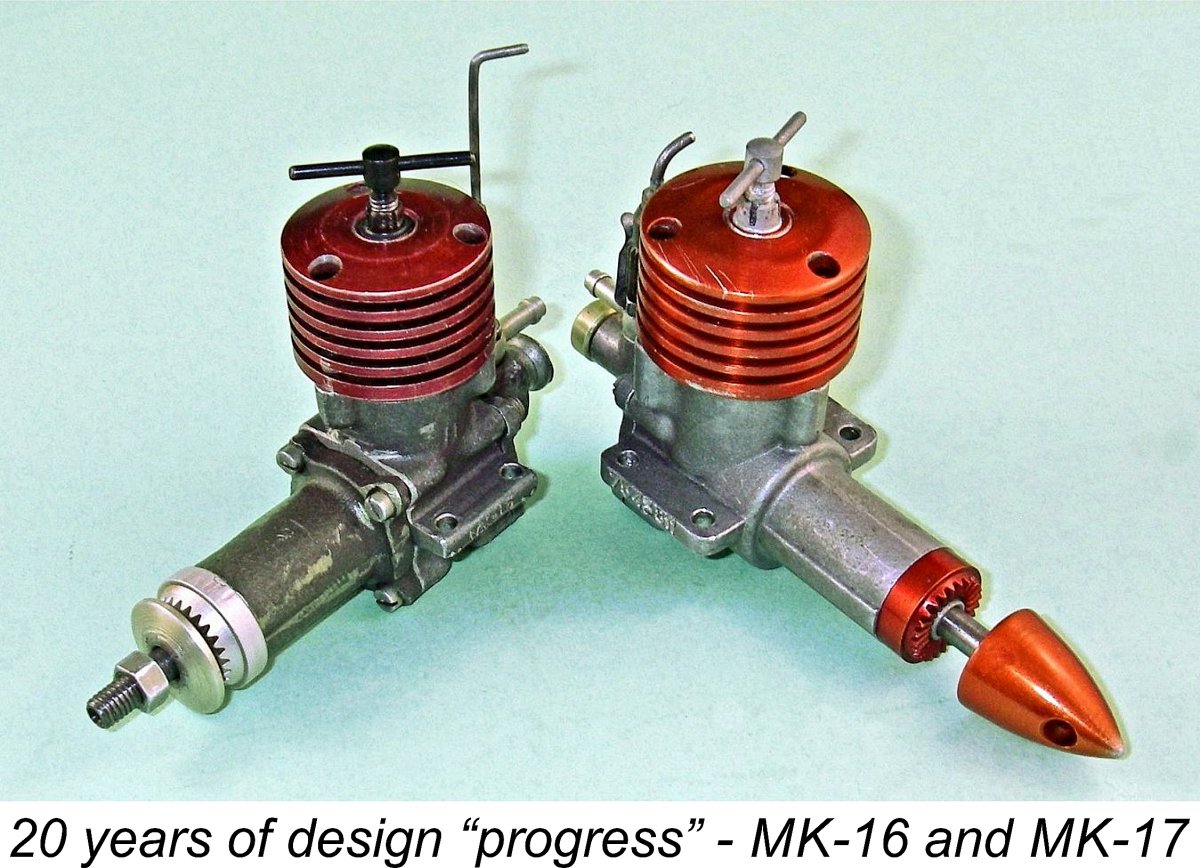

Mind you, the MK 1.48 cc models were by no means unique among Russian model engines in enjoying an unusually long production life. It appears that when it came to maintaining a supply of useable low-cost engines for the “average” modeller to use in gaining experience, DOSAAF saw no reason to replace a given design in the absence of some very pressing motivation. If an engine did the job in terms of providing aspiring aeromodellers with an easy-handling and dependable powerplant with which to gain experience or just have fun, why replace it? We can look at the 35 year production life of the MD-5 Kometa as another example. The 2.5 cc MK-12V stayed the course for some 23 years, while even the RITM 2.5 cc diesel survived for 17 years or so in various guises. For me, an ongoing puzzle is ...... why the name change?!? When the MK-17 appeared in around 1975, the MK-16 had already been in production for 20 years under that name. So why wasn't the MK-17 released as simply the 4th variant of an already highly regarded 1.5 cc sports diesel? After all, it was very little changed in reality. The most probable explanation seems to me to be that DOSAAF wanted to create the impression that the MK-17 was a revised design rather than merely "more of the same", thus implying some degree of improvement to impress potential users and perhaps persuade existing MK-16 users to make the switch. It may also be no coincidence that the name change more or less coincided with Novoexport's major export push in the early to mid 1970's. The idea may well have been to allow them to promote the MK-17 as a "new improved" model, which it really wasn't. Whatever the reasoning involved, the fact remains that the MK-16/17 series must be viewed as one of the all-time great classic model diesel lines of its displacement. A series production life of over 35 years speaks eloquently to this, as do the many thousands of satisfied users who have enjoyed flying with one of these excellent engines. Well done, Vladimir Petukhov - a great legacy!! _____________________ Article Ⓒ Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2020

|

||

| |

In this article I’ll present a focused review and bench test of one of the first legitimate International-standard contest engines to come out of early post-WW2 Russia. I’ll be reviewing the 1955 initial variant of the 1.48 cc MK-16 diesel seen at the left. This fine little powerplant was designed by Vladimir I. Petukhov, one of Russia's leading free flight competitors of the 1940's and '50's, as a free flight competition motor. In its competition guise, it was designated as the MK-16K model. It proved to be the first of an extended series of basically similar engines extending all the way into the 1990's.

In this article I’ll present a focused review and bench test of one of the first legitimate International-standard contest engines to come out of early post-WW2 Russia. I’ll be reviewing the 1955 initial variant of the 1.48 cc MK-16 diesel seen at the left. This fine little powerplant was designed by Vladimir I. Petukhov, one of Russia's leading free flight competitors of the 1940's and '50's, as a free flight competition motor. In its competition guise, it was designated as the MK-16K model. It proved to be the first of an extended series of basically similar engines extending all the way into the 1990's.  In his ground-breaking 1953 article entitled “Russia’s Engines” which appeared in the September 1953 issue of “Model Airplane News”, Peter Chinn commented that the Russian engines of which he was then aware appeared to be at least 5 years behind their Western contemporaries in design terms. What Chinn (and consequently his readers) evidently failed to appreciate was the fact that this was not down to any lack of knowledge or ability among Russian designers, but rather to the very different expectations which Russian competition power modellers placed upon their engines up to the early 1950’s.

In his ground-breaking 1953 article entitled “Russia’s Engines” which appeared in the September 1953 issue of “Model Airplane News”, Peter Chinn commented that the Russian engines of which he was then aware appeared to be at least 5 years behind their Western contemporaries in design terms. What Chinn (and consequently his readers) evidently failed to appreciate was the fact that this was not down to any lack of knowledge or ability among Russian designers, but rather to the very different expectations which Russian competition power modellers placed upon their engines up to the early 1950’s.  Consequently, all-out power was not a significant factor in Russian design thinking at this time - what was wanted was the dependable delivery of plenty of mid-range grunt and good fuel economy over extended periods of engine operation. It was this design focus which led to the 1950's Western perception that Russian model engine designs were lagging far behind design advances in other countries. This was an unfair disparagement of the abilities of Russian designers - the truth was that those designers were every bit as capable as their Western counterparts. They were simply designing to meet very different performance criteria.

Consequently, all-out power was not a significant factor in Russian design thinking at this time - what was wanted was the dependable delivery of plenty of mid-range grunt and good fuel economy over extended periods of engine operation. It was this design focus which led to the 1950's Western perception that Russian model engine designs were lagging far behind design advances in other countries. This was an unfair disparagement of the abilities of Russian designers - the truth was that those designers were every bit as capable as their Western counterparts. They were simply designing to meet very different performance criteria.  The consequent efforts of OSOAVIAHIM, the State-controlled organization responsible (among many other things) for the development and organization of Soviet aeromodelling, seem to have been quite successful. Aeromodelling appears to have been just as popular in the USSR as it was elsewhere, although Russian activity was essentially invisible to observers in other countries due to political and liguistic barriers. The attached image of a line-up of competitors at a 1947 Moscow contest speaks eloquently to the capabilities and enthusiasm of Russian aeromodellers of the time. Modellers the world over would have got along just fine with these lads - leave the ideological squabbles to the politicians!

The consequent efforts of OSOAVIAHIM, the State-controlled organization responsible (among many other things) for the development and organization of Soviet aeromodelling, seem to have been quite successful. Aeromodelling appears to have been just as popular in the USSR as it was elsewhere, although Russian activity was essentially invisible to observers in other countries due to political and liguistic barriers. The attached image of a line-up of competitors at a 1947 Moscow contest speaks eloquently to the capabilities and enthusiasm of Russian aeromodellers of the time. Modellers the world over would have got along just fine with these lads - leave the ideological squabbles to the politicians!  To many in the present day and age, the fact that the Communist regimes of the 1950’s came to see model airplane competition in this light may appear a bit surprising. It’s a question of context - to understand this perspective, we have to mentally transport ourselves back over

To many in the present day and age, the fact that the Communist regimes of the 1950’s came to see model airplane competition in this light may appear a bit surprising. It’s a question of context - to understand this perspective, we have to mentally transport ourselves back over  By the start of the period covered by our main subject, the management of the aeromodelling movement in the USSR formerly entrusted to OSOAVIAHIM had been assumed by a new organization called DOSAAF (

By the start of the period covered by our main subject, the management of the aeromodelling movement in the USSR formerly entrusted to OSOAVIAHIM had been assumed by a new organization called DOSAAF (

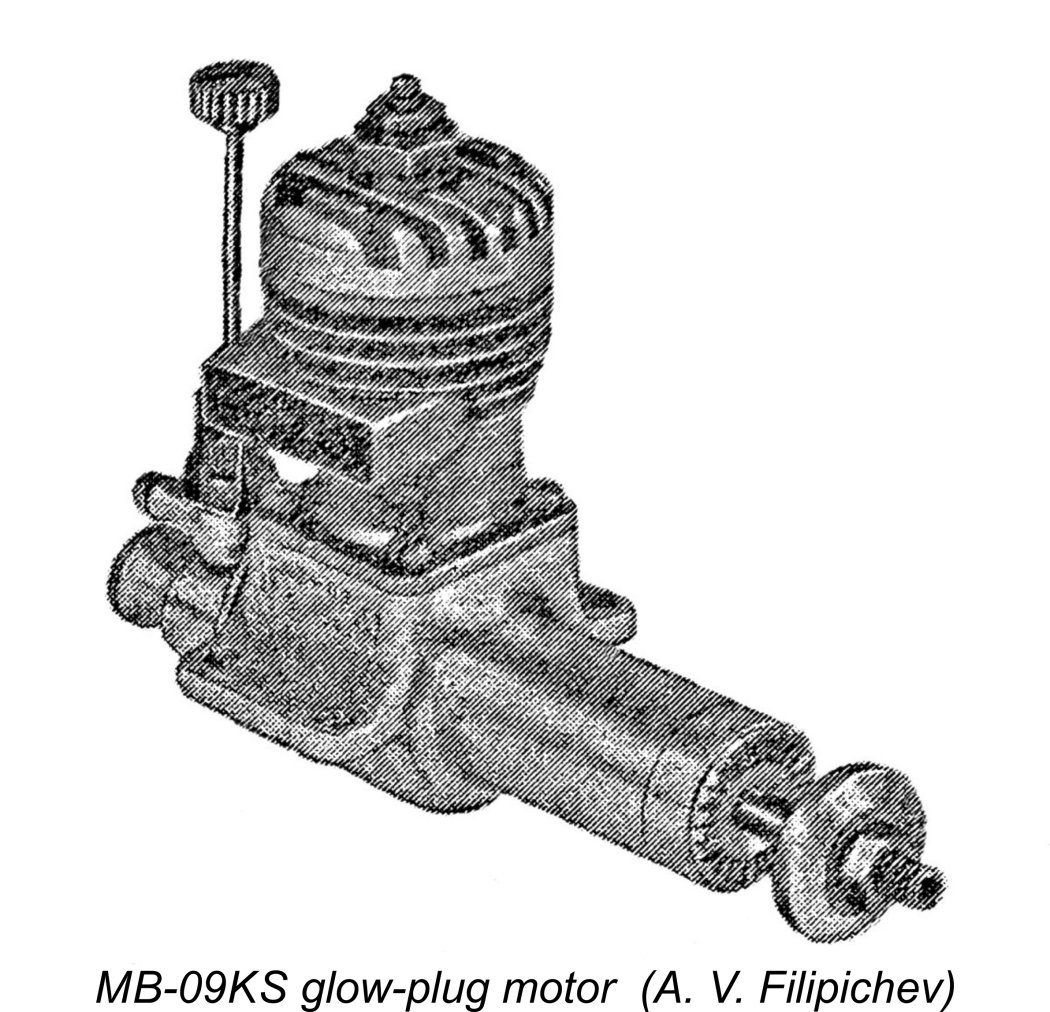

Petukhov’s first attempt to create an engine which would serve well as an International free flight powerplant was Russia’s first truly up-to-date competition glow-plug motor, the 2.5 cc MB-09KS of 1952. This unit made no pretence to be anything other than an all-out racing engine. Although its construction was a bit on the antiquated side with an integrally-finned bolt-on steel cylinder having a brazed-on bypass and exhaust stack, the MB-09KS did incorporate such then up-to-date features as cross-flow loop scavenging, a twin ball-race crankshaft, disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction, a non-metallic disc valve rotor, a big-bore intake and a remote needle valve with a single-nozzle jet. Another relatively advanced feature in hindsight was the use in some examples of a lightweight lapped cast iron piston, a route which many others (including Super Tigre beginning in 1955) were later to follow.

Petukhov’s first attempt to create an engine which would serve well as an International free flight powerplant was Russia’s first truly up-to-date competition glow-plug motor, the 2.5 cc MB-09KS of 1952. This unit made no pretence to be anything other than an all-out racing engine. Although its construction was a bit on the antiquated side with an integrally-finned bolt-on steel cylinder having a brazed-on bypass and exhaust stack, the MB-09KS did incorporate such then up-to-date features as cross-flow loop scavenging, a twin ball-race crankshaft, disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction, a non-metallic disc valve rotor, a big-bore intake and a remote needle valve with a single-nozzle jet. Another relatively advanced feature in hindsight was the use in some examples of a lightweight lapped cast iron piston, a route which many others (including Super Tigre beginning in 1955) were later to follow.  broke a whole series of All-Union 2.5 cc speed records, culminating in 1956 with a speed of 183 km/hr (113.7 mph, on two lines in 1956, remember). This speed would have been good enough to win the previous year’s World Control Line Speed Championship quite handily! Even in 1956, it would have given Gajevski 3

broke a whole series of All-Union 2.5 cc speed records, culminating in 1956 with a speed of 183 km/hr (113.7 mph, on two lines in 1956, remember). This speed would have been good enough to win the previous year’s World Control Line Speed Championship quite handily! Even in 1956, it would have given Gajevski 3 The initial result of Petukhov’s efforts was the 1953 appearance of a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) twin ball-race 1.48 cc diesel designated the MK-15K. At the time of this model's appearance in prototype form, the MK-15 was envisioned by its designer as a free flight contest engine. This being the case, the K suffix doubtless stood for Конкуренция (Competition) - the FAI had yet to formally adopt the 2.5 cc displacement standard for International power contests.

The initial result of Petukhov’s efforts was the 1953 appearance of a crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) twin ball-race 1.48 cc diesel designated the MK-15K. At the time of this model's appearance in prototype form, the MK-15 was envisioned by its designer as a free flight contest engine. This being the case, the K suffix doubtless stood for Конкуренция (Competition) - the FAI had yet to formally adopt the 2.5 cc displacement standard for International power contests.  By this point in time, Petukhov was well on top of the business of designing a competitive free flight powerplant. Like his earlier MB-09KS model, the MK-16K was a relatively advanced design for its day, actually drawing to some extent upon the design of its 2.5 cc glow-plug predecessor. It featured a twin ball-race crankshaft mounted in a separate bolt-on front housing along with RRV induction and a racing-style remote needle valve with single-nozzle fuel jet and a banjo fuel pickup, very much along the lines of the components used in the MB-09KS.

By this point in time, Petukhov was well on top of the business of designing a competitive free flight powerplant. Like his earlier MB-09KS model, the MK-16K was a relatively advanced design for its day, actually drawing to some extent upon the design of its 2.5 cc glow-plug predecessor. It featured a twin ball-race crankshaft mounted in a separate bolt-on front housing along with RRV induction and a racing-style remote needle valve with single-nozzle fuel jet and a banjo fuel pickup, very much along the lines of the components used in the MB-09KS.

The production version of Petukhov’s MK-16K model seems to have appeared in 1955. The process of getting the engine to the production stage was not quite as straightforward as it might appear. As mentioned above, the prototypes were fully machined from bar stock, but it was understandably decided that this would not serve for large-scale series manufacture. The design was therefore amended to feature die-cast major components, including the crankcase, front housing and backplate. Both of the latter components continued to be removable, being secured with 4 machine screws apiece.

The production version of Petukhov’s MK-16K model seems to have appeared in 1955. The process of getting the engine to the production stage was not quite as straightforward as it might appear. As mentioned above, the prototypes were fully machined from bar stock, but it was understandably decided that this would not serve for large-scale series manufacture. The design was therefore amended to feature die-cast major components, including the crankcase, front housing and backplate. Both of the latter components continued to be removable, being secured with 4 machine screws apiece.

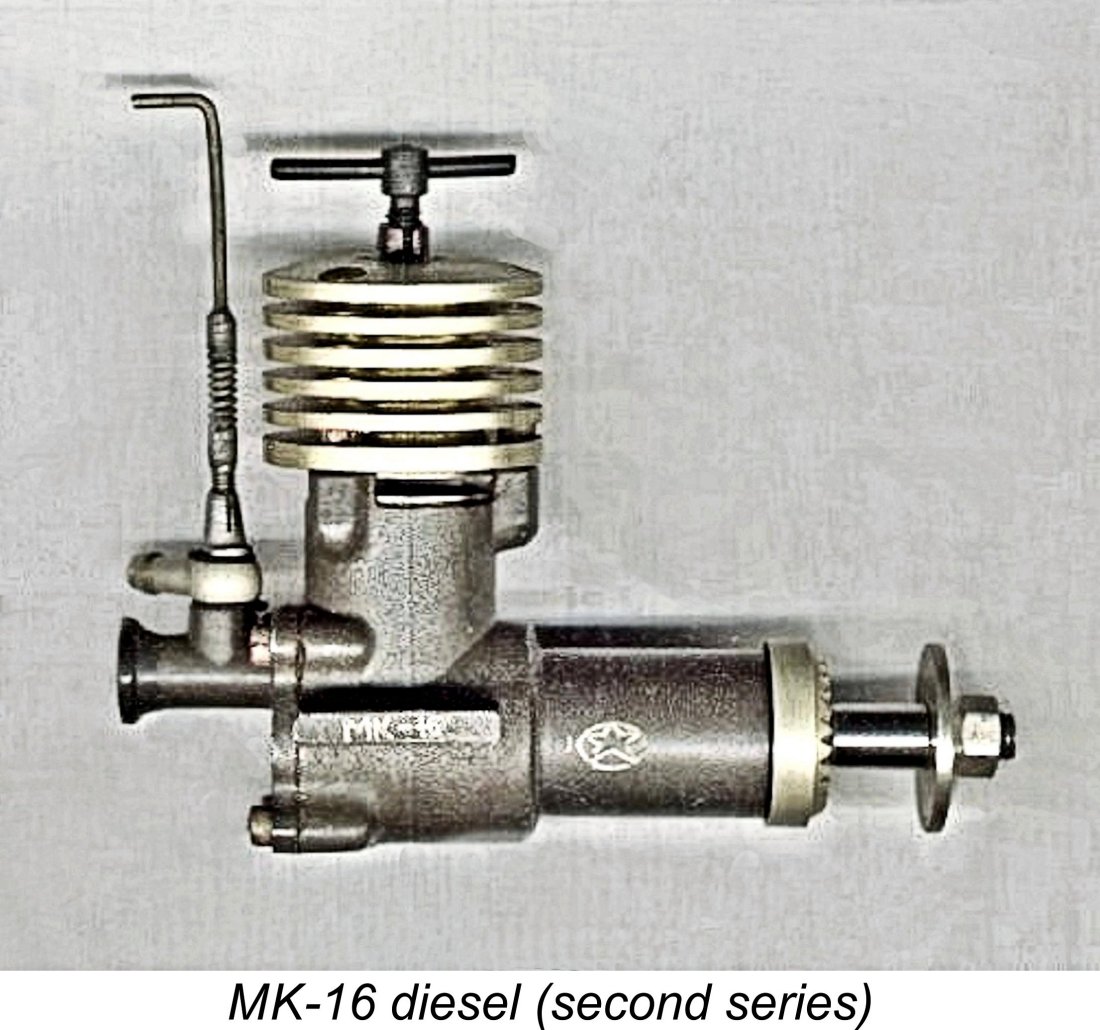

At some point in time, the design was further simplified through the elimination of the removable front housing. In this revised form, the MK-16 passed through two more variants lacking the K suffix and featuring integrally-cast main bearing housings instead of the former detachable component. At present I have no information regarding the dates of the various design transitions. I'm very much open to the receipt of additional information!

At some point in time, the design was further simplified through the elimination of the removable front housing. In this revised form, the MK-16 passed through two more variants lacking the K suffix and featuring integrally-cast main bearing housings instead of the former detachable component. At present I have no information regarding the dates of the various design transitions. I'm very much open to the receipt of additional information!  Although the exact dates are a little obscure, it appears to have been at some point in the mid 1970’s that the MK-16’s successor, the 1.48 cc MK-17 twin ball-race RRV diesel, made its appearance. Peter Chinn first discussed this model in his “Latest Engine News” column in the February 1976 issue of “Aeromodeller”, characterizing it as a replacement for the MK-16. He cited a performance claim of 0.15 BHP @ 12,000 rpm for the revised design - a little more power, but at lower rpm.

Although the exact dates are a little obscure, it appears to have been at some point in the mid 1970’s that the MK-16’s successor, the 1.48 cc MK-17 twin ball-race RRV diesel, made its appearance. Peter Chinn first discussed this model in his “Latest Engine News” column in the February 1976 issue of “Aeromodeller”, characterizing it as a replacement for the MK-16. He cited a performance claim of 0.15 BHP @ 12,000 rpm for the revised design - a little more power, but at lower rpm.  The MK-17 was really nothing more than a further development of the third variant of the MK-16, with which it is often confused “across the room”. Apart from being clearly marked as the MK-16, the earlier models all bore a star cartouche engraved or cast onto their main bearing housings. This was missing from the MK-17, which is clearly identified as such on its main casting. The MK-17 also featured a separate venturi insert and adjustable rotor mounting pin secured by a set-screw. These are clearly shown in the backplate view at lower right. There is thus no real basis for any confusion following a close inspection.

The MK-17 was really nothing more than a further development of the third variant of the MK-16, with which it is often confused “across the room”. Apart from being clearly marked as the MK-16, the earlier models all bore a star cartouche engraved or cast onto their main bearing housings. This was missing from the MK-17, which is clearly identified as such on its main casting. The MK-17 also featured a separate venturi insert and adjustable rotor mounting pin secured by a set-screw. These are clearly shown in the backplate view at lower right. There is thus no real basis for any confusion following a close inspection.

Although it has clearly been bench-run, this example does not appear to have been mounted in a model - there are no witness marks around the mounting holes. Even so, it looks and feels as if it is well run-in and all ready for testing. Just to be on the safe side, I elected to give it a few shake-down runs on an 9x4 airscrew.

Although it has clearly been bench-run, this example does not appear to have been mounted in a model - there are no witness marks around the mounting holes. Even so, it looks and feels as if it is well run-in and all ready for testing. Just to be on the safe side, I elected to give it a few shake-down runs on an 9x4 airscrew.  Further evidence of this characteristic came upon closer investigation of the engine's control response characteristics. I found that response to the fuel neede was completely normal and quite satisfactory unless one went a little leaner than the sweet spot. Instead of exhibiting the usual crackling misfire on a slightly too-lean mixture, the engine made its views known far more directly - it simply stopped dead! No warning at all - it just stopped!

Further evidence of this characteristic came upon closer investigation of the engine's control response characteristics. I found that response to the fuel neede was completely normal and quite satisfactory unless one went a little leaner than the sweet spot. Instead of exhibiting the usual crackling misfire on a slightly too-lean mixture, the engine made its views known far more directly - it simply stopped dead! No warning at all - it just stopped!

Just out of interest, I decided to run some comparative tests on an example of the MK-17 which replaced the MK-16 in the mid 1970's. Engine number 7543811 has clearly seen some use and has a slightly shortened needle valve, but is otherwise complete, original and in fine mechanical condition. The first two digits appear to indicate the year of manufacture. I've seen numbers as high as 92, suggesting that production may still have been ongoing at that date. New-in-Box examples of the MK-17 were undoubtedly still being marketed at that time.

Just out of interest, I decided to run some comparative tests on an example of the MK-17 which replaced the MK-16 in the mid 1970's. Engine number 7543811 has clearly seen some use and has a slightly shortened needle valve, but is otherwise complete, original and in fine mechanical condition. The first two digits appear to indicate the year of manufacture. I've seen numbers as high as 92, suggesting that production may still have been ongoing at that date. New-in-Box examples of the MK-17 were undoubtedly still being marketed at that time.

If an engine's merits may fairly be judged by the length of time over which it remained in production in one form or another, the MK-16/17 series must have its place among the most successful series of all time. One can look at such units as the Oliver Tiger, Fox 35 and

If an engine's merits may fairly be judged by the length of time over which it remained in production in one form or another, the MK-16/17 series must have its place among the most successful series of all time. One can look at such units as the Oliver Tiger, Fox 35 and