|

|

Jodhpur Jewels - the Sharma Engines

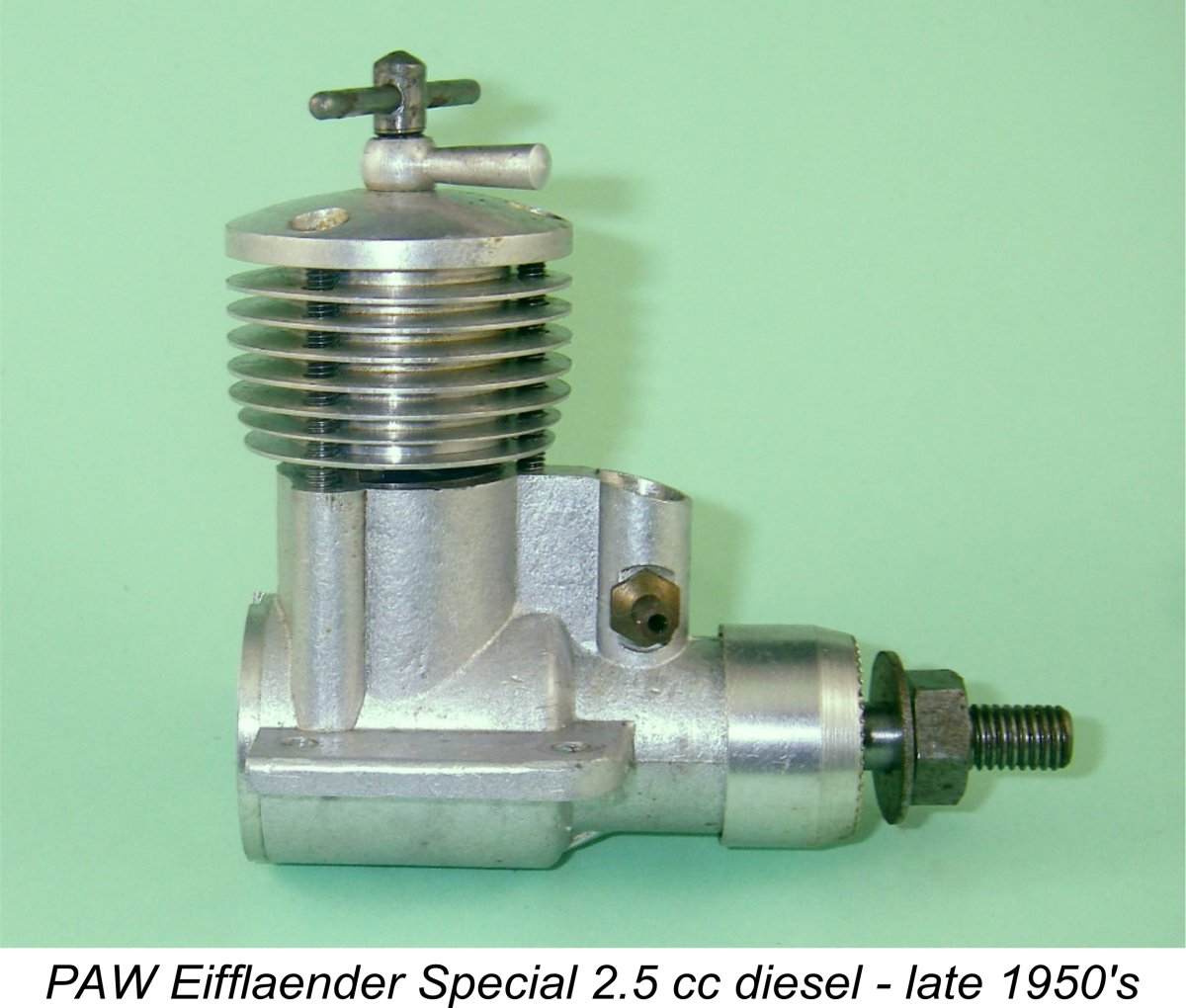

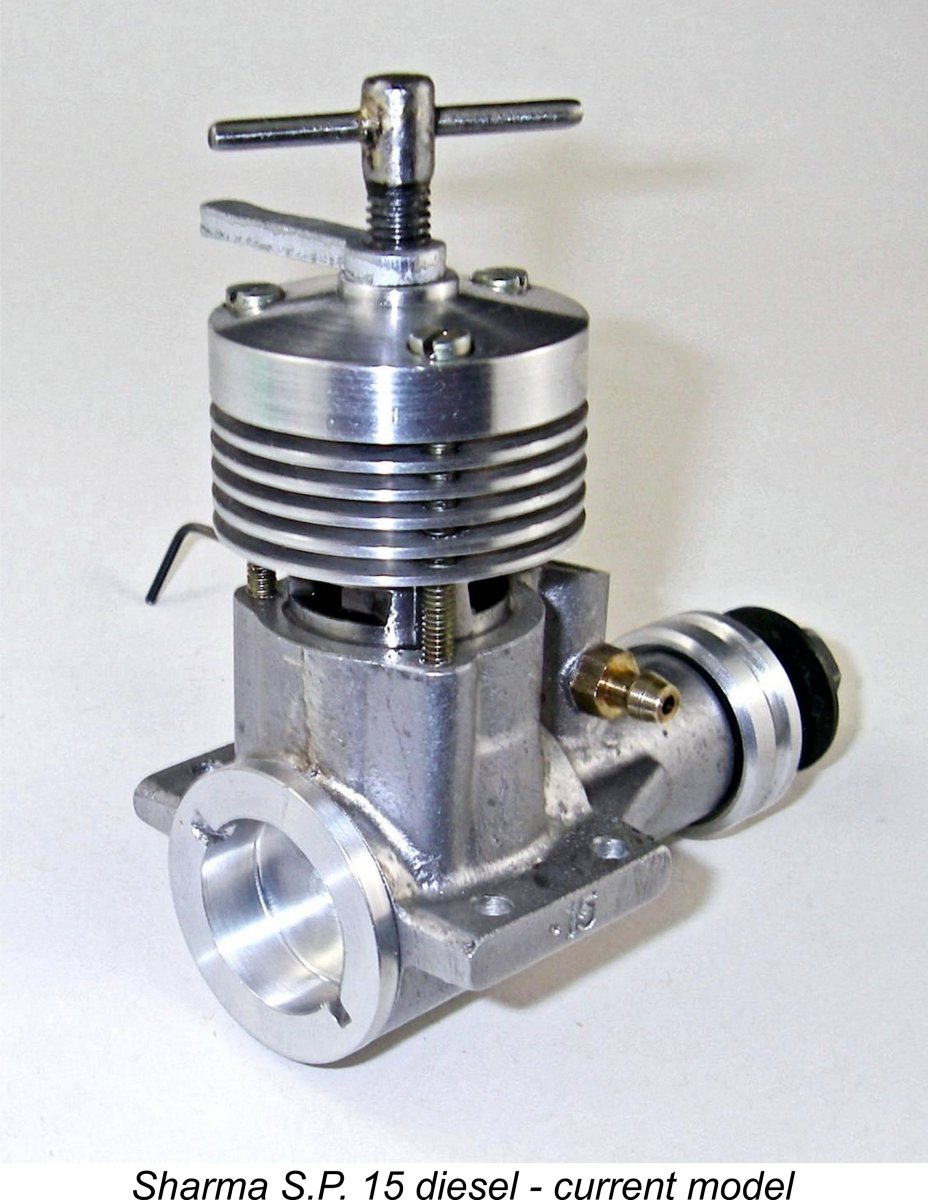

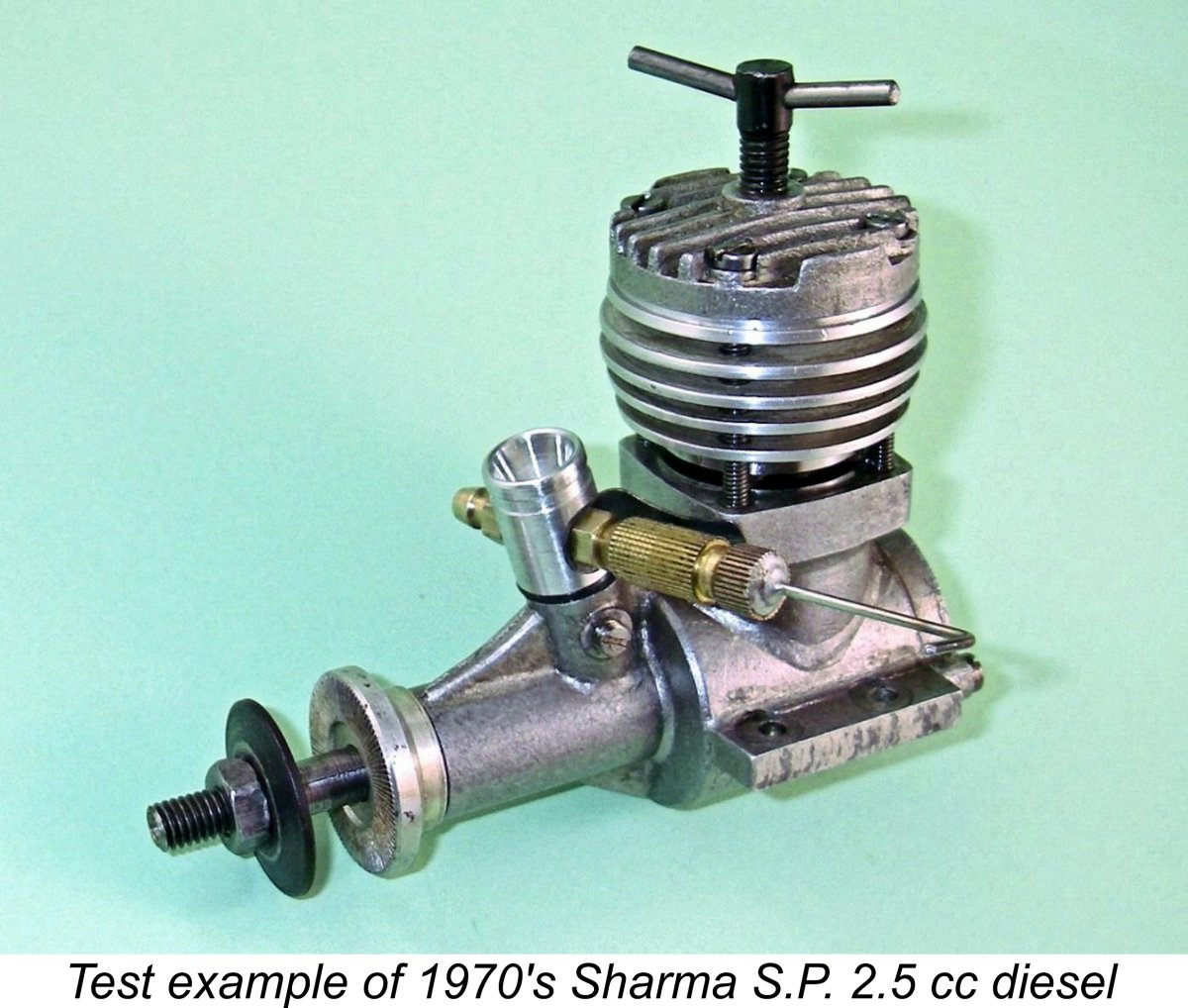

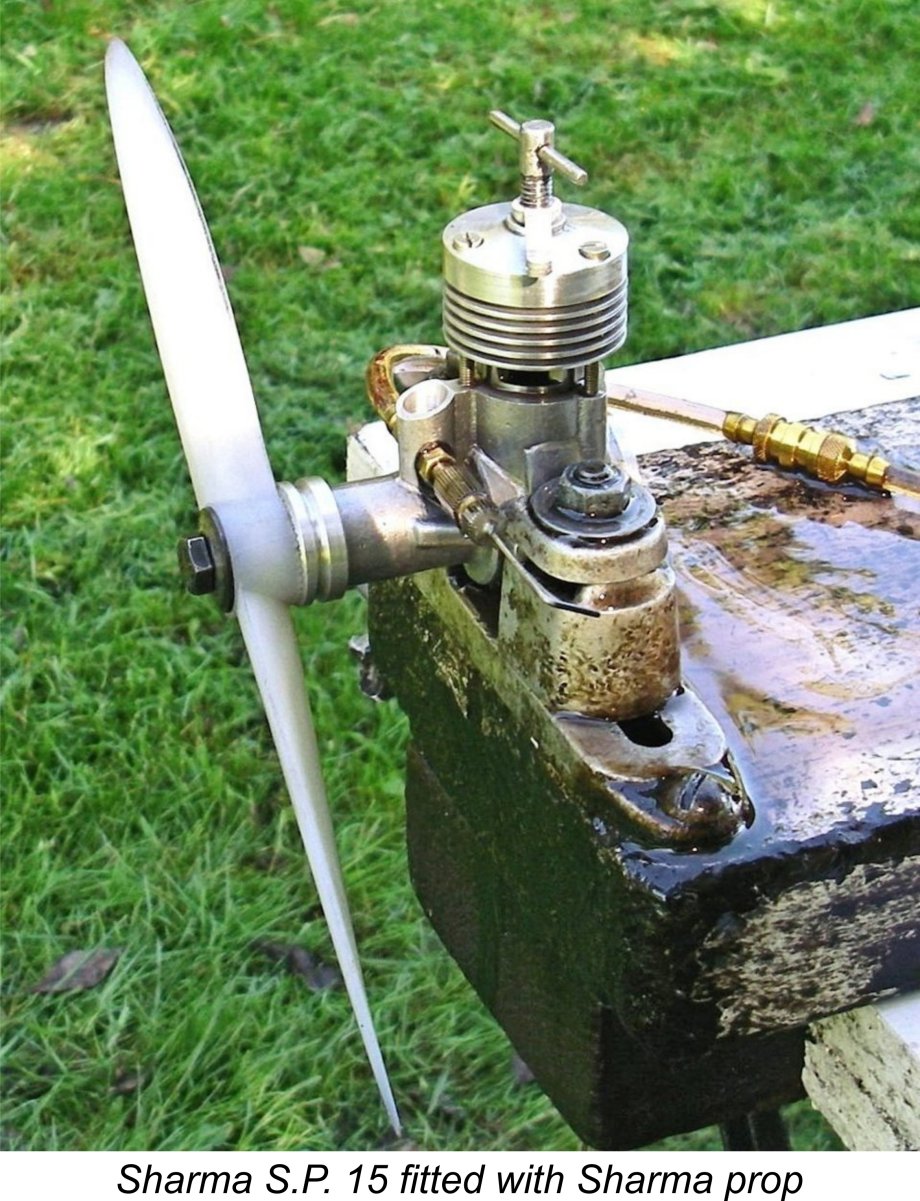

This took the form of the neat 2.5 cc (0.15 cuin.) diesel of unmistakably P.A.W. design inspiration which is illustrated at the left. The engine was an Indian-made Sharma S.P. 15 which I had then recently acquired from my late friend Ed Carlson of Carlson Engine Imports in Phoenix, Arizona. At the time, I knew absolutely nothing about this manufacturer, having acquired the motor as much out of curiosity as anything else and frankly not expecting it to be up to all that much. However, I had been very pleasantly surprised both at its quality and at its level of performance. Hence my decision to bring it with me to England to show to the Eifflaenders.

Of course, design similarity is only skin deep, and in the case of the Sharma engines even the skin is recognizably different, as the attached image of that very engine (which I still use regularly 26 years later) with a 1970’s-vintage fixed-venturi P.A.W. 249 DS will confirm. You couldn’t mistake one for the other – we’re not speaking about a replica here! Moreover, things are very different indeed internally, as we shall see in due course. Even so, it’s readily apparent that the Sharma S.P. engines draw their underlying design inspiration from the P.A.W. models. This is completely understandable when we consider the tried-and-true excellence of the P.A.W. engines over the years – few designs have stood the test of time so well. In fact, as my Australian mate Bob Allan has observed, if you set out today to design the ideal general-purpose model diesel engine with a completely clean slate and no pre-conceptions, you’d almost certainly end up with a P.A.W.!

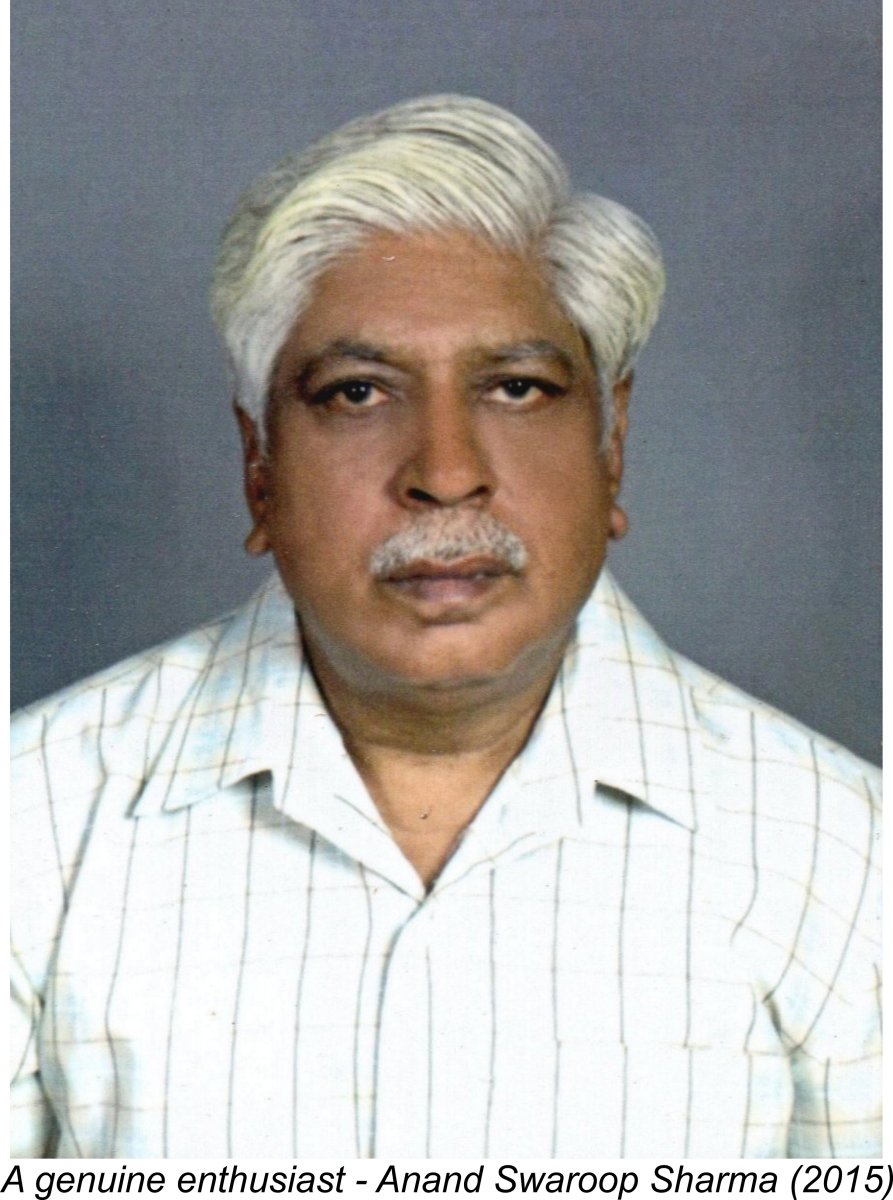

However, the Sharma designer was by no means content to merely imitate! He clearly thought a good deal about various aspects of the basic P.A.W. layout, making his own changes quite freely when and where he felt justified in doing so. The result was a range of model diesels which, while giving the initial impression of being P.A.W. clones, were in fact as original in design terms as any other model diesel. We’ll explore the differences during the course of this article. But before we do so, it’s well worth spending some time reviewing the history of the Sharma model engine range. Before tackling this task, I wish to acknowledge the outstanding cooperation of Mr. Vivek Sharma, the eldest son of the founder and still owner of Sharma Model Aero Engines & Propellers, Mr. Anand Swaroop Sharma. Vivek was more than generous in providing me with the necessary background information along with a number of relevant images. As if this wasn’t enough, he also provided me with test samples of the past and present Sharma model engine range, together with a selection of the Sharma propellers for evaluation. I’d like to record my very sincere gratitude to Vivek for his great kindness in assisting me to this extent. That pleasant duty done, let’s proceed with a summary of the history of the Sharma model engine range. Company History

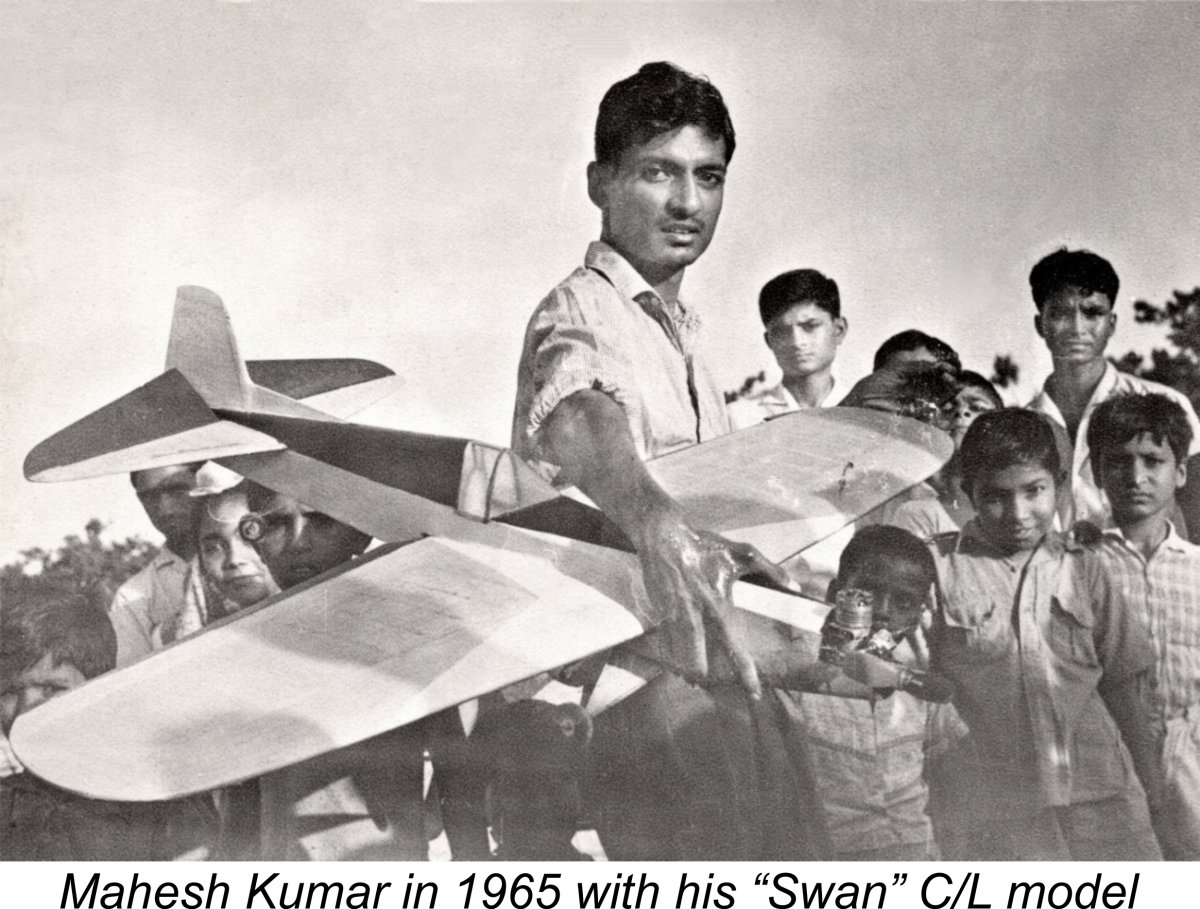

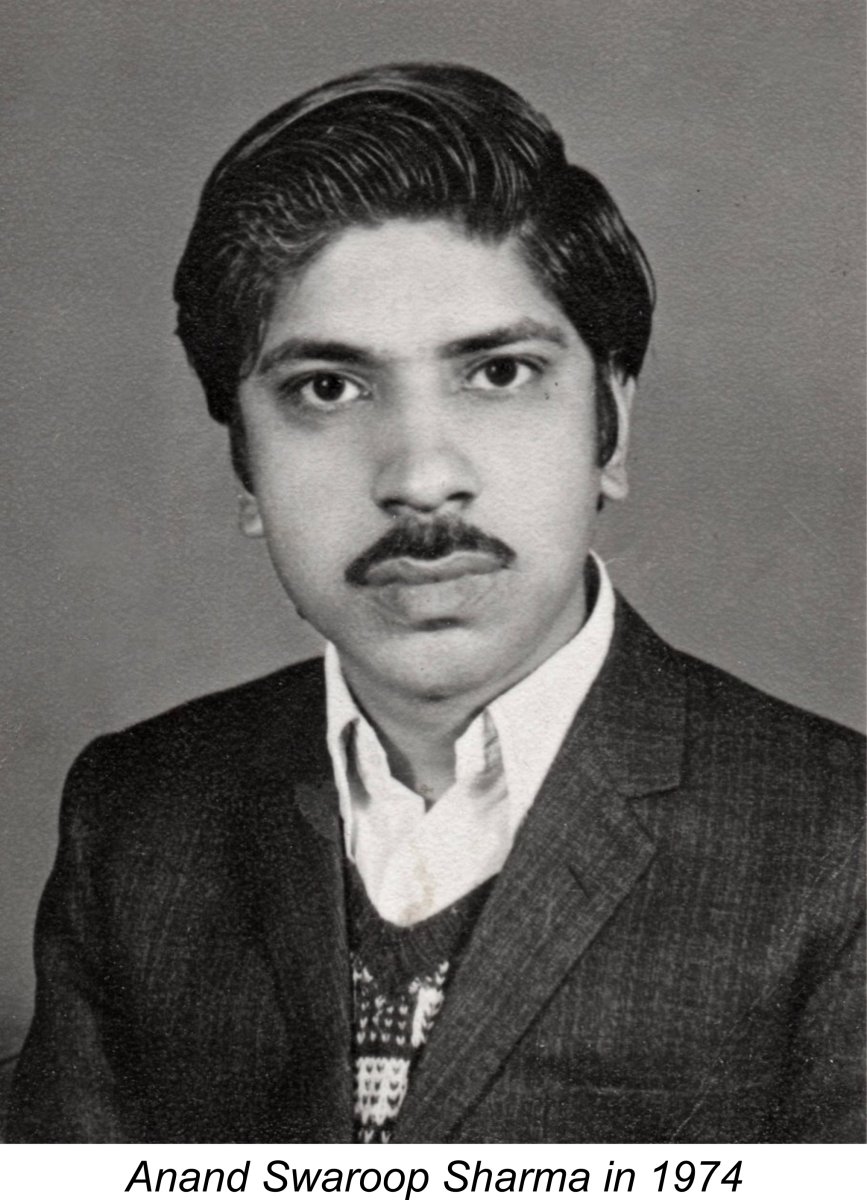

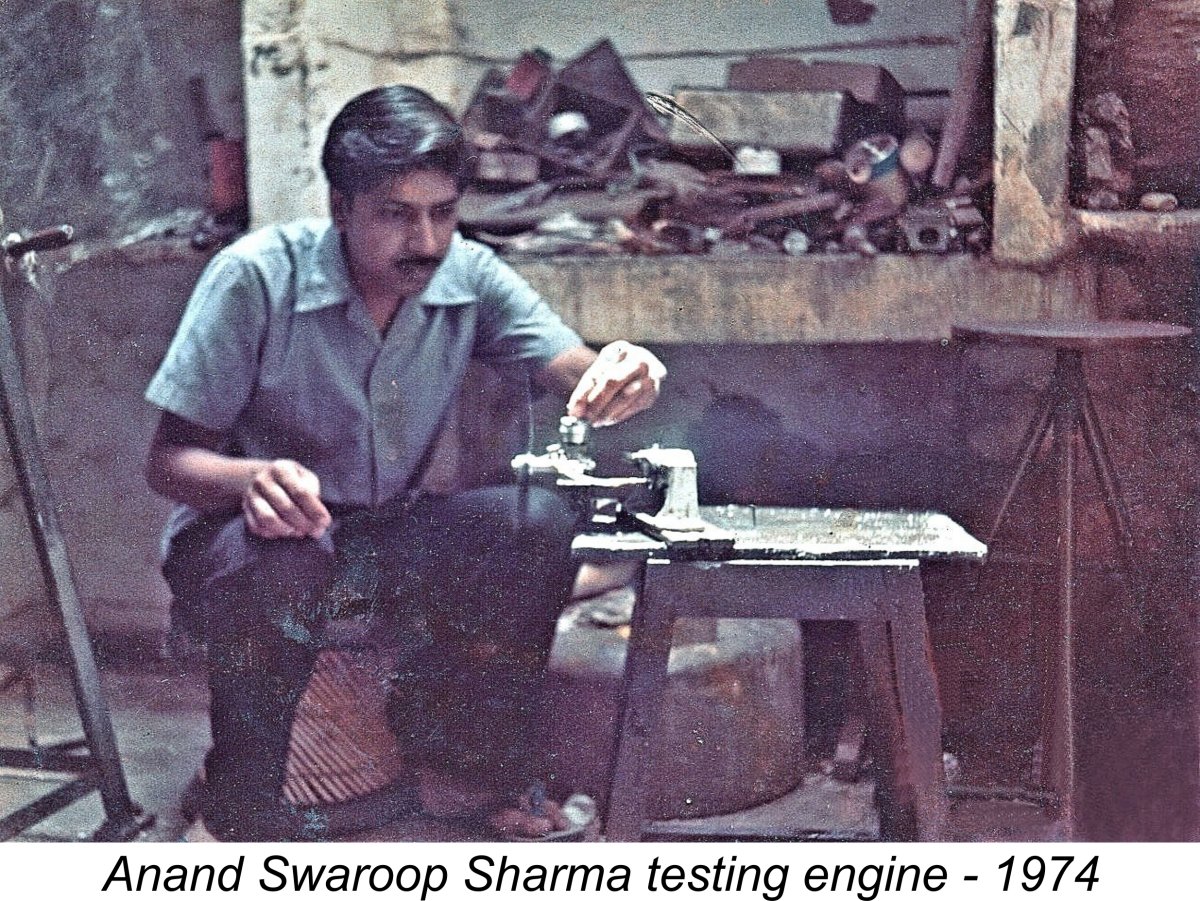

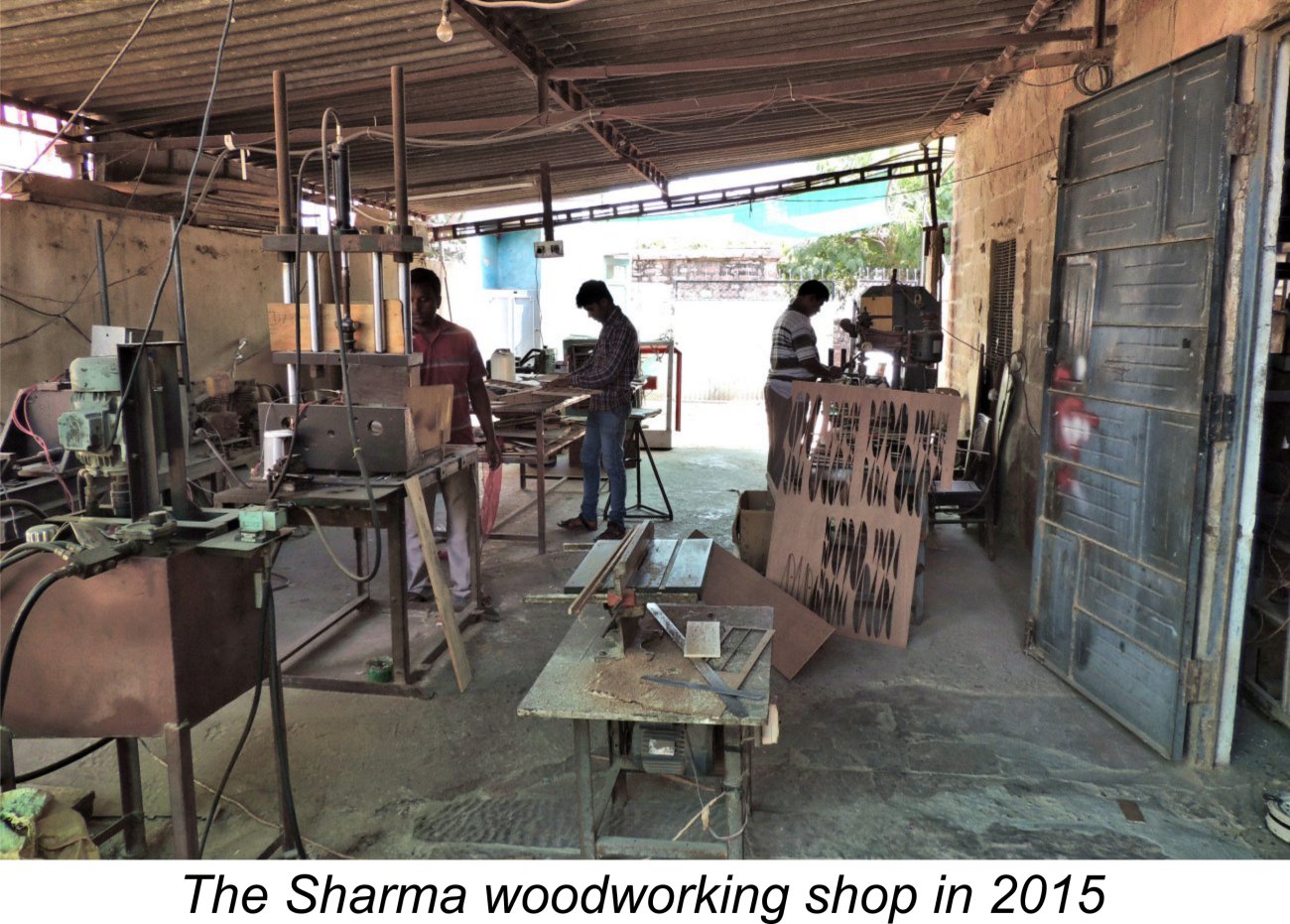

The Sharma S.P. (Sharma Products) range of model aero engines was manufactured by Sharma Model Aero Engines & Propellers of Jodhpur, a city located in the state of Rajasthan in north-western India. The company’s actual address was; Sharma Model Aero Engines & Propellers Jai Narain Building Ratanada Road Jodhpur – 342 001 (Raj.) India It may come as something of a surprise to many readers to learn that the Sharma company had been manufacturing model aero engines for well over four decades at my original time of writing (2017). This was no fledgling or fly-by-night company – it was a very experienced and dedicated long-term manufacturer of model engines and related products. Although the company was not officially established until 1974, the origins of the Sharma model engines go back considerably further than that. The direct involvement of the Sharma family with model I/C powerplants actually commenced during the school-days of Mahesh Kumar Sharma (1943 – 2010) and his younger brother Anand Swaroop Sharma (1947 - ). For personal reasons, Mahesh Kumar Sharma preferred to be known only as Mahesh Kumar. I will refer to him by that name for the balance of this article. In passing, it's perhaps worth mentioning that I asked Vivek Sharma if his late uncle's preferred use of the Kumar name indicated some kind of connection with the Kumar family of Calcutta, who owned the Aurora Model Manufacturing Co. Pvt. Ltd. of that city. Vivek told me that there was in fact no family connection, although the two firms had business dealings from time to time. Apparently the name Kumar is commonly used as a middle name by followers of the Hindu religion. In the ancient language of India, the term Kumar was used as a prefix to denote a batchelor male, while the name Kumari denoted an unmarried female. In recent times the terms have been transferred from pre-marital perfixes to official middle names which are retained after marriage given the difficulty of making a legal name change. During the period when they were growing up together, the two brothers developed an intense interest in mechanical technology in general. They were fortunate in having an understanding and perceptive father, Mr. Jainaraian Sharma (?? – 1977), who was a civil engineer having responsibility for two of the major water storage dams in the region of Jodhpur. Noticing his two sons’ interest in mechanical technology, the elder Mr. Sharma kindly presented them with an Astoba 2 lathe to facilitate their putting some of their ideas into practise. It was using this piece of equipment that the brothers subsequently constructed their first model aero engines, albeit at this early stage strictly for their own personal use. The Sharma brothers’ interest and active involvement in aeromodelling began in 1960, when they first saw control-line models being flown by members of India’s National Cadet Corps (N.C.C.), an organization which had as one of Vivek Sharma recalled that the first engine constructed by his uncle with the assistance of his father was a 2.5 cc (.15 cuin.) diesel which ran well. Having successfully produced this engine, they went on to construct a range of other types, still using the Astoba 2 lathe which had been a gift from their father. The attached illustration shows Mahesh Kumar in 1965 at the age of 22 years with his large control line model “SWAN” which was powered by a plain-bearing .35 cuin. glow-plug engine made by the two brothers. At this stage, they were still producing engines strictly for their own use. The brothers both went on to enhance their knowledge and abilities through higher education. Mahesh Kumar obtained a Diploma in Mechanical Engineering, subsequently working at Jodhpur Engineering College as a demonstrator in charge of the machine shop. Anand Swaroop Sharma also obtained a Diploma in Mechanical Engineering, after which he followed in his father’s footsteps by going to work for the Jodhpur Irrigation Department as a junior mechanical engineer. The engines made and used by the Sharma brothers during this early period performed very well by the standards then prevailing in India, where model engines were in increasingly high demand as the popularity of aeromodelling steadily grew. This did not go unnoticed by others involved in the hobby. By the early 1970’s the aeromodelling movement in India was entering a rapid growth phase, but there was a problem – a lack of domestically-produced modelling goods, very much including engines. Most of the modelling materials required to sustain the hobby in India had to be imported – a far from satisfactory situation. Among In 1974, recognizing the business opportunity implicit in this situation, the 27 year old Anand Swaroop Sharma left his post with the Jodhpur Irrigation Department to establish Sharma Model Aero Engines & Propellers with the generous support and assistance of his elder brother Mahesh Kumar. Their father Mr. Jainaraian Sharma also provided technical support for the venture during the early years, although sadly he died in the year 1977 only three years after the establishment of the business. One of Anand Swaroop Sharma’s first moves following the establishment of the company was to approach the N.C.C. authorities to seek their formal approval of his products. This approach resulted in an agreement with the N.C.C. whereby the bulk of the company’s products would be purchased by the N.C.C., thus assuring Mr. Sharma of a steady market for his engines. Thus began an association with the training programs of India’s defence forces which was still ongoing as of 2017. The objective from the outset was to produce a series of simple, rugged, easy-starting and durable “sport” engines to high standards of quality and dependability. This meant sticking with tried and This being the case, the very logical decision was taken to use a well-established existing model as the basis for the design of the first Sharma engines. The model chosen at this time was the original Oliver-ported FROG 249 BB which had first appeared in England in late 1955. This model had been very popular in India, reaching that country in sufficient numbers that examples were readily available for study.

In reality, front ball-races contribute relatively little to sports engine performance - in fact, experience has shown that a single ball-race design can out-perform a twin ball-race model if there is the slightest misalignment betwen the two races. Accordingly, this was a completely logical change, particularly from a production complexity standpoint.

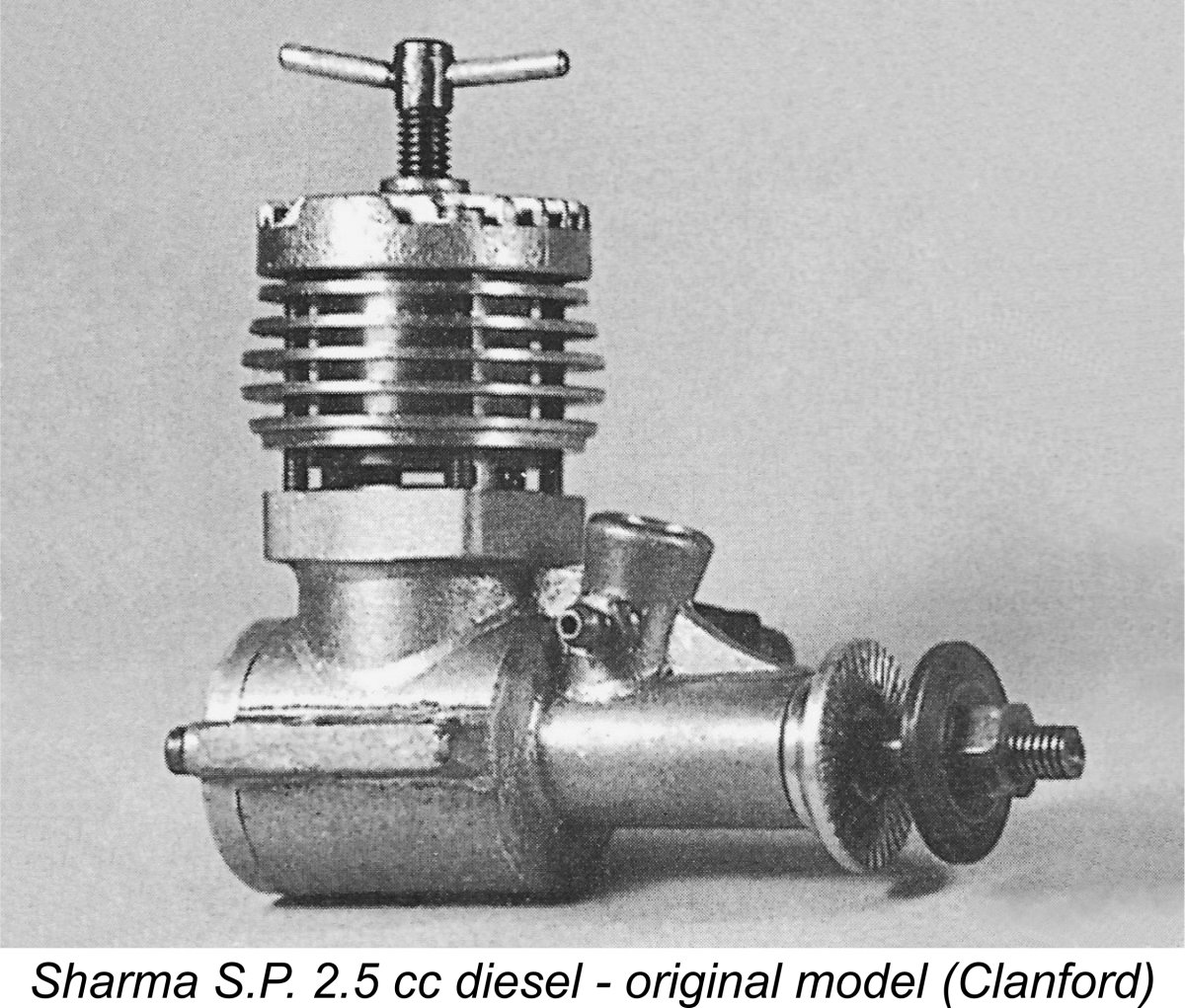

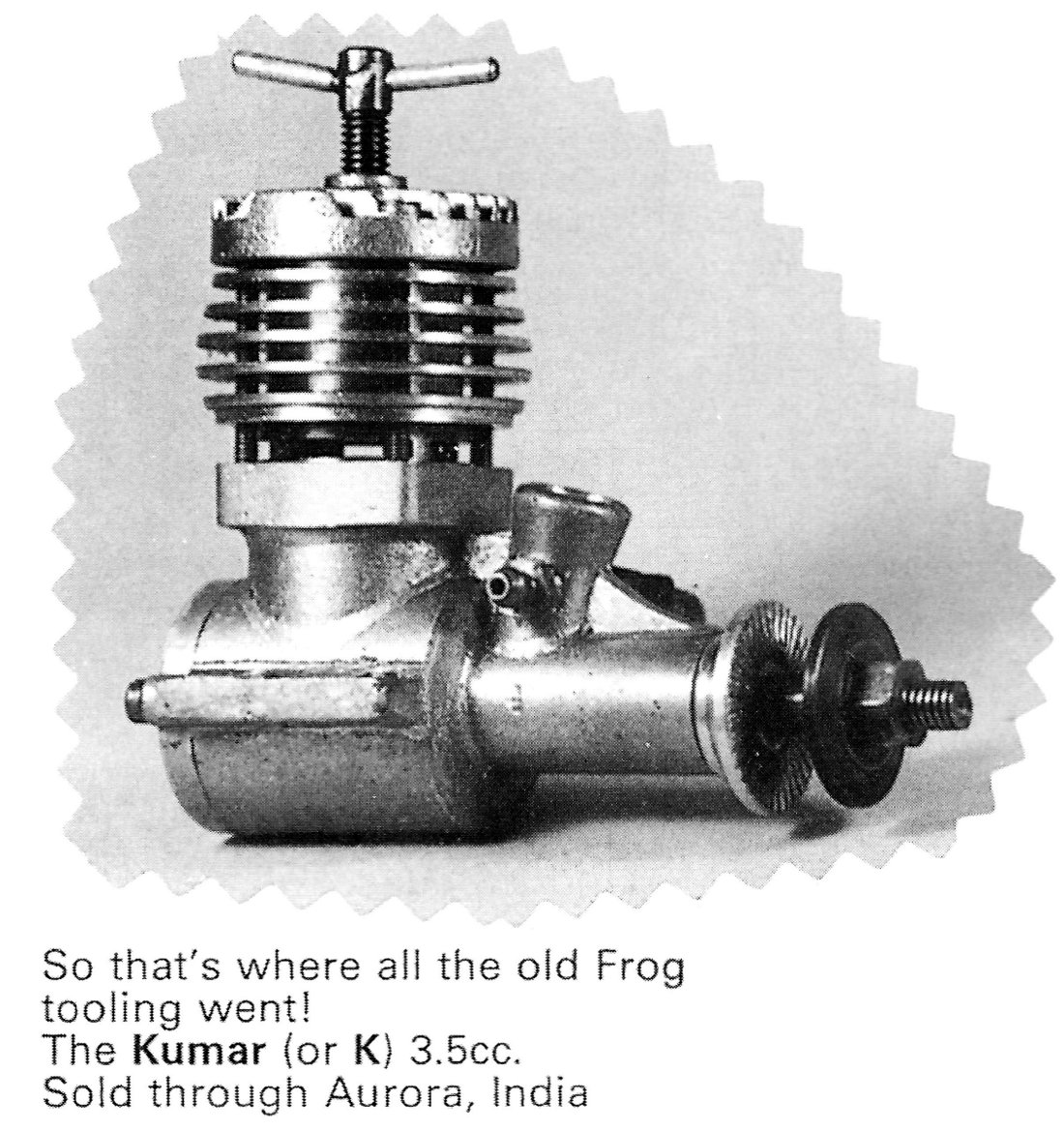

The original Sharma 2.5 cc diesel illustrated above had a stubby intake which was cast integrally with the main crankcase. Later examples like that seen at the left featured a revised intake having a larger spigot into which either a U/C venturi or an R/C throttle could be installed. This was the first Sharma R/C engine. The Sharma throttles were very neatly moulded from a suitable reinforced plastic material. A matching 9x6 moulded propeller was also produced, becoming the first in a long line of Sharma propellers. These propellers continued in production as of 2017. More of them below in their place. At this point it's worth taking some time to correct yet another (!!) error in Mike Clanford's well known 1987 book "Pictorial A-Z of Vintage and Classic Model Airplane Engines". The error this time is to be found on page 103, where an illustration of an early example of the Sharma 2.5 cc diesel appears. However, this illustration is wrongly captioned as an Aurora K350 3.5 cc diesel along with the comment "So that's where all the old FROG tooling went!".

The identification error most likely arises from the apparent fact that Clanford was not aware of the Sharma engines at his time of publication in 1987 - there is no entry for the Sharma marque. Clanford was probably aware of the illustrated engine's Indian origin and simply assumed that it "must" be an Aurora given his lack of knowledge of any Indian alternative. The incorrect displacement merely reflects the fact that he didn't measure the engine to check (or had no opportunity to do so), while the comment about the FROG tooling was pure unsubstantiated (and incorrect) conjecture on his part. It's the numerous errors of this nature as well as the many dating errors which occur throughout the book that require one to view any information extracted from Clanford's work with great caution. As I have said many times in numerous articles, the book is a very interesting browse for which Mike Clanford richly deserves our thanks - we're far better off with it than without it. However, it cannot credibly be cited as an authoritative reference. Returning now to our main theme, once established as a manufacturer of model engines and propellers, the company steadily expanded the range of its products. The FROG-based Sharma 2.5 cc diesel continued as the company’s flagship model engine product until 1980, being marketed in both R/C and U/C versions as noted earlier. The company also expanded its range of nylon propellers during this period.

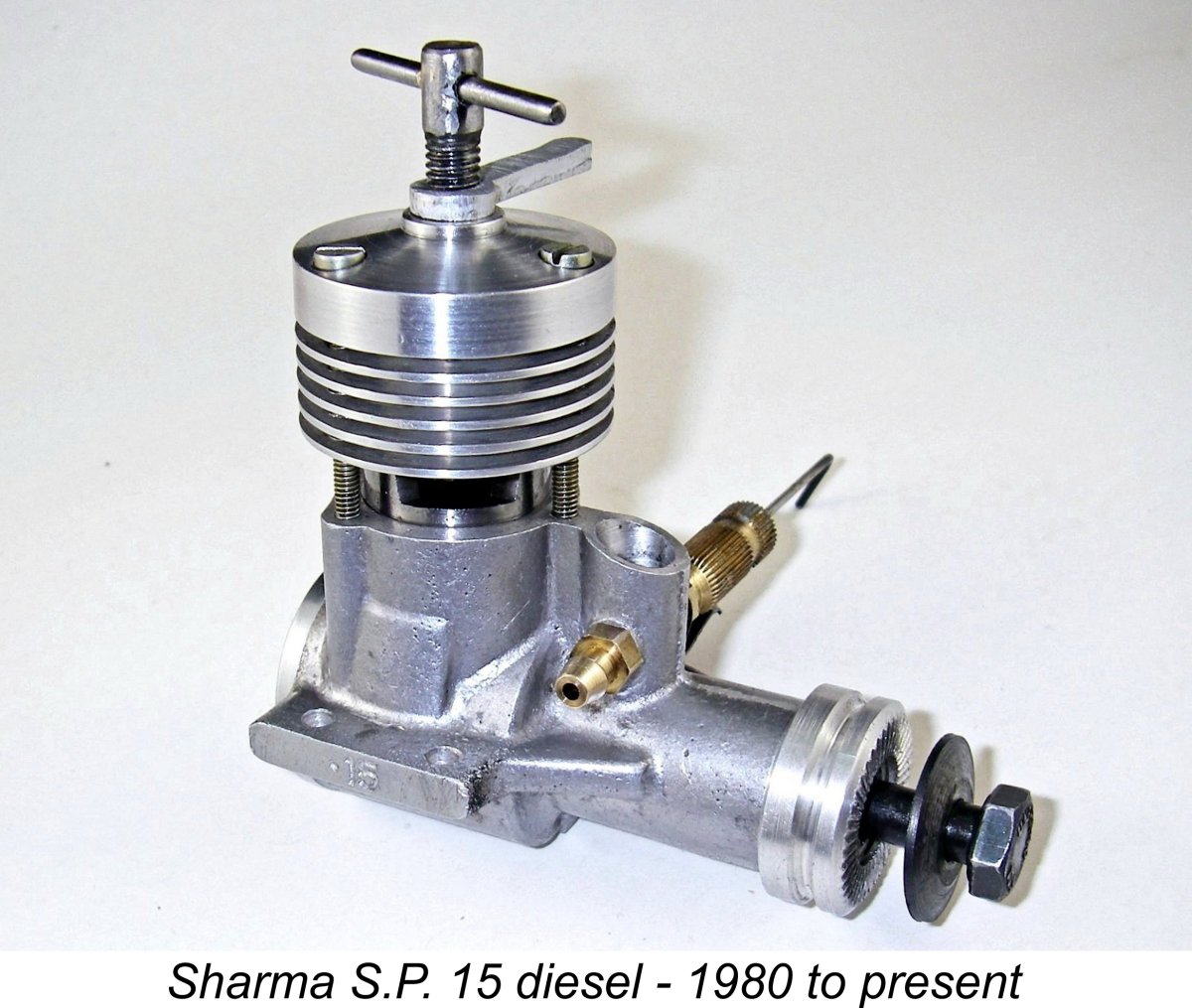

Once again, although many elements of the P.A.W. design were adopted without change (why mess with a good thing?), the designer introduced a number of distinctive features, as we shall see later. The most significant departures from the previous Sharma design were the style of transfer porting, the stroke/bore relationship and the omission of the former single ball-race. At this stage, the range was expanded to include plain bearing diesels of 1.5 cc, 2.5 cc, 3.2 cc & 3.9 cc displacements, all built to a common design. In 1988 several plain bearing glow-plug models were also added to the range, appearing in both .15 cuin. and .23 cuin. displacements. These latter models were offered in both C/L and R/C versions. They were mainly marketed within India and were not big sellers, consequently being withdrawn from production in 1996 as more up-to-date alternatives became more readily available from other manufacturers. The 3.9 cc diesel model was also dropped from the range at some point. However, the other diesel models carried on, as they were still doing in 2017.

The company continued its expansion, adding model kits (both control line and R/C) before subsequently moving into the field of ARF (Almost Ready to Fly) models. It also became active in the import sector, bringing in a number of model engines from elsewhere in addition to balsa wood and numerous modelling accessories. All of these activities were continuing as of 2017. At that time, the range of in-house products included:

In addition to carrying on its own production, the company was now also importing some items like balsa wood, brushless electric motors and peripherals, radios and peripherals, etc. Their associated marketing company Aero Model India was also offering online sales through its web store.

My valued correspondent Vivek Sharma (1978 - ), who is Anand Swaroop Sharma’s eldest son, served as the manager for sales, purchases, research & development and overall production programs. Vivek’s younger brother Vishal Sharma (1981 - ) served as manager for engine production, new products and custom-made products. Both Vivek and Vishal Sharma are trained mechanical engineers, hence being very well qualified for their respective roles.

The Sharma company had a number of business lines which were not directly related to model production. Among these was the development and production of aerial targets, aerial target towing models and other equipment for the training of the Indian defence forces. In fact, as of 2017 model engine manufacture was continuing at a relatively small scale. Vivek Sharma told me that at that time the company was producing only around 80 – 100 engines per month of all types. The glow-plug models had long been discontinued, but all of the diesel models apart from the 3.9 cc offering remained available. Vivek estimated that over the years Sharma had produced between 15,000 and 18,000 engines in total, taking all models into account.

Until a few years ago, Sharma had distributors in a number of other countries. The late Ed Carlson of Carlson Engine imports in Phoenix, Arizona was one such distributor – it was Ed who supplied me with my first Sharma diesel back in 1997. However, as time went by Ed no longer stocked these engines – indeed, Vivek Sharma told me that this was true worldwide and that stocks of engines were no longer held anywhere outside of India. All sales outside of India were now direct from the company. This of course was a reflection of the continuing shrinkage of the world-wide market for model I/C engines as the brushless electrics continued their seemingly inexorable takeover. In that regard, I received a few independent reports to the effect that some people had been frustrated in their attempts to buy engines through Sharma’s previously-mentioned on-line store. In response to my request for a comment on this issue, Vivek confirmed that such difficulties did indeed exist for overseas customers due to the fact that legal restrictions in India prevented the operation of the website's payment system for such individuals. He advised would-be overseas purchasers to select which model(s) they wish to purchase and then contact Sharma directly by email. The company would respond immediately with an invoice complete with payment options. Items purchased in this way were generally shipped using the EMS courier service unless otherwise specified by the The engines were supplied in attractive blue boxes with white lettering. A comprehensive and well-written instruction sheet accompanied each engine, along with a length of suitable fuel tubing. The Sharma company maintained a very direct relationship with the aeromodelling movement in India through its participation in the newly-formed Aero Modelers Association India, the country's first national aeromodelling organization. This Association was established to support and encourage the hobby throughout India. At the original time of writing in February 2017, the Association had just sponsored its second National Championship meeting, at which just about every type of R/C and C/L model aircraft imaginable was flown along with a number of chuck glider events.

Now that we’ve taken a look at the company which manufactured the Sharma model engine range, it’s time to begin our examination of a few of the engines which they produced. The flagship range of Sharma diesel models were all designed and constructed to a common basic design specification, making it redundant to provide a detailed description of each of them individually. This being the case, I’ll content myself with setting out a detailed description of perhaps the most popular Sharma model – the .15 cuin. (2.5 cc) diesel. The Sharma 15 Diesel

The crankcase had acquired a pair of small “bulges” on each side to facilitate the accommodation of the required swing clearance space for the con-rod while maintaining adequate thickness of the crankcase wall. In addition, the case had its upper deck lowered somewhat to accommodate the accessory exhaust collector with which the engines were now supplied (see below). The same consideration had necessitated the elimination of the lower cooling fin on the cylinder jacket as well as the 30 degrees or so of sub-piston induction formerly incorporated. The elimination of sub-piston induction was also made necessary by the need to have the optional R/C throttle work as well as possible. The comp screw was also a little different. Otherwise, the engine remained essentially unchanged in functional terms.

A number of control-line vintage combat customers (including myself and a few of my club-mates) opted for this version since it allowed both the angling-back of the needle valve to minimize the potential for breakage in a crash and also allowed the fitting of a silicone “dork tube” to minimize the ingress of dirt during an unplanned “landing”! The batch of Sharma 15 “combat specials” that were supplied some years ago to our small group of vintage diesel combat fliers in Western Canada featured this venturi arrangement along with such refinements as a smaller and lighter needle and a more substantial wrap-around prop driver. These components may be seen in the above illustration of my own example. Apart from these refinements, the engines were identical to the standard model such as my own 1997 unit illustrated previously. Vivek Sharma told me that the company remained willing to fill special orders for engines modified in this way in both .15 and .19 cuin. displacements for vintage speed-limited combat use.

Weight of the Sharma 15 diesel is a fairly hefty 178 gm (6.28 ounces). This is a substantial figure for a plain bearing 2.5 cc diesel - indeed, it's almost the same as the earlier 1970's single ball-race model mentioned above. However, once again this weight reflects the extremely sturdy construction of the engine. Much of the seeming excess weight is to be found in the very sturdy crankshaft and thick-walled cylinder - extra material put to very good use. I can see a number of areas in which some slight reduction in weight could have been achieved. The rather tall comp screw could certainly be made shorter and could be centrally drilled. Both of these measures could also be applied to the steel prop bolt. The use of a light alloy prop washer would also help, and I could readily see the possibility of designing a significantly lighter needle valve assembly. Indeed, the "combat special" version of the engine already featured just such an assembly. That said, all of the engine’s components are extremely sturdy and appear to be made to last. Hence these remarks should be read as comments rather than as criticisms. Any owner could easily apply such modifications if desired. My own previously-illustrated 1997 flying example of the engine has been modified in these respects, getting the weight down to 171 gm (6.03 ounces). Not much, but every little bit helps! The engine’s timing figures are interesting. The exhaust opens at 107 degrees after top dead centre for a total exhaust period of 146 degrees. The transfer ports open only a little later at 113 degrees after top dead centre for a total transfer period of 134 degrees and a blowdown period of only 6 degrees. Finally, the rotary induction valve opens at 80 degrees after bottom dead centre and closes at 40 degrees after top dead centre for a total induction period of 140 degrees. There is no sub-piston induction on the current model. The above cylinder port timing figures seem perfectly rational to me. However, I have to say that I feel that the induction figures could be improved upon. The main issue is the late opening of the induction cycle. As matters stand, the induction cycle does not commence until 13 degrees after the transfer ports have closed. It’s far better to have the induction port open at least partially at that point so that the rising piston is immediately able to begin to draw mixture into the crankcase. I actually modified the shaft port in my 1997 flying example to have it open 25 degrees earlier so that it is already beginning to open when the transfer ports close. This resulted in a measurable improvement in performance. I felt that this would be a worthwhile and easily implemented production change for the manufacturer to consider, and I understand that the production engines were subsequently modified to reflect this recommendation.

The comp screw thread is 1 BA. Unusually, the tommy bar is actually brazed in its correct location – seemingly the final solution to the not-uncommon problem of a tommy bar working loose! A sturdy comp locking lever is provided, although this does not appear to be really necessary in actual use given the excellent fit of the contra-piston. Indeed, one of the most noteworthy attributes of the Sharma engines is the general closeness of their fits. The cylinder assembly highlights this point – the cylinder is actually a moderate push fit in the crankcase recess, while the cooling jacket is a moderate press fit onto the upper cylinder. The original Oliver engines were noted for the fact that you had to relieve “compression” by removing the comp screw in order to fit the cooling jacket – the Sharma takes this to the next level! Removal of the jacket requires that it be warmed a little, or that the comp screw be used to push the cylinder out. Reassembly once again requires the use of a little heat.

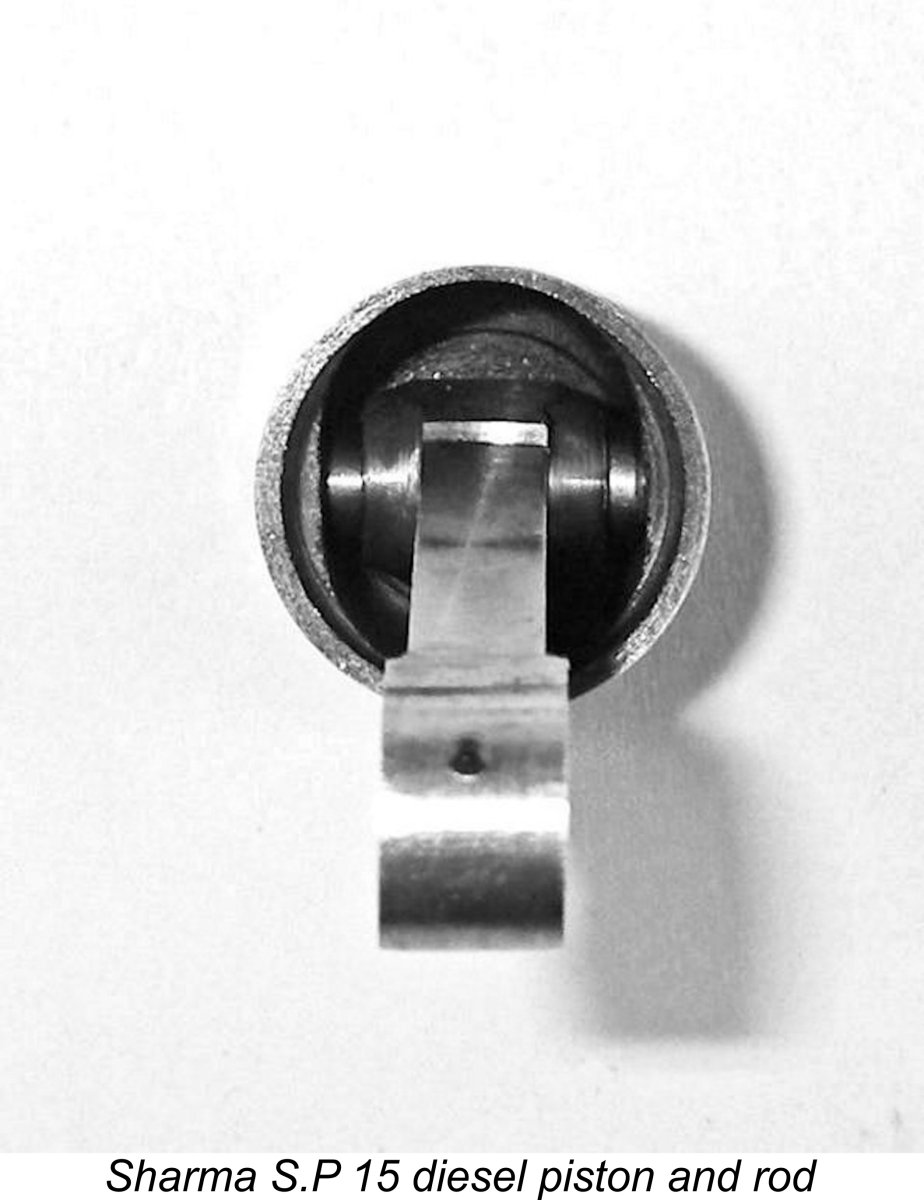

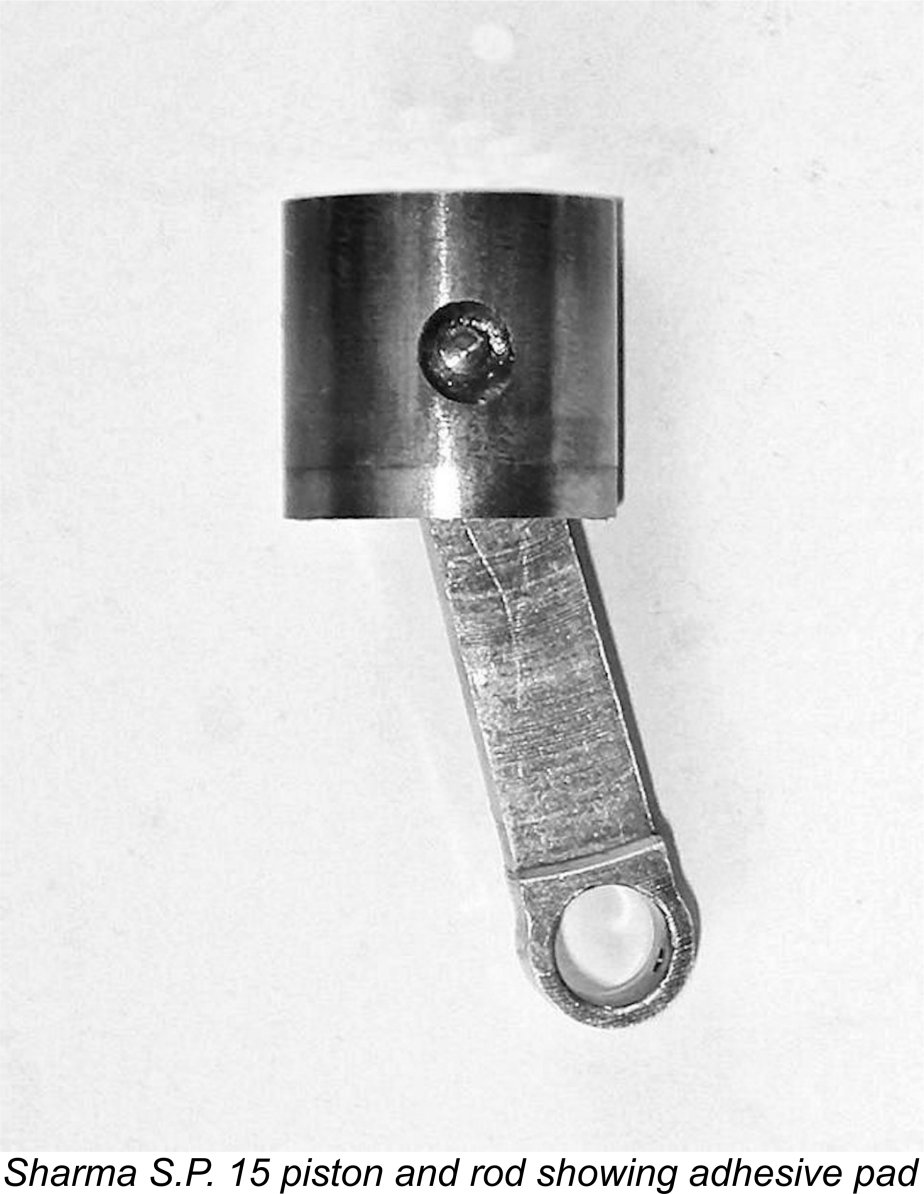

Looking now at the cylinder itself, porting is standard P.A.W. style with three very large internal bypass flutes separated by three milled exhaust apertures. All ports are very cleanly and accurately machined. The cast iron contra piston has a squish bowl formed in it to encourage swirl of mixture and hence more rapid combustion around top dead centre. The cast iron piston has a flat top. It is milled internally to lighten it to the extent possible. It is a superb fit in the bore The con-rod is a real work of art which has been created by a combination of milling and turning. It appears to be unusually sturdy for an engine of this size. The bearing length at the small end is more than adequate to ensure excellent stability, while the fits at both ends are beyond reproach. An oil hole is provided at the big end. The one potentially controversial aspect of the piston/rod assembly is the security of the gudgeon (wrist) pin. It will be appreciated that the presence of that very large bypass flute at the front of the cylinder imposes an absolute requirement that the pin be prevented from moving out of its bosses in that direction, otherwise fouling of the bypass and consequent bore damage may result. P.A.W. get around this by not reaming the front piston boss all the way through and installing the gudgeon pin from the rear, which is marked with a punch-mark on the piston crown. The pin hangs up on the un-reamed portion of the front boss and cannot move any further forward, while the cylinder wall prevents any rearward movement.

Feeling that there must be more to this assembly than meets the eye, I asked Vivek Sharma to comment on this point. Vivek confirmed that the pin is in fact a press fit in the piston bosses and that the adhesive is there purely as a sacrificial end-pad in the very unlikely event of the pin shifting in its bosses. For added security, the pin is held in place using Loctite 638 threadlocking adhesive. This seems to me to represent a very satisfactory approach. Vivek told me that in all the years that the Sharma 15 was on the market, they had very few requests for replacement con-rods which would require the removal of the gudgeon pin. The crankshaft is a one-piece steel component having a counterbalanced crankweb to go along with very generous dimensions of all of its stressed elements. The surface finishes of both the crankpin and main journal are outstanding – fine grinding appears to be a Sharma speciality! Main journal diameter is a whopping 11.10 The crankshaft induction port is cut with an end-mill (as opposed to the Woodruff key cutter used by PAW), creating an opening of race-track form with nicely rounded ends and no obvious stress-raising features. Frankly, this shaft looks bullet-proof to me! It is also machined and ground to an impeccable fit in its bearing. Speaking of the main bearing, this is equipped with a beautifully-finished cast iron bushing. This component has a rectangular aperture cut into it at the point where it intersects the base of the circular intake venturi. This opening corresponds with the elongated crankshaft induction port to give very rapid opening and closing of the induction system. P.A.W. abandoned this approach years ago, and I have to say that its retention by Sharma reflects very positively upon the design integrity of their engines. The needle valve assembly is a relatively massive affair – I would have thought that a far lighter unit could have been developed for this engine. That said, the components perform their task very well indeed, as I know from direct experience (see below). Spraybar diameter is 0.145 in. (3.70 mm), while the venturi throat diameter is 0.241 in. (6.12 mm). The needle thread is 4 BA.

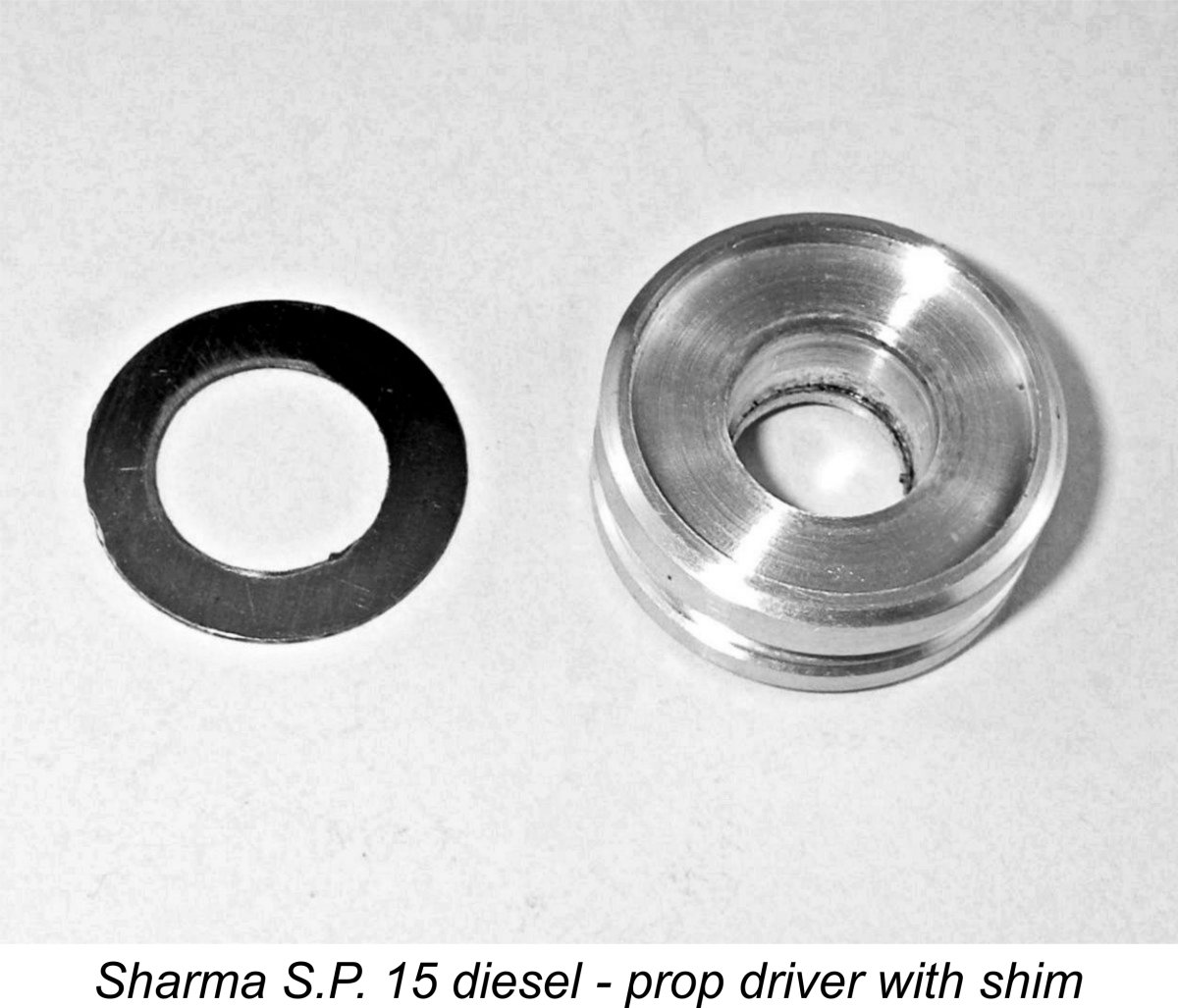

To make a good thing even better, a thin steel shim is inserted in this recess so that the front of the main bearing housing and the rear of the prop driver both bear upon steel surfaces as opposed to each other. Alloy-on-steel is a far superior wearing combination to alloy-on-alloy! The end-float of the crankshaft is perfectly adjusted so that the end of the crankpin does not quite make contact with the backplate when the shaft is set back for any reason.

Somewhat intriguingly, the rear of the backplate bears a scribe mark which just happens to be located at the top when the backplate is tightened. Why?!? The answer becomes clear when you remove the backplate and look inside. The outer diameter of the backplate “spigot” which protrudes into the crankcase is sufficiently large that the piston skirt would contact it at bottom dead centre. To deal with this, a small flat is hand-filed at the same location as the afore-mentioned scribe mark, so that at that one point there is sufficient clearance. The correct location of the mark and associated hand-filed flat are obviously established through a preliminary test-fitting. Why not merely turn the internal segment of the backplate down to a smaller diameter, you ask? Simple – to do so would increase crankcase volume, thus potentially reducing pumping efficiency. The designer was clearly very concerned with the optimization of this important function of any two-stroke engine.

The final component worth noting is the very neat molded nylon exhaust collector which was mentioned earlier in passing. When fitted, this is sandwiched between the cooling jacket and the top of the crankcase. It directs the exhaust well out to the side of the engine through a rectangular exhaust stack. This would be very useful in a scale or R/C situation in which it is desirable to get exhaust residues away from the model. It might also have some effect upon noise levels, albeit at some cost in terms of performance. I'll test this in a subsequent section of this article. The quality of the engine’s construction is absolutely first-rate in all respects. At its early 2017 quoted price of 3,450 rupees (US$55.00) plus postage direct from Sharma, it represented outstanding value for money. The Other Sharma Diesel Models

Unlike its .15 cuin. cousin, the 09 model was a short-stroke engine having nominal bore and stroke measurements of 13.00 mm and 11.5 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 1.53 cc (0.093 cuin.). Somewhat oddly, this put it just over the British ½A limit of 1.5 cc, but well within the corresponding US figure of 0.199 cuin. It weighed in at 118 gm (4.16 ounces). As with the 15 model, this is quite a lot of weight for a 1.5 cc plain bearing diesel, but once again that weight was put to very good use in terms of durability. The threads used in this model differed somewhat from their equivalents in the large models. The cylinder assembly The 19 model was based upon the 15 crankcase – the mounting holes were identically spaced, making the replacement of a 15 with a 19 perfectly straightforward if more power was required. The extra displacement was achieved entirely through an increase in the bore from 14.5 mm to 16.3 mm, leaving the 14.86 mm stroke unchanged. This made the 19 model a short-stroke engine, like its smaller 09 brother in the range. The actual calculated displacement of this model was 3.10 cc (0.189 cuin.), making it a genuine "19". The engine weighed 188 gm (6.63 ounces) – very little more than the 15 model described earlier. All threads were the same as those used in the 15 model. Now, having described the various Sharma models, both past and more recent, it's time to put them on the test bench to see how they perform! I'll begin with retrospective tests of a couple of the earlier Sharma models and then proceed to evaluate their current offerings. The Original Sharma S.P. 2.5 Diesel on Test

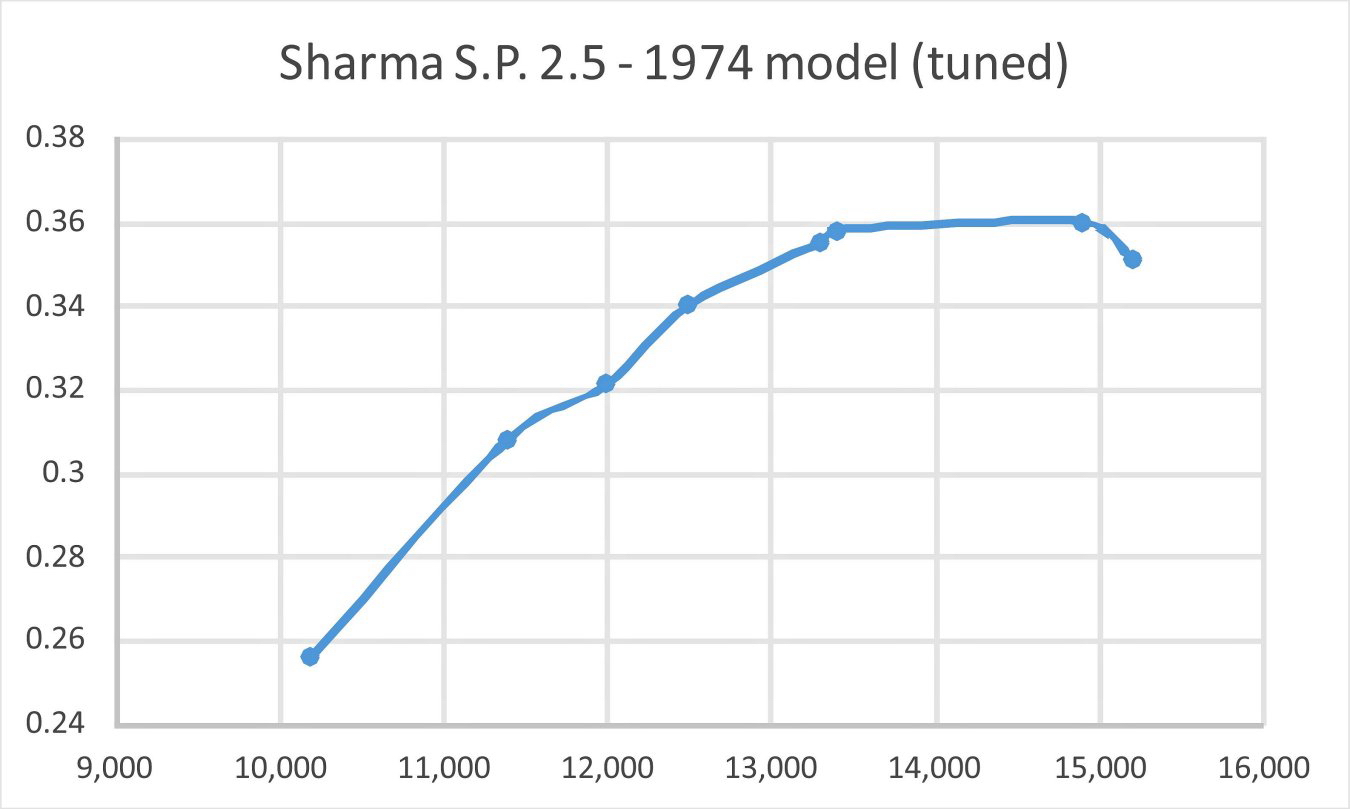

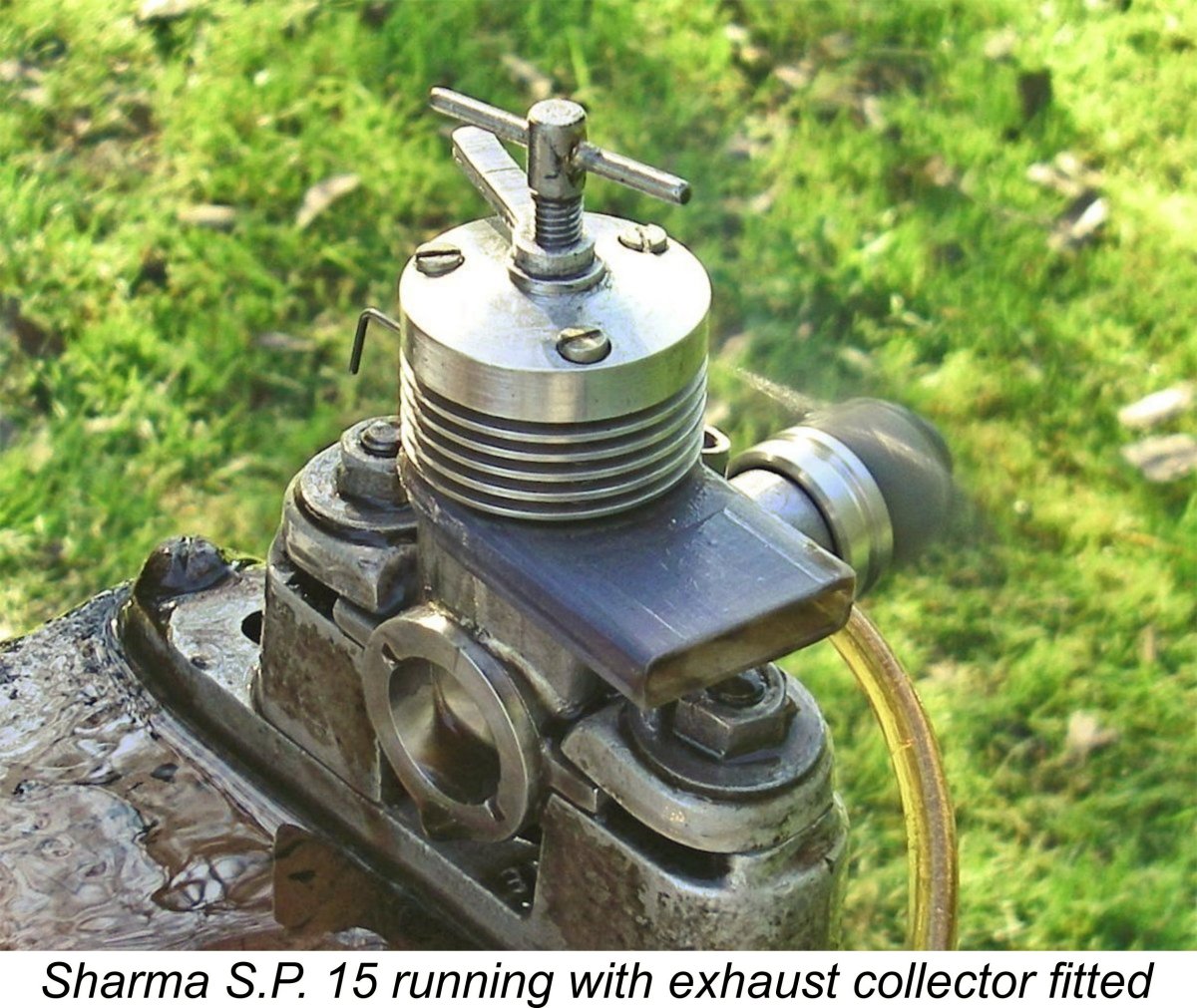

This is one of the Sharma models which never found its way beyond India's borders in significant numbers. They're almost never seen today on eBay or elsewhere. The only reason that I have one of these units available for testing is that Vivek Sharma was kind enough to present me with an example from his own collection. He had used this engine himself for some years, but it had not seen any action for a decade or more when he passed it along to me. It's really difficult for me to adequately express my gratitude to Vivek. The engine was supplied with one of Sharma's very neat moulded plastic R/C throttles, as illustrated earlier. Since I'm a control-line man at heart, I made a replica U/C venturi for the engine, as seen in the accompanying images. In addition, because I was planning to try this engine in the air I took it apart and made a few modifications to improve its breathing somewhat. I found it to be extremely well made, like all Sharma engines of my Upon re-assembling the engine with all components in the same orientation as before, I mounted it in the test stand and gave it a few shake-down runs on a 9x6 APC prop to settle things down after the rebuild. I found the engine very easy to start from cold provided a small prime was given. Hot restarts required only a choked flick with the fuel line full. Response to the controls was excellent, with a perfectly-fitted contra piston displaying no tendency either to freeze or to run back. After satisfying myself that the rebuilt engine was well settled down once more, I ran a suitable series of test props. Running qualities proved to be first-class, with no tendency to misfire or sag at any time. Fair enough, but what really did surprise me was the engine's performance! Even allowing for the fact that I had applied a few minor tweaks, I have to say that the results far exceeded my highest expectations, to the extent that I actually went back and rechecked most of the props just to make sure that I had been reading the tachometer correctly! All re-checked figures were within 50 or so RPM of the initial readings. The readily reproducible and hence confirmed results obtained are shown in the following table along with the derived power curve.

The two WB props in the above list are wide blade items created by cutting down larger props to fill several torque absorption gaps in my test set. I still seem to be missing an intermediate airscrew between the two 8x4 props! Looks as if I should trim the 8x4 WB prop a little more and then re-calibrate it. The above figures represent a truly astonishing performance for a 1970's radially-ported diesel of basically mid 1950's design. I clearly missed the peak, but the engine appears to develop around 0.364 BHP @ 14,400 RPM. As I stated earlier, I was so amazed by these figures that I went back and re-did most of the props just to be sure, getting more or less the same readings on each prop. I know that the engine is tuned, but I'm not that talented a tuner - the basic design and construction must be pretty sound. The engine is also very well run in, having been used for some years by Vivek Sharma in his own models. That probably accounts for some of the engine's outstanding performance. I'm sure that there will be readers who will doubt the veracity of the above results. All I can say is - if you're ever in my area, let's get together and we'll repeat the test! I have no doubt at all that the above results are readily reproducible at any time. The Sharma 15 Glow-Plug Model on Test

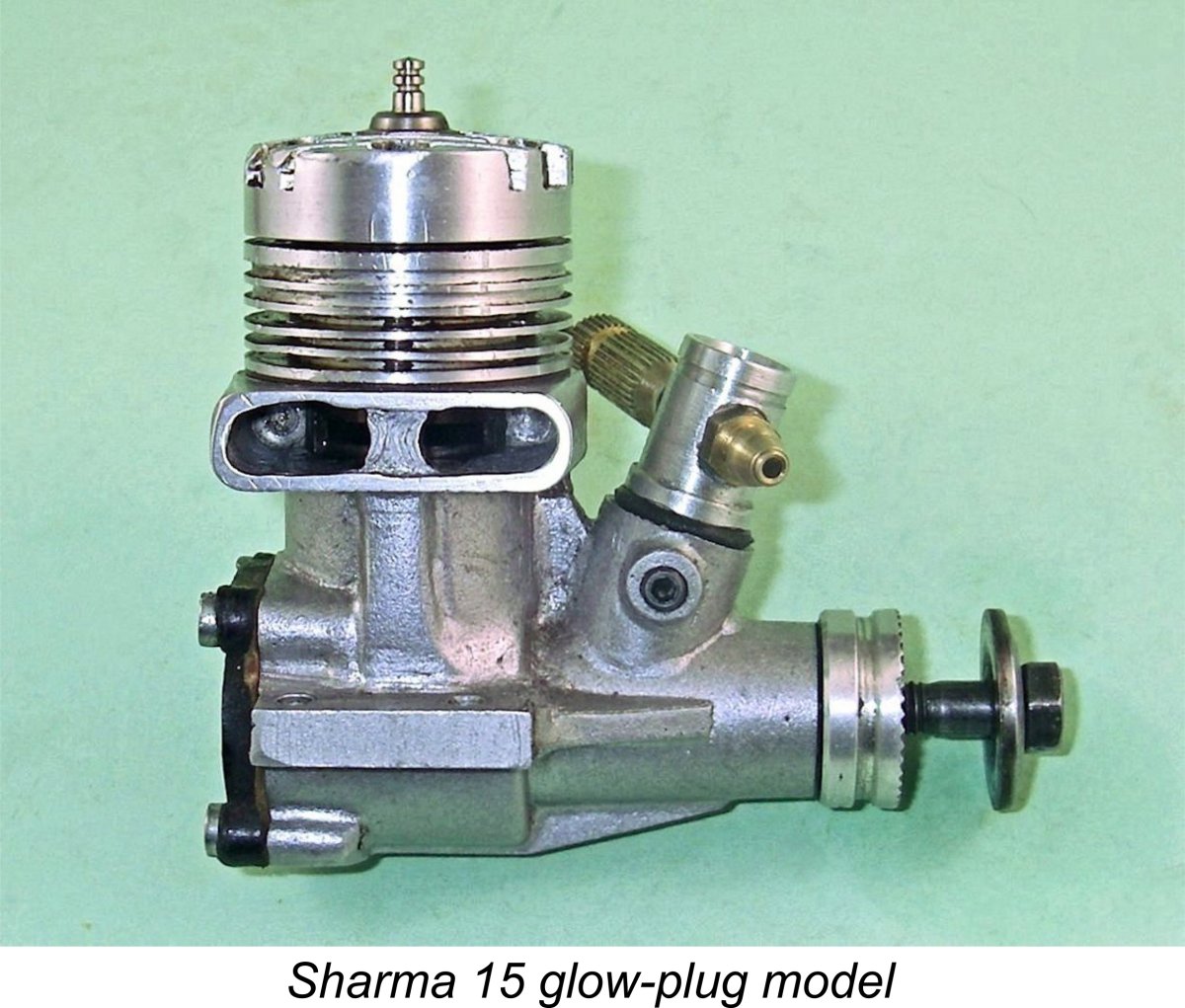

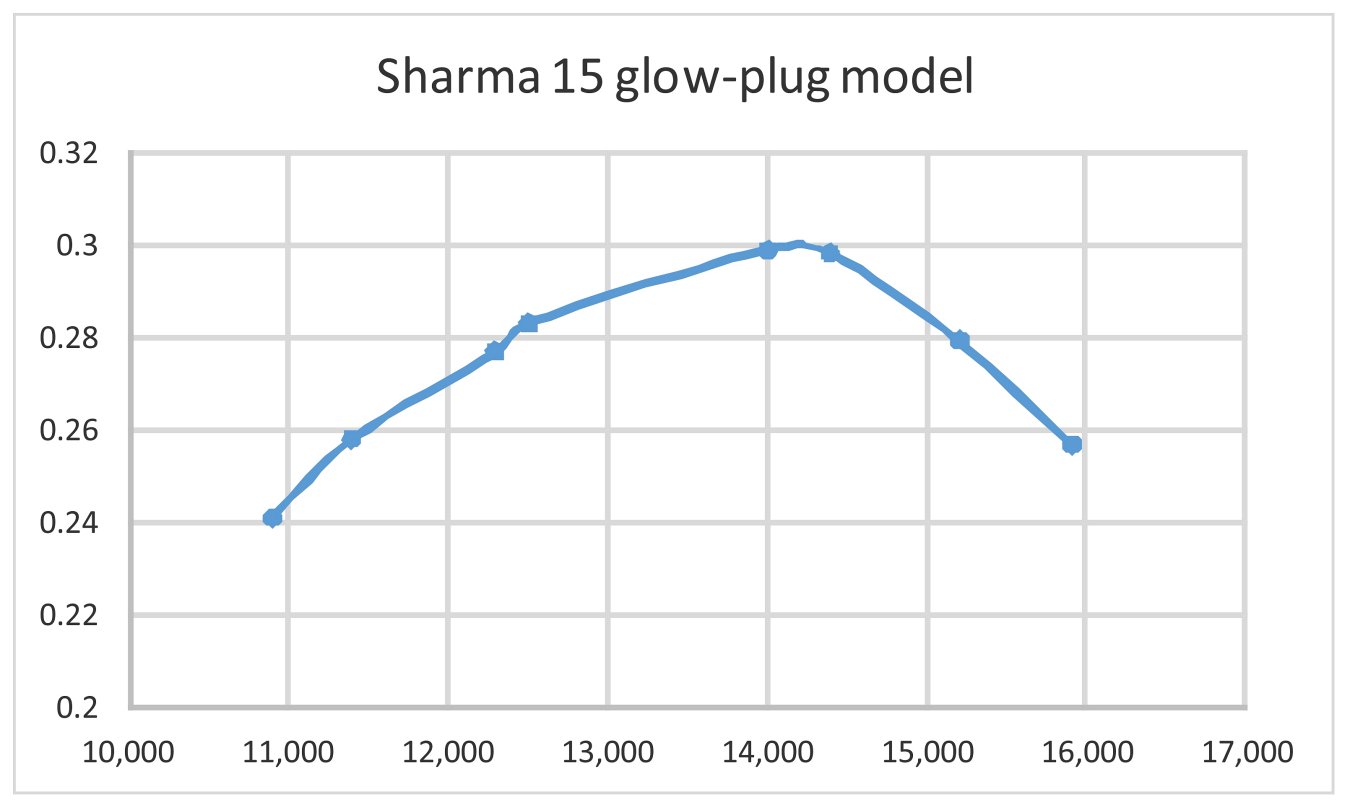

As with the previously-tested 1970's diesel model, the Sharma glow-plug motors never reached the export market in any numbers. As a result, they are very seldom encountered outside India today. However, thanks once again to the great kindness of my valued friend Mr. Vivek Sharma, a completely original and highly servicable example of the .15 C/L glow-plug model was made available to me for retrospective evaluation and test. This example had been assembled from a combination of left-over components plus a newly-made one-off piston/cylinder assembly. Consequently it was quite tight as received, requiring a full break-in prior to testing. All fits as supplied were beyond reproach apart fom the previously-noted tightness. This neat little engine displays no outstanding or unusual design features. In fact, it's pretty much a throw-back to the 2.5 cc sport glow-plug motors of the late 1950's and early 1960's. It's a simple plain-bearing Despite its retrospective general layout, the engine does display some notable features which might be expected to enhance performance. The crankshaft induction port features the standard Sharma "race-track" pattern which affords relatively rapid opening and closing of the induction system at a minimal penalty in terms of structural strength. Gas access to the lower bypass passage is enhanced by a pair of circular piston skirt ports which match smilar openings formed in the lower cylinder liner on the bypass side. This should also enhance piston cooling. Finally, the cylinder head has a nice centrally-located hemispherical bowl shape with a generous squish band. The piston baffle is accommodated by a slot milled neatly across the lower surface of the head. Measured compression ratio is 7.5 to 1.

During this process I used a needle setting which was just on the four-stroke side of the break between two-stroking and four-stroking, leaning out to a smooth two-stroke setting for the final 20 seconds or so to get the piston up to full operating temperature. After stopping the hot engine by interrupting the fuel supply, I then allowed complete cooling prior to re-starting. In this manner the components were put through a series of complete heat cycles - an essential feature of the break-in for any iron-and-steel piston/cylinder combination. Once the break-in was complete, the engine felt really good - clearly all ready for testing. Accordingly, I ran an appropriate set of suitable props from my calibrated test set using a fuel containing 10% nitromethane. Running qualities proved to be excellent at all speeds tested - the engine required a small prime for starting, but usually went on the first or second flick if this was administered. Running qualities were all that could be desired - smooth and steady with no tendency to sag at any time. I found that the needle setting was a bit on the critical side for best leaned-out performance, but the optimum setting was easily established and held nonetheless thanks to the very positive ratchet action of the needle tensioning spring. The results obtained were as follows:

As with the previous model, the above figures suggest that I need to trim the 8x4 WB prop a little and re-calibrate it in order to fill a glaring gap in my test set. The above figures reflect a peak output of around 0.300 BHP @ 14,200 RPM with a nicely flattened peak. Not as good as the previously-tested diesel by any means, but still pretty fair going for a 2.5 cc glow-plug motor of this rather retrospective design layout. There's no doubt in my mind that this engine would make a highly acceptable sport-flying powerplant. Moreover, I suspect that it would last practically forever. The Current Sharma Diesel Models on Test We now move on to the testing of the more recent Sharma diesel models which remained available as of 2017. It's becoming a bit of a broken record at this point, but once again I must extend my very sincere thanks to my valued friend Mr. Vivek Sharma for making these engines available to me for testing. Without his assistance in this regard, this article could never have been completed. As stated earlier, the relatively modest production figures allowed all Sharma engines to be test-run at the factory - a throw-back to an earlier era. The instruction sheet stated that each engine was taken up to 12,000 RPM and held there for a minimum of 5 minutes. Vivek Sharma confirmed that this was still the case. On the basis of this factory test running, the company claimed that no break-in was required for these engines. Well, that may be true in terms of the engines’ internal fits and finishes – I commented earlier on the excellence of these attributes. However, that’s only part of the story. Readers of my earlier article on classic model diesel break-in will recall that one of the main goals in breaking-in such an engine is to complete the dimensional stabilization and surface hardening of the cast iron piston in its steel cylinder. The only path to the accomplishment of these goals is the subjecting of the engine to a series of complete heat cycles.

This is understandable when we consider that the type of bypass porting used eliminates much of the cylinder wall in the lower part of the bore, inevitably promoting higher surface pressures due to the side-thrust of the piston being absorbed by a relatively small cylinder wall area. P.A.W. also used to recommend higher-than-average oil contents in the fuels used for their similarly-ported engines. I have always used a fuel meeting these lubricant specifications in my “classic” diesels, hence having a good supply on hand. Using this fuel, I put each engine through a nominal 30-minute break-in period in a series of 5 minute slightly rich and under-compressed runs on a larger prop, leaning out for the final 30 seconds to get the piston up to full operating temperature before stopping the engine by interrupting the fuel supply. I then allowed complete cooling before the next run, thus ensuring that each such run represented a full heat cycle. This latter step is critical, albeit all too often ignored. At the end of this treatment, the engines all felt truly superb. If anything, they all remained slightly tight around top dead centre, but only marginally so. I suspect that a few hours of running in the air would be required to eliminate this entirely – my very experienced 1997 2.5 cc example feels absolutely perfect. I put a couple of additional leaned-out runs on each engine in the 13,000 RPM region, after which I judged them all to be ready for testing. Following the completion of this process, each engine was tested using a suitable range of calibrated test props. All of them were found to share a number of very positive characteristics. Firstly, none of them required a prime for starting – a few choked flicks were invariably sufficient. This represented an improvement over the handling of the original 1970's FROG-inspired model tested earlier, which did usually require a prime for cold starting. Secondly, they all exhibited excellent response to the controls. The needle in particular provided an unusually precise level of control over the fuel mixture. Those assemblies may be heavy and bulky, but they really work! The contra pistons all proved to be perfectly fitted, and the compression screw locking levers were not required, although they would doubtless come into their own as the engines became more worn. As a result of these characteristics, optimal settings were very easily established and held. Running qualities were extremely good – no trace of a misfire and no evidence of sagging at any time. The measured prop–RPM figures and associated power curves are shown below along with some commentary upon the results. Sharma S.P. 09 diesel

The Sharma .09 diesel proved to be just such an engine. The test example was an unmodified unit right out of the box. It would be difficult for me to praise this little motor's performance too highly. It was an unfailingly good starter, never needing a prime at any time. Response to both controls was very positive without any sign of “touchiness”, making the establishment of optimum settings very easy indeed. Both controls also held their settings firmly at all times. Running qualities were all that one could wish for – dead smooth, with no trace of a misfire and only a very slight tendency to sag by 100 RPM or so as the cylinder reached full operating temperature. This of course may have been a function of the fuel used, which was my standard test blend of 42% kerosene, 30% ether and 28% castor oil, with an additional 2½ % of octyl nitrate added to the overall mix. To further underscore its general excellence, the little Sharma delivered an unexpectedly sprightly performance. The following figures were obtained on test:

As noted earlier, the APC 8x4 WB prop is a one-off cut-down APC 9x4 item created and calibrated to fill a gap in my test set of propellers. As can be seen, the Sharma .09 delivered an excellent performance, generating better than average torque and peaking at around 14,100 RPM, where it developed some 0.220 BHP. When we consider that this engine is a plain bearing unit of basically 1960 design in terms of its general layout, we have to see this as a very fine showing indeed! Combined with its fine handling, the engine’s demonstrated ability to swing a relatively large prop quite happily would make it an excellent choice for events such as Free Flight Scale, which require an engine that can handle such props. Sharma S.P. 15 diesel This engine was also a brand new unmodified example of its type. It started and ran every bit as well as its smaller brother. When cold, it started readily with a couple of choked flicks and a few harder starting flicks. Hot restarts were instantaneous with just a single choked flick on a full fuel line as a preliminary. The 15 was just as responsive to the controls as the 09, making it very easy to set. The following figures were obtained on test:

As will be readily apparent from the above results, the Sharma 15 did not come close to achieving the stellar specific output of 144 BHP/litre measured for its .09 companion, managing only a relatively modest figure of 110 BHP/litre based upon an indicated peak output of around 0.270 BHP @ 14,200 RPM. It’s a little difficult to understand this difference, since both engines follow a more-or-less identical design path. The only thing that I can think of is that rather odd induction timing with its very late opening. Even so, the measured output is a perfectly acceptable figure for a fine-handling and well-built plain bearing diesel intended primarily for sport flying applications.

I found that the collector did very little to muffle the engine – there might possibly have been a slight reduction in overall sound pressure, while the quality of the exhaust note was perhaps a little less harsh with the collector fitted. In terms of performance, the engine matched most of the above figures, with the few exceptions being only 100 or so RPM down. The collector was extremely effective in directing exhaust resides away from the engine’s longitudinal axis. Based on this test, I found absolutely no reason not to use the collector, and much to be potentially gained in terms of model cleanliness. Many users would find this to be a very worthwhile accessory. In passing, it's worth noting that a recent re-test of my modified and well-used 1997 example of the Sharma 15 diesel yielded a peak output of around 0.325 BHP @ 14,300 RPM. Same peaking speed, but significantly more torque. For a plain-bearing 2.5 cc diesel of classic design, this is an excellent performance which clearly reflects the potential that is undeniably present in this design. Sharma S.P. 19 diesel

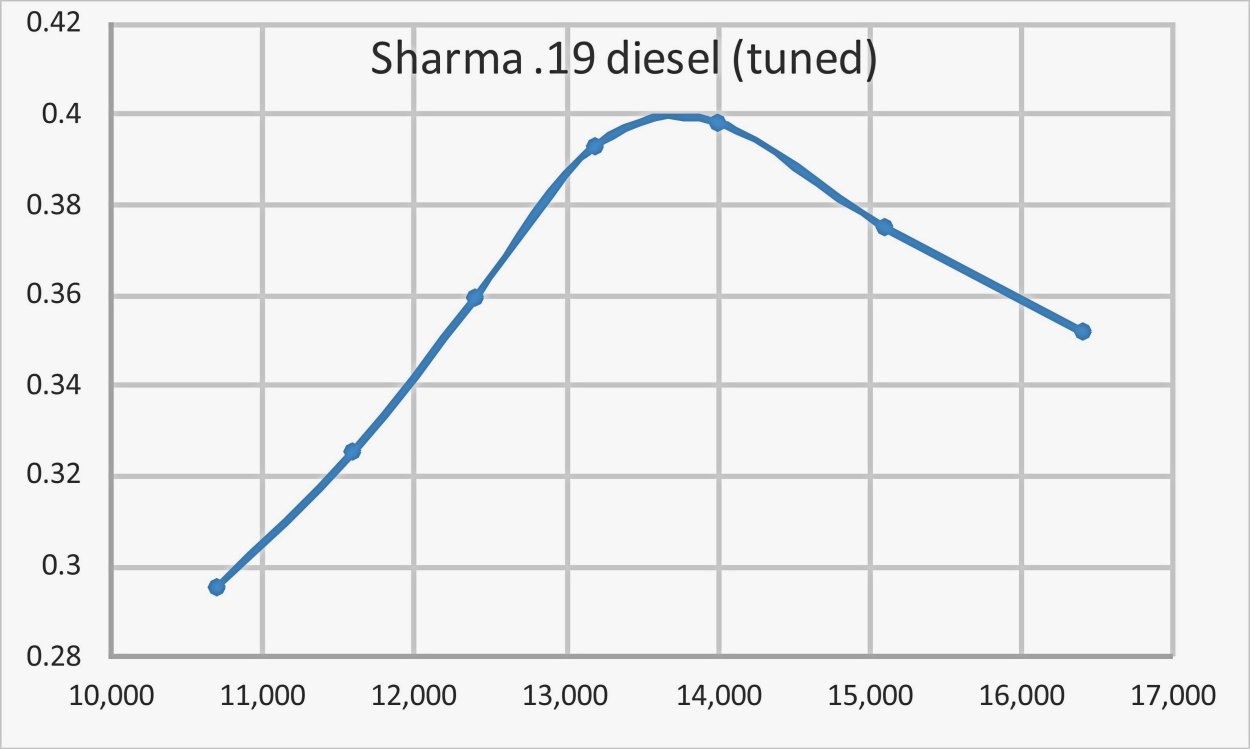

However, there was no ethical impediment to my undertaking a test of the fixed-venturi 19 model which I had personally modified to realize the engine's full potential for my own use in control-line service. I had reconfigured the crankshaft induction port for earlier opening of the induction system, added a pair of radial flow channels to the exit of the shaft's central gas passage and created three cutaways in the lower piston skirt at the bypass locations. The latter modification both improves gas access to the bypass passages at bottom dead centre and lightens the piston. The modified Sharma 19 started and ran just as well as its two smaller companions tested earlier. As with the others, no prime was required for starting, while running qualities were beyond criticism. As with the other engines tested, the compression locking lever supplied with the engine was not needed - the contra-piston was perfectly fitted and held its setting firmly at all times. Response to boh controls was excellent. The performance delivered by the modified Sharma 19 was well up to expectations, as witness the following test results:

The above figures reflect the development of some very useable torque at moderate RPM. The implied peak output of around 0.400 BHP @ 13,800 RPM is very good indeed for a plain bearing radially-ported engine of this displacement, reflecting a specific output of 129 BHP/litre. This latter figure falls almost exactly in between the comparable figures for the unmodified .09 and .15 models. A noteworthy feature of the power curve is the relatively broad peak - the engine is equalling or bettering an output of 0.38 BHP at all speeds between 12,800 and 14,800 RPM. Overall, a very user-friendly engine with extremely useful performance characteristics. Its quality and sturdiness are such that it should give many hours of excellent service. This one went on to see some good use in my hands! The Sharma Propellers I mentioned at the outset that Vivek Sharma provided me with a set of the company’s propellers for evaluation. These are very nicely moulded out of quite stiff but still flexible white glass-filled nylon. The shape of these props is very much along traditional lines rather than reflecting any modern theories of airscrew design. However, given the fact that they are not marketed as high-performance competition airscrews, I personally do not see this as a criticism – merely an observation. As of 2017 the props were reasonably priced at between 230 and 398 rupees (US$3.50 - $ 6.00) each depending on size. Most of the pr The units supplied were as follows: 20x10 (As marked, measured size 20.5x10 - 8x4) 20x15 (As marked, measured size 20.5x10 - 8x6) 23x10 (As marked, measured size 23.2x10 - 9x4) 23x15 (Unmarked - measured size 23.9x15 – 93/8x6) 26x15 (Unmarked - measured size 26.6x15 - 10½x6) 12x6 (as marked, confirmed by measurement) Vivek very thoughtfully sent me two examples each of the 8x4, 8x6, 9x4, 9x6, 10¼x6 and 12x6 sizes. This allowed me to gain some idea of the consistency of manufacture of these props as well as their aerodynamic consistency. The company also made a 7x4 propeller, but no examples of this were included. I found the weights of the two props of each size with which I was supplied to be extremely consistent. My small scale is only accurate to within 1 gm, hence being insufficiently sensitive to distinguish between two examples of the same prop. This was true even of the larger sizes, indicating good moulding consistency.

In terms of performance, I tried duplicate examples of a number of appropriate Sharma airscrews during my testing of the Sharma 09 and 15 diesels. The figures obtained were as follows:

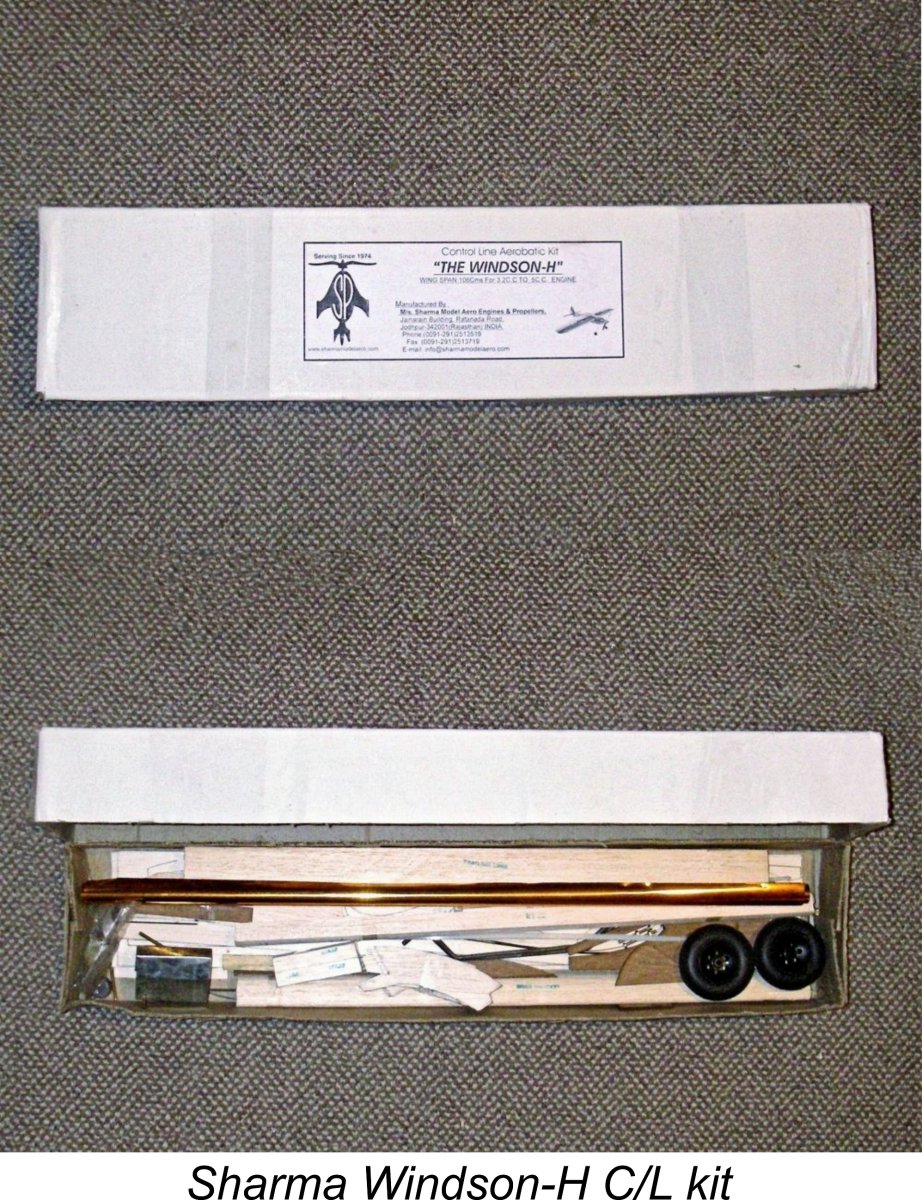

The above figures indicate a perfectly acceptable degree of aerodynamic consistency between different examples of the same moulded airscrew. None of the pairs tested exceeded a difference of 200 rpm. In my view, these props would serve their purchasers very well indeed. The Sharma Kits

Although I still haven't found time to build this model, I can report that the kit is remarkably comprehensive, with an excellent full-sized plan and all hardware necessary to complete the model, even including the wedge tank and engine mounting hardware. The wood components are pre-fabricated from material of very acceptable quality. All parts are stamped with their identification so that they can easily be located on the plan and assembled correctly. I have no doubt that this kit would build up very easily into a fine model. As mentioned earlier, the 2017 Sharma model aircraft range included five different chuck glider kits, three different control-line model kits and some 14 different R/C model kits and ARF models. There's little doubt in my mind that the company was providing a valuable service to Indian aeromodellers in making these kits available. As with the Sharma engines and propellers, anyone wishing to inquire about obtaining one of these kits was advised to contact the Sharma company by email. Conclusion In an era in which model I/C engine manufacturers are leaving the field at a depressing rate, it was refreshing to find a manufacturer in 2017 who was continuing to plug away towards his first half century in business quietly doing what his company has always done very well indeed – making quality model engines in limited quantities along with well-produced model aircraft kits and accessories. Such manufacturers are all the more to be treasured because of their ever-dwindling numbers in an age in which people would rather push buttons than get their hands oily! As an update to the above comments, I confess to a fear that this happy situation had not survived to 2023. The Sharma website still came up on call, but it no longer appeared to be maintained. Moreover, my emails to Vivek went unanswered. It appears that the electric revolution may have claimed another victim.................... Even so, if a well-made and reasonably-priced model diesel from a long-established quality manufacturer working in an unusual location has any appeal, rest assured that you will not be disappointed if you manage to track one down! As a satisfied Sharma user myself since 1997, I can personally attest to the fine qualities of this excellent range of model diesels! I can recommend them without reservation! _______________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, BC, Canada First Published March 2017 Updated November 2023 |

||

| |

During a visit to England in the autumn of 1997 (twenty-seven years ago at the present time of writing - how time flies!), I made a pilgrimage to visit

During a visit to England in the autumn of 1997 (twenty-seven years ago at the present time of writing - how time flies!), I made a pilgrimage to visit  Upon my producing this engine for their examination, the Eifflaenders instantly recognized its design inspiration! Tony’s immediate comment was “Blimey, we never made this! Where’s me royalties?!?” The engine was immediately mounted in the P.A.W. test stand, proceeding to give a very good account of itself by comparison with established test figures for its plain bearing 2.5 cc P.A.W. counterpart. The boys were quite impressed………...

Upon my producing this engine for their examination, the Eifflaenders instantly recognized its design inspiration! Tony’s immediate comment was “Blimey, we never made this! Where’s me royalties?!?” The engine was immediately mounted in the P.A.W. test stand, proceeding to give a very good account of itself by comparison with established test figures for its plain bearing 2.5 cc P.A.W. counterpart. The boys were quite impressed………... In reality, very few model engines can truly be said to be original designs – almost all of them draw upon various features of their competitors and predecessors. The fact that the Sharma designer clearly drew inspiration from the basic P.A.W. design is a compliment to that range, but nothing more.

In reality, very few model engines can truly be said to be original designs – almost all of them draw upon various features of their competitors and predecessors. The fact that the Sharma designer clearly drew inspiration from the basic P.A.W. design is a compliment to that range, but nothing more.

its goals the fostering of an interest in aeronautics among its cadet members. Inspired by this experience, the brothers promptly began to construct model engines for their own use. At this time their ages were 17 and 13 respectively. Despite their youth, they were already highly capable machinists.

its goals the fostering of an interest in aeronautics among its cadet members. Inspired by this experience, the brothers promptly began to construct model engines for their own use. At this time their ages were 17 and 13 respectively. Despite their youth, they were already highly capable machinists. those who had taken note of the efforts of the Sharma brothers were representatives of the previously-mentioned National Cadet Corps (N.C.C.). The lack of domestic model engines was a particular problem for them given their ongoing need for a steady supply of engines to be used in the aeronautical education of their cadet ranks through active participation in aeromodelling. The steadily growing Indian aeromodelling community at large was similarly challenged by a lack of readily available powerplants.

those who had taken note of the efforts of the Sharma brothers were representatives of the previously-mentioned National Cadet Corps (N.C.C.). The lack of domestic model engines was a particular problem for them given their ongoing need for a steady supply of engines to be used in the aeronautical education of their cadet ranks through active participation in aeromodelling. The steadily growing Indian aeromodelling community at large was similarly challenged by a lack of readily available powerplants. tested design and construction concepts rather than pursuing as-yet unexplored design directions. From the outset, Anand Swaroop Sharma very sensibly recognized the previously-noted fact that few model engines were in fact truly original and that “sports” model engine design as it stood in 1974 had got to where it was through the long-term development and field-testing of a number of design concepts which had stood the test of time and hence were very well established. Why re-invent the wheel?!?

tested design and construction concepts rather than pursuing as-yet unexplored design directions. From the outset, Anand Swaroop Sharma very sensibly recognized the previously-noted fact that few model engines were in fact truly original and that “sports” model engine design as it stood in 1974 had got to where it was through the long-term development and field-testing of a number of design concepts which had stood the test of time and hence were very well established. Why re-invent the wheel?!? In taking this design as his basic standard, Mr. Sharma demonstrated another trait which was to continue down through the years – a willingness to adapt and modify as he saw fit. That first series-production Sharma 2.5 cc diesel was no exception. It was very clearly based upon the original 1955 FROG 249 with upwardly-drilled transfer ports between the exhaust apertures. I

In taking this design as his basic standard, Mr. Sharma demonstrated another trait which was to continue down through the years – a willingness to adapt and modify as he saw fit. That first series-production Sharma 2.5 cc diesel was no exception. It was very clearly based upon the original 1955 FROG 249 with upwardly-drilled transfer ports between the exhaust apertures. I Nominal bore and stroke of this model were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). The engine weighed in at a checked 180 gm (6.35 ounces). While this is a lot for a 2.5 cc sports diesel, it must be recalled that the primary design aims were durability and dependability. In those respects, the rather high weight was simply a reflection of the engine's unusually sturdy construction. Based upon a critical examination of my own example, all fits and finishes were beyond reproach - well up to the best prevailing standards worldwide. Moreover, the engine delivered an excellent performance, as will become apparent later.

Nominal bore and stroke of this model were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cuin.). The engine weighed in at a checked 180 gm (6.35 ounces). While this is a lot for a 2.5 cc sports diesel, it must be recalled that the primary design aims were durability and dependability. In those respects, the rather high weight was simply a reflection of the engine's unusually sturdy construction. Based upon a critical examination of my own example, all fits and finishes were beyond reproach - well up to the best prevailing standards worldwide. Moreover, the engine delivered an excellent performance, as will become apparent later.  This image (reproduced at the right with its caption) may set the standard for Clanford's very interesting but woefully under-researched book - it embodies no fewer than three errors in a single entry! Firstly, the engine is not an Aurora K-series unit - rather, it's unquestionably a Sharma product from the mid 1970's. Secondly, its displacement is 2.5 cc, not 3.5 cc - Sharma never made a 3.5 cc version of this design. And thirdly, neither Sharma nor Aurora ever purchased any dies or tooling from the owners of the FROG marque - all their dies and tooling were created in-house from scratch, although both companies freely acknowledged the FROG design influence which is evident in their respective ball-race models.

This image (reproduced at the right with its caption) may set the standard for Clanford's very interesting but woefully under-researched book - it embodies no fewer than three errors in a single entry! Firstly, the engine is not an Aurora K-series unit - rather, it's unquestionably a Sharma product from the mid 1970's. Secondly, its displacement is 2.5 cc, not 3.5 cc - Sharma never made a 3.5 cc version of this design. And thirdly, neither Sharma nor Aurora ever purchased any dies or tooling from the owners of the FROG marque - all their dies and tooling were created in-house from scratch, although both companies freely acknowledged the FROG design influence which is evident in their respective ball-race models.  As things turned out, that original FROG-based 2.5 cc engine was destined to be the only ball-race model ever manufactured by the Sharma company. In 1980 a major change took place in the company’s design direction. The former FROG-influenced ball-race design was abandoned in favor of a comprehensively revised range of plain-bearing model engines based upon the well-established and highly successful designs which had been produced in England for many years by P.A.W.. It is this series which remained in production as of 2017.

As things turned out, that original FROG-based 2.5 cc engine was destined to be the only ball-race model ever manufactured by the Sharma company. In 1980 a major change took place in the company’s design direction. The former FROG-influenced ball-race design was abandoned in favor of a comprehensively revised range of plain-bearing model engines based upon the well-established and highly successful designs which had been produced in England for many years by P.A.W.. It is this series which remained in production as of 2017.  The Sharma glow-plug models never appear to have reached the Western market in quantity during their period of manufacture. Hence they are little known among modellers outside of India, few of whom are even aware that Sharma ever made glow-plug engines. However, thanks to the kindness of Mr. Vivek Sharma, I have a complete, original and highly servicable example of the 15 C/L glow-plug model on hand. Since this engine represents a completely valid expression of the company's abilities in fields other than model diesel design and manufacture, I've included a retrospective test of this unit which will appear below in its place.

The Sharma glow-plug models never appear to have reached the Western market in quantity during their period of manufacture. Hence they are little known among modellers outside of India, few of whom are even aware that Sharma ever made glow-plug engines. However, thanks to the kindness of Mr. Vivek Sharma, I have a complete, original and highly servicable example of the 15 C/L glow-plug model on hand. Since this engine represents a completely valid expression of the company's abilities in fields other than model diesel design and manufacture, I've included a retrospective test of this unit which will appear below in its place.  Having been started as a family venture, it’s really nice to be able to report that as of my original time of writing in 2017 the company remained very much a Sharma family business after well over 40 years in operation. The company was still owned by its founder, Mr. Anand Swaroop Sharma, who remained very active in the conduct of the company’s operations. He is seen at the left in the accompanying photograph checking the plans for a new 1 meter wingspan R/C electric model kit called the VEE-ONE which was designed by his younger son Vishal.

Having been started as a family venture, it’s really nice to be able to report that as of my original time of writing in 2017 the company remained very much a Sharma family business after well over 40 years in operation. The company was still owned by its founder, Mr. Anand Swaroop Sharma, who remained very active in the conduct of the company’s operations. He is seen at the left in the accompanying photograph checking the plans for a new 1 meter wingspan R/C electric model kit called the VEE-ONE which was designed by his younger son Vishal. Anand Swaroop Sharma’s nephew Sudhir Sharma (1964 - ) was in charge of model kit production, while Vivek Sharma’s wife Mrs. Shalini Sharma was responsible for the accounts and bookkeeping. Since Mrs. Sharma has a Master’s degree in commerce, she too was very well qualified for her position with the company. Hence virtually the entire business continued to be under the direct management of well-qualified members of the Sharma family.

Anand Swaroop Sharma’s nephew Sudhir Sharma (1964 - ) was in charge of model kit production, while Vivek Sharma’s wife Mrs. Shalini Sharma was responsible for the accounts and bookkeeping. Since Mrs. Sharma has a Master’s degree in commerce, she too was very well qualified for her position with the company. Hence virtually the entire business continued to be under the direct management of well-qualified members of the Sharma family. The workforce in 2017 was comprised of 14 individuals, only about 5 or 6 of whom were involved in model engine manufacture. Other workers were involved with propeller, kit and ARF manufacture as well as other company activities.

The workforce in 2017 was comprised of 14 individuals, only about 5 or 6 of whom were involved in model engine manufacture. Other workers were involved with propeller, kit and ARF manufacture as well as other company activities. customer. Speaking personally, I always found EMS to be very efficient.

customer. Speaking personally, I always found EMS to be very efficient. The yellow profile control-line model seen in the left foreground of the image at the above right is a Senior Peacemaker built from a Sharma kit and powered by a Sharma .19 diesel turning a 9x6 prop. A similar model was also flown at the meeting using a Sharma .15 diesel fitted with an 8x6 airscrew. The image at the left shows this latter model in flight at the same meeting

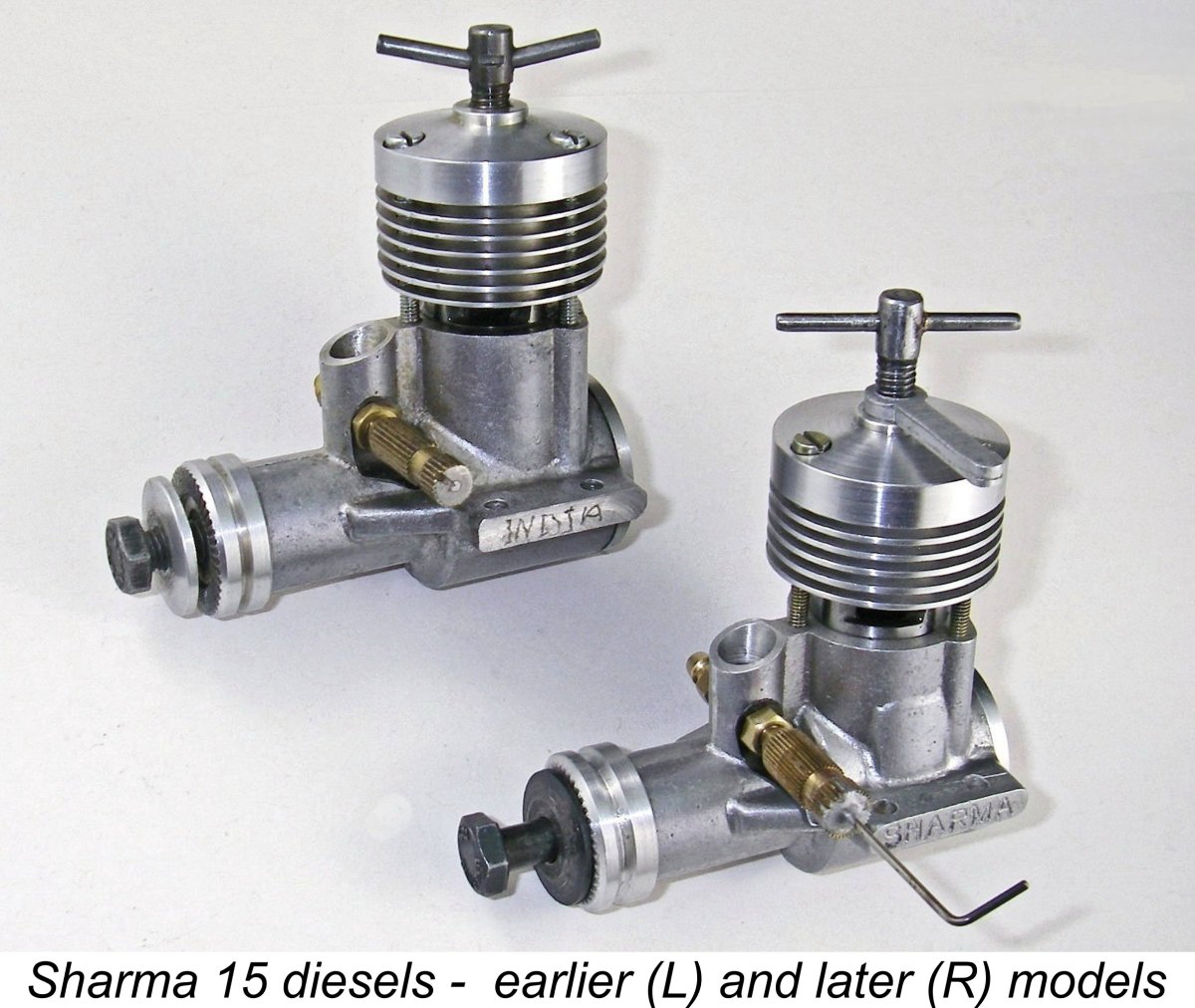

The yellow profile control-line model seen in the left foreground of the image at the above right is a Senior Peacemaker built from a Sharma kit and powered by a Sharma .19 diesel turning a 9x6 prop. A similar model was also flown at the meeting using a Sharma .15 diesel fitted with an 8x6 airscrew. The image at the left shows this latter model in flight at the same meeting  The post-1980 Sharma 15 diesel was a basically conventional plain bearing radially-ported crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model diesel which followed the P.A.W. design formula fairly closely, albeit with a number of distinctive departures from the P.A.W. design. This model evolved in detail over the years, as the attached comparative image of my original well-used example from 1997 with the 2016 model supplied by Vivek Sharma for this evaluation will confirm.

The post-1980 Sharma 15 diesel was a basically conventional plain bearing radially-ported crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model diesel which followed the P.A.W. design formula fairly closely, albeit with a number of distinctive departures from the P.A.W. design. This model evolved in detail over the years, as the attached comparative image of my original well-used example from 1997 with the 2016 model supplied by Vivek Sharma for this evaluation will confirm. Both this model and the companion .19 model were offered in two versions. The control-line/free flight model like that illustrated above and tested for this article (see below) had a venturi intake which was cast in unit with the rest of the crankcase. However, there was an alternative version as illustrated at the left. This used a different crankcase casting in which the intake was angled forward, shortened and drilled out to accept either a separate venturi insert or an R/C throttle. The latter components were secured using socket-head grub screws.

Both this model and the companion .19 model were offered in two versions. The control-line/free flight model like that illustrated above and tested for this article (see below) had a venturi intake which was cast in unit with the rest of the crankcase. However, there was an alternative version as illustrated at the left. This used a different crankcase casting in which the intake was angled forward, shortened and drilled out to accept either a separate venturi insert or an R/C throttle. The latter components were secured using socket-head grub screws.  The illustration at the right shows the 2016 engine's compnents. The first and perhaps most significant departures from the P.A.W. design are to be found in the Sharma's bore and stroke measurements. Unlike its P.A.W. counterpart, the Sharma 15 is a long-stroke engine having bore and stroke measurements of 14.50 and 14.86 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.45 cc (0.149 cuin.). This displacement is identical to that of the short-stroke P.A.W., which achieves that displacement by using bore and stroke dimensions of 15.16 mm and 13.59 mm. Both engines meet both the FAI displacement limit of 2.5 cc and the US equivalent limit of 0.15 cuin.

The illustration at the right shows the 2016 engine's compnents. The first and perhaps most significant departures from the P.A.W. design are to be found in the Sharma's bore and stroke measurements. Unlike its P.A.W. counterpart, the Sharma 15 is a long-stroke engine having bore and stroke measurements of 14.50 and 14.86 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.45 cc (0.149 cuin.). This displacement is identical to that of the short-stroke P.A.W., which achieves that displacement by using bore and stroke dimensions of 15.16 mm and 13.59 mm. Both engines meet both the FAI displacement limit of 2.5 cc and the US equivalent limit of 0.15 cuin. Turning now to the engine’s physical construction attributes, the cylinder is the one component that is close to being a direct P.A.W. copy. It is of purely cylindrical outward form, externally ground to a very fine finish and plugging into a matching recess at the top of the gravity die-cast crankcase to seat on a narrow ledge at the base of that recess. It is held in place by a turned light alloy cooling jacket which is retained by three 6 BA screws.

Turning now to the engine’s physical construction attributes, the cylinder is the one component that is close to being a direct P.A.W. copy. It is of purely cylindrical outward form, externally ground to a very fine finish and plugging into a matching recess at the top of the gravity die-cast crankcase to seat on a narrow ledge at the base of that recess. It is held in place by a turned light alloy cooling jacket which is retained by three 6 BA screws.  The closeness of this latter fit has two distinct benefits. Firstly, the resulting intimate contact between the cooling jacket and the cylinder can only be beneficial in terms of cooling. And secondly, the engine can be dismantled when necessary without disturbing the cylinder alignment upon reassembly as long as the cylinder is left snugly installed in the cooling jacket. All that’s necessary is to mark the assembly so that it can be re-installed in the same orientation. The comp screw and locking lever fulfil this requirement admirably.

The closeness of this latter fit has two distinct benefits. Firstly, the resulting intimate contact between the cooling jacket and the cylinder can only be beneficial in terms of cooling. And secondly, the engine can be dismantled when necessary without disturbing the cylinder alignment upon reassembly as long as the cylinder is left snugly installed in the cooling jacket. All that’s necessary is to mark the assembly so that it can be re-installed in the same orientation. The comp screw and locking lever fulfil this requirement admirably. – you simply couldn’t ask for better. A new engine was actually a little tight at the upper end of the stroke, but that worked itself out with a few hours of running. The instructions claim (and Vivek Sharma confirmed) that each engine is test-run at the factory and is held at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes, hence needing little running in. This mirrors the approach taken in the old days by P.A.W., who used to run new engines up to 13,000 rpm prior to despatch, advising that little further running-in was required.

– you simply couldn’t ask for better. A new engine was actually a little tight at the upper end of the stroke, but that worked itself out with a few hours of running. The instructions claim (and Vivek Sharma confirmed) that each engine is test-run at the factory and is held at 12,000 rpm for 5 minutes, hence needing little running in. This mirrors the approach taken in the old days by P.A.W., who used to run new engines up to 13,000 rpm prior to despatch, advising that little further running-in was required.  However, the Sharma design does not adopt this simple and effective strategy. Instead, the gudgeon pin appears at first sight to be held in position by a layer of some kind of high temperature adhesive placed in the outer ends of each piston boss. Frankly, this doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence when first encountered! That said, my original 1997 example which has been in regular service now for 26 years with many hours of air time to its credit is still hanging in there perfectly.

However, the Sharma design does not adopt this simple and effective strategy. Instead, the gudgeon pin appears at first sight to be held in position by a layer of some kind of high temperature adhesive placed in the outer ends of each piston boss. Frankly, this doesn’t inspire a lot of confidence when first encountered! That said, my original 1997 example which has been in regular service now for 26 years with many hours of air time to its credit is still hanging in there perfectly. mm (0.437 in.) with an internal gas passage diameter of 6.22 mm (0.245 in.). This leaves plenty of metal for adequate strength.

mm (0.437 in.) with an internal gas passage diameter of 6.22 mm (0.245 in.). This leaves plenty of metal for adequate strength. The prop is retained by a M6x1 bolt with a steel washer. The use of a separate prop bolt represents another departure from the P.A.W. design, which uses a threaded extension of the crankshaft. However, the really interesting element of the prop mounting system is the prop driver. At first sight this seems to be a conventional item which is located on a taper formed at the front of the shaft. However, it is recessed at the rear so that it actually encloses the front portion of the main bearing housing. This does much to discourage the ingress of dirt into the bearing as a result of a crash – it is in fact a modification which I have routinely made on my plain bearing or single ball race PAW motors in the past.

The prop is retained by a M6x1 bolt with a steel washer. The use of a separate prop bolt represents another departure from the P.A.W. design, which uses a threaded extension of the crankshaft. However, the really interesting element of the prop mounting system is the prop driver. At first sight this seems to be a conventional item which is located on a taper formed at the front of the shaft. However, it is recessed at the rear so that it actually encloses the front portion of the main bearing housing. This does much to discourage the ingress of dirt into the bearing as a result of a crash – it is in fact a modification which I have routinely made on my plain bearing or single ball race PAW motors in the past. The engine is completed with a screw-in backplate. The thread for this is formed to very close limits – adequate lubrication is required when removing or re-installing the backplate to guard against possible galling and thread seizure.

The engine is completed with a screw-in backplate. The thread for this is formed to very close limits – adequate lubrication is required when removing or re-installing the backplate to guard against possible galling and thread seizure.  No gaskets are used either for the backplate or at the base of the cylinder. The very close fit of the latter component in its recess ensures a leak-free joint, while the backplate seal depends on the very accurately-machined thread as well as excellent surface finishes. A submerged base compression leak test indicated no observable leakage from these locations.

No gaskets are used either for the backplate or at the base of the cylinder. The very close fit of the latter component in its recess ensures a leak-free joint, while the backplate seal depends on the very accurately-machined thread as well as excellent surface finishes. A submerged base compression leak test indicated no observable leakage from these locations. In addition to the .15 cuin. model just described, the Sharma company offered diesels in .09 cuin. (1.5 cc) and .19 cuin. (3.2 cc) displacements. These followed the same construction pattern and material specification as the 15 model in all respects, making it unnecessary to describe them in detail. Both of these models were available in both standard and R/C versions.

In addition to the .15 cuin. model just described, the Sharma company offered diesels in .09 cuin. (1.5 cc) and .19 cuin. (3.2 cc) displacements. These followed the same construction pattern and material specification as the 15 model in all respects, making it unnecessary to describe them in detail. Both of these models were available in both standard and R/C versions.  screws were M2.5x0.45 items, while the comp screw and prop bolt threads were both M5x0.8.

screws were M2.5x0.45 items, while the comp screw and prop bolt threads were both M5x0.8.  My first test subject is the original Sharma S.P. 2.5 diesel which was manufactured betwen 1974 and 1980. As stated earlier, this model was based in large part upon the old FROG 249 BB of 1955 with its four upwardly drilled transfer ports. However, the Sharma rendition dispensed with the front ball race. It did however retain the sub-piston induction feature of the FROG 249 BB. The engine weighs 180 gm (6.35 ounces) as illustrated.

My first test subject is the original Sharma S.P. 2.5 diesel which was manufactured betwen 1974 and 1980. As stated earlier, this model was based in large part upon the old FROG 249 BB of 1955 with its four upwardly drilled transfer ports. However, the Sharma rendition dispensed with the front ball race. It did however retain the sub-piston induction feature of the FROG 249 BB. The engine weighs 180 gm (6.35 ounces) as illustrated. acquaintance. It had obviously had a fair bit of previous use, but all fits remained superb. In particular, the single ball race had a real quality feel to it. I was quite impressed!

acquaintance. It had obviously had a fair bit of previous use, but all fits remained superb. In particular, the single ball race had a real quality feel to it. I was quite impressed!

As mentioned earlier, it's not widely known that the Sharma company made a couple of glow-plug models over an eight year period extending from 1988 to 1996. These models were offered in .15 cuin. (2.5 cc) and .23 cuin. (3.77 cc) displacements. Both C/L and R/C models were produced to a basically identical design.