|

|

Sincere Flattery – the Baby Cyclone Copies By Maris Dislers

Mixing existing and new elements in a fresh design is standard engineering practice - almost all model engines display elements of earlier designs. First-timers setting out to manufacture an unfamiliar product will generally stay close to an established design which has proved its worth. In the early days of powered model aircraft, the USA was streets ahead of other countries, greatly influencing foreign designers who were trying to catch up. Doing some research on this topic, I was surprised to discover the extent to which the Baby Cyclone had inspired similar engines, far and wide. That line is somewhat blurred by one’s personal views regarding how much a “copy” has to differ from the original before becoming something evidently different. My own arbitrary limit excludes the Morton Challenger, I.M.P. Intermote and Aero Precision 820 for their quite different crankcase construction, despite their adoption of other core design elements from the Baby Cyclone. Now back to the souce - the original Baby Cyclone! The Original Baby Cyclone

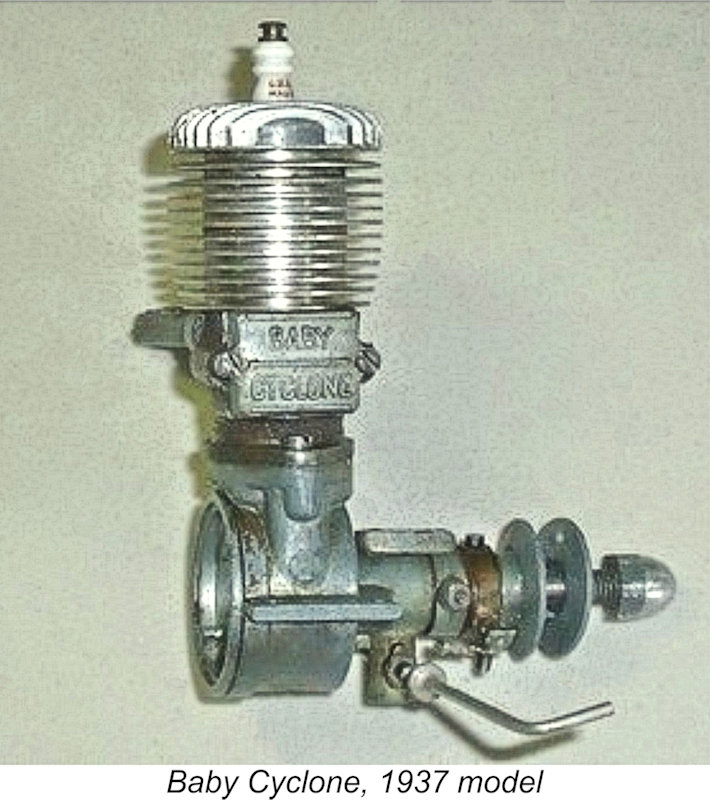

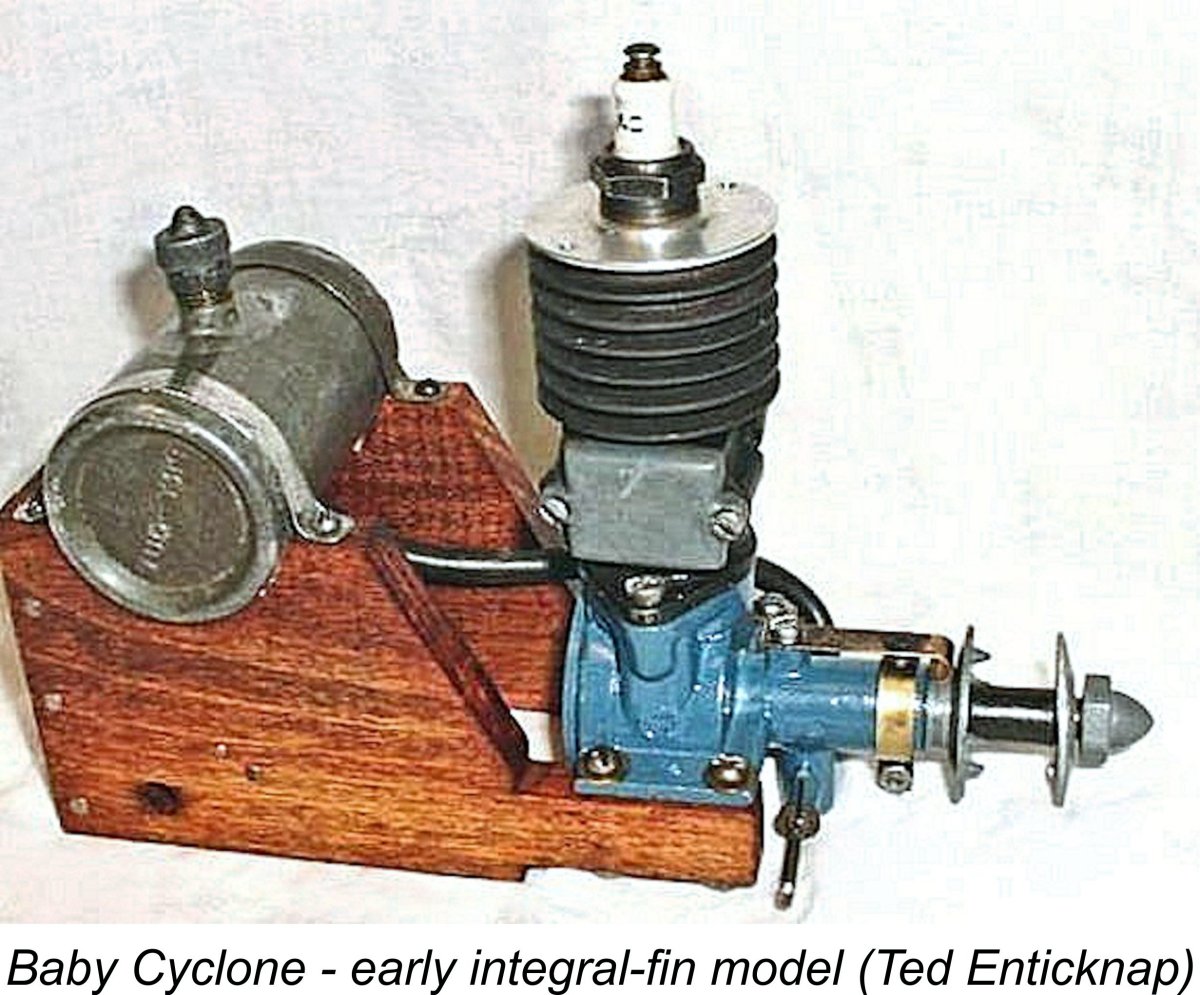

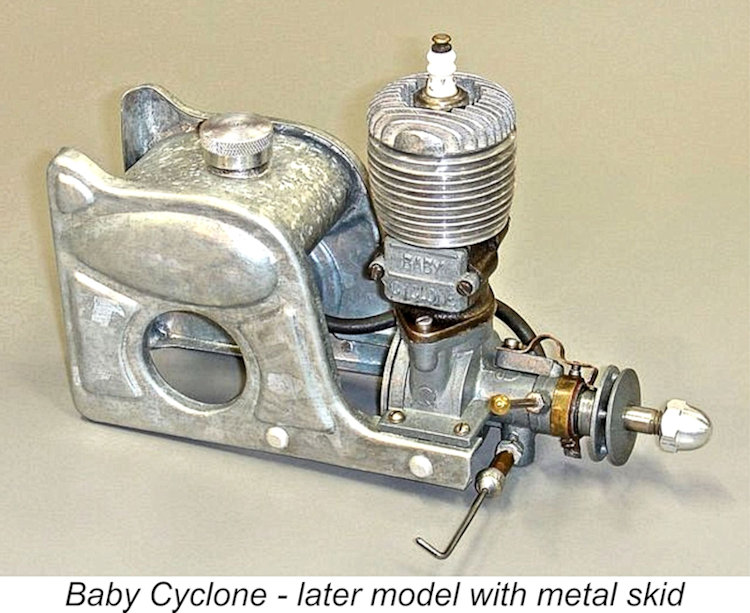

Atwood's much smaller engine made for the 1934 Nationals in Akron, Ohio was hampered by the use of too light an oil grade in the fuel for the very hot conditions. Nonetheless, it went on to power Bill’s 1935 California State Championship-winning model, impressing aircraft industry entrepreneur Major C. C. Moseley enough to inspire him to buy the design and hire Bill to bring it into production at Moseley’s “Aircraft Industries Corporation” plant located at Grand Central Terminal in Glendale, California some 12 miles to the north of downtown Los Angeles. Moseley had first encountered Atwood at a model contest prize-giving in 1928 and had followed his subsequent career with interest. The first Baby Cyclone engines reached the market by Christmas 1935 at a time when the available model aero engine options were still very few. The engine was an immediate commercial success, with almost 20,000 examples being produced and sold over the next four years. A number of these somehow found their way to overseas countries, where they could serve as sources of design inspiration.

Mel Anderson continued to develop the Baby Cyclone after Bill Atwood left to pursue other opportunities in late 1936. Another notable Moseley employee during this period was future model engine design maestro Ira Hassad, whose primary responsibility was the lapping of the pistons to a perfect fit in their cylinders. Production (or at least supply) stretched into 1940, going through the original X and then A to F models. Along the way, the engine underwent relatively minor changes to such features as cooling fins, adjustable ignition timing arrangements, needle valve configuration and mounting skid. It was well made and enticingly presented. Lavish advertisements included $150 prize offers for anyone winning at the Nationals using their engine; an engine/kit/propeller bundle deal; and reports of a hundred-hour durability test. By The Baby Cyclone crankcase was die-cast in zinc alloy. It had beam mounting lugs, an updraught carburettor (to avoid flooding), a plain bronze crankshaft bearing and a screw-in rear cover. Other features included a cast iron cylinder with two-screw base flange mount and (in most versions) aluminium cooling fins; a detachable bypass cover, typically with “Baby Cyclone” cast in relief; a screw-in aluminium head (later models had vertical head fins clamped on by the spark plug); a cast iron piston with skirt port feeding an external bypass passage; crossflow loop scavenging; and a steel crankshaft with screw-in crankpin. The engine was originally supplied on a wooden skid mount with tank, coil and condenser. The skid for later models was made from stamped steel.

During the early days, competitions in the USA focused upon flight duration from a given fuel allocation based on model weight. This approach placed a premium on good handling and fuel efficiency. The handling issue was particularly important at this time given the fact that good handling resulted in less of the limited fuel allocation being consumed during starting, leaving more of it available for actually powering the flight itself. Moreover, the majority of participants in this then-new field were inherently inexperienced - power flying had not been around long enough for them to become experienced! Combined with its good power output, the Baby Cyclone’s excellent fuel efficiency by comparison with the side-port opposition along with its easy handling allowed the engine to win many competitions before the rules were changed to an engine run-time formula, which favoured higher horsepower over fuel efficiency. At that point, the competion from other contemporary designs intensified. For perspective, test results for the original Baby Cyclone suggested maximum efficiency at around 5,500 RPM for 0.20 BHP and 37 oz-in torque. The development of the engine from that starting point led eventually to the appearance of the final variant, the Model F. This model was tested by "Model Airplane News" in 1938, with the results appearing in the July 1938 issue of the magazine. An output of some 0.22 BHP @ 6,800 RPM was reported - a significant improvement over the earlier numbers, and quite acceptable figures by the standards of 1938. No wonder that other model engine makers both in the USA and in many other countries around the world took note! Let's have a look at the results stemming from this influence.......... USA

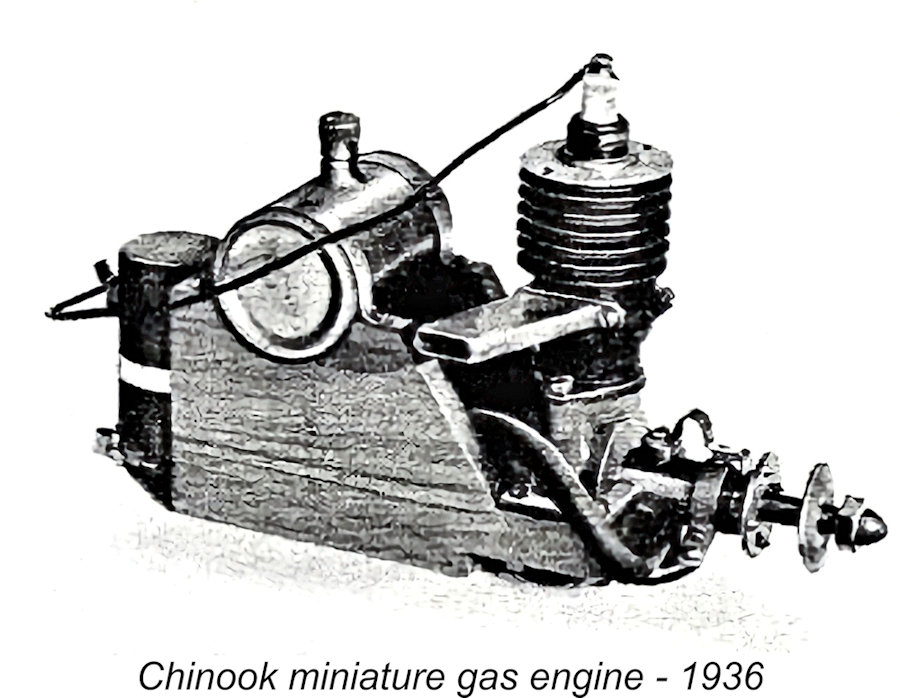

The Chinook was basically a reverse-engineered first Model X Baby Cyclone, but with cylinder reversed and other minor Haines Hobby House of Reading, Pennsylvania later marketed the Wensen 36, which was very clearly a Baby Cyclone derivative. This engine featured a sand cast aluminium crankcase and an iron cylinder with integrally-machined fins. The 1946 and 1947 variants of the Wensen differed slightly in casting thickness. In his review of the Wensen for SAM Speaks, Charlie Bruce recorded a steady 4,600 RPM with a Hi-Thrust 13x8 propeller, around the same as a Baby Cyclone. Not so exciting by comparison with then-available alternatives. Australia

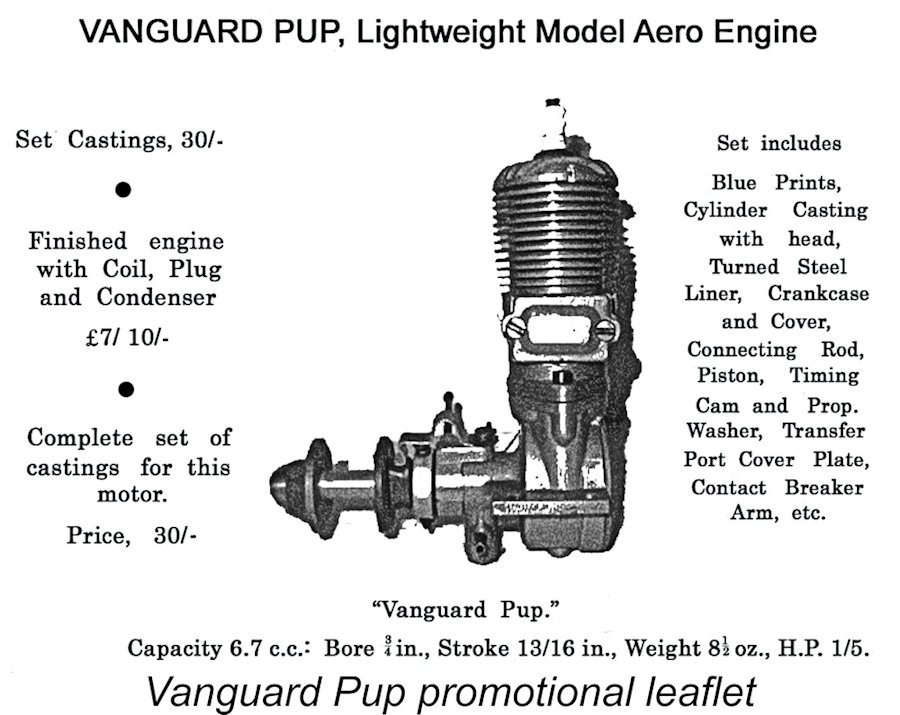

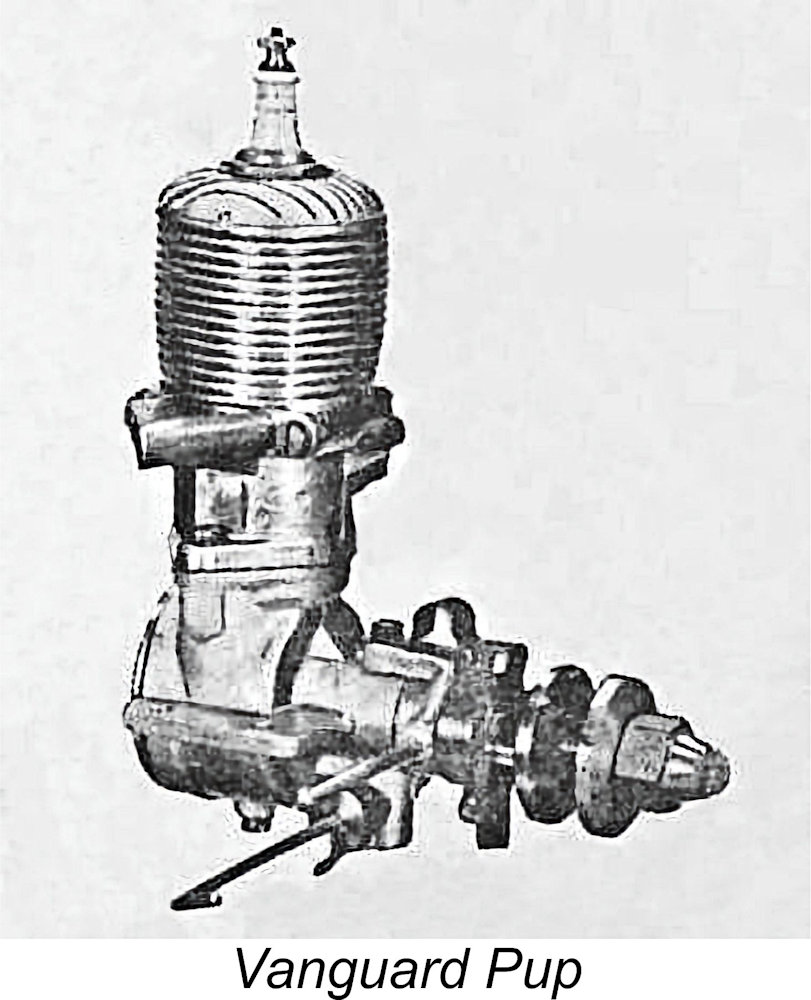

The Vanguard Pup was one of the optional ready-to-run or kit/plan engines available from the Model Dockyard in Melbourne. Probably introduced in 1938, it remained in the catalogues until 1950. It featured a die-cast aluminium crankcase, cylinder block, head, timer and backplate along with a zinc-alloy prop driver The engine initially featured a blind-bored cylinder, but this was soon revised to incorporate a screw-in head. The cylinder orientation was reversed from that of the original Baby Cyclone and the engine was timed for clockwise running, which retained its adherents at the time. Ready-to-run engines were very well made, but were only made available in small numbers. Those constructed from casting kit sets were of highly variable quality depending upon the skill of the individual builders. New Zealand

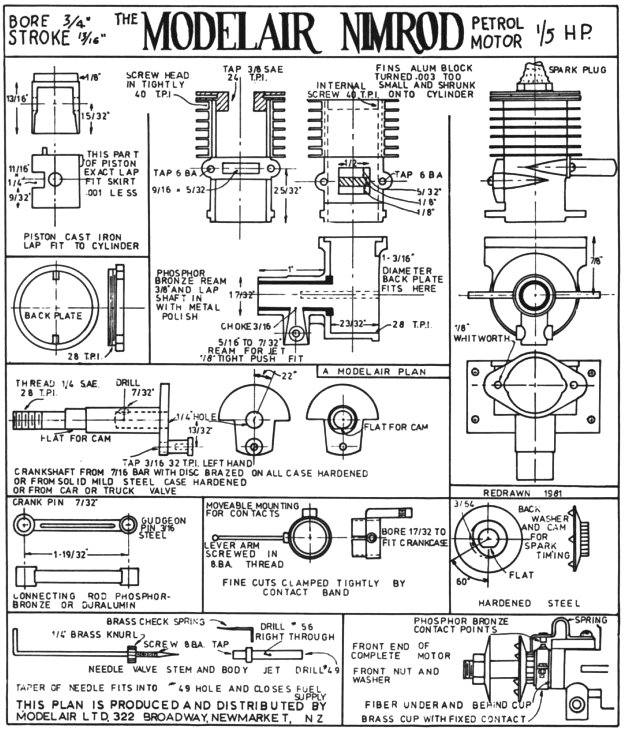

“The story of the Nimrod goes back over 40 years, to prior to WW II. I do not know the actual date of production, but I would say about 1938/9, as import licensing was imposed on the country then, which made obtaining engines from USA more difficult. They were made on our present premises and my father (Fred) was instrumental in the design which was inspired by the very early Baby Cyke. They were available as a kit of castings and also ready to run. We have no records of how many were made, but my guess is about 50. I saw one a couple of years ago which was complete except for the “make-and-break” points. Only one size was made”. Bore and stroke of the Nimrod were exact duplicates of those applied to the original Baby Cyclone at ¾ in. (19.05 mm) and 13/16 in. (20.64 mm) respectively for a swept volume of .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) We could not find an image of this super-rare engine – it seems that very few examples survive. The attached plan of the engine is the sole remaining hard evidence of its existence and design features. Czechoslovakia

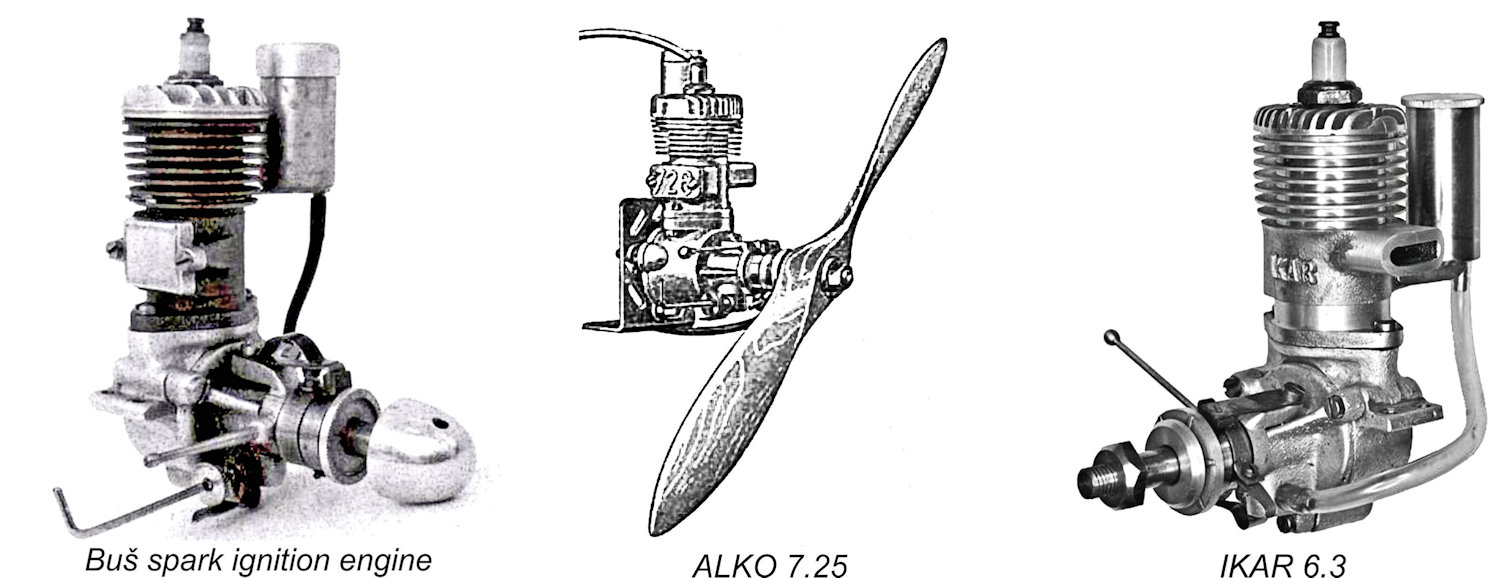

Other similar Czech engines of this type include the ALKO 7.25 by Alois Korda, IKAR 6.3 by Konrad Pahr and the subsequent IPRO-IKAR, which did not achieve intended post-war series production. In addition, several DIY kit designs were available from the well-kmown M.K. Moučka hobby store in Prague. The quality of these Czech-made engines was generally quite high.

Germany

Japan

Russia

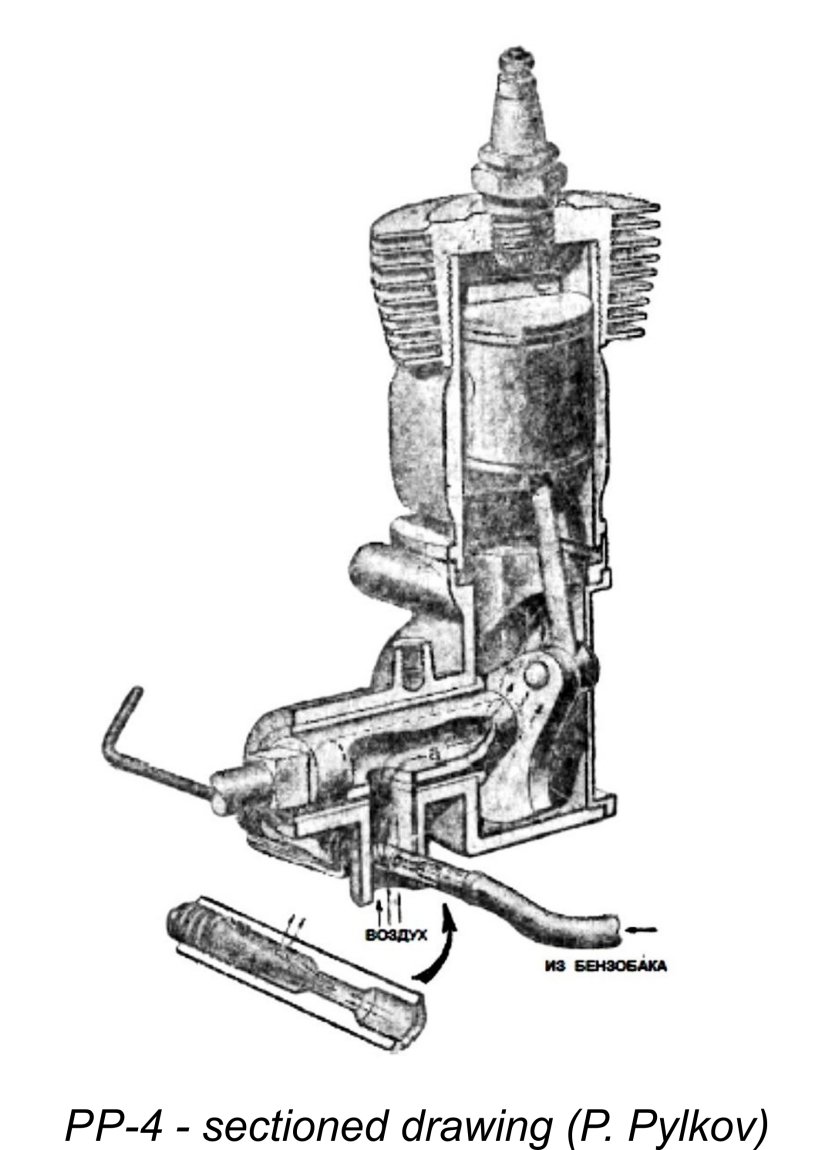

DIY engine builders needed the Russian-language book Gasoline Motors by P. Pylkov. First published in 1940, it provided detailed instructions for building the 5.82 cc Pylkov PP-4, which was a duly-acknowledged near-clone of the Baby Cyclone. This engine was evidently designed in 1937, since a contestant named Petrov set a new USSR distance record of 14.37 km with his PP-4 powered model at the 1937 All-Union Championship – Russian competitions of the day were all run on a percentage-of-record basis. The PP-4 evidently proved to be sufficiently popular among home constructors to justify the 1940 publication of Pylkov's book. Given the engine's home-constructed status, it's reasonable to suppose that both quality and performance were very much influenced by the skill of the individual constructor. No image of an actual example of this engine appears to be available. Sweden

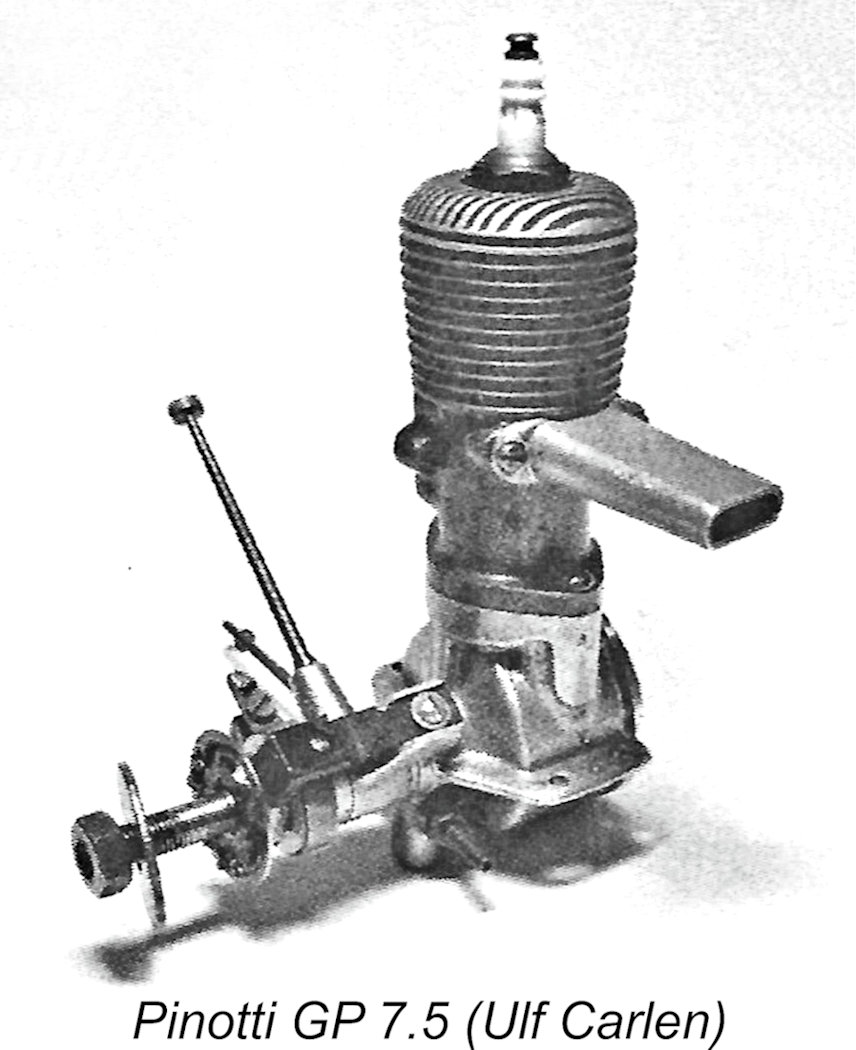

All engines produced by Pinotti were superbly made in small quantities and were very well-liked by users. In 1943 Pinotti turned his attention to compression ignition (diesel) engines. United Kingdom

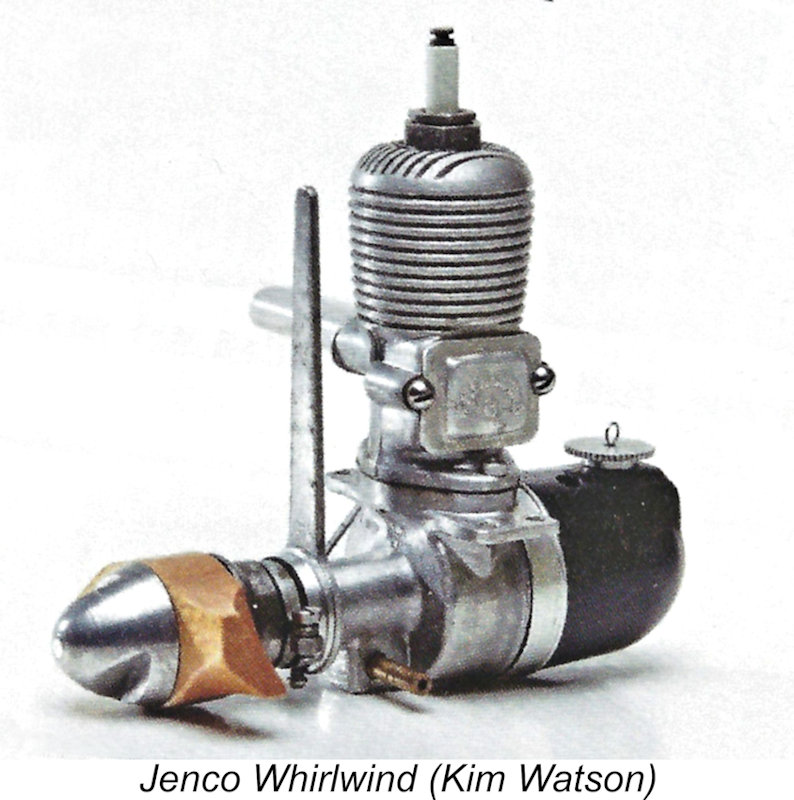

The engine was finally brought into small-scale production in 1945 by Jenco Engineering Co. Ltd. of Hinkley in Leicestershire as the Jenco Whirlwind Six. This company was a two-man "garden shed" outfit consisting of Jenkins and partner Jack Fletcher. With various modifications along the way, the Jenco remained on offer in very limited numbers until 1949. Interesting departures from the general Baby Cyclone formula included mounting lugs positioned well above the crankshaft axis; a steel liner in a blind aluminium cylinder casting; a hard chromium plated crankshaft; a long spring needle extension; a rear-mounted streamlined bakelite fuel tank; and The engine was priced at £7 16s 9d (£7.84) complete with stamped steel mounting bracket, coil, condenser and 11x9 propeller. Some examples were exported to Australia for powering portable sheep shearing apparatus. One wonders how the sheep reacted to the noise ........! Introduced in mid-1946, the Reeves spark-ignition engine was first advertised as a set of castings, blueprints and some machined parts for an engine of 5 cc or 6 cc swept volume at the buyer’s option. A limited quantity of completed engines from this “backyard enterprise” were available to first comers. The engine passed through several variants. Although the Reeves possessed some significant original features, such as four-bolt cylinder attachment and a bypass supplied directly from the crankcase (not via a piston skirt port), the basic Baby Cyclone design still clearly lay at the core of the Reeves configuration. A test of the Reeves published in the November 1948 issue of “Model Aircraft” reported a sharply peaked power curve showing 0.155 BHP at 5,100 RPM or 0.166 BHP at 6,700 with glow plug ignition and nitrated fuel. An example reportedly flew a 68-inch span cabin model weighing 3 lb. 3 oz. quite admirably. Latter-day tests confirm that the Reeves ran quite well. Conclusion As I hope I’ve demonstrated, the Baby Cyclone of 1935 proved to be one of the most influential model engine designs to emerge during the pioneering era. It richly deserves to take its place alongside other similarly-influential pioneering designs such as the Brown Junior, Dyno I and Hornet 60! ___________________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, South Australia First published November 2025 |

| |

In this article I’ll catalogue the influence on model engine design of one of the trend-setting models which appeared in America during the pioneering era – the Baby Cyclone sparkie of 1935 - 1939.

In this article I’ll catalogue the influence on model engine design of one of the trend-setting models which appeared in America during the pioneering era – the Baby Cyclone sparkie of 1935 - 1939. In 1932, the 21-year-old

In 1932, the 21-year-old  Later biographies differ in detail – particularly regarding the extent to which Major Moseley’s ideas contributed to the design of the eventual production Baby Cyclone. However, the engine's most original feature was its use of crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction, at a time when side-port induction was very much the standard. Credit for that feature was co-shared with Mel Anderson and was probably inspired by the latest full-scale marine outboard motor developments.

Later biographies differ in detail – particularly regarding the extent to which Major Moseley’s ideas contributed to the design of the eventual production Baby Cyclone. However, the engine's most original feature was its use of crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction, at a time when side-port induction was very much the standard. Credit for that feature was co-shared with Mel Anderson and was probably inspired by the latest full-scale marine outboard motor developments.

Bore and stroke dimensions of the Baby Cyclone were ¾ inch (19.05 mm) and 13/16 inch (20.64 mm) respectively for a swept volume of .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) Weight with tank, coil and condenser was 10.5 oz. (290 gm). The bare weight was 7 oz. (359 gm).

Bore and stroke dimensions of the Baby Cyclone were ¾ inch (19.05 mm) and 13/16 inch (20.64 mm) respectively for a swept volume of .359 cuin. (5.88 cc) Weight with tank, coil and condenser was 10.5 oz. (290 gm). The bare weight was 7 oz. (359 gm).

Modelair Ltd. is an iconic Aukland hobby business, founded before WW2 by Fred MacDonald. In 1982, his son Angus related the following about the Modelair Nimrod model engine.

Modelair Ltd. is an iconic Aukland hobby business, founded before WW2 by Fred MacDonald. In 1982, his son Angus related the following about the Modelair Nimrod model engine. The Baby Cyclone influenced many Czech small-volume engine makers, each of whom added his own design elements. The earliest examples were probably made by Gustav Bušek in 1937. Bušek was one of Czechoslovakia's most prominent designers and manufacturers of model engines. Without a screw-cutting lathe available, his Buš engines featured bolt-on crankshaft housings and heads. They were made in 6.3 and 6.9 cc versions. They were followed by the lighter Letná 6.3 in 1939 with a cast aluminium cylinder housing and a steel liner fabricated from salvaged aircraft tube.

The Baby Cyclone influenced many Czech small-volume engine makers, each of whom added his own design elements. The earliest examples were probably made by Gustav Bušek in 1937. Bušek was one of Czechoslovakia's most prominent designers and manufacturers of model engines. Without a screw-cutting lathe available, his Buš engines featured bolt-on crankshaft housings and heads. They were made in 6.3 and 6.9 cc versions. They were followed by the lighter Letná 6.3 in 1939 with a cast aluminium cylinder housing and a steel liner fabricated from salvaged aircraft tube.

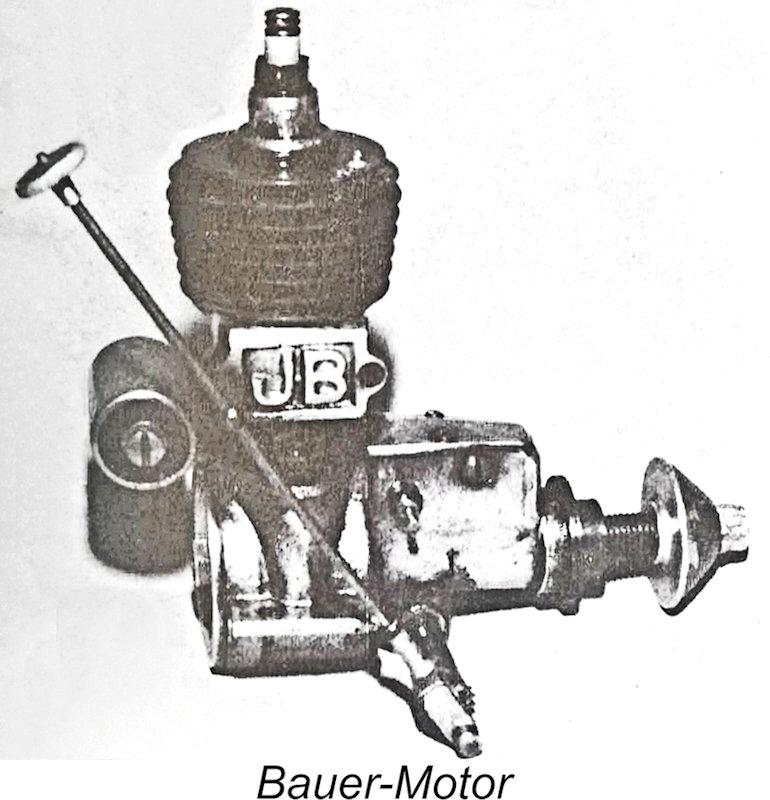

Thought to have been created in 1937, the Bauer-Motor was designe

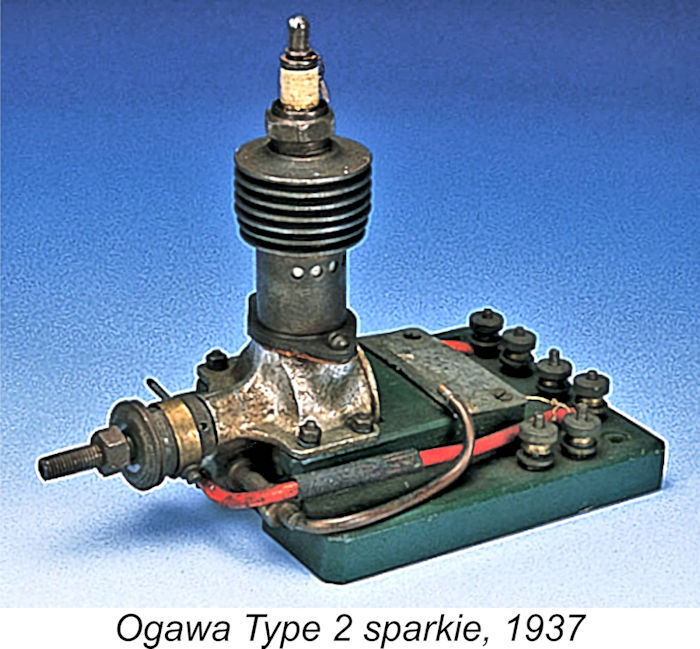

Thought to have been created in 1937, the Bauer-Motor was designe Still feeling their way, Shigeo Ogawa’s budding

Still feeling their way, Shigeo Ogawa’s budding  Pre-WW2 Russian model engine makers were strongly influenced by designs from other countries - even those originating in the idealogically-opposed USA. The Soviet Union’s most widely-used pre-war model engine was the AMM-1, which was a close copy of the Brown Junior. The engines in the AMM series were widely distributed through State-controlled Soviet modelling clubs.

Pre-WW2 Russian model engine makers were strongly influenced by designs from other countries - even those originating in the idealogically-opposed USA. The Soviet Union’s most widely-used pre-war model engine was the AMM-1, which was a close copy of the Brown Junior. The engines in the AMM series were widely distributed through State-controlled Soviet modelling clubs.  Giancarlo Pinotti’s somewhat heavy

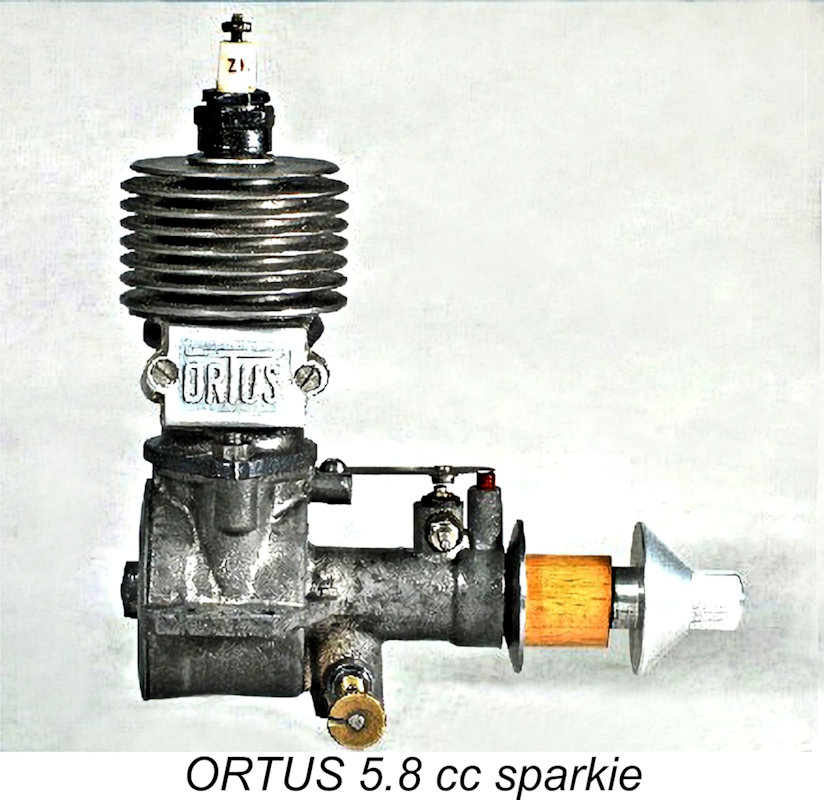

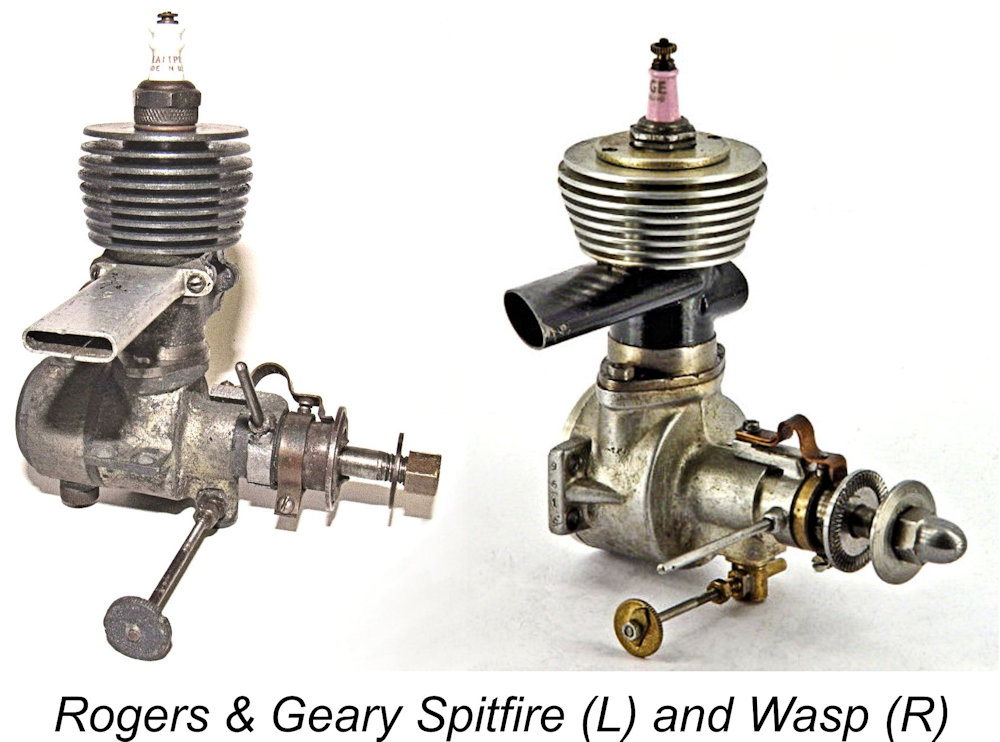

Giancarlo Pinotti’s somewhat heavy  Re-interpreting the Baby Cyclone design in a smaller size, Rogers and Geary of Leicester offered their 2.5 cc Spitfire in 1936. This unit featured a magnesium beam-mount crankcase and an iron cylinder with integral fins. It was followed by the 3.5 cc Hornet and 6 cc Wasp of much the same design, but with aluminium cooling fins. The Wasp featured narrow rear lugs for radial mounting inside a two-piece spinner-shaped aluminium nose cone.

Re-interpreting the Baby Cyclone design in a smaller size, Rogers and Geary of Leicester offered their 2.5 cc Spitfire in 1936. This unit featured a magnesium beam-mount crankcase and an iron cylinder with integral fins. It was followed by the 3.5 cc Hornet and 6 cc Wasp of much the same design, but with aluminium cooling fins. The Wasp featured narrow rear lugs for radial mounting inside a two-piece spinner-shaped aluminium nose cone.