|

|

Kiwi Kuriosities - the Katipo Diesels

I’ve already covered the Katipo series in an earlier article which appeared on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website in October 2010. Sadly, my mate Ron left us in early 2014 without sharing the access codes for his heavily-encrypted site. Because no maintenance has since been possible, the MEN site is slowly but perceptibly deteriorating - an inevitable process which can have only one ending in the long run. I was unwilling to risk the loss of the information so painstakingly gathered on the Katipo engines over a period of years, hence the article’s re-publication here in somewhat revised form.

The Katipo engines are rarely encountered today, particularly outside New Zealand - my late and much-missed mate Ron Chernich characterized them as the proverbial rocking horse droppings! As we shall see, this situation may not be solely related to production volumes. There's also a dearth of published information about these elusive little motors. Time to do what can be done to correct this situation! I've been fortunate enough to have stumbled across a few examples over the years, also having had some credible inside information about them periodically dropped into my lap from several well-connected sources in New Zealand. My good fortune in both respects has placed me in a position to share a few facts about the Katipo line which appear to be generally little-known. Indeed, some of the very limited published information regarding these engines requires correction! Sources The following account was based initially on a combination of my own observations with information received many years ago from a single individual. My initial source of anecdotal information was a resident of Gisborne, New Zealand named Bill Cooksey, with whom I was in correspondence way back in May 1980 - all of 30 years prior to my original time of writing in 2010, and now 44 years ago in 2024! Since he was legally blind, Bill corresponded using tapes - amazingly, I still have the relevant tape in playable condition. The 2010 re-discovery of this long-forgotten tape tucked away in my bloated pile of “stuff” coupled with a number of prior requests for information from fellow collectors inspired me to set about the preparation of my original article. Although Bill was seemingly in a position to be quite well-informed on the subject, there was little doubt in my mind that there was more to the Katipo story than he was able to share with me. It was my very sincere hope that the initial publication of this material might jog a few memories and encourage the sharing of further information which could be used to expand or correct the original article. In the above context, it's nice to be able to report that following the initial publication of the article on MEN in 2010, my hopes were amply fulfilled through the receipt of further information from two New Zealand residents who were able to add significantly to the story as I had originally set it down. One was Ross Purdy and the other was Chris Murphy. Both of these gentlemen were able to fill in a number of gaps in my tale which hopefully add interest and credibility to the account. My sincere thanks go out to both Ross and Chris. It turned out that Chris Murphy had also been in contact with Bill Cooksey in the early 1980’s only a year or two after my own interactions with him. He recalled that Bill was a retired Lieutenant-Colonel in the US Air Force who had relocated to the coastal community of Gisborne on New Zealand's North Island. He was apparently a person of strongly-held opinions, right or wrong, with a bit of a tendency towards name-dropping. As far as Chris was aware, he relocated back to the USA towards the end of his life and was heard from no more. At the time when he contacted me in 1980, Bill was a long-time member of the Model Engine Collectors Association (MECA) who was looking to trade for a few surplus engines that I had on hand. When he first contacted me, he told me that he might be able to offer a Katipo as a trade item. My immediate response (also by tape) was "Katipo? What the hell's that?" The tape that I still have is his reply to that question. Sometimes being an inveterate packrat pays off! Having acknowledged my sources, I can now get on with the task of presenting the Katipo story as I’ve come to know it. A Summary of the Katipo Venture Thankfully, my openly-admitted ignorance of the Katipo engines encouraged my original correspondent Bill Cooksey to share all that he knew with me. The surviving tape consists of a quite lengthy monologue on the subject. Bill began LPV Ltd. 175 Marua Road Panmure, Auckland 6 New Zealand Panmure is a south-eastern suburb of Auckland located some 11 km from the city centre. Marua Road is still very much in evidence today, and the section around number Chris Murphy advised that the initials LPV stood for "Low Pressure Valves". The name arose from the fact that the previously-established business of the company was the manufacture of various plumbing fittings for domestic and commercial use, in particular shower mixing valves. The company was owned by a certain Mr. Morrie Jensen. Bill Cooksey claimed to have known Mr. Jensen personally prior to his death in August 1979, less than a year prior to my communications with Bill. Prior to hearing from Chris Murphy, I had been contacted by another New Zealand resident named Ross Purdy. Ross knew several individuals who had been associated with the Katipo engines. One such individual was Angus MacDonald, former owner of a long-established modelling business called Modelair which is still very much in business today (2022). It seems that the Katipo engines were in fact made for distribution through Modelair, thus being something of a "house brand" for that company. My thanks to Ross for sharing this information. As it happens, their involvement with the Katipo marque was not Modelair's first venture into the field of model engines. In 1940, the future model engine manufacturer Vern Pepperell spent three months working for Fred Macdonald (Angus MacDonald's father?!?) at Modelair machining castings and components for the short-lived Modelair Nimrod spark ignition motors. Evidently the inconvenience of WW2 put paid to that venture. The question arises as to the motivation for LPV becoming involved in a manufacturing venture that was so different from their established business line. There's a clear implication that someone at LPV must have had at least a passing interest in models and model engines. Or perhaps Angus MacDonald and Morrie Jensen were mates and one persuaded the other to get involved. But over and above that, Chris Murphy rightly pointed out that there may well have been a perception of a legitimate business opportunity that could net the participants some cold hard cash. At the time, the New Zealand government would have levied both customs duty and sales tax on imported engines. As domestic products, the Katipo engines would have been exempt from these charges, allowing them to be sold at very competitive prices. Indeed, it's quite possible that the manufacturers may have been eligible for a production subsidy, particularly if export sales formed part of their prospectus. Partially on the basis of the above economic considerations, there was actually relatively limited import competition on the New Zealand model diesel market. Indeed, that market was quite small in any case, since New Zealand had a population of only some 2.8 million at the time, perhaps 1,500 of whom were serious model builders.

This left the diesel-minded New Zealand modeller with an over-the-counter choice between the expensive Taifun and Webra models, the reasonably priced but rather lacklustre D-C engines and the relatively inexpensive Katipo. If it had come close to matching the others in terms of quality and performance, at least in a sport-flying context, the bargain-priced Katipo should have fared quite well in such a market. However, the various shortcomings of the Katipo (of which more below) became apparent rather quickly, preventing it from achieving any great market share - bad news unquestionably travels much faster than good news. If there were ever any plans to offer the engines for export, they came to nothing in the end.

The exact displacement of the engine is a bit ambiguous. The boxes claim that it's 1.49 cc, but the measured bore and stroke of one of my three Mk. I Katipos are 13.36 mm (0.526 in.) x 10.32 mm (0.406 in.) respectively for an actual displacement of 1.45 cc. I know this because I had to rebore it to repair some damage sustained through the time-honored "blade in the ports" approach to cylinder removal! They never learn…………… I had occasion to re-check these figures very carefully during the course of a further repair, with essentially the same results allowing for the rebore. I'm therefore completely comfortable regarding their accuracy.

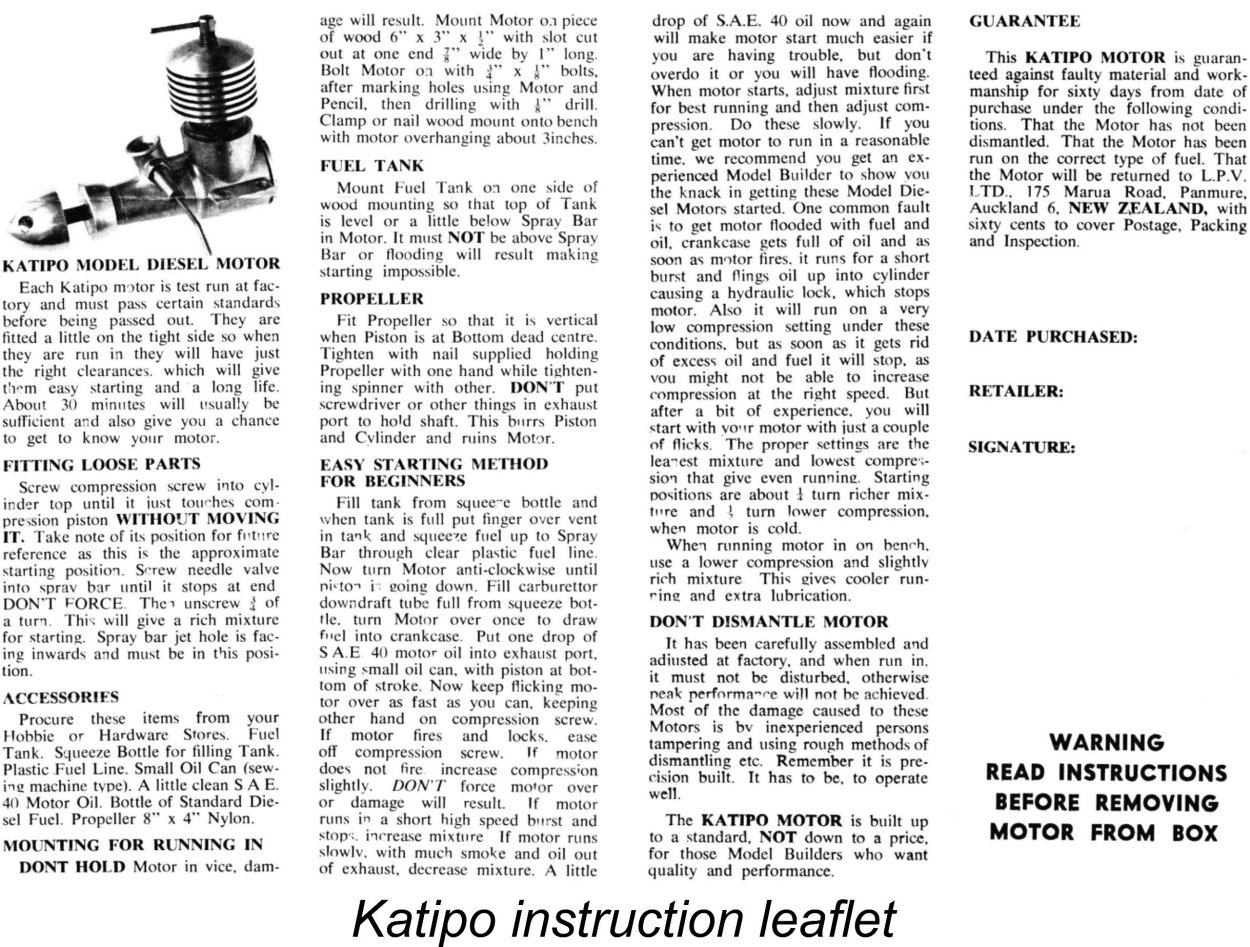

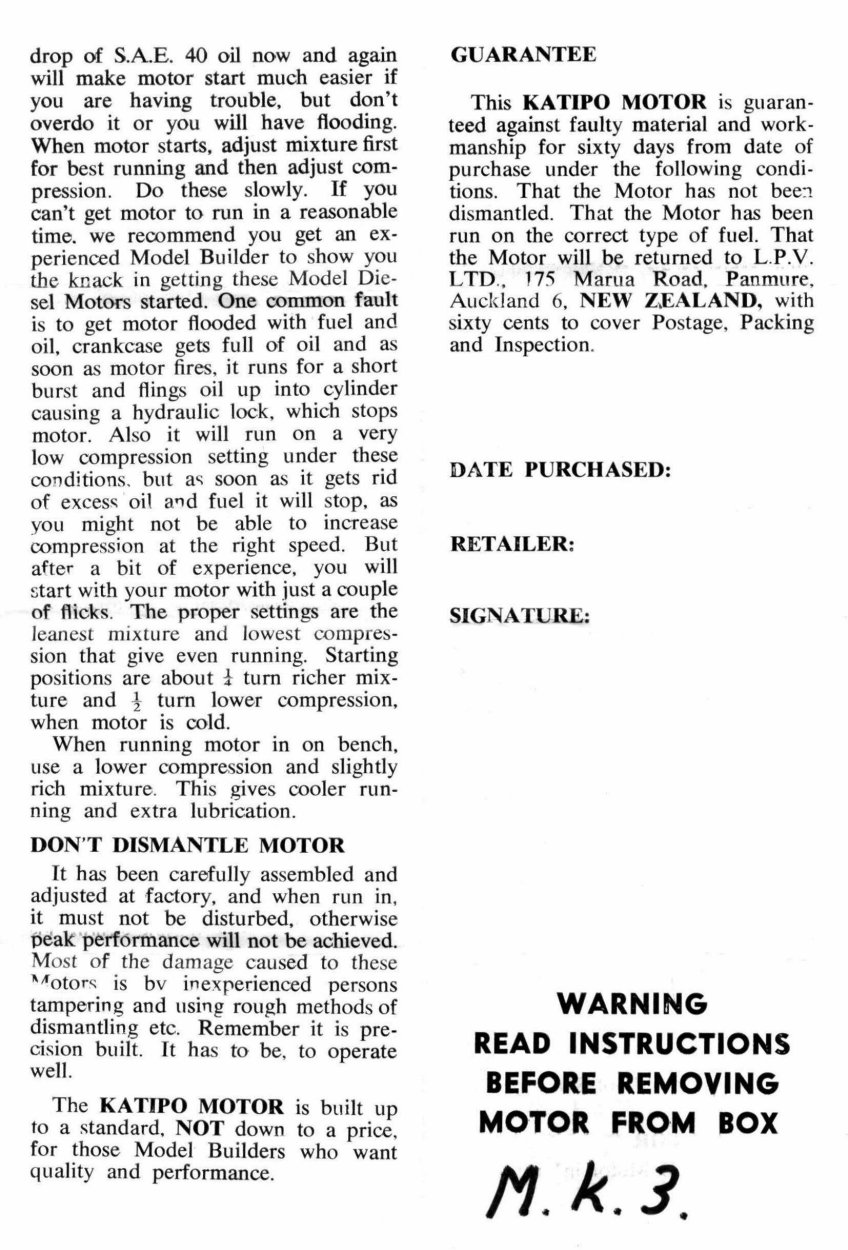

The literature supplied with the engines claimed specifically that the motors were "built up to a standard, NOT down to a price". I must say that my two NIB examples seem very well made indeed as regards fits and finish, and the best of my other three examples (which remains completely original and appears little used, if at all) is just as well fitted. I've never run any of my three pristine examples, for reasons which will become apparent below. However, they have probably all had a little running - Bill Cooksey specifically mentioned that all engines were test-run prior to dispatch. Shades of an earlier era................ That being said, Chris Murphy was able to provide a more balanced viewpoint on the basis of actual experience with a far larger sample of engines. When he was a junior in the Dunedin MAC on New Zealand's South Island around 1969-72, the Katipo engines had already become objects of derision. Interestingly, this was due primarily to their reported tendency towards poor compression, their consequent general inability to start and their total lack of power in the seemingly rare event that one could be made to run. Chris recalled nothing being said about fragility at that stage. Still, it appears that my rather well-made examples may have been anything but typical.

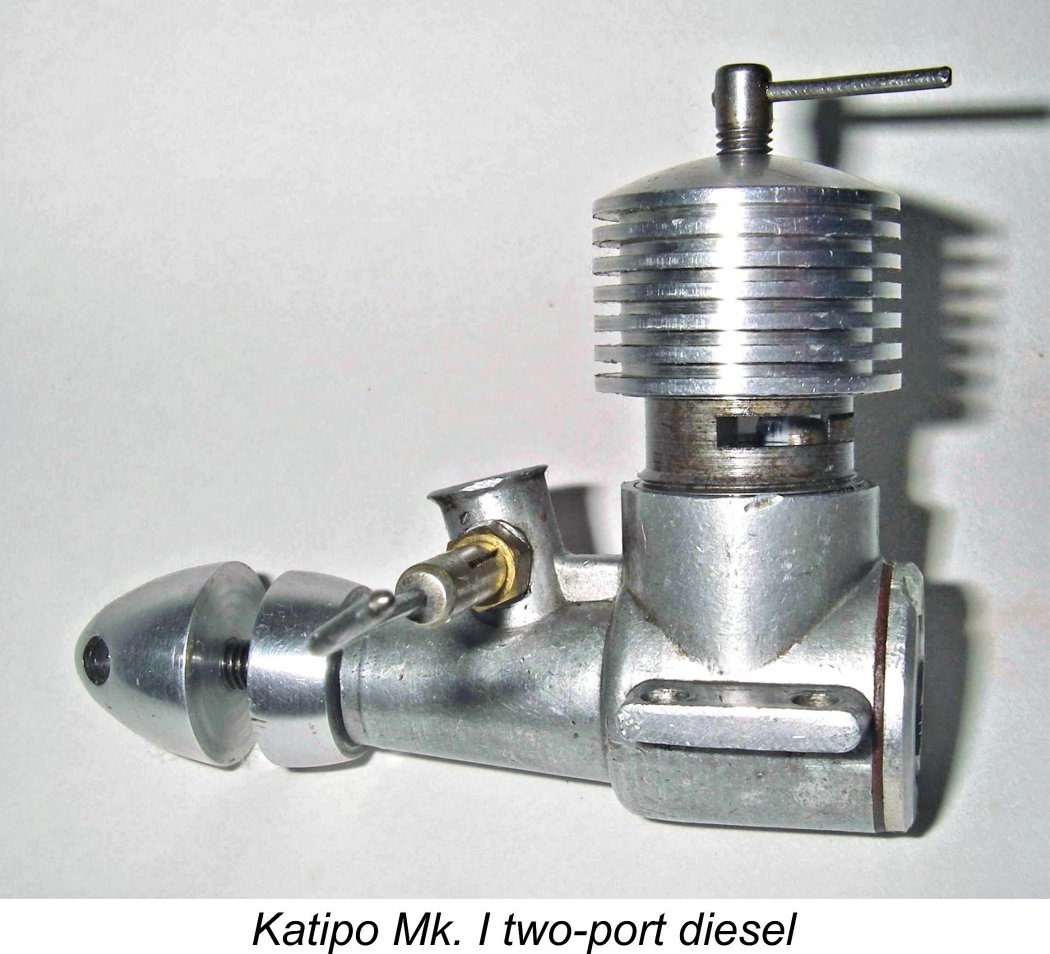

Bill also made the comment based on his own experience that the three-port version was significantly less frequently encountered than the two-porter. He stated that the three-port model was the later of the two, and on this point Mike Clanford agrees with him in his useful but frequently-unreliable 1987 book “Pictorial A-Z of Model Engines” in which illustrations of both models appear on page 105. But of course that book had yet to be published when the taped discussion recorded here took place in 1980. Once again, Chris Murphy was able to clarify this point for us. He confirmed that the two-port design was indeed the earlier of the two but that it was fairly quickly found to be mechanically flawed. The cylinder screws into the crankcase and seats on a ledge. The generously-proportioned transfer flutes fore and aft weaken the lower wall to the extent that when screwed home and fully tightened the cylinder base could distort out of round due to the wedging action of the screw threads, the result being that the engine would become tight over bottom dead centre. It was apparently this problem that led to the redesign of the cylinder porting to the three-port version. There's no reason at all to doubt this interpretation of the facts, but I can only say that none of my own two-porters exhibit evidence of this problem.

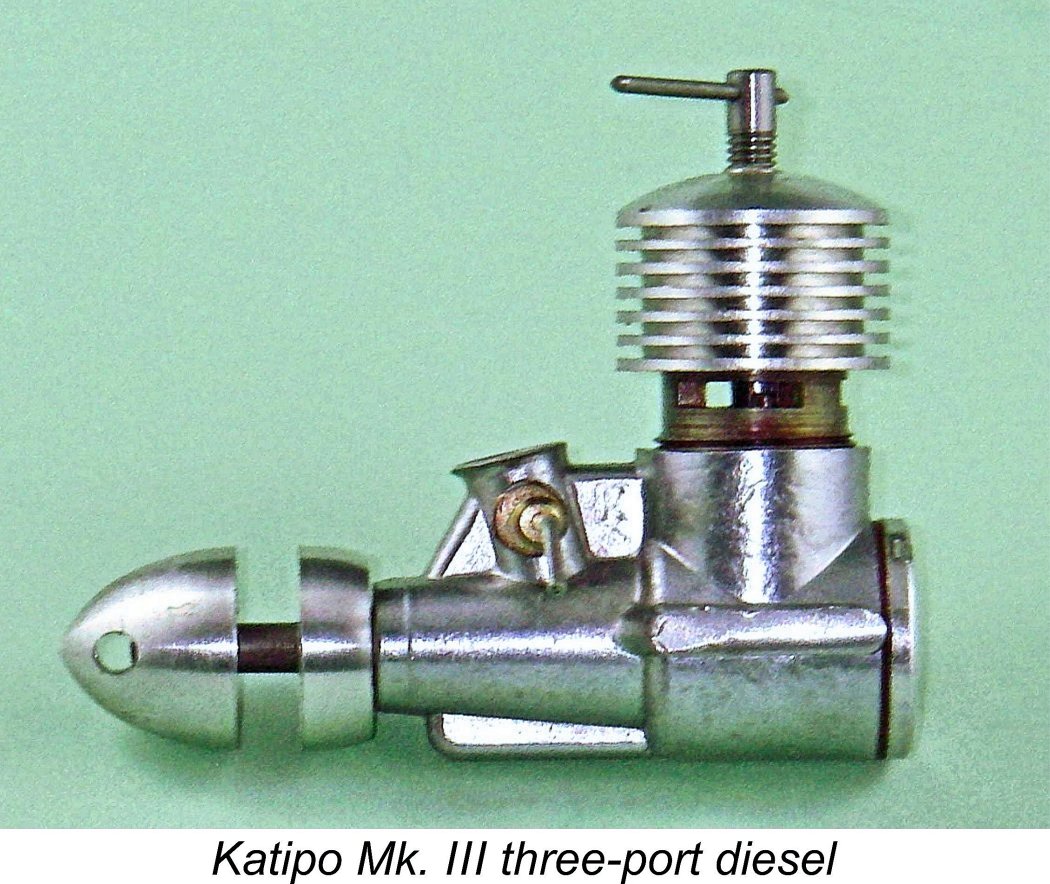

I subsequently acquired examples of both types, confirming my correspondents’ information regarding the nature of the two designs. Quite apart from the comment about the mechanical issues with the cylinder design, there are plenty of other indications of the later origin of the three port model. Although very similar, the three-port case has been somewhat strengthened by comparison with that of the two-porter, with the mounting lugs being thicker and additional reinforcement being added to the main bearing. In addition, the letter K is cast in relief onto the enlarged gusset just behind the intake. There is no identification whatsoever on the two-port cases, which are completely unbraced.

Both models use internal flute-type transfers of quite generous proportions which overlap the exhaust to a significant degree. This overlap allowed the designer to use relatively conservative timing for the exhaust ports (approximately 60 degrees each side of bottom dead centre), since the overlapping transfers still remain open for a sufficient period. Accordingly, we would expect these engines to yield quite good mid-range torque figures despite their very short stroke. This expectation is fulfilled in practice, as we shall see.

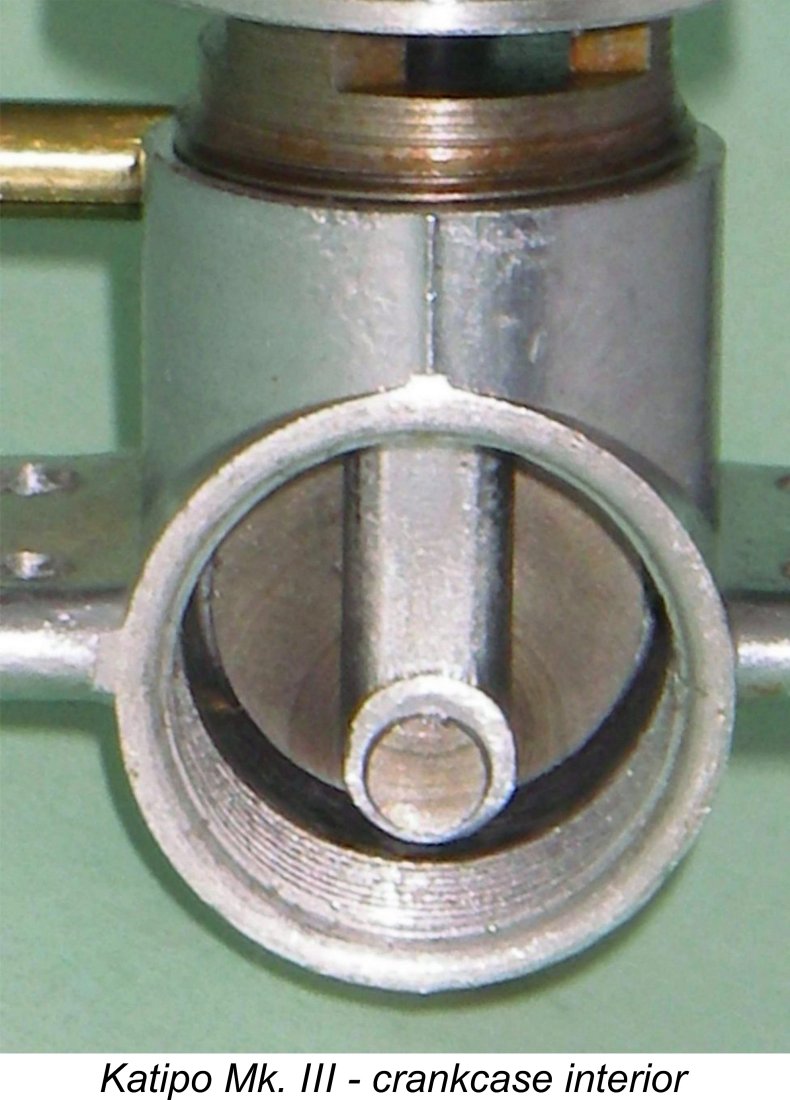

An unusual feature of the design is the diameter of its crankshaft journal - all of 0.377 in. (9.60 mm), or a nominal 3/8 in. This is a relatively massive diameter for a 1.5 cc diesel - some engines of over double the displacement don't have a shaft this big! Mind you, the internal gas passage is pretty large too for a classic diesel of this displacement at 0.218 in (5.54 mm or a nominal 7/32 in.), so the extra wall thickness should be good for strength. But read on................ The aluminium alloy prop driver engages with a self-releasing taper at the front of the shaft. The one unusual feature of this component is the absence of any form of knurling on the face to discourage prop slippage. Presumably this was to provide some protection against shaft damage in the event of a crash. In It appears that user feedback eventually led to the development of an improved prop driver design. Chris Murphy kindly sent along several images of a Mk. II Katipo which has been fitted with an improved prop driver having a somewhat minimal band of knurling on its front face. This appears to be a second sub-variant of the Katipo Mk. II which may be encountered. I’m aware of several other examples displaying this feature. In all other respects the engines are completely conventional crankshaft front rotary valve diesels with no remarkable design features. The shaft induction register hole is round rather than squared off, and induction timing is again quite conservative. The crankweb is of plain disc form with no counterweight whatsoever. The hardened steel shaft runs directly in the material of the case. The sturdy alloy con-rod appears to be a forging. The needle valve with its split brass thimble for tension is totally conventional too. The weight of 105 gm (3.7 ounces) is perhaps a little over the odds for a plain-bearing 1.5 cc diesel of its day. The unusually massive shaft doubtless accounts for much of the extra. I was told by Bill Cooksey that the engines were all produced in the mid to late 1960's and that production had been terminated by 1970. This is consistent with other information received regarding the range. Chris Murphy recalled that the engines were still available in 1969 at his local model shop in Dunedin (Eclipse Radio and Hobbies in Stuart Street), although they had already attracted a reputation as a lemon by that stage and demand must have been falling sharply as a result. It's entirely possible that production may have ceased as of 1969 as a result of the effect of this negative reputation upon sales. Unsold examples evidently hung about for some time after production actually ended - this is quite the usual thing in such cases. Chris recalled that they were still to be seen in certain model shops until around 1972, at which point they quietly faded away.

At the time of the first flight of this model, Peter had a leg in a cast as a result of a motorcycle accident. The model took off just fine, but Peter’s cast prevented him from turning fast enough to keep up, with the inevitable result! The engine was then oiled and put away, not to re-appear for 42 years until Peter read the original article on MEN and approached me with a trade offer which I accepted. This engine remains in fine original condition, with excellent fits throughout following its break-in and single flight. The fact that it had survived a fair bit of running in Peter's hands emboldened me to give it a few runs myself. Happily, the little Katipo started up very easily and ran just fine. If they had all been this good and had stayed together, there would have been little about which to complain. Bill Cooksey was not sure how many Katipos were actually produced, but he had learned from Morrie Jensen that the manufacturing took place in batches on a relatively small scale. This is certainly consistent with the present-day scarcity of surviving examples, plus the probability that LPV were carrying on with their other product lines at the same time. They may in fact have made batches of engines simply to utilize their production facilities during slack periods. The fact that none of the engines carry serial numbers leaves us with no way of coming up with any actual production figures after the fact. Extensive inquiries conducted in New Zealand by Chris Murphy confirmed that no-one who was then still around seemed to have any definite knowledge regarding production figures. Based upon the number of these engines which he had encountered over the years, Chris was inclined to think that if all versions are taken into account, the total number must have been at least many hundreds and could perhaps have gone into four figures. It would take numbers of this sort to justify the cost of having a crankcase die produced and periodically modified. Still, by world standards it’s clear that the number manufactured was very small.

The reported circumstances under which production was terminated are a little unusual! According to Bill Cooksey, Mr. Jensen somehow ended up with a sizeable batch of crankshafts which were seriously flawed. Some of the bad shafts evidently went into engines of all types; it's not exactly clear how. According to Mr. Jensen as related to Bill Cooksey, the shafts from this batch were so fragile that they sometimes used to break on a backfire while merely flipping over to start during their factory test! Others failed after a period of use, but one way or another they all failed! Obviously there was a problem either with the material or the heat treatment - as mentioned earlier, the basic shaft design seems unusually sturdy. It's unclear how this issue arose - could Jensen have got a sub-specification batch of steel and not realized it? Or perhaps he contracted out the heat treatment or even the entire crankshaft production, and the screw-up occurred at that end outside his control. According to Ross Purdy, Angus MacDonald (former owner of Modelair) believed that the problem arose from the shafts being insufficiently tempered, thus being left excessively brittle. However, in his recollection the original shafts had generally been OK - it was a later batch which let the engines down. How large that batch may have been cannot now be determined. Presumably Peter Metcalf's successfully-run Mk. I example had one of the earlier shafts fitted. Regardless, there was Mr. Jensen with a batch of untrustworthy cranks for which he'd presumably paid, plus a growing backlog of engines with broken cranks and no reliable replacements! There must have been a healthy list of claimants under the sixty-day guarantee with which the engines were sold, but since Mr. Jensen lacked the parts to refurbish these engines to an acceptable standard, he was unable to honour the guarantee. He was apparently a stickler for doing things right, and this situation miffed him so much that he decided there and then to withdraw the engine from the market and return to his original product line, simply taking his lumps rather than getting a replacement batch of cranks made up. End of the story, and he died a decade or so later. The LPV company itself did not die with Mr. Jensen. According to New Zealand corporate archives, it remained on the books until February 22nd, 2016, albeit at a different address by the time of its dissolution. Interestingly, a Jensen family connection appears to have been maintained all along, because one of the last company Directors was a lady named Lois Elaine Jensen.............relationship to Morrie Jensen unknown.

Oddly, the shaft failed by shearing right across the actual web - rather different from the more usual journal fracture immediately forward of the crankweb or at the crankshaft induction port. The appearance was of a brittle fatigue failure. Clearly there was a chronic problem with either the material or the heat treatment (or perhaps both) - this is why I have no intention of ever running my other apparently unused examples! It appears reasonable to deduce that this issue must have contributed significantly to the engine's seeming rarity today. They weren't made in large numbers to begin with, and if a good proportion of them broke their cranks and spares weren't available either because the firm had stopped making them or because there were no "good" cranks available in any case, they probably ended up in the rubbish bin along with all the ones that wouldn't start! The few survivors are the "runners" that either got "good" cranks or didn't get run much!

The last tid-bit recorded by Bill Cooksey was the reported fact that according to their users the engines "ran like a hairy goat!" when they did run! A Google search on this colourful Antipodean phrase indicates that it is generally used in Australia and elsewhere to describe the performance of a race-horse or automobile that underperforms badly in action, presumably reflecting the commonly-held view of the Katipo’s performance in service! Despite this, I can confirm that both of the two-porters that I've run started very well indeed (in contrast, it seems, to many of the long-ago originals) and showed good promise, although the new piston which I had to fit to one of them beforehand to replace the badly-scored original has never been fully run in and is still a bit tight. See below for some test data. The Katipos Come to Canada! I never completed a trade with Bill Cooksey that involved a Katipo, hence remaining in ignorance of what a Katipo actually looked like! The tape went into my "odds and ends" archive, not to be re-discovered until 2010. I subsequently (and at the time unknowingly) got my own first Katipo (the aforementioned and much-abused 2-porter that I later rebored and ran until the crank broke) in 1981, over a year after the exchange of information recorded above. It showed up unannounced and unidentified in a box of miscellaneous bits and pieces which was a throw-in element of a much larger MECA trade. The guy who sent it my way had no more idea of what it was than I did! Because it had no markings and was unreported in any of the literature of which I was then aware, I was unable to identify it myself - there was nothing to connect it with the almost-forgotten tape which was by then languishing in my archives.

In my own case, all of this changed when a New-in-Box (NIB) three-port engine showed up at a MECA swap meet in 1984. It was of course clearly identified on the box, and I still vaguely recalled the unusual Katipo name from the taped exchange of four years previously. So I wasted no time in grabbing it! I immediately recognized my neglected 2-porter from the literature in the box, had my wonderful little "Eureka!" moment and immediately set about getting that nearly-forgotten little curiosity back in running condition now that I knew that it was a legitimate collectible with some provenance behind it. Ran well as it turned out, at least until the crank broke! But a new crank can be made.............. The box is interesting in that it's really too small for the engine! The unit will only fit inside with the comp screw and needle removed, and even then it's tight. The instruction leaflet includes a note about assembling the loose components onto the engine. The second two-porter arrived in 1986, again at a MECA swap meet. It was in much better condition than the other two-porter and seemed more or less unrun, a state in which it remains today. Finally, I acquired a third 2-porter from Peter Metcalf as mentioned earlier. I've only ever seen two other examples in the metal since that time, so I guess I did well to get my oily paws on these three! The Katipo Mk. I on Test

Unfortunately, Stu’s article doesn’t help us very much because he couldn’t get either of the two engines sent by Bill Cooksey to run! Evidently neither example had sufficient compression to permit a start. Stu contented himself with providing a few details regarding the engines’ production history, also citing a few dimensions. His reported weight matched my own figure precisely. His stated bore measurement of 0.525 in. also agreed well enough with my own measurements, but his quoted stroke of 0.425 in. was some 0.019 in greater than the measurement obtained from my own Mk. I example prior to the shaft breakage. Anyway, this left it down to me to obtain a few performance figures for one of these engines. Accordingly, I went ahead with making a new crankshaft and conrod for my original "runner" Katipo Mk. I. I was glad not to have lost the piston as well, since I had already made that once! In fact, the engine ended up with a full set of working components of my own making! This does not affect the originality of the design, however, since I faithfully copied all On a re-test after a 30 minute break-in for its new components, the engine started quite readily, although a light prime was required - choking alone didn't seem to do the job. Once started, the little Katipo ran very steadily and was easy to set. Running at optimized settings was very smooth and consistent, with no trace of sagging. The new contra-piston that I made as part of the rebore was still a bit "sticky", but that would ease in time. Somewhat strangely in view of Chris Murphy's comments, I experienced no difficulties with prop slippage at any time. Power was nothing special, but there was plenty of mid-range urge there for sport-flying purposes. A few sample propeller-rpm figures are as follows:

The above data seem to imply a power peak of around 0.136 BHP at 11,000 rpm or thereabouts. The peak seems to be reasonably flat - 0.130 BHP (95% of the peak) is available at all speeds between 9,800 and 11,800 rpm. Not a particularly remarkable performance then, but well in line with typical plain bearing sports diesel performance expectations during the 1960's, and the still-tight rebuilt engine would doubtless improve a little if freed up some more. Perhaps the goat has shed just a little hair …………!! The motor clearly produces pretty good torque at moderate revs, and a "fat" 7x6 prop or an 8x6 cut down to 7½x6 would be the one to use for C/L flying, with a fast 8x4 (the maker's recommended prop) or an 8x3 being well matched for free flight use. The Third Model - the Katipo Mk. III

As it turned out, this is indeed a third variant of the engine. In most respects, it is identical to the Mk. II version, retaining the three-port cylinder plus all of the other main design features. It's also very well fitted. The major difference appears to be the form of the crankcase casting. As can be seen, the band of material that was cast onto the Mk. II Removal of the backplate reveals that the only readily-apparent internal change is a significant increase in the thickness of the connecting rod. The former rod actually appeared to be fairly substantial for an engine of this displacement, so one can only assume that the makers were trying a stiffer rod to see if this might The one rather odd feature of the Mk. III is its return to the use of the plain prop driver instead of the improved component seen on Chris Murphy's second variant of the Mk. II. Why use a component that had reportedly proved to be problematic when they clearly had a superior item available? The logical inference is that this was part of a final batch of engines that were assembled from parts on hand, and they simply used the earlier prop driver because it was there to be used. There are many precedents for this with other manufacturers. This is the sole example of this variant that has ever crossed my path, and it seems to be by far the least common version of the engine. I'm aware of a few others out there, but they seem to be relatively thin on the ground. It's hard to imagine that there could be any other variants, but you never know, so if anyone finds yet another version, please share it with us! In that context, it seems only fair to report that Bill Cooksey told Chris Murphy that there was indeed another variant which had the letter K cast within a circle onto the cylinder spigot portion of the crankcase. Reader Goran Milosavljevic actually has two examples of the Mk. III variant. Most interestingly, one of these is a very competently executed marine version of the engine. The manufacturer’s literature makes no mention of such a model, making it undeniably possible that this is a conversion carried out by a capable owner. However, it could equally well be a product of the original manufacturers - there’s no way of knowing. Either way, it’s an interesting piece! I’ve included Goran's accompanying image here with the proviso that the engine's provenance is uncertain pending the receipt of further information. My sincere thanks to Goran! Conclusion The Katipo saga is a testament to the way in which the best-laid plans can be derailed by a single set-back. The basic Katipo design was perfectly sound if somewhat less than inspired, and the engines were attractive little units which certainly had the potential to give long and dependable service if they had been manufactured to a consistently higher standard than they were. Had it not been for the accident of the bad crankshafts, they would probably have done just that and would be both far more readily available and far better remembered today. As it was, the 4th commercial era of New Zealand model engine manufacturing ended somewhat ignominiously. Too bad……….. it had potential! ________________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN October 2010 Revised edition published here November 2022

|

||

| |

Off to New Zealand this time for a look at one of the relatively few commercial model engine ranges produced in that country. I'll be examining the Katipo engines, which were a short-lived series of 1.5 cc diesels produced in relatively small numbers in Auckland, New Zealand during the latter part of the 1960's.

Off to New Zealand this time for a look at one of the relatively few commercial model engine ranges produced in that country. I'll be examining the Katipo engines, which were a short-lived series of 1.5 cc diesels produced in relatively small numbers in Auckland, New Zealand during the latter part of the 1960's.

By the late 1960's the glow-plug motor was well and truly in the ascendant. Chris recalled that only

By the late 1960's the glow-plug motor was well and truly in the ascendant. Chris recalled that only  Whatever the motivation for their introduction, it's by no means certain that Morrie Jensen was the designer of the Katipo engines. The name of the actual individual responsible has been lost in the mists of time. The basis for the engine's name is debatable, but the fact that a katipo is a highly venomous spider peculiar to New Zealand strongly implies that this was a poke at the contemporary Australian Taipan line, which was named after a highly venomous snake indigenous to Australia!

Whatever the motivation for their introduction, it's by no means certain that Morrie Jensen was the designer of the Katipo engines. The name of the actual individual responsible has been lost in the mists of time. The basis for the engine's name is debatable, but the fact that a katipo is a highly venomous spider peculiar to New Zealand strongly implies that this was a poke at the contemporary Australian Taipan line, which was named after a highly venomous snake indigenous to Australia! Old-school designers within the British sphere of influence during this period still clung to a tendency to work with nominal dimensions expressed in fractions of an inch. Why beats me given the fact that they invariably expressed their displacements in cubic centimetres (cc)!! I strongly suspect that the Katipo's nominal design bore and stroke figures were 17/32 in. (13.49 mm or 0.531 in.) and 13/32 in. (10.32 mm or .406 in.) respectively, which would yield a displacement of 1.48 cc. Regardless, this is an unusually short-stroke design, with a bore/stroke ratio of approximately 1.3 to 1. The short stroke explains the relatively squat and compact appearance of the engine. Despite this compactness, the unit weighs in at a relatively hefty 3.7 ounces (105 gm).

Old-school designers within the British sphere of influence during this period still clung to a tendency to work with nominal dimensions expressed in fractions of an inch. Why beats me given the fact that they invariably expressed their displacements in cubic centimetres (cc)!! I strongly suspect that the Katipo's nominal design bore and stroke figures were 17/32 in. (13.49 mm or 0.531 in.) and 13/32 in. (10.32 mm or .406 in.) respectively, which would yield a displacement of 1.48 cc. Regardless, this is an unusually short-stroke design, with a bore/stroke ratio of approximately 1.3 to 1. The short stroke explains the relatively squat and compact appearance of the engine. Despite this compactness, the unit weighs in at a relatively hefty 3.7 ounces (105 gm).  Bill Cooksey claimed that there were two versions of the engine, one with Cox-style twin-opposed transfer and exhaust ports and the other with a more "traditional" circumferential porting layout utilizing three radially-disposed transfer and exhaust ports. Both variants were based upon very similar aluminium alloy crankcases which were apparently produced by gravity die-casting. These cases give the impression of being very sturdy indeed, especially that of the three-porter. As we shall see later, Bill was in error in claiming that there were only two versions - in fact, Chris Murphy confirmed that Bill himself soon became aware of a third variant, of which more in its place below.

Bill Cooksey claimed that there were two versions of the engine, one with Cox-style twin-opposed transfer and exhaust ports and the other with a more "traditional" circumferential porting layout utilizing three radially-disposed transfer and exhaust ports. Both variants were based upon very similar aluminium alloy crankcases which were apparently produced by gravity die-casting. These cases give the impression of being very sturdy indeed, especially that of the three-porter. As we shall see later, Bill was in error in claiming that there were only two versions - in fact, Chris Murphy confirmed that Bill himself soon became aware of a third variant, of which more in its place below. Regardless, Chris stated that the above chain of events led to the three-port engines being actually far more commonly encountered in New Zealand than the two-port models, in direct contrast to Bill's comments. Chris estimated that he had probably seen 20 examples of the Katipo and owned 4 of them over the previous 40 or more years, with the three-port models predominating throughout.

Regardless, Chris stated that the above chain of events led to the three-port engines being actually far more commonly encountered in New Zealand than the two-port models, in direct contrast to Bill's comments. Chris estimated that he had probably seen 20 examples of the Katipo and owned 4 of them over the previous 40 or more years, with the three-port models predominating throughout. In addition, the photo in the literature with my NIB examples shows a two-porter even though the engines in the boxes are three-porters. The most logical interpretation is that LPV already had a good stock of leaflets for the former two-porter and didn't bother to produce a revised instruction sheet when they updated the design. Hence, I believe it to be entirely appropriate to refer to the two-porter as the Mk. I and the original version of the three-porter as the Mk. II. I will adhere to this protocol in the following text.

In addition, the photo in the literature with my NIB examples shows a two-porter even though the engines in the boxes are three-porters. The most logical interpretation is that LPV already had a good stock of leaflets for the former two-porter and didn't bother to produce a revised instruction sheet when they updated the design. Hence, I believe it to be entirely appropriate to refer to the two-porter as the Mk. I and the original version of the three-porter as the Mk. II. I will adhere to this protocol in the following text. In both variants, the cylinder simply screws into the crankcase to locate on a shelf below the female case threads. The aluminium alloy cooling jacket in turn screws onto the externally-threaded cylinder top. The backplate in both cases is also a screw-in item. Both cooling jacket and backplate are turned from bar stock - all pretty conventional stuff. The use of a pressed-in gudgeon (wrist) pin is mandatory if fouling of the transfers is to be avoided - there's no positive "stop" location when the cylinder is screwed in, and the design has to accommodate any final position, just like the Cox series, for example.

In both variants, the cylinder simply screws into the crankcase to locate on a shelf below the female case threads. The aluminium alloy cooling jacket in turn screws onto the externally-threaded cylinder top. The backplate in both cases is also a screw-in item. Both cooling jacket and backplate are turned from bar stock - all pretty conventional stuff. The use of a pressed-in gudgeon (wrist) pin is mandatory if fouling of the transfers is to be avoided - there's no positive "stop" location when the cylinder is screwed in, and the design has to accommodate any final position, just like the Cox series, for example. my own direct experience, prop slippage during starting does not seem to be an issue provided the aluminium alloy spinner nut is securely tightened. In fairness, it must be said that Chris Murphy disagrees with me on this point. In his recollection, these were absolute pains to tighten to the point where slippage did not occur using the crude Modelair “Rev” nylon props of the era. Perhaps it all depended on the material of the prop which was being used.

my own direct experience, prop slippage during starting does not seem to be an issue provided the aluminium alloy spinner nut is securely tightened. In fairness, it must be said that Chris Murphy disagrees with me on this point. In his recollection, these were absolute pains to tighten to the point where slippage did not occur using the crude Modelair “Rev” nylon props of the era. Perhaps it all depended on the material of the prop which was being used. There is persuasive evidence to the effect that not all examples of the Katipo were quite as bad as their reputation. Several years after the original publication of this article on MEN, I acquired another Katipo Mk. I (my third) in a trade with Wellington resident Peter Metcalf. Peter told me that he had bought the engine new from a local model shop in 1969 in blissful ignorance of its reputation. Apparently this one started and ran just fine, because Peter encountered no difficulty in running it in on the bench in accordance with the maker’s instructions (30 minutes on an 8x4), after which he mounted it in a control-line model.

There is persuasive evidence to the effect that not all examples of the Katipo were quite as bad as their reputation. Several years after the original publication of this article on MEN, I acquired another Katipo Mk. I (my third) in a trade with Wellington resident Peter Metcalf. Peter told me that he had bought the engine new from a local model shop in 1969 in blissful ignorance of its reputation. Apparently this one started and ran just fine, because Peter encountered no difficulty in running it in on the bench in accordance with the maker’s instructions (30 minutes on an 8x4), after which he mounted it in a control-line model.  The dating supplied by my various correspondents is in direct contradiction to the published information in Mike Clanford's previously-cited A-Z Pictorial, which states on unspecified evidence that the Katipos were made in 1955. This is clearly wrong (Wot?!? Clanford wrong again? Surely not.....). It's undeniably true that the Taipan engines by that name were not around in 1955 to be "poked at" by the Katipo name! I’m completely confident that the engines actually date to the mid to late 1960’s as asserted by all other sources.

The dating supplied by my various correspondents is in direct contradiction to the published information in Mike Clanford's previously-cited A-Z Pictorial, which states on unspecified evidence that the Katipos were made in 1955. This is clearly wrong (Wot?!? Clanford wrong again? Surely not.....). It's undeniably true that the Taipan engines by that name were not around in 1955 to be "poked at" by the Katipo name! I’m completely confident that the engines actually date to the mid to late 1960’s as asserted by all other sources. It's unclear how many of the bad cranks made it into the hands of modellers, but some certainly did - one of my Mk. I Katipos (the one that I rebored) suffered a major crank failure after only 45 minutes or so of running in my hands following its rebore. The failure took place while the engine was running fairly fast, and the rod was destroyed as well. The engine had clearly done some previous running in the hands of others, so I have no way of knowing how long the crankshaft actually lasted in service.

It's unclear how many of the bad cranks made it into the hands of modellers, but some certainly did - one of my Mk. I Katipos (the one that I rebored) suffered a major crank failure after only 45 minutes or so of running in my hands following its rebore. The failure took place while the engine was running fairly fast, and the rod was destroyed as well. The engine had clearly done some previous running in the hands of others, so I have no way of knowing how long the crankshaft actually lasted in service.

Following the initial 2010 publication of this article on MEN, I was fortunate enough to acquire yet another NIB example of the engine. I did so because the papers with this unit proclaimed it to be a Mk. III Katipo, something of which I had never heard at the time. The identification was hand-written onto the same leaflet which had accompanied the previous two models, but it had the look of an "official" addition rather than an owner identification.

Following the initial 2010 publication of this article on MEN, I was fortunate enough to acquire yet another NIB example of the engine. I did so because the papers with this unit proclaimed it to be a Mk. III Katipo, something of which I had never heard at the time. The identification was hand-written onto the same leaflet which had accompanied the previous two models, but it had the look of an "official" addition rather than an owner identification.