|

|

Russian Export Initiative - the OTM Engines

Some very useful core information on this range is to be found in the well-produced German-language book by Viktor Khodyeyev of Ukraine entitled “Modellmotoren Made in USSR”. Although this book is annoyingly short on details at times, it is nonetheless a very useful and highly recommended reference on commercially-produced Russia model engines of the pre-modern era. I freely acknowledge having consulted it during the preparation of this article, with my sincere thanks to Viktor.

DOSAAF’s support of aeromodelling during those decades was based upon the view that it might foster the development of aerodynamic and technical skills which could have relevance for subsequent military service. In addition, Russian success in the international contest sphere would have considerable propaganda value given the fact that the results of such contests were followed keenly by a far wider spectrum of interested individuals than is the case today. However, by the early 1970’s aeromodelling was no longer seen solely as either a propaganda vehicle or an activity which might increase a participant’s knowledge and understanding of aerodynamics and related technical fields having potential benefit to air force recruitment. Those perceptions doubtless persisted, but the manufacture of model engines was now increasingly seen as a potential means of securing valuable foreign currency through the export of Russian-made products. In a nutshell, model engine production in Russia was in the process of becoming viewed as a commercial activity, just as it was elsewhere. In keeping with this evolving viewpoint, State agencies other than DOSAAF began to take an interest in the design and commercial manufacture of model engines. One such agency was the Russian Ministry of Light Industry, which concerned itself with the development of smaller-scale industries of potential value to the It’s unclear when the decision was taken to have OTM develop a series of model engines, presumably in consultation with DOSAAF, but their efforts resulted in the 1972 release of a series of three model compression ignition (diesel) units of varying displacements. From the outset, the primary emphasis was very much upon the export of these engines to Western countries. The marketing of these and a few other Russian engines was undertaken by a State-sponsored Moscow-based commercial organization called НОВОЭКСПОРТ (Novoexport). This organisation became better known in the modelling world for the prolific series of model cars which it exported in great numbers under its own name. The three OTM model diesels were reportedly produced at various manufacturing facilities within the USSR. Perhaps because of this, their quality was somewhat variable. The castings were generally well-produced, but the internal fits and finishes in certain examples undoubtedly left something to be desired. A good one was quite acceptable, but not all examples came up to the same level of quality.

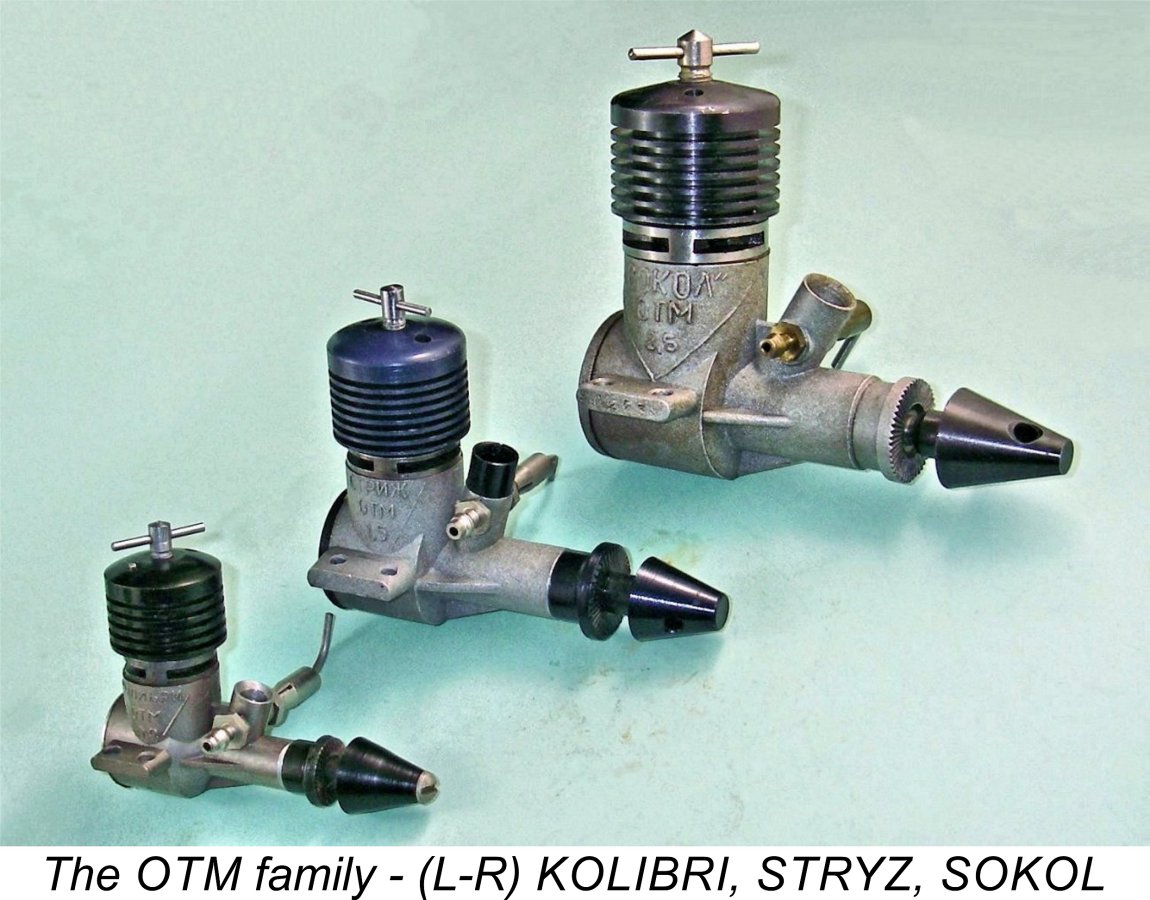

All three engines were constructed to a common design, hence looking very similar. Despite the 1972 design date, they had an undeniable 1950’s aura about them. They were simple 1950’s-style plain-bearing diesels featuring crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction allied to radial cylinder porting. No fastenings were used in their construction - instead, they utilized a screw-in assembly throughout, both cylinder and backplate being installed in this manner. For the most part, their screw-on cooling jackets were anodized black. Unfortunately, the anodizing tended to fade quite rapidly under the influence of heat and contact with fuel. The engines all appear to have been test-run at the manufacturing facility. All of the New-in-Box examples that I have ever seen have been well gummed up with castor oil residue, requiring unsticking prior to use. Let’s look at the three OTM models in turn. The OTM 2.5 - the SOKOL

Somewhat unusually for the early 1970’s, the 2.5 cc SOKOL model was a long-stroke design. Actual bore and stroke measurements were 14.5 mm and 15.0 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 2.48 cc (0.151 cuin.). The engine weighed a commendably light 140 gm (4.94 ounces), much of which was in the very substantial cylinder.

The one-piece hardened steel crankshaft featured a rather thin crankweb with arcs of material cut away on each side of the 5 mm dia. crankpin to provide some counterbalance. Main journal diameter was 10 mm. This appears at first sight to be a fairly generous dimension until we learn that the central induction passage was bored to 7 mm, leaving what appears to be a rather marginal wall thickness of only 1.5 mm (0.059 in.). Even though the crankshaft induction port is a perfectly circular hole, I would still expect crankshaft failures to be a not-uncommon occurrence. That said, I have yet to encounter one of these engines with a broken shaft, or indeed to break one myself despite years of trying, indicating that the material must be of quite good quality.

The SOKOL was manufactured at a factory in Kiev, Ukraine, which was referred to in the instruction leaflet as the “SOKOL Pilot Plant” (in Russian, naturally). The factory in question apparently specialized in the manufacture of hunting and fishing equipment. The SOKOL was by far the most-produced of the three OTM models, being distributed in the USSR and elsewhere in considerable numbers. It was also the best-made of the three models - most examples actually displayed quite acceptable quality, although a few left something to be desired. The prospective buyer was undoubtedly participating in a bit of a lottery!

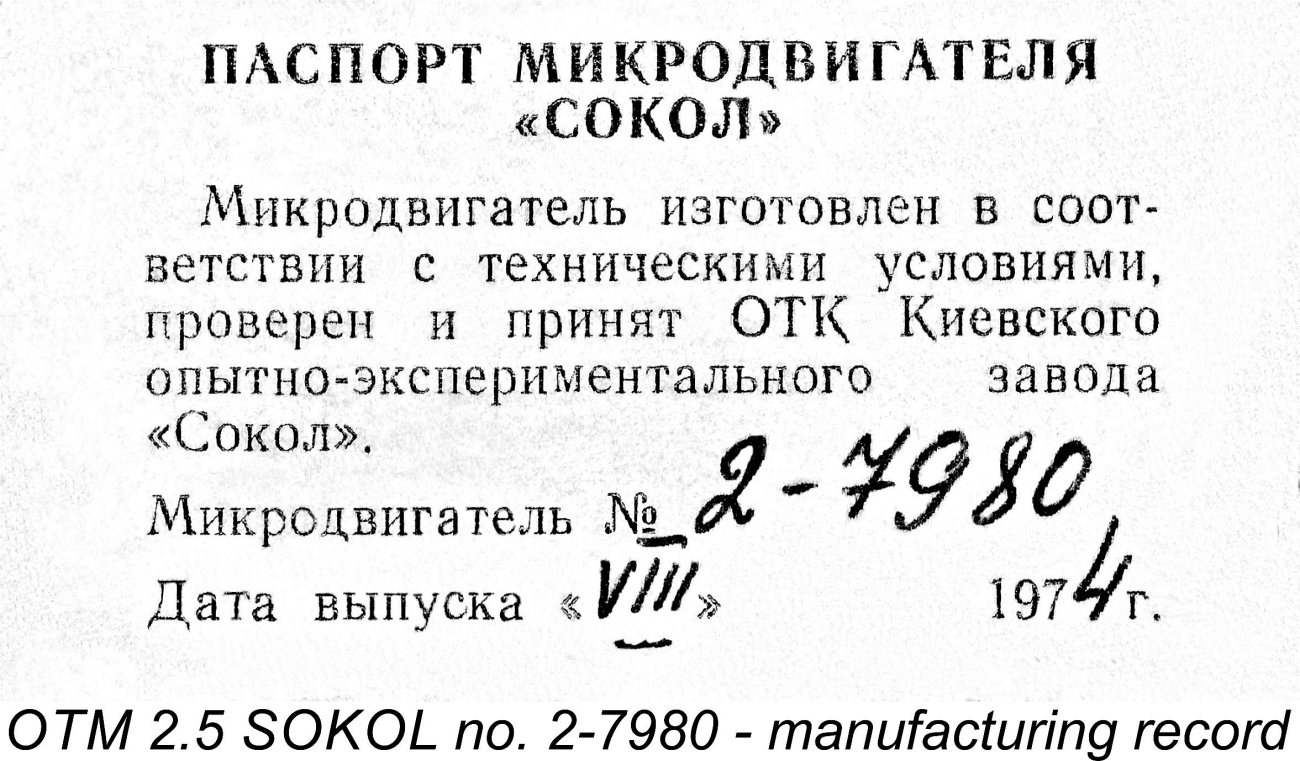

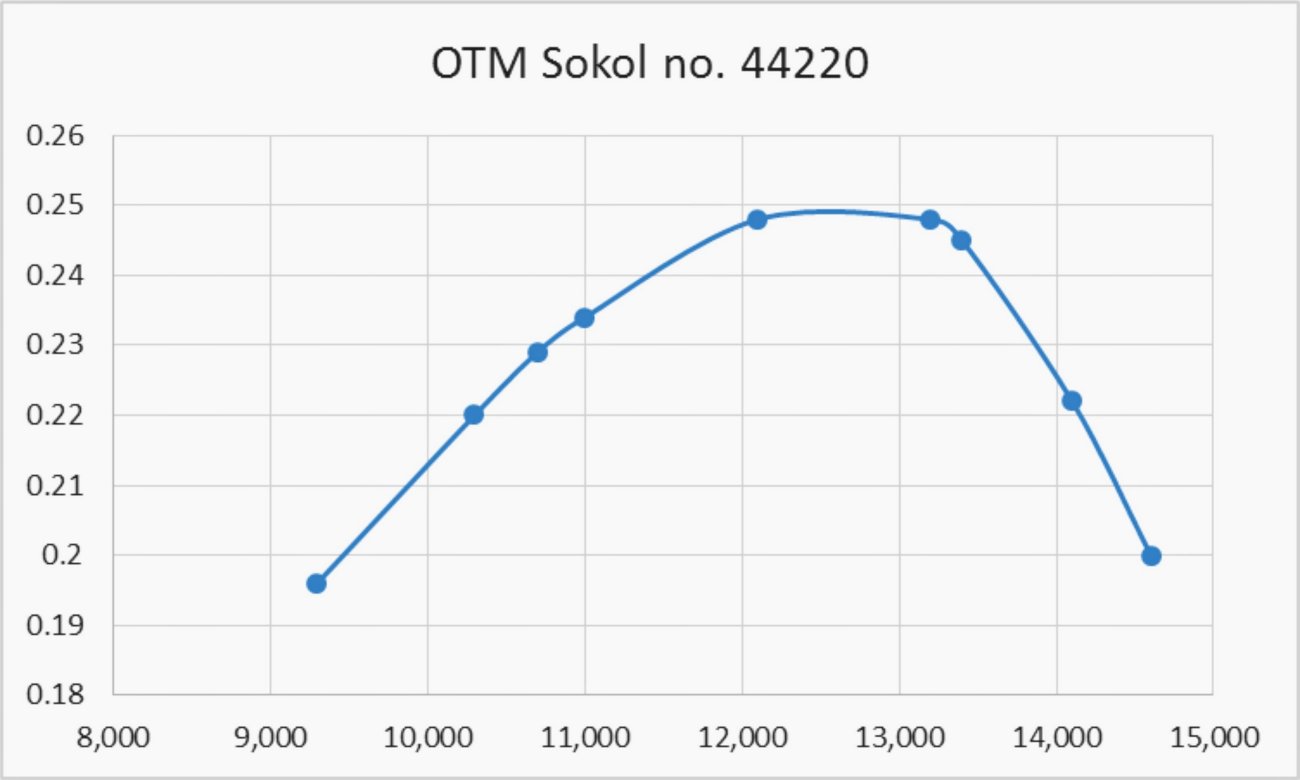

A comprehensive Russian-language instruction sheet was also included. When they began to import the SOKOL into England in 1973, the Modellers Den of Bath produced an English-language translation of the main points for the benefit of customers in Western countries. This was included with all of the examples sold by that company. The SOKOL engines are also distinguished from their smaller siblings which were reportedly made elsewhere by displaying serial numbers. Although I’ve been unable to discern any design or construction differences, the engines were evidently numbered in two distinct sequences. There was one sequence which was purely numerical - I have engine nos. 44220, 42239 and 44241 in this series. The other sequence had a number 2 added as a prefix - I have engine nos. 2-7492 2-7980 and 2-12979 in this series. Viktor Khodyeyev illustrated engine no. 2-14759 in his previously-referenced book. This is the A review of manufacturing dates is revealing. The instruction leaflet for each engine was both serial-numbered and dated. The date given is the particular engine’s “release” date, which I take to mean the date on which it left the factory. Interestingly enough, all of the dates which have so far come to my attention have been in the year 1974. The earliest dated example is engine no. 42239, which was released in June 1974. Engine no. 2-7980 was released in August 1974, implying that the switch to the 2 prefix dates to the period June-August 1974. Later engines nos. 2-12979 and 2-14759 were both released in October 1974. The implication is that up to June 1974 some 45,000 examples of the SOKOL had been produced. Since the engine was apparently introduced in 1972, the implied production rate over the two year period is around 1800 engines per month - a not inconceivable figure. At around June 1974 the 2 prefix was added and the numbering sequence evidently restarted, for reasons which remain unclear. 7980 units had been produced This data seems to suggest that up to the end of October 1974 at least 57,000 engines had been manufactured. Production remained at a high level as of that date, but must surely have tapered off fairly soon thereafter - it’s difficult to see the market continuing to absorb these engines as fast as they were then being manufactured. That said, it’s clear from the number of survivors that the engine was distributed and sold in very significant numbers both within and outside of the USSR. Oddly enough considering the fact that it was by far the most widely-exported member of the OTM range, the SOKOL was the only one of the three never to be the subject of a published review in the English-language modelling media. The designers claimed an output of 0.18 Kw (0.241 BHP) @ 14,000 rpm for the SOKOL. Based on my own experiences, this appears to be a perfectly credible claim for a good example of the engine. In support of this perception, during the writing of this article I took a break to test one of my own "experienced" but unmodified examples. Although well used to the point that its black anodizing was largely gone, the test engine remained in excellent mechanical condition, with good bearing fits and outstanding compression. It proved to be a notably prompt starter on a small exhaust prime, also being very responsive to the controls and hence easy to set. Running qualities throughout were beyond reproach. The following data were obtained:

The above data imply a peak output of around 0.250 BHP @ 12,800 RPM - very consistent with the Russian manufacturer's claim. I encountered no mechanical difficulties at all during the course of this fairly strenuous test, which amply confirmed my impression that a good example of the Sokol was a completely satisfactory engine to use in non-competition applications.

After a suitable break-in, I installed this engine in a vintage combat model, where it performed very well indeed in the 64 mph vintage diesel category which was then in force in our area. A bench test following some air time implied an output of around 0.305 BHP @ 13,900 rpm - a useful improvement over the figures obtained for the stock unmodified unit and a very good performance indeed for a plain-Jane sports diesel of this type weighing only 136 gm (4.8 ounces)! The engine has now had well over four hours of running time in the air, with no problems of any kind presenting themselves. The OTM 1.5 - the STRYZ

Turning to the technical details, the cylinder of this model was distinguished from that of its larger companion in the range by featuring only three exhaust ports and interposing bypass channels instead of four. The intake too was different in that it featured a separate insert which was retained in place by the spraybar. However, in all other respects the design was identical - merely at a smaller scale. That said, some examples featured dark blue anodizing instead of the more common black coloration. An example is illustrated here. Like the SOKOL, the STRYZ crankcase was sand-blasted to an attractive matte finish.

The manufacturers claimed a peak output of 0.11 Kw (0.147 BHP) @ 15,000 RPM for this model. Looking objectively at the engine’s design, I can readily envision a good example achieving such figures. However, since both of my own examples are New-in-Box, I have chosen not to risk compromising their integrity by running them in and testing them. I am therefore unable to confirm or refute the manufacturer’s claims. The STRYZ (or OTM 1.5 if you prefer) was sold in a rather flimsy cardboard box as opposed to the hard plastic case in which the larger SOKOL was supplied. Moreover, these engines were not serial-numbered. The general style of manufacture is consistent with the understanding that the STRYZ was made in a different facility to that which produced the SOKOL.

Like the SOKOL, the STRYZ was supplied with a rather crude tool for removing or tightening the backplate and cylinder comoponents. However, in this case the cylinder removal section relied upon a "hook" which was intended to engage with one of the pillars separating the exhaust ports. This hook lacked precision, creating the possibility that its use had some potential to mar the bore at the edge of the exhaust port. Best left unused, in my opinion. In his review of the STRYZ which was published in the November 1984 issue of “Model Builder“ magazine (long after the manufacture of the engines had ceased), Stu Richmond reported that the quality of his example was well below normal Western standards, hence electing not to even run it. He had obtained it from a collector friend in Czechoslovakia (as Czechia still was at the time) and viewed it himself as a collector’s curiosity rather than as a practical engine to use. The STRYZ is certainly the least commonly-encountered member of the OTM family.

Although there's no evidence that the OTM engines were ever produced in glow-plug form, I have encountered an example of the STRYZ which had been very competently converted to glow-plug ignition. A check with the former owner confirmed that this was an owner initiative as opposed to a factory effort. All I can say is that it was extremely well done - the guy raised the cylinder with a shim to increase both exhaust and transfer periods, presumably to support the higher operating speeds likely desirable in glow-plug form. The head button was machined to yield a compression ratio of around 8.5 to 1, also consistent with operation at higher speeds. The top of the domed cooling jacket was machined to improve access to the plug. The engine obviously performed well enough to receive a considerable amount of use in the hands of its former owner. The rod bearings display some wear, but compression remains outstanding. I have run this engine, finding it to be an easy starter with what appears to be a perfectly adequate performance in a sport flying context. The OTM 0.8 - the KOLIBRI

Like the 1.5 cc STRYZ, the KOLIBRI featured a cylinder having three sets of ports instead of the four used in the SOKOL. It also used a slot-head screw which engaged with a tapped hole at the front of the shaft to secure the prop. It was the sole member of the OTM family to have its crankcase casting left in its as-cast state rather than being sandblasted. In all other respects, its design was essentially identical to that of its larger companions in the range.

Chinn commented upon a few manufacturing defects which were apparent with his tested unit, possibly reducing its performance a little. Maris Dislers has confirmed that the quality of this model was somewhat variable in his experience. I can only report that I appear to have been more fortunate than either Chinn or Maris - my own three examples are all seemingly manufactured to quite acceptable standards. They all turn over with minimal play in the bearings along with excellent compression. How well they would stand up in service is quite another matter…………… The log book which I’ve been keeping since the early 1970’s records the fact that way back when I acquired my first example of the KOLIBRI during the mid 1970’s, I ran it in to see how it would perform - I was then contemplating using it in a model, although in the end I never did so. This was not due to any perceived shortcomings with the engine, which apparently started and ran quite well - I recorded no adverse comments. I didn’t take any prop-rpm figures at the time, but did record my impression that performance seemed to be well up to the expected standard for a 0.8 cc plain bearing sports diesel. Chinn’s reported figures undoubtedly confirm this impression. Summary and Conclusion The OTM engines seem to have been at the forefront of a new Soviet trend in being created primarily as an international marketing initiative as opposed to an effort to support domestic modellers within the USSR. They evidently found their way into a number of countries beyond the already-crumbling Iron Curtain. They were imported to Britain in substantial numbers by The Modeller’s Den of Bath in Somerset and (later) by Modusa. Distributors in other countries also took a hand in the world-wide marketing of the engines. Despite this fairly widespread distribution, it has to be said that the major attraction of these engines to buyers in Western countries was the simple fact that they were made in Russia! In design terms, they were a throwback to the 1950’s! However, at the time in question the export of Russian engines to other countries was only just getting started. Consequently, the idea of owing a Russian-made engine possessed considerable novelty attraction to many modellers and collectors. I clearly recall being similarly motivated when buying my own first examples.

As a result, demand for the engines soon tapered off. Production seems to have continued into the latter half of the 1970’s, but had almost certainly ceased by the end of the decade. In the end, the SOKOL ended up being sold in considerable numbers outside Russia, consequently being a not uncommon engine today. The two smaller models were less widely distributed, hence being somewhat less frequently encountered. Still, these engines represent a serious and generally successful early attempt by the Russian authorities to establish Russian-made engines in the international consumer marketplace. They certainly paved the way for the longer-term success of such units as the 1.5 cc MK-17. Their fulfilment of this role undoubtedly justifies their recognition as a significant Russian model engine marque. ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published

|

||

| |

In an

In an  During the 1950’s and 1960's, the development and distribution of Russian-made model engines was largely managed by DOSAAF (Russian: ДОСААФ as in the attached logo), a State-sponsored paramilitary organization which oversaw a number of sporting activities of potential propaganda or military benefit to the State. Roughly translated, the Russian name for which these initials stood meant “Volunteer Society for Cooperation with the Army, Air Force and Navy”. DOSAAF will do me just fine, thank you very much ..........

During the 1950’s and 1960's, the development and distribution of Russian-made model engines was largely managed by DOSAAF (Russian: ДОСААФ as in the attached logo), a State-sponsored paramilitary organization which oversaw a number of sporting activities of potential propaganda or military benefit to the State. Roughly translated, the Russian name for which these initials stood meant “Volunteer Society for Cooperation with the Army, Air Force and Navy”. DOSAAF will do me just fine, thank you very much ..........

The engines in the OTM series all received various “bird” names. The largest unit was a 2.5 cc model named the OTM 2.5 SOKOL (in Russian, СОКОЛ), which translates to “Falcon”. It was accompanied by two smaller units. The 1.5 cc model was called the OTM 1.5 STRYZ (in Russian, ϹТРИЖ), meaning “Swift”, while the little 0.8 cc design was named the OTM 0.8 KOLIBRI (in Russian, КОЛИБРИ), meaning “Hummingbird”.

The engines in the OTM series all received various “bird” names. The largest unit was a 2.5 cc model named the OTM 2.5 SOKOL (in Russian, СОКОЛ), which translates to “Falcon”. It was accompanied by two smaller units. The 1.5 cc model was called the OTM 1.5 STRYZ (in Russian, ϹТРИЖ), meaning “Swift”, while the little 0.8 cc design was named the OTM 0.8 KOLIBRI (in Russian, КОЛИБРИ), meaning “Hummingbird”. The accompanying component illustration from Viktor Khodyeyev’s book shows the main features of the SOKOL’s construction quite well. The working components were generally well machined, although the surface finishes in some examples fell a little short of being ideal, as did some of the fits. The castings were of quite acceptable quality and were sand-blasted to an attractive matte finish, though a few examples have been seen with a kind of metallic silver-grey paint on their cases. Some such examples have featured gold-anodized cooling jackets in addition.

The accompanying component illustration from Viktor Khodyeyev’s book shows the main features of the SOKOL’s construction quite well. The working components were generally well machined, although the surface finishes in some examples fell a little short of being ideal, as did some of the fits. The castings were of quite acceptable quality and were sand-blasted to an attractive matte finish, though a few examples have been seen with a kind of metallic silver-grey paint on their cases. Some such examples have featured gold-anodized cooling jackets in addition.  Peter Chinn included a description of the SOKOL in his “Latest Engine News” column in the September 1973 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. He confirmed the above measurements, also giving exhaust and transfer periods of 140 degrees and 120 degrees respectively. These are quite rational figures for an engine of this character. Cylinder porting was basically conventional, featuring four milled exhaust apertures with four internal bypass/transfer channels spaced between them.

Peter Chinn included a description of the SOKOL in his “Latest Engine News” column in the September 1973 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. He confirmed the above measurements, also giving exhaust and transfer periods of 140 degrees and 120 degrees respectively. These are quite rational figures for an engine of this character. Cylinder porting was basically conventional, featuring four milled exhaust apertures with four internal bypass/transfer channels spaced between them. Chinn noted that the crankshaft induction port opened at 57 degrees after bottom dead centre and closed at 33 degrees after top dead centre. These figures give a total induction period of 156 degrees - once again, a not unreasonable figure for an engine of this specification. As supplied, there was no sub-piston induction.

Chinn noted that the crankshaft induction port opened at 57 degrees after bottom dead centre and closed at 33 degrees after top dead centre. These figures give a total induction period of 156 degrees - once again, a not unreasonable figure for an engine of this specification. As supplied, there was no sub-piston induction. The SOKOL’s different manufacturing origin from those of its stablemates was reflected in its packaging, which consisted of a moulded plastic tray with a clear plastic cover. Both portions of this container were made of rather brittle material - exercise care when handling one! The SOKOL was the only OTM model to feature such packaging. The box included a somewhat crude tool for removing the backplate and cylinder components as well as a package of mounting fasteners of rather indifferent quality.

The SOKOL’s different manufacturing origin from those of its stablemates was reflected in its packaging, which consisted of a moulded plastic tray with a clear plastic cover. Both portions of this container were made of rather brittle material - exercise care when handling one! The SOKOL was the only OTM model to feature such packaging. The box included a somewhat crude tool for removing the backplate and cylinder components as well as a package of mounting fasteners of rather indifferent quality.

Several decades ago now, just for fun I tried doing a bit of a tune-up on engine number 2-7492. I improved the induction arrangements somewhat, installed a PAW needle valve assembly, lightened the piston, added sub-piston induction and extended the internally-formed transfer flutes upwards between the exhausts to reduce the blow-down period to around 5 degrees. While I was at this, I made a new precisely-fitted rod of far superior material. I also cut flats into the upper edges of the cooling jacket to facilitate the tightening of the cylinder.

Several decades ago now, just for fun I tried doing a bit of a tune-up on engine number 2-7492. I improved the induction arrangements somewhat, installed a PAW needle valve assembly, lightened the piston, added sub-piston induction and extended the internally-formed transfer flutes upwards between the exhausts to reduce the blow-down period to around 5 degrees. While I was at this, I made a new precisely-fitted rod of far superior material. I also cut flats into the upper edges of the cooling jacket to facilitate the tightening of the cylinder. I’ll admit to being a little uncertain regarding the best spelling to use in naming this model phonetically using Latin script! The first four Cryllic characters of the engine’s Russian name of ϹТРИЖ seem clear enough - my on-line

I’ll admit to being a little uncertain regarding the best spelling to use in naming this model phonetically using Latin script! The first four Cryllic characters of the engine’s Russian name of ϹТРИЖ seem clear enough - my on-line  Unlike the SOKOL, the STRYZ featured conventional over-square internal geometry. Bore and stroke were 12.5 mm and 12.0 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 1.47 cc (0.0899 cuin.). Weight was a quite reasonable 70 gm (2.47 ounces).

Unlike the SOKOL, the STRYZ featured conventional over-square internal geometry. Bore and stroke were 12.5 mm and 12.0 mm respectively for a calculated displacement of 1.47 cc (0.0899 cuin.). Weight was a quite reasonable 70 gm (2.47 ounces).  The instruction leaflet supplied with the engine was now rendered in English, French and German as well as Russian. This provides further evidence of the level of effort that was being put into the marketing of these engines outside the USSR. Unfortunately, no dating information was included in these sheets.

The instruction leaflet supplied with the engine was now rendered in English, French and German as well as Russian. This provides further evidence of the level of effort that was being put into the marketing of these engines outside the USSR. Unfortunately, no dating information was included in these sheets.  Stu did however express the view that the engine would probably perform at a level which gave full satisfaction to its Russian users. I can only state for the record that the fits and finishes in both of my own NIB examples seem quite acceptable, with almost zero play in the bearings and excellent compression. I’m quite certain that they would both run well if carefully broken in. How long they would last in service is another question, to which I have no answer.

Stu did however express the view that the engine would probably perform at a level which gave full satisfaction to its Russian users. I can only state for the record that the fits and finishes in both of my own NIB examples seem quite acceptable, with almost zero play in the bearings and excellent compression. I’m quite certain that they would both run well if carefully broken in. How long they would last in service is another question, to which I have no answer.  This little unit enjoys a unique distinction - it was the smallest-displacement engine ever to enter series production in Russia during the classic era. It was even more over-square than its 1.5 cc companion in the range, featuring bore and stroke dimensions of 10.5 mm and 9.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.78 cc (0.0476 cuin.). It weighed in at a pretty average 45 gm (1.59 ounces). I have three examples of this engine, all of which are complete with their boxes.

This little unit enjoys a unique distinction - it was the smallest-displacement engine ever to enter series production in Russia during the classic era. It was even more over-square than its 1.5 cc companion in the range, featuring bore and stroke dimensions of 10.5 mm and 9.0 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.78 cc (0.0476 cuin.). It weighed in at a pretty average 45 gm (1.59 ounces). I have three examples of this engine, all of which are complete with their boxes.  Claimed output of the little KOLIBRI was 0.05 Kw (0.067 BHP) @ 15,000 RPM. Happily, we are able to check this claim against the figures reported by the ever-dependable Peter Chinn, who published test reports on the engine in both “Model Airplane News” (

Claimed output of the little KOLIBRI was 0.05 Kw (0.067 BHP) @ 15,000 RPM. Happily, we are able to check this claim against the figures reported by the ever-dependable Peter Chinn, who published test reports on the engine in both “Model Airplane News” ( Once the curious buyers had a chance to get more closely acquainted with the engines, it became apparent that in quality and performance terms they had nothing to offer the aeromodellers of the Western countries, who could readily obtain engines of similar displacements and design characteristics offering significantly higher quality and performance. This was particularly true of the two smaller models, which seem to have fallen somewhat short of the quality embodied in many examples of the larger SOKOL design.

Once the curious buyers had a chance to get more closely acquainted with the engines, it became apparent that in quality and performance terms they had nothing to offer the aeromodellers of the Western countries, who could readily obtain engines of similar displacements and design characteristics offering significantly higher quality and performance. This was particularly true of the two smaller models, which seem to have fallen somewhat short of the quality embodied in many examples of the larger SOKOL design.