|

|

The Classic Fuji 15 Twin-Stack Series

Apart from the individuality of its design, the original Fuji 15 of early 1955 is highly significant in that it was the first-ever Japanese model engine to appear in the 2.5 cc displacement category, which had then just been adopted by the FAI as the standard for International power model competition (excluding R/C and control-line stunt). Although it was no threat in performance terms to the competing models which soon followed from other Japanese manufacturers, the fact remains that it led the way. Thankfully from the standpoint of the over-worked Fuji researcher, the number of design variants to be dealt with in this article is quite small - the Fuji enterprise was less prolific in this category than it was in most of the others. Given the fact that the 15 class attracted more attention from the majority of manufacturers than any other given its international competition status from 1955 onwards, this statement may seem surprising. However, it becomes completely intelligible when one realizes that the Fuji management team appears to have made a conscious business decision quite early on to distance themselves from the competition arena and its attendant (and costly) development programs, concentrating instead on the production of inexpensive but dependable engines for the sport/recreational fliers who far outnumbered their hard-core competition colleagues.

Thus the 15-1 model is the first known Fuji .15 cuin. design, while the 15-4 is the fourth variant in the same sequence. All of these first four models were identified by Fuji themselves simply as the Fuji 15, hence the need for some additional means of identification. By the time we get to 1961, the Fuji manufacturers had recognized the need to clearly identify succeeding design variants and had followed the lead of Enya and O.S. in applying model numbers to their designs, rendered as Roman numerals. Thus the 1961 update of the Fuji 15 twin-stack design was identified by Fuji as the 15-II, even though it is actually the fifth design variant in the .15 cuin. sequence! All of its predecessors were simply called the Fuji 15. To keep things in sequential order, I’ve stuck to my system throughout, and hence the Fuji 15-II appears in my Fuji catalogue as model 15-5, correctly indicating its position in the .15 cuin. design sequence. I must emphasize that these model identification codes are mine alone, having nothing to do with Fuji themselves. I also recognize that these designations may be subject to change if additional design variants are identified in the future. However, I hope that readers and collectors may find them as useful as McCoy aficionados have found the "Engine Collector's Journal" (ECJ) model numbering system for the McCoy engines established years ago by my late and much-missed friend Tim Dannels. I must also stress the fact that given the paucity of printed material relating to these engines, what follows is based almost entirely upon my own observations of the limited number of examples to which I have direct or indirect access as well as my deductions based upon the very informative promotional material put out from time to time by Fuji themselves in the form of leaflets which accompanied the engines. I freely admit that my present knowledge of this series is undoubtedly incomplete and that other variants may exist of which I’m presently unaware. I also caution readers that the given dates are best estimates only based on presently-available information. Many of these dates could well be out by a year or more. It is my sincere hope that the publication of this article may stimulate the sharing of further information which could help to refine the information presented herein. All contributions gratefully and openly acknowledged! Now, before I get down to the main task at hand, a little historical background is in order for the benefit of readers who are unfamiliar with the early history of the Fuji marque. Those already familiar with this material are invited to skip to the subsequent sections of this article. Background

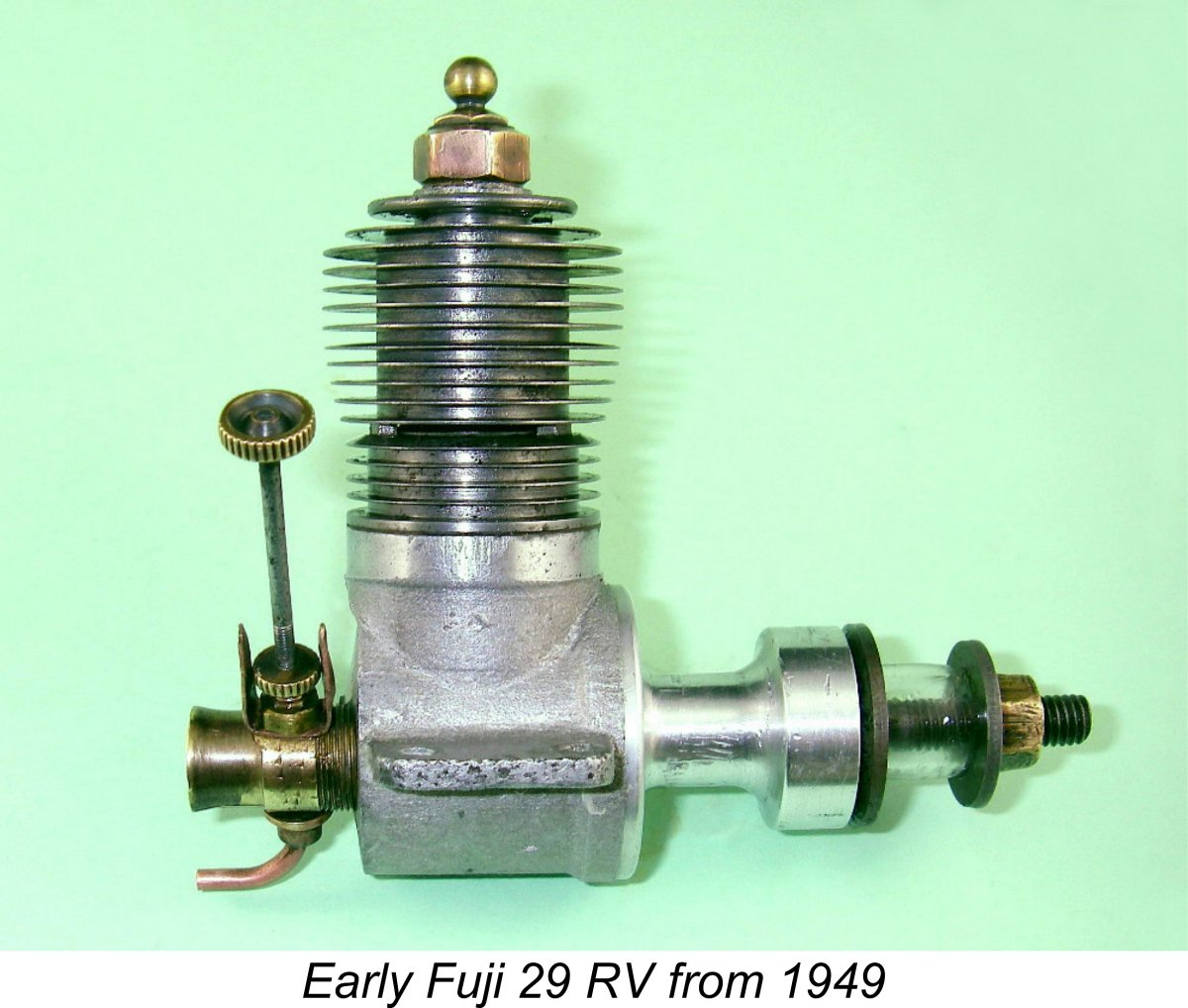

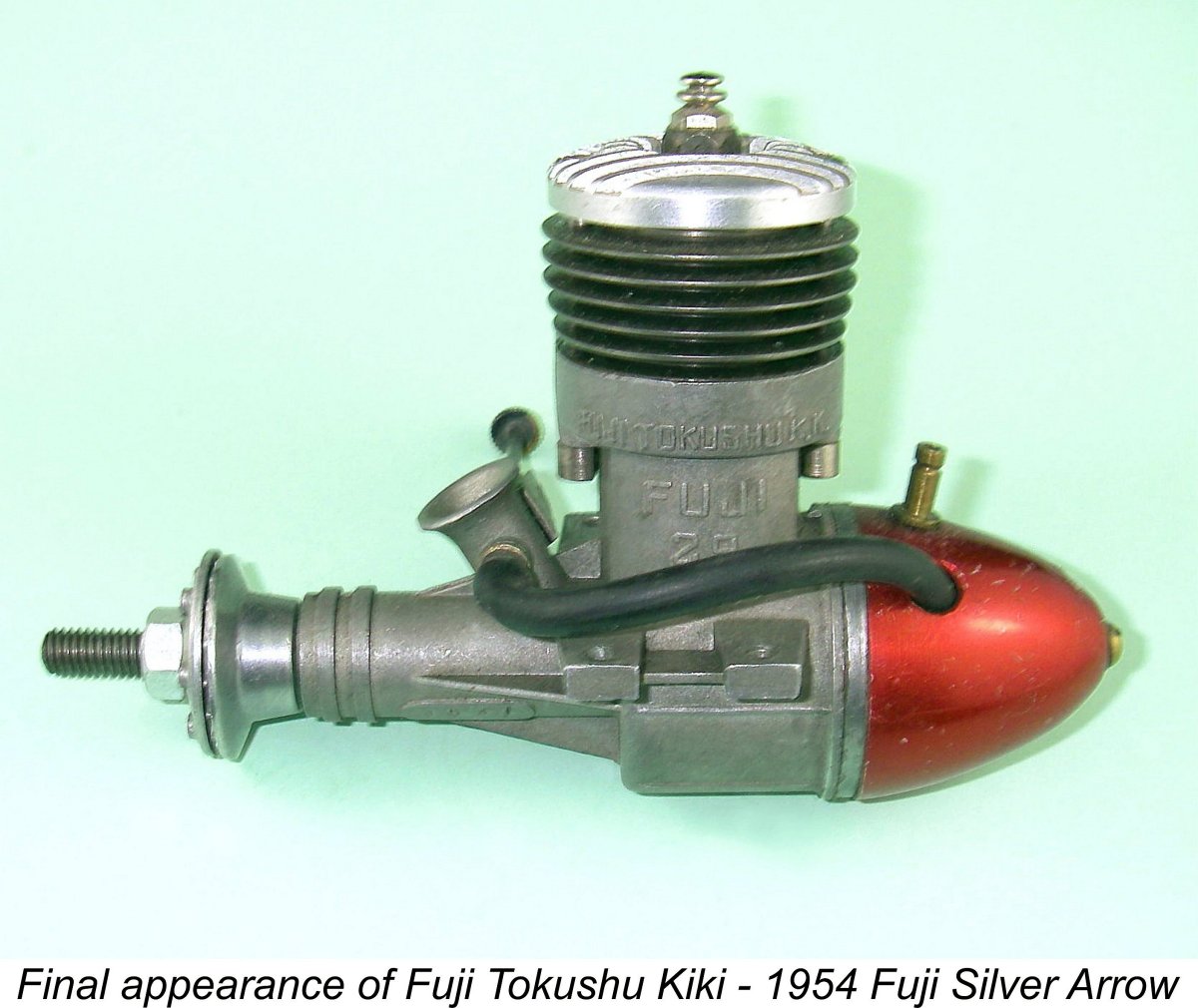

The full story of these units and the succeeding Fuji .29 cuin. models has been recounted in a separate article to be found elsewhere on this website. Articles on the .099 cuin. models and .049 cuin. models produced by the company also appear here. The leaflets and box labels associated with the earliest Fuji products confirm that the original manufacturer of the range was a Tokyo-based company known as Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work. This translates more or less into "Fuji Specialty Machine Shop". The company appears to have been located in the Kyobashi district of Tokyo. The manufacture of the Fuji engines by Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work evidently continued from 1949 through to 1954. At that point, two new corporate entities entered the picture. These were Fuji Bussan KK and the Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd. Both names appeared on the packaging and promotional material supplied with the engines - the "KK" company name appeared on the The name "Fuji Bussan" translates very roughly into "Fuji Products", which is completely consistent with the companies' business activities. Under Japanese corporate law the KK and Co. Ltd. company registrations were (and are) entirely distinct. The "KK" form of company registration had been in existence for many years, having first been used in 1873. The letters stand for "Kabushiki Kaisha", which translates into "Stock Company" and is thus more or less synonymous with the familiar American term Corporation (in Britain, a Publicly Listed Company (PLC), or Akitengesellschaft (AG) in Germany). This form of registration required the posting of a very substantial bond as well as the use of a registered trade-mark, but it did allow the company to trade its stock on the open market. By contrast, the "Co. Ltd." form of company registration was relatively new, having been introduced shortly after the conclusion of WW2. This step was possibly motivated by the greatly increased post-war level of interaction with Western society in general, but it's perhaps more likely that it was intended to provide smaller Japanese businesses with greater flexibility during their start-up and expansion phases. The revitalization of the war-shattered Japanese economy was the primary challenge at this time, and the new registration option was doubtless intended to encourage small-scale entrepreneurial activity. This form of registration had far lower bonding requirements as well as limiting the company's liability, the downside being that there were severe restrictions upon the company's ability to raise outside capital. It was perhaps best suited to small self-financed family-owned operations - the Enya Metal Products Co. Ltd. is a familiar example. Given the above facts, the two distinct registrations would appear at first sight to imply that Fuji Bussan KK and the Fuji Bussan Co. Ltd. were separate corporate entities. However, this cannot by any means be taken for granted - it is entirely possible that the two companies were in fact one and the same! Odd though this may seem, it appears that under Japanese corporate law there was nothing to stop a KK registered company from representing itself as a Co. Ltd. organization in a promotional context, although the reverse would not be permitted. This might be seen as an advantage for international markets in which such a representation would be more comfortably familiar. There are precedents for this approach being adopted by others. It was from this point onwards that we see a greatly increased level of concern with the marketing of the engines as opposed to merely their manufacture. There's no doubt at all that the Fuji Bussan organization entered the picture with marketing ambitions which extended well beyond Japanese shores. Their advent coincided with a significant upgrading and Anglicization of Fuji's packaging, while leaflets accompanying engines destined for overseas markets were now also printed in somewhat clumsy English. These moves reflected a sincere effort to market the engines world-wide for the first time. The record shows that this effort was quite successful, allowing the venture to survive for the following two-and-a-half decades. This brings us up to the middle of the 1950’s and the point in time at which the Fuji .15 cuin. twin-stack models which form our central subject first made their appearance. Having summarized the corporate history of the Fuji model engine manufacturing enterprise up to this point, it’s time to resume discussion of the engines themselves. To do so, we have to return for the moment to the early 1950’s, when the Fuji Tokushu Kiki company was still manufacturing the range. Expansion of the Fuji Range

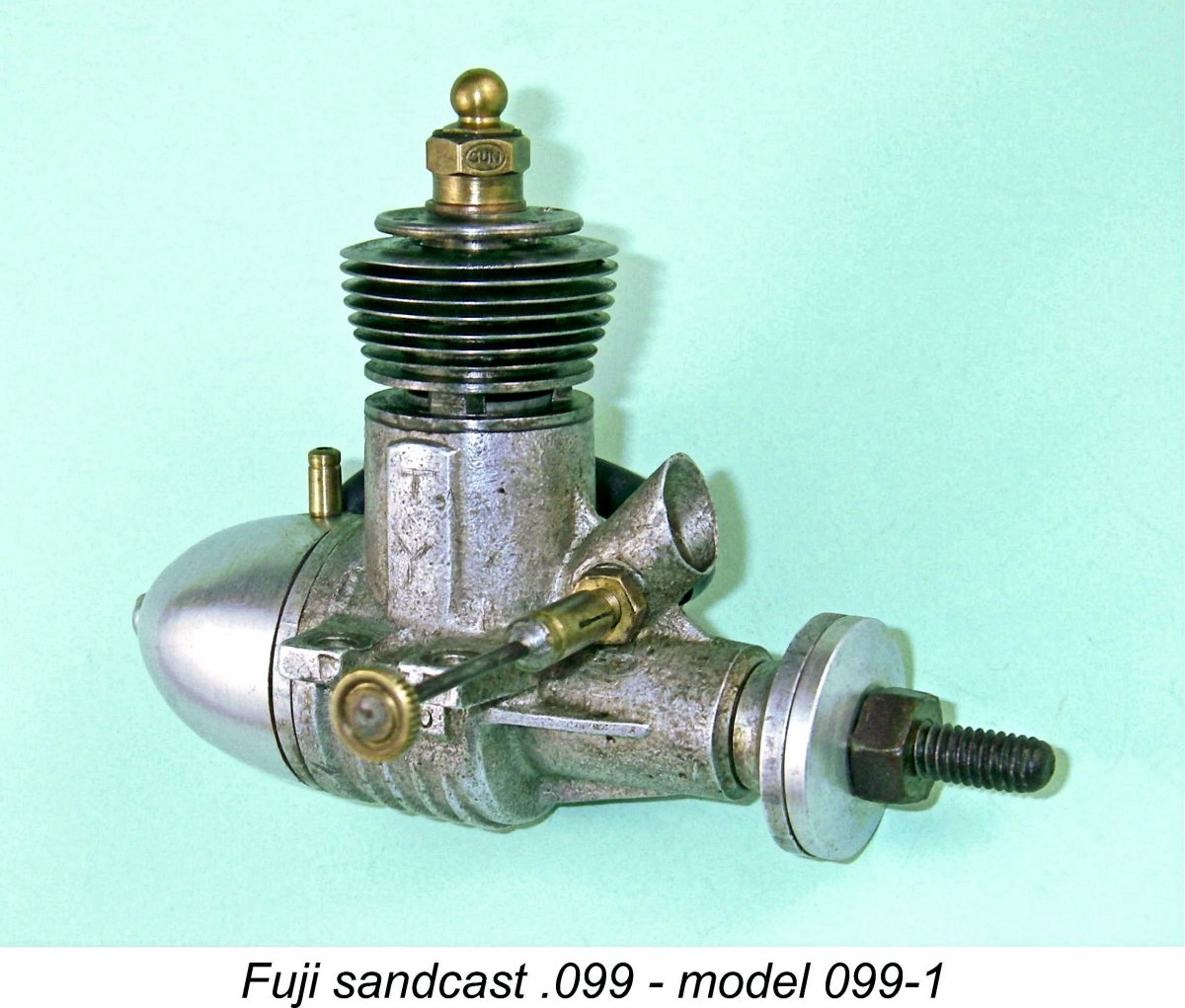

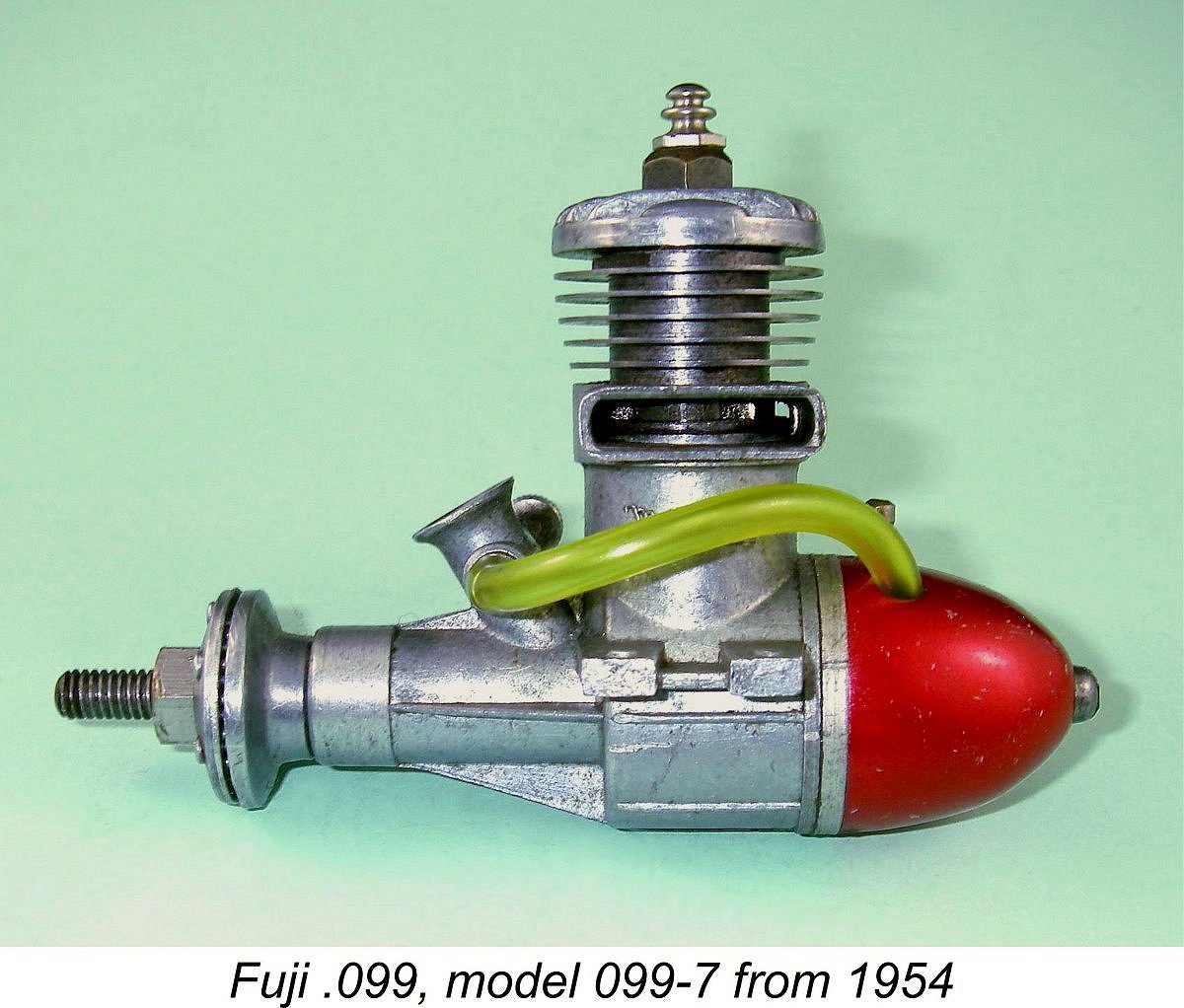

In a review of the Fuji .099 cuin. models which may be found elsewhere on this website, I commented upon the fact that the .099 cuin. displacement category appears to have occupied the same market niche in Japan that the .049 “½A” category did in the USA during the 1950’s. That is, they were seen as the main “economy” entry-level and sport-flying displacement category. If you were a beginner or a sport flyer in 1950’s Japan, you probably bought an .099!

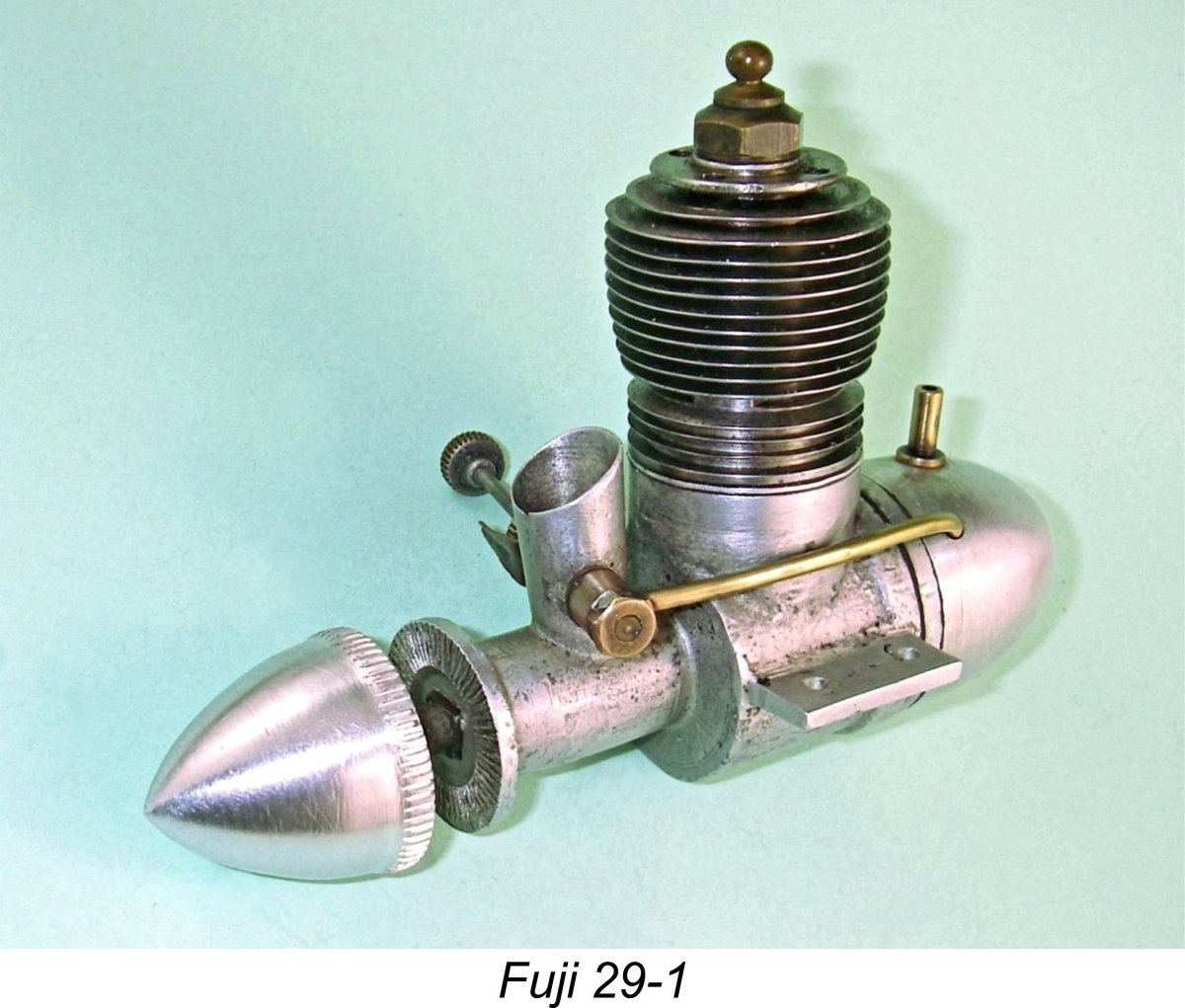

During their first few years in business, Fuji focused on gaining a foothold in the marketplace with their two basic FRV models, although the RRV version of the .29 cuin. unit also continued in limited production at this time. The engines appear to have sold quite well, to the point that by the latter part of 1950 Fuji felt ready to begin the further expansion of their range. They did so by moving into a displacement category that had previously been almost completely unexploited by Japanese manufacturers - the .049 “½A” category which had become so immensely popular in America beginning in 1949.

Further development of the three Fuji models now in production continued into 1953, with a surprising number of variants being manufactured. In early 1952 the range was further expanded with new sandcast Fuji models in the .19 and .35 cu. in. categories. These both followed the established Fuji design pattern utilizing FRV induction and radial cylinder porting with blind-bored cylinders. Once again, Fuji continued its pioneering tradition by being among the first Japanese makers to market an engine in the .35 cuin. class. During the latter part of 1952, the company began a progressive switch from sand-casting to pressure die-casting for all of their cast components, which they produced in-house at this stage. By early 1954, all of their products apart from their radially-ported .19 and .35 cu. in. models were produced using pressure die-casting. As a result of all this activity, the company entered 1954 as a significant player in the domestic Japanese model engine market with an impressive range of designs in the .049, .099, .19, .29 and .35 cuin. categories. All of these relatively low-priced engines were very well made if somewhat lacking in external “polish" and design sophistication. As yet there had been little if any attempt to market them internationally - the domestic and nearby Asian markets apparently absorbed all of the still relatively limited production. As previously noted, it was at this point that the Fuji Bussan Co. replaced the Fuji Tokushu Kiki company as the manufacturers of the Fuji range. At the same time, the FAI was considering the long-touted adoption of the 2.5 cc displacement category as the new standard for International competition, a decision which was finally ratified prior to the start of the 1955 International contest season. Appreciating the increased prestige which this decision was bound to impart to the .15 cuin. category, the new manufacturers decided to expand their range once again, this time by entering the .15 cuin. (2.5 cc) category with their own offering. It's likely that they did so in the expectation that the greatly enhanced international prominence of the 2.5 cc displacement category would create a heightened level of acceptance of a 2.5 cc Fuji design in the overseas markets which they were now hoping to challenge. Once again, there is no question that they were the first Japanese manufacturers to take this step, although others quickly followed their lead. Let’s begin our investigation of the Fuji 15 twin-stack models by examining the model that got the Fuji Bussan Co. started in this important category. The Original Fuji 15 (Model 15-1)

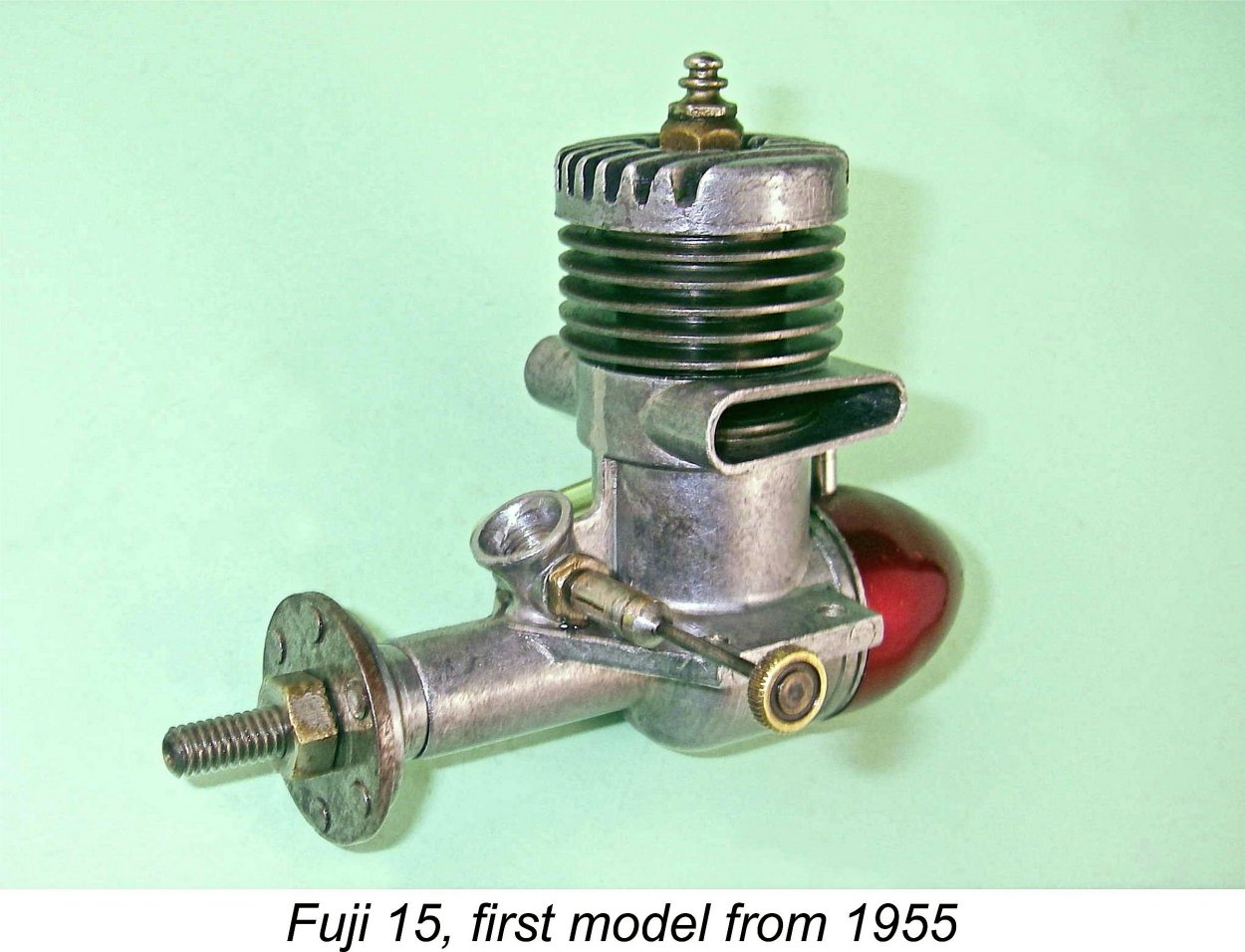

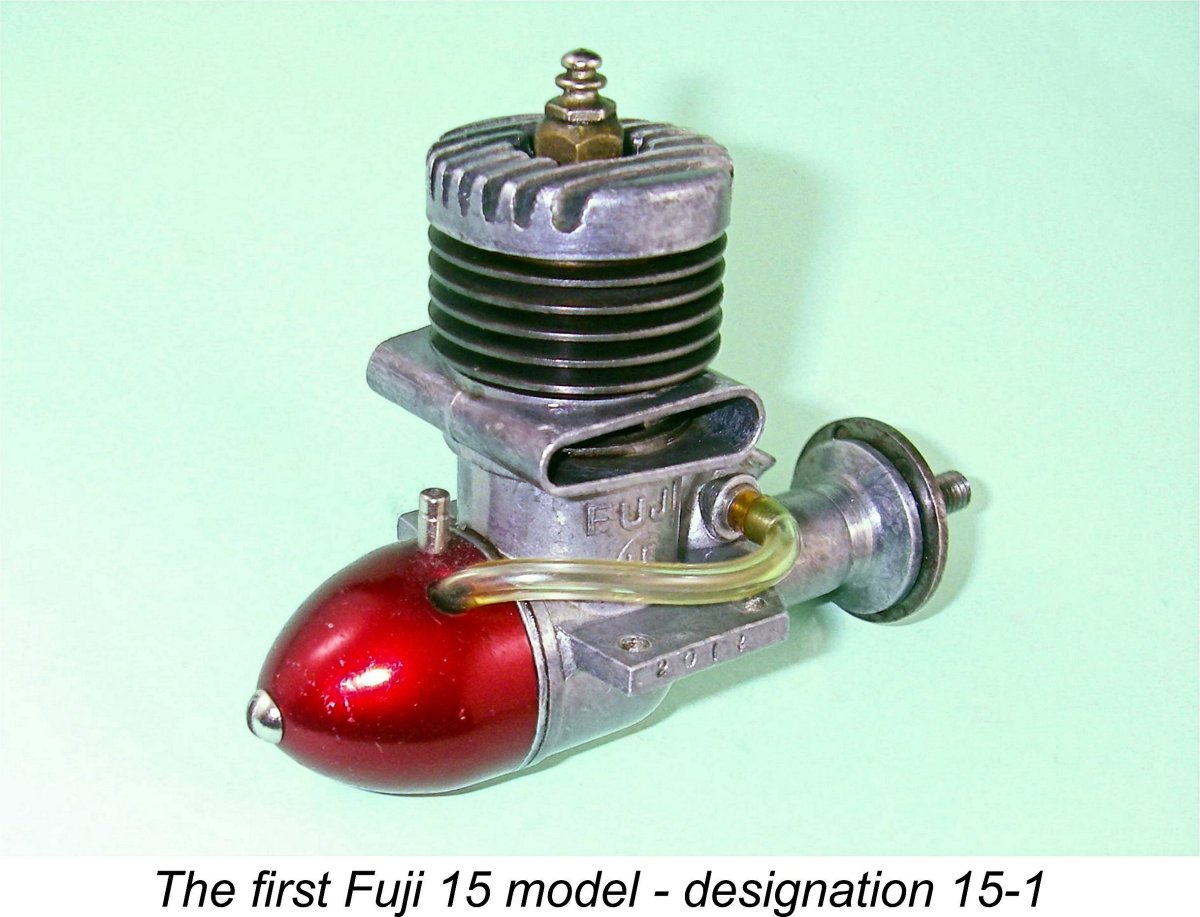

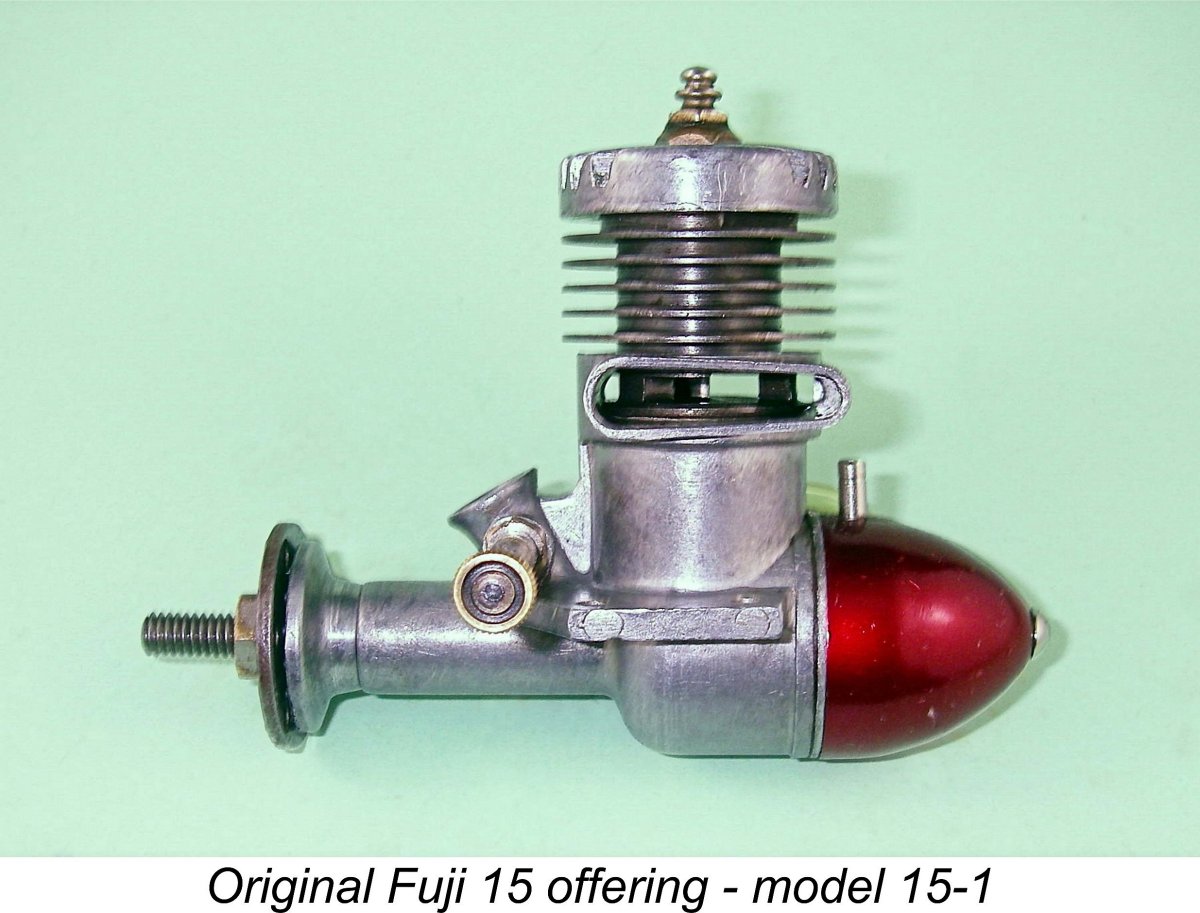

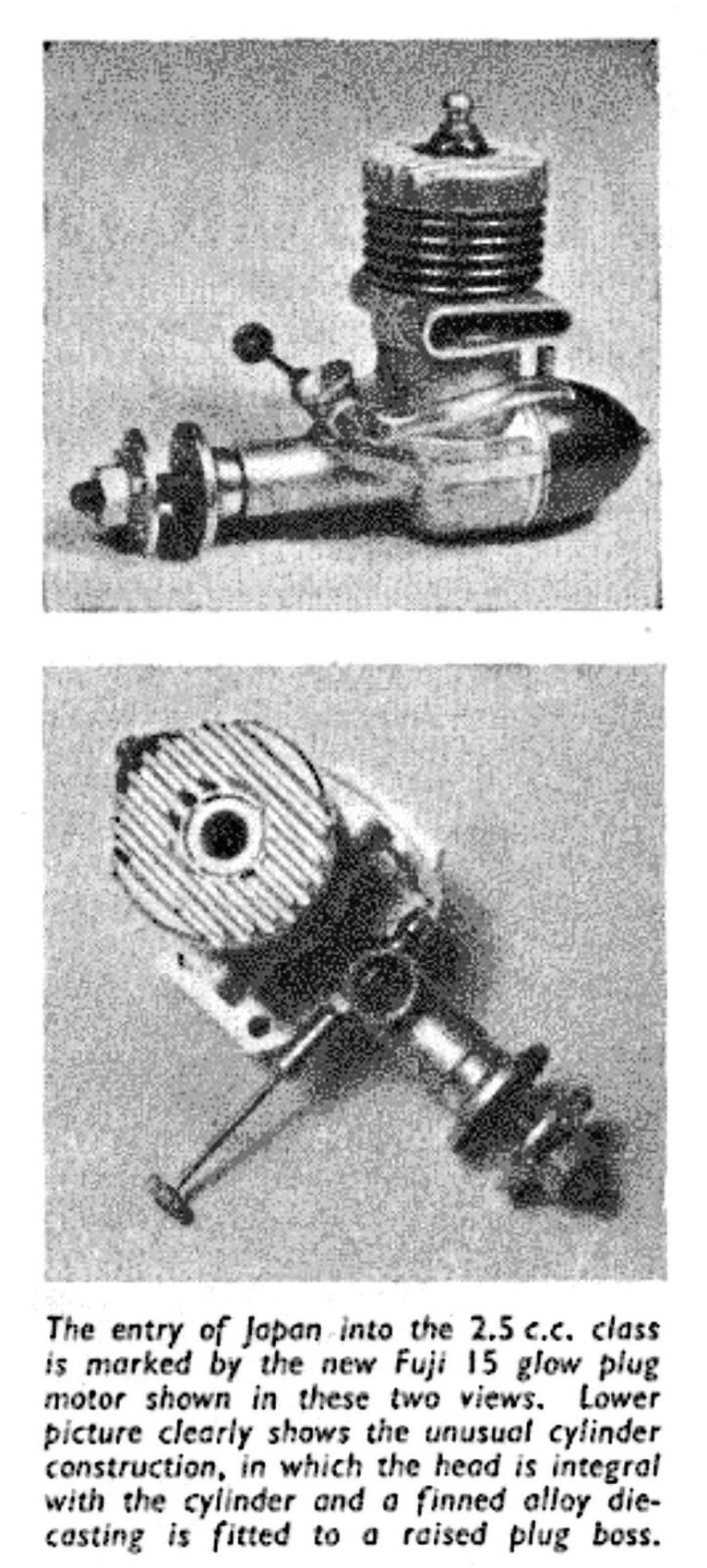

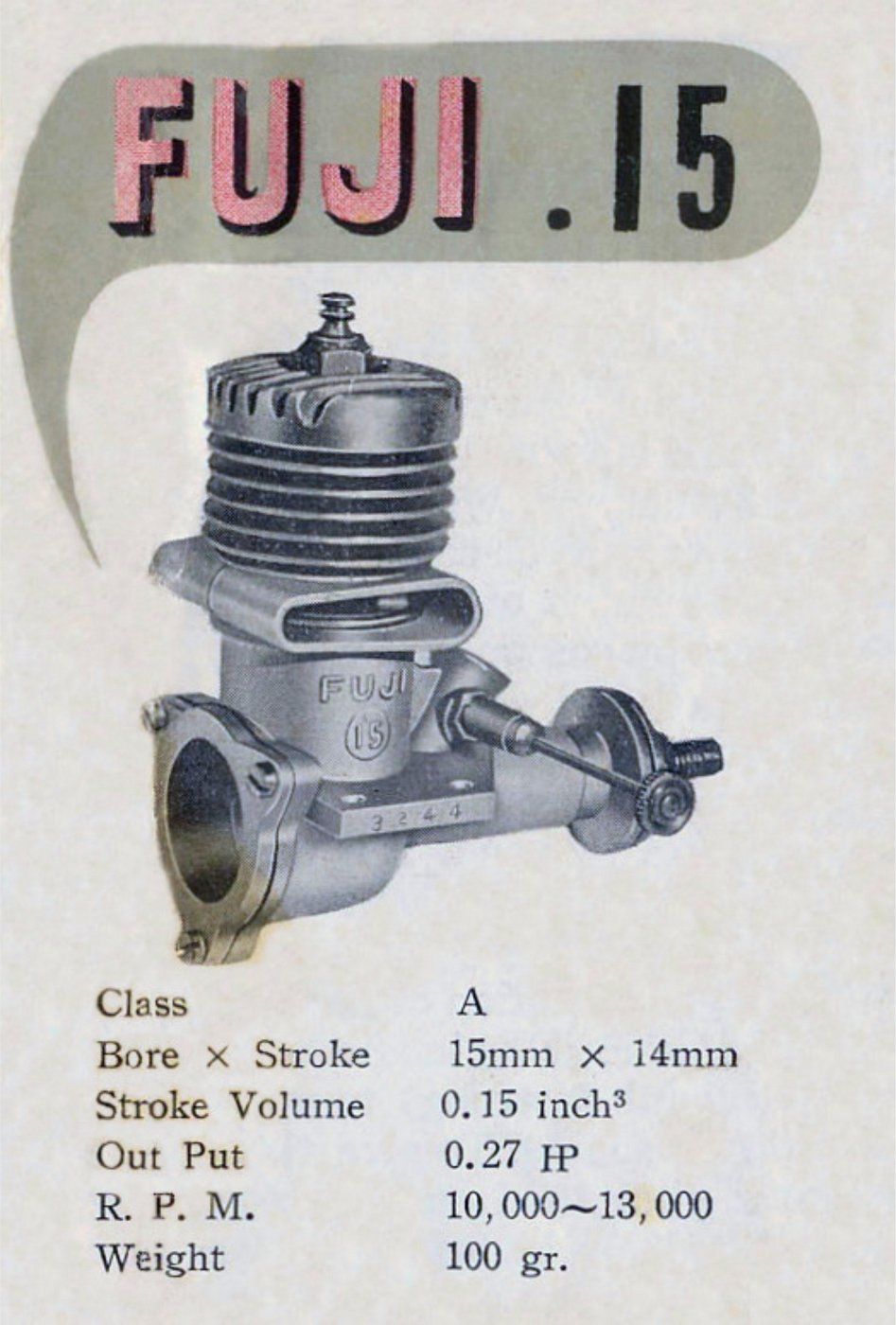

The early history of the other Fuji displacement categories mentioned previously is somewhat obscured by the fact that those series originated during the early post-WW2 period when the activities of Japanese engine manufacturers were not under scrutiny by the English-language modelling media. However, this is not true of the Fuji 15 series, thanks to its relatively late arrival compared to the other models in the Fuji line-up. By the time of the Fuji 15's appearance, the international modelling media had begun to take a serious ongoing interest in the activities of the Japanese model engine industry, Fuji very much included. According to Peter Chinn, the Fuji 15 was introduced in February 1955. Writing a few months later, Chinn stated that he had received one of these engines for evaluation shortly after its release. This may have come about as a result of the Fuji Bussan Co. sending one to him in order to get his views on its sales potential outside Japan. As perhaps the world’s most widely-recognized authority on model engines at the time, Chinn was often approached in this way by manufacturers wanting an informed reaction to their new products. Lucky man!! The Fuji .15 was included in Chinn’s “International Engine Review” which was published in two parts in the April and May 1955 issues of “Model Aircraft” magazine. The part dealing with glow-plug motors was published in the May issue. The table of model glow-plug engines for 1954/55 included the Fuji 15, although details of its major dimensions were unavailable at the time. The only statistics given were the displacement of .15 cuin. and its weight of 3.9 ounces. In a footnote to this table, Chinn stated that the bore and stroke were of the order of 15 mm and 14 mm respectively - evidently he had not taken exact measurements prior to writing his article. These figures proved to be nominally correct, being consistent with those for all later variants of the engine during the “classic” era covered in this article. Chinn also stated quite unambiguously that this was the first Japanese engine in the International 2.5 cc class to make its appearance, although he was later to note that it was soon followed by the rival Mamiya .15. Enya and O.S. were also quick to release .15 cuin. models of their own later in the same year.

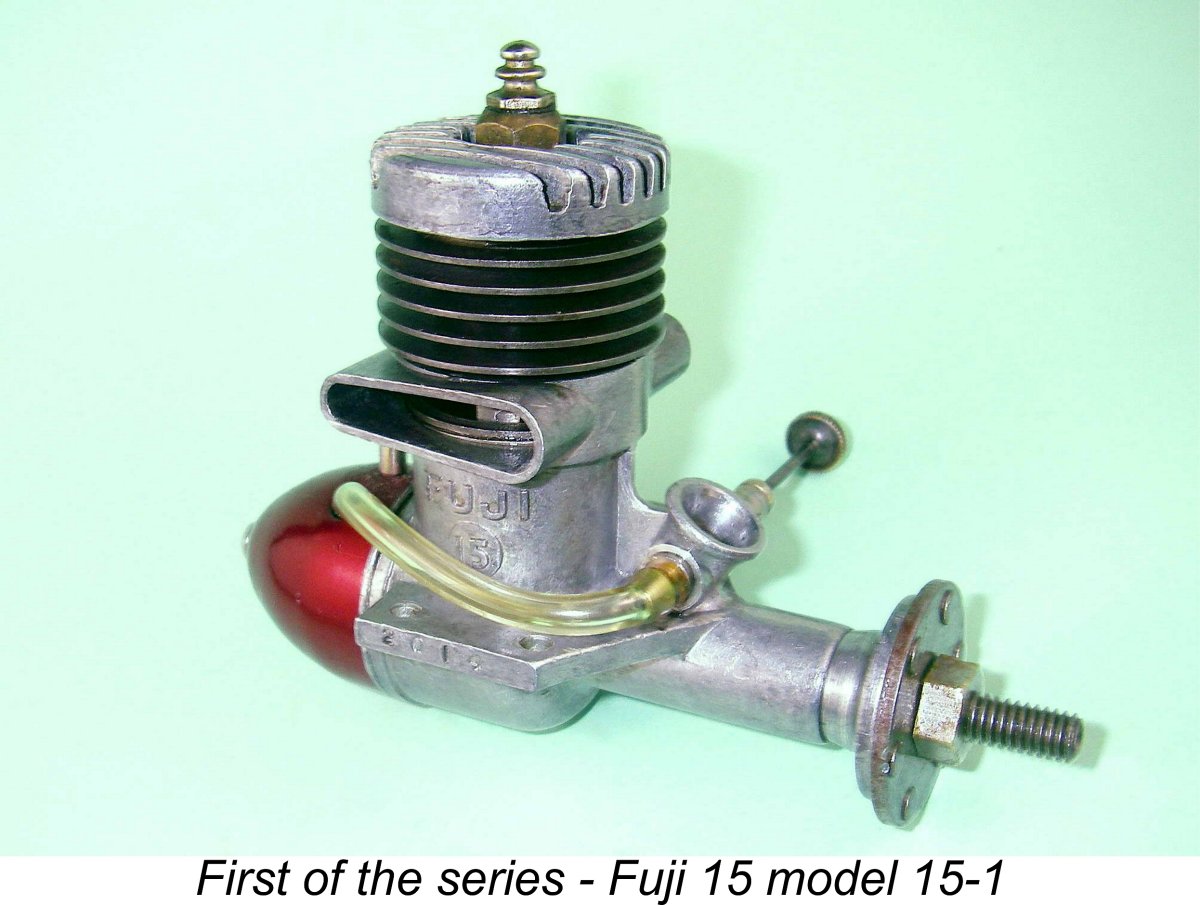

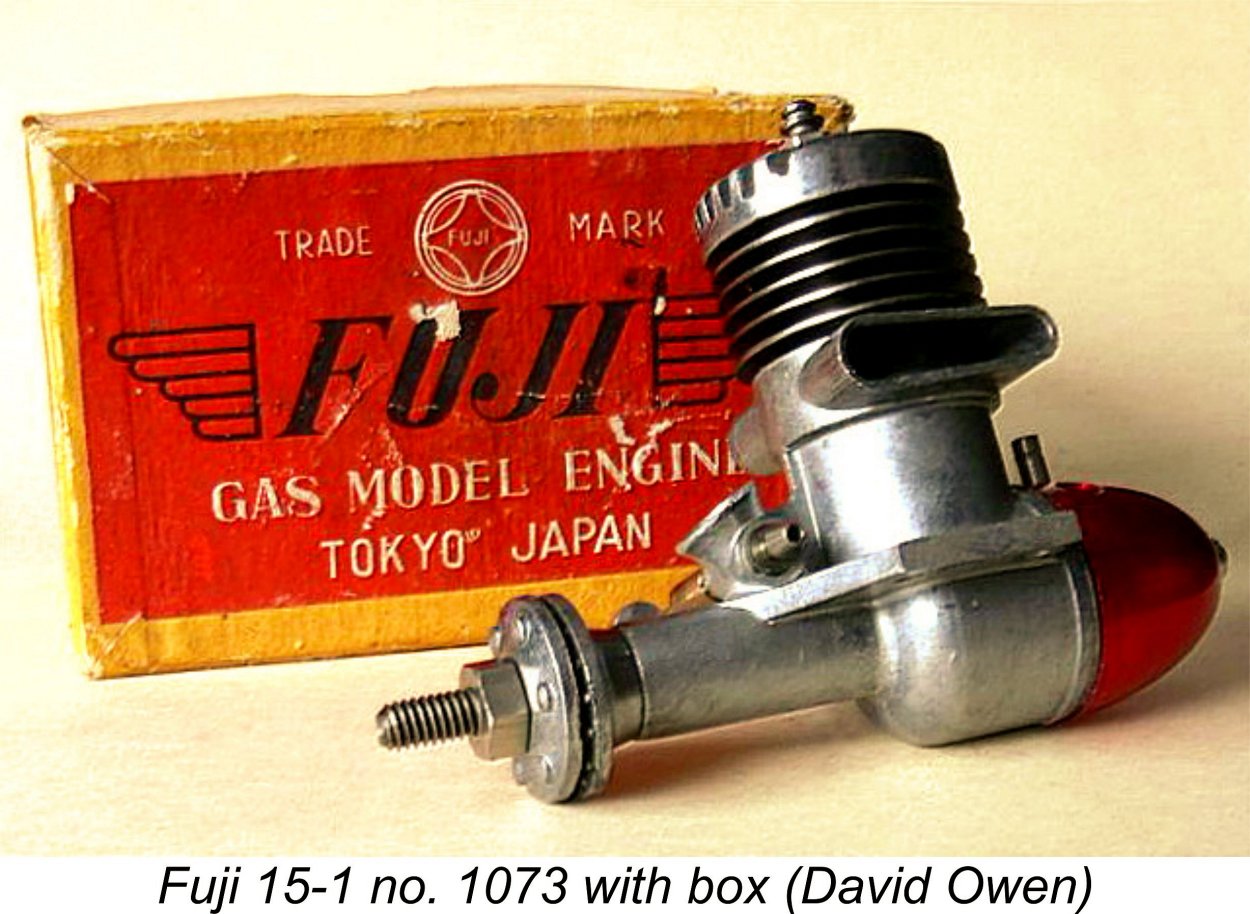

The June 1955 article included two photos of the original Fuji 15. These are reproduced at the left, together with Chinn's caption. In the main text of the article, Chinn commented upon the unusual design characteristics of the engine as well as its low price while stating that it “….. does not teach us anything about high performance” - a gentle way of saying that he had found its power output to be very much on the modest side! A further photograph appeared in an article on Japanese model engines which was published in the November 1956 issue of “Model Airplane News”, almost certainly long after the design had been supplanted by the second design variant in the series (of which more below). The model 15-1 with which we are concerned here bore a marked resemblance to the then-current Fuji .099 cuin. model (the 099-7 variant). Like its smaller stable-mate, it featured a well-produced die-cast crankcase with twin exhaust stacks, one on each side. On the 15 model, these stacks were tapered towards the rear, presumably for styling reasons, also being angled inwards towards the rear at their outer ends in plan view. One very welcome feature of the new 15 case was the elimination of the inherently weak “twin expansion” mounting lugs used on the smaller model in favour of conventional solid lugs – a good move! In common with the companion .099 model 099-7, the case was given a lightly tumbled finish. A blind-bored cast-iron screw-in cylinder with radial porting was employed, with the three exhaust ports discharging into the two stacks, again following the arrangement established with the .099 series. The compression ratio provided by the blind bore was a rather marginal 6.5:1 by direct volumetric measurement. Clearly relatively modest operating speeds were anticipated, as was the use of a “hot” glow-plug. A high-nitro fuel would also help, although why one would use such a fuel in an engine of this rather basic specification is anyone's guess! The same type of transfer porting was also employed, with three upwardly-angled transfer ports drilled through the cylinder wall between the exhaust ports - in essence, "Oliver porting". These transfer ports overlapped the exhaust ports almost completely. They were supplied with mixture through bypass passages formed by machining three flats into the outer cylinder wall below the exhaust port belt in line with the transfer ports. These flats interrupted the male threads which secured the cylinder in the crankcase. Cylinder port timing was relatively conservative. The exhaust ports opened at 115° ATDC for a total exhaust period of 130°. The almost complete overlap of the transfer ports resulted in a blow-down period of only around 5º and a transfer period of 120º.

Crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction was employed in conjunction with a bronze-bushed main bearing. The induction port in the 8 mm diameter crankshaft journal was of rectangular form. Induction timing was surprisingly aggressive when compared with the cylinder port timing - the shaft port opened extremely early at only 25º ABDC and closed at 40º ATDC for an unusually lengthy and seemingly inappropriate induction period of 195º. The needle valve was apparently the same one as used on the companion .099 model, using a split thimble for tension and having a brass control knob at the outer end. The thimble engaged with an extremely fine thread on the spraybar, doubtless contributing to the potential for extremely precise setting of the needle. At the rear, this model employed a screw-in backplate having provision for the mounting of a tank. This tank was in fact the same component as used on the companion .099 cuin. model, being anodized red.

In that context, it may be relevant to note that in years of looking I’ve yet to encounter a Fuji leaflet which features this model. This would be best explained by the idea that the initial examples of this engine released in February 1955 were accompanied by leaflets taken from existing stocks of the earlier 1954 document which did not include the .15 (my New-in-Box example no. 1073 is an example) and that the period of production was sufficiently short that the following variant to be described next appeared before the company got around to printing a batch of updated leaflets. Overall, it’s probable that by the end of 1955, or early 1956 at the latest, the original Fuji 15 just described had been replaced by the next model in the series. But before we consider that model, let’s find out how the first variant actually performed. The First Fuji 15 on Test

The fact that Chinn never published a test of the engine despite having done much to draw attention to its introduction is consistent with this notion - whenever Chinn found himself unable to comment positively on a newly-introduced model from a manufacturer with whom he clearly enjoyed a collegial relationship, his usual practise was to say nothing at all. Having several examples of this relatively rare motor on hand, I felt that this omission placed me under an obligation to conduct my own testing for better or worse. One of my examples is illustrated engine number 1073 formerly owned by my late and still greatly missed friend David Owen. This one is New-in-Box and apparently unused, and I was keen to keep it that way. My other example, engine number 2014, is in almost equally fine original condition but has no box and is missing its tank, also clearly having done some running in the past. It was this example that was selected for testing on this occasion.

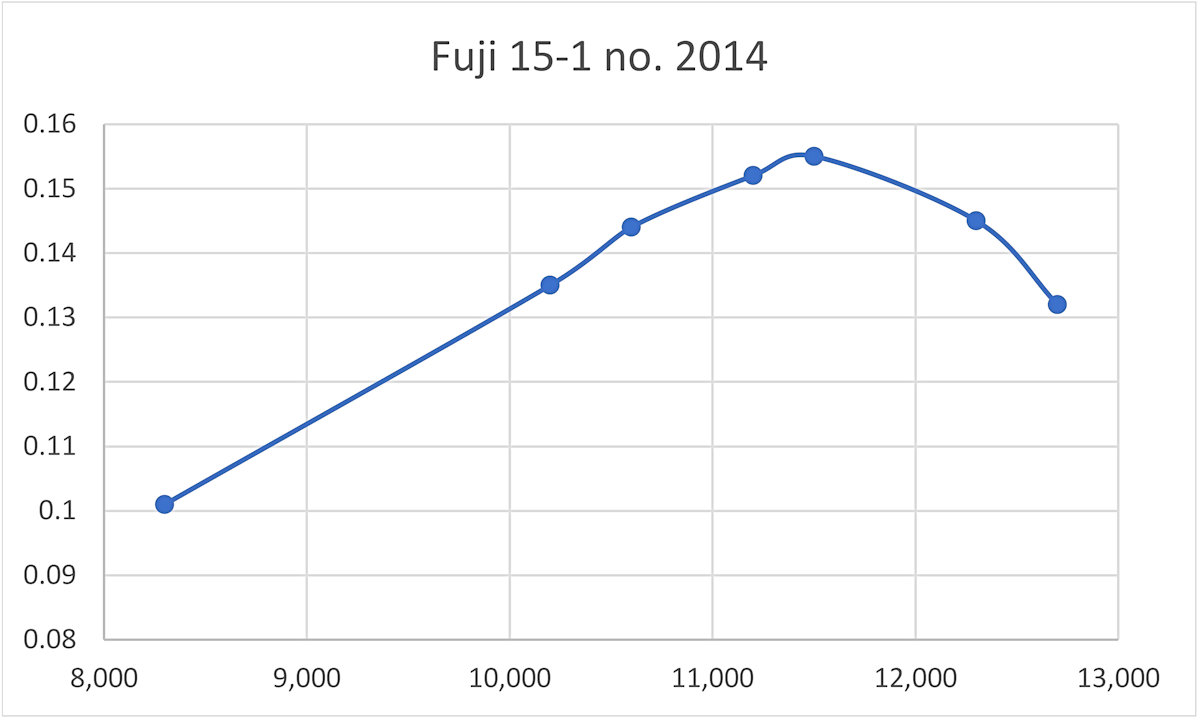

The chosen props were all APC items, for which I have well-established power absorption coefficients. Based on previous experience, I judged that the selected group should bracket the peak pretty well. The chosen sizes were 8x6, 8x5, 7½x4 WB, 8x4, 7x6, 7x5 and 7x4. The 7½x4 WB prop is a cut-down APC 9x4 calibrated to fill a gap in my suite of test airscrews. A "hot" Fox glow-plug was used for this test. Securely mounted in the test stand, the Fuji felt good when flicked over, although the very low compression ratio was readily apparent. Following a few choked tuns to fill the fuel line and a modest exhaust prime, the engine started on the second flick. It maintained this exemplary starting behavior throughout the test. Response to the needle valve was found to be very progressive, doubtless due to the very fine thread used for the needle's thimble. The optimal needle setting was very easily found for all props tested. The engine ran absolutely smoothly throughout, with lower-than-average levels of vibration. I was actually quite impressed with the Fuji's user-friendly operating characteristics! The following data were recorded on test:

It appears that Peter Chinn wasn't stretching the truth in saying that the original Fuji 15 "does not teach us anything about high performance"! My test example (which may or may not be typical) developed a peak output of around 0.155 BHP @ 11,600 RPM. There's little doubt that the engine's unusually low compression ratio had a good deal to do with its seeming unwillingness to run much above 12,500 RPM. Not a particularly earth-shattering performance, one might say, but it should be recalled that we're talking here about an engine weighing only 3.9 ounces. When the engine's outstanding handling and seemingly sturdy construction are taken into account, it's clear that Fuji were offering a very user-friendly model powerplant which would have served its owners well provided that their performance expectations were kept in check. It would have made an excellent beginner's engine. An 8x4 prop would seem to suit it perfectly for free flight work, while an 8x5 should work well in control line service. The Second Fuji 15 (Model 15-2)

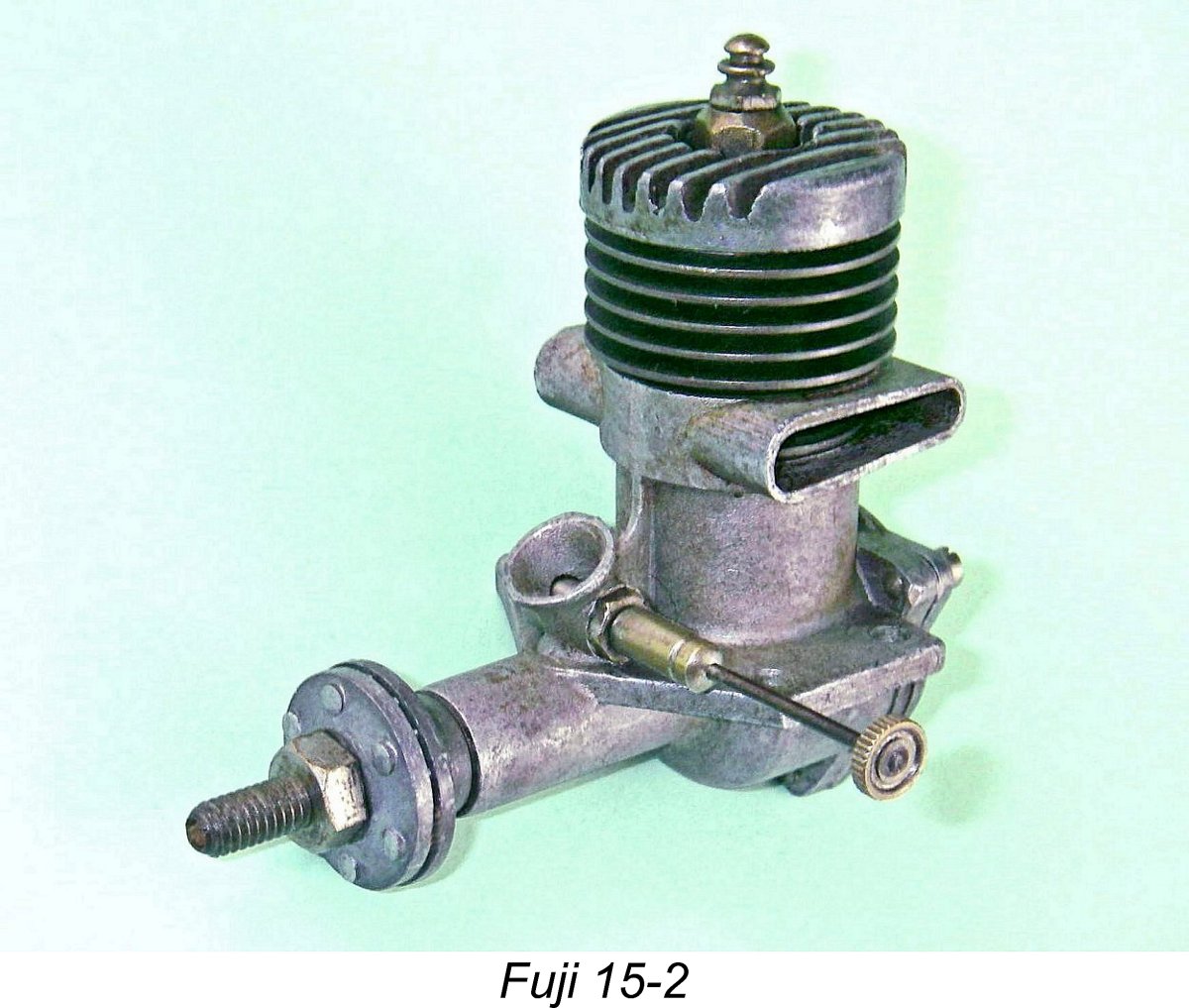

The second variant of this engine appeared at first glance to be essentially identical to its predecessor in most respects. The most obvious change was the replacement of the screw-in backplate and its associated tank with a die-cast bolt-on backplate having no provision for a tank. This backplate was secured by three screws which engaged with tapped holes in three small lugs cast onto the case at the rear. The only other visible change was the application of a matte finish to the castings in place of the shiny finish which had characterised the original model. The same modification was applied to the revised .099 cuin. model 099-8 which was introduced at more or less the same time. The needle valve continued to be of the split-thimble type at this stage. I learned long ago by hard experience that disturbing a well-settled example of one of these engines unnecessarily is extremely unwise, since the correct cylinder head fin alignment is almost never replicated upon reassembly. However, the major operational parameters for the engine could be checked without disturbing the assembly. Such measurements confirmed that there were a number of internal modifications of considerable significance. Perhaps the most significant change was an increase in the compression ratio from 6.5 to 1 to a measured 8 to 1. This change was easily accomplished by machining the blind bore to a slightly reduced depth - it wouldn't take much. The cylinder port timing was also amended. The exhaust now opened at only 110º ATDC for a slightly greater exhaust period of 140º. The transfer ports continued to overlap the exhaust ports almost completely, resulting in an unchanged blowdown period of around 5º and an expanded transfer period of 130º. The induction timing was also amended. The crankshaft induction port now opened a little later at around 35º ABDC and closed a little earlier at approximately 30º ATDC for a seemingly more appropriate induction period of 175º. This must have been accomplished by a small reduction in the annular width of the crankshaft induction port, which in turn might have increased shaft durability somewhat.

This variant appears in a number of Fuji promotional leaflets in association with other models which are consistent with the speculative dating given above. These leaflets depict engine number 3244, which confirms the structural details given above. The clearly legible serial number also confirms that the leaflet was prepared after at least 3244 examples had been made, which probably dates the document to the latter part of 1956. The information with this image of the Fuji 15 confirms that the bore and stroke were nominally 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for an unchanged calculated displacement of 2.47 cc (0.151 cu. in.). These dimensions were to be maintained throughout the “classic” Fuji 15 design sequence. Weight was given as 100 gm (3.53 ounces), although my own example weighs in at 106 gm (3.74 ounces). Perhaps the factory-quoted weight was for the bare engine without a plug?!? The makers claimed a maximum output of 0.27 BHP at some undefined speed between 10,000 and 13,000 rpm. This claim seems more than a trifle optimistic to me since it slightly exceeds the independently-measured output of the contemporary World Championship-winning O.S. Max-I 15! This claim will be tested in the following section of this article. The lowest presently-known serial number for this model appears on my own previously-illustrated engine number 2193. On the basis of this observation, it is unclear whether or not the serial numbering sequence was restarted at 0001 for this second variant or whether it simply carried on in an unbroken sequence from the previous model. The absence of a letter prefix to distinguish one sequence from the other suggests that the latter possibility was in fact the case. If this is true, then the switch occurred between engine numbers 2014 and 2193. The highest serial number of my present acquaintance for this variant is 6894. If the numbering sequence did include the original 15-1 variant, the implication is that perhaps only 2,000 or so examples of that model were made - a perfectly reasonable figure. This in turn would imply the subsequent production of at least 5,000 examples of the 15-2 variant. However, the latter figure would be substantially higher if in fact the serial numbering sequence was re-started at 0001. I must repeat that at present I have insufficient data to settle this question authoritatively one way or the other. The Second Fuji 15 Variant on Test

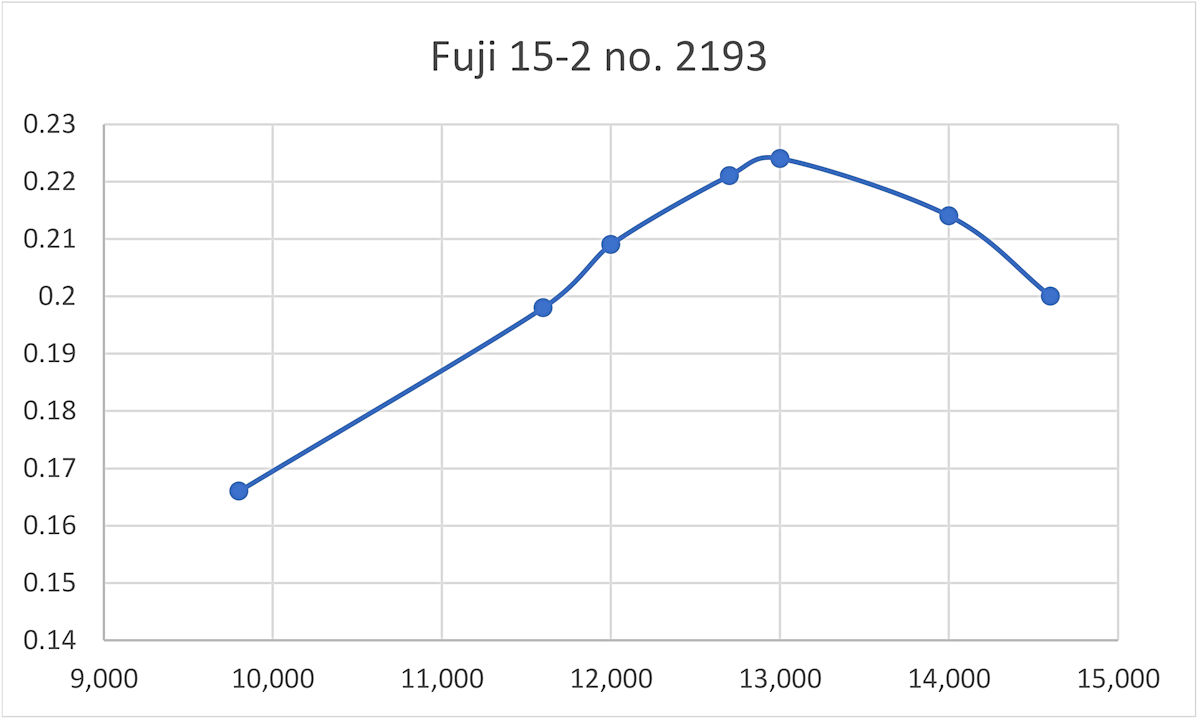

This test was conducted at the same session as that for the 15-1 model reported earlier, using the same fuel and glow-plug along with the same suite of test airscrews. It thus permitted a direct comparison to be made between the two models. Set up in the test stand, the increased compression ratio was readily apparent to the flicking finger when the engine was flipped over. The 15-2 started just as readily as its 15-1 predecessor in the test stand, also needling extremely well and running flawlessly throughout the test. It was immediately apparent that the previously-described modifications had raised the engine's level of performance significantly. The following performance data were recorded during this test:

The Fuji 15-2 clearly out-performed its 15-1 predecessor by a considerable margin. We would expect this given the effect of the previously-described internal changes on the engine's operating parameters. The higher compression ratio in particular allowed the 15-2 to run completely smoothly well into the 14,000 RPM bracket. Peak output was found to be around 0.225 BHP @ 13,300 RPM. This offers no support for the manufacturer's claim of 0.27 BHP, although the peaking speed is broadly consistent with that claim. However, there's no denying the fact that the designer had clearly identified some of the weaknesses in the original design and had moved very quickly and effectively to address them. He was clearly learning on the job, and was learning well! The Third Fuji 15 (Model 15-3)

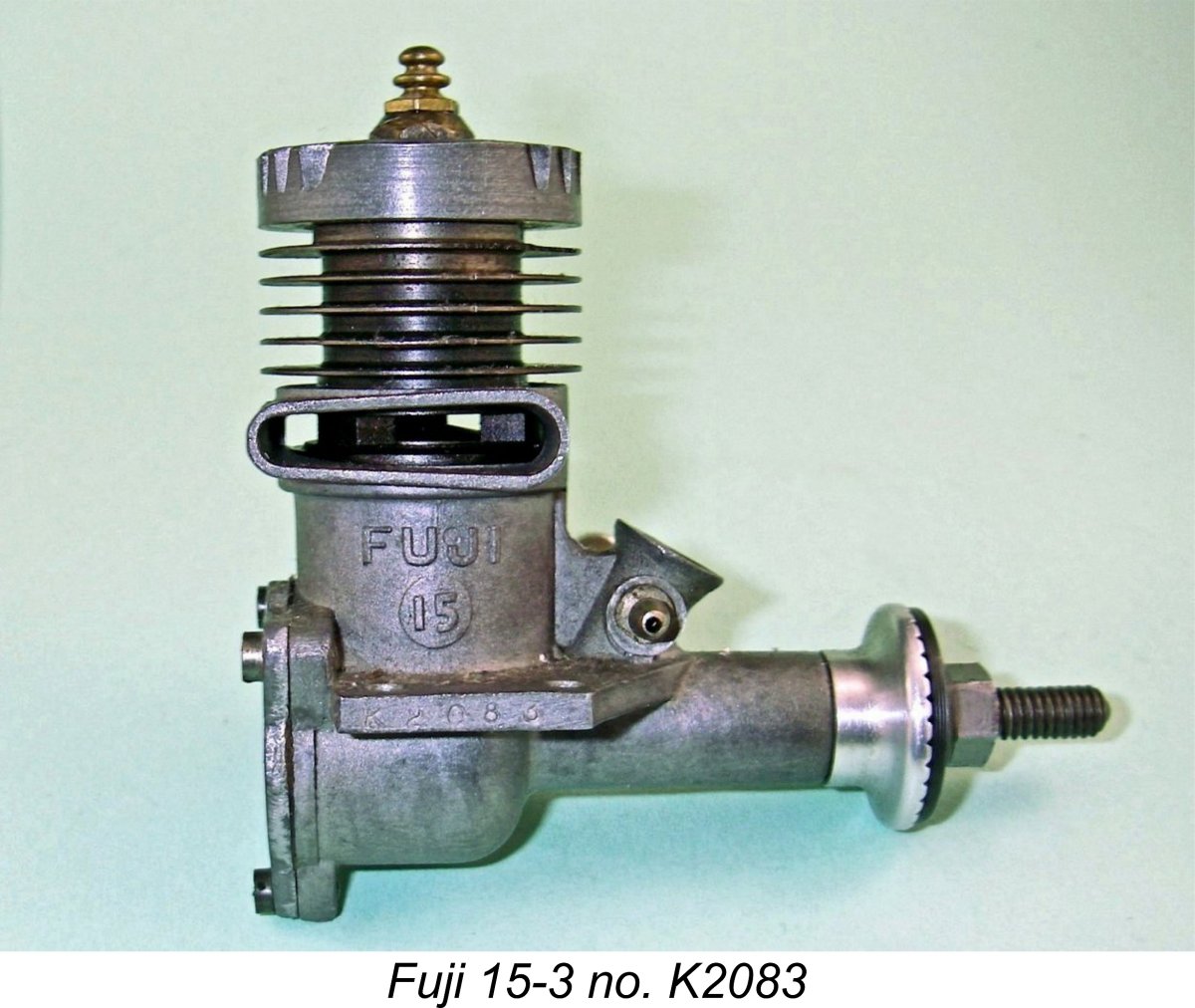

The sequence appears to have been restarted at 0001, but now the prefix letter “K” was placed in front of the number to distinguish it from the previous numerical sequence. Since I’ve confirmed the existence of engines bearing the numbers K0722, K2078, K2083 and K2671 in this series, it’s an inescapable inference that the numbering sequence was re-started from K0001. It appears from the change in the serial number sequence that Fuji themselves saw this as a distinct variant. However, based on the examples in my possession, I have to say that the only readily apparent change in this model was the replacement of the former split-thimble needle valve with what was in the process of becoming Fuji’s new standard needle valve. This revised component used a serrated thimble which was tensioned by a single-leaf spring clip. Beyond this, I’ve so far been unable to discern any differences between the two variants - measurements of the engine's operating parameters (compression ratio and port timing) remain essentially unchanged. Still, I have bowed to Fuji’s apparent conviction that the needle valve switch and perhaps other internal or material changes of which I’m not aware made this a new model, assigning the identification code 15-3 accordingly. The strong possibility exists that the change in the numbering system merely reflected a change of manufacturing arrangements. In my previously-published study on the Fuji range in general, I noted that in around 1957 the Fuji manufacturers appear to have responded to their increasingly successful penetration of the world market by making arrangements to expand their production capacity quite substantially. The change in the numbering system may be nothing more than an effort to delineate the engines produced under the new arrangements from those produced earlier. The redesigned needle valve assembly may also coincide with the change in manufacturing arrangements.

If this logic is correct, the K-numbered examples date from 1959 and should have the spring-clip needle valve, while those lacking the K prefix are pre-1959 and should feature the split-thimble needle valve. The presently-available serial number evidence suggests that the K-numbered series remained in production for perhaps 18 months, assuming that the former production rate was continued. During that period, around 3,000 examples seem to have been produced. As stated earlier, I’ve been unable to detect any significant functional design differences between this variant and its predecessor. Accordingly, I saw little point in subjecting my example, engine number K2083, to a full bench test. I did try the APC 8x4 prop on it, recording a speed of 12,800 RPM, only 100 RPM faster than the 15-2 tested previously. This is well within the range of variation to be expected between two examples of the same mass-produced design, creating the expectation that a full test would merely show that the 15-3 performs at much the same level as the earlier 15-2 example for which results were reported above.

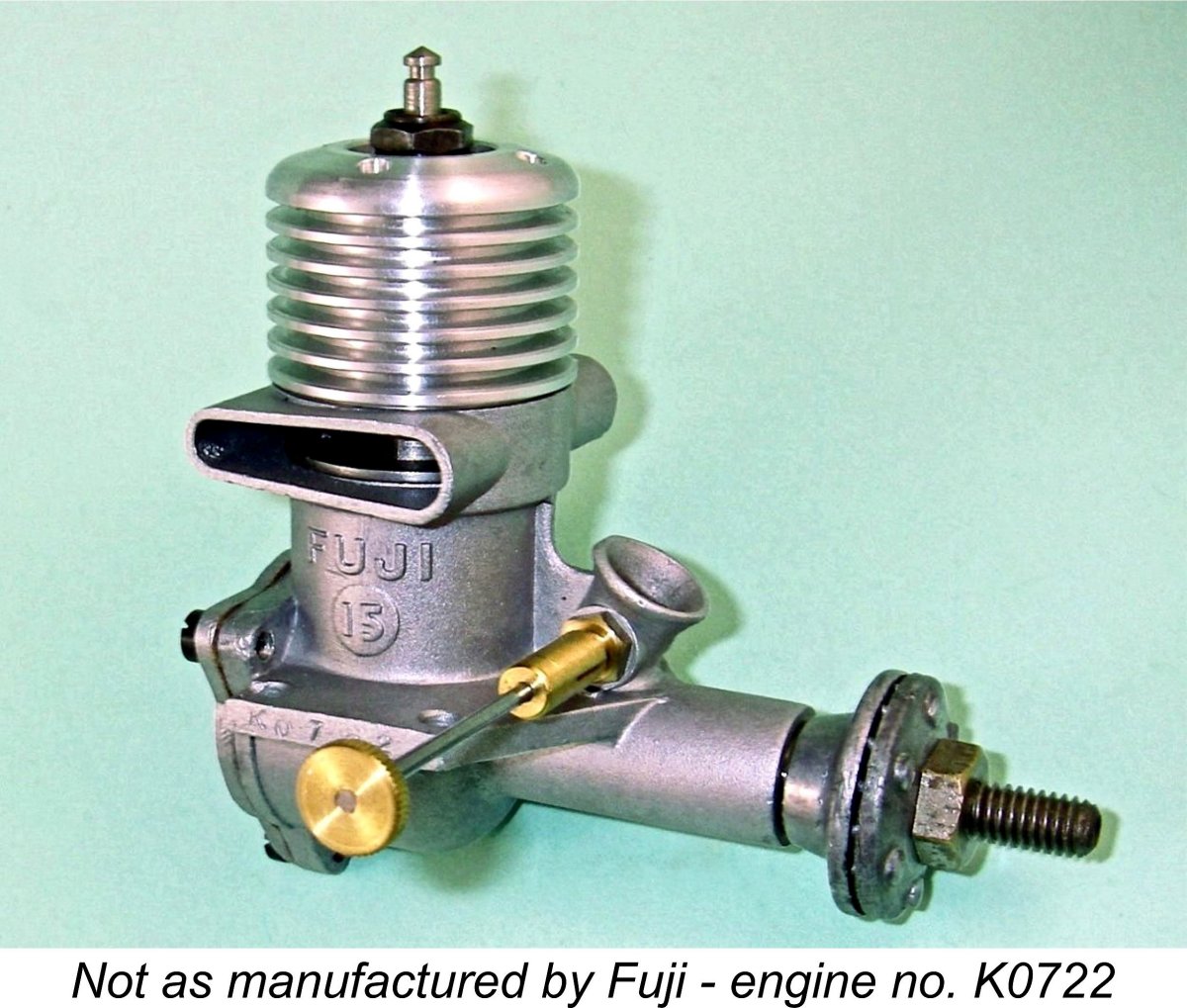

Apart from that, the serial number and the 8 mm diameter shaft prove beyond doubt that this is a modified example of the 15-3 variant, apart from the fact that it retains the split-thimble needle valve assembly of the earlier 15-2 model. Perhaps the earlier examples of the 15-3 utilized such assemblies while stocks lasted. The possibility that this is in fact a further variant of the production 2.5 cc engines manufactured by Fuji is rather persuasively refuted by the serial number K0722, which places the crankcase relatively early on in the production sequence of the 15-3 described above. If this was in fact a new production version of the engine, there's little doubt that Fuji would have assigned a new serial numbering sequence, as they invariably did in other such instances. As far as the record shows, this variant never appeared in any Fuji promotional literature of which I'm aware. To me, it appears far more likely that this was an experimental unit constructed by Fuji to test the revised cylinder concept, using an example of the Fuji 15-3 as the basis. A very nice piece of work, but not a Fuji production model as it stands. I mention it purely because there may be a few other examples out there, making it important to avoid any distortion of the historical record. The Fourth Fuji 15 (Model 15-4) At some point, most likely in 1960, a number of significant design changes were implemented on the Fuji 15 twin-stack model. The basic design layout remained unaltered, but the crankshaft diameter was increased from its former 8 mm to 10 mm, while a new style of venturi intake was adopted. These changes required the use of a revised die to cast the crankcase, which otherwise remained essentially unchanged. The prop driver was also slightly revised. The intake venturi now took the form of a cylindrical stub into which a separate venturi insert was installed. This provided the option of using venturi inserts of different throat diameters depending on the application. However, it almost certainly also represents a recognition by the Fuji manufacturers of the increasing importance of the R/C market, since the revised design also allowed for the fitting of an R/C throttle.

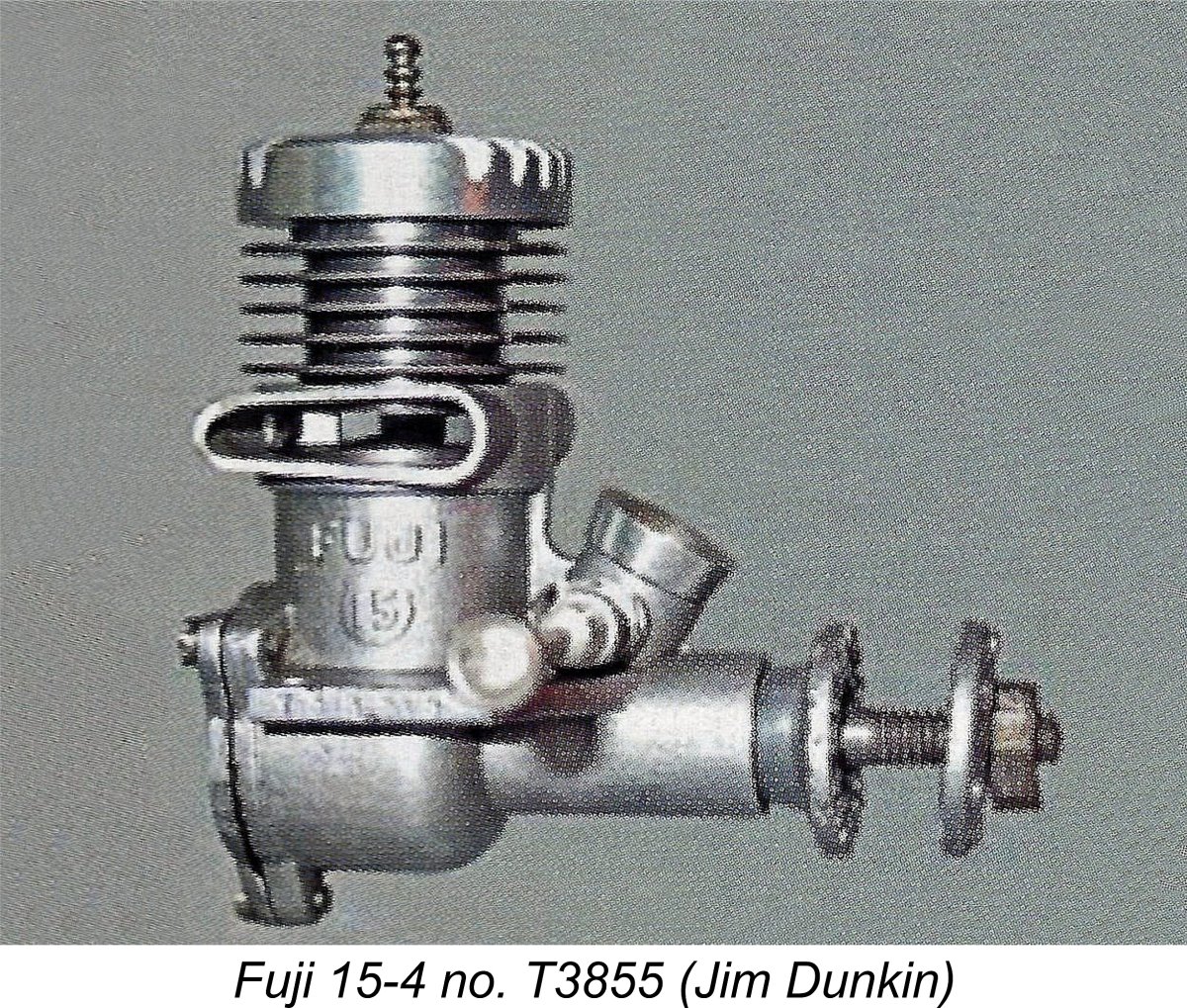

Apart from the changes noted above, the engines in this series appear to have been essentially identical to their immediate predecessors in the range. I don’t have an example of this model to check, but it seems likely that the shaft diameter was increased to accommodate an enlarged internal gas passage, the intention being to improve the engine’s performance. It would be interesting to run a test if the opportunity ever came up. The engines in this series evidently bore serial numbers having a “T” prefix. The only confirmed serial number that I presently have is engine number T3855, which is illustrated on page 204 of Jim Dunkin’s previously-cited reference work on the world’s 2.5 cc engines. Since there’s no numerical overlap, it’s impossible to say whether or not the numbers carried on consecutively from the previous K-prefixed examples, with only the letter prefix being changed, or whether the sequence was restarted at T0001. If the latter, a surprisingly high production rate is indicated.

Given the coincidence of these two factors, it seems not unlikely that the 1957 expansion of Fuji’s production capacity was accomplished by contracting out much of the work to the newly-established Tannan company. This must have been a successful collaboration, because in 1959 Tannan Industrial assumed full responsibility for the ongoing development and manufacture of the Fuji range. The Fuji Bussan Co. continued to be involved, but thenceforth confined its role to the promotion and marketing of the engines. The appearance of the revised 15-3 and 15-4 variants of the Fuji 15 may well coincide with the change in manufacturing responsibilities, with the addition of the "K" and “T” (for Tannan) prefixes marking the change. This would also explain what appears to have been an accelerated production rate for the 15-4 model. The Fifth Fuji 15 - the 15-II (Model 15-5)

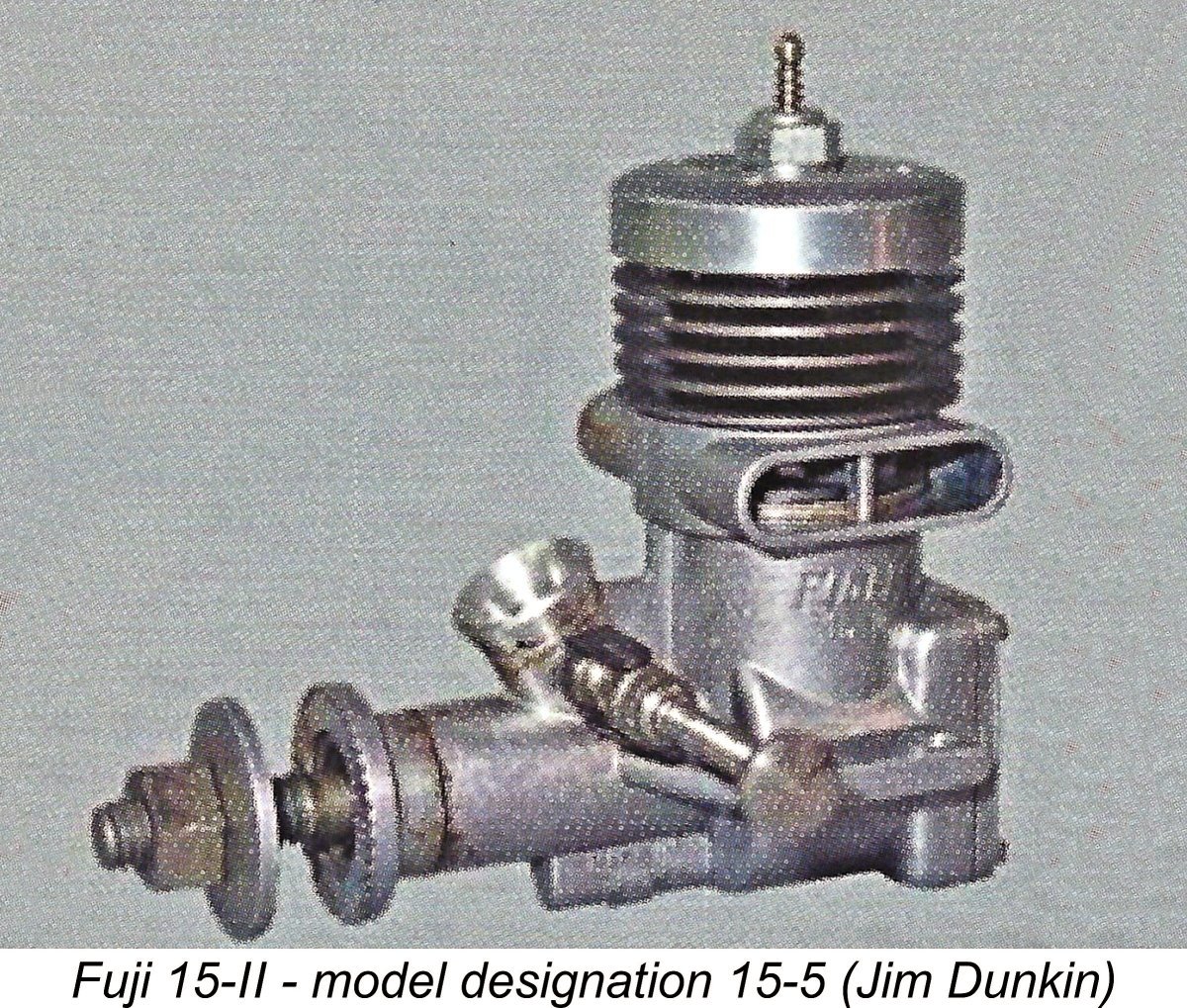

The new model appears to have represented something of a move towards standardization of the design of the mid-sized Fuji models from .099 cuin. up to .199 cu. in. The revised models in all three displacement categories shared many design features. All were twin-stack models which retained the time-honoured blind-bored screw-in cylinder with radial porting and integral cooling fins. However, a major change was the design of the cylinder head, which was still a dummy but was now a screw-on component instead of the former swaged-on unit. This engaged with an externally-cut thread on the plug installation spigot at the top of the cylinder. This was undoubtedly a significant structural improvement.

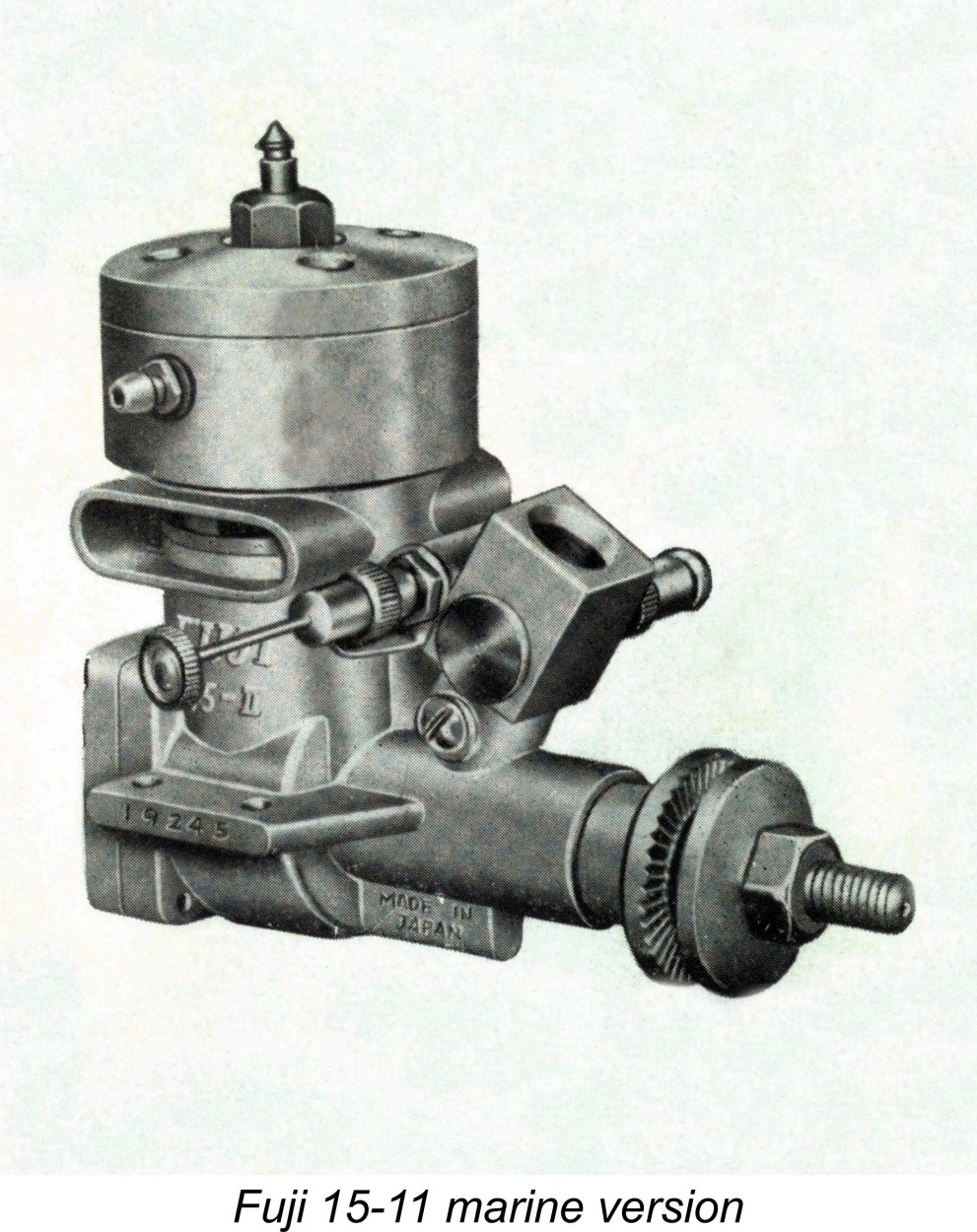

However, by the time the manufacturers (Tannan Industrial by this time) were ready to release the similarly-designed 15 and 19 models, probably a year or more later, they had decided that the time had come to follow the lead of Enya and O.S. by assigning a model numeral to their new offerings. The revised 15 and 19 were accordingly known as the 15-II and the 19-II respectively, being identified accordingly on their main castings. Both of these revised models had similarly-configured cases which were more heavily constructed, presumably for strength. The exhaust stacks were now symmetrically oval in shape and were no longer angled towards the rear. In addition, the 15 and 19 engines now featured four-bolt backplates, along with the strange extrusion beneath the main bearing which had first appeared on the 099-13 model some time previously. The needle valve was now a flexible spring-shaft component patterned directly upon the contemporary Enya design.

The images which are available confirm the general layout of the engine quite well, making it absolutely clear that the 15-II looked essentially identical to the contemporary 19-II, the only difference being the displacement. In the absence of any other currently-available images, these will have to do! My own 19-II is a retro-converted marine version bearing the serial number 3286. Bore and stroke of the Fuji 15-II remained unchanged at 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. The performance claim of 0.27 BHP was also unchanged, but the weight given for this model was 125 gm - some 25 gm heavier than the previous model, presumably due to the more substantial construction. A direct examination of my own example of the companion 19-II model reveals that the revised design continued to feature a rectangular induction port in the crankshaft, giving more rapid opening and closing of the intake system. It seems reasonable to assume that the same feature remained in evidence on the 15-II at the same time, as it had been from the very first Fuji 15 model. Certainly all subsequent Fuji 15 models incorporated such a shaft port. Another change was to be seen in the carburettor arrangements. By the time that the 15-II and companion 19-II appeared on the scene, the R/C field was well on its way to taking over as the dominant market sector. In consequence, the ability of a given engine to accept an R/C throttle was becoming increasingly important. The earlier Fuji 15’s up to the 15-4 model had not incorporated any provisions for this - they retained the traditional integrally-cast bell-mouth venturi which was ill-adapted for use with a throttle. However, the 15-4 had introduced the separate removable venturi insert, and this feature was carried over to the 15-II (our model 15-5, remember) and its 19-II companion. There can be little doubt that this feature was intended to facilitate the production of R/C versions of these engines. In this context, one point mentioned in a somewhat tattered but still legible leaflet image of the 15-II aero model is the fact that a “speed” venturi was supplied with the “standard” version of the engine. Presumably this was a big-bore venturi which would enhance performance at some cost in terms of handling and suction. We saw that the presently-available serial number evidence implies that at least 20,000 of these units were produced. This begs the question - where are they now?!? This model is very seldom encountered on the international collector market – I’ve been looking in vain for years! Presumably most of those produced were sold on the Japanese and Asian markets. The engine was admittedly a bit out of step with the world market elsewhere. Pending the finding of an actual example of this model, that’s about as far as I can credibly go at this stage. Change of Design Philosophy - the Fuji 15-III (Model 15-6)

It must have been painfully obvious to Fuji that a number of their existing models stood little chance of competing successfully in this increasingly competitive market. By this time, two imperatives were inescapably presenting themselves to engine manufacturers wishing to compete on the world stage. The first of these was the upsurge in the popularity of R/C, to the point where the R/C engine market had become dominant, with un-throttled control-line or free-flight engines now commanding an ever-shrinking market share. The second was the increasing pressure for the use of silencers (aka mufflers) as noise became more and more of an issue in an increasingly less tolerant world. In order to compete successfully in this evolving market, manufacturers now had to design engines which were amenable to the fitting of an R/C throttle. Indeed, the R/C version of a given engine had now for the most part become the primary variant, with the un-throttled model being of secondary importance - the reverse of the previous situation. The other design requirement arising from the above considerations was the ability of a given model to accept an effective silencer. Several members of the existing Fuji range signally failed to meet the second of the above criteria. These included the twin-stack 15 model. With its twin stacks, this design was ill-adapted to the fitting of a silencer, although it did now feature a generic carburettor mounting which could readily accept a throttle unit. Moreover, performance standards had risen significantly during the late 1950’s and early 1960’s. The radial porting still used on the Fuji .099, .15 and .19 cuin. models was by this time very much an anachronism. Consequently, competing loop-scavenged models from other makers were leaving the Fuji engines in their dust performance-wise. Although Fuji had maintained its policy of staying out of the performance rat-race and concentrating on producing low-cost and dependable sport-flying engines, the performance gap had now grown to the point where the lower cost of the Fuji models could no longer justify the sacrifice in performance, even in a sport-flying context. Accordingly, Fuji now elected to abandon their time-honoured radial porting and follow all of their competitors into the loop-scavenging camp.

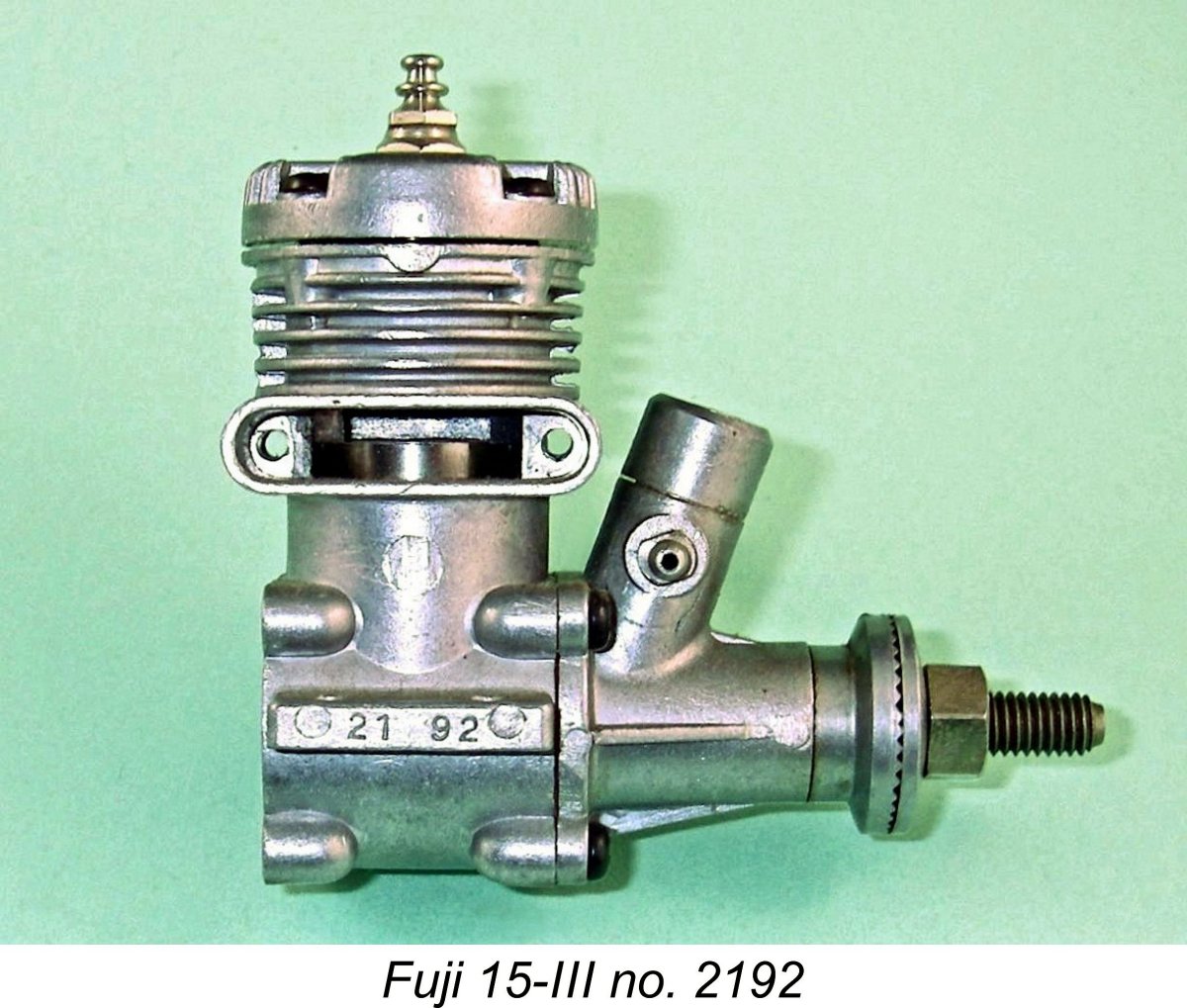

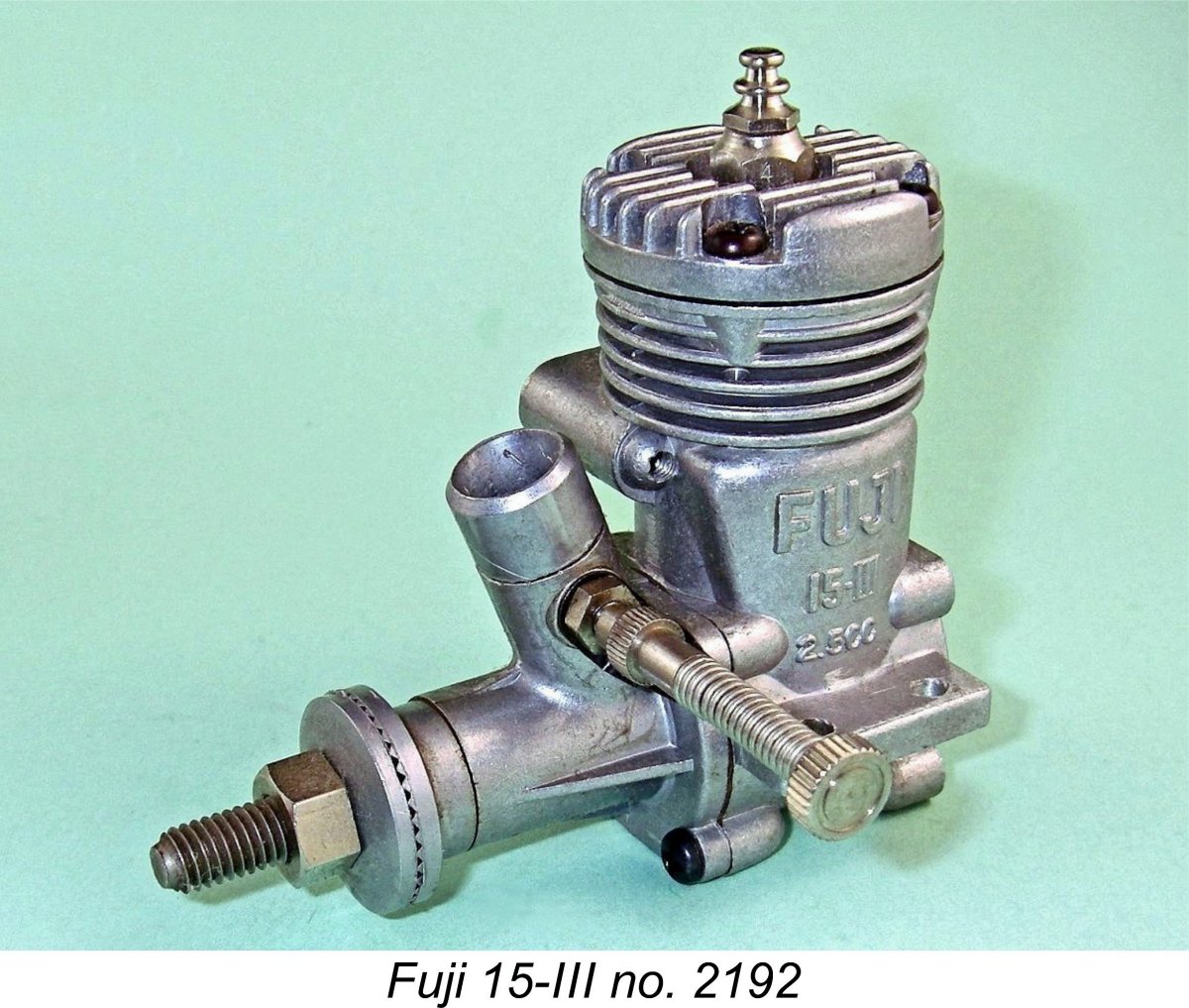

The new model continued a rather uninspiring but widespread trend in being essentially an Enya clone, thus paying a very high compliment to Saburo Enya's design talents. It followed the established Enya pattern in using a main casting which incorporated the cooling jacket, the exhaust stack, the main crankcase and the backplate in a single casting. The bronze-bushed main bearing with its FRV intake provisions was carried in a separate housing which was attached to the front of the crankcase by four screws. The Fuji 15-III followed the design pattern of the Enya 15-II very closely. It featured the massive lower cylinder design with twin internal-flute bypass passages which had been pioneered by Enya in their outstanding 09-II model 3002 of 1959 and subsequently applied to their 15-II model 3302 of 1960. For the first time in the Fuji 15 series, a baffle piston was employed. The apparent cast-in bypass bulge visible on the left-hand side of the case was a dummy, presumably included for cosmetic reasons. The former blind bore was gone, being replaced by an open-ended bore which was topped by a conventional cylinder head of cast alloy. This was retained by four screws, using a gasket to ensure a seal. The glow plug continued to be centrally located. The venturi was a separate component which was inserted into a cylindrically-bored intake housing and retained there by the spraybar. This made the fitting of an R/C throttle very convenient indeed, allowing an R/C version to be placed on the market in short order. The needle valve was of straight Enya pattern, having the familiar flexible stem pioneered by that company. The fitting of a silencer was accommodated by the provision of tapped holes fore and aft in the rear wall of the single exhaust stack. A neat and quite effective matching silencer was quickly made available. Bore and stroke remained unchanged at 15 mm and 14 mm respectively. The claimed weight of 135 gm (4.76 ounces) was once again somewhat higher than that of the discontinued 15-II, no doubt due to the rather massive cylinder liner. This weight claim is not confirmed by direct measurement - my examples all weigh in at around 143 gm (5.04 ounces). Perhaps the cited weight was measured without a plug.

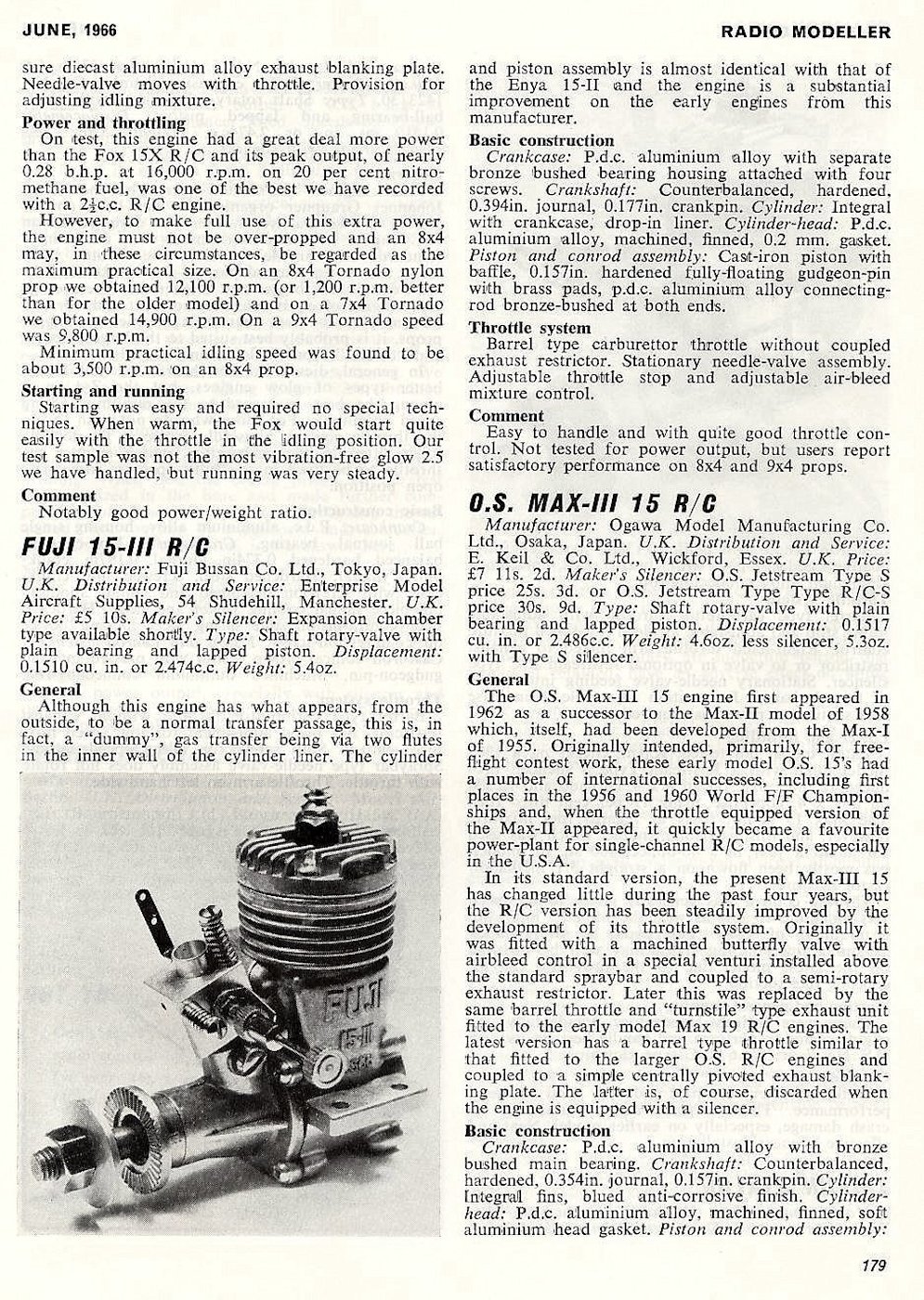

An article discussing the R/C version of this model appeared in the June 1966 issue of “Radio Modeller” magazine. The article provided details of the engine’s construction, also reporting that performance had been found to be “satisfactory” on 8x4 and 9x4 airscrews. Throttle response was said to be “quite good”, and handling was reported as “easy”. Sounds like a case of praising with faint damns.......! Unfortunately, no performance figures were reported. With the introduction of this model and its smaller 099S companion, Fuji had finally abandoned their former design individuality in favour of adopting the “formula” which was by this time more or less expected of any manufacturer hoping to succeed in what may be seen in retrospect as an already-shrinking market for model engines worldwide. There’s little question that the new model offered a higher performance potential than its twin-stack radially-ported predecessor due to the more direct bypass and the more efficient combustion chamber. However, the changes resulted in an engine which completely lacked the individuality of the twin-stack models with which Fuji had become universally associated.

However, you can’t argue with success! The Fuji 15-III was widely distributed world-wide, and production figures were significantly higher than they had been for any of the previous models in this series. Consequently, these engines are by no means uncommon today, and I've confirmed serial numbers for them ranging from 2192 all the way up to 29718. The indication is that the serial numbering sequence was restarted for this model and that at least 30,000 of them were manufactured in total before the design was replaced in around 1970 by the further improved Fuji 15-IV model.

All of these latter companies produced 2.5 cc models which were essentially direct Enya clones. Although not as well made as their Enya progenitors, these engines sold for considerably lower prices while also performing at an adequate level for the sport-flying applications to which they were generally assigned. Many modellers saw them as offering better value for money (mistakenly in my personal view), accordingly purchasing them instead of the Enya originals and thus depriving Enya of needed sales. The price-driven market (as opposed to quality-driven) which resulted cannot have helped the Enya cause, nor were the interests of the modelling movement in general well served by the shift in focus from quality and performance to price. A comparative test of the Fuji 15-III, the Thunder Tiger 15, the SLH 15A and the SASSI 15-II against the Enya 15-II upon which those models were all based may be found elsewhere on this website. Conclusion The members of the Fuji 15 twin-stack series may not have set any performance records for their displacement category, but they remain among the most individualistic glow-plug designs of the middle “classic” period. As the standardization of model engine design progressed throughout the 1950’s and into the 1960’s, the Fuji 15 series continued to plough its own design furrow, much to the gratification of model engine enthusiasts everywhere. The 1964 release of the Fuji 15-III marked the end of the road for this unique series. I for one was sorry to see them go, although I fully understood the reasons why the manufacturers were left with no choice other than to adapt to a changing marketplace. I’m just glad that their twin-stack models were made in sufficient numbers that a good few of them remain today to be enjoyed by those who appreciate out-of-the-rut model engine designs! ____________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published |

||

| |

The Fuji marque from Japan occupies a rather special place in my personal affections, largely because the designs which its various manufacturers produced during the first 15 years following the conclusion of WW2 were refreshingly out of the rut. Among the engines manufactured during this period, none were more individualistic than the company’s successive twin-stack .15 cuin. (2.47 cc) models. In this article, I’ll present an overview of this series, along with a few performance tests of examples on hand.

The Fuji marque from Japan occupies a rather special place in my personal affections, largely because the designs which its various manufacturers produced during the first 15 years following the conclusion of WW2 were refreshingly out of the rut. Among the engines manufactured during this period, none were more individualistic than the company’s successive twin-stack .15 cuin. (2.47 cc) models. In this article, I’ll present an overview of this series, along with a few performance tests of examples on hand.  As a preliminary, it’s necessary to draw the reader’s attention to the classification system that I’ve chosen to apply to all of the various Fuji models in this and

As a preliminary, it’s necessary to draw the reader’s attention to the classification system that I’ve chosen to apply to all of the various Fuji models in this and  The Fuji marque appears to have got its start in early 1949 with a fairly roughly-finished but well-fitted and highly servicable sandcast .29 cuin. (5 cc) crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) glowplug model. This was quickly subjected to some design refinements and was then joined by a twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) model. All of these early designs featured radial cylinder porting.

The Fuji marque appears to have got its start in early 1949 with a fairly roughly-finished but well-fitted and highly servicable sandcast .29 cuin. (5 cc) crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) glowplug model. This was quickly subjected to some design refinements and was then joined by a twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) model. All of these early designs featured radial cylinder porting.  instruction leaflets supplied with the engines, while the boxes carried the "Co. Ltd." company name. The name Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work disappeared completely from the Fuji record as of 1954, making its final appearance in that year on the cases of the later variant of the .29 cuin. (5 cc) Fuji Silver Arrow model.

instruction leaflets supplied with the engines, while the boxes carried the "Co. Ltd." company name. The name Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work disappeared completely from the Fuji record as of 1954, making its final appearance in that year on the cases of the later variant of the .29 cuin. (5 cc) Fuji Silver Arrow model. As previously noted, both variants of the introductory Fuji .29 models from 1949 featured radial cylinder porting but utilized crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) and disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction respectively. These designs were soon refined into somewhat more elegant configurations, while the company’s thoughts began to turn to the expansion of the range.

As previously noted, both variants of the introductory Fuji .29 models from 1949 featured radial cylinder porting but utilized crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) and disc rear rotary valve (RRV) induction respectively. These designs were soon refined into somewhat more elegant configurations, while the company’s thoughts began to turn to the expansion of the range.  Accordingly, once Fuji Tokushu Kiki got off the ground with their two .29 cuin. offerings, their next move was the late 1949 introduction of a very simple sandcast .099 cuin. model (model 099-1). This was very similar in external appearance to the companion .29 cuin. FRV offering but featured a completely different bypass arrangement. I've described the various

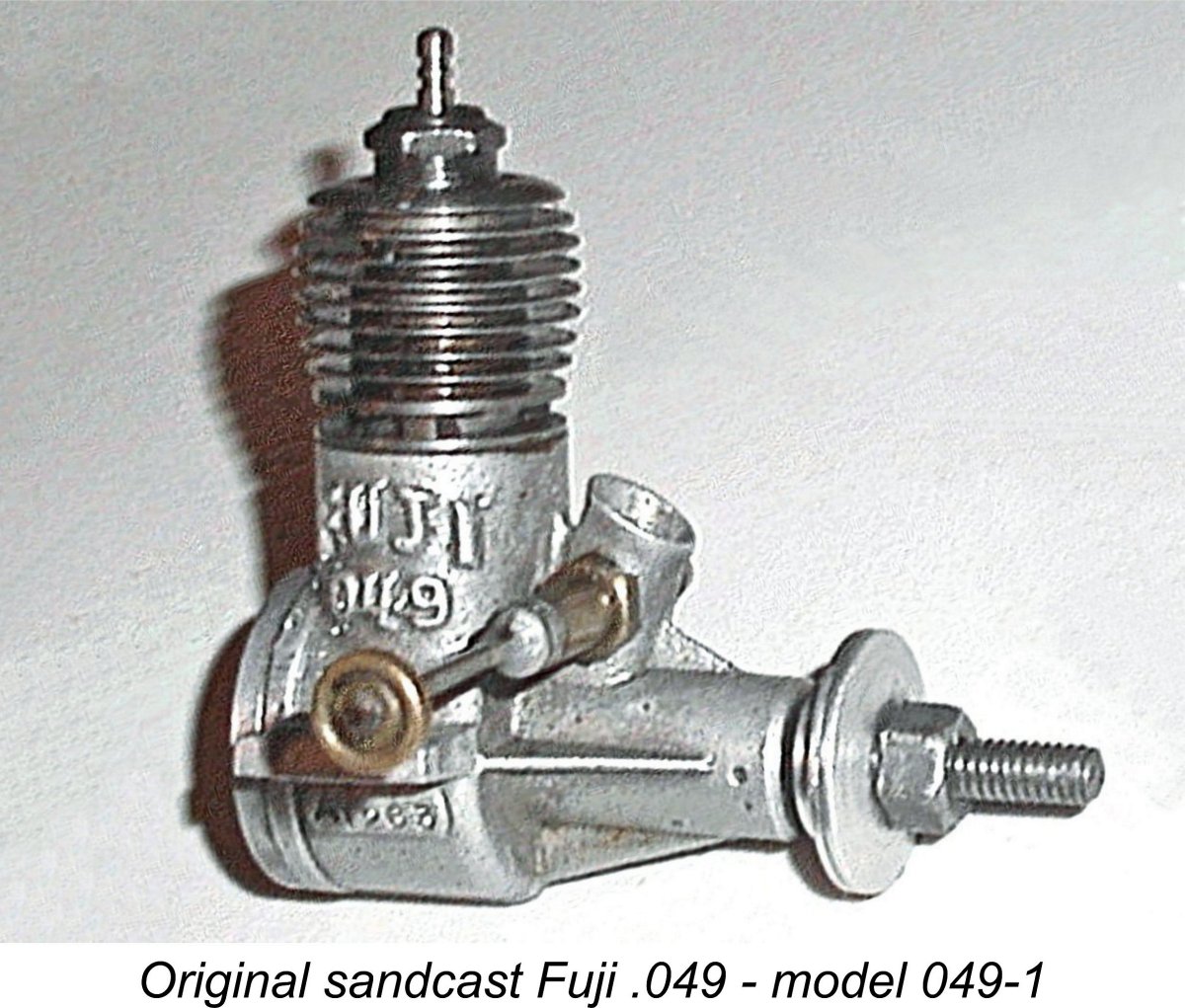

Accordingly, once Fuji Tokushu Kiki got off the ground with their two .29 cuin. offerings, their next move was the late 1949 introduction of a very simple sandcast .099 cuin. model (model 099-1). This was very similar in external appearance to the companion .29 cuin. FRV offering but featured a completely different bypass arrangement. I've described the various  Like its predecessors in the range, the original Fuji .049 (model 049-1) was a sandcast engine featuring FRV induction and radial cylinder porting. This new model established something of a pattern with Fuji - they were repeatedly among the first Japanese manufacturers to enter a hitherto-unexploited displacement category. The only other contemporary Japanese ½A model was the

Like its predecessors in the range, the original Fuji .049 (model 049-1) was a sandcast engine featuring FRV induction and radial cylinder porting. This new model established something of a pattern with Fuji - they were repeatedly among the first Japanese manufacturers to enter a hitherto-unexploited displacement category. The only other contemporary Japanese ½A model was the  I may as well start right out by stating that the first Fuji .15 model of 1955 is a relatively rare engine today, due no doubt in large part to the fact that it was in production for less than a year. Moreover, very few of them seem to have left Japanese shores. In his

I may as well start right out by stating that the first Fuji .15 model of 1955 is a relatively rare engine today, due no doubt in large part to the fact that it was in production for less than a year. Moreover, very few of them seem to have left Japanese shores. In his  No images of the Fuji 15 were included with this article, but this was soon set right by the publication of a further article by Chinn in the June 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The subject on this occasion was the worldwide availability of 2.5 cc engines suitable for International competition under the then recently adopted FAI engine displacement rules.

No images of the Fuji 15 were included with this article, but this was soon set right by the publication of a further article by Chinn in the June 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The subject on this occasion was the worldwide availability of 2.5 cc engines suitable for International competition under the then recently adopted FAI engine displacement rules.  The rest of the engine was very similar indeed to the companion .099 model. A die-cast cylinder head of aluminium alloy was located on the top of the cylinder. However, like that of the smaller model and the companion .19 and .35 models, this was in fact a dummy, presumably placed there strictly for styling reasons. It may have had some functional role as a heat sink, but the engine would run perfectly well without it thanks to its blind bore. The head was simply swaged in place around the cast-iron boss provided for the glow-plug installation thread, presumably after the cylinder had been screwed down hard! Care must be exercised when handling one of these engines to avoid any loosening of the head. Once loosened, it’s very difficult to re-establish a stable location.

The rest of the engine was very similar indeed to the companion .099 model. A die-cast cylinder head of aluminium alloy was located on the top of the cylinder. However, like that of the smaller model and the companion .19 and .35 models, this was in fact a dummy, presumably placed there strictly for styling reasons. It may have had some functional role as a heat sink, but the engine would run perfectly well without it thanks to its blind bore. The head was simply swaged in place around the cast-iron boss provided for the glow-plug installation thread, presumably after the cylinder had been screwed down hard! Care must be exercised when handling one of these engines to avoid any loosening of the head. Once loosened, it’s very difficult to re-establish a stable location.  The two examples of this engine in my possession at the time of writing bear the serial numbers 1073 and 2014. The former example is that previously owned by my late friend David Owen. On the basis of only two examples, I’m unable to present any credible estimates regarding probable production figures. However, it seems likely that this initial variant did not remain long in production - a further reason for its relative rarity today.

The two examples of this engine in my possession at the time of writing bear the serial numbers 1073 and 2014. The former example is that previously owned by my late friend David Owen. On the basis of only two examples, I’m unable to present any credible estimates regarding probable production figures. However, it seems likely that this initial variant did not remain long in production - a further reason for its relative rarity today.  As far as I can ascertain, the introductory model of the Fuji 15 was never the subject of a published test in the English-language modelling media. All that we have in that regard is Peter Chinn's rather loud if diplomatically-worded hint mentioned earlier that he had tested his example of the engine and found it to be a somewhat underwhelming performer!

As far as I can ascertain, the introductory model of the Fuji 15 was never the subject of a published test in the English-language modelling media. All that we have in that regard is Peter Chinn's rather loud if diplomatically-worded hint mentioned earlier that he had tested his example of the engine and found it to be a somewhat underwhelming performer!  I decided that I would test the engine using the same seven props and the same 15% nitro fuel that I had used for tests of other 2.5 cc engines of similar date and specification. I might not get a fully representative power curve, but the comparative prop/RPM figures would certainly provide a good impression of the relative performances of the various models tested.

I decided that I would test the engine using the same seven props and the same 15% nitro fuel that I had used for tests of other 2.5 cc engines of similar date and specification. I might not get a fully representative power curve, but the comparative prop/RPM figures would certainly provide a good impression of the relative performances of the various models tested.

It doesn’t seem to have taken Fuji long to realize that most buyers of a 2.5 cc engine would wish to make their own fuel supply arrangements, whether for free flight or control line. Indeed, this was true of many models in the range, and it was at this point that the company began to omit the tanks from an increasing number of their products. Among these was the revised version of the Fuji 15. This variant likely appeared in late 1955 or perhaps early 1956.

It doesn’t seem to have taken Fuji long to realize that most buyers of a 2.5 cc engine would wish to make their own fuel supply arrangements, whether for free flight or control line. Indeed, this was true of many models in the range, and it was at this point that the company began to omit the tanks from an increasing number of their products. Among these was the revised version of the Fuji 15. This variant likely appeared in late 1955 or perhaps early 1956.  Taken together, these changes would lead us to expect a significantly improved performance from this variant. That expectation will be tested in the following section of this article.

Taken together, these changes would lead us to expect a significantly improved performance from this variant. That expectation will be tested in the following section of this article.  I was interested in confirming whether or not the changes that produced this second variant had indeed resulted in the anticipated improved level of performance. Perhaps more importantly, I also wanted to test the manufacturer’s seemingly extravagant performance claim. Accordingly, I elected to conduct a test on my own example number 2193. This example has had some running, but remains in first class condition, being complete and original in all respects.

I was interested in confirming whether or not the changes that produced this second variant had indeed resulted in the anticipated improved level of performance. Perhaps more importantly, I also wanted to test the manufacturer’s seemingly extravagant performance claim. Accordingly, I elected to conduct a test on my own example number 2193. This example has had some running, but remains in first class condition, being complete and original in all respects.

It’s actually a little unclear whether or not the next variant to be discussed should really be viewed as a separate model. Presently-available serial number data confirm beyond argument that after at least 6894 examples of the Fuji 15 had been made (and possibly more), there was a change in the numbering system.

It’s actually a little unclear whether or not the next variant to be discussed should really be viewed as a separate model. Presently-available serial number data confirm beyond argument that after at least 6894 examples of the Fuji 15 had been made (and possibly more), there was a change in the numbering system.  It must be said that the revised needle design provided far more stable needle valve control than the former system. It may be significant to note that the same change was undoubtedly applied to both the Fuji .049 and .099 models beginning in 1959. It seems reasonable to date the parallel change on the 15 model to the same time, since there seems to be no logic in the idea that Fuji would continue to make different versions of the same needle valve assembly, which was subsequently used on all models from .049 up to .15 cuin.

It must be said that the revised needle design provided far more stable needle valve control than the former system. It may be significant to note that the same change was undoubtedly applied to both the Fuji .049 and .099 models beginning in 1959. It seems reasonable to date the parallel change on the 15 model to the same time, since there seems to be no logic in the idea that Fuji would continue to make different versions of the same needle valve assembly, which was subsequently used on all models from .049 up to .15 cuin.  Engine number K0722 in my possession represents an anomaly which deserves mention here. It is a very well finished example of the 15-3 variant now under discussion, but it has been substantially (and very skillfully) modified. The crankcase and backplate have been very professionally vapour-blasted, while the integral cooling fins have been turned off and the cylinder externally threaded to accept a screw-on alloy cooling jacket.

Engine number K0722 in my possession represents an anomaly which deserves mention here. It is a very well finished example of the 15-3 variant now under discussion, but it has been substantially (and very skillfully) modified. The crankcase and backplate have been very professionally vapour-blasted, while the integral cooling fins have been turned off and the cylinder externally threaded to accept a screw-on alloy cooling jacket.  A few examples of the earlier 15 models were fitted with throttles by their owners – Jim Dunkin illustrates an example on page 204 of his excellent

A few examples of the earlier 15 models were fitted with throttles by their owners – Jim Dunkin illustrates an example on page 204 of his excellent  Although this is admittedly pure speculation, it appears quite likely that this particular change in the numbering sequence had something to do with the fact that in 1959 the primary responsibility for the manufacture of the Fuji engines was taken over by a company called Tannan Industrial of Yamakita, in the shadow of the engines’ namesake Mount Fuji. A search of on-line Japanese corporate records reveals that this company had been established in October 1957, more or less coincidentally with the previously-noted expansion of Fuji’s production capacity which is revealed by an analysis of serial numbers for the

Although this is admittedly pure speculation, it appears quite likely that this particular change in the numbering sequence had something to do with the fact that in 1959 the primary responsibility for the manufacture of the Fuji engines was taken over by a company called Tannan Industrial of Yamakita, in the shadow of the engines’ namesake Mount Fuji. A search of on-line Japanese corporate records reveals that this company had been established in October 1957, more or less coincidentally with the previously-noted expansion of Fuji’s production capacity which is revealed by an analysis of serial numbers for the  The next model in the Fuji 15 line turned out to be the final variant of the Fuji 15 twin-stack series. If our previous conjectures based on serial numbers and implied production rates are anywhere near accurate, it seems reasonable to date this model’s introduction to some time in 1961. The other models which appear with it in the company leaflets in which it is featured are consistent with this dating.

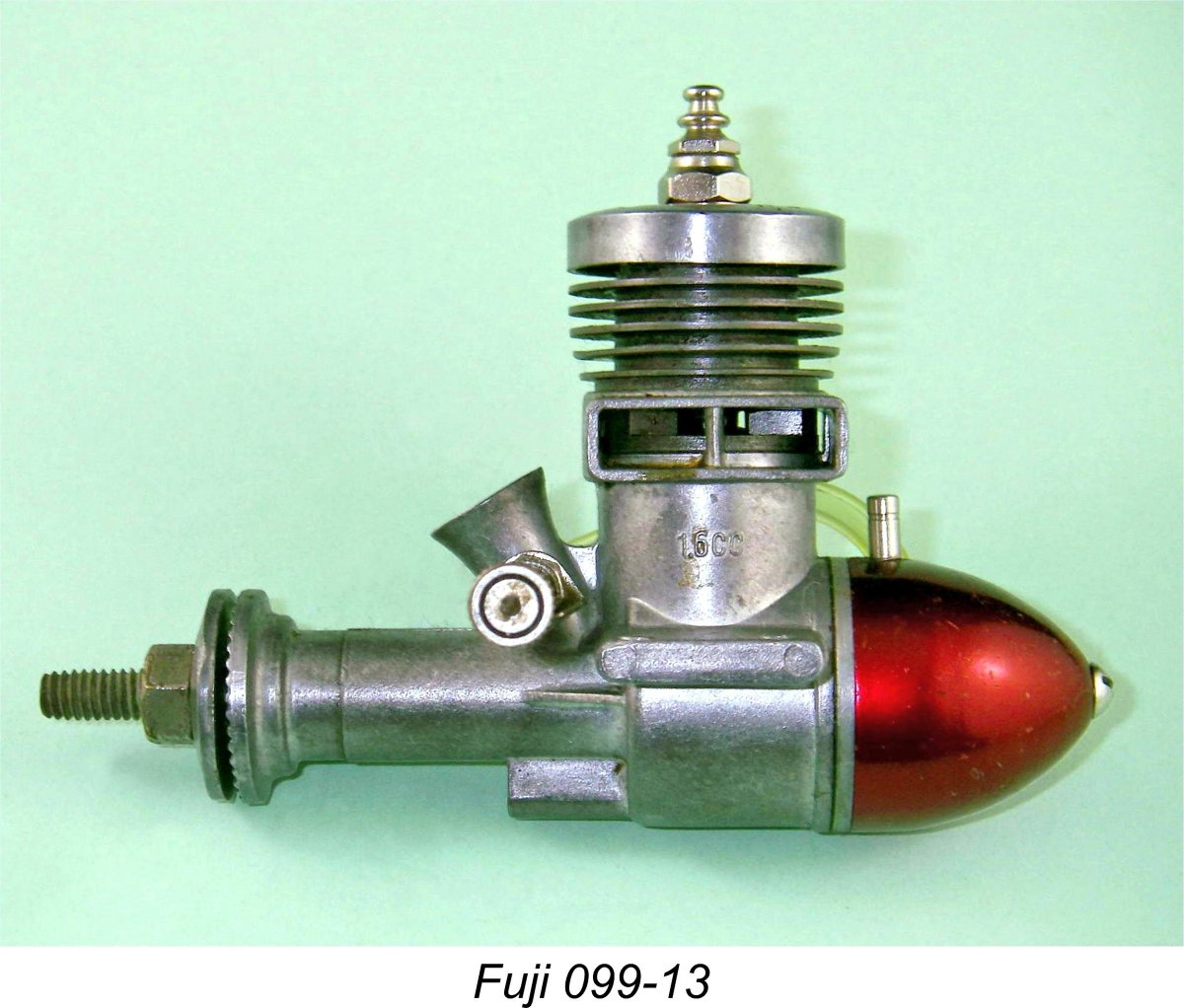

The next model in the Fuji 15 line turned out to be the final variant of the Fuji 15 twin-stack series. If our previous conjectures based on serial numbers and implied production rates are anywhere near accurate, it seems reasonable to date this model’s introduction to some time in 1961. The other models which appear with it in the company leaflets in which it is featured are consistent with this dating.  The first model to receive this treatment was the Fuji .099 (model 099-13) which seems to have appeared in late 1959 or thereabouts. This model retained the screw-in backplate along with the time-honoured red tank, but also introduced the odd little cast-on extrusion beneath the main bearing which was soon to appear on the 15 and 19 models as well. The purpose of this remains unclear - it seems inappropriately designed to be used for a pressure fitting, yet it is far more substantial than necessary for a simple web. This engine continued to be known as the Fuji .099.

The first model to receive this treatment was the Fuji .099 (model 099-13) which seems to have appeared in late 1959 or thereabouts. This model retained the screw-in backplate along with the time-honoured red tank, but also introduced the odd little cast-on extrusion beneath the main bearing which was soon to appear on the 15 and 19 models as well. The purpose of this remains unclear - it seems inappropriately designed to be used for a pressure fitting, yet it is far more substantial than necessary for a simple web. This engine continued to be known as the Fuji .099.  The only reproducible image that I’ve been able to track down for the Fuji 15-II aero model is the previously-reproduced photo which appears in Jim Dunkin’s previously-mentioned book on the world’s 2.5 cc engines. There’s also a promotional image from a leaflet which belongs with a water-cooled marine version. This bears the clearly-legible serial number 19245, indicating that quite a few of them were made during the three to four years or so that they seem to have remained in production. I've attached both images for reference.

The only reproducible image that I’ve been able to track down for the Fuji 15-II aero model is the previously-reproduced photo which appears in Jim Dunkin’s previously-mentioned book on the world’s 2.5 cc engines. There’s also a promotional image from a leaflet which belongs with a water-cooled marine version. This bears the clearly-legible serial number 19245, indicating that quite a few of them were made during the three to four years or so that they seem to have remained in production. I've attached both images for reference.  By 1964, the Fuji Bussan company which retained responsibility for marketing the Fuji range appears to have embarked upon a quite serious and generally successful effort to penetrate the worldwide marketplace. This of course meant that they would have to compete in the open market with well-established domestic competition from Enya and O.S as well as that from overseas manufacturers in America, Britain, Europe and Australia.

By 1964, the Fuji Bussan company which retained responsibility for marketing the Fuji range appears to have embarked upon a quite serious and generally successful effort to penetrate the worldwide marketplace. This of course meant that they would have to compete in the open market with well-established domestic competition from Enya and O.S as well as that from overseas manufacturers in America, Britain, Europe and Australia.  The result was the 1964 release of two entirely new designs of very similar (and completely conventional) layout - the Fuji .099S (model 099-14) and the Fuji 15-III (model 15-6). Here we are concerned with the .15-III model, which despite its name was in fact the sixth distinct design variant of the Fuji 15 series, replacing the previously-described Fuji 15-II.

The result was the 1964 release of two entirely new designs of very similar (and completely conventional) layout - the Fuji .099S (model 099-14) and the Fuji 15-III (model 15-6). Here we are concerned with the .15-III model, which despite its name was in fact the sixth distinct design variant of the Fuji 15 series, replacing the previously-described Fuji 15-II.