|

|

Japanese Enigma - the HGK Engines

Anyone attempting to write about the HGK engines is immediately faced with a significant challenge – an almost complete lack of primary source material in the English language. A commentary about the range by Kosaki Jinichi appeared in the Japanese modelling media in May 2005, but the translation of this into intelligible English proved to be very difficult. Even so, reading between the lines of a very imperfect translation yielded a fair amount of useful information, leaving us extremely grateful to Kosaki Jinichi for taking the trouble to enlighten us.

I'm also extremely grateful to my good mate Maris Dislers (from my own original hometown of Adelaide, South Australia) for the very considerable amount of practical assistance and encouragement which he extended to me during the preparation of this article. This included the conduct of a bench test of one of the HGK high-performance 2.5 cc motors, the HGK 15N. Couldn't have done it without ya, mate!! The HGK engines burst out of nowhere on the Japanese domestic model engine manufacturing scene in the mid-1970’s, but disappeared just as fast only twelve years later. The engines were manufactured to very high standards, also performing very well indeed in most cases. They featured a real technical innovation – a die-cast aluminium cylinder block incorporating a bore which was chrome-plated directly onto the aluminium cylinder block itself and then micro-ground to its final fit and finish, thus eliminating the need for a separate liner. This was a pioneering application of the now widely-accepted AAC (alumium/aluminum/chrome) piston/cylinder technology which was so universally employed in latter-day pylon racing engines. However, the HGK models also suffered from a number of design and construction issues which were never fully resolved during the heyday of the range. In any field of innovation, it's the pioneers who first encounter the problems ........... The makers of the engines identified themselves on the instruction sheets as the Hashioka Technical Laboratory (in Japanese, Hashioka Gijutsuken Kyūsho, hence the initials HGK). The address given in the literature was apparently that of an office building in Tokyo – Room 709, Furukawa Building, 1.2.7.3, Nishigahara, Kita-ku (Kita Ward), Tokyo. It seems highly unlikely that this was the location at which the engines were actually manufactured. Indeed, Kosaki Jinichi confirmed that certain elements of the manufacturing were contracted out by Hashioka. The Hashioka organization seemingly had no prior history of involvement in the model industry. Based on information obtained by Luis Petersen during his October 1978 visit, the company had evidently been engaged in the precision machining business prior to their entry into the model engine field. Luis was told that the company's entry into that field coincided with a downturn in the demand for their services in other areas of precision engineering. Their chief model engine designer Masao Obha had been an aeromodeller for some 30 years, primarily in the control line field using models which were often powered by engines of his own creation. His enthusiasm was doubtless instrumental in promoting the company's move into the commercial manufacture of model engines. The nature and extent of any market research which may have been undertaken in connection with the development of the HGK engines are unknown. However, the style of the initial products as well as the reported participation in the venture of several high-profile Japanese exponents of C/L speed flying and R/C model boat racing makes it clear that the high-performance market was the target from the outset. This seems a little odd in some ways – the high-performance competition arena always represented a niche market, and one which was already well served by a number of established "name" manufacturers. Not only that, but the overall world market for model engines was already well into the decline which began in the late 1950’s and has continued to the present day. Consequently, the fledgling company was competing for a share of a well-served niche market within an overall model engine market which was already well into a fairly steep decline. This being the case, it’s difficult to see how the entry of a small new company into the chosen specialized field could have been seen as an economically-viable step to take. It would appear that the entry of the company into this market must surely have been driven far more by a passionate interest in high performance model engines than by any economic considerations.

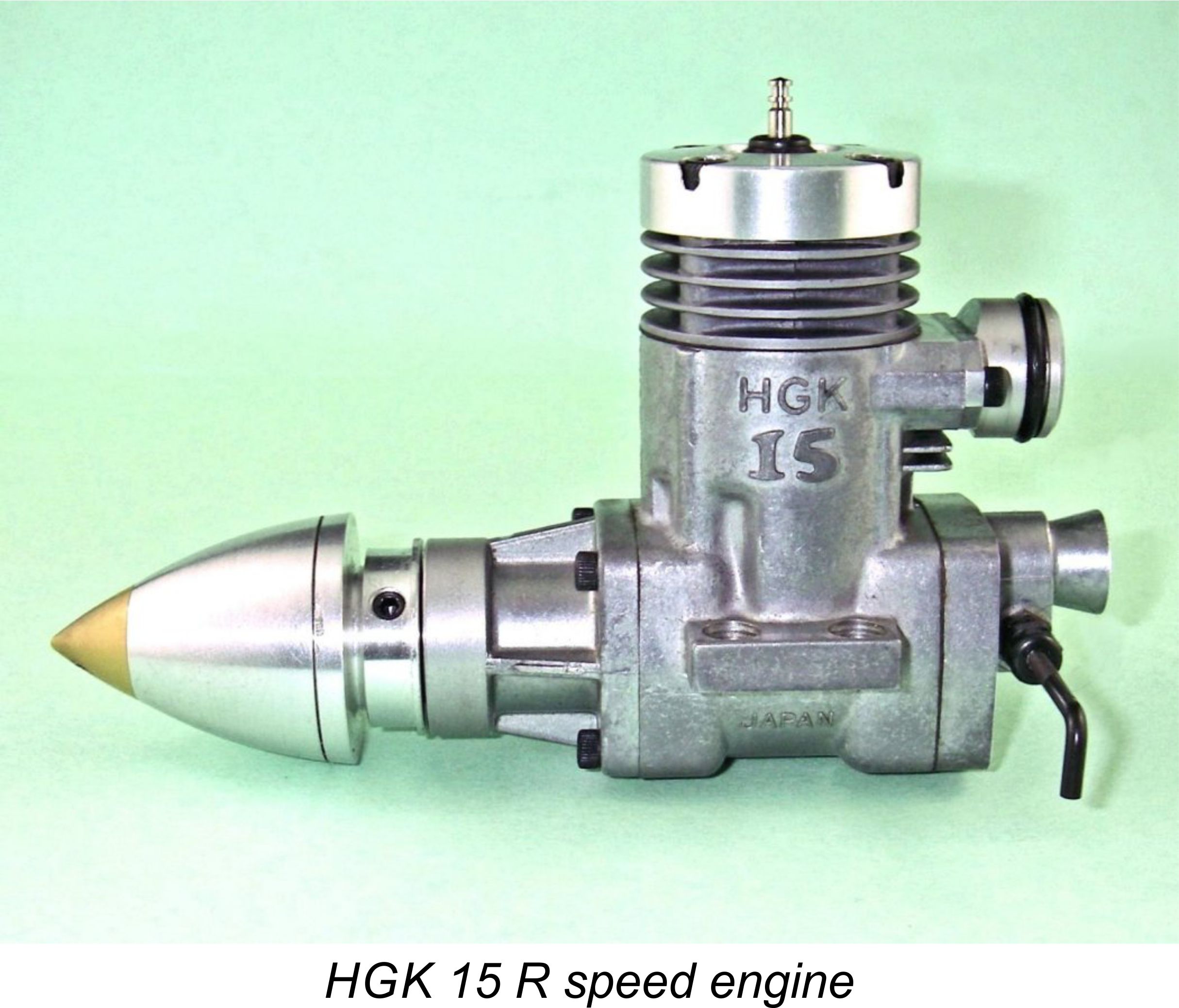

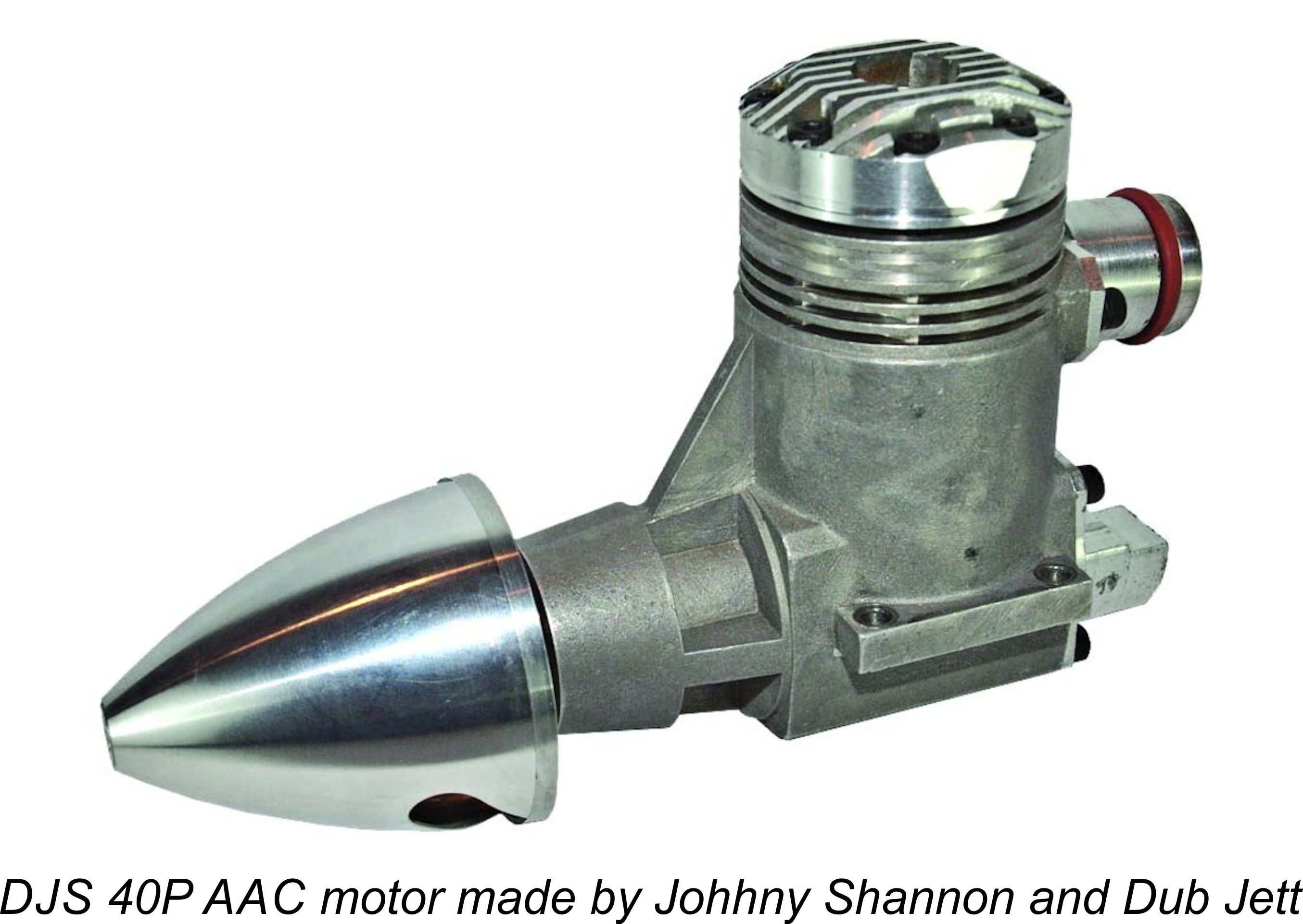

The HGK 15R’s most obvious departure from the established design formula for speed engines was its use of a monobloc cylinder casting of aluminium alloy which dispensed altogether with the usual steel or plated brass cylinder liner. Instead, the casting incorporated a cylinder bore which was machined integrally within the alloy casting itself, after which it was hard chrome-plated and then micro-ground to final dimensions. A plain piston of aluminium alloy operated within this bore. This form of construction became known as AAC (aluminium-aluminium-chrome), a system which was used successfully by the late great Bill Wisniewski (1929 - 2007) in the fully-developed versions of his custom-built TWA engines. The HGK 15R represented the first-ever application of this technology to a commercial model engine, even preceding many of the ABC (aluminium-brass-chrome) designs which were beginning to appear at around this time.

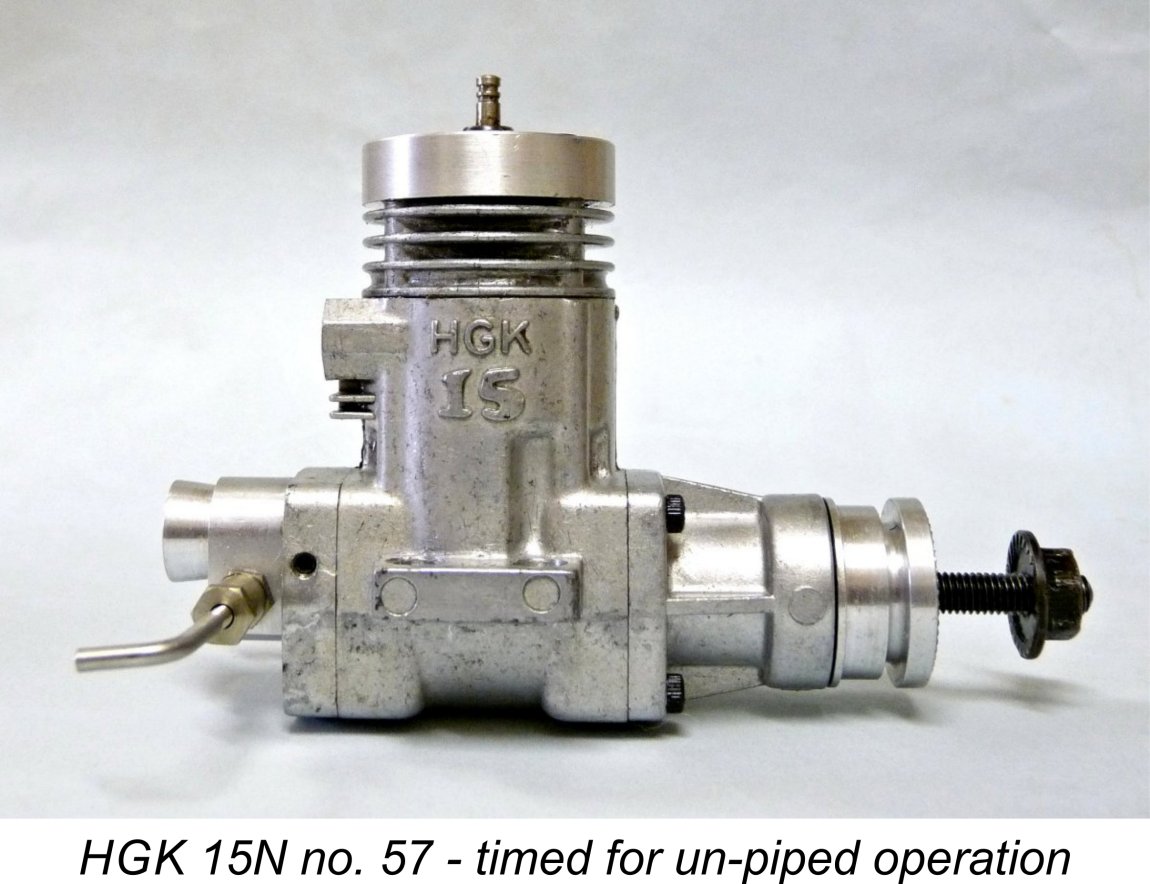

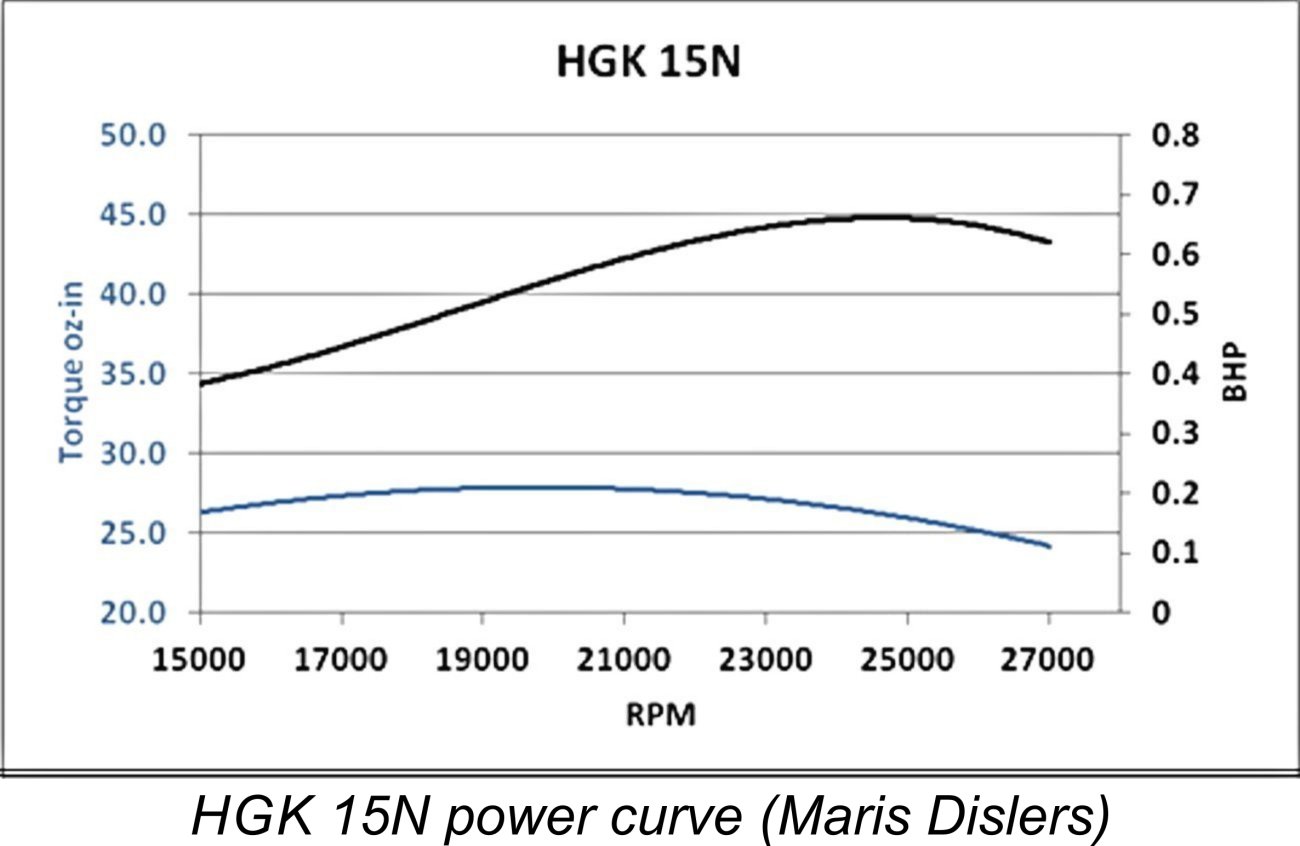

One of the most important questions to be answered was whether or not the direct chrome plating of an aluminium alloy bore (ADC12 specification) was sufficiently durable for high performance model engine use. This question took some years to answer definitively, leaving an air of uncertainty hanging over the new model and its relatives in the interim. The HGK 15R was sold in a complete package with pipe, speed spinner and all accessories. It was of course specifically intended for use in control-line speed. There was also a basic model without the pipe and spinner but including the pipe adaptor and appropriately-sized Allen key set. This It appears that the HGK 15N was sold in two variants - one intended for use with a pipe, and one intended for unpiped operation. My own example has an exhaust period of approximately 172 degrees with a healthy lead over the transfer ports - typical of piped engine timing at the time in question and essentially identical to the comparable figure for the HGK 15R. However, at the time of writing (2015) my good mate Maris Dislers had another example of the 15N on hand which had an exhaust timing period of only 155 degrees - clearly tailored to high-speed operation without a pipe. It thus appears that the engine was offered in two distinct variants. All that would have been necessary would have been to produce two different cylinder castings. My example of the HGK 15N actually appears identical to the 15R throughout apart from the prop driver and the fact that the cylinder was cast from a slightly different die which produced a component having the lower of the three cylinder cooling grooves filled in, leaving only the upper two two open. This may Another difference which may in fact reflect a design change on the later versions of the HGK 15R was the use of a slightly re-designed fuel delivery system. Both the 15R and 15N in my posession feature intake venturis having a 7 mm (0.275 in.) throat diameter which are supplied by remote needle valves. However, that in my 15R speed engine employs a transverse fuel nozzle which extends half-way across the venturi throat to discharge at the axial centre line of the venturi, very much in the style pioneered by Ira Hassad in 1940. By contrast, the 15N employs a peripheral ring of small jets placed around the inner wall of the venturi throat, in the fashion made popular by the Cox models of the 1950's and 1960's. It's possible that this design also appeared on later examples of the 15R. A very interesting observation relates to the issue of serial numbers. Although my HGK 15R bears no serial number that I can discover, my illustrated example of the HGK 15N Maris had been looking for an excuse to test the illustrated un-piped example of the HGK 15N which happened to be in his possession when this article was in preparation. The development of this article appeared to offer the perfect opportunity!! After securing the agreement of the engine's owner, Maris ran a series of tests using standard FAI F2A fuel, which is a blend of 80% methanol with 20% castor oil. This was the required blend at the time when the HGK 15N was on current offer as an FAI free flight motor, so it makes for a fair evaluation of the engine's The tested example had clearly had some use, and an internal inspection revealed that the original piston showed signs of being a little out of round, a condition which by all accounts is not typical of HGK products. It may be that the engine had suffered a few lean runs or had been supplied with inadequate lubrication. Whatever the reason, the result was that compression seal was rather less than adequate for dependable hand starting. It could be hand-started, but the task was a bit of a chore. Once running, the engine handled very well, also displaying excellent running qualities. Needle adjustment was by no means critical, while vibration levels remained quite low even at 27,000 rpm. As mentioned earlier, a single McCoy MC-9 plug survived the entire testing to which the engine was subjected. The propeller/rpm figures achieved by the engine are shown in the following table, together with the derived power curve.

The attached power curve implies a peak output on straight fuel of around 0.700 BHP @ 24,800 rpm. Considering the fact that the HGK 15N came out in 1974, Maris rightly characterized this as a very good performance indeed for an un-piped engine of that date running on straight methanol/castor fuel. In the pantheon of commercial 2.5 cc racing engines of its day, the HGK 15N would have sat below the Rossi R.15 Mk. 2, about on par with the earlier Rossi R.15 Mk. 1 and ahead of the Taipan 15 TBR and K&B 15 Series 72. As Maris wryly noted, the Super Tigre 15's would by then have felt very much that they were in the wrong decade! The one fly in the ointment was the leaky piston seal and consequent difficult hand-starting, which would have put this example of the HGK 15N out of the running entirely for events like Goodyear in which hand starting was required. That said, it's unfair to condemn the entire series outright on the basis of a single flawed example. My own new and seemingly unrun example appears to have more than adequate compression seal for hand starting. Perhaps many of them did. Just for fun, Maris decided to try the engine on a fuel containing 30% nitromethane. Because of the difficult hand starting, he didn't bother to obtain a full suite of figures on that fuel, which would in any case have been illegal for use in any FAI competition class for which the HGK 15N would have been eligible. However, a few spot checks on the faster props showed speed increases of around 1,100 - 1,500 rpm on that fuel. This implies a peak output of at least 0.75 BHP @ 26,000 rpm. Not too shabby for an un-piped 2.5 cc engine dating from 1974! Still in search of further entertainment, Maris dug out a piston from an Irvine 2.5 cc speed engine. This was a perfect match for the balance of the standard HGK components apart from not having the cutaway in the front of the HGK's lower piston skirt which was evidently intended to improve gas access to the boost port. More critically, the Irvine piston had a diameter which was some 3 - 4 microns greater than the original HGK item. With this piston fitted, Maris could easily hand-start the HGK, although the piston fit remained slacker than ideal when the engine was hot. Using standard F2A fuel, a spot check on the APC 7x3 prop with this piston fitted yielded an identical speed of 24,800 rpm. Perhaps the improved piston fit was cancelled out by the missing boost port cutaway, or perhaps that cutaway doesn't actually contribute to improved performance. Really doesn't matter at this point, does it? Setting aside the matter of the leaky piston fit (which may or may not be typical), the fact remains that Maris's test revealed the HGK 15N as undoubtedly a potential contest winner in its day. Leaves you wondering what kind of figures might have come out of a good example of the piped HGK 15R.......... Regardless, our grateful thanks to Maris for undertaking this most informative test!

About half of the limited number of engines that ended up being made were exported, most notably to George Aldrich in America, who reportedly bought a shipment of several hundred examples with the intention of reworking them for re-sale to US competition modellers. George later commented that the early examples were set up far too loosely, with insufficient bore taper. The company apparently did eventually get this right, but by that time they were on the point of going out of business. George ended up selling off his stock as collector engines.

In HGK's defence, they may have reasoned quite logically that since both the piston and cylinder were made of the same material, the fit should be relatively unaffected by temperature. This may have led them to use a fit which was intended to maintaining a minimal friction condition, including the top of the stroke. The fact that this theory doesn't work in practise simply underscores the fact that high-performance model engine design is at least as much a black art as a science! A number of examples of the HGK 15R were also imported to the USA by Shamrock Competition Imports of New Orleans, Louisiana, who also handled the OPS and Picco ranges. My own NIB example of the fully equipped HGK 15R bears that company's stamp upon the box. Since relatively few if any of the engines sold either by George Aldrich or Shamrock were ever used in anger, they remain in quite wide circulation on today’s collector market, albeit typically selling in late 2014 at prices in the US$300 range for a New In Box example complete with all accessories. It must soon have become obvious to the company that they were not going to make it on the basis of sales of the HGK 15R and 15N. Accordingly, a far less expensive plain bearing Schnuerle-ported FRV side-exhaust version known as the HGK 15S was quickly developed for sport and general purpose applications. This model was of course timed for operation without a pipe, using a conventional muffler instead. The 15S made its trade debut at the April 1976 Osaka Model Show, as reported by Peter Chinn in his "Foreign Notes" column in the August 1976 issue of "Model Airplane News".

Even when taking what may have appeared to them to be a retrograde step, the company was unable to resist the siren call of high performance. This quickly led them to develop a high-performance “X” version of the 15S. This was in effect a plain bearing 15S turned end for end and fitted with a twin ball-race shaft in a manner highly reminiscent of the far earlier Super Tigre G.30 and G.32 diesels of the late 1950's. My illustrated example bears the serial number 51 stamped onto the top of the right-hand mounting lug. The backplate of the 15S crankcase was replaced by a bolt-on twin ball-race front end assembly, which was An inescapable consequence of the use of the standard 15S crankcase casting as the basis for the HGK 15SX was the fact that the exhaust stack was oriented to the left side of the engine rather than more conventionally to the right. This could only have been avoided by the production of a revised die, a step which economic considerations evidently did not encourage. Maximum use appears to have been made of components which were already in the production schedule.

The HGK 15SX had a considerably higher performance than the standard 15S. It was evidently designed primarily for the then-burgeoning Quarter-Midget class of R/C pylon racing in the USA, for which application it was fitted with a grey Perry carburettor. Shamrock Competition Imports imported these engines into the USA for a while, but they were apparently put out of the running by the previously-mentioned tendency towards loose piston fits. The Nelson 15 ended up ruling the Quarter-Midget scene, which lasted in its .15 cuin. form until 1994, when the lack of ongoing interest in the class forced a switch to .40 cuin. displacement engines. The standard un-throttled version of this engine as shown here was clearly quite suitable for use in the Although some successes had been achieved, all was not well - a significant performance limitation had by now been revealed. As originally developed, there was almost no taper in the cylinder, which had a very adverse effect upon torque development. As mentioned previously, an AAC set-up needs to be squeak-tight around top dead centre and progressively less tight as the piston descends, a fact which the HGK designers had evidently failed to appreciate during the early stages. A dedicated machine was required to put the correct taper into the bore. Hashioka had sub-contracted the bore finishing to an outside company, but the sub-contractor apparently could not afford to purchase the necessary dedicated machine tooling. As a result, the consistent realization of the optimum bore taper remained problematic, although bore circularity was reportedly always outstanding. Another issue arose from a switch to a different piston material (Sumitomo Light Metal's Hyper 19 alloy) in order to facilitate production. Unfortunately, the thermal coefficient of expansion of this material was slightly larger, causing distortion of the piston and consequent leakage at high temperatures and high speeds. Could this be the explanation for the problems encountered with Maris Dislers' test example of the HGK 15N?!? In addition, the four cylinder installation bolts often caused leakage from the head gasket by distorting the head as a result of not uniformly accommodating the thermal expansion of the cylinder. Moreover, although the circularity of the cylinder bore achieved through the plating and grinding processes used was of the highest order, the bore taper and piston material issues were not fully resolved until the damage to the reputation of the range had already been done. In retrospect, it’s clear that this goes far to explain HGK’s relatively short market tenure.

There was also a very high-performance .21 cuin. aero model called the HGK 21SR on which the backplate of the standard 21SF twin ball-race FRV model as seen at the left was replaced by a rear cover which accommodated a disc rotary valve designed very much along the lines of that featured on the HGK 15R model. The stub of the original FRV induction system was retained at the front but was not machined to accommodate the carburetor. This model seems to be quite rare today, implying that not that many were manufactured. This latter comment actually appears to be true of most of the all-out competition HGK models. Even in their country of origin the HGK engines remained something of an enigma to many. For one thing, they were relatively expensive – even the basic HGK 21S aero unit sold in Japan for 12,500 yen, and this was of course some 35 or more years ago now at a time when the yen traded at around ¥220 to the US dollar. The equivalent domestic price of around US$57.00 was well above the asking prices of many competing models from other contemporary Japanese manufacturers. It would be equivalent to around $200 in 2015 dollars – a very steep price for a standard plain-bearing sports .21 cuin. engine. No doubt this factor restricted the circulation of these engines within the modelling community. Even so, at the time of Luis Petersen's 1978 visit the company was clearly still doing quite well. Despite the recent advent of competing units such as the massively popular O.S. 20, the HGK range continued to attract sufficient market attention to justify continued development and production. Engines were being manufactured in displacements of .15, .21 and .45 cuin., and there were plans to extend the range to include both a .61 cuin. model and a 1.8 cc unit specifically for model car applications. Luis was told that the company was then producing some 30,000 engines annually, most of which were R/C types. Apart from sales manager Ohkawa and chief designer Masao Obha, some half-dozen men were employed in the company offices carrying out such duties as servicing, packing and shipping the engines. A further eight men were employed in the adjacent workshop where the engines were manufactured. In early 1980, ownership of the HGK brand was transferred from Hashioka Technical Laboratory to a new limited company known as HGK Products Co. Ltd. located in Shibuya-ku, Tokyo, some distance to the south of the former location in Kita-ku. Records extracted from Google Japan show that this company name was filed on June 16th, 1978 and finally registered on January 29th, 1980. The goods and services provided by the newly-registered company were summarized as “model engines and parts thereof”, implying that this was the sole business activity with which the new company was involved.

One of the first outcomes of the company’s reorganization was a change in the style of the boxes in which the engines were sold. Instead of the rather uninspiring plain tan boxes with brown or red lettering, the boxes were now quite strikingly decorated with red and black panelling with white letters. Evidently some attention was now being paid to the presentation of the engines in the marketplace. The next significant outcome of the change of ownership was the wholesale abandonment of the company's various RRV "racing" models, which had seemingly proved to be uneconomic to manufacture. Instead, the reorganized company moved quickly to expand the range into what they evidently saw as promising market areas not formerly covered. Chief among these was the far larger sports R/C market, which included cars and helicopters as well as fixed-wing aircraft.

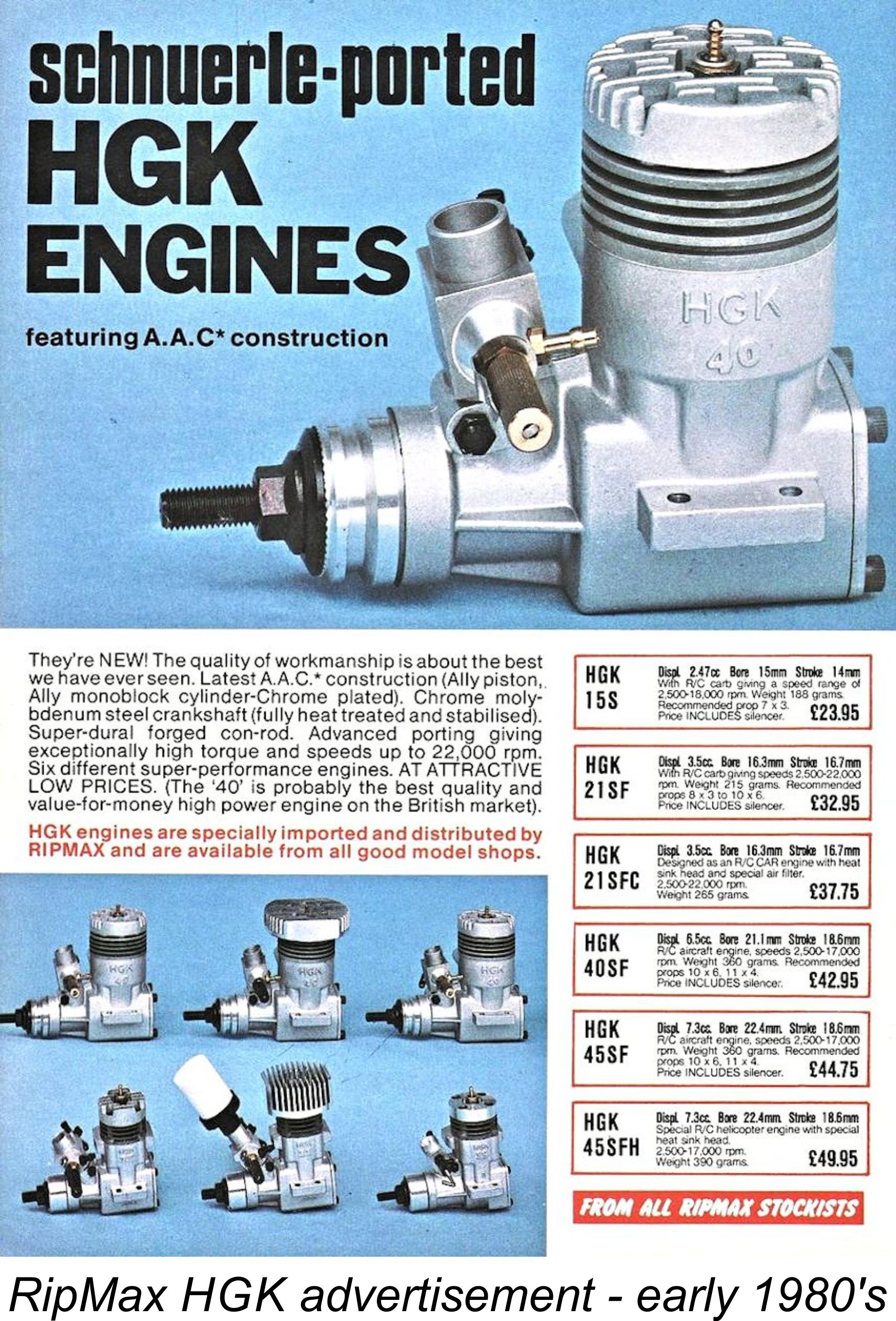

Perhaps their greatest success was getting the HGK range picked up by RipMax in Britain. As previously mentioned, the uneconomic high-performance pure racing models such as the 15R, 15N, 15SX and 21SR had been dropped by this time, with the continuing focus being on the high-performance R/C market. The range advertised by RipMax in the early 1980’s consisted of the 15S aero model, the 21SF aero model, the 21SFC car engine, the 40SF and 45SF aero models and the 45SFH helicopter unit. All of these designs were FRV models which were fitted with R/C throttles. A limited edition RRV version of the HGK 45 reportedly remained available, although this was not advertised by RipMax. It appears that the 1.8 cc car engine mentioned by Luis Petersen never actually materialized.

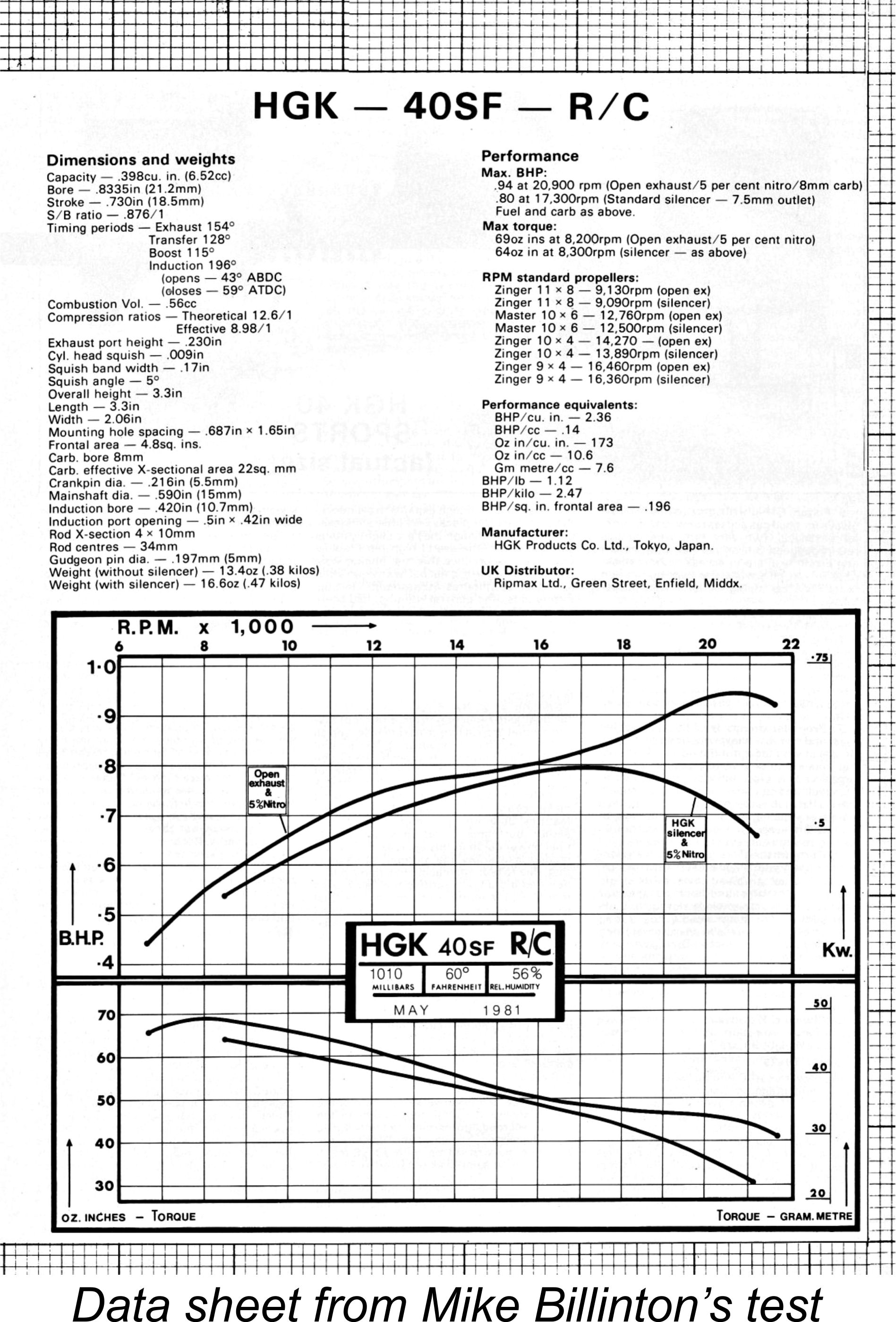

Billinton began by pointing out the inevitable challenges facing any small company attempting to compete in the highly competitive Japanese model engine manufacturing industry. He noted that success in this market environment required a combination of technical excellence and fine-tuned business acumen, together with adequate start-up financing. He stated that while the tested HGK model (the 40SF R/C) was manufactured to very high standards as well as incorporating a significant degree of design innovation, some doubt remained regarding the company’s ability to sustain their involvement in the industry from a purely business standpoint. The test report then presented a very detailed description of the engine’s main design and construction features, very much focusing upon the then-innovative AAC piston/liner combination. By this time it would appear that the company was The engine proved to be very easy to start, the use of an electric starter only being resorted to on a very few occasions. In keeping with the manufacturer’s instructions, only a very brief running-in period of some 15 minutes or so was found to be necessary. All tests were conducted using a 5% nitro fuel having a 20% castor oil content.

A second series of tests was then run with the manufacturer’s standard muffler fitted but with all other parameters unchanged. In this form the engine was found to develop 0.80 BHP @ 17,300 rpm – again nothing special, but a perfectly acceptable sports R/C performance using a muffler. Very significantly, the main effect of the muffler was found to be a restriction of the top end performance above 17,000 rpm – below that point, propeller/rpm figures were only marginally affected. Billinton also commented that the muffler was surprisingly effective in terms of noise suppression – more so than he had anticipated. The R/C throttle fitted to the engine was of HGK’s own manufacture – reliance was no longer placed upon the Perry carburettor used earlier. Billinton commented that the HGK unit was extremely well designed and constructed, allowing for very precise mixture control at all speeds. Pickup from idle on a 10x4 prop was found to be “impressively swift and certain”, even when challenged by repeated sudden full-range throttle movements in both directions. Billinton characterized this unit as being “one of the most easy and pleasant to handle”, also commenting favorably upon its apparent durability. Billinton’s summary was very positive indeed. He characterized the engine as being “well suited to its main role as an R/C sports motor; very rugged and accurately produced”. He noted in passing that the motor had “grown on one” during the test to the point where its return to the suppliers might be somewhat delayed! Billinton’s closing comment was sadly prophetic in hindsight. He stated that “it would certainly be unfortunate if commercial and competitive pressures within Japan were to cause undue problems for this range of engines, which offer some interest and variety because of their slightly unusual mechanical makeup”. Taken together with his previous comments at the start of his report, this statement clearly implies that even at this stage the word had somehow got around that the HGK range was having difficulty maintaining its presence in the model engine marketplace. Indeed, subsequent events fully bore out Billinton’s reservations. Despite the clearly sincere efforts of the manufacturers as well as Billinton’s very positive test report, the marketplace continued to view the HGK engines with a certain amount of trepidation. Apart from the residual (but by now seemingly unfounded) ongoing concerns regarding the bore taper issue, there were also persistent rumors about the chrome plating spalling off (i.e.,"peeling") from the aluminium alloy bore. In fairness to the manufacturers, I have to say that I have never encountered any first-hand confirmatory evidence with respect to this issue – certainly, Billinton reported no such issues in his previously-summarized test. However, the rumors circulated nonetheless.

Even more interestingly, towards the end of the company’s active involvement in the industry, a number of diesel models were developed. It had been found that the standard HGK design using a chrome plated aluminum block with four cylinder hold-down bolts seemed to be suitable for diesels. The diesel models were envisioned primarily for use in R/C cars, notably in .21 cuin. form. Interestingly, the original prototypes used a cast iron piston, still operating in a plated aluminium bore. At this stage of development, the prototypes used variable compression, with the contra-piston being set into a recess in the aluminum head. Apologies for the poor quality of the attached image, but it's the only one of the prototype model that I could find. Anyone having a better image to offer is cordially invited to share it here, with full acknowledgement! Unfortunately, when used with a cast iron piston the greater thermal expansion of the cylinder bore resulted in loss of compression seal at high temperatures. The Moko Research organization was retained to re-design the engine to utilize an aluminium piston. This reportedly resulted in very consistent operation due to the careful matching of the thermal expansion characteristics of the piston and cylinder. This ability to match those characteristics is one of the great advantages of the use of AAC or ABC piston/cylinder technology. Prototype testing of the improvements developed by the Moko Research organization demonstrated that diesel versions of all models were now practicable, in particular the .21 cubic inch model which was seen as having considerable potential as a car engine. It appeared that the optimum piston specification and The company did get as far as announcing two of the re-developed diesel models. Most intriguingly, these were a pair of fixed compression diesels in both .15 and .21 cuin. displacements. These were designated the 15SFD and 21FSD respectively. Apologies for the poor quality of the attached images of these prototypes, but these are all that I could find, and any image is surely better than none! There was also apparently a .40 cuin. fixed compression diesel prototype, but this was never formally announced. These designs were the first new fixed-compression diesels to be announced in over 35 years! The fixed-compression models weren’t quite as fixed as all that – a system of shims was incorporated which allowed the operator to quickly alter the compression ratio to suit different fuels and ambient conditions.

During the wind-up phase in the first half of 1986, the company’s remaining assets were purchased by the American RJL organization (later combined with MECOA). However, this deal apparently did not turn out too well - Randy Linsalato of RJL commented that RJL received far fewer finished parts than expected upon the conclusion of the deal. Looking back over the short history of the HGK range, it’s readily apparent that the organization which initially created these engines was perhaps more interested in the research and development aspects of model racing engine design than they were in the promotion and development of their concepts into a commercially-viable range covering all areas of the market. As suggested by Mike Billinton, there seems to have been a lack of focus upon the business aspects of the venture. Instead of developing a few readily saleable models and then evolving a sound market strategy through which the investment in those models might be recovered and some working capital accumulated, the company seem to have expended much of its effort in developing a whole host of new models for which the market prospects were either undeveloped or strictly limited. Indeed, the sheer range of the company’s new model development activities may have been a significant factor in diverting their focus and resources away from the resolution of several pressing generic technical issues which bedeviled the marque throughout its history. In particular, this lack of focus may go far towards explaining why it took them so long to finalize the optimum bore configuration and settle upon the ideal combination of materials – basically, their development efforts were spread too thin. The fact that they were a very small concern having such a wide-ranging research and development program which sales were clearly insufficient to support in the long term could only have acerbated this issue. Based upon the very limited or even non-existent production figures for many of the models which were developed at least to the prototype stage, it seems doubtful that many of the designs ever repaid their development costs. Overall, the activities of the company seem to provide a classic example of the often-stated concept that the most certain way to make a small fortune from manufacturing model engines is to start with a large fortune!

Other areas in which the company appears to have misjudged the situation were those of market research and model diversification. Their initial narrow focus upon racing engines limited them to a specialist and hence limited market area in which their sales prospects were relatively poor given the well-established competition. By contrast, during their later period following the reorganization of the company in 1980, they appear to have reacted to market conditions by simultaneously developing a relatively wide range of different models for many of which there was once again a relatively limited market potential given the existing competition from other far larger and already firmly-entrenched manufacturers. They might have done better to identify just a few additional niche markets and focus upon those, rather than attempt to take on the big guns wholesale in a wide range of different market areas. Regardless, after only a twelve year presence in the model engine business the HGK range was consigned to history. The company left us a legacy of some very well-made engines displaying considerable design originality, albeit with a few flaws. Although by no means common, they do still turn up from time to time on eBay and elsewhere. Anyone acquiring one will become the owner of a well-made and technically interesting piece of modelling history which will certainly enhance any collection. _______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published July 2015 Updated June 2025 - Luis Petersen's factory visit

|

|

| |

Here we take a look at a short-lived range of high-quality model engines which originated in Japan in the mid 1970’s but did not manage to gain a long-term foothold in the model engine market despite being extremely well made and incorporating some innovative features. We'll be examining the range of high-performance engines marketed under the HGK banner.

Here we take a look at a short-lived range of high-quality model engines which originated in Japan in the mid 1970’s but did not manage to gain a long-term foothold in the model engine market despite being extremely well made and incorporating some innovative features. We'll be examining the range of high-performance engines marketed under the HGK banner. Another very useful source of information came from my good mate Luis Petersen of Denmark, who spent three months working in Japan in late 1978. During this period, Luis had an opportunity to visit the HGK production facilities and speak with several of the principal participants in the venture, doing so in mid-October 1978. Luis was accompanied on this visit by an interpreter, allowing him to communicate freely with the company's sales manager Mr. Ohkawa and chief engine designer Mr. Masao Obha. A summary account of his visit was published in May 1979 in the pages of the Danish modelling magazine "Modelflyvenyt", as reproduced here at the right. I'm most grateful to Luis for making this material available to me.

Another very useful source of information came from my good mate Luis Petersen of Denmark, who spent three months working in Japan in late 1978. During this period, Luis had an opportunity to visit the HGK production facilities and speak with several of the principal participants in the venture, doing so in mid-October 1978. Luis was accompanied on this visit by an interpreter, allowing him to communicate freely with the company's sales manager Mr. Ohkawa and chief engine designer Mr. Masao Obha. A summary account of his visit was published in May 1979 in the pages of the Danish modelling magazine "Modelflyvenyt", as reproduced here at the right. I'm most grateful to Luis for making this material available to me.  Be that as it may, Kosaki Jinichi tells us that Hashioka finalized the design and commenced production of their introductory offering, the piped rear exhaust 15R C/L speed engine, in 1974. This very well-produced engine generally followed the established layout which was considered mandatory at the time to achieve a successful contest record. It was a high speed 2.5 cc Schnuerle-ported twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) glow-plug engine which was specifically designed for use with a tuned pipe. It was not suitable for head-to-head racing events like rat racing or Goodyear – its main practical application was in the FAI control line speed category.

Be that as it may, Kosaki Jinichi tells us that Hashioka finalized the design and commenced production of their introductory offering, the piped rear exhaust 15R C/L speed engine, in 1974. This very well-produced engine generally followed the established layout which was considered mandatory at the time to achieve a successful contest record. It was a high speed 2.5 cc Schnuerle-ported twin ball-race disc rear rotary valve (RRV) glow-plug engine which was specifically designed for use with a tuned pipe. It was not suitable for head-to-head racing events like rat racing or Goodyear – its main practical application was in the FAI control line speed category. For context, it’s important to remember that this was during the heyday of the FRV Rossi R.15, which retained its iron piston at this stage, as did other competing models like the Kosmic 15. The AAC technology was therefore completely new and extremely radical as far as almost all then-current modellers were concerned. Not unreasonably, this led many individuals to question the durability of the chrome-plated aluminium cylinder bore which was a central feature of the new design.

For context, it’s important to remember that this was during the heyday of the FRV Rossi R.15, which retained its iron piston at this stage, as did other competing models like the Kosmic 15. The AAC technology was therefore completely new and extremely radical as far as almost all then-current modellers were concerned. Not unreasonably, this led many individuals to question the durability of the chrome-plated aluminium cylinder bore which was a central feature of the new design.  bare-bones offering was sold as the HGK 15N. Because it was not supplied with a pipe, it could be sold in a far smaller box than the 15R. Its intended use was apparently FAI free flight. Both forms of the engine were sold in relatively plain tan-coloured boxes with red or brown lettering.

bare-bones offering was sold as the HGK 15N. Because it was not supplied with a pipe, it could be sold in a far smaller box than the 15R. Its intended use was apparently FAI free flight. Both forms of the engine were sold in relatively plain tan-coloured boxes with red or brown lettering.  be clearly seen in the attached images. Presumably this reflected the fact that in free flight service the runs would be considerably shorter than with the speed unit. The reduction in cooling area resulting from this minor modification would have allowed the engine to reach its optimum operating temperature slightly faster. The example in Maris's care exhibited the same feature.

be clearly seen in the attached images. Presumably this reflected the fact that in free flight service the runs would be considerably shorter than with the speed unit. The reduction in cooling area resulting from this minor modification would have allowed the engine to reach its optimum operating temperature slightly faster. The example in Maris's care exhibited the same feature.  bears the serial number 56 stamped onto the top of the left mounting lug, while the example in Maris's keeping at the time of writing bore the number 57 in the same location. This creates the impression that the two engines came off the line consecutively! This is extremely odd when we consider the fact that they are timed quite differently. It would appear either that the two variants were randomly included in the same numbering sequence or that both variants had their own sequences starting at 1, making the apparent consecutive sequence between the two cited examples a case of mere concidence.

bears the serial number 56 stamped onto the top of the left mounting lug, while the example in Maris's keeping at the time of writing bore the number 57 in the same location. This creates the impression that the two engines came off the line consecutively! This is extremely odd when we consider the fact that they are timed quite differently. It would appear either that the two variants were randomly included in the same numbering sequence or that both variants had their own sequences starting at 1, making the apparent consecutive sequence between the two cited examples a case of mere concidence.

The market for a new cutting-edge speed engine from a previously-unknown manufacturer using unproven technology turned out to be quite limited. Of course, this might have been expected given the technological uncertainties involved as well as the heavy existing commercial competition from the likes of Rossi, Kosmic and Super Tigre. Consequently, only a few hundred of these engines were produced at the outset, with a few more small batches being made later.

The market for a new cutting-edge speed engine from a previously-unknown manufacturer using unproven technology turned out to be quite limited. Of course, this might have been expected given the technological uncertainties involved as well as the heavy existing commercial competition from the likes of Rossi, Kosmic and Super Tigre. Consequently, only a few hundred of these engines were produced at the outset, with a few more small batches being made later. The fact that the original HGK engines had relatively loose piston-cylinder fits is most likely a reflection of the fact that as of 1974 the use of AAC piston/cylinder technology was right on the cutting edge of model engine design - no-one had much if any practical experience with the use of this technology at that time. It was later learned through such experience that the bore in an AAC set-up has to be tapered so that the piston is squeak-tight at TDC if the engine is to work well at its peak. That lesson presumably had yet to be learned as of 1974.

The fact that the original HGK engines had relatively loose piston-cylinder fits is most likely a reflection of the fact that as of 1974 the use of AAC piston/cylinder technology was right on the cutting edge of model engine design - no-one had much if any practical experience with the use of this technology at that time. It was later learned through such experience that the bore in an AAC set-up has to be tapered so that the piston is squeak-tight at TDC if the engine is to work well at its peak. That lesson presumably had yet to be learned as of 1974. The HGK 15S retained the AAC technology on which the company had pinned its hopes, but was in most other respects a relatively conventional high-performance sports engine of its day. It proved to be quite successful, remaining in production at modest levels for some years. A similar .21 cuin. HGK 21SF model soon followed, although this had a ball-race crankshaft from the outset.

The HGK 15S retained the AAC technology on which the company had pinned its hopes, but was in most other respects a relatively conventional high-performance sports engine of its day. It proved to be quite successful, remaining in production at modest levels for some years. A similar .21 cuin. HGK 21SF model soon followed, although this had a ball-race crankshaft from the outset. in fact the same unit used on the 15R. At the other end of the case, the former integrally-cast plain bearing was truncated and bored blind from the crankcase end. A drum valve ran in this bearing, which was now of course located at the rear of the engine. On the standard version of the revised model, this valve was fed with fuel mixture by the same big-bore peripheral-jet carburettor unit used in the HGK 15N. The cylinder porting was however timed for use either open or with a muffler rather than a tuned pipe.

in fact the same unit used on the 15R. At the other end of the case, the former integrally-cast plain bearing was truncated and bored blind from the crankcase end. A drum valve ran in this bearing, which was now of course located at the rear of the engine. On the standard version of the revised model, this valve was fed with fuel mixture by the same big-bore peripheral-jet carburettor unit used in the HGK 15N. The cylinder porting was however timed for use either open or with a muffler rather than a tuned pipe.

control-line Goodyear event which was then very popular. A poster on a widely-read modelling forum recalled that the standard version of the engine did quite well in the Goodyear event in Britain during the late 1970’s. Its success was apparently due in large part to its very easy starting coupled with a more than adequate performance. This comment certainly suggests that many of these engines had perfectly acceptable piston fits. Nonetheless, the HGK 15SX was produced in relatively small numbers – quite understandable in view of the comparatively limited and highly competitive market for contest powerplants in this category.

control-line Goodyear event which was then very popular. A poster on a widely-read modelling forum recalled that the standard version of the engine did quite well in the Goodyear event in Britain during the late 1970’s. Its success was apparently due in large part to its very easy starting coupled with a more than adequate performance. This comment certainly suggests that many of these engines had perfectly acceptable piston fits. Nonetheless, the HGK 15SX was produced in relatively small numbers – quite understandable in view of the comparatively limited and highly competitive market for contest powerplants in this category. The company’s most commercially successful product was their .21 car engine, the HGK 21SFC model, of which they reportedly made around 20,000 examples over the years. This was a car conversion of their less successful 21SF aero model. As always, the engines were supplied complete with all accessories, including the muffler and any required Allen keys.

The company’s most commercially successful product was their .21 car engine, the HGK 21SFC model, of which they reportedly made around 20,000 examples over the years. This was a car conversion of their less successful 21SF aero model. As always, the engines were supplied complete with all accessories, including the muffler and any required Allen keys.  Reading between the lines, it's hard to avoid the suspicion that the key players in the original Hashioka company such as designer Masao Obha were interested only in high performance engines. Once they realized that the company was not going to survive purely on the basis of the high-performance market, they evidently lost interest. The marked change in management focus following the transfer of ownership of the range fully supports this view.

Reading between the lines, it's hard to avoid the suspicion that the key players in the original Hashioka company such as designer Masao Obha were interested only in high performance engines. Once they realized that the company was not going to survive purely on the basis of the high-performance market, they evidently lost interest. The marked change in management focus following the transfer of ownership of the range fully supports this view.  As a first step, a small number of .40 and .45 cubic inch FRV models were manufactured (about 200 units each, according to Kosaki Jinichi). Most of these were exported, presumably to test the world market response.

As a first step, a small number of .40 and .45 cubic inch FRV models were manufactured (about 200 units each, according to Kosaki Jinichi). Most of these were exported, presumably to test the world market response. A test by the late Mike Billinton of one of the advertised models, the HGK 40SF R/C, appeared in the August 1981 issue of the British magazine "Radio Control Models & Electronics". Since this is the only English-language media review of one of these engines that seems to have been published, I thought that it might be of interest to summarize the findings.

A test by the late Mike Billinton of one of the advertised models, the HGK 40SF R/C, appeared in the August 1981 issue of the British magazine "Radio Control Models & Electronics". Since this is the only English-language media review of one of these engines that seems to have been published, I thought that it might be of interest to summarize the findings.

The first series of tests was conducted with an open exhaust (no muffler) together with an 8 mm diameter carburettor intake and a 3.5 mm diameter spraybar. In this form, the engine was found to peak at a speed of 20,900 rpm, at which point it developed 0.94 BHP. This of course is an unusually high peaking speed for a “sports” glow-plug motor, although by 1981 standards the actual output was nothing special.

The first series of tests was conducted with an open exhaust (no muffler) together with an 8 mm diameter carburettor intake and a 3.5 mm diameter spraybar. In this form, the engine was found to peak at a speed of 20,900 rpm, at which point it developed 0.94 BHP. This of course is an unusually high peaking speed for a “sports” glow-plug motor, although by 1981 standards the actual output was nothing special. The possibility undeniably exists that there may have been some substance to this concern in the early years of the marque's existence. My good friend Johnny Shannon, a noted US speed flier and engine constructor, has pointed out that as of 1974 when the HGK engines made their initial appearance, the use of AAC piston/cylinder technology was very new indeed and probably far less well understood than it later became. The application of chrome plating to an aluminium base material is not that dificult, but requires extremely close process controls. Everything is critical - temperature, current density, time. Johnny (who has first-hand experience with the contruction and operation of AAC engines) says that once you have it down it goes very well, until it doesn’t! The only way to know how well it went is to go directly from plating to the hone. If the chome has not bonded securely to the aluminium, the hone will show spalling within three passes. If this happens, the only remedy is to discard the contents of the cleaning and zinc baths and start over. It may have taken Hashioka some time to learn these lessons, since they were right at the leading edge of this technology.

The possibility undeniably exists that there may have been some substance to this concern in the early years of the marque's existence. My good friend Johnny Shannon, a noted US speed flier and engine constructor, has pointed out that as of 1974 when the HGK engines made their initial appearance, the use of AAC piston/cylinder technology was very new indeed and probably far less well understood than it later became. The application of chrome plating to an aluminium base material is not that dificult, but requires extremely close process controls. Everything is critical - temperature, current density, time. Johnny (who has first-hand experience with the contruction and operation of AAC engines) says that once you have it down it goes very well, until it doesn’t! The only way to know how well it went is to go directly from plating to the hone. If the chome has not bonded securely to the aluminium, the hone will show spalling within three passes. If this happens, the only remedy is to discard the contents of the cleaning and zinc baths and start over. It may have taken Hashioka some time to learn these lessons, since they were right at the leading edge of this technology.  It would appear that this issue was eventually resolved, assuming that it arose at all. Even so, the re-organized company continued to struggle, fighting a losing battle against the sales power of the major competing marques of the day. Despite this, they continued to doggedly pursue the development of new models and new product lines. For example, the .61 cuin. model mentioned in Luis Petersen's previously-cited 1979 article reportedly remained under development as of mid-1981, although it never appeared in production form.

It would appear that this issue was eventually resolved, assuming that it arose at all. Even so, the re-organized company continued to struggle, fighting a losing battle against the sales power of the major competing marques of the day. Despite this, they continued to doggedly pursue the development of new models and new product lines. For example, the .61 cuin. model mentioned in Luis Petersen's previously-cited 1979 article reportedly remained under development as of mid-1981, although it never appeared in production form.  bore taper configuration for use with a chrome-plated aluminium bore had at last been found, but too late. If the change in the piston material and the correction of the cylinder taper issue had been introduced by the makers early on, the market assessment of these engines might well have been far more favourable.

bore taper configuration for use with a chrome-plated aluminium bore had at last been found, but too late. If the change in the piston material and the correction of the cylinder taper issue had been introduced by the makers early on, the market assessment of these engines might well have been far more favourable. Despite these announcements, it appears that none of the diesel models ever actually reached the marketplace in quantity, evidently stalling at the prototype stage or very soon thereafter. It had become quite clear by this time that the HGK range was heading rapidly for commercial oblivion, likely leading to a reluctance to throw good money after bad. The HGK venture was finally wound up in mid 1986 following the death of the company president. Reference to Japanese corporate records confirms that the company’s name registration expired on July 11

Despite these announcements, it appears that none of the diesel models ever actually reached the marketplace in quantity, evidently stalling at the prototype stage or very soon thereafter. It had become quite clear by this time that the HGK range was heading rapidly for commercial oblivion, likely leading to a reluctance to throw good money after bad. The HGK venture was finally wound up in mid 1986 following the death of the company president. Reference to Japanese corporate records confirms that the company’s name registration expired on July 11