|

|

The David Stanger Story By Adrian Duncan with Ron Chernich

An invaluable source of information on David Stanger is to be found on the outstanding “Antique Model Aircraft” website. A number of images which appear here originated on that site and are reproduced here with my grateful thanks and acknowledgement. I have preserved all of Ron’s comments on Stanger, merely editing and re-organizing them for greater clarity and also adding some additional information, including a number of additional images which weren’t available to Ron. I also corrected a few errors. That said, this article remains as much Ron’s work as mine. I hope you enjoy it! David Stanger - Model Aviation Pioneer

The achievements of these pioneers were not the establishment of the records themselves. Their true significance lay in the astonishing amount of creativity, craftsmanship, experimentation and just plain hard work that lay behind those achievements. For example, Stanger not only built his engines, but also constructed the lathe on which they were made as well as the micrometer and protractor used to establish dimensions and angles. He also designed and built the models for his engines to power. As if that wasn't enough, he also made his own spark plugs! In the period extending from the initial experiments in powered heavier-than-air flight right up until almost the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, aero engines of any size were essentially unavailable commercially. Consequently, would-be aviators had virtually no option but to design and build both the airframe and the power plant of their flying machines. The Wright brothers designed the engine for their Wright Flyer themselves, but passed its actual construction over to their friend Charlie Taylor. In England, the young Geoffrey de Havilland had to design his own engine before commencing the design of his first aeroplane, farming out the engine's actual construction to the Iris Car Company in 1909.

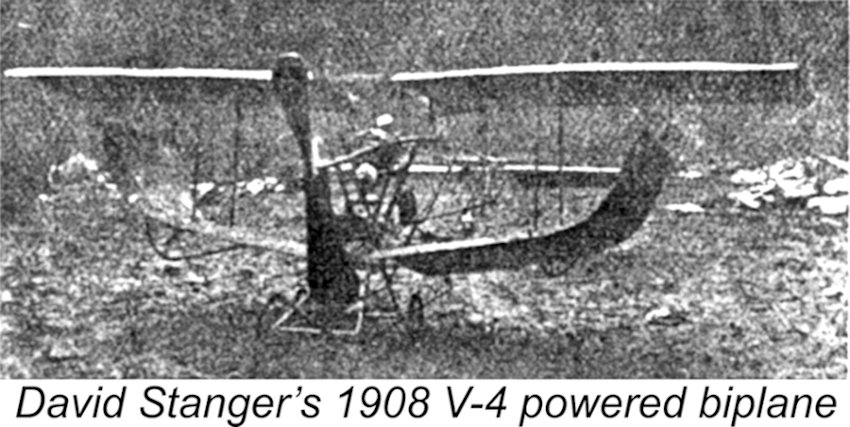

Stanger’s achievement in designing and building an engine of such small dimensions by the standards of the day which operated with a high degree of efficiency by those same standards can only reflect positively on his deep appreciation of rapidly-evolving I/C engine principles and design at a time when such knowledge was confined mainly to the few who had previously attempted to build full-sized engines with varying degrees of success. When considering Stanger’s first engine, it is important for context to relate the date of its design to other aeronautical events of the period. That engine was designed only eighteen months after the Wright brothers achieved the world’s first controlled flight by a manned engine-powered aircraft, and four years before Bleriot flew across the Channel. It is an often under-appreciated fact that the development of powered free flight model aircraft lagged only a year or two behind the emergence of full-sized powered aviation. Today’s free flight power modellers are participating in a branch of their hobby that is as old as aviation itself! Stanger was understandably proud of his achievement in creating this engine. He wrote to the newly founded “AERO” magazine describing the four-cylinder four-stroke V-4 engine that he had designed, stating his belief that it was the smallest aero engine in the world at the time. His letter, which appeared in the magazine’s March 1st, 1910 issue, described the engine as weighing 5½ pounds (88 ounces) complete with gravity-fed carburettor and petrol tank. He estimated the power output as 1¼ BHP at 1,300 rpm with a 29 in. diameter prop having a pitch of 36 in., producing a thrust of around 7 pounds. Plenty of low-end torque on tap! The engine’s four cylinders each had a 1.25 in. bore and a 1.5 in. stroke for a total displacement of 7.36 cuin. (120 cc). An interesting feature of Stanger's V-4 engine was the array of small holes radially spaced around part of the lower portion of the bore so that they opened when the piston neared bottom dead centre – almost like late-opening two-stroke exhausts. The purpose of these holes was to assist the exhaust valve by offering an initial pathway for the exhaust gas just prior to the start of the exhaust stroke – a kind of two-stroke/four-stroke hybrid system. The effect of this would be to minimize the internal gas pressure against which the camshaft would have to open the exhaust valve in each cylinder, greatly reducing the loads imposed on the valve gear. However, the holes would also be open near the end of the inlet stroke, thus serving to supplement the function of the atmospheric inlet valve in a manner rather analogous to sub-piston induction in a two-stroke. The near-contemporary Englsh model engine designer W. G. Jopson was to incorporate this idea in his own 55 cc four-stroke opposed twin of 1910.

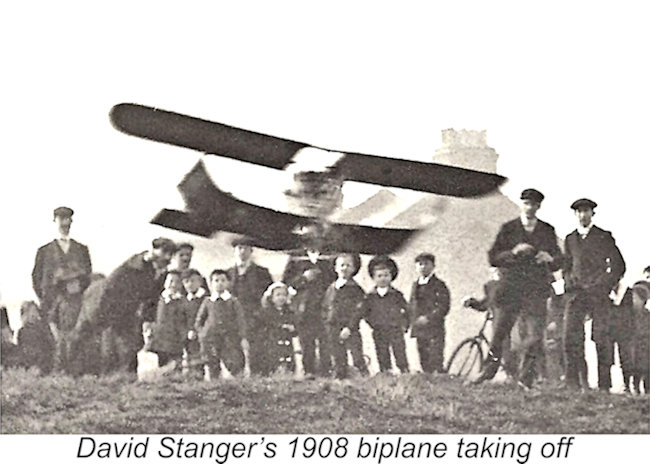

This model and its V-4 powerplant made a series of successful flights beginning in 1908. Unlike Samuel Langley's Aerodrome no. 5, Stanger's In my opinion, this achievement was considerably more significant than Stanger’s previously-mentioned 51-second record flight of 1914. However, it is the latter flight that is universally recorded in the literature while, with the singular exception of the David Stanger entry in the “Engine Collectors' Journal”, his earlier achievements have received no mention.

These trans-Atlantic achievements do not detract in the least from David Stanger's concurrent efforts during the pioneering model aircraft era, as he was a true pioneer of powered model flight in his own country and in his own right. He achieved what he did quite independently, entirely on the basis of his own engineering and aeronautical abilities.

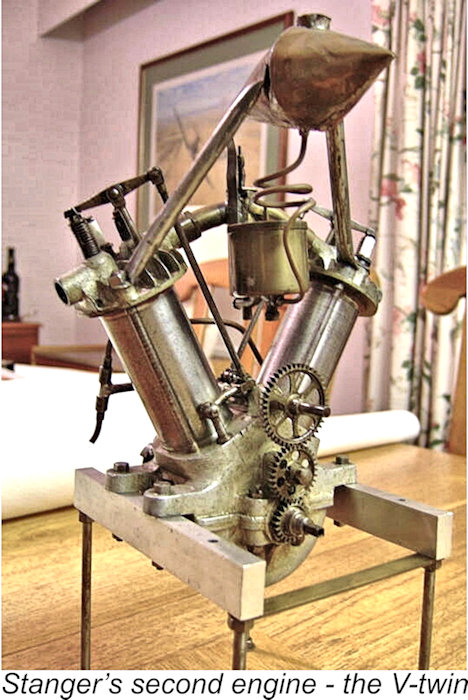

Like those of its V-4 predecessor, the steel cylinders had no fins - these engines weren't designed to run for long periods or at high speeds! The only fins were those formed on the cast iron heads. The pistons were also cast iron, fitted with two rings each. The crankcase of both engines was cast in aluminium alloy. The crankshaft of the V-4 was fabricated, running in bronze bushes, while the V-2 featured a one-piece crankshaft with big-end caps on the conrods. The spark plugs and other ignition equipment for these engines were made by Stanger himself, as was the lathe using which they were built.

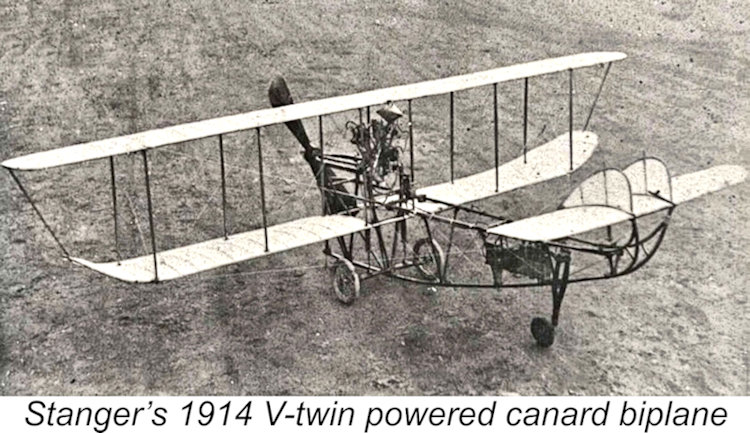

Unless you knew what you were looking at, the “Flight” drawings could easily be taken as depicting details of a typical full-size aircraft of the period! Stanger was in effect paralleling full-sized pioneers like Geoffrey de Havilland and Harry Hawker in their airframe construction techniques. The main differences were the aircraft’s smaller size and the need for built-in three-axis stability to replace that provided as necessary by a human pilot's use of the controls.

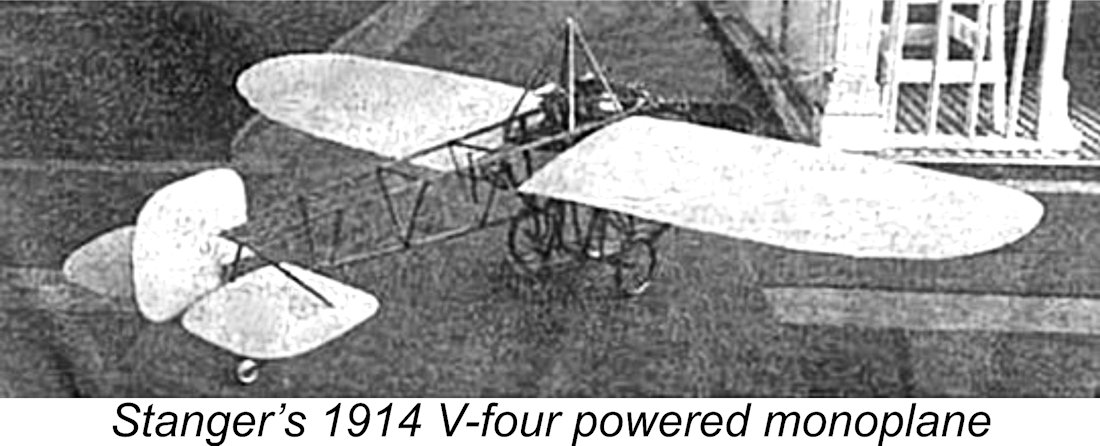

Both the V-2 powered canard pusher biplane and the V-4 powered tractor monoplane were exhibited by Stanger at the 1914 Aero Show held at Olympia in West Kensington, London. A highlight of the show must have been the flying demonstrations that Stanger conducted with both models at Hendon Aerodrome (you can just see the delight expressed in the body language of the London Bobbies at left and right in this photo of Stanger releasing the monoplane).

Shortly after this historic achievement, the outbreak of World War 1 put a temporary stop to David Stanger’s model flying experiments. However, Stanger resumed his experimental activities after the war, designing at least three more types of This was followed in 1926 by a three-cylinder in-line 15 cc two-stroke unit. This engine had a three-division crankcase and was fitted with a twin-choke carburettor having individual needle valves on each choke but with both chokes supplied by a single float chamber. It must have been something to hear when running!

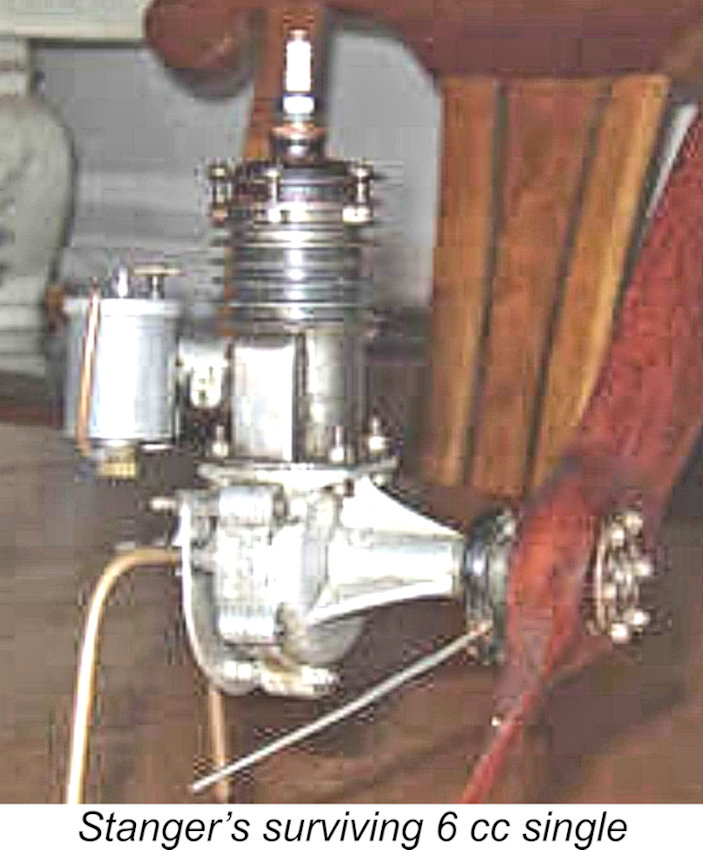

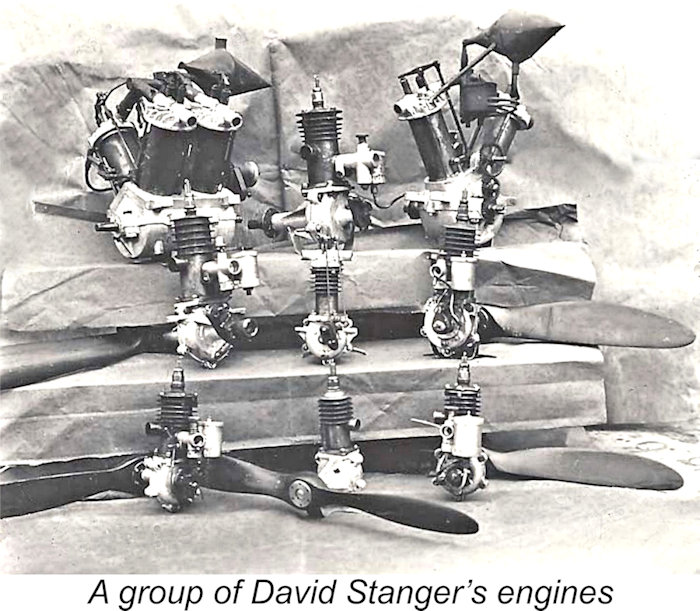

I have no knowledge of the present whereabouts of David Stanger’s surviving engines. Writing to SAM Speaks in The surviving engines listed by Moulton included the original 1906 four cylinder four-stroke which David Stanger used in 1908 to power the first-ever British petrol-driven model aircraft to fly successfully. The second survivor was the twin cylinder unit of 1913 with which Stanger set his inaugural record in 1914. The third surviving engine in Lt. Cdr. Greenhaigh’s care at Moulton's time of writing was the single-cylinder 6 cc unit which was so far ahead of its time. Finally, the three-cylinder two-stroke unit has also survived to be added subsequently to the collection. It was hoped that these examples of a true pioneer's work would eventually be displayed in a permanent museum in London. I don’t know if this hope was ever fulfilled, or where these historic engines are now…………...I only hope that they haven't vanished forever into some private collection. Even though Stanger is remembered mainly for his V-configuration engines and his 1914 record, his other accomplishments deserve to be remembered as well. He was truly a pioneer model aviator and engine builder. I hope that you've enjoyed this summary of the achievements of one of the true pioneers of powered model airplane flight! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published February 2026

|

| |

While 51 seconds may not seem like a long time, 18 years definitely is! The trick, as such, is to determine what constitutes an "official" record for a given category and identify who recognizes it. On the other side of the Atlantic, Samuel Langley's steam-powered

While 51 seconds may not seem like a long time, 18 years definitely is! The trick, as such, is to determine what constitutes an "official" record for a given category and identify who recognizes it. On the other side of the Atlantic, Samuel Langley's steam-powered

During the same period, automotive engineer and pioneering aeromodelling enthusiast David Stanger had become fascinated by the prospect of achieving powered model flight and had designed and built his own petrol engine intended for that use. His first engine was a four-cylinder 120 cc air-cooled four-stroke V-4 type. It was designed in 1905 and built by the 35 year-old Stanger in his own workshop in 1906.

During the same period, automotive engineer and pioneering aeromodelling enthusiast David Stanger had become fascinated by the prospect of achieving powered model flight and had designed and built his own petrol engine intended for that use. His first engine was a four-cylinder 120 cc air-cooled four-stroke V-4 type. It was designed in 1905 and built by the 35 year-old Stanger in his own workshop in 1906.

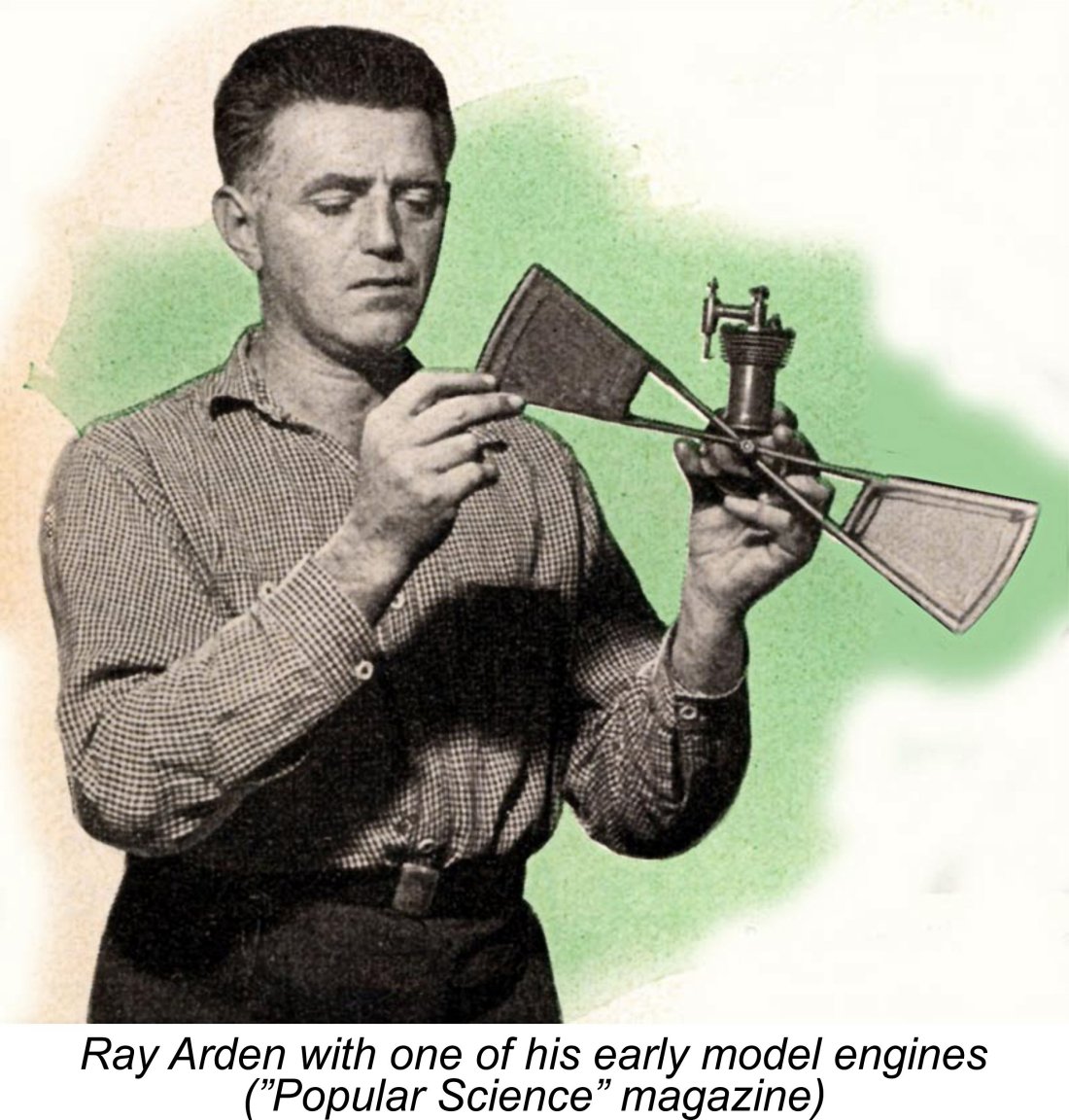

Stanger had no way of knowing about the research and experimentation going on concurrently in the USA at this time. In 1906 Augustus Herring was displaying a two-pound gas engine mounted in a biplane model, but no reports of its flights are in evidence. Ray Arden, then 16 years old, chummed around with Herring and learned all he could about Herring's engine. By 1907, Arden had built his own single-cylinder engine and by 1908 he had flown a six-foot wingspan model with his 1907 engine for a distance of 100 yds. By 1910 Arden had further refined his engine and airplane to the point where he was making flights of over one mile. The fact that this engine also used a very early form of one of Arden's most famous contributions to the modelling world, the glow-plug, is often overlooked.

Stanger had no way of knowing about the research and experimentation going on concurrently in the USA at this time. In 1906 Augustus Herring was displaying a two-pound gas engine mounted in a biplane model, but no reports of its flights are in evidence. Ray Arden, then 16 years old, chummed around with Herring and learned all he could about Herring's engine. By 1907, Arden had built his own single-cylinder engine and by 1908 he had flown a six-foot wingspan model with his 1907 engine for a distance of 100 yds. By 1910 Arden had further refined his engine and airplane to the point where he was making flights of over one mile. The fact that this engine also used a very early form of one of Arden's most famous contributions to the modelling world, the glow-plug, is often overlooked. Stanger's second engine was a four-stroke V-twin weighing 42 oz, less than half the weight of his first. This should come as no surprise, as it was in effect one-half of the V-4. Both engines featured cam-operated exhaust valves and automatic atmospherically-activated inlet valves. Internal lubrication was achieved using mechanically-driven oil pumps, while manual lubrication was used on the exposed valve gear.

Stanger's second engine was a four-stroke V-twin weighing 42 oz, less than half the weight of his first. This should come as no surprise, as it was in effect one-half of the V-4. Both engines featured cam-operated exhaust valves and automatic atmospherically-activated inlet valves. Internal lubrication was achieved using mechanically-driven oil pumps, while manual lubrication was used on the exposed valve gear.  The prestigious “Flight” magazine for April 25

The prestigious “Flight” magazine for April 25 The monoplane had a 10-foot wingspan, with a chord of 2 feet. Its single wing incorporated a modest degree of dihedral - Stanger was clearly well aware of the resulting benefits in terms of pilotless stability. All-up weight was 20 pounds (320 ounces). The fuselage was of triangular section braced with 300 lb. breaking-strain piano wire. The V-4 engine had now been developed to a point where it drove a 30 in. dia. x 22 in. pitch prop at 1,600 RPM.

The monoplane had a 10-foot wingspan, with a chord of 2 feet. Its single wing incorporated a modest degree of dihedral - Stanger was clearly well aware of the resulting benefits in terms of pilotless stability. All-up weight was 20 pounds (320 ounces). The fuselage was of triangular section braced with 300 lb. breaking-strain piano wire. The V-4 engine had now been developed to a point where it drove a 30 in. dia. x 22 in. pitch prop at 1,600 RPM.

Stanger also built a number of single-cylinder two-stroke engines. The smallest of these had a displacement of only 1 cc. The single-cylinder series of engines powered models with both biplane and monoplane configurations. One of these engines, a 6 cc model built in 1925, was clearly well ahead of its time, looking far more like a late-1930’s design than one dating from 1925. A fascinating feature of this unit was that it had a mechanical timer driven by a shaft extension at the rear which cut the ignition after a pre-determined running time.

Stanger also built a number of single-cylinder two-stroke engines. The smallest of these had a displacement of only 1 cc. The single-cylinder series of engines powered models with both biplane and monoplane configurations. One of these engines, a 6 cc model built in 1925, was clearly well ahead of its time, looking far more like a late-1930’s design than one dating from 1925. A fascinating feature of this unit was that it had a mechanical timer driven by a shaft extension at the rear which cut the ignition after a pre-determined running time.  Despite his obvious attraction to aviation, David Stanger was an automotive engineer by profession, a fact evident in many aspects of his engine designs. In 1901 he had designed and built his own motor car, and between 1919 and 1923 he produced a series of

Despite his obvious attraction to aviation, David Stanger was an automotive engineer by profession, a fact evident in many aspects of his engine designs. In 1901 he had designed and built his own motor car, and between 1919 and 1923 he produced a series of  Stanger eventually retired, settling in Somerset in England’s West Country. He was still alive in 1948 at age 77 – I don’t know when he finally passed away. His sons Alfred and John both became professional engineers, also building many fine models. John continued to use the micrometer that his father had made until his own retirement in 1958.

Stanger eventually retired, settling in Somerset in England’s West Country. He was still alive in 1948 at age 77 – I don’t know when he finally passed away. His sons Alfred and John both became professional engineers, also building many fine models. John continued to use the micrometer that his father had made until his own retirement in 1958.