|

|

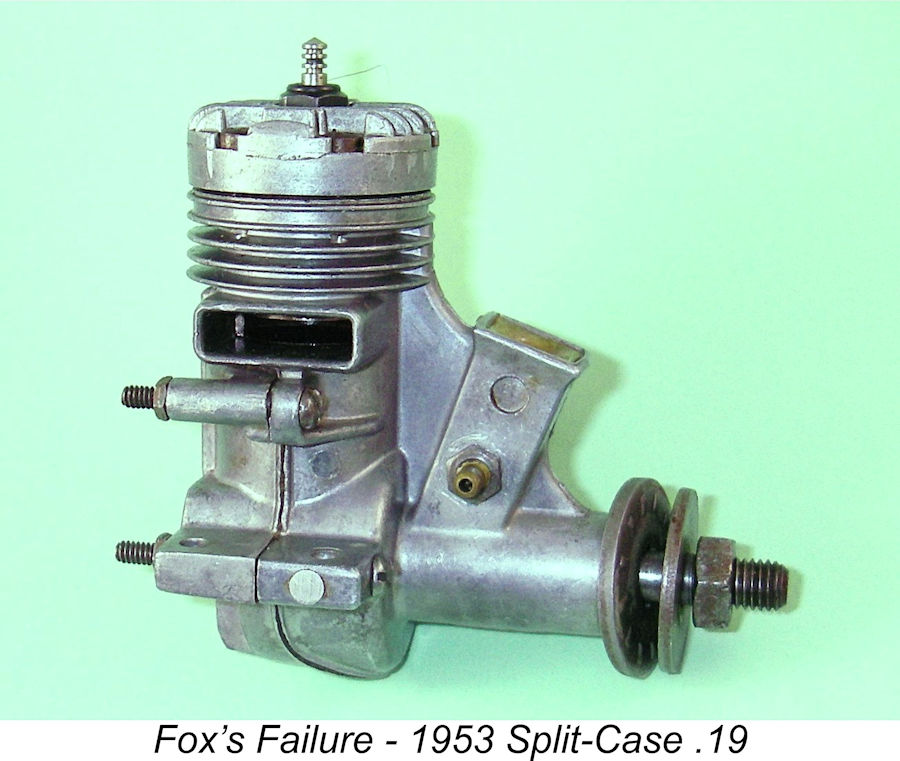

Duke's Forgotten Failure – the 1953 Fox .19 Split-Case Model

Born in 1920, Duke Fox (Duke was his given name, not a nickname!) had been involved with aeromodelling from an early age. He began designing model engines on the side during wartime military service, constructing his first engine, a sandcast .59 cuin. sparkie, in 1943. His first designs to be manufactured in series on a commercial basis were the .49 and .59 cuin. “Hi-Speed” and “Hi-Torque” spark ignition units made by Claude C. Slate in Los Angeles, California. These engines appeared in 1947. Slate made and sold them on the basis of royalty payments to Duke Fox as the designer.

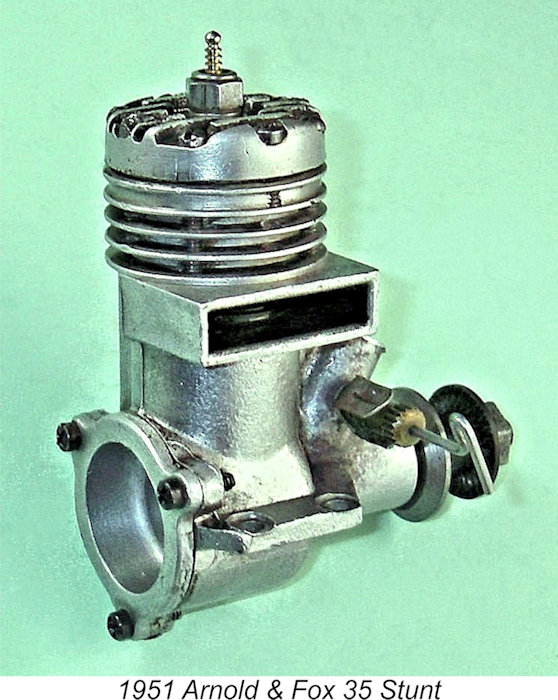

In the summer of 1949, Duke joined forces with an expert machinist and toolmaker named Dale Arnold, who had been making the crankshafts and cylinder blanks for the original Fox .35’s. The two formed a new company, Arnold & Fox Engineering Co. of North Hollywood, California. They produced further upgraded models of the .35 and .59 cuin. models, also adding .29 cuin. stunt and racing models to their portfolio. All engines produced by this partnership were glow-plug units. The castings In 1952 a salesman from Ranger Diecast came around trying to drum up business. He made a proposal to the partners to replace the permanent mold castings that they were then using with die-castings. This offer came at just the right time, since the old permanent molds had made a lot of castings by this time and were getting pretty tired. Duke and Dale gave them the go-ahead, and before too long Fox 29’s and 35’s were being built around die-castings instead of components produced from permanent molds. At the same time, they switched from a four-screw head to a far more secure six-screw head, having already gone to a three-screw backplate. Otherwise, the components remained unchanged at this stage. At around the same time, Duke Fox acquired a pull broach rig, which the partners used to broach the bearings and cylinder bores in preparation for honing. The pull broach worked far better on the cylinders than trying to ream or bore them. In late 1952 the partnership began to come under considerable strain due to some domestic issues faced by Dale Arnold. According to Duke’s recollections, Dale’s wife was demanding that he take more money out of the business than its cash flow at the time would allow. To back up this demand, she refused to counter-sign the mortgage papers necessary to finance the purchase of new equipment. This issue was resolved quite amicably by Dale agreeing to bow out for a buy-out payment of $5,000 – considerably less than his share of the business was apparently worth at the time. Duke always paid tribute to Dale for his unselfish cooperation in resolving this rather sensitive issue.

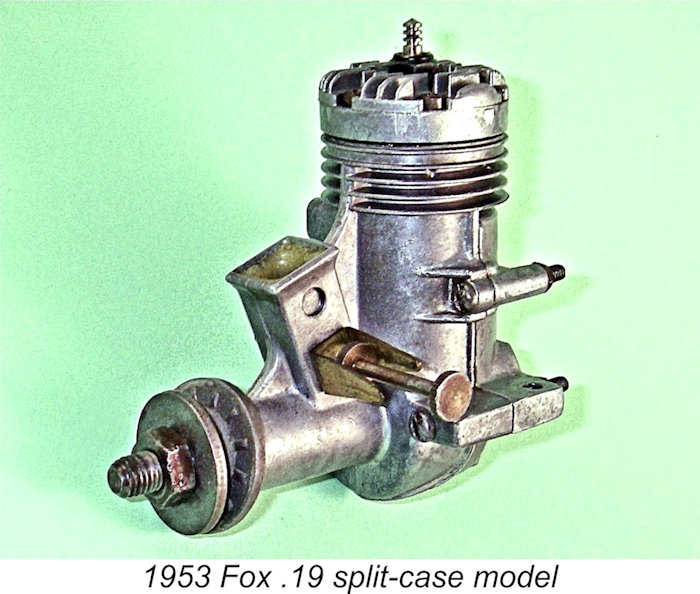

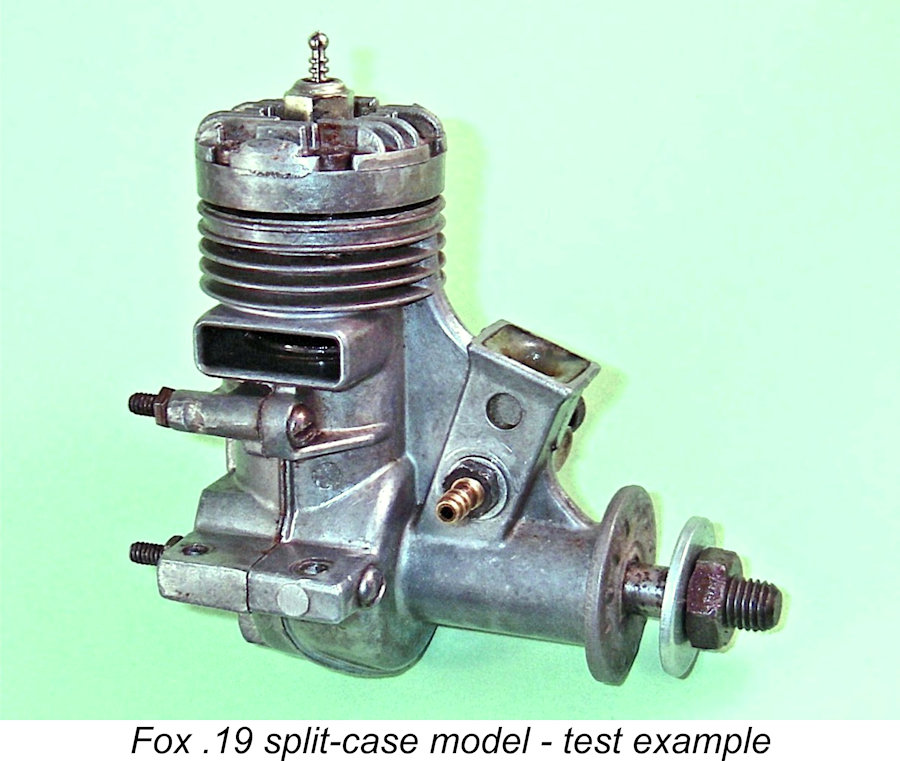

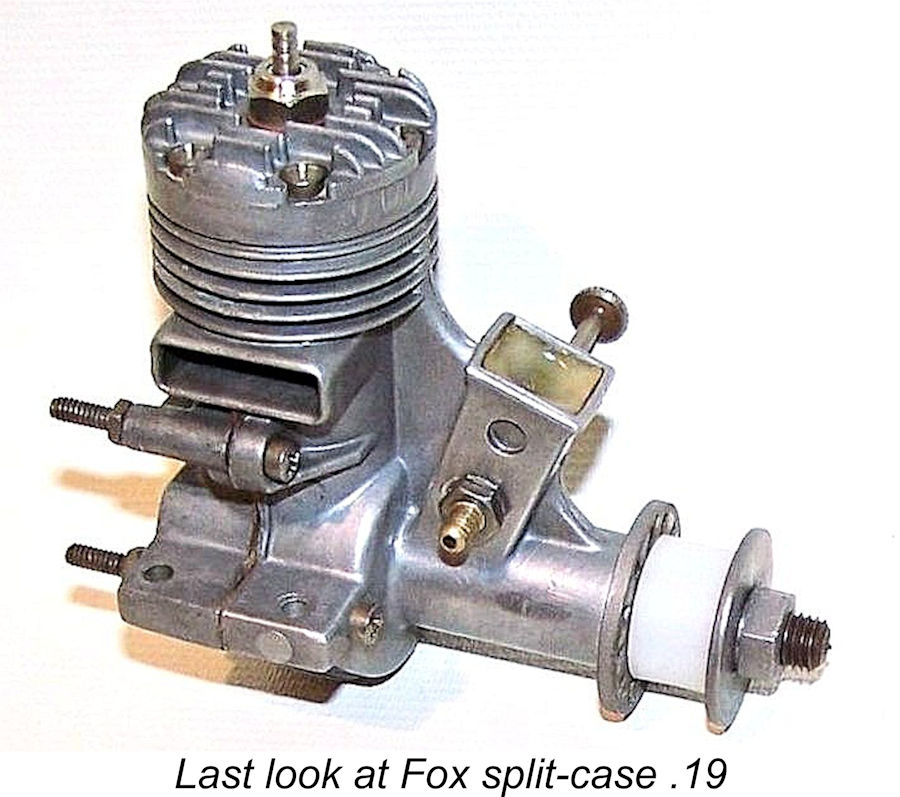

During this organizational crisis, Duke had already begun to think about adding a .19 cuin. model to the range. In developing a design for this new model, he planned to use the pull broach to machine the main casting to accommodate the sleeve rather than bore it. This was the primary reason for the unusual design of our subject engine, the split-case 19 of early 1953. The arrangement provided the required clearance to allow the broach to be pulled through. However, when Duke came to actually broach the first castings, he found that the castings themselves just didn't have enough strength to withstand the broaching pressure. In the end, this forced a return to the conventional boring approach, essentially negating the primary basis for the split-case design. Even so, the design was completed on the basis of that case, since the required dies had already been created and castings had been produced.

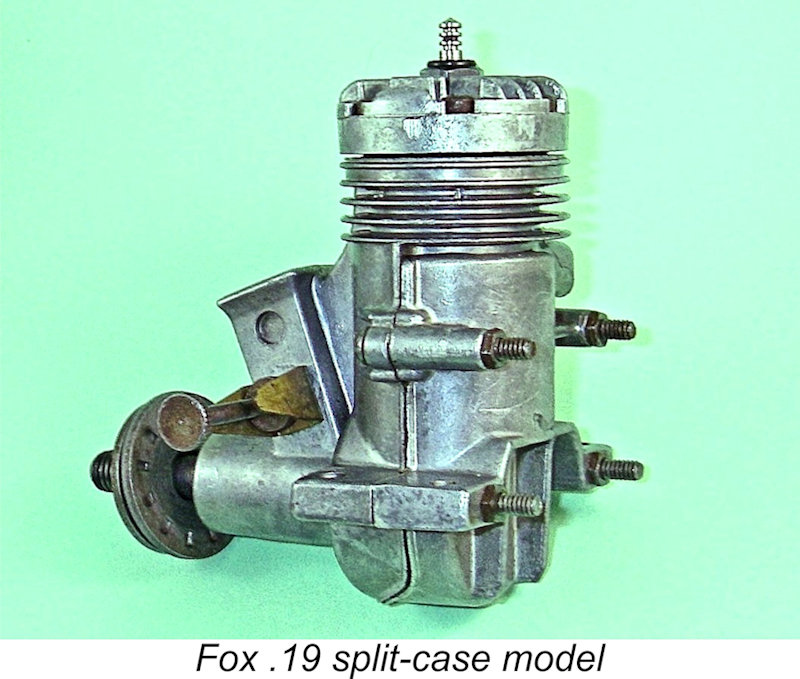

Bore and stroke of the .19 were 0.650 and 0.600 inches respectively for a calculated displacement of 0.199 cuin. (3.26 cc). These dimensions were to be retained throughout the somewhat intermittent life of the Fox .19 series. Weight of this unit was a checked 5.11 ounces (145 gm) – commendably light for a powerplant of this displacement. Volumetrically-measured compression ratio was a relatively modest 7:1.

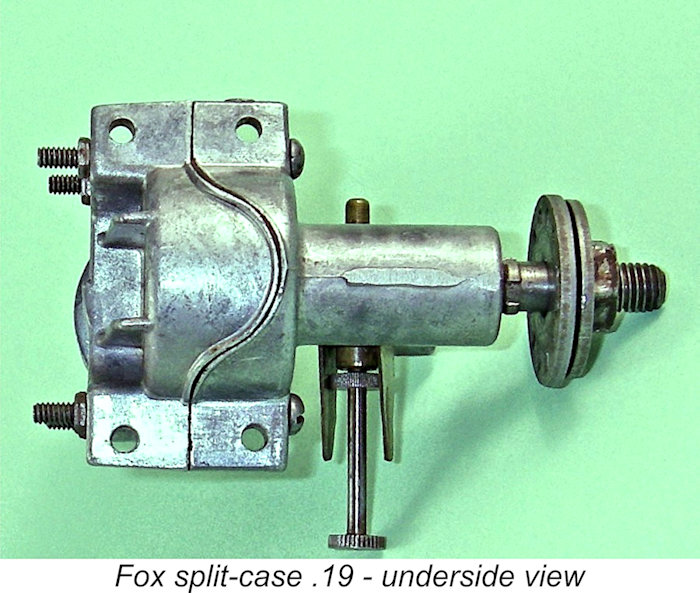

The two crankcase halves were held together by four axially-aligned bolts and nuts. The engine featured a lapped cast iron baffle piston running in a steel liner. The crankshaft ran in an un-bushed plain bearing. The shaft was splined to fit an O&R-supplied steel prop driver. Induction took place through a square venturi with a plastic insert - indeed, this was the first Fox engine to incorporate the square intake structure which was to be featured in a number of future Fox designs. The engine was also offered as a two-speed model with an extra needle valve added. No markings of any kind appeared on the case. Examples of the new .19 were duly distributed to the various model shops. A number of them were sold fairly quickly and went into service. However, it was at this point that things began to turn ugly! It was soon found that the case was extremely prone to fracturing immediately below the exhaust stack, often doing so When one looks at the engine from the exhaust side, the basic reason for this behavior becomes quite clear. The crankcase is vertically split in a zig-zag fashion. The parting line between the two crankcase halves makes a half-circle at the base of the case, as seen in the earlier illustration of the engine's underside. It is this feature which was intended to allow the passage of the pull broach. The parting line then diverges to arrive exactly at the mid-point of the left and right-hand beam mounting lugs, which are therefore split. The parting line then heads vertically upwards on both sides until just below the level of the exhaust stack behind the upper crankcase bolt. It then makes a sharp right-angle turn to the rear – this may be difficult to see in the If you think about this for a moment, it should become quite clear that above the upper crankcase bolts, there’s nothing restraining the rear half of the cylinder casting from separating vertically from its rear neighbor – the two crankcase halves are separated at that point by what amounts to a friction wrap with no securing fastener. Hence the rear half of the upper cylinder casting (which is formed integrally with the front casting, remember) is completely unsupported in a vertical sense, relying entirely upon the material of the front crankcase half to maintain its position. Unfortunately, this material only provides direct support for the front half of the upper cylinder casting. This is guaranteed to impose what amounts to a cyclic bending stress on the front casting during operation, a situation made far worse by the presence of a tight right-angle bend behind the upper bolt in exactly the right position to act as a stress raiser. This bend will be subject to significant cyclic tension stresses during operation. It wouldn’t have taken too much running for metal fatigue to initiate a stress crack at that bend, quickly leading to catastrophic failure. Experience in the field amply confirmed this assessment. It's actually rather remarkable that a designer of Duke Fox’s undoubted calibre would have missed this very obvious design flaw. It’s perhaps equally remarkable that he evidently failed to appreciate the inevitable sealing problems which would arise from such a long and convoluted parting line between the two halves of the crankcase. But such problems didn’t take long to manifest themselves – maintaining an adequate base seal in this engine proved to be extremely problematic, quite apart from the major structural flaw. Quickly becoming aware of these issues, Fox moved very rapidly to address them. Production of the split-case .19 was halted immediately, after the production of a relatively modest number of examples, and Duke worked overtime to come up with a revised one-piece case along the lines of that used very successfully in the 29 and 35 models. Since the accommodation for the cylinder installation was back to being bored rather than broached, the split case was redundant anyway.

In his later autobiography, Duke recalled that the response to this recall was overwhelming! In fact, he commented that for a while it looked like somebody else was making them, because he seemed to be getting back more than he’d distributed!! In his recollection, it wasn’t that big a deal to strip the returned split-case models and install their internal components into the new one-piece cases. The un-sold examples returned from the dealers could then be re-sold as new, while others went back to their owners. Duke believed that relatively few examples of the original engine found their way into the hands of modellers before the problems with the design became apparent and the word got around. Consequently, the majority of the engines that were retro-fitted with the new cases were unsold examples returned from dealer stocks. After comparing the number returned with the number manufactured and distributed, Duke estimated that only some 40 or 50 examples remained un-returned and hence in original split-case configuration following the conclusion of the recall program. Based on the apparent present-day number of survivors, I would guess that Duke's figure may represent a slight under-estimation, but the .19 split-case model is definitely among the least common Fox products today - they don't show up all that often. The surviving examples are by definition those that for one reason or another were not returned under the terms of the recall.

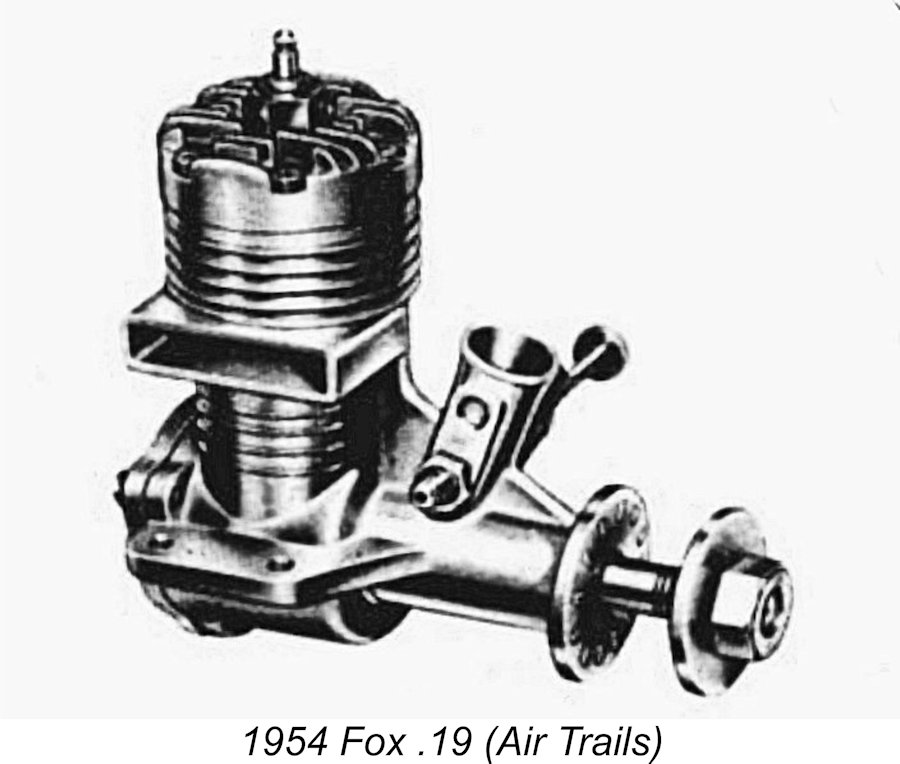

Although it was a dependable performer which exhibited none of the fragility of its predecessor, Duke noted ruefully that this engine never quite performed at a comparable level to that of the K&B .19 which was its main competition. He tried very hard to sort it out, but never really succeeded. Duke did recall one particular example of the 1954 Fox .19 which out-turned every other tested example by around 1,000 RPM! Needless to say, he worked very hard to find an explanation for this superiority – he felt that if they had all run like that one example, he would have sold many more .19’s than he actually did! However, it apparently seemed to be identical to all the others. Duke never did unlock the secrets of that one outstanding motor – it seemed to be a case of all the parts fitting and working together in some kind of magic combination! So much of model engine performance falls into the realm of black magic ................

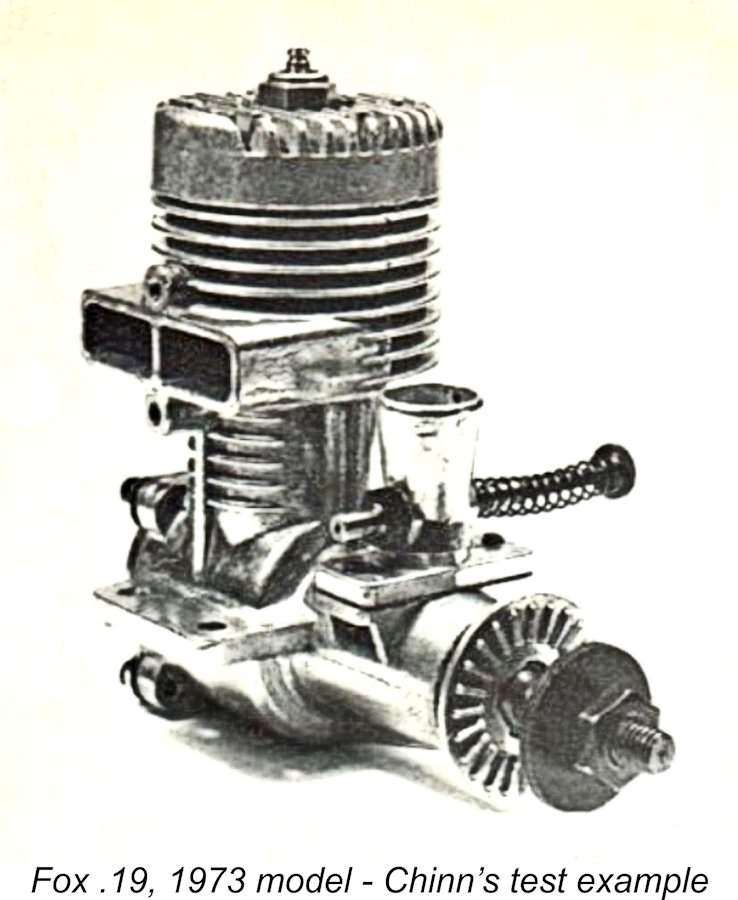

The revived Fox .19 was the subject of a test by Peter Chinn which was published in the April 1974 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Chinn reported an excellent performance, finding a peak output of 0.39 BHP @ 17,000 RPM using a fuel containing only 5% nitro. A test of the same engine appeared in the May 1974 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN), again written by Chinn. For that test, Chinn also reported the engine’s performance on Fox Missile Mist fuel containing 25% nitro, finding a peak output of 0.45 BHP @ 17,900 RPM. Never let it be said that Duke Fox couldn’t design a great plain-bearing .19 cuin. powerplant! Happily, the drama of the 1953 split-case debacle was never repeated. Thankfully too, it was quickly forgotten, hence doing no significant harm to the fine reputation of Duke Fox and his engines. Duke passed away in 1991 with his legend untarnished! A Very Quick User Impression Having a couple of nice examples of the Fox .19 split-case model on hand, I felt that it would be appropriate for this article to fire one up briefly just to get a feel for the engine’s handling and running characteristics. It also seemed only right that I should get a few photos to prove that this deservedly much-maligned engine did run ........for a while, at least!

Given the very obvious structural weakness inherent in the engine’s design, I realized that any significant amount of running would be guaranteed to fracture the case eventually. However, the proposed test engine didn't appear to have done all that much running in the past - once the issue with the case failures in service became widely known, the owner evidently took it out of service while it was still intact. This of course explains why it's still with us – any surviving split-case Fox .19 must inherently have very little running time! One wonders why the owner didn't take advantage of the recall program ..............but I'm glad that he didn't! I reckoned that I would have a sporting chance of putting one or two more careful runs on the engine with no harm being done. The pursuit of knowledge made this worth the risk, anyway ……… I decided up front that I would use a low-nitro fuel and would put on at most ten minutes of running using a typical airscrew for a .19 cuin. glow-plug motor of the period. In that context, I made reference to the test of the 1954 Fox .19 which appeared in Air Trails “Hobbies for Young Men” during that year. The tester found that this version of the Fox .19 turned a 9x4 airscrew of unspecified brand at just over 13,000 RPM. If that prop had been a latter-day Taipan 9x4, the implied output at that speed would have been in the order of 0.400 BHP. A test of the same engine in “Flying Models” reported generally comparable results. Showing due consideration for Duke Fox’s otherwise well-earned reputation, neither test report made any reference to the preceding split-case debacle. I decided that in order to minimize cyclic stresses, the use of a lightweight prop with a low angular moment of inertia would be appropriate. Looking through my prop stash, I selected a BY&O 9x5 wood airscrew as my test load. Most of the running would be rich, purely to allow me to get a few running photos. That done, I planned to limit the leaned-out two-stroke running to a couple of short bursts to establish the speed at which this prop was turned. Fingers crossed, I mounted the selected example very carefully in the test stand with the chosen prop fitted. To accommodate the slightly uneven faces of the split mounting lugs, I wrapped them in fibrous material to help spread the mounting stresses.

....... but only for a very little while - the engine started on the second flick! A couple of test re-starts indicated that this was the norm - one never had to exert oneself! Once running, the engine settled down to a nice smooth four-stroke while I bustled about taking photos from various angles, just to prove that these things really did run! Their problem wasn't their handling or ability to run well - it was staying together while doing so.............

Having secured my photos and checked out the engine's re-starting qualities, I leaned it out briefly. Running in this condition was dead smooth despite the crankcase leak. However, the engine only got the BY&O 9x5 airscrew up to 9,900 RPM - somewhat less than the previously-quoted test figures from "Air Trails" would lead one to expect. The indicated output at this speed is in the order of 0.259 BHP - not all that bad on straight fuel at this relatively low speed, but not too spectacular either. I suspect that the engine would beat this handily in the absence of any crankcase leak. A little nitro would doubtless also work wonders! Moreover, the engine's actual peaking speed is almost certainly somewhat higher than this. I'd guess that it would almost certainly get past 0.300 BHP at somewhere in the region of 12,000 RPM, particularly if supplied with a little nitro. Having obtained this reading, I shut the engine down, feeling thankful that it remained in one piece! I'm glad to have experienced the sight and sound of one of these engines running well, but it's not an experience that I plan to repeat! Summary and Conclusion

Obviously, the many returns under warranty must have made the engine’s designer Ted Martin aware of these issues in short order. He moved quickly to re-design the problematic components, eventually bringing the engine up to a very dependable status combined with light weight and excellent performance by the standards of the day. However, AMCO stopped short of initiating a full recall – rather, they adopted a policy of simply replacing the problematic components with their updated replacements as and when the engines were returned for service. This positive response to a set of design issues did much to maintain the high regard in which the AMCO engines continued to be held despite these failures.

Hence, while the initial release of the Fox .19 with a serious design flaw cannot be said to be a unique circumstance, the official factory recall of this model appears to be the sole instance of such a step being taken by a model engine manufacturer. The fact that this course was adopted speaks very highly to the integrity of one of the most talented model engine designers of them all – Duke Fox. The closest thing to an actual recall by a manufacturer other than Duke Fox came in 1957 from the highly respected Italian manufacturer Giovanni Barbini. It was found that The surviving examples of this latter engine are by definition those that were not returned following the recall. In Duke Fox’s recollection, there weren’t too many of those. Nevertheless, examples in fine condition do show up from time to time – I’ve somehow acquired two of them over the years and have seen photos of a few others. Any surviving Fox .19 split-case will undoubtedly have seen little or no use – there’s no such thing as a “well-used” example of this engine, since it wouldn’t still be in one piece if it had done much running! Accordingly, almost all surviving examples are in near-new condition. So this is definitely not an engine to consider using in a classic model – it will not survive such use for any length of time. However, as a conversation piece with an interesting background, it’s well worth a place in the collection of anyone interested in engines with an unusual tale to tell! Just don’t run it too much and treat it respectfully if you do run it …………. __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published April 2025 |

| |

In this relatively short article, I’ll take a look at what appears to be something of a rarity in model engine history – a design by a well-respected and extremely successful designer/manufacturer which was a notable failure in technical terms. I’m referring to the infamous Fox .19 split-case model of 1953, which was undoubtedly the most notable false start in the long and illustrious history of the well-known series of engines designed by the legendary Duke Fox. This might be seen as Duke Fox’s Edsel!

In this relatively short article, I’ll take a look at what appears to be something of a rarity in model engine history – a design by a well-respected and extremely successful designer/manufacturer which was a notable failure in technical terms. I’m referring to the infamous Fox .19 split-case model of 1953, which was undoubtedly the most notable false start in the long and illustrious history of the well-known series of engines designed by the legendary Duke Fox. This might be seen as Duke Fox’s Edsel!

were produced from permanent molds. The venture was very successful, with the Fox .35 quickly becoming the stunt motor of choice among serious control-line aerobatic enthusiasts, winning everything in sight. Consequently, the Fox name soon became extremely well known and highly regarded in aeromodelling circles.

were produced from permanent molds. The venture was very successful, with the Fox .35 quickly becoming the stunt motor of choice among serious control-line aerobatic enthusiasts, winning everything in sight. Consequently, the Fox name soon became extremely well known and highly regarded in aeromodelling circles.

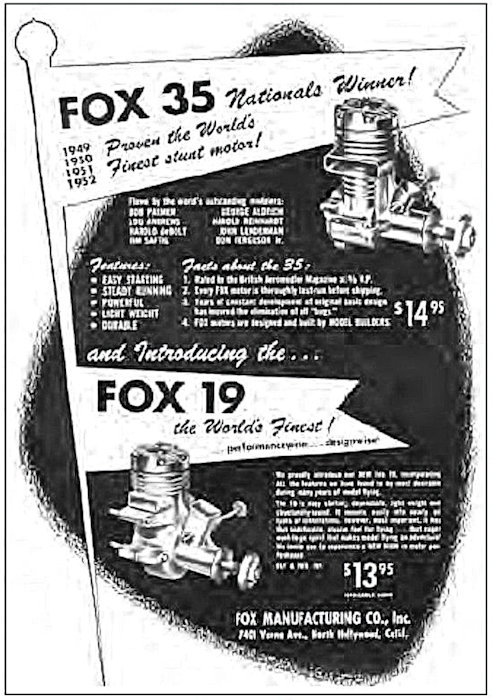

The split-case Fox .19 was actually designed during the final months of the Arnold & Fox Engineering Co. partnership. The final advertisement under that trade-name appeared in “Model Airplane News” (MAN) in March 1953. The following month of April 1953 saw the appearance in MAN of the first advertisement under the Fox Manufacturing Co. Inc. trade name. This advertisement (reproduced above at the right) featured the well-established Fox 35 along with the initial advertising appearance of the new Fox .19. The two models sold for $14.95 and $13.95 respectively.

The split-case Fox .19 was actually designed during the final months of the Arnold & Fox Engineering Co. partnership. The final advertisement under that trade-name appeared in “Model Airplane News” (MAN) in March 1953. The following month of April 1953 saw the appearance in MAN of the first advertisement under the Fox Manufacturing Co. Inc. trade name. This advertisement (reproduced above at the right) featured the well-established Fox 35 along with the initial advertising appearance of the new Fox .19. The two models sold for $14.95 and $13.95 respectively. The Fox .19 featured a die-cast head which was secured using 6 machine screws. The engine was built up around two quite intricate pressure die-castings, with the front half of the crankcase being cast integrally with the main bearing housing and upper cylinder jacket. The crankcase was split along a highly unusual parting line between the two halves which made it up. The form of this parting line at the base of the crankcase was specifically created to allow the passage of the pull broach through the cylinder installation bore. Hopefully the accompanying underside view will clarify this comment.

The Fox .19 featured a die-cast head which was secured using 6 machine screws. The engine was built up around two quite intricate pressure die-castings, with the front half of the crankcase being cast integrally with the main bearing housing and upper cylinder jacket. The crankcase was split along a highly unusual parting line between the two halves which made it up. The form of this parting line at the base of the crankcase was specifically created to allow the passage of the pull broach through the cylinder installation bore. Hopefully the accompanying underside view will clarify this comment. after only an hour or two of running. Clearly a metal fatigue issue. Moreover, a hard crash was often sufficient to fracture the case on its own. The number of engines being returned under guarantee with fractured crankcases must have made Duke Fox keenly aware of this issue in very short order.

after only an hour or two of running. Clearly a metal fatigue issue. Moreover, a hard crash was often sufficient to fracture the case on its own. The number of engines being returned under guarantee with fractured crankcases must have made Duke Fox keenly aware of this issue in very short order.

As soon as the first batch of these cases was available, Duke did the only thing that he could reasonably do – he initiated a model recall, one of the very few such recalls in model engine history! Owners were invited to return their engines to the factory to have their internal components transferred into the new one-piece cases. Dealers were also asked to return any new unsold stock remaining on their shelves.

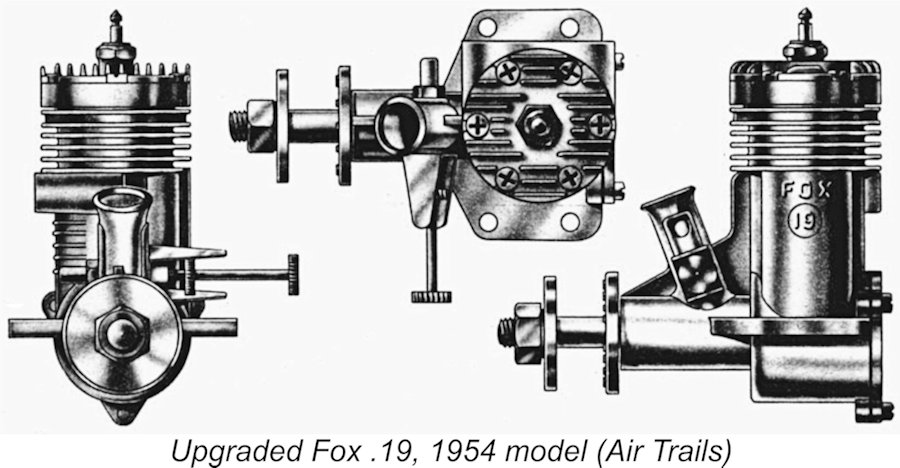

As soon as the first batch of these cases was available, Duke did the only thing that he could reasonably do – he initiated a model recall, one of the very few such recalls in model engine history! Owners were invited to return their engines to the factory to have their internal components transferred into the new one-piece cases. Dealers were also asked to return any new unsold stock remaining on their shelves. The retro-fitted engines immediately became the production version of the Fox .19, generally referred to as the 1954 model. This engine used the same internal components as the 1953 split-case rendition, the only difference being the one-piece crankcase casting. In this form, the engine was pretty much a scaled-down Fox 35.

The retro-fitted engines immediately became the production version of the Fox .19, generally referred to as the 1954 model. This engine used the same internal components as the 1953 split-case rendition, the only difference being the one-piece crankcase casting. In this form, the engine was pretty much a scaled-down Fox 35.  As it was, the 1954 Fox .19 was rather overshadowed by its K&B rival, consequently becoming only a modest seller and being withdrawn in late 1954 in conjunction with Fox's relocation to Fort Smith, Arkansas. It has become another of the less commonly-encountered Fox models today. Indeed, his experience with the 1953-54 Fox .19 models seems to have dampened Duke’s enthusiasm for persisting with engines in this displacement category. Apart from a brief re-appearance in 1957 following the company's consolidation at Fort Smith, the .19 cuin. displacement category was un-represented in the Fox range until 1973, when a new plain-bearing Fox .19 model based on the .25 cuin. design made its debut.

As it was, the 1954 Fox .19 was rather overshadowed by its K&B rival, consequently becoming only a modest seller and being withdrawn in late 1954 in conjunction with Fox's relocation to Fort Smith, Arkansas. It has become another of the less commonly-encountered Fox models today. Indeed, his experience with the 1953-54 Fox .19 models seems to have dampened Duke’s enthusiasm for persisting with engines in this displacement category. Apart from a brief re-appearance in 1957 following the company's consolidation at Fort Smith, the .19 cuin. displacement category was un-represented in the Fox range until 1973, when a new plain-bearing Fox .19 model based on the .25 cuin. design made its debut. After a close examination, I decided to use what appeared to be my slightly less pristine example for this test. Both of my engines were in perfect original condition with no sign of any crack development in their cases, but one of them had evidently done more previous running than its seemingly un-run twin, to judge by the operating residues which presented themselves when the engine was received. In fact, it actually appeared to have been mounted in a model at some point - the witness marks on the mounting lugs suggested as much. It suffered from what appeared to be a minor crankcase leak at the base of the split (doubtless a common failing with this design), but undoubtedly retained sufficient crankcase compression to run OK. I wasn't going to dismantle it to try to fix this! Cylinder compression was excellent, while all bearings displayed minmal wear.

After a close examination, I decided to use what appeared to be my slightly less pristine example for this test. Both of my engines were in perfect original condition with no sign of any crack development in their cases, but one of them had evidently done more previous running than its seemingly un-run twin, to judge by the operating residues which presented themselves when the engine was received. In fact, it actually appeared to have been mounted in a model at some point - the witness marks on the mounting lugs suggested as much. It suffered from what appeared to be a minor crankcase leak at the base of the split (doubtless a common failing with this design), but undoubtedly retained sufficient crankcase compression to run OK. I wasn't going to dismantle it to try to fix this! Cylinder compression was excellent, while all bearings displayed minmal wear.  The engine felt really good when flicked over – excellent compression, with no trace of binding and a healthy transfer "pop" despite the base leakage. So far, so good ………… Filling the tank with some straight methanol/castor fuel containing 30% castor oil (Duke specified plenty of castor in his fuels!), I opened the needle valve some four turns and choked to fill the fuel line. That done, I administered a small exhaust prime, lit the plug and started flicking.........

The engine felt really good when flicked over – excellent compression, with no trace of binding and a healthy transfer "pop" despite the base leakage. So far, so good ………… Filling the tank with some straight methanol/castor fuel containing 30% castor oil (Duke specified plenty of castor in his fuels!), I opened the needle valve some four turns and choked to fill the fuel line. That done, I administered a small exhaust prime, lit the plug and started flicking......... Once the engine was running, it became apparent that the previously-observed leak at the base of the crankcase was undoubtedly of sufficient magnitude to affect performance to some degree - a steady stream of liquid fuel could be observed squeezing out of the leak spot. That said, the engine still started and ran very well despite this handicap.

Once the engine was running, it became apparent that the previously-observed leak at the base of the crankcase was undoubtedly of sufficient magnitude to affect performance to some degree - a steady stream of liquid fuel could be observed squeezing out of the leak spot. That said, the engine still started and ran very well despite this handicap.  Reviewing the preceding tale, I can think of only two comparable situations involving the high-profile release of new model engine designs from name manufacturers which embodied serious design flaws. The first of these is the saga of the

Reviewing the preceding tale, I can think of only two comparable situations involving the high-profile release of new model engine designs from name manufacturers which embodied serious design flaws. The first of these is the saga of the  The original 1959 version of the 3.5 cc

The original 1959 version of the 3.5 cc  some (but not all) examples of the excellent 1956 Barbini B.40 TN racing glow-plug motor had been bored slightly oversize, putting them just over the FAI displacement limit of 2.5 cc. Barbini offered to refit any returned oversized engines with correctly-dimensioned components at his own expense. However, this fell well short of constituting a blanket recall, nor was it based on a fundamental design error as in the case of the Fox .19.

some (but not all) examples of the excellent 1956 Barbini B.40 TN racing glow-plug motor had been bored slightly oversize, putting them just over the FAI displacement limit of 2.5 cc. Barbini offered to refit any returned oversized engines with correctly-dimensioned components at his own expense. However, this fell well short of constituting a blanket recall, nor was it based on a fundamental design error as in the case of the Fox .19.