|

|

The Classic Fuji .099 Models

The results of my research into the Fuji engines were published in serial form on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website beginning in October 2011. This included a pair of focused articles on the Fuji .099 models. I’m re-publishing those articles here in combined form mainly to prevent their loss as Ron’s now-frozen and administratively-inaccessible site steadily deteriorates due to lack of any opportunity to maintain it. I've also taken advantage of the opportunity to add a few more details which have come to light since the publication of the original article. Before proceeding any further, a few acknowledgements are very much in order. First, I must pay tribute to my friend and colleague Mel Reid of Harrogate, Yorkshire, England. Mel spent countless hours researching Google Japan for information on the various corporate entities which guided the fortunes of the Fuji marque. He was also most generous in sharing information gleaned from his own extensive collection of Fuji products as well as reviewing drafts with a critical yet always constructive eye. I freely acknowledge that I could not have completed this series of articles without his help. Secondly, I must acknowledge the ongoing support and unfailing help which I received from the late David Owen of Woolongong, Australia. David's assistance in researching serial numbers and providing images and other data from his own Fuji collection was quite invaluable. Throughout our association, David never let me down, and he came through again in fine style on this occasion. Thanks, mate – I miss you! Finally, having acknowledged the considerable assistance that I received during the writing of these articles, I must emphasize that the responsibility for any errors and omissions is mine and mine alone. Now, a little background to get the ball rolling .............. Background

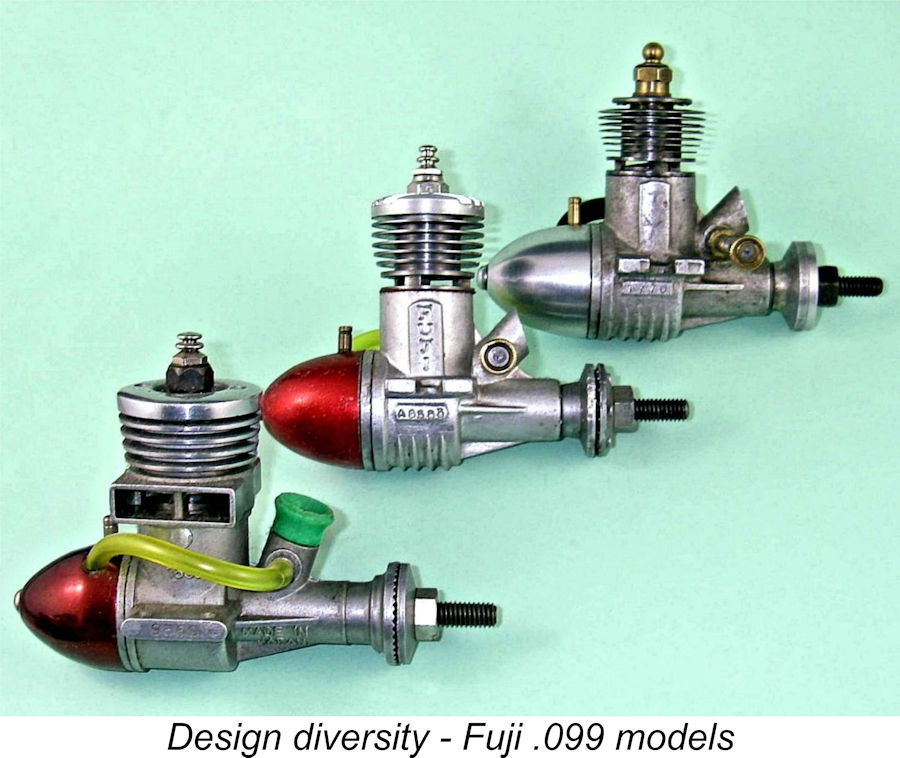

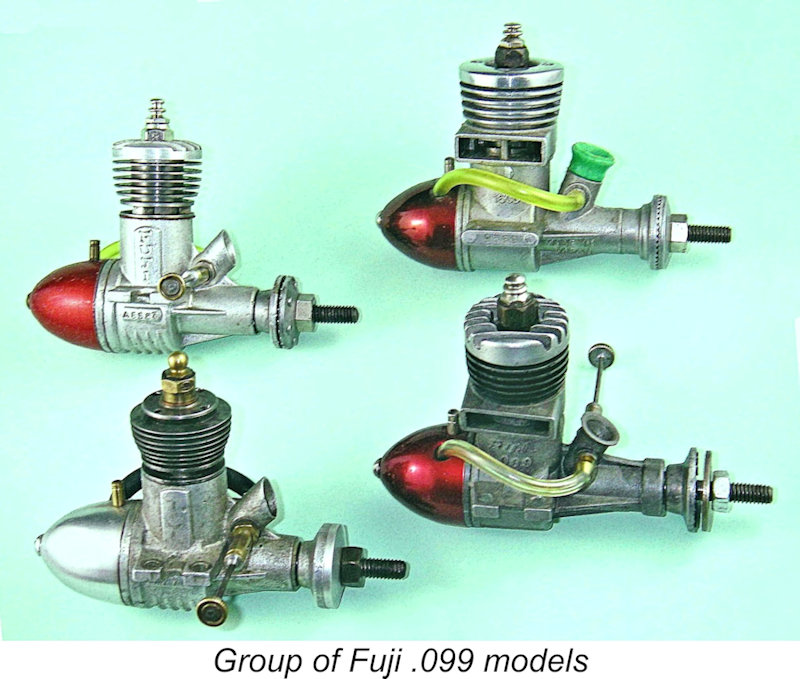

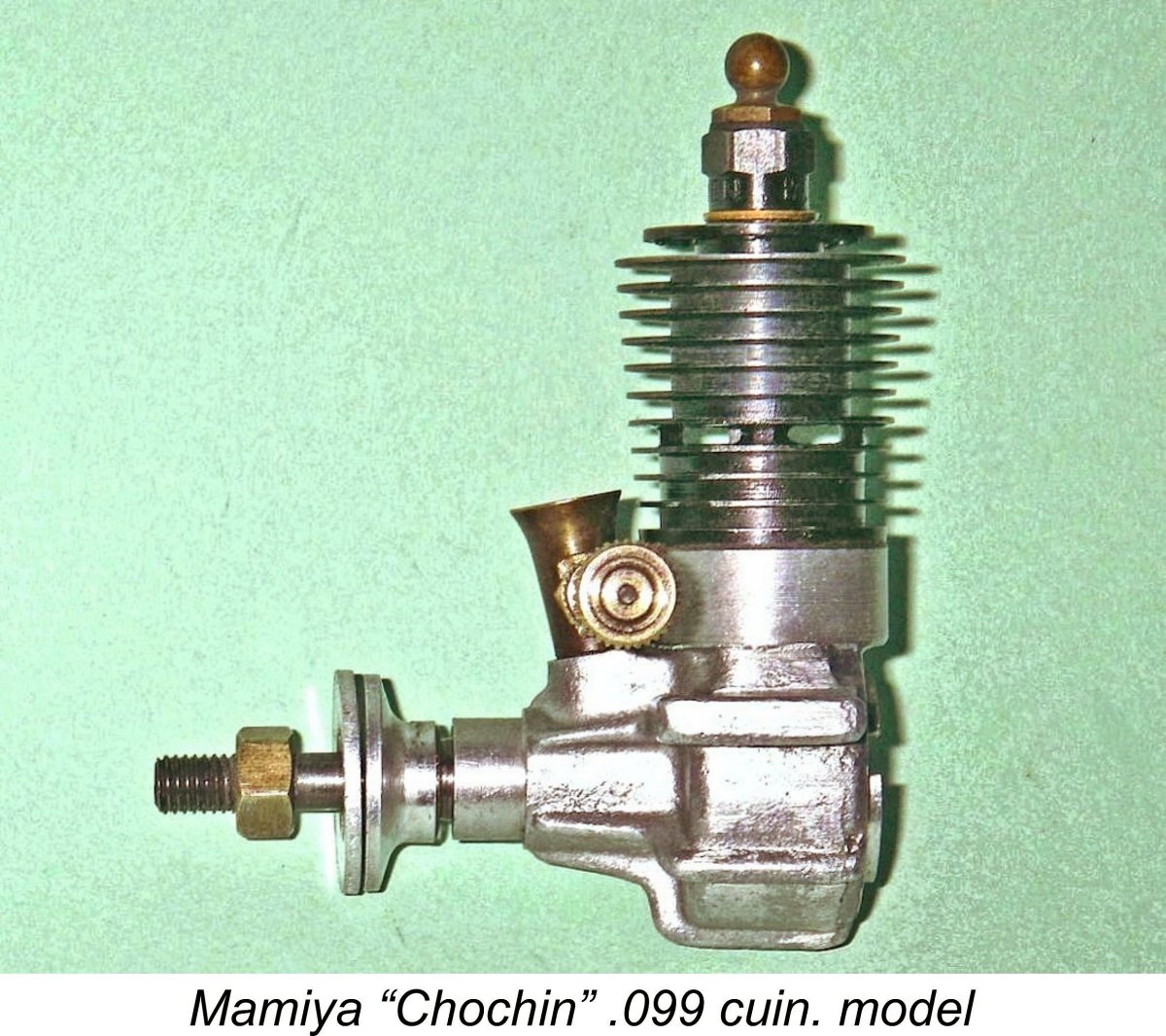

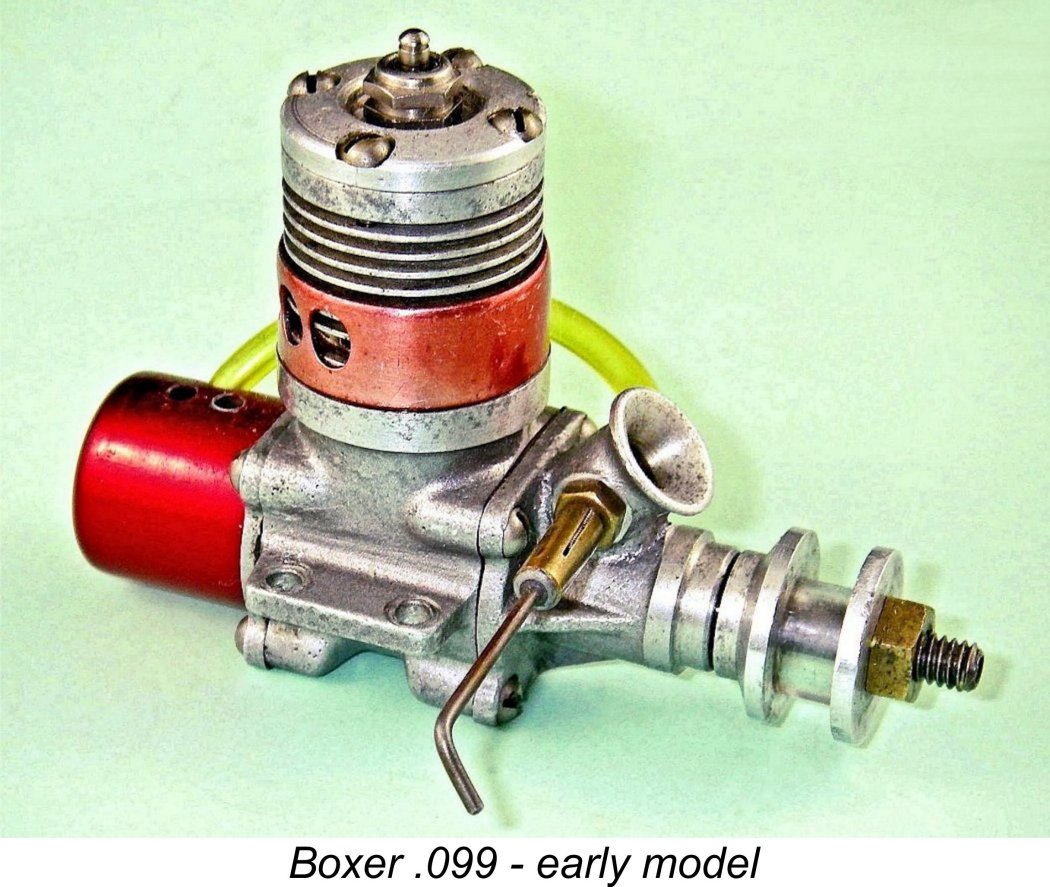

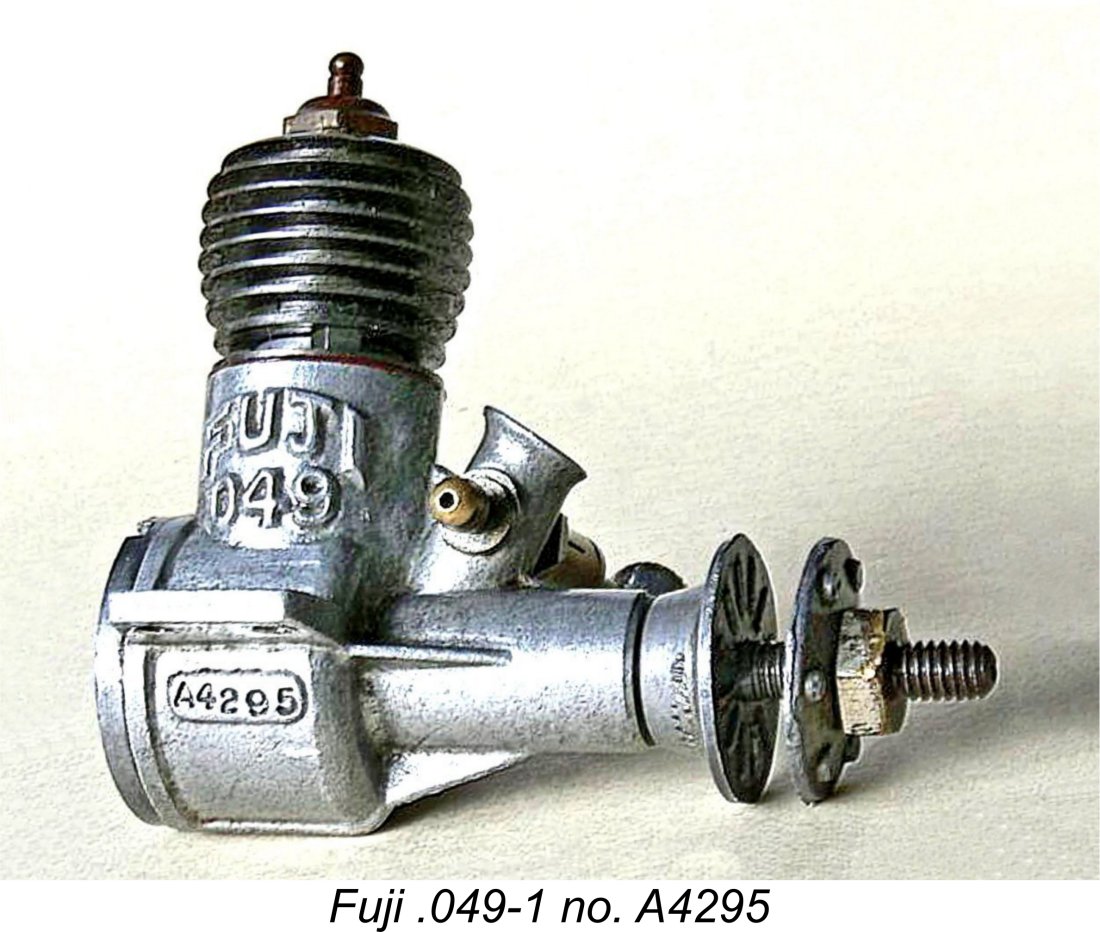

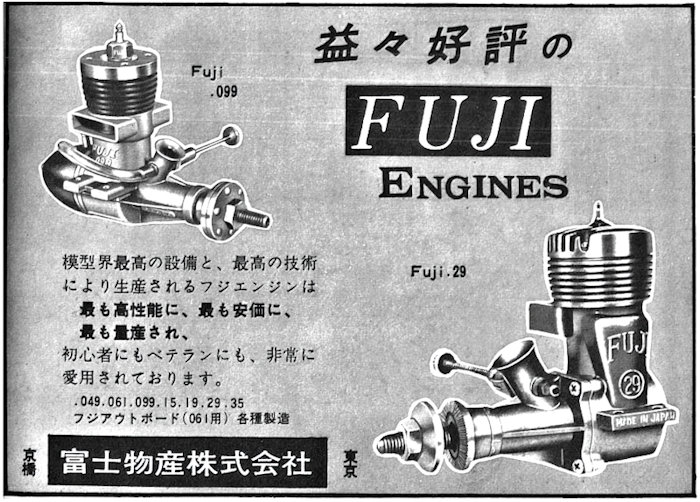

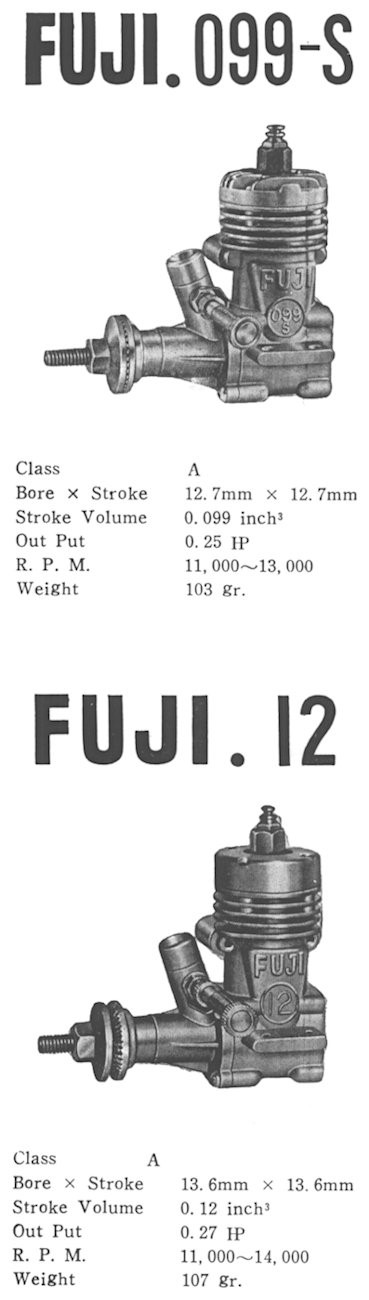

Based on the attention paid to the .099 cuin. (1.62 cc) displacement category by Japanese model aero engine manufacturers during the first few post-WW2 decades, it would appear that this displacement category enjoyed a very high level of customer support in the Asian markets in which the Fuji engines initially competed. Indeed, the .099 category seems to have come to occupy the same major market niche in South-East Asia which the .049 models did in the 1950's American market.

By contrast, the .049 displacement category was largely ignored by Japanese manufacturers In this article I’ll confine my attention to the series of .099 cuin. models produced under the Fuji banner over the years during the "classic" era. Being fortunate enough to have direct or indirect access to a fairly representative selection of the various Fuji .099 models offered during the marque's first two decades of existence, I’m probably in as good a position as anyone outside of Japan to make a reasonably well-informed attempt to document the development of these intriguing and highly collectible little engines during my period of interest. As far as I’m aware, my 2011 efforts and those of my colleagues represented the first time that anyone had attempted to present an in-depth survey of the Fuji range in the English language. It wasn’t easy, and I recognize that there are still sizable gaps in my knowledge as well as some matters about which my deductions are far from confirmed. However, it seemed better to present what I do know (or think I know!) than to do nothing. And if my fellow engine aficionados find something of interest in such information as I can offer, I'll be well rewarded. If nothing else, this survey should help readers to date any Fuji .099 models in their possession. Naturally, if someone comes up with a model with which I'm presently unfamiliar or can clarify a few dates or events for me, please send the details along - no-one will be better pleased than I, and any input will be freely and gratefully acknowledged.

In my separate overview article on the Fuji venture in general, I commented on the desirability of adopting an identification protocol for the various Fuji models. To meet this need, I have assigned model numbers to each of the variants to be described in my focused articles on the various Fuji series. It's crucial to note that these numbers are mine, not Fuji's, and are assigned purely for convenience in specifying the model(s) to which reference is being made. The assigned numbers indicate the displacement followed by the chronological position of the variant in question within the design sequence of Fuji models having that displacement. The need to do this may best be appreciated by the realization that there were no fewer than 17 distinct models in the Fuji .099 series during the classic era and that all but three of them were designated by their manufacturers as the Fuji .099! Not very helpful in distinguishing between the various models - something better was definitely needed! To illustrate my system with a couple of examples, model number 099-4 identifies the fourth known variant of the Fuji .099 cuin. series. Similarly, the 29-2 designation applies to the second identified variant in the Fuji .29 cuin. sequence. The headings of the various sections of this article follow this identification protocol throughout. Enough said – let’s get to it! 1st Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-1)

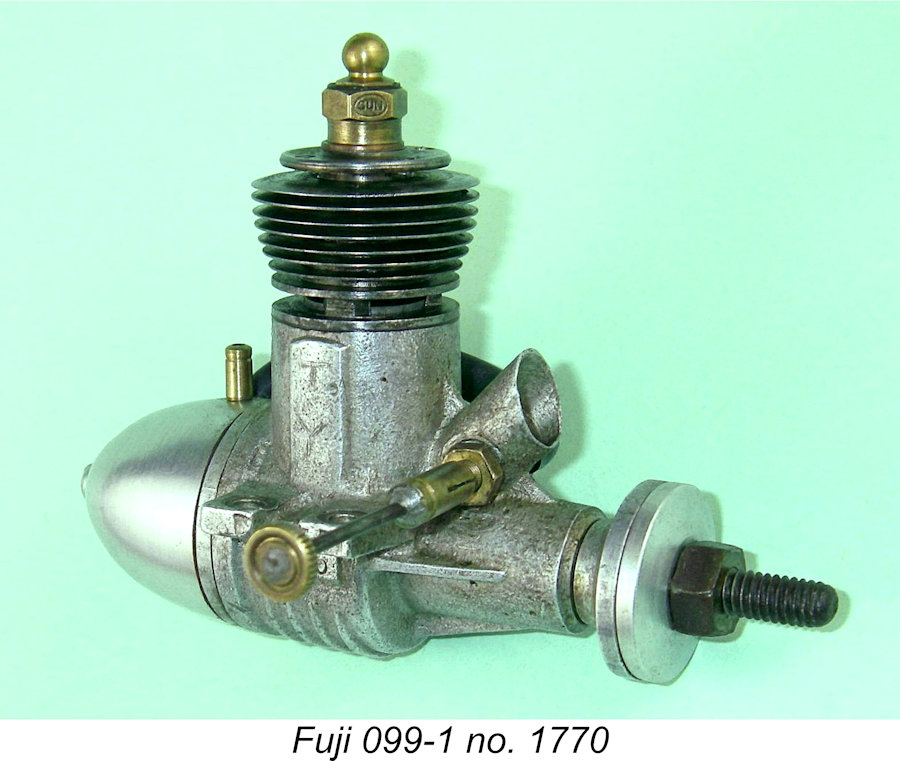

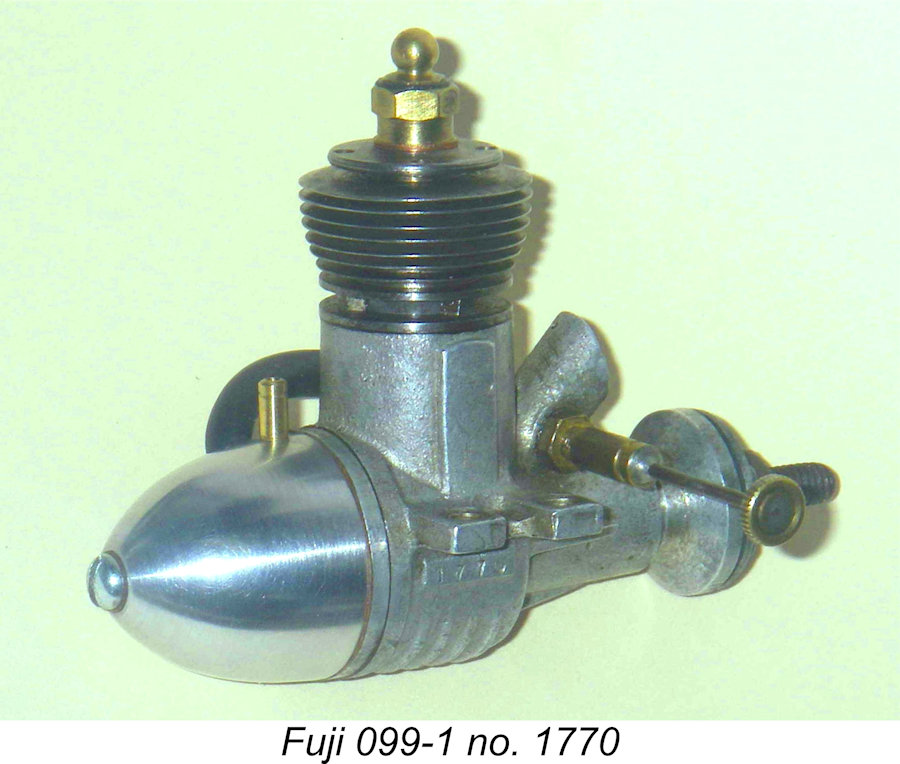

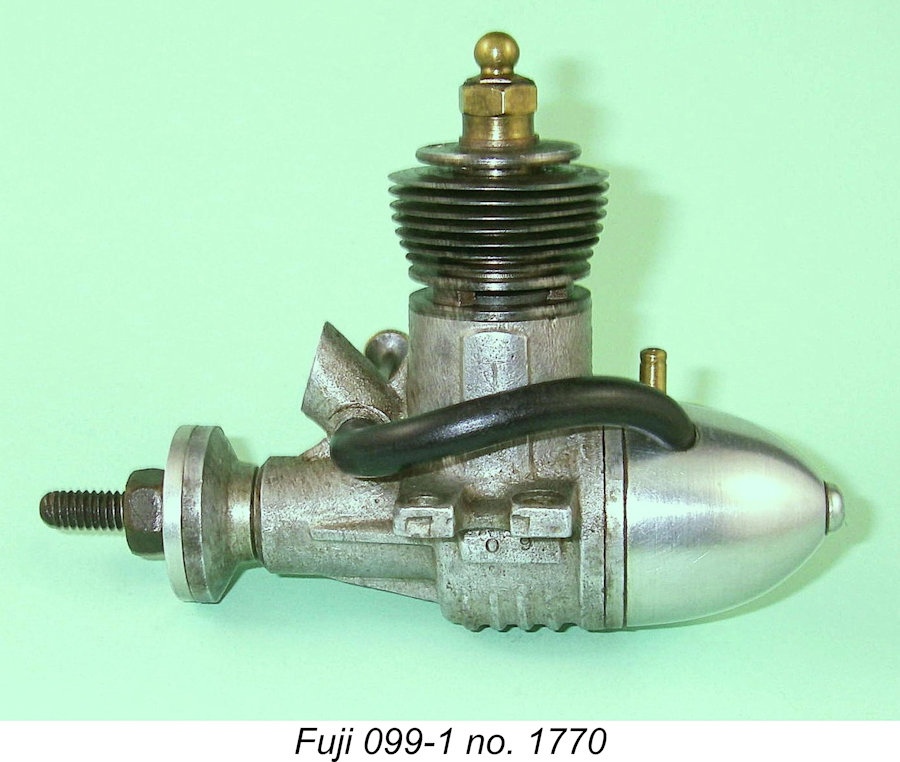

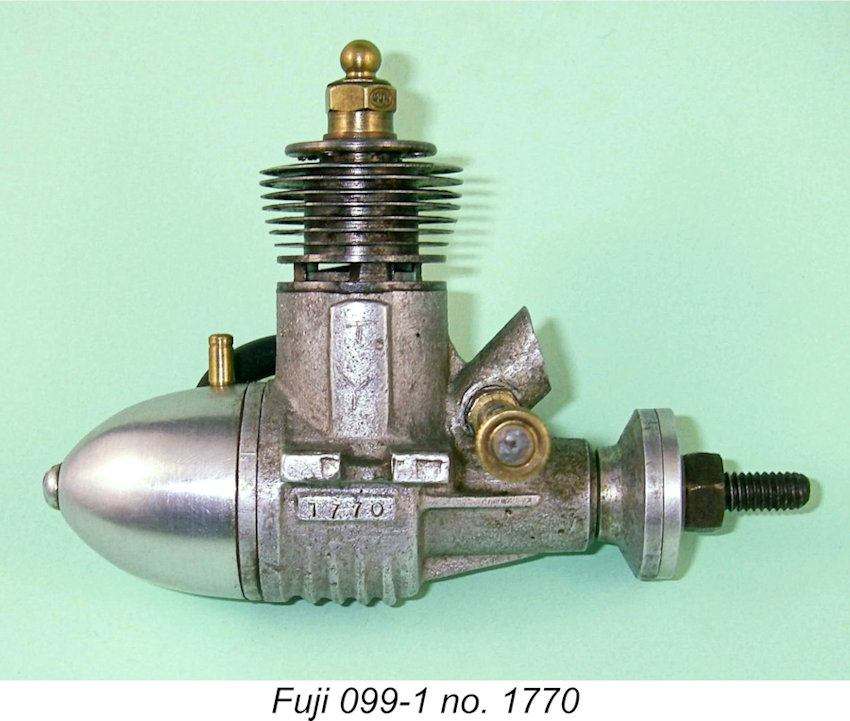

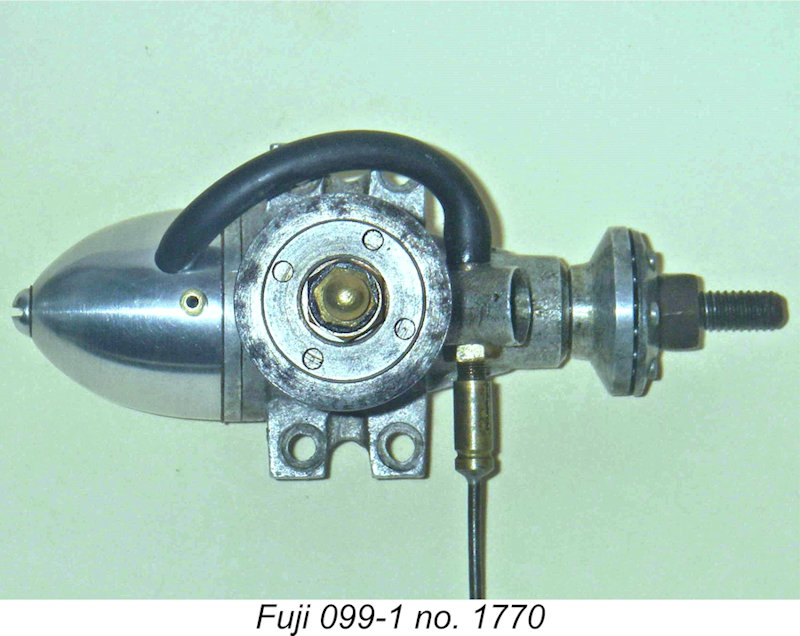

Although an extremely simple engine which was clearly designed to be produced with the minimum possible amount of complex machining work, it is nonetheless a design of considerable distinctiveness. Since all of the subsequent models in the series evolved from this original design, it's worth spending some time describing it fully. The illustrated engine bears the serial number 1770. At present the highest confirmed serial number of which I’m aware for one of these models is 3501, indicating that total production was likely quite small - probably no more than four thousand or so. The simplicity of the design is underscored by the fact that the engine consists of only 16 individual components, including the tank, tank mounting screw, glow-plug, prop driver, prop nut, prop washer, spraybar, spraybar nut and needle! Can't get much more basic than that and still end up with a motor that runs! The tank mounting screw was the only screw used in the assembly, both the cylinder and backplate being of the screw-in pattern. All cast components were produced by sand-casting. Bore and stroke measurements are square at 12.70 mm and 12.70 mm each for an actual displacement of 1.61 cc (0.098 cuin). These dimensions were to be retained in all Fuji .099 models throughout the period under discussion. The engine weighs exactly 3 ounces complete with tank, plug and fuel tubing.

These engines were originally supplied as illustrated with a plain aluminium tank similar to that used on the companion Fuji 29 model, of which much more elsewhere. However, many examples encountered today have mistakenly been retro-fitted with the later red-anodized tanks that were to become something of a Fuji trademark with their .099 engines (and others) for many years. The Fuji .099 series were to retain their back tanks up to the early 1970's, long after practically all other manufacturers outside of Britain had discarded this once-common feature. In the above context, it should be noted that the tank mounting "step" machined onto the backplate perimeter on this early model has a slightly larger diameter than that encountered on the later variants. Accordingly, the tanks from the later models will not fit an unmodified Model 099-1 backplate without forcing. Unfortunately, some examples are encountered in which the backplate has been re-machined to take a later red tank. Others may well have been retro-fitted with a backplate from a later model. I don’t endorse such modifications of an engine of this rarity, but they do appear! Others have a later tank forced or swaged into position.

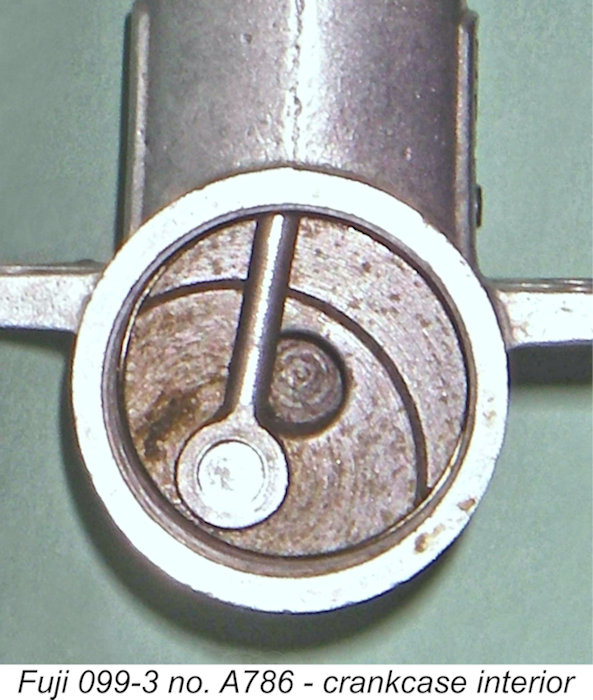

This mounting lug set-up looks (and is!) extremely vulnerable to cracking or shearing during a hard crash. The situation is compounded by the fact that the case material is relatively porous as cast. I have encountered several Fuji models having fractured lugs of this type. Indeed, sister 099-1 engine number 2220 in my own collection has a cracked lug which has been very neatly repaired, while 099-3 number A786 (see below) has an un-repaired broken lug. The fracture on the latter example exposes the porosity of the crankcase material.

The best approach to minimizing the risk of damage to the lugs during use appears to be to make a pair of 1/8 in. thick rectangular alloy plates of the appropriate size and drilled with two holes apiece at the correct spacing to allow passage of the mounting bolts. These are positioned on top of the lugs, acting in effect as clamps to distribute mounting stresses throughout the mounting lug system rather than concentrating it at the mounting holes. More importantly, they do much to spread crash-related shock loadings throughout the entire mounting lug system rather than relying solely upon the rather skimpy "expansions" around the mounting holes. On most of these engines, the name "FUJI" is stamped vertically into the right-hand side of the upper crankcase (facing forward). This stamping was clearly done prior to the case being brushed and tumbled to a bright finish, since the letters have smooth edges and a similar surface finish to the rest of the case. On engine number 1770, the "FUJI" identification has been omitted - presumably this was a "Friday afternoon special" and someone either forgot or just couldn't be bothered to do the stamping! If that engine were a postage stamp, it would be worth a lot of money!

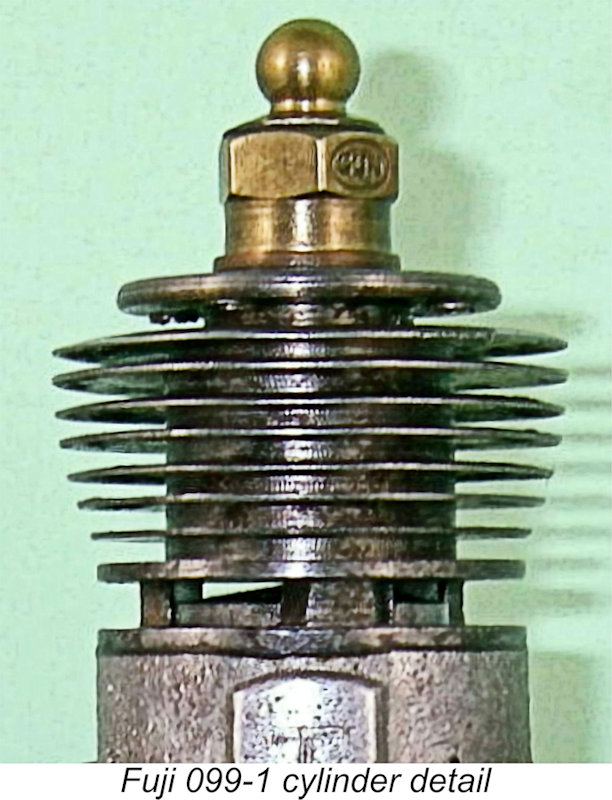

The front of the main bearing on the crankcase of this variant is machined into the form of a steep taper which matches the bearing end diameter to that of the rear of the prop driver. This is the only Fuji .099 model to feature such a provision. The case incorporates a spectacular-looking forward-facing intake for the crankshaft rotary valve. This appears to be intended to take advantage of the "ram air" effect to effectively "supercharge" the engine - a theory which has not stood the test of time. The externally-visible angle of this intake is misleading - it rather gives the impression that induction is routed through the crankweb. In reality, the actual venturi throat is drilled internally off-axis at a somewhat less dramatic forward angle, meeting the upper bearing surface in the usual location just forward of the front crankcase wall. This leaves an unbroken length of upper journal forward of the crankweb to provide a base seal and an unbroken bearing surface. A conventional needle valve assembly consisting of a spraybar and a rigid needle is fitted into this venturi. The needle features a brass thimble which is split for tension, also sporting a knurled brass control knob at the outer end. Variations of this component were to be used on all subsequent Fuji .099 models up to 1958 or thereabouts. The crankshaft itself features a counterbalanced full-disc crankweb and a round induction port to match the base of the venturi. Main journal diameter is 8 mm, with an internal gas passage diameter of 5 mm. The prop driver is located on the shaft by a square section milled onto the front of the journal which keys into a square-shaped broached opening in the centre of the machined alloy prop driver. Interestingly, the prop driver face is completely plain with no knurling, presumably to allow some prop slippage in the event of a crash and thus help to prevent breakage of the working parts. The driving faces of both the prop driver and the plain machined prop washer are generously relieved in the centre, perhaps to ensure that the engine's operating torque is transmitted though the outer circumference of the drive set-up with less chance of incidental slippage during normal operation. I have experienced no slippage problems with these rather docile low-compression motors. T This variant of the screw-in cylinder Fuji .099 is one of only three of which I'm aware which do not feature a separate alloy head mounted on top of the cylinder. On this first version, seven of the eight cooling fins are turned very thin indeed and appear highly vulnerable to damage - please take care when handling one of these! The top fin is significantly smaller in diameter and thicker than the others and has four holes drilled equilaterally around its circumference to allow for the use of a suitable pin wrench to unscrew and re-tighten the cylinder. Please use the proper tools and techniques if you really must dismantle one of these models! Better yet – leave well alone!

The porting arrangements on this model are in some respects analogous to those used in the contemporary American OK Cub models, the first of which had also been introduced in 1949. An unthreaded annular space around the full circumference of the outer cylinder wall just below the exhaust port belt feeds the cylinder through three transfer ports drilled upwards at an angle between the three exhaust ports. The tops of the transfer ports overlap the bottom of the exhaust ports very slightly. A similar unthreaded annular space is provided internally at the top of the crankcase casting. The result of this arrangement is the creation of an unthreaded annular passage encircling the cylinder at transfer port level, exactly as per the OK Cub design. The advantage is that the functioning of the transfer ports should in theory be independent of the position in which the screw-in cylinder happens to end up when tightened. The difference between the Fuji and OK systems is the manner in which the annular passage is supplied with gas from the lower crankcase. Instead of the twin bypass passages of the OK set-up which interrupt the female thread in the case at the sides, the male cylinder screw-in thread in the Fuji is interrupted by three flat channels milled into the outer wall of the lower cylinder directly below the transfer ports. These act as bypass passages to feed both the transfer ports and the annular space around the cylinder, which then assumes a flow-balancing function by promoting the even distribution of gas between the three transfer ports regardless of the cylinder orientation when screwed home. The corresponding female thread in the case itself is uninterrupted. This same set-up was later to be adopted in the original Elfin 1.49 and 1.8 BR models of 1954.

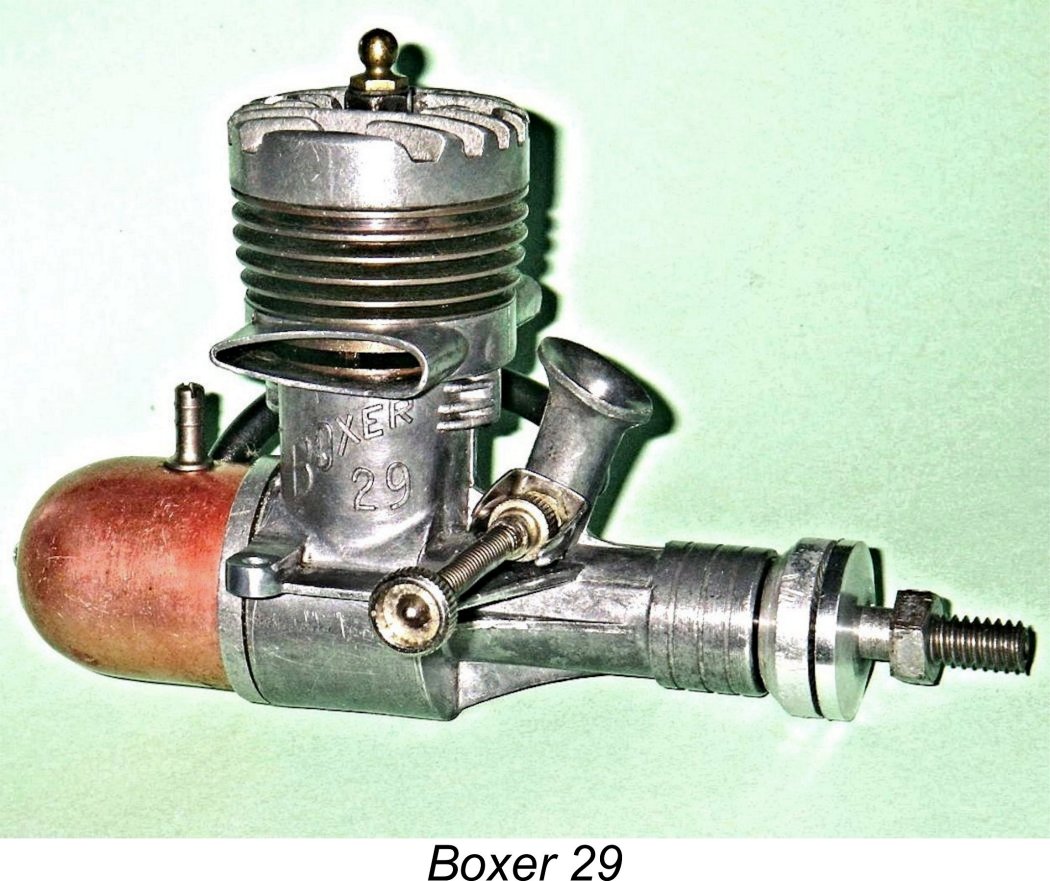

It's worth recalling for context at this point that the .099 model just described was accompanied by a sandcast Fuji .29 cuin. model of generally similar design but featuring a very different transfer porting system. This model is fully described in my companion study of the Fuji 29/35 models. A neat little sandcast .049 model of generally similar design was also introduced during the Fuji company's first few years. This model too is fully described in a separate article. Other models soon followed - indeed, the range was destined to expand quite rapidly over the next 5 years or so, as we shall see in due course. 2nd Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-2)

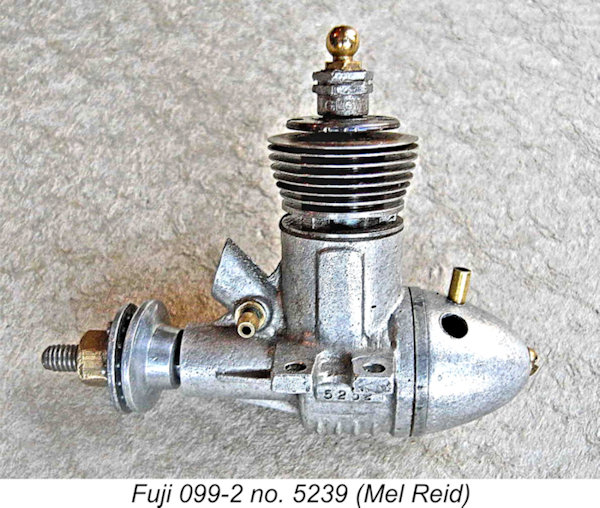

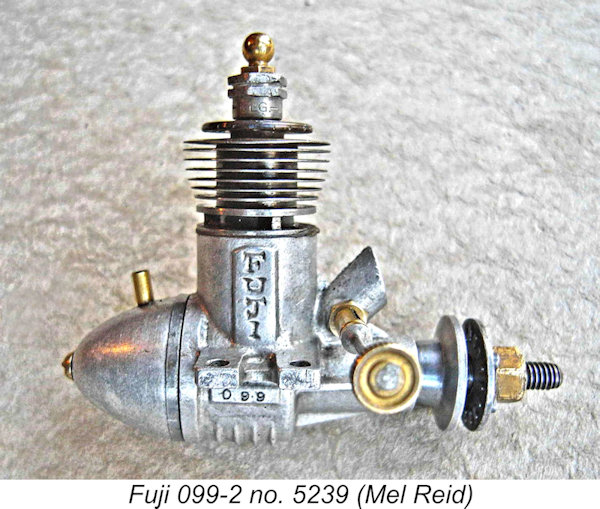

This variant of the engine retains the same cylinder fin configuration and appears identical to its predecessor at first glance. However, there are in fact several differences which are not immediately obvious. The tank is still made of plain aluminium but now has a slightly smaller internal diameter, similar to that used on the later red-tank models to be described in subsequent sections of this article. The tank is also 2 mm shorter than that used on the 099-1 model. The backplate has been modified with a thicker rim having a slightly smaller diameter shoulder to locate the re-designed tank. Consequently, a red tank from a later model will fit this variant without modification or forcing.

The squared end to the crankshaft for keying to the prop driver has been replaced in this example by the more common single flat arrangement seen on later models of the engine, although the shaft is otherwise unchanged from that of the previous model. This is one of the anomalies presented by the early Fuji engines, since I’m aware of at least one later variant of the Fuji .099 which retains the earlier square keying system for the prop driver. It would appear possible that Fuji was experimenting with different shaft designs at this time and released engines in the same series having different shaft configurations. Alternatively, this could represent the fitting of a replacement shaft by an owner. We shall encounter such anomalies again when we examine the next model in the series. On the cited example, the serial number has been placed on the other side of the engine and "09" replaced by "099". Of course, this may just be an operator-related anomaly as opposed to a wholesale

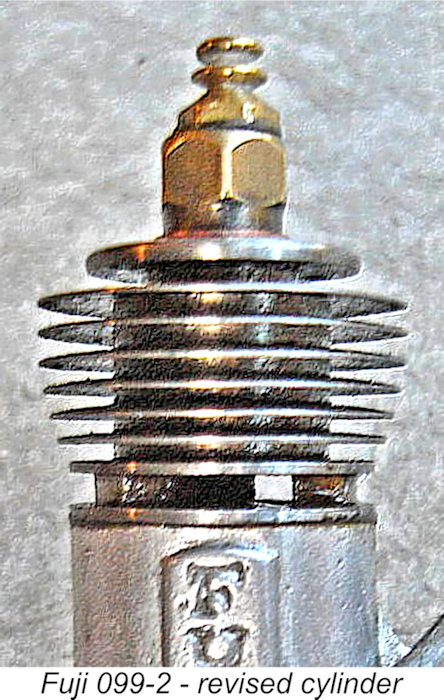

The result was the fitting of a revised cylinder featuring slightly thicker and hence somewhat less fragile cooling fins. The cylinder height and porting remained unaltered, and to allow for the increased fin thickness the number of fins was reduced by one. Hence there were now only six thin cooling fins between the port belt and the thick upper flange. The revised cylinder continued to feature the blind bore and plain unadorned head of its predecessor. At the time when this cylinder first appeared on the Fuji .099 model, the manufacturers clearly didn't consider this one change to warrant the recogntion of the revised engine as a new model, since performance was in no way enhanced. Accordingly, the serial numbering sequence for the 099-2 continue uninterrupted at this point in time. Engines featuring the revised cylinder bearing the serial numbers 8247 and 9873 have appeared on eBay. These examples conformed in all respects to the 099-2 design described above apart from the fitting of the revised six-fin cylinder. This evidence appears to confirm that serial numbers for the 099-2 likely reached into the 10000 range. 3rd Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-3)

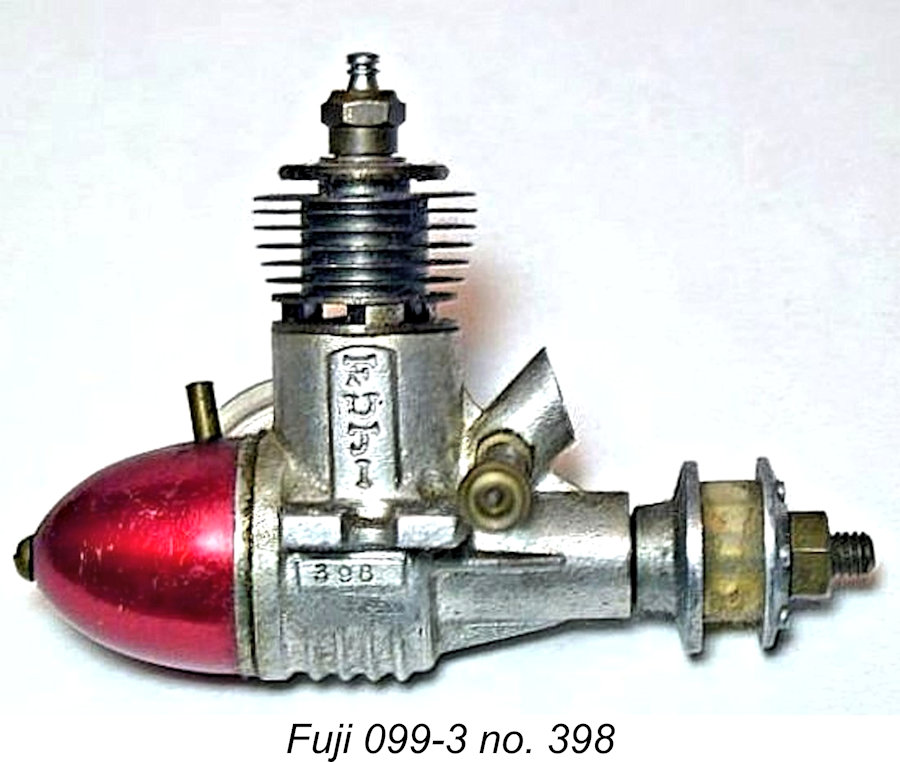

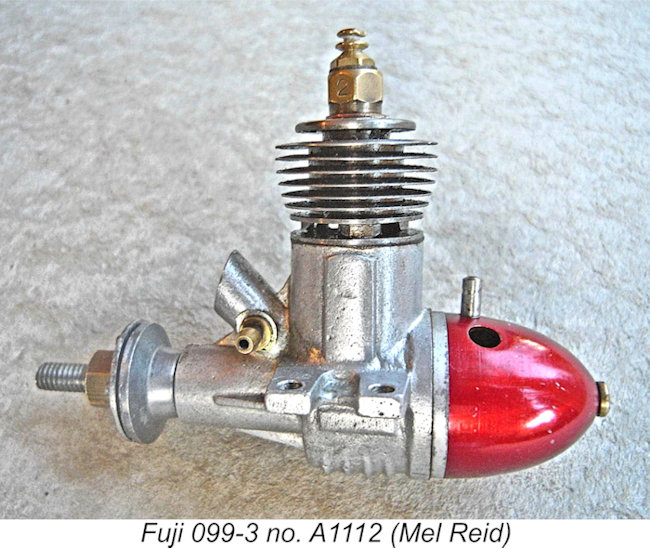

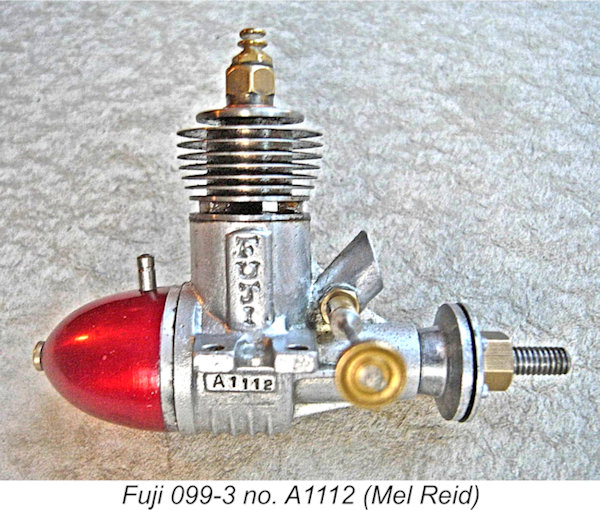

To recognize the enhanced performance now available, the serial numbering sequence was re-started at 1. Initially, this new sequence appears to have been purely numerical - I'm aware of the illustrated 099-3 example bearing the serial number 398. However, the factory very quickly recognized that this would create confusion when spare parts were ordered, hence adding an "A" letter prefix to the numbers.

Another performance-enhancing modification was a slight increase in the diameter of the induction hole in the centre of the crankshaft from 5 mm to 5.5 mm - the unchanged 8 mm journal diameter was clearly considered to be able to accomodate this. The shafts of the 099-2 and 099-3 variants are therefore quite distinct. A further change was in the method of producing several of the components. For the first time, we begin to see the use of pressure die-casting, albeit as yet on a small scale. The backplate, prop driver and prop washer of this variant were produced by the die-casting method, replacing the fully-machined components used previously. However, the main crankcase casting continued to be produced by sand-casting, in fact being identical to that used in the previous model. The conrod also continued to be the same steel component that had been used all along.

A later example of the same model (number A1112) uses the same single-flat prop driver keying system as that seen on 099-2 engine number 5239. This is a further indication that Fuji may have been experimenting with different shaft configurations. A special batch of prop drivers must have been broached to create a square-section recess to fit a corresponding batch of square-keyed shafts.

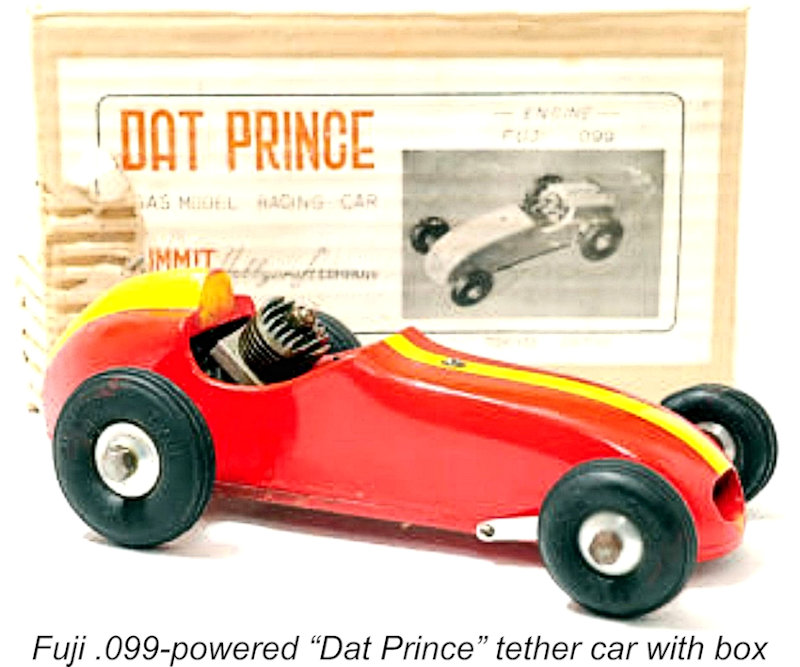

Finally, the serial number continued to appear in the cast-on rectangular "panel" beneath the right-hand mounting lugs, but the former .09 designation which had appeared in the left-hand panel was no longer present. In contrast to the previous model, the serial number was apparently stamped on before the tumbling process, since its edges are rounded like those of the "FUJI" name which continued to appear on the right-hand side of the case above the mounting lugs. In all other respects, this model was identical to its predecessor. The lowest confirmed serial number for this variant is 398, with the An anomaly of which I've been made aware was engine number H1171 of this type. I believe that the "H" was probably struck in error by a worker who mistook an H punch for the correct A tool. Such erroneous strikes are by no means uncommon. Based on the limited serial number data presently on hand, it seems that this variant appeared after perhaps some 10,000 examples of the two previous models had been produced in total. The time required for the fledgling company to make this number of engines (along with the concurrent production of their .29 model) argues that the variant just described probably appeared at some indeterminate point during the latter part of the year 1950 or perhaps early 1951. One little-remembered fact is that the Fuji .099 engines quickly became well-known in Japan for powering a series of small tether cars. These cars were not produced by Fuji Tokushu Kiki These early Fuji-powered cars are quite rare outside of Japan, selling for relatively high prices when they do appear. They featured sand-cast aluminium chassis with the powerplant mounted transversely at the rear. Indications are that the serial numbers which appeared on the chassis and on the powerplant were matched - a recent eBay offering featured such a car which bore the matching serial number 2501 on both the chassis and the engine. The engine in this car was a Fuji 099-3 model like that just described.

In 1949 Shimatani designed and marketed a wooden-bodied car called the Dat Prince, which was powered by the then-new Fuji .099 engine. This car was evidently well received, remaining in production for a number of years and actually finding its way to Britain, where it was offered as a plan by the British "Model Maker" magazine (Plan no. MM/385). Shimatani then switched back to cast aluminium chassis, introduced his "Midgetee" line using mainly (but not exclusively) Fuji .099 and .29 engines. Today these are the most familiar Fuji-powered cars. Shimatani's tether cars are often mistakenly referred to as "Fuji cars", although they are in fact products of a completely separate company and were sometimes sold with powerplants other than those from Fuji. The engines from all sources were presumably supplied in batches under contract. It would seem that they must have been supplied un-numbered so that they could be marked with the same number as their chassis during their assembly by Mr. Shimatani and his colleagues. 4th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-4)

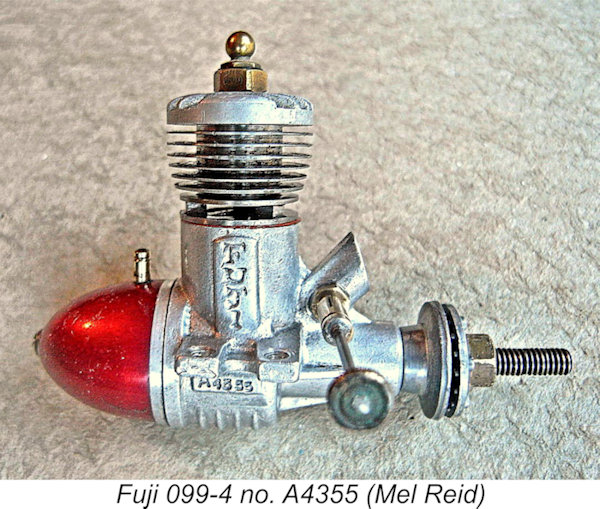

At some indeterminate point in 1951, according to the very scanty information available on the Model Engine Company of America (MECOA) web site, the company decided to make a few further changes to the .099 model described above. Oddly enough, it appears that Fuji did not bother to start a new serial number sequence at this time, instead simply carrying on with the "A" prefix numerical sequence begun with the previous variant. They were to reprise this anomaly again in the future, as we shall see in due course. Whatever Fuji's opinion at the time, the changes evident in the revised model are more than sufficient for present-day collectors who care about such things to regard this as a distinct variant. The illustrated example of the revised model bears the serial number A4355, while the highest recorded number for one of these models is A5744. The lowest serial number of my acquaintance for this variant is A2593 which appeared on eBay some time ago. This latter figure The changes embodied in the revised design were once again focused for the most part upon the cylinder. The sand-cast crankcase with its stamped "FUJI" identification was unchanged from that of the previous model, and the serial number was stamped as before on the side of the crankcase under the right-hand mounting lug. As before, no indication of the displacement appeared anywhere on the engine. Rather oddly, Fuji failed once more to take advantage of the opportunity to eliminate the chronically fragile "twin expansion" mounting lugs. They remained an un-addressed weakness of the design. The basic design concept remained unchanged, the one-piece screw-in cylinder with radial porting, six integral fins and blind bore being retained. However, the cylinder was now machined from steel - a long-overdue improvement. The most immediately obvious change was to be seen in the upper cylinder configuration. The former thick upper fin with its four holes for the application of a pin wrench was eliminated in favour of a central boss of relatively small diameter, through which the plug installation hole was drilled and tapped. A separate finned "cylinder head" machined from light alloy bar-stock was pressed onto this boss (presumably after the cylinder was screwed down really hard) and swaged in place using a punch at four points around the circumference of the joint between the head and the boss. It must be understood that the bore of this model remained blind - the new head was in fact a "dummy" which really only served a cosmetic function and reduced the engine's visual tendency towards "squat-ness". The engines will run perfectly well with the "head" entirely removed. This feature mirrored the similar arrangement which had been pioneered in America by O&R and had first appeared in Japan a year or so previously on Hope's original "New 29" model.

Another change, and not one for the better in my personal view, was the final elimination of the square-section keying of the prop driver to the shaft in favour of a single flat milled into one side of the shaft, with the die-cast prop driver having a corresponding internal "key" to lock it to the shaft. This arrangement is far more prone to wear and eventual failure than the square section used originally, making it hard to understand why this change was made. A taper fitting is more durable than either, of course. Be that as it may, the single-flat locking system was to survive for the rest of the long production life of the classic Fuji .099 series. Presumably, cost considerations once again played a role in this decision. This model also featured a further expansion of the use of die-casting in the production of these engines. The former steel conrod was replaced in this variant by a pressure die-casting in light alloy featuring a bronze-bushed big end - a definite move in the right direction. Otherwise, the revised model was essentially identical to its predecessor, including the slightly enlarged central gas passage in the shaft. The full-disc counterbalanced crankweb was retained unaltered as was the use of a simple round hole for the induction port in the shaft. The only change to the shaft was the provision of a shoulder on the crankpin at its junction with the crankweb to keep the revised rod clear of the crankweb during operation. Bore and stroke were identical, and the weight too remained the same at 3 ounces exactly all complete. Based on the fact that the lowest serial number yet encountered for the next variant to be described is A7167, it would appear that perhaps as many as 4,000 examples of the 099-4 variant may have been manufactured in total. 5th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-5)

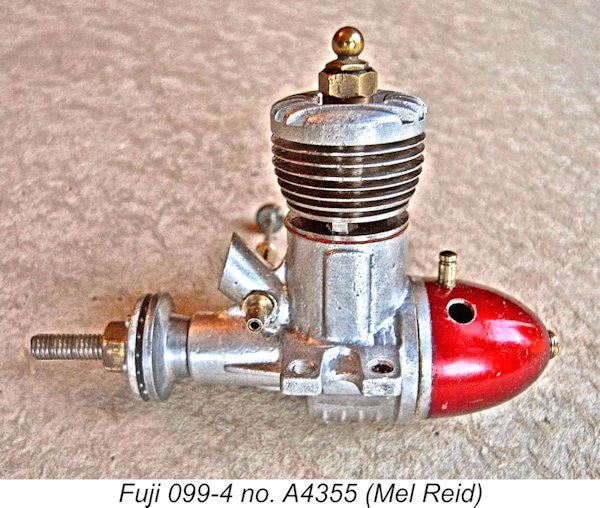

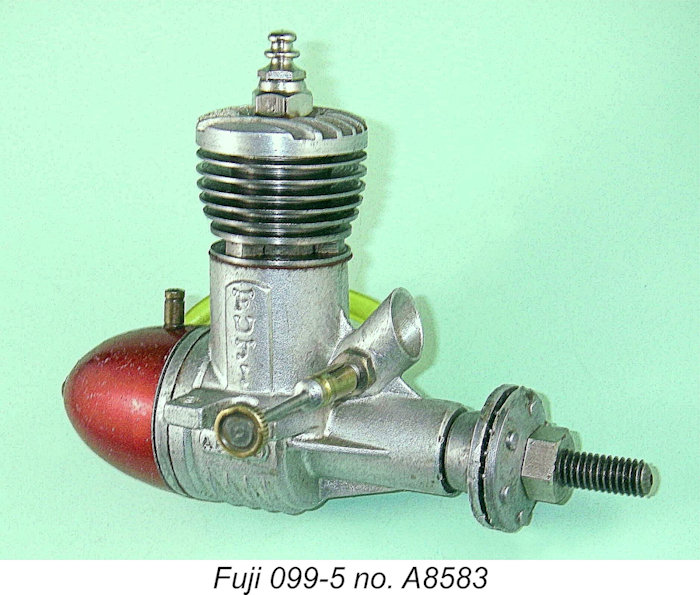

The porting arrangements remained unaltered in this variant, but the revised model featured an upper cylinder having fewer and thicker cooling fins yet again - presumably even the six somewhat thicker fins on the third and fourth variants had been found to be too vulnerable to damage. There were now only five relatively thick and hence far sturdier fins above the exhaust port belt instead of the former six.

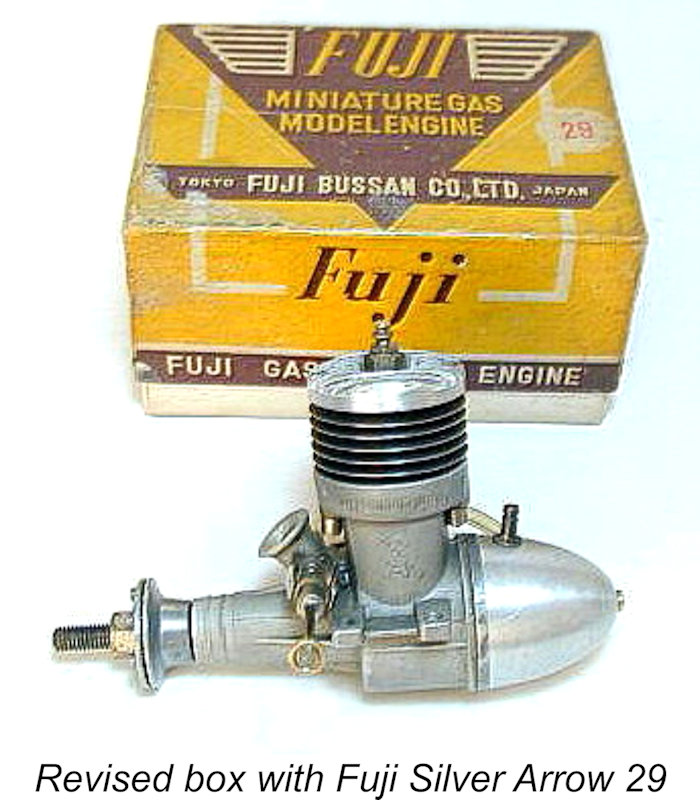

By rough volumetric measurement, the compression ratio of around 8:1 was unaltered by the raising of the cylinder, so it seems that the machining specifications of the blind bore must have been amended to lower the cylinder head in order to maintain the compression ratio. The engine was otherwise unchanged from its predecessor, including the retention of the fully-machined swaged-on cylinder head. As noted earlier, the lowest serial number yet confirmed for one of these models is A7167, while the highest number of my present acquaintance is engine number A9462. If these numbers were near the lower and upper limits, this would imply that this should by rights be one of the rarest Fuji .099 models. However, nice examples of this variant turn up with surprising frequency. Either they were really treasured or they didn't get used much! More probably, the This model of the Fuji .099 appears to have remained in production until mid-1953. By that point in time, the engines were packed in a plain and quite sturdy dark yellow cardboard box with an attractive blue or red label on top featuring English-language lettering. This shows that penetration of the English-speaking market was beginning to assume some importance for the company. At this time the label included a neat little circular trade-mark in addition to the familiar "winged" Fuji trade-name. The trade mark was later to be dropped, although the "winged" Fuji trade name was retained for some years thereafter. The manufacturers continued to be identified as Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work. Interlude: The Silver Arrow 29 (model 29-6) and the Adoption of Die-casting at Fuji It's now necessary to leave our main subject briefly in order to document a major production change which was phased in by Fuji over a period of time beginning in 1950. This was the progressive elimination of sand-casting in connection with the production of the cast components of the Fuji range in general. According to Japanese sources, one of the characteristics which always set Fuji apart from their domestic rivals was the fact that, alone among Japanese manufacturers of this era, they pursued a policy of doing all of their own manufacturing in-house - they did not sub-contract any aspect of the production of their model engines. This included the production of the required castings. There are indications that they may have departed from this practice at a later stage, as documented in my overview article, but even then they appear to have retained ultimate control over their own manufacturing activities. A general switch to die-casting for all models would clearly require a major investment in the acquisition of the necessary equipment and know-how at Fuji's own production facilities - no small undertaking! The company appears to have adopted a very rational phased approach to this issue. We have seen that they first tried their hand at die-casting on a very small scale with a few of the minor components of their 1950 .099 model (099-3), later adding the conrod of their 1951 .099 variant (099-4) to their die-casting repertoire. It would seem that their purpose in doing this was to gain first-hand experience with the new technology as well as test its economic benefits (if any). They were clearly hedging their bets at this time, since the balance of the cast components for the range as it then stood continued to be produced by sand-casting.

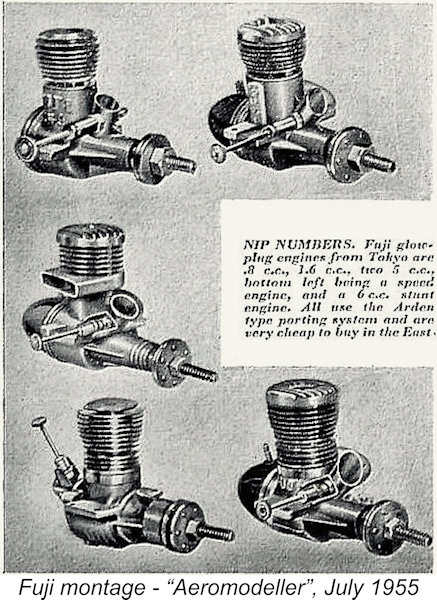

By this time too, the scale of engine production and the scope of the range had reached levels at which the use of sand-casting was no longer viable if the company was to continue to expand. Clearly their sales prospects were now sufficiently promising for a major investment in die-casting technology to be deemed worthwhile. However, at the time of which we are now speaking the company was still a relatively small concern by industrial standards. Consequently, a wholesale switch to die-casting for the entire range would represent a level of investment which the company might find difficult to justify or even to finance. For this reason, the The first Fuji model to be produced entirely by die-casting was the .29 cuin. Silver Arrow (model 29-6). This was Fuji's first loop-scavenged design, and it supplanted the original radial-ported 29 series mentioned earlier. It appears to have been introduced in the latter half of 1952. I’ve described this Suffice it for now to say that Fuji clearly learned well from their experiences with the Silver Arrow. They were to give ample proof as time went by that their die-casting skills were second to none in the model engine manufacturing field, regardless of one's standards of comparison. The other models in the range continued to be offered in their sand-cast configurations, a fact which is confirmed by a range illustration published somewhat belatedly in the July 1955 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine. Despite the publication date, this illustration is clearly a Fuji promotional montage showing the range as it existed in early 1953, since the disc-valve sand-cast .29 "racing" model 29RV-2 (which was phased out during that year) is still illustrated and the .15 model (introduced in early 1955) is not included. However, the die-cast Silver Arrow, which survived until late 1955, is very much in evidence alongside its sand-cast siblings, including the 099-5 model described earlier. Apart from being the first Fuji model to be die-cast throughout, the Silver Arrow is significant in that it represents the first step in what was to be a gradual but inexorable move away from the old (and it must be said, individualistic) Fuji radial-ported designs towards the completely conventional loop-scavenged designs that were to come. But that was still in the future as of 1952. For now, let's return to our discussion of the Fuji .099 models. 6th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-6) - First of the "Menasco" Series

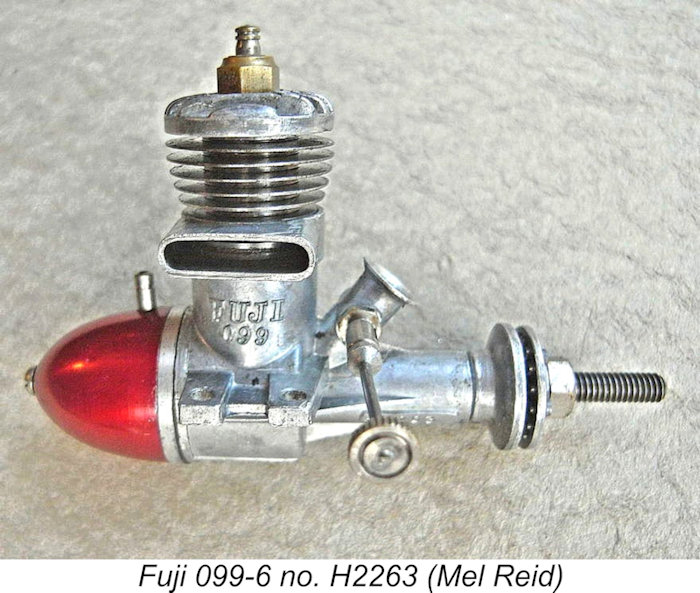

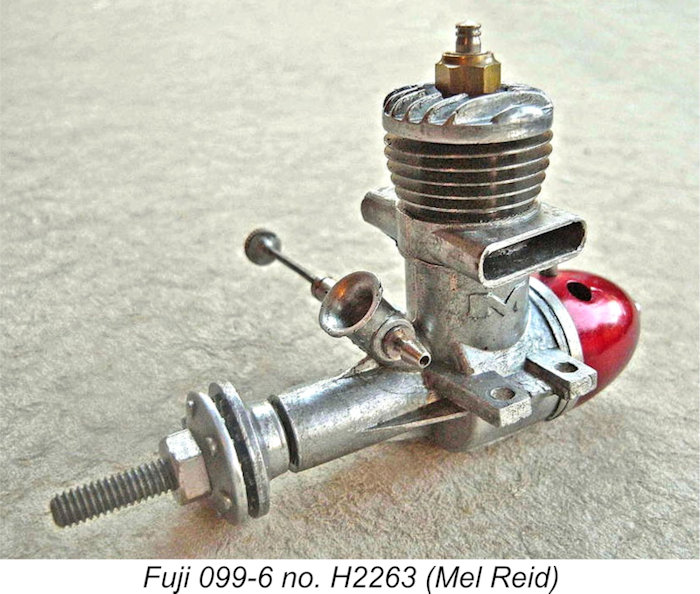

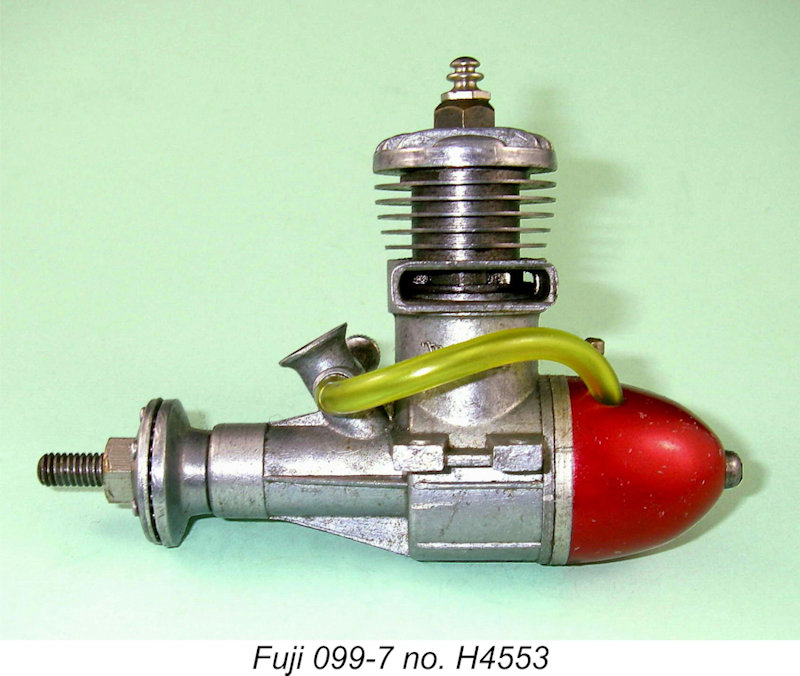

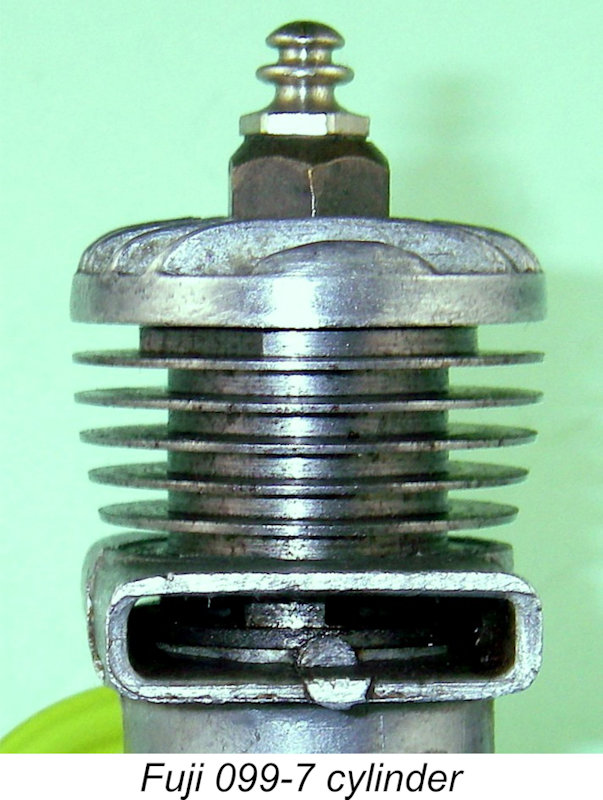

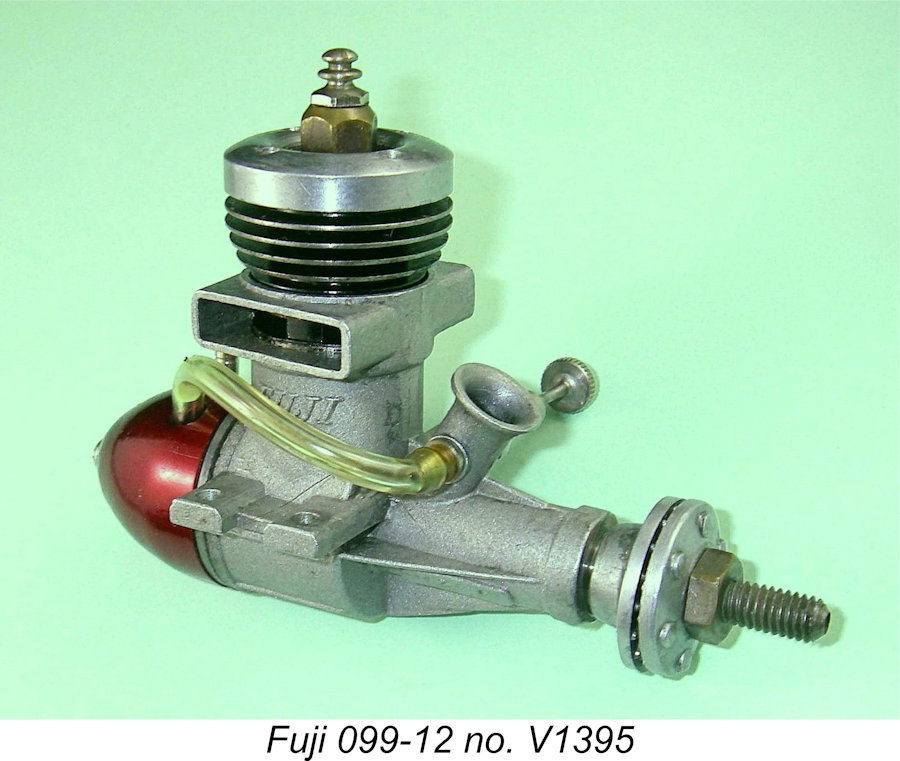

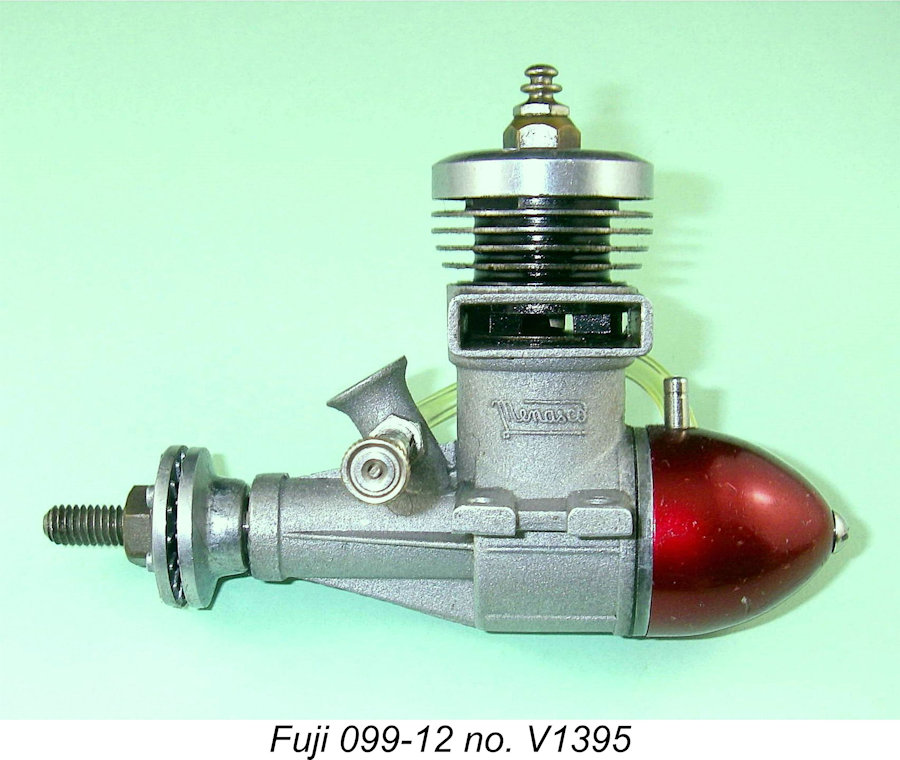

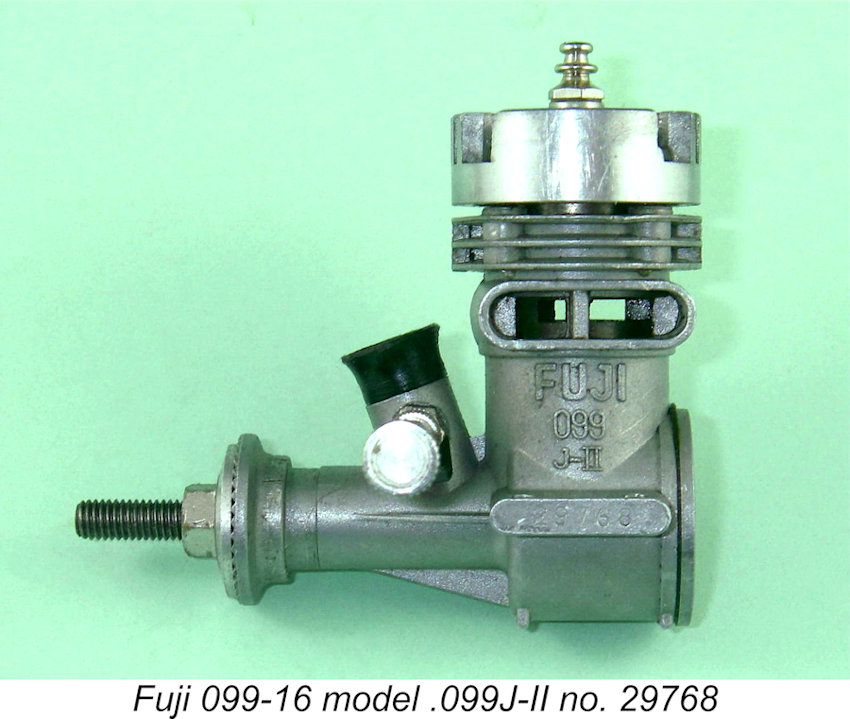

The manufacturers understandably saw this as a distinct variant, since they re-started the serial number sequence with the addition of the prefix "H" to the numerical value. The illustrated example bears the serial number H2263, which is the highest number yet encountered for one of these models, the lowest being H0276 (eBay offering).

I’ve also taken note of similar engine number HR1 59 (as written) which appeared on eBay some time ago. As far as I could tell, that example was identical in all respects to the others in this H-prefix series, hence I’m presently unable to explain this seeming anomalous number. With this model and several of its companions in the range, Fuji introduced yet another trade-mark feature which was to be applied to other Fuji models and was destined to last for some time on the .09, .15 and .19 designs - the well-known Fuji "twin stack" crankcase. They appear to have been influenced by O.S. in adopting this feature, since O.S. had used the twin-stack configuration on their .29 cuin. models since 1948 and had used the same arrangement on their competing 1951 "New .099" model. KO also used the twin stack configuration in their .099 model of 1953, and Mamiya were soon to follow suit with their revised 1954 9X .099 model as well as their .15 offering of the same year. Twin stacks were "in"!! Oddly enough, Fuji failed yet again to take advantage of the opportunity presented by the creation of the new die to eliminate the very evident weakness represented by the "twin expansion" mounting lugs. These continued to be featured on the new model, as did the rather problematic "single-flat" keying of the prop driver onto the crankshaft.

The internal porting arrangements were unchanged from the previous model. However, the use of die-casting with its closer dimensional control of the finished castings encouraged the designer to reduce the outside diameter of the upper case "spigot" into which the cylinder screwed from 19.5 mm to 19 mm even. This was achieved by marginally reducing the wall thickness of the case. Absent too was the spectacular "ram air" intake, which was replaced by a far less striking stubby angled venturi of conventional bell-mouthed form. The crankshaft was made considerably longer than that of its predecessor, and the induction port in the crankshaft was now cut square in typical American fashion to give more rapid opening and closing. The small "flat" cast into the crankcase for the serial number was now located on the lower right side of the main bearing rather than beneath the right-hand mounting lug. The final change was the addition of the twin stacks, which served no functional purpose other than perhaps to reduce the tendency for dirt to enter the cylinder during a crash. On this model, these stacks were relatively small in sectional area and had rounded corners.

Apart from the technical changes documented above, the new .099 model also marked the beginning of an interesting brand-name association which was to continue throughout the balance of the 1950's in various forms. The new die incorporated the name "Fuji 099" cast onto the right-hand side of the case (looking forward) under the stack on that side. The area beneath the left-hand stack bore the letter "M" cast in relief. It was soon to become apparent that this mysterious letter "M" stood for Menasco, a then-famous name in full-sized American air racing. Although at present I can offer absolutely no direct supporting evidence, the application of the Menasco name to these engines appears at first sight to suggest some kind of a tie-in between Fuji and the American Menasco Motors Company of Los Angeles, California. The implication is that the Fuji manufacturers had serious intentions of penetrating the American market at this time and had entered into an agreement with Menasco to allow the use of the Menasco name to add a touch of "brand recognition" to their US marketing efforts. Oddly enough though, the Menasco name was only ever directly associated with the Fuji .099 models. Even more oddly, the name appears never to have been used in any of Fuji's promotional leaflets. Strange .......wish we knew more!

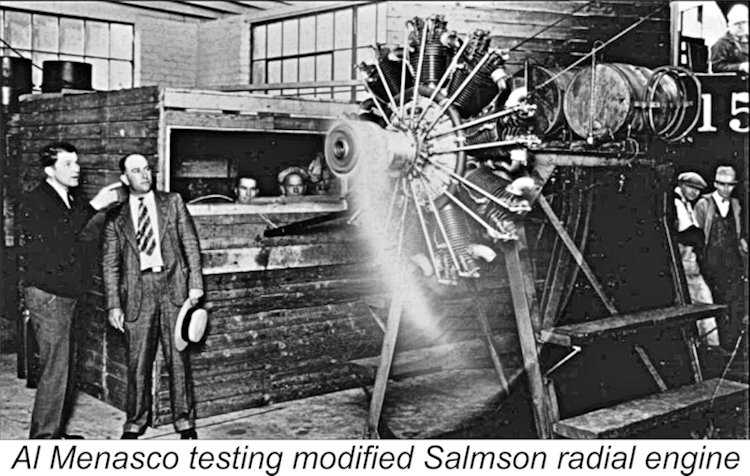

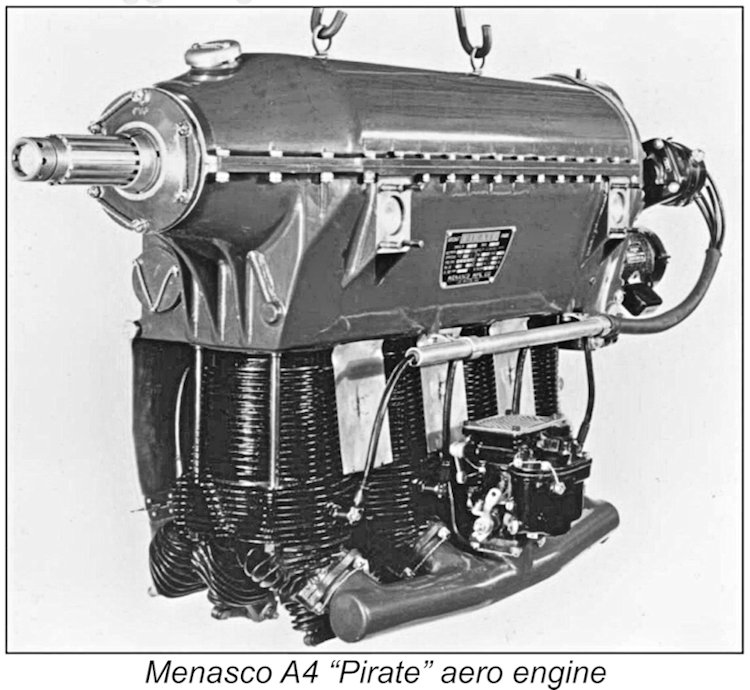

The company's first product was an air-cooled rebuild of a French-made Salmson radial aero engine. Would you stand where Menasco is standing during a test of one of these engines? And without hearing protection?!? Different days ........... In 1929, Menasco introduced the A4 "Pirate", the first example of what was to become its main product line, the inverted in-line high-performance aero engine. Apart from their excellent performance, these engines afforded much-improved forward visibility to the pilot. By the outbreak of WW2 in late 1941 (as far as the USA and Japan were concerned), the name of Menasco was well and truly identified in the American public mind with high performance full-sized aircraft.

The Menasco company remained in business over the years, changing its name to Menasco Aerospace and being noted more recently for its high-tech landing gear. After becoming a part of Coltec Industries, Menasco Aerospace was acquired by Goodrich Aerospace in 1999. It seems worth recalling at this point that the connection of the Menasco name with the Fuji .099 series came about at around the same time as the company was marketing their "Silver Arrow" .29 model 29-6. The name "Silver Arrow" was popularly applied to the famous stable of Auto Union and (later) Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix racing cars which were so widely known in the early fifties. The use of the Menasco name may have been no more than a parallel marketing ploy intended to impart a "racing" cachet to the .099 engines bearing this designation. If so, it was clearly aimed directly at the US market. In various forms, the "Menasco" Fuji .099 models were to remain in production throughout the remainder of the 1950's, finding their way all over the world in the process as Fuji expanded their international marketing efforts with considerable success. Let's now look at the further variants in the order in which the observable design progression and other evidence suggest that they appeared. 7th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-7) - Second of the "Menasco" Series

The design changes which produced the 099-7 model evidently appeared after perhaps 3000 or so examples of the first "Menasco" Fuji .099 (model 099-6) had been made. Engine number H2263 is presently the highest serial number of which I’m aware for the 099-6 variant, and by the time we reach serial number H4553 we see the changes which gave rise to Model 099-7 now under discussion. This implies that the company did not see the changes involved to be sufficient to The highest serial number of which I’m aware for the revised model is H5444. The implication is that perhaps 3000 examples of this model were produced in total. The frequency with which Fuji were amending their .099 design during this period meant that the numbers of each variant actually produced were quite small.

Another observable change was the addition of an expansion at the front of the main bearing which was machined to form a fairly lengthy "collar" at that point. The bearing length of this model was slightly longer than that of the previous variant, but this was offset by the prop driver having a shorter length that that of its predecessor. The prop overhang was thus unchanged. The crankshaft journal length was made slightly longer to match the longer bearing, but the threaded portion of the shaft at the front was shortened, giving an overall reduction in crankshaft length. Presumably the length of thread formerly provided had been (correctly) judged excessive in the context of the props normally used with this engine. Apart from the changes noted, the engine remained indistinguishable from its predecessor. The fact that an illustration of this variant appeared in the July 1954 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine proves that it was certainly on the market as of the first half of 1954, allowing for editorial lead-time. Meanwhile, Back at Head Office………………… It was at about this time that the Fuji engines ceased to be identified with Fuji Tokushu Kiki Work and were instead credited on the leaflets to a new company named Fuji Bussan, a name which was to be retained for the balance of our study period. The term "bussan" means more or less "products", so the new business entity translated very roughly into Fuji Products.

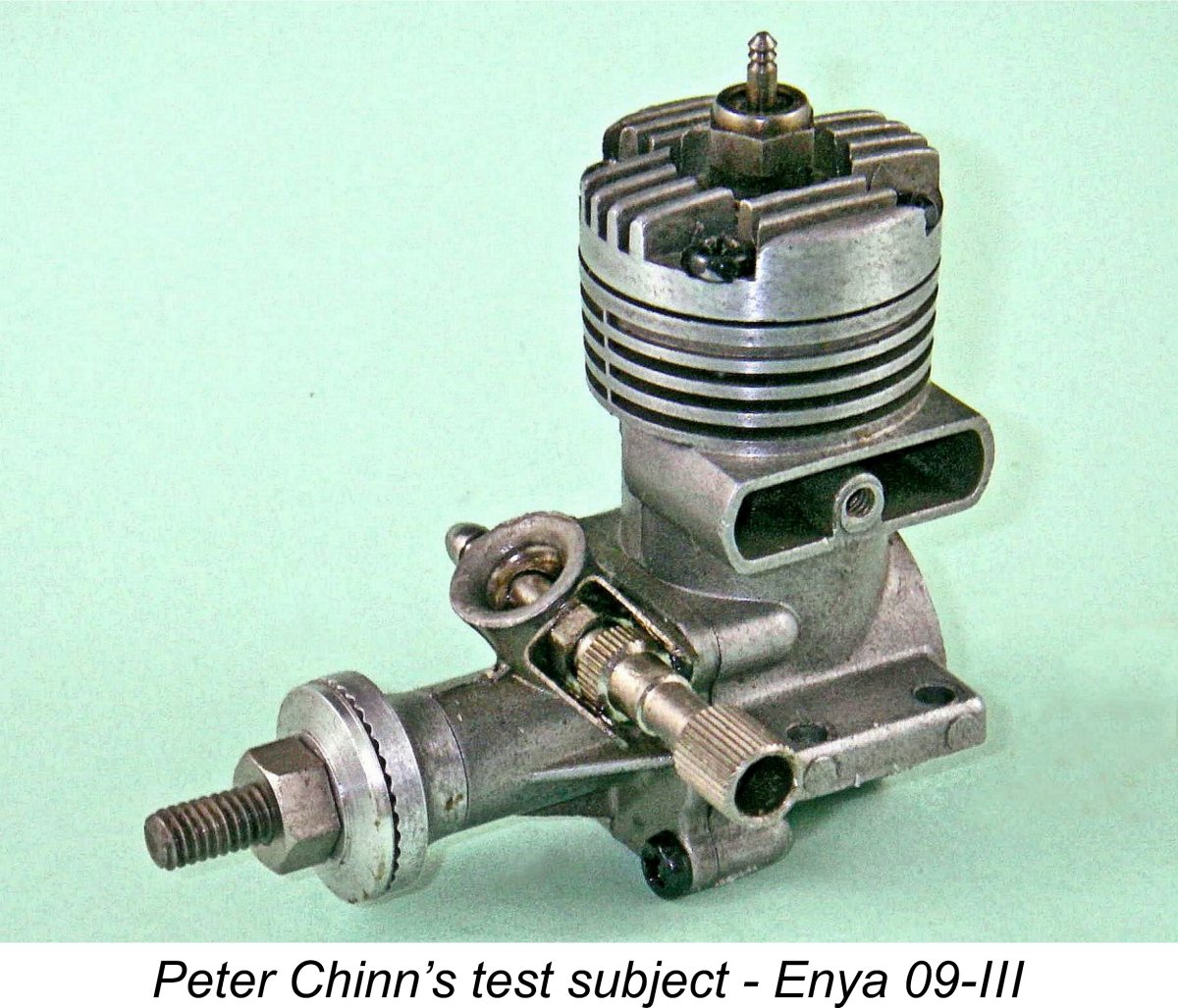

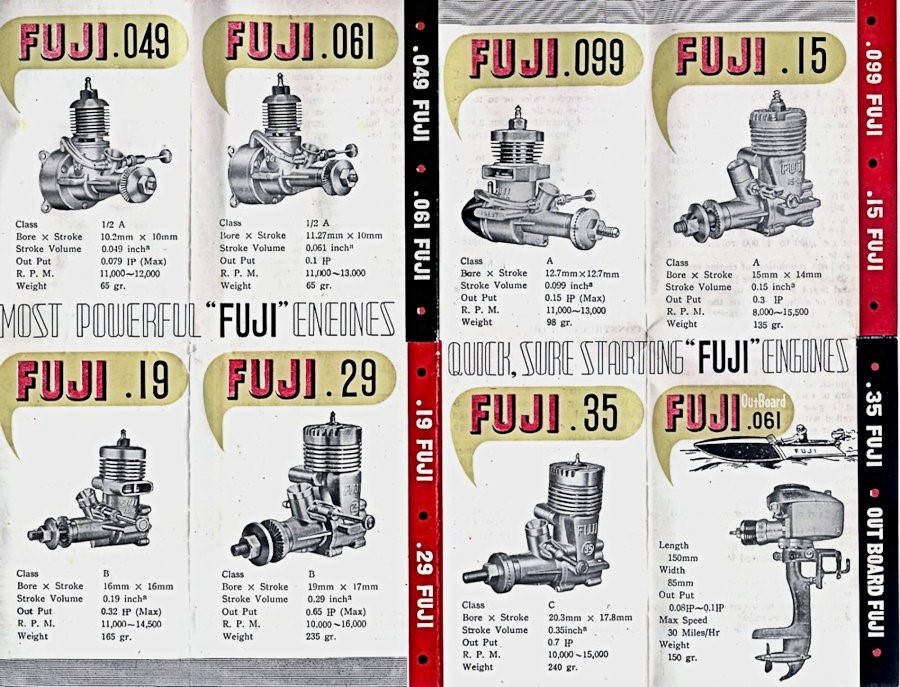

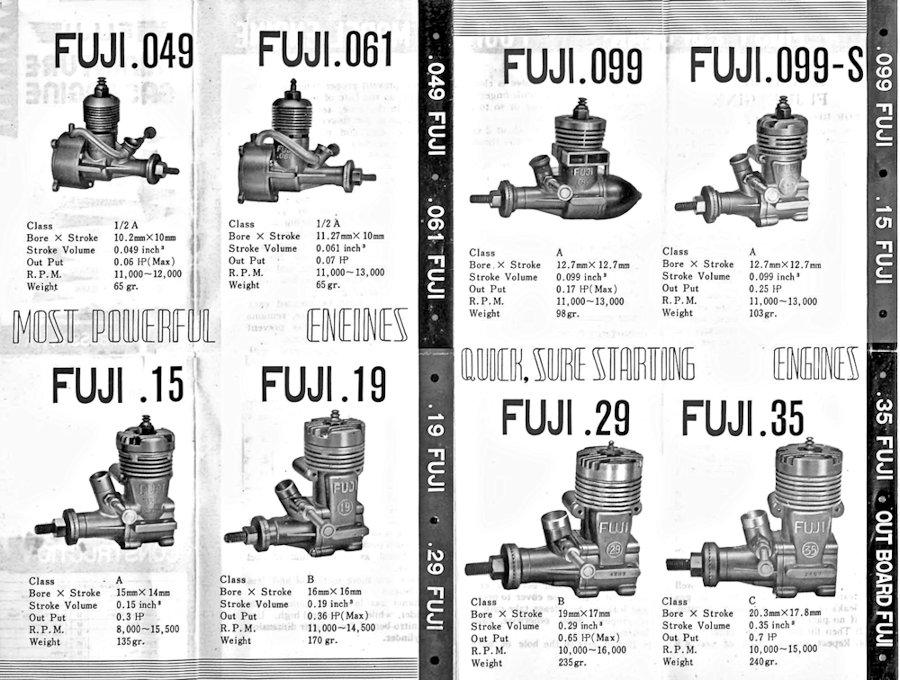

The Fuji range had expanded considerably by this time. The 1954/55 summary of the world's model glow-plug engines prepared by Peter Chinn (“Model Aircraft”, May 1955) confirmed that as of that period the .099 was accompanied by companion Fuji models in the .049, .15, .19. .29 and .35 cuin displacement categories. However, the previously-mentioned "racing" version of the Fuji 29 had reportedly been discontinued at some point in 1953. A careful consideration of this impressive list underscores the fact that at this time Fuji continued to lead its rival Japanese manufacturers into some new market areas - it had been early in the field with .049, .099 and .35 cuin. models, while the original twin-stack .15 cuin. model introduced in early 1955 was the first-ever commercially-made Japanese engine in the 2.5 cc international competition displacement category. Peter Chinn specifically commented on this in a footnote to his 1954/55 listing. Now, back to the Fuji .099 models ... 8th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-8) - Third of the "Menasco" Series

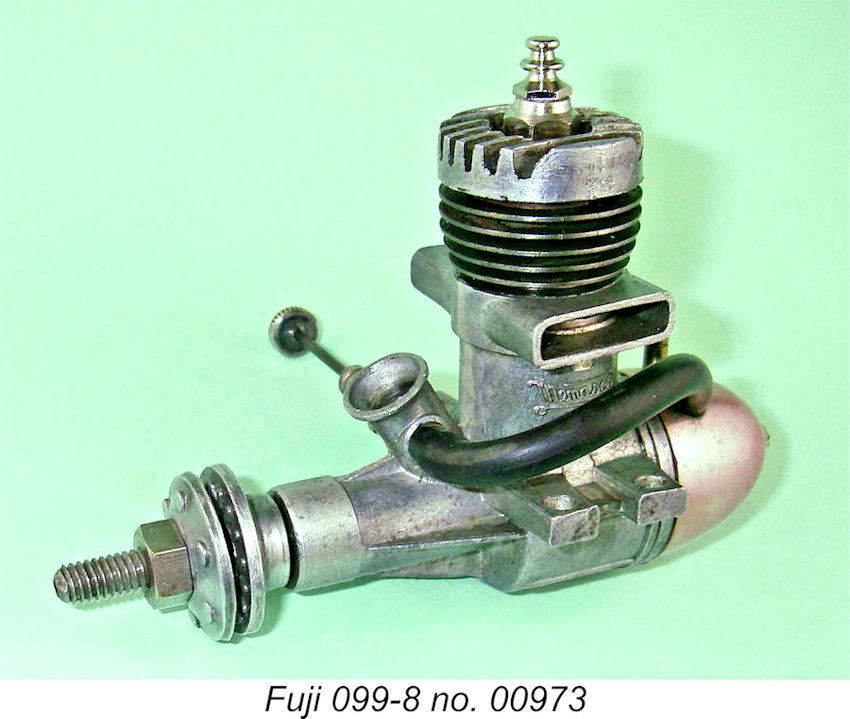

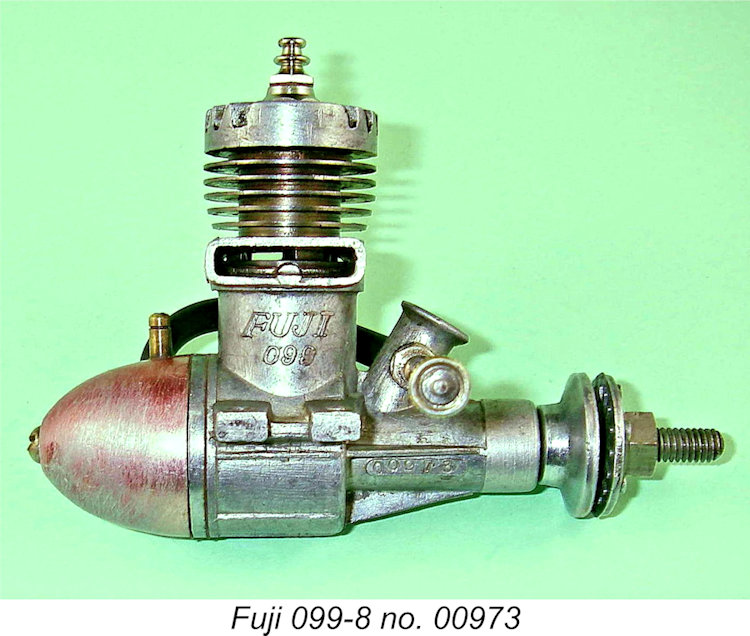

These changes resulted in the appearance of the eighth model of the Fuji .099 and the third member of the series to carry the Menasco association. Fuji themselves undoubtedly saw this as a distinct variant since they re-started the serial numbering system at 00001. The sole example of my present acquaintance is illustrated engine number 00973. It appears that by this time Fuji had become somewhat sensitive to the issue of the relative fragility of the "twin-expansion" mounting lugs. One may wonder why they didn't simply do away with these altogether and go to a pair of solid lugs. However, they did not do so - instead, they took steps to increase the strength of the existing design.

The cylinder head was also changed in this model. The staked-on cast alloy component of its predecessor was retained, but the casting was substantially higher than the former component and had far sharper edges. This change alone gave the revised model a very distinctive appearance by comparison, as the attached images will show. In all other respects, the new model was identical to its predecessor. This appears to be one of the rarer Fuji .099 variants - the illustrated engine bearing the serial number 00973 is the sole example which I've ever encountered. At present I have no way of knowing how many were made, but the number can't have been high. 9th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-9) - Fourth of the "Menasco" Series

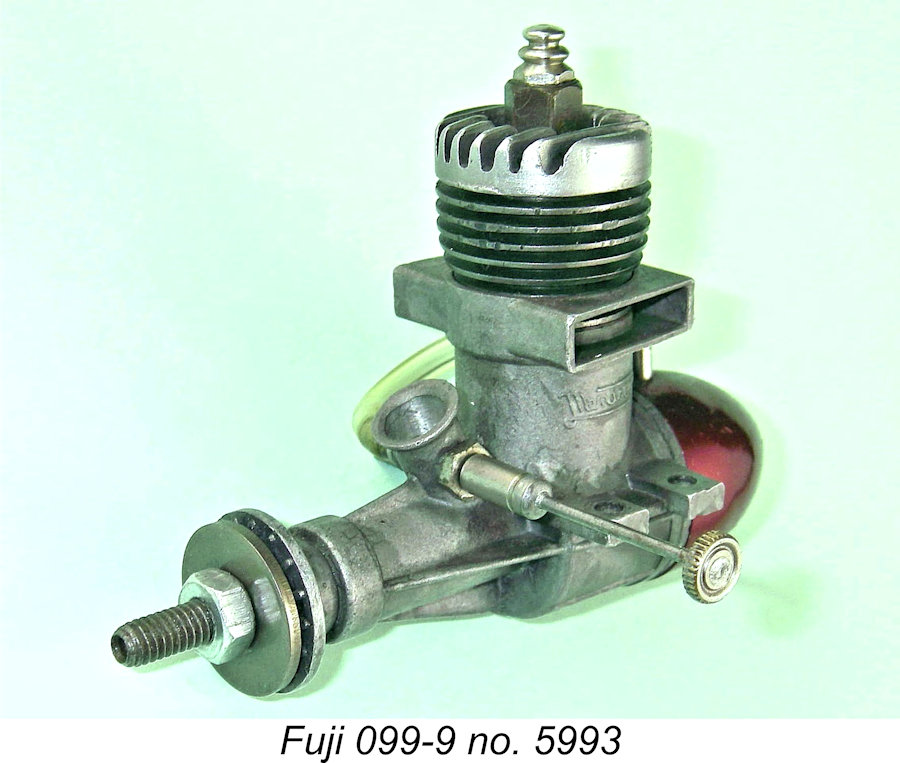

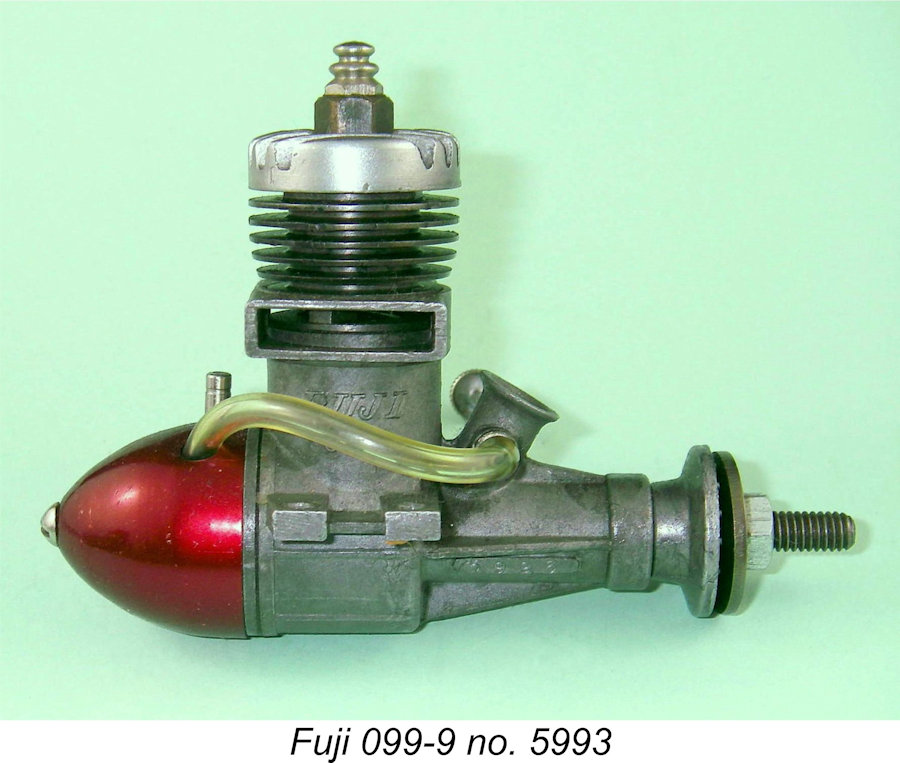

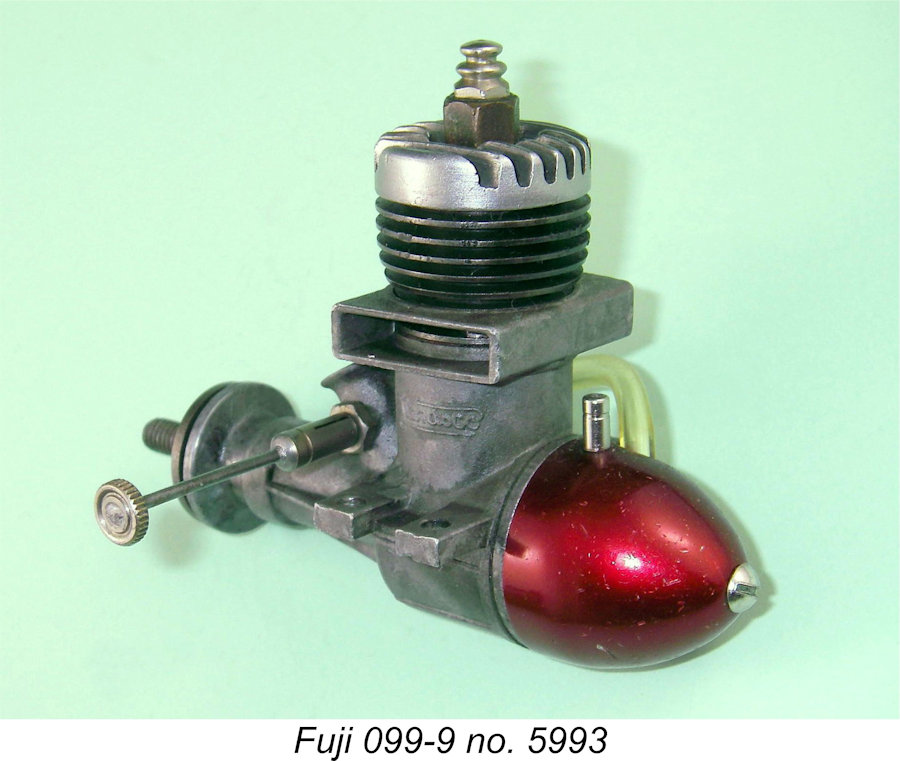

The basic design approach of a radially-ported screw-in steel cylinder with integral fins, blind bore and swaged-on head was retained along with the twin-stack case configuration. However, the outside diameter of the upper crankcase spigot into which the cylinder was threaded was increased from 19 mm to 20 mm. This allowed the lower cylinder wall to be made a little thicker, which in turn allowed for an increase in the size and depth of the three flats machined into the lower cylinder O/D to feed the transfer ports. The intent was clearly to improve transfer efficiency by providing bypass passages having a larger area.

The revised case featured twin stacks which were considerably larger than those formerly used. These larger stacks had squared-off corners as opposed to the rounded corners of their predecessors. Another very minor change to the crankcase was a reduction in the length of the "collar" at the front of the main bearing. This coincided with a slight reduction in the length of the main bearing, the crankshaft journal length being amended to match. Moreover, the "collar" was not machined externally like its predecessor, being left in its as-cast state.

Bore and stroke remained unaltered, but the more substantial cylinder resulted in a slight increase in the all-up weight from 3 ounces even to 3.2 ounces. The only other change was the application of a matte finish to the cast components This was apparently created by vapour-blasting. Illustrated engine no. 5993 typifies this model, while the highest serial number that I’ve recorded to date for this variant is engine number 6064. It would appear that the switch to the revised model may not have been accompanied by a return of the serial number sequence to engine number 1. At present, the lowest serial number that I've recorded for one of these engines is 01879, which is greater than my sole serial number of 00973 for the previous variant. It's possible that Fuji did not see the changes as being sufficient to warrant a re-starting of the number sequence, although this is undeniably inconsistent with their response to other changes. It's also possible that I'm simply missing some key serial numbers. Either way, this issue remains unresolved.

My own spot test of "Menasco" Fuji 099-9 no. 02065 confirmed that it turns a 7x4 Taipan G/F prop very comfortably at a steady 12,500 RPM on 15% nitro fuel, implying an output at that speed of around 0.13 BHP based on an estimated power coefficient for that prop - a little down on the manufacturer's claim, but not outrageously so. Starting is very easy, running is ultra-smooth and the engine needles extremely well. The engines were far from the gutless wonders that they were sometimes portrayed as - they actually performed quite adequately by the standards of 1956 for sports engines of their displacement. 10th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-10) - Fifth of the "Menasco" Series

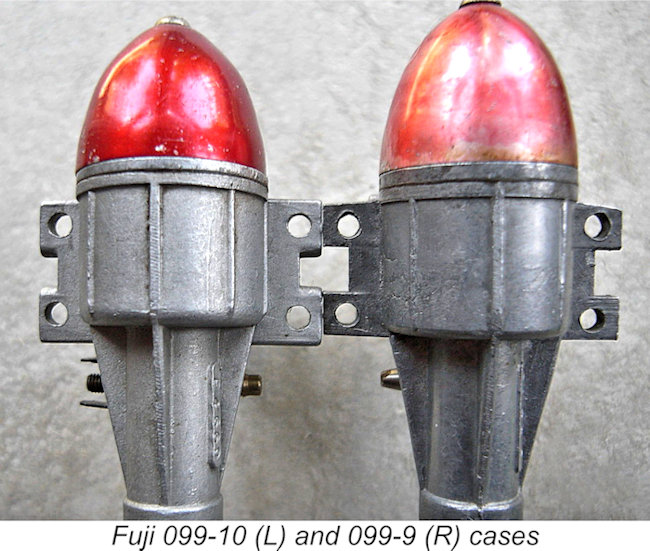

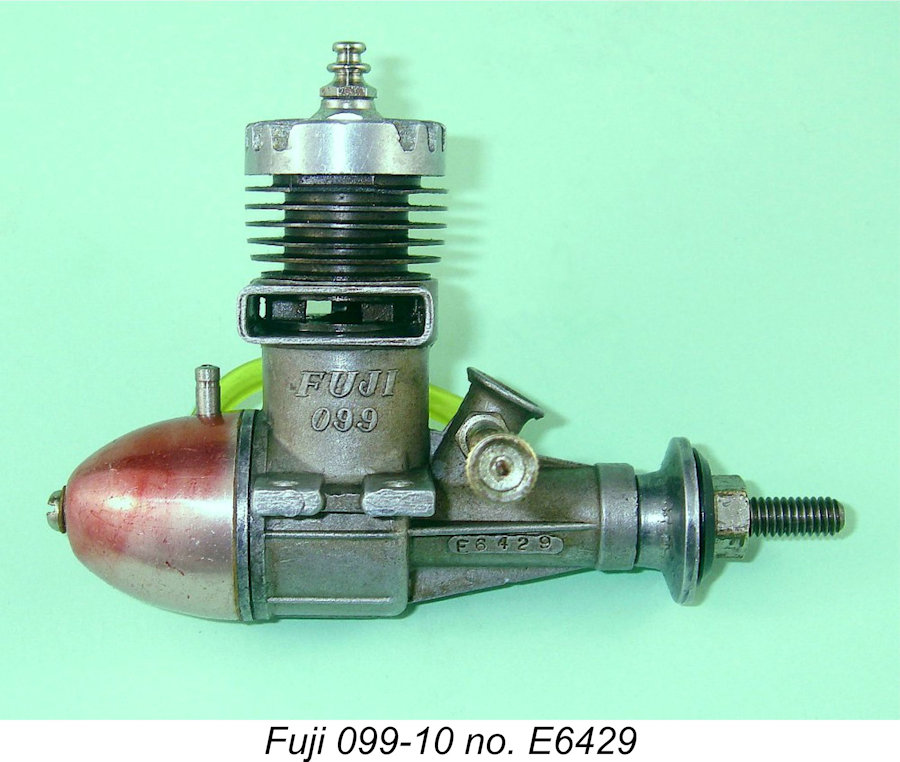

The first model in this series, and the fifth Fuji .099 model to bear the Menasco name, focused once again upon changes to the crankcase. After trying the effect of thicker and broader expansions on the mounting lugs with the 099-8 model described earlier, the company had inexplicably reverted to the thinner expansions with the 099-9 model just described. They now elected to go back once again to more substantial expansions, but by trying a different approach - seemingly they were aware of the strength issue but were having difficulty making up their minds on its resolution!

Another change, and a welcome one at that, was the inclusion of a pair of lugs in the interior of the backplate recess. These allowed for easy removal and re-tightening of the backplate without risk of damage. The cylinder head on this variant reverted to the slightly more angular profile of the 099-8 model, although it was otherwise The changes which produced this variant were clearly seen by the manufacturers as justifying a re-start of the serial number sequence. They also acknowledged the changes by adding an "E" letter prefix to the serial numbers applied to the revised cases, thus avoiding the duplication of serial numbers between this and the previous variant. This model seems to have been made in reasonable numbers - my highest recorded serial number for one of these units appears on illustrated engine no. E6429, confirming that production must have reached around 7000 as a minimum. An anomaly reported by my mate Allan Brown is engine no. L4860 of this type. I have no explanation for the anomalous letter prefix. Readers of my article on the corporate history of the Fuji enterprise may recall that it was around this time that Tannan Industries may well have become involved in the manufacture of the Fuji range. Some of the changes which are apparent in this variant may possibly arise from some level of involvement by Tannan, although I can't state this as an established fact on the basis of present evidence. Hopefully some reader having greater knowledge than I do will enlighten me on this point. 11th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-11) - Sixth of the "Menasco" Series

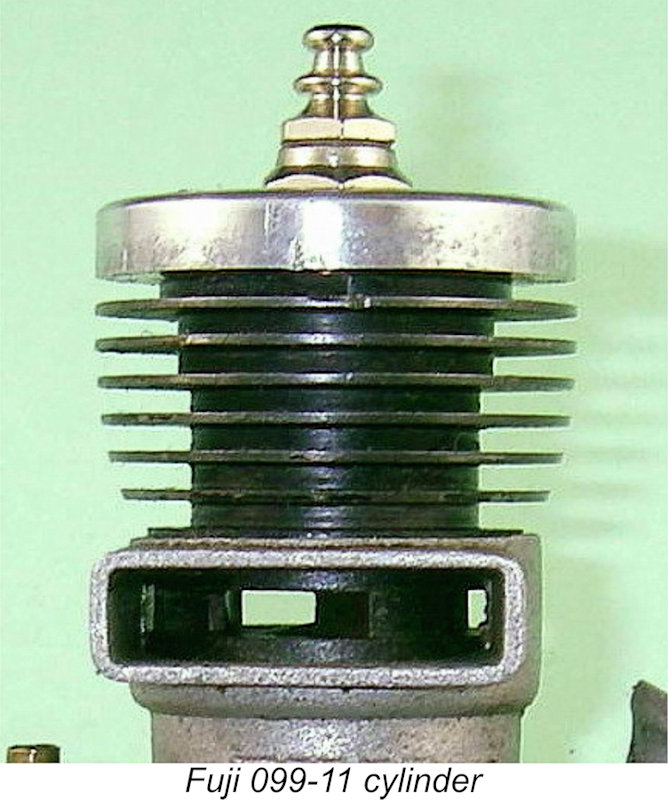

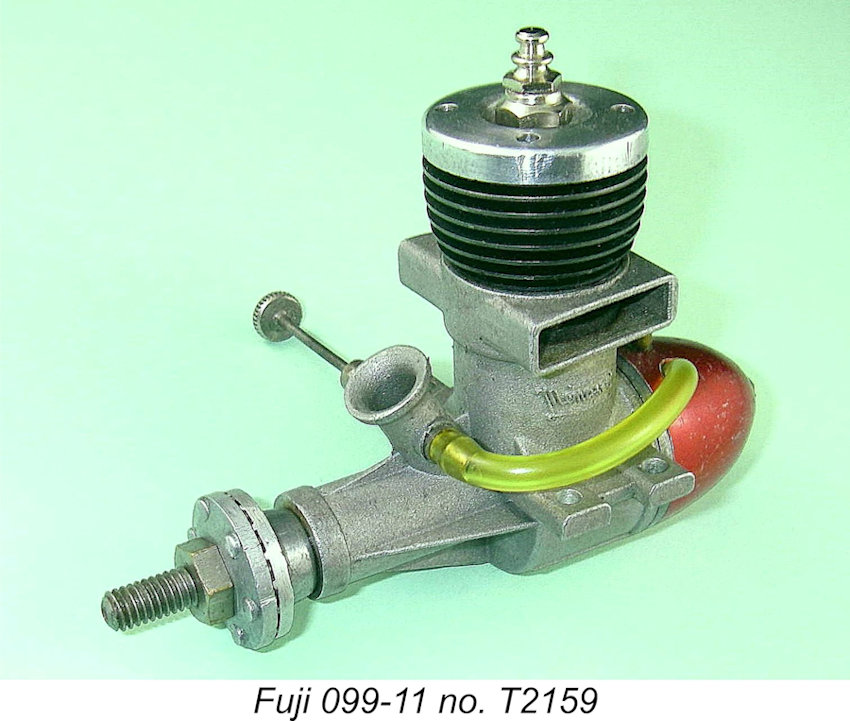

The reason for this change was most likely the fact that the continued use of a screw-in cylinder with a staked-on head made retention of the correct alignment of the head cooling fins rather problematic. If the cylinder became loose, as can easily occur with this type of assembly, or had to be removed for repair purposes, it was rare for the same head fin alignment to be re-established when the component was re-tightened.

Naturally, the cylinder had to be made substantially taller to accommodate the threaded recess for the head. This characteristic makes this version of the Fuji .099 readily distinguishable at a glance from the other variants in the Menasco series. There were 6 integrally-machined cooling fins between the upper surface of the exhaust stacks and the lower surface of the head, instead of the former 5 fins. The outside diameters of these fins and the revised cylinder head were also 2 mm greater than those of the previous model. The un-finned head was provided with four holes into which a pin spanner could be inserted for tightening.

Otherwise, the engine was essentially unchanged apart from the use of a somewhat lighter sand-blasted matte finish on the crankcase than that applied to the previous model. The extended "twin expansion" mounting lugs with no lateral taper were retained, although their vertical thickness reverted yet again to the thinner dimension seen on the 099-9 model. The upper corners of these expansions were now rounded instead of being squared-off. The retention of this highly vulnerable mounting lug design continues to baffle me!

The model just described was still in evidence in September 1959, when it appeared in an "Aeromodeller" advertisement for the Fuji range. However, there is reason to believe (based on the 29 model which appears in that advertisement) that the photograph may have been a "file" illustration supplied by the factory and may well date from 1958.

In addition to the 099-11 model described above, the twin-stack 15 is still in evidence along with the tankless .049 glow model with alternative beam and radial mounting along with a Cox-style twin-port cylinder. Rather oddly, the .19 model is not mentioned in this advertisement, although it had certainly been in existence for some years, appearing in Fuji's leaflets and Japanese-language advertisements. It appears that it may not have been imported into Britain, where there was no recognized competition class exclusively for this size of powerplant.

This highlights the fact that Fuji had by this time abandoned any ambitions (if they ever had any) of trying to compete with the likes of Enya and O.S. in performance terms. Instead, they had positioned themselves in the marketplace as offering an attractive and well-made "economy" range which offered more than acceptable performance and longevity for sport-flying purposes at a very reasonable price. In effect, they had carved themselves a market niche which was then relatively free from direct domestic competition. One interesting observation that may be made at this point is the fact that as of 1957 the Fuji Bussan company was still advertising from a location in the Kyobashi district of Tokyo, where the earlier Fuji Tokushu Kiki company had reportedly started way back in 1949. The accompanying Japanese-language advertisement for the Fuji 099-11 model just described confirms this location. The Kyobashi district was already beginning to move upmarket in a business context, and it's possible that the company retained their head offices there but had relocated their actual manufacturing activities elsewhere. I leave this as a matter for further research by others. 12th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-12) - Seventh and Last of the "Menasco" Series

It seems likely that this change was driven both by cost considerations and by the realization that if a plain head was retained there was no longer any concern with regard to the alignment of the cylinder and head regardless of how the head was attached. The company did however improve the security of the dummy head by changing the method of attachment - the boss at the top of the cylinder which accomodated both the plug and the head was now externally threaded, with the head itself being centrally tapped to engage with this threaded boss. After the head was screwed on tightly, it was swaged in position with the swaging now extended around the full circumference of the interface. Little chance of one of these heads coming loose!

The change in the method of head attachment eliminated the need for the threaded recess in the top of the cylinder as used in the previous model, so the cylinder was once again shortened, there being only 4 fins instead of the former 6. The cylinder configuration below the fins appears to have been unchanged from the previous model, however. The result was an engine that was actually very similar to the earlier 099-9 variant but with a modified cylinder, a plain un-finned head and improved security provisions for the head. It retained the same case design with the twin expansion lugs and similar cast-on identification.

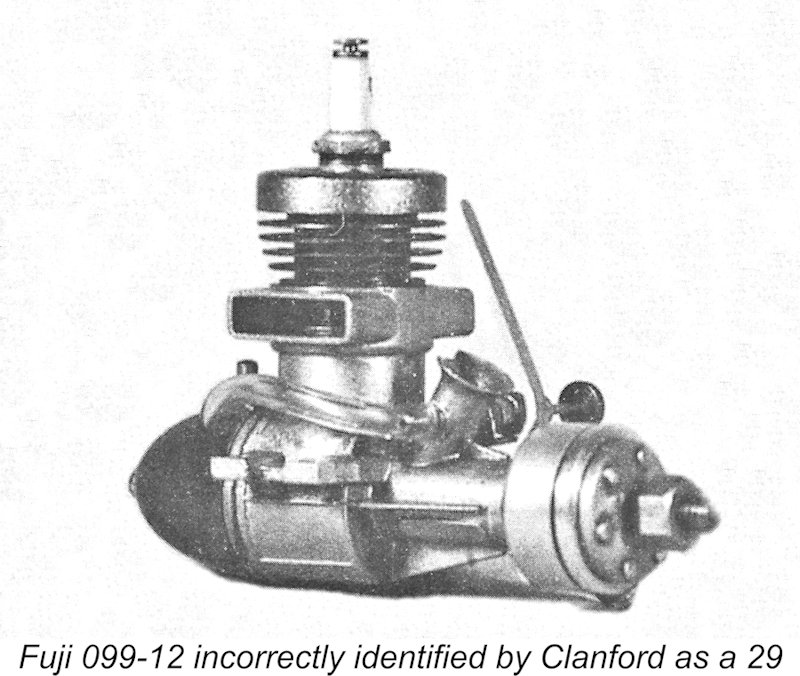

The circumstance which gives the model just described a special place in the history of the Fuji .099 series is the fact that, as events were to prove, it was to be the seventh and last of the Fuji .099 models to carry the "Menasco" identification. Mike Clanford's very useful but often inaccurate A-Z book includes an illustration of one of these models which has been converted to spark ignition. This illustration is reproduced here at the left. The original may be found on page 84 of Clanford's book, and it is incorrectly identified as a 1955 Fuji 29! There is however no question that this is an owner conversion of one of the 099-12 glow-plug models just described. Meanwhile, Back at the Factory……………… I have now carried the tale of the Fuji .099 models almost to the end of the 1950's as well as to the end of the "Menasco" series, of which the model just described (Model 099-12) was to be the final example. Since it's important to remain mindful of the context in which the Fuji .099 series was continuing to evolve, it's time once again to step away from that series briefly and catch up with what had been happening with the rest of the Fuji range during the period just covered.

The Fuji .049 remained in production in its tankless configuration, albeit with a re-designed cylinder which reverted to radial porting, thus ending Fuji's experiment with Cox-style porting. Full details may be found in my companion article on the Fuji .049/.061 models. The radial port version of the Fuji 19 was also continued at this time. At some point, likely in 1959, it acquired twin stacks of its own, thus taking on the appearance of an oversized .099 model.

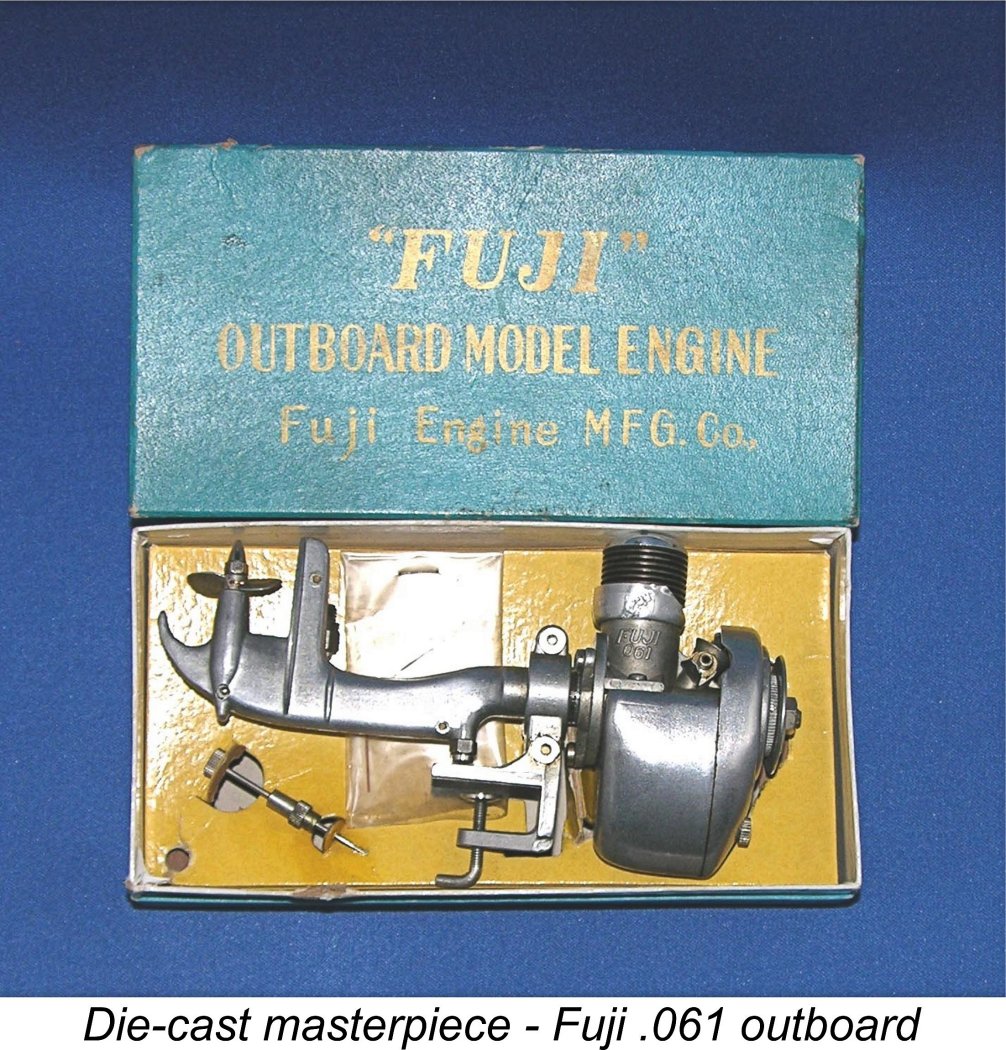

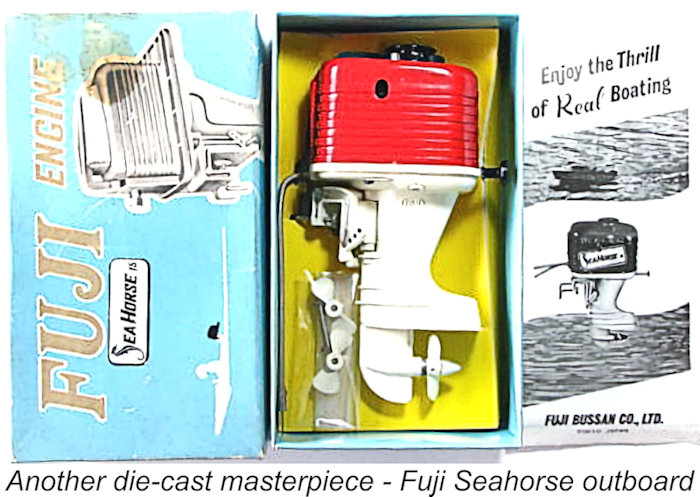

At this point, it's also necessary to remind the reader that the development and manufacturing activities connected with the Fuji range appear to have undergone some very substantial changes as of 1958 or thereabouts. Firstly, the scope of the range had begun to expand significantly. 1957 had seen the introduction of several outboard motor models (.049 and .061 cuin.) which displayed an almost virtuosic mastery of the die- The clear implication of this is that Fuji had somehow engineered a significant expansion of both their technical capabilities and their manufacturing capacity, at the same time engaging a more dynamic design team. At present we don't know how this was managed - whether by developing additional in-house capacity or by out-sourcing their design and production in whole or in part. The possibility exists that Tannan Industrial, who are definitely known to have taken up the manufacture of the Fuji range as of the late 1960's, may in fact have entered the production and perhaps the development picture at this earlier point. Having caught up with the rest of the Fuji range, it's now time to return to our main thread - the Fuji .099 story. We left that story in late 1958 when the twelfth model of the Fuji .099 (and the seventh of the Menasco series) had entered production. It's now time to carry the tale forward into a new decade - the swinging sixties! 13th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-13)

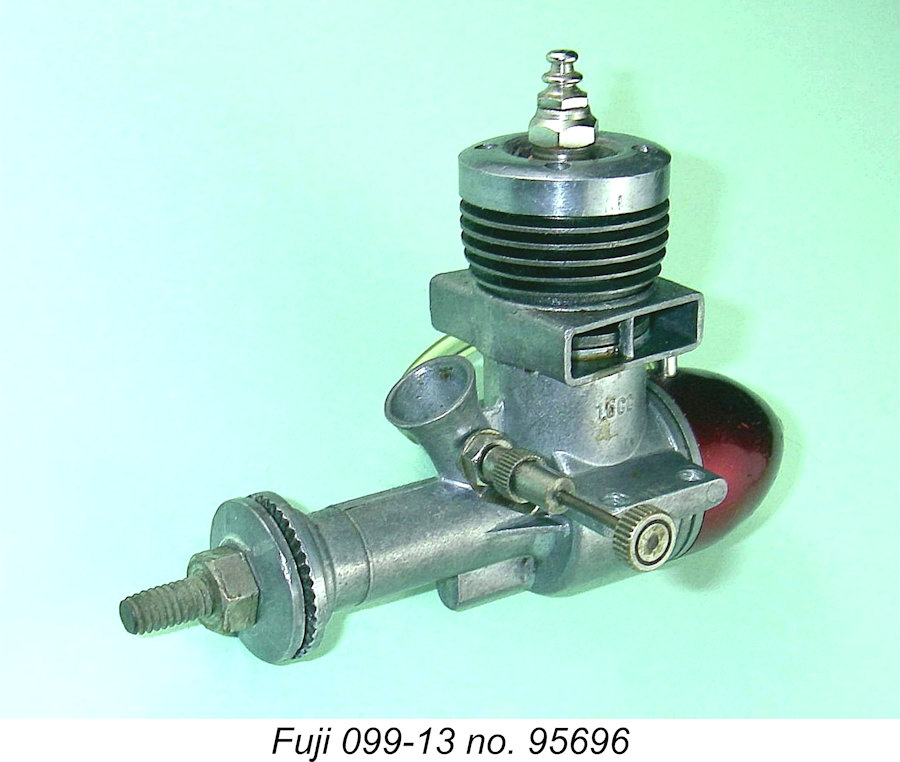

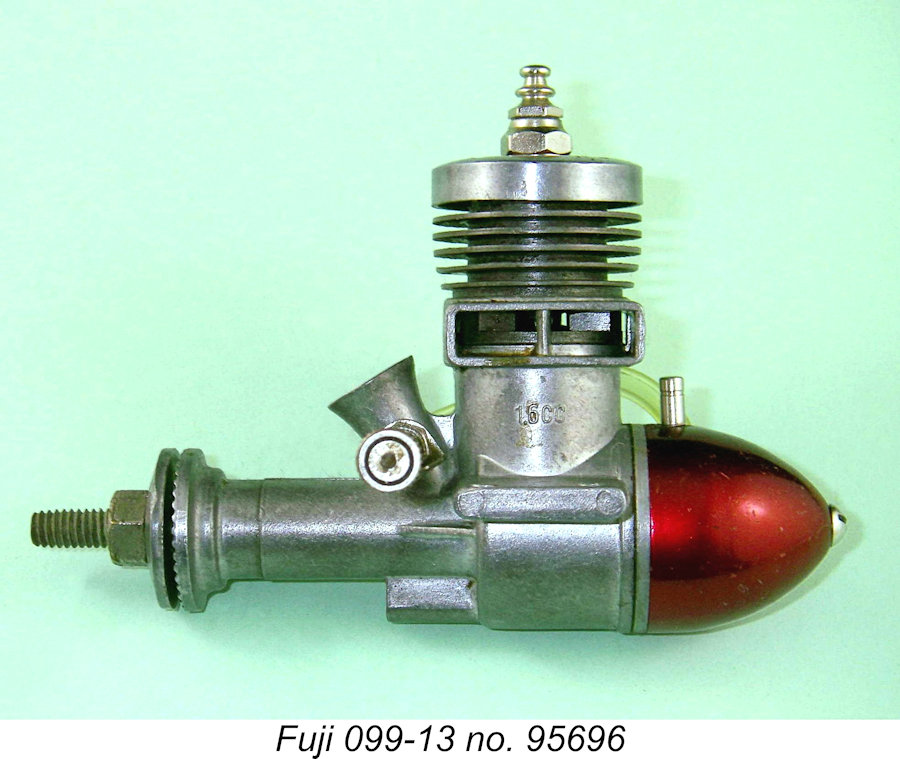

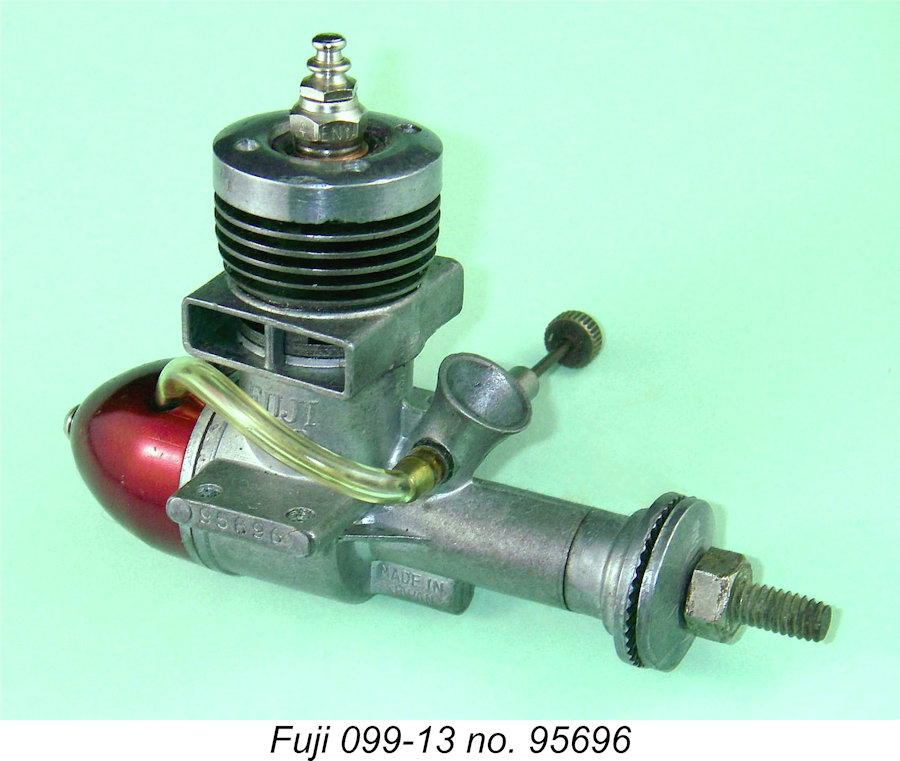

The purpose of the protrusion beneath the main bearing is presently unclear - it appears to be less than ideal for use as a pressure tapping point. Perhaps it was for mounting a starter spring? This notion seems to be contradicted by the fact that the contemporary twin-stack models of the Fuji 15 and 19 also featured a similar protrusion in the same location. Perhaps some kind reader can enlighten me………... But this wasn't the only change. At long last, this model saw the final elimination of the rather vulnerable "twin expansion" mounting lugs in favor of conventional solid lugs of quite substantial dimensions. About time - a change that was long overdue, in my personal opinion! This one improvement made the engine far less susceptible to crash damage.

Another change was the elimination of the split-thimble needle valve assembly which had been used on all previous Fuji .099 models in favor of a far more dependable unit using a knurled thimble which was tensioned with a single-leaf spring clip. This design was to appear on all subsequent Fuji .099 models during the "classic" era with which we are concerned here. It is extremely stable in use and holds its setting perfectly at all times. The blind-bored cylinder and plain un-finned cylinder head which had first appeared on the previous model were both carried over to this new variant. The far more secure method of securing the head onto the cylinder which had been introduced on the previous model was also retained.

An illustration in a Fuji brochure from this period shows an example of this variant bearing the clearly legible serial number 15897. The fact that I have illustrated engine number 95696 on hand implies that this variant was produced in quite significant numbers over a period of some years. Indeed, this may have been the Fuji .099 twin-stack model that remained in production for the longest period of any such model - present indications are that it was to remain in production until 1965. As noted earlier, Fuji Bussan had now clearly made arrangements for a quantum expansion of the production capacity for the Fuji range. It's entirely possible that Tannan Industrial had already assumed full responsibility for Fuji production, although I can't state this as a fact on the basis of present information. Regardless, the serial numbers quoted in the previous paragraph confirm the manufacture of over 96,000 examples of the new .099 cuin model during its apparent six-year production life - a very impressive rate of 16,000 units per year, which is far in excess of previous production figures based on known serial numbers. Where are they all now?

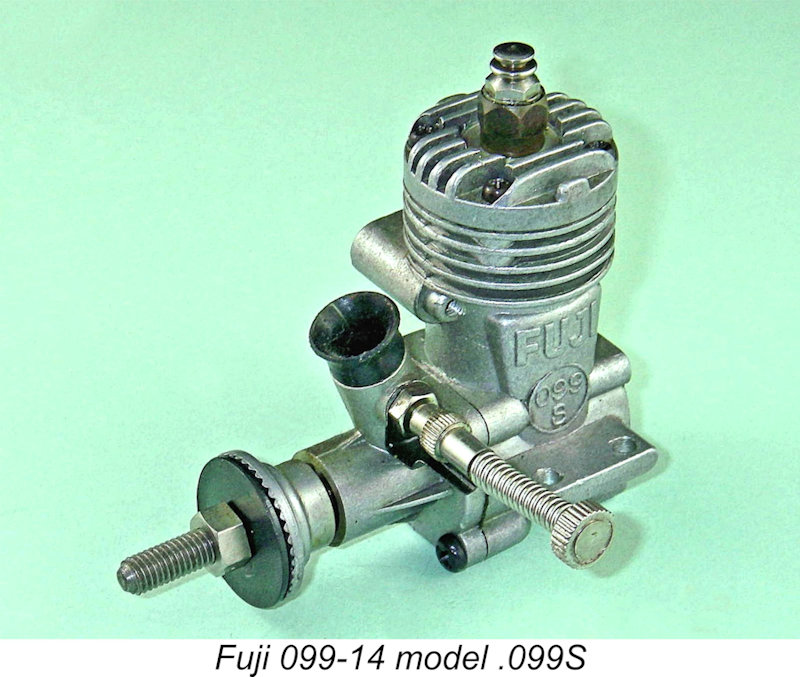

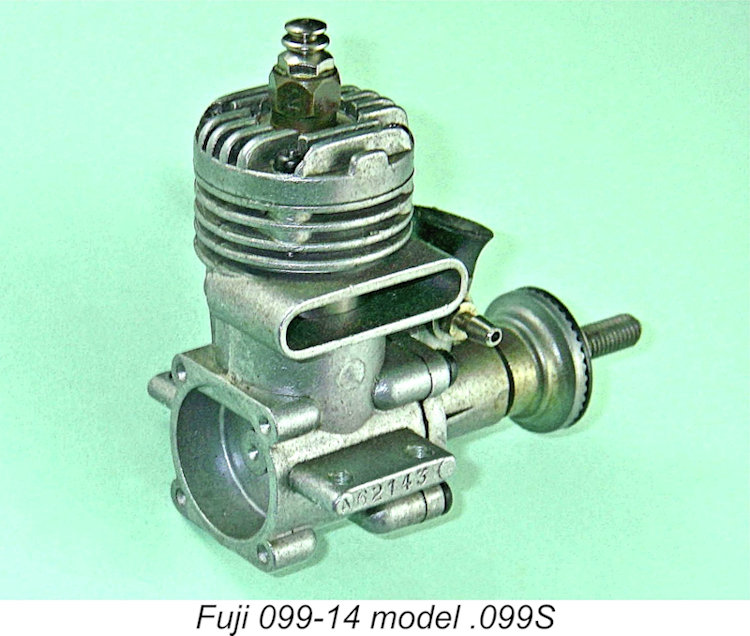

By this time too the other engines in the Fuji range had been joined by an .061 cuin. model which was basically a bored-out version of the established .049 model. Both the .049 and .061 models had now acquired radial tank mounts and were also available in well-crafted outboard motor versions for marine enthusiasts. These display a virtuosic command of the die-casting process and are prized collectors' items today along with the .15 cuin. "Seahorse" outboard models which came later. It's worth reminding ourselves in passing that Fuji used yet another company name on the boxes in which some of these outboards were supplied - the "Fuji Engine Mfg. Co". 14th Model, Fuji .099S (Model 099-14) The model 099-13 described in the previous section appears to have sold well and to have remained in production into the mid-1960's. However, by the early 1960's the writing was clearly on the wall for the old twin-stack radial-port .099 - indeed, it O.S. had persevered for some years with their 1951 "New .099" model which bore a striking resemblance to the Menasco Fuji .099 models (or more likely vice versa!). However, by 1957 they had replaced this offering with the completely revised Pet .099 model, and followed this up in 1959 with a much-improved version of this model in the form of the low-priced Pet-II. This was real competition for Fuji in the "economy" market which was their main rice bowl! It very likely prompted the 1959 introduction of the Fuji 099-13 model just described.

As a result of all of the above activity, by the early 1960's the O.S. and Enya companies were going from strength to strength, Throughout this period, Fuji had stood pat with their existing and increasingly venerable radial port twin-stack .099 models, making only the relatively minor changes documented above as time went by. I noted earlier that they had long since abandoned any pretense of trying to compete with the likes of O.S. and Enya in the performance arena. Instead, they had positioned themselves in the marketplace as suppliers of dependable low-priced general-purpose engines which were well-made and represented outstanding value for money for the average sport flier who was not concerned with ultimate performance. However, with the kind of performance advances coupled with lower prices now being achieved by their major Japanese competitors, the performance gap was becoming too wide to justify the marginally lower cost of the Fuji model. Accordingly, some kind of movement on the part of Fuji became inevitable if they wished to remain in the .099 field. It's clear from subsequent events that the company was very attached to the twin-stack .099 layout with which their name had become so closely identified. This being the case, their first thought would doubtless have been to update their existing twin-stack model. However, it would have been painfully apparent to them at the outset that to accomplish this they would have to switch from radial porting to a more efficient scavenging system. It would have been equally clear that the retention of the twin-stack configuration represented a significant impediment to the upgrading of that system. In effect, the Fuji twin-stack design was approaching the end of its development road. The Fuji designers clearly recognized this. But they had to do something, and they had to do it fast!

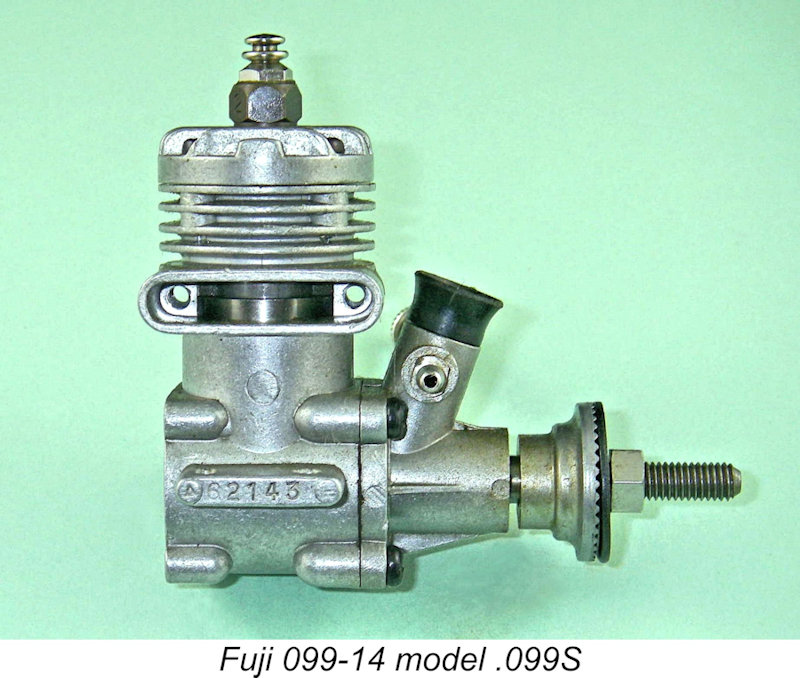

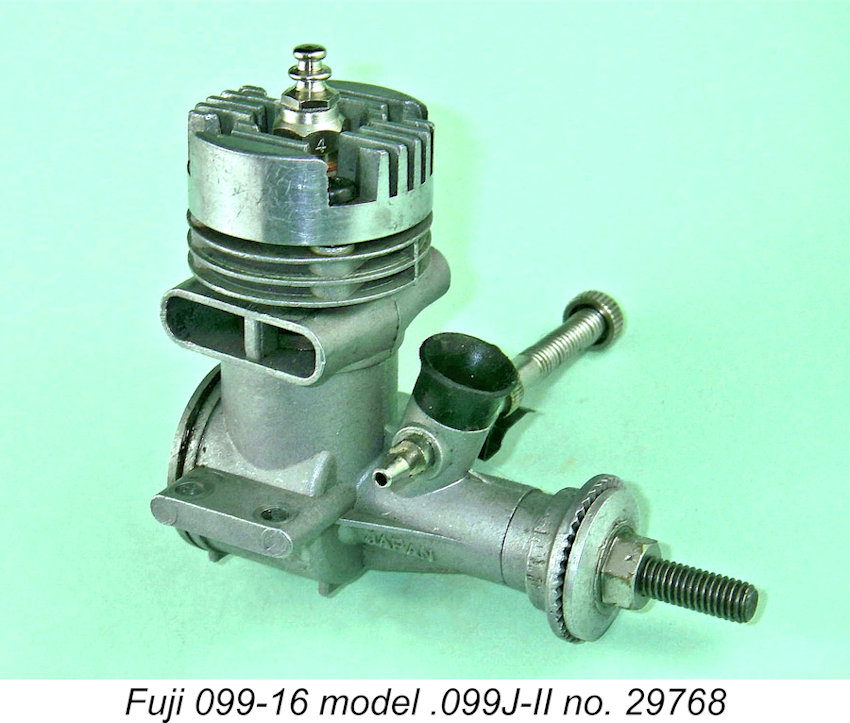

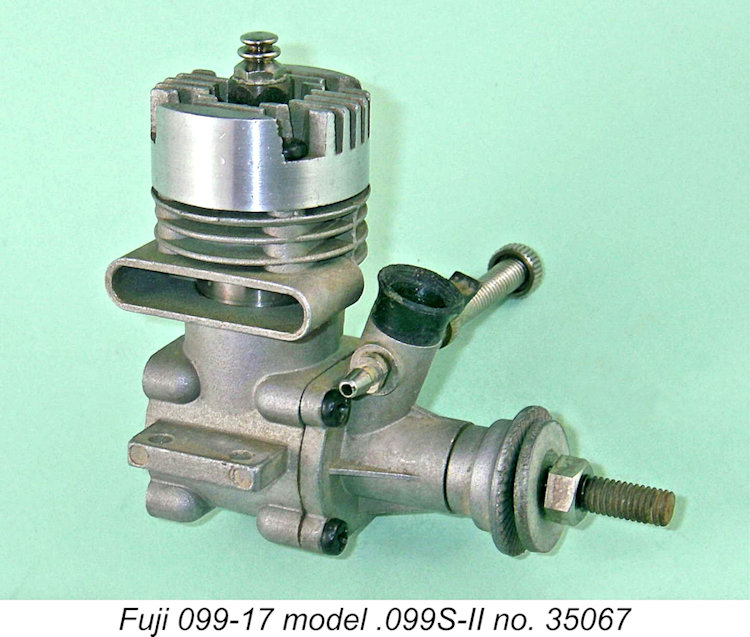

The serial numbers of the two examples in my possession are A62143 and A62336. It appears from this that the letter A was added to the serial number sequence for this model to distinguish it from its twin-stack companions. These numbers also appear to confirm that the 099S was manufactured in substantial numbers.

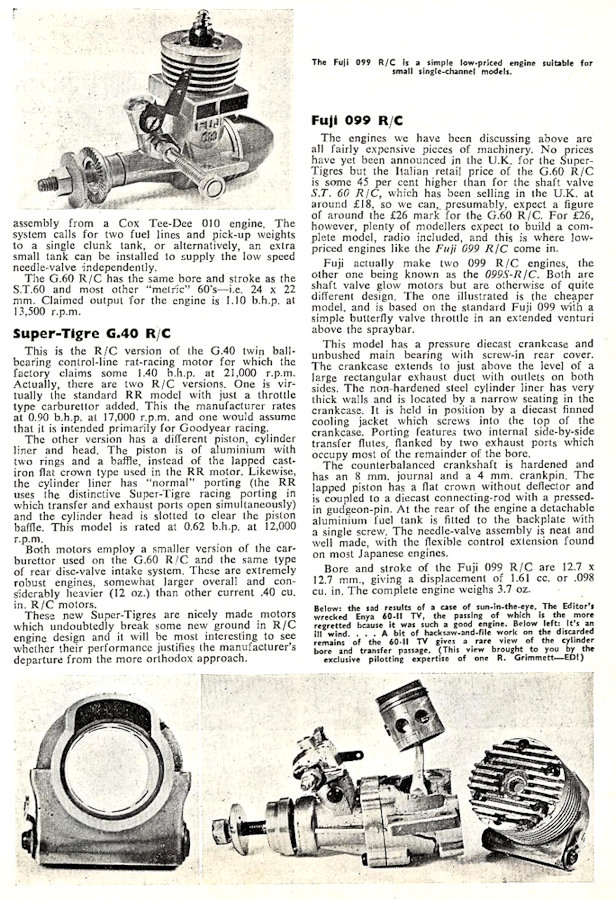

The main casting was a completely conventional die-cast component incorporating the exhaust stack located on the right-hand side as well as the cooling fins above the stack and an integrally-cast backplate. The shallow "bypass bulge" on the left side of the main casting was a dummy. Naturally, the distinctive twin stacks were gone, and the needle valve had been amended from its former rigid design to a flexible spring set-up along the lines of those which had been used for years by Enya and O.S. The integrally-cast bell-mouth venturi had also gone, being replaced by a tubular stub intake which could accept either a control-line venturi or an R/C throttle. The earliest examples of the new model had machined light alloy venturi inserts, while later examples featured molded plastic inserts. Initially these plastic inserts were of the same bright green material that was used on the next version of the twin-stack model (to be described in a following section), but later examples like the one illustrated had black plastic inserts.

Despite the absence of a tank, weight had crept up further to 3.8 ounces, mainly due to the massive cylinder liner. The one thing that remained unchanged in this design was the bore/stroke combination - still at the same 12.70 mm and 12.70 mm for an unchanged displacement of 1.61 cc (0.098 cuin.). Unfortunately, the changes resulted in an engine which, while in theory offering a rather higher performance potential than its twin-stack companion due to the more direct bypass and the more efficient combustion chamber, completely lacked the individuality of the twin-stack models with which Fuji had become universally associated. For me, and I suspect for many other aficionados of classic Japanese engines, the advent of the .099S represented the final irrevocable step towards the elimination of the technical distinctiveness of the Fuji line-up. Most of the other engines in the Fuji line-up had by then become Enya clones, and now the .099 series was clearly well on the way towards joining them. In essence, the .099S differed little from the competing products of other Japanese makers. In fact, from a short distance one could scarcely distinguish this engine from its Enya, O.S. and recently-introduced Ueda competition!

Chinn characterized the .099S as an engine which was "easy to handle" and which had "a performance that the average modeller should find fully adequate". He characterized the engine overall as "soundly made, reasonably priced and not in the least tricky to handle". Despite these positive comments, it seems clear when reading between the lines that Chinn found this engine somewhat less than inspiring .............. One interesting comment made by Chinn in his write-up of this test was the statement (written in early 1967) that the Fuji range had been "manufactured for about a dozen years", i.e., since 1954/1955! We know for a fact that this is in error by a good 5 years, and this reinforces the view that Chinn really only became aware of the Fuji range in about 1955 and remained more or less unaware of the range's very interesting history prior to that time. Doubtless the language barrier had a lot to do with this. Chinn also commented that the Fuji range was not widely distributed in the US and Europe and that the UK was at this time (1967) one of their major export markets. He named the then-current UK distributors as the large Hobbies Ltd. organization. It seems that this firm had only recently assumed the Fuji distributorship, since a June 1966 article in “Radio Modeller” magazine regarding the Fuji 15-III had named the UK Fuji distributors at that time as Enterprise Model Aircraft Supplies of Manchester. An Intriguing Offshoot: the Fuji .12

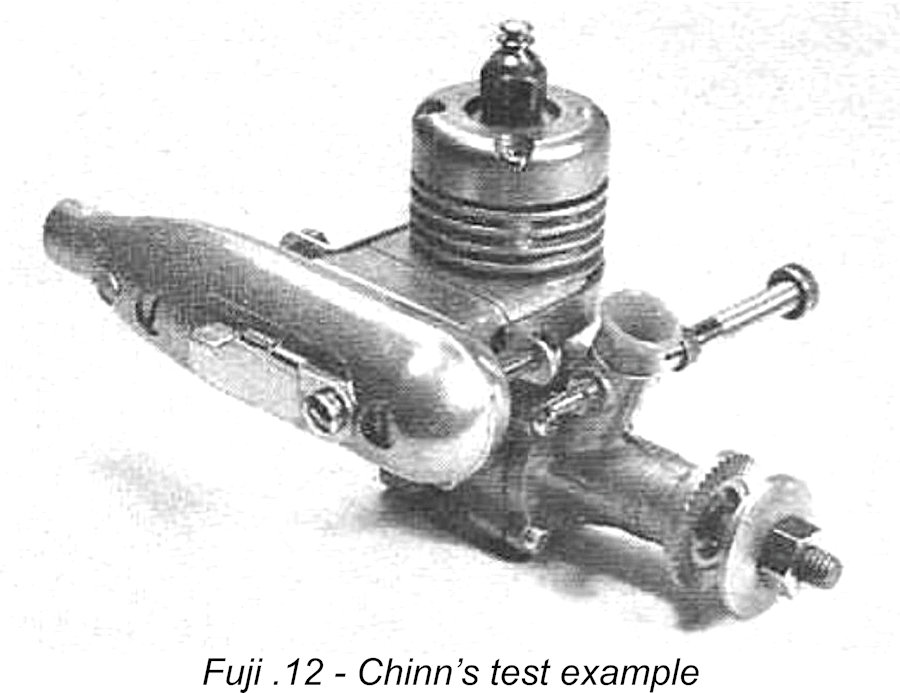

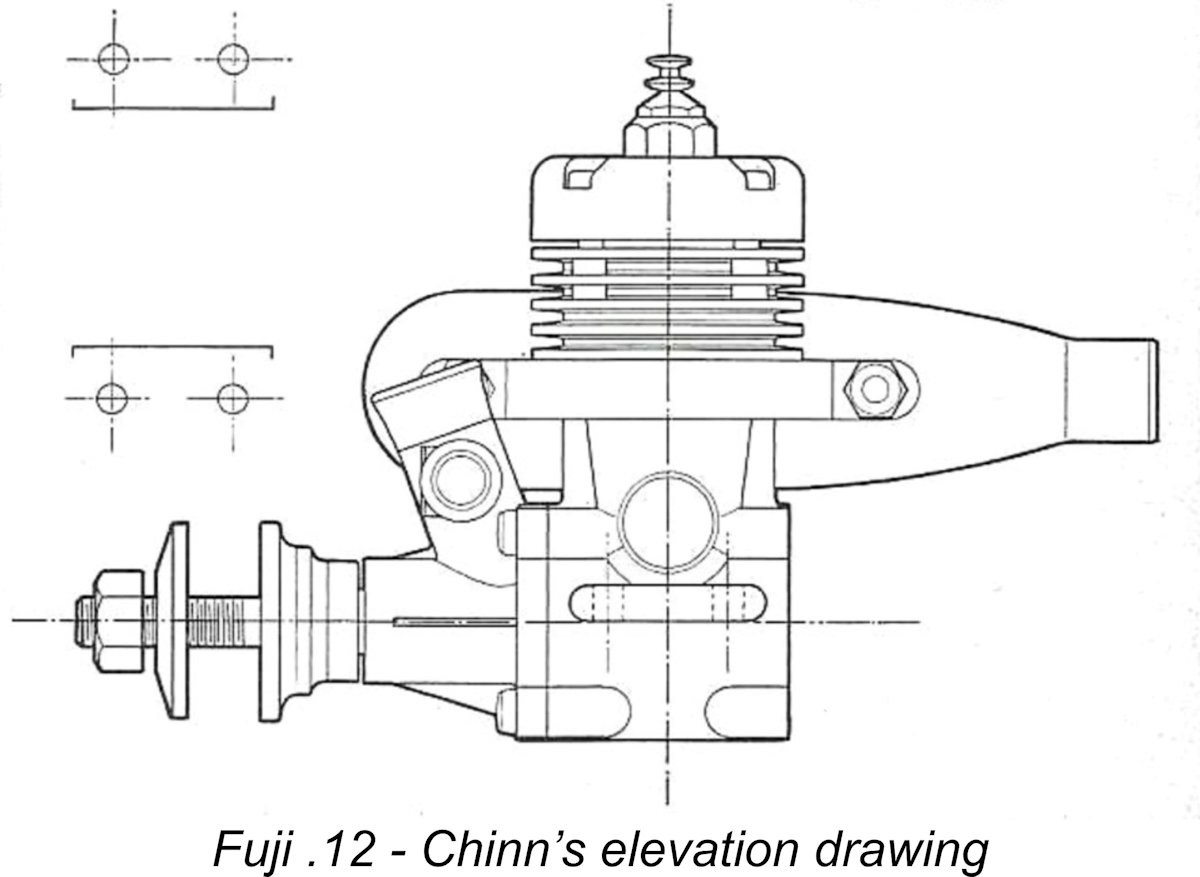

This engine had an actual displacement of 1.975 cc (.1205 cuin), a figure which had not been widely used since the early days of post-war model engine manufacturing because it did not correspond to any of the recognized competition classes. Most unusually, the additional displacement was achieved by increasing both the bore and the stroke of the 099S by 0.9 mm to a figure of 13.6 mm apiece. The result was an engine which retained the perfectly square bore and stroke measurements of its smaller relative as well as its main design features. In appearance, the .12 was very similar to the 099S apart from being a little taller on account of the longer stroke. It also featured a plain unfinned cylinder head in place of the finned component used on the .099S. It might be easy to suppose from this that the two models shared many of their components, but in fact this was not the case - the .12 was an all-new production which merely used the same main casting as its smaller relative, and even that component was machined to different specifications. Very few of the .12's components were interchangeable with those of the smaller model.

The above figures offer a clue as to the intended market for the .12 with its rather odd displacement. It was clearly aimed at sport fliers who wanted a little more power from an easy-to-handle and lightweight glow motor of typical .099 cuin. (1.5 cc) size and weight. The fact that its mounting was interchangeable with that of the 099S meant that anyone finding that the smaller engine did not provide sufficient urge now had an easy upgrade available. Chinn specifically noted this in his report. Setting aside the displacement difference, the .12 was in effect the "high performance option" in the context of the mid-1960's Fuji .099 range.

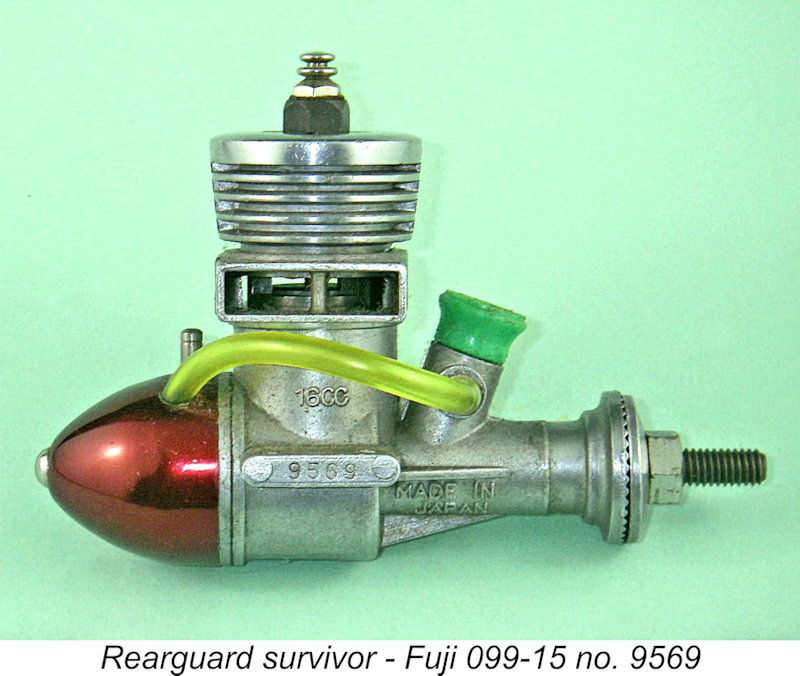

Chinn also commented that the UK distributor of the Fuji engines had changed yet again. As of 1967, when he had tested the 099S, the UK distributors had been Hobbies Ltd., but in his 1969 test of the .12, Chinn reported that the Fuji range was now being distributed by Mainstream Productions. It appears from this that Fuji was experiencing some difficulty in retaining a UK distributor - they had gone through at least three distributors during the period 1966 - 1969. It actually seems possible that the .12 had not been well received in the world marketplace, perhaps due to its rather odd displacement, and its relatively late appearance on the British market in 1969 may have represented an attempt by the makers to unload surplus unsold stocks of this model onto the British market, which was by then becoming one of Fuji's more significant overseas sales areas. If this was so, actual production may well have ceased by that time. It may be significant that the .12 never seems to have appeared as a full-time member of the Fuji line-up as depicted on the leaflets which came with their engines - its appearances were evidently confined to the supplementary leaflet illustrated earlier. This implies a relatively short period of actual production followed by a fairly lengthy sell-off period. Time now to return to our review of the main Fuji .099 series. 15th Model, Fuji .099 (Model 099-15)

It's not completely clear when the Fuji .099 twin-stack model 099-13 described earlier was finally supplanted by the drastically revised twin-stack model to be described next, but it was most likely sometime in 1965. The reasons for my proposing this date are complex, but I find them quite convincing and will continue to do so until someone proves me wrong! Let's see if I can convince you ..........

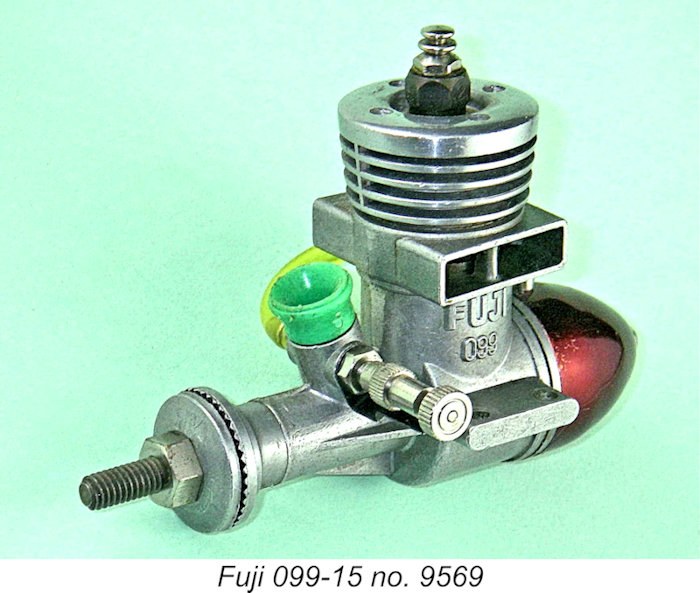

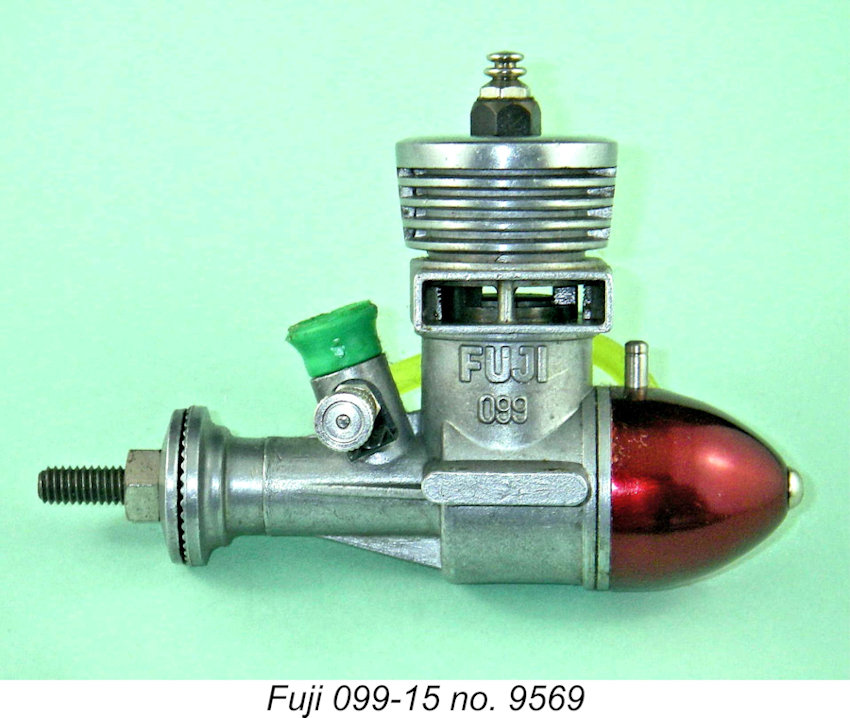

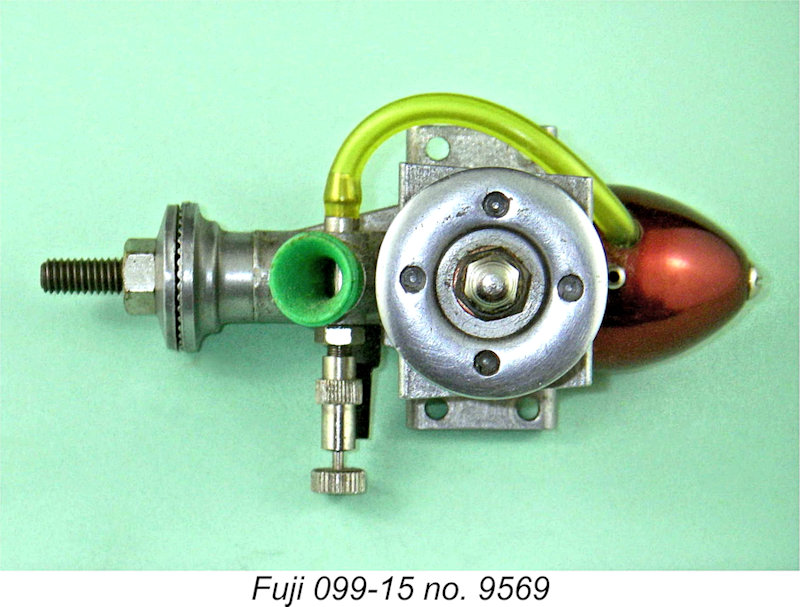

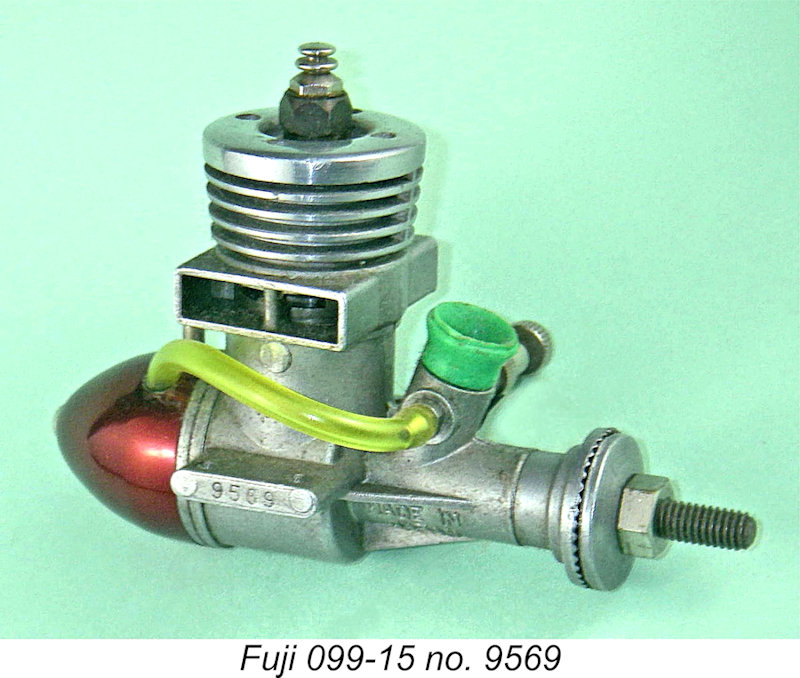

Taking the above evidence as a whole, it seems likely to me that it was in 1965 - a year after the introduction of the .099S - that Fuji came up with what perhaps may legitimately be considered the definitive Fuji twin-stack model - the fifteenth model Fuji .099 and the second post-Menasco Fuji twin-stack variant. This excellent and interesting little engine represented a complete re-think of the basic Fuji .099 twin-stack design. Bore and stroke remained unchanged and the revised crankcase retained the stronger conventional mounting lugs which had been introduced on the previous twin-stack model. However, a significant change was the elimination of the former bell-mouth venturi intake in favour of a cylindrical stub venturi which could accept either a conventional venturi insert or an R/C throttle. This was clearly done as a standardization measure to bring the new twin-stack model into step with the companion 099S, which featured an identical venturi set-up. Another change was the disappearance of the odd protrusion beneath the main bearing which had been a feature of the previous model. This was replaced by a conventional gusset as seen on earlier variants. The only other external change to the lower crankcase was the switching of the identification markings to opposite sides from their previous location - the left side of the case (facing forward) now bore the "Fuji 099" designation while the "1.6 cc" notation appeared on the right-hand side. One wonders why they felt the need to do this ...........

Both cylinder and head button were retained by a screw-on cast alloy cylinder jacket with integrally-cast cooling fins which was externally threaded at its base and engaged with an internally-threaded section of the upper crankcase above the exhaust ports. The system was in fact the same as that used on a number of the earlier Davies-Charlton and M.E. diesel engines. The installation flange of the head button was sandwiched between the top of the liner and the inside face of the jacket, the top of which was bored out sufficiently to allow access to the plug mounting hole in the head button. A gasket was used to seal the head button to the top of the cylinder liner. The elimination of the former head was a very good move in terms of the engine's structural integrity. However, it offered no relief from the problem of alignment of the head button with the piston. The use of a plain disc head button secured by a screw-on jacket meant that the annular positioning of the button when tightened down could not be guaranteed. This being the case, there was no way that an upstanding baffle like that employed in the .099S could be used. But this wasn't seen as a problem! It's clear that the Fuji designer had fond recollections of the porting arrangements which had been applied to the 1952-55 Silver Arrow .29 cuin. model mentioned earlier. He decided to utilize a similar porting set-up in the new .099 model. However, he also wanted to retain the brand-recognition power of the trade-mark Fuji "twin-stack" arrangement which in previous years had set the Fuji .099 apart from its competition in a visual sense at least and had by now become something of a "cult" among sport fliers.

To deal with the limitation that an upstanding piston baffle could not be used, the designer reverted once again to the step in the piston crown which had been employed in the Silver Arrow model. In the case of the new .099, the relatively narrow transfer passages allowed this step to be milled as a straight segment across the piston crown rather than following the piston wall in annular fashion. It is an inescapable fact that this results in a combustion chamber shape at top dead centre which is less than ideal - a "pocket" is created which tends to concentrate gas to the bypass side away from the centrally-located ignition source. This in turn will tend to delay the full involvement of the charge in the combustion process. The presence of the crankweb and induction system at the front of the case created impediments to the provision of a bypass bulge like that which had been used on the Silver Arrow model. Accordingly, a leaf was taken out of Enya's book and the cylinder wall was made very thick so that twin side-by-side bypass passages could be milled directly into the cylinder wall at the front. This approach had of course already been used in the Fuji .099S (Model 099-14) described in the previous section. But this didn't completely solve all of the problems, and compromises had to be accepted. In order to locate the twin exhaust ports somewhere near correctly to line up with the twin stacks, it was necessary for the twin bypass passages to be made relatively narrow. This might well be expected to have an adverse effect upon transfer gas flow efficiency at higher speeds, although the consequent high transfer gas velocities at low speeds might reasonably be expected to aid starting.

None of these arguments were sufficient to deter the Fuji designer from putting this arrangement into practice, and there is no doubt that it works quite well enough for all normal purposes, even in un-modified form. The result was a really distinctive-looking little engine which was far sturdier than its twin-stack predecessors and had if anything a slightly better performance. Weight remained well under control too, measuring up at 3.5 ounces all-inclusive with tank. This was some 0.3 ounces less than the companion 099S model without a tank. The manufacturers claimed an output of 0.17 BHP at 13,000 rpm - slightly higher than their claim for the old radial-ported model. Based on my own experience, this claim seems highly optimistic for an unmodified unit, but the engines certainly run quite well enough for the sport-flying purposes for which they were intended. They are also remarkably sturdy as well as being very well made. And in my possibly biased view, they're among the prettiest and most individualistic little .099 engines ever produced - the red tanks, green venturis, tumbled cases and twin stacks make a really eye-catching combination!

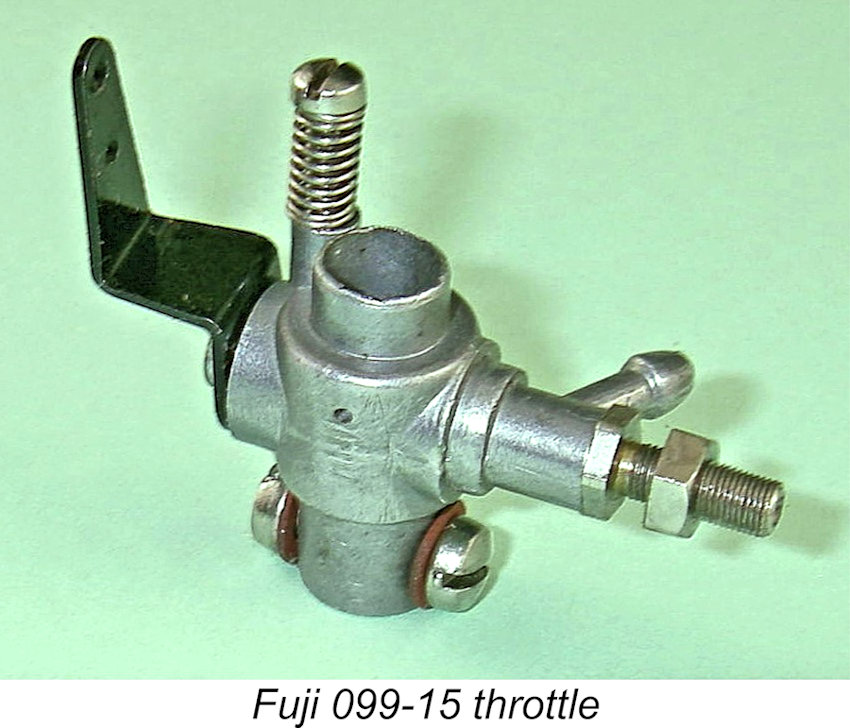

From the outset, an R/C version of this model was offered alongside the control line/free flight unit. The R/C carburettor initially supplied with these engines was extremely rudimentary, consisting of a simple butterfly restrictor located co-axially with the spraybar. Air bleed was fixed, being provided simply by a hole drilled through the centre of the The R/C version of the twin-stack Fuji .099 model 099-15 was briefly discussed in the previously-noted article which appeared in the British magazine “Radio Modeller” in December 1966 as one of a lengthy and very informative series of articles on R/C engines then on the British market. Unfortunately, no performance figures were given. It appears that the engines were serial-numbered sequentially as they came off the line, regardless of whether they were R/C or control-line models. Serial numbers of both variants are freely intermingled in my experience. My own lowest serial-numbered example of this very neat little engine bears the number 9568. This engine has lost its box, but my next higher numbered example (NIB engine s/n 20111) was supplied in the two-tone green box with what must be a left-over leaflet still showing the former model. It appears that they continued to use the old leaflet as long as stocks remained, regardless of whether or not it matched the engine with which it was supplied!

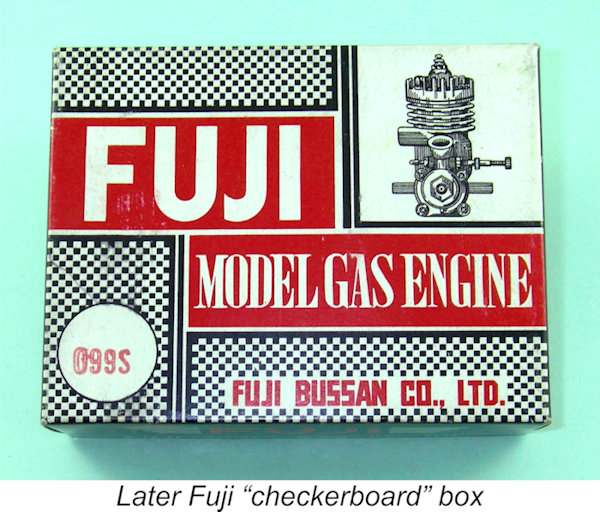

This red and white "checkerboard" box style was to last until the early 1970's, when a further change took place to a plain red box with white lettering. The checkerboard box marked the final appearance of the "winged Fuji" trade-mark which had appeared on the boxes since the beginning - the new trade-mark on the plain red boxes was simply the word "Fuji" inside an oval border.