|

|

The Micron 2.8 cc Diesel

Accessible information about engines from the pioneering era in France has hitherto been in relatively short supply, at least in the English language. In large part, this is due to the fact that French engines were never exported in significant numbers to other countries. My French friend and colleague Christian Farcy has commented that the main reason why French engines never made much of a mark outside France is that French manufacturers tended to confine their thinking to "French market" rather than "global market". Put another way, they "thought small". Their products certainly had sufficient merit to support overseas marketing efforts, but they didn't know how to pursue such initiatives, nor did they take the trouble to find out. Their focus on the domestic market greatly limited their market scope and hence their production potential. Micron did make some efforts during the early 1970's, but it was a case of too little, too late.

The focused development of the model diesel engine in France preceded British and American efforts along those lines by a good four years, giving the French a commanding early lead in this field. Consequently, at the time when the first British commercial model diesels appeared in mid-1946, no fewer than 11 French manufacturers were already offering model diesels! Some of these firms had been active for up to five years at that point in time. Among these was the firm of Moteurs Micron, makers of our subject engine, the Micron 2.8 cc diesel, who had been producing model engines since 1941.

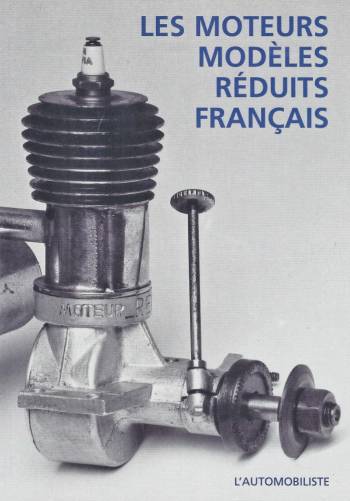

Fortunately, an excellent reference is readily available to anyone having an interest in this subject. This is the invaluable "Les Moteurs Modèles Réduits Français" (French Model Engines) compiled and edited by Adrien Maeght, with photographs by M. Phélizon. Published in the millennium year of 2000 by Éditions de L’Automobiliste of Paris, this lavishly illustrated high-quality soft-cover book presents its text in both French and English, thus making it readily accessible to many readers all over the world, including myself. No-one having even a peripheral interest in the fascinating history of model engine development and manufacture in general, and in France in particular, can afford to be without a copy. Although now long out of print, copies of the book periodically become available both through Amazon France and eBay France, which is how I obtained my copy. However, the book is not cheap – typically you’ll pay somewhere around 65 euros (US$80.00). Well worth it, though – what price knowledge?? There’s no other equivalent publication. In a very real sense, this is the French equivalent of the late Tim Dannels’ invaluable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (AMEE). The book is not completely free from error or omission, but for the most part it’s a dependable source. It’s certainly the best available reference on French engines. I freely acknowledge having drawn extensively upon this extremely useful work when carrying out the research for this article. I have also used a number of illustrations from the book, all of which are acknowledged in the captions. My sincere thanks to Adrien Maeght and his colleagues! Now, having listed my principal source with my grateful acknowledgement, it’s time to look into the background leading up to the appearance of the Micron 2.8 cc diesel. Background

During the subsequent decade, Thalheim produced a number of “full size” ETHA (Ernst Thalheim) two-stroke stationary engines, according to the customer’s particular requirements. These included single cylinder farm engines, an inline twin cylinder 500 cc (30 cuin.) boat engine rated at 20 HP and a 106 cc (6.5 cuin.) boxer twin engine reportedly used in a light aircraft (perhaps a power-assisted glider?). A range of 12 “model” size ETHA’s ranging from 0.4 cc to 25 cc were also individually constructed to order during this period. These were most likely marketed as table-top curios for the mechanically minded, much like miniature steam and Stirling Cycle engines. At this stage, Thalheim does not appear to have had any strong interest in the field of powered model aircraft.

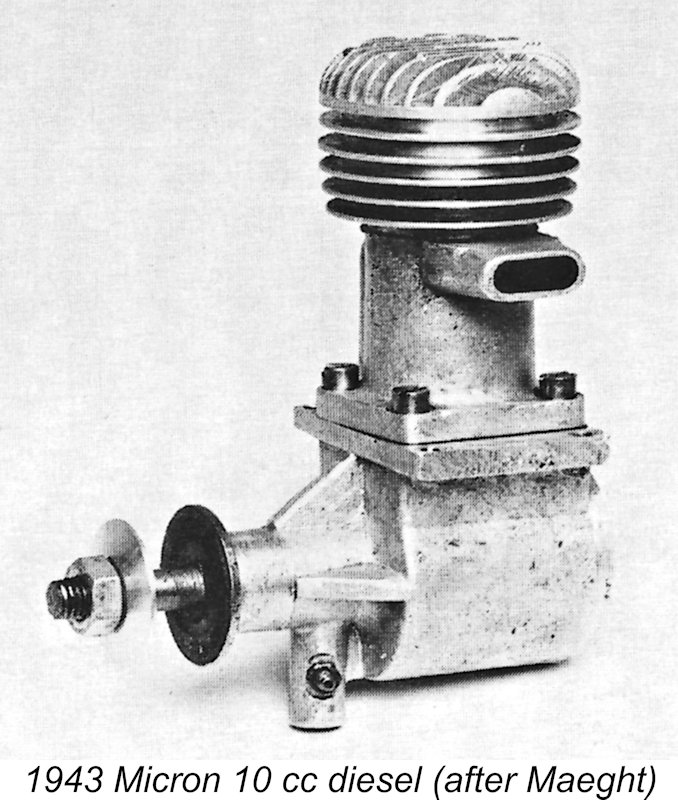

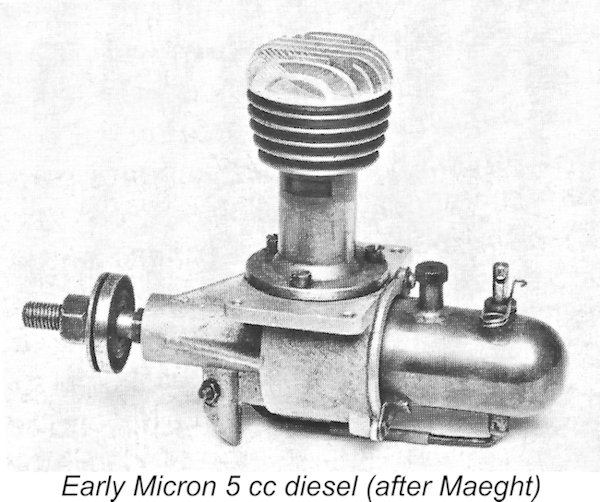

Despite the general European preoccupation with the Naturally, both French aeromodelling enthusiasts and engine constructors were greatly intrigued by this new technology. Among them was a Parisian enthusiast and skilled machinist named André Gladieux who had already cut his teeth in 1941 by producing a few The situation in France at this time was greatly complicated by the fact that much of the French homeland, including the area around Paris, was occupied by the Germans during Although it undoubtedly inhibited production volumes, the ongoing German occupation did not prevent model diesel manufacture in France from beginning to take off in 1943. Apart from Gladieux with his Micron 5 cc and 10 cc designs, a host of other French model diesel designs appeared more or less simultaneously during that year. These included offerings from Allouchéry, Fulgur, Jide, Marquet, Morin and STAB. It’s worth remembering that all of this activity came three years prior to the appearance of the first British production diesels – quite a head start! An interesting observation is the fact that unlike the pioneering diesels being developed more or less simultaneously in Italy and Sweden, few if any of these early French models displayed much Dyno influence – the French designers evidently preferred to plough their own design furrow.

There’s little doubt that although a market for model engines must have existed in occupied France, any such market must surely have been highly constrained during the war years. However, as the war drew towards its increasingly foreseeable conclusion following the August 1944 liberation of Paris, things began to move quite rapidly. Established manufacturers like Gladieux moved quickly to increase production, while new manufacturers emerged to join the fun.

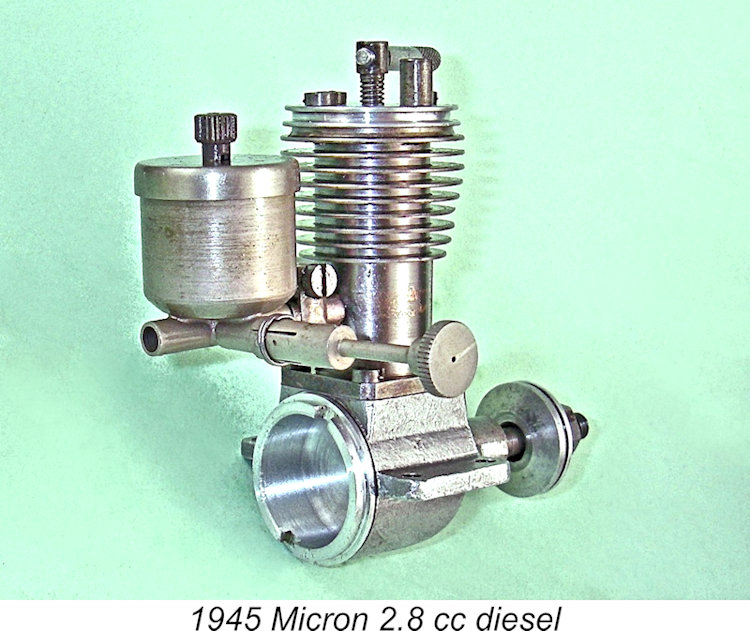

However, Gladieux was not content to stand pat in design terms. He already recognized that while fixed compression was a perfectly practical design approach for relatively low-speed diesels, it had its limitations, particularly with respect to the narrow operating speed range to which such engines were confined by their built-in ignition timing. He saw that the use of variable compression offered a pathway towards greater operating flexibility and higher overall performance. The result of such deliberations was the 1945 appearance of his first variable-compression diesel design, the Micron 2.8 cc diesel which forms our main subject. Description

The engine was built up around a gravity die-cast crankcase of aluminium alloy. The steel cylinder was secured to the case with four machine screws. The cooling fins were machined directly onto the cylinder – a good design in that it avoided the possibility of a heat dam forming between the cylinder liner and a separate slip-on jacket. The cylinder featured a brazed-on bypass channel at the front in addition to brazed-on intake and exhaust pipes. An unusual feature of the engine was its use of a single exhaust pipe of relatively small diameter. Why not two exhausts, one on each side?? We’ll never know …………

The single-arm compression screw had a knurled handle for improved grip. It acted upon a cast-iron contra-piston of substantial depth. The heads of early models were left plain, but later examples featured a red-anodized coloration. Moving on downwards, the flat-topped cast-iron piston was an extremely heavy component – no attempt was made to lighten it by internal machining. The gudgeon (wrist) pin had a diameter of only 3 mm – pretty marginal for an engine of this displacement, especially with that heavy big-bore piston reversing its direction with every revolution. The con-rods in some examples were made of aluminium alloy with a cast iron bushing in the big end bearing, while others were machined from bronze. The rod drove a one-piece steel crankshaft having a plain disc crankweb with no counterbalancing. Given the engine’s unusually high reciprocating weight, one would expect vibration levels to be quite significant! The shaft ran in a cast iron bushing installed in the main bearing housing. The prop driver engaged with the shaft on a fairly steeply-angled self-releasing taper. A simple prop-nut and washer were used to secure the prop. The odd example has shown up with a spinner nut fitted, but this is a later owner addition – the sole Micron model ever to feature a spinner nut as delivered was the blue-headed 2.5 cc team race diesel of 1968.

The needle was the excellent Micron design featuring an unthreaded brass split thimble which was tensioned against the unthreaded outer spraybar by a coil spring wrap. The actual thread was externally formed on the steel needle itself, engaging with an internal thread inside the spraybar. This design provided extremely fine fuel mixture adjustment along with outstanding smoothness and setting security.

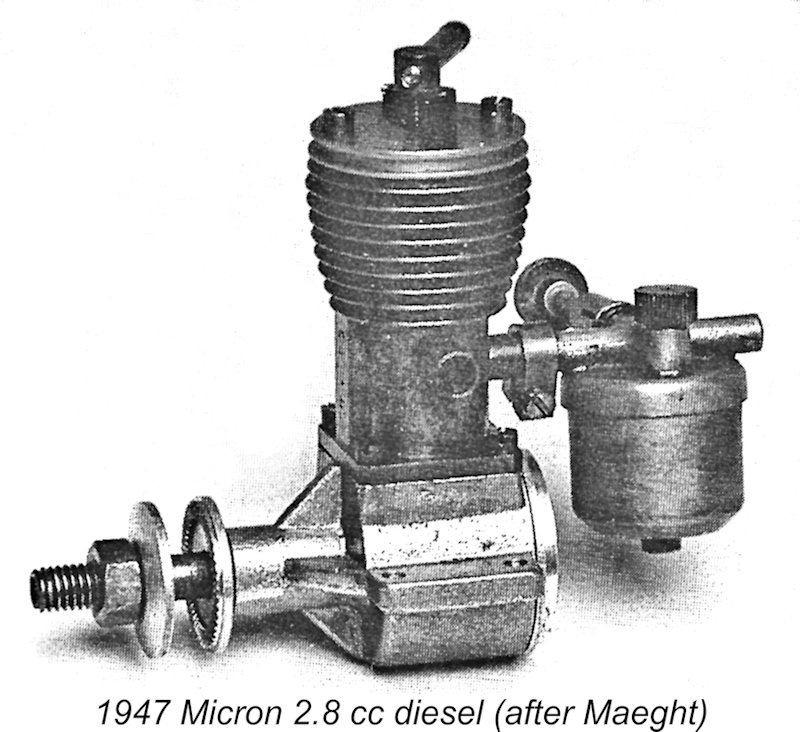

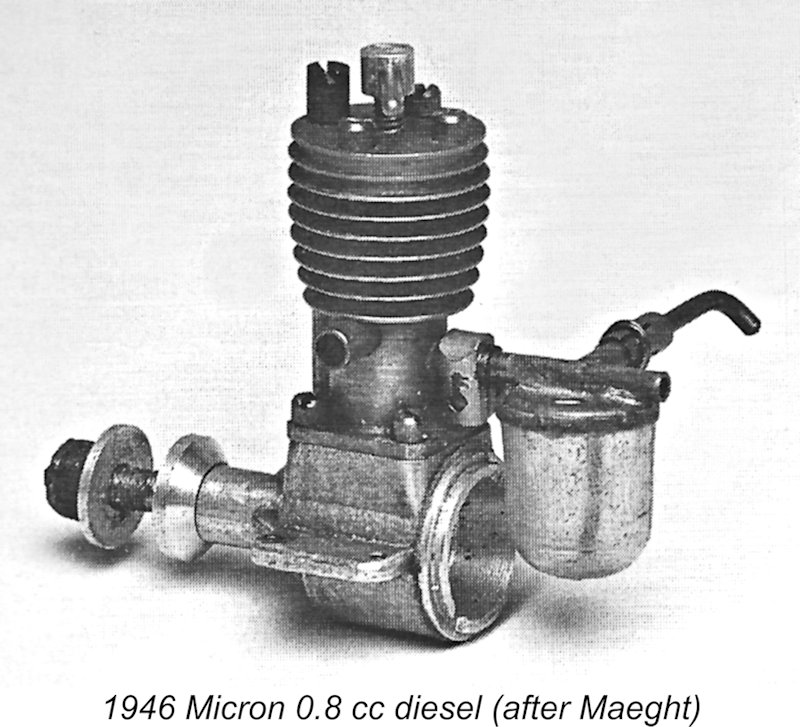

According to the information set out in the 1946 catalogue entry for this model, the Micron 2.8 had enjoyed considerable contest success during 1945, both The Micron 2.8 seems to have been quite successful in sales terms, remaining in production from 1945 through to 1951. A 0.8 cc model built to more or less the same design was introduced in 1946. The over-the-intake tank location on the 2.8 cc model was apparently abandoned in 1947 in favour of the more conventional under-slung tank. Like all Micron engines, the quality of construction of this engine was beyond criticism. There were a few design issues (see below) – Gladieux was still very much in learning mode at this time. However, the engine’s manufacturing quality shone through in all areas of its construction. OK, so now we know something about the engine. How does it run? Only one way to find out! The Micron 2.8 cc Diesel on Test

However, the best-laid schemes ……… when I set the engine up in the test stand to give it a try, it turned out that once the thick storage oil was diluted with fuel, the compression simply vanished! There was no way that I was going to get it to run, not even with an oil prime. Fortunately, my Kiwi mate Dean Clarke is a As it turned out, Dean found quite a few matters requiring attention - the engine was in even worse shape than I had believed. Apart from the absent compression which required that the cylinder be rebored, it turned out that the ridiculously skinny 3 mm dia. gudgeon pin had broken in two places, When finishing the replacement piston, Dean milled it out internally to reduce its weight well below that of the original. His efforts bore fruit – the combined reciprocating weight of the piston/gudgeon pin/con-rod assembly went down from a bloated 18 gm to a far more appropriate 12 gm. A substantially improved performance with significantly less vibration and reduced mechanical stresses should result from this change. While he was at it, Dean also replaced the original crankcase (which had an open mounting hole) with an undamaged component which he happened to have in his parts stash. He also came up with an as-new tank and needle valve assembly to replace the original assembly, which had been subjected to some butchery by a previous owner. The engine was now in better-than-new condition! It’s hard for me to adequately express my thanks to Dean for his splendid efforts!!

I had some trouble at first – the engine just didn’t want to know! I eventually moved the compression stop screw forward one position to allow the use of a little more compression, and that did the trick. The engine began firing, after which a start was soon achieved. As we might expect with the location of the tank above the intake, there was a definite tendency for the engine to become flooded if left standing after fuelling. The gravity-induced dripping of fuel into the intake was quite slow – the needle only had to be opened around 1¼ turns, so the rate of fuel deposition was minimal. Even so, it turned out once I got on top of things that the trick was to fill the tank with the needle closed, and then go for an immediate start, not allowing time for excess fuel to build up in the case.

Running qualities were somewhat less positive. The main issue was a definite tendency to detonate when leaned out. Careful setting of the needle could minimize this behavior, but it never quite went away. Running was generally very steady, but the tendency towards detonation remained a factor. That said, once a given setting was established, the engine ran the tank out with no issues.

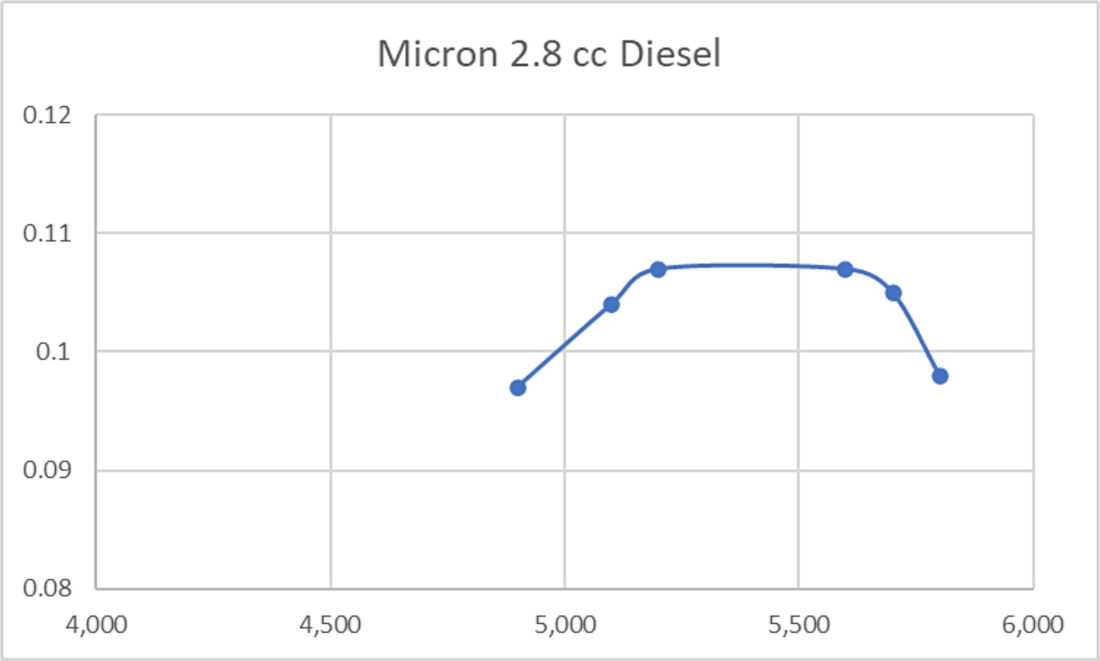

Probably as a result of this, the engine actually turned the test prop at a slightly higher speed than I had been anticipating. Once I had put a half-dozen slightly rich and under-compressed tanks of fuel through the engine to settle Dean’s careful work down, I tried the engine fully leaned out for a brief period at the end of the last run. It turned the Zinger 11x7 prop at 5,200 RPM – a little better than the 5,000 RPM than I had predicted. The implied output at that speed was around 0.107 BHP. Continuing the break-in by confinng the leaned-out running to a very brief period near the end of a rich run on a full tank, I then tried a slightly “slower” Zinger 12x5, which the Micron spun at 5,100 RPM – around 0.104 BHP. A switch to an even slower Top Flite 11x10½ pulled the engine down to 4,900 RPM – about 0.097 BHP. Clearly I was moving away from the peak. Going the other way. I tried a slightly lighter load by fitting a Top Despite the rather narrow speed range covered by these readings, it seemed to me that I had bracketed the peak very nicely – the Micron as tested evidently delivered a peak output of some 0.11 BHP @ 5,400 RPM. Indications were that it would be extremely reluctant to run at speeds above 6,000 RPM – in typical sideport fashion, power fell off very sharply once the peak had been passed. Regardless, this is a slightly better performance than that claimed by the manufacturer, who cited an output of 0.098 BHP @ 4,800 RPM. Moreover, there's little doubt that performance would improve a little more following completion of the break-in procedure. Any improvement can undoubtedly be attributed to Dean Clarke’s seemingly effective measures to reduce reciprocating weight. As it now stands, the engine would be a perfectly satisfactory powerplant for a modest-sized free flight model of the type that was popular in 1945 when this unit was first created. Its easy handling in particular would have endeared it to its users. Conclusion As stated earlier, the Micron 2.8 cc diesel remained in production for some 6 years from 1945 to 1951. The only really substantial change was the general adoption in 1947 of the under-slung fuel tank in place of the former top-mounted gravity-feed arrangement. Production of the Micron 5 cc fixed-compression diesel continued throughout this period, as it was to do at some level until 1962.

It was perhaps fitting that the very last diesel to be produced by Moteurs Micron was the limited-edition "collector's special" version of the original Micron 5 cc fixed-compression model of 1943. This limited edition offering was produced in relatively small numbers during 1976. It differed from the 1943 version in having a cast cylinder head as opposed to a fully-machined component. It was also sold without a tank. The famous Micron series of model diesels thus ended as it had begun. All of these later Micron diesels upheld the very high manufacturing standards which characterised the Micron range throughout. However, it was the 5 cc fixed-compression diesel model of 1943 and the 1945 2.8 cc variable-compression diesel which established those standards. As such, they richly deserve our respectful remembrance! _______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published December 2024 |

| |

In this article, I’ll take a look at another French classic – the Micron 2.8 cc diesel of 1945. This will be my sixth article dealing with a French engine – I’ve previously covered the

In this article, I’ll take a look at another French classic – the Micron 2.8 cc diesel of 1945. This will be my sixth article dealing with a French engine – I’ve previously covered the

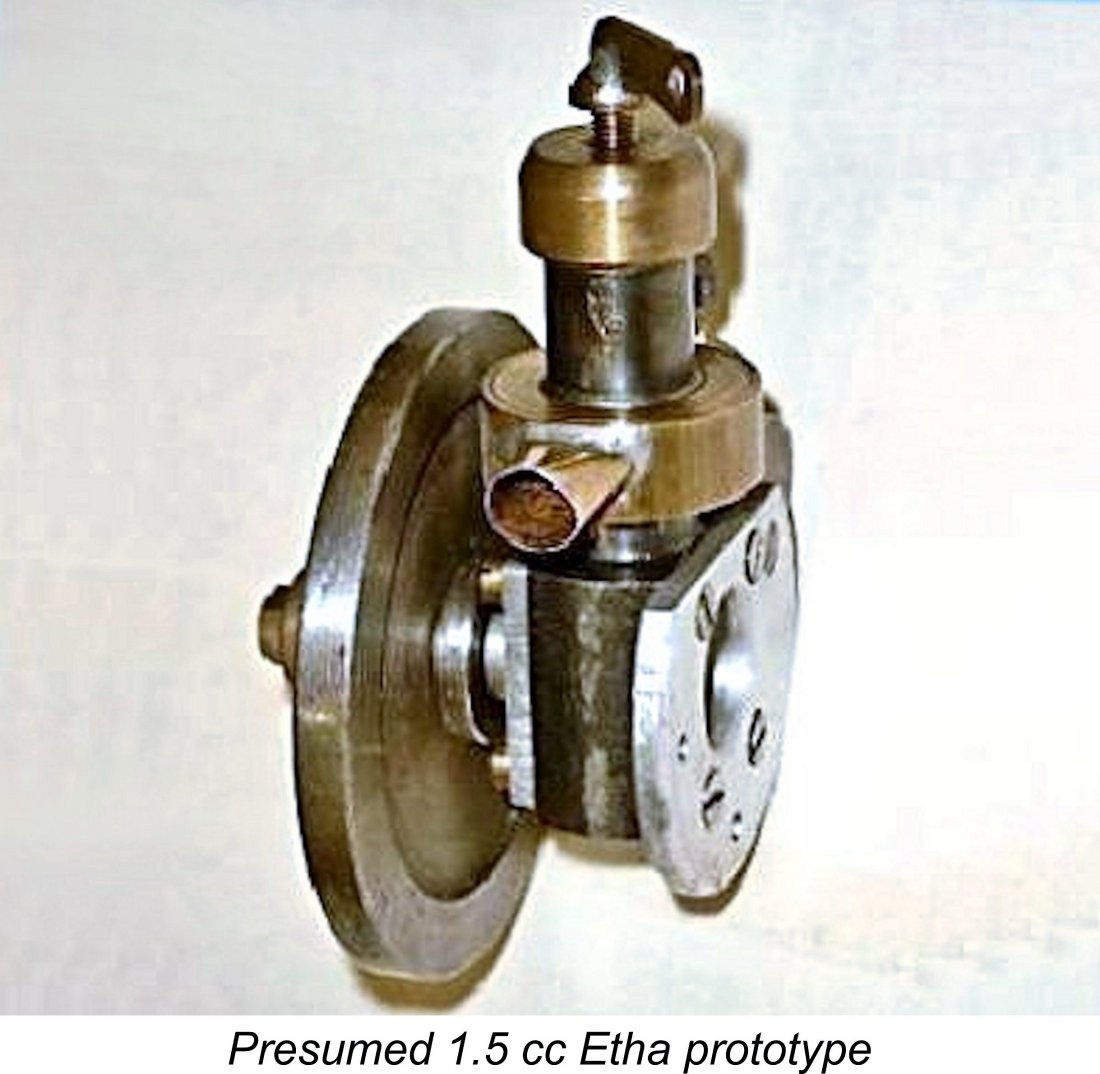

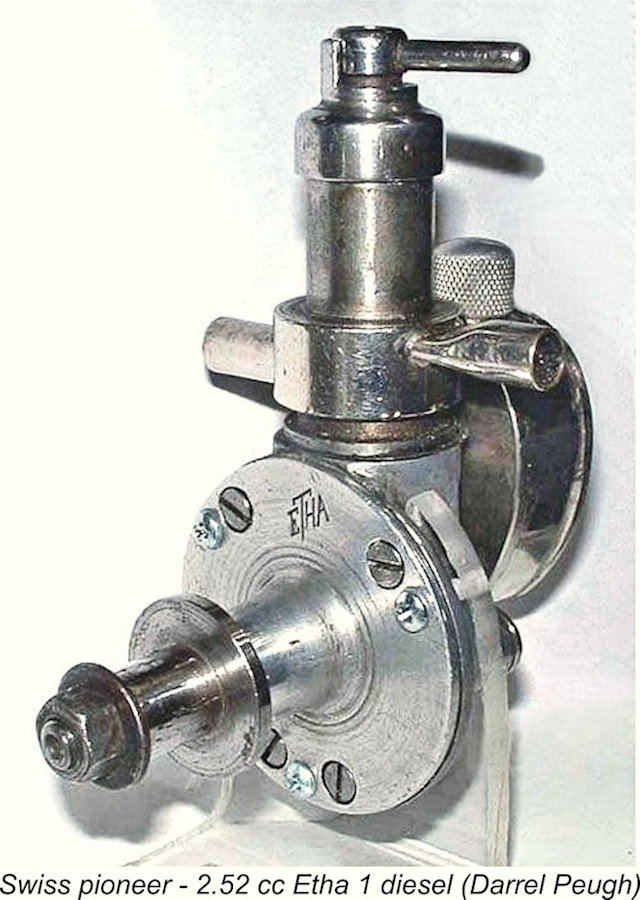

In a number of previous articles, I’ve traced the initial appearance of the model compression ignition (aka somewhat incorrectly “diesel”) engine all the way back to December 17

In a number of previous articles, I’ve traced the initial appearance of the model compression ignition (aka somewhat incorrectly “diesel”) engine all the way back to December 17 The growing availability of proven spark ignition engines from America and the German Kratmo company in the mid to late 1930’s ignited Swiss interest in powered models. Perhaps some saw the potential in Thalheim’s unusual little engines, if their power-to-weight ratios could be improved. At this point, Thalheim’s creativity seems to have been re-invigorated, leading him to further refine his own compression ignition engine design concept specifically for model aero applications. Assertions by some that his ETHA 1 and 2 engines date as far back as 1938 in commercial form are only tentatively substantiated, but the engines were certainly already there when the far better-known Swiss 2 cc Dyno-1 from Klemez-Schenk arrived in 1941. A test by Maris Dislers of a replica

The growing availability of proven spark ignition engines from America and the German Kratmo company in the mid to late 1930’s ignited Swiss interest in powered models. Perhaps some saw the potential in Thalheim’s unusual little engines, if their power-to-weight ratios could be improved. At this point, Thalheim’s creativity seems to have been re-invigorated, leading him to further refine his own compression ignition engine design concept specifically for model aero applications. Assertions by some that his ETHA 1 and 2 engines date as far back as 1938 in commercial form are only tentatively substantiated, but the engines were certainly already there when the far better-known Swiss 2 cc Dyno-1 from Klemez-Schenk arrived in 1941. A test by Maris Dislers of a replica

Gladieux took steps initially to increase production of his established 5 cc fixed-compression diesel, for which a considerable demand now existed. This engine went from strength to strength, winning almost everything in sight during 1945 and 1946. It exerted a strong influence over designs from manufacturers outside France, such as the makers of the 1947

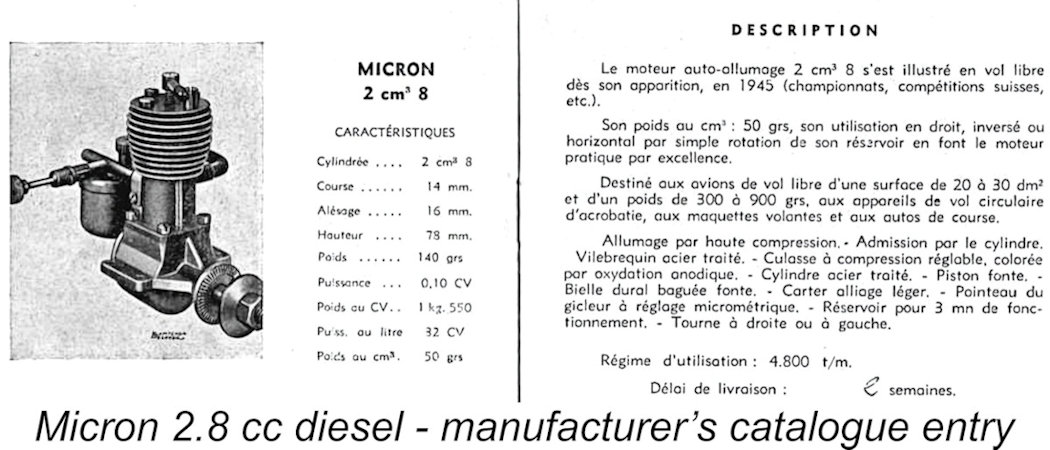

Gladieux took steps initially to increase production of his established 5 cc fixed-compression diesel, for which a considerable demand now existed. This engine went from strength to strength, winning almost everything in sight during 1945 and 1946. It exerted a strong influence over designs from manufacturers outside France, such as the makers of the 1947  The Micron 2.8 cc diesel was a basically conventional design by 1945 standards, although it did present a few unusual features. It was a straightforward plain bearing sideport diesel, its main departure from then-conventional practise being its short-stroke internal geometry. Bore and stroke measurements were 16 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.81 cc. Weight was 135 gm (4.76 ounces). An identical engine having bore and stroke dimensions of 15.5 mm and 13 mm respectively was also produced, having a displacement of 2.45 cc. This variant was evidently produced in somewhat smaller numbers - surviving examples appear to be far less common than those of the 2.8 cc model.

The Micron 2.8 cc diesel was a basically conventional design by 1945 standards, although it did present a few unusual features. It was a straightforward plain bearing sideport diesel, its main departure from then-conventional practise being its short-stroke internal geometry. Bore and stroke measurements were 16 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.81 cc. Weight was 135 gm (4.76 ounces). An identical engine having bore and stroke dimensions of 15.5 mm and 13 mm respectively was also produced, having a displacement of 2.45 cc. This variant was evidently produced in somewhat smaller numbers - surviving examples appear to be far less common than those of the 2.8 cc model.  At the top, the light alloy cylinder head was attached to the cylinder by four screws. One of these had an elongated cylindrical head, serving as a compression screw stop. The engine could be tested initially with a conventional short screw in place of the stop, allowing the compression setting to be established before the longer screw was installed in what was found to be the appropriate location.

At the top, the light alloy cylinder head was attached to the cylinder by four screws. One of these had an elongated cylindrical head, serving as a compression screw stop. The engine could be tested initially with a conventional short screw in place of the stop, allowing the compression setting to be established before the longer screw was installed in what was found to be the appropriate location.  At the rear, the brazed-up fuel supply assembly incorporated the intake venturi, needle valve and tank body in a single unit. This assembly plugged into the brazed-on intake stub on the cylinder. This stub was split so that it could be tightened onto the intake tube using a neat alloy clamp to secure the assembly. The design allowed the engine to be mounted in any desired orientation simply by slackening off the clamp and rotating the tank assembly to suit.

At the rear, the brazed-up fuel supply assembly incorporated the intake venturi, needle valve and tank body in a single unit. This assembly plugged into the brazed-on intake stub on the cylinder. This stub was split so that it could be tightened onto the intake tube using a neat alloy clamp to secure the assembly. The design allowed the engine to be mounted in any desired orientation simply by slackening off the clamp and rotating the tank assembly to suit.  The tanks on the original variants were located above the intake, giving gravity feed. This appears to imply that inverted mounting of the engine was the favoured orientation. The illustrated example is one of these units. Later examples were amended to have the tank located below the intake, relying on suction to draw fuel from the tank. The tank had ample capacity – the manufacturer claimed that it would provide a running time of up to 3 minutes, which testing proves to be more or less correct. Oddly enough in view of the engine’s intended free flight primary applications, no cut-out was incorporated.

The tanks on the original variants were located above the intake, giving gravity feed. This appears to imply that inverted mounting of the engine was the favoured orientation. The illustrated example is one of these units. Later examples were amended to have the tank located below the intake, relying on suction to draw fuel from the tank. The tank had ample capacity – the manufacturer claimed that it would provide a running time of up to 3 minutes, which testing proves to be more or less correct. Oddly enough in view of the engine’s intended free flight primary applications, no cut-out was incorporated.  domestically and in Swiss competitions. It was said to be suitable for free flight models having wing areas of between 300 and 460 in

domestically and in Swiss competitions. It was said to be suitable for free flight models having wing areas of between 300 and 460 in The manufacturer’s promotional leaflet relating to this engine gives its operating speed as 4,800 RPM and its peak output as 0.10 CV (0.098 BHP). Maeght’s entry for this model rounds these figures off by recording a claim that it developed 0.10 BHP at 5,000 RPM – not incompatible figures. Taking the two claims together, we find that the Micron might be expected to turn a Zinger 11x7 wood prop at right around 5,000 RPM. Rather a lot of prop for a 2.8 cc engine, but this was 1945! I elected to begin with that airscrew and see how things developed.

The manufacturer’s promotional leaflet relating to this engine gives its operating speed as 4,800 RPM and its peak output as 0.10 CV (0.098 BHP). Maeght’s entry for this model rounds these figures off by recording a claim that it developed 0.10 BHP at 5,000 RPM – not incompatible figures. Taking the two claims together, we find that the Micron might be expected to turn a Zinger 11x7 wood prop at right around 5,000 RPM. Rather a lot of prop for a 2.8 cc engine, but this was 1945! I elected to begin with that airscrew and see how things developed.  world-class model engine restorer – check out my article on the

world-class model engine restorer – check out my article on the

Upon its return home, the Micron went straight back into the test stand. As before, I began with the Zinger 11x7 wood prop. I used a mineral oil-based equal-parts ether/kerosene/oil fuel, which seems to work fine in low-revving sideport motors and does not cause any after-run gumming tendencies.

Upon its return home, the Micron went straight back into the test stand. As before, I began with the Zinger 11x7 wood prop. I used a mineral oil-based equal-parts ether/kerosene/oil fuel, which seems to work fine in low-revving sideport motors and does not cause any after-run gumming tendencies.

On the plus side of the ledger, the very small exhaust pipe had one definite upside – noise levels were remarkably low. I didn’t even need to wear my usual ear-muffs! Moreover, vibration levels seemed quite reasonable, doubtless thanks in large part to Dean Clarke’s measures to reduce reciprocating weight.

On the plus side of the ledger, the very small exhaust pipe had one definite upside – noise levels were remarkably low. I didn’t even need to wear my usual ear-muffs! Moreover, vibration levels seemed quite reasonable, doubtless thanks in large part to Dean Clarke’s measures to reduce reciprocating weight.