|

|

The Taplin Story and the Taplin Tempest

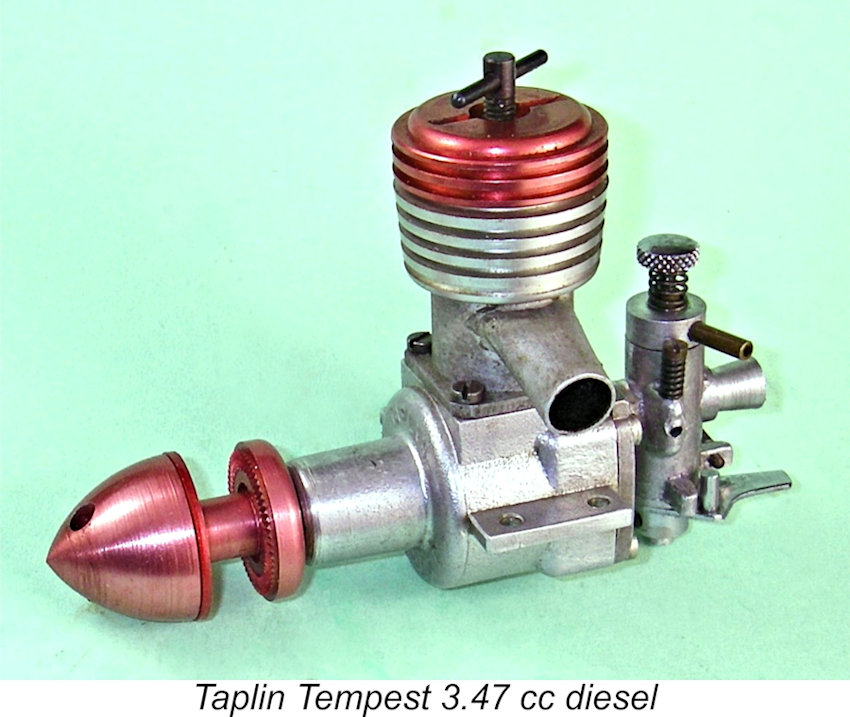

Prior to 1970, all of the commercially-marketed Taplin engines had been in-line alternate-firing twin-cylinder diesels. They were very well-made units which handled easily and ran extremely smoothly with minimal vibration. However, they were unusually heavy by model aircraft standards, also falling well short of matching then-current performance standards for their displacements. As a result, the majority of them appear to have been sold as water-cooled marine models, in which form they were well able to provide their owners with excellent service. However, by the late 1960's even the marine models had fallen out of favour as model boaters increasingly gravitated away from diesel power. The 1970 Tempest stands out among the Taplin offerings not only because it was the final Taplin model of them all but because it was the only single-cylinder model ever offered by its manufacturers. Unfortunately for the company, the Tempest was woefully out of step with the marketplace as it then existed - R/C aeromodellers in general had come out in favour of mid-sized and larger glow-plug engines by this time, while model boat enthusiasts were losing interest in diesel powerplants. As a result, the Tempest failed to make any meaningful impression upon the market, only remaining in production by its original manufacturers for a very short time. Good original examples are in very short supply today. My original intention when commencing this project was simply to review the Taplin Tempest in isolation. However, I soon realized that this would make very little sense – in order to place the Tempest in context, it would be necessary to provide the reader with a summary of the history of the Taplin venture which produced it and the muti-talented individual who established that venture - Colonel H. J. Taplin. This is actually a task that is long overdue, at least in terms of being made readily available online. This topic has previously been very well documented by my friend and colleague Mike Noakes, whose series of articles in the long-defunct “Model Engine World” (MEW) magazine from April-December 1997 included a full history of the Taplin engines. Mike’s very informative articles were focused primarily upon the creation of a replica of the original prototype Taplin Twin which was based upon E.D. 2 cc piston/cylinder components. However, Mike also included some invaluable historical information, to which I’ve made reference here. Moreover, when contacted during the preparation of this article, Mike was kind enough to provide scans of a number of documents relating to the lives of the personalities involved, many of which are reproduced here. Thanks, mate! However, even more help than this was soon forthcoming! Learning that I was looking into the life and work of the Taplins, my valued friend Marcus Tidmarsh undertook his own line of in-depth research into Colonel Taplin's activities, uncovering many obscure details of his earlier and middle years. Almost none of these details have been made public previously. He also provided scans of a number of additional documents which clarified the Taplin story even further, as well as a number of period photographs. My debt to Marcus cannot be overstated! By combining the findings of both Mike and Marcus, it has been possible to develop a fairly comprehensive start-to-finish picture of the life and work of Colonel Harold John Taplin. This article is every bit as much their work as mine - I merely held the pen. It's a far more interesting story than I had been expecting, and one well worth telling! Quite apart from his involvement with model engines, Colonel Taplin had a wide-ranging earlier life which reads almost like an adventure novel! I must also acknowledge the invaluable assistance provided by my Aussie mate Gordon Beeby, who did much to sort out the advertising and media records for the Taplin engines. Finally, I'm most grateful to my valued mate Kevin Richards for setting me straight on a few errors which had crept into the original version of this article. Thanks, gents!! The greatest advantage of print media such as MEW is that it’s permanent – as long as the documents are well cared for, they can last indefinitely. However, the downside is that the information is only available to those who have access to surviving documents. Moreover, it cannot be updated without a reprint. In today’s electronic world, the availability and ongoing currency of information is enormously enhanced by its being presented on-line in updatable sources such as this website, although such sources tend to be rather ephemeral, lasting only as long as the platform on which they are based. Take note - this website is no exception! Even so, I considered it worthwhile to present the information here. So, without further ado, let’s get to it!! The Taplin Venture – an Overview

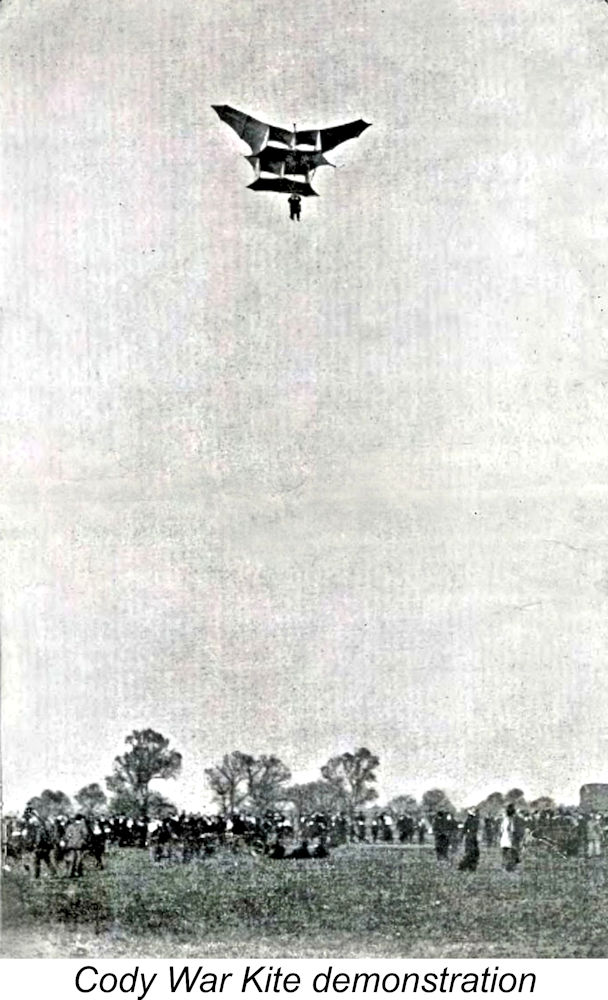

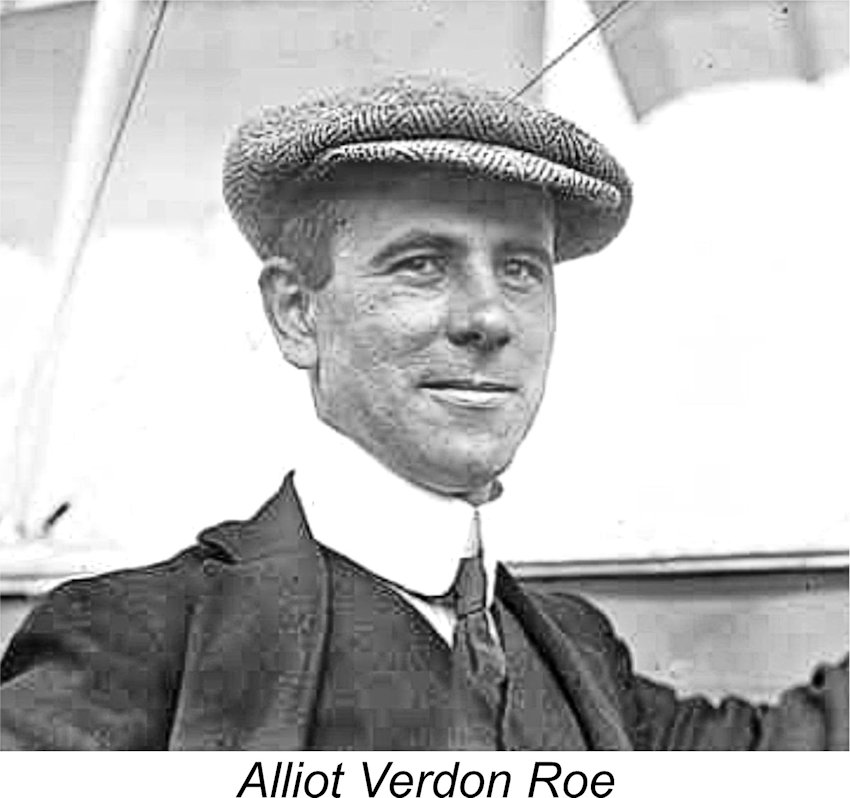

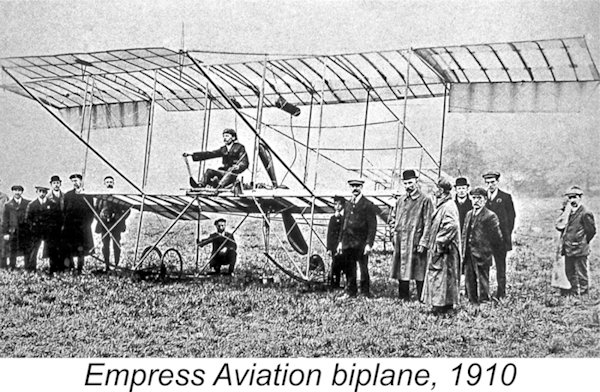

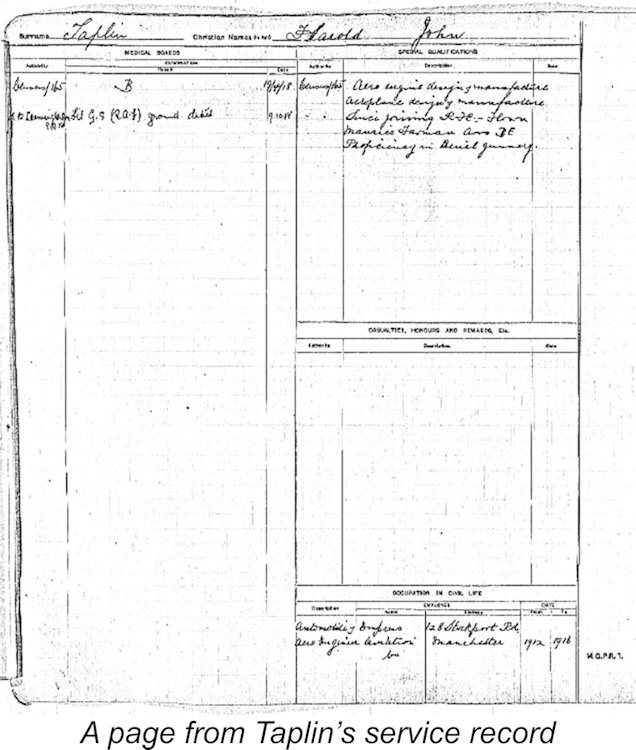

Taplin's father Thomas (1855 - 1926) was a Colonial Broker, an official responsible for negotiating trade agreements between Young Harold Taplin seems to have been air-minded from an early age. In a letter written to the “Daily Mirror” which appeared in their December 22nd, 1966 issue, the Colonel recalled having served as one of the test “guinea-pigs” at the age of 12 during the 1903 demonstrations at Alexandra Palace of the so-called “war kites” developed by American-born British resident S. F. Cody (not to be confused with the unrelated Buffalo Bill Cody). These man-carrying kites were intended for use as military aerial observation tools, thus reviving an ancient Chinese concept. Perhaps inspired by the views from 100 feet up in the air, Taplin recalled subsequently building several large box kites in 1906 at the age of 15 which he and a friend used to hoist cameras aloft for the purpose of taking early aerial photos. Taplin’s interest in model aircraft developed quite early on. During 1906, at the age of 15, he built his first such In January 1910, Alliot Roe relocated to Manchester to establish the iconic A. V. Roe and Company (Avro) aircraft manufacturing firm. Taplin remained in London - the 1911 Census indicates that at 20 years old, he still resided with his parents at 16 Lordship Park, Stoke Newington, London. His occupation at this time was recorded as being that of a ship broker's clerk. Evidently he found work where it was available. However, Taplin’s abiding interests lay in the engineering field. It’s not clear whether or not he ever acquired formal engineering qualifications, but in 1912, at the age of 21, he began a career as an automobile and aero engineer with Empress Aviation of 128 Stockport Road in Manchester, England. Although there’s no evidence, his former employer and now Manchester resident A. V. Roe may have had something to do with facilitating this move. At the very least, Taplin's earlier experience working for Roe must surely have helped him to secure this position.

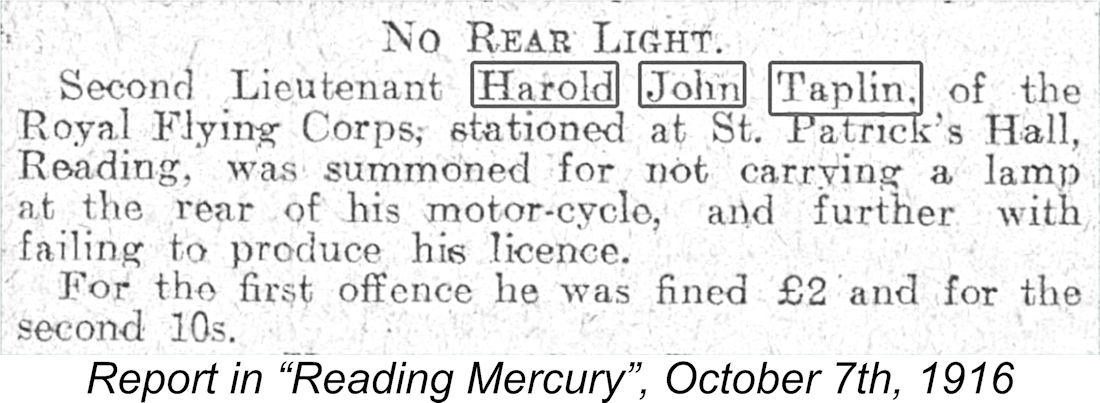

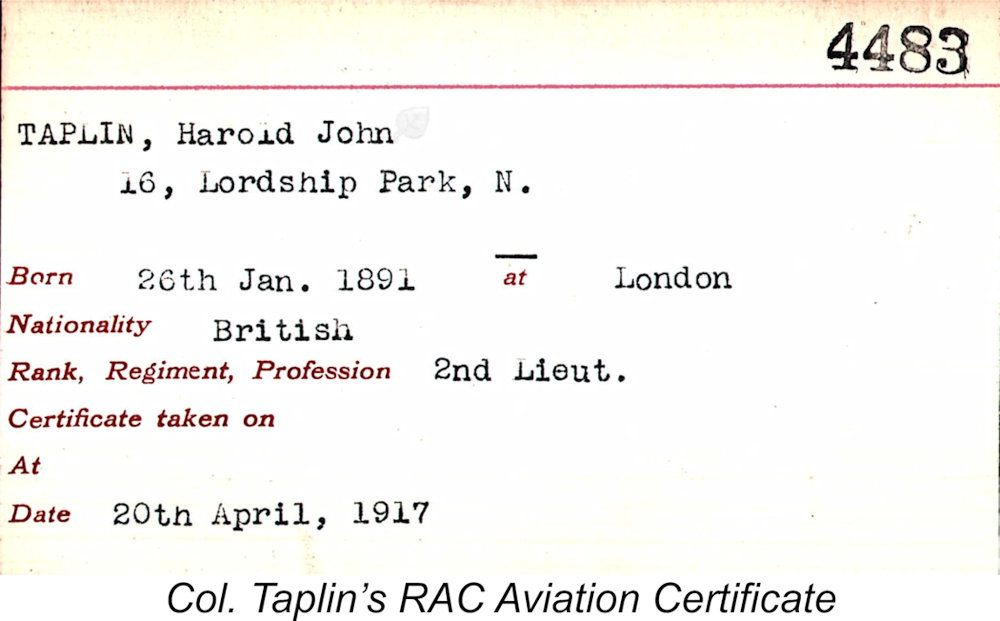

Despite the company's name, they never made a single complete car and produced only one experimental aircraft in 1910 which made a few “bunny hops” but never actually flew. Their aero engine, on which Taplin presumably worked, was a close copy of the French Gnome design, to the point that company owner Charles Fletcher was ultimately sued successfully by the Gnome Engine Company for the unauthorized use of their design, bankrupting him. Regardless, this is where Taplin acquired his reputation as an expert in aero engine design and production. However, WW1 soon intervened. Initially, Taplin was required to continue in his reserved occupation role until the unexpectedly serious personnel losses in France forced a change in government regulations, allowing him to apply for a commission as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which he did in 1916. Effective from the 17th of August 1916, the 25 year-old Taplin was commissioned into the Special Reserve of the RFC as a direct entrant holding the rank of probationary Second Lieutenant. He then underwent aeronautical training while stationed at St. Patrick’s Hall, No. 1 School of Military Aeronautics, a facility which the RFC had commandeered from University College, Reading in 1915. His flight training spanned some months, beginning with a Farman Longhorn While stationed at Reading, Taplin had a minor run-in with the law! A media report in the “Reading Mercury” for October 7th, 1916 stated that he had been fined £2 for failing to display a rear light on his motorcycle and a further 10s (£0.5) for failing to produce his license on demand. Bad boy!! In late December 1916, Taplin was deployed to France. Because of his prior aircraft engineering expertise he was tasked with undertaking aircraft maintenance and repair responsibilities, consequently doing very little flying. He was appointed as an engineering specialist with the technical rank of Engine Officer, 3rd Class.

Having obtained the necessary certificate, Taplin's commission in the RFC as a Pilot 2nd Lieutenant was confirmed on The accompanying image of Taplin in full WW1 flying kit must date from this period. We know from later documentation that he was a "compact" individual standing only 5 ft 8 in., with blue eyes and brown hair. In early 1918, Taplin was promoted to Acting Captain. On April 1st, 1918, the RFC and RNAS were combined to form the Royal Air Force (RAF). Soon thereafter, Captain Taplin was transferred to the newly-established RAF South East Command. He assumed command of an RAF facility situated on Salisbury Plain, probably No. 8 Training Depot at RAF Netheravon, which was one of several RAF bases to be located on Salisbury Plain. This facility had been set up in April 1918 to train aircrew, groundcrew, specialist signalers and fitters. Captain Taplin’s specialist expertise in the areas of engine and aircraft maintenance would have been well matched to this assignment. Aside from his military duties, Taplin evidently continued to apply his mind to the resolution of emerging challenges relating to the flying of full-scale aircraft. At some point in 1918 he applied for a Patent for a novel non-gyroscopic two-axis flight stabilization device (aka auto-pilot) that functioned in response to differential aerodynamic pressures. As we shall see, an aircraft using this device was eventually test-flown in the USA in 1926, but the idea never caught on – the gyroscopic designs, most notably the Sperry units, carried the day.

After WW1, Taplin returned to working in the engineering field, although details of the next stage of his life are in short supply. The post-war Census of 1921 (June 19th) found him back living with his parents at 16 Lordship Park in Stoke Newington, London. His occupation at this time was recorded as a Mechanical Engineer employed at 159 Hornsey Road, Islington, London, where he apparently worked for a firm called Gerrard Wire Tying Machines Limited, whose core business was the supply of machinery and hardware for the construction and securing of containers of various sorts. The property on The next period in Taplin’s life is essentially undocumented – there’s a glaring gap covering the entire period covering 1922 through to late 1926. Our only glimpse of him during this period confirms that he was still resident in London and still working for Gerrard Wire Tying Machines Ltd. as of March 1925. On March 6th, 1925 he applied for a Patent for a new staple design, which he assigned to his employers in accordance with prevailing practise. The implication is that he had been employed all along by the Gerrard company. Marcus Tidmarsh learned that during the 1920’s, the UK was very strict about ensuring that all passenger liners submitted full passenger lists and destination details before being allowed to leave any UK port. All such records have now been digitised and placed in the public domain. Checking this resource, Marcus was able to confirm that no record exists of Taplin having left the UK at any point prior to late 1926. He was still resident at 16 Lordship Park throughout this period.

Obviously, Harold Taplin would not have been able to continue living in the house once it was put up for sale. However, matters were far from bleak. Despite losing his residence, he would likely have received a substantial sum of money following the sale of assets. Marcus Tidmarsh estimated that having regard to then-current property values in this relatively upmarket area, Harold Taplin’s share might have amounted to the present-day equivalent of around £500,000. Probate was granted on May 11th, 1926, at which point Taplin would have found himself homeless but relatively wealthy, possibly holding the cash equivalent of a good ten year’s wages. Once his late father’s affairs had been settled, Taplin looked to his future. Having lost both his father and his home, he was clearly open to a complete change of scene. Perhaps fortuitously, just such an opportunity appears to have presented itself at this time. Although completely undocumented, the circumstantial evidence suggests that Taplin's employer, Gerrard Wire Tying Machines Ltd., somehow received a commission from a firm in Spokane, Washington, USA to design an innovative box-making machine.

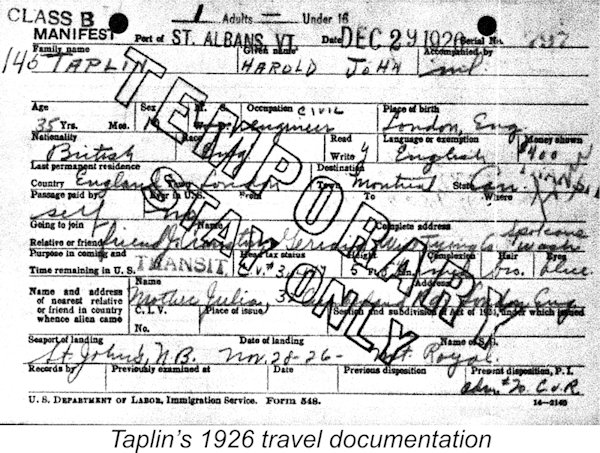

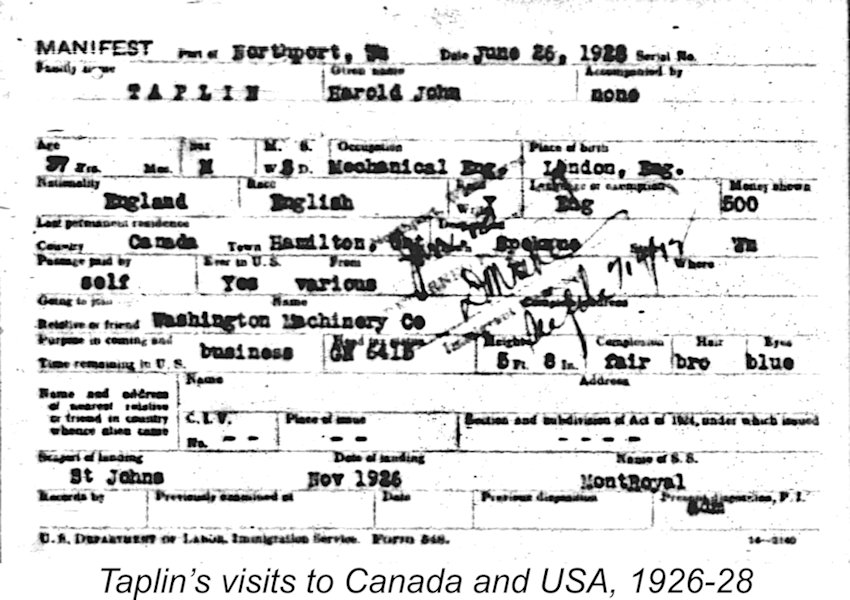

Although there’s no documentary evidence, it seems likely that Taplin was assigned (or perhaps requested an assignment) to relocate to North America to work in Spokane with the Washington Machinery & Supply Co. to design the new machine at the location where it would be manufactured. Gerrard Wire Tying Machines Ltd. were then engaged in establishing offices and warehouse facilities in Montreal, Quebec and Hamilton, Ontario, with their Canadian manufacturing facility being established in Hamilton. Taplin may also have been assigned to make periodic visits to Canada on their behalf to assist in the development of these facilities. In this scenario, Taplin was assigned to the box-making machine project, necessitating a trip to Spokane, USA while still presumably working for Gerrard (who were taking steps to move into the US market at this time and may have seen Taplin as a kind of emissary). The design of the box-making machine would have been undertaken on a contractual basis in such a case, although for convenience Taplin may have been placed on the Washington Machinery & Supply Co. payroll purely to simplify the book-keeping. Regardless of the details, what is definitely known is that on November 17th, 1926, Taplin went to the US Consulate in London to obtain a temporary-stay US Visa (26304). Two days later he was on a ship bound for Canada. The Canadian Pacific steamship SS Montroyal, on which Taplin was travelling, docked at St. John, Spokane was home to a number of former WW1 military aviators, some of whom may well have been Taplin's former comrades-in-arms. He seems to have enjoyed a close relationship with the local aviation community from the outset. According to several documents preserved by no less an authority than NASA, during that first visit in December 1926 Taplin outfitted an aircraft with his aerodynamically-activated auto-pilot system which he had developed back in 1918, as mentioned earlier. Taplin's sytem utilized a pair of vanes which controlled the aircraft's ailerons and elevator, thus maintaining its axial and longitudinal stability without intervention from the pilot. All the pilot had to do was control the rudder and throttle. The device was known as "George", a name commonly applied to auto-pilot systems. Since the US visa using which Taplin made his December 1926 visit to Spokane was only a short-stay document, he had no choice other than to return to Canada in late December 1926 following his test of "George". He headed east once more, returning to Canada via St. Albans, Vermont on December 28th, 1926 and stating his destination as Montreal, Quebec. Although presently unproven, it seems highly likely that his purpose in visiting Canada was to advise Gerrard's Canadian representatives regarding the commissioning of the company’s manufacturing facility in Hamilton, since he subsequently spent some time in that city. The Hamilton facility is known to have been established in 1927, so the timing fits. However, it's clear that Taplin must have applied immediately for a longer-term US visa while in Canada, because in early 1927 he returned to Spokane, presumably to start work on the box-making machine.

To relieve the stress arising from the box-making machine project, Taplin continued his experiments with "George", further cementing his relationship with the local fly-boys. By August of 1927 he had brought the system to a point at which he clearly believed it to be a success, because he wrote a letter to the "Western Mail" newspaper advising of his achievement. The report appeared in the September 16th, 1927 issue of the newspaper. Unfortunately, Colonel Taplin's recollections of his time in Spokane appear to have become a little confused over the years! In that 1957 interview, he made a number of startements which can be proved to be wrong. He got both the date and the name of his auto-pilot wrong, calling the latter "Gerry", perhaps confusing it with the name of his employer at the time. He also characterized the test aircraft as a model instead of the full-sized airplane that it actually was. Perhaps the interviewer imaginatively filled in a few "gaps" simply to create some padding for the main article! The design of the box-making machine appears to have been completed by early 1928. At that point, and still apparently working for Gerrard Wire Tying Machines Ltd., Taplin evidently returned to Canada, presumably to become involved with Gerrard's Hamilton, Ontario manufacturing facility which was now operational. He certainly spent some time as a resident in that city in 1928.

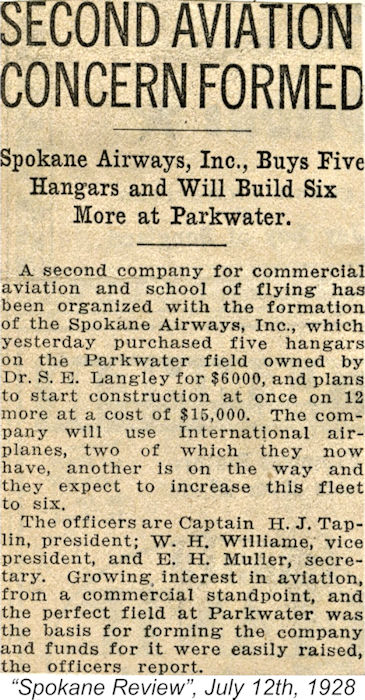

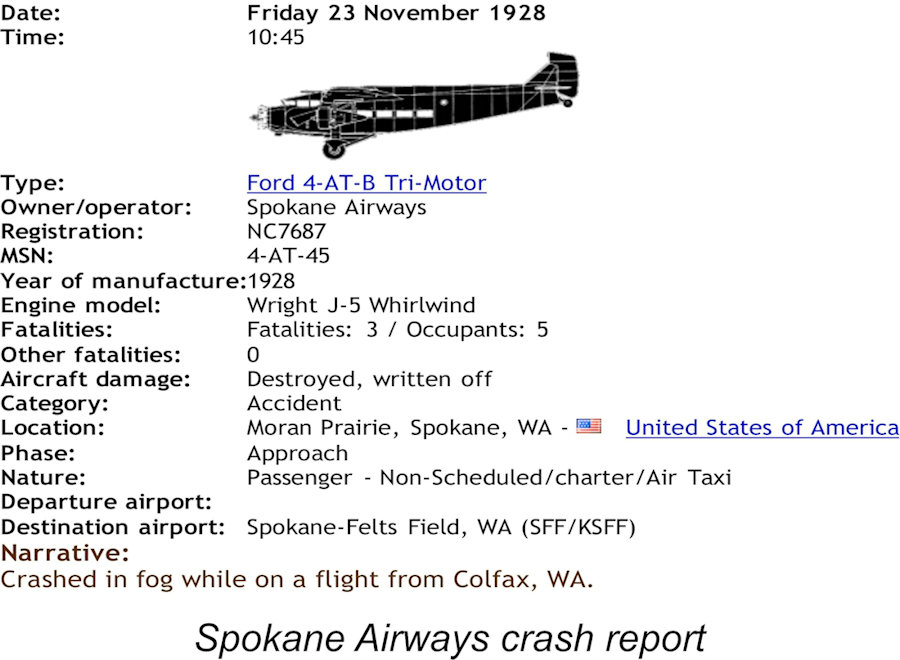

Presumably since the new airline didn’t yet exist, Taplin used his connection with the Washington Machinery & Supply Co. to facilitate his re-entry into the USA. He immediately headed west from Hamilton, apparently travelling by the Canadian Pacific Railway to Trail, British Columbia, Canada, which was located on the Columbia River just north of where it crossed into the USA. From there, he travelled Once safely landed in the USA, Taplin threw himself into the new airline venture, serving as President of the company. The establishment of Spokane Airways was announced in the July 12th, 1928 issue of the “Spokane Review” newspaper, which reported that the venture was starting out with only two aircraft but had plans to expand to a fleet of six in the near future, including three Tri-Motors. Five hangars were purchased at Felts Field in the Parkwater area of Spokane to accommodate this fleet. A later article dated July 17th, 1928 provided a little more information. The new organization intended to offer flying instruction, air taxi services, freight transportation and aircraft sales. The flight instructors were all experienced WW1 military aviators. They included the experienced WW1 flight instructor Captain Tom Symons, who was Spokane’s first commercially-licensed pilot, as well as ex-RFC flier Lieutenant William H. Williams, the latter also serving as company Vice-President. It appears more than likely that these individuals were wartime comrades of Captain Taplin, hence the business association. Sadly, fortune did not smile on this venture. On November 23rd, 1928 disaster struck when the first of the company’s Ford Tri-Motors crashed on nearby Moran Prairie during a fog-bound approach to Felts Field from the south on a flight from Colfax, Washington, writing off the aircraft. At least four of the five individuals on board were Spokane aviators. Three of them were killed in the crash, and another died later. It’s likely that at least some of them were Taplin’s close friends and former comrades-in-arms.

Although the accident was undoubtedly a tragedy for all involved, it may well have benefited a future generation of modellers. If the accident had not occurred, Taplin might well have stayed in North America, in which case the Taplin diesels would never have been developed. Every event has its long-term consequences, both positive and negative ...........

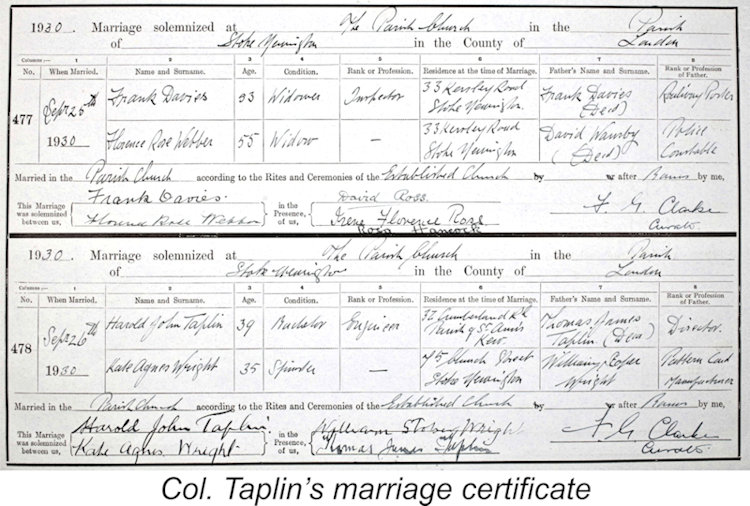

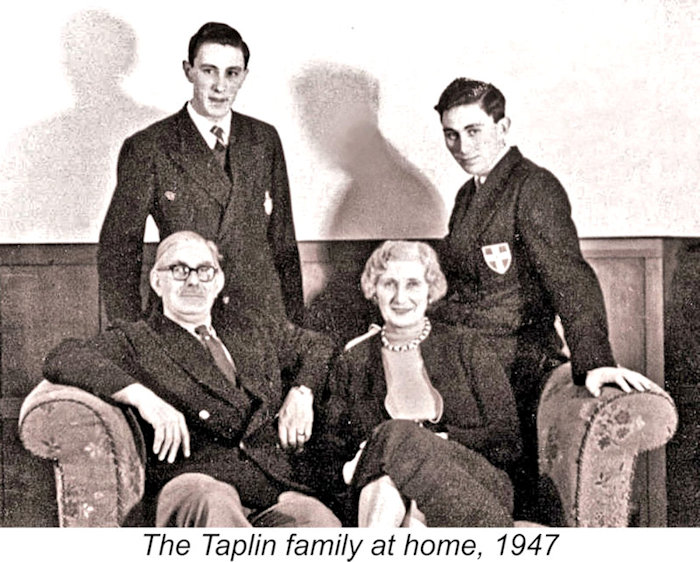

The Taplin’s wedding was sufficiently newsworthy to be reported in the contemporary local media. It turns out that Kate Agnes Wright was the daughter of a former Mayor of Stoke Newington, one William Stoper Wright, who was Mayor from 1907 through 1908 and died in September 1934, some four years after the wedding. After the wedding, the Taplins relocated to Wembley in South London, where they set up their family home at 207 Wembley Hill Road. Taplin’s employment at this time is obscure, but he did apply for a US patent for an image transfer press in January 1931. The Taplins’ first son John Donald Taplin was born at Wembley on May 26th, 1932, to be followed on June 20th, 1936 by his younger brother Michael Taplin. Both were to play key roles in the unfolding of the Taplin model engine story. In February 1937, Taplin and his family were still living on Wembley Hill Road. However, later in that same year of 1937 he accepted an engineering job offer that required the family to relocate to Solihull, a town adjacent to Birmingham, England. The 1939 Land & Surveys Register confirms that he was employed as a Steel Mill Superintendent and that the whole family were living on School Road in Hockley Heath, Solihull.

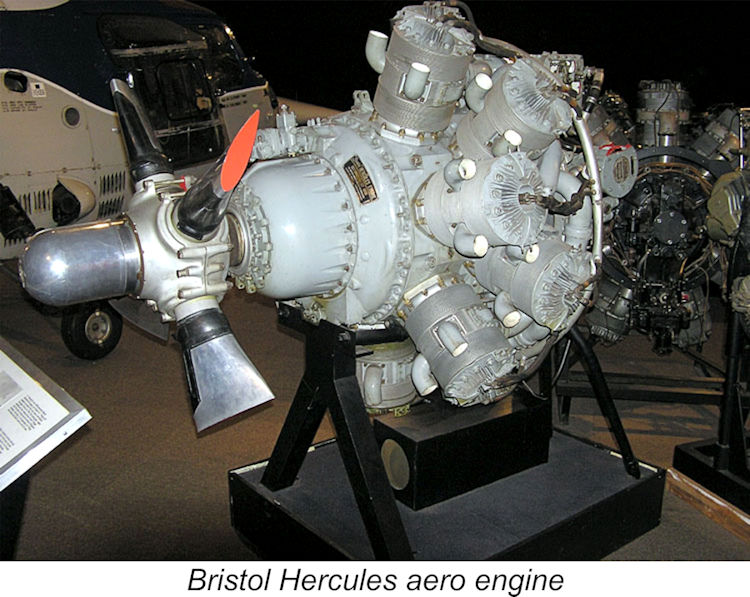

Rover's "shadow" factories were established in the mid to late 1930’s to manufacture components of the Bristol Hercules sleeve valve radial aircraft engine. Their duplication at different locations was intended to provide a hedge against Hercules production being halted due to bomb damage in the increasingly likely event of war with Germany - a case of putting the eggs in more than one basket! The Bristol Hercules engines subsequently powered numerous World War II aircraft, most notably the Short Stirling, Bristol Beaufighter, Handley Page Halifax and Avro Lancaster Mk. II. Check here for a video of one of these beasts actually running! And you thought that model engines could pose operational challenges .....!?! Show this video to the wife and point out the advantages of collecting model aero engines!! The Lancaster Mk. II was the only Lancaster variant not to use Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The development of the Mk. II Lancaster using the Bristol powerplants was intended to allow the continuation of Lancaster production even if the supply of Merlin engines failed for any reason. Over 57,000 examples of the Hercules ended up being produced.

Apart from his ongoing work on steel production as well as his Home Guard activities, Taplin also collaborated with the RAF on the development of auto-pilot control systems, presumably drawing on his experience with “George” during his sojourn in America. Since he was not a member of the RAF, he must have done so as a civilian consultant. Taplin continued his Home Guard activities throughout the war, eventually assuming command of the 37th Battalion with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. The accompanying image provided by Marcus Tidmarsh was taken on November 20th, 1944 at the Battalion's drill house on Golden Hillock Road in Birmingham. It shows the 53-year-old Col. Taplin in the centre of the front row (wearing a beret) with the officers and staff of his Battalion. The Home Guard was stood down in December 1944, since the threat of invasion had clearly evaporated by that time. At this point, Taplin became a civilian once more. Rather unusually, he was permitted to retain his rank of Lieutenant Colonel in civilian life, a privilege not normally extended once the King's commission has been rescinded. His contribution to the war effort was clearly valued very highly! Although always first and foremost a mechanical engineer, Taplin understandably wore his military title proudly for the rest of his life. Colonel Taplin (as he now was) clearly wasted no time in renewing his involvement with models! Soon after VE Day (May 8th, 1945), he completed his first radio-controlled model aircraft. This signaled the beginning of a lifelong involvement with radio-controlled planes and boats, generally using equipment of his own design. When interviewed, he always claimed that the use of R/C was simply a means to an end – his real love was the models themselves rather than the radio control systems that he designed to control them. After WW2 officially ended on September 2nd, 1945, Colonel Taplin began searching for a suitable location to establish his own engineering business. Using the experience gained over eight years of being a Steel Mill Superintendent, he intended to make precision drawn wire using machinery of his own design and construction. This ambition may well have stemmed from his earlier experience working for Gerrard Wire Tying Machines Ltd. - that too had involved working with wire. While on a family holiday at Birchington-on-Sea in Kent, Taplin learned of a long-disused Methodist Chapel for sale on Albion Road. After visiting the building, he made the decision to purchase it for conversion into an engineering workshop. Later in 1946, the Taplin family relocated to a rented house called Shrublands located nearby in Minnis Bay, Birchington.

At the outset, Taplin's new venture had no involvement with model engines, instead being concerned with the production of extremely accurate and consistent wire. In support of this activity, Colonel Taplin soon developed some innovative equipment designed to address the accuracy and consistency requirements. On December 12th, 1946 he applied for British Patent no. GB3666446A covering a device for straightening metal wire and rod. On September 2nd, 1947 he made a further application for British Patent no. GB2629846A covering an improved hydraulic wire drawing machine. Conventional machines of the time were chain-driven, producing wire of lower consistency, so this was a significant improvement. This latter machine was extremely successful - a British-made machine based on this technology was later purchased by Swedish interests, as recorded in the previously-cited 1957 newspaper article. Wire production may sound a bit mundane, but in fact it was an extremely challenging process. Marcus Tidmarsh found a magazine article in which a former Taplin employee explained the process. It involved drawing strands of material through a series of specially-formed dies of decreasing diameter, using powdered soap as the lubricant. The finished wires had to be held to diametric tolerances of +/- 0.0002 inches - around one-tenth the thickness of a cigarette paper. Once the required diameter was achieved, the finished wires were cut into suitable lengths for sale. The periodic wash-downs to remove the inevitable build-up of soap powder routinely resulted in Colonel Taplin having the cleanest factory floors to be found anywhere! The market for Col. Taplin's product was surprisingly broad. The Ministry of Defence was a major customer, since precision wire had many military applications. The wire could be further trimmed into suitable lengths for such products as springs and gear shafts for clocks, watches and electronic equipment, as well as tiny hinges for spectacles, cigarette lighters and toys. Musical string manufacturers were also potential clients. Model engine manufacturers used wire to form the needle valve tensioning springs in common use - E.D. likely obtained their spring materials from Taplin. Colonel Taplin's other customers included such firms as Plessey, General Electric, Ronson and Dunhill. The firm also produced drawn plastic materials for toy makers such as Rovex and Lines Brothers. They even produced some unusual plastic extrusions for Wrigley's Chewing Gum, for which the workforce was rewarded by the client with a huge box of Wrigley's product! In order for the wire to be useful to the firm's customers, an extremely high level of manufacturing consistency had to be maintained. The special equipment which Colonel Taplin had devised produced high-quality wire of unusual consistency. He quickly gained a reputation for producing the best precision wire in the country. Of course, it wasn't all work - everyone needs some forms of relaxation, and Colonel Taplin was no exception. Marcus Tidmarsh found a number of articles which confirm that Taplin kept fish as a hobby, being quite knowledgeable about the maintenance of their health. He was also a keen gardener, growing vegetables and winning numerous prizes for them.

Be that as it may, the Taplin name first came to the wide attention of the aeromodelling world in 1948, when Col. Taplin and his 12 year-old son Michael (as pilot) used a sideport 2 cc E.D. Comp Special to set a claimed record for the newly-established Society of Model Aeronautical Engineers (S.M.A.E.) Class II (2.5 cc) control-line speed category. The Taplins claimed a speed of 144.75 km/hr (89.95 mph) - some going for an old “stove-pipe” side-port 2 cc diesel!! Quite understandably, this claim was widely doubted - after all, the claimed speed exceeded the maximum figures recorded previously in Britain for any engine up to and including 5 cc! Even purpose-built British 10 cc racing engines like the newly-introduced Nordec RG10 were having trouble The Taplins were openly challenged to repeat this performance in front of independent witnesses, but they refused to do so. In any case, the record was soon beaten as the rules were tightened and both model and engine designs advanced, making the matter appear moot. Out of curiosity, in 1996 my mate Chris Coote demonstrated quite clearly that the Taplins could have achieved the claimed speed, but only by dint of strenuous whipping (which was not banned under the S.M.A.E. rules then in force). I’ve covered this matter in detail elsewhere.

The Colonel's initial design displayed some structural shortcomings and was quickly taken over by Southampton model shop owner Peter Cock, winner of the inaugural Gold Trophy in 1948. After implementing a number of structural changes, Peter Cock arranged to have his revised design produced as a kit for sale under his Kandoo Products trade-name, still using the "Radio Queen" model name. Although it can't be proved, it seems likely that these kits were produced for Cock by Phil Smith's Model Aircraft (Bournemouth) firm which manufactured the Veron kits. Colonel Taplin himself became an enthusiastic long-term user of the modified design. This design became very successful, to the point that E.D. subsequently placed an order for 1,000 kits to be sold exclusively under their own trade-name. This was the sole model aircraft kit to be marketed by E.D. An example of this model powered (or perhaps more correctly, under-powered!) by an E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV "Hunter" diesel and equipped with E.D. radio control gear became the first model aircraft to make a successful flight across the English Channel, a feat which it achieved on September 21st, 1954. Returning to 1949, the growing reputation of Col. Taplin's wire-drawing business had resulted in a surge of orders from major customers such as Plessey and General Electric, which threatened to engulf Taplin’s existing production capacity. By late 1949 this had reached the point at which he either had to expand or start rejecting some lucrative orders. Not surprisingly, the Colonel chose to adopt the former course. To accomplish this, Taplin urgently needed to enlarge his factory, but had to raise outside capital to do so. This was most readily accomplished as a limited company - banks are hesitant to invest in an individually-owned company because, as Marcus Tidmarsh so aptly put it, if anything After securing the necessary financing, Taplin built a two-storey annexe to the existing former chapel building, expanding and becoming even more successful with his wire production. He was soon using all available space once again. The former chapel and adjacent two-storey annexe are seen in the accompanying period photograph which was kindly supplied by Marcus Tidmarsh. For my money, the chapel wins hands-down in the architectural department ...... Using the car in the image as his scaling reference, Marcus estimated the floor area of the original chapel building as around 2,500 square feet, while the new annexe offered some 3,100 square feet per floor, giving a total area of about 8,700 square feet. The annexe thus increased the available floor space by a factor of at least three.

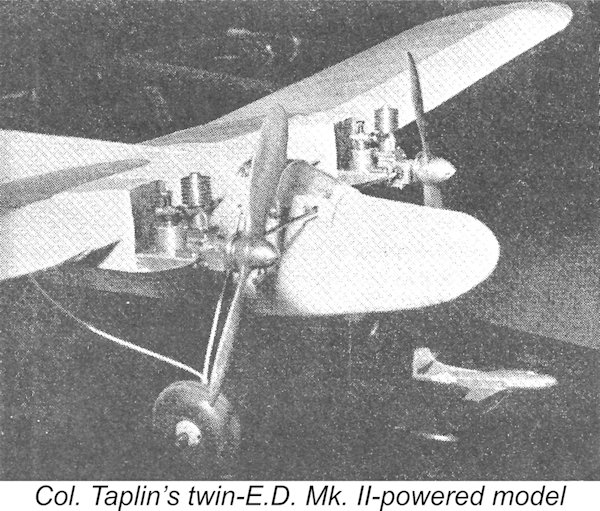

As can be seen in the accompanying illustration extracted from the later edition of Col. C. E. Bowden's well-known book "Diesel Model Engines", the engines were synchronized through the use of a laterally-aligned gear-driven shaft which passed through the fuselage to connect the two powerplants. They were constrained by the gearing to rotate at the same speed in oppposite directions. This historic event was reported in the March 11th, 1950 edition of the “East Kent Times and Mail” newspaper. In its issue dated March 28, 1950, the “East Kent Times and Mail” reported on Colonel Taplin's ambitious plan to cross the English Channel with his twin-engine "Radio Queen" aircraft. The Colonel intended to control the aircraft via radio control from a high-speed launch which would accompany the aircraft during the Channel flight. However, it appears that this attempt never materialized, leaving it to E.D. to make the first crossing in 1954, as mentioned earlier. Perhaps E.D. talked Taplin out of it in order to leave that first crossing as a milestone for E.D. themselves to establish!

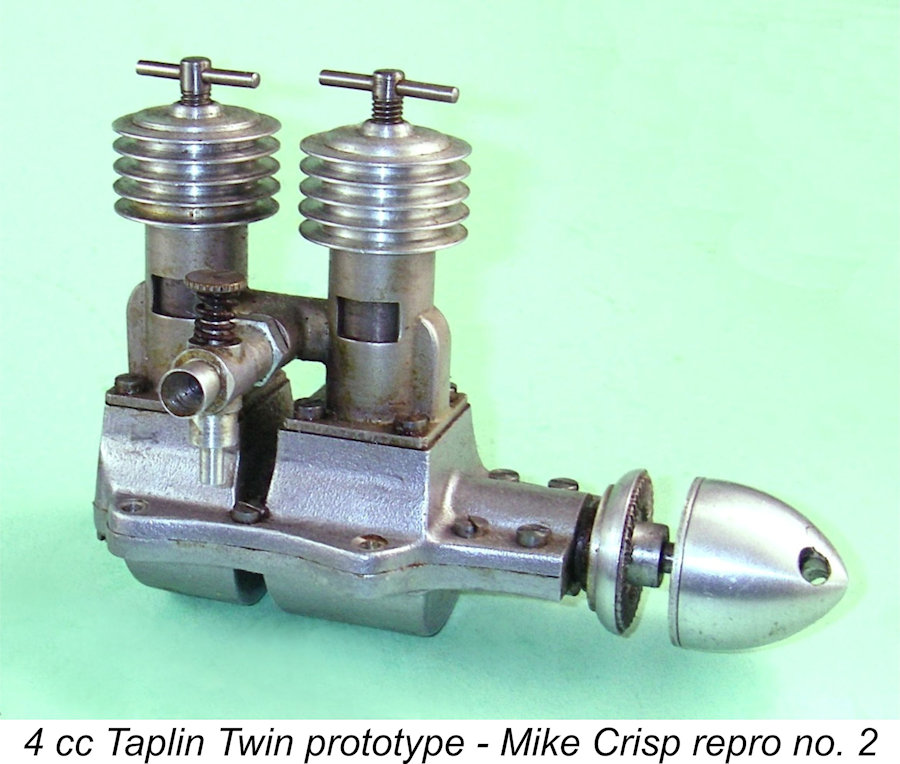

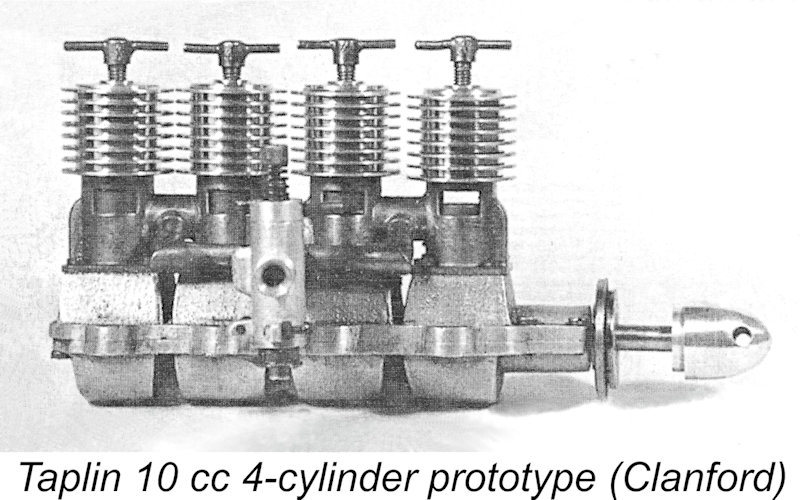

Col. Taplin also built a water-cooled version which he demonstrated successfully in a model boat. He later experimented with 5 cc versions of the design using two E.D. Mk. III piston/cylinder sets. There was even a one-off 4-cylinder prototype! While working on his multi-cylinder diesel concept, Taplin did some experimenting in other areas. In November 1952, he successfully modified a 123 cc motorcycle to run on diesel fuel. The converted engine utilized a specially designed cylinder head patented by Colonel H. J. Taplin. The “Kentish Express” newspaper reported on this ground-breaking modification in its December 19th, 1952 edition. Meanwhile, Taplin’s wire production business was going from strength to strength. By early 1953 the increasing renown of Birchington Engineering for its exceptional quality wire production had caught the interest of “Machinery” magazine, leading to a scheduled visit to the factory to facilitate an in-depth feature on the company and its manufacturing processes. The July 1953 issue of the magazine (Volume 83) featured a comprehensive illustrated nine-page article detailing Birchington Engineering's innovative wire drawing techniques. This article is still referred to by those involved in wire drawing 70 years later!

During this period, Col. Taplin continued his development work in relation to the application of radio control to model boats. His activities in this context actually made him a bit of a media star! In 1954 a Pathé newsreel clip The footage to be found here also shows the Colonel in 1958 demonstrating his proposed radio-controlled “lifeboat” as well as some additional shots of his electric-powered "Radio Queen". This latter model made Britain's first-ever un-tethered flight by an electric-powered model, a feat which it accomplished on June 30th, 1957 at Chalgrove Airfield in Oxfordshire. Michael Taplin, now 21 years old, reprised his feat of 1948 by acting as pilot on this occasion. The event was reported in the September 1957 issue of "Aeromodeller".

Although his Birchington Engineering company was constantly busy on other work, Col. Taplin continued his development efforts in relation to his twin-cylinder diesel concept with which he had been experimenting as a hobby since 1952, working on it as and when time permitted. He was now assisted by his sons Michael (1936 – 1976) and John (1932 - 1990), who had joined him in his engineering business after serving apprenticeships there. By early 1958 they had constructed several 7 cc prototypes using sand-cast cases and utilizing E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter piston/cylinder sets and other components. The accompanying "Aeromodeller" image shows Col. Taplin in 1958 testing a prototype Twin with Michael (C) and John (R). When considering the commercial production of the now-developed 7 cc twin-cylinder diesel, Col. Taplin had a problem - he had neither the staff, tools nor space to make the complete engines himself. The continuing involvement of E.D. represented a practical solution, since the Mk. I Twin was designed around E.D. Mk. IV 346 components which were already in production by E.D. The early prototype Taplin Twins had also been designed around existing E.D. components, so this was simply a commercialisation of what had been going on previously at the prototype level. The Taplins' efforts finally bore fruit in late 1958, when the first commercial 7 cc Taplin Twin was released to the modelling public. Many of the key components were manufactured by E.D., who naturally retained the rights to those components, which included the cylinders (modified for sideport induction), the pistons and rods, the contra-pistons and heads, the comp screws and the front-end components. The rest of the engine was manufactured by Birchington Engineering, who also carried out the assembly. Even so, model engine production was to remain something of a sideline throughout.

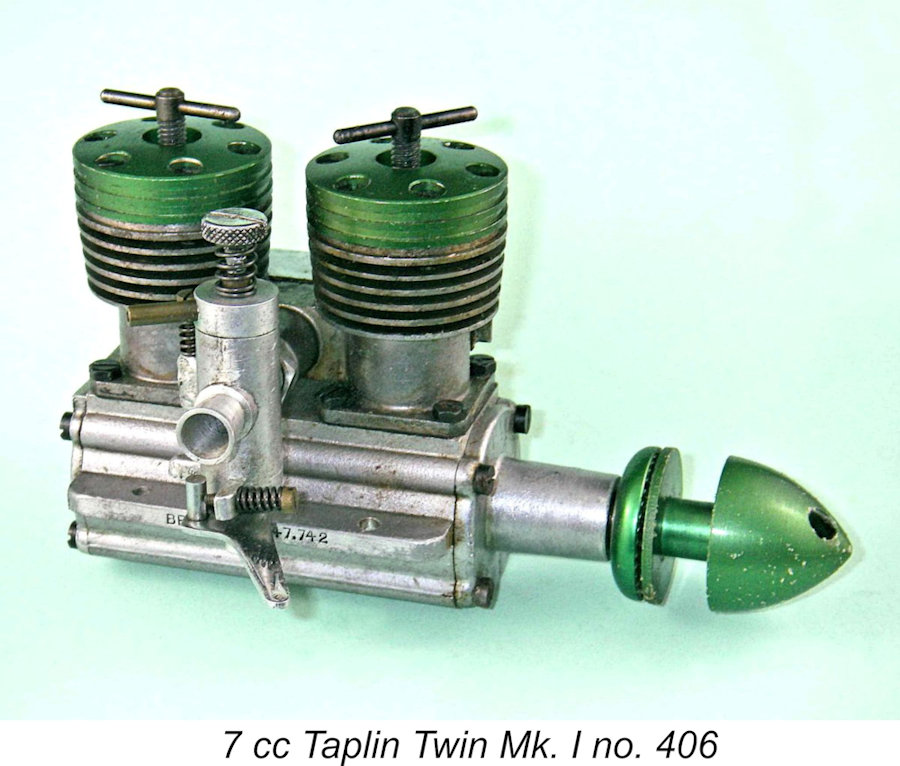

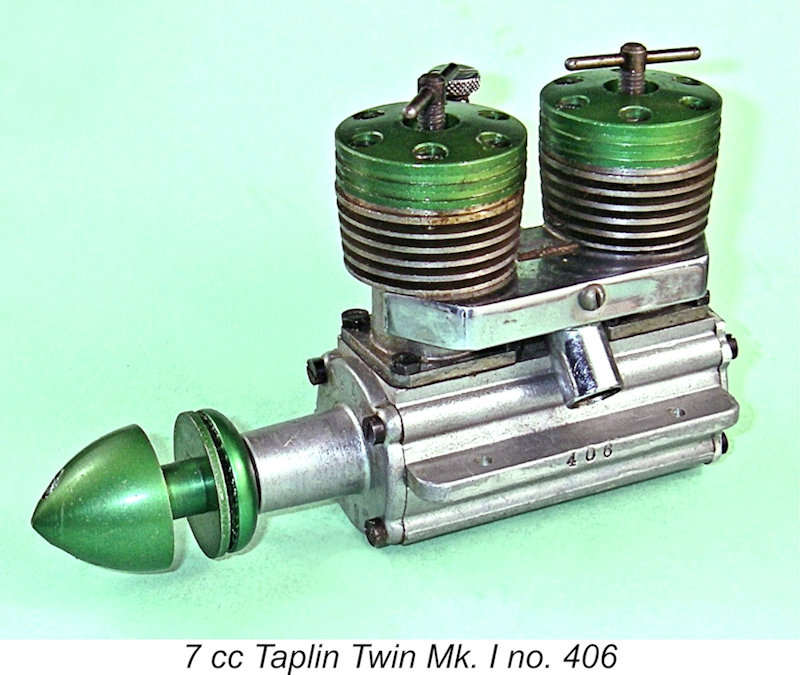

Although not identified as such at the outset, the original 7 cc version of the Taplin Twin may legitimately be referred to as the Mk. I model in the context of the overall range. It turned out to be the Taplin Twin variant which achieved the highest production figures, being manufactured from late 1958 through to mid 1961, with steady sales throughout. It was based upon two E.D. Mk. IV 3.46 cc Hunter piston/cylinder sets modified for side-port induction, giving it an actual displacement of 6.92 cc. It also used E.D Mk. IV heads, rods and front-end components. Kevin Richards reported that the very early examples of the 7 cc Mk. I Taplin Twin differed somewhat from the later examples. He owned a very early Mk. 1 bearing the serial number S110. The crankcase of this example was quite a rough sandcasting with a clearly delineated moulding flash line showing that the original pattern for the crankcase was made of two pieces joined fore and aft. In addition, the front shaft housing did not have the designation "Taplin Twin" cast into it. Finally, the front housing retaining screws were not drilled for the security wires which were a feature of all the later twins. Kevin's other Mk. I example bore the serial number 501.

The Twin's weight was no impediment to its use in model boats, leaving us unsurprised to learn that the water-cooled marine version out-sold the aero model by some margin. In either form, it gained praise for its excellent quality, very easy starting and ultra-smooth operation thanks to its alternate-firing configuration. The first-rate functioning of its very well-designed R/C throttle was also widely appreciated. The range of accessories offered by Birchington Engineering for the Taplin Twin included a matching 2½ in. x 2½ in. stainless steel water-screw, a universal joint, a nickel-plated Burgess silencer and an 80 cc marine tank, also nickel plated. Serving the model boat fraternity was clearly a priority.

With ratification of the Dance/Skeels record still pending, the Taplins “adjusted” their prize offer to an award of £50 to any British modeller breaking an existing World Record for duration, altitude, speed or point-to-point distance using a Taplin Twin powerplant. In a clear response to the Adcock situation, claims based upon closed-circuit distances were specifically excluded! The prize was to be awarded for records established after June 15th, 1960. This date actually seems to have left Dance and Skeels high and dry – to win the £50, they’d have to break their own record! All such fun and games aside, the Taplins took advantage of any opportunity to promote their product. Apart from the ongoing advertising campaign, their efforts included the presentation of trophies and cash prizes at various high-profile model competitions.

The Hydro-Jet allowed the boat to be operated in very shallow water, also providing a high degree of manoeuvrability. The maker claimed that it would propel an 8 lb. boat at up to 9 mph with the ability to execute extremely sharp turns. It was supposedly intended to be an accessory for use with the 7 cc Taplin Twin Mk. I, but in fact the 1¼ in. dia. nylon Ripmax impeller provided an insufficient load for that engine, allowing potentially problematic over-speeding. The Hydro-Jet was far better matched to engines developing a lower power output. The Hydro-Jet was not Colonel Taplin's invention, but was actually the brainchild of a New Zealander, one Ross Baker, who apparently held several patents relating to water jet propulsion of full-sized vessels. It's not known how Col. Taplin and Ross Baker crossed paths. Regardless, the Colonel spent a considerable amount of time perfecting the design of his company's model-sized offering, sadly without much commercial success. Relatively few examples were sold, and surviving units are extremely rare these days. The obvious installation challenges clearly put people off.

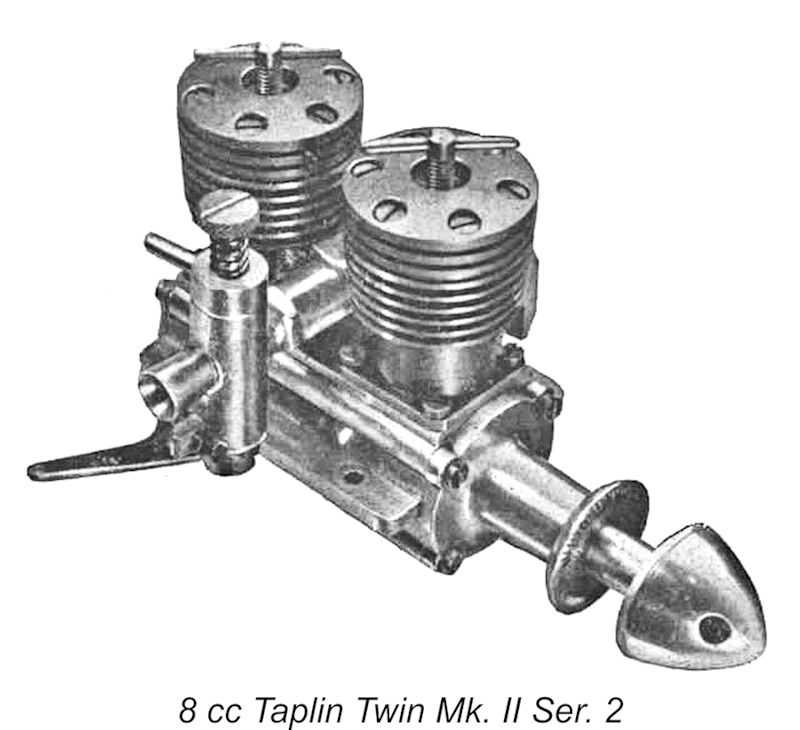

It seems that plans for a model upgrade had already been made prior to the E.D. fire. Indications from the advertising record are that production of the Mk. I Taplin Twin had actually ended by mid-1961 – the last Birchington advertisement for the engine that Gordon Beeby could find was the May 1961 placement in “Radio Control Models & Electronics” (RCM&E) magazine, although there may have been a few later ads. As far as the dealers went, Roland Scott had dropped the engine as of late 1961, while Arthur Mullet dropped it after January 1962. It thus appears that production of the Mk. I twin had ended in mid-1961, with stocks being allowed to run down prior to the release of a replacement model. The clear inference is that the company was already planning to introduce the Mk. II version fairly early in 1962 and understandably didn’t want to compete with themselves. However, the unexpected April 1962 E.D. fire put a severe crimp into this plan, since E.D. had lost much of the relevant tooling and could no longer supply all of the finished components as they had been doing. They may have continued to supply those components of which they retained stocks or which they remained able to manufacture, but other components would have had to be out-sourced. The contracting-out of the manufacture of these components by others made no sense economically, besides which E.D. still owned the rights to those components, even if they could no longer manufacture them. That left Col. Taplin with only two choices - either revise the design and develop expanded production capacity or abandon his favorite aspect of his professional activities. Not surprisingly, he chose the former course. However, to do so he had to make some design changes in order to minimize or even eliminate the use of E.D. components or facsimilies thereof. He spent the It would appear that setting up the new facilities at Margate occupied the bulk of 1962. The imminent appearance of the Mk. II Taplin Twin was announced in the “Motor Mart” feature in the December 1962 issue of “Aeromodeller”, with deliveries expected during that month. The new model was first advertised by Birchington Engineering in the December 1962 issue of RCM&E, with the first “Aeromodeller” advertisement appearing in the January 1963 issue, as reproduced at the right. Despite the fact that the engines were now manufactured by Dinton Engineering, they continued to be marketed under the Birchington Engineering banner. Dinton Engineering Limited was formally incorporated on the 21st of February 1963 (company number 00751037). From the outset, it was under the control of John Taplin. All engine and R/C equipment production was now transferred to Dinton Engineering Limited in Margate. This location was better as it was closer to prospective workers than the old factory, which now could expand even further into wire production. Although it was generally very similar to its Mk. I progenitor, the Mk. II Twin did embody some significant changes, most of which were clearly aimed at minimizing the use of modified E.D. components. For one thing, the cylinder bores were now hard-chrome plated. The plating on the Taplin engines was carried out all along by a firm called Kent Electro-Platers Ltd. This company was owned by Ivor Morgan, who had previously been involved with George Nurthen in the production of the famous Gannet 15 cc four-stroke engines in Whitstable, Kent beginning in 1958. In addition to the new bore treatment, the crankshafts were now nickel-plated. Both this and the chrome plating of the bores appear to have represented the company’s response to some well-documented corrosion problems which had been of particular concern to the model boating fraternity, who remained the engine’s largest user group.

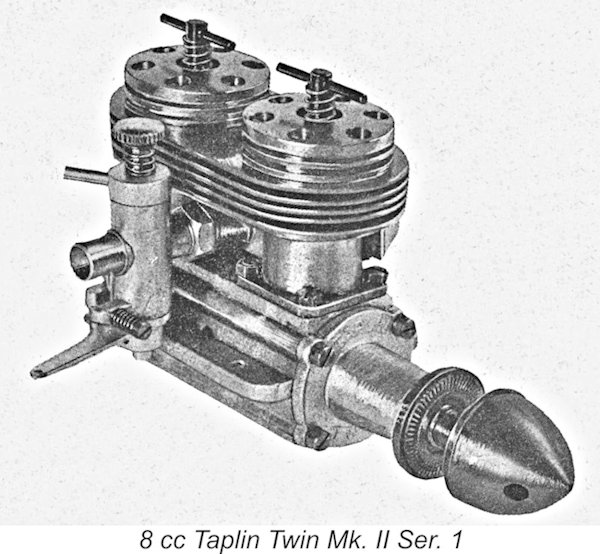

The other shaft bearings continued to be ball races. Ron Warring created considerable confusion by stating in his test report (see below) that the rear bearing on the front shaft was a roller bearing, but Kevin Richards pointed out that this is incorrect. In order to distinguish clearly between the Mk. I and Mk. II models, the color anodizing of the Mk. II’s alloy components was changed from green to red. As a result of these changes, none of the new model's components infringed upon E.D.'s design rights, leaving the Taplins free to manufacture them. The early advertisements for the new Taplin Twin Mk. II aero model showed a unique finning arrangement using a red-anodized set of stacked alloy fins which embraced both cylinders, from which the former integrally-machined fins had been removed. For convenience, we might refer to this as the Series 1 variant of the Tapin Twin Mk. II. The advantage of this design was that the same cylinders could be used for both air-cooled and water-cooled models.

Kevin Richards advised that engine numbers for these variants started at 5001. He believed that only about 30 aircooled versions were made by the factory. Over the years three examples had passed through his hands, two of them being New-in-Box. All bore serial numbers between 5018 and 5027. The sole example of this variant which came to the attention of Mike Noakes was numbered A5108. Kevin believed either that this number was mis-reported or that it was not a factory-constructed example. It appears that the new cooling fin style was not judged to be a success, because a number of these engines were quickly converted by having the stacked longitudinal fins replaced with individual cooling jackets turned from plain aluminium. This appears to have been a stop-gap measure to convert engines already manufactured but not shipped - the majority of the Taplin Twin Mk. II engines reverted to the integrally-formed fins on the steel cylinders, as featured in the Mk. I model. It seems convenient to refer to this as the Series 2 variant of the Taplin Twin Mk. II.

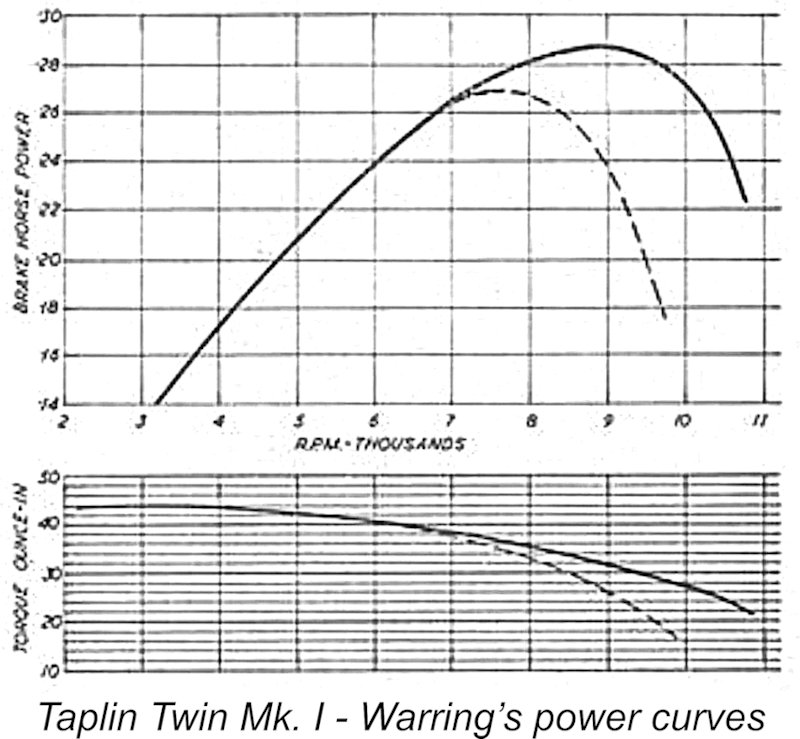

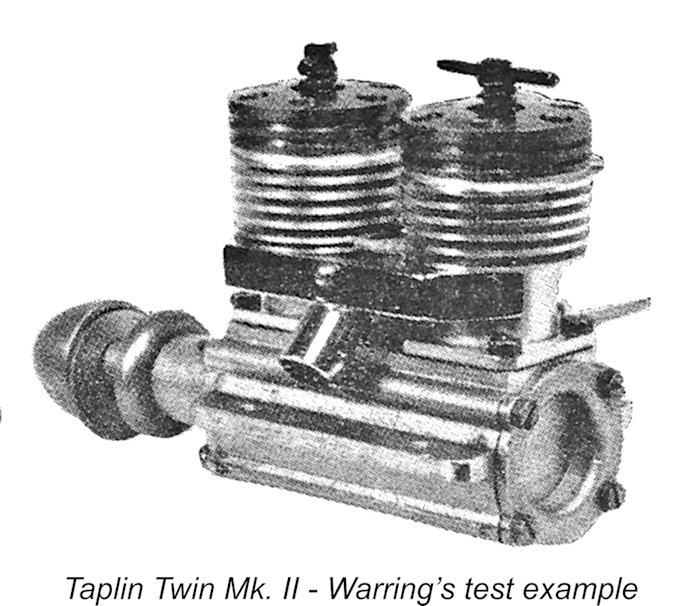

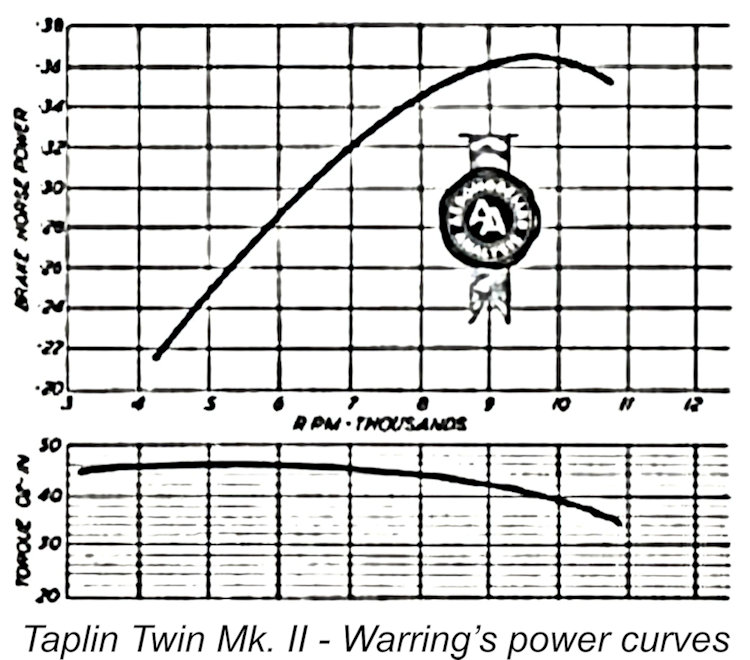

A test of the Taplin Twin Mk. II by Ron Warring appeared in the April 1963 issue of “Aeromodeller”. The engine tested by Warring was an early Series 2 example which had been converted using individual aluminium alloy cooling jackets in the manner descibed above. It was thus not typical of the Mk. II Twins, the majority of which featured integrally-formed cooling fins, as mentioned earlier. While recognizing the Mk. II Twin as being in a category of its own due to its weight and relatively low output, Warring was extremely complimentary regarding the engine's handling qualities and flexibility of operation, characterizing it as being “one of the easiest starting engines of any type” that he had ever handled. He stated for the record that it was “certainly easier to start and simpler to handle” than some beginners’ engines of his experience!

However, even in model boating circles the popularity of diesel power in general was now on the wane. It’s apparent from the relative numbers of present-day survivors that sales of the Taplin Twin were now shrinking fairly steadily, although sales interest was evidently still sufficient to justify continued production. At some point along the way, a replacement backplate assembly incorporating a recoil starter was developed into prototype form for use with this engine, but this never went into production.

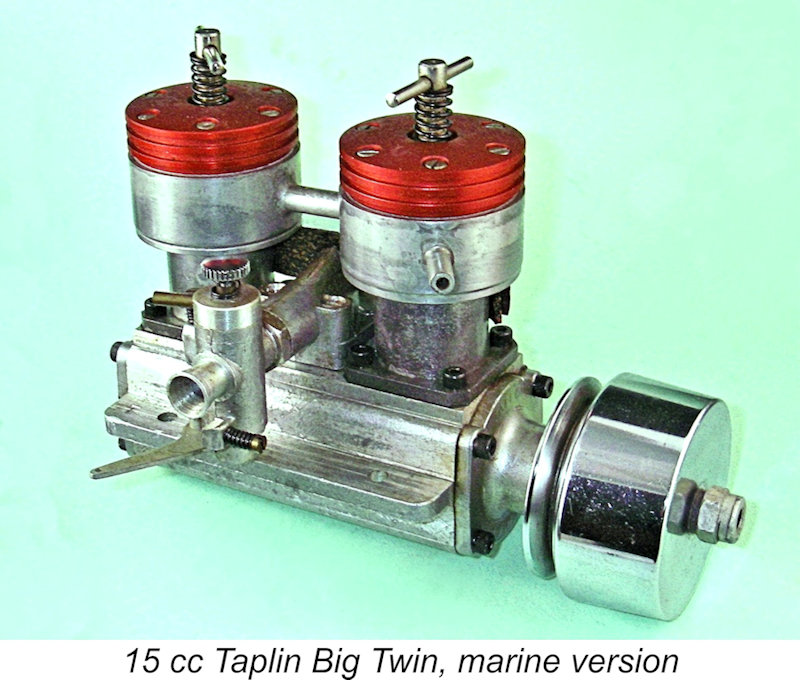

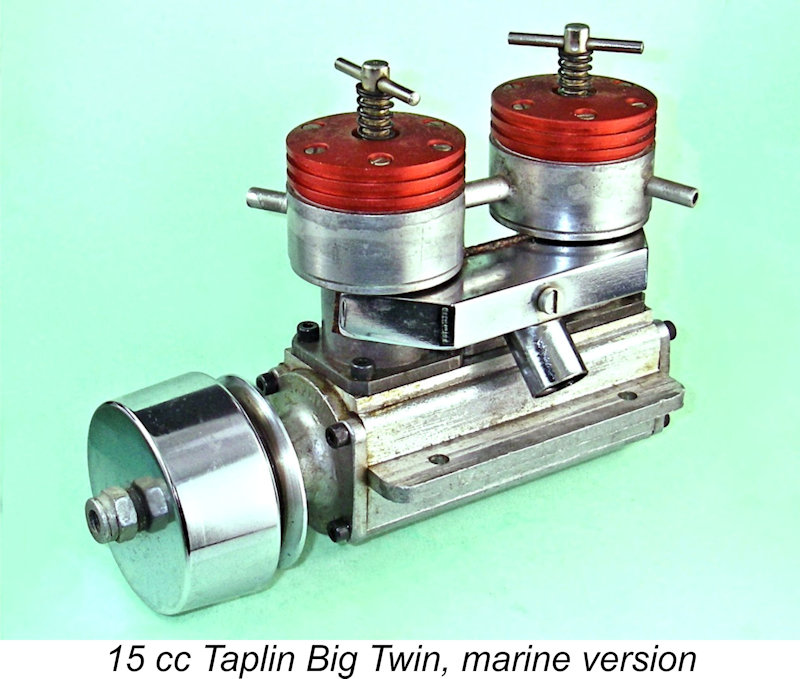

With bore and stroke dimensions of 0.827 in. (21 mm) and 0.846 in. (21.5 mm) respectively, the Big Twin boasted a displacement of 14.89 cc. It was a bit of a door-stopper in terms of weight – the marine version weighed in at all of 54 ounces (1531 gm). Only very large models need apply! The engine was clearly aimed predominantly at the marine market, although aero versions were produced. The Big Twin appeared at first glance to be nothing more than a scaled up 8 cc model. However, in reality it differed in one important respect – the former sideport induction was replaced by a crankshaft rotary valve timed by the central crankshaft and feeding front and rear crankcases alternately. This meant that the engine would only run in one direction. The company claimed that the switch to rotary valve induction had broadened the engine’s operating speed range considerably – an operating range of 500 – 12,000 RPM was cited, with a peak power output of over 0.50 BHP. To me, the lower speed claim appears somewhat open to question …………

The Big Twin turned out to be the last model engine design with which Colonel Taplin was personally involved – all subsequent products were the responsibility of his son John working from Dinton Engineering. Colonel Taplin evidently retired at this point, although he continued to live in Birchington on St. Mildred’s Avenue. His younger son Michael assumed responsibility for the management of Birchington Engineering, leaving John free to continue to run Dinton Engineering. From a letter that he wrote subsequently to the London Sunday Mirror newspaper, we learn that Col. Taplin had experienced a brush with throat cancer. This letter appeared in the paper's December 17th, 1967 issue. It's unclear exactly when this issue arose or whether it had anything to do with the Colonel's retirement and subsequent death - all that was said is that the condition was treated with radioactive isotopes. The Colonel was a cigarette smoker, which probably caused his condition. Colonel Taplin died suddenly on April 20th, 1969 at age 78 during a short holiday visit to Malta, where he was interred in St. John’s churchyard, Valletta, Malta. He left an estate valued at £8,549 – a considerable sum by the standards of the day, although it seems likely that at least some of his assets were held out of his estate by various means.

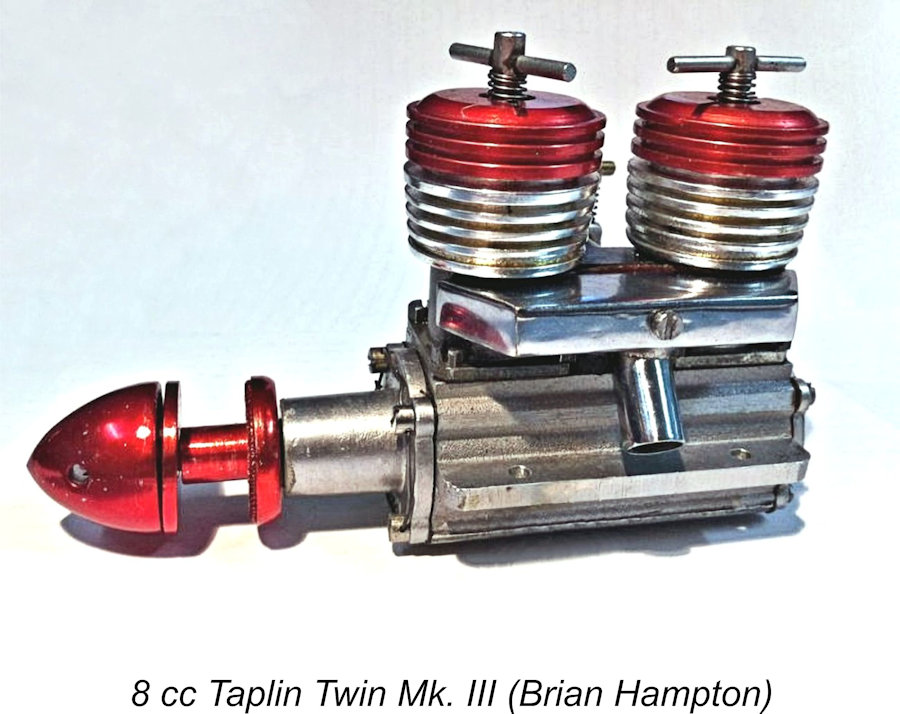

Serial numbers for this model lay in the W4xxx range for almost all examples. Since the engine was easily switched from air to water cooling or vice versa, it seems to have been felt that a single common sequence would suffice. The major difference between the Mk. II and Mk. III versions of the Twin was a switch from bolt-on cylinder heads to cooling jackets secured by screw-on heads. The intent of this modification was to allow the use of the same cylinders for both aero and marine variants. However, the Achilles’ Heel of this arrangement reportedly proved to be a distressing tendency for the screw-on heads to unscrew during operation.

Like all Taplin engines, the quality of the Mk. III’s construction was beyond criticism. However, the attention of both aeromodellers and model boat enthusiasts had switched decisively away from large diesel engines by this time. As a result, the Taplin Twin Mk. III failed to attract much attention from the modelling community at large. The number sold was miniscule by comparison with the figures achieved by the original Mk. I model. In mid 1969 Dinton Engineering sold the manufacturing rights and a sizeable inventory of residual components for the Taplin Twin Mk. III to the Aurora Model Manufacturing Co. Pvt. Ltd. of Calcutta, India (now correctly rendered as Kolkata). This decision may have been catalyzed at least in part by the April 1969 death of Col. Taplin, who was no longer around to be saddened by the abandonment of his beloved Twin. The Aurora company continued the production of the engine using a combination of original parts and components manufactured in India by Aurora. The quality of these examples was somewhat variable, but a good one was really good. They appear to have been offered only in aero configuration. Mike Noakes conducted an owner survey in connection with his previously-cited series of articles on the Taplin engines which appeared in installments during 1997 in the pages of MEW. His findings are of considerable interest. They are summarized in the following table.

These numbers included both air-cooled and water-cooled examples. It’s pretty clear from the above table that the original 7 cc model was by far the best seller and that sales figures declined steadily throughout the 1960’s. Mike estimated that production of the Taplin engines by the original manufacturers probably did not exceed 4,000 – 5,000 units in total. It appears that Dinton Engineering produced far more components than they actually ended up building into complete engines. Even as late as 1990, when John Taplin tragically died from cancer at the premature age of 58, a considerable number of original components for various models still remained. Most of these were built up by others into complete reproduction engines. The majority of the reproductions included in Mike Noakes’ survey were Aurora renditions of the Taplin Twin Mk. III. Mike Noakes believed that Mike Clanford had a hand in the majority of the reproductions originating in England. Kevin Richards supported this conclusion, stating that Clanford originally lived at Sutton in Surrey before moving to Cromer in Norfolk. Kevin was a Fire officer with Norfolk Fire Service at the time, with Cromer as part of his patch. He used to visit Clanford fairly regularly, and he recalled seeing multiple boxes full of Taplin components during these visits. Resuscitation Attempt – the Taplin Tempest

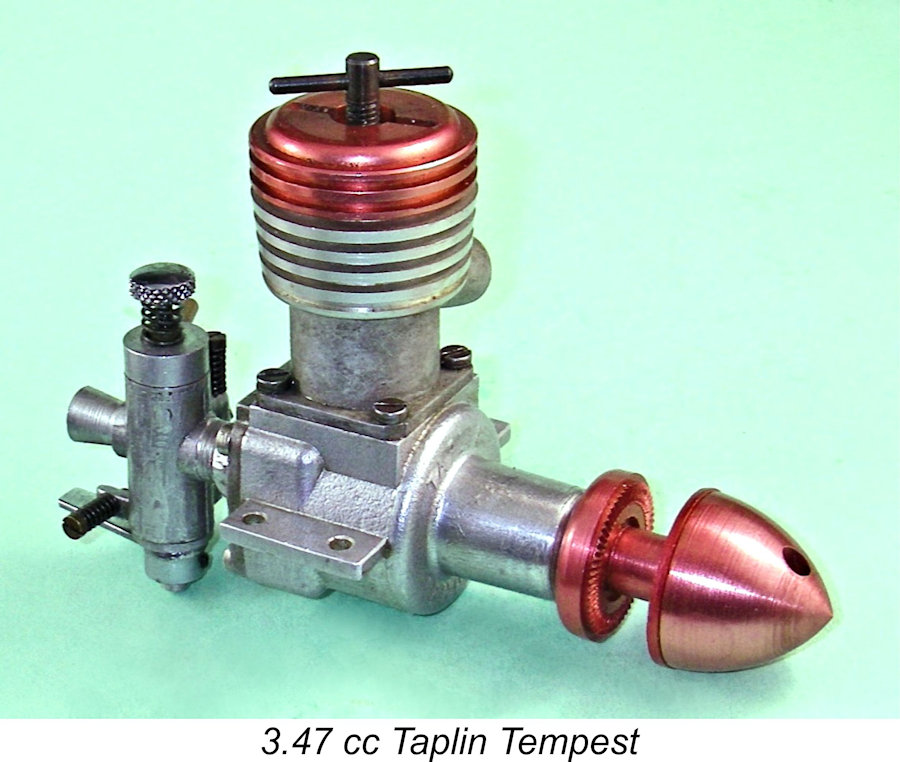

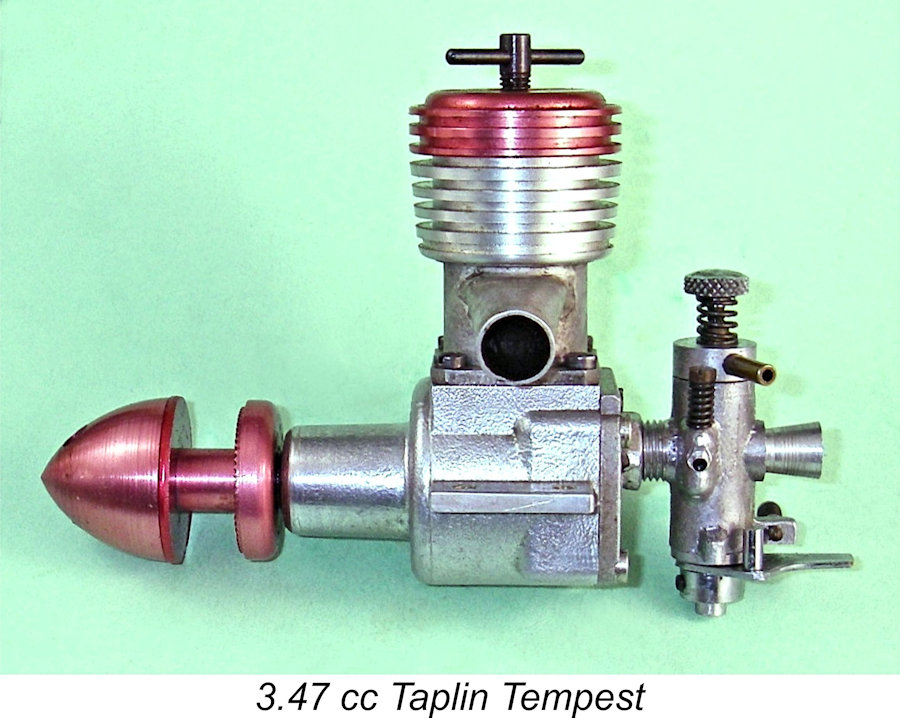

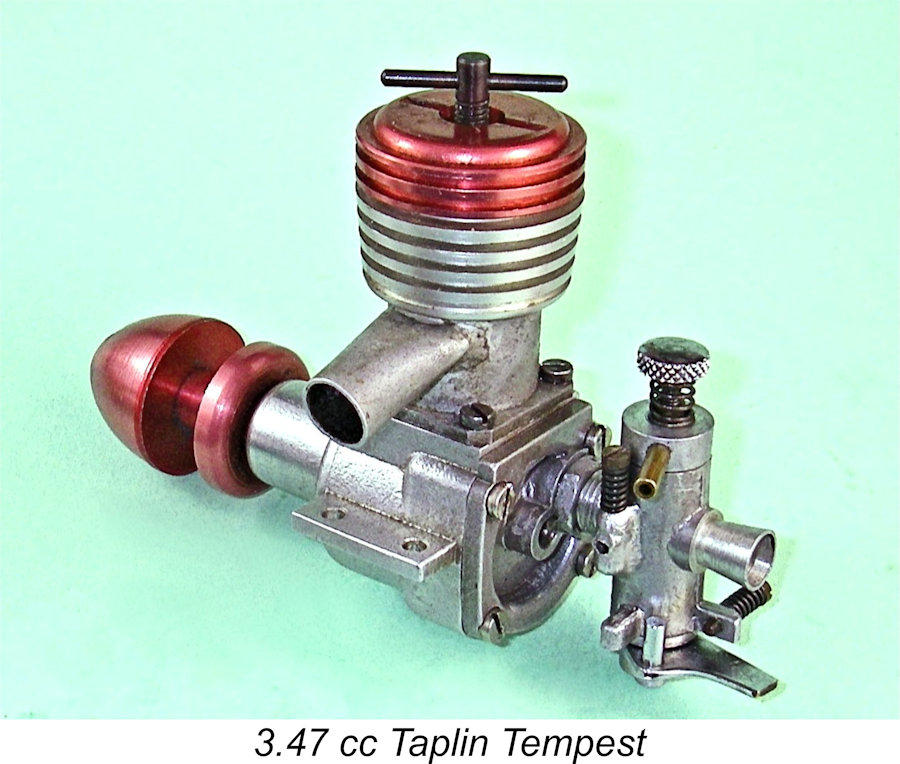

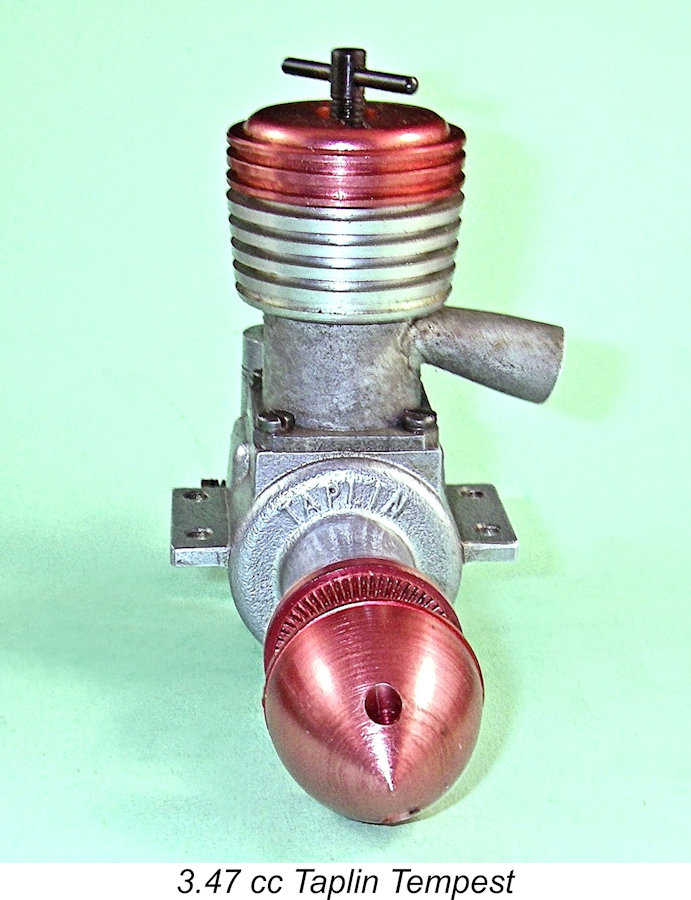

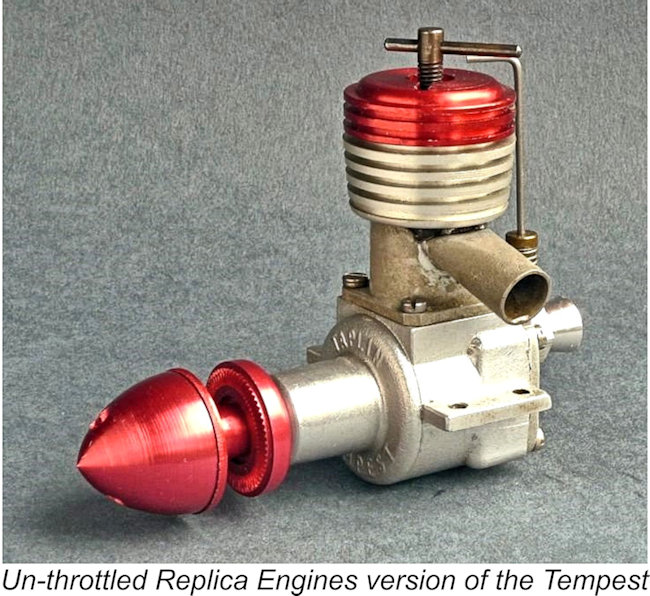

We saw earlier that following the death of his father in April 1969, John Taplin had given up on the Taplin Twin Mk. III, selling the design to the Indian Aurora company. However, it appears that he was reluctant to abandon the model engine field completely. The Tempest seems to have been a last-ditch attempt to re-generate the flagging interest in the Taplin engines. It was designed by John Taplin and manufactured by Dinton Engineering. It entered the market in early 1970. In many respects, the Tempest came across as a direct derivative of the earlier E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV Hunter. Like that of the Hunter, the Tempest’s bore was no longer chrome plated. Bore and stroke figures were identical to those of the Hunter at 0.657 in. (16.69 mm) and 0.625 in. (15.87 mm) respectively for a displacement of 3.46 cc. Cylinder porting too was essentially identical, with two internally-formed bypass/transfer flutes directly opposite the A retrograde step in this context was the retention of a rotary disc made of aluminium alloy, a material which had long been recognized as being quite unsuitable for this service. Worse yet, the discs in the original examples of the Tempest were mounted on fixed central pins made of brass. The very early example tested by Peter Chinn developed a considerable amount of wear in only some 2 hours of running. This issue was brought to the attention of John Taplin, who informed Chinn that a switch to a steel pin had already been implemented for the production models released for general sale. My own example has just such a pin. Some elements of the earlier design of the Taplin Twin Mk. III were carried over to the new model. The same form of cylinder construction was used, with a slip-on alloy cooling jacket being secured by a red-anodized screw-on head. This made conversion of the engines from aero to marine configuration and vice versa a very simple matter indeed.

The Tempest’s crankshaft continued to be supported by a rear ball race and a front needle roller bearing. The R/C throttle with which the Tempest was supplied adhered to the familiar and very effective design which had been featured on the Taplin engines from the outset. To my eyes, the carburettor looks very much out of place on the Tempest - a more compact design would have been a better match for the rest of the engine. In the case of the Tempest, the use of this component created a control situation which presented a bit of a challenge to manage. When mounted on a Twin, the carburettor was aligned to the right at 90 degrees from the engine’s axis, with the control arm aligned similarly and moving fore and aft. When mounted on the Tempest, this arm moved from side to side, greatly complicating the required servo linkage. It would probably be necessary to use a bellcrank to activate this control in a model.

With a weight of 243 gm (8.57 ounces) for the aero version, the Tempest was no lightweight. This must have represented a strong discouragement to prospective users in model aircraft service. By 1970 the R/C aero market was completely dominated by lighter and far more powerful glow-plug engines – an overweight and underpowered diesel based on an original design going back to 1949 stood no chance in this market. Moreover, the model boating fraternity had now largely abandoned diesel engines. Consequently, the engine was not a market success, and relatively few were made. The company never even seems to have felt the costs of running advertisements for the Tempest in “Aeromodeller” to be justified – certainly, my mate Gordon Beeby was unable to find any such advertisements. The Tempest was included in Mike Noakes’ previously-cited owner survey of Taplin engines. Only 7 examples were reported, bearing It is well known that in the early 1980's a company called Replica Engines of Thornton Heath in Surrey obtained a stock of original 15 cc Big Twin and 3.46 cc Tempest components which they built up into complete engines. They began advertising these engines under their own name in April 1982, continuing to do so until September 1982. Some of these engines did not feature the unique Taplin throttle, using an unthrottled intake resembling that previously used on the E.D. 3.46 cc Mk. IV of the 1950’s - evidently they ran out of throttles before the other components. Gordon Beeby reported that Michael's Models of Finchley listed the Replica Engines Taplin Tempest regularly between August 1982 and April 1985. The time taken for them to sell their stock implies that the engines were very slow sellers. I have no information regarding the number of these reproductions sold. None seem to have been reported in Mike Noakes’ survey. My own illustrated example appears to be one of the Replica Engines reproductions, since it does not bear a serial number. The Tempest on Test

There appeared to me to be little point in repeating Chinn’s full test with my own example of the Tempest – his test figures were generally very reliable. However, I saw value in setting the engine up in the test stand to give it a few runs, just to experience and report on its handling and running qualities at first hand. My example of the Tempest appears to be one of those assembled from original components by Replica Engines, since it does not bear a serial number. It is in near-mint condition, its only flaw being a truncated throttle control arm.

Set up in the test stand with the APC 9x6 prop fitted, the engine felt pretty good, although the piston/cylinder fit was undoubtedly a bit on the tight side. On the other hand, the main bearing felt delightfully free thanks to the combination of a rear ball race and front needle roller bearing. I anticipated no starting difficulties. For these runs I formed a bent paper clip into a suitable shape to lock the otherwise-unrestrained throttle in the “open” position. I found that starting was best achieved by administering one or two choked flicks on a full fuel line followed by a “dry” exhaust prime (exhaust port closed). This introduces just a sniff of fuel into the cylinder when the engine is flipped over. Using this approach, starting was very prompt once the correct compression setting had been established. Running was absolutely smooth, but I would assess the vibration levels as high – the unbalanced crankdisc and relatively heavy piston probably had much to do with this.

I found the mixture control provided by the Taplin carburettor to be rather more vaguely-defined than with most engines – the engine seemed to run equally well over a range of at least a ¼ turn of the needle valve control. One good thing was that if one went a little too lean, the engine didn’t stop – it merely slowed a little and began to misfire. Opening the needle a little cured these symptoms immediately. This behavior greatly facilitated the establishment of the best needle setting. Although I’m not an R/C guy, I did give the throttle a try, removing my paper clip lock to do so. Without really fine-tuning the carburettor, I found that a low speed of 2,500 RPM on the 9x6 prop was pretty reliable, while response upon re-opening the throttle was very prompt and dependable, with the engine picking up and settling down very quickly. Again, Chinn was right – the Tempest throttles very well for a diesel! My engine didn’t appear to match Chinn’s example for performance – when carefully adjusted at the end of the final run, I only saw 9,100 RPM on the APC 9x6 – around 0.184 BHP at that speed. However, my Tempest is still quite tight – objectively speaking, I would expect a substantial improvement after an hour or so of additional running. I believe that Chinn’s performance figures are probably typical for a well run-in example of the Tempest. Kevin Richards supported my impression that the Tempest was a very pleasant engine to use. He flew one in a Junior 60, in which it behaved well. He also had an example which had a normal E.D. Hunter venturi. It was also a very good little engine. Both of Kevin's engines bore serial numbers which began with an "S" prefix, indicating that they were original Dinton Engineering products. Conclusion

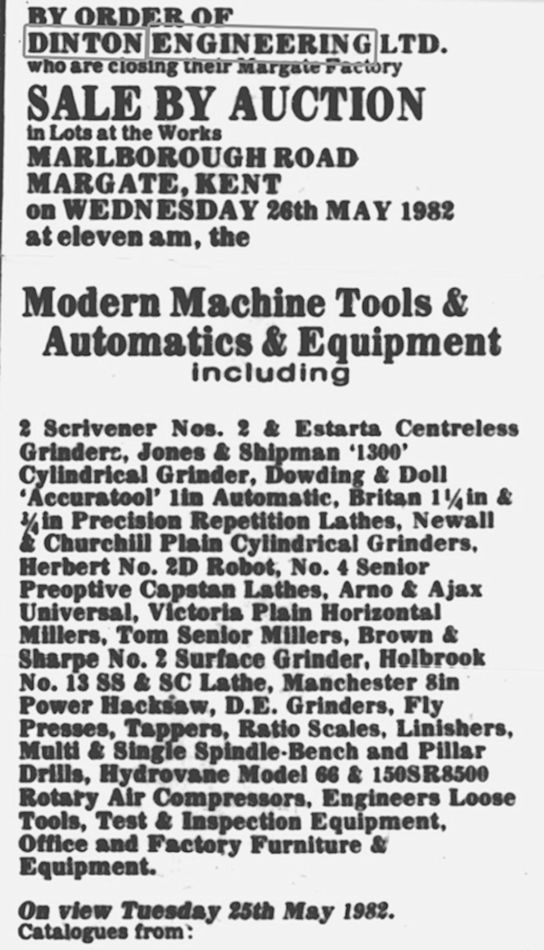

The sale of Dinton Engineering's equipment was announced in the "Kentish Express" supplement of May 14th, 1982. The advertisement, which is reproduced here, shows very clearly that Dinton Engineering had an extremely well-equipped machine shop. The timing of the appearance of the Replica Engines replicas mentioned earlier suggests that the residual Taplin engine components were sold off at the same time. However, for some unknown reason the Dinton Engineering company was not wound up at this time. The former Birchington Engineering site on Albion Road continued to be known locally as "Taplin's" for years. The unused structures deteriorated steadily, and by 1989 both the old and the new Albion Road buildings had been demolished. After a long period of dormancy, Birchington Engineering was finally wound up soon after John Taplin's death in 1990. The site lay dormant for a while thereafter.

Dinton Engineering lasted somewhat longer, at least in name. As of 2024, Dinton Engineering Limited continued to be listed on Companies House records, despite having been dormant since 1993. This status can be attributed to Cutform (Wire) Limited, the company that acquired Dinton Engineering Limited, having become insolvent in 2009. It appears that the profitability of precision wire manufacturing had declined in the face of ever-changing technology, forcing the cessation of operations. Getting back to the engines, the introduction of the Taplin Tempest in early 1970 stands as a testament to John Taplin’s sincere desire to remain in the model engine manufacturing business despite the flagging interest in his company’s flagship twin-cylinder products. He was clearly hoping that a somewhat more practical and “familiar” single-cylinder R/C diesel might attract some buyer interest. However, it appears that his head was being ruled by his heart in this instance – it’s perfectly clear in hindsight that the Tempest stood no chance at all of succeeding in the marketplace as it stood in 1970. The very small number of these engines actually completed by the original manufacturer stands as eloquent testimony to the engine’s failure to attract any interest among either aero or boat modellers of the time. Still, the Tempest remains an item of great interest to present-day collectors. Its unique heritage as well as its highly individualistic appearance and relative rarity combine to maintain its status as a desirable collector’s item. I’ve certainly appreciated the opportunity to experience my own example! __________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published October 2024 |

|

| |

In this article, I’ll share some information about the well-known Taplin engines in general and the last model engine to be released under the Taplin trade-name in particular. This was the 3.47 cc Taplin Tempest single-cylinder R/C diesel of 1970. This unusual-looking engine was a last-ditch attempt on the part of its manuf

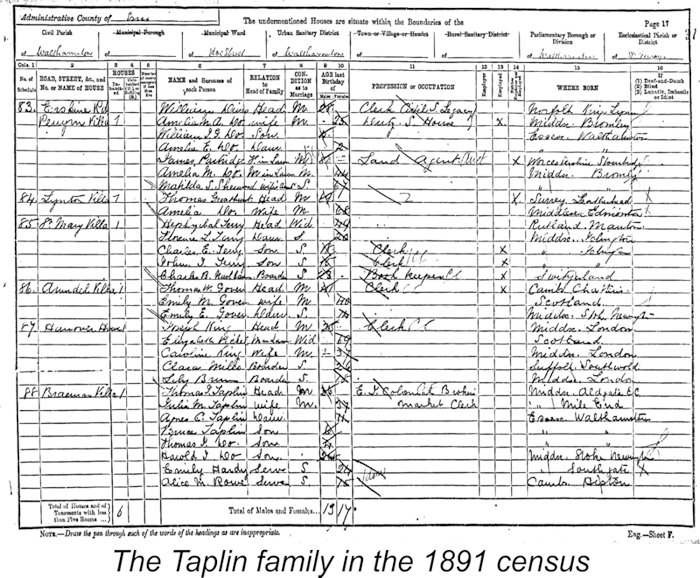

In this article, I’ll share some information about the well-known Taplin engines in general and the last model engine to be released under the Taplin trade-name in particular. This was the 3.47 cc Taplin Tempest single-cylinder R/C diesel of 1970. This unusual-looking engine was a last-ditch attempt on the part of its manuf The individual responsible for the creation of the Taplin model engine series was Colonel Harold John Taplin, widely known in model circles as just plain “Taps”. He was born on January 26

The individual responsible for the creation of the Taplin model engine series was Colonel Harold John Taplin, widely known in model circles as just plain “Taps”. He was born on January 26

trainer, progressing to an Avro 504 built by his former employer Alliot Verdon Roe, and culminating on a Royal Aircraft Factory B.E. 2e.

trainer, progressing to an Avro 504 built by his former employer Alliot Verdon Roe, and culminating on a Royal Aircraft Factory B.E. 2e.

When WW2 broke out, Taplin was 48 years old and engaged in a reserved occupation. Although he would undoubtedly have been willing to serve his country in whatever capacity seemed most valuable, his continued work in support of firearms and aero engine manufacture was doubtless seen as the most valuable contribution that he could make. RAF records confirm that he never rejoined his old Service – instead, he volunteered for the Land Defence Volunteers (LDV, officially re-named the

When WW2 broke out, Taplin was 48 years old and engaged in a reserved occupation. Although he would undoubtedly have been willing to serve his country in whatever capacity seemed most valuable, his continued work in support of firearms and aero engine manufacture was doubtless seen as the most valuable contribution that he could make. RAF records confirm that he never rejoined his old Service – instead, he volunteered for the Land Defence Volunteers (LDV, officially re-named the

After the dust settled from this controversy, Col. Taplin returned to the further development of his wire-drawing business. His part-time involvement with modelling continued, with an increasing focus upon radio control for both model boats and model aircraft. He joined the Thanet Model Aero Club, becoming its Hon. Secretary. He appears to have deveoped a good long-term working relationship with E.D. during this period. In 1949 he produced the original design of the 82 in. span “Radio Queen” aircraft expressly intended for radio control applications.

After the dust settled from this controversy, Col. Taplin returned to the further development of his wire-drawing business. His part-time involvement with modelling continued, with an increasing focus upon radio control for both model boats and model aircraft. He joined the Thanet Model Aero Club, becoming its Hon. Secretary. He appears to have deveoped a good long-term working relationship with E.D. during this period. In 1949 he produced the original design of the 82 in. span “Radio Queen” aircraft expressly intended for radio control applications.

While all this was going on, Col. Taplin continued his part-time but clearly passionate involvement with models. In early March 1950, he achieved a significant milestone by conducting the world’s first flight of a twin-engine radio-controlled aircraft. The seven-and-a-half minute flight took place at RAF Mansion. The aircraft was a simplified variation of Colonel Taplin’s "Radio Queen" model, which had been modified to accommodate two

While all this was going on, Col. Taplin continued his part-time but clearly passionate involvement with models. In early March 1950, he achieved a significant milestone by conducting the world’s first flight of a twin-engine radio-controlled aircraft. The seven-and-a-half minute flight took place at RAF Mansion. The aircraft was a simplified variation of Colonel Taplin’s "Radio Queen" model, which had been modified to accommodate two

was filmed showing him testing his radio-controlled boats at Margate. Thanks to the diligence of Graham White, this footage of the 63 year-old Col. Taplin at work has been preserved and may be

was filmed showing him testing his radio-controlled boats at Margate. Thanks to the diligence of Graham White, this footage of the 63 year-old Col. Taplin at work has been preserved and may be  Returning to 1954, the always well-informed Peter Chinn had been following Col. Taplin’s engine development efforts with interest. His regular column in the May 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” was entitled “Twin Cylinder Topics”, and included a description of Col. Taplin’s 5 cc prototype twin based on E.D. Mk. III components.

Returning to 1954, the always well-informed Peter Chinn had been following Col. Taplin’s engine development efforts with interest. His regular column in the May 1955 issue of “Model Aircraft” was entitled “Twin Cylinder Topics”, and included a description of Col. Taplin’s 5 cc prototype twin based on E.D. Mk. III components.  The relevant Patent number 747742 was stamped onto one of the mounting lugs of each engine. The engines also bore serial numbers which appear to have been assigned in a straight numerical sequence, with the prefix “W” added to the numbers of engines fitted with water-cooled cylinders for marine use. The same numerical sequence seems to have covered both aero and marine variants - the "W" prefixes were applied intermittently to numbers in the main sequence as required. My own illustrated example bears the serial number 406.

The relevant Patent number 747742 was stamped onto one of the mounting lugs of each engine. The engines also bore serial numbers which appear to have been assigned in a straight numerical sequence, with the prefix “W” added to the numbers of engines fitted with water-cooled cylinders for marine use. The same numerical sequence seems to have covered both aero and marine variants - the "W" prefixes were applied intermittently to numbers in the main sequence as required. My own illustrated example bears the serial number 406.

The Taplin cause must have been helped by Ron Warring’s very positive

The Taplin cause must have been helped by Ron Warring’s very positive  Birchington Engineering Co. Ltd. advertised the Taplin Twin quite energetically. One promotion which they publicized in late 1959 promised an award of £75 to the first British individual to establish a duly-ratified International Record for radio-controlled model aircraft using a Taplin Twin powerplant. On May 8

Birchington Engineering Co. Ltd. advertised the Taplin Twin quite energetically. One promotion which they publicized in late 1959 promised an award of £75 to the first British individual to establish a duly-ratified International Record for radio-controlled model aircraft using a Taplin Twin powerplant. On May 8 However, some complications then ensued. It turned out that a certain Mr. C. D. Adcock had already established a Taplin-powered record on February 13

However, some complications then ensued. It turned out that a certain Mr. C. D. Adcock had already established a Taplin-powered record on February 13 An interesting accessory which appeared in late 1961 from Birchington Engineering was the Taplin-Baker Hydro-Jet. This device functioned pretty much like a water turbine in reverse! It drew water up through a large aperture in the bottom of the boat's hull into an appropriately-shaped conduit inside the boat. An engine-driven impeller mounted inside the conduit then forced the water out horizontally at high velocity through a smaller-diameter outlet in the stern of the vessel. The lateral direction of the discharge was controlled by a moveable nozzle which was activated by a tiller. This took the place of a conventional rudder.

An interesting accessory which appeared in late 1961 from Birchington Engineering was the Taplin-Baker Hydro-Jet. This device functioned pretty much like a water turbine in reverse! It drew water up through a large aperture in the bottom of the boat's hull into an appropriately-shaped conduit inside the boat. An engine-driven impeller mounted inside the conduit then forced the water out horizontally at high velocity through a smaller-diameter outlet in the stern of the vessel. The lateral direction of the discharge was controlled by a moveable nozzle which was activated by a tiller. This took the place of a conventional rudder.  By early 1962 the original 7 cc Taplin Twin had been in production for over three years with no changes of any significance. It was definitely time to consider an upgrade to the now well-established design. The need for change was underscored by the disastrous arson-caused fire of April 29

By early 1962 the original 7 cc Taplin Twin had been in production for over three years with no changes of any significance. It was definitely time to consider an upgrade to the now well-established design. The need for change was underscored by the disastrous arson-caused fire of April 29

Sadly, the 15 cc Big Twin proved to be far from the sales success that it was hoped to be. Only some 200 – 300 examples ended up being sold by Taplin. Most of those that survive today are reproductions created by others, many using original Taplin components, of which quite a few evidently remained when the original production ended. The original examples all bear the Taplin Patent number as well as serial numbers having the letter “D” included as a prefix. My own illustrated example is clearly a repro – it does not display the Taplin Patent number and bears no serial number at all. The sole marking is the letter “T” stamped on top of the right-hand mounting lug.

Sadly, the 15 cc Big Twin proved to be far from the sales success that it was hoped to be. Only some 200 – 300 examples ended up being sold by Taplin. Most of those that survive today are reproductions created by others, many using original Taplin components, of which quite a few evidently remained when the original production ended. The original examples all bear the Taplin Patent number as well as serial numbers having the letter “D” included as a prefix. My own illustrated example is clearly a repro – it does not display the Taplin Patent number and bears no serial number at all. The sole marking is the letter “T” stamped on top of the right-hand mounting lug. Following the retirement of his father, John Taplin’s initial project was a re-design of the 8 cc Taplin Twin, now completing its fourth year of production. He had actually intended to implement these changes back in 1964, but pressure of other business precluded this at the time. The revised model finally appeared in early 1967 as the Taplin Twin Mk. III.

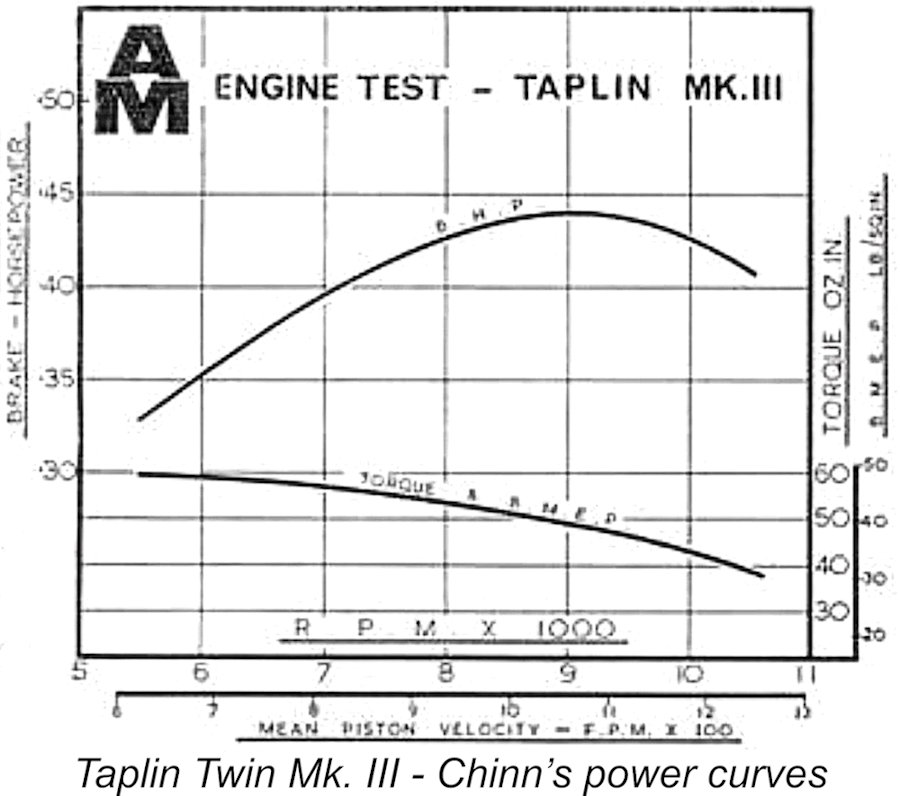

Following the retirement of his father, John Taplin’s initial project was a re-design of the 8 cc Taplin Twin, now completing its fourth year of production. He had actually intended to implement these changes back in 1964, but pressure of other business precluded this at the time. The revised model finally appeared in early 1967 as the Taplin Twin Mk. III.  The Taplin Twin Mk. III was the subject of a

The Taplin Twin Mk. III was the subject of a  The Taplin Tempest which formed the initial inspiration for this article stands apart from the other Taplin engines in several ways. It was the only single-cylinder unit ever developed by the company. It was also the sole Taplin design to feature disc rear rotary valve induction. Finally, it was the very last model engine to be produced by its manufacturers.

The Taplin Tempest which formed the initial inspiration for this article stands apart from the other Taplin engines in several ways. It was the only single-cylinder unit ever developed by the company. It was also the sole Taplin design to feature disc rear rotary valve induction. Finally, it was the very last model engine to be produced by its manufacturers.

The carried-over features gave the Tempest an unmistakable “Taplin look” – you couldn’t confuse it with the product of any other manufacturer. The major point of departure from previous models was the inclusion of a downward-angled stub exhaust pipe which was attached to the cylinder using a high melting point solder. This made the fitting of a conventional muffler impossible, although it did provide a convenient attachment point for a tubular conduit to lead exhaust gases away from the engine.

The carried-over features gave the Tempest an unmistakable “Taplin look” – you couldn’t confuse it with the product of any other manufacturer. The major point of departure from previous models was the inclusion of a downward-angled stub exhaust pipe which was attached to the cylinder using a high melting point solder. This made the fitting of a conventional muffler impossible, although it did provide a convenient attachment point for a tubular conduit to lead exhaust gases away from the engine.

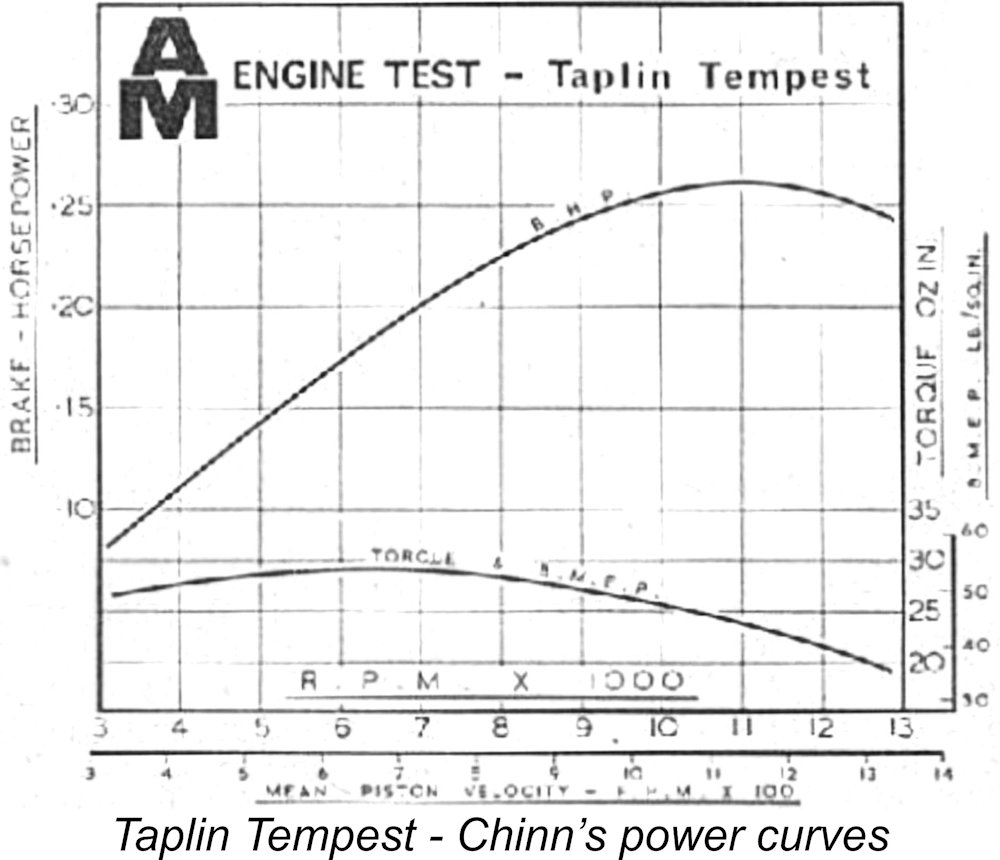

The Tempest was the subject of a

The Tempest was the subject of a  This example has never been mounted – indeed, it appears to have done little or no previous running. Upon close inspection, it proved to be rather tight, to the point that a full-length break-in would clearly be necessary to unlock its full performance potential. Since I had no plans to fly it, I could see little point in expending the time, fuel and neighbourly “forbearance capital” which this would entail. Instead, I decided to confine my efforts to putting a few runs on the Tempest using an APC 9x6 airscrew, just to experience its handling and running qualities. If Peter Chinn’s power curves were to be relied upon, the engine should turn this prop at somewhere in the region of 10,000 RPM.