|

|

The E.D. Baby 0.46 cc Diesel by Adrian Duncan with Ron Chernich

Ron’s excellent and very informative article has doubtless filled this need admirably since its 2008 publication. Unfortunately, my greatly-missed mate Ron left us in early 2014 without passing on the access codes to his heavily encrypted site. Consequently, no maintenance or updating of that site has since been possible, making it inevitable that a slow but inexorable process of deterioration is taking place over time. It’s this issue that has led me to transfer a number of what I consider to be the more important articles over to my own site. This is one of them. Ron’s article is sufficiently comprehensive that the information which it contains fully merits preservation in full. However, I felt that it would benefit from a certain degree of reorganization. In addition, I found a few statements which appeared at best misleading and at worst incorrect. Finally, I was able to add some important information which was not included in Ron's original text. Accordingly, the text of the following article should be read as an amalgam of Ron’s original comments and my own observations, with a few corrections and additions which appeared to me to be desirable. In particular, Ron completely missed one trick – he didn’t include a latter-day test report on the engine beyond some general commentary on its starting and running qualities. He also missed an important design change to which the engine was subjected. These were omissions which I was in a position to rectify! Having set the stage, it’s time to review the background to the appearance of this cute little diesel. Background

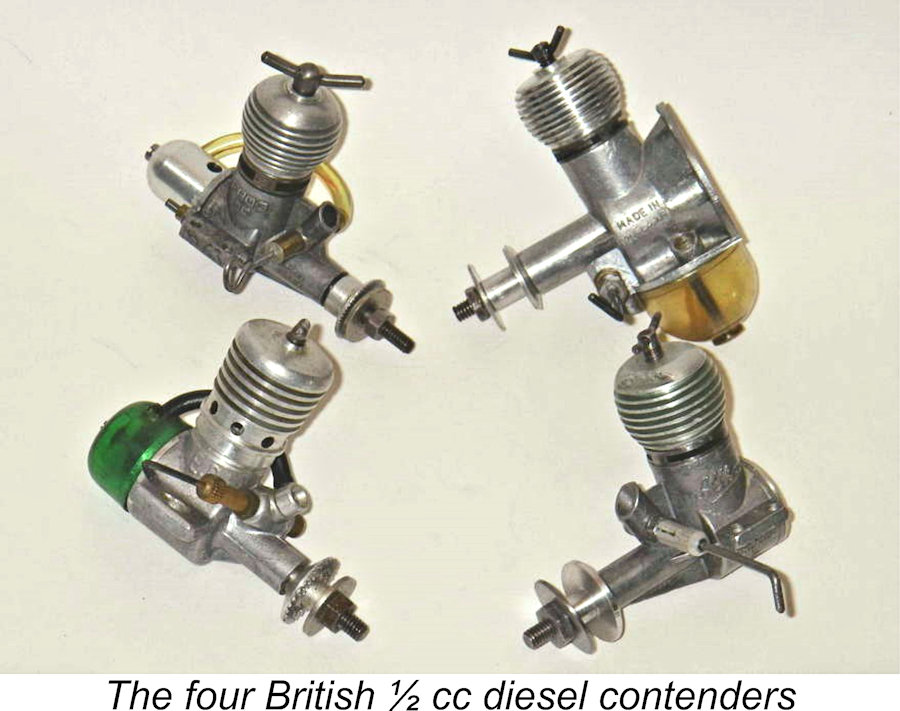

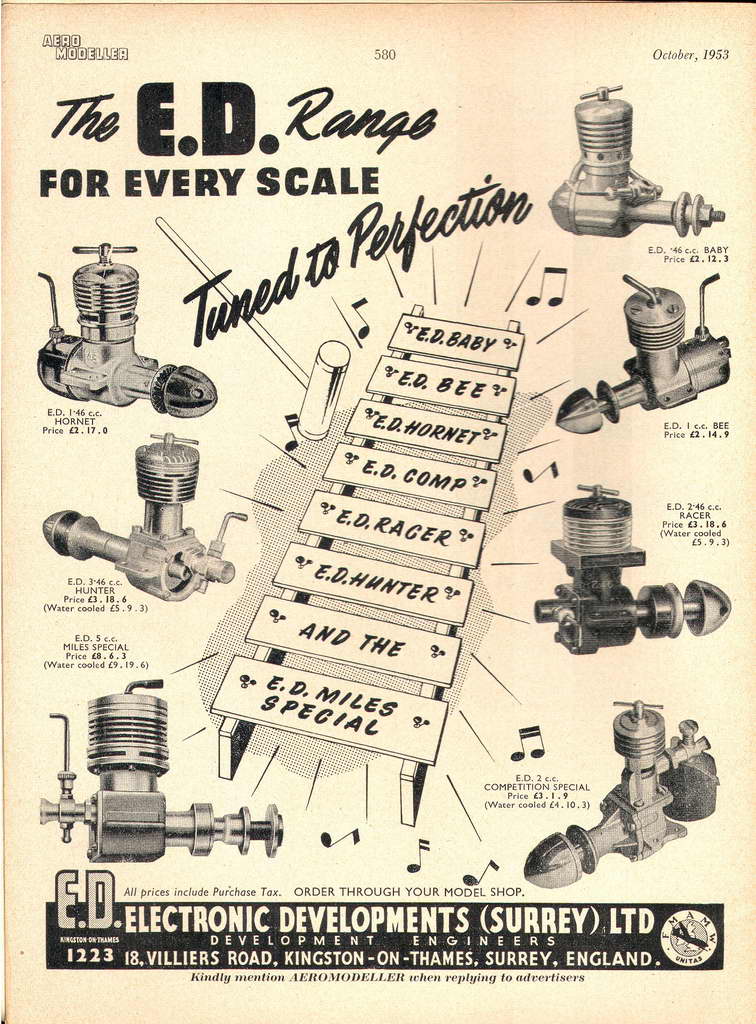

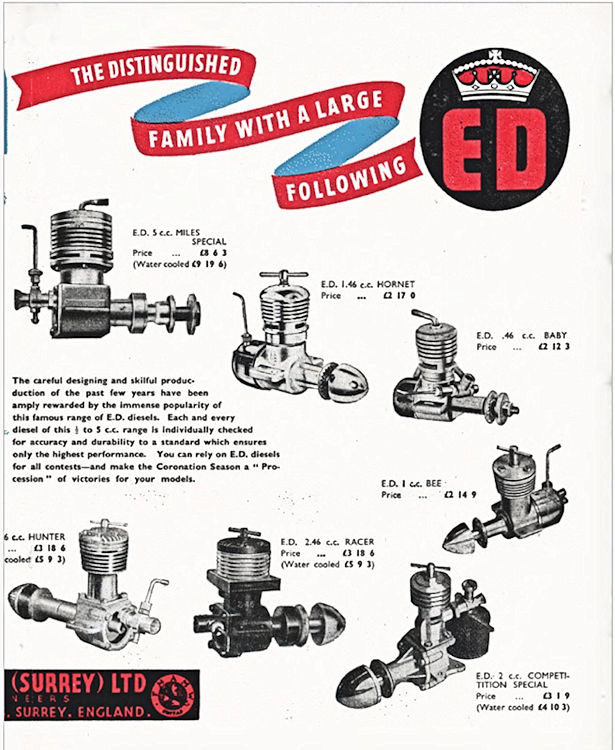

In reality, it would be more accurate to say that these manufacturers returned attention to the small engine category, since engines of this kind were actually nothing new in the context of the British model engine marketplace. There had been the 1947 Ace 0.5 cc, the 1948 Comet 0.4 cc, the 1948 Kalper .32 cc and the 1948 Kemp Hawk 0.2 cc models. However, none of these offerings had truly captured the attention of the British aeromodelling community at large, hence surviving in the market for only a few years. The resumption of British interest in such engines was most likely in response to interest sparked by the widely-reported eruption of ½A (.049 cuin.) glow-plug engines in the USA. It was clearly anticipated that a similar small-engine craze would develop in Britain and the Commonwealth countries. In a British context, the choice of compression ignition over glow was logical given the fact that this was the predominant type of motor in use by modellers in England and her associated Commonwealth countries at the time. Consequently, it was the type with which both British manufacturers and their customers were most familiar. With a broad range of choices available, individual aeromodellers could These small diesels tended to be more expensive to manufacture than their larger counterparts, since the required level of manufacturing precision generally increased with diminishing size. Despite this, they had to be sold at competitive prices - somewhat illogically, people expected to pay less for a smaller engine. The profit margin to be realized from these small units was therefore somewhat constrained. From a user's standpoint, the little 'uns were somewhat more challenging than their larger counterparts when it came to handling. They also required greater care during operation if handling damage was to be avoided. Despite these disadvantages, almost all of these manufacturers' products attracted their share of market The broader problem was that the almost simultaneous release of four competing models in the “½ cc diesel” category quickly led to over-saturation of what proved to be something of a “bubble” market. The craze for small diesels had been based largely upon the novelty appeal of these small engines. Once the novelty wore off a little, the craze subsided fairly quickly, leaving a continuing but relatively modest demand. This ongoing In this review, we'll look at E.D.'s entry into the ½ cc diesel sweepstakes, the 0.46 cc E.D. Baby. The Baby appeared in February 1952, only a few months after the introduction of the iconic 2.46 cc E.D. Mk. III Series II Racer. It was first advertised in the March 1952 issue of “Aeromodeller”, which actually hit the news-stands in mid-February. It ended up remaining in production at some level until early to mid 1961. The Racer was the first E.D. design to be openly associated with the name of Basil Miles as its designer. Although his name was never associated directly with the Baby, it seems all but certain that the design of the Baby should also be credited to Miles. Design and Construction

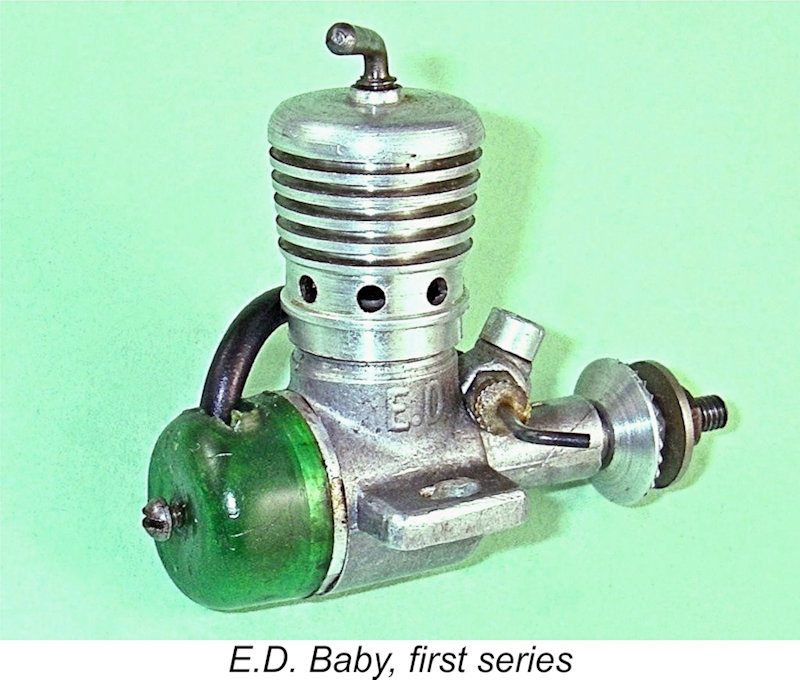

As stated earlier, the Baby was almost certainly designed by Basil Miles, who also seems to have designed the related 1.46 cc Hornet of late 1952 with which the Baby shared its transfer design. In both the Baby and Hornet, the cylinder liner had three sawn exhaust slits cut through its location flange. Three identical transfer slits were located immediately below this flange. The diameter of the liner’s lower extension below the flange was somewhat smaller than the opening which accommodated it in the upper crankcase. The liner was centered and pressed down onto the case by the cooling jacket which screwed onto a male As with the Hornet, the use of vertically “stacked” exhaust and transfer slits prevented the provision of any overlap between the exhaust and transfer ports, restricting the transfer period significantly while at the same time forcing a rather early opening of the exhaust. Even with a modest transfer period of only some 82 degrees, the exhaust period was still held to a somewhat excessive 154 degrees. Strangely, this does not seem to have mattered - once the starting technique and setting requirements are understood, a Baby will start promptly, run very well and exhibit good flexibility in terms of running adjustments. Perhaps its long-stroke internal geometry helps here.

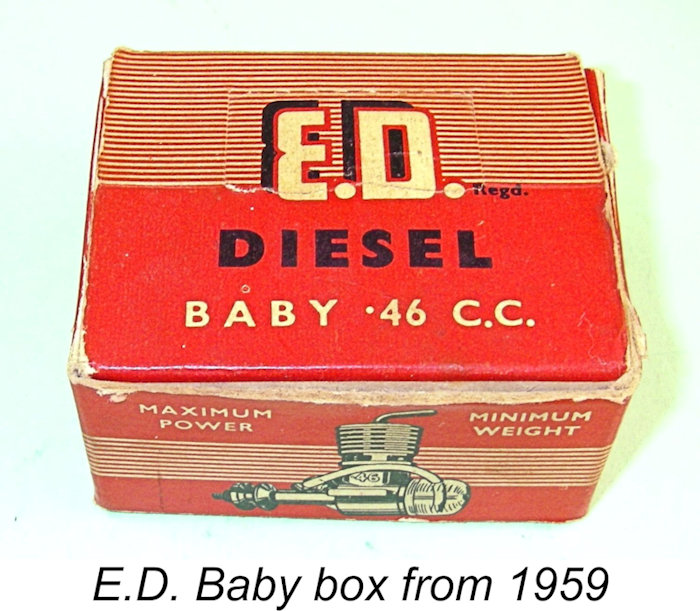

The engine was completed by a screw-in backplate with a threaded central boss for the 8BA screw which secured the tank in place. This tank was molded from a translucent plastic material - some were green, others yellow. Unfortunately, these tanks tend to distort and crack with age. The fuel tubing fitted to early engines was not transparent. The backplate was tightened by the usual provision of a saw slit across the diameter, requiring the tank to seal on its front face rather than around the locating lip on the backplate. This pretty much amounted to a leak waiting to happen when the tank plastic distorted – in fact, it often didn’t have to wait too long! The filler hole and fuel line exit also represented good leak opportunities, but in practice fuel usually didn’t leak away faster than the wee beastie could be started, while a quick top-upsquirt before release could provide a good minute of running - more than Unlike the ½ cc offerings from Allbon and FROG which featured the conventional four-bolt mounting pattern, the Baby lugs had only two elongated holes. This permitted a degree of side-thrust adjustment if the case was not too tight between the engine bearers - sometimes intentionally, sometimes not! Three successive box styles were used in the packaging of the Baby. The first boxes were very much along the lines of the common early Mk. I Bee box, being fabricated from fairly stiff cardboard. The second box came into use in the mid-1950's. It was made from thinner cardboard with a predominantly red coloration. The engines produced from 1960 onwards came in boxes made of blue-printed cardboard, very much along the lines of the boxes used for the ill-starred E.D. Pep 0.8 cc model. Serial Numbers and Production Figures

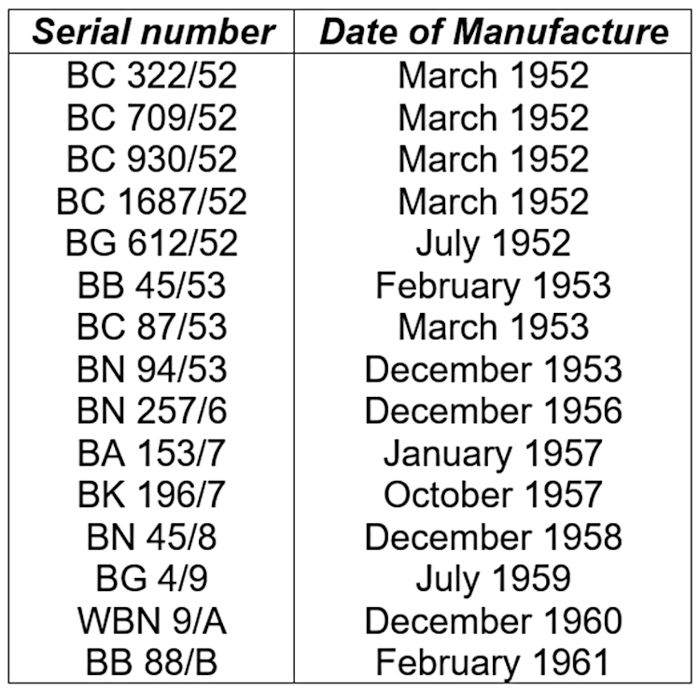

When considering the issues of serial numbers and production figures for any E.D. model, my first step is always to consult with my mate Kevin Richards. Apart from being the ranking world expert on all matters relating to the E.D. model engine range, Kevin has one of the largest collections of E.D. engines to be found anywhere. When it came to the E.D. Baby, Kevin was able to provide no fewer than eleven confirmed numbers for this engine. Along with my own four examples, this created a database of 15 numbers upon which to base a few conclusions. The serial numbers applied to their engines by E.D. were more like a coding scheme than a sequence, hence appearing rather "opaque" to the uninitiated. The system used by E.D. is fully explained in my separate article covering the E.D. story. It is unusually informative, each sequence being unique to the type of engine, the year and month of production and the position of the engine within that month’s production sequence. Can't get any more informative than that! Suffice it to say here that the model designator for the Baby was the letter "B". The rest of the numbering system followed that detailed in my article on the E.D. Story, with a second letter indicating the month of production, followed by the number of the engine in that months' batch and finally an indication of the year of production. So for example, E.D. Baby no. BC 322/52 was the 322nd example of the Baby produced in March 1952. The letter W before the B indicated a watercooled marine example.

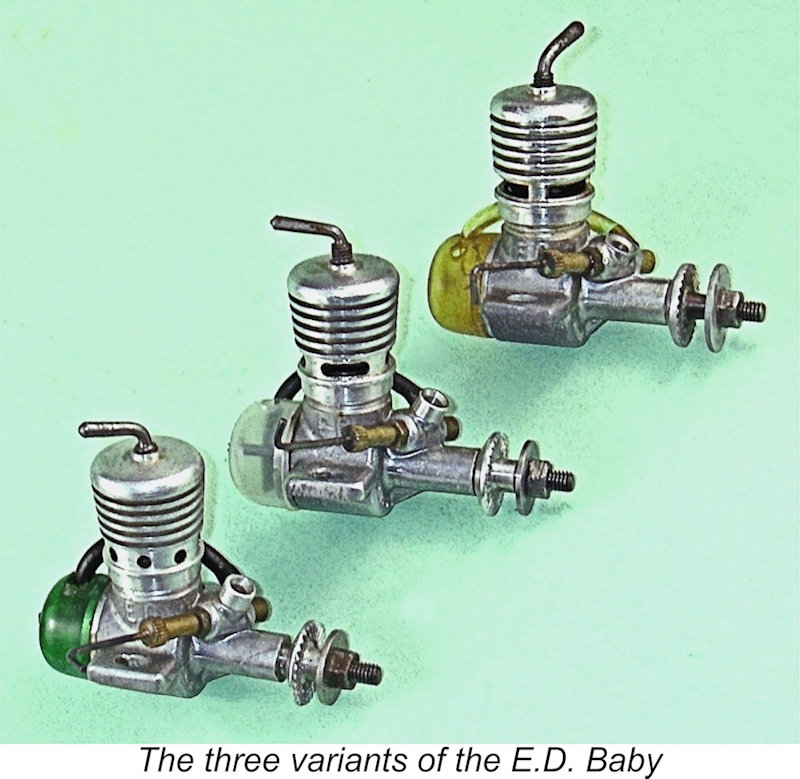

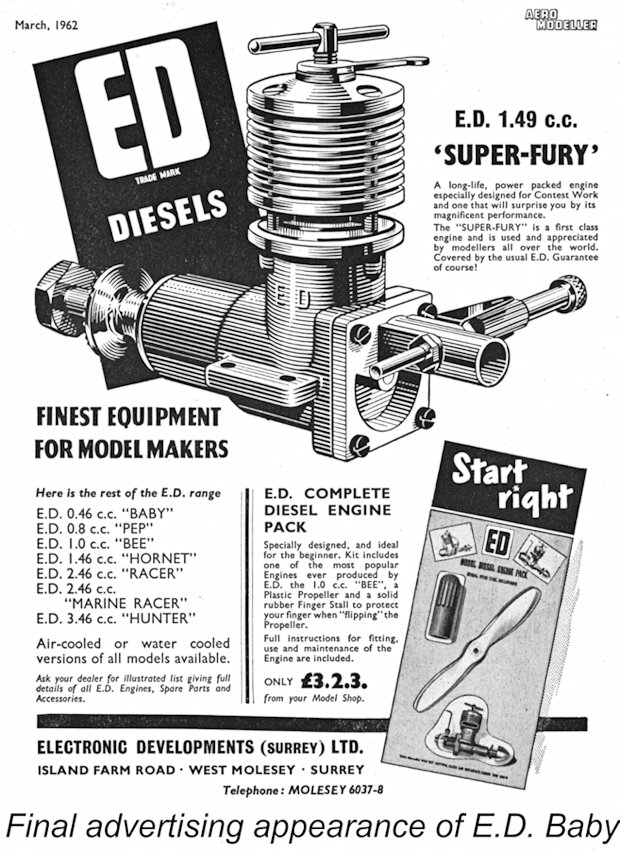

However, the craze soon ran its course. By early 1953 monthly production figures were only a fraction of those that had been achieved out of the starting gate. The largest batch number after 1952 is 257, and even that was part of the usual increased production batch for December 1956 to deal with the hoped-for Christmas rush. At this time, monthly production seems to have stabilized at perhaps 200 examples per month, or 2,400 examples a year. By 1958 it seems clear that production figures had slumped even further. Two-digit batch numbers become the norm, implying that annual production had dipped below 1,000 units. Even so, some level of demand must still have existed - as late as February 1961 we see evidence that at least 88 examples were produced during that month. That said, it's likely that by this time the engine was only being produced periodically in discrete batches, purely to maintain a small inventory to deal with whatever demand remained - many months may have gone by with no production at all. Kevin reckoned that at some point in 1961 E.D. simply let the Baby slip quietly off the production table. The continued listing of the engine in E.D. advertising until early 1962 (see below) almost certainly represented an attempt to shift existing unsold inventory. So what does it all add up to? We can't be definitive on the subject of overall production figures, but we can say with some confidence that the data which we do have suggest quite strongly that between 15,000 and 20,000 examples of the Baby may well have been produced in total during the engine's nine-year production life. Not a bad record! Variants of the E.D. Baby In the following paragraphs, reference will be made to the two major variants of the Baby which for clarity will be referred to as the “Series I” and “Series II” versions of the engine. It’s important to note that E.D. themselves never drew this distinction, neither was the “Series II” label applied by “Aeromodeller” in their mini-review of the later version that appeared as an appendix to the Allbon Bambi review in the August 1954 issue. The first version of the Baby had been reviewed in the June 1952 edition but was never identified as the “Series I” version.

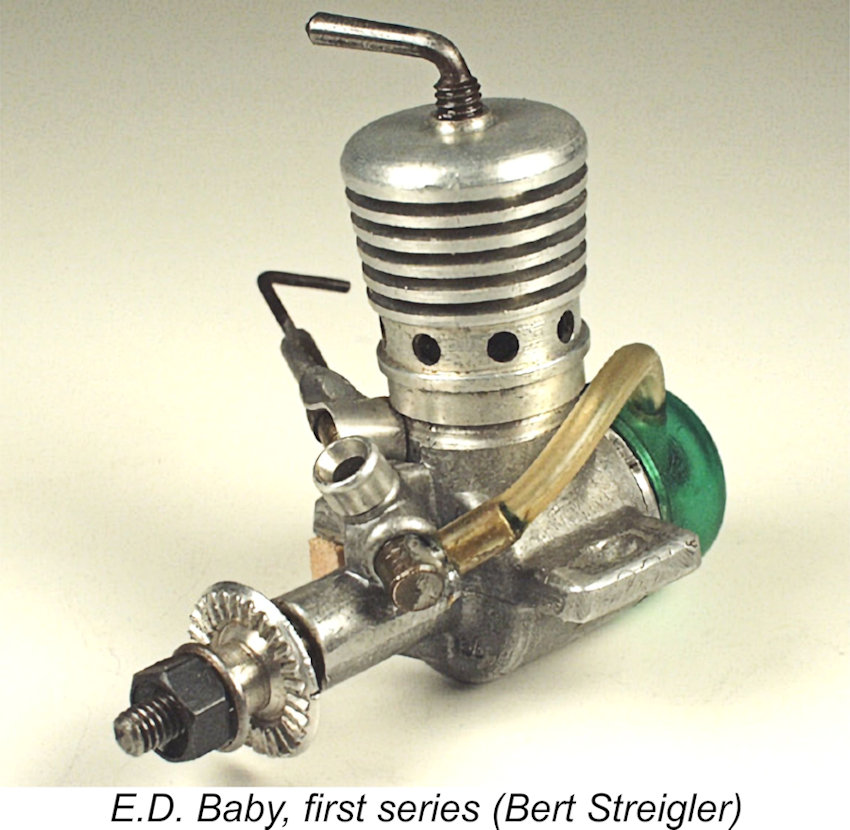

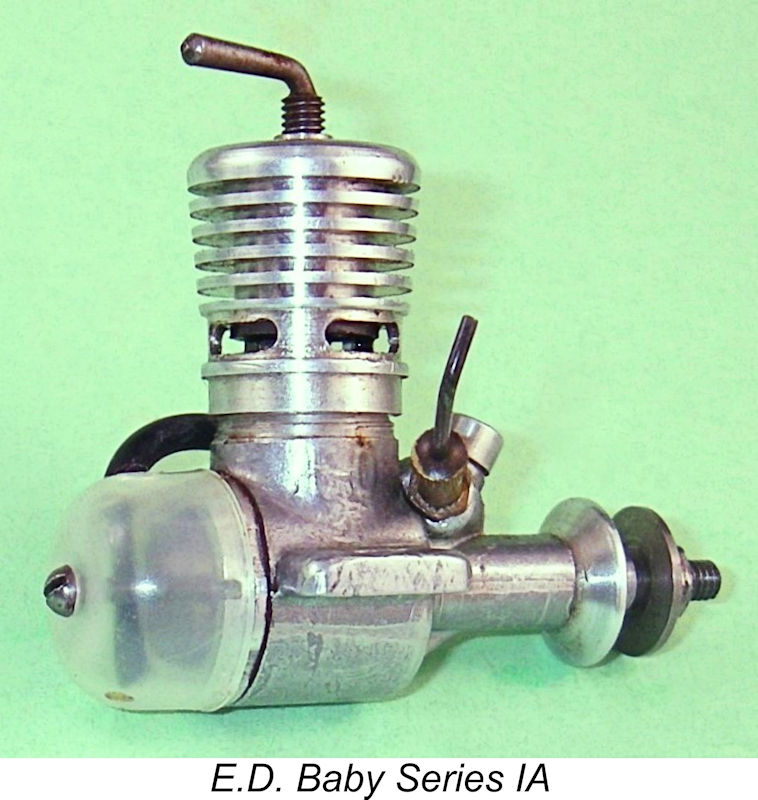

The Series I version of the Baby was first announced in the March 1952 issue of “Aeromodeller”, as reproduced at the right. It featured front rotary valve (FRV) crankshaft induction with the needle valve swept distinctly upwards and rearwards on the right-hand side (looking forward in the direction of flight). This was a nice feature given the proximity of the needle to the prop on such a small engine, although the alignment effectively prevented the needle and spraybar from being swapped side for side. Another notable feature of the engine was the ring of ocean liner-like "port-hole" exhaust apertures in the lower jacket, eight in number. Note also that the photo in the Although the tommy-bar comp screw continued to appear in the advertising for some time, close inspection of the illustration in the October 1953 "Aeromodeller" advertisement reproduced at the left shows some evidence that this may have been drawn in. The more familiar and more cheaply-made comp screw was a bent "L" shaped affair, similar to that seen on the E.D. Bee and Miles Special in the same advertising placement. The publication of this photo in October 1953 is odd too, because as we shall see, the Series I “port-hole” exhaust model shown in the image was a thing of the past by this time! Indeed, production of the original version appears to have lasted only for the first year or so of the engine's nine-year production life. During that first year, E.D. evidently became aware of a handling issue to which the original Baby was prone, namely, the ease with which the Series I variant could be flooded by an over-vigorous port prime. This issue arose because experience showed (and still shows today) that a port prime is more or less essential for cold starting. The small size of the “port-hole” openings (3/32 in. diameter) made it hard to dribble only a little fuel through to the To avoid a major flood, the most practical technique was to bring the prop up to close the exhaust, give a hearty squirt, then bend down and blow away most of the fuel. A bit awkward, and even then the engine tended to start very rich. It was generally necessary to back off compression quite a bit before going for a start, “catching” the engine by increasing compression as the excess fuel burned off once a start had been achieved. E.D.’s initial attempt to deal with this issue manifested itself in the form of a “twilight” variant which we might legitimately designate as the “Series IA” model. In this variant, the lands between pairs of “port-holes” were milled away to produce four round-ended slits. This arrangement produced the best compromise between opening size and strength, but one shudders to contemplate the added cost of manufacture when applied to what was supposed to be an economy-priced model.

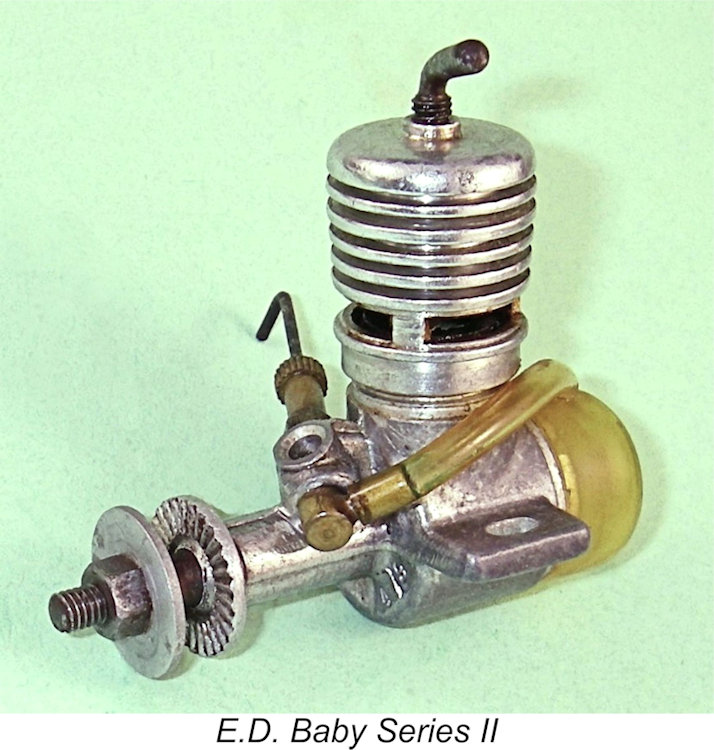

E.D. quickly replaced the four round-ended openings of the Series IA variant with the more familiar three milled slots for exhaust discharge. This change identifies the Series II version of the engine which was to remain in production at some level down to early to mid 1961. Engines fitted with the new-style cooling jacket had begun to appear by February 1953. However, the Series II variant did not appear in E.D.’s advertising until the June 1953 issue of “Model Aircraft” as reproduced below at the right. Oddly enough, the advertising illustrations then reverted to the Series I model with tommy bar comp screw – the Series II version did not re-appear in the ads until the October 1953 placement in “Model Aircraft”. Thereafter, the advertising images of the Series I and Series II variants continued to alternate for some time – go figure! The logic (or lack thereof!) guiding E.D.’s advertising campaign sometimes defies rational analysis…………..

It should be clear that the cyclic vertical loads imposed on the cylinder during operation had to be resisted solely by the three narrow columns of material which separated the three exhaust slits in the lower jacket. These columns provided a significantly reduced cross-sectional area of metal to resist these forces. Moreover, the sharp edges of the slits clearly had the potential to create stress concentrations which could affect the long-term structural integrity of the intervening columns as metal fatigue set in. The late Ron Chernich once had the opportunity to witness at first-hand what happened when all three columns of a Series II jacket let go at the same time! This happened during the ROG launch of a small free-flight model from a taxiway at RAAF Amberley air base in the late 1960's. The cylinder head and liner must have shot 50 feet into the air, to the great amusement of all present. It took them ages to find it in the grass and worse yet, it was Ron’s engine!

However, a further change was soon introduced. This was the expansion of the lower cylinder liner to occupy the crankcase installation bore completely. Transfer and bypass were now accomplished through the provision of three internally-formed channels in the inner lower cylinder wall. This allowed the provision of a considerably extended transfer period along with a substantial degree of overlap between transfer and exhaust ports. The transfer now overlapped the exhaust to a considerable degree. Kevin's engine number BG 67/53 from July 1953, which is also New-in-Box, is of this type. The conical top of the piston and corresponding concavity in the contra-piston were now replaced by more simply-manufactured flat-topped components. Even though the original conical design should theoretically yield improve scavenging, it was found that in practice there was no measurable difference. Oddly enough, the introduction of these quite significant design revisions passed unnoticed in the contemporary modelling media until January 1954, when the changes were mentioned by Peter Chinn in his "Accent on Power" column in that month's issue of "Model Aircraft", at least 6 months after their introduction. The steel "dog-bone" conrod was retained, as were all other features of the earlier model, including the neat little soldered-in elbow on the spray bar which enabled the fuel line to follow a quite compact path back to the tank. The tiny, narrow-necked spray bar had no needle "seat", so fuel metering was less than perfect. Fortunately, on small sport engines, once set to a running position, precise fuel regulation is not critical - a fact noted by contemporary reviewers of the engine. The venturi insert mentioned earlier is worthy of comment, as not all engines had one. To complicate matters, the presence or absence is not related to the "Series" number – engine of both Series with and without inserts have been reported, including examples of the Series IA “twilight” model. My own Series IA unit is an example which does have an insert, as does my own Series I engine. The Series I engine tested by Ron Warring in June 1952 also featured the insert, as did the example tested the following month by Peter Chinn. It thus appears that the insert was an early addition. The only theory that Ron could offer was that the screw-cutting of the cylinder installation thread on the upper crankcase created a situation where the tool was likely to clobber the venturi top before the required thread reach was achieved. This forced the venturi to be cast very short. Even though it works in the absence of an insert, raw fuel drops can be seen leaping from the venturi under the influence of blow-back while the engine is running.

The first model of the Baby was reviewed by Ron Warring in the June 1952 issue of “Aeromodeller”. A month later, the rival magazine “Model Aircraft” carried their own review. Although this latter piece was un-credited, it was almost certainly written by Peter Chinn. The engines involved in both tests were Series I models. Production of the Baby in its Series II configuration continued at a progressively diminishing level until shortly before the disastrous E.D. fire of April 1962 as described in my E.D. story article. The Baby was still included in the list of available models which was featured in E.D.'s March 1962 advertising placement, although by that time the examples on offer were almost certainly previously-manufactured New Old Stock. The Baby was one of the designs that did not manage to make the legendary Phoenix-like rise from the ashes. Perhaps it could have, but the market had moved away from small diesels, giving E.D. a golden excuse to drop it from the range. Operation and Applications

The normal prop would be in the 5x4 to 7x3 range. The accompanying photo shows Ron Chernich's self-constructed replica Baby turning a 6x4 Master paint-stirrer at 7,700 RPM, which is typical for the original. However, reported test figures and associated commentary both suggest that the engine needs to be operated at a considerably higher speed than this to give of its best.

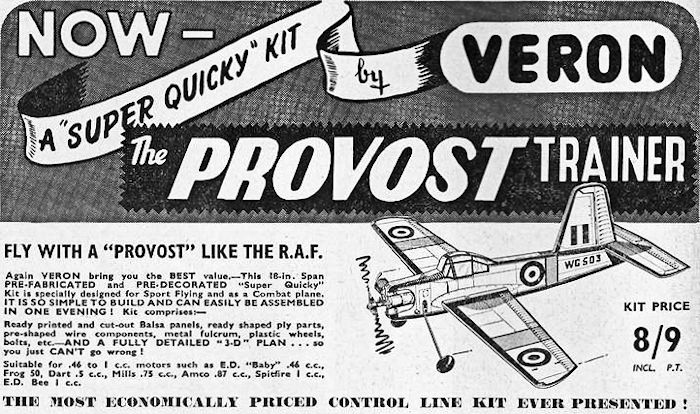

Like all of its ½ cc diesel contemporaries, the Baby was best suited to powering small free-flight models, although control-line applications were by no means excluded. A number of kits were produced for the British ½ cc engines, including several which were intended specifically for the Baby. KeilKraft had a delightful little symmetrical-wing "stunter" called the “Joker” which I'm sure could have performed well in hands other than mine! Many plans appeared for small free flight models specifically showing the Baby, which was clearly held in quite high regard by small-model designers of its day. These designs included a number of relatively intricate scale free-flight biplanes and innumerable sport free-flight Ron Chernich recalled that the Series II Baby was the second-ever engine that he bought new as a very young lad, and he remembered the long cycle ride to collect it from the Nundah Sports S It was with this engine, mounted in a Veron Percival Provost profile trainer, that Ron learned to fly control line, running around in circles with one arm hooked about the Hills Hoist in his aunt's back-yard. Years later, it powered his first free flight models, including cabin, low-wing and delta types. Ahhhhh............ fine nostalgic memories all, and ample reason for Ron to declare the E.D. Baby to be a wonderful little engine well able to capture the hearts of young and old! The Motor Boys Reproduction Project

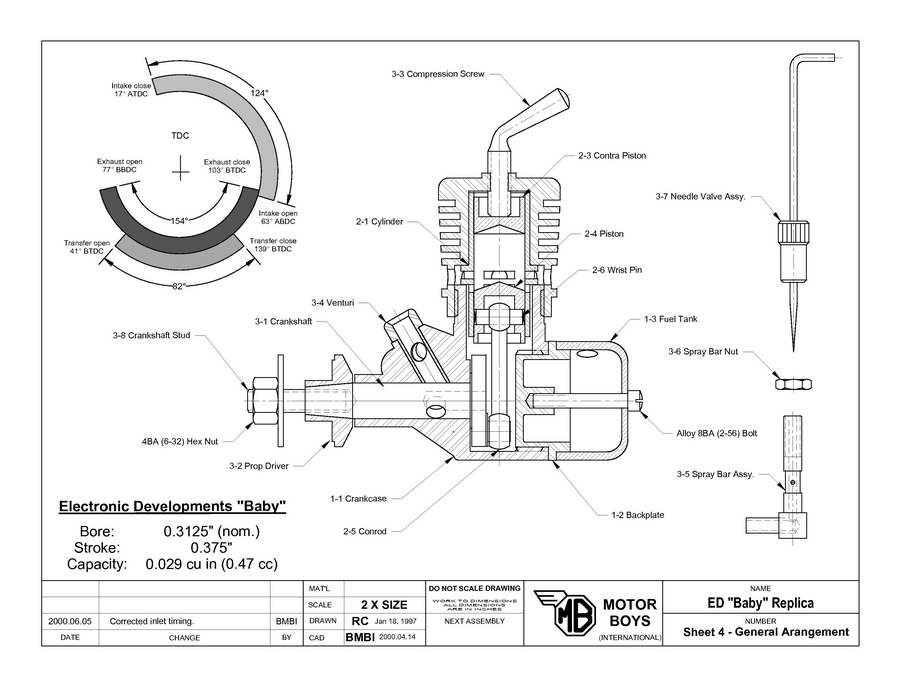

As the accompanying G/A drawing will confirm, the Motor Boys reproductions were based very closely upon the Series I version of the Baby with its slot transfer ports. The major departure was the replacement of the original’s 4BA threaded prop retaining extension with a more practical screw-in stud arrangement, better suited to amateur construction where hardening of the shaft without inducing distortion would be extremely problematic. The E.D. Baby on Test

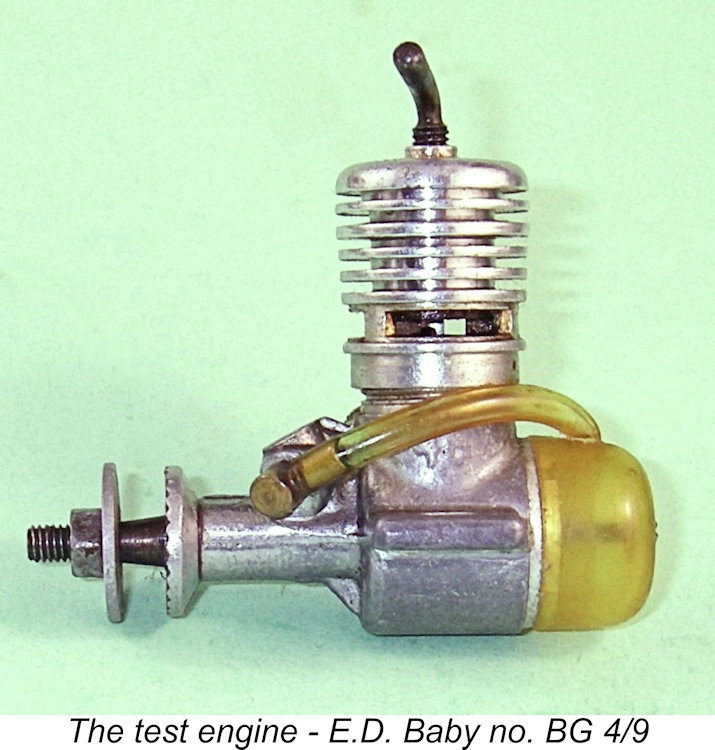

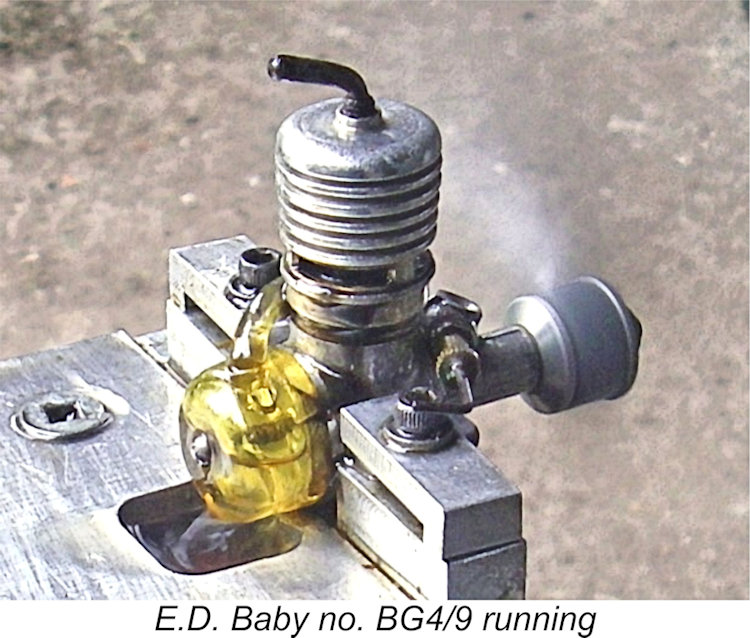

To answer this question, I dug out my Series II example no. BG4/9. Although still LNIB, this engine had been run in by me when first acquired, although I had never got around to flying it. The serial number says that it was the fourth example of the Baby made in July 1959. Before being sold, this engine spent many years languishing on the shelf as New Old Stock – I bought it new in Canada in 1966! At the time I was planning to use it in a small free flight model which somehow never got built. It’s a telling sign of different days that I bought the engine over the counter from the hobby department of the major Woodwards Department Store in Vancouver – this was a time when major department stores had hobby departments!

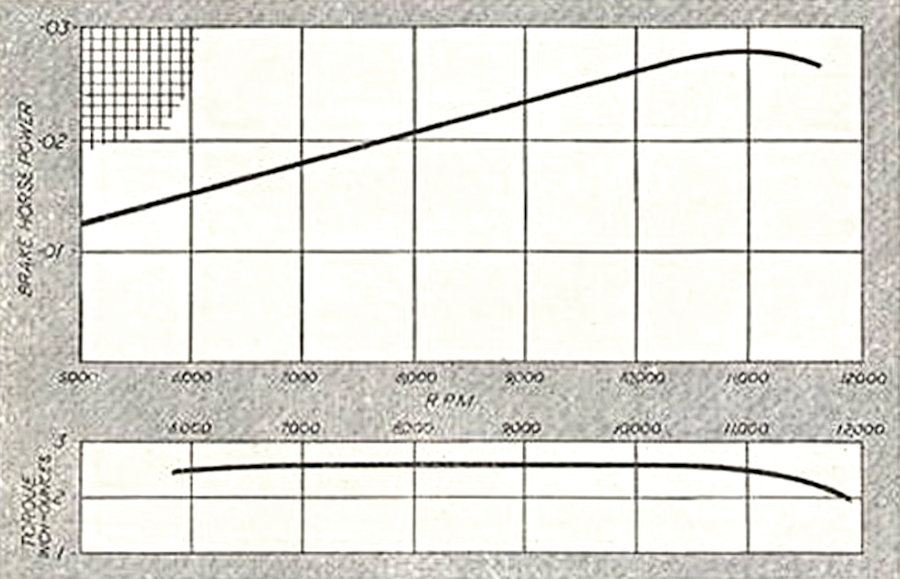

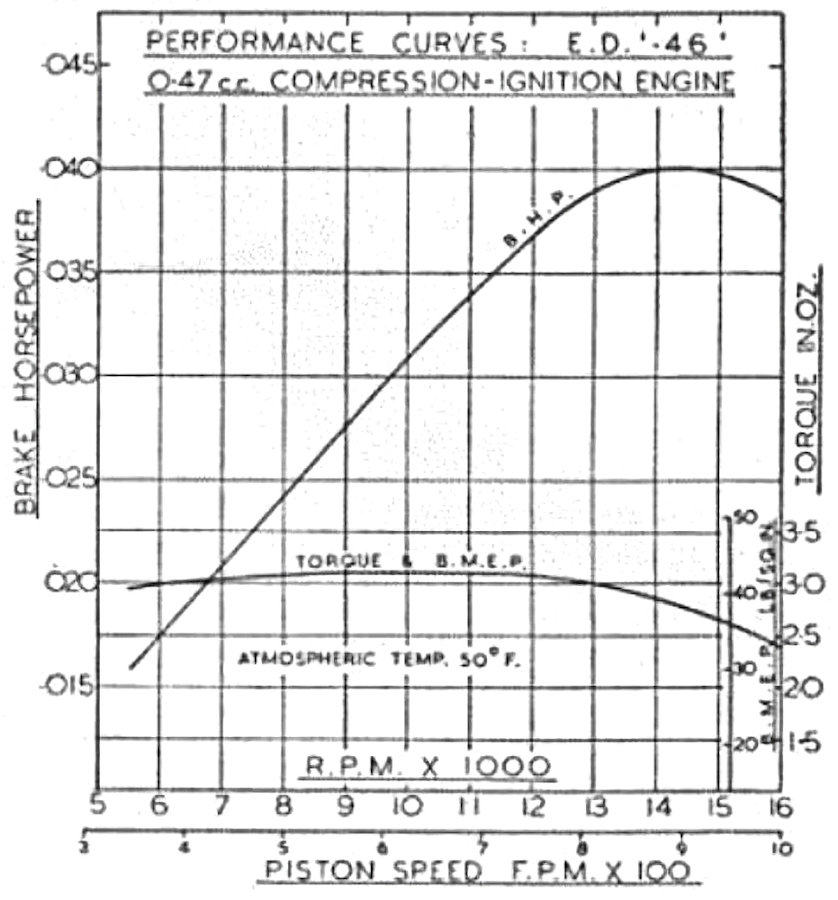

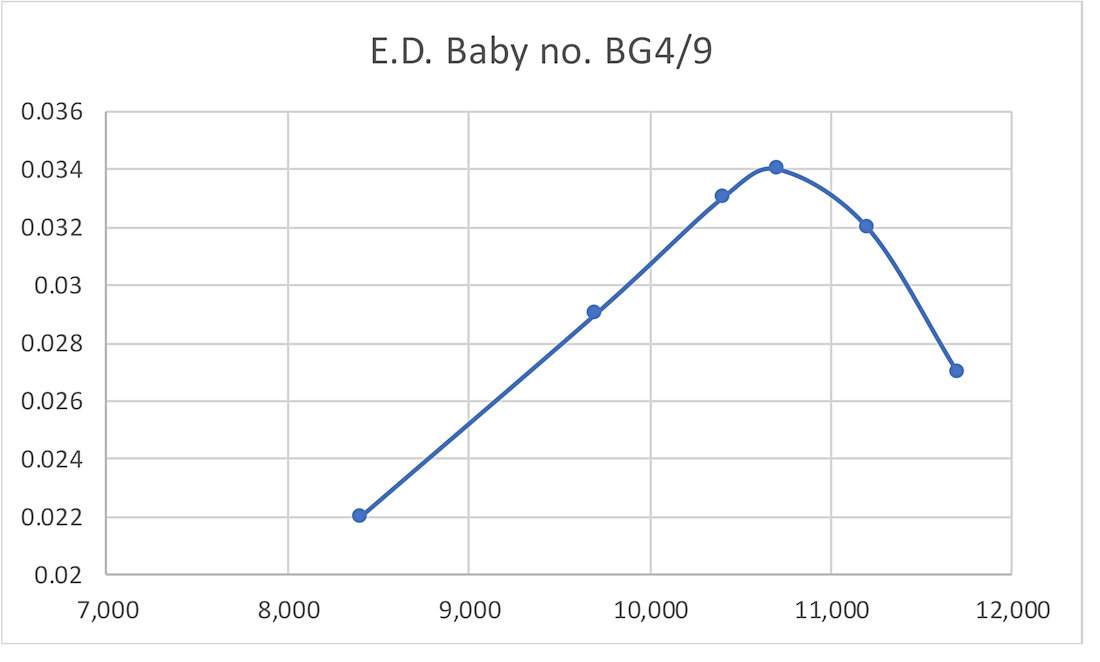

By way of compensation, the accompanying performance curves seen at the right show that Chinn achieved significantly better performance figures than Warring had done, reporting a commendable peak output of 0.040 BHP @ 14,000 RPM. Perhaps Chinn got a good ‘un – small diesels were notorious for performance variations between two examples of the same model. Finally, there was the mini-review of the Series II variant which appeared in the August 1954 issue of “Aeromodeller”. In terms of peak output, the reported findings The manufacturer's performance claim was 0.040 BHP @ 12,000 RPM. The fact that the reported outputs vary considerably while the peaking speeds are all over the shop seems to me to confirm the frequently-stated observation that differences in performance between two examples of the same engine tend to vary ever more widely with decreasing displacements. The effects of even minor departures from the optimum tolerances become magnified as displacements go down. In terms of prop selection for my own planned test, I deduced from the above figures that a peak output of around 0.030 BHP @ 12,000 RPM might be a reasonable expectation for this engine. Turning a Cox 5x3 prop at 12,000 RPM requires an output of around 0.030 BHP, implying that the Baby might well reach its peak with this prop. I therefore decided to begin with a somewhat slower Cox 6x4 and work up the speed scale from there by trying progressively lighter loads down to the Cox 5x3. I was very pleased to find that the Baby fitted perfectly into the small home-made test stand which I had created years previously to accommodate really small motors. This made testing far easier because access to the needle valve was maintained with the engine mounted in this stand. Larger stands tend to interfere with this control due to its exaggerated rearward rake. I began with a Cox 6x4 airscrew fitted. This is an unusually "slow" prop of this size, which I was sure would have the engine operating well below its peak. I would get a reading on this prop and then move down the load scale to find the peak. I used my standard small-engine test fuel of 35% kerosene, 35% ether and 30% castor oil, with 2% added cetane booster. The first issue that I encountered was the usual one with E.D. plastic tanks - a significant fuel leak! All of the plastic-tank E.D. models (the Baby, Bee and Hornet) are prone to this problem, which is ascerbated by the fact that the tanks tend to distort and crack with age. The fuel didn't exactly gush out of the tank, but it did drip pretty steadily. The leakage was sufficiently rapid that a start had to be achieved pretty The approach that I adopted was to choke the engine to fill the fuel line, administer an exhaust prime and start flicking. Once firing commenced, indicating that the engine was all ready to start, I filled the tank and then quickly resumed flicking. Since the Baby proved to be a very prompt starter using this technique, most of the fuel in the tank went to its intended use. I'd honestly rate the engine as a very easy starter provided the correct approach is adopted. It turned out that an exhaust prime was more or less essential for starting. However, even a modest prime tended to get an excess of fuel into the cylinder. As per Ron's suggestion noted earlier, it was best to back off compression, get the engine going and then "catch" it by raising the compression as the prime burned off. Using this approach, starting was invariably very prompt. Once running, the Baby showed itself to be an excellent performer, running dead smoothly without missing a beat. Response to both controls was quite progressive, making the establishment of optimum settings completely straightforward. Overall, the engine was a pleasure to test! The following data were obtained.

These figures offer no support for those reported by Peter Chinn. The indicated peak output was around 0.034 BHP @ 10,700 RPM - a similiar peaking speed to that reported by Warring in his original test, although my example appeared to develop more torque at the same speeds. My engine displayed no great desire to run at speeds beyond the high 11,000 RPM range, in contrast to both Chinn's test and Warring's later figures, which showed peak power being developed at significantly higher speeds.

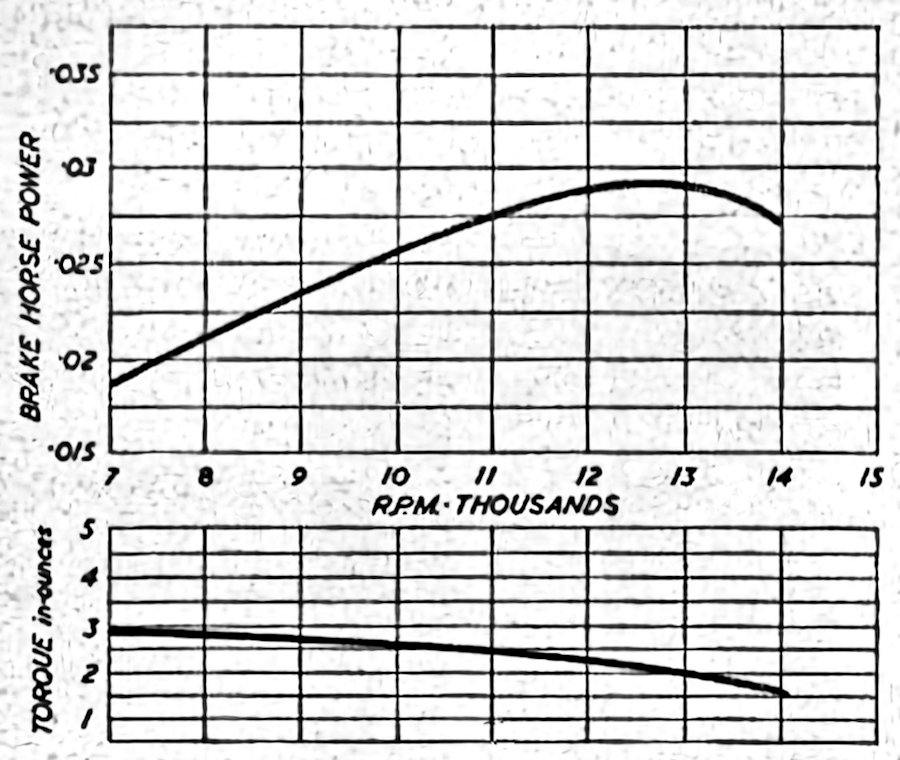

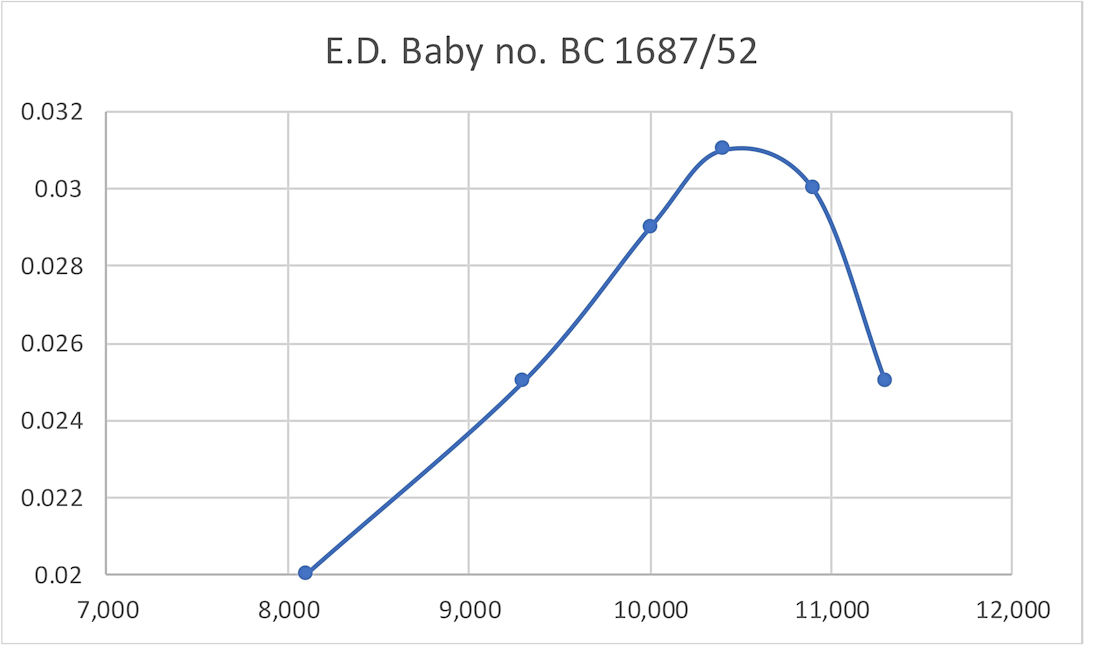

Recognizing the fact that test engine number BG4/9 was fitted with the later cylinder with internally-formed bypass/transfer channels, I was interested to see how the earlier version with the slit transfer ports would measure up. To that end, I decided to test my Series IA unit, engine number BC 1687/52. As described earlier, this example retained the sawn slit transfer ports of the Series I model but was fitted with the Series IA cooling jacket with four exhaust apertures created by joining the "port-hole" openings in pairs. This example was fitted with a high-quality aftermarket nylon tank which (wonder of wonders!) didn't leak at all! What a bonus! The engine proved to be just as good a starter and runner as its predecessor in the test stand. It performed flawlessly, responding very progressively to the controls and never missing a beat. However, it didn't quite come up to the performance of the Series II variant tested beforehand. The following data tell the story.

As can be seen, the Series IA variant was some 300 - 400 RPM down on its sibling across the range of tested airscrews. I must say that I wasn't particularly surprised at this - the restricted transfer period imposed by the slit-type transfer ports along with the absence of any exhaust/transfer overlap would lead one to expect such a result. Even so, the implied peak output of around 0.031 BHP @ 10,500 RPM isn't all that far off the performance of the later model. In a small sport free flight model, you wouldn't notice the difference! This variant of the Baby would have constituted a more than acceptable sports powerplant by 1953 standards. Conclusion

So kudos to Basil Miles, who was almost certainly the designer of the Baby. He gave modellers of the era a simple and sturdy little powerplant which would have provided its owners with hours of fun. Can't ask for more than that!! __________________________

Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published August 2024 |

||

| |

Tucked away in the depths of the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful but sadly now-frozen “

Tucked away in the depths of the late Ron Chernich’s wonderful but sadly now-frozen “ Those wishing to learn about the early years of the E.D. enterprise are referred to my broadly-focused article on the

Those wishing to learn about the early years of the E.D. enterprise are referred to my broadly-focused article on the  support their favourite maker:

support their favourite maker:  attention, at least for a time. The most notable exception was the

attention, at least for a time. The most notable exception was the

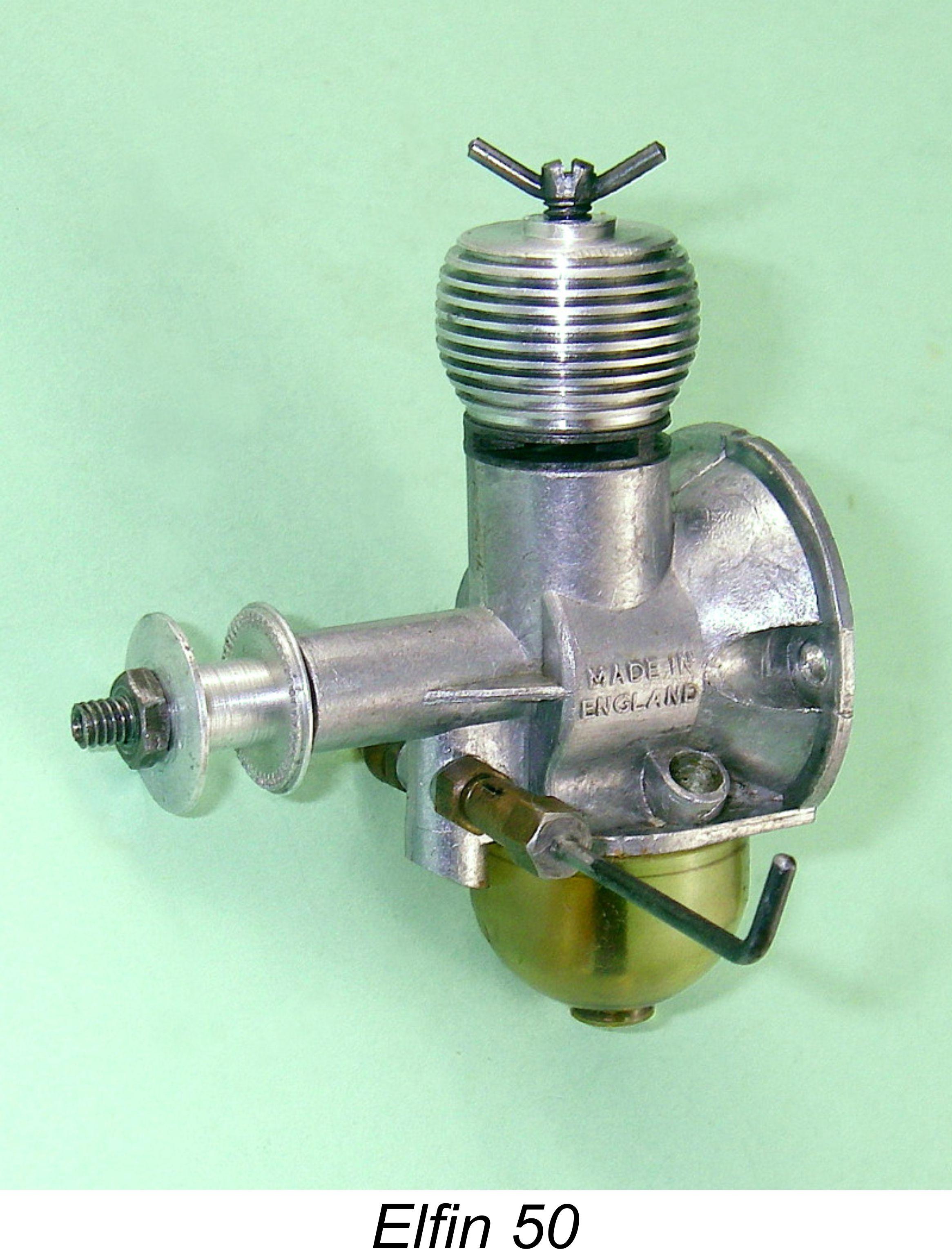

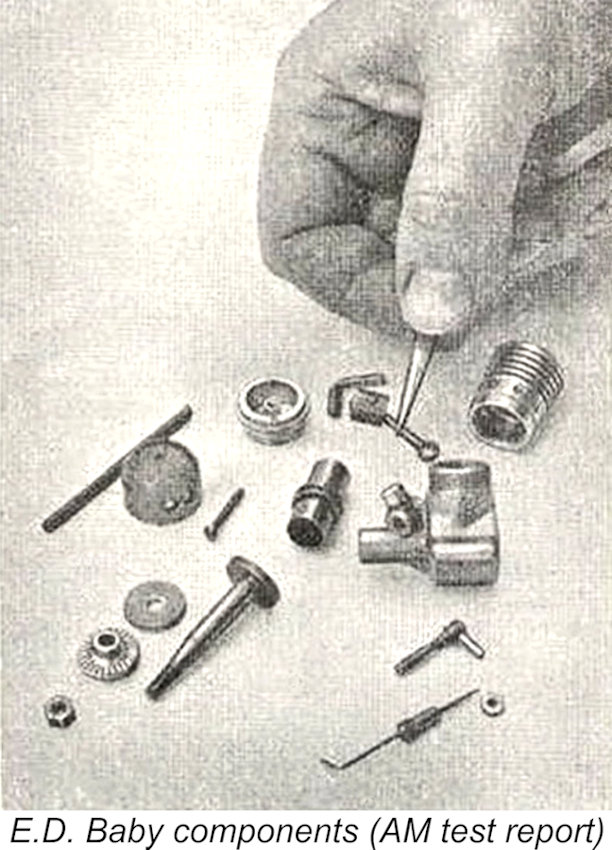

The E.D. Baby was a plain bearing front rotary valve (FRV) compression ignition engine featuring long-stroke internal geometry. Nominal bore and stroke were 0.3125 in. (7.93 mm) and 0.375 in. (9.52 mm) respectively for a stroke/bore ratio of 1.2 to 1 and a calculated nominal displacement of 0.470 cc (0.0287 cuin.). The cited displacement of 0.46 cc seems to have arisen simply because someone at E.D. liked “point four six”! The engine weighed in at a checked 1.42 ounces (40 gm) complete with tank and fuel tubing.

The E.D. Baby was a plain bearing front rotary valve (FRV) compression ignition engine featuring long-stroke internal geometry. Nominal bore and stroke were 0.3125 in. (7.93 mm) and 0.375 in. (9.52 mm) respectively for a stroke/bore ratio of 1.2 to 1 and a calculated nominal displacement of 0.470 cc (0.0287 cuin.). The cited displacement of 0.46 cc seems to have arisen simply because someone at E.D. liked “point four six”! The engine weighed in at a checked 1.42 ounces (40 gm) complete with tank and fuel tubing. thread formed on the upper crankcase. The space between the crankcase bore and the lower cylinder liner formed a 360° bypass passage feeding the three transfer ports. Exhaust gases were discharged through openings formed in the circumference of the lower cooling jacket. While the whole arrangement was gasket-less, experience shows that it worked quite well at Baby and Hornet sizes.

thread formed on the upper crankcase. The space between the crankcase bore and the lower cylinder liner formed a 360° bypass passage feeding the three transfer ports. Exhaust gases were discharged through openings formed in the circumference of the lower cooling jacket. While the whole arrangement was gasket-less, experience shows that it worked quite well at Baby and Hornet sizes. The steel conrod, gudgeon pin and cast iron piston were quite conventional, though tiny. The piston had a shallow conical crown, with the contra-piston being configured to match. The one-piece steel crankshaft ran unbushed in the die-cast aluminium crankcase. Although the full-disc crankweb was unbalanced, this causes no problems at all at this size. The crankshaft was tapered at its forward end to secure the alloy prop driver, which incorporated a boss in its center, presumably because E.D. knew that most suitable props would have a larger hole in their center than the major diameter of the small 4BA threaded protrusion of the crankshaft.

The steel conrod, gudgeon pin and cast iron piston were quite conventional, though tiny. The piston had a shallow conical crown, with the contra-piston being configured to match. The one-piece steel crankshaft ran unbushed in the die-cast aluminium crankcase. Although the full-disc crankweb was unbalanced, this causes no problems at all at this size. The crankshaft was tapered at its forward end to secure the alloy prop driver, which incorporated a boss in its center, presumably because E.D. knew that most suitable props would have a larger hole in their center than the major diameter of the small 4BA threaded protrusion of the crankshaft.

It was E.D.'s practice to stamp all their engines with a meaningful if not always completely accurate serial number. This was generally applied to the edge of a mounting lug. However, being rather on the small side, the Baby received its number in an arc on the lower front face of the crankcase.

It was E.D.'s practice to stamp all their engines with a meaningful if not always completely accurate serial number. This was generally applied to the edge of a mounting lug. However, being rather on the small side, the Baby received its number in an arc on the lower front face of the crankcase.  The accompanying table shows the serial numbers which Kevin and I are able to confirm between us. Although no definitive conclusions can be drawn legitimately from a 15-number sample, some general observations are very much in order. First, it's abundantly clear that production of the Baby was heavily skewed towards the first year of production. The size of the introductory batch is particularly noteworthy - at least 1687 examples were manufactured in March 1952 alone. Even in July of that same year, monthly production still exceeded 612 examples. These figures doubtless reflect the "½ cc craze" period to which reference was made earlier. We might conclude that as many as 9,000 examples may have been made during that first year.

The accompanying table shows the serial numbers which Kevin and I are able to confirm between us. Although no definitive conclusions can be drawn legitimately from a 15-number sample, some general observations are very much in order. First, it's abundantly clear that production of the Baby was heavily skewed towards the first year of production. The size of the introductory batch is particularly noteworthy - at least 1687 examples were manufactured in March 1952 alone. Even in July of that same year, monthly production still exceeded 612 examples. These figures doubtless reflect the "½ cc craze" period to which reference was made earlier. We might conclude that as many as 9,000 examples may have been made during that first year.  Even though no official distinction exists and the changes are subtle, they are sufficiently significant that some means of identifying the distinct variants will be very convenient. For that reason, we'll maintain these designations for the purposes of this article, on the clear understanding that they do not represent any manufacturer’s designations. They are ours and ours alone.

Even though no official distinction exists and the changes are subtle, they are sufficiently significant that some means of identifying the distinct variants will be very convenient. For that reason, we'll maintain these designations for the purposes of this article, on the clear understanding that they do not represent any manufacturer’s designations. They are ours and ours alone.  introductory advertisement depicts a conventional "tommy-bar" style compression screw, while the engine lacks a venturi insert. Actual production models appear to have been fitted more or less from the outset with a single-arm comp screw.

introductory advertisement depicts a conventional "tommy-bar" style compression screw, while the engine lacks a venturi insert. Actual production models appear to have been fitted more or less from the outset with a single-arm comp screw.

E.D. evidently agreed with this assessment, because this sub-variant didn’t last long, never being featured either in E.D.’s advertising or in media commentary at any time. It is probably the rarest version of the E.D. Baby today.

E.D. evidently agreed with this assessment, because this sub-variant didn’t last long, never being featured either in E.D.’s advertising or in media commentary at any time. It is probably the rarest version of the E.D. Baby today. Externally, the Series I “port-hole” exhausts had been replaced in the Series II variant with a more practical arrangement consisting of three sawn radial slits. Apart from reducing the number of operations required to produce the cooling jacket, the change in the exhaust arrangements made port priming considerably easier as it greatly reduced the problem of flooding during port priming. The advertising photo also clearly showed the addition of a venturi insert that extended the inlet and permitted a more efficient conical opening, along with the single-arm comp screw reflecting that actually fitted to production engines.

Externally, the Series I “port-hole” exhausts had been replaced in the Series II variant with a more practical arrangement consisting of three sawn radial slits. Apart from reducing the number of operations required to produce the cooling jacket, the change in the exhaust arrangements made port priming considerably easier as it greatly reduced the problem of flooding during port priming. The advertising photo also clearly showed the addition of a venturi insert that extended the inlet and permitted a more efficient conical opening, along with the single-arm comp screw reflecting that actually fitted to production engines. The initial examples of the E.D Baby Series II evidently continued to feature the slit transfer ports which had been used in the Mk. I models. Kevin Richards' engine number BB 45/53 from February 1953 is of this type, using the new cooling jacket along with the old-style cylinder and conical piston crown. It is New-in-Box, thus having impeccable provenance. This continued use of the old Mk. I cylinder for a period of time was probably a move by E.D. to use up existing parts inventory, something which they frequently did when introducing revised designs.

The initial examples of the E.D Baby Series II evidently continued to feature the slit transfer ports which had been used in the Mk. I models. Kevin Richards' engine number BB 45/53 from February 1953 is of this type, using the new cooling jacket along with the old-style cylinder and conical piston crown. It is New-in-Box, thus having impeccable provenance. This continued use of the old Mk. I cylinder for a period of time was probably a move by E.D. to use up existing parts inventory, something which they frequently did when introducing revised designs.

The Baby can either be a delight to operate or a right little piggy of a thing! The difference is in the fuel, the engine management approach and how well run-in (or run-out!) the particular example happens to be. Like all small diesels, it is happiest with a fuel having a higher ether content, say 40%, although easy starting and good performance are perfectly possible with a straight 1:1:1 mix aided and abetted by operator experience.

The Baby can either be a delight to operate or a right little piggy of a thing! The difference is in the fuel, the engine management approach and how well run-in (or run-out!) the particular example happens to be. Like all small diesels, it is happiest with a fuel having a higher ether content, say 40%, although easy starting and good performance are perfectly possible with a straight 1:1:1 mix aided and abetted by operator experience.

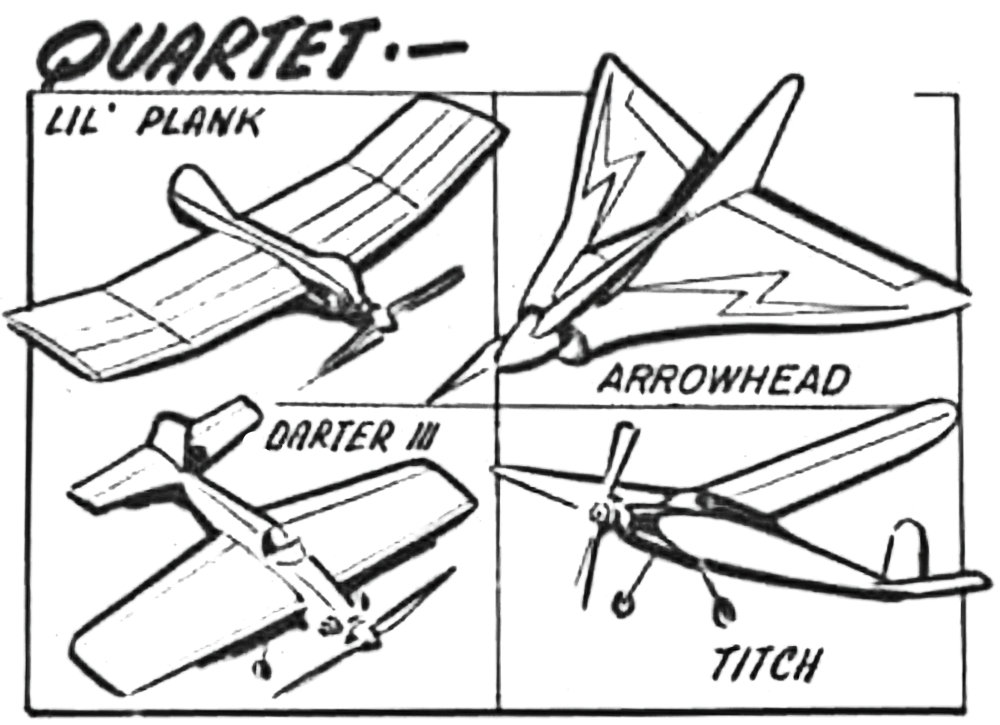

cabin designs, not to mention flying wings, deltas, and even the odd flying saucer! A noteworthy set of four plans was offered in late 1952 by the Aeromodeller Plans Service under the collective title “

cabin designs, not to mention flying wings, deltas, and even the odd flying saucer! A noteworthy set of four plans was offered in late 1952 by the Aeromodeller Plans Service under the collective title “

Beginning in the year 2000, Ron Chernich and his fellow members of

Beginning in the year 2000, Ron Chernich and his fellow members of

Next up was Peter Chinn, whose

Next up was Peter Chinn, whose

Still, this is actually quite a useful sports performance for a 0.47 cc diesel of the 1950's. On a specific output basis (BHP per cc), it clearly out-performed all of the British 0.8 cc glow-plug motors which constituted the next British small-engine craze beginning in 1959. Coupled with the little engine's fine handling and seemingly sturdy construction, I'd rate it as an excellent choice for modellers "back then" who were looking for a positive small-diesel experience in a sport-flying context. A "fast" 6x4 prop would appear to suit the Baby perfectly.

Still, this is actually quite a useful sports performance for a 0.47 cc diesel of the 1950's. On a specific output basis (BHP per cc), it clearly out-performed all of the British 0.8 cc glow-plug motors which constituted the next British small-engine craze beginning in 1959. Coupled with the little engine's fine handling and seemingly sturdy construction, I'd rate it as an excellent choice for modellers "back then" who were looking for a positive small-diesel experience in a sport-flying context. A "fast" 6x4 prop would appear to suit the Baby perfectly.

Any review of a classic model engine must necessarily assess its qualities in the context of the time and place into which it was introduced. Viewed from a 1952 standpoint, the E.D. Baby must be seen as a successful venture into the ½ cc diesel sweepstakes on the part of E.D. The Allbon Dart clearly had a performance edge, as did the FROG 50, but who in 1952 was looking at ½ cc diesels as competition powerplants? What buyers of such engines were looking for was a dependable small-displacement powerplant that would start easily, perform well over the long haul and get a small model aloft with a high level of consistency. The E.D. Baby would have fulfilled such requirements perfectly.

Any review of a classic model engine must necessarily assess its qualities in the context of the time and place into which it was introduced. Viewed from a 1952 standpoint, the E.D. Baby must be seen as a successful venture into the ½ cc diesel sweepstakes on the part of E.D. The Allbon Dart clearly had a performance edge, as did the FROG 50, but who in 1952 was looking at ½ cc diesels as competition powerplants? What buyers of such engines were looking for was a dependable small-displacement powerplant that would start easily, perform well over the long haul and get a small model aloft with a high level of consistency. The E.D. Baby would have fulfilled such requirements perfectly.