|

|

The Second Generation OK Cubs By Maris Dislers

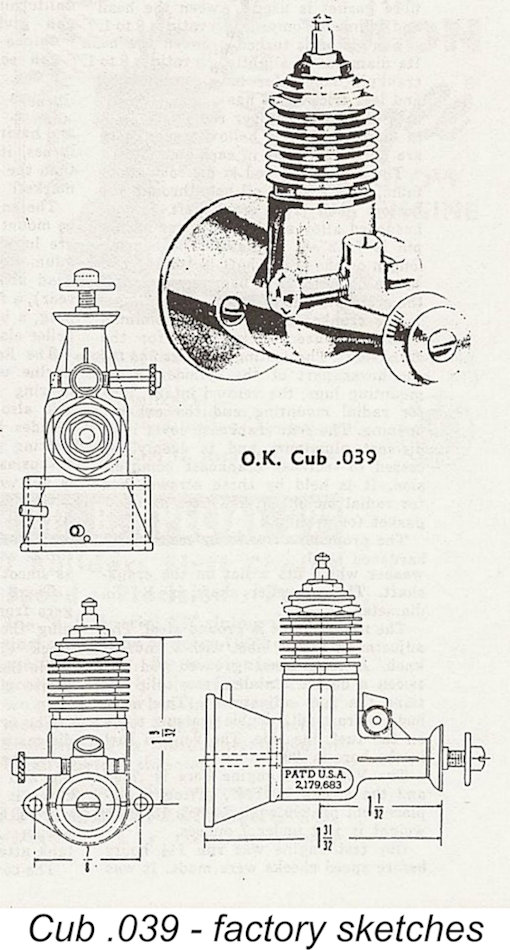

In this article, I’ll carry the story forward from that point up until the appearance of the very last OK Cub models. I’ll begin with the OK Cub .039 model of 1950. A New Model - the OK Cub .039

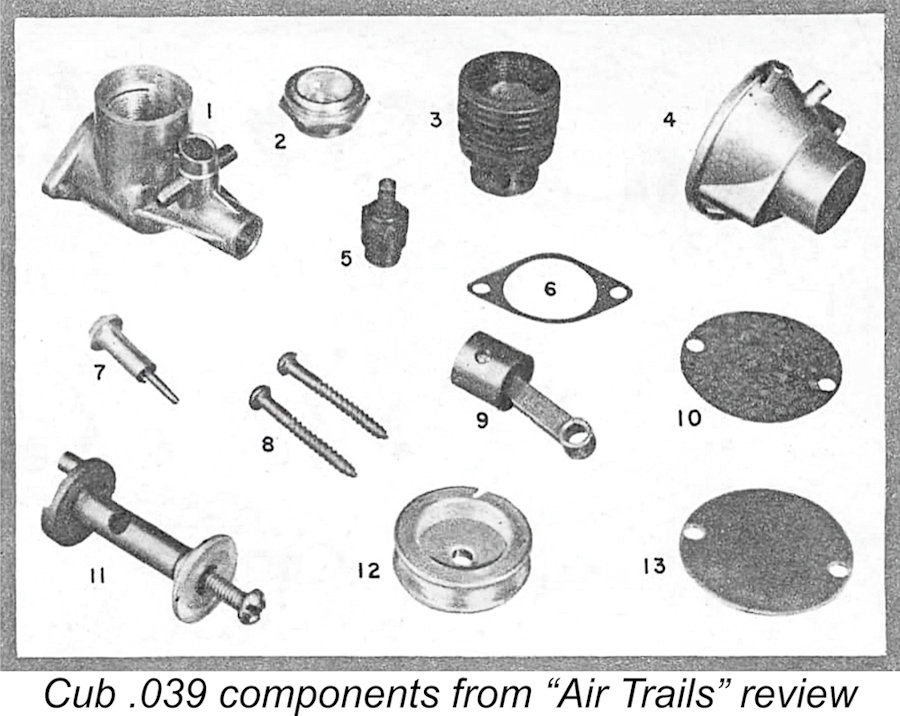

The new Cub .039 represented a notable step forward in design terms. Refer to my previous article describing the early OK Cubs for general design details. The numbers specific to the .039 were as follows: Bore and stroke were 0.390 in. (9.91 mm) and 0.334 in. (8.84 mm) for an over-square bore/stroke ratio of 1.17: 1 and a swept volume of .0399 cu. in. (0.65 cc). Weight with tank was 1.54 oz. (44 gm). The engine was priced at $4.95, a little less than the .049. These engines came complete with glow plug, propeller and a lightweight pulley (retained by the propeller mounting screw) for easy pull-cord starting. The .039’s tank had a brass pipe drawing fuel from the lower-right side (“pilot’s view”), best suited for a control line model. However, suitable free flight kits were also available on the market and while it would then not completely drain the tank, the inlet position accommodated both upright and sidewinder cylinder orientations. The OK Cub .039 on testAs usual, the “Flying Models” review quoted test RPM figures from six different propeller sizes and brands, making an objective assessment difficult. The reported figures included 11,900 RPM with the supplied Kaysun 5.5 x 4 propeller (roughly implying an output of 0.038 BHP at that speed - Ed.). The ”Air Trails” review was scant on test results (again as usual) but pointed out the folly of judging this engine by maximum achievable RPM when its true value lay in the 11,000 – 12,000 RPM range.

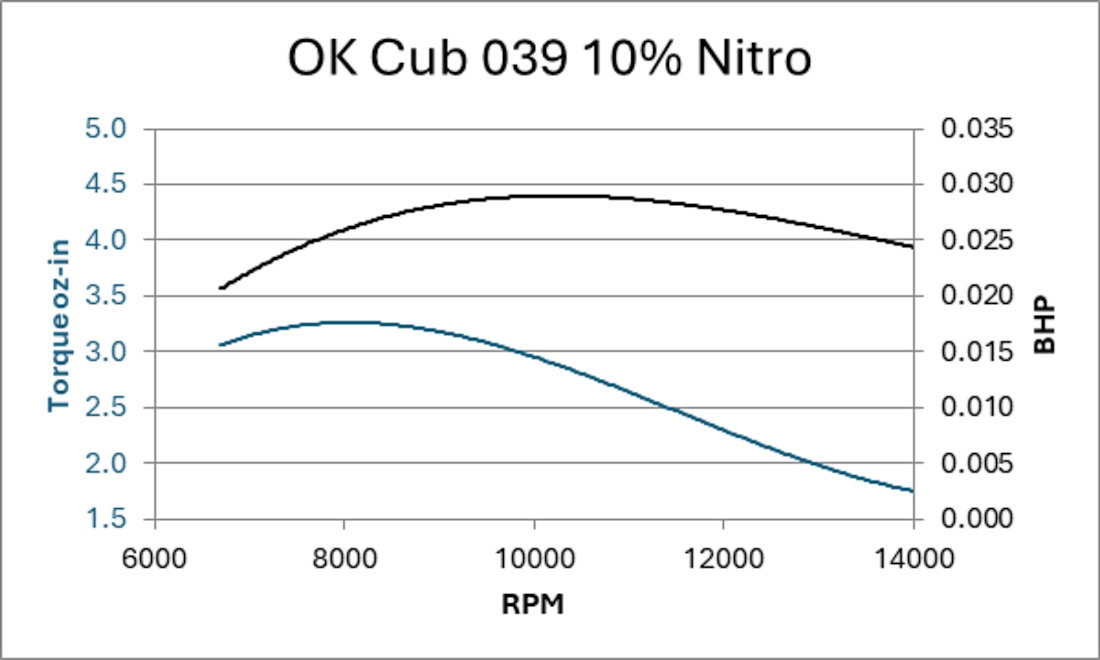

This is clearly an easy-going engine aimed at novices. The cord and pulley method produced instant starts when primed correctly. Four drops into the venturi and a drop in the exhaust proved adequate for our engine. Hand starting was also good, with no knocking tendency. That said, it’s easy for an old hand to forget the perils of learning that technique by a raw novice! Needle response was not unduly sensitive and running was reasonably steady across a wide range of near-peak settings. The short thimble is very close to both the exhaust and propeller, making adjustments uncomfortable and somewhat risky for the novice. Tweaking for absolute top RPM can be a little tricky, as the needle meters fuel at the outlet jets and any sideways load can have a noticeable effect. Our approach was to let go of the needle between adjustments to assess the effect. The following data were recorded on test.

Our results showed torque peaking at 8,000 RPM before declining relatively rapidly as RPM went up, such that power output reached a maximum of just under 0.03 BHP around 10,000 RPM with a relatively flat peak trend. A still quite reasonable .025 BHP was available around 14,000 RPM, but the engine ran out of puff The OK Cub .039 was last advertised in December 1953. The engine thus had a relatively short production run, explaining why examples are relatively scarce nowadays. The identity of the Cub .039 can easily be confirmed by measuring the cylinder O/D of .675 in. (17.15 mm). Its nearest rival, K&B’s Torpedo Jr. .035, also had a short production life from late 1949 to April 1952. Perhaps both models weren’t sufficiently distinct from their more popular .049 siblings. Folk familiar with Bert Striegler’s iconic “Ebenezer” sport FF model should note that the two examples shown in the “Aeromodeller” construction article show OK Cub .049 and Torp. Jr. .035 engines respectively. These motors represent ideal power for this model, as is a half-cc diesel running easy or a Cox Pee Wee .020. The Second-Generation OK Cub .049s

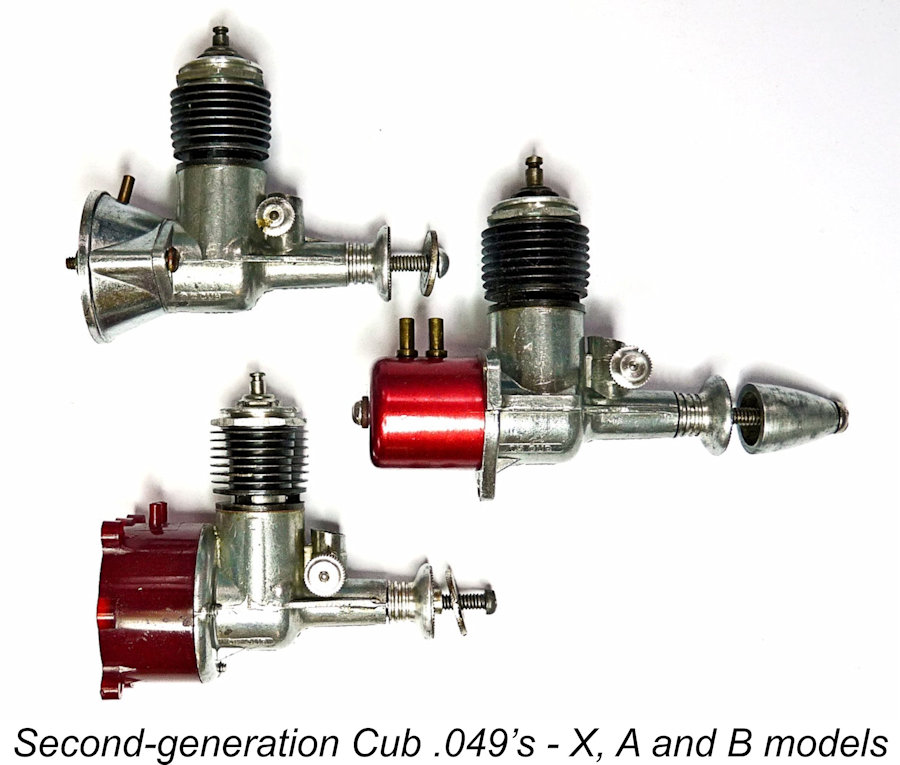

The OK Cub .049X and companion OK Cub .14 reached the model shops for the Christmas 1952 season. The .14 was a new size, perhaps intended to be the first American engine in line with the FAI’s proposed displacement standard for international free flight and control line competitions, but possibly also intended to fill a gap in the range distinct from the crowd of engines around the AMA’s .200 cuin. Class A threshold. A Cub .199 version of this engine was subsequently added to the range. The .049X was billed as a high-performance engine for experienced users. It was presented as a companion to the established Cub .049. It carried over the 039’s crankcase and tank design. In fact, the tank and the alternative short new tank-less rear cover were interchangeable between the two models. The same 1.17:1 over-square bore/stroke ratio and other design features was also caried over from the smaller engine.

In summary, the .049X represented an extensive redesign of the original theme, with a view to lower weight, higher power and higher operating speed. It was in production for less than two years. Ready-To-Fly (RTF) control line model airplanes were becoming big business by this time, and substantial numbers of the original .049 and .049X Cubs went into A-J Firebaby models. The .049B Cub powered Comet’s first RTF model, the Sabre 44 of 1954, and OK Cubs became the regular

A new die was now created with a full-circle rear mounting flange and two-screw attachment to the firewall. This version was perhaps only sold with the A-J Firebaby RTF model. This model retained a screw-in backplate like the .049B. The advantage of the new mounting was that slightly loose mounting screws would not cause a crankcase compression leak and poor running.

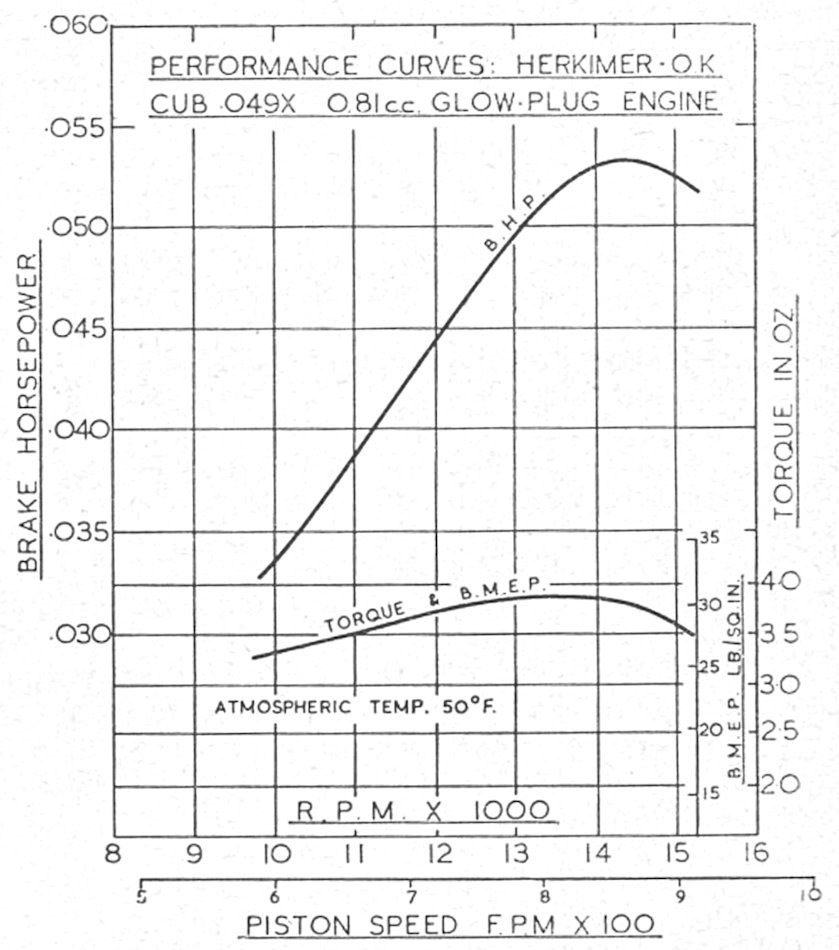

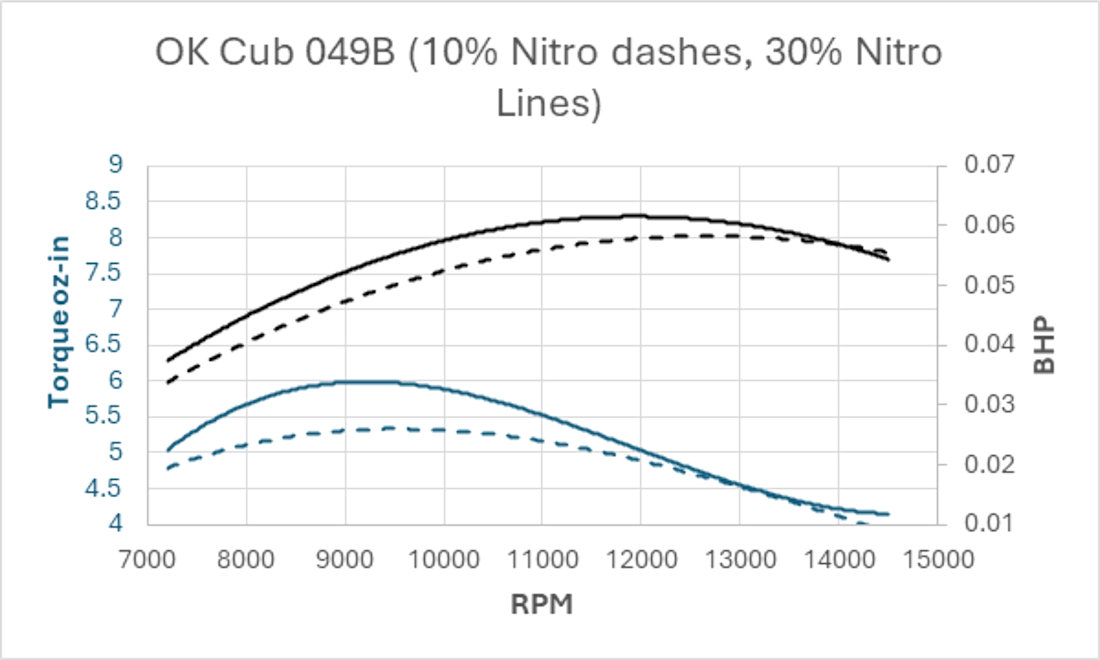

Aimed specifically at control line flyers, this model boasted a large fuel capacity and sold for $4.95. It was widely used in Comet RTF models. Remaining stocks of the .049X were perhaps becoming harder to sell at $5.75. From mid-1958 onwards, the Cub .049A was sold in a cardboard and plastic “bubble pack” at the reduced price of $3.95, including propeller. The owner only had to install the fuel tank and fuel line. It's worth mentioning in passing that in the latter part of 1955 the old Hothead 29 glow-plug model from 1948 was finally replaced by a pair of more up-to-date OK Cub units having displacements of .29 and .35 cuin. These were the largest OK Cub models ever to appear. They generally followed the design layout established by the Cub .049B model. Although generally under-rated, they were surprisingly good (if noisy!) runners which remained on Herkimer's books until 1960. A video of a Cub .29 running may be found here. More of these models from Adrian elsewhere in due course. OK Cub .049 Tests“Flying Models”, “Air Trails” and “Model Airplane News” magazines all carried reviews of the various Cub .049’s as they reached the market. Many of these tests may be accessed on the very informative Sceptre Flight website. Inevitably, much information was repeated from one model to the next. However, reviewers Typical American testing practice reported RPM values from a range of propellers, stopping short of presenting performance curves. Some reviewers sought out the highest achievable RPM from the Cub, in keeping with popular fashion. The engines could reach over 17,000 RPM with light loads......... but then, so what?!? Engine review No. 51 in “Model Aircraft” covering the OK Cub .049X did provide the performance curves seen at the right, demonstrating this engine’s key characteristics more clearly. The torque curve built towards its maximum at 13,500 RPM - only 1000 RPM before peak power was reached at 14,500 RPM. This is noteworthy, as the optimum working range was therefore very narrow. Reviewers pointed out that the older long-stroke model was better suited for use with larger propellers. Peak power of the new model was found to be .053 BHP versus .043 BHP from the original Cub .049. Our .049B ran well on a fuel containing 10% nitromethane. It did show some misfiring at 14,500 RPM that could not be eliminated even with careful mixture adjustment.The following data were recorded.

As our trends show, it was scarcely worth seeking more when peak power speeds had already been exceeded. Our example delivered .058 BHP in the 12,000 to 13,000 RPM region. The use of a 30% nitro fuel boosted low end performance quite well, but the gain ebbed with lighter loads, as zeroing in on a clean run became more difficult. Nevertheless, peak power then topped the .06 BHP line. This squares up well enough against the published .049X results. The contemporary OK Cub .049A would of course perform at around the same level since the two engines were functionally identical. The 1960 A & B Cubs

Oddly enough, this change was not heralded in Herkimer’s adverts. We found only one possible reference in the January 1961 issue of “Model Airplane News” (MAN), which appeared on the stands in mid-December 1960, just in time for Christmas. A small bit of text (no illustration) states: “All-new OK Cub 049A. Completely redesigned for greater power-smoother operation. Only $3.95”. Somewhat confusingly, this might have referred to the reed valve engine.

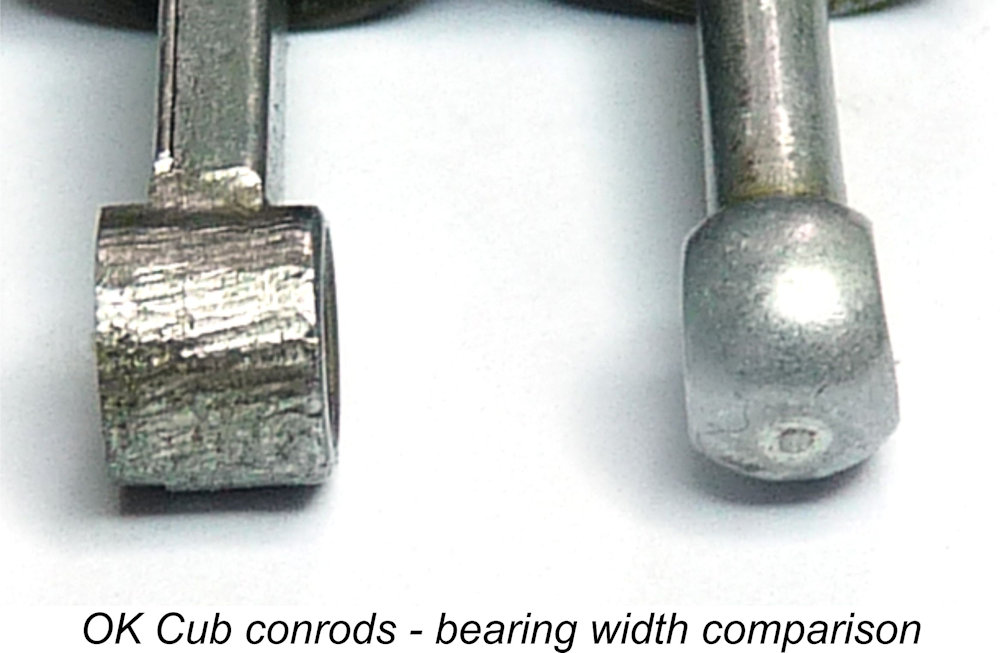

It only became clear later that the cast conrod has a wider big end bearing. The narrower, later conrod fits the older crankpin, but that pin lacks the expanded-diameter boss at its base as on later crankshafts. This created the problem that our conrod could wander too far forward when running, causing gouging of the shank by the protruding crankshaft counterbalance. Not good, but not fatal either. Ours is now sorted with a machined spacer ring on the crankpin. The 1960 049B on Test

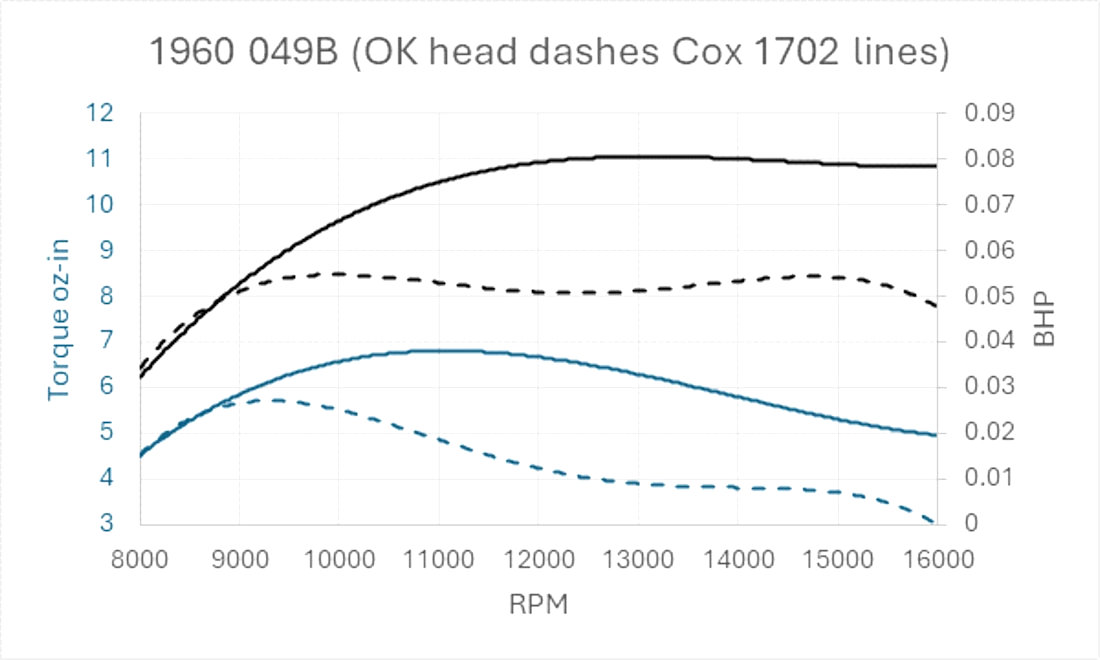

The reason for this is easily seen with the glow head removed, even allowing for the conical piston crown. At top dead centre the piston crown stops appreciably short of approaching the glow heat seat. The best that could be said is that the glow head extended the useable running range along the RPM scale, but provided no power gain over the regular glow plug version. Bumping up nitro in the fuel would help, although this approach was not consistent with the formulation of Herkimer’s OK branded fuel. There was no easy way to correct the obvious cylinder design fault. However, a fix was available - a higher compression head. After we substituted a high compression Cox 1702 “TD” glow head, this updated Cub ran superbly in subsequent tests. The following data tell the story.

In summary, the OK CUB 049X, .049A and .049B engines offered good value, had a long life and were well suited to use by a novice. As noted earlier, the Atwood Wasp and then the Cox Thermal Hopper were more powerful, dominating ½A competition flying during this era. The “common knowledge” that the OK Cub 049 is low on power might have arisen from running those engines with a typical ½A propeller. In summary, an apparent cylinder design error negated the potential performance gain resulting from switching to a glow head with integral filament. Our final tests of a 1960 .049B with higher compression head demonstrate that this later model had the potential to be a darn good ½A engine. OK Cubs for today’s userThe OK Cub .049’s make a nice change from the ubiquitous Cox .049 models. Since they represented the bulk of Herkimer’s 1 million-plus engine output, they aren’t rare by any means. Here are my tips for getting the best from your OK Cub .049X, .049A or .049B:

Guy Eaves had his OK Cub .049B turning a Cox 5x3 prop at a little over 16,000 RPM (.084 BHP by my reckoning). Details of his rework may be found in “Model Engine World”, October 1995 and November 1995 issues. Briefly, steps include polishing the crankshaft journal, selecting preferred variants of individual parts (e.g. dual bypass channels in crankcase, lighter piston, widest exhaust slots), deburring, radiusing the lower edges of transfer ports and smoothing surfaces to improve gas flow. Eliminating air leaks and perhaps replacing the NVA with Cox brass assembly also helps. Postscript and subsequent Cub enginesThe OK Cub .024, .049A and B, .074 and .099 engines soldiered on to the very end. The following quote is taken from Tim Dannells’ “American Model Engine Encyclopedia” (sic), Vol 2. “The last ad for Herkimer Tool and Model Works appeared in the June/July 1964 Flying Models and addressed only the .024 Cub and a variety of their powered cars. NOTE: The Herkimer Tool and Model Works continued building engines at a much-reduced scale until 1969. Then until 1975 manufacturing ceased and business was only repairs and selling remaining engines and parts from stock. When Comet shut its doors in the early 60’s, a huge inventory of OK .059’s (Comet 06’s) and 049A’s from the Comet Regulus ended up back in Herkimer’s hands. Ted Brebeck and his father Charles L Brebeck (not jr.) opened Mohawk Engineering Co. mainly to sell off this huge supply of .059s, popular in Europe as they were basically 1 cc displacement. (Do any of our European readers recall imported them at that time MD?) Mohawk was operated from 1964 until 1966, then all stock was transferred back to Herkimer Tool and Model Works. In 1975 the Herkimer Tool and Model Works became OK Engine Company (the “Tool” works having been sold). Basically, no new engines were produced after 1969 unless noted. Engines were assembled from parts stock or with a very few small items manufactured.” A slightly different history comes from the Herkimer Tool and Machining Corp. website (downloaded in 2018 while it was still “live”) “… After the war Herkimer returned to subcontract machining and production of the model airplane engines ended for a while in 1965. In 1960 the plant relocated across town to the current address. The sub-contract machining business was growing and the factory expanded three times since then. In 1973 Ellis Green purchased the business and changed the name to Herkimer Tool and Machining Corp. and reinstated production of the HO 1/87th Scale model railroad cars under the “OK” trade name. Herkimer produced these fine quality model railroad passenger cars until the division was sold in 1997 back to the grandson of the founder who also resumed production of some of the gas engines…” It seems that the model engine division was sold to Ted Brebeck, trading as the OK Engine Company in 1975, but he did not buy the model railroad side until 1997. Quoting AMEE Vol. 2 again: “Between 1975 and 1997 OK Engine Co. sold rebuilt .049A & B engines at the rate of around 500 per year. 1997 to 1999 a short run of 500 new .049A and .049B engines were assembled from parts.” These engines were distributed quite widely by Neville Palmer, packed in a polythene bag and light cardboard backing with spare glow plug, decals and 5-inch red Kaysun propeller. They were bargain-priced. Dick Roberts tested one of each for “Aeromodeller” May 1998 and “Model Engine World” Aug 1998. The results were not flattering, but I suspect that Dick’s choice of test propellers had them overrevving, missing the sweet spot. Certainly, the supplied red Kaysun propeller (meant for the OK Cub 024) was unsuitable. The following small batches of OK engines are known to have been released periodically by OK Engine Co. 1998 25th Anniversary Mohawk-Cub. At its core, an .049B, but featured a blue-anodized tank and prop driver. 1998 OK Cub 049C. At its core an 049B, with a nylon 049A fuel tank mounted on rear via an aluminium adapter plate. 1998 OK Cub 047Fcd. An 049C, but with a beryllium-copper fixed compression head, blind drilled/threaded for a glow plug. This was intended to pre-heat the engine so that it would start (and continue to run) using model diesel engine fuel. Fcd heads for retrofitting Cub .024 .049 .074 and .099 were also made. These were perhaps inspired by the Furco Gadget using the same old-school “hot bulb” principle. 1999 Mohawk CO2, used an .024 crankshaft in a new crankcase machined from hexagonal bar stock. New cylinder made to suit had fewer fins Circa 2010 reed valve engines (now designated 049R and 06R). These used new heads with regular ¼-32 glow plug in place of the glow head. The .049R had a lug-less crankcase, while the .06R featured lugs. 2012 OK Cub 049BR Styled on the prototype 1960 049R racing engine but built on regular 049B crankcase with front intake milled off (leaving unused intake opening exposed). Featured a new rear cover/reed valve and intake tube. The head was the same as that used on the .049R and .06R. 2014 OK Cub .025 - Cub 024 with needle/seat from larger reed-valve Cub. The head accommodated a regular glow plug. ________________________ Article © Maris Dislers, Glandore, S. Australia First published March 2024

|

||

| |

In a

In a  Herkimer’s line-up for 1950 ranged from its CO

Herkimer’s line-up for 1950 ranged from its CO To digress briefly, the Wasp exemplified Bob Holland’s quest for minimal weight and maximum power. Easily exceeding its earlier competitors in terms of power to weight ratio, it also set the trend towards high-speed performance by achieving its maximum power output at a racy 15,000 RPM. Flyers attracted to the new AMA ½A free flight duration class would be drawn straight to a shop selling Wasps, and models thus powered took all the top ½A trophies at the 1952 AMA Nationals.

To digress briefly, the Wasp exemplified Bob Holland’s quest for minimal weight and maximum power. Easily exceeding its earlier competitors in terms of power to weight ratio, it also set the trend towards high-speed performance by achieving its maximum power output at a racy 15,000 RPM. Flyers attracted to the new AMA ½A free flight duration class would be drawn straight to a shop selling Wasps, and models thus powered took all the top ½A trophies at the 1952 AMA Nationals.

soon after. Fuel with 30% nitro would certainly push peak power, since it added 400-500 RPM on a given prop, but the engine seemed less happy with it. Maybe adding a few head shims would help if a small gain is desired. We’d say that the “Air Trails” reviewer’s advice to operate the engine at moderate speeds was well founded, with one proviso. The venturi choke area of 4.4 mm

soon after. Fuel with 30% nitro would certainly push peak power, since it added 400-500 RPM on a given prop, but the engine seemed less happy with it. Maybe adding a few head shims would help if a small gain is desired. We’d say that the “Air Trails” reviewer’s advice to operate the engine at moderate speeds was well founded, with one proviso. The venturi choke area of 4.4 mm Beginning in late 1952, after seeing the original Cub line-up become well established, Herkimer progressively introduced three new .049 engines based on shared working components but with different crankcase configurations. We’ll look at performance after going through the timeline and individual details.

Beginning in late 1952, after seeing the original Cub line-up become well established, Herkimer progressively introduced three new .049 engines based on shared working components but with different crankcase configurations. We’ll look at performance after going through the timeline and individual details. One new feature was the .049X’s squared-off crankshaft intake port. The casting for the crankcase intake throat was cored to provide an approximately rectangular register opening and a larger effective choke area than the original .049. The crankshaft rotary valve opened at 30 degrees ABDC and closed at 35 degrees ATDC for a total 185 degree induction period, much more generous than the original design’s 135 degrees. Exhaust and transfer openings of 130 degrees and 110 degrees respectively were a little milder than before. However, the shorter stroke reduced the piston velocity, so that the time those ports were open was relatively longer. Weight was 1.4 oz. (40 gm) with tank.

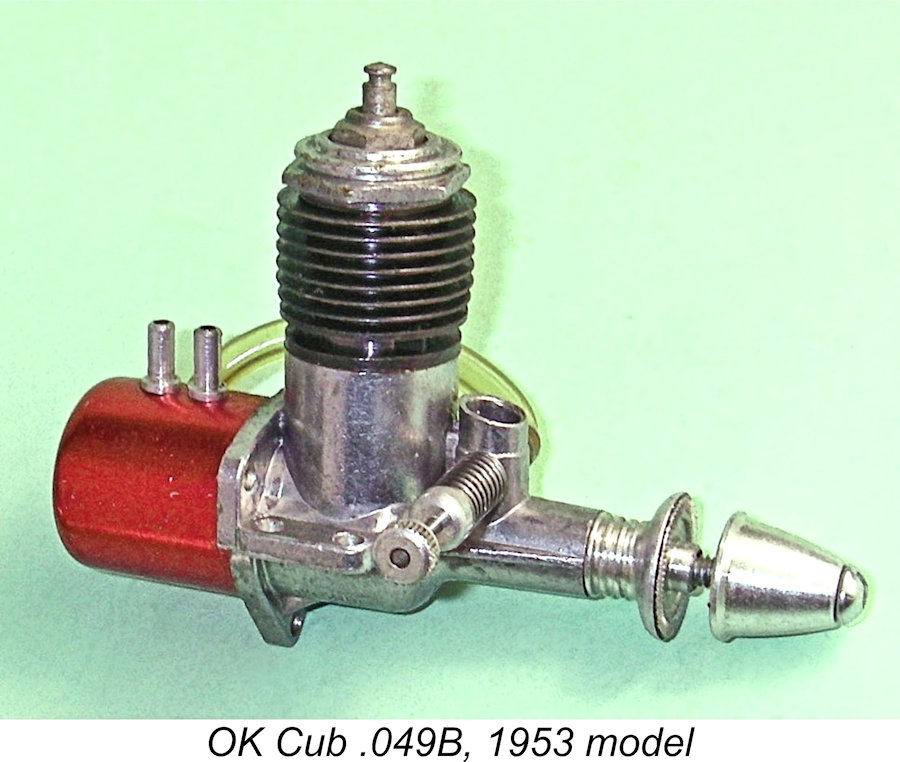

One new feature was the .049X’s squared-off crankshaft intake port. The casting for the crankcase intake throat was cored to provide an approximately rectangular register opening and a larger effective choke area than the original .049. The crankshaft rotary valve opened at 30 degrees ABDC and closed at 35 degrees ATDC for a total 185 degree induction period, much more generous than the original design’s 135 degrees. Exhaust and transfer openings of 130 degrees and 110 degrees respectively were a little milder than before. However, the shorter stroke reduced the piston velocity, so that the time those ports were open was relatively longer. Weight was 1.4 oz. (40 gm) with tank. First introduced in July 1953, the OK Cub 049B replaced the original .049 model. It was billed as “a brand new, lighter, more powerful OK .049 CUB that retains all the famous OK rugged design features you want.” In reality, since all of the working components were carried over from the .049X, the design was not exactly “brand new”. The engine featured the same .420 in. bore and .360 in. stroke. However, the crankcase was new, having a combination of beam or radial mounting options like the old model. The .049B also sported an extended prop driver for easier access to the needle valve; a stamped red-anodized aluminium fuel tank; and a racy spinner nut. It offered good value at $4.95, including propeller. The .049X continued for some time as the “competition” version.

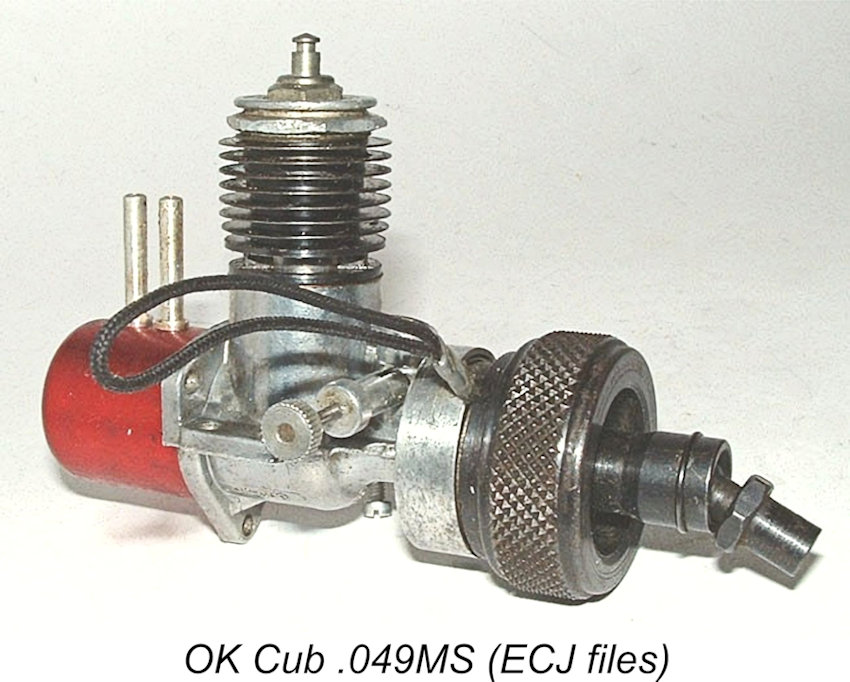

First introduced in July 1953, the OK Cub 049B replaced the original .049 model. It was billed as “a brand new, lighter, more powerful OK .049 CUB that retains all the famous OK rugged design features you want.” In reality, since all of the working components were carried over from the .049X, the design was not exactly “brand new”. The engine featured the same .420 in. bore and .360 in. stroke. However, the crankcase was new, having a combination of beam or radial mounting options like the old model. The .049B also sported an extended prop driver for easier access to the needle valve; a stamped red-anodized aluminium fuel tank; and a racy spinner nut. It offered good value at $4.95, including propeller. The .049X continued for some time as the “competition” version. power source for Comet’s models thereafter. Along with various modifications of Cubs for specific Comet applications, Herkimer introduced a recoil starter for several of its Cubs - the OK Cub 049S based on the “B” crankcase and OK Cub 049MS which also had a flywheel and universal coupling for marine applications. Buyers could choose a build-your-own engine kit, labelled the OK Cub 049K, containing a suitable propeller, sub-assemblies and small parts for assembling an 049B.

power source for Comet’s models thereafter. Along with various modifications of Cubs for specific Comet applications, Herkimer introduced a recoil starter for several of its Cubs - the OK Cub 049S based on the “B” crankcase and OK Cub 049MS which also had a flywheel and universal coupling for marine applications. Buyers could choose a build-your-own engine kit, labelled the OK Cub 049K, containing a suitable propeller, sub-assemblies and small parts for assembling an 049B. By 1954 it was clear to ½A competition flyers that anyone not using a Cox Thermal Hopper would need a very good thermal to get near the trophies! It appears that Herkimer decided to withdraw from the "performance" market at this point, focusing instead upon their RTF powerplants and consumer-grade sports engines.

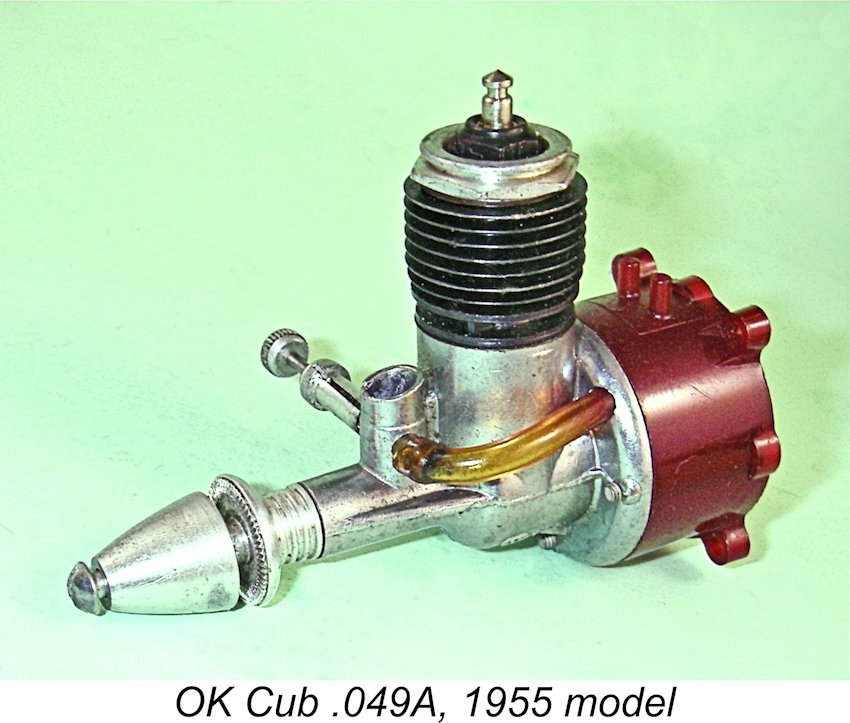

By 1954 it was clear to ½A competition flyers that anyone not using a Cox Thermal Hopper would need a very good thermal to get near the trophies! It appears that Herkimer decided to withdraw from the "performance" market at this point, focusing instead upon their RTF powerplants and consumer-grade sports engines.  The definitive OK Cub 049A was first advertised in April 1955. The crankcase casting retained vestigial flats where the original two mounting screw holes had previously been located. This model was equipped with a red nylon fuel tank/mount attached to the crankcase flange with four screws from behind. Its firewall mounting screw pattern was identical to that of the Cox Space Bug. Weight was just under 1.5 oz.

The definitive OK Cub 049A was first advertised in April 1955. The crankcase casting retained vestigial flats where the original two mounting screw holes had previously been located. This model was equipped with a red nylon fuel tank/mount attached to the crankcase flange with four screws from behind. Its firewall mounting screw pattern was identical to that of the Cox Space Bug. Weight was just under 1.5 oz.

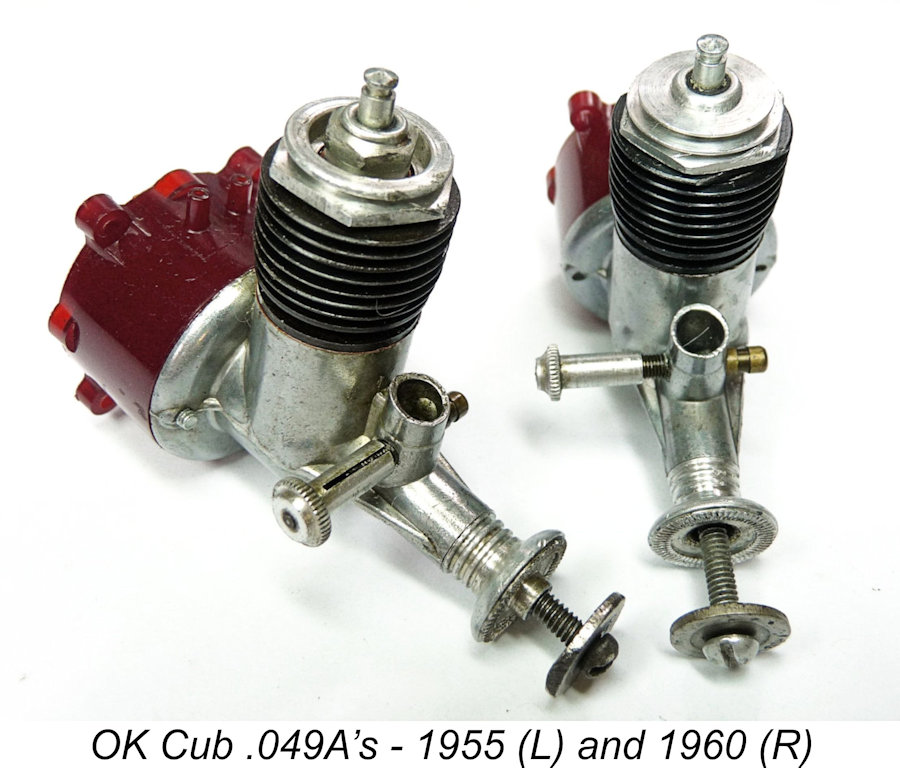

In 1960, in parallel with the new reed valve .049 and .06 engines (see

In 1960, in parallel with the new reed valve .049 and .06 engines (see  We assembled our test example from an existing .049B bottom end and a new 510H cylinder, piston, rod assembly and G-4 glow head, supplied by Ted Brebeck a couple of years ago. This is NOT the assembly used in the .049R reed valve engine. They do not interchange, as the crankcase deck height and other details are different.

We assembled our test example from an existing .049B bottom end and a new 510H cylinder, piston, rod assembly and G-4 glow head, supplied by Ted Brebeck a couple of years ago. This is NOT the assembly used in the .049R reed valve engine. They do not interchange, as the crankcase deck height and other details are different. The engine started and ran well. Tests figures seemed fine with large propellers, but the ignition became obviously retarded as the load was reduced, to the extent that sustainable RPM once the battery was disconnected dropped significantly. We cross-checked the Herkimer head by substituting a functionally equivalent Cox hemi head, without improvement. The element was fine, but the compression ratio was clearly too low.

The engine started and ran well. Tests figures seemed fine with large propellers, but the ignition became obviously retarded as the load was reduced, to the extent that sustainable RPM once the battery was disconnected dropped significantly. We cross-checked the Herkimer head by substituting a functionally equivalent Cox hemi head, without improvement. The element was fine, but the compression ratio was clearly too low. Same as the .059 reed valve engine. With its extra stroke, that one is still fine, but the .049B’s power trend sagged, lifting slightly with the smallest test propellers when we kept the battery connected until the engine was thoroughly warmed up and tuned in before disconnection and RPM checks.

Same as the .059 reed valve engine. With its extra stroke, that one is still fine, but the .049B’s power trend sagged, lifting slightly with the smallest test propellers when we kept the battery connected until the engine was thoroughly warmed up and tuned in before disconnection and RPM checks.

Competitors in Early ½A Nostalgia FF events will likely use a Wasp 049 engine as their first preference. Engines with glow heads are not allowed in this event, but some clever fettling can lift the OK Cub .049 X, A or B performance considerably, and they are reputed to take high-nitro fuel reasonably well for those last few RPM.

Competitors in Early ½A Nostalgia FF events will likely use a Wasp 049 engine as their first preference. Engines with glow heads are not allowed in this event, but some clever fettling can lift the OK Cub .049 X, A or B performance considerably, and they are reputed to take high-nitro fuel reasonably well for those last few RPM.