|

|

More Clone Wars – the Kharkov MK-2.5 vs. the MVVS 25-D

I see the primary difference between latter-day replicas and “classic” clones as being their motivation. The replicas were (and are) latter-day creations intended to satisfy a desire among collectors to experience classic engines which had long been out of production, hence no longer being readily available. The Mills, Elfin 149 and Elfin 249 replicas covered elsewhere on this website are typical examples. By contrast, the clones were contemporaries of the original engines on which they were based, being produced in order to provide modellers in geographic areas where the originals were not available with the opportunity to use essentially identical powerplants.

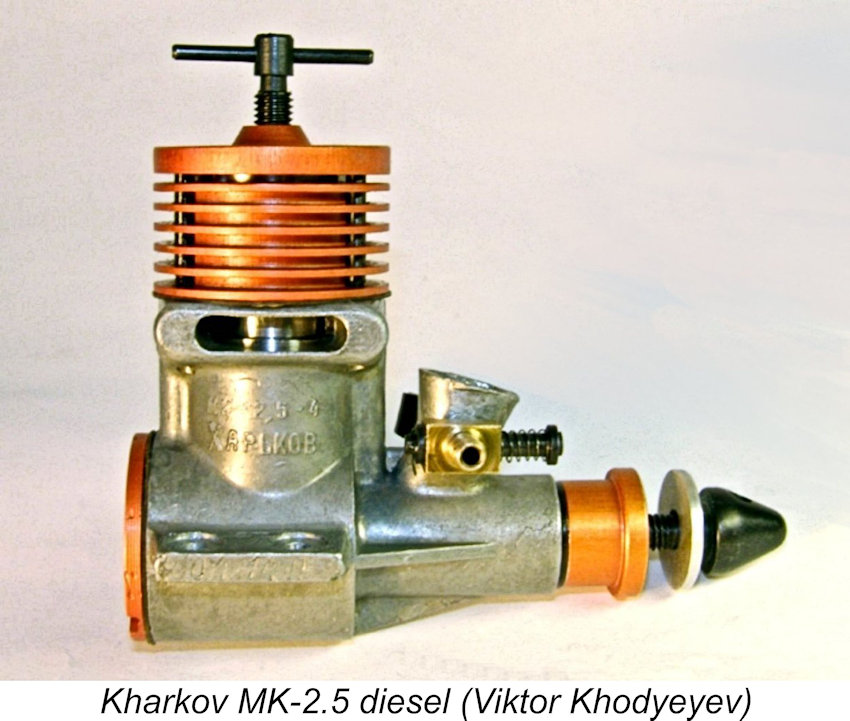

All of these engines qualify as clones rather than replicas since they all appeared at times when the original models on which they were based remained in concurrent production elsewhere by their original manufacturers. In this article, I’ll present an evaluation of another prominent Russian clone, the 2.5 cc Kharkov MK-2.5 (Russian XAPbKOB MK-2.5) of 1960. This engine was a faithful copy of the 1958 MVVS 25-D from Czechoslovakia (as Czechia was then).

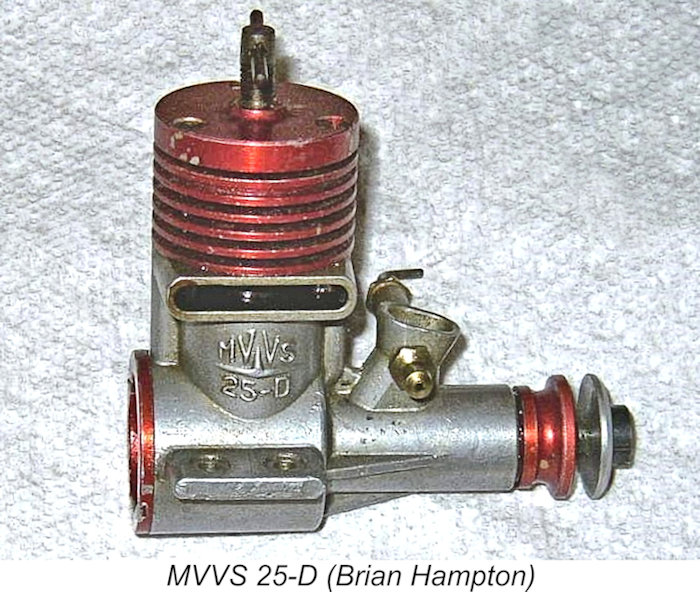

The 25-D quickly became recognized as the most powerful plain-bearing 2.5 cc diesel which had yet appeared anywhere, matching several highly-regarded contemporary ball-race models for power output. It was also notable for its unusually light weight of only 133 gm (4.7 ounces) which the omission of ball-races made possible. Few contemporary high-performance diesels could match its power-to-weight ratio. Despite this, its construction was extremely sturdy – the weight was used where it counted! It should come as no surprise to learn that the DOSAAF organization which oversaw the development of aeromodelling technology in the USSR should see the MVVS 25-D as a design which would serve very well as a powerplant for the use of Russian aeromodellers wishing to gain valuable competition experience, thus raising the standard of aeromodelling competition in the USSR. The problem was that the relatively small MVVS workshop could not make the engine in sufficient quantities to satisfy the needs of both Czech modellers and their Russian colleagues.

It’s unclear whether the production of these clones was authorized by MVVS. To me, it seems perhaps more likely that the Russians simply went ahead with their plans on the basis that it was easier to seek after-the-fact forgiveness from their Communist colleagues than to obtain up-front permission! After all, Czechoslovakia was firmly under Russian control, even if that control was exercised from behind the scenes. It’s worth noting that the 25-D was not the only MVVS design to receive the Russian cloning treatment at this time – the Kharkov MK-2.5 was joined in the same year of 1960 by the MD-2.5 “Moscow” racing glow-plug engine, which was in essence a clone of the very successful MVVS 2.5R/1958.

This factory specialized in the manufacture of precision equipment for the aviation and aerospace industries, but its activities also included the production of photographic equipment. These business lines required a capacity for working to a high level of precision, a company asset which transitioned well to the manufacture of model aero engines. The FED company survived the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union, remaining very much in business as of 2024. Given the skills and experience possessed by its manufacturers, it should come as no surprise to learn that the standard of manufacture of the Kharkov MK-2.5 diesel greatly surpassed that displayed in the average example of the companion MD-2.5 Moscow glow-plug model. Indeed, it could stand comparison with many contemporary engines of British manufacture. It was probably to achieve that very end that the manufacture of the Kharkov MK-2.5 was entrusted by DOSAAF to the FED plant in Kharkiv – they were just beginning to assign the manufacture of certain engines to military and aerospace workshops in cases where a higher standard of quality was deemed necessary. Before proceeding further, it's worth noting in passing that the Russian "clone" era did not end with the MVVS copies noted above. In 1962 the MD-2.5 Moscow copy of the MVVS 2.5R/1958 was replaced by the MD-2.5 Meteor, which was a close copy of the Super Tigre G.20/15 V "Jubilee" model from Italy. Like its Italian progenitor, the Meteor was manufactured in both glow-plug and diesel versions. It was actually quite a good engine - I used one of the diesel models very successfully for years. Even then, the Russians weren't done! In 1983 they revived the practise of cloning once again by releasing the ZSTKAM 2.5 KR piped speed engine. This was an almost exact copy of the record-breaking Rossi R-15 from Italy. I plan to cover the various engines released under the ZSTKAM designation in a separate article on this website. The MVVS 25-D and Kharkov MK-2.5 Compared

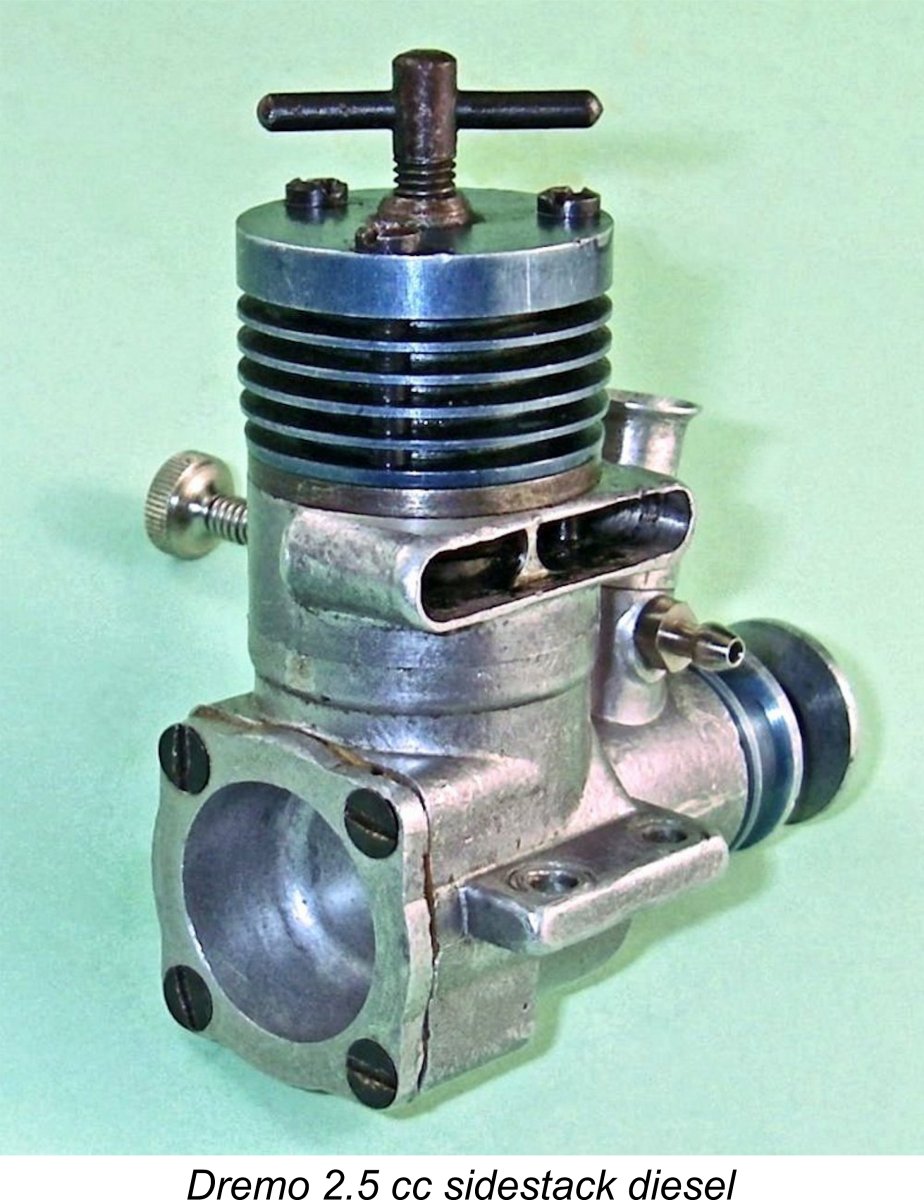

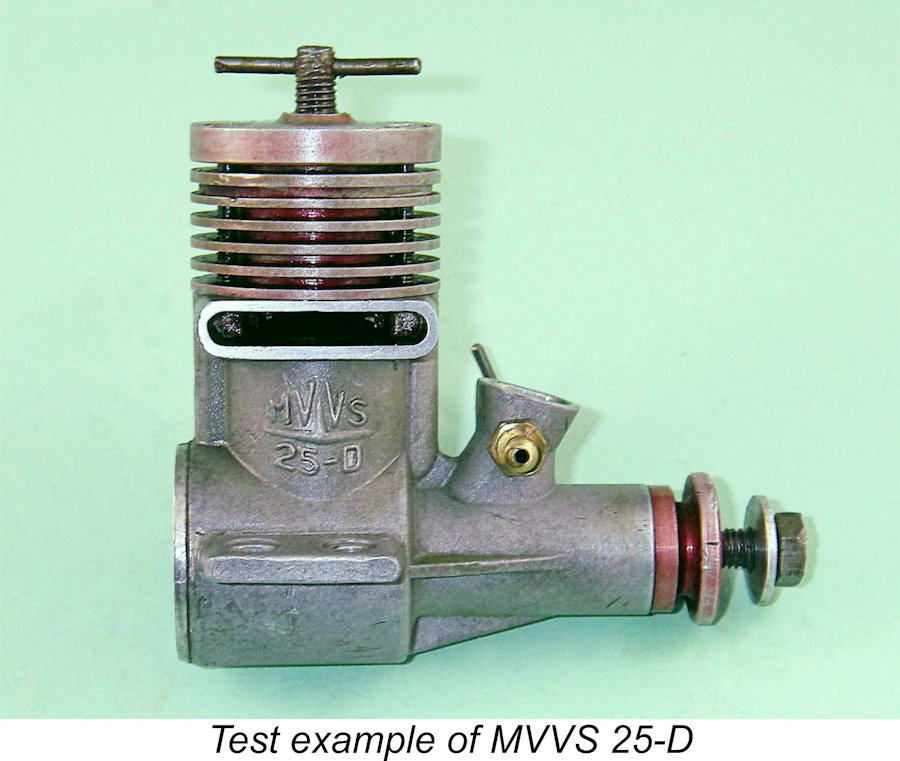

Both engines were basically relatively simple plain bearing diesels featuring a well-developed crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) induction system. Bore and stroke of both models were 15 mm and 14 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.47 cc. Weights were very similar, although my illustrated example of the Kharkov weighs in at 139 gm, a little higher than the 133 gm measured for the MVVS. One thing that the manufacturers of the Kharkov got wrong (in common with many other makers of “clones” and replicas) was the spacing of the mounting holes. I’ve said it many times, and I’ll say it again – this is one point that makers of “clones” and replicas should get right – matching the hole spacing to that of the original allows an owner to elect to use the replica for normal flying, reserving the possibly scarcer and more valuable original for special occasions or demonstration flights. The holes of the Kharkov are set at an identical lateral spacing to those of the MVVS, but their longitudinal spacing is just sufficiently different that the two models are not interchangeable in the same model. Extremely frustrating!!

The engines’ most distinctive shared features were their use of cross-flow loop scavenging allied to a modified form of the bypass-transfer system which had been pioneered by Enya in their 2.5 cc D15-1 diesel of 1956. This utilized twin bypass passages located fore and aft which fed a single rectangular transfer port located opposite the exhaust. The accompanying component view from the “Model Aircraft” test report should help to clarify the form of the twin bypass passages.

The real innovation introduced by MVVS and copied in the Kharkov was the form of the transfer port. Although milled to a rectangular shape, this was cut at an oblique 10-degree upward angle towards the exhaust. This caused the outer ends of the transfer port (those closest to the exhaust) to open earlier than the rest, with the balance of the port opening progressively as the piston descended. This presaged the full-blown Schnürle porting system which was soon to come into favor, since the outer ends of the transfer port served the same function as the two main ports of the Schnürle system by opening early to initiate gas flow from opposite sides, while the central portion of the transfer port opened later to approximate the function of the boost port. Both the MVVS and Kharkov renditions of this design were optionally supplied with two distinct spraybars. One was a conventional straight-through component, while the other had an integrally-formed spring-loaded fuel cut-out. This cut-out was spring-loaded in the “open” position – the plunger had to be pulled to shut off the fuel supply, thereby stopping the engine. Some kind of mechanical timer is implied. This cut-out may be seen in the image below at the right showing engine no. 03790. The cooling jackets, prop drivers and backplates of both models were color-anodized. Those components on the MVVS were anodized red, while the Kharkov appeared with both red and gold anodizing.

The MVVS 25-D engines don’t appear to have borne serial numbers. By contrast, the Kharkov MK-25 units all seem to have borne such numbers stamped on the outer end of the right-hand mounting lug. This was typical of Russian engines at the time in question, almost all of which displayed such numbers. The numbers of which I’m presently aware are 03784, 03790 (seen at the right), 08176 and 09548. These numbers imply that at least some 10,000 examples may have been made. This figure may sound quite high, but in reality it’s a very modest total by Soviet standards. OK, so much for a description of these two basically identical engines. Now we get to the question that I’m sure you’re all asking with growing impatience – how does the Russian clone stack up performance-wise with its Czech progenitor? Only one way to find out ……….. undertake a direct performance comparison! The Kharkov MK-25 and MVVS 25-D in the Modelling Media

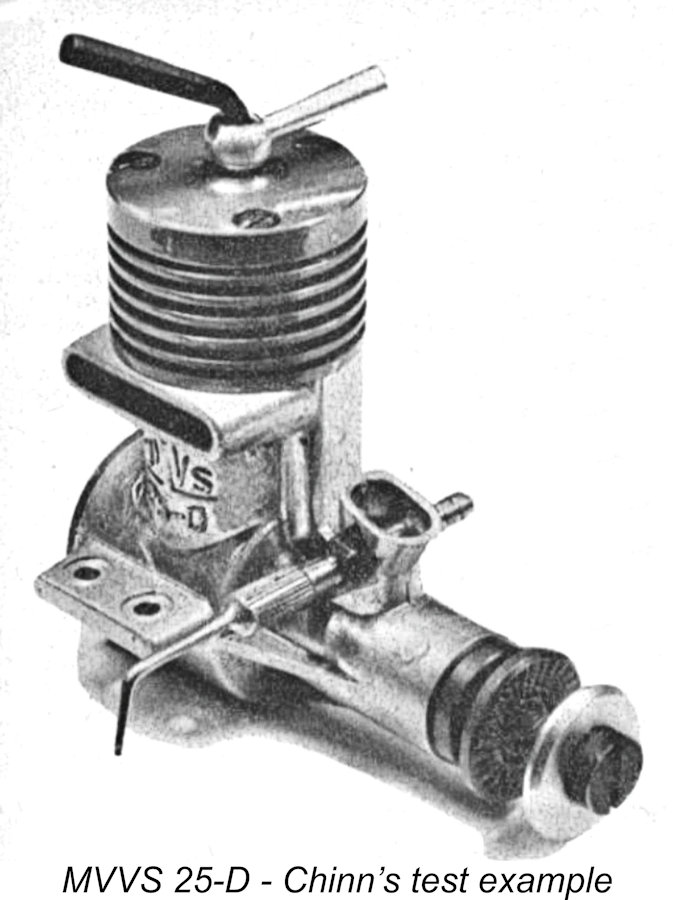

Chinn first described the engine in considerable detail in his regular “Latest Engine News” column in the October 1958 issue of “Model Aircraft”. He claimed that his test engine was the first example to make it across the Iron Curtain to the West. He drew attention to the obvious influence of the Enya D15-1 on the design of the 25-D, also commenting on the oblique transfer port which distinguished the MVVS from its Enya predecessor. He noted that some 100 examples of the 25-D had been produced in 1958 – a high figure by then-prevailing MVVS standards, since full-scale series production of multiple designs on a commercial basis did not really get into full stride until 1959. In his subsequent test report in the November 1958 issue of the magazine, Chinn stated that there was some doubt that any further production of the 25-D would take place in 1959, since the MVVS workshop was then very much focused on the development of stunt and speed engines for the high-profile 1959-1960 International contests in addition to initiating the transition from a subsidized constructor of State-sponsored “specials” to a commercial manufacturer. The number of surviving examples suggests that some additional production did in fact take place in 1959 or possibly 1960.

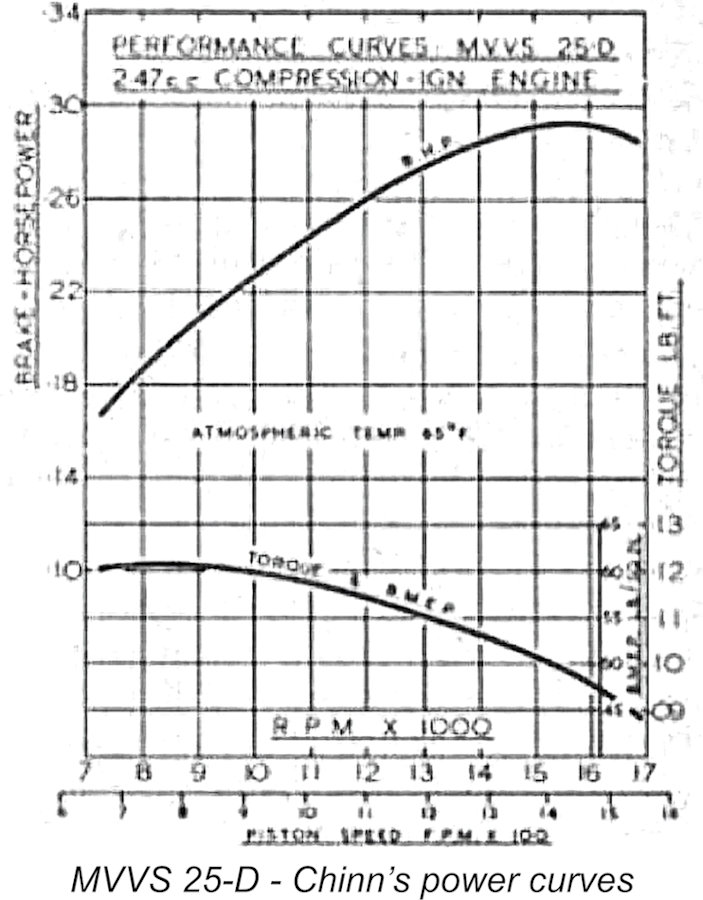

Starting was found to be quite straightforward using conventional techniques. The engine apparently did not require port priming, although a slight opening of the needle from the running setting evidently proved to be helpful. The only reported anomaly was a very loosely-fitted contra-piston, requiring the use of the comp screw locking lever with which the engine was supplied. The MVVS showed a marked preference for running at the higher speeds, where the running was said to be “steady and smooth”. It was less happy at lower speeds, also displaying a tendency towards increased levels of vibration which were not present at higher speeds. This being the case, Chinn saw no reason for the user not to exploit the Chinn’s summary of his opinion of this engine was entirely positive. He characterized the MVVS 25-D as “an impressive engine” and “certainly the most powerful plain bearing 2.5 cc diesel yet produced”. He rated it as “one of the top three or four 2.5 cc engines available anywhere in the world today”. A tough act for the Kharkov MK-2.5 “clone” to follow! As far as I’m aware, no commentary on the Kharkov MK-2.5 ever appeared in the English-language modelling media, nor was a bench test ever published. The engine was included in the late Jim Dunkin’s invaluable “Reference Book of .15 ci / 2.5 cc Model Airplane Engines” and was given a page in Viktor Khodyeyev’s extremely useful German-language book “Modellmotoren Made in USSR”. However, neither of these references included any first-hand performance data. All that I can report is that according to Khodyeyev, the manufacturers claimed a peak output of 0.25 kW (0.335 BHP), with a maximum operating speed of 16,000 RPM. This claim exceeded that made by MVVS for the 25-D by a significant margin. It’s clear that this is a claim that requires testing – let’s get right to it! The Kharkov MK-25 and MVVS 25-D Go Toe to Toe

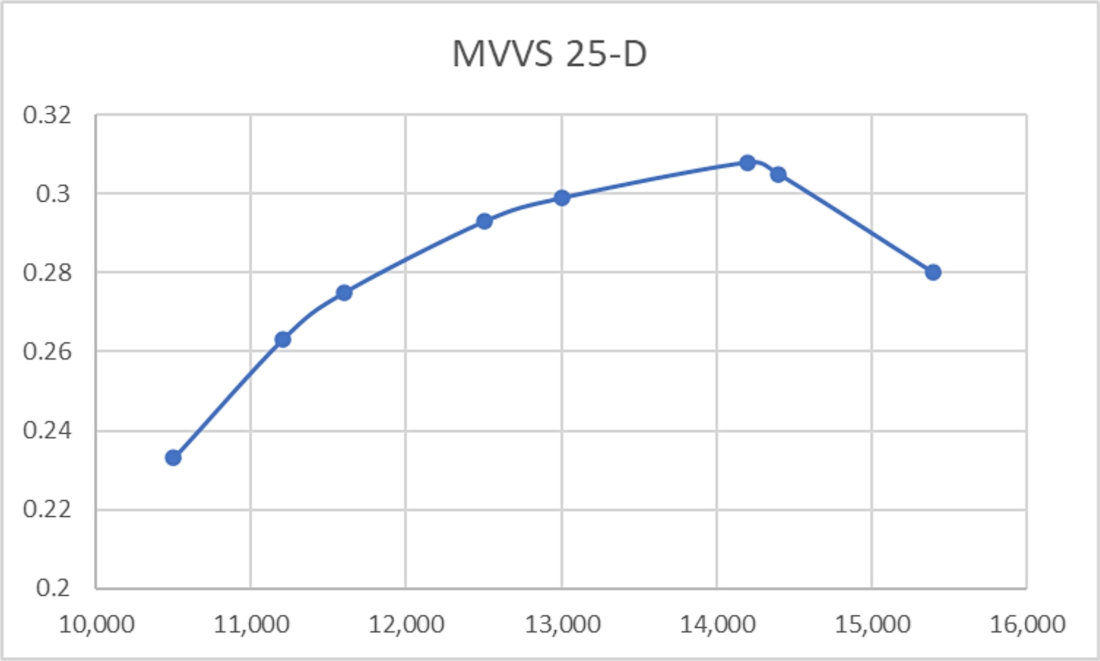

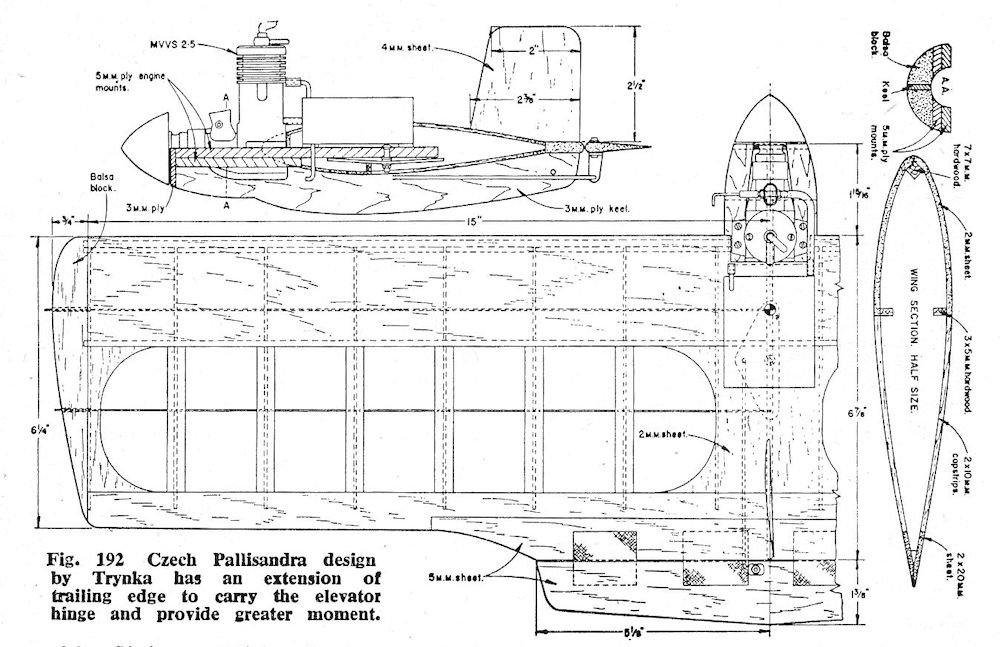

I first tested the MVVS way back in 1998 at a time when I was planning to put it into control-line service. The test figures more or less confirmed the level of performance reported by Peter Chinn, implying that my engine developed a peak output of around 0.301 BHP @ 14,300 RPM at that time. The 25-D subsequently accumulated several hours of hard running in the air, most “authentically” in a look-alike replica of the “Pallisandra” combat model, a very successful design by a Czech flier named Since it had accumulated several hours of airborne running time since its 1998 test, the possibility existed that the engine’s performance might have improved a little. Certainly, all fits remained excellent, with first-class compression. A re-test was very much in order!

I decided to test both engines on the same day using the same fuel and the same set of test props. The brew employed was my usual “classic diesel” mix containing kerosene, ether and castor oil in 40/35/25 proportions respectively, with 2% Amsoil Cetane Boost added. This formula generally allows medium and high-speed diesels to operate effectively. First into the test stand was the MVVS. Renewing old acquaintance with this motor reminded me of its somewhat unusual starting behavior. When mounted upright as in a test stand, choking had the effect of flooding the crankcase but accomplishing little else – the engine simply refused to fire. Fuel seems to have some difficulty finding its way up into the cylinder.

It turned out that the amount of fuel in the cylinder had to be “just right” for starting. My notes from past use of the engine in models bear this out – the prime had to be just right. The usual approach was to administer a modest prime and then immediately start to flick. It generally took a bit of flicking with no response at all, and then the engine would suddenly burst into life with no preliminary popping – one flick, it was dead, and the next flick, it was going!

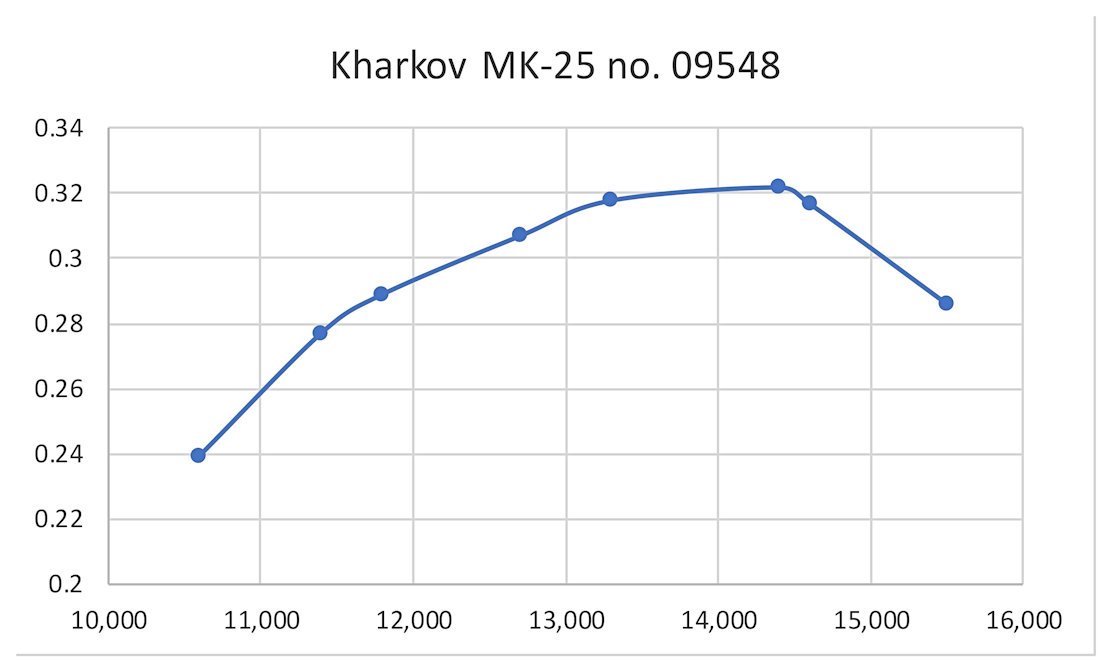

Once running, things really started to go with a swing! Running was absolutely smooth and mis-free, with very positive response to the controls. Vibration too was minimal as far as I could detect. I was amply reminded of why I enjoyed using this engine for flying purposes back in the day! After running a series of test props past the MVVS (results below), it was the turn of the Kharkov MK-2.5. Given the extent to which the Kharkov is a copy of the MVVS, it came as no surprise to me to find that its handling and running characteristics matched those of its MVVS ancestor more or less exactly. It too would have been a fully satisfactory powerplant for use in a model. Now we get to the meat of the matter – the performance comparison! The following data were measured for the two engines, running on the same day and using the same fuel and props.

The APC 7½x4 is a wide-blade airscrew created by cutting down an APC 9x4 and trimming/calibrating it to fill a glaring gap in my personal table of power absorption coefficients. The above figures yield the following power curves.

I will admit to having found these results quite surprising, to the point that I went back and re-checked a few of the readings. No surprises from the MVVS – it seems to have performed at more or less the same level that it did on the last occasion that I tested it way back in 1998. On that occasion, I derived a peak output of around 0.301 BHP @ 14,300 RPM using a completely But look at the figures for the Kharkov! It out-performed its MVVS ancestor right across the tested range! The difference was admittedly small, to the point that you’d probably barely notice it in a flying application. But it’s nonetheless to the credit of the Ukrainian makers of the Kharkov that their rendition of the MVVS design gave absolutely nothing away in performance terms. Moreover, the engine’s quality, while not perhaps fully up to MVVS's extremely high standard, was more than adequate to allow the design to reach its full potential. It will be recalled that the makers of the Kharkov claimed a peak output of 0.335 BHP at unspecified RPM. On test, my example recorded figures of around 0.325 BHP @ 14,000 RPM – near enough to the maker’s claim to lead me to believe that a “good” example (which mine may or may not be) might well reach the manufacturer’s claim.

More and more, the seemingly popular impression that the average Russian modeller during the Iron Curtain era had no access to good model engines appears to be far more of a myth than reality. There were certainly some very bad apples, but experience with such engines as the Kharkov, the RITM and the 1.48 cc MK-16 shows quite clearly that there were some very acceptable Russian "consumer grade" engines floating around as of the late 1950's and early 1960's! I would have been pleased to use any of them! Both engines came through this test completely unscathed, showing no evidence of any developing mechanical issues and clearly being ready for more. If you couldn’t get an MVVS original, an example of the Kharkov would have done you proud, as many a Russian modeller must have discovered! ___________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2024 |

||||

| |

Regular readers will doubtless be aware by now that I have always had a certain fascination with close copies (aka “clones”) of classic model engines by contemporary producers other than their original designers/constructors. I do not include “collectors’ replicas” in the “clone” category – such replicas are chiefly intended to provide latter-day collectors with opportunities to experience the operation of long out-of-production engines which have become too scarce to remain in general circulation and hence readily available. Rather, I’m speaking of copies of engines which remained in production or at least wide circulation at the time when the copies were produced but were not available in the geographic areas in which the clones made their contemporary appearance.

Regular readers will doubtless be aware by now that I have always had a certain fascination with close copies (aka “clones”) of classic model engines by contemporary producers other than their original designers/constructors. I do not include “collectors’ replicas” in the “clone” category – such replicas are chiefly intended to provide latter-day collectors with opportunities to experience the operation of long out-of-production engines which have become too scarce to remain in general circulation and hence readily available. Rather, I’m speaking of copies of engines which remained in production or at least wide circulation at the time when the copies were produced but were not available in the geographic areas in which the clones made their contemporary appearance. Although they didn’t have anything approaching a monopoly when it came to clone production, the past masters of the cloning art were undoubtedly the Russians. Their cloning activities dated all the way back to the 1930’s, when the

Although they didn’t have anything approaching a monopoly when it came to clone production, the past masters of the cloning art were undoubtedly the Russians. Their cloning activities dated all the way back to the 1930’s, when the  The MVVS 25-D was a greatly simplified plain bearing derivative of the earlier 2.5D/1958 twin ball-race diesel which had made such a positive impression at the 1958 World Free Flight Championship meeting held at Cranfield, England. It first appeared later in 1958 and was one of several designs to be put into limited production by the MVVS workshops, along with the

The MVVS 25-D was a greatly simplified plain bearing derivative of the earlier 2.5D/1958 twin ball-race diesel which had made such a positive impression at the 1958 World Free Flight Championship meeting held at Cranfield, England. It first appeared later in 1958 and was one of several designs to be put into limited production by the MVVS workshops, along with the  The obvious fix was to arrange for the production of a series of copies of the engine in one of the numerous Soviet workshops over which DOSAAF had some level of control. This is exactly what the Russians did commencing in 1960. The MVVS clone with which they came up was designated the Kharkov MK-2.5.

The obvious fix was to arrange for the production of a series of copies of the engine in one of the numerous Soviet workshops over which DOSAAF had some level of control. This is exactly what the Russians did commencing in 1960. The MVVS clone with which they came up was designated the Kharkov MK-2.5. It's interesting to note that responsibility for the production of the two contemporary Russian MVVS clones was split between two different production facilities. Indeed, both models were specifically named for their cities of origin. The MD-2.5 “Moscow” glow-plug model was manufactured to somewhat “flexible” standards at DOSAAF’s MARZ (Russian MAP3) aircraft maintenance facility in Moscow, while the manufacture of the Kharkov MK-2.5 was entrusted to the

It's interesting to note that responsibility for the production of the two contemporary Russian MVVS clones was split between two different production facilities. Indeed, both models were specifically named for their cities of origin. The MD-2.5 “Moscow” glow-plug model was manufactured to somewhat “flexible” standards at DOSAAF’s MARZ (Russian MAP3) aircraft maintenance facility in Moscow, while the manufacture of the Kharkov MK-2.5 was entrusted to the  Even so, the MK-2.5 was reportedly produced in relatively small numbers by comparison with other contemporary Russian engines – presumably it was never more than a sideline production as far as FED was concerned.

Even so, the MK-2.5 was reportedly produced in relatively small numbers by comparison with other contemporary Russian engines – presumably it was never more than a sideline production as far as FED was concerned.  This section of the article presents little problem in terms of composition, because the plain fact is that the Kharkov is virtually identical to its MVVS progenitor! In essence, to describe one is to describe the other.

This section of the article presents little problem in terms of composition, because the plain fact is that the Kharkov is virtually identical to its MVVS progenitor! In essence, to describe one is to describe the other.

The idea was that the opposing streams of incoming mixture would meet in the middle on the transfer side of the cylinder and mutually deflect each other upwards rather than creating any significant movement in the direction of the exhaust. In this way, directional control of the incoming mixture was achieved without the use of a piston baffle - in effect, the opposing gas streams baffled each other! A variant of the same system was used in the very rare

The idea was that the opposing streams of incoming mixture would meet in the middle on the transfer side of the cylinder and mutually deflect each other upwards rather than creating any significant movement in the direction of the exhaust. In this way, directional control of the incoming mixture was achieved without the use of a piston baffle - in effect, the opposing gas streams baffled each other! A variant of the same system was used in the very rare  Like all MVVS engines, the quality of the 25-D was beyond reproach. All bearings were perfectly fitted, as was the piston in its cylinder. It has to be said in all fairness that if my examples are anything to go by, the Kharkov came very close to matching the MVVS for quality – a credit to the capabilities of the FED plant in Kharkiv. Although clearly having seen considerable use in the past, my two MK-2.5’s both remain very well fitted, with good bearing fits and excellent compression. The FET plant appears to have been one of the better production facilities at DOSAAF’s disposal at the time in question.

Like all MVVS engines, the quality of the 25-D was beyond reproach. All bearings were perfectly fitted, as was the piston in its cylinder. It has to be said in all fairness that if my examples are anything to go by, the Kharkov came very close to matching the MVVS for quality – a credit to the capabilities of the FED plant in Kharkiv. Although clearly having seen considerable use in the past, my two MK-2.5’s both remain very well fitted, with good bearing fits and excellent compression. The FET plant appears to have been one of the better production facilities at DOSAAF’s disposal at the time in question. When approaching the task of evaluating any classic model engine, it’s always instructive to review what has been reported previously with respect to the engine’s characteristics and performance. In the present instance, we are fortunate enough to have both a published description and a

When approaching the task of evaluating any classic model engine, it’s always instructive to review what has been reported previously with respect to the engine’s characteristics and performance. In the present instance, we are fortunate enough to have both a published description and a  Since he had already described the engine in some detail, Chinn was able to focus his test report on its performance characteristics. After a 30-minute precautionary break-in period, he proceeded to put the engine through a full bench test.

Since he had already described the engine in some detail, Chinn was able to focus his test report on its performance characteristics. After a 30-minute precautionary break-in period, he proceeded to put the engine through a full bench test.

I’m fortunate enough to have used examples of both the Kharkov MK-2.5 and the MVVS 25-D on hand for testing. I’ve never used either of my two Kharkov’s, but the MVVS has seen considerable airtime in my hands, hence being extremely well run-in. The former red anodizing has faded over time, and the original needle valve has been replaced with a P.A.W. item. However, the engine remains in first-class running condition. Both of my Kharkovs appear to have had similar amounts of previous use, also suffering from a degree of fading of the color anodizing.

I’m fortunate enough to have used examples of both the Kharkov MK-2.5 and the MVVS 25-D on hand for testing. I’ve never used either of my two Kharkov’s, but the MVVS has seen considerable airtime in my hands, hence being extremely well run-in. The former red anodizing has faded over time, and the original needle valve has been replaced with a P.A.W. item. However, the engine remains in first-class running condition. Both of my Kharkovs appear to have had similar amounts of previous use, also suffering from a degree of fading of the color anodizing.

Both of my Kharkov MK-2.5 units also appeared to have had considerable experience in the air. However, their fits too remained extremely good. I saw no reason why they shouldn’t deliver completely representative levels of performance on test. I would objectively say that both my Kharkov MK-2.5’s and my MVVS 25-D have accumulated very comparable running times. It was a toss-up which of my two examples of the Kharkov should be used for this comparative test. In the end, I elected to go with engine number 09548 since like my MVVS 25-D it was fitted with a P.A.W. needle valve assembly, making it virtually a clone of its competition.

Both of my Kharkov MK-2.5 units also appeared to have had considerable experience in the air. However, their fits too remained extremely good. I saw no reason why they shouldn’t deliver completely representative levels of performance on test. I would objectively say that both my Kharkov MK-2.5’s and my MVVS 25-D have accumulated very comparable running times. It was a toss-up which of my two examples of the Kharkov should be used for this comparative test. In the end, I elected to go with engine number 09548 since like my MVVS 25-D it was fitted with a P.A.W. needle valve assembly, making it virtually a clone of its competition. It's therefore necessary to introduce a little fuel into the cylinder by means of an exhaust prime. The problem here seems to be that with the engine’s domed piston crown and extremely wide transfer port, most of the prime goes straight down the bypass into the crankcase! A few primes, and you’re flooded! This is one engine that would probably be easier to start when inverted, as it generally would be in a team race application.

It's therefore necessary to introduce a little fuel into the cylinder by means of an exhaust prime. The problem here seems to be that with the engine’s domed piston crown and extremely wide transfer port, most of the prime goes straight down the bypass into the crankcase! A few primes, and you’re flooded! This is one engine that would probably be easier to start when inverted, as it generally would be in a team race application.