|

|

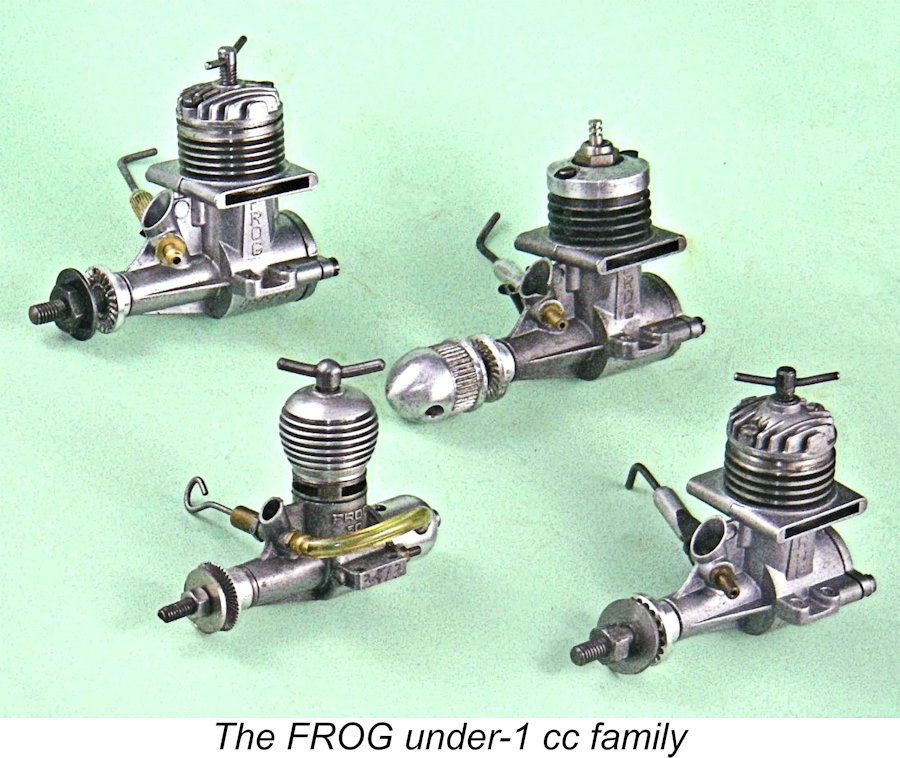

The Tadpoles - the Under-1cc FROG Motors

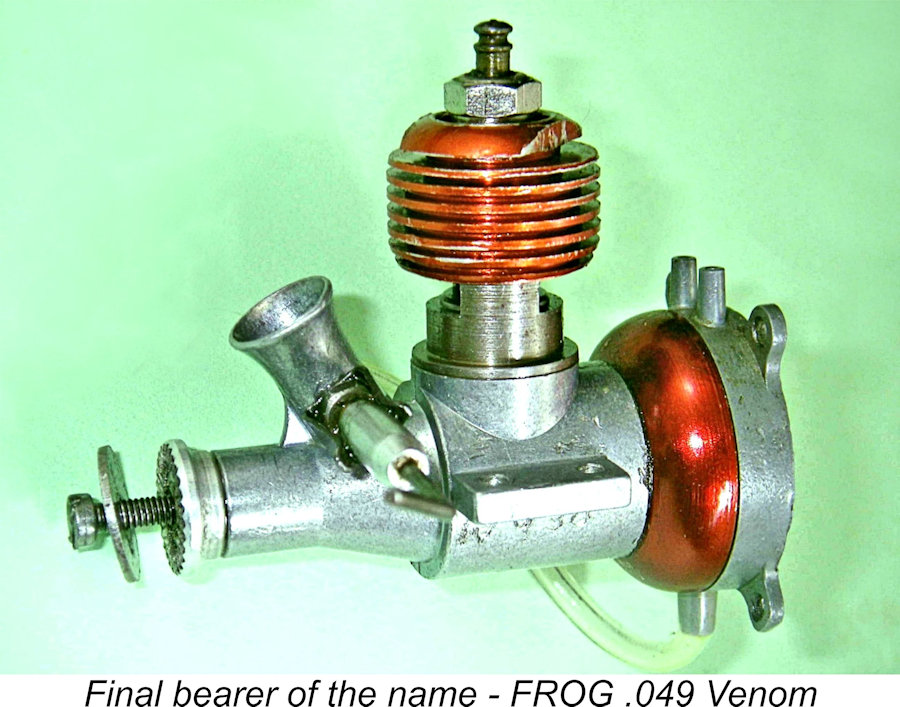

However, it proved to be impossible to treat the FROG .049 in isolation, since its story is inextricably entwined with that of its diesel progenitor, the FROG 80, the seeds of which were themselves planted some years earlier. The FROG .049 was in effect simply a glow-plug conversion of the FROG 80, albeit with a few distinctive design features. In turn, its design greatly influenced that of the later diesel models. Accordingly, to review it in isolation would require me to ignore its proper place in the history of the FROG range in general. No-one would learn very much from such an exercise!

Before doing so, I'd like to record my grateful acknowledgement of the considerable assistance rendered to me by my good mate and valued colleague Kevin Richards. Apart from his role as Membership Secretary and Treasurer of SAM 35, Kevin is best known as the world's leading authority on the E.D. range. However, he knows a thing or two about FROG’s as well! The value of the contribution that he made to this study in terms of both data and commentary cannot be overstated - many thanks, mate! My original article on the FROG under-1 cc models was published in December 2010 on the late Ron Chernich’s “Model Engine News” (MEN) website. I’m re-publishing it here partly to prevent its loss as Ron’s now-frozen and administratively-inaccessible site steadily deteriorates due to the lack of any opportunity to maintain it, but also to take advantage of the opportunity to revise certain aspects of the text to reflect additional details which have since come to light. In that context, I would be remiss if I failed to acknowledge the contribution to the original MEN article which was made by the late and greatly-missed MEN Editor Ron Chernich. Ron took time from his busy schedule to dig out a number of tests and advertisements that I didn't have at the time, also making a number of helpful suggestions. Only support like this makes it possible to claim any sort of authority for these articles, and Ron's contribution was of immense value in that regard. Now on with our story ……………. Background

Due to its preoccupation with the conduct of the war, Britain was very much a latecomer in terms of model diesel development, but caught up very rapidly following the conclusion of the conflict. One of the British firms which took a leading part in this early post-war activity was International Model Aircraft (IMA). IMA was one of the oldest-established model aircraft manufacturers in the world, having been founded in 1931 by Charles Wilmot, John Wilmot and Joe Mansour. In 1932, in order to enhance its marketing potential, IMA entered into partnership with the prominent Lines Brothers organization, whose marketing reach extended not only throughout Britain but also to many other parts of the world. This would prove to be a very durable and successful partnership. The trade-name "FROG" ("Flies Right Off Ground") was used by IMA from the outset for their popular flying model kits, later being carried over to their engines which began to appear in 1946. A detailed and well-illustrated history of FROG and all its products may be found in the excellent and highly-recommended hardcover book by Richard Lines and Leif Hellström entitled “FROG Model Aircraft 1932-1976”. I’ve covered the early history of the FROG model engine range in my separate article on the early FROG models – I do not intend to repeat that material here. Suffice it to say for now that by 1951 the original FROG “bicycle spoke” models had come and gone, with the range now consisting of the FROG 150 and 250 diesels and the FROG 500 glow-plug model. The stage was set for a further expansion of the FROG model engine range. The ½ cc Diesel Revolution of 1951/52

Despite this, there was undoubtedly a viable market for small engines in Britain, where flying fields of adequate area were relatively few and far between in and around major population centres. In addition, noise was an issue for urban modellers even in those more tolerant times. Consequently, the challenge facing British model engine manufacturers was to develop small-displacement engines which produced substantially more power than their sub-miniature predecessors while at the same time remaining sufficiently compact and light to be useable in very small models.

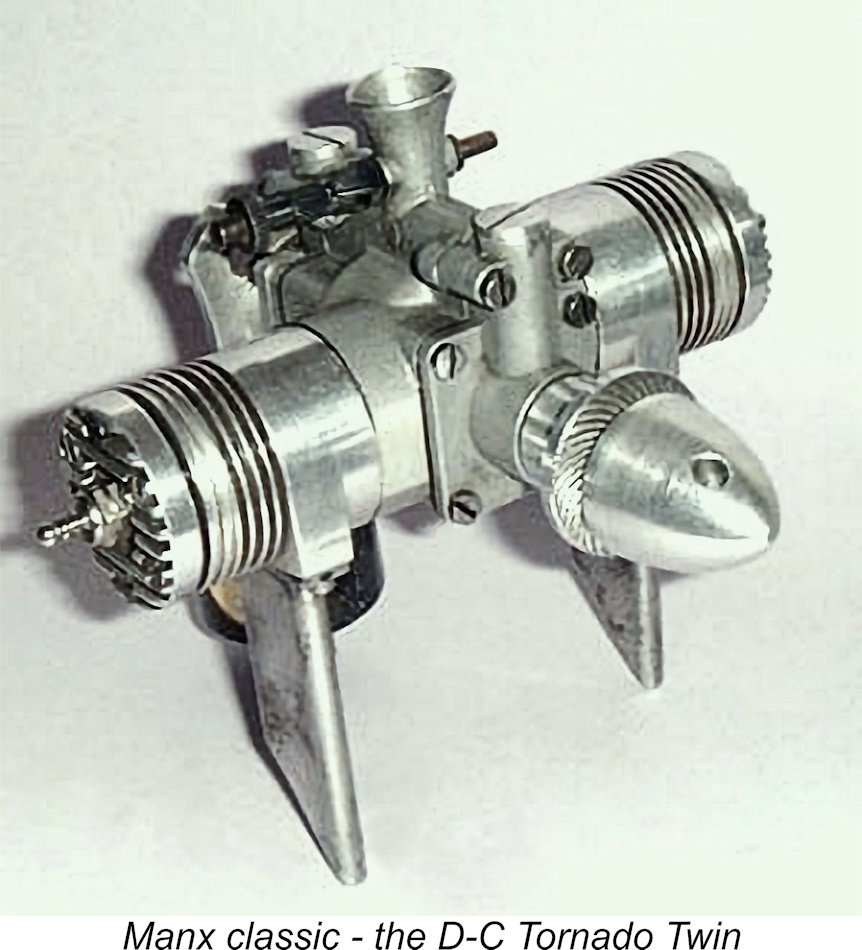

Dennis Allen of later Allen-Mercury fame was working with Allbon at this time, almost certainly playing a significant role in the development of the Dart. Another luminary who was working for Allbon as of 1950 was future FROG model engine designer George Fletcher, of whom we shall be hearing more in due course. The neat little Dart met all of the requirements set out above - it was compact, very light and remarkably powerful for its displacement. Despite a selling price of £3 5s 0d (£3.25 in “modern” money), which was a fair chunk of change in 1950 Britain, the marketplace was more than ready for the Dart when it appeared in August 1950. Several very positive published test reports resulted in demand quickly outstripping Allbon's ability to manufacture the engine in his Sunbury-on-Thames workshop. To add to his problems, Allbon was caught up in the fall-out from the infamous Purchase Tax case which eventually forced him into a 1952 merger with Davies-Charlton (D-C) Ltd., as related elsewhere.

The attractiveness of these small engines to mainstream British modellers arose from a number of factors. They weren't significantly cheaper than many of their larger brethren, but in the far-off days when most aeromodellers lived up to their hobby's name by actually building their own models, airframes for these little units were both easy and less expensive to build, while the finished models were far more readily transported. Moreover, such models, particularly those of the control-line variety, could be flown on smaller fields. Finally, the noise levels and fuel costs associated with running these little powerplants were far lower than those of the larger engines generally used by competition fliers. Although the new breed of ½ cc diesels handily outperformed their sub-miniature 1940's predecessors and could actually give some of the contemporary American .049 glow-plug models a run for their money, they had undeniable limitations. For one thing, they were somewhat trickier to handle and more susceptible to handling damage than their larger counterparts, which made them less suitable for beginners. For another, their power output was still on the marginal side, especially when it came to the control-line field which was then so popular in Britain. Finally, they tended to wear out more rapidly than their larger contemporaries due to the greater sensitivity of smaller diesels to piston/cylinder wear in particular - the same amount of wear has a far greater negative effect on cylinder leakdown with small bores. For all of the above reasons, the ½ cc fad in Britain didn't last all that long, even though several of the protagonists remained in production for quite a few years. However, the previously-cited advantages of smaller engines remained in effect. Consequently, the continued growth in the popularity of control-line flying in Britain during the first half of the 1950's kept the pressure on domestic engine manufacturers to produce further updated designs having even more power while still remaining as light and compact as possible.

D-C Ltd. clearly saw the Merlin as an alternative to the Dart rather than as a competitor - the Dart remained in production alongside the Merlin, as it was to do for many years to come. However, the Merlin did have the distinction of being the first British second-generation rotary valve diesel design to appear in the ¾ ccdisplacement category which had hitherto been the preserve of the rather old-fashioned side-port Mills .75 and the far more up-to-date McCoy and OK .049 cuin. diesel models from America. In hindsight, it's now also possible to see that the appearance of the Merlin signaled the onset of a price war among British manufacturers which was eventually to stifle the development of new models and cut profit margins to the point of non-viability for all but a few of the more specialized producers.

The Merlin was undoubtedly a very useful performer which sold at a most attractive price and did a creditable job of flying small sport control-line and other models, as I know from extensive first-hand experience. It became extremely popular, undoubtedly attracting its share of sales attention away from the little ½ cc designs, including the FROG 50. Perhaps more significantly, it also drew sales away from the 1 cc competition, including that from D-C Ltd. themselves. The success of the Merlin must eventually have made it clear to IMA both that there was a viable market for under-1 cc engines and that they could no longer ignore the need to develop a further upgraded model in that displacement category if they wished to remain in competition for a share of that market. Since it is IMA’s involvement in this phase of the story which concerns us here, from this point on I’ll focus on their FROG range. 1952 - Forerunner of the FROG 80 - the FROG 50

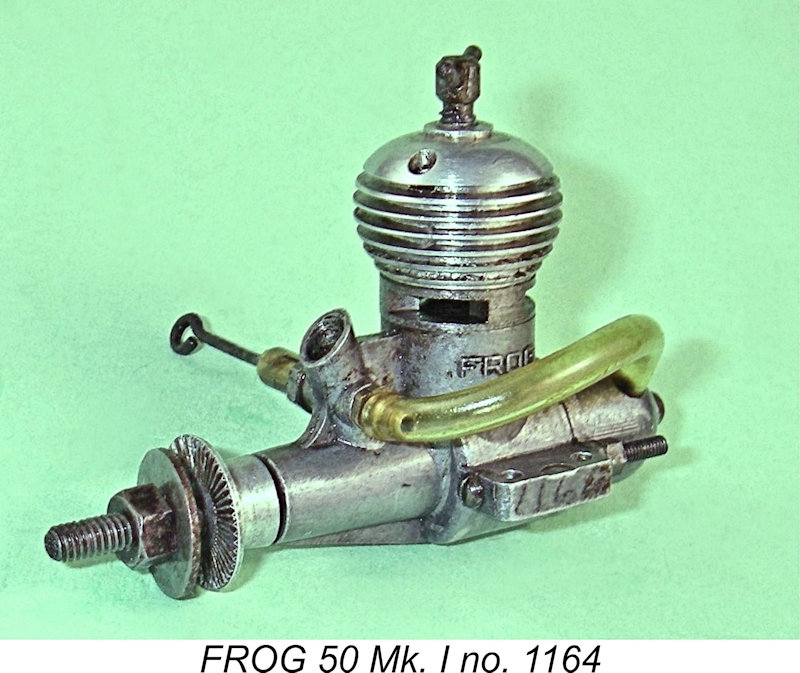

After spending much of 1951 in the development stage and then having to wait its turn in IMA's busy production program, the little FROG 50 was finally announced in a full-page three-tone advertisement which appeared in the February 1952 issue of “Model Aircraft”, as reproduced at the left. The introductory price of the engine was a highly competitive £2 9s 6d (£2.48), although this was reduced to £2 5s 0d (£2.25) in February 1953. Interestingly, the illustration of the engine in this initial advertisement showed a single-armed compression lever. Although this illustration was to appear in FROG advertisements for several more years, the single-armed comp screw didn't last long, being replaced almost immediately with the more familiar Y-shaped twin-armed control. The comp screw used originally had an absurdly small and sharp-edged thin-wire tommy bar which was both inconvenient and at times painful to use. To add insult to injury, the transverse needle valve assembly placed the fingers uncomfortably close to the prop disc. Grazed knuckles guaranteed!

From a comparative standpoint, these figures are consistent with other tests by the two individuals - Chinn generally tended to find more power than Warring for the same engine and commonly also found that power at higher peak RPM although not in this instance. Presumably this was down to differences in the respective engine management and testing techniques. Both reviews were generally favorable, although the fiddly little compression screw, transverse needle alignment, "challenging" starting qualities and general "finicky-ness" of the engine came in for some criticism from both reviewers.

This change appears to have occurred after perhaps some 3000 examples of the original Mk. I were produced - my own illustrated example serial number 3513 has the larger comp screw while retaining the original Mk. I cylinder. Kevin Richards also had a record of engine number 4321 of this type. That example also had a longer fuel tank fitted. This relatively minor variant has sometimes been referred to as the FROG 50 Mk. II, with the following model referred to as the Mk. III. However, neither the factory nor contemporary reviewers ever applied such designations - both the first and second variants of the FROG 50 were officially designated as Mk. I's. To me, this makes perfect sense – a change to a different comp screw scarcely constitutes a rational basis for assigning a new Mk. number.

The new model addressed the major remaining handling concern regarding the original model by raking the needle back to get the fingers further away from the prop. The updated model also featured revised transfer porting arrangements using external bypass passages feeding upwardly-inclined drilled transfer ports in place of the former internal flute bypass arrangements. The longer fuel tank which had been fitted to some of the later examples of the Mk. I had now become standard, as had the enlarged comp screw and taller cooling jacket. A revised crankshaft having both a larger main journal diameter and a larger crankpin was now featured - it appears that failures had been experienced with the original components. Finally, the crankcase was strengthened somewhat by the addition of an integrally-cast "strap" of additional material around the outside diameter in the vicinity of the con-rod’s operating location. Taken all together, these changes were more than sufficient to warrant the assignation of a new Mk. number. Indeed, the Mk. II was actually a completely different engine! Sales of the FROG 50 were evidently just about sufficient to justify continued production for almost 5 years, albeit at a relatively modest level of perhaps at most some 2500 units per year if known serial numbers are anything to go by. The highest serial number of my present acquaintance is Mk. II engine number 12058 which was owned by reader Bob Beaumont. Kevin Richards recalled that the handling difficulties which were experienced by both testers and owners (himself included!) contributed to a progressively increasing degree of sales resistance - he mentioned seeing a FROG 50 in his local hobby shop in 1959 (three years after production had ceased!) which was still there when the shop closed its doors in 1965!

However, by this time the FROG 50 had become irrelevant to IMA's evolving plans for their model engine range - the company was already in the process of replacing it with a new and somewhat larger model bearing almost no resemblance to its smaller predecessor. Indeed, the appearance of the new model known as the FROG 80 had been announced in the previous issue of “Model Aircraft”! This being the case, the publication of a test on a discontinued model would seem at first glance to indicate that Chinn had been caught on the wrong foot! However, this is highly unlikely - Chinn was unusually well-informed regarding the plans of the various British model engine manufacturers, often being consulted by them when developing new models. In reality, a careful reading of the report clearly indicates that it had actually been written some 9 months previously and had presumably been submitted for the Editor to use as a "filler". The text refers to the FROG 50 Mk. II having been "introduced just over a year ago " and that the Mk I version of the same engine had first appeared "three years earlier". Since the latter date is well-documented as February 1952, simple arithmetic dates the writing of this report pretty firmly to around April of 1956. The insertion of the report after the discontinuation of the engine and without correcting the redundant timeframes mentioned in the text was clearly an editorial oversight rather than a miscue by Chinn. 1957 - the FROG 80 Mk. I Diesel Appears

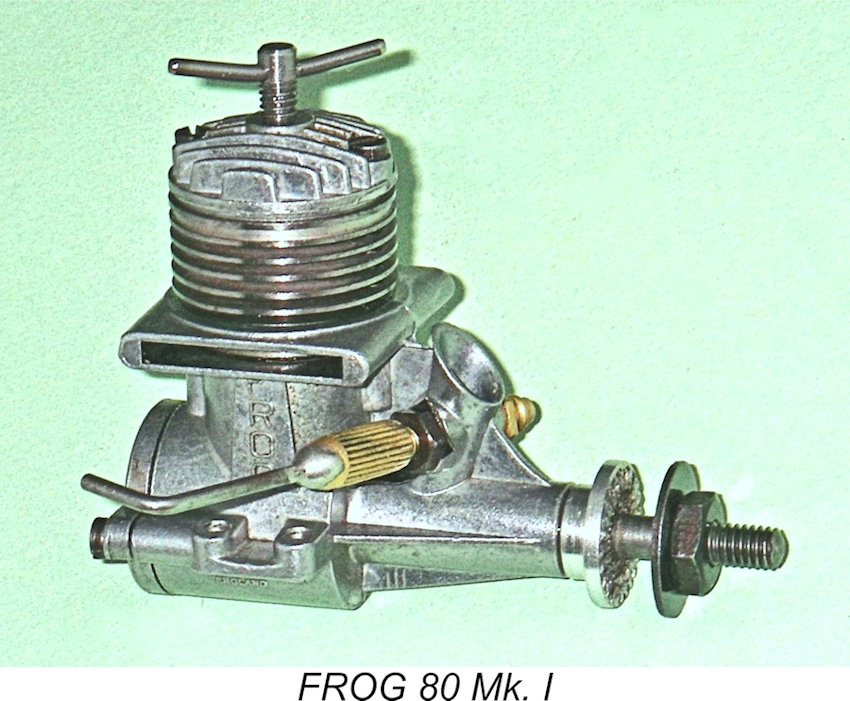

The new model was the subject of comment in the regular "Motor Mart" feature in the February 1957 issue of “Aeromodeller” - the same month as that in which Chinn's mini-test of the FROG 50 Mk. II appeared belatedly in the rival “Model Aircraft” publication. Production of the FROG 50 appears to have ceased more or less concurrently with the 80's appearance - it certainly disappeared from IMA's advertising at this time, although examples evidently remained available from dealers for a considerable time thereafter. In the "Motor Mart" article, “Aeromodeller” served notice of their intention to publish a Ron Warring test of the new model in their March 1957 issue. Chinn and “Model Aircraft” were quick to react, with tests appearing in the March 1957 issues of both magazines. Warring’s test in “Aeromodeller” reported figures which closely approached those which he had obtained a few years earlier for the rival Allbon Merlin. Warring extracted 0.051 BHP @ 11,000 rpm from the FROG 80 Mk. I as opposed to his reported 0.057 BHP @ 13,000 RPM for the Merlin. While the FROG’s actual peak power figure was some 12% down on Warring's figure for the Merlin, it was released at significantly lower rpm, making the FROG 80 far more of a torque-producer than its Manx rival, thus being able to swing a larger and hence more efficient Peter Chinn's contemporary test in “Model Aircraft” was equally positive. He began by stating that the new 80 was "a better engine in every respect" than the 50 which it was intended to replace. He commented that "its starting, general behavior and running qualities are most certainly superior to those of the earlier model". An output of 0.064 BHP was recorded at a speed of 11,800 rpm, both figures being somewhat higher than those obtained by Warring. As mentioned earlier, this is a typical characteristic of the tests conducted by the two individuals on the same engine - Chinn tended to find higher peak output figures at higher rpm than Warring. As an example, in his January 1955 test of the Allbon Merlin, Chinn had reported a peak output of 0.062 BHP @ 12,800 RPM, topping Warring's figures for the same engine. Regardless, on the basis of the above tests as well as its low price, it's clear that IMA had a worthy contender on their hands in the ¾ cc sports diesel category. Let's have a look at this engine to see what made it tick. The FROG 80 Mk. I - Description

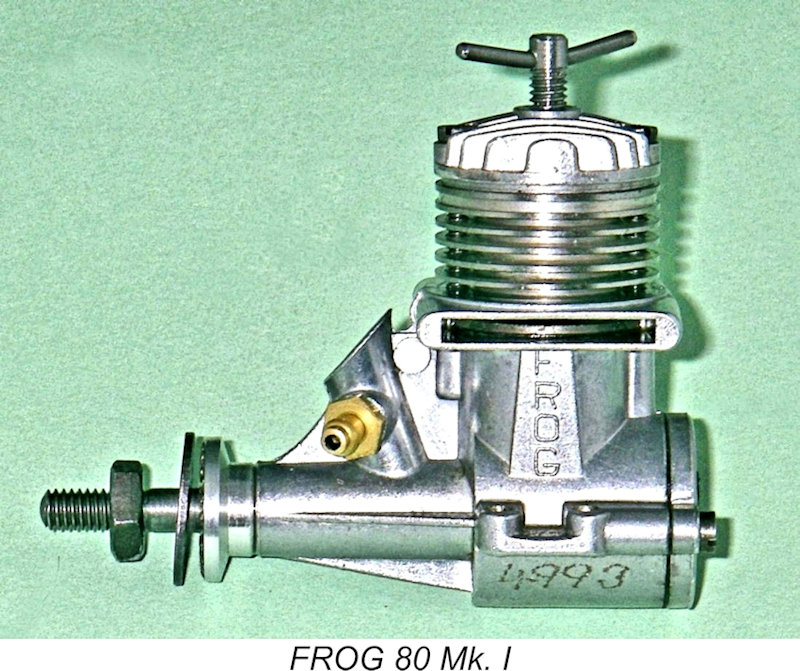

Beneath the skin, the FROG 80 Mk. I was basically a more-or-less conventional reverse-flow scavenged plain bearing crankshaft front rotary valve (FRV) model diesel of its era. However, it did possess a number of features which set it apart from its competition.

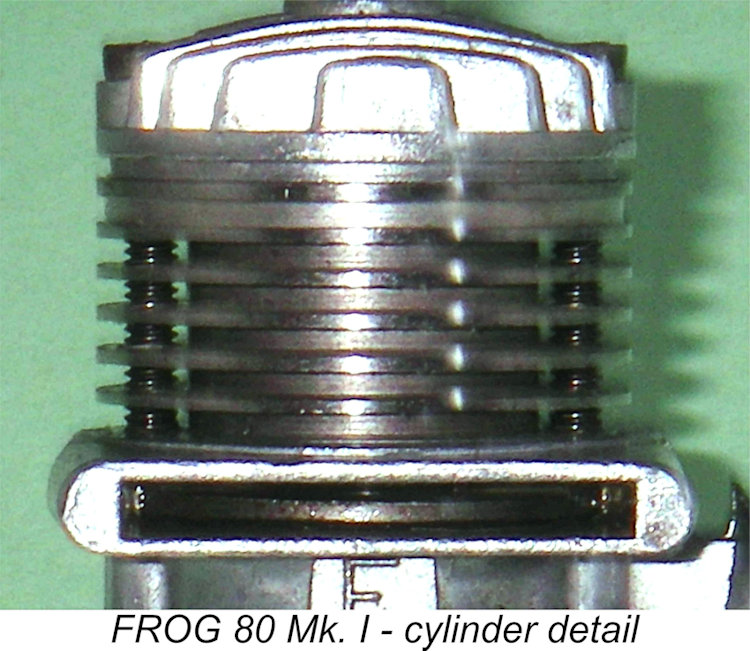

Looking at one of these engines today, its most striking visual attributes are the twin exhaust stacks and the deeply finned cylinder head. But the real heart of this design is clearly the cylinder assembly. The engine uses a case-hardened steel cylinder liner having integrally-machined cooling fins. There are four thin fins above the exhaust stacks, with a thicker flange at the top immediately below the cylinder head to add some stiffness at that point.

The main problem which can arise with this assembly is distortion due to the uneven distribution of the hold-down forces around the cylinder - an inevitable consequence of the use of only two screws. This is a particular issue when dismantling a FROG 80 for any reason - it can be difficult to re-establish precisely the same "set" in the cylinder upon re-assembly. This is one engine that is definitely best left alone once run in with the cylinder assembly fully tightened. It's also important to ensure that the hold-down screws don't work loose.

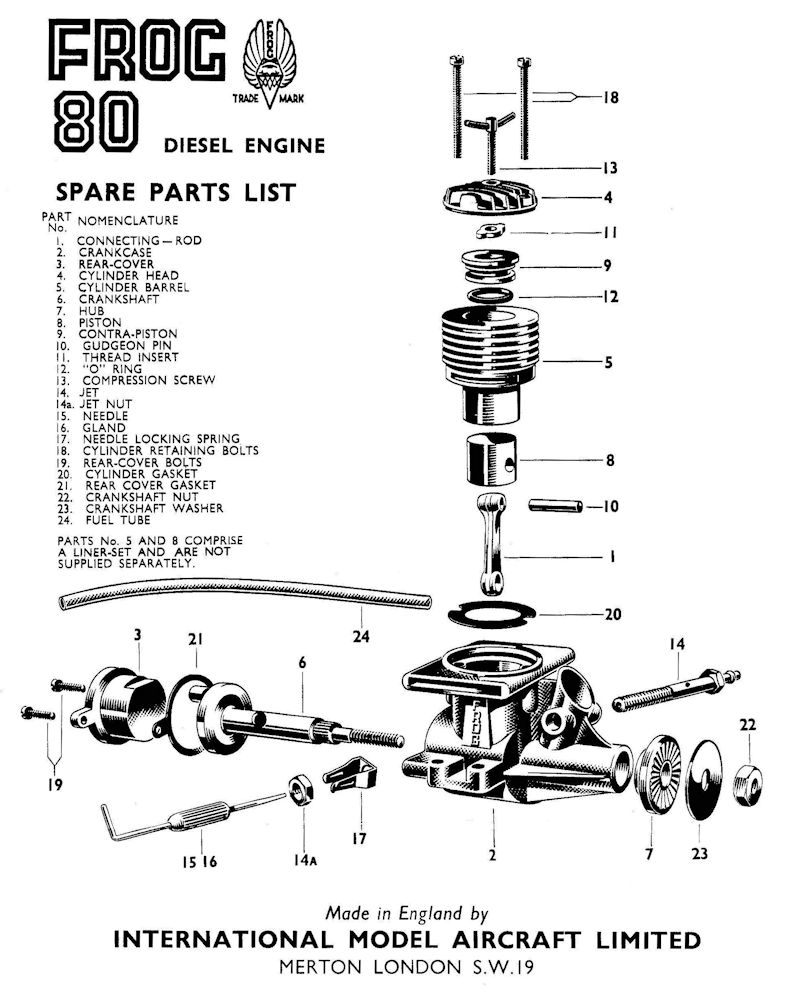

This system works perfectly in practice, although the rather loose "feel" of the O-ring contra piston takes some getting used to. Chinn upheld the system quite strongly in his test report, stating that it functioned extremely well in operation. He recalled having defended the use of O-rings in the earlier McCoy and OK diesels, seeing no reason to change his views. He also mentioned that the O-rings in question were manufactured by the Burtonwood Engineering Co., who had reportedly estimated the working life of the O-rings at something in excess of 100 operating hours. The absence of any real friction between the contra piston and the cylinder meant that compression run-back would be a major problem in the absence of any means to control it. To deal with this issue, the Frog 80 featured a nylon insert in the cylinder head which gripped the comp screw sufficiently tightly to maintain the compression setting under all normal operating conditions. This idea too was borrowed from the McCoy and OK Cub diesels, although the material used was different. It is very effective in practise, and the idea was also applied to the later FROG 349 models, albeit without the O-Ring seal on the contra-piston. Turning now to the porting, the cylinder is provided with twin opposing exhaust slots sawn through the substantial exhaust port flange. These two ports feed directly into the two exhaust stacks, one on each side. Twin opposed transfer slots are provided fore and aft immediately below the exhaust flange at 90 degrees to the exhaust ports. The two apparent bypass passages cast beneath the exhaust stacks at the sides are in fact dummies - the bypass is actually formed by the space between the inner crankcase wall and the lower cylinder outside wall. This space is interrupted at two points fore and aft by the expansions for the hold-down screws. Somewhat awkwardly, these interruptions occur directly in front of the two transfer slots, which are partially obstructed and are in effect fed from both sides as a result. The flat-topped cast iron piston is of relatively lightweight construction. The 0.125 in. diameter gudgeon (wrist) pin links the piston to a forged alloy connecting rod. This in turn connects to a one-piece steel crankshaft through a 0.141 in. diameter crankpin machined in a single piece with the plain unbalanced crankdisc and the crankshaft journal. The main journal diameter is a nominal 0.250 in. (6.35 mm) with a 0.140 (3.56 mm) diameter central gas passage allied to a round crankshaft induction port. It appears that IMA may have experienced problems with shaft breakages with the earlier examples, since the diameter of the central gas passage was later reduced to 0.125 in. (3.17 mm), presumably to increase the strength of the shaft by increasing the wall thickness. The shaft runs in a plain bearing formed directly in the material of the crankcase casting. The aluminium alloy prop driver is secured by being force-fitted over a splined protrusion at the front of the shaft behind the prop mounting thread. A conventional prop nut and washer are used to retain the airscrew.

The backplate is another pressure die-casting in light alloy which is held in place by a pair of 8 BA screws and is fitted with a gasket to ensure a seal. No tank was fitted as supplied, but an accessory back tank was offered from the outset as an optional accessory at a cost of 3s 6d (18p). This was completely fuel-proof, being made of nylon with a metal front face. It was secured by the same two screws that held the backplate in place. This tank remained available for the duration of IMA's manufacture of the FROG 0.8 cc models, but none of the various diesel models were ever at any time supplied with tanks out of the box - they remained optional accessories throughout. Since the previously-mentioned price war between British manufacturers was now well and truly underway, the new FROG engine was clearly designed with a view towards minimizing production costs. For instance, the only machining done on the crankcase casting was the reaming and honing of the main bearing to fit, the drilling of the mounting holes and the drilling and tapping of the four holes for the various assembly screws.

All of the engines carried hand-engraved serial numbers, in keeping with other FROG designs. No attempt was made by IMA to distinguish between different models through the use of model identification letters in the serial number - the engines of each type simply started at one and went on up from there. This of course created duplicate serial number sequences among the various models produced by IMA. The highest FROG 80 Mk. I serial number of my present acquaintance is 14021, strongly suggesting that at least that many were made. But overall production could have been substantially higher - my present sample is far too small to provide conclusive information in that regard. It's worth noting that the later examples of the FROG 80 Mk. I are very slightly different from the earlier ones - my own illustrated engine number 9710 (which is NIB) exemplifies this minor variant. The cylinders and comp screws of these examples were blued rather than being left in their natural steel finish, while the cylinder head die was amended to create a slightly taller component with an emergent hemispherical top interrupting the fins, together with a longer comp screw spigot. In addition, these engines featured the previously-mentioned smaller 0.125 in. diameter central gas passage in the crankshaft. But these changes are insufficient to justify calling this a different model - it's merely a point of which to be aware. 1959—the British ½A Glow-Plug Revolution

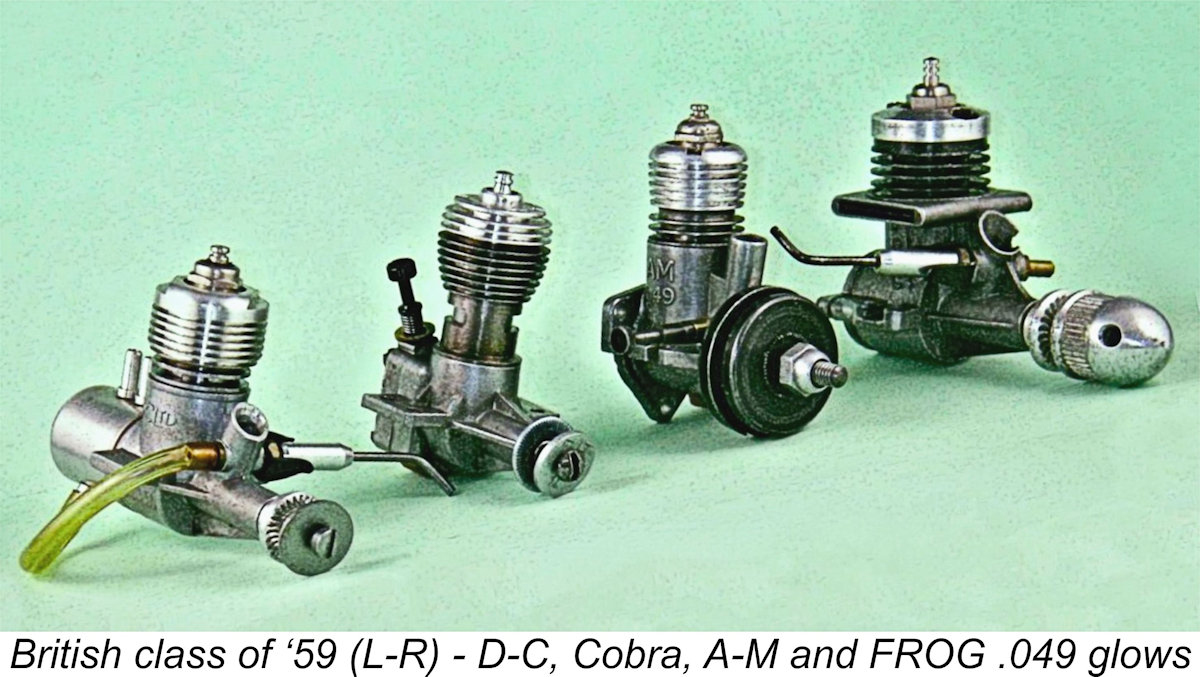

Things got rolling with the early 1959 introduction of the excellent Merco 29 and 35 glow-plug stunt engines, which joined the well-established but now rather antiquated FROG 500 in this category. This widely-publicized event showed British modellers that domestic manufacturers were fully Moreover, the importation of the excellent glow-plug motors being produced in Japan by O.S., Enya and Fuji (among others) was on the rise, spurred on by some very positive published test reports and high-profile contest successes. In addition, the growing popularity of radio control was making British modellers increasingly aware of the superior throttling characteristics of glow-plug engines. Taken together, these initiatives resulted in the British marketplace becoming increasingly receptive to the broader use of glow-plug ignition in place of the hitherto almost universal diesel. In the smaller displacement categories, the importation to Britain of the Cox range of ½A (.049 cuin.) glow- In early 1959 a number of British manufacturers evaluated the situation, deciding pretty much simultaneously to enter the ½A glow-plug motor market themselves. This led immediately to a virtual replay of the 1951-52 half-cc diesel revolution, albeit this time with ½A glow-plug motors as the contestants. One of the participants in this chain of events was of course International Model Aircraft.

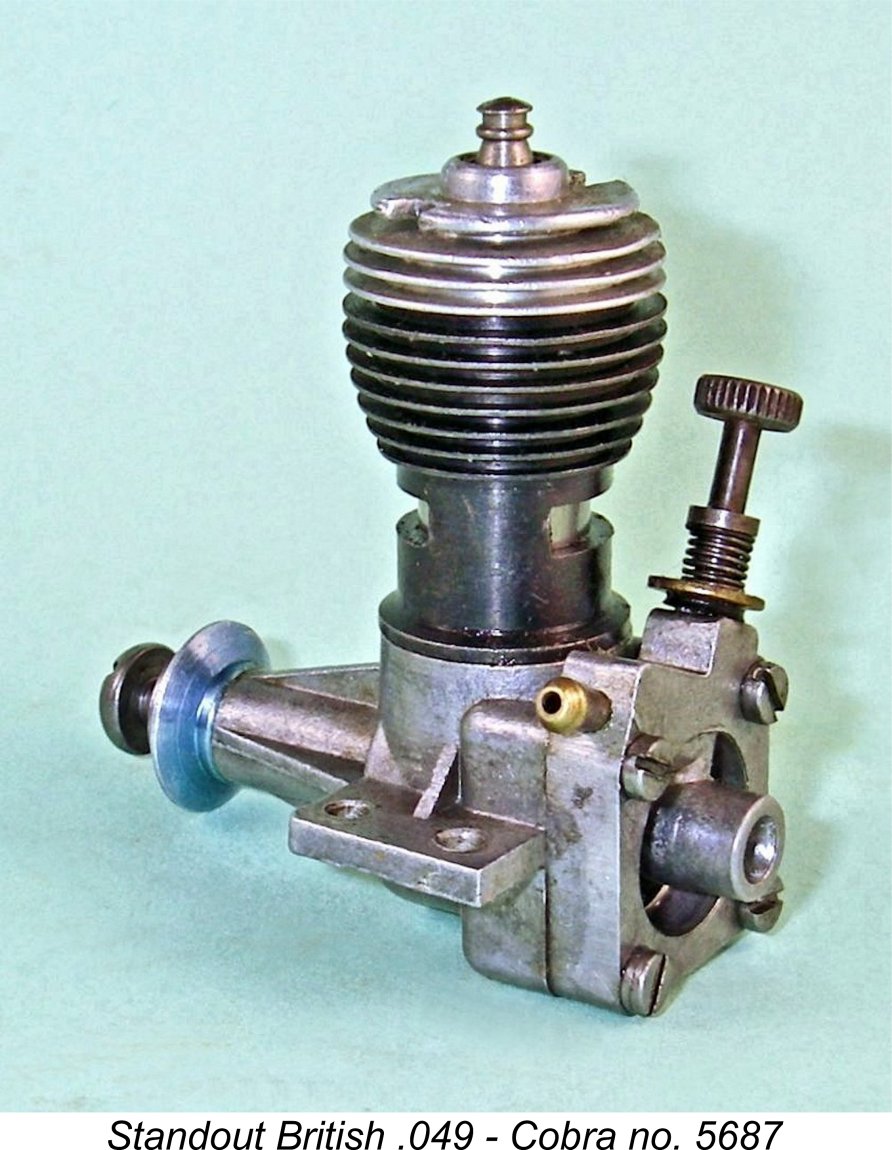

However, the only company to take this route was John Rodwell Ltd. of Hornchurch, Essex with their Cox-influenced but nonetheless original Cobra .049 which was marketed in association with KeilKraft. In many respects this was the best of the British ½A glow-plug contenders, although it did not meet with the success that it deserved, fading from the scene quite quickly. See my companion article on the Cobra for more information.

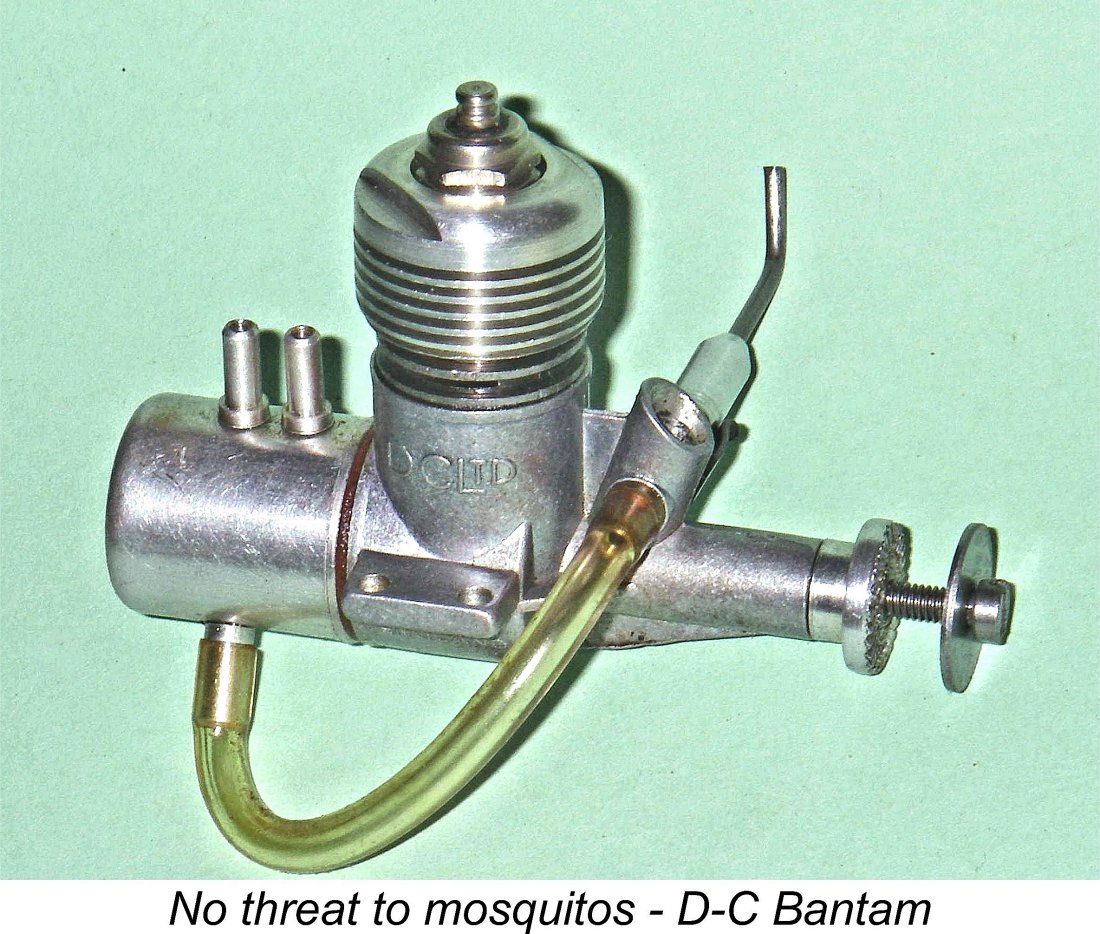

The third possibility was to take the very simple route of producing a glow-plug version of an established diesel design already on the company's books. This was a time-honored approach on the part of British manufacturers, having been adopted at various times by such makers as E.D., Davies-Charlton, Allbon, Kemp, AMCO and J.B., to name just a few. Such an approach had the benefit of side-stepping the bulk of the development costs very nicely. It would maximize the use of components and tooling which were already in the company's production program, thus minimizing production costs. However, there was a downside - experience over the years had clearly demonstrated that the simple switch from diesel to glow-plug ignition rarely resulted in the best-possible performer. None of the earlier glow-plug conversions of diesel models had matched their diesel progenitors in performance terms. Nonetheless, this was the route taken by both D-C Ltd. and IMA with their D-C Bantam and FROG .049 models respectively. It's been a while coming, but at long last we're finally ready to take a look at IMA's entry into the 1959 British ½A glow-plug sweepstakes - the FROG .049 1959 - The FROG .049

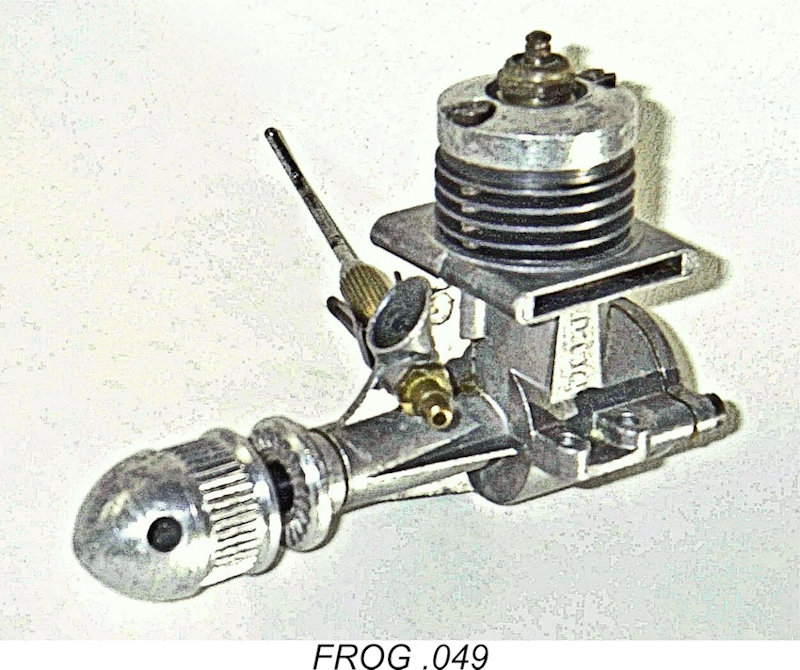

For better or worse, IMA had decided that the line of least resistance towards the development of their own .049 cuin. glow-plug model lay in simply converting their existing and well-proven 80 diesel model to glow-plug ignition. However, it is to the credit of IMA's chief engine designer George Fletcher that he seems to have realized that a direct conversion might not yield the best results. Accordingly, while IMA management evidently directed Fletcher to control costs by maximizing the use of components of the 80 diesel which were already in IMA's production program, Fletcher was given sufficient leeway to permit experimenting with changes in the cylinder arrangements to maximize the engine's potential in glow-plug form.

Obviously, the first things to go were the contra-piston and diesel cylinder head. A revised un-finned head was produced from turned aluminium alloy. This alone seems to indicate that the manufacturers anticipated relatively low production figures for the FROG .049 - a casting produced by a modified diesel head die would have made more sense if large-volume production was anticipated. The head was secured by the same two-screw arrangement which had been used in the 80 diesel, with no supplementary screws to further seal the head to the cylinder. It was centrally drilled and tapped for a short-reach glow plug, with a combustion chamber of hemispherical form. It was deeply spigoted into the upper cylinder, thus largely filling the space vacated by the missing contra-piston. A gasket was used to create a seal.

The steel cylinder itself was also changed quite significantly. The twin opposed exhaust ports were considerably larger than those used on the FROG 80 diesel, being both wider and taller. In addition, the length of the cylinder below the exhaust port flange was slightly shortened. The piston used in the .049 had a slightly higher crown and a consequently longer skirt than that of the 80, the net result being a slightly later opening of the exhaust ports in the .049 compared with the 80. This later exhaust opening was made possible both by the larger port area and by the fact that the transfer arrangements were also substantially altered. In place of the two horizontal transfer slots milled fore and aft into the lower cylinder of the 80 diesel, there were now four upwardly-angled drilled holes arranged fore and aft in pairs between the two exhaust slots. As with the FROG 80, these were fed from the space between the inner wall of the upper crankcase and the outer wall of the lower cylinder, but now there was one transfer hole on each side of the two protrusions which accommodated the cylinder hold-down screws. The presence of those two protrusions thus became irrelevant in terms of gas flow. More importantly, the revised transfer port design allowed for a degree of overlap between exhaust and transfer, something which had not been possible with the original design. Hence the slightly later exhaust opening could be accomplished with no loss in transfer duration - in fact, the .049 had a slightly greater transfer period than the 80 despite the taller piston crown.

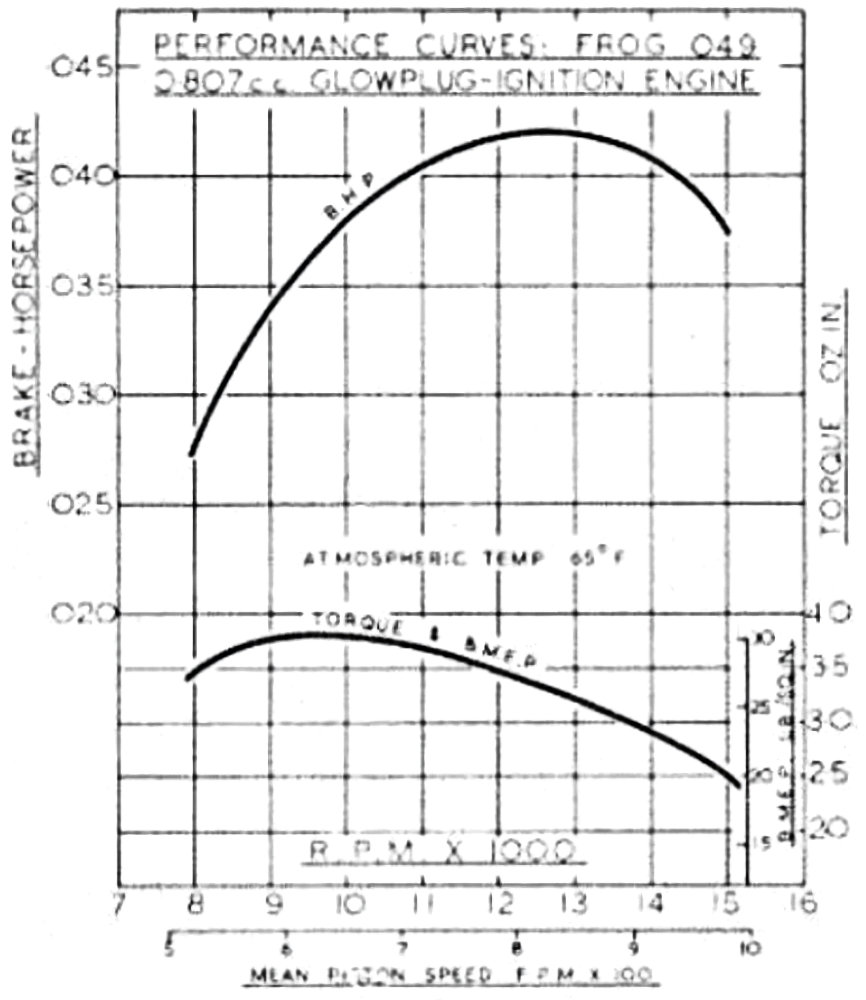

The only other change was the replacement of the standard prop-nut and washer of the 80 with a rather bulky turned and knurled aluminium alloy spinner nut. This was provided to allow owners the option of using a cord to pull-start the engine, assisted starting being something of a competitive preoccupation with British model engine manufacturers at the time. In reality, the engine was such an easy hand-starter that measures of this sort were quite unnecessary - all the spinner did was to add extra bulk and weight to the engine. In all other respects, the FROG .049 was identical to its 80 diesel stablemate. Bore and stroke were unchanged at 10.16 mm and 9.91 mm respectively for a displacement of 0.804 cc (0.049 cu. in.). As one would expect, the glow-plug version was very slightly lighter than its diesel counterpart at 51 gm (1.8 ounces). It would have been a little lighter yet if it hadn't been for that overly bulky spinner nut......although that could easily be replaced if desired. As it was, the FROG .049 was the heaviest and by far the most bulky of the various British ½A glow-plug contenders. It was also the only one which could be directly compared with the diesel model upon which it was based given the fact that both versions had identical displacements (unlike the similarly-related D-C Dart and Bantam) and shared many components. Let's see how it fared in that respect. The FROG .049 On Test Oddly enough, there was a considerable delay between the appearance of the FROG .049 and the publication of its first test. Initial tests of new British models usually followed hard on the heels of the engines' introduction, but not so in this case. Peter Chinn and “Model Aircraft” were first into print, with Chinn's test of the FROG .049 appearing in the December 1959 issue, a month in advance of the publication of Ron Warring's test in the rival “Aeromodeller” magazine. This was some seven months after the engine's initial appearance - most unusual! Chinn's report was interesting insofar as he found that starting, while very dependable, was not quite as quick as might be expected. He reported that after priming, some 30 seconds of flicking were typically required to achieve a start, and even cord starting required up to five pulls. I can only comment that this is completely contrary to my own experience - on the basis of three examples of my direct hands-on acquaintance, I've found that the FROG .049 is one of the easiest starting small engines of them all, with only a couple of leisurely flicks being required following a prime and a hand-turn to get a "bump" in the usual glow-plug fashion. The thought occurs that perhaps Chinn had a plug problem....... or maybe his example of the engine was flawed in some subtle way?

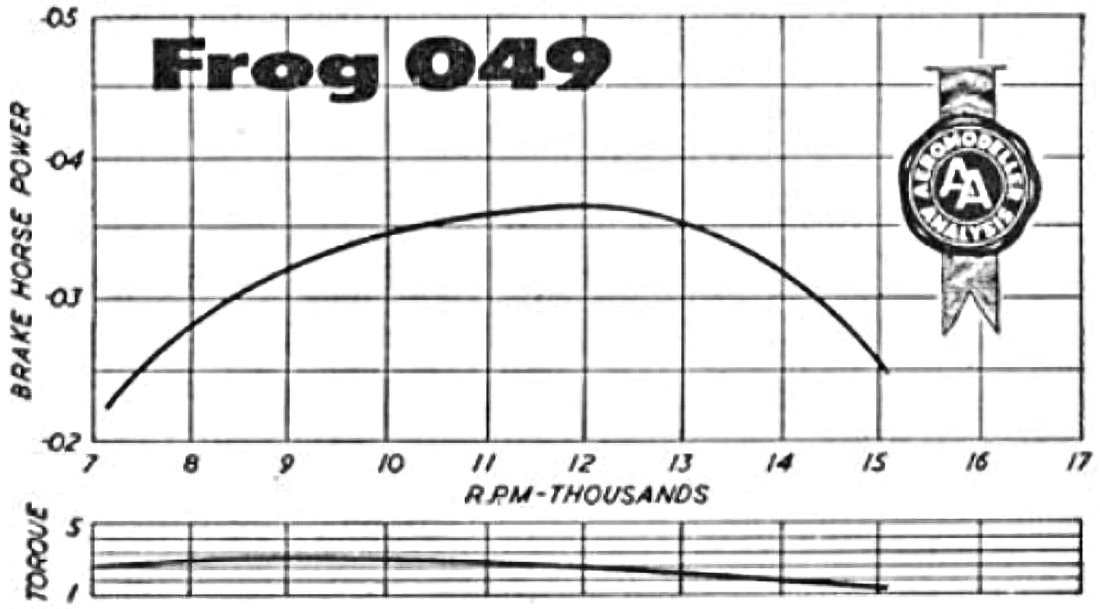

Runing on FROG Red Glow Plus fuel (which I believe to have contained 15% nitromethane), Chinn reported a peak power figure of 0.042 BHP at around 12,700 rpm. This output is some 33% down on that obtained by Chinn in March 1957 for the 80 Mk. I diesel, albeit at slightly higher revs. It is however significantly higher than the figure obtained by Chinn a few months later for the rival D-C Bantam. Chinn could only extract 0.035 BHP at 12,600 rpm from that notably anaemic model. Chinn refrained from giving his usual closing summary of the engine's qualities - he confined himself in this instance to simply reporting the facts recorded during his examination and subsequent test. Reading between the lines, one gets the impression that he was somewhat underwhelmed by the FROG .049! “Aeromodeller” magazine may have been beaten to the punch on their test of the FROG .049, but they more than made up for this in the following month by publishing an unusual triple test in their January 1960 issue. This was a head-to-head encounter between the three British glow-plug .049 contenders which had successively appeared during 1959 - the FROG .049, A-M .049 and D-C Bantam. Warring's tests of the D-C and A-M offerings scooped Chinn's by several months. However, it would appear that in their haste to get these tests into print, “Aeromodeller” fell headlong into a trap when it came to the D-C Bantam - all the evidence points to the near-certainty that they knowingly or otherwise tested the prototype version of the Bantam, which had a far higher performance than the production model. This led to greatly inflated expectations of the Bantam among contemporary modellers, which were brought crashing to the ground both by actual experience with the engine and by Chinn's far more representative test report which appeared in the March 1960 issue of “Model Aircraft”. The credibility of both Warring and D-C Ltd. was undoubtedly harmed by this incident given the near-certainly that D-C Ltd. must have realized what had happened but said nothing. See my separate article on the Bantam for the gory details.

Once again, we see the typical pattern of tests on the same engine conducted by the two individuals - Chinn recorded both a higher peak output and a higher peaking speed than Warring. However, it’s interesting to note that the proportional shortfall in peak power recorded by both individuals for the .049 compared to the 80 diesel is very similar - Warring recorded a 28% shortfall as compared with Chinn's 33%. In that respect, the two tests are quite consistent. In summary, IMA's decision to join the ranks of the British .049 glow-plug manufacturers by simply converting their existing diesel model had seemingly backfired. The direct consequence of their taking this approach was that they ended up with the heaviest, most expensive and most bulky of the various contenders, and moreover one which didn't approach the performance of its diesel counterpart. Hardly a recipe for success! The FROG .049 in the Marketplace - a Personal Recollection

Having already developed a sense of curiosity regarding glow-plug engines, I read Ron Warring's January 1960 triple test in “Aeromodeller” with great interest. I have to confess that Warring's report left me feeling quite indifferent to the FROG .049 - it was by far the bulkiest, heaviest and most costly of the three contenders as well as being the least sturdy performer of the group, based on Warring's comparative figures. In addition, I already had an "experienced" but still very servicable FROG 80 diesel, which clearly outperformed the .049 glow version by a considerable margin. Why switch?!?

At that point, the damage was done - I was off the Brit ½A glows and back to using my trusty little diesels. Even so, I would probably have given the far more progressive Cobra .049 a try, but it never showed up in any of the hobby shops in my area.

IMA did make quite serious efforts to promote the engine. They continued to feature it front and centre in their advertising throughout much of 1960, offering it in two forms - the basic no-frills model at £2 9s 6d (£2.47) and the so-called "Presentation Set" version at £2 17s 6d (£2.87). The latter offering included the accessory back tank mentioned earlier as well as a tommy bar for the spinner nut and a matching FROG airscrew. However, the engine itself was unchanged. This was the sole offering of any of the FROG 0.8 cc models which included the tank. IMA also developed flying model kits specifically intended for the FROG .049.

IMA management must have been painfully aware of this situation. The fact that they never rolled the price of the FROG .049 back to match seems to indicate that they had no leeway to do so if they were to maintain a reasonable profit margin. Evidently, they had only two alternatives - either sell the engine at the established price or concede defeat and withdraw it.

This is a good illustration of an often-overlooked outcome of the price war between British manufacturers which had been instigated by Davies-Charlton Ltd. and had now been raging for some time. British modellers at the time were more than happy to take advantage of this situation, but failed to see the long-term negative effects arising from the consequent erosion of profit margins to a bare minimum. In the context of the relatively small British market, there was now little economic justification for the development of new models - the necessary financial incentives simply weren't there. As a result, British manufacturers had now entered a period of standing pat on their existing designs or minor variants thereof, leading to complete stagnation in the face of more progressive developments elsewhere. It's a little ironic that both D-C Ltd. and IMA, who had done much to provoke this price war, were both eventually engulfed by its effects. Apart from the commercial aspect, the real crusher was the inescapable fact that the FROG .049 was after all simply a glow-plug version of an established diesel. That model was considerably more powerful than its .049 glow relative and moreover cost less. So why would anyone contemplate a switch?!? Looking at things in light of the above comments, it becomes crystal clear in hindsight that the FROG .049 never really had a chance once the various competing models arrived on the scene. Although it appears that IMA continued to sell the engine in limited quantities for some time, by early 1961 the FROG .049 had disappeared from their advertising. 1961 - the FROG 80 Mk. II The changes to the cylinder of the FROG 80 to produce the FROG .049 left IMA in a situation in which they were producing two very similar engines which differed mainly in their cylinder and cylinder head arrangements. There would be clear cost benefits if the commonality of parts could be further increased. In particular, utilizing a common cylinder would represent a real saving. In late 1960, IMA finally decided to do something about this. The result was the early 1961 appearance of the FROG 80 Mk. II diesel. The main change from its Mk. I predecessor was the adoption of the .049 cylinder with its larger exhaust ports and drilled transfer ports in place of the smaller exhausts and milled transfer slots used in the original 80 cylinder. This resulted in the only externally-visible difference between this version and its predecessor - there was one less cooling fin to go along with the slightly taller head which was carried over from the later examples of the FROG 80 Mk. I. Despite this change, the piston of the original 80 was retained unaltered. It will be recalled that this component had a lower crown than the taller piston used in the .049. The result was earlier opening of both the exhaust and transfer ports by comparison with both the original 80 Mk. I and the .049. Presumably this change was driven largely by the need to create more space above the piston crown at top dead centre to accommodate the contra piston. Another change was the dropping of the O-ring contra piston in favor of a conventional lapped component - although this must have represented an increase in production cost, customer feedback had evidently shown that die-hard diesel users preferred the "feel" of a lapped contra. Apart from these amendments, the FROG 80 Mk. II was unchanged from its predecessor.

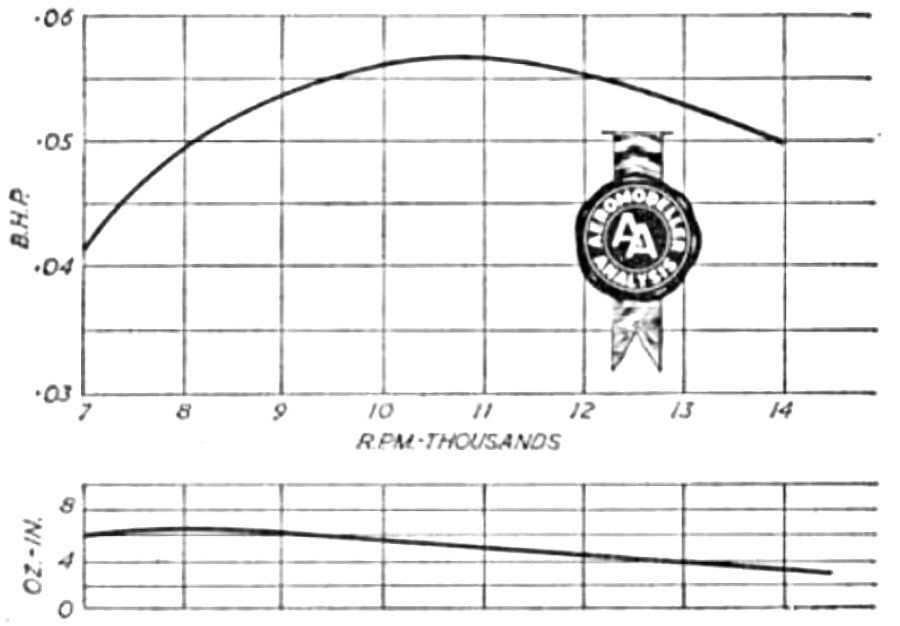

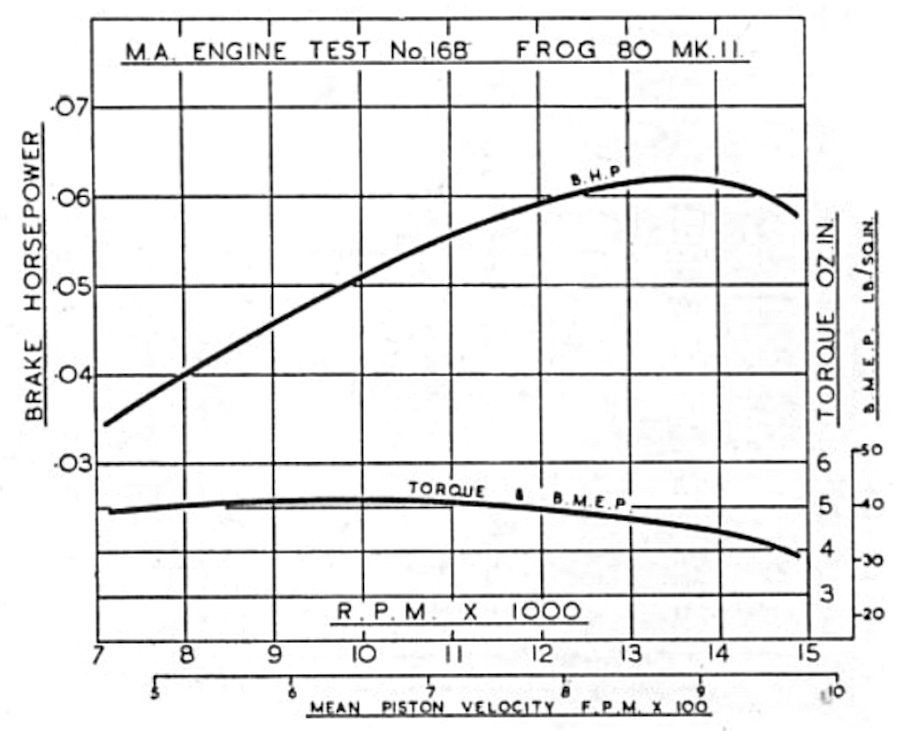

This variant was the subject of a further Ron Warring test report which appeared in the November 1961 issue of “Aeromodeller”. Once again, Warring was generally very complimentary regarding the engine's handling and running qualities, although he commented on the increased noise level resulting from the earlier exhaust port opening! The accompanying power curve above at the left confirms that Warring was able to measure a modest but nonetheless useful performance improvement, finding a peak output of 0.057 BHP @ 11,000 rpm - roughly a 10% improvement in output. The peaking speed was unchanged from the figure obtained by The rival “Model Aircraft” magazine countered Warring's report with their own test of the FROG 80 Mk. II by Peter Chinn. This appeared in their November 1961 issue opposite Warring's "Aeromodeller" test. The power curve reproduced at the right confirms the fact that Chinn was able to report a peak output of 0.062 BHP, fractionally down from the 0.064 BHP measured in 1957 for the FROG 80 Mk. I but at a significantly higher speed of 13,600 RPM as opposed to 11,800 RPM. Once again, the reported results from the two rival testers followed the established pattern of Chinn extracting somewhat superior figures to those reported by Warring. However, the difference is far more marked than usual in this instance, particularly with respect to peaking speed. This leaves me wondering if Warring somehow got a flawed example to test. We'll never know!! 1962 - a Change of Manufacturer The FROG 80 Mk. II diesel continued to be produced by IMA into the first half of the year 1962. At that point, however, things changed completely when a decision was taken by Lines Brothers, the parent company of IMA, to end production of the entire FROG line-up of flying model kits and engines. The reasons for this decision are now obscure, but presumably the flying model side of IMA's business simply wasn't seen as sufficiently profitable to justify its continuation - no doubt the aforementioned price war contributed to this At the time when IMA's production of the FROG model engine range ceased, significant stocks of completed engines and parts remained on hand. These continued to be sold off by the A. A. Hales organization of Potters Bar in Hertfordshire, just north of London. The June 1963 advertisement which is reproduced here at the left is a typical Hales placement of this period. Hales were one of IMA's major distributors, also producing their own range of model kits under the "Yeoman" label - anyone remember the "Dixielander", the "Bantam Cock", and the "Scorcher"? They later became a full member of the Lines Group of companies. The cessation of engine production by IMA left George Fletcher looking for fresh employment, which he soon found with the nearby E.D. company at West Molesey. Interestingly enough, he replaced his former IMA colleague Gordon Cornell as chief designer for E.D., the latter having joined E.D. in 1959 and left in 1961 following some philosophical differences of opinion with the then-current E.D. management. As a result of their ongoing marketing of the existing stocks of FROG engines, the Hales organization clearly detected a level of continuing demand for the FROG range which would not be met solely through the liquidation of existing stocks. In 1964 they became a full member of the Lines Group, at which point arrangements were made with Lines Brothers to have all of the FROG engine designs, dies and tooling transferred to IMA's old rivals D-C Ltd. on the Isle of Man. Thenceforth the FROG engines were manufactured by D-C Ltd. under contract to A. A. Hales. The FROG 80 Mk. II diesel was one of the models initially manufactured by D-C Ltd. under this arrangement.

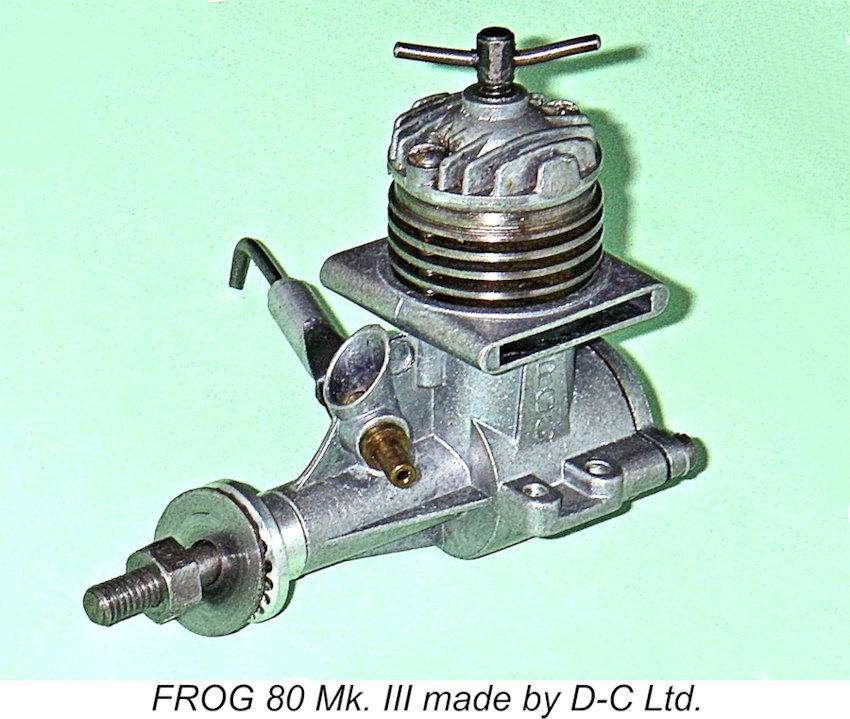

It must be said that the quality of the FROG engines appeared to suffer somewhat by the change of manufacturer. It's my personal impression that the 80's (and other FROG models) made by D-C Ltd. never quite matched the IMA originals for consistency in terms of quality. However, they generally worked OK, while at least spare parts continued to be available for a few more years. Examples of the FROG engines manufactured by D-C Ltd are easily identified by the fact that they carry a model identification letter in front of the serial number. It appears that when A. A. Hales arranged for D-C Ltd. to resume production, they re-started the serial number sequence for each model at 1, simply adding a letter prior to the number to define the particular model. As far as I can determine, the identification letters were as follows:

† Probably assembled from existing parts by D-C Ltd rather than manufactured by them.

It's actually possible that the examples of the FROG 80 Mk. II produced by D-C Ltd. were also assembled from existing parts rather than being manufactured by D-C Ltd. The Mk. II engines produced by D-C Ltd. may be distinguished from the IMA-manufactured examples by the C prefix attached to their serial numbers. The only such Mk. II serial number of which I’m presently aware is C8860, which was NIB with all papers and thus had excellent provenance. As will be seen shortly, we know that D-C Ltd. didn't manufacture the FROG 80 Mk. II for very long. This being the case, the magnitude of this number implies that D-C Ltd. did not restart the serial number sequence in this case, probably because they were already contemplating the replacement of the Mk. II with a further updated model. If this view is correct, then the possibility exists that a combined total of perhaps as many as 9,000 examples of the FROG 80 Mk. II may have been produced by IMA and D-C Ltd. during the three-year period between early 1961 and early to mid 1964. We'd need a good few additional serial numbers to be any more definite than that. 1964 - the FROG 80 Mk. III

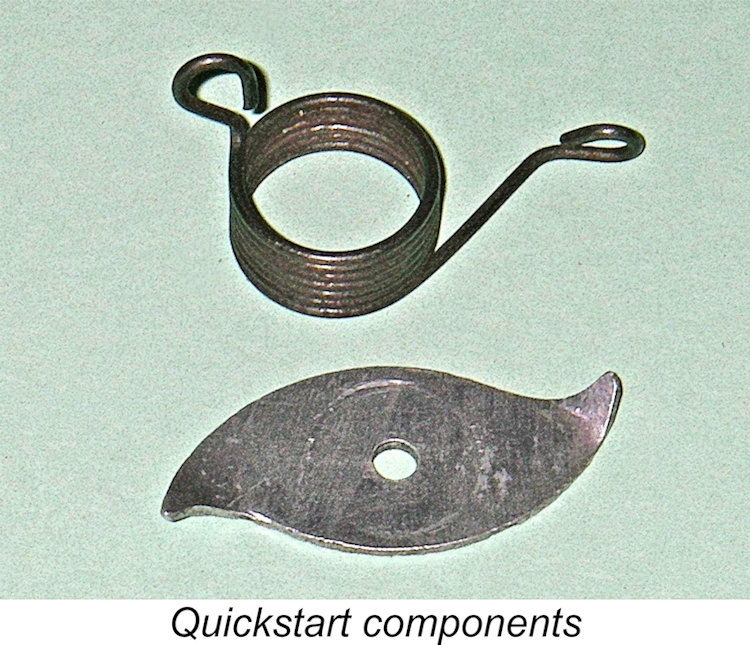

In reality, the engine was little changed from the earlier FROG 80 Mk. II. It featured the same porting and structural arrangements, with most of the components remaining interchangeable between the two models. However, both the exhaust and transfer ports were further enlarged. In addition, the hardened steel cylinder was stiffened somewhat through a thickening of the integrally-machined cooling fins which continued to be used, the number of these fins being unchanged. The top edge of the upper cylinder flange was slightly beveled as well, while the cylinder overall was some 0.025 in. longer than that of the Mk. II.

The only other apparent change was the use of a standard D-C needle valve assembly instead of the former IMA item with serrated brass thimble. The overall result was a really nice little diesel with a further-enhanced performance courtesy of the slightly enlarged ports. Thanks presumably to the inclusion of the starter spring set-up, the selling price had crept back up a little to £2 4s 6d (£2.22), but that was still a reasonably competitive price allowing for inflation. Although it was never tested in the contemporary modelling media, there's little doubt that the Mk. III FROG 80 diesel was the best version of that engine ever to appear - both Kevin Richards and I agree on that point on the basis of direct experience with multiple examples. They are really good runners! End of the Road As the 1960's drew on, it became increasingly obvious to most modellers that a number of the old-established British model engine ranges such as E.D., D-C and FROG had stagnated to the point where they had become increasingly out of step with the evolving modelling marketplace. New models were eagerly awaited from established British manufacturers, but they failed to materialize for the most part, almost certainly for the economic reasons discussed earlier. Moreover, R/C flying was now predominant in place of the formerly popular control- It was inevitable that any model engine range which was based on "traditional" sports diesels would encounter increasing difficulty remaining afloat in such a marketplace. And indeed this was the case with the FROG range. As far as I can determine, A. A. Hales' final consumer market advertisement for the D-C-produced FROG engines appeared in the April 1966 issue of “Aeromodeller” magazine, as reproduced at the left. Although IMA had continued to produce the FROG plastic kit range in great volume after 1962, they too ceased advertising in “Aeromodeller” after June 1966. This was doubtless driven by the fact that the majority of “Aeromodeller” readers were interested in flying models as opposed to static display creations. Despite this, it appears that plastic kit production continued at some level up to 1971, when the parent Triang company entered receivership and the FROG molds were sold to producers in the Eastern Bloc and elsewhere. Following the collapse of the former Lines Brothers empire, the Tri-ang Works remained dormant on the site at Morden Road until 1973, when the facility was converted to serve as a production centre for a major bed manufacturer, Sleepeezee Ltd. The location was re-numbered 61 Morden Road at this time. Sleepeezee remained at this location until 2008, when the site was cleared and re-landscaped to house the vast Big Yellow Box storage company, which rents storage rooms for the use of business and residential clients. This company continues to occupy the site today. There are no surviving traces of the former Lines Brothers factory, although much of the surrounding area remains in use for industrial purposes. My thanks to Sarah Gould of the Borough of Merton for this information. Since the April '66 ad from A. A. Hales included the FROG 80 Mk. III, that model seems to have survived to the very end of production of the mainstream FROG engine range, having remained in production in various forms for at least nine years - not a bad record! It's presently unclear how long, if at all, production of the FROG engines by D-C Ltd. continued past this point in time. Kevin Richards confirmed that despite the absence of any further advertising, new engines remained available through dealers until at least 1970. Kevin bought brand-new boxed examples of both the 349 BB and the 249 BB from his local hobby shop in that year, and he still had the 249 BB new in the box complete with 1970 date-stamped factory guarantee! This cannot of course be taken as hard evidence of continued manufacture as of that date - it's entirely possible and even likely that Hales and D-C Ltd. were simply selling off New-Old-Stock by that time. But it does confirm that the FROG engines remained available from dealers for a considerably longer period than might be supposed from the advertising evidence alone. This said, it seems almost certain that manufacture of the "classic" FROG engines (including the FROG 80 Mk. III) had ceased by the end of 1970.

In January 1972, Alan Hales bought back the A. A. Hales brand from the Lines Brothers liquidators. A few advertisements for FROG engines were placed thereafter by Hales (February 1972 and September 1972), but these probably represented no more than an effort to liquidate New Old Stock. It seems certain that no new manufacturing was undertaken. The FROG name appears to have finally disappeared from the model engine marketplace by 1973. So ended the final chapter in the 27-year story of a proud name in British model engine history. It's a great shame that it had to end that way, but a combination of changing market conditions along with a failure by management, or perhaps a simple lack of the necessary resources, to respond appropriately to these changes had made the end inevitable. It's a sad fact that far too many pioneering British model engine ranges met a similar fate. Conclusion

The FROG 0.8 cc engines are sturdy and dependable little powerplants which are still well able to offer good service to any owner interested in flying "classic" model aircraft. The Mk. II and Mk. III diesel versions are particularly to be recommended if they are to be used for actual flying. However, all variants of the FROG 80 series are fine collectibles in their own right. The diesel models were made in sufficiently large numbers that good examples remain readily available today on eBay and elsewhere at by no means prohibitive prices. The .049 glow-plug models were manufactured in far smaller numbers, hence being significantly harder to track down, but they are out there (and more expensive when you succeed!). Any of the engines described in this article is well worth adding to any collection of British model engines from the "classic" era. So go ahead - keep your eyes open and grab one if it comes up! You won't regret it! _______________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published on MEN December 2010 This revised edition published here October 2023

|

|

| |

In other articles, I've looked at three of the contenders in the British ½A "glow-plug revolution" which began in mid-1959 and continued for a few years thereafter before almost all of the participating models faded from the scene, leaving the

In other articles, I've looked at three of the contenders in the British ½A "glow-plug revolution" which began in mid-1959 and continued for a few years thereafter before almost all of the participating models faded from the scene, leaving the  So in order to make sense of the FROG .049 story, it's necessary to review the history of the FROG under-1 cc models in general - to do otherwise would be to misrepresent the context in which the FROG .049 came into being. I therefore have to go back some 8 years from 1959 to pick up the thread which led to the successive creation of the FROG 50 and 80 diesels and subsequently the FROG .049.

So in order to make sense of the FROG .049 story, it's necessary to review the history of the FROG under-1 cc models in general - to do otherwise would be to misrepresent the context in which the FROG .049 came into being. I therefore have to go back some 8 years from 1959 to pick up the thread which led to the successive creation of the FROG 50 and 80 diesels and subsequently the FROG .049. The model diesel (or more correctly, compression ignition) engine first appeared in

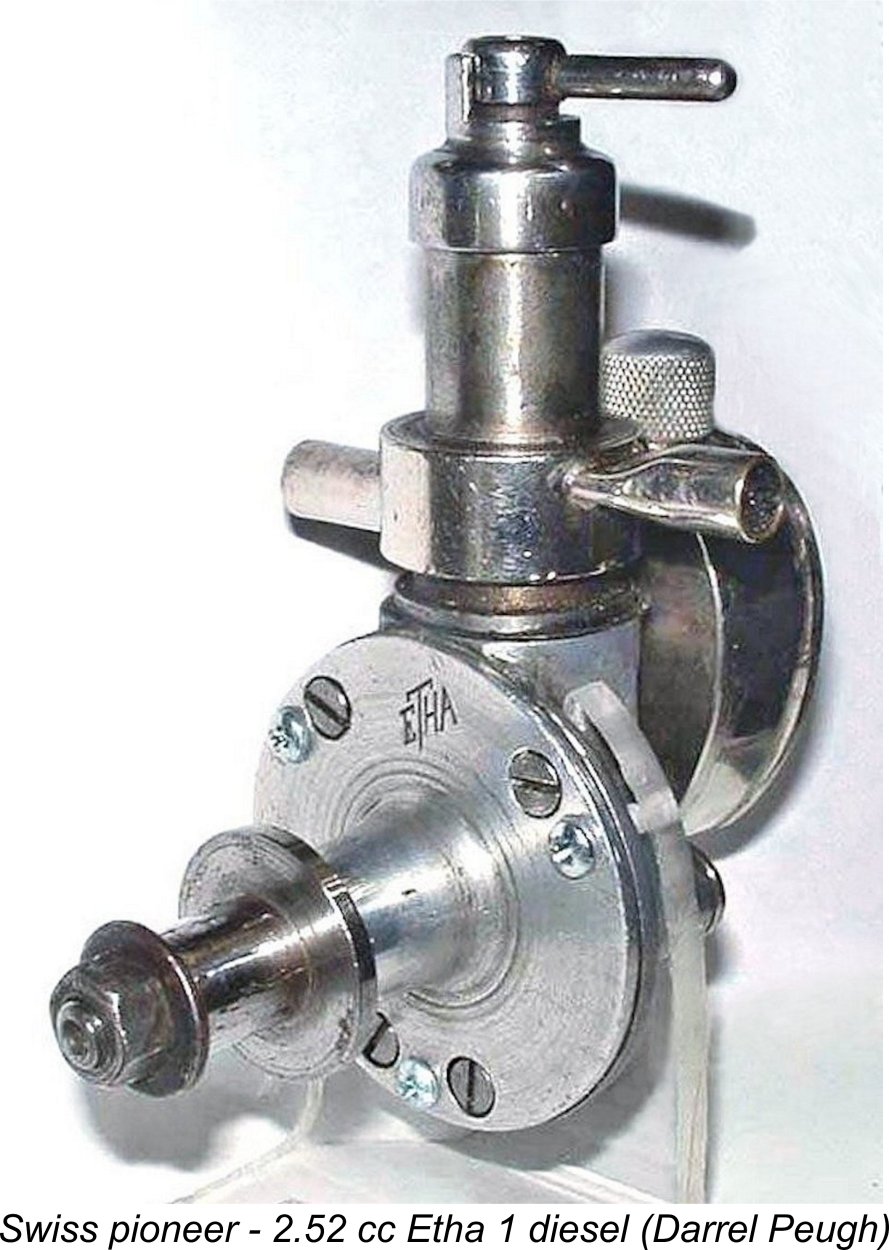

The model diesel (or more correctly, compression ignition) engine first appeared in  As I’ve recounted in a separate article on the

As I’ve recounted in a separate article on the  The first designer to come up with a really effective response to this challenge was

The first designer to come up with a really effective response to this challenge was  Allbon's immediate success with the Dart was by no means lost upon others, and no fewer than three other competing manufacturers (

Allbon's immediate success with the Dart was by no means lost upon others, and no fewer than three other competing manufacturers ( Once again, the lead was taken by Alan Allbon, who was now working in association with D-C Ltd.. Allbon wasted little time in getting to work developing a slightly larger model which gave a bit more urge while retaining much of the compactness of its ½ cc Dart companion. This new design appeared in October 1954 in the shape of the D-C manufactured

Once again, the lead was taken by Alan Allbon, who was now working in association with D-C Ltd.. Allbon wasted little time in getting to work developing a slightly larger model which gave a bit more urge while retaining much of the compactness of its ½ cc Dart companion. This new design appeared in October 1954 in the shape of the D-C manufactured

IMA's initial entry into the ½ cc sweepstakes took the form of the neat and compact little FROG 50 diesel. With its FRV induction, internal flute bypass passages and radial porting, this was basically a scaled-down version of IMA's contemporary 1.5 cc model, the well-established and highly-regarded

IMA's initial entry into the ½ cc sweepstakes took the form of the neat and compact little FROG 50 diesel. With its FRV induction, internal flute bypass passages and radial porting, this was basically a scaled-down version of IMA's contemporary 1.5 cc model, the well-established and highly-regarded

An unattributed mini-test of the

An unattributed mini-test of the  The market entry of the FROG 80 diesel was announced through the publication of a full-page two-tone advertisement in the January 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”, as reproduced at the right. The quoted selling price of the new engine was a very competitive £2 5s 0d (£2.25), matching that of the FROG 50. More engine for the same money!

The market entry of the FROG 80 diesel was announced through the publication of a full-page two-tone advertisement in the January 1957 issue of “Model Aircraft”, as reproduced at the right. The quoted selling price of the new engine was a very competitive £2 5s 0d (£2.25), matching that of the FROG 50. More engine for the same money!

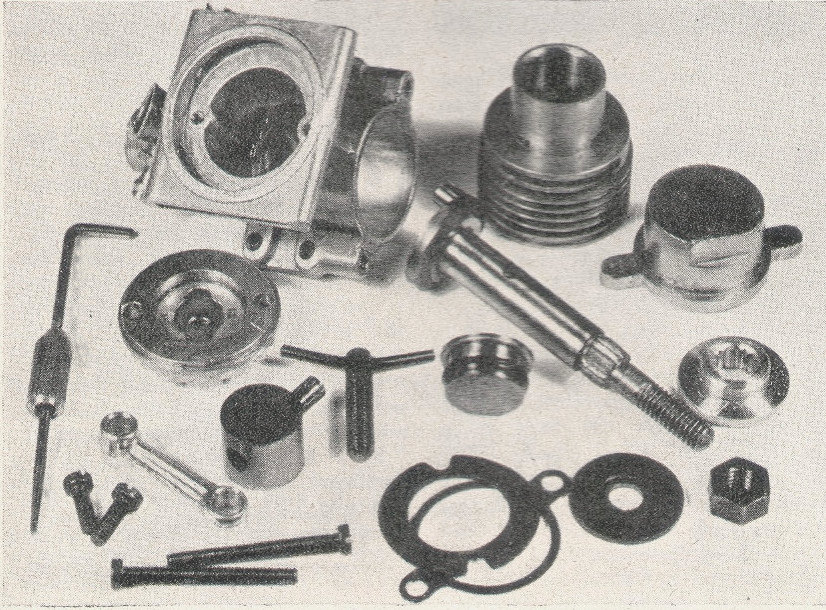

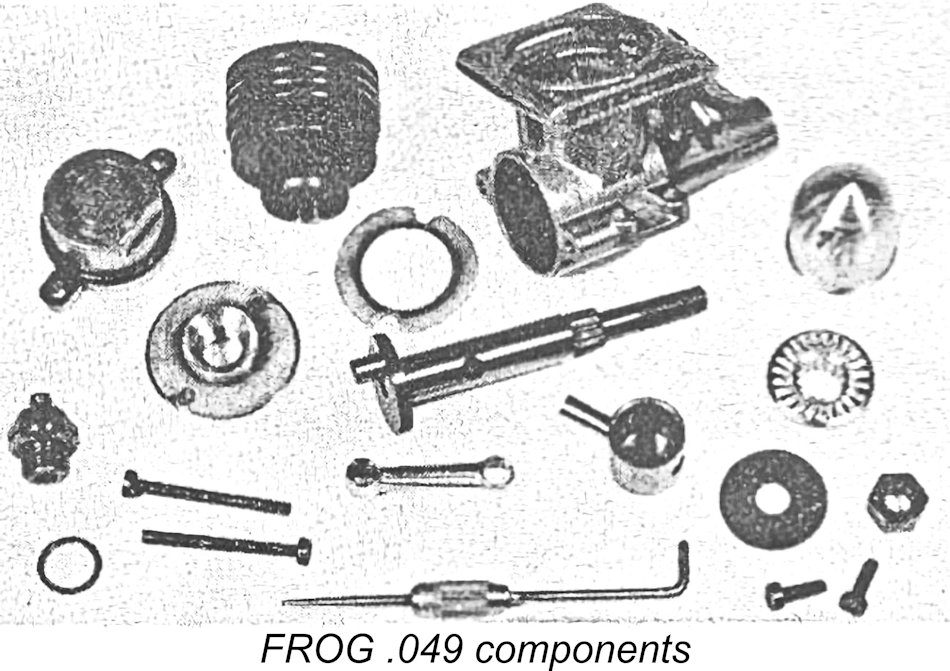

The attentive reader may recall that my primary initial motivation for commencing this review was to describe IMA's entry into the 1959 British ½A glow-plug sweepstakes with their FROG .049. Accordingly, it may seem redundant to dwell at length upon the diesel predecessor of that model. However, this is far from the case given the fact that the FROG .049 was in effect simply a glow-plug conversion of the earlier diesel. Hence an understanding of one informs our understanding of the other. The accompanying component view from the "Model Aircraft" test report as well as the factory parts illustration reproduced below should help to illustrate much of the following description.

The attentive reader may recall that my primary initial motivation for commencing this review was to describe IMA's entry into the 1959 British ½A glow-plug sweepstakes with their FROG .049. Accordingly, it may seem redundant to dwell at length upon the diesel predecessor of that model. However, this is far from the case given the fact that the FROG .049 was in effect simply a glow-plug conversion of the earlier diesel. Hence an understanding of one informs our understanding of the other. The accompanying component view from the "Model Aircraft" test report as well as the factory parts illustration reproduced below should help to illustrate much of the following description.

The steel contra-piston is highly unusual for a British engine in using a synthetic rubber O-ring to maintain a gas seal. It also has a flange at the top which prevents it from being screwed down too far into the bore and risking either pre-ignition or a hydraulic lock - a good "beginner" feature. The design in fact mirrors that used in the earlier McCoy and OK Cub diesels which had appeared in the USA beginning in early 1953.

The steel contra-piston is highly unusual for a British engine in using a synthetic rubber O-ring to maintain a gas seal. It also has a flange at the top which prevents it from being screwed down too far into the bore and risking either pre-ignition or a hydraulic lock - a good "beginner" feature. The design in fact mirrors that used in the earlier McCoy and OK Cub diesels which had appeared in the USA beginning in early 1953. The engine uses a standard FROG 150 needle valve assembly which is angled back and slightly upwards to the right (facing forward). This keeps the fingers well clear of the prop disc but makes sidewinder mounting in a control-line model a bit problematic since the needle cannot be re-fitted from the opposite side. A spring clip engages with a serrated brass thimble to maintain needle settings very effectively.

The engine uses a standard FROG 150 needle valve assembly which is angled back and slightly upwards to the right (facing forward). This keeps the fingers well clear of the prop disc but makes sidewinder mounting in a control-line model a bit problematic since the needle cannot be re-fitted from the opposite side. A spring clip engages with a serrated brass thimble to maintain needle settings very effectively. The result was a well-made, easy starting and individualistically-styled engine having a useful "sports" performance for its displacement and selling for a most reasonable price. Ron Warring characterized it as "a real winner for popular use". And indeed it did find its fair share of buyers over the four years following its introduction, competing with the Allbon Merlin and the Mills .75 for sales in the ¾ cc diesel category. One of my own first diesels was in fact a somewhat "experienced" and extremely second-hand example of one of these engines, and I got a lot of good use out of it once I mastered the art of model diesel starting!

The result was a well-made, easy starting and individualistically-styled engine having a useful "sports" performance for its displacement and selling for a most reasonable price. Ron Warring characterized it as "a real winner for popular use". And indeed it did find its fair share of buyers over the four years following its introduction, competing with the Allbon Merlin and the Mills .75 for sales in the ¾ cc diesel category. One of my own first diesels was in fact a somewhat "experienced" and extremely second-hand example of one of these engines, and I got a lot of good use out of it once I mastered the art of model diesel starting!  It's taken a while, but now we've finally come to the meat of the matter! I noted earlier that throughout the 1950's British modellers had generally remained true to the diesel for all but a few specialized modelling applications. However, overseas progress in the design of glow-plug engines for purposes other than racing was accelerating as the fifties drew on, and by the time 1959 rolled around the stage was set for a major shift in the perception of the glow-plug motor in the eyes of British modellers.

It's taken a while, but now we've finally come to the meat of the matter! I noted earlier that throughout the 1950's British modellers had generally remained true to the diesel for all but a few specialized modelling applications. However, overseas progress in the design of glow-plug engines for purposes other than racing was accelerating as the fifties drew on, and by the time 1959 rolled around the stage was set for a major shift in the perception of the glow-plug motor in the eyes of British modellers. capable of producing world-class engines of that type. The innovative and technically very successful

capable of producing world-class engines of that type. The innovative and technically very successful

Now there were three potential pathways to entry into this market. The first was to develop the company's own design, drawing as always upon the better attributes of established and well-proven designs already on the market but incorporating a blend of such features intended to enhance the engine's attractiveness to British buyers. Although development costs might be expected to be higher, this should by rights result in a better overall design.

Now there were three potential pathways to entry into this market. The first was to develop the company's own design, drawing as always upon the better attributes of established and well-proven designs already on the market but incorporating a blend of such features intended to enhance the engine's attractiveness to British buyers. Although development costs might be expected to be higher, this should by rights result in a better overall design.  Another option was to side-step the entire development process at one fell swoop by simply purchasing the rights to an established design which had already been fully developed and proved by others. This was the route taken by Allen-Mercury. The design with which they became associated was that of the then-current Wen-Mac .049 from America. Their

Another option was to side-step the entire development process at one fell swoop by simply purchasing the rights to an established design which had already been fully developed and proved by others. This was the route taken by Allen-Mercury. The design with which they became associated was that of the then-current Wen-Mac .049 from America. Their  Indeed, IMA had themselves gone this route a few years previously with their

Indeed, IMA had themselves gone this route a few years previously with their  The FROG .049 achieved what may well have been one of the objectives set by the IMA Board of Directors - it was the first of the British .049 glow-plug motors to put in an appearance on the domestic market. The engine was in production by May 1959, being formally announced in July 1959 as reflected in the advertisement which is reproduced here. It thus beat the rival

The FROG .049 achieved what may well have been one of the objectives set by the IMA Board of Directors - it was the first of the British .049 glow-plug motors to put in an appearance on the domestic market. The engine was in production by May 1959, being formally announced in July 1959 as reflected in the advertisement which is reproduced here. It thus beat the rival  As one would expect under these circumstances, the resulting design necessarily remained very similar to the 80 diesel described previously. Accordingly, the bulk of my earlier description of that model applies equally to the .049 glow unit. The accompanying component view may help to remind the reader of the main points. The only major differences were to be found in the cylinder assembly.

As one would expect under these circumstances, the resulting design necessarily remained very similar to the 80 diesel described previously. Accordingly, the bulk of my earlier description of that model applies equally to the .049 glow unit. The accompanying component view may help to remind the reader of the main points. The only major differences were to be found in the cylinder assembly.

Another change was the cylinder finning. The cooling fins were integrally machined as before, but there was now one less fin between the exhaust stacks and the upper cylinder flange, the cylinder itself being slightly shorter and the fins being more widely spaced. The cylinder walls were also fractionally thinner. Finally, the cylinder was blued instead of being left in its plain case-hardened state as before. It seems likely that it was at this point that the companion FROG 80 Mk. I received its own blued cylinder and taller head, as mentioned earlier. The use in both models of the revised shaft with the slightly smaller central gas passage seems also to date from the introduction of the FROG .049.

Another change was the cylinder finning. The cooling fins were integrally machined as before, but there was now one less fin between the exhaust stacks and the upper cylinder flange, the cylinder itself being slightly shorter and the fins being more widely spaced. The cylinder walls were also fractionally thinner. Finally, the cylinder was blued instead of being left in its plain case-hardened state as before. It seems likely that it was at this point that the companion FROG 80 Mk. I received its own blued cylinder and taller head, as mentioned earlier. The use in both models of the revised shaft with the slightly smaller central gas passage seems also to date from the introduction of the FROG .049. Once having got the engine going, Chinn reported even and consistent running, albeit with a slightly higher level of vibration than might be expected. In hindsight, it does appear that this motor with its slightly heavier piston might have benefited from a degree of counterbalance being applied to the crankweb.

Once having got the engine going, Chinn reported even and consistent running, albeit with a slightly higher level of vibration than might be expected. In hindsight, it does appear that this motor with its slightly heavier piston might have benefited from a degree of counterbalance being applied to the crankweb. Returning to the FROG .049, Warring's test was generally very positive - far more so in fact than Chinn's had been. The handling of the engine came in for the highest praise, in stark contrast to Chinn's evaluation but very much in line with my own experience of several examples. The running qualities also came in for positive comment, a view which I can also endorse from personal experience. However, like Chinn, Warring was unable to approach the performance figures which he had obtained almost 3 years previously for the FROG 80 Mk. I diesel. Instead of the figure of 0.051 BHP @ 11,000 rpm for the FROG 80, Warring could only extract 0.037 BHP from the FROG .049 on 15% nitromethane, albeit at a slightly higher speed of 12,000 rpm.

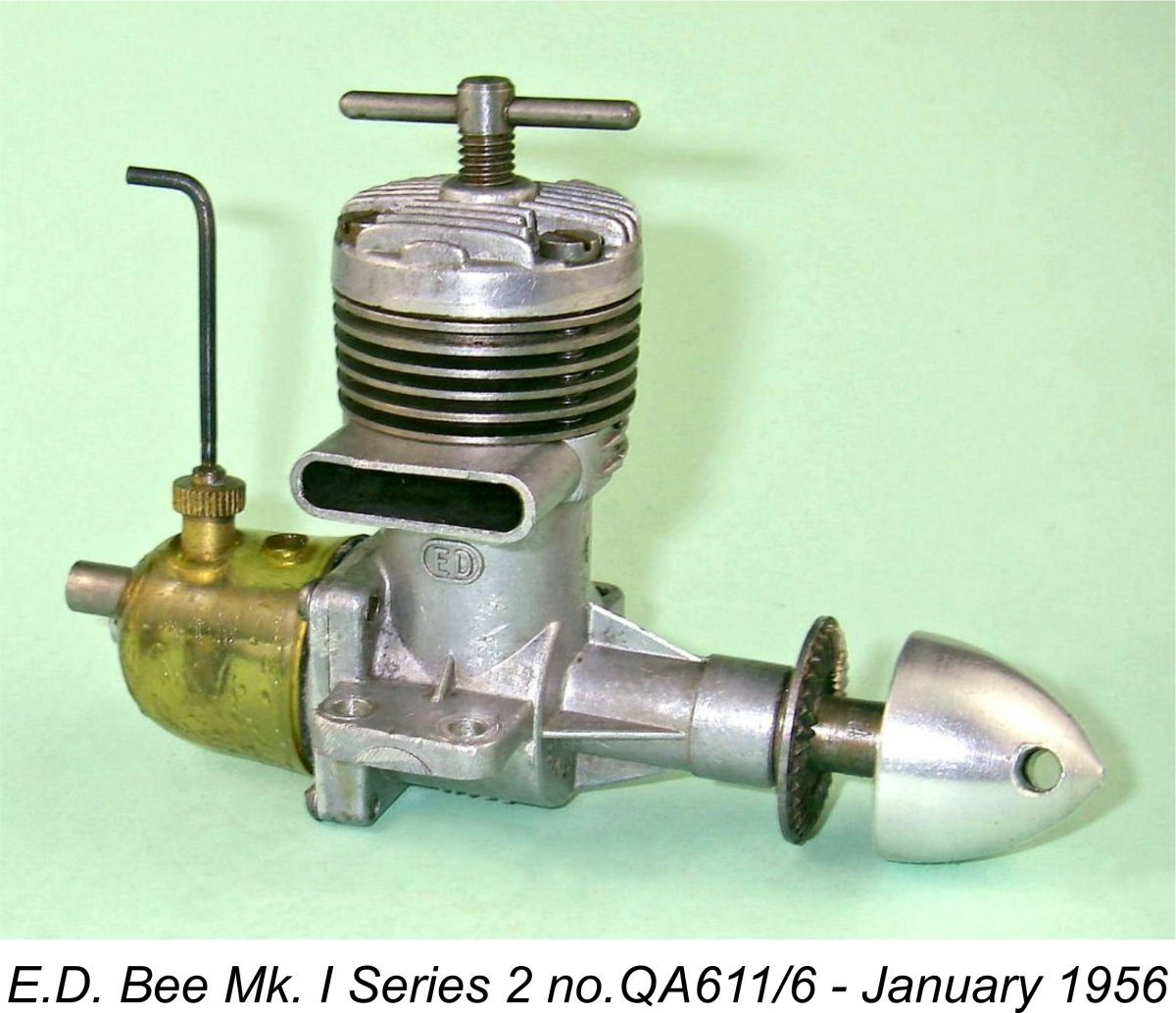

Returning to the FROG .049, Warring's test was generally very positive - far more so in fact than Chinn's had been. The handling of the engine came in for the highest praise, in stark contrast to Chinn's evaluation but very much in line with my own experience of several examples. The running qualities also came in for positive comment, a view which I can also endorse from personal experience. However, like Chinn, Warring was unable to approach the performance figures which he had obtained almost 3 years previously for the FROG 80 Mk. I diesel. Instead of the figure of 0.051 BHP @ 11,000 rpm for the FROG 80, Warring could only extract 0.037 BHP from the FROG .049 on 15% nitromethane, albeit at a slightly higher speed of 12,000 rpm. At the time when the various British .049 glow-plug models appeared, I was just getting started on my power modelling career. My parents had given me a brand-new Series 2 E.D. Bee for my 12

At the time when the various British .049 glow-plug models appeared, I was just getting started on my power modelling career. My parents had given me a brand-new Series 2 E.D. Bee for my 12 I was in fact one of those who was lured into a false sense of admiration for the

I was in fact one of those who was lured into a false sense of admiration for the  My reaction was evidently typical - the FROG .049 appears to have achieved very limited sales success. All indications from known serial numbers are that perhaps only some 2000 examples were produced in total. It's likely that production only continued for as long as it did because most of the components were in production anyway for the far more successful 80 diesel. They may have produced enough .049 piston/cylinder sets and heads in the initial batches to create a residual stock sufficient to sustain some level of production for a time at least.

My reaction was evidently typical - the FROG .049 appears to have achieved very limited sales success. All indications from known serial numbers are that perhaps only some 2000 examples were produced in total. It's likely that production only continued for as long as it did because most of the components were in production anyway for the far more successful 80 diesel. They may have produced enough .049 piston/cylinder sets and heads in the initial batches to create a residual stock sufficient to sustain some level of production for a time at least. However, IMA were facing a number of stark realities about which little or nothing could be done. Firstly, there was no hiding from the fact that the FROG .049 was by far the most expensive of the various British ½A glow-plug models. The late 1959 appearance of the D-C Bantam at only £1 14s 6d (£1.73) must have come as a terrific shock to IMA management - they had clearly had no idea that they would be facing price competition at that level. The

However, IMA were facing a number of stark realities about which little or nothing could be done. Firstly, there was no hiding from the fact that the FROG .049 was by far the most expensive of the various British ½A glow-plug models. The late 1959 appearance of the D-C Bantam at only £1 14s 6d (£1.73) must have come as a terrific shock to IMA management - they had clearly had no idea that they would be facing price competition at that level. The  The first of these courses of action was hampered by the fact that they had the heaviest, bulkiest and most expensive of the various competing models. Not only that, but it offered no performance advantage over most of the competing offerings. There was thus no basis for any potential customer to justify the purchase of the FROG .049 over any of its competitors, and there was nothing that IMA could do about this short of undertaking a complete re-design from scratch. This would clearly have been uneconomic given the competition which they now faced.

The first of these courses of action was hampered by the fact that they had the heaviest, bulkiest and most expensive of the various competing models. Not only that, but it offered no performance advantage over most of the competing offerings. There was thus no basis for any potential customer to justify the purchase of the FROG .049 over any of its competitors, and there was nothing that IMA could do about this short of undertaking a complete re-design from scratch. This would clearly have been uneconomic given the competition which they now faced.

Warring for the original FROG 80, but there had been an increase in torque, leading to the higher peak BHP figure. Another welcome attribute was the far flatter power curve, which resulted in 0.05 BHP (the peak output of the former model) being exceeded at all speeds between 8,000 and 14,000 rpm - an unusually wide useable speed range.

Warring for the original FROG 80, but there had been an increase in torque, leading to the higher peak BHP figure. Another welcome attribute was the far flatter power curve, which resulted in 0.05 BHP (the peak output of the former model) being exceeded at all speeds between 8,000 and 14,000 rpm - an unusually wide useable speed range. conclusion, to the lasting detriment of British aeromodelling. However, the popular FROG plastic kits continued in large-scale production by IMA for some years to come. Interestingly enough, so did the production by IMA of Pedigree dolls (!), a line which IMA had been quietly producing since 1950 alongside the plastic kits! It's all plastic molding, after all………….

conclusion, to the lasting detriment of British aeromodelling. However, the popular FROG plastic kits continued in large-scale production by IMA for some years to come. Interestingly enough, so did the production by IMA of Pedigree dolls (!), a line which IMA had been quietly producing since 1950 alongside the plastic kits! It's all plastic molding, after all…………. Not all of the FROG engine range went into reproduction. The abandoned designs included the outstanding

Not all of the FROG engine range went into reproduction. The abandoned designs included the outstanding  The use of this system was a very sensible idea, since IMA had simply numbered the engines of each displacement sequentially starting at one, consequently generating complete sets of duplicate serial numbers! The approach taken by A. A. Hales eliminated the duplicates, making each number unique.

The use of this system was a very sensible idea, since IMA had simply numbered the engines of each displacement sequentially starting at one, consequently generating complete sets of duplicate serial numbers! The approach taken by A. A. Hales eliminated the duplicates, making each number unique. Regardless of the true facts surrounding D-C Ltd.'s production of the FROG 80 Mk. II, we know for certain that soon after they took over the manufacture of the FROG range in 1964, D-C Ltd. began to manufacture a further minor variant of the engine which was referred to as the FROG 80 Mk. III. The fact that this was seen by A. A. Hales as a distinct variant is demonstrated by the fact that, as reflected in the above model identification table, they assigned a different model identification letter to it. They also appear to have restarted the serial number sequence - I know of several Mk. III engines having lower numbers than the highest Mk. II number of which I’m aware.

Regardless of the true facts surrounding D-C Ltd.'s production of the FROG 80 Mk. II, we know for certain that soon after they took over the manufacture of the FROG range in 1964, D-C Ltd. began to manufacture a further minor variant of the engine which was referred to as the FROG 80 Mk. III. The fact that this was seen by A. A. Hales as a distinct variant is demonstrated by the fact that, as reflected in the above model identification table, they assigned a different model identification letter to it. They also appear to have restarted the serial number sequence - I know of several Mk. III engines having lower numbers than the highest Mk. II number of which I’m aware. Internally, the main change was the use of a slightly shorter conrod in the Mk. III, the gudgeon pin hole being relocated further down the piston skirt to allow for this while retaining essentially the same port timing. The reasoning behind this change is a bit obscure, since its effect would be to increase the side-thrust of the piston against the cylinder wall during operation - not at first sight a desirable outcome. It seems not unlikely that the change was motivated simply by a desire to further increase the commonality of parts in the D-C production program by using a standard rod that was already in the program - perhaps that of the Merlin or the Bantam. Up to the present, I have had no opportunity to check out this theory through direct comparison of components.