|

|

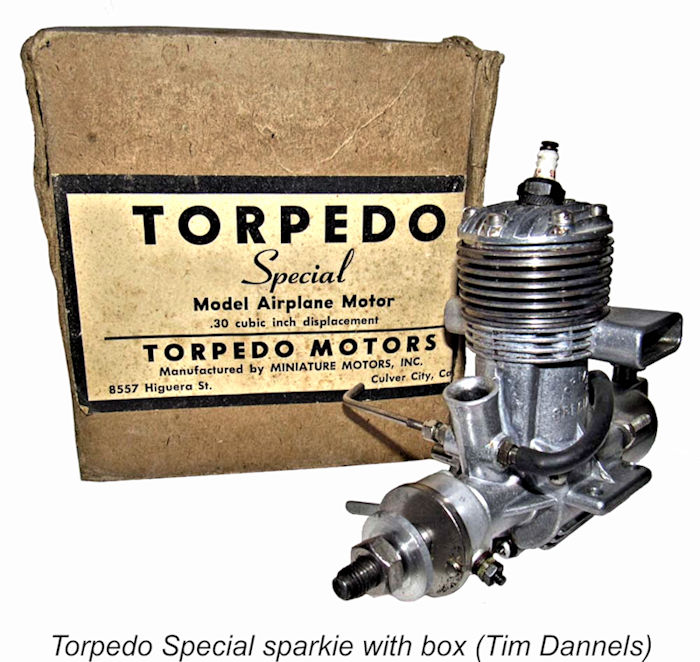

Twin Stack Teaser - the Torpedo Special

This engine commands attention for two reasons. Firstly, it was a highly distinctive out-of-the-rut design featuring cross-flow loop scavenging using a front transfer port allied to rear-facing exhausts which discharged through twin stacks. A bit reminiscent of the E.D Bee! And secondly, it became involved in a dispute Despite these reasons for paying it some attention, almost nothing has been written previously about this engine. It put in an appearance in an article by Bob Reuter which was published all of 56 years ago in the March-April 1969 issue of the late Tim Dannels' “Engine Collectors’ Journal”, but that article focused primarily on the various “Torpedo” engines designed by Bill Atwood. The inclusion of the Torpedo Special implied that it was an Atwood design, whereas in fact he had nothing to do with it. The Torpedo Special is also featured in Tim's indispensable “American Model Engine Encyclopedia”, albeit quite correctly with absolutely no suggestion of any involvement by Bill Atwood. That’s the extent of previously-published information, and some of it is misleading. As a result of this under-documentation, a number of legends have long surrounded the Torpedo Special. These include the notion that it was a Bill Atwood design, which it wasn't. There's also been a mistaken impression that it was an oddball design from K&B. This was based strictly on the Torpedo name - in reality, K&B had absolutely nothing to do with it. Time to set the record straight! Before going any further, I'd like to draw the reader's attention to the fact that the one person who has ensured that the Torpedo Special story is still there to be recounted is the aforementioned Tim Dannels. Without his previously-noted efforts, this story would have been irretrievably lost. Tim also provided several of the images which accompany this article. We are all very much in his debt. Having acknowledged my indebtedness to Tim, I’ll begin this article by attempting to untangle the story of the name dispute as best I can. The Torpedo Name Dispute

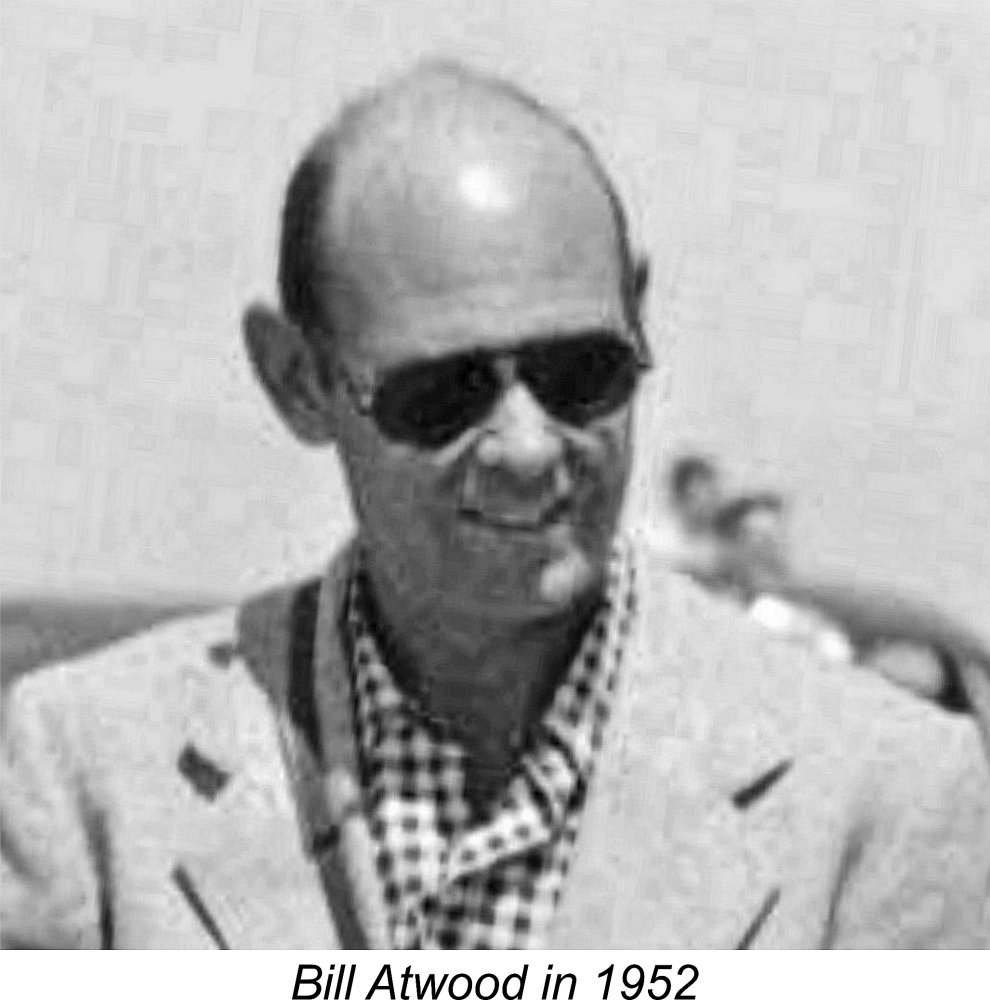

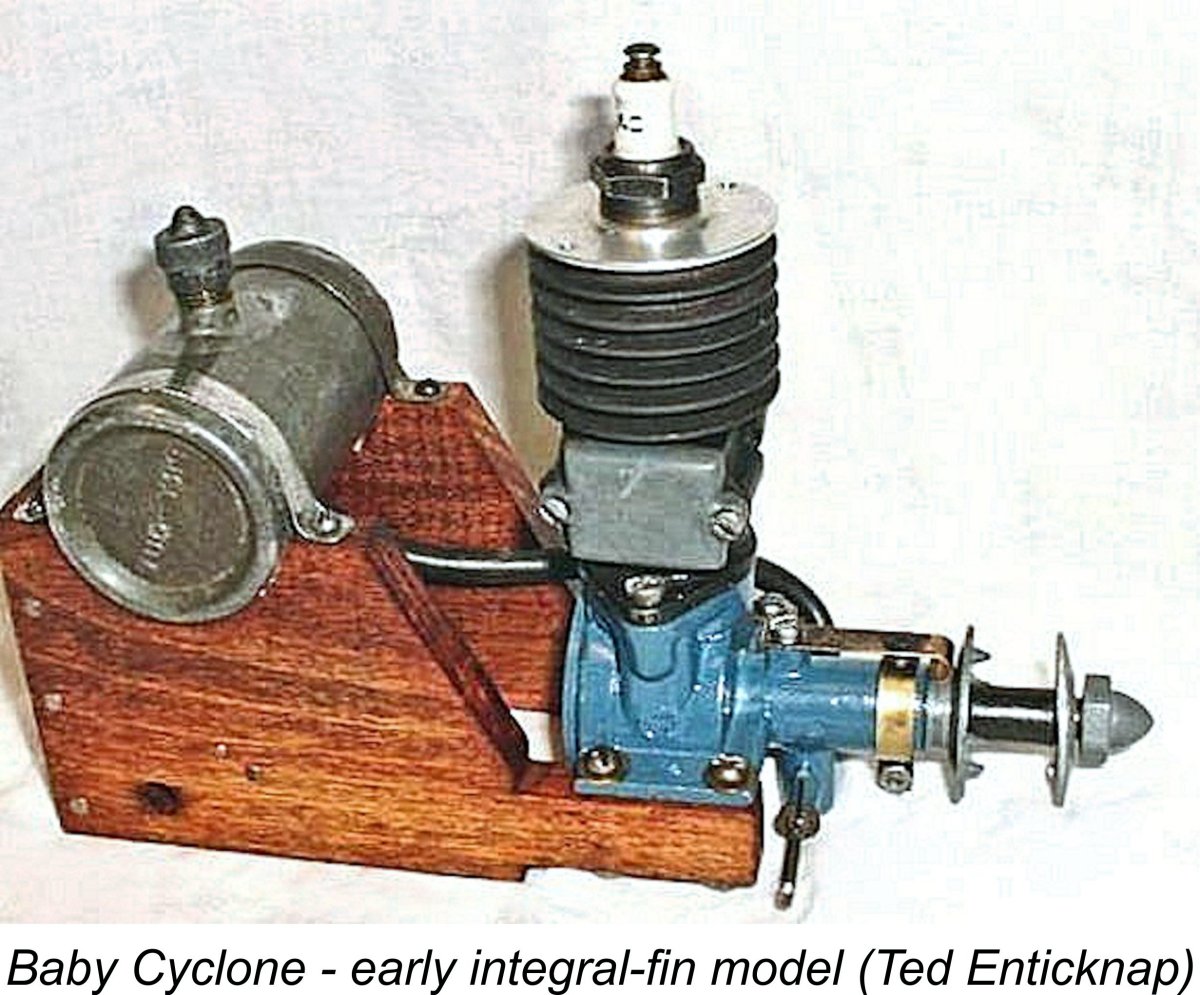

Atwood first became involved with the commercial manufacture of model engines in 1934 when he went to work for Major Corliss C. Moseley’s Aircraft Industries Corporation at Glendale, California producing the Atwood-designed Baby Cyclone engine. In 1938, Atwood left Moseley to go to work for the Los Angeles-based Automatic Screw Machine Company which had actually been producing many components for the Baby Cyclone engines. I’ve covered this early period in detail in my separate article on the Atwood Crown Champion series. Atwood was soon joined at his new company by another of his former colleagues at Moseley’s operation, namely Ira Hassad, who was to go on to greater things on his own account as recounted elsewhere. A new entity called Phantom Motors, Hi–Speed Division was established by the company, whereupon Bill proceeded to design and develop the very successful Phantom line of Bullet and Hi-Speed engines for his new employers. Of greatest relevance to this story are Bill's 1939 Hi-Speed Torpedo and 1940 Phantom Torpedo models.

Unfortunately, production of the Phantom, Bullet, and Hi-Speed engines was pushed so rapidly at the outset that design flaws which would have been sorted out through a more protracted development program found their way into the earlier examples. Notable among these were too-thin heads, which frequently warped and caused compression leaks. To reduce the propensity for corrosion of the magnesium castings, some models were given a crackle-finish paint coating.

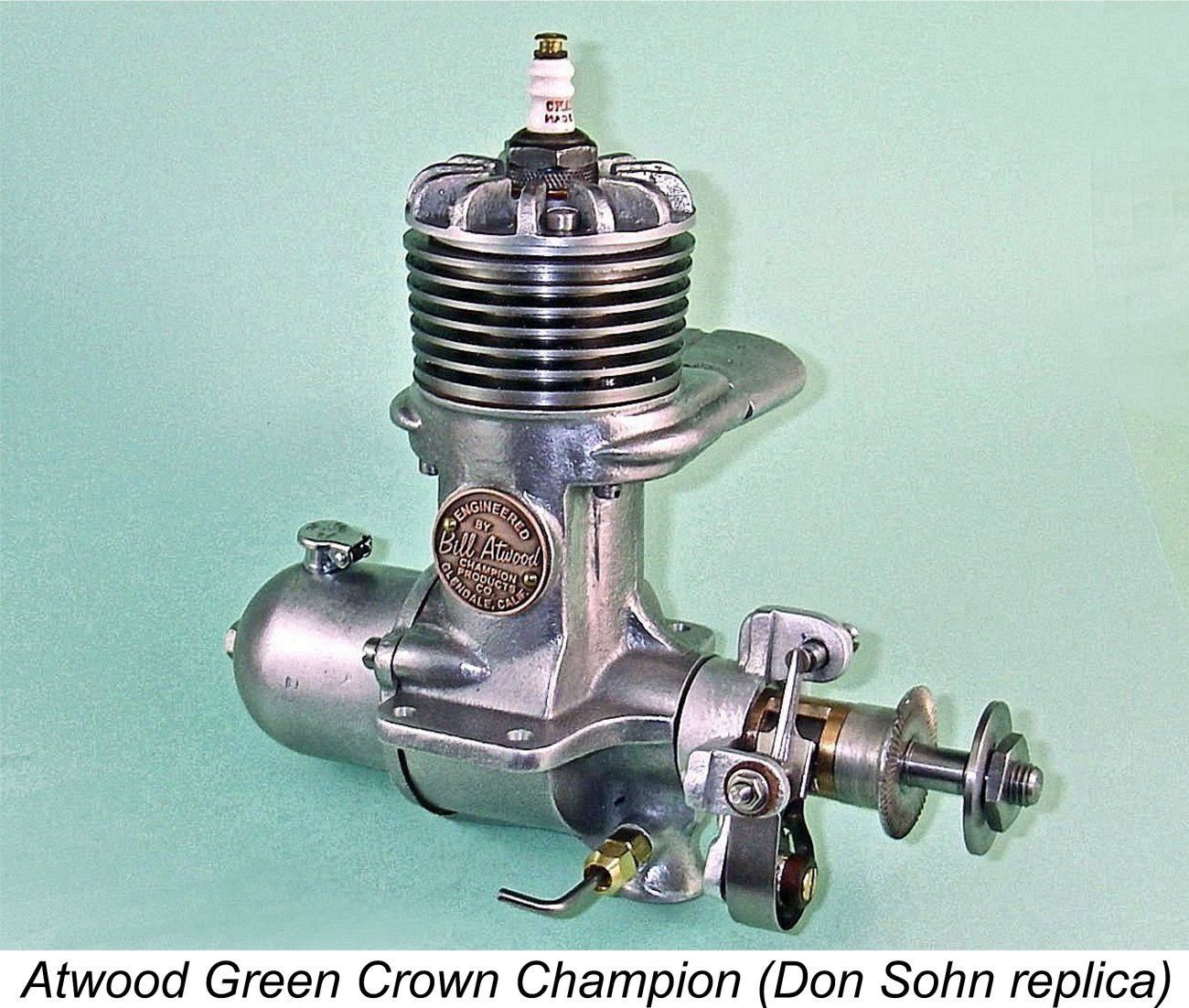

The success of the Champion engines induced a couple of individuals named Shaw and Kaw (sounds like a comedy team!) to persuade Bill to finally leave Phantom Motors (and his own Champion Products company) in early 1941 to join them in manufacturing and further promoting the latest Champion engines. Bill did so, at the same time apparently retaining all rights to the Torpedo, Bullet and Champion names and designs. The means by which he did so are unclear - one would expect Phantom Motors (now owned by Arthur Andersen) to retain the rights to the first two names. For reasons which are now lost, the association with Shaw and Kaw proved to be a very brief one, ending later in 1941. Thereafter, Bill joined forces with Wetzel Motors of 420 S. Manhattan Place, Los Angeles, California, with whom he continued to manufacture his revised Champion designs. The December 1941 entry of America into WW2 signalled a major change for Bill, since his talents were now needed for the war effort. After working for a time as a toolmaker and maintaining a “hobby” connection with the Champion engines, he became a full-time glider pilot instructor for the US Army Air Corps. Wetzel kept the dies and parts inventory, assembling a few engines during the war years from pre-war parts stock.

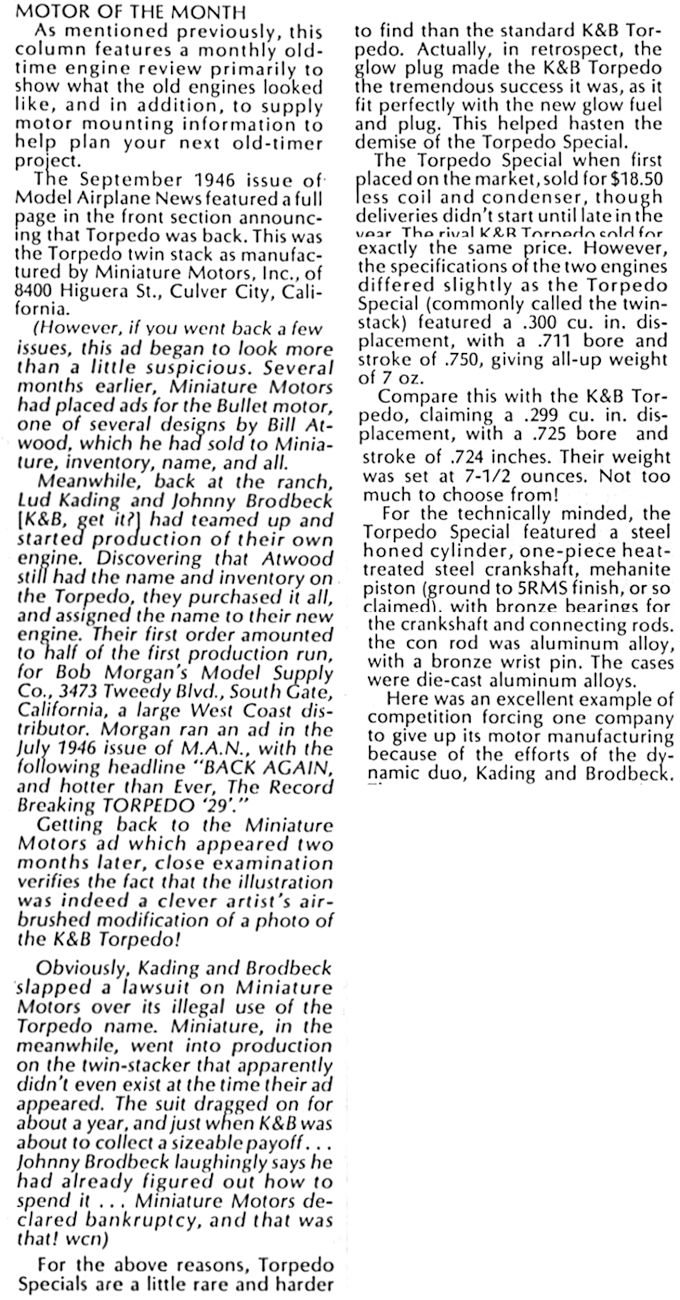

The Wetzel and Atwood partnership did not long survive the end of WW2, ending in late 1945. In fact, this highlights a recurring aspect of Bill Atwood’s career which the reader may have noticed by now - none of his various partnerships seem to have lasted long. The reasons for this remain unclear. This pattern was to continue through the 1950’s up to the point in 1960 when Bill finally settled down to work for Cox right up until his somewhat untimely death in 1978 at the rather premature age of 67. Returning to late 1945, when Bill was only 35 years old, we come at last to the heart of the matter under discussion. When the Wetzel & Atwood partnership split in late 1945, there appears to have been a difference of opinion over who This led Wetzel to sell the rights to the Torpedo and Bullet names and designs to Miniature Motors, a subsidiary of the Fearless Camera Company of Culver City, California. Fair enough, but unfortunately Bill Atwood simultaneously sold the Torpedo name, goodwill and sundry residual components to John Brodbeck (the B of K&B), along with a promise never to compete with John in the .29 class. The initial advertisement for the K&B Torpedo 29 appeared in "Model Airplane News" (MAN) in July 1946, proving that the name purchase had been completed by that time. This resulted in the creation of a situation in which both John Brodbeck and Miniature Motors had good reason to believe that they had purchased the right to develop their products using the Torpedo name and drawing upon the earlier Atwood designs. Clearly this was a situation which could only be resolved through legal avenues. The consequence was a lawsuit in which at least three parties were involved. However, perhaps in view of the stature in the modelling world of several participants, there appears to have been a determined subsequent effort to sweep the whole affair under the rug. We don’t even have a definitive list of the parties involved, nor do we have any confirmed details of the All that we have is a reference to the court case which appeared in the late John Pond's "Plug Sparks" feature in the July 1978 issue of "Model Builder". My grateful thanks go to Gordon Beeby of Australia for drawing my attention to this reference, the original text of which is reproduced at the right. John Pond's article included an anecdotal recollection of John Brodbeck years later saying that this court case dragged on for about a year and that he was the eventual winner, with Miniature Motors being required to pay out a sizeable cash settlement. By John's reported account, Miniature Motors avoided the payment of this settlement by the simple expedient of declaring bankrupcy! Of course, this is a third-hand report of something that John Brodbeck is supposed to have said about an incident that was decades in the past. Such recollections are notoriously unreliable, and there's no supporting evidence. Indeed, the idea that Miniature Motors were found entirely liable seems difficult to accept - if they purchased the Torpedo name from Wetzel in good faith, then they were as much of an aggrieved party as Brodbeck. The real villain of the piece was Wetzel for selling something that he didn't own.

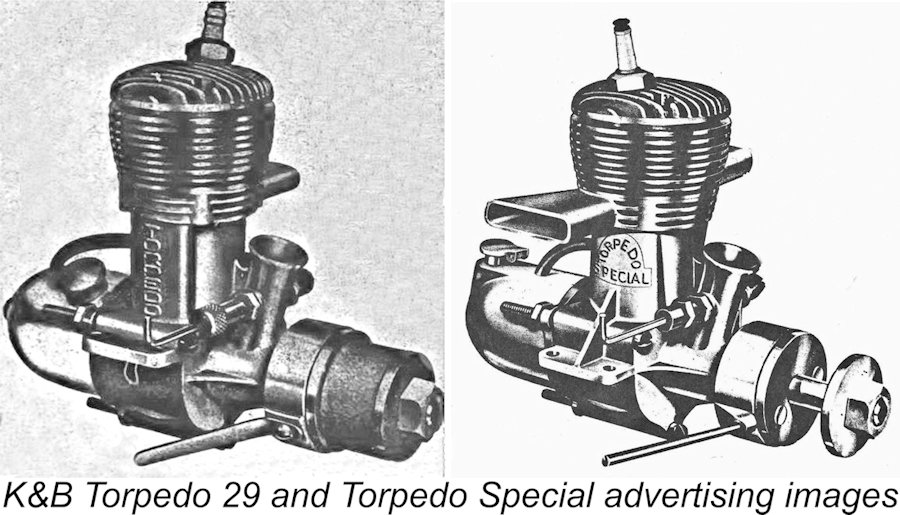

The introductory advertisement for the Torpedo Special appeared in MAN a few months later in September 1946. Admittedly the image of the engine showed it in an identical pose to the earlier K&B image, while the cooling fin profile appeared more or less identical. However, there were so many differences elsewhere that it's really hard to see the Torpedo Special image Another ambiguity here is the fact that the acquisition of the Bullet name by Miniature Motors was apparently never challenged. If Wetzel's sale of the Torpedo name to Miniature Motors was illegal, then so was the concurrent sale of the Bullet name. Despite this, Miniature Motors' ongoing use of the Bullet name seems never to have been challenged. I see a significant inconsistency here ......... The final flaw in the story as attributed to John Brodbeck is that by his account the lawsuit must have been settled in 1947. How then did Miniature Motors continue in business well into 1949, as they clearly did based on their production and further development of the Torpedo Special in glow-plug form? How did they keep John Brodbeck at arm's length for over two years following the conclusion of the court case? The notion that they withdrew from the model engine business by declaring bankrupcy is quite credible, but that was a common way of disposing of an economically non-viable subsidiary company by its parent organization. All that we can say for certain is that Bill Atwood never again used the Torpedo or Bullet names, applying his own Atwood name to his subsequent designs along with the continued use of the Champion designation for some years. John Brodbeck and Lud Kading went on to great success developing a long line of engines bearing the Torpedo name, being very careful to identify them first and foremost as K&B products. As for Miniature Motors, they proceeded to develop and market their own line of Bullet and Torpedo Special engines by those names, continuing to do so into the glow-plug era until finally abandoning the model engine field in 1949 or early 1950. It thus appears that the lawsuit changed nothing as far as the use of the Bullet and Torpedo names was concerned. We'll never know the true facts of this particular matter. Having summarized the controversy surrounding the naming issue, we’re now in a position to take a close-up look at the products with which Miniature Motors challenged the market. The Miniature Motors Engines

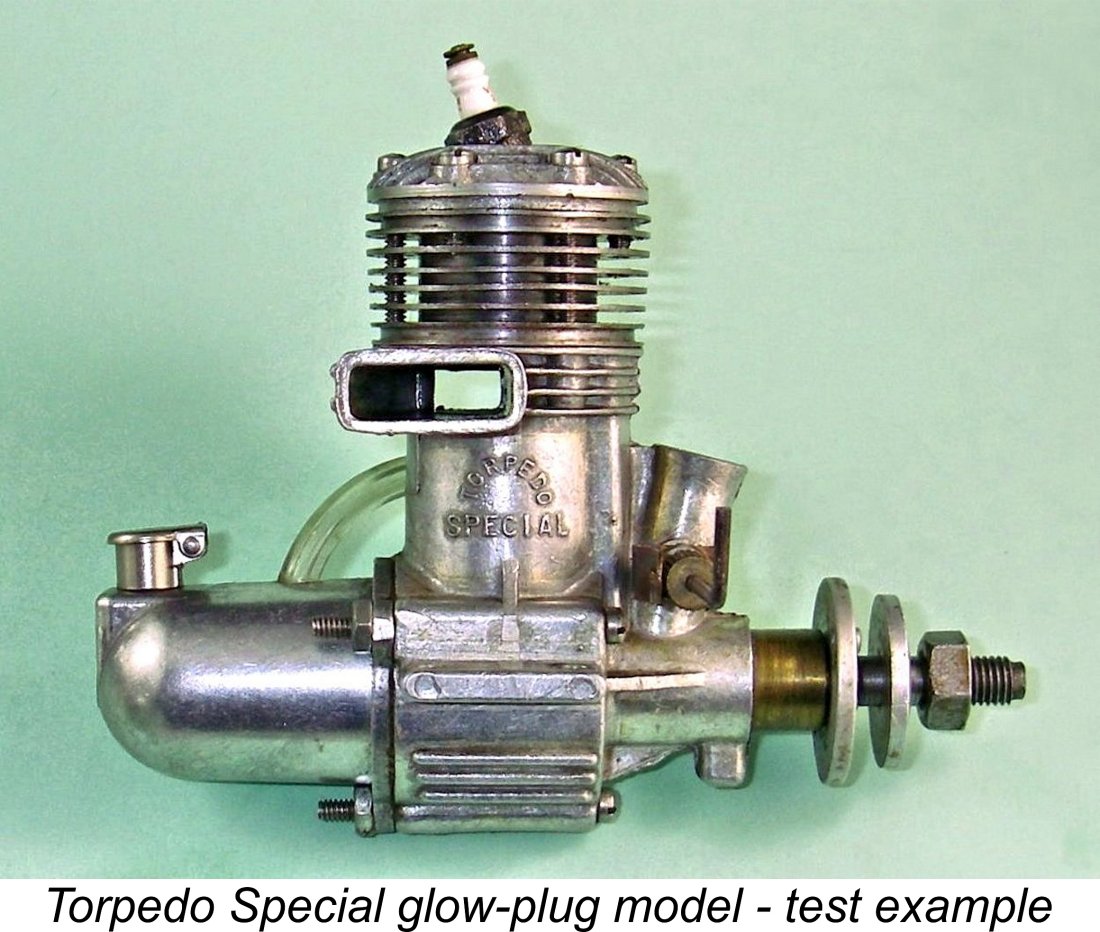

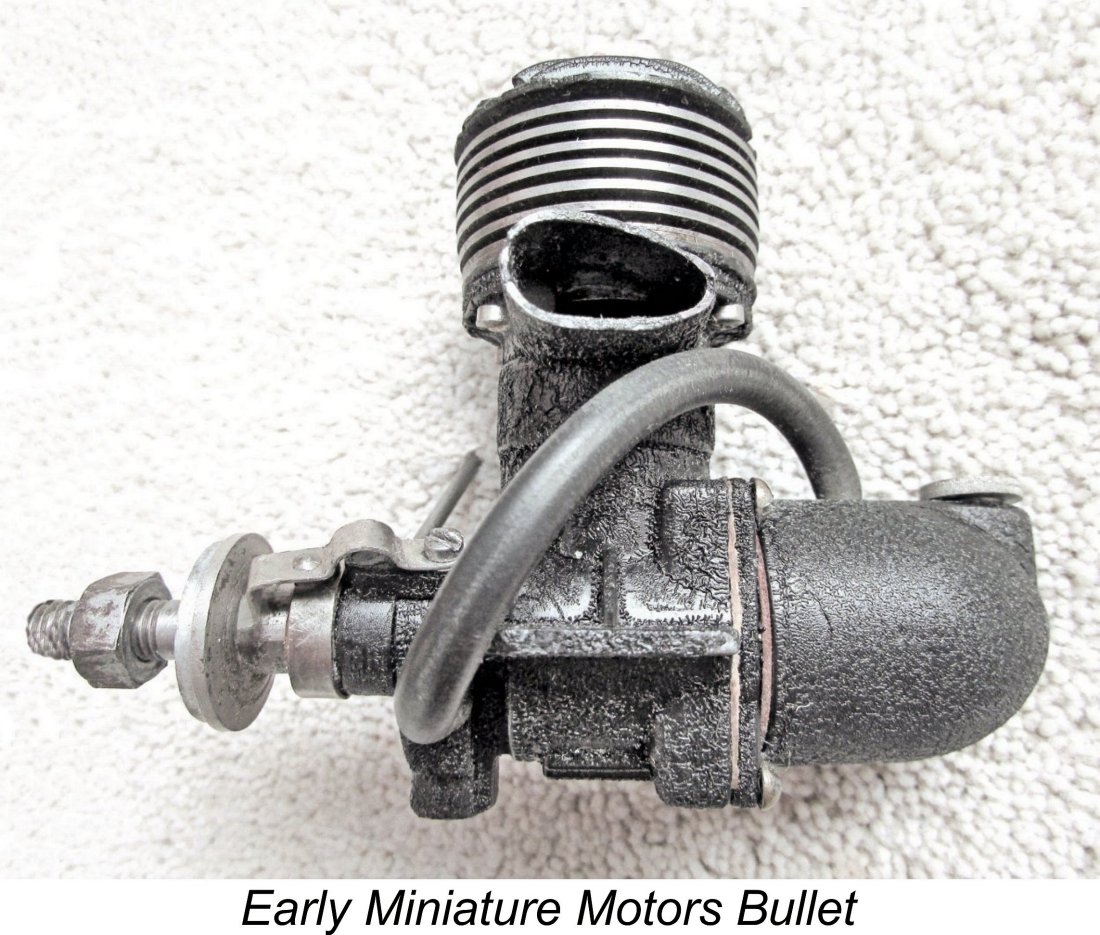

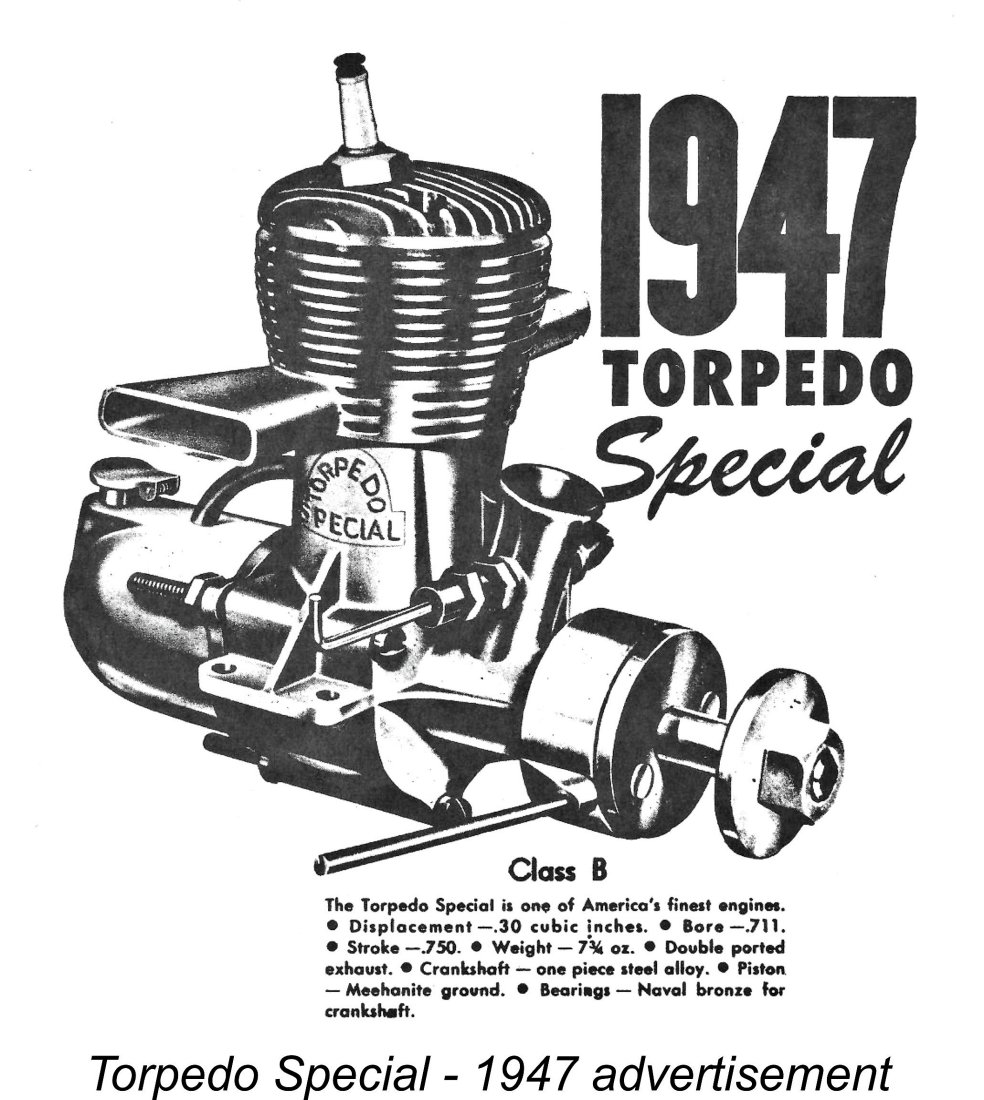

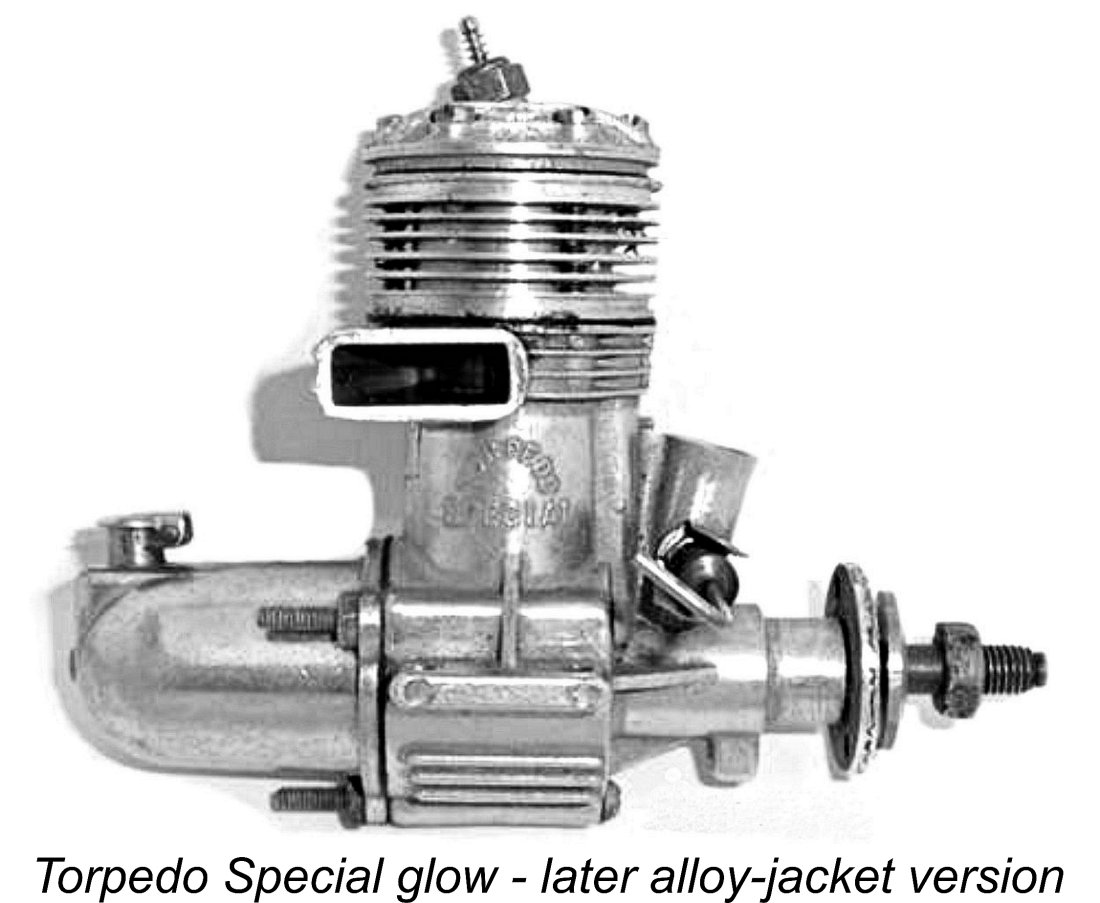

All castings were initially produced in magnesium alloy, some of which were painted with a metallic grey crackle paint to reduced their tendency towards corrosion. The illustrated example is one of these units. Later variants switched to aluminium alloy castings, thereby definitively solving the problem. The engines bore the identification “Bullet Motor” cast in relief in a circle on the bypass. This model evidently appeared first because it could be brought into production with a minimum of delay thanks to being modelled upon an existing design. However, Miniature Motors clearly wished to plough their own furrow in design terms. To that end, they tasked their shop foreman Zip Grandell with developing a new slightly larger model which would represent a very definite and obvious departure from the Bullet and Phantom Torpedo designs. Grandell clearly relished this opportunity. The design that he came up with was very different from the Bullet in many respects. The most obvious change was the effective rotation of the steel cylinder through The engine was named the Torpedo Special. This has had the somewhat unfortunate latter-day effect of creating a seemingly widespread belief that it was merely an oddball K&B product, which it most definitely was not - K&B had absolutely nothing The Torpedo Special model engine appeared later in 1946. The initial advertisement appeared in the September 1946 issue of MAN, as seen at the left. The engine featured bore and stroke dimensions of 0.711 in. (18.06 mm) and 0.750 in. (19.05 mm). These slightly long-stroke figures yield a displacement of 0.298 cuin. (4.88 cc). The cited bare weight of the original spark ignition version was 7.75 ounces (220 gm). Complete with plug, tank and fuel tubing, my glow-plug examples both weigh in at a checked 8.43 ounces (239 gm). With its spectacular twin rearward-oriented stacks, front bypass passage and rearward-angled plug, the Torpedo Special undoubtedly presented a refreshingly“different” appearance. It may have carried the Torpedo name, but there could be no suggestion of any direct design influence from the original Bill Atwood-designed Hi-Speed and Phantom Torpedo models or the later K&B Torpedo designs. The Twin-Stack Torp was a Zip Grandell creation all the way!

The steel cylinder featured integral cooling fins which were machined in unit. Both cylinder and head were retained by three long machine screws which passed through holes in the head and cooling fins to engage with tapped holes in the upper crankcase casting. Three short additional screws engaged with tapped holes in the topmost cylinder flange to enhance the security of the head seal. Given the rather unusual port orientation, the pressure die-cast crankcase unit was necessarily a little different! The transfer port was supplied through a somewhat restrictive The other noteworthy feature of the case was the presence of integrally-cast stiffening webs on the upper surfaces of both beam mounting lugs. While these may have had some value in enhancing the crash-resistance of the lugs, they make it very difficult to mount the engine in a conventional test stand. Because of this, all too many examples of the engine have had these webs either damaged or removed. The rest of the engine was more or less conventional, hence requiring little comment here. The one-piece steel crankshaft ran in a bronze bushing. The prop driver was keyed to the front of the shaft using a single flat on one side of the forward shaft extension. Experience has shown that prop drivers secured in this way almost invariably develop an annular "wobble" quite rapidly in service. The prop was secured using a conventional nut and washer as illustrated here. The aluminium alloy spinner nuts which have been seen on a few examples appear to be later owner add-ons.

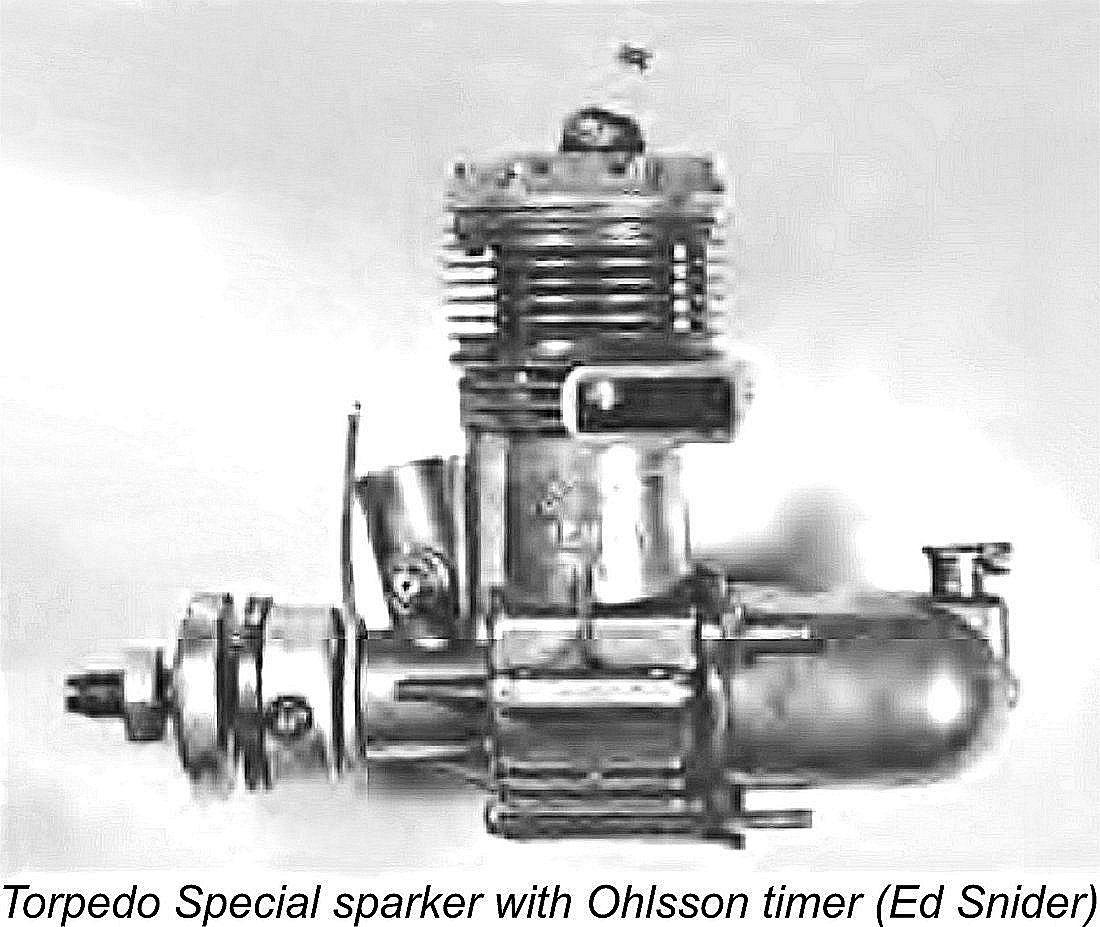

At the rear, a nicely-executed cast aluminium alloy tank having a spring-loaded Gits filler cap was fitted. Understandably enough, many owners discarded these tanks, preferring to make their own fuel supply arrangements. Consequently, many examples encountered today are missing their tanks. The original 1946 model was of course a spark ignition unit which used an Ohlsson-style timer - in fact, the timers were reportedly supplied by Ohlsson. It appears that the original intention Although the advertisements showed a K&B-style timer and all examples originally featured the associated timer screw boss as cast, engines featuring such a timer were apparently never produced by Miniature Motors. The examples that occasionally show up today with such timers are conversions carried out by later collectors, probably using glow-plug cases which retained the timer screw boss.

Another change that appears to date from mid to late 1948 was the elimination of the integrally-formed steel cooling fins on the cylinder through the use of a separate slip-on cooling jacket made from aluminium alloy. This was presumably an attempt to shave some weight. Engines of this configuration were never supplied as spark ignition units.

While production of the Torpedo Special had been proceeding, the 0.276 cuin. (4.52 cc) Bullet also remained in production all along. It passed through a number of design revisions, culminating in the Bullet Model 100 glow-plug unit of early 1949. The Torpedo Special engines were sold in plain cardboard boxes with stick-on labels. Perhaps somewhat provocatively, the name "TORPEDO MOTORS" appeared on the label in large font - clearly, the resolution of the My valued mate Gordon Beeby of Australia has dug deep into the advertising record relating to the Torpedo Special. His much-appreciated efforts have provided a high level of clarity regarding the end of Miniature Motor's involvement with model engine production. The most important information in this regard is found in a full-page advertisement which was placed in the June 1949 issue of "Air Trails". This advertisement (below left) announced a factory close-out of both the Torpedo Special and Bullet powerplants at bargain prices of $4.95 and $5.95 respectively. The advertisement included the company's explanation for their taking this step. They claimed that it was "because we're so busy making precision camera and television equipment that it is impractical Despite the remarkably low prices at which these engines were now offered, they seem to have sold very slowly. Miniature Motors continued to run different renditions of these close-out ads periodically all the way up to May 1950. That final advertisement stated that 250 Bullets remained unsold, along with 1300 Torpedo Specials. Since this was the final advertisement, one wonders what became of all those unsold engines .............. How many examples were made? Unfortunately, the engines didn't bear serial numbers, leaving us with no way of developing a reliable estimate on that basis. When questioned in 2021, my late and much-missed mate Tim Dannels reported that although he had disposed of quite a few engines for others, including several 400+ major collections, he had only ever encountered around 6-8 examples of the Twin-Stack Torp out of all the thousands of motors that had passed through his hands. It thus appears that the Torpedo Special is a relatively scarce engine today. Surviving glow-plug models seem to out-number the original spark ignition versions with Ohlsson timers by some margin. Tim had never encountered a Torpedo Special sparker with a K&B timer. The engine still (2025) makes periodic appearances on eBay and elsewhere, implying that a reasonable number of examples must have been made. However, it tends to sell for relatively modest prices, seemingly reflecting a lower level of collector interest than might be expected. This is likely due to the relative absence of authoritative information regarding the engine's origins. Hopefully the appearance of this article will change that! However, that’s another story that has yet to be written! For the moment, we need to stay focused upon our main subject - the Torpedo Special. Let’s try to learn something about this unusual-looking engine’s performance - over to the test stand! The Torpedo Special Sparkie on Test

Accordingly, the first test candidate was my completely original and seemingly little-used spark ignition model. This example has done some running in the past but remains in excellent all-original condition, with outstanding compression and perfectly fitted bearings. Like all other Miniature Motors products, it features an Ohlsson-style timer which passed its timer function test with flying colours. I decided to commence operations with a 10x6 APC airscrew, which I felt would likely have been a typical prop size to use in control line service. I used my usual classic sparkie brew of 75% Coleman Camp Fuel (white gas) and 25% SAE 60 mineral oil (AeroShell 120). Most users back in the day would have run their engines on such a mix. The sparks were supplied by one of my Larry Davidson SSIGNCO transistor-triggered spark ignition support systems. I've found these systems to be completely reliable and extremely effective in taking almost all of the pain out of spark ignition operation. I used the engine's original Champion V-2 spark plug, which checked out as being in perfect working order. I also used the engine's original back tank throughout the testing.

Actually, it didn't take much sticking! The engine endeared itself to me immediately by starting on the second flick after who knows how many years on the shelf! I'd set it a little rich, but it burbled away happily waiting for me to set the controls correctly. Every time I run a sparkie, I'm reminded once again just how easy they are to start and set. It's a great pity that relatively few present-day enthusiasts appear to be prepared to give spark ignition a try - they'd be pleasantly surprised if they did! Moreover, white gas and mineral oil are both significantly cheaper and easier to get than methanol and castor oil (or diesel fuel ingredients for that matter). I encourage everyone who has not already done so to read my in-depth article on spark ignition operation.

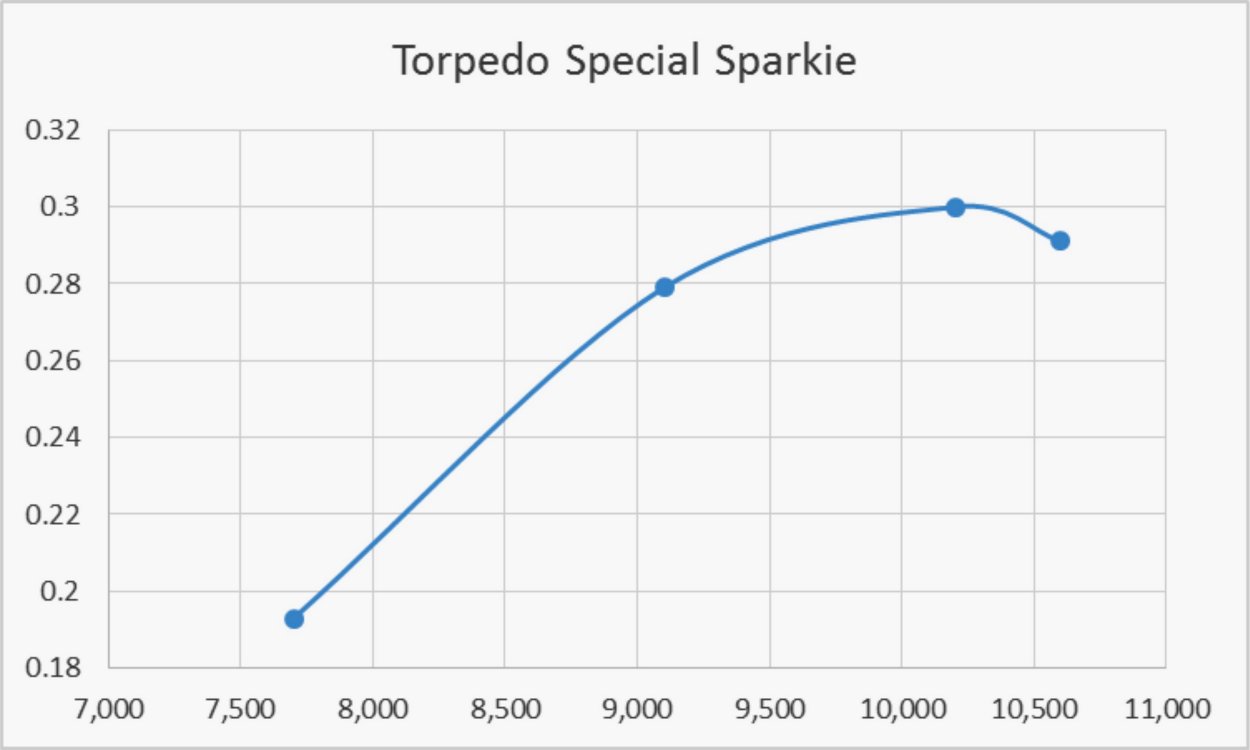

Accordingly, all that the Torpedo Special required was an advance of the ignition timing by turning the timer arm against the direction of rotation (equivalent to increasing compression in a diesel), followed by a leaning-out of the needle valve. Then a final check of the ignition timing to ensure that it was advanced by exactly the right amount for maximum revs, and I had one Torpedo Special running perfectly with no trace of a misfire or any sign of sagging. I found that the engine was turning the 10x6 APC airscrew at a steady 9,100 RPM, which was pretty much in the expected range for that prop. I then tried a 10x4 APC, finding that the speed had increased to 10,200 RPM with the running still being completely smooth. However, a further load reduction to a 9x6 APC only got the engine up to 10,600 RPM, while a slight but persistent misfire now crept in which could not be cured either with the timer or the needle valve. This indicated that the coil was no longer becoming fully saturated on each cycle - the engine had reached the limits of its timer configuration. The following data were recorded:

As can be seen, it became evident that the engine was peaking at 10,200 RPM on the 10x4 prop. By the time that it reached up into the mid 10,000 RPM range the ignition system had clearly reached its limits and the engine was past its peak output. There was clearly no point in pushing it up to any higher speeds. Even so, the implied output of 0.300 BHP @ 10,200 RPM really ain't half bad for a 0.298 cuin. (4.88 cc) plain bearing sparkie of 1946 vintage running on white gas! Factor in the engine's outstanding starting and running qualities to go along with its sturdy construction, and it's clear that Miniature Motors were offering a very good product! On this showing, the 10x6 prop would suit the engine perfectly in control line service. An 11x4 would doubtless have worked well in a free flight application. Of course, everything changed in November 1947 with the appearance of the commercial miniature glow-plug. This development opened the door to the general use of methanol-based fuels along with the addition of such power-enhancing fuel constituents as nitromethane. We'd expect a substantial performance increase to result from these technological changes. Let's see how they worked out with the Torpedo Special! The Torpedo Special Glow-Plug Model on Test

I chose the example that has had its mounting lug bracing webs neatly milled off, as opposed to being filed. The extreme care and precision with which this has been done may suggest that this was a factory modification - most owners would have simply filed the webs off. While I don’t endorse such modifications to a collectible engine, the removal of the webs does make it a lot easier to set the engine up in a test stand. To compensate for this loss, the engine retains its undrilled timer screw boss! I'd run this example before following its acquisition in the dim and distant past, but hadn't recorded any performance data beyond noting in my log book that it proved to be a very easy starter and a fine runner, albeit not spectacularly powerful. For this test, I elected to used a 10% nitro fuel containing a good proportion of castor oil. I also decided to begin the test using an a APC 10x6 prop, which I felt should be an appropriate load for a 1940's glow-plug motor of this displacement. In order to conserve the engine’s original still-functional long-reach Champion glow-plug, I fitted a long-reach Fox plug of far more recent manufacture. The absence of the webs on the mounting lugs made the installation of this particular Torpedo Special in the test stand very straightforward indeed. Once installed, the engine felt really good when flicked over - excellent compression seal with no trace of excessive friction and nice tight bearings. I'd actually rate the general standard of fitting as above average. Since this example had been used in the past, I anticipated no need to subject it to an extended break-in period.

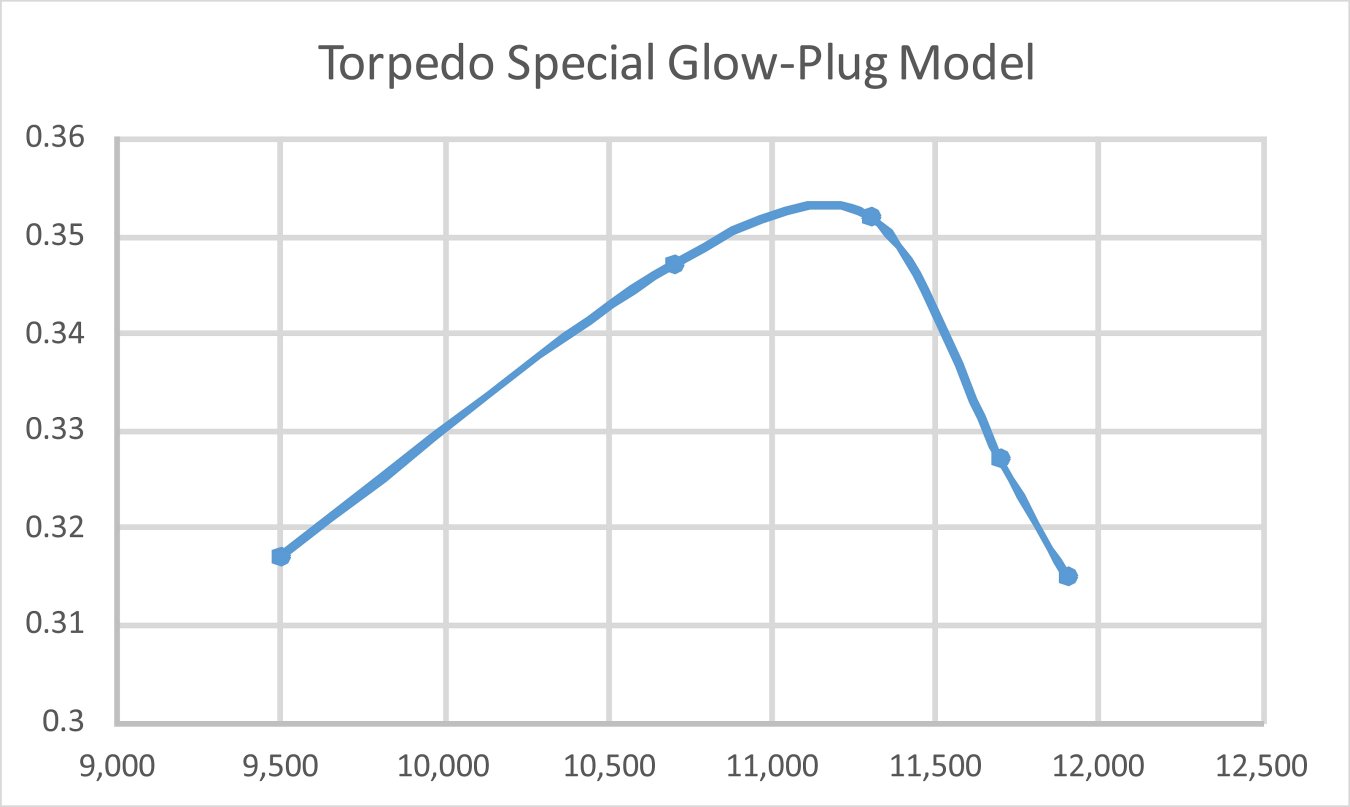

My long-ago log book entry for this engine didn't lie - the glow-plug Torpedo Special showed itself to be an instant starter on a full fuel line followed by a modest exhaust prime. Once running, it immediately picked up on the fuel line and settled down, waiting for me to adjust the needle to the optimum setting. The plug lead could be removed immediately upon starting with no loss of speed. Response to the needle was all that could be desired. Once leaned out to the peak, running was smooth and completely mis-free, with no tendency to sag. The tankful of fuel gave me ample time to set the needle and take a speed reading. I found that the APC 10x6 was turned at a smooth and steady 9,500 rpm - not bad for a .298 cuin. glow-plug motor of this vintage, and some 400 RPM faster than the speed which the sparkie version had managed on the same prop using white gas. Since it was pretty clear that on this prop the engine was operating below its peak, I proceeded to try a series of progressively lighter loads. Running remained completely smooth and steady throughout. The following data were eventually obtained.

The above figures imply a peak output of around 0.353 BHP @ 11,200 rpm. Apart from the more potent fuel used, the absence of the timer with its operational limitations clearly allowed the glow-plug variant to run completely smoothly at higher speeds than those obtainable in spark ignition form. The not-unexpected result was a higher peaking speed along with an improved peak output. I'd rate this as a pretty respectable performance on 10% nitro for a general-purpose engine whose design effectively dates back to 1946! For comparison, Peter Chinn measured a peak output of 0.370 BHP @ 12,000 rpm on low-nitro fuel for the late 1949 FROG 500. The Torpedo Special was well in the hunt among general-purpose plain-bearing 5 cc powerplants of the late 1940's. Mind you, model engine performance standards were rising rapidly at this time as the appropriate design criteria for successful glow-plug operation became increasingly well understood. By late 1949 the performance of the Torpedo Special fell considerably short of that being achieved by other contemporary models. Only a complete re-design would have kept it competitive, and Miniature Motors clearly saw no economic benefit arising from the implementation of such a program, preferring instead to abandon the model engine field. Conclusion

My own evaluation and test has demonstrated that in either spark ignition or glow-plug form, the "Twin-Stack Torp" was a very sturdy performer by the standards of the mid to late 1940's. It also handled extremely well and was seemingly built to last. There's no doubt in my mind that it would have given full satisfaction to any user back during its heyday. The main argument against its potential for present-day use is the extreme difficulty of arranging a suitable noise reduction system. Although logic would persuade us that the engine should have been made in significant numbers, it's an odd fact that good complete examples show up relatively rarely today on the collector market. I hope that the publication of this article will stimulate a higher level of interest in this unusual engine, perhaps even leading to the appearance of a few more examples! ________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published September 2025 Revised October 2025 - further information on the name-sale lawsuit, plus greater clarity on the end of production. |

||

| |

Here I’ll take a look at a somewhat unusual representative of the many .29 cuin. (5 cc) engines produced in America during the early post-WW2 period which saw the focus of US model engine designers switch decisively from spark to glow-plug ignition. I’ll be looking at the highly individualistic Torpedo Special model which was produced in both spark ignition and glow-plug forms by Miniature Motors of 8557 Higuera Street in Culver City, California between 1946 and 1950. This model is widely referred to by collectors as the “Twin-Stack Torp”. It's one of my favorite mid-sized American designs from the early post-WW2 era.

Here I’ll take a look at a somewhat unusual representative of the many .29 cuin. (5 cc) engines produced in America during the early post-WW2 period which saw the focus of US model engine designers switch decisively from spark to glow-plug ignition. I’ll be looking at the highly individualistic Torpedo Special model which was produced in both spark ignition and glow-plug forms by Miniature Motors of 8557 Higuera Street in Culver City, California between 1946 and 1950. This model is widely referred to by collectors as the “Twin-Stack Torp”. It's one of my favorite mid-sized American designs from the early post-WW2 era.

Our tale begins with the pre-WW2 activities of Bill Atwood, who established a reputation for engaging in a higher-than-average level of “wheeling and dealing” in the model trade. He was also notable for the seemingly endless succession of companies for which he worked, at times simultaneously! His full story would be a fascinating one if we could ever unravel it!

Our tale begins with the pre-WW2 activities of Bill Atwood, who established a reputation for engaging in a higher-than-average level of “wheeling and dealing” in the model trade. He was also notable for the seemingly endless succession of companies for which he worked, at times simultaneously! His full story would be a fascinating one if we could ever unravel it! In designing the Phantom series of engines, Bill introduced one of his most significant design innovations. Up to that time, bypass passages had typically been fastened to the outsides of cylinders by welds, brazing, clamps or screws - the Baby Cyclone illustrated above is a typical example. Bill now devised the “drop-in” cylinder, which utilized an expanded crankcase casting to provide a passage for bypass gas flow between crankcase and cylinder. This method reduced weight and potentially distorting stresses upon the cylinder walls. It continued to be used on most latter-day model engines, as well as on some industrial two-cycle engines.

In designing the Phantom series of engines, Bill introduced one of his most significant design innovations. Up to that time, bypass passages had typically been fastened to the outsides of cylinders by welds, brazing, clamps or screws - the Baby Cyclone illustrated above is a typical example. Bill now devised the “drop-in” cylinder, which utilized an expanded crankcase casting to provide a passage for bypass gas flow between crankcase and cylinder. This method reduced weight and potentially distorting stresses upon the cylinder walls. It continued to be used on most latter-day model engines, as well as on some industrial two-cycle engines. In 1940, while still working for Phantom Motors, Bill established a separate company of his own called Champion Products Co. of Glendale, California. Under this name, he began to design and produce his own engines in his home shop. The result was the successive appearance of limited numbers of Atwood’s various Crown Champion designs, which were followed by larger numbers of his Atwood Champion and Super Champion models. I’ve covered those products in detail

In 1940, while still working for Phantom Motors, Bill established a separate company of his own called Champion Products Co. of Glendale, California. Under this name, he began to design and produce his own engines in his home shop. The result was the successive appearance of limited numbers of Atwood’s various Crown Champion designs, which were followed by larger numbers of his Atwood Champion and Super Champion models. I’ve covered those products in detail  In early 1945, as war production was slowing down, metals were once more available in limited quantities for non-military purposes. At this point, Atwood resumed his association with Wetzel under the name Wetzel & Atwood, once more producing Champion engines. These engines were popularized in the rapidly-developing control line stunt field by Davis Slagle, who used a Champion to win everything in sight during 1946. He later switched to Super Cyclone power, continuing his run of success with that unit.

In early 1945, as war production was slowing down, metals were once more available in limited quantities for non-military purposes. At this point, Atwood resumed his association with Wetzel under the name Wetzel & Atwood, once more producing Champion engines. These engines were popularized in the rapidly-developing control line stunt field by Davis Slagle, who used a Champion to win everything in sight during 1946. He later switched to Super Cyclone power, continuing his run of success with that unit. owned what. During the war, the dies for the Hi-Speed Torpedo had been lost, but the design and the name both remained on the books, as did those of the Bullet. Each partner evidently thought that he retained rights to earlier Atwood designs and names, including the Torpedo and Bullet.

owned what. During the war, the dies for the Hi-Speed Torpedo had been lost, but the design and the name both remained on the books, as did those of the Bullet. Each partner evidently thought that he retained rights to earlier Atwood designs and names, including the Torpedo and Bullet.

Another comment that appears in John Pond's article is the notion that the promotional image of the Torpedo Special which appeared in their advertisements was simply a touched-up rendition of the promotional image used by K&B to promote their K&B Torpedo 29 model! That image first appeared in a July 1946 advertising placement in MAN by the prominent model goods distribution firm of Morgan Model Supply Co. of South Gate, California. According to John Brodbeck, Bob Morgan had purchased half of the initial production run of the K&B 29, thus helping to jump-start the K&B venture.

Another comment that appears in John Pond's article is the notion that the promotional image of the Torpedo Special which appeared in their advertisements was simply a touched-up rendition of the promotional image used by K&B to promote their K&B Torpedo 29 model! That image first appeared in a July 1946 advertising placement in MAN by the prominent model goods distribution firm of Morgan Model Supply Co. of South Gate, California. According to John Brodbeck, Bob Morgan had purchased half of the initial production run of the K&B 29, thus helping to jump-start the K&B venture.

Following the acquisition of the Bullet and Torpedo names from Wetzel, Miniature Motors immediately asserted their right to the Bullet name and design by introducing a 0.276 cuin. model known simply as the Bullet Motor. This model appeared in early 1946. It was basically very similar to Bill Atwood’s 1940 Phantom Bullet apart from featuring a rectangular backplate attached to the case with four screws in place of the former three.

Following the acquisition of the Bullet and Torpedo names from Wetzel, Miniature Motors immediately asserted their right to the Bullet name and design by introducing a 0.276 cuin. model known simply as the Bullet Motor. This model appeared in early 1946. It was basically very similar to Bill Atwood’s 1940 Phantom Bullet apart from featuring a rectangular backplate attached to the case with four screws in place of the former three.  90 degrees to bring the transfer port to the front. Inevitably, this meant orienting the exhaust to the rear. A high baffle was used on the crown of the lapped meehanite piston, and this was formed transversely near the front of the piston to conform with the frontal location of the transfer port.

90 degrees to bring the transfer port to the front. Inevitably, this meant orienting the exhaust to the rear. A high baffle was used on the crown of the lapped meehanite piston, and this was formed transversely near the front of the piston to conform with the frontal location of the transfer port. to do with it. The name may possibly have been inspired by the publicity which had been attracted to the Tucker Torpedo Special, a supercharged rear-engined Miller race car which was entered by automotive entrepeneur

to do with it. The name may possibly have been inspired by the publicity which had been attracted to the Tucker Torpedo Special, a supercharged rear-engined Miller race car which was entered by automotive entrepeneur

I'm fortunate enough to have very nice examples of both spark ignition and glow-plug ignition models of the Torpedo Special on hand. This being the case, I felt that it would be right to test them in the order in which they appeared to challenge the market.

I'm fortunate enough to have very nice examples of both spark ignition and glow-plug ignition models of the Torpedo Special on hand. This being the case, I felt that it would be right to test them in the order in which they appeared to challenge the market.  The first step was to use a continuity tester to establish the position of the timer arm required to open the points and initiate the spark just before top dead centre for starting. Having done this, I set the engine up in the test stand and ran a quick plug-out ignition system check. Finding that I had a good hot spark, I re-installed the plug, set the timer in the pre-determined position, opened the needle valve a few turns, filled the tank and fuel line, administered a "dry" prime (exhaust ports closed), switched on the ignition and got stuck in.

The first step was to use a continuity tester to establish the position of the timer arm required to open the points and initiate the spark just before top dead centre for starting. Having done this, I set the engine up in the test stand and ran a quick plug-out ignition system check. Finding that I had a good hot spark, I re-installed the plug, set the timer in the pre-determined position, opened the needle valve a few turns, filled the tank and fuel line, administered a "dry" prime (exhaust ports closed), switched on the ignition and got stuck in.