|

|

Barbini 2.5 cc Special

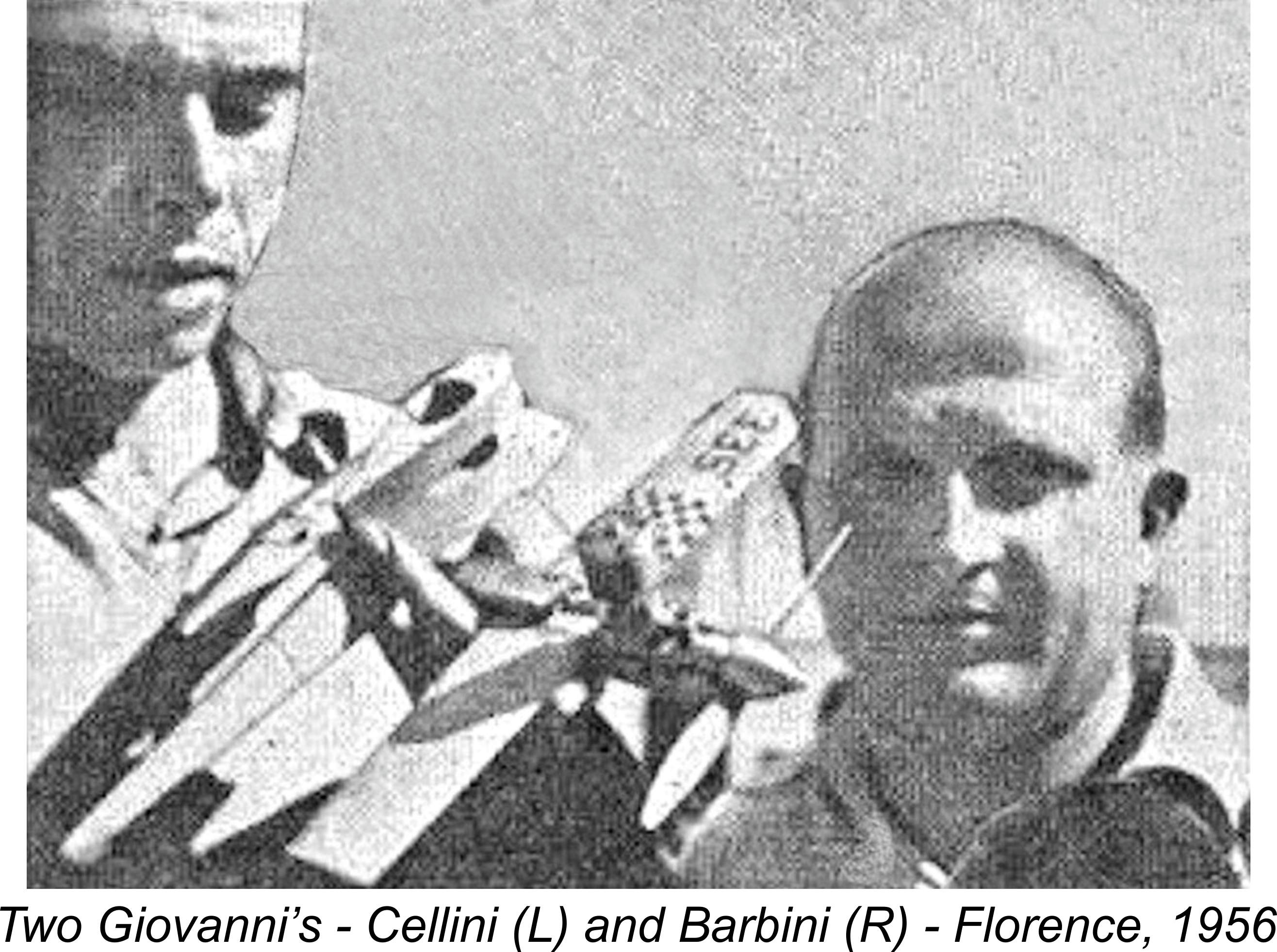

In a separate article to be found on this website, I outlined the history of the Barbini model engines which were produced in Italy in relatively small numbers by Giovanni Barbini, originally in Milan and later in San Stino di Livenza near Venice. The Barbini engines are notable for the very high standards to which they were manufactured. Among the most memorable achievements of Giovanni Barbini and his 2.5 cc powerplants were the third and sixth places achieved at the World Control Line Speed Championships in 1956 and 1957 respectively against extremely strong International opposition. That story has been fully recounted elsewhere.

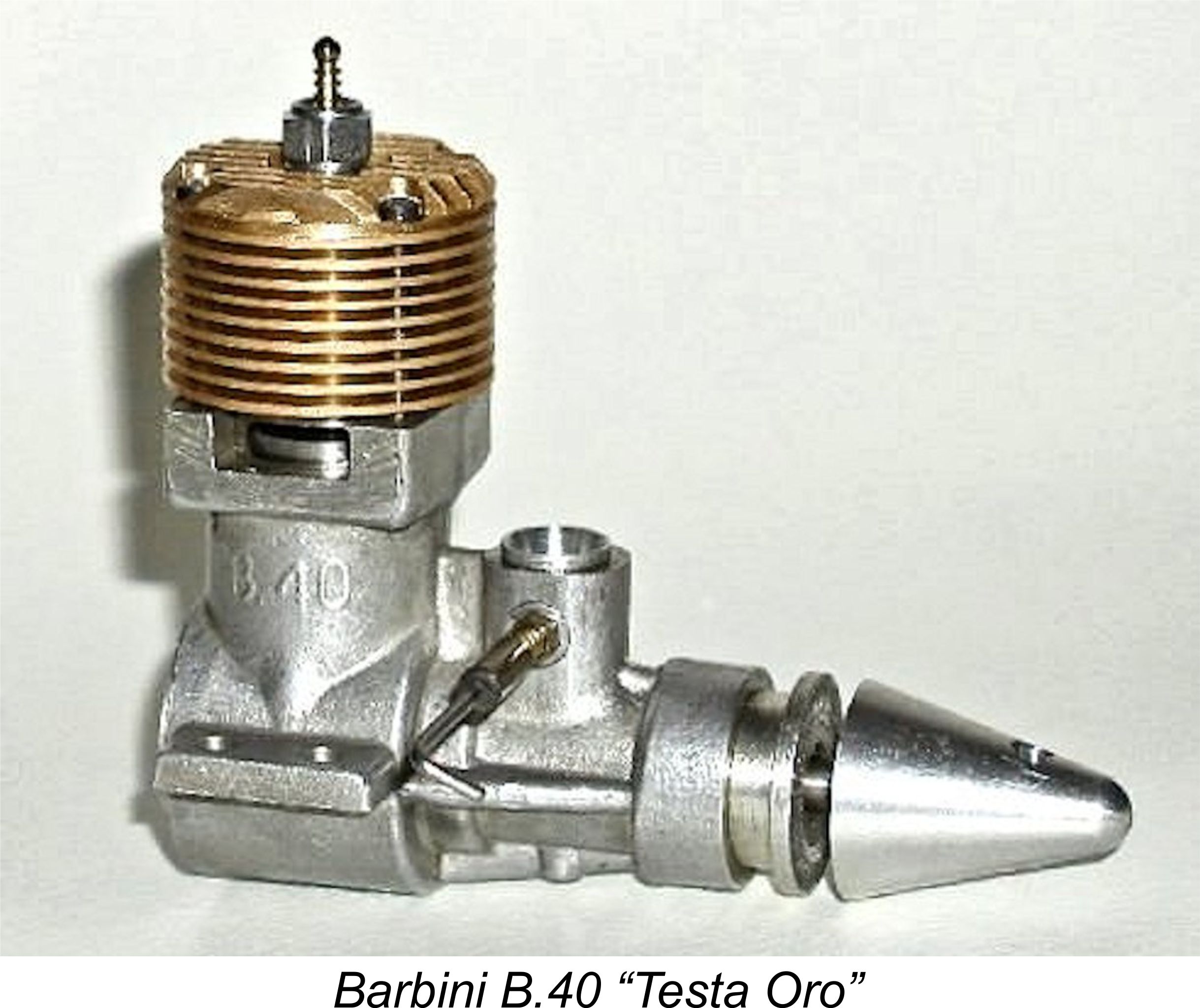

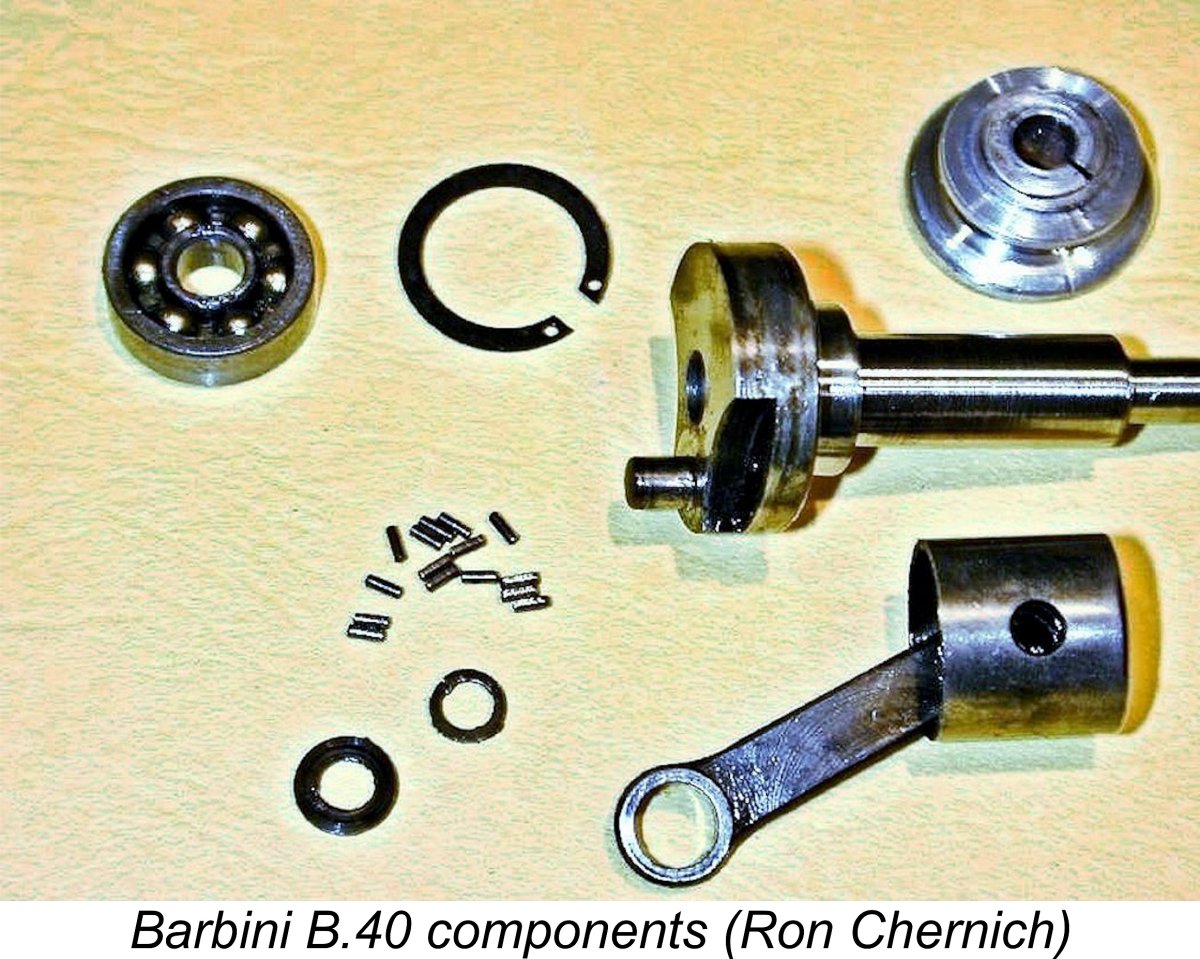

The only other such design which I can immediately bring to mind is the radially-ported Webra 2.5R glow-plug model of 1956 which was based upon the very successful Mach I diesel. The Webra 2.5R was potentially a far better engine than its reputation might suggest, as I've demonstrated through the publication of my own analysis and test. The cylinder porting used in the Barbini B.40 TN was basically the same as that used in America by Cox and Holland in their respective high-performance models. There were two generously-dimensioned exhaust ports, one on each side, with very large upwardly-angled transfer ports located between them fore and aft. In the case of the Barbini design, the transfer ports penetrated through the cylinder wall, being supplied with mixture externally by way of the annular space between the outer lower cylinder wall and the inner surface of the upper crankcase. That annular space thus functioned as the bypass. Unusually, the B.40 TN also featured long-stroke internal geometry, having bore and stroke dimensions of 14.5 mm and 15 mm respectively for a displacement of 2.48 cc (0.151 cuin.). This was another arrangement which had fallen out of favour among racing engine designers as of the mid 1950’s. As if all of this unorthodoxy wasn’t enough, the B.40 TN also incorporated Barbini’s unique and very effective combination ball/roller bearing crankshaft in which the rear roller bearing took the major lateral loadings while the front ball race accommodated the axial thrust loadings. I explained the rationale for this very logical design in my earlier article. Bert Rivers would have done well to copy this arrangement in his Rivers diesels..............

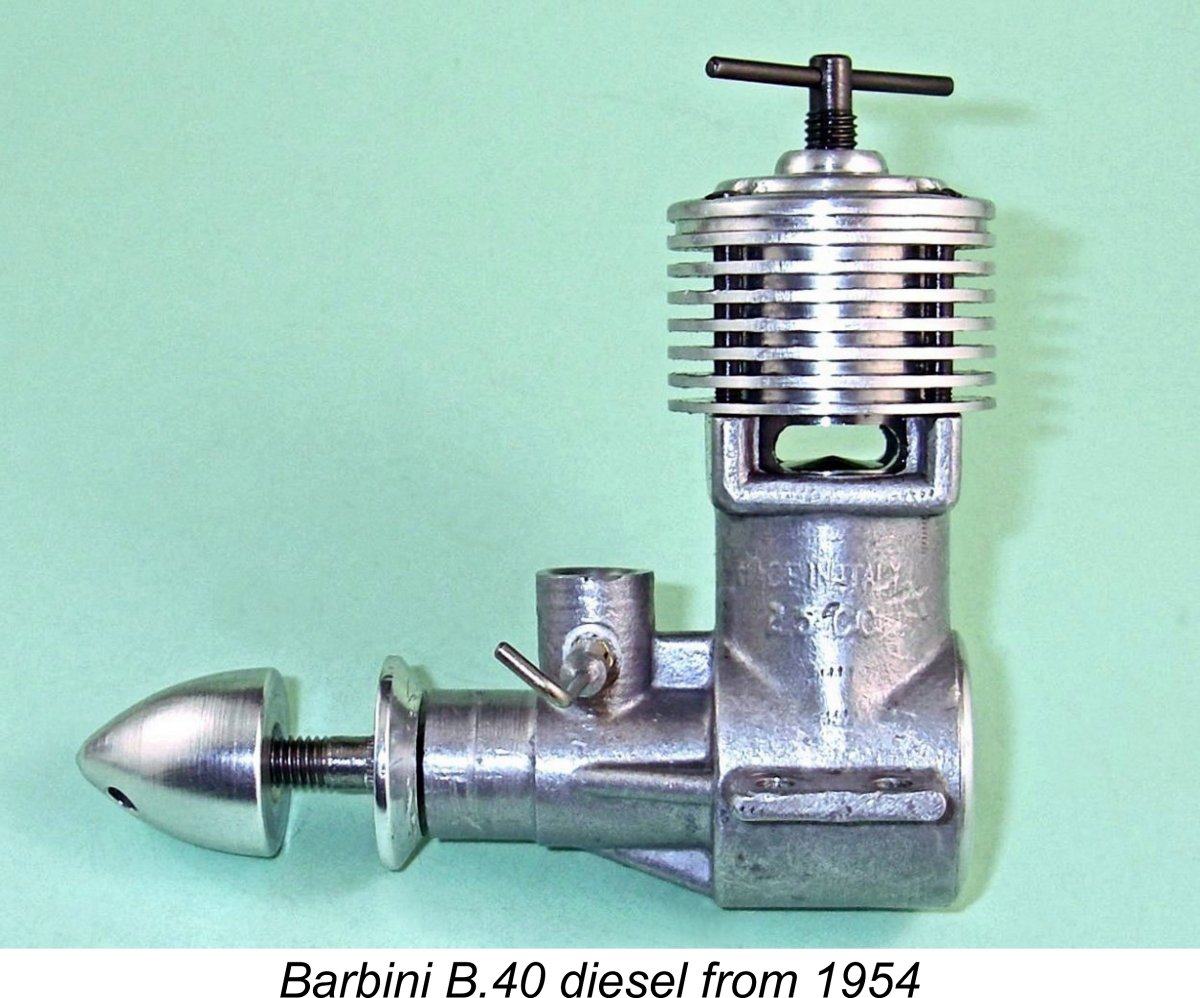

The development of the B.40 TN had been preceded by the 1954 appearance of a plain bearing 2.5 cc diesel simply named the Barbini B.40. This first variant of the B.40 design was a utilitarian-looking but very well made and extremely serviceable unit which drew high praise from Peter Chinn for the quality of its construction. It was the subject of a test by Chinn which appeared in the July 1956 issue of “Model Aircraft”. Chinn reported a peak output of 0.230 BHP @ 12,500 RPM, a perfectly respectable figure in 1956 for a plain bearing 2.5 cc diesel. Both the quality and performance of my own example completely bear out Chinn’s assessment. The 1955 announcement by the FAI that the following year's World Control Line Speed Championship meeting was to be held in September 1956 at Florence, Italy immediately drew Barbini’s attention towards the potential of a high performance version of his B.40 diesel. Here was a golden opportunity to display the merits of the Barbini engines before both the Italian modelling public and the international audience. However, successful participation in this event would require the development of a glow-plug “racing” version of the engine. Given the need to support the shaft of such a design in something better than a plain bearing, a new crankcase casting would clearly be among the requirements. Barbini approached this self-imposed challenge very logically and methodically, taking the basic design of his B.40 diesel as his starting point. Not being a top-flight speed flier himself, he recognized the need to Barbini and Cellini spent the better part of a year working together to develop and test the engine which powered Cellini to a highly creditable third place in the strongly-contested 1956 World Control Line Speed Championship meeting held in September at Florence. Cellini's speed beat all of the fancied Super Tigre entries from Bologna. It’s likely that a number of experimental variants were tested before the design of what was to become the Barbini B.40 TN was finalized. The individual from whom I obtained the "special" which forms our central subject had acquired it from an elderly former modeller living in Venice, Italy. That gentleman apparently believed that the engine is an experimental design made by Barbini in 1956 for testing by Cellini during the preparations for their joint participation in the Florence meeting. Not having direct access to the original source of this second-hand information, I was unable to form an authoritative opinion regarding the veracity of this claim. However, I felt that it was certainly a possibility that merited consideration. However, before considering the possible origins of this particular engine, we need to begin by looking at the differences between it and the “standard” Barbini B.40 design. The Barbini 2.5 cc “Special” Described

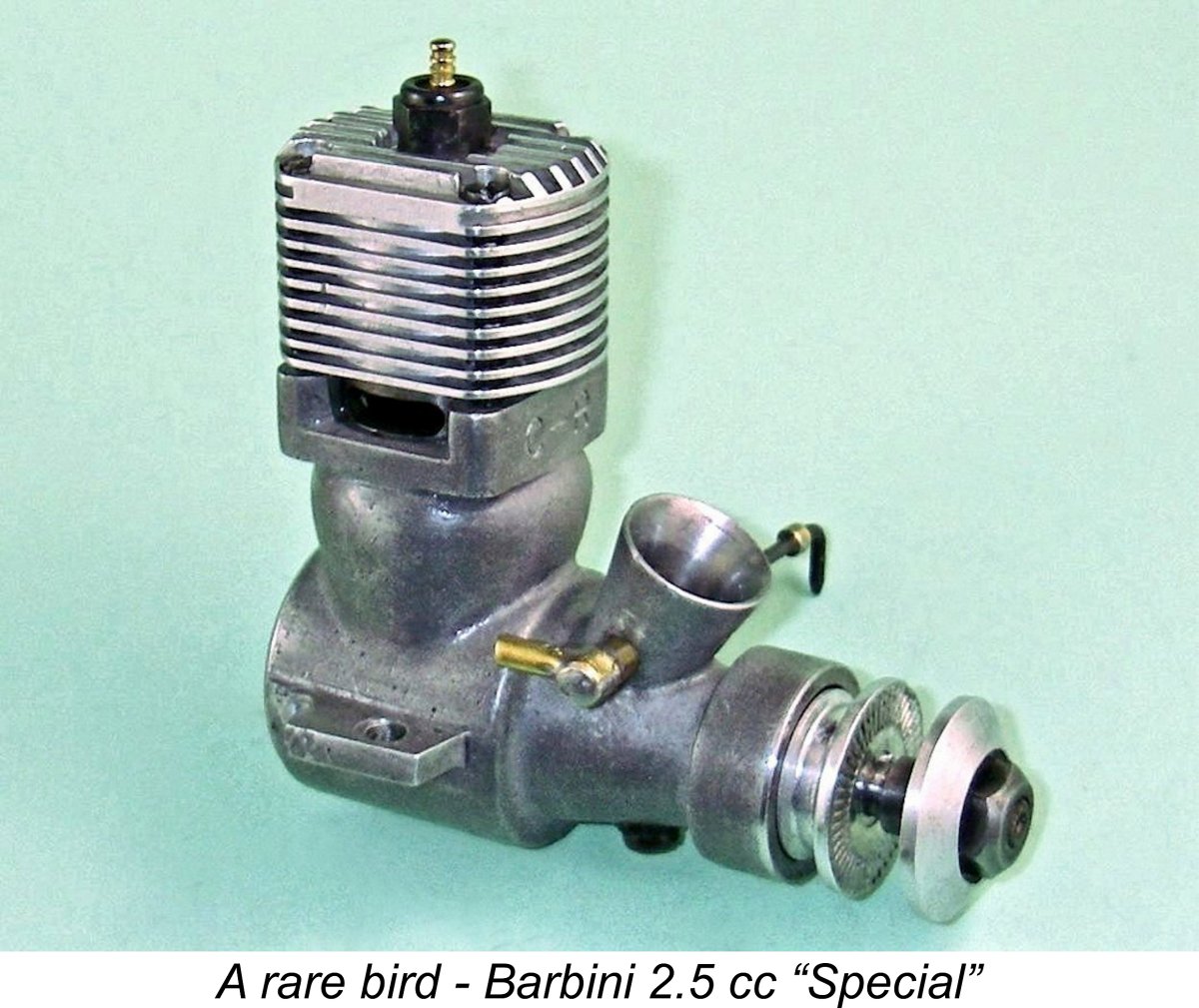

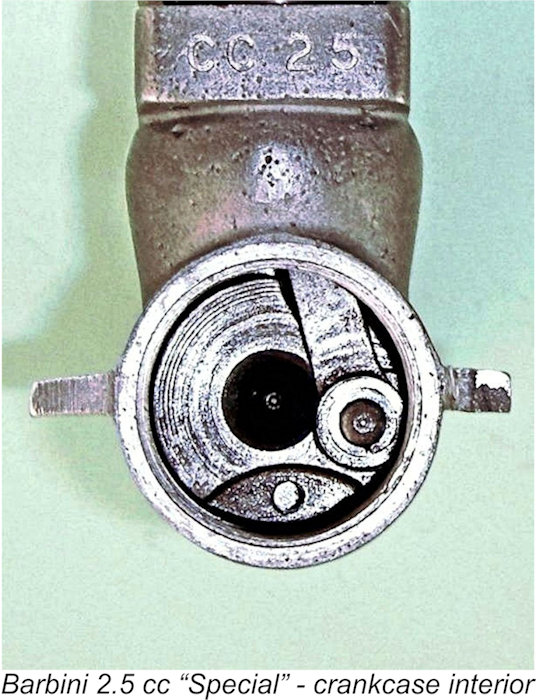

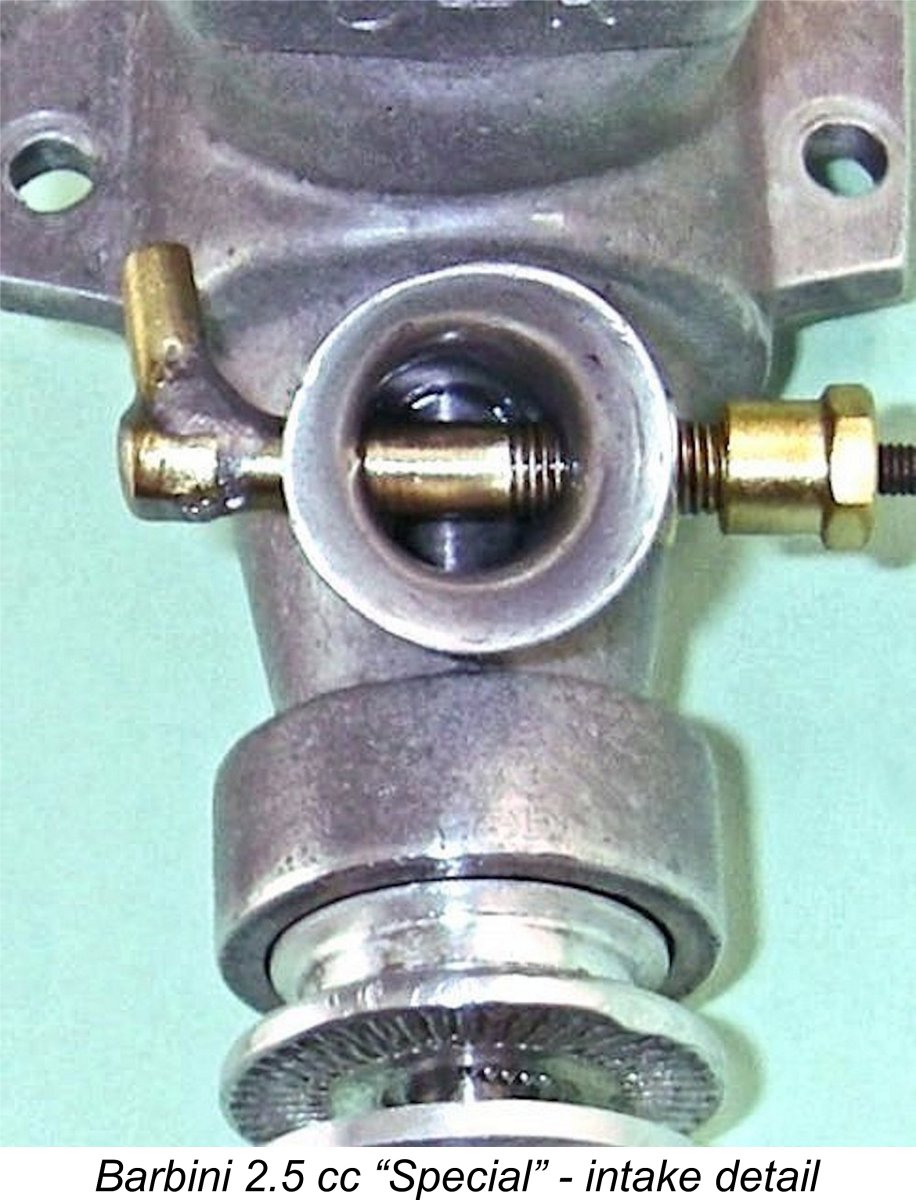

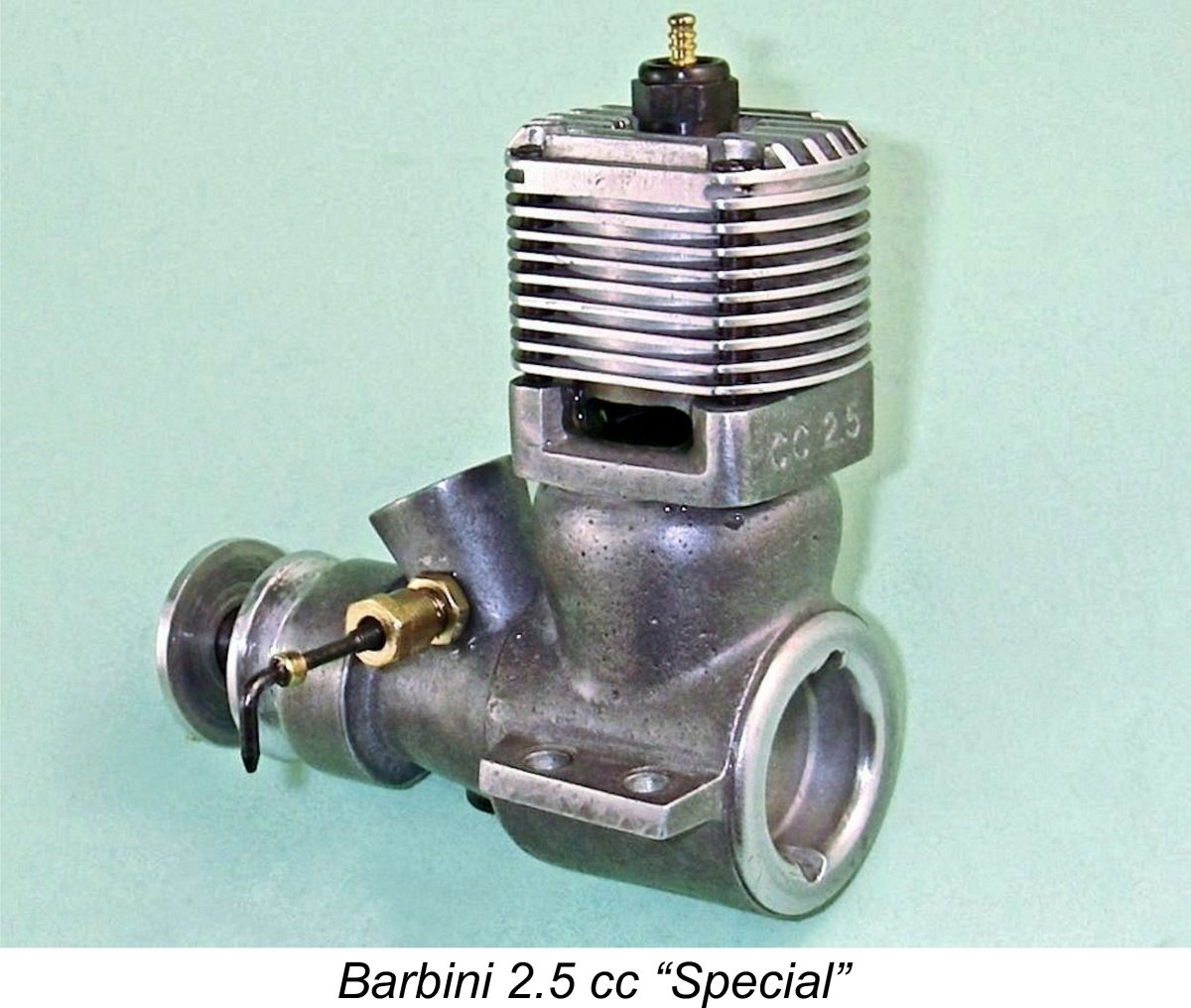

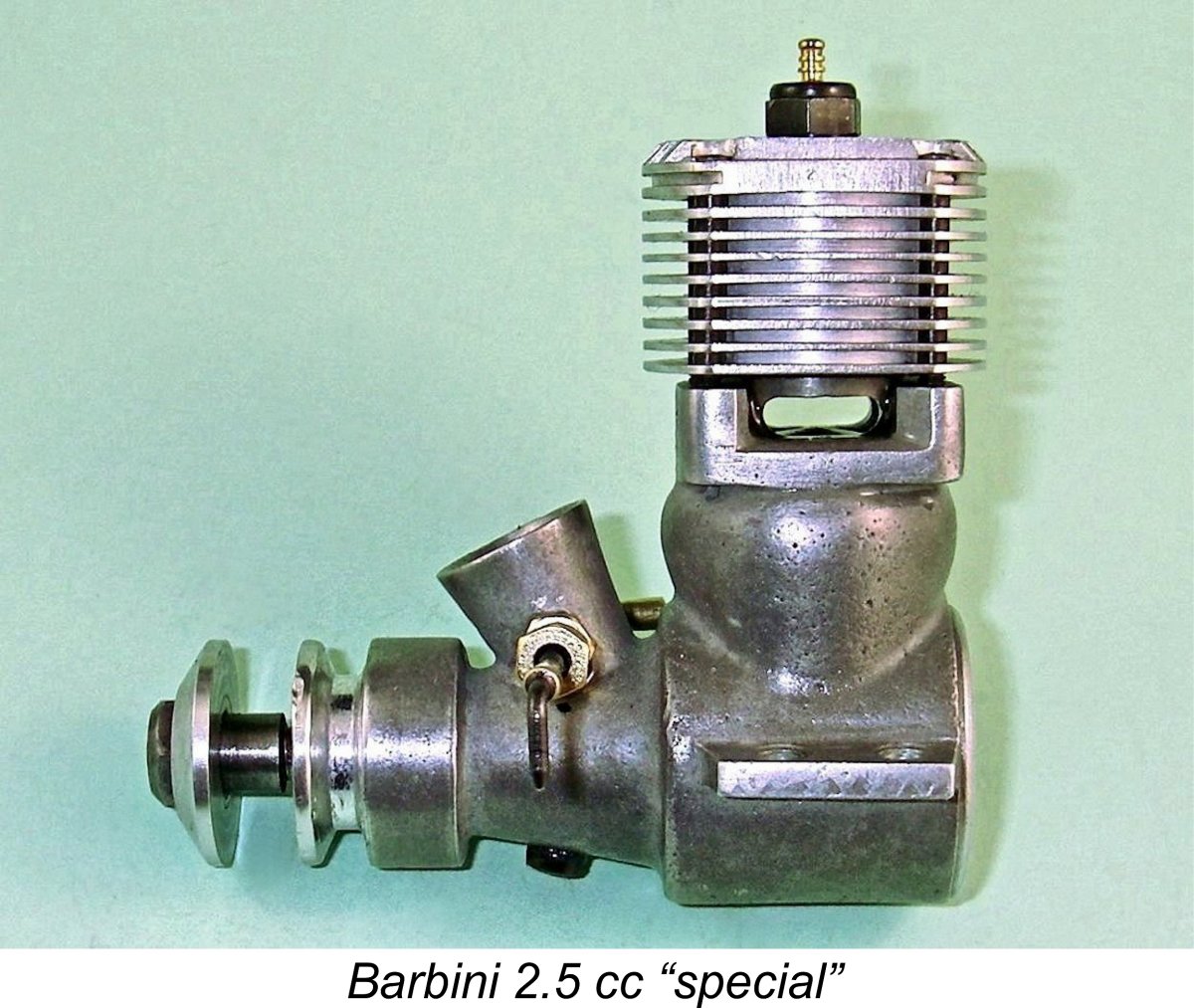

It’s immediately obvious that the large-bore forward-raked intake on this crankcase should facilitate improved induction. An internal inspection with the backplate removed also confirms that the “bulge bypass” has the effect of considerably increasing the engine’s bypass capacity by creating a far wider annular gap between the outer cylinder liner and the inner crankcase wall. This is accompanied by the presence of two cutaways in the lower piston skirt fore and aft at the transfer port locations. Taken together, we would expect these features to result in a significantly stronger-running engine, particularly at the top end. The bore of the intake is such that the engine is clearly intended to operate on pressure fuel feed. To facilitate this, a crankshaft-timed pressure tapping point is provided beneath the intake.

The sides of the combined cooling jacket and head have been neatly shaved to facilitate cowling in a speed model – Cellini’s third-place engine at Florence in 1956 was identically modified. This feature leaves us in no doubt regarding the engine's intended application. There’s no trace of any residual anodizing on the un-modified areas of this component, implying that it is not a modified production-line component. The checked compression ratio of 9:1 seems somewhat on the high side for an engine which was intended (like the original Barbini B.40 TN) to operate on high-nitro fuels. I was unwilling to disturb what appeared to be excellent head and crankcase seals by taking the engine apart, so I’m unable to comment on any modifications to the head which may have produced this seemingly elevated compression ratio. It would however be an aid to high-speed performance on low-nitro fuels. More of this in its place below ……….. As noted earlier, the engine is neatly machine-engraved with the letters “C-R” on the front of the crankcase near the top. The significance of these letters is very much an open question. They could be the initials of the individual who put this engine together, or they could be the initials of a previous owner. There’s no way of knowing at this point in time. The corresponding location at the rear of the case is equally neatly engraved “CC 2.5” as written. The quality of the machine-engraved figures at both front and rear implies that they were added by a well-equipped and highly capable initial constructor rather than by some later owner. One-off owner engravings are almost never this neat and precise. Possible Origins The absence of any of the usual markings associated with the Barbini 2.5 cc engines becomes readily understandable if we accept that this must surely be a B.40-based development prototype built up around a non-standard main casting. The questions are – who made it; when; and in what context? If any reader is able to shed any light on the question of origin, please get in touch!! Lacking any such input, we need first to deal with the perfectly reasonable original suggestion that this is one of the 1956 development prototypes tested by Barbini and Cellini prior to the 1956 championship meeting. To investigate this suggestion, I was fortunate enough to be able once more to call upon the assistance of my valued Italian colleague Walter Barbui, who helped me so much during the writing of my original Barbini article.

Bruno was able to inform us quite authoritatively that this engine is definitely not one of the 1956 development models. His statement is borne out by the fact that the engine used so successfully by Cellini at Florence in 1956 featured the standard B.40 crankcase. Given the significantly less restricted breathing provided by the modified case of the "special", it's hard to see Barbini and Cellini retreating from that case configuration back to the standard pattern. OK, so on Bruno's first-hand evidence we can rule out the possibility that this is a 1956 development prototype, as claimed (doubtless in good faith) by the engine’s former owner. However, that’s not the only credible possibility. The engine could equally well be a later experiment by some individual other than Barbini to see if the basic Barbini B.40 design had any more to give.

Accordingly, the Barbini 2.5 cc "special" now under consideration may well be the outcome of such discussions. It may be in effect a non-standard variant of the engine built to custom order for the Rossi brothers. The fact that the combined head/cooling jacket displays no traces of anodizing is consistent with this view - the same was true of Cellini's 1956 powerplant. Why bother anodizing a component intended for a competition "special"? The shaving of the cooling fins is also identical to that displayed on Cellini's engine.

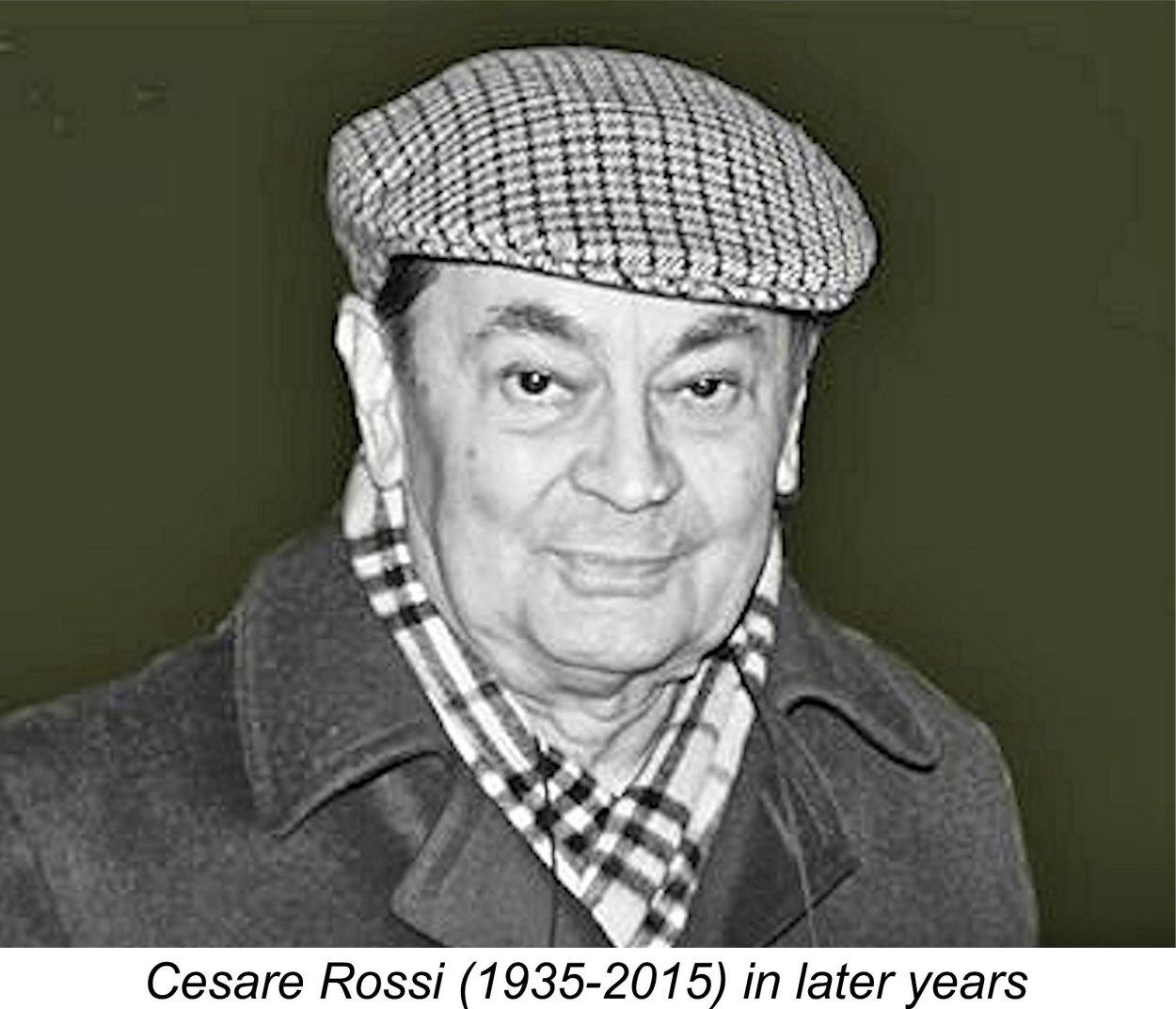

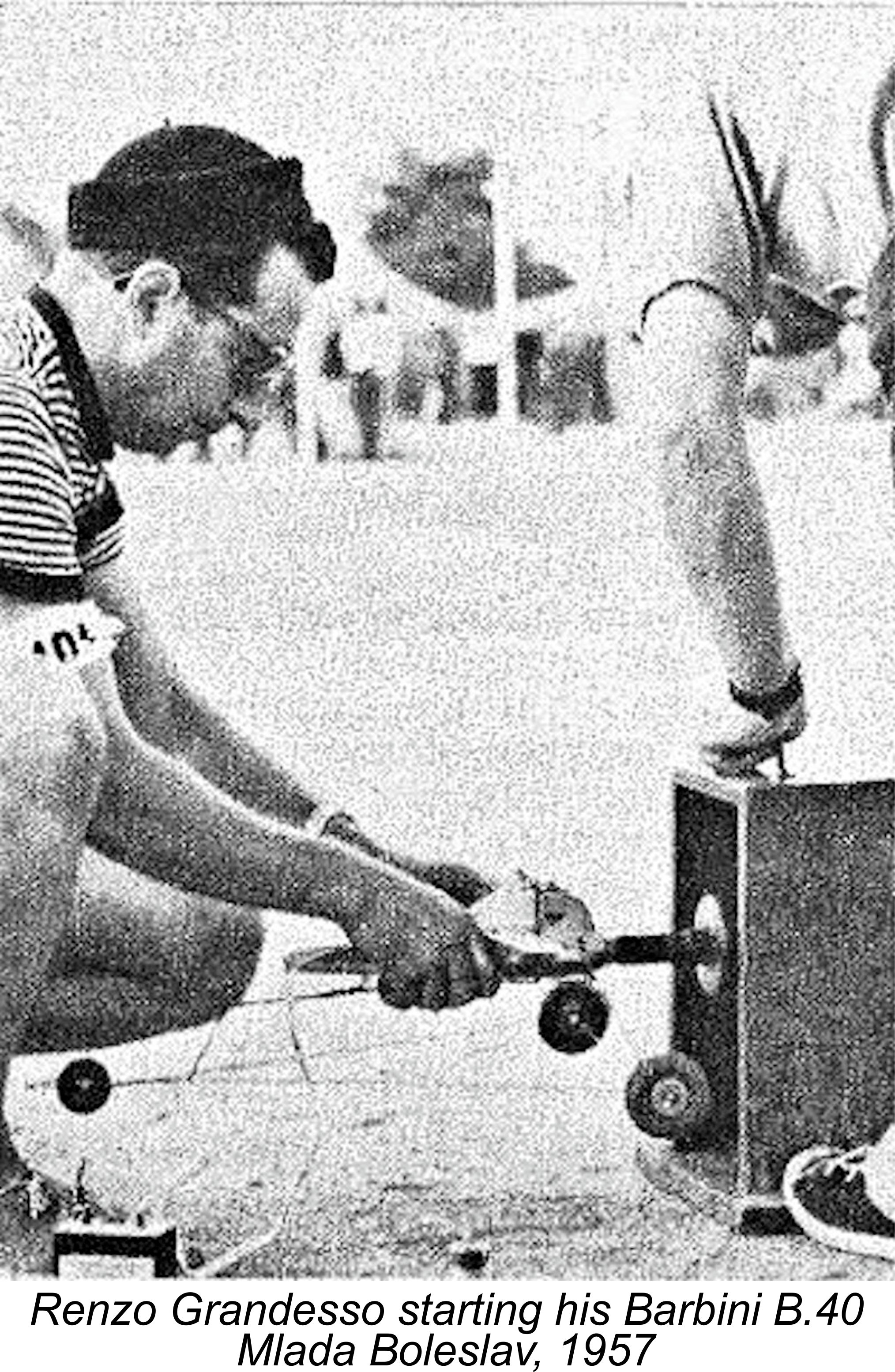

If this hypothesis is correct, then the most probable date for this engine is 1957. The engraved "C-R" initials would stand for Cesare Rossi, making this one of his competition engines. A tempting thought in historical terms, but nothing more than an unproven hypothesis as matters stand. Bruno recalled that another frequent visitor to the Barbini workshop during this period was Renzo Grandesso, who used one of the engines to place a very creditable sixth in the 1957 World Championship event, once again ahead of all the Super Tigres. It's undeniably possible that Grandesso, rather than the Rossis, was the instigator of this "special" and that Cesare Rossi merely used one of the modified engines developed by Grandesso, having his initials engraved on his own example(s) to distinguish it from others. Indeed, Grandesso's very fast engine which topped all the Super Tigres in 1957 might well have been one of these "specials". Either way, the results achieved don't seem to have been sufficient to encourage further development of the "special" design concept. Note that this doesn't imply that the modified engine performed poorly - merely that any improvement was more than matched by parallel improvements introduced by the competing designers of the MVVS and Super Tigre models, among others. Both the Rossi brothers and Renzo Grandesso switched to Super Tigre power for 1958, with very impressive results thereafter. For his own part, Giovanni Barbini continued to develop his B.40 competition design using the standard crankcase which had appeared in 1956. The final version of the B.40 was the further-tweaked B.40 TO (“Testa Oro” - Gold Head) model which appeared in 1960. However, the B.40 TO continued to use a slightly modified standard B.40 crankcase.

At this point we have to consider yet another possibility. The "special" could be the work of some individual working on his own quite independently from Barbini. Such an individual would have had to possess casting and machining capabilities on par with those of Barbini himself. There weren't too many such individuals .............. The fact that the “special” has no anodized parts would appear at first glance to form an objection to this idea. We would expect the cooling jacket of a modified B.40 to retain some evidence of the black or gold anodizing which characterized the B.40 TN and B.40 TO respectively. In point of fact, we see no such evidence. If this wasn’t a Barbini production per se, one of those models must surely have been used by others as the basis for the "special". However, this objection is easily dealt with. The measured compression ratio of 9:1 for the “special” is somewhat higher than the 8:1 figure for the standard B.40, which was intended to operate on a high-nitro fuel. This strongly suggests that the combined head/cooling jacket of the “special” is also a custom-made item produced by the constructor of this engine with a different combustion chamber configuration, possibly incorporating a squish band. If so, we would not expect to see any anodizing. As stated earlier, I was unwilling to disturb the well-established seals by dismantling the engine to check this point. This in turn leads us to yet another possible interpretation of the evidence. After the previously-documented fiasco of the 1960 World Control Line Speed Championships in which bitter disputes arose over fuel formulations (which were unrestricted at that point in time), the FAI announced that from 1961 onwards they would require the use of straight methanol/castor oil fuel with no additives. This would require the incorporation of somewhat higher compression ratios for best results. In engine design terms, this rule amendment changed the game significantly – combustion efficiency became even more important.

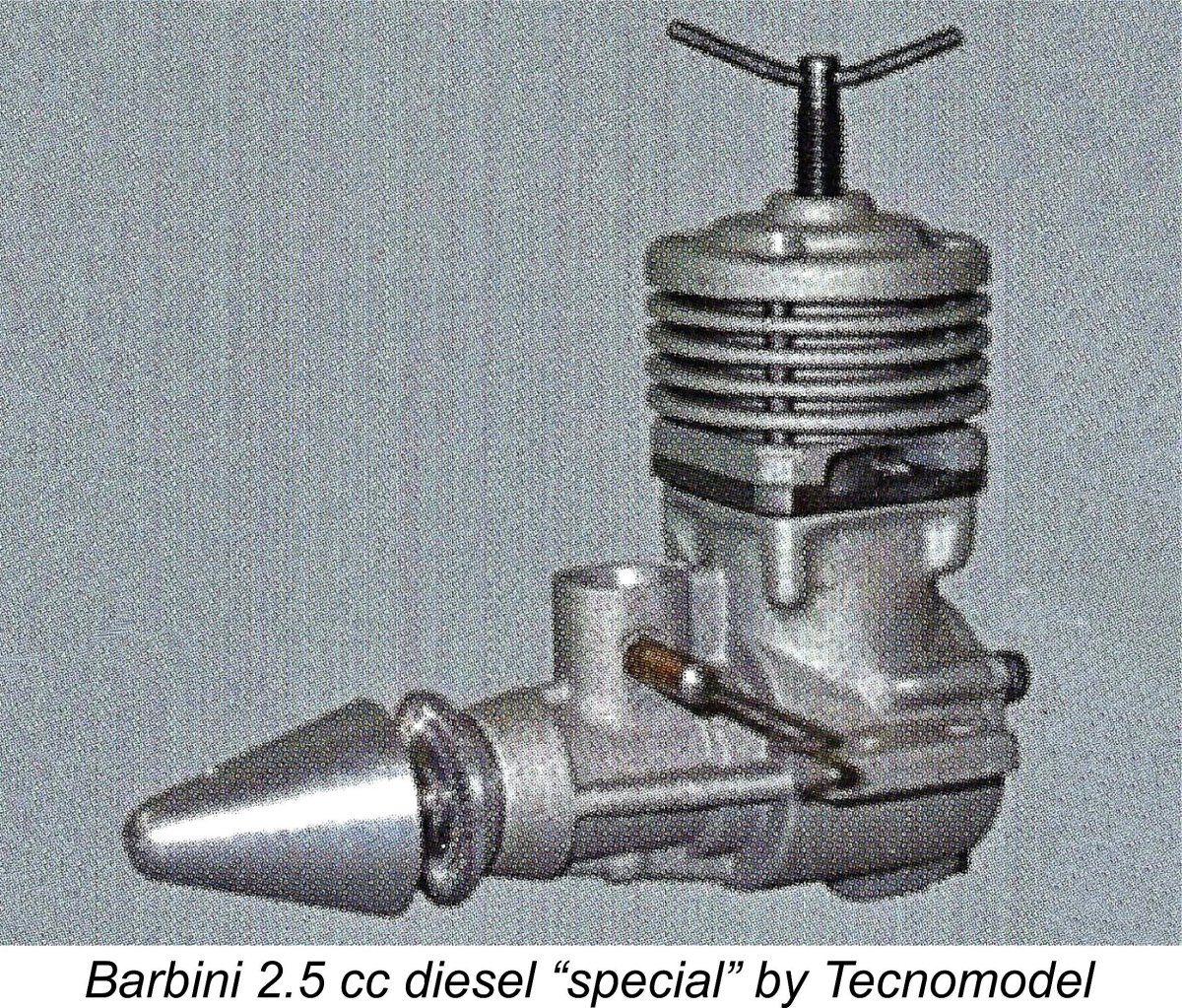

The quality of construction displayed in the "special" is exceptionally high throughout. Whoever did this was very well equipped with machine tools and aluminium alloy casting equipment, along with a very good knowledge of how to use them. As far as I’m concerned, this pretty much rules out the possibility of this being a “home construction” effort by an individual modeller working alone – the machine engraving alone would seem to preclude this. OK, so is it possible to suggest a credible candidate other than Giovanni Barbini himself for recognition as the constructor of this unit under this last scenario? As it happens, such a candidate can be identified! During the early 1960’s one of the distributors of the Barbini engines was a Milan-based firm called Tecnomodel which was owned at the time by a certain Mr. Taccani. This company had ready access to examples of the Barbini engines, also Like the glow-plug “special” now under consideration, the Tecnomodel diesel incorporated Barbini working components installed in Tecnomodel’s own crankcase. Apparently only three examples of the diesel "special" were produced. If the subject 2.5 cc glow-plug unit is indeed a Technomodel effort, then it appears safe to assume that it was probably made in correspondingly low numbers. Certainly, it's the only example that I've ever run across. The major objection to this hypothesis is the presence of those pesky "C-R" initials, which don't appear to have any relevance to an effort by Technomodel. Rather, they strongly support the earlier scenario from 1957. Walter Barbui and I are in agreement that while there's absolutely no hard evidence to support the idea that this is a Tecnomodel experiment, it is nontheless a possibility that can't be ruled out. As Barbini distributors, Tecnomodel certainly had a vested interest in trying to keep the Barbini engines competitive. It’s entirely possible that they may have seen the forthcoming fuel regulation changes as an opportunity to determine whether or not a suitably tweaked Barbini powerplant could return to the top level of competition. If this scenario is indeed the correct one, then the probable date of the engine's production would be brought up to 1960-61 in anticipation of the forthcoming FAI fuel regulation change. If this was in fact how things went, the results of the experiment appear to have fallen somewhat short. The record shows that no Barbini-powered models appeared at the 1961 World Control Line Speed Championship meet held in September of that year at Genk, Belgium. Italian honour was upheld by a phalanx of Super Tigres, which were unable to prevent the MOKI and MVVS squads from monopolizing the first three places. Business as usual …………… Incidentally, Tecnomodel is still very much in business today, almost 60 years later! They now produce very high-end model car kits which are sold all over the world. Check out their website! As matters stand, that’s as far as we can go in exploring this engine’s possible origins. If any reader knows more, please get in touch! All input will be gratefully received and fully acknowledged. The Barbini 2.5 cc Special on Test

We already saw that the “special’s” healthy 9:1 compression ratio suggests that it may have been expressly intended to operate on the new “straight” fuel required by the FAI beginning in 1961. I didn't have any such fuel on hand, nor have I had any luck in finding any. The best that I could do was use some 10% brew that I had in my fuel locker. I figured that this would not harm the engine if a cold plug was used. With the wide-open intake, it was clear that suction fuel feed would not suffice. I rigged up a gravity feed system which I hoped would overcome this problem. Feeling that all was now ready, I fuelled up, lit the plug and got stuck in. Alas for high hopes!! The first couple of flicks produced firing bursts, but after the second such burst the engine suddenly felt really weird, with lots of play in the rod bearings and a periodic tendency to lock up when turned over. Something had clearly let go, which put an immediate end to any further testing attempts.

Fortunately, no other damage appeared to have been done. This was entirely due to the fact that the engine was not actually running when the failure occurred. Although I'll never be able to prove it, I strongly suspect that this failure was due to some previous owner having dismantled the bearing, most likely out of simple curiosity, and re-assembling it using the same retaining split washer. The groove at the end of the crankpin into which the split washer contracts is very shallow, and I would consider it essential to use a new split washer every time. Failure to do so would be to invite trouble. An obvious immediate fix was to replace the roller bearing with a pressed-in bronze bushing. My valued Italian friend Walter Barbui had told me that this modification has been successfully applied in the past to other examples, most commonly with the Testa Rossa diesel version of the B.40 with which such failures are not unheard-of. However, I wanted to keep this engine completely original if possible. Accordingly, I consulted once again with Walter, who in turn contacted Bruno Barbini once more. It turned out that Bruno still had a supply of the correct retaining washers and split washers. Thanks to the kindness of my two Italian friends, I was soon in possession of two sets of the required components. Believe me, the re-assembly of the B.40's needle roller big end bearing is not for the faint of heart or dim of eye!! This is one assembly that should be left strictly alone unless absolutely necessary! Those tiny rollers have an exasperating tendency to spring out of the grip of the tweezers, and I was very thankful indeed that I had had the foresight to conduct the entire operation in a large and deep Tupperware basin under a very strong light!! Once again, Walter Barbui was an invaluable source of pertinent advice. He informed me that the correct approach is to free the crankpin from all traces of solvent and then apply a liberal helping of heavy grease all around it. One then inserts the rollers into the grease, which holds them in place around the pin. When they are all in position, one simply drops the conrod onto the rollers, followed by the retaining washer and split washer in that order. Should have thought of that myself - it's the same way that one reassembles the needle roller bearings in the Rivers diesels! Been there, done that .............. Since the rod was already in place around the crankpin (sans rollers), I used a slightly different variant of the same procedure. I packed the annular space between the rod bearing shell and the crankpin with grease and used fine tweezers to insert the rollers one by one into the grease-filled annular space. It was a really taxing exercise, but thankfully all battles eventually come to an end! The bearing was finally back together with all-new retention components. With the backplate replaced, the engine was once more complete. With that accomplished, I decided not to tempt fate by renewing my attempt to test the engine. I'm certain that the engine would acquit itself very well, but the fact is that actual performance figures for this mega-rare unit would be of purely academic interest. No sense in risking the creation of another crankcase-full of loose rollers - once is enough! Summary and Conclusion Well, there you have it - make what you will of this information! This Barbini 2.5 cc “special” was evidently not a Giovanni Barbini "original", since he worked throughout with the original crankcase that he developed in 1956. Rather, the "special" seems to have been inspired by someone other than Barbini himself, albeit possibly one who was directly associated with Barbini. The engine certainly uses the working components from one of Barbini's B.40 competition units, and may in fact have been produced by him to special order. If this is the correct interpretation, then the most probable instigator is Cesare Rossi, who is known to have been a Barbini user prior to 1958 and whose initials undoubtedly appear on the engine. This scenario would date the engine to 1957. Alternatively, the "special" may represent a slightly later attempt by others to create an updated version of the B.40 which might be competitive against the other leading contemporary powerplants following the general “de-tuning” of those units as a result of the switch to straight fuel for 1961. The most likely candidate for having carried out such an experiment is Tecnomodel of Milan, Italy. As Barbini distributors, they had both the motivation for promoting the Barbini range and unrestricted access to the requisite working components. They also possessed the necessary machining and foundry capabilities. If this scenario is the correct one, it would advance the date of the "special's" creation to 1960-61 in anticipation of the forthcoming changes to the FAI fuel regulations. Which of these possibilities is correct? The knowledge that the Rossi brothers were associates of Giovanni Barbini prior to 1958, coupled with the "C-R" initials engraved on the engine, inclines me towards the first explanation. That would make this an ex-Cesare Rossi competition powerplant - a historically significant finding for those of us interested in control line speed during the "classic" era. Sadly, the march of time has deprived us of the opportunity to clarify this matter at first hand. Ugo Rossi died (I believe) in 2001, while Cesare Rossi followed him in 2015 after a long period of success with his NovaRossi range. So there we have to leave it for now. If any reader can fill in the gaps, please get in touch! All input will be gratefully and openly acknowledged. _______________________________ Article © Adrian C. Duncan, Coquitlam, British Columbia, Canada First published November 2024 |

| |

Here’s yet another installment in my now long-running series of tests of classic 2.5 cc racing engines from the 1950’s and early 1960’s. This time I’ll be going some way off the beaten track to look at a seemingly one-off or at least extremely rare 2.5 cc “special” which clearly has an interesting story to tell if only we could unravel it! The engine is undoubtedly a very competently-produced derivative of the Barbini B.40 TN racing glow-plug engine from Italy, but the questions of its origin and date of manufacture are very much open to discussion.

Here’s yet another installment in my now long-running series of tests of classic 2.5 cc racing engines from the 1950’s and early 1960’s. This time I’ll be going some way off the beaten track to look at a seemingly one-off or at least extremely rare 2.5 cc “special” which clearly has an interesting story to tell if only we could unravel it! The engine is undoubtedly a very competently-produced derivative of the Barbini B.40 TN racing glow-plug engine from Italy, but the questions of its origin and date of manufacture are very much open to discussion.

associate himself with an expert competitor who could undertake the required flight testing, thus freeing Barbini himself to focus upon the development and construction of the new engine design. To meet this need, he chose to collaborate with a rising young Italian speed maestro by the name of Giovanni Cellini.

associate himself with an expert competitor who could undertake the required flight testing, thus freeing Barbini himself to focus upon the development and construction of the new engine design. To meet this need, he chose to collaborate with a rising young Italian speed maestro by the name of Giovanni Cellini.  I may as well begin by stating that the differences between this “special” and the standard Barbini B.40 TN are relatively minimal. The internals (ball and roller crankshaft bearings, needle roller big end bearing, crankshaft, con-rod, piston, cylinder liner, backplate, prop driver, etc.) are all exactly as featured in the “standard” Barbini B.40 TN and fully described in my

I may as well begin by stating that the differences between this “special” and the standard Barbini B.40 TN are relatively minimal. The internals (ball and roller crankshaft bearings, needle roller big end bearing, crankshaft, con-rod, piston, cylinder liner, backplate, prop driver, etc.) are all exactly as featured in the “standard” Barbini B.40 TN and fully described in my  This leads us to consider what (if any) advantages this unit might have over the standard model. Externally, it is distinguished by four features. Firstly, its crankcase has a forward-raked intake venturi of considerably larger internal diameter than the standard vertical component. Secondly, the case has a notable “bulge” around its upper portion immediately below the exhaust ducts. Thirdly, the case dispenses with the standard Barbini’s stiffening webs around the main bearing housing in favour of a taper-profiled housing which expands towards the rear to provide the

This leads us to consider what (if any) advantages this unit might have over the standard model. Externally, it is distinguished by four features. Firstly, its crankcase has a forward-raked intake venturi of considerably larger internal diameter than the standard vertical component. Secondly, the case has a notable “bulge” around its upper portion immediately below the exhaust ducts. Thirdly, the case dispenses with the standard Barbini’s stiffening webs around the main bearing housing in favour of a taper-profiled housing which expands towards the rear to provide the

Fair enough - can we suggest the identity of an individual who might have been responsible for the development of this "special"? As it happens, we certainly can! Bruno advised that before they switched to Super Tigre power in 1958, the Rossi brothers Ugo and Cesare both used Barbini powerplants in competition. To Bruno's first-hand knowledge, the two brothers repeatedly visited the Barbini workshops in person, thus having the opportunity to meet face to face with Giovanni Barbini to discuss any potential modifications to the B.40 that they may have had in mind.

Fair enough - can we suggest the identity of an individual who might have been responsible for the development of this "special"? As it happens, we certainly can! Bruno advised that before they switched to Super Tigre power in 1958, the Rossi brothers Ugo and Cesare both used Barbini powerplants in competition. To Bruno's first-hand knowledge, the two brothers repeatedly visited the Barbini workshops in person, thus having the opportunity to meet face to face with Giovanni Barbini to discuss any potential modifications to the B.40 that they may have had in mind.

This FAI decision raises the possiblity that whoever constructed this “special” may have seen the amended fuel regulations as potentially bringing top level engine performance back down to a point to which the Barbini could be elevated back to competitiveness. If so, this engine would represent someone’s effort to produce a revised version of the Barbini B.40 which would be competitive on straight fuel. The improvements to the induction and bypass systems as well as the increase in the compression ratio are all completely consistent with such an objective. This would bring the most probable date for this engine’s construction forward to 1960-61.

This FAI decision raises the possiblity that whoever constructed this “special” may have seen the amended fuel regulations as potentially bringing top level engine performance back down to a point to which the Barbini could be elevated back to competitiveness. If so, this engine would represent someone’s effort to produce a revised version of the Barbini B.40 which would be competitive on straight fuel. The improvements to the induction and bypass systems as well as the increase in the compression ratio are all completely consistent with such an objective. This would bring the most probable date for this engine’s construction forward to 1960-61.  possessing both precision machining and aluminium casting capability. They are known to have produced at least one other “special”, which was based on a Barbini 2.5 cc diesel model. This engine is illustrated on page 176 of the late Jim Dunkin’s invaluable

possessing both precision machining and aluminium casting capability. They are known to have produced at least one other “special”, which was based on a Barbini 2.5 cc diesel model. This engine is illustrated on page 176 of the late Jim Dunkin’s invaluable  Both the witness marks on the mounting lugs and the state of the piston crown and wearing surfaces clearly confirmed that this engine had been used in the past. It was obviously well run in, with absolutely perfect running fits throughout. I therefore decided that only a few shake-down runs would be required to gain some operational familiarity prior to putting the engine through a full test. No point in putting any more running time than necessary on such a rare engine.

Both the witness marks on the mounting lugs and the state of the piston crown and wearing surfaces clearly confirmed that this engine had been used in the past. It was obviously well run in, with absolutely perfect running fits throughout. I therefore decided that only a few shake-down runs would be required to gain some operational familiarity prior to putting the engine through a full test. No point in putting any more running time than necessary on such a rare engine.  Upon returning to my home workshop, I removed the backplate to see what was up. The problem was immediately obvious - the small split washer which retains the needle rollers in the big end bearing had failed, allowing those tiny rollers to spill out unchecked into the crankcase. The periodic locking-up was caused by one or other of the rollers becoming temporarily wedged in the very narrow annular space between the crankcase and the outer rim of the crankdisc. There are 15 of these rollers, and thankfully I was able to recover all of them from inside the case.

Upon returning to my home workshop, I removed the backplate to see what was up. The problem was immediately obvious - the small split washer which retains the needle rollers in the big end bearing had failed, allowing those tiny rollers to spill out unchecked into the crankcase. The periodic locking-up was caused by one or other of the rollers becoming temporarily wedged in the very narrow annular space between the crankcase and the outer rim of the crankdisc. There are 15 of these rollers, and thankfully I was able to recover all of them from inside the case.